User login

University taking aim at racial disparities in COVID vaccine trials

Although recent months have seen the arrival of several promising vaccines to combat COVID-19, many researchers have been concerned about the shortage of Black and Latinx volunteers in their pivotal trials.

Minority groups have long been underrepresented in clinical research. The pandemic’s inequitable fallout has heightened the need for more inclusive COVID-19 trials. By one estimate, Black Americans are three times more likely to become infected with SARS-Cov-2 and twice as likely to die from it, compared with their White counterparts.

It was therefore welcome news this past November when the Maryland-based biotech company Novavax unveiled their plans to boost participation among specific minority groups during the phase 3 trial of their COVID-19 vaccine candidate NVX-CoV2373. To help them in their efforts, the company tapped Howard University, in Washington, D.C., to be a clinical test site. The goal was to enroll 300 Black and Latinx volunteers through a recruitment registry at the Coronavirus Prevention Network.

“We have seen quite a good number of participants in the registry, and many are African American, who are the ones we are trying to reach in the trial,” explained Siham Mahgoub, MD, medical director of the Center of Infectious Diseases Management and Research and principal investigator for the Novavax trial at Howard University, Washington. “It’s very important for people of color to participate in the trial because we want to make sure these vaccines work in people of color,” Dr. Mahgoub said.

Over the years, Howard University has hosted several important clinical trials and studies, and its participation in the multi-institutional Georgetown–Howard Universities Center for Clinical and Translational Science consortium brings crucial infrastructural value. By bringing this vaccine trial to one of the most esteemed historically Black colleges or universities (HBCUs), researchers hoped to address a sense of hesitancy among possible participants that is prompted in part by the tragic history of medical testing in the Black community.

“The community trusts Howard,” said Dr. Mahgoub. “I think it’s great having Howard and an HBCU host this trial, because these are people who look like them.”

Lisa M. Dunkle, MD, vice president and global medical lead for coronavirus vaccine at Novavax, explained that, in addition to Howard being located close to the company’s headquarters, the university seemed like a great fit for the overall mission.

“As part of our goal to achieve a representative trial population that includes communities who are disproportionately impacted by the pandemic, we sought out some of the HBCUs to include in our trial sites. We hoped that this might encourage people of color to enroll and to increase their comfort level with vaccines in general,” Dr. Dunkle said.

Building more representative clinical trials

For decades, research on some of the most groundbreaking vaccines and treatments have been based on the results of studies conducted with predominately White participants, despite the fact that a much more demographically varied general population would ultimately receive them. This has led to calls to include people of different races and ethnic backgrounds in trials.

Homogeneity in clinical trials is discouraged, but trials are not heavily regulated in this regard. In 1993, Congress passed the Revitalization Act, which requires that trials that are conducted by the National Institutes of Health include women and members of minority groups among their cohorts. However, the number or proportion of such participants is not specified.

Underrepresentation in clinical trials also reflects a general unwillingness by members of ethnic minorities to volunteer because of the deeply unsettling history of such trials in minority communities. Among some Black persons, it is not uncommon for names like Tuskegee, Henrietta Lacks, and J. Marion Simms to be mentioned when giving reasons for not participating.

“There is certainly some dark history in how minorities have been treated by our health care system, and it’s not surprising that there is some fear and distrust,” said Dr. Dunkle. “By recruiting people of color into clinical trials that are governed with strict standards, we can begin to change perceptions and attitudes.”

Vaccine hesitancy is not only rooted in the past. The current state of medical care also has some potential trial participants worried. Misinformation, inequity in health care access, and low health literacy contribute to the current fears of scientific development.

A trial designed to engender trust

Having information about the vaccine come from trusted voices in the community is a key means of overcoming hesitancy. Howard University President Wayne Frederick, MD, reached out to a pastor of a local Black church to have more participants enroll in the trial. One who answered the call to action was Stephanie Williams, an elementary school teacher in Montgomery County, Maryland. When she saw that her pastor was participating in the Novavax trial and when she considered the devastation she had seen from COVID-19, she was on board.

“We had about three sessions where he shared his experiences. He also shared some links to read about it more,” Ms. Williams said. “When I saw that he took it, that gave me a lot of confidence. Since I’m going be going into the classroom, I wanted to be sure that I was well protected.”

Transparency is key to gaining more participation, explained Dr. Maghoub. Webinar-based information sessions have proven particularly important in achieving this.

“We do a lot of explaining in very simple language to make sure everyone understands about the vaccine. The participants have time to ask questions during the webinar, and at any time [during the trial], if a participant feels that it is not right for them, they can stop. They have time to learn about the trial and give consent. People often think they are like guinea pigs in trials, but they are not. They must give consent.”

There are signs that the approach has been successful. Over a period of 4-5 weeks, the Howard site enrolled 150 participants, of whom 30% were Black and 20% were Latinx.

Novavax has been in business for more than 3 decades but hasn’t seen the booming success that their competitors have. The company has noted progress in developing vaccines against Middle East respiratory syndrome and severe acute respiratory syndrome. However, they missed the mark in clinical trials, failing twice in 3 years to develop a respiratory syncytial virus vaccine administered through maternal immunizations.

From being on the verge of closing, Novavax has since made a dramatic turnaround after former President Trump awarded the company $1.6 billion dollars in July 2020 as part of Operation Warp Speed. If trial results are promising, the Novavax vaccine could enter the market in a few months, representing not only a new therapeutic option but perhaps a new model for building inclusivity in clinical trials.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although recent months have seen the arrival of several promising vaccines to combat COVID-19, many researchers have been concerned about the shortage of Black and Latinx volunteers in their pivotal trials.

Minority groups have long been underrepresented in clinical research. The pandemic’s inequitable fallout has heightened the need for more inclusive COVID-19 trials. By one estimate, Black Americans are three times more likely to become infected with SARS-Cov-2 and twice as likely to die from it, compared with their White counterparts.

It was therefore welcome news this past November when the Maryland-based biotech company Novavax unveiled their plans to boost participation among specific minority groups during the phase 3 trial of their COVID-19 vaccine candidate NVX-CoV2373. To help them in their efforts, the company tapped Howard University, in Washington, D.C., to be a clinical test site. The goal was to enroll 300 Black and Latinx volunteers through a recruitment registry at the Coronavirus Prevention Network.

“We have seen quite a good number of participants in the registry, and many are African American, who are the ones we are trying to reach in the trial,” explained Siham Mahgoub, MD, medical director of the Center of Infectious Diseases Management and Research and principal investigator for the Novavax trial at Howard University, Washington. “It’s very important for people of color to participate in the trial because we want to make sure these vaccines work in people of color,” Dr. Mahgoub said.

Over the years, Howard University has hosted several important clinical trials and studies, and its participation in the multi-institutional Georgetown–Howard Universities Center for Clinical and Translational Science consortium brings crucial infrastructural value. By bringing this vaccine trial to one of the most esteemed historically Black colleges or universities (HBCUs), researchers hoped to address a sense of hesitancy among possible participants that is prompted in part by the tragic history of medical testing in the Black community.

“The community trusts Howard,” said Dr. Mahgoub. “I think it’s great having Howard and an HBCU host this trial, because these are people who look like them.”

Lisa M. Dunkle, MD, vice president and global medical lead for coronavirus vaccine at Novavax, explained that, in addition to Howard being located close to the company’s headquarters, the university seemed like a great fit for the overall mission.

“As part of our goal to achieve a representative trial population that includes communities who are disproportionately impacted by the pandemic, we sought out some of the HBCUs to include in our trial sites. We hoped that this might encourage people of color to enroll and to increase their comfort level with vaccines in general,” Dr. Dunkle said.

Building more representative clinical trials

For decades, research on some of the most groundbreaking vaccines and treatments have been based on the results of studies conducted with predominately White participants, despite the fact that a much more demographically varied general population would ultimately receive them. This has led to calls to include people of different races and ethnic backgrounds in trials.

Homogeneity in clinical trials is discouraged, but trials are not heavily regulated in this regard. In 1993, Congress passed the Revitalization Act, which requires that trials that are conducted by the National Institutes of Health include women and members of minority groups among their cohorts. However, the number or proportion of such participants is not specified.

Underrepresentation in clinical trials also reflects a general unwillingness by members of ethnic minorities to volunteer because of the deeply unsettling history of such trials in minority communities. Among some Black persons, it is not uncommon for names like Tuskegee, Henrietta Lacks, and J. Marion Simms to be mentioned when giving reasons for not participating.

“There is certainly some dark history in how minorities have been treated by our health care system, and it’s not surprising that there is some fear and distrust,” said Dr. Dunkle. “By recruiting people of color into clinical trials that are governed with strict standards, we can begin to change perceptions and attitudes.”

Vaccine hesitancy is not only rooted in the past. The current state of medical care also has some potential trial participants worried. Misinformation, inequity in health care access, and low health literacy contribute to the current fears of scientific development.

A trial designed to engender trust

Having information about the vaccine come from trusted voices in the community is a key means of overcoming hesitancy. Howard University President Wayne Frederick, MD, reached out to a pastor of a local Black church to have more participants enroll in the trial. One who answered the call to action was Stephanie Williams, an elementary school teacher in Montgomery County, Maryland. When she saw that her pastor was participating in the Novavax trial and when she considered the devastation she had seen from COVID-19, she was on board.

“We had about three sessions where he shared his experiences. He also shared some links to read about it more,” Ms. Williams said. “When I saw that he took it, that gave me a lot of confidence. Since I’m going be going into the classroom, I wanted to be sure that I was well protected.”

Transparency is key to gaining more participation, explained Dr. Maghoub. Webinar-based information sessions have proven particularly important in achieving this.

“We do a lot of explaining in very simple language to make sure everyone understands about the vaccine. The participants have time to ask questions during the webinar, and at any time [during the trial], if a participant feels that it is not right for them, they can stop. They have time to learn about the trial and give consent. People often think they are like guinea pigs in trials, but they are not. They must give consent.”

There are signs that the approach has been successful. Over a period of 4-5 weeks, the Howard site enrolled 150 participants, of whom 30% were Black and 20% were Latinx.

Novavax has been in business for more than 3 decades but hasn’t seen the booming success that their competitors have. The company has noted progress in developing vaccines against Middle East respiratory syndrome and severe acute respiratory syndrome. However, they missed the mark in clinical trials, failing twice in 3 years to develop a respiratory syncytial virus vaccine administered through maternal immunizations.

From being on the verge of closing, Novavax has since made a dramatic turnaround after former President Trump awarded the company $1.6 billion dollars in July 2020 as part of Operation Warp Speed. If trial results are promising, the Novavax vaccine could enter the market in a few months, representing not only a new therapeutic option but perhaps a new model for building inclusivity in clinical trials.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although recent months have seen the arrival of several promising vaccines to combat COVID-19, many researchers have been concerned about the shortage of Black and Latinx volunteers in their pivotal trials.

Minority groups have long been underrepresented in clinical research. The pandemic’s inequitable fallout has heightened the need for more inclusive COVID-19 trials. By one estimate, Black Americans are three times more likely to become infected with SARS-Cov-2 and twice as likely to die from it, compared with their White counterparts.

