User login

HCV screening risk factors in pregnant women need updating

“Because risk-factor screening has obvious limitations, universal screening in pregnancy has been suggested to allow for linkage to postpartum care and identification of children for future testing and treatment,” wrote Mona Prasad, DO, of Ohio State University, Columbus, and colleagues.

In a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, the researchers reviewed data from women with singleton pregnancies presenting for prenatal care prior to 23 weeks’ gestation during 2012-2015. Of these, 254 tested positive for the hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibody, for a seroprevalence rate of 2.4 cases per 1,000 women.

The researchers conducted a case-control analysis of 131 women who tested positive and 251 controls to identify HCV infection risk factors based on interviews and chart reviews. They found that risk factors significantly associated with positive HCV antibodies included injection drug use (adjusted odds ratio, 22.9), a history of blood transfusion (aOR, 3.7), having an HCV-infected partner (aOR, 6.3), having had more than three sexual partners (aOR, 5.3), and smoking during pregnancy (aOR, 2.4).

In an unadjusted analysis, the researchers confirmed two of the risk factors currently recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for screening for HCV: injection drug use and being born to a mother with HCV infection, but not dialysis, organ transplantation, or HIV infection.

“Our results demonstrate that current risk factors could be contemporized,” Dr. Prasad and colleagues noted. “The currently accepted risk factors such as exposure to clotting factors, dialysis, and organ transplants are unlikely to be found. A thorough assessment of injection drug use history, smoking, transfusions, number of sexual partners, and partners with HCV infection is more sensitive in an obstetric population.”

The study findings were limited by several factors including possible selection bias and inclusion of only 65% of eligible women who were HCV positive, as well as a lack of screening data from 2016 to the present, which may not reflect the impact of the recent opioid epidemic, the researchers noted. However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size, and the generalizability of the study population.

“Our results regarding prevalence rates and risk factors of HCV antibody among pregnant women in the United States will be valuable to policymakers as they weigh the costs and benefits of universal screening,” Dr. Prasad and associates concluded.

Although universal screening has the potential to be more cost effective, given the small population of pregnant women eligible for treatment and lack of an available treatment, “the rationale is weaker for unique universal HCV screening recommendations for pregnant women,” they said.

By contrast, Sammy Saab, MD, MPH, of the University of California, Los Angeles; Ravina Kullar, PharmD, MPH, of Gilead Sciences, Foster City, Calif.; and Prabhu Gounder, MD, MPH, of the Los Angeles Department of Public Health, wrote an accompanying commentary in favor of universal HCV screening for pregnant women, in part because of the increase in HCV in the younger population overall.

“For many women of reproductive age, pregnancy is one of their few points of contact with their health care provider; therefore, pregnancy could provide a crucial time for targeting this population,” they noted.

Risk-based screening is of limited effectiveness because patients are not identified by way of current screening tools or they decline to reveal risk factors that providers might miss, the editorialists said. Pregnancy has not been shown to affect the accuracy of HCV tests, and identifying infections in mothers allows for screening in children as well.

“The perinatal hepatitis B virus infection program, which has been implemented in several state and local public health departments, could serve as an example for how to conduct surveillance for mothers with HCV infection and to ensure that HCV-exposed children receive appropriate follow-up testing and linkage to care,” the editorialists concluded.

The study was supported in part by multiple grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Prasad disclosed funding from Ohio State University and from Gilead. Coauthors had links with pharmaceutical companies, associations, and organizations – most unrelated to this study. The editorialists had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCES: Prasad M et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:778-88; Saab S et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:773-7.

“Because risk-factor screening has obvious limitations, universal screening in pregnancy has been suggested to allow for linkage to postpartum care and identification of children for future testing and treatment,” wrote Mona Prasad, DO, of Ohio State University, Columbus, and colleagues.

In a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, the researchers reviewed data from women with singleton pregnancies presenting for prenatal care prior to 23 weeks’ gestation during 2012-2015. Of these, 254 tested positive for the hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibody, for a seroprevalence rate of 2.4 cases per 1,000 women.

The researchers conducted a case-control analysis of 131 women who tested positive and 251 controls to identify HCV infection risk factors based on interviews and chart reviews. They found that risk factors significantly associated with positive HCV antibodies included injection drug use (adjusted odds ratio, 22.9), a history of blood transfusion (aOR, 3.7), having an HCV-infected partner (aOR, 6.3), having had more than three sexual partners (aOR, 5.3), and smoking during pregnancy (aOR, 2.4).

In an unadjusted analysis, the researchers confirmed two of the risk factors currently recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for screening for HCV: injection drug use and being born to a mother with HCV infection, but not dialysis, organ transplantation, or HIV infection.

“Our results demonstrate that current risk factors could be contemporized,” Dr. Prasad and colleagues noted. “The currently accepted risk factors such as exposure to clotting factors, dialysis, and organ transplants are unlikely to be found. A thorough assessment of injection drug use history, smoking, transfusions, number of sexual partners, and partners with HCV infection is more sensitive in an obstetric population.”

The study findings were limited by several factors including possible selection bias and inclusion of only 65% of eligible women who were HCV positive, as well as a lack of screening data from 2016 to the present, which may not reflect the impact of the recent opioid epidemic, the researchers noted. However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size, and the generalizability of the study population.

“Our results regarding prevalence rates and risk factors of HCV antibody among pregnant women in the United States will be valuable to policymakers as they weigh the costs and benefits of universal screening,” Dr. Prasad and associates concluded.

Although universal screening has the potential to be more cost effective, given the small population of pregnant women eligible for treatment and lack of an available treatment, “the rationale is weaker for unique universal HCV screening recommendations for pregnant women,” they said.

By contrast, Sammy Saab, MD, MPH, of the University of California, Los Angeles; Ravina Kullar, PharmD, MPH, of Gilead Sciences, Foster City, Calif.; and Prabhu Gounder, MD, MPH, of the Los Angeles Department of Public Health, wrote an accompanying commentary in favor of universal HCV screening for pregnant women, in part because of the increase in HCV in the younger population overall.

“For many women of reproductive age, pregnancy is one of their few points of contact with their health care provider; therefore, pregnancy could provide a crucial time for targeting this population,” they noted.

Risk-based screening is of limited effectiveness because patients are not identified by way of current screening tools or they decline to reveal risk factors that providers might miss, the editorialists said. Pregnancy has not been shown to affect the accuracy of HCV tests, and identifying infections in mothers allows for screening in children as well.

“The perinatal hepatitis B virus infection program, which has been implemented in several state and local public health departments, could serve as an example for how to conduct surveillance for mothers with HCV infection and to ensure that HCV-exposed children receive appropriate follow-up testing and linkage to care,” the editorialists concluded.

The study was supported in part by multiple grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Prasad disclosed funding from Ohio State University and from Gilead. Coauthors had links with pharmaceutical companies, associations, and organizations – most unrelated to this study. The editorialists had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCES: Prasad M et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:778-88; Saab S et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:773-7.

“Because risk-factor screening has obvious limitations, universal screening in pregnancy has been suggested to allow for linkage to postpartum care and identification of children for future testing and treatment,” wrote Mona Prasad, DO, of Ohio State University, Columbus, and colleagues.

In a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, the researchers reviewed data from women with singleton pregnancies presenting for prenatal care prior to 23 weeks’ gestation during 2012-2015. Of these, 254 tested positive for the hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibody, for a seroprevalence rate of 2.4 cases per 1,000 women.

The researchers conducted a case-control analysis of 131 women who tested positive and 251 controls to identify HCV infection risk factors based on interviews and chart reviews. They found that risk factors significantly associated with positive HCV antibodies included injection drug use (adjusted odds ratio, 22.9), a history of blood transfusion (aOR, 3.7), having an HCV-infected partner (aOR, 6.3), having had more than three sexual partners (aOR, 5.3), and smoking during pregnancy (aOR, 2.4).

In an unadjusted analysis, the researchers confirmed two of the risk factors currently recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for screening for HCV: injection drug use and being born to a mother with HCV infection, but not dialysis, organ transplantation, or HIV infection.

“Our results demonstrate that current risk factors could be contemporized,” Dr. Prasad and colleagues noted. “The currently accepted risk factors such as exposure to clotting factors, dialysis, and organ transplants are unlikely to be found. A thorough assessment of injection drug use history, smoking, transfusions, number of sexual partners, and partners with HCV infection is more sensitive in an obstetric population.”

