User login

Fine-tune staging for better SCC risk stratification

ORLANDO – When caring for individuals with sun-damaged skin, dermatologists need comfort with the full spectrum of photo-related skin disease. From assessment and treatment of actinic keratoses (AKs) and field cancerization, to long-term follow-up of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs), appropriate treatment and staging can improve patient quality of life and reduce health care costs, Vishal Patel, MD, said at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

said Dr. Patel, director of cutaneous oncology at George Washington University Cancer Center, Washington. On the other hand, he added, “field disease can be a marker for invasive squamous cell carcinoma risk, and it requires field treatment.” Treatment that reduces field disease is primary prevention because it decreases the formation of invasive SCC, he noted.

“But this level of disease – AKs and SCC in situ – doesn’t kill people,” he emphasized. “I want to leave you with an ability to stage this disease,” said Dr. Patel, noting that SCC mortality may eventually surpass melanoma mortality as deaths from the latter decline and numbers of older Americans with high ultraviolet light exposure and other risk factors climb.

While the majority of AKs regress within 5 years, he looks at the total burden of AKs as a marker for field cancerization “because having less than five in situ or actinic lesions puts you at less than a 1% risk of squamous cell carcinoma formation. Having more than 20 increases that risk 20-fold to 20%,” he said. “That’s the way we need to start thinking about this: Is this a disease – or a symptom?”

Rather than thinking of each AK or SCC in situ as a separate disease event, “the disease we need to be focusing on and treating is field cancerization,” he continued. Within this context, “we should not be thinking that … we need to be aggressive in our management,” which is what results in high costs.

“The reality is that this is a big quality of life issue for our patients. So what do we do?” Field treatment is appropriate for field disease, he said. Dr. Patel said that at GW only field treatment is used; destructive treatment for AKs and SCC in situ is not used. In the absence of patient and lesion characteristics that elevate risk,“surgery is really not the standard of care for in situ lesions for us,” he commented.

“We start by discerning the field disease from the invasive disease” with an initial round of field treatment and, if needed, adjunctive oral chemoprophylaxis. “We lather, rinse, and repeat” the field therapy, continuously if needed, Dr. Patel said.

“We like to do that because we can then identify those specific lesions we want to go after. No cryosurgery, no destructive therapy, because we run the risk of burying those tumors under the scar. They may recur and make it more difficult to accurately stage them in the future,” he noted.

“I like to be more sophisticated in thinking about our approach to the outcomes of these individual lesions,” he said. When it comes to excising lesions that have been biopsied and show invasive SCC, “disc excision may be a more cost-effective way to treat many low-risk SCCs,” he noted. In any case, “removal with clear surgical margins is key.”

Primary tumors with such low-risk attributes as diameter under a centimeter and thickness under 2 mm; well-defined borders; location on the trunk, neck, or extremities; well-differentiated histology; and lack of perineural invasion can all be considered for a disc technique, especially if the patient is immunocompetent without background chronic inflammation or a history of prior radiation therapy.

Staging SCCs, said Dr. Patel, is where things really get tricky. Older staging systems for SCC “led us to overtreat nonaggressive disease and undertreat aggressive disease. I think we have the responsibility to lead the charge to having a more sophisticated approach.” For example, patients whose tumors were staged T2 in the American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) 7 classification system were most likely to have poor outcomes – in part because so few tumors were staged higher – which meant AJCC 7 didn’t provide adequate differentiation for useful risk prognostication.

A group of researchers at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH), Boston, “came up with a better system to better differentiate those T2 tumors into a high-risk and a low-risk subtype,” according to Dr. Patel.

With use of validated risk factors, the investigators applied a long list of risk factors to 2,000 tumors to see which risk factors, taken individually, were really contributing to poor outcomes. Eventually, four risk factors that made the most difference were identified: size greater than 2 cm, poor tumor differentiation, perineural invasion greater than 0.1 mm in diameter, and tumor invasion beyond subcutaneous fat. “I really want to highlight the size portion of those risk factors,” said Dr. Patel. “Something I’d like you to do in your clinical practice is to measure and document the size of the lesion. … That really, clearly helps” with risk prognostication.

These four factors were then used to break out a T2a stage for tumors with one risk factor and a T2b stage for tumors with two or three risk factors. Tumors with no risk factors are stage T1, and those with all four risk factors are stage T3. In situ SCC is T0.

Applying this new staging system to a 2,000-patient cohort with SCC yielded clear separation in outcomes including recurrence, nodal metastasis, disease-specific death, and overall survival between patients with the T2a and T2b tumors (P less than .001 for all; J Clin Oncol. 2014 Feb 1;32[4]:327-34).

While AJCC 8 is “significantly better” than AJCC 7 in its incorporation of meaningful risk factors into the SCC staging system, “it still underperforms in comparison” with the BWH staging system using the 2000 patient cohort, he said. Recent work has shown the BWH classification system to have superior specificity and positive predictive value in detecting nodal metastasis and disease-specific death in higher-grade tumors. But both BWH and AJCC 8 need further refinement.

“So what are the staging pearls to take home?” Dr. Patel asked. “First, utilize a staging system.” “Staging of SCC utilizing should be done routinely. Most data seems to suggest that the BWH system appears to outperform AJCC 8, and it is what we currently use routinely at GW,” he said.

Patients who are T1 by BWH criteria, with no risk factors, are at low or even no risk, he noted. He pointed out that of the nearly 1,400 patients who met T1 criteria, there were just eight local recurrences, one nodal metastasis, and no distant metastases or deaths. Knowing this should guide physicians on a treatment path that will reduce costs and provide patients with peace of mind, he said.

In the BWH schema, T2a patients fared almost as well, with a 2% risk of nodal metastasis and an overall 1% risk of disease-specific death. “T2a disease is low risk, in my mind. Most of these patients will go on to do well,” he said.

By contrast, “there may be a number of tumors that you are missing” that are candidates for close follow-up if the BWH criteria are not being used, said Dr. Patel. These are the T2b tumors. “For those patients, we want to aggressively follow them and think about a more aggressive management plan.”

The bottom line is that BWH T2b and T3 tumors are both high risk, and management needs to acknowledge this, he said. The current protocol in our cutaneous oncology program includes using routine radiologic nodal staging in patients with BWH stage 2b and above SCCs and considering sentinel lymph node biopsy for certain individuals.

For patients with BWH T2b and T3 tumors, dermatologists should give consideration to tertiary care or cancer center referrals so they have access to the full spectrum of diagnostic and therapeutic modalities and the opportunity to participate in clinical trials, Dr. Patel said.

Dr. Patel reported that he is a speaker for Regeneron/Sanofi and a cofounder of the Skin Cancer Outcomes (SCOUT) consortium.

This article was updated 2/9/2019

ORLANDO – When caring for individuals with sun-damaged skin, dermatologists need comfort with the full spectrum of photo-related skin disease. From assessment and treatment of actinic keratoses (AKs) and field cancerization, to long-term follow-up of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs), appropriate treatment and staging can improve patient quality of life and reduce health care costs, Vishal Patel, MD, said at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

said Dr. Patel, director of cutaneous oncology at George Washington University Cancer Center, Washington. On the other hand, he added, “field disease can be a marker for invasive squamous cell carcinoma risk, and it requires field treatment.” Treatment that reduces field disease is primary prevention because it decreases the formation of invasive SCC, he noted.

“But this level of disease – AKs and SCC in situ – doesn’t kill people,” he emphasized. “I want to leave you with an ability to stage this disease,” said Dr. Patel, noting that SCC mortality may eventually surpass melanoma mortality as deaths from the latter decline and numbers of older Americans with high ultraviolet light exposure and other risk factors climb.

While the majority of AKs regress within 5 years, he looks at the total burden of AKs as a marker for field cancerization “because having less than five in situ or actinic lesions puts you at less than a 1% risk of squamous cell carcinoma formation. Having more than 20 increases that risk 20-fold to 20%,” he said. “That’s the way we need to start thinking about this: Is this a disease – or a symptom?”

Rather than thinking of each AK or SCC in situ as a separate disease event, “the disease we need to be focusing on and treating is field cancerization,” he continued. Within this context, “we should not be thinking that … we need to be aggressive in our management,” which is what results in high costs.

“The reality is that this is a big quality of life issue for our patients. So what do we do?” Field treatment is appropriate for field disease, he said. Dr. Patel said that at GW only field treatment is used; destructive treatment for AKs and SCC in situ is not used. In the absence of patient and lesion characteristics that elevate risk,“surgery is really not the standard of care for in situ lesions for us,” he commented.

“We start by discerning the field disease from the invasive disease” with an initial round of field treatment and, if needed, adjunctive oral chemoprophylaxis. “We lather, rinse, and repeat” the field therapy, continuously if needed, Dr. Patel said.

“We like to do that because we can then identify those specific lesions we want to go after. No cryosurgery, no destructive therapy, because we run the risk of burying those tumors under the scar. They may recur and make it more difficult to accurately stage them in the future,” he noted.

“I like to be more sophisticated in thinking about our approach to the outcomes of these individual lesions,” he said. When it comes to excising lesions that have been biopsied and show invasive SCC, “disc excision may be a more cost-effective way to treat many low-risk SCCs,” he noted. In any case, “removal with clear surgical margins is key.”

Primary tumors with such low-risk attributes as diameter under a centimeter and thickness under 2 mm; well-defined borders; location on the trunk, neck, or extremities; well-differentiated histology; and lack of perineural invasion can all be considered for a disc technique, especially if the patient is immunocompetent without background chronic inflammation or a history of prior radiation therapy.

Staging SCCs, said Dr. Patel, is where things really get tricky. Older staging systems for SCC “led us to overtreat nonaggressive disease and undertreat aggressive disease. I think we have the responsibility to lead the charge to having a more sophisticated approach.” For example, patients whose tumors were staged T2 in the American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) 7 classification system were most likely to have poor outcomes – in part because so few tumors were staged higher – which meant AJCC 7 didn’t provide adequate differentiation for useful risk prognostication.

A group of researchers at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH), Boston, “came up with a better system to better differentiate those T2 tumors into a high-risk and a low-risk subtype,” according to Dr. Patel.

With use of validated risk factors, the investigators applied a long list of risk factors to 2,000 tumors to see which risk factors, taken individually, were really contributing to poor outcomes. Eventually, four risk factors that made the most difference were identified: size greater than 2 cm, poor tumor differentiation, perineural invasion greater than 0.1 mm in diameter, and tumor invasion beyond subcutaneous fat. “I really want to highlight the size portion of those risk factors,” said Dr. Patel. “Something I’d like you to do in your clinical practice is to measure and document the size of the lesion. … That really, clearly helps” with risk prognostication.

These four factors were then used to break out a T2a stage for tumors with one risk factor and a T2b stage for tumors with two or three risk factors. Tumors with no risk factors are stage T1, and those with all four risk factors are stage T3. In situ SCC is T0.

Applying this new staging system to a 2,000-patient cohort with SCC yielded clear separation in outcomes including recurrence, nodal metastasis, disease-specific death, and overall survival between patients with the T2a and T2b tumors (P less than .001 for all; J Clin Oncol. 2014 Feb 1;32[4]:327-34).

While AJCC 8 is “significantly better” than AJCC 7 in its incorporation of meaningful risk factors into the SCC staging system, “it still underperforms in comparison” with the BWH staging system using the 2000 patient cohort, he said. Recent work has shown the BWH classification system to have superior specificity and positive predictive value in detecting nodal metastasis and disease-specific death in higher-grade tumors. But both BWH and AJCC 8 need further refinement.

“So what are the staging pearls to take home?” Dr. Patel asked. “First, utilize a staging system.” “Staging of SCC utilizing should be done routinely. Most data seems to suggest that the BWH system appears to outperform AJCC 8, and it is what we currently use routinely at GW,” he said.

Patients who are T1 by BWH criteria, with no risk factors, are at low or even no risk, he noted. He pointed out that of the nearly 1,400 patients who met T1 criteria, there were just eight local recurrences, one nodal metastasis, and no distant metastases or deaths. Knowing this should guide physicians on a treatment path that will reduce costs and provide patients with peace of mind, he said.

In the BWH schema, T2a patients fared almost as well, with a 2% risk of nodal metastasis and an overall 1% risk of disease-specific death. “T2a disease is low risk, in my mind. Most of these patients will go on to do well,” he said.

By contrast, “there may be a number of tumors that you are missing” that are candidates for close follow-up if the BWH criteria are not being used, said Dr. Patel. These are the T2b tumors. “For those patients, we want to aggressively follow them and think about a more aggressive management plan.”

The bottom line is that BWH T2b and T3 tumors are both high risk, and management needs to acknowledge this, he said. The current protocol in our cutaneous oncology program includes using routine radiologic nodal staging in patients with BWH stage 2b and above SCCs and considering sentinel lymph node biopsy for certain individuals.

For patients with BWH T2b and T3 tumors, dermatologists should give consideration to tertiary care or cancer center referrals so they have access to the full spectrum of diagnostic and therapeutic modalities and the opportunity to participate in clinical trials, Dr. Patel said.

Dr. Patel reported that he is a speaker for Regeneron/Sanofi and a cofounder of the Skin Cancer Outcomes (SCOUT) consortium.

This article was updated 2/9/2019

ORLANDO – When caring for individuals with sun-damaged skin, dermatologists need comfort with the full spectrum of photo-related skin disease. From assessment and treatment of actinic keratoses (AKs) and field cancerization, to long-term follow-up of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs), appropriate treatment and staging can improve patient quality of life and reduce health care costs, Vishal Patel, MD, said at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

said Dr. Patel, director of cutaneous oncology at George Washington University Cancer Center, Washington. On the other hand, he added, “field disease can be a marker for invasive squamous cell carcinoma risk, and it requires field treatment.” Treatment that reduces field disease is primary prevention because it decreases the formation of invasive SCC, he noted.

“But this level of disease – AKs and SCC in situ – doesn’t kill people,” he emphasized. “I want to leave you with an ability to stage this disease,” said Dr. Patel, noting that SCC mortality may eventually surpass melanoma mortality as deaths from the latter decline and numbers of older Americans with high ultraviolet light exposure and other risk factors climb.

While the majority of AKs regress within 5 years, he looks at the total burden of AKs as a marker for field cancerization “because having less than five in situ or actinic lesions puts you at less than a 1% risk of squamous cell carcinoma formation. Having more than 20 increases that risk 20-fold to 20%,” he said. “That’s the way we need to start thinking about this: Is this a disease – or a symptom?”

Rather than thinking of each AK or SCC in situ as a separate disease event, “the disease we need to be focusing on and treating is field cancerization,” he continued. Within this context, “we should not be thinking that … we need to be aggressive in our management,” which is what results in high costs.

