User login

Atypical case of cutaneous MCL mimics SPTCL

An atypical case of cutaneous mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) with histomorphological features mimicking subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL) highlights a “potential pitfall,” according to investigators.

This unusual case stresses the importance of molecular cytogenetics and/or immunohistochemistry for panniculitis-type lymphomas, reported lead author Caroline Laggis, MD of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and colleagues.

“While morphologic features of SPTCL, specifically rimming of adipocytes by neoplastic lymphoid cells, have been documented in other types of lymphomas, this case is exceptional in that the morphologic features of SPTCL are showed in secondary cutaneous involvement by MCL,” the investigators wrote. Their report is in Journal of Cutaneous Pathology.

The patient was a 69-year-old man who presented with 2-year history of night sweats and fever of unknown origin, and, closer to presentation, weight loss and tender bumps under the skin of his pelvic region.

Subsequent computed tomography and excisional lymph node biopsy led to a diagnosis of MCL, with a Mantle Cell Lymphoma International Prognostic Index of 5, suggesting aggressive, intermediate-risk disease. Further imaging showed involvement of the nasopharynx, and cervical and mediastinal lymph nodes.

Bendamustine and rituximab chemotherapy was given unremarkably until the final cycle, at which point the patient presented with tender subcutaneous nodules on his lower legs. Histopathology from punch biopsies revealed “a dense infiltrate of monomorphic, mitotically active lymphoid cells with infiltration between the deep dermal collagen and the adipocytes in subcutaneous fat,” the investigators wrote, noting that the infiltrative cells were blastoid and 70% expressed cyclin D1, supporting cutaneous involvement of his systemic MCL.

Treatment was switched to ibrutinib and selinexor via a clinical trial, which led to temporary improvement of leg lesions; when the lesions returned, biopsy was performed with the same histopathological result. Lenalidomide and rituximab were started, but without success, and disease spread to the central nervous system.

Another biopsy of the skin lesions again supported cutaneous MCL, with tumor cells rimming individual adipocytes.

Because of this atypical morphology, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was conducted, revealing t(11;14)(q13:32) positivity, thereby “confirming the diagnosis of cutaneous involvement by systemic MCL,” the investigators wrote.

Genomic sequencing revealed abnormalities of “ataxia-telangiectasia mutated, mechanistic target of rapamycin kinase (mTOR), BCL6 corepressor, and FAS-associated factor 1, as well as the expected mutation in IGH-CCND1, leading to cyclin D1 upregulation.”

Subsequent treatment was unsuccessful, and the patient died from his disease.

“The complex and central role that mTOR plays in adipose homeostasis may link our tumor to its preference to the adipose tissue, although further investigation is warranted regarding specific genomic alterations in lymphomas and the implications these mutations have in the involvement of tumor cells with cutaneous and adipose environments,” the investigators wrote.

The investigators did not report conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Laggis C et al. 2019 Apr 8. doi:10.1111/cup.13471.

An atypical case of cutaneous mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) with histomorphological features mimicking subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL) highlights a “potential pitfall,” according to investigators.

This unusual case stresses the importance of molecular cytogenetics and/or immunohistochemistry for panniculitis-type lymphomas, reported lead author Caroline Laggis, MD of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and colleagues.

“While morphologic features of SPTCL, specifically rimming of adipocytes by neoplastic lymphoid cells, have been documented in other types of lymphomas, this case is exceptional in that the morphologic features of SPTCL are showed in secondary cutaneous involvement by MCL,” the investigators wrote. Their report is in Journal of Cutaneous Pathology.

The patient was a 69-year-old man who presented with 2-year history of night sweats and fever of unknown origin, and, closer to presentation, weight loss and tender bumps under the skin of his pelvic region.

Subsequent computed tomography and excisional lymph node biopsy led to a diagnosis of MCL, with a Mantle Cell Lymphoma International Prognostic Index of 5, suggesting aggressive, intermediate-risk disease. Further imaging showed involvement of the nasopharynx, and cervical and mediastinal lymph nodes.

Bendamustine and rituximab chemotherapy was given unremarkably until the final cycle, at which point the patient presented with tender subcutaneous nodules on his lower legs. Histopathology from punch biopsies revealed “a dense infiltrate of monomorphic, mitotically active lymphoid cells with infiltration between the deep dermal collagen and the adipocytes in subcutaneous fat,” the investigators wrote, noting that the infiltrative cells were blastoid and 70% expressed cyclin D1, supporting cutaneous involvement of his systemic MCL.

Treatment was switched to ibrutinib and selinexor via a clinical trial, which led to temporary improvement of leg lesions; when the lesions returned, biopsy was performed with the same histopathological result. Lenalidomide and rituximab were started, but without success, and disease spread to the central nervous system.

Another biopsy of the skin lesions again supported cutaneous MCL, with tumor cells rimming individual adipocytes.

Because of this atypical morphology, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was conducted, revealing t(11;14)(q13:32) positivity, thereby “confirming the diagnosis of cutaneous involvement by systemic MCL,” the investigators wrote.

Genomic sequencing revealed abnormalities of “ataxia-telangiectasia mutated, mechanistic target of rapamycin kinase (mTOR), BCL6 corepressor, and FAS-associated factor 1, as well as the expected mutation in IGH-CCND1, leading to cyclin D1 upregulation.”

Subsequent treatment was unsuccessful, and the patient died from his disease.

“The complex and central role that mTOR plays in adipose homeostasis may link our tumor to its preference to the adipose tissue, although further investigation is warranted regarding specific genomic alterations in lymphomas and the implications these mutations have in the involvement of tumor cells with cutaneous and adipose environments,” the investigators wrote.

The investigators did not report conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Laggis C et al. 2019 Apr 8. doi:10.1111/cup.13471.

An atypical case of cutaneous mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) with histomorphological features mimicking subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL) highlights a “potential pitfall,” according to investigators.

This unusual case stresses the importance of molecular cytogenetics and/or immunohistochemistry for panniculitis-type lymphomas, reported lead author Caroline Laggis, MD of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and colleagues.

“While morphologic features of SPTCL, specifically rimming of adipocytes by neoplastic lymphoid cells, have been documented in other types of lymphomas, this case is exceptional in that the morphologic features of SPTCL are showed in secondary cutaneous involvement by MCL,” the investigators wrote. Their report is in Journal of Cutaneous Pathology.

The patient was a 69-year-old man who presented with 2-year history of night sweats and fever of unknown origin, and, closer to presentation, weight loss and tender bumps under the skin of his pelvic region.

Subsequent computed tomography and excisional lymph node biopsy led to a diagnosis of MCL, with a Mantle Cell Lymphoma International Prognostic Index of 5, suggesting aggressive, intermediate-risk disease. Further imaging showed involvement of the nasopharynx, and cervical and mediastinal lymph nodes.

Bendamustine and rituximab chemotherapy was given unremarkably until the final cycle, at which point the patient presented with tender subcutaneous nodules on his lower legs. Histopathology from punch biopsies revealed “a dense infiltrate of monomorphic, mitotically active lymphoid cells with infiltration between the deep dermal collagen and the adipocytes in subcutaneous fat,” the investigators wrote, noting that the infiltrative cells were blastoid and 70% expressed cyclin D1, supporting cutaneous involvement of his systemic MCL.

Treatment was switched to ibrutinib and selinexor via a clinical trial, which led to temporary improvement of leg lesions; when the lesions returned, biopsy was performed with the same histopathological result. Lenalidomide and rituximab were started, but without success, and disease spread to the central nervous system.

Another biopsy of the skin lesions again supported cutaneous MCL, with tumor cells rimming individual adipocytes.

Because of this atypical morphology, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was conducted, revealing t(11;14)(q13:32) positivity, thereby “confirming the diagnosis of cutaneous involvement by systemic MCL,” the investigators wrote.

Genomic sequencing revealed abnormalities of “ataxia-telangiectasia mutated, mechanistic target of rapamycin kinase (mTOR), BCL6 corepressor, and FAS-associated factor 1, as well as the expected mutation in IGH-CCND1, leading to cyclin D1 upregulation.”

Subsequent treatment was unsuccessful, and the patient died from his disease.

“The complex and central role that mTOR plays in adipose homeostasis may link our tumor to its preference to the adipose tissue, although further investigation is warranted regarding specific genomic alterations in lymphomas and the implications these mutations have in the involvement of tumor cells with cutaneous and adipose environments,” the investigators wrote.

The investigators did not report conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Laggis C et al. 2019 Apr 8. doi:10.1111/cup.13471.