The study findings were limited by several factors including possible selection bias and inclusion of only 65% of eligible women who were HCV positive, as well as a lack of screening data from 2016 to the present, which may not reflect the impact of the recent opioid epidemic, the researchers noted. However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size, and the generalizability of the study population.

“Our results regarding prevalence rates and risk factors of HCV antibody among pregnant women in the United States will be valuable to policymakers as they weigh the costs and benefits of universal screening,” Dr. Prasad and associates concluded.

Although universal screening has the potential to be more cost effective, given the small population of pregnant women eligible for treatment and lack of an available treatment, “the rationale is weaker for unique universal HCV screening recommendations for pregnant women,” they said.

By contrast, Sammy Saab, MD, MPH, of the University of California, Los Angeles; Ravina Kullar, PharmD, MPH, of Gilead Sciences, Foster City, Calif.; and Prabhu Gounder, MD, MPH, of the Los Angeles Department of Public Health, wrote an accompanying commentary in favor of universal HCV screening for pregnant women, in part because of the increase in HCV in the younger population overall.

“For many women of reproductive age, pregnancy is one of their few points of contact with their health care provider; therefore, pregnancy could provide a crucial time for targeting this population,” they noted.

Risk-based screening is of limited effectiveness because patients are not identified by way of current screening tools or they decline to reveal risk factors that providers might miss, the editorialists said. Pregnancy has not been shown to affect the accuracy of HCV tests, and identifying infections in mothers allows for screening in children as well.

“The perinatal hepatitis B virus infection program, which has been implemented in several state and local public health departments, could serve as an example for how to conduct surveillance for mothers with HCV infection and to ensure that HCV-exposed children receive appropriate follow-up testing and linkage to care,” the editorialists concluded.

The study was supported in part by multiple grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Prasad disclosed funding from Ohio State University and from Gilead. Coauthors had links with pharmaceutical companies, associations, and organizations – most unrelated to this study. The editorialists had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCES: Prasad M et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:778-88; Saab S et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:773-7.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

HIV shortens life expectancy 9 years, healthy life expectancy 16 years

Despite highly effective antiretroviral therapy, HIV still shortens life expectancy by 9 years and healthy life expectancy free of comorbidities 16 years, according to a review of HIV patients and matched controls at Kaiser Permanente facilities in California and the mid-Atlantic states during 2000-2016.

The good news is that starting antiretroviral therapy (ART) when CD4 counts are 500 cells/mm3 or higher closes the mortality gap. People who do so can expect to live into their mid-80s, the same as people without HIV, and the years they can expect to be free of diabetes and cancer is catching up to uninfected people, although the gap for other comorbidities hasn’t changed and the overall comorbidity gap remains 16 years, according to the report, which was presented at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections

“We were excited about finding no difference in lifespan for people starting ART with high CD4 counts, but we were surprised by how wide the gap was for the number of comorbidity free years. Greater attention to comorbidity prevention is needed,” said study lead Julia Marcus, PhD, an infectious disease epidemiologist and assistant professor of population medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The team estimated the average number of total and comorbidity-free years of life remaining at age 21 for 39,000 people with HIV who were matched 1:10 with 387,767 uninfected adults by sex, race/ethnicity, year, and medical center.

Overall, adults with HIV could expect to live until they were 77 years old, versus 86 years for people without HIV, during 2014-2016. It’s a large improvement over the 22 year gap during 2000-2003, when the numbers were 59 versus 81 years, respectively, Dr. Marcus reported at the virtual meeting, which was scheduled to be in Boston, but held online this year because of concerns about spreading the COVID-19 virus.

But the overall comorbidity gap didn’t budge during 2000-2016. People with HIV during 2014-2016 could expect to be comorbidity free until age 36 years, versus 52 years for the general population, the same 16-year difference during 2000-2003, when the numbers were age 32 versus age 48 years.

During 2014-2016, liver disease came 24 years sooner with HIV, and chronic kidney disease 17 years, chronic lung disease 16 years, cancer 9 years, and diabetes and cancer both 8 years sooner. Early ART didn’t narrow the gap for most comorbidities. Dr. Marcus didn’t address the reasons for the differences, except to note that “smoking rates were definitely higher among people with HIV.”

The results weren’t broken down by sex, but the majority of subjects, 88%, were men. The mean age was 41 years, and about half were white, with most of the rest either black or Hispanic. Transmission was among men who have sex with men in 70% of the cases, heterosexual sex in 20%, and IV drug accounted for the rest. Almost a third of the subjects started ART with CD4 counts at or above 500 cells/mm3.

Dr. Marcus said the results are likely generalizable to most insured people with HIV, but also that comorbidity screening might be higher in the HIV population, which could have affected the results.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Marcus is an adviser for Gilead.

SOURCE: Marcus JL et al. CROI 2020. Abstract 151.

Despite highly effective antiretroviral therapy, HIV still shortens life expectancy by 9 years and healthy life expectancy free of comorbidities 16 years, according to a review of HIV patients and matched controls at Kaiser Permanente facilities in California and the mid-Atlantic states during 2000-2016.

The good news is that starting antiretroviral therapy (ART) when CD4 counts are 500 cells/mm3 or higher closes the mortality gap. People who do so can expect to live into their mid-80s, the same as people without HIV, and the years they can expect to be free of diabetes and cancer is catching up to uninfected people, although the gap for other comorbidities hasn’t changed and the overall comorbidity gap remains 16 years, according to the report, which was presented at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections

“We were excited about finding no difference in lifespan for people starting ART with high CD4 counts, but we were surprised by how wide the gap was for the number of comorbidity free years. Greater attention to comorbidity prevention is needed,” said study lead Julia Marcus, PhD, an infectious disease epidemiologist and assistant professor of population medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The team estimated the average number of total and comorbidity-free years of life remaining at age 21 for 39,000 people with HIV who were matched 1:10 with 387,767 uninfected adults by sex, race/ethnicity, year, and medical center.

Overall, adults with HIV could expect to live until they were 77 years old, versus 86 years for people without HIV, during 2014-2016. It’s a large improvement over the 22 year gap during 2000-2003, when the numbers were 59 versus 81 years, respectively, Dr. Marcus reported at the virtual meeting, which was scheduled to be in Boston, but held online this year because of concerns about spreading the COVID-19 virus.

But the overall comorbidity gap didn’t budge during 2000-2016. People with HIV during 2014-2016 could expect to be comorbidity free until age 36 years, versus 52 years for the general population, the same 16-year difference during 2000-2003, when the numbers were age 32 versus age 48 years.

During 2014-2016, liver disease came 24 years sooner with HIV, and chronic kidney disease 17 years, chronic lung disease 16 years, cancer 9 years, and diabetes and cancer both 8 years sooner. Early ART didn’t narrow the gap for most comorbidities. Dr. Marcus didn’t address the reasons for the differences, except to note that “smoking rates were definitely higher among people with HIV.”

The results weren’t broken down by sex, but the majority of subjects, 88%, were men. The mean age was 41 years, and about half were white, with most of the rest either black or Hispanic. Transmission was among men who have sex with men in 70% of the cases, heterosexual sex in 20%, and IV drug accounted for the rest. Almost a third of the subjects started ART with CD4 counts at or above 500 cells/mm3.

Dr. Marcus said the results are likely generalizable to most insured people with HIV, but also that comorbidity screening might be higher in the HIV population, which could have affected the results.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Marcus is an adviser for Gilead.

SOURCE: Marcus JL et al. CROI 2020. Abstract 151.

Despite highly effective antiretroviral therapy, HIV still shortens life expectancy by 9 years and healthy life expectancy free of comorbidities 16 years, according to a review of HIV patients and matched controls at Kaiser Permanente facilities in California and the mid-Atlantic states during 2000-2016.

The good news is that starting antiretroviral therapy (ART) when CD4 counts are 500 cells/mm3 or higher closes the mortality gap. People who do so can expect to live into their mid-80s, the same as people without HIV, and the years they can expect to be free of diabetes and cancer is catching up to uninfected people, although the gap for other comorbidities hasn’t changed and the overall comorbidity gap remains 16 years, according to the report, which was presented at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections

“We were excited about finding no difference in lifespan for people starting ART with high CD4 counts, but we were surprised by how wide the gap was for the number of comorbidity free years. Greater attention to comorbidity prevention is needed,” said study lead Julia Marcus, PhD, an infectious disease epidemiologist and assistant professor of population medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The team estimated the average number of total and comorbidity-free years of life remaining at age 21 for 39,000 people with HIV who were matched 1:10 with 387,767 uninfected adults by sex, race/ethnicity, year, and medical center.

