User login

What Does Health Equity in Dermatology Look Like?

SAN DIEGO —.

It also means embracing diversity, which she defined as diversity of thinking. “If you look at the literature, diversity in higher education and health profession training settings is associated with better educational outcomes for all students,” Dr. Treadwell, professor emeritus of dermatology and pediatrics at Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, said in a presentation on health equity during the plenary session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “Each person brings a variety of experiences and perspectives. This provides a wide range of opinions and different ways to look at things. Racial and ethnic minority providers can help health organization reduce cultural and linguistic barriers and improve cultural competence.”

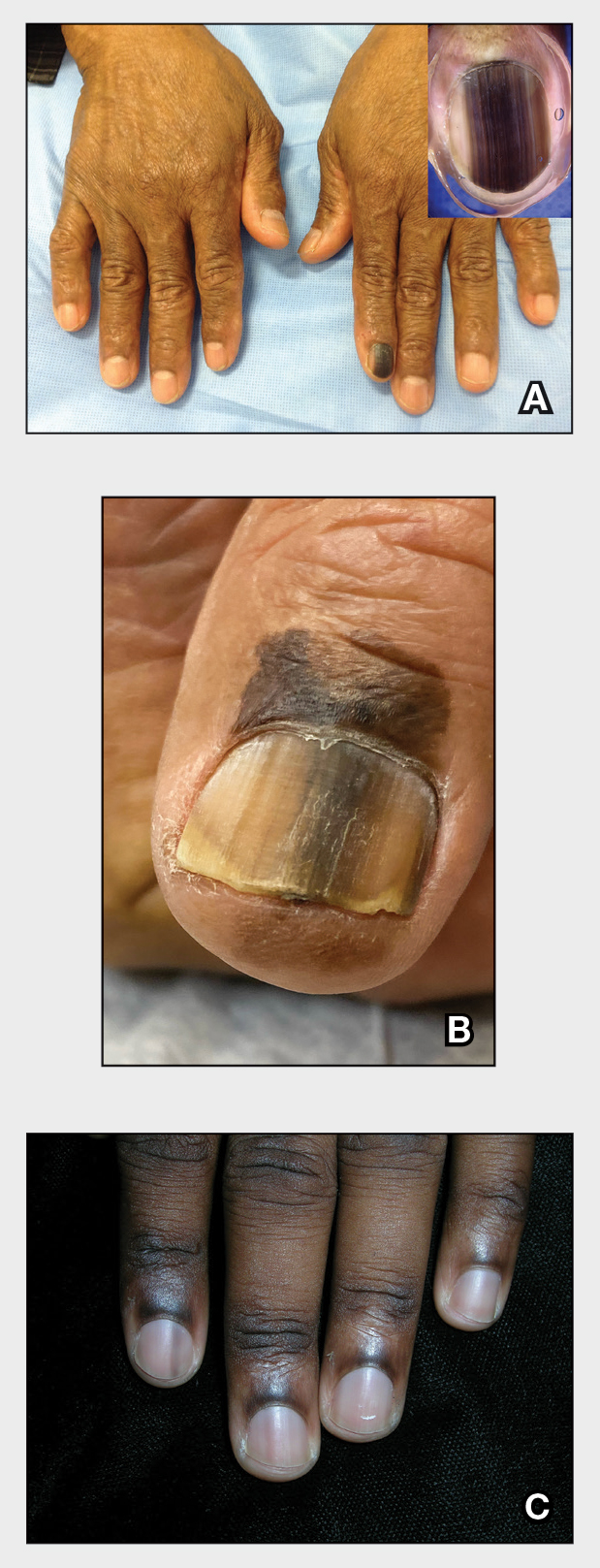

Such efforts matter, she continued, because according to the United States Census, Black individuals make up 13.6% of the population, while Latinx individuals represent 19.1% of the population. “So, melanin matters,” she said. “If you look at a dermatology textbook, a high percentage [of cases] are identified as Caucasian individuals, which results in an overrepresentation of Caucasians in photographs. That can result in delayed or missed diagnoses [in different skin types]. If you are contributing to cases in textbooks, make sure you have a variety of different skin types so that individuals who are referring to the textbooks will be more equipped.”

Practicing dermatologists can support diversity by offering opportunities to underrepresented in medicine (URM) students, “African-American students, Hispanic students, and Native American students,” said Dr. Treadwell, who was chief of pediatric dermatology at Riley Hospital for Children in Indianapolis from 1987 to 2004. “You also want to be encouraging,” she said.

Dermatologists can also support diversity by providing precepting opportunities, “because many [medical] students may not have connections and networks. Providing those opportunities is important,” she said. Another way to help is to be a mentor to young dermatologists. “I certainly have had mentors in my career who have been very helpful,” she said. “They’ve given me advice about things I was not familiar with.”

Dr. Treadwell suggested the Skin of Color Society as an organization that can assist with networking, mentoring, and research efforts. She also cited the Society for Pediatric Dermatology’s Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Committee, formed in 2020. One of its initiatives was assembling a special issue of Pediatric Dermatology dedicated to DEI issues, which was published in November 2021.

Dr. Treadwell concluded her presentation by encouraging dermatologists to find ways to care for uninsured or underinsured patients, particularly those with skin of color. This might involve work at a county hospital “to provide access, to serve the patients ... and helping to decrease some the issues in terms of health equity,” she said.

Dr. Treadwell reported having no relevant disclosures. At the plenary session, she presented the John Kenney Jr., MD Lifetime Achievement Award and Lectureship.

SAN DIEGO —.

It also means embracing diversity, which she defined as diversity of thinking. “If you look at the literature, diversity in higher education and health profession training settings is associated with better educational outcomes for all students,” Dr. Treadwell, professor emeritus of dermatology and pediatrics at Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, said in a presentation on health equity during the plenary session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “Each person brings a variety of experiences and perspectives. This provides a wide range of opinions and different ways to look at things. Racial and ethnic minority providers can help health organization reduce cultural and linguistic barriers and improve cultural competence.”

Such efforts matter, she continued, because according to the United States Census, Black individuals make up 13.6% of the population, while Latinx individuals represent 19.1% of the population. “So, melanin matters,” she said. “If you look at a dermatology textbook, a high percentage [of cases] are identified as Caucasian individuals, which results in an overrepresentation of Caucasians in photographs. That can result in delayed or missed diagnoses [in different skin types]. If you are contributing to cases in textbooks, make sure you have a variety of different skin types so that individuals who are referring to the textbooks will be more equipped.”

Practicing dermatologists can support diversity by offering opportunities to underrepresented in medicine (URM) students, “African-American students, Hispanic students, and Native American students,” said Dr. Treadwell, who was chief of pediatric dermatology at Riley Hospital for Children in Indianapolis from 1987 to 2004. “You also want to be encouraging,” she said.

Dermatologists can also support diversity by providing precepting opportunities, “because many [medical] students may not have connections and networks. Providing those opportunities is important,” she said. Another way to help is to be a mentor to young dermatologists. “I certainly have had mentors in my career who have been very helpful,” she said. “They’ve given me advice about things I was not familiar with.”

Dr. Treadwell suggested the Skin of Color Society as an organization that can assist with networking, mentoring, and research efforts. She also cited the Society for Pediatric Dermatology’s Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Committee, formed in 2020. One of its initiatives was assembling a special issue of Pediatric Dermatology dedicated to DEI issues, which was published in November 2021.

Dr. Treadwell concluded her presentation by encouraging dermatologists to find ways to care for uninsured or underinsured patients, particularly those with skin of color. This might involve work at a county hospital “to provide access, to serve the patients ... and helping to decrease some the issues in terms of health equity,” she said.

Dr. Treadwell reported having no relevant disclosures. At the plenary session, she presented the John Kenney Jr., MD Lifetime Achievement Award and Lectureship.

SAN DIEGO —.

It also means embracing diversity, which she defined as diversity of thinking. “If you look at the literature, diversity in higher education and health profession training settings is associated with better educational outcomes for all students,” Dr. Treadwell, professor emeritus of dermatology and pediatrics at Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, said in a presentation on health equity during the plenary session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “Each person brings a variety of experiences and perspectives. This provides a wide range of opinions and different ways to look at things. Racial and ethnic minority providers can help health organization reduce cultural and linguistic barriers and improve cultural competence.”

Such efforts matter, she continued, because according to the United States Census, Black individuals make up 13.6% of the population, while Latinx individuals represent 19.1% of the population. “So, melanin matters,” she said. “If you look at a dermatology textbook, a high percentage [of cases] are identified as Caucasian individuals, which results in an overrepresentation of Caucasians in photographs. That can result in delayed or missed diagnoses [in different skin types]. If you are contributing to cases in textbooks, make sure you have a variety of different skin types so that individuals who are referring to the textbooks will be more equipped.”

Practicing dermatologists can support diversity by offering opportunities to underrepresented in medicine (URM) students, “African-American students, Hispanic students, and Native American students,” said Dr. Treadwell, who was chief of pediatric dermatology at Riley Hospital for Children in Indianapolis from 1987 to 2004. “You also want to be encouraging,” she said.

Dermatologists can also support diversity by providing precepting opportunities, “because many [medical] students may not have connections and networks. Providing those opportunities is important,” she said. Another way to help is to be a mentor to young dermatologists. “I certainly have had mentors in my career who have been very helpful,” she said. “They’ve given me advice about things I was not familiar with.”

Dr. Treadwell suggested the Skin of Color Society as an organization that can assist with networking, mentoring, and research efforts. She also cited the Society for Pediatric Dermatology’s Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Committee, formed in 2020. One of its initiatives was assembling a special issue of Pediatric Dermatology dedicated to DEI issues, which was published in November 2021.

Dr. Treadwell concluded her presentation by encouraging dermatologists to find ways to care for uninsured or underinsured patients, particularly those with skin of color. This might involve work at a county hospital “to provide access, to serve the patients ... and helping to decrease some the issues in terms of health equity,” she said.

Dr. Treadwell reported having no relevant disclosures. At the plenary session, she presented the John Kenney Jr., MD Lifetime Achievement Award and Lectureship.

FROM AAD 2024

The Role of Dermatology in Identifying and Reporting a Primary Varicella Outbreak

To the Editor:

Cases of primary varicella-zoster virus (VZV) are relatively uncommon in the United States since the introduction of the varicella vaccine in 1995, with an overall decline in cases of more than 97%.1 Prior to the vaccine, 70% of hospitalizations occurred in children; subsequently, hospitalizations among the pediatric population (aged ≤20 years) declined by 97%. Compared to children, adults and immunocompromised patients with VZV infection may present with more severe disease and experience more complications.1

Most children in the United States are vaccinated against VZV, with 90.3% receiving at least 1 dose by 24 months of age.2 However, many countries do not implement universal varicella vaccination for infants.3 As a result, physicians should remember to include primary varicella in the differential when clinically correlated, especially when evaluating patients who have immigrated to the United States or who may be living in unvaccinated communities. We report 2 cases of primary VZV manifesting in adults to remind readers of the salient clinical features of this disease and how dermatologists play a critical role in early and accurate identification of diseases that can have wide-reaching public health implications.

