User login

SCOT-HEART: CTA cuts MIs in patients with stable chest pain

MUNICH –

Although the absolute numbers were small – 48 clinical events in the intervention group and 81 among patients who had standard care – the difference was significant and wasn’t associated with any increase in invasive coronary procedures, David E. Newby, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The study, presented August 25, was published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM 2018; DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805971

The data suggest that 63 patients with stable chest pain would need to undergo CTA to prevent one fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction over 5 years, said Dr. Newby, the BHF John Wheatley professor of cardiology at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland.

He presented 5-year results of the SCOT-HEART study, an open-label trial that randomized 4,146 patients with stable chest pain to standard care plus CTA, or standard care alone. The primary endpoint was nonfatal myocardial infarction or death from coronary heart disease at 5 years. The 3-year results were previously reported.

“This is one of the most impactful studies in cardiovascular medicine. It’s a groundbreaking trial,” commented Todd C. Villines, MD, a designated discussant for the report at the meeting. SCOT-HEART “looked at the additive value of CTA compared with usual care using functional testing with an exercise stress test. It showed that when you visualize coronary atherosclerosis [with CTA] and change medical management based on whether or not plaque is present it drove a significant decrease in MIs,” noted Dr. Villines, a cardiologist affiliated with Georgetown University Medical School in Washington, and immediate past president of the Society of Cardiovascular CT.

Patients were recruited from 12 cardiology centers across Scotland and followed for a mean of 4.8 years, amassing 20,254 patient-years of follow-up. They were a mean of 57 years old; 41% had nonanginal chest pain, 35% typical angina, and 24% atypical angina About half were current or former smokers, a third had hypertension, and half had hypercholesterolemia. Resting EEG was normal in 85%.

Patients who underwent CTA were more likely to start preventive therapies (19% vs. 14.7%; odds ratio, 1.4) and antianginal therapies (13% vs. 10.7%; hazard ratio, 1.27). And although there were more revascularizations in that group early on, the numbers were similar by the end of follow-up (13.5% vs. 13%). After 12 months, CTA patients were 30% less likely to undergo invasive coronary angiography (HR, 0.70) and 41% less likely to undergo a coronary revascularization (HR, 0.59).

“This would be consistent with both the emergence of unrecognized disease and nonfatal myocardial infarction in the standard-care group and the reduction in disease progression in the CTA group owing to the implementation of lifestyle modifications and preventive therapies,” Dr. Newby and colleagues wrote in the NEJM paper.

The composite clinical endpoint occurred in 2.3% of the CTA group and 3.9% of the standard care group – a significant risk differential of 41% (HR, 0.59). The primary driver of this benefit was a significantly lower rate of nonfatal myocardial infarction (HR, 0.60) among CTA patients.

There was no evidence of a subgroup effect, Dr. Newby noted. Among the 48 CTA patients who experienced a clinical event, 22 had obstructive disease, 17 had nonobstructive disease, and three had normal coronary arteries (six patients assigned to the procedure didn’t return for it).

There was a slightly higher event rate among patients with possible angina than among those with nonanginal pain (3.1% vs. 1.8%), but the 5-year difference between the treatment groups was not significantly different.

“Our findings suggest that the use of CTA resulted in more correct diagnoses of coronary heart disease than standard care alone, which, in turn, led to the use of appropriate therapies and this change in management resulted in fewer clinical events in the CTA group than in the standard-care group,” Dr. Newby noted. “Patients who receive a correct diagnosis are also more likely to receive appropriate preventive therapies and may have greater motivation to implement healthy lifestyle modification.”

“The SCOT-HEART data solidify coronary CTA as the best first-line test for patients without established coronary disease,” especially now that a report documented that clinicians worldwide are performing coronary CTA using lower levels of radiation exposure to patients, commented Dr. Villines in an interview. During the same session where Dr. Newby reported the SCOT-HEART results, an international team of researchers reported results of a survey of CTA methods used at 61 centers in 32 countries, including several U.S. sites. The results from the survey showed that in 2017 patients undergoing coronary CTA received a median radiation dose of 2.7 mSv and a median dose-length product of 195 mGy*cm, both representing a 78% relative reduction compared with the median doses received during CTA when a similar survey ran in 2007 (Eur Heart J. 2018 Aug 25; doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehy546).

In contrast, for patients with established coronary artery disease functional tests using stress imaging remain best, Dr. Villines said. “What SCOT-HEART said was that when you use coronary CTA in a population without established coronary disease you can identify not only whether the patient has obstructive disease but do they have coronary atherosclerosis, and that is prognostic and valuable. You miss that with functional testing.”

The Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government funded the study. Dr. Newby has received grants from Seimens. Dr. Villines had no relevant commercial disclosures.

Updated 8/27/18: Mitchel L. Zoler contributed commentary by Dr. Todd C. Villines, and additional data and discussion from the presentation, to this article.

SOURCE: Newby DE et al. NEJM 2018; DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805971.

Clinical information gleaned from CTA can drive the treatment of chest pain far beyond simply making a correct diagnosis, Udo Hoffmann, MD, and James Udelson, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (NEJM 2018 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMo1809203).

The 41% lower rate of nonfatal myocardial infarction or death from coronary heart disease seen in the 5-year SCOT-HEART data came without the additional financial or clinical cost of invasive coronary procedures.

“The relative risk reductions observed in the SCOT-HEART trial are like those observed in recent secondary prevention trials, which prompts speculation about the mechanism. In trials of diagnostic testing strategies, it is the downstream management – presumably driven by the testing results – that affects outcomes.”

Coronary revascularization probably didn’t play a major role in the benefit, given the similar between-group rates. So, the key must lie elsewhere. A look at a similar study, which found quite different results, may help.

The Prospective Multicenter Imaging Study for Evaluation of Chest Pain (PROMISE) randomized similar chest pain patients to either CTA or functional testing but showed no significant benefit of CTA over 2 years. It compared CTA primarily to nuclear imaging or echocardiogram, with only 10% getting an exercise ECG. In SCOT-HEART the comparator standardized strategy was predominantly stress ECG testing, and only 10% had an imaging test.

“An analysis of PROMISE shows that a substantial proportion of myocardial infarctions occurred in patients with nonobstructive coronary artery disease identified by CTA – disease that would not be detected by functional testing. It would be reasonable to consider aggressive secondary prevention in these patients, although this specific approach has not been evaluated in a clinical trial. We also believe that leveraging data from trials such as SCOT-HEART and PROMISE may allow more efficient targeting of noninvasive testing while continuing to drive improvement in vascular outcomes.”

Dr. Hoffmann is a cardiac radiologist at Harvard Medical School and Dr. Udelson is director of the Nuclear Cardiology Laboratory at Tufts Medical Center, both of Boston.

Clinical information gleaned from CTA can drive the treatment of chest pain far beyond simply making a correct diagnosis, Udo Hoffmann, MD, and James Udelson, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (NEJM 2018 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMo1809203).

The 41% lower rate of nonfatal myocardial infarction or death from coronary heart disease seen in the 5-year SCOT-HEART data came without the additional financial or clinical cost of invasive coronary procedures.

“The relative risk reductions observed in the SCOT-HEART trial are like those observed in recent secondary prevention trials, which prompts speculation about the mechanism. In trials of diagnostic testing strategies, it is the downstream management – presumably driven by the testing results – that affects outcomes.”

Coronary revascularization probably didn’t play a major role in the benefit, given the similar between-group rates. So, the key must lie elsewhere. A look at a similar study, which found quite different results, may help.

The Prospective Multicenter Imaging Study for Evaluation of Chest Pain (PROMISE) randomized similar chest pain patients to either CTA or functional testing but showed no significant benefit of CTA over 2 years. It compared CTA primarily to nuclear imaging or echocardiogram, with only 10% getting an exercise ECG. In SCOT-HEART the comparator standardized strategy was predominantly stress ECG testing, and only 10% had an imaging test.

“An analysis of PROMISE shows that a substantial proportion of myocardial infarctions occurred in patients with nonobstructive coronary artery disease identified by CTA – disease that would not be detected by functional testing. It would be reasonable to consider aggressive secondary prevention in these patients, although this specific approach has not been evaluated in a clinical trial. We also believe that leveraging data from trials such as SCOT-HEART and PROMISE may allow more efficient targeting of noninvasive testing while continuing to drive improvement in vascular outcomes.”

Dr. Hoffmann is a cardiac radiologist at Harvard Medical School and Dr. Udelson is director of the Nuclear Cardiology Laboratory at Tufts Medical Center, both of Boston.