Overall, adults with HIV could expect to live until they were 77 years old, versus 86 years for people without HIV, during 2014-2016. It’s a large improvement over the 22 year gap during 2000-2003, when the numbers were 59 versus 81 years, respectively, Dr. Marcus reported at the virtual meeting, which was scheduled to be in Boston, but held online this year because of concerns about spreading the COVID-19 virus.

But the overall comorbidity gap didn’t budge during 2000-2016. People with HIV during 2014-2016 could expect to be comorbidity free until age 36 years, versus 52 years for the general population, the same 16-year difference during 2000-2003, when the numbers were age 32 versus age 48 years.

During 2014-2016, liver disease came 24 years sooner with HIV, and chronic kidney disease 17 years, chronic lung disease 16 years, cancer 9 years, and diabetes and cancer both 8 years sooner. Early ART didn’t narrow the gap for most comorbidities. Dr. Marcus didn’t address the reasons for the differences, except to note that “smoking rates were definitely higher among people with HIV.”

The results weren’t broken down by sex, but the majority of subjects, 88%, were men. The mean age was 41 years, and about half were white, with most of the rest either black or Hispanic. Transmission was among men who have sex with men in 70% of the cases, heterosexual sex in 20%, and IV drug accounted for the rest. Almost a third of the subjects started ART with CD4 counts at or above 500 cells/mm3.

Dr. Marcus said the results are likely generalizable to most insured people with HIV, but also that comorbidity screening might be higher in the HIV population, which could have affected the results.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Marcus is an adviser for Gilead.

SOURCE: Marcus JL et al. CROI 2020. Abstract 151.

FROM CROI 2020

Physicians pessimistic despite increased COVID-19 test kits

according to a survey.

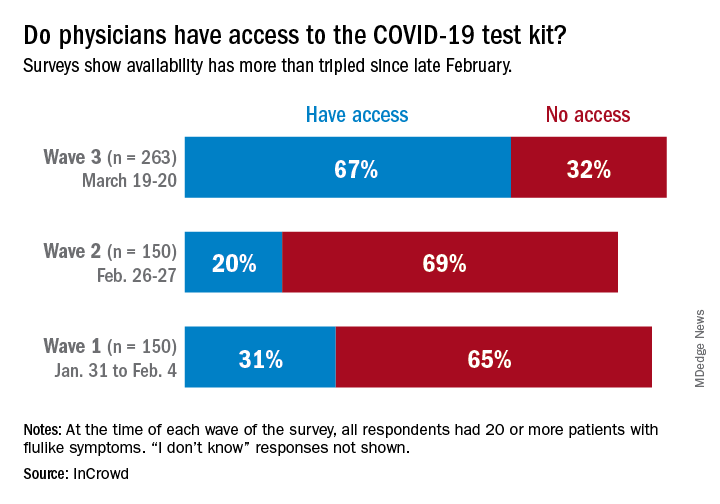

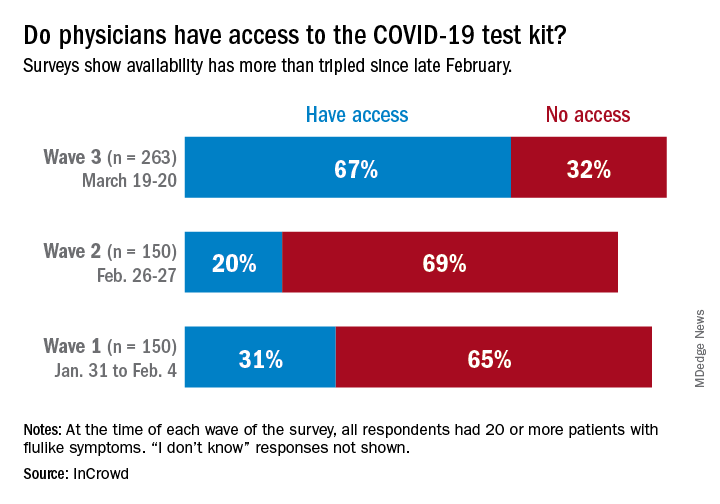

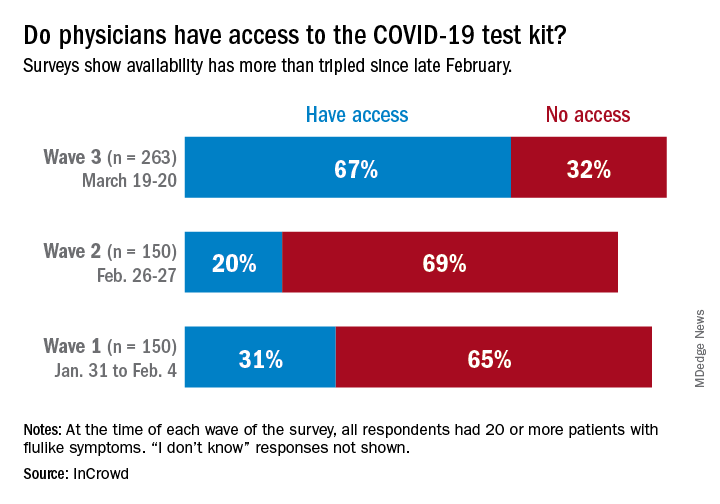

One positive finding from the physicians who participated in this survey March 19-20 was that the availability of COVID-19 test kits has more than doubled since late February.

Reported access to test kits went from 31% in the first wave of a series of surveys (Jan. 31–Feb. 4), down to 20% in the second (Feb. 26-27), and then jumped to 67% by the third wave (March 19-20), InCrowd reported March 26.

Views on several other COVID-related topics were negative among the majority of responding physicians – all of whom had or were currently treating 20 or more patients with flu-like symptoms at the time of the survey.

“Their frustrations and concerns about their ability to protect themselves while meeting upcoming patient care levels has increased significantly in the last 3 months,” Daniel S. Fitzgerald, CEO and president of InCrowd, said in a written statement.

In the third wave, 78% of respondents were “concerned for the safety of loved ones due to my exposure as a physician to COVID-19” and only 16% believed that their facility was “staffed adequately to treat the influx of patients anticipated in the next 30 days,” InCrowd said.

One primary care physician from California elaborated on the issue of safety equipment: “First, [the CDC] said we need N95 masks and other masks would not protect us. As those are running out then they said just use regular surgical masks. Now they are saying use bandannas and scarves! It’s like they don’t care about the safety of the people who will be treating the ill! We don’t want to bring it home to our families!”

“Overall, morale appears low, with few optimistic about the efficacy of public-private collaboration (21%), their own safety given current PPE [personal protective equipment] supply (13%), and the U.S.’s ability to ‘flatten the curve’ (12%),” InCrowd noted in the report.

The first two waves each had 150 respondents, but the number increased to 263 for wave 3, with similar proportions – about 50% emergency medicine or critical care specialists, 25% pediatricians, and 25% primary care physicians – in all three.

according to a survey.

One positive finding from the physicians who participated in this survey March 19-20 was that the availability of COVID-19 test kits has more than doubled since late February.

Reported access to test kits went from 31% in the first wave of a series of surveys (Jan. 31–Feb. 4), down to 20% in the second (Feb. 26-27), and then jumped to 67% by the third wave (March 19-20), InCrowd reported March 26.

Views on several other COVID-related topics were negative among the majority of responding physicians – all of whom had or were currently treating 20 or more patients with flu-like symptoms at the time of the survey.

“Their frustrations and concerns about their ability to protect themselves while meeting upcoming patient care levels has increased significantly in the last 3 months,” Daniel S. Fitzgerald, CEO and president of InCrowd, said in a written statement.

In the third wave, 78% of respondents were “concerned for the safety of loved ones due to my exposure as a physician to COVID-19” and only 16% believed that their facility was “staffed adequately to treat the influx of patients anticipated in the next 30 days,” InCrowd said.

One primary care physician from California elaborated on the issue of safety equipment: “First, [the CDC] said we need N95 masks and other masks would not protect us. As those are running out then they said just use regular surgical masks. Now they are saying use bandannas and scarves! It’s like they don’t care about the safety of the people who will be treating the ill! We don’t want to bring it home to our families!”