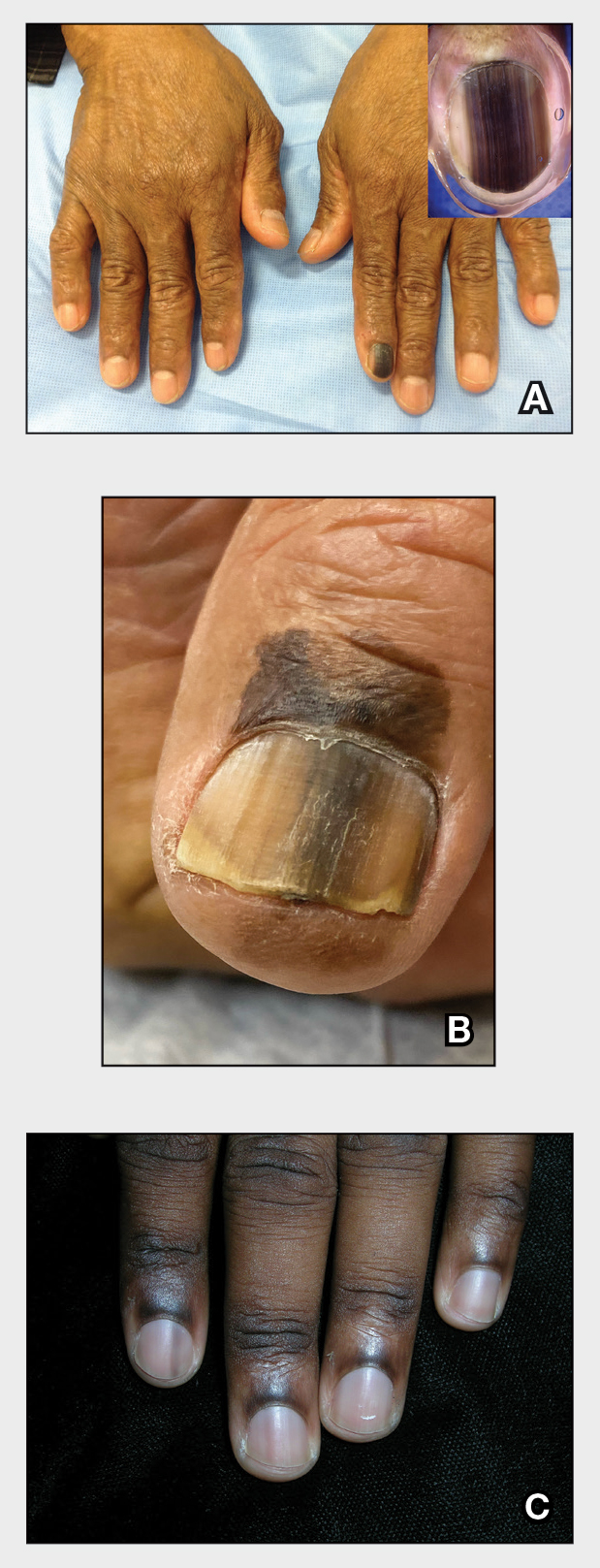

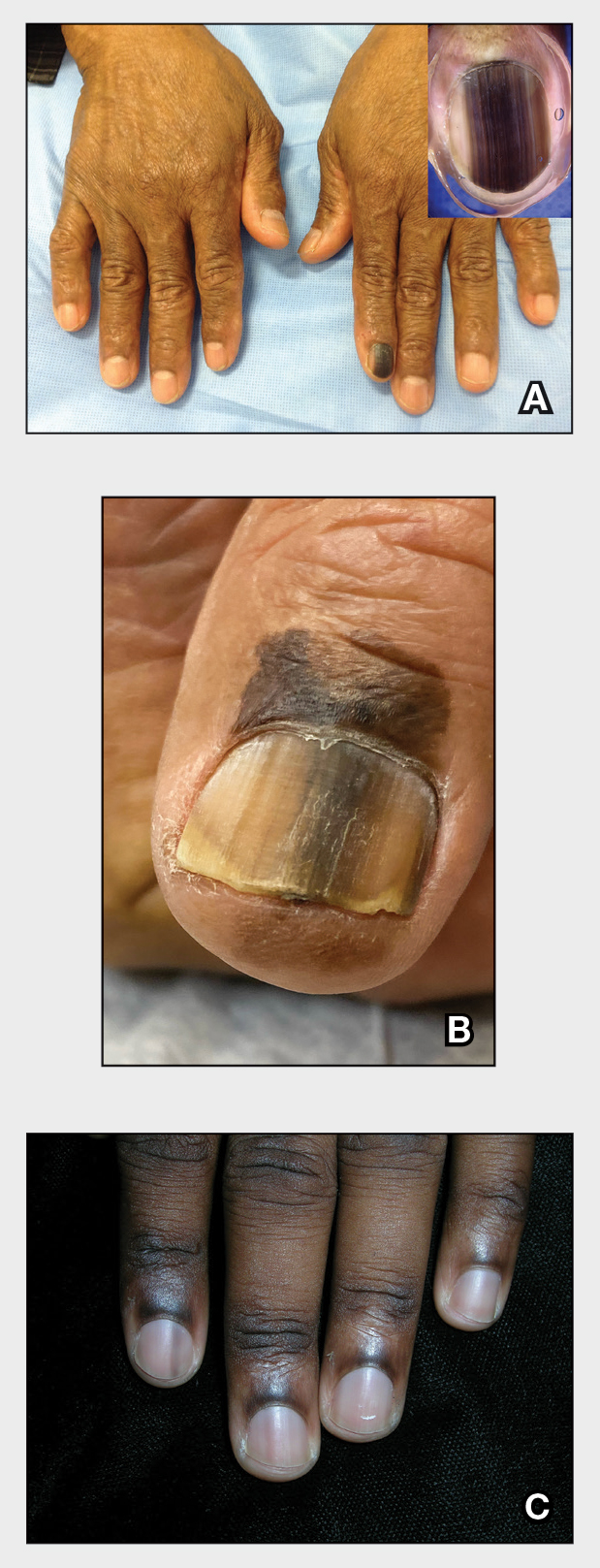

A 26-year-old man with no relevant medical history presented to the emergency department with an itchy and painful rash of 5 days’ duration that began on the trunk and spread to the face, lips, feet, hands, arms, and legs. He also reported shortness of breath, cough, and chills, and he had a temperature of 100.8 °F (38.2 °C). Physical examination revealed numerous erythematous papules and vesiculopustules, some with central umbilication and some with overlying gold crusts (Figure 1).

Later that day, a 47-year-old man with no relevant medical history presented to the same emergency department with a rash along with self-reported fever and sore throat of 3 days’ duration. Physical examination found innumerable erythematous vesicopustules scattered on the face, scalp, neck, trunk, arms, and legs, some with a “dew drop on a rose petal” appearance and some with overlying hemorrhagic crust (Figure 2).

Although infection was of primary concern for the first patient, the presentation of the second patient prompted specific concern for primary VZV infection in both patients, who were placed on airborne and contact isolation precautions.

