User login

Acquired Perforating Dermatosis in a Skin Graft

Case Report

A 57-year-old black woman with a history of dialysis-dependent end-stage renal disease, diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, diastolic congestive heart failure, and chronic bronchitis was admitted to Howard University Hospital (Washington, DC) for acute chest pain and shortness of breath. During her hospital stay the dermatology team was consulted for evaluation of two 1.6-cm teardrop-shaped, yellow-white-chalky plaques noted in the center of an atrophic, hyperpigmented, shiny, contracted split-thickness skin graft (STSG) on the right posterior forearm (Figure 1). Twenty years prior, the patient received STSGs on the right and left forearm secondary to caustic burns. Two months before the current admission she noticed 2 adjacent teardrop-shaped white plaques within the center of the STSG on the right forearm. At a 3-month follow-up, she had developed more lesions within both graft sites of the bilateral forearm. There was no notable pruritus associated with the lesions.

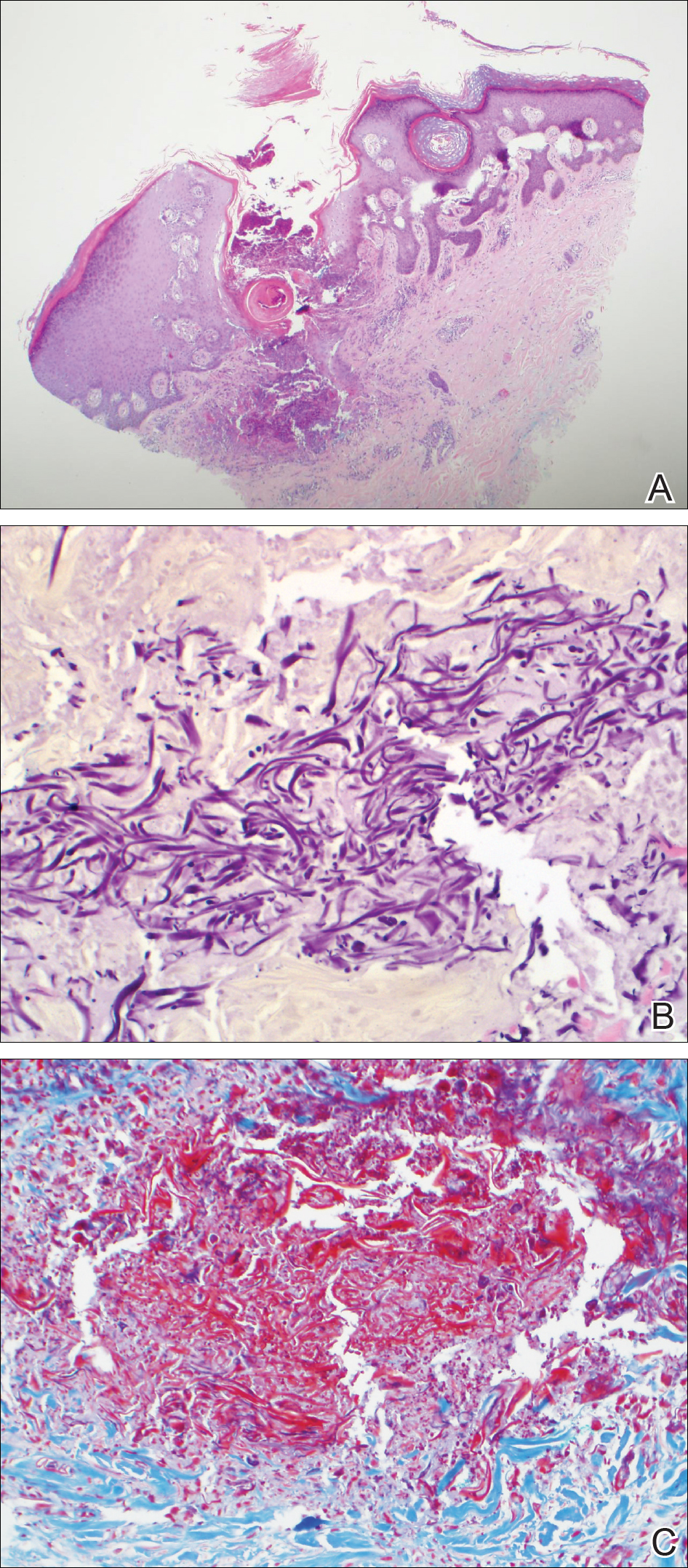

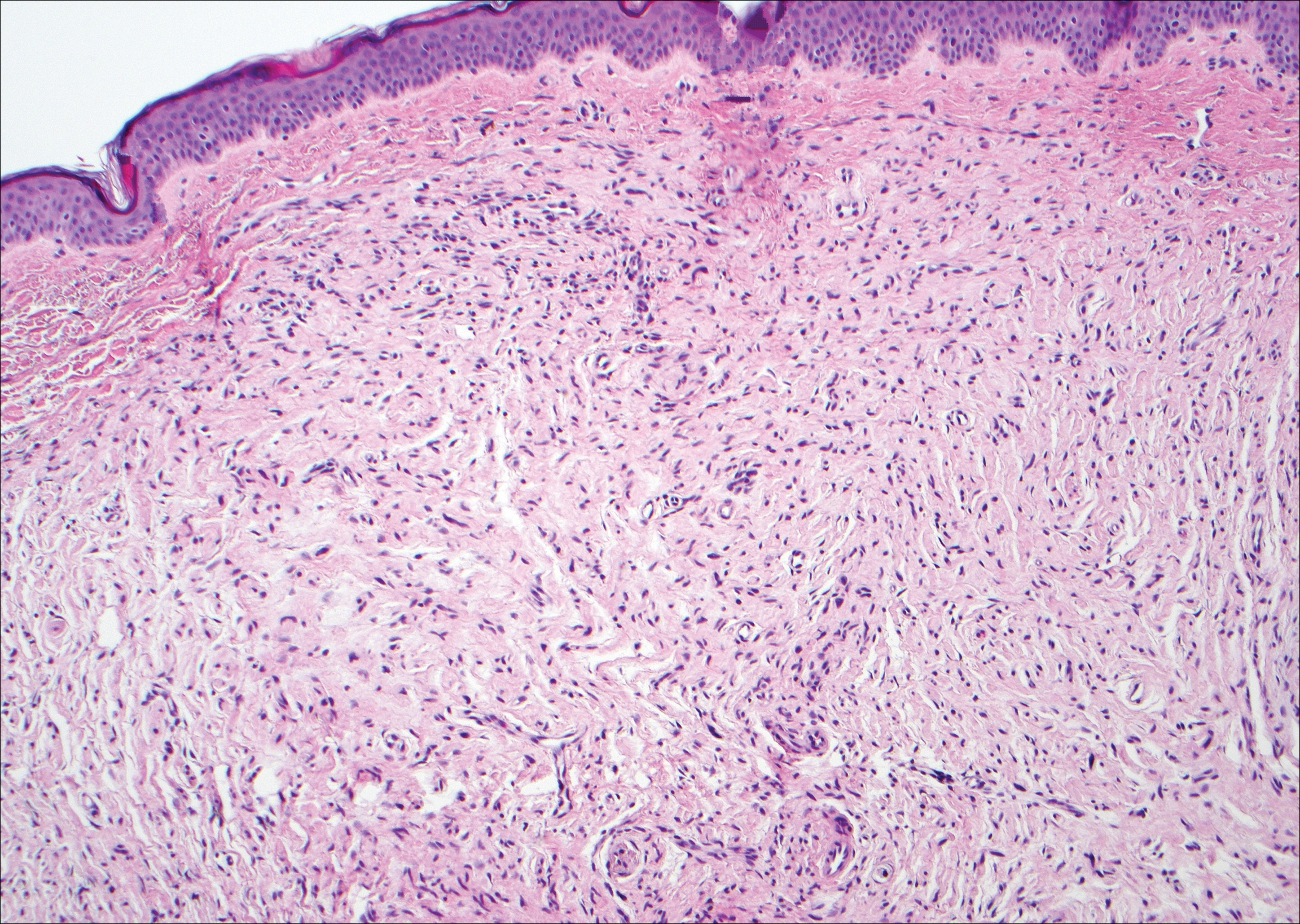

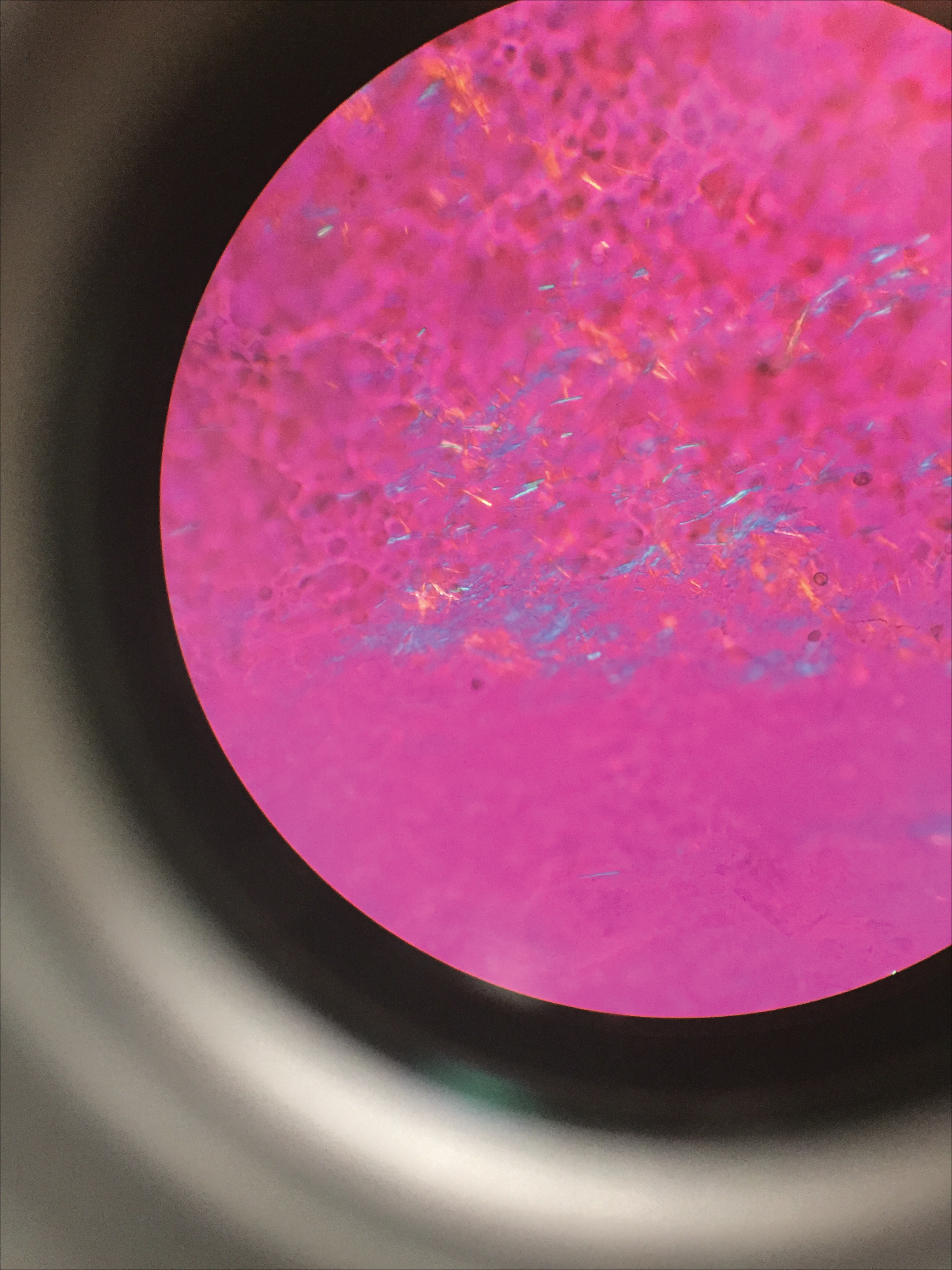

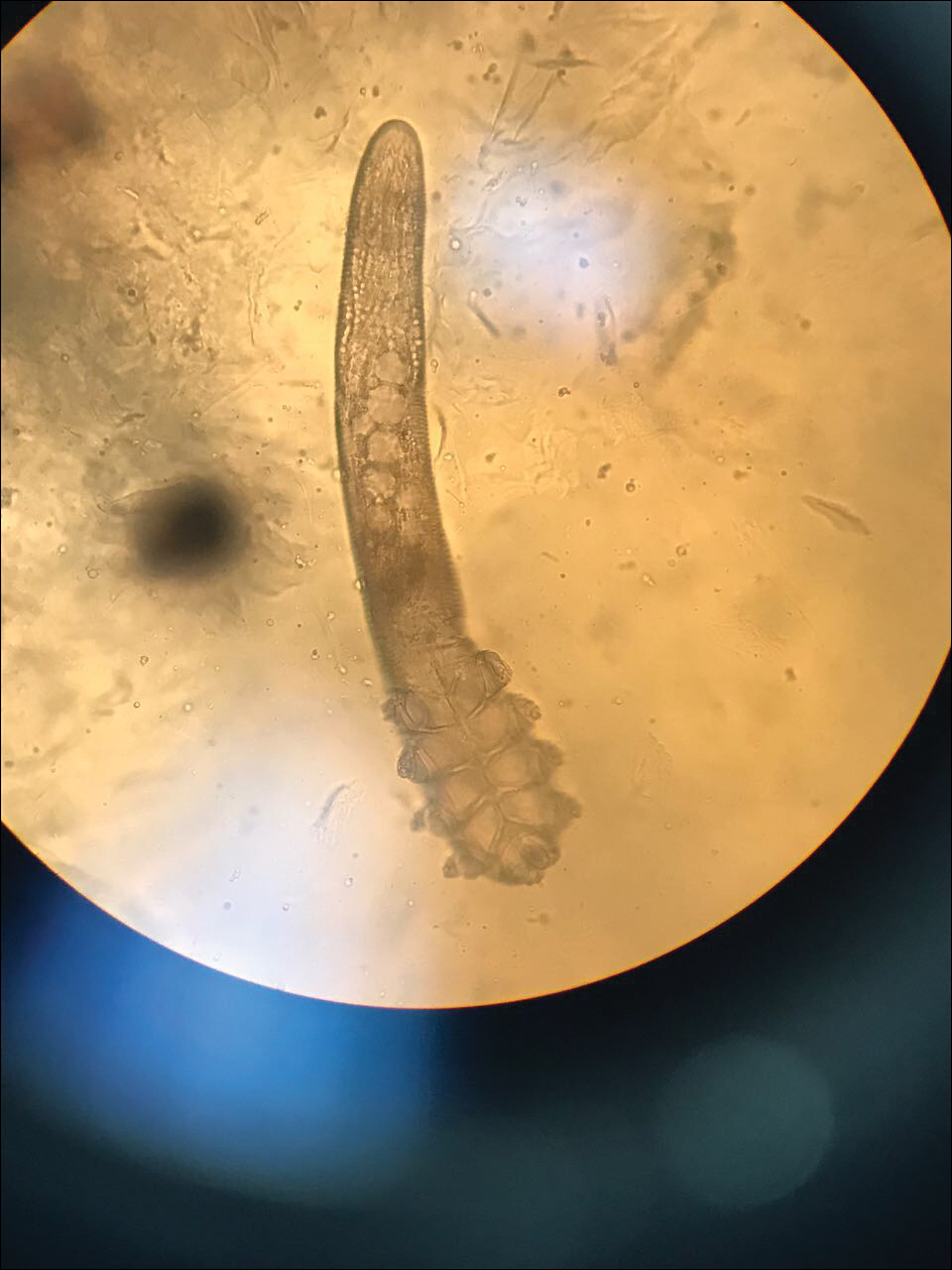

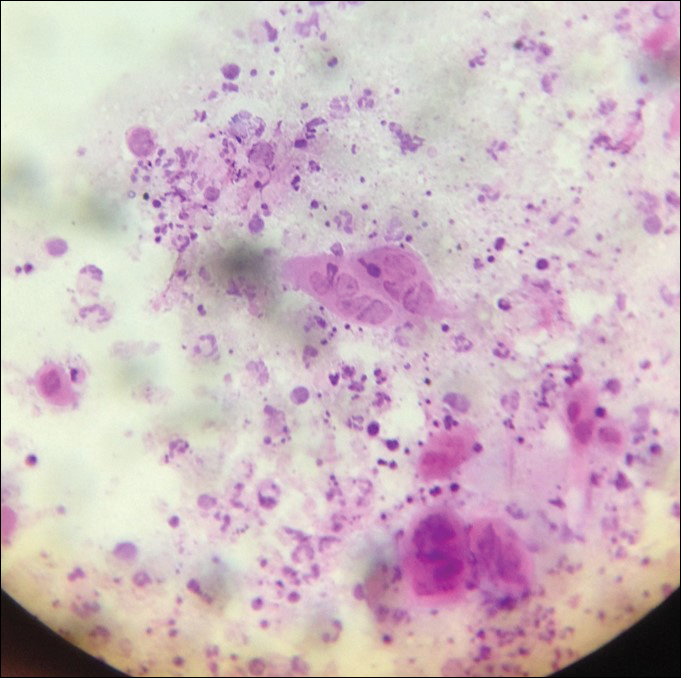

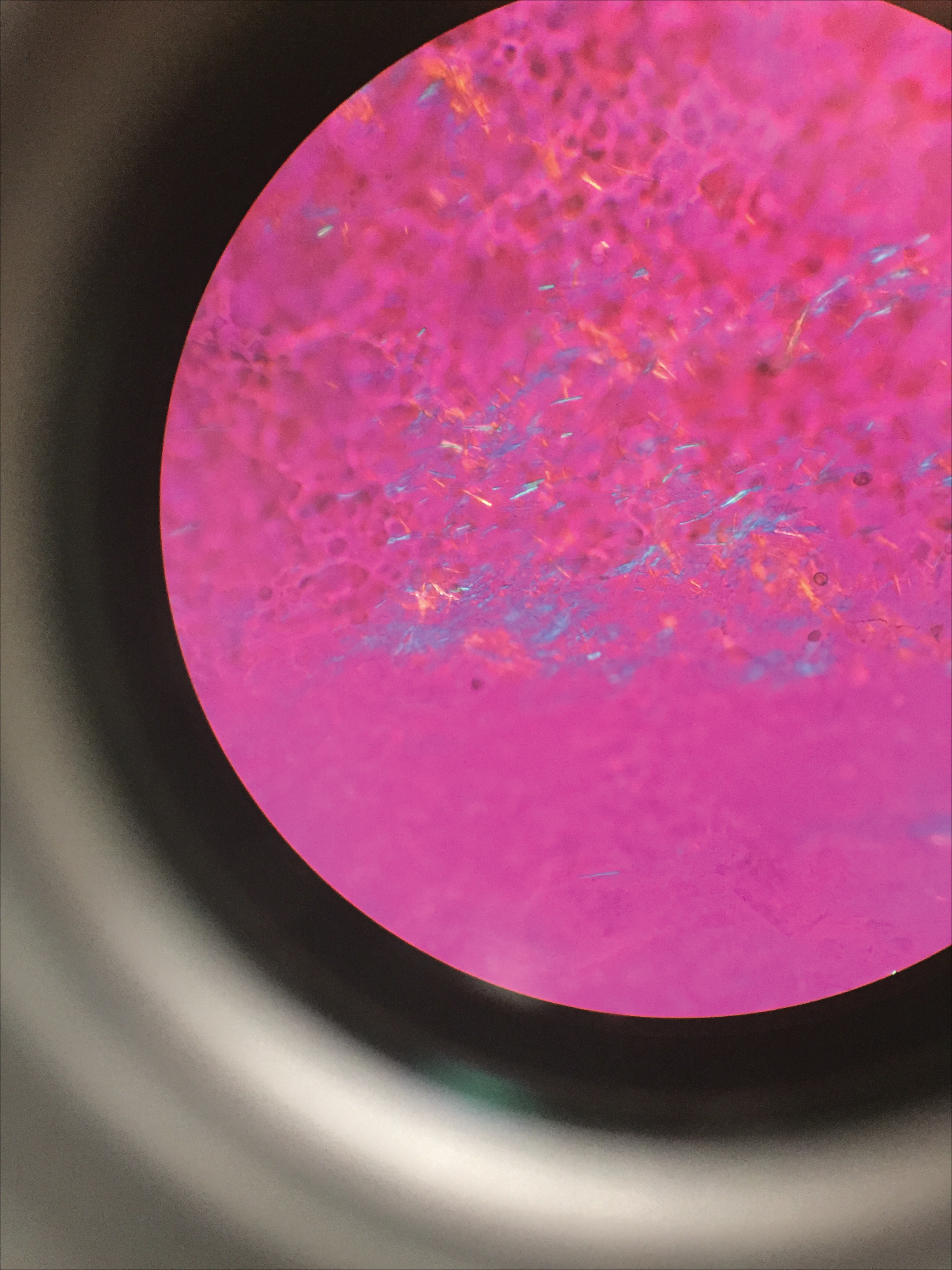

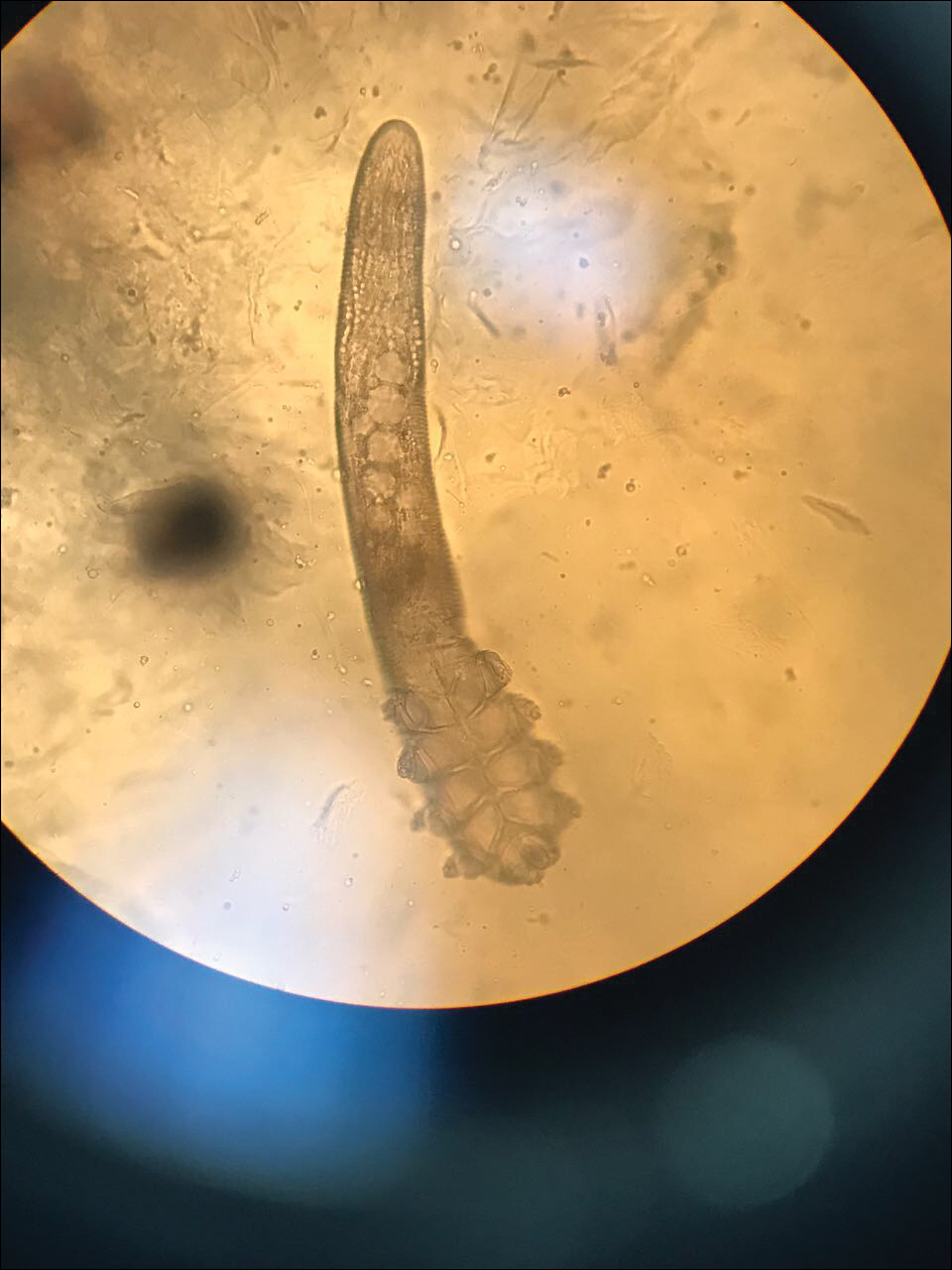

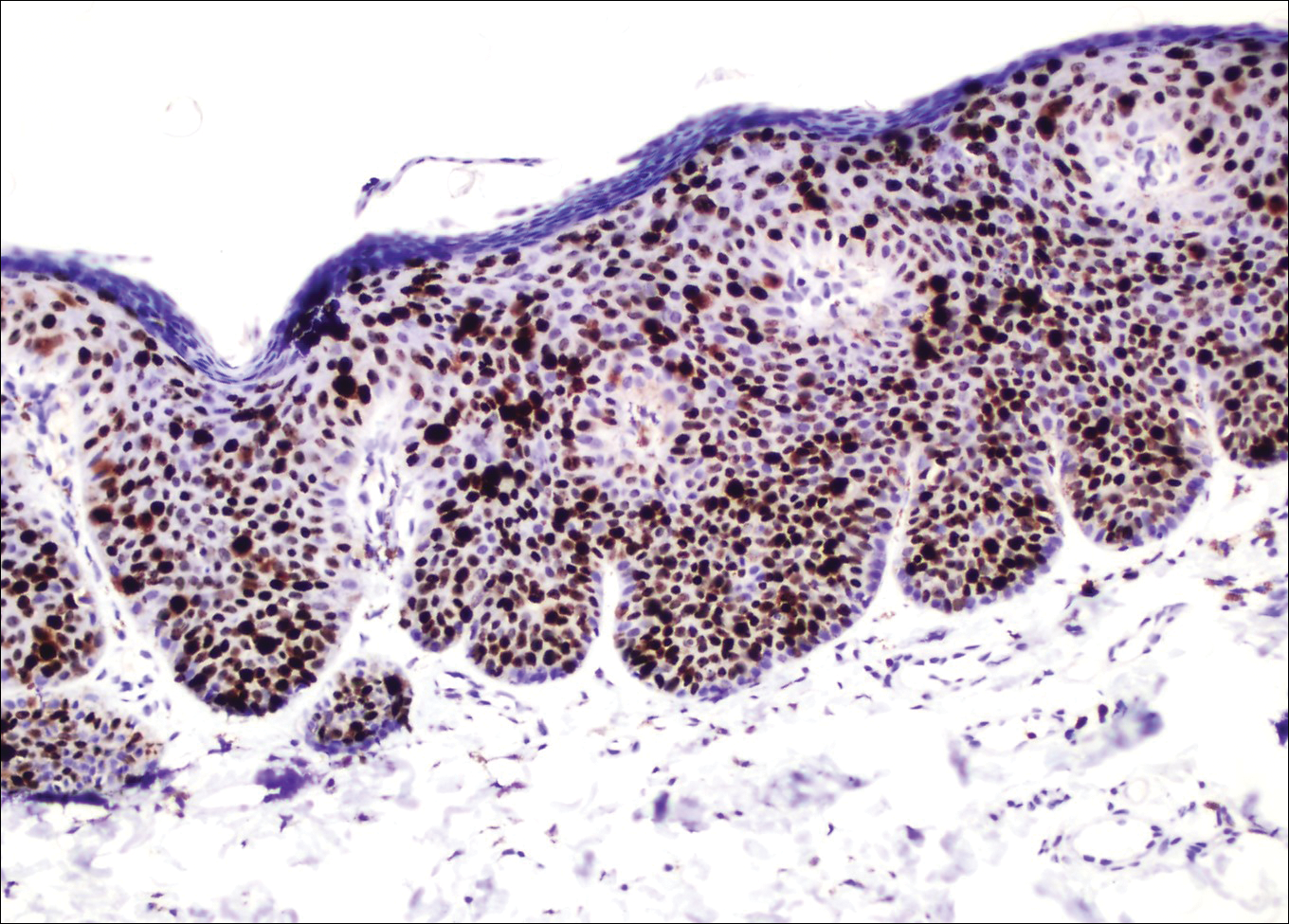

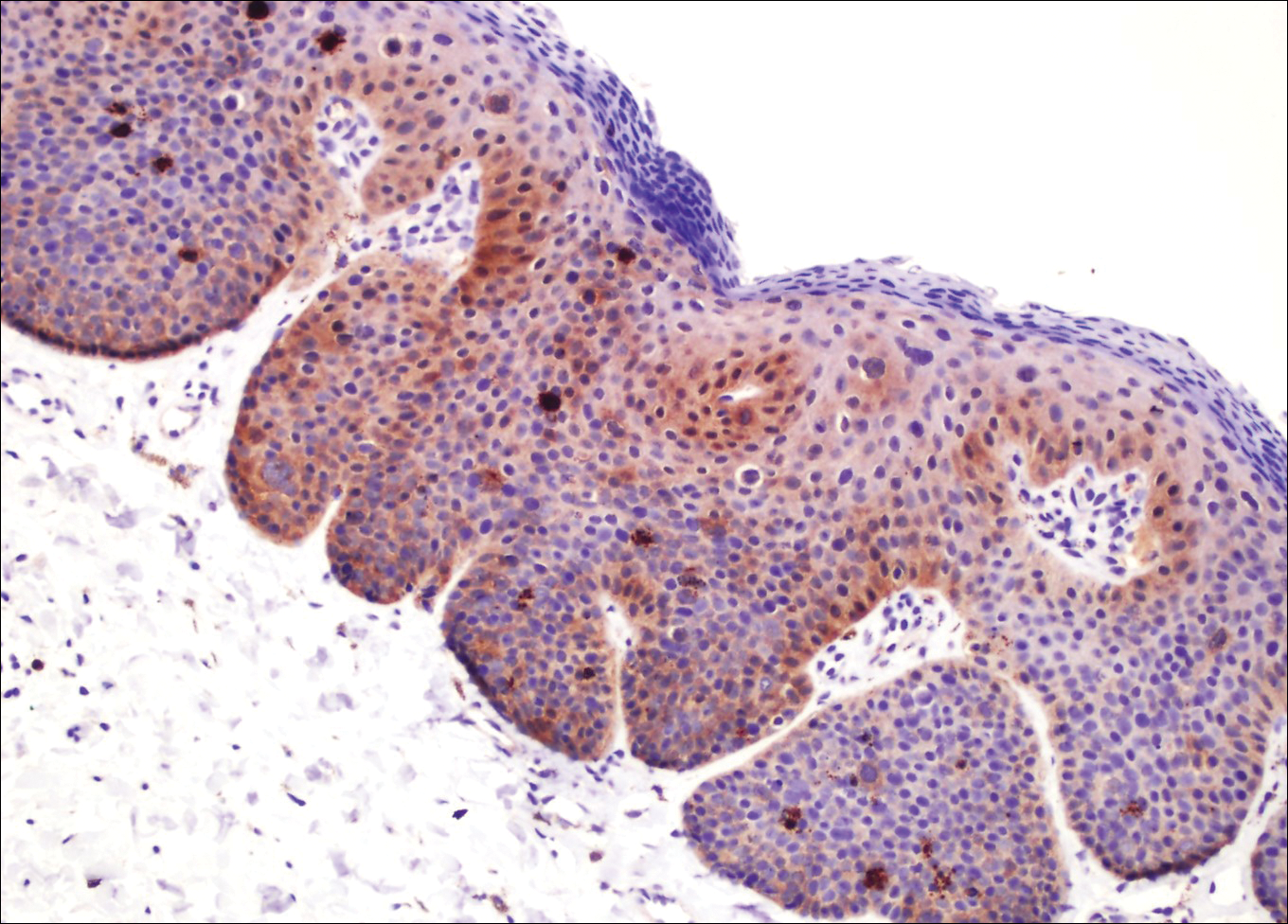

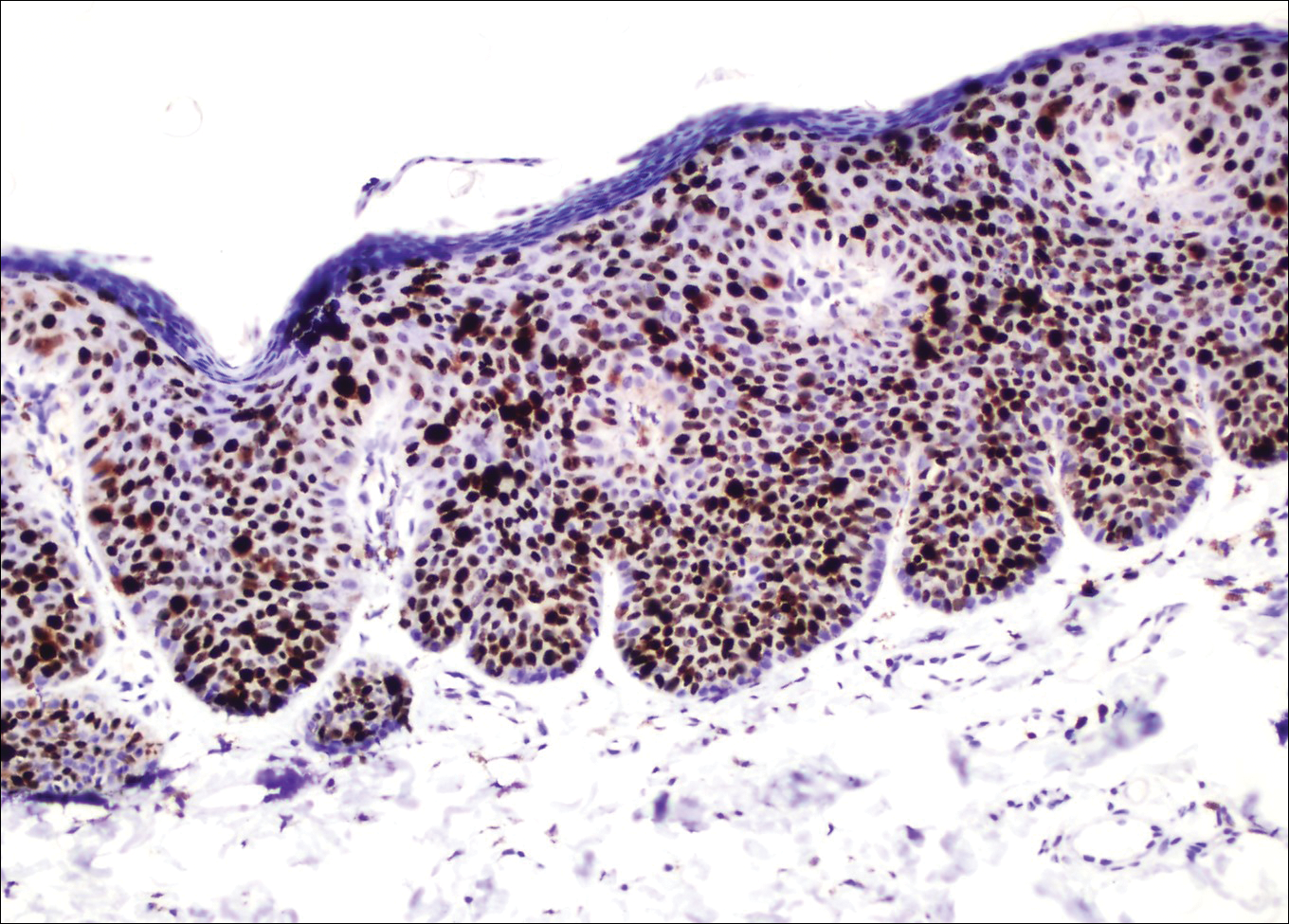

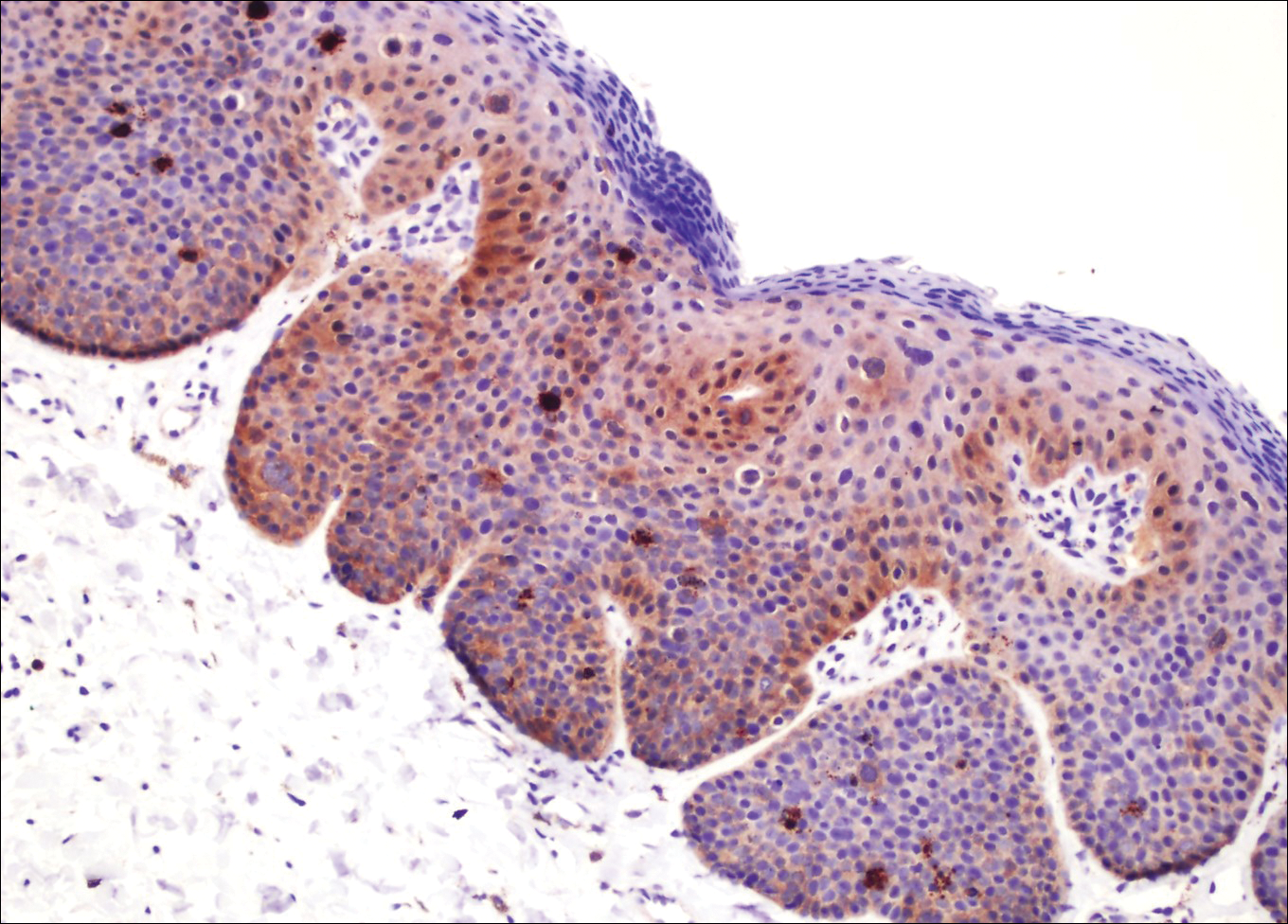

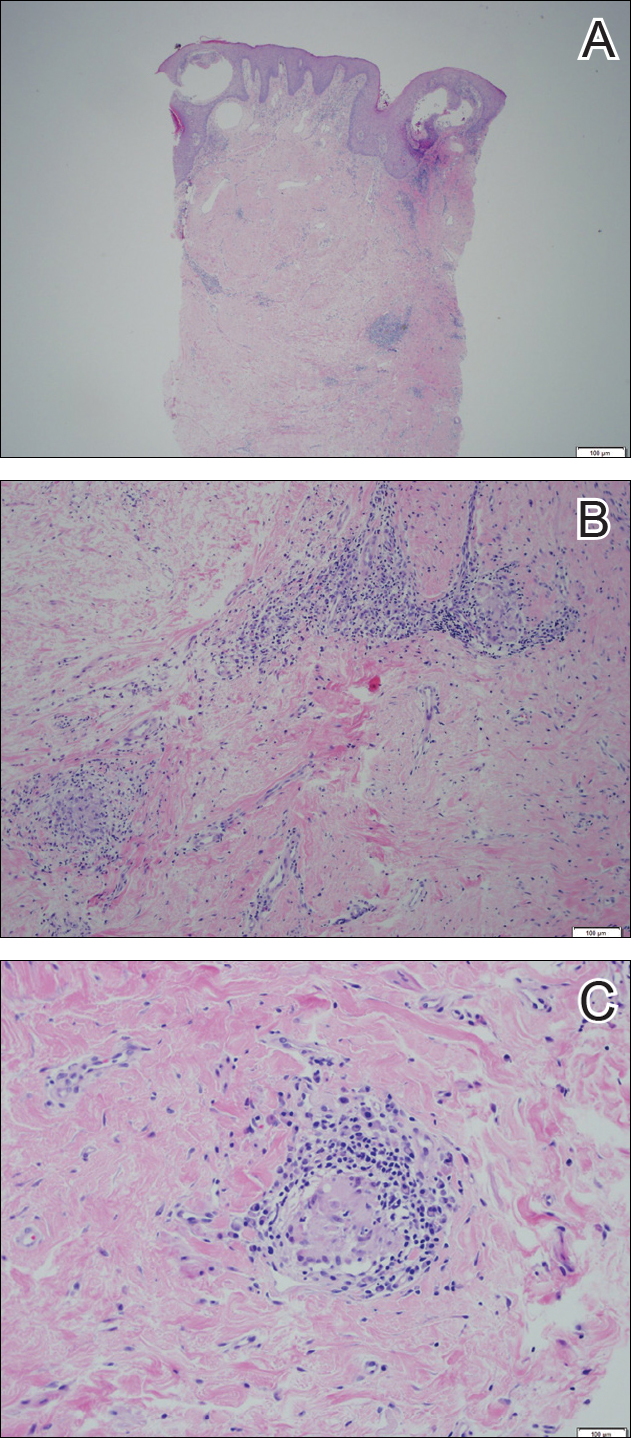

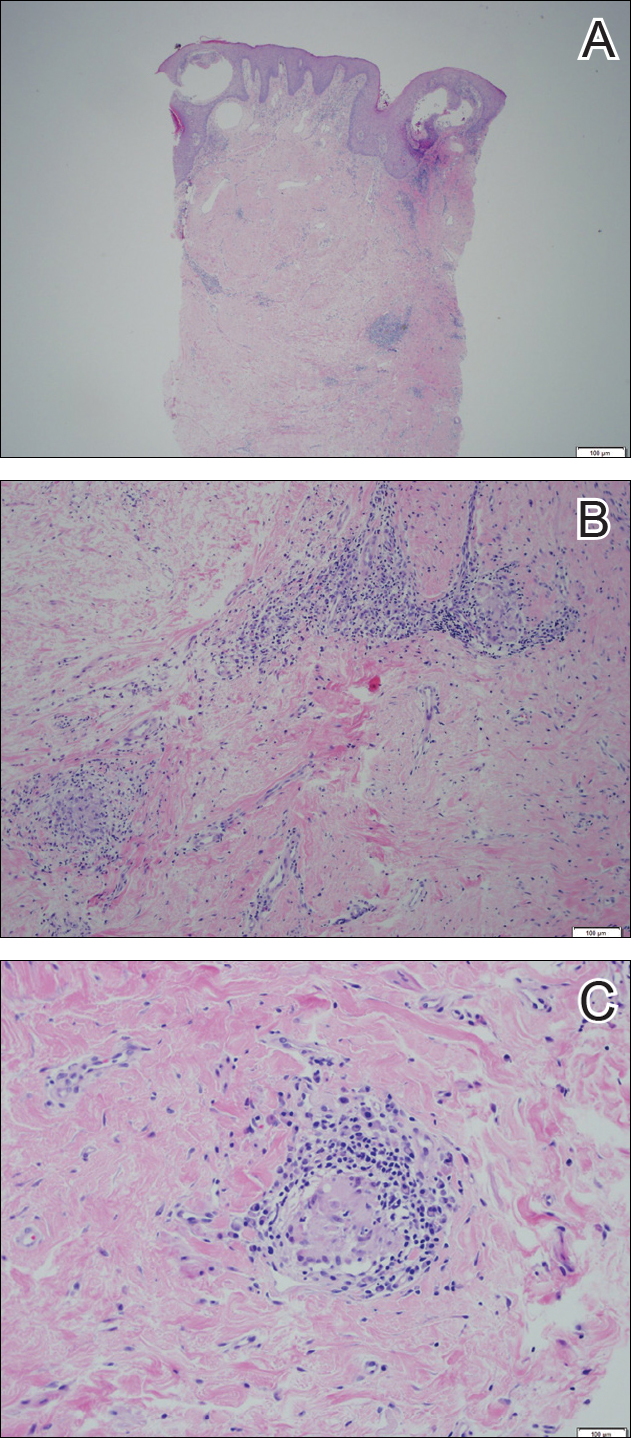

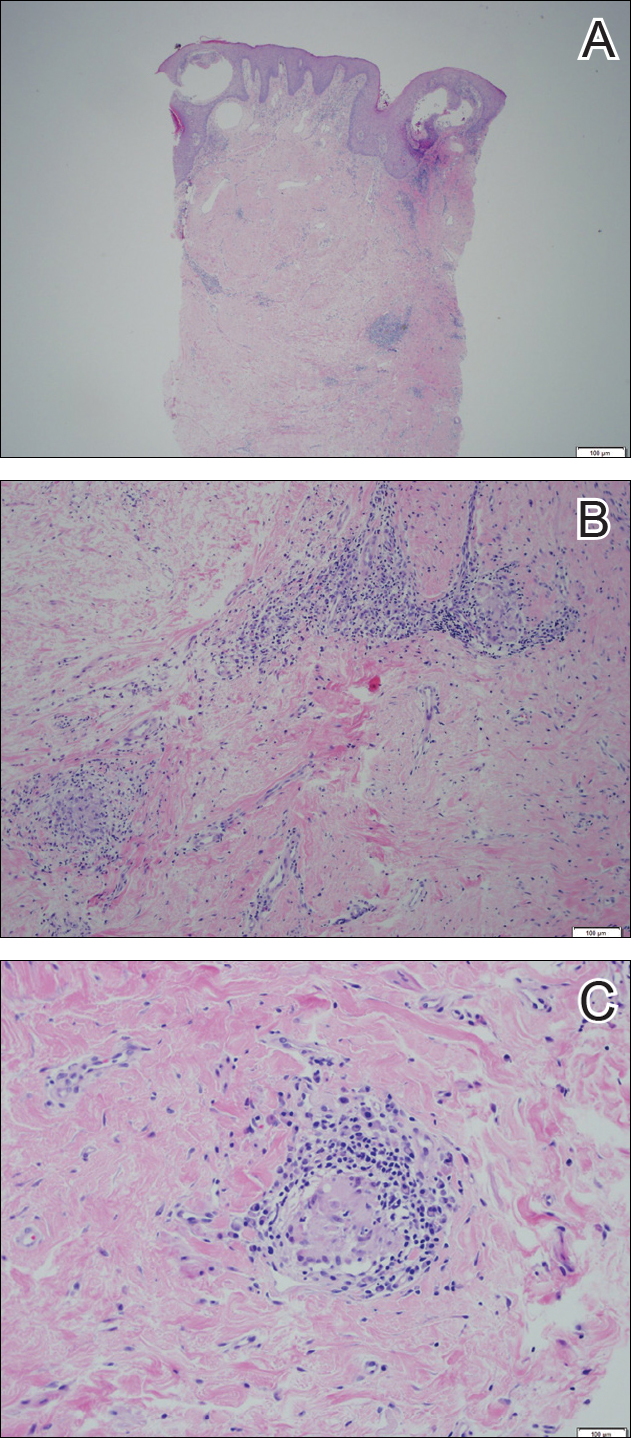

