User login

CDC creates interactive education module to improve RMSF recognition

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has created a first-of-its-kind interactive training module to help physicians both recognize and diagnose Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF).

A record number of cases of RMSF were reported to the CDC in 2017 (6,248, up from 4,269 in 2016), but less than 1% of those cases had sufficient laboratory evidence to be confirmed. The CDC education module includes scenarios based on real cases to aid providers in recognizing RMSF and differentiating it from similar diseases. CME is available for physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, veterinarians, nurses, epidemiologists, public health professionals, educators, and health communicators.

The disease initially presents with nonspecific symptoms such as fever, headache, or rash, but if left untreated, patients may require the amputation of fingers, toes, or limbs because of low blood flow; heart and lung specialty care; and ICU management. About 20% of untreated cases are fatal; half of these deaths occur within 8 days of initial presentation.

“Rocky Mountain spotted fever can be deadly if not treated early – yet cases often go unrecognized because the signs and symptoms are similar to those of many other diseases. With tickborne diseases on the rise in the U.S., this training will better equip health care providers to identify, diagnose, and treat this potentially fatal disease,” said CDC director Robert R. Redfield, MD.

Find the full press release on the CDC website.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has created a first-of-its-kind interactive training module to help physicians both recognize and diagnose Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF).

A record number of cases of RMSF were reported to the CDC in 2017 (6,248, up from 4,269 in 2016), but less than 1% of those cases had sufficient laboratory evidence to be confirmed. The CDC education module includes scenarios based on real cases to aid providers in recognizing RMSF and differentiating it from similar diseases. CME is available for physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, veterinarians, nurses, epidemiologists, public health professionals, educators, and health communicators.

The disease initially presents with nonspecific symptoms such as fever, headache, or rash, but if left untreated, patients may require the amputation of fingers, toes, or limbs because of low blood flow; heart and lung specialty care; and ICU management. About 20% of untreated cases are fatal; half of these deaths occur within 8 days of initial presentation.

“Rocky Mountain spotted fever can be deadly if not treated early – yet cases often go unrecognized because the signs and symptoms are similar to those of many other diseases. With tickborne diseases on the rise in the U.S., this training will better equip health care providers to identify, diagnose, and treat this potentially fatal disease,” said CDC director Robert R. Redfield, MD.

Find the full press release on the CDC website.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has created a first-of-its-kind interactive training module to help physicians both recognize and diagnose Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF).

A record number of cases of RMSF were reported to the CDC in 2017 (6,248, up from 4,269 in 2016), but less than 1% of those cases had sufficient laboratory evidence to be confirmed. The CDC education module includes scenarios based on real cases to aid providers in recognizing RMSF and differentiating it from similar diseases. CME is available for physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, veterinarians, nurses, epidemiologists, public health professionals, educators, and health communicators.

The disease initially presents with nonspecific symptoms such as fever, headache, or rash, but if left untreated, patients may require the amputation of fingers, toes, or limbs because of low blood flow; heart and lung specialty care; and ICU management. About 20% of untreated cases are fatal; half of these deaths occur within 8 days of initial presentation.

“Rocky Mountain spotted fever can be deadly if not treated early – yet cases often go unrecognized because the signs and symptoms are similar to those of many other diseases. With tickborne diseases on the rise in the U.S., this training will better equip health care providers to identify, diagnose, and treat this potentially fatal disease,” said CDC director Robert R. Redfield, MD.

Find the full press release on the CDC website.

Is it measles? – Diagnosis and management for the pediatric provider

The mother of an 8-month-old calls your office and is hysterical. Her daughter has had cough for a few days with high fevers and now has developed a full body rash. She is worried about measles and is on her way to your office.

We are in the middle of a measles epidemic, there’s no denying it. Measles was declared eliminated in 2000, but reported cases in the United States have been on the rise, and are now at the highest number since 2014. Five months into 2019, there have been 839 reported cases as of May 13). Measles outbreaks (defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as three or more cases) have been reported in California, Georgia, Maryland, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania. When vaccination rates fall, it is easy for measles to spread. The virus is highly contagious in nonimmune people, because of its airborne spread and its persistence in the environment for hours.

First – is it really measles?

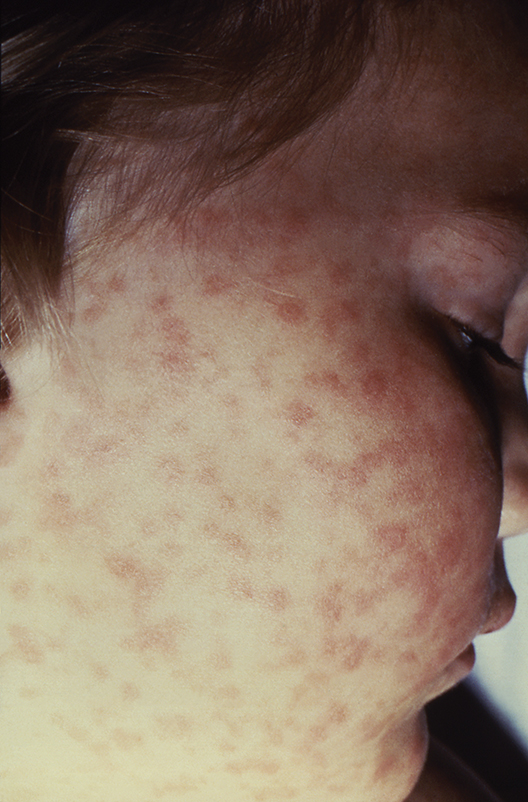

It can be difficult to distinguish the maculopapular rash of measles from similar rashes that occur with more benign viral illnesses. Adding to the challenge, the last major measles outbreak in the United States was over 2 decades ago, and many practicing pediatricians have never seen a single case. So, what clinical features can help distinguish measles from other febrile illnesses?

The prodromal phase of measles lasts approximately 2-4 days and children have high fevers (103°-105° F), anorexia, and malaise. Conjunctivitis, coryza, and cough develop during this phase, and precede any rash. Koplik spots appear during the prodromal phase, but are not seen in all cases. These spots are 1- to 3-mm blue-white lesions on an erythematous base on the buccal mucosa, classically opposite the first molar. The spots often slough once the rash appears. The rash appears 2-4 days after the onset of fever, and is initially maculopapular and blanching. The first lesions appear on the face and neck, and the rash spreads cranial to caudal, typically sparing palms and soles. After days 3-4, the rash will no longer blanch. High fevers persist for 2-4 more days with rash, ongoing respiratory symptoms, conjunctivitis, and pharyngitis. Note that the fever will persist even with development of the rash, unlike in roseola.

It is not only important to diagnosis measles from a public health standpoint, but also because measles can have severe complications, especially in infants and children under 5 years. During the 1989-1991 outbreak, the mortality rate was 2.2 deaths per 1,000 cases (J Infect Dis. 2004 May 1. doi: 10.1086/377694).

Six percent of patients develop pneumonia, which in infants and toddlers can lead to respiratory distress or failure requiring hospitalization. Pneumonia is responsible for 60% of measles deaths, according to the CDC “Pink Book,” Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases, chapter 13 on measles, 13th Ed., 2015. Ocular complications include keratitis and corneal ulceration. Measles also can cause serious neurologic complications. Encephalitis, seen in 1 per 1,000 cases, usually arises several days after the rash and may present with seizure or encephalopathy. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), an inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system, occurs in approximately 1 per 1,000 cases, typically presents during the recovery phase (1-2 weeks after rash), and can have long-term sequelae. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) is a progressive and fatal neurodegenerative disorder, and presents 7-10 years after measles infection.

Should you transfer the patient to a hospital?

Unless there is a medical need for the child to be admitted, sending a patient with potential measles to the hospital is not necessary, and can cause exposure to a large group of medical personnel, and patients who cannot be vaccinated (such as infants, immunocompromised patients, and pregnant women). However, if there is concern for complications such as seizures, encephalitis, or pneumonia, then transfer is indicated. Call the accepting hospital in advance so the staff can prepare for the patient. During transfer, place a standard face mask on the patient and instruct the patient not to remove it.

For hospitals accepting a suspected measles case, meet the patient outside of the facility and ensure that the patient is wearing a standard face mask. All staff interacting with the patient should practice contact and airborne precautions (N95 respirator mask). Take the patient directly to an isolation room with negative airflow. Caution pregnant staff that they should not have contact with the patient.

Which diagnostic tests should you use?

