User login

Improving Dermatologic Care for South Asian Patients: Understanding Religious and Cultural Practices

Traditional garments are particularly important in both Sikhism and Islam. Sikhs began wearing symbolic garments in the 16th century as markers of their identity during periods of religious persecution. Today, many Sikhs continue to maintain this tradition of wearing the Five Ks—kesh (uncut hair, often tied in a turban), kanga (wooden hair comb), kirpan (symbolic dagger), kachha (cotton underwear), and kara (steel bracelet).2 Similarly, Islamic traditions also provide guidance for clothing. Many Muslim women wear the hijab (headscarf), a garment that originated as protective headgear for nomadic desert cultures and has come to symbolize modest dress. Traditionally, the hijab is worn in the presence of all men who are not immediate relatives, although patients may make exceptions for medical care. Some Muslim men also may cover their heads with a skullcap and/or maintain long beards (occasionally dyed with henna pigment) as a way of keeping continuity with the tradition of the Prophet Muhammad and his companions.3

Certain styles of headwear can cause high tension on hair follicles and have been associated with traction alopecia.4 Persistent use of the same turban, hijab, or comb also may lead to seborrheic dermatitis or fungal scalp infections. Dermatologists should advise patients about these potential challenges and suggest modifications in accordance with the patient’s religious beliefs; for example, providers can suggest removing headwear at night, using prophylactic antifungal shampoos, and/or tying the hair in a ponytail or loosening the headgear to reduce traction.

Although Hinduism does not have a unifying garment or hair tradition in the vein of Sikhism or Islam, all 3 religions share a strong emphasis on bodily modesty, which may affect dermatologic examinations. Patients from all 3 religions may seek to expose as little skin as possible during a physical examination, and many patients may be uncomfortable with a physician of the opposite gender. Dermatologists may find the following practices to be helpful5:

• Talk through each aspect of the skin examination while it is being performed and expose the least amount of skin necessary during the process

• Offer the patient a chaperone or a same-gender provider, if possible

• Empower patients to assist in adjusting garments themselves to help the physician visualize all parts of the skin

Some Sikhs also may have specific concerns regarding cutting their hair. One aspect of kesh is that every hair is sacred, and thus, many Sikhs refrain from removing hair on any part of the body. As such, providers should carefully obtain the patient’s informed consent before performing any procedure or physical examination maneuvers (eg, hair pull test) that may result in loss of hair.2

Physicians of all disciplines can help address these challenges through increased outreach and cultural awareness; for example, dermatologists can create skin care pamphlets translated into various South Asian languages and distribute them at houses of worship or other community centers. This may help patients identify their skin needs and seek appropriate care. The onus must be on physicians to make these patients feel comfortable seeking care by creating nonjudgmental, culturally knowledgeable clinical environments. When asking about social history, the physician might consider asking an open-ended question such as, “What role does religion/spirituality play in your life?” They can then proceed to ask specific questions about practices that might affect the patient’s care.5

Given the current coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, South Asian patients may be even further discouraged from seeking dermatologic care. By understanding religious traditions and taking steps to address biases, dermatologists can help mitigate health care disparities and provide culturally competent care to South Asian patients.

- Nadimpalli SB, Cleland CM, Hutchinson MK, et al. The association between discrimination and the health of Sikh Asian Indians. Health Psychol. 2016;35:351-355.

- The five Ks. BBC website. Updated September 29, 2009. Accessed February 4, 2021. https://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/sikhism/customs/fiveks.shtml

- Islam. BBC website. Accessed February 2, 2021. https://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/islam/

- James J, Saladi RN, Fox JL. Traction alopecia in Sikh male patients. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20:497-498.

- Hussain A. Recommendations for culturally competent dermatology care of Muslim patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:388-389.

Traditional garments are particularly important in both Sikhism and Islam. Sikhs began wearing symbolic garments in the 16th century as markers of their identity during periods of religious persecution. Today, many Sikhs continue to maintain this tradition of wearing the Five Ks—kesh (uncut hair, often tied in a turban), kanga (wooden hair comb), kirpan (symbolic dagger), kachha (cotton underwear), and kara (steel bracelet).2 Similarly, Islamic traditions also provide guidance for clothing. Many Muslim women wear the hijab (headscarf), a garment that originated as protective headgear for nomadic desert cultures and has come to symbolize modest dress. Traditionally, the hijab is worn in the presence of all men who are not immediate relatives, although patients may make exceptions for medical care. Some Muslim men also may cover their heads with a skullcap and/or maintain long beards (occasionally dyed with henna pigment) as a way of keeping continuity with the tradition of the Prophet Muhammad and his companions.3

Certain styles of headwear can cause high tension on hair follicles and have been associated with traction alopecia.4 Persistent use of the same turban, hijab, or comb also may lead to seborrheic dermatitis or fungal scalp infections. Dermatologists should advise patients about these potential challenges and suggest modifications in accordance with the patient’s religious beliefs; for example, providers can suggest removing headwear at night, using prophylactic antifungal shampoos, and/or tying the hair in a ponytail or loosening the headgear to reduce traction.

Although Hinduism does not have a unifying garment or hair tradition in the vein of Sikhism or Islam, all 3 religions share a strong emphasis on bodily modesty, which may affect dermatologic examinations. Patients from all 3 religions may seek to expose as little skin as possible during a physical examination, and many patients may be uncomfortable with a physician of the opposite gender. Dermatologists may find the following practices to be helpful5:

• Talk through each aspect of the skin examination while it is being performed and expose the least amount of skin necessary during the process

• Offer the patient a chaperone or a same-gender provider, if possible

• Empower patients to assist in adjusting garments themselves to help the physician visualize all parts of the skin

Some Sikhs also may have specific concerns regarding cutting their hair. One aspect of kesh is that every hair is sacred, and thus, many Sikhs refrain from removing hair on any part of the body. As such, providers should carefully obtain the patient’s informed consent before performing any procedure or physical examination maneuvers (eg, hair pull test) that may result in loss of hair.2

Physicians of all disciplines can help address these challenges through increased outreach and cultural awareness; for example, dermatologists can create skin care pamphlets translated into various South Asian languages and distribute them at houses of worship or other community centers. This may help patients identify their skin needs and seek appropriate care. The onus must be on physicians to make these patients feel comfortable seeking care by creating nonjudgmental, culturally knowledgeable clinical environments. When asking about social history, the physician might consider asking an open-ended question such as, “What role does religion/spirituality play in your life?” They can then proceed to ask specific questions about practices that might affect the patient’s care.5

Given the current coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, South Asian patients may be even further discouraged from seeking dermatologic care. By understanding religious traditions and taking steps to address biases, dermatologists can help mitigate health care disparities and provide culturally competent care to South Asian patients.

Traditional garments are particularly important in both Sikhism and Islam. Sikhs began wearing symbolic garments in the 16th century as markers of their identity during periods of religious persecution. Today, many Sikhs continue to maintain this tradition of wearing the Five Ks—kesh (uncut hair, often tied in a turban), kanga (wooden hair comb), kirpan (symbolic dagger), kachha (cotton underwear), and kara (steel bracelet).2 Similarly, Islamic traditions also provide guidance for clothing. Many Muslim women wear the hijab (headscarf), a garment that originated as protective headgear for nomadic desert cultures and has come to symbolize modest dress. Traditionally, the hijab is worn in the presence of all men who are not immediate relatives, although patients may make exceptions for medical care. Some Muslim men also may cover their heads with a skullcap and/or maintain long beards (occasionally dyed with henna pigment) as a way of keeping continuity with the tradition of the Prophet Muhammad and his companions.3

Certain styles of headwear can cause high tension on hair follicles and have been associated with traction alopecia.4 Persistent use of the same turban, hijab, or comb also may lead to seborrheic dermatitis or fungal scalp infections. Dermatologists should advise patients about these potential challenges and suggest modifications in accordance with the patient’s religious beliefs; for example, providers can suggest removing headwear at night, using prophylactic antifungal shampoos, and/or tying the hair in a ponytail or loosening the headgear to reduce traction.

Although Hinduism does not have a unifying garment or hair tradition in the vein of Sikhism or Islam, all 3 religions share a strong emphasis on bodily modesty, which may affect dermatologic examinations. Patients from all 3 religions may seek to expose as little skin as possible during a physical examination, and many patients may be uncomfortable with a physician of the opposite gender. Dermatologists may find the following practices to be helpful5:

• Talk through each aspect of the skin examination while it is being performed and expose the least amount of skin necessary during the process

• Offer the patient a chaperone or a same-gender provider, if possible

• Empower patients to assist in adjusting garments themselves to help the physician visualize all parts of the skin

Some Sikhs also may have specific concerns regarding cutting their hair. One aspect of kesh is that every hair is sacred, and thus, many Sikhs refrain from removing hair on any part of the body. As such, providers should carefully obtain the patient’s informed consent before performing any procedure or physical examination maneuvers (eg, hair pull test) that may result in loss of hair.2

Physicians of all disciplines can help address these challenges through increased outreach and cultural awareness; for example, dermatologists can create skin care pamphlets translated into various South Asian languages and distribute them at houses of worship or other community centers. This may help patients identify their skin needs and seek appropriate care. The onus must be on physicians to make these patients feel comfortable seeking care by creating nonjudgmental, culturally knowledgeable clinical environments. When asking about social history, the physician might consider asking an open-ended question such as, “What role does religion/spirituality play in your life?” They can then proceed to ask specific questions about practices that might affect the patient’s care.5

Given the current coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, South Asian patients may be even further discouraged from seeking dermatologic care. By understanding religious traditions and taking steps to address biases, dermatologists can help mitigate health care disparities and provide culturally competent care to South Asian patients.