A 4-mm punch biopsy showed an orthokeratotic plug with basophilic inflammatory debris adjacent to acanthotic epidermis, necrotic basophilic debris at the superficial dermis with epidermal canals extending from the base of the lesion superiorly, and transepidermal elimination of elastic fibers (Figure 2A). A Verhoeff-van Gieson stain revealed the necrotic basophilic debris located in the superficial dermis admixed with a cluster of black wavy elastic fibers establishing the identity of the perforating substance (Figure 2B). Masson trichrome stain revealed loss of collagen structure within the aggregate of elastic fibers adjacent to the epidermis and no collagen within epidermal canals (Figure 2C). These histopathologic findings together with the clinical presentation were consistent with a diagnosis of acquired perforating dermatosis (APD).

Comment

Presentation

Acquired perforating dermatosis is a dermatologic condition characterized by multiple pruritic, dome-shaped papules and plaques with central keratotic plugs giving a craterlike appearance.1-4 A green-brown or black crust with an erythematous border typically surrounds the primary lesions.4 Acquired perforating dermatosis favors a distribution over the trunk, gluteal region, and the extensor surfaces of the upper and lower extremities. Palmoplantar, intertriginous, and mucous membrane regions typically are spared.4 Occasionally, APD may present as generalized nodules and papules. Our case consisting of lesions that were localized to STSGs on the forearms supports the typical distribution; however, the presentation of APD occurring within a skin graft is unique.

