User login

Recalcitrant Solitary Erythematous Scaly Patch on the Foot

The Diagnosis: Pagetoid Reticulosis

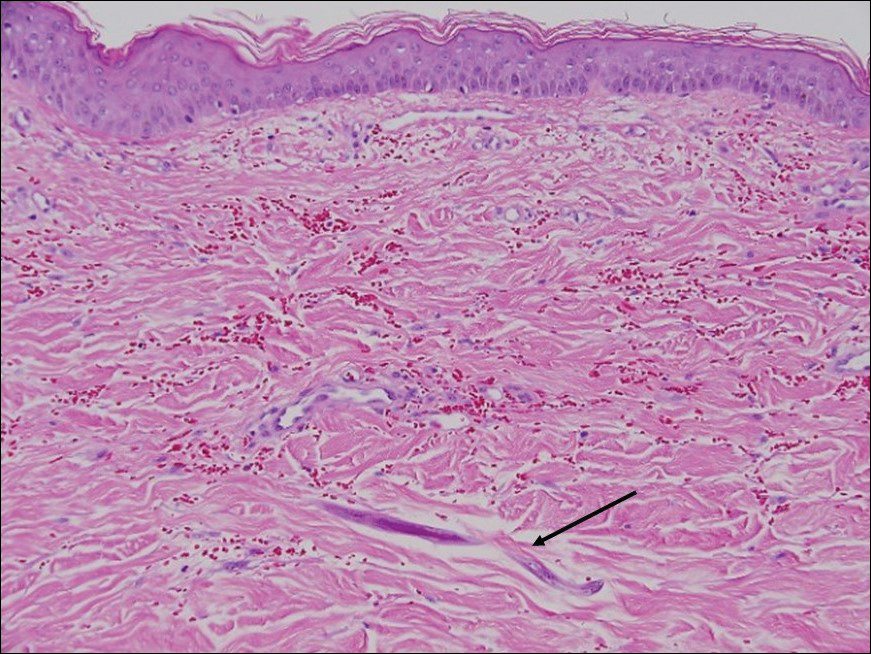

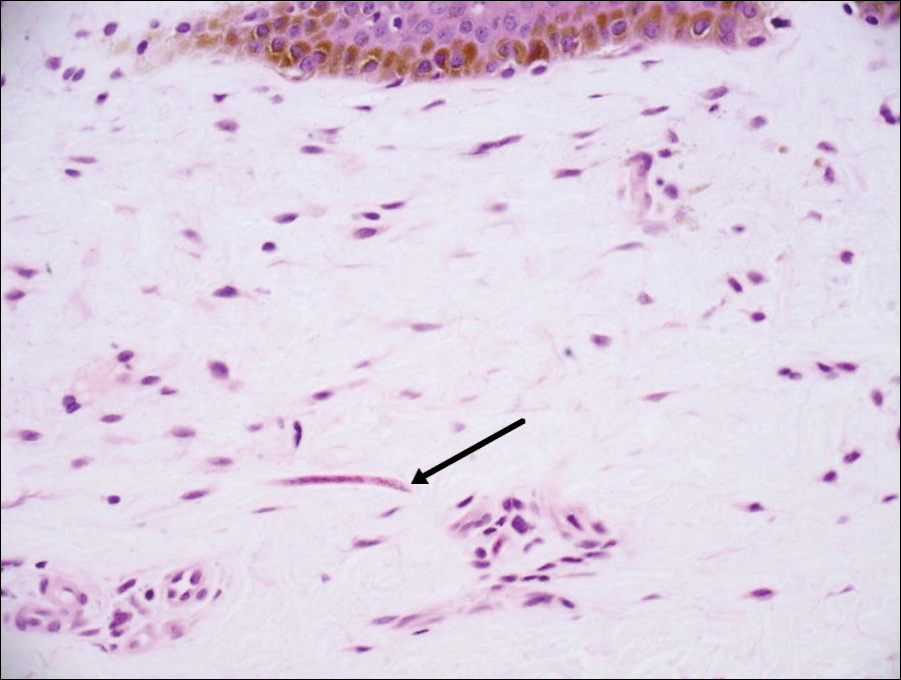

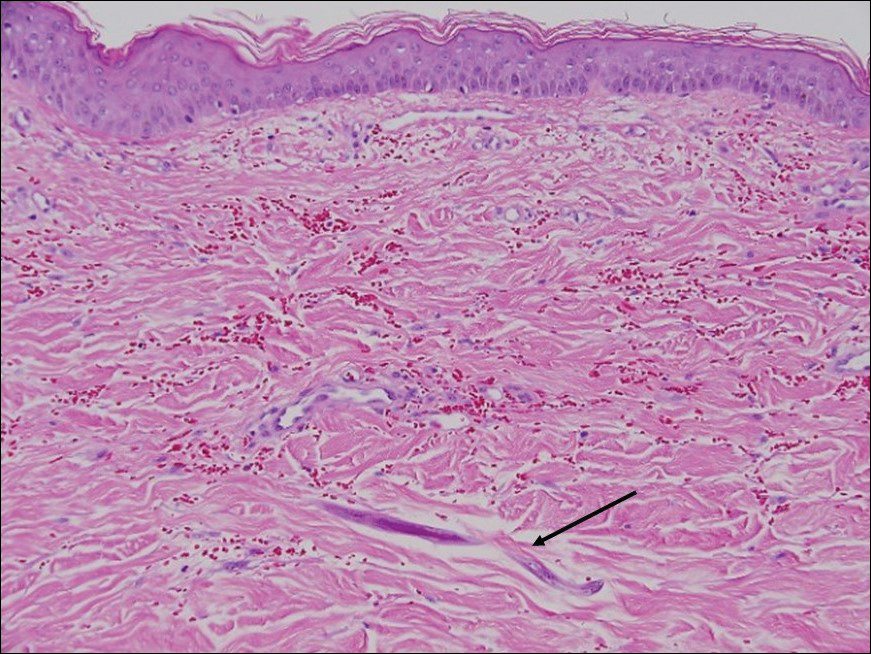

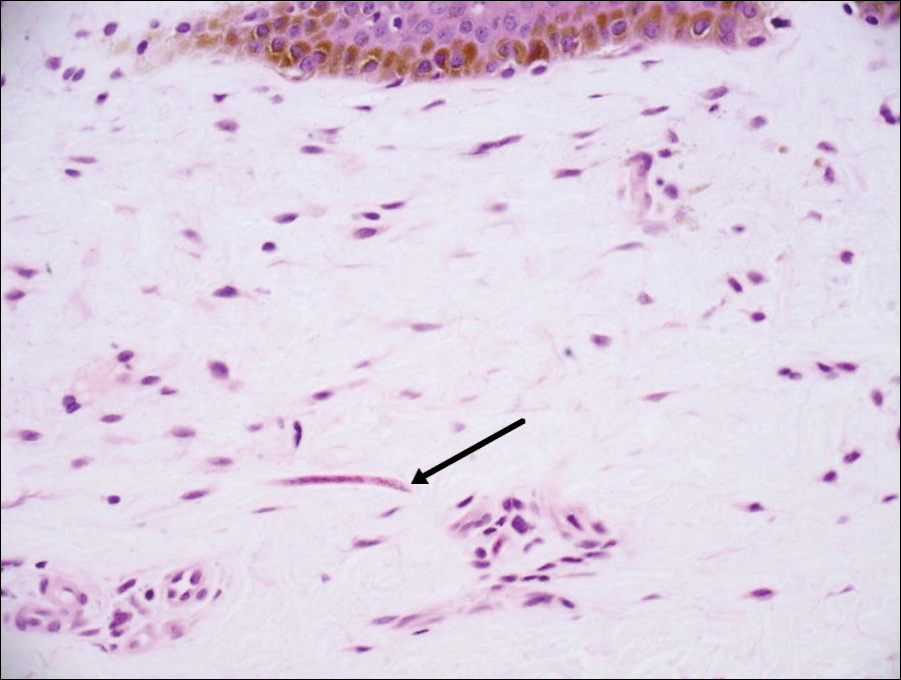

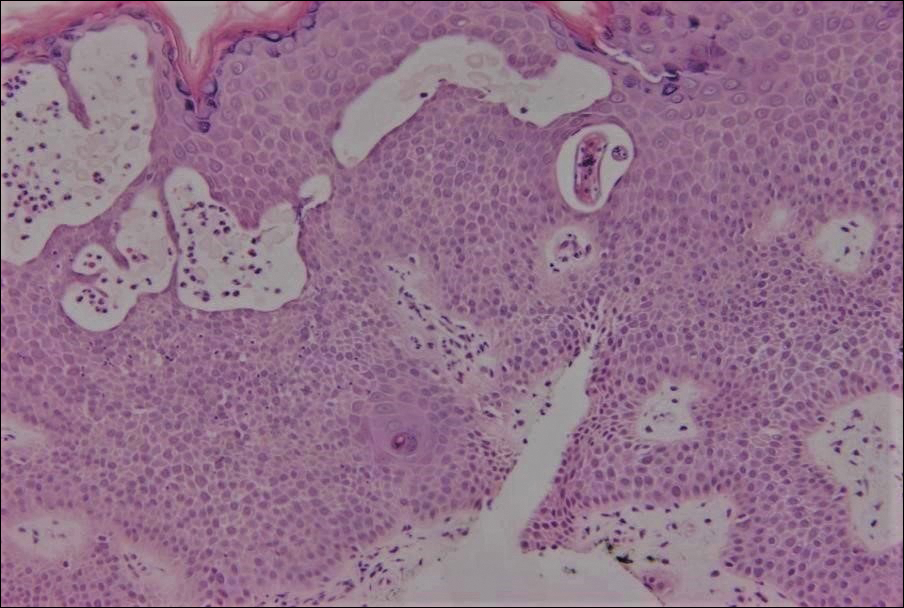

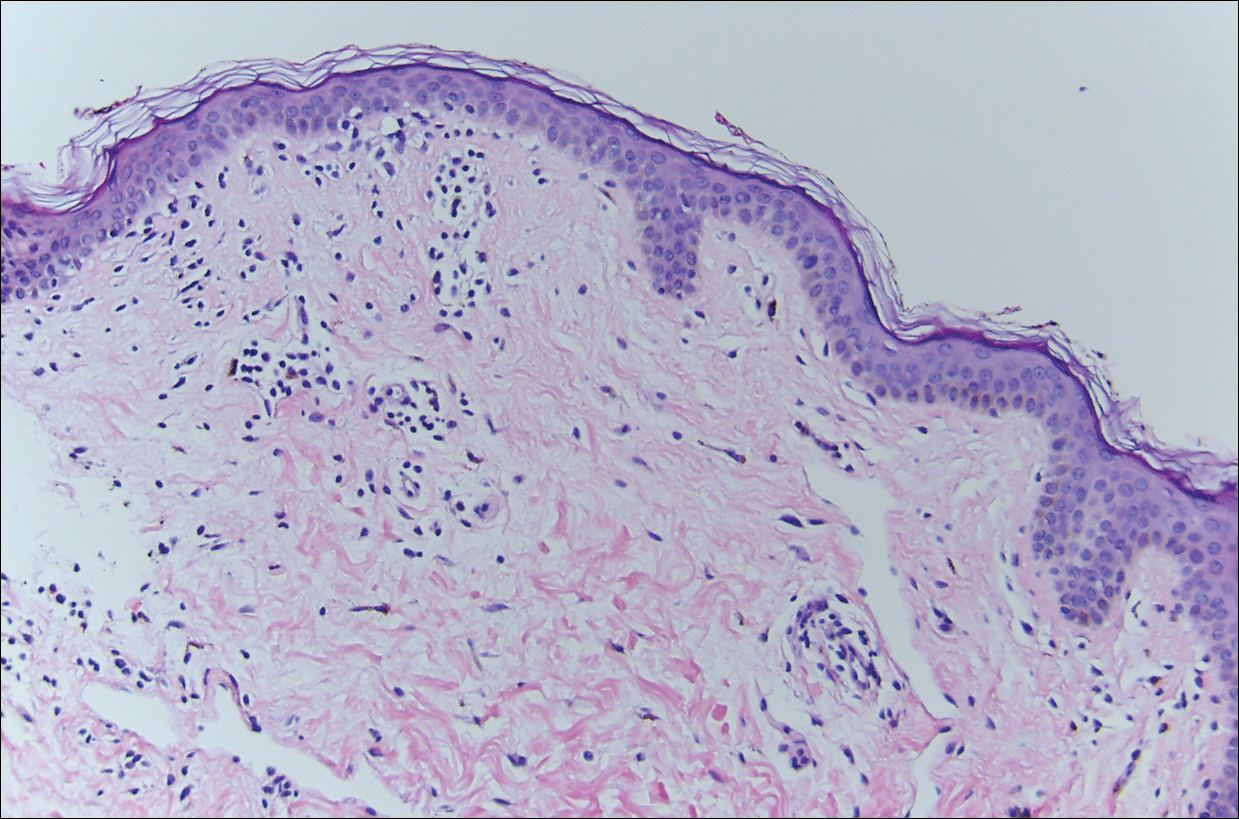

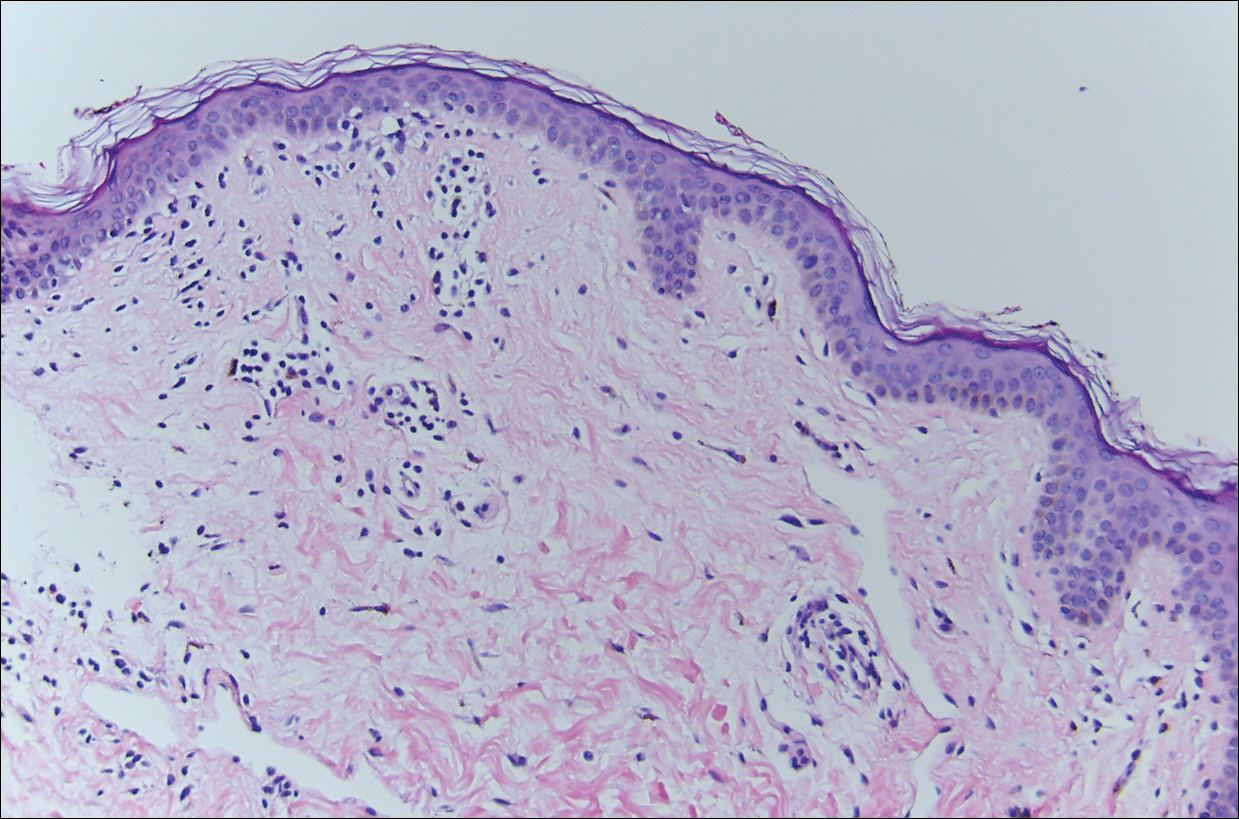

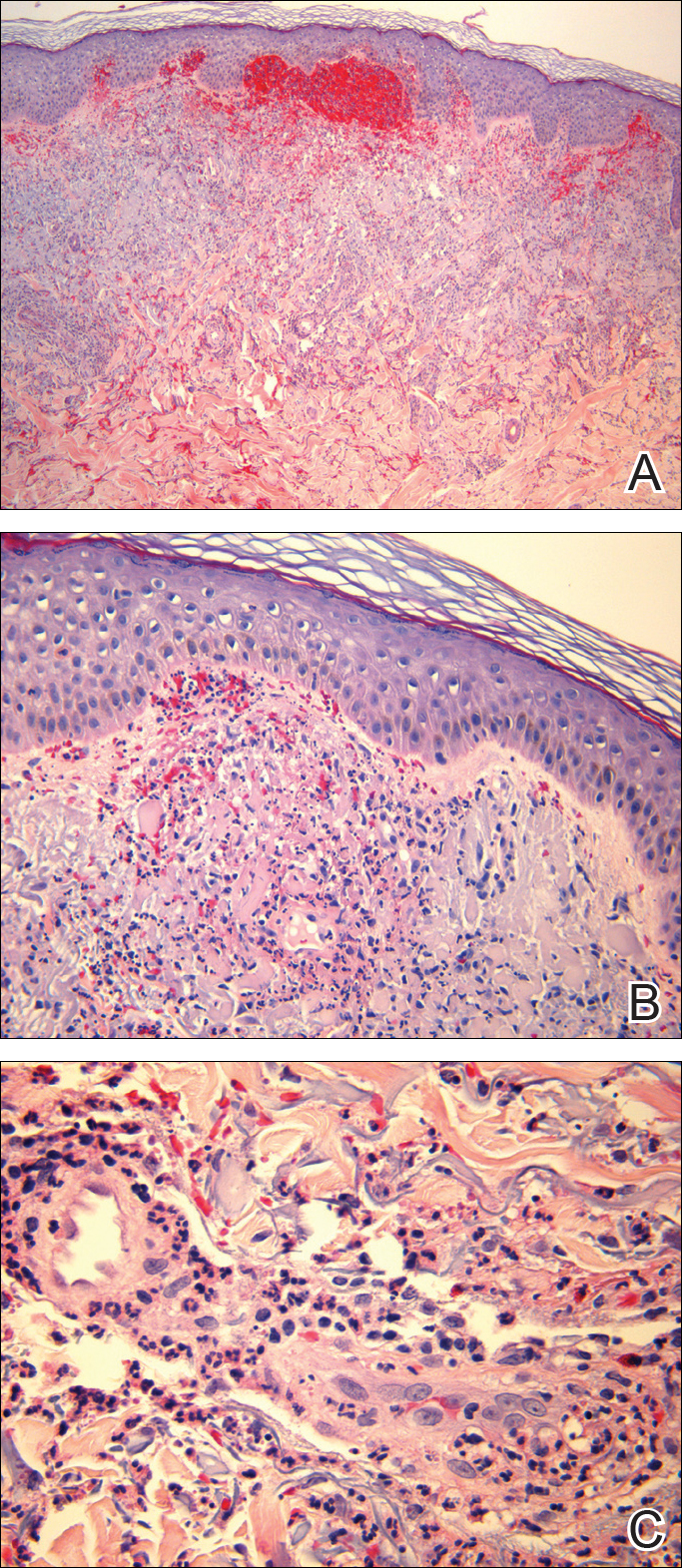

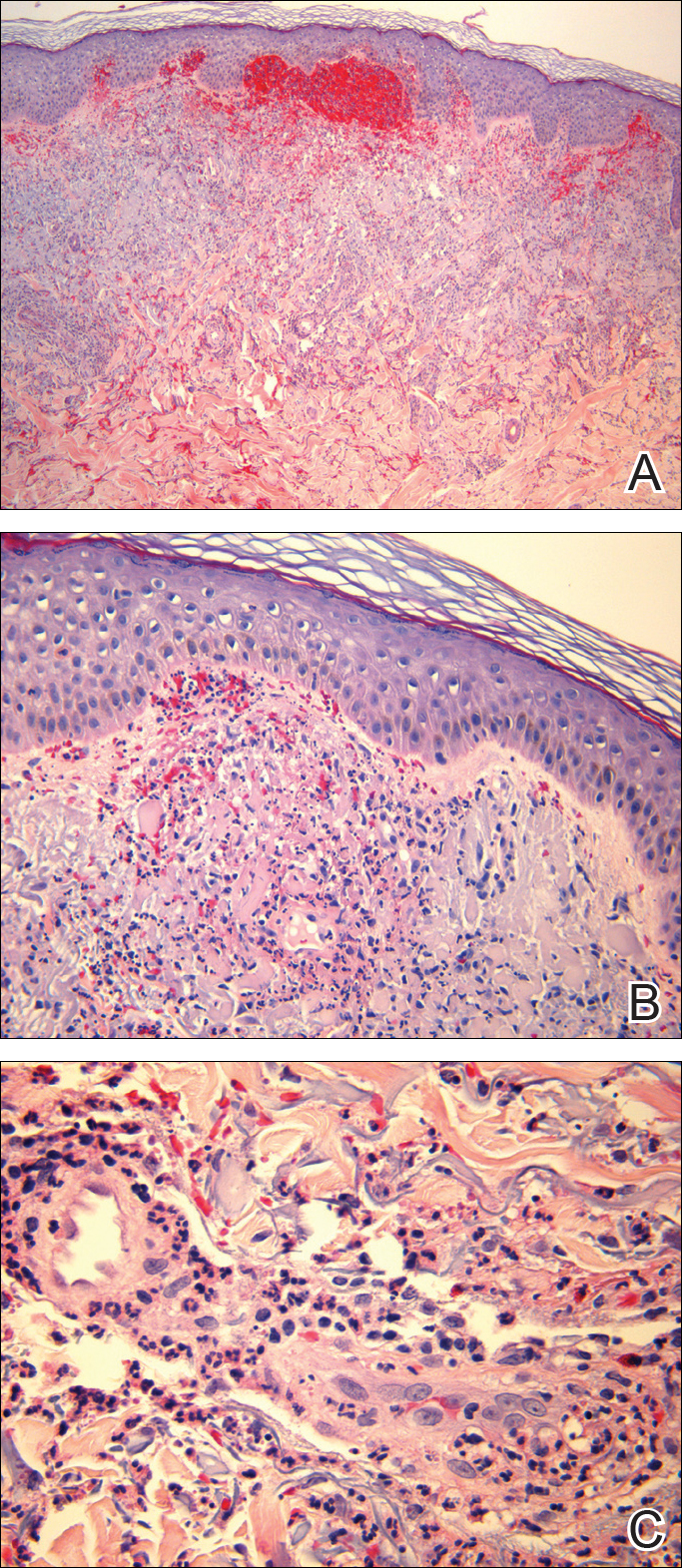

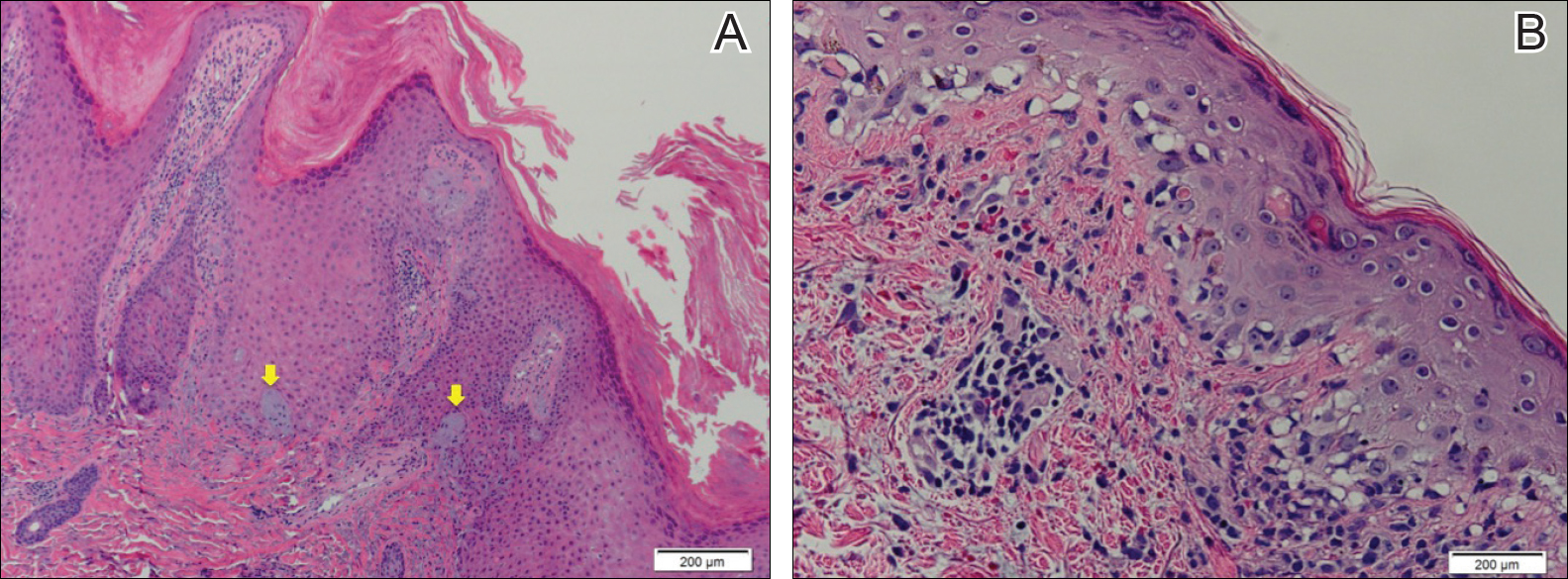

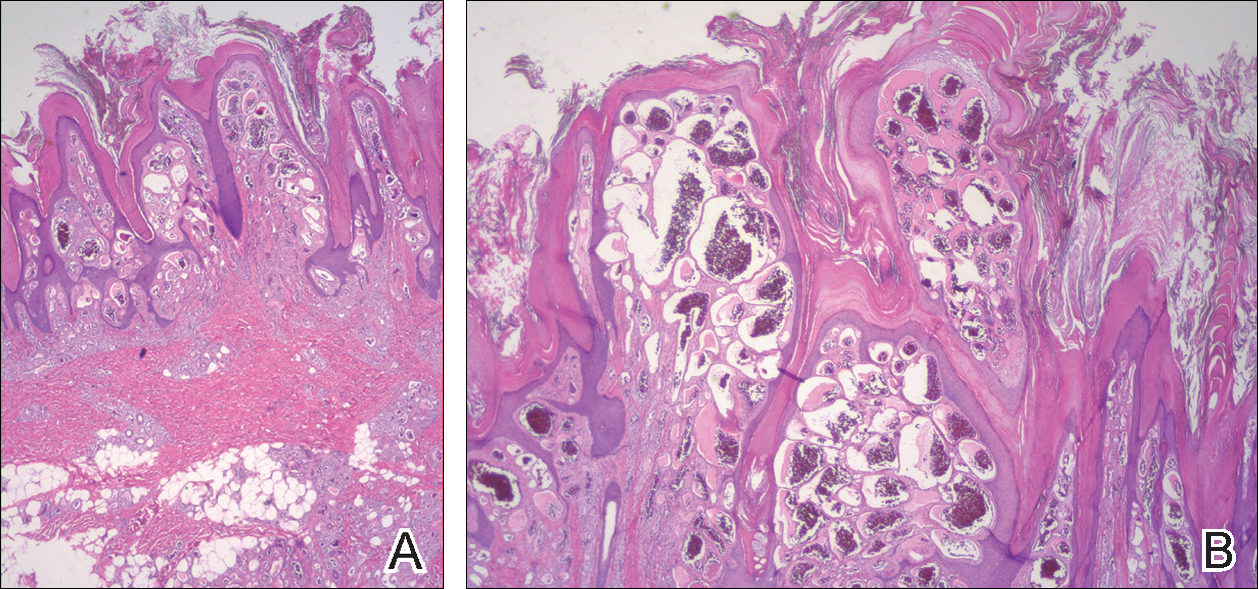

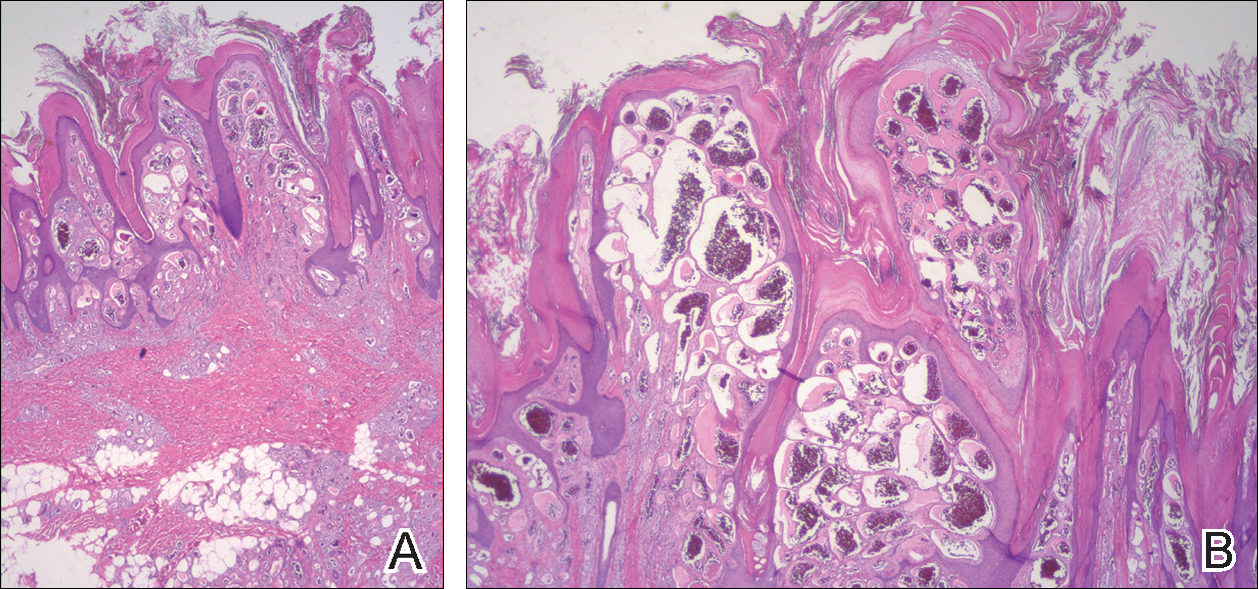

Histopathologic examination demonstrated a dense infiltrate and psoriasiform pattern epidermal hyperplasia (Figure, A). There was conspicuous epidermotropism of moderately enlarged, hyperchromatic lymphocytes. Intraepidermal lymphocytes were slightly larger, darker, and more convoluted than those in the subjacent dermis (Figure, B). These cells exhibited CD3+ T-cell differentiation with an abnormal CD4-CD7-CD8- phenotype (Figure, C). The histopathologic finding of atypical epidermotropic T-cell infiltrate was compatible with a rare variant of mycosis fungoides known as pagetoid reticulosis (PR). After discussing the diagnosis and treatment options, the patient elected to begin with a conservative approach to therapy. We prescribed fluocinonide ointment 0.05% twice daily under occlusion. At 1 month follow-up, the patient experienced marked improvement of the erythema and scaling of the lesion.

Pagetoid reticulosis is a primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that has been categorized as an indolent localized variant of mycosis fungoides. This rare skin disorder was originally described by Woringer and Kolopp in 19391 and was further renamed in 1973 by Braun-Falco et al.2 At that time the term pagetoid reticulosis was introduced due to similarities in histopathologic findings seen in Paget disease of the nipple. Two variants of the disease have been described since then: the localized type and the disseminated type. The localized type, also known as Woringer-Kolopp disease (WKD), typically presents as a persistent, sharply localized, scaly patch that slowly expands over several years. The lesion is classically located on the extensor surface of the hand or foot and often is asymptomatic. Due to the benign presentation, WKD can easily be confused with much more common diseases, such as psoriasis or fungal infections, resulting in a substantial delay in the diagnosis. The patient will often report a medical history notable for frequent office visits and numerous failed therapies. Even though it is exceedingly uncommon, these findings should prompt the practitioner to add WKD to their differential. The disseminated type of PR (also known as Ketron-Goodman disease) is characterized by diffuse cutaneous involvement, carries a much more progressive course, and often leads to a poor outcome.3 The histopathologic features of WKD and Ketron-Goodman disease are identical, and the 2 types are distinguished on clinical grounds alone.

