User login

An Analysis of the Involvement and Attitudes of Resident Physicians in Reporting Errors in Patient Care

From Adelante Healthcare, Mesa, AZ (Dr. Chin), University Hospitals of Cleveland, Cleveland, OH (Drs. Delozier, Bascug, Levine, Bejanishvili, and Wynbrandt and Janet C. Peachey, Rachel M. Cerminara, and Sharon M. Darkovich), and Houston Methodist Hospitals, Houston, TX (Dr. Bhakta).

Abstract

Background: Resident physicians play an active role in the reporting of errors that occur in patient care. Previous studies indicate that residents significantly underreport errors in patient care.

Methods: Fifty-four of 80 eligible residents enrolled at University Hospitals–Regional Hospitals (UH-RH) during the 2018-2019 academic year completed a survey assessing their knowledge and experience in completing Patient Advocacy and Shared Stories (PASS) reports, which serve as incident reports in the UH health system in reporting errors in patient care. A series of interventions aimed at educating residents about the PASS report system were then conducted. The 54 residents who completed the first survey received it again 4 months later.

Results: Residents demonstrated greater understanding of when filing PASS reports was appropriate after the intervention, as significantly more residents reported having been involved in a situation where they should have filed a PASS report but did not (P = 0.036).

Conclusion: In this study, residents often did not report errors in patient care because they simply did not know the process for doing so. In addition, many residents often felt that the reporting of patient errors could be used as a form of retaliation.

Keywords: resident physicians; quality improvement; high-value care; medical errors; patient safety.

Resident physicians play a critical role in patient care. Residents undergo extensive supervised training in order to one day be able to practice medicine in an unsupervised setting, with the goal of providing the highest quality of care possible. One study reported that primary care provided by residents in a training program is of similar or higher quality than that provided by attending physicians.1

Besides providing high-quality care, it is important that residents play an active role in the reporting of errors that occur regarding patient care as well as in identifying events that may compromise patient safety and quality.2 In fact, increased reporting of patient errors has been shown to decrease liability-related costs for hospitals.3 Unfortunately, physicians, and residents in particular, have historically been poor reporters of errors in patient care.4 This is especially true when comparing physicians to other health professionals, such as nurses, in error reporting.5

Several studies have examined the involvement of residents in reporting errors in patient care. One recent study showed that a graduate medical education financial incentive program significantly increased the number of patient safety events reported by residents and fellows.6 This study, along with several others, supports the concept of using incentives to help improve the reporting of errors in patient care for physicians in training.7-10 Another study used Quality Improvement Knowledge Assessment Tool (QIKAT) scores to assess quality improvement (QI) knowledge. The study demonstrated that self-assessment scores of QI skills using QIKAT scores improved following a targeted intervention.11 Because further information on the involvement and attitudes of residents in reporting errors in patient care is needed, University Hospitals of Cleveland (UH) designed and implemented a QI study during the 2018-2019 academic year. This prospective study used anonymous surveys to objectively examine the involvement and attitudes of residents in reporting errors in patient care.

Methods

The UH health system uses Patient Advocacy and Shared Stories (PASS) reports as incident reports to not only disclose errors in patient care but also to identify any events that may compromise patient safety and quality. Based on preliminary review, nurses, ancillary staff, and administrators file the majority of PASS reports.

The study group consisted of residents at University Hospitals–Regional Hospitals (UH-RH), which is comprised of 2 hospitals: University Hospitals–Richmond Medical Center (UH-RMC) and University Hospitals –Bedford Medical Center (UH-BMC). UH-RMC and UH-BMC are 2 medium-sized university-affiliated community hospitals located in the Cleveland metropolitan area in Northeast Ohio. Both serve as clinical training sites for Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine and Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine, the latter of which helped fund this study. The study was submitted to the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of University Hospitals of Cleveland and granted “not human subjects research” status as a QI study.

Surveys

UH-RH offers residency programs in dermatology, emergency medicine, family medicine, internal medicine, orthopedic surgery, and physical medicine and rehabilitation, along with a 1-year transitional/preliminary year. A total of 80 residents enrolled at UH-RH during the 2018-2019 academic year. All 80 residents at UH-RH received an email in December 2018 asking them to complete an anonymous survey regarding the PASS report system. The survey was administered using the REDCap software system and consisted of 15 multiple-choice questions. As an incentive for completing the survey, residents were offered a $10 Amazon gift card. The gift cards were funded through a research grant from Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine. Residents were given 1 week to complete the survey. At the end of the week, 54 of 80 residents completed the first survey.

Following the first survey, efforts were undertaken by the study authors, in conjunction with the quality improvement department at UH-RH, to educate residents about the PASS report system. These interventions included giving a lecture on the PASS report system during resident didactic sessions, sending an email to all residents about the PASS report system, and providing residents an opportunity to complete an optional online training course regarding the PASS report system. As an incentive for completing the online training course, residents were offered a $10 Amazon gift card. As before, the gift cards were funded through a research grant from Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine.

A second survey was administered in April 2019, 4 months after the first survey. To determine whether the intervention made an impact on the involvement and attitudes of residents in the reporting errors in patient care, only residents who completed the first survey were sent the second survey. The second survey consisted of the same questions as the first survey and was also administered using the REDCap software system. As an incentive for completing the survey, residents were offered another $10 Amazon gift card, again were funded through a research grant from Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine. Residents were given 1 week to complete the survey.

Analysis

Chi-square analyses were utilized to examine differences between preintervention and postintervention responses across categories. All analyses were conducted using R statistical software, version 3.6.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