Clinical information gleaned from CTA can drive the treatment of chest pain far beyond simply making a correct diagnosis, Udo Hoffmann, MD, and James Udelson, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (NEJM 2018 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMo1809203).

The 41% lower rate of nonfatal myocardial infarction or death from coronary heart disease seen in the 5-year SCOT-HEART data came without the additional financial or clinical cost of invasive coronary procedures.

“The relative risk reductions observed in the SCOT-HEART trial are like those observed in recent secondary prevention trials, which prompts speculation about the mechanism. In trials of diagnostic testing strategies, it is the downstream management – presumably driven by the testing results – that affects outcomes.”

Coronary revascularization probably didn’t play a major role in the benefit, given the similar between-group rates. So, the key must lie elsewhere. A look at a similar study, which found quite different results, may help.

The Prospective Multicenter Imaging Study for Evaluation of Chest Pain (PROMISE) randomized similar chest pain patients to either CTA or functional testing but showed no significant benefit of CTA over 2 years. It compared CTA primarily to nuclear imaging or echocardiogram, with only 10% getting an exercise ECG. In SCOT-HEART the comparator standardized strategy was predominantly stress ECG testing, and only 10% had an imaging test.

“An analysis of PROMISE shows that a substantial proportion of myocardial infarctions occurred in patients with nonobstructive coronary artery disease identified by CTA – disease that would not be detected by functional testing. It would be reasonable to consider aggressive secondary prevention in these patients, although this specific approach has not been evaluated in a clinical trial. We also believe that leveraging data from trials such as SCOT-HEART and PROMISE may allow more efficient targeting of noninvasive testing while continuing to drive improvement in vascular outcomes.”

Dr. Hoffmann is a cardiac radiologist at Harvard Medical School and Dr. Udelson is director of the Nuclear Cardiology Laboratory at Tufts Medical Center, both of Boston.

MUNICH –

Although the absolute numbers were small – 48 clinical events in the intervention group and 81 among patients who had standard care – the difference was significant and wasn’t associated with any increase in invasive coronary procedures, David E. Newby, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The study, presented August 25, was published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM 2018; DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805971

The data suggest that 63 patients with stable chest pain would need to undergo CTA to prevent one fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction over 5 years, said Dr. Newby, the BHF John Wheatley professor of cardiology at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland.

He presented 5-year results of the SCOT-HEART study, an open-label trial that randomized 4,146 patients with stable chest pain to standard care plus CTA, or standard care alone. The primary endpoint was nonfatal myocardial infarction or death from coronary heart disease at 5 years. The 3-year results were previously reported.

“This is one of the most impactful studies in cardiovascular medicine. It’s a groundbreaking trial,” commented Todd C. Villines, MD, a designated discussant for the report at the meeting. SCOT-HEART “looked at the additive value of CTA compared with usual care using functional testing with an exercise stress test. It showed that when you visualize coronary atherosclerosis [with CTA] and change medical management based on whether or not plaque is present it drove a significant decrease in MIs,” noted Dr. Villines, a cardiologist affiliated with Georgetown University Medical School in Washington, and immediate past president of the Society of Cardiovascular CT.

Patients were recruited from 12 cardiology centers across Scotland and followed for a mean of 4.8 years, amassing 20,254 patient-years of follow-up. They were a mean of 57 years old; 41% had nonanginal chest pain, 35% typical angina, and 24% atypical angina About half were current or former smokers, a third had hypertension, and half had hypercholesterolemia. Resting EEG was normal in 85%.

Patients who underwent CTA were more likely to start preventive therapies (19% vs. 14.7%; odds ratio, 1.4) and antianginal therapies (13% vs. 10.7%; hazard ratio, 1.27). And although there were more revascularizations in that group early on, the numbers were similar by the end of follow-up (13.5% vs. 13%). After 12 months, CTA patients were 30% less likely to undergo invasive coronary angiography (HR, 0.70) and 41% less likely to undergo a coronary revascularization (HR, 0.59).

“This would be consistent with both the emergence of unrecognized disease and nonfatal myocardial infarction in the standard-care group and the reduction in disease progression in the CTA group owing to the implementation of lifestyle modifications and preventive therapies,” Dr. Newby and colleagues wrote in the NEJM paper.

The composite clinical endpoint occurred in 2.3% of the CTA group and 3.9% of the standard care group – a significant risk differential of 41% (HR, 0.59). The primary driver of this benefit was a significantly lower rate of nonfatal myocardial infarction (HR, 0.60) among CTA patients.

There was no evidence of a subgroup effect, Dr. Newby noted. Among the 48 CTA patients who experienced a clinical event, 22 had obstructive disease, 17 had nonobstructive disease, and three had normal coronary arteries (six patients assigned to the procedure didn’t return for it).

There was a slightly higher event rate among patients with possible angina than among those with nonanginal pain (3.1% vs. 1.8%), but the 5-year difference between the treatment groups was not significantly different.

“Our findings suggest that the use of CTA resulted in more correct diagnoses of coronary heart disease than standard care alone, which, in turn, led to the use of appropriate therapies and this change in management resulted in fewer clinical events in the CTA group than in the standard-care group,” Dr. Newby noted. “Patients who receive a correct diagnosis are also more likely to receive appropriate preventive therapies and may have greater motivation to implement healthy lifestyle modification.”

“The SCOT-HEART data solidify coronary CTA as the best first-line test for patients without established coronary disease,” especially now that a report documented that clinicians worldwide are performing coronary CTA using lower levels of radiation exposure to patients, commented Dr. Villines in an interview. During the same session where Dr. Newby reported the SCOT-HEART results, an international team of researchers reported results of a survey of CTA methods used at 61 centers in 32 countries, including several U.S. sites. The results from the survey showed that in 2017 patients undergoing coronary CTA received a median radiation dose of 2.7 mSv and a median dose-length product of 195 mGy*cm, both representing a 78% relative reduction compared with the median doses received during CTA when a similar survey ran in 2007 (Eur Heart J. 2018 Aug 25; doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehy546).

In contrast, for patients with established coronary artery disease functional tests using stress imaging remain best, Dr. Villines said. “What SCOT-HEART said was that when you use coronary CTA in a population without established coronary disease you can identify not only whether the patient has obstructive disease but do they have coronary atherosclerosis, and that is prognostic and valuable. You miss that with functional testing.”

The Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government funded the study. Dr. Newby has received grants from Seimens. Dr. Villines had no relevant commercial disclosures.

Updated 8/27/18: Mitchel L. Zoler contributed commentary by Dr. Todd C. Villines, and additional data and discussion from the presentation, to this article.

SOURCE: Newby DE et al. NEJM 2018; DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805971.

MUNICH –

Although the absolute numbers were small – 48 clinical events in the intervention group and 81 among patients who had standard care – the difference was significant and wasn’t associated with any increase in invasive coronary procedures, David E. Newby, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The study, presented August 25, was published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM 2018; DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805971

The data suggest that 63 patients with stable chest pain would need to undergo CTA to prevent one fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction over 5 years, said Dr. Newby, the BHF John Wheatley professor of cardiology at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland.

He presented 5-year results of the SCOT-HEART study, an open-label trial that randomized 4,146 patients with stable chest pain to standard care plus CTA, or standard care alone. The primary endpoint was nonfatal myocardial infarction or death from coronary heart disease at 5 years. The 3-year results were previously reported.

“This is one of the most impactful studies in cardiovascular medicine. It’s a groundbreaking trial,” commented Todd C. Villines, MD, a designated discussant for the report at the meeting. SCOT-HEART “looked at the additive value of CTA compared with usual care using functional testing with an exercise stress test. It showed that when you visualize coronary atherosclerosis [with CTA] and change medical management based on whether or not plaque is present it drove a significant decrease in MIs,” noted Dr. Villines, a cardiologist affiliated with Georgetown University Medical School in Washington, and immediate past president of the Society of Cardiovascular CT.

Patients were recruited from 12 cardiology centers across Scotland and followed for a mean of 4.8 years, amassing 20,254 patient-years of follow-up. They were a mean of 57 years old; 41% had nonanginal chest pain, 35% typical angina, and 24% atypical angina About half were current or former smokers, a third had hypertension, and half had hypercholesterolemia. Resting EEG was normal in 85%.