Histopathologic features of PR are unique and often distinct in comparison to mycosis fungoides. Pagetoid reticulosis often is described as epidermal hyperplasia with parakeratosis, prominent acanthosis, and excessive epidermotropism of atypical lymphocytes scattered throughout the epidermis.3 The distinct pattern of epidermotropism seen in PR is the characteristic finding. Review of immunocytochemistry from reported cases has shown that CD marker expression of neoplastic T cells in PR can be variable in nature.4 Although it is known that immunophenotyping can be useful in diagnosing and distinguishing PR from other types of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, the clinical significance of the observed phenotypic variation remains a mystery. As of now, it appears to be prognostically irrelevant.5

There are numerous therapeutic options available for PR. Depending on the size and extent of the disease, surgical excision and radiotherapy may be an option and are the most effective.6 For patients who are not good candidates or opt out of these options, there are various pharmacotherapies that also have proven to work. Traditional therapies include topical corticosteroids, corticosteroid injections, and phototherapy. However, more recent trials with retinoids, such as alitretinoin or bexarotene, appear to offer a promising therapeutic approach.7

Pagetoid reticulosis is a true malignant lymphoma of T-cell lineage, but it typically carries an excellent prognosis. Rare cases have been reported to progress to disseminated lymphoma.8 Therefore, long-term follow-up for a patient diagnosed with PR is recommended.

- Woringer FR, Kolopp P. Lésion érythémato-squameuse polycyclique de l'avant-bras évoluantdepuis 6 ans chez un garçonnet de 13 ans. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1939;10:945-948.

- Braun-Falco O, Marghescu S, Wolff HH. Pagetoid reticulosis--Woringer-Kolopp's disease [in German]. Hautarzt. 1973;24:11-21.

- Haghighi B, Smoller BR, Leboit PE, et al. Pagetoid reticulosis (Woringer-Kolopp disease): an immunophenotypic, molecular, and clinicopathologic study. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:502-510.

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- Mourtzinos N, Puri PK, Wang G, et al. CD4/CD8 double negative pagetoid reticulosis: a case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:491-496.

- Lee J, Viakhireva N, Cesca C, et al. Clinicopathologic features and treatment outcomes in Woringer-Kolopp disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:706-712.

- Schmitz L, Bierhoff E, Dirschka T. Alitretinoin: an effective treatment option for pagetoid reticulosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:1194-1195.

- Ioannides G, Engel MF, Rywlin AM. Woringer-Kolopp disease (pagetoid reticulosis). Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:153-158.

The Diagnosis: Pagetoid Reticulosis

Histopathologic examination demonstrated a dense infiltrate and psoriasiform pattern epidermal hyperplasia (Figure, A). There was conspicuous epidermotropism of moderately enlarged, hyperchromatic lymphocytes. Intraepidermal lymphocytes were slightly larger, darker, and more convoluted than those in the subjacent dermis (Figure, B). These cells exhibited CD3+ T-cell differentiation with an abnormal CD4-CD7-CD8- phenotype (Figure, C). The histopathologic finding of atypical epidermotropic T-cell infiltrate was compatible with a rare variant of mycosis fungoides known as pagetoid reticulosis (PR). After discussing the diagnosis and treatment options, the patient elected to begin with a conservative approach to therapy. We prescribed fluocinonide ointment 0.05% twice daily under occlusion. At 1 month follow-up, the patient experienced marked improvement of the erythema and scaling of the lesion.

