User login

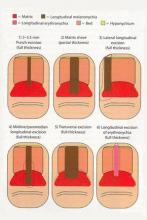

Nail Biopsy: 6 Techniques to Biopsy the Nail Matrix

Nail matrix biopsies are performed to confirm a diagnosis or surgically remove a skin lesion that is affecting the growth of the nail plate. The procedure may be used to identify:

- Inflammatory conditions such as nail psoriasis and lichen planus

- Benign tumors

- Solitary melanonychia

- Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

- Other nail disorders

Nail biopsy can lead to complications such as bleeding, infection, or scarring. Postoperative scarring can cause permanent nail splitting, dystrophy, or both.

In a Cosmetic Dermatology article, “Matrix Biopsy of Longitudinal Melanonychia and Longitudinal Erythronychia: A Step-by-Step Approach,” Drs. Siobhan C. Collins and Nathaniel J. Jellinek review 6 techniques used to biopsy the nail matrix.

- Punch excision

- Matrix shave

- Lateral longitudinal excision

- Midline/paramedian longitudinal excision

- Transverse excision

- Longitudinal excision of erythronychia

In the setting of longitudinal melanonychia (to diagnose nail melanoma or SCC) and longitudinal erythronychia (to diagnose SCC and rarely amelanotic melanoma or basal cell carcinoma), the techniques they describe accomplish 3 fundamental goals of nail surgery:

- Obtain adequate tissue via an excisional biopsy to make an accurate diagnosis and avoid sampling error

- Avoid unnecessary trauma to surrounding nail tissues by the judicious use of partial plate avulsions whenever feasible

- Avoid unnecessary postoperative nail scarring whenever possible

Dermatologists must be confident when performing nail biopsies and the techniques discussed by the authors will help approach nail surgery with more certainty.

At the 73rd Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, Dr. Jellinek provides a hands-on approach to nail surgery. On Saturday, March 21, he will provide tips for nail surgeries at the “Medical and Surgical Management of Nail Disorders” lecture.

For more information, read the Collins and Jellinek article from Cosmetic Dermatology.

Nail matrix biopsies are performed to confirm a diagnosis or surgically remove a skin lesion that is affecting the growth of the nail plate. The procedure may be used to identify:

- Inflammatory conditions such as nail psoriasis and lichen planus

- Benign tumors

- Solitary melanonychia

- Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

- Other nail disorders

Nail biopsy can lead to complications such as bleeding, infection, or scarring. Postoperative scarring can cause permanent nail splitting, dystrophy, or both.

In a Cosmetic Dermatology article, “Matrix Biopsy of Longitudinal Melanonychia and Longitudinal Erythronychia: A Step-by-Step Approach,” Drs. Siobhan C. Collins and Nathaniel J. Jellinek review 6 techniques used to biopsy the nail matrix.

- Punch excision

- Matrix shave

- Lateral longitudinal excision

- Midline/paramedian longitudinal excision

- Transverse excision

- Longitudinal excision of erythronychia

In the setting of longitudinal melanonychia (to diagnose nail melanoma or SCC) and longitudinal erythronychia (to diagnose SCC and rarely amelanotic melanoma or basal cell carcinoma), the techniques they describe accomplish 3 fundamental goals of nail surgery:

- Obtain adequate tissue via an excisional biopsy to make an accurate diagnosis and avoid sampling error

- Avoid unnecessary trauma to surrounding nail tissues by the judicious use of partial plate avulsions whenever feasible

- Avoid unnecessary postoperative nail scarring whenever possible

Dermatologists must be confident when performing nail biopsies and the techniques discussed by the authors will help approach nail surgery with more certainty.

At the 73rd Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, Dr. Jellinek provides a hands-on approach to nail surgery. On Saturday, March 21, he will provide tips for nail surgeries at the “Medical and Surgical Management of Nail Disorders” lecture.

For more information, read the Collins and Jellinek article from Cosmetic Dermatology.

Nail matrix biopsies are performed to confirm a diagnosis or surgically remove a skin lesion that is affecting the growth of the nail plate. The procedure may be used to identify:

- Inflammatory conditions such as nail psoriasis and lichen planus

- Benign tumors

- Solitary melanonychia

- Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

- Other nail disorders

Nail biopsy can lead to complications such as bleeding, infection, or scarring. Postoperative scarring can cause permanent nail splitting, dystrophy, or both.

In a Cosmetic Dermatology article, “Matrix Biopsy of Longitudinal Melanonychia and Longitudinal Erythronychia: A Step-by-Step Approach,” Drs. Siobhan C. Collins and Nathaniel J. Jellinek review 6 techniques used to biopsy the nail matrix.

- Punch excision

- Matrix shave

- Lateral longitudinal excision

- Midline/paramedian longitudinal excision

- Transverse excision

- Longitudinal excision of erythronychia

In the setting of longitudinal melanonychia (to diagnose nail melanoma or SCC) and longitudinal erythronychia (to diagnose SCC and rarely amelanotic melanoma or basal cell carcinoma), the techniques they describe accomplish 3 fundamental goals of nail surgery:

- Obtain adequate tissue via an excisional biopsy to make an accurate diagnosis and avoid sampling error

- Avoid unnecessary trauma to surrounding nail tissues by the judicious use of partial plate avulsions whenever feasible

- Avoid unnecessary postoperative nail scarring whenever possible

Dermatologists must be confident when performing nail biopsies and the techniques discussed by the authors will help approach nail surgery with more certainty.

At the 73rd Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, Dr. Jellinek provides a hands-on approach to nail surgery. On Saturday, March 21, he will provide tips for nail surgeries at the “Medical and Surgical Management of Nail Disorders” lecture.

For more information, read the Collins and Jellinek article from Cosmetic Dermatology.

What Is Your Diagnosis? Extramammary Paget Disease

A 70-year-old man presented with a nonpruritic erythematous scaly plaque in the left suprapubic region of 6 months’ duration that had failed to respond to terbinafine cream 1% after 1 month of treatment of suspected tinea cruris. His medical history was remarkable for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, benign prostatic hyperplasia, an abdominal aortic aneurysm, alcohol dependence, tobacco use disorder, and unintentional weight loss of 15 lb over the last year.

The Diagnosis: Extramammary Paget Disease

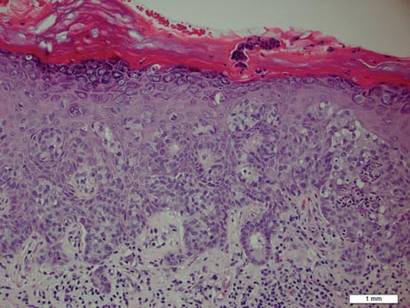

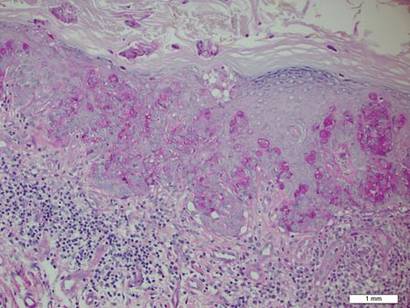

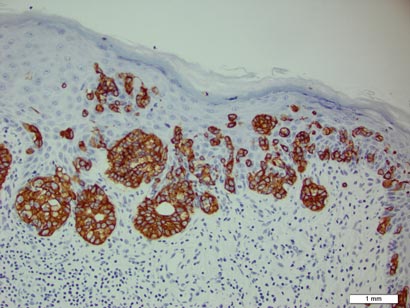

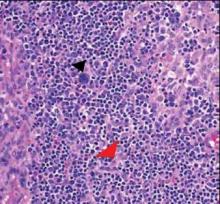

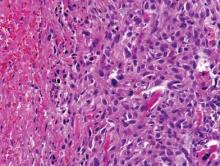

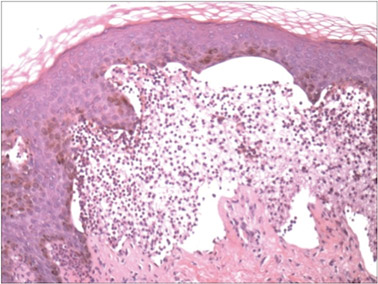

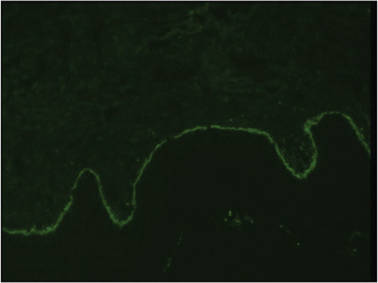

A biopsy of the plaque revealed an intraepidermal proliferation of large cells with abundant clear cytoplasm and large vesicular nuclei distributed throughout the epidermis (Figure 1). The neoplastic cells stained positive for both periodic acid–Schiff stain (Figure 2) and CK7 (Figure 3). Chemistry and liver function panel, urine analysis, carcinoembryonic antigen levels, and prostate-specific antigen levels were within reference range. A complete blood cell count revealed mild megaloblastic anemia. Subsequent computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed an abdominal aortic aneurysm and prostatic enlargement without any evidence of potential malignancies. Colonoscopy revealed multiple hyperplastic polyps and a tubular adenoma. Cystoscopy was normal, except for evidence of prostate enlargement. Urine cytology was unremarkable. The patient was referred for excision of the lesion with Mohs micrographic surgery. Follow-up was recommended every 3 months for the first 2 years following surgery and every 6 months thereafter to monitor for recurrence or secondary neoplasms.

|

Sir James Paget first described mammary Paget disease of the nipple in 1874 in his report of 15 women with skin eruptions of the nipple and areola and subsequent carcinoma of the underlying breast.1 Paget also described a patient with a similar eruption on the glans penis and Crocker2 described extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) of the scrotum and penis in 1889. The principle difference between mammary Paget disease and EMPD is the anatomic location.