“The reality is that this is a big quality of life issue for our patients. So what do we do?” Field treatment is appropriate for field disease, he said. Dr. Patel said that at GW only field treatment is used; destructive treatment for AKs and SCC in situ is not used. In the absence of patient and lesion characteristics that elevate risk,“surgery is really not the standard of care for in situ lesions for us,” he commented.

“We start by discerning the field disease from the invasive disease” with an initial round of field treatment and, if needed, adjunctive oral chemoprophylaxis. “We lather, rinse, and repeat” the field therapy, continuously if needed, Dr. Patel said.

“We like to do that because we can then identify those specific lesions we want to go after. No cryosurgery, no destructive therapy, because we run the risk of burying those tumors under the scar. They may recur and make it more difficult to accurately stage them in the future,” he noted.

“I like to be more sophisticated in thinking about our approach to the outcomes of these individual lesions,” he said. When it comes to excising lesions that have been biopsied and show invasive SCC, “disc excision may be a more cost-effective way to treat many low-risk SCCs,” he noted. In any case, “removal with clear surgical margins is key.”

Primary tumors with such low-risk attributes as diameter under a centimeter and thickness under 2 mm; well-defined borders; location on the trunk, neck, or extremities; well-differentiated histology; and lack of perineural invasion can all be considered for a disc technique, especially if the patient is immunocompetent without background chronic inflammation or a history of prior radiation therapy.

Staging SCCs, said Dr. Patel, is where things really get tricky. Older staging systems for SCC “led us to overtreat nonaggressive disease and undertreat aggressive disease. I think we have the responsibility to lead the charge to having a more sophisticated approach.” For example, patients whose tumors were staged T2 in the American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) 7 classification system were most likely to have poor outcomes – in part because so few tumors were staged higher – which meant AJCC 7 didn’t provide adequate differentiation for useful risk prognostication.

A group of researchers at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH), Boston, “came up with a better system to better differentiate those T2 tumors into a high-risk and a low-risk subtype,” according to Dr. Patel.

With use of validated risk factors, the investigators applied a long list of risk factors to 2,000 tumors to see which risk factors, taken individually, were really contributing to poor outcomes. Eventually, four risk factors that made the most difference were identified: size greater than 2 cm, poor tumor differentiation, perineural invasion greater than 0.1 mm in diameter, and tumor invasion beyond subcutaneous fat. “I really want to highlight the size portion of those risk factors,” said Dr. Patel. “Something I’d like you to do in your clinical practice is to measure and document the size of the lesion. … That really, clearly helps” with risk prognostication.

These four factors were then used to break out a T2a stage for tumors with one risk factor and a T2b stage for tumors with two or three risk factors. Tumors with no risk factors are stage T1, and those with all four risk factors are stage T3. In situ SCC is T0.

Applying this new staging system to a 2,000-patient cohort with SCC yielded clear separation in outcomes including recurrence, nodal metastasis, disease-specific death, and overall survival between patients with the T2a and T2b tumors (P less than .001 for all; J Clin Oncol. 2014 Feb 1;32[4]:327-34).

While AJCC 8 is “significantly better” than AJCC 7 in its incorporation of meaningful risk factors into the SCC staging system, “it still underperforms in comparison” with the BWH staging system using the 2000 patient cohort, he said. Recent work has shown the BWH classification system to have superior specificity and positive predictive value in detecting nodal metastasis and disease-specific death in higher-grade tumors. But both BWH and AJCC 8 need further refinement.

“So what are the staging pearls to take home?” Dr. Patel asked. “First, utilize a staging system.” “Staging of SCC utilizing should be done routinely. Most data seems to suggest that the BWH system appears to outperform AJCC 8, and it is what we currently use routinely at GW,” he said.

Patients who are T1 by BWH criteria, with no risk factors, are at low or even no risk, he noted. He pointed out that of the nearly 1,400 patients who met T1 criteria, there were just eight local recurrences, one nodal metastasis, and no distant metastases or deaths. Knowing this should guide physicians on a treatment path that will reduce costs and provide patients with peace of mind, he said.

In the BWH schema, T2a patients fared almost as well, with a 2% risk of nodal metastasis and an overall 1% risk of disease-specific death. “T2a disease is low risk, in my mind. Most of these patients will go on to do well,” he said.

By contrast, “there may be a number of tumors that you are missing” that are candidates for close follow-up if the BWH criteria are not being used, said Dr. Patel. These are the T2b tumors. “For those patients, we want to aggressively follow them and think about a more aggressive management plan.”

The bottom line is that BWH T2b and T3 tumors are both high risk, and management needs to acknowledge this, he said. The current protocol in our cutaneous oncology program includes using routine radiologic nodal staging in patients with BWH stage 2b and above SCCs and considering sentinel lymph node biopsy for certain individuals.

For patients with BWH T2b and T3 tumors, dermatologists should give consideration to tertiary care or cancer center referrals so they have access to the full spectrum of diagnostic and therapeutic modalities and the opportunity to participate in clinical trials, Dr. Patel said.

Dr. Patel reported that he is a speaker for Regeneron/Sanofi and a cofounder of the Skin Cancer Outcomes (SCOUT) consortium.

This article was updated 2/9/2019

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ODAC 2019

Paraneoplastic Dermatomyositis Presenting With Interesting Cutaneous Findings

To the Editor:

We report an interesting clinical case of dermatomyositis (DM) that presented with an associated malignancy (small cell lung cancer). This patient also had an unusual clinical finding of predominantly unilateral, confluent, erythematous papules on the knee, a cutaneous sign that is seldom described in the DM literature. This case serves to reinforce the classic findings and associations of DM, in addition to the uncommon manifestation of predominantly unilateral papules on the knee.

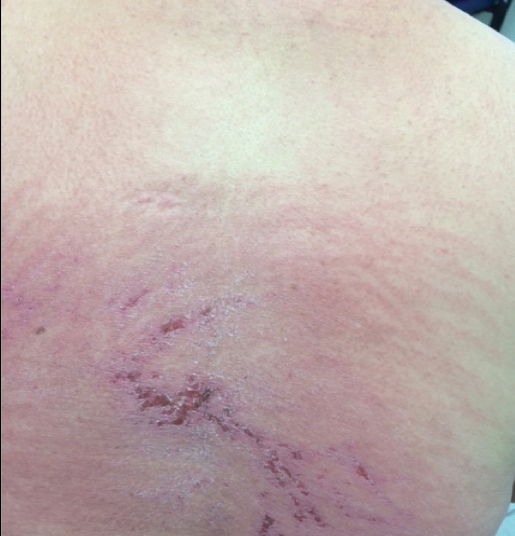

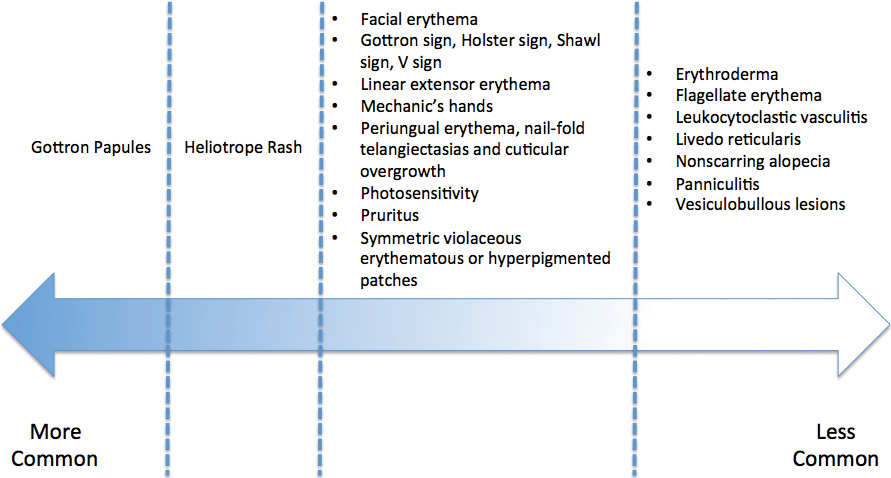

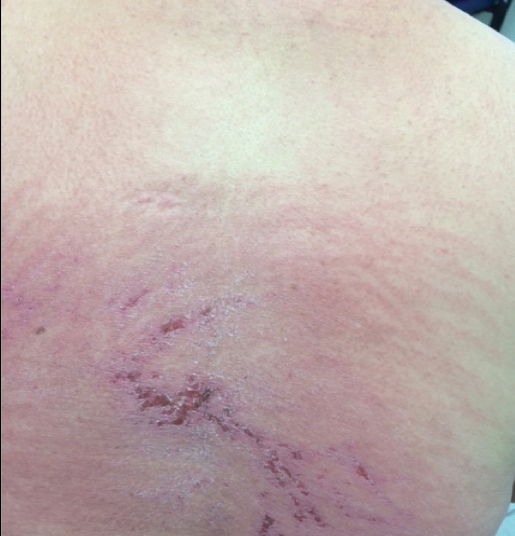

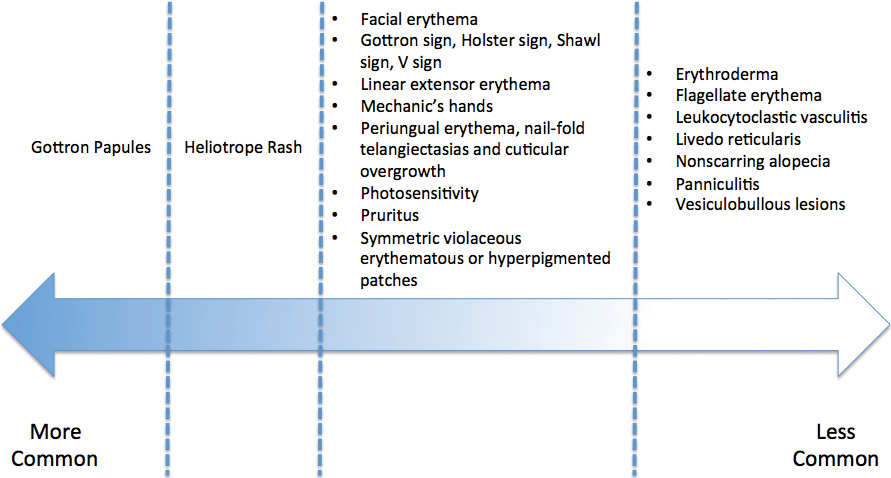

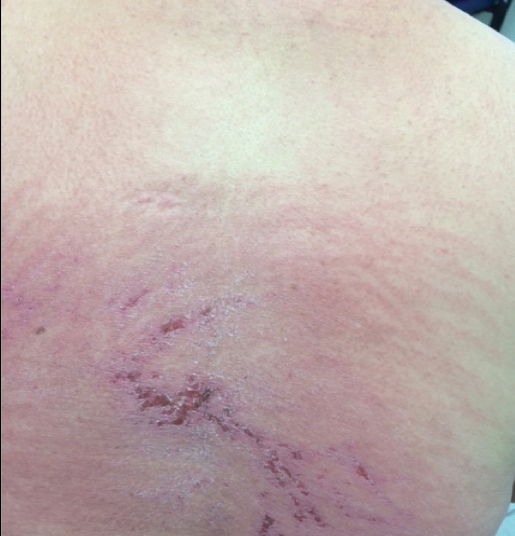

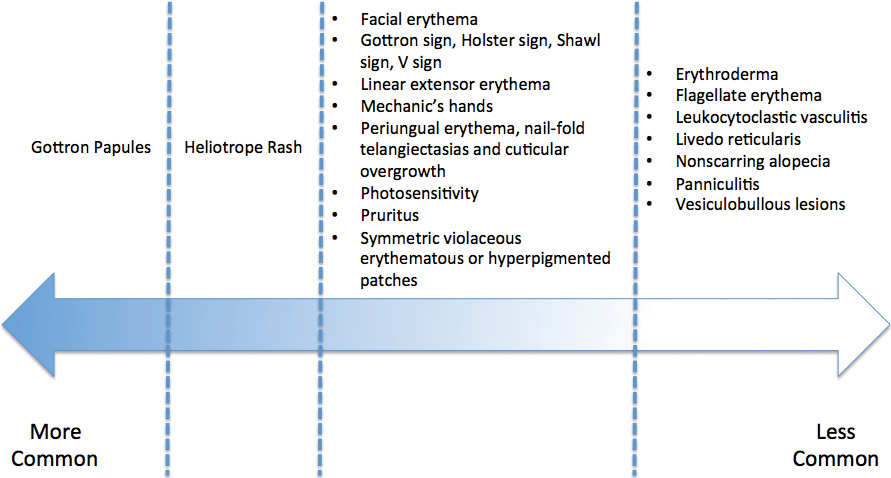

A 68-year-old woman presented with several cutaneous manifestations including the classic findings of photo distributed erythema on the arms and face, a heliotrope rash, Gottron papules, and confluent pink papules on the left knee (Figure 1). The patient also had one of the more rare manifestations of DM, flagellate erythema on the back (Figure 2). She had a history of breast cancer and was found to have metastatic small cell lung cancer at the time of the DM diagnosis.

