User login

Granuloma Faciale in Woman With Levamisole-Induced Vasculitis

To the Editor:

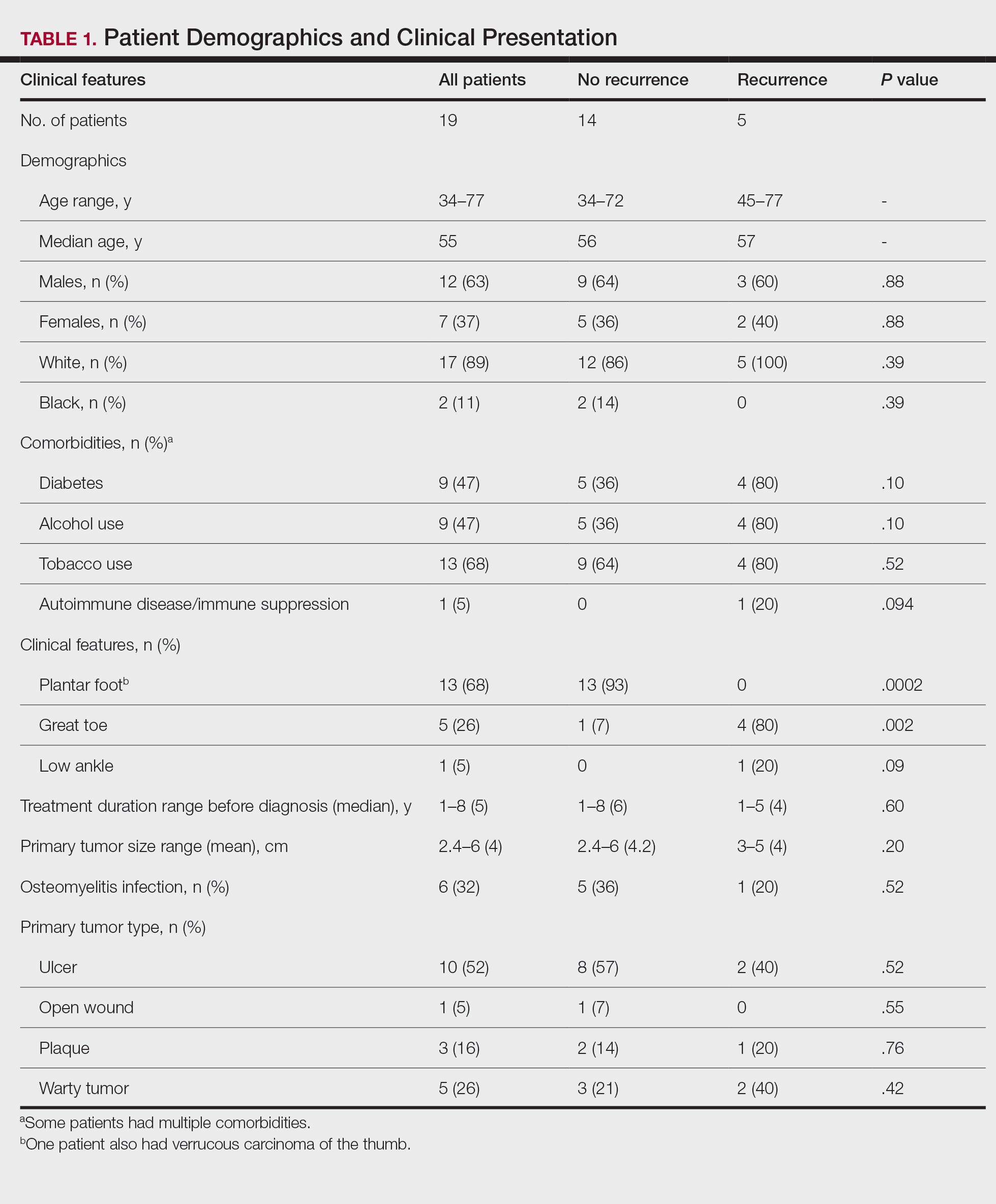

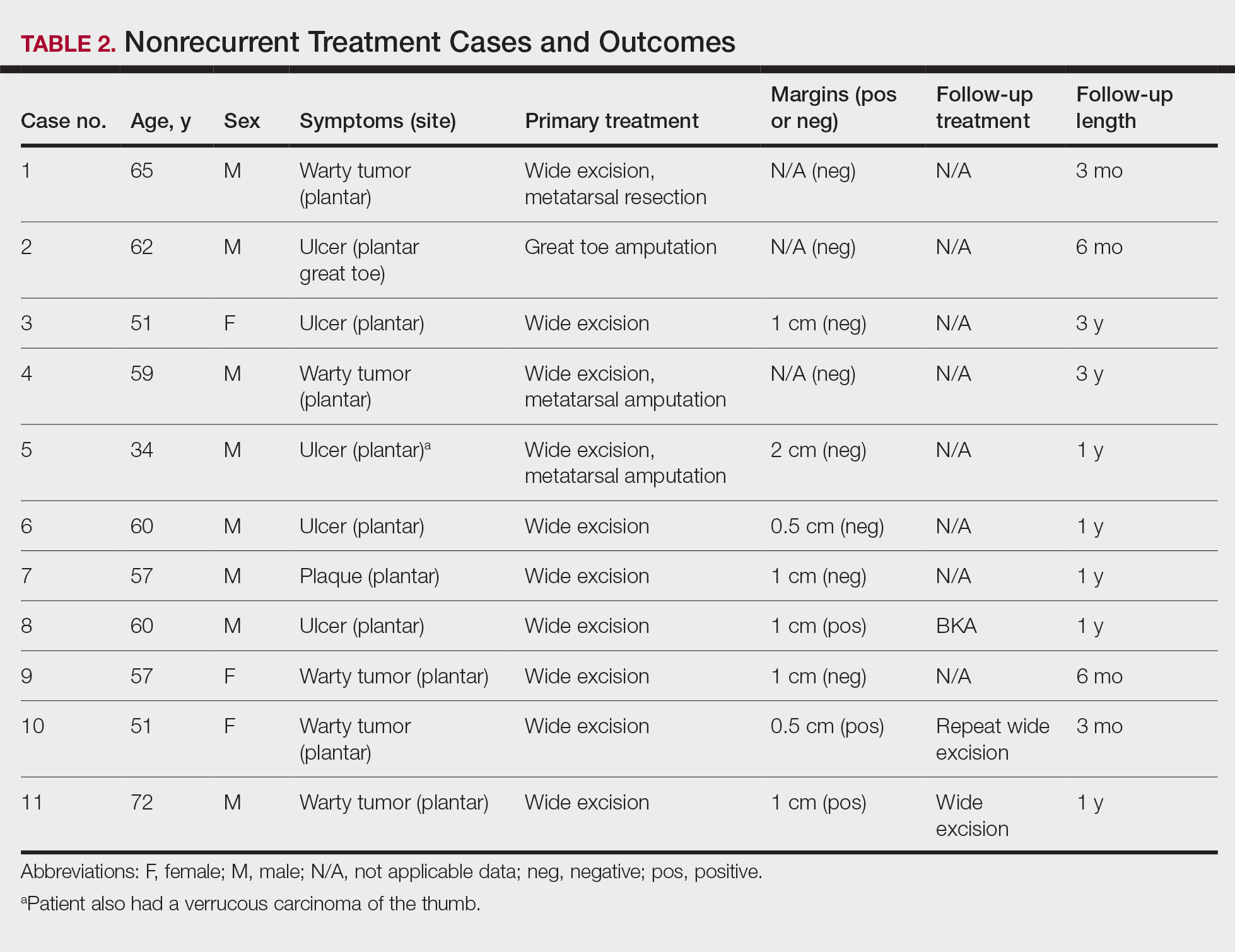

A 53-year-old Hispanic woman presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of an expanding plaque on the right cheek of 2 months’ duration. The patient stated the plaque began as a pimple, which she picked with subsequent spread laterally across the cheek. The area was intermittently tender, but she denied tingling, burning, or pruritus of the site. She had been treated with doxycycline and amoxicillin–clavulanic acid prior to presentation without improvement. She had a history of levamisole-induced vasculitis approximately 6 months prior. A review of systems was notable for diffuse joint pain. The patient denied tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use in the preceding 3 months and denied any changes in her medications or in health within the last year.

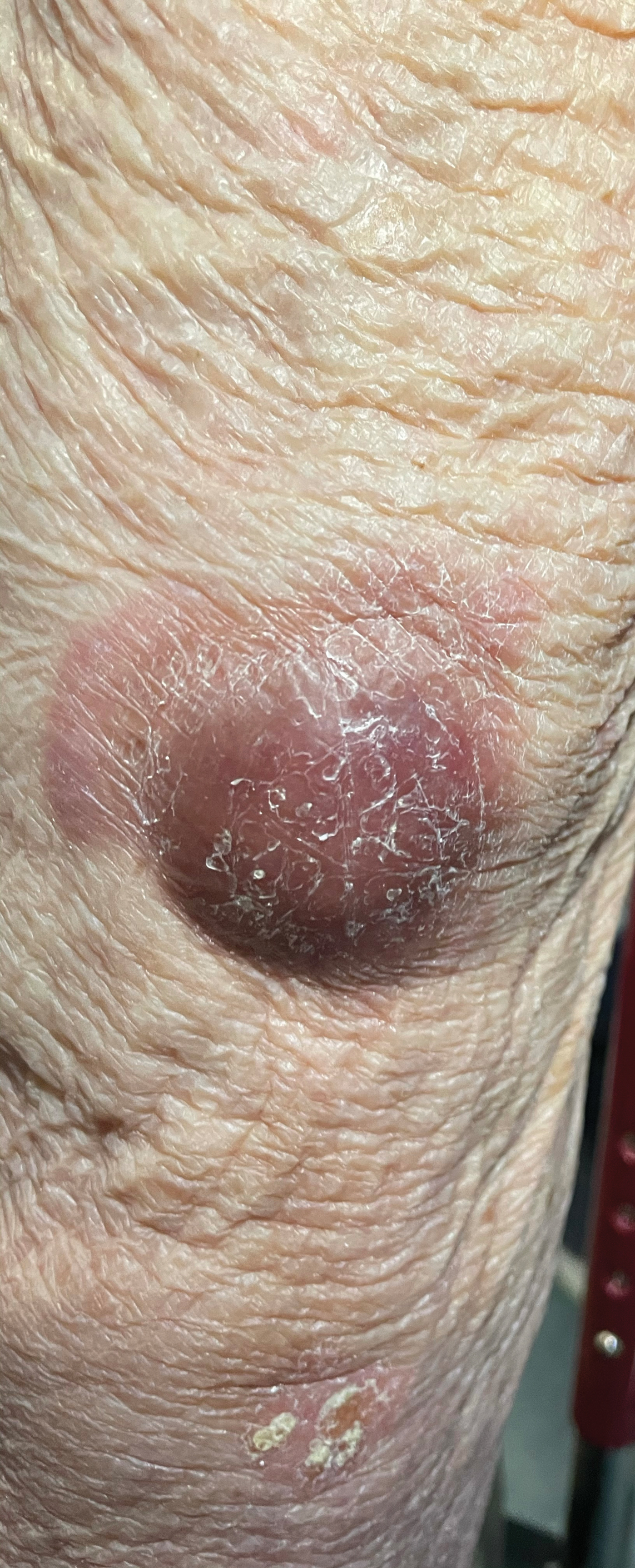

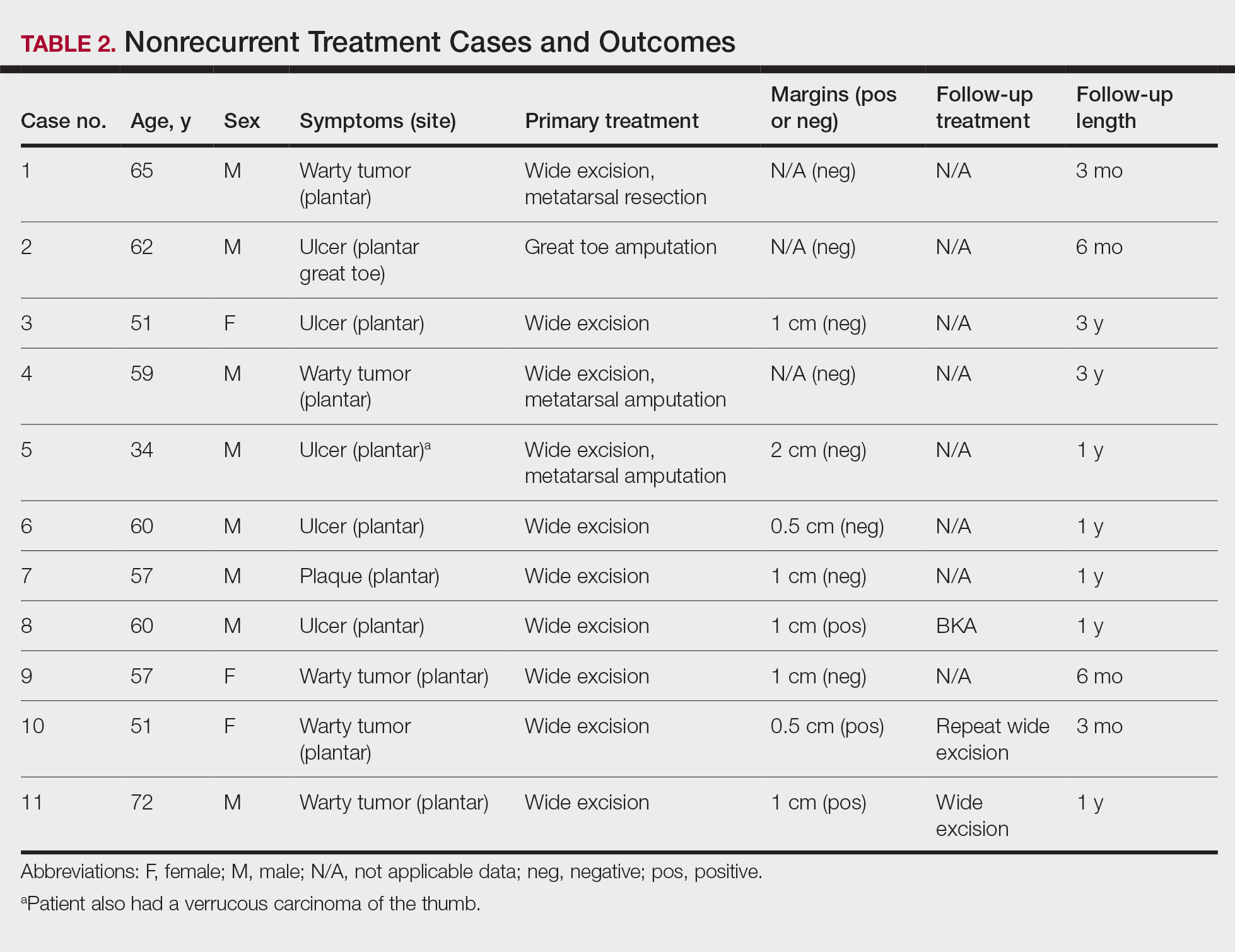

Physical examination revealed a well-appearing, alert, and afebrile patient with a pink, well-demarcated plaque on the right cheek (Figure 1). The borders of the plaque were indurated, and the lateral aspect of the plaque was eroded secondary to digital manipulation by the patient. She had no cervical lymphadenopathy. There were no other abnormal cutaneous findings.

