User login

Stains and Smears: Resident Guide to Bedside Diagnostic Testing

Dermatologists are fortunate to specialize in the organ that is most accessible to evaluation. Although we use the physical examination to formulate the initial differential diagnosis, at times we must rely on ancillary tests to narrow down the diagnosis. Various bedside testing modalities—potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, Tzanck smear, mineral oil preparation, and Gram stain—are most useful in diagnosing infectious causes of cutaneous disease. This guide serves as a useful reference for residents on how to perform these tests and which conditions they can help diagnose. Several of these procedures have no standard protocol for performing them; the literature is littered with various methodologies, fixatives, and stains, and as such, this article will attempt to describe a technique that is convenient and quick to perform with readily available materials while still offering high diagnostic utility.

KOH Preparation

A standard in the armamentarium of a dermatologist, the KOH preparation is invaluable to diagnose fungal and yeast infections. Although there are many available preparations including varying concentrations of KOH, dimethyl sulfoxide, and various inks, the procedure is similar for all of them.1 The first step involves collecting the specimen, which can be scale from an active border of suspected cutaneous dermatophyte or Malassezia infection, debris from suspected candidiasis, or hair shafts plucked from an area of alopecia of presumed tinea capitis. A no. 15 blade can be used to scrape the specimen onto a microscope slide, though a second microscope slide can be used in lieu of a blade in patients who will not remain still, and then a coverslip is placed. Two drops of the KOH solution of your choice are then placed on opposite ends of the coverslip, allowing capillary action to spread the stain evenly. A paper towel can be folded in half and pushed down on the surface of the coverslip to spread the stain and soak up any excess, and this pressure also can help the KOH solution digest the keratin in the specimen. Briefly heating the underside of the slide (below boiling point) will help digest the keratin; this step is not necessary when you are using a KOH preparation with dimethyl sulfoxide. Although many dermatologists view the slide almost immediately, ideally at least 5 minutes should pass before it is read. Particularly thick specimens may require additional digestion time, so setting them aside for later review may help visualize infectious agents. In a busy clinic where an immediate diagnosis may not be requisite and a prescription can be called in pending the result, waiting to review the slide may be feasible.

Tzanck Smear

The Tzanck smear is a useful cytopathologic test in the rapid diagnosis of herpetic lesions, though it cannot differentiate between herpes simplex virus type 1, herpes simplex virus type 2, and varicella-zoster virus. It also has shown utility for rapid diagnosis of protean other dermatologic conditions including autoimmune blistering disorders, cutaneous malignancies, and other infectious processes, though it has been superseded by histopathology in most cases.2 An ideal sample is collected by scraping the base of a fresh blister with a no. 15 blade or a second microscope slide. The scrapings then are smeared onto another microscope slide and allowed to air-dry briefly. Then, Wright-Giemsa stain is dispensed to cover the sample and allowed to sit for 15 minutes before being washed off with sterile water. After air-drying, the sample is examined for the presence of clumped multinucleated giant cells, a feature that confirms herpetic infection and allows rapid initiation of antiviral medication.3

Mineral Oil Preparation

A mineral oil preparation has utility in diagnosing ectoparasitic infestation. In the case of scabies, a positive microscopic examination is diagnostic and requires no further testing, allowing for rapid initiation of therapy. This technique also is useful in diagnosing rosacea related to Demodex, which requires a treatment algorithm that differs from the classic papulopustular rosacea which it mimics.4

Mineral oil preparations can be rapidly performed and interpreted. Several drops of mineral oil are placed onto a microscope slide and a no. 15 blade is dipped into this oil prior to scraping the sample lesion. For scabies, a burrow is scraped repeatedly with the blade, and the debris is collected in the mineral oil. Occasionally, the mite can be dermoscopically visualized as a jet plane or arrowhead at the leading edge of a burrow; scraping should be focused in the vicinity of the mite.5 A coverslip is applied to the microscope slide and examination for the mite, egg casings, and scybala can be performed with microscopy.6 For Demodex infestation, a facial pustule can be expressed or several eyelash hairs can be plucked and suspended in mineral oil. Examination of this specimen is identical to scabies.

Gram Stain

The Gram stain is invaluable in classifying bacteria, and a properly performed test can narrow the identification of a causative organism based on cellular morphology. Although it is more technically complex than other bedside diagnostic maneuvers, it can be rapidly performed once the sequence of stains is mastered. The collected sample is smeared onto a glass slide and then briefly passed over a flame several times to heat-fix the specimen. Caution should be taken to avoid direct or prolonged flame contact with the underside of the slide. After fixation, the staining can be performed. First, crystal violet is instilled onto the slide and remains on for 30 seconds before being rinsed off with sink water. Then, Gram iodine is used for 30 seconds, followed by another rinse in water. Next, pour the decolorizer solution over the slide until the runoff is clear, and then rinse in water. Finally, flood with safranin counterstain for 30 seconds and give the slide a final rinse. After air-drying, it is ready to be interpreted.7

Final Thoughts

Although the modern dermatologist has access to biopsies, cultures, and sophisticated diagnostic techniques, it is important to remember these useful bedside tests. The ability to rapidly pin a diagnosis is particularly useful on the consultative service where critically ill patients can benefit from identification of a causative pathogen sooner rather than later. Residents should master these stains in their training, as this knowledge may prove to be invaluable in their careers.

1. Trozak DJ, Tennenhouse DJ, Russell JJ. Dermatology Skills for Primary Care: An Illustrated Guide. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2006.

2. Kelly B, Shimoni T. Reintroducing the Tzanck smear. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:141-152.

3. Singhi M, Gupta L. Tzanck smear: a useful diagnostic tool. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:295.

4. Elston DM. Demodex mites: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:502-504.

5. Dupuy A, Dehen L, Bourrat E, et al. Accuracy of standard dermoscopy for diagnosing scabies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:53-62.

6. Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Duncan K, et al. Dermatology Essentials. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

7. Ruocco E, Baroni A, Donnarumma G, et al. Diagnostic procedures in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:548-556.

Dermatologists are fortunate to specialize in the organ that is most accessible to evaluation. Although we use the physical examination to formulate the initial differential diagnosis, at times we must rely on ancillary tests to narrow down the diagnosis. Various bedside testing modalities—potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, Tzanck smear, mineral oil preparation, and Gram stain—are most useful in diagnosing infectious causes of cutaneous disease. This guide serves as a useful reference for residents on how to perform these tests and which conditions they can help diagnose. Several of these procedures have no standard protocol for performing them; the literature is littered with various methodologies, fixatives, and stains, and as such, this article will attempt to describe a technique that is convenient and quick to perform with readily available materials while still offering high diagnostic utility.

KOH Preparation

A standard in the armamentarium of a dermatologist, the KOH preparation is invaluable to diagnose fungal and yeast infections. Although there are many available preparations including varying concentrations of KOH, dimethyl sulfoxide, and various inks, the procedure is similar for all of them.1 The first step involves collecting the specimen, which can be scale from an active border of suspected cutaneous dermatophyte or Malassezia infection, debris from suspected candidiasis, or hair shafts plucked from an area of alopecia of presumed tinea capitis. A no. 15 blade can be used to scrape the specimen onto a microscope slide, though a second microscope slide can be used in lieu of a blade in patients who will not remain still, and then a coverslip is placed. Two drops of the KOH solution of your choice are then placed on opposite ends of the coverslip, allowing capillary action to spread the stain evenly. A paper towel can be folded in half and pushed down on the surface of the coverslip to spread the stain and soak up any excess, and this pressure also can help the KOH solution digest the keratin in the specimen. Briefly heating the underside of the slide (below boiling point) will help digest the keratin; this step is not necessary when you are using a KOH preparation with dimethyl sulfoxide. Although many dermatologists view the slide almost immediately, ideally at least 5 minutes should pass before it is read. Particularly thick specimens may require additional digestion time, so setting them aside for later review may help visualize infectious agents. In a busy clinic where an immediate diagnosis may not be requisite and a prescription can be called in pending the result, waiting to review the slide may be feasible.

Tzanck Smear

The Tzanck smear is a useful cytopathologic test in the rapid diagnosis of herpetic lesions, though it cannot differentiate between herpes simplex virus type 1, herpes simplex virus type 2, and varicella-zoster virus. It also has shown utility for rapid diagnosis of protean other dermatologic conditions including autoimmune blistering disorders, cutaneous malignancies, and other infectious processes, though it has been superseded by histopathology in most cases.2 An ideal sample is collected by scraping the base of a fresh blister with a no. 15 blade or a second microscope slide. The scrapings then are smeared onto another microscope slide and allowed to air-dry briefly. Then, Wright-Giemsa stain is dispensed to cover the sample and allowed to sit for 15 minutes before being washed off with sterile water. After air-drying, the sample is examined for the presence of clumped multinucleated giant cells, a feature that confirms herpetic infection and allows rapid initiation of antiviral medication.3

Mineral Oil Preparation

A mineral oil preparation has utility in diagnosing ectoparasitic infestation. In the case of scabies, a positive microscopic examination is diagnostic and requires no further testing, allowing for rapid initiation of therapy. This technique also is useful in diagnosing rosacea related to Demodex, which requires a treatment algorithm that differs from the classic papulopustular rosacea which it mimics.4

Mineral oil preparations can be rapidly performed and interpreted. Several drops of mineral oil are placed onto a microscope slide and a no. 15 blade is dipped into this oil prior to scraping the sample lesion. For scabies, a burrow is scraped repeatedly with the blade, and the debris is collected in the mineral oil. Occasionally, the mite can be dermoscopically visualized as a jet plane or arrowhead at the leading edge of a burrow; scraping should be focused in the vicinity of the mite.5 A coverslip is applied to the microscope slide and examination for the mite, egg casings, and scybala can be performed with microscopy.6 For Demodex infestation, a facial pustule can be expressed or several eyelash hairs can be plucked and suspended in mineral oil. Examination of this specimen is identical to scabies.

Gram Stain

The Gram stain is invaluable in classifying bacteria, and a properly performed test can narrow the identification of a causative organism based on cellular morphology. Although it is more technically complex than other bedside diagnostic maneuvers, it can be rapidly performed once the sequence of stains is mastered. The collected sample is smeared onto a glass slide and then briefly passed over a flame several times to heat-fix the specimen. Caution should be taken to avoid direct or prolonged flame contact with the underside of the slide. After fixation, the staining can be performed. First, crystal violet is instilled onto the slide and remains on for 30 seconds before being rinsed off with sink water. Then, Gram iodine is used for 30 seconds, followed by another rinse in water. Next, pour the decolorizer solution over the slide until the runoff is clear, and then rinse in water. Finally, flood with safranin counterstain for 30 seconds and give the slide a final rinse. After air-drying, it is ready to be interpreted.7

Final Thoughts

Although the modern dermatologist has access to biopsies, cultures, and sophisticated diagnostic techniques, it is important to remember these useful bedside tests. The ability to rapidly pin a diagnosis is particularly useful on the consultative service where critically ill patients can benefit from identification of a causative pathogen sooner rather than later. Residents should master these stains in their training, as this knowledge may prove to be invaluable in their careers.