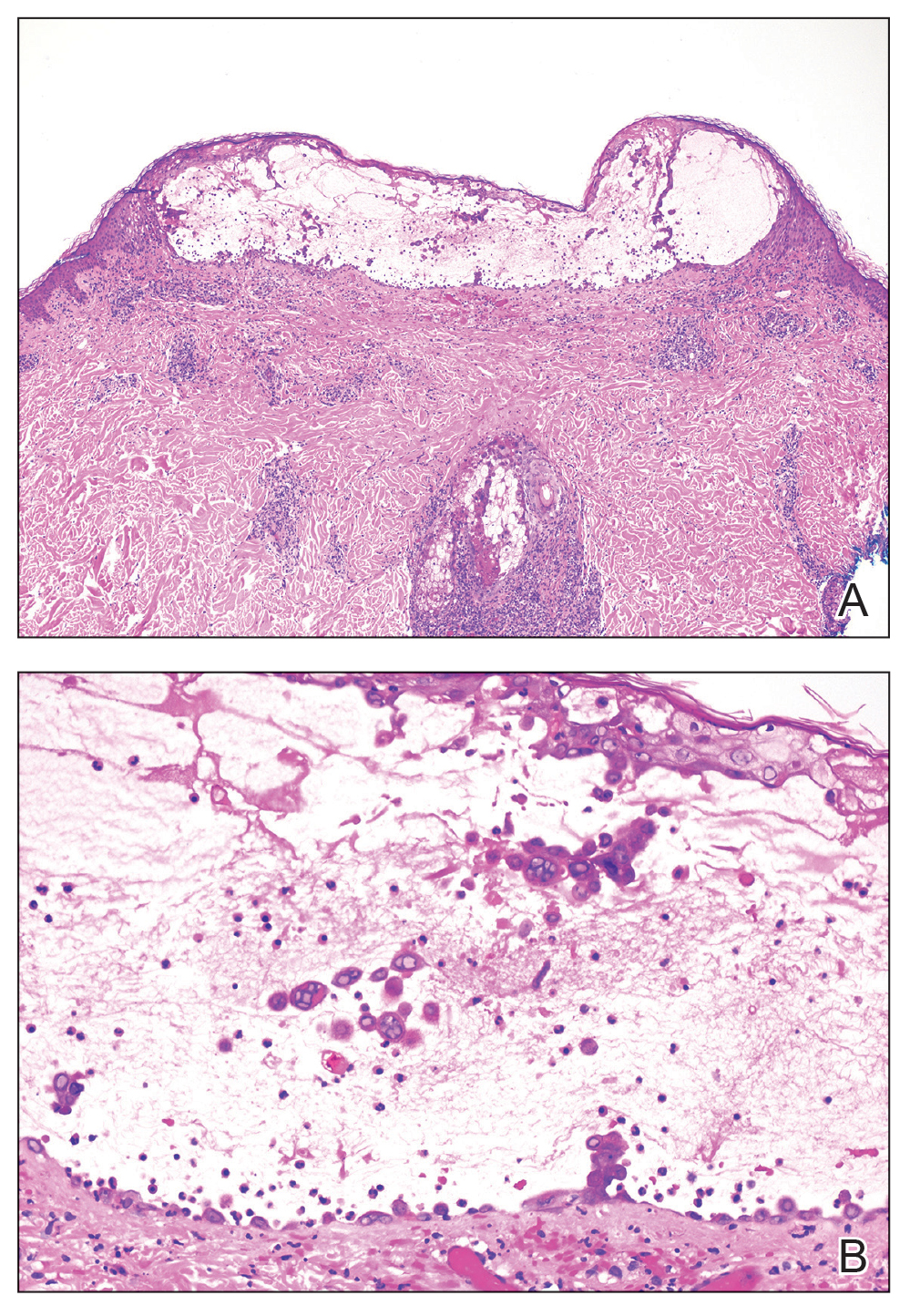

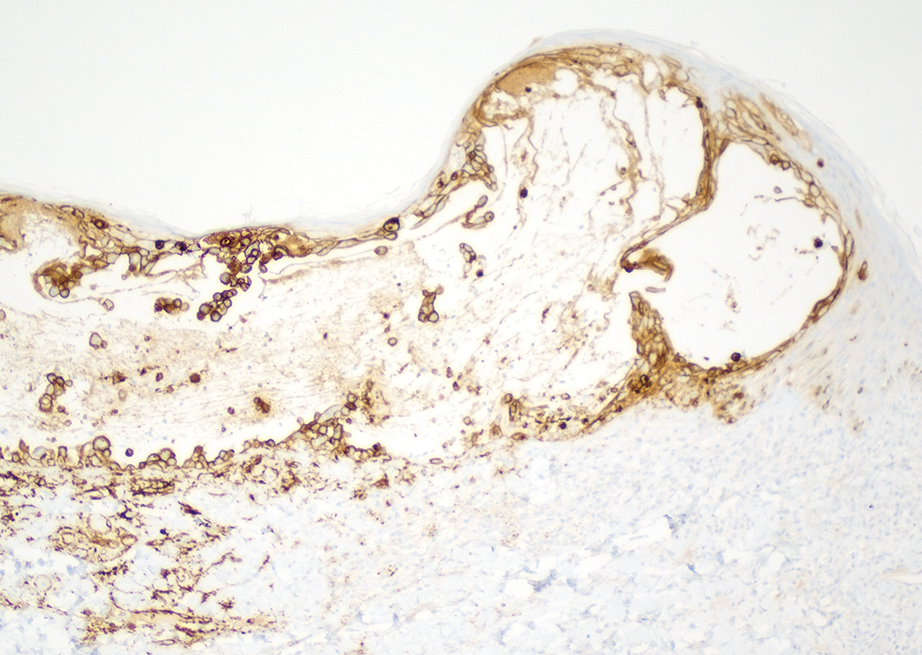

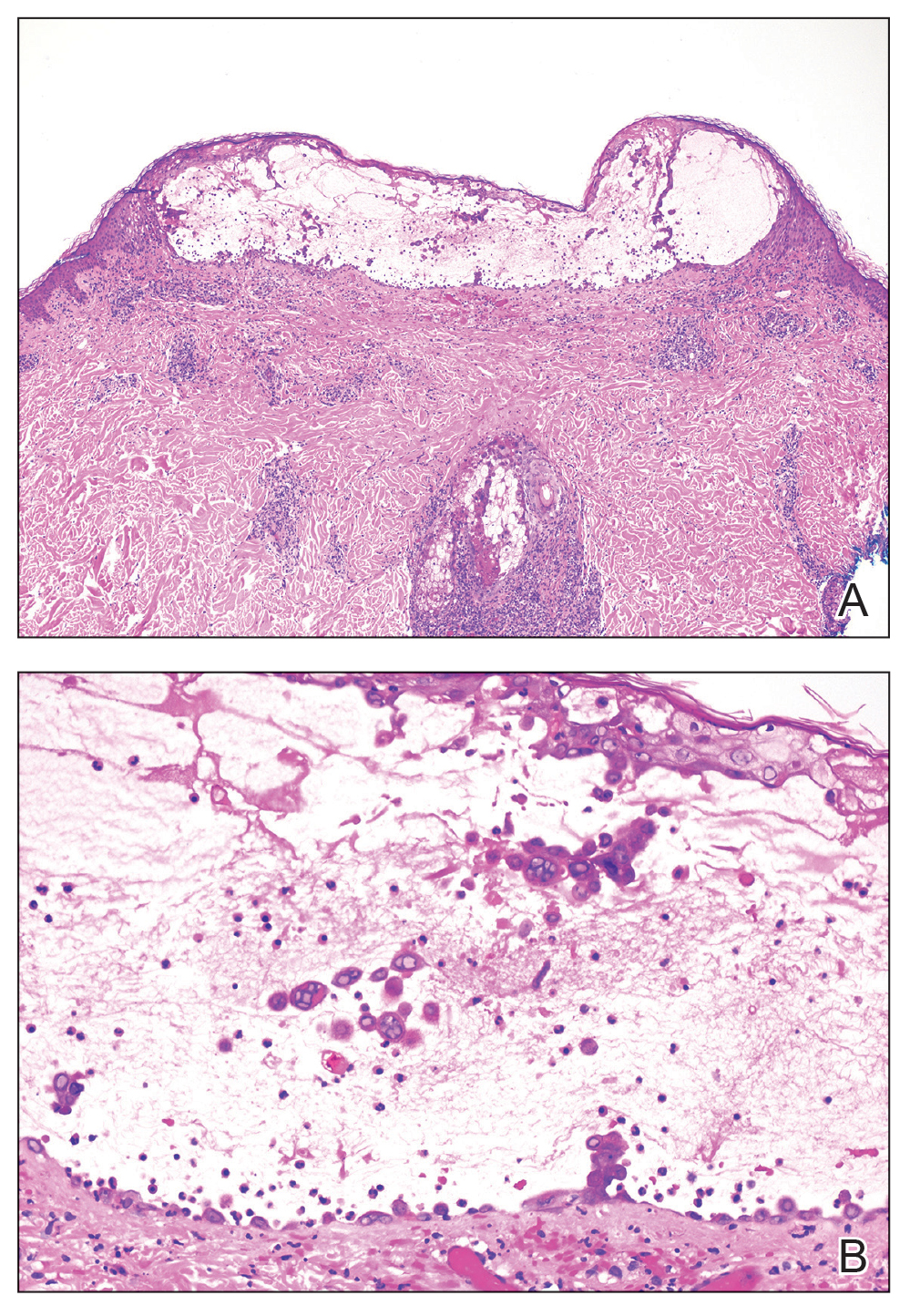

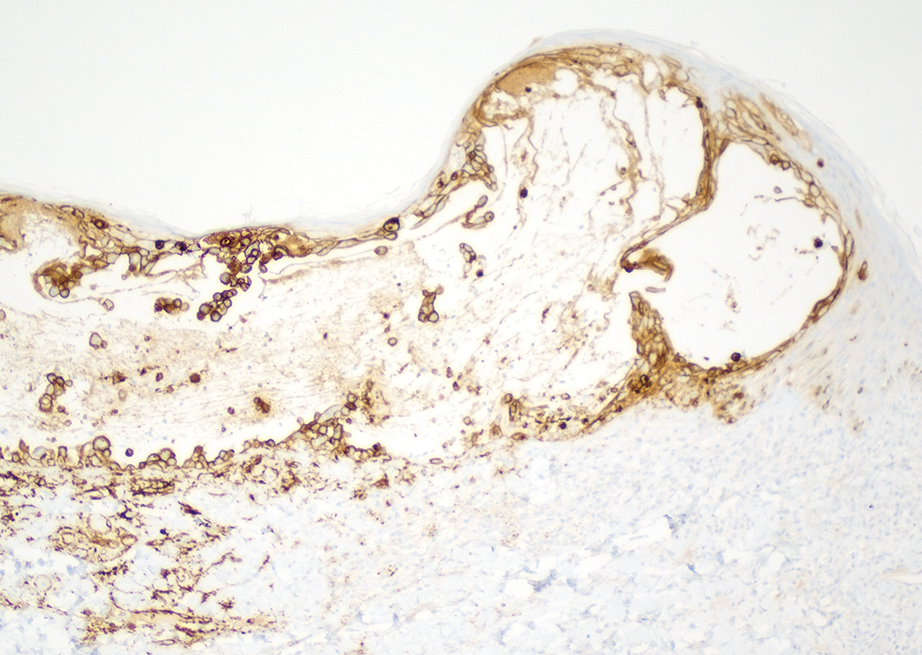

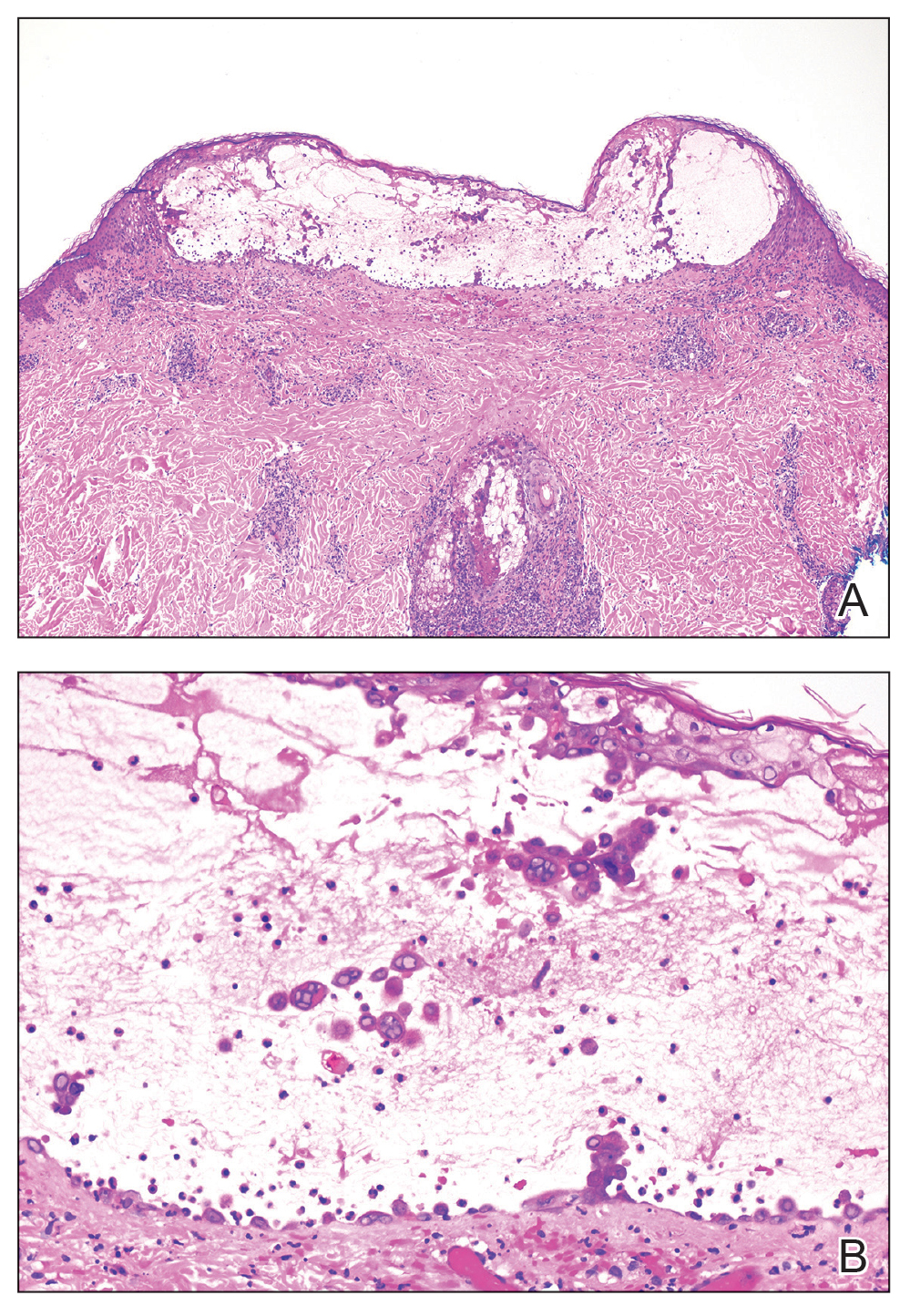

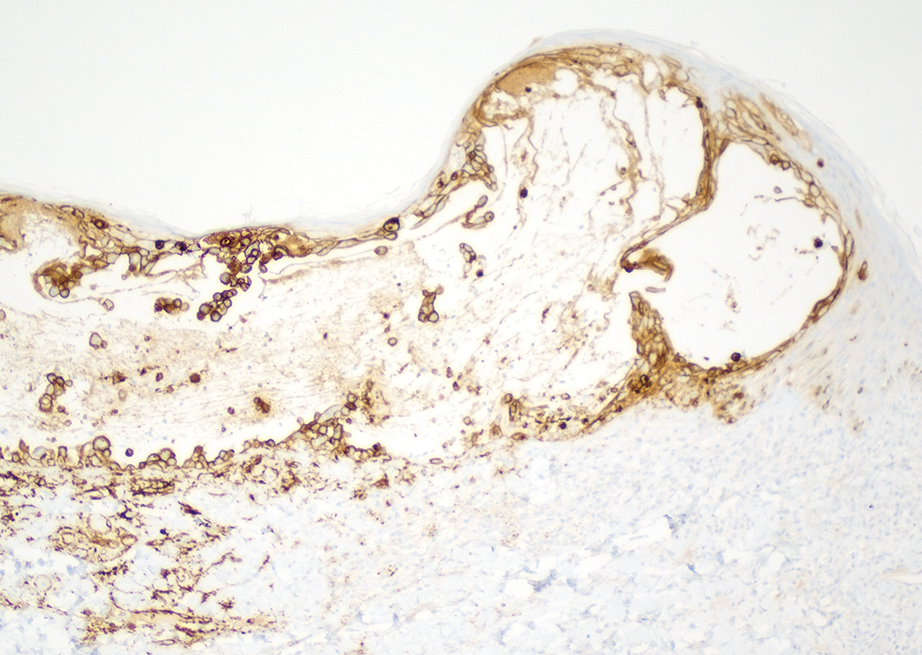

Skin biopsies from both patients showed acantholytic blisters, hair follicle necrosis, and marked dermal inflammation (Figure 3). Herpetic viral changes were seen in keratinocytes, with steel-grey nuclei, multinucleated keratinocytes, and chromatin margination. An immunostain for VZV was diffusely positive, and VZV antibody IgG was positive (Figure 4).

Upon additional questioning, both patients reported recent exposure to VZV-like illnesses in family members without a history of international travel. Neither of the patients was sure of their vaccination status or prior infection history. Both patients received intravenous acyclovir 10 mg/kg administered every 8 hours. Both patients experienced improvement and were discharged after 3 days on oral valacyclovir (1 g 3 times daily for a 7-day treatment course).

The similar presentation and timing of these 2 VZV cases caused concern for an unidentified community outbreak. The infection control team was notified; additionally, per hospital protocol the state health department was alerted as well as the clinicians and staff of the hospital with a request to be vigilant for further cases.

Despite high vaccination rates in the United States, outbreaks of varicella still occur, particularly among unvaccinated individuals, and a robust and efficient response is necessary to control the spread of such outbreaks.4 Many states, including Arkansas where our cases occurred, have laws mandating report of VZV cases to the department of health.5 Dermatologists play an important role in reporting cases, aiding in diagnosis through recognition of the physical examination findings, obtaining appropriate biopsy, and recommending additional laboratory testing.

Typical skin manifestations include a pruritic rash of macules, papules, vesicles, and crusted lesions distributed throughout the trunk, face, arms, and legs. Because new lesions appear over several days, they will be in different stages of healing, resulting in the simultaneous presence of papules, vesicles, and crusted lesions.6 This unique characteristic helps distinguish VZV from other skin diseases such as smallpox or mpox (monkeypox), which generally show lesions in similar stages of evolution.

Biopsy also can aid in identification. Viruses in the herpes family reveal similar histopathologic characteristics, including acantholysis and vesicle formation, intranuclear inclusions with margination of chromatin, multinucleation, and nuclear molding.7 Immunohistochemistry can be used to differentiate VZV from herpes simplex virus; however, neither microscopic examination nor immunohistochemistry distinguish primary VZV infection from herpes zoster (HZ).8

The mpox rash progresses more slowly than a VZV rash and has a centrifugal rather than central distribution that can involve the palms and soles. Lymphadenopathy is a characteristic finding in mpox.9 Rickettsialpox is distinguished from VZV primarily by the appearance of brown or black eschar after the original papulovesicular lesions dry out.10 Atypical hand, foot, and mouth disease can manifest in adults as widespread papulovesicular lesions. This form is associated with coxsackievirus A6 and may require direct fluorescent antibody assay or polymerase chain reaction of keratinocytes to rule out VZV.11

Herpes zoster occurs in older adults with a history of primary VZV.6 It manifests as vesicular lesions confined to 1 or 2 adjacent dermatomes vs the diffuse spread of VZV over the entire body. However, HZ can become disseminated in immunocompromised individuals, making it difficult to clinically distinguish from VZV.6 Serology can be helpful, as high IgM titers indicate an acute primary VZV infection. Subsequently increased IgG titers steadily wane over time and spike during reactivation.12

Dermatology and infectious disease consultations in our cases yielded a preliminary diagnosis through physical examination that was confirmed by biopsy and subsequent laboratory testing, which allowed for a swift response by the infection control team including isolation precautions to control a potential outbreak. Patients with VZV should remain in respiratory isolation until all lesions have crusted over.6

Individuals who had face-to-face indoor contact for at least 5 minutes or who shared a living space with an infected individual should be assessed for VZV immunity, which is defined as confirmed prior immunization or infection.5,13 Lack of VZV immunity requires postexposure prophylaxis—active immunization for the immunocompetent and passive immunization for the immunocompromised.13 Ultimately, no additional cases were reported in the community where our patients resided.

Immunocompetent children with primary VZV require supportive care only. Oral antiviral therapy is the treatment of choice for immunocompetent adults or anyone at increased risk for complications, while intravenous antivirals are recommended for the immunocompromised or those with VZV-related complications.14 A similar approach is used for HZ. Uncomplicated cases are treated with oral antivirals, and complicated cases (eg, HZ ophthalmicus) are treated with intravenous antivirals.15 Commonly used antivirals include acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir.14

