User login

Black Veterans Less Likely to Get COVID-Specific Treatments at VAMCs

Black veterans hospitalized with COVID-19 were less likely to be treated with evidence-based treatments, in a study conducted in 130 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers between March 1, 2020, and February 28, 2022.

The study involved 12,135 Black veterans and 40,717 White veterans. Most patients hospitalized during period 1 (March-September 2020) were Black veterans and the proportion of White patients increased over time. The latter 3 periods, which included the Delta- and Omicron-predominant periods, saw the most admissions.

Controlling for the site of treatment, Black patients were equally likely to be admitted to the intensive care unit (40% vs 43%). However, they were less likely to receive steroids, remdesivir, or immunomodulatory drugs.

The researchers say their data confirm other findings from 41 US health care systems participating in the National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network (PCORNet), which found lower use of monoclonal antibody treatment for COVID infection for patients who identified as Asian, Black, Hispanic, American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, or multiple races.

The researchers did not observe consistent differences in clinical outcomes between Black and White patients. After adjusting for demographics, chronic health conditions, severity of acute illness, and receipt of COVID-19–specific treatments, there was no association of Black race with hospital mortality or 30-day readmission. Black and White patients had a similar burden of preexisting health conditions. Of 38,782 patients discharged, 14% were readmitted within 30 days; the median time to readmission for both groups was 9 days.

Differences in care were partially explained by within- and between-hospital differences, the researchers say. They also cite research that demonstrated a poorer quality of care for hospitals with higher monthly COVID-19 discharges and hospital size.

The study results contradict the assumptions that differences in inpatient treatment by race and ethnicity may be due to differences in clinical indications for medication use based on age and comorbidities, such as chronic kidney or liver disease, the researchers say. For one thing, the VA issued a systemwide COVID-19 response plan that included specific treatment guidelines and distribution plans. But they also point to recent reports that have suggested that occult hypoxemia not detected by pulse oximetry occurs “far more often in Black patients than White patients,” which could result in delayed or missed opportunities to treat patients with COVID-19.

Black veterans hospitalized with COVID-19 were less likely to be treated with evidence-based treatments, in a study conducted in 130 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers between March 1, 2020, and February 28, 2022.

The study involved 12,135 Black veterans and 40,717 White veterans. Most patients hospitalized during period 1 (March-September 2020) were Black veterans and the proportion of White patients increased over time. The latter 3 periods, which included the Delta- and Omicron-predominant periods, saw the most admissions.

Controlling for the site of treatment, Black patients were equally likely to be admitted to the intensive care unit (40% vs 43%). However, they were less likely to receive steroids, remdesivir, or immunomodulatory drugs.

The researchers say their data confirm other findings from 41 US health care systems participating in the National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network (PCORNet), which found lower use of monoclonal antibody treatment for COVID infection for patients who identified as Asian, Black, Hispanic, American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, or multiple races.

The researchers did not observe consistent differences in clinical outcomes between Black and White patients. After adjusting for demographics, chronic health conditions, severity of acute illness, and receipt of COVID-19–specific treatments, there was no association of Black race with hospital mortality or 30-day readmission. Black and White patients had a similar burden of preexisting health conditions. Of 38,782 patients discharged, 14% were readmitted within 30 days; the median time to readmission for both groups was 9 days.

Differences in care were partially explained by within- and between-hospital differences, the researchers say. They also cite research that demonstrated a poorer quality of care for hospitals with higher monthly COVID-19 discharges and hospital size.

The study results contradict the assumptions that differences in inpatient treatment by race and ethnicity may be due to differences in clinical indications for medication use based on age and comorbidities, such as chronic kidney or liver disease, the researchers say. For one thing, the VA issued a systemwide COVID-19 response plan that included specific treatment guidelines and distribution plans. But they also point to recent reports that have suggested that occult hypoxemia not detected by pulse oximetry occurs “far more often in Black patients than White patients,” which could result in delayed or missed opportunities to treat patients with COVID-19.

Black veterans hospitalized with COVID-19 were less likely to be treated with evidence-based treatments, in a study conducted in 130 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers between March 1, 2020, and February 28, 2022.

The study involved 12,135 Black veterans and 40,717 White veterans. Most patients hospitalized during period 1 (March-September 2020) were Black veterans and the proportion of White patients increased over time. The latter 3 periods, which included the Delta- and Omicron-predominant periods, saw the most admissions.

Controlling for the site of treatment, Black patients were equally likely to be admitted to the intensive care unit (40% vs 43%). However, they were less likely to receive steroids, remdesivir, or immunomodulatory drugs.

The researchers say their data confirm other findings from 41 US health care systems participating in the National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network (PCORNet), which found lower use of monoclonal antibody treatment for COVID infection for patients who identified as Asian, Black, Hispanic, American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, or multiple races.

The researchers did not observe consistent differences in clinical outcomes between Black and White patients. After adjusting for demographics, chronic health conditions, severity of acute illness, and receipt of COVID-19–specific treatments, there was no association of Black race with hospital mortality or 30-day readmission. Black and White patients had a similar burden of preexisting health conditions. Of 38,782 patients discharged, 14% were readmitted within 30 days; the median time to readmission for both groups was 9 days.

Differences in care were partially explained by within- and between-hospital differences, the researchers say. They also cite research that demonstrated a poorer quality of care for hospitals with higher monthly COVID-19 discharges and hospital size.

The study results contradict the assumptions that differences in inpatient treatment by race and ethnicity may be due to differences in clinical indications for medication use based on age and comorbidities, such as chronic kidney or liver disease, the researchers say. For one thing, the VA issued a systemwide COVID-19 response plan that included specific treatment guidelines and distribution plans. But they also point to recent reports that have suggested that occult hypoxemia not detected by pulse oximetry occurs “far more often in Black patients than White patients,” which could result in delayed or missed opportunities to treat patients with COVID-19.

Race and gender: Tailoring treatment for sleep disorders is preferred and better

While trials of various interventions for obstructive sleep apnea and insomnia were effective, there was a strong suggestion that tailoring them according to the race/gender of the target populations strengthens engagement and improvements, according to a presentation by Dayna A. Johnson, PhD, MPH, at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST).

Dr. Johnson, assistant professor at Emory University in Atlanta, stated that determinants of sleep disparities are multifactorial across the lifespan, from in utero to aging, but it was also important to focus on social determinants of poor sleep.

The complexity of factors, she said, calls for multilevel interventions beyond screening and treatment. In addition, neighborhood factors including safety, noise and light pollution, ventilation, and thermal comfort come into play.

Dr. Johnson cited the example of parents who work multiple jobs to provide for their families: “Minimum wage is not a livable wage, and parents may not be available to ensure that children have consistent bedtimes.” Interventions, she added, may have to be at the neighborhood level, including placing sleep specialists in the local neighborhood “where the need is.” Cleaning up a neighborhood reduces crime and overall health, while light shielding in public housing can lower light pollution.

Observing that African Americans have higher rates of obstructive sleep apnea, Dr. Johnson and colleagues designed a screening tool specifically for African Americans with five prediction models with increasing levels of factor measurements (from 4 to 10). The prediction accuracy across the models ascended in lockstep with the number of measures from 74.0% to 76.1%, with the simplest model including only age, body mass index, male sex, and snoring. The latter model added witnessed apneas, high depressive symptoms, two measures of waist and neck size, and sleepiness. Dr. Johnson pointed out that accuracy for well-established predictive models is notably lower: STOP-Bang score ranges from 56% to 66%; NoSAS ranges from 58% to 66% and the HCHS prediction model accuracy is 70%. Dr. Johnson said that a Latino model they developed was more accurate than the traditional models, but not as accurate as their model for African Americans.