Dermatologists are fortunate to specialize in the organ that is most accessible to evaluation. Although we use the physical examination to formulate the initial differential diagnosis, at times we must rely on ancillary tests to narrow down the diagnosis. Various bedside testing modalities—potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, Tzanck smear, mineral oil preparation, and Gram stain—are most useful in diagnosing infectious causes of cutaneous disease. This guide serves as a useful reference for residents on how to perform these tests and which conditions they can help diagnose. Several of these procedures have no standard protocol for performing them; the literature is littered with various methodologies, fixatives, and stains, and as such, this article will attempt to describe a technique that is convenient and quick to perform with readily available materials while still offering high diagnostic utility.

KOH Preparation

A standard in the armamentarium of a dermatologist, the KOH preparation is invaluable to diagnose fungal and yeast infections. Although there are many available preparations including varying concentrations of KOH, dimethyl sulfoxide, and various inks, the procedure is similar for all of them.1 The first step involves collecting the specimen, which can be scale from an active border of suspected cutaneous dermatophyte or Malassezia infection, debris from suspected candidiasis, or hair shafts plucked from an area of alopecia of presumed tinea capitis. A no. 15 blade can be used to scrape the specimen onto a microscope slide, though a second microscope slide can be used in lieu of a blade in patients who will not remain still, and then a coverslip is placed. Two drops of the KOH solution of your choice are then placed on opposite ends of the coverslip, allowing capillary action to spread the stain evenly. A paper towel can be folded in half and pushed down on the surface of the coverslip to spread the stain and soak up any excess, and this pressure also can help the KOH solution digest the keratin in the specimen. Briefly heating the underside of the slide (below boiling point) will help digest the keratin; this step is not necessary when you are using a KOH preparation with dimethyl sulfoxide. Although many dermatologists view the slide almost immediately, ideally at least 5 minutes should pass before it is read. Particularly thick specimens may require additional digestion time, so setting them aside for later review may help visualize infectious agents. In a busy clinic where an immediate diagnosis may not be requisite and a prescription can be called in pending the result, waiting to review the slide may be feasible.

Tzanck Smear

The Tzanck smear is a useful cytopathologic test in the rapid diagnosis of herpetic lesions, though it cannot differentiate between herpes simplex virus type 1, herpes simplex virus type 2, and varicella-zoster virus. It also has shown utility for rapid diagnosis of protean other dermatologic conditions including autoimmune blistering disorders, cutaneous malignancies, and other infectious processes, though it has been superseded by histopathology in most cases.2 An ideal sample is collected by scraping the base of a fresh blister with a no. 15 blade or a second microscope slide. The scrapings then are smeared onto another microscope slide and allowed to air-dry briefly. Then, Wright-Giemsa stain is dispensed to cover the sample and allowed to sit for 15 minutes before being washed off with sterile water. After air-drying, the sample is examined for the presence of clumped multinucleated giant cells, a feature that confirms herpetic infection and allows rapid initiation of antiviral medication.3

Mineral Oil Preparation

A mineral oil preparation has utility in diagnosing ectoparasitic infestation. In the case of scabies, a positive microscopic examination is diagnostic and requires no further testing, allowing for rapid initiation of therapy. This technique also is useful in diagnosing rosacea related to Demodex, which requires a treatment algorithm that differs from the classic papulopustular rosacea which it mimics.4

Mineral oil preparations can be rapidly performed and interpreted. Several drops of mineral oil are placed onto a microscope slide and a no. 15 blade is dipped into this oil prior to scraping the sample lesion. For scabies, a burrow is scraped repeatedly with the blade, and the debris is collected in the mineral oil. Occasionally, the mite can be dermoscopically visualized as a jet plane or arrowhead at the leading edge of a burrow; scraping should be focused in the vicinity of the mite.5 A coverslip is applied to the microscope slide and examination for the mite, egg casings, and scybala can be performed with microscopy.6 For Demodex infestation, a facial pustule can be expressed or several eyelash hairs can be plucked and suspended in mineral oil. Examination of this specimen is identical to scabies.

Gram Stain

The Gram stain is invaluable in classifying bacteria, and a properly performed test can narrow the identification of a causative organism based on cellular morphology. Although it is more technically complex than other bedside diagnostic maneuvers, it can be rapidly performed once the sequence of stains is mastered. The collected sample is smeared onto a glass slide and then briefly passed over a flame several times to heat-fix the specimen. Caution should be taken to avoid direct or prolonged flame contact with the underside of the slide. After fixation, the staining can be performed. First, crystal violet is instilled onto the slide and remains on for 30 seconds before being rinsed off with sink water. Then, Gram iodine is used for 30 seconds, followed by another rinse in water. Next, pour the decolorizer solution over the slide until the runoff is clear, and then rinse in water. Finally, flood with safranin counterstain for 30 seconds and give the slide a final rinse. After air-drying, it is ready to be interpreted.7

Final Thoughts

Although the modern dermatologist has access to biopsies, cultures, and sophisticated diagnostic techniques, it is important to remember these useful bedside tests. The ability to rapidly pin a diagnosis is particularly useful on the consultative service where critically ill patients can benefit from identification of a causative pathogen sooner rather than later. Residents should master these stains in their training, as this knowledge may prove to be invaluable in their careers.

1. Trozak DJ, Tennenhouse DJ, Russell JJ. Dermatology Skills for Primary Care: An Illustrated Guide. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2006.

2. Kelly B, Shimoni T. Reintroducing the Tzanck smear. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:141-152.

3. Singhi M, Gupta L. Tzanck smear: a useful diagnostic tool. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:295.

4. Elston DM. Demodex mites: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:502-504.

5. Dupuy A, Dehen L, Bourrat E, et al. Accuracy of standard dermoscopy for diagnosing scabies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:53-62.

6. Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Duncan K, et al. Dermatology Essentials. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

7. Ruocco E, Baroni A, Donnarumma G, et al. Diagnostic procedures in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:548-556.

1. Trozak DJ, Tennenhouse DJ, Russell JJ. Dermatology Skills for Primary Care: An Illustrated Guide. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2006.

2. Kelly B, Shimoni T. Reintroducing the Tzanck smear. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:141-152.

3. Singhi M, Gupta L. Tzanck smear: a useful diagnostic tool. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:295.

4. Elston DM. Demodex mites: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:502-504.

5. Dupuy A, Dehen L, Bourrat E, et al. Accuracy of standard dermoscopy for diagnosing scabies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:53-62.

6. Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Duncan K, et al. Dermatology Essentials. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

7. Ruocco E, Baroni A, Donnarumma G, et al. Diagnostic procedures in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:548-556.

Granular Cell Tumor

Granular cell tumors (GCTs) tend to present as solitary nodules, not uncommonly affecting the dorsum of the tongue but also involving the skin, breasts, and internal organs.1 Cutaneous GCTs typically present as 0.5- to 3-cm firm nodules with a verrucous or eroded surface.2 They most commonly present in dark-skinned, middle-aged women but have been reported in all age groups and in both sexes.3 Multiple GCTs are reported in up to 25% of cases, rarely in association with LEOPARD syndrome (consisting of lentigines, electrocardiographic abnormalities, ocular hypertelorism, pulmonary stenosis, abnormalities of genitalia, retardation of growth, and deafness).4 Granular cell tumors generally are benign with a metastatic rate of approximately 3%.2