FROM JOURNAL OF CUTANEOUS PATHOLOGY

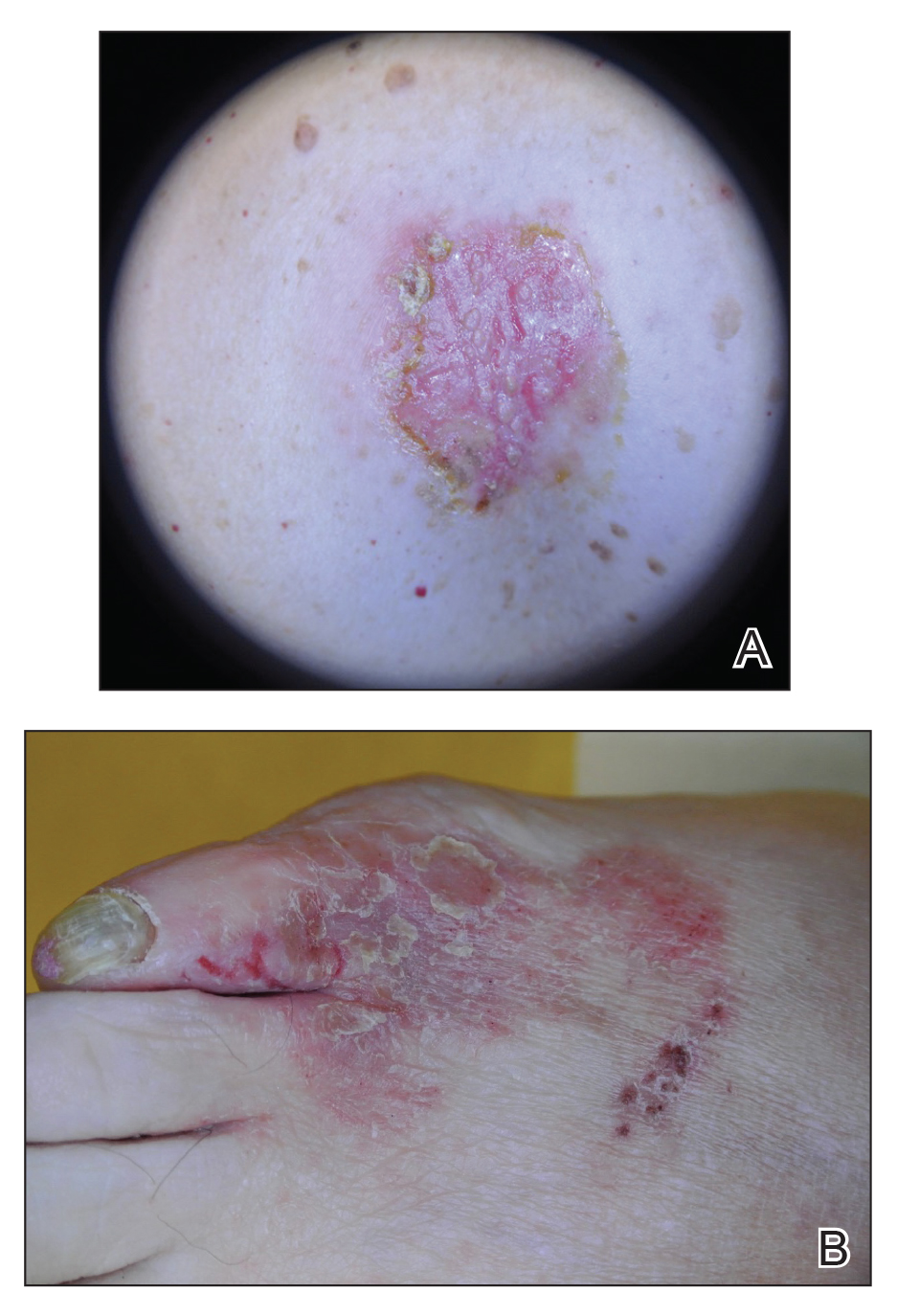

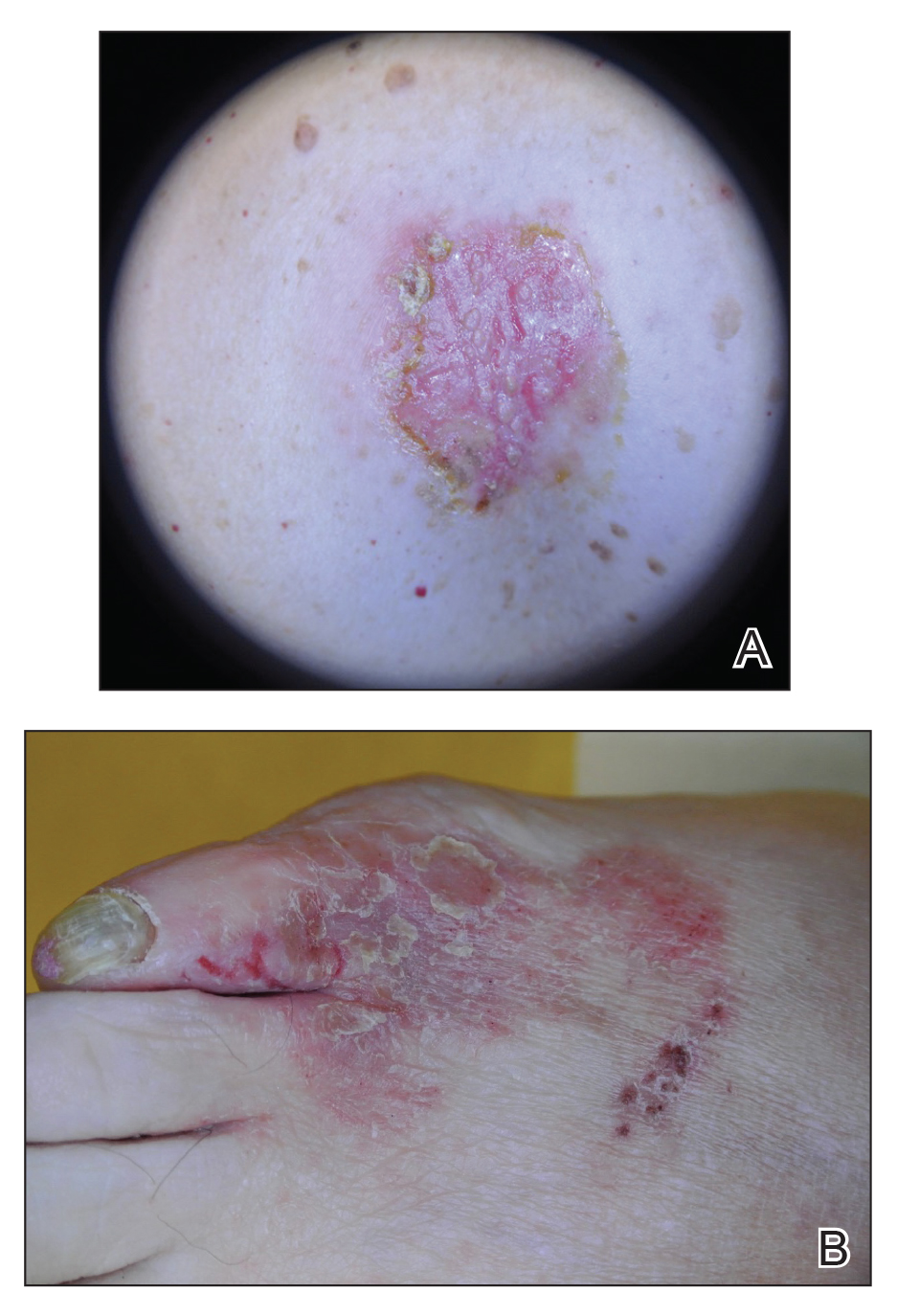

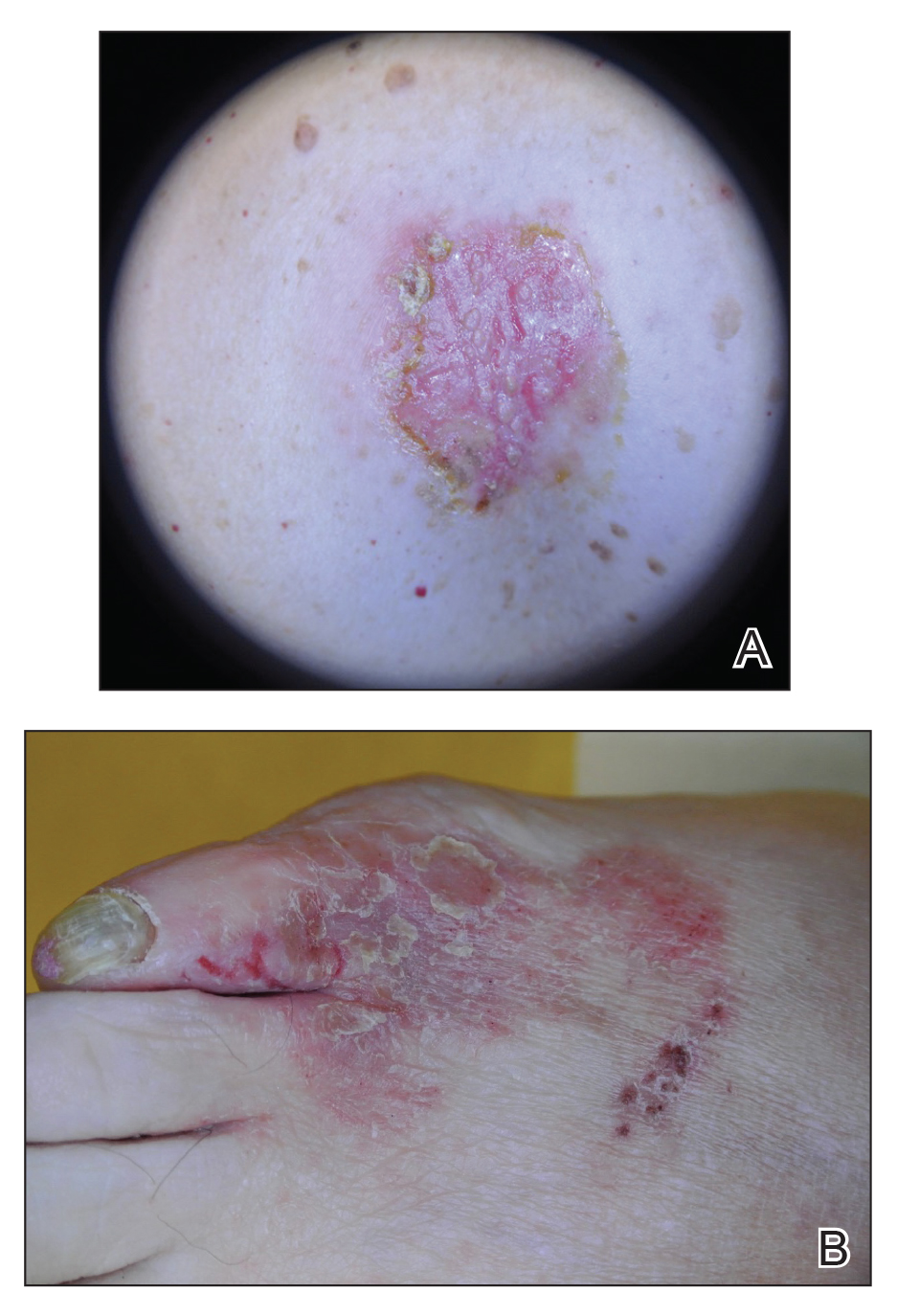

Enlarging Nodule on the Thigh

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Adenocarcinoma of the Colon

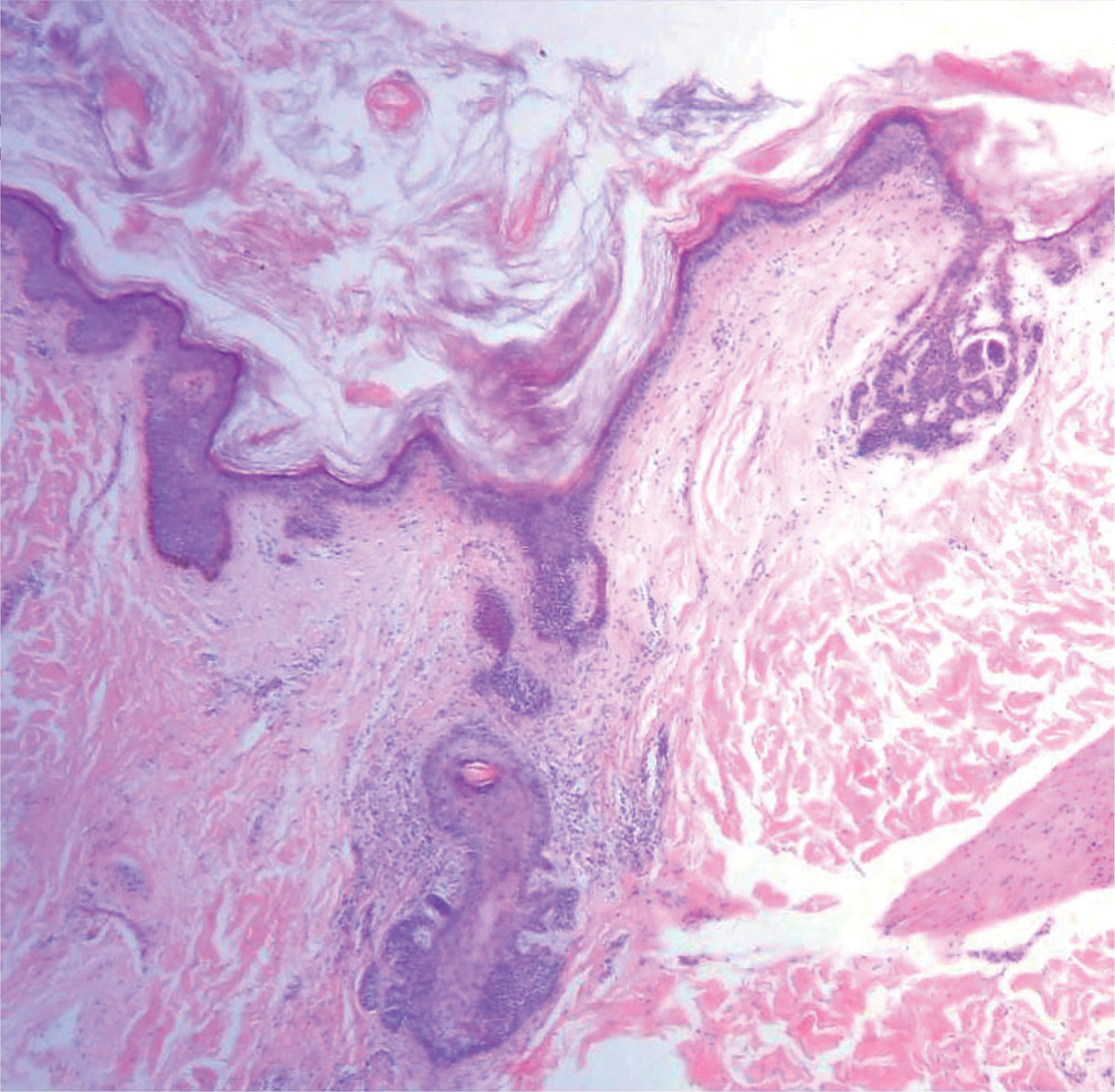

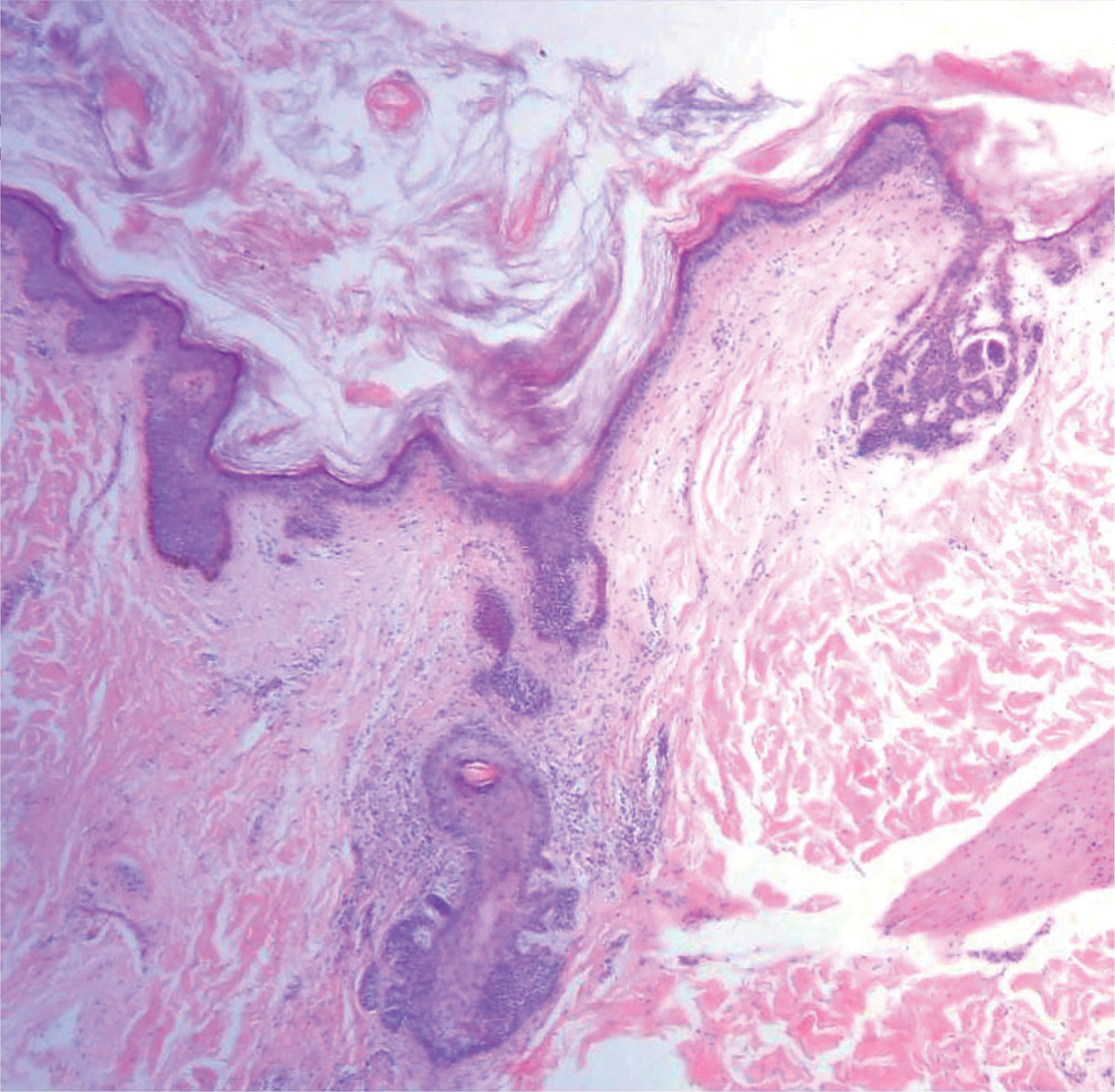

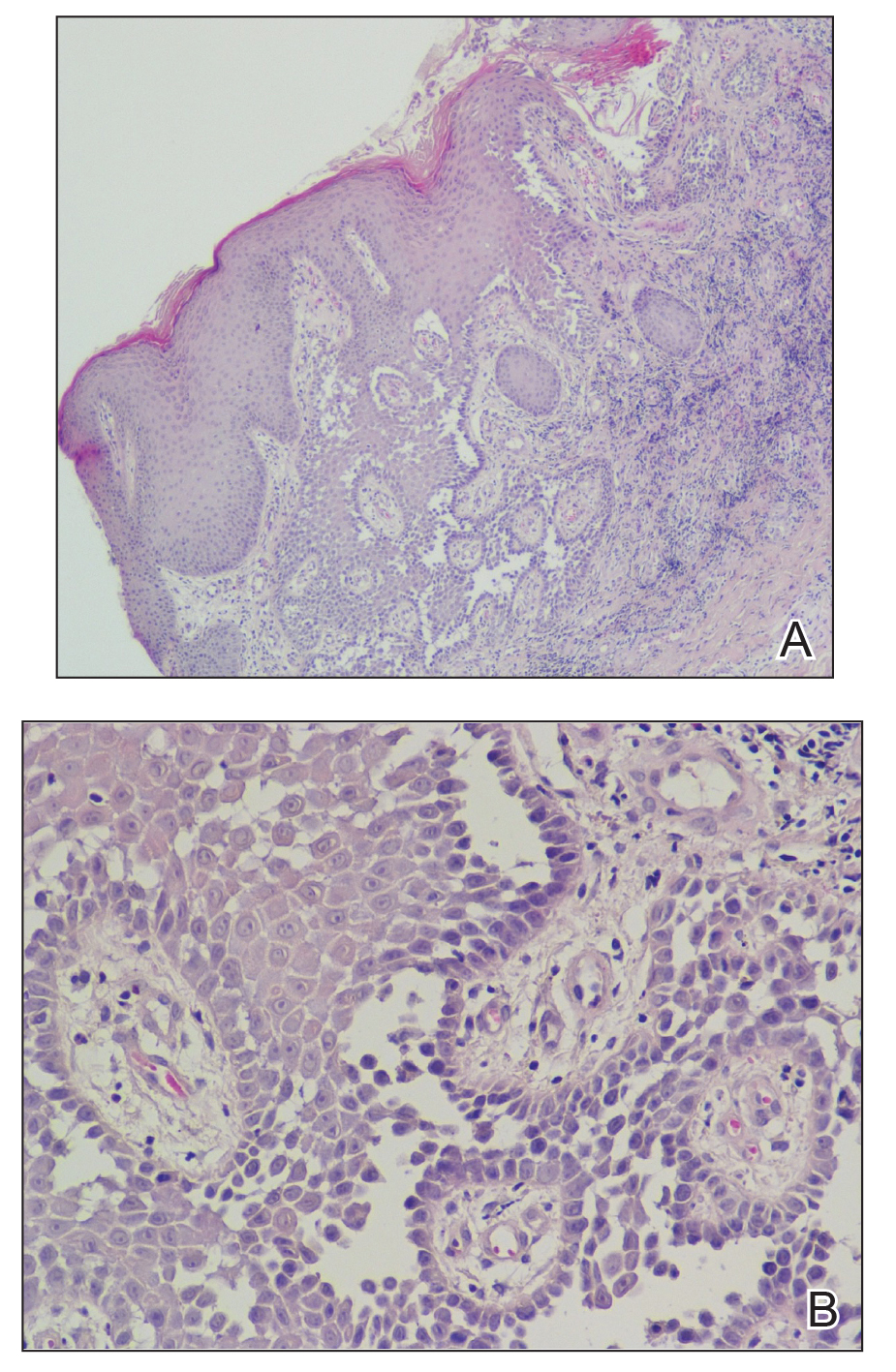

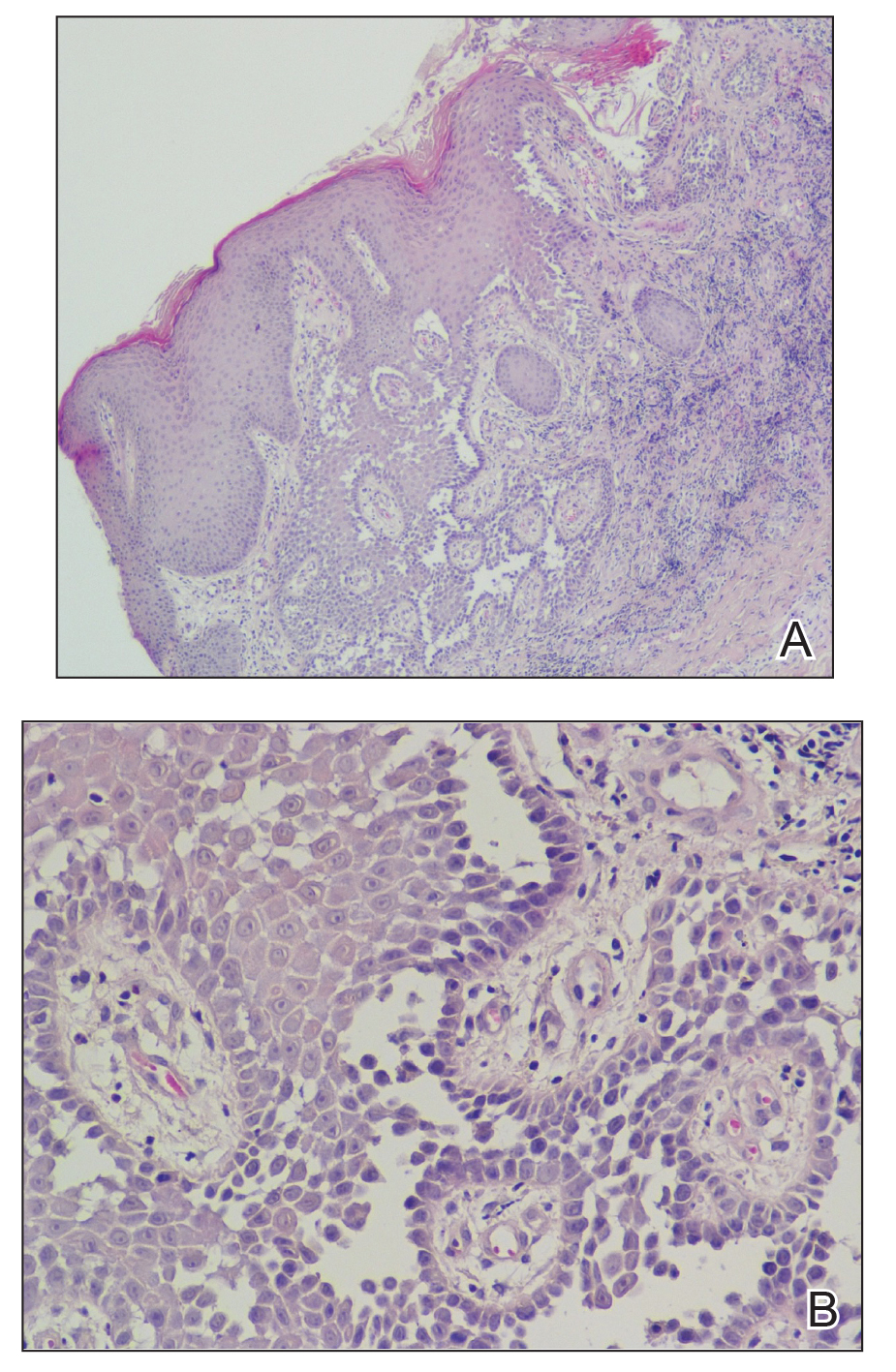

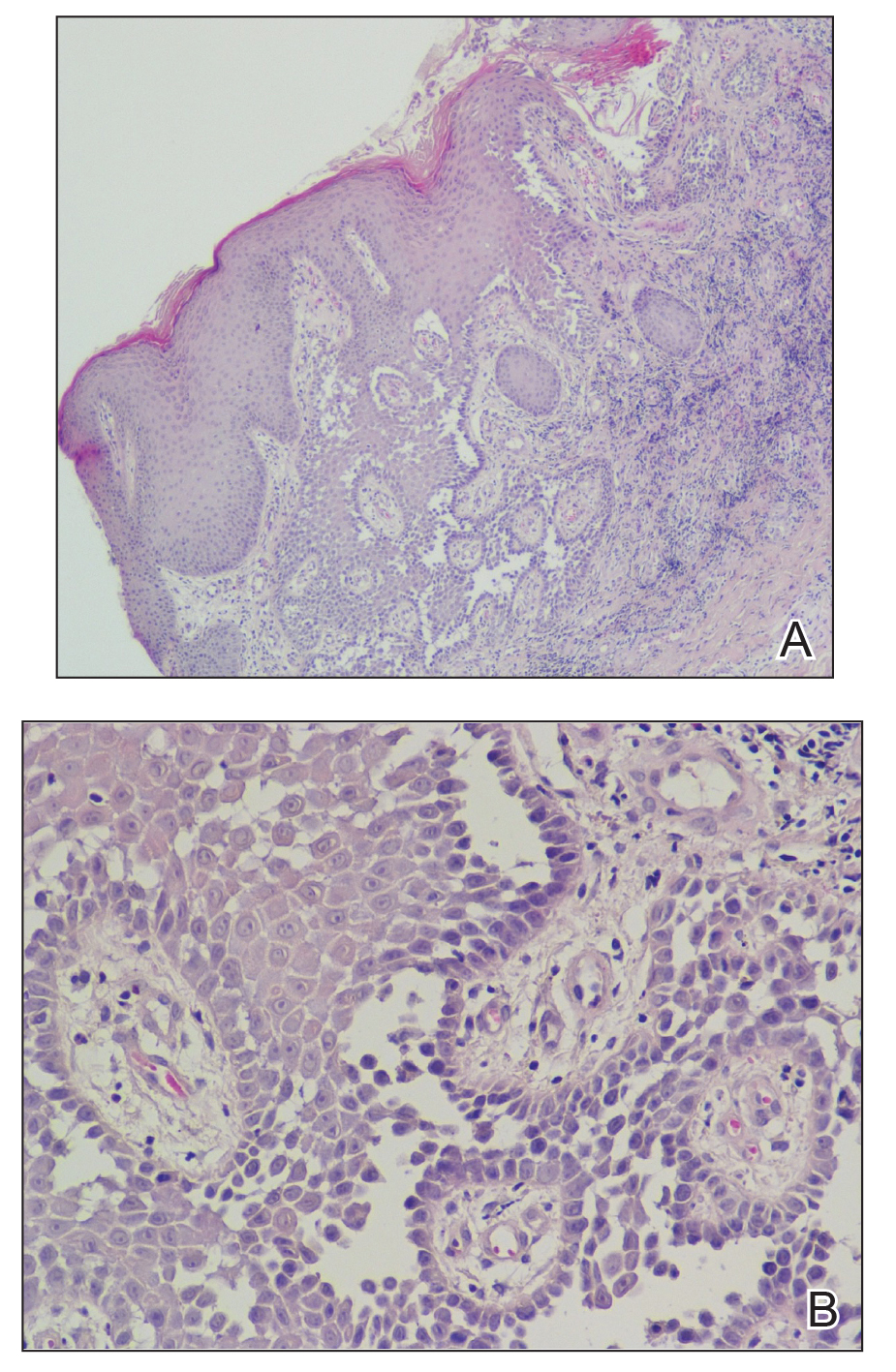

Cutaneous adenocarcinomas are uncommon, whether they present as a primary lesion or metastatic disease. In our patient, the histologic findings and immunohistochemical staining pattern were consistent with metastatic adenocarcinoma of the colon, an uncommon clinical presentation.

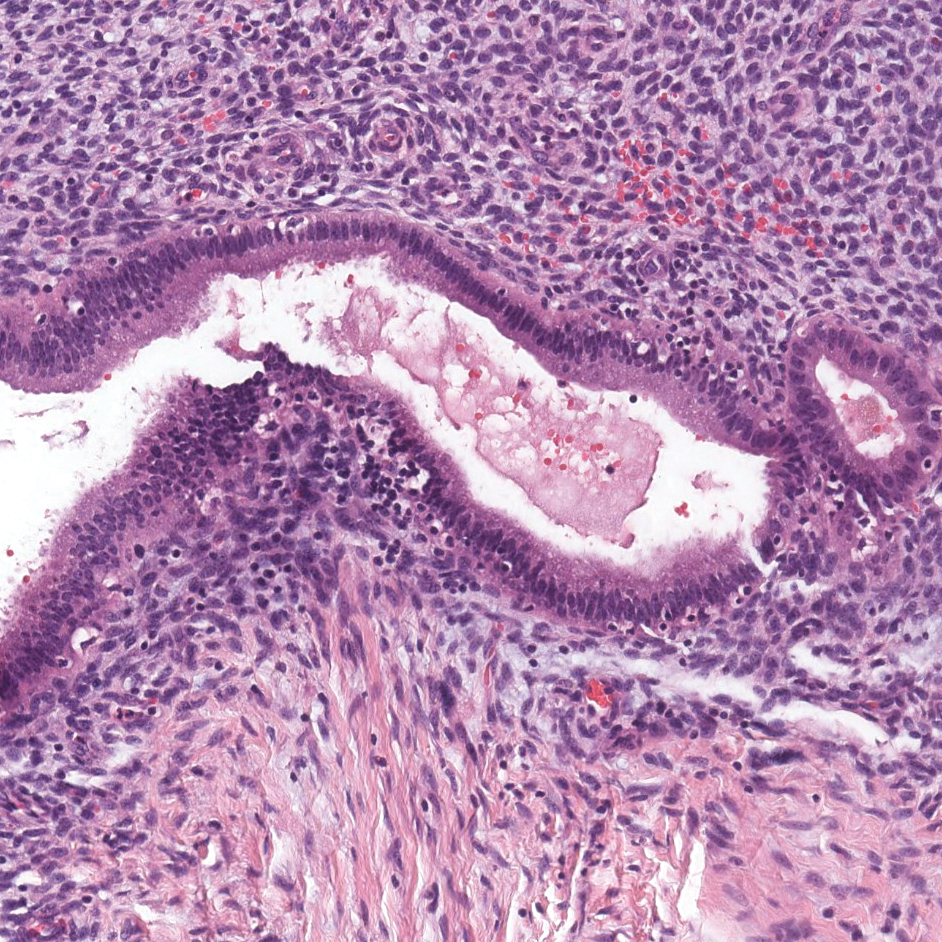

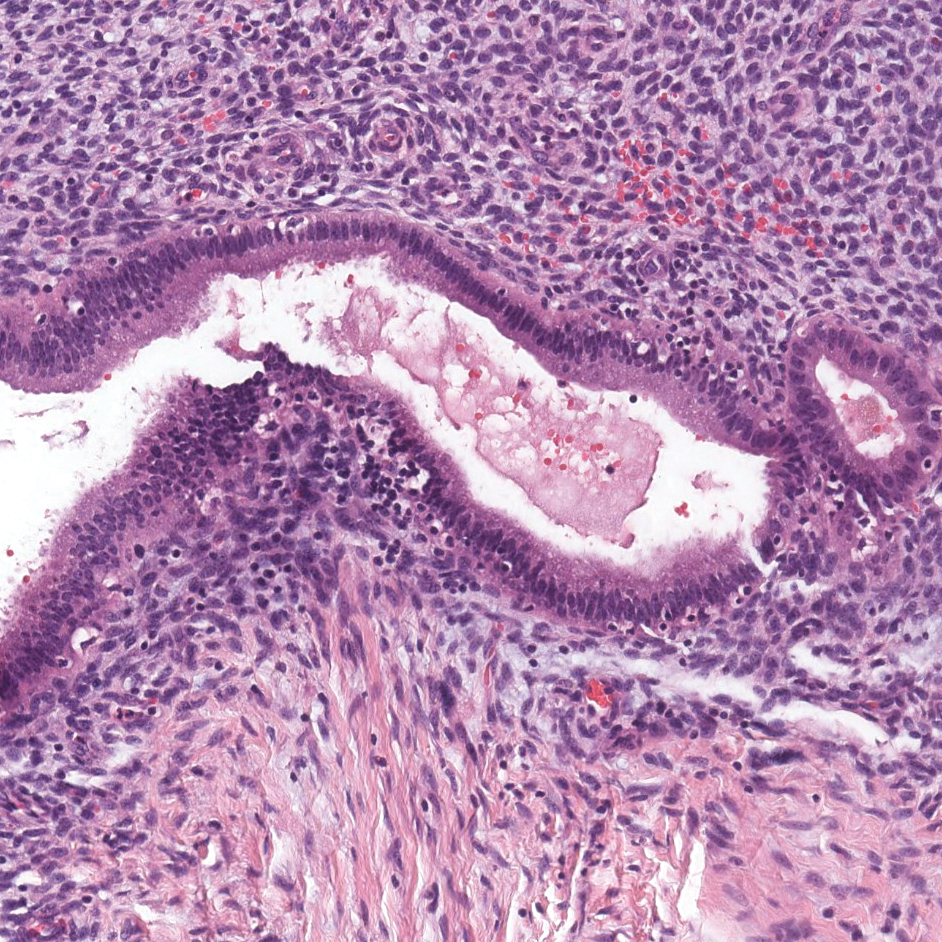

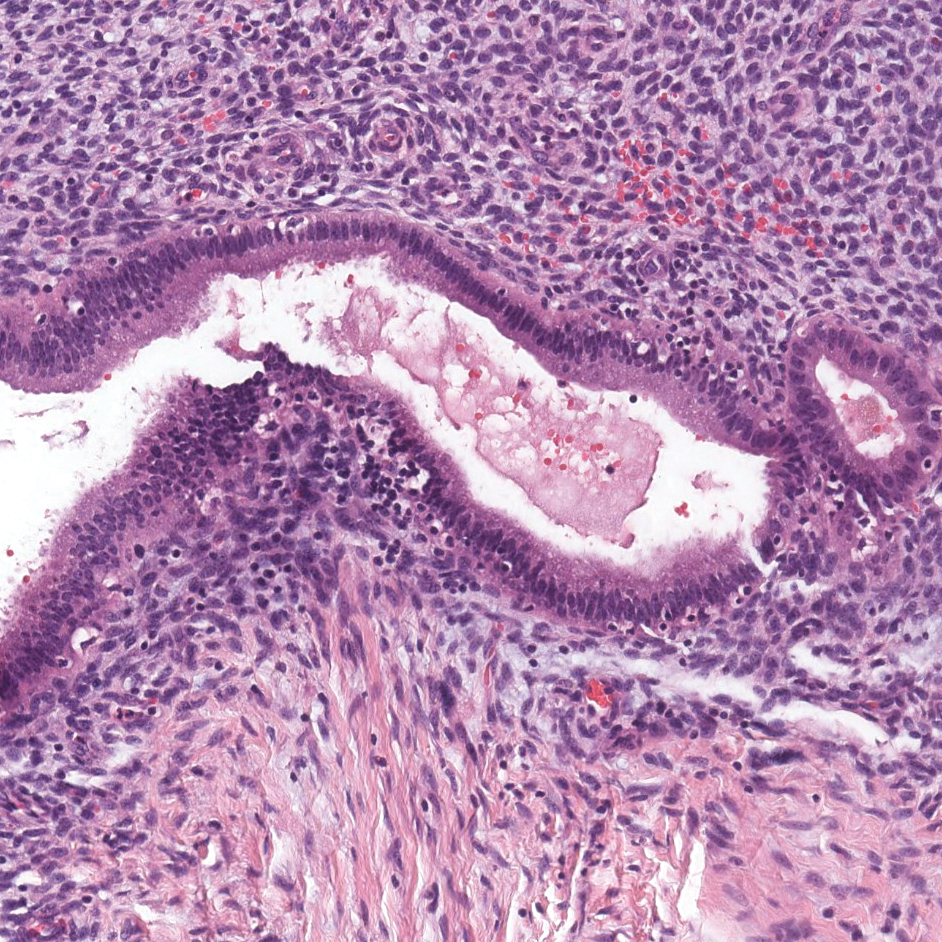

Colonic adenocarcinoma can cause cutaneous metastasis in 3% of cases. The most common sites of metastases include the abdomen, chest, and back.1 On histologic examination, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections of cutaneous metastatic adenocarcinoma illustrate a malignant gland-forming neoplasm in the dermis with luminal mucin and necrotic debris (quiz image). The glands are lined by tall columnar epithelial cells with hyperchromatic nuclei. Alternatively, poorly differentiated morphology can be seen with fewer glands and more infiltrating nests of tumor cells.2 Immunohistochemically, colonic adenocarcinoma typically is negative for cytokeratin (CK) 7 and positive for CK20 and caudal type homeobox transcription factor 2 (CDX-2).3

Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma is characterized by islands of neoplastic cells floating in pools of mucin (Figure 1). It may be indistinguishable from metastatic mucinous carcinomas of the colon or breast. Immunohistochemistry can be helpful in differentiating metastatic breast vs colon carcinoma. Cytokeratin 7, GATA binding protein 3, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, and estrogen receptor will be positive in carcinomas of the breast and will be negative in colonic adenocarcinomas.4-6 Furthermore, lesional cells in metastatic adenocarcinoma of the colon are positive for CDX-2 and CK20, while those in metastatic carcinoma of the breast are negative.2 Immunohistochemistry also can differentiate primary cutaneous carcinoma from metastatic adenocarcinoma. When used in combination, p63 and podoplanin (D2-40) offer a highly sensitive and specific indicator of a primary cutaneous neoplasm, as both demonstrate either focal or diffuse positivity in this setting. In contrast, these stains typically are negative in metastatic adenocarcinomas of the skin.7

Endometriosis affects 1% to 2% of all reproductive-age females, of which extrapelvic manifestations account for only 0.5% to 1.0% of cases.8 Histologically, extrapelvic endometriosis is characterized by the triad of endometrial-type glands, endometrial stroma, and hemorrhage or hemosiderin deposition (Figure 2). The glands can enlarge and demonstrate architectural distortion with partial lack of polarity. These features initially can be concerning for adenocarcinoma, but on closer examination, nuclear morphology is regular and mitoses are absent.8,9 The diagnosis usually can be rendered with H&E alone; however, immunohistochemical stains for CD10 and estrogen receptor can highlight the endometrial stroma.10 Furthermore, endometrial glands will stain positive for paired box gene 8 (PAX8), a marker that is not expressed within the gastrointestinal tract and associated malignancies.11

cytoplasm (H&E, original magnification ×100).