- Nadimpalli SB, Cleland CM, Hutchinson MK, et al. The association between discrimination and the health of Sikh Asian Indians. Health Psychol. 2016;35:351-355.

- The five Ks. BBC website. Updated September 29, 2009. Accessed February 4, 2021. https://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/sikhism/customs/fiveks.shtml

- Islam. BBC website. Accessed February 2, 2021. https://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/islam/

- James J, Saladi RN, Fox JL. Traction alopecia in Sikh male patients. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20:497-498.

- Hussain A. Recommendations for culturally competent dermatology care of Muslim patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:388-389.

- Nadimpalli SB, Cleland CM, Hutchinson MK, et al. The association between discrimination and the health of Sikh Asian Indians. Health Psychol. 2016;35:351-355.

- The five Ks. BBC website. Updated September 29, 2009. Accessed February 4, 2021. https://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/sikhism/customs/fiveks.shtml

- Islam. BBC website. Accessed February 2, 2021. https://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/islam/

- James J, Saladi RN, Fox JL. Traction alopecia in Sikh male patients. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20:497-498.

- Hussain A. Recommendations for culturally competent dermatology care of Muslim patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:388-389.

Practice Points

- Providers should familiarize themselves with traditional garments of Sikhism and Islam, including head coverings and other symbolic items.

- Inform patients about health-conscious methods of wearing traditional headwear, such as removing certain headwear at night and tying hair in methods to avoid causing traction alopecia.

- Talk through each aspect of the skin examination while it is being performed and expose the least amount of skin necessary during the process. Offer the patient a chaperone or a same-gender provider, if possible.

- Empower patients to assist in adjusting garments themselves to help the physician visualize all parts of the skin.

Racial/ethnic disparities in cesarean rates increase with greater maternal education

While the likelihood of a cesarean delivery usually drops as maternal education level increases, the disparities seen in cesarean rates between White and Black or Hispanic women actually increase with more maternal education, according to findings from a new study presented at the Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Typically, higher maternal education is associated with a lower likelihood of cesarean delivery, but this protective effect is much smaller for Black women and nonexistent for Hispanic women, leading to bigger gaps between these groups and White women, found Yael Eliner, MD, an ob.gyn. residency applicant at Boston University who conducted this research with her colleagues in the ob.gyn. department at Lenox Hill Hospital, New York, and Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y..

Researchers have previously identified racial and ethnic disparities in a wide range of maternal outcomes, including mortality, overall morbidity, preterm birth, low birth weight, fetal growth restriction, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, diabetes, and cesarean deliveries. But the researchers wanted to know if the usual protective effects seen for cesarean deliveries existed in the racial and ethnic groups with these disparities. Past studies have already found that the protective effect of maternal education is greater for White women than Black women with infant mortality and overall self-rated health.

The researchers conducted a retrospective analysis of all low-risk nulliparous, term, singleton, vertex live births to U.S. residents from 2016 to 2019 by using the natality database of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. They looked only at women who were non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian, and Hispanic women. They excluded women with pregestational and gestational diabetes, chronic hypertension, and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

Maternal education levels were stratified into those without a high school diploma, high school graduates (including those with some college credit), college graduates, and those with advanced degrees. The total population included 2,969,207 mothers with a 23.4% cesarean delivery rate.

Before considering education or other potential confounders, the cesarean delivery rate was 27.4% in Black women and 25.6% in Asian women, compared with 22.4% in White women and 23% in Hispanic women (P < .001).

Among those with less than a high school education, Black (20.9%), Asian (23.1%), and Hispanic (17.9% cesarean delivery prevalence was greater than that among White women (17.2%) (P < .001). The same was true among those with a high school education (with or without some college): 22% of White women in this group had cesarean deliveries compared with 26.3% of Black women, 26.3% of Asian women, and 22.5% of Hispanic women (P < .001).

At higher levels of education, the disparities not only persisted but actually increased.

The prevalence of cesarean deliveries was 23% in White college graduates, compared with 32.5% of Black college graduates, 26.3% of Asian college graduates, and 27.7% of Hispanic college graduates (P < .001). Similarly, in those with an advanced degree, the prevalence of cesarean deliveries in their population set was 23.6% of Whites, 36.3% of Blacks, 26.1% of Asians, and 30.1% of Hispanics (P < .001).

After adjusting for maternal education as well as age, prepregnancy body mass index, weight gain during pregnancy, insurance type, and neonatal birth weight, the researchers still found substantial disparities in cesarean delivery rates. Black women had 1.54 times greater odds of cesarean delivery than White women (P < .001). Similarly, the odds were 1.45 times greater for Asian women and 1.24 times greater for Hispanic women (P < .001).

Controlling for race, ethnicity, and the other confounders, women with less than a high school education or a high school diploma had similar likelihoods of cesarean delivery. The likelihood of a cesarean delivery was slightly reduced for women with a college degree (odds ratio, 0.93) or advanced degree (OR, 0.88). But this protective effect did not dampen racial/ethnic disparities. In fact, even greater disparities were seen at higher levels of education.

“At each level of education, all the racial/ethnic groups had significantly higher odds of a cesarean delivery than White women,” Dr. Eliner said. “Additionally, the racial/ethnic disparity in cesarean delivery rates increased with increasing level of education, and we specifically see a meaningful jump in the odds ratio at the college graduate level.”

She pointed out that the OR for cesarean delivery in Black women was 1.4 times greater than White women in the group with less than a high school education and 1.44 times greater in those with high school diplomas. Then it jumped to 1.69 in the college graduates group and 1.7 in the advanced degree group.

Higher maternal education was associated with a lower likelihood of cesarean delivery in White women and Asian women. White women with advanced degrees were 17% less likely to have a cesarean than White women with less than a high school education, and the respective reduction in risk was 19% for Asian women.

In Black women, however, education has a much smaller protective effect: An advanced degree reduced the odds of a cesarean delivery by only 7% and no significant difference showed up between high school graduates and college graduates, Dr. Eliner reported.

In Hispanic women, no protective effect showed up, and the odds of a cesarean delivery actually increased slightly in high school and college graduates above those with less than a high school education.

Dr. Eliner discussed a couple possible reasons for a less protective effect from maternal education in Black and Hispanic groups, including higher levels of chronic stress found in past research among racial/ethnic minorities with higher levels of education.

“The impact of racism as a chronic stressor and its association with adverse obstetric and prenatal outcomes is an emerging theme in health disparity research and is yet to be fully understood,” Dr. Eliner said in an interview. “Nonetheless, there is some evidence suggesting that racial/ethnic minorities with higher levels of education suffer from higher levels of stress.”

Implicit and explicit interpersonal bias and institutional racism may also play a role in the disparities, she said, and these factors may disproportionately affect the quality of care for more educated women. She also suggested that White women may be more comfortable advocating for their care.

“While less educated women from all racial/ethnic groups may lack the self-advocacy skills to discuss their labor course, educated White women may be more confident than women from educated minority groups,” Dr. Eliner told attendees. “They may therefore be better equipped to discuss the need for a cesarean delivery with their provider.”

Dr. Eliner elaborated on this: “Given the historical and current disparities of the health care system, women in racial/ethnic minorities may potentially be guarded in their interaction with medical professionals, with a reduced trust in the health care system, and may thus not feel empowered to advocate for themselves in this setting,” she said.

Allison Bryant Mantha, MD, MPH, vice chair for quality, equity, and safety in the ob.gyn. department at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, suggested that bias and racism may play a role in this self-advocacy as well.

“I’m wondering if it might not be equally plausible that the advocacy might be met differently by who’s delivering the message,” Dr. Bryant Mantha said. “I think from the story of Dr. Susan Moore and patients who advocate for themselves, I think that we know there is probably some differential by who’s delivering the message.”

Finally, even though education is usually highly correlated with income and frequently used as a proxy for it, but the effect of education on income varies by race/ethnicity.

Since education alone is not sufficient to reduce these disparities, potential interventions should focus on increasing awareness of the disparities and the role of implicit bias, improving patients’ trust in the medical system, and training more doctors from underrepresented groups, Dr. Eliner said.

“I was also wondering about the overall patient choice,” said Sarahn M. Wheeler, MD, an assistant professor of ob.gyn. at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C., who comoderated the session with Dr. Bryant Mantha. “Did we have any understanding of differences in patient values systems that might go into some of these differences in findings as well? There are lots of interesting concepts to explore and that this abstract brings up.”