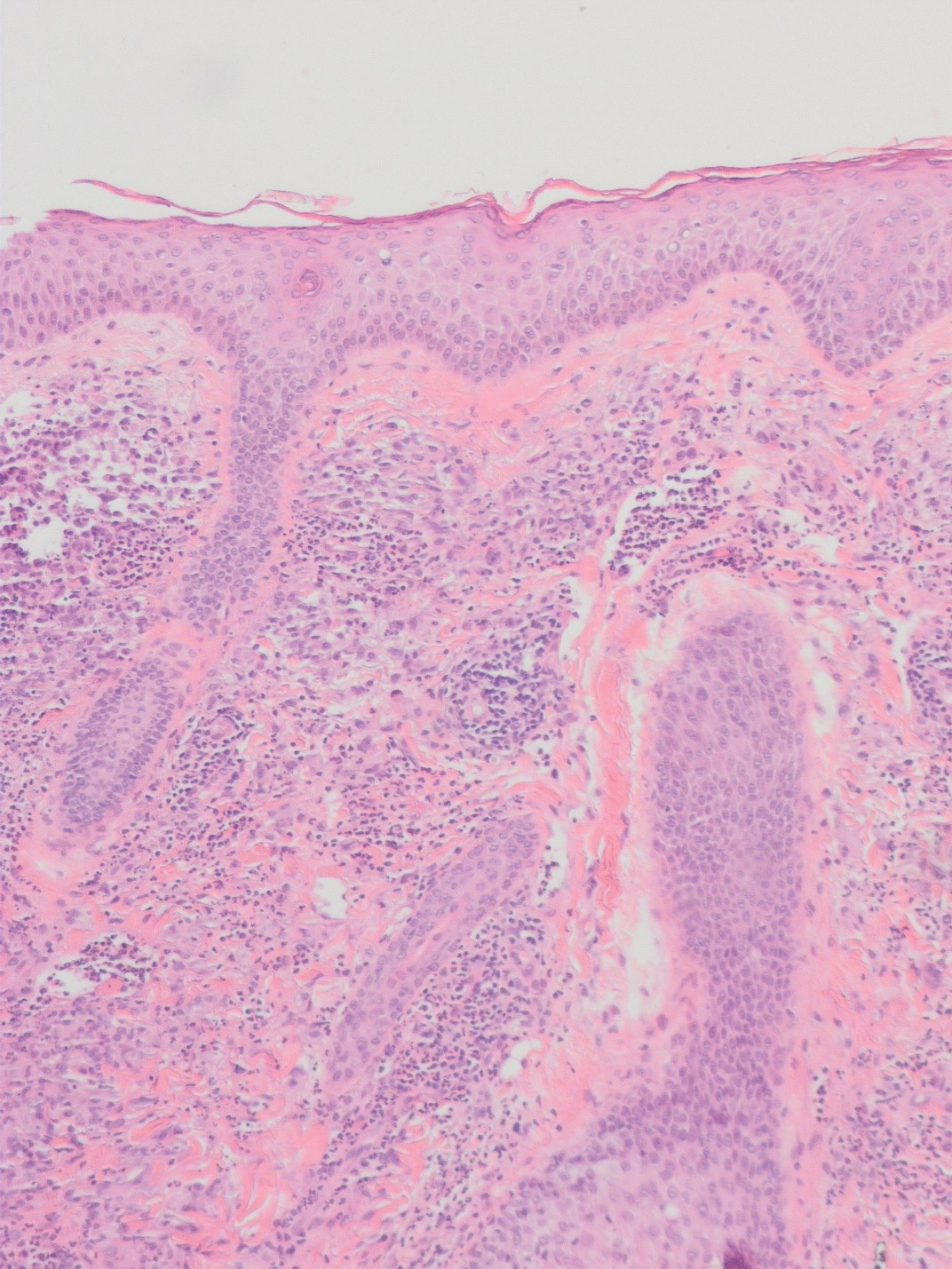

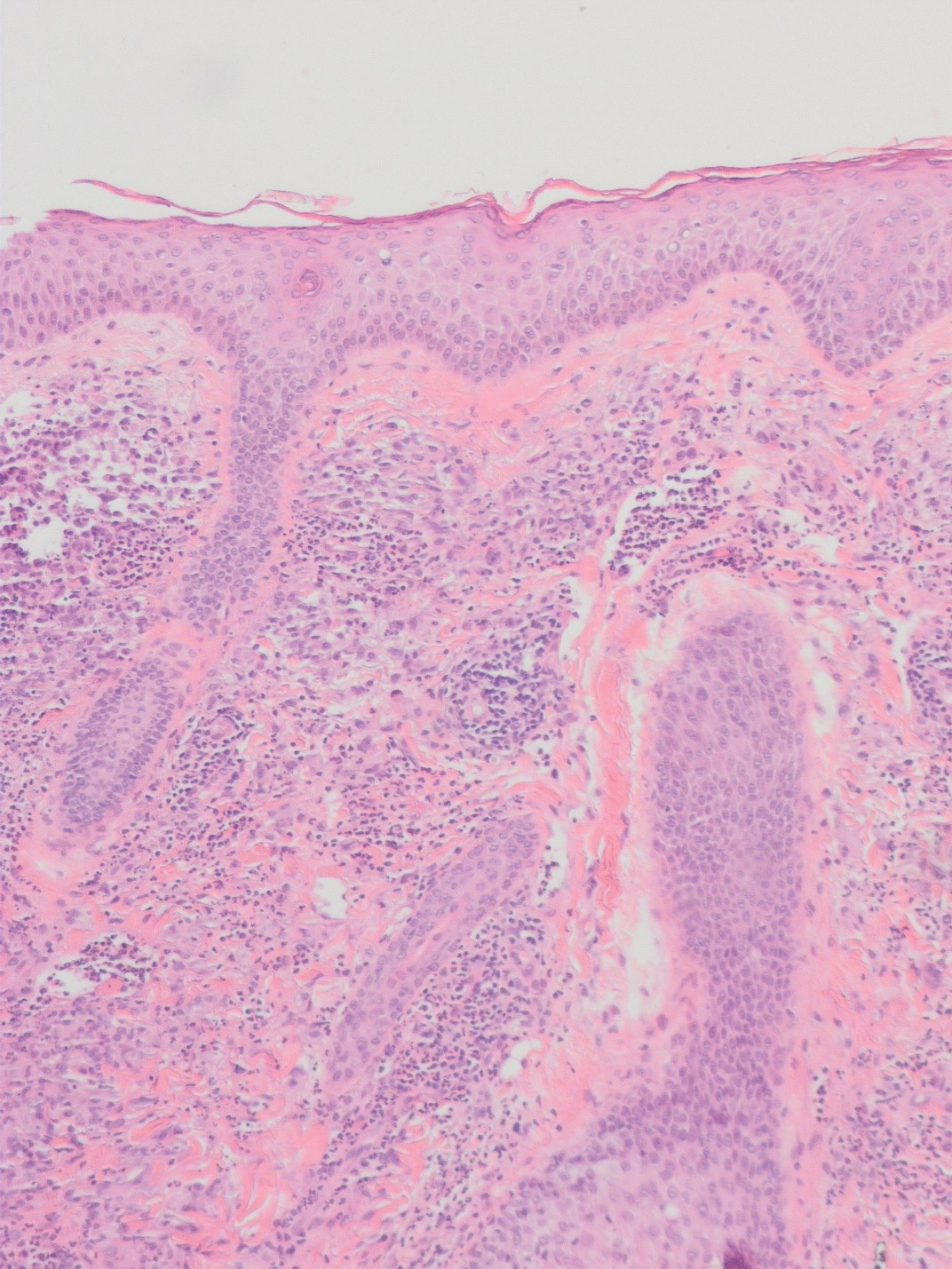

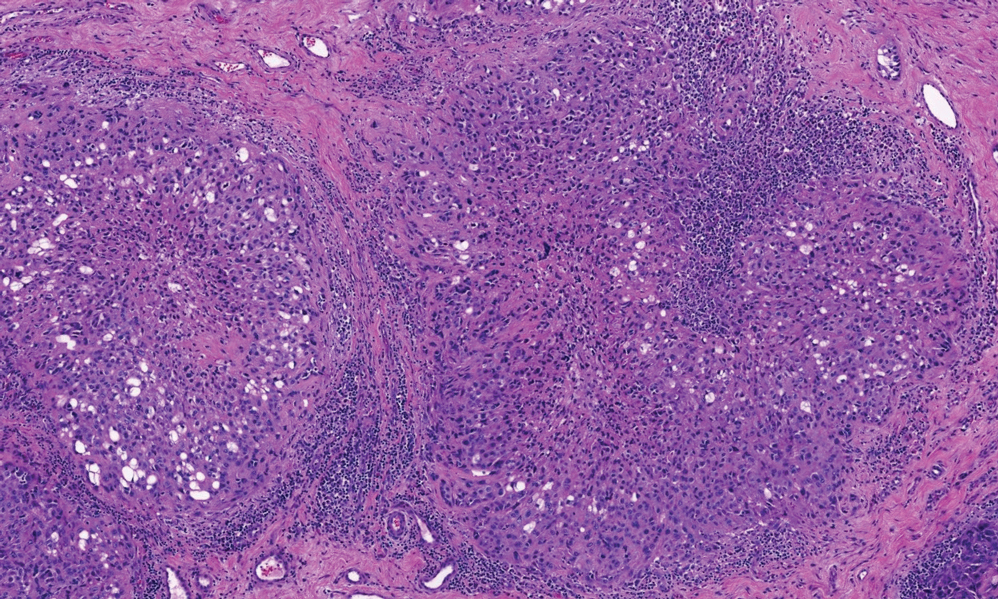

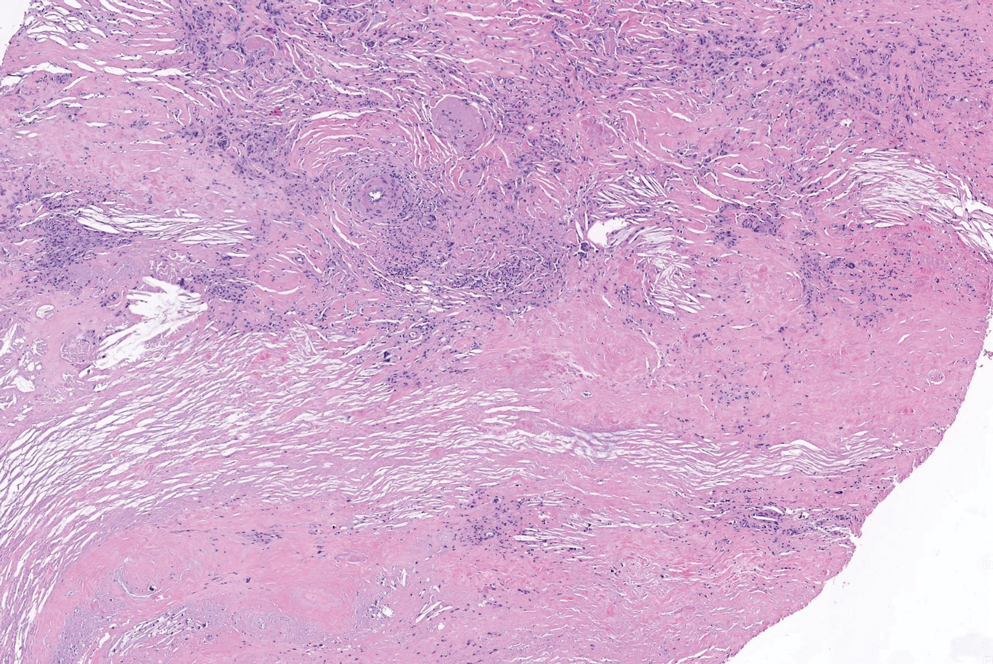

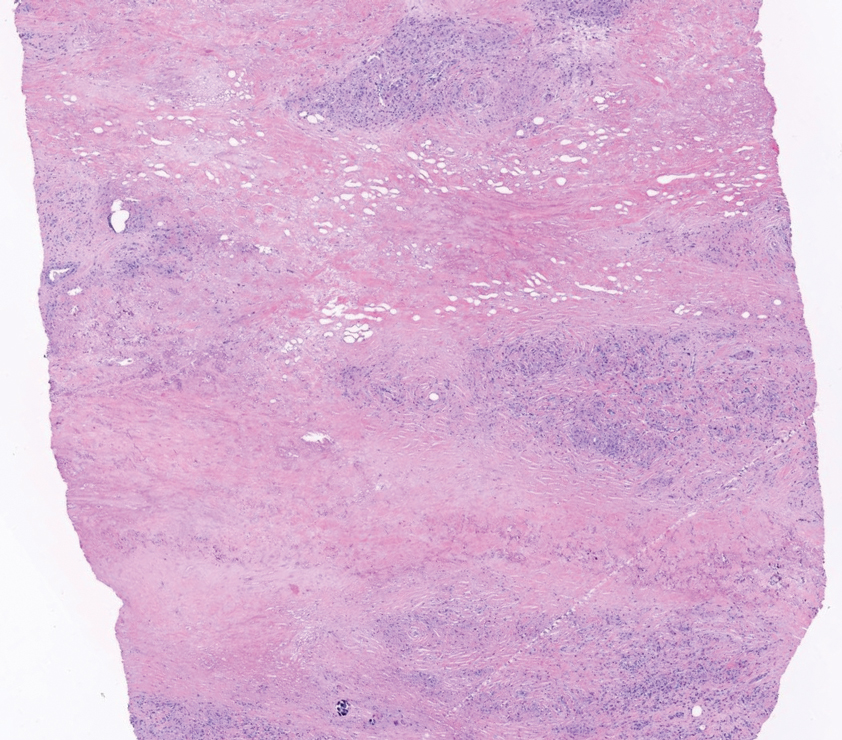

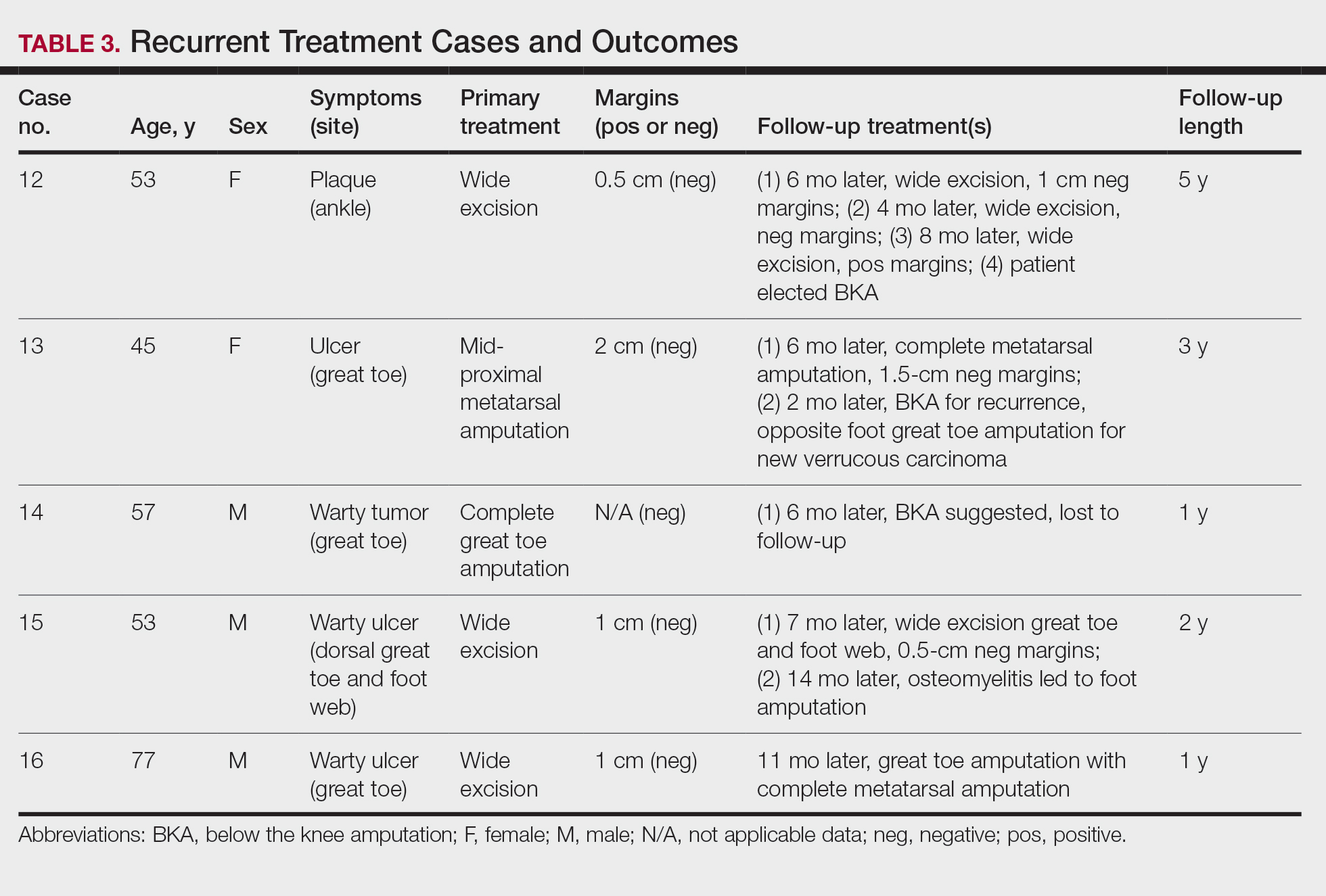

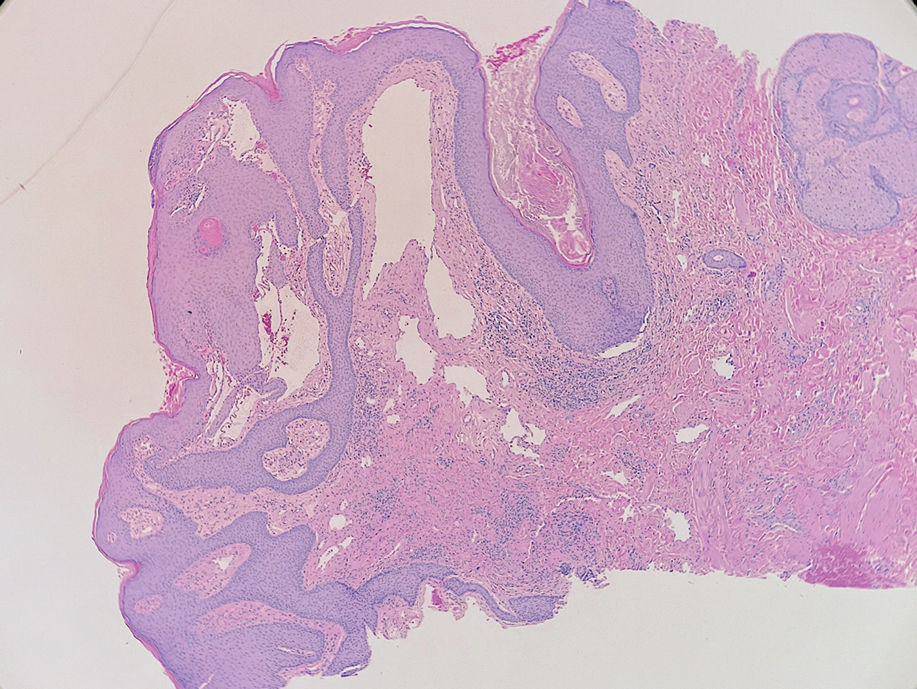

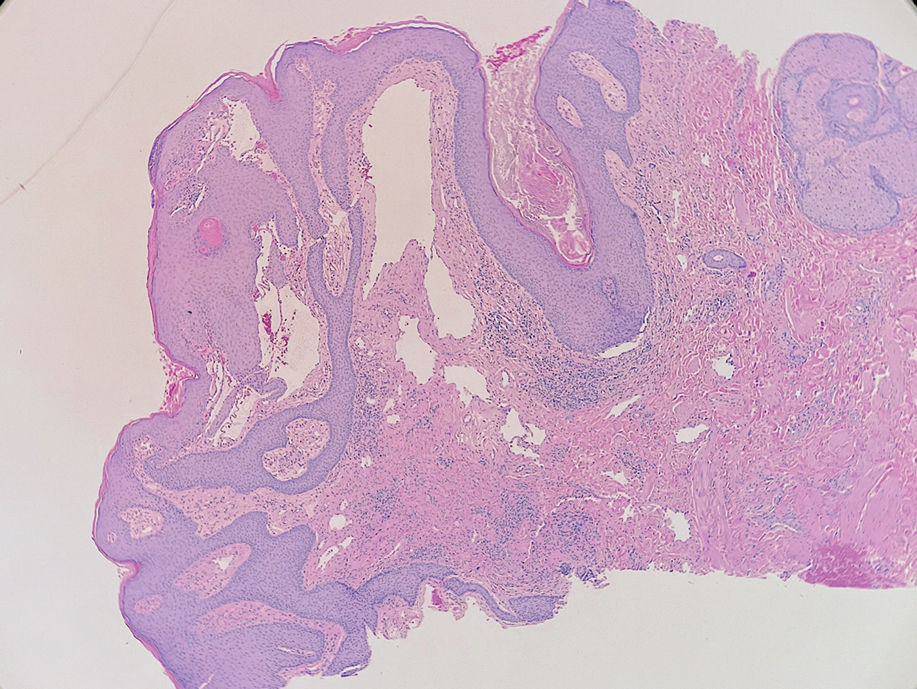

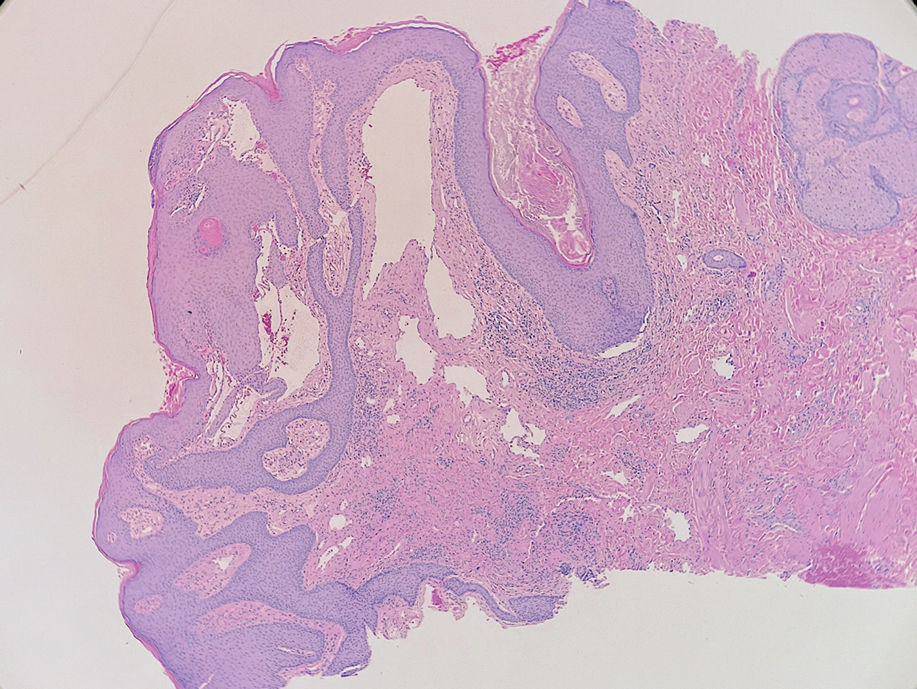

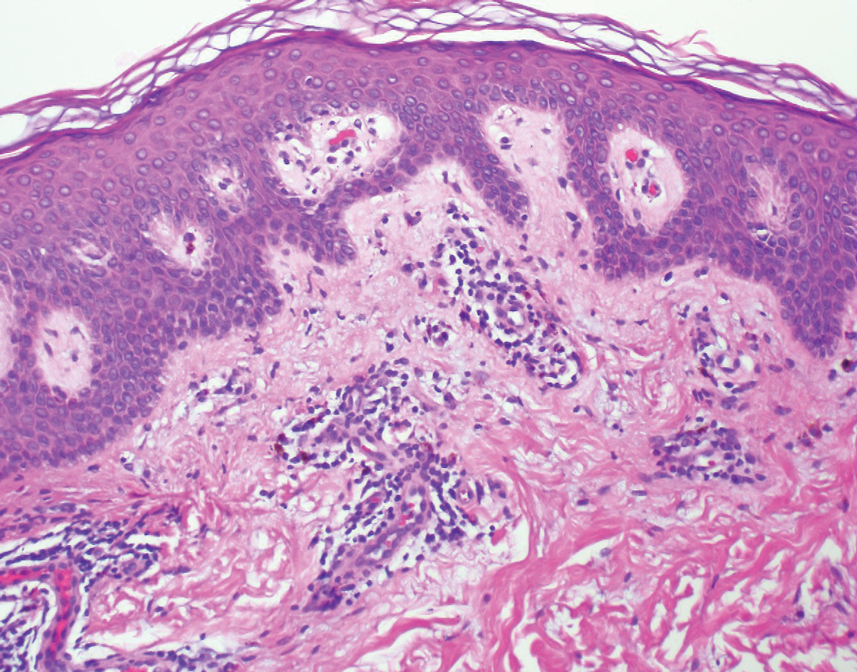

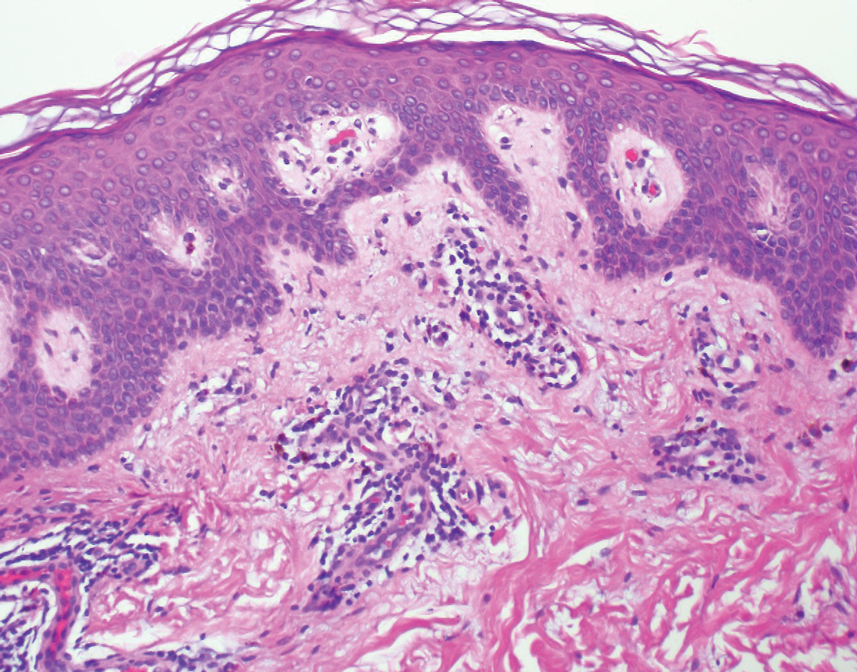

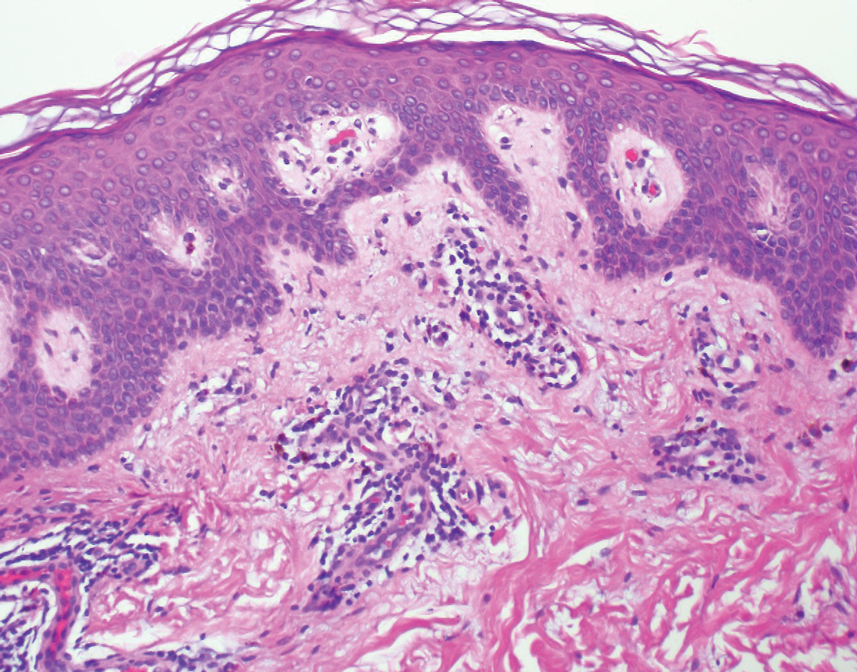

There is a broad differential diagnosis for a pink expanding plaque on the face, which requires histopathologic correlation for correct diagnosis. Three broad categories in the differential are infectious (eg, bacterial, fungal), medication related (eg, fixed drug eruption), and granulomatous (eg, granuloma faciale [GF], sarcoidosis, tumid lupus, leprosy, granulomatous rosacea). A biopsy of the lesion revealed a mixed inflammatory cell dermal infiltrate with perivascular accentuation and intense vasculitis that was consistent with GF (Figure 2). Gomori methenamine-silver, periodic acid–Schiff, Fite-Faraco, acid-fast bacilli, and Gram staining were negative for organisms. Tissue cultures were negative for bacterial, mycobacterial, and fungal etiology. The patient was started on high-potency topical steroids with a 50% improvement in the appearance of the skin lesion at 1-month follow-up.

Granuloma faciale is a rare chronic inflammatory dermatosis with a predilection for the face that is difficult to diagnose and treat. The diagnosis is based on clinical and histologic findings, and it typically presents as single or multiple, well-demarcated, red-brown nodules, papules, or plaques that range from several millimeters to centimeters in diameter.1,2 Extrafacial lesions may be seen.3 Granuloma faciale usually is asymptomatic but occasionally has associated pruritus and rarely ulceration. The prevalence and pathophysiology of GF is not well defined; however, GF more commonly is reported in middle-aged White males.1

Histologic examination of GF reveals a mixed inflammatory cellular infiltrate in the upper dermis. A grenz zone, which is a narrow area of the papillary dermis uninvolved by the underlying pathology, may be seen.1 Contrary to the name, granulomas are not found histologically. Rather, vascular changes or damage frequently are present and may indicate a small vessel vasculitis pathologic mechanism. Granuloma faciale also has been associated with follicular ostia accentuation and telangiectases.4