From an epidemiologic standpoint, APD is more likely to affect men than women (1.5:1 ratio). Additionally, APD’s affected age range is 29 to 96 years (mean, 56.8 years),5 which is consistent with our patient’s age. Acquired perforating dermatosis has no racial predilection, though there is a predominance among black patients with concomitant chronic renal failure, as seen in our patient.3

Pathogenesis

The etiology of APD remains unknown.6 Some believe that the uremic or calcium deposits on the skin of patients with chronic kidney disease may trigger chronic pruritus, leading to epithelial hyperplasia and the development of perforating lesions.1,3 A prominent theory in the literature is that superficial trauma, such as scratching, induces necrosis of tissue, facilitating transepidermal elimination of connective tissue components.7 The Köbner phenomenon, which can easily be induced by scratching the skin, supports this idea.8 Fujimoto et al9 suggested that scratching exposes keratinocytes to advanced glycation end product–modified extracellular matrix proteins, particularly types I and III collagen. This exposure leads to the terminal differentiation of keratinocytes with the advanced glycation end receptor (CD36) followed by the upward movement of keratinocytes with glycated collagen. Others postulate fibronectin, involved in epidermal cell signaling, locomotion, and differentiation, is an antigenic trigger because patients with DM and uremia have increased levels of fibronectin in the serum and at sites of perforating skin lesions.10

Diseases Associated With APD

Acquired perforating dermatosis is an umbrella term for perforating disease found in adults. It is associated with systemic diseases, such as DM and pruritus of renal failure.11 Our patient had both dialysis-dependent end-stage renal disease and DM. Acquired perforating dermatosis is observed in 4.5% to 11% of patients on hemodialysis12,13; however, APD may occur prior to or in the absence of dialysis.3 Other examples of systemic conditions associated with APD include obstructive uropathy, chronic nephritis, anuria, and hypertensive nephrosclerosis. Koebnerization also may trigger lesions to manifest in a linear pattern after localized trauma to the skin.7 Acquired perforating dermatosis is associated with other types of trauma, such as healing herpes zoster, or following exposure to drugs, such as tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors, bevacizumab, telaprevir, sorafenib, sirolimus, and indinavir.14-16 Rarely, there have been associations with a history of insect bites, scabies, lymphoma, and hepatobiliary disease.1-3

Histopathology

Acquired perforating dermatosis is classified as a perforating disease, along with reactive perforating collagenosis, elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS), perforating folliculitis, and perforating calcific elastosis. Perforating diseases are histologically characterized by the transepidermal penetration and elimination of altered connective tissue and inflammatory cells.5 Each disease differs based on their clinical and histological characteristics.

Histologic sections of APD show a plug of crusting or hyperkeratosis with variable parakeratosis, acanthosis, and occasional dyskeratotic keratinocytes. In the dermis, aggregates of neutrophils, lymphocytes, macrophages, or multinucleated giant cells may be found.17 The histologic findings vary depending on the stage of evolution of the individual lesion. Early lesions show a concave depression with acanthosis, vacuolation of basal keratinocytes, and dermal inflammation.4 Additionally, transepidermal channels filled with keratin, pyknotic nuclear debris, inflammatory cells, elastin, or collagen can be noted.3 Over time, the elastic fibers, as detected by the Verhoeff-van Gieson stain, dissipate and the collagen acquires a basophilic staining. Adjacent to the channels, the basement membrane remains intact in early lesions but later shows discontinuities and electron-dense fibrinlike material.3 Occasionally, amorphous degenerated material within the perforations is the major histologic finding.11 Usually, the material cannot be clearly identified as collagen or elastin, but sometimes both are present.

In our case, we identified elastin as the perforating substance, which is less common than collagen, the typical perforating substance in APD. Elastin has occasionally been seen to serve as the only perforating substance from APD lesions among patients. Abe et al18 reported that the biopsy of a Japanese patient with keratotic follicular papules and serpiginous-arranged papules demonstrated elimination of atypical elastin fibers from the transepidermal channels. This patient was diagnosed with APD as well as EPS and perforating folliculitis based on the clinical presentation.18 Kim et al19 studied 30 Korean patients with APD. One had serpiginous hyperkeratotic plaques along the upper extremity and trunk that revealed transepidermal channels containing coarse elastic fibers and basophilic debris; however, due to the serpiginous morphology of lesions, both Abe et al18 and Kim et al19 favored a diagnosis of acquired EPS. Saray et al20 conducted a retrospective study of 22 Turkish patients with APD; 1 patient had a painful hyperkeratotic papule on the auricle that on histopathology showed degenerated elastin perforating through the keratotic plug, features similar to our case.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses include perforating diseases14,19 as well as other disorders that exhibit the Köbner phenomenon, such as psoriasis, lichen planus, and verruca vulgaris.21,22 Also, it is not uncommon for patients with APD to have coexisting folliculitis or prurigo nodularis.22

Treatment

Management is focused on treating the symptoms. For pruritus, sedating antihistamines and other antipruritic agents are efficacious.23 Topical, intra-lesional, or systemic corticosteroids and topical retinoids have shown variable resolution in APD lesions.24 Some case reports describe topical menthol, salicylic acid, sulfur, benzoyl peroxide, systemic antibiotics (eg, clindamycin, doxycycline), and allopurinol for elevated uric acid levels as effective treatment methods.6 Narrowband UVB phototherapy is beneficial for APD and renal disease.25,26 Renal transplantation has been curative for some patients with APD.27 Given that our patient’s lesions were asymptomatic, no treatment was offered at the time.

Conclusion

Our patient presented with APD localized exclusively to the site of a skin graft, and histologic examination identified elastin as the primary perforating substance. A medical history of DM and chronic kidney disease predisposes patients to APD. This case suggests that skin graft sites may be predisposed to the development of APD.

- Rodney IJ, Taylor CS, Cohen G. Derm Dx: what are these pruritic nodules? The Dermatologist. October 15, 2009. http://www.the-dermatologist.com/content/derm-dx-what-are-these-pruritic-nodules. Accessed September 18, 2018.

- Gagnon, AL, Desai T. Dermatological diseases in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Nephropathol. 2013;2:104-109.

- Kurban MS, Boueiz A, Kibbi AG. Cutaneous manifestations of chronic kidney disease. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:255-264.

- Wagner G, Sachse MM. Acquired reactive perforating dermatosis [published online May 29, 2013]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:723-729; 723-730.

- Karpouzis A, Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: current status. J Dermatol. 2010;37:585-592.

- Healy R, Cerio R, Hollingsworth A, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis associated with pregnancy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:621-623.

- Cordova KB, Oberg TJ, Malik M, et al. Dermatologic conditions seen in end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2009;22:45-55.

- Satchell AC, Crotty K, Lee S. Reactive perforating collagenosis: a condition that may be underdiagnosed. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:284-287.

- Fujimoto E, Kobayashi T, Fujimoto N, et al. AGE-modified collagens I and III induce keratinocyte terminal differentiation through AGE receptor CD36: epidermal-dermal interaction in acquired perforating dermatosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:405-414.

- Bilezikci B, Sechkin D, Demirhan B. Acquired perforating dermatosis in patients with chronic renal failure: a possible role for fibronectin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:230-232.

- Rapini RP, Herbert AA, Drucker CR. Acquired perforating dermatosis. evidence for combined transepidermal elimination of both collagen and elastic fibers. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:1074-1078.

- Hurwitz RM, Melton ME, Creech FT, et al. Perforating folliculitis in association with hemodialysis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1982;4:101-108.

- Morton CA, Henderson IS, Jones MC, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in a British dialysis population. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:671-677.

- Lübbe J, Sorg O, Malé PJ, et al. Sirolimus-induced inflammatory papules with acquired reactive perforating collagenosis [published online January 9, 2008]. Dermatology. 2008;216:239-242.

- Pernet C, Pageaux GP, Guillot B, et al. Telaprevir-induced acquired perforating dermatosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1371-1372.

- Severino-Freire M, Sibaud V, Tournier E, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis associated with sorafenib therapy [published online September 11, 2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:328-330.

- Zelger B, Hintner H, Auböck J, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis. transepidermal elimination of DNA material and possible role of leukocytes in pathogenesis. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:695-700.

- Abe R, Murase S, Nomura Y, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis appearing as elastosis perforans serpiginosa and perforating folliculitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:653-654.

- Kim SW, Kim MS, Lee JH, et al. A clinicopathologic study of thirty cases of acquired perforating dermatosis in Korea. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:162-171.

- Saray Y, Seçkin D, Bilezikçi B. Acquired perforating dermatosis: clinicopathological features in twenty-two cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:679-688.

- Carter VH, Constantine VS. Kyrle’s disease. I. clinical findings in five cases and review of literature. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:624-632.

- Robinson-Bostom L, Digiovanna JJ. Cutaneous manifestations of end-stage renal disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:975-986.

- Hong SB, Park JH, Ihm CG, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in patients with chronic renal failure and diabetes mellitus. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19:283-288.

- Morton CA, Henderson IS, Jones MC, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in a British dialysis population. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:671-677.

- Ohe S, Danno K, Sasaki H, et al. Treatment of acquired perforating dermatosis with narrowband ultraviolet B. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:892-894.

- Sezer E, Erkek E. Acquired perforating dermatosis successfully treated with photodynamic therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:50-52.

- Saldanha LF, Gonick HC, Rodriguez HJ, et al. Silicon-related syndrome in dialysis patients. Nephron. 1997;77:48-56.

Case Report

A 57-year-old black woman with a history of dialysis-dependent end-stage renal disease, diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, diastolic congestive heart failure, and chronic bronchitis was admitted to Howard University Hospital (Washington, DC) for acute chest pain and shortness of breath. During her hospital stay the dermatology team was consulted for evaluation of two 1.6-cm teardrop-shaped, yellow-white-chalky plaques noted in the center of an atrophic, hyperpigmented, shiny, contracted split-thickness skin graft (STSG) on the right posterior forearm (Figure 1). Twenty years prior, the patient received STSGs on the right and left forearm secondary to caustic burns. Two months before the current admission she noticed 2 adjacent teardrop-shaped white plaques within the center of the STSG on the right forearm. At a 3-month follow-up, she had developed more lesions within both graft sites of the bilateral forearm. There was no notable pruritus associated with the lesions.

A 4-mm punch biopsy showed an orthokeratotic plug with basophilic inflammatory debris adjacent to acanthotic epidermis, necrotic basophilic debris at the superficial dermis with epidermal canals extending from the base of the lesion superiorly, and transepidermal elimination of elastic fibers (Figure 2A). A Verhoeff-van Gieson stain revealed the necrotic basophilic debris located in the superficial dermis admixed with a cluster of black wavy elastic fibers establishing the identity of the perforating substance (Figure 2B). Masson trichrome stain revealed loss of collagen structure within the aggregate of elastic fibers adjacent to the epidermis and no collagen within epidermal canals (Figure 2C). These histopathologic findings together with the clinical presentation were consistent with a diagnosis of acquired perforating dermatosis (APD).

Comment

Presentation

Acquired perforating dermatosis is a dermatologic condition characterized by multiple pruritic, dome-shaped papules and plaques with central keratotic plugs giving a craterlike appearance.1-4 A green-brown or black crust with an erythematous border typically surrounds the primary lesions.4 Acquired perforating dermatosis favors a distribution over the trunk, gluteal region, and the extensor surfaces of the upper and lower extremities. Palmoplantar, intertriginous, and mucous membrane regions typically are spared.4 Occasionally, APD may present as generalized nodules and papules. Our case consisting of lesions that were localized to STSGs on the forearms supports the typical distribution; however, the presentation of APD occurring within a skin graft is unique.

From an epidemiologic standpoint, APD is more likely to affect men than women (1.5:1 ratio). Additionally, APD’s affected age range is 29 to 96 years (mean, 56.8 years),5 which is consistent with our patient’s age. Acquired perforating dermatosis has no racial predilection, though there is a predominance among black patients with concomitant chronic renal failure, as seen in our patient.3

Pathogenesis

The etiology of APD remains unknown.6 Some believe that the uremic or calcium deposits on the skin of patients with chronic kidney disease may trigger chronic pruritus, leading to epithelial hyperplasia and the development of perforating lesions.1,3 A prominent theory in the literature is that superficial trauma, such as scratching, induces necrosis of tissue, facilitating transepidermal elimination of connective tissue components.7 The Köbner phenomenon, which can easily be induced by scratching the skin, supports this idea.8 Fujimoto et al9 suggested that scratching exposes keratinocytes to advanced glycation end product–modified extracellular matrix proteins, particularly types I and III collagen. This exposure leads to the terminal differentiation of keratinocytes with the advanced glycation end receptor (CD36) followed by the upward movement of keratinocytes with glycated collagen. Others postulate fibronectin, involved in epidermal cell signaling, locomotion, and differentiation, is an antigenic trigger because patients with DM and uremia have increased levels of fibronectin in the serum and at sites of perforating skin lesions.10

Diseases Associated With APD

Acquired perforating dermatosis is an umbrella term for perforating disease found in adults. It is associated with systemic diseases, such as DM and pruritus of renal failure.11 Our patient had both dialysis-dependent end-stage renal disease and DM. Acquired perforating dermatosis is observed in 4.5% to 11% of patients on hemodialysis12,13; however, APD may occur prior to or in the absence of dialysis.3 Other examples of systemic conditions associated with APD include obstructive uropathy, chronic nephritis, anuria, and hypertensive nephrosclerosis. Koebnerization also may trigger lesions to manifest in a linear pattern after localized trauma to the skin.7 Acquired perforating dermatosis is associated with other types of trauma, such as healing herpes zoster, or following exposure to drugs, such as tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors, bevacizumab, telaprevir, sorafenib, sirolimus, and indinavir.14-16 Rarely, there have been associations with a history of insect bites, scabies, lymphoma, and hepatobiliary disease.1-3

Histopathology

Acquired perforating dermatosis is classified as a perforating disease, along with reactive perforating collagenosis, elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS), perforating folliculitis, and perforating calcific elastosis. Perforating diseases are histologically characterized by the transepidermal penetration and elimination of altered connective tissue and inflammatory cells.5 Each disease differs based on their clinical and histological characteristics.

Histologic sections of APD show a plug of crusting or hyperkeratosis with variable parakeratosis, acanthosis, and occasional dyskeratotic keratinocytes. In the dermis, aggregates of neutrophils, lymphocytes, macrophages, or multinucleated giant cells may be found.17 The histologic findings vary depending on the stage of evolution of the individual lesion. Early lesions show a concave depression with acanthosis, vacuolation of basal keratinocytes, and dermal inflammation.4 Additionally, transepidermal channels filled with keratin, pyknotic nuclear debris, inflammatory cells, elastin, or collagen can be noted.3 Over time, the elastic fibers, as detected by the Verhoeff-van Gieson stain, dissipate and the collagen acquires a basophilic staining. Adjacent to the channels, the basement membrane remains intact in early lesions but later shows discontinuities and electron-dense fibrinlike material.3 Occasionally, amorphous degenerated material within the perforations is the major histologic finding.11 Usually, the material cannot be clearly identified as collagen or elastin, but sometimes both are present.

In our case, we identified elastin as the perforating substance, which is less common than collagen, the typical perforating substance in APD. Elastin has occasionally been seen to serve as the only perforating substance from APD lesions among patients. Abe et al18 reported that the biopsy of a Japanese patient with keratotic follicular papules and serpiginous-arranged papules demonstrated elimination of atypical elastin fibers from the transepidermal channels. This patient was diagnosed with APD as well as EPS and perforating folliculitis based on the clinical presentation.18 Kim et al19 studied 30 Korean patients with APD. One had serpiginous hyperkeratotic plaques along the upper extremity and trunk that revealed transepidermal channels containing coarse elastic fibers and basophilic debris; however, due to the serpiginous morphology of lesions, both Abe et al18 and Kim et al19 favored a diagnosis of acquired EPS. Saray et al20 conducted a retrospective study of 22 Turkish patients with APD; 1 patient had a painful hyperkeratotic papule on the auricle that on histopathology showed degenerated elastin perforating through the keratotic plug, features similar to our case.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses include perforating diseases14,19 as well as other disorders that exhibit the Köbner phenomenon, such as psoriasis, lichen planus, and verruca vulgaris.21,22 Also, it is not uncommon for patients with APD to have coexisting folliculitis or prurigo nodularis.22

Treatment

Management is focused on treating the symptoms. For pruritus, sedating antihistamines and other antipruritic agents are efficacious.23 Topical, intra-lesional, or systemic corticosteroids and topical retinoids have shown variable resolution in APD lesions.24 Some case reports describe topical menthol, salicylic acid, sulfur, benzoyl peroxide, systemic antibiotics (eg, clindamycin, doxycycline), and allopurinol for elevated uric acid levels as effective treatment methods.6 Narrowband UVB phototherapy is beneficial for APD and renal disease.25,26 Renal transplantation has been curative for some patients with APD.27 Given that our patient’s lesions were asymptomatic, no treatment was offered at the time.

Conclusion

Our patient presented with APD localized exclusively to the site of a skin graft, and histologic examination identified elastin as the primary perforating substance. A medical history of DM and chronic kidney disease predisposes patients to APD. This case suggests that skin graft sites may be predisposed to the development of APD.

Case Report

A 57-year-old black woman with a history of dialysis-dependent end-stage renal disease, diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, diastolic congestive heart failure, and chronic bronchitis was admitted to Howard University Hospital (Washington, DC) for acute chest pain and shortness of breath. During her hospital stay the dermatology team was consulted for evaluation of two 1.6-cm teardrop-shaped, yellow-white-chalky plaques noted in the center of an atrophic, hyperpigmented, shiny, contracted split-thickness skin graft (STSG) on the right posterior forearm (Figure 1). Twenty years prior, the patient received STSGs on the right and left forearm secondary to caustic burns. Two months before the current admission she noticed 2 adjacent teardrop-shaped white plaques within the center of the STSG on the right forearm. At a 3-month follow-up, she had developed more lesions within both graft sites of the bilateral forearm. There was no notable pruritus associated with the lesions.

A 4-mm punch biopsy showed an orthokeratotic plug with basophilic inflammatory debris adjacent to acanthotic epidermis, necrotic basophilic debris at the superficial dermis with epidermal canals extending from the base of the lesion superiorly, and transepidermal elimination of elastic fibers (Figure 2A). A Verhoeff-van Gieson stain revealed the necrotic basophilic debris located in the superficial dermis admixed with a cluster of black wavy elastic fibers establishing the identity of the perforating substance (Figure 2B). Masson trichrome stain revealed loss of collagen structure within the aggregate of elastic fibers adjacent to the epidermis and no collagen within epidermal canals (Figure 2C). These histopathologic findings together with the clinical presentation were consistent with a diagnosis of acquired perforating dermatosis (APD).

Comment

Presentation

Acquired perforating dermatosis is a dermatologic condition characterized by multiple pruritic, dome-shaped papules and plaques with central keratotic plugs giving a craterlike appearance.1-4 A green-brown or black crust with an erythematous border typically surrounds the primary lesions.4 Acquired perforating dermatosis favors a distribution over the trunk, gluteal region, and the extensor surfaces of the upper and lower extremities. Palmoplantar, intertriginous, and mucous membrane regions typically are spared.4 Occasionally, APD may present as generalized nodules and papules. Our case consisting of lesions that were localized to STSGs on the forearms supports the typical distribution; however, the presentation of APD occurring within a skin graft is unique.

From an epidemiologic standpoint, APD is more likely to affect men than women (1.5:1 ratio). Additionally, APD’s affected age range is 29 to 96 years (mean, 56.8 years),5 which is consistent with our patient’s age. Acquired perforating dermatosis has no racial predilection, though there is a predominance among black patients with concomitant chronic renal failure, as seen in our patient.3

Pathogenesis

The etiology of APD remains unknown.6 Some believe that the uremic or calcium deposits on the skin of patients with chronic kidney disease may trigger chronic pruritus, leading to epithelial hyperplasia and the development of perforating lesions.1,3 A prominent theory in the literature is that superficial trauma, such as scratching, induces necrosis of tissue, facilitating transepidermal elimination of connective tissue components.7 The Köbner phenomenon, which can easily be induced by scratching the skin, supports this idea.8 Fujimoto et al9 suggested that scratching exposes keratinocytes to advanced glycation end product–modified extracellular matrix proteins, particularly types I and III collagen. This exposure leads to the terminal differentiation of keratinocytes with the advanced glycation end receptor (CD36) followed by the upward movement of keratinocytes with glycated collagen. Others postulate fibronectin, involved in epidermal cell signaling, locomotion, and differentiation, is an antigenic trigger because patients with DM and uremia have increased levels of fibronectin in the serum and at sites of perforating skin lesions.10

Diseases Associated With APD

Acquired perforating dermatosis is an umbrella term for perforating disease found in adults. It is associated with systemic diseases, such as DM and pruritus of renal failure.11 Our patient had both dialysis-dependent end-stage renal disease and DM. Acquired perforating dermatosis is observed in 4.5% to 11% of patients on hemodialysis12,13; however, APD may occur prior to or in the absence of dialysis.3 Other examples of systemic conditions associated with APD include obstructive uropathy, chronic nephritis, anuria, and hypertensive nephrosclerosis. Koebnerization also may trigger lesions to manifest in a linear pattern after localized trauma to the skin.7 Acquired perforating dermatosis is associated with other types of trauma, such as healing herpes zoster, or following exposure to drugs, such as tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors, bevacizumab, telaprevir, sorafenib, sirolimus, and indinavir.14-16 Rarely, there have been associations with a history of insect bites, scabies, lymphoma, and hepatobiliary disease.1-3

Histopathology

Acquired perforating dermatosis is classified as a perforating disease, along with reactive perforating collagenosis, elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS), perforating folliculitis, and perforating calcific elastosis. Perforating diseases are histologically characterized by the transepidermal penetration and elimination of altered connective tissue and inflammatory cells.5 Each disease differs based on their clinical and histological characteristics.

Histologic sections of APD show a plug of crusting or hyperkeratosis with variable parakeratosis, acanthosis, and occasional dyskeratotic keratinocytes. In the dermis, aggregates of neutrophils, lymphocytes, macrophages, or multinucleated giant cells may be found.17 The histologic findings vary depending on the stage of evolution of the individual lesion. Early lesions show a concave depression with acanthosis, vacuolation of basal keratinocytes, and dermal inflammation.4 Additionally, transepidermal channels filled with keratin, pyknotic nuclear debris, inflammatory cells, elastin, or collagen can be noted.3 Over time, the elastic fibers, as detected by the Verhoeff-van Gieson stain, dissipate and the collagen acquires a basophilic staining. Adjacent to the channels, the basement membrane remains intact in early lesions but later shows discontinuities and electron-dense fibrinlike material.3 Occasionally, amorphous degenerated material within the perforations is the major histologic finding.11 Usually, the material cannot be clearly identified as collagen or elastin, but sometimes both are present.

In our case, we identified elastin as the perforating substance, which is less common than collagen, the typical perforating substance in APD. Elastin has occasionally been seen to serve as the only perforating substance from APD lesions among patients. Abe et al18 reported that the biopsy of a Japanese patient with keratotic follicular papules and serpiginous-arranged papules demonstrated elimination of atypical elastin fibers from the transepidermal channels. This patient was diagnosed with APD as well as EPS and perforating folliculitis based on the clinical presentation.18 Kim et al19 studied 30 Korean patients with APD. One had serpiginous hyperkeratotic plaques along the upper extremity and trunk that revealed transepidermal channels containing coarse elastic fibers and basophilic debris; however, due to the serpiginous morphology of lesions, both Abe et al18 and Kim et al19 favored a diagnosis of acquired EPS. Saray et al20 conducted a retrospective study of 22 Turkish patients with APD; 1 patient had a painful hyperkeratotic papule on the auricle that on histopathology showed degenerated elastin perforating through the keratotic plug, features similar to our case.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses include perforating diseases14,19 as well as other disorders that exhibit the Köbner phenomenon, such as psoriasis, lichen planus, and verruca vulgaris.21,22 Also, it is not uncommon for patients with APD to have coexisting folliculitis or prurigo nodularis.22

Treatment

Management is focused on treating the symptoms. For pruritus, sedating antihistamines and other antipruritic agents are efficacious.23 Topical, intra-lesional, or systemic corticosteroids and topical retinoids have shown variable resolution in APD lesions.24 Some case reports describe topical menthol, salicylic acid, sulfur, benzoyl peroxide, systemic antibiotics (eg, clindamycin, doxycycline), and allopurinol for elevated uric acid levels as effective treatment methods.6 Narrowband UVB phototherapy is beneficial for APD and renal disease.25,26 Renal transplantation has been curative for some patients with APD.27 Given that our patient’s lesions were asymptomatic, no treatment was offered at the time.

Conclusion

Our patient presented with APD localized exclusively to the site of a skin graft, and histologic examination identified elastin as the primary perforating substance. A medical history of DM and chronic kidney disease predisposes patients to APD. This case suggests that skin graft sites may be predisposed to the development of APD.

- Rodney IJ, Taylor CS, Cohen G. Derm Dx: what are these pruritic nodules? The Dermatologist. October 15, 2009. http://www.the-dermatologist.com/content/derm-dx-what-are-these-pruritic-nodules. Accessed September 18, 2018.

- Gagnon, AL, Desai T. Dermatological diseases in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Nephropathol. 2013;2:104-109.

- Kurban MS, Boueiz A, Kibbi AG. Cutaneous manifestations of chronic kidney disease. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:255-264.

- Wagner G, Sachse MM. Acquired reactive perforating dermatosis [published online May 29, 2013]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:723-729; 723-730.

- Karpouzis A, Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: current status. J Dermatol. 2010;37:585-592.

- Healy R, Cerio R, Hollingsworth A, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis associated with pregnancy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:621-623.

- Cordova KB, Oberg TJ, Malik M, et al. Dermatologic conditions seen in end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2009;22:45-55.

- Satchell AC, Crotty K, Lee S. Reactive perforating collagenosis: a condition that may be underdiagnosed. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:284-287.

- Fujimoto E, Kobayashi T, Fujimoto N, et al. AGE-modified collagens I and III induce keratinocyte terminal differentiation through AGE receptor CD36: epidermal-dermal interaction in acquired perforating dermatosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:405-414.

- Bilezikci B, Sechkin D, Demirhan B. Acquired perforating dermatosis in patients with chronic renal failure: a possible role for fibronectin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:230-232.