It was therefore welcome news this past November when the Maryland-based biotech company Novavax unveiled their plans to boost participation among specific minority groups during the phase 3 trial of their COVID-19 vaccine candidate NVX-CoV2373. To help them in their efforts, the company tapped Howard University, in Washington, D.C., to be a clinical test site. The goal was to enroll 300 Black and Latinx volunteers through a recruitment registry at the Coronavirus Prevention Network.

“We have seen quite a good number of participants in the registry, and many are African American, who are the ones we are trying to reach in the trial,” explained Siham Mahgoub, MD, medical director of the Center of Infectious Diseases Management and Research and principal investigator for the Novavax trial at Howard University, Washington. “It’s very important for people of color to participate in the trial because we want to make sure these vaccines work in people of color,” Dr. Mahgoub said.

Over the years, Howard University has hosted several important clinical trials and studies, and its participation in the multi-institutional Georgetown–Howard Universities Center for Clinical and Translational Science consortium brings crucial infrastructural value. By bringing this vaccine trial to one of the most esteemed historically Black colleges or universities (HBCUs), researchers hoped to address a sense of hesitancy among possible participants that is prompted in part by the tragic history of medical testing in the Black community.

“The community trusts Howard,” said Dr. Mahgoub. “I think it’s great having Howard and an HBCU host this trial, because these are people who look like them.”

Lisa M. Dunkle, MD, vice president and global medical lead for coronavirus vaccine at Novavax, explained that, in addition to Howard being located close to the company’s headquarters, the university seemed like a great fit for the overall mission.

“As part of our goal to achieve a representative trial population that includes communities who are disproportionately impacted by the pandemic, we sought out some of the HBCUs to include in our trial sites. We hoped that this might encourage people of color to enroll and to increase their comfort level with vaccines in general,” Dr. Dunkle said.

Building more representative clinical trials

For decades, research on some of the most groundbreaking vaccines and treatments have been based on the results of studies conducted with predominately White participants, despite the fact that a much more demographically varied general population would ultimately receive them. This has led to calls to include people of different races and ethnic backgrounds in trials.

Homogeneity in clinical trials is discouraged, but trials are not heavily regulated in this regard. In 1993, Congress passed the Revitalization Act, which requires that trials that are conducted by the National Institutes of Health include women and members of minority groups among their cohorts. However, the number or proportion of such participants is not specified.

Underrepresentation in clinical trials also reflects a general unwillingness by members of ethnic minorities to volunteer because of the deeply unsettling history of such trials in minority communities. Among some Black persons, it is not uncommon for names like Tuskegee, Henrietta Lacks, and J. Marion Simms to be mentioned when giving reasons for not participating.

“There is certainly some dark history in how minorities have been treated by our health care system, and it’s not surprising that there is some fear and distrust,” said Dr. Dunkle. “By recruiting people of color into clinical trials that are governed with strict standards, we can begin to change perceptions and attitudes.”

Vaccine hesitancy is not only rooted in the past. The current state of medical care also has some potential trial participants worried. Misinformation, inequity in health care access, and low health literacy contribute to the current fears of scientific development.

A trial designed to engender trust

Having information about the vaccine come from trusted voices in the community is a key means of overcoming hesitancy. Howard University President Wayne Frederick, MD, reached out to a pastor of a local Black church to have more participants enroll in the trial. One who answered the call to action was Stephanie Williams, an elementary school teacher in Montgomery County, Maryland. When she saw that her pastor was participating in the Novavax trial and when she considered the devastation she had seen from COVID-19, she was on board.

“We had about three sessions where he shared his experiences. He also shared some links to read about it more,” Ms. Williams said. “When I saw that he took it, that gave me a lot of confidence. Since I’m going be going into the classroom, I wanted to be sure that I was well protected.”

Transparency is key to gaining more participation, explained Dr. Maghoub. Webinar-based information sessions have proven particularly important in achieving this.

“We do a lot of explaining in very simple language to make sure everyone understands about the vaccine. The participants have time to ask questions during the webinar, and at any time [during the trial], if a participant feels that it is not right for them, they can stop. They have time to learn about the trial and give consent. People often think they are like guinea pigs in trials, but they are not. They must give consent.”

There are signs that the approach has been successful. Over a period of 4-5 weeks, the Howard site enrolled 150 participants, of whom 30% were Black and 20% were Latinx.

Novavax has been in business for more than 3 decades but hasn’t seen the booming success that their competitors have. The company has noted progress in developing vaccines against Middle East respiratory syndrome and severe acute respiratory syndrome. However, they missed the mark in clinical trials, failing twice in 3 years to develop a respiratory syncytial virus vaccine administered through maternal immunizations.

From being on the verge of closing, Novavax has since made a dramatic turnaround after former President Trump awarded the company $1.6 billion dollars in July 2020 as part of Operation Warp Speed. If trial results are promising, the Novavax vaccine could enter the market in a few months, representing not only a new therapeutic option but perhaps a new model for building inclusivity in clinical trials.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Urine drug screening: A guide to monitoring Tx with controlled substances

An estimated 20 million patients in the United States have a substance use disorder (SUD), with hundreds of millions of prescriptions for controlled substances written annually. Consequently, urine drug screening (UDS) has become widely utilized to evaluate and treat patients with an SUD or on chronic opioid or benzodiazepine therapy.1

Used appropriately, UDS can be a valuable tool; there is ample evidence, however, that it has been misused, by some physicians, to stigmatize patients who use drugs of abuse,2 profile patients racially,2 profit from excessive testing,3 and inappropriately discontinue treatment.4

A patient-centered approach. We have extensive clinical experience in the use and interpretation of urine toxicology, serving as clinical leads in busy family medicine residency practices that care for patients with SUDs, and are often consulted regarding patients on chronic opioid or benzodiazepine therapy. We have encountered countless situations in which the correct interpretation of UDS is critical to providing care.

Over time, and after considerable trial and error, we developed the patient-centered approach to urine toxicology described in this article. We believe that the medical evidence strongly supports our approach to the appropriate use and interpretation of urine toxicology in clinical practice. Our review here is intended as a resource when you consider implementing a UDS protocol or are struggling with the management of unexpected results.

Urine toxicology for therapeutic drug monitoring

Prescribing a controlled substance carries inherent risks, including diversion, nonmedical use, and development of an SUD. Prescribed medications, particularly opioids and benzodiazepines, have been linked to a large increase in overdose deaths over the past decade.5 Several strategies have been investigated to mitigate risk (see “How frequently should a patient be tested?,” later in the article).

Clinical judgment—ie, when a physician orders a drug test upon suspecting that a patient is diverting a prescribed drug or has developed an SUD—has been shown to be highly inaccurate. Implicit racial bias might affect the physician’s judgment, leading to changes in testing and test interpretation. For example, Black patients were found to be 10% more likely to have drug screening ordered while being treated with long-term opioid therapy and 2 to 3 times more likely to have their medication discontinued as a result of a marijuana- or cocaine-positive test.2

Other studies have shown that testing patients for “bad behavior,” so to speak—reporting a prescription lost or stolen, consuming more than the prescribed dosage, visiting the office without an appointment, having multiple drug intolerances and allergies, and making frequent telephone calls to the practice—is ineffective.6 Patients with these behaviors were slightly more likely to unexpectedly test positive, or negative, on their UDS; however, many patients without suspect behavior also were found to have abnormal toxicology results.6 Data do not support therapeutic drug monitoring only of patients selected on the basis of aberrant behavior.6

Continue to: Questions and concerns about urine drug screening

Questions and concerns about urine drug screening

Why not just ask the patient? Studies have evaluated whether patient self-reporting of adherence is a feasible alternative to laboratory drug screening. Regrettably, patients have repeatedly been shown to underreport their use of both prescribed and illicit drugs.7,8

That question leads to another: Why do patients lie to their physician? It is easy to assume malicious intent, but a variety of obstacles might dissuade a patient from being fully truthful with their physician:

- Monetary gain. A small, but real, percentage of medications are diverted by patients for this reason.9

- Addiction, pseudo-addiction due to tolerance, and self-medication for psychological symptoms are clinically treatable syndromes that can lead to underreporting of prescribed and nonprescribed drug and alcohol use.

- Shame. Addiction is a highly stigmatized disease, and patients might simply be ashamed to admit that they need treatment: 13% to 38% of patients receiving chronic opioid therapy in a pain management or primary care setting have a clinically diagnosable SUD.10,11

Is consent needed to test or to share test results? Historically, UDS has been performed on patients without their consent or knowledge.12 Patients give a urine specimen to their physician for a variety of reasons; it seems easy to “add on” UDS. Evidence is clear, however, that confronting a patient about an unexpected test result can make the clinical outcome worse—often resulting in irreparable damage to the patient–physician relationship.12,13 Unless the patient is experiencing a medical emergency, guidelines unanimously recommend obtaining consent prior to testing.1,5,14

Federal law requires written permission from the patient for the physician to disclose information about alcohol or substance use, unless the information is expressly needed to provide care during a medical emergency. Substance use is highly stigmatized, and patients might—legitimately—fear that sharing their history could undermine their care.1,12,14

How frequently should a patient be tested? Experts recommend utilizing a risk-based strategy to determine the frequency of UDS.1,5,15 Validated risk-assessment questionnaires include:

- Opioid Risk Tool for Opioid Use Disorder (ORT-OUD)a

- Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients With Pain–Revised (SOAPP-R)b

- Diagnosis, Intractability, Risk and Efficacy (DIRE)c

- Addiction Behaviors Checklist (ABC).d

Continue to: Each of these tools...

Each of these tools takes less than 5 minutes to administer and can be used by a primary care physician to objectively quantify the risk of prescribing; there is no evidence for the use of 1 of these screeners over the others.15 It is recommended that you choose a questionnaire that works for you and incorporate the risk assessment into prescribing any high-risk medication.1,5,15