Many cases of GF have been misdiagnosed as sarcoidosis, lymphoma, lupus, and basal cell carcinoma.1 In addition, GF shares many clinical and histologic features with erythema elevatum diutinum (EED). However, the defining features that suggest EED over GF is that EED has a predilection for the skin overlying the joints. Histopathologically, EED displays granulomas and fibrosis with few eosinophils.5,6

The variable response of GF to treatments and lack of efficacy data have contributed to the complexity and uncertainty of managing GF. The current first-line therapies are topical tacrolimus,7 cryotherapy,8 or corticosteroid therapy.9

- Ortonne N, Wechsler J, Bagot M, et al. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathologic study of 66 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1002-1009.

- Marcoval J, Moreno A, Peyr J. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:269-273.

- Nasiri S, Rahimi H, Farnaghi A, et al. Granuloma faciale with disseminated extra facial lesions. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:5.

- Roustan G, Sánchez Yus E, Salas C, et al. Granuloma faciale with extrafacial lesions. Dermatology. 1999;198:79-82.

- LeBoit PE. Granuloma faciale: a diagnosis deserving of dignity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:440-443.

- Ziemer M, Koehler MJ, Weyers W. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a chronic leukocytoclastic vasculitis microscopically indistinguishable from granuloma faciale? J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:876-883.

- Cecchi R, Pavesi M, Bartoli L, et al. Topical tacrolimus in the treatment of granuloma faciale. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1463-1465.

- Panagiotopoulos A, Anyfantakis V, Rallis E, et al. Assessment of the efficacy of cryosurgery in the treatment of granuloma faciale. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:357-360.

- Radin DA, Mehregan DR. Granuloma faciale: distribution of the lesions and review of the literature. Cutis. 2003;72:213-219.