“Overall, morale appears low, with few optimistic about the efficacy of public-private collaboration (21%), their own safety given current PPE [personal protective equipment] supply (13%), and the U.S.’s ability to ‘flatten the curve’ (12%),” InCrowd noted in the report.

The first two waves each had 150 respondents, but the number increased to 263 for wave 3, with similar proportions – about 50% emergency medicine or critical care specialists, 25% pediatricians, and 25% primary care physicians – in all three.

according to a survey.

One positive finding from the physicians who participated in this survey March 19-20 was that the availability of COVID-19 test kits has more than doubled since late February.

Reported access to test kits went from 31% in the first wave of a series of surveys (Jan. 31–Feb. 4), down to 20% in the second (Feb. 26-27), and then jumped to 67% by the third wave (March 19-20), InCrowd reported March 26.

Views on several other COVID-related topics were negative among the majority of responding physicians – all of whom had or were currently treating 20 or more patients with flu-like symptoms at the time of the survey.

“Their frustrations and concerns about their ability to protect themselves while meeting upcoming patient care levels has increased significantly in the last 3 months,” Daniel S. Fitzgerald, CEO and president of InCrowd, said in a written statement.

In the third wave, 78% of respondents were “concerned for the safety of loved ones due to my exposure as a physician to COVID-19” and only 16% believed that their facility was “staffed adequately to treat the influx of patients anticipated in the next 30 days,” InCrowd said.

One primary care physician from California elaborated on the issue of safety equipment: “First, [the CDC] said we need N95 masks and other masks would not protect us. As those are running out then they said just use regular surgical masks. Now they are saying use bandannas and scarves! It’s like they don’t care about the safety of the people who will be treating the ill! We don’t want to bring it home to our families!”

“Overall, morale appears low, with few optimistic about the efficacy of public-private collaboration (21%), their own safety given current PPE [personal protective equipment] supply (13%), and the U.S.’s ability to ‘flatten the curve’ (12%),” InCrowd noted in the report.

The first two waves each had 150 respondents, but the number increased to 263 for wave 3, with similar proportions – about 50% emergency medicine or critical care specialists, 25% pediatricians, and 25% primary care physicians – in all three.

Less pain with a cancer drug to treat anal HPV, but it’s expensive

At the end of 6 months of low-dose pomalidomide (Pomalyst), more than half of men who have sex with men had partial or complete clearance of long-standing, grade 3 anal lesions from human papillomavirus, irrespective of HIV status; the number increased to almost two-thirds when they were checked at 12 months, according to a 26-subject study said in video presentation of his research during the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections, which was presented online this year. CROI organizers chose to hold a virtual meeting because of concerns about the spread of COVID-19.

“Therapy induced durable and continuous clearance of anal HSIL [high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions]. Further study in HPV-associated premalignancy is warranted to follow up this small, single arm study,” said study lead Mark Polizzotto, MD, PhD, head of the therapeutic and vaccine research program at the Kirby Institute in Sydney.

HPV anal lesions, and subsequent HSIL and progression to anal cancer, are prevalent among men who have sex with men. The risk increases with chronic lesions and concomitant HIV infection.

Pomalidomide is potentially a less painful alternative to options such as freezing and laser ablation, and it may have a lower rate of recurrence, but it’s expensive. Copays range upward from $5,000 for a month supply, according to GoodRx. Celgene, the maker of the drug, offers financial assistance.

Pomalidomide is a derivative of thalidomide that’s approved for multiple myeloma and also has shown effect against a viral lesion associated with HIV, Kaposi sarcoma. The drug is a T-cell activator, and since T-cell activation also is key to spontaneous anal HSIL clearance, Dr. Polizzotto and team wanted to take a look to see if it could help, he said.

The men in the study were at high risk for progression to anal cancer. With a median lesion duration of more than 3 years, and at least one case out past 7 years, spontaneous clearance wasn’t in the cards. The lesions were all grade 3 HSIL, which means severe dysplasia, and more than half of the subjects had HPV genotype 16, and the rest had other risky genotypes. Ten subjects also had HIV, which also increases the risk of anal cancer.

Pomalidomide was given in back-to-back cycles for 6 months, each consisting of 2 mg orally for 3 weeks, then 1 week off, along with a thrombolytic, usually aspirin, given the black box warning of blood clots. The dose was half the 5-mg cycle for Kaposi’s.

The overall response rate – complete clearance or a partial clearance of at least a 50% on high-resolution anoscopy – was 50% at 6 months (12/24), including four complete responses (4/15, 27%) in subjects without HIV, as well as four in the HIV group (4/9, 44%).

On follow-up at month 12, “we saw something we did not expect. Strikingly, with no additional therapy in the interim, we saw a deepening of response in a number of subjects.” The overall response rate climbed to 63% (15/24), including 33% complete response in the HIV-free group (5/15) and HIV-positive group (3/9).

Some did lose their response in the interim, however, and the study team is working to figure out if it was do to a recurrence or a new infection.

A general pattern of immune activation on treatment, including increased systemic CD4+ T-cell responses to HPV during therapy, supported the investigator’s hunch of an immunologic mechanism of action, Dr. Polizzotto said.

There were four instances of grade 3 neutropenia over eight treatment cycles, and one possibly related angina attack, but other than that, adverse reactions were generally mild and self-limited, mostly to grade 1 or 2 neutropenia, constipation, fatigue, and rash, with no idiosyncratic reactions in the HIV group or loss of viral suppression, and no discontinuations because of side effects.

The men in the study were aged 40-50 years, with a median age of 54 years; all but one were white. The median lesion involved a quarter of the anal ring, but sometimes more than half.

The work was funded by the Cancer Institute of New South Wales, the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, and Celgene. Dr. Polizzotto disclosed patents with Celgene and research funding from the company.

SOURCE: Polizzotto M et al. CROI 2020. Abstract 70

At the end of 6 months of low-dose pomalidomide (Pomalyst), more than half of men who have sex with men had partial or complete clearance of long-standing, grade 3 anal lesions from human papillomavirus, irrespective of HIV status; the number increased to almost two-thirds when they were checked at 12 months, according to a 26-subject study said in video presentation of his research during the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections, which was presented online this year. CROI organizers chose to hold a virtual meeting because of concerns about the spread of COVID-19.

“Therapy induced durable and continuous clearance of anal HSIL [high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions]. Further study in HPV-associated premalignancy is warranted to follow up this small, single arm study,” said study lead Mark Polizzotto, MD, PhD, head of the therapeutic and vaccine research program at the Kirby Institute in Sydney.

HPV anal lesions, and subsequent HSIL and progression to anal cancer, are prevalent among men who have sex with men. The risk increases with chronic lesions and concomitant HIV infection.

Pomalidomide is potentially a less painful alternative to options such as freezing and laser ablation, and it may have a lower rate of recurrence, but it’s expensive. Copays range upward from $5,000 for a month supply, according to GoodRx. Celgene, the maker of the drug, offers financial assistance.

Pomalidomide is a derivative of thalidomide that’s approved for multiple myeloma and also has shown effect against a viral lesion associated with HIV, Kaposi sarcoma. The drug is a T-cell activator, and since T-cell activation also is key to spontaneous anal HSIL clearance, Dr. Polizzotto and team wanted to take a look to see if it could help, he said.

The men in the study were at high risk for progression to anal cancer. With a median lesion duration of more than 3 years, and at least one case out past 7 years, spontaneous clearance wasn’t in the cards. The lesions were all grade 3 HSIL, which means severe dysplasia, and more than half of the subjects had HPV genotype 16, and the rest had other risky genotypes. Ten subjects also had HIV, which also increases the risk of anal cancer.

Pomalidomide was given in back-to-back cycles for 6 months, each consisting of 2 mg orally for 3 weeks, then 1 week off, along with a thrombolytic, usually aspirin, given the black box warning of blood clots. The dose was half the 5-mg cycle for Kaposi’s.

The overall response rate – complete clearance or a partial clearance of at least a 50% on high-resolution anoscopy – was 50% at 6 months (12/24), including four complete responses (4/15, 27%) in subjects without HIV, as well as four in the HIV group (4/9, 44%).

On follow-up at month 12, “we saw something we did not expect. Strikingly, with no additional therapy in the interim, we saw a deepening of response in a number of subjects.” The overall response rate climbed to 63% (15/24), including 33% complete response in the HIV-free group (5/15) and HIV-positive group (3/9).