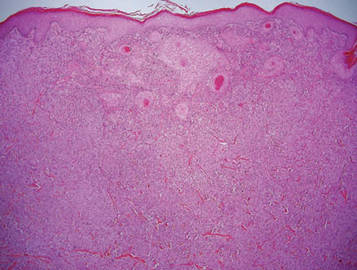

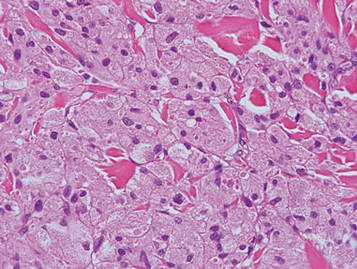

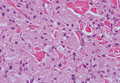

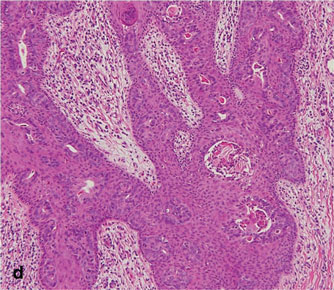

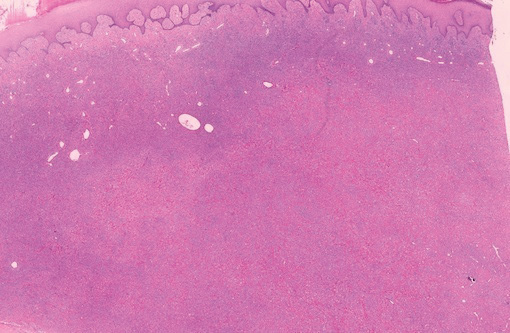

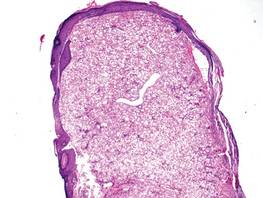

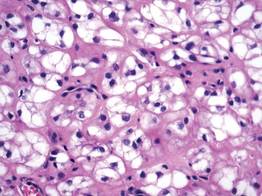

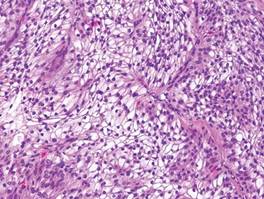

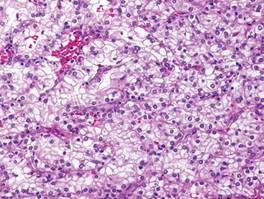

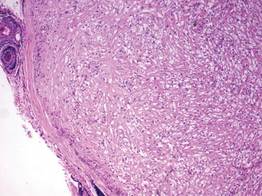

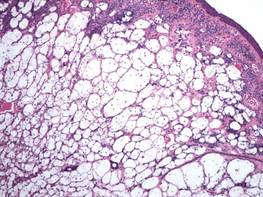

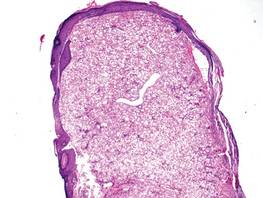

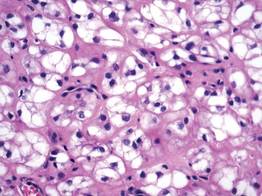

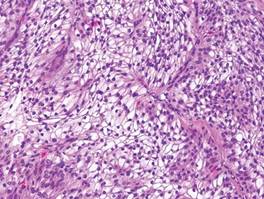

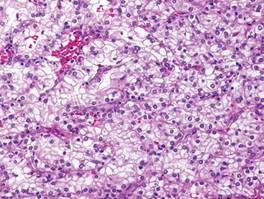

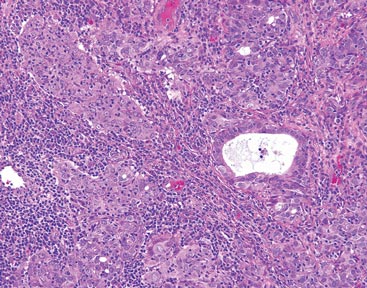

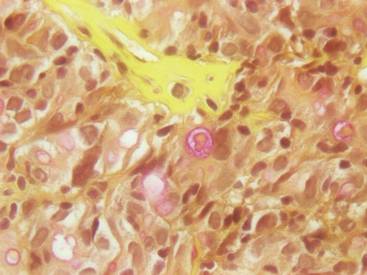

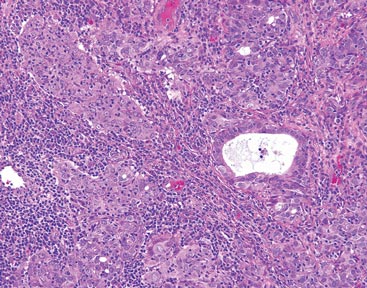

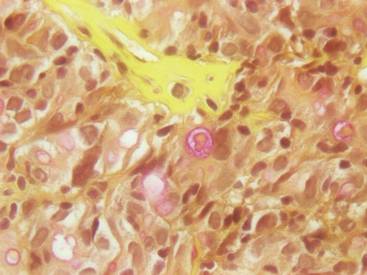

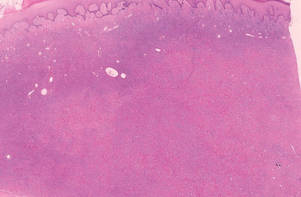

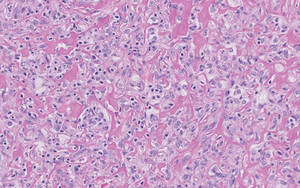

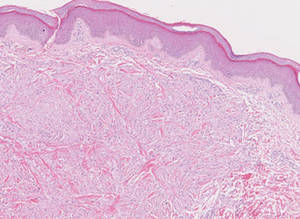

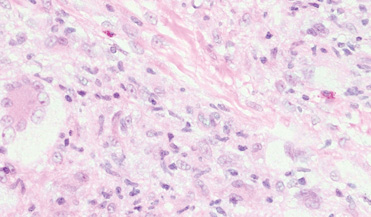

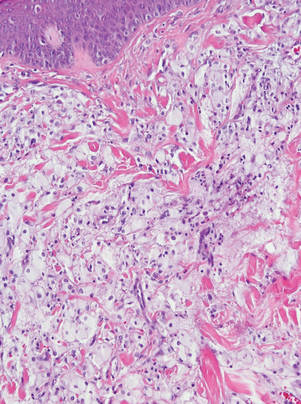

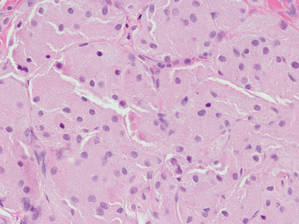

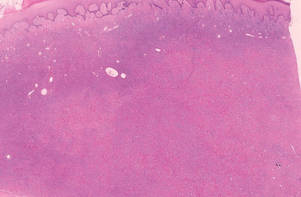

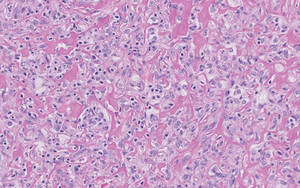

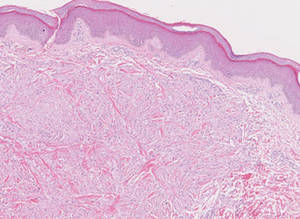

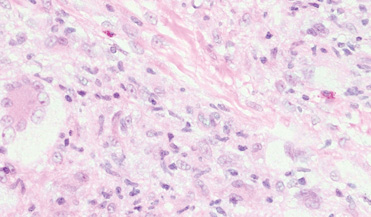

Granular cell tumors are histopathologically characterized by sheets of large polygonal cells with small, round, central nuclei; cytoplasm that is eosinophilic, coarse, and granular, as well as periodic acid–Schiff positive and diastase resistant; and distinct cytoplasmic membranes (Figure 1). Pustulo-ovoid bodies of Milian often generally appear as larger eosinophilic granules surrounded by a clear halo (Figure 2).5 Increased mitotic activity, a high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, pleomorphism, and necrosis suggest malignancy.6

|

|

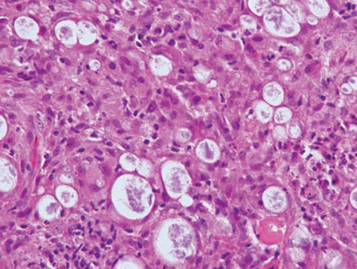

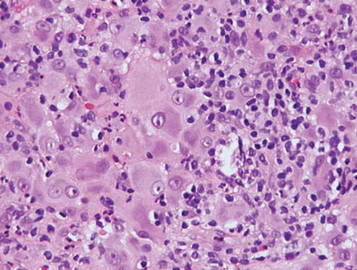

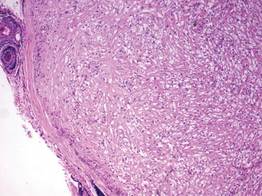

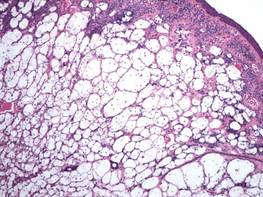

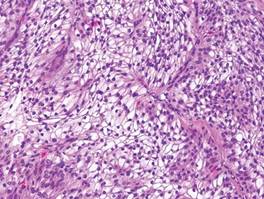

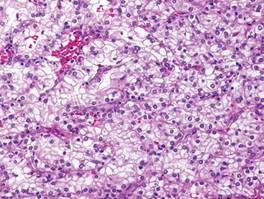

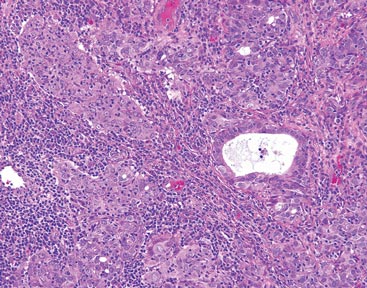

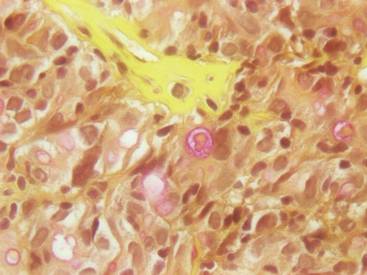

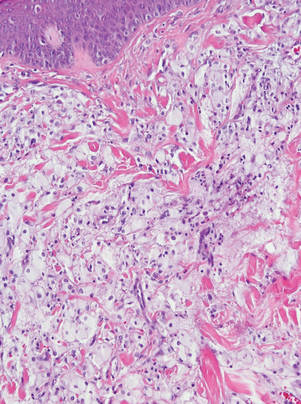

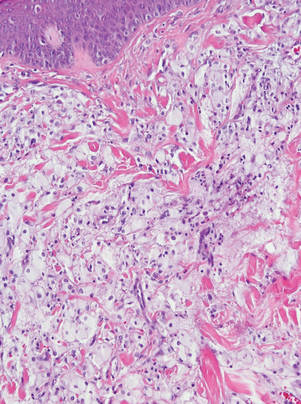

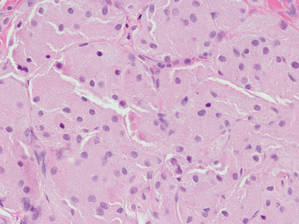

Lepromatous leprosy is characterized by sheets of histiocytes with vacuolated cytoplasm, some with clumped amphophilic bacilli known as globi (Figure 3). Mastocytoma can be distinguished from GCTs by the “fried egg” appearance of the mast cells (Figure 4). Although mast cells have a pale granular cytoplasm, they are smaller and lack pustulo-ovoid bodies and the polygonal shape of GCT cells. Reticulohistiocytoma, on the other hand, has two-toned dusty rose ground glass histiocytes (Figure 5), and xanthelasma can be distinguished histologically from GCT by the presence of a foamy rather than granular cytoplasm (Figure 6).

|

|

|

|

1. Elston DM, Ko C, Ferringer TC, et al, eds. Dermatopathology: Requisites in Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2009.

2. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012.

3. van de Loo S, Thunnissen E, Postmus P, et al. Granular cell tumor of the oral cavity; a case series including a case of metachronous occurrence in the tongue and the lung [published online ahead of print June 1, 2014]. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. doi:10.4317/medoral.19867.

4. Schrader KA, Nelson TN, De Luca A, et al. Multiple granular cell tumors are an associated feature of LEOPARD syndrome caused by mutation in PTPN11. Clin Genet. 2009;75:185-189.

5. Epstein DS, Pashaei S, Hunt E Jr, et al. Pustulo-ovoid bodies of Milian in granular cell tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:405-409.

6. Fanburg-Smith JC, Meis-Kindblom JM, Fante R, et al. Malignant granular cell tumor of soft tissue: diagnostic criteria and clinicopathologic correlation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:779-794.

