User login

Clinical Characteristics and HLA Alleles of a Family With Simultaneously Occurring Alopecia Areata

Alopecia areata (AA) presents as sudden, nonscarring, recurrent hair loss characterized by well-circumscribed hairless patches. Although AA may be observed on any hair-bearing areas of the body, the most commonly affected sites are the scalp, beard area, eyebrows, and eyelashes.1 The incidence of AA is 1% to 2% in the general population and it is more common in males than females younger than 40 years.2 Although the majority of patients present with self-limited and well-circumscribed hairless patches that resolve within 2 years, 7% to 10% display a chronic and severe prognosis.3

The etiopathogenesis of AA is not clearly understood, but its occurrence and progression can involve immune dysfunction, genetic predisposition, infections, and physical and psychological trauma.2 Alopecia areata is observed to occur sporadically in most patients. Family history has been found in 3% to 42% of cases, but simultaneous occurrence of AA in family members is rare.4 In this case series, we present 4 cases of active AA lesions occurring simultaneously in a family who also had associated psychologic disorders.

Case Series

Patient 1 (Proband)

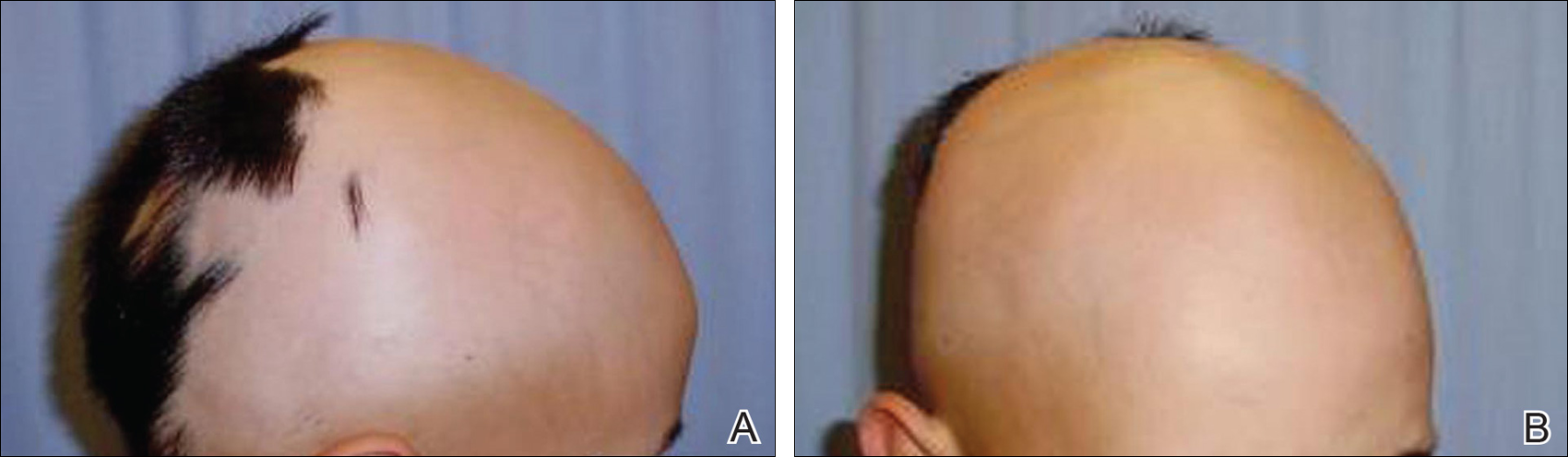

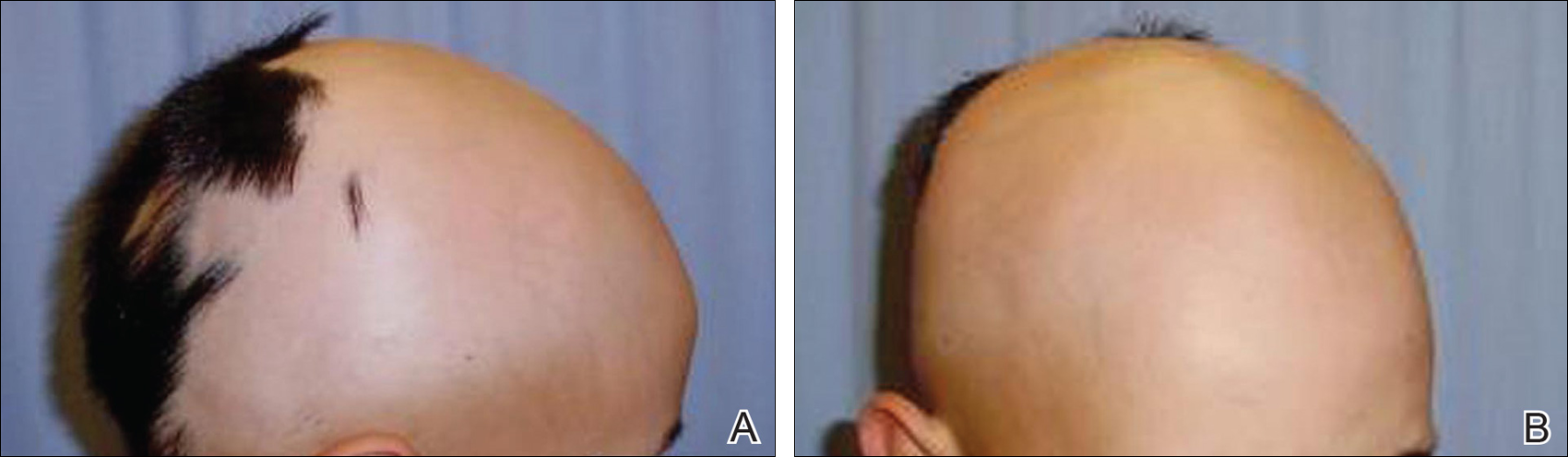

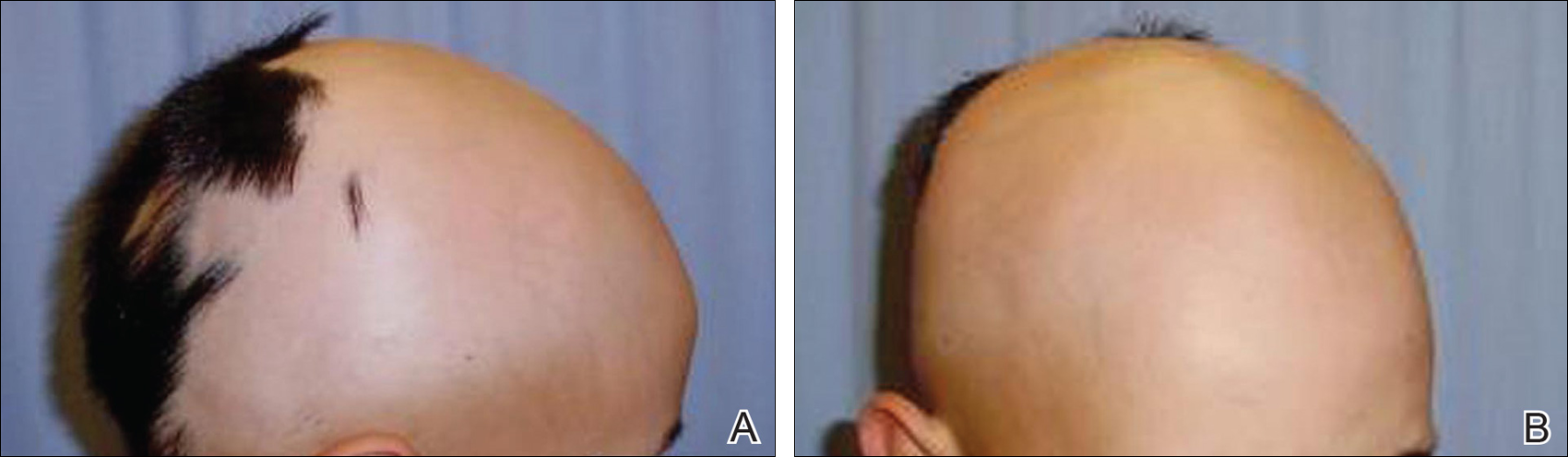

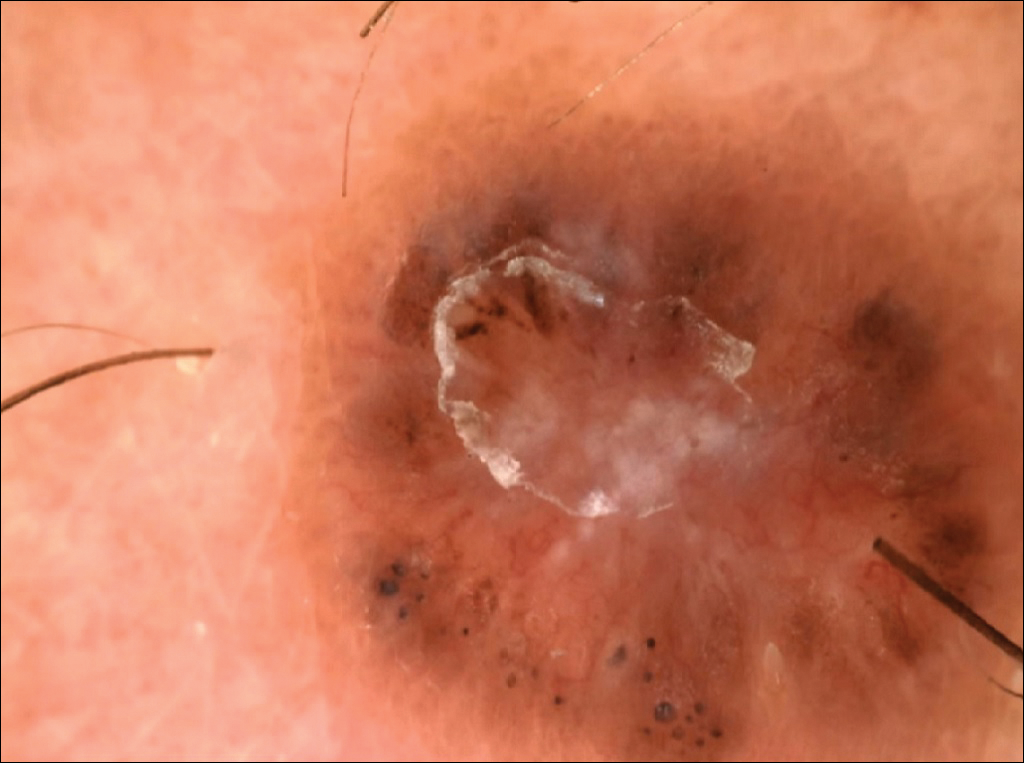

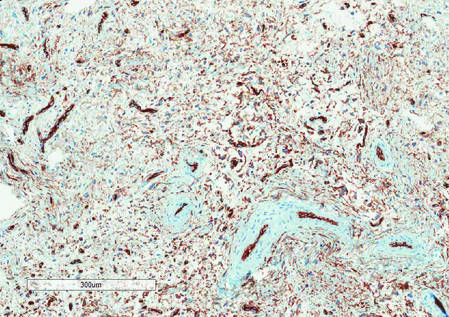

An 11-year-old boy presented with a 6-year history of ongoing AA with recurrent improvement and relapses on the scalp, eyebrows, and eyelashes. Various topical and oral medications had been prescribed by several outside dermatologists; however, these treatments provided minimal benefit and resulted in the recurrence of AA. Dermatologic examination revealed hair loss on the entire frontal, parietal, and temporal regions of the scalp, as well as half of the occipital region and one-third of the lateral side of the eyebrows (Figure 1). Psychological evaluation revealed introvert personality characteristics, lack of self-confidence, and signs of depression and anxiety.