Extramammary Paget disease is a rare condition that typically affects patients aged 50 to 80 years and is more common in women and white-skinned races.3 Extramammary Paget disease frequently targets cutaneous sites that are rich in apocrine glands. The most commonly affected site is the vulva followed by perineal, perianal, scrotal, and penile skin. Less commonly, the axillae, buttocks, thighs, eyelids, and external auditory canals may be affected.4

Patients with EMPD typically present with well-demarcated, nonresolving, erythematous and eczematous plaques that may have associated crusting, scaling, papillomatous excrescences, lichenification, ulceration, or bleeding. The most common symptom is pruritus, followed by burning, irritation, pain, and tenderness.5 Ten percent of patients are asymptomatic. The average interval between symptom onset and diagnosis is 2 years.5

Histopathology reveals diffusely infiltrating, irregular, neoplastic Paget cells within the epidermis that are large and vacuolated with abundant pale bluish cytoplasm and large vesicular nuclei, which may be centrally or laterally compressed. The cells may be distributed singly or in groups as strands, nests, or glandular patterns within the lower epidermis, rete ridges, and adnexal structures. Hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and parakeratosis may also be present. Paget cells stain for immunohistochemical markers of apocrine and eccrine derivation including low-molecular-weight cytokeratins, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, periodic acid–Schiff stain, and carcinoembryonic antigen.5 Perrotto et al6 studied 98 specimens from 61 patients and found that CK7 was positive in all EMPD specimens, while CK20 and gross cystic disease fluid protein 15 were positive in large subsets of both primary and secondary EMPD. Cases of EMPD secondary to anorectal adenocarcinoma were largely ERBB2 (formerly HER2/neu) negative and CDX2 positive.6

Diagnosis of EMPD should be followed by a thorough investigation for underlying carcinomas. In a review of 197 cases of EMPD, 24% of patients with EMPD had an associated underlying in situ or invasive adnexal apocrine carcinoma, which was associated with a higher mortality rate than in patients without this underlying malignancy. Additionally, 12% of EMPD patients had an associated underlying internal malignancy.7 These malignancies may include carcinomas of the urethra, bladder, vagina, cervix, endometrium, prostate, colon, and rectum. Perianal EMPD has a higher frequency of associated malignancies than vulvar EMPD.5 The location of EMPD is related to the location of the underlying malignancy; for example, perianal EMPD is associated with colorectal adenocarcinomas, and EMPD of the penis, scrotum, and groin is associated with genitourinary malignancies. Investigations to search for associated malignancies in patients with EMPD may include pelvic ultrasonography and/or magnetic resonance imaging, hysteroscopy, colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, cystoscopy, intravenous pyelogram, mammogram, and/or chest radiograph.

The most effective treatment of EMPD is margin-controlled surgical excision. High local recurrence rates may be due to irregular margins, multicentricity, and the tendency of EMPD to involve clinically normal-appearing skin. Hendi et al8 noted that EMPD may actually be unifocal with subclinical fingerlike projections extending beyond the main body of the tumor, requiring CK7 immunostaining for visualization to ensure complete margin control. The recurrence rate after standard surgical excision is 33% to 60%. The recurrence rate after excision via Mohs micrographic surgery is 16% for primary EMPD and 50% for recurrent EMPD.9 Other treatment modalities include radiotherapy, topical chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil or imiquimod, and photodynamic therapy.10-13 Combined systemic chemotherapy with trastuzumab and paclitaxel can be considered for the treatment of ERBB2-positive EMPD.14

For patients with chronic genital or perianal lesions that are unresponsive to treatment, dermatologists should maintain a high index of suspicion for EMPD. If a patient is diagnosed with EMPD, a full-body skin examination should be performed with palpation of all lymph nodes. Imaging studies directed at the anatomic location of the involved skin should be utilized to search for an underlying internal malignancy.

1. Paget J. On disease of the mammary areola preceding cancer of the mammary gland. St Bartholomew Hosp Rep. 1874;10:87-89.

2. Crocker H. Paget’s disease affecting the scrotum and penis. Trans Pathol Soc Lond. 1889;40:187-191.

3. Zollo JD, Zeitouni NC. The Roswell Park Cancer Institute experience with extramammary Paget’s disease. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:59-65.

4. Heymann WR. Extramammary Paget’s disease. Clin Dermatol. 1993;11:83-87.5. Shepherd V, Davidson EJ, Davies-Humphreys J. Extramammary Paget’s disease. BJOG. 2005;112:273-279.

6. Perrotto J, Abbott JJ, Ceilley RI, et al. The role of immunohistochemistry in discriminating primary from secondary extramammary Paget disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:137-143.

7. Chanda JJ. Extramammary Paget’s disease: prognosis and relationship to internal malignancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:1009-1014.

8. Hendi A, Perdikis G, Snow JL. Unifocality of extramammary Paget disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:811-813.

9. Hendi A, Brodland DG, Zitelli JA. Extramammary Paget’s disease: surgical treatment with mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:767-773.10. Zampogna JC, Flowers FP, Roth WI, et al. Treatment of primary limited cutaneous extramammary Paget’s disease with topical imiquimod monotherapy: two case reports. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:S229-S235.

11. Beleznay KM, Levesque MA, Gill S. Response to 5-fluorouracil in metastatic extramammary Paget disease of the scrotum presenting as pancytopenia and back pain. Curr Oncol. 2009;16:81-83.

12. Kitagawa KH, Bogner P, Zeitouni NC. Photodynamic therapy with methyl-aminolevulinate for the treatment of double extramammary Paget’s disease. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:1043-1046.

13. Hata M, Omura M, Koike I, et al. Role of radiotherapy as curative treatment of extramammary Paget’s disease. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;80:47-54.

14. Takahagi S, Noda H, Kamegashira A, et al. Metastatic extramammary Paget’s disease treated with paclitaxel and trastuzumab combination chemotherapy. J Dermatol. 2009;36:457-461.

A 70-year-old man presented with a nonpruritic erythematous scaly plaque in the left suprapubic region of 6 months’ duration that had failed to respond to terbinafine cream 1% after 1 month of treatment of suspected tinea cruris. His medical history was remarkable for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, benign prostatic hyperplasia, an abdominal aortic aneurysm, alcohol dependence, tobacco use disorder, and unintentional weight loss of 15 lb over the last year.

The Diagnosis: Extramammary Paget Disease

A biopsy of the plaque revealed an intraepidermal proliferation of large cells with abundant clear cytoplasm and large vesicular nuclei distributed throughout the epidermis (Figure 1). The neoplastic cells stained positive for both periodic acid–Schiff stain (Figure 2) and CK7 (Figure 3). Chemistry and liver function panel, urine analysis, carcinoembryonic antigen levels, and prostate-specific antigen levels were within reference range. A complete blood cell count revealed mild megaloblastic anemia. Subsequent computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed an abdominal aortic aneurysm and prostatic enlargement without any evidence of potential malignancies. Colonoscopy revealed multiple hyperplastic polyps and a tubular adenoma. Cystoscopy was normal, except for evidence of prostate enlargement. Urine cytology was unremarkable. The patient was referred for excision of the lesion with Mohs micrographic surgery. Follow-up was recommended every 3 months for the first 2 years following surgery and every 6 months thereafter to monitor for recurrence or secondary neoplasms.

|

Sir James Paget first described mammary Paget disease of the nipple in 1874 in his report of 15 women with skin eruptions of the nipple and areola and subsequent carcinoma of the underlying breast.1 Paget also described a patient with a similar eruption on the glans penis and Crocker2 described extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) of the scrotum and penis in 1889. The principle difference between mammary Paget disease and EMPD is the anatomic location.

Extramammary Paget disease is a rare condition that typically affects patients aged 50 to 80 years and is more common in women and white-skinned races.3 Extramammary Paget disease frequently targets cutaneous sites that are rich in apocrine glands. The most commonly affected site is the vulva followed by perineal, perianal, scrotal, and penile skin. Less commonly, the axillae, buttocks, thighs, eyelids, and external auditory canals may be affected.4

Patients with EMPD typically present with well-demarcated, nonresolving, erythematous and eczematous plaques that may have associated crusting, scaling, papillomatous excrescences, lichenification, ulceration, or bleeding. The most common symptom is pruritus, followed by burning, irritation, pain, and tenderness.5 Ten percent of patients are asymptomatic. The average interval between symptom onset and diagnosis is 2 years.5

Histopathology reveals diffusely infiltrating, irregular, neoplastic Paget cells within the epidermis that are large and vacuolated with abundant pale bluish cytoplasm and large vesicular nuclei, which may be centrally or laterally compressed. The cells may be distributed singly or in groups as strands, nests, or glandular patterns within the lower epidermis, rete ridges, and adnexal structures. Hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and parakeratosis may also be present. Paget cells stain for immunohistochemical markers of apocrine and eccrine derivation including low-molecular-weight cytokeratins, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, periodic acid–Schiff stain, and carcinoembryonic antigen.5 Perrotto et al6 studied 98 specimens from 61 patients and found that CK7 was positive in all EMPD specimens, while CK20 and gross cystic disease fluid protein 15 were positive in large subsets of both primary and secondary EMPD. Cases of EMPD secondary to anorectal adenocarcinoma were largely ERBB2 (formerly HER2/neu) negative and CDX2 positive.6

Diagnosis of EMPD should be followed by a thorough investigation for underlying carcinomas. In a review of 197 cases of EMPD, 24% of patients with EMPD had an associated underlying in situ or invasive adnexal apocrine carcinoma, which was associated with a higher mortality rate than in patients without this underlying malignancy. Additionally, 12% of EMPD patients had an associated underlying internal malignancy.7 These malignancies may include carcinomas of the urethra, bladder, vagina, cervix, endometrium, prostate, colon, and rectum. Perianal EMPD has a higher frequency of associated malignancies than vulvar EMPD.5 The location of EMPD is related to the location of the underlying malignancy; for example, perianal EMPD is associated with colorectal adenocarcinomas, and EMPD of the penis, scrotum, and groin is associated with genitourinary malignancies. Investigations to search for associated malignancies in patients with EMPD may include pelvic ultrasonography and/or magnetic resonance imaging, hysteroscopy, colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, cystoscopy, intravenous pyelogram, mammogram, and/or chest radiograph.

The most effective treatment of EMPD is margin-controlled surgical excision. High local recurrence rates may be due to irregular margins, multicentricity, and the tendency of EMPD to involve clinically normal-appearing skin. Hendi et al8 noted that EMPD may actually be unifocal with subclinical fingerlike projections extending beyond the main body of the tumor, requiring CK7 immunostaining for visualization to ensure complete margin control. The recurrence rate after standard surgical excision is 33% to 60%. The recurrence rate after excision via Mohs micrographic surgery is 16% for primary EMPD and 50% for recurrent EMPD.9 Other treatment modalities include radiotherapy, topical chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil or imiquimod, and photodynamic therapy.10-13 Combined systemic chemotherapy with trastuzumab and paclitaxel can be considered for the treatment of ERBB2-positive EMPD.14

For patients with chronic genital or perianal lesions that are unresponsive to treatment, dermatologists should maintain a high index of suspicion for EMPD. If a patient is diagnosed with EMPD, a full-body skin examination should be performed with palpation of all lymph nodes. Imaging studies directed at the anatomic location of the involved skin should be utilized to search for an underlying internal malignancy.