Pagetoid reticulosis is a primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that has been categorized as an indolent localized variant of mycosis fungoides. This rare skin disorder was originally described by Woringer and Kolopp in 19391 and was further renamed in 1973 by Braun-Falco et al.2 At that time the term pagetoid reticulosis was introduced due to similarities in histopathologic findings seen in Paget disease of the nipple. Two variants of the disease have been described since then: the localized type and the disseminated type. The localized type, also known as Woringer-Kolopp disease (WKD), typically presents as a persistent, sharply localized, scaly patch that slowly expands over several years. The lesion is classically located on the extensor surface of the hand or foot and often is asymptomatic. Due to the benign presentation, WKD can easily be confused with much more common diseases, such as psoriasis or fungal infections, resulting in a substantial delay in the diagnosis. The patient will often report a medical history notable for frequent office visits and numerous failed therapies. Even though it is exceedingly uncommon, these findings should prompt the practitioner to add WKD to their differential. The disseminated type of PR (also known as Ketron-Goodman disease) is characterized by diffuse cutaneous involvement, carries a much more progressive course, and often leads to a poor outcome.3 The histopathologic features of WKD and Ketron-Goodman disease are identical, and the 2 types are distinguished on clinical grounds alone.

Histopathologic features of PR are unique and often distinct in comparison to mycosis fungoides. Pagetoid reticulosis often is described as epidermal hyperplasia with parakeratosis, prominent acanthosis, and excessive epidermotropism of atypical lymphocytes scattered throughout the epidermis.3 The distinct pattern of epidermotropism seen in PR is the characteristic finding. Review of immunocytochemistry from reported cases has shown that CD marker expression of neoplastic T cells in PR can be variable in nature.4 Although it is known that immunophenotyping can be useful in diagnosing and distinguishing PR from other types of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, the clinical significance of the observed phenotypic variation remains a mystery. As of now, it appears to be prognostically irrelevant.5

There are numerous therapeutic options available for PR. Depending on the size and extent of the disease, surgical excision and radiotherapy may be an option and are the most effective.6 For patients who are not good candidates or opt out of these options, there are various pharmacotherapies that also have proven to work. Traditional therapies include topical corticosteroids, corticosteroid injections, and phototherapy. However, more recent trials with retinoids, such as alitretinoin or bexarotene, appear to offer a promising therapeutic approach.7

Pagetoid reticulosis is a true malignant lymphoma of T-cell lineage, but it typically carries an excellent prognosis. Rare cases have been reported to progress to disseminated lymphoma.8 Therefore, long-term follow-up for a patient diagnosed with PR is recommended.

The Diagnosis: Pagetoid Reticulosis

Histopathologic examination demonstrated a dense infiltrate and psoriasiform pattern epidermal hyperplasia (Figure, A). There was conspicuous epidermotropism of moderately enlarged, hyperchromatic lymphocytes. Intraepidermal lymphocytes were slightly larger, darker, and more convoluted than those in the subjacent dermis (Figure, B). These cells exhibited CD3+ T-cell differentiation with an abnormal CD4-CD7-CD8- phenotype (Figure, C). The histopathologic finding of atypical epidermotropic T-cell infiltrate was compatible with a rare variant of mycosis fungoides known as pagetoid reticulosis (PR). After discussing the diagnosis and treatment options, the patient elected to begin with a conservative approach to therapy. We prescribed fluocinonide ointment 0.05% twice daily under occlusion. At 1 month follow-up, the patient experienced marked improvement of the erythema and scaling of the lesion.

Pagetoid reticulosis is a primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that has been categorized as an indolent localized variant of mycosis fungoides. This rare skin disorder was originally described by Woringer and Kolopp in 19391 and was further renamed in 1973 by Braun-Falco et al.2 At that time the term pagetoid reticulosis was introduced due to similarities in histopathologic findings seen in Paget disease of the nipple. Two variants of the disease have been described since then: the localized type and the disseminated type. The localized type, also known as Woringer-Kolopp disease (WKD), typically presents as a persistent, sharply localized, scaly patch that slowly expands over several years. The lesion is classically located on the extensor surface of the hand or foot and often is asymptomatic. Due to the benign presentation, WKD can easily be confused with much more common diseases, such as psoriasis or fungal infections, resulting in a substantial delay in the diagnosis. The patient will often report a medical history notable for frequent office visits and numerous failed therapies. Even though it is exceedingly uncommon, these findings should prompt the practitioner to add WKD to their differential. The disseminated type of PR (also known as Ketron-Goodman disease) is characterized by diffuse cutaneous involvement, carries a much more progressive course, and often leads to a poor outcome.3 The histopathologic features of WKD and Ketron-Goodman disease are identical, and the 2 types are distinguished on clinical grounds alone.

Histopathologic features of PR are unique and often distinct in comparison to mycosis fungoides. Pagetoid reticulosis often is described as epidermal hyperplasia with parakeratosis, prominent acanthosis, and excessive epidermotropism of atypical lymphocytes scattered throughout the epidermis.3 The distinct pattern of epidermotropism seen in PR is the characteristic finding. Review of immunocytochemistry from reported cases has shown that CD marker expression of neoplastic T cells in PR can be variable in nature.4 Although it is known that immunophenotyping can be useful in diagnosing and distinguishing PR from other types of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, the clinical significance of the observed phenotypic variation remains a mystery. As of now, it appears to be prognostically irrelevant.5

There are numerous therapeutic options available for PR. Depending on the size and extent of the disease, surgical excision and radiotherapy may be an option and are the most effective.6 For patients who are not good candidates or opt out of these options, there are various pharmacotherapies that also have proven to work. Traditional therapies include topical corticosteroids, corticosteroid injections, and phototherapy. However, more recent trials with retinoids, such as alitretinoin or bexarotene, appear to offer a promising therapeutic approach.7

Pagetoid reticulosis is a true malignant lymphoma of T-cell lineage, but it typically carries an excellent prognosis. Rare cases have been reported to progress to disseminated lymphoma.8 Therefore, long-term follow-up for a patient diagnosed with PR is recommended.

- Woringer FR, Kolopp P. Lésion érythémato-squameuse polycyclique de l'avant-bras évoluantdepuis 6 ans chez un garçonnet de 13 ans. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1939;10:945-948.

- Braun-Falco O, Marghescu S, Wolff HH. Pagetoid reticulosis--Woringer-Kolopp's disease [in German]. Hautarzt. 1973;24:11-21.

- Haghighi B, Smoller BR, Leboit PE, et al. Pagetoid reticulosis (Woringer-Kolopp disease): an immunophenotypic, molecular, and clinicopathologic study. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:502-510.

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- Mourtzinos N, Puri PK, Wang G, et al. CD4/CD8 double negative pagetoid reticulosis: a case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:491-496.

- Lee J, Viakhireva N, Cesca C, et al. Clinicopathologic features and treatment outcomes in Woringer-Kolopp disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:706-712.

- Schmitz L, Bierhoff E, Dirschka T. Alitretinoin: an effective treatment option for pagetoid reticulosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:1194-1195.

- Ioannides G, Engel MF, Rywlin AM. Woringer-Kolopp disease (pagetoid reticulosis). Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:153-158.

- Woringer FR, Kolopp P. Lésion érythémato-squameuse polycyclique de l'avant-bras évoluantdepuis 6 ans chez un garçonnet de 13 ans. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1939;10:945-948.

- Braun-Falco O, Marghescu S, Wolff HH. Pagetoid reticulosis--Woringer-Kolopp's disease [in German]. Hautarzt. 1973;24:11-21.

- Haghighi B, Smoller BR, Leboit PE, et al. Pagetoid reticulosis (Woringer-Kolopp disease): an immunophenotypic, molecular, and clinicopathologic study. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:502-510.

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- Mourtzinos N, Puri PK, Wang G, et al. CD4/CD8 double negative pagetoid reticulosis: a case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:491-496.

- Lee J, Viakhireva N, Cesca C, et al. Clinicopathologic features and treatment outcomes in Woringer-Kolopp disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:706-712.

- Schmitz L, Bierhoff E, Dirschka T. Alitretinoin: an effective treatment option for pagetoid reticulosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:1194-1195.

- Ioannides G, Engel MF, Rywlin AM. Woringer-Kolopp disease (pagetoid reticulosis). Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:153-158.

An 80-year-old man with a history of malignant melanoma and squamous cell carcinoma presented to the dermatology clinic with a chronic rash of 20 years' duration on the right ankle that extended to the instep of the right foot. His medical history was notable for hypertension and hyperlipidemia. Family history was unremarkable. The patient described the rash as red and scaly but denied associated pain or pruritus. Over the last 2 to 3 years he had tried treating the affected area with petroleum jelly, topical and oral antifungals, and mild topical steroids with minimal improvement. Complete review of systems was performed and was negative other than some mild constipation. Physical examination revealed an erythematous scaly patch on the dorsal aspect of the right ankle. Potassium hydroxide preparation and fungal culture swab yielded negative results, and a shave biopsy was performed.

Expanding Uses of Propranolol in Dermatology

Since the serendipitous discovery of expedited involution of infantile hemangiomas (IHs) with propranolol in 2008,1 current research has proliferated to discern the mechanism of action of beta-blockers in the care of IHs. Propranolol is a nonselective beta-blocker with a structure similar to catecholamines and thus competes for β-adrenergic receptors. Blocking β1-receptors is cardioselective, leading to decreased heart rate and myocardial contractility, while blocking β2-receptors leads to inhibition of smooth muscle relaxation and decreased glycogenolysis. The endothelial cells of IH express β2-adrenergic receptors; the mechanistic role of propranolol in these lesions is surmised to be due to vasoconstriction, decreased angiogenesis through inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor, and subsequent endothelial cell apoptosis.2

After this breakthrough finding, a subsequent novel development was made when an ophthalmologist demonstrated that timolol, a topical beta-blocker, could be utilized to expedite IH involution and prevent ocular complications such as amblyopia secondary to the mass effect of the lesion. Guo and Ni3 prescribed the commercially available ophthalmologic solution of timolol maleate 0.5% for twice-daily use for 5 weeks. Remarkable reduction in the periorbital IH without rebound phenomenon was observed.3 A recent multicenter retrospective cohort of more than 700 patients with IH were treated with topical timolol with a 70% success rate, corresponding to 10% improvement from baseline; this study highlights the efficacy of timolol while confirming the safety of the medication.4

Systemic beta-blockers for IH have been used predominately for critical sites such as the nasal tip, lip, ear, perineum, and periocular area; ulcerated lesions or those that may be prone to leave a fibrofatty tissue residue after involution also have been targeted. Contraindications for use include premature infants younger than 5 weeks, infants weighing less than 2 kg, history of asthma or bronchospasm, heart rate less than 80 beats per minute, blood pressure less than 50/30 mm Hg, or hypersensitivity to the medication.5 Current guidelines for propranolol initiation vary; some dermatologists consult cardiology prior to initiation, while others perform routine vitals and an indication-driven electrocardiogram as needed based on family history of cardiac disease, maternal history of connective tissue disease, congenital heart block, or abnormal vital signs.

Given the demonstrated long-term safety of propranolol and the acceptable side-effect profile, the use of beta-blockers for IH has become increasingly mainstream. Three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have evaluated the efficacy and minimal adverse effects of propranolol for IH. The first RCT evaluated 40 patients who received either placebo or propranolol 2 mg/kg daily (divided into 3 doses) for 6 months; IH growth stopped by week 4 in the treatment group and the largest volume difference in IH was seen at week 12.6 Léauté-Labrèze et al7 demonstrated that propranolol could be given earlier to patients and at higher doses; the treatment group included 7 patients at 3 mg/kg daily of propranolol for 15 days, followed by 15 additional days of 4 mg/kg daily of propranolol. A statistically significant (P=.004) decrease in IH volume, quantified by use of ultrasonography, was exhibited by the propranolol group.7 Lastly, the largest RCT (N=456) established the efficacy of propranolol 3 mg/kg daily for 6 months with a 60% successful treatment rate compared to 4% for patients receiving placebo.8

Given the efficacy of propranolol for IH, other investigators have experimented with nonselective beta-blockers for other dermatologic conditions. In addition to second-line use for flushing, hyperhidrosis, and adrenergic urticaria, the future of propranolol is expanding for vascular lesions in particular.9 Chow et al10 highlighted a case of progressive angiosarcoma of the scalp that responded to propranolol hydrochloride therapy at 40 mg 3 times daily with extensive regression; propranolol was given in addition to chemotherapy and radiation. The tumor was biopsied before and after propranolol therapy and exhibited a 34% decrease in the proliferative index (Ki-67).10 Interestingly, Chisholm et al11 evaluated the expression of β-adrenergic expression in 141 vascular lesions; endothelial cell expression of β2-adrenergic receptors was found positive in 100% of IHs, 67% of kaposiform hemangioendotheliomas, 41% of angiosarcomas, 50% of pyogenic granulomas, and 75% of Kaposi sarcomas, to name merely a few studied lesions.

These data have spurred physicians to further seek beta-blocker dermatologic use in specific patient populations. For example, Meseguer-Yebra et al12 employed timolol solution 0.5% twice daily for 12 weeks for 2 human immunodeficiency virus–negative patients with limited Kaposi sarcoma of the right thigh and foot; no clinical evidence of recurrence was seen at 20 months, and one of the patients had a subsequent biopsy performed with negative human herpesvirus 8 staining after therapy. In the pediatric arena, topical timolol has been used for both port-wine stains and pyogenic granulomas.13-15 Two lesions of pyogenic granulomas on the scalp of a child were treated with timolol ophthalmic solution 0.5% under occlusion for 4 weeks with resolution.15 Propranolol also has been utilized as adjunctive therapy for aggressive pediatric vascular lesions such as kaposiform hemangioendothelioma with promising results and additionally reducing the duration of therapy needed with vincristine.2

In summary, propranolol and timolol have made an indelible impression on the field of pediatric dermatology and have demonstrated a burgeoning role in the dermatologic arena. The use of nonselective beta-blockers for the management of vascular lesions can serve as adjunctive or monotherapy for certain patient populations. The relatively low adverse risk profile of propranolol makes it a versatile tool to use both systemically and topically. Although the authors of the study assessing the β2-adrenergic expression in vascular lesions admittedly stated that the positivity of the receptors does not necessarily correlate with therapeutic management, it is an interesting subject area with much potential in the future.11 This review serves to illuminate the expanding role of beta-blockers in dermatology.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Dumas de la Roque E, Hubiche T, et al. Propranolol for severe hemangiomas of infancy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2649-2651.

- Hermans DJ, van Beynum IM, van der Vijver RJ, et al. Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma with Kasabach-Merritt syndrome: a new indication for propranolol treatment. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33:E171-E173.

- Guo S, Ni N. Topical treatment for capillary hemangioma of the eyelid using beta-blocker solution. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:255-256.

- Püttgen K, Lucky A, Adams D, et al. Topical timolol maleate treatment of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2016;138:3.

- Drolet BA, Frommelt PC, Chamlin SL, et al. Initiation and use of propranolol for infantile hemangioma: report of a consensus conference. Pediatrics. 2013;131:128-140.

- Hogeling M, Adams S, Wargon O. A randomized controlled trial of propranolol for infantile hemangiomas [published online July 25, 2011]. Pediatrics. 2011;128:E259-E266.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Dumas de la Roque E, Nacka F, et al. Doubleblind randomized pilot trial evaluating the efficacy of oral propranolol on infantile haemangiomas in infants < 4 months of age. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:181-183.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Hoeger P, Mazereeuw-Hautier J, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of oral propranolol in infantile hemangioma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:735-746.

- Shelley WB, Shelley ED. Adrenergic urticaria: a new form of stress induced hives. Lancet. 1985;2:1031-1033.

- Chow W, Amaya CN, Rains S, et al. Growth attenuation of cutaneous angiosarcoma with propranolol-mediated β-blockade. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1226-1229.

- Chisholm KM, Chang KW, Truong MT, et al. β-adrenergic receptor expression in vascular tumors. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1446-1451.

- Meseguer-Yebra C, Cardeñoso-Álvarez, ME, Bordel-Gómez MT, et al. Successful treatment of classic Kaposi sarcoma with topical timolol: report of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:860-862.

- Passeron T, Maza A, Fontas E, et al. Treatment of port wine stains and pulsed dye laser and topical timolol: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1350-1353.

- Wine LL, Goff KL, Lam JM, et al. Treatment of pediatric pyogenic granulomas using β-adrenergic receptor antagonist. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:203-207.

- Knöpfel N, Escudero-Góngora Mdel M, Bauzà A, et al. Timolol for the treatment of pyogenic granuloma (PG) in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:E105-E106.