Turning to specific interventions, and underscoring higher levels of stress and anxiety among African American and Hispanic populations, Dr. Johnson cited MINDS (Mindfulness Intervention to Improve Sleep and Reduce Diabetes Risk Among a Diverse Sample in Atlanta), her study at Emory University of mindfulness meditation. Although prior studies have confirmed sleep benefits of mindfulness meditation, studies tailored for African American or Hispanic populations have been lacking.

The MINDS pilot study investigators enrolled 17 individuals (mostly women, with a mixture of racial and ethnic groups comprising Black, White, Asian and Hispanic patients) with poor sleep quality as measured by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Most patients, Dr. Johnson said, were overweight. Because of COVID restrictions on clinic visits, the diabetes portion of the study was dropped. All participants received at least 3 days of instruction on mindfulness meditation, on dealing with stress and anxiety, and on optimum sleep health practices. While PSQI scores higher than 5 are considered to indicate poor sleep quality, the mean PSQI score at study outset in MINDS was 9.2, she stated.

After 30 days of the intervention, stress (on a perceived stress scale) was improved, as were PSQI scores and actigraphy measures of sleep duration, efficiency and wakefulness after sleep onset, Dr. Johnson reported. “Participants found the mindfulness app to be acceptable and appropriate, and to reduce time to falling asleep,” Dr. Johnson said.

Qualitative data gathered post intervention from four focus groups (two to six participants in each; 1-1.5 hours in length), revealed general acceptability of the MINDS app. It showed also that among those with 50% or more adherence to the intervention, time to falling asleep was reduced, as were sleep awakenings at night. The most striking finding, Dr. Johnson said, was that individuals from among racial/ethnic minorities expressed appreciation of the diversity of the meditation instructors, and said that they preferred instruction from a person of their own race and sex. Findings would be even more striking with a larger sample size, Dr. Johnson speculated.

Citing TASHE (Tailored Approach to Sleep Health Education), a further observational study on obstructive sleep apnea knowledge conducted at New York University, Dr. Johnson addressed the fact that current messages are not tailored to race/ethnic minorities with low-to-moderate symptom knowledge. Also, a 3-arm randomized clinical trial of Internet-delivered treatment (Sleep Healthy or SHUTI) with a version revised for Black women (SHUTI-BWHS) showed findings similar to those of other studies cited and suggested: “Tailoring may be necessary to increase uptake and sustainability and to improve sleep among racial/ethnic minorities.”

Dr. Johnson noted, in closing, that Black/African American individuals have higher risk for obstructive sleep apnea than that of their White counterparts and lower rates of screening for treatment.

Dr. Johnson’s research was funded by the National Institutes of Health; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Woodruff Health Sciences Center; Synergy Award; Rollins School of Public Health Dean’s Pilot and Innovation Award; and Georgia Center for Diabetes Translation Research Pilot and Feasibility award program. She reported no relevant conflicts.

While trials of various interventions for obstructive sleep apnea and insomnia were effective, there was a strong suggestion that tailoring them according to the race/gender of the target populations strengthens engagement and improvements, according to a presentation by Dayna A. Johnson, PhD, MPH, at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST).

Dr. Johnson, assistant professor at Emory University in Atlanta, stated that determinants of sleep disparities are multifactorial across the lifespan, from in utero to aging, but it was also important to focus on social determinants of poor sleep.

The complexity of factors, she said, calls for multilevel interventions beyond screening and treatment. In addition, neighborhood factors including safety, noise and light pollution, ventilation, and thermal comfort come into play.

Dr. Johnson cited the example of parents who work multiple jobs to provide for their families: “Minimum wage is not a livable wage, and parents may not be available to ensure that children have consistent bedtimes.” Interventions, she added, may have to be at the neighborhood level, including placing sleep specialists in the local neighborhood “where the need is.” Cleaning up a neighborhood reduces crime and overall health, while light shielding in public housing can lower light pollution.

Observing that African Americans have higher rates of obstructive sleep apnea, Dr. Johnson and colleagues designed a screening tool specifically for African Americans with five prediction models with increasing levels of factor measurements (from 4 to 10). The prediction accuracy across the models ascended in lockstep with the number of measures from 74.0% to 76.1%, with the simplest model including only age, body mass index, male sex, and snoring. The latter model added witnessed apneas, high depressive symptoms, two measures of waist and neck size, and sleepiness. Dr. Johnson pointed out that accuracy for well-established predictive models is notably lower: STOP-Bang score ranges from 56% to 66%; NoSAS ranges from 58% to 66% and the HCHS prediction model accuracy is 70%. Dr. Johnson said that a Latino model they developed was more accurate than the traditional models, but not as accurate as their model for African Americans.

Turning to specific interventions, and underscoring higher levels of stress and anxiety among African American and Hispanic populations, Dr. Johnson cited MINDS (Mindfulness Intervention to Improve Sleep and Reduce Diabetes Risk Among a Diverse Sample in Atlanta), her study at Emory University of mindfulness meditation. Although prior studies have confirmed sleep benefits of mindfulness meditation, studies tailored for African American or Hispanic populations have been lacking.

The MINDS pilot study investigators enrolled 17 individuals (mostly women, with a mixture of racial and ethnic groups comprising Black, White, Asian and Hispanic patients) with poor sleep quality as measured by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Most patients, Dr. Johnson said, were overweight. Because of COVID restrictions on clinic visits, the diabetes portion of the study was dropped. All participants received at least 3 days of instruction on mindfulness meditation, on dealing with stress and anxiety, and on optimum sleep health practices. While PSQI scores higher than 5 are considered to indicate poor sleep quality, the mean PSQI score at study outset in MINDS was 9.2, she stated.

After 30 days of the intervention, stress (on a perceived stress scale) was improved, as were PSQI scores and actigraphy measures of sleep duration, efficiency and wakefulness after sleep onset, Dr. Johnson reported. “Participants found the mindfulness app to be acceptable and appropriate, and to reduce time to falling asleep,” Dr. Johnson said.

Qualitative data gathered post intervention from four focus groups (two to six participants in each; 1-1.5 hours in length), revealed general acceptability of the MINDS app. It showed also that among those with 50% or more adherence to the intervention, time to falling asleep was reduced, as were sleep awakenings at night. The most striking finding, Dr. Johnson said, was that individuals from among racial/ethnic minorities expressed appreciation of the diversity of the meditation instructors, and said that they preferred instruction from a person of their own race and sex. Findings would be even more striking with a larger sample size, Dr. Johnson speculated.

Citing TASHE (Tailored Approach to Sleep Health Education), a further observational study on obstructive sleep apnea knowledge conducted at New York University, Dr. Johnson addressed the fact that current messages are not tailored to race/ethnic minorities with low-to-moderate symptom knowledge. Also, a 3-arm randomized clinical trial of Internet-delivered treatment (Sleep Healthy or SHUTI) with a version revised for Black women (SHUTI-BWHS) showed findings similar to those of other studies cited and suggested: “Tailoring may be necessary to increase uptake and sustainability and to improve sleep among racial/ethnic minorities.”

Dr. Johnson noted, in closing, that Black/African American individuals have higher risk for obstructive sleep apnea than that of their White counterparts and lower rates of screening for treatment.

Dr. Johnson’s research was funded by the National Institutes of Health; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Woodruff Health Sciences Center; Synergy Award; Rollins School of Public Health Dean’s Pilot and Innovation Award; and Georgia Center for Diabetes Translation Research Pilot and Feasibility award program. She reported no relevant conflicts.

While trials of various interventions for obstructive sleep apnea and insomnia were effective, there was a strong suggestion that tailoring them according to the race/gender of the target populations strengthens engagement and improvements, according to a presentation by Dayna A. Johnson, PhD, MPH, at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST).

Dr. Johnson, assistant professor at Emory University in Atlanta, stated that determinants of sleep disparities are multifactorial across the lifespan, from in utero to aging, but it was also important to focus on social determinants of poor sleep.

The complexity of factors, she said, calls for multilevel interventions beyond screening and treatment. In addition, neighborhood factors including safety, noise and light pollution, ventilation, and thermal comfort come into play.