Our cases highlight the ongoing risk for varicella outbreaks in unvaccinated or undervaccinated communities. Physician vigilance is necessary, and dermatology plays a particularly important role in swift and accurate detection of VZV, as demonstrated in our cases by the recognition of classic physical examination findings of erythematous and vesicular papules in each of the patients. Because primary VZV infection can result in life-threatening complications including hepatitis, encephalitis, and pancreatitis, prompt identification and initiation of therapy is important.6 Similarly, quick notification of public health officials about detected primary VZV cases is vital to containing potential community outbreaks.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chickenpox (varicella) for healthcare professionals. Published October 21, 2022. Accessed March 6, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/chickenpox/hcp/index.html#vaccination-impact

- National Center for Health Statistics. Immunization. Published June 13, 2023. Accessed March 6, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/immunize.htm

- Lee YH, Choe YJ, Lee J, et al. Global varicella vaccination programs. Clin Exp Pediatr. 2022;65:555. doi:10.3345/CEP.2021.01564

- Leung J, Lopez AS, Marin M. Changing epidemiology of varicella outbreaks in the United States during the Varicella Vaccination Program, 1995–2019. J Infect Dis. 2022;226(suppl 4):S400-S406.

- Arkansas Department of Health. Rules Pertaining to Reportable Diseases. Published September 11, 2023. Accessed March 6, 2024. https://www.healthy.arkansas.gov/images/uploads/rules/ReportableDiseaseList.pdf

- Pergam S, Limaye A; The AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Varicella zoster virus (VZV). Am J Transplant. 2009;9(suppl 4):S108-S115. doi:10.1111/J.1600-9143.2009.02901.X

- Hoyt B, Bhawan J. Histological spectrum of cutaneous herpes infections. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:609-619. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000148

- Oumarou Hama H, Aboudharam G, Barbieri R, et al. Immunohistochemical diagnosis of human infectious diseases: a review. Diagn Pathol. 2022;17. doi:10.1186/S13000-022-01197-5

- World Health Organization. Mpox (monkeypox). Published April 18, 2023. Accessed March 7, 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/monkeypox

- Akram SM, Jamil RT, Gossman W. Rickettsia akari (Rickettsialpox). StatPearls [Internet]. Updated May 8, 2023. Accessed February 29, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448081/

- Lott JP, Liu K, Landry ML, et al. Atypical hand-foot-mouth disease associated with coxsackievirus A6 infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:736. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2013.07.024

- Petrun B, Williams V, Brice S. Disseminated varicella-zoster virus in an immunocompetent adult. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21. doi:10.5070/D3213022343

- Kimberlin D, Barnett E, Lynfield R, et al. Exposure to specific pathogens. In: Red Book: 2021-2024 Report of the Committee of Infectious Disease. 32nd ed. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2021:1007-1009.

- Treatment of varicella (chickenpox) infection. UpToDate [Internet]. Updated February 7, 2024. Accessed March 6, 2024. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-varicella-chickenpox-infection

- Treatment of herpes zoster in the immunocompetent host. UpToDate [Internet]. Updated November 29, 2023. Accessed March 6, 2024. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-herpes-zoster

To the Editor:

Cases of primary varicella-zoster virus (VZV) are relatively uncommon in the United States since the introduction of the varicella vaccine in 1995, with an overall decline in cases of more than 97%.1 Prior to the vaccine, 70% of hospitalizations occurred in children; subsequently, hospitalizations among the pediatric population (aged ≤20 years) declined by 97%. Compared to children, adults and immunocompromised patients with VZV infection may present with more severe disease and experience more complications.1

Most children in the United States are vaccinated against VZV, with 90.3% receiving at least 1 dose by 24 months of age.2 However, many countries do not implement universal varicella vaccination for infants.3 As a result, physicians should remember to include primary varicella in the differential when clinically correlated, especially when evaluating patients who have immigrated to the United States or who may be living in unvaccinated communities. We report 2 cases of primary VZV manifesting in adults to remind readers of the salient clinical features of this disease and how dermatologists play a critical role in early and accurate identification of diseases that can have wide-reaching public health implications.

A 26-year-old man with no relevant medical history presented to the emergency department with an itchy and painful rash of 5 days’ duration that began on the trunk and spread to the face, lips, feet, hands, arms, and legs. He also reported shortness of breath, cough, and chills, and he had a temperature of 100.8 °F (38.2 °C). Physical examination revealed numerous erythematous papules and vesiculopustules, some with central umbilication and some with overlying gold crusts (Figure 1).