- Rapini RP, Herbert AA, Drucker CR. Acquired perforating dermatosis. evidence for combined transepidermal elimination of both collagen and elastic fibers. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:1074-1078.

- Hurwitz RM, Melton ME, Creech FT, et al. Perforating folliculitis in association with hemodialysis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1982;4:101-108.

- Morton CA, Henderson IS, Jones MC, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in a British dialysis population. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:671-677.

- Lübbe J, Sorg O, Malé PJ, et al. Sirolimus-induced inflammatory papules with acquired reactive perforating collagenosis [published online January 9, 2008]. Dermatology. 2008;216:239-242.

- Pernet C, Pageaux GP, Guillot B, et al. Telaprevir-induced acquired perforating dermatosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1371-1372.

- Severino-Freire M, Sibaud V, Tournier E, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis associated with sorafenib therapy [published online September 11, 2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:328-330.

- Zelger B, Hintner H, Auböck J, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis. transepidermal elimination of DNA material and possible role of leukocytes in pathogenesis. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:695-700.

- Abe R, Murase S, Nomura Y, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis appearing as elastosis perforans serpiginosa and perforating folliculitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:653-654.

- Kim SW, Kim MS, Lee JH, et al. A clinicopathologic study of thirty cases of acquired perforating dermatosis in Korea. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:162-171.

- Saray Y, Seçkin D, Bilezikçi B. Acquired perforating dermatosis: clinicopathological features in twenty-two cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:679-688.

- Carter VH, Constantine VS. Kyrle’s disease. I. clinical findings in five cases and review of literature. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:624-632.

- Robinson-Bostom L, Digiovanna JJ. Cutaneous manifestations of end-stage renal disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:975-986.

- Hong SB, Park JH, Ihm CG, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in patients with chronic renal failure and diabetes mellitus. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19:283-288.

- Morton CA, Henderson IS, Jones MC, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in a British dialysis population. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:671-677.

- Ohe S, Danno K, Sasaki H, et al. Treatment of acquired perforating dermatosis with narrowband ultraviolet B. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:892-894.

- Sezer E, Erkek E. Acquired perforating dermatosis successfully treated with photodynamic therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:50-52.

- Saldanha LF, Gonick HC, Rodriguez HJ, et al. Silicon-related syndrome in dialysis patients. Nephron. 1997;77:48-56.

- Rodney IJ, Taylor CS, Cohen G. Derm Dx: what are these pruritic nodules? The Dermatologist. October 15, 2009. http://www.the-dermatologist.com/content/derm-dx-what-are-these-pruritic-nodules. Accessed September 18, 2018.

- Gagnon, AL, Desai T. Dermatological diseases in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Nephropathol. 2013;2:104-109.

- Kurban MS, Boueiz A, Kibbi AG. Cutaneous manifestations of chronic kidney disease. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:255-264.

- Wagner G, Sachse MM. Acquired reactive perforating dermatosis [published online May 29, 2013]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:723-729; 723-730.

- Karpouzis A, Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: current status. J Dermatol. 2010;37:585-592.

- Healy R, Cerio R, Hollingsworth A, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis associated with pregnancy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:621-623.

- Cordova KB, Oberg TJ, Malik M, et al. Dermatologic conditions seen in end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2009;22:45-55.

- Satchell AC, Crotty K, Lee S. Reactive perforating collagenosis: a condition that may be underdiagnosed. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:284-287.

- Fujimoto E, Kobayashi T, Fujimoto N, et al. AGE-modified collagens I and III induce keratinocyte terminal differentiation through AGE receptor CD36: epidermal-dermal interaction in acquired perforating dermatosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:405-414.

- Bilezikci B, Sechkin D, Demirhan B. Acquired perforating dermatosis in patients with chronic renal failure: a possible role for fibronectin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:230-232.

- Rapini RP, Herbert AA, Drucker CR. Acquired perforating dermatosis. evidence for combined transepidermal elimination of both collagen and elastic fibers. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:1074-1078.

- Hurwitz RM, Melton ME, Creech FT, et al. Perforating folliculitis in association with hemodialysis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1982;4:101-108.

- Morton CA, Henderson IS, Jones MC, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in a British dialysis population. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:671-677.

- Lübbe J, Sorg O, Malé PJ, et al. Sirolimus-induced inflammatory papules with acquired reactive perforating collagenosis [published online January 9, 2008]. Dermatology. 2008;216:239-242.

- Pernet C, Pageaux GP, Guillot B, et al. Telaprevir-induced acquired perforating dermatosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1371-1372.

- Severino-Freire M, Sibaud V, Tournier E, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis associated with sorafenib therapy [published online September 11, 2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:328-330.

- Zelger B, Hintner H, Auböck J, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis. transepidermal elimination of DNA material and possible role of leukocytes in pathogenesis. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:695-700.

- Abe R, Murase S, Nomura Y, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis appearing as elastosis perforans serpiginosa and perforating folliculitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:653-654.

- Kim SW, Kim MS, Lee JH, et al. A clinicopathologic study of thirty cases of acquired perforating dermatosis in Korea. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:162-171.

- Saray Y, Seçkin D, Bilezikçi B. Acquired perforating dermatosis: clinicopathological features in twenty-two cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:679-688.

- Carter VH, Constantine VS. Kyrle’s disease. I. clinical findings in five cases and review of literature. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:624-632.

- Robinson-Bostom L, Digiovanna JJ. Cutaneous manifestations of end-stage renal disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:975-986.

- Hong SB, Park JH, Ihm CG, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in patients with chronic renal failure and diabetes mellitus. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19:283-288.

- Morton CA, Henderson IS, Jones MC, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in a British dialysis population. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:671-677.

- Ohe S, Danno K, Sasaki H, et al. Treatment of acquired perforating dermatosis with narrowband ultraviolet B. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:892-894.

- Sezer E, Erkek E. Acquired perforating dermatosis successfully treated with photodynamic therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:50-52.

- Saldanha LF, Gonick HC, Rodriguez HJ, et al. Silicon-related syndrome in dialysis patients. Nephron. 1997;77:48-56.

Practice Points

- Acquired perforating dermatosis (APD) presents as pruritic crateriform papules and plaques with central keratotic plugs.

- A medical history of diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease predisposes patients to APD. This case suggests that skin graft sites may be predisposed to the development of APD.