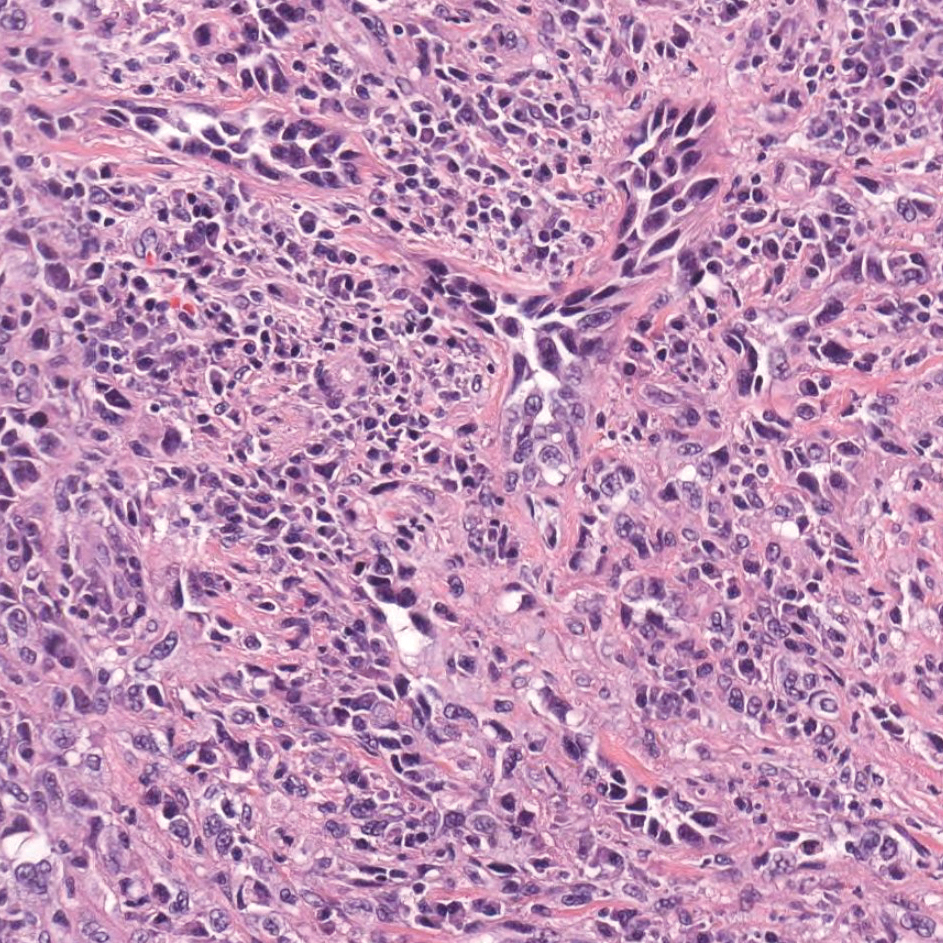

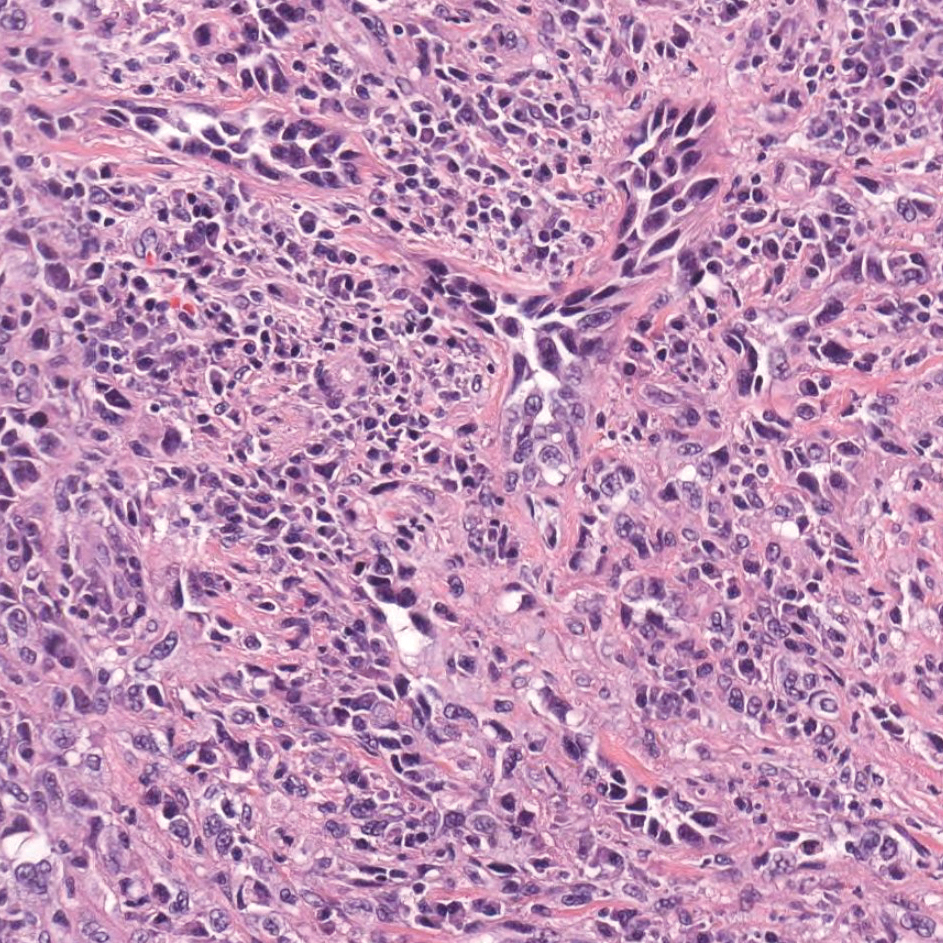

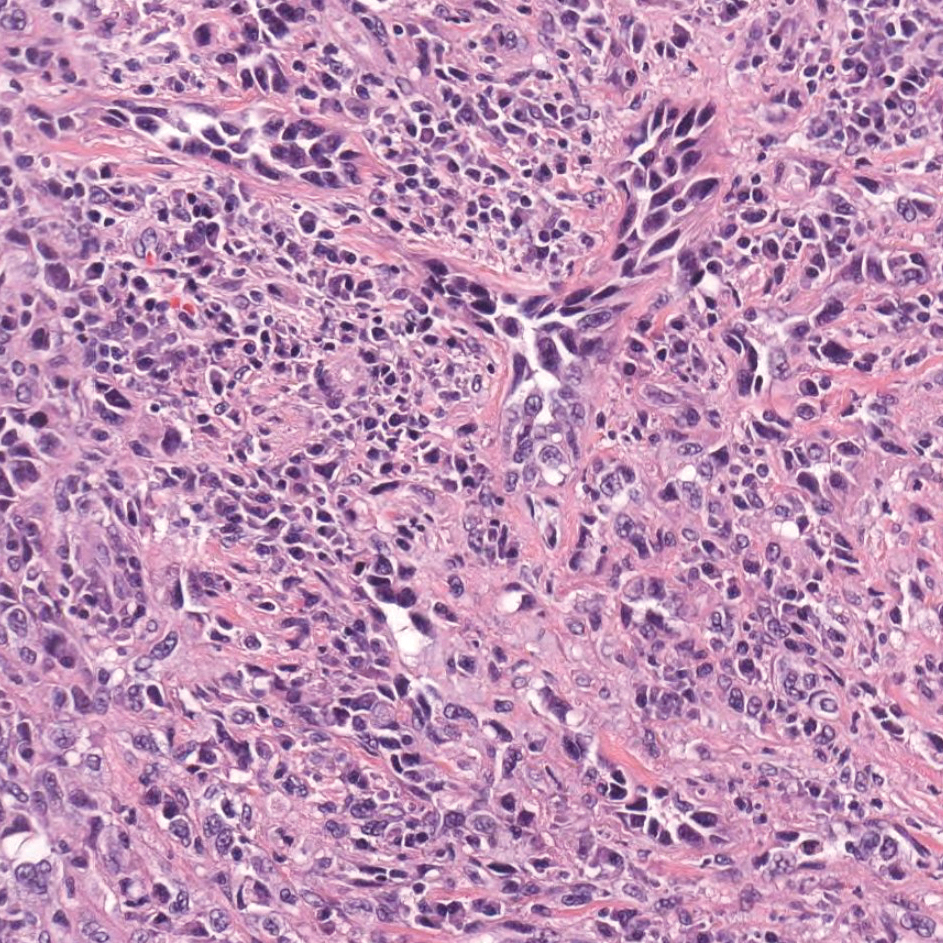

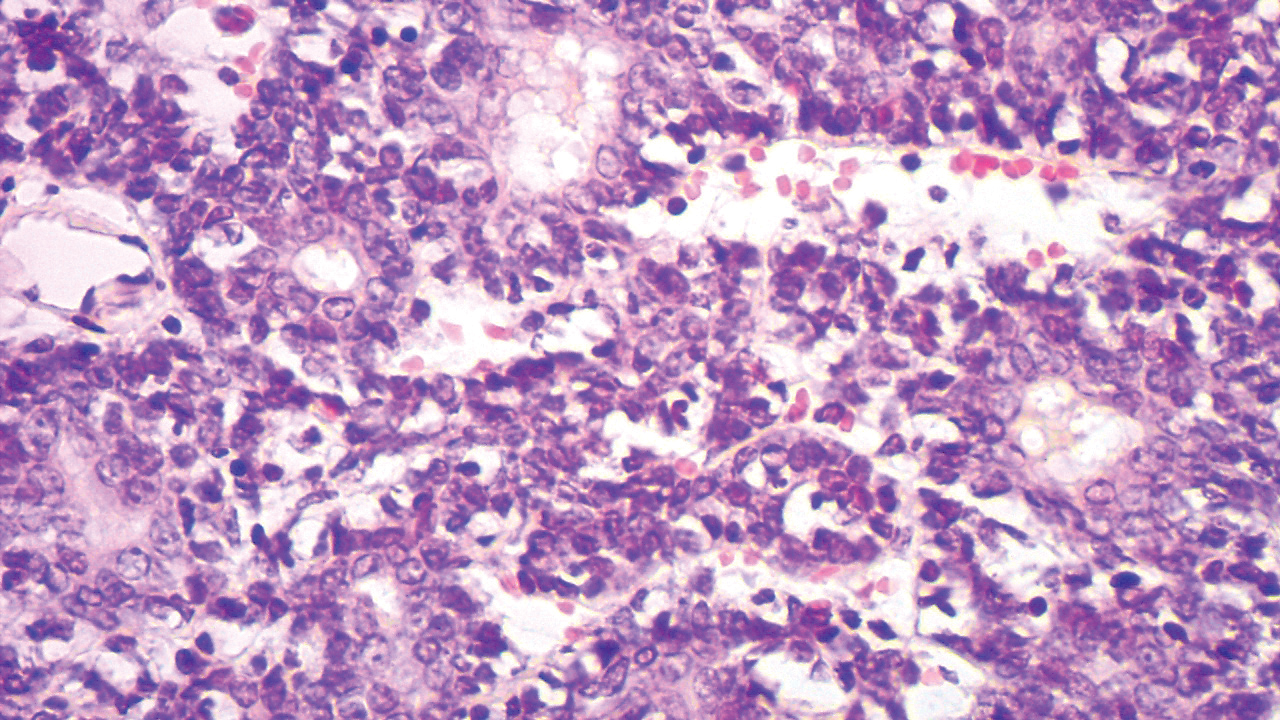

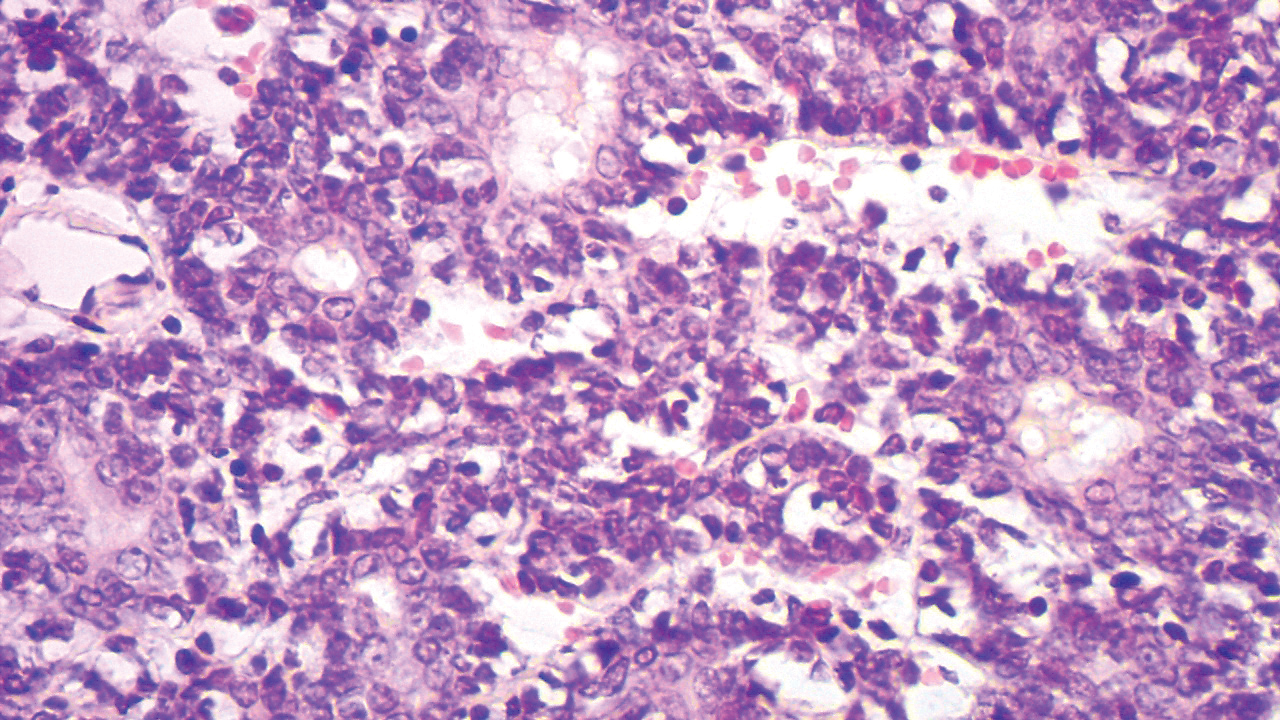

Primary cutaneous angiosarcoma may mimic adenocarcinoma, as the endothelial-lined vessels can be confused as malignant glands (Figure 3). Angiosarcoma often is seen in 1 of 3 clinical presentations: the head and neck of elderly patients, postradiation treatment, and chronic lymphedema.12,13 Regardless of the location, the disease carries a poor prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate of 12% following initial diagnosis.13 Angiosarcoma is characterized by malignant endothelial cells dissecting through the dermis. Although the histology can be deceptively bland in some cases, the neoplasm most commonly demonstrates notable atypia with a multilayered endothelium and occasional intravascular atypical cells ("fish in the creek appearance").13,14 There can be frequent mitoses, and the atypical cells may show intracytoplasmic lumina containing red blood cells. The lesional cells are positive for endothelial markers such as erythroblast transformation specific related gene (ERG), CD31, CD34, and friend leukemia integration factor 1 (FLI-1).15,16

Breast cancer also can cause cutaneous metastases in approximately 20% of cases, with the most common presenting site being the anterior chest wall.17 Macroscopically, these lesions appear most commonly as painless nodules but also as telangiectatic, erysipeloid, fibrotic, and alopecic lesions.17-19 The histologic findings from H&E-stained sections of a cutaneous metastasis of breast cancer are variable and depend on the specific tumor subtype (eg, ductal, lobular, mucinous). However, the classic histologic presentation is that of nests and cords of malignant epithelial cells with variable gland formation. Often, tumor cells infiltrate in a single-file fashion (Figure 4).17 Although inflammatory breast carcinoma is a strictly clinical diagnosis, the presence of tumor cells in the lymphovascular spaces is a histologic clue to this diagnosis. Immunohistochemically, GATA binding protein 3 is helpful in identifying both hormone receptor-positive and -negative breast cancer subtypes that have metastasized.20

Within the histologic differential diagnoses, the most useful tool to diagnose metastatic adenocarcinoma of the colon often is a thorough clinical history. In the absence of a clinical history of adenocarcinoma, immunohistochemistry can be a useful adjunct to aid in the correct characterization and classification of a malignant gland-forming tumor.2,3,6

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

- Kumar V, Robbins SL. Robbins Basic Pathology. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier; 2007.

- Taliano RJ, LeGolvan M, Resnick MB. Immunohistochemistry of colorectal carcinoma: current practice and evolving applications. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:151-163.

- Kamalpour L, Brindise RT, Nodzenski M, et al. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after surgery. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:380-384.

- Roshan MH, Tambo A, Pace NP. The role of testosterone in colorectal carcinoma: pathomechanisms and open questions. EPMA J. 2016;7:22.

- Mazoujian G, Pinkus GS, Davis S, et al. Immunohistochemistry of a gross cystic disease fluid protein (GCDFP-15) of the breast. a marker of apocrine epithelium and breast carcinomas with apocrine features. Am J Pathol. 1983;110:105-112.

- Plaza JA, Ortega PF, Stockman DL, et al. Value of p63 and podoplanin (D2-40) immunoreactivity in the distinction between primary cutaneous tumors and adenocarcinomas metastatic to the skin: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 79 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:403-410.

- Machairiotis N, Stylianaki A, Dryllis G, et al. Extrapelvic endometriosis: a rare entity or an under diagnosed condition? Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:194.

- Chen H, Luo Q, Liu S, et al. Rectal mucosal endometriosis primarily misinterpreted as adenocarcinoma: a case report and review of literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:5902-5907.

- Terada S, Miyata Y, Nakazawa H, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of an ectopic endometriosis in the uterine round ligament. Diagn Pathol. 2006;1:27.

- Yemelyanova A, Gown AM, Wu LS, et al. PAX8 expression in uterine adenocarcinomas and mesonephric proliferations. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2014;33:492-499.

- Farid M, Ong WS, Lee MJ, et al. Cutaneous versus non-cutaneous angiosarcoma: clinicopathologic features and treatment outcomes in 60 patients at a single Asian cancer centre. Oncology. 2013;85:182-190.

- Requena C, Sendra E, Llombart B, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: clinical and pathology study of 16 cases. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:457-465.

- Schmidt AP, Tjarks BJ, Lynch DW. Gone fishing: a unique histologic pattern in cutaneous angiosarcoma. Cutis. 2018;101:270-272.

- Sullivan HC, Edgar MA, Cohen C, et al. The utility of ERG, CD31 and CD34 in the cytological diagnosis of angiosarcoma: an analysis of 25 cases. J Clin Pathol. 2015;68:44-50.

- Rossi S, Orvieto E, Furlanetto A, et al. Utility of the immunohistochemical detection of FLI-1 expression in round cell and vascular neoplasm using a monoclonal antibody. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:547-552.

- Tan AR. Cutaneous manifestations of breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 2016;43:331-334.

- Schwartz RA, Wiederkehr M, Lambert WC. Secondary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: metastatic breast cancer. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(2, pt 1):234-235.

- Mallon E, Dawber RP. Alopecia neoplastica without alopecia: a unique presentation of breast carcinoma scalp metastasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(2, pt 2):319-321.

- Braxton DR, Cohen C, Siddiqui MT. Utility of GATA3 immunohistochemistry for diagnosis of metastatic breast carcinoma in cytology specimens. Diagn Cytopathol. 2015;43:271-277.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Adenocarcinoma of the Colon

Cutaneous adenocarcinomas are uncommon, whether they present as a primary lesion or metastatic disease. In our patient, the histologic findings and immunohistochemical staining pattern were consistent with metastatic adenocarcinoma of the colon, an uncommon clinical presentation.

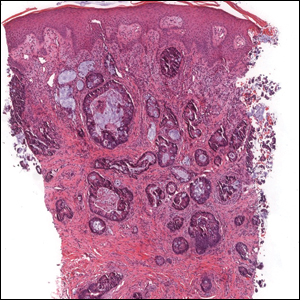

Colonic adenocarcinoma can cause cutaneous metastasis in 3% of cases. The most common sites of metastases include the abdomen, chest, and back.1 On histologic examination, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections of cutaneous metastatic adenocarcinoma illustrate a malignant gland-forming neoplasm in the dermis with luminal mucin and necrotic debris (quiz image). The glands are lined by tall columnar epithelial cells with hyperchromatic nuclei. Alternatively, poorly differentiated morphology can be seen with fewer glands and more infiltrating nests of tumor cells.2 Immunohistochemically, colonic adenocarcinoma typically is negative for cytokeratin (CK) 7 and positive for CK20 and caudal type homeobox transcription factor 2 (CDX-2).3

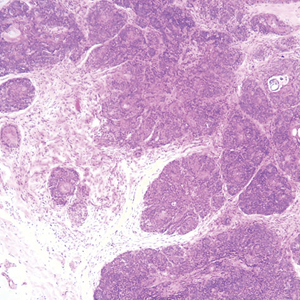

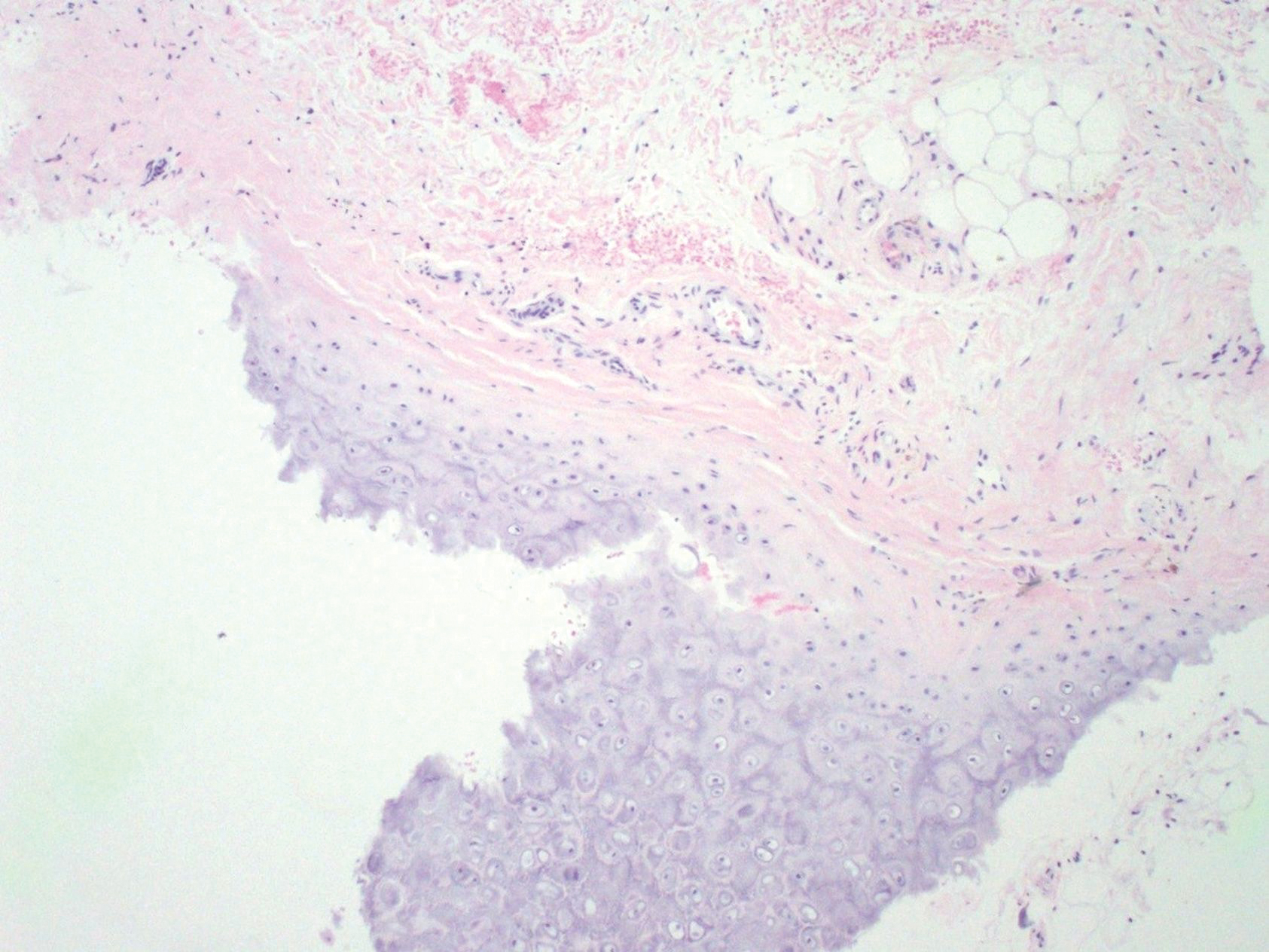

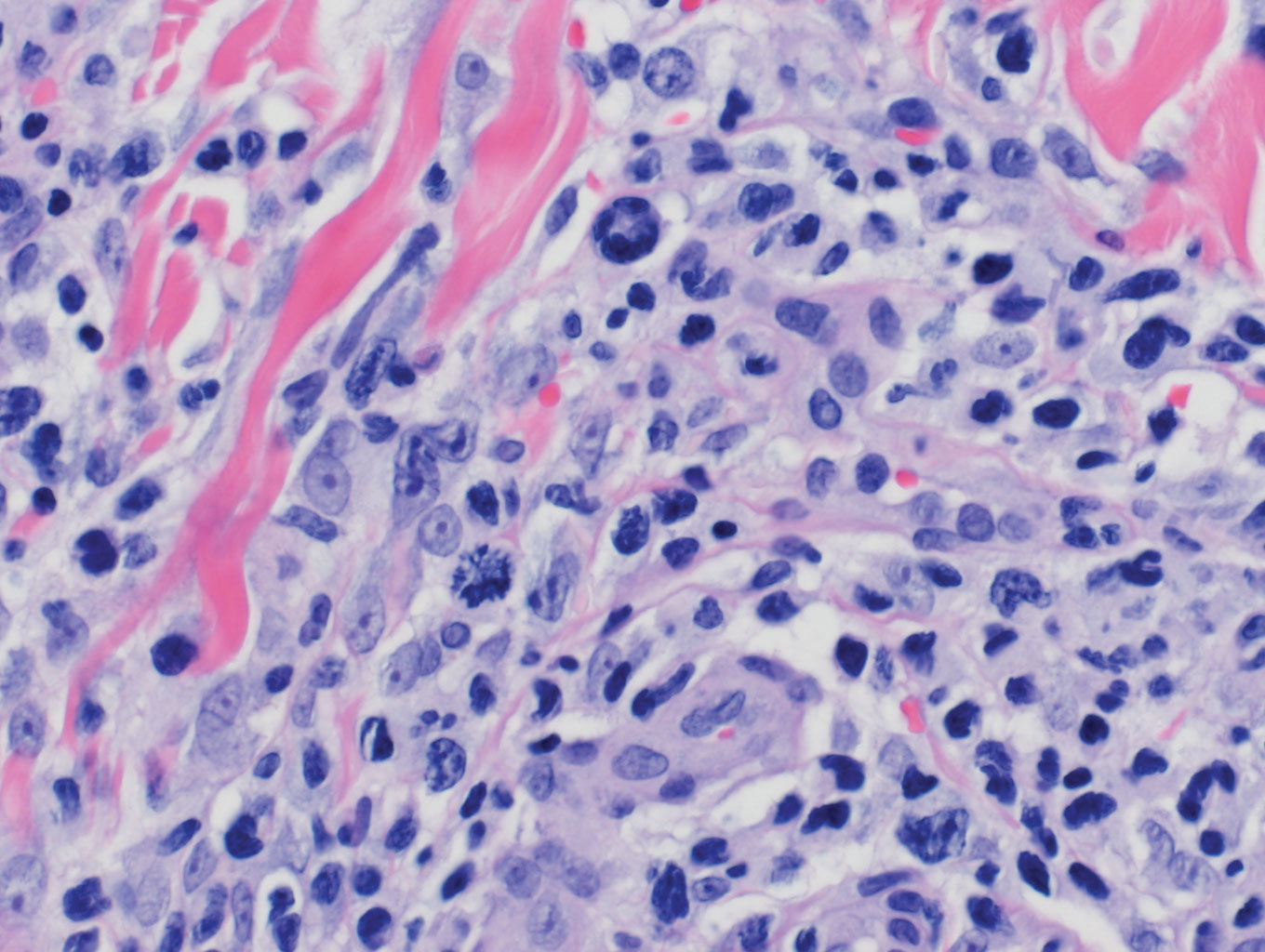

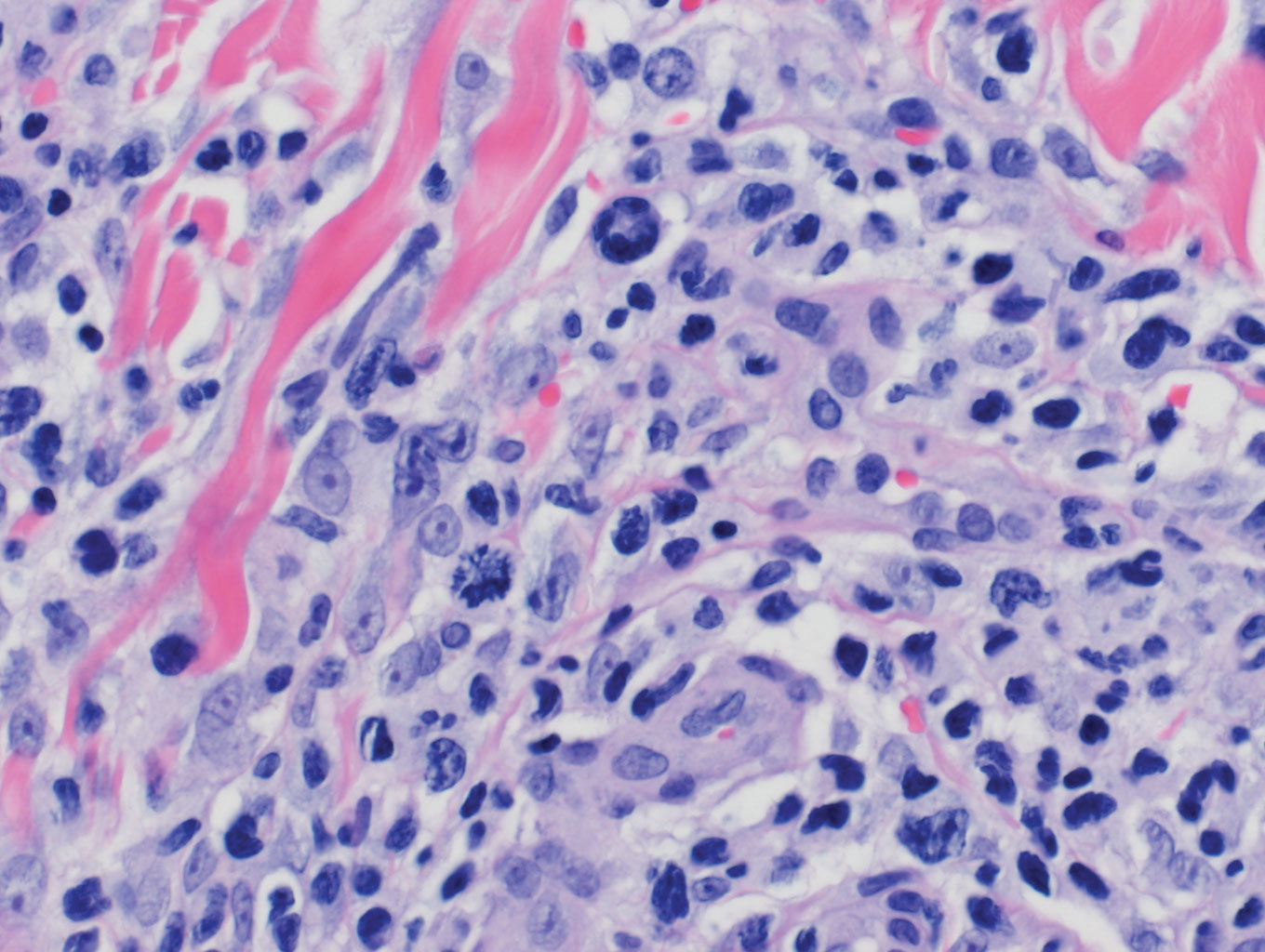

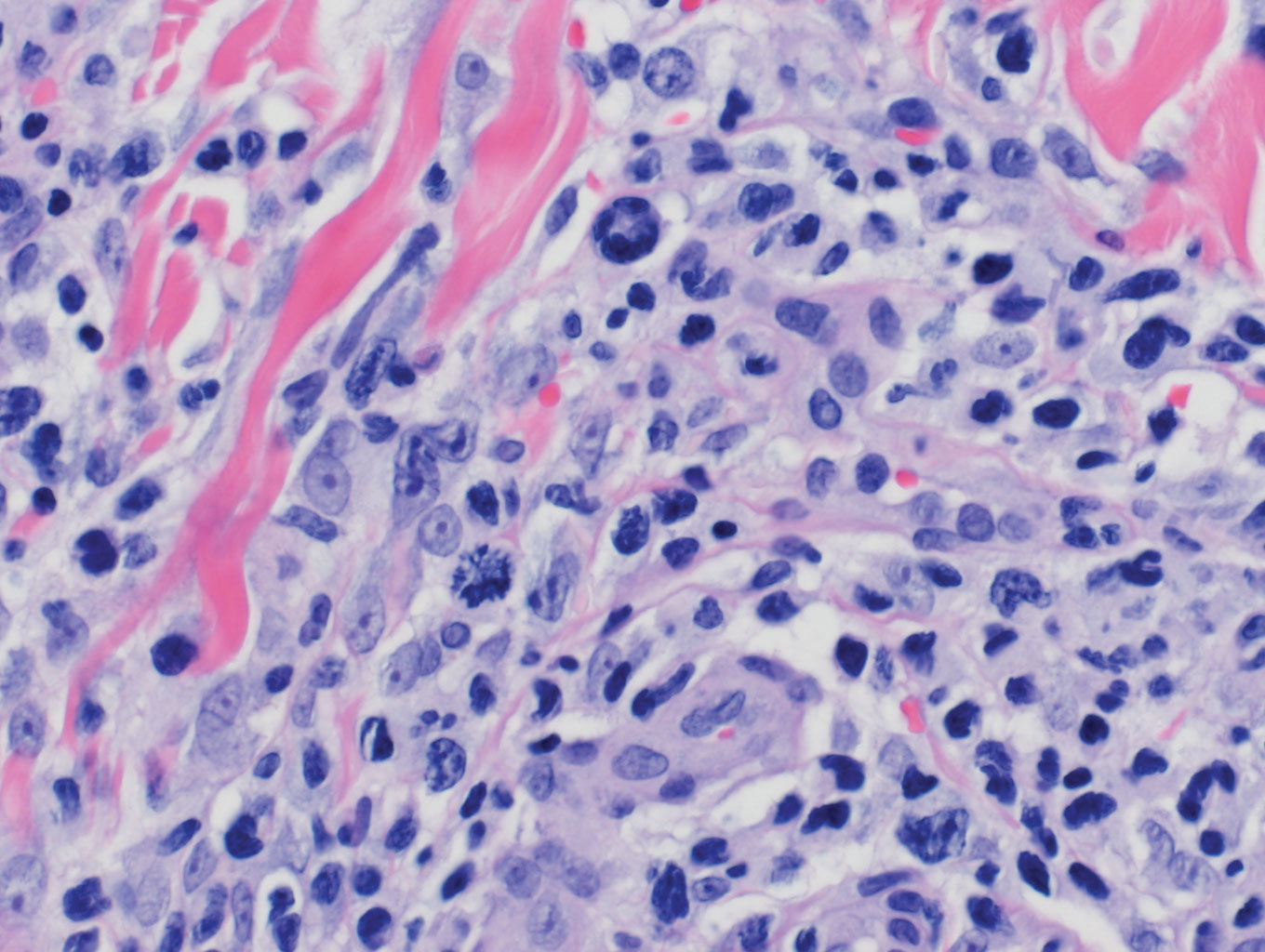

Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma is characterized by islands of neoplastic cells floating in pools of mucin (Figure 1). It may be indistinguishable from metastatic mucinous carcinomas of the colon or breast. Immunohistochemistry can be helpful in differentiating metastatic breast vs colon carcinoma. Cytokeratin 7, GATA binding protein 3, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, and estrogen receptor will be positive in carcinomas of the breast and will be negative in colonic adenocarcinomas.4-6 Furthermore, lesional cells in metastatic adenocarcinoma of the colon are positive for CDX-2 and CK20, while those in metastatic carcinoma of the breast are negative.2 Immunohistochemistry also can differentiate primary cutaneous carcinoma from metastatic adenocarcinoma. When used in combination, p63 and podoplanin (D2-40) offer a highly sensitive and specific indicator of a primary cutaneous neoplasm, as both demonstrate either focal or diffuse positivity in this setting. In contrast, these stains typically are negative in metastatic adenocarcinomas of the skin.7