Dr. Eliner, Dr. Wheeler, and Dr. Bryant Mantha had no disclosures.

While the likelihood of a cesarean delivery usually drops as maternal education level increases, the disparities seen in cesarean rates between White and Black or Hispanic women actually increase with more maternal education, according to findings from a new study presented at the Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Typically, higher maternal education is associated with a lower likelihood of cesarean delivery, but this protective effect is much smaller for Black women and nonexistent for Hispanic women, leading to bigger gaps between these groups and White women, found Yael Eliner, MD, an ob.gyn. residency applicant at Boston University who conducted this research with her colleagues in the ob.gyn. department at Lenox Hill Hospital, New York, and Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y..

Researchers have previously identified racial and ethnic disparities in a wide range of maternal outcomes, including mortality, overall morbidity, preterm birth, low birth weight, fetal growth restriction, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, diabetes, and cesarean deliveries. But the researchers wanted to know if the usual protective effects seen for cesarean deliveries existed in the racial and ethnic groups with these disparities. Past studies have already found that the protective effect of maternal education is greater for White women than Black women with infant mortality and overall self-rated health.

The researchers conducted a retrospective analysis of all low-risk nulliparous, term, singleton, vertex live births to U.S. residents from 2016 to 2019 by using the natality database of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. They looked only at women who were non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian, and Hispanic women. They excluded women with pregestational and gestational diabetes, chronic hypertension, and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

Maternal education levels were stratified into those without a high school diploma, high school graduates (including those with some college credit), college graduates, and those with advanced degrees. The total population included 2,969,207 mothers with a 23.4% cesarean delivery rate.

Before considering education or other potential confounders, the cesarean delivery rate was 27.4% in Black women and 25.6% in Asian women, compared with 22.4% in White women and 23% in Hispanic women (P < .001).

Among those with less than a high school education, Black (20.9%), Asian (23.1%), and Hispanic (17.9% cesarean delivery prevalence was greater than that among White women (17.2%) (P < .001). The same was true among those with a high school education (with or without some college): 22% of White women in this group had cesarean deliveries compared with 26.3% of Black women, 26.3% of Asian women, and 22.5% of Hispanic women (P < .001).

At higher levels of education, the disparities not only persisted but actually increased.

The prevalence of cesarean deliveries was 23% in White college graduates, compared with 32.5% of Black college graduates, 26.3% of Asian college graduates, and 27.7% of Hispanic college graduates (P < .001). Similarly, in those with an advanced degree, the prevalence of cesarean deliveries in their population set was 23.6% of Whites, 36.3% of Blacks, 26.1% of Asians, and 30.1% of Hispanics (P < .001).

After adjusting for maternal education as well as age, prepregnancy body mass index, weight gain during pregnancy, insurance type, and neonatal birth weight, the researchers still found substantial disparities in cesarean delivery rates. Black women had 1.54 times greater odds of cesarean delivery than White women (P < .001). Similarly, the odds were 1.45 times greater for Asian women and 1.24 times greater for Hispanic women (P < .001).

Controlling for race, ethnicity, and the other confounders, women with less than a high school education or a high school diploma had similar likelihoods of cesarean delivery. The likelihood of a cesarean delivery was slightly reduced for women with a college degree (odds ratio, 0.93) or advanced degree (OR, 0.88). But this protective effect did not dampen racial/ethnic disparities. In fact, even greater disparities were seen at higher levels of education.

“At each level of education, all the racial/ethnic groups had significantly higher odds of a cesarean delivery than White women,” Dr. Eliner said. “Additionally, the racial/ethnic disparity in cesarean delivery rates increased with increasing level of education, and we specifically see a meaningful jump in the odds ratio at the college graduate level.”

She pointed out that the OR for cesarean delivery in Black women was 1.4 times greater than White women in the group with less than a high school education and 1.44 times greater in those with high school diplomas. Then it jumped to 1.69 in the college graduates group and 1.7 in the advanced degree group.

Higher maternal education was associated with a lower likelihood of cesarean delivery in White women and Asian women. White women with advanced degrees were 17% less likely to have a cesarean than White women with less than a high school education, and the respective reduction in risk was 19% for Asian women.

In Black women, however, education has a much smaller protective effect: An advanced degree reduced the odds of a cesarean delivery by only 7% and no significant difference showed up between high school graduates and college graduates, Dr. Eliner reported.

In Hispanic women, no protective effect showed up, and the odds of a cesarean delivery actually increased slightly in high school and college graduates above those with less than a high school education.

Dr. Eliner discussed a couple possible reasons for a less protective effect from maternal education in Black and Hispanic groups, including higher levels of chronic stress found in past research among racial/ethnic minorities with higher levels of education.

“The impact of racism as a chronic stressor and its association with adverse obstetric and prenatal outcomes is an emerging theme in health disparity research and is yet to be fully understood,” Dr. Eliner said in an interview. “Nonetheless, there is some evidence suggesting that racial/ethnic minorities with higher levels of education suffer from higher levels of stress.”

Implicit and explicit interpersonal bias and institutional racism may also play a role in the disparities, she said, and these factors may disproportionately affect the quality of care for more educated women. She also suggested that White women may be more comfortable advocating for their care.

“While less educated women from all racial/ethnic groups may lack the self-advocacy skills to discuss their labor course, educated White women may be more confident than women from educated minority groups,” Dr. Eliner told attendees. “They may therefore be better equipped to discuss the need for a cesarean delivery with their provider.”

Dr. Eliner elaborated on this: “Given the historical and current disparities of the health care system, women in racial/ethnic minorities may potentially be guarded in their interaction with medical professionals, with a reduced trust in the health care system, and may thus not feel empowered to advocate for themselves in this setting,” she said.

Allison Bryant Mantha, MD, MPH, vice chair for quality, equity, and safety in the ob.gyn. department at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, suggested that bias and racism may play a role in this self-advocacy as well.

“I’m wondering if it might not be equally plausible that the advocacy might be met differently by who’s delivering the message,” Dr. Bryant Mantha said. “I think from the story of Dr. Susan Moore and patients who advocate for themselves, I think that we know there is probably some differential by who’s delivering the message.”

Finally, even though education is usually highly correlated with income and frequently used as a proxy for it, but the effect of education on income varies by race/ethnicity.

Since education alone is not sufficient to reduce these disparities, potential interventions should focus on increasing awareness of the disparities and the role of implicit bias, improving patients’ trust in the medical system, and training more doctors from underrepresented groups, Dr. Eliner said.

“I was also wondering about the overall patient choice,” said Sarahn M. Wheeler, MD, an assistant professor of ob.gyn. at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C., who comoderated the session with Dr. Bryant Mantha. “Did we have any understanding of differences in patient values systems that might go into some of these differences in findings as well? There are lots of interesting concepts to explore and that this abstract brings up.”

Dr. Eliner, Dr. Wheeler, and Dr. Bryant Mantha had no disclosures.

While the likelihood of a cesarean delivery usually drops as maternal education level increases, the disparities seen in cesarean rates between White and Black or Hispanic women actually increase with more maternal education, according to findings from a new study presented at the Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Typically, higher maternal education is associated with a lower likelihood of cesarean delivery, but this protective effect is much smaller for Black women and nonexistent for Hispanic women, leading to bigger gaps between these groups and White women, found Yael Eliner, MD, an ob.gyn. residency applicant at Boston University who conducted this research with her colleagues in the ob.gyn. department at Lenox Hill Hospital, New York, and Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y..

Researchers have previously identified racial and ethnic disparities in a wide range of maternal outcomes, including mortality, overall morbidity, preterm birth, low birth weight, fetal growth restriction, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, diabetes, and cesarean deliveries. But the researchers wanted to know if the usual protective effects seen for cesarean deliveries existed in the racial and ethnic groups with these disparities. Past studies have already found that the protective effect of maternal education is greater for White women than Black women with infant mortality and overall self-rated health.

The researchers conducted a retrospective analysis of all low-risk nulliparous, term, singleton, vertex live births to U.S. residents from 2016 to 2019 by using the natality database of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. They looked only at women who were non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian, and Hispanic women. They excluded women with pregestational and gestational diabetes, chronic hypertension, and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

Maternal education levels were stratified into those without a high school diploma, high school graduates (including those with some college credit), college graduates, and those with advanced degrees. The total population included 2,969,207 mothers with a 23.4% cesarean delivery rate.

Before considering education or other potential confounders, the cesarean delivery rate was 27.4% in Black women and 25.6% in Asian women, compared with 22.4% in White women and 23% in Hispanic women (P < .001).

Among those with less than a high school education, Black (20.9%), Asian (23.1%), and Hispanic (17.9% cesarean delivery prevalence was greater than that among White women (17.2%) (P < .001). The same was true among those with a high school education (with or without some college): 22% of White women in this group had cesarean deliveries compared with 26.3% of Black women, 26.3% of Asian women, and 22.5% of Hispanic women (P < .001).