Dr. Johnson cited the example of parents who work multiple jobs to provide for their families: “Minimum wage is not a livable wage, and parents may not be available to ensure that children have consistent bedtimes.” Interventions, she added, may have to be at the neighborhood level, including placing sleep specialists in the local neighborhood “where the need is.” Cleaning up a neighborhood reduces crime and overall health, while light shielding in public housing can lower light pollution.

Observing that African Americans have higher rates of obstructive sleep apnea, Dr. Johnson and colleagues designed a screening tool specifically for African Americans with five prediction models with increasing levels of factor measurements (from 4 to 10). The prediction accuracy across the models ascended in lockstep with the number of measures from 74.0% to 76.1%, with the simplest model including only age, body mass index, male sex, and snoring. The latter model added witnessed apneas, high depressive symptoms, two measures of waist and neck size, and sleepiness. Dr. Johnson pointed out that accuracy for well-established predictive models is notably lower: STOP-Bang score ranges from 56% to 66%; NoSAS ranges from 58% to 66% and the HCHS prediction model accuracy is 70%. Dr. Johnson said that a Latino model they developed was more accurate than the traditional models, but not as accurate as their model for African Americans.

Turning to specific interventions, and underscoring higher levels of stress and anxiety among African American and Hispanic populations, Dr. Johnson cited MINDS (Mindfulness Intervention to Improve Sleep and Reduce Diabetes Risk Among a Diverse Sample in Atlanta), her study at Emory University of mindfulness meditation. Although prior studies have confirmed sleep benefits of mindfulness meditation, studies tailored for African American or Hispanic populations have been lacking.

The MINDS pilot study investigators enrolled 17 individuals (mostly women, with a mixture of racial and ethnic groups comprising Black, White, Asian and Hispanic patients) with poor sleep quality as measured by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Most patients, Dr. Johnson said, were overweight. Because of COVID restrictions on clinic visits, the diabetes portion of the study was dropped. All participants received at least 3 days of instruction on mindfulness meditation, on dealing with stress and anxiety, and on optimum sleep health practices. While PSQI scores higher than 5 are considered to indicate poor sleep quality, the mean PSQI score at study outset in MINDS was 9.2, she stated.

After 30 days of the intervention, stress (on a perceived stress scale) was improved, as were PSQI scores and actigraphy measures of sleep duration, efficiency and wakefulness after sleep onset, Dr. Johnson reported. “Participants found the mindfulness app to be acceptable and appropriate, and to reduce time to falling asleep,” Dr. Johnson said.

Qualitative data gathered post intervention from four focus groups (two to six participants in each; 1-1.5 hours in length), revealed general acceptability of the MINDS app. It showed also that among those with 50% or more adherence to the intervention, time to falling asleep was reduced, as were sleep awakenings at night. The most striking finding, Dr. Johnson said, was that individuals from among racial/ethnic minorities expressed appreciation of the diversity of the meditation instructors, and said that they preferred instruction from a person of their own race and sex. Findings would be even more striking with a larger sample size, Dr. Johnson speculated.

Citing TASHE (Tailored Approach to Sleep Health Education), a further observational study on obstructive sleep apnea knowledge conducted at New York University, Dr. Johnson addressed the fact that current messages are not tailored to race/ethnic minorities with low-to-moderate symptom knowledge. Also, a 3-arm randomized clinical trial of Internet-delivered treatment (Sleep Healthy or SHUTI) with a version revised for Black women (SHUTI-BWHS) showed findings similar to those of other studies cited and suggested: “Tailoring may be necessary to increase uptake and sustainability and to improve sleep among racial/ethnic minorities.”

Dr. Johnson noted, in closing, that Black/African American individuals have higher risk for obstructive sleep apnea than that of their White counterparts and lower rates of screening for treatment.

Dr. Johnson’s research was funded by the National Institutes of Health; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Woodruff Health Sciences Center; Synergy Award; Rollins School of Public Health Dean’s Pilot and Innovation Award; and Georgia Center for Diabetes Translation Research Pilot and Feasibility award program. She reported no relevant conflicts.

FROM CHEST 2022

Higher rates of PTSD, BPD in transgender vs. cisgender psych patients

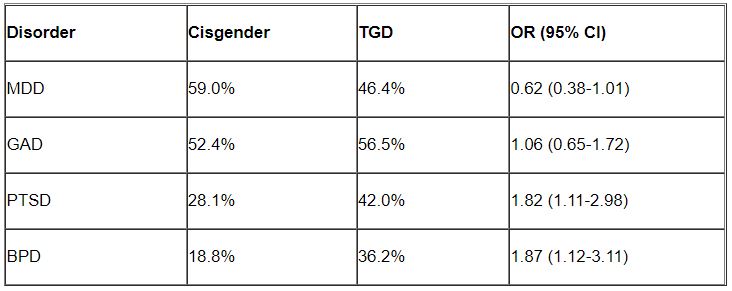

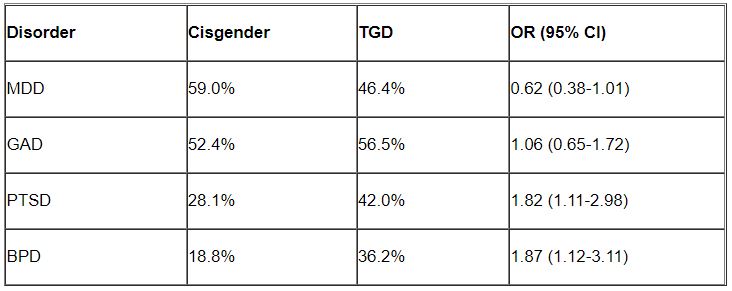

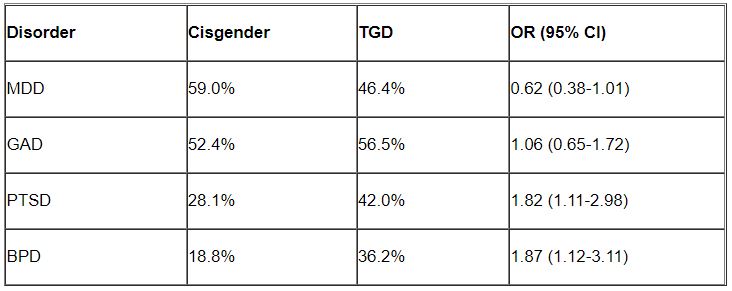

Although mood disorders, depression, and anxiety were the most common diagnoses in both TGD and cisgender patients, “when we compared the diagnostic profiles [of TGD patients] to those of cisgender patients, we found an increased prevalence of PTSD and BPD,” study investigator Mark Zimmerman, MD, professor of psychiatry and human behavior, Brown University, Providence, R.I., told this news organization.

“What we concluded is that psychiatric programs that wish to treat TGD patients should either have or should develop expertise in treating PTSD and BPD, not just mood and anxiety disorders,” Dr. Zimmerman said.

The study was published online September 26 in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

‘Piecemeal literature’

TGD individuals “experience high rates of various forms of psychopathology in general and when compared with cisgender persons,” the investigators note.

They point out that most empirical evidence has relied upon the use of brief, unstructured psychodiagnostic assessment measures and assessment of a “limited constellation of psychiatric symptoms domains,” resulting in a “piecemeal literature wherein each piece of research documents elevations in one – or a few – diagnostic domains.”

Studies pointing to broader psychosocial health variables have often relied upon self-reported measures. In addition, in studies that utilized a structured interview approach, none “used a formal interview procedure to assess psychiatric diagnoses” and most focused only on a “limited number of psychiatric conditions based on self-reports of past diagnosis.”

The goal of the current study was to use semistructured interviews administered by professionals to compare the diagnostic profiles of a samples of TGD and cisgender patients who presented for treatment at a single naturalistic, clinically acute setting – a partial hospital program.