Patients who underwent CTA were more likely to start preventive therapies (19% vs. 14.7%; odds ratio, 1.4) and antianginal therapies (13% vs. 10.7%; hazard ratio, 1.27). And although there were more revascularizations in that group early on, the numbers were similar by the end of follow-up (13.5% vs. 13%). After 12 months, CTA patients were 30% less likely to undergo invasive coronary angiography (HR, 0.70) and 41% less likely to undergo a coronary revascularization (HR, 0.59).

“This would be consistent with both the emergence of unrecognized disease and nonfatal myocardial infarction in the standard-care group and the reduction in disease progression in the CTA group owing to the implementation of lifestyle modifications and preventive therapies,” Dr. Newby and colleagues wrote in the NEJM paper.

The composite clinical endpoint occurred in 2.3% of the CTA group and 3.9% of the standard care group – a significant risk differential of 41% (HR, 0.59). The primary driver of this benefit was a significantly lower rate of nonfatal myocardial infarction (HR, 0.60) among CTA patients.

There was no evidence of a subgroup effect, Dr. Newby noted. Among the 48 CTA patients who experienced a clinical event, 22 had obstructive disease, 17 had nonobstructive disease, and three had normal coronary arteries (six patients assigned to the procedure didn’t return for it).

There was a slightly higher event rate among patients with possible angina than among those with nonanginal pain (3.1% vs. 1.8%), but the 5-year difference between the treatment groups was not significantly different.

“Our findings suggest that the use of CTA resulted in more correct diagnoses of coronary heart disease than standard care alone, which, in turn, led to the use of appropriate therapies and this change in management resulted in fewer clinical events in the CTA group than in the standard-care group,” Dr. Newby noted. “Patients who receive a correct diagnosis are also more likely to receive appropriate preventive therapies and may have greater motivation to implement healthy lifestyle modification.”

“The SCOT-HEART data solidify coronary CTA as the best first-line test for patients without established coronary disease,” especially now that a report documented that clinicians worldwide are performing coronary CTA using lower levels of radiation exposure to patients, commented Dr. Villines in an interview. During the same session where Dr. Newby reported the SCOT-HEART results, an international team of researchers reported results of a survey of CTA methods used at 61 centers in 32 countries, including several U.S. sites. The results from the survey showed that in 2017 patients undergoing coronary CTA received a median radiation dose of 2.7 mSv and a median dose-length product of 195 mGy*cm, both representing a 78% relative reduction compared with the median doses received during CTA when a similar survey ran in 2007 (Eur Heart J. 2018 Aug 25; doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehy546).

In contrast, for patients with established coronary artery disease functional tests using stress imaging remain best, Dr. Villines said. “What SCOT-HEART said was that when you use coronary CTA in a population without established coronary disease you can identify not only whether the patient has obstructive disease but do they have coronary atherosclerosis, and that is prognostic and valuable. You miss that with functional testing.”

The Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government funded the study. Dr. Newby has received grants from Seimens. Dr. Villines had no relevant commercial disclosures.

Updated 8/27/18: Mitchel L. Zoler contributed commentary by Dr. Todd C. Villines, and additional data and discussion from the presentation, to this article.

SOURCE: Newby DE et al. NEJM 2018; DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805971.

REPORTING FROM THE ESC CONGRESS 2018

Key clinical point: Coronary computed tomographic angiography reduced the risk of poor cardiovascular outcomes in patients with stable chest pain.

Major finding: Patients who had CTA were 41% less likely to have a nonfatal heart attack or cardiovascular death at 5 years.

Study details: SCOT-HEART randomized 4,146 patients to either CTA or standard diagnostic care.

Disclosures: The Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government funded the study. Dr. Newby has received grants from Seimens.

Source: Newby DE et al. NEJM 2018; DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805971.

ED key to reducing pediatric asthma x-rays

ATLANTA – but accomplishing this goal takes more than a new clinical practice guideline, according to a quality improvement team at the Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

The team eventually reduced the chest x-ray rate for pediatric asthma exacerbations from 30% to 15% without increasing 3-day all-cause readmissions, but it took some sleuthing in the ED and good relations with staff. “We were way out in left field when we started this. Working in silos is never ideal,” said senior project member David Johnson, MD, a pediatric hospitalist and assistant professor of pediatrics at Vanderbilt.

It’s been known for a while that chest x-rays are almost always a waste of time and money for asthma exacerbations, and national guidelines recommend against them. X-rays don’t improve outcomes and needlessly expose children to radiation.

In 2014, some of the providers at Vanderbilt, which has about 1,700 asthma encounters a year, realized that the institution’s 30% x-ray rate was a problem. The quality improvement team hoped a new guideline would address the issue, but that didn’t happen. “We roll out clinical practice guidelines” from on high, “and think people will magically change their behavior,” but they don’t, Dr. Johnson said at the annual Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

The guideline was not being fully implemented. So the team asked the ED what was the standard procedure for a child presenting with asthma exacerbation. It turned out that the ED had a dyspnea order set that the team ”had no idea existed.” Chest x-rays were at the top of the list; next came blood gases, ventilation-perfusion scans, and leg Dopplers, he said.

The investigators tried to get rid of the whole order set but were unsuccessful. The ED department did, however, let the team eliminate chest x-rays in the default order set in July 2015. That helped, but more changes were needed.

The next conversation was to figure out why x-rays were being ordered in the first place. ED staff said they were worried about missing something, especially pneumonia. They also thought they were helping hospitalists by getting x-rays before sending kids to the ward even though, in reality, it didn’t matter whether x-rays were done a few hours later on the floor. ED providers also said that ill-appearing children often got better after a few hours but were kept back from discharge because x-ray results were still pending and that sometimes these results revealed problems at 3 a.m. that had nothing to do with why the patients were in the ED but still required a work-up.

This discussion opened a door. The ED staff didn’t want to order unnecessary x-rays, either. That led to talks about letting kids declare themselves a bit before x-rays were ordered. ED staff liked the idea, so the guidelines were updated in early 2016 to say that chest x-rays should only be ordered if there is persistent severe respiratory distress with hypoxia, there are focal findings that don’t improve after 12 hours of treatment, or there were concerns for pneumomediastinum or collapsed lung. The updated guidelines were posted in work areas and brought home by resident education. A reminder was added to the electronic medical record system that popped up when someone tried to order a chest x-ray for an child with asthma.

It worked. Chest x-ray rates in asthma fell to 15%, and have remained there since.

“We gave them permission to take their foot off the throttle and wait a little bit, and we don’t have more kids bouncing back from reduced x-rays.” The approach is “probably generalizable everywhere,” Dr. Johnson said.

It was essential that an ED fellow, Caroline Watnick, MD, led the effort and eventually bridged the gap between hospitalists and ED providers. In the end, “the change wasn’t something from the outside,” Dr. Johnson said.

There was no industry funding, and Dr. Johnson didn’t have any disclosures. The Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting is sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

ATLANTA – but accomplishing this goal takes more than a new clinical practice guideline, according to a quality improvement team at the Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

The team eventually reduced the chest x-ray rate for pediatric asthma exacerbations from 30% to 15% without increasing 3-day all-cause readmissions, but it took some sleuthing in the ED and good relations with staff. “We were way out in left field when we started this. Working in silos is never ideal,” said senior project member David Johnson, MD, a pediatric hospitalist and assistant professor of pediatrics at Vanderbilt.

It’s been known for a while that chest x-rays are almost always a waste of time and money for asthma exacerbations, and national guidelines recommend against them. X-rays don’t improve outcomes and needlessly expose children to radiation.

In 2014, some of the providers at Vanderbilt, which has about 1,700 asthma encounters a year, realized that the institution’s 30% x-ray rate was a problem. The quality improvement team hoped a new guideline would address the issue, but that didn’t happen. “We roll out clinical practice guidelines” from on high, “and think people will magically change their behavior,” but they don’t, Dr. Johnson said at the annual Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

The guideline was not being fully implemented. So the team asked the ED what was the standard procedure for a child presenting with asthma exacerbation. It turned out that the ED had a dyspnea order set that the team ”had no idea existed.” Chest x-rays were at the top of the list; next came blood gases, ventilation-perfusion scans, and leg Dopplers, he said.

The investigators tried to get rid of the whole order set but were unsuccessful. The ED department did, however, let the team eliminate chest x-rays in the default order set in July 2015. That helped, but more changes were needed.