Multiple Pink Papules on the Chest and Upper Abdomen

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Metastases

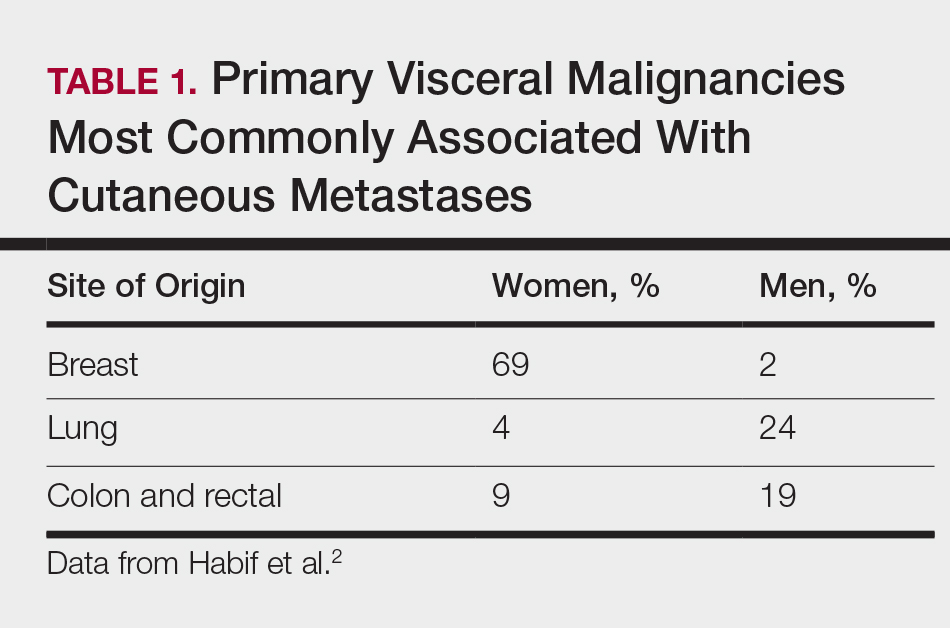

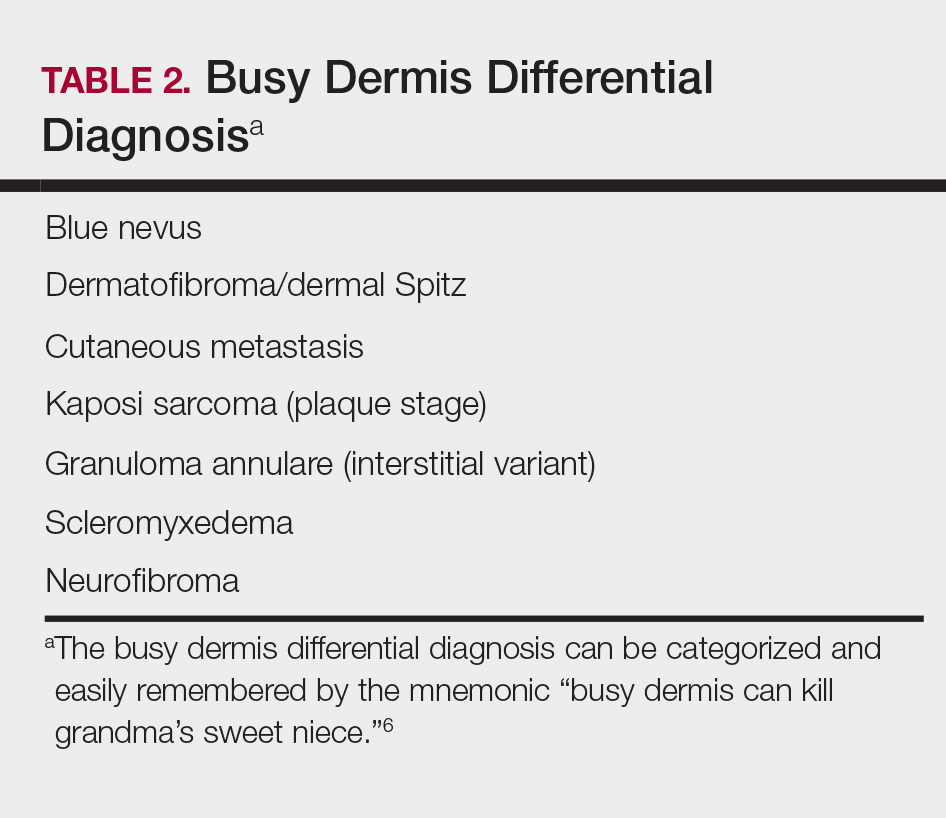

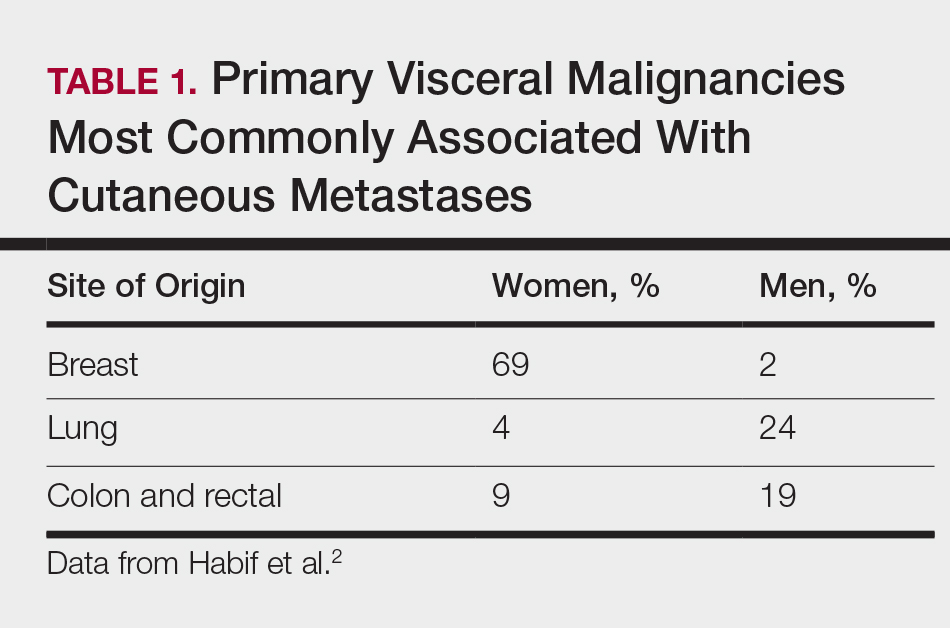

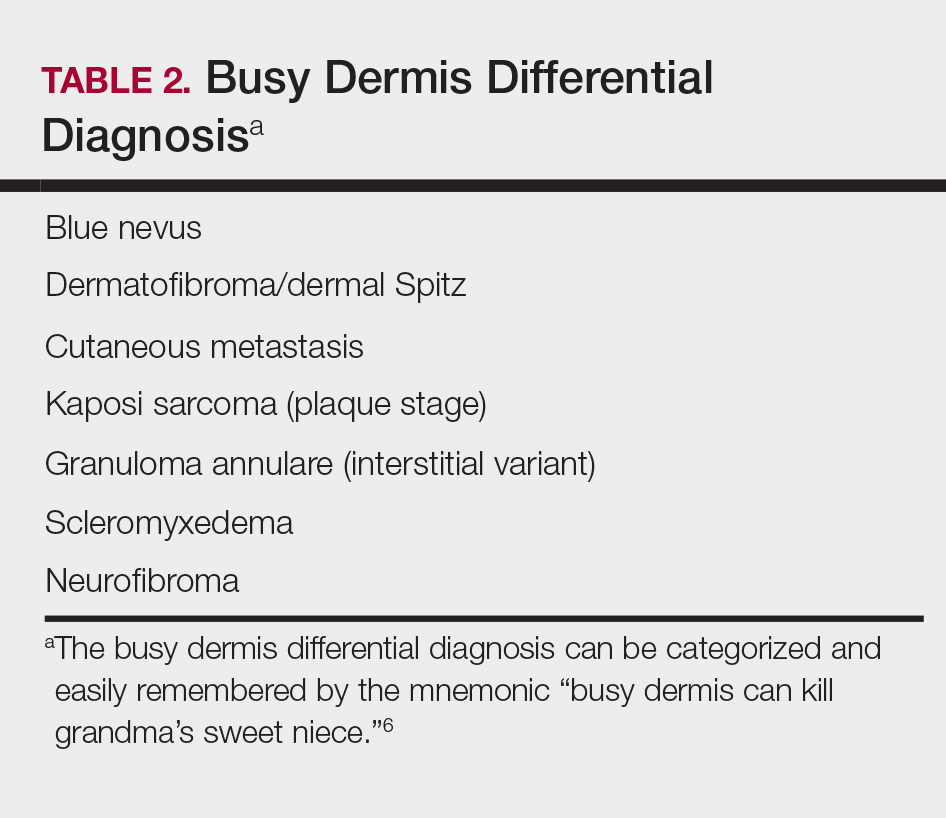

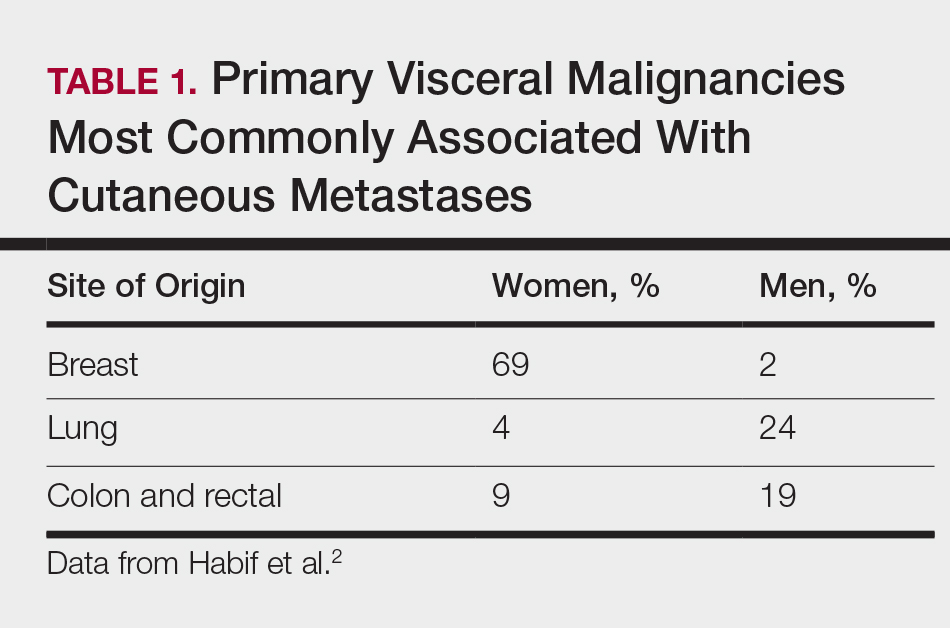

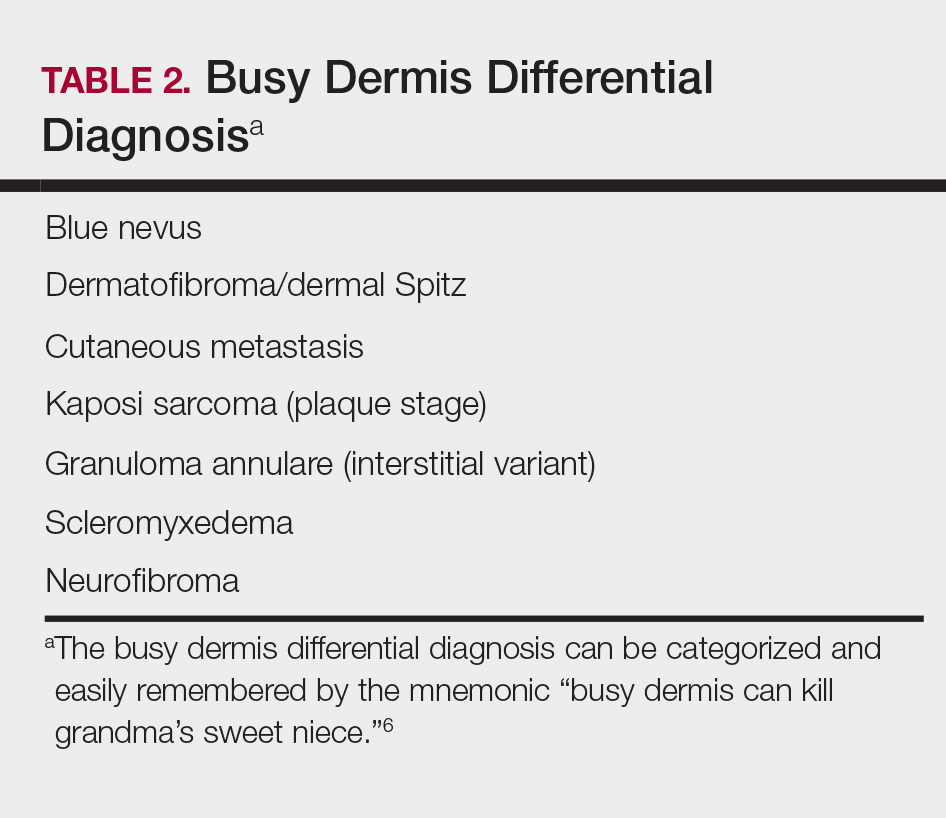

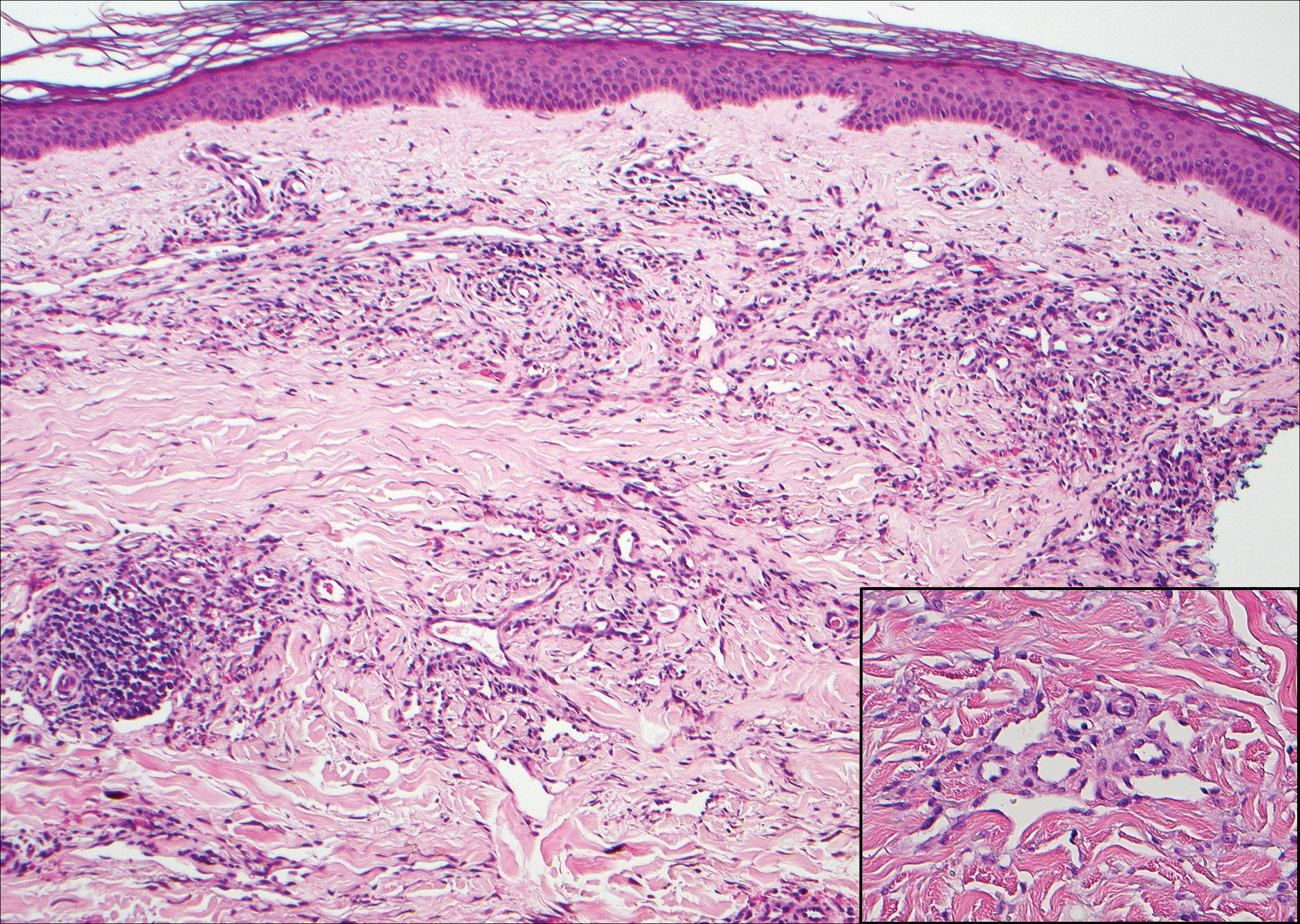

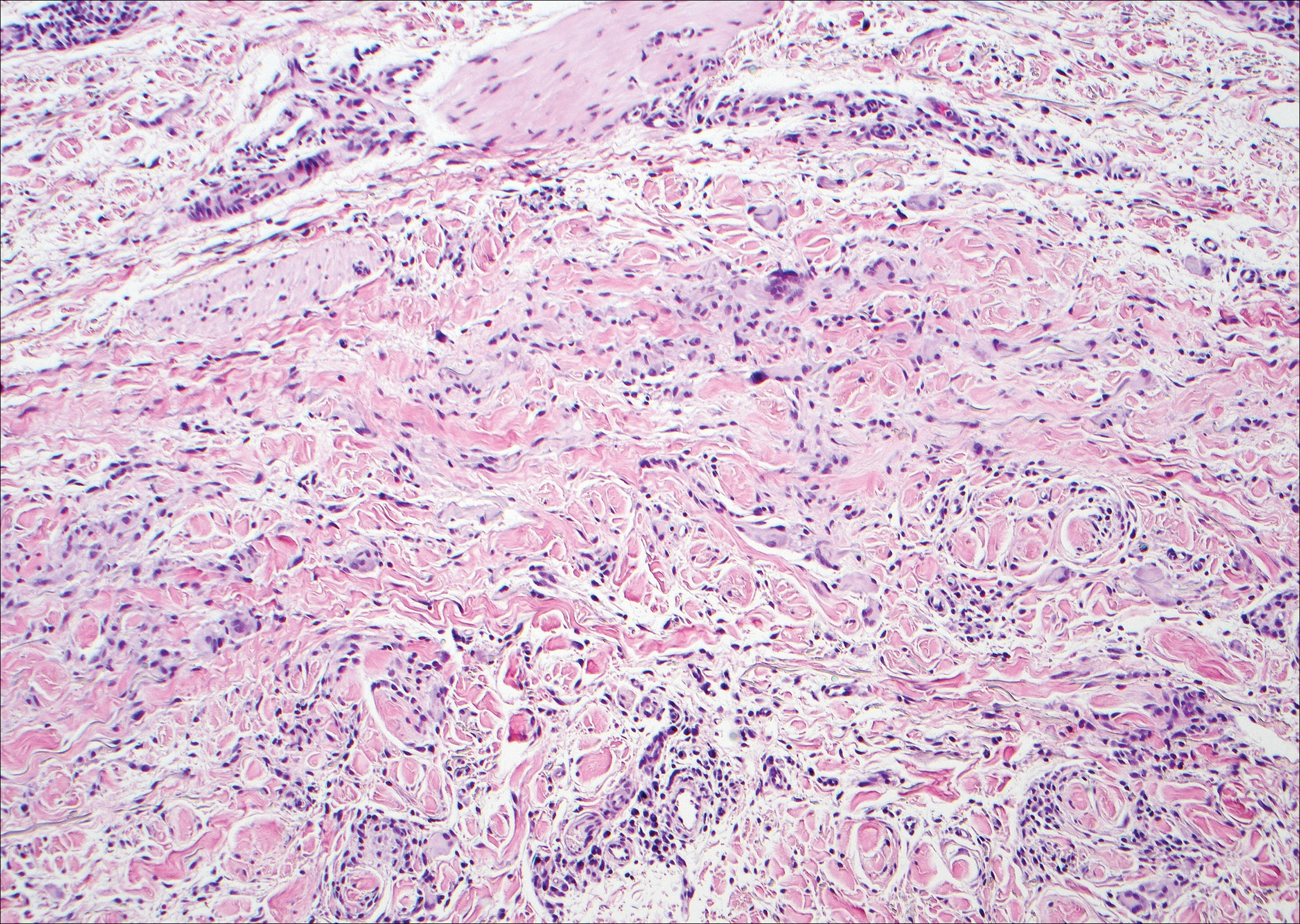

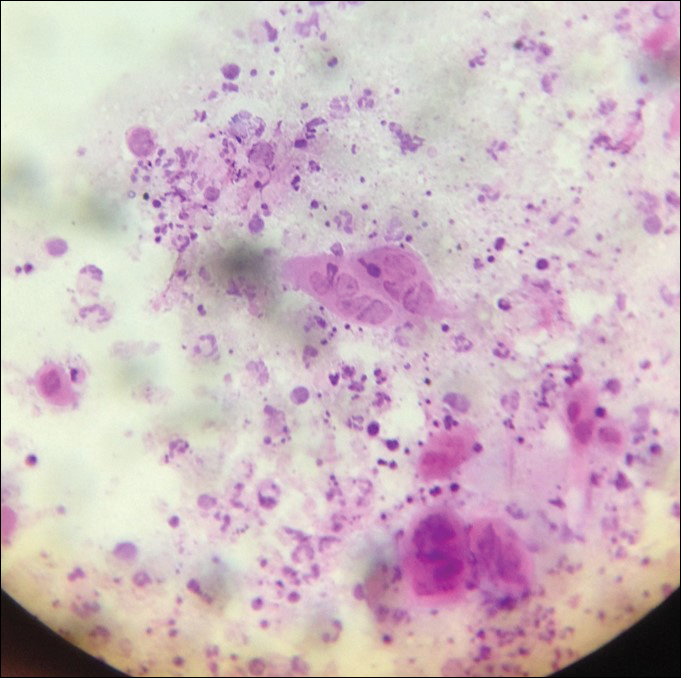

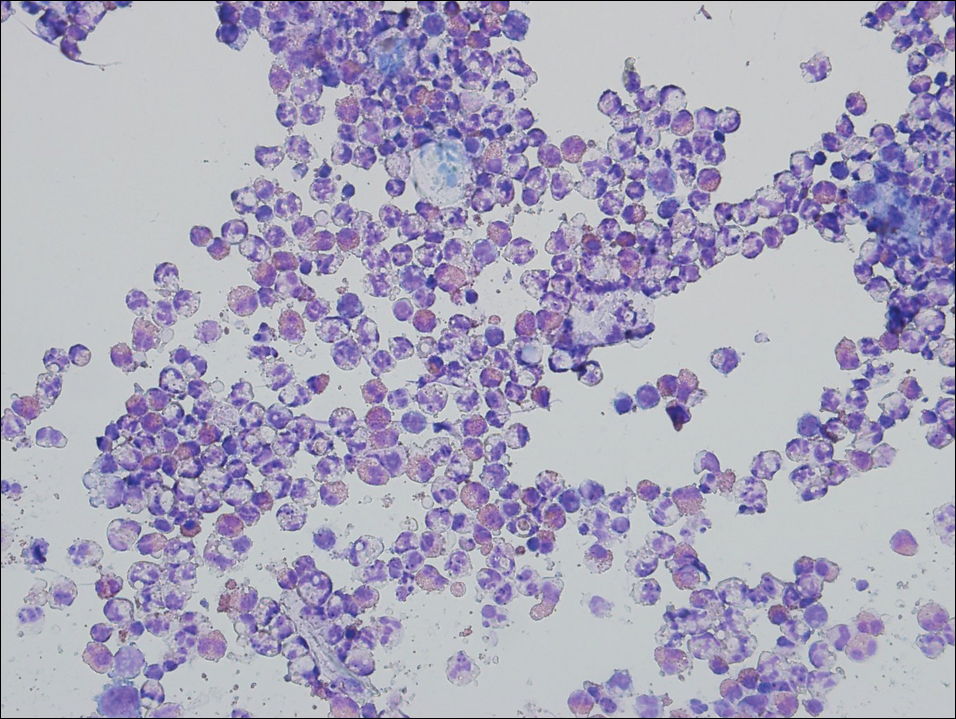

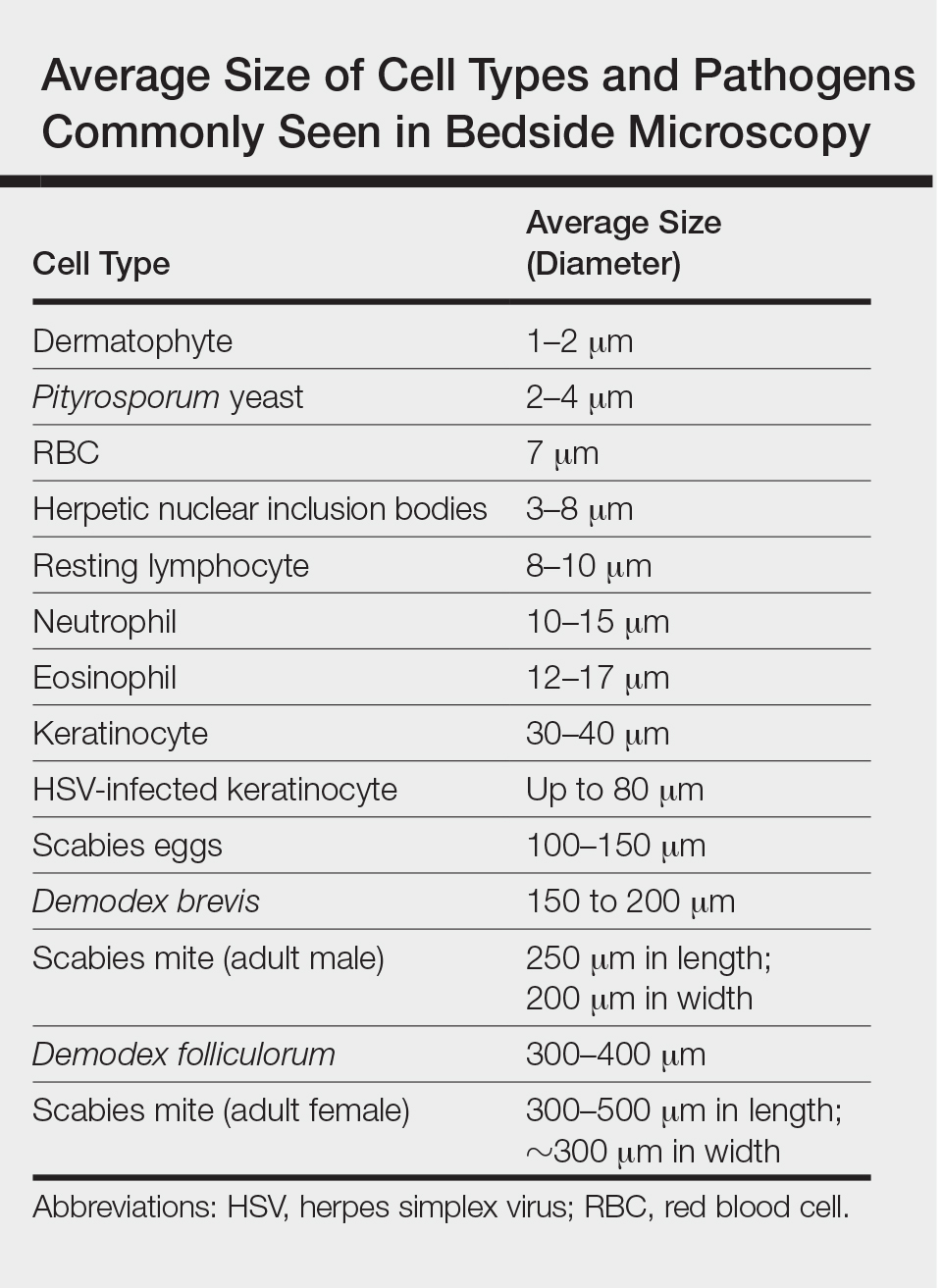

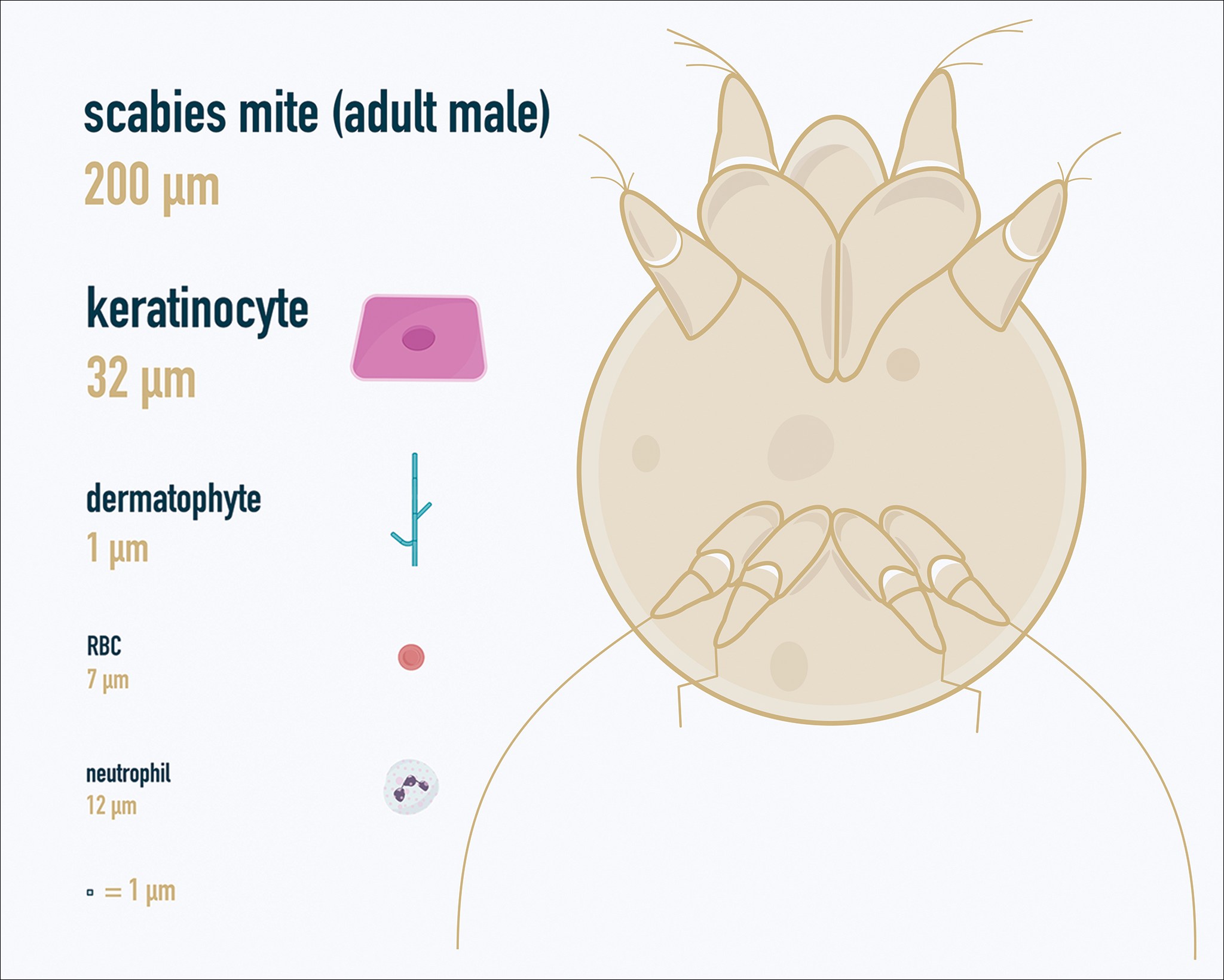

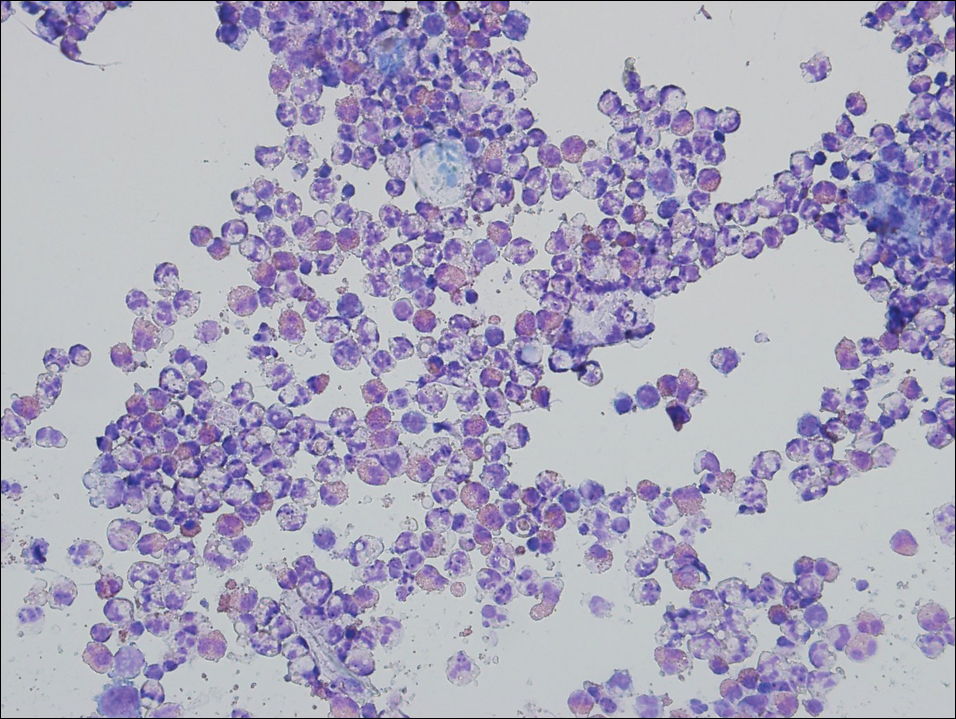

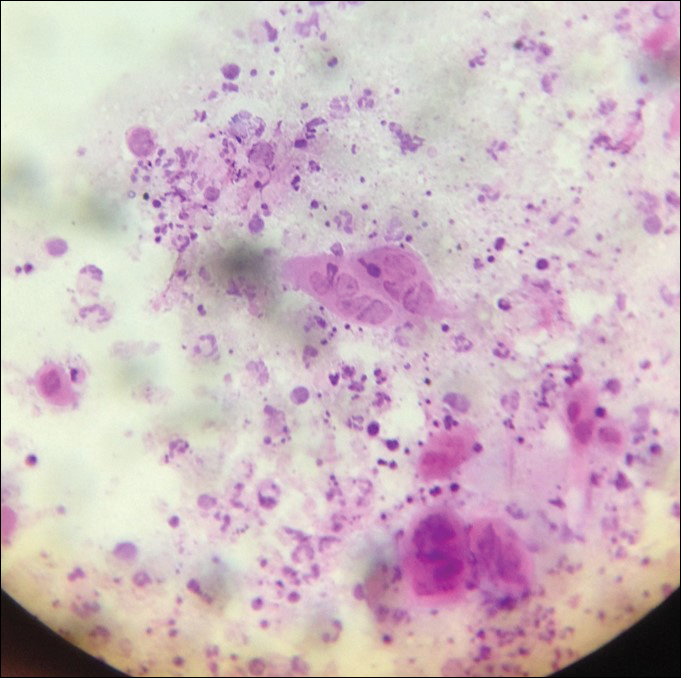

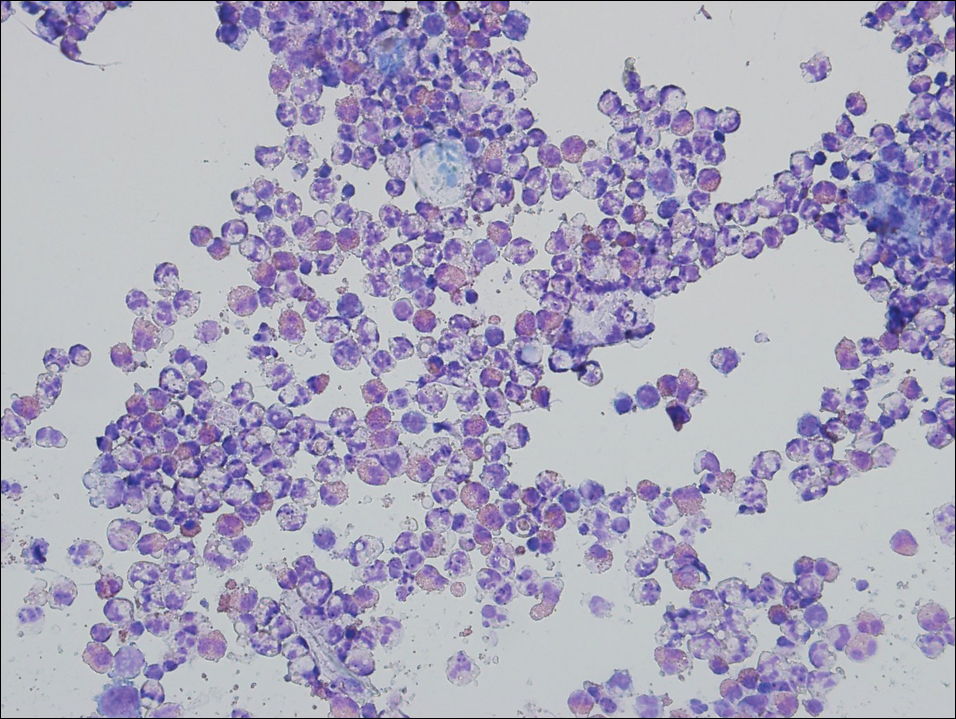

Cutaneous metastases (CMs) can present in an otherwise asymptomatic patient as the only sign of an underlying disease process. In women, the most common cause of CM is breast carcinoma.1-3 Cutaneous metastases are found in approximately 25% of all patients with breast carcinoma,1 and breast carcinomas represent approximately 69% of all CMs found in women (Table 1).2 Cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma (CMBC) is associated with a poor prognosis with a mean survival of approximately 6 months at the time of diagnosis.1,3 It commonly presents as a collection of flesh-colored, firm, asymptomatic, and rapidly appearing papules and nodules that can resemble cysts or fibrous tumors.1,3,4 They typically are located on the chest wall or abdomen near the site of the underlying malignancy.1-3 The histologic features of CMBC can include hyperchromatic tumor cells infiltrating between the collagen fibers in a characteristic single file manner,3,5 giving the appearance of a busy dermis, a nonspecific term to describe a focally hypercellular dermis at low-power magnification (Table 2).5,6 Cords and clusters of atypical cells with intracytoplasmic vacuoles or well-developed ducts also can be seen (quiz image [inset]). The carcinoma en cuirasse subtype of CMBC is characterized by a fibrotic scarlike plaque on the chest wall.1,3 If a punch biopsy is obtained, the specimen typically appears rectangular rather than tapered because of the sclerotic dermal collagen.6 In contrast, inflammatory carcinoma (carcinoma erysipelatoides) presents as an erythematous plaque resembling cellulitis due to the lymphatics being congested by tumor cells.3 Immunohistochemistry is a valuable tool in diagnosis. Positive staining is seen with cytokeratin 7, gross cystic disease fluid protein-15, mammaglobin, and GATA-3.1,3,6