At higher levels of education, the disparities not only persisted but actually increased.

The prevalence of cesarean deliveries was 23% in White college graduates, compared with 32.5% of Black college graduates, 26.3% of Asian college graduates, and 27.7% of Hispanic college graduates (P < .001). Similarly, in those with an advanced degree, the prevalence of cesarean deliveries in their population set was 23.6% of Whites, 36.3% of Blacks, 26.1% of Asians, and 30.1% of Hispanics (P < .001).

After adjusting for maternal education as well as age, prepregnancy body mass index, weight gain during pregnancy, insurance type, and neonatal birth weight, the researchers still found substantial disparities in cesarean delivery rates. Black women had 1.54 times greater odds of cesarean delivery than White women (P < .001). Similarly, the odds were 1.45 times greater for Asian women and 1.24 times greater for Hispanic women (P < .001).

Controlling for race, ethnicity, and the other confounders, women with less than a high school education or a high school diploma had similar likelihoods of cesarean delivery. The likelihood of a cesarean delivery was slightly reduced for women with a college degree (odds ratio, 0.93) or advanced degree (OR, 0.88). But this protective effect did not dampen racial/ethnic disparities. In fact, even greater disparities were seen at higher levels of education.

“At each level of education, all the racial/ethnic groups had significantly higher odds of a cesarean delivery than White women,” Dr. Eliner said. “Additionally, the racial/ethnic disparity in cesarean delivery rates increased with increasing level of education, and we specifically see a meaningful jump in the odds ratio at the college graduate level.”

She pointed out that the OR for cesarean delivery in Black women was 1.4 times greater than White women in the group with less than a high school education and 1.44 times greater in those with high school diplomas. Then it jumped to 1.69 in the college graduates group and 1.7 in the advanced degree group.

Higher maternal education was associated with a lower likelihood of cesarean delivery in White women and Asian women. White women with advanced degrees were 17% less likely to have a cesarean than White women with less than a high school education, and the respective reduction in risk was 19% for Asian women.

In Black women, however, education has a much smaller protective effect: An advanced degree reduced the odds of a cesarean delivery by only 7% and no significant difference showed up between high school graduates and college graduates, Dr. Eliner reported.

In Hispanic women, no protective effect showed up, and the odds of a cesarean delivery actually increased slightly in high school and college graduates above those with less than a high school education.

Dr. Eliner discussed a couple possible reasons for a less protective effect from maternal education in Black and Hispanic groups, including higher levels of chronic stress found in past research among racial/ethnic minorities with higher levels of education.

“The impact of racism as a chronic stressor and its association with adverse obstetric and prenatal outcomes is an emerging theme in health disparity research and is yet to be fully understood,” Dr. Eliner said in an interview. “Nonetheless, there is some evidence suggesting that racial/ethnic minorities with higher levels of education suffer from higher levels of stress.”

Implicit and explicit interpersonal bias and institutional racism may also play a role in the disparities, she said, and these factors may disproportionately affect the quality of care for more educated women. She also suggested that White women may be more comfortable advocating for their care.

“While less educated women from all racial/ethnic groups may lack the self-advocacy skills to discuss their labor course, educated White women may be more confident than women from educated minority groups,” Dr. Eliner told attendees. “They may therefore be better equipped to discuss the need for a cesarean delivery with their provider.”

Dr. Eliner elaborated on this: “Given the historical and current disparities of the health care system, women in racial/ethnic minorities may potentially be guarded in their interaction with medical professionals, with a reduced trust in the health care system, and may thus not feel empowered to advocate for themselves in this setting,” she said.

Allison Bryant Mantha, MD, MPH, vice chair for quality, equity, and safety in the ob.gyn. department at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, suggested that bias and racism may play a role in this self-advocacy as well.

“I’m wondering if it might not be equally plausible that the advocacy might be met differently by who’s delivering the message,” Dr. Bryant Mantha said. “I think from the story of Dr. Susan Moore and patients who advocate for themselves, I think that we know there is probably some differential by who’s delivering the message.”

Finally, even though education is usually highly correlated with income and frequently used as a proxy for it, but the effect of education on income varies by race/ethnicity.

Since education alone is not sufficient to reduce these disparities, potential interventions should focus on increasing awareness of the disparities and the role of implicit bias, improving patients’ trust in the medical system, and training more doctors from underrepresented groups, Dr. Eliner said.

“I was also wondering about the overall patient choice,” said Sarahn M. Wheeler, MD, an assistant professor of ob.gyn. at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C., who comoderated the session with Dr. Bryant Mantha. “Did we have any understanding of differences in patient values systems that might go into some of these differences in findings as well? There are lots of interesting concepts to explore and that this abstract brings up.”

Dr. Eliner, Dr. Wheeler, and Dr. Bryant Mantha had no disclosures.