A 70-year-old man presented with a nonpruritic erythematous scaly plaque in the left suprapubic region of 6 months’ duration that had failed to respond to terbinafine cream 1% after 1 month of treatment of suspected tinea cruris. His medical history was remarkable for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, benign prostatic hyperplasia, an abdominal aortic aneurysm, alcohol dependence, tobacco use disorder, and unintentional weight loss of 15 lb over the last year.

The Diagnosis: Extramammary Paget Disease

A biopsy of the plaque revealed an intraepidermal proliferation of large cells with abundant clear cytoplasm and large vesicular nuclei distributed throughout the epidermis (Figure 1). The neoplastic cells stained positive for both periodic acid–Schiff stain (Figure 2) and CK7 (Figure 3). Chemistry and liver function panel, urine analysis, carcinoembryonic antigen levels, and prostate-specific antigen levels were within reference range. A complete blood cell count revealed mild megaloblastic anemia. Subsequent computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed an abdominal aortic aneurysm and prostatic enlargement without any evidence of potential malignancies. Colonoscopy revealed multiple hyperplastic polyps and a tubular adenoma. Cystoscopy was normal, except for evidence of prostate enlargement. Urine cytology was unremarkable. The patient was referred for excision of the lesion with Mohs micrographic surgery. Follow-up was recommended every 3 months for the first 2 years following surgery and every 6 months thereafter to monitor for recurrence or secondary neoplasms.

|

Sir James Paget first described mammary Paget disease of the nipple in 1874 in his report of 15 women with skin eruptions of the nipple and areola and subsequent carcinoma of the underlying breast.1 Paget also described a patient with a similar eruption on the glans penis and Crocker2 described extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) of the scrotum and penis in 1889. The principle difference between mammary Paget disease and EMPD is the anatomic location.

Extramammary Paget disease is a rare condition that typically affects patients aged 50 to 80 years and is more common in women and white-skinned races.3 Extramammary Paget disease frequently targets cutaneous sites that are rich in apocrine glands. The most commonly affected site is the vulva followed by perineal, perianal, scrotal, and penile skin. Less commonly, the axillae, buttocks, thighs, eyelids, and external auditory canals may be affected.4

Patients with EMPD typically present with well-demarcated, nonresolving, erythematous and eczematous plaques that may have associated crusting, scaling, papillomatous excrescences, lichenification, ulceration, or bleeding. The most common symptom is pruritus, followed by burning, irritation, pain, and tenderness.5 Ten percent of patients are asymptomatic. The average interval between symptom onset and diagnosis is 2 years.5

Histopathology reveals diffusely infiltrating, irregular, neoplastic Paget cells within the epidermis that are large and vacuolated with abundant pale bluish cytoplasm and large vesicular nuclei, which may be centrally or laterally compressed. The cells may be distributed singly or in groups as strands, nests, or glandular patterns within the lower epidermis, rete ridges, and adnexal structures. Hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and parakeratosis may also be present. Paget cells stain for immunohistochemical markers of apocrine and eccrine derivation including low-molecular-weight cytokeratins, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, periodic acid–Schiff stain, and carcinoembryonic antigen.5 Perrotto et al6 studied 98 specimens from 61 patients and found that CK7 was positive in all EMPD specimens, while CK20 and gross cystic disease fluid protein 15 were positive in large subsets of both primary and secondary EMPD. Cases of EMPD secondary to anorectal adenocarcinoma were largely ERBB2 (formerly HER2/neu) negative and CDX2 positive.6

Diagnosis of EMPD should be followed by a thorough investigation for underlying carcinomas. In a review of 197 cases of EMPD, 24% of patients with EMPD had an associated underlying in situ or invasive adnexal apocrine carcinoma, which was associated with a higher mortality rate than in patients without this underlying malignancy. Additionally, 12% of EMPD patients had an associated underlying internal malignancy.7 These malignancies may include carcinomas of the urethra, bladder, vagina, cervix, endometrium, prostate, colon, and rectum. Perianal EMPD has a higher frequency of associated malignancies than vulvar EMPD.5 The location of EMPD is related to the location of the underlying malignancy; for example, perianal EMPD is associated with colorectal adenocarcinomas, and EMPD of the penis, scrotum, and groin is associated with genitourinary malignancies. Investigations to search for associated malignancies in patients with EMPD may include pelvic ultrasonography and/or magnetic resonance imaging, hysteroscopy, colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, cystoscopy, intravenous pyelogram, mammogram, and/or chest radiograph.

The most effective treatment of EMPD is margin-controlled surgical excision. High local recurrence rates may be due to irregular margins, multicentricity, and the tendency of EMPD to involve clinically normal-appearing skin. Hendi et al8 noted that EMPD may actually be unifocal with subclinical fingerlike projections extending beyond the main body of the tumor, requiring CK7 immunostaining for visualization to ensure complete margin control. The recurrence rate after standard surgical excision is 33% to 60%. The recurrence rate after excision via Mohs micrographic surgery is 16% for primary EMPD and 50% for recurrent EMPD.9 Other treatment modalities include radiotherapy, topical chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil or imiquimod, and photodynamic therapy.10-13 Combined systemic chemotherapy with trastuzumab and paclitaxel can be considered for the treatment of ERBB2-positive EMPD.14

For patients with chronic genital or perianal lesions that are unresponsive to treatment, dermatologists should maintain a high index of suspicion for EMPD. If a patient is diagnosed with EMPD, a full-body skin examination should be performed with palpation of all lymph nodes. Imaging studies directed at the anatomic location of the involved skin should be utilized to search for an underlying internal malignancy.

1. Paget J. On disease of the mammary areola preceding cancer of the mammary gland. St Bartholomew Hosp Rep. 1874;10:87-89.

2. Crocker H. Paget’s disease affecting the scrotum and penis. Trans Pathol Soc Lond. 1889;40:187-191.

3. Zollo JD, Zeitouni NC. The Roswell Park Cancer Institute experience with extramammary Paget’s disease. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:59-65.

4. Heymann WR. Extramammary Paget’s disease. Clin Dermatol. 1993;11:83-87.5. Shepherd V, Davidson EJ, Davies-Humphreys J. Extramammary Paget’s disease. BJOG. 2005;112:273-279.

6. Perrotto J, Abbott JJ, Ceilley RI, et al. The role of immunohistochemistry in discriminating primary from secondary extramammary Paget disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:137-143.

7. Chanda JJ. Extramammary Paget’s disease: prognosis and relationship to internal malignancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:1009-1014.

8. Hendi A, Perdikis G, Snow JL. Unifocality of extramammary Paget disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:811-813.

9. Hendi A, Brodland DG, Zitelli JA. Extramammary Paget’s disease: surgical treatment with mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:767-773.10. Zampogna JC, Flowers FP, Roth WI, et al. Treatment of primary limited cutaneous extramammary Paget’s disease with topical imiquimod monotherapy: two case reports. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:S229-S235.

11. Beleznay KM, Levesque MA, Gill S. Response to 5-fluorouracil in metastatic extramammary Paget disease of the scrotum presenting as pancytopenia and back pain. Curr Oncol. 2009;16:81-83.

12. Kitagawa KH, Bogner P, Zeitouni NC. Photodynamic therapy with methyl-aminolevulinate for the treatment of double extramammary Paget’s disease. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:1043-1046.

13. Hata M, Omura M, Koike I, et al. Role of radiotherapy as curative treatment of extramammary Paget’s disease. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;80:47-54.

14. Takahagi S, Noda H, Kamegashira A, et al. Metastatic extramammary Paget’s disease treated with paclitaxel and trastuzumab combination chemotherapy. J Dermatol. 2009;36:457-461.

1. Paget J. On disease of the mammary areola preceding cancer of the mammary gland. St Bartholomew Hosp Rep. 1874;10:87-89.

2. Crocker H. Paget’s disease affecting the scrotum and penis. Trans Pathol Soc Lond. 1889;40:187-191.

3. Zollo JD, Zeitouni NC. The Roswell Park Cancer Institute experience with extramammary Paget’s disease. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:59-65.

4. Heymann WR. Extramammary Paget’s disease. Clin Dermatol. 1993;11:83-87.5. Shepherd V, Davidson EJ, Davies-Humphreys J. Extramammary Paget’s disease. BJOG. 2005;112:273-279.

6. Perrotto J, Abbott JJ, Ceilley RI, et al. The role of immunohistochemistry in discriminating primary from secondary extramammary Paget disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:137-143.

7. Chanda JJ. Extramammary Paget’s disease: prognosis and relationship to internal malignancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:1009-1014.

8. Hendi A, Perdikis G, Snow JL. Unifocality of extramammary Paget disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:811-813.

9. Hendi A, Brodland DG, Zitelli JA. Extramammary Paget’s disease: surgical treatment with mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:767-773.10. Zampogna JC, Flowers FP, Roth WI, et al. Treatment of primary limited cutaneous extramammary Paget’s disease with topical imiquimod monotherapy: two case reports. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:S229-S235.

11. Beleznay KM, Levesque MA, Gill S. Response to 5-fluorouracil in metastatic extramammary Paget disease of the scrotum presenting as pancytopenia and back pain. Curr Oncol. 2009;16:81-83.

12. Kitagawa KH, Bogner P, Zeitouni NC. Photodynamic therapy with methyl-aminolevulinate for the treatment of double extramammary Paget’s disease. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:1043-1046.

13. Hata M, Omura M, Koike I, et al. Role of radiotherapy as curative treatment of extramammary Paget’s disease. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;80:47-54.

14. Takahagi S, Noda H, Kamegashira A, et al. Metastatic extramammary Paget’s disease treated with paclitaxel and trastuzumab combination chemotherapy. J Dermatol. 2009;36:457-461.