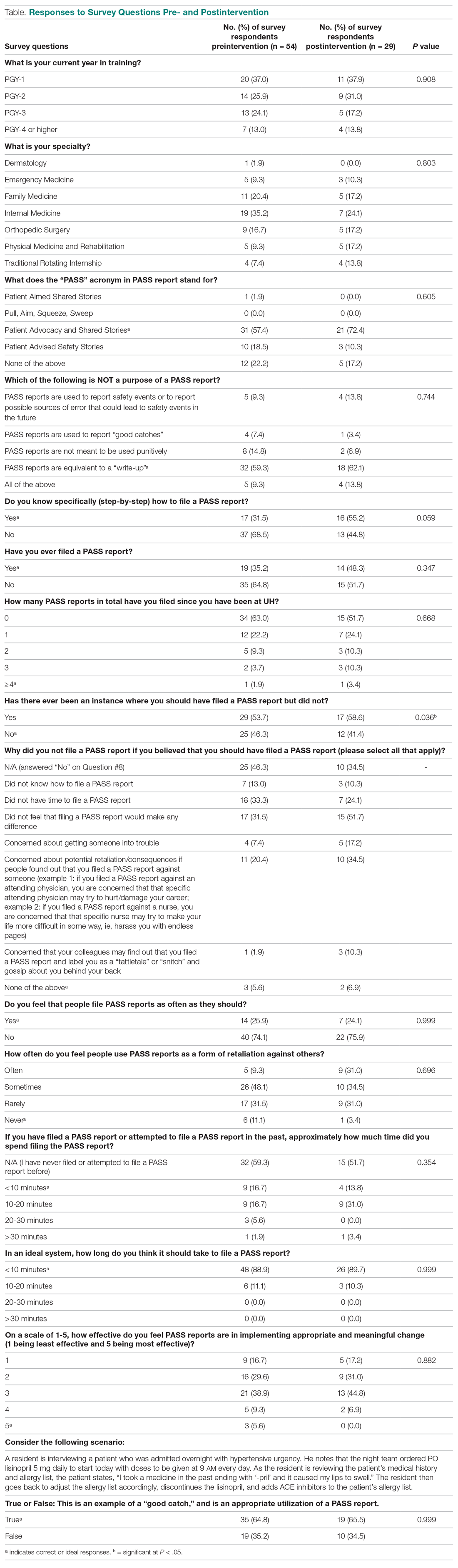

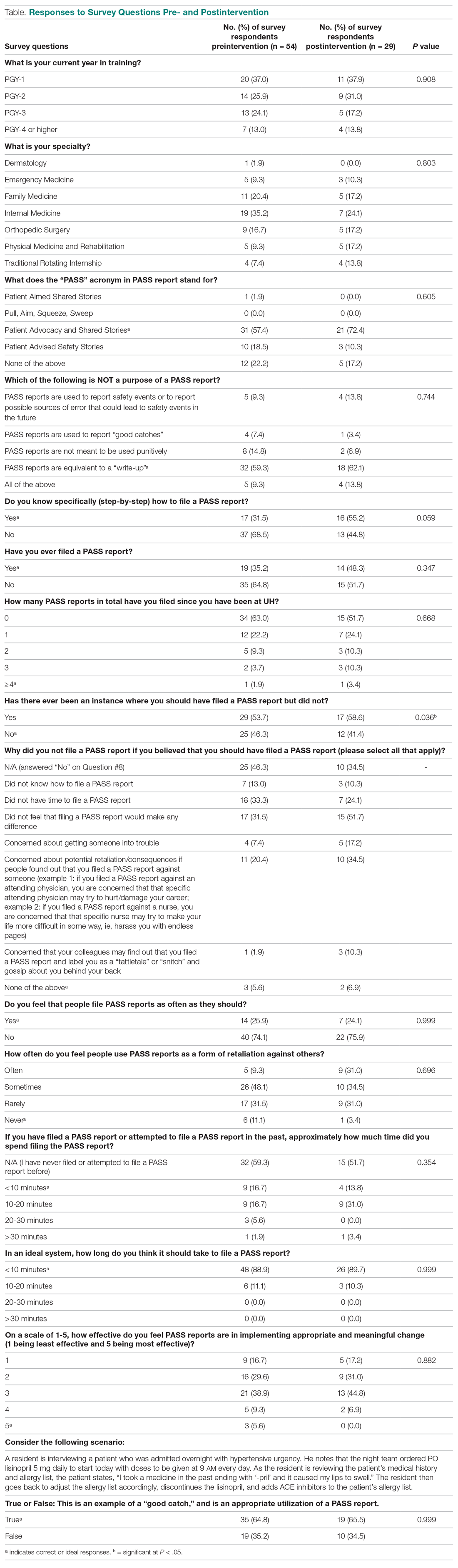

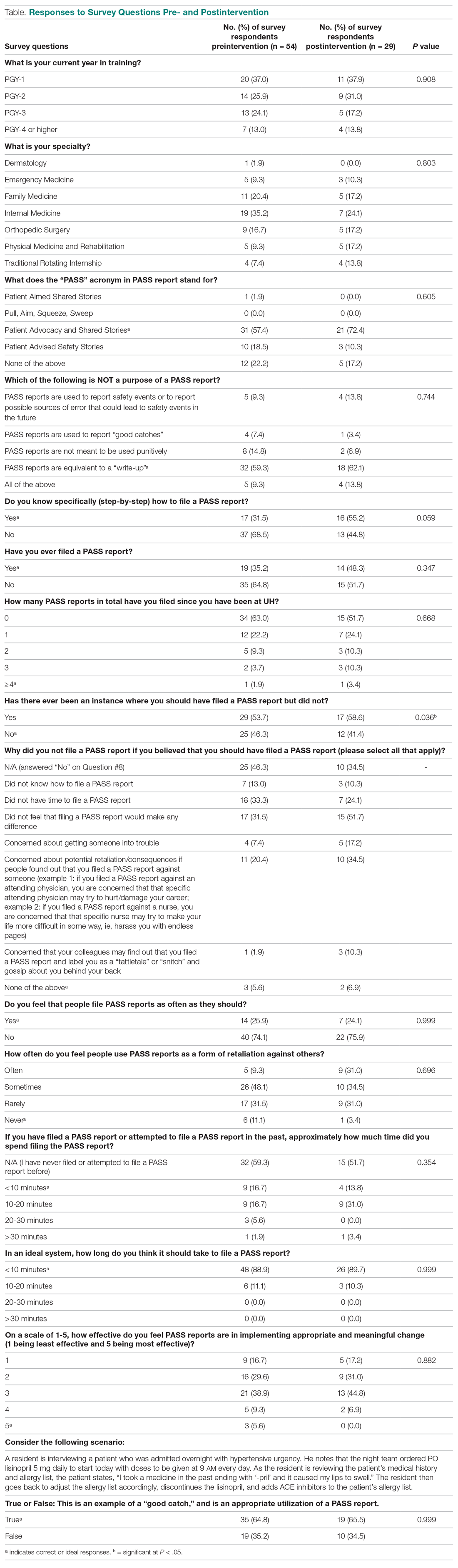

A total of 54 of 80 eligible residents responded to the first survey (Table). Twenty-nine of 54 eligible residents responded to the second survey. Postintervention, significantly more residents indicated being involved in a situation where they should have filed a PASS report but did not (58.6% vs 53.7%; P = 0.036). Improvement was seen in PASS knowledge postintervention, where fewer residents reported not knowing how to file a PASS report (31.5% vs 55.2%; P = 0.059). No other improvements were significant, nor were there significant differences in responses between any other categories pre- and postintervention.