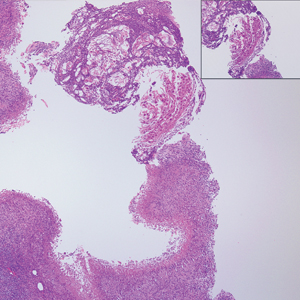

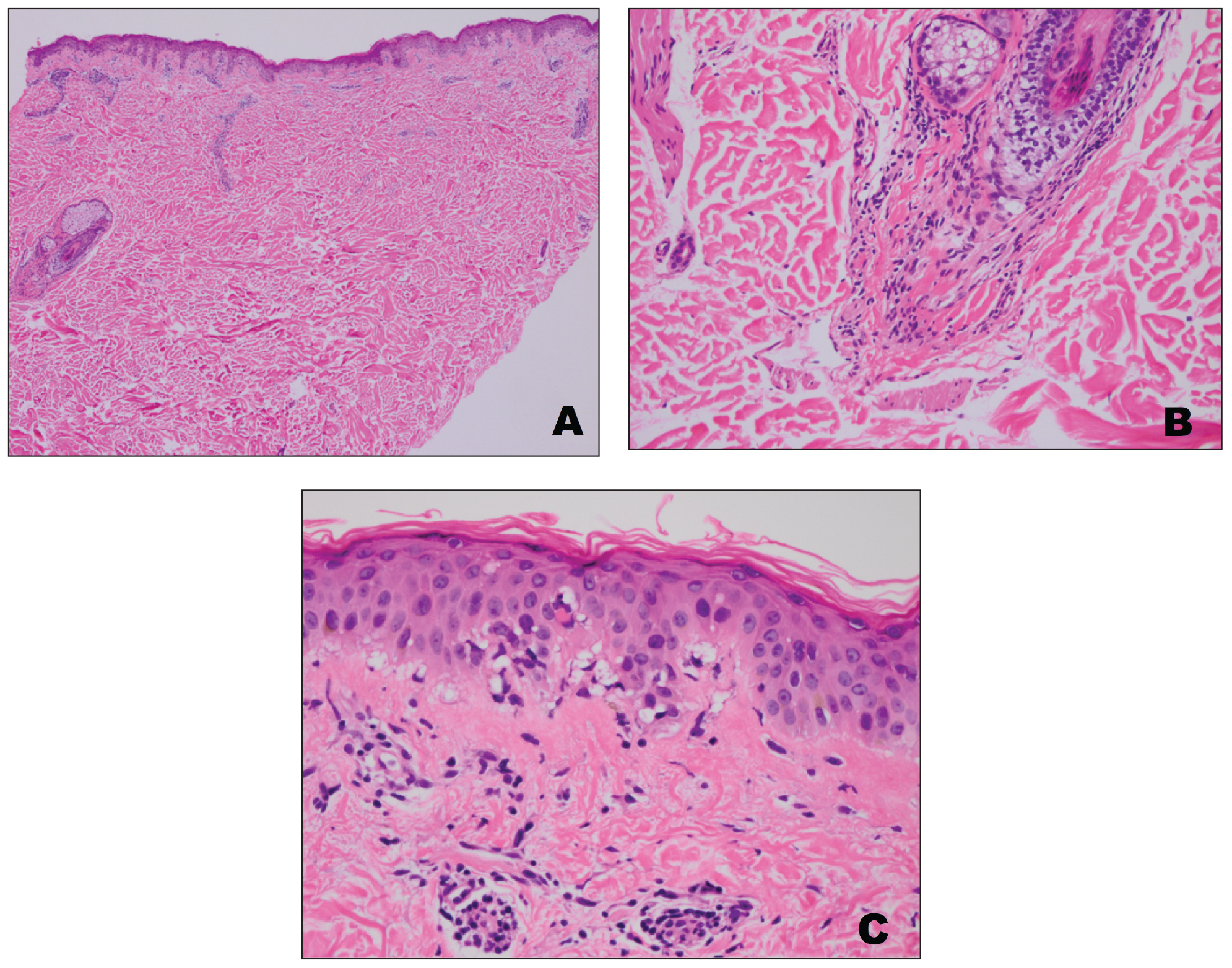

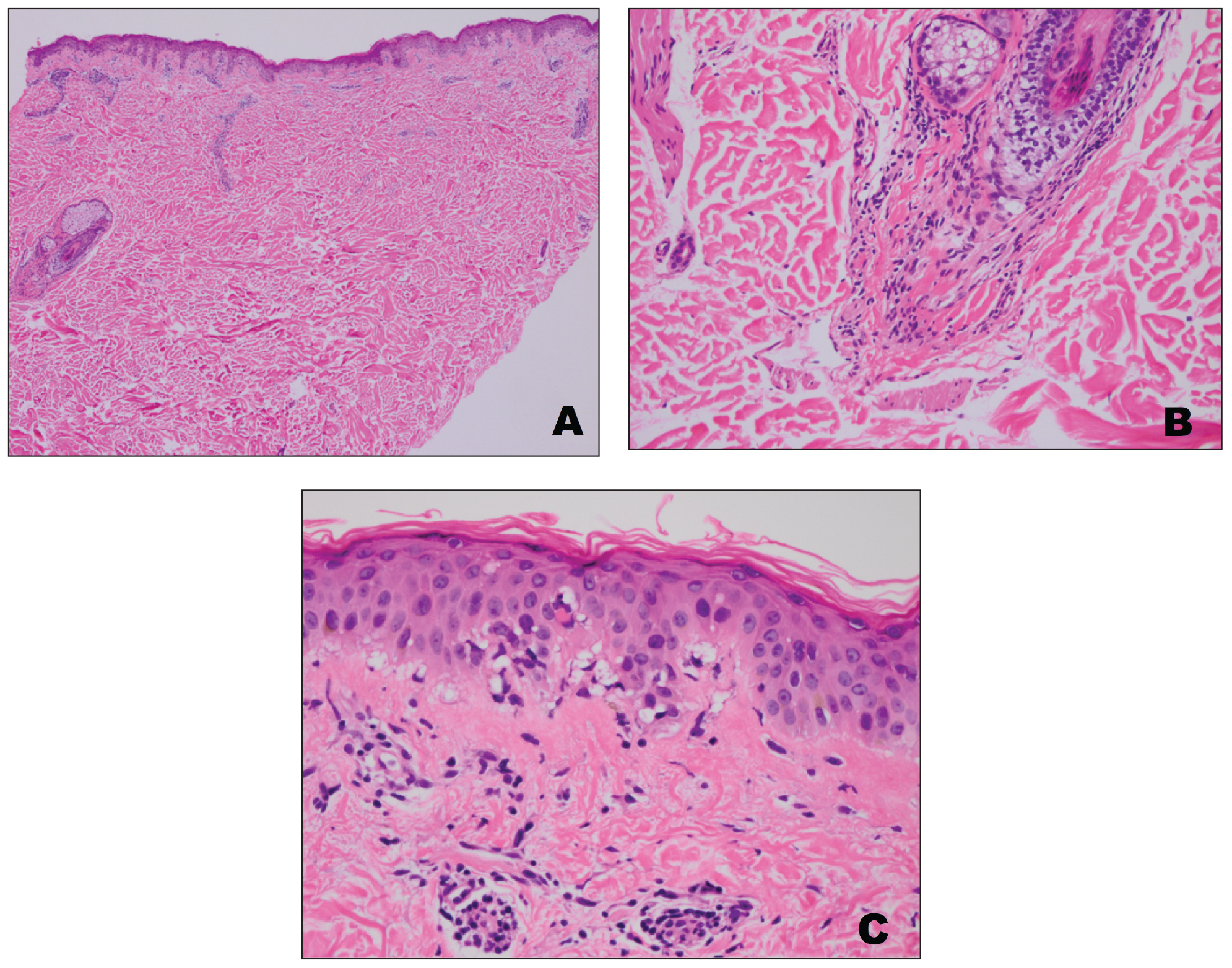

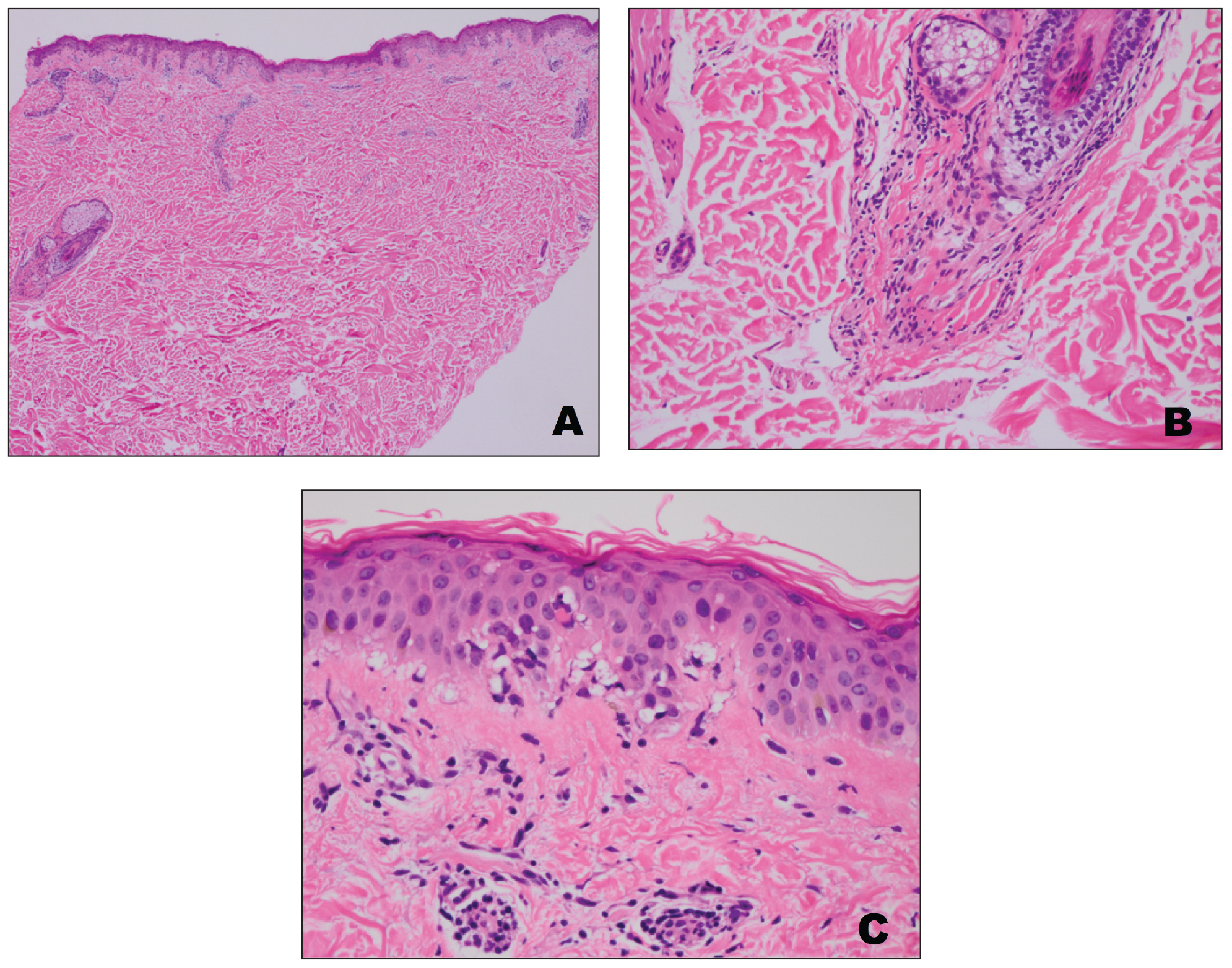

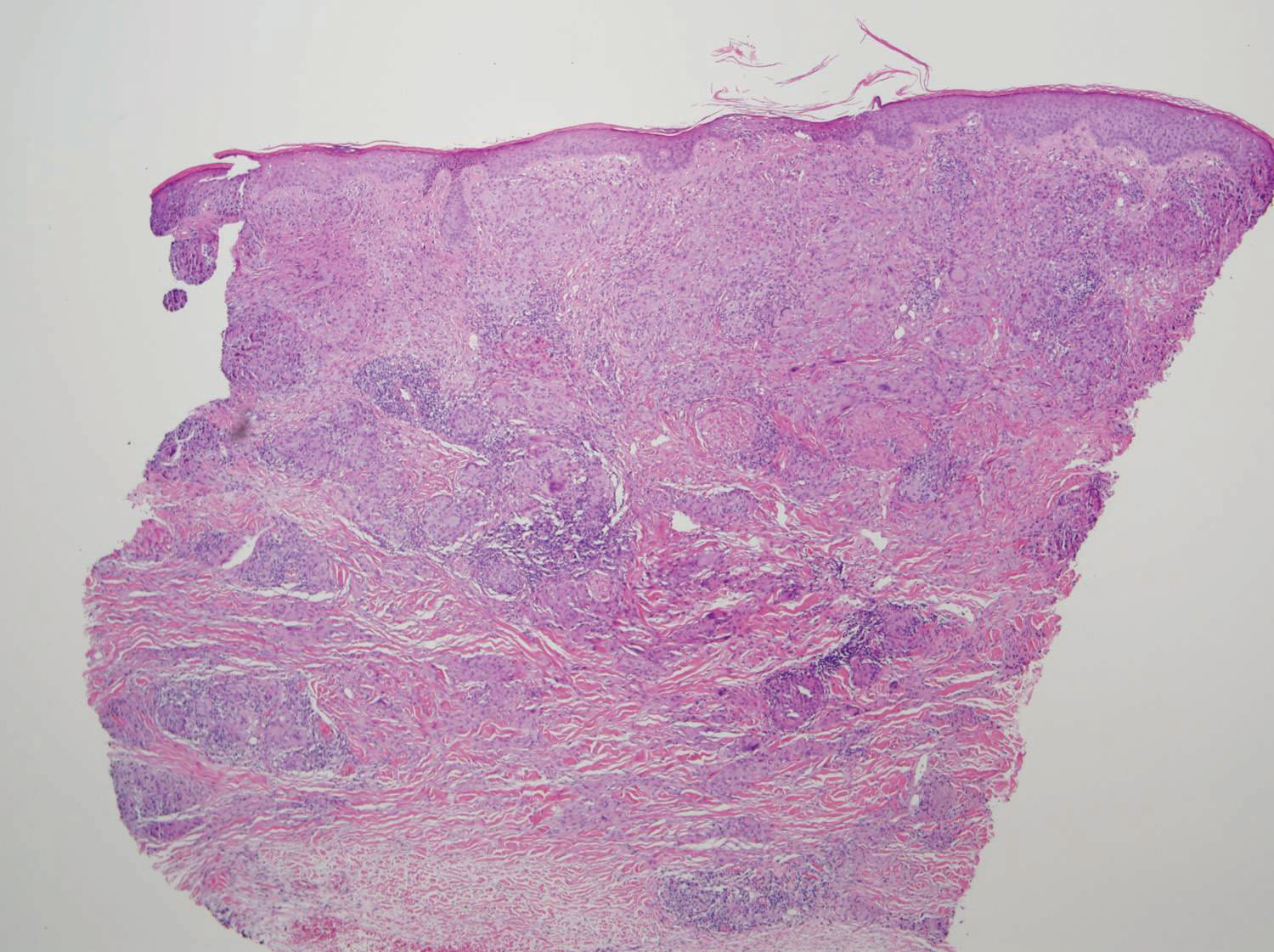

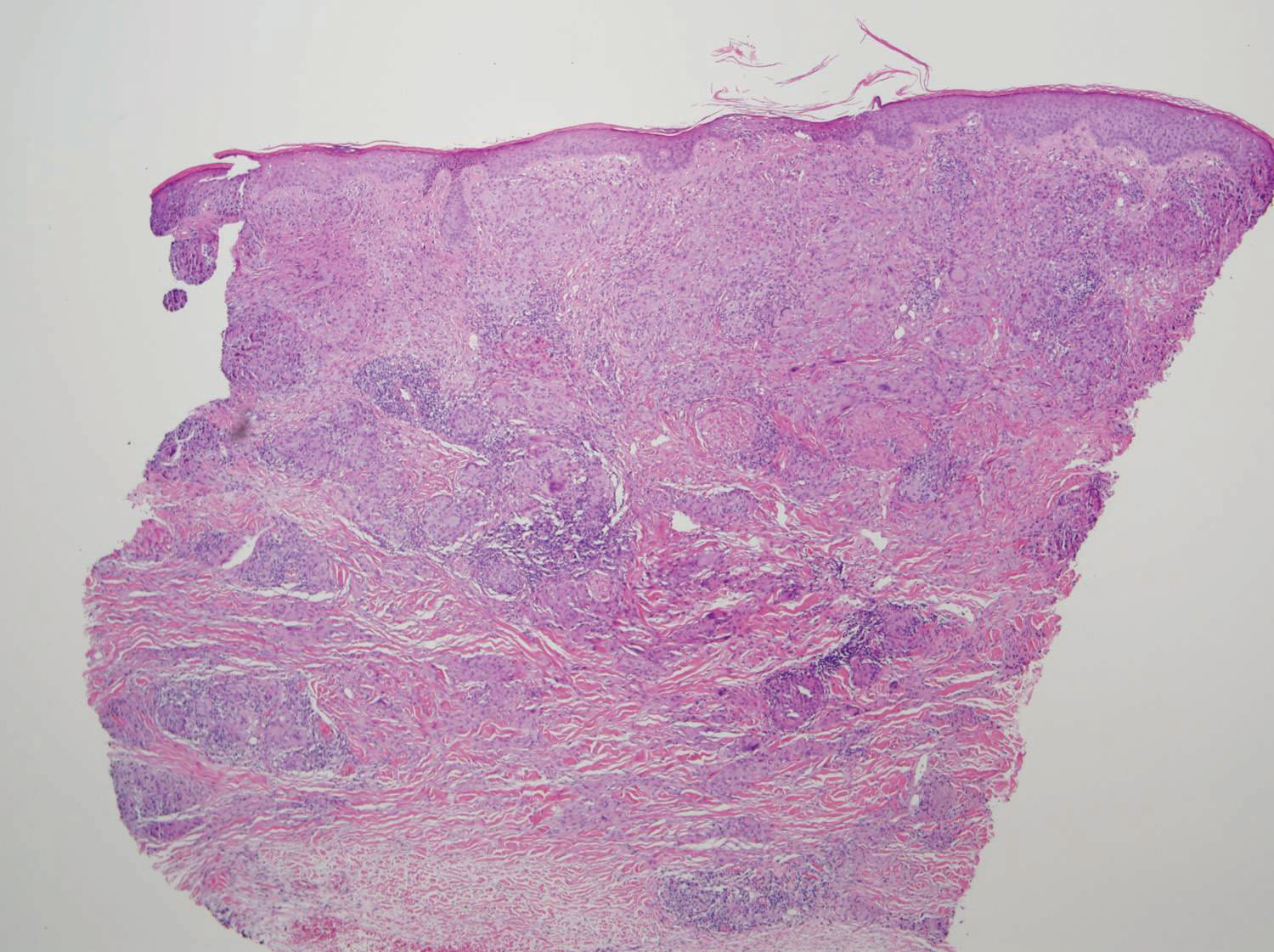

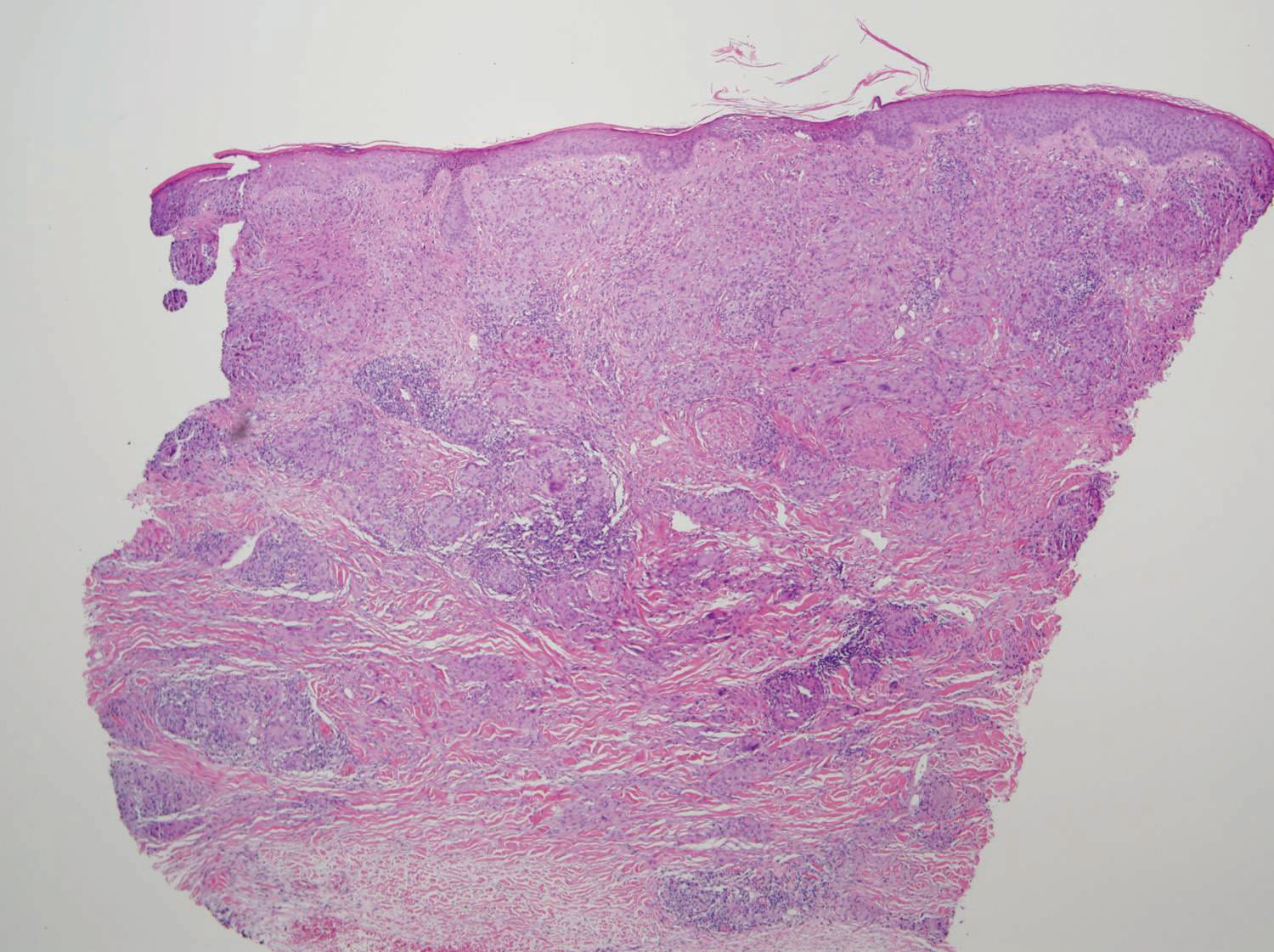

A punch biopsy from an area of flagellate erythema on the back revealed an interface dermatitis with a superficial, perivascular, lymphocyte-predominant inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 3). Alcian blue and colloidal iron stains revealed a marked increase in papillary dermal mucin. With the characteristic changes on skin biopsy and the classic skin findings present in our patient, we felt confident diagnosing her with DM. At the time of diagnosis, the patient also was found to have metastatic small cell lung cancer, suggesting a true paraneoplastic relationship.

The association of DM and amyopathic DM with internal malignancy is well known. Bohan and Peter1 noted an overall figure ranging from 15% to 34% with an increased frequency in patients with skin and muscle involvement.1 Hill et al5 examined this link in a population-based study that identified corresponding malignancies. Specifically, they noted cancers to arise most frequently in the airway (eg, lung, trachea, bronchus), ovaries, breasts, colorectal region, and stomach.5 There also has been work performed to identify if certain dermatologic findings may be associated with a higher risk of malignancy.6,7 A meta-analysis by Wang et al6 showed that Gottron sign did not have an association with cancer, but findings of cutaneous necrosis did have an association. It is unknown if the specific cutaneous findings in our patient, including the predominantly unilateral papules on the knee, may have been a clue to the underlying malignancy.

In summary, we believe that our patient presented with the classic manifestations of DM in addition to the curious cutaneous sign of predominantly unilateral, confluent, erythematous papules on the knee, a clinical finding that may aid in the diagnosis of DM and also may alert the clinician to a possible underlying malignancy.

- Bohan A, Peter JB. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (first of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1975;292:344-347.

- Santmyire-Rosenberger B, Dugan EM. Skin involvement in dermatomyositis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2003;15:714-722.

- Callen JP. Dermatomyositis. Lancet. 2000;355:53-57.

- Lister RK, Cooper ES, Paige DG. Papules and pustules of the elbows and knees: an uncommon clinical sign of dermatomyositis in oriental children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:37-40.

- Hill CL, Zhang Y, Sigurgeirsson B, et al. Frequency of specific cancer types in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a population-based study. Lancet. 2001;357:96-100.

- Wang J, Guo G, Chen G, et al. Meta‐analysis of the association of dermatomyositis and polymyositis with cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:838-847.

- Chen YJ, Wu CY, Shen JL. Predicting factors of malignancy in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a case–control study. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:825-831.

To the Editor:

We report an interesting clinical case of dermatomyositis (DM) that presented with an associated malignancy (small cell lung cancer). This patient also had an unusual clinical finding of predominantly unilateral, confluent, erythematous papules on the knee, a cutaneous sign that is seldom described in the DM literature. This case serves to reinforce the classic findings and associations of DM, in addition to the uncommon manifestation of predominantly unilateral papules on the knee.

A 68-year-old woman presented with several cutaneous manifestations including the classic findings of photo distributed erythema on the arms and face, a heliotrope rash, Gottron papules, and confluent pink papules on the left knee (Figure 1). The patient also had one of the more rare manifestations of DM, flagellate erythema on the back (Figure 2). She had a history of breast cancer and was found to have metastatic small cell lung cancer at the time of the DM diagnosis.

A punch biopsy from an area of flagellate erythema on the back revealed an interface dermatitis with a superficial, perivascular, lymphocyte-predominant inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 3). Alcian blue and colloidal iron stains revealed a marked increase in papillary dermal mucin. With the characteristic changes on skin biopsy and the classic skin findings present in our patient, we felt confident diagnosing her with DM. At the time of diagnosis, the patient also was found to have metastatic small cell lung cancer, suggesting a true paraneoplastic relationship.

The association of DM and amyopathic DM with internal malignancy is well known. Bohan and Peter1 noted an overall figure ranging from 15% to 34% with an increased frequency in patients with skin and muscle involvement.1 Hill et al5 examined this link in a population-based study that identified corresponding malignancies. Specifically, they noted cancers to arise most frequently in the airway (eg, lung, trachea, bronchus), ovaries, breasts, colorectal region, and stomach.5 There also has been work performed to identify if certain dermatologic findings may be associated with a higher risk of malignancy.6,7 A meta-analysis by Wang et al6 showed that Gottron sign did not have an association with cancer, but findings of cutaneous necrosis did have an association. It is unknown if the specific cutaneous findings in our patient, including the predominantly unilateral papules on the knee, may have been a clue to the underlying malignancy.