Onchocerciasis

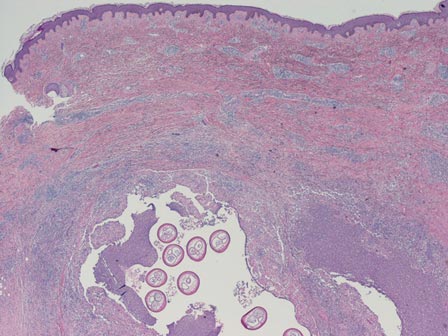

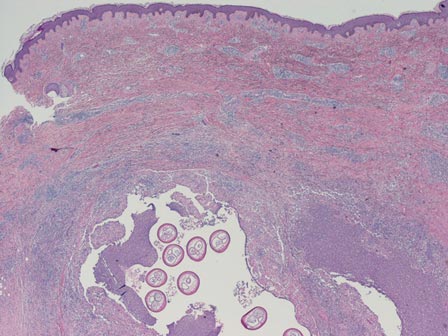

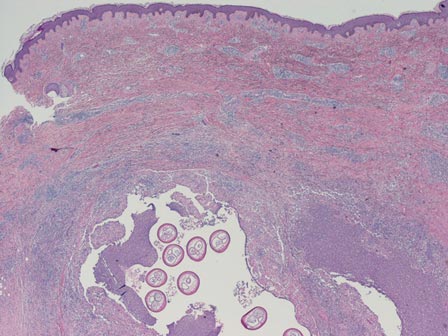

The larvae of Onchocerca volvulus, a nematode that is most commonly found in tropical Africa, Yemen, Central America, and South America, are transmitted by flies of the genus Simulium that breed near fast-flowing rivers.1 The flies bite the host and transmit the larvae, and the larvae then mature into adults within the skin and subcutis, forming nodules that typically are not painful. The worms may reside within the skin for years and produce microfilariae, which can migrate and cause visual impairment, blindness, or a pruritic papular rash.1

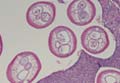

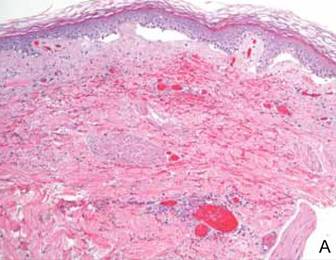

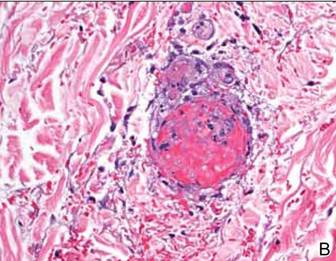

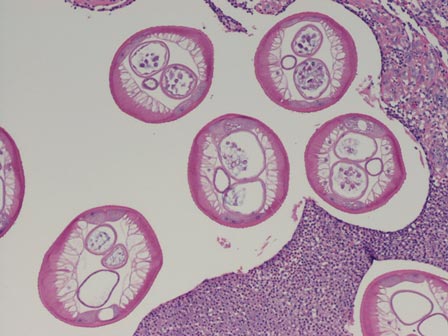

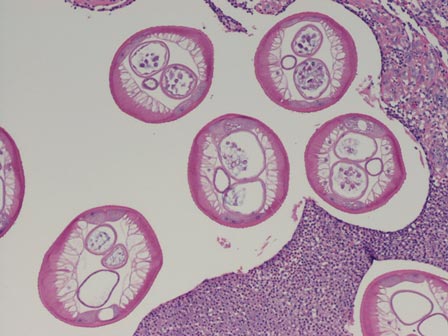

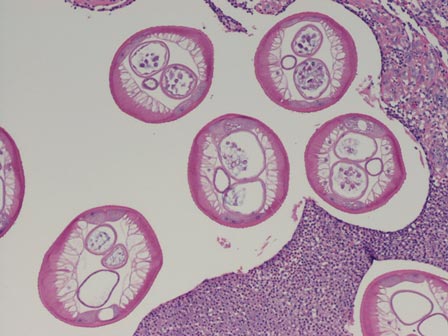

The nematode produces a nodule within the dermis or subcutis with surrounding fibrous tissue and a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with eosinophils (Figure 1). In some cases, microfilariae can be seen within the lymphatics or within the uteri of the worms.1 Male and female worms typically are present and have a corrugated cuticle with a thin underlying layer of striated muscle. The females have paired uteri, which usually contain microfilariae2 (Figure 2).

|

|

Dirofilaria repens also is a nematode that produces a subcutaneous nodule with an inflammatory reaction. This worm typically has a thick cuticle with longitudinal ridges, long thick muscle, and lateral cords.3 Additionally, because humans are not the usual host, Dirofilaria species do not complete their lifecycle and typically are not gravid, unlike Onchocerca species.

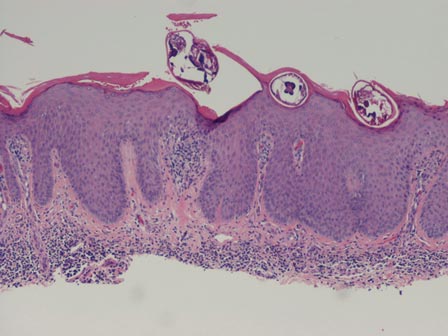

Myiasis is the presence of fly larvae within the skin. The larvae demonstrate a thick hyaline cuticle with pigmented brown-yellow spikes (Figure 3). There is a thick muscular layer under the cuticle and a tubular tracheal system containing vertical striations. The digestive system has an epithelial lining with prominent vessels. Adipose tissue with granulated cytoplasm, prominent nuclei, and coarse chromatin also are present.4

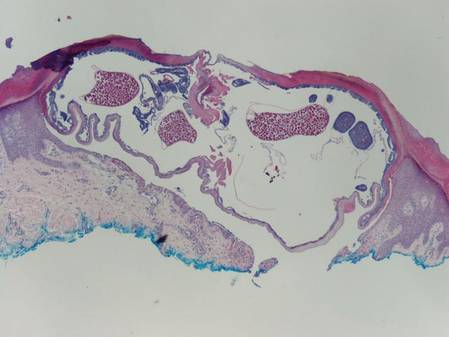

Scabies mites (Figure 4), ova, and scybala are present within the stratum corneum. A mixed inflammatory infiltrate also can be present.1 Tungiasis is caused by burrowing fleas and typically occurs on acral skin; therefore, it is more frequently found in the superficial portion of the skin. Erythrocytes usually are present in the gastrointestinal tract, and the females usually are gravid.2 A surrounding mixed inflammatory infiltrate is present, and necrosis also can occur (Figure 5).1

|

|

1. Weedon D. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010.

2. Elston DM, Ferringer T. Dermatopathology: Requisites in Dermatology. Edinburgh, Scotland: Saunders Elsevier; 2008.

3. Tzanetou K, Gasteratos S, Pantazopoulou A, et al. Subcutaneous dirofilariasis caused by Dirofilaria repens in Greece: a case report. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:892-895.

4. Fernandez-Flores A, Saeb-Lima M. Pulse granuloma of the lip: morphologic clues in its differential diagnosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:394-399.

The larvae of Onchocerca volvulus, a nematode that is most commonly found in tropical Africa, Yemen, Central America, and South America, are transmitted by flies of the genus Simulium that breed near fast-flowing rivers.1 The flies bite the host and transmit the larvae, and the larvae then mature into adults within the skin and subcutis, forming nodules that typically are not painful. The worms may reside within the skin for years and produce microfilariae, which can migrate and cause visual impairment, blindness, or a pruritic papular rash.1

The nematode produces a nodule within the dermis or subcutis with surrounding fibrous tissue and a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with eosinophils (Figure 1). In some cases, microfilariae can be seen within the lymphatics or within the uteri of the worms.1 Male and female worms typically are present and have a corrugated cuticle with a thin underlying layer of striated muscle. The females have paired uteri, which usually contain microfilariae2 (Figure 2).

|

|

Dirofilaria repens also is a nematode that produces a subcutaneous nodule with an inflammatory reaction. This worm typically has a thick cuticle with longitudinal ridges, long thick muscle, and lateral cords.3 Additionally, because humans are not the usual host, Dirofilaria species do not complete their lifecycle and typically are not gravid, unlike Onchocerca species.

Myiasis is the presence of fly larvae within the skin. The larvae demonstrate a thick hyaline cuticle with pigmented brown-yellow spikes (Figure 3). There is a thick muscular layer under the cuticle and a tubular tracheal system containing vertical striations. The digestive system has an epithelial lining with prominent vessels. Adipose tissue with granulated cytoplasm, prominent nuclei, and coarse chromatin also are present.4

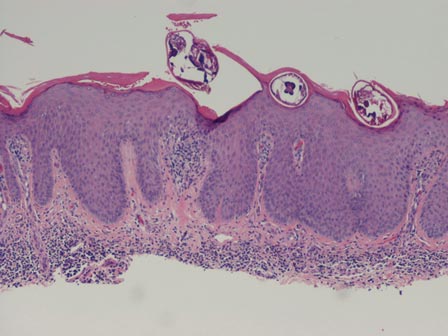

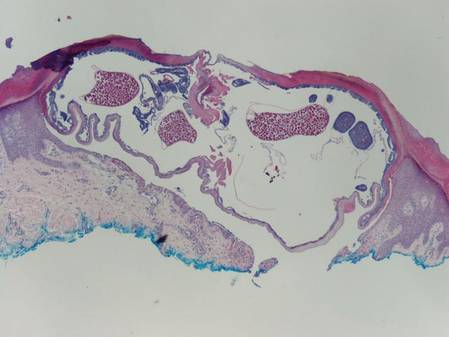

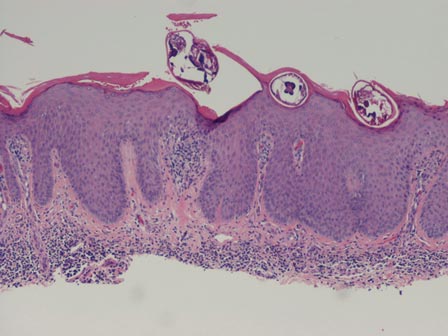

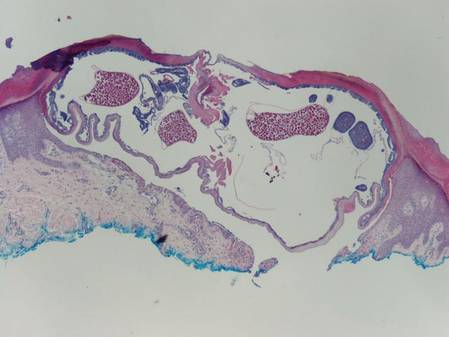

Scabies mites (Figure 4), ova, and scybala are present within the stratum corneum. A mixed inflammatory infiltrate also can be present.1 Tungiasis is caused by burrowing fleas and typically occurs on acral skin; therefore, it is more frequently found in the superficial portion of the skin. Erythrocytes usually are present in the gastrointestinal tract, and the females usually are gravid.2 A surrounding mixed inflammatory infiltrate is present, and necrosis also can occur (Figure 5).1

|

|

The larvae of Onchocerca volvulus, a nematode that is most commonly found in tropical Africa, Yemen, Central America, and South America, are transmitted by flies of the genus Simulium that breed near fast-flowing rivers.1 The flies bite the host and transmit the larvae, and the larvae then mature into adults within the skin and subcutis, forming nodules that typically are not painful. The worms may reside within the skin for years and produce microfilariae, which can migrate and cause visual impairment, blindness, or a pruritic papular rash.1

The nematode produces a nodule within the dermis or subcutis with surrounding fibrous tissue and a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with eosinophils (Figure 1). In some cases, microfilariae can be seen within the lymphatics or within the uteri of the worms.1 Male and female worms typically are present and have a corrugated cuticle with a thin underlying layer of striated muscle. The females have paired uteri, which usually contain microfilariae2 (Figure 2).

|

|

Dirofilaria repens also is a nematode that produces a subcutaneous nodule with an inflammatory reaction. This worm typically has a thick cuticle with longitudinal ridges, long thick muscle, and lateral cords.3 Additionally, because humans are not the usual host, Dirofilaria species do not complete their lifecycle and typically are not gravid, unlike Onchocerca species.