FROM THE PREGNANCY MEETING

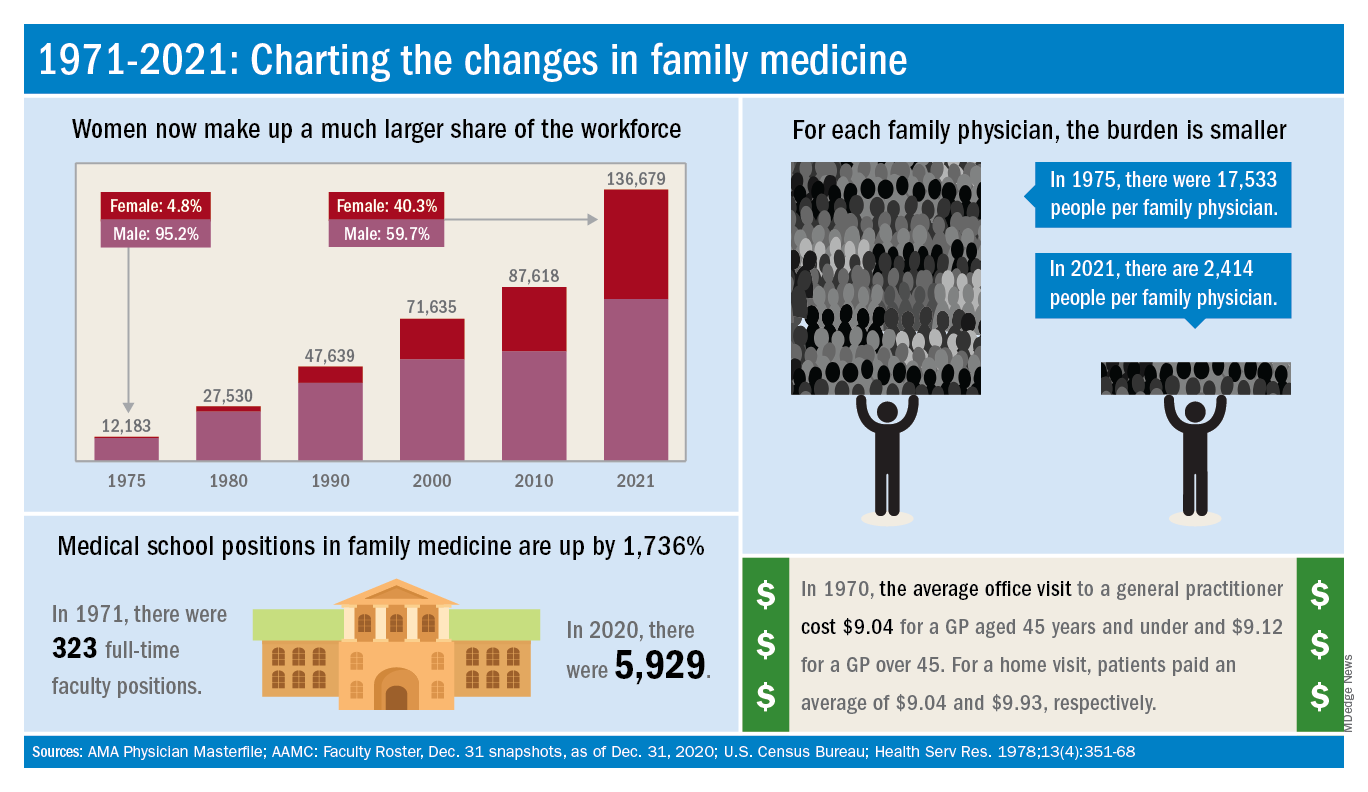

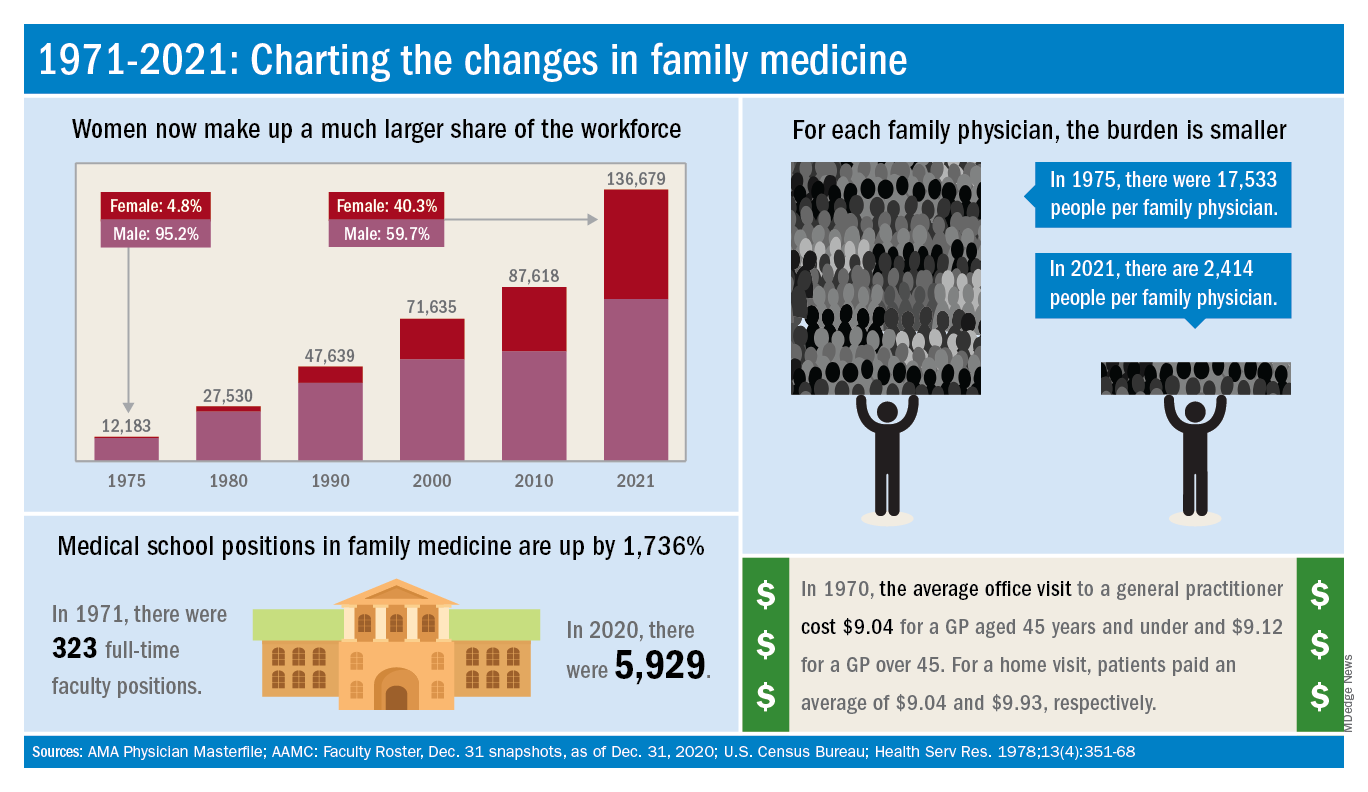

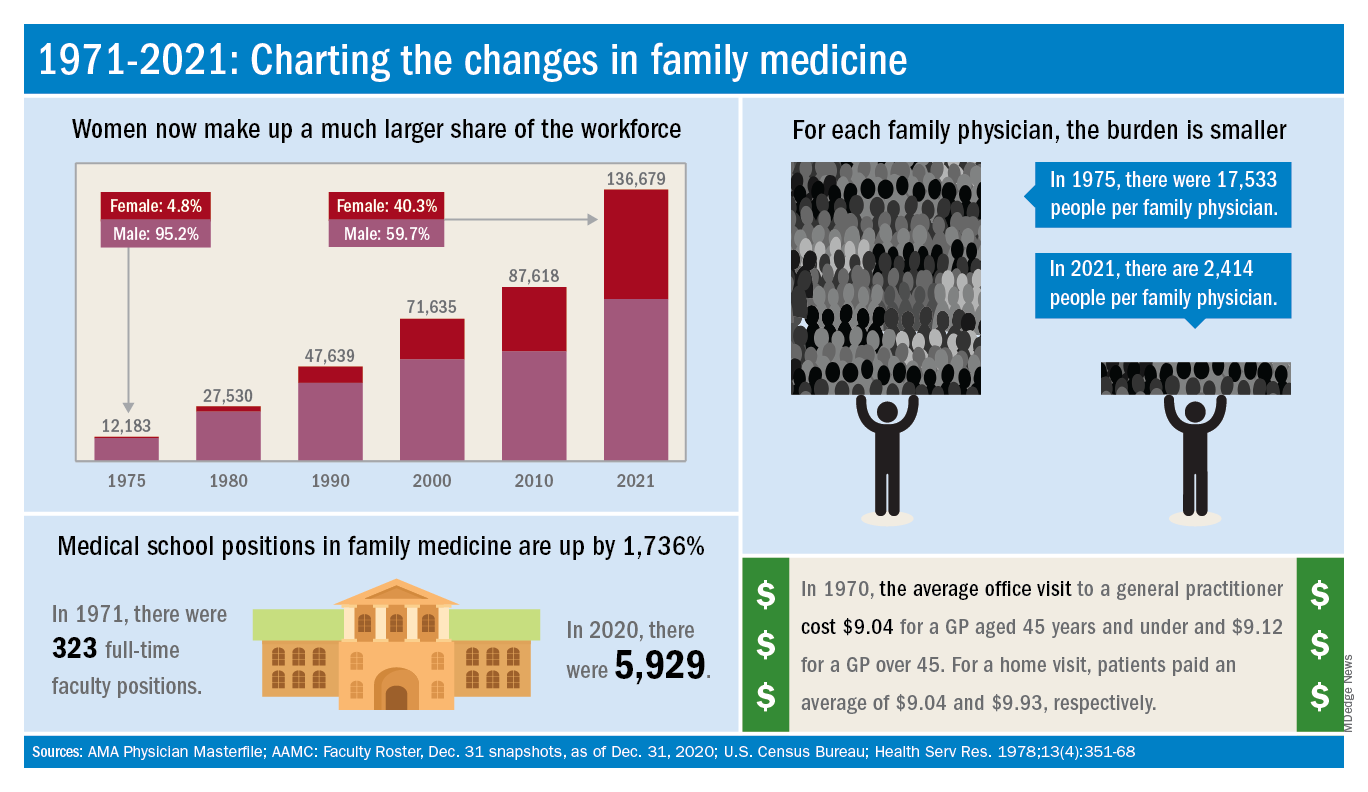

Family medicine has grown; its composition has evolved

and the men and women who practice it are no exception.

The family medicine workforce of 2021 is not the workforce of 1971. Not even close. Although we would like to give a huge shout-out to anyone who can claim to be a member of both.

Today’s FP workforce is, first of all, much larger than it was in 1971, although we can’t actually prove it because the American Medical Association’s data for that year are “only available in books that are locked away at the empty AMA headquarters,” according to a member of the AMA media relations staff who is, like so many people these days, working at home because of the pandemic.

The face of family medicine in 1975 vs. today

Today’s workforce is much larger than it was in 1975, when there were just over 12,000 family physicians in the United States. As of January 2021, the total was approaching 137,000, including all “physicians and residents in patient care, research, administration, teaching, retired, inactive, etc.,” the AMA explained.

Family physicians as a group are much more diverse than they were in 1975. That year, 8.3% of FPs were international medical graduates (IMGs). By 2010, IMGs made up almost 23% of the workforce, and in the 2020 resident match, 37% of the 4,662 available family medicine slots were filled by IMGs.

Women have made even greater inroads into the family physician ranks over the last 5 decades. In 1975, less than 5% of all FPs were females, but by 2021 the proportion of females in the specialty was just over 40%.

In the first 5 years of the family practice era, 1969-1973, only 12 women and 31 IMGs graduated from FP residency programs, those numbers representing 3.2% and 8.3%, respectively, of the total of 372, according to a 1996 study in JAMA. By 1990-1993, women made up 33% and IMGs 14% of the 9,400 graduates.

Another group that increased its presence in family medicine is doctors of osteopathy, who went from zero residency graduates in 1969-1973 to over 1,100 (11.8%) in 1990-1993, the JAMA report noted. By 2020, almost 1,400 osteopathic physicians entered family medicine residencies, filling 30% of all slots available, according to the National Resident Matching Program.

The medical schools producing all these new residents have raised their games since 1971: the number of full-time faculty in family medicine departments rose from 323 to 5,929 in 2020, based on data from the Association of American Medical Colleges (Faculty Roster, Dec. 31 snapshots, as of Dec. 31, 2020).

A shortage or a surplus of FPs?

It has been suggested, however, that all is not well in primary care land. A study conducted by the American Academy of Family Physicians in 2016 – a year after 2,463 graduates of MD- and DO-granting medical schools entered family medicine residencies – concluded “that the current medical school system is failing, collectively, to produce the primary care workforce that is needed to achieve optimal health.”