Some did lose their response in the interim, however, and the study team is working to figure out if it was do to a recurrence or a new infection.

A general pattern of immune activation on treatment, including increased systemic CD4+ T-cell responses to HPV during therapy, supported the investigator’s hunch of an immunologic mechanism of action, Dr. Polizzotto said.

There were four instances of grade 3 neutropenia over eight treatment cycles, and one possibly related angina attack, but other than that, adverse reactions were generally mild and self-limited, mostly to grade 1 or 2 neutropenia, constipation, fatigue, and rash, with no idiosyncratic reactions in the HIV group or loss of viral suppression, and no discontinuations because of side effects.

The men in the study were aged 40-50 years, with a median age of 54 years; all but one were white. The median lesion involved a quarter of the anal ring, but sometimes more than half.

The work was funded by the Cancer Institute of New South Wales, the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, and Celgene. Dr. Polizzotto disclosed patents with Celgene and research funding from the company.

SOURCE: Polizzotto M et al. CROI 2020. Abstract 70

At the end of 6 months of low-dose pomalidomide (Pomalyst), more than half of men who have sex with men had partial or complete clearance of long-standing, grade 3 anal lesions from human papillomavirus, irrespective of HIV status; the number increased to almost two-thirds when they were checked at 12 months, according to a 26-subject study said in video presentation of his research during the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections, which was presented online this year. CROI organizers chose to hold a virtual meeting because of concerns about the spread of COVID-19.

“Therapy induced durable and continuous clearance of anal HSIL [high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions]. Further study in HPV-associated premalignancy is warranted to follow up this small, single arm study,” said study lead Mark Polizzotto, MD, PhD, head of the therapeutic and vaccine research program at the Kirby Institute in Sydney.

HPV anal lesions, and subsequent HSIL and progression to anal cancer, are prevalent among men who have sex with men. The risk increases with chronic lesions and concomitant HIV infection.

Pomalidomide is potentially a less painful alternative to options such as freezing and laser ablation, and it may have a lower rate of recurrence, but it’s expensive. Copays range upward from $5,000 for a month supply, according to GoodRx. Celgene, the maker of the drug, offers financial assistance.

Pomalidomide is a derivative of thalidomide that’s approved for multiple myeloma and also has shown effect against a viral lesion associated with HIV, Kaposi sarcoma. The drug is a T-cell activator, and since T-cell activation also is key to spontaneous anal HSIL clearance, Dr. Polizzotto and team wanted to take a look to see if it could help, he said.

The men in the study were at high risk for progression to anal cancer. With a median lesion duration of more than 3 years, and at least one case out past 7 years, spontaneous clearance wasn’t in the cards. The lesions were all grade 3 HSIL, which means severe dysplasia, and more than half of the subjects had HPV genotype 16, and the rest had other risky genotypes. Ten subjects also had HIV, which also increases the risk of anal cancer.

Pomalidomide was given in back-to-back cycles for 6 months, each consisting of 2 mg orally for 3 weeks, then 1 week off, along with a thrombolytic, usually aspirin, given the black box warning of blood clots. The dose was half the 5-mg cycle for Kaposi’s.

The overall response rate – complete clearance or a partial clearance of at least a 50% on high-resolution anoscopy – was 50% at 6 months (12/24), including four complete responses (4/15, 27%) in subjects without HIV, as well as four in the HIV group (4/9, 44%).

On follow-up at month 12, “we saw something we did not expect. Strikingly, with no additional therapy in the interim, we saw a deepening of response in a number of subjects.” The overall response rate climbed to 63% (15/24), including 33% complete response in the HIV-free group (5/15) and HIV-positive group (3/9).

Some did lose their response in the interim, however, and the study team is working to figure out if it was do to a recurrence or a new infection.

A general pattern of immune activation on treatment, including increased systemic CD4+ T-cell responses to HPV during therapy, supported the investigator’s hunch of an immunologic mechanism of action, Dr. Polizzotto said.

There were four instances of grade 3 neutropenia over eight treatment cycles, and one possibly related angina attack, but other than that, adverse reactions were generally mild and self-limited, mostly to grade 1 or 2 neutropenia, constipation, fatigue, and rash, with no idiosyncratic reactions in the HIV group or loss of viral suppression, and no discontinuations because of side effects.

The men in the study were aged 40-50 years, with a median age of 54 years; all but one were white. The median lesion involved a quarter of the anal ring, but sometimes more than half.

The work was funded by the Cancer Institute of New South Wales, the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, and Celgene. Dr. Polizzotto disclosed patents with Celgene and research funding from the company.

SOURCE: Polizzotto M et al. CROI 2020. Abstract 70

FROM CROI 2020

Visceral fat predicts NAFLD fibrosis, progression in HIV

Increased visceral fat predicts both the presence of hepatic fibrosis in HIV patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and also its progression, according to a report at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections.

Among 58 people with NAFLD and well-controlled HIV, mostly men, a “striking 43% had evidence of fibrosis” on liver biopsy, a quarter with severe stage 3 fibrosis. Visceral fat content on MRI predicted fibrosis (284 cm2 among fibrotic patients vs. 212 cm2 among nonfibrotic patients, P = .005), but body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, subcutaneous fat, and hepatic fat content did not, said investigators led by Lindsay Fourman, MD, an attending physician at the Neuroendocrine & Pituitary Tumor Clinical Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Among 24 subjects with a second liver biopsy a year later, 38% had fibrosis progression, more than half from no fibrosis at baseline. Baseline visceral fat (306 cm2 among progressors versus 212 cm2, P = .04) again predicted progression, after adjustment for baseline BMI, hepatic fat content, and NAFLD activity score.

For every 25 cm2 rise in baseline visceral fat, the team found a 40% increased odds of fibrosis progression (P = .03). Body mass index was stable among subjects, so progression was not related to sudden weight gain. Dr. Fourman noted that people with HIV can have normal BMIs, but still significant accumulation of visceral fat.

The mean rate of progression was 0.2 stages per year. “To put this into perspective, the rate of fibrosis progression among NAFLD in the general population has been quoted to be about 0.03 stages per year.” Among HIV patients, it’s “more than sixfold higher,” she said in a video presentation of her research at the meeting, which was presented online this year. CROI organizers chose to hold a virtual meeting due to concerns about the spread of COVID-19.

Overall, visceral adiposity is “a novel clinical predictor of accelerated” progression in people with HIV. “Therapies to reduce visceral fat may be particularly effective in HIV-associated NAFLD,” she said.

The findings come from a trial of one such therapy, the growth hormone releasing hormone analogue tesamorelin (Egrifta). It’s approved for reduction of excess abdominal fat in HIV patients with lipodystrophy. Dr. Fourman and her colleagues recently reported a more than 30% reduction in liver fat, versus placebo, among HIV patients with NAFLD after a year of treatment, and a lower rate of fibrosis progression at 10.5% versus 37.5% (Lancet HIV. 2019 Dec;6[12]:e821-30).

In their follow-up study reported at the meeting, people with fibrosis at baseline also had higher NAFLD activity scores (3.6 points vs. 2.0 points; P < .0001), as well as higher ALT (41 U/L vs. 23 U/L, P = .002) and AST levels (44 U/L vs. 24 U/L; P = .0003).

Baseline BMI, liver fat content, NAFLD activity score, liver enzymes, waist circumference, CD4 count, and HIV duration, a median of 16 years in the study, did not predict progression, but activity scores, hemoglobin A1C, and C-reactive protein increased as fibrosis progressed.

“We really can’t speak from our own data” if HIV regimens might have had a role in progression. Sixty-two percent of the subjects were on integrase inhibitors, and integrase inhibitors are associated with weight gain, but their effect on visceral weight gain is unclear, plus BMIs were stable. Also, there was no difference in HIV regimens among the more than 100 people screened for the study between those with NAFDL and those without.

The subjects were 54 years old, on average. The average liver fat content at baseline was about 14%, and average baseline BMI just over 30 kg/m2. In addition to the 62% on integrase inhibitors, 40% were on nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, and 24% were on protease inhibitors.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Fourman is a paid consultant to Theratechnologies, maker of tesamorelin.

SOURCE: Fourman LT et al. CROI 2020, Abstract 128

Increased visceral fat predicts both the presence of hepatic fibrosis in HIV patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and also its progression, according to a report at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections.