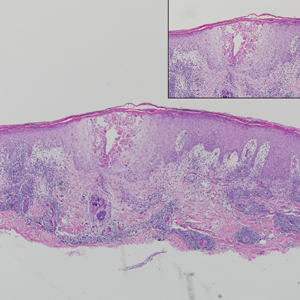

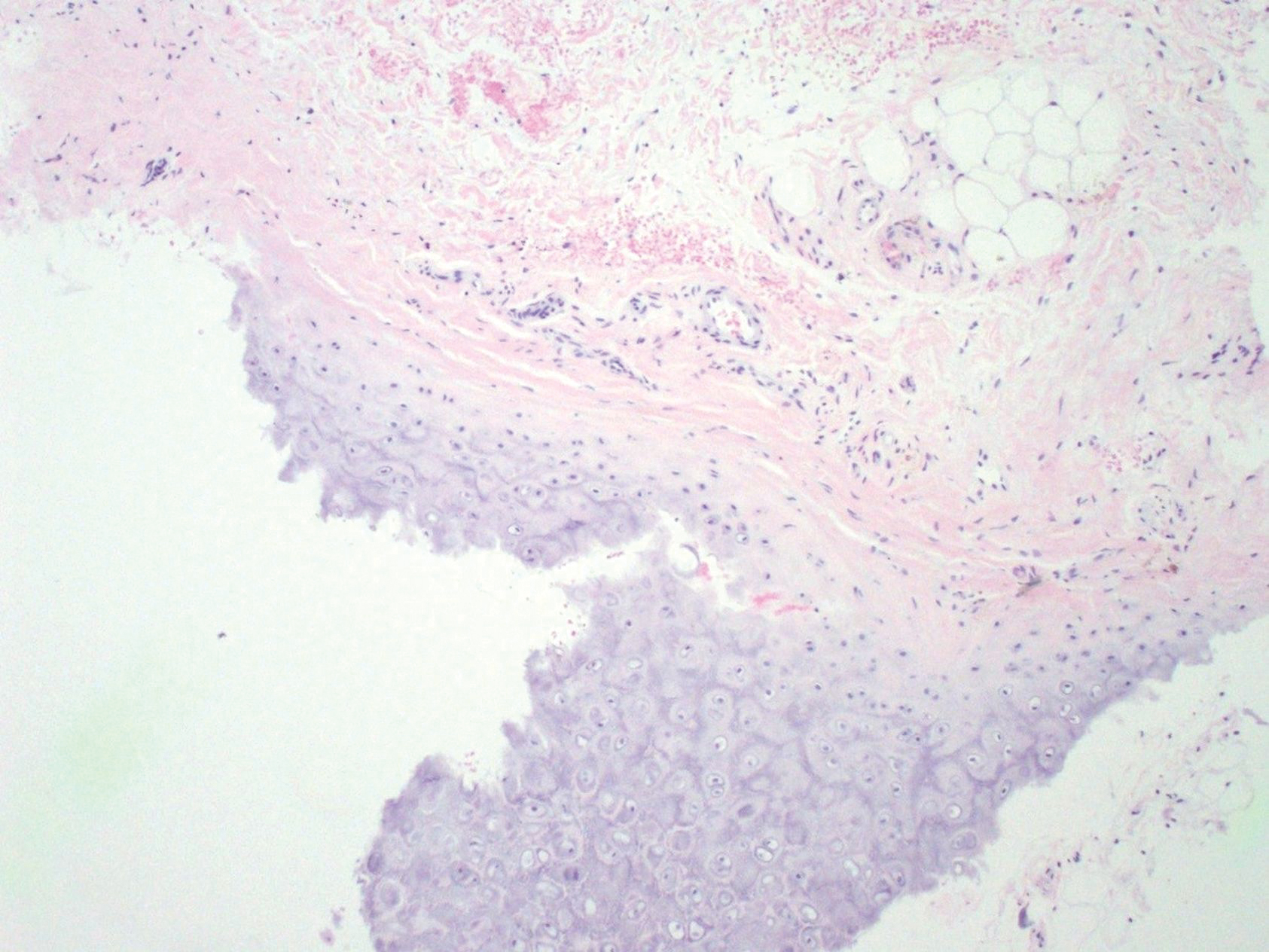

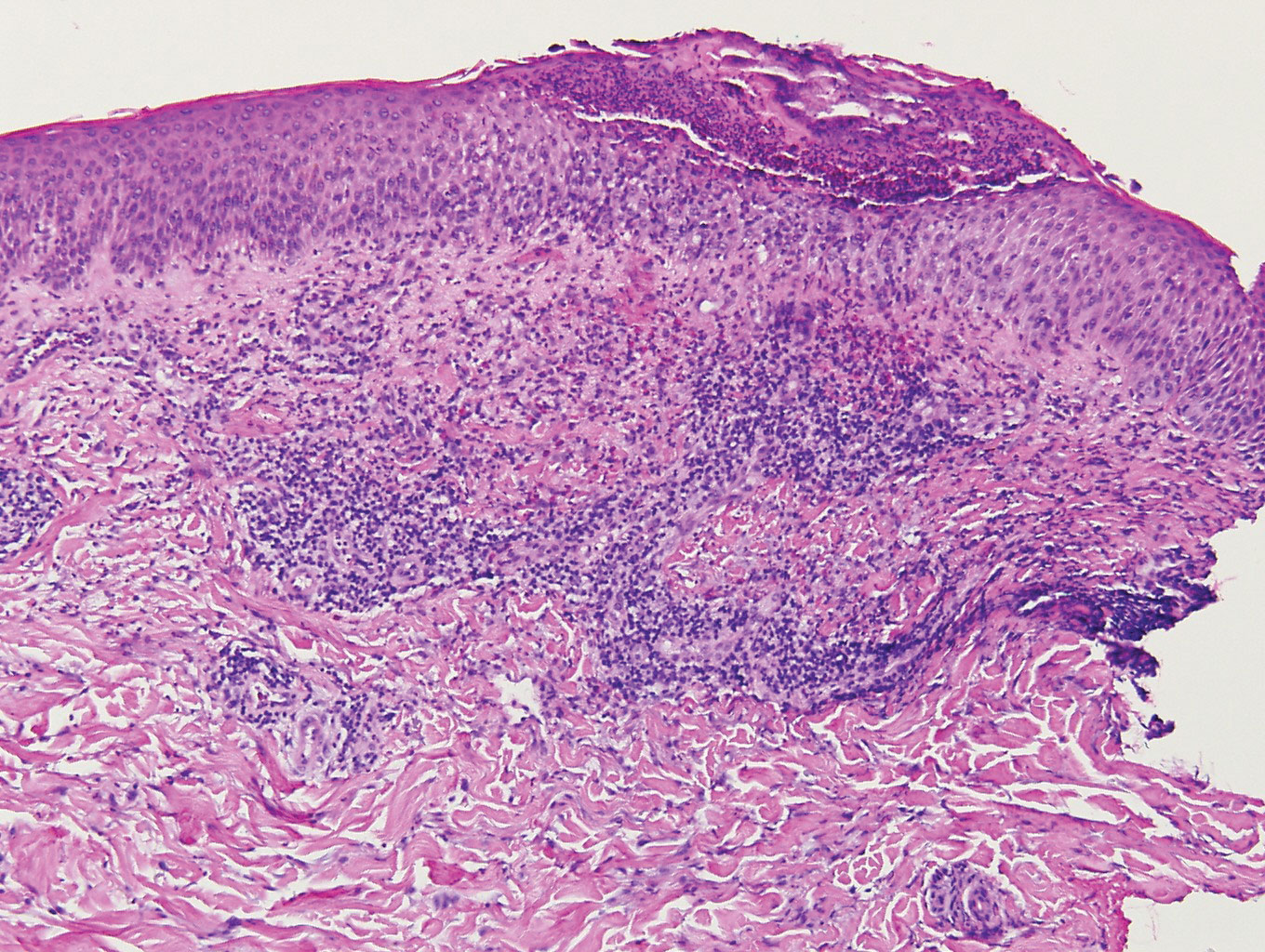

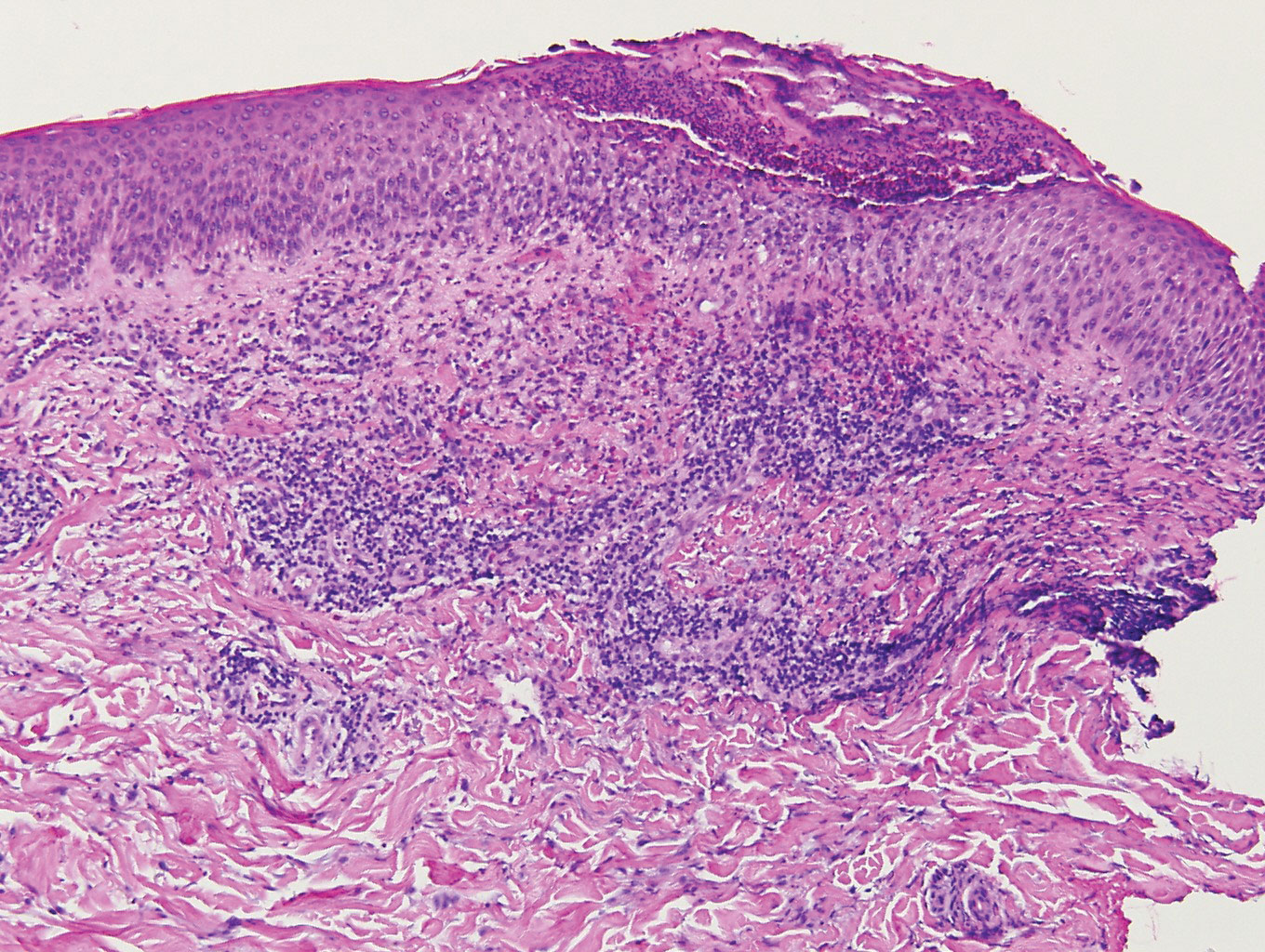

Endometriosis affects 1% to 2% of all reproductive-age females, of which extrapelvic manifestations account for only 0.5% to 1.0% of cases.8 Histologically, extrapelvic endometriosis is characterized by the triad of endometrial-type glands, endometrial stroma, and hemorrhage or hemosiderin deposition (Figure 2). The glands can enlarge and demonstrate architectural distortion with partial lack of polarity. These features initially can be concerning for adenocarcinoma, but on closer examination, nuclear morphology is regular and mitoses are absent.8,9 The diagnosis usually can be rendered with H&E alone; however, immunohistochemical stains for CD10 and estrogen receptor can highlight the endometrial stroma.10 Furthermore, endometrial glands will stain positive for paired box gene 8 (PAX8), a marker that is not expressed within the gastrointestinal tract and associated malignancies.11

cytoplasm (H&E, original magnification ×100).

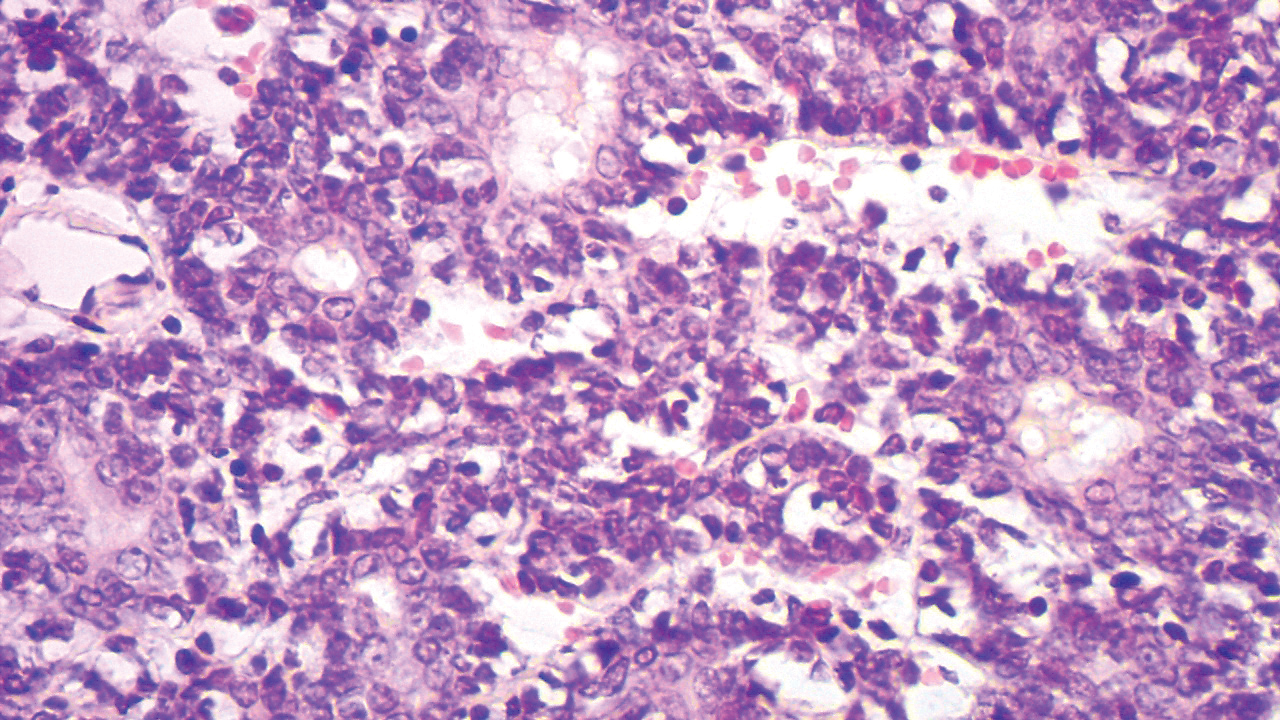

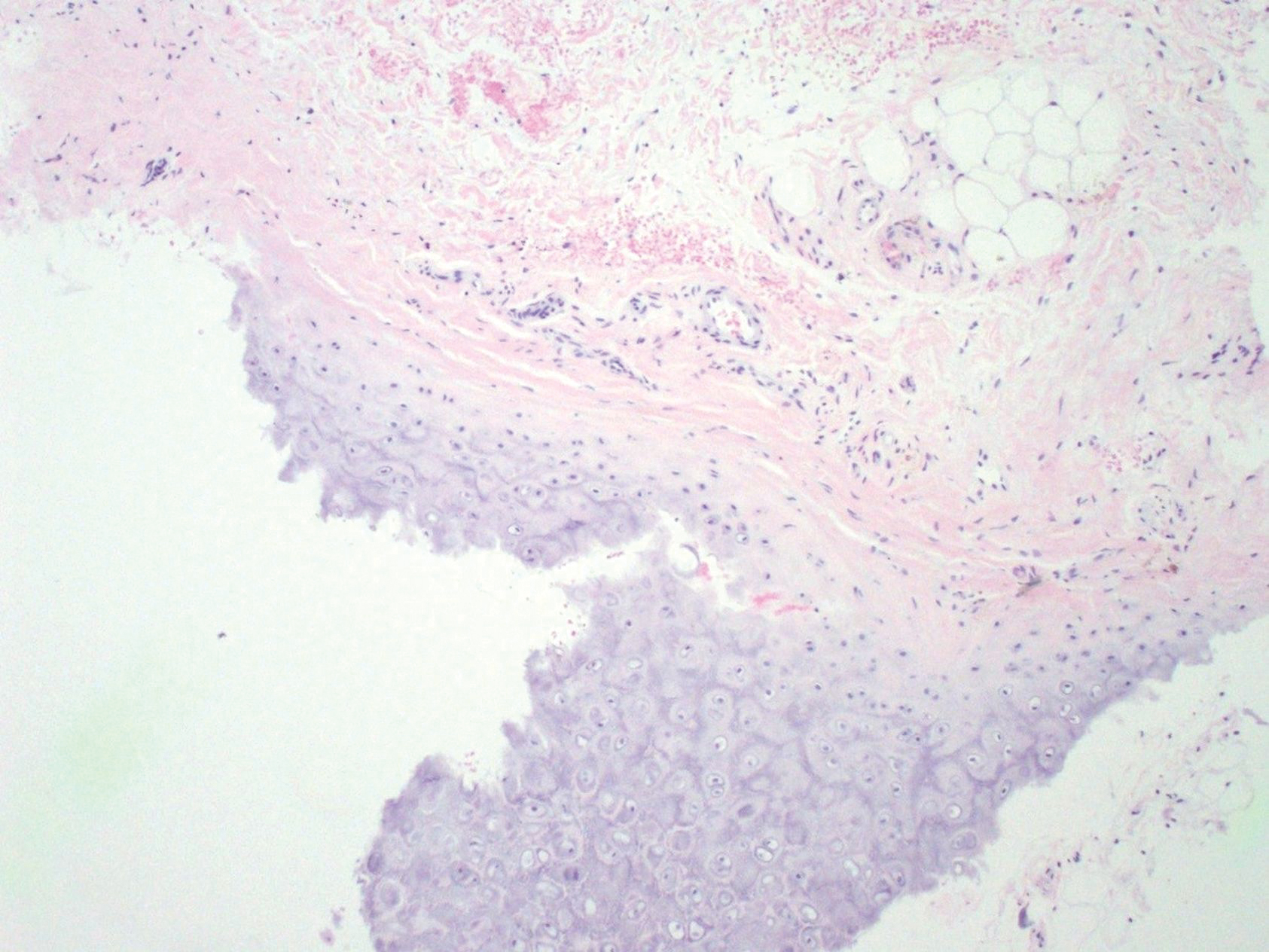

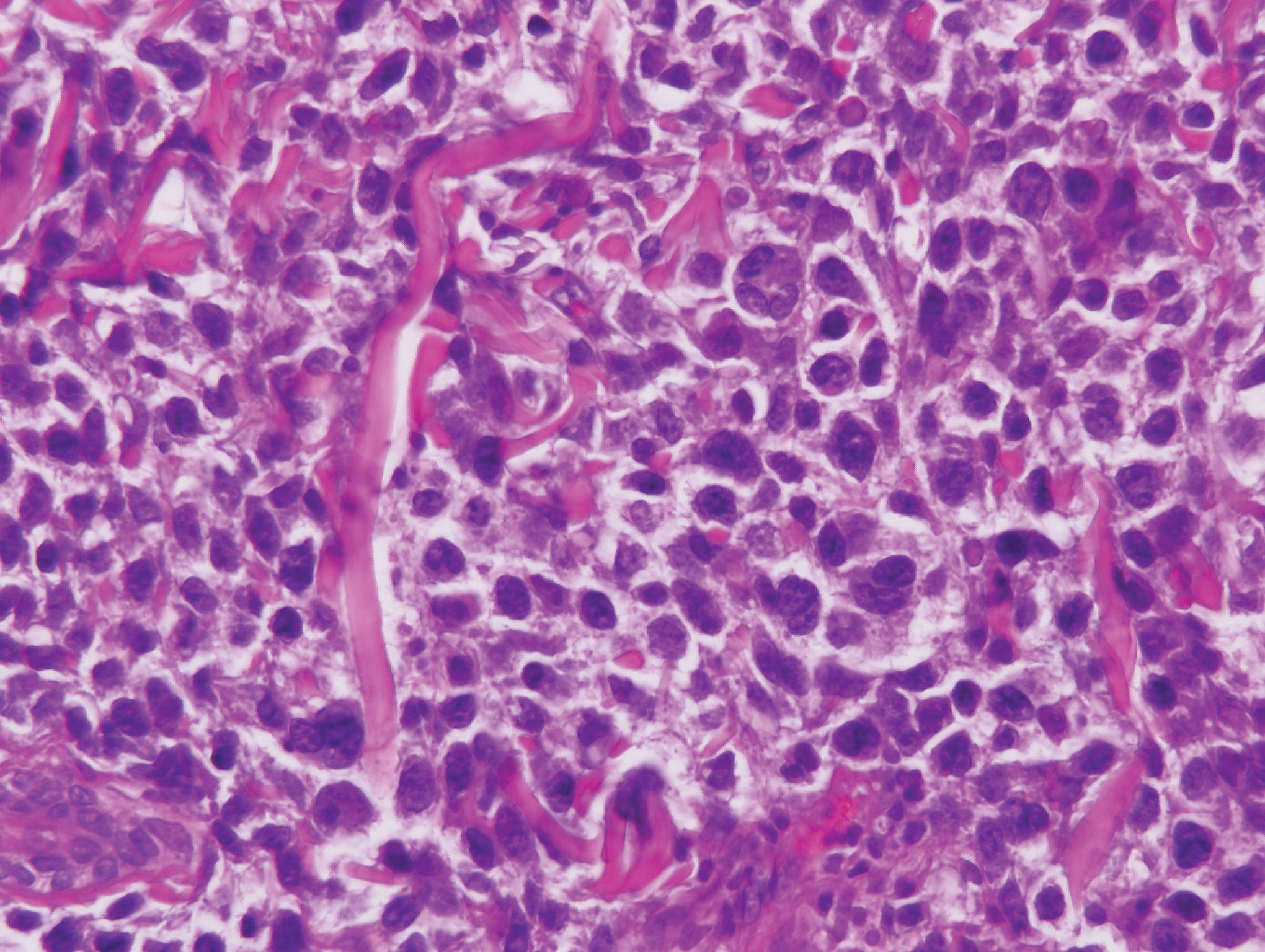

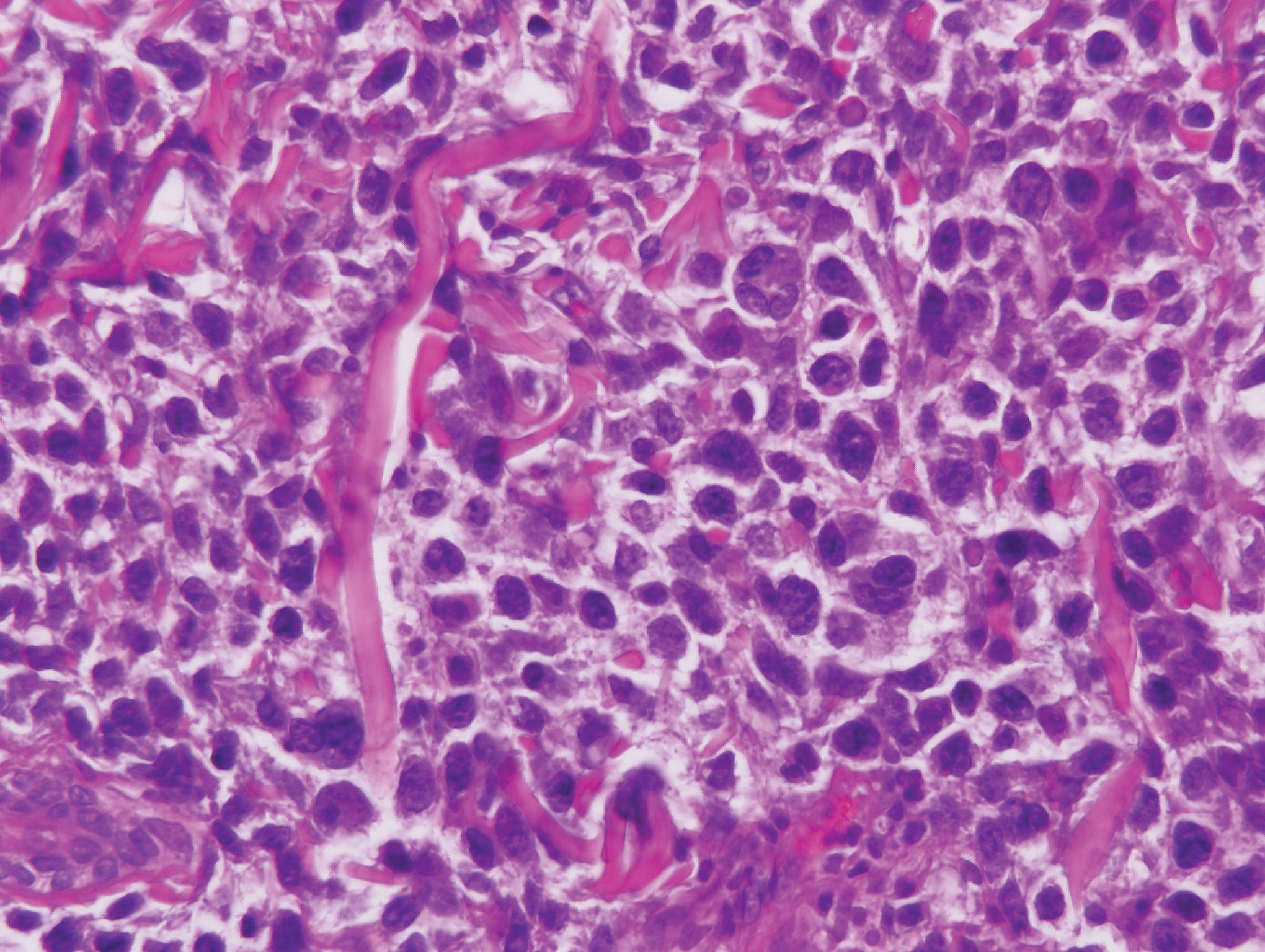

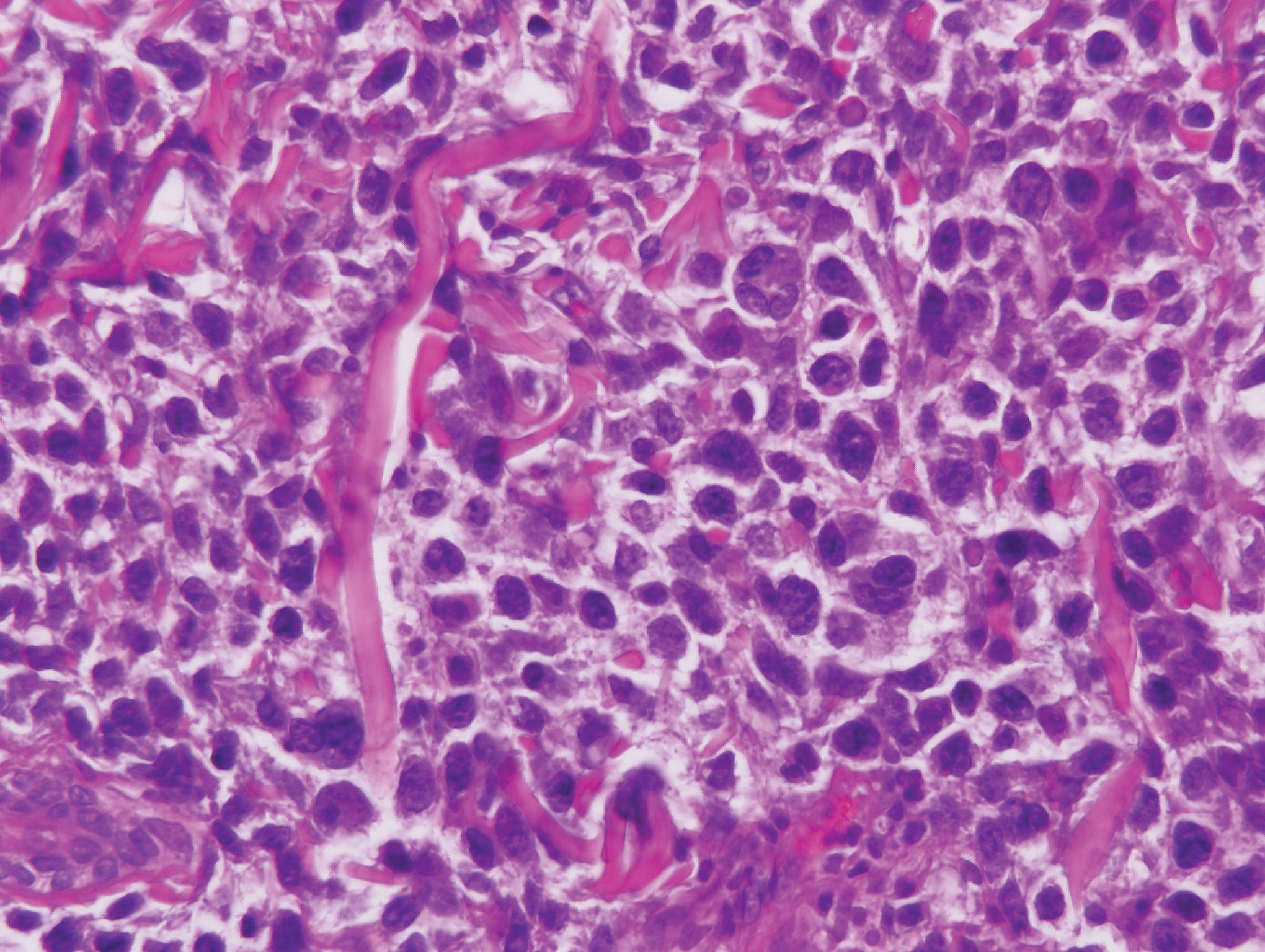

Primary cutaneous angiosarcoma may mimic adenocarcinoma, as the endothelial-lined vessels can be confused as malignant glands (Figure 3). Angiosarcoma often is seen in 1 of 3 clinical presentations: the head and neck of elderly patients, postradiation treatment, and chronic lymphedema.12,13 Regardless of the location, the disease carries a poor prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate of 12% following initial diagnosis.13 Angiosarcoma is characterized by malignant endothelial cells dissecting through the dermis. Although the histology can be deceptively bland in some cases, the neoplasm most commonly demonstrates notable atypia with a multilayered endothelium and occasional intravascular atypical cells ("fish in the creek appearance").13,14 There can be frequent mitoses, and the atypical cells may show intracytoplasmic lumina containing red blood cells. The lesional cells are positive for endothelial markers such as erythroblast transformation specific related gene (ERG), CD31, CD34, and friend leukemia integration factor 1 (FLI-1).15,16