Patient 2 (Proband’s Father)

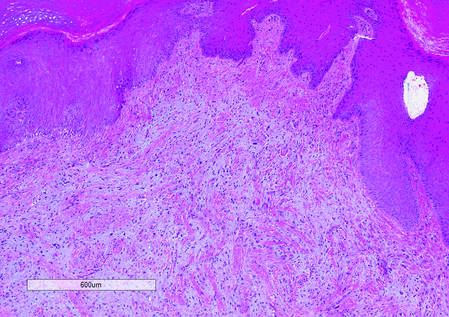

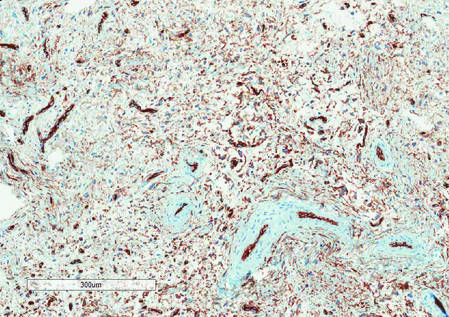

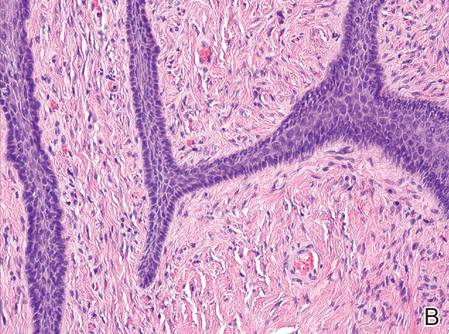

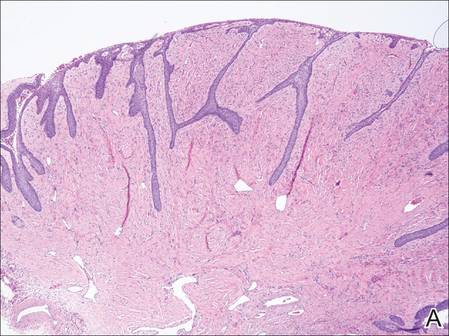

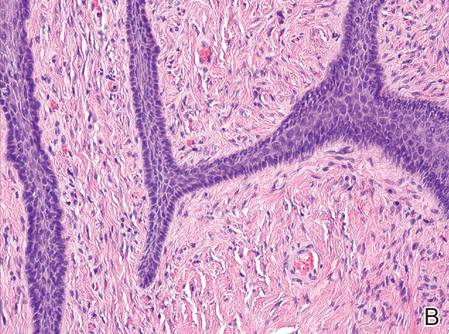

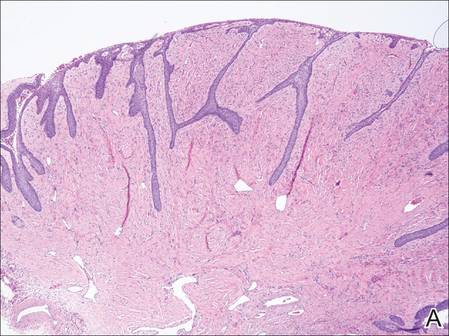

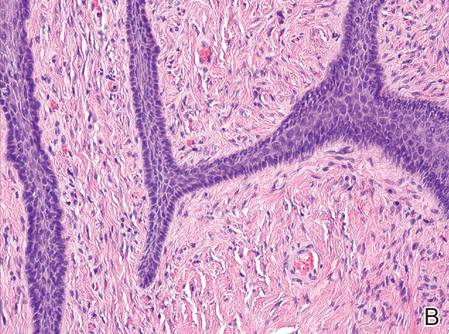

A 38-year-old man presented with a 16-year history of recurrent loss and regrowth of hair on the scalp and beard area and white spots on the penis and arms. He previously had not undergone any treatments. Dermatologic examination revealed well-circumscribed, 1- to 4-cm, hairless patches on the occipital region of the scalp and in the beard area (Figure 2A) and multiple, 2- to 10-mm, vitiliginous lesions on both forearms (Figure 2B) and the penis. The patient had been unemployed for 6 months. Psychological evaluation revealed obsessive-compulsive disorder and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder.

Patient 3 (Proband’s Mother)

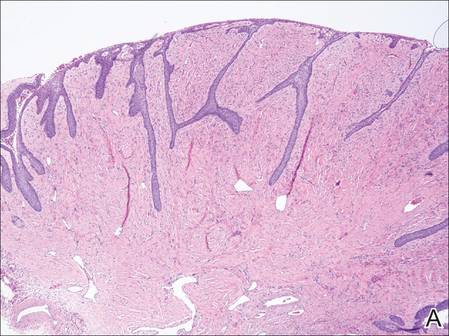

A 32-year-old woman presented with a 3-year history of chronic AA. She previously had not undergone any treatments. Dermatologic examination revealed 2 well-circumscribed, 3- to 4-cm patches of hair loss on the occipital and left temporal regions of the scalp (Figure 3). Psychological evaluation revealed obsessive-compulsive personality disorder and depression. The patient did not have any autoimmune diseases.

Patient 4 (Proband’s Sister)

A 10-year-old girl presented with a 6-year history of recurrent, self-limited AA on various areas of scalp. She previously had not undergone any treatments. Dermatologic examination revealed a 3-cm hairless patch on the occipital region of the scalp (Figure 4). Psychiatric evaluation revealed narcissistic personality disorder, anxiety, and lack of self-confidence.

Laboratory Evaluation and HLA Antigen DNA Typing

Laboratory testing including complete blood cell count; liver, kidney, and thyroid function; and vitamin B12, zinc, folic acid, and fasting blood sugar levels were performed in all patients.

HLA antigen DNA typing was performed by polymerase chain reaction with sequence-specific primers in all patients after informed consent was obtained.

Clinical and laboratory examinations revealed no symptoms or findings of Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus infections, cicatricial alopecia, or connective tissue diseases in any of the patients. HLA antigen DNA typing revealed the following HLA alleles: B*35/40, C*04/15, DRB1*08/10, and DQB1*03/05 in patient 1; B*04/13, C*06/15, DRB1*07/10, and DQB1*02/05 in patient 2; B*33/37, C*04/06, DRB1*08/15, and DQ*06/06 in patient 3; B*13/37, C*06/06, DRB1*07/15, and DQB1*02/06 in patient 4.