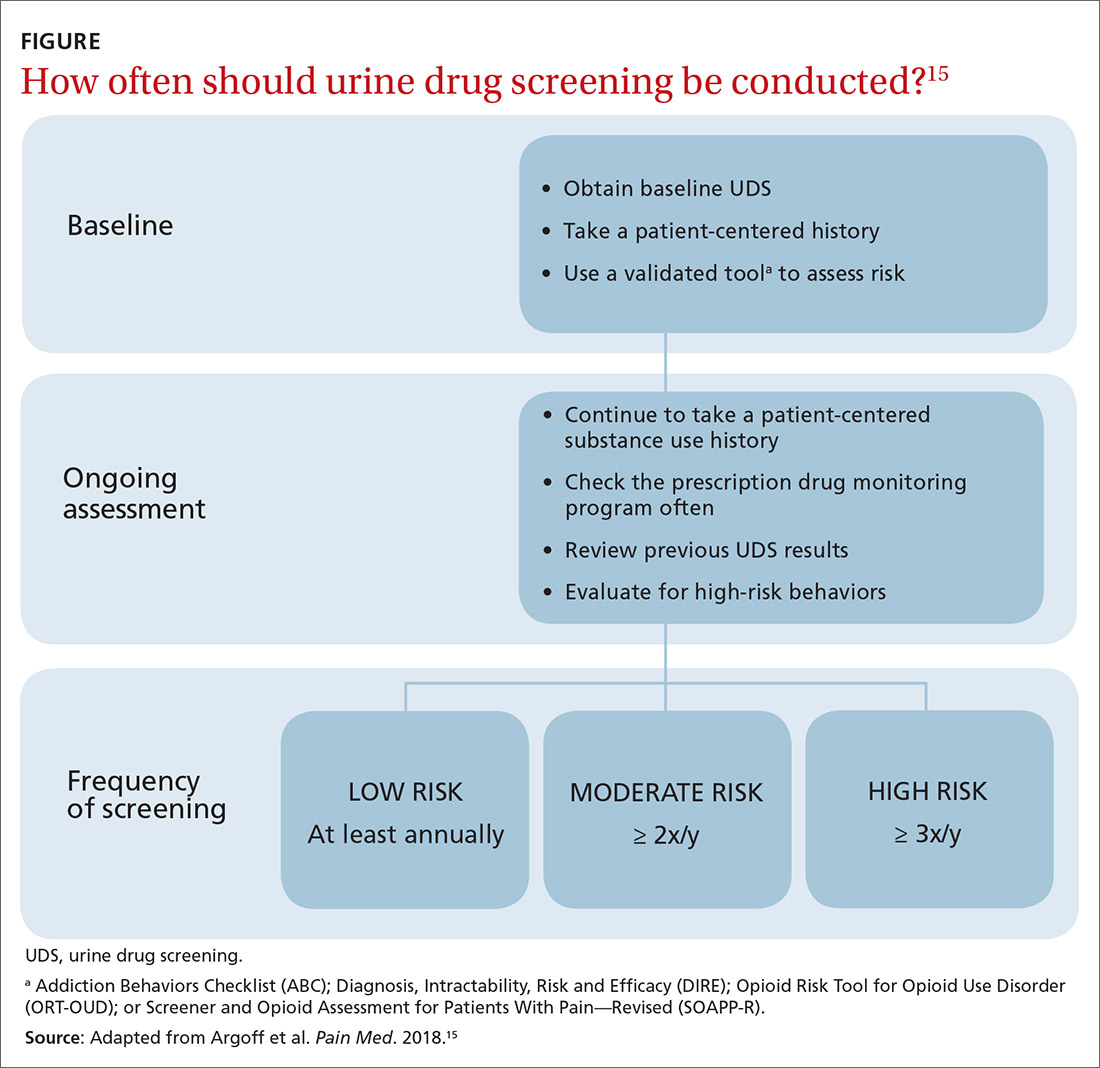

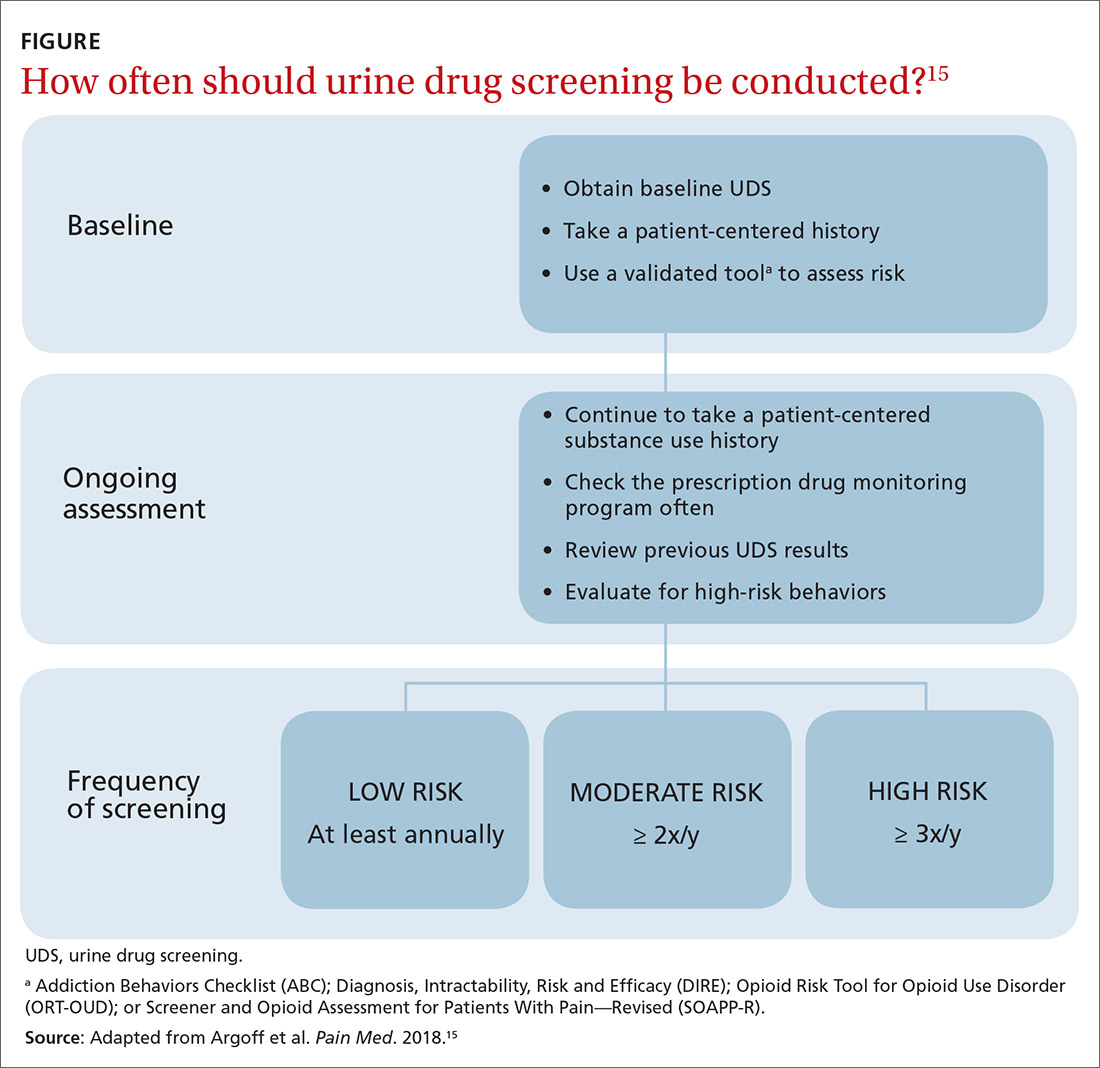

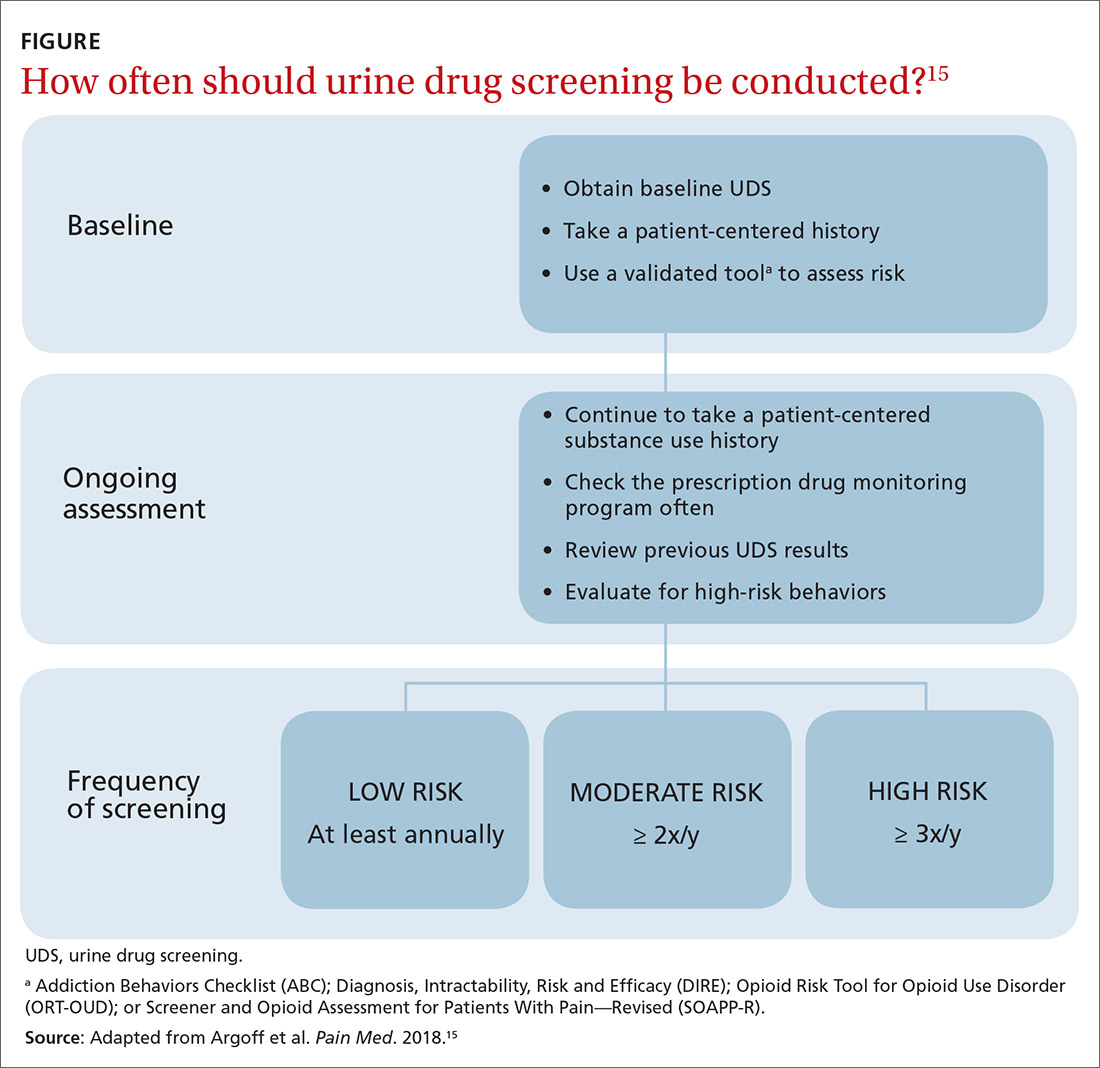

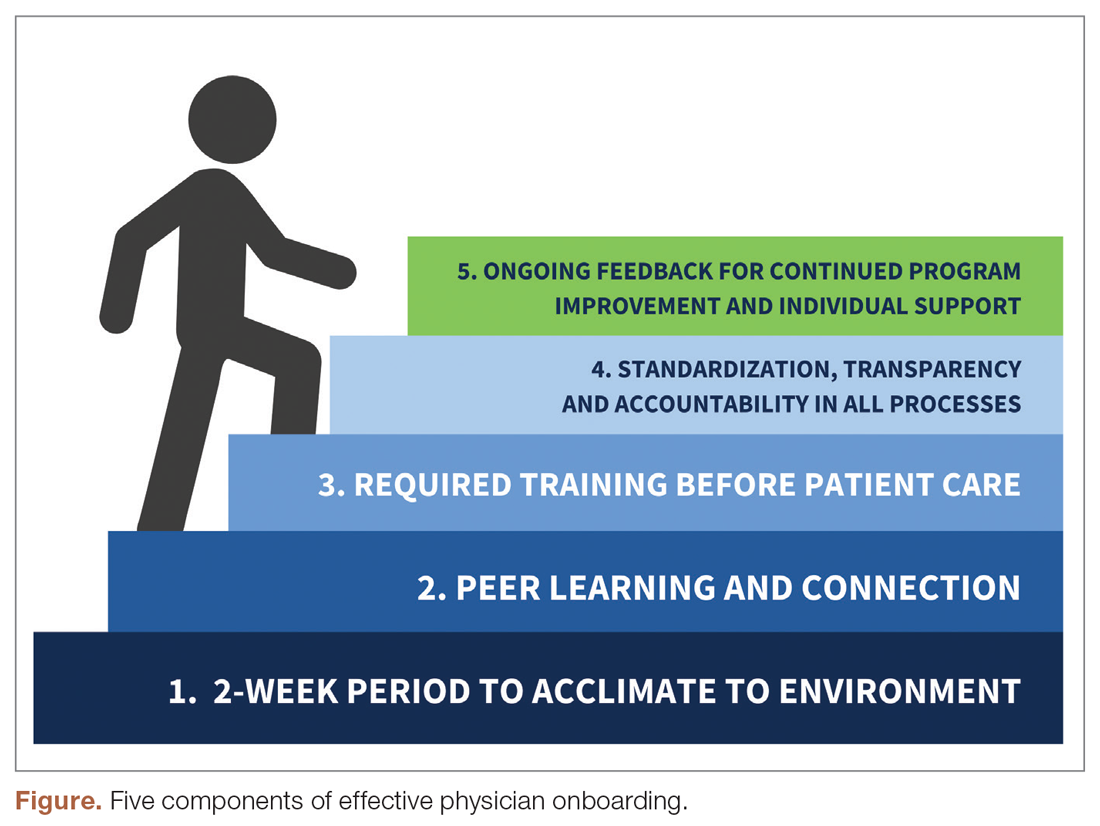

Once you have completed an initial risk assessment, the frequency of UDS can be based on ongoing assessment that incorporates baseline testing, patient self-reporting, toxicology results, behavioral monitoring, and state database monitoring through a prescription drug monitoring program. Annual screening is appropriate in low-risk patients; moderate-risk patients should be screened twice a year, and high-risk patients should be screened at least every 4 months (FIGURE).15

Many state and federal agencies, health systems, employers, and insurers mandate the frequency of testing through guidelines or legislation. These regulations often are inconsistent with the newest medical evidence.15 Consult local guidelines and review the medical evidence and consensus recommendations on UDS.

What are the cost considerations in providing UDS? Insurers have been billed as much as $4000 for definitive chromatography testing (described later).3 This has led to insurance fraud, when drug-testing practices with a financial interest routinely use large and expensive test panels, test too frequently, or unnecessarily send for confirmatory or quantitative analysis of all positive tests.3,14 Often, insurers refuse to pay for unnecessary testing, leaving patients with significant indebtedness.3,14 Take time to review the evidence and consensus recommendations on UDS to avoid waste, potential accusations of fraud, and financial burden on your patients.

Urine toxicology for addiction treatment

UDS protocols in addiction settings are often different from those in which a controlled substance is being prescribed.

Continue to: Routine and random testing

Routine and random testing. Two common practices when treating addiction are to perform UDS on all patients, at every visit, or to test randomly.1 These practices can be problematic, however. Routine testing at every visit can make urine-tampering more likely and is often unnecessary for stable patients. Random testing can reduce the risk of urine-tampering, but it is often difficult for primary care clinics to institute such a protocol. Some clinics have patients provide a urine specimen at every visit and then only send tests to the lab based on randomization.1

Contingency management—a behavioral intervention in which a patient is rewarded, or their performance is reinforced, when they display evidence of positive change—is the most effective strategy used in addiction medicine to determine the frequency of patient visits and UDS.14,16 High-risk patients with self-reported active substance use or UDS results consistent with substance use, or both, are seen more often; as their addiction behavior diminishes, visits and UDS become less frequent. If addiction behavior increases, the patient is seen more often. Keep in mind that addiction behavior decreases over months of treatment, not immediately upon initiation.14,17 For contingency management to be successful, patient-centered interviewing and UDS will need to be employed frequently as the patient works toward meaningful change.14

The technology of urine drug screening

Two general techniques are used for UDS: immunoassay and chromatography. Each plays an important role in clinical practice; physicians must therefore maintain a basic understanding of the mechanism of each technique and their comparable advantages and disadvantages. Such an understanding allows for (1) matching the appropriate technique to the individual clinical scenario and (2) correctly interpreting results.

Immunoassay technology is used for point-of-care and rapid laboratory UDS, using antibodies to detect the drug or drug metabolite of interest. Antibodies utilized in immunoassays are designed to selectively bind a specific antigen—ie, a unique chemical structure within the drug of choice. Once bound, the antigen–antibody complex can be exploited for detection through various methods.