Granular cell tumors (GCTs) tend to present as solitary nodules, not uncommonly affecting the dorsum of the tongue but also involving the skin, breasts, and internal organs.1 Cutaneous GCTs typically present as 0.5- to 3-cm firm nodules with a verrucous or eroded surface.2 They most commonly present in dark-skinned, middle-aged women but have been reported in all age groups and in both sexes.3 Multiple GCTs are reported in up to 25% of cases, rarely in association with LEOPARD syndrome (consisting of lentigines, electrocardiographic abnormalities, ocular hypertelorism, pulmonary stenosis, abnormalities of genitalia, retardation of growth, and deafness).4 Granular cell tumors generally are benign with a metastatic rate of approximately 3%.2

Granular cell tumors are histopathologically characterized by sheets of large polygonal cells with small, round, central nuclei; cytoplasm that is eosinophilic, coarse, and granular, as well as periodic acid–Schiff positive and diastase resistant; and distinct cytoplasmic membranes (Figure 1). Pustulo-ovoid bodies of Milian often generally appear as larger eosinophilic granules surrounded by a clear halo (Figure 2).5 Increased mitotic activity, a high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, pleomorphism, and necrosis suggest malignancy.6

|

|

Lepromatous leprosy is characterized by sheets of histiocytes with vacuolated cytoplasm, some with clumped amphophilic bacilli known as globi (Figure 3). Mastocytoma can be distinguished from GCTs by the “fried egg” appearance of the mast cells (Figure 4). Although mast cells have a pale granular cytoplasm, they are smaller and lack pustulo-ovoid bodies and the polygonal shape of GCT cells. Reticulohistiocytoma, on the other hand, has two-toned dusty rose ground glass histiocytes (Figure 5), and xanthelasma can be distinguished histologically from GCT by the presence of a foamy rather than granular cytoplasm (Figure 6).

|

|

|

|

Granular cell tumors (GCTs) tend to present as solitary nodules, not uncommonly affecting the dorsum of the tongue but also involving the skin, breasts, and internal organs.1 Cutaneous GCTs typically present as 0.5- to 3-cm firm nodules with a verrucous or eroded surface.2 They most commonly present in dark-skinned, middle-aged women but have been reported in all age groups and in both sexes.3 Multiple GCTs are reported in up to 25% of cases, rarely in association with LEOPARD syndrome (consisting of lentigines, electrocardiographic abnormalities, ocular hypertelorism, pulmonary stenosis, abnormalities of genitalia, retardation of growth, and deafness).4 Granular cell tumors generally are benign with a metastatic rate of approximately 3%.2

Granular cell tumors are histopathologically characterized by sheets of large polygonal cells with small, round, central nuclei; cytoplasm that is eosinophilic, coarse, and granular, as well as periodic acid–Schiff positive and diastase resistant; and distinct cytoplasmic membranes (Figure 1). Pustulo-ovoid bodies of Milian often generally appear as larger eosinophilic granules surrounded by a clear halo (Figure 2).5 Increased mitotic activity, a high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, pleomorphism, and necrosis suggest malignancy.6

|

|

Lepromatous leprosy is characterized by sheets of histiocytes with vacuolated cytoplasm, some with clumped amphophilic bacilli known as globi (Figure 3). Mastocytoma can be distinguished from GCTs by the “fried egg” appearance of the mast cells (Figure 4). Although mast cells have a pale granular cytoplasm, they are smaller and lack pustulo-ovoid bodies and the polygonal shape of GCT cells. Reticulohistiocytoma, on the other hand, has two-toned dusty rose ground glass histiocytes (Figure 5), and xanthelasma can be distinguished histologically from GCT by the presence of a foamy rather than granular cytoplasm (Figure 6).

|

|

|

|

1. Elston DM, Ko C, Ferringer TC, et al, eds. Dermatopathology: Requisites in Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2009.

2. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012.

3. van de Loo S, Thunnissen E, Postmus P, et al. Granular cell tumor of the oral cavity; a case series including a case of metachronous occurrence in the tongue and the lung [published online ahead of print June 1, 2014]. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. doi:10.4317/medoral.19867.

4. Schrader KA, Nelson TN, De Luca A, et al. Multiple granular cell tumors are an associated feature of LEOPARD syndrome caused by mutation in PTPN11. Clin Genet. 2009;75:185-189.

5. Epstein DS, Pashaei S, Hunt E Jr, et al. Pustulo-ovoid bodies of Milian in granular cell tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:405-409.

6. Fanburg-Smith JC, Meis-Kindblom JM, Fante R, et al. Malignant granular cell tumor of soft tissue: diagnostic criteria and clinicopathologic correlation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:779-794.

1. Elston DM, Ko C, Ferringer TC, et al, eds. Dermatopathology: Requisites in Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2009.

2. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012.

3. van de Loo S, Thunnissen E, Postmus P, et al. Granular cell tumor of the oral cavity; a case series including a case of metachronous occurrence in the tongue and the lung [published online ahead of print June 1, 2014]. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. doi:10.4317/medoral.19867.

4. Schrader KA, Nelson TN, De Luca A, et al. Multiple granular cell tumors are an associated feature of LEOPARD syndrome caused by mutation in PTPN11. Clin Genet. 2009;75:185-189.

5. Epstein DS, Pashaei S, Hunt E Jr, et al. Pustulo-ovoid bodies of Milian in granular cell tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:405-409.

6. Fanburg-Smith JC, Meis-Kindblom JM, Fante R, et al. Malignant granular cell tumor of soft tissue: diagnostic criteria and clinicopathologic correlation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:779-794.

Nodular Extramammary Paget Disease With Fibroepitheliomatous Hyperplasia

Extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is an uncommon neoplasm that most commonly occurs in the anogenital region but can arise in any area of the skin or mucosa.1 On clinical examination, EMPD typically presents as a sharply demarcated, erythematous, eczematoid, weeping lesion with varying degrees of induration; it rarely presents as a palpable mass or evenly raised nodule.2 Microscopically, it may be accompanied by varying degrees of epidermal hyperplasia.1 In particular, fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia contains lacy strands of squamous epithelium resembling fibroepithelioma of Pinkus.3 We report a case of EMPD in a 90-year-old man who presented with a verrucous nodule in the pubic area that histologically demonstrated fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia with lacy strands of squamous epithelium.

Case Report

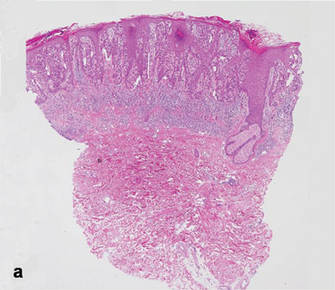

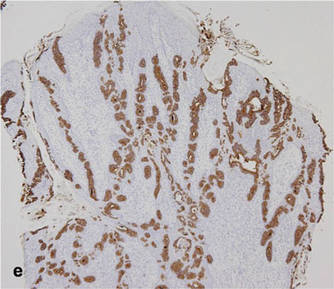

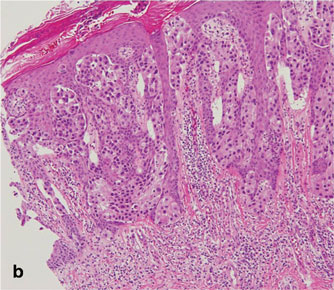

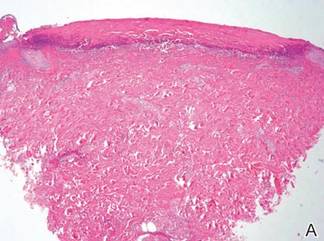

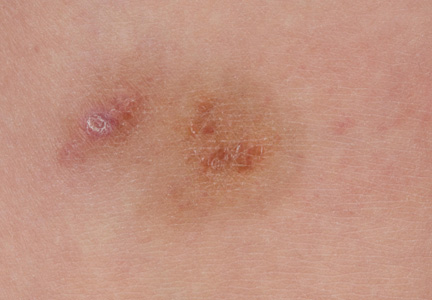

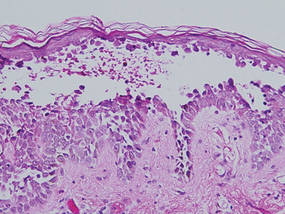

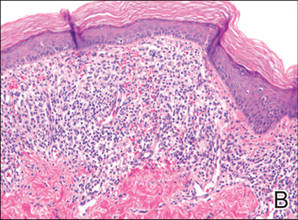

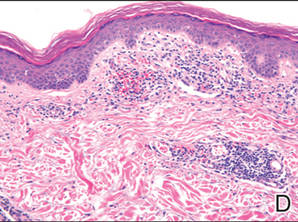

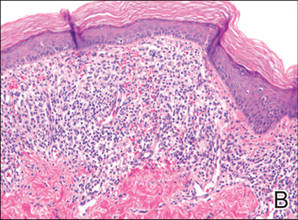

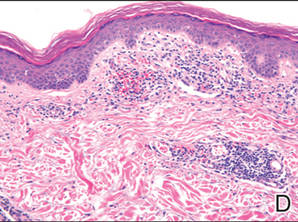

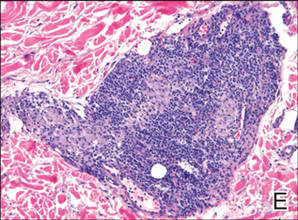

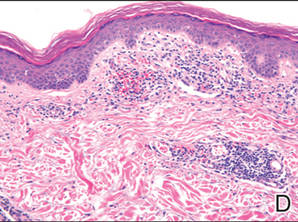

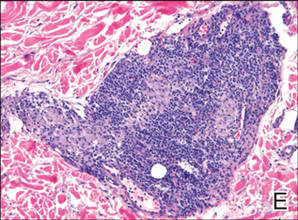

A 90-year-old man presented with asymptomatic, well-demarcated, erythematous plaques in the pubic area of 5 years’ duration, along with a 3.0×2.5-cm nodule on the left side of the pubic area (Figure 1). Laboratory test results including a complete blood cell count, blood chemistry, and routine urinalysis were within reference range. Punch biopsies were taken from each plaque and nodule, as marked with arrows in Figure 1. Histopathologically, the plaques were seen to contain a number of large round cells with abundant pale cytoplasm and pleomorphic hyperchromatic nuclei that were present at various levels of the epidermis where they formed nests and clusters but did not extend into the dermis (Figures 2A and 2B). The nodule contained lacy strands of squamous epithelium extending from the epidermis to the mid dermis as well as many glandular structures (Figures 2C and 2D). The cells in the epidermis stained positively with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and cytokeratin 7 (Figure 2E). We also tested for S-100 protein to rule out malignant melanoma, which was negative.