Since the serendipitous discovery of expedited involution of infantile hemangiomas (IHs) with propranolol in 2008,1 current research has proliferated to discern the mechanism of action of beta-blockers in the care of IHs. Propranolol is a nonselective beta-blocker with a structure similar to catecholamines and thus competes for β-adrenergic receptors. Blocking β1-receptors is cardioselective, leading to decreased heart rate and myocardial contractility, while blocking β2-receptors leads to inhibition of smooth muscle relaxation and decreased glycogenolysis. The endothelial cells of IH express β2-adrenergic receptors; the mechanistic role of propranolol in these lesions is surmised to be due to vasoconstriction, decreased angiogenesis through inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor, and subsequent endothelial cell apoptosis.2

After this breakthrough finding, a subsequent novel development was made when an ophthalmologist demonstrated that timolol, a topical beta-blocker, could be utilized to expedite IH involution and prevent ocular complications such as amblyopia secondary to the mass effect of the lesion. Guo and Ni3 prescribed the commercially available ophthalmologic solution of timolol maleate 0.5% for twice-daily use for 5 weeks. Remarkable reduction in the periorbital IH without rebound phenomenon was observed.3 A recent multicenter retrospective cohort of more than 700 patients with IH were treated with topical timolol with a 70% success rate, corresponding to 10% improvement from baseline; this study highlights the efficacy of timolol while confirming the safety of the medication.4

Systemic beta-blockers for IH have been used predominately for critical sites such as the nasal tip, lip, ear, perineum, and periocular area; ulcerated lesions or those that may be prone to leave a fibrofatty tissue residue after involution also have been targeted. Contraindications for use include premature infants younger than 5 weeks, infants weighing less than 2 kg, history of asthma or bronchospasm, heart rate less than 80 beats per minute, blood pressure less than 50/30 mm Hg, or hypersensitivity to the medication.5 Current guidelines for propranolol initiation vary; some dermatologists consult cardiology prior to initiation, while others perform routine vitals and an indication-driven electrocardiogram as needed based on family history of cardiac disease, maternal history of connective tissue disease, congenital heart block, or abnormal vital signs.

Given the demonstrated long-term safety of propranolol and the acceptable side-effect profile, the use of beta-blockers for IH has become increasingly mainstream. Three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have evaluated the efficacy and minimal adverse effects of propranolol for IH. The first RCT evaluated 40 patients who received either placebo or propranolol 2 mg/kg daily (divided into 3 doses) for 6 months; IH growth stopped by week 4 in the treatment group and the largest volume difference in IH was seen at week 12.6 Léauté-Labrèze et al7 demonstrated that propranolol could be given earlier to patients and at higher doses; the treatment group included 7 patients at 3 mg/kg daily of propranolol for 15 days, followed by 15 additional days of 4 mg/kg daily of propranolol. A statistically significant (P=.004) decrease in IH volume, quantified by use of ultrasonography, was exhibited by the propranolol group.7 Lastly, the largest RCT (N=456) established the efficacy of propranolol 3 mg/kg daily for 6 months with a 60% successful treatment rate compared to 4% for patients receiving placebo.8

Given the efficacy of propranolol for IH, other investigators have experimented with nonselective beta-blockers for other dermatologic conditions. In addition to second-line use for flushing, hyperhidrosis, and adrenergic urticaria, the future of propranolol is expanding for vascular lesions in particular.9 Chow et al10 highlighted a case of progressive angiosarcoma of the scalp that responded to propranolol hydrochloride therapy at 40 mg 3 times daily with extensive regression; propranolol was given in addition to chemotherapy and radiation. The tumor was biopsied before and after propranolol therapy and exhibited a 34% decrease in the proliferative index (Ki-67).10 Interestingly, Chisholm et al11 evaluated the expression of β-adrenergic expression in 141 vascular lesions; endothelial cell expression of β2-adrenergic receptors was found positive in 100% of IHs, 67% of kaposiform hemangioendotheliomas, 41% of angiosarcomas, 50% of pyogenic granulomas, and 75% of Kaposi sarcomas, to name merely a few studied lesions.

These data have spurred physicians to further seek beta-blocker dermatologic use in specific patient populations. For example, Meseguer-Yebra et al12 employed timolol solution 0.5% twice daily for 12 weeks for 2 human immunodeficiency virus–negative patients with limited Kaposi sarcoma of the right thigh and foot; no clinical evidence of recurrence was seen at 20 months, and one of the patients had a subsequent biopsy performed with negative human herpesvirus 8 staining after therapy. In the pediatric arena, topical timolol has been used for both port-wine stains and pyogenic granulomas.13-15 Two lesions of pyogenic granulomas on the scalp of a child were treated with timolol ophthalmic solution 0.5% under occlusion for 4 weeks with resolution.15 Propranolol also has been utilized as adjunctive therapy for aggressive pediatric vascular lesions such as kaposiform hemangioendothelioma with promising results and additionally reducing the duration of therapy needed with vincristine.2

In summary, propranolol and timolol have made an indelible impression on the field of pediatric dermatology and have demonstrated a burgeoning role in the dermatologic arena. The use of nonselective beta-blockers for the management of vascular lesions can serve as adjunctive or monotherapy for certain patient populations. The relatively low adverse risk profile of propranolol makes it a versatile tool to use both systemically and topically. Although the authors of the study assessing the β2-adrenergic expression in vascular lesions admittedly stated that the positivity of the receptors does not necessarily correlate with therapeutic management, it is an interesting subject area with much potential in the future.11 This review serves to illuminate the expanding role of beta-blockers in dermatology.

Since the serendipitous discovery of expedited involution of infantile hemangiomas (IHs) with propranolol in 2008,1 current research has proliferated to discern the mechanism of action of beta-blockers in the care of IHs. Propranolol is a nonselective beta-blocker with a structure similar to catecholamines and thus competes for β-adrenergic receptors. Blocking β1-receptors is cardioselective, leading to decreased heart rate and myocardial contractility, while blocking β2-receptors leads to inhibition of smooth muscle relaxation and decreased glycogenolysis. The endothelial cells of IH express β2-adrenergic receptors; the mechanistic role of propranolol in these lesions is surmised to be due to vasoconstriction, decreased angiogenesis through inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor, and subsequent endothelial cell apoptosis.2

After this breakthrough finding, a subsequent novel development was made when an ophthalmologist demonstrated that timolol, a topical beta-blocker, could be utilized to expedite IH involution and prevent ocular complications such as amblyopia secondary to the mass effect of the lesion. Guo and Ni3 prescribed the commercially available ophthalmologic solution of timolol maleate 0.5% for twice-daily use for 5 weeks. Remarkable reduction in the periorbital IH without rebound phenomenon was observed.3 A recent multicenter retrospective cohort of more than 700 patients with IH were treated with topical timolol with a 70% success rate, corresponding to 10% improvement from baseline; this study highlights the efficacy of timolol while confirming the safety of the medication.4

Systemic beta-blockers for IH have been used predominately for critical sites such as the nasal tip, lip, ear, perineum, and periocular area; ulcerated lesions or those that may be prone to leave a fibrofatty tissue residue after involution also have been targeted. Contraindications for use include premature infants younger than 5 weeks, infants weighing less than 2 kg, history of asthma or bronchospasm, heart rate less than 80 beats per minute, blood pressure less than 50/30 mm Hg, or hypersensitivity to the medication.5 Current guidelines for propranolol initiation vary; some dermatologists consult cardiology prior to initiation, while others perform routine vitals and an indication-driven electrocardiogram as needed based on family history of cardiac disease, maternal history of connective tissue disease, congenital heart block, or abnormal vital signs.

Given the demonstrated long-term safety of propranolol and the acceptable side-effect profile, the use of beta-blockers for IH has become increasingly mainstream. Three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have evaluated the efficacy and minimal adverse effects of propranolol for IH. The first RCT evaluated 40 patients who received either placebo or propranolol 2 mg/kg daily (divided into 3 doses) for 6 months; IH growth stopped by week 4 in the treatment group and the largest volume difference in IH was seen at week 12.6 Léauté-Labrèze et al7 demonstrated that propranolol could be given earlier to patients and at higher doses; the treatment group included 7 patients at 3 mg/kg daily of propranolol for 15 days, followed by 15 additional days of 4 mg/kg daily of propranolol. A statistically significant (P=.004) decrease in IH volume, quantified by use of ultrasonography, was exhibited by the propranolol group.7 Lastly, the largest RCT (N=456) established the efficacy of propranolol 3 mg/kg daily for 6 months with a 60% successful treatment rate compared to 4% for patients receiving placebo.8

Given the efficacy of propranolol for IH, other investigators have experimented with nonselective beta-blockers for other dermatologic conditions. In addition to second-line use for flushing, hyperhidrosis, and adrenergic urticaria, the future of propranolol is expanding for vascular lesions in particular.9 Chow et al10 highlighted a case of progressive angiosarcoma of the scalp that responded to propranolol hydrochloride therapy at 40 mg 3 times daily with extensive regression; propranolol was given in addition to chemotherapy and radiation. The tumor was biopsied before and after propranolol therapy and exhibited a 34% decrease in the proliferative index (Ki-67).10 Interestingly, Chisholm et al11 evaluated the expression of β-adrenergic expression in 141 vascular lesions; endothelial cell expression of β2-adrenergic receptors was found positive in 100% of IHs, 67% of kaposiform hemangioendotheliomas, 41% of angiosarcomas, 50% of pyogenic granulomas, and 75% of Kaposi sarcomas, to name merely a few studied lesions.

These data have spurred physicians to further seek beta-blocker dermatologic use in specific patient populations. For example, Meseguer-Yebra et al12 employed timolol solution 0.5% twice daily for 12 weeks for 2 human immunodeficiency virus–negative patients with limited Kaposi sarcoma of the right thigh and foot; no clinical evidence of recurrence was seen at 20 months, and one of the patients had a subsequent biopsy performed with negative human herpesvirus 8 staining after therapy. In the pediatric arena, topical timolol has been used for both port-wine stains and pyogenic granulomas.13-15 Two lesions of pyogenic granulomas on the scalp of a child were treated with timolol ophthalmic solution 0.5% under occlusion for 4 weeks with resolution.15 Propranolol also has been utilized as adjunctive therapy for aggressive pediatric vascular lesions such as kaposiform hemangioendothelioma with promising results and additionally reducing the duration of therapy needed with vincristine.2

In summary, propranolol and timolol have made an indelible impression on the field of pediatric dermatology and have demonstrated a burgeoning role in the dermatologic arena. The use of nonselective beta-blockers for the management of vascular lesions can serve as adjunctive or monotherapy for certain patient populations. The relatively low adverse risk profile of propranolol makes it a versatile tool to use both systemically and topically. Although the authors of the study assessing the β2-adrenergic expression in vascular lesions admittedly stated that the positivity of the receptors does not necessarily correlate with therapeutic management, it is an interesting subject area with much potential in the future.11 This review serves to illuminate the expanding role of beta-blockers in dermatology.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Dumas de la Roque E, Hubiche T, et al. Propranolol for severe hemangiomas of infancy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2649-2651.

- Hermans DJ, van Beynum IM, van der Vijver RJ, et al. Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma with Kasabach-Merritt syndrome: a new indication for propranolol treatment. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33:E171-E173.

- Guo S, Ni N. Topical treatment for capillary hemangioma of the eyelid using beta-blocker solution. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:255-256.

- Püttgen K, Lucky A, Adams D, et al. Topical timolol maleate treatment of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2016;138:3.

- Drolet BA, Frommelt PC, Chamlin SL, et al. Initiation and use of propranolol for infantile hemangioma: report of a consensus conference. Pediatrics. 2013;131:128-140.

- Hogeling M, Adams S, Wargon O. A randomized controlled trial of propranolol for infantile hemangiomas [published online July 25, 2011]. Pediatrics. 2011;128:E259-E266.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Dumas de la Roque E, Nacka F, et al. Doubleblind randomized pilot trial evaluating the efficacy of oral propranolol on infantile haemangiomas in infants < 4 months of age. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:181-183.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Hoeger P, Mazereeuw-Hautier J, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of oral propranolol in infantile hemangioma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:735-746.

- Shelley WB, Shelley ED. Adrenergic urticaria: a new form of stress induced hives. Lancet. 1985;2:1031-1033.

- Chow W, Amaya CN, Rains S, et al. Growth attenuation of cutaneous angiosarcoma with propranolol-mediated β-blockade. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1226-1229.

- Chisholm KM, Chang KW, Truong MT, et al. β-adrenergic receptor expression in vascular tumors. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1446-1451.

- Meseguer-Yebra C, Cardeñoso-Álvarez, ME, Bordel-Gómez MT, et al. Successful treatment of classic Kaposi sarcoma with topical timolol: report of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:860-862.

- Passeron T, Maza A, Fontas E, et al. Treatment of port wine stains and pulsed dye laser and topical timolol: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1350-1353.

- Wine LL, Goff KL, Lam JM, et al. Treatment of pediatric pyogenic granulomas using β-adrenergic receptor antagonist. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:203-207.

- Knöpfel N, Escudero-Góngora Mdel M, Bauzà A, et al. Timolol for the treatment of pyogenic granuloma (PG) in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:E105-E106.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Dumas de la Roque E, Hubiche T, et al. Propranolol for severe hemangiomas of infancy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2649-2651.

- Hermans DJ, van Beynum IM, van der Vijver RJ, et al. Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma with Kasabach-Merritt syndrome: a new indication for propranolol treatment. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33:E171-E173.

- Guo S, Ni N. Topical treatment for capillary hemangioma of the eyelid using beta-blocker solution. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:255-256.

- Püttgen K, Lucky A, Adams D, et al. Topical timolol maleate treatment of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2016;138:3.

- Drolet BA, Frommelt PC, Chamlin SL, et al. Initiation and use of propranolol for infantile hemangioma: report of a consensus conference. Pediatrics. 2013;131:128-140.

- Hogeling M, Adams S, Wargon O. A randomized controlled trial of propranolol for infantile hemangiomas [published online July 25, 2011]. Pediatrics. 2011;128:E259-E266.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Dumas de la Roque E, Nacka F, et al. Doubleblind randomized pilot trial evaluating the efficacy of oral propranolol on infantile haemangiomas in infants < 4 months of age. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:181-183.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Hoeger P, Mazereeuw-Hautier J, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of oral propranolol in infantile hemangioma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:735-746.

- Shelley WB, Shelley ED. Adrenergic urticaria: a new form of stress induced hives. Lancet. 1985;2:1031-1033.

- Chow W, Amaya CN, Rains S, et al. Growth attenuation of cutaneous angiosarcoma with propranolol-mediated β-blockade. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1226-1229.

- Chisholm KM, Chang KW, Truong MT, et al. β-adrenergic receptor expression in vascular tumors. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1446-1451.

- Meseguer-Yebra C, Cardeñoso-Álvarez, ME, Bordel-Gómez MT, et al. Successful treatment of classic Kaposi sarcoma with topical timolol: report of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:860-862.

- Passeron T, Maza A, Fontas E, et al. Treatment of port wine stains and pulsed dye laser and topical timolol: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1350-1353.

- Wine LL, Goff KL, Lam JM, et al. Treatment of pediatric pyogenic granulomas using β-adrenergic receptor antagonist. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:203-207.

- Knöpfel N, Escudero-Góngora Mdel M, Bauzà A, et al. Timolol for the treatment of pyogenic granuloma (PG) in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:E105-E106.