Chromatography–mass spectrometry is considered the gold standard for UDS, yielding confirmatory results. This is a 2-step process: Chromatography separates components within a specimen; mass spectrometry then identifies those components. Most laboratories employ liquid, rather than gas, chromatography. The specificity of the liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry method is such that a false-positive result is, essentially, impossible.18

Continue to: How is the appropriate tests elected for urine drug screening?

How is the appropriate tests elected for urine drug screening?

Variables that influence your choice of the proper test method include the clinical question at hand; cost; the urgency of obtaining results; and the stakes in that decision (ie, will the results be used to simply change the dosage of a medication or, of greater consequence, to determine fitness for employment or inform criminal justice decisions?). Each method of UDS has advantages that can be utilized and disadvantages that must be considered to obtain an accurate and useful result.

Immunoassay provides rapid results, is relatively easy to perform, and is, comparatively, inexpensive.1,14 The speed of results makes this method particularly useful in settings such as the emergency department, where rapid results are crucial. Ease of use makes immunoassay ideal for the office, where non-laboratory staff can be trained to properly administer the test.

A major disadvantage of immunoassay technology, however, is interference resulting in both false-positive and false-negative results, which is discussed in detail in the next section. Immunoassay should be considered a screening test that yields presumptive results.

Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry is exquisitely specific and provides confirmatory test results—major advantages of the method. However, specificity comes at a price: significantly increased cost and longer wait time for results (typically days, if specimens are sent out to a laboratory). These barriers can make it impractical to employ this method in routine practice.

Interpretation of results: Not so fast

Interpreting UDS results is not as simple as noting a positive or negative result. Physicians must understand the concept of interference, so that results can be appropriately interpreted and confirmed. This is crucial when results influence clinical decisions; inappropriate action, taken on the basis of presumptive results, can have severe consequences for the patient–provider relationship and the treatment plan.1,14

Continue to: Interference falls into 2 categories...

Interference falls into 2 categories: variables inherent in the testing process and patient variables.

Antibody cross-reactivity. A major disadvantage of immunoassay technology is interference that results in false-positive and false-negative results.19,20 The source of this interference is antibody cross-reactivity—the degree to which an antibody binds to structurally similar compounds. Antibody–antigen interactions are incredibly complex; although assay antibodies are engineered to specifically detect a drug class of interest, reactivity with other, structurally similar compounds is unavoidable.

Nevertheless, cross-reactivity is a useful phenomenon that allows broad testing for multiple drugs within a class. For example, most point-of-care tests for benzodiazepines reliably detect diazepam and chlordiazepoxide. Likewise, opiate tests reliably detect natural opiates, such as morphine and codeine. Cross-reactivity is not limitless, however; most benzodiazepine immunoassays have poor reactivity to clonazepam and lorazepam, making it possible that a patient taking clonazepam tests negative for benzodiazepine on an immunoassay.14,20 Similarly, standard opioid tests have only moderate cross-reactivity for semisynthetic opioids, such as hydrocodone and hydromorphone; poor cross-reactivity for oxycodone and oxymorphone; and essentially no cross-reactivity for full synthetics, such as fentanyl and methadone.14

It is the responsibility of the ordering physician to understand cross-reactivity to various drugs within a testing class.