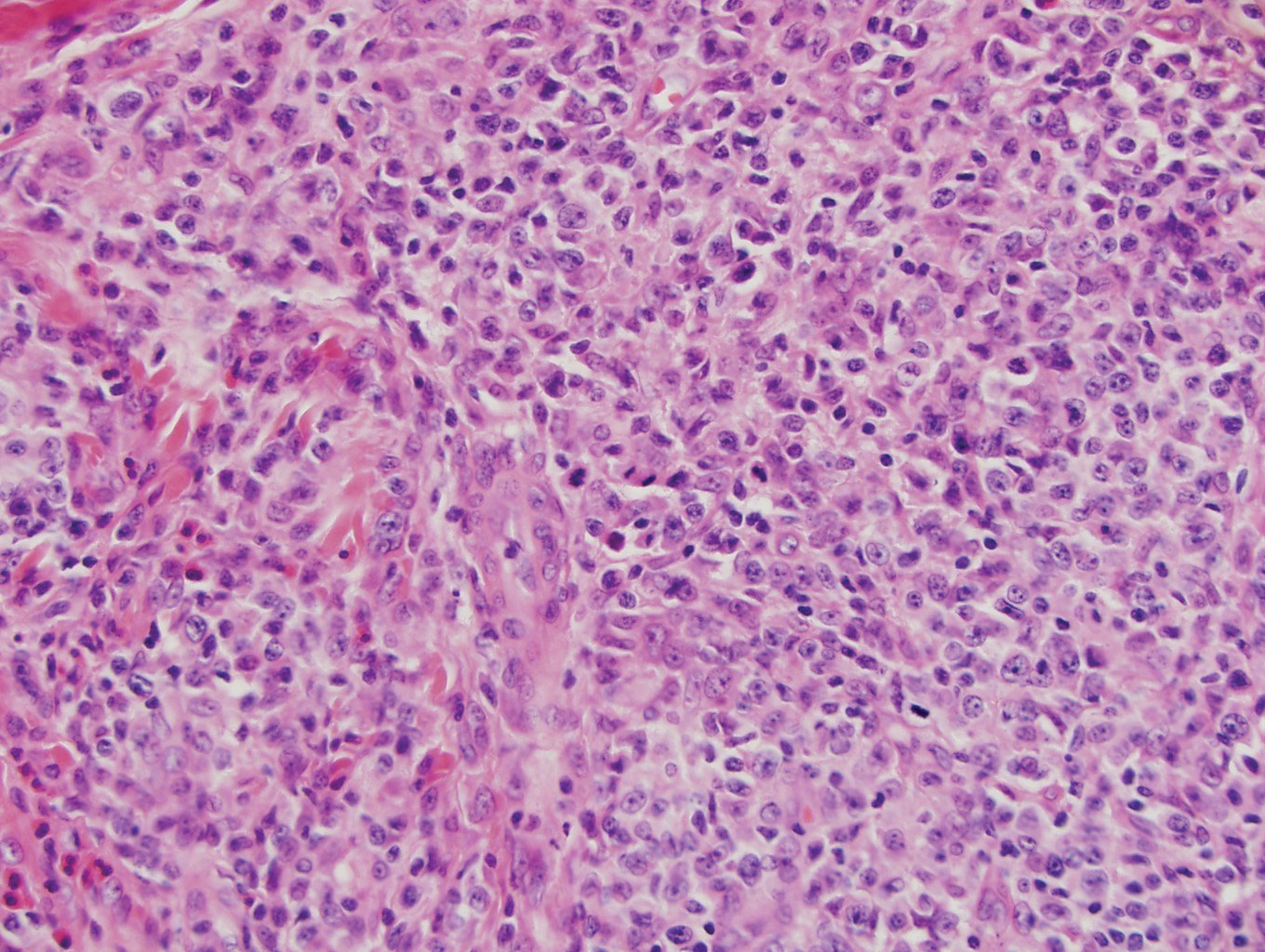

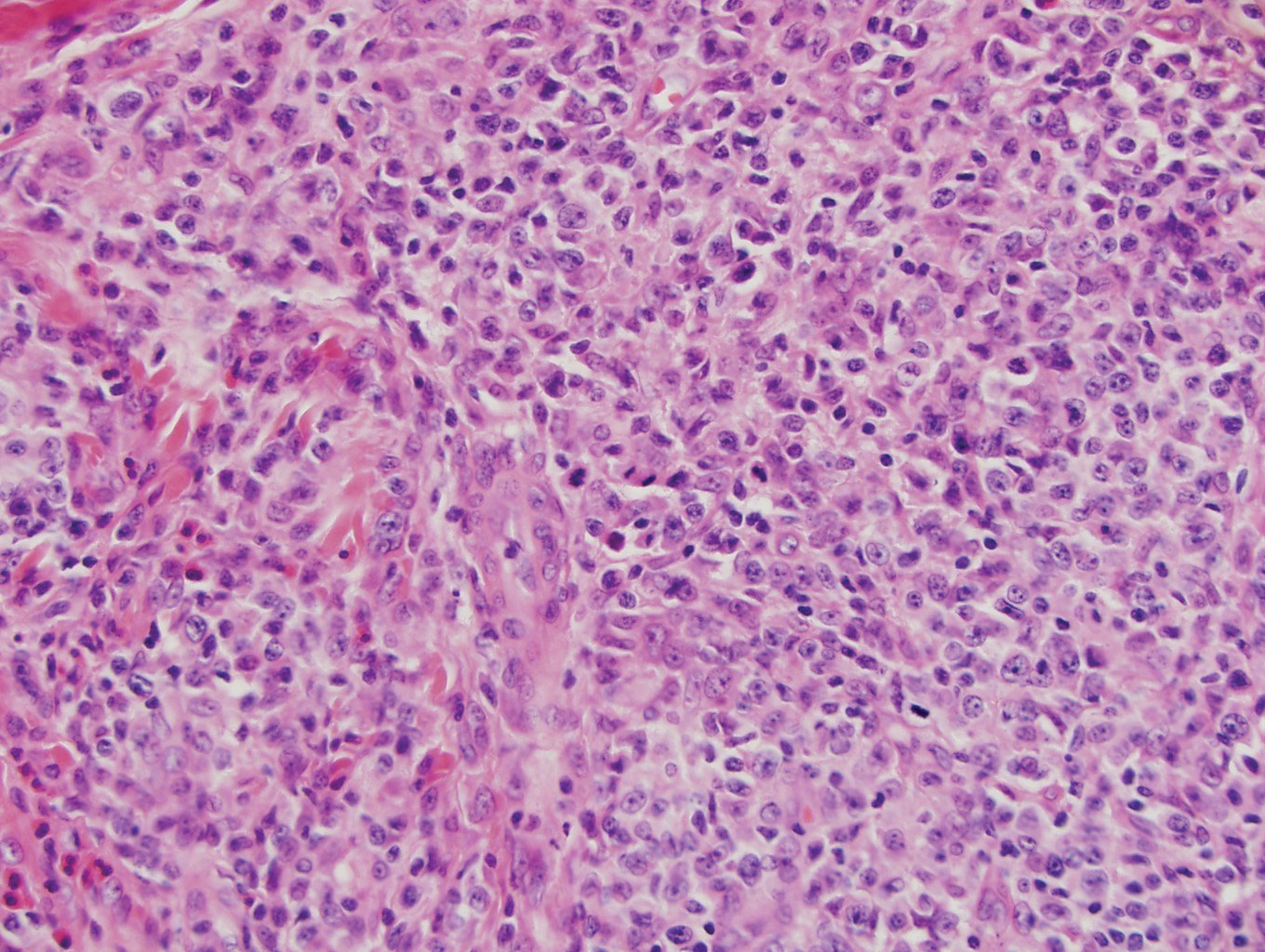

Breast cancer also can cause cutaneous metastases in approximately 20% of cases, with the most common presenting site being the anterior chest wall.17 Macroscopically, these lesions appear most commonly as painless nodules but also as telangiectatic, erysipeloid, fibrotic, and alopecic lesions.17-19 The histologic findings from H&E-stained sections of a cutaneous metastasis of breast cancer are variable and depend on the specific tumor subtype (eg, ductal, lobular, mucinous). However, the classic histologic presentation is that of nests and cords of malignant epithelial cells with variable gland formation. Often, tumor cells infiltrate in a single-file fashion (Figure 4).17 Although inflammatory breast carcinoma is a strictly clinical diagnosis, the presence of tumor cells in the lymphovascular spaces is a histologic clue to this diagnosis. Immunohistochemically, GATA binding protein 3 is helpful in identifying both hormone receptor-positive and -negative breast cancer subtypes that have metastasized.20

Within the histologic differential diagnoses, the most useful tool to diagnose metastatic adenocarcinoma of the colon often is a thorough clinical history. In the absence of a clinical history of adenocarcinoma, immunohistochemistry can be a useful adjunct to aid in the correct characterization and classification of a malignant gland-forming tumor.2,3,6

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Adenocarcinoma of the Colon

Cutaneous adenocarcinomas are uncommon, whether they present as a primary lesion or metastatic disease. In our patient, the histologic findings and immunohistochemical staining pattern were consistent with metastatic adenocarcinoma of the colon, an uncommon clinical presentation.

Colonic adenocarcinoma can cause cutaneous metastasis in 3% of cases. The most common sites of metastases include the abdomen, chest, and back.1 On histologic examination, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections of cutaneous metastatic adenocarcinoma illustrate a malignant gland-forming neoplasm in the dermis with luminal mucin and necrotic debris (quiz image). The glands are lined by tall columnar epithelial cells with hyperchromatic nuclei. Alternatively, poorly differentiated morphology can be seen with fewer glands and more infiltrating nests of tumor cells.2 Immunohistochemically, colonic adenocarcinoma typically is negative for cytokeratin (CK) 7 and positive for CK20 and caudal type homeobox transcription factor 2 (CDX-2).3

Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma is characterized by islands of neoplastic cells floating in pools of mucin (Figure 1). It may be indistinguishable from metastatic mucinous carcinomas of the colon or breast. Immunohistochemistry can be helpful in differentiating metastatic breast vs colon carcinoma. Cytokeratin 7, GATA binding protein 3, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, and estrogen receptor will be positive in carcinomas of the breast and will be negative in colonic adenocarcinomas.4-6 Furthermore, lesional cells in metastatic adenocarcinoma of the colon are positive for CDX-2 and CK20, while those in metastatic carcinoma of the breast are negative.2 Immunohistochemistry also can differentiate primary cutaneous carcinoma from metastatic adenocarcinoma. When used in combination, p63 and podoplanin (D2-40) offer a highly sensitive and specific indicator of a primary cutaneous neoplasm, as both demonstrate either focal or diffuse positivity in this setting. In contrast, these stains typically are negative in metastatic adenocarcinomas of the skin.7

Endometriosis affects 1% to 2% of all reproductive-age females, of which extrapelvic manifestations account for only 0.5% to 1.0% of cases.8 Histologically, extrapelvic endometriosis is characterized by the triad of endometrial-type glands, endometrial stroma, and hemorrhage or hemosiderin deposition (Figure 2). The glands can enlarge and demonstrate architectural distortion with partial lack of polarity. These features initially can be concerning for adenocarcinoma, but on closer examination, nuclear morphology is regular and mitoses are absent.8,9 The diagnosis usually can be rendered with H&E alone; however, immunohistochemical stains for CD10 and estrogen receptor can highlight the endometrial stroma.10 Furthermore, endometrial glands will stain positive for paired box gene 8 (PAX8), a marker that is not expressed within the gastrointestinal tract and associated malignancies.11

cytoplasm (H&E, original magnification ×100).

Primary cutaneous angiosarcoma may mimic adenocarcinoma, as the endothelial-lined vessels can be confused as malignant glands (Figure 3). Angiosarcoma often is seen in 1 of 3 clinical presentations: the head and neck of elderly patients, postradiation treatment, and chronic lymphedema.12,13 Regardless of the location, the disease carries a poor prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate of 12% following initial diagnosis.13 Angiosarcoma is characterized by malignant endothelial cells dissecting through the dermis. Although the histology can be deceptively bland in some cases, the neoplasm most commonly demonstrates notable atypia with a multilayered endothelium and occasional intravascular atypical cells ("fish in the creek appearance").13,14 There can be frequent mitoses, and the atypical cells may show intracytoplasmic lumina containing red blood cells. The lesional cells are positive for endothelial markers such as erythroblast transformation specific related gene (ERG), CD31, CD34, and friend leukemia integration factor 1 (FLI-1).15,16

Breast cancer also can cause cutaneous metastases in approximately 20% of cases, with the most common presenting site being the anterior chest wall.17 Macroscopically, these lesions appear most commonly as painless nodules but also as telangiectatic, erysipeloid, fibrotic, and alopecic lesions.17-19 The histologic findings from H&E-stained sections of a cutaneous metastasis of breast cancer are variable and depend on the specific tumor subtype (eg, ductal, lobular, mucinous). However, the classic histologic presentation is that of nests and cords of malignant epithelial cells with variable gland formation. Often, tumor cells infiltrate in a single-file fashion (Figure 4).17 Although inflammatory breast carcinoma is a strictly clinical diagnosis, the presence of tumor cells in the lymphovascular spaces is a histologic clue to this diagnosis. Immunohistochemically, GATA binding protein 3 is helpful in identifying both hormone receptor-positive and -negative breast cancer subtypes that have metastasized.20

Within the histologic differential diagnoses, the most useful tool to diagnose metastatic adenocarcinoma of the colon often is a thorough clinical history. In the absence of a clinical history of adenocarcinoma, immunohistochemistry can be a useful adjunct to aid in the correct characterization and classification of a malignant gland-forming tumor.2,3,6

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

- Kumar V, Robbins SL. Robbins Basic Pathology. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier; 2007.

- Taliano RJ, LeGolvan M, Resnick MB. Immunohistochemistry of colorectal carcinoma: current practice and evolving applications. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:151-163.

- Kamalpour L, Brindise RT, Nodzenski M, et al. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after surgery. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:380-384.

- Roshan MH, Tambo A, Pace NP. The role of testosterone in colorectal carcinoma: pathomechanisms and open questions. EPMA J. 2016;7:22.

- Mazoujian G, Pinkus GS, Davis S, et al. Immunohistochemistry of a gross cystic disease fluid protein (GCDFP-15) of the breast. a marker of apocrine epithelium and breast carcinomas with apocrine features. Am J Pathol. 1983;110:105-112.

- Plaza JA, Ortega PF, Stockman DL, et al. Value of p63 and podoplanin (D2-40) immunoreactivity in the distinction between primary cutaneous tumors and adenocarcinomas metastatic to the skin: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 79 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:403-410.

- Machairiotis N, Stylianaki A, Dryllis G, et al. Extrapelvic endometriosis: a rare entity or an under diagnosed condition? Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:194.

- Chen H, Luo Q, Liu S, et al. Rectal mucosal endometriosis primarily misinterpreted as adenocarcinoma: a case report and review of literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:5902-5907.

- Terada S, Miyata Y, Nakazawa H, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of an ectopic endometriosis in the uterine round ligament. Diagn Pathol. 2006;1:27.

- Yemelyanova A, Gown AM, Wu LS, et al. PAX8 expression in uterine adenocarcinomas and mesonephric proliferations. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2014;33:492-499.

- Farid M, Ong WS, Lee MJ, et al. Cutaneous versus non-cutaneous angiosarcoma: clinicopathologic features and treatment outcomes in 60 patients at a single Asian cancer centre. Oncology. 2013;85:182-190.

- Requena C, Sendra E, Llombart B, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: clinical and pathology study of 16 cases. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:457-465.

- Schmidt AP, Tjarks BJ, Lynch DW. Gone fishing: a unique histologic pattern in cutaneous angiosarcoma. Cutis. 2018;101:270-272.

- Sullivan HC, Edgar MA, Cohen C, et al. The utility of ERG, CD31 and CD34 in the cytological diagnosis of angiosarcoma: an analysis of 25 cases. J Clin Pathol. 2015;68:44-50.

- Rossi S, Orvieto E, Furlanetto A, et al. Utility of the immunohistochemical detection of FLI-1 expression in round cell and vascular neoplasm using a monoclonal antibody. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:547-552.

- Tan AR. Cutaneous manifestations of breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 2016;43:331-334.

- Schwartz RA, Wiederkehr M, Lambert WC. Secondary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: metastatic breast cancer. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(2, pt 1):234-235.

- Mallon E, Dawber RP. Alopecia neoplastica without alopecia: a unique presentation of breast carcinoma scalp metastasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(2, pt 2):319-321.

- Braxton DR, Cohen C, Siddiqui MT. Utility of GATA3 immunohistochemistry for diagnosis of metastatic breast carcinoma in cytology specimens. Diagn Cytopathol. 2015;43:271-277.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

- Kumar V, Robbins SL. Robbins Basic Pathology. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier; 2007.

- Taliano RJ, LeGolvan M, Resnick MB. Immunohistochemistry of colorectal carcinoma: current practice and evolving applications. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:151-163.

- Kamalpour L, Brindise RT, Nodzenski M, et al. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after surgery. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:380-384.

- Roshan MH, Tambo A, Pace NP. The role of testosterone in colorectal carcinoma: pathomechanisms and open questions. EPMA J. 2016;7:22.

- Mazoujian G, Pinkus GS, Davis S, et al. Immunohistochemistry of a gross cystic disease fluid protein (GCDFP-15) of the breast. a marker of apocrine epithelium and breast carcinomas with apocrine features. Am J Pathol. 1983;110:105-112.

- Plaza JA, Ortega PF, Stockman DL, et al. Value of p63 and podoplanin (D2-40) immunoreactivity in the distinction between primary cutaneous tumors and adenocarcinomas metastatic to the skin: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 79 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:403-410.

- Machairiotis N, Stylianaki A, Dryllis G, et al. Extrapelvic endometriosis: a rare entity or an under diagnosed condition? Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:194.

- Chen H, Luo Q, Liu S, et al. Rectal mucosal endometriosis primarily misinterpreted as adenocarcinoma: a case report and review of literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:5902-5907.

- Terada S, Miyata Y, Nakazawa H, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of an ectopic endometriosis in the uterine round ligament. Diagn Pathol. 2006;1:27.

- Yemelyanova A, Gown AM, Wu LS, et al. PAX8 expression in uterine adenocarcinomas and mesonephric proliferations. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2014;33:492-499.

- Farid M, Ong WS, Lee MJ, et al. Cutaneous versus non-cutaneous angiosarcoma: clinicopathologic features and treatment outcomes in 60 patients at a single Asian cancer centre. Oncology. 2013;85:182-190.

- Requena C, Sendra E, Llombart B, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: clinical and pathology study of 16 cases. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:457-465.

- Schmidt AP, Tjarks BJ, Lynch DW. Gone fishing: a unique histologic pattern in cutaneous angiosarcoma. Cutis. 2018;101:270-272.

- Sullivan HC, Edgar MA, Cohen C, et al. The utility of ERG, CD31 and CD34 in the cytological diagnosis of angiosarcoma: an analysis of 25 cases. J Clin Pathol. 2015;68:44-50.

- Rossi S, Orvieto E, Furlanetto A, et al. Utility of the immunohistochemical detection of FLI-1 expression in round cell and vascular neoplasm using a monoclonal antibody. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:547-552.

- Tan AR. Cutaneous manifestations of breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 2016;43:331-334.

- Schwartz RA, Wiederkehr M, Lambert WC. Secondary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: metastatic breast cancer. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(2, pt 1):234-235.

- Mallon E, Dawber RP. Alopecia neoplastica without alopecia: a unique presentation of breast carcinoma scalp metastasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(2, pt 2):319-321.

- Braxton DR, Cohen C, Siddiqui MT. Utility of GATA3 immunohistochemistry for diagnosis of metastatic breast carcinoma in cytology specimens. Diagn Cytopathol. 2015;43:271-277.

A 68-year-old patient presented with an enlarging flesh-colored nodule on the thigh that was positive for cytokeratin 20 and negative for cytokeratin 7.

Symmetric Lichen Amyloidosis: An Atypical Location on the Bilateral Extensor Surfaces of the Arms

To the Editor:

Lichen amyloidosis (LA) classically presents as a pruritic, hyperkeratotic, papular eruption localized to the pretibial surface of the legs.1 Nonpruritic and generalized variants have been reported but are rare.2 Although it is the most common subtype of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis, LA is a benign condition but is difficult to eradicate.1 The precise pathophysiology is poorly understood, but chronic frictional irritation is closely associated with the eruption. We present a nongeneralized case of LA in an atypical location.

A healthy 30-year-old woman presented with an intermittent itchy rash on the elbows and knees of 2 years’ duration. The patient was first diagnosed with lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) and initially responded well to treatment with fluocinonide ointment 0.05%. Nearly 2 years after the initial presentation, she developed recurrent symptoms and sought further treatment. She reported frequent scratching in association with episodes of anxiety. Examination revealed numerous 1- to 3-mm, flesh-colored to light brown, monomorphic, dome-shaped papules over the extensor surfaces of the bilateral arms and left pretibial surface (Figure 1).

papules (1–3 mm) over the extensor surfaces of the bilateral arms.