Discussion

Errors in patient care are a common occurrence in the hospital setting. Reporting errors when they happen is important for hospitals to gain data and better care for patients, but studies show that patient errors are usually underreported. This is concerning, as data on errors and other aspects of patient care are needed to inform quality improvement programs.

This study measured residents’ attitudes and knowledge regarding the filing of a PASS report. It also aimed to increase both the frequency of and knowledge about filing a PASS report with interventions. The results from each survey indicated a statistically significant increase in knowledge of when to file a PASS report. In the first survey, 53.7% of residents responded they they were involved in an instance where they should have filed a PASS report but did not. In the second survey, 58.5% of residents reported being involved in an instance where they should have filed a PASS report but did not. This difference was statistically significant (P = 0.036), sugesting that the intervention was successful at increasing residents’ knowledge regarding PASS reports and the appropriate times to file a PASS report.

The survey results also showed a trend toward increasing aggregate knowledge level of how to file PASS reports on the first survey and second surveys (from 31.5% vs 55.2%. This demonstrates an increase in knowledge of how to file a PASS report among residents at our hospital after the intervention. It should be noted that the intervention that was performed in this study was simple, easy to perform, and can be completed at any hospital system that uses a similar system for reporting patient errors.

Another important trend indicating the effectiveness of the intervention was a 15% increase in knowledge of what the PASS report acronym stands for, along with a 13.1% aggregate increase in the number of residents who filed a PASS report. This indicated that residents may have wanted to file a PASS report previously but simply did not know how to until the intervention. In addition, there was also a decrease in the aggregate percentages of residents who had never filed a PASS report and an increase in how many PASS reports were filed.

While PASS reports are a great way for hospitals to gain data and insight into problems at their sites, there was also a negative view of PASS reports. For example, a large percentage of residents indicated that filing a PASS report would not make any difference and that PASS reports are often used as a form of retaliation, either against themselves as the submitter or the person(s) mentioned in the PASS report. More specifically, more than 50% of residents felt that PASS reports were sometimes or often used as a form of retaliation against others. While many residents correctly identified in the survey that PASS reports are not equivalent to a “write-up,” it is concerning that they still feel there is a strong potential for retaliation when filing a PASS report. This finding is unfortunate but matches the results of a multicenter study that found that 44.6% of residents felt uncomfortable reporting patient errors, possibly secondary to fear of retaliation, along with issues with the reporting system.12

It is interesting to note that a minority of residents indicated that they feel that PASS reports are filed as often as they should be (25.9% on first survey and 24.1% on second survey). This is concerning, as the data gathered through PASS reports is used to improve patient care. However, the percentage reported in our study, although low, is higher than that reported in a similar study involving patients with Medicare insurance, which showed that only 14% of patient safety events were reported.13 These results demonstrate that further interventions are necessary in order to ensure that a PASS report is filed each time a patient safety event occurs.

Another finding of note is that the majority of residents also feel that the process of filing a PASS report is too time consuming. The majority of residents who have completed a PASS report stated that it took them between 10 and 20 minutes to complete a PASS report, but those same individuals also feel that it should take < 10 minutes to complete a PASS report. This is an important issue for hospital systems to address. Reducing the time it takes to file a PASS report may facilitate an increase in the amount of PASS reports filed.

We administered our surveys using email outreach to residents asking them to complete an anonymous online survey regarding the PASS report system using the REDCap software system. Researchers have various ways of administering surveys, ranging from paper surveys, emails, and even mobile apps. One study showed that online surveys tend to have higher response rates compared to non-online surveys, such as paper surveys and telephone surveys, which is likely due to the ease of use of online surveys.14 At the same time, unsolicited email surveys have been shown to have a negative influence on response rates. Mobile apps are a new way of administering surveys. However, research has not found any significant difference in the time required to complete the survey using mobile apps compared to other forms of administering surveys. In addition, surveys using mobile apps did not have increased response rates compared to other forms of administering surveys.15

To increase the response rate of our surveys, we offered gift cards to the study population for completing the survey. Studies have shown that surveys that offer incentives tend to have higher response rates than surveys that do not.16 Also, in addition to serving as a method for gathering data from our study population, we used our surveys as an intervention to increase awareness of PASS reporting, as reported in other studies. For example, another study used the HABITS questionnaire to not only gather information about children’s diet, but also to promote behavioral change towards healthy eating habits.17

This study had several limitations. First, the study was conducted using an anonymous online survey, which means we could not clarify questions that residents found confusing or needed further explanation. For example, 17 residents indicated in the first survey that they knew how to PASS report, but 19 residents indicated in the same survey that they have filed a PASS report in the past.

A second limitation of the study was that fewer residents completed the second survey (29 of 54 eligible residents) compared to the first survey (54 of 80 eligible residents). This may have impacted the results of the analysis, as certain findings were not statistically significant, despite trends in the data.

A third limitation of the study is that not all of the residents that completed the first and second surveys completed the entire intervention. For example, some residents did not attend the didactic lecture discussing PASS reports, and as such may not have received the appropriate training prior to completing the second survey.

The findings from this study can be used by the residency programs at UH-RH and by residency programs across the country to improve the involvement and attitudes of residents in reporting errors in patient care. Hospital staff need to be encouraged and educated on how to better report patient errors and the importance of reporting these errors. It would benefit hospital systems to provide continued and targeted training to familiarize physicians with the process of reporting patient errors, and take steps to reduce the time it takes to report patient errors. By increasing the reporting of errors, hospitals will be able to improve patient care through initiatives aimed at preventing errors.

Conclusion

Residents play an important role in providing high-quality care for patients. Part of providing high-quality care is the reporting of errors in patient care when they occur. Physicians, and in particular, residents, have historically underreported errors in patient care. Part of this underreporting results from residents not knowing or understanding the process of filing a report and feeling that the reports could be used as a form of retaliation. For hospital systems to continue to improve patient care, it is important for residents to not only know how to report errors in patient care but to feel comfortable doing so.

Corresponding author: Andrew J. Chin, DO, MS, MPH, Department of Internal Medicine, Adelante Healthcare, 1705 W Main St, Mesa, AZ 85201; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

Funding: This study was funded by a research grant provided by Lake Eric College of Osteopathic Medicine to Andrew J. Chin and Anish Bhakta.