In summary, we believe that our patient presented with the classic manifestations of DM in addition to the curious cutaneous sign of predominantly unilateral, confluent, erythematous papules on the knee, a clinical finding that may aid in the diagnosis of DM and also may alert the clinician to a possible underlying malignancy.

To the Editor:

We report an interesting clinical case of dermatomyositis (DM) that presented with an associated malignancy (small cell lung cancer). This patient also had an unusual clinical finding of predominantly unilateral, confluent, erythematous papules on the knee, a cutaneous sign that is seldom described in the DM literature. This case serves to reinforce the classic findings and associations of DM, in addition to the uncommon manifestation of predominantly unilateral papules on the knee.

A 68-year-old woman presented with several cutaneous manifestations including the classic findings of photo distributed erythema on the arms and face, a heliotrope rash, Gottron papules, and confluent pink papules on the left knee (Figure 1). The patient also had one of the more rare manifestations of DM, flagellate erythema on the back (Figure 2). She had a history of breast cancer and was found to have metastatic small cell lung cancer at the time of the DM diagnosis.

A punch biopsy from an area of flagellate erythema on the back revealed an interface dermatitis with a superficial, perivascular, lymphocyte-predominant inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 3). Alcian blue and colloidal iron stains revealed a marked increase in papillary dermal mucin. With the characteristic changes on skin biopsy and the classic skin findings present in our patient, we felt confident diagnosing her with DM. At the time of diagnosis, the patient also was found to have metastatic small cell lung cancer, suggesting a true paraneoplastic relationship.

The association of DM and amyopathic DM with internal malignancy is well known. Bohan and Peter1 noted an overall figure ranging from 15% to 34% with an increased frequency in patients with skin and muscle involvement.1 Hill et al5 examined this link in a population-based study that identified corresponding malignancies. Specifically, they noted cancers to arise most frequently in the airway (eg, lung, trachea, bronchus), ovaries, breasts, colorectal region, and stomach.5 There also has been work performed to identify if certain dermatologic findings may be associated with a higher risk of malignancy.6,7 A meta-analysis by Wang et al6 showed that Gottron sign did not have an association with cancer, but findings of cutaneous necrosis did have an association. It is unknown if the specific cutaneous findings in our patient, including the predominantly unilateral papules on the knee, may have been a clue to the underlying malignancy.

In summary, we believe that our patient presented with the classic manifestations of DM in addition to the curious cutaneous sign of predominantly unilateral, confluent, erythematous papules on the knee, a clinical finding that may aid in the diagnosis of DM and also may alert the clinician to a possible underlying malignancy.

- Bohan A, Peter JB. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (first of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1975;292:344-347.

- Santmyire-Rosenberger B, Dugan EM. Skin involvement in dermatomyositis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2003;15:714-722.

- Callen JP. Dermatomyositis. Lancet. 2000;355:53-57.

- Lister RK, Cooper ES, Paige DG. Papules and pustules of the elbows and knees: an uncommon clinical sign of dermatomyositis in oriental children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:37-40.

- Hill CL, Zhang Y, Sigurgeirsson B, et al. Frequency of specific cancer types in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a population-based study. Lancet. 2001;357:96-100.

- Wang J, Guo G, Chen G, et al. Meta‐analysis of the association of dermatomyositis and polymyositis with cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:838-847.

- Chen YJ, Wu CY, Shen JL. Predicting factors of malignancy in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a case–control study. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:825-831.

- Bohan A, Peter JB. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (first of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1975;292:344-347.

- Santmyire-Rosenberger B, Dugan EM. Skin involvement in dermatomyositis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2003;15:714-722.

- Callen JP. Dermatomyositis. Lancet. 2000;355:53-57.

- Lister RK, Cooper ES, Paige DG. Papules and pustules of the elbows and knees: an uncommon clinical sign of dermatomyositis in oriental children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:37-40.

- Hill CL, Zhang Y, Sigurgeirsson B, et al. Frequency of specific cancer types in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a population-based study. Lancet. 2001;357:96-100.