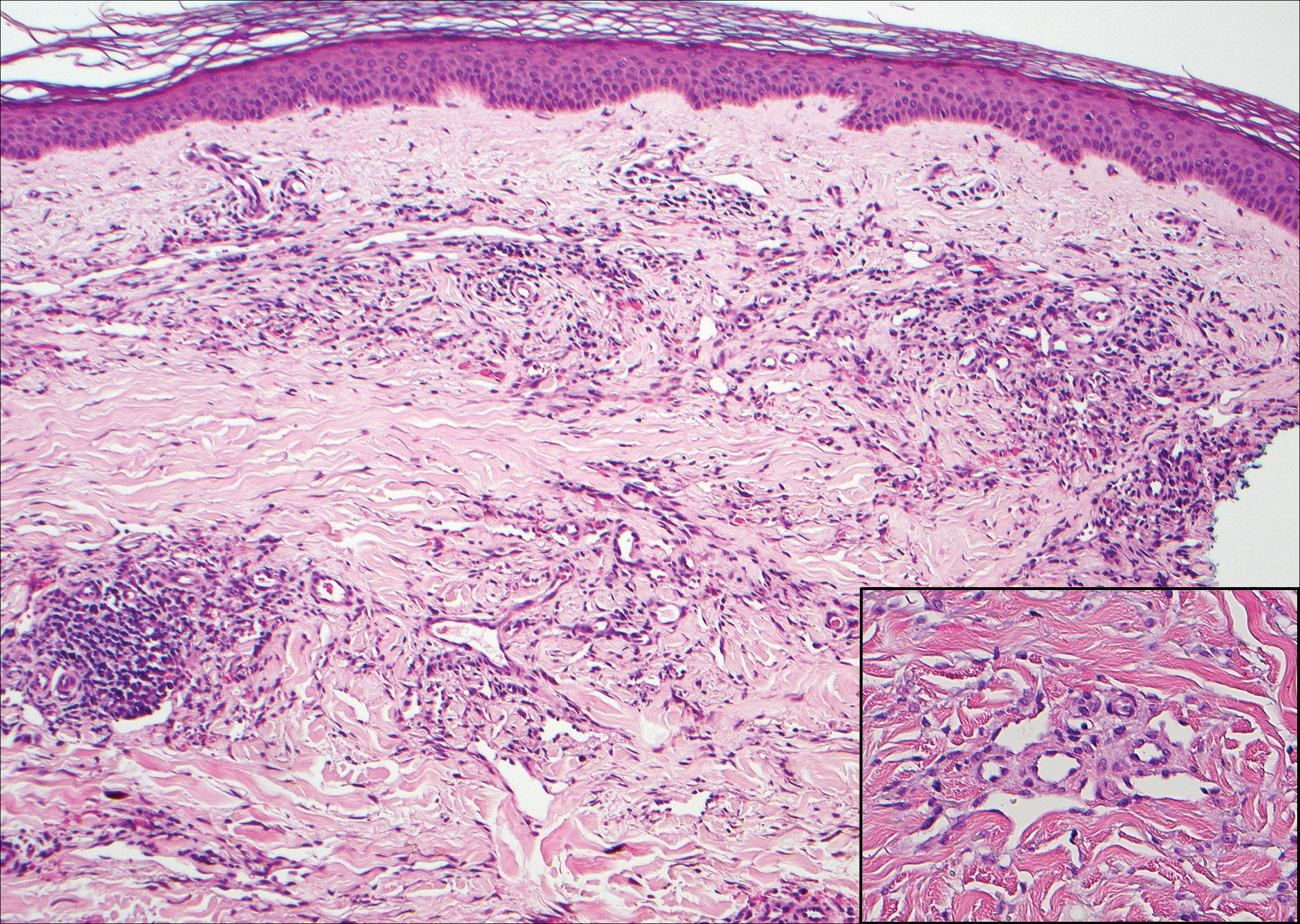

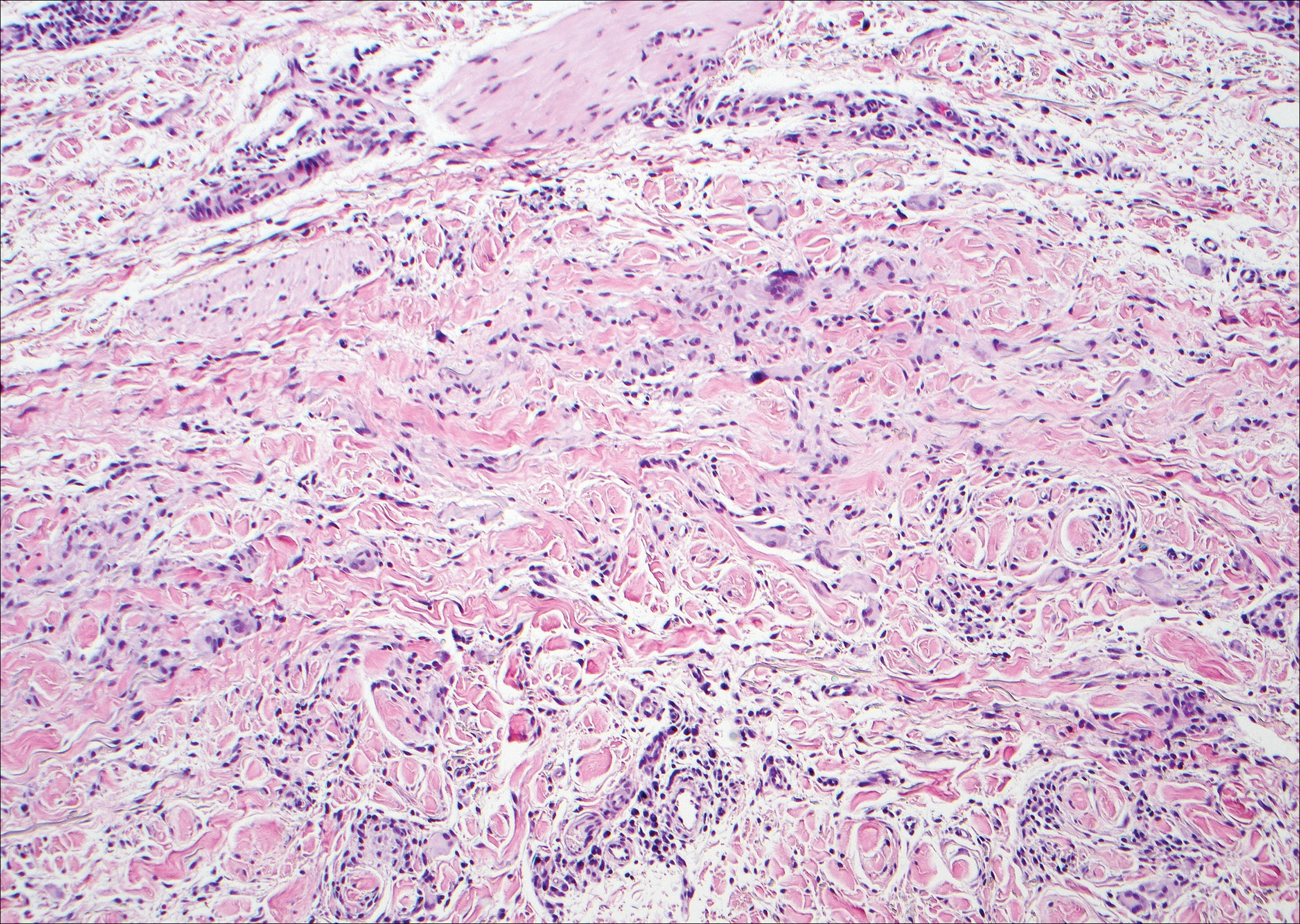

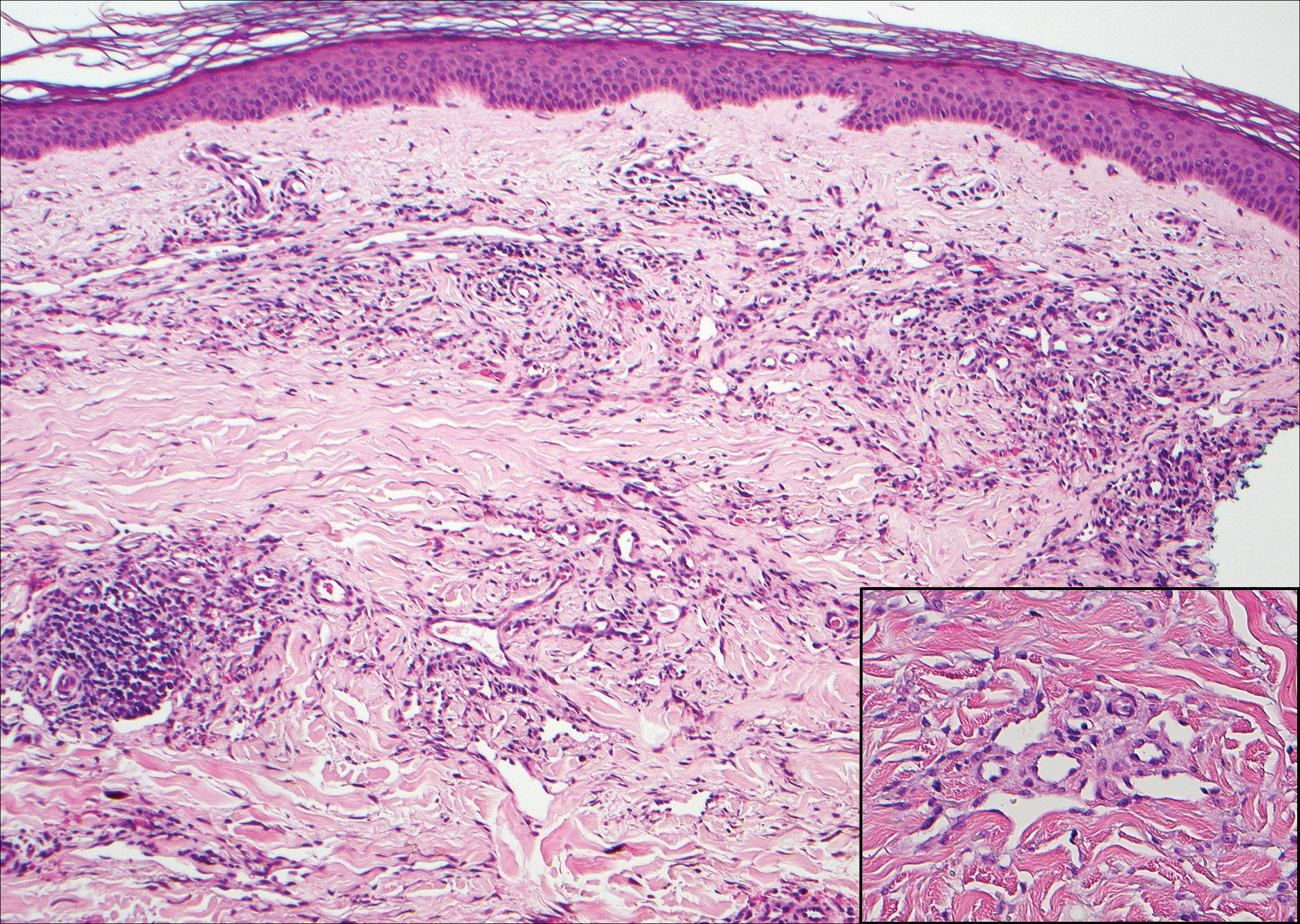

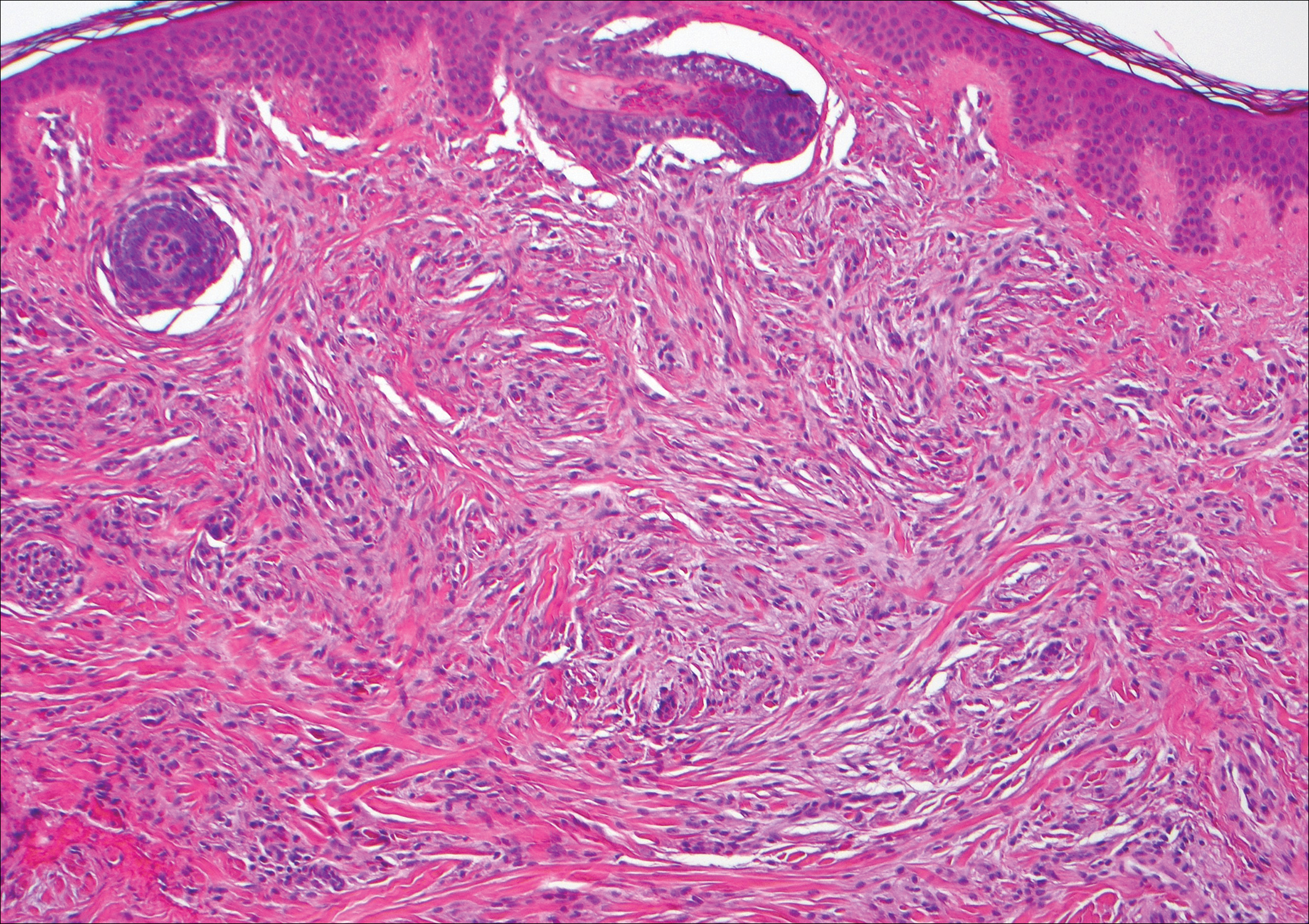

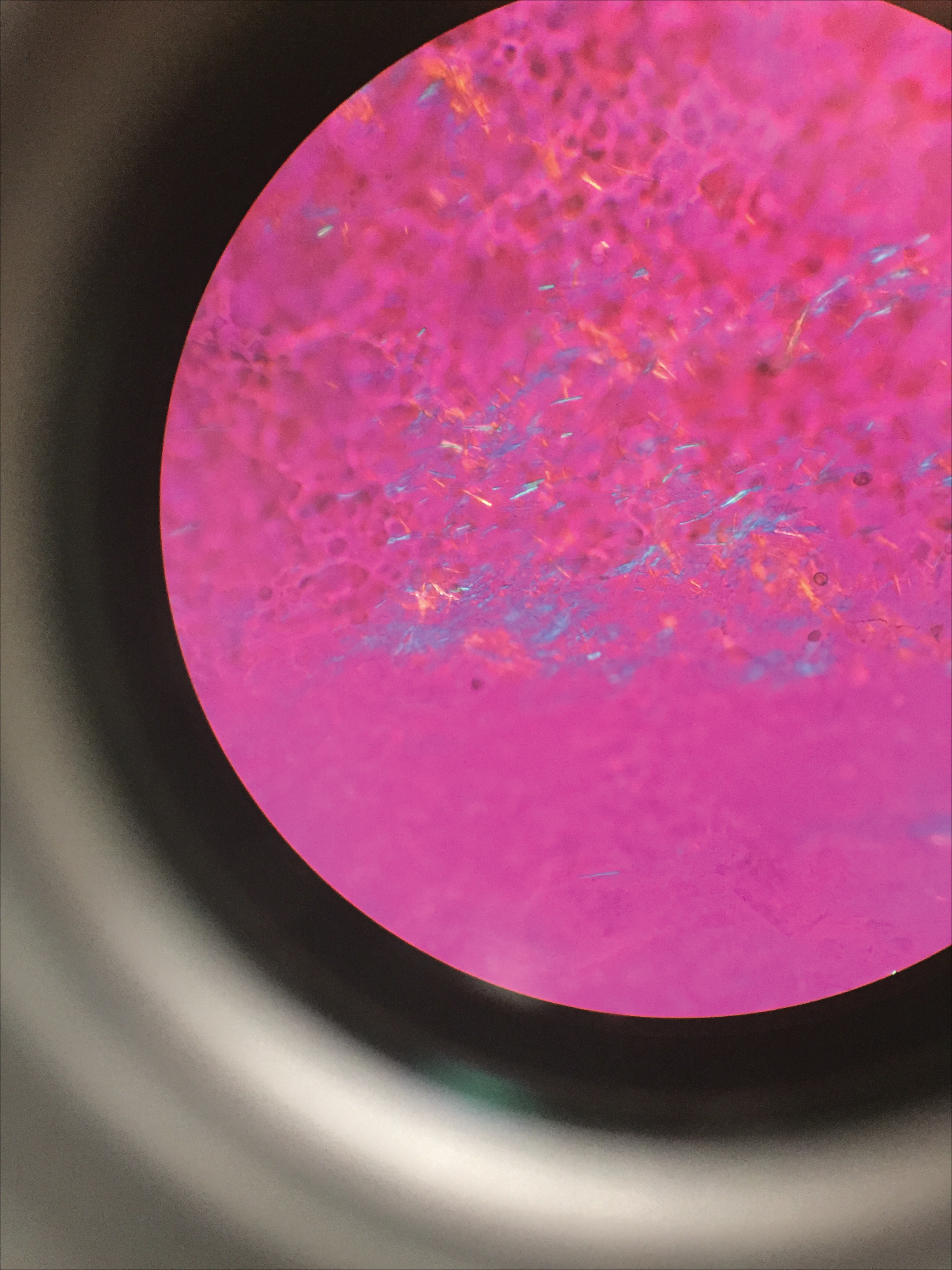

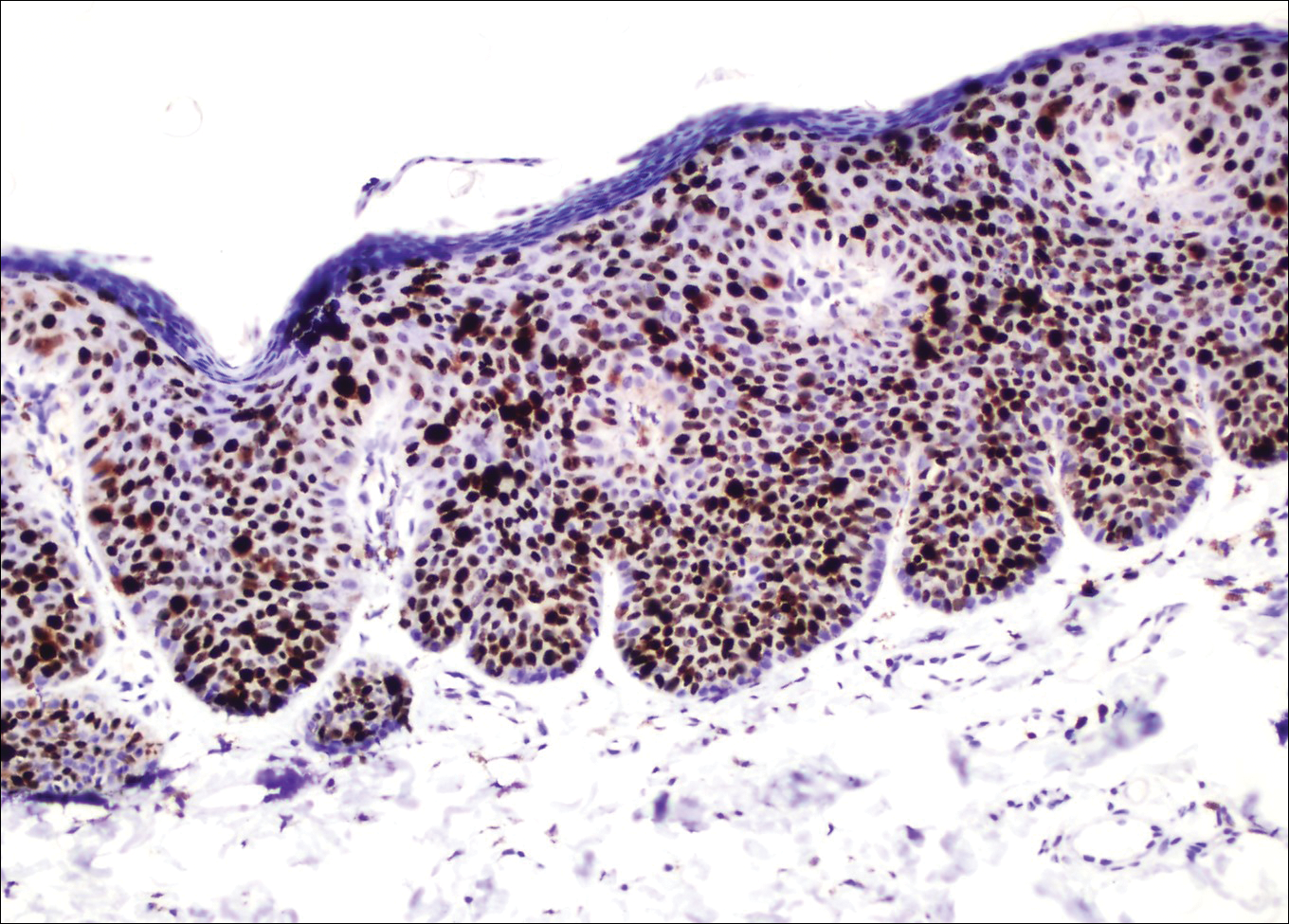

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a low-grade endothelial malignancy associated with human herpesvirus 8.3,4 Kaposi sarcoma can be divided into 4 main subtypes: classic KS, African KS, AIDS-related KS, and immunosuppression-associated KS that occurs in patients with diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus. The cutaneous lesions are similar between subtypes and present as dark reddish purple macules that may enlarge or become nodular lesions.3,4 Histologically, 3 distinct stages of progression are described: patch, plaque, and tumor. The plaque stage has the appearance of a busy dermis due to the rapid proliferation of vascular structures within the dermis.3,6 A useful histologic feature known as the promontory sign can be seen as the proliferating tumor causes preexisting structures to project into vascular spaces (Figure 1).6 Immunohistochemistry for the endothelial and lymphatic markers CD31 and D2-40, respectively, are positive and may aid in the diagnosis.3 Staining for the latent nuclear antigen-1 of human herpesvirus 8 is a highly specific marker used to diagnose KS and can further distinguish it from the other busy dermis lesions.3