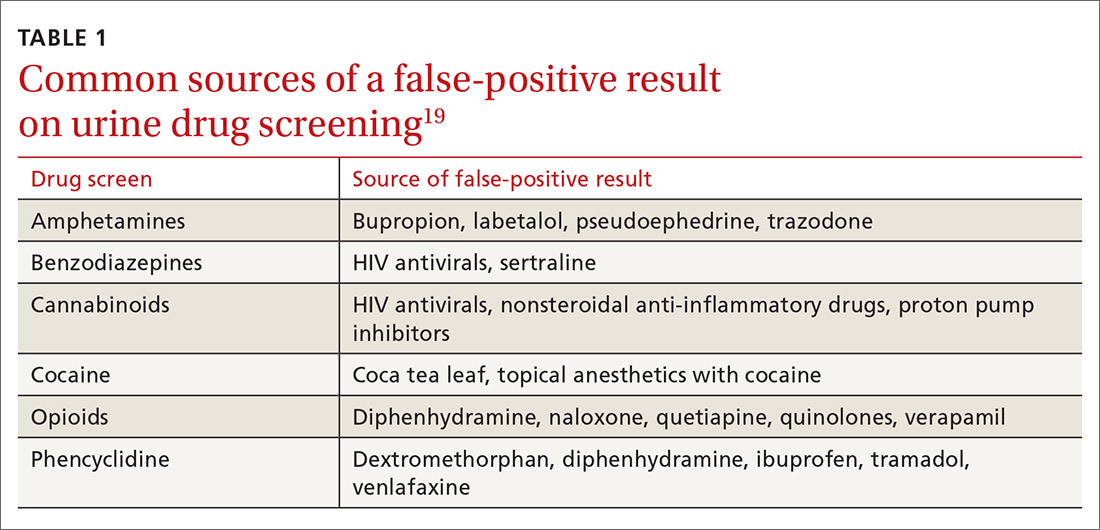

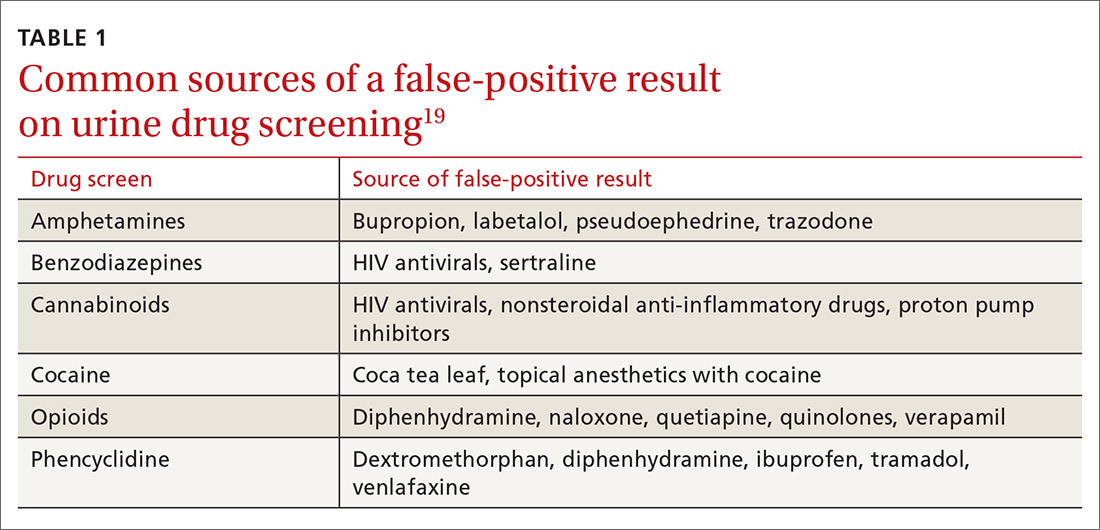

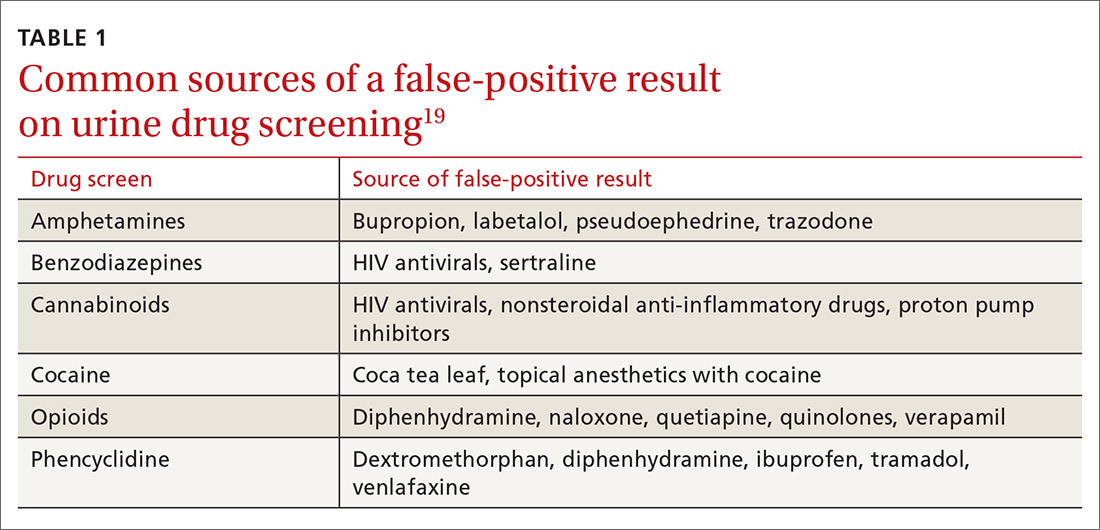

Whereas weak cross-reactivity to drugs within a class can be a source of false-negative results, cross-reactivity to drugs outside the class of interest is a source of false-positive results. An extensive review of drugs that cause false-positive immunoassay screening tests is outside the scope of this article; commonly prescribed medications implicated in false-positive results are listed in TABLE 1.19

Continue to: In general...

In general, amphetamine immunoassays produce frequent false-positive results, whereas cocaine and cannabinoid assays are more specific.1,18 Common over-the-counter medications, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, decongestants, and antacids, can yield false-positive results, highlighting the need to obtain a comprehensive medication list from patients, including over-the-counter and herbal medications, before ordering UDS. Because of the complexity of cross-reactivity, it might not be possible to identify the source of a false-positive result.14

Patient variables. Intentional effort to skew results is another source of interference. The frequency of this effort varies by setting and the potential consequences of results—eg, employment testing or substance use treatment—and a range of attempts have been reported in the literature.21,22 Common practices are dilution, adulteration, and substitution.20,23

- Dilution lowers the concentration of the drug of interest below the detection limit of the assay by directly adding water to the urine specimen, drinking copious amounts of fluid, taking a diuretic, or a combination of these practices.

- Adulteration involves adding a substance to urine that interferes with the testing mechanism: for example, bleach, household cleaners, eye drops, and even commercially available products expressly marketed to interfere with UDS.24

- Substitution involves providing urine or a urine-like substance for testing that did not originate from the patient.

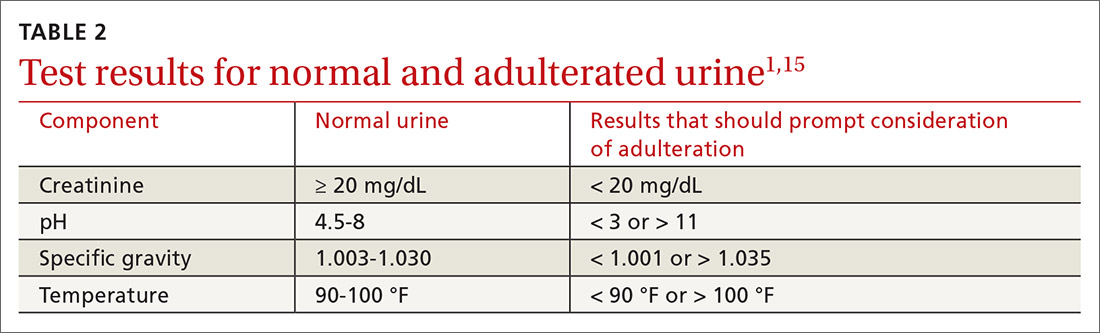

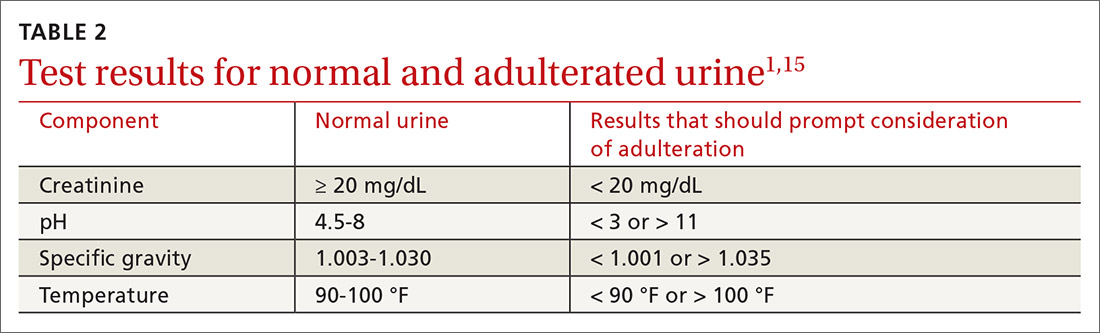

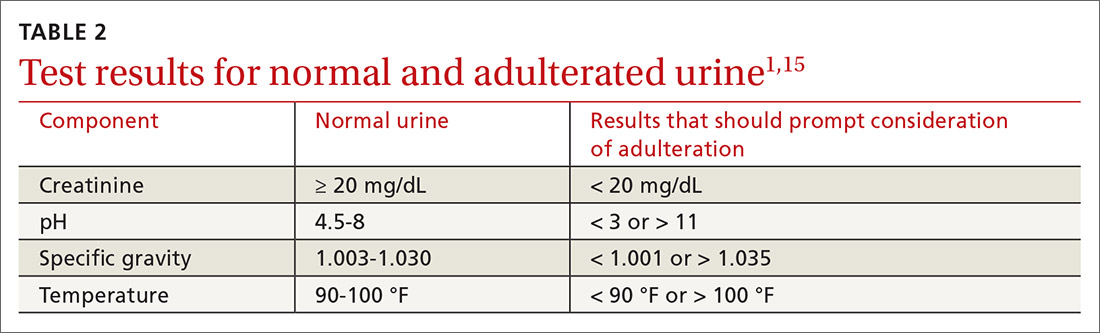

Methods to minimize patient-related interference include observed collection and specimen validity testing for pH, creatinine, and adulterants (TABLE 2).1,15 Efforts to detect patient interference must be balanced against concerns about privacy, personnel resources, and the cost of expanded testing.14,19,20