Flesh-Colored Nodule With Underlying Sclerotic Plaque

The Diagnosis: Collision Tumor

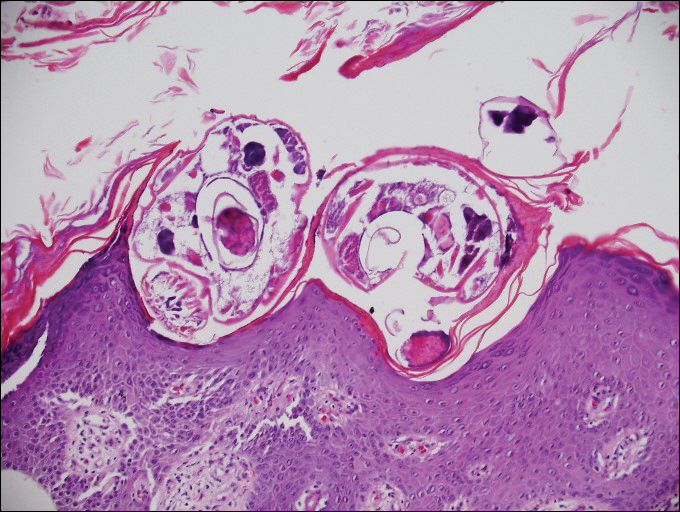

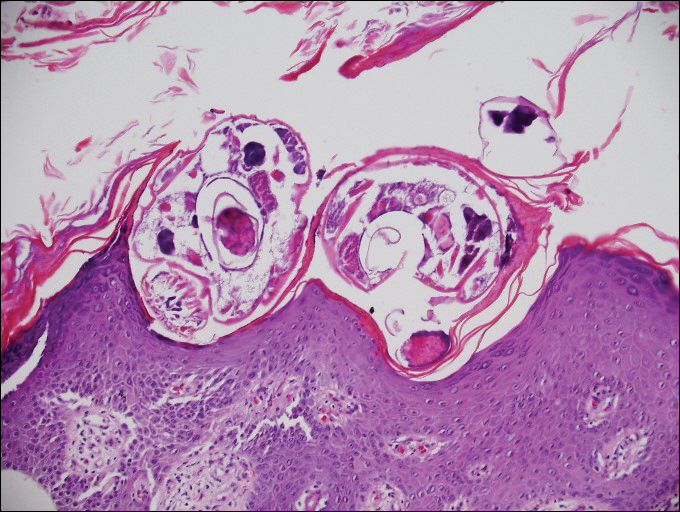

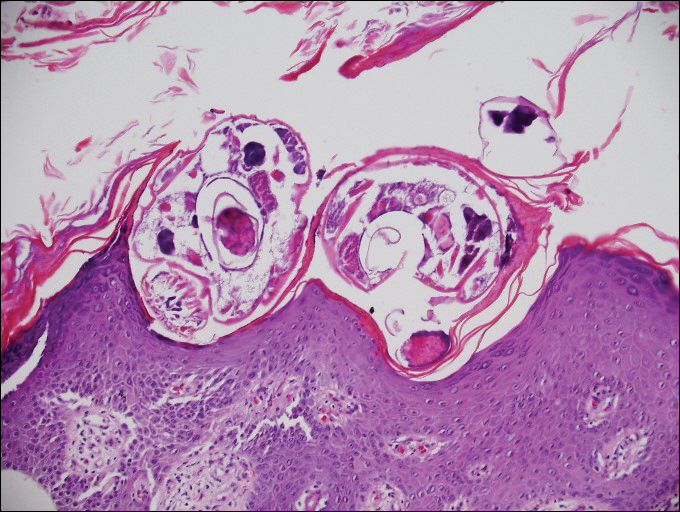

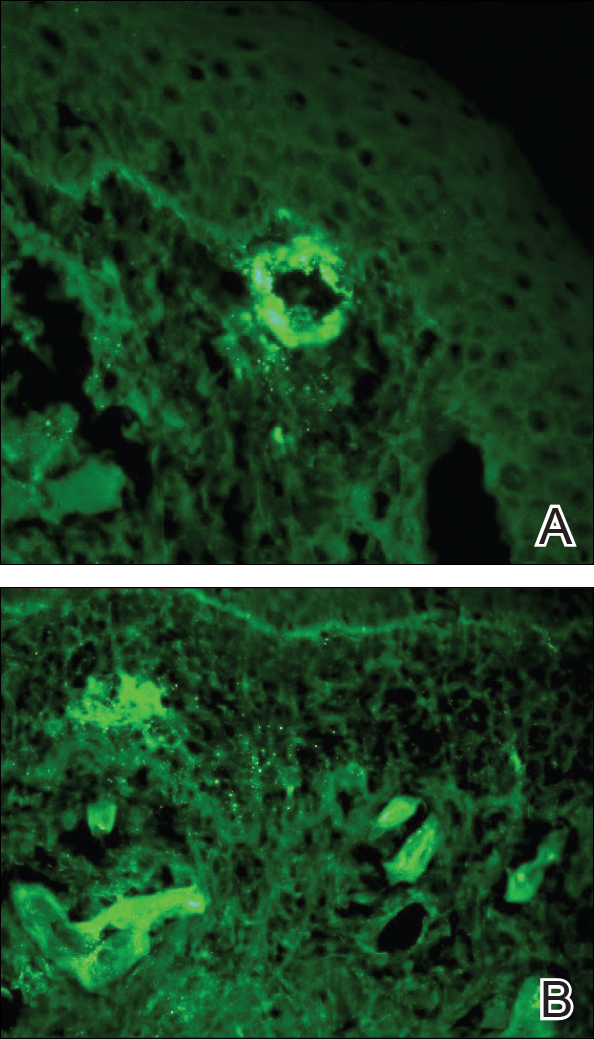

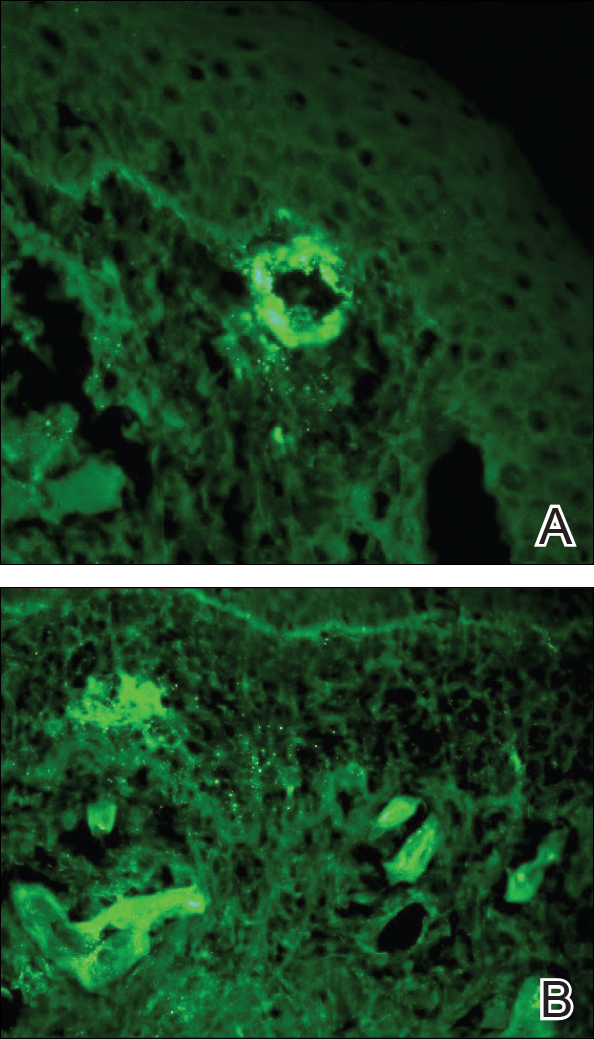

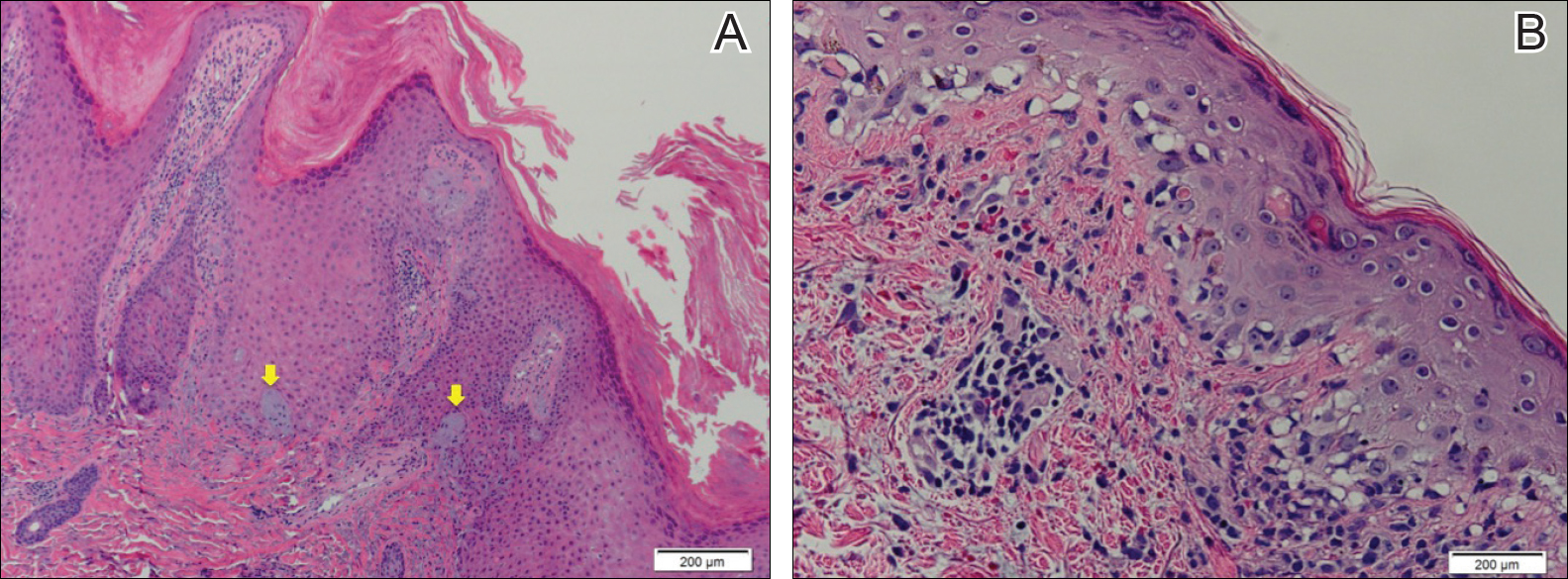

Excisional biopsy and histopathological examination demonstrated a collision tumor composed of a benign intradermal melanocytic nevus, tumor of follicular infundibulum, and an underlying sclerosing epithelial neoplasm, with a differential diagnosis of desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, morpheaform basal cell carcinoma, and microcystic adnexal carcinoma (Figure).

Common acquired melanocytic nevus presents clinically as a macule, papule, or nodule with smooth regular borders. The pigmented variant displays an evenly distributed pigment on the lesion. Intradermal melanocytic nevus often presents as a flesh-colored nodule, as in our case. Histopathologically, benign intradermal nevus typically is composed of a proliferation of melanocytes that exhibit dispersion as they go deeper in the dermis and maturation that manifests as melanocytes becoming smaller and more spindled in the deeper portions of the lesion.1 These 2 characteristics plus the bland cytology seen in the present case confirm the benign characteristic of this lesion (Figure, B).

In addition to the benign intradermal melanocytic nevus, an adjacent tumor of follicular infundibulum was noted. Tumor of follicular infundibulum is a rare adnexal tumor. It occurs frequently on the head and neck and shows some female predominance.2,3 Multiple lesions and eruptive lesions are rare forms that also have been reported.4 Histopathologically, the tumor demonstrates an epithelial plate that is present in the papillary dermis and is connected to the epidermis at multiple points with attachment to the follicular outer root sheath. Peripheral palisading is characteristically present above an eosinophilic basement membrane (Figure, A). Rare reports have documented sebaceous and eccrine differentiation.5,6

Tumor of follicular infundibulum has been reported to be associated with other tumors. Organoid nevus (nevus sebaceous), trichilemmal tumor, and fibroma have been reported to occur as a collision tumor with tumor of follicular infundibulum. An association with Cowden disease also has been described.7 Biopsies that represent partial samples should be interpreted cautiously, as step sections can reveal basal cell carcinoma.

The term sclerosing epithelial neoplasm describes tumors that share a paisley tielike epithelial pattern and sclerotic stroma. Small specimens often require clinicopathologic correlation (Figure, C). The differential diagnosis includes morpheaform basal cell carcinoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, and microcystic adnexal carcinoma. A panel of stains using Ber-EP4, PHLDA1, cytokeratin 15, and cytokeratin 19 has been proposed to help differentiate these entities.8 CD34 and cytokeratin 20 also have been used with varying success in small specimens.9,10

- Ferringer T, Peckham S, Ko CJ, et al. Melanocytic neoplasms. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, eds. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:105-109.

- Headington JT. Tumors of the hair follicle. Am J Pathol. 1976;85:480-505.

- Davis DA, Cohen PR. Hair follicle nevus: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:135-138.

- Ikeda S, Kawada J, Yaguchi H, et al. A case of unilateral, systematized linear hair follicle nevi associated with epidermal nevus-like lesions. Dermatology. 2003;206:172-174.

- Mehregan AH. Hair follicle tumors of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 1985;12:189-195.

- Mahalingam M, Bhawan J, Finn R, et al. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum with sebaceous differentiation. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:314-317.

- Cribier B, Grosshans E. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum: a clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:979-984.

- Sellheyer K, Nelson P, Kutzner H, et al. The immunohistochemical differential diagnosis of microcystic adnexal carcinoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and morpheaform basal cell carcinoma using BerEP4 and stem cell markers. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:363-370.

- Abesamis-Cubillan E, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, LeBoit PE. Merkel cells and sclerosing epithelial neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:311-315.

- Smith KJ, Williams J, Corbett D, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: an immunohistochemical study including markers of proliferation and apoptosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:464-471.

The Diagnosis: Collision Tumor

Excisional biopsy and histopathological examination demonstrated a collision tumor composed of a benign intradermal melanocytic nevus, tumor of follicular infundibulum, and an underlying sclerosing epithelial neoplasm, with a differential diagnosis of desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, morpheaform basal cell carcinoma, and microcystic adnexal carcinoma (Figure).

Common acquired melanocytic nevus presents clinically as a macule, papule, or nodule with smooth regular borders. The pigmented variant displays an evenly distributed pigment on the lesion. Intradermal melanocytic nevus often presents as a flesh-colored nodule, as in our case. Histopathologically, benign intradermal nevus typically is composed of a proliferation of melanocytes that exhibit dispersion as they go deeper in the dermis and maturation that manifests as melanocytes becoming smaller and more spindled in the deeper portions of the lesion.1 These 2 characteristics plus the bland cytology seen in the present case confirm the benign characteristic of this lesion (Figure, B).

In addition to the benign intradermal melanocytic nevus, an adjacent tumor of follicular infundibulum was noted. Tumor of follicular infundibulum is a rare adnexal tumor. It occurs frequently on the head and neck and shows some female predominance.2,3 Multiple lesions and eruptive lesions are rare forms that also have been reported.4 Histopathologically, the tumor demonstrates an epithelial plate that is present in the papillary dermis and is connected to the epidermis at multiple points with attachment to the follicular outer root sheath. Peripheral palisading is characteristically present above an eosinophilic basement membrane (Figure, A). Rare reports have documented sebaceous and eccrine differentiation.5,6

Tumor of follicular infundibulum has been reported to be associated with other tumors. Organoid nevus (nevus sebaceous), trichilemmal tumor, and fibroma have been reported to occur as a collision tumor with tumor of follicular infundibulum. An association with Cowden disease also has been described.7 Biopsies that represent partial samples should be interpreted cautiously, as step sections can reveal basal cell carcinoma.

The term sclerosing epithelial neoplasm describes tumors that share a paisley tielike epithelial pattern and sclerotic stroma. Small specimens often require clinicopathologic correlation (Figure, C). The differential diagnosis includes morpheaform basal cell carcinoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, and microcystic adnexal carcinoma. A panel of stains using Ber-EP4, PHLDA1, cytokeratin 15, and cytokeratin 19 has been proposed to help differentiate these entities.8 CD34 and cytokeratin 20 also have been used with varying success in small specimens.9,10

The Diagnosis: Collision Tumor

Excisional biopsy and histopathological examination demonstrated a collision tumor composed of a benign intradermal melanocytic nevus, tumor of follicular infundibulum, and an underlying sclerosing epithelial neoplasm, with a differential diagnosis of desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, morpheaform basal cell carcinoma, and microcystic adnexal carcinoma (Figure).

Common acquired melanocytic nevus presents clinically as a macule, papule, or nodule with smooth regular borders. The pigmented variant displays an evenly distributed pigment on the lesion. Intradermal melanocytic nevus often presents as a flesh-colored nodule, as in our case. Histopathologically, benign intradermal nevus typically is composed of a proliferation of melanocytes that exhibit dispersion as they go deeper in the dermis and maturation that manifests as melanocytes becoming smaller and more spindled in the deeper portions of the lesion.1 These 2 characteristics plus the bland cytology seen in the present case confirm the benign characteristic of this lesion (Figure, B).

In addition to the benign intradermal melanocytic nevus, an adjacent tumor of follicular infundibulum was noted. Tumor of follicular infundibulum is a rare adnexal tumor. It occurs frequently on the head and neck and shows some female predominance.2,3 Multiple lesions and eruptive lesions are rare forms that also have been reported.4 Histopathologically, the tumor demonstrates an epithelial plate that is present in the papillary dermis and is connected to the epidermis at multiple points with attachment to the follicular outer root sheath. Peripheral palisading is characteristically present above an eosinophilic basement membrane (Figure, A). Rare reports have documented sebaceous and eccrine differentiation.5,6

Tumor of follicular infundibulum has been reported to be associated with other tumors. Organoid nevus (nevus sebaceous), trichilemmal tumor, and fibroma have been reported to occur as a collision tumor with tumor of follicular infundibulum. An association with Cowden disease also has been described.7 Biopsies that represent partial samples should be interpreted cautiously, as step sections can reveal basal cell carcinoma.

The term sclerosing epithelial neoplasm describes tumors that share a paisley tielike epithelial pattern and sclerotic stroma. Small specimens often require clinicopathologic correlation (Figure, C). The differential diagnosis includes morpheaform basal cell carcinoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, and microcystic adnexal carcinoma. A panel of stains using Ber-EP4, PHLDA1, cytokeratin 15, and cytokeratin 19 has been proposed to help differentiate these entities.8 CD34 and cytokeratin 20 also have been used with varying success in small specimens.9,10

- Ferringer T, Peckham S, Ko CJ, et al. Melanocytic neoplasms. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, eds. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:105-109.

- Headington JT. Tumors of the hair follicle. Am J Pathol. 1976;85:480-505.

- Davis DA, Cohen PR. Hair follicle nevus: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:135-138.

- Ikeda S, Kawada J, Yaguchi H, et al. A case of unilateral, systematized linear hair follicle nevi associated with epidermal nevus-like lesions. Dermatology. 2003;206:172-174.

- Mehregan AH. Hair follicle tumors of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 1985;12:189-195.

- Mahalingam M, Bhawan J, Finn R, et al. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum with sebaceous differentiation. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:314-317.

- Cribier B, Grosshans E. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum: a clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:979-984.

- Sellheyer K, Nelson P, Kutzner H, et al. The immunohistochemical differential diagnosis of microcystic adnexal carcinoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and morpheaform basal cell carcinoma using BerEP4 and stem cell markers. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:363-370.

- Abesamis-Cubillan E, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, LeBoit PE. Merkel cells and sclerosing epithelial neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:311-315.

- Smith KJ, Williams J, Corbett D, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: an immunohistochemical study including markers of proliferation and apoptosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:464-471.

- Ferringer T, Peckham S, Ko CJ, et al. Melanocytic neoplasms. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, eds. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:105-109.

- Headington JT. Tumors of the hair follicle. Am J Pathol. 1976;85:480-505.

- Davis DA, Cohen PR. Hair follicle nevus: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:135-138.

- Ikeda S, Kawada J, Yaguchi H, et al. A case of unilateral, systematized linear hair follicle nevi associated with epidermal nevus-like lesions. Dermatology. 2003;206:172-174.

- Mehregan AH. Hair follicle tumors of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 1985;12:189-195.

- Mahalingam M, Bhawan J, Finn R, et al. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum with sebaceous differentiation. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:314-317.

- Cribier B, Grosshans E. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum: a clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:979-984.

- Sellheyer K, Nelson P, Kutzner H, et al. The immunohistochemical differential diagnosis of microcystic adnexal carcinoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and morpheaform basal cell carcinoma using BerEP4 and stem cell markers. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:363-370.

- Abesamis-Cubillan E, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, LeBoit PE. Merkel cells and sclerosing epithelial neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:311-315.

- Smith KJ, Williams J, Corbett D, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: an immunohistochemical study including markers of proliferation and apoptosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:464-471.

A 54-year-old man presented with a flesh-colored lesion on the chin. The nodule measured 0.6 cm in diameter. There was an underlying sclerotic plaque with indistinct borders.