To the Editor:

A 53-year-old Hispanic woman presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of an expanding plaque on the right cheek of 2 months’ duration. The patient stated the plaque began as a pimple, which she picked with subsequent spread laterally across the cheek. The area was intermittently tender, but she denied tingling, burning, or pruritus of the site. She had been treated with doxycycline and amoxicillin–clavulanic acid prior to presentation without improvement. She had a history of levamisole-induced vasculitis approximately 6 months prior. A review of systems was notable for diffuse joint pain. The patient denied tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use in the preceding 3 months and denied any changes in her medications or in health within the last year.

Physical examination revealed a well-appearing, alert, and afebrile patient with a pink, well-demarcated plaque on the right cheek (Figure 1). The borders of the plaque were indurated, and the lateral aspect of the plaque was eroded secondary to digital manipulation by the patient. She had no cervical lymphadenopathy. There were no other abnormal cutaneous findings.

There is a broad differential diagnosis for a pink expanding plaque on the face, which requires histopathologic correlation for correct diagnosis. Three broad categories in the differential are infectious (eg, bacterial, fungal), medication related (eg, fixed drug eruption), and granulomatous (eg, granuloma faciale [GF], sarcoidosis, tumid lupus, leprosy, granulomatous rosacea). A biopsy of the lesion revealed a mixed inflammatory cell dermal infiltrate with perivascular accentuation and intense vasculitis that was consistent with GF (Figure 2). Gomori methenamine-silver, periodic acid–Schiff, Fite-Faraco, acid-fast bacilli, and Gram staining were negative for organisms. Tissue cultures were negative for bacterial, mycobacterial, and fungal etiology. The patient was started on high-potency topical steroids with a 50% improvement in the appearance of the skin lesion at 1-month follow-up.

Granuloma faciale is a rare chronic inflammatory dermatosis with a predilection for the face that is difficult to diagnose and treat. The diagnosis is based on clinical and histologic findings, and it typically presents as single or multiple, well-demarcated, red-brown nodules, papules, or plaques that range from several millimeters to centimeters in diameter.1,2 Extrafacial lesions may be seen.3 Granuloma faciale usually is asymptomatic but occasionally has associated pruritus and rarely ulceration. The prevalence and pathophysiology of GF is not well defined; however, GF more commonly is reported in middle-aged White males.1

Histologic examination of GF reveals a mixed inflammatory cellular infiltrate in the upper dermis. A grenz zone, which is a narrow area of the papillary dermis uninvolved by the underlying pathology, may be seen.1 Contrary to the name, granulomas are not found histologically. Rather, vascular changes or damage frequently are present and may indicate a small vessel vasculitis pathologic mechanism. Granuloma faciale also has been associated with follicular ostia accentuation and telangiectases.4

Many cases of GF have been misdiagnosed as sarcoidosis, lymphoma, lupus, and basal cell carcinoma.1 In addition, GF shares many clinical and histologic features with erythema elevatum diutinum (EED). However, the defining features that suggest EED over GF is that EED has a predilection for the skin overlying the joints. Histopathologically, EED displays granulomas and fibrosis with few eosinophils.5,6

The variable response of GF to treatments and lack of efficacy data have contributed to the complexity and uncertainty of managing GF. The current first-line therapies are topical tacrolimus,7 cryotherapy,8 or corticosteroid therapy.9

To the Editor:

A 53-year-old Hispanic woman presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of an expanding plaque on the right cheek of 2 months’ duration. The patient stated the plaque began as a pimple, which she picked with subsequent spread laterally across the cheek. The area was intermittently tender, but she denied tingling, burning, or pruritus of the site. She had been treated with doxycycline and amoxicillin–clavulanic acid prior to presentation without improvement. She had a history of levamisole-induced vasculitis approximately 6 months prior. A review of systems was notable for diffuse joint pain. The patient denied tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use in the preceding 3 months and denied any changes in her medications or in health within the last year.

Physical examination revealed a well-appearing, alert, and afebrile patient with a pink, well-demarcated plaque on the right cheek (Figure 1). The borders of the plaque were indurated, and the lateral aspect of the plaque was eroded secondary to digital manipulation by the patient. She had no cervical lymphadenopathy. There were no other abnormal cutaneous findings.

There is a broad differential diagnosis for a pink expanding plaque on the face, which requires histopathologic correlation for correct diagnosis. Three broad categories in the differential are infectious (eg, bacterial, fungal), medication related (eg, fixed drug eruption), and granulomatous (eg, granuloma faciale [GF], sarcoidosis, tumid lupus, leprosy, granulomatous rosacea). A biopsy of the lesion revealed a mixed inflammatory cell dermal infiltrate with perivascular accentuation and intense vasculitis that was consistent with GF (Figure 2). Gomori methenamine-silver, periodic acid–Schiff, Fite-Faraco, acid-fast bacilli, and Gram staining were negative for organisms. Tissue cultures were negative for bacterial, mycobacterial, and fungal etiology. The patient was started on high-potency topical steroids with a 50% improvement in the appearance of the skin lesion at 1-month follow-up.

Granuloma faciale is a rare chronic inflammatory dermatosis with a predilection for the face that is difficult to diagnose and treat. The diagnosis is based on clinical and histologic findings, and it typically presents as single or multiple, well-demarcated, red-brown nodules, papules, or plaques that range from several millimeters to centimeters in diameter.1,2 Extrafacial lesions may be seen.3 Granuloma faciale usually is asymptomatic but occasionally has associated pruritus and rarely ulceration. The prevalence and pathophysiology of GF is not well defined; however, GF more commonly is reported in middle-aged White males.1

Histologic examination of GF reveals a mixed inflammatory cellular infiltrate in the upper dermis. A grenz zone, which is a narrow area of the papillary dermis uninvolved by the underlying pathology, may be seen.1 Contrary to the name, granulomas are not found histologically. Rather, vascular changes or damage frequently are present and may indicate a small vessel vasculitis pathologic mechanism. Granuloma faciale also has been associated with follicular ostia accentuation and telangiectases.4

Many cases of GF have been misdiagnosed as sarcoidosis, lymphoma, lupus, and basal cell carcinoma.1 In addition, GF shares many clinical and histologic features with erythema elevatum diutinum (EED). However, the defining features that suggest EED over GF is that EED has a predilection for the skin overlying the joints. Histopathologically, EED displays granulomas and fibrosis with few eosinophils.5,6

The variable response of GF to treatments and lack of efficacy data have contributed to the complexity and uncertainty of managing GF. The current first-line therapies are topical tacrolimus,7 cryotherapy,8 or corticosteroid therapy.9

- Ortonne N, Wechsler J, Bagot M, et al. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathologic study of 66 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1002-1009.

- Marcoval J, Moreno A, Peyr J. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:269-273.

- Nasiri S, Rahimi H, Farnaghi A, et al. Granuloma faciale with disseminated extra facial lesions. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:5.

- Roustan G, Sánchez Yus E, Salas C, et al. Granuloma faciale with extrafacial lesions. Dermatology. 1999;198:79-82.

- LeBoit PE. Granuloma faciale: a diagnosis deserving of dignity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:440-443.

- Ziemer M, Koehler MJ, Weyers W. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a chronic leukocytoclastic vasculitis microscopically indistinguishable from granuloma faciale? J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:876-883.

- Cecchi R, Pavesi M, Bartoli L, et al. Topical tacrolimus in the treatment of granuloma faciale. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1463-1465.

- Panagiotopoulos A, Anyfantakis V, Rallis E, et al. Assessment of the efficacy of cryosurgery in the treatment of granuloma faciale. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:357-360.

- Radin DA, Mehregan DR. Granuloma faciale: distribution of the lesions and review of the literature. Cutis. 2003;72:213-219.

- Ortonne N, Wechsler J, Bagot M, et al. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathologic study of 66 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1002-1009.

- Marcoval J, Moreno A, Peyr J. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:269-273.

- Nasiri S, Rahimi H, Farnaghi A, et al. Granuloma faciale with disseminated extra facial lesions. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:5.

- Roustan G, Sánchez Yus E, Salas C, et al. Granuloma faciale with extrafacial lesions. Dermatology. 1999;198:79-82.

- LeBoit PE. Granuloma faciale: a diagnosis deserving of dignity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:440-443.

- Ziemer M, Koehler MJ, Weyers W. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a chronic leukocytoclastic vasculitis microscopically indistinguishable from granuloma faciale? J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:876-883.

- Cecchi R, Pavesi M, Bartoli L, et al. Topical tacrolimus in the treatment of granuloma faciale. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1463-1465.

- Panagiotopoulos A, Anyfantakis V, Rallis E, et al. Assessment of the efficacy of cryosurgery in the treatment of granuloma faciale. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:357-360.

- Radin DA, Mehregan DR. Granuloma faciale: distribution of the lesions and review of the literature. Cutis. 2003;72:213-219.

Practice Points

- Granuloma faciale is a benign dermal process presenting with a red-brown plaque on the face of adults that typically is not ulcerated unless physically manipulated.

- Skin biopsy often is required for correct diagnosis.

- Granuloma faciale does not resolve spontaneously and tends to be chronic.