The next conversation was to figure out why x-rays were being ordered in the first place. ED staff said they were worried about missing something, especially pneumonia. They also thought they were helping hospitalists by getting x-rays before sending kids to the ward even though, in reality, it didn’t matter whether x-rays were done a few hours later on the floor. ED providers also said that ill-appearing children often got better after a few hours but were kept back from discharge because x-ray results were still pending and that sometimes these results revealed problems at 3 a.m. that had nothing to do with why the patients were in the ED but still required a work-up.

This discussion opened a door. The ED staff didn’t want to order unnecessary x-rays, either. That led to talks about letting kids declare themselves a bit before x-rays were ordered. ED staff liked the idea, so the guidelines were updated in early 2016 to say that chest x-rays should only be ordered if there is persistent severe respiratory distress with hypoxia, there are focal findings that don’t improve after 12 hours of treatment, or there were concerns for pneumomediastinum or collapsed lung. The updated guidelines were posted in work areas and brought home by resident education. A reminder was added to the electronic medical record system that popped up when someone tried to order a chest x-ray for an child with asthma.

It worked. Chest x-ray rates in asthma fell to 15%, and have remained there since.

“We gave them permission to take their foot off the throttle and wait a little bit, and we don’t have more kids bouncing back from reduced x-rays.” The approach is “probably generalizable everywhere,” Dr. Johnson said.

It was essential that an ED fellow, Caroline Watnick, MD, led the effort and eventually bridged the gap between hospitalists and ED providers. In the end, “the change wasn’t something from the outside,” Dr. Johnson said.

There was no industry funding, and Dr. Johnson didn’t have any disclosures. The Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting is sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

ATLANTA – but accomplishing this goal takes more than a new clinical practice guideline, according to a quality improvement team at the Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

The team eventually reduced the chest x-ray rate for pediatric asthma exacerbations from 30% to 15% without increasing 3-day all-cause readmissions, but it took some sleuthing in the ED and good relations with staff. “We were way out in left field when we started this. Working in silos is never ideal,” said senior project member David Johnson, MD, a pediatric hospitalist and assistant professor of pediatrics at Vanderbilt.

It’s been known for a while that chest x-rays are almost always a waste of time and money for asthma exacerbations, and national guidelines recommend against them. X-rays don’t improve outcomes and needlessly expose children to radiation.

In 2014, some of the providers at Vanderbilt, which has about 1,700 asthma encounters a year, realized that the institution’s 30% x-ray rate was a problem. The quality improvement team hoped a new guideline would address the issue, but that didn’t happen. “We roll out clinical practice guidelines” from on high, “and think people will magically change their behavior,” but they don’t, Dr. Johnson said at the annual Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

The guideline was not being fully implemented. So the team asked the ED what was the standard procedure for a child presenting with asthma exacerbation. It turned out that the ED had a dyspnea order set that the team ”had no idea existed.” Chest x-rays were at the top of the list; next came blood gases, ventilation-perfusion scans, and leg Dopplers, he said.

The investigators tried to get rid of the whole order set but were unsuccessful. The ED department did, however, let the team eliminate chest x-rays in the default order set in July 2015. That helped, but more changes were needed.

The next conversation was to figure out why x-rays were being ordered in the first place. ED staff said they were worried about missing something, especially pneumonia. They also thought they were helping hospitalists by getting x-rays before sending kids to the ward even though, in reality, it didn’t matter whether x-rays were done a few hours later on the floor. ED providers also said that ill-appearing children often got better after a few hours but were kept back from discharge because x-ray results were still pending and that sometimes these results revealed problems at 3 a.m. that had nothing to do with why the patients were in the ED but still required a work-up.

This discussion opened a door. The ED staff didn’t want to order unnecessary x-rays, either. That led to talks about letting kids declare themselves a bit before x-rays were ordered. ED staff liked the idea, so the guidelines were updated in early 2016 to say that chest x-rays should only be ordered if there is persistent severe respiratory distress with hypoxia, there are focal findings that don’t improve after 12 hours of treatment, or there were concerns for pneumomediastinum or collapsed lung. The updated guidelines were posted in work areas and brought home by resident education. A reminder was added to the electronic medical record system that popped up when someone tried to order a chest x-ray for an child with asthma.

It worked. Chest x-ray rates in asthma fell to 15%, and have remained there since.

“We gave them permission to take their foot off the throttle and wait a little bit, and we don’t have more kids bouncing back from reduced x-rays.” The approach is “probably generalizable everywhere,” Dr. Johnson said.

It was essential that an ED fellow, Caroline Watnick, MD, led the effort and eventually bridged the gap between hospitalists and ED providers. In the end, “the change wasn’t something from the outside,” Dr. Johnson said.

There was no industry funding, and Dr. Johnson didn’t have any disclosures. The Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting is sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

REPORTING FROM PHM 2018

Key clinical point: Reduction of chest x-rays for routine pediatric asthma exacerbations in the ED can be accomplished with a team effort.

Major finding: A team project reduced x-rays for pediatric asthma exacerbations from 30% to 15% without increasing 3-day, all-cause readmissions.

Study details: Pre/post quality improvement analysis of asthma encounters in the Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital, Nashville, Tenn., starting in 2014.

Disclosures: There was no industry funding, and the presenter didn’t have any disclosures.

Neuroimaging may often be unneeded in ED seizure treatment

Neuroimaging may be appropriate only for specific types of patients with recurrent seizures who present at emergency departments because the scans are otherwise unlikely to prompt acute changes in treatment, a new multicenter study suggests.

“Going forward, our results should help ED providers determine which patients are more likely to derive benefit from neuroimaging and which patients are not likely to benefit,” lead author Martin Salinsky, MD, of Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said in an interview. “They can be more selective in ordering scans and reduce the total number obtained.”

As the study authors noted in their report, published July 18 in Epilepsia, “head CT is generally considered a benign procedure. However, overuse is problematic.”

The scans are costly and expose patients to radiation equivalent to 10 chest x-rays, the authors wrote. Scans can complicate care by clogging ED work flow and producing false positives, and patients often seize while undergoing scans, creating even more complications, they added.

“There is very little information in the medical literature that would help guide ED providers in their decision of whether to obtain neuroimaging on a patient who presents with a recurrent seizure,” Dr. Salinsky said. “Without this information, the tendency is to be cautious and obtain scans in more patients.”

For the study, the researchers tracked 822 consecutive ED visits for nonindex – recurrent – epileptic seizures at Oregon Health & Science University and VA Portland Health Care medical centers. (Nonindex seizures accounted for 78% of the total seizures that prompted ED care.)

The study subjects were adults treated for seizure as the main complaint. Patients who had a history of seizures but hadn’t had one for at least 5 years were excluded.

Of the total nonindex seizures, 46% of those resulted in neuroimaging.

“The overall yield of neuroimaging in this patient group was 2%-3%,” Dr. Salinsky said, referring to the percentage of patients whose scans resulted in an acute change in management.

False positives due to imaging artifacts were subsequently discovered in 3 of the 11 patients whose neuroimaging prompted an acute change in management. When the false positives were removed, the yield of acute management changes prompted by neuroimaging decreased to 2.1% overall.

“Three clinical factors – acute head trauma, prolonged alteration of consciousness, and focal neurological examination [at presentation] – were associated with an increased yield of imaging,” he said. “Absent all three factors, the yield in our patients was zero.”

At the two medical centers, the percentages of patients with acute head trauma were 10% and 15%. Prolonged alteration of consciousness occurred in 6% at both centers, and focal neurological examination at presentation was observed in 12% and 14%.

A fourth factor, presentation with status epilepticus/acute repetitive seizures, “bordered on statistical significance and might have reached significance in a larger series,” the authors wrote.

As they put it, “these results support a more conservative use of ED neuroimaging for nonindex seizures, based on clinical factors at the time of presentation. ... without specific indications, ED neuroimaging for nonindex seizures is unlikely to result in an acute change in care.”

The study authors estimated that hundreds of millions of dollars could be saved annually in the United States if neuroimaging in these ED patients could be cut in half.

No study funding was reported, and the authors reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Salinsky M et al. Epilepsia. 2018 July 18. doi: 10.1111/epi.14518

Neuroimaging may be appropriate only for specific types of patients with recurrent seizures who present at emergency departments because the scans are otherwise unlikely to prompt acute changes in treatment, a new multicenter study suggests.

“Going forward, our results should help ED providers determine which patients are more likely to derive benefit from neuroimaging and which patients are not likely to benefit,” lead author Martin Salinsky, MD, of Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said in an interview. “They can be more selective in ordering scans and reduce the total number obtained.”

As the study authors noted in their report, published July 18 in Epilepsia, “head CT is generally considered a benign procedure. However, overuse is problematic.”