Pruritic Rash on the Buttock

Cutaneous Larva Migrans

Cutaneous larva migrans (CLM) is caused by the larval migration of animal hookworms. Ancylostoma braziliense, Ancylostoma ceylanicum, and Ancylostoma caninum are the species most commonly associated with the disease. The hookworm is endemic to tropical and subtropical climates in areas such as Africa, Southeast Asia, South America, and the southeastern United States.1 Although cats and dogs are most commonly affected, humans can be infected if they are exposed to sand or soil containing hookworm larvae, often due to contamination from animal feces.2 Cutaneous larva migrans is characterized by pruritic erythematous papules and linear or serpiginous, reddish brown, elevated tracks most commonly appearing on the feet, buttocks, thighs, and lower legs; however, lesions can appear anywhere. In human hosts, the larvae travel in the epidermis and are unable to invade the dermis; it is speculated that they lack the collagenase enzymes required to penetrate the basement membrane before invading the dermis.2

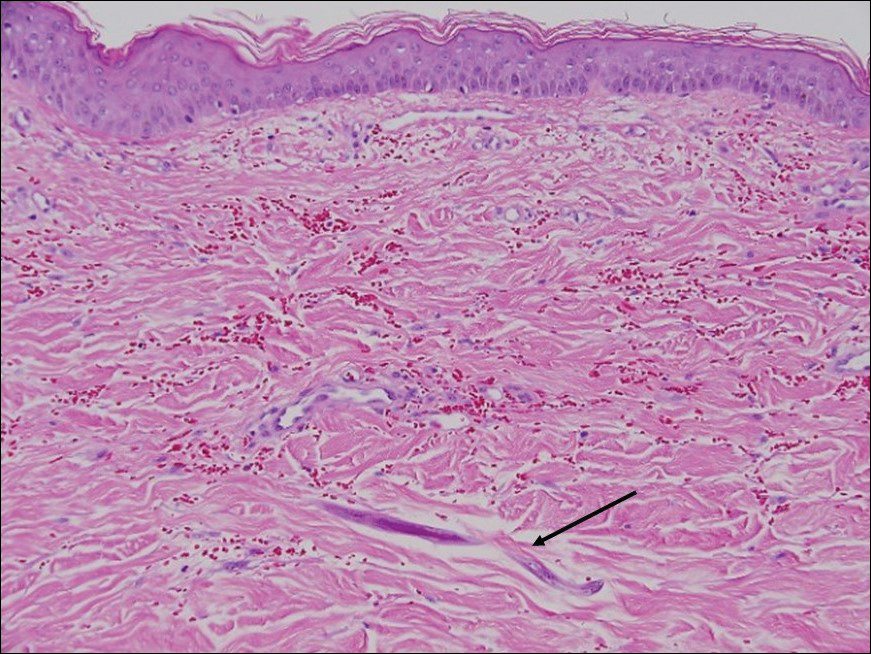

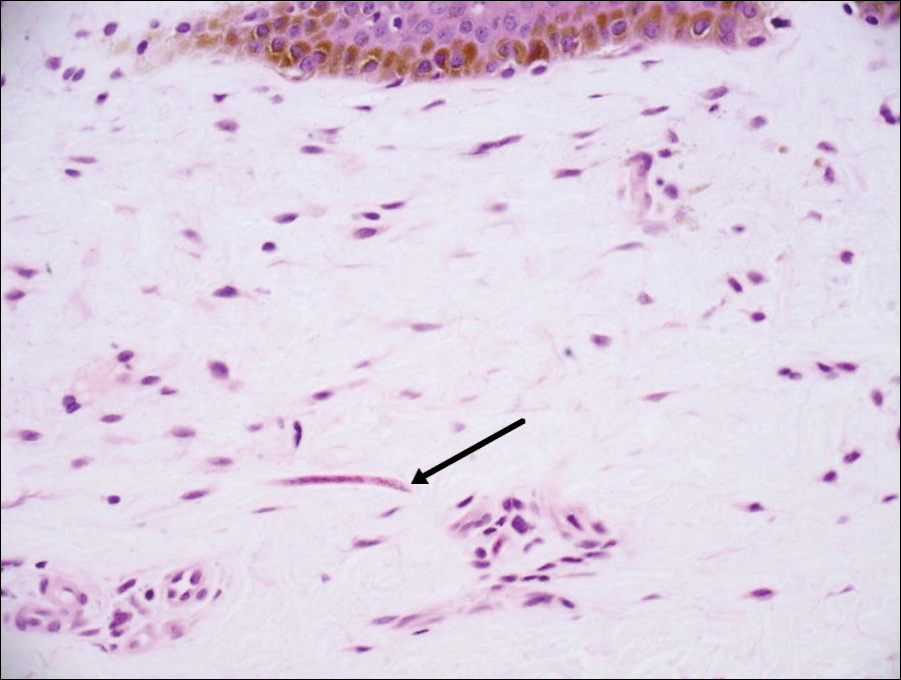

On histopathology, there typically are small cavities in the epidermis corresponding to the track of the larvae.3 There often is a spongiotic dermatitis with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate following the larvae with scattered eosinophils. The migrating larvae may be up to 1 mm in size and have bilateral double alae, or winglike projections, on the side of the body (Figure 1).4 The larvae are difficult to find on histopathology because they often travel beyond the areas that demonstrate clinical findings. The diagnosis of CLM is mostly clinical, but if a biopsy is performed, the specimen should be taken ahead of the track.

Disseminated strongyloidiasis is caused by Strongyloides stercoralis. When filariform larvae migrate out of the intestinal tract into the skin, they can cause an urticarial rash and serpiginous patterns on the skin that can move 5 to 15 cm per hour, a clinical condition known as larva currens. In immunocompromised individuals, there can be hyperinfection with diffuse petechial thumbprint purpura seen clinically, which characteristically radiate from the periumbilical area.1 On pathology, there may be numerous larvae found between the dermal collagen bundles, measuring 9 to 15 µm in diameter. Rarely, they also can be found in small blood vessels.3 They often are accompanied by extravasated red blood cells in the tissues (Figure 2).

Myiasis represents the largest pathogen in the differential diagnosis for CLM. In myiasis, fly larvae will infest human tissue, usually by forming a small cavity in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue. The larvae are visible to the human eye and can be up to several centimeters in length. In the skin, the histology of myiasis usually is accompanied by a heavy mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate with many eosinophils. Fragments of the larvae are seen encased by a thick chitinous cuticle with widely spaced spines or pigmented setae (Figure 3) on the surface of the cuticle.5 Layers of striated muscle and internal organs may be seen beneath the cuticle.3

Onchocerciasis, or river blindness, is a parasitic disease caused by Onchocerca volvulus that is most often seen in sub-Saharan Africa. It may cause the skin finding of an onchocercoma, a subcutaneous nodule made up of Onchocerca nematodes. However, when the filaria disseminate, it may cause onchocerciasis with cutaneous findings of an eczematous dermatitis with itching and lichenification.1 In onchocercal dermatitis, microfilariae may be found in the dermis and there may be a mild dermal chronic inflammatory infiltrate with eosinophils.3 These microfilariae are smaller than Strongyloides larvae (Figure 4).

Sarcoptes scabiei are mites that are pathologically found limited to the stratum corneum. There often is a spongiotic dermatitis as the mite travels with an accompanying mixed cell inflammatory infiltrate with many eosinophils. One or more mites may be seen with or without eggs and excreta or scybala (Figure 5). Pink pigtails may be seen connected to the stratum corneum, representing egg fragments or casings left behind after the mite hatches.3 The female mite measures up to 0.4 mm in length.3

- Lupi O, Downing C, Lee M, et al. Mucocutaneous manifestations of helminth infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:929-944.

- James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016.

- Patterson J. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016.

- Milner D. Diagnostic Pathology: Infectious Diseases. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

- Ferringer T, Peckham S, Ko CJ, et al. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013.

Cutaneous Larva Migrans

Cutaneous larva migrans (CLM) is caused by the larval migration of animal hookworms. Ancylostoma braziliense, Ancylostoma ceylanicum, and Ancylostoma caninum are the species most commonly associated with the disease. The hookworm is endemic to tropical and subtropical climates in areas such as Africa, Southeast Asia, South America, and the southeastern United States.1 Although cats and dogs are most commonly affected, humans can be infected if they are exposed to sand or soil containing hookworm larvae, often due to contamination from animal feces.2 Cutaneous larva migrans is characterized by pruritic erythematous papules and linear or serpiginous, reddish brown, elevated tracks most commonly appearing on the feet, buttocks, thighs, and lower legs; however, lesions can appear anywhere. In human hosts, the larvae travel in the epidermis and are unable to invade the dermis; it is speculated that they lack the collagenase enzymes required to penetrate the basement membrane before invading the dermis.2

On histopathology, there typically are small cavities in the epidermis corresponding to the track of the larvae.3 There often is a spongiotic dermatitis with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate following the larvae with scattered eosinophils. The migrating larvae may be up to 1 mm in size and have bilateral double alae, or winglike projections, on the side of the body (Figure 1).4 The larvae are difficult to find on histopathology because they often travel beyond the areas that demonstrate clinical findings. The diagnosis of CLM is mostly clinical, but if a biopsy is performed, the specimen should be taken ahead of the track.

Disseminated strongyloidiasis is caused by Strongyloides stercoralis. When filariform larvae migrate out of the intestinal tract into the skin, they can cause an urticarial rash and serpiginous patterns on the skin that can move 5 to 15 cm per hour, a clinical condition known as larva currens. In immunocompromised individuals, there can be hyperinfection with diffuse petechial thumbprint purpura seen clinically, which characteristically radiate from the periumbilical area.1 On pathology, there may be numerous larvae found between the dermal collagen bundles, measuring 9 to 15 µm in diameter. Rarely, they also can be found in small blood vessels.3 They often are accompanied by extravasated red blood cells in the tissues (Figure 2).

Myiasis represents the largest pathogen in the differential diagnosis for CLM. In myiasis, fly larvae will infest human tissue, usually by forming a small cavity in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue. The larvae are visible to the human eye and can be up to several centimeters in length. In the skin, the histology of myiasis usually is accompanied by a heavy mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate with many eosinophils. Fragments of the larvae are seen encased by a thick chitinous cuticle with widely spaced spines or pigmented setae (Figure 3) on the surface of the cuticle.5 Layers of striated muscle and internal organs may be seen beneath the cuticle.3

Onchocerciasis, or river blindness, is a parasitic disease caused by Onchocerca volvulus that is most often seen in sub-Saharan Africa. It may cause the skin finding of an onchocercoma, a subcutaneous nodule made up of Onchocerca nematodes. However, when the filaria disseminate, it may cause onchocerciasis with cutaneous findings of an eczematous dermatitis with itching and lichenification.1 In onchocercal dermatitis, microfilariae may be found in the dermis and there may be a mild dermal chronic inflammatory infiltrate with eosinophils.3 These microfilariae are smaller than Strongyloides larvae (Figure 4).

Sarcoptes scabiei are mites that are pathologically found limited to the stratum corneum. There often is a spongiotic dermatitis as the mite travels with an accompanying mixed cell inflammatory infiltrate with many eosinophils. One or more mites may be seen with or without eggs and excreta or scybala (Figure 5). Pink pigtails may be seen connected to the stratum corneum, representing egg fragments or casings left behind after the mite hatches.3 The female mite measures up to 0.4 mm in length.3

Cutaneous Larva Migrans

Cutaneous larva migrans (CLM) is caused by the larval migration of animal hookworms. Ancylostoma braziliense, Ancylostoma ceylanicum, and Ancylostoma caninum are the species most commonly associated with the disease. The hookworm is endemic to tropical and subtropical climates in areas such as Africa, Southeast Asia, South America, and the southeastern United States.1 Although cats and dogs are most commonly affected, humans can be infected if they are exposed to sand or soil containing hookworm larvae, often due to contamination from animal feces.2 Cutaneous larva migrans is characterized by pruritic erythematous papules and linear or serpiginous, reddish brown, elevated tracks most commonly appearing on the feet, buttocks, thighs, and lower legs; however, lesions can appear anywhere. In human hosts, the larvae travel in the epidermis and are unable to invade the dermis; it is speculated that they lack the collagenase enzymes required to penetrate the basement membrane before invading the dermis.2

On histopathology, there typically are small cavities in the epidermis corresponding to the track of the larvae.3 There often is a spongiotic dermatitis with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate following the larvae with scattered eosinophils. The migrating larvae may be up to 1 mm in size and have bilateral double alae, or winglike projections, on the side of the body (Figure 1).4 The larvae are difficult to find on histopathology because they often travel beyond the areas that demonstrate clinical findings. The diagnosis of CLM is mostly clinical, but if a biopsy is performed, the specimen should be taken ahead of the track.

Disseminated strongyloidiasis is caused by Strongyloides stercoralis. When filariform larvae migrate out of the intestinal tract into the skin, they can cause an urticarial rash and serpiginous patterns on the skin that can move 5 to 15 cm per hour, a clinical condition known as larva currens. In immunocompromised individuals, there can be hyperinfection with diffuse petechial thumbprint purpura seen clinically, which characteristically radiate from the periumbilical area.1 On pathology, there may be numerous larvae found between the dermal collagen bundles, measuring 9 to 15 µm in diameter. Rarely, they also can be found in small blood vessels.3 They often are accompanied by extravasated red blood cells in the tissues (Figure 2).

Myiasis represents the largest pathogen in the differential diagnosis for CLM. In myiasis, fly larvae will infest human tissue, usually by forming a small cavity in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue. The larvae are visible to the human eye and can be up to several centimeters in length. In the skin, the histology of myiasis usually is accompanied by a heavy mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate with many eosinophils. Fragments of the larvae are seen encased by a thick chitinous cuticle with widely spaced spines or pigmented setae (Figure 3) on the surface of the cuticle.5 Layers of striated muscle and internal organs may be seen beneath the cuticle.3

Onchocerciasis, or river blindness, is a parasitic disease caused by Onchocerca volvulus that is most often seen in sub-Saharan Africa. It may cause the skin finding of an onchocercoma, a subcutaneous nodule made up of Onchocerca nematodes. However, when the filaria disseminate, it may cause onchocerciasis with cutaneous findings of an eczematous dermatitis with itching and lichenification.1 In onchocercal dermatitis, microfilariae may be found in the dermis and there may be a mild dermal chronic inflammatory infiltrate with eosinophils.3 These microfilariae are smaller than Strongyloides larvae (Figure 4).

Sarcoptes scabiei are mites that are pathologically found limited to the stratum corneum. There often is a spongiotic dermatitis as the mite travels with an accompanying mixed cell inflammatory infiltrate with many eosinophils. One or more mites may be seen with or without eggs and excreta or scybala (Figure 5). Pink pigtails may be seen connected to the stratum corneum, representing egg fragments or casings left behind after the mite hatches.3 The female mite measures up to 0.4 mm in length.3

- Lupi O, Downing C, Lee M, et al. Mucocutaneous manifestations of helminth infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:929-944.

- James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016.

- Patterson J. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016.

- Milner D. Diagnostic Pathology: Infectious Diseases. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

- Ferringer T, Peckham S, Ko CJ, et al. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013.

- Lupi O, Downing C, Lee M, et al. Mucocutaneous manifestations of helminth infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:929-944.

- James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016.

- Patterson J. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016.

- Milner D. Diagnostic Pathology: Infectious Diseases. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

- Ferringer T, Peckham S, Ko CJ, et al. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013.

An 18-year-old man presented with a several-week history of an expanding pruritic serpiginous and linear eruption on the buttock. The patient recently had spent some time vacationing at the beach in the southeastern United States. Physical examination revealed erythematous linear papules and serpiginous raised tracks on the buttock. A biopsy of the lesion was performed.