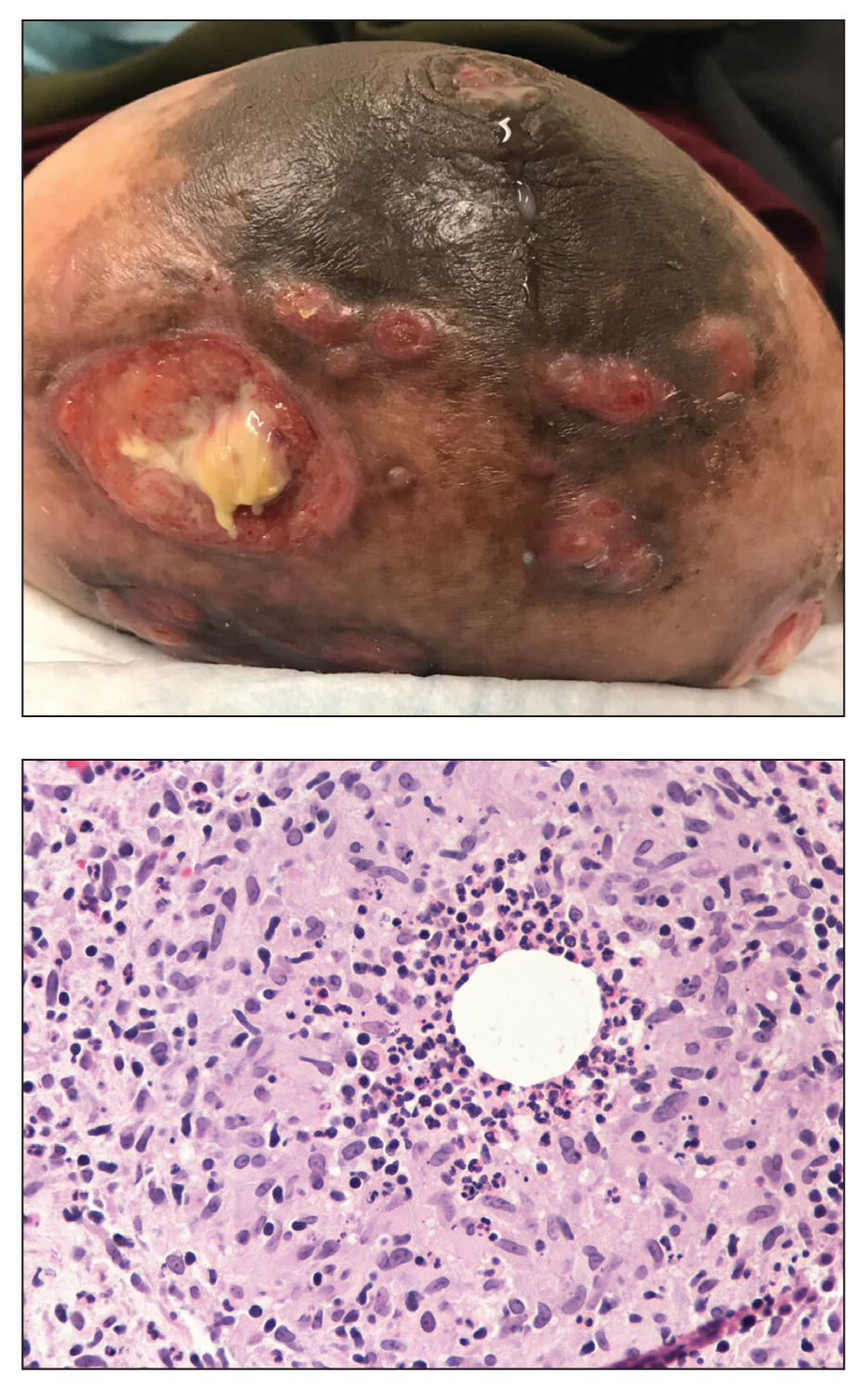

Violaceous Nodules on the Lower Leg

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

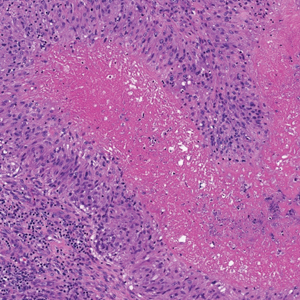

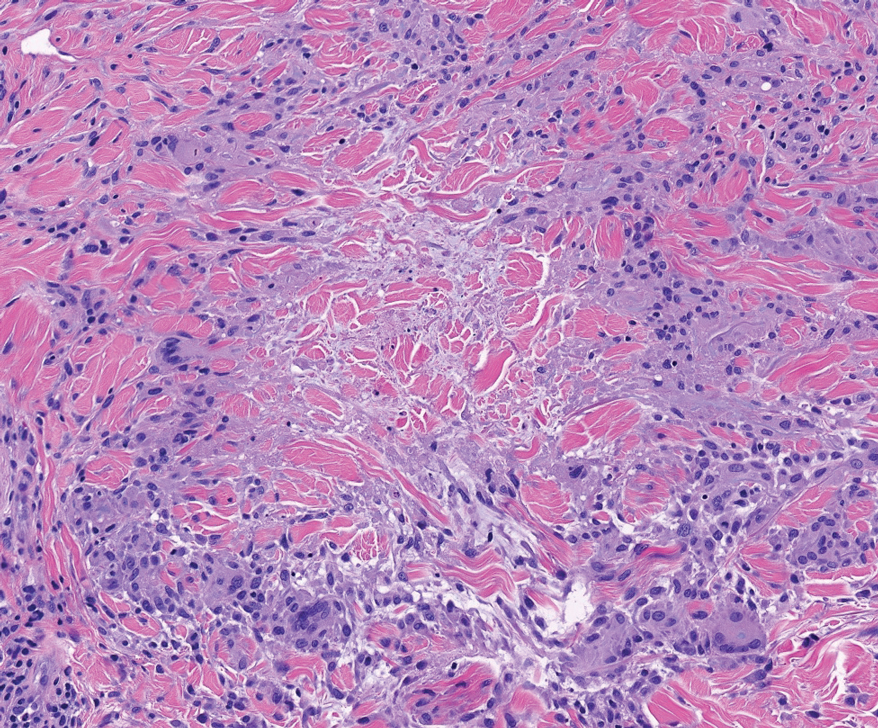

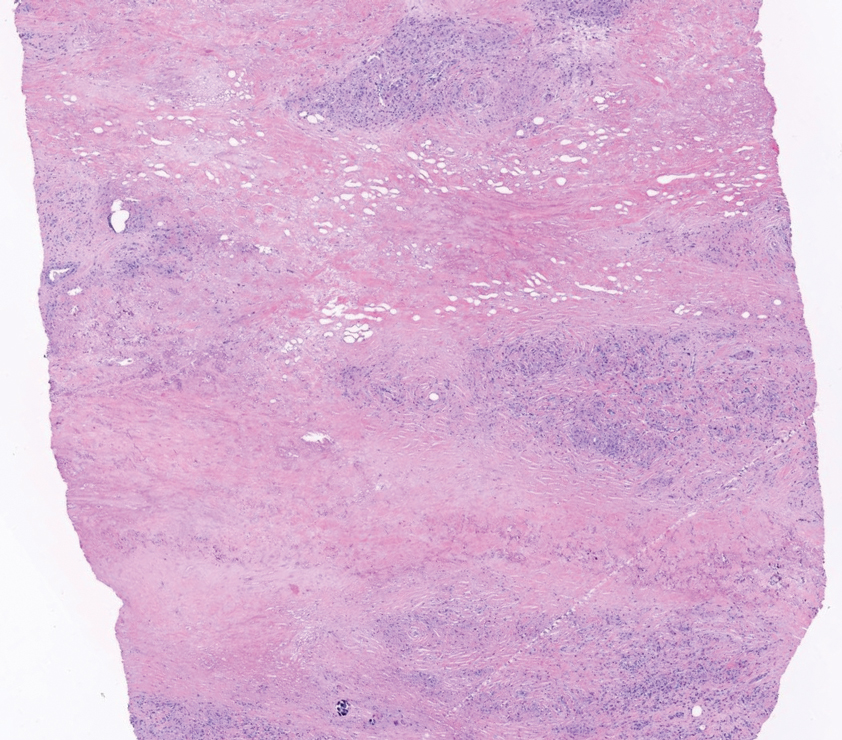

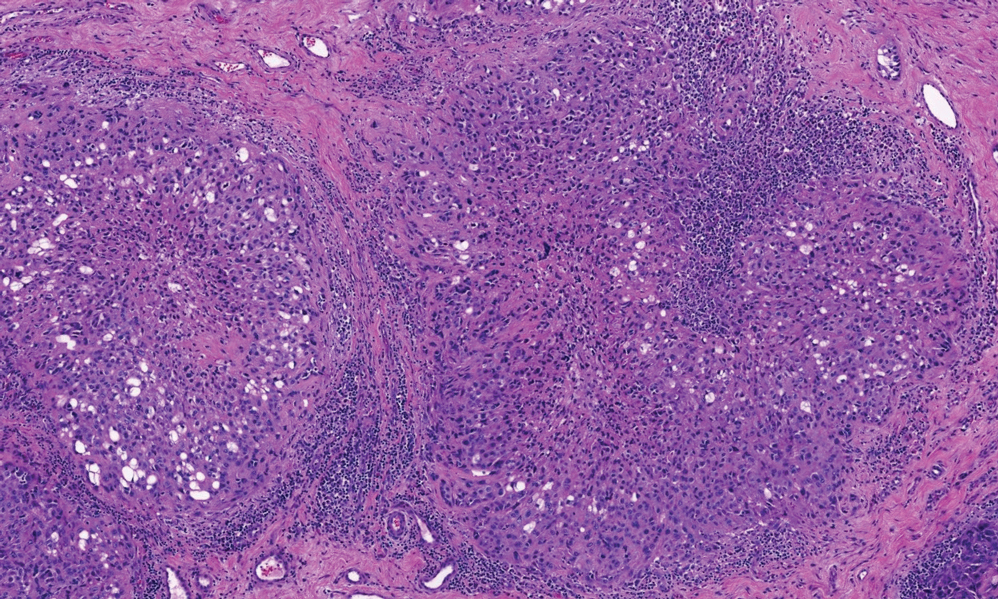

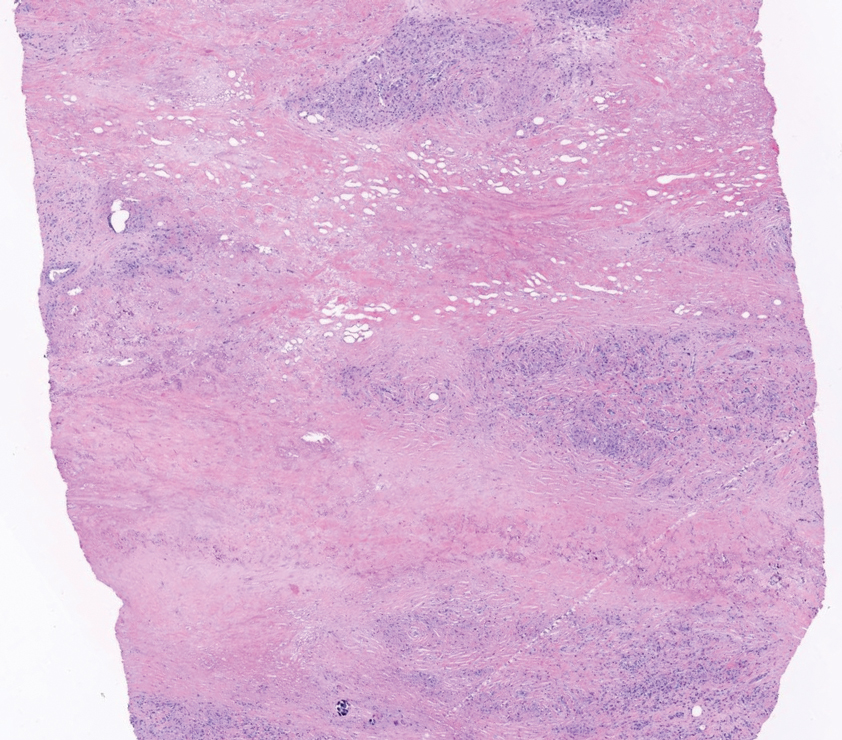

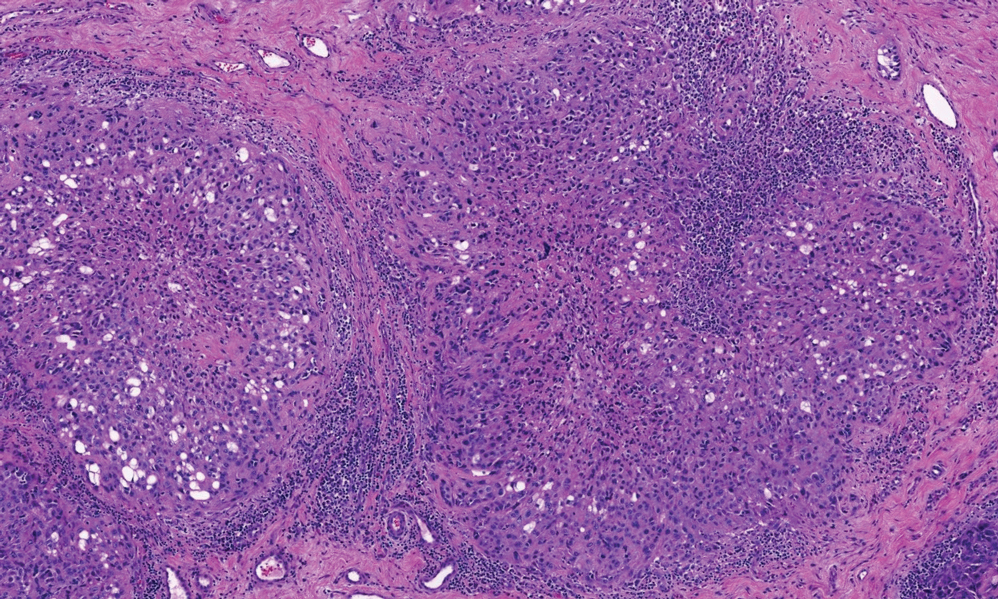

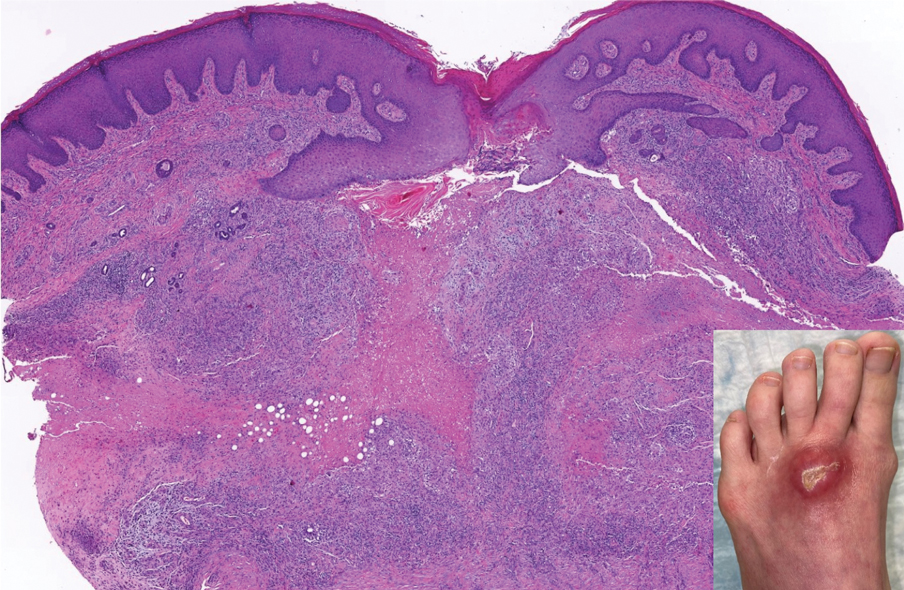

Shave biopsies of 3 lesions revealed a dense, diffuse, atypical lymphoid infiltrate occupying the entirety of the dermis and obscuring the dermoepidermal junction. The infiltrate consisted predominantly of largesized lymphoid cells with fine chromatin and conspicuous nucleoli (Figure). Immunohistochemistry was positive for CD45 and CD20, indicating B-cell lineage. Bcl-2, multiple myeloma oncogene 1, and forkhead box protein P1 also were expressed in the vast majority of lesional cells, distinguishing the lesion from other forms of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas.1 These findings were consistent with large B-cell lymphoma with a high proliferation index, consistent with primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, which often presents on the lower leg.2 The patient had a negative systemic workup including bone marrow biopsy. He was started on the R-CEOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, etoposide, vincristine, prednisone) chemotherapy regimen.

Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, is an intermediately aggressive and rare form of B-cell lymphoma with a poor prognosis that primarily affects elderly female patients. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, accounts for only 1% to 3% of cutaneous lymphomas and approximately 10% to 20% of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas.2 It typically presents as multiple red-brown or bluish nodules on the lower extremities or trunk. Presentation as a solitary nodule also is possible.1,2 Histologic analysis of primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, reveals large cells with round nuclei (immunoblasts and centroblasts), and the immunohistochemical profile shows strong Bcl-2 expression often accompanied by the multiple myeloma oncogene 1 protein.3 The 5-year survival rate is approximately 50%, which is lower than other types of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas, and the progression of disease is characterized by frequent relapses and involvement of extracutaneous regions such as the lymph nodes, bone marrow, and central nervous system.1,2,4 Patients with multiple tumors on the leg have a particularly poor prognosis; in particular, having 1 or more lesions on the leg results in a 43% 3-year survival rate while having multiple lesions has a 36% 3-year survival rate compared with a 77% 3-year survival rate for patients with the non–leg subtype or a single lesion.3 Treatment with rituximab has been shown to be effective in at least short-term control of the disease, and the R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) regimen is the standard of treatment.3,4

Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, can mimic multiple other cutaneous presentations of disease. Myeloid sarcoma (leukemia cutis) is a rare condition that presents as an extramedullary tumor often simultaneously with the onset or relapse of acute myeloid leukemia.5 Our patient had no history of leukemia, but myeloid sarcoma may predate acute myeloid leukemia in about a quarter of cases.5 It most commonly presents histologically as a diffuse dermal infiltrate that splays between collagen bundles and often is associated with an overlying Grenz zone. A nodular, or perivascular and periadnexal, pattern also may be seen. Upon closer inspection, the infiltrate is composed of immature myeloid cells (blasts) with background inflammation occasionally containing eosinophils. The immunohistochemical profile varies depending on the type of differentiation and degree of maturity of the cells. The histologic findings in our patient were inconsistent with myeloid sarcoma.

Erythema elevatum diutinum (EED) usually presents as dark red, brown, or violaceous papules or plaques and often is found on the extensor surfaces. It often is associated with hematologic abnormalities as well as recurrent bacterial or viral infections.6 Histologically, EED initially manifests as leukocytoclastic vasculitis with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate typically featuring an abundance of neutrophils, making this condition unlikely in this case. As the lesion progresses, fibrosis and scarring ensue as inflammation wanes. The fibrosis often is described as having an onion skin–like pattern, which is characteristic of established EED lesions. Our patient had no history of vasculitis, and the histologic findings were inconsistent with EED.

Angiosarcoma can present as a central nodule surrounded by an erythematous plaque. Although potentially clinically similar to primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, angiosarcoma was unlikely in this case because of an absence of lymphedema and no history of radiation to the leg, both of which are key historical features of angiosarcoma.7 Additionally, the histology of cutaneous angiosarcoma is marked by vascular proliferation, which was not seen in the lesion biopsied in our patient. The histology of angiosarcoma is that of an atypical vascular proliferation, and a hallmark feature is infiltration between collagen, often referred to as giving the appearance of dissection between collagen bundles. The degree of atypia can vary widely, and epithelioid variants exist, producing a potential diagnostic pitfall. Lesional cells are positive for vascular markers, which can be used for confirmation of the endothelial lineage.

Sarcoidosis is notorious for its mimicry, which can be the case both clinically and histologically. Characteristic pathology of sarcoidosis is that of well-formed epithelioid granulomas with minimal associated inflammation and lack of caseating necrosis. Our patient had no known history of systemic sarcoidosis, and the pathologic features of noncaseating granulomas were not present. As a diagnosis of exclusion, correlation with special stains and culture studies is necessary to exclude an infectious process. The differential diagnosis for sarcoidal granulomatous dermatitis also includes foreign body reaction, inflammatory bowel disease, and granulomatous cheilitis, among others.

- Athalye L, Nami N, Shitabata P. A rare case of primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type. Cutis. 2018;102:E31-E34.

- Sokol L, Naghashpour M, Glass LF. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: recent advances in diagnosis and management. Cancer Control. 2012;19:236-244. doi:10.1177/107327481201900308

- Grange F, Beylot-Barry M, Courville P, et al. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type: clinicopathologic features and prognostic analysis in 60 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1144-1150. doi:10.1001/archderm.143.9.1144

- Patsatsi A, Kyriakou A, Karavasilis V, et al. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, with multiple local relapses: case presentation and brief review of literature. Hippokratia. 2013;17:174-176.

- Avni B, Koren-Michowitz M. Myeloid sarcoma: current approach and therapeutic options. Ther Adv Hematol. 2011;2:309-316.

- Yiannias JA, el-Azhary RA, Gibson LE. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a clinical and histopathologic study of 13 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:38-44.

- Scholtz J, Mishra MM, Simman R. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the lower leg. Cutis. 2018;102:E8-E11.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

Shave biopsies of 3 lesions revealed a dense, diffuse, atypical lymphoid infiltrate occupying the entirety of the dermis and obscuring the dermoepidermal junction. The infiltrate consisted predominantly of largesized lymphoid cells with fine chromatin and conspicuous nucleoli (Figure). Immunohistochemistry was positive for CD45 and CD20, indicating B-cell lineage. Bcl-2, multiple myeloma oncogene 1, and forkhead box protein P1 also were expressed in the vast majority of lesional cells, distinguishing the lesion from other forms of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas.1 These findings were consistent with large B-cell lymphoma with a high proliferation index, consistent with primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, which often presents on the lower leg.2 The patient had a negative systemic workup including bone marrow biopsy. He was started on the R-CEOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, etoposide, vincristine, prednisone) chemotherapy regimen.

Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, is an intermediately aggressive and rare form of B-cell lymphoma with a poor prognosis that primarily affects elderly female patients. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, accounts for only 1% to 3% of cutaneous lymphomas and approximately 10% to 20% of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas.2 It typically presents as multiple red-brown or bluish nodules on the lower extremities or trunk. Presentation as a solitary nodule also is possible.1,2 Histologic analysis of primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, reveals large cells with round nuclei (immunoblasts and centroblasts), and the immunohistochemical profile shows strong Bcl-2 expression often accompanied by the multiple myeloma oncogene 1 protein.3 The 5-year survival rate is approximately 50%, which is lower than other types of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas, and the progression of disease is characterized by frequent relapses and involvement of extracutaneous regions such as the lymph nodes, bone marrow, and central nervous system.1,2,4 Patients with multiple tumors on the leg have a particularly poor prognosis; in particular, having 1 or more lesions on the leg results in a 43% 3-year survival rate while having multiple lesions has a 36% 3-year survival rate compared with a 77% 3-year survival rate for patients with the non–leg subtype or a single lesion.3 Treatment with rituximab has been shown to be effective in at least short-term control of the disease, and the R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) regimen is the standard of treatment.3,4

Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, can mimic multiple other cutaneous presentations of disease. Myeloid sarcoma (leukemia cutis) is a rare condition that presents as an extramedullary tumor often simultaneously with the onset or relapse of acute myeloid leukemia.5 Our patient had no history of leukemia, but myeloid sarcoma may predate acute myeloid leukemia in about a quarter of cases.5 It most commonly presents histologically as a diffuse dermal infiltrate that splays between collagen bundles and often is associated with an overlying Grenz zone. A nodular, or perivascular and periadnexal, pattern also may be seen. Upon closer inspection, the infiltrate is composed of immature myeloid cells (blasts) with background inflammation occasionally containing eosinophils. The immunohistochemical profile varies depending on the type of differentiation and degree of maturity of the cells. The histologic findings in our patient were inconsistent with myeloid sarcoma.

Erythema elevatum diutinum (EED) usually presents as dark red, brown, or violaceous papules or plaques and often is found on the extensor surfaces. It often is associated with hematologic abnormalities as well as recurrent bacterial or viral infections.6 Histologically, EED initially manifests as leukocytoclastic vasculitis with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate typically featuring an abundance of neutrophils, making this condition unlikely in this case. As the lesion progresses, fibrosis and scarring ensue as inflammation wanes. The fibrosis often is described as having an onion skin–like pattern, which is characteristic of established EED lesions. Our patient had no history of vasculitis, and the histologic findings were inconsistent with EED.

Angiosarcoma can present as a central nodule surrounded by an erythematous plaque. Although potentially clinically similar to primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, angiosarcoma was unlikely in this case because of an absence of lymphedema and no history of radiation to the leg, both of which are key historical features of angiosarcoma.7 Additionally, the histology of cutaneous angiosarcoma is marked by vascular proliferation, which was not seen in the lesion biopsied in our patient. The histology of angiosarcoma is that of an atypical vascular proliferation, and a hallmark feature is infiltration between collagen, often referred to as giving the appearance of dissection between collagen bundles. The degree of atypia can vary widely, and epithelioid variants exist, producing a potential diagnostic pitfall. Lesional cells are positive for vascular markers, which can be used for confirmation of the endothelial lineage.

Sarcoidosis is notorious for its mimicry, which can be the case both clinically and histologically. Characteristic pathology of sarcoidosis is that of well-formed epithelioid granulomas with minimal associated inflammation and lack of caseating necrosis. Our patient had no known history of systemic sarcoidosis, and the pathologic features of noncaseating granulomas were not present. As a diagnosis of exclusion, correlation with special stains and culture studies is necessary to exclude an infectious process. The differential diagnosis for sarcoidal granulomatous dermatitis also includes foreign body reaction, inflammatory bowel disease, and granulomatous cheilitis, among others.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

Shave biopsies of 3 lesions revealed a dense, diffuse, atypical lymphoid infiltrate occupying the entirety of the dermis and obscuring the dermoepidermal junction. The infiltrate consisted predominantly of largesized lymphoid cells with fine chromatin and conspicuous nucleoli (Figure). Immunohistochemistry was positive for CD45 and CD20, indicating B-cell lineage. Bcl-2, multiple myeloma oncogene 1, and forkhead box protein P1 also were expressed in the vast majority of lesional cells, distinguishing the lesion from other forms of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas.1 These findings were consistent with large B-cell lymphoma with a high proliferation index, consistent with primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, which often presents on the lower leg.2 The patient had a negative systemic workup including bone marrow biopsy. He was started on the R-CEOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, etoposide, vincristine, prednisone) chemotherapy regimen.

Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, is an intermediately aggressive and rare form of B-cell lymphoma with a poor prognosis that primarily affects elderly female patients. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, accounts for only 1% to 3% of cutaneous lymphomas and approximately 10% to 20% of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas.2 It typically presents as multiple red-brown or bluish nodules on the lower extremities or trunk. Presentation as a solitary nodule also is possible.1,2 Histologic analysis of primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, reveals large cells with round nuclei (immunoblasts and centroblasts), and the immunohistochemical profile shows strong Bcl-2 expression often accompanied by the multiple myeloma oncogene 1 protein.3 The 5-year survival rate is approximately 50%, which is lower than other types of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas, and the progression of disease is characterized by frequent relapses and involvement of extracutaneous regions such as the lymph nodes, bone marrow, and central nervous system.1,2,4 Patients with multiple tumors on the leg have a particularly poor prognosis; in particular, having 1 or more lesions on the leg results in a 43% 3-year survival rate while having multiple lesions has a 36% 3-year survival rate compared with a 77% 3-year survival rate for patients with the non–leg subtype or a single lesion.3 Treatment with rituximab has been shown to be effective in at least short-term control of the disease, and the R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) regimen is the standard of treatment.3,4

Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, can mimic multiple other cutaneous presentations of disease. Myeloid sarcoma (leukemia cutis) is a rare condition that presents as an extramedullary tumor often simultaneously with the onset or relapse of acute myeloid leukemia.5 Our patient had no history of leukemia, but myeloid sarcoma may predate acute myeloid leukemia in about a quarter of cases.5 It most commonly presents histologically as a diffuse dermal infiltrate that splays between collagen bundles and often is associated with an overlying Grenz zone. A nodular, or perivascular and periadnexal, pattern also may be seen. Upon closer inspection, the infiltrate is composed of immature myeloid cells (blasts) with background inflammation occasionally containing eosinophils. The immunohistochemical profile varies depending on the type of differentiation and degree of maturity of the cells. The histologic findings in our patient were inconsistent with myeloid sarcoma.

Erythema elevatum diutinum (EED) usually presents as dark red, brown, or violaceous papules or plaques and often is found on the extensor surfaces. It often is associated with hematologic abnormalities as well as recurrent bacterial or viral infections.6 Histologically, EED initially manifests as leukocytoclastic vasculitis with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate typically featuring an abundance of neutrophils, making this condition unlikely in this case. As the lesion progresses, fibrosis and scarring ensue as inflammation wanes. The fibrosis often is described as having an onion skin–like pattern, which is characteristic of established EED lesions. Our patient had no history of vasculitis, and the histologic findings were inconsistent with EED.

Angiosarcoma can present as a central nodule surrounded by an erythematous plaque. Although potentially clinically similar to primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, angiosarcoma was unlikely in this case because of an absence of lymphedema and no history of radiation to the leg, both of which are key historical features of angiosarcoma.7 Additionally, the histology of cutaneous angiosarcoma is marked by vascular proliferation, which was not seen in the lesion biopsied in our patient. The histology of angiosarcoma is that of an atypical vascular proliferation, and a hallmark feature is infiltration between collagen, often referred to as giving the appearance of dissection between collagen bundles. The degree of atypia can vary widely, and epithelioid variants exist, producing a potential diagnostic pitfall. Lesional cells are positive for vascular markers, which can be used for confirmation of the endothelial lineage.

Sarcoidosis is notorious for its mimicry, which can be the case both clinically and histologically. Characteristic pathology of sarcoidosis is that of well-formed epithelioid granulomas with minimal associated inflammation and lack of caseating necrosis. Our patient had no known history of systemic sarcoidosis, and the pathologic features of noncaseating granulomas were not present. As a diagnosis of exclusion, correlation with special stains and culture studies is necessary to exclude an infectious process. The differential diagnosis for sarcoidal granulomatous dermatitis also includes foreign body reaction, inflammatory bowel disease, and granulomatous cheilitis, among others.

- Athalye L, Nami N, Shitabata P. A rare case of primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type. Cutis. 2018;102:E31-E34.

- Sokol L, Naghashpour M, Glass LF. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: recent advances in diagnosis and management. Cancer Control. 2012;19:236-244. doi:10.1177/107327481201900308

- Grange F, Beylot-Barry M, Courville P, et al. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type: clinicopathologic features and prognostic analysis in 60 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1144-1150. doi:10.1001/archderm.143.9.1144

- Patsatsi A, Kyriakou A, Karavasilis V, et al. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, with multiple local relapses: case presentation and brief review of literature. Hippokratia. 2013;17:174-176.

- Avni B, Koren-Michowitz M. Myeloid sarcoma: current approach and therapeutic options. Ther Adv Hematol. 2011;2:309-316.

- Yiannias JA, el-Azhary RA, Gibson LE. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a clinical and histopathologic study of 13 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:38-44.

- Scholtz J, Mishra MM, Simman R. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the lower leg. Cutis. 2018;102:E8-E11.

- Athalye L, Nami N, Shitabata P. A rare case of primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type. Cutis. 2018;102:E31-E34.

- Sokol L, Naghashpour M, Glass LF. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: recent advances in diagnosis and management. Cancer Control. 2012;19:236-244. doi:10.1177/107327481201900308

- Grange F, Beylot-Barry M, Courville P, et al. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type: clinicopathologic features and prognostic analysis in 60 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1144-1150. doi:10.1001/archderm.143.9.1144

- Patsatsi A, Kyriakou A, Karavasilis V, et al. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, with multiple local relapses: case presentation and brief review of literature. Hippokratia. 2013;17:174-176.

- Avni B, Koren-Michowitz M. Myeloid sarcoma: current approach and therapeutic options. Ther Adv Hematol. 2011;2:309-316.

- Yiannias JA, el-Azhary RA, Gibson LE. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a clinical and histopathologic study of 13 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:38-44.

- Scholtz J, Mishra MM, Simman R. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the lower leg. Cutis. 2018;102:E8-E11.

A 79-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with 4 enlarging, asymptomatic, violaceous, desquamating nodules on the left pretibial region and calf of 3 months’ duration. He denied any constitutional symptoms such as night sweats or weight loss. His medical history included a malignant melanoma on the left ear that was excised 5 years prior. He also had a history of peripheral edema, hypertension, and rheumatoid arthritis, as well as a 50-pack-year history of smoking. Physical examination revealed 2 large nodules measuring 3.0×3.0 cm each and 2 smaller nodules measuring 1.0×1.0 cm each. There was no appreciable lymphadenopathy.

PLA testing brings nuance to the diagnosis of early-stage melanoma

BOSTON – Although

One such test, the Pigmented Lesional Assay (PLA) uses adhesive patches applied to lesions of concern at the bedside to extract RNA from the stratum corneum to help determine the risk for melanoma.

At the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, Caroline C. Kim, MD, director of melanoma and pigmented lesion clinics at Newton Wellesley Dermatology, Wellesley Hills, Mass., and Tufts Medical Center, Boston, spoke about the PLA, which uses genetic expression profiling to measure the expression level of specific genes that are associated with melanoma: PRAME (preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma) and LINC00518 (LINC). There are four possible results of the test: Aberrant expression of both LINC and PRAME (high risk); aberrant expression of a single gene (moderate risk); aberrant expression of neither gene (low risk); or inconclusive.

Validation data have shown a sensitivity of 91% and a specificity of 69% for the PLA, with a 99% negative predictive value; so a lesion that tested negative by PLA has a less than 1% chance of being melanoma. In addition, a study published in 2020 found that the addition of TERT (telomerase reverse transcriptase) mutation analyses increased the sensitivity of the PLA to 97%.

While the high negative predictive value is helpful to consider in clinical scenarios to rule-out melanoma for borderline lesions, one must consider the positive predictive value as well and how this may impact clinical care, Dr. Kim said. In a study examining outcomes of 381 lesions, 51 were PLA positive (single or double) and were biopsied, of which 19 (37%) revealed a melanoma diagnosis. In a large U.S. registry study of 3,418 lesions, 324 lesions that were PLA double positive were biopsied, with 18.7% revealing a melanoma diagnosis.

“No test is perfect, and this applies to PLA, even if you get a double-positive or double-negative test result,” Dr. Kim said. “You want to make sure that patients are aware of false positives and negatives. However, PLA could be an additional piece of data to inform your decision to proceed with biopsy on select borderline suspicious pigmented lesions. More studies are needed to better understand the approach to single- and double-positive PLA results.”

The PLA kit contains adhesive patches and supplies and a FedEx envelope for return to DermTech, the test’s manufacturer, for processing. The patches can be applied to lesions at least 4 mm in diameter; multiple kits are recommended for those greater than 16 mm in diameter. The test is not validated for lesions located on mucous membranes, palms, soles, nails, or on ulcerated or bleeding lesions, nor for those that have been previously biopsied. It is also not validated for use in pediatric patients or in those with skin types IV or higher. Results are returned in 2-3 days. If insurance does not cover the test, the cost to the patient is approximately $50 per lesion or a maximum of $150, according to Dr. Kim.

Use in clinical practice

In Dr. Kim’s clinical experience, the PLA can be considered for suspicious pigmented lesions on cosmetically sensitive areas and for suspicious lesions in areas difficult to biopsy or excise. For example, she discussed the case of a 72-year-old woman with a family history of melanoma, who presented to her clinic with a longstanding pigmented lesion on her right upper and lower eyelids that had previously been treated with laser. She had undergone multiple prior biopsies over 12 years, which caused mild to moderate atypical melanocytic proliferation. The PLA result was double negative for PRAME and LINC in her upper and lower eyelid, “which provided reassurance to the patient,” Dr. Kim said. The patient continues to be followed closely for any clinical changes.

Another patient, a 67-year-old woman, was referred to Dr. Kim from out of state for a teledermatology visit early in the COVID-19 pandemic. The patient had a lesion on her right calf that was hard, raised, and pink, did not resemble other lesions on her body, and had been present for a few weeks. “Her husband had recently passed away from brain cancer and she was very concerned about melanoma,” Dr. Kim recalled. “She lived alone, and the adult son was with her during the teledermatology call to assist. The patient asked about the PLA test, and given her difficulty going to a medical office at the time, we agreed to help her with this test.” The patient and her son arranged another teledermatology visit with Dr. Kim after receiving the kit in the mail from DermTech, and Dr. Kim coached them on how to properly administer the test. The results came back as PRAME negative and LINC positive. A biopsy with a local provider was recommended and the pathology results showed an inflamed seborrheic keratosis.

“This case exemplifies a false-positive result. We should be sure to make patients aware of this possibility,” Dr. Kim said.

Incorporating PLA into clinical practice requires certain workflow considerations, with paperwork to fill out in addition to performing the adhesive test, collection of insurance information, mailing the kit via FedEx, retrieving the results, and following up with the patient, said Dr. Kim. “For select borderline pigmented lesions, I discuss the rationale of the test with patients, the possibility of false-positive and false-negative results and the need to return for a biopsy when there is positive result. Clinical follow-up is recommended for negative results. There is also the possibility of charge to the patient if the test is not covered by their insurance.”

Skin biopsy still the gold standard

Despite the availability of the PLA as an assessment tool, Dr. Kim emphasized that skin biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosing melanoma. “Future prospective randomized clinical trials are needed to examine the role of genetic expression profiling in staging and managing patients,” she said.

In 2019, she and her colleagues surveyed 42 pigmented lesion experts in the United States about why they ordered one of three molecular tests on the market or not and how results affected patient treatment. The proportion of clinicians who ordered the tests ranged from 21% to 29%. The top 2 reasons respondents chose for not ordering the PLA test specifically were: “Feel that further validation studies are necessary” (20%) and “do not feel it would be useful in my practice” (18%).

Results of a larger follow-up survey on usage patterns of PLA of both pigmented lesion experts and general clinicians on this topic are expected to be published shortly.

Dr. Kim reported having no disclosures related to her presentation.

BOSTON – Although

One such test, the Pigmented Lesional Assay (PLA) uses adhesive patches applied to lesions of concern at the bedside to extract RNA from the stratum corneum to help determine the risk for melanoma.