1. Zallman L, Ma J, Xiao L, Lasser KE. Quality of US primary care delivered by resident and staff physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(11):1193-1197.

2. Bagain JP. The future of graduate medical education: a systems-based approach to ensure patient safety. Acad Med. 2015;90(9):1199-1202.

3. Kachalia A, Kaufman SR, Boothman R, et al. Liability claims and costs before and after implementation of a medical disclosure program. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(4):213-221.

4. Kaldjian LC, Jones EW, Wu BJ, et al. Reporting medical errors to improve patient safety: a survey of physicians in teaching hospitals. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(1):40-46.

5. Rowin EJ, Lucier D, Pauker SG, et al. Does error and adverse event reporting by physicians and nurses differ? Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34(9):537-545.

6. Turner DA, Bae J, Cheely G, et al. Improving resident and fellow engagement in patient safety through a graduate medical education incentive program. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10(6):671-675.

7. Macht R, Balen A, McAneny D, Hess D. A multifaceted intervention to increase surgery resident engagement in reporting adverse events. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(6):e117-e122.

8. Scott DR, Weimer M, English C, et al. A novel approach to increase residents’ involvement in reporting adverse events. Acad Med. 2011;86(6):742-746.

9. Stewart DA, Junn J, Adams MA, et al. House staff participation in patient safety reporting: identification of predominant barriers and implementation of a pilot program. South Med J. 2016;109(7):395-400.

10. Vidyarthi AR, Green AL, Rosenbluth G, Baron RB. Engaging residents and fellows to improve institution-wide quality: the first six years of a novel financial incentive program. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):460-468.

11. Fok MC, Wong RY. Impact of a competency based curriculum on quality improvement among internal medicine residents. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:252.

12. Wijesekera TP, Sanders L, Windish DM. Education and reporting of diagnostic errors among physicians in internal medicine training programs. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(11):1548-1549.

13. Levinson DR. Hospital incident reporting systems do not capture most patient harm. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Inspector General. January 2012. Report No. OEI-06-09-00091.

14. Evans JR, Mathur A. The value of online surveys. Internet Research. 2005;15(2):192-219.

15. Marcano Belisario JS, Jamsek J, Huckvale K, et al. Comparison of self‐administered survey questionnaire responses collected using mobile apps versus other methods. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2015;7:MR000042.

16. Manfreda KL, Batagelj Z, Vehovar V. Design of web survey questionnaires: three basic experiments. J Comput Mediat Commun. 2002;7(3):JCMC731.

17. Wright ND, Groisman‐Perelstein AE, Wylie‐Rosett J, et al. A lifestyle assessment and intervention tool for pediatric weight management: the HABITS questionnaire. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2011;24(1):96-100.

From Adelante Healthcare, Mesa, AZ (Dr. Chin), University Hospitals of Cleveland, Cleveland, OH (Drs. Delozier, Bascug, Levine, Bejanishvili, and Wynbrandt and Janet C. Peachey, Rachel M. Cerminara, and Sharon M. Darkovich), and Houston Methodist Hospitals, Houston, TX (Dr. Bhakta).

Abstract

Background: Resident physicians play an active role in the reporting of errors that occur in patient care. Previous studies indicate that residents significantly underreport errors in patient care.

Methods: Fifty-four of 80 eligible residents enrolled at University Hospitals–Regional Hospitals (UH-RH) during the 2018-2019 academic year completed a survey assessing their knowledge and experience in completing Patient Advocacy and Shared Stories (PASS) reports, which serve as incident reports in the UH health system in reporting errors in patient care. A series of interventions aimed at educating residents about the PASS report system were then conducted. The 54 residents who completed the first survey received it again 4 months later.

Results: Residents demonstrated greater understanding of when filing PASS reports was appropriate after the intervention, as significantly more residents reported having been involved in a situation where they should have filed a PASS report but did not (P = 0.036).

Conclusion: In this study, residents often did not report errors in patient care because they simply did not know the process for doing so. In addition, many residents often felt that the reporting of patient errors could be used as a form of retaliation.

Keywords: resident physicians; quality improvement; high-value care; medical errors; patient safety.

Resident physicians play a critical role in patient care. Residents undergo extensive supervised training in order to one day be able to practice medicine in an unsupervised setting, with the goal of providing the highest quality of care possible. One study reported that primary care provided by residents in a training program is of similar or higher quality than that provided by attending physicians.1

Besides providing high-quality care, it is important that residents play an active role in the reporting of errors that occur regarding patient care as well as in identifying events that may compromise patient safety and quality.2 In fact, increased reporting of patient errors has been shown to decrease liability-related costs for hospitals.3 Unfortunately, physicians, and residents in particular, have historically been poor reporters of errors in patient care.4 This is especially true when comparing physicians to other health professionals, such as nurses, in error reporting.5

Several studies have examined the involvement of residents in reporting errors in patient care. One recent study showed that a graduate medical education financial incentive program significantly increased the number of patient safety events reported by residents and fellows.6 This study, along with several others, supports the concept of using incentives to help improve the reporting of errors in patient care for physicians in training.7-10 Another study used Quality Improvement Knowledge Assessment Tool (QIKAT) scores to assess quality improvement (QI) knowledge. The study demonstrated that self-assessment scores of QI skills using QIKAT scores improved following a targeted intervention.11 Because further information on the involvement and attitudes of residents in reporting errors in patient care is needed, University Hospitals of Cleveland (UH) designed and implemented a QI study during the 2018-2019 academic year. This prospective study used anonymous surveys to objectively examine the involvement and attitudes of residents in reporting errors in patient care.

Methods

The UH health system uses Patient Advocacy and Shared Stories (PASS) reports as incident reports to not only disclose errors in patient care but also to identify any events that may compromise patient safety and quality. Based on preliminary review, nurses, ancillary staff, and administrators file the majority of PASS reports.

The study group consisted of residents at University Hospitals–Regional Hospitals (UH-RH), which is comprised of 2 hospitals: University Hospitals–Richmond Medical Center (UH-RMC) and University Hospitals –Bedford Medical Center (UH-BMC). UH-RMC and UH-BMC are 2 medium-sized university-affiliated community hospitals located in the Cleveland metropolitan area in Northeast Ohio. Both serve as clinical training sites for Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine and Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine, the latter of which helped fund this study. The study was submitted to the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of University Hospitals of Cleveland and granted “not human subjects research” status as a QI study.