- Wang J, Guo G, Chen G, et al. Meta‐analysis of the association of dermatomyositis and polymyositis with cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:838-847.

- Chen YJ, Wu CY, Shen JL. Predicting factors of malignancy in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a case–control study. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:825-831.

Practice Points

- Dermatomyositis has myriad cutaneous features including the shawl sign, the heliotrope sign, and Gottron papules.

- Less commonly, patients can present with the Holster sign (poikiloderma of the lateral thighs).

- Even less commonly, as in this report, patients can present with a psoriasiform papular eruption on the knees or with flagellate erythema on the back.

Annular Elastolytic Giant Cell Granuloma: Mysterious Enlarging Scarring Lesions

To the Editor:

A 52-year-old woman with a medical history of migraines and cervicalgia presented with lesions on the right arm, back, and right calf. The patient stated that the lesions began as small papules that had grown over 13 months, with the largest papule on the right forearm. She reported no itching, bleeding, pain, discharge, or other symptoms associated with the lesions. She had a multiple-year history of similar lesions that did not respond to treatment with antifungals, moderate-potency steroids, and other over-the-counter creams. The lesions would resolve spontaneously with scarring and subsequently recur. Prior skin biopsies were inconclusive. The patient did not report any systemic symptoms or a personal or family history of connective tissue diseases.

Physical examination revealed a 4-cm asymmetric, annular, erythematous plaque with central clearing on the right dorsal forearm with defined margins except over the distal aspect (Figure 1). She also had several 1- to 2-cm erythematous, nummular, asymmetric plaques on the right upper arm with well-defined margins. She had several lesions over the central and left sides of the upper back that were similar to the lesions on the upper arm.

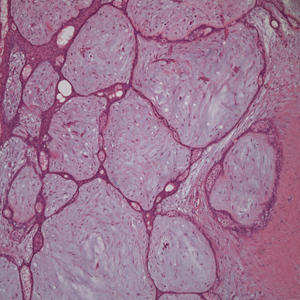

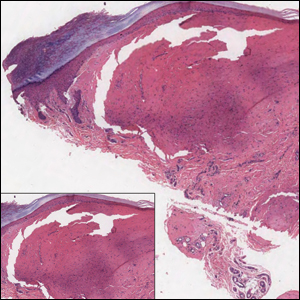

Two 4-mm punch biopsies of the right dorsal forearm and left side of the upper back revealed similar histologic features with a predominantly unremarkable epidermis. The dermis revealed a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with prominent multinucleated giant cells organized into foreign body–type granulomas that extended into the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue (Figure 2). In the granulomatous areas, there was a near-complete loss of elastic fibers with focal elastophagocytosis highlighted with Verhoeff-van Gieson (elastin) stain (Figure 3). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and Fite stains for microorganisms were negative, and there was an absence of necrobiosis, lipids, and mucin.

The histologic findings of a granulomatous dermatitis with loss of elastic fibers and elastophagocytosis in addition to the patient’s clinical presentation and history were consistent with the diagnosis of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma (AEGCG). Infectious and other granulomatous diseases including sarcoidosis were ruled out via clinical history, unremarkable laboratory analysis (ie, complete blood cell count, chemistry panel, antinuclear antibody, urinalysis), and a normal chest radiograph. The histologic findings via the various stains were instrumental to the diagnosis. The patient was treated with fluocinonide and subsequently lost to follow-up.

Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma is an uncommon cutaneous disease that presents with recurring annular plaques with raised erythematous borders and subsequent residual scarring.1 O’Brien2 originally described this condition in 1975 as an actinic granuloma due to similar histologic findings in areas of the patient’s sun-exposed skin. Ragaz and Ackerman3 disputed O’Brien’s2 description, claiming granulomatous inflammation was a primary pathologic process and not a consequence to damaged elastotic material. In 1979, Hanke et al4 termed the lesions as AEGCG because he did not find a correlation to the sun-exposed areas of the patients and did not see solar elastosis.

Although AEGCG has an unclear pathogenesis, cellular immunologic reactions induced by modified function of elastic fibers’ antigenicity contribute to AEGCG formation.5 Therefore, environmental and host factors may play a role in its etiopathogenesis. In one study, 37% of 38 Japanese patients with AEGCG were found to have definitive or latent diabetes mellitus, raising the possible role of diabetes in the structural damage of the elastic fibers.6

Patients typically are middle-aged women who present clinically with red or atrophic plaques that have slightly elevated borders. They have centripetal spread with a resulting atrophic center.7 Clinically, the differential diagnosis of this condition includes actinic granuloma, granuloma annulare, and granuloma multiforme.8

Histologically, AEGCG has a granulomatous component with multinucleated giant cells in the upper and mid dermis. This component typically is distributed peripherally to a central zone that lacks elastic tissue. Elastophagocytosis, a classic finding in AEGCG, is the phagocytosis of elastic fibers that can microscopically be seen in the cytoplasm of histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. There also is an absence of necrobiosis, lipids, mucin, and a palisading arrangement of the granulomas. These findings distinguish AEGCG from granuloma annulare and necrobiosis lipoidica, the primary histologic differential diagnoses.9 In addition, consideration of entities consistently exhibiting elastophagocytosis such as mid-dermal elastolysis, papillary dermal elastolysis, actinic granuloma, and granulomatous slack skin should be considered.5,10,11

Therapy for AEGCG is broad and includes topical, intralesional, and systemic corticosteroids. Hydroxychloroquine, isotretinoin, clofazimine, dapsone, photochemotherapy, and cyclosporine also have been utilized with varying results. Other reports show improvement with surgical excision, cryotherapy, or cauterization of small lesions.12-15

1. Tock CL, Cohen PR. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Cutis. 1998;62:181-187.

2. O’Brien JP. Actinic granuloma: an annular connective tissue disorder affecting sun- and heat-damaged (elastotic) skin. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:460-466.

3. Ragaz A, Ackerman AB. Is actinic granuloma a specific condition? Am J Dermatopathol. 1979;1:43-50.

4. Hanke CW, Bailin PL, Roenigk HH Jr. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. a clinicopathologic study of five cases and a review of similar entities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1979;1:413-421.

5. El-Khoury J, Kurban M, Abbas O. Elastophagocytosis: underlying mechanisms and associated cutaneous entities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:934-44.

6. Aso Y, Izaki Y, Teraki Y. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma associated with diabetes mellitus: a case report and review of the Japanese literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:917-919.

7. Pestoni C, Pereiro M Jr, Toribio J. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma produced on an old burn scar and spreading after a mechanical trauma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2003;83:312-313.

8. Oka M, Kunisada M, Nishigori C. Generalized annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma with sparing of striae distensae. J Dermatol. 2013;40:220-222.

9. Limas C. The spectrum of primary cutaneous elastolytic granulomas and their distinction from granuloma annulare: a clinicopathological analysis. Histopathology. 2004;44:277-282.

10. McGrae JD Jr. Actinic granuloma: a clinical, histopathologic, and immunocytochemical study. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:43-47.

11. Shah A, Safaya A. Granulomatous slack skin disease: a review, in comparison with mycosis fungoides. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1472-1478.

12. Chou WT, Tsai TF, Hung CM, et al. Multiple annular erythematous plaques on the back. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma (AEGCG). Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:727-728.

13. Pérez-Pérez L, Garcia-Gavin J, Alleque F, et al. Successful treatment of generalized elastolytic giant cell granuloma with psoralen-ultraviolet A. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:264-266.

14. Babuna G, Buyukbabani N, Yazganoglu KD, et al. Effective treatment with hydroxychloroquine in a case of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:110-111.

15. Can B, Kavala M, Türkoglu Z, et al. Successful treatment of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma with hydroxylchloroquine. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:509-511.

To the Editor:

A 52-year-old woman with a medical history of migraines and cervicalgia presented with lesions on the right arm, back, and right calf. The patient stated that the lesions began as small papules that had grown over 13 months, with the largest papule on the right forearm. She reported no itching, bleeding, pain, discharge, or other symptoms associated with the lesions. She had a multiple-year history of similar lesions that did not respond to treatment with antifungals, moderate-potency steroids, and other over-the-counter creams. The lesions would resolve spontaneously with scarring and subsequently recur. Prior skin biopsies were inconclusive. The patient did not report any systemic symptoms or a personal or family history of connective tissue diseases.

Physical examination revealed a 4-cm asymmetric, annular, erythematous plaque with central clearing on the right dorsal forearm with defined margins except over the distal aspect (Figure 1). She also had several 1- to 2-cm erythematous, nummular, asymmetric plaques on the right upper arm with well-defined margins. She had several lesions over the central and left sides of the upper back that were similar to the lesions on the upper arm.

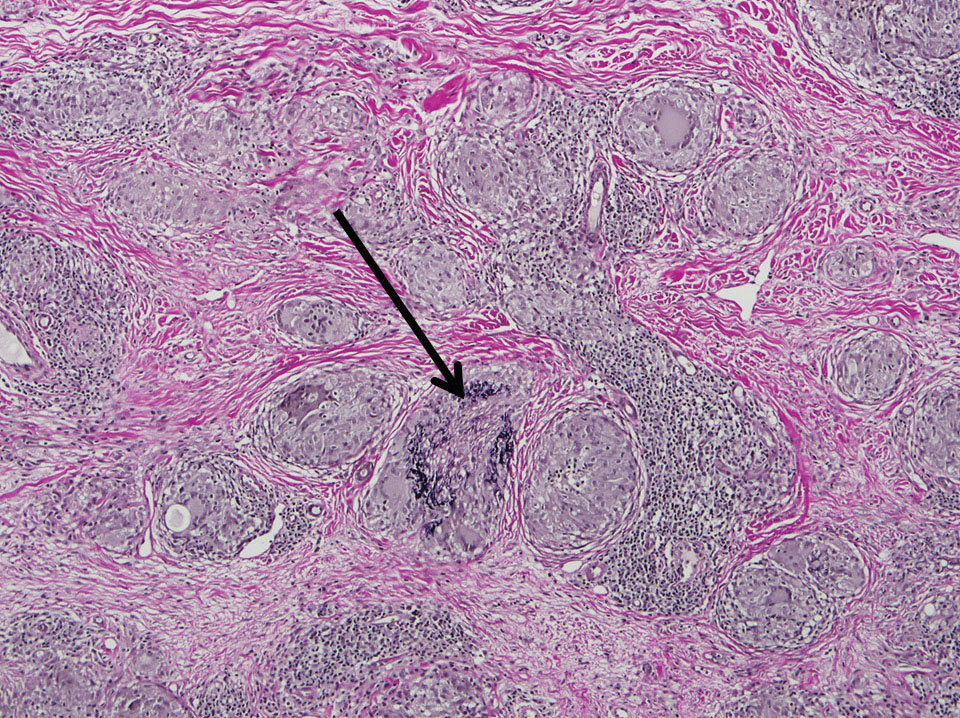

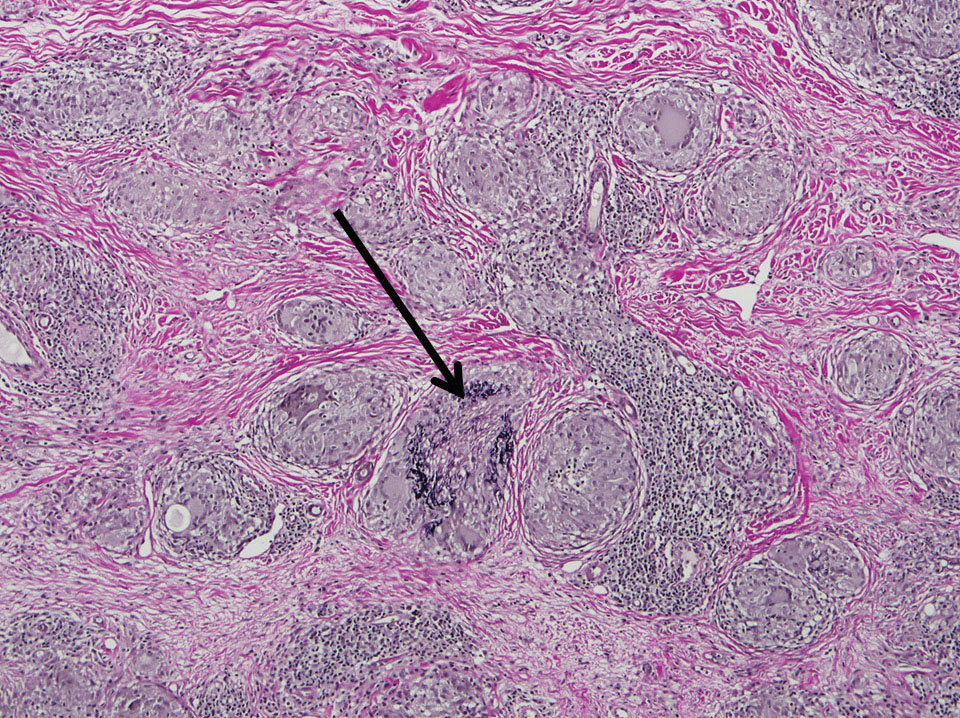

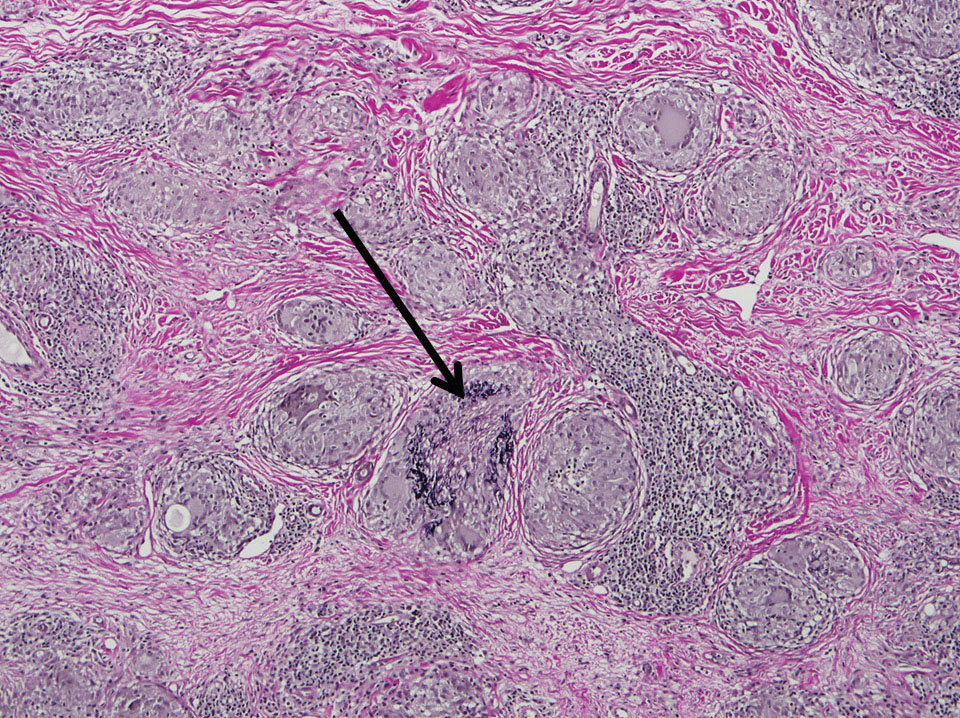

Two 4-mm punch biopsies of the right dorsal forearm and left side of the upper back revealed similar histologic features with a predominantly unremarkable epidermis. The dermis revealed a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with prominent multinucleated giant cells organized into foreign body–type granulomas that extended into the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue (Figure 2). In the granulomatous areas, there was a near-complete loss of elastic fibers with focal elastophagocytosis highlighted with Verhoeff-van Gieson (elastin) stain (Figure 3). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and Fite stains for microorganisms were negative, and there was an absence of necrobiosis, lipids, and mucin.