Based on both the clinical and histological features, a diagnosis of EMPD with fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia was made. It was recommended that the patient undergo further evaluation and treatment; he declined due to his financial situation and was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Comment

Clinically, EMPD usually presents as a patch of macular erythema, an erythematous eruption, or erythematous papules and plaques.4 The palpable nodule seen in our patient is not a common presentation of EMPD. Pruritus is the most common symptom of EMPD, occurring in 70% of patients.5 Other symptoms include burning, irritation, pain, tenderness, bleeding, and swelling. Ten percent of EMPD cases are asymptomatic.5

Histologically, Paget cells primarily involve the epidermis where they usually form clusters or solid nests. In more than 90% of EMPD cases, the Paget cells contain cytoplasmic mucin that stains positively with mucicarmine and PAS. Immunohistochemical staining for cytokeratin 7, gross cystic disease fluid protein-15, S-100 protein, and CEA sometimes may be needed to differentiate from mimickers such as Bowen disease and superficial spreading melanoma.6 In our patient, the tumor cells stained positive for cytokeratin 7, CEA, and PAS. Malignant melanoma was ruled out with a test for S-100 protein.

|

|

Extramammary Paget disease often is associated with epidermal hyperplasia, which can be classified as squamous, papillomatous, or fibroepitheliomatous.3 Microscopically, squamous hyperplasia is characterized by prominent thickening of the epidermis from diffuse plaquelike hyperplasia and is usually associated with hyperkeratosis. Papillomatous hyperplasia has an exophytic papillary or verrucous architecture and is associated with parakeratosis. Fibroepitheliomatous, or fibroepitheliomalike, hyperplasia generally consists of a discrete, broad, elevated plaque or nodule produced by hyperplasia of keratinocytes that form lacy strands of squamous epithelium.3 The biphasic pattern of proliferating epidermis and entrapped dermis simulates a so-called fibroepithelioma. Paget cells can be seen within the lacy strands of epidermal columns and in the acanthotic surface component.2 The finding of fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia in anogenital skin should prompt a search for the diagnostic Paget cells to eliminate a fibroepithelioma of Pinkus variant of basal cell carcinoma, though the latter is uncommon and rarely occurs at this site.7

Of the 3 types of epidermal hyperplasia, our case demonstrated the fibroepitheliomatous type. There may be some relationship between EMPD and fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia because most reported cases of EMPD with fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia have occurred in the anogenital region. Also, epidermal hyperplasia is more frequent in anogenital Paget disease than in axillary Paget disease.8

Conclusion

Our case showed the unique finding of a verrucous nodular EMPD lesion in which peculiar histological features presented as extensions of the tumor cells forming lacy strands of squamous epithelium from the epidermis to the mid dermis as well as many glandular structures.

1. Lloyd J, Flanagan AM. Mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease. J Clin Pathol. 2000;53:742-749.

2. Billings SD, Roth LM. Pseudoinvasive, nodular extramam-mary Paget’s disease of the vulva. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1998;122:471-474.

3. Brainard JA, Hart WR. Proliferative epidermal lesions associated with anogenital Paget’s disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:543-552.

4. Neuhaus IM, Grekin RC. Mammary and extramammary Paget disease. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. Vol 1. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2008:1094-1098.

5. Shepherd V, Davidson EJ, Davies-Humphreys J. Extramammary Paget’s disease. BJOG. 2005;112:273-279.

6. Kim JC, Kim HC, Jeong CS, et al. Extramammary Paget’s disease with aggressive behavior: a report of two cases. J Korean Med Sci. 1999;14:223-226.

7. Rahbari H, Mehregan AH. Basal cell epitheliomas in usual and unusual sites. J Cutan Pathol. 1979;6:425-431.

8. Ishida-Yamamoto A, Sato K, Wada T, et al. Fibroepithelioma-like changes occurring in perianal Paget’s disease with rectal mucinous carcinoma: case report and review of 49 cases of extramammary Paget’s disease. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:185-189.

Extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is an uncommon neoplasm that most commonly occurs in the anogenital region but can arise in any area of the skin or mucosa.1 On clinical examination, EMPD typically presents as a sharply demarcated, erythematous, eczematoid, weeping lesion with varying degrees of induration; it rarely presents as a palpable mass or evenly raised nodule.2 Microscopically, it may be accompanied by varying degrees of epidermal hyperplasia.1 In particular, fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia contains lacy strands of squamous epithelium resembling fibroepithelioma of Pinkus.3 We report a case of EMPD in a 90-year-old man who presented with a verrucous nodule in the pubic area that histologically demonstrated fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia with lacy strands of squamous epithelium.

Case Report

A 90-year-old man presented with asymptomatic, well-demarcated, erythematous plaques in the pubic area of 5 years’ duration, along with a 3.0×2.5-cm nodule on the left side of the pubic area (Figure 1). Laboratory test results including a complete blood cell count, blood chemistry, and routine urinalysis were within reference range. Punch biopsies were taken from each plaque and nodule, as marked with arrows in Figure 1. Histopathologically, the plaques were seen to contain a number of large round cells with abundant pale cytoplasm and pleomorphic hyperchromatic nuclei that were present at various levels of the epidermis where they formed nests and clusters but did not extend into the dermis (Figures 2A and 2B). The nodule contained lacy strands of squamous epithelium extending from the epidermis to the mid dermis as well as many glandular structures (Figures 2C and 2D). The cells in the epidermis stained positively with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and cytokeratin 7 (Figure 2E). We also tested for S-100 protein to rule out malignant melanoma, which was negative.

Based on both the clinical and histological features, a diagnosis of EMPD with fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia was made. It was recommended that the patient undergo further evaluation and treatment; he declined due to his financial situation and was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Comment

Clinically, EMPD usually presents as a patch of macular erythema, an erythematous eruption, or erythematous papules and plaques.4 The palpable nodule seen in our patient is not a common presentation of EMPD. Pruritus is the most common symptom of EMPD, occurring in 70% of patients.5 Other symptoms include burning, irritation, pain, tenderness, bleeding, and swelling. Ten percent of EMPD cases are asymptomatic.5

Histologically, Paget cells primarily involve the epidermis where they usually form clusters or solid nests. In more than 90% of EMPD cases, the Paget cells contain cytoplasmic mucin that stains positively with mucicarmine and PAS. Immunohistochemical staining for cytokeratin 7, gross cystic disease fluid protein-15, S-100 protein, and CEA sometimes may be needed to differentiate from mimickers such as Bowen disease and superficial spreading melanoma.6 In our patient, the tumor cells stained positive for cytokeratin 7, CEA, and PAS. Malignant melanoma was ruled out with a test for S-100 protein.

|

|

Extramammary Paget disease often is associated with epidermal hyperplasia, which can be classified as squamous, papillomatous, or fibroepitheliomatous.3 Microscopically, squamous hyperplasia is characterized by prominent thickening of the epidermis from diffuse plaquelike hyperplasia and is usually associated with hyperkeratosis. Papillomatous hyperplasia has an exophytic papillary or verrucous architecture and is associated with parakeratosis. Fibroepitheliomatous, or fibroepitheliomalike, hyperplasia generally consists of a discrete, broad, elevated plaque or nodule produced by hyperplasia of keratinocytes that form lacy strands of squamous epithelium.3 The biphasic pattern of proliferating epidermis and entrapped dermis simulates a so-called fibroepithelioma. Paget cells can be seen within the lacy strands of epidermal columns and in the acanthotic surface component.2 The finding of fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia in anogenital skin should prompt a search for the diagnostic Paget cells to eliminate a fibroepithelioma of Pinkus variant of basal cell carcinoma, though the latter is uncommon and rarely occurs at this site.7

Of the 3 types of epidermal hyperplasia, our case demonstrated the fibroepitheliomatous type. There may be some relationship between EMPD and fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia because most reported cases of EMPD with fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia have occurred in the anogenital region. Also, epidermal hyperplasia is more frequent in anogenital Paget disease than in axillary Paget disease.8

Conclusion

Our case showed the unique finding of a verrucous nodular EMPD lesion in which peculiar histological features presented as extensions of the tumor cells forming lacy strands of squamous epithelium from the epidermis to the mid dermis as well as many glandular structures.

Extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is an uncommon neoplasm that most commonly occurs in the anogenital region but can arise in any area of the skin or mucosa.1 On clinical examination, EMPD typically presents as a sharply demarcated, erythematous, eczematoid, weeping lesion with varying degrees of induration; it rarely presents as a palpable mass or evenly raised nodule.2 Microscopically, it may be accompanied by varying degrees of epidermal hyperplasia.1 In particular, fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia contains lacy strands of squamous epithelium resembling fibroepithelioma of Pinkus.3 We report a case of EMPD in a 90-year-old man who presented with a verrucous nodule in the pubic area that histologically demonstrated fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia with lacy strands of squamous epithelium.

Case Report

A 90-year-old man presented with asymptomatic, well-demarcated, erythematous plaques in the pubic area of 5 years’ duration, along with a 3.0×2.5-cm nodule on the left side of the pubic area (Figure 1). Laboratory test results including a complete blood cell count, blood chemistry, and routine urinalysis were within reference range. Punch biopsies were taken from each plaque and nodule, as marked with arrows in Figure 1. Histopathologically, the plaques were seen to contain a number of large round cells with abundant pale cytoplasm and pleomorphic hyperchromatic nuclei that were present at various levels of the epidermis where they formed nests and clusters but did not extend into the dermis (Figures 2A and 2B). The nodule contained lacy strands of squamous epithelium extending from the epidermis to the mid dermis as well as many glandular structures (Figures 2C and 2D). The cells in the epidermis stained positively with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and cytokeratin 7 (Figure 2E). We also tested for S-100 protein to rule out malignant melanoma, which was negative.

Based on both the clinical and histological features, a diagnosis of EMPD with fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia was made. It was recommended that the patient undergo further evaluation and treatment; he declined due to his financial situation and was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Comment

Clinically, EMPD usually presents as a patch of macular erythema, an erythematous eruption, or erythematous papules and plaques.4 The palpable nodule seen in our patient is not a common presentation of EMPD. Pruritus is the most common symptom of EMPD, occurring in 70% of patients.5 Other symptoms include burning, irritation, pain, tenderness, bleeding, and swelling. Ten percent of EMPD cases are asymptomatic.5

Histologically, Paget cells primarily involve the epidermis where they usually form clusters or solid nests. In more than 90% of EMPD cases, the Paget cells contain cytoplasmic mucin that stains positively with mucicarmine and PAS. Immunohistochemical staining for cytokeratin 7, gross cystic disease fluid protein-15, S-100 protein, and CEA sometimes may be needed to differentiate from mimickers such as Bowen disease and superficial spreading melanoma.6 In our patient, the tumor cells stained positive for cytokeratin 7, CEA, and PAS. Malignant melanoma was ruled out with a test for S-100 protein.

|

|

Extramammary Paget disease often is associated with epidermal hyperplasia, which can be classified as squamous, papillomatous, or fibroepitheliomatous.3 Microscopically, squamous hyperplasia is characterized by prominent thickening of the epidermis from diffuse plaquelike hyperplasia and is usually associated with hyperkeratosis. Papillomatous hyperplasia has an exophytic papillary or verrucous architecture and is associated with parakeratosis. Fibroepitheliomatous, or fibroepitheliomalike, hyperplasia generally consists of a discrete, broad, elevated plaque or nodule produced by hyperplasia of keratinocytes that form lacy strands of squamous epithelium.3 The biphasic pattern of proliferating epidermis and entrapped dermis simulates a so-called fibroepithelioma. Paget cells can be seen within the lacy strands of epidermal columns and in the acanthotic surface component.2 The finding of fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia in anogenital skin should prompt a search for the diagnostic Paget cells to eliminate a fibroepithelioma of Pinkus variant of basal cell carcinoma, though the latter is uncommon and rarely occurs at this site.7

Of the 3 types of epidermal hyperplasia, our case demonstrated the fibroepitheliomatous type. There may be some relationship between EMPD and fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia because most reported cases of EMPD with fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia have occurred in the anogenital region. Also, epidermal hyperplasia is more frequent in anogenital Paget disease than in axillary Paget disease.8

Conclusion

Our case showed the unique finding of a verrucous nodular EMPD lesion in which peculiar histological features presented as extensions of the tumor cells forming lacy strands of squamous epithelium from the epidermis to the mid dermis as well as many glandular structures.