Myiasis is the presence of fly larvae within the skin. The larvae demonstrate a thick hyaline cuticle with pigmented brown-yellow spikes (Figure 3). There is a thick muscular layer under the cuticle and a tubular tracheal system containing vertical striations. The digestive system has an epithelial lining with prominent vessels. Adipose tissue with granulated cytoplasm, prominent nuclei, and coarse chromatin also are present.4

Scabies mites (Figure 4), ova, and scybala are present within the stratum corneum. A mixed inflammatory infiltrate also can be present.1 Tungiasis is caused by burrowing fleas and typically occurs on acral skin; therefore, it is more frequently found in the superficial portion of the skin. Erythrocytes usually are present in the gastrointestinal tract, and the females usually are gravid.2 A surrounding mixed inflammatory infiltrate is present, and necrosis also can occur (Figure 5).1

|

|

1. Weedon D. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010.

2. Elston DM, Ferringer T. Dermatopathology: Requisites in Dermatology. Edinburgh, Scotland: Saunders Elsevier; 2008.

3. Tzanetou K, Gasteratos S, Pantazopoulou A, et al. Subcutaneous dirofilariasis caused by Dirofilaria repens in Greece: a case report. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:892-895.

4. Fernandez-Flores A, Saeb-Lima M. Pulse granuloma of the lip: morphologic clues in its differential diagnosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:394-399.

1. Weedon D. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010.

2. Elston DM, Ferringer T. Dermatopathology: Requisites in Dermatology. Edinburgh, Scotland: Saunders Elsevier; 2008.

3. Tzanetou K, Gasteratos S, Pantazopoulou A, et al. Subcutaneous dirofilariasis caused by Dirofilaria repens in Greece: a case report. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:892-895.

4. Fernandez-Flores A, Saeb-Lima M. Pulse granuloma of the lip: morphologic clues in its differential diagnosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:394-399.

Pseudoglandular Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second most common form of skin cancer. Pseudoglandular SCC, also known as adenoid SCC or acantholytic SCC, is an uncommon variant that was first described by Lever1 in 1947 as an adenoacanthoma of the sweat glands. Of the many variants of SCC, pseudoglandular SCC generally is considered to behave aggressively with intermediate (3%–10%) risk for metastasis.2 The metastatic potential of pseudoglandular SCC may be conferred in part by diminished expression of intercellular adhesion molecules, including desmoglein 3, epithelial cadherin, and syn-decan 1.3,4 Pseudoglandular SCC presents most often on sun-damaged skin of elderly patients, especially the face and ears, as a pink or red nodule with central ulceration and a raised indurated border. It may be mistaken clinically for basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or keratoacanthoma.

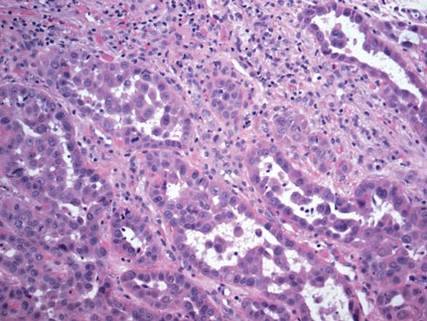

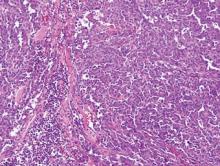

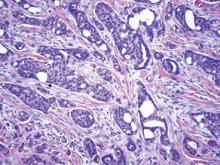

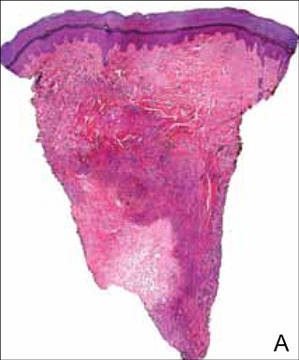

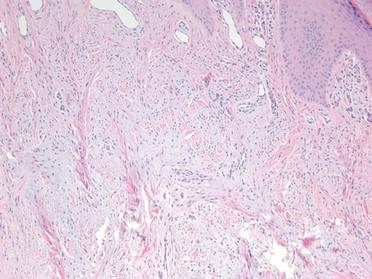

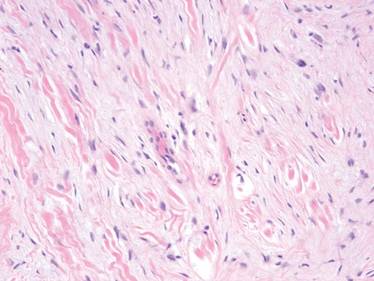

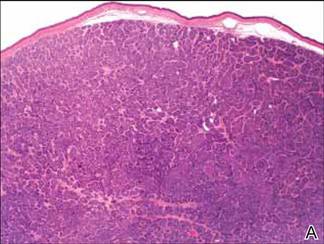

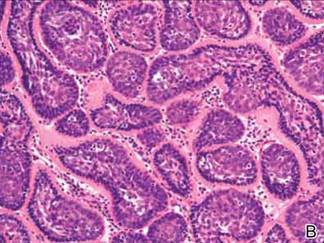

On microscopic examination, the lesion is predominantly located in the dermis and may extend to the subcutis. There usually is connection to the overlying epidermis, which often shows hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis. Epidermal squamous dysplasia may be present. The dermis typically contains nests of squamous cells with a variable degree of central acantholysis. The morphology on low-power magnification consists of tubules of irregular size and shape, which are present either focally or throughout the lesion (Figure 1). The tubules are typically admixed with foci of keratinization. One or more layers of cohesive cells line the tubules. Partial keratinization may be found in the lining of tubules with more than 1 cell layer. The tumor cells are polygonal with eosinophilic cytoplasm, ovoid hyperchromatic or vesicular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli. Mitoses are common. The tubular lumina are filled with acantholytic cells, either singly or in small clusters, which may demonstrate residual bridging to tubular lining cells (Figure 2). The acantholytic cells show some variability in size and may be large, multinucleated, or keratinized. The tubules may contain material that is amorphous, basophilic, periodic acid–Schiff positive, diastase sensitive, and mucicarmine negative.5 Eccrine ducts at the periphery of the tumor may show reactive dilatation and proliferation. Tumor cells show positive immunostaining for epithelial membrane antigen, 34βE12, CK5/6, and tumor protein p63.6-8 There is negative immunostaining for carcinoembryonic antigen, amylase, S-100 protein, and factor VIII.5

|

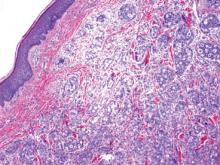

The differential diagnosis includes adenoid BCC, angiosarcoma, eccrine carcinoma, and metastatic adenocarcinoma of the skin. In adenoid BCC, excess stromal mucin imparts pseudoglandular architecture (Figure 3). However, features of conventional BCC, including peripheral nuclear palisading and retraction artifact often are present as well.

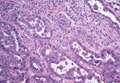

Angiosarcoma shows slitlike vascular spaces lined by hyperchromatic endothelial cells (Figure 4). Further, there is positive immunostaining for vascular markers CD31 and CD34.

In eccrine carcinoma, there are invasive ductal structures lined by either a single or double layer of cells that may contain luminal material that is periodic acid–Schiff positive and diastase resistant (Figure 5).9 The tumor cells show positive immunostaining for cytokeratins, epithelial membrane antigen, carcinoembryonic antigen, and S-100 protein.10

Pseudoglandular SCC is susceptible to misdiagnosis as adenocarcinoma by sampling error if biopsies do not capture areas with typical features of SCC, including dysplastic squamous epithelium and keratinization. Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the skin is more likely to present with multiple nodules in older individuals. Lack of epidermal connection of the tumor and minimal to no acantholytic dyskeratosis further support cutaneous metastasis (Figure 6). Review of the patient’s clinical history might be helpful if adenocarcinoma was previously diagnosed. Immunohistochemical evaluation may aid in the prediction of the primary site in patients with metastatic adenocarcinoma of unknown origin.11

1. Lever WF. Adenocanthoma of sweat glands; carcinoma of sweat glands with glandular and epidermal elements: report of four cases. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1947;56:157-171.

2. Bonerandi JJ, Beauvillain C, Caquant L, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and precursor lesions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(suppl 5):1-51.

3. Griffin JR, Wriston CC, Peters MS, et al. Decreased expression of intercellular adhesion molecules in acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma compared with invasive well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;139:442-447.

4. Bayer-Garner IB, Smoller BR. The expression of syndecan-1 is preferentially reduced compared with that of E-cadherin in acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:83-89.

5. Nappi O, Pettinato G, Wick MR. Adenoid (acantholytic) squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 1989;16:114-121.

6. Sajin M, Hodorogea Prisăcaru A, Luchian MC, et al. Acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma: pathological study of nine cases with review of literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:279-283.

7. Gray Y, Robidoux HJ, Farrell DS, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma detected by high-molecular-weight cytokeratin immunostaining mimicking atypical fibroxanthoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:799-802.

8. Kanitakis J, Chouvet B. Expression of p63 in cutaneous metastases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:753-758.