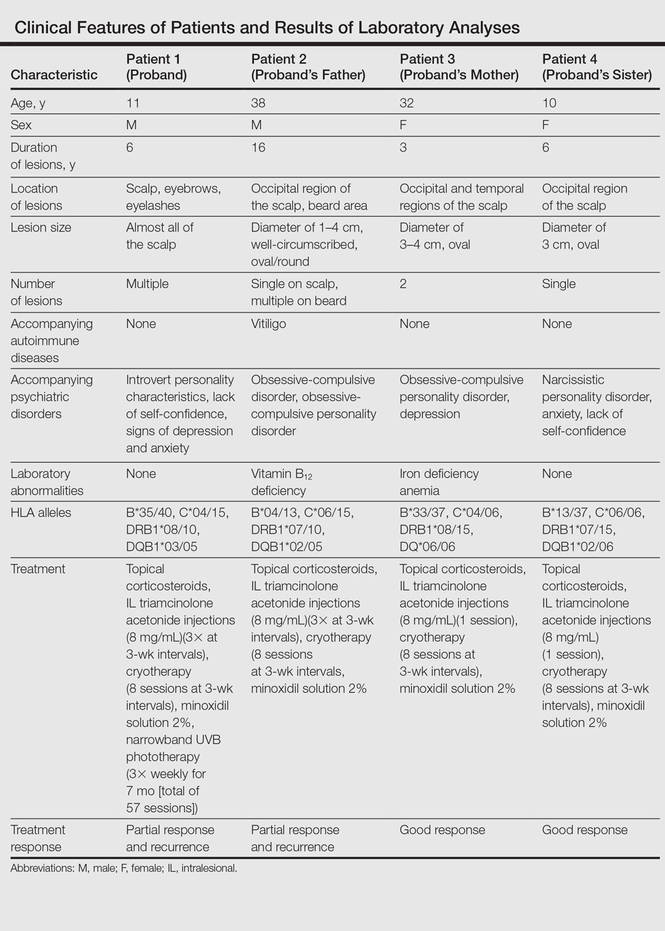

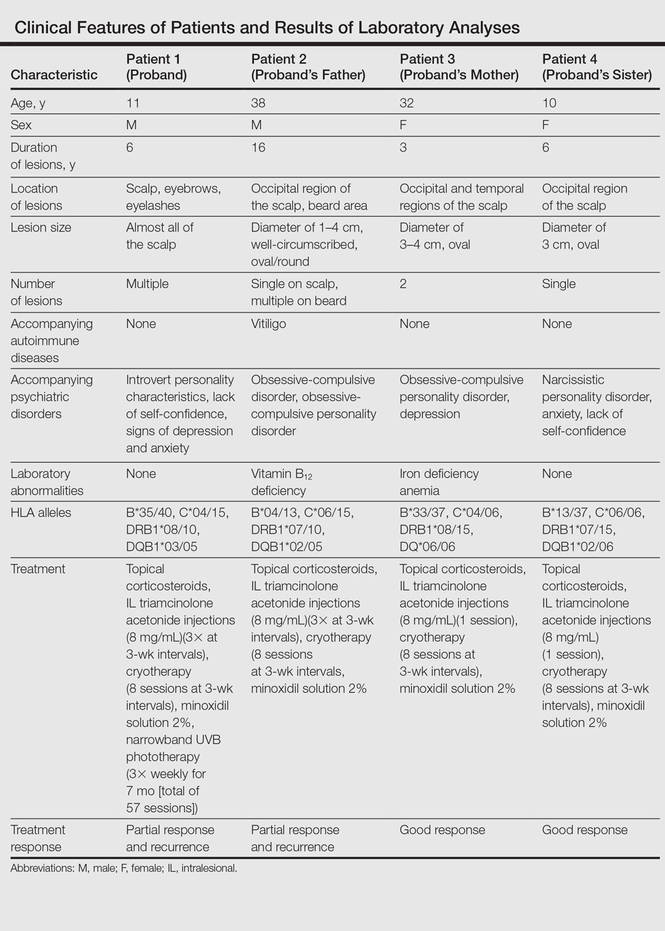

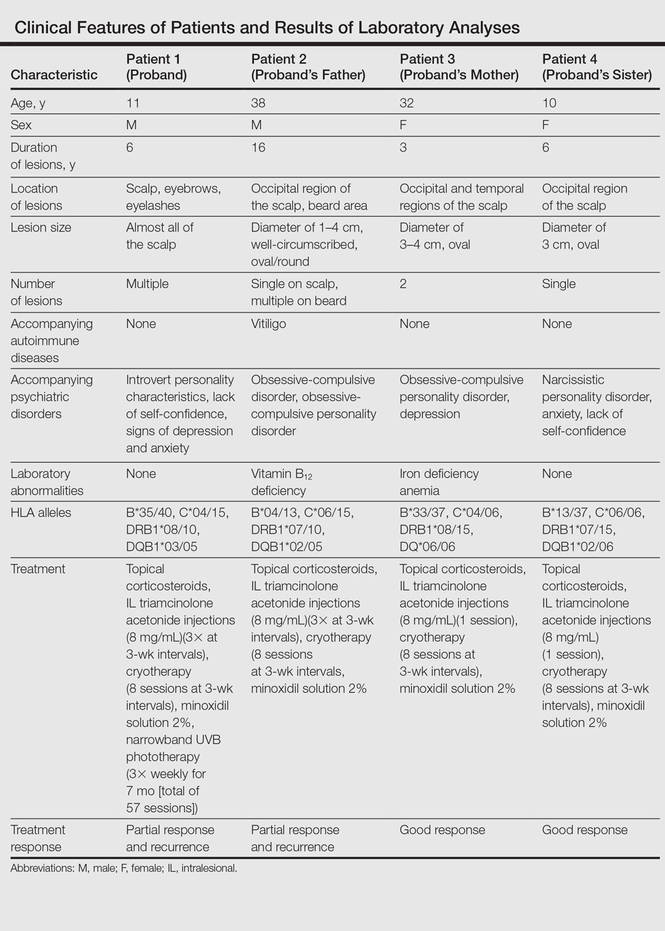

Laboratory testing revealed vitamin B12 deficiency in patient 2 and iron deficiency anemia in patient 3; all other laboratory tests were within reference range. Antithyroglobulin and antithyroid peroxidase autoantibodies were all negative. Clinical features and laboratory analyses for all patients are summarized in the Table.

Treatment

All patients were recommended psychiatric therapy and started on dermatologic treatments. Topical corticosteroids, intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (8 mg/mL) injections into areas of hair loss, 8 total sessions of cryotherapy administered at 3-week intervals, and minoxidil solution 2% were administered respectively to all 4 patients. Alopecia areata in patients 3 and 4 completely regressed; however, no benefit was observed in patients 1 and 2 after 1 year of treatment. Because there was no response to the prior interventions, patient 1 was started on treatment with cyclosporine 2.5 mg/kg twice daily. However, therapy was discontinued after 1 month and treatment with narrowband UVB (3 times per week for 7 months [total of 57 sessions]) and topical corticosteroids were initiated (Table). The patient partially benefited from these regimens and recurrence was observed during the course of the treatment.

Although it was recommended that all 4 patients undergo psychiatric treatment and follow-up regularly with a psychiatrist, the patients declined. After approximately 1 year of dermatologic treatment, all 4 patients were lost to follow-up.

Comment

The etiopathogenesis of AA is unclear, but there is strong evidence suggesting that it is a T-cell–mediated autoimmune disease targeting the hair follicles. Common association of AA with autoimmune diseases such as vitiligo and thyroiditis support the immunological origin of the disease.3 In our case, patient 2 had AA along with vitiligo, but no associated autoimmune diseases (eg, vitiligo, diabetes mellitus, pernicious anemia, thyroid diseases) were noted in the other patients. Genetic and environmental factors are known to be influential as much as immune dysfunction in the etiology of AA.2

The presence of family history in 20% of patients supports the genetic predisposition of AA.4 In a genetic study by Martinez-Mir et al,5 susceptibility loci for AA were demonstrated on chromosomes 6, 10, 16, and 18. HLA antigen alleles, which provide predisposition to AA, have been investigated and associations with many different HLA antigens have been described for AA. In these studies, a relationship between AA and HLA class I antigens was not determined. Notable results mainly focused on HLA class II antigens.6-8 Colombe et al7 and Marques Da Costa et al8 demonstrated that long-lasting alopecia totalis or alopecia universalis (AT/AU) patients had a strong relationship with HLA-DRB1*1104; DRB1*04/05 was reported to be the most frequent HLA group among all patients with AA.6-10 In contrast, we did not detect these alleles in our patients. Colombe et al7,11 noted that HLA-DQB1*03 is a marker for both patch-type AA and AT/AU. Colombe et al10 showed that HLA-DQB1*03 was present in more than 80% of patients (N=286) with long-lasting AA. Barahmani et al9 confirmed a strong association between HLA-DQB1*0301, DRB1*1104, and AT/AU. In our patients, we detected HLA-DQB1*03/05 in patient 1 who had the earliest onset and most severe presentation of AA. In some studies, HLA-DRB1*03 was found to be less frequent in patients with AA, and this allele was suggested to be a protective factor.6,12 However, this allele was not detected in any of our patients.

The association of HLA alleles and AA has been investigated in Turkish patients with AA.13-15 Akar et al13 and Kavak et al14 detected that the frequency of HLA-DQB1*03 allele was remarkably higher in patients with AA than in healthy controls. These results were consistent with Colombe et al.10 On the other hand, Kavak et al14 reported that the frequency of HLA-DR16 was decreased in the patient group with AA. In another study, the frequency of HLA-B62 was increased in patients with AA compared to healthy controls.15 The HLA-DQB1*03 allele was found to be associated with AA in only patient 1 in our case series, and HLA alleles were not commonly shared among the 4 patients. Additionally, lack of consanguinity between patients 2 and 3 (the parents) also suggested that genetic factors were not involved in our familial cases.

Blaumeiser et al16 reported a lifetime risk of 7.4% in parents and 7.1% in siblings of 206 AA patients; however, because these studies investigated the presence of AA in any given life period of the family members, their results do not reflect frequency of simultaneous AA presence within one family. In a literature search using PubMed, Google Scholar, and other national databases for the terms alopecia areata as well as family, sibling, concurrently, concomitant, co-existent, and simultaneously, only 2 cases involving a husband and wife and 1 case of 2 siblings who concurrently had AA have been previously reported.17,18 Simultaneous presence of AA in more than 3 members of the same family is rare, and these cases have been observed in different generations and time periods.19 Among our patients, despite different age of onset and duration, AA was simultaneously present in the entire family.

Moreover, Rodriguez et al20 reported that the concordance rate of AA in identical twins was 42% and dizygotic twins was 10%. Environmental factors and infections also have been implicated in the etiology of AA. Infections caused by viruses such as cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus have been thought to be potential triggering factors; however, no evidence has been found.21,22 The clinical and laboratory examinations in our study did not reveal any presence and/or history of any known infectious disease, and there was no history of contact with water infected by acrylamide or a similar chemical.

Various life events and intense psychological stress may play an important role in triggering AA. Depression, hysteria, psychopathic deviance, psychasthenia, schizophrenia, anxiety, health concerns, bizarre thoughts, and family problems were found to be more frequent in patients with AA than healthy controls.23 The most common psychological disorders associated with AA are generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, adjustment disorders, and phobias.1,24 Ruiz-Doblado et al25 determined the presence of psychiatric comorbidities in 66% (21/32) of AA cases. Chu et al26 reported that the differences in ages of onset of AA revealed differences in psychiatric comorbidities. The risk for depression was higher in patients with AA younger than 20 years. An increased rate of anxiety was detected with patients with an onset of AA between the ages of 20 and 39 years. Obsessive-compulsive disorder and anxiety were more common in patients aged 40 to 59 years. Interestingly, the investigators also observed that approximately 50% of psychiatric disorders occurred prior to onset of AA.26 One study showed higher rates of stressful life events in children than in controls.27 Ghanizadeh24 reported at least 1 psychiatric disorder in 78% (11/14) of children and adolescents with AA. In the same study, obsessive-compulsive disorder was found to be the second common condition following major depression in AA.24

In our patients, psychiatric evaluations revealed obsessive-compulsive personality disorder in patients 2 and 3, depression in patient 3, and symptoms of anxiety with a lack of self-confidence in patients 1 and 4. Psychiatric disorders affecting the entire family may stem from unemployment of the father. Similar to the results noted in prior studies, depression, the most commonly associated psychiatric disorder of AA, was present in 2 of 4 patients. Obsessive-compulsive disorder, the second most common psychiatric disorder among AA patients, was present in patients 2 and 3. These results indicate that AA may be associated with shared stressful events and psychiatric disorders. Therefore, in addition to dermatologic treatment, it was recommended that all patients undergo psychiatric treatment and follow-up regularly with a psychiatrist; however, the patients declined. At the end of a 1-year treatment period and follow-up, resistance to therapy with minimal recovery followed by a rapid recurrence was determined in patients 1 and 2.

Conclusion

This report demonstrated that familial AA was strongly associated with psychological disorders that were detected in all patients. In our patients, HLA alleles did not seem to have a role in the development of familial AA. These results suggest that HLA was not associated with AA triggered by psychological stress. We believe that psychological disorders and stressful life events may play an important role in the occurrence of AA and lead to the development of resistance against treatment in familial and resistant AA cases.

- García-Hernández MJ, Ruiz-Doblado S, Rodriguez-Pichardo A, et al. Alopecia areata, stress and psychiatric disorders: a review. J Dermatol. 1999;26:625-632.

- Bhat YJ, Manzoor S, Khan AR, et al. Trace element levels in alopecia areata. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:29-31.

- Alexis AF, Dudda-Subramanya R, Sinha AA. Alopecia areata: autoimmune basis of hair loss. Eur J Dermatol. 2004;14:364-370.

- Green J, Sinclair RD. Genetics of alopecia areata. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:213-218.

- Martinez-Mir A, Zlotogorski A, Gordon D, et al.Genomewide scan for linkage reveals evidence of several susceptibility loci for alopecia areata. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:316-328.

- Entz P, Blaumeiser B, Betz RC, et al. Investigation of the HLA-DRB1 locus in alopecia areata. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:363-367.

- Colombe BW, Price VH, Khoury EL, et al. HLA class II alleles in long-standing alopecia totalis/alopecia universalis and long-standing patchy alopecia areata differentiate these two clinical groups. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;104(suppl 5):4-5.

- Marques Da Costa C, Dupont E, Van der Cruys M, et al. Earlier occurrence of severe alopecia areata in HLA-DRB1*11-positive patients. Dermatology. 2006;213:12-14.