The scans are costly and expose patients to radiation equivalent to 10 chest x-rays, the authors wrote. Scans can complicate care by clogging ED work flow and producing false positives, and patients often seize while undergoing scans, creating even more complications, they added.

“There is very little information in the medical literature that would help guide ED providers in their decision of whether to obtain neuroimaging on a patient who presents with a recurrent seizure,” Dr. Salinsky said. “Without this information, the tendency is to be cautious and obtain scans in more patients.”

For the study, the researchers tracked 822 consecutive ED visits for nonindex – recurrent – epileptic seizures at Oregon Health & Science University and VA Portland Health Care medical centers. (Nonindex seizures accounted for 78% of the total seizures that prompted ED care.)

The study subjects were adults treated for seizure as the main complaint. Patients who had a history of seizures but hadn’t had one for at least 5 years were excluded.

Of the total nonindex seizures, 46% of those resulted in neuroimaging.

“The overall yield of neuroimaging in this patient group was 2%-3%,” Dr. Salinsky said, referring to the percentage of patients whose scans resulted in an acute change in management.

False positives due to imaging artifacts were subsequently discovered in 3 of the 11 patients whose neuroimaging prompted an acute change in management. When the false positives were removed, the yield of acute management changes prompted by neuroimaging decreased to 2.1% overall.

“Three clinical factors – acute head trauma, prolonged alteration of consciousness, and focal neurological examination [at presentation] – were associated with an increased yield of imaging,” he said. “Absent all three factors, the yield in our patients was zero.”

At the two medical centers, the percentages of patients with acute head trauma were 10% and 15%. Prolonged alteration of consciousness occurred in 6% at both centers, and focal neurological examination at presentation was observed in 12% and 14%.

A fourth factor, presentation with status epilepticus/acute repetitive seizures, “bordered on statistical significance and might have reached significance in a larger series,” the authors wrote.

As they put it, “these results support a more conservative use of ED neuroimaging for nonindex seizures, based on clinical factors at the time of presentation. ... without specific indications, ED neuroimaging for nonindex seizures is unlikely to result in an acute change in care.”

The study authors estimated that hundreds of millions of dollars could be saved annually in the United States if neuroimaging in these ED patients could be cut in half.

No study funding was reported, and the authors reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Salinsky M et al. Epilepsia. 2018 July 18. doi: 10.1111/epi.14518

Neuroimaging may be appropriate only for specific types of patients with recurrent seizures who present at emergency departments because the scans are otherwise unlikely to prompt acute changes in treatment, a new multicenter study suggests.

“Going forward, our results should help ED providers determine which patients are more likely to derive benefit from neuroimaging and which patients are not likely to benefit,” lead author Martin Salinsky, MD, of Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said in an interview. “They can be more selective in ordering scans and reduce the total number obtained.”

As the study authors noted in their report, published July 18 in Epilepsia, “head CT is generally considered a benign procedure. However, overuse is problematic.”

The scans are costly and expose patients to radiation equivalent to 10 chest x-rays, the authors wrote. Scans can complicate care by clogging ED work flow and producing false positives, and patients often seize while undergoing scans, creating even more complications, they added.

“There is very little information in the medical literature that would help guide ED providers in their decision of whether to obtain neuroimaging on a patient who presents with a recurrent seizure,” Dr. Salinsky said. “Without this information, the tendency is to be cautious and obtain scans in more patients.”

For the study, the researchers tracked 822 consecutive ED visits for nonindex – recurrent – epileptic seizures at Oregon Health & Science University and VA Portland Health Care medical centers. (Nonindex seizures accounted for 78% of the total seizures that prompted ED care.)

The study subjects were adults treated for seizure as the main complaint. Patients who had a history of seizures but hadn’t had one for at least 5 years were excluded.

Of the total nonindex seizures, 46% of those resulted in neuroimaging.

“The overall yield of neuroimaging in this patient group was 2%-3%,” Dr. Salinsky said, referring to the percentage of patients whose scans resulted in an acute change in management.

False positives due to imaging artifacts were subsequently discovered in 3 of the 11 patients whose neuroimaging prompted an acute change in management. When the false positives were removed, the yield of acute management changes prompted by neuroimaging decreased to 2.1% overall.

“Three clinical factors – acute head trauma, prolonged alteration of consciousness, and focal neurological examination [at presentation] – were associated with an increased yield of imaging,” he said. “Absent all three factors, the yield in our patients was zero.”

At the two medical centers, the percentages of patients with acute head trauma were 10% and 15%. Prolonged alteration of consciousness occurred in 6% at both centers, and focal neurological examination at presentation was observed in 12% and 14%.

A fourth factor, presentation with status epilepticus/acute repetitive seizures, “bordered on statistical significance and might have reached significance in a larger series,” the authors wrote.

As they put it, “these results support a more conservative use of ED neuroimaging for nonindex seizures, based on clinical factors at the time of presentation. ... without specific indications, ED neuroimaging for nonindex seizures is unlikely to result in an acute change in care.”

The study authors estimated that hundreds of millions of dollars could be saved annually in the United States if neuroimaging in these ED patients could be cut in half.

No study funding was reported, and the authors reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Salinsky M et al. Epilepsia. 2018 July 18. doi: 10.1111/epi.14518

FROM EPILEPSIA

Key clinical point: In emergency departments, patients with seizure disorders and nonindex seizures may need neuroimaging only if they have acute head trauma, prolonged alteration of consciousness, or focal neurological examination at presentation.

Major finding: Absent the three factors above, neuroimaging did not prompt any acute changes in management.

Study details: Retrospective examination of 822 consecutive ED visits for nonindex seizures in patients with seizure disorders at two medical centers.

Disclosures: No study funding was reported, and the study authors reported no relevant disclosures.

Source: Salinsky M et al. Epilepsia. 2018 Jul 18. doi: 10.1111/epi.14518.

High users of CT pulmonary angiograms have lower diagnostic yields

Clinical question: What physician characteristics are associated with CT pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) diagnostic yield?

Background: Overuse of CTPAs for pulmonary embolism evaluation exposes patients to unnecessary testing and harmful ionizing radiation. Physician characteristics influence ordering practice. Identifying specific characteristics can provide an intervention for reducing overutilization.

Study design: Retrospective analysis.

Setting: Academic teaching hospital in Montreal, Canada.

Synopsis: Investigators reviewed 1,394 CTPAs ordered by 182 physicians at an academic teaching hospital during 2014-2016, with 199 (14.3%) positive studies and 1,195 (85.7%) negative studies. Physician years of experience, physician sex, and emergency medicine specialty were not associated with diagnostic yield. However, the diagnostic yield decreased with the total number of scans ordered per physician. For every 10 additional scans ordered, the odds of a positive test were reduced (odds ratio, 0.76; 95% confidence interval, 0.73-0.79). For physicians who ordered more than 50 studies, the percentage of positive studies was only 5%.

This study’s results show that overuse of CTPA is associated with decreased diagnostic yield. A limitation of the study was that pretest probabilities for pulmonary embolism could not be calculated because of inadequate charting, which would have determined whether CTPA was the appropriate test (as opposed to D-dimer).

Bottom line: Physicians who order higher numbers of CTPAs have lower diagnostic yields.

Citation: Chong J et al. Association of lower diagnostic yield with high users of CT pulmonary angiogram. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Mar 1;178(3):412-3.

Dr. Komsoukaniants is a hospitalist at UC San Diego Health and an assistant clinical professor at the University of California, San Diego.

Clinical question: What physician characteristics are associated with CT pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) diagnostic yield?

Background: Overuse of CTPAs for pulmonary embolism evaluation exposes patients to unnecessary testing and harmful ionizing radiation. Physician characteristics influence ordering practice. Identifying specific characteristics can provide an intervention for reducing overutilization.

Study design: Retrospective analysis.

Setting: Academic teaching hospital in Montreal, Canada.

Synopsis: Investigators reviewed 1,394 CTPAs ordered by 182 physicians at an academic teaching hospital during 2014-2016, with 199 (14.3%) positive studies and 1,195 (85.7%) negative studies. Physician years of experience, physician sex, and emergency medicine specialty were not associated with diagnostic yield. However, the diagnostic yield decreased with the total number of scans ordered per physician. For every 10 additional scans ordered, the odds of a positive test were reduced (odds ratio, 0.76; 95% confidence interval, 0.73-0.79). For physicians who ordered more than 50 studies, the percentage of positive studies was only 5%.