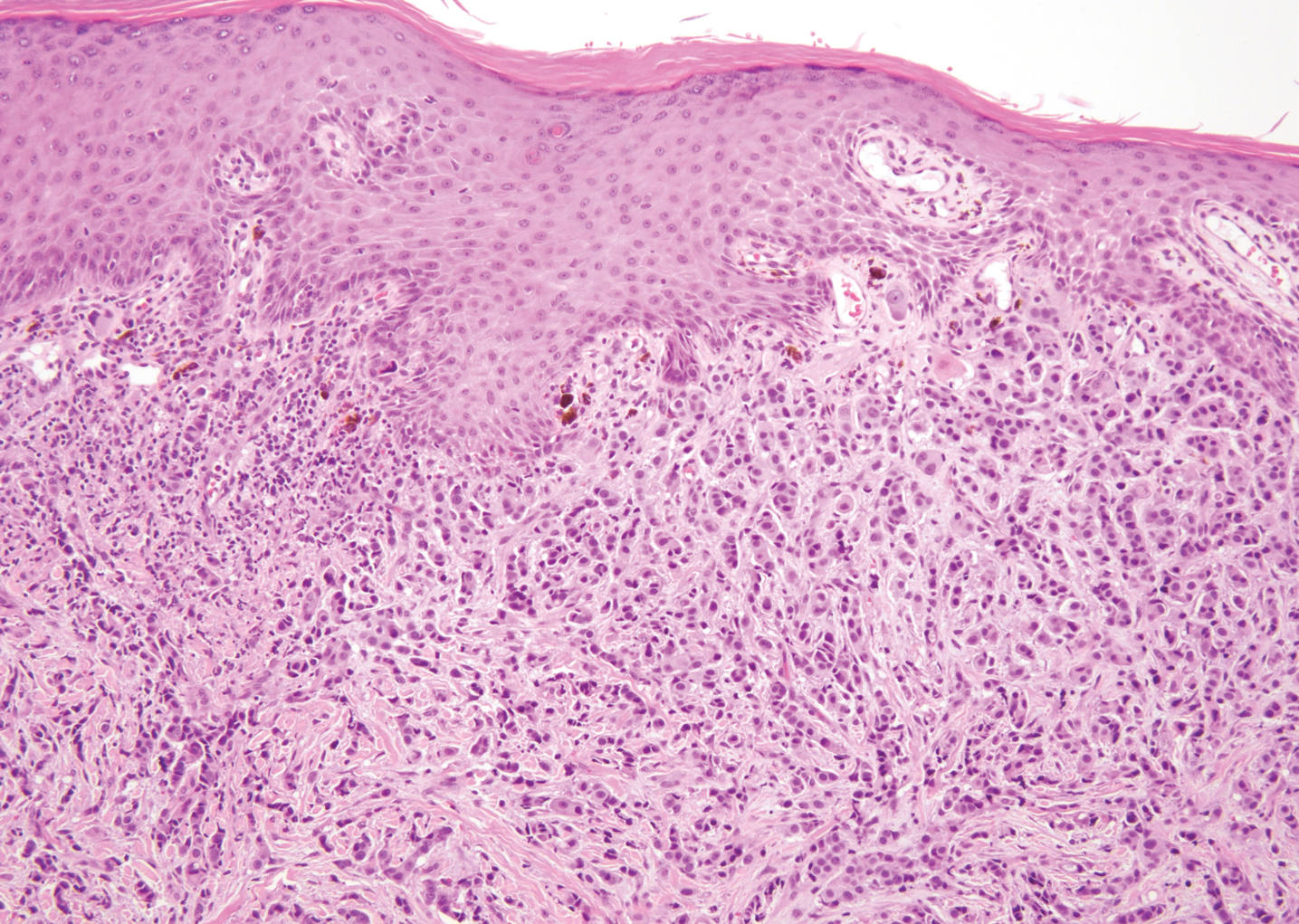

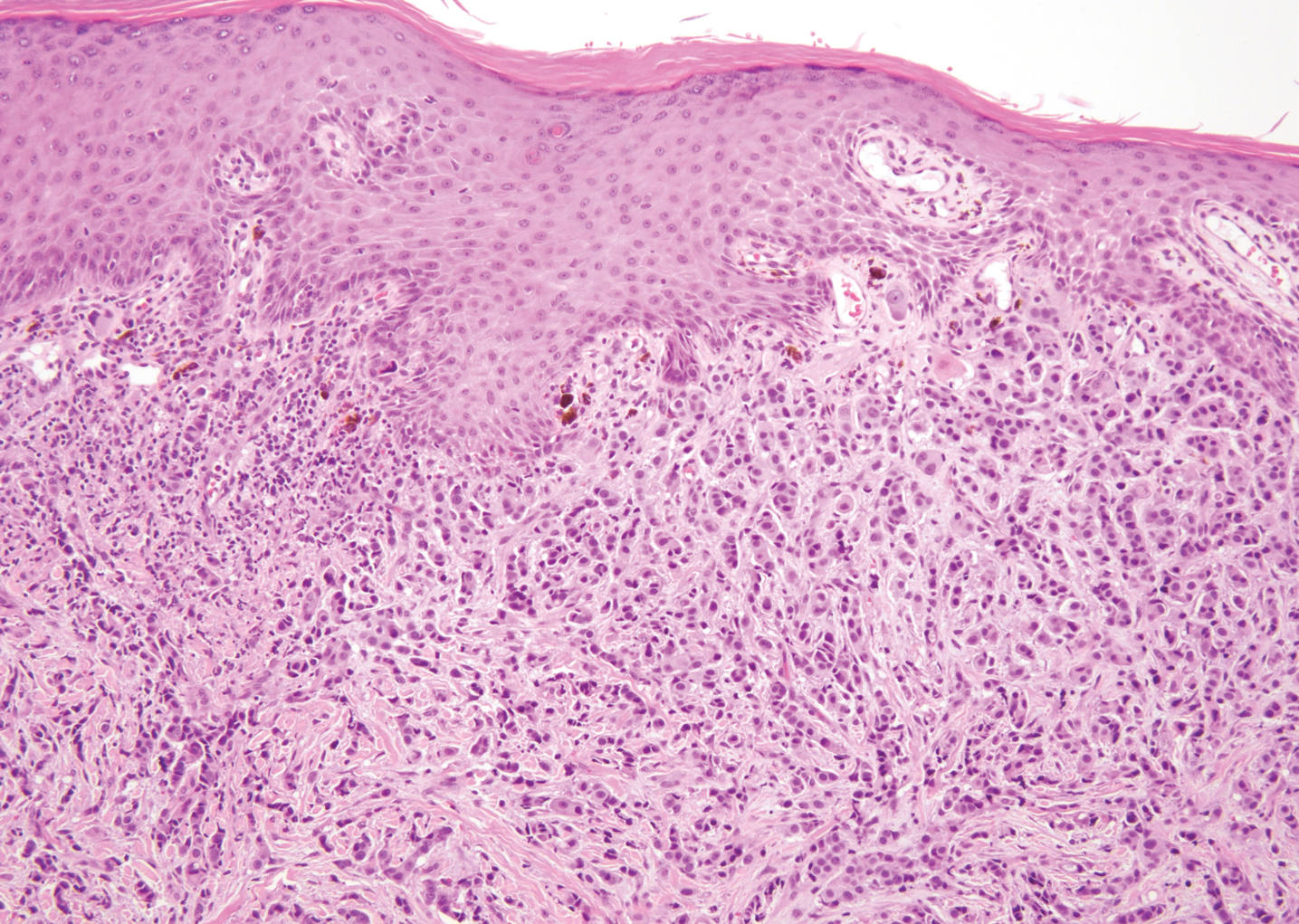

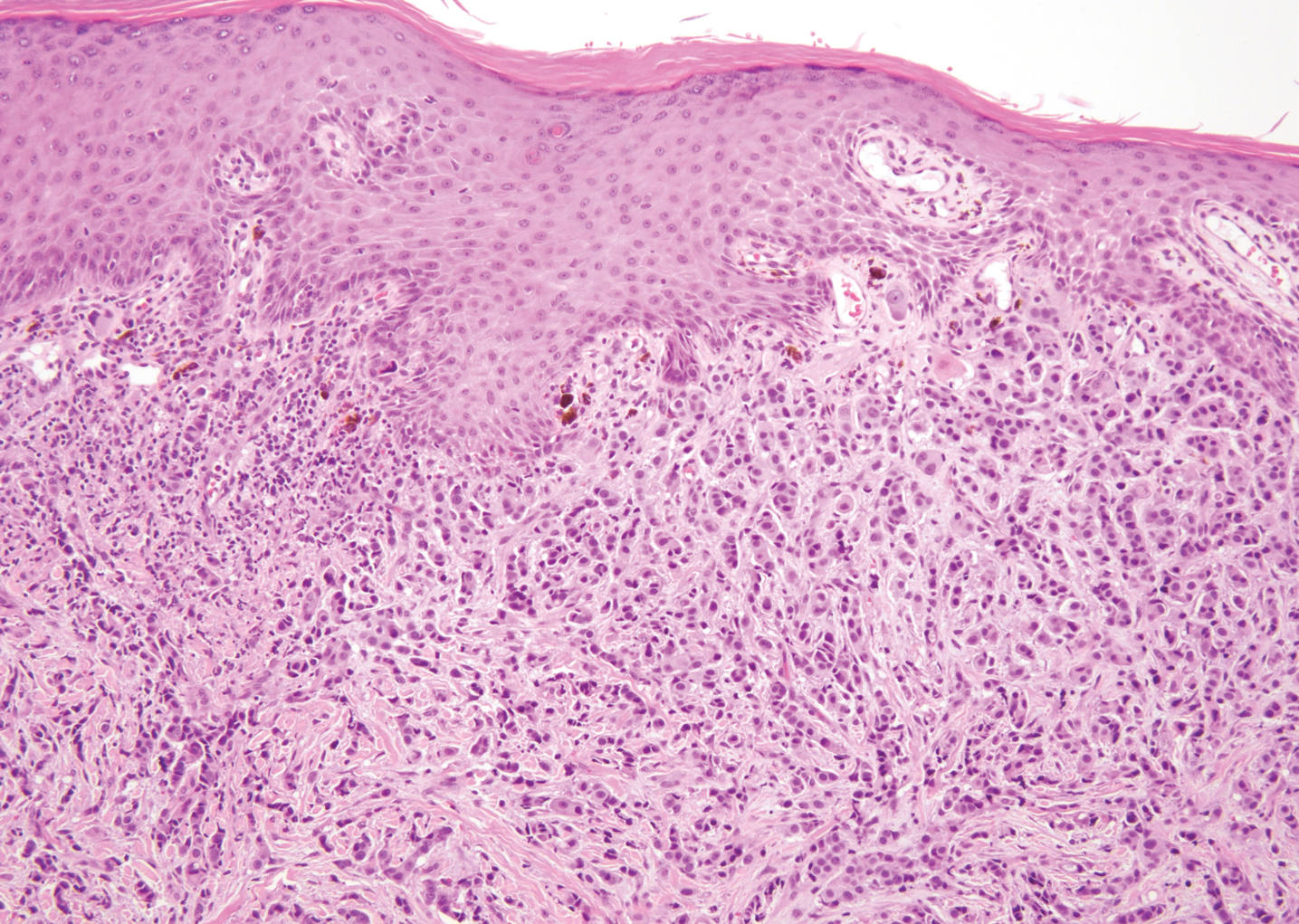

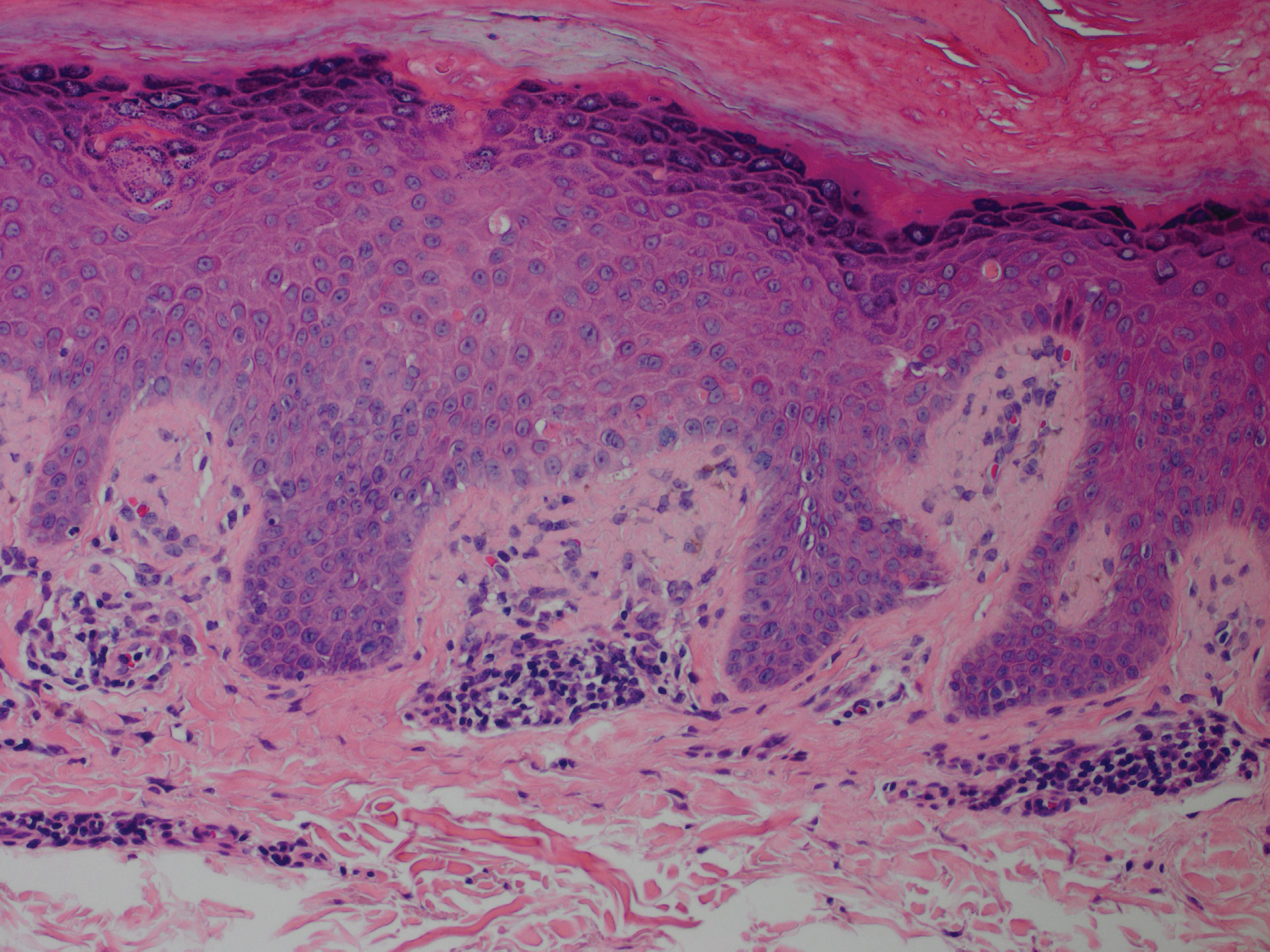

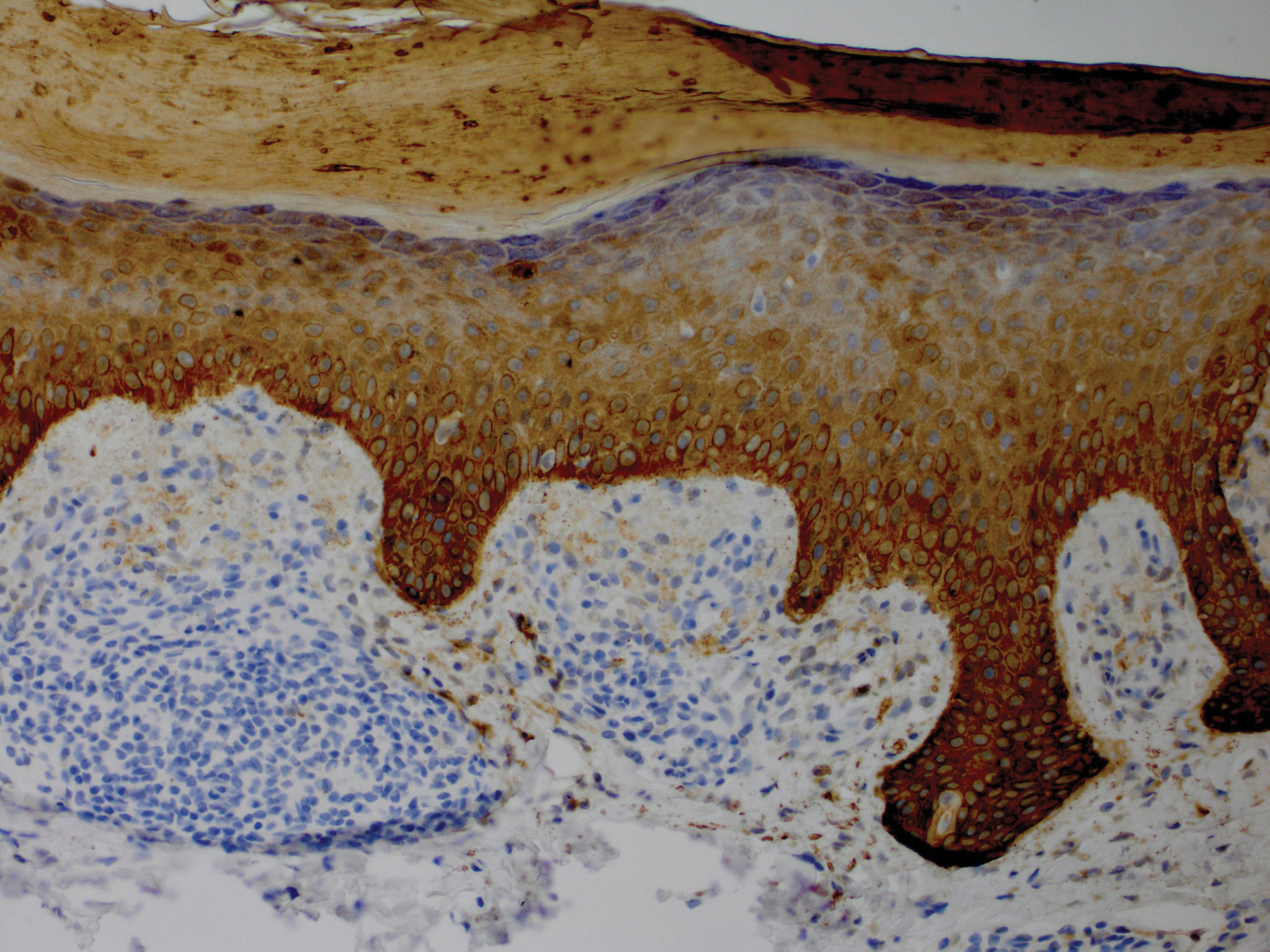

Although in an atypical location, LA was clinically suspected due to the morphology, and a biopsy was performed given the evolving nature of the lesions. The differential diagnosis included LSC, hypertrophic lichen planus, papular mucinosis, prurigo nodularis, and pretibial myxedema. Pathology revealed small eosinophilic globules in the papillary dermis (Figure 2), and cytokeratin 5/6 immunostaining showed amorphous papillary dermal deposits consistent with keratin-derived amyloid deposition (Figure 3). The deposits stained positive for Congo red and displayed apple green birefringence under polarized light. Thus, the diagnosis of LA was confirmed. After limited success with triamcinolone ointment 0.1%, the patient was transitioned to clobetasol cream 0.05% with notable physical and symptomatic improvement.

Amyloidosis is histopathologically characterized by extracellular deposits of amyloid, a polypeptide that polymerizes to form cross-β sheets.3 It is believed that the deposits seen in localized amyloidosis result from local production of amyloid, as opposed to the deposition of circulating light chains that is characteristic of systemic amyloidosis.3 Lichen amyloidosis is the most common subtype of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis.1 The amyloid in this condition has been found to react immunohistochemically with antikeratin antibody, leading to the conclusion that the amyloid is formed by degeneration of keratinocytes locally due to chronic rubbing and scratching.

4-6

The possibility remains that this patient first presented with LSC 2 years prior and secondarily developed LA due to chronic trauma. Indeed, LA has been proposed as a variant of LSC. In both conditions, scratching seems to be the most important factor in the development of lesions. It has been proposed that treatment should primarily focus on the amelioration of pruritus.5

Five percent to 10% of cases of LA have been found to have some form of upper extremity involvement.7 However, these cases typically are associated with a generalized presentation involving the trunk and arms.2,7 Our patient had no evidence of disease elsewhere. When evaluating a localized, pruritic, monomorphic, papular eruption on the extensor surfaces of the arms, LA may be an important consideration.

- Tay CH, Dacosta JL. Lichen amyloidosis. clinical study of 40 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1970;82:129-136.

- Kandhari R, Ramesh V, Singh A. A generalized, non-pruritic variant of lichen amyloidosis: a case report and a brief review. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:328.

- Biewend ML, Menke DM, Calamia KT. The spectrum of localized amyloidosis: a case series of 20 patients and review of the literature. Amyloid. 2006;13:135-142.

- Jambrosic J, From L, Hanna W. Lichen amyloidosus. ultrastructure and pathogenesis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1984;6:151-158.

- Weyers W, Weyers I, Bonczkowitz M, et al. Lichen amyloidosis: a consequence of scratching. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:923-928.

- Kumakiri M, Hashimoto K. Histogenesis of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis: sequential change of epidermal keratinocytes to amyloid via filamentous degeneration. J Invest Dermatol. 1979;73:150-162.

- Salim T, Shenoi SD, Balachandran C, et al. Lichen amyloidosus: a study of clinical, histopathologic and immunofluorescence findings in 30 cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:166-169.

To the Editor:

Lichen amyloidosis (LA) classically presents as a pruritic, hyperkeratotic, papular eruption localized to the pretibial surface of the legs.1 Nonpruritic and generalized variants have been reported but are rare.2 Although it is the most common subtype of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis, LA is a benign condition but is difficult to eradicate.1 The precise pathophysiology is poorly understood, but chronic frictional irritation is closely associated with the eruption. We present a nongeneralized case of LA in an atypical location.

A healthy 30-year-old woman presented with an intermittent itchy rash on the elbows and knees of 2 years’ duration. The patient was first diagnosed with lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) and initially responded well to treatment with fluocinonide ointment 0.05%. Nearly 2 years after the initial presentation, she developed recurrent symptoms and sought further treatment. She reported frequent scratching in association with episodes of anxiety. Examination revealed numerous 1- to 3-mm, flesh-colored to light brown, monomorphic, dome-shaped papules over the extensor surfaces of the bilateral arms and left pretibial surface (Figure 1).

papules (1–3 mm) over the extensor surfaces of the bilateral arms.

Although in an atypical location, LA was clinically suspected due to the morphology, and a biopsy was performed given the evolving nature of the lesions. The differential diagnosis included LSC, hypertrophic lichen planus, papular mucinosis, prurigo nodularis, and pretibial myxedema. Pathology revealed small eosinophilic globules in the papillary dermis (Figure 2), and cytokeratin 5/6 immunostaining showed amorphous papillary dermal deposits consistent with keratin-derived amyloid deposition (Figure 3). The deposits stained positive for Congo red and displayed apple green birefringence under polarized light. Thus, the diagnosis of LA was confirmed. After limited success with triamcinolone ointment 0.1%, the patient was transitioned to clobetasol cream 0.05% with notable physical and symptomatic improvement.

Amyloidosis is histopathologically characterized by extracellular deposits of amyloid, a polypeptide that polymerizes to form cross-β sheets.3 It is believed that the deposits seen in localized amyloidosis result from local production of amyloid, as opposed to the deposition of circulating light chains that is characteristic of systemic amyloidosis.3 Lichen amyloidosis is the most common subtype of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis.1 The amyloid in this condition has been found to react immunohistochemically with antikeratin antibody, leading to the conclusion that the amyloid is formed by degeneration of keratinocytes locally due to chronic rubbing and scratching.

4-6

The possibility remains that this patient first presented with LSC 2 years prior and secondarily developed LA due to chronic trauma. Indeed, LA has been proposed as a variant of LSC. In both conditions, scratching seems to be the most important factor in the development of lesions. It has been proposed that treatment should primarily focus on the amelioration of pruritus.5

Five percent to 10% of cases of LA have been found to have some form of upper extremity involvement.7 However, these cases typically are associated with a generalized presentation involving the trunk and arms.2,7 Our patient had no evidence of disease elsewhere. When evaluating a localized, pruritic, monomorphic, papular eruption on the extensor surfaces of the arms, LA may be an important consideration.

To the Editor:

Lichen amyloidosis (LA) classically presents as a pruritic, hyperkeratotic, papular eruption localized to the pretibial surface of the legs.1 Nonpruritic and generalized variants have been reported but are rare.2 Although it is the most common subtype of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis, LA is a benign condition but is difficult to eradicate.1 The precise pathophysiology is poorly understood, but chronic frictional irritation is closely associated with the eruption. We present a nongeneralized case of LA in an atypical location.

A healthy 30-year-old woman presented with an intermittent itchy rash on the elbows and knees of 2 years’ duration. The patient was first diagnosed with lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) and initially responded well to treatment with fluocinonide ointment 0.05%. Nearly 2 years after the initial presentation, she developed recurrent symptoms and sought further treatment. She reported frequent scratching in association with episodes of anxiety. Examination revealed numerous 1- to 3-mm, flesh-colored to light brown, monomorphic, dome-shaped papules over the extensor surfaces of the bilateral arms and left pretibial surface (Figure 1).

papules (1–3 mm) over the extensor surfaces of the bilateral arms.

Although in an atypical location, LA was clinically suspected due to the morphology, and a biopsy was performed given the evolving nature of the lesions. The differential diagnosis included LSC, hypertrophic lichen planus, papular mucinosis, prurigo nodularis, and pretibial myxedema. Pathology revealed small eosinophilic globules in the papillary dermis (Figure 2), and cytokeratin 5/6 immunostaining showed amorphous papillary dermal deposits consistent with keratin-derived amyloid deposition (Figure 3). The deposits stained positive for Congo red and displayed apple green birefringence under polarized light. Thus, the diagnosis of LA was confirmed. After limited success with triamcinolone ointment 0.1%, the patient was transitioned to clobetasol cream 0.05% with notable physical and symptomatic improvement.

Amyloidosis is histopathologically characterized by extracellular deposits of amyloid, a polypeptide that polymerizes to form cross-β sheets.3 It is believed that the deposits seen in localized amyloidosis result from local production of amyloid, as opposed to the deposition of circulating light chains that is characteristic of systemic amyloidosis.3 Lichen amyloidosis is the most common subtype of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis.1 The amyloid in this condition has been found to react immunohistochemically with antikeratin antibody, leading to the conclusion that the amyloid is formed by degeneration of keratinocytes locally due to chronic rubbing and scratching.

4-6

The possibility remains that this patient first presented with LSC 2 years prior and secondarily developed LA due to chronic trauma. Indeed, LA has been proposed as a variant of LSC. In both conditions, scratching seems to be the most important factor in the development of lesions. It has been proposed that treatment should primarily focus on the amelioration of pruritus.5

Five percent to 10% of cases of LA have been found to have some form of upper extremity involvement.7 However, these cases typically are associated with a generalized presentation involving the trunk and arms.2,7 Our patient had no evidence of disease elsewhere. When evaluating a localized, pruritic, monomorphic, papular eruption on the extensor surfaces of the arms, LA may be an important consideration.

- Tay CH, Dacosta JL. Lichen amyloidosis. clinical study of 40 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1970;82:129-136.

- Kandhari R, Ramesh V, Singh A. A generalized, non-pruritic variant of lichen amyloidosis: a case report and a brief review. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:328.

- Biewend ML, Menke DM, Calamia KT. The spectrum of localized amyloidosis: a case series of 20 patients and review of the literature. Amyloid. 2006;13:135-142.

- Jambrosic J, From L, Hanna W. Lichen amyloidosus. ultrastructure and pathogenesis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1984;6:151-158.

- Weyers W, Weyers I, Bonczkowitz M, et al. Lichen amyloidosis: a consequence of scratching. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:923-928.

- Kumakiri M, Hashimoto K. Histogenesis of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis: sequential change of epidermal keratinocytes to amyloid via filamentous degeneration. J Invest Dermatol. 1979;73:150-162.

- Salim T, Shenoi SD, Balachandran C, et al. Lichen amyloidosus: a study of clinical, histopathologic and immunofluorescence findings in 30 cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:166-169.

- Tay CH, Dacosta JL. Lichen amyloidosis. clinical study of 40 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1970;82:129-136.

- Kandhari R, Ramesh V, Singh A. A generalized, non-pruritic variant of lichen amyloidosis: a case report and a brief review. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:328.

- Biewend ML, Menke DM, Calamia KT. The spectrum of localized amyloidosis: a case series of 20 patients and review of the literature. Amyloid. 2006;13:135-142.

- Jambrosic J, From L, Hanna W. Lichen amyloidosus. ultrastructure and pathogenesis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1984;6:151-158.

- Weyers W, Weyers I, Bonczkowitz M, et al. Lichen amyloidosis: a consequence of scratching. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:923-928.

- Kumakiri M, Hashimoto K. Histogenesis of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis: sequential change of epidermal keratinocytes to amyloid via filamentous degeneration. J Invest Dermatol. 1979;73:150-162.

- Salim T, Shenoi SD, Balachandran C, et al. Lichen amyloidosus: a study of clinical, histopathologic and immunofluorescence findings in 30 cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:166-169.

Practice Points

- Lichen amyloidosis (LA) classically presents as a pruritic and papular eruption localized to the pretibial surface of the legs.

- Nonpruritic and generalized variants are rare.

- This case represents a pruritic and nongeneralized

case located on the arms; LA should be considered

for any localized and pruritic eruption on the arms.

Acral Flesh-Colored Papules on the Fingers

The Diagnosis: Lichen Nitidus

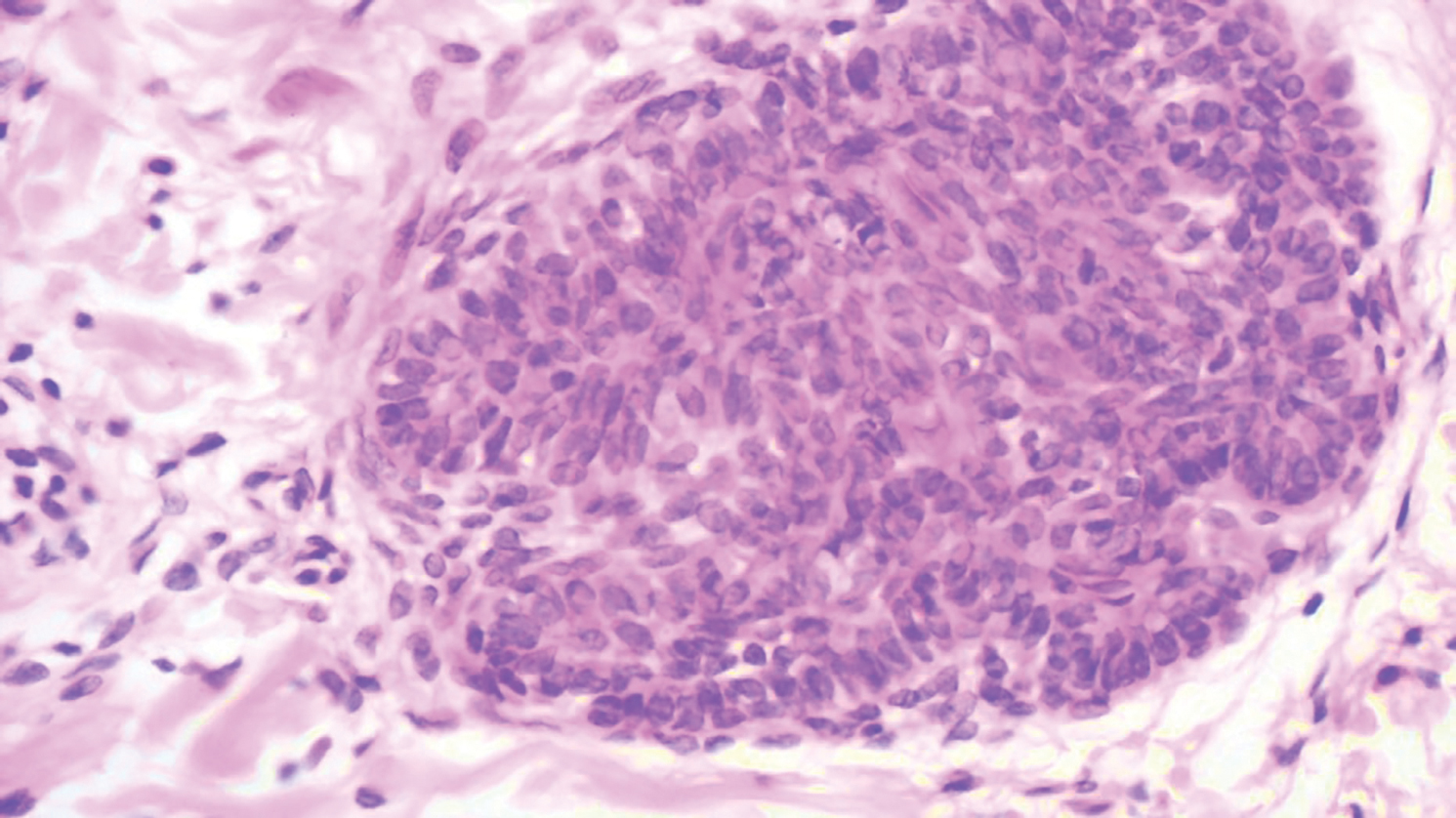

Our patient represents a case of lichen nitidus (LN) that was diagnosed through clinicopathologic correlation, with the pathology results showing a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis enclosed by acanthotic rete ridges on either side. Lichen nitidus was first described by Pinkus in 1901 as a variant of lichen planus.1 It is a rare chronic inflammatory disease that is most prevalent in children and adolescents.2 Clinically, the lesions appear as 1- to 2-mm, shiny, flesh-colored papules with central umbilication.3 Typically, lesions are localized and discrete; however, vesicular, hemorrhagic, perforating, spinous follicular, linear, generalized, and actinic variants all have been reported in the literature. Lichen nitidus has a predilection for the lower abdomen, medial thighs, penis, forearms, ventral wrists, and hands.4 Cases of LN have been reported on the palms, soles, nails, and mucosa, presenting a diagnostic challenge.5 The pathogenesis of LN is unknown, and all races and sexes are affected equally.6

Histopathologically, LN has distinct findings including a well-circumscribed lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis embraced by elongated and acanthotic rete ridges.2 These histopathologic characteristics were seen in our patient's biopsy specimen (Figure) and have been described as the ball-and-claw configuration. Lichen nitidus may be pruritic but typically is asymptomatic.7 It often spontaneously regresses within months to years without any treatment7; however, successful outcomes have been seen with topical steroids, UVA/UVB phototherapy, and retinoids.2 Our patient was treated with topical steroids.

The differential diagnosis for LN includes verruca plana, dyshidrotic eczema, acral persistent papular mucinosis (APPM), and molluscum contagiosum. Verruca plana can occur as 1- to 5-mm, grouped, flesh-colored papules on the face, neck, dorsal hands, wrists, or knees.8 Most commonly, verruca plana occurs due to human papillomavirus type 3 and less commonly human papillomavirus types 10, 27, and 41. Verruca plana is easily differentiated from LN on pathology with findings of epidermal hyperkeratosis, irregular acanthosis, and koilocytic changes.8

Dyshidrotic eczema is a pruritic vesicular rash that is classically distributed symmetrically on the palmar aspects of the hands and lateral fingers.9 Histopathology of the lesions reveals spongiosis with an epidermal lymphocytic infiltrate. Exacerbating factors include exposure to allergens, stress, fungal infections, and genetic predisposition.9

Acral persistent papular mucinosis can present as multiple, 2- to 5-mm, flesh-colored papules on the dorsal aspects of the hands.10 However, the demographic is different from LN, as APPM most commonly affects middle-aged females versus adolescents. Lesions of APPM may multiply or spontaneously remit over time. Acral persistent papular mucinosis generally is asymptomatic but can be treated with cryotherapy, topical corticosteroids, electrodesiccation, or CO2 lasers for cosmetic purposes. Acral persistent papular mucinosis can be easily distinguished from LN on histology, as it will show areas of focal, well-circumscribed mucin in the papillary dermis and a spared Grenz zone.10

Molluscum contagiosum is a common viral skin infection caused by the poxvirus that affects children and adults.11 The skin lesions appear as 2- to 4-mm, dome-shaped, flesh-colored papules with central umbilication on the limbs, trunk, or face. Clinicians may choose to monitor lesions of molluscum contagiosum, as it is a self-limited condition, or it may be treated with cryotherapy, salicylic acid, imiquimod, curettage, laser, or cimetidine.11 On histology, epidermal budlike proliferations can be appreciated in the dermis, and characteristic large, eosinophilic, intracytoplasmic inclusion or molluscum bodies are found in the epidermis.12

- Barber HW. Case of lichen nitidus (Pinkus) or tuberculide lichéniforme et nitida (Chatellier). Proc R Soc Med. 1924;17:39.