1. Lloyd J, Flanagan AM. Mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease. J Clin Pathol. 2000;53:742-749.

2. Billings SD, Roth LM. Pseudoinvasive, nodular extramam-mary Paget’s disease of the vulva. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1998;122:471-474.

3. Brainard JA, Hart WR. Proliferative epidermal lesions associated with anogenital Paget’s disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:543-552.

4. Neuhaus IM, Grekin RC. Mammary and extramammary Paget disease. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. Vol 1. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2008:1094-1098.

5. Shepherd V, Davidson EJ, Davies-Humphreys J. Extramammary Paget’s disease. BJOG. 2005;112:273-279.

6. Kim JC, Kim HC, Jeong CS, et al. Extramammary Paget’s disease with aggressive behavior: a report of two cases. J Korean Med Sci. 1999;14:223-226.

7. Rahbari H, Mehregan AH. Basal cell epitheliomas in usual and unusual sites. J Cutan Pathol. 1979;6:425-431.

8. Ishida-Yamamoto A, Sato K, Wada T, et al. Fibroepithelioma-like changes occurring in perianal Paget’s disease with rectal mucinous carcinoma: case report and review of 49 cases of extramammary Paget’s disease. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:185-189.

1. Lloyd J, Flanagan AM. Mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease. J Clin Pathol. 2000;53:742-749.

2. Billings SD, Roth LM. Pseudoinvasive, nodular extramam-mary Paget’s disease of the vulva. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1998;122:471-474.

3. Brainard JA, Hart WR. Proliferative epidermal lesions associated with anogenital Paget’s disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:543-552.

4. Neuhaus IM, Grekin RC. Mammary and extramammary Paget disease. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. Vol 1. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2008:1094-1098.

5. Shepherd V, Davidson EJ, Davies-Humphreys J. Extramammary Paget’s disease. BJOG. 2005;112:273-279.

6. Kim JC, Kim HC, Jeong CS, et al. Extramammary Paget’s disease with aggressive behavior: a report of two cases. J Korean Med Sci. 1999;14:223-226.

7. Rahbari H, Mehregan AH. Basal cell epitheliomas in usual and unusual sites. J Cutan Pathol. 1979;6:425-431.

8. Ishida-Yamamoto A, Sato K, Wada T, et al. Fibroepithelioma-like changes occurring in perianal Paget’s disease with rectal mucinous carcinoma: case report and review of 49 cases of extramammary Paget’s disease. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:185-189.

- Extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) should be considered in the clinical differential diagnosis of verrucous nodules in the pubic area.

- Histopathologically, EMPD in the anogenital area could show fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia with lacy strands of squamous epithelium.

Hypopigmented Facial Papules on the Cheeks

The Diagnosis: Tumor of the Follicular Infundibulum

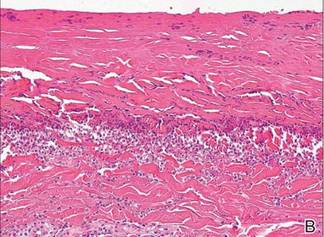

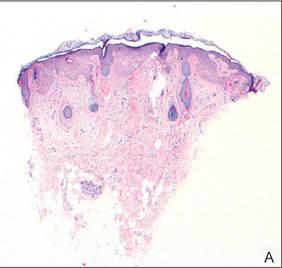

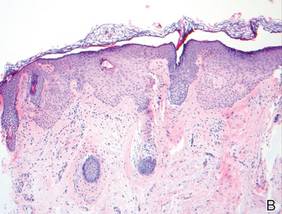

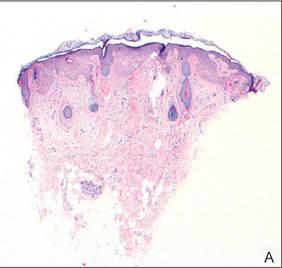

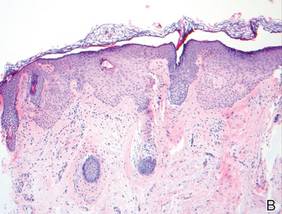

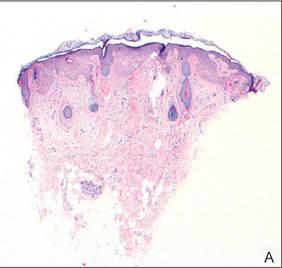

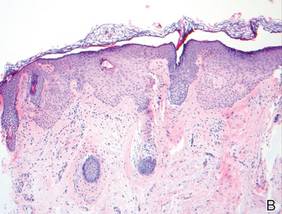

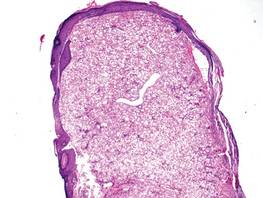

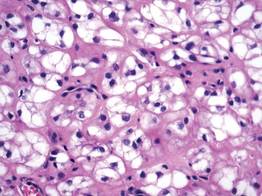

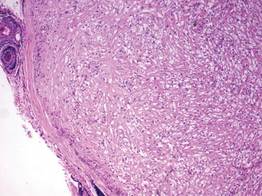

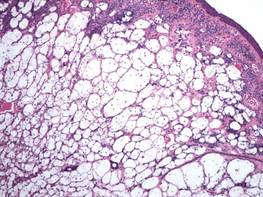

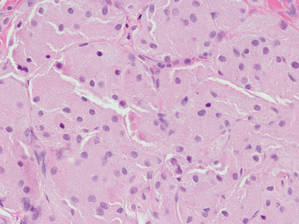

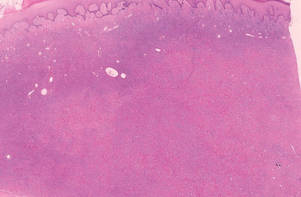

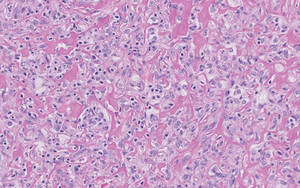

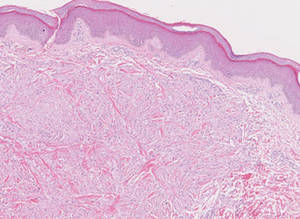

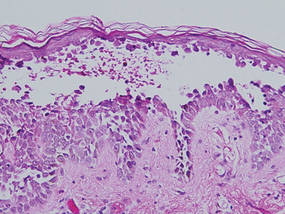

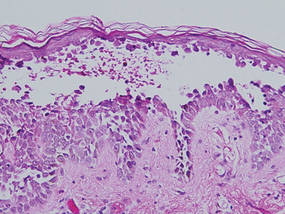

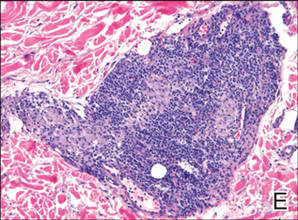

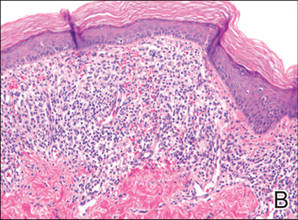

Histopathologic findings from a facial papule in our patient revealed multifocal hyperplasia of anastomosing follicular infundibular cells with multiple connections to the overlying epidermis (Figure). There was no atypia. Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid–Schiff stains for fungi were negative. The combined clinical presentation and histopathologic findings supported the diagnosis of multiple tumor of the follicular infundibulum (TFI).

Tumor of the follicular infundibulum was diagnosed based on a biopsy from the right cheek that revealed multifocal hyperplasia of anastomosing follicular infundibular cells with multiple connections to the overlying epidermis (A and B)(H&E, original magnifications ×40 and ×100). |

Tumor of the follicular infundibulum is an uncommon benign neoplasm that was first described in 1961 by Mehregan and Butler.1 The reported frequency is 10 per 100,000 biopsies.2 The majority of cases have been reported as solitary lesions, and multiple TFI are rare.3 Tumor of the follicular infundibulum affects middle-aged and elderly individuals with a female predominance.4 Multiple lesions generally range in number from 10 to 20, but there are few reports of more than 100 lesions.2,3,5,6 The solitary tumors often are initially misdiagnosed as basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) or seborrheic keratosis. Multiple TFI have been described variably as hypopigmented, flesh-colored and pink, flat and slightly depressed macules and thin papules. Sites of predilection include the scalp, face, neck, and upper trunk.2,3,5

There is no histopathologic difference between solitary and multiple TFI. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum displays a characteristic pale platelike proliferation of keratinocytes within the upper dermis attached to the overlying epidermis. The proliferating cells stain positive with periodic acid–Schiff, diastase-digestible glycogen is present in the cells at the base of the tumor, and a thickened network or brushlike pattern of elastic fibers surrounds the periphery of the tumor.1 Tumor of the follicular infundibulum is occasionally discovered incidentally on biopsy and has been observed in the margin of wide excisions of a variety of neoplasms including BCC.7 Based on the close association of TFI and BCC in the same specimens, Weyers et al7 concluded that TFI may be a nonaggressive type of BCC. Cribier and Grosshans2 reported 2 cases of TFI overlying a nevus sebaceous and a fibroma.

Treatment of TFI includes topical keratolytics, topical retinoic acid,5 imiquimod,8 topical steroids, and oral etretinate,6 all of which result in minimal improvement or incomplete resolution. Destructive treatments include cryotherapy, curettage, electrosurgery, laser ablation, and surgical excision, but all may lead to an unacceptable cosmetic result.

1. Mehregan AH, Butler JD. A tumor of follicular infundibulum. Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:78-81.

2. Cribier B, Grosshans E. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum: a clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:979-984.

3. Kolenik SA 3rd, Bolognia JL, Castiglione FM Jr, et al. Multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:282-284.

4. Ackerman AB, Reddy VB, Soyer HP. Neoplasms With Follicular Differentiation. New York, NY: Ardor Scribendi; 2001.

5. Kossard S, Finley AG, Poyzer K, et al. Eruptive infundibulomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:361-366.

6. Schnitzler L, Civatte J, Robin F, et al. Multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum with basocellular degeneration. apropos of a case [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1987;114:551-556.

7. Weyers W, Horster S, Diaz-Cascajo C. Tumor of follicular infundibulum is basal cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:634-641.

8. Martin JE, Hsu M, Wang LC. An unusual clinical presentation of multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:885-886.