Diagnosis can be made based on serum antibody tests (measles IgM and IgG), throat or urine viral cultures, and nasopharyngeal and throat specimen polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. The CDC recommends obtaining a serum sample for measles IgM testing and a throat swab for PCR in all suspected cases, but local health departments vary in their specific testing recommendations. Familiarize yourself with the tests recommended by your local department of health, and where they prefer testing on outpatients to be done. Confirmed measles should be reported to your department of health.

What are considerations for community pediatric offices?

Update families in emails to call ahead if they suspect measles. This way the office can prepare a room for the family, and have the family immediately brought back without exposing staff and other families in the waiting area. It may be more prudent to examine these children at the end of the clinic day as the virus can persist for up to 2 hours on fomites and in the air. Therefore, all waiting areas and shared air spaces (including those with shared air ducts) should be cleared for 2 hours after the patient leaves.

When should you provide prophylaxis after exposure?

A patient with suspected measles does not require immediate vaccination. If it is measles, it is already too late to vaccinate. If measles is ruled out, the child should follow the standard measles vaccination guidelines.

Individuals are contagious from 4 days before to 4 days after the rash appears.

If measles is confirmed, all people who are unvaccinated or undervaccinated and were exposed to the confirmed case during the contagious period should be vaccinated within 72 hours of exposure. Infants 6 months or older may safely receive the MMR vaccine. However, infants vaccinated with MMR before their first birthday must be vaccinated again at age 12-15 months (greater than 28 days after prior vaccine) and at 4-6 years. Immunoglobulin prophylaxis should be given intramuscularly in exposed infants ages birth to less than 6 months, and in those ages 6-12 months who present beyond the 72-hour window. Unvaccinated or undervaccinated, exposed individuals at high risk for complications from measles (immunocompromised, pregnant) also should receive immunoglobulin.

What should you tell traveling families?

Several countries have large, ongoing measles outbreaks, including Israel, Ukraine, and the Philippines. Before international travel, infants 6-11 months should receive one dose of MMR vaccine, and children 12 months and older need two doses separated by at least 28 days. For unvaccinated or undervaccinated children, consider advising families to hold off travel to high-risk countries, or understand the indications to vaccinate a child upon return.

Dr. Angelica DesPain is a pediatric emergency medicine fellow at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington. She said she has no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Emily Willner is a pediatric emergency medicine attending at Children’s National Medical Center, and an assistant professor of pediatrics and emergency medicine at George Washington University, Washington. She has no relevant financial disclosures.

The mother of an 8-month-old calls your office and is hysterical. Her daughter has had cough for a few days with high fevers and now has developed a full body rash. She is worried about measles and is on her way to your office.

We are in the middle of a measles epidemic, there’s no denying it. Measles was declared eliminated in 2000, but reported cases in the United States have been on the rise, and are now at the highest number since 2014. Five months into 2019, there have been 839 reported cases as of May 13). Measles outbreaks (defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as three or more cases) have been reported in California, Georgia, Maryland, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania. When vaccination rates fall, it is easy for measles to spread. The virus is highly contagious in nonimmune people, because of its airborne spread and its persistence in the environment for hours.

First – is it really measles?

It can be difficult to distinguish the maculopapular rash of measles from similar rashes that occur with more benign viral illnesses. Adding to the challenge, the last major measles outbreak in the United States was over 2 decades ago, and many practicing pediatricians have never seen a single case. So, what clinical features can help distinguish measles from other febrile illnesses?

The prodromal phase of measles lasts approximately 2-4 days and children have high fevers (103°-105° F), anorexia, and malaise. Conjunctivitis, coryza, and cough develop during this phase, and precede any rash. Koplik spots appear during the prodromal phase, but are not seen in all cases. These spots are 1- to 3-mm blue-white lesions on an erythematous base on the buccal mucosa, classically opposite the first molar. The spots often slough once the rash appears. The rash appears 2-4 days after the onset of fever, and is initially maculopapular and blanching. The first lesions appear on the face and neck, and the rash spreads cranial to caudal, typically sparing palms and soles. After days 3-4, the rash will no longer blanch. High fevers persist for 2-4 more days with rash, ongoing respiratory symptoms, conjunctivitis, and pharyngitis. Note that the fever will persist even with development of the rash, unlike in roseola.

It is not only important to diagnosis measles from a public health standpoint, but also because measles can have severe complications, especially in infants and children under 5 years. During the 1989-1991 outbreak, the mortality rate was 2.2 deaths per 1,000 cases (J Infect Dis. 2004 May 1. doi: 10.1086/377694).

Six percent of patients develop pneumonia, which in infants and toddlers can lead to respiratory distress or failure requiring hospitalization. Pneumonia is responsible for 60% of measles deaths, according to the CDC “Pink Book,” Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases, chapter 13 on measles, 13th Ed., 2015. Ocular complications include keratitis and corneal ulceration. Measles also can cause serious neurologic complications. Encephalitis, seen in 1 per 1,000 cases, usually arises several days after the rash and may present with seizure or encephalopathy. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), an inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system, occurs in approximately 1 per 1,000 cases, typically presents during the recovery phase (1-2 weeks after rash), and can have long-term sequelae. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) is a progressive and fatal neurodegenerative disorder, and presents 7-10 years after measles infection.

Should you transfer the patient to a hospital?

Unless there is a medical need for the child to be admitted, sending a patient with potential measles to the hospital is not necessary, and can cause exposure to a large group of medical personnel, and patients who cannot be vaccinated (such as infants, immunocompromised patients, and pregnant women). However, if there is concern for complications such as seizures, encephalitis, or pneumonia, then transfer is indicated. Call the accepting hospital in advance so the staff can prepare for the patient. During transfer, place a standard face mask on the patient and instruct the patient not to remove it.

For hospitals accepting a suspected measles case, meet the patient outside of the facility and ensure that the patient is wearing a standard face mask. All staff interacting with the patient should practice contact and airborne precautions (N95 respirator mask). Take the patient directly to an isolation room with negative airflow. Caution pregnant staff that they should not have contact with the patient.

Which diagnostic tests should you use?

Diagnosis can be made based on serum antibody tests (measles IgM and IgG), throat or urine viral cultures, and nasopharyngeal and throat specimen polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. The CDC recommends obtaining a serum sample for measles IgM testing and a throat swab for PCR in all suspected cases, but local health departments vary in their specific testing recommendations. Familiarize yourself with the tests recommended by your local department of health, and where they prefer testing on outpatients to be done. Confirmed measles should be reported to your department of health.

What are considerations for community pediatric offices?

Update families in emails to call ahead if they suspect measles. This way the office can prepare a room for the family, and have the family immediately brought back without exposing staff and other families in the waiting area. It may be more prudent to examine these children at the end of the clinic day as the virus can persist for up to 2 hours on fomites and in the air. Therefore, all waiting areas and shared air spaces (including those with shared air ducts) should be cleared for 2 hours after the patient leaves.

When should you provide prophylaxis after exposure?

A patient with suspected measles does not require immediate vaccination. If it is measles, it is already too late to vaccinate. If measles is ruled out, the child should follow the standard measles vaccination guidelines.

Individuals are contagious from 4 days before to 4 days after the rash appears.

If measles is confirmed, all people who are unvaccinated or undervaccinated and were exposed to the confirmed case during the contagious period should be vaccinated within 72 hours of exposure. Infants 6 months or older may safely receive the MMR vaccine. However, infants vaccinated with MMR before their first birthday must be vaccinated again at age 12-15 months (greater than 28 days after prior vaccine) and at 4-6 years. Immunoglobulin prophylaxis should be given intramuscularly in exposed infants ages birth to less than 6 months, and in those ages 6-12 months who present beyond the 72-hour window. Unvaccinated or undervaccinated, exposed individuals at high risk for complications from measles (immunocompromised, pregnant) also should receive immunoglobulin.

What should you tell traveling families?

Several countries have large, ongoing measles outbreaks, including Israel, Ukraine, and the Philippines. Before international travel, infants 6-11 months should receive one dose of MMR vaccine, and children 12 months and older need two doses separated by at least 28 days. For unvaccinated or undervaccinated children, consider advising families to hold off travel to high-risk countries, or understand the indications to vaccinate a child upon return.

Dr. Angelica DesPain is a pediatric emergency medicine fellow at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington. She said she has no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Emily Willner is a pediatric emergency medicine attending at Children’s National Medical Center, and an assistant professor of pediatrics and emergency medicine at George Washington University, Washington. She has no relevant financial disclosures.