The histologic findings of a granulomatous dermatitis with loss of elastic fibers and elastophagocytosis in addition to the patient’s clinical presentation and history were consistent with the diagnosis of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma (AEGCG). Infectious and other granulomatous diseases including sarcoidosis were ruled out via clinical history, unremarkable laboratory analysis (ie, complete blood cell count, chemistry panel, antinuclear antibody, urinalysis), and a normal chest radiograph. The histologic findings via the various stains were instrumental to the diagnosis. The patient was treated with fluocinonide and subsequently lost to follow-up.

Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma is an uncommon cutaneous disease that presents with recurring annular plaques with raised erythematous borders and subsequent residual scarring.1 O’Brien2 originally described this condition in 1975 as an actinic granuloma due to similar histologic findings in areas of the patient’s sun-exposed skin. Ragaz and Ackerman3 disputed O’Brien’s2 description, claiming granulomatous inflammation was a primary pathologic process and not a consequence to damaged elastotic material. In 1979, Hanke et al4 termed the lesions as AEGCG because he did not find a correlation to the sun-exposed areas of the patients and did not see solar elastosis.

Although AEGCG has an unclear pathogenesis, cellular immunologic reactions induced by modified function of elastic fibers’ antigenicity contribute to AEGCG formation.5 Therefore, environmental and host factors may play a role in its etiopathogenesis. In one study, 37% of 38 Japanese patients with AEGCG were found to have definitive or latent diabetes mellitus, raising the possible role of diabetes in the structural damage of the elastic fibers.6

Patients typically are middle-aged women who present clinically with red or atrophic plaques that have slightly elevated borders. They have centripetal spread with a resulting atrophic center.7 Clinically, the differential diagnosis of this condition includes actinic granuloma, granuloma annulare, and granuloma multiforme.8

Histologically, AEGCG has a granulomatous component with multinucleated giant cells in the upper and mid dermis. This component typically is distributed peripherally to a central zone that lacks elastic tissue. Elastophagocytosis, a classic finding in AEGCG, is the phagocytosis of elastic fibers that can microscopically be seen in the cytoplasm of histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. There also is an absence of necrobiosis, lipids, mucin, and a palisading arrangement of the granulomas. These findings distinguish AEGCG from granuloma annulare and necrobiosis lipoidica, the primary histologic differential diagnoses.9 In addition, consideration of entities consistently exhibiting elastophagocytosis such as mid-dermal elastolysis, papillary dermal elastolysis, actinic granuloma, and granulomatous slack skin should be considered.5,10,11

Therapy for AEGCG is broad and includes topical, intralesional, and systemic corticosteroids. Hydroxychloroquine, isotretinoin, clofazimine, dapsone, photochemotherapy, and cyclosporine also have been utilized with varying results. Other reports show improvement with surgical excision, cryotherapy, or cauterization of small lesions.12-15

To the Editor:

A 52-year-old woman with a medical history of migraines and cervicalgia presented with lesions on the right arm, back, and right calf. The patient stated that the lesions began as small papules that had grown over 13 months, with the largest papule on the right forearm. She reported no itching, bleeding, pain, discharge, or other symptoms associated with the lesions. She had a multiple-year history of similar lesions that did not respond to treatment with antifungals, moderate-potency steroids, and other over-the-counter creams. The lesions would resolve spontaneously with scarring and subsequently recur. Prior skin biopsies were inconclusive. The patient did not report any systemic symptoms or a personal or family history of connective tissue diseases.

Physical examination revealed a 4-cm asymmetric, annular, erythematous plaque with central clearing on the right dorsal forearm with defined margins except over the distal aspect (Figure 1). She also had several 1- to 2-cm erythematous, nummular, asymmetric plaques on the right upper arm with well-defined margins. She had several lesions over the central and left sides of the upper back that were similar to the lesions on the upper arm.

Two 4-mm punch biopsies of the right dorsal forearm and left side of the upper back revealed similar histologic features with a predominantly unremarkable epidermis. The dermis revealed a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with prominent multinucleated giant cells organized into foreign body–type granulomas that extended into the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue (Figure 2). In the granulomatous areas, there was a near-complete loss of elastic fibers with focal elastophagocytosis highlighted with Verhoeff-van Gieson (elastin) stain (Figure 3). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and Fite stains for microorganisms were negative, and there was an absence of necrobiosis, lipids, and mucin.

The histologic findings of a granulomatous dermatitis with loss of elastic fibers and elastophagocytosis in addition to the patient’s clinical presentation and history were consistent with the diagnosis of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma (AEGCG). Infectious and other granulomatous diseases including sarcoidosis were ruled out via clinical history, unremarkable laboratory analysis (ie, complete blood cell count, chemistry panel, antinuclear antibody, urinalysis), and a normal chest radiograph. The histologic findings via the various stains were instrumental to the diagnosis. The patient was treated with fluocinonide and subsequently lost to follow-up.

Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma is an uncommon cutaneous disease that presents with recurring annular plaques with raised erythematous borders and subsequent residual scarring.1 O’Brien2 originally described this condition in 1975 as an actinic granuloma due to similar histologic findings in areas of the patient’s sun-exposed skin. Ragaz and Ackerman3 disputed O’Brien’s2 description, claiming granulomatous inflammation was a primary pathologic process and not a consequence to damaged elastotic material. In 1979, Hanke et al4 termed the lesions as AEGCG because he did not find a correlation to the sun-exposed areas of the patients and did not see solar elastosis.

Although AEGCG has an unclear pathogenesis, cellular immunologic reactions induced by modified function of elastic fibers’ antigenicity contribute to AEGCG formation.5 Therefore, environmental and host factors may play a role in its etiopathogenesis. In one study, 37% of 38 Japanese patients with AEGCG were found to have definitive or latent diabetes mellitus, raising the possible role of diabetes in the structural damage of the elastic fibers.6

Patients typically are middle-aged women who present clinically with red or atrophic plaques that have slightly elevated borders. They have centripetal spread with a resulting atrophic center.7 Clinically, the differential diagnosis of this condition includes actinic granuloma, granuloma annulare, and granuloma multiforme.8

Histologically, AEGCG has a granulomatous component with multinucleated giant cells in the upper and mid dermis. This component typically is distributed peripherally to a central zone that lacks elastic tissue. Elastophagocytosis, a classic finding in AEGCG, is the phagocytosis of elastic fibers that can microscopically be seen in the cytoplasm of histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. There also is an absence of necrobiosis, lipids, mucin, and a palisading arrangement of the granulomas. These findings distinguish AEGCG from granuloma annulare and necrobiosis lipoidica, the primary histologic differential diagnoses.9 In addition, consideration of entities consistently exhibiting elastophagocytosis such as mid-dermal elastolysis, papillary dermal elastolysis, actinic granuloma, and granulomatous slack skin should be considered.5,10,11

Therapy for AEGCG is broad and includes topical, intralesional, and systemic corticosteroids. Hydroxychloroquine, isotretinoin, clofazimine, dapsone, photochemotherapy, and cyclosporine also have been utilized with varying results. Other reports show improvement with surgical excision, cryotherapy, or cauterization of small lesions.12-15

1. Tock CL, Cohen PR. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Cutis. 1998;62:181-187.

2. O’Brien JP. Actinic granuloma: an annular connective tissue disorder affecting sun- and heat-damaged (elastotic) skin. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:460-466.

3. Ragaz A, Ackerman AB. Is actinic granuloma a specific condition? Am J Dermatopathol. 1979;1:43-50.

4. Hanke CW, Bailin PL, Roenigk HH Jr. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. a clinicopathologic study of five cases and a review of similar entities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1979;1:413-421.

5. El-Khoury J, Kurban M, Abbas O. Elastophagocytosis: underlying mechanisms and associated cutaneous entities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:934-44.

6. Aso Y, Izaki Y, Teraki Y. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma associated with diabetes mellitus: a case report and review of the Japanese literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:917-919.

7. Pestoni C, Pereiro M Jr, Toribio J. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma produced on an old burn scar and spreading after a mechanical trauma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2003;83:312-313.

8. Oka M, Kunisada M, Nishigori C. Generalized annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma with sparing of striae distensae. J Dermatol. 2013;40:220-222.

9. Limas C. The spectrum of primary cutaneous elastolytic granulomas and their distinction from granuloma annulare: a clinicopathological analysis. Histopathology. 2004;44:277-282.

10. McGrae JD Jr. Actinic granuloma: a clinical, histopathologic, and immunocytochemical study. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:43-47.

11. Shah A, Safaya A. Granulomatous slack skin disease: a review, in comparison with mycosis fungoides. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1472-1478.

12. Chou WT, Tsai TF, Hung CM, et al. Multiple annular erythematous plaques on the back. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma (AEGCG). Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:727-728.

13. Pérez-Pérez L, Garcia-Gavin J, Alleque F, et al. Successful treatment of generalized elastolytic giant cell granuloma with psoralen-ultraviolet A. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:264-266.

14. Babuna G, Buyukbabani N, Yazganoglu KD, et al. Effective treatment with hydroxychloroquine in a case of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:110-111.

15. Can B, Kavala M, Türkoglu Z, et al. Successful treatment of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma with hydroxylchloroquine. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:509-511.

1. Tock CL, Cohen PR. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Cutis. 1998;62:181-187.

2. O’Brien JP. Actinic granuloma: an annular connective tissue disorder affecting sun- and heat-damaged (elastotic) skin. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:460-466.

3. Ragaz A, Ackerman AB. Is actinic granuloma a specific condition? Am J Dermatopathol. 1979;1:43-50.

4. Hanke CW, Bailin PL, Roenigk HH Jr. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. a clinicopathologic study of five cases and a review of similar entities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1979;1:413-421.

5. El-Khoury J, Kurban M, Abbas O. Elastophagocytosis: underlying mechanisms and associated cutaneous entities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:934-44.

6. Aso Y, Izaki Y, Teraki Y. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma associated with diabetes mellitus: a case report and review of the Japanese literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:917-919.

7. Pestoni C, Pereiro M Jr, Toribio J. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma produced on an old burn scar and spreading after a mechanical trauma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2003;83:312-313.

8. Oka M, Kunisada M, Nishigori C. Generalized annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma with sparing of striae distensae. J Dermatol. 2013;40:220-222.

9. Limas C. The spectrum of primary cutaneous elastolytic granulomas and their distinction from granuloma annulare: a clinicopathological analysis. Histopathology. 2004;44:277-282.

10. McGrae JD Jr. Actinic granuloma: a clinical, histopathologic, and immunocytochemical study. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:43-47.

11. Shah A, Safaya A. Granulomatous slack skin disease: a review, in comparison with mycosis fungoides. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1472-1478.

12. Chou WT, Tsai TF, Hung CM, et al. Multiple annular erythematous plaques on the back. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma (AEGCG). Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:727-728.

13. Pérez-Pérez L, Garcia-Gavin J, Alleque F, et al. Successful treatment of generalized elastolytic giant cell granuloma with psoralen-ultraviolet A. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:264-266.

14. Babuna G, Buyukbabani N, Yazganoglu KD, et al. Effective treatment with hydroxychloroquine in a case of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:110-111.

15. Can B, Kavala M, Türkoglu Z, et al. Successful treatment of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma with hydroxylchloroquine. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:509-511.

Practice Points

- Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma (AEGCG) should be kept in the differential diagnosis when assessing a middle-aged woman with recurring annular plaques with a raised border and an atrophic center on both sun-exposed and sun-protected areas of the body.

- Histologically, AEGCG classically has a granulomatous component in the dermis that lacks elastic tissue and has no necrobiosis, lipids, or mucin. Staining with elastin may be necessary to highlight these areas as well as demonstrate elastophagocytosis.

Solitary Nodule on the Thigh

The Diagnosis: Ruptured Molluscum

Molluscum contagiosum (MC) is caused by a DNA virus (MC virus) belonging to the poxvirus family. Molluscum contagiosum is common and predominantly seen in children and young adults. In sexually active adults, the lesions commonly occur in the genital region, abdomen, and inner thighs. In immunocompromised individuals, including those with AIDS, the lesions are more extensive and may cause disfigurement.1 Molluscum contagiosum involving epidermoid cysts has been reported.2

Histopathologically, MC can be classified as noninflammatory or inflammatory. In noninflamed lesions, multiple large, intracytoplasmic, eosinophilic inclusions (Henderson-Paterson bodies) appear within the lobulated endophytic and hyperplastic epidermis. Ultrastructurally, these bodies show membrane-bound collections of MC virus.1 Replicating Henderson-Paterson bodies can result in rupture and inflammation. This case demonstrates a palisading granuloma containing keratin with few Henderson-Paterson bodies (quiz image) due to prior rupture of a molluscum or molluscoid cyst.