The Diagnosis: Tumor of the Follicular Infundibulum

Histopathologic findings from a facial papule in our patient revealed multifocal hyperplasia of anastomosing follicular infundibular cells with multiple connections to the overlying epidermis (Figure). There was no atypia. Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid–Schiff stains for fungi were negative. The combined clinical presentation and histopathologic findings supported the diagnosis of multiple tumor of the follicular infundibulum (TFI).

Tumor of the follicular infundibulum was diagnosed based on a biopsy from the right cheek that revealed multifocal hyperplasia of anastomosing follicular infundibular cells with multiple connections to the overlying epidermis (A and B)(H&E, original magnifications ×40 and ×100). |

Tumor of the follicular infundibulum is an uncommon benign neoplasm that was first described in 1961 by Mehregan and Butler.1 The reported frequency is 10 per 100,000 biopsies.2 The majority of cases have been reported as solitary lesions, and multiple TFI are rare.3 Tumor of the follicular infundibulum affects middle-aged and elderly individuals with a female predominance.4 Multiple lesions generally range in number from 10 to 20, but there are few reports of more than 100 lesions.2,3,5,6 The solitary tumors often are initially misdiagnosed as basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) or seborrheic keratosis. Multiple TFI have been described variably as hypopigmented, flesh-colored and pink, flat and slightly depressed macules and thin papules. Sites of predilection include the scalp, face, neck, and upper trunk.2,3,5

There is no histopathologic difference between solitary and multiple TFI. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum displays a characteristic pale platelike proliferation of keratinocytes within the upper dermis attached to the overlying epidermis. The proliferating cells stain positive with periodic acid–Schiff, diastase-digestible glycogen is present in the cells at the base of the tumor, and a thickened network or brushlike pattern of elastic fibers surrounds the periphery of the tumor.1 Tumor of the follicular infundibulum is occasionally discovered incidentally on biopsy and has been observed in the margin of wide excisions of a variety of neoplasms including BCC.7 Based on the close association of TFI and BCC in the same specimens, Weyers et al7 concluded that TFI may be a nonaggressive type of BCC. Cribier and Grosshans2 reported 2 cases of TFI overlying a nevus sebaceous and a fibroma.

Treatment of TFI includes topical keratolytics, topical retinoic acid,5 imiquimod,8 topical steroids, and oral etretinate,6 all of which result in minimal improvement or incomplete resolution. Destructive treatments include cryotherapy, curettage, electrosurgery, laser ablation, and surgical excision, but all may lead to an unacceptable cosmetic result.

The Diagnosis: Tumor of the Follicular Infundibulum

Histopathologic findings from a facial papule in our patient revealed multifocal hyperplasia of anastomosing follicular infundibular cells with multiple connections to the overlying epidermis (Figure). There was no atypia. Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid–Schiff stains for fungi were negative. The combined clinical presentation and histopathologic findings supported the diagnosis of multiple tumor of the follicular infundibulum (TFI).

Tumor of the follicular infundibulum was diagnosed based on a biopsy from the right cheek that revealed multifocal hyperplasia of anastomosing follicular infundibular cells with multiple connections to the overlying epidermis (A and B)(H&E, original magnifications ×40 and ×100). |

Tumor of the follicular infundibulum is an uncommon benign neoplasm that was first described in 1961 by Mehregan and Butler.1 The reported frequency is 10 per 100,000 biopsies.2 The majority of cases have been reported as solitary lesions, and multiple TFI are rare.3 Tumor of the follicular infundibulum affects middle-aged and elderly individuals with a female predominance.4 Multiple lesions generally range in number from 10 to 20, but there are few reports of more than 100 lesions.2,3,5,6 The solitary tumors often are initially misdiagnosed as basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) or seborrheic keratosis. Multiple TFI have been described variably as hypopigmented, flesh-colored and pink, flat and slightly depressed macules and thin papules. Sites of predilection include the scalp, face, neck, and upper trunk.2,3,5

There is no histopathologic difference between solitary and multiple TFI. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum displays a characteristic pale platelike proliferation of keratinocytes within the upper dermis attached to the overlying epidermis. The proliferating cells stain positive with periodic acid–Schiff, diastase-digestible glycogen is present in the cells at the base of the tumor, and a thickened network or brushlike pattern of elastic fibers surrounds the periphery of the tumor.1 Tumor of the follicular infundibulum is occasionally discovered incidentally on biopsy and has been observed in the margin of wide excisions of a variety of neoplasms including BCC.7 Based on the close association of TFI and BCC in the same specimens, Weyers et al7 concluded that TFI may be a nonaggressive type of BCC. Cribier and Grosshans2 reported 2 cases of TFI overlying a nevus sebaceous and a fibroma.

Treatment of TFI includes topical keratolytics, topical retinoic acid,5 imiquimod,8 topical steroids, and oral etretinate,6 all of which result in minimal improvement or incomplete resolution. Destructive treatments include cryotherapy, curettage, electrosurgery, laser ablation, and surgical excision, but all may lead to an unacceptable cosmetic result.

1. Mehregan AH, Butler JD. A tumor of follicular infundibulum. Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:78-81.

2. Cribier B, Grosshans E. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum: a clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:979-984.

3. Kolenik SA 3rd, Bolognia JL, Castiglione FM Jr, et al. Multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:282-284.

4. Ackerman AB, Reddy VB, Soyer HP. Neoplasms With Follicular Differentiation. New York, NY: Ardor Scribendi; 2001.

5. Kossard S, Finley AG, Poyzer K, et al. Eruptive infundibulomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:361-366.

6. Schnitzler L, Civatte J, Robin F, et al. Multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum with basocellular degeneration. apropos of a case [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1987;114:551-556.

7. Weyers W, Horster S, Diaz-Cascajo C. Tumor of follicular infundibulum is basal cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:634-641.

8. Martin JE, Hsu M, Wang LC. An unusual clinical presentation of multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:885-886.

1. Mehregan AH, Butler JD. A tumor of follicular infundibulum. Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:78-81.

2. Cribier B, Grosshans E. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum: a clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:979-984.

3. Kolenik SA 3rd, Bolognia JL, Castiglione FM Jr, et al. Multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:282-284.

4. Ackerman AB, Reddy VB, Soyer HP. Neoplasms With Follicular Differentiation. New York, NY: Ardor Scribendi; 2001.

5. Kossard S, Finley AG, Poyzer K, et al. Eruptive infundibulomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:361-366.

6. Schnitzler L, Civatte J, Robin F, et al. Multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum with basocellular degeneration. apropos of a case [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1987;114:551-556.

7. Weyers W, Horster S, Diaz-Cascajo C. Tumor of follicular infundibulum is basal cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:634-641.

8. Martin JE, Hsu M, Wang LC. An unusual clinical presentation of multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:885-886.

A 73-year-old woman presented with multiple mildly pruritic, hypopigmented, thin papules involving both cheeks of 5 months’ duration. The patient had no improvement with ketoconazole cream 2% and hydrocortisone cream 1% used daily for 1 month for presumed tinea versicolor. Physical examination revealed 10 ill-defined, 2- to 5-mm, round and oval, smooth hypopigmented, slightly raised papules located on the lower aspect of both cheeks.

Sulfur Spring Dermatitis

Sulfur spring dermatitis is characterized by multiple punched-out erosions and pits. In prior case reports, patients often presented with painful swollen lesions that developed within 24 hours of bathing in hot sulfur springs.1 Because spa therapy and thermal spring baths are common in modern society, dermatologists should be aware of sulfur spring dermatitis as a potential adverse effect.

Case Report

A healthy 65-year-old man presented with painful skin lesions on the legs that developed after bathing for 25 minutes in a hot sulfur spring 1 day prior. The patient had no history of dermatologic disease. He reported a 10-year history of bathing in a hot sulfur spring for 20 minutes every 3 days in the winter. This time, he bathed 5 minutes longer than usual. No skin condition was noted prior to bathing, but he reported feeling a tickling sensation and scratching the legs while he was immersed in the water. One hour after bathing, he noted confluent, punched-out, round ulcers with peripheral erythema on the thighs and shins (Figure 1).

|

|

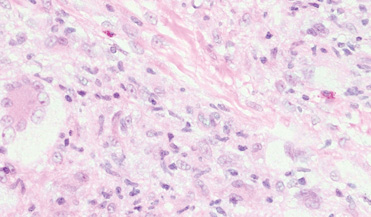

A skin biopsy revealed sharply demarcated, homogeneous coagulation necrosis of the epidermis. Many neutrophils were present under the necrosis (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff and acid-fast stains were negative for infectious organisms, and a skin tissue culture yielded negative results. Intensive wound care was started with nitrofurazone ointment 0.2%. The ulcers healed gradually in the following months with scar formation and hyperpigmentation.

Comment

Thermal sulfur baths are a form of balneotherapy promoted in many cultures for improvement of skin conditions; however, certain uncommon skin problems may occur after bathing in hot sulfur springs.2 In particular, sulfur spring dermatitis is a potential adverse effect.

Thermal sulfur water is known to exert anti-inflammatory, keratoplastic, and antipruriginous effects. As a result, it often is used in many cultures as an alternative treatment of various skin conditions.2-4 Moreover, thermal sulfur baths are popular in northeastern Asian countries for their effects on mental health.5 Hot springs in northern Taiwan, which contain large amounts of hydrogen sulfide, sulfate, and sulfur differ from other thermal springs in that they are rather acidic in nature and release geothermal energy from volcanic activity.6 In addition to hot sulfur springs, there are neutral salt and CO2 springs in Taiwan.5 However, spring dermatitis has only been associated with bathing in hot sulfur springs due to high concentrations of hydrogen sulfide that break down keratin and cause dissolution of the stratum corneum.7

The incidence of sulfur spring dermatitis is unknown. Although the largest known case series reported 44 cases occurring within a decade in Taiwan,1 it is rarely seen in our daily practice. Previously reported cases of sulfur spring dermatitis noted clinical findings of swelling of the affected area followed by punched-out erosions with surrounding erythema. Most lesions gradually healed with dry brownish crusts. A patch test with sulfur spring water and sulfur compounds showed negative results; therefore, the mechanism is unlikely to be allergic reaction.1 The clinical differential diagnosis includes factitious ulcers as well as viral and fungal infections. A tissue culture should be performed to exclude infectious conditions.

This characteristic skin disease does not present in all individuals after bathing in hot sulfur springs. Lesions may present anywhere on the body with a predilection for skin folds, including the penis and scrotum. Preexisting skin conditions such as pruritus and xerosis are considered to be contributing factors. The possible etiology of sulfur spring dermatitis may be acid irritation from the unstable amount of soluble sulfur in the water, which is enhanced by the heat.1 In our patient, no prior skin disease was noted, but he scratched the skin on the thighs while bathing, which may have contributed to the development of lesions in this area rather than in the skin folds.