- Barahmani N, de Andrade M, Slusser JP, et al. Human leukocyte antigen class II alleles are associated with risk of alopecia areata. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:240-243.

- Colombe BW, Lou CD, Price VH. The genetic basis of alopecia areata: HLA associations with patchy alopecia areata versus alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4:216-219.

- Colombe BW, Price VH, Khoury EL, et al. HLA class II antigen associations help to define two types of alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(5, pt 1):757-764.

- Broniarczyk-Dyła G, Prusińska-Bratoś M, Dubla-Berner M, et al. The protective role of the HLA-DR locus in patients with various clinical types of alopecia areata. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz). 2002;50:333-336.

- Akar A, Orkunuglu E, Sengul A, et al. HLA class II alleles in patients with alopecia areata. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12:236-239.

- Kavak A, Baykal C, Ozarmagan G, et al. HLA in alopecia areata. Int J Dermatol. 2000;30:589-592.

- Aliagaoglu C, Pirim I, Atasoy M, et al. Association between alopecia areata and HLA class I and II in Turkey. J Dermatol. 2005;32:711-714.

- Blaumeiser B, Goot I, Fimmers R, et al. Familial aggregation of alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:627-632.

- Zalka AD, Byarlay JA, Goldsmith LA. Alopecia a deux: simultaneous occurrence of alopecia in a husband and wife. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:390-392.

- Menon R, Kiran C. Concomitant presentation of alopecia areata in siblings: a rare occurrence. Int J Trichology. 2012;4:86-88.

- Valsecchi R, Vicari O, Frigeni A, et al. Familial alopecia areata-genetic susceptibility or coincidence? Acta Derm Venereol (Stockh). 1985;65:175-177.

- Rodriguez TA, Fernandes KE, Dresser KL, et al. Concordance rate of alopecia areata in identical twins supports both genetic and environmental factors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:525-527.

- Rodriguez TA, Duvic M. Onset of alopecia areata after Epstein Barr virus infectious mononucleosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:137-139.

- Offidani A, Amerio P, Bernardini ML, et al. Role of cytomegalovirus replication in alopecia areata pathogenesis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2000;4:63-65.

- Alfani S, Antinone V, Mozzetta A, et al. Psychological status of patients with alopecia areata. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:304-306.

- Ghanizadeh A. Comorbidity of psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents with alopecia areata in a child and adolescent psychiatry clinical sample. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:1118-1120.

- Ruiz-Doblado S, Carrizosa A, Garcia-Hernandez MJ. Alopecia areata: psychiatric comorbidity and adjustment to illness. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:434-437.

- Chu SY, Chen YJ, Tseng WC, et al. Psychiatric comorbidities in patients with alopecia areata in Taiwan: a case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:525-531.

- Manolache L, Petrescu-Seceleanu D, Benea V. Alopecia areata and stressful events in children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:107-109.

Alopecia areata (AA) presents as sudden, nonscarring, recurrent hair loss characterized by well-circumscribed hairless patches. Although AA may be observed on any hair-bearing areas of the body, the most commonly affected sites are the scalp, beard area, eyebrows, and eyelashes.1 The incidence of AA is 1% to 2% in the general population and it is more common in males than females younger than 40 years.2 Although the majority of patients present with self-limited and well-circumscribed hairless patches that resolve within 2 years, 7% to 10% display a chronic and severe prognosis.3

The etiopathogenesis of AA is not clearly understood, but its occurrence and progression can involve immune dysfunction, genetic predisposition, infections, and physical and psychological trauma.2 Alopecia areata is observed to occur sporadically in most patients. Family history has been found in 3% to 42% of cases, but simultaneous occurrence of AA in family members is rare.4 In this case series, we present 4 cases of active AA lesions occurring simultaneously in a family who also had associated psychologic disorders.

Case Series

Patient 1 (Proband)

An 11-year-old boy presented with a 6-year history of ongoing AA with recurrent improvement and relapses on the scalp, eyebrows, and eyelashes. Various topical and oral medications had been prescribed by several outside dermatologists; however, these treatments provided minimal benefit and resulted in the recurrence of AA. Dermatologic examination revealed hair loss on the entire frontal, parietal, and temporal regions of the scalp, as well as half of the occipital region and one-third of the lateral side of the eyebrows (Figure 1). Psychological evaluation revealed introvert personality characteristics, lack of self-confidence, and signs of depression and anxiety.

Patient 2 (Proband’s Father)

A 38-year-old man presented with a 16-year history of recurrent loss and regrowth of hair on the scalp and beard area and white spots on the penis and arms. He previously had not undergone any treatments. Dermatologic examination revealed well-circumscribed, 1- to 4-cm, hairless patches on the occipital region of the scalp and in the beard area (Figure 2A) and multiple, 2- to 10-mm, vitiliginous lesions on both forearms (Figure 2B) and the penis. The patient had been unemployed for 6 months. Psychological evaluation revealed obsessive-compulsive disorder and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder.

Patient 3 (Proband’s Mother)

A 32-year-old woman presented with a 3-year history of chronic AA. She previously had not undergone any treatments. Dermatologic examination revealed 2 well-circumscribed, 3- to 4-cm patches of hair loss on the occipital and left temporal regions of the scalp (Figure 3). Psychological evaluation revealed obsessive-compulsive personality disorder and depression. The patient did not have any autoimmune diseases.

Patient 4 (Proband’s Sister)

A 10-year-old girl presented with a 6-year history of recurrent, self-limited AA on various areas of scalp. She previously had not undergone any treatments. Dermatologic examination revealed a 3-cm hairless patch on the occipital region of the scalp (Figure 4). Psychiatric evaluation revealed narcissistic personality disorder, anxiety, and lack of self-confidence.

Laboratory Evaluation and HLA Antigen DNA Typing

Laboratory testing including complete blood cell count; liver, kidney, and thyroid function; and vitamin B12, zinc, folic acid, and fasting blood sugar levels were performed in all patients.

HLA antigen DNA typing was performed by polymerase chain reaction with sequence-specific primers in all patients after informed consent was obtained.

Clinical and laboratory examinations revealed no symptoms or findings of Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus infections, cicatricial alopecia, or connective tissue diseases in any of the patients. HLA antigen DNA typing revealed the following HLA alleles: B*35/40, C*04/15, DRB1*08/10, and DQB1*03/05 in patient 1; B*04/13, C*06/15, DRB1*07/10, and DQB1*02/05 in patient 2; B*33/37, C*04/06, DRB1*08/15, and DQ*06/06 in patient 3; B*13/37, C*06/06, DRB1*07/15, and DQB1*02/06 in patient 4.

Laboratory testing revealed vitamin B12 deficiency in patient 2 and iron deficiency anemia in patient 3; all other laboratory tests were within reference range. Antithyroglobulin and antithyroid peroxidase autoantibodies were all negative. Clinical features and laboratory analyses for all patients are summarized in the Table.

Treatment

All patients were recommended psychiatric therapy and started on dermatologic treatments. Topical corticosteroids, intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (8 mg/mL) injections into areas of hair loss, 8 total sessions of cryotherapy administered at 3-week intervals, and minoxidil solution 2% were administered respectively to all 4 patients. Alopecia areata in patients 3 and 4 completely regressed; however, no benefit was observed in patients 1 and 2 after 1 year of treatment. Because there was no response to the prior interventions, patient 1 was started on treatment with cyclosporine 2.5 mg/kg twice daily. However, therapy was discontinued after 1 month and treatment with narrowband UVB (3 times per week for 7 months [total of 57 sessions]) and topical corticosteroids were initiated (Table). The patient partially benefited from these regimens and recurrence was observed during the course of the treatment.

Although it was recommended that all 4 patients undergo psychiatric treatment and follow-up regularly with a psychiatrist, the patients declined. After approximately 1 year of dermatologic treatment, all 4 patients were lost to follow-up.

Comment

The etiopathogenesis of AA is unclear, but there is strong evidence suggesting that it is a T-cell–mediated autoimmune disease targeting the hair follicles. Common association of AA with autoimmune diseases such as vitiligo and thyroiditis support the immunological origin of the disease.3 In our case, patient 2 had AA along with vitiligo, but no associated autoimmune diseases (eg, vitiligo, diabetes mellitus, pernicious anemia, thyroid diseases) were noted in the other patients. Genetic and environmental factors are known to be influential as much as immune dysfunction in the etiology of AA.2

The presence of family history in 20% of patients supports the genetic predisposition of AA.4 In a genetic study by Martinez-Mir et al,5 susceptibility loci for AA were demonstrated on chromosomes 6, 10, 16, and 18. HLA antigen alleles, which provide predisposition to AA, have been investigated and associations with many different HLA antigens have been described for AA. In these studies, a relationship between AA and HLA class I antigens was not determined. Notable results mainly focused on HLA class II antigens.6-8 Colombe et al7 and Marques Da Costa et al8 demonstrated that long-lasting alopecia totalis or alopecia universalis (AT/AU) patients had a strong relationship with HLA-DRB1*1104; DRB1*04/05 was reported to be the most frequent HLA group among all patients with AA.6-10 In contrast, we did not detect these alleles in our patients. Colombe et al7,11 noted that HLA-DQB1*03 is a marker for both patch-type AA and AT/AU. Colombe et al10 showed that HLA-DQB1*03 was present in more than 80% of patients (N=286) with long-lasting AA. Barahmani et al9 confirmed a strong association between HLA-DQB1*0301, DRB1*1104, and AT/AU. In our patients, we detected HLA-DQB1*03/05 in patient 1 who had the earliest onset and most severe presentation of AA. In some studies, HLA-DRB1*03 was found to be less frequent in patients with AA, and this allele was suggested to be a protective factor.6,12 However, this allele was not detected in any of our patients.

The association of HLA alleles and AA has been investigated in Turkish patients with AA.13-15 Akar et al13 and Kavak et al14 detected that the frequency of HLA-DQB1*03 allele was remarkably higher in patients with AA than in healthy controls. These results were consistent with Colombe et al.10 On the other hand, Kavak et al14 reported that the frequency of HLA-DR16 was decreased in the patient group with AA. In another study, the frequency of HLA-B62 was increased in patients with AA compared to healthy controls.15 The HLA-DQB1*03 allele was found to be associated with AA in only patient 1 in our case series, and HLA alleles were not commonly shared among the 4 patients. Additionally, lack of consanguinity between patients 2 and 3 (the parents) also suggested that genetic factors were not involved in our familial cases.

Blaumeiser et al16 reported a lifetime risk of 7.4% in parents and 7.1% in siblings of 206 AA patients; however, because these studies investigated the presence of AA in any given life period of the family members, their results do not reflect frequency of simultaneous AA presence within one family. In a literature search using PubMed, Google Scholar, and other national databases for the terms alopecia areata as well as family, sibling, concurrently, concomitant, co-existent, and simultaneously, only 2 cases involving a husband and wife and 1 case of 2 siblings who concurrently had AA have been previously reported.17,18 Simultaneous presence of AA in more than 3 members of the same family is rare, and these cases have been observed in different generations and time periods.19 Among our patients, despite different age of onset and duration, AA was simultaneously present in the entire family.