9. Plaza JA, Prieto VG. Neoplastic Lesions of the Skin. New York, NY: Demos Medical Publishing; 2014.

10. Swanson PE, Cherwitz DL, Neumann MP, et al. Eccrine sweat gland carcinoma: an histologic and immunohistochemical study of 32 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1987;14:65-86.

11. Dennis JL, Hvidsten TR, Wit EC, et al. Markers of adenocarcinoma characteristic of the site of origin: development of a diagnostic algorithm. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3766-3772.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second most common form of skin cancer. Pseudoglandular SCC, also known as adenoid SCC or acantholytic SCC, is an uncommon variant that was first described by Lever1 in 1947 as an adenoacanthoma of the sweat glands. Of the many variants of SCC, pseudoglandular SCC generally is considered to behave aggressively with intermediate (3%–10%) risk for metastasis.2 The metastatic potential of pseudoglandular SCC may be conferred in part by diminished expression of intercellular adhesion molecules, including desmoglein 3, epithelial cadherin, and syn-decan 1.3,4 Pseudoglandular SCC presents most often on sun-damaged skin of elderly patients, especially the face and ears, as a pink or red nodule with central ulceration and a raised indurated border. It may be mistaken clinically for basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or keratoacanthoma.

On microscopic examination, the lesion is predominantly located in the dermis and may extend to the subcutis. There usually is connection to the overlying epidermis, which often shows hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis. Epidermal squamous dysplasia may be present. The dermis typically contains nests of squamous cells with a variable degree of central acantholysis. The morphology on low-power magnification consists of tubules of irregular size and shape, which are present either focally or throughout the lesion (Figure 1). The tubules are typically admixed with foci of keratinization. One or more layers of cohesive cells line the tubules. Partial keratinization may be found in the lining of tubules with more than 1 cell layer. The tumor cells are polygonal with eosinophilic cytoplasm, ovoid hyperchromatic or vesicular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli. Mitoses are common. The tubular lumina are filled with acantholytic cells, either singly or in small clusters, which may demonstrate residual bridging to tubular lining cells (Figure 2). The acantholytic cells show some variability in size and may be large, multinucleated, or keratinized. The tubules may contain material that is amorphous, basophilic, periodic acid–Schiff positive, diastase sensitive, and mucicarmine negative.5 Eccrine ducts at the periphery of the tumor may show reactive dilatation and proliferation. Tumor cells show positive immunostaining for epithelial membrane antigen, 34βE12, CK5/6, and tumor protein p63.6-8 There is negative immunostaining for carcinoembryonic antigen, amylase, S-100 protein, and factor VIII.5

|

The differential diagnosis includes adenoid BCC, angiosarcoma, eccrine carcinoma, and metastatic adenocarcinoma of the skin. In adenoid BCC, excess stromal mucin imparts pseudoglandular architecture (Figure 3). However, features of conventional BCC, including peripheral nuclear palisading and retraction artifact often are present as well.

Angiosarcoma shows slitlike vascular spaces lined by hyperchromatic endothelial cells (Figure 4). Further, there is positive immunostaining for vascular markers CD31 and CD34.

In eccrine carcinoma, there are invasive ductal structures lined by either a single or double layer of cells that may contain luminal material that is periodic acid–Schiff positive and diastase resistant (Figure 5).9 The tumor cells show positive immunostaining for cytokeratins, epithelial membrane antigen, carcinoembryonic antigen, and S-100 protein.10

Pseudoglandular SCC is susceptible to misdiagnosis as adenocarcinoma by sampling error if biopsies do not capture areas with typical features of SCC, including dysplastic squamous epithelium and keratinization. Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the skin is more likely to present with multiple nodules in older individuals. Lack of epidermal connection of the tumor and minimal to no acantholytic dyskeratosis further support cutaneous metastasis (Figure 6). Review of the patient’s clinical history might be helpful if adenocarcinoma was previously diagnosed. Immunohistochemical evaluation may aid in the prediction of the primary site in patients with metastatic adenocarcinoma of unknown origin.11

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second most common form of skin cancer. Pseudoglandular SCC, also known as adenoid SCC or acantholytic SCC, is an uncommon variant that was first described by Lever1 in 1947 as an adenoacanthoma of the sweat glands. Of the many variants of SCC, pseudoglandular SCC generally is considered to behave aggressively with intermediate (3%–10%) risk for metastasis.2 The metastatic potential of pseudoglandular SCC may be conferred in part by diminished expression of intercellular adhesion molecules, including desmoglein 3, epithelial cadherin, and syn-decan 1.3,4 Pseudoglandular SCC presents most often on sun-damaged skin of elderly patients, especially the face and ears, as a pink or red nodule with central ulceration and a raised indurated border. It may be mistaken clinically for basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or keratoacanthoma.

On microscopic examination, the lesion is predominantly located in the dermis and may extend to the subcutis. There usually is connection to the overlying epidermis, which often shows hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis. Epidermal squamous dysplasia may be present. The dermis typically contains nests of squamous cells with a variable degree of central acantholysis. The morphology on low-power magnification consists of tubules of irregular size and shape, which are present either focally or throughout the lesion (Figure 1). The tubules are typically admixed with foci of keratinization. One or more layers of cohesive cells line the tubules. Partial keratinization may be found in the lining of tubules with more than 1 cell layer. The tumor cells are polygonal with eosinophilic cytoplasm, ovoid hyperchromatic or vesicular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli. Mitoses are common. The tubular lumina are filled with acantholytic cells, either singly or in small clusters, which may demonstrate residual bridging to tubular lining cells (Figure 2). The acantholytic cells show some variability in size and may be large, multinucleated, or keratinized. The tubules may contain material that is amorphous, basophilic, periodic acid–Schiff positive, diastase sensitive, and mucicarmine negative.5 Eccrine ducts at the periphery of the tumor may show reactive dilatation and proliferation. Tumor cells show positive immunostaining for epithelial membrane antigen, 34βE12, CK5/6, and tumor protein p63.6-8 There is negative immunostaining for carcinoembryonic antigen, amylase, S-100 protein, and factor VIII.5

|

The differential diagnosis includes adenoid BCC, angiosarcoma, eccrine carcinoma, and metastatic adenocarcinoma of the skin. In adenoid BCC, excess stromal mucin imparts pseudoglandular architecture (Figure 3). However, features of conventional BCC, including peripheral nuclear palisading and retraction artifact often are present as well.

Angiosarcoma shows slitlike vascular spaces lined by hyperchromatic endothelial cells (Figure 4). Further, there is positive immunostaining for vascular markers CD31 and CD34.

In eccrine carcinoma, there are invasive ductal structures lined by either a single or double layer of cells that may contain luminal material that is periodic acid–Schiff positive and diastase resistant (Figure 5).9 The tumor cells show positive immunostaining for cytokeratins, epithelial membrane antigen, carcinoembryonic antigen, and S-100 protein.10

Pseudoglandular SCC is susceptible to misdiagnosis as adenocarcinoma by sampling error if biopsies do not capture areas with typical features of SCC, including dysplastic squamous epithelium and keratinization. Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the skin is more likely to present with multiple nodules in older individuals. Lack of epidermal connection of the tumor and minimal to no acantholytic dyskeratosis further support cutaneous metastasis (Figure 6). Review of the patient’s clinical history might be helpful if adenocarcinoma was previously diagnosed. Immunohistochemical evaluation may aid in the prediction of the primary site in patients with metastatic adenocarcinoma of unknown origin.11

1. Lever WF. Adenocanthoma of sweat glands; carcinoma of sweat glands with glandular and epidermal elements: report of four cases. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1947;56:157-171.

2. Bonerandi JJ, Beauvillain C, Caquant L, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and precursor lesions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(suppl 5):1-51.

3. Griffin JR, Wriston CC, Peters MS, et al. Decreased expression of intercellular adhesion molecules in acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma compared with invasive well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;139:442-447.

4. Bayer-Garner IB, Smoller BR. The expression of syndecan-1 is preferentially reduced compared with that of E-cadherin in acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:83-89.

5. Nappi O, Pettinato G, Wick MR. Adenoid (acantholytic) squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 1989;16:114-121.

6. Sajin M, Hodorogea Prisăcaru A, Luchian MC, et al. Acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma: pathological study of nine cases with review of literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:279-283.

7. Gray Y, Robidoux HJ, Farrell DS, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma detected by high-molecular-weight cytokeratin immunostaining mimicking atypical fibroxanthoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:799-802.

8. Kanitakis J, Chouvet B. Expression of p63 in cutaneous metastases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:753-758.

9. Plaza JA, Prieto VG. Neoplastic Lesions of the Skin. New York, NY: Demos Medical Publishing; 2014.

10. Swanson PE, Cherwitz DL, Neumann MP, et al. Eccrine sweat gland carcinoma: an histologic and immunohistochemical study of 32 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1987;14:65-86.

11. Dennis JL, Hvidsten TR, Wit EC, et al. Markers of adenocarcinoma characteristic of the site of origin: development of a diagnostic algorithm. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3766-3772.

1. Lever WF. Adenocanthoma of sweat glands; carcinoma of sweat glands with glandular and epidermal elements: report of four cases. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1947;56:157-171.

2. Bonerandi JJ, Beauvillain C, Caquant L, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and precursor lesions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(suppl 5):1-51.

3. Griffin JR, Wriston CC, Peters MS, et al. Decreased expression of intercellular adhesion molecules in acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma compared with invasive well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;139:442-447.

4. Bayer-Garner IB, Smoller BR. The expression of syndecan-1 is preferentially reduced compared with that of E-cadherin in acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:83-89.

5. Nappi O, Pettinato G, Wick MR. Adenoid (acantholytic) squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 1989;16:114-121.

6. Sajin M, Hodorogea Prisăcaru A, Luchian MC, et al. Acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma: pathological study of nine cases with review of literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:279-283.

7. Gray Y, Robidoux HJ, Farrell DS, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma detected by high-molecular-weight cytokeratin immunostaining mimicking atypical fibroxanthoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:799-802.

8. Kanitakis J, Chouvet B. Expression of p63 in cutaneous metastases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:753-758.

9. Plaza JA, Prieto VG. Neoplastic Lesions of the Skin. New York, NY: Demos Medical Publishing; 2014.

10. Swanson PE, Cherwitz DL, Neumann MP, et al. Eccrine sweat gland carcinoma: an histologic and immunohistochemical study of 32 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1987;14:65-86.