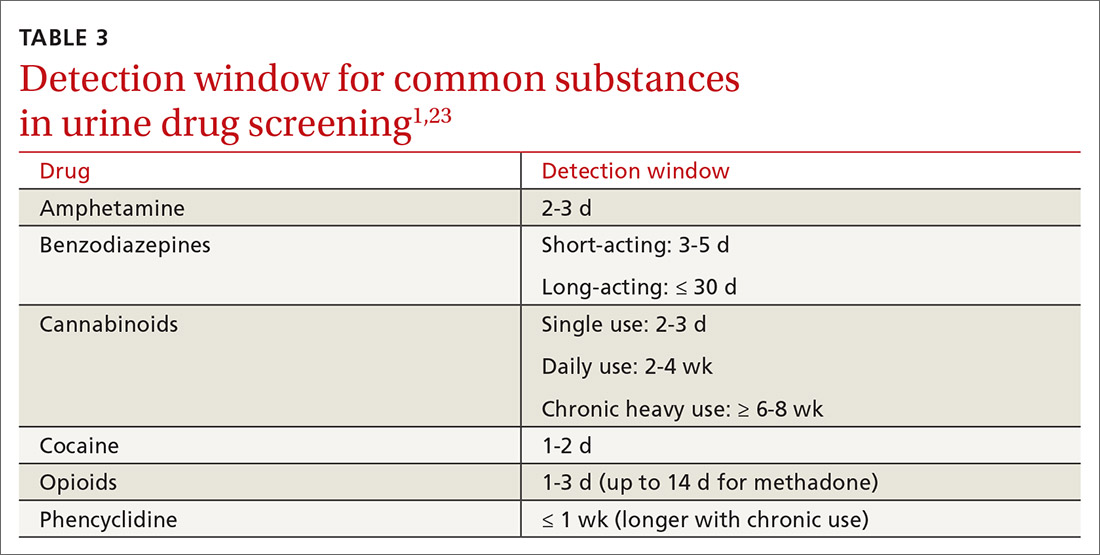

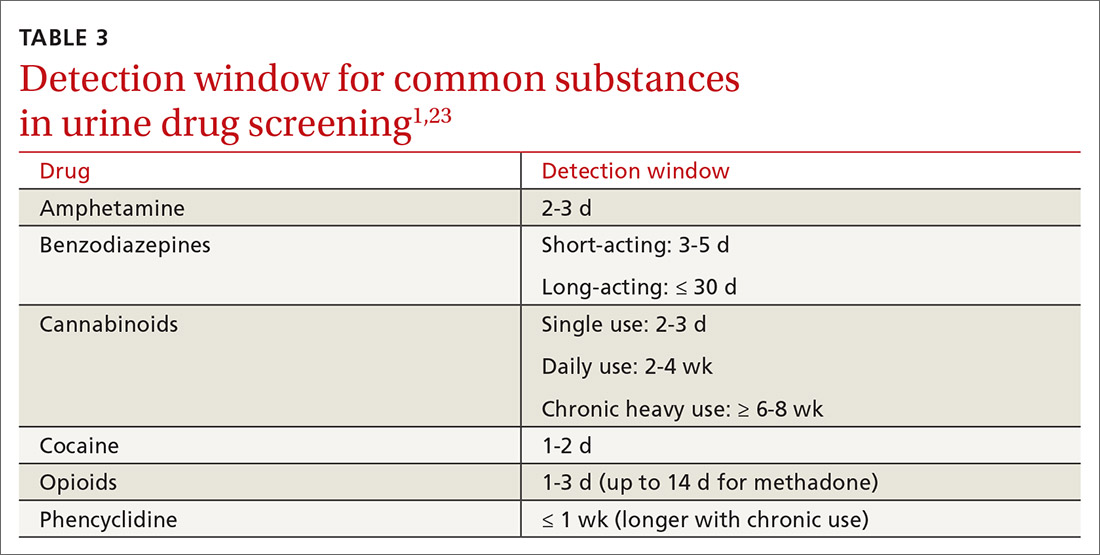

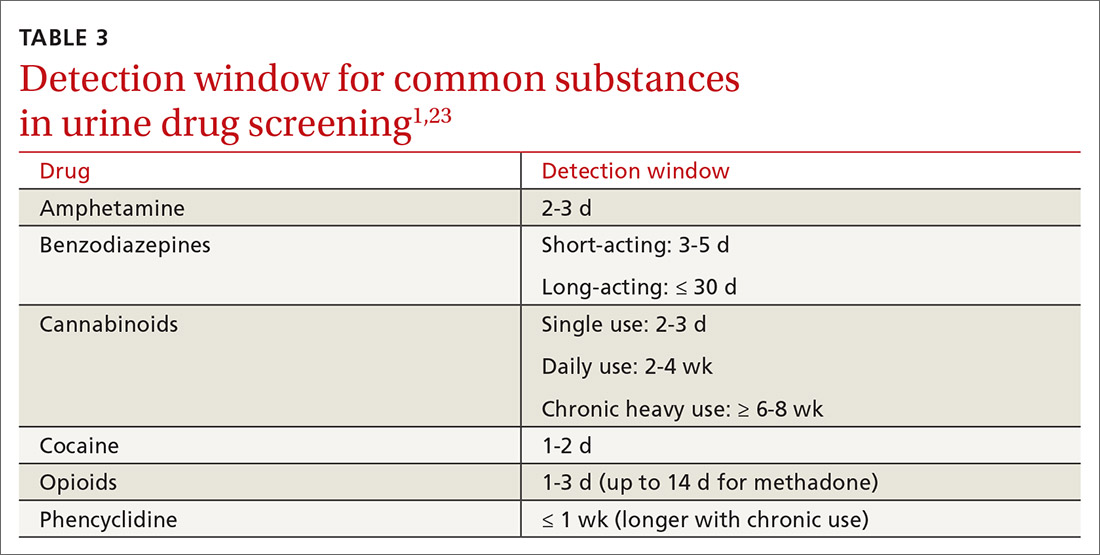

Additional aspects inherent to the testing process, such as cutoff concentrations and detection windows, can lead to interference. Laboratories must set reporting cutoffs, and specimens with a drug concentration present but below the cutoff value are reported as a negative result. Detection windows are complex and are influenced by inherent properties of the drug, including metabolic pathway and route and frequency of use.1 A given patient might well be using a substance, but if the specimen was obtained outside the detection window, a false-negative result might be reported (TABLE 31,23).

Managing test results

Appropriate management of UDS results is built on the foundation of understanding the testing mechanism, selecting the correct test, and properly interpreting results. Drug testing is, ultimately, a therapeutic tool used to monitor treatment, provide reinforcement, and explore substance use behavior; results of testing should be employed to achieve those objectives.1,4,14 A negative or expected UDS result can be utilized as positive reinforcement for a patient who is adherent to the treatment plan—much the way objective weight loss in an obese patient can provide encouragement to continue lifestyle changes.

Continue to: Test results should be presented...

Test results should be presented in an objective, nonconfrontational, and compassionate manner, not with stigmatizing language, such as “clean” or “dirty.”1,13,14 Using stigmatizing terms such as “substance abuser” instead of “person with a substance use disorder” has been shown, even among highly trained health care professionals, to have a negative effect on patient care.13

Inevitably, you will encounter an unexpected result, and therefore must develop a rational, systematic, and compassionate management approach. “Unexpected result” is a broad term that includes results that conflict with

- a patient’s self-report

- your understanding of what the patient is taking (using)

- prescribed medications

- a patient’s typical substance use pattern.

When faced with an unexpected test result, first, ensure that the result in question is reliable. If a screening test yields an unanticipated finding—especially if it conflicts with the patient’s self-reporting—make every effort to seek confirmation if you are going to be making a significant clinical decision because of the result.1,14

Second, use your understanding of interference to consider the result in a broader context. If confirmatory results are inconsistent with a patient’s self-report, discuss whether there has been a break in the physician–patient relationship and emphasize that recurrent use or failure to adhere to a treatment plan has clear consequences.1,14 Modify the treatment plan to address the inconsistent finding by escalating care, adjusting medications, and connecting the patient to additional resources.

Third, keep in mind that a positive urine test is not diagnostic of an SUD. Occasional drug use is extremely common17 and should not categorically lead to a change in the treatment plan. Addiction is, fundamentally, a disease of disordered reward, motivation, and behavior that is defined by the consequences of substance use, not substance use per se,25 and an SUD diagnosis is complex, based on clinical history, physical examination, and laboratory testing. Similarly, a negative UDS result does not rule out an SUD.4,10

Continue to: Fourth, patient dismissal...

Fourth, patient dismissal is rarely an appropriate initial response to UDS results. Regrettably, some physicians misinterpret urine toxicology results and inappropriately discharge patients on that basis.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guideline for prescribing opioids has increased utilization of UDS in primary care settings but does not provide the necessary education on proper use of the tool, which has resulted in a rise in misinterpretation and inappropriate discharge.13,26

If recurrent aberrant behavior is detected (by history or urine toxicology), do not abruptly discontinue the patient’s medication(s). Inform the patient of your concern, taper medication, and refer the patient to addiction treatment. Abrupt discontinuation of an opioid or benzodiazepine can lead to significant harm.1,14

CORRESPONDENCE

John Hayes, DO, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, 1121 E North Avenue, Milwaukee, WI, 53212; [email protected]

1. TAP 32: Clinical drug testing in primary care. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, US Department of Health & Human Services; 2012. Technical Assistance Publication (TAP) 32; HHS Publication No. (SMA) 12-4668. 2012. Accessed March 19, 2021. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/sma12-4668.pdf

2. Gaither JR, Gordon K, Crystal S, et al. Racial disparities in discontinuation of long-term opioid therapy following illicit drug use among black and white patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;192:371-376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.05.033

3. Segal, David. In pursuit of liquid gold. The New York Times. December 27, 2017. Accessed March 19, 2021. https://nyti.ms/2E2GTOU

4. Ceasar R, Chang J, Zamora K, et al. Primary care providers’ experiences with urine toxicology tests to manage prescription opioid misuse and substance use among chronic noncancer pain patients in safety net health care settings. Subst Abus. 2016;37:154-160. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2015.1132293

5. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain — United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-49. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1

6. Katz NP, Sherburne S, Beach M, et al. Behavioral monitoring and urine toxicology testing in patients receiving long-term opioid therapy. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:1097-1102. https://doi.org/ 10.1213/01.ane.0000080159.83342.b5

7. Wilcox CE, Bogenschutz MP, Nakazawa M, et al. Concordance between self-report and urine drug screen data in adolescent opioid dependent clinical trial participants. Addict Behav. 2013;38:2568-2574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.05.015

8. Zanis DA, McLellan AT, Randall M. Can you trust patient self-reports of drug use during treatment? Drug Alcohol Depend. 1994;35:127-132. https://doi.org/10.1016/0376-8716(94)90119-8

9. Jones CM, Paulozzi LJ, Mack KA. Sources of prescription opioid pain relievers by frequency of past-year nonmedical use: United States, 2008-2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:802-803. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12809

10. Katz N, Fanciullo GJ. Role of urine toxicology testing in the management of chronic opioid therapy. Clin J Pain. 2002;18(4 suppl):S76-S82. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002508-200207001-00009

11. Vowles KE, McEntee ML, Julnes PS, et al. Rates of opioid misuse, abuse, and addiction in chronic pain: a systematic review and data synthesis. Pain. 2015;156:569-576. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.j.pain.0000460357.01998.f1

12. Warner EA, Walker RM, Friedmann PD. Should informed consent be required for laboratory testing for drugs of abuse in medical settings? Am J Med. 2003;115:54-58. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00236-5

13. Kelly JF, Wakeman SE, Saitz R. Stop talking ‘dirty’: clinicians, language, and quality of care for the leading cause of preventable death in the United States. Am J Med. 2015;128:8-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.07.043

14. Jarvis M, Williams J, Hurford M, et al. Appropriate use of drug testing in clinical addiction medicine. J Addict Med. 2017;11:163-173. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000323

15. Argoff CE, Alford DP, Fudin J, et al. Rational urine drug monitoring in patients receiving opioids for chronic pain: consensus recommendations. Pain Med. 2018;19:97-117. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnx285

16 Ainscough TS, McNeill A, Strang J, et al. Contingency management interventions for non-prescribed drug use during treatment for opiate addiction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;178:318-339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.05.028

17. Blum K, Han D, Femino J, et al. Systematic evaluation of “compliance” to prescribed treatment medications and “abstinence” from psychoactive drug abuse in chemical dependence programs: data from the comprehensive analysis of reported drugs. PLoS One. 2014;9:e104275. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0104275

18. Miller SC, Fiellin DA, Rosenthal RN, et al. The ASAM Principles of Addiction Medicine. 6th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2018.

19. Saitman A, Park H-D, Fitzgerald RL. False-positive interferences of common urine drug screen immunoassays: a review. J Anal Toxicol. 2014;38:387-396. https://doi.org/10.1093/jat/bku075

20. Smith MP, Bluth MH. Common interferences in drug testing. Clin Lab Med. 2016;36:663-671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cll.2016.07.006

21. George S, Braithwaite RA. An investigation into the extent of possible dilution of specimens received for urinary drugs of abuse screening. Addiction. 1995;90:967-970. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.9079679.x

22. Beck O, Bohlin M, Bragd F, et al. Adulteration of urine drug testing—an exaggerated cause of concern. [Article in Swedish] Lakartidningen. 2000;97:703-706.

23. Kale N. Urine drug tests: ordering and interpreting results. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99:33-39.

24. Dasgupta A. The effects of adulterants and selected ingested compounds on drugs-of-abuse testing in urine. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:491-503. https://doi.org/10.1309/FQY06F8XKTQPM149

25. Definition of addiction. American Society of Addiction Medicine Web site. Updated October 21, 2019. Accessed February 20, 2021. https://www.asam.org/resources/definition-of-addiction

26. Kroenke K, Alford DP, Argoff C, et al. Challenges with Implementing the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Opioid Guideline: A Consensus Panel Report. Pain Med. 2019;20:724-735. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pny307

An estimated 20 million patients in the United States have a substance use disorder (SUD), with hundreds of millions of prescriptions for controlled substances written annually. Consequently, urine drug screening (UDS) has become widely utilized to evaluate and treat patients with an SUD or on chronic opioid or benzodiazepine therapy.1

Used appropriately, UDS can be a valuable tool; there is ample evidence, however, that it has been misused, by some physicians, to stigmatize patients who use drugs of abuse,2 profile patients racially,2 profit from excessive testing,3 and inappropriately discontinue treatment.4

A patient-centered approach. We have extensive clinical experience in the use and interpretation of urine toxicology, serving as clinical leads in busy family medicine residency practices that care for patients with SUDs, and are often consulted regarding patients on chronic opioid or benzodiazepine therapy. We have encountered countless situations in which the correct interpretation of UDS is critical to providing care.

Over time, and after considerable trial and error, we developed the patient-centered approach to urine toxicology described in this article. We believe that the medical evidence strongly supports our approach to the appropriate use and interpretation of urine toxicology in clinical practice. Our review here is intended as a resource when you consider implementing a UDS protocol or are struggling with the management of unexpected results.