Warnings about physician shortages are nothing new, but how about the other side of the coin? The Jan. 15, 1981, issue of Family Practice News covered a somewhat controversial report from the Graduate Medical Education National Advisory Committee, which projected a surplus of 3,000 FPs, and as many as 70,000 physicians overall, by the year 1990.

Just a few months later, in the June 15, 1981, issue of FPN, an AAFP officer predicted that “the flood of new physicians in the next decade may affect family practice more than any other specialty.”

Mostly, though, the issue is shortages. In 2002, a status report on family practice from the Robert Graham Center acknowledged that “many centers of academic medicine continue to resist the development of family practice and primary care. ... Family medicine remains a true counterculture in these environments, and students may continue to face significant discouragement in response to interest they may express in becoming a family physician.”

and the men and women who practice it are no exception.

The family medicine workforce of 2021 is not the workforce of 1971. Not even close. Although we would like to give a huge shout-out to anyone who can claim to be a member of both.

Today’s FP workforce is, first of all, much larger than it was in 1971, although we can’t actually prove it because the American Medical Association’s data for that year are “only available in books that are locked away at the empty AMA headquarters,” according to a member of the AMA media relations staff who is, like so many people these days, working at home because of the pandemic.

The face of family medicine in 1975 vs. today

Today’s workforce is much larger than it was in 1975, when there were just over 12,000 family physicians in the United States. As of January 2021, the total was approaching 137,000, including all “physicians and residents in patient care, research, administration, teaching, retired, inactive, etc.,” the AMA explained.

Family physicians as a group are much more diverse than they were in 1975. That year, 8.3% of FPs were international medical graduates (IMGs). By 2010, IMGs made up almost 23% of the workforce, and in the 2020 resident match, 37% of the 4,662 available family medicine slots were filled by IMGs.

Women have made even greater inroads into the family physician ranks over the last 5 decades. In 1975, less than 5% of all FPs were females, but by 2021 the proportion of females in the specialty was just over 40%.

In the first 5 years of the family practice era, 1969-1973, only 12 women and 31 IMGs graduated from FP residency programs, those numbers representing 3.2% and 8.3%, respectively, of the total of 372, according to a 1996 study in JAMA. By 1990-1993, women made up 33% and IMGs 14% of the 9,400 graduates.

Another group that increased its presence in family medicine is doctors of osteopathy, who went from zero residency graduates in 1969-1973 to over 1,100 (11.8%) in 1990-1993, the JAMA report noted. By 2020, almost 1,400 osteopathic physicians entered family medicine residencies, filling 30% of all slots available, according to the National Resident Matching Program.

The medical schools producing all these new residents have raised their games since 1971: the number of full-time faculty in family medicine departments rose from 323 to 5,929 in 2020, based on data from the Association of American Medical Colleges (Faculty Roster, Dec. 31 snapshots, as of Dec. 31, 2020).

A shortage or a surplus of FPs?

It has been suggested, however, that all is not well in primary care land. A study conducted by the American Academy of Family Physicians in 2016 – a year after 2,463 graduates of MD- and DO-granting medical schools entered family medicine residencies – concluded “that the current medical school system is failing, collectively, to produce the primary care workforce that is needed to achieve optimal health.”

Warnings about physician shortages are nothing new, but how about the other side of the coin? The Jan. 15, 1981, issue of Family Practice News covered a somewhat controversial report from the Graduate Medical Education National Advisory Committee, which projected a surplus of 3,000 FPs, and as many as 70,000 physicians overall, by the year 1990.

Just a few months later, in the June 15, 1981, issue of FPN, an AAFP officer predicted that “the flood of new physicians in the next decade may affect family practice more than any other specialty.”

Mostly, though, the issue is shortages. In 2002, a status report on family practice from the Robert Graham Center acknowledged that “many centers of academic medicine continue to resist the development of family practice and primary care. ... Family medicine remains a true counterculture in these environments, and students may continue to face significant discouragement in response to interest they may express in becoming a family physician.”

and the men and women who practice it are no exception.

The family medicine workforce of 2021 is not the workforce of 1971. Not even close. Although we would like to give a huge shout-out to anyone who can claim to be a member of both.

Today’s FP workforce is, first of all, much larger than it was in 1971, although we can’t actually prove it because the American Medical Association’s data for that year are “only available in books that are locked away at the empty AMA headquarters,” according to a member of the AMA media relations staff who is, like so many people these days, working at home because of the pandemic.

The face of family medicine in 1975 vs. today

Today’s workforce is much larger than it was in 1975, when there were just over 12,000 family physicians in the United States. As of January 2021, the total was approaching 137,000, including all “physicians and residents in patient care, research, administration, teaching, retired, inactive, etc.,” the AMA explained.

Family physicians as a group are much more diverse than they were in 1975. That year, 8.3% of FPs were international medical graduates (IMGs). By 2010, IMGs made up almost 23% of the workforce, and in the 2020 resident match, 37% of the 4,662 available family medicine slots were filled by IMGs.

Women have made even greater inroads into the family physician ranks over the last 5 decades. In 1975, less than 5% of all FPs were females, but by 2021 the proportion of females in the specialty was just over 40%.

In the first 5 years of the family practice era, 1969-1973, only 12 women and 31 IMGs graduated from FP residency programs, those numbers representing 3.2% and 8.3%, respectively, of the total of 372, according to a 1996 study in JAMA. By 1990-1993, women made up 33% and IMGs 14% of the 9,400 graduates.

Another group that increased its presence in family medicine is doctors of osteopathy, who went from zero residency graduates in 1969-1973 to over 1,100 (11.8%) in 1990-1993, the JAMA report noted. By 2020, almost 1,400 osteopathic physicians entered family medicine residencies, filling 30% of all slots available, according to the National Resident Matching Program.

The medical schools producing all these new residents have raised their games since 1971: the number of full-time faculty in family medicine departments rose from 323 to 5,929 in 2020, based on data from the Association of American Medical Colleges (Faculty Roster, Dec. 31 snapshots, as of Dec. 31, 2020).

A shortage or a surplus of FPs?

It has been suggested, however, that all is not well in primary care land. A study conducted by the American Academy of Family Physicians in 2016 – a year after 2,463 graduates of MD- and DO-granting medical schools entered family medicine residencies – concluded “that the current medical school system is failing, collectively, to produce the primary care workforce that is needed to achieve optimal health.”

Warnings about physician shortages are nothing new, but how about the other side of the coin? The Jan. 15, 1981, issue of Family Practice News covered a somewhat controversial report from the Graduate Medical Education National Advisory Committee, which projected a surplus of 3,000 FPs, and as many as 70,000 physicians overall, by the year 1990.

Just a few months later, in the June 15, 1981, issue of FPN, an AAFP officer predicted that “the flood of new physicians in the next decade may affect family practice more than any other specialty.”

Mostly, though, the issue is shortages. In 2002, a status report on family practice from the Robert Graham Center acknowledged that “many centers of academic medicine continue to resist the development of family practice and primary care. ... Family medicine remains a true counterculture in these environments, and students may continue to face significant discouragement in response to interest they may express in becoming a family physician.”

Cardiovascular trials lose more women than men

A new analysis of 11 phase 3/4 cardiovascular clinical trials conducted by the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) group shows that women are more likely than men to discontinue study medications, and to withdraw from trials. The differences could not be explained by different frequencies of reporting adverse events, or by baseline differences.

The findings are significant, since cardiovascular drugs are routinely prescribed to women based on clinical trials that are populated largely by men, according to lead study author Emily Lau, MD, who is an advanced cardiology fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. “It highlights an important disparity in clinical research in cardiology, because if women are already not represented well in clinical trials, and if once in clinical trials they don’t complete the study, it’s very hard to extrapolate the clinical trial findings to our female population in an accurate way,” Dr. Lau said in an interview. She also noted that sex-specific and reproductive factors are increasingly recognized as being important in the development and progression of cardiovascular disease.

The study was published in the journal Circulation.

The study refutes previously advanced explanations for higher withdrawal among women, including sex difference and comorbidities, according to an accompanying editorial by Sofia Sederholm Lawesson, MD, PhD, Eva Swahn, MD, PhD, and Joakim Alfredsson, MD, PhD, of Linköping University, Sweden. They also pointed out that the study found a larger between-sex difference in failure to adhere to study drug in North America (odds ratio, 1.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.30-1.41), but a more moderate difference among participants in Europe/Middle East/Africa (OR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.09-1.17) and Asia/Pacific (OR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.03-1.23) regions. And there were no sex differences at all among South/Central American populations.

They noted that high rates of nonadherence increase the chances of a false negative finding and overestimation of drug safety. “We know the associations between nonadherence and clinical outcomes. The next step should be to better understand the underlying reasons for, as well as consistent reporting of, nonadherence, and discontinuation in RCTs,” the editorial authors wrote.

Dr. Lau suggested a simple method to better understand reasons for withdrawal: Addition of questions to the case report form that asks about reasons for drug discontinuation or study withdrawal. “Was it an adverse event? Was it because I’m a mother of three and I can’t get to the clinical trial site after work and also pick up my kids? Are there societal barriers for women, or was it the experience of the clinical trial that was maybe less favorable for women compared to men? Or maybe there are medical reasons we simply don’t know. Something as simple as asking those questions can help us better understand the barriers to female retention,” said Dr. Lau.