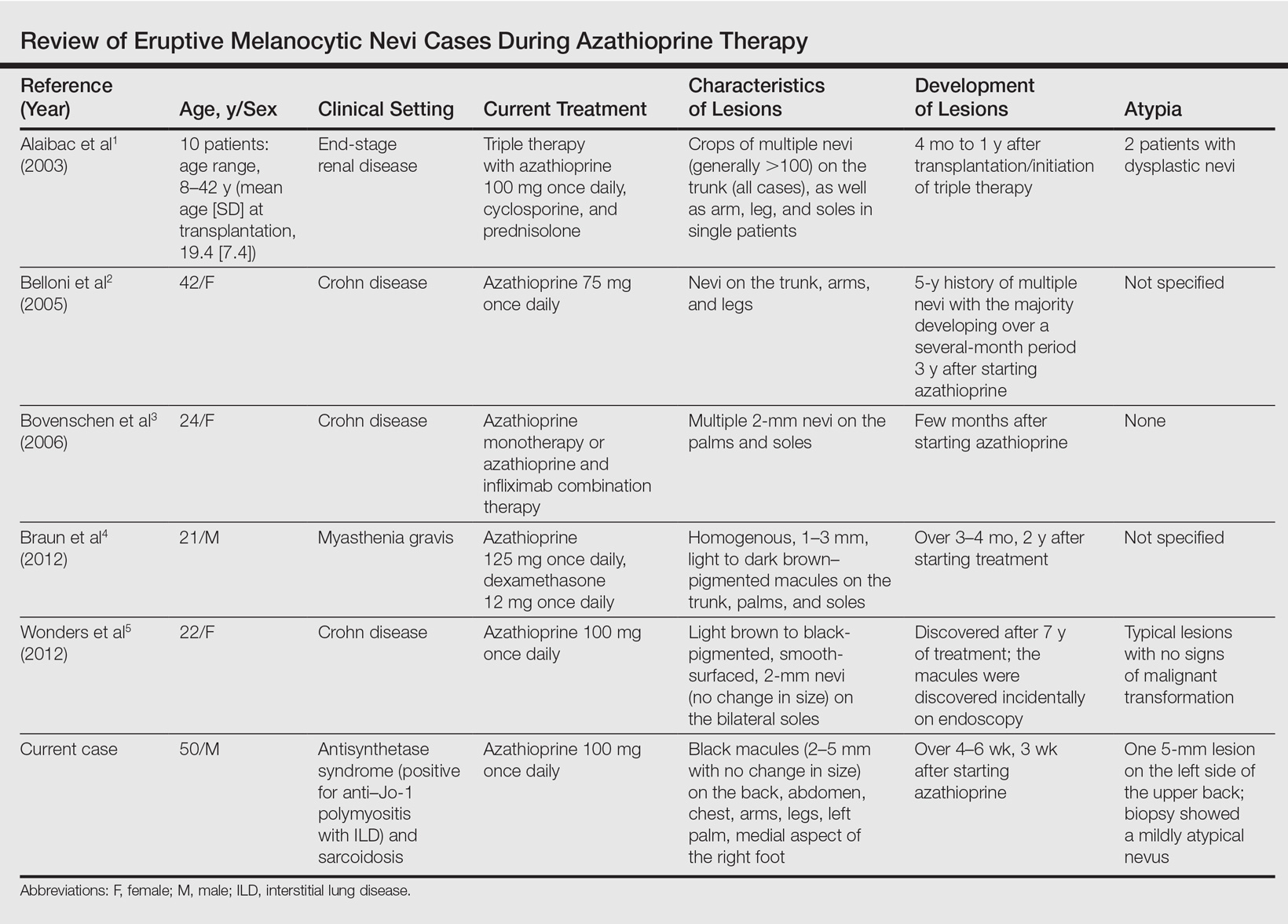

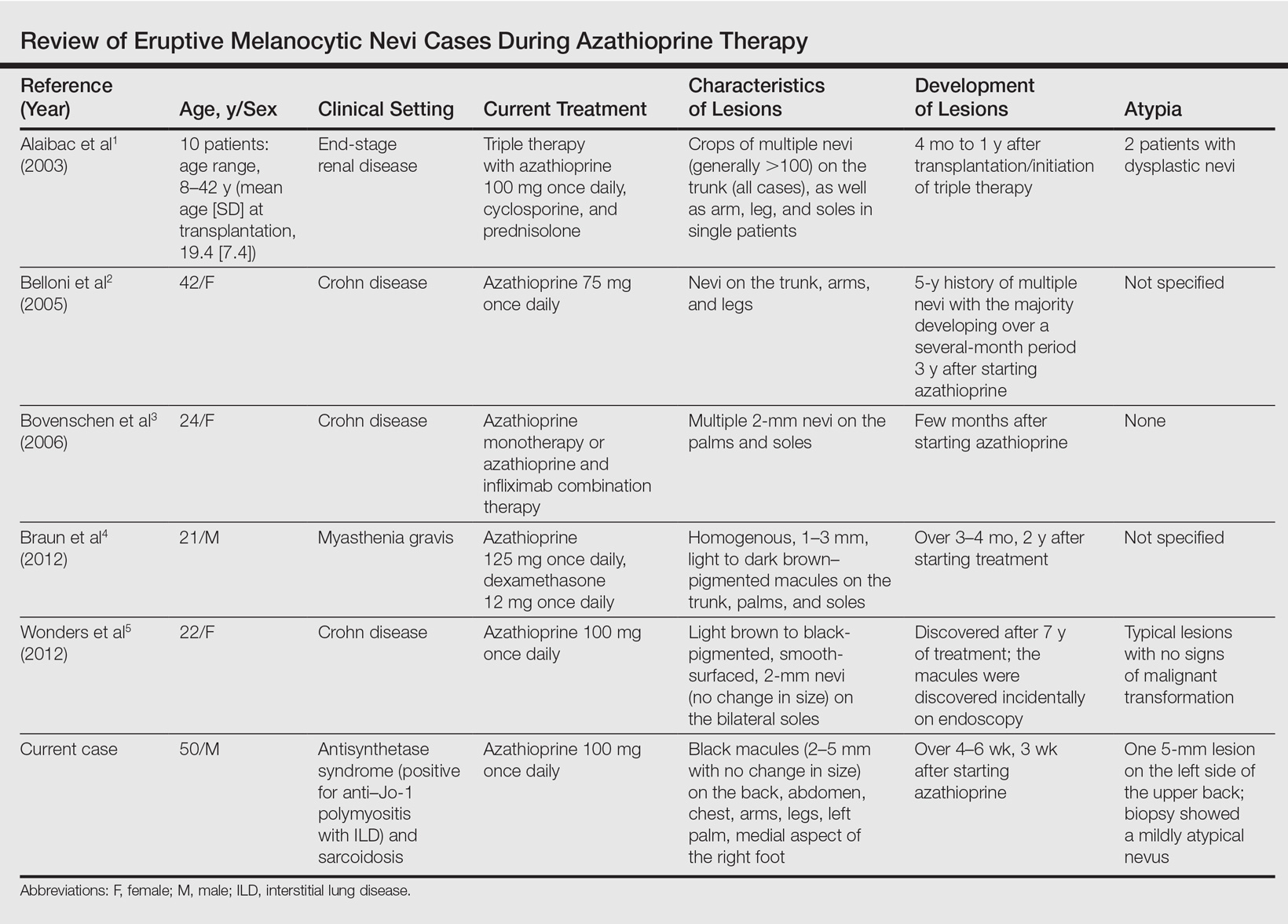

Eruptive Melanocytic Nevi During Azathioprine Therapy for Antisynthetase Syndrome