Dr. Zimmerman said that there was an additional motive for conducting the study. “There has been discussion in the field as to whether or not transgender or gender-diverse individuals all have borderline personality disorder, but that hasn’t been our clinical impression.”

Rather, Dr. Zimmerman and colleagues believe TGD people “may have had more difficult childhoods and more difficult adjustments in society because of societal attitudes and have to deal with that stress, whether it be microaggressions or overt bullying and aggression.” The study was designed to investigate this issue.

In addition, studies conducted in primary care programs in individuals seeking gender-affirming surgery have “reported a limited number of psychiatric diagnoses, but we were wondering whether, amongst psychiatric patients specifically, there were differences in diagnostic profiles between transgender and gender-diverse patients and cisgender patients. If so, what might the implications be for providing care for this population?”

TGD not synonymous with borderline

To investigate, the researchers administered semistructured diagnostic interviews for DSM-IV disorders to 2,212 psychiatric patients (66% cisgender women, 30.8% cisgender men, 3.1% TGD; mean [standard deviation] age 36.7 [14.4] years) presenting to the Rhode Island Hospital Department of Psychiatry Partial Hospital Program between April 2014 and January 2021.

Patients also completed a demographic questionnaire including their assigned sex at birth and their current gender identity.

Most patients (44.9%) were single, followed by 23.5% who were married, 14.1% living in a relationship as if married, 12.0% divorced, 3.6% separated, and 1.9% widowed.

Almost three-quarters of participants (73.2%) identified as White, followed by Hispanic (10.7%), Black (6.7%), “other” or a combination of racial/ethnic backgrounds (6.6%), and Asian (2.7%).

There were no differences between cisgender and TGD groups in terms of race or education, but the TGD patients were significantly younger compared with their cisgender counterparts and were significantly more likely to have never been married.

The average number of psychiatric diagnoses in the sample was 3.05 (± 1.73), with TGD patients having a larger number of psychiatric diagnoses than did their cisgender peers (an average of 3.54 ± 1.88 vs. 3.04 ± 1.72, respectively; t = 2.37; P = .02).

Major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) were the most common disorders among both cisgender and TGD patients. However, after controlling for age, the researchers found that TGD patients were significantly more likely than were the cisgender patients to be diagnosed with PTSD and BPD (P < .05 for both).

“Of note, only about one-third of the TGD individuals were diagnosed with BPD, so it is important to realize that transgender or gender-diverse identity is not synonymous with BPD, as some have suggested,” noted Dr. Zimmerman, who is also the director of the outpatient division at the Partial Hospital Program, Rhode Island Hospital.

A representative sample?

Commenting on the study, Jack Drescher, MD, distinguished life fellow of the American Psychiatric Association and clinical professor of psychiatry, Columbia University, New York, called the findings “interesting” but noted that a limitation of the study is that it included “a patient population with likely more severe psychiatric illness, since they were all day hospital patients.”

The question is whether similar findings would be obtained in a less severely ill population, said Dr. Drescher, who is also a senior consulting analyst for sexuality and gender at Columbia University and was not involved with the study. “The patients in the study may not be representative of the general population, either cisgender or transgender.”

Dr. Drescher was “not surprised” by the finding regarding PTSD because the finding “is consistent with our understanding of the kinds of traumas that transgender people go through in day-to-day life.”

He noted that some people misunderstand the diagnostic criterion in BPD of identity confusion and think that because people with gender dysphoria may be confused about their identity, it means that all people who are transgender have borderline personality disorder, “but that’s not true.”

Dr. Zimmerman agreed. “The vast majority of individuals with BPD do not have a transgender or gender-diverse identity, and TGD should not be equated with BPD,” he said.

No source of study funding was disclosed. Dr. Zimmerman and coauthors and Dr. Drescher report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although mood disorders, depression, and anxiety were the most common diagnoses in both TGD and cisgender patients, “when we compared the diagnostic profiles [of TGD patients] to those of cisgender patients, we found an increased prevalence of PTSD and BPD,” study investigator Mark Zimmerman, MD, professor of psychiatry and human behavior, Brown University, Providence, R.I., told this news organization.

“What we concluded is that psychiatric programs that wish to treat TGD patients should either have or should develop expertise in treating PTSD and BPD, not just mood and anxiety disorders,” Dr. Zimmerman said.

The study was published online September 26 in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

‘Piecemeal literature’

TGD individuals “experience high rates of various forms of psychopathology in general and when compared with cisgender persons,” the investigators note.

They point out that most empirical evidence has relied upon the use of brief, unstructured psychodiagnostic assessment measures and assessment of a “limited constellation of psychiatric symptoms domains,” resulting in a “piecemeal literature wherein each piece of research documents elevations in one – or a few – diagnostic domains.”

Studies pointing to broader psychosocial health variables have often relied upon self-reported measures. In addition, in studies that utilized a structured interview approach, none “used a formal interview procedure to assess psychiatric diagnoses” and most focused only on a “limited number of psychiatric conditions based on self-reports of past diagnosis.”

The goal of the current study was to use semistructured interviews administered by professionals to compare the diagnostic profiles of a samples of TGD and cisgender patients who presented for treatment at a single naturalistic, clinically acute setting – a partial hospital program.

Dr. Zimmerman said that there was an additional motive for conducting the study. “There has been discussion in the field as to whether or not transgender or gender-diverse individuals all have borderline personality disorder, but that hasn’t been our clinical impression.”

Rather, Dr. Zimmerman and colleagues believe TGD people “may have had more difficult childhoods and more difficult adjustments in society because of societal attitudes and have to deal with that stress, whether it be microaggressions or overt bullying and aggression.” The study was designed to investigate this issue.

In addition, studies conducted in primary care programs in individuals seeking gender-affirming surgery have “reported a limited number of psychiatric diagnoses, but we were wondering whether, amongst psychiatric patients specifically, there were differences in diagnostic profiles between transgender and gender-diverse patients and cisgender patients. If so, what might the implications be for providing care for this population?”

TGD not synonymous with borderline

To investigate, the researchers administered semistructured diagnostic interviews for DSM-IV disorders to 2,212 psychiatric patients (66% cisgender women, 30.8% cisgender men, 3.1% TGD; mean [standard deviation] age 36.7 [14.4] years) presenting to the Rhode Island Hospital Department of Psychiatry Partial Hospital Program between April 2014 and January 2021.

Patients also completed a demographic questionnaire including their assigned sex at birth and their current gender identity.

Most patients (44.9%) were single, followed by 23.5% who were married, 14.1% living in a relationship as if married, 12.0% divorced, 3.6% separated, and 1.9% widowed.

Almost three-quarters of participants (73.2%) identified as White, followed by Hispanic (10.7%), Black (6.7%), “other” or a combination of racial/ethnic backgrounds (6.6%), and Asian (2.7%).

There were no differences between cisgender and TGD groups in terms of race or education, but the TGD patients were significantly younger compared with their cisgender counterparts and were significantly more likely to have never been married.

The average number of psychiatric diagnoses in the sample was 3.05 (± 1.73), with TGD patients having a larger number of psychiatric diagnoses than did their cisgender peers (an average of 3.54 ± 1.88 vs. 3.04 ± 1.72, respectively; t = 2.37; P = .02).

Major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) were the most common disorders among both cisgender and TGD patients. However, after controlling for age, the researchers found that TGD patients were significantly more likely than were the cisgender patients to be diagnosed with PTSD and BPD (P < .05 for both).

“Of note, only about one-third of the TGD individuals were diagnosed with BPD, so it is important to realize that transgender or gender-diverse identity is not synonymous with BPD, as some have suggested,” noted Dr. Zimmerman, who is also the director of the outpatient division at the Partial Hospital Program, Rhode Island Hospital.

A representative sample?

Commenting on the study, Jack Drescher, MD, distinguished life fellow of the American Psychiatric Association and clinical professor of psychiatry, Columbia University, New York, called the findings “interesting” but noted that a limitation of the study is that it included “a patient population with likely more severe psychiatric illness, since they were all day hospital patients.”