Moreover, Rodriguez et al20 reported that the concordance rate of AA in identical twins was 42% and dizygotic twins was 10%. Environmental factors and infections also have been implicated in the etiology of AA. Infections caused by viruses such as cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus have been thought to be potential triggering factors; however, no evidence has been found.21,22 The clinical and laboratory examinations in our study did not reveal any presence and/or history of any known infectious disease, and there was no history of contact with water infected by acrylamide or a similar chemical.

Various life events and intense psychological stress may play an important role in triggering AA. Depression, hysteria, psychopathic deviance, psychasthenia, schizophrenia, anxiety, health concerns, bizarre thoughts, and family problems were found to be more frequent in patients with AA than healthy controls.23 The most common psychological disorders associated with AA are generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, adjustment disorders, and phobias.1,24 Ruiz-Doblado et al25 determined the presence of psychiatric comorbidities in 66% (21/32) of AA cases. Chu et al26 reported that the differences in ages of onset of AA revealed differences in psychiatric comorbidities. The risk for depression was higher in patients with AA younger than 20 years. An increased rate of anxiety was detected with patients with an onset of AA between the ages of 20 and 39 years. Obsessive-compulsive disorder and anxiety were more common in patients aged 40 to 59 years. Interestingly, the investigators also observed that approximately 50% of psychiatric disorders occurred prior to onset of AA.26 One study showed higher rates of stressful life events in children than in controls.27 Ghanizadeh24 reported at least 1 psychiatric disorder in 78% (11/14) of children and adolescents with AA. In the same study, obsessive-compulsive disorder was found to be the second common condition following major depression in AA.24

In our patients, psychiatric evaluations revealed obsessive-compulsive personality disorder in patients 2 and 3, depression in patient 3, and symptoms of anxiety with a lack of self-confidence in patients 1 and 4. Psychiatric disorders affecting the entire family may stem from unemployment of the father. Similar to the results noted in prior studies, depression, the most commonly associated psychiatric disorder of AA, was present in 2 of 4 patients. Obsessive-compulsive disorder, the second most common psychiatric disorder among AA patients, was present in patients 2 and 3. These results indicate that AA may be associated with shared stressful events and psychiatric disorders. Therefore, in addition to dermatologic treatment, it was recommended that all patients undergo psychiatric treatment and follow-up regularly with a psychiatrist; however, the patients declined. At the end of a 1-year treatment period and follow-up, resistance to therapy with minimal recovery followed by a rapid recurrence was determined in patients 1 and 2.

Conclusion

This report demonstrated that familial AA was strongly associated with psychological disorders that were detected in all patients. In our patients, HLA alleles did not seem to have a role in the development of familial AA. These results suggest that HLA was not associated with AA triggered by psychological stress. We believe that psychological disorders and stressful life events may play an important role in the occurrence of AA and lead to the development of resistance against treatment in familial and resistant AA cases.

Alopecia areata (AA) presents as sudden, nonscarring, recurrent hair loss characterized by well-circumscribed hairless patches. Although AA may be observed on any hair-bearing areas of the body, the most commonly affected sites are the scalp, beard area, eyebrows, and eyelashes.1 The incidence of AA is 1% to 2% in the general population and it is more common in males than females younger than 40 years.2 Although the majority of patients present with self-limited and well-circumscribed hairless patches that resolve within 2 years, 7% to 10% display a chronic and severe prognosis.3

The etiopathogenesis of AA is not clearly understood, but its occurrence and progression can involve immune dysfunction, genetic predisposition, infections, and physical and psychological trauma.2 Alopecia areata is observed to occur sporadically in most patients. Family history has been found in 3% to 42% of cases, but simultaneous occurrence of AA in family members is rare.4 In this case series, we present 4 cases of active AA lesions occurring simultaneously in a family who also had associated psychologic disorders.

Case Series

Patient 1 (Proband)

An 11-year-old boy presented with a 6-year history of ongoing AA with recurrent improvement and relapses on the scalp, eyebrows, and eyelashes. Various topical and oral medications had been prescribed by several outside dermatologists; however, these treatments provided minimal benefit and resulted in the recurrence of AA. Dermatologic examination revealed hair loss on the entire frontal, parietal, and temporal regions of the scalp, as well as half of the occipital region and one-third of the lateral side of the eyebrows (Figure 1). Psychological evaluation revealed introvert personality characteristics, lack of self-confidence, and signs of depression and anxiety.

Patient 2 (Proband’s Father)

A 38-year-old man presented with a 16-year history of recurrent loss and regrowth of hair on the scalp and beard area and white spots on the penis and arms. He previously had not undergone any treatments. Dermatologic examination revealed well-circumscribed, 1- to 4-cm, hairless patches on the occipital region of the scalp and in the beard area (Figure 2A) and multiple, 2- to 10-mm, vitiliginous lesions on both forearms (Figure 2B) and the penis. The patient had been unemployed for 6 months. Psychological evaluation revealed obsessive-compulsive disorder and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder.

Patient 3 (Proband’s Mother)

A 32-year-old woman presented with a 3-year history of chronic AA. She previously had not undergone any treatments. Dermatologic examination revealed 2 well-circumscribed, 3- to 4-cm patches of hair loss on the occipital and left temporal regions of the scalp (Figure 3). Psychological evaluation revealed obsessive-compulsive personality disorder and depression. The patient did not have any autoimmune diseases.

Patient 4 (Proband’s Sister)

A 10-year-old girl presented with a 6-year history of recurrent, self-limited AA on various areas of scalp. She previously had not undergone any treatments. Dermatologic examination revealed a 3-cm hairless patch on the occipital region of the scalp (Figure 4). Psychiatric evaluation revealed narcissistic personality disorder, anxiety, and lack of self-confidence.

Laboratory Evaluation and HLA Antigen DNA Typing

Laboratory testing including complete blood cell count; liver, kidney, and thyroid function; and vitamin B12, zinc, folic acid, and fasting blood sugar levels were performed in all patients.

HLA antigen DNA typing was performed by polymerase chain reaction with sequence-specific primers in all patients after informed consent was obtained.

Clinical and laboratory examinations revealed no symptoms or findings of Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus infections, cicatricial alopecia, or connective tissue diseases in any of the patients. HLA antigen DNA typing revealed the following HLA alleles: B*35/40, C*04/15, DRB1*08/10, and DQB1*03/05 in patient 1; B*04/13, C*06/15, DRB1*07/10, and DQB1*02/05 in patient 2; B*33/37, C*04/06, DRB1*08/15, and DQ*06/06 in patient 3; B*13/37, C*06/06, DRB1*07/15, and DQB1*02/06 in patient 4.

Laboratory testing revealed vitamin B12 deficiency in patient 2 and iron deficiency anemia in patient 3; all other laboratory tests were within reference range. Antithyroglobulin and antithyroid peroxidase autoantibodies were all negative. Clinical features and laboratory analyses for all patients are summarized in the Table.

Treatment

All patients were recommended psychiatric therapy and started on dermatologic treatments. Topical corticosteroids, intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (8 mg/mL) injections into areas of hair loss, 8 total sessions of cryotherapy administered at 3-week intervals, and minoxidil solution 2% were administered respectively to all 4 patients. Alopecia areata in patients 3 and 4 completely regressed; however, no benefit was observed in patients 1 and 2 after 1 year of treatment. Because there was no response to the prior interventions, patient 1 was started on treatment with cyclosporine 2.5 mg/kg twice daily. However, therapy was discontinued after 1 month and treatment with narrowband UVB (3 times per week for 7 months [total of 57 sessions]) and topical corticosteroids were initiated (Table). The patient partially benefited from these regimens and recurrence was observed during the course of the treatment.

Although it was recommended that all 4 patients undergo psychiatric treatment and follow-up regularly with a psychiatrist, the patients declined. After approximately 1 year of dermatologic treatment, all 4 patients were lost to follow-up.

Comment

The etiopathogenesis of AA is unclear, but there is strong evidence suggesting that it is a T-cell–mediated autoimmune disease targeting the hair follicles. Common association of AA with autoimmune diseases such as vitiligo and thyroiditis support the immunological origin of the disease.3 In our case, patient 2 had AA along with vitiligo, but no associated autoimmune diseases (eg, vitiligo, diabetes mellitus, pernicious anemia, thyroid diseases) were noted in the other patients. Genetic and environmental factors are known to be influential as much as immune dysfunction in the etiology of AA.2

The presence of family history in 20% of patients supports the genetic predisposition of AA.4 In a genetic study by Martinez-Mir et al,5 susceptibility loci for AA were demonstrated on chromosomes 6, 10, 16, and 18. HLA antigen alleles, which provide predisposition to AA, have been investigated and associations with many different HLA antigens have been described for AA. In these studies, a relationship between AA and HLA class I antigens was not determined. Notable results mainly focused on HLA class II antigens.6-8 Colombe et al7 and Marques Da Costa et al8 demonstrated that long-lasting alopecia totalis or alopecia universalis (AT/AU) patients had a strong relationship with HLA-DRB1*1104; DRB1*04/05 was reported to be the most frequent HLA group among all patients with AA.6-10 In contrast, we did not detect these alleles in our patients. Colombe et al7,11 noted that HLA-DQB1*03 is a marker for both patch-type AA and AT/AU. Colombe et al10 showed that HLA-DQB1*03 was present in more than 80% of patients (N=286) with long-lasting AA. Barahmani et al9 confirmed a strong association between HLA-DQB1*0301, DRB1*1104, and AT/AU. In our patients, we detected HLA-DQB1*03/05 in patient 1 who had the earliest onset and most severe presentation of AA. In some studies, HLA-DRB1*03 was found to be less frequent in patients with AA, and this allele was suggested to be a protective factor.6,12 However, this allele was not detected in any of our patients.

The association of HLA alleles and AA has been investigated in Turkish patients with AA.13-15 Akar et al13 and Kavak et al14 detected that the frequency of HLA-DQB1*03 allele was remarkably higher in patients with AA than in healthy controls. These results were consistent with Colombe et al.10 On the other hand, Kavak et al14 reported that the frequency of HLA-DR16 was decreased in the patient group with AA. In another study, the frequency of HLA-B62 was increased in patients with AA compared to healthy controls.15 The HLA-DQB1*03 allele was found to be associated with AA in only patient 1 in our case series, and HLA alleles were not commonly shared among the 4 patients. Additionally, lack of consanguinity between patients 2 and 3 (the parents) also suggested that genetic factors were not involved in our familial cases.

Blaumeiser et al16 reported a lifetime risk of 7.4% in parents and 7.1% in siblings of 206 AA patients; however, because these studies investigated the presence of AA in any given life period of the family members, their results do not reflect frequency of simultaneous AA presence within one family. In a literature search using PubMed, Google Scholar, and other national databases for the terms alopecia areata as well as family, sibling, concurrently, concomitant, co-existent, and simultaneously, only 2 cases involving a husband and wife and 1 case of 2 siblings who concurrently had AA have been previously reported.17,18 Simultaneous presence of AA in more than 3 members of the same family is rare, and these cases have been observed in different generations and time periods.19 Among our patients, despite different age of onset and duration, AA was simultaneously present in the entire family.