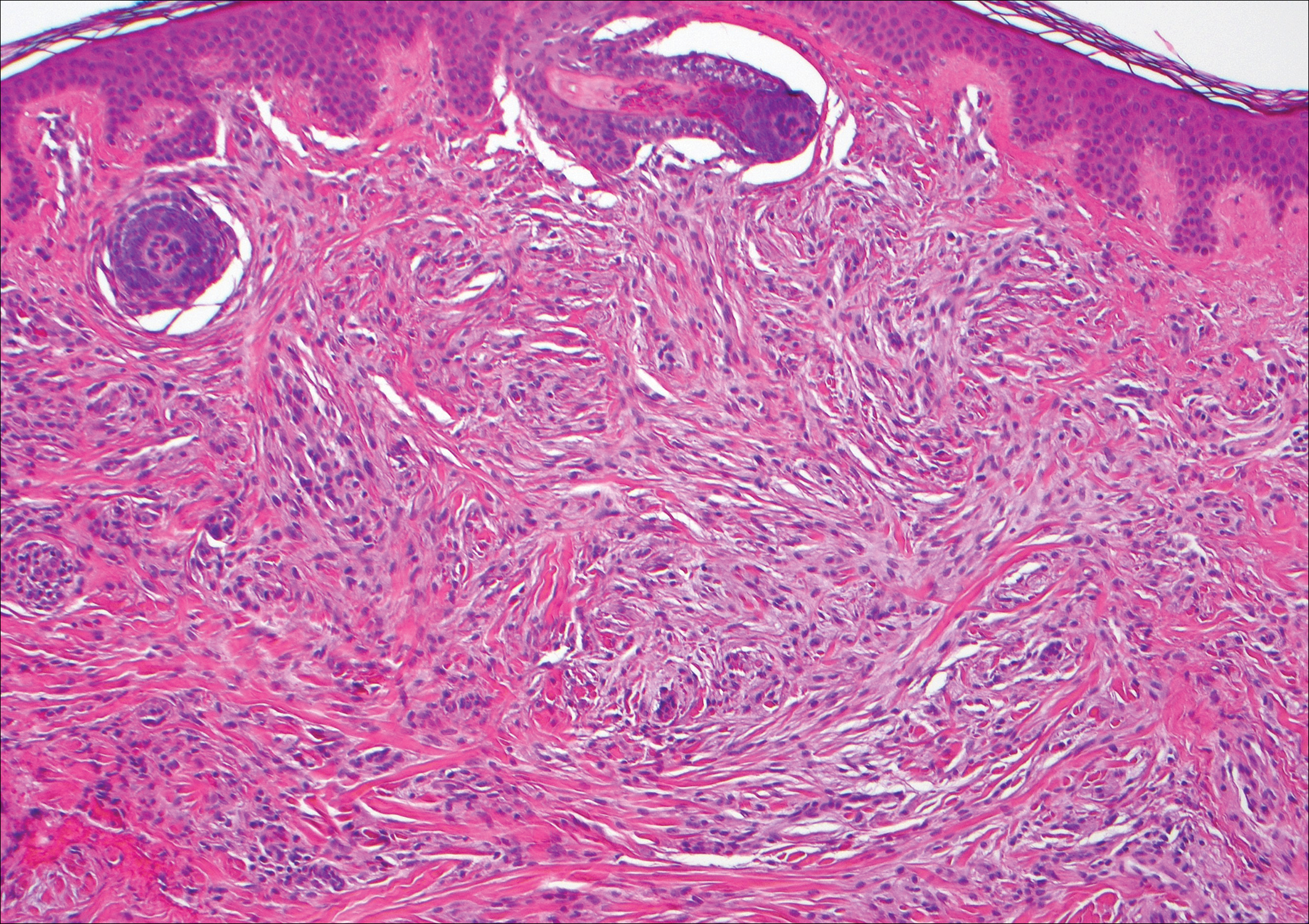

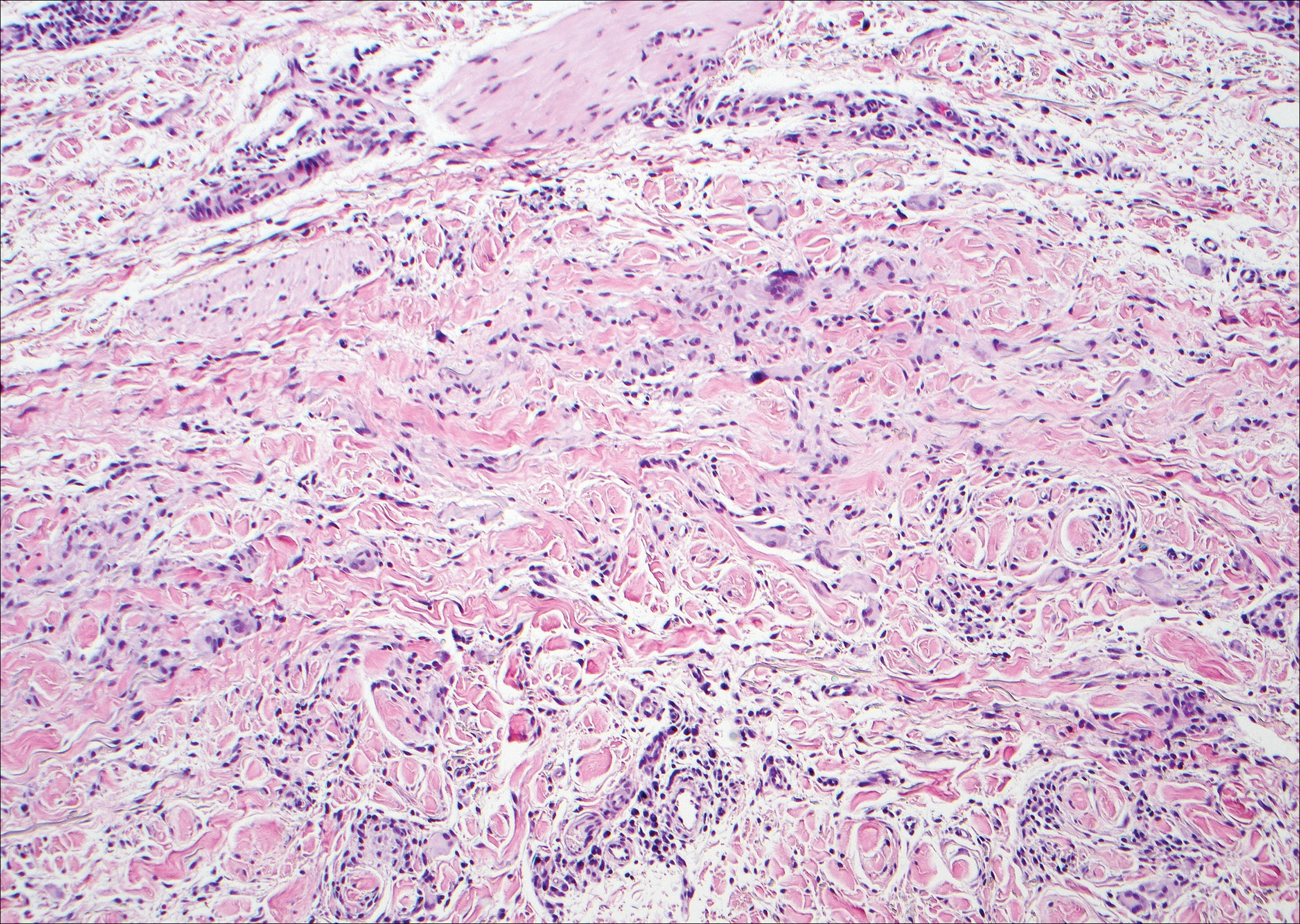

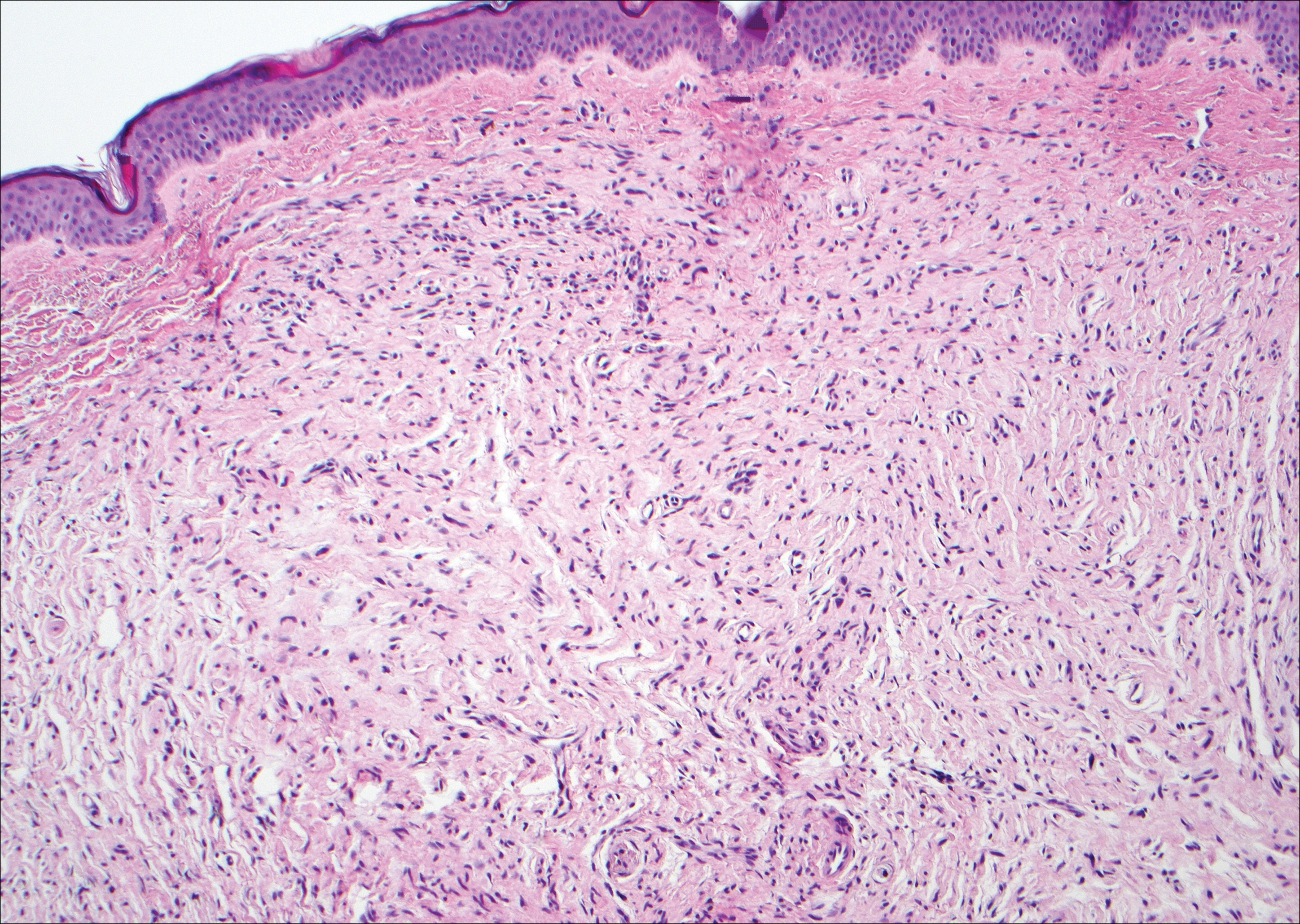

Granuloma annulare (GA) is characterized by rings of small, firm, pink to flesh-colored papules with a variable disease duration.4 Histologically, the interstitial variant of GA is characterized by a scattered inflammatory infiltrate consisting of histiocytes and lymphocytes located between altered collagen fibers in the superficial to mid dermis (Figure 2).3,6 Occasional eosinophils and increased dermal mucin are useful features to distinguish interstitial GA from other entities in the busy dermis differential.7

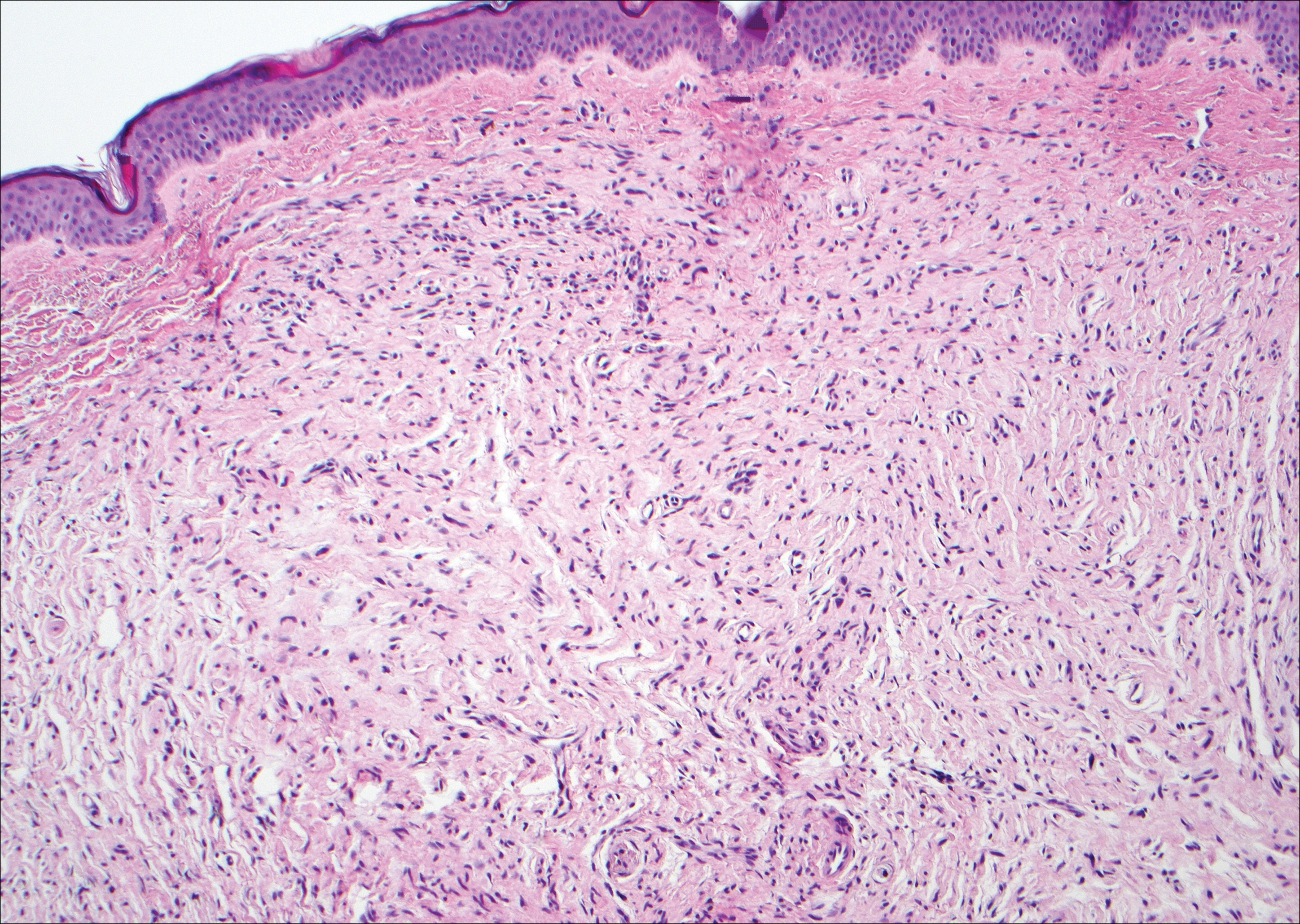

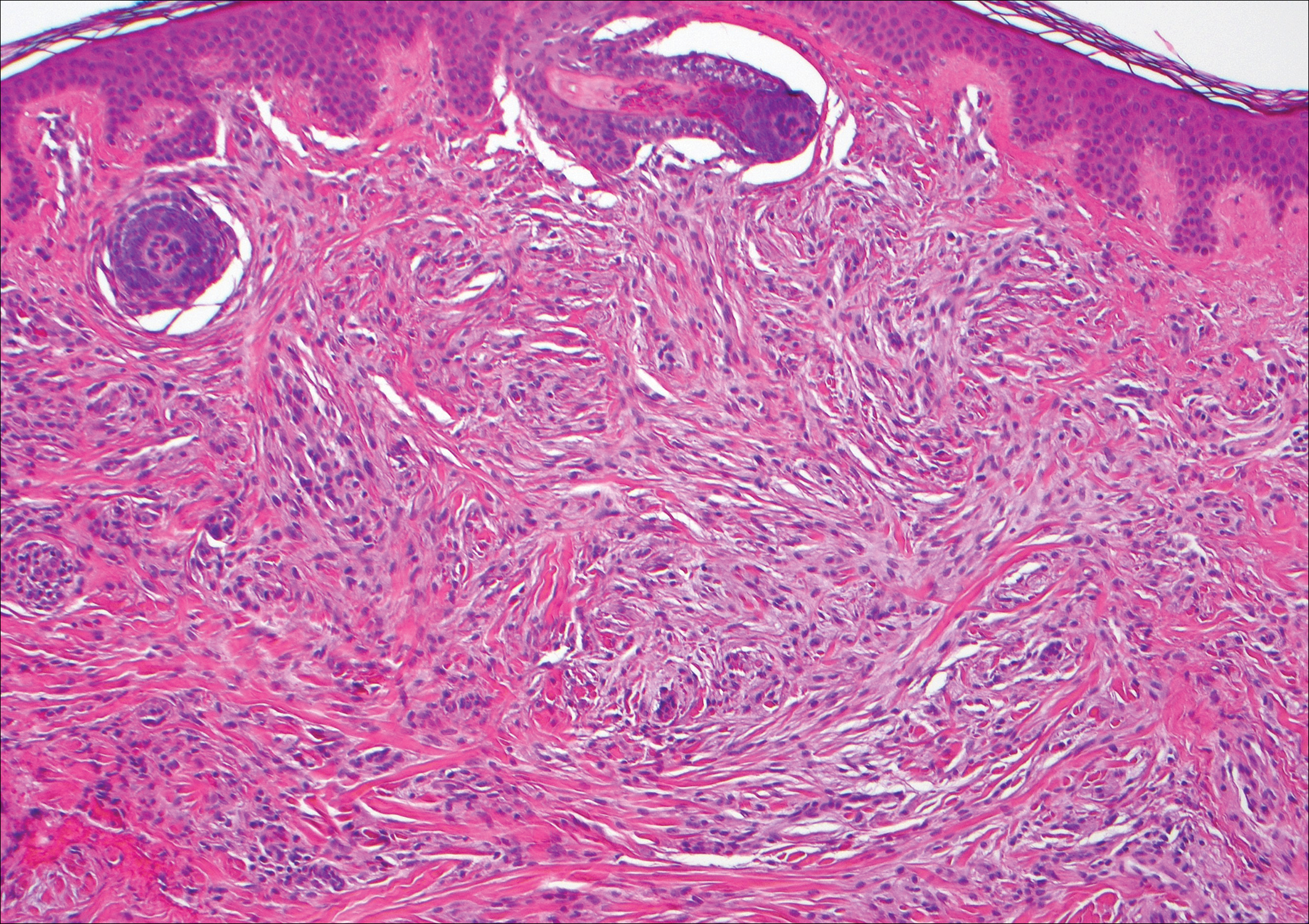

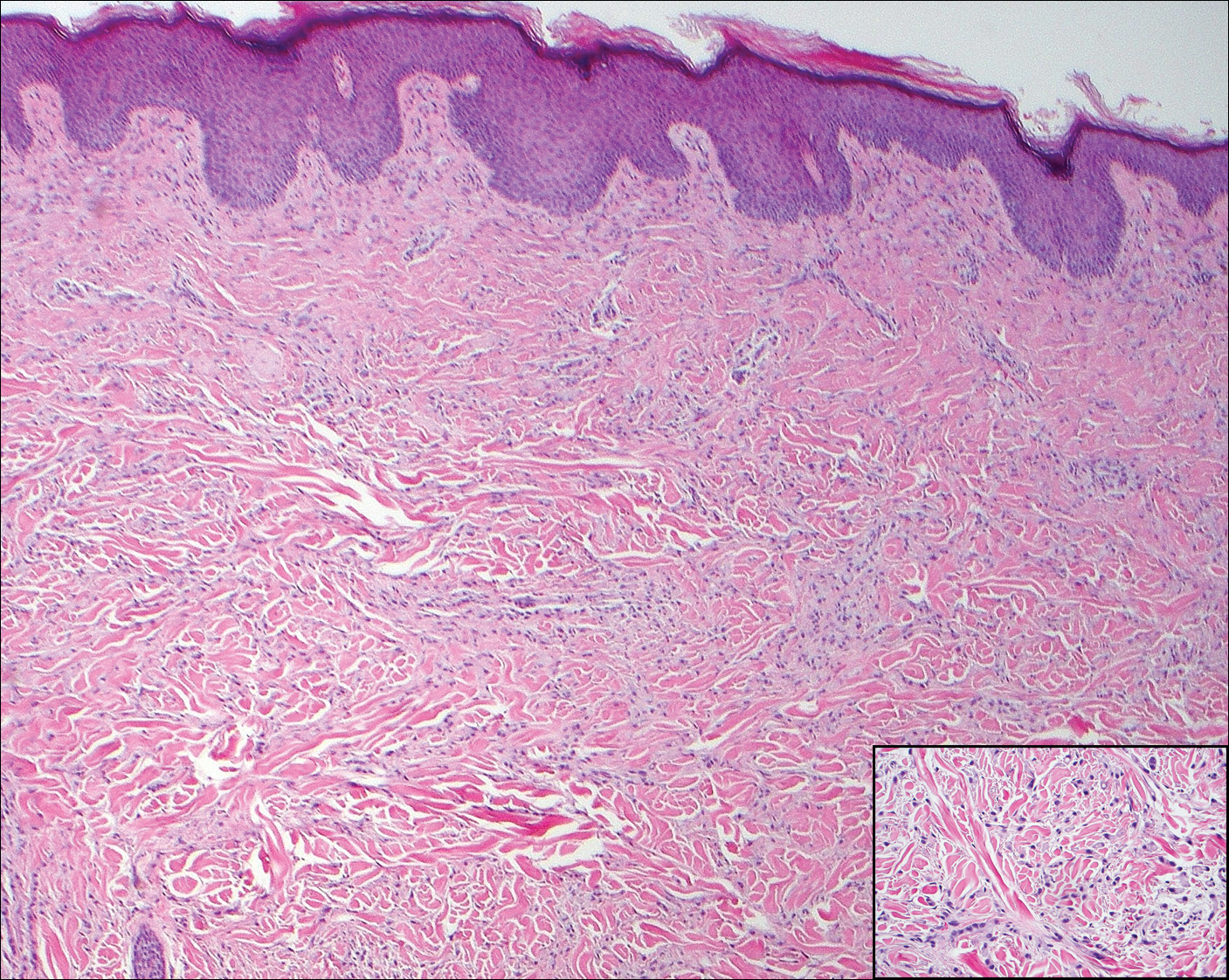

Scleromyxedema, also known as generalized lichen myxedematosus, is a rare mucinosis.3,8 Although its pathogenesis is unknown, it has been suggested that paraproteins related to the underlying gammopathy act to stimulate fibroblast proliferation and mucin overproduction.8 Clinically, characteristic widespread firm, waxy, dome-shaped papules are present over the head, upper trunk, and extremities.3,8 Histologically, scleromyxedema is characterized by increased dermal fibroblasts, mucin, and fibrosis, leading to the appearance of a busy dermis (Figure 3).3,6

Neurofibromas are common benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors that can occur sporadically or in the setting of neurofibromatosis.3-5 They present as soft, flesh-colored papules or nodules most commonly located on the trunk and limbs.4 Histologically, neurofibromas are nonencapsulated tumors composed of abundant spindle cells with comma-shaped nuclei diffusely arranged in a pale myxoid stroma (Figure 4). Scattered mast cells can be visualized at higher magnification.3,6

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Habif TP, Dinulos JGH, Chapman MS, et al. Skin Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment. 4th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier; 2017.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al, eds. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2016.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, eds. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

- Silverman RA, Rabinowitz AD. Eosinophils in the cellular infiltrate of granuloma annulare. J Cutan Pathol. 1985;12:13-17.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Metastases

Cutaneous metastases (CMs) can present in an otherwise asymptomatic patient as the only sign of an underlying disease process. In women, the most common cause of CM is breast carcinoma.1-3 Cutaneous metastases are found in approximately 25% of all patients with breast carcinoma,1 and breast carcinomas represent approximately 69% of all CMs found in women (Table 1).2 Cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma (CMBC) is associated with a poor prognosis with a mean survival of approximately 6 months at the time of diagnosis.1,3 It commonly presents as a collection of flesh-colored, firm, asymptomatic, and rapidly appearing papules and nodules that can resemble cysts or fibrous tumors.1,3,4 They typically are located on the chest wall or abdomen near the site of the underlying malignancy.1-3 The histologic features of CMBC can include hyperchromatic tumor cells infiltrating between the collagen fibers in a characteristic single file manner,3,5 giving the appearance of a busy dermis, a nonspecific term to describe a focally hypercellular dermis at low-power magnification (Table 2).5,6 Cords and clusters of atypical cells with intracytoplasmic vacuoles or well-developed ducts also can be seen (quiz image [inset]). The carcinoma en cuirasse subtype of CMBC is characterized by a fibrotic scarlike plaque on the chest wall.1,3 If a punch biopsy is obtained, the specimen typically appears rectangular rather than tapered because of the sclerotic dermal collagen.6 In contrast, inflammatory carcinoma (carcinoma erysipelatoides) presents as an erythematous plaque resembling cellulitis due to the lymphatics being congested by tumor cells.3 Immunohistochemistry is a valuable tool in diagnosis. Positive staining is seen with cytokeratin 7, gross cystic disease fluid protein-15, mammaglobin, and GATA-3.1,3,6

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a low-grade endothelial malignancy associated with human herpesvirus 8.3,4 Kaposi sarcoma can be divided into 4 main subtypes: classic KS, African KS, AIDS-related KS, and immunosuppression-associated KS that occurs in patients with diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus. The cutaneous lesions are similar between subtypes and present as dark reddish purple macules that may enlarge or become nodular lesions.3,4 Histologically, 3 distinct stages of progression are described: patch, plaque, and tumor. The plaque stage has the appearance of a busy dermis due to the rapid proliferation of vascular structures within the dermis.3,6 A useful histologic feature known as the promontory sign can be seen as the proliferating tumor causes preexisting structures to project into vascular spaces (Figure 1).6 Immunohistochemistry for the endothelial and lymphatic markers CD31 and D2-40, respectively, are positive and may aid in the diagnosis.3 Staining for the latent nuclear antigen-1 of human herpesvirus 8 is a highly specific marker used to diagnose KS and can further distinguish it from the other busy dermis lesions.3

Granuloma annulare (GA) is characterized by rings of small, firm, pink to flesh-colored papules with a variable disease duration.4 Histologically, the interstitial variant of GA is characterized by a scattered inflammatory infiltrate consisting of histiocytes and lymphocytes located between altered collagen fibers in the superficial to mid dermis (Figure 2).3,6 Occasional eosinophils and increased dermal mucin are useful features to distinguish interstitial GA from other entities in the busy dermis differential.7

Scleromyxedema, also known as generalized lichen myxedematosus, is a rare mucinosis.3,8 Although its pathogenesis is unknown, it has been suggested that paraproteins related to the underlying gammopathy act to stimulate fibroblast proliferation and mucin overproduction.8 Clinically, characteristic widespread firm, waxy, dome-shaped papules are present over the head, upper trunk, and extremities.3,8 Histologically, scleromyxedema is characterized by increased dermal fibroblasts, mucin, and fibrosis, leading to the appearance of a busy dermis (Figure 3).3,6

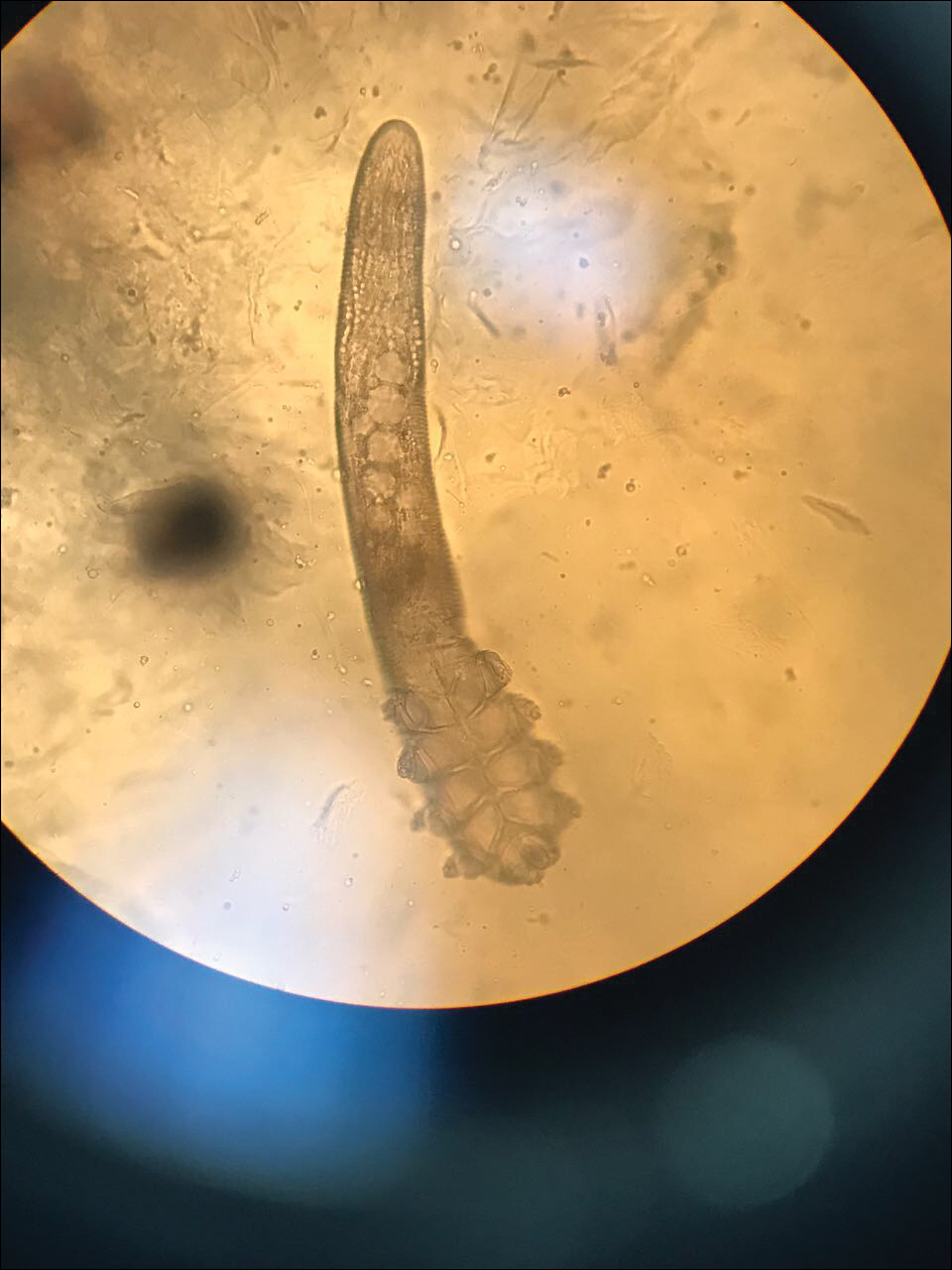

Neurofibromas are common benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors that can occur sporadically or in the setting of neurofibromatosis.3-5 They present as soft, flesh-colored papules or nodules most commonly located on the trunk and limbs.4 Histologically, neurofibromas are nonencapsulated tumors composed of abundant spindle cells with comma-shaped nuclei diffusely arranged in a pale myxoid stroma (Figure 4). Scattered mast cells can be visualized at higher magnification.3,6