Later that day, a 47-year-old man with no relevant medical history presented to the same emergency department with a rash along with self-reported fever and sore throat of 3 days’ duration. Physical examination found innumerable erythematous vesicopustules scattered on the face, scalp, neck, trunk, arms, and legs, some with a “dew drop on a rose petal” appearance and some with overlying hemorrhagic crust (Figure 2).

Although infection was of primary concern for the first patient, the presentation of the second patient prompted specific concern for primary VZV infection in both patients, who were placed on airborne and contact isolation precautions.

Skin biopsies from both patients showed acantholytic blisters, hair follicle necrosis, and marked dermal inflammation (Figure 3). Herpetic viral changes were seen in keratinocytes, with steel-grey nuclei, multinucleated keratinocytes, and chromatin margination. An immunostain for VZV was diffusely positive, and VZV antibody IgG was positive (Figure 4).

Upon additional questioning, both patients reported recent exposure to VZV-like illnesses in family members without a history of international travel. Neither of the patients was sure of their vaccination status or prior infection history. Both patients received intravenous acyclovir 10 mg/kg administered every 8 hours. Both patients experienced improvement and were discharged after 3 days on oral valacyclovir (1 g 3 times daily for a 7-day treatment course).

The similar presentation and timing of these 2 VZV cases caused concern for an unidentified community outbreak. The infection control team was notified; additionally, per hospital protocol the state health department was alerted as well as the clinicians and staff of the hospital with a request to be vigilant for further cases.

Despite high vaccination rates in the United States, outbreaks of varicella still occur, particularly among unvaccinated individuals, and a robust and efficient response is necessary to control the spread of such outbreaks.4 Many states, including Arkansas where our cases occurred, have laws mandating report of VZV cases to the department of health.5 Dermatologists play an important role in reporting cases, aiding in diagnosis through recognition of the physical examination findings, obtaining appropriate biopsy, and recommending additional laboratory testing.

Typical skin manifestations include a pruritic rash of macules, papules, vesicles, and crusted lesions distributed throughout the trunk, face, arms, and legs. Because new lesions appear over several days, they will be in different stages of healing, resulting in the simultaneous presence of papules, vesicles, and crusted lesions.6 This unique characteristic helps distinguish VZV from other skin diseases such as smallpox or mpox (monkeypox), which generally show lesions in similar stages of evolution.

Biopsy also can aid in identification. Viruses in the herpes family reveal similar histopathologic characteristics, including acantholysis and vesicle formation, intranuclear inclusions with margination of chromatin, multinucleation, and nuclear molding.7 Immunohistochemistry can be used to differentiate VZV from herpes simplex virus; however, neither microscopic examination nor immunohistochemistry distinguish primary VZV infection from herpes zoster (HZ).8

The mpox rash progresses more slowly than a VZV rash and has a centrifugal rather than central distribution that can involve the palms and soles. Lymphadenopathy is a characteristic finding in mpox.9 Rickettsialpox is distinguished from VZV primarily by the appearance of brown or black eschar after the original papulovesicular lesions dry out.10 Atypical hand, foot, and mouth disease can manifest in adults as widespread papulovesicular lesions. This form is associated with coxsackievirus A6 and may require direct fluorescent antibody assay or polymerase chain reaction of keratinocytes to rule out VZV.11

Herpes zoster occurs in older adults with a history of primary VZV.6 It manifests as vesicular lesions confined to 1 or 2 adjacent dermatomes vs the diffuse spread of VZV over the entire body. However, HZ can become disseminated in immunocompromised individuals, making it difficult to clinically distinguish from VZV.6 Serology can be helpful, as high IgM titers indicate an acute primary VZV infection. Subsequently increased IgG titers steadily wane over time and spike during reactivation.12

Dermatology and infectious disease consultations in our cases yielded a preliminary diagnosis through physical examination that was confirmed by biopsy and subsequent laboratory testing, which allowed for a swift response by the infection control team including isolation precautions to control a potential outbreak. Patients with VZV should remain in respiratory isolation until all lesions have crusted over.6

Individuals who had face-to-face indoor contact for at least 5 minutes or who shared a living space with an infected individual should be assessed for VZV immunity, which is defined as confirmed prior immunization or infection.5,13 Lack of VZV immunity requires postexposure prophylaxis—active immunization for the immunocompetent and passive immunization for the immunocompromised.13 Ultimately, no additional cases were reported in the community where our patients resided.

Immunocompetent children with primary VZV require supportive care only. Oral antiviral therapy is the treatment of choice for immunocompetent adults or anyone at increased risk for complications, while intravenous antivirals are recommended for the immunocompromised or those with VZV-related complications.14 A similar approach is used for HZ. Uncomplicated cases are treated with oral antivirals, and complicated cases (eg, HZ ophthalmicus) are treated with intravenous antivirals.15 Commonly used antivirals include acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir.14

Our cases highlight the ongoing risk for varicella outbreaks in unvaccinated or undervaccinated communities. Physician vigilance is necessary, and dermatology plays a particularly important role in swift and accurate detection of VZV, as demonstrated in our cases by the recognition of classic physical examination findings of erythematous and vesicular papules in each of the patients. Because primary VZV infection can result in life-threatening complications including hepatitis, encephalitis, and pancreatitis, prompt identification and initiation of therapy is important.6 Similarly, quick notification of public health officials about detected primary VZV cases is vital to containing potential community outbreaks.

To the Editor:

Cases of primary varicella-zoster virus (VZV) are relatively uncommon in the United States since the introduction of the varicella vaccine in 1995, with an overall decline in cases of more than 97%.1 Prior to the vaccine, 70% of hospitalizations occurred in children; subsequently, hospitalizations among the pediatric population (aged ≤20 years) declined by 97%. Compared to children, adults and immunocompromised patients with VZV infection may present with more severe disease and experience more complications.1

Most children in the United States are vaccinated against VZV, with 90.3% receiving at least 1 dose by 24 months of age.2 However, many countries do not implement universal varicella vaccination for infants.3 As a result, physicians should remember to include primary varicella in the differential when clinically correlated, especially when evaluating patients who have immigrated to the United States or who may be living in unvaccinated communities. We report 2 cases of primary VZV manifesting in adults to remind readers of the salient clinical features of this disease and how dermatologists play a critical role in early and accurate identification of diseases that can have wide-reaching public health implications.

A 26-year-old man with no relevant medical history presented to the emergency department with an itchy and painful rash of 5 days’ duration that began on the trunk and spread to the face, lips, feet, hands, arms, and legs. He also reported shortness of breath, cough, and chills, and he had a temperature of 100.8 °F (38.2 °C). Physical examination revealed numerous erythematous papules and vesiculopustules, some with central umbilication and some with overlying gold crusts (Figure 1).

Later that day, a 47-year-old man with no relevant medical history presented to the same emergency department with a rash along with self-reported fever and sore throat of 3 days’ duration. Physical examination found innumerable erythematous vesicopustules scattered on the face, scalp, neck, trunk, arms, and legs, some with a “dew drop on a rose petal” appearance and some with overlying hemorrhagic crust (Figure 2).

Although infection was of primary concern for the first patient, the presentation of the second patient prompted specific concern for primary VZV infection in both patients, who were placed on airborne and contact isolation precautions.

Skin biopsies from both patients showed acantholytic blisters, hair follicle necrosis, and marked dermal inflammation (Figure 3). Herpetic viral changes were seen in keratinocytes, with steel-grey nuclei, multinucleated keratinocytes, and chromatin margination. An immunostain for VZV was diffusely positive, and VZV antibody IgG was positive (Figure 4).

Upon additional questioning, both patients reported recent exposure to VZV-like illnesses in family members without a history of international travel. Neither of the patients was sure of their vaccination status or prior infection history. Both patients received intravenous acyclovir 10 mg/kg administered every 8 hours. Both patients experienced improvement and were discharged after 3 days on oral valacyclovir (1 g 3 times daily for a 7-day treatment course).

The similar presentation and timing of these 2 VZV cases caused concern for an unidentified community outbreak. The infection control team was notified; additionally, per hospital protocol the state health department was alerted as well as the clinicians and staff of the hospital with a request to be vigilant for further cases.

Despite high vaccination rates in the United States, outbreaks of varicella still occur, particularly among unvaccinated individuals, and a robust and efficient response is necessary to control the spread of such outbreaks.4 Many states, including Arkansas where our cases occurred, have laws mandating report of VZV cases to the department of health.5 Dermatologists play an important role in reporting cases, aiding in diagnosis through recognition of the physical examination findings, obtaining appropriate biopsy, and recommending additional laboratory testing.

Typical skin manifestations include a pruritic rash of macules, papules, vesicles, and crusted lesions distributed throughout the trunk, face, arms, and legs. Because new lesions appear over several days, they will be in different stages of healing, resulting in the simultaneous presence of papules, vesicles, and crusted lesions.6 This unique characteristic helps distinguish VZV from other skin diseases such as smallpox or mpox (monkeypox), which generally show lesions in similar stages of evolution.

Biopsy also can aid in identification. Viruses in the herpes family reveal similar histopathologic characteristics, including acantholysis and vesicle formation, intranuclear inclusions with margination of chromatin, multinucleation, and nuclear molding.7 Immunohistochemistry can be used to differentiate VZV from herpes simplex virus; however, neither microscopic examination nor immunohistochemistry distinguish primary VZV infection from herpes zoster (HZ).8

The mpox rash progresses more slowly than a VZV rash and has a centrifugal rather than central distribution that can involve the palms and soles. Lymphadenopathy is a characteristic finding in mpox.9 Rickettsialpox is distinguished from VZV primarily by the appearance of brown or black eschar after the original papulovesicular lesions dry out.10 Atypical hand, foot, and mouth disease can manifest in adults as widespread papulovesicular lesions. This form is associated with coxsackievirus A6 and may require direct fluorescent antibody assay or polymerase chain reaction of keratinocytes to rule out VZV.11

Herpes zoster occurs in older adults with a history of primary VZV.6 It manifests as vesicular lesions confined to 1 or 2 adjacent dermatomes vs the diffuse spread of VZV over the entire body. However, HZ can become disseminated in immunocompromised individuals, making it difficult to clinically distinguish from VZV.6 Serology can be helpful, as high IgM titers indicate an acute primary VZV infection. Subsequently increased IgG titers steadily wane over time and spike during reactivation.12

Dermatology and infectious disease consultations in our cases yielded a preliminary diagnosis through physical examination that was confirmed by biopsy and subsequent laboratory testing, which allowed for a swift response by the infection control team including isolation precautions to control a potential outbreak. Patients with VZV should remain in respiratory isolation until all lesions have crusted over.6

Individuals who had face-to-face indoor contact for at least 5 minutes or who shared a living space with an infected individual should be assessed for VZV immunity, which is defined as confirmed prior immunization or infection.5,13 Lack of VZV immunity requires postexposure prophylaxis—active immunization for the immunocompetent and passive immunization for the immunocompromised.13 Ultimately, no additional cases were reported in the community where our patients resided.