Surveys

UH-RH offers residency programs in dermatology, emergency medicine, family medicine, internal medicine, orthopedic surgery, and physical medicine and rehabilitation, along with a 1-year transitional/preliminary year. A total of 80 residents enrolled at UH-RH during the 2018-2019 academic year. All 80 residents at UH-RH received an email in December 2018 asking them to complete an anonymous survey regarding the PASS report system. The survey was administered using the REDCap software system and consisted of 15 multiple-choice questions. As an incentive for completing the survey, residents were offered a $10 Amazon gift card. The gift cards were funded through a research grant from Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine. Residents were given 1 week to complete the survey. At the end of the week, 54 of 80 residents completed the first survey.

Following the first survey, efforts were undertaken by the study authors, in conjunction with the quality improvement department at UH-RH, to educate residents about the PASS report system. These interventions included giving a lecture on the PASS report system during resident didactic sessions, sending an email to all residents about the PASS report system, and providing residents an opportunity to complete an optional online training course regarding the PASS report system. As an incentive for completing the online training course, residents were offered a $10 Amazon gift card. As before, the gift cards were funded through a research grant from Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine.

A second survey was administered in April 2019, 4 months after the first survey. To determine whether the intervention made an impact on the involvement and attitudes of residents in the reporting errors in patient care, only residents who completed the first survey were sent the second survey. The second survey consisted of the same questions as the first survey and was also administered using the REDCap software system. As an incentive for completing the survey, residents were offered another $10 Amazon gift card, again were funded through a research grant from Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine. Residents were given 1 week to complete the survey.

Analysis

Chi-square analyses were utilized to examine differences between preintervention and postintervention responses across categories. All analyses were conducted using R statistical software, version 3.6.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

A total of 54 of 80 eligible residents responded to the first survey (Table). Twenty-nine of 54 eligible residents responded to the second survey. Postintervention, significantly more residents indicated being involved in a situation where they should have filed a PASS report but did not (58.6% vs 53.7%; P = 0.036). Improvement was seen in PASS knowledge postintervention, where fewer residents reported not knowing how to file a PASS report (31.5% vs 55.2%; P = 0.059). No other improvements were significant, nor were there significant differences in responses between any other categories pre- and postintervention.

Discussion

Errors in patient care are a common occurrence in the hospital setting. Reporting errors when they happen is important for hospitals to gain data and better care for patients, but studies show that patient errors are usually underreported. This is concerning, as data on errors and other aspects of patient care are needed to inform quality improvement programs.

This study measured residents’ attitudes and knowledge regarding the filing of a PASS report. It also aimed to increase both the frequency of and knowledge about filing a PASS report with interventions. The results from each survey indicated a statistically significant increase in knowledge of when to file a PASS report. In the first survey, 53.7% of residents responded they they were involved in an instance where they should have filed a PASS report but did not. In the second survey, 58.5% of residents reported being involved in an instance where they should have filed a PASS report but did not. This difference was statistically significant (P = 0.036), sugesting that the intervention was successful at increasing residents’ knowledge regarding PASS reports and the appropriate times to file a PASS report.

The survey results also showed a trend toward increasing aggregate knowledge level of how to file PASS reports on the first survey and second surveys (from 31.5% vs 55.2%. This demonstrates an increase in knowledge of how to file a PASS report among residents at our hospital after the intervention. It should be noted that the intervention that was performed in this study was simple, easy to perform, and can be completed at any hospital system that uses a similar system for reporting patient errors.

Another important trend indicating the effectiveness of the intervention was a 15% increase in knowledge of what the PASS report acronym stands for, along with a 13.1% aggregate increase in the number of residents who filed a PASS report. This indicated that residents may have wanted to file a PASS report previously but simply did not know how to until the intervention. In addition, there was also a decrease in the aggregate percentages of residents who had never filed a PASS report and an increase in how many PASS reports were filed.

While PASS reports are a great way for hospitals to gain data and insight into problems at their sites, there was also a negative view of PASS reports. For example, a large percentage of residents indicated that filing a PASS report would not make any difference and that PASS reports are often used as a form of retaliation, either against themselves as the submitter or the person(s) mentioned in the PASS report. More specifically, more than 50% of residents felt that PASS reports were sometimes or often used as a form of retaliation against others. While many residents correctly identified in the survey that PASS reports are not equivalent to a “write-up,” it is concerning that they still feel there is a strong potential for retaliation when filing a PASS report. This finding is unfortunate but matches the results of a multicenter study that found that 44.6% of residents felt uncomfortable reporting patient errors, possibly secondary to fear of retaliation, along with issues with the reporting system.12

It is interesting to note that a minority of residents indicated that they feel that PASS reports are filed as often as they should be (25.9% on first survey and 24.1% on second survey). This is concerning, as the data gathered through PASS reports is used to improve patient care. However, the percentage reported in our study, although low, is higher than that reported in a similar study involving patients with Medicare insurance, which showed that only 14% of patient safety events were reported.13 These results demonstrate that further interventions are necessary in order to ensure that a PASS report is filed each time a patient safety event occurs.

Another finding of note is that the majority of residents also feel that the process of filing a PASS report is too time consuming. The majority of residents who have completed a PASS report stated that it took them between 10 and 20 minutes to complete a PASS report, but those same individuals also feel that it should take < 10 minutes to complete a PASS report. This is an important issue for hospital systems to address. Reducing the time it takes to file a PASS report may facilitate an increase in the amount of PASS reports filed.

We administered our surveys using email outreach to residents asking them to complete an anonymous online survey regarding the PASS report system using the REDCap software system. Researchers have various ways of administering surveys, ranging from paper surveys, emails, and even mobile apps. One study showed that online surveys tend to have higher response rates compared to non-online surveys, such as paper surveys and telephone surveys, which is likely due to the ease of use of online surveys.14 At the same time, unsolicited email surveys have been shown to have a negative influence on response rates. Mobile apps are a new way of administering surveys. However, research has not found any significant difference in the time required to complete the survey using mobile apps compared to other forms of administering surveys. In addition, surveys using mobile apps did not have increased response rates compared to other forms of administering surveys.15

To increase the response rate of our surveys, we offered gift cards to the study population for completing the survey. Studies have shown that surveys that offer incentives tend to have higher response rates than surveys that do not.16 Also, in addition to serving as a method for gathering data from our study population, we used our surveys as an intervention to increase awareness of PASS reporting, as reported in other studies. For example, another study used the HABITS questionnaire to not only gather information about children’s diet, but also to promote behavioral change towards healthy eating habits.17

This study had several limitations. First, the study was conducted using an anonymous online survey, which means we could not clarify questions that residents found confusing or needed further explanation. For example, 17 residents indicated in the first survey that they knew how to PASS report, but 19 residents indicated in the same survey that they have filed a PASS report in the past.