At the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, Caroline C. Kim, MD, director of melanoma and pigmented lesion clinics at Newton Wellesley Dermatology, Wellesley Hills, Mass., and Tufts Medical Center, Boston, spoke about the PLA, which uses genetic expression profiling to measure the expression level of specific genes that are associated with melanoma: PRAME (preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma) and LINC00518 (LINC). There are four possible results of the test: Aberrant expression of both LINC and PRAME (high risk); aberrant expression of a single gene (moderate risk); aberrant expression of neither gene (low risk); or inconclusive.

Validation data have shown a sensitivity of 91% and a specificity of 69% for the PLA, with a 99% negative predictive value; so a lesion that tested negative by PLA has a less than 1% chance of being melanoma. In addition, a study published in 2020 found that the addition of TERT (telomerase reverse transcriptase) mutation analyses increased the sensitivity of the PLA to 97%.

While the high negative predictive value is helpful to consider in clinical scenarios to rule-out melanoma for borderline lesions, one must consider the positive predictive value as well and how this may impact clinical care, Dr. Kim said. In a study examining outcomes of 381 lesions, 51 were PLA positive (single or double) and were biopsied, of which 19 (37%) revealed a melanoma diagnosis. In a large U.S. registry study of 3,418 lesions, 324 lesions that were PLA double positive were biopsied, with 18.7% revealing a melanoma diagnosis.

“No test is perfect, and this applies to PLA, even if you get a double-positive or double-negative test result,” Dr. Kim said. “You want to make sure that patients are aware of false positives and negatives. However, PLA could be an additional piece of data to inform your decision to proceed with biopsy on select borderline suspicious pigmented lesions. More studies are needed to better understand the approach to single- and double-positive PLA results.”

The PLA kit contains adhesive patches and supplies and a FedEx envelope for return to DermTech, the test’s manufacturer, for processing. The patches can be applied to lesions at least 4 mm in diameter; multiple kits are recommended for those greater than 16 mm in diameter. The test is not validated for lesions located on mucous membranes, palms, soles, nails, or on ulcerated or bleeding lesions, nor for those that have been previously biopsied. It is also not validated for use in pediatric patients or in those with skin types IV or higher. Results are returned in 2-3 days. If insurance does not cover the test, the cost to the patient is approximately $50 per lesion or a maximum of $150, according to Dr. Kim.

Use in clinical practice

In Dr. Kim’s clinical experience, the PLA can be considered for suspicious pigmented lesions on cosmetically sensitive areas and for suspicious lesions in areas difficult to biopsy or excise. For example, she discussed the case of a 72-year-old woman with a family history of melanoma, who presented to her clinic with a longstanding pigmented lesion on her right upper and lower eyelids that had previously been treated with laser. She had undergone multiple prior biopsies over 12 years, which caused mild to moderate atypical melanocytic proliferation. The PLA result was double negative for PRAME and LINC in her upper and lower eyelid, “which provided reassurance to the patient,” Dr. Kim said. The patient continues to be followed closely for any clinical changes.

Another patient, a 67-year-old woman, was referred to Dr. Kim from out of state for a teledermatology visit early in the COVID-19 pandemic. The patient had a lesion on her right calf that was hard, raised, and pink, did not resemble other lesions on her body, and had been present for a few weeks. “Her husband had recently passed away from brain cancer and she was very concerned about melanoma,” Dr. Kim recalled. “She lived alone, and the adult son was with her during the teledermatology call to assist. The patient asked about the PLA test, and given her difficulty going to a medical office at the time, we agreed to help her with this test.” The patient and her son arranged another teledermatology visit with Dr. Kim after receiving the kit in the mail from DermTech, and Dr. Kim coached them on how to properly administer the test. The results came back as PRAME negative and LINC positive. A biopsy with a local provider was recommended and the pathology results showed an inflamed seborrheic keratosis.

“This case exemplifies a false-positive result. We should be sure to make patients aware of this possibility,” Dr. Kim said.

Incorporating PLA into clinical practice requires certain workflow considerations, with paperwork to fill out in addition to performing the adhesive test, collection of insurance information, mailing the kit via FedEx, retrieving the results, and following up with the patient, said Dr. Kim. “For select borderline pigmented lesions, I discuss the rationale of the test with patients, the possibility of false-positive and false-negative results and the need to return for a biopsy when there is positive result. Clinical follow-up is recommended for negative results. There is also the possibility of charge to the patient if the test is not covered by their insurance.”

Skin biopsy still the gold standard

Despite the availability of the PLA as an assessment tool, Dr. Kim emphasized that skin biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosing melanoma. “Future prospective randomized clinical trials are needed to examine the role of genetic expression profiling in staging and managing patients,” she said.

In 2019, she and her colleagues surveyed 42 pigmented lesion experts in the United States about why they ordered one of three molecular tests on the market or not and how results affected patient treatment. The proportion of clinicians who ordered the tests ranged from 21% to 29%. The top 2 reasons respondents chose for not ordering the PLA test specifically were: “Feel that further validation studies are necessary” (20%) and “do not feel it would be useful in my practice” (18%).

Results of a larger follow-up survey on usage patterns of PLA of both pigmented lesion experts and general clinicians on this topic are expected to be published shortly.

Dr. Kim reported having no disclosures related to her presentation.

BOSTON – Although

One such test, the Pigmented Lesional Assay (PLA) uses adhesive patches applied to lesions of concern at the bedside to extract RNA from the stratum corneum to help determine the risk for melanoma.

At the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, Caroline C. Kim, MD, director of melanoma and pigmented lesion clinics at Newton Wellesley Dermatology, Wellesley Hills, Mass., and Tufts Medical Center, Boston, spoke about the PLA, which uses genetic expression profiling to measure the expression level of specific genes that are associated with melanoma: PRAME (preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma) and LINC00518 (LINC). There are four possible results of the test: Aberrant expression of both LINC and PRAME (high risk); aberrant expression of a single gene (moderate risk); aberrant expression of neither gene (low risk); or inconclusive.

Validation data have shown a sensitivity of 91% and a specificity of 69% for the PLA, with a 99% negative predictive value; so a lesion that tested negative by PLA has a less than 1% chance of being melanoma. In addition, a study published in 2020 found that the addition of TERT (telomerase reverse transcriptase) mutation analyses increased the sensitivity of the PLA to 97%.

While the high negative predictive value is helpful to consider in clinical scenarios to rule-out melanoma for borderline lesions, one must consider the positive predictive value as well and how this may impact clinical care, Dr. Kim said. In a study examining outcomes of 381 lesions, 51 were PLA positive (single or double) and were biopsied, of which 19 (37%) revealed a melanoma diagnosis. In a large U.S. registry study of 3,418 lesions, 324 lesions that were PLA double positive were biopsied, with 18.7% revealing a melanoma diagnosis.

“No test is perfect, and this applies to PLA, even if you get a double-positive or double-negative test result,” Dr. Kim said. “You want to make sure that patients are aware of false positives and negatives. However, PLA could be an additional piece of data to inform your decision to proceed with biopsy on select borderline suspicious pigmented lesions. More studies are needed to better understand the approach to single- and double-positive PLA results.”

The PLA kit contains adhesive patches and supplies and a FedEx envelope for return to DermTech, the test’s manufacturer, for processing. The patches can be applied to lesions at least 4 mm in diameter; multiple kits are recommended for those greater than 16 mm in diameter. The test is not validated for lesions located on mucous membranes, palms, soles, nails, or on ulcerated or bleeding lesions, nor for those that have been previously biopsied. It is also not validated for use in pediatric patients or in those with skin types IV or higher. Results are returned in 2-3 days. If insurance does not cover the test, the cost to the patient is approximately $50 per lesion or a maximum of $150, according to Dr. Kim.

Use in clinical practice

In Dr. Kim’s clinical experience, the PLA can be considered for suspicious pigmented lesions on cosmetically sensitive areas and for suspicious lesions in areas difficult to biopsy or excise. For example, she discussed the case of a 72-year-old woman with a family history of melanoma, who presented to her clinic with a longstanding pigmented lesion on her right upper and lower eyelids that had previously been treated with laser. She had undergone multiple prior biopsies over 12 years, which caused mild to moderate atypical melanocytic proliferation. The PLA result was double negative for PRAME and LINC in her upper and lower eyelid, “which provided reassurance to the patient,” Dr. Kim said. The patient continues to be followed closely for any clinical changes.

Another patient, a 67-year-old woman, was referred to Dr. Kim from out of state for a teledermatology visit early in the COVID-19 pandemic. The patient had a lesion on her right calf that was hard, raised, and pink, did not resemble other lesions on her body, and had been present for a few weeks. “Her husband had recently passed away from brain cancer and she was very concerned about melanoma,” Dr. Kim recalled. “She lived alone, and the adult son was with her during the teledermatology call to assist. The patient asked about the PLA test, and given her difficulty going to a medical office at the time, we agreed to help her with this test.” The patient and her son arranged another teledermatology visit with Dr. Kim after receiving the kit in the mail from DermTech, and Dr. Kim coached them on how to properly administer the test. The results came back as PRAME negative and LINC positive. A biopsy with a local provider was recommended and the pathology results showed an inflamed seborrheic keratosis.

“This case exemplifies a false-positive result. We should be sure to make patients aware of this possibility,” Dr. Kim said.

Incorporating PLA into clinical practice requires certain workflow considerations, with paperwork to fill out in addition to performing the adhesive test, collection of insurance information, mailing the kit via FedEx, retrieving the results, and following up with the patient, said Dr. Kim. “For select borderline pigmented lesions, I discuss the rationale of the test with patients, the possibility of false-positive and false-negative results and the need to return for a biopsy when there is positive result. Clinical follow-up is recommended for negative results. There is also the possibility of charge to the patient if the test is not covered by their insurance.”

Skin biopsy still the gold standard

Despite the availability of the PLA as an assessment tool, Dr. Kim emphasized that skin biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosing melanoma. “Future prospective randomized clinical trials are needed to examine the role of genetic expression profiling in staging and managing patients,” she said.

In 2019, she and her colleagues surveyed 42 pigmented lesion experts in the United States about why they ordered one of three molecular tests on the market or not and how results affected patient treatment. The proportion of clinicians who ordered the tests ranged from 21% to 29%. The top 2 reasons respondents chose for not ordering the PLA test specifically were: “Feel that further validation studies are necessary” (20%) and “do not feel it would be useful in my practice” (18%).

Results of a larger follow-up survey on usage patterns of PLA of both pigmented lesion experts and general clinicians on this topic are expected to be published shortly.

Dr. Kim reported having no disclosures related to her presentation.

AT AAD 22

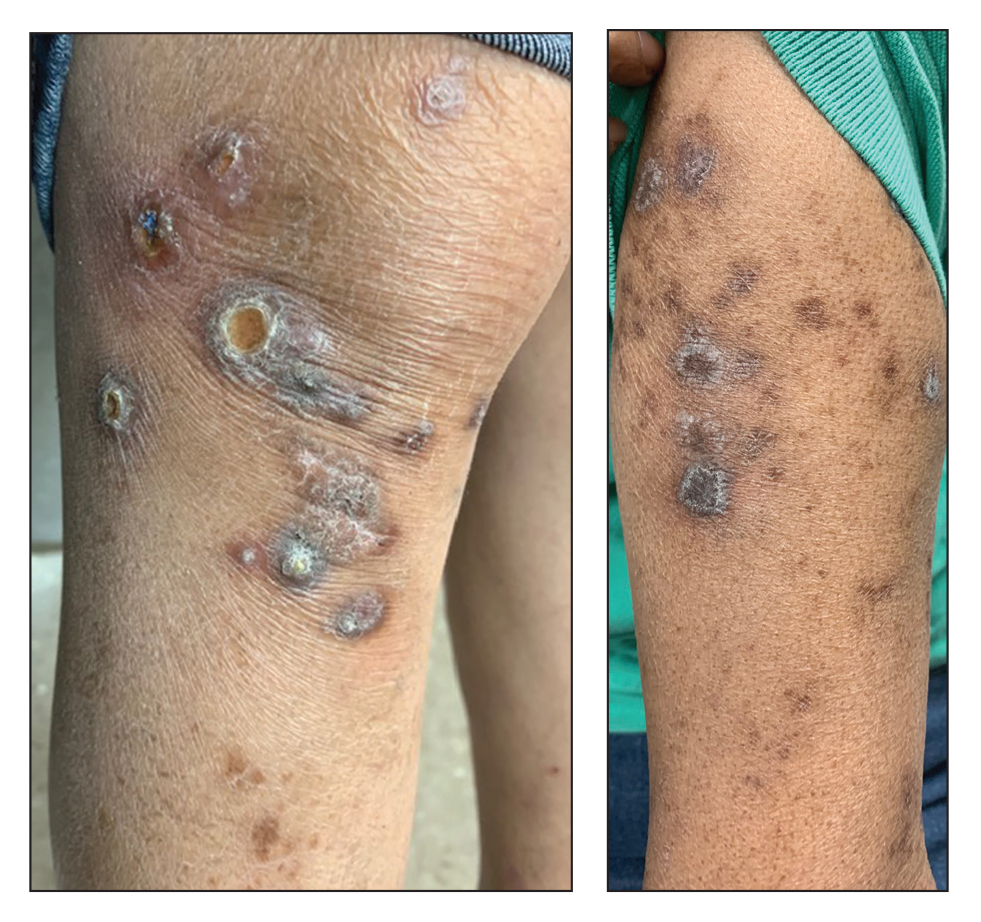

Ulcerating Nodule on the Foot

The Diagnosis: Perforating Rheumatoid Nodule

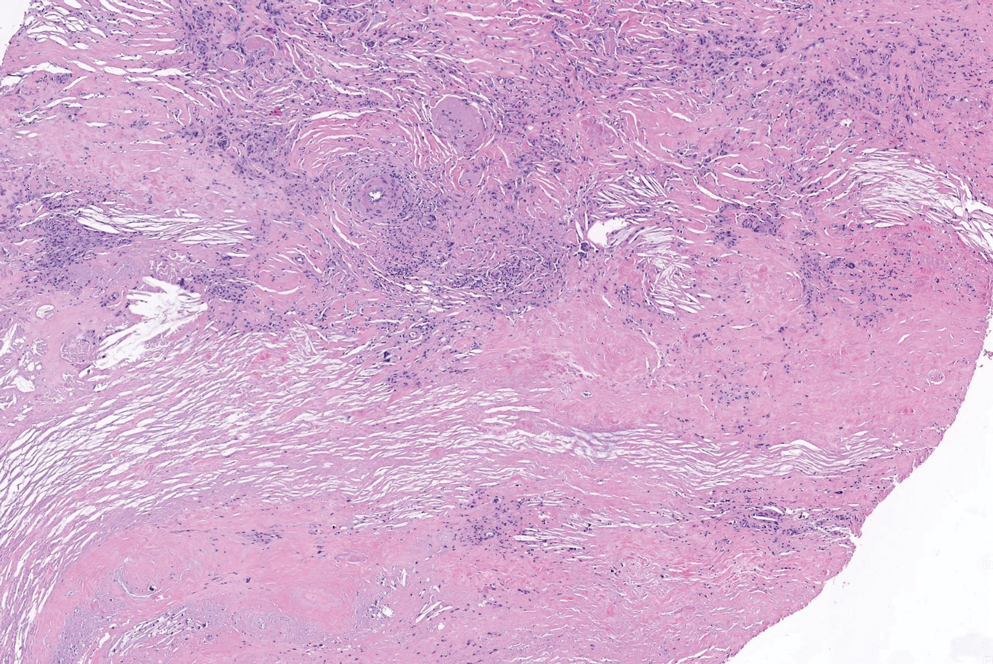

Perforating rheumatoid nodule (RN) is a variant of RN that demonstrates necrobiotic material extruding through the epidermis via the process of transepidermal elimination.1 The necrobiotic material contains fibrin and often harbors karyorrhectic debris. The pathogenesis of RN remains unclear; possible mechanisms include a small vessel vasculitis or mechanical trauma inciting a localized aggregation of inflammatory products and rheumatoid factor complexes. This induces macrophage activation, fibrin deposition, and necrosis.2 The majority of patients with RNs have detectable rheumatoid factor and anticyclic citrullinated protein in the blood.3 Rheumatoid nodules are the most common cutaneous manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and will develop in 30% to 40% of RA patients.4,5 They typically are associated with advanced RA but may precede the onset of clinically severe RA in 5% to 10% of patients.5 Rheumatoid nodules generally range in size from 2 mm to 5 cm and are slightly more prevalent in men than in women. They present as firm painless masses typically on the extensor surfaces of the hands and olecranon process but can occur over any tendinous or ligamentlike structure.6,7 Perforating RNs are most common on areas subjected to pressure or repeated trauma, such as the sacrum.