Immunocompetent children with primary VZV require supportive care only. Oral antiviral therapy is the treatment of choice for immunocompetent adults or anyone at increased risk for complications, while intravenous antivirals are recommended for the immunocompromised or those with VZV-related complications.14 A similar approach is used for HZ. Uncomplicated cases are treated with oral antivirals, and complicated cases (eg, HZ ophthalmicus) are treated with intravenous antivirals.15 Commonly used antivirals include acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir.14

Our cases highlight the ongoing risk for varicella outbreaks in unvaccinated or undervaccinated communities. Physician vigilance is necessary, and dermatology plays a particularly important role in swift and accurate detection of VZV, as demonstrated in our cases by the recognition of classic physical examination findings of erythematous and vesicular papules in each of the patients. Because primary VZV infection can result in life-threatening complications including hepatitis, encephalitis, and pancreatitis, prompt identification and initiation of therapy is important.6 Similarly, quick notification of public health officials about detected primary VZV cases is vital to containing potential community outbreaks.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chickenpox (varicella) for healthcare professionals. Published October 21, 2022. Accessed March 6, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/chickenpox/hcp/index.html#vaccination-impact

- National Center for Health Statistics. Immunization. Published June 13, 2023. Accessed March 6, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/immunize.htm

- Lee YH, Choe YJ, Lee J, et al. Global varicella vaccination programs. Clin Exp Pediatr. 2022;65:555. doi:10.3345/CEP.2021.01564

- Leung J, Lopez AS, Marin M. Changing epidemiology of varicella outbreaks in the United States during the Varicella Vaccination Program, 1995–2019. J Infect Dis. 2022;226(suppl 4):S400-S406.

- Arkansas Department of Health. Rules Pertaining to Reportable Diseases. Published September 11, 2023. Accessed March 6, 2024. https://www.healthy.arkansas.gov/images/uploads/rules/ReportableDiseaseList.pdf

- Pergam S, Limaye A; The AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Varicella zoster virus (VZV). Am J Transplant. 2009;9(suppl 4):S108-S115. doi:10.1111/J.1600-9143.2009.02901.X

- Hoyt B, Bhawan J. Histological spectrum of cutaneous herpes infections. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:609-619. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000148

- Oumarou Hama H, Aboudharam G, Barbieri R, et al. Immunohistochemical diagnosis of human infectious diseases: a review. Diagn Pathol. 2022;17. doi:10.1186/S13000-022-01197-5

- World Health Organization. Mpox (monkeypox). Published April 18, 2023. Accessed March 7, 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/monkeypox

- Akram SM, Jamil RT, Gossman W. Rickettsia akari (Rickettsialpox). StatPearls [Internet]. Updated May 8, 2023. Accessed February 29, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448081/

- Lott JP, Liu K, Landry ML, et al. Atypical hand-foot-mouth disease associated with coxsackievirus A6 infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:736. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2013.07.024

- Petrun B, Williams V, Brice S. Disseminated varicella-zoster virus in an immunocompetent adult. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21. doi:10.5070/D3213022343

- Kimberlin D, Barnett E, Lynfield R, et al. Exposure to specific pathogens. In: Red Book: 2021-2024 Report of the Committee of Infectious Disease. 32nd ed. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2021:1007-1009.

- Treatment of varicella (chickenpox) infection. UpToDate [Internet]. Updated February 7, 2024. Accessed March 6, 2024. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-varicella-chickenpox-infection

- Treatment of herpes zoster in the immunocompetent host. UpToDate [Internet]. Updated November 29, 2023. Accessed March 6, 2024. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-herpes-zoster

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chickenpox (varicella) for healthcare professionals. Published October 21, 2022. Accessed March 6, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/chickenpox/hcp/index.html#vaccination-impact

- National Center for Health Statistics. Immunization. Published June 13, 2023. Accessed March 6, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/immunize.htm

- Lee YH, Choe YJ, Lee J, et al. Global varicella vaccination programs. Clin Exp Pediatr. 2022;65:555. doi:10.3345/CEP.2021.01564

- Leung J, Lopez AS, Marin M. Changing epidemiology of varicella outbreaks in the United States during the Varicella Vaccination Program, 1995–2019. J Infect Dis. 2022;226(suppl 4):S400-S406.

- Arkansas Department of Health. Rules Pertaining to Reportable Diseases. Published September 11, 2023. Accessed March 6, 2024. https://www.healthy.arkansas.gov/images/uploads/rules/ReportableDiseaseList.pdf

- Pergam S, Limaye A; The AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Varicella zoster virus (VZV). Am J Transplant. 2009;9(suppl 4):S108-S115. doi:10.1111/J.1600-9143.2009.02901.X

- Hoyt B, Bhawan J. Histological spectrum of cutaneous herpes infections. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:609-619. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000148

- Oumarou Hama H, Aboudharam G, Barbieri R, et al. Immunohistochemical diagnosis of human infectious diseases: a review. Diagn Pathol. 2022;17. doi:10.1186/S13000-022-01197-5

- World Health Organization. Mpox (monkeypox). Published April 18, 2023. Accessed March 7, 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/monkeypox

- Akram SM, Jamil RT, Gossman W. Rickettsia akari (Rickettsialpox). StatPearls [Internet]. Updated May 8, 2023. Accessed February 29, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448081/

- Lott JP, Liu K, Landry ML, et al. Atypical hand-foot-mouth disease associated with coxsackievirus A6 infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:736. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2013.07.024

- Petrun B, Williams V, Brice S. Disseminated varicella-zoster virus in an immunocompetent adult. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21. doi:10.5070/D3213022343

- Kimberlin D, Barnett E, Lynfield R, et al. Exposure to specific pathogens. In: Red Book: 2021-2024 Report of the Committee of Infectious Disease. 32nd ed. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2021:1007-1009.

- Treatment of varicella (chickenpox) infection. UpToDate [Internet]. Updated February 7, 2024. Accessed March 6, 2024. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-varicella-chickenpox-infection

- Treatment of herpes zoster in the immunocompetent host. UpToDate [Internet]. Updated November 29, 2023. Accessed March 6, 2024. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-herpes-zoster

Practice Points

- Primary varicella is a relatively infrequent occurrence since the introduction of vaccination, creating the need for a reminder on the importance of including it in the differential when clinically appropriate.

- When outbreaks do happen, typically among unvaccinated communities, swift identification via physical examination and histology is imperative to allow infection control teams and public health officials to quickly take action.

Money, Ethnicity, and Access Linked to Cervical Cancer Disparities

These findings come from analyses of insurance data gathered via the Cervical Cancer Geo-Analyzer tool, a publicly available online instrument designed to provide visual representation of recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer burden across metropolitan statistical areas in the United States over multiple years.

[Reporting the findings of] “this study is the first step to optimize healthcare resources allocations, advocate for policy changes that will minimize access barriers, and tailor education for modern treatment options to help reduce and improve outcomes for cervical cancer in US patients,” said Tara Castellano, MD, an author and presenter of this new research, at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer, held in San Diego.

Seeing Cancer Cases

Dr. Castellano and colleagues previously reported that the Geo-Analyzer tool effectively provides quantified evidence of cervical cancer disease burden and graphic representation of geographical variations across the United States for both incident and recurrent/metastatic cervical cancer.

In the current analysis, Dr. Castellano, of Louisiana State University School of Medicine in New Orleans, discussed potential factors related to cervical cancer incidence and geographic variations.

The study builds on previous studies that have shown that Black and Hispanic women have longer time to treatment and worse cervical cancer outcomes than White women.

For example, in a study published in the International Journal of Gynecologic Cancer, Marilyn Huang, MD, and colleagues from the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, Florida, and other centers in Miami looked at time to treatment in a diverse population of 274 women starting therapy for cervical cancer.

They found that insurance type (private, public, or none) contributed to delay in treatment initiation regardless of the treatment modality, and that the patient’s language and institution of diagnosis also influenced time to treatment.

In a separate scientific poster presented at SGO 2024, Dr. Castellano and colleagues reported that, among women with newly diagnosed endometrial cancer, the median time to treatment was 7 days longer for both Hispanic and Black women, compared with non-Hispanic White women. In addition, Black women had a 7-day longer time to receiving their first therapy for advanced disease. All of these differences were statistically significant.

Dr. Castellano told this news organization that the time-to-treatment disparities in the endometrial cancer study were determined by diagnostic codes and the timing of insurance claims.

Reasons for the disparities may include more limited access to care and structural and systemic biases in the healthcare systems where the majority of Black and Hispanic patients live, she said.

Insurance Database

In the new study on cervical cancer, Dr. Castellano and her team defined cervical cancer burden as prevalent cervical cancer diagnosis per 100,000 eligible women enrolled in a commercial insurance plan, Medicaid, or Medicare Advantage. Recurrent or metastatic cancer was determined to be the proportion of patients with cervical cancer who initiated systemic therapy.

The goals of the study were to provide a visualization of geographical distribution of cervical cancer in the US, and to quantify associations between early or advanced cancers with screening rates, poverty level, race/ethnicity, and access to brachytherapy.

The administrative claims database queried for the study included information on 75,521 women (median age 53) with a first diagnosis of cervical cancer from 2015 through 2022, and 14,033 women with recurrent or metastatic malignancies (median age 59 years).

Distribution of cases was higher in the South compared with in other US regions (37% vs approximately 20% for other regions).

Looking at the association between screening rates and disease burden from 2017 through 2022, the Geo-Analyzer showed that higher screening rates were significantly associated with decreased burden of new cases only in the South, whereas higher screening rates were associated with lower recurrent/metastatic disease burden in the Midwest and South, but a higher disease burden in the West.

In all regions, there was a significant association between decreased early cancer burden in areas with high percentages of women of Asian heritage, and significantly increased burden in areas with large populations of women of Hispanic origin.

The only significant association of race/ethnicity with recurrent/metastatic burden was a decrease in the Midwest in populations with large Asian populations.

An analysis of the how poverty levels affected screening and disease burden showed that in areas with a high percentage of low-income households there were significant associations with decreased cervical cancer screening and higher burden of newly diagnosed cases.

Poverty levels were significantly associated with recurrent/metastatic cancers only in the South.

The investigators also found that the presence of one or more brachytherapy centers within a ZIP-3 region (that is, a large geographic area designated by the first 3 digits of ZIP codes rather than 5-digit city codes) was associated with a 2.7% reduction in recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer burden (P less than .001).

Demographic Marker?

Reasons for disparities are complex and may involve a combination of inadequate health literacy and social and economic circumstances, said Cesar Castro, MD, commenting on the new cervical cancer study.

He noted in an interview that “the concept that a single Pap smear is often insufficient to capture precancerous changes, and hence the need for serial testing every 3 years, can be lost on individuals who also have competing challenges securing paychecks and/or dependent care. Historical barriers such as perceptions of the underlying cause of cervical cancer, the HPV virus, being a sexually transmitted disease and hence a taboo subject, also underpin decision-making. These sentiments have also fueled resistance towards HPV vaccination in young girls and boys.”