11. Dennis JL, Hvidsten TR, Wit EC, et al. Markers of adenocarcinoma characteristic of the site of origin: development of a diagnostic algorithm. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3766-3772.

What Is Your Diagnosis? Acquired Lymphangiectasia

A 19-year-old woman presented with an umbilical mass of 5 months’ duration that had grown in size. Physical examination revealed a 1×1-cm brownish, pedunculated, cauliflower-shaped lesion on the umbilicus. There were no other signs or symptoms of disease. The patient’s personal and family disease history were unremarkable. An excisional biopsy was performed.

The Diagnosis: Acquired Lymphangiectasia

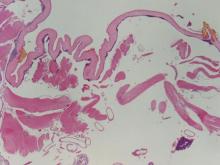

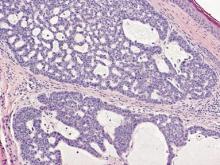

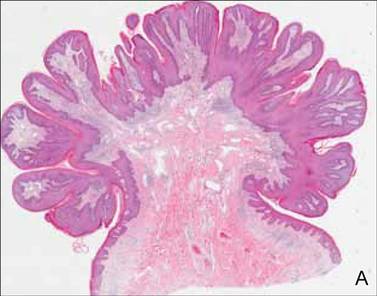

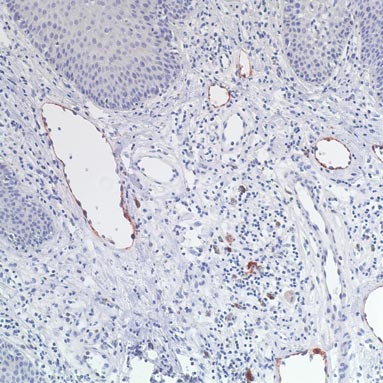

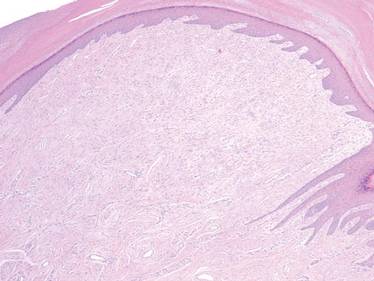

On histopathology numerous dilated channels lined by a single flat layer of endothelial cells were noted within the dermis. The overlying epidermis was papillomatous and acanthotic (Figure 1). The endothelial cells lining the dilated channels were D2-40 positive (Figure 2). Furthermore, the channels contained a pinkish amorphous material and a few red blood cells. The surrounding stroma showed scattered lymphocyte infiltration. These findings were consistent with lymphangiectasia. The lesion has not recurred 4 years following total excision.

|

Acquired lymphangiectasia is known by various names, including lymphangioma, acquired lymphangioma, and acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum, which has led to confusion.1 Acquired lymphangiectasia, which is characterized by dilated superficial lymphatics, develops following damage to previously normal lymphatic channels, leading to a buildup of lymph pressure and backflow.2 Acquired lymphangiectasia has been reported as clinically and histologically indistinguishable from lymphangioma circumscriptum2; however, unlike in lymphangiectasia, the suffix -oma denotes a tumor. Our case matched more closely with the typical concept of lymphangiectasia rather than lymphangioma.

Clinical findings of acquired lymphangiectasia usually include translucent, flat or slightly raised, 2- to 5-mm, flesh-colored papules and vesicles.3,4 Acquired lymphangiectasia has been described with lesions that have verrucous surfaces mimicking warts, condyloma acuminata, or molluscum contagiosum.5,6 Our case suggests that acquired lymphangiectasia also can present with a pedunculated cauliflowerlike appearance. In general, it develops secondary to certain conditions such as recovery from trauma or surgery, postsurgical fibrosis, and irradiation. Lymphangiectasia often is seen on the arms, axillae, chest wall, and genital area in women and the scrotum, penis, thighs, and pubic region in men, both who have undergone radical surgery and irradiation for treatment of breast and prostate cancer, respectively.3 Our patient did not report any history of trauma to the umbilicus.

On histopathology acquired lymphangiectasia typically shows edematous polypoid nodules with dilated lymphatics. The overlying epidermis usually shows a spectrum of proliferation ranging from mild acanthosis to florid pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with marked hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis. The distinctive finding of lymphangiectasia is the presence of dilated lymphatic spaces within the dermis. The dilated channels are filled with lymphatic fluid and often red and white blood cells. The single layer of flattened endothelial cells generally exhibits immunoreactivity to D2-40 and CD31.1

Treatment of lymphangiectasia is focused on reducing the pressure within the lymph vessels and managing consequent lymphedema with compression dressings. Simple surgical excision of lesions on sites such as the vulva or legs often is effective.3 If surgical intervention is not an option, cryotherapy, sclerotherapy, cauterization, and treatment with CO2 lasers also have been utilized with good outcomes.7 In the current case, total surgical excision was performed, which provided good results.

1. Stewart CJ, Chan T, Platten M. Acquired lymphangiectasia (‘lymphangioma circumscriptum’) of the vulva: a report of eight cases. Pathology. 2009;41:448-453.

2. Celis AV, Gaughf CN, Sangueza OP, et al. Acquired lymphangiectasis. South Med J. 1999;92:69-72.

3. Verma SB. Lymphangiectasias of the skin: victims of confusing nomenclature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:566-569.

4. Mortimer PS. Disorder of lymphatic vessels. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. Vol 3. 8th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:48.28-48.29.

5. Sharma R, Tomar S, Chandra M. Acquired vulval lymphangiectases mimicking genital warts. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2002;68:166-167.

6. Horn LC, Kühndel K, Pawlowitsch T, et al. Acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum of the vulva mimicking genital warts. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;123:118-120.

7. Patel GA, Schwartz RA. Cutaneous lymphangioma circumscriptum: frog spawn on the skin. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1290-1295.

A 19-year-old woman presented with an umbilical mass of 5 months’ duration that had grown in size. Physical examination revealed a 1×1-cm brownish, pedunculated, cauliflower-shaped lesion on the umbilicus. There were no other signs or symptoms of disease. The patient’s personal and family disease history were unremarkable. An excisional biopsy was performed.

The Diagnosis: Acquired Lymphangiectasia

On histopathology numerous dilated channels lined by a single flat layer of endothelial cells were noted within the dermis. The overlying epidermis was papillomatous and acanthotic (Figure 1). The endothelial cells lining the dilated channels were D2-40 positive (Figure 2). Furthermore, the channels contained a pinkish amorphous material and a few red blood cells. The surrounding stroma showed scattered lymphocyte infiltration. These findings were consistent with lymphangiectasia. The lesion has not recurred 4 years following total excision.

|

Acquired lymphangiectasia is known by various names, including lymphangioma, acquired lymphangioma, and acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum, which has led to confusion.1 Acquired lymphangiectasia, which is characterized by dilated superficial lymphatics, develops following damage to previously normal lymphatic channels, leading to a buildup of lymph pressure and backflow.2 Acquired lymphangiectasia has been reported as clinically and histologically indistinguishable from lymphangioma circumscriptum2; however, unlike in lymphangiectasia, the suffix -oma denotes a tumor. Our case matched more closely with the typical concept of lymphangiectasia rather than lymphangioma.

Clinical findings of acquired lymphangiectasia usually include translucent, flat or slightly raised, 2- to 5-mm, flesh-colored papules and vesicles.3,4 Acquired lymphangiectasia has been described with lesions that have verrucous surfaces mimicking warts, condyloma acuminata, or molluscum contagiosum.5,6 Our case suggests that acquired lymphangiectasia also can present with a pedunculated cauliflowerlike appearance. In general, it develops secondary to certain conditions such as recovery from trauma or surgery, postsurgical fibrosis, and irradiation. Lymphangiectasia often is seen on the arms, axillae, chest wall, and genital area in women and the scrotum, penis, thighs, and pubic region in men, both who have undergone radical surgery and irradiation for treatment of breast and prostate cancer, respectively.3 Our patient did not report any history of trauma to the umbilicus.

On histopathology acquired lymphangiectasia typically shows edematous polypoid nodules with dilated lymphatics. The overlying epidermis usually shows a spectrum of proliferation ranging from mild acanthosis to florid pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with marked hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis. The distinctive finding of lymphangiectasia is the presence of dilated lymphatic spaces within the dermis. The dilated channels are filled with lymphatic fluid and often red and white blood cells. The single layer of flattened endothelial cells generally exhibits immunoreactivity to D2-40 and CD31.1

Treatment of lymphangiectasia is focused on reducing the pressure within the lymph vessels and managing consequent lymphedema with compression dressings. Simple surgical excision of lesions on sites such as the vulva or legs often is effective.3 If surgical intervention is not an option, cryotherapy, sclerotherapy, cauterization, and treatment with CO2 lasers also have been utilized with good outcomes.7 In the current case, total surgical excision was performed, which provided good results.

A 19-year-old woman presented with an umbilical mass of 5 months’ duration that had grown in size. Physical examination revealed a 1×1-cm brownish, pedunculated, cauliflower-shaped lesion on the umbilicus. There were no other signs or symptoms of disease. The patient’s personal and family disease history were unremarkable. An excisional biopsy was performed.

The Diagnosis: Acquired Lymphangiectasia

On histopathology numerous dilated channels lined by a single flat layer of endothelial cells were noted within the dermis. The overlying epidermis was papillomatous and acanthotic (Figure 1). The endothelial cells lining the dilated channels were D2-40 positive (Figure 2). Furthermore, the channels contained a pinkish amorphous material and a few red blood cells. The surrounding stroma showed scattered lymphocyte infiltration. These findings were consistent with lymphangiectasia. The lesion has not recurred 4 years following total excision.

|

Acquired lymphangiectasia is known by various names, including lymphangioma, acquired lymphangioma, and acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum, which has led to confusion.1 Acquired lymphangiectasia, which is characterized by dilated superficial lymphatics, develops following damage to previously normal lymphatic channels, leading to a buildup of lymph pressure and backflow.2 Acquired lymphangiectasia has been reported as clinically and histologically indistinguishable from lymphangioma circumscriptum2; however, unlike in lymphangiectasia, the suffix -oma denotes a tumor. Our case matched more closely with the typical concept of lymphangiectasia rather than lymphangioma.