Moreover, Rodriguez et al20 reported that the concordance rate of AA in identical twins was 42% and dizygotic twins was 10%. Environmental factors and infections also have been implicated in the etiology of AA. Infections caused by viruses such as cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus have been thought to be potential triggering factors; however, no evidence has been found.21,22 The clinical and laboratory examinations in our study did not reveal any presence and/or history of any known infectious disease, and there was no history of contact with water infected by acrylamide or a similar chemical.

Various life events and intense psychological stress may play an important role in triggering AA. Depression, hysteria, psychopathic deviance, psychasthenia, schizophrenia, anxiety, health concerns, bizarre thoughts, and family problems were found to be more frequent in patients with AA than healthy controls.23 The most common psychological disorders associated with AA are generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, adjustment disorders, and phobias.1,24 Ruiz-Doblado et al25 determined the presence of psychiatric comorbidities in 66% (21/32) of AA cases. Chu et al26 reported that the differences in ages of onset of AA revealed differences in psychiatric comorbidities. The risk for depression was higher in patients with AA younger than 20 years. An increased rate of anxiety was detected with patients with an onset of AA between the ages of 20 and 39 years. Obsessive-compulsive disorder and anxiety were more common in patients aged 40 to 59 years. Interestingly, the investigators also observed that approximately 50% of psychiatric disorders occurred prior to onset of AA.26 One study showed higher rates of stressful life events in children than in controls.27 Ghanizadeh24 reported at least 1 psychiatric disorder in 78% (11/14) of children and adolescents with AA. In the same study, obsessive-compulsive disorder was found to be the second common condition following major depression in AA.24

In our patients, psychiatric evaluations revealed obsessive-compulsive personality disorder in patients 2 and 3, depression in patient 3, and symptoms of anxiety with a lack of self-confidence in patients 1 and 4. Psychiatric disorders affecting the entire family may stem from unemployment of the father. Similar to the results noted in prior studies, depression, the most commonly associated psychiatric disorder of AA, was present in 2 of 4 patients. Obsessive-compulsive disorder, the second most common psychiatric disorder among AA patients, was present in patients 2 and 3. These results indicate that AA may be associated with shared stressful events and psychiatric disorders. Therefore, in addition to dermatologic treatment, it was recommended that all patients undergo psychiatric treatment and follow-up regularly with a psychiatrist; however, the patients declined. At the end of a 1-year treatment period and follow-up, resistance to therapy with minimal recovery followed by a rapid recurrence was determined in patients 1 and 2.

Conclusion

This report demonstrated that familial AA was strongly associated with psychological disorders that were detected in all patients. In our patients, HLA alleles did not seem to have a role in the development of familial AA. These results suggest that HLA was not associated with AA triggered by psychological stress. We believe that psychological disorders and stressful life events may play an important role in the occurrence of AA and lead to the development of resistance against treatment in familial and resistant AA cases.

- García-Hernández MJ, Ruiz-Doblado S, Rodriguez-Pichardo A, et al. Alopecia areata, stress and psychiatric disorders: a review. J Dermatol. 1999;26:625-632.

- Bhat YJ, Manzoor S, Khan AR, et al. Trace element levels in alopecia areata. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:29-31.

- Alexis AF, Dudda-Subramanya R, Sinha AA. Alopecia areata: autoimmune basis of hair loss. Eur J Dermatol. 2004;14:364-370.

- Green J, Sinclair RD. Genetics of alopecia areata. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:213-218.

- Martinez-Mir A, Zlotogorski A, Gordon D, et al.Genomewide scan for linkage reveals evidence of several susceptibility loci for alopecia areata. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:316-328.

- Entz P, Blaumeiser B, Betz RC, et al. Investigation of the HLA-DRB1 locus in alopecia areata. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:363-367.

- Colombe BW, Price VH, Khoury EL, et al. HLA class II alleles in long-standing alopecia totalis/alopecia universalis and long-standing patchy alopecia areata differentiate these two clinical groups. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;104(suppl 5):4-5.

- Marques Da Costa C, Dupont E, Van der Cruys M, et al. Earlier occurrence of severe alopecia areata in HLA-DRB1*11-positive patients. Dermatology. 2006;213:12-14.

- Barahmani N, de Andrade M, Slusser JP, et al. Human leukocyte antigen class II alleles are associated with risk of alopecia areata. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:240-243.

- Colombe BW, Lou CD, Price VH. The genetic basis of alopecia areata: HLA associations with patchy alopecia areata versus alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4:216-219.

- Colombe BW, Price VH, Khoury EL, et al. HLA class II antigen associations help to define two types of alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(5, pt 1):757-764.

- Broniarczyk-Dyła G, Prusińska-Bratoś M, Dubla-Berner M, et al. The protective role of the HLA-DR locus in patients with various clinical types of alopecia areata. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz). 2002;50:333-336.

- Akar A, Orkunuglu E, Sengul A, et al. HLA class II alleles in patients with alopecia areata. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12:236-239.

- Kavak A, Baykal C, Ozarmagan G, et al. HLA in alopecia areata. Int J Dermatol. 2000;30:589-592.

- Aliagaoglu C, Pirim I, Atasoy M, et al. Association between alopecia areata and HLA class I and II in Turkey. J Dermatol. 2005;32:711-714.

- Blaumeiser B, Goot I, Fimmers R, et al. Familial aggregation of alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:627-632.

- Zalka AD, Byarlay JA, Goldsmith LA. Alopecia a deux: simultaneous occurrence of alopecia in a husband and wife. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:390-392.

- Menon R, Kiran C. Concomitant presentation of alopecia areata in siblings: a rare occurrence. Int J Trichology. 2012;4:86-88.

- Valsecchi R, Vicari O, Frigeni A, et al. Familial alopecia areata-genetic susceptibility or coincidence? Acta Derm Venereol (Stockh). 1985;65:175-177.

- Rodriguez TA, Fernandes KE, Dresser KL, et al. Concordance rate of alopecia areata in identical twins supports both genetic and environmental factors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:525-527.

- Rodriguez TA, Duvic M. Onset of alopecia areata after Epstein Barr virus infectious mononucleosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:137-139.

- Offidani A, Amerio P, Bernardini ML, et al. Role of cytomegalovirus replication in alopecia areata pathogenesis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2000;4:63-65.

- Alfani S, Antinone V, Mozzetta A, et al. Psychological status of patients with alopecia areata. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:304-306.

- Ghanizadeh A. Comorbidity of psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents with alopecia areata in a child and adolescent psychiatry clinical sample. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:1118-1120.

- Ruiz-Doblado S, Carrizosa A, Garcia-Hernandez MJ. Alopecia areata: psychiatric comorbidity and adjustment to illness. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:434-437.

- Chu SY, Chen YJ, Tseng WC, et al. Psychiatric comorbidities in patients with alopecia areata in Taiwan: a case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:525-531.

- Manolache L, Petrescu-Seceleanu D, Benea V. Alopecia areata and stressful events in children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:107-109.

- García-Hernández MJ, Ruiz-Doblado S, Rodriguez-Pichardo A, et al. Alopecia areata, stress and psychiatric disorders: a review. J Dermatol. 1999;26:625-632.

- Bhat YJ, Manzoor S, Khan AR, et al. Trace element levels in alopecia areata. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:29-31.

- Alexis AF, Dudda-Subramanya R, Sinha AA. Alopecia areata: autoimmune basis of hair loss. Eur J Dermatol. 2004;14:364-370.

- Green J, Sinclair RD. Genetics of alopecia areata. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:213-218.

- Martinez-Mir A, Zlotogorski A, Gordon D, et al.Genomewide scan for linkage reveals evidence of several susceptibility loci for alopecia areata. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:316-328.

- Entz P, Blaumeiser B, Betz RC, et al. Investigation of the HLA-DRB1 locus in alopecia areata. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:363-367.

- Colombe BW, Price VH, Khoury EL, et al. HLA class II alleles in long-standing alopecia totalis/alopecia universalis and long-standing patchy alopecia areata differentiate these two clinical groups. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;104(suppl 5):4-5.

- Marques Da Costa C, Dupont E, Van der Cruys M, et al. Earlier occurrence of severe alopecia areata in HLA-DRB1*11-positive patients. Dermatology. 2006;213:12-14.

- Barahmani N, de Andrade M, Slusser JP, et al. Human leukocyte antigen class II alleles are associated with risk of alopecia areata. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:240-243.

- Colombe BW, Lou CD, Price VH. The genetic basis of alopecia areata: HLA associations with patchy alopecia areata versus alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4:216-219.

- Colombe BW, Price VH, Khoury EL, et al. HLA class II antigen associations help to define two types of alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(5, pt 1):757-764.

- Broniarczyk-Dyła G, Prusińska-Bratoś M, Dubla-Berner M, et al. The protective role of the HLA-DR locus in patients with various clinical types of alopecia areata. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz). 2002;50:333-336.

- Akar A, Orkunuglu E, Sengul A, et al. HLA class II alleles in patients with alopecia areata. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12:236-239.

- Kavak A, Baykal C, Ozarmagan G, et al. HLA in alopecia areata. Int J Dermatol. 2000;30:589-592.

- Aliagaoglu C, Pirim I, Atasoy M, et al. Association between alopecia areata and HLA class I and II in Turkey. J Dermatol. 2005;32:711-714.

- Blaumeiser B, Goot I, Fimmers R, et al. Familial aggregation of alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:627-632.

- Zalka AD, Byarlay JA, Goldsmith LA. Alopecia a deux: simultaneous occurrence of alopecia in a husband and wife. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:390-392.

- Menon R, Kiran C. Concomitant presentation of alopecia areata in siblings: a rare occurrence. Int J Trichology. 2012;4:86-88.

- Valsecchi R, Vicari O, Frigeni A, et al. Familial alopecia areata-genetic susceptibility or coincidence? Acta Derm Venereol (Stockh). 1985;65:175-177.

- Rodriguez TA, Fernandes KE, Dresser KL, et al. Concordance rate of alopecia areata in identical twins supports both genetic and environmental factors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:525-527.

- Rodriguez TA, Duvic M. Onset of alopecia areata after Epstein Barr virus infectious mononucleosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:137-139.

- Offidani A, Amerio P, Bernardini ML, et al. Role of cytomegalovirus replication in alopecia areata pathogenesis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2000;4:63-65.

- Alfani S, Antinone V, Mozzetta A, et al. Psychological status of patients with alopecia areata. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:304-306.

- Ghanizadeh A. Comorbidity of psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents with alopecia areata in a child and adolescent psychiatry clinical sample. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:1118-1120.