- Frey MN, Luzzatto L, Seidel GB, et al. Case for diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:561-563.

- Pielop JA, Hsu S. Tiny, skin-colored papules on the arms and hands. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:343-344.

- Cho EB, Kim HY, Park EJ, et al. Three cases of lichen nitidus associated with various cutaneous diseases. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:505-509.

- Podder I, Mohanty S, Chandra S, et al. Isolated palmar lichen nitidus--a diagnostic challenge: first case from Eastern India. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:308-309.

- Chen W, Schramm M, Zouboulis C. Generalized lichen nitidus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:630-631.

- Rallis E, Verros C, Moussatou V, et al. Generalized purpuric lichen nitidus: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:5.

- Pavithra S, Mallya H, Pai GS. Extensive presentation of verruca plana in a healthy individual. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:324-325.

- Paulsen L, Geller D, Guggenbiller M. Symmetrical vesicular eruption on the palms. Am Fam Physician. 2012;15:811-812.

- Alvarez-Garrido H, Najera L, Garrido-Rios A, et al. Acral persistent papular mucinosis: is it an under-diagnosed disease? Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:10

- Diaconu R, Oprea B, Vasilescu M, et al. Inflamed molluscum contagiosum in a 6-year-old boy: a case report. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2015;56:843-845.

- Krishnamurthy J, Nagappa D. The cytology of molluscum contagiosum mimicking skin adnexal tumor. J Cytol. 2010;27:74.

The Diagnosis: Lichen Nitidus

Our patient represents a case of lichen nitidus (LN) that was diagnosed through clinicopathologic correlation, with the pathology results showing a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis enclosed by acanthotic rete ridges on either side. Lichen nitidus was first described by Pinkus in 1901 as a variant of lichen planus.1 It is a rare chronic inflammatory disease that is most prevalent in children and adolescents.2 Clinically, the lesions appear as 1- to 2-mm, shiny, flesh-colored papules with central umbilication.3 Typically, lesions are localized and discrete; however, vesicular, hemorrhagic, perforating, spinous follicular, linear, generalized, and actinic variants all have been reported in the literature. Lichen nitidus has a predilection for the lower abdomen, medial thighs, penis, forearms, ventral wrists, and hands.4 Cases of LN have been reported on the palms, soles, nails, and mucosa, presenting a diagnostic challenge.5 The pathogenesis of LN is unknown, and all races and sexes are affected equally.6

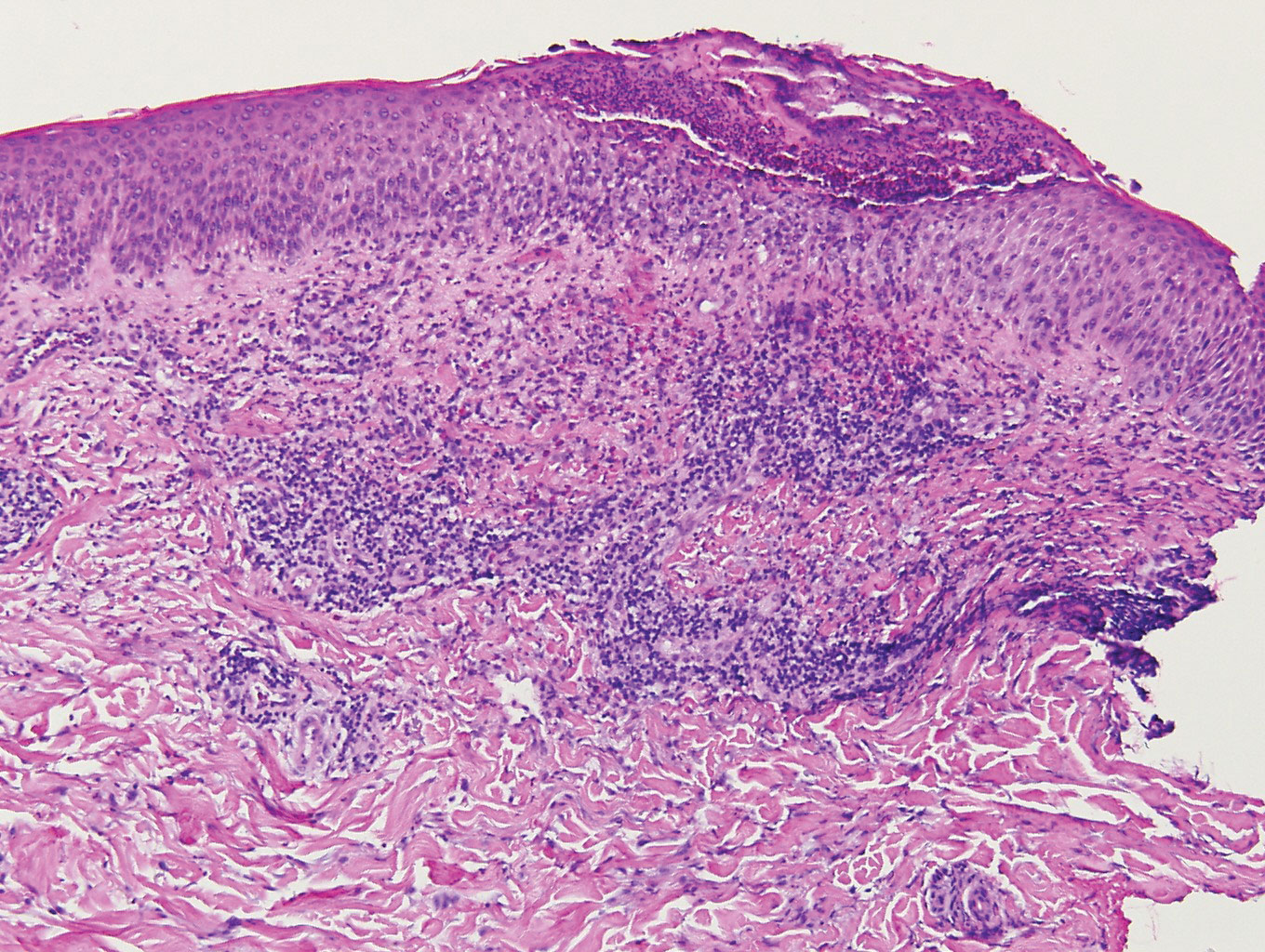

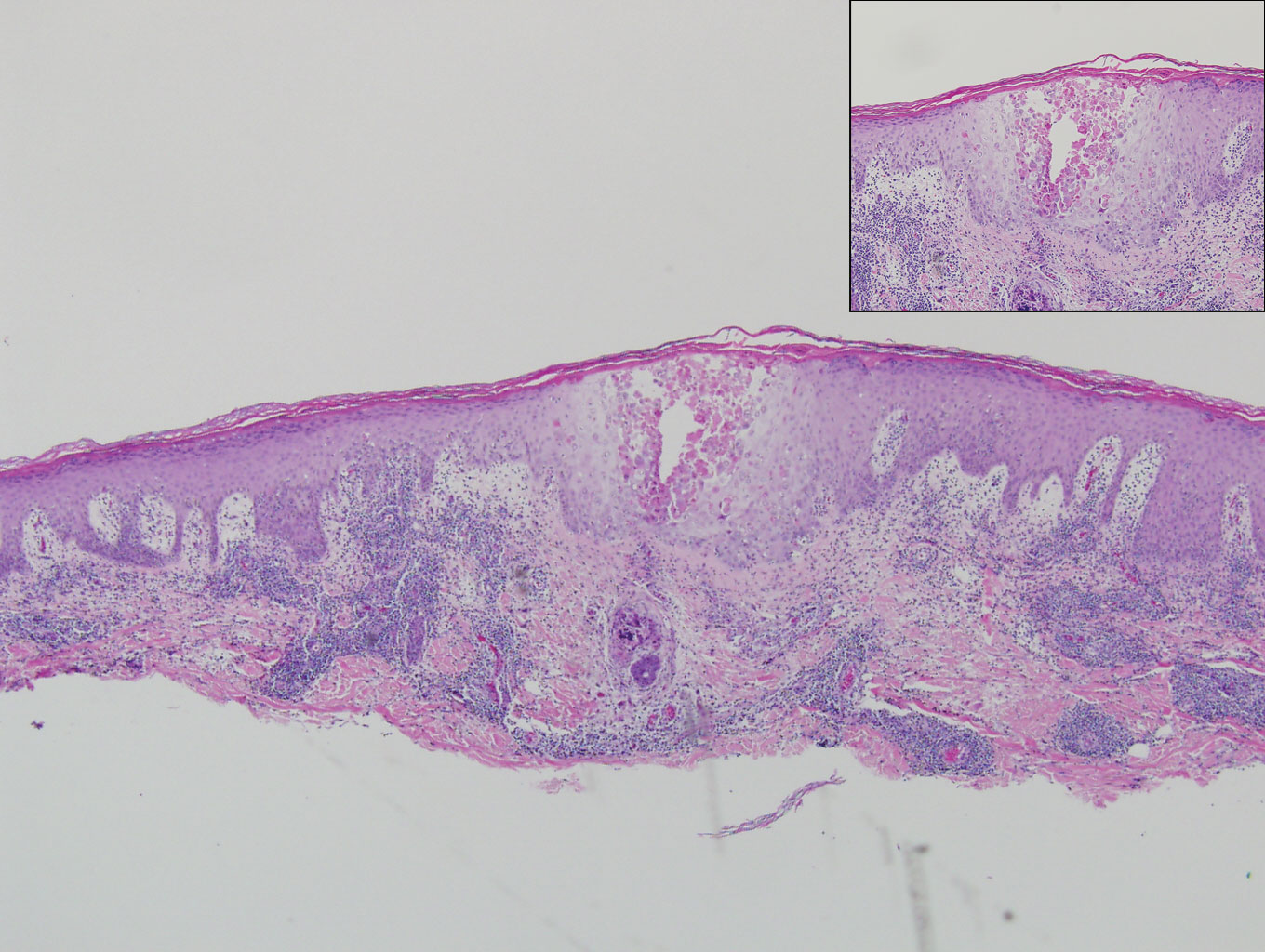

Histopathologically, LN has distinct findings including a well-circumscribed lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis embraced by elongated and acanthotic rete ridges.2 These histopathologic characteristics were seen in our patient's biopsy specimen (Figure) and have been described as the ball-and-claw configuration. Lichen nitidus may be pruritic but typically is asymptomatic.7 It often spontaneously regresses within months to years without any treatment7; however, successful outcomes have been seen with topical steroids, UVA/UVB phototherapy, and retinoids.2 Our patient was treated with topical steroids.

The differential diagnosis for LN includes verruca plana, dyshidrotic eczema, acral persistent papular mucinosis (APPM), and molluscum contagiosum. Verruca plana can occur as 1- to 5-mm, grouped, flesh-colored papules on the face, neck, dorsal hands, wrists, or knees.8 Most commonly, verruca plana occurs due to human papillomavirus type 3 and less commonly human papillomavirus types 10, 27, and 41. Verruca plana is easily differentiated from LN on pathology with findings of epidermal hyperkeratosis, irregular acanthosis, and koilocytic changes.8

Dyshidrotic eczema is a pruritic vesicular rash that is classically distributed symmetrically on the palmar aspects of the hands and lateral fingers.9 Histopathology of the lesions reveals spongiosis with an epidermal lymphocytic infiltrate. Exacerbating factors include exposure to allergens, stress, fungal infections, and genetic predisposition.9

Acral persistent papular mucinosis can present as multiple, 2- to 5-mm, flesh-colored papules on the dorsal aspects of the hands.10 However, the demographic is different from LN, as APPM most commonly affects middle-aged females versus adolescents. Lesions of APPM may multiply or spontaneously remit over time. Acral persistent papular mucinosis generally is asymptomatic but can be treated with cryotherapy, topical corticosteroids, electrodesiccation, or CO2 lasers for cosmetic purposes. Acral persistent papular mucinosis can be easily distinguished from LN on histology, as it will show areas of focal, well-circumscribed mucin in the papillary dermis and a spared Grenz zone.10

Molluscum contagiosum is a common viral skin infection caused by the poxvirus that affects children and adults.11 The skin lesions appear as 2- to 4-mm, dome-shaped, flesh-colored papules with central umbilication on the limbs, trunk, or face. Clinicians may choose to monitor lesions of molluscum contagiosum, as it is a self-limited condition, or it may be treated with cryotherapy, salicylic acid, imiquimod, curettage, laser, or cimetidine.11 On histology, epidermal budlike proliferations can be appreciated in the dermis, and characteristic large, eosinophilic, intracytoplasmic inclusion or molluscum bodies are found in the epidermis.12

The Diagnosis: Lichen Nitidus

Our patient represents a case of lichen nitidus (LN) that was diagnosed through clinicopathologic correlation, with the pathology results showing a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis enclosed by acanthotic rete ridges on either side. Lichen nitidus was first described by Pinkus in 1901 as a variant of lichen planus.1 It is a rare chronic inflammatory disease that is most prevalent in children and adolescents.2 Clinically, the lesions appear as 1- to 2-mm, shiny, flesh-colored papules with central umbilication.3 Typically, lesions are localized and discrete; however, vesicular, hemorrhagic, perforating, spinous follicular, linear, generalized, and actinic variants all have been reported in the literature. Lichen nitidus has a predilection for the lower abdomen, medial thighs, penis, forearms, ventral wrists, and hands.4 Cases of LN have been reported on the palms, soles, nails, and mucosa, presenting a diagnostic challenge.5 The pathogenesis of LN is unknown, and all races and sexes are affected equally.6

Histopathologically, LN has distinct findings including a well-circumscribed lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis embraced by elongated and acanthotic rete ridges.2 These histopathologic characteristics were seen in our patient's biopsy specimen (Figure) and have been described as the ball-and-claw configuration. Lichen nitidus may be pruritic but typically is asymptomatic.7 It often spontaneously regresses within months to years without any treatment7; however, successful outcomes have been seen with topical steroids, UVA/UVB phototherapy, and retinoids.2 Our patient was treated with topical steroids.

The differential diagnosis for LN includes verruca plana, dyshidrotic eczema, acral persistent papular mucinosis (APPM), and molluscum contagiosum. Verruca plana can occur as 1- to 5-mm, grouped, flesh-colored papules on the face, neck, dorsal hands, wrists, or knees.8 Most commonly, verruca plana occurs due to human papillomavirus type 3 and less commonly human papillomavirus types 10, 27, and 41. Verruca plana is easily differentiated from LN on pathology with findings of epidermal hyperkeratosis, irregular acanthosis, and koilocytic changes.8

Dyshidrotic eczema is a pruritic vesicular rash that is classically distributed symmetrically on the palmar aspects of the hands and lateral fingers.9 Histopathology of the lesions reveals spongiosis with an epidermal lymphocytic infiltrate. Exacerbating factors include exposure to allergens, stress, fungal infections, and genetic predisposition.9

Acral persistent papular mucinosis can present as multiple, 2- to 5-mm, flesh-colored papules on the dorsal aspects of the hands.10 However, the demographic is different from LN, as APPM most commonly affects middle-aged females versus adolescents. Lesions of APPM may multiply or spontaneously remit over time. Acral persistent papular mucinosis generally is asymptomatic but can be treated with cryotherapy, topical corticosteroids, electrodesiccation, or CO2 lasers for cosmetic purposes. Acral persistent papular mucinosis can be easily distinguished from LN on histology, as it will show areas of focal, well-circumscribed mucin in the papillary dermis and a spared Grenz zone.10

Molluscum contagiosum is a common viral skin infection caused by the poxvirus that affects children and adults.11 The skin lesions appear as 2- to 4-mm, dome-shaped, flesh-colored papules with central umbilication on the limbs, trunk, or face. Clinicians may choose to monitor lesions of molluscum contagiosum, as it is a self-limited condition, or it may be treated with cryotherapy, salicylic acid, imiquimod, curettage, laser, or cimetidine.11 On histology, epidermal budlike proliferations can be appreciated in the dermis, and characteristic large, eosinophilic, intracytoplasmic inclusion or molluscum bodies are found in the epidermis.12

- Barber HW. Case of lichen nitidus (Pinkus) or tuberculide lichéniforme et nitida (Chatellier). Proc R Soc Med. 1924;17:39.

- Frey MN, Luzzatto L, Seidel GB, et al. Case for diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:561-563.

- Pielop JA, Hsu S. Tiny, skin-colored papules on the arms and hands. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:343-344.

- Cho EB, Kim HY, Park EJ, et al. Three cases of lichen nitidus associated with various cutaneous diseases. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:505-509.

- Podder I, Mohanty S, Chandra S, et al. Isolated palmar lichen nitidus--a diagnostic challenge: first case from Eastern India. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:308-309.

- Chen W, Schramm M, Zouboulis C. Generalized lichen nitidus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:630-631.

- Rallis E, Verros C, Moussatou V, et al. Generalized purpuric lichen nitidus: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:5.

- Pavithra S, Mallya H, Pai GS. Extensive presentation of verruca plana in a healthy individual. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:324-325.

- Paulsen L, Geller D, Guggenbiller M. Symmetrical vesicular eruption on the palms. Am Fam Physician. 2012;15:811-812.

- Alvarez-Garrido H, Najera L, Garrido-Rios A, et al. Acral persistent papular mucinosis: is it an under-diagnosed disease? Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:10

- Diaconu R, Oprea B, Vasilescu M, et al. Inflamed molluscum contagiosum in a 6-year-old boy: a case report. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2015;56:843-845.

- Krishnamurthy J, Nagappa D. The cytology of molluscum contagiosum mimicking skin adnexal tumor. J Cytol. 2010;27:74.

- Barber HW. Case of lichen nitidus (Pinkus) or tuberculide lichéniforme et nitida (Chatellier). Proc R Soc Med. 1924;17:39.

- Frey MN, Luzzatto L, Seidel GB, et al. Case for diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:561-563.

- Pielop JA, Hsu S. Tiny, skin-colored papules on the arms and hands. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:343-344.

- Cho EB, Kim HY, Park EJ, et al. Three cases of lichen nitidus associated with various cutaneous diseases. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:505-509.

- Podder I, Mohanty S, Chandra S, et al. Isolated palmar lichen nitidus--a diagnostic challenge: first case from Eastern India. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:308-309.

- Chen W, Schramm M, Zouboulis C. Generalized lichen nitidus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:630-631.

- Rallis E, Verros C, Moussatou V, et al. Generalized purpuric lichen nitidus: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:5.

- Pavithra S, Mallya H, Pai GS. Extensive presentation of verruca plana in a healthy individual. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:324-325.

- Paulsen L, Geller D, Guggenbiller M. Symmetrical vesicular eruption on the palms. Am Fam Physician. 2012;15:811-812.

- Alvarez-Garrido H, Najera L, Garrido-Rios A, et al. Acral persistent papular mucinosis: is it an under-diagnosed disease? Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:10

- Diaconu R, Oprea B, Vasilescu M, et al. Inflamed molluscum contagiosum in a 6-year-old boy: a case report. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2015;56:843-845.

- Krishnamurthy J, Nagappa D. The cytology of molluscum contagiosum mimicking skin adnexal tumor. J Cytol. 2010;27:74.

A 13-year-old otherwise healthy adolescent boy presented to the dermatology clinic for a rash on the bilateral dorsal hands of approximately 1 year’s duration. The rash was asymptomatic with no pain or pruritus reported. Physical examination revealed a well-nourished adolescent boy in no acute distress with 1- to 2-mm flesh-colored papules clustered on the bilateral dorsal fingers.

Unilateral Facial Papules and Plaques

The Diagnosis: Unilateral Dermatomal Trichoepithelioma

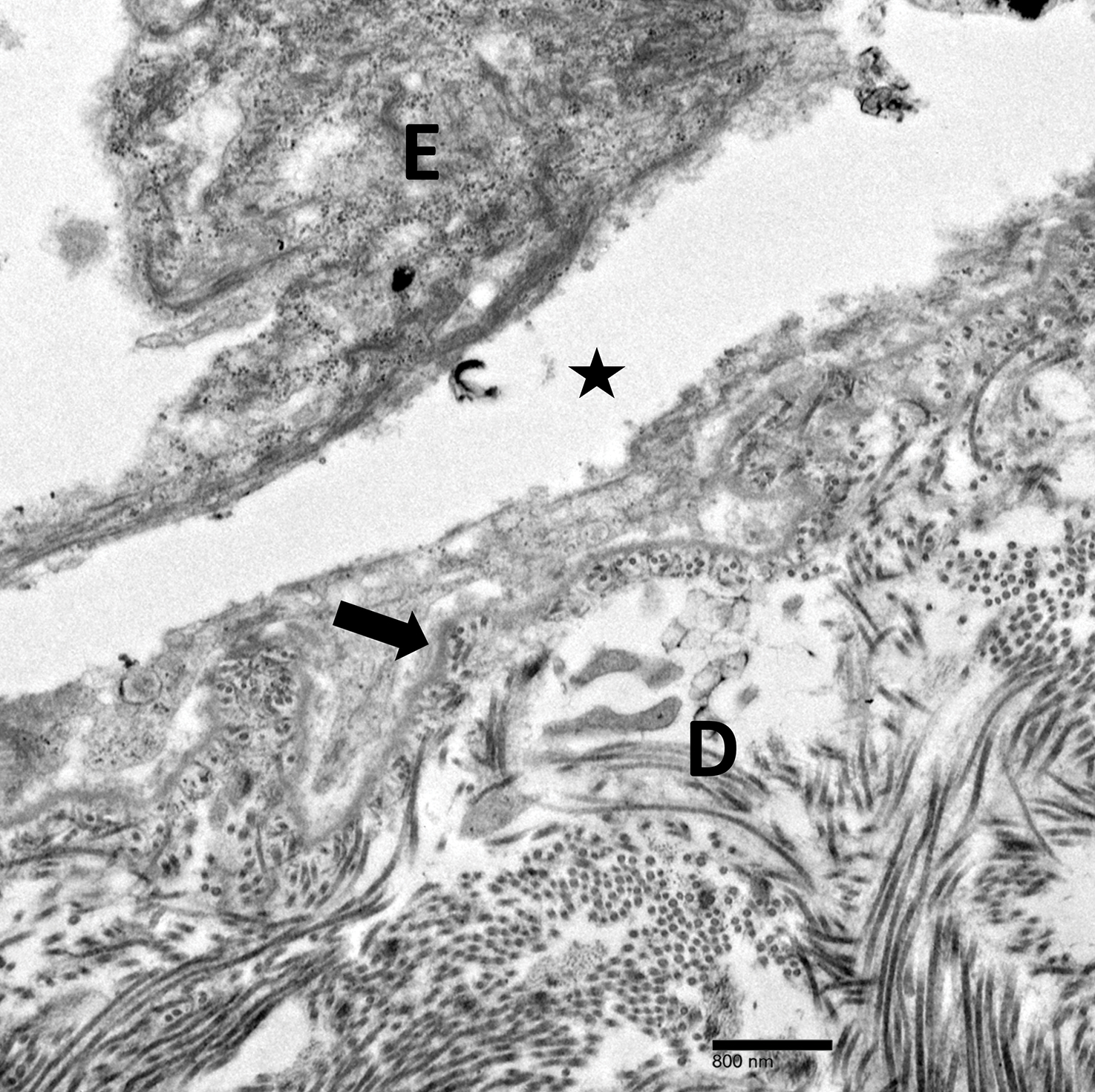

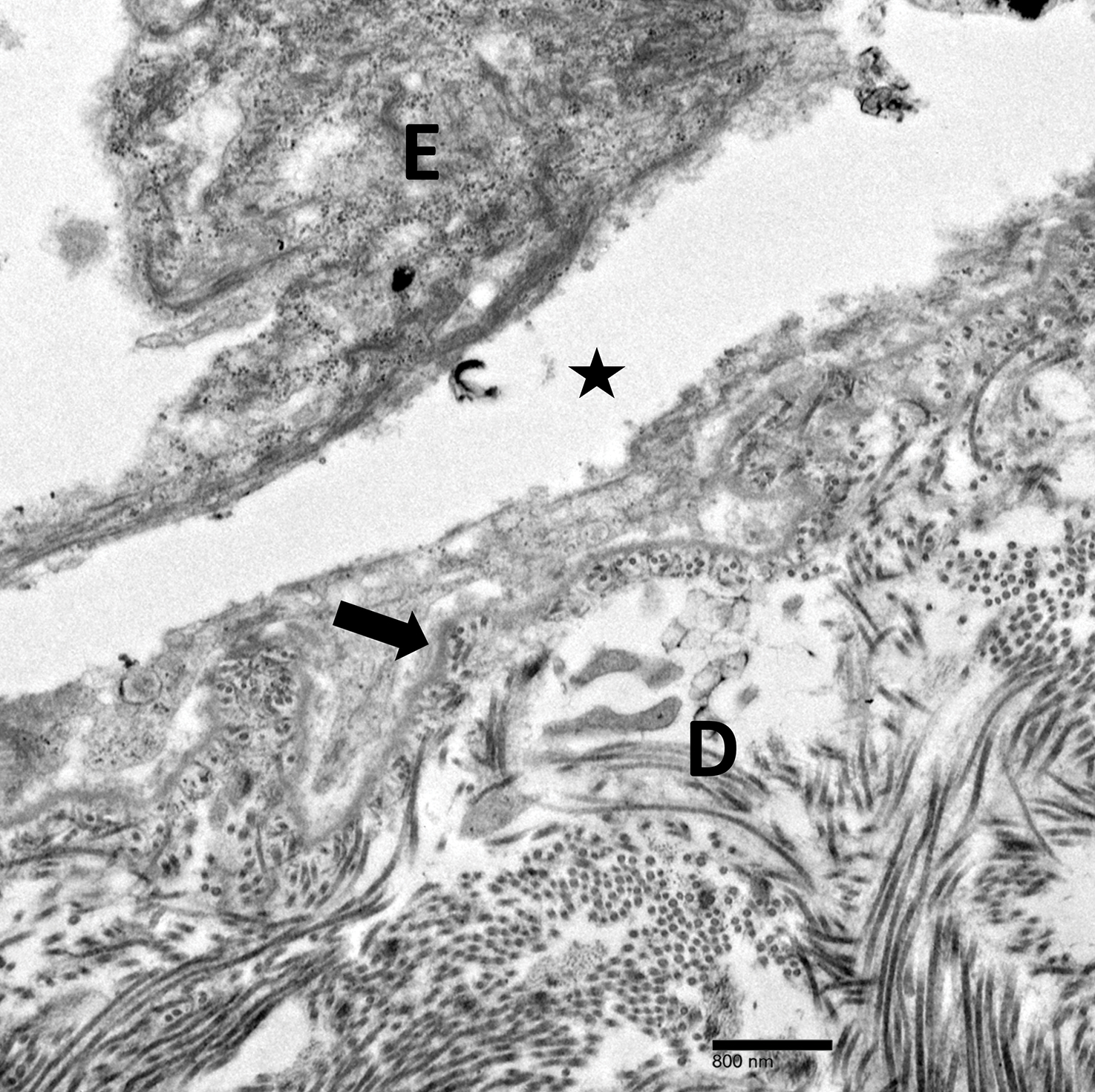

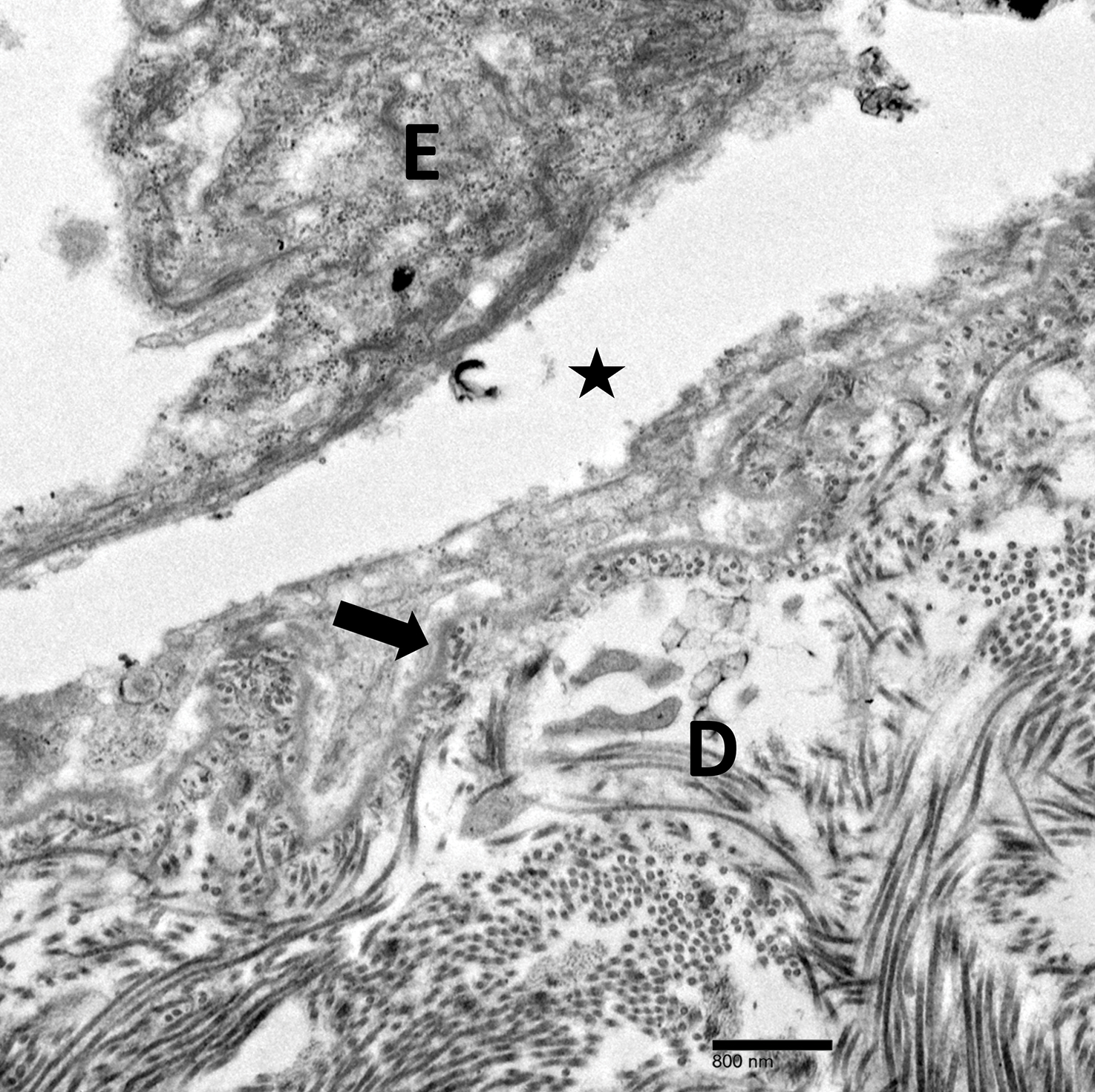

Adnexal lesions presenting with a linear and/or dermatomal pattern rarely have been reported. Bolognia et al1 performed a comprehensive review of Blaschko lines and skin conditions that follow such a pattern. The authors found that adnexal-related lesions included linear nevus comedonicus, linear basal cell nevus with comedones (linear basaloid follicular hamartoma), unilateral nevoid basal cell carcinoma (BCC), linear trichoepithelioma, linear trichodiscoma, linear hamartoma of the follicular infundibulum, nevus sebaceous, syringocystadenoma papilliferum, porokeratotic eccrine ostial and dermal duct nevus, linear eccrine poroma, linear spiradenoma, linear syringoma, and linear eccrine syringofibroadenoma.1

Trichoepithelioma is a hair follicle-related neoplastic lesion presenting most commonly as the autosomal-dominant multiple familial type with lesions mainly centered on the face. Initial genetic studies associated the disease with loss of heterozygosity in the 9p21 region and further studies identified mutations in the CYLD (cylindromatosis [turban tumor syndrome]) gene on chromosome 16q12-q13.2,3 Unilateral, linear, and dermatomal forms of trichoepithelioma rarely are reported. In 1986, Geffner et al4 reported a case of linear and dermatomal trichoepithelioma in a 10-year-old girl. In addition to discrete solitary lesions affecting the face, she developed lesions on the left shoulder, left side of the trunk, and left lower leg following dermatomal distribution. In 2006, 2 cases of dermatomal trichoepitheliomas affecting the face in children, as in our case, were reported.5,6 Another case involving the neck was reported in 2016.7 Although classic multiple familial trichoepithelioma can be part of conditions such as Brooke-Spiegler8 and Rombo syndromes,9 no syndromal association has been reported thus far with the unilateral, linear, or dermatomal variants.