The question is whether similar findings would be obtained in a less severely ill population, said Dr. Drescher, who is also a senior consulting analyst for sexuality and gender at Columbia University and was not involved with the study. “The patients in the study may not be representative of the general population, either cisgender or transgender.”

Dr. Drescher was “not surprised” by the finding regarding PTSD because the finding “is consistent with our understanding of the kinds of traumas that transgender people go through in day-to-day life.”

He noted that some people misunderstand the diagnostic criterion in BPD of identity confusion and think that because people with gender dysphoria may be confused about their identity, it means that all people who are transgender have borderline personality disorder, “but that’s not true.”

Dr. Zimmerman agreed. “The vast majority of individuals with BPD do not have a transgender or gender-diverse identity, and TGD should not be equated with BPD,” he said.

No source of study funding was disclosed. Dr. Zimmerman and coauthors and Dr. Drescher report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although mood disorders, depression, and anxiety were the most common diagnoses in both TGD and cisgender patients, “when we compared the diagnostic profiles [of TGD patients] to those of cisgender patients, we found an increased prevalence of PTSD and BPD,” study investigator Mark Zimmerman, MD, professor of psychiatry and human behavior, Brown University, Providence, R.I., told this news organization.

“What we concluded is that psychiatric programs that wish to treat TGD patients should either have or should develop expertise in treating PTSD and BPD, not just mood and anxiety disorders,” Dr. Zimmerman said.

The study was published online September 26 in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

‘Piecemeal literature’

TGD individuals “experience high rates of various forms of psychopathology in general and when compared with cisgender persons,” the investigators note.

They point out that most empirical evidence has relied upon the use of brief, unstructured psychodiagnostic assessment measures and assessment of a “limited constellation of psychiatric symptoms domains,” resulting in a “piecemeal literature wherein each piece of research documents elevations in one – or a few – diagnostic domains.”

Studies pointing to broader psychosocial health variables have often relied upon self-reported measures. In addition, in studies that utilized a structured interview approach, none “used a formal interview procedure to assess psychiatric diagnoses” and most focused only on a “limited number of psychiatric conditions based on self-reports of past diagnosis.”

The goal of the current study was to use semistructured interviews administered by professionals to compare the diagnostic profiles of a samples of TGD and cisgender patients who presented for treatment at a single naturalistic, clinically acute setting – a partial hospital program.

Dr. Zimmerman said that there was an additional motive for conducting the study. “There has been discussion in the field as to whether or not transgender or gender-diverse individuals all have borderline personality disorder, but that hasn’t been our clinical impression.”

Rather, Dr. Zimmerman and colleagues believe TGD people “may have had more difficult childhoods and more difficult adjustments in society because of societal attitudes and have to deal with that stress, whether it be microaggressions or overt bullying and aggression.” The study was designed to investigate this issue.

In addition, studies conducted in primary care programs in individuals seeking gender-affirming surgery have “reported a limited number of psychiatric diagnoses, but we were wondering whether, amongst psychiatric patients specifically, there were differences in diagnostic profiles between transgender and gender-diverse patients and cisgender patients. If so, what might the implications be for providing care for this population?”

TGD not synonymous with borderline

To investigate, the researchers administered semistructured diagnostic interviews for DSM-IV disorders to 2,212 psychiatric patients (66% cisgender women, 30.8% cisgender men, 3.1% TGD; mean [standard deviation] age 36.7 [14.4] years) presenting to the Rhode Island Hospital Department of Psychiatry Partial Hospital Program between April 2014 and January 2021.

Patients also completed a demographic questionnaire including their assigned sex at birth and their current gender identity.

Most patients (44.9%) were single, followed by 23.5% who were married, 14.1% living in a relationship as if married, 12.0% divorced, 3.6% separated, and 1.9% widowed.

Almost three-quarters of participants (73.2%) identified as White, followed by Hispanic (10.7%), Black (6.7%), “other” or a combination of racial/ethnic backgrounds (6.6%), and Asian (2.7%).

There were no differences between cisgender and TGD groups in terms of race or education, but the TGD patients were significantly younger compared with their cisgender counterparts and were significantly more likely to have never been married.

The average number of psychiatric diagnoses in the sample was 3.05 (± 1.73), with TGD patients having a larger number of psychiatric diagnoses than did their cisgender peers (an average of 3.54 ± 1.88 vs. 3.04 ± 1.72, respectively; t = 2.37; P = .02).

Major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) were the most common disorders among both cisgender and TGD patients. However, after controlling for age, the researchers found that TGD patients were significantly more likely than were the cisgender patients to be diagnosed with PTSD and BPD (P < .05 for both).

“Of note, only about one-third of the TGD individuals were diagnosed with BPD, so it is important to realize that transgender or gender-diverse identity is not synonymous with BPD, as some have suggested,” noted Dr. Zimmerman, who is also the director of the outpatient division at the Partial Hospital Program, Rhode Island Hospital.

A representative sample?

Commenting on the study, Jack Drescher, MD, distinguished life fellow of the American Psychiatric Association and clinical professor of psychiatry, Columbia University, New York, called the findings “interesting” but noted that a limitation of the study is that it included “a patient population with likely more severe psychiatric illness, since they were all day hospital patients.”

The question is whether similar findings would be obtained in a less severely ill population, said Dr. Drescher, who is also a senior consulting analyst for sexuality and gender at Columbia University and was not involved with the study. “The patients in the study may not be representative of the general population, either cisgender or transgender.”

Dr. Drescher was “not surprised” by the finding regarding PTSD because the finding “is consistent with our understanding of the kinds of traumas that transgender people go through in day-to-day life.”

He noted that some people misunderstand the diagnostic criterion in BPD of identity confusion and think that because people with gender dysphoria may be confused about their identity, it means that all people who are transgender have borderline personality disorder, “but that’s not true.”

Dr. Zimmerman agreed. “The vast majority of individuals with BPD do not have a transgender or gender-diverse identity, and TGD should not be equated with BPD,” he said.

No source of study funding was disclosed. Dr. Zimmerman and coauthors and Dr. Drescher report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JOURNAL OF CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY

Dementia prevalence study reveals inequities

based on new U.S. data from The Health and Retirement Study (HRS).

These inequities likely stem from structural racism and income inequality, necessitating a multifaceted response at an institutional level, according to lead author Jennifer J. Manly, PhD, a professor of neuropsychology in neurology at the Gertrude H. Sergievsky Center and the Taub Institute for Research in Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease at Columbia University, New York.

A more representative dataset

Between 2001 and 2003, a subset of HRS participants underwent extensive neuropsychological assessment in the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study (ADAMS), providing data which have since been cited by hundreds of published studies, the investigators wrote in JAMA Neurology. Those data, however, failed to accurately represent the U.S. population at the time, and have not been updated since.

“The ADAMS substudy was small, and the limited inclusion of Black, Hispanic, and American Indian or Alaska Native participants contributed to lack of precision of estimates among minoritized racial and ethnic groups that have been shown to experience a higher burden of cognitive impairment and dementia,” Dr. Manly and colleagues wrote.

The present analysis used a more representative dataset from HRS participants who were 65 years or older in 2016. From June 2016 to October 2017, 3,496 of these individuals underwent comprehensive neuropsychological test battery and informant interview, with dementia and MCI classified based on standard diagnostic criteria.

In total, 393 people were classified with dementia (10%), while 804 had MCI (22%), both of which approximate estimates reported by previous studies, according to the investigators. In further alignment with past research, age was a clear risk factor; each 5-year increment added 17% and 95% increased risk of MCI and dementia, respectively.

Compared with college-educated participants, individuals who did not graduate from high school had a 60% increased risk for both dementia (odds ratio, 1.6; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.3) and MCI (OR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.2-2.2). Other educational strata were not associated with significant differences in risk.