Dr. Castro, who is Program Director for Gynecologic Oncology at the Mass General Cancer Center in Boston, pointed out that treatments for cervical cancer often involve surgery or a combination of chemotherapy and radiation, and that side effects from these interventions may be especially disruptive to the lives of women who are breadwinners or caregivers for their families.

“These are the shackles that poverty places on many Black and Hispanic women notably in under-resourced regions domestically and globally,” he said.

The study was supported by Seagen and Genmab. Dr. Castellano disclosed consulting fees from GSK and Nykode and grant support from BMS. Dr. Castro reported no relevant conflicts of interest and was not involved in either of the studies presented at the meeting.

These findings come from analyses of insurance data gathered via the Cervical Cancer Geo-Analyzer tool, a publicly available online instrument designed to provide visual representation of recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer burden across metropolitan statistical areas in the United States over multiple years.

[Reporting the findings of] “this study is the first step to optimize healthcare resources allocations, advocate for policy changes that will minimize access barriers, and tailor education for modern treatment options to help reduce and improve outcomes for cervical cancer in US patients,” said Tara Castellano, MD, an author and presenter of this new research, at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer, held in San Diego.

Seeing Cancer Cases

Dr. Castellano and colleagues previously reported that the Geo-Analyzer tool effectively provides quantified evidence of cervical cancer disease burden and graphic representation of geographical variations across the United States for both incident and recurrent/metastatic cervical cancer.

In the current analysis, Dr. Castellano, of Louisiana State University School of Medicine in New Orleans, discussed potential factors related to cervical cancer incidence and geographic variations.

The study builds on previous studies that have shown that Black and Hispanic women have longer time to treatment and worse cervical cancer outcomes than White women.

For example, in a study published in the International Journal of Gynecologic Cancer, Marilyn Huang, MD, and colleagues from the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, Florida, and other centers in Miami looked at time to treatment in a diverse population of 274 women starting therapy for cervical cancer.

They found that insurance type (private, public, or none) contributed to delay in treatment initiation regardless of the treatment modality, and that the patient’s language and institution of diagnosis also influenced time to treatment.

In a separate scientific poster presented at SGO 2024, Dr. Castellano and colleagues reported that, among women with newly diagnosed endometrial cancer, the median time to treatment was 7 days longer for both Hispanic and Black women, compared with non-Hispanic White women. In addition, Black women had a 7-day longer time to receiving their first therapy for advanced disease. All of these differences were statistically significant.

Dr. Castellano told this news organization that the time-to-treatment disparities in the endometrial cancer study were determined by diagnostic codes and the timing of insurance claims.

Reasons for the disparities may include more limited access to care and structural and systemic biases in the healthcare systems where the majority of Black and Hispanic patients live, she said.

Insurance Database

In the new study on cervical cancer, Dr. Castellano and her team defined cervical cancer burden as prevalent cervical cancer diagnosis per 100,000 eligible women enrolled in a commercial insurance plan, Medicaid, or Medicare Advantage. Recurrent or metastatic cancer was determined to be the proportion of patients with cervical cancer who initiated systemic therapy.

The goals of the study were to provide a visualization of geographical distribution of cervical cancer in the US, and to quantify associations between early or advanced cancers with screening rates, poverty level, race/ethnicity, and access to brachytherapy.

The administrative claims database queried for the study included information on 75,521 women (median age 53) with a first diagnosis of cervical cancer from 2015 through 2022, and 14,033 women with recurrent or metastatic malignancies (median age 59 years).

Distribution of cases was higher in the South compared with in other US regions (37% vs approximately 20% for other regions).

Looking at the association between screening rates and disease burden from 2017 through 2022, the Geo-Analyzer showed that higher screening rates were significantly associated with decreased burden of new cases only in the South, whereas higher screening rates were associated with lower recurrent/metastatic disease burden in the Midwest and South, but a higher disease burden in the West.

In all regions, there was a significant association between decreased early cancer burden in areas with high percentages of women of Asian heritage, and significantly increased burden in areas with large populations of women of Hispanic origin.

The only significant association of race/ethnicity with recurrent/metastatic burden was a decrease in the Midwest in populations with large Asian populations.

An analysis of the how poverty levels affected screening and disease burden showed that in areas with a high percentage of low-income households there were significant associations with decreased cervical cancer screening and higher burden of newly diagnosed cases.

Poverty levels were significantly associated with recurrent/metastatic cancers only in the South.

The investigators also found that the presence of one or more brachytherapy centers within a ZIP-3 region (that is, a large geographic area designated by the first 3 digits of ZIP codes rather than 5-digit city codes) was associated with a 2.7% reduction in recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer burden (P less than .001).

Demographic Marker?

Reasons for disparities are complex and may involve a combination of inadequate health literacy and social and economic circumstances, said Cesar Castro, MD, commenting on the new cervical cancer study.

He noted in an interview that “the concept that a single Pap smear is often insufficient to capture precancerous changes, and hence the need for serial testing every 3 years, can be lost on individuals who also have competing challenges securing paychecks and/or dependent care. Historical barriers such as perceptions of the underlying cause of cervical cancer, the HPV virus, being a sexually transmitted disease and hence a taboo subject, also underpin decision-making. These sentiments have also fueled resistance towards HPV vaccination in young girls and boys.”

Dr. Castro, who is Program Director for Gynecologic Oncology at the Mass General Cancer Center in Boston, pointed out that treatments for cervical cancer often involve surgery or a combination of chemotherapy and radiation, and that side effects from these interventions may be especially disruptive to the lives of women who are breadwinners or caregivers for their families.

“These are the shackles that poverty places on many Black and Hispanic women notably in under-resourced regions domestically and globally,” he said.

The study was supported by Seagen and Genmab. Dr. Castellano disclosed consulting fees from GSK and Nykode and grant support from BMS. Dr. Castro reported no relevant conflicts of interest and was not involved in either of the studies presented at the meeting.

These findings come from analyses of insurance data gathered via the Cervical Cancer Geo-Analyzer tool, a publicly available online instrument designed to provide visual representation of recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer burden across metropolitan statistical areas in the United States over multiple years.

[Reporting the findings of] “this study is the first step to optimize healthcare resources allocations, advocate for policy changes that will minimize access barriers, and tailor education for modern treatment options to help reduce and improve outcomes for cervical cancer in US patients,” said Tara Castellano, MD, an author and presenter of this new research, at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer, held in San Diego.

Seeing Cancer Cases

Dr. Castellano and colleagues previously reported that the Geo-Analyzer tool effectively provides quantified evidence of cervical cancer disease burden and graphic representation of geographical variations across the United States for both incident and recurrent/metastatic cervical cancer.

In the current analysis, Dr. Castellano, of Louisiana State University School of Medicine in New Orleans, discussed potential factors related to cervical cancer incidence and geographic variations.

The study builds on previous studies that have shown that Black and Hispanic women have longer time to treatment and worse cervical cancer outcomes than White women.

For example, in a study published in the International Journal of Gynecologic Cancer, Marilyn Huang, MD, and colleagues from the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, Florida, and other centers in Miami looked at time to treatment in a diverse population of 274 women starting therapy for cervical cancer.

They found that insurance type (private, public, or none) contributed to delay in treatment initiation regardless of the treatment modality, and that the patient’s language and institution of diagnosis also influenced time to treatment.

In a separate scientific poster presented at SGO 2024, Dr. Castellano and colleagues reported that, among women with newly diagnosed endometrial cancer, the median time to treatment was 7 days longer for both Hispanic and Black women, compared with non-Hispanic White women. In addition, Black women had a 7-day longer time to receiving their first therapy for advanced disease. All of these differences were statistically significant.

Dr. Castellano told this news organization that the time-to-treatment disparities in the endometrial cancer study were determined by diagnostic codes and the timing of insurance claims.

Reasons for the disparities may include more limited access to care and structural and systemic biases in the healthcare systems where the majority of Black and Hispanic patients live, she said.

Insurance Database

In the new study on cervical cancer, Dr. Castellano and her team defined cervical cancer burden as prevalent cervical cancer diagnosis per 100,000 eligible women enrolled in a commercial insurance plan, Medicaid, or Medicare Advantage. Recurrent or metastatic cancer was determined to be the proportion of patients with cervical cancer who initiated systemic therapy.

The goals of the study were to provide a visualization of geographical distribution of cervical cancer in the US, and to quantify associations between early or advanced cancers with screening rates, poverty level, race/ethnicity, and access to brachytherapy.

The administrative claims database queried for the study included information on 75,521 women (median age 53) with a first diagnosis of cervical cancer from 2015 through 2022, and 14,033 women with recurrent or metastatic malignancies (median age 59 years).

Distribution of cases was higher in the South compared with in other US regions (37% vs approximately 20% for other regions).

Looking at the association between screening rates and disease burden from 2017 through 2022, the Geo-Analyzer showed that higher screening rates were significantly associated with decreased burden of new cases only in the South, whereas higher screening rates were associated with lower recurrent/metastatic disease burden in the Midwest and South, but a higher disease burden in the West.

In all regions, there was a significant association between decreased early cancer burden in areas with high percentages of women of Asian heritage, and significantly increased burden in areas with large populations of women of Hispanic origin.

The only significant association of race/ethnicity with recurrent/metastatic burden was a decrease in the Midwest in populations with large Asian populations.

An analysis of the how poverty levels affected screening and disease burden showed that in areas with a high percentage of low-income households there were significant associations with decreased cervical cancer screening and higher burden of newly diagnosed cases.

Poverty levels were significantly associated with recurrent/metastatic cancers only in the South.

The investigators also found that the presence of one or more brachytherapy centers within a ZIP-3 region (that is, a large geographic area designated by the first 3 digits of ZIP codes rather than 5-digit city codes) was associated with a 2.7% reduction in recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer burden (P less than .001).

Demographic Marker?

Reasons for disparities are complex and may involve a combination of inadequate health literacy and social and economic circumstances, said Cesar Castro, MD, commenting on the new cervical cancer study.

He noted in an interview that “the concept that a single Pap smear is often insufficient to capture precancerous changes, and hence the need for serial testing every 3 years, can be lost on individuals who also have competing challenges securing paychecks and/or dependent care. Historical barriers such as perceptions of the underlying cause of cervical cancer, the HPV virus, being a sexually transmitted disease and hence a taboo subject, also underpin decision-making. These sentiments have also fueled resistance towards HPV vaccination in young girls and boys.”

Dr. Castro, who is Program Director for Gynecologic Oncology at the Mass General Cancer Center in Boston, pointed out that treatments for cervical cancer often involve surgery or a combination of chemotherapy and radiation, and that side effects from these interventions may be especially disruptive to the lives of women who are breadwinners or caregivers for their families.

“These are the shackles that poverty places on many Black and Hispanic women notably in under-resourced regions domestically and globally,” he said.