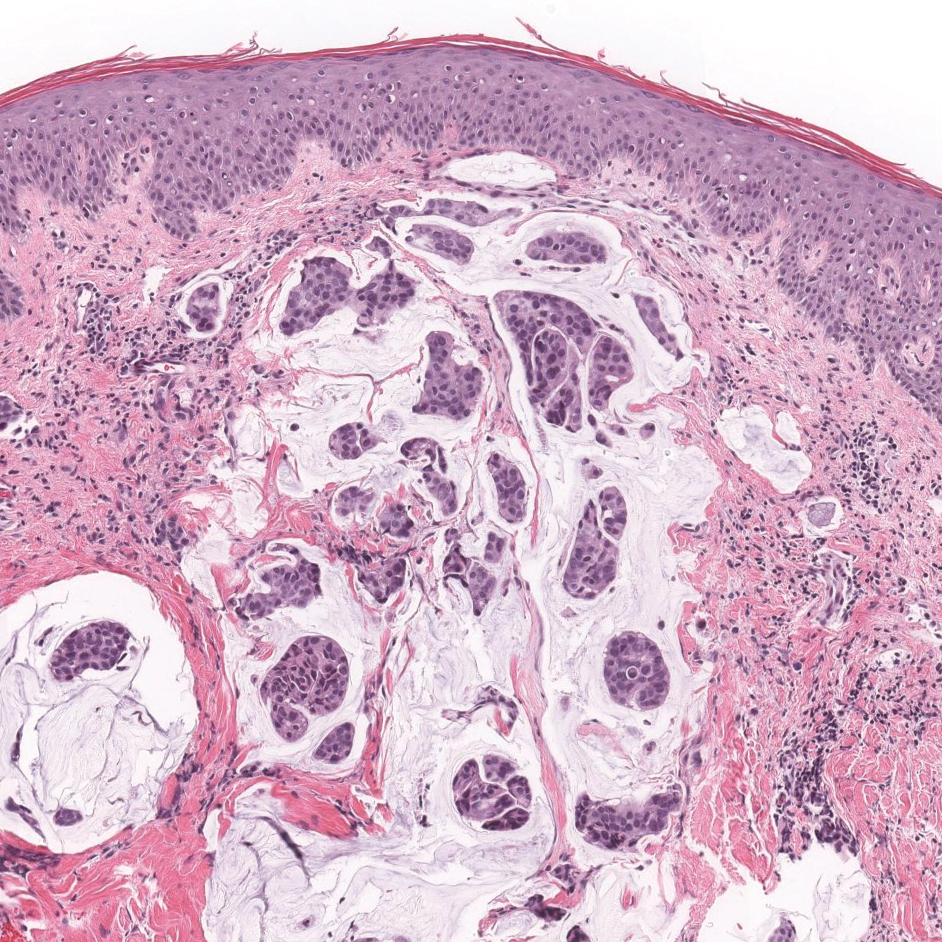

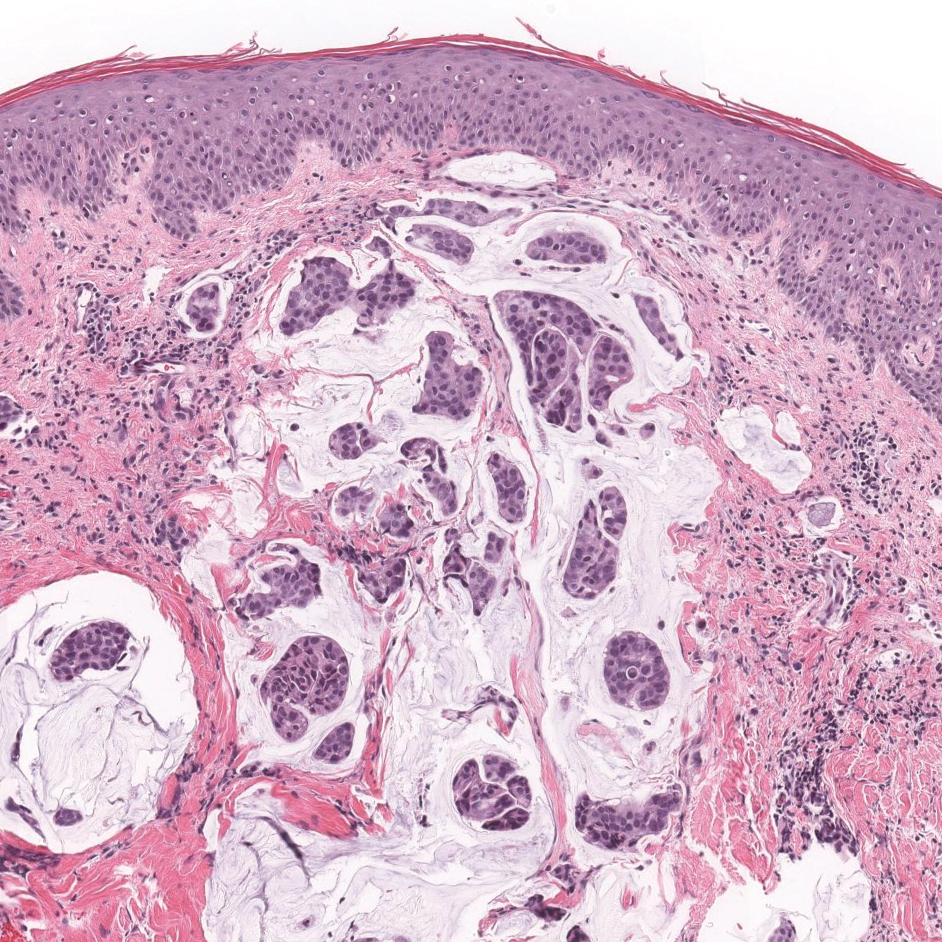

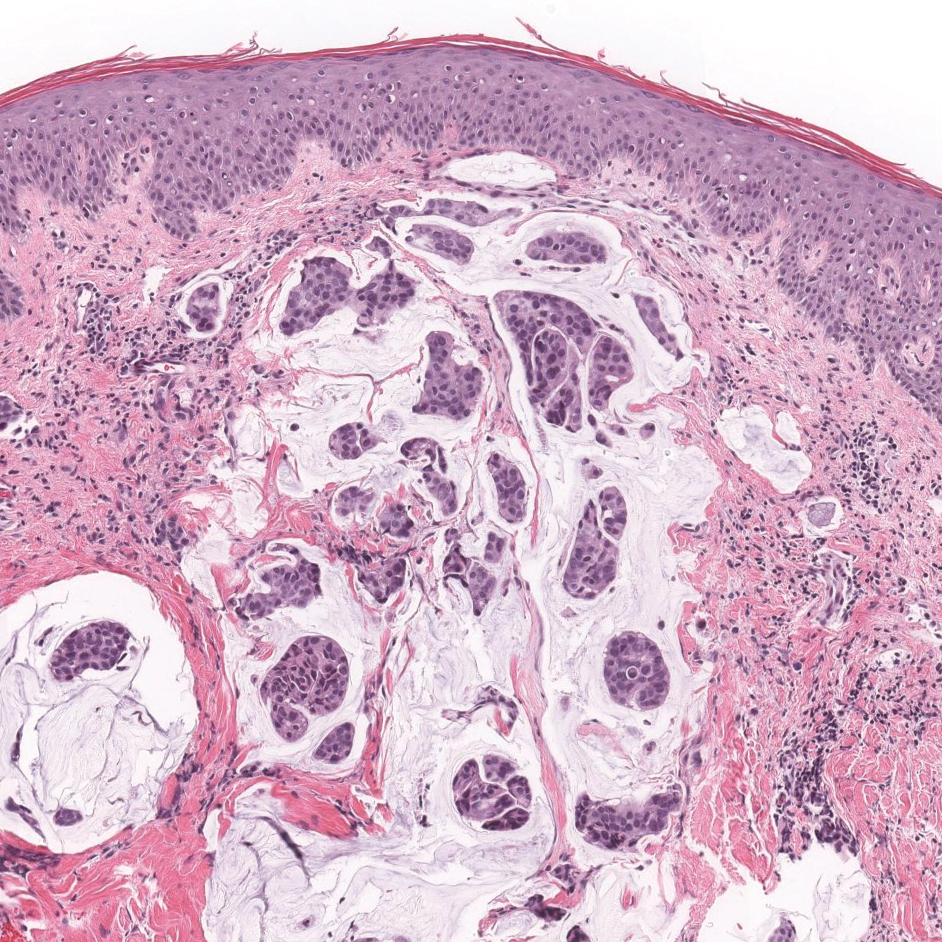

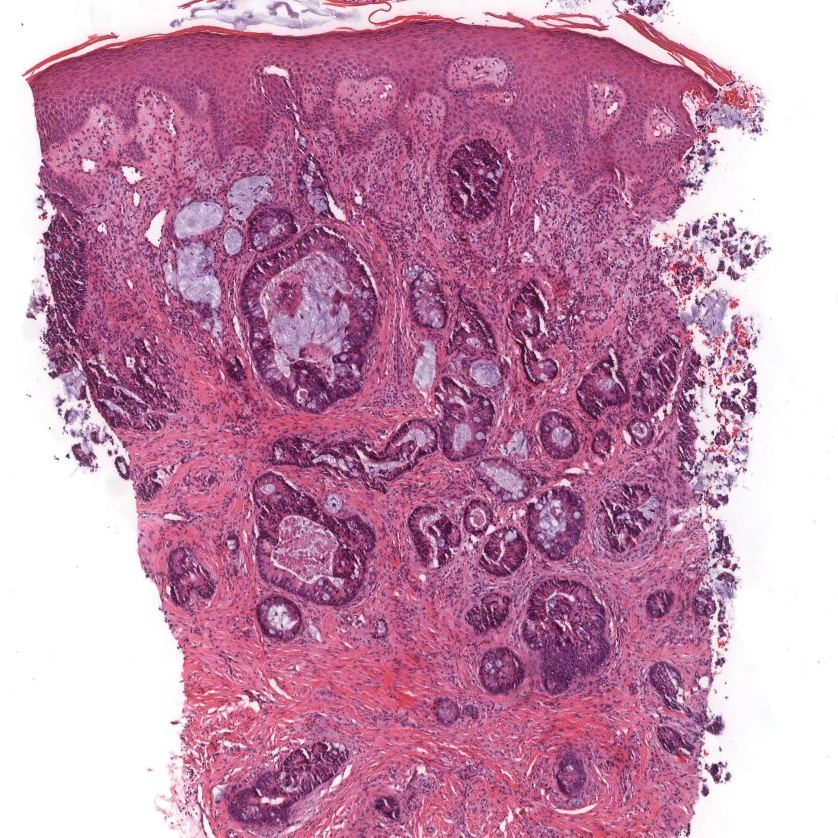

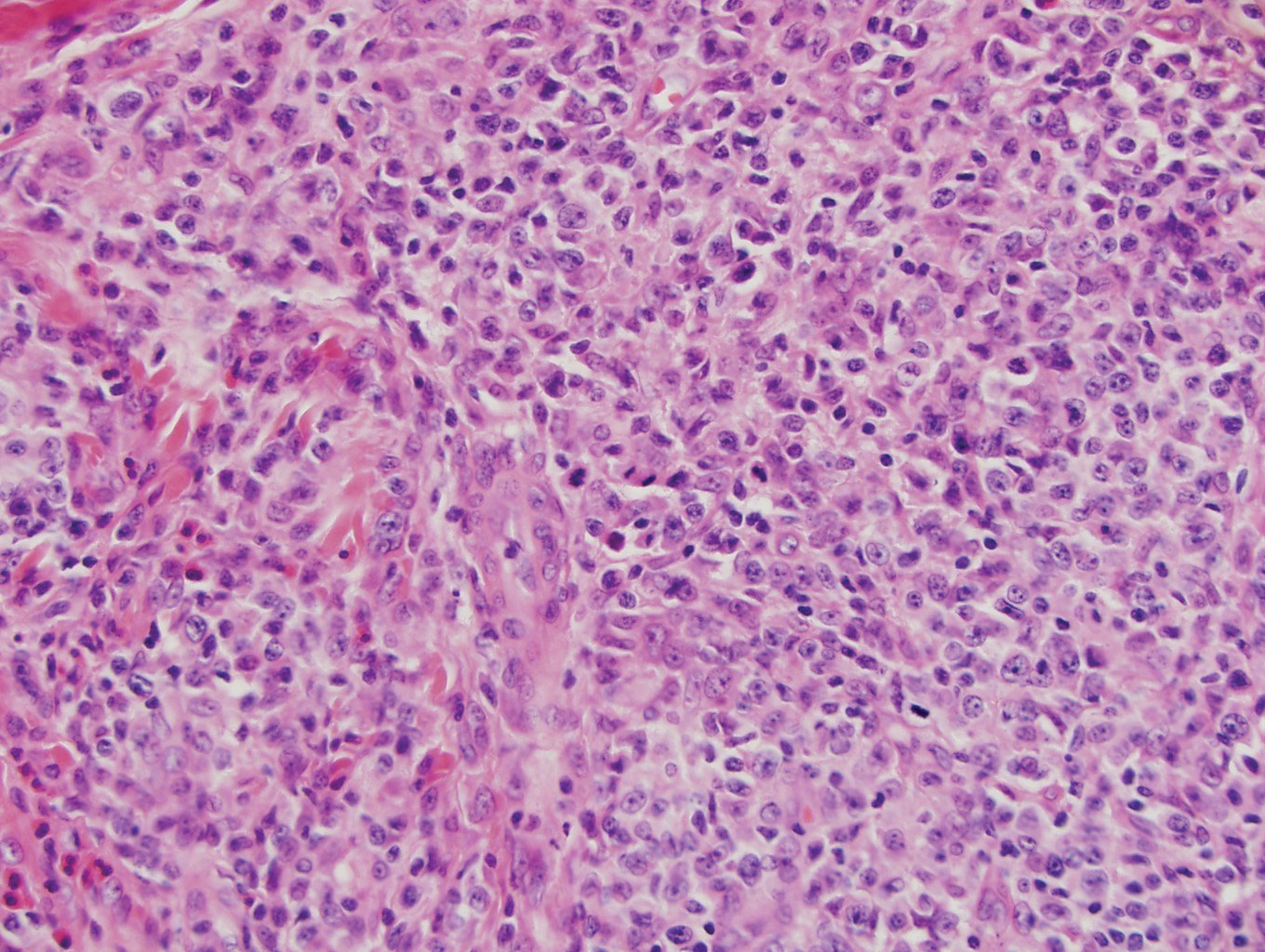

Our case showed typical histopathologic features of trichoepithelioma, including discrete islands of basaloid cells in the dermis set in a conspicuous fibroblastic stroma. Focal connection with the epidermis was present. Most of the islands showed peripheral palisading and horn cysts lined by eosinophilic cells. The fibroblastic component was tightly adherent to the epithelial component, and only stromal clefts were detected. Papillary mesenchymal bodies also were detected as oval aggregates of fibroblastic cells invaginating into epithelial islands to form hair papillae.

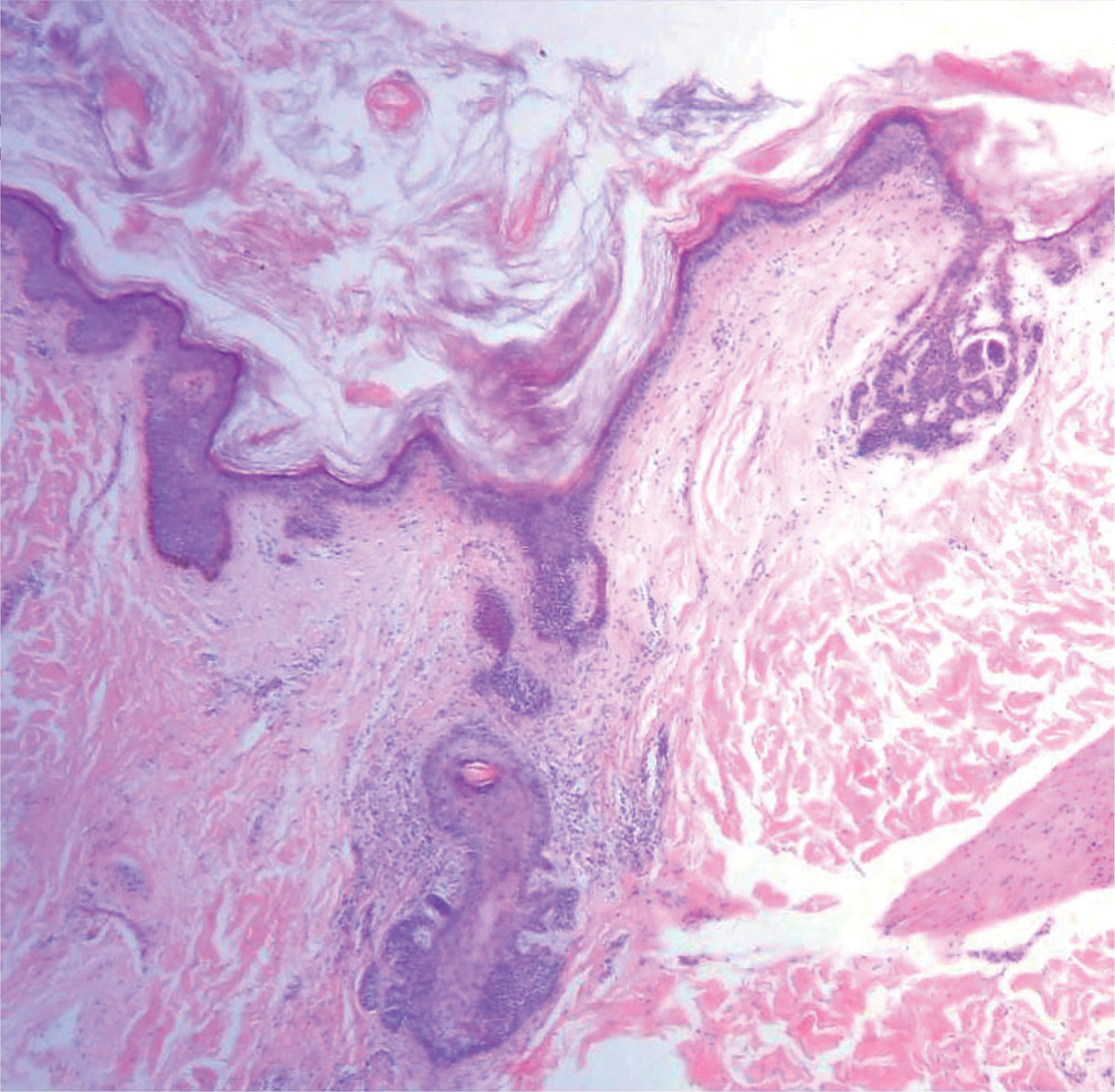

Histopathologically, the 2 most important differential diagnoses of trichoepithelioma include BCC and basaloid follicular hamartoma. In differentiating BCC from trichoepithelioma, the presence of dense fibroblastic stroma and papillary mesenchymal bodies characterize trichoepithelioma, while a fibromucinous stroma with mucinous retraction artifacts and clefting between the basaloid islands and the stroma characterize BCC (Figure 1).10 Immunohistochemical studies using antibodies against Bcl-2, CD34, CD10, androgen receptor, Ki-67, cytokeratin 19, and PHLDA1 (pleckstrin homologylike domain family A member 1) have reportedly been utilized to differentiate trichoepithelioma from BCC.11,12 Basaloid follicular hamartoma is characterized by thin anastomosing strands and branching cords of undifferentiated basaloid cells that replace or associate hair follicles in a latticelike pattern (Figure 2). The strands usually are vertically oriented perpendicular to the epidermis. Peripheral palisading is possible, and the basaloid strands are surrounded with cellular connective tissue stroma.13 Tumor islands in eccrine poroma show broad connections with the epidermis and are composed of poroid cells that show evident ductal differentiation with eosinophilic cuticles (Figure 3).14 Spiradenoma is characterized by capsulated deep-seated tumorous nodules not connected with the epidermis and composed of light and dark cells with ductal differentiation and vascular stroma (Figure 4). Scattered lymphocytes within the tumor lobules and in the stroma also are seen. Eosinophilic hyaline globules rarely can be present.15

Many pathologists consider trichoepithelioma as the superficial variant of trichoblastoma. According to the recent World Health Organization classification of benign tumors with follicular differentiation, trichoepithelioma is considered synonymous with trichoblastoma.16

Trichoepitheliomas are benign tumors, and therapy is mainly directed at removal for cosmetic purposes. Several methods of removal are available including electrocautery, laser therapy, and surgery. Awareness of the possible dermatomal distribution of hair follicle and other adnexal-related conditions is important, and such lesions should be thought of in the differential diagnosis of unilateral and/or dermatomal lesions.

- Bolognia JL, Orlow SJ, Glick SA. Lines of Blaschko. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(2, pt 1):157-190.

- Harada H, Hashimoto K, Ko MS. The gene for multiple familial trichoepithelioma maps to chromosome 9p21. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;107:41-43.

- Zheng G, Hu L, Huang W, et al. CYLD mutation causes multiple familial trichoepithelioma in three Chinese families. Hum Mutat. 2004;23:400.

- Geffner RE, Goslen JB, Santa Cruz DJ. Linear and dermatomal trichoepitheliomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14(5, pt 2):927-930.

- Chang YC, Colome-Grimmer M, Kelly E. Multiple trichoepitheliomas in the lines of Blaschko. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:149-151.

- Strauss RM, Merchant WJ, Stainforth JM, et al. Unilateral naevoid trichoepitheliomas on the face of a child. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;6:778-780.

- Laska AJ, Belli RA, Kobayashi TT. Linear trichoepithelioma on the neck of a 15-year-old girl. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22. pii:13030/qt87b6h4q8.

- Rasmussen JE. A syndrome of trichoepitheliomas, milia and cylindroma. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:610-614.

- Michaelson G, Olsson E, Westermark P. The Rombo syndrome. Acta Derm Venereol. 1981;61:497-503.

- Brooke JD, Fitzpatrick JE, Golitz LE. Papillary mesenchymal bodies: a histologic finding useful in differentiating trichoepitheliomas from basal cell carcinomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21(3, pt 1):523-528.

- Mostafa NA, Assaf M, Elhakim S, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of immunohistochemical markers in differentiation between basal cell carcinoma and trichoepithelioma in small biopsy specimens. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:807-816.

- Poniecka AW, Alexis JB. An immunohistochemical study of basal cell carcinoma and trichoepithelioma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:332-336.

- Abdel-Halim MRE, Fawzy M, Saleh M, et al. Linear unilateral basal cell nevus with comedones (linear nevoid basaloid follicular hamartoma): a case report. J Egypt Womens Dermatol Soc. 2016;13:46-48.

- Hyman AB, Brownstein MH. Eccrine poroma: analysis of 45 new cases. Dermatologica. 1969;138:28-38.

- Mambo NC. Eccrine spiradenoma: clinical and pathologic study of 49 tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 1983;10:312-320.

- Kutzner H, Kaddu S, Kanitakis J, et al. Trichoblastoma. In: Elder D, Massi D, Scolyer RA, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Skin Tumours. 4th ed. Lyon, France: IARC; 2018.

The Diagnosis: Unilateral Dermatomal Trichoepithelioma

Adnexal lesions presenting with a linear and/or dermatomal pattern rarely have been reported. Bolognia et al1 performed a comprehensive review of Blaschko lines and skin conditions that follow such a pattern. The authors found that adnexal-related lesions included linear nevus comedonicus, linear basal cell nevus with comedones (linear basaloid follicular hamartoma), unilateral nevoid basal cell carcinoma (BCC), linear trichoepithelioma, linear trichodiscoma, linear hamartoma of the follicular infundibulum, nevus sebaceous, syringocystadenoma papilliferum, porokeratotic eccrine ostial and dermal duct nevus, linear eccrine poroma, linear spiradenoma, linear syringoma, and linear eccrine syringofibroadenoma.1

Trichoepithelioma is a hair follicle-related neoplastic lesion presenting most commonly as the autosomal-dominant multiple familial type with lesions mainly centered on the face. Initial genetic studies associated the disease with loss of heterozygosity in the 9p21 region and further studies identified mutations in the CYLD (cylindromatosis [turban tumor syndrome]) gene on chromosome 16q12-q13.2,3 Unilateral, linear, and dermatomal forms of trichoepithelioma rarely are reported. In 1986, Geffner et al4 reported a case of linear and dermatomal trichoepithelioma in a 10-year-old girl. In addition to discrete solitary lesions affecting the face, she developed lesions on the left shoulder, left side of the trunk, and left lower leg following dermatomal distribution. In 2006, 2 cases of dermatomal trichoepitheliomas affecting the face in children, as in our case, were reported.5,6 Another case involving the neck was reported in 2016.7 Although classic multiple familial trichoepithelioma can be part of conditions such as Brooke-Spiegler8 and Rombo syndromes,9 no syndromal association has been reported thus far with the unilateral, linear, or dermatomal variants.

Our case showed typical histopathologic features of trichoepithelioma, including discrete islands of basaloid cells in the dermis set in a conspicuous fibroblastic stroma. Focal connection with the epidermis was present. Most of the islands showed peripheral palisading and horn cysts lined by eosinophilic cells. The fibroblastic component was tightly adherent to the epithelial component, and only stromal clefts were detected. Papillary mesenchymal bodies also were detected as oval aggregates of fibroblastic cells invaginating into epithelial islands to form hair papillae.