Compared with White participants, Black individuals had an 80% increased risk of dementia (OR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.2-2.7), but no increased risk of MCI. Conversely, non-White Hispanic individuals had a 40% increased risk of MCI (OR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.0-2.0), but no increased risk of dementia, compared with White participants.

“Older adults racialized as Black and Hispanic are more likely to develop cognitive impairment and dementia because of historical and current structural racism and income inequality that restrict access to brain-health benefits and increase exposure to harm,” Dr. Manly said in a written comment.

These inequities deserve a comprehensive response, she added.

“Actions and policies that decrease discriminatory and aggressive policing policies, invest in schools that serve children that are racialized as Black and Hispanic, repair housing and economic inequalities, and provide equitable access to mental and physical health, can help to narrow disparities in later life cognitive impairment,” Dr. Manly said. “Two other areas of focus for policy makers are the shortage in the workforce of dementia care specialists, and paid family leave for caregiving.”

Acknowledging the needs of the historically underrepresented

Lealani Mae Acosta, MD, MPH, associate professor of neurology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., applauded the investigators for their “conscious effort to expand representation of historically underrepresented minorities.”

The findings themselves support what has been previously reported, Dr. Acosta said in an interview, including the disproportionate burden of cognitive disorders among people of color and those with less education.

Clinicians need to recognize that certain patient groups face increased risks of cognitive disorders, and should be screened accordingly, Dr. Acosta said, noting that all aging patients should undergo such screening. The push for screening should also occur on a community level, along with efforts to build trust between at-risk populations and health care providers.

While Dr. Acosta reiterated the importance of these new data from Black and Hispanic individuals, she noted that gaps in representation remain, and methods of characterizing populations deserve refinement.

“I’m a little bit biased because I’m an Asian physician,” Dr. Acosta said. “As much as I’m glad that they’re highlighting these different disparities, there weren’t enough [participants in] specific subgroups like American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, to be able to identify specific trends within [those groups] that are, again, historically underrepresented patient populations.”

Grouping all people of Asian descent may also be an oversimplification, she added, as differences may exist between individuals originating from different countries.

“We always have to be careful about lumping certain groups together in analyses,” Dr. Acosta said. “That’s just another reminder to us – as clinicians, as researchers – that we need to do better by our patients by expanding research opportunities, and really studying these historically underrepresented populations.”

The study was supported by the National Institute on Aging. The investigators disclosed additional relationships with the Alzheimer’s Association and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Acosta reported no relevant competing interests.

based on new U.S. data from The Health and Retirement Study (HRS).

These inequities likely stem from structural racism and income inequality, necessitating a multifaceted response at an institutional level, according to lead author Jennifer J. Manly, PhD, a professor of neuropsychology in neurology at the Gertrude H. Sergievsky Center and the Taub Institute for Research in Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease at Columbia University, New York.

A more representative dataset

Between 2001 and 2003, a subset of HRS participants underwent extensive neuropsychological assessment in the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study (ADAMS), providing data which have since been cited by hundreds of published studies, the investigators wrote in JAMA Neurology. Those data, however, failed to accurately represent the U.S. population at the time, and have not been updated since.

“The ADAMS substudy was small, and the limited inclusion of Black, Hispanic, and American Indian or Alaska Native participants contributed to lack of precision of estimates among minoritized racial and ethnic groups that have been shown to experience a higher burden of cognitive impairment and dementia,” Dr. Manly and colleagues wrote.

The present analysis used a more representative dataset from HRS participants who were 65 years or older in 2016. From June 2016 to October 2017, 3,496 of these individuals underwent comprehensive neuropsychological test battery and informant interview, with dementia and MCI classified based on standard diagnostic criteria.

In total, 393 people were classified with dementia (10%), while 804 had MCI (22%), both of which approximate estimates reported by previous studies, according to the investigators. In further alignment with past research, age was a clear risk factor; each 5-year increment added 17% and 95% increased risk of MCI and dementia, respectively.

Compared with college-educated participants, individuals who did not graduate from high school had a 60% increased risk for both dementia (odds ratio, 1.6; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.3) and MCI (OR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.2-2.2). Other educational strata were not associated with significant differences in risk.

Compared with White participants, Black individuals had an 80% increased risk of dementia (OR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.2-2.7), but no increased risk of MCI. Conversely, non-White Hispanic individuals had a 40% increased risk of MCI (OR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.0-2.0), but no increased risk of dementia, compared with White participants.

“Older adults racialized as Black and Hispanic are more likely to develop cognitive impairment and dementia because of historical and current structural racism and income inequality that restrict access to brain-health benefits and increase exposure to harm,” Dr. Manly said in a written comment.

These inequities deserve a comprehensive response, she added.

“Actions and policies that decrease discriminatory and aggressive policing policies, invest in schools that serve children that are racialized as Black and Hispanic, repair housing and economic inequalities, and provide equitable access to mental and physical health, can help to narrow disparities in later life cognitive impairment,” Dr. Manly said. “Two other areas of focus for policy makers are the shortage in the workforce of dementia care specialists, and paid family leave for caregiving.”

Acknowledging the needs of the historically underrepresented

Lealani Mae Acosta, MD, MPH, associate professor of neurology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., applauded the investigators for their “conscious effort to expand representation of historically underrepresented minorities.”

The findings themselves support what has been previously reported, Dr. Acosta said in an interview, including the disproportionate burden of cognitive disorders among people of color and those with less education.

Clinicians need to recognize that certain patient groups face increased risks of cognitive disorders, and should be screened accordingly, Dr. Acosta said, noting that all aging patients should undergo such screening. The push for screening should also occur on a community level, along with efforts to build trust between at-risk populations and health care providers.

While Dr. Acosta reiterated the importance of these new data from Black and Hispanic individuals, she noted that gaps in representation remain, and methods of characterizing populations deserve refinement.

“I’m a little bit biased because I’m an Asian physician,” Dr. Acosta said. “As much as I’m glad that they’re highlighting these different disparities, there weren’t enough [participants in] specific subgroups like American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, to be able to identify specific trends within [those groups] that are, again, historically underrepresented patient populations.”

Grouping all people of Asian descent may also be an oversimplification, she added, as differences may exist between individuals originating from different countries.

“We always have to be careful about lumping certain groups together in analyses,” Dr. Acosta said. “That’s just another reminder to us – as clinicians, as researchers – that we need to do better by our patients by expanding research opportunities, and really studying these historically underrepresented populations.”

The study was supported by the National Institute on Aging. The investigators disclosed additional relationships with the Alzheimer’s Association and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Acosta reported no relevant competing interests.

based on new U.S. data from The Health and Retirement Study (HRS).

These inequities likely stem from structural racism and income inequality, necessitating a multifaceted response at an institutional level, according to lead author Jennifer J. Manly, PhD, a professor of neuropsychology in neurology at the Gertrude H. Sergievsky Center and the Taub Institute for Research in Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease at Columbia University, New York.

A more representative dataset

Between 2001 and 2003, a subset of HRS participants underwent extensive neuropsychological assessment in the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study (ADAMS), providing data which have since been cited by hundreds of published studies, the investigators wrote in JAMA Neurology. Those data, however, failed to accurately represent the U.S. population at the time, and have not been updated since.

“The ADAMS substudy was small, and the limited inclusion of Black, Hispanic, and American Indian or Alaska Native participants contributed to lack of precision of estimates among minoritized racial and ethnic groups that have been shown to experience a higher burden of cognitive impairment and dementia,” Dr. Manly and colleagues wrote.

The present analysis used a more representative dataset from HRS participants who were 65 years or older in 2016. From June 2016 to October 2017, 3,496 of these individuals underwent comprehensive neuropsychological test battery and informant interview, with dementia and MCI classified based on standard diagnostic criteria.