Among 58 people with NAFLD and well-controlled HIV, mostly men, a “striking 43% had evidence of fibrosis” on liver biopsy, a quarter with severe stage 3 fibrosis. Visceral fat content on MRI predicted fibrosis (284 cm2 among fibrotic patients vs. 212 cm2 among nonfibrotic patients, P = .005), but body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, subcutaneous fat, and hepatic fat content did not, said investigators led by Lindsay Fourman, MD, an attending physician at the Neuroendocrine & Pituitary Tumor Clinical Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Among 24 subjects with a second liver biopsy a year later, 38% had fibrosis progression, more than half from no fibrosis at baseline. Baseline visceral fat (306 cm2 among progressors versus 212 cm2, P = .04) again predicted progression, after adjustment for baseline BMI, hepatic fat content, and NAFLD activity score.

For every 25 cm2 rise in baseline visceral fat, the team found a 40% increased odds of fibrosis progression (P = .03). Body mass index was stable among subjects, so progression was not related to sudden weight gain. Dr. Fourman noted that people with HIV can have normal BMIs, but still significant accumulation of visceral fat.

The mean rate of progression was 0.2 stages per year. “To put this into perspective, the rate of fibrosis progression among NAFLD in the general population has been quoted to be about 0.03 stages per year.” Among HIV patients, it’s “more than sixfold higher,” she said in a video presentation of her research at the meeting, which was presented online this year. CROI organizers chose to hold a virtual meeting due to concerns about the spread of COVID-19.

Overall, visceral adiposity is “a novel clinical predictor of accelerated” progression in people with HIV. “Therapies to reduce visceral fat may be particularly effective in HIV-associated NAFLD,” she said.

The findings come from a trial of one such therapy, the growth hormone releasing hormone analogue tesamorelin (Egrifta). It’s approved for reduction of excess abdominal fat in HIV patients with lipodystrophy. Dr. Fourman and her colleagues recently reported a more than 30% reduction in liver fat, versus placebo, among HIV patients with NAFLD after a year of treatment, and a lower rate of fibrosis progression at 10.5% versus 37.5% (Lancet HIV. 2019 Dec;6[12]:e821-30).

In their follow-up study reported at the meeting, people with fibrosis at baseline also had higher NAFLD activity scores (3.6 points vs. 2.0 points; P < .0001), as well as higher ALT (41 U/L vs. 23 U/L, P = .002) and AST levels (44 U/L vs. 24 U/L; P = .0003).

Baseline BMI, liver fat content, NAFLD activity score, liver enzymes, waist circumference, CD4 count, and HIV duration, a median of 16 years in the study, did not predict progression, but activity scores, hemoglobin A1C, and C-reactive protein increased as fibrosis progressed.

“We really can’t speak from our own data” if HIV regimens might have had a role in progression. Sixty-two percent of the subjects were on integrase inhibitors, and integrase inhibitors are associated with weight gain, but their effect on visceral weight gain is unclear, plus BMIs were stable. Also, there was no difference in HIV regimens among the more than 100 people screened for the study between those with NAFDL and those without.

The subjects were 54 years old, on average. The average liver fat content at baseline was about 14%, and average baseline BMI just over 30 kg/m2. In addition to the 62% on integrase inhibitors, 40% were on nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, and 24% were on protease inhibitors.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Fourman is a paid consultant to Theratechnologies, maker of tesamorelin.

SOURCE: Fourman LT et al. CROI 2020, Abstract 128

Increased visceral fat predicts both the presence of hepatic fibrosis in HIV patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and also its progression, according to a report at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections.

Among 58 people with NAFLD and well-controlled HIV, mostly men, a “striking 43% had evidence of fibrosis” on liver biopsy, a quarter with severe stage 3 fibrosis. Visceral fat content on MRI predicted fibrosis (284 cm2 among fibrotic patients vs. 212 cm2 among nonfibrotic patients, P = .005), but body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, subcutaneous fat, and hepatic fat content did not, said investigators led by Lindsay Fourman, MD, an attending physician at the Neuroendocrine & Pituitary Tumor Clinical Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Among 24 subjects with a second liver biopsy a year later, 38% had fibrosis progression, more than half from no fibrosis at baseline. Baseline visceral fat (306 cm2 among progressors versus 212 cm2, P = .04) again predicted progression, after adjustment for baseline BMI, hepatic fat content, and NAFLD activity score.

For every 25 cm2 rise in baseline visceral fat, the team found a 40% increased odds of fibrosis progression (P = .03). Body mass index was stable among subjects, so progression was not related to sudden weight gain. Dr. Fourman noted that people with HIV can have normal BMIs, but still significant accumulation of visceral fat.

The mean rate of progression was 0.2 stages per year. “To put this into perspective, the rate of fibrosis progression among NAFLD in the general population has been quoted to be about 0.03 stages per year.” Among HIV patients, it’s “more than sixfold higher,” she said in a video presentation of her research at the meeting, which was presented online this year. CROI organizers chose to hold a virtual meeting due to concerns about the spread of COVID-19.

Overall, visceral adiposity is “a novel clinical predictor of accelerated” progression in people with HIV. “Therapies to reduce visceral fat may be particularly effective in HIV-associated NAFLD,” she said.

The findings come from a trial of one such therapy, the growth hormone releasing hormone analogue tesamorelin (Egrifta). It’s approved for reduction of excess abdominal fat in HIV patients with lipodystrophy. Dr. Fourman and her colleagues recently reported a more than 30% reduction in liver fat, versus placebo, among HIV patients with NAFLD after a year of treatment, and a lower rate of fibrosis progression at 10.5% versus 37.5% (Lancet HIV. 2019 Dec;6[12]:e821-30).

In their follow-up study reported at the meeting, people with fibrosis at baseline also had higher NAFLD activity scores (3.6 points vs. 2.0 points; P < .0001), as well as higher ALT (41 U/L vs. 23 U/L, P = .002) and AST levels (44 U/L vs. 24 U/L; P = .0003).

Baseline BMI, liver fat content, NAFLD activity score, liver enzymes, waist circumference, CD4 count, and HIV duration, a median of 16 years in the study, did not predict progression, but activity scores, hemoglobin A1C, and C-reactive protein increased as fibrosis progressed.

“We really can’t speak from our own data” if HIV regimens might have had a role in progression. Sixty-two percent of the subjects were on integrase inhibitors, and integrase inhibitors are associated with weight gain, but their effect on visceral weight gain is unclear, plus BMIs were stable. Also, there was no difference in HIV regimens among the more than 100 people screened for the study between those with NAFDL and those without.

The subjects were 54 years old, on average. The average liver fat content at baseline was about 14%, and average baseline BMI just over 30 kg/m2. In addition to the 62% on integrase inhibitors, 40% were on nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, and 24% were on protease inhibitors.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Fourman is a paid consultant to Theratechnologies, maker of tesamorelin.

SOURCE: Fourman LT et al. CROI 2020, Abstract 128

FROM CROI 2020

FMT appears safe and effective for IBD patients with recurrent C. difficile

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) appears safe and effective for treating recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), according to an ongoing prospective trial.

Most patients were cured of C. difficile after one fecal transplant, reported Jessica Allegretti, MD, associate director of the Crohn’s and Colitis Center at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“[For patients without IBD], fecal microbiota transplantation has been shown to be very effective for the treatment of recurrent C. diff,” Dr. Allegretti said at the annual Gut Microbiota for Health World Summit.

But similar data for patients with IBD are scarce, and this knowledge gap has high clinical relevance, Dr. Allegretti said. She noted that C. difficile infections are eight times more common among patients with IBD, and risk of recurrence is increased 4.5-fold.

According to Dr. Allegretti, three small clinical trials have tested FMT for treating recurrent C. difficile infections in patients with IBD.

“[These studies were] somewhat prospective, but [data] mainly retrospectively collected, as they relied heavily on chart review for the assessment of IBD disease activity,” she said at the meeting sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association and the European Society for Neurogastroenterology and Motility..

Across the trials, C. difficile infection cure rates were comparable with non-IBD cohorts; but disease flare rates ranged from 17.9% to 54%, which raised concern that FMT may trigger inflammation.