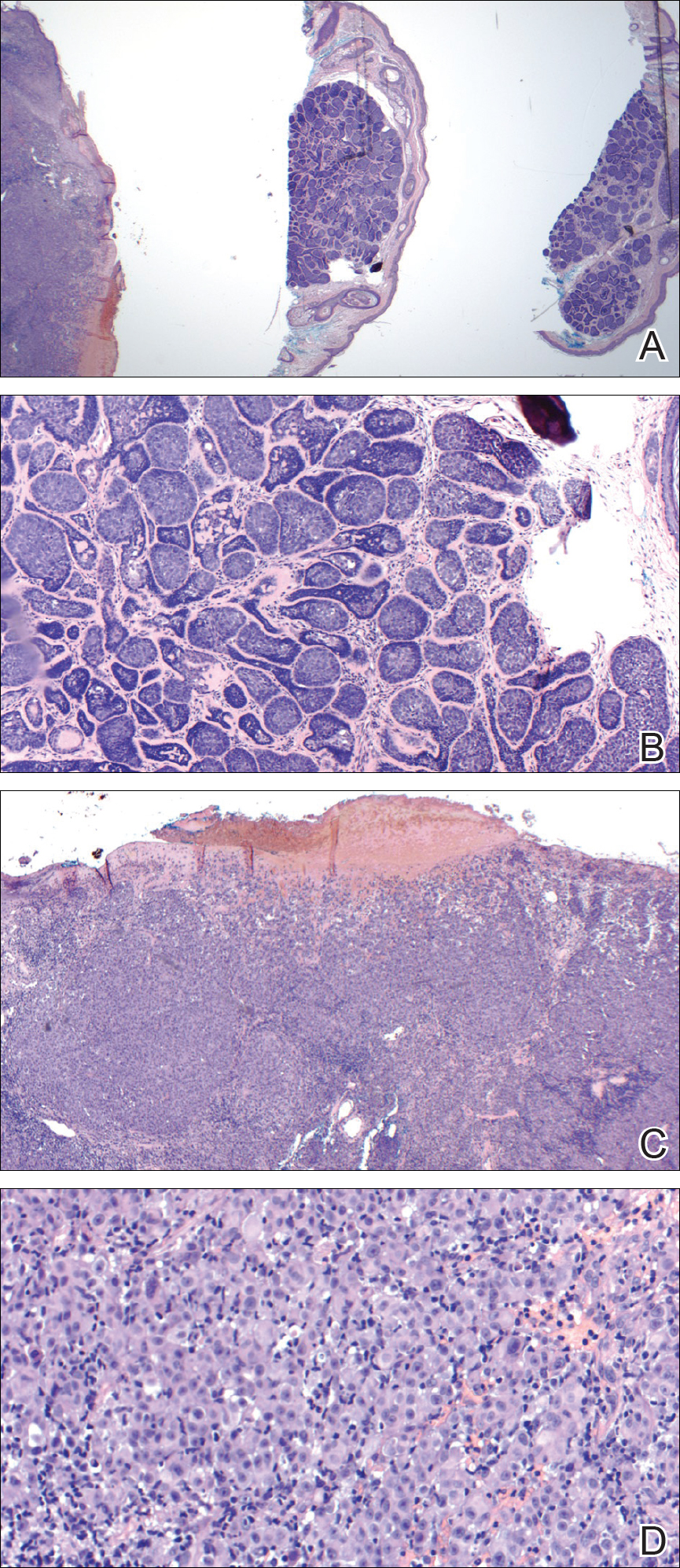

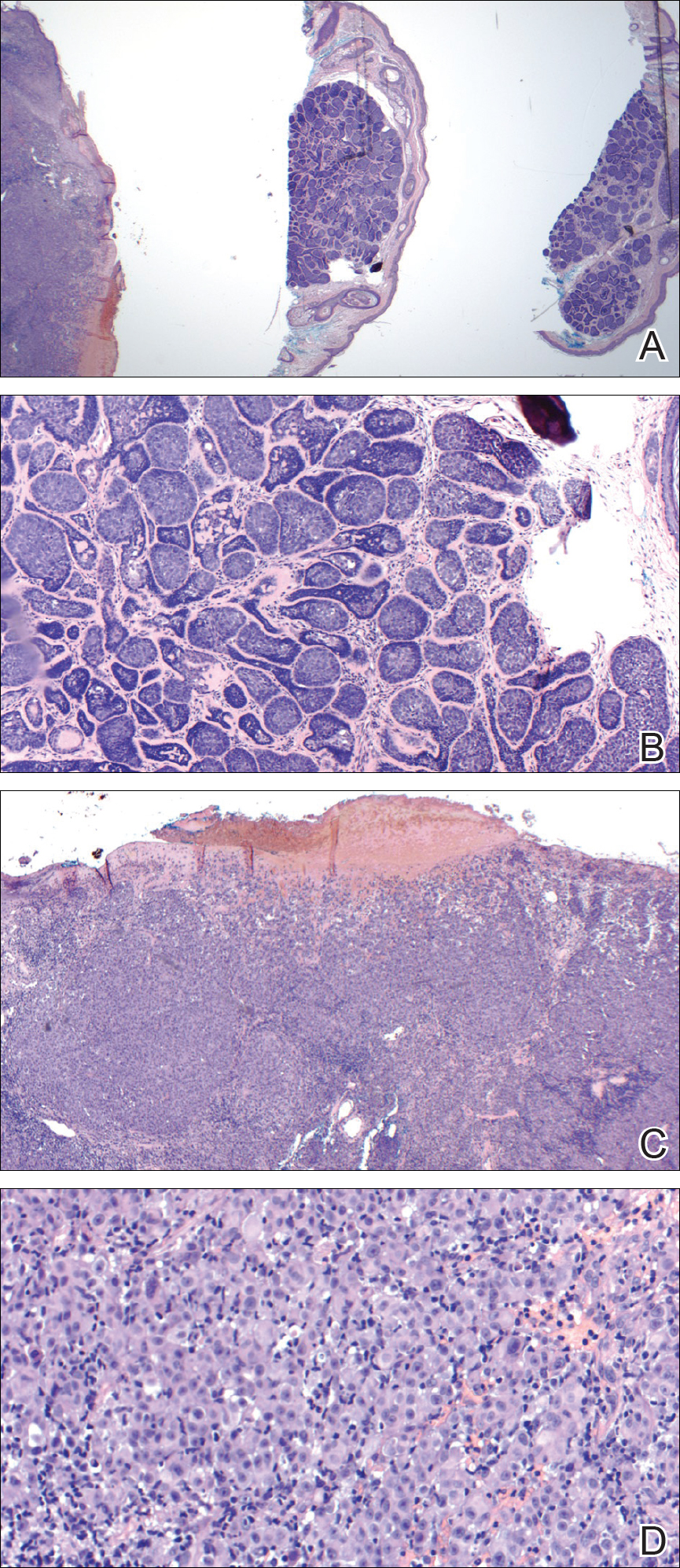

Rheumatoid nodules, the most characteristic histopathologic lesions of rheumatoid arthritis, are most commonly found in the subcutis at points of pressure and may occur in connective tissue of numerous organs. Rheumatoid nodules are firm, nontender, and mobile within the subcutaneous tissue but may be fixed to underlying structures including the periosteum, tendons, or bursae.3,4 Occasionally, superficial nodules may perforate the epidermis.5 The inner central necrobiotic zone appears as intensely eosinophilic, amorphous fibrin and other cellular debris. This central area is surrounded by histiocytes in a palisaded configuration (Figure 1). Multinucleated foreign body giant cells also may be present. Occasionally, mast cells, eosinophils, and neutrophils are present.6,7

Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei presents with multiple discrete, smooth, yellow-brown to red, dome-shaped papules. The lesions typically are located on the central and lateral sides of the face and infrequently involve the neck. Other sites including the axillae, arms, hands, legs, and groin occasionally can be involved. Diascopy may reveal an apple jelly color.8,9 The histopathologic hallmark of lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei is an epithelioid cell granuloma with central necrosis (Figure 2).

Epithelioid sarcoma (ES) is a soft tissue tumor with a known propensity for local recurrence, regional lymph node involvement, sporotrichoid spread, and distant metastases.10 The name was coined by Enzinger11 in 1970 during a review of 62 cases of a “peculiar form of sarcoma that has repeatedly been confused with a chronic inflammatory process, a necrotizing granuloma, and a squamous cell carcinoma.” Epithelioid sarcoma tends to grow slowly in a nodular or multinodular manner along fascial structures and tendons, often with central necrosis and ulceration of the overlying skin. Histopathologically, classic ES shows nodular masses of uniform plump epithelioid cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and prominent central necrosis. A biphasic pattern is typical with spindle cells merging with epithelioid cells. Cellular atypia is relatively mild and mitoses are rare (Figure 3). Recurrent or metastatic lesions can show a greater degree of pleomorphism.12 Given the low-grade atypia in early lesions, this sarcoma is easily misdiagnosed as granulomatous dermatitis. Immunohistochemically, the majority of ES cases are positive for cytokeratins and epithelial membrane antigen; SMARCB1/INI-1 expression is characteristically lost.13

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener granulomatosis) is an autoimmune vasculitis highly associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Clinical manifestations include systemic necrotizing vasculitis; necrotizing glomerulonephritis; and granulomatous inflammation, which predominantly involves the upper respiratory tract, skin, and mucosa.14,15 Skin involvement may be the initial manifestation of the disease and consists of palpable purpura, papules, ulcerations, vesicles, subcutaneous nodules, necrotizing ulcerations, papulonecrotic lesions, and petechiae. None of the findings are pathognomonic. The cutaneous histopathologic spectrum includes leukocytoclastic vasculitis, extravascular palisading granulomas, and granulomatous vasculitis.16 In the acute lesions of granulomatosis with polyangiitis, the predominant pattern of inflammation is not granulomatous but purulent with the appearance of an abscess. As it evolves, it develops a central zone of necrosis with extensive karyorrhectic debris and palisades of macrophages with scattered multinucleated giant cells (Figure 4).17

1. Nandhini G, Rajkumar K, Kanth KS, et al. Molluscum contagiosum in a 12-year-old child—report of a case and review of literature. J Int Oral Health. 2015;7:63-66.

2. Phelps A, Murphy M, Elaba Z, et al. Molluscum contagiosum virus infection in benign cutaneous epithelial cystic lesions-report of 2 cases with different pathogenesis? Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:740-742.

3. Sayah A, English JC 3rd. Rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:191-209; quiz 210-192.

4. Sibbitt WL Jr, Williams RC Jr. Cutaneous manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Dermatol. 1982;21:563-572.

5. Barzilai A, Huszar M, Shpiro D, et al. Pseudorheumatoid nodules in adults: a juxta-articular form of nodular granuloma annulare. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:1-5.

6. Garcia-Patos V. Rheumatoid nodule. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:100-107.

7. Patterson JW. Rheumatoid nodule and subcutaneous granuloma annulare. a comparative histologic study. Am J Dermatopathol. 1988;10:1-8.

8. Sehgal VN, Srivastava G, Aggarwal AK, et al. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei part II: an overview. Skinmed. 2005;4:234-238.

9. Cymerman R, Rosenstein R, Shvartsbeyn M, et al. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21. pii:13030/qt6b83q5gp.

10. Sobanko JF, Meijer L, Nigra TP. Epithelioid sarcoma: a review and update. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2009;2:49-54.

11. Enzinger FM. Epitheloid sarcoma. a sarcoma simulating a granuloma or a carcinoma. Cancer. 1970;26:1029-1041.

12. Fisher C. Epithelioid sarcoma of Enzinger. Adv Anat Pathol. 2006;13:114-121.

13. Miettinen M, Fanburg-Smith JC, Virolainen M, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma: an immunohistochemical analysis of 112 classical and variant cases and a discussion of the differential diagnosis. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:934-942.

14. Lutalo PM, D’Cruz DP. Diagnosis and classification of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (aka Wegener’s granulomatosis)[published online January 29, 2014]. J Autoimmun. 2014;48-49:94-98.

15. Frances C, Du LT, Piette JC, et al. Wegener’s granulomatosis. dermatological manifestations in 75 cases with clinicopathologic correlation. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:861-867.

16. Daoud MS, Gibson LE, DeRemee RA, et al. Cutaneous Wegener’s granulomatosis: clinical, histopathologic, and immunopathologic features of thirty patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:605-612.

17. Jennette JC. Nomenclature and classification of vasculitis: lessons learned from granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s granulomatosis). Clin Exp Immunol. 2011;164 (suppl 1):7-10.

The Diagnosis: Ruptured Molluscum

Molluscum contagiosum (MC) is caused by a DNA virus (MC virus) belonging to the poxvirus family. Molluscum contagiosum is common and predominantly seen in children and young adults. In sexually active adults, the lesions commonly occur in the genital region, abdomen, and inner thighs. In immunocompromised individuals, including those with AIDS, the lesions are more extensive and may cause disfigurement.1 Molluscum contagiosum involving epidermoid cysts has been reported.2

Histopathologically, MC can be classified as noninflammatory or inflammatory. In noninflamed lesions, multiple large, intracytoplasmic, eosinophilic inclusions (Henderson-Paterson bodies) appear within the lobulated endophytic and hyperplastic epidermis. Ultrastructurally, these bodies show membrane-bound collections of MC virus.1 Replicating Henderson-Paterson bodies can result in rupture and inflammation. This case demonstrates a palisading granuloma containing keratin with few Henderson-Paterson bodies (quiz image) due to prior rupture of a molluscum or molluscoid cyst.