A second limitation of the study was that fewer residents completed the second survey (29 of 54 eligible residents) compared to the first survey (54 of 80 eligible residents). This may have impacted the results of the analysis, as certain findings were not statistically significant, despite trends in the data.

A third limitation of the study is that not all of the residents that completed the first and second surveys completed the entire intervention. For example, some residents did not attend the didactic lecture discussing PASS reports, and as such may not have received the appropriate training prior to completing the second survey.

The findings from this study can be used by the residency programs at UH-RH and by residency programs across the country to improve the involvement and attitudes of residents in reporting errors in patient care. Hospital staff need to be encouraged and educated on how to better report patient errors and the importance of reporting these errors. It would benefit hospital systems to provide continued and targeted training to familiarize physicians with the process of reporting patient errors, and take steps to reduce the time it takes to report patient errors. By increasing the reporting of errors, hospitals will be able to improve patient care through initiatives aimed at preventing errors.

Conclusion

Residents play an important role in providing high-quality care for patients. Part of providing high-quality care is the reporting of errors in patient care when they occur. Physicians, and in particular, residents, have historically underreported errors in patient care. Part of this underreporting results from residents not knowing or understanding the process of filing a report and feeling that the reports could be used as a form of retaliation. For hospital systems to continue to improve patient care, it is important for residents to not only know how to report errors in patient care but to feel comfortable doing so.

Corresponding author: Andrew J. Chin, DO, MS, MPH, Department of Internal Medicine, Adelante Healthcare, 1705 W Main St, Mesa, AZ 85201; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

Funding: This study was funded by a research grant provided by Lake Eric College of Osteopathic Medicine to Andrew J. Chin and Anish Bhakta.

From Adelante Healthcare, Mesa, AZ (Dr. Chin), University Hospitals of Cleveland, Cleveland, OH (Drs. Delozier, Bascug, Levine, Bejanishvili, and Wynbrandt and Janet C. Peachey, Rachel M. Cerminara, and Sharon M. Darkovich), and Houston Methodist Hospitals, Houston, TX (Dr. Bhakta).

Abstract

Background: Resident physicians play an active role in the reporting of errors that occur in patient care. Previous studies indicate that residents significantly underreport errors in patient care.

Methods: Fifty-four of 80 eligible residents enrolled at University Hospitals–Regional Hospitals (UH-RH) during the 2018-2019 academic year completed a survey assessing their knowledge and experience in completing Patient Advocacy and Shared Stories (PASS) reports, which serve as incident reports in the UH health system in reporting errors in patient care. A series of interventions aimed at educating residents about the PASS report system were then conducted. The 54 residents who completed the first survey received it again 4 months later.

Results: Residents demonstrated greater understanding of when filing PASS reports was appropriate after the intervention, as significantly more residents reported having been involved in a situation where they should have filed a PASS report but did not (P = 0.036).

Conclusion: In this study, residents often did not report errors in patient care because they simply did not know the process for doing so. In addition, many residents often felt that the reporting of patient errors could be used as a form of retaliation.

Keywords: resident physicians; quality improvement; high-value care; medical errors; patient safety.

Resident physicians play a critical role in patient care. Residents undergo extensive supervised training in order to one day be able to practice medicine in an unsupervised setting, with the goal of providing the highest quality of care possible. One study reported that primary care provided by residents in a training program is of similar or higher quality than that provided by attending physicians.1

Besides providing high-quality care, it is important that residents play an active role in the reporting of errors that occur regarding patient care as well as in identifying events that may compromise patient safety and quality.2 In fact, increased reporting of patient errors has been shown to decrease liability-related costs for hospitals.3 Unfortunately, physicians, and residents in particular, have historically been poor reporters of errors in patient care.4 This is especially true when comparing physicians to other health professionals, such as nurses, in error reporting.5

Several studies have examined the involvement of residents in reporting errors in patient care. One recent study showed that a graduate medical education financial incentive program significantly increased the number of patient safety events reported by residents and fellows.6 This study, along with several others, supports the concept of using incentives to help improve the reporting of errors in patient care for physicians in training.7-10 Another study used Quality Improvement Knowledge Assessment Tool (QIKAT) scores to assess quality improvement (QI) knowledge. The study demonstrated that self-assessment scores of QI skills using QIKAT scores improved following a targeted intervention.11 Because further information on the involvement and attitudes of residents in reporting errors in patient care is needed, University Hospitals of Cleveland (UH) designed and implemented a QI study during the 2018-2019 academic year. This prospective study used anonymous surveys to objectively examine the involvement and attitudes of residents in reporting errors in patient care.

Methods

The UH health system uses Patient Advocacy and Shared Stories (PASS) reports as incident reports to not only disclose errors in patient care but also to identify any events that may compromise patient safety and quality. Based on preliminary review, nurses, ancillary staff, and administrators file the majority of PASS reports.

The study group consisted of residents at University Hospitals–Regional Hospitals (UH-RH), which is comprised of 2 hospitals: University Hospitals–Richmond Medical Center (UH-RMC) and University Hospitals –Bedford Medical Center (UH-BMC). UH-RMC and UH-BMC are 2 medium-sized university-affiliated community hospitals located in the Cleveland metropolitan area in Northeast Ohio. Both serve as clinical training sites for Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine and Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine, the latter of which helped fund this study. The study was submitted to the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of University Hospitals of Cleveland and granted “not human subjects research” status as a QI study.

Surveys

UH-RH offers residency programs in dermatology, emergency medicine, family medicine, internal medicine, orthopedic surgery, and physical medicine and rehabilitation, along with a 1-year transitional/preliminary year. A total of 80 residents enrolled at UH-RH during the 2018-2019 academic year. All 80 residents at UH-RH received an email in December 2018 asking them to complete an anonymous survey regarding the PASS report system. The survey was administered using the REDCap software system and consisted of 15 multiple-choice questions. As an incentive for completing the survey, residents were offered a $10 Amazon gift card. The gift cards were funded through a research grant from Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine. Residents were given 1 week to complete the survey. At the end of the week, 54 of 80 residents completed the first survey.