To investigate further, Dr. Allegretti and her colleagues designed a prospective trial that is set to enroll 50 patients with IBD. Among 37 patients treated to date, a slight majority were women (56.8%), about one-third had Crohn’s disease (37.8%), and two-thirds had ulcerative colitis (62.2%). The average baseline calprotectin level, which measures inflammation in the intestines, was 1,804.8 microg/g of feces, which is far above the upper limit of 50 microg/g.

“This is a very inflamed patient population,” Dr. Allegretti said.

Out of these 37 patients, 34 (92%) were cured of C. difficile infection after only one fecal transplant, and the remaining three patients were cured after a second FMT.

“They all did very well,” Dr. Allegretti said.

Concerning IBD clinical scores, all patients with Crohn’s disease either had unchanged or improved disease. Among those with ulcerative colitis, almost all had unchanged or improved disease, except for one patient who had a de novo flare.

Early microbiome analyses showed patients had increased alpha diversity and richness after FMT that was sustained through week 12. Because only three patients had recurrence, numbers were too small to generate predictive data based on relative abundance.

Dr. Allegretti continued her presentation with a review of FMT for IBD in general.

“For Crohn’s disease, the role [of microbiome manipulation] seems a bit more clear,” Dr. Allegretti said, considering multiple effective treatments that alter gut flora, such as antibiotics.

In contrast, the role for microbiome manipulation in treating ulcerative colitis “has remained a bit unclear,” she said. Although some probiotics appear effective for treating mild disease, other microbiome-altering treatments, such as diversion of fecal stream, antibiotics, and bowel rest, have fallen short.

Still, pooled data from four randomized clinical trials showed that FMT led to remission in 28% of patients with ulcerative colitis, compared with 9% who receive placebo.

“You may be thinking that seems a bit underwhelming compared to the 90% or so cure rate we get for C. diff trials,” Dr. Allegretti said. “However, if you look at our other biologic trials in IBD, 28% puts FMT on par with our other IBD therapies.”

According to Dr. Allegretti, at least three stool-based, FMT-like therapeutics are poised to become commercially available in the next few years for the treatment of C. difficile infection, including broad- and narrow-spectrum enema bags and oral capsules.

“I certainly think we will start to see off-label usage in our IBD patients, and we will start to have an easier and more systemic way of utilizing these microbiome-based therapies,” Dr. Allegretti said. “They will be coming to market, and when they do, whether or not we are allowed to still do traditional FMT in its current form remains unseen. The FDA may not allow us to do that in the future when we have an FDA-approved product.”Dr. Allegretti disclosed relationships with Merck, Openbiome, Finch Therapeutics, and others.

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) appears safe and effective for treating recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), according to an ongoing prospective trial.

Most patients were cured of C. difficile after one fecal transplant, reported Jessica Allegretti, MD, associate director of the Crohn’s and Colitis Center at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“[For patients without IBD], fecal microbiota transplantation has been shown to be very effective for the treatment of recurrent C. diff,” Dr. Allegretti said at the annual Gut Microbiota for Health World Summit.

But similar data for patients with IBD are scarce, and this knowledge gap has high clinical relevance, Dr. Allegretti said. She noted that C. difficile infections are eight times more common among patients with IBD, and risk of recurrence is increased 4.5-fold.

According to Dr. Allegretti, three small clinical trials have tested FMT for treating recurrent C. difficile infections in patients with IBD.

“[These studies were] somewhat prospective, but [data] mainly retrospectively collected, as they relied heavily on chart review for the assessment of IBD disease activity,” she said at the meeting sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association and the European Society for Neurogastroenterology and Motility..

Across the trials, C. difficile infection cure rates were comparable with non-IBD cohorts; but disease flare rates ranged from 17.9% to 54%, which raised concern that FMT may trigger inflammation.

To investigate further, Dr. Allegretti and her colleagues designed a prospective trial that is set to enroll 50 patients with IBD. Among 37 patients treated to date, a slight majority were women (56.8%), about one-third had Crohn’s disease (37.8%), and two-thirds had ulcerative colitis (62.2%). The average baseline calprotectin level, which measures inflammation in the intestines, was 1,804.8 microg/g of feces, which is far above the upper limit of 50 microg/g.

“This is a very inflamed patient population,” Dr. Allegretti said.

Out of these 37 patients, 34 (92%) were cured of C. difficile infection after only one fecal transplant, and the remaining three patients were cured after a second FMT.

“They all did very well,” Dr. Allegretti said.

Concerning IBD clinical scores, all patients with Crohn’s disease either had unchanged or improved disease. Among those with ulcerative colitis, almost all had unchanged or improved disease, except for one patient who had a de novo flare.

Early microbiome analyses showed patients had increased alpha diversity and richness after FMT that was sustained through week 12. Because only three patients had recurrence, numbers were too small to generate predictive data based on relative abundance.

Dr. Allegretti continued her presentation with a review of FMT for IBD in general.

“For Crohn’s disease, the role [of microbiome manipulation] seems a bit more clear,” Dr. Allegretti said, considering multiple effective treatments that alter gut flora, such as antibiotics.

In contrast, the role for microbiome manipulation in treating ulcerative colitis “has remained a bit unclear,” she said. Although some probiotics appear effective for treating mild disease, other microbiome-altering treatments, such as diversion of fecal stream, antibiotics, and bowel rest, have fallen short.

Still, pooled data from four randomized clinical trials showed that FMT led to remission in 28% of patients with ulcerative colitis, compared with 9% who receive placebo.

“You may be thinking that seems a bit underwhelming compared to the 90% or so cure rate we get for C. diff trials,” Dr. Allegretti said. “However, if you look at our other biologic trials in IBD, 28% puts FMT on par with our other IBD therapies.”

According to Dr. Allegretti, at least three stool-based, FMT-like therapeutics are poised to become commercially available in the next few years for the treatment of C. difficile infection, including broad- and narrow-spectrum enema bags and oral capsules.

“I certainly think we will start to see off-label usage in our IBD patients, and we will start to have an easier and more systemic way of utilizing these microbiome-based therapies,” Dr. Allegretti said. “They will be coming to market, and when they do, whether or not we are allowed to still do traditional FMT in its current form remains unseen. The FDA may not allow us to do that in the future when we have an FDA-approved product.”Dr. Allegretti disclosed relationships with Merck, Openbiome, Finch Therapeutics, and others.

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) appears safe and effective for treating recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), according to an ongoing prospective trial.

Most patients were cured of C. difficile after one fecal transplant, reported Jessica Allegretti, MD, associate director of the Crohn’s and Colitis Center at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“[For patients without IBD], fecal microbiota transplantation has been shown to be very effective for the treatment of recurrent C. diff,” Dr. Allegretti said at the annual Gut Microbiota for Health World Summit.

But similar data for patients with IBD are scarce, and this knowledge gap has high clinical relevance, Dr. Allegretti said. She noted that C. difficile infections are eight times more common among patients with IBD, and risk of recurrence is increased 4.5-fold.

According to Dr. Allegretti, three small clinical trials have tested FMT for treating recurrent C. difficile infections in patients with IBD.

“[These studies were] somewhat prospective, but [data] mainly retrospectively collected, as they relied heavily on chart review for the assessment of IBD disease activity,” she said at the meeting sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association and the European Society for Neurogastroenterology and Motility..

Across the trials, C. difficile infection cure rates were comparable with non-IBD cohorts; but disease flare rates ranged from 17.9% to 54%, which raised concern that FMT may trigger inflammation.

To investigate further, Dr. Allegretti and her colleagues designed a prospective trial that is set to enroll 50 patients with IBD. Among 37 patients treated to date, a slight majority were women (56.8%), about one-third had Crohn’s disease (37.8%), and two-thirds had ulcerative colitis (62.2%). The average baseline calprotectin level, which measures inflammation in the intestines, was 1,804.8 microg/g of feces, which is far above the upper limit of 50 microg/g.

“This is a very inflamed patient population,” Dr. Allegretti said.

Out of these 37 patients, 34 (92%) were cured of C. difficile infection after only one fecal transplant, and the remaining three patients were cured after a second FMT.

“They all did very well,” Dr. Allegretti said.

Concerning IBD clinical scores, all patients with Crohn’s disease either had unchanged or improved disease. Among those with ulcerative colitis, almost all had unchanged or improved disease, except for one patient who had a de novo flare.

Early microbiome analyses showed patients had increased alpha diversity and richness after FMT that was sustained through week 12. Because only three patients had recurrence, numbers were too small to generate predictive data based on relative abundance.