In total, 393 people were classified with dementia (10%), while 804 had MCI (22%), both of which approximate estimates reported by previous studies, according to the investigators. In further alignment with past research, age was a clear risk factor; each 5-year increment added 17% and 95% increased risk of MCI and dementia, respectively.

Compared with college-educated participants, individuals who did not graduate from high school had a 60% increased risk for both dementia (odds ratio, 1.6; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.3) and MCI (OR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.2-2.2). Other educational strata were not associated with significant differences in risk.

Compared with White participants, Black individuals had an 80% increased risk of dementia (OR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.2-2.7), but no increased risk of MCI. Conversely, non-White Hispanic individuals had a 40% increased risk of MCI (OR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.0-2.0), but no increased risk of dementia, compared with White participants.

“Older adults racialized as Black and Hispanic are more likely to develop cognitive impairment and dementia because of historical and current structural racism and income inequality that restrict access to brain-health benefits and increase exposure to harm,” Dr. Manly said in a written comment.

These inequities deserve a comprehensive response, she added.

“Actions and policies that decrease discriminatory and aggressive policing policies, invest in schools that serve children that are racialized as Black and Hispanic, repair housing and economic inequalities, and provide equitable access to mental and physical health, can help to narrow disparities in later life cognitive impairment,” Dr. Manly said. “Two other areas of focus for policy makers are the shortage in the workforce of dementia care specialists, and paid family leave for caregiving.”

Acknowledging the needs of the historically underrepresented

Lealani Mae Acosta, MD, MPH, associate professor of neurology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., applauded the investigators for their “conscious effort to expand representation of historically underrepresented minorities.”

The findings themselves support what has been previously reported, Dr. Acosta said in an interview, including the disproportionate burden of cognitive disorders among people of color and those with less education.

Clinicians need to recognize that certain patient groups face increased risks of cognitive disorders, and should be screened accordingly, Dr. Acosta said, noting that all aging patients should undergo such screening. The push for screening should also occur on a community level, along with efforts to build trust between at-risk populations and health care providers.

While Dr. Acosta reiterated the importance of these new data from Black and Hispanic individuals, she noted that gaps in representation remain, and methods of characterizing populations deserve refinement.

“I’m a little bit biased because I’m an Asian physician,” Dr. Acosta said. “As much as I’m glad that they’re highlighting these different disparities, there weren’t enough [participants in] specific subgroups like American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, to be able to identify specific trends within [those groups] that are, again, historically underrepresented patient populations.”

Grouping all people of Asian descent may also be an oversimplification, she added, as differences may exist between individuals originating from different countries.

“We always have to be careful about lumping certain groups together in analyses,” Dr. Acosta said. “That’s just another reminder to us – as clinicians, as researchers – that we need to do better by our patients by expanding research opportunities, and really studying these historically underrepresented populations.”

The study was supported by the National Institute on Aging. The investigators disclosed additional relationships with the Alzheimer’s Association and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Acosta reported no relevant competing interests.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Concerning trend of growing subarachnoid hemorrhage rates in Black people

Results of a new study based on hospital discharge data show Black people have disproportionately high rates of SAH versus other racial groups. Compared with White and Hispanic people, who had an average of 10 cases per 100,000, or Asian people, with 8 per 100,000 people, Black people had an average of 15 cases per 100,000 population.

Whereas case rates held steady for other racial groups in the study over a 10-year period, Black people were the only racial group for whom SAH incidence increased over time, at a rate of 1.8% per year.

“Root causes of the higher SAH incidence in Black [people] are complex and likely extend beyond simple differences in risk factor characteristics to other socioeconomic factors including level of education, poverty level, lack of insurance, access to quality care, and structural racism,” study investigator Fadar Oliver Otite, MD, assistant professor of neurology at SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, said in an interview.

“Addressing this racial disparity will require multidisciplinary factors targeted not just at subarachnoid hemorrhage risk factors but also at socioeconomic equity,” he added.

The study was published online in Neurology.

Uncontrolled hypertension

The average incidence of SAH for all participants was 11 cases per 100,000 people. Men had an average rate of 10 cases and women an average rate of 13 cases per 100,000.

As expected, incidence increased with age: For middle-aged men, the average was four cases per 100,000 people whereas for men 65 and older, the average was 22 cases.

Dr. Otite and his team combined U.S. Census data with two state hospitalization databases in New York and Florida and found that there were nearly 40,000 people hospitalized for SAH between 2007 and 2017. To find annual incidences of SAH per 100,000 population, they calculated the number of SAH cases and the total adult population for the year.

“Smoking and hypertension are two of the strongest risk factors for subarachnoid hemorrhage,” Dr. Otite said. “Hypertension is more prevalent in Black people in the United States, and Black patients with hypertension are more likely to have it uncontrolled.”

Racism, toxic stress

Anjail Sharieff, MD, associate professor of neurology at UT Health, Houston, said aside from a high rate of common SAH risk factors such as hypertension, Black Americans also face a barrage of inequities to health education and quality health care that contributes to higher SAH rates.

“The impact of toxic stress related to racism and discrimination experiences, and chronic stress related to poverty, can contribute to hypertension in Black people,” Dr. Sharieff said, adding that these factors contribute to stroke risk and are not usually accounted for in studies.

Dr. Sharieff said many of her first-time patients end up in her office due to a heart attack or stroke because they were previously uninsured and did not have access to primary care. “We need to begin leveraging trust with people in communities – meeting people where they are,” to educate them about hypertension and other health issues, she said.

A shining example of community engagement to reduce hypertension in Black communities was the Cedars-Sinai Barbershop Study, where 52 barbershops in Los Angeles implemented blood pressure checks and interventions among customers. A year later, the project was still working.

“Once we can identify the health problems in Black communities,” said Dr. Sharieff, “we can treat them.”

Dr. Otite and Dr. Sharieff report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Results of a new study based on hospital discharge data show Black people have disproportionately high rates of SAH versus other racial groups. Compared with White and Hispanic people, who had an average of 10 cases per 100,000, or Asian people, with 8 per 100,000 people, Black people had an average of 15 cases per 100,000 population.

Whereas case rates held steady for other racial groups in the study over a 10-year period, Black people were the only racial group for whom SAH incidence increased over time, at a rate of 1.8% per year.

“Root causes of the higher SAH incidence in Black [people] are complex and likely extend beyond simple differences in risk factor characteristics to other socioeconomic factors including level of education, poverty level, lack of insurance, access to quality care, and structural racism,” study investigator Fadar Oliver Otite, MD, assistant professor of neurology at SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, said in an interview.

“Addressing this racial disparity will require multidisciplinary factors targeted not just at subarachnoid hemorrhage risk factors but also at socioeconomic equity,” he added.

The study was published online in Neurology.

Uncontrolled hypertension

The average incidence of SAH for all participants was 11 cases per 100,000 people. Men had an average rate of 10 cases and women an average rate of 13 cases per 100,000.

As expected, incidence increased with age: For middle-aged men, the average was four cases per 100,000 people whereas for men 65 and older, the average was 22 cases.

Dr. Otite and his team combined U.S. Census data with two state hospitalization databases in New York and Florida and found that there were nearly 40,000 people hospitalized for SAH between 2007 and 2017. To find annual incidences of SAH per 100,000 population, they calculated the number of SAH cases and the total adult population for the year.

“Smoking and hypertension are two of the strongest risk factors for subarachnoid hemorrhage,” Dr. Otite said. “Hypertension is more prevalent in Black people in the United States, and Black patients with hypertension are more likely to have it uncontrolled.”

Racism, toxic stress

Anjail Sharieff, MD, associate professor of neurology at UT Health, Houston, said aside from a high rate of common SAH risk factors such as hypertension, Black Americans also face a barrage of inequities to health education and quality health care that contributes to higher SAH rates.

“The impact of toxic stress related to racism and discrimination experiences, and chronic stress related to poverty, can contribute to hypertension in Black people,” Dr. Sharieff said, adding that these factors contribute to stroke risk and are not usually accounted for in studies.