Following the first survey, efforts were undertaken by the study authors, in conjunction with the quality improvement department at UH-RH, to educate residents about the PASS report system. These interventions included giving a lecture on the PASS report system during resident didactic sessions, sending an email to all residents about the PASS report system, and providing residents an opportunity to complete an optional online training course regarding the PASS report system. As an incentive for completing the online training course, residents were offered a $10 Amazon gift card. As before, the gift cards were funded through a research grant from Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine.

A second survey was administered in April 2019, 4 months after the first survey. To determine whether the intervention made an impact on the involvement and attitudes of residents in the reporting errors in patient care, only residents who completed the first survey were sent the second survey. The second survey consisted of the same questions as the first survey and was also administered using the REDCap software system. As an incentive for completing the survey, residents were offered another $10 Amazon gift card, again were funded through a research grant from Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine. Residents were given 1 week to complete the survey.

Analysis

Chi-square analyses were utilized to examine differences between preintervention and postintervention responses across categories. All analyses were conducted using R statistical software, version 3.6.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

A total of 54 of 80 eligible residents responded to the first survey (Table). Twenty-nine of 54 eligible residents responded to the second survey. Postintervention, significantly more residents indicated being involved in a situation where they should have filed a PASS report but did not (58.6% vs 53.7%; P = 0.036). Improvement was seen in PASS knowledge postintervention, where fewer residents reported not knowing how to file a PASS report (31.5% vs 55.2%; P = 0.059). No other improvements were significant, nor were there significant differences in responses between any other categories pre- and postintervention.

Discussion

Errors in patient care are a common occurrence in the hospital setting. Reporting errors when they happen is important for hospitals to gain data and better care for patients, but studies show that patient errors are usually underreported. This is concerning, as data on errors and other aspects of patient care are needed to inform quality improvement programs.

This study measured residents’ attitudes and knowledge regarding the filing of a PASS report. It also aimed to increase both the frequency of and knowledge about filing a PASS report with interventions. The results from each survey indicated a statistically significant increase in knowledge of when to file a PASS report. In the first survey, 53.7% of residents responded they they were involved in an instance where they should have filed a PASS report but did not. In the second survey, 58.5% of residents reported being involved in an instance where they should have filed a PASS report but did not. This difference was statistically significant (P = 0.036), sugesting that the intervention was successful at increasing residents’ knowledge regarding PASS reports and the appropriate times to file a PASS report.

The survey results also showed a trend toward increasing aggregate knowledge level of how to file PASS reports on the first survey and second surveys (from 31.5% vs 55.2%. This demonstrates an increase in knowledge of how to file a PASS report among residents at our hospital after the intervention. It should be noted that the intervention that was performed in this study was simple, easy to perform, and can be completed at any hospital system that uses a similar system for reporting patient errors.

Another important trend indicating the effectiveness of the intervention was a 15% increase in knowledge of what the PASS report acronym stands for, along with a 13.1% aggregate increase in the number of residents who filed a PASS report. This indicated that residents may have wanted to file a PASS report previously but simply did not know how to until the intervention. In addition, there was also a decrease in the aggregate percentages of residents who had never filed a PASS report and an increase in how many PASS reports were filed.

While PASS reports are a great way for hospitals to gain data and insight into problems at their sites, there was also a negative view of PASS reports. For example, a large percentage of residents indicated that filing a PASS report would not make any difference and that PASS reports are often used as a form of retaliation, either against themselves as the submitter or the person(s) mentioned in the PASS report. More specifically, more than 50% of residents felt that PASS reports were sometimes or often used as a form of retaliation against others. While many residents correctly identified in the survey that PASS reports are not equivalent to a “write-up,” it is concerning that they still feel there is a strong potential for retaliation when filing a PASS report. This finding is unfortunate but matches the results of a multicenter study that found that 44.6% of residents felt uncomfortable reporting patient errors, possibly secondary to fear of retaliation, along with issues with the reporting system.12

It is interesting to note that a minority of residents indicated that they feel that PASS reports are filed as often as they should be (25.9% on first survey and 24.1% on second survey). This is concerning, as the data gathered through PASS reports is used to improve patient care. However, the percentage reported in our study, although low, is higher than that reported in a similar study involving patients with Medicare insurance, which showed that only 14% of patient safety events were reported.13 These results demonstrate that further interventions are necessary in order to ensure that a PASS report is filed each time a patient safety event occurs.

Another finding of note is that the majority of residents also feel that the process of filing a PASS report is too time consuming. The majority of residents who have completed a PASS report stated that it took them between 10 and 20 minutes to complete a PASS report, but those same individuals also feel that it should take < 10 minutes to complete a PASS report. This is an important issue for hospital systems to address. Reducing the time it takes to file a PASS report may facilitate an increase in the amount of PASS reports filed.

We administered our surveys using email outreach to residents asking them to complete an anonymous online survey regarding the PASS report system using the REDCap software system. Researchers have various ways of administering surveys, ranging from paper surveys, emails, and even mobile apps. One study showed that online surveys tend to have higher response rates compared to non-online surveys, such as paper surveys and telephone surveys, which is likely due to the ease of use of online surveys.14 At the same time, unsolicited email surveys have been shown to have a negative influence on response rates. Mobile apps are a new way of administering surveys. However, research has not found any significant difference in the time required to complete the survey using mobile apps compared to other forms of administering surveys. In addition, surveys using mobile apps did not have increased response rates compared to other forms of administering surveys.15

To increase the response rate of our surveys, we offered gift cards to the study population for completing the survey. Studies have shown that surveys that offer incentives tend to have higher response rates than surveys that do not.16 Also, in addition to serving as a method for gathering data from our study population, we used our surveys as an intervention to increase awareness of PASS reporting, as reported in other studies. For example, another study used the HABITS questionnaire to not only gather information about children’s diet, but also to promote behavioral change towards healthy eating habits.17

This study had several limitations. First, the study was conducted using an anonymous online survey, which means we could not clarify questions that residents found confusing or needed further explanation. For example, 17 residents indicated in the first survey that they knew how to PASS report, but 19 residents indicated in the same survey that they have filed a PASS report in the past.

A second limitation of the study was that fewer residents completed the second survey (29 of 54 eligible residents) compared to the first survey (54 of 80 eligible residents). This may have impacted the results of the analysis, as certain findings were not statistically significant, despite trends in the data.

A third limitation of the study is that not all of the residents that completed the first and second surveys completed the entire intervention. For example, some residents did not attend the didactic lecture discussing PASS reports, and as such may not have received the appropriate training prior to completing the second survey.