The mother of an 8-month-old calls your office and is hysterical. Her daughter has had cough for a few days with high fevers and now has developed a full body rash. She is worried about measles and is on her way to your office.

We are in the middle of a measles epidemic, there’s no denying it. Measles was declared eliminated in 2000, but reported cases in the United States have been on the rise, and are now at the highest number since 2014. Five months into 2019, there have been 839 reported cases as of May 13). Measles outbreaks (defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as three or more cases) have been reported in California, Georgia, Maryland, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania. When vaccination rates fall, it is easy for measles to spread. The virus is highly contagious in nonimmune people, because of its airborne spread and its persistence in the environment for hours.

First – is it really measles?

It can be difficult to distinguish the maculopapular rash of measles from similar rashes that occur with more benign viral illnesses. Adding to the challenge, the last major measles outbreak in the United States was over 2 decades ago, and many practicing pediatricians have never seen a single case. So, what clinical features can help distinguish measles from other febrile illnesses?

The prodromal phase of measles lasts approximately 2-4 days and children have high fevers (103°-105° F), anorexia, and malaise. Conjunctivitis, coryza, and cough develop during this phase, and precede any rash. Koplik spots appear during the prodromal phase, but are not seen in all cases. These spots are 1- to 3-mm blue-white lesions on an erythematous base on the buccal mucosa, classically opposite the first molar. The spots often slough once the rash appears. The rash appears 2-4 days after the onset of fever, and is initially maculopapular and blanching. The first lesions appear on the face and neck, and the rash spreads cranial to caudal, typically sparing palms and soles. After days 3-4, the rash will no longer blanch. High fevers persist for 2-4 more days with rash, ongoing respiratory symptoms, conjunctivitis, and pharyngitis. Note that the fever will persist even with development of the rash, unlike in roseola.

It is not only important to diagnosis measles from a public health standpoint, but also because measles can have severe complications, especially in infants and children under 5 years. During the 1989-1991 outbreak, the mortality rate was 2.2 deaths per 1,000 cases (J Infect Dis. 2004 May 1. doi: 10.1086/377694).

Six percent of patients develop pneumonia, which in infants and toddlers can lead to respiratory distress or failure requiring hospitalization. Pneumonia is responsible for 60% of measles deaths, according to the CDC “Pink Book,” Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases, chapter 13 on measles, 13th Ed., 2015. Ocular complications include keratitis and corneal ulceration. Measles also can cause serious neurologic complications. Encephalitis, seen in 1 per 1,000 cases, usually arises several days after the rash and may present with seizure or encephalopathy. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), an inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system, occurs in approximately 1 per 1,000 cases, typically presents during the recovery phase (1-2 weeks after rash), and can have long-term sequelae. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) is a progressive and fatal neurodegenerative disorder, and presents 7-10 years after measles infection.

Should you transfer the patient to a hospital?

Unless there is a medical need for the child to be admitted, sending a patient with potential measles to the hospital is not necessary, and can cause exposure to a large group of medical personnel, and patients who cannot be vaccinated (such as infants, immunocompromised patients, and pregnant women). However, if there is concern for complications such as seizures, encephalitis, or pneumonia, then transfer is indicated. Call the accepting hospital in advance so the staff can prepare for the patient. During transfer, place a standard face mask on the patient and instruct the patient not to remove it.

For hospitals accepting a suspected measles case, meet the patient outside of the facility and ensure that the patient is wearing a standard face mask. All staff interacting with the patient should practice contact and airborne precautions (N95 respirator mask). Take the patient directly to an isolation room with negative airflow. Caution pregnant staff that they should not have contact with the patient.

Which diagnostic tests should you use?

Diagnosis can be made based on serum antibody tests (measles IgM and IgG), throat or urine viral cultures, and nasopharyngeal and throat specimen polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. The CDC recommends obtaining a serum sample for measles IgM testing and a throat swab for PCR in all suspected cases, but local health departments vary in their specific testing recommendations. Familiarize yourself with the tests recommended by your local department of health, and where they prefer testing on outpatients to be done. Confirmed measles should be reported to your department of health.

What are considerations for community pediatric offices?

Update families in emails to call ahead if they suspect measles. This way the office can prepare a room for the family, and have the family immediately brought back without exposing staff and other families in the waiting area. It may be more prudent to examine these children at the end of the clinic day as the virus can persist for up to 2 hours on fomites and in the air. Therefore, all waiting areas and shared air spaces (including those with shared air ducts) should be cleared for 2 hours after the patient leaves.

When should you provide prophylaxis after exposure?

A patient with suspected measles does not require immediate vaccination. If it is measles, it is already too late to vaccinate. If measles is ruled out, the child should follow the standard measles vaccination guidelines.

Individuals are contagious from 4 days before to 4 days after the rash appears.

If measles is confirmed, all people who are unvaccinated or undervaccinated and were exposed to the confirmed case during the contagious period should be vaccinated within 72 hours of exposure. Infants 6 months or older may safely receive the MMR vaccine. However, infants vaccinated with MMR before their first birthday must be vaccinated again at age 12-15 months (greater than 28 days after prior vaccine) and at 4-6 years. Immunoglobulin prophylaxis should be given intramuscularly in exposed infants ages birth to less than 6 months, and in those ages 6-12 months who present beyond the 72-hour window. Unvaccinated or undervaccinated, exposed individuals at high risk for complications from measles (immunocompromised, pregnant) also should receive immunoglobulin.

What should you tell traveling families?

Several countries have large, ongoing measles outbreaks, including Israel, Ukraine, and the Philippines. Before international travel, infants 6-11 months should receive one dose of MMR vaccine, and children 12 months and older need two doses separated by at least 28 days. For unvaccinated or undervaccinated children, consider advising families to hold off travel to high-risk countries, or understand the indications to vaccinate a child upon return.

Dr. Angelica DesPain is a pediatric emergency medicine fellow at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington. She said she has no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Emily Willner is a pediatric emergency medicine attending at Children’s National Medical Center, and an assistant professor of pediatrics and emergency medicine at George Washington University, Washington. She has no relevant financial disclosures.

Fournier gangrene cases surge in patients using SGLT2 inhibitors

since the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a 2018 warning about this rare but serious infection, researchers say.

Health care providers prescribing SGLT2 inhibitors to patients with diabetes should have a high index of suspicion for the signs and symptoms of Fournier gangrene, given its substantial morbidity and mortality, according to Susan J. Bersoff-Matcha, MD, and her colleagues at the FDA.

“Although the risk for [Fournier gangrene] is low, serious infection should be considered and weighed against the benefits of SGLT2 inhibitor therapy,” said Dr. Bersoff-Matcha and co-authors in their recent report published in the Annals of Internal Medicine (2019 May 6. doi: 10.7326/M19-0085).

In the previous warning, FDA officials said 12 cases of Fournier gangrene in patients taking an SGLT2 inhibitor had been reported to the agency or in medical literature from March 2013, when the first such inhibitor was approved, and May 2018.

In this latest report, a total of 55 Fournier gangrene cases had been reported in patients receiving SGLT2 inhibitors from March 2, 2013 through January 31, 2019.

The influx of reports may have been prompted by growing awareness of the safety issue, investigators said, but could also reflect the increasing prevalence of diabetes combined with SGLT2 inhibitor use. The researchers also noted that diabetes is a comorbidity in 32% to 66% of cases of Fournier gangrene.

But the likliehood that diabetes mellitus alone causes Fournier gangrene seems unlikley, given that Dr. Bersoff-Matcha and co-authors only found 19 Fournier gangrene cases associated with other classes of antiglycemic agents reported to the FDA or in the literature over a 35-year time frame.

“If Fournier gangrene were associated only with diabetes mellitus and not SGLT2 inhibitors, we would expect far more cases reported with the other antiglycemic agents, considering the 35-year timeframe and the large number of agents,” they said in their report.

Cases were reported for all FDA-approved SGLT2 inhibitors besides ertugliflozin, an agent approved for use in the U.S. in December 2017. The lack of cases reported for this drug could be related to its limited time on the market, the investigators said.

Fournier gangrene, marked by rapidly progressing necrotizing infection of the genitalia, perineum, and perianal region, requires antibiotics and immediate surgery, according to Dr. Bersoff-Matcha and colleagues.