Urine toxicology for therapeutic drug monitoring

Prescribing a controlled substance carries inherent risks, including diversion, nonmedical use, and development of an SUD. Prescribed medications, particularly opioids and benzodiazepines, have been linked to a large increase in overdose deaths over the past decade.5 Several strategies have been investigated to mitigate risk (see “How frequently should a patient be tested?,” later in the article).

Clinical judgment—ie, when a physician orders a drug test upon suspecting that a patient is diverting a prescribed drug or has developed an SUD—has been shown to be highly inaccurate. Implicit racial bias might affect the physician’s judgment, leading to changes in testing and test interpretation. For example, Black patients were found to be 10% more likely to have drug screening ordered while being treated with long-term opioid therapy and 2 to 3 times more likely to have their medication discontinued as a result of a marijuana- or cocaine-positive test.2

Other studies have shown that testing patients for “bad behavior,” so to speak—reporting a prescription lost or stolen, consuming more than the prescribed dosage, visiting the office without an appointment, having multiple drug intolerances and allergies, and making frequent telephone calls to the practice—is ineffective.6 Patients with these behaviors were slightly more likely to unexpectedly test positive, or negative, on their UDS; however, many patients without suspect behavior also were found to have abnormal toxicology results.6 Data do not support therapeutic drug monitoring only of patients selected on the basis of aberrant behavior.6

Continue to: Questions and concerns about urine drug screening

Questions and concerns about urine drug screening

Why not just ask the patient? Studies have evaluated whether patient self-reporting of adherence is a feasible alternative to laboratory drug screening. Regrettably, patients have repeatedly been shown to underreport their use of both prescribed and illicit drugs.7,8

That question leads to another: Why do patients lie to their physician? It is easy to assume malicious intent, but a variety of obstacles might dissuade a patient from being fully truthful with their physician:

- Monetary gain. A small, but real, percentage of medications are diverted by patients for this reason.9

- Addiction, pseudo-addiction due to tolerance, and self-medication for psychological symptoms are clinically treatable syndromes that can lead to underreporting of prescribed and nonprescribed drug and alcohol use.

- Shame. Addiction is a highly stigmatized disease, and patients might simply be ashamed to admit that they need treatment: 13% to 38% of patients receiving chronic opioid therapy in a pain management or primary care setting have a clinically diagnosable SUD.10,11

Is consent needed to test or to share test results? Historically, UDS has been performed on patients without their consent or knowledge.12 Patients give a urine specimen to their physician for a variety of reasons; it seems easy to “add on” UDS. Evidence is clear, however, that confronting a patient about an unexpected test result can make the clinical outcome worse—often resulting in irreparable damage to the patient–physician relationship.12,13 Unless the patient is experiencing a medical emergency, guidelines unanimously recommend obtaining consent prior to testing.1,5,14

Federal law requires written permission from the patient for the physician to disclose information about alcohol or substance use, unless the information is expressly needed to provide care during a medical emergency. Substance use is highly stigmatized, and patients might—legitimately—fear that sharing their history could undermine their care.1,12,14

How frequently should a patient be tested? Experts recommend utilizing a risk-based strategy to determine the frequency of UDS.1,5,15 Validated risk-assessment questionnaires include:

- Opioid Risk Tool for Opioid Use Disorder (ORT-OUD)a

- Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients With Pain–Revised (SOAPP-R)b

- Diagnosis, Intractability, Risk and Efficacy (DIRE)c

- Addiction Behaviors Checklist (ABC).d

Continue to: Each of these tools...

Each of these tools takes less than 5 minutes to administer and can be used by a primary care physician to objectively quantify the risk of prescribing; there is no evidence for the use of 1 of these screeners over the others.15 It is recommended that you choose a questionnaire that works for you and incorporate the risk assessment into prescribing any high-risk medication.1,5,15

Once you have completed an initial risk assessment, the frequency of UDS can be based on ongoing assessment that incorporates baseline testing, patient self-reporting, toxicology results, behavioral monitoring, and state database monitoring through a prescription drug monitoring program. Annual screening is appropriate in low-risk patients; moderate-risk patients should be screened twice a year, and high-risk patients should be screened at least every 4 months (FIGURE).15

Many state and federal agencies, health systems, employers, and insurers mandate the frequency of testing through guidelines or legislation. These regulations often are inconsistent with the newest medical evidence.15 Consult local guidelines and review the medical evidence and consensus recommendations on UDS.

What are the cost considerations in providing UDS? Insurers have been billed as much as $4000 for definitive chromatography testing (described later).3 This has led to insurance fraud, when drug-testing practices with a financial interest routinely use large and expensive test panels, test too frequently, or unnecessarily send for confirmatory or quantitative analysis of all positive tests.3,14 Often, insurers refuse to pay for unnecessary testing, leaving patients with significant indebtedness.3,14 Take time to review the evidence and consensus recommendations on UDS to avoid waste, potential accusations of fraud, and financial burden on your patients.

Urine toxicology for addiction treatment

UDS protocols in addiction settings are often different from those in which a controlled substance is being prescribed.

Continue to: Routine and random testing

Routine and random testing. Two common practices when treating addiction are to perform UDS on all patients, at every visit, or to test randomly.1 These practices can be problematic, however. Routine testing at every visit can make urine-tampering more likely and is often unnecessary for stable patients. Random testing can reduce the risk of urine-tampering, but it is often difficult for primary care clinics to institute such a protocol. Some clinics have patients provide a urine specimen at every visit and then only send tests to the lab based on randomization.1

Contingency management—a behavioral intervention in which a patient is rewarded, or their performance is reinforced, when they display evidence of positive change—is the most effective strategy used in addiction medicine to determine the frequency of patient visits and UDS.14,16 High-risk patients with self-reported active substance use or UDS results consistent with substance use, or both, are seen more often; as their addiction behavior diminishes, visits and UDS become less frequent. If addiction behavior increases, the patient is seen more often. Keep in mind that addiction behavior decreases over months of treatment, not immediately upon initiation.14,17 For contingency management to be successful, patient-centered interviewing and UDS will need to be employed frequently as the patient works toward meaningful change.14

The technology of urine drug screening

Two general techniques are used for UDS: immunoassay and chromatography. Each plays an important role in clinical practice; physicians must therefore maintain a basic understanding of the mechanism of each technique and their comparable advantages and disadvantages. Such an understanding allows for (1) matching the appropriate technique to the individual clinical scenario and (2) correctly interpreting results.

Immunoassay technology is used for point-of-care and rapid laboratory UDS, using antibodies to detect the drug or drug metabolite of interest. Antibodies utilized in immunoassays are designed to selectively bind a specific antigen—ie, a unique chemical structure within the drug of choice. Once bound, the antigen–antibody complex can be exploited for detection through various methods.

Chromatography–mass spectrometry is considered the gold standard for UDS, yielding confirmatory results. This is a 2-step process: Chromatography separates components within a specimen; mass spectrometry then identifies those components. Most laboratories employ liquid, rather than gas, chromatography. The specificity of the liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry method is such that a false-positive result is, essentially, impossible.18

Continue to: How is the appropriate tests elected for urine drug screening?

How is the appropriate tests elected for urine drug screening?

Variables that influence your choice of the proper test method include the clinical question at hand; cost; the urgency of obtaining results; and the stakes in that decision (ie, will the results be used to simply change the dosage of a medication or, of greater consequence, to determine fitness for employment or inform criminal justice decisions?). Each method of UDS has advantages that can be utilized and disadvantages that must be considered to obtain an accurate and useful result.

Immunoassay provides rapid results, is relatively easy to perform, and is, comparatively, inexpensive.1,14 The speed of results makes this method particularly useful in settings such as the emergency department, where rapid results are crucial. Ease of use makes immunoassay ideal for the office, where non-laboratory staff can be trained to properly administer the test.

A major disadvantage of immunoassay technology, however, is interference resulting in both false-positive and false-negative results, which is discussed in detail in the next section. Immunoassay should be considered a screening test that yields presumptive results.

Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry is exquisitely specific and provides confirmatory test results—major advantages of the method. However, specificity comes at a price: significantly increased cost and longer wait time for results (typically days, if specimens are sent out to a laboratory). These barriers can make it impractical to employ this method in routine practice.

Interpretation of results: Not so fast

Interpreting UDS results is not as simple as noting a positive or negative result. Physicians must understand the concept of interference, so that results can be appropriately interpreted and confirmed. This is crucial when results influence clinical decisions; inappropriate action, taken on the basis of presumptive results, can have severe consequences for the patient–provider relationship and the treatment plan.1,14

Continue to: Interference falls into 2 categories...

Interference falls into 2 categories: variables inherent in the testing process and patient variables.

Antibody cross-reactivity. A major disadvantage of immunoassay technology is interference that results in false-positive and false-negative results.19,20 The source of this interference is antibody cross-reactivity—the degree to which an antibody binds to structurally similar compounds. Antibody–antigen interactions are incredibly complex; although assay antibodies are engineered to specifically detect a drug class of interest, reactivity with other, structurally similar compounds is unavoidable.

Nevertheless, cross-reactivity is a useful phenomenon that allows broad testing for multiple drugs within a class. For example, most point-of-care tests for benzodiazepines reliably detect diazepam and chlordiazepoxide. Likewise, opiate tests reliably detect natural opiates, such as morphine and codeine. Cross-reactivity is not limitless, however; most benzodiazepine immunoassays have poor reactivity to clonazepam and lorazepam, making it possible that a patient taking clonazepam tests negative for benzodiazepine on an immunoassay.14,20 Similarly, standard opioid tests have only moderate cross-reactivity for semisynthetic opioids, such as hydrocodone and hydromorphone; poor cross-reactivity for oxycodone and oxymorphone; and essentially no cross-reactivity for full synthetics, such as fentanyl and methadone.14

It is the responsibility of the ordering physician to understand cross-reactivity to various drugs within a testing class.

Whereas weak cross-reactivity to drugs within a class can be a source of false-negative results, cross-reactivity to drugs outside the class of interest is a source of false-positive results. An extensive review of drugs that cause false-positive immunoassay screening tests is outside the scope of this article; commonly prescribed medications implicated in false-positive results are listed in TABLE 1.19

Continue to: In general...

In general, amphetamine immunoassays produce frequent false-positive results, whereas cocaine and cannabinoid assays are more specific.1,18 Common over-the-counter medications, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, decongestants, and antacids, can yield false-positive results, highlighting the need to obtain a comprehensive medication list from patients, including over-the-counter and herbal medications, before ordering UDS. Because of the complexity of cross-reactivity, it might not be possible to identify the source of a false-positive result.14

Patient variables. Intentional effort to skew results is another source of interference. The frequency of this effort varies by setting and the potential consequences of results—eg, employment testing or substance use treatment—and a range of attempts have been reported in the literature.21,22 Common practices are dilution, adulteration, and substitution.20,23

- Dilution lowers the concentration of the drug of interest below the detection limit of the assay by directly adding water to the urine specimen, drinking copious amounts of fluid, taking a diuretic, or a combination of these practices.