The findings from this study can be used by the residency programs at UH-RH and by residency programs across the country to improve the involvement and attitudes of residents in reporting errors in patient care. Hospital staff need to be encouraged and educated on how to better report patient errors and the importance of reporting these errors. It would benefit hospital systems to provide continued and targeted training to familiarize physicians with the process of reporting patient errors, and take steps to reduce the time it takes to report patient errors. By increasing the reporting of errors, hospitals will be able to improve patient care through initiatives aimed at preventing errors.

Conclusion

Residents play an important role in providing high-quality care for patients. Part of providing high-quality care is the reporting of errors in patient care when they occur. Physicians, and in particular, residents, have historically underreported errors in patient care. Part of this underreporting results from residents not knowing or understanding the process of filing a report and feeling that the reports could be used as a form of retaliation. For hospital systems to continue to improve patient care, it is important for residents to not only know how to report errors in patient care but to feel comfortable doing so.

Corresponding author: Andrew J. Chin, DO, MS, MPH, Department of Internal Medicine, Adelante Healthcare, 1705 W Main St, Mesa, AZ 85201; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

Funding: This study was funded by a research grant provided by Lake Eric College of Osteopathic Medicine to Andrew J. Chin and Anish Bhakta.

1. Zallman L, Ma J, Xiao L, Lasser KE. Quality of US primary care delivered by resident and staff physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(11):1193-1197.

2. Bagain JP. The future of graduate medical education: a systems-based approach to ensure patient safety. Acad Med. 2015;90(9):1199-1202.

3. Kachalia A, Kaufman SR, Boothman R, et al. Liability claims and costs before and after implementation of a medical disclosure program. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(4):213-221.

4. Kaldjian LC, Jones EW, Wu BJ, et al. Reporting medical errors to improve patient safety: a survey of physicians in teaching hospitals. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(1):40-46.

5. Rowin EJ, Lucier D, Pauker SG, et al. Does error and adverse event reporting by physicians and nurses differ? Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34(9):537-545.

6. Turner DA, Bae J, Cheely G, et al. Improving resident and fellow engagement in patient safety through a graduate medical education incentive program. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10(6):671-675.

7. Macht R, Balen A, McAneny D, Hess D. A multifaceted intervention to increase surgery resident engagement in reporting adverse events. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(6):e117-e122.

8. Scott DR, Weimer M, English C, et al. A novel approach to increase residents’ involvement in reporting adverse events. Acad Med. 2011;86(6):742-746.

9. Stewart DA, Junn J, Adams MA, et al. House staff participation in patient safety reporting: identification of predominant barriers and implementation of a pilot program. South Med J. 2016;109(7):395-400.

10. Vidyarthi AR, Green AL, Rosenbluth G, Baron RB. Engaging residents and fellows to improve institution-wide quality: the first six years of a novel financial incentive program. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):460-468.

11. Fok MC, Wong RY. Impact of a competency based curriculum on quality improvement among internal medicine residents. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:252.

12. Wijesekera TP, Sanders L, Windish DM. Education and reporting of diagnostic errors among physicians in internal medicine training programs. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(11):1548-1549.

13. Levinson DR. Hospital incident reporting systems do not capture most patient harm. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Inspector General. January 2012. Report No. OEI-06-09-00091.

14. Evans JR, Mathur A. The value of online surveys. Internet Research. 2005;15(2):192-219.

15. Marcano Belisario JS, Jamsek J, Huckvale K, et al. Comparison of self‐administered survey questionnaire responses collected using mobile apps versus other methods. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2015;7:MR000042.

16. Manfreda KL, Batagelj Z, Vehovar V. Design of web survey questionnaires: three basic experiments. J Comput Mediat Commun. 2002;7(3):JCMC731.

17. Wright ND, Groisman‐Perelstein AE, Wylie‐Rosett J, et al. A lifestyle assessment and intervention tool for pediatric weight management: the HABITS questionnaire. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2011;24(1):96-100.

1. Zallman L, Ma J, Xiao L, Lasser KE. Quality of US primary care delivered by resident and staff physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(11):1193-1197.

2. Bagain JP. The future of graduate medical education: a systems-based approach to ensure patient safety. Acad Med. 2015;90(9):1199-1202.

3. Kachalia A, Kaufman SR, Boothman R, et al. Liability claims and costs before and after implementation of a medical disclosure program. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(4):213-221.

4. Kaldjian LC, Jones EW, Wu BJ, et al. Reporting medical errors to improve patient safety: a survey of physicians in teaching hospitals. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(1):40-46.

5. Rowin EJ, Lucier D, Pauker SG, et al. Does error and adverse event reporting by physicians and nurses differ? Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34(9):537-545.

6. Turner DA, Bae J, Cheely G, et al. Improving resident and fellow engagement in patient safety through a graduate medical education incentive program. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10(6):671-675.

7. Macht R, Balen A, McAneny D, Hess D. A multifaceted intervention to increase surgery resident engagement in reporting adverse events. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(6):e117-e122.

8. Scott DR, Weimer M, English C, et al. A novel approach to increase residents’ involvement in reporting adverse events. Acad Med. 2011;86(6):742-746.

9. Stewart DA, Junn J, Adams MA, et al. House staff participation in patient safety reporting: identification of predominant barriers and implementation of a pilot program. South Med J. 2016;109(7):395-400.

10. Vidyarthi AR, Green AL, Rosenbluth G, Baron RB. Engaging residents and fellows to improve institution-wide quality: the first six years of a novel financial incentive program. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):460-468.

11. Fok MC, Wong RY. Impact of a competency based curriculum on quality improvement among internal medicine residents. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:252.

12. Wijesekera TP, Sanders L, Windish DM. Education and reporting of diagnostic errors among physicians in internal medicine training programs. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(11):1548-1549.

13. Levinson DR. Hospital incident reporting systems do not capture most patient harm. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Inspector General. January 2012. Report No. OEI-06-09-00091.

14. Evans JR, Mathur A. The value of online surveys. Internet Research. 2005;15(2):192-219.

15. Marcano Belisario JS, Jamsek J, Huckvale K, et al. Comparison of self‐administered survey questionnaire responses collected using mobile apps versus other methods. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2015;7:MR000042.

16. Manfreda KL, Batagelj Z, Vehovar V. Design of web survey questionnaires: three basic experiments. J Comput Mediat Commun. 2002;7(3):JCMC731.

17. Wright ND, Groisman‐Perelstein AE, Wylie‐Rosett J, et al. A lifestyle assessment and intervention tool for pediatric weight management: the HABITS questionnaire. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2011;24(1):96-100.