“Serious complications and death are likely if Fournier gangrene is not recognized immediately and surgical intervention is not carried out within the first few hours of diagnosis,” they said in the report.

Of the 55 cases reported in patients receiving SGLT2 inhibitors, 39 were men and 16 were women, with an average of 9 months from the start of treatment to the event, investigators said.

At least 25 patients required multiple surgeries, including one patient who had 17 trips to the operating room, they said. A total of 8 patients had a fecal diversion procedure, and 4 patients had skin grafting.

Six patients had multiple encounters with a provider before being diagnosed, suggesting that the provider may have not recognized the infection due to its nonspecific symptoms, which include fatigue, fever, and malaise.

“Pain that seems out of proportion to findings on physical examination is a strong clinical indicator of necrotizing fasciitis and may be the most important diagnostic clue,” Dr. Bersoff-Matcha and co-authors said in their report.

The incidence of Fournier gangrene in patients taking SGLT2 inhibitors can’t be established by these cases reported to the FDA, which are spontaneously provided by health care providers and patients, investigators said.

“We suspect that our numbers underestimate the true burden,” they said in their report.

Dr. Bersoff-Matcha and co-authors disclosed no conflicts of interest related to their report.

SOURCE: Bersoff-Matcha SJ, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 May 6. Doi: doi:10.7326/M19-0085.

This article was updated May 9, 2019.

since the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a 2018 warning about this rare but serious infection, researchers say.

Health care providers prescribing SGLT2 inhibitors to patients with diabetes should have a high index of suspicion for the signs and symptoms of Fournier gangrene, given its substantial morbidity and mortality, according to Susan J. Bersoff-Matcha, MD, and her colleagues at the FDA.

“Although the risk for [Fournier gangrene] is low, serious infection should be considered and weighed against the benefits of SGLT2 inhibitor therapy,” said Dr. Bersoff-Matcha and co-authors in their recent report published in the Annals of Internal Medicine (2019 May 6. doi: 10.7326/M19-0085).

In the previous warning, FDA officials said 12 cases of Fournier gangrene in patients taking an SGLT2 inhibitor had been reported to the agency or in medical literature from March 2013, when the first such inhibitor was approved, and May 2018.

In this latest report, a total of 55 Fournier gangrene cases had been reported in patients receiving SGLT2 inhibitors from March 2, 2013 through January 31, 2019.

The influx of reports may have been prompted by growing awareness of the safety issue, investigators said, but could also reflect the increasing prevalence of diabetes combined with SGLT2 inhibitor use. The researchers also noted that diabetes is a comorbidity in 32% to 66% of cases of Fournier gangrene.

But the likliehood that diabetes mellitus alone causes Fournier gangrene seems unlikley, given that Dr. Bersoff-Matcha and co-authors only found 19 Fournier gangrene cases associated with other classes of antiglycemic agents reported to the FDA or in the literature over a 35-year time frame.

“If Fournier gangrene were associated only with diabetes mellitus and not SGLT2 inhibitors, we would expect far more cases reported with the other antiglycemic agents, considering the 35-year timeframe and the large number of agents,” they said in their report.

Cases were reported for all FDA-approved SGLT2 inhibitors besides ertugliflozin, an agent approved for use in the U.S. in December 2017. The lack of cases reported for this drug could be related to its limited time on the market, the investigators said.

Fournier gangrene, marked by rapidly progressing necrotizing infection of the genitalia, perineum, and perianal region, requires antibiotics and immediate surgery, according to Dr. Bersoff-Matcha and colleagues.

“Serious complications and death are likely if Fournier gangrene is not recognized immediately and surgical intervention is not carried out within the first few hours of diagnosis,” they said in the report.

Of the 55 cases reported in patients receiving SGLT2 inhibitors, 39 were men and 16 were women, with an average of 9 months from the start of treatment to the event, investigators said.

At least 25 patients required multiple surgeries, including one patient who had 17 trips to the operating room, they said. A total of 8 patients had a fecal diversion procedure, and 4 patients had skin grafting.

Six patients had multiple encounters with a provider before being diagnosed, suggesting that the provider may have not recognized the infection due to its nonspecific symptoms, which include fatigue, fever, and malaise.

“Pain that seems out of proportion to findings on physical examination is a strong clinical indicator of necrotizing fasciitis and may be the most important diagnostic clue,” Dr. Bersoff-Matcha and co-authors said in their report.

The incidence of Fournier gangrene in patients taking SGLT2 inhibitors can’t be established by these cases reported to the FDA, which are spontaneously provided by health care providers and patients, investigators said.

“We suspect that our numbers underestimate the true burden,” they said in their report.

Dr. Bersoff-Matcha and co-authors disclosed no conflicts of interest related to their report.

SOURCE: Bersoff-Matcha SJ, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 May 6. Doi: doi:10.7326/M19-0085.

This article was updated May 9, 2019.

since the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a 2018 warning about this rare but serious infection, researchers say.

Health care providers prescribing SGLT2 inhibitors to patients with diabetes should have a high index of suspicion for the signs and symptoms of Fournier gangrene, given its substantial morbidity and mortality, according to Susan J. Bersoff-Matcha, MD, and her colleagues at the FDA.

“Although the risk for [Fournier gangrene] is low, serious infection should be considered and weighed against the benefits of SGLT2 inhibitor therapy,” said Dr. Bersoff-Matcha and co-authors in their recent report published in the Annals of Internal Medicine (2019 May 6. doi: 10.7326/M19-0085).

In the previous warning, FDA officials said 12 cases of Fournier gangrene in patients taking an SGLT2 inhibitor had been reported to the agency or in medical literature from March 2013, when the first such inhibitor was approved, and May 2018.

In this latest report, a total of 55 Fournier gangrene cases had been reported in patients receiving SGLT2 inhibitors from March 2, 2013 through January 31, 2019.

The influx of reports may have been prompted by growing awareness of the safety issue, investigators said, but could also reflect the increasing prevalence of diabetes combined with SGLT2 inhibitor use. The researchers also noted that diabetes is a comorbidity in 32% to 66% of cases of Fournier gangrene.

But the likliehood that diabetes mellitus alone causes Fournier gangrene seems unlikley, given that Dr. Bersoff-Matcha and co-authors only found 19 Fournier gangrene cases associated with other classes of antiglycemic agents reported to the FDA or in the literature over a 35-year time frame.

“If Fournier gangrene were associated only with diabetes mellitus and not SGLT2 inhibitors, we would expect far more cases reported with the other antiglycemic agents, considering the 35-year timeframe and the large number of agents,” they said in their report.

Cases were reported for all FDA-approved SGLT2 inhibitors besides ertugliflozin, an agent approved for use in the U.S. in December 2017. The lack of cases reported for this drug could be related to its limited time on the market, the investigators said.

Fournier gangrene, marked by rapidly progressing necrotizing infection of the genitalia, perineum, and perianal region, requires antibiotics and immediate surgery, according to Dr. Bersoff-Matcha and colleagues.

“Serious complications and death are likely if Fournier gangrene is not recognized immediately and surgical intervention is not carried out within the first few hours of diagnosis,” they said in the report.

Of the 55 cases reported in patients receiving SGLT2 inhibitors, 39 were men and 16 were women, with an average of 9 months from the start of treatment to the event, investigators said.

At least 25 patients required multiple surgeries, including one patient who had 17 trips to the operating room, they said. A total of 8 patients had a fecal diversion procedure, and 4 patients had skin grafting.

Six patients had multiple encounters with a provider before being diagnosed, suggesting that the provider may have not recognized the infection due to its nonspecific symptoms, which include fatigue, fever, and malaise.

“Pain that seems out of proportion to findings on physical examination is a strong clinical indicator of necrotizing fasciitis and may be the most important diagnostic clue,” Dr. Bersoff-Matcha and co-authors said in their report.

The incidence of Fournier gangrene in patients taking SGLT2 inhibitors can’t be established by these cases reported to the FDA, which are spontaneously provided by health care providers and patients, investigators said.

“We suspect that our numbers underestimate the true burden,” they said in their report.

Dr. Bersoff-Matcha and co-authors disclosed no conflicts of interest related to their report.

SOURCE: Bersoff-Matcha SJ, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 May 6. Doi: doi:10.7326/M19-0085.

This article was updated May 9, 2019.

FROM THE ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: The number of Fournier gangrene cases reported in patients receiving sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors has increased in the time since an FDA warning was issued about this rare but potentially serious infection.