The analysis included data from 135,879 men (72%) and 51,812 women (28%) enrolled in the trials. After adjustment for baseline differences, women were more likely than were men to permanently discontinue study drug (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.22: P < .001), which did not vary by study duration. The finding was consistent regardless of the type of drug studied, as well as across placebo and active study arms.

Women also were more likely to prematurely discontinue study drug (trial-adjusted OR, 1.18; P < .001). The rate of drug discontinuation due to adverse event was identical in both men and women, at 36%.

Women were more likely to withdraw consent than were men in a meta-analysis and when individual patient-level results were pooled (aOR, 1.26; P < .001 for both).

Dr. Lau received funding from the National Institutes of Health and has no relevant financial disclosures. The editorial authors had various disclosures, including lecture fees from Bayer, Pfizer, and Boehringer Ingelheim, and they served on advisory boards for AstraZeneca and MSD.

A new analysis of 11 phase 3/4 cardiovascular clinical trials conducted by the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) group shows that women are more likely than men to discontinue study medications, and to withdraw from trials. The differences could not be explained by different frequencies of reporting adverse events, or by baseline differences.

The findings are significant, since cardiovascular drugs are routinely prescribed to women based on clinical trials that are populated largely by men, according to lead study author Emily Lau, MD, who is an advanced cardiology fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. “It highlights an important disparity in clinical research in cardiology, because if women are already not represented well in clinical trials, and if once in clinical trials they don’t complete the study, it’s very hard to extrapolate the clinical trial findings to our female population in an accurate way,” Dr. Lau said in an interview. She also noted that sex-specific and reproductive factors are increasingly recognized as being important in the development and progression of cardiovascular disease.

The study was published in the journal Circulation.

The study refutes previously advanced explanations for higher withdrawal among women, including sex difference and comorbidities, according to an accompanying editorial by Sofia Sederholm Lawesson, MD, PhD, Eva Swahn, MD, PhD, and Joakim Alfredsson, MD, PhD, of Linköping University, Sweden. They also pointed out that the study found a larger between-sex difference in failure to adhere to study drug in North America (odds ratio, 1.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.30-1.41), but a more moderate difference among participants in Europe/Middle East/Africa (OR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.09-1.17) and Asia/Pacific (OR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.03-1.23) regions. And there were no sex differences at all among South/Central American populations.

They noted that high rates of nonadherence increase the chances of a false negative finding and overestimation of drug safety. “We know the associations between nonadherence and clinical outcomes. The next step should be to better understand the underlying reasons for, as well as consistent reporting of, nonadherence, and discontinuation in RCTs,” the editorial authors wrote.

Dr. Lau suggested a simple method to better understand reasons for withdrawal: Addition of questions to the case report form that asks about reasons for drug discontinuation or study withdrawal. “Was it an adverse event? Was it because I’m a mother of three and I can’t get to the clinical trial site after work and also pick up my kids? Are there societal barriers for women, or was it the experience of the clinical trial that was maybe less favorable for women compared to men? Or maybe there are medical reasons we simply don’t know. Something as simple as asking those questions can help us better understand the barriers to female retention,” said Dr. Lau.

The analysis included data from 135,879 men (72%) and 51,812 women (28%) enrolled in the trials. After adjustment for baseline differences, women were more likely than were men to permanently discontinue study drug (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.22: P < .001), which did not vary by study duration. The finding was consistent regardless of the type of drug studied, as well as across placebo and active study arms.

Women also were more likely to prematurely discontinue study drug (trial-adjusted OR, 1.18; P < .001). The rate of drug discontinuation due to adverse event was identical in both men and women, at 36%.

Women were more likely to withdraw consent than were men in a meta-analysis and when individual patient-level results were pooled (aOR, 1.26; P < .001 for both).

Dr. Lau received funding from the National Institutes of Health and has no relevant financial disclosures. The editorial authors had various disclosures, including lecture fees from Bayer, Pfizer, and Boehringer Ingelheim, and they served on advisory boards for AstraZeneca and MSD.

A new analysis of 11 phase 3/4 cardiovascular clinical trials conducted by the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) group shows that women are more likely than men to discontinue study medications, and to withdraw from trials. The differences could not be explained by different frequencies of reporting adverse events, or by baseline differences.

The findings are significant, since cardiovascular drugs are routinely prescribed to women based on clinical trials that are populated largely by men, according to lead study author Emily Lau, MD, who is an advanced cardiology fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. “It highlights an important disparity in clinical research in cardiology, because if women are already not represented well in clinical trials, and if once in clinical trials they don’t complete the study, it’s very hard to extrapolate the clinical trial findings to our female population in an accurate way,” Dr. Lau said in an interview. She also noted that sex-specific and reproductive factors are increasingly recognized as being important in the development and progression of cardiovascular disease.

The study was published in the journal Circulation.

The study refutes previously advanced explanations for higher withdrawal among women, including sex difference and comorbidities, according to an accompanying editorial by Sofia Sederholm Lawesson, MD, PhD, Eva Swahn, MD, PhD, and Joakim Alfredsson, MD, PhD, of Linköping University, Sweden. They also pointed out that the study found a larger between-sex difference in failure to adhere to study drug in North America (odds ratio, 1.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.30-1.41), but a more moderate difference among participants in Europe/Middle East/Africa (OR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.09-1.17) and Asia/Pacific (OR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.03-1.23) regions. And there were no sex differences at all among South/Central American populations.

They noted that high rates of nonadherence increase the chances of a false negative finding and overestimation of drug safety. “We know the associations between nonadherence and clinical outcomes. The next step should be to better understand the underlying reasons for, as well as consistent reporting of, nonadherence, and discontinuation in RCTs,” the editorial authors wrote.

Dr. Lau suggested a simple method to better understand reasons for withdrawal: Addition of questions to the case report form that asks about reasons for drug discontinuation or study withdrawal. “Was it an adverse event? Was it because I’m a mother of three and I can’t get to the clinical trial site after work and also pick up my kids? Are there societal barriers for women, or was it the experience of the clinical trial that was maybe less favorable for women compared to men? Or maybe there are medical reasons we simply don’t know. Something as simple as asking those questions can help us better understand the barriers to female retention,” said Dr. Lau.

The analysis included data from 135,879 men (72%) and 51,812 women (28%) enrolled in the trials. After adjustment for baseline differences, women were more likely than were men to permanently discontinue study drug (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.22: P < .001), which did not vary by study duration. The finding was consistent regardless of the type of drug studied, as well as across placebo and active study arms.

Women also were more likely to prematurely discontinue study drug (trial-adjusted OR, 1.18; P < .001). The rate of drug discontinuation due to adverse event was identical in both men and women, at 36%.

Women were more likely to withdraw consent than were men in a meta-analysis and when individual patient-level results were pooled (aOR, 1.26; P < .001 for both).

Dr. Lau received funding from the National Institutes of Health and has no relevant financial disclosures. The editorial authors had various disclosures, including lecture fees from Bayer, Pfizer, and Boehringer Ingelheim, and they served on advisory boards for AstraZeneca and MSD.

FROM CIRCULATION

Seen or viewed: A black hematologist’s perspective

After a long day in hematology clinic, I skimmed the inpatient list to see if any of my patients had been admitted. Seeing Ms. Short’s name (changed for privacy), a delightful African American woman I met during my early days of fellowship, had me making the trek to the hospital. She was living with multiple myeloma complicated by extramedullary manifestations that had significantly impacted her quality of life.

During our first encounter, she showed me a growing left subscapular mass the size of an orange that was erythematous, hot, painful, and irritated. As an enthusiastic first-year fellow, I wanted to be aggressive in addressing her concerns in response to her obvious distress about this mass. Ultimately, she left clinic with antibiotics and an appointment with radiation oncology to see if they could use radiation to shrink the subscapular mass.

When I went back in to discuss the plan with her, she grabbed my hand, looked me in my eyes and said: “Thank you, I’ve been mentioning this for a while and you’re the first person to get something done about it.” In that moment I knew that she felt seen.

By the time I made it over to the hospital, she was getting settled in her room to start another cycle of cytoreductive chemotherapy.

“I told them I had a Black doctor!” she exclaimed as I walked into her hospital room. “I was looking for you today in clinic ... I kept telling them I had a Black doctor, but the nurses kept telling me no, that there were only Black nurse practitioners.” She had repeatedly told the staff that I, her “Black doctor,” did indeed exist, and she went on to describe me as “you know, the [heavy-chested] and short Black doctor I saw early this fall.” To this day, her description still makes me chuckle.

Though I laughed at her description, it hurt that I had worked in a clinic for 6 months yet was invisible. Initially disappointed, I left Ms. Short’s room with a smile on my face, energized and encouraged.