- Adulteration involves adding a substance to urine that interferes with the testing mechanism: for example, bleach, household cleaners, eye drops, and even commercially available products expressly marketed to interfere with UDS.24

- Substitution involves providing urine or a urine-like substance for testing that did not originate from the patient.

Methods to minimize patient-related interference include observed collection and specimen validity testing for pH, creatinine, and adulterants (TABLE 2).1,15 Efforts to detect patient interference must be balanced against concerns about privacy, personnel resources, and the cost of expanded testing.14,19,20

Additional aspects inherent to the testing process, such as cutoff concentrations and detection windows, can lead to interference. Laboratories must set reporting cutoffs, and specimens with a drug concentration present but below the cutoff value are reported as a negative result. Detection windows are complex and are influenced by inherent properties of the drug, including metabolic pathway and route and frequency of use.1 A given patient might well be using a substance, but if the specimen was obtained outside the detection window, a false-negative result might be reported (TABLE 31,23).

Managing test results

Appropriate management of UDS results is built on the foundation of understanding the testing mechanism, selecting the correct test, and properly interpreting results. Drug testing is, ultimately, a therapeutic tool used to monitor treatment, provide reinforcement, and explore substance use behavior; results of testing should be employed to achieve those objectives.1,4,14 A negative or expected UDS result can be utilized as positive reinforcement for a patient who is adherent to the treatment plan—much the way objective weight loss in an obese patient can provide encouragement to continue lifestyle changes.

Continue to: Test results should be presented...

Test results should be presented in an objective, nonconfrontational, and compassionate manner, not with stigmatizing language, such as “clean” or “dirty.”1,13,14 Using stigmatizing terms such as “substance abuser” instead of “person with a substance use disorder” has been shown, even among highly trained health care professionals, to have a negative effect on patient care.13

Inevitably, you will encounter an unexpected result, and therefore must develop a rational, systematic, and compassionate management approach. “Unexpected result” is a broad term that includes results that conflict with

- a patient’s self-report

- your understanding of what the patient is taking (using)

- prescribed medications

- a patient’s typical substance use pattern.

When faced with an unexpected test result, first, ensure that the result in question is reliable. If a screening test yields an unanticipated finding—especially if it conflicts with the patient’s self-reporting—make every effort to seek confirmation if you are going to be making a significant clinical decision because of the result.1,14

Second, use your understanding of interference to consider the result in a broader context. If confirmatory results are inconsistent with a patient’s self-report, discuss whether there has been a break in the physician–patient relationship and emphasize that recurrent use or failure to adhere to a treatment plan has clear consequences.1,14 Modify the treatment plan to address the inconsistent finding by escalating care, adjusting medications, and connecting the patient to additional resources.

Third, keep in mind that a positive urine test is not diagnostic of an SUD. Occasional drug use is extremely common17 and should not categorically lead to a change in the treatment plan. Addiction is, fundamentally, a disease of disordered reward, motivation, and behavior that is defined by the consequences of substance use, not substance use per se,25 and an SUD diagnosis is complex, based on clinical history, physical examination, and laboratory testing. Similarly, a negative UDS result does not rule out an SUD.4,10

Continue to: Fourth, patient dismissal...

Fourth, patient dismissal is rarely an appropriate initial response to UDS results. Regrettably, some physicians misinterpret urine toxicology results and inappropriately discharge patients on that basis.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guideline for prescribing opioids has increased utilization of UDS in primary care settings but does not provide the necessary education on proper use of the tool, which has resulted in a rise in misinterpretation and inappropriate discharge.13,26

If recurrent aberrant behavior is detected (by history or urine toxicology), do not abruptly discontinue the patient’s medication(s). Inform the patient of your concern, taper medication, and refer the patient to addiction treatment. Abrupt discontinuation of an opioid or benzodiazepine can lead to significant harm.1,14

CORRESPONDENCE

John Hayes, DO, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, 1121 E North Avenue, Milwaukee, WI, 53212; [email protected]

An estimated 20 million patients in the United States have a substance use disorder (SUD), with hundreds of millions of prescriptions for controlled substances written annually. Consequently, urine drug screening (UDS) has become widely utilized to evaluate and treat patients with an SUD or on chronic opioid or benzodiazepine therapy.1

Used appropriately, UDS can be a valuable tool; there is ample evidence, however, that it has been misused, by some physicians, to stigmatize patients who use drugs of abuse,2 profile patients racially,2 profit from excessive testing,3 and inappropriately discontinue treatment.4

A patient-centered approach. We have extensive clinical experience in the use and interpretation of urine toxicology, serving as clinical leads in busy family medicine residency practices that care for patients with SUDs, and are often consulted regarding patients on chronic opioid or benzodiazepine therapy. We have encountered countless situations in which the correct interpretation of UDS is critical to providing care.

Over time, and after considerable trial and error, we developed the patient-centered approach to urine toxicology described in this article. We believe that the medical evidence strongly supports our approach to the appropriate use and interpretation of urine toxicology in clinical practice. Our review here is intended as a resource when you consider implementing a UDS protocol or are struggling with the management of unexpected results.

Urine toxicology for therapeutic drug monitoring

Prescribing a controlled substance carries inherent risks, including diversion, nonmedical use, and development of an SUD. Prescribed medications, particularly opioids and benzodiazepines, have been linked to a large increase in overdose deaths over the past decade.5 Several strategies have been investigated to mitigate risk (see “How frequently should a patient be tested?,” later in the article).

Clinical judgment—ie, when a physician orders a drug test upon suspecting that a patient is diverting a prescribed drug or has developed an SUD—has been shown to be highly inaccurate. Implicit racial bias might affect the physician’s judgment, leading to changes in testing and test interpretation. For example, Black patients were found to be 10% more likely to have drug screening ordered while being treated with long-term opioid therapy and 2 to 3 times more likely to have their medication discontinued as a result of a marijuana- or cocaine-positive test.2

Other studies have shown that testing patients for “bad behavior,” so to speak—reporting a prescription lost or stolen, consuming more than the prescribed dosage, visiting the office without an appointment, having multiple drug intolerances and allergies, and making frequent telephone calls to the practice—is ineffective.6 Patients with these behaviors were slightly more likely to unexpectedly test positive, or negative, on their UDS; however, many patients without suspect behavior also were found to have abnormal toxicology results.6 Data do not support therapeutic drug monitoring only of patients selected on the basis of aberrant behavior.6

Continue to: Questions and concerns about urine drug screening

Questions and concerns about urine drug screening

Why not just ask the patient? Studies have evaluated whether patient self-reporting of adherence is a feasible alternative to laboratory drug screening. Regrettably, patients have repeatedly been shown to underreport their use of both prescribed and illicit drugs.7,8

That question leads to another: Why do patients lie to their physician? It is easy to assume malicious intent, but a variety of obstacles might dissuade a patient from being fully truthful with their physician:

- Monetary gain. A small, but real, percentage of medications are diverted by patients for this reason.9

- Addiction, pseudo-addiction due to tolerance, and self-medication for psychological symptoms are clinically treatable syndromes that can lead to underreporting of prescribed and nonprescribed drug and alcohol use.

- Shame. Addiction is a highly stigmatized disease, and patients might simply be ashamed to admit that they need treatment: 13% to 38% of patients receiving chronic opioid therapy in a pain management or primary care setting have a clinically diagnosable SUD.10,11

Is consent needed to test or to share test results? Historically, UDS has been performed on patients without their consent or knowledge.12 Patients give a urine specimen to their physician for a variety of reasons; it seems easy to “add on” UDS. Evidence is clear, however, that confronting a patient about an unexpected test result can make the clinical outcome worse—often resulting in irreparable damage to the patient–physician relationship.12,13 Unless the patient is experiencing a medical emergency, guidelines unanimously recommend obtaining consent prior to testing.1,5,14

Federal law requires written permission from the patient for the physician to disclose information about alcohol or substance use, unless the information is expressly needed to provide care during a medical emergency. Substance use is highly stigmatized, and patients might—legitimately—fear that sharing their history could undermine their care.1,12,14

How frequently should a patient be tested? Experts recommend utilizing a risk-based strategy to determine the frequency of UDS.1,5,15 Validated risk-assessment questionnaires include:

- Opioid Risk Tool for Opioid Use Disorder (ORT-OUD)a

- Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients With Pain–Revised (SOAPP-R)b

- Diagnosis, Intractability, Risk and Efficacy (DIRE)c

- Addiction Behaviors Checklist (ABC).d

Continue to: Each of these tools...

Each of these tools takes less than 5 minutes to administer and can be used by a primary care physician to objectively quantify the risk of prescribing; there is no evidence for the use of 1 of these screeners over the others.15 It is recommended that you choose a questionnaire that works for you and incorporate the risk assessment into prescribing any high-risk medication.1,5,15

Once you have completed an initial risk assessment, the frequency of UDS can be based on ongoing assessment that incorporates baseline testing, patient self-reporting, toxicology results, behavioral monitoring, and state database monitoring through a prescription drug monitoring program. Annual screening is appropriate in low-risk patients; moderate-risk patients should be screened twice a year, and high-risk patients should be screened at least every 4 months (FIGURE).15

Many state and federal agencies, health systems, employers, and insurers mandate the frequency of testing through guidelines or legislation. These regulations often are inconsistent with the newest medical evidence.15 Consult local guidelines and review the medical evidence and consensus recommendations on UDS.

What are the cost considerations in providing UDS? Insurers have been billed as much as $4000 for definitive chromatography testing (described later).3 This has led to insurance fraud, when drug-testing practices with a financial interest routinely use large and expensive test panels, test too frequently, or unnecessarily send for confirmatory or quantitative analysis of all positive tests.3,14 Often, insurers refuse to pay for unnecessary testing, leaving patients with significant indebtedness.3,14 Take time to review the evidence and consensus recommendations on UDS to avoid waste, potential accusations of fraud, and financial burden on your patients.

Urine toxicology for addiction treatment

UDS protocols in addiction settings are often different from those in which a controlled substance is being prescribed.

Continue to: Routine and random testing

Routine and random testing. Two common practices when treating addiction are to perform UDS on all patients, at every visit, or to test randomly.1 These practices can be problematic, however. Routine testing at every visit can make urine-tampering more likely and is often unnecessary for stable patients. Random testing can reduce the risk of urine-tampering, but it is often difficult for primary care clinics to institute such a protocol. Some clinics have patients provide a urine specimen at every visit and then only send tests to the lab based on randomization.1

Contingency management—a behavioral intervention in which a patient is rewarded, or their performance is reinforced, when they display evidence of positive change—is the most effective strategy used in addiction medicine to determine the frequency of patient visits and UDS.14,16 High-risk patients with self-reported active substance use or UDS results consistent with substance use, or both, are seen more often; as their addiction behavior diminishes, visits and UDS become less frequent. If addiction behavior increases, the patient is seen more often. Keep in mind that addiction behavior decreases over months of treatment, not immediately upon initiation.14,17 For contingency management to be successful, patient-centered interviewing and UDS will need to be employed frequently as the patient works toward meaningful change.14

The technology of urine drug screening

Two general techniques are used for UDS: immunoassay and chromatography. Each plays an important role in clinical practice; physicians must therefore maintain a basic understanding of the mechanism of each technique and their comparable advantages and disadvantages. Such an understanding allows for (1) matching the appropriate technique to the individual clinical scenario and (2) correctly interpreting results.