Major finding: The previous FDA warning noted 12 reported cases from March 1, 2013 through March 1, 2018. This latest report included a total of 55 cases reported through January 31, 2019.

Study details: A review of spontaneous postmarketing cases of Fournier gangrene reported to the FDA or in the medical literature.

Disclosures: Authors disclosed no conflicts of interest related to the study.

Source: Bersoff-Matcha SJ, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 May 6.

Delaying antibiotics in elderly with UTI linked to higher sepsis, death rates

results of a large, population-based study suggest.

The risk of bloodstream infection was more than seven times greater in patients who did not receive antibiotics immediately after seeing a general practitioner for a UTI versus those who did, according to results of the study based on primary care records and other data for nearly 160,000 U.K. patients aged 65 years or older. Death rates and hospital admissions were significantly higher for these patients, according to the study published in The BMJ by Myriam Gharbi, PharmD, Phd, Imperial College London, and her colleagues.

The publication of these findings coincides with an increase in Escherichia coli bloodstream infections in England.

“Our study suggests the early initiation of antibiotics for UTI in older high risk adult populations (especially men aged [older than] 85 years) should be recommended to prevent serious complications,” Dr. Gharbi and her coauthors said in their report.

The population-based cohort study comprised 157,264 adult primary care patients at least 65 years of age who had one or more suspected or confirmed lower UTIs from November 2007 to May 2015. The researchers found that health care providers had diagnosed a total of 312,896 UTI episodes in these patients during the period they studied. In 7.2% (22,534) of the UTI episodes, the researchers were unable to find records of the patients having been prescribed antibiotics by a general practitioner within 7 days of the UTI diagnosis. These 22,534 episodes included those that occurred in patients who had a complication before an antibiotic was prescribed. An additional 6.2% (19,292) of the episodes occurred in patients who were prescribed antibiotics, but not during their first UTI-related visit to a general practitioner or on the same day of such a visit. The researchers classified this group of patients as having been prescribed antibiotics on a deferred or delayed basis, as they were not prescribed such drugs within 7 days of their visit.

Overall, there were 1,539 cases (0.5% of the total number of UTIs) of bloodstream infection within 60 days of the initial urinary tract infection diagnosis, the researchers reported.

The bloodstream infection rate was 2.9% for patients who were not prescribed antibiotics ever or prior to an infection occurring, 2.2% in those who were prescribed antibiotics on a deferred basis, and 0.2% in those who were prescribed antibiotics immediately, meaning during their first visit to a general practitioner for a UTI or on the same day of such a visit (P less than .001). After adjustment for potential confounding variables such as age, sex, and region, the patients classified as having not been prescribed antibiotics or having been prescribed antibiotics on a deferred basis were significantly more likely to have a bloodstream infection within 60 days of their visit to a health care provider, compared with those who received antibiotics immediately, with odds ratios of 8.08 (95% confidence interval, 7.12-9.16) and 7.12 (95% CI, 6.22-8.14), respectively.

Hospital admissions after a UTI episode were nearly twice as high in the no- or deferred-antibiotics groups (27.0% and 26.8%, respectively), compared with the group that received antibiotics right away (14.8%), the investigators reported. The lengths of hospital stays were 12.1 days for the group classified as having not been prescribed antibiotics, 7.7 days for the group subject to delayed antibiotic prescribing, and 6.3 days for the group who received antibiotics immediately.

Deaths within 60 days of experiencing a urinary tract infection occurred in 5.4% of patients in the no-antibiotics group, 2.8% of the deferred-antibiotics group, and 1.6% of the immediate-antibiotics group. After adjustment for covariates, a regression analysis showed the risks for all-cause mortality were 1.16 and 2.18 times higher in the deferred-antibiotics group and the no-antibiotics group, respectively, according to the paper.

In the immediate-antibiotics group, those patients who received nitrofurantoin had a “small but significant increase” in 60-day survival versus those who received trimethoprim, the investigators noted in the discussion section of their report.

“This increase could reflect either higher levels of resistance to trimethoprim or a healthier population treated with nitrofurantoin, the latest being not recommended for patients with poor kidney function,” the researchers wrote.

This study was supported by the National Institute for Health Research and other U.K. sources. One study coauthor reported working as an epidemiologist with GSK in areas not related to the study.

SOURCE: Gharbi M et al. BMJ. 2019 Feb 27. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l525.

This study linking primary care prescribing to serious infections in elderly patients with urinary tract infections is timely, as rates of bloodstream infection and mortality are increasing in this age group, according to Alastair D. Hay, MB.ChB, a professor at University of Bristol, England.

“Prompt treatment should be offered to older patients, men (who are at higher risk than women), and those living in areas of greater socioeconomic deprivation who are at the highest risk of bloodstream infections,” Dr. Hay said in an editorial accompanying the report by Gharbi et al.

That said, the link between prescribing and infection in this particular study may not be causal: “The implications are likely to be more nuanced than primary care doctors risking the health of older adults to meet targets for antimicrobial stewardship,” Dr. Hay noted.

Doctors are cautious when managing infections in vulnerable groups, evidence shows, and the deferred prescribing reported in this study is likely not the same as the delayed prescribing seen in primary care, he explained.

“Most clinicians issue a prescription on the day of presentation, with verbal advice to delay treatment, rather than waiting for a patient to return or issuing a postdated prescription,” he said. “The group given immediate antibiotics in the study by Gharbi and colleagues likely contained some patients managed in this way.”

Patients who apparently had no prescription in this retrospective analysis may have had a same-day admission with a bloodstream infection; moreover, a number of bloodstream infections in older people are due to urinary tract bacteria, and so would not be prevented by treatment for urinary tract infection, Dr. Hay said.

“Further research is needed to establish whether treatment should be initiated with a broad or a narrow spectrum antibiotic and to identify those in whom delaying treatment (while awaiting investigation) is safe,” he concluded.

Dr. Hay is a professor in the Centre for Academic Primary Care, University of Bristol, England. His editorial appears in The BMJ (2019 Feb 27. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l780). Dr. Hay declared that he is a member of the managing common infections guideline committee for the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).

This study linking primary care prescribing to serious infections in elderly patients with urinary tract infections is timely, as rates of bloodstream infection and mortality are increasing in this age group, according to Alastair D. Hay, MB.ChB, a professor at University of Bristol, England.

“Prompt treatment should be offered to older patients, men (who are at higher risk than women), and those living in areas of greater socioeconomic deprivation who are at the highest risk of bloodstream infections,” Dr. Hay said in an editorial accompanying the report by Gharbi et al.

That said, the link between prescribing and infection in this particular study may not be causal: “The implications are likely to be more nuanced than primary care doctors risking the health of older adults to meet targets for antimicrobial stewardship,” Dr. Hay noted.

Doctors are cautious when managing infections in vulnerable groups, evidence shows, and the deferred prescribing reported in this study is likely not the same as the delayed prescribing seen in primary care, he explained.

“Most clinicians issue a prescription on the day of presentation, with verbal advice to delay treatment, rather than waiting for a patient to return or issuing a postdated prescription,” he said. “The group given immediate antibiotics in the study by Gharbi and colleagues likely contained some patients managed in this way.”

Patients who apparently had no prescription in this retrospective analysis may have had a same-day admission with a bloodstream infection; moreover, a number of bloodstream infections in older people are due to urinary tract bacteria, and so would not be prevented by treatment for urinary tract infection, Dr. Hay said.

“Further research is needed to establish whether treatment should be initiated with a broad or a narrow spectrum antibiotic and to identify those in whom delaying treatment (while awaiting investigation) is safe,” he concluded.

Dr. Hay is a professor in the Centre for Academic Primary Care, University of Bristol, England. His editorial appears in The BMJ (2019 Feb 27. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l780). Dr. Hay declared that he is a member of the managing common infections guideline committee for the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).

This study linking primary care prescribing to serious infections in elderly patients with urinary tract infections is timely, as rates of bloodstream infection and mortality are increasing in this age group, according to Alastair D. Hay, MB.ChB, a professor at University of Bristol, England.

“Prompt treatment should be offered to older patients, men (who are at higher risk than women), and those living in areas of greater socioeconomic deprivation who are at the highest risk of bloodstream infections,” Dr. Hay said in an editorial accompanying the report by Gharbi et al.

That said, the link between prescribing and infection in this particular study may not be causal: “The implications are likely to be more nuanced than primary care doctors risking the health of older adults to meet targets for antimicrobial stewardship,” Dr. Hay noted.