Clinical findings of acquired lymphangiectasia usually include translucent, flat or slightly raised, 2- to 5-mm, flesh-colored papules and vesicles.3,4 Acquired lymphangiectasia has been described with lesions that have verrucous surfaces mimicking warts, condyloma acuminata, or molluscum contagiosum.5,6 Our case suggests that acquired lymphangiectasia also can present with a pedunculated cauliflowerlike appearance. In general, it develops secondary to certain conditions such as recovery from trauma or surgery, postsurgical fibrosis, and irradiation. Lymphangiectasia often is seen on the arms, axillae, chest wall, and genital area in women and the scrotum, penis, thighs, and pubic region in men, both who have undergone radical surgery and irradiation for treatment of breast and prostate cancer, respectively.3 Our patient did not report any history of trauma to the umbilicus.

On histopathology acquired lymphangiectasia typically shows edematous polypoid nodules with dilated lymphatics. The overlying epidermis usually shows a spectrum of proliferation ranging from mild acanthosis to florid pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with marked hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis. The distinctive finding of lymphangiectasia is the presence of dilated lymphatic spaces within the dermis. The dilated channels are filled with lymphatic fluid and often red and white blood cells. The single layer of flattened endothelial cells generally exhibits immunoreactivity to D2-40 and CD31.1

Treatment of lymphangiectasia is focused on reducing the pressure within the lymph vessels and managing consequent lymphedema with compression dressings. Simple surgical excision of lesions on sites such as the vulva or legs often is effective.3 If surgical intervention is not an option, cryotherapy, sclerotherapy, cauterization, and treatment with CO2 lasers also have been utilized with good outcomes.7 In the current case, total surgical excision was performed, which provided good results.

1. Stewart CJ, Chan T, Platten M. Acquired lymphangiectasia (‘lymphangioma circumscriptum’) of the vulva: a report of eight cases. Pathology. 2009;41:448-453.

2. Celis AV, Gaughf CN, Sangueza OP, et al. Acquired lymphangiectasis. South Med J. 1999;92:69-72.

3. Verma SB. Lymphangiectasias of the skin: victims of confusing nomenclature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:566-569.

4. Mortimer PS. Disorder of lymphatic vessels. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. Vol 3. 8th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:48.28-48.29.

5. Sharma R, Tomar S, Chandra M. Acquired vulval lymphangiectases mimicking genital warts. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2002;68:166-167.

6. Horn LC, Kühndel K, Pawlowitsch T, et al. Acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum of the vulva mimicking genital warts. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;123:118-120.

7. Patel GA, Schwartz RA. Cutaneous lymphangioma circumscriptum: frog spawn on the skin. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1290-1295.

1. Stewart CJ, Chan T, Platten M. Acquired lymphangiectasia (‘lymphangioma circumscriptum’) of the vulva: a report of eight cases. Pathology. 2009;41:448-453.

2. Celis AV, Gaughf CN, Sangueza OP, et al. Acquired lymphangiectasis. South Med J. 1999;92:69-72.

3. Verma SB. Lymphangiectasias of the skin: victims of confusing nomenclature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:566-569.

4. Mortimer PS. Disorder of lymphatic vessels. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. Vol 3. 8th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:48.28-48.29.

5. Sharma R, Tomar S, Chandra M. Acquired vulval lymphangiectases mimicking genital warts. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2002;68:166-167.

6. Horn LC, Kühndel K, Pawlowitsch T, et al. Acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum of the vulva mimicking genital warts. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;123:118-120.

7. Patel GA, Schwartz RA. Cutaneous lymphangioma circumscriptum: frog spawn on the skin. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1290-1295.

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell Lymphoma Presenting as Purpura Fulminans

Purpura fulminans is a hematologic emergency, with clinical skin necrosis and laboratory testing showing disseminated intravascular coagulation. The thrombotic occlusion usually affects small and medium-sized blood vessels and may involve any organ. Purpura fulminans has been implicated with sepsis, most commonly meningococcal infections; other infections such as Staphylococcus aureus, groups A and B β-hemolytic streptococci, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Haemophilus influenzae; and as a sequela to benign childhood infections, such as varicella. Other associations with purpura fulminans include autoimmune disease and heritable or acquired deficiency of anticoagulant proteins, most commonly protein C. We present a rare case of purpura fulminans as the presenting sign of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL), an aggressive primary nodal peripheral T-cell lymphoma with a high mortality rate and nonspecific skin manifestations in roughly half of all patients involved.

Case Report

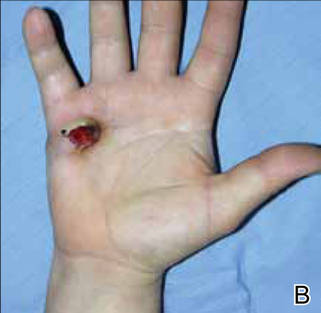

A 56-year-old woman presented with purpuric patches on the left foot (Figure 1A). Seven days after presentation the lesion progressed into ecchymotic geographic plaques and hemorrhagic bullae that spread upward and contralaterally, sparing the digits, trunk, head, neck, and mucous membranes. Ultimately, the involved skin became necrotic and involved 20% of the body surface area (Figure 1B). The lesions were painful with a burning sensation but were not pruritic. The patient also reported intermittent fevers, chills, myalgia, nausea, and shortness of breath. Enlarged lymph nodes were present in the right cervical chain. She denied new medications; stated she had been in good health prior to this episode; and had no history of spontaneous abortion, neurologic symptoms, or other serious illness.

|

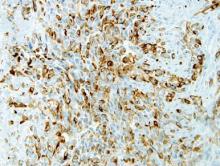

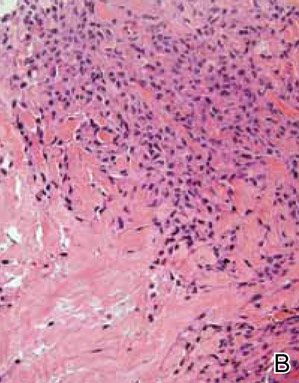

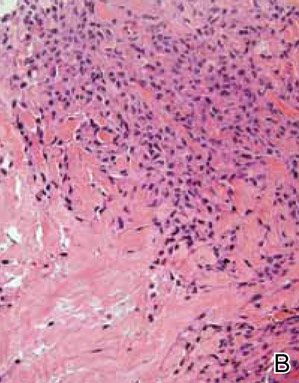

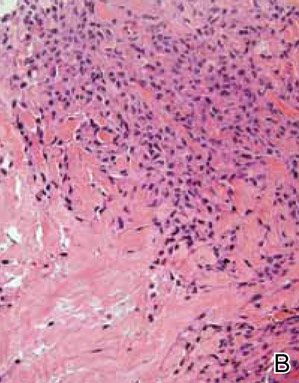

Computed tomography showed prominent diffuse mediastinal, mesenteric, retroperitoneal, and pelvic lymphadenopathy with involvement of the cervical and inguinal areas. Laboratory values showed thrombocytopenia and increased fibrin degradation products. Blood and tissue cultures were negative; the patient also had a negative viral serology, except for Epstein-Barr virus IgG titers (>1:2560). A skin biopsy of the left thigh demonstrated venules and capillaries in the mid and superficial dermis filled with fibrin thrombi without vasculitis (Figure 2). A lymph node biopsy was consistent with a diagnosis of AITL. The lymph node architecture was largely effaced by a polymorphous lymphoid infiltrate that predominantly expanded into paracortical areas and was associated with a prominent arborizing vascular proliferation. The infiltrate was composed of lymphocytes ranging in size from small to medium, with ample cytoplasm, coarsely clumped chromatin, and mildly irregular nuclear membranes. Large atypical lymphocytes with features of immunoblasts were easily identified. An associated inflammatory background composed of eosinophils, plasma cells, and histiocytes was present (Figure 3). The atypical lymphocytes stained positive for CD3and CD10 on immunohistochemistry. Additionally, a subset of large immunoblastlike lymphocytes was positive for Epstein-Barr–encoded small RNAs by in situ hybridization.

|

The patient was started on rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone. She received 2 cycles with positive response based on subsequent computed tomography and positron emission tomography scans that showed regression of her disease as well as the lack of formation of new skin lesions. She was transferred to a burn unit where she had continuing treatment and skin grafts. Despite 2 cycles of chemotherapy, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and daily wound care management, the patient died secondary to sepsis 6 months after presentation.

Comment

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma is a primary nodal lymphoma with occasional cutaneous involvement. Cutaneous manifestations occur in roughly half of all patients with AITL1 and have mainly been described as erythematous macules and papules that can resemble a viral exanthem or a drug reaction.2 However, other skin manifestations include urticaria, papulovesicular lesions, nodules, erythroderma,3 and to a lesser degree purpura.4 The lesions have been noted to occur prior to, concurrent with, or anytime during the disease.3,5,6 This aggressive lymphoma has mortality rates ranging from 50% to 72%, and median survival ranges from 11 to 30 months.6

To arrive at the correct diagnosis of AITL, a nodal biopsy with immunochemistry is necessary. Classic findings on histopathology include effacement of normal architecture, marked vascular proliferation, and aggregates of atypical lymphoid cells. CD10 has been shown to be a good objective criterion for the diagnosis of AITL,4 with characteristic tumor cells expressing CD10. Nodal Epstein-Barr virus–positive lymphocytes often are present.2 Other T-cell lymphomas with primarily nodal presentation along with peripheral T-cell lymphoma include peripheral T-cell lymphoma unspecified type and anaplastic large cell lymphoma, according to the World Health Organization classification.7 Anaplastic large cell lymphoma is easily distinguished from AITL based on histopathology, immunostaining, and clinical presentation. Until recently, peripheral T-cell lymphoma unspecified type and reactive lymphoid hyperplasia presented a challenge to differentiate from AITL, especially in the early phases of the disease; however, the introduction of CD10 as a phenotypic marker has been instrumental in distinguishing AITL from other T-cell lymphomas with primary nodal involvement.1,4

The development of purpura fulminans and disseminated intravascular coagulation in a patient with AITL is rare. Although the exact mechanism for the thrombus formation in the skin has not been elucidated, purpura fulminans typically develops secondary to a severe infection. The exact incidence of purpura fulminans in the setting of AITL is unknown, but purpura as a cutaneous eruption has been associated as a clinical finding in AITL.6 Although our case may be a rare presentation of AITL, a prompt and accurate diagnosis can drastically change the prognosis of this aggressive disease.

1. Ferry JA. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Adv Anat Pathol. 2002;9:273-279.