This study’s results show that overuse of CTPA is associated with decreased diagnostic yield. A limitation of the study was that pretest probabilities for pulmonary embolism could not be calculated because of inadequate charting, which would have determined whether CTPA was the appropriate test (as opposed to D-dimer).

Bottom line: Physicians who order higher numbers of CTPAs have lower diagnostic yields.

Citation: Chong J et al. Association of lower diagnostic yield with high users of CT pulmonary angiogram. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Mar 1;178(3):412-3.

Dr. Komsoukaniants is a hospitalist at UC San Diego Health and an assistant clinical professor at the University of California, San Diego.

Clinical question: What physician characteristics are associated with CT pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) diagnostic yield?

Background: Overuse of CTPAs for pulmonary embolism evaluation exposes patients to unnecessary testing and harmful ionizing radiation. Physician characteristics influence ordering practice. Identifying specific characteristics can provide an intervention for reducing overutilization.

Study design: Retrospective analysis.

Setting: Academic teaching hospital in Montreal, Canada.

Synopsis: Investigators reviewed 1,394 CTPAs ordered by 182 physicians at an academic teaching hospital during 2014-2016, with 199 (14.3%) positive studies and 1,195 (85.7%) negative studies. Physician years of experience, physician sex, and emergency medicine specialty were not associated with diagnostic yield. However, the diagnostic yield decreased with the total number of scans ordered per physician. For every 10 additional scans ordered, the odds of a positive test were reduced (odds ratio, 0.76; 95% confidence interval, 0.73-0.79). For physicians who ordered more than 50 studies, the percentage of positive studies was only 5%.

This study’s results show that overuse of CTPA is associated with decreased diagnostic yield. A limitation of the study was that pretest probabilities for pulmonary embolism could not be calculated because of inadequate charting, which would have determined whether CTPA was the appropriate test (as opposed to D-dimer).

Bottom line: Physicians who order higher numbers of CTPAs have lower diagnostic yields.

Citation: Chong J et al. Association of lower diagnostic yield with high users of CT pulmonary angiogram. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Mar 1;178(3):412-3.

Dr. Komsoukaniants is a hospitalist at UC San Diego Health and an assistant clinical professor at the University of California, San Diego.

Osmotic demyelination syndrome due to hyperosmolar hyperglycemia

A 55-year-old man with a 20-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus was admitted to the hospital after presenting to the emergency department with an acute change in mental status. Three days earlier, he had begun to feel abdominal discomfort and dizziness, which gradually worsened.

On presentation, his Glasgow Coma Scale score was 13 out of 15 (eye-opening response 3 of 4, verbal response 4 of 5, motor response 6 of 6), his blood pressure was 221/114 mm Hg, and other vital signs were normal. Physical examination including a neurologic examination was normal. No gait abnormality or ataxia was noted.

When asked about current medications, he said that 2 years earlier he had missed an appointment with his primary care physician and so had never obtained refills of his diabetes medications.

Results of laboratory testing were as follows:

- Blood glucose 1,011 mg/dL (reference range 65–110)

- Hemoglobin A1c 17.8% (4%–5.6%)

- Sodium 126 mmol/L (135–145)

- Sodium corrected for serum glucose 141 mmol/L

- Potassium 3.2 mmol/L (3.5–5.0)

- Blood urea nitrogen 43.8 mg/dL (8–21)

- Calculated serum osmolality 324 mosm/kg (275–295).

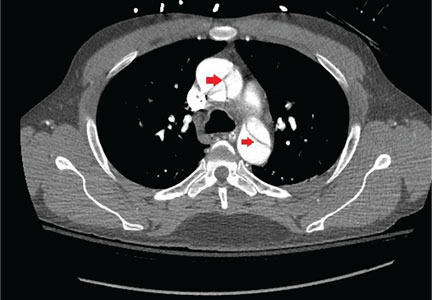

Blood gas analysis showed no acidosis. Tests for urinary and serum ketones were negative. Computed tomography (CT) of the head without contrast was normal.

Based on the results of the evaluation, the patient’s condition was diagnosed as a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state, presumably from dehydration and noncompliance with diabetes medications. His altered mental status was also attributed to this diagnosis. He was started on aggressive hydration and insulin infusion to correct the blood glucose level. Repeat laboratory testing 7 hours after admission revealed a blood glucose of 49 mg/dL, sodium 148 mmol/L, blood urea nitrogen 43 mg/dL, and calculated serum osmolality 290 mosm/kg.

The insulin infusion was suspended, and glucose infusion was started. With this treatment, his blood glucose level stabilized, but his Glasgow Coma Scale score was unchanged from the time of presentation. A neurologic examination at this time showed bilateral dysmetria. Cranial nerves were normal. Motor examination showed normal tone with a Medical Research Council score of 5 of 5 in all extremities. Sensory examination revealed a glove-and-stocking pattern of loss of vibratory sensation. Tendon reflexes were normal except for diminished bilateral knee-jerk and ankle-jerk responses.

OSMOTIC DEMYELINATION SYNDROME

Central pontine myelinolysis is a pivotal manifestation of the syndrome and is characterized by progressive lethargy, quadriparesis, dysarthria, ophthalmoplegia, dysphasia, ataxia, and reflex changes. Clinical symptoms of extrapontine myelinolysis are variable.4

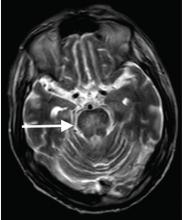

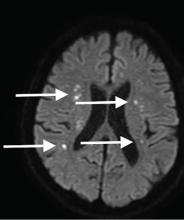

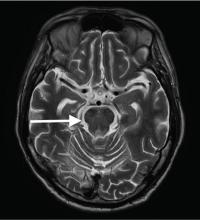

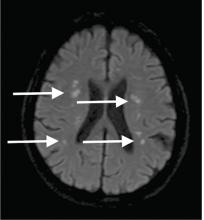

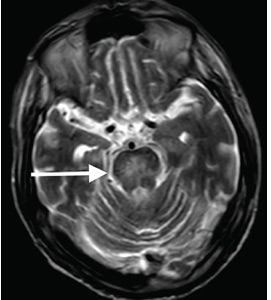

Although CT may underestimate osmotic demyelination syndrome, the typical radiologic findings on brain MRI are hyperintense lesions in the central pons or associated extrapontine structures on T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences.4

A precise definition of hyperosmolar hyperglycemia does not exist. The Joint British Diabetes Societies for Inpatient Care suggested the following features: a measured osmolality of 320 mosm/kg or higher, a blood glucose level of 541 mg/dL or higher, severe dehydration, and feeling unwell.5

Our patient’s clinical course and high hemoglobin A1c suggested prolonged hyperglycemia and high serum osmolality before his admission. After his admission, aggressive hydration and insulin therapy corrected the hyperglycemia and serum osmolality too rapidly for his brain cells to adjust to the change. It was reasonable to suspect a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state as one of the main causes of his mental status change and ataxia. This, along with lack of improvement in his impaired metal status and new-onset ataxia despite treatment, led to suspicion of osmotic demyelination syndrome. His diminished bilateral knee-jerk and ankle-jerk responses more likely represented diabetic neuropathy rather than osmotic demyelination syndrome.

Osmotic demyelination syndrome has seldom been reported as a complication of hyperosmolar hyperglycemia.6–13 And extrapontine myelinolysis with hyperosmolar hyperglycemia is extremely rare, with only 2 reports to date to the best of our knowledge.6,10

There is no specific treatment for osmotic demyelination syndrome except for supportive care and treatment of coexisting conditions. Once an osmotic derangement is identified, we recommend correcting chronically elevated serum glucose values gradually to avoid overtreatment, just as we would do with elevated serum sodium levels. Changes in neurologic findings, serum blood glucose level, and serum osmolality should be followed closely. A review showed that a favorable recovery from osmotic demyelination syndrome is possible even with severe neurologic deficits.4

TAKE-AWAY POINTS

- Osmotic demyelination syndrome is a rare but severe complication of a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state.

- Physicians should be aware not only of changes in serum sodium, but also of changes in serum osmolality and serum glucose.

- When a new-onset neurologic deficit is found during treatment of a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state, suspect osmotic demyelination syndrome, monitor changes in serum osmolality, and consider brain MRI.