Dr. Sharieff said many of her first-time patients end up in her office due to a heart attack or stroke because they were previously uninsured and did not have access to primary care. “We need to begin leveraging trust with people in communities – meeting people where they are,” to educate them about hypertension and other health issues, she said.

A shining example of community engagement to reduce hypertension in Black communities was the Cedars-Sinai Barbershop Study, where 52 barbershops in Los Angeles implemented blood pressure checks and interventions among customers. A year later, the project was still working.

“Once we can identify the health problems in Black communities,” said Dr. Sharieff, “we can treat them.”

Dr. Otite and Dr. Sharieff report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Results of a new study based on hospital discharge data show Black people have disproportionately high rates of SAH versus other racial groups. Compared with White and Hispanic people, who had an average of 10 cases per 100,000, or Asian people, with 8 per 100,000 people, Black people had an average of 15 cases per 100,000 population.

Whereas case rates held steady for other racial groups in the study over a 10-year period, Black people were the only racial group for whom SAH incidence increased over time, at a rate of 1.8% per year.

“Root causes of the higher SAH incidence in Black [people] are complex and likely extend beyond simple differences in risk factor characteristics to other socioeconomic factors including level of education, poverty level, lack of insurance, access to quality care, and structural racism,” study investigator Fadar Oliver Otite, MD, assistant professor of neurology at SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, said in an interview.

“Addressing this racial disparity will require multidisciplinary factors targeted not just at subarachnoid hemorrhage risk factors but also at socioeconomic equity,” he added.

The study was published online in Neurology.

Uncontrolled hypertension

The average incidence of SAH for all participants was 11 cases per 100,000 people. Men had an average rate of 10 cases and women an average rate of 13 cases per 100,000.

As expected, incidence increased with age: For middle-aged men, the average was four cases per 100,000 people whereas for men 65 and older, the average was 22 cases.

Dr. Otite and his team combined U.S. Census data with two state hospitalization databases in New York and Florida and found that there were nearly 40,000 people hospitalized for SAH between 2007 and 2017. To find annual incidences of SAH per 100,000 population, they calculated the number of SAH cases and the total adult population for the year.

“Smoking and hypertension are two of the strongest risk factors for subarachnoid hemorrhage,” Dr. Otite said. “Hypertension is more prevalent in Black people in the United States, and Black patients with hypertension are more likely to have it uncontrolled.”

Racism, toxic stress

Anjail Sharieff, MD, associate professor of neurology at UT Health, Houston, said aside from a high rate of common SAH risk factors such as hypertension, Black Americans also face a barrage of inequities to health education and quality health care that contributes to higher SAH rates.

“The impact of toxic stress related to racism and discrimination experiences, and chronic stress related to poverty, can contribute to hypertension in Black people,” Dr. Sharieff said, adding that these factors contribute to stroke risk and are not usually accounted for in studies.

Dr. Sharieff said many of her first-time patients end up in her office due to a heart attack or stroke because they were previously uninsured and did not have access to primary care. “We need to begin leveraging trust with people in communities – meeting people where they are,” to educate them about hypertension and other health issues, she said.

A shining example of community engagement to reduce hypertension in Black communities was the Cedars-Sinai Barbershop Study, where 52 barbershops in Los Angeles implemented blood pressure checks and interventions among customers. A year later, the project was still working.

“Once we can identify the health problems in Black communities,” said Dr. Sharieff, “we can treat them.”

Dr. Otite and Dr. Sharieff report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NEUROLOGY

Study reveals racial disparities in advanced HF therapies

A new study shows that Black Americans received ventricular assist devices (VADs) and heart transplants about half as often as White Americans, even when receiving care at an advanced heart failure (HF) center.

The analysis, drawn from 377 patients treated at one of 21 VAD centers in the United States as part of the RIVIVAL study, found that 22.3% of White adults received a heart transplant or VAD, compared with 11% of Black adults.

“That’s what is so concerning to us, that we’re seeing this pattern within this select population. I think it would be too reasonable to hypothesize that it very well could be worse in the general population,” study author Thomas Cascino, MD, MSc, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, commented.

The study was published online in Circulation: Heart Failure, and it builds on previous work by the researchers, showing that patient preference for early VAD therapy is associated with higher New York Heart Association (NYHA) class and lower income level but not race.

In the present analysis, the number of Black and White participants who said they “definitely or probably” wanted VAD therapy was similar (27% vs. 29%), as was the number wanting “any and all life-sustaining therapies” (74% vs. 65%).

Two-thirds of the cohort was NYHA class III, the average EuroQoL visual analog scale (EQ-VAS) score was 64.6 among the 100 participants who identified as Black and 62.1 in the 277 White participants, and the average age was 58 and 61 years, respectively.

Death rates were also similar during the 2-year follow-up: 18% of Black patients and 13% of White patients.

After controlling for multiple clinical and social determinants of health, including age, Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulator Support (INTERMACS) patient profile, EQ-VAS score, and level of education, Black participants had a 55% lower rate of VAD or transplant, compared with White participants (hazard ratio, 0.45; 95% confidence interval, 0.23-0.85). Adding VAD preference to the model did not affect the association.

“Our study suggests that we as providers may be making decisions differently,” Dr. Cascino said. “We can’t say for sure what the reasons are but certainly structural racism, discrimination, and provider biases are the things I worry about.”

“There’s an absolute need for us to look inwards, reflect, and acknowledge that we are likely playing a role in this and then start to be part of the change,” he added.

“The lives disabled or lost are simply too many,” coauthor Wendy Taddei-Peters, PhD, a clinical trials project official at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, said in an NIH statement. “An immediate step could be to require implicit bias training, particularly for transplant and VAD team members.”

Other suggestions are better tracking of underserved patients and the reasons why they do not receive VAD or become listed for transplant; inclusion of psychosocial components into decision-making about advanced therapy candidacy; and having “disparity experts” join in heart team meetings to help identify biases in real time.

Commenting on the study, Khadijah Breathett, MD, HF/transplant cardiologist and tenured associate professor of medicine, Indiana University Bloomington, said, “I’m glad there’s more push for awareness, because there’s still a population of people that don’t believe this is a real problem.”

Dr. Breathett, who is also a racial equity researcher, noted that the findings are similar to those of multiple studies suggesting racial disparities in HF care. In her own 2019 study of 400 providers shown identical clinical vignettes except for race, survey results and think-aloud interviews showed that decisions about advanced HF therapies are hierarchal and not democratic, social history and adherence are the most influential factors, and Black men are seen as not trustworthy and adherent, despite identical social histories, which ultimately led to White men being offered transplantation and Black men VAD implantation. The bias was particularly evident among older providers.

“This problem is real,” Dr. Breathett said. “The process of allocating life-saving therapies is not fair, and there is some level of discrimination that’s taking place towards persons of color, particularly Black patients. It’s time that we consider how we fix these issues.”

To see whether centers can move the needle and put systemic level changes into practice, Dr. Breathett and colleagues are launching the Seeking Objectivity in Allocation of Advanced Heart Failure (SOCIAL HF) Therapies Trial at 14 sites in the United States. It will measure the number of minority and female patients receiving advanced HF therapies at centers randomized to usual care or HF training, including evidence-based bias reduction training, use of objective measures of social support, and changes to facilitate group dynamics. The trial is set to start in January and be completed in September 2026.

“The main takeaway from this study is that it highlights and re-highlights the fact that racial disparities do exist in access to advanced therapy care,” Jaimin Trivedi, MD, MPH, associate professor of cardiothoracic surgery and director of clinical research and bioinformatics, University of Louisville, Ky., said in an interview.

He also called for education and training for all professionals, not just during residency or fellowship, to specifically identify issues with Black patients and encourage Black patients and their family members to get more involved in their HF care.

Dr. Trivedi said that further studies should examine why death rates were similar in the study despite the observed disparities in VAD implantation and transplantation.