The study was supported by Seagen and Genmab. Dr. Castellano disclosed consulting fees from GSK and Nykode and grant support from BMS. Dr. Castro reported no relevant conflicts of interest and was not involved in either of the studies presented at the meeting.

FROM SGO 2024

You Can’t Spell ‘Medicine’ Without D, E, and I

Please note that this is a commentary, an opinion piece: my opinion. The statements here do not necessarily represent those of this news organization or any of the myriad people or institutions that comprise this corner of the human universe.

Some days, speaking as a long-time physician and editor, I wish that there were no such things as race or ethnicity or even geographic origin for that matter. We can’t get away from sex, gender, disability, age, or culture. I’m not sure about religion. I wish people were just people.

But race is deeply embedded in the American experience — an almost invisible but inevitable presence in all of our thoughts and expressions about human activities.

In medical education (for eons it seems) the student has been taught to mention race in the first sentence of a given patient presentation, along with age and sex. In human epidemiologic research, race is almost always a studied variable. In clinical and basic medical research, looking at the impact of race on this, that, or the other is commonplace. “Mixed race not otherwise specified” is ubiquitous in the United States yet blithely ignored by most who tally these statistics. Race is rarely gene-specific. It is more of a social and cultural construct but with plainly visible overt phenotypic markers — an almost infinite mix of daily reality.

Our country, and much of Western civilization in 2024, is based on the principle that all men are created equal, although the originators of that notion were unaware of their own “equity-challenged” situation.

Many organizations, in and out of government, are now understanding, developing, and implementing programs (and thought/language patterns) to socialize diversity, equity, and inclusion (known as DEI) into their culture. It should not be surprising that many who prefer the status quo are not happy with the pressure from this movement and are using whatever methods are available to them to prevent full DEI. Such it always is.

The trusty Copilot from Bing provides these definitions:

- Diversity refers to the presence of variety within the organizational workforce. This includes aspects such as gender, culture, ethnicity, religion, disability, age, and opinion.

- Equity encompasses concepts of fairness and justice. It involves fair compensation, substantive equality, and addressing societal disparities. Equity also considers unique circumstances and adjusts treatment to achieve equal outcomes.

- Inclusion focuses on creating an organizational culture where all employees feel heard, fostering a sense of belonging and integration.

I am more than proud that my old domain of peer-reviewed, primary source, medical (and science) journals is taking a leading role in this noble, necessary, and long overdue movement for medicine.

As the central repository and transmitter of new medical information, including scientific studies, clinical medicine reports, ethics measures, and education, medical journals (including those deemed prestigious) have historically been among the worst offenders in perpetuating non-DEI objectives in their leadership, staffing, focus, instructions for authors, style manuals, and published materials.

This issue came to a head in March 2021 when a JAMA podcast about racism in American medicine was followed by this promotional tweet: “No physician is racist, so how can there be structural racism in health care?”

Reactions and actions were rapid, strong, and decisive. After an interregnum at JAMA, a new editor in chief, Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, PhD, MD, MAS, was named. She and her large staff of editors and editorial board members from the multijournal JAMA Network joined a worldwide movement of (currently) 56 publishing organizations representing 15,000 journals called the Joint Commitment for Action on Inclusion and Diversity in Publishing.

A recent JAMA editorial with 29 authors describes the entire commitment initiative of publishers-editors. It reports JAMA Network data from 2023 and 2024 from surveys of 455 editors (a 91% response rate) about their own gender (five choices), ethnic origins or geographic ancestry (13 choices), and race (eight choices), demonstrating considerable progress toward DEI goals. The survey’s complex multinational classifications may not jibe with the categorizations used in some countries (too bad that “mixed” is not “mixed in” — a missed opportunity).

This encouraging movement will not fix it all. But when people of certain groups are represented at the table, that point of view is far more likely to make it into the lexicon, language, and omnipresent work products, potentially changing cultural norms. Even the measurement of movement related to disparity in healthcare is marred by frequent variations of data accuracy. More consistency in what to measure can help a lot, and the medical literature can be very influential.

A personal anecdote: When I was a professor at UC Davis in 1978, Allan Bakke, MD, was my student. Some of you will remember the saga of affirmative action on admissions, which was just revisited in the light of a recent decision by the US Supreme Court.

Back in 1978, the dean at UC Davis told me that he kept two file folders on the admission processes in different desk drawers. One categorized all applicants and enrollees by race, and the other did not. Depending on who came to visit and ask questions, he would choose one or the other file to share once he figured out what they were looking for (this is not a joke).

The strength of the current active political pushback against the entire DEI movement has deep roots and should not be underestimated. There will be a lot of to-ing and fro-ing.

French writer Victor Hugo is credited with stating, “There is nothing as powerful as an idea whose time has come.” A majority of Americans, physicians, and other healthcare professionals believe in basic fairness. The time for DEI in all aspects of medicine is now.

Dr. Lundberg, editor in chief of Cancer Commons, disclosed having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Please note that this is a commentary, an opinion piece: my opinion. The statements here do not necessarily represent those of this news organization or any of the myriad people or institutions that comprise this corner of the human universe.

Some days, speaking as a long-time physician and editor, I wish that there were no such things as race or ethnicity or even geographic origin for that matter. We can’t get away from sex, gender, disability, age, or culture. I’m not sure about religion. I wish people were just people.

But race is deeply embedded in the American experience — an almost invisible but inevitable presence in all of our thoughts and expressions about human activities.

In medical education (for eons it seems) the student has been taught to mention race in the first sentence of a given patient presentation, along with age and sex. In human epidemiologic research, race is almost always a studied variable. In clinical and basic medical research, looking at the impact of race on this, that, or the other is commonplace. “Mixed race not otherwise specified” is ubiquitous in the United States yet blithely ignored by most who tally these statistics. Race is rarely gene-specific. It is more of a social and cultural construct but with plainly visible overt phenotypic markers — an almost infinite mix of daily reality.

Our country, and much of Western civilization in 2024, is based on the principle that all men are created equal, although the originators of that notion were unaware of their own “equity-challenged” situation.

Many organizations, in and out of government, are now understanding, developing, and implementing programs (and thought/language patterns) to socialize diversity, equity, and inclusion (known as DEI) into their culture. It should not be surprising that many who prefer the status quo are not happy with the pressure from this movement and are using whatever methods are available to them to prevent full DEI. Such it always is.

The trusty Copilot from Bing provides these definitions:

- Diversity refers to the presence of variety within the organizational workforce. This includes aspects such as gender, culture, ethnicity, religion, disability, age, and opinion.

- Equity encompasses concepts of fairness and justice. It involves fair compensation, substantive equality, and addressing societal disparities. Equity also considers unique circumstances and adjusts treatment to achieve equal outcomes.

- Inclusion focuses on creating an organizational culture where all employees feel heard, fostering a sense of belonging and integration.

I am more than proud that my old domain of peer-reviewed, primary source, medical (and science) journals is taking a leading role in this noble, necessary, and long overdue movement for medicine.

As the central repository and transmitter of new medical information, including scientific studies, clinical medicine reports, ethics measures, and education, medical journals (including those deemed prestigious) have historically been among the worst offenders in perpetuating non-DEI objectives in their leadership, staffing, focus, instructions for authors, style manuals, and published materials.

This issue came to a head in March 2021 when a JAMA podcast about racism in American medicine was followed by this promotional tweet: “No physician is racist, so how can there be structural racism in health care?”

Reactions and actions were rapid, strong, and decisive. After an interregnum at JAMA, a new editor in chief, Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, PhD, MD, MAS, was named. She and her large staff of editors and editorial board members from the multijournal JAMA Network joined a worldwide movement of (currently) 56 publishing organizations representing 15,000 journals called the Joint Commitment for Action on Inclusion and Diversity in Publishing.

A recent JAMA editorial with 29 authors describes the entire commitment initiative of publishers-editors. It reports JAMA Network data from 2023 and 2024 from surveys of 455 editors (a 91% response rate) about their own gender (five choices), ethnic origins or geographic ancestry (13 choices), and race (eight choices), demonstrating considerable progress toward DEI goals. The survey’s complex multinational classifications may not jibe with the categorizations used in some countries (too bad that “mixed” is not “mixed in” — a missed opportunity).

This encouraging movement will not fix it all. But when people of certain groups are represented at the table, that point of view is far more likely to make it into the lexicon, language, and omnipresent work products, potentially changing cultural norms. Even the measurement of movement related to disparity in healthcare is marred by frequent variations of data accuracy. More consistency in what to measure can help a lot, and the medical literature can be very influential.

A personal anecdote: When I was a professor at UC Davis in 1978, Allan Bakke, MD, was my student. Some of you will remember the saga of affirmative action on admissions, which was just revisited in the light of a recent decision by the US Supreme Court.

Back in 1978, the dean at UC Davis told me that he kept two file folders on the admission processes in different desk drawers. One categorized all applicants and enrollees by race, and the other did not. Depending on who came to visit and ask questions, he would choose one or the other file to share once he figured out what they were looking for (this is not a joke).

The strength of the current active political pushback against the entire DEI movement has deep roots and should not be underestimated. There will be a lot of to-ing and fro-ing.

French writer Victor Hugo is credited with stating, “There is nothing as powerful as an idea whose time has come.” A majority of Americans, physicians, and other healthcare professionals believe in basic fairness. The time for DEI in all aspects of medicine is now.

Dr. Lundberg, editor in chief of Cancer Commons, disclosed having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Please note that this is a commentary, an opinion piece: my opinion. The statements here do not necessarily represent those of this news organization or any of the myriad people or institutions that comprise this corner of the human universe.

Some days, speaking as a long-time physician and editor, I wish that there were no such things as race or ethnicity or even geographic origin for that matter. We can’t get away from sex, gender, disability, age, or culture. I’m not sure about religion. I wish people were just people.

But race is deeply embedded in the American experience — an almost invisible but inevitable presence in all of our thoughts and expressions about human activities.

In medical education (for eons it seems) the student has been taught to mention race in the first sentence of a given patient presentation, along with age and sex. In human epidemiologic research, race is almost always a studied variable. In clinical and basic medical research, looking at the impact of race on this, that, or the other is commonplace. “Mixed race not otherwise specified” is ubiquitous in the United States yet blithely ignored by most who tally these statistics. Race is rarely gene-specific. It is more of a social and cultural construct but with plainly visible overt phenotypic markers — an almost infinite mix of daily reality.

Our country, and much of Western civilization in 2024, is based on the principle that all men are created equal, although the originators of that notion were unaware of their own “equity-challenged” situation.

Many organizations, in and out of government, are now understanding, developing, and implementing programs (and thought/language patterns) to socialize diversity, equity, and inclusion (known as DEI) into their culture. It should not be surprising that many who prefer the status quo are not happy with the pressure from this movement and are using whatever methods are available to them to prevent full DEI. Such it always is.

The trusty Copilot from Bing provides these definitions:

- Diversity refers to the presence of variety within the organizational workforce. This includes aspects such as gender, culture, ethnicity, religion, disability, age, and opinion.