- Brown WD. Osmotic demyelination disorders: central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis. Curr Opin Neurol 2000; 13(6):691–697. pmid:11148672

- Laureno R, Karp BI. Myelinolysis after correction of hyponatraemia. Ann Intern Med 1997; 126(1):57–62. pmid:8992924

- Adams RD, Victor M, Mancall EL. Central pontine myelinolysis: a hitherto undescribed disease occurring in alcoholic and malnourished patients. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry 1959; 81(2):154–172. pmid:13616772

- Singh TD, Fugate JE, Rabinstein AA. Central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis: a systematic review. Eur J Neurol 2014; 21(12):1443–1450. doi:10.1111/ene.12571

- Scott AR; Joint British Diabetes Societies (JBDS) for Inpatient Care; JBDS Hyperosmolar Hyperglycaemic Guidelines Group. Management of hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state in adults with diabetes. Diabet Med 2015; 32(6):714–724. doi:10.1111/dme.12757

- McComb RD, Pfeiffer RF, Casey JH, Wolcott G, Till DJ. Lateral pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis associated with hypernatremia and hyperglycemia. Clin Neuropathol 1989; 8(6):284–288. pmid:2695277

- O’Malley G, Moran C, Draman MS, et al. Central pontine myelinolysis complicating treatment of the hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar state. Ann Clin Biochem 2008; 45(pt 4):440–443. doi:10.1258/acb.2008.007171

- Burns JD, Kosa SC, Wijdicks EF. Central pontine myelinolysis in a patient with hyperosmolar hyperglycemia and consistently normal serum sodium. Neurocrit Care 2009; 11(2):251–254. doi:10.1007/s12028-009-9241-9

- Mao S, Liu Z, Ding M. Central pontine myelinolysis in a patient with epilepsia partialis continua and hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar state. Ann Clin Biochem 2011; 48(pt 1):79–82. doi:10.1258/acb.2010.010152. Epub 2010 Nov 23.

- Guerrero WR, Dababneh H, Nadeau SE. Hemiparesis, encephalopathy, and extrapontine osmotic myelinolysis in the setting of hyperosmolar hyperglycemia. J Clin Neurosci 2013; 20(6):894–896. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2012.05.045

- Hegazi MO, Mashankar A. Central pontine myelinolysis in the hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state. Med Princ Pract 2013; 22(1):96–99. doi:10.1159/000341718

- Rodríguez-Velver KV, Soto-Garcia AJ, Zapata-Rivera MA, Montes-Villarreal J, Villarreal-Pérez JZ, Rodríguez-Gutiérrez R. Osmotic demyelination syndrome as the initial manifestation of a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state. Case Rep Neurol Med 2014; 2014:652523. doi:10.1155/2014/652523

- Chang YM. Central pontine myelinolysis associated with diabetic hyperglycemia. JSM Clin Case Rep 2014; 2(6):1059.

A 55-year-old man with a 20-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus was admitted to the hospital after presenting to the emergency department with an acute change in mental status. Three days earlier, he had begun to feel abdominal discomfort and dizziness, which gradually worsened.

On presentation, his Glasgow Coma Scale score was 13 out of 15 (eye-opening response 3 of 4, verbal response 4 of 5, motor response 6 of 6), his blood pressure was 221/114 mm Hg, and other vital signs were normal. Physical examination including a neurologic examination was normal. No gait abnormality or ataxia was noted.

When asked about current medications, he said that 2 years earlier he had missed an appointment with his primary care physician and so had never obtained refills of his diabetes medications.

Results of laboratory testing were as follows:

- Blood glucose 1,011 mg/dL (reference range 65–110)

- Hemoglobin A1c 17.8% (4%–5.6%)

- Sodium 126 mmol/L (135–145)

- Sodium corrected for serum glucose 141 mmol/L

- Potassium 3.2 mmol/L (3.5–5.0)

- Blood urea nitrogen 43.8 mg/dL (8–21)

- Calculated serum osmolality 324 mosm/kg (275–295).

Blood gas analysis showed no acidosis. Tests for urinary and serum ketones were negative. Computed tomography (CT) of the head without contrast was normal.

Based on the results of the evaluation, the patient’s condition was diagnosed as a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state, presumably from dehydration and noncompliance with diabetes medications. His altered mental status was also attributed to this diagnosis. He was started on aggressive hydration and insulin infusion to correct the blood glucose level. Repeat laboratory testing 7 hours after admission revealed a blood glucose of 49 mg/dL, sodium 148 mmol/L, blood urea nitrogen 43 mg/dL, and calculated serum osmolality 290 mosm/kg.

The insulin infusion was suspended, and glucose infusion was started. With this treatment, his blood glucose level stabilized, but his Glasgow Coma Scale score was unchanged from the time of presentation. A neurologic examination at this time showed bilateral dysmetria. Cranial nerves were normal. Motor examination showed normal tone with a Medical Research Council score of 5 of 5 in all extremities. Sensory examination revealed a glove-and-stocking pattern of loss of vibratory sensation. Tendon reflexes were normal except for diminished bilateral knee-jerk and ankle-jerk responses.

OSMOTIC DEMYELINATION SYNDROME

Central pontine myelinolysis is a pivotal manifestation of the syndrome and is characterized by progressive lethargy, quadriparesis, dysarthria, ophthalmoplegia, dysphasia, ataxia, and reflex changes. Clinical symptoms of extrapontine myelinolysis are variable.4

Although CT may underestimate osmotic demyelination syndrome, the typical radiologic findings on brain MRI are hyperintense lesions in the central pons or associated extrapontine structures on T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences.4

A precise definition of hyperosmolar hyperglycemia does not exist. The Joint British Diabetes Societies for Inpatient Care suggested the following features: a measured osmolality of 320 mosm/kg or higher, a blood glucose level of 541 mg/dL or higher, severe dehydration, and feeling unwell.5

Our patient’s clinical course and high hemoglobin A1c suggested prolonged hyperglycemia and high serum osmolality before his admission. After his admission, aggressive hydration and insulin therapy corrected the hyperglycemia and serum osmolality too rapidly for his brain cells to adjust to the change. It was reasonable to suspect a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state as one of the main causes of his mental status change and ataxia. This, along with lack of improvement in his impaired metal status and new-onset ataxia despite treatment, led to suspicion of osmotic demyelination syndrome. His diminished bilateral knee-jerk and ankle-jerk responses more likely represented diabetic neuropathy rather than osmotic demyelination syndrome.

Osmotic demyelination syndrome has seldom been reported as a complication of hyperosmolar hyperglycemia.6–13 And extrapontine myelinolysis with hyperosmolar hyperglycemia is extremely rare, with only 2 reports to date to the best of our knowledge.6,10

There is no specific treatment for osmotic demyelination syndrome except for supportive care and treatment of coexisting conditions. Once an osmotic derangement is identified, we recommend correcting chronically elevated serum glucose values gradually to avoid overtreatment, just as we would do with elevated serum sodium levels. Changes in neurologic findings, serum blood glucose level, and serum osmolality should be followed closely. A review showed that a favorable recovery from osmotic demyelination syndrome is possible even with severe neurologic deficits.4

TAKE-AWAY POINTS

- Osmotic demyelination syndrome is a rare but severe complication of a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state.

- Physicians should be aware not only of changes in serum sodium, but also of changes in serum osmolality and serum glucose.

- When a new-onset neurologic deficit is found during treatment of a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state, suspect osmotic demyelination syndrome, monitor changes in serum osmolality, and consider brain MRI.

A 55-year-old man with a 20-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus was admitted to the hospital after presenting to the emergency department with an acute change in mental status. Three days earlier, he had begun to feel abdominal discomfort and dizziness, which gradually worsened.

On presentation, his Glasgow Coma Scale score was 13 out of 15 (eye-opening response 3 of 4, verbal response 4 of 5, motor response 6 of 6), his blood pressure was 221/114 mm Hg, and other vital signs were normal. Physical examination including a neurologic examination was normal. No gait abnormality or ataxia was noted.

When asked about current medications, he said that 2 years earlier he had missed an appointment with his primary care physician and so had never obtained refills of his diabetes medications.

Results of laboratory testing were as follows:

- Blood glucose 1,011 mg/dL (reference range 65–110)

- Hemoglobin A1c 17.8% (4%–5.6%)

- Sodium 126 mmol/L (135–145)

- Sodium corrected for serum glucose 141 mmol/L

- Potassium 3.2 mmol/L (3.5–5.0)

- Blood urea nitrogen 43.8 mg/dL (8–21)

- Calculated serum osmolality 324 mosm/kg (275–295).

Blood gas analysis showed no acidosis. Tests for urinary and serum ketones were negative. Computed tomography (CT) of the head without contrast was normal.