- Ruiz-Doblado S, Carrizosa A, Garcia-Hernandez MJ. Alopecia areata: psychiatric comorbidity and adjustment to illness. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:434-437.

- Chu SY, Chen YJ, Tseng WC, et al. Psychiatric comorbidities in patients with alopecia areata in Taiwan: a case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:525-531.

- Manolache L, Petrescu-Seceleanu D, Benea V. Alopecia areata and stressful events in children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:107-109.

Practice Points

- The etiopathogenesis of alopecia areata (AA) is not clearly understood, but its occurrence and progression can involve immune dysfunction, genetic predisposition, infections, and physical and psychological trauma.

- Alopecia areata is observed to occur sporadically in most patients. Simultaneous presence of AA in more than 3 members of the same family is rare, and these cases have been observed in different generations and time periods.

- HLA antigen alleles, which provide predisposition to AA, have been investigated, and associations with many different HLA antigens have been described for AA. In previous studies, HLA-DQB1*03 allele was reported as the most common HLA allele in patients with AA.

- Psychological disorders and shared stressful life events may play an important role in the occurrence of AA and lead to the development of resistance against treatment in familial and resistant AA cases.

VIDEO: The ins and outs of JAK ihibitors for alopecia

NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF. – The promise of Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors for alopecia seems to be holding up in the practice of Dr. Natasha Mesinkovska, a dermatologist at the University of California, Irvine.

There’s been much excitement about JAK inhibitors since Yale researchers reported in 2014 that tofacitinib (Xeljanz), a JAK inhibitor approved in the United States for rheumatoid arthritis, appeared to grow a full head of hair, plus body hair, in an essentially hairless 25-year-old man with plaque psoriasis. JAK inhibitors have been under investigation for alopecia ever since. Meanwhile, they are being used off label for hair loss around the country.

In her own practice, Dr. Mesinkovska estimates that about two-thirds of patients have some degree of hair regrowth, with particularly satisfying results in men. About 40 of her alopecia patients have opted for JAK inhibitors so far.

In an interview at the Summit in Aesthetic Medicine, Dr. Mesinkovska shared her insights and tips, as well as promising alopecia results for the psoriasis biologic ustekinumab (Stelara), an interleukin-12 and -23 antagonist. “This is a very exciting time for alopecia areata,” she said.

The Summit in Aesthetic Medicine is held by the Global Academy for Medical Education. Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF. – The promise of Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors for alopecia seems to be holding up in the practice of Dr. Natasha Mesinkovska, a dermatologist at the University of California, Irvine.

There’s been much excitement about JAK inhibitors since Yale researchers reported in 2014 that tofacitinib (Xeljanz), a JAK inhibitor approved in the United States for rheumatoid arthritis, appeared to grow a full head of hair, plus body hair, in an essentially hairless 25-year-old man with plaque psoriasis. JAK inhibitors have been under investigation for alopecia ever since. Meanwhile, they are being used off label for hair loss around the country.

In her own practice, Dr. Mesinkovska estimates that about two-thirds of patients have some degree of hair regrowth, with particularly satisfying results in men. About 40 of her alopecia patients have opted for JAK inhibitors so far.

In an interview at the Summit in Aesthetic Medicine, Dr. Mesinkovska shared her insights and tips, as well as promising alopecia results for the psoriasis biologic ustekinumab (Stelara), an interleukin-12 and -23 antagonist. “This is a very exciting time for alopecia areata,” she said.

The Summit in Aesthetic Medicine is held by the Global Academy for Medical Education. Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF. – The promise of Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors for alopecia seems to be holding up in the practice of Dr. Natasha Mesinkovska, a dermatologist at the University of California, Irvine.

There’s been much excitement about JAK inhibitors since Yale researchers reported in 2014 that tofacitinib (Xeljanz), a JAK inhibitor approved in the United States for rheumatoid arthritis, appeared to grow a full head of hair, plus body hair, in an essentially hairless 25-year-old man with plaque psoriasis. JAK inhibitors have been under investigation for alopecia ever since. Meanwhile, they are being used off label for hair loss around the country.

In her own practice, Dr. Mesinkovska estimates that about two-thirds of patients have some degree of hair regrowth, with particularly satisfying results in men. About 40 of her alopecia patients have opted for JAK inhibitors so far.

In an interview at the Summit in Aesthetic Medicine, Dr. Mesinkovska shared her insights and tips, as well as promising alopecia results for the psoriasis biologic ustekinumab (Stelara), an interleukin-12 and -23 antagonist. “This is a very exciting time for alopecia areata,” she said.

The Summit in Aesthetic Medicine is held by the Global Academy for Medical Education. Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE SUMMIT IN AESTHETIC MEDICINE

Keys to alopecia areata might lie in gut microbiome

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Wiping out the gut microbiome with antibiotics prevented alopecia areata in a study of mice, providing evidence that the gut microbiome may play a role in alopecia, Dr. James Chen reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

The finding shows that the bacterial culprits in alopecia “reside in the gut microbiome, and not in the skin,” said Dr. Chen, a postdoctoral research fellow in medical genetics at Columbia University, New York.

Alopecia areata is mediated by autoreactive NKG2D+ CD8+ T cells. Aberrations in the human microbiome underlie several other autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and type I diabetes, Dr. Chen noted. “The gut microbiome also has been linked to skin conditions, such as acne, psoriasis, and atopic dermatitis,” he added. “So we asked, if we deplete this microbiome with an antibiotic cocktail, do we see an effect on alopecia?”

To find out, he and his coinvestigators grafted skin from C3H/Hej mice, which spontaneously develop alopecia, onto healthy younger mice, causing them to develop alopecia 6-10 weeks later. “Strikingly, we found that treating unaffected mice with an oral antibiotic cocktail prior to grafting completely prevented the development of alopecia areata, and this remained true through 15 weeks,” he said. “This is the first evidence that the gut microbiome could be implicated in alopecia, based on the absence of the phenotype that we see in treated mice.”

The researchers also evaluated whether the skin microbiomes of antibiotic-treated and control mice differed, and determined that the skin samples resembled each other in terms of overall bacterial load and bacterial taxonomic clustering patterns. That suggests that the skin microbiome is not involved in alopecia areata, Dr. Chen said.

Finally, the investigators transferred NKG2D+ CD8+ T cells from the cutaneous lymph nodes of alopecic mice to normal mice that had been pretreated with antibiotics. The treated mice had little infiltration of these T cells into the skin, and lower overall T-cell levels than control mice, Dr. Chen reported.

The investigators are now testing combinations of antibiotics and fecal transplants to pinpoint which gut bacteria make mice susceptible to hair loss. Doing so “will have significant implications on both our understanding of alopecia areata susceptibility, as well as actionable therapeutic targets for treatment” in humans, Dr. Chen said.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Medical Research Council, the Dermatology Foundation, Locks of Love Foundation, and NYSTEM (New York State Stem Cell Science). Dr. Chen had no financial disclosures.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Wiping out the gut microbiome with antibiotics prevented alopecia areata in a study of mice, providing evidence that the gut microbiome may play a role in alopecia, Dr. James Chen reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

The finding shows that the bacterial culprits in alopecia “reside in the gut microbiome, and not in the skin,” said Dr. Chen, a postdoctoral research fellow in medical genetics at Columbia University, New York.

Alopecia areata is mediated by autoreactive NKG2D+ CD8+ T cells. Aberrations in the human microbiome underlie several other autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and type I diabetes, Dr. Chen noted. “The gut microbiome also has been linked to skin conditions, such as acne, psoriasis, and atopic dermatitis,” he added. “So we asked, if we deplete this microbiome with an antibiotic cocktail, do we see an effect on alopecia?”

To find out, he and his coinvestigators grafted skin from C3H/Hej mice, which spontaneously develop alopecia, onto healthy younger mice, causing them to develop alopecia 6-10 weeks later. “Strikingly, we found that treating unaffected mice with an oral antibiotic cocktail prior to grafting completely prevented the development of alopecia areata, and this remained true through 15 weeks,” he said. “This is the first evidence that the gut microbiome could be implicated in alopecia, based on the absence of the phenotype that we see in treated mice.”

The researchers also evaluated whether the skin microbiomes of antibiotic-treated and control mice differed, and determined that the skin samples resembled each other in terms of overall bacterial load and bacterial taxonomic clustering patterns. That suggests that the skin microbiome is not involved in alopecia areata, Dr. Chen said.

Finally, the investigators transferred NKG2D+ CD8+ T cells from the cutaneous lymph nodes of alopecic mice to normal mice that had been pretreated with antibiotics. The treated mice had little infiltration of these T cells into the skin, and lower overall T-cell levels than control mice, Dr. Chen reported.

The investigators are now testing combinations of antibiotics and fecal transplants to pinpoint which gut bacteria make mice susceptible to hair loss. Doing so “will have significant implications on both our understanding of alopecia areata susceptibility, as well as actionable therapeutic targets for treatment” in humans, Dr. Chen said.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Medical Research Council, the Dermatology Foundation, Locks of Love Foundation, and NYSTEM (New York State Stem Cell Science). Dr. Chen had no financial disclosures.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Wiping out the gut microbiome with antibiotics prevented alopecia areata in a study of mice, providing evidence that the gut microbiome may play a role in alopecia, Dr. James Chen reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

The finding shows that the bacterial culprits in alopecia “reside in the gut microbiome, and not in the skin,” said Dr. Chen, a postdoctoral research fellow in medical genetics at Columbia University, New York.

Alopecia areata is mediated by autoreactive NKG2D+ CD8+ T cells. Aberrations in the human microbiome underlie several other autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and type I diabetes, Dr. Chen noted. “The gut microbiome also has been linked to skin conditions, such as acne, psoriasis, and atopic dermatitis,” he added. “So we asked, if we deplete this microbiome with an antibiotic cocktail, do we see an effect on alopecia?”

To find out, he and his coinvestigators grafted skin from C3H/Hej mice, which spontaneously develop alopecia, onto healthy younger mice, causing them to develop alopecia 6-10 weeks later. “Strikingly, we found that treating unaffected mice with an oral antibiotic cocktail prior to grafting completely prevented the development of alopecia areata, and this remained true through 15 weeks,” he said. “This is the first evidence that the gut microbiome could be implicated in alopecia, based on the absence of the phenotype that we see in treated mice.”

The researchers also evaluated whether the skin microbiomes of antibiotic-treated and control mice differed, and determined that the skin samples resembled each other in terms of overall bacterial load and bacterial taxonomic clustering patterns. That suggests that the skin microbiome is not involved in alopecia areata, Dr. Chen said.

Finally, the investigators transferred NKG2D+ CD8+ T cells from the cutaneous lymph nodes of alopecic mice to normal mice that had been pretreated with antibiotics. The treated mice had little infiltration of these T cells into the skin, and lower overall T-cell levels than control mice, Dr. Chen reported.