Doctors are cautious when managing infections in vulnerable groups, evidence shows, and the deferred prescribing reported in this study is likely not the same as the delayed prescribing seen in primary care, he explained.

“Most clinicians issue a prescription on the day of presentation, with verbal advice to delay treatment, rather than waiting for a patient to return or issuing a postdated prescription,” he said. “The group given immediate antibiotics in the study by Gharbi and colleagues likely contained some patients managed in this way.”

Patients who apparently had no prescription in this retrospective analysis may have had a same-day admission with a bloodstream infection; moreover, a number of bloodstream infections in older people are due to urinary tract bacteria, and so would not be prevented by treatment for urinary tract infection, Dr. Hay said.

“Further research is needed to establish whether treatment should be initiated with a broad or a narrow spectrum antibiotic and to identify those in whom delaying treatment (while awaiting investigation) is safe,” he concluded.

Dr. Hay is a professor in the Centre for Academic Primary Care, University of Bristol, England. His editorial appears in The BMJ (2019 Feb 27. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l780). Dr. Hay declared that he is a member of the managing common infections guideline committee for the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).

results of a large, population-based study suggest.

The risk of bloodstream infection was more than seven times greater in patients who did not receive antibiotics immediately after seeing a general practitioner for a UTI versus those who did, according to results of the study based on primary care records and other data for nearly 160,000 U.K. patients aged 65 years or older. Death rates and hospital admissions were significantly higher for these patients, according to the study published in The BMJ by Myriam Gharbi, PharmD, Phd, Imperial College London, and her colleagues.

The publication of these findings coincides with an increase in Escherichia coli bloodstream infections in England.

“Our study suggests the early initiation of antibiotics for UTI in older high risk adult populations (especially men aged [older than] 85 years) should be recommended to prevent serious complications,” Dr. Gharbi and her coauthors said in their report.

The population-based cohort study comprised 157,264 adult primary care patients at least 65 years of age who had one or more suspected or confirmed lower UTIs from November 2007 to May 2015. The researchers found that health care providers had diagnosed a total of 312,896 UTI episodes in these patients during the period they studied. In 7.2% (22,534) of the UTI episodes, the researchers were unable to find records of the patients having been prescribed antibiotics by a general practitioner within 7 days of the UTI diagnosis. These 22,534 episodes included those that occurred in patients who had a complication before an antibiotic was prescribed. An additional 6.2% (19,292) of the episodes occurred in patients who were prescribed antibiotics, but not during their first UTI-related visit to a general practitioner or on the same day of such a visit. The researchers classified this group of patients as having been prescribed antibiotics on a deferred or delayed basis, as they were not prescribed such drugs within 7 days of their visit.

Overall, there were 1,539 cases (0.5% of the total number of UTIs) of bloodstream infection within 60 days of the initial urinary tract infection diagnosis, the researchers reported.

The bloodstream infection rate was 2.9% for patients who were not prescribed antibiotics ever or prior to an infection occurring, 2.2% in those who were prescribed antibiotics on a deferred basis, and 0.2% in those who were prescribed antibiotics immediately, meaning during their first visit to a general practitioner for a UTI or on the same day of such a visit (P less than .001). After adjustment for potential confounding variables such as age, sex, and region, the patients classified as having not been prescribed antibiotics or having been prescribed antibiotics on a deferred basis were significantly more likely to have a bloodstream infection within 60 days of their visit to a health care provider, compared with those who received antibiotics immediately, with odds ratios of 8.08 (95% confidence interval, 7.12-9.16) and 7.12 (95% CI, 6.22-8.14), respectively.

Hospital admissions after a UTI episode were nearly twice as high in the no- or deferred-antibiotics groups (27.0% and 26.8%, respectively), compared with the group that received antibiotics right away (14.8%), the investigators reported. The lengths of hospital stays were 12.1 days for the group classified as having not been prescribed antibiotics, 7.7 days for the group subject to delayed antibiotic prescribing, and 6.3 days for the group who received antibiotics immediately.

Deaths within 60 days of experiencing a urinary tract infection occurred in 5.4% of patients in the no-antibiotics group, 2.8% of the deferred-antibiotics group, and 1.6% of the immediate-antibiotics group. After adjustment for covariates, a regression analysis showed the risks for all-cause mortality were 1.16 and 2.18 times higher in the deferred-antibiotics group and the no-antibiotics group, respectively, according to the paper.

In the immediate-antibiotics group, those patients who received nitrofurantoin had a “small but significant increase” in 60-day survival versus those who received trimethoprim, the investigators noted in the discussion section of their report.

“This increase could reflect either higher levels of resistance to trimethoprim or a healthier population treated with nitrofurantoin, the latest being not recommended for patients with poor kidney function,” the researchers wrote.

This study was supported by the National Institute for Health Research and other U.K. sources. One study coauthor reported working as an epidemiologist with GSK in areas not related to the study.

SOURCE: Gharbi M et al. BMJ. 2019 Feb 27. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l525.

results of a large, population-based study suggest.

The risk of bloodstream infection was more than seven times greater in patients who did not receive antibiotics immediately after seeing a general practitioner for a UTI versus those who did, according to results of the study based on primary care records and other data for nearly 160,000 U.K. patients aged 65 years or older. Death rates and hospital admissions were significantly higher for these patients, according to the study published in The BMJ by Myriam Gharbi, PharmD, Phd, Imperial College London, and her colleagues.

The publication of these findings coincides with an increase in Escherichia coli bloodstream infections in England.

“Our study suggests the early initiation of antibiotics for UTI in older high risk adult populations (especially men aged [older than] 85 years) should be recommended to prevent serious complications,” Dr. Gharbi and her coauthors said in their report.

The population-based cohort study comprised 157,264 adult primary care patients at least 65 years of age who had one or more suspected or confirmed lower UTIs from November 2007 to May 2015. The researchers found that health care providers had diagnosed a total of 312,896 UTI episodes in these patients during the period they studied. In 7.2% (22,534) of the UTI episodes, the researchers were unable to find records of the patients having been prescribed antibiotics by a general practitioner within 7 days of the UTI diagnosis. These 22,534 episodes included those that occurred in patients who had a complication before an antibiotic was prescribed. An additional 6.2% (19,292) of the episodes occurred in patients who were prescribed antibiotics, but not during their first UTI-related visit to a general practitioner or on the same day of such a visit. The researchers classified this group of patients as having been prescribed antibiotics on a deferred or delayed basis, as they were not prescribed such drugs within 7 days of their visit.

Overall, there were 1,539 cases (0.5% of the total number of UTIs) of bloodstream infection within 60 days of the initial urinary tract infection diagnosis, the researchers reported.

The bloodstream infection rate was 2.9% for patients who were not prescribed antibiotics ever or prior to an infection occurring, 2.2% in those who were prescribed antibiotics on a deferred basis, and 0.2% in those who were prescribed antibiotics immediately, meaning during their first visit to a general practitioner for a UTI or on the same day of such a visit (P less than .001). After adjustment for potential confounding variables such as age, sex, and region, the patients classified as having not been prescribed antibiotics or having been prescribed antibiotics on a deferred basis were significantly more likely to have a bloodstream infection within 60 days of their visit to a health care provider, compared with those who received antibiotics immediately, with odds ratios of 8.08 (95% confidence interval, 7.12-9.16) and 7.12 (95% CI, 6.22-8.14), respectively.

Hospital admissions after a UTI episode were nearly twice as high in the no- or deferred-antibiotics groups (27.0% and 26.8%, respectively), compared with the group that received antibiotics right away (14.8%), the investigators reported. The lengths of hospital stays were 12.1 days for the group classified as having not been prescribed antibiotics, 7.7 days for the group subject to delayed antibiotic prescribing, and 6.3 days for the group who received antibiotics immediately.

Deaths within 60 days of experiencing a urinary tract infection occurred in 5.4% of patients in the no-antibiotics group, 2.8% of the deferred-antibiotics group, and 1.6% of the immediate-antibiotics group. After adjustment for covariates, a regression analysis showed the risks for all-cause mortality were 1.16 and 2.18 times higher in the deferred-antibiotics group and the no-antibiotics group, respectively, according to the paper.

In the immediate-antibiotics group, those patients who received nitrofurantoin had a “small but significant increase” in 60-day survival versus those who received trimethoprim, the investigators noted in the discussion section of their report.