The skin biopsy specimen demonstrated epidermal coagulation necrosis, mild superficial dermal damage, and preservation of the pilosebaceous appendages. The ulcers were painful during healing and resolved with scarring and hyperpigmentation. The histopathologic findings and clinical course in our patient were similar to cases of superficial second-degree burns.8 It is possible that the keratoplastic effect of sulfur at high concentrations along with thermal water caused the skin condition.

Conclusion

Individuals who engage in thermal sulfur baths should be aware of potential adverse effects such as sulfur spring dermatitis, especially those with preexisting skin disorders.

1. Sun CC, Sue MS. Sulfur spring dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;32:31-34.

2. Matz H, Orion E, Wolf R. Balneotherapy in dermatology. Dermatol Ther. 2003;16:132-140.

3. Leslie KS, Millington GW, Levell NJ. Sulphur and skin: from Satan to Saddam! J Cosmet Dermatol. 2004;3:94-98.

4. Millikan LE. Unapproved treatments or indications in dermatology: physical therapy including balneotherapy. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:125-129.

5. Nirei H, Furuno K, Kusuda T. Medical geology in Japan. In: Selinus O, Finkelman RB, Centeno JA, eds. Medical Geology: A Regional Synthesis. New York, NY: Springer; 2010:329-354.

6. Liu CM, Song SR, Chen YL, et al. Characteristics and origins of hot springs in the Tatun Volcano Group in northern Taiwan. Terr Atmos Ocean Sci. 2011;22:475-489.

7. Lin AN, Reimer RJ, Carter DM. Sulfur revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:553-558.

8. Weedon D. Reaction to physical agents. In: Weedon D. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier Health; 2010:525-540.

Sulfur spring dermatitis is characterized by multiple punched-out erosions and pits. In prior case reports, patients often presented with painful swollen lesions that developed within 24 hours of bathing in hot sulfur springs.1 Because spa therapy and thermal spring baths are common in modern society, dermatologists should be aware of sulfur spring dermatitis as a potential adverse effect.

Case Report

A healthy 65-year-old man presented with painful skin lesions on the legs that developed after bathing for 25 minutes in a hot sulfur spring 1 day prior. The patient had no history of dermatologic disease. He reported a 10-year history of bathing in a hot sulfur spring for 20 minutes every 3 days in the winter. This time, he bathed 5 minutes longer than usual. No skin condition was noted prior to bathing, but he reported feeling a tickling sensation and scratching the legs while he was immersed in the water. One hour after bathing, he noted confluent, punched-out, round ulcers with peripheral erythema on the thighs and shins (Figure 1).

|

|

A skin biopsy revealed sharply demarcated, homogeneous coagulation necrosis of the epidermis. Many neutrophils were present under the necrosis (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff and acid-fast stains were negative for infectious organisms, and a skin tissue culture yielded negative results. Intensive wound care was started with nitrofurazone ointment 0.2%. The ulcers healed gradually in the following months with scar formation and hyperpigmentation.

Comment

Thermal sulfur baths are a form of balneotherapy promoted in many cultures for improvement of skin conditions; however, certain uncommon skin problems may occur after bathing in hot sulfur springs.2 In particular, sulfur spring dermatitis is a potential adverse effect.

Thermal sulfur water is known to exert anti-inflammatory, keratoplastic, and antipruriginous effects. As a result, it often is used in many cultures as an alternative treatment of various skin conditions.2-4 Moreover, thermal sulfur baths are popular in northeastern Asian countries for their effects on mental health.5 Hot springs in northern Taiwan, which contain large amounts of hydrogen sulfide, sulfate, and sulfur differ from other thermal springs in that they are rather acidic in nature and release geothermal energy from volcanic activity.6 In addition to hot sulfur springs, there are neutral salt and CO2 springs in Taiwan.5 However, spring dermatitis has only been associated with bathing in hot sulfur springs due to high concentrations of hydrogen sulfide that break down keratin and cause dissolution of the stratum corneum.7

The incidence of sulfur spring dermatitis is unknown. Although the largest known case series reported 44 cases occurring within a decade in Taiwan,1 it is rarely seen in our daily practice. Previously reported cases of sulfur spring dermatitis noted clinical findings of swelling of the affected area followed by punched-out erosions with surrounding erythema. Most lesions gradually healed with dry brownish crusts. A patch test with sulfur spring water and sulfur compounds showed negative results; therefore, the mechanism is unlikely to be allergic reaction.1 The clinical differential diagnosis includes factitious ulcers as well as viral and fungal infections. A tissue culture should be performed to exclude infectious conditions.

This characteristic skin disease does not present in all individuals after bathing in hot sulfur springs. Lesions may present anywhere on the body with a predilection for skin folds, including the penis and scrotum. Preexisting skin conditions such as pruritus and xerosis are considered to be contributing factors. The possible etiology of sulfur spring dermatitis may be acid irritation from the unstable amount of soluble sulfur in the water, which is enhanced by the heat.1 In our patient, no prior skin disease was noted, but he scratched the skin on the thighs while bathing, which may have contributed to the development of lesions in this area rather than in the skin folds.

The skin biopsy specimen demonstrated epidermal coagulation necrosis, mild superficial dermal damage, and preservation of the pilosebaceous appendages. The ulcers were painful during healing and resolved with scarring and hyperpigmentation. The histopathologic findings and clinical course in our patient were similar to cases of superficial second-degree burns.8 It is possible that the keratoplastic effect of sulfur at high concentrations along with thermal water caused the skin condition.

Conclusion

Individuals who engage in thermal sulfur baths should be aware of potential adverse effects such as sulfur spring dermatitis, especially those with preexisting skin disorders.

Sulfur spring dermatitis is characterized by multiple punched-out erosions and pits. In prior case reports, patients often presented with painful swollen lesions that developed within 24 hours of bathing in hot sulfur springs.1 Because spa therapy and thermal spring baths are common in modern society, dermatologists should be aware of sulfur spring dermatitis as a potential adverse effect.

Case Report

A healthy 65-year-old man presented with painful skin lesions on the legs that developed after bathing for 25 minutes in a hot sulfur spring 1 day prior. The patient had no history of dermatologic disease. He reported a 10-year history of bathing in a hot sulfur spring for 20 minutes every 3 days in the winter. This time, he bathed 5 minutes longer than usual. No skin condition was noted prior to bathing, but he reported feeling a tickling sensation and scratching the legs while he was immersed in the water. One hour after bathing, he noted confluent, punched-out, round ulcers with peripheral erythema on the thighs and shins (Figure 1).

|

|

A skin biopsy revealed sharply demarcated, homogeneous coagulation necrosis of the epidermis. Many neutrophils were present under the necrosis (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff and acid-fast stains were negative for infectious organisms, and a skin tissue culture yielded negative results. Intensive wound care was started with nitrofurazone ointment 0.2%. The ulcers healed gradually in the following months with scar formation and hyperpigmentation.

Comment

Thermal sulfur baths are a form of balneotherapy promoted in many cultures for improvement of skin conditions; however, certain uncommon skin problems may occur after bathing in hot sulfur springs.2 In particular, sulfur spring dermatitis is a potential adverse effect.

Thermal sulfur water is known to exert anti-inflammatory, keratoplastic, and antipruriginous effects. As a result, it often is used in many cultures as an alternative treatment of various skin conditions.2-4 Moreover, thermal sulfur baths are popular in northeastern Asian countries for their effects on mental health.5 Hot springs in northern Taiwan, which contain large amounts of hydrogen sulfide, sulfate, and sulfur differ from other thermal springs in that they are rather acidic in nature and release geothermal energy from volcanic activity.6 In addition to hot sulfur springs, there are neutral salt and CO2 springs in Taiwan.5 However, spring dermatitis has only been associated with bathing in hot sulfur springs due to high concentrations of hydrogen sulfide that break down keratin and cause dissolution of the stratum corneum.7

The incidence of sulfur spring dermatitis is unknown. Although the largest known case series reported 44 cases occurring within a decade in Taiwan,1 it is rarely seen in our daily practice. Previously reported cases of sulfur spring dermatitis noted clinical findings of swelling of the affected area followed by punched-out erosions with surrounding erythema. Most lesions gradually healed with dry brownish crusts. A patch test with sulfur spring water and sulfur compounds showed negative results; therefore, the mechanism is unlikely to be allergic reaction.1 The clinical differential diagnosis includes factitious ulcers as well as viral and fungal infections. A tissue culture should be performed to exclude infectious conditions.

This characteristic skin disease does not present in all individuals after bathing in hot sulfur springs. Lesions may present anywhere on the body with a predilection for skin folds, including the penis and scrotum. Preexisting skin conditions such as pruritus and xerosis are considered to be contributing factors. The possible etiology of sulfur spring dermatitis may be acid irritation from the unstable amount of soluble sulfur in the water, which is enhanced by the heat.1 In our patient, no prior skin disease was noted, but he scratched the skin on the thighs while bathing, which may have contributed to the development of lesions in this area rather than in the skin folds.

The skin biopsy specimen demonstrated epidermal coagulation necrosis, mild superficial dermal damage, and preservation of the pilosebaceous appendages. The ulcers were painful during healing and resolved with scarring and hyperpigmentation. The histopathologic findings and clinical course in our patient were similar to cases of superficial second-degree burns.8 It is possible that the keratoplastic effect of sulfur at high concentrations along with thermal water caused the skin condition.

Conclusion

Individuals who engage in thermal sulfur baths should be aware of potential adverse effects such as sulfur spring dermatitis, especially those with preexisting skin disorders.

1. Sun CC, Sue MS. Sulfur spring dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;32:31-34.

2. Matz H, Orion E, Wolf R. Balneotherapy in dermatology. Dermatol Ther. 2003;16:132-140.

3. Leslie KS, Millington GW, Levell NJ. Sulphur and skin: from Satan to Saddam! J Cosmet Dermatol. 2004;3:94-98.

4. Millikan LE. Unapproved treatments or indications in dermatology: physical therapy including balneotherapy. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:125-129.

5. Nirei H, Furuno K, Kusuda T. Medical geology in Japan. In: Selinus O, Finkelman RB, Centeno JA, eds. Medical Geology: A Regional Synthesis. New York, NY: Springer; 2010:329-354.

6. Liu CM, Song SR, Chen YL, et al. Characteristics and origins of hot springs in the Tatun Volcano Group in northern Taiwan. Terr Atmos Ocean Sci. 2011;22:475-489.

7. Lin AN, Reimer RJ, Carter DM. Sulfur revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:553-558.

8. Weedon D. Reaction to physical agents. In: Weedon D. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier Health; 2010:525-540.

1. Sun CC, Sue MS. Sulfur spring dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;32:31-34.