Case Report

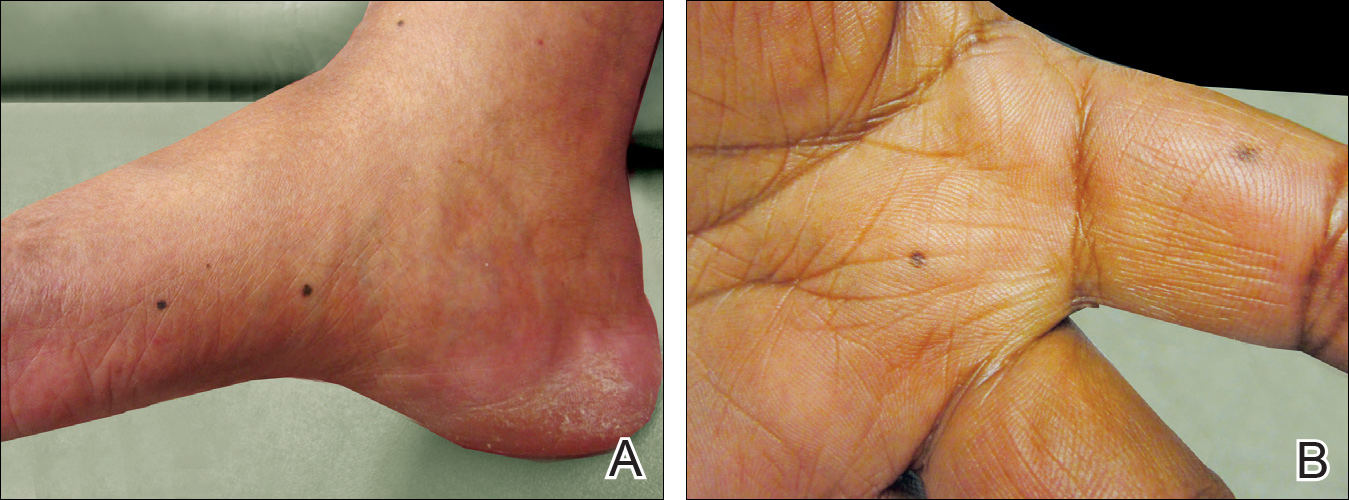

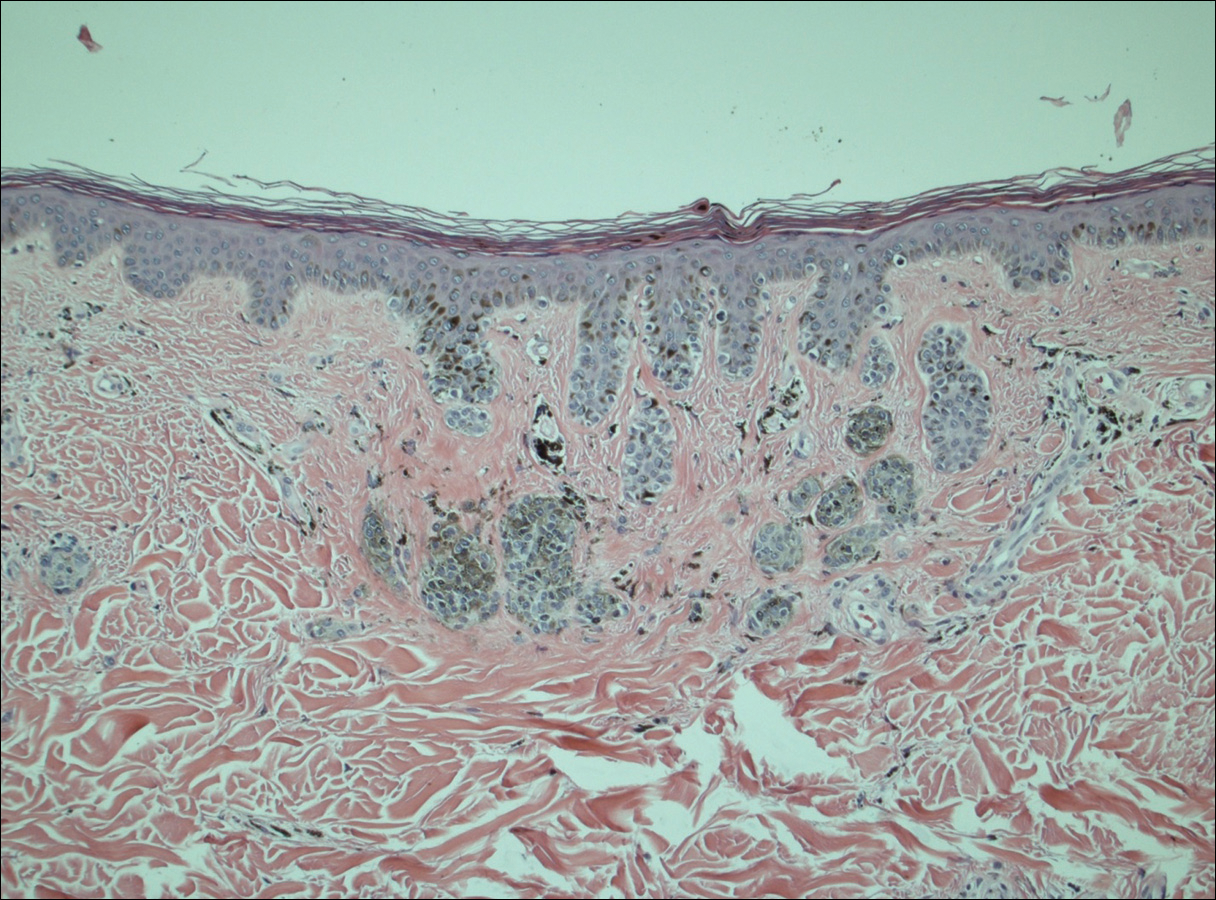

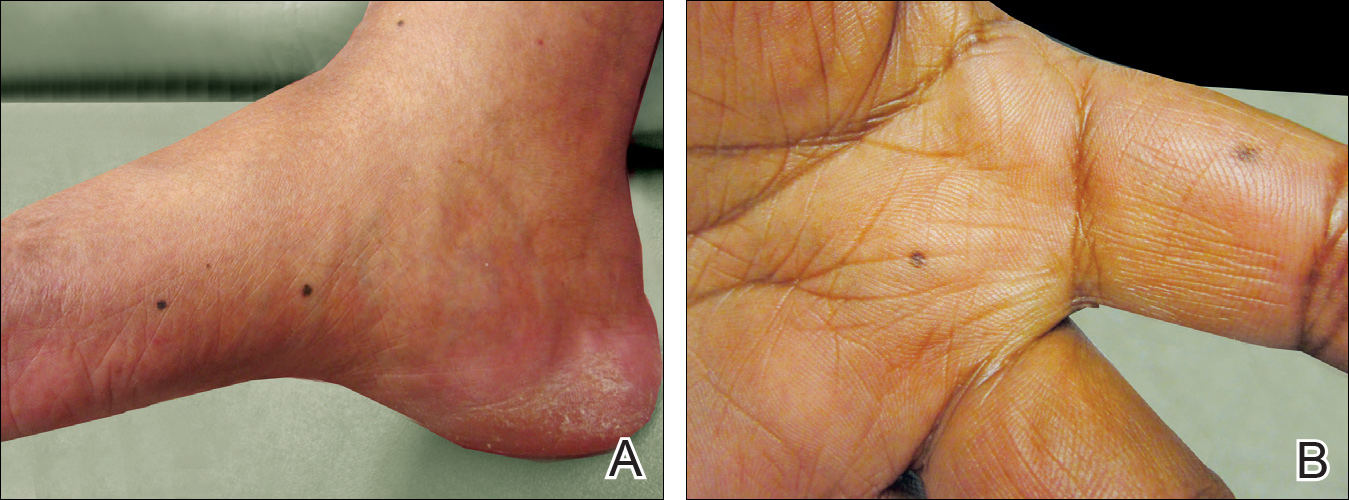

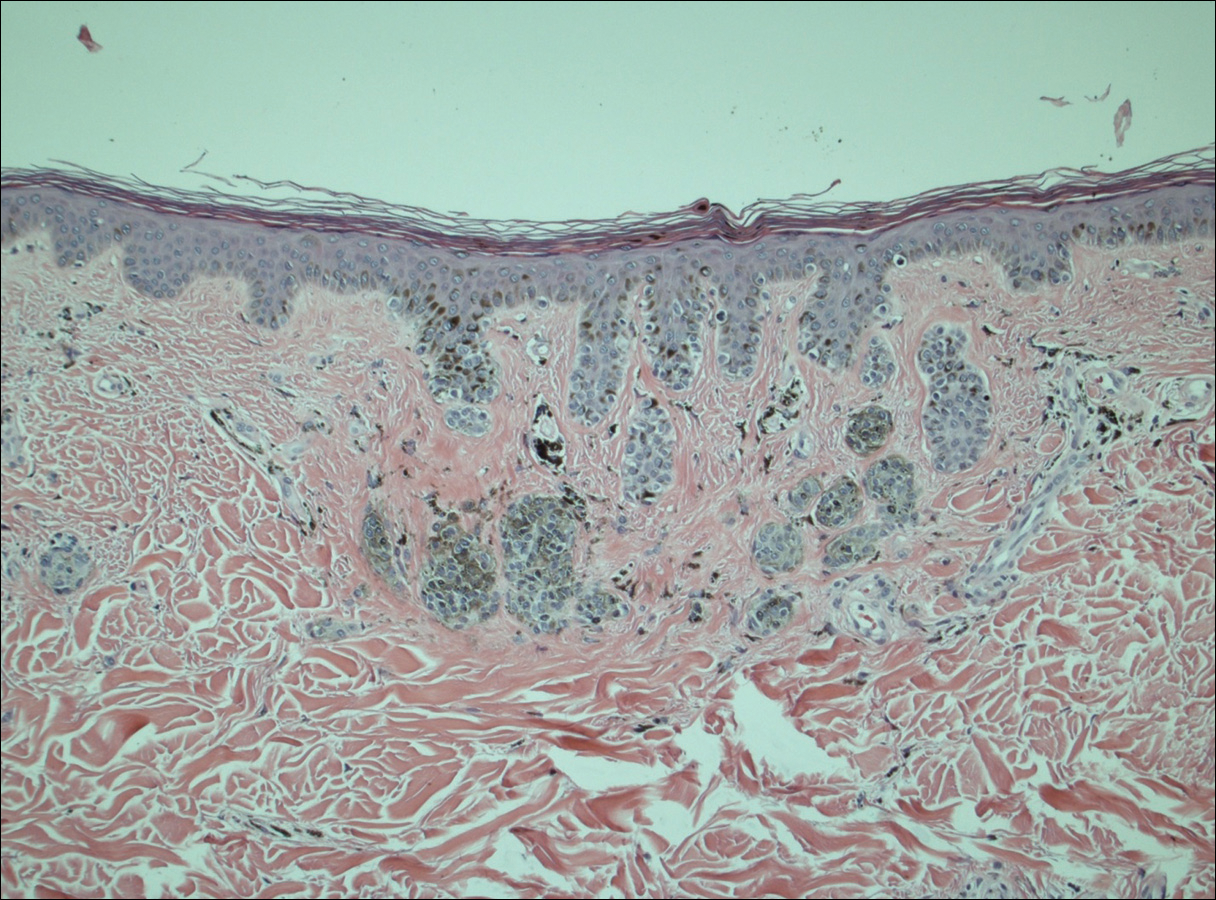

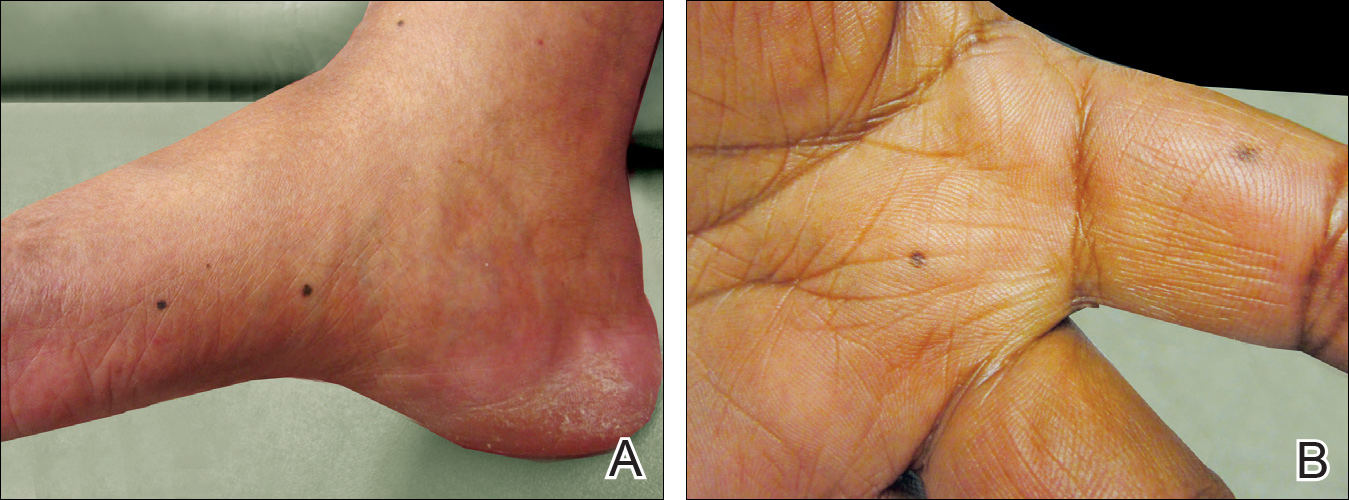

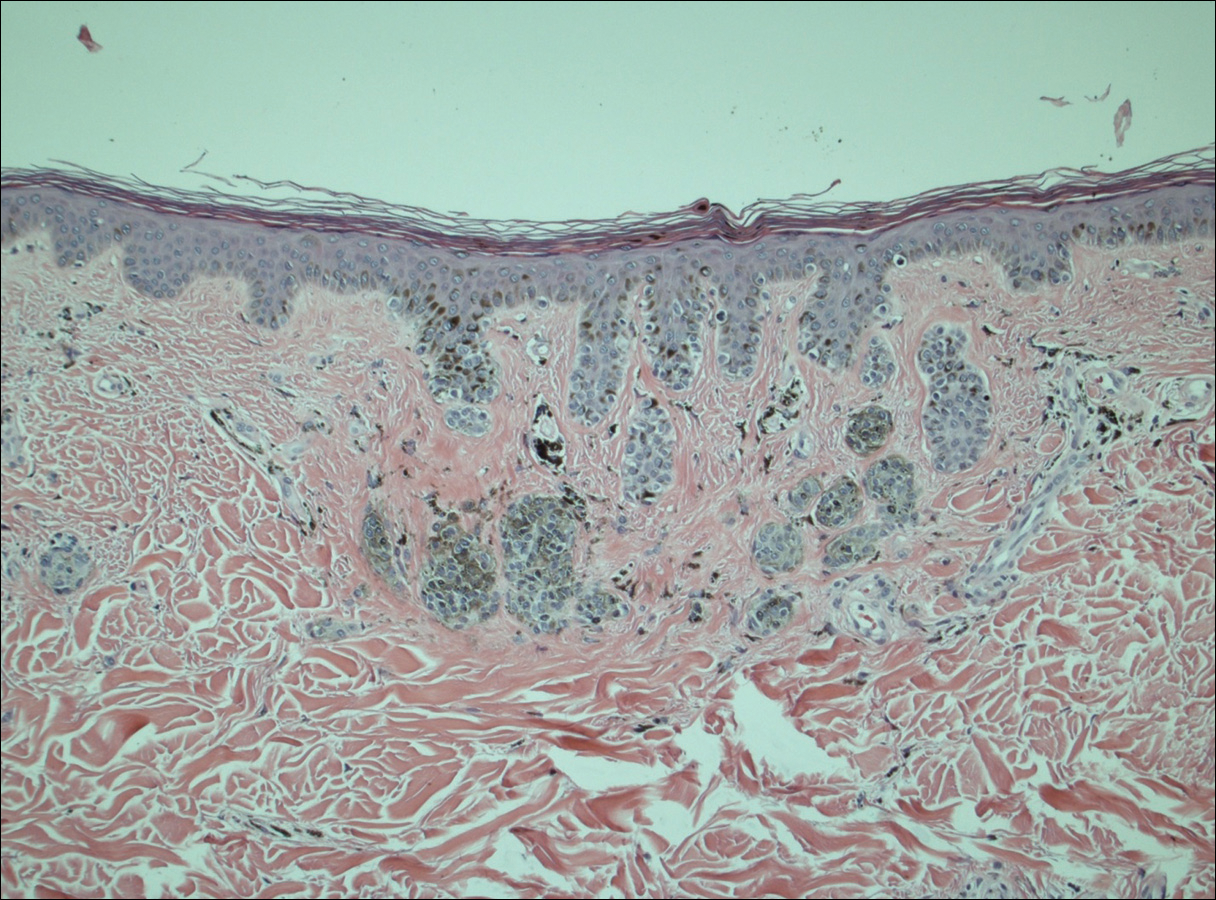

A 50-year-old man with a history of antisynthetase syndrome (positive for anti–Jo-1 polymyositis with interstitial lung disease) and sarcoidosis presented for evaluation of numerous new moles. The lesions had developed on the trunk, arms, legs, hands, and feet approximately 3 weeks after starting azathioprine 100 mg once daily for pulmonary and muscular involvement of antisynthetase syndrome. He denied any preceding cutaneous inflammation or sunburns. He had no personal or family history of skin cancer, and no family members had multiple nevi. Physical examination revealed 30 to 40 benign-appearing, 2- to 5-mm, hyperpigmented macules scattered on the medial aspect of the right foot (Figure 1A), left palm (Figure 1B), back, abdomen, chest, arms, and legs. A larger, somewhat asymmetric, irregularly bordered, and irregularly pigmented macule was noted on the left side of the upper back. A punch biopsy of the lesion revealed a benign, mildly atypical lentiginous compound nevus (Figure 2). Pathology confirmed that the lesions represented eruptive melanocytic nevi (EMN). The patient continued azathioprine therapy and was followed with regular full-body skin examinations. Mycophenolate mofetil was suggested as an alternative therapy, if clinically appropriate, though this change has not been made by the patient’s rheumatologists.

Comment

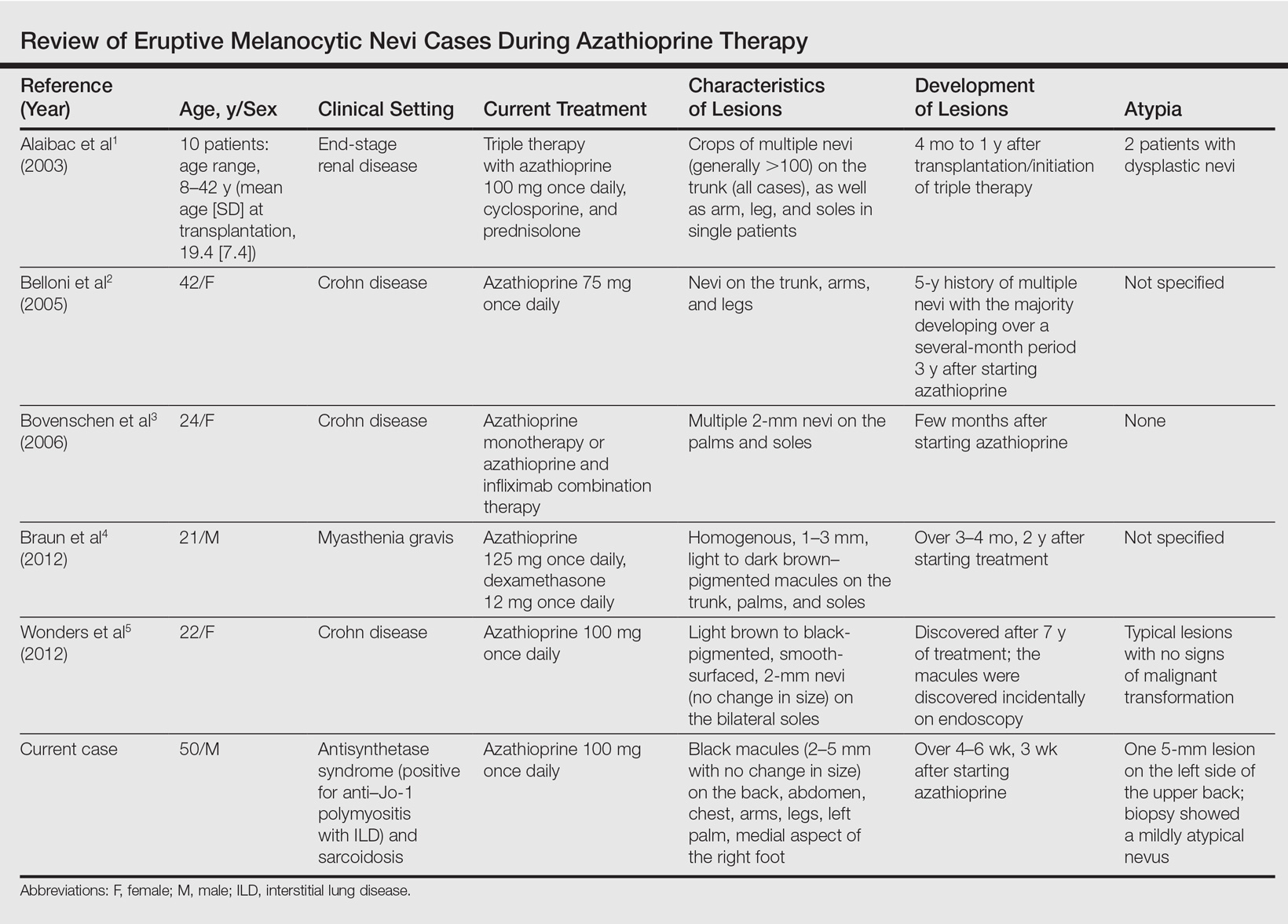

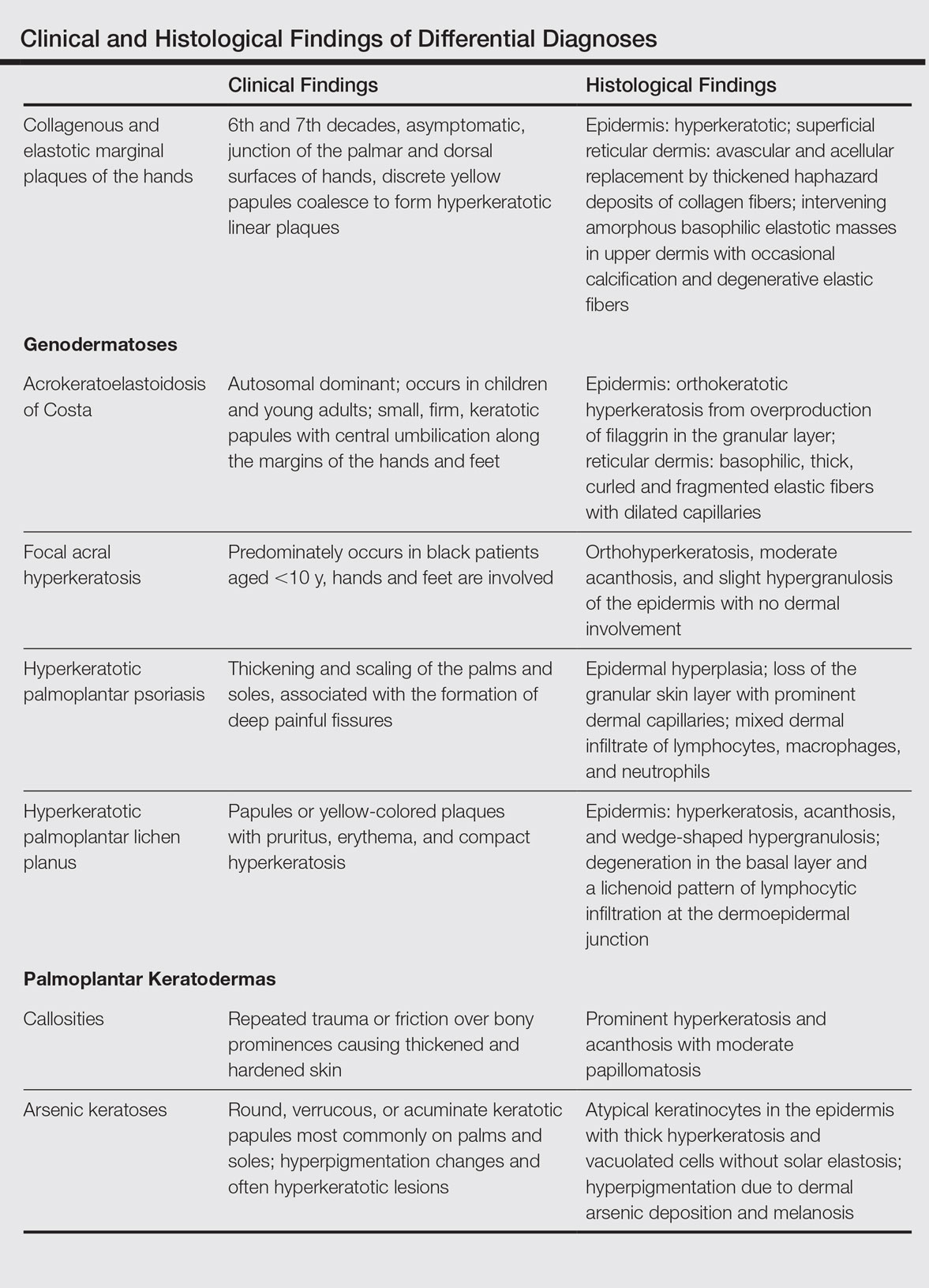

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms eruptive melanocytic nevi and azathioprine revealed 14 cases of EMN in the setting of azathioprine therapy, either during azathioprine monotherapy or in combination with other immunosuppressants, including systemic corticosteroids, biologics, and cyclosporine (Table).1-5 The majority of these cases occurred in renal transplant patients,1 with 3 additional cases reported in the setting of Crohn disease,2,3,5 and another in a patient with myasthenia gravis.4 Patients ranged in age from 8 to 42 years (mean age, 22 years), with lesions developing a few months to up to 7 years after starting therapy. When specified, the reported lesions typically were small, ranging from 1 to 3 mm in size, and developed rapidly over a couple of months with a predilection for the palms, soles, and trunk. Although dysplastic nevi were described in only 2 patients, melanomas were not detected.

Various hypotheses have sought to explain the largely unknown etiology of EMN. Bovenschen et al3 suggested that immunocompromised patients have diminished immune surveillance in the skin, which allows for unchecked proliferation of melanocytes. Specifically, immune suppression may induce melanocyte-stimulating hormone or melanoma growth stimulatory activity, with composition-specific growth in skin at the palms and soles.3,4 The preferential growth on the palms and soles suggests that those regions may have special sensitivity to melanocyte-stimulating hormone.4 Woodhouse and Maytin6 postulated that the increased density of eccrine sweat glands in the palms and soles as well as the absence of pilosebaceous units and apocrine glands and plentiful Pacinian and Meissner corpuscles may allow for a unique response to circulating melanocytic growth factors. Another hypothesis suggests the presence of genetic factors that allow subclinical nests of nevus cells to form, which become clinical eruptions following chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy.3 Azathioprine also has been suggested to induce various transcription factors that play a critical role in differentiation and proliferation of melanocytic stem cells, which leads to the formation of nevi.4 Our case and others similar to it implore that further studies be done to determine the molecular mechanism driving this phenomenon and whether a specific genetic predisposition exists that lowers the threshold for rapid proliferation of melanocytes given an immunosuppressed status.2

The risk for melanoma development in cases of EMN is unknown. Although our review of the literature did not reveal any melanomas reported in cases attributed to azathioprine, a theoretical risk exists given the established associations between melanoma and immunosuppression as well as increased numbers of nevi.6 Accordingly, these patients should be followed with regular skin examinations and biopsies of atypical-appearing lesions as indicated.2,3,5 Braun et al4 also suggested the discontinuance of azathioprine and switch to mycophenolic acid, which has not been noted to cause such eruptions; this drug was recommended in our case.

- Alaibac M, Piaserico S, Rossi CR, et al. Eruptive melanocytic nevi in patients with renal allografts: report of 10 cases with dermoscopic findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1020-1022.

- Belloni FA, Piaserico S, Zattra E, et al. Dermoscopic features of eruptive melanocytic naevi in an adult patient receiving immunosuppressive therapy for Crohn’s disease. Melanoma Res. 2005;15:223-224.

- Bovenschen HJ, Tjioe M, Vermaat H, et al. Induction of eruptive benign melanocytic naevi by immune suppressive agents, including biologicals. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:880-884.

- Braun SA, Helbig D, Frank J, et al. Eruptive melanocytic nevi during azathioprine therapy in myasthenia gravis [in German]. Hautarzt. 2012;63:756-759.

- Wonders J, De Boer N, Van Weyenberg S. Spot diagnosis: eruptive melanocytic naevi during azathioprine therapy in Crohn’s disease [published online March 6, 2012]. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:636.

- Woodhouse J, Maytin EV. Eruptive nevi of the palms and soles. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(5 suppl 1):S96-S100.

Case Report

A 50-year-old man with a history of antisynthetase syndrome (positive for anti–Jo-1 polymyositis with interstitial lung disease) and sarcoidosis presented for evaluation of numerous new moles. The lesions had developed on the trunk, arms, legs, hands, and feet approximately 3 weeks after starting azathioprine 100 mg once daily for pulmonary and muscular involvement of antisynthetase syndrome. He denied any preceding cutaneous inflammation or sunburns. He had no personal or family history of skin cancer, and no family members had multiple nevi. Physical examination revealed 30 to 40 benign-appearing, 2- to 5-mm, hyperpigmented macules scattered on the medial aspect of the right foot (Figure 1A), left palm (Figure 1B), back, abdomen, chest, arms, and legs. A larger, somewhat asymmetric, irregularly bordered, and irregularly pigmented macule was noted on the left side of the upper back. A punch biopsy of the lesion revealed a benign, mildly atypical lentiginous compound nevus (Figure 2). Pathology confirmed that the lesions represented eruptive melanocytic nevi (EMN). The patient continued azathioprine therapy and was followed with regular full-body skin examinations. Mycophenolate mofetil was suggested as an alternative therapy, if clinically appropriate, though this change has not been made by the patient’s rheumatologists.

Comment