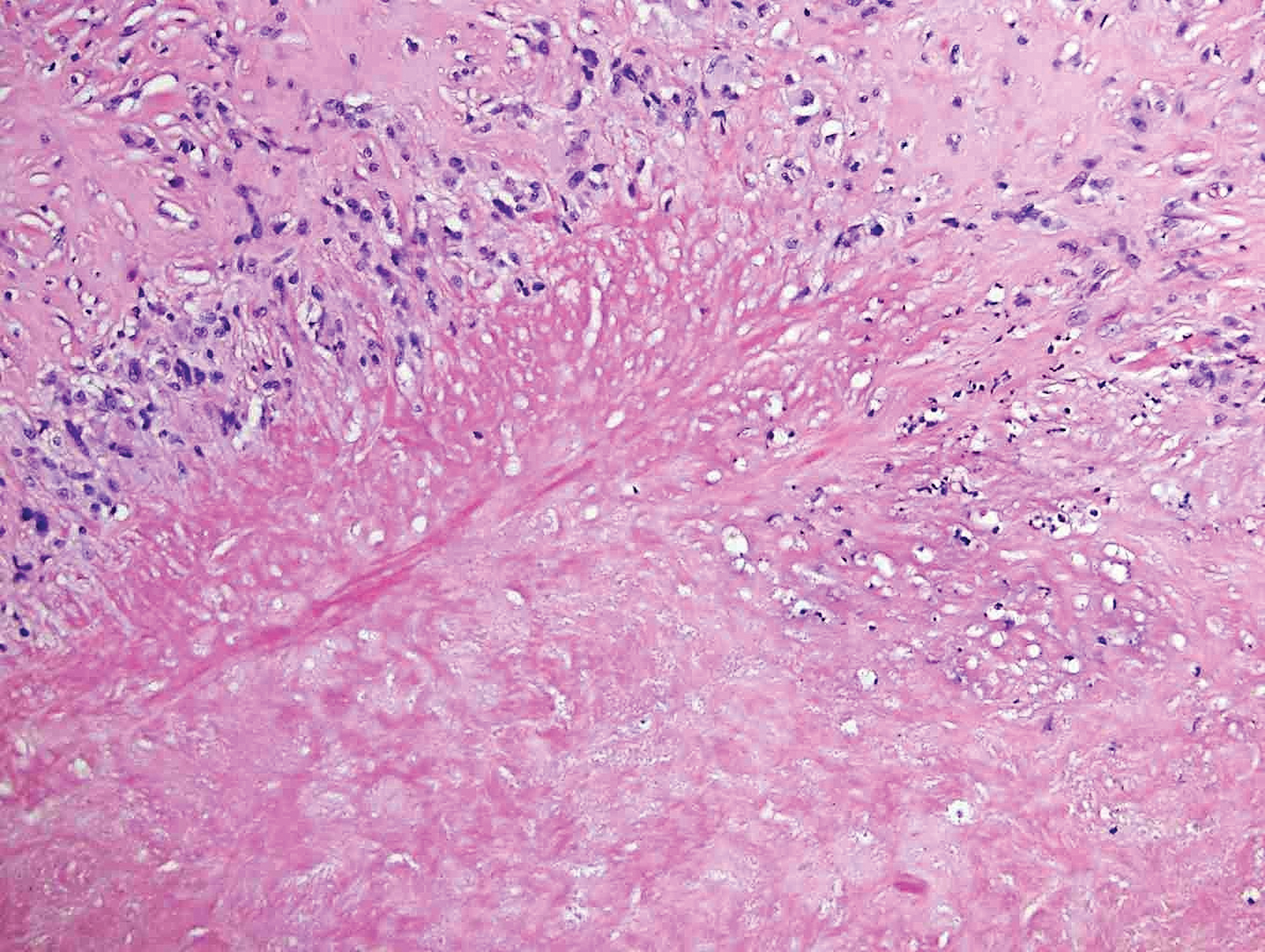

Rheumatoid nodules, the most characteristic histopathologic lesions of rheumatoid arthritis, are most commonly found in the subcutis at points of pressure and may occur in connective tissue of numerous organs. Rheumatoid nodules are firm, nontender, and mobile within the subcutaneous tissue but may be fixed to underlying structures including the periosteum, tendons, or bursae.3,4 Occasionally, superficial nodules may perforate the epidermis.5 The inner central necrobiotic zone appears as intensely eosinophilic, amorphous fibrin and other cellular debris. This central area is surrounded by histiocytes in a palisaded configuration (Figure 1). Multinucleated foreign body giant cells also may be present. Occasionally, mast cells, eosinophils, and neutrophils are present.6,7

Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei presents with multiple discrete, smooth, yellow-brown to red, dome-shaped papules. The lesions typically are located on the central and lateral sides of the face and infrequently involve the neck. Other sites including the axillae, arms, hands, legs, and groin occasionally can be involved. Diascopy may reveal an apple jelly color.8,9 The histopathologic hallmark of lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei is an epithelioid cell granuloma with central necrosis (Figure 2).

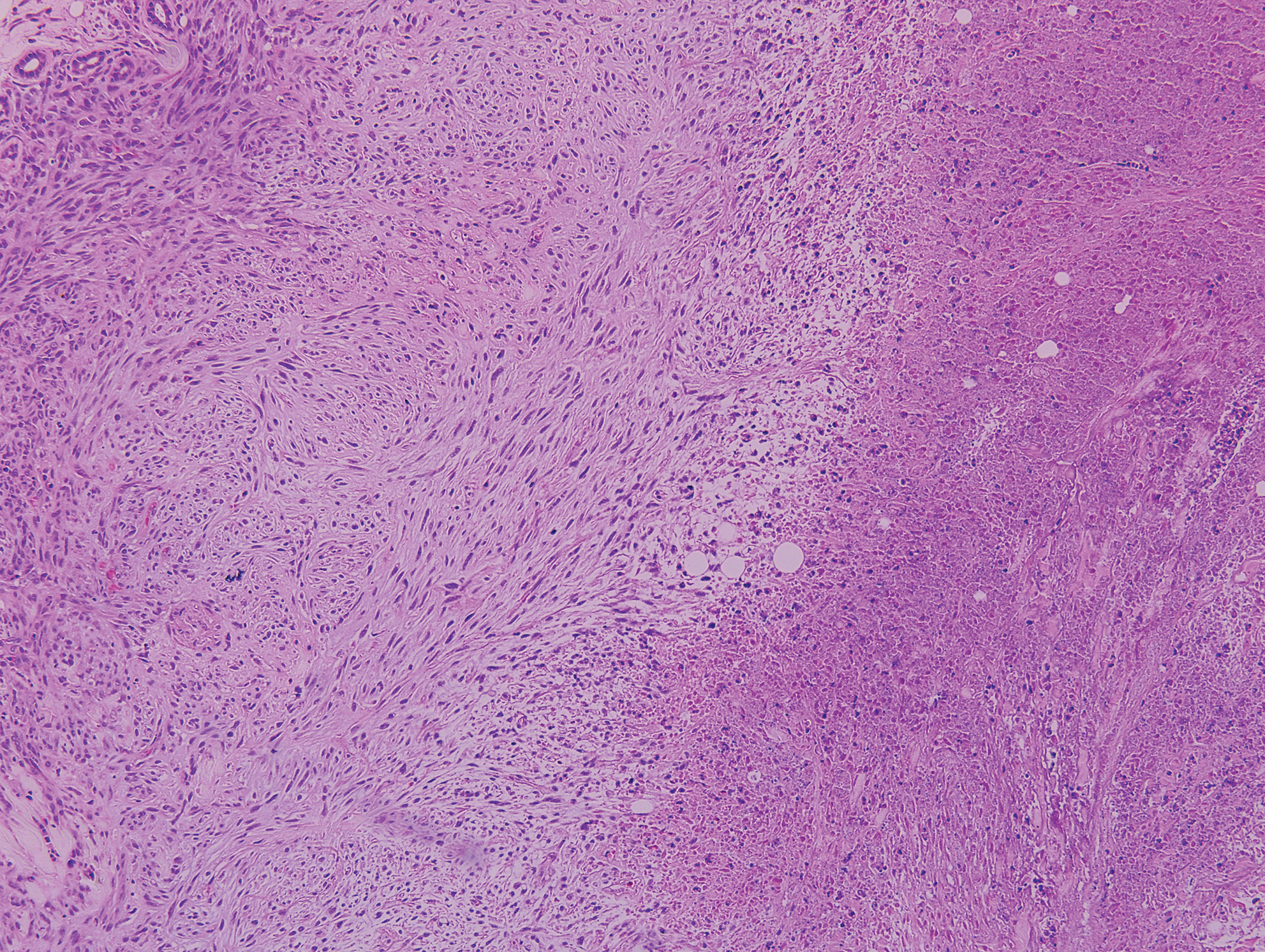

Epithelioid sarcoma (ES) is a soft tissue tumor with a known propensity for local recurrence, regional lymph node involvement, sporotrichoid spread, and distant metastases.10 The name was coined by Enzinger11 in 1970 during a review of 62 cases of a “peculiar form of sarcoma that has repeatedly been confused with a chronic inflammatory process, a necrotizing granuloma, and a squamous cell carcinoma.” Epithelioid sarcoma tends to grow slowly in a nodular or multinodular manner along fascial structures and tendons, often with central necrosis and ulceration of the overlying skin. Histopathologically, classic ES shows nodular masses of uniform plump epithelioid cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and prominent central necrosis. A biphasic pattern is typical with spindle cells merging with epithelioid cells. Cellular atypia is relatively mild and mitoses are rare (Figure 3). Recurrent or metastatic lesions can show a greater degree of pleomorphism.12 Given the low-grade atypia in early lesions, this sarcoma is easily misdiagnosed as granulomatous dermatitis. Immunohistochemically, the majority of ES cases are positive for cytokeratins and epithelial membrane antigen; SMARCB1/INI-1 expression is characteristically lost.13

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener granulomatosis) is an autoimmune vasculitis highly associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Clinical manifestations include systemic necrotizing vasculitis; necrotizing glomerulonephritis; and granulomatous inflammation, which predominantly involves the upper respiratory tract, skin, and mucosa.14,15 Skin involvement may be the initial manifestation of the disease and consists of palpable purpura, papules, ulcerations, vesicles, subcutaneous nodules, necrotizing ulcerations, papulonecrotic lesions, and petechiae. None of the findings are pathognomonic. The cutaneous histopathologic spectrum includes leukocytoclastic vasculitis, extravascular palisading granulomas, and granulomatous vasculitis.16 In the acute lesions of granulomatosis with polyangiitis, the predominant pattern of inflammation is not granulomatous but purulent with the appearance of an abscess. As it evolves, it develops a central zone of necrosis with extensive karyorrhectic debris and palisades of macrophages with scattered multinucleated giant cells (Figure 4).17

The Diagnosis: Ruptured Molluscum

Molluscum contagiosum (MC) is caused by a DNA virus (MC virus) belonging to the poxvirus family. Molluscum contagiosum is common and predominantly seen in children and young adults. In sexually active adults, the lesions commonly occur in the genital region, abdomen, and inner thighs. In immunocompromised individuals, including those with AIDS, the lesions are more extensive and may cause disfigurement.1 Molluscum contagiosum involving epidermoid cysts has been reported.2

Histopathologically, MC can be classified as noninflammatory or inflammatory. In noninflamed lesions, multiple large, intracytoplasmic, eosinophilic inclusions (Henderson-Paterson bodies) appear within the lobulated endophytic and hyperplastic epidermis. Ultrastructurally, these bodies show membrane-bound collections of MC virus.1 Replicating Henderson-Paterson bodies can result in rupture and inflammation. This case demonstrates a palisading granuloma containing keratin with few Henderson-Paterson bodies (quiz image) due to prior rupture of a molluscum or molluscoid cyst.

Rheumatoid nodules, the most characteristic histopathologic lesions of rheumatoid arthritis, are most commonly found in the subcutis at points of pressure and may occur in connective tissue of numerous organs. Rheumatoid nodules are firm, nontender, and mobile within the subcutaneous tissue but may be fixed to underlying structures including the periosteum, tendons, or bursae.3,4 Occasionally, superficial nodules may perforate the epidermis.5 The inner central necrobiotic zone appears as intensely eosinophilic, amorphous fibrin and other cellular debris. This central area is surrounded by histiocytes in a palisaded configuration (Figure 1). Multinucleated foreign body giant cells also may be present. Occasionally, mast cells, eosinophils, and neutrophils are present.6,7

Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei presents with multiple discrete, smooth, yellow-brown to red, dome-shaped papules. The lesions typically are located on the central and lateral sides of the face and infrequently involve the neck. Other sites including the axillae, arms, hands, legs, and groin occasionally can be involved. Diascopy may reveal an apple jelly color.8,9 The histopathologic hallmark of lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei is an epithelioid cell granuloma with central necrosis (Figure 2).

Epithelioid sarcoma (ES) is a soft tissue tumor with a known propensity for local recurrence, regional lymph node involvement, sporotrichoid spread, and distant metastases.10 The name was coined by Enzinger11 in 1970 during a review of 62 cases of a “peculiar form of sarcoma that has repeatedly been confused with a chronic inflammatory process, a necrotizing granuloma, and a squamous cell carcinoma.” Epithelioid sarcoma tends to grow slowly in a nodular or multinodular manner along fascial structures and tendons, often with central necrosis and ulceration of the overlying skin. Histopathologically, classic ES shows nodular masses of uniform plump epithelioid cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and prominent central necrosis. A biphasic pattern is typical with spindle cells merging with epithelioid cells. Cellular atypia is relatively mild and mitoses are rare (Figure 3). Recurrent or metastatic lesions can show a greater degree of pleomorphism.12 Given the low-grade atypia in early lesions, this sarcoma is easily misdiagnosed as granulomatous dermatitis. Immunohistochemically, the majority of ES cases are positive for cytokeratins and epithelial membrane antigen; SMARCB1/INI-1 expression is characteristically lost.13

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener granulomatosis) is an autoimmune vasculitis highly associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Clinical manifestations include systemic necrotizing vasculitis; necrotizing glomerulonephritis; and granulomatous inflammation, which predominantly involves the upper respiratory tract, skin, and mucosa.14,15 Skin involvement may be the initial manifestation of the disease and consists of palpable purpura, papules, ulcerations, vesicles, subcutaneous nodules, necrotizing ulcerations, papulonecrotic lesions, and petechiae. None of the findings are pathognomonic. The cutaneous histopathologic spectrum includes leukocytoclastic vasculitis, extravascular palisading granulomas, and granulomatous vasculitis.16 In the acute lesions of granulomatosis with polyangiitis, the predominant pattern of inflammation is not granulomatous but purulent with the appearance of an abscess. As it evolves, it develops a central zone of necrosis with extensive karyorrhectic debris and palisades of macrophages with scattered multinucleated giant cells (Figure 4).17

1. Nandhini G, Rajkumar K, Kanth KS, et al. Molluscum contagiosum in a 12-year-old child—report of a case and review of literature. J Int Oral Health. 2015;7:63-66.

2. Phelps A, Murphy M, Elaba Z, et al. Molluscum contagiosum virus infection in benign cutaneous epithelial cystic lesions-report of 2 cases with different pathogenesis? Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:740-742.

3. Sayah A, English JC 3rd. Rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:191-209; quiz 210-192.

4. Sibbitt WL Jr, Williams RC Jr. Cutaneous manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Dermatol. 1982;21:563-572.

5. Barzilai A, Huszar M, Shpiro D, et al. Pseudorheumatoid nodules in adults: a juxta-articular form of nodular granuloma annulare. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:1-5.

6. Garcia-Patos V. Rheumatoid nodule. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:100-107.

7. Patterson JW. Rheumatoid nodule and subcutaneous granuloma annulare. a comparative histologic study. Am J Dermatopathol. 1988;10:1-8.

8. Sehgal VN, Srivastava G, Aggarwal AK, et al. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei part II: an overview. Skinmed. 2005;4:234-238.

9. Cymerman R, Rosenstein R, Shvartsbeyn M, et al. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21. pii:13030/qt6b83q5gp.

10. Sobanko JF, Meijer L, Nigra TP. Epithelioid sarcoma: a review and update. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2009;2:49-54.

11. Enzinger FM. Epitheloid sarcoma. a sarcoma simulating a granuloma or a carcinoma. Cancer. 1970;26:1029-1041.

12. Fisher C. Epithelioid sarcoma of Enzinger. Adv Anat Pathol. 2006;13:114-121.

13. Miettinen M, Fanburg-Smith JC, Virolainen M, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma: an immunohistochemical analysis of 112 classical and variant cases and a discussion of the differential diagnosis. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:934-942.

14. Lutalo PM, D’Cruz DP. Diagnosis and classification of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (aka Wegener’s granulomatosis)[published online January 29, 2014]. J Autoimmun. 2014;48-49:94-98.