“This increase could reflect either higher levels of resistance to trimethoprim or a healthier population treated with nitrofurantoin, the latest being not recommended for patients with poor kidney function,” the researchers wrote.

This study was supported by the National Institute for Health Research and other U.K. sources. One study coauthor reported working as an epidemiologist with GSK in areas not related to the study.

SOURCE: Gharbi M et al. BMJ. 2019 Feb 27. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l525.

FROM THE BMJ

2019 ID update for dermatologists: Ticks are the “ride of choice” for arthropods

ORLANDO – New tricks from ticks, near-zero Zika, and the perils of personal grooming: Dermatologists have a lot to think about along the infectious disease spectrum in 2019, according to Justin Finch, MD, speaking at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

Anaphylaxis from alpha-gal syndrome is on the rise, caused in part by the geographic spread of the Lone Star tick. Beginning in 2006, isolated cases of an anaphylactic reaction to cetuximab, the epidermal growth factor receptor antagonist used to treat certain cancers, began to be seen in a curious geographic distribution. “The anaphylaxis cases were restricted to the southeastern United States, the home of the Lone Star tick,” said Dr. Finch, of the department of dermatology at the University of Connecticut, Farmington.

With some detective work, physicians and epidemiologists eventually determined that patients were reacting to an oligosaccharide called galactose-alpha–1,3-galactose (alpha-gal) found in cetuximab. This protein is also found in the meat of nonprimate mammals; individuals in the southeastern United States, where the Lone Star tick is endemic, had been sensitized via exposure to alpha-gal from Lone Star tick bites.

“Alpha-gal syndrome is on the rise,” said Dr. Finch, driven by the increased spread of this tick. Individuals who are sensitized develop delayed anaphylaxis 2-7 hours after ingesting red meat such as beef, pork, or lamb. “Ask about it,” said Dr. Finch, in patients who develop urticaria, dyspnea, angioedema, or hypotension without a clear offender. Because of the delay between allergen ingestion and anaphylaxis, it can be hard to connect the dots.

A number of drugs other than cetuximab contain alpha-gal, so patients must also be told to avoid these agents, said Dr. Finch, who noted that alpha-gal syndrome isn’t the only emerging culprit for tick-borne diseases. “The tick is the ride of choice for arthropod-borne diseases in the U.S.,” he added. “Year after year, tick-borne diseases top mosquito-borne diseases in the U.S.” Zika’s explosion in 2016 made that year the exception to the rule.

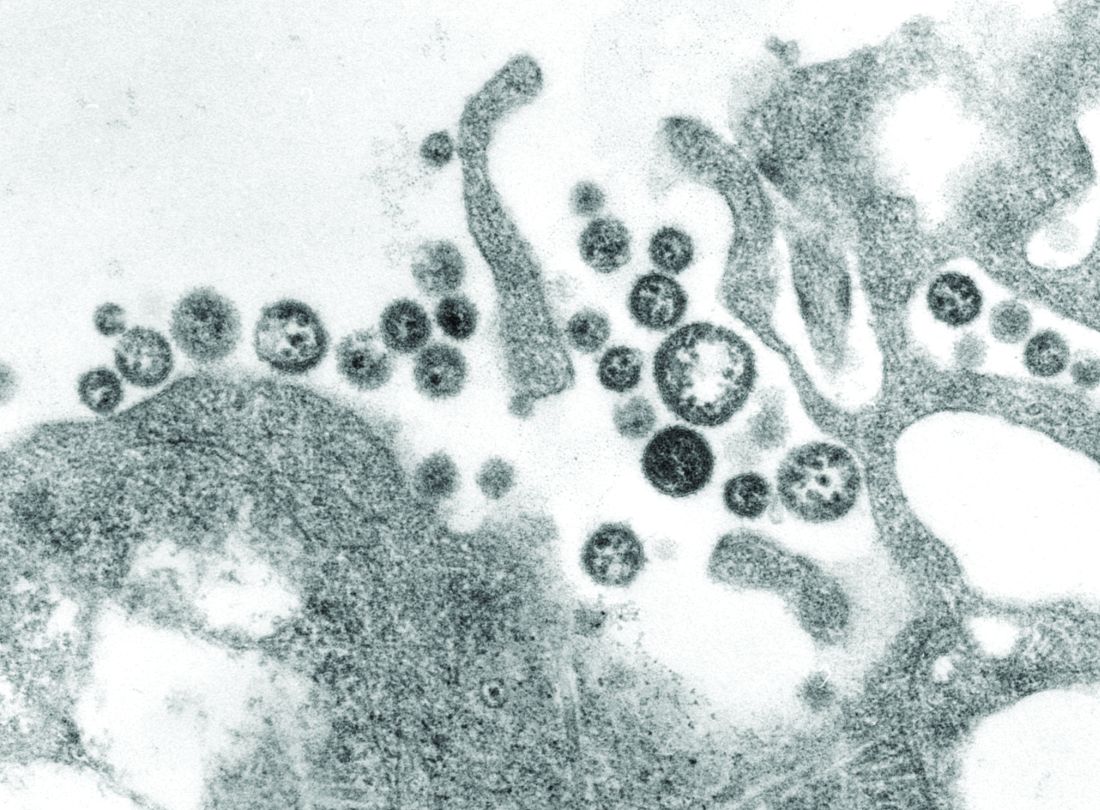

Now, Zika virus may be on the wane – the number of case reports have plummeted both in the United States and in Central and South America this past year – but it hasn’t completely gone away. “It looks like it fell off all the maps,” but the virus is still present at low levels, he said.

When Zika virus is symptomatic, there’s often a nonspecific maculopapular rash. Critically, Dr. Finch said, “women with a rash are four times as likely to have adverse congenital outcomes. This is the important point for us to take home as dermatologists. ... It’s really important to have a high index of suspicion and to screen these women as they are coming into our clinic.”

Turning back to ticks, Lyme disease continues to be a problem in endemic areas in the Northeast, the mid-Atlantic region, and the Midwest, said Dr. Finch, so it’s a perennial on the differential diagnosis for dermatologists.

An Asian tick new to North America was seen for the first time in New Jersey in the summer of 2017. The Asian longhorned tick carries a phlebovirus that causes severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome, a disease with a 15% fatality rate. The reservoir host of this virus in Asia isn’t known, said Dr. Finch, adding that no cases of the virus have yet been seen in the United States. As of November 2018, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the tick had been found in nine states (Arkansas, Connecticut, Maryland, North Carolina, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia).

“What’s not on the rise? Pubic lice. We are destroying their natural habitat!” said Dr. Finch, citing surveys about personal grooming that show that more than 90% of women remove at least some of their pubic hair. Most college campuses are currently reporting essentially no cases of pubic lice, he noted.

However, the same personal grooming practices may be contributing to increases in molluscum contagiosum, herpes simplex virus, some strains of human papillomavirus, and cutaneous Streptococcus pyogenes infections, he said.

Another STI has had a resurgence in geographic pockets around the nation and among specific populations, said Dr. Finch. Syphilis is on the rise among gay and bisexual men and African Americans. Known as the “great imitator,” syphilis should be on the differential for dermatologists when the clinical picture isn’t quite adding up. “Think of this, and screen with an RPR [rapid plasma reagin],” he said.

Finally, an old enemy is back: A total of 11 measles outbreaks were reported in 2018. “We need to know about measles because of the complications,” said Dr. Finch. Even years later, such dire sequelae as subacute sclerosing panencephalitis can crop up, he added.

After a 2-week incubation period, measles begins with a fever and cough, congestion, and conjunctivitis. The rash begins on the head and spreads inferiorly by day 3. As the rash blooms, the classic morbilliform eruption becomes apparent. A biopsy of affected skin will be nonspecific; measles is diagnosed with a nasopharyngeal culture and serologic assay. Dr. Finch pointed out that dermatologists are unlikely to see measles in its earliest stages because their expertise will be called on only after it becomes clear that the patient is not experiencing just a mild illness with a viral exanthem.

When there’s suspicion for measles, a full-body skin exam is needed. “Koplik’s spots – the gray white papules on the buccal mucosa – are not pathognomonic in themselves, but in the clinical scenario of a person with measles” they can help the dermatologist make a definitive call, he said.

Vitamin A can be given to a patient with active measles, but prevention via immunization at age 12 months and 5 years is the only way to stop the disease, Dr. Finch noted.