The investigators are now testing combinations of antibiotics and fecal transplants to pinpoint which gut bacteria make mice susceptible to hair loss. Doing so “will have significant implications on both our understanding of alopecia areata susceptibility, as well as actionable therapeutic targets for treatment” in humans, Dr. Chen said.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Medical Research Council, the Dermatology Foundation, Locks of Love Foundation, and NYSTEM (New York State Stem Cell Science). Dr. Chen had no financial disclosures.

AT THE 2016 SID ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Using antibiotics to eliminate the gut microbiome in mice prevented them from developing alopecia.

Major finding: The mice also had lower levels of cytotoxic T-cell infiltration into the skin, compared with alopecic controls.

Data source: A study of C3H/Hej (alopecic) mice and healthy young mice that received skin grafts from the alopecic phenotype.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Medical Research Council, the Dermatology Foundation, Locks of Love Foundation, and NYSTEM (New York State Stem Cell Science). Dr. Chen had no financial disclosures.

JAK inhibitor improves alopecia, with caveats

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – The Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor tofacitinib dramatically improved several cases of alopecia areata (AA), although some patients relapsed to worse than baseline after completing treatment in a small open label pilot trial.

“Regrowth was demonstrated in 11 out of 12 patients on tofacitinib. Seven out of 12 patients achieved more than 50% regrowth,” Dr. Shawn Sidharthan reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

Worldwide, alopecia areata, which is caused by immune-mediated destruction of hair follicles, has a lifetime incidence of about 2% (Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:397-403). But there are no Food and Drug Administration–approved treatments for AA. Tofacitinib (Xeljanz), which is approved by the FDA for moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis in adults, is a JAK1 and JAK3 inhibitor that curbs the interferon-gamma response inflammatory pathway, said Dr. Sidharthan of the department of dermatology and genetics at Columbia University, New York.

AA shares the same interferon response pathway, and tofacitinib prevented alopecia in mice and led to hair regrowth in a patient with alopecia universalis, he noted.

The single-arm trial included seven patients with moderate to severe patchy AA and five patients with alopecia totalis or alopecia universalis. Patients were treated for 6 months. They initially received 5 mg tofacitinib orally twice daily, which was increased to 10 mg twice daily to improve response. The investigators evaluated patients based on SALT (Severity of Alopecia Tool) scores and the Alopecia Areata Disease Activity Index (ALADIN), which uses three-dimensional bioinformatics to identify groups of genes linked to alopecia.

Seven of 12 patients experienced at least 50% regrowth, including six patients who only improved on 10 mg tofacitinib twice daily, Dr. Sidharthan said. Three additional patients “had good regrowth, but not 50%,” he reported. Among the two remaining patients, one had full regrowth, but dropped out of the study because of uncontrolled hypertension, and one patient with alopecia universalis had little or no regrowth.

Notably, two patients began shedding hair after stopping tofacitinib during the observation period of the study, and their final SALT scores were worse than baseline, Dr. Sidharthan said.

Laboratory monitoring of the cohort revealed no severe adverse events, but one patient paused treatment because of thrombocytopenia. The patient’s platelet count normalized after 2 weeks off tofacitinib, and remained normal when the dose was gradually increased to 10 mg twice daily. Another patient developed leukocytosis that resolved during the off-treatment observation period. One patient who did not comply with instructions to avoid alcohol had elevated liver function tests and was taken off the study. Two patients experienced self-limiting diarrhea, and one patient developed trace hematuria, Dr. Sidharthan noted.

In the study, ALADIN scores correlated with clinical response, he said.

He and his coinvestigators concluded that the overall results “provide a strong rationale for larger clinical trials using JAK inhibitors in alopecia areata,” he said.

Dr. Sidharthan noted that another oral JAK inhibitor, ruxolitinib (Jakafi), led to nearly full hair regrowth in three patients with alopecia in a Columbia University study (Nat Med. 2014 Sep; 20[9]:1043-9).

The Locks of Love Foundation funded the research. Dr. Sidharthan, a clinical research fellow in dermatology at Columbia, had no disclosures.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – The Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor tofacitinib dramatically improved several cases of alopecia areata (AA), although some patients relapsed to worse than baseline after completing treatment in a small open label pilot trial.

“Regrowth was demonstrated in 11 out of 12 patients on tofacitinib. Seven out of 12 patients achieved more than 50% regrowth,” Dr. Shawn Sidharthan reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

Worldwide, alopecia areata, which is caused by immune-mediated destruction of hair follicles, has a lifetime incidence of about 2% (Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:397-403). But there are no Food and Drug Administration–approved treatments for AA. Tofacitinib (Xeljanz), which is approved by the FDA for moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis in adults, is a JAK1 and JAK3 inhibitor that curbs the interferon-gamma response inflammatory pathway, said Dr. Sidharthan of the department of dermatology and genetics at Columbia University, New York.

AA shares the same interferon response pathway, and tofacitinib prevented alopecia in mice and led to hair regrowth in a patient with alopecia universalis, he noted.

The single-arm trial included seven patients with moderate to severe patchy AA and five patients with alopecia totalis or alopecia universalis. Patients were treated for 6 months. They initially received 5 mg tofacitinib orally twice daily, which was increased to 10 mg twice daily to improve response. The investigators evaluated patients based on SALT (Severity of Alopecia Tool) scores and the Alopecia Areata Disease Activity Index (ALADIN), which uses three-dimensional bioinformatics to identify groups of genes linked to alopecia.

Seven of 12 patients experienced at least 50% regrowth, including six patients who only improved on 10 mg tofacitinib twice daily, Dr. Sidharthan said. Three additional patients “had good regrowth, but not 50%,” he reported. Among the two remaining patients, one had full regrowth, but dropped out of the study because of uncontrolled hypertension, and one patient with alopecia universalis had little or no regrowth.

Notably, two patients began shedding hair after stopping tofacitinib during the observation period of the study, and their final SALT scores were worse than baseline, Dr. Sidharthan said.

Laboratory monitoring of the cohort revealed no severe adverse events, but one patient paused treatment because of thrombocytopenia. The patient’s platelet count normalized after 2 weeks off tofacitinib, and remained normal when the dose was gradually increased to 10 mg twice daily. Another patient developed leukocytosis that resolved during the off-treatment observation period. One patient who did not comply with instructions to avoid alcohol had elevated liver function tests and was taken off the study. Two patients experienced self-limiting diarrhea, and one patient developed trace hematuria, Dr. Sidharthan noted.

In the study, ALADIN scores correlated with clinical response, he said.

He and his coinvestigators concluded that the overall results “provide a strong rationale for larger clinical trials using JAK inhibitors in alopecia areata,” he said.

Dr. Sidharthan noted that another oral JAK inhibitor, ruxolitinib (Jakafi), led to nearly full hair regrowth in three patients with alopecia in a Columbia University study (Nat Med. 2014 Sep; 20[9]:1043-9).

The Locks of Love Foundation funded the research. Dr. Sidharthan, a clinical research fellow in dermatology at Columbia, had no disclosures.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – The Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor tofacitinib dramatically improved several cases of alopecia areata (AA), although some patients relapsed to worse than baseline after completing treatment in a small open label pilot trial.

“Regrowth was demonstrated in 11 out of 12 patients on tofacitinib. Seven out of 12 patients achieved more than 50% regrowth,” Dr. Shawn Sidharthan reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

Worldwide, alopecia areata, which is caused by immune-mediated destruction of hair follicles, has a lifetime incidence of about 2% (Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:397-403). But there are no Food and Drug Administration–approved treatments for AA. Tofacitinib (Xeljanz), which is approved by the FDA for moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis in adults, is a JAK1 and JAK3 inhibitor that curbs the interferon-gamma response inflammatory pathway, said Dr. Sidharthan of the department of dermatology and genetics at Columbia University, New York.

AA shares the same interferon response pathway, and tofacitinib prevented alopecia in mice and led to hair regrowth in a patient with alopecia universalis, he noted.

The single-arm trial included seven patients with moderate to severe patchy AA and five patients with alopecia totalis or alopecia universalis. Patients were treated for 6 months. They initially received 5 mg tofacitinib orally twice daily, which was increased to 10 mg twice daily to improve response. The investigators evaluated patients based on SALT (Severity of Alopecia Tool) scores and the Alopecia Areata Disease Activity Index (ALADIN), which uses three-dimensional bioinformatics to identify groups of genes linked to alopecia.

Seven of 12 patients experienced at least 50% regrowth, including six patients who only improved on 10 mg tofacitinib twice daily, Dr. Sidharthan said. Three additional patients “had good regrowth, but not 50%,” he reported. Among the two remaining patients, one had full regrowth, but dropped out of the study because of uncontrolled hypertension, and one patient with alopecia universalis had little or no regrowth.

Notably, two patients began shedding hair after stopping tofacitinib during the observation period of the study, and their final SALT scores were worse than baseline, Dr. Sidharthan said.

Laboratory monitoring of the cohort revealed no severe adverse events, but one patient paused treatment because of thrombocytopenia. The patient’s platelet count normalized after 2 weeks off tofacitinib, and remained normal when the dose was gradually increased to 10 mg twice daily. Another patient developed leukocytosis that resolved during the off-treatment observation period. One patient who did not comply with instructions to avoid alcohol had elevated liver function tests and was taken off the study. Two patients experienced self-limiting diarrhea, and one patient developed trace hematuria, Dr. Sidharthan noted.

In the study, ALADIN scores correlated with clinical response, he said.

He and his coinvestigators concluded that the overall results “provide a strong rationale for larger clinical trials using JAK inhibitors in alopecia areata,” he said.

Dr. Sidharthan noted that another oral JAK inhibitor, ruxolitinib (Jakafi), led to nearly full hair regrowth in three patients with alopecia in a Columbia University study (Nat Med. 2014 Sep; 20[9]:1043-9).

The Locks of Love Foundation funded the research. Dr. Sidharthan, a clinical research fellow in dermatology at Columbia, had no disclosures.

AT THE 2016 SID ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Tofacitinib dramatically improved several cases of alopecia areata, but some patients relapsed after stopping treatment.

Major finding: Eleven of 12 patients experienced regrowth, including seven with at least 50% regrowth, but two patients relapsed to worse than baseline after stopping treatment.

Data source: The single-center open-label pilot trial evaluated tofacitinib in 12 patients with alopecia areata, totalis, or universalis.

Disclosures: The Locks of Love Foundation funded the research. Dr. Shawn Sidharthan had no disclosures.

Skin Lesions in Patients Treated With Imatinib Mesylate: A 5-Year Prospective Study

Imatinib mesylate (IM) represents the first-line treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs). Its pharmacological activity is related to a specific action on several tyrosine kinases in different tumors, including Bcr-Abl in CML, c-Kit (CD117) in GIST, and platelet-derived growth factor receptor in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans.1,2

Imatinib mesylate has been shown to improve progression-free survival and overall survival2; however, it also has several side effects. Among the adverse effects (AEs), less than 10% are nonhematologic, such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, muscle cramps, and cutaneous reactions.3,4

We followed patients who were treated with IM for 5 years to identify AEs of therapy.

Methods