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Metastases

Cutaneous metastases (CMs) can present in an otherwise asymptomatic patient as the only sign of an underlying disease process. In women, the most common cause of CM is breast carcinoma.1-3 Cutaneous metastases are found in approximately 25% of all patients with breast carcinoma,1 and breast carcinomas represent approximately 69% of all CMs found in women (Table 1).2 Cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma (CMBC) is associated with a poor prognosis with a mean survival of approximately 6 months at the time of diagnosis.1,3 It commonly presents as a collection of flesh-colored, firm, asymptomatic, and rapidly appearing papules and nodules that can resemble cysts or fibrous tumors.1,3,4 They typically are located on the chest wall or abdomen near the site of the underlying malignancy.1-3 The histologic features of CMBC can include hyperchromatic tumor cells infiltrating between the collagen fibers in a characteristic single file manner,3,5 giving the appearance of a busy dermis, a nonspecific term to describe a focally hypercellular dermis at low-power magnification (Table 2).5,6 Cords and clusters of atypical cells with intracytoplasmic vacuoles or well-developed ducts also can be seen (quiz image [inset]). The carcinoma en cuirasse subtype of CMBC is characterized by a fibrotic scarlike plaque on the chest wall.1,3 If a punch biopsy is obtained, the specimen typically appears rectangular rather than tapered because of the sclerotic dermal collagen.6 In contrast, inflammatory carcinoma (carcinoma erysipelatoides) presents as an erythematous plaque resembling cellulitis due to the lymphatics being congested by tumor cells.3 Immunohistochemistry is a valuable tool in diagnosis. Positive staining is seen with cytokeratin 7, gross cystic disease fluid protein-15, mammaglobin, and GATA-3.1,3,6

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a low-grade endothelial malignancy associated with human herpesvirus 8.3,4 Kaposi sarcoma can be divided into 4 main subtypes: classic KS, African KS, AIDS-related KS, and immunosuppression-associated KS that occurs in patients with diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus. The cutaneous lesions are similar between subtypes and present as dark reddish purple macules that may enlarge or become nodular lesions.3,4 Histologically, 3 distinct stages of progression are described: patch, plaque, and tumor. The plaque stage has the appearance of a busy dermis due to the rapid proliferation of vascular structures within the dermis.3,6 A useful histologic feature known as the promontory sign can be seen as the proliferating tumor causes preexisting structures to project into vascular spaces (Figure 1).6 Immunohistochemistry for the endothelial and lymphatic markers CD31 and D2-40, respectively, are positive and may aid in the diagnosis.3 Staining for the latent nuclear antigen-1 of human herpesvirus 8 is a highly specific marker used to diagnose KS and can further distinguish it from the other busy dermis lesions.3

Granuloma annulare (GA) is characterized by rings of small, firm, pink to flesh-colored papules with a variable disease duration.4 Histologically, the interstitial variant of GA is characterized by a scattered inflammatory infiltrate consisting of histiocytes and lymphocytes located between altered collagen fibers in the superficial to mid dermis (Figure 2).3,6 Occasional eosinophils and increased dermal mucin are useful features to distinguish interstitial GA from other entities in the busy dermis differential.7

Scleromyxedema, also known as generalized lichen myxedematosus, is a rare mucinosis.3,8 Although its pathogenesis is unknown, it has been suggested that paraproteins related to the underlying gammopathy act to stimulate fibroblast proliferation and mucin overproduction.8 Clinically, characteristic widespread firm, waxy, dome-shaped papules are present over the head, upper trunk, and extremities.3,8 Histologically, scleromyxedema is characterized by increased dermal fibroblasts, mucin, and fibrosis, leading to the appearance of a busy dermis (Figure 3).3,6

Neurofibromas are common benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors that can occur sporadically or in the setting of neurofibromatosis.3-5 They present as soft, flesh-colored papules or nodules most commonly located on the trunk and limbs.4 Histologically, neurofibromas are nonencapsulated tumors composed of abundant spindle cells with comma-shaped nuclei diffusely arranged in a pale myxoid stroma (Figure 4). Scattered mast cells can be visualized at higher magnification.3,6

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Habif TP, Dinulos JGH, Chapman MS, et al. Skin Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment. 4th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier; 2017.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al, eds. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2016.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, eds. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

- Silverman RA, Rabinowitz AD. Eosinophils in the cellular infiltrate of granuloma annulare. J Cutan Pathol. 1985;12:13-17.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Habif TP, Dinulos JGH, Chapman MS, et al. Skin Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment. 4th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier; 2017.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al, eds. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2016.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, eds. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

- Silverman RA, Rabinowitz AD. Eosinophils in the cellular infiltrate of granuloma annulare. J Cutan Pathol. 1985;12:13-17.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72.

A 56-year-old woman presented with multiple asymptomatic lesions of 2 months' duration. On physical examination firm pink papules were noted dispersed across the upper abdomen, chest, and back. A 5-mm punch biopsy was obtained.

Adult-Onset Still Disease: Persistent Pruritic Papular Rash With Unique Histopathologic Findings

Adult-onset Still disease (AOSD) is a systemic inflammatory condition that clinically manifests as spiking fevers, arthralgia, evanescent skin rash, and lymphadenopathy. 1 The most commonly used criteria for diagnosing AOSD are the Yamaguchi criteria. 2 The major criteria include high fever for more than 1 week, arthralgia for more than 2 weeks, leukocytosis, and an evanescent skin rash. The minor criteria consist of sore throat, lymphadenopathy and/or splenomegaly, liver dysfunction, and negative rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibodies. Classically, the skin rash is described as an evanescent, salmon-colored erythema involving the extremities. Nevertheless, unusual cutaneous eruptions have been reported in AOSD, including persistent pruritic papules and plaques. 3 Importantly, this atypical rash demonstrates specific histologic findings that are not found on routine histopathology of a typical evanescent rash. We describe 2 patients with this atypical cutaneous eruption along with the unique histopathologic findings of AOSD.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 23-year-old Chinese woman presented with periodic fevers, persistent rash, and joint pain of 2 years’ duration. Her medical history included splenectomy for hepatosplenomegaly as well as evaluation by hematology for lymphadenopathy; a cervical lymph node biopsy showed lymphoid and follicular hyperplasia.

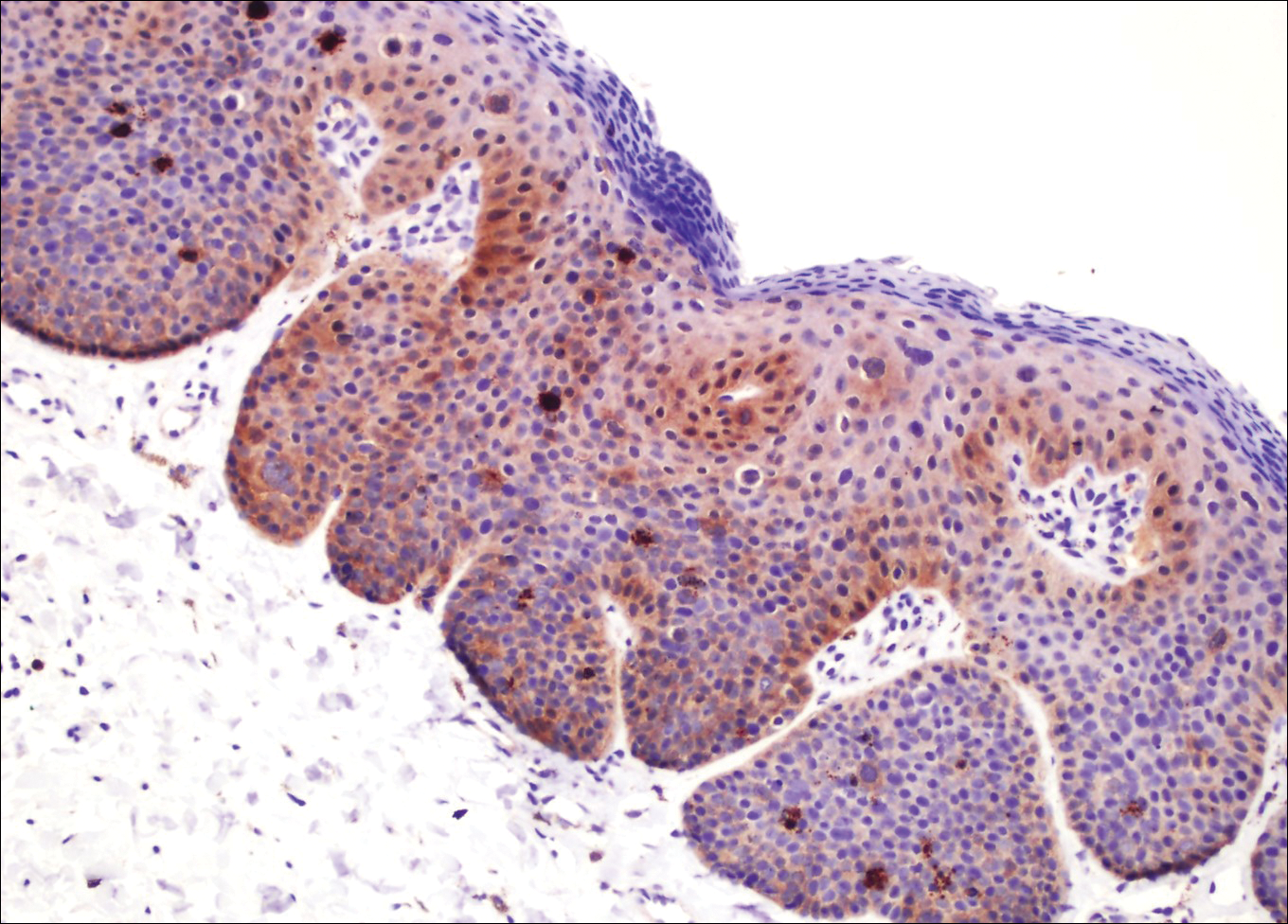

Twenty days later, the patient was referred to the dermatology department for evaluation of the persistent rash. The patient described a history of flushing of the face, severe joint pain in both arms and legs, aching muscles, and persistent sore throat. The patient did not report any history of drug ingestion. Physical examination revealed a fever (temperature, 39.2°C); swollen nontender lymph nodes in the neck, axillae, and groin; and salmon-colored and hyperpigmented patches and thin plaques over the neck, chest, abdomen, and arms (Figure 1). A splenectomy scar also was noted. Peripheral blood was collected for laboratory analyses, which revealed transaminitis and moderate hyperferritinemia (Table). An autoimmune panel was negative for rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. The patient was admitted to the hospital, and a skin biopsy was performed. Histology showed superficial dyskeratotic keratinocytes and sparse perivascular infiltration of neutrophils in the upper dermis (Figure 2).

The patient was diagnosed with AOSD based on fulfillment of the Yamaguchi criteria.2 She was treated with methylprednisolone 60 mg daily and was discharged 14 days later. At 16-month follow-up, the patient demonstrated complete resolution of symptoms with a maintenance dose of prednisolone (7.5 mg daily).

Patient 2

A 23-year-old black woman presented to the emergency department 3 months postpartum with recurrent high fevers, worsening joint pain, and persistent itchy rash of 2 months’ duration. The patient had no history of travel, autoimmune disease, or sick contacts. She occasionally took aspirin for joint pain. Physical examination revealed a fever (temperature, 39.1°C) along with hyperpigmented patches and thin scaly hyperpigmented papules coalescing into a poorly demarcated V-shaped plaque on the upper back and posterior neck, extending to the chest in a shawl-like distribution (Figure 3). Submental lymphadenopathy was present. The spleen was not palpable.

Peripheral blood was collected for laboratory analysis and demonstrated transaminitis and a markedly high ferritin level (Table). An autoimmune panel was negative for rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Skin biopsy was performed and demonstrated many necrotic keratinocytes, singly and in aggregates, distributed from the spinous layer to the stratum corneum. A neutrophilic infiltrate was present in the papillary dermis (Figure 4).

The patient met the Yamaguchi criteria and was subsequently diagnosed with AOSD. She was treated with intravenous methylprednisolone 20 mg every 8 hours and was discharged 1 week later on oral prednisone 60 mg daily to be tapered over a period of months. At 2-week follow-up, the patient continued to experience rash and joint pain; oral methotrexate 10 mg weekly was added to her regimen, as well as vitamin D, calcium, and folic acid supplementation. At the next 2-week follow-up the patient noted improvement in the rash as well as the joint pain, but both still persisted. Prednisone was decreased to 50 mg daily and methotrexate was increased to 15 mg weekly. The patient continued to show improvement over the subsequent 3 months, during which prednisone was tapered to 10 mg daily and methotrexate was increased to 20 mg weekly. The patient showed resolution of symptoms at 3-month follow-up on this regimen, with plans to continue the prednisone taper and maintain methotrexate dosing.

Comment

Adult-onset Still disease is a systemic inflammatory condition that clinically manifests as spiking fevers, arthralgia, salmon-pink evanescent erythema, and lymphadenopathy.2 The condition also can cause liver dysfunction, splenomegaly, pericarditis, pleuritis, renal dysfunction, and a reactive hemophagocytic syndrome.1 Furthermore, one review of the literature described an association with delayed-onset malignancy.4 Early diagnosis is important yet challenging, as AOSD is a diagnosis of exclusion. The Yamaguchi criteria are the most widely used method of diagnosis and demonstrate more than 90% sensitivity.In addition to the Yamaguchi criteria, marked hyperferritinemia is characteristic of AOSD and can act as an indicator of disease activity.5 Interestingly, both of our patients had elevated ferritin levels, with patient 2 showing marked elevation (Table). In both patients, all major criteria were fulfilled, except the typical skin rash.

The skin rash in AOSD, classically consisting of an evanescent, salmon-pink erythema predominantly involving the extremities, has been observed in up to 87% of AOSD patients.5 The histology of the typical evanescent rash is nonspecific, characterized by a relatively sparse, perivascular, mixed inflammatory infiltrate. Notably, other skin manifestations may be found in patients with AOSD.1,2,5-16 Persistent pruritic papules and plaques are the most commonly reported nonclassical rash, presenting as erythematous, slightly scaly papules and plaques with a linear configuration typically on the trunk.2 Both of our patients presented with this atypical eruption. Importantly, the histopathology of this unique rash displays distinctive features, which can aid in early diagnosis. Findings include dyskeratotic keratinocytes in the cornified layers as well as in the epidermis, and a sparse neutrophilic and/or lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis without vasculitis. These findings were evident in both histopathologic studies of our patients (Figures 2 and 4). Although not present in our patients, dermal mucin deposition has been demonstrated in some reports.1,13,15

A 2015 review of the literature yielded 30 cases of AOSD with pruritic persistent papules and plaques.4 The study confirmed a linear, erythematous or brown rash on the back and neck in the majority of cases. Histologic findings were congruent with those reported in our 2 cases: necrotic keratinocytes in the upper epidermis with a neutrophilic infiltrate in the upper dermis without vasculitis. Most patients showed rapid resolution of the rash and symptoms with the use of prednisone, prednisolone, or intravenous pulsed methylprednisolone. Interestingly, a range of presentations were noted, including prurigo pigmentosalike urticarial papules; lichenoid papules; and dermatographismlike, dermatomyositislike, and lichen amyloidosis–like rashes.4 In our report, patient 2 presented with a rash in a dermat-omyositislike shawl distribution. It has been suggested that patients with dermatomyositislike rashes require more potent immunotherapy as compared to patients with other rash morphologies.4 The need for methotrexate in addition to a prednisone taper in the clinical course of patient 2 lends further support to this observation.

Conclusion

A clinically and pathologically distinct form of cutaneous disease—AOSD with persistent pruritic papules and plaques—was observed in our 2 patients. These histopathologic findings facilitated timely diagnosis in both patients. A range of clinical morphologies may exist in AOSD, an awareness of which is paramount. Adult-onset Still disease should be included in the differential diagnosis of a dermatomyositislike presentation in a shawl distribution. Prompt diagnosis is essential to ensure adequate therapy.

- Yamamoto T. Cutaneous manifestations associated with adult-onset Still’s disease: important diagnostic values. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:2233-2237.

- Yamaguchi M, Ohta A, Tsunematsu T, et al. Preliminary criteria for classification of adult Still’s disease. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:424-431.

- Lee JY, Yang CC, Hsu MM. Histopathology of persistent papules and plaques in adult-onset Still’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:1003-1008.

- Sun NZ, Brezinski EA, Berliner J, et al. Updates in adult-onset Still disease: atypical cutaneous manifestations and associates with delayed malignancy [published online June 6, 2015]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:294-303.

- Schwarz-Eywill M, Heilig B, Bauer H, et al. Evaluation of serum ferritin as a marker for adult Still’s disease activity. Ann Rheum Dis. 1992;51:683-685.

- Ohta A, Yamaguchi M, Tsunematsu T, et al. Adult Still’s disease: a multicenter survey of Japanese patients. J Rheumatol. 1990;17:1058-1063.

- Kaur S, Bambery P, Dhar S. Persistent dermal plaque lesions in adult onset Still’s disease. Dermatology. 1994;188:241-242.

- Lübbe J, Hofer M, Chavaz P, et al. Adult onset Still’s disease with persistent plaques. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:710-713.

- Suzuki K, Kimura Y, Aoki M, et al. Persistent plaques and linear pigmentation in adult-onset Still’s disease. Dermatology. 2001;202:333-335.

- Fujii K, Konishi K, Kanno Y, et al. Persistent generalized erythema in adult-onset Still’s disease. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:824-825.

- Thien Huong NT, Pitche P, Minh Hoa T, et al. Persistent pigmented plaques in adult-onset Still’s disease. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2005;132:693-696.

- Lee JY, Yang CC, Hsu MM. Histopathology of persistent papules and plaques in adult-onset Still’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:1003-1008.

- Wolgamot G, Yoo J, Hurst S, et al. Unique histopathologic findings in a patient with adult-onset Still’s disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;49:194-196.

- Fortna RR, Gudjonsson JE, Seidel G, et al. Persistent pruritic papules and plaques: a characteristic histopathologic presentation seen in a subset of patients with adult-onset and juvenile Still’s disease. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:932-937.

- Yang CC, Lee JY, Liu MF, et al. Adult-onset Still’s disease with persistent skin eruption and fatal respiratory failure in a Taiwanese woman. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:593-594.

- Azeck AG, Littlewood SM. Adult-onset Still’s disease with atypical cutaneous features. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:360-363.

Adult-onset Still disease (AOSD) is a systemic inflammatory condition that clinically manifests as spiking fevers, arthralgia, evanescent skin rash, and lymphadenopathy. 1 The most commonly used criteria for diagnosing AOSD are the Yamaguchi criteria. 2 The major criteria include high fever for more than 1 week, arthralgia for more than 2 weeks, leukocytosis, and an evanescent skin rash. The minor criteria consist of sore throat, lymphadenopathy and/or splenomegaly, liver dysfunction, and negative rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibodies. Classically, the skin rash is described as an evanescent, salmon-colored erythema involving the extremities. Nevertheless, unusual cutaneous eruptions have been reported in AOSD, including persistent pruritic papules and plaques. 3 Importantly, this atypical rash demonstrates specific histologic findings that are not found on routine histopathology of a typical evanescent rash. We describe 2 patients with this atypical cutaneous eruption along with the unique histopathologic findings of AOSD.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 23-year-old Chinese woman presented with periodic fevers, persistent rash, and joint pain of 2 years’ duration. Her medical history included splenectomy for hepatosplenomegaly as well as evaluation by hematology for lymphadenopathy; a cervical lymph node biopsy showed lymphoid and follicular hyperplasia.

Twenty days later, the patient was referred to the dermatology department for evaluation of the persistent rash. The patient described a history of flushing of the face, severe joint pain in both arms and legs, aching muscles, and persistent sore throat. The patient did not report any history of drug ingestion. Physical examination revealed a fever (temperature, 39.2°C); swollen nontender lymph nodes in the neck, axillae, and groin; and salmon-colored and hyperpigmented patches and thin plaques over the neck, chest, abdomen, and arms (Figure 1). A splenectomy scar also was noted. Peripheral blood was collected for laboratory analyses, which revealed transaminitis and moderate hyperferritinemia (Table). An autoimmune panel was negative for rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. The patient was admitted to the hospital, and a skin biopsy was performed. Histology showed superficial dyskeratotic keratinocytes and sparse perivascular infiltration of neutrophils in the upper dermis (Figure 2).

The patient was diagnosed with AOSD based on fulfillment of the Yamaguchi criteria.2 She was treated with methylprednisolone 60 mg daily and was discharged 14 days later. At 16-month follow-up, the patient demonstrated complete resolution of symptoms with a maintenance dose of prednisolone (7.5 mg daily).

Patient 2

A 23-year-old black woman presented to the emergency department 3 months postpartum with recurrent high fevers, worsening joint pain, and persistent itchy rash of 2 months’ duration. The patient had no history of travel, autoimmune disease, or sick contacts. She occasionally took aspirin for joint pain. Physical examination revealed a fever (temperature, 39.1°C) along with hyperpigmented patches and thin scaly hyperpigmented papules coalescing into a poorly demarcated V-shaped plaque on the upper back and posterior neck, extending to the chest in a shawl-like distribution (Figure 3). Submental lymphadenopathy was present. The spleen was not palpable.

Peripheral blood was collected for laboratory analysis and demonstrated transaminitis and a markedly high ferritin level (Table). An autoimmune panel was negative for rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Skin biopsy was performed and demonstrated many necrotic keratinocytes, singly and in aggregates, distributed from the spinous layer to the stratum corneum. A neutrophilic infiltrate was present in the papillary dermis (Figure 4).

The patient met the Yamaguchi criteria and was subsequently diagnosed with AOSD. She was treated with intravenous methylprednisolone 20 mg every 8 hours and was discharged 1 week later on oral prednisone 60 mg daily to be tapered over a period of months. At 2-week follow-up, the patient continued to experience rash and joint pain; oral methotrexate 10 mg weekly was added to her regimen, as well as vitamin D, calcium, and folic acid supplementation. At the next 2-week follow-up the patient noted improvement in the rash as well as the joint pain, but both still persisted. Prednisone was decreased to 50 mg daily and methotrexate was increased to 15 mg weekly. The patient continued to show improvement over the subsequent 3 months, during which prednisone was tapered to 10 mg daily and methotrexate was increased to 20 mg weekly. The patient showed resolution of symptoms at 3-month follow-up on this regimen, with plans to continue the prednisone taper and maintain methotrexate dosing.

Comment

Adult-onset Still disease is a systemic inflammatory condition that clinically manifests as spiking fevers, arthralgia, salmon-pink evanescent erythema, and lymphadenopathy.2 The condition also can cause liver dysfunction, splenomegaly, pericarditis, pleuritis, renal dysfunction, and a reactive hemophagocytic syndrome.1 Furthermore, one review of the literature described an association with delayed-onset malignancy.4 Early diagnosis is important yet challenging, as AOSD is a diagnosis of exclusion. The Yamaguchi criteria are the most widely used method of diagnosis and demonstrate more than 90% sensitivity.In addition to the Yamaguchi criteria, marked hyperferritinemia is characteristic of AOSD and can act as an indicator of disease activity.5 Interestingly, both of our patients had elevated ferritin levels, with patient 2 showing marked elevation (Table). In both patients, all major criteria were fulfilled, except the typical skin rash.

The skin rash in AOSD, classically consisting of an evanescent, salmon-pink erythema predominantly involving the extremities, has been observed in up to 87% of AOSD patients.5 The histology of the typical evanescent rash is nonspecific, characterized by a relatively sparse, perivascular, mixed inflammatory infiltrate. Notably, other skin manifestations may be found in patients with AOSD.1,2,5-16 Persistent pruritic papules and plaques are the most commonly reported nonclassical rash, presenting as erythematous, slightly scaly papules and plaques with a linear configuration typically on the trunk.2 Both of our patients presented with this atypical eruption. Importantly, the histopathology of this unique rash displays distinctive features, which can aid in early diagnosis. Findings include dyskeratotic keratinocytes in the cornified layers as well as in the epidermis, and a sparse neutrophilic and/or lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis without vasculitis. These findings were evident in both histopathologic studies of our patients (Figures 2 and 4). Although not present in our patients, dermal mucin deposition has been demonstrated in some reports.1,13,15

A 2015 review of the literature yielded 30 cases of AOSD with pruritic persistent papules and plaques.4 The study confirmed a linear, erythematous or brown rash on the back and neck in the majority of cases. Histologic findings were congruent with those reported in our 2 cases: necrotic keratinocytes in the upper epidermis with a neutrophilic infiltrate in the upper dermis without vasculitis. Most patients showed rapid resolution of the rash and symptoms with the use of prednisone, prednisolone, or intravenous pulsed methylprednisolone. Interestingly, a range of presentations were noted, including prurigo pigmentosalike urticarial papules; lichenoid papules; and dermatographismlike, dermatomyositislike, and lichen amyloidosis–like rashes.4 In our report, patient 2 presented with a rash in a dermat-omyositislike shawl distribution. It has been suggested that patients with dermatomyositislike rashes require more potent immunotherapy as compared to patients with other rash morphologies.4 The need for methotrexate in addition to a prednisone taper in the clinical course of patient 2 lends further support to this observation.

Conclusion

A clinically and pathologically distinct form of cutaneous disease—AOSD with persistent pruritic papules and plaques—was observed in our 2 patients. These histopathologic findings facilitated timely diagnosis in both patients. A range of clinical morphologies may exist in AOSD, an awareness of which is paramount. Adult-onset Still disease should be included in the differential diagnosis of a dermatomyositislike presentation in a shawl distribution. Prompt diagnosis is essential to ensure adequate therapy.