Based on the results of the evaluation, the patient’s condition was diagnosed as a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state, presumably from dehydration and noncompliance with diabetes medications. His altered mental status was also attributed to this diagnosis. He was started on aggressive hydration and insulin infusion to correct the blood glucose level. Repeat laboratory testing 7 hours after admission revealed a blood glucose of 49 mg/dL, sodium 148 mmol/L, blood urea nitrogen 43 mg/dL, and calculated serum osmolality 290 mosm/kg.

The insulin infusion was suspended, and glucose infusion was started. With this treatment, his blood glucose level stabilized, but his Glasgow Coma Scale score was unchanged from the time of presentation. A neurologic examination at this time showed bilateral dysmetria. Cranial nerves were normal. Motor examination showed normal tone with a Medical Research Council score of 5 of 5 in all extremities. Sensory examination revealed a glove-and-stocking pattern of loss of vibratory sensation. Tendon reflexes were normal except for diminished bilateral knee-jerk and ankle-jerk responses.

OSMOTIC DEMYELINATION SYNDROME

Central pontine myelinolysis is a pivotal manifestation of the syndrome and is characterized by progressive lethargy, quadriparesis, dysarthria, ophthalmoplegia, dysphasia, ataxia, and reflex changes. Clinical symptoms of extrapontine myelinolysis are variable.4

Although CT may underestimate osmotic demyelination syndrome, the typical radiologic findings on brain MRI are hyperintense lesions in the central pons or associated extrapontine structures on T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences.4

A precise definition of hyperosmolar hyperglycemia does not exist. The Joint British Diabetes Societies for Inpatient Care suggested the following features: a measured osmolality of 320 mosm/kg or higher, a blood glucose level of 541 mg/dL or higher, severe dehydration, and feeling unwell.5

Our patient’s clinical course and high hemoglobin A1c suggested prolonged hyperglycemia and high serum osmolality before his admission. After his admission, aggressive hydration and insulin therapy corrected the hyperglycemia and serum osmolality too rapidly for his brain cells to adjust to the change. It was reasonable to suspect a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state as one of the main causes of his mental status change and ataxia. This, along with lack of improvement in his impaired metal status and new-onset ataxia despite treatment, led to suspicion of osmotic demyelination syndrome. His diminished bilateral knee-jerk and ankle-jerk responses more likely represented diabetic neuropathy rather than osmotic demyelination syndrome.

Osmotic demyelination syndrome has seldom been reported as a complication of hyperosmolar hyperglycemia.6–13 And extrapontine myelinolysis with hyperosmolar hyperglycemia is extremely rare, with only 2 reports to date to the best of our knowledge.6,10

There is no specific treatment for osmotic demyelination syndrome except for supportive care and treatment of coexisting conditions. Once an osmotic derangement is identified, we recommend correcting chronically elevated serum glucose values gradually to avoid overtreatment, just as we would do with elevated serum sodium levels. Changes in neurologic findings, serum blood glucose level, and serum osmolality should be followed closely. A review showed that a favorable recovery from osmotic demyelination syndrome is possible even with severe neurologic deficits.4

TAKE-AWAY POINTS

- Osmotic demyelination syndrome is a rare but severe complication of a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state.

- Physicians should be aware not only of changes in serum sodium, but also of changes in serum osmolality and serum glucose.

- When a new-onset neurologic deficit is found during treatment of a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state, suspect osmotic demyelination syndrome, monitor changes in serum osmolality, and consider brain MRI.

- Brown WD. Osmotic demyelination disorders: central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis. Curr Opin Neurol 2000; 13(6):691–697. pmid:11148672

- Laureno R, Karp BI. Myelinolysis after correction of hyponatraemia. Ann Intern Med 1997; 126(1):57–62. pmid:8992924

- Adams RD, Victor M, Mancall EL. Central pontine myelinolysis: a hitherto undescribed disease occurring in alcoholic and malnourished patients. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry 1959; 81(2):154–172. pmid:13616772

- Singh TD, Fugate JE, Rabinstein AA. Central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis: a systematic review. Eur J Neurol 2014; 21(12):1443–1450. doi:10.1111/ene.12571

- Scott AR; Joint British Diabetes Societies (JBDS) for Inpatient Care; JBDS Hyperosmolar Hyperglycaemic Guidelines Group. Management of hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state in adults with diabetes. Diabet Med 2015; 32(6):714–724. doi:10.1111/dme.12757

- McComb RD, Pfeiffer RF, Casey JH, Wolcott G, Till DJ. Lateral pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis associated with hypernatremia and hyperglycemia. Clin Neuropathol 1989; 8(6):284–288. pmid:2695277

- O’Malley G, Moran C, Draman MS, et al. Central pontine myelinolysis complicating treatment of the hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar state. Ann Clin Biochem 2008; 45(pt 4):440–443. doi:10.1258/acb.2008.007171

- Burns JD, Kosa SC, Wijdicks EF. Central pontine myelinolysis in a patient with hyperosmolar hyperglycemia and consistently normal serum sodium. Neurocrit Care 2009; 11(2):251–254. doi:10.1007/s12028-009-9241-9

- Mao S, Liu Z, Ding M. Central pontine myelinolysis in a patient with epilepsia partialis continua and hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar state. Ann Clin Biochem 2011; 48(pt 1):79–82. doi:10.1258/acb.2010.010152. Epub 2010 Nov 23.

- Guerrero WR, Dababneh H, Nadeau SE. Hemiparesis, encephalopathy, and extrapontine osmotic myelinolysis in the setting of hyperosmolar hyperglycemia. J Clin Neurosci 2013; 20(6):894–896. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2012.05.045

- Hegazi MO, Mashankar A. Central pontine myelinolysis in the hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state. Med Princ Pract 2013; 22(1):96–99. doi:10.1159/000341718

- Rodríguez-Velver KV, Soto-Garcia AJ, Zapata-Rivera MA, Montes-Villarreal J, Villarreal-Pérez JZ, Rodríguez-Gutiérrez R. Osmotic demyelination syndrome as the initial manifestation of a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state. Case Rep Neurol Med 2014; 2014:652523. doi:10.1155/2014/652523

- Chang YM. Central pontine myelinolysis associated with diabetic hyperglycemia. JSM Clin Case Rep 2014; 2(6):1059.

- Brown WD. Osmotic demyelination disorders: central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis. Curr Opin Neurol 2000; 13(6):691–697. pmid:11148672

- Laureno R, Karp BI. Myelinolysis after correction of hyponatraemia. Ann Intern Med 1997; 126(1):57–62. pmid:8992924

- Adams RD, Victor M, Mancall EL. Central pontine myelinolysis: a hitherto undescribed disease occurring in alcoholic and malnourished patients. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry 1959; 81(2):154–172. pmid:13616772

- Singh TD, Fugate JE, Rabinstein AA. Central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis: a systematic review. Eur J Neurol 2014; 21(12):1443–1450. doi:10.1111/ene.12571

- Scott AR; Joint British Diabetes Societies (JBDS) for Inpatient Care; JBDS Hyperosmolar Hyperglycaemic Guidelines Group. Management of hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state in adults with diabetes. Diabet Med 2015; 32(6):714–724. doi:10.1111/dme.12757

- McComb RD, Pfeiffer RF, Casey JH, Wolcott G, Till DJ. Lateral pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis associated with hypernatremia and hyperglycemia. Clin Neuropathol 1989; 8(6):284–288. pmid:2695277

- O’Malley G, Moran C, Draman MS, et al. Central pontine myelinolysis complicating treatment of the hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar state. Ann Clin Biochem 2008; 45(pt 4):440–443. doi:10.1258/acb.2008.007171

- Burns JD, Kosa SC, Wijdicks EF. Central pontine myelinolysis in a patient with hyperosmolar hyperglycemia and consistently normal serum sodium. Neurocrit Care 2009; 11(2):251–254. doi:10.1007/s12028-009-9241-9

- Mao S, Liu Z, Ding M. Central pontine myelinolysis in a patient with epilepsia partialis continua and hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar state. Ann Clin Biochem 2011; 48(pt 1):79–82. doi:10.1258/acb.2010.010152. Epub 2010 Nov 23.

- Guerrero WR, Dababneh H, Nadeau SE. Hemiparesis, encephalopathy, and extrapontine osmotic myelinolysis in the setting of hyperosmolar hyperglycemia. J Clin Neurosci 2013; 20(6):894–896. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2012.05.045