Dr. Allegretti continued her presentation with a review of FMT for IBD in general.

“For Crohn’s disease, the role [of microbiome manipulation] seems a bit more clear,” Dr. Allegretti said, considering multiple effective treatments that alter gut flora, such as antibiotics.

In contrast, the role for microbiome manipulation in treating ulcerative colitis “has remained a bit unclear,” she said. Although some probiotics appear effective for treating mild disease, other microbiome-altering treatments, such as diversion of fecal stream, antibiotics, and bowel rest, have fallen short.

Still, pooled data from four randomized clinical trials showed that FMT led to remission in 28% of patients with ulcerative colitis, compared with 9% who receive placebo.

“You may be thinking that seems a bit underwhelming compared to the 90% or so cure rate we get for C. diff trials,” Dr. Allegretti said. “However, if you look at our other biologic trials in IBD, 28% puts FMT on par with our other IBD therapies.”

According to Dr. Allegretti, at least three stool-based, FMT-like therapeutics are poised to become commercially available in the next few years for the treatment of C. difficile infection, including broad- and narrow-spectrum enema bags and oral capsules.

“I certainly think we will start to see off-label usage in our IBD patients, and we will start to have an easier and more systemic way of utilizing these microbiome-based therapies,” Dr. Allegretti said. “They will be coming to market, and when they do, whether or not we are allowed to still do traditional FMT in its current form remains unseen. The FDA may not allow us to do that in the future when we have an FDA-approved product.”Dr. Allegretti disclosed relationships with Merck, Openbiome, Finch Therapeutics, and others.

FROM GMFH 2020

Focus groups seek transgender experience with HIV prevention

A pair of focus groups explored the experience of transgender patients with HIV prevention, finding many were discouraged by experiences of care that was not culturally competent and affirming.

The findings, including other important themes, were published in Pediatrics.

The pair of online asynchronous focus groups, conducted by Holly B. Fontenot, PhD, RN/NP, of the Fenway Institute in Boston, and colleagues, sought input from 30 transgender participants from across the United States. Eleven were aged 13-18 years, and 19 were aged 18-24 years, with an average age of 19. Most (70%) were white, and the remainder were African American (7%), Asian American (3%), multiracial (17%), and other (3%); 10% identified as Hispanic. Participants were given multiple options for reporting gender identity; 27% reported identifying as transgender males, 17% reported identifying as transgender females, and the rest identified with other terms, including 27% using one or more terms.

The quantitative analysis found four common themes, which the study explored in depth: “barriers to self-efficacy in sexual decision making; safety concerns, fear, and other challenges in forming romantic and/or sexual relationships; need for support and education; and desire for affirmative and culturally competent experiences and interactions.”

Based on their findings, the authors suggested ways of improving transgender youth experiences:

- Increasing provider knowledge and skills in providing affirming care through transgender health education programs.

- Addressing the barriers, such as stigma and lack of accessibility.

- Expanding sexual health education to be more inclusive regarding gender identities, sexual orientations, and definitions of sex.

Providers also need to include information on sexually transmitted infection and HIV prevention, including “discussion of safer sexual behaviors, negotiation and consent, sexual and physical assault, condoms, lubrication, STI and HIV testing, human papillomavirus vaccination, and PrEP [preexposure prophylaxis]” the authors emphasized.

Dr. Fontenot and associates determined that this study’s findings were consistent with what’s known about adult transgender patients, but this study provides more context regarding transgender youth experiences.

“It is important to elicit transgender youth experiences and perspectives related to HIV risk and preventive services,” they concluded. “This study provided a greater understanding of barriers to and facilitators of youth obtaining HIV preventive services and sexual health education.”

Limitations of the study included that non–English speaking participants were excluded, and that participants were predominantly white, non-Hispanic, and assigned female sex at birth.

This study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and NORC at The University of Chicago. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Fontenot HB et al., Pediatrics. 2020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2204.

A pair of focus groups explored the experience of transgender patients with HIV prevention, finding many were discouraged by experiences of care that was not culturally competent and affirming.

The findings, including other important themes, were published in Pediatrics.

The pair of online asynchronous focus groups, conducted by Holly B. Fontenot, PhD, RN/NP, of the Fenway Institute in Boston, and colleagues, sought input from 30 transgender participants from across the United States. Eleven were aged 13-18 years, and 19 were aged 18-24 years, with an average age of 19. Most (70%) were white, and the remainder were African American (7%), Asian American (3%), multiracial (17%), and other (3%); 10% identified as Hispanic. Participants were given multiple options for reporting gender identity; 27% reported identifying as transgender males, 17% reported identifying as transgender females, and the rest identified with other terms, including 27% using one or more terms.

The quantitative analysis found four common themes, which the study explored in depth: “barriers to self-efficacy in sexual decision making; safety concerns, fear, and other challenges in forming romantic and/or sexual relationships; need for support and education; and desire for affirmative and culturally competent experiences and interactions.”

Based on their findings, the authors suggested ways of improving transgender youth experiences:

- Increasing provider knowledge and skills in providing affirming care through transgender health education programs.

- Addressing the barriers, such as stigma and lack of accessibility.

- Expanding sexual health education to be more inclusive regarding gender identities, sexual orientations, and definitions of sex.

Providers also need to include information on sexually transmitted infection and HIV prevention, including “discussion of safer sexual behaviors, negotiation and consent, sexual and physical assault, condoms, lubrication, STI and HIV testing, human papillomavirus vaccination, and PrEP [preexposure prophylaxis]” the authors emphasized.

Dr. Fontenot and associates determined that this study’s findings were consistent with what’s known about adult transgender patients, but this study provides more context regarding transgender youth experiences.

“It is important to elicit transgender youth experiences and perspectives related to HIV risk and preventive services,” they concluded. “This study provided a greater understanding of barriers to and facilitators of youth obtaining HIV preventive services and sexual health education.”

Limitations of the study included that non–English speaking participants were excluded, and that participants were predominantly white, non-Hispanic, and assigned female sex at birth.

This study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and NORC at The University of Chicago. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Fontenot HB et al., Pediatrics. 2020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2204.

A pair of focus groups explored the experience of transgender patients with HIV prevention, finding many were discouraged by experiences of care that was not culturally competent and affirming.

The findings, including other important themes, were published in Pediatrics.

The pair of online asynchronous focus groups, conducted by Holly B. Fontenot, PhD, RN/NP, of the Fenway Institute in Boston, and colleagues, sought input from 30 transgender participants from across the United States. Eleven were aged 13-18 years, and 19 were aged 18-24 years, with an average age of 19. Most (70%) were white, and the remainder were African American (7%), Asian American (3%), multiracial (17%), and other (3%); 10% identified as Hispanic. Participants were given multiple options for reporting gender identity; 27% reported identifying as transgender males, 17% reported identifying as transgender females, and the rest identified with other terms, including 27% using one or more terms.

The quantitative analysis found four common themes, which the study explored in depth: “barriers to self-efficacy in sexual decision making; safety concerns, fear, and other challenges in forming romantic and/or sexual relationships; need for support and education; and desire for affirmative and culturally competent experiences and interactions.”

Based on their findings, the authors suggested ways of improving transgender youth experiences:

- Increasing provider knowledge and skills in providing affirming care through transgender health education programs.

- Addressing the barriers, such as stigma and lack of accessibility.

- Expanding sexual health education to be more inclusive regarding gender identities, sexual orientations, and definitions of sex.

Providers also need to include information on sexually transmitted infection and HIV prevention, including “discussion of safer sexual behaviors, negotiation and consent, sexual and physical assault, condoms, lubrication, STI and HIV testing, human papillomavirus vaccination, and PrEP [preexposure prophylaxis]” the authors emphasized.

Dr. Fontenot and associates determined that this study’s findings were consistent with what’s known about adult transgender patients, but this study provides more context regarding transgender youth experiences.

“It is important to elicit transgender youth experiences and perspectives related to HIV risk and preventive services,” they concluded. “This study provided a greater understanding of barriers to and facilitators of youth obtaining HIV preventive services and sexual health education.”

Limitations of the study included that non–English speaking participants were excluded, and that participants were predominantly white, non-Hispanic, and assigned female sex at birth.

This study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and NORC at The University of Chicago. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Fontenot HB et al., Pediatrics. 2020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2204.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Cardiac symptoms can be first sign of COVID-19