My time with Ms. Short prompted me to ruminate on my experience as a Black physician. To put it in perspective, 5% of all physicians are Black, 2% are Black women, and 2.3% are oncologists, even though African Americans make up 13% of the general U.S. population. I reside in a space where I am simultaneously scrutinized because I am one of the few (or the only) Black physicians in the building, and yet I am invisible because my colleagues and coworkers routinely ignore my presence.

Black physicians, let alone hematologists, are so rare that nurses often cannot fathom that a Black woman could be more than a nurse practitioner. Sadly, this is the tip of the iceberg of some of the negative experiences I, and other Black doctors, have had.

How I present myself must be carefully curated to make progress in my career. My peers and superiors seem to hear me better when my hair is straight and not in its naturally curly state. My introversion has been interpreted as being standoffish or disinterested. Any tone other than happy is interpreted as “aggressive” or “angry”. Talking “too much” to Black support staff was reported to my program, as it was viewed as suspicious, disruptive, and “appearances matter”.

I am also expected to be nurturing in ways that White physicians are not required to be. In my presence, White physicians have denigrated an entire patient population that is disproportionately Black by calling them “sicklers.” If there is an interpersonal conflict, I must think about the long-term consequences of voicing my perspective. My non-Black colleagues do not have to think about these things.

Imagine dealing with this at work, then on your commute home being worried about the reality that you may be pulled over and become the next name on the ever-growing list of Black women and men murdered at the hands of police. The cognitive and emotional impact of being invisible is immense and cumulative over the years.

My Blackness creates a bias of inferiority that cannot be overcome by respectability, compliance, professionalism, training, and expertise. This is glaringly apparent on both sides of the physician-patient relationship. Black patients’ concerns are routinely overlooked and dismissed, as seen with Ms. Short, and are reflected in the Black maternal death rate, pain control in Black versus White patients, and personal experience as a patient and an advocate for my family members.

Patients have looked me in the face and said, “all lives matter,” displaying their refusal to recognize that systematic racism and inequality exist. These facts and experiences are the antithesis of “primum non nocere.”

Sadly, my and Ms. Short’s experiences are not singular ones, and racial bias in medicine is a diagnosed, but untreated cancer. Like the malignancies I treat, ignoring the problem has not made it go away; therefore, it continues to fester and spread, causing more destruction. It is of great importance and concern that all physicians recognize, reflect, and correct their implicit biases not only toward their patients, but also colleagues and trainees.

It seems that health care professionals can talk the talk, as many statements have been made against racism and implicit bias in medicine, but can we take true and meaningful action to begin the journey to equity and justice?

I would like to thank Adrienne Glover, MD, MaKenzie Hodge, MD, Maranatha McLean, MD, and Darion Showell, MD, for our stimulating conversations that helped me put pen to paper. I’d also like to thank my family for being my editors.

Daphanie D. Taylor, MD, is a hematology/oncology fellow PGY-6 at Levine Cancer Institute, Charlotte, N.C.

References and further reading

Roy L. “‘It’s My Calling To Change The Statistics’: Why We Need More Black Female Physicians.” Forbes Magazine, 27 Feb. 2020.

“Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019.” Association of American Medical Colleges, 2019.

“Facts & Figures: Diversity in Oncology.” American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2020 Jan 16.

After a long day in hematology clinic, I skimmed the inpatient list to see if any of my patients had been admitted. Seeing Ms. Short’s name (changed for privacy), a delightful African American woman I met during my early days of fellowship, had me making the trek to the hospital. She was living with multiple myeloma complicated by extramedullary manifestations that had significantly impacted her quality of life.

During our first encounter, she showed me a growing left subscapular mass the size of an orange that was erythematous, hot, painful, and irritated. As an enthusiastic first-year fellow, I wanted to be aggressive in addressing her concerns in response to her obvious distress about this mass. Ultimately, she left clinic with antibiotics and an appointment with radiation oncology to see if they could use radiation to shrink the subscapular mass.

When I went back in to discuss the plan with her, she grabbed my hand, looked me in my eyes and said: “Thank you, I’ve been mentioning this for a while and you’re the first person to get something done about it.” In that moment I knew that she felt seen.

By the time I made it over to the hospital, she was getting settled in her room to start another cycle of cytoreductive chemotherapy.

“I told them I had a Black doctor!” she exclaimed as I walked into her hospital room. “I was looking for you today in clinic ... I kept telling them I had a Black doctor, but the nurses kept telling me no, that there were only Black nurse practitioners.” She had repeatedly told the staff that I, her “Black doctor,” did indeed exist, and she went on to describe me as “you know, the [heavy-chested] and short Black doctor I saw early this fall.” To this day, her description still makes me chuckle.

Though I laughed at her description, it hurt that I had worked in a clinic for 6 months yet was invisible. Initially disappointed, I left Ms. Short’s room with a smile on my face, energized and encouraged.

My time with Ms. Short prompted me to ruminate on my experience as a Black physician. To put it in perspective, 5% of all physicians are Black, 2% are Black women, and 2.3% are oncologists, even though African Americans make up 13% of the general U.S. population. I reside in a space where I am simultaneously scrutinized because I am one of the few (or the only) Black physicians in the building, and yet I am invisible because my colleagues and coworkers routinely ignore my presence.

Black physicians, let alone hematologists, are so rare that nurses often cannot fathom that a Black woman could be more than a nurse practitioner. Sadly, this is the tip of the iceberg of some of the negative experiences I, and other Black doctors, have had.

How I present myself must be carefully curated to make progress in my career. My peers and superiors seem to hear me better when my hair is straight and not in its naturally curly state. My introversion has been interpreted as being standoffish or disinterested. Any tone other than happy is interpreted as “aggressive” or “angry”. Talking “too much” to Black support staff was reported to my program, as it was viewed as suspicious, disruptive, and “appearances matter”.

I am also expected to be nurturing in ways that White physicians are not required to be. In my presence, White physicians have denigrated an entire patient population that is disproportionately Black by calling them “sicklers.” If there is an interpersonal conflict, I must think about the long-term consequences of voicing my perspective. My non-Black colleagues do not have to think about these things.

Imagine dealing with this at work, then on your commute home being worried about the reality that you may be pulled over and become the next name on the ever-growing list of Black women and men murdered at the hands of police. The cognitive and emotional impact of being invisible is immense and cumulative over the years.

My Blackness creates a bias of inferiority that cannot be overcome by respectability, compliance, professionalism, training, and expertise. This is glaringly apparent on both sides of the physician-patient relationship. Black patients’ concerns are routinely overlooked and dismissed, as seen with Ms. Short, and are reflected in the Black maternal death rate, pain control in Black versus White patients, and personal experience as a patient and an advocate for my family members.

Patients have looked me in the face and said, “all lives matter,” displaying their refusal to recognize that systematic racism and inequality exist. These facts and experiences are the antithesis of “primum non nocere.”

Sadly, my and Ms. Short’s experiences are not singular ones, and racial bias in medicine is a diagnosed, but untreated cancer. Like the malignancies I treat, ignoring the problem has not made it go away; therefore, it continues to fester and spread, causing more destruction. It is of great importance and concern that all physicians recognize, reflect, and correct their implicit biases not only toward their patients, but also colleagues and trainees.

It seems that health care professionals can talk the talk, as many statements have been made against racism and implicit bias in medicine, but can we take true and meaningful action to begin the journey to equity and justice?

I would like to thank Adrienne Glover, MD, MaKenzie Hodge, MD, Maranatha McLean, MD, and Darion Showell, MD, for our stimulating conversations that helped me put pen to paper. I’d also like to thank my family for being my editors.

Daphanie D. Taylor, MD, is a hematology/oncology fellow PGY-6 at Levine Cancer Institute, Charlotte, N.C.

References and further reading

Roy L. “‘It’s My Calling To Change The Statistics’: Why We Need More Black Female Physicians.” Forbes Magazine, 27 Feb. 2020.

“Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019.” Association of American Medical Colleges, 2019.

“Facts & Figures: Diversity in Oncology.” American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2020 Jan 16.

After a long day in hematology clinic, I skimmed the inpatient list to see if any of my patients had been admitted. Seeing Ms. Short’s name (changed for privacy), a delightful African American woman I met during my early days of fellowship, had me making the trek to the hospital. She was living with multiple myeloma complicated by extramedullary manifestations that had significantly impacted her quality of life.

During our first encounter, she showed me a growing left subscapular mass the size of an orange that was erythematous, hot, painful, and irritated. As an enthusiastic first-year fellow, I wanted to be aggressive in addressing her concerns in response to her obvious distress about this mass. Ultimately, she left clinic with antibiotics and an appointment with radiation oncology to see if they could use radiation to shrink the subscapular mass.

When I went back in to discuss the plan with her, she grabbed my hand, looked me in my eyes and said: “Thank you, I’ve been mentioning this for a while and you’re the first person to get something done about it.” In that moment I knew that she felt seen.

By the time I made it over to the hospital, she was getting settled in her room to start another cycle of cytoreductive chemotherapy.