Dr. Finch reported that he has no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – New tricks from ticks, near-zero Zika, and the perils of personal grooming: Dermatologists have a lot to think about along the infectious disease spectrum in 2019, according to Justin Finch, MD, speaking at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

Anaphylaxis from alpha-gal syndrome is on the rise, caused in part by the geographic spread of the Lone Star tick. Beginning in 2006, isolated cases of an anaphylactic reaction to cetuximab, the epidermal growth factor receptor antagonist used to treat certain cancers, began to be seen in a curious geographic distribution. “The anaphylaxis cases were restricted to the southeastern United States, the home of the Lone Star tick,” said Dr. Finch, of the department of dermatology at the University of Connecticut, Farmington.

With some detective work, physicians and epidemiologists eventually determined that patients were reacting to an oligosaccharide called galactose-alpha–1,3-galactose (alpha-gal) found in cetuximab. This protein is also found in the meat of nonprimate mammals; individuals in the southeastern United States, where the Lone Star tick is endemic, had been sensitized via exposure to alpha-gal from Lone Star tick bites.

“Alpha-gal syndrome is on the rise,” said Dr. Finch, driven by the increased spread of this tick. Individuals who are sensitized develop delayed anaphylaxis 2-7 hours after ingesting red meat such as beef, pork, or lamb. “Ask about it,” said Dr. Finch, in patients who develop urticaria, dyspnea, angioedema, or hypotension without a clear offender. Because of the delay between allergen ingestion and anaphylaxis, it can be hard to connect the dots.

A number of drugs other than cetuximab contain alpha-gal, so patients must also be told to avoid these agents, said Dr. Finch, who noted that alpha-gal syndrome isn’t the only emerging culprit for tick-borne diseases. “The tick is the ride of choice for arthropod-borne diseases in the U.S.,” he added. “Year after year, tick-borne diseases top mosquito-borne diseases in the U.S.” Zika’s explosion in 2016 made that year the exception to the rule.

Now, Zika virus may be on the wane – the number of case reports have plummeted both in the United States and in Central and South America this past year – but it hasn’t completely gone away. “It looks like it fell off all the maps,” but the virus is still present at low levels, he said.

When Zika virus is symptomatic, there’s often a nonspecific maculopapular rash. Critically, Dr. Finch said, “women with a rash are four times as likely to have adverse congenital outcomes. This is the important point for us to take home as dermatologists. ... It’s really important to have a high index of suspicion and to screen these women as they are coming into our clinic.”

Turning back to ticks, Lyme disease continues to be a problem in endemic areas in the Northeast, the mid-Atlantic region, and the Midwest, said Dr. Finch, so it’s a perennial on the differential diagnosis for dermatologists.

An Asian tick new to North America was seen for the first time in New Jersey in the summer of 2017. The Asian longhorned tick carries a phlebovirus that causes severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome, a disease with a 15% fatality rate. The reservoir host of this virus in Asia isn’t known, said Dr. Finch, adding that no cases of the virus have yet been seen in the United States. As of November 2018, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the tick had been found in nine states (Arkansas, Connecticut, Maryland, North Carolina, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia).

“What’s not on the rise? Pubic lice. We are destroying their natural habitat!” said Dr. Finch, citing surveys about personal grooming that show that more than 90% of women remove at least some of their pubic hair. Most college campuses are currently reporting essentially no cases of pubic lice, he noted.

However, the same personal grooming practices may be contributing to increases in molluscum contagiosum, herpes simplex virus, some strains of human papillomavirus, and cutaneous Streptococcus pyogenes infections, he said.

Another STI has had a resurgence in geographic pockets around the nation and among specific populations, said Dr. Finch. Syphilis is on the rise among gay and bisexual men and African Americans. Known as the “great imitator,” syphilis should be on the differential for dermatologists when the clinical picture isn’t quite adding up. “Think of this, and screen with an RPR [rapid plasma reagin],” he said.

Finally, an old enemy is back: A total of 11 measles outbreaks were reported in 2018. “We need to know about measles because of the complications,” said Dr. Finch. Even years later, such dire sequelae as subacute sclerosing panencephalitis can crop up, he added.

After a 2-week incubation period, measles begins with a fever and cough, congestion, and conjunctivitis. The rash begins on the head and spreads inferiorly by day 3. As the rash blooms, the classic morbilliform eruption becomes apparent. A biopsy of affected skin will be nonspecific; measles is diagnosed with a nasopharyngeal culture and serologic assay. Dr. Finch pointed out that dermatologists are unlikely to see measles in its earliest stages because their expertise will be called on only after it becomes clear that the patient is not experiencing just a mild illness with a viral exanthem.

When there’s suspicion for measles, a full-body skin exam is needed. “Koplik’s spots – the gray white papules on the buccal mucosa – are not pathognomonic in themselves, but in the clinical scenario of a person with measles” they can help the dermatologist make a definitive call, he said.

Vitamin A can be given to a patient with active measles, but prevention via immunization at age 12 months and 5 years is the only way to stop the disease, Dr. Finch noted.

Dr. Finch reported that he has no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – New tricks from ticks, near-zero Zika, and the perils of personal grooming: Dermatologists have a lot to think about along the infectious disease spectrum in 2019, according to Justin Finch, MD, speaking at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

Anaphylaxis from alpha-gal syndrome is on the rise, caused in part by the geographic spread of the Lone Star tick. Beginning in 2006, isolated cases of an anaphylactic reaction to cetuximab, the epidermal growth factor receptor antagonist used to treat certain cancers, began to be seen in a curious geographic distribution. “The anaphylaxis cases were restricted to the southeastern United States, the home of the Lone Star tick,” said Dr. Finch, of the department of dermatology at the University of Connecticut, Farmington.

With some detective work, physicians and epidemiologists eventually determined that patients were reacting to an oligosaccharide called galactose-alpha–1,3-galactose (alpha-gal) found in cetuximab. This protein is also found in the meat of nonprimate mammals; individuals in the southeastern United States, where the Lone Star tick is endemic, had been sensitized via exposure to alpha-gal from Lone Star tick bites.

“Alpha-gal syndrome is on the rise,” said Dr. Finch, driven by the increased spread of this tick. Individuals who are sensitized develop delayed anaphylaxis 2-7 hours after ingesting red meat such as beef, pork, or lamb. “Ask about it,” said Dr. Finch, in patients who develop urticaria, dyspnea, angioedema, or hypotension without a clear offender. Because of the delay between allergen ingestion and anaphylaxis, it can be hard to connect the dots.

A number of drugs other than cetuximab contain alpha-gal, so patients must also be told to avoid these agents, said Dr. Finch, who noted that alpha-gal syndrome isn’t the only emerging culprit for tick-borne diseases. “The tick is the ride of choice for arthropod-borne diseases in the U.S.,” he added. “Year after year, tick-borne diseases top mosquito-borne diseases in the U.S.” Zika’s explosion in 2016 made that year the exception to the rule.

Now, Zika virus may be on the wane – the number of case reports have plummeted both in the United States and in Central and South America this past year – but it hasn’t completely gone away. “It looks like it fell off all the maps,” but the virus is still present at low levels, he said.

When Zika virus is symptomatic, there’s often a nonspecific maculopapular rash. Critically, Dr. Finch said, “women with a rash are four times as likely to have adverse congenital outcomes. This is the important point for us to take home as dermatologists. ... It’s really important to have a high index of suspicion and to screen these women as they are coming into our clinic.”

Turning back to ticks, Lyme disease continues to be a problem in endemic areas in the Northeast, the mid-Atlantic region, and the Midwest, said Dr. Finch, so it’s a perennial on the differential diagnosis for dermatologists.

An Asian tick new to North America was seen for the first time in New Jersey in the summer of 2017. The Asian longhorned tick carries a phlebovirus that causes severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome, a disease with a 15% fatality rate. The reservoir host of this virus in Asia isn’t known, said Dr. Finch, adding that no cases of the virus have yet been seen in the United States. As of November 2018, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the tick had been found in nine states (Arkansas, Connecticut, Maryland, North Carolina, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia).

“What’s not on the rise? Pubic lice. We are destroying their natural habitat!” said Dr. Finch, citing surveys about personal grooming that show that more than 90% of women remove at least some of their pubic hair. Most college campuses are currently reporting essentially no cases of pubic lice, he noted.

However, the same personal grooming practices may be contributing to increases in molluscum contagiosum, herpes simplex virus, some strains of human papillomavirus, and cutaneous Streptococcus pyogenes infections, he said.