The diagnosis usually is clinical; however, in cases of diagnostic uncertainty, RN can be distinguished by its histologic appearance. Rheumatoid nodules demonstrate granulomatous palisading necrobiosis with a central zone of highly eosinophilic fibrinoid necrobiosis surrounded by palisading mononuclear cells and an outer zone of granulation tissue. There may be a mixed chronic inflammatory infiltrate predominantly composed of lymphocytes and histiocytes in the background.

Rheumatoid nodules typically do not require treatment; however, perforation is known to increase the risk for infection, and surgical excision generally is indicated for prophylaxis against infection, though nodules may recur in the excision area.1,3,8 Alternatively, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and intralesional corticosteroids may effectively reduce the size of RNs. The differential diagnosis for perforating RNs includes epithelioid sarcoma, perforating granuloma annulare, necrobiotic xanthogranuloma, and necrobiosis lipoidica.

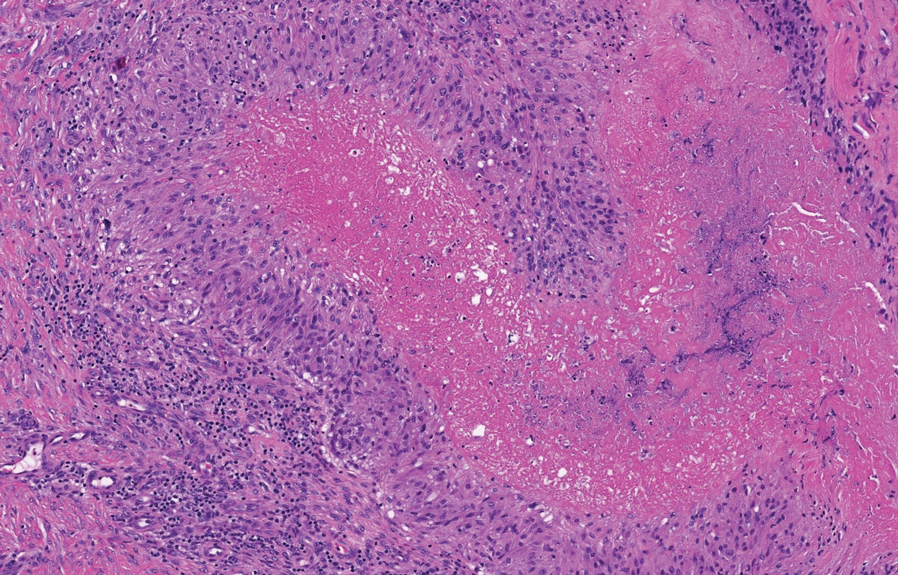

Epithelioid sarcoma is a malignant soft tissue tumor typically found on the upper extremities of adolescent or young adult males. They usually present as hard tender nodules that commonly ulcerate. Epithelioid sarcoma makes up less than 1% of soft tissue sarcomas.9 Although rare, they present a diagnostic pitfall, as the histology may mimic an inflammatory palisaded granulomatous dermatitis similar to RN and granuloma annulare, thus a high index of suspicion is required to not overlook this aggressive malignancy. Histology is typified by nodular aggregates of epithelioid cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and often with central zones of necrosis (Figure 1). Epithelioid sarcoma displays immunoreactivity to cytokeratin, CD34, and epithelial membrane antigen, but loss of integrase interactor 1 expression. Cytologic abnormalities such as pleomorphism and hyperchromatism can be helpful in distinguishing between epithelioid sarcoma and RN.

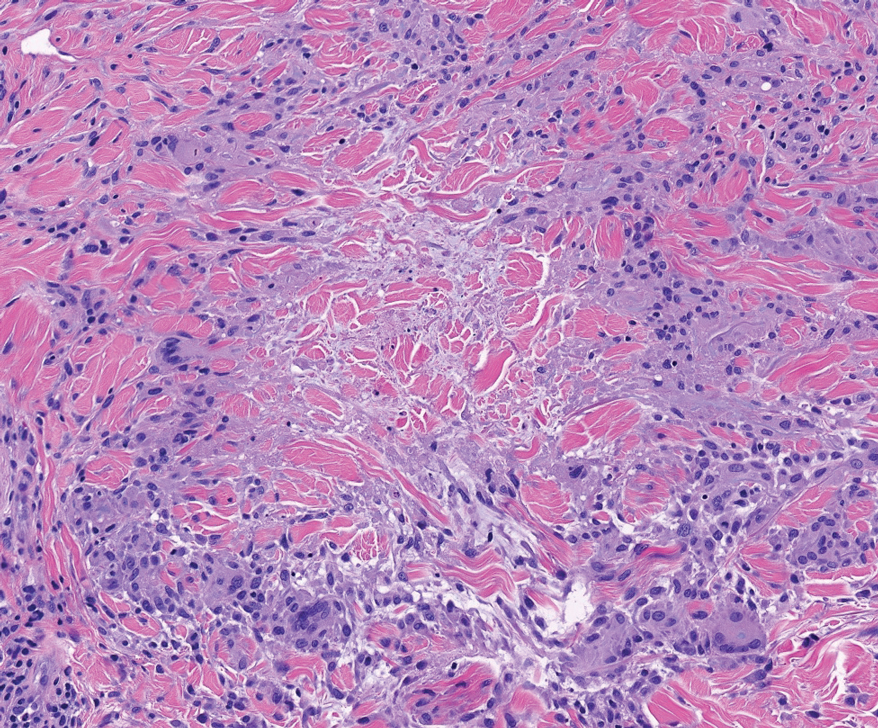

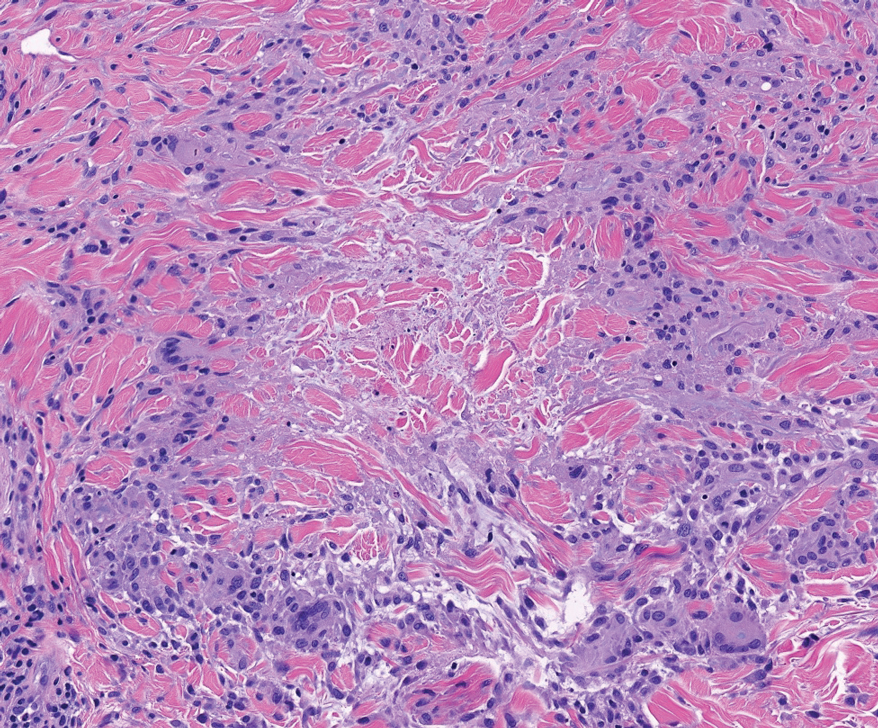

Perforating granuloma annulare is a rare subtype of granuloma annulare that presents with flesh- to red-colored papules that develop central crust or scale. Perforating granuloma annulare composes approximately 5% of granuloma annulare cases. Perforating granuloma annulare can develop on any region of the body but has an affinity for the extensor surfaces of the extremities. It most frequently occurs in young women and rarely presents as a single lesion.10 Granuloma annulare typically is not associated with joint pain, and thus it differs from most cases of RNs. Histologically, it presents with an inflammatory palisading granuloma. There may be overlying epidermal thinning or parakeratosis, which can progress to perforation and extrusion of necrobiotic material. In comparison with RN, perforating granuloma annulare displays mucin deposition in the necrobiotic zones in lieu of fibrin (Figure 2).10,11

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is a rare chronic form of non-Langerhans histiocytosis that characteristically presents with yellow or violaceous indurated plaques and nodules in a periorbital distribution. It often is associated with monoclonal gammopathy of IgG-κ. Lesions will ulcerate in 40% to 50% of patients.12 The mean age at presentation is in the sixth decade of life, and it is moderately predominant in females.13 Histopathology demonstrates palisading granulomatous formations with a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and zones of necrobiosis in the mid dermis extending into the panniculus. Characteristic histologic features that are variably present in necrobiotic xanthogranuloma but typically absent in RN include neutrophilic debris, cholesterol clefts, and Touton or foreign body giant cells (Figure 3).13

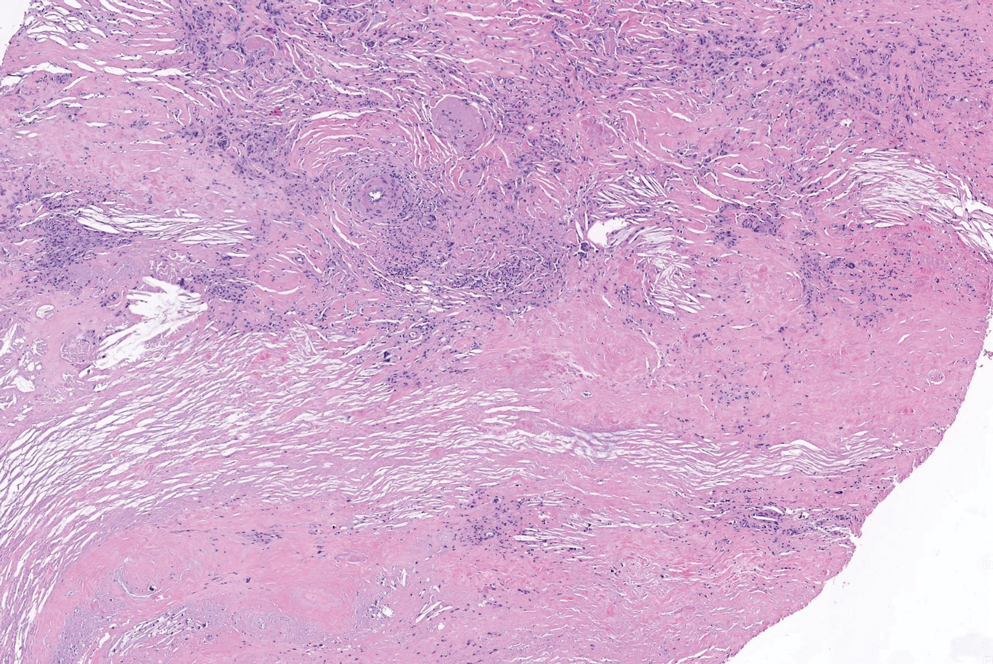

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a rare chronic granulomatous disease characterized by well-demarcated, atrophic, yellow-brown plaques on the pretibial surfaces. It typically presents in the third decade of life in women, and most cases are associated with diabetes mellitus types 1 or 2 or autoimmune conditions.14 Necrobiosis lipoidica begins as asymptomatic papules that enlarge progressively over months to years. They can become pruritic or painful and often develop ulceration. Histopathology shows horizontal zones of palisading histiocytes with intervening necrobiosis. An inflammatory infiltrate containing plasma cells also may be present (Figure 4).

- Horn RT Jr, Goette DK. Perforating rheumatoid nodule. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:696-697.

- Tilstra JS, Lienesch DW. Rheumatoid nodules. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:361-371. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.004

- Kaye BR, Kaye RL, Bobrove A. Rheumatoid nodules. review of the spectrum of associated conditions and proposal of a new classification, with a report of four seronegative cases. Am J Med. 1984;76:279-292. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(84)90787-3

- Nyhäll-Wåhlin BM, Jacobsson LT, Petersson IF, et al; BARFOT study group. Smoking is a strong risk factor for rheumatoid nodules in early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:601-606. doi:10.1136/ard.2005.039172

- Turesson C, O’Fallon WM, Crowson CS, et al. Occurrence of extraarticular disease manifestations is associated with excess mortality in a community-based cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:62-67.

- Bang S, Kim Y, Jang K, et al. Clinicopathologic features of rheumatoid nodules: a retrospective analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38:3041-3048. doi:10.1007/s10067-019-04668-1

- Chaganti S, Joshy S, Hariharan K, et al. Rheumatoid nodule presenting as Morton’s neuroma. J Orthop Traumatol. 2013;14:219-222. doi:10.1007/s10195-012-0215-x

- Sayah A, English JC 3rd. Rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:191-209; quiz 210-212. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.07.023

- de Visscher SA, van Ginkel RJ, Wobbes T, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma: still an only surgically curable disease. Cancer. 2006;107:606-612. doi:10.1002/cncr.22037

- Penas PF, Jones-Caballero M, Fraga J, et al. Perforating granuloma annulare. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:340-348. doi:10.1046 /j.1365-4362.1997.00047.x

- Gale M, Gilbert E, Blumenthal D. Isolated rheumatoid nodules: a diagnostic dilemma. Case Rep Med. 2015;2015:352352. doi:10.1155/2015/352352

- Wood AJ, Wagner MV, Abbott JJ, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: a review of 17 cases with emphasis on clinical and pathologic correlation. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:279-284. doi:10.1001 /archdermatol.2008.583

- Nelson CA, Zhong CS, Hashemi DA, et al. A multicenter crosssectional study and systematic review of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with proposed diagnostic criteria. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:270-279. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4221

- Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:343-360. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.003

The Diagnosis: Perforating Rheumatoid Nodule

Perforating rheumatoid nodule (RN) is a variant of RN that demonstrates necrobiotic material extruding through the epidermis via the process of transepidermal elimination.1 The necrobiotic material contains fibrin and often harbors karyorrhectic debris. The pathogenesis of RN remains unclear; possible mechanisms include a small vessel vasculitis or mechanical trauma inciting a localized aggregation of inflammatory products and rheumatoid factor complexes. This induces macrophage activation, fibrin deposition, and necrosis.2 The majority of patients with RNs have detectable rheumatoid factor and anticyclic citrullinated protein in the blood.3 Rheumatoid nodules are the most common cutaneous manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and will develop in 30% to 40% of RA patients.4,5 They typically are associated with advanced RA but may precede the onset of clinically severe RA in 5% to 10% of patients.5 Rheumatoid nodules generally range in size from 2 mm to 5 cm and are slightly more prevalent in men than in women. They present as firm painless masses typically on the extensor surfaces of the hands and olecranon process but can occur over any tendinous or ligamentlike structure.6,7 Perforating RNs are most common on areas subjected to pressure or repeated trauma, such as the sacrum.

The diagnosis usually is clinical; however, in cases of diagnostic uncertainty, RN can be distinguished by its histologic appearance. Rheumatoid nodules demonstrate granulomatous palisading necrobiosis with a central zone of highly eosinophilic fibrinoid necrobiosis surrounded by palisading mononuclear cells and an outer zone of granulation tissue. There may be a mixed chronic inflammatory infiltrate predominantly composed of lymphocytes and histiocytes in the background.

Rheumatoid nodules typically do not require treatment; however, perforation is known to increase the risk for infection, and surgical excision generally is indicated for prophylaxis against infection, though nodules may recur in the excision area.1,3,8 Alternatively, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and intralesional corticosteroids may effectively reduce the size of RNs. The differential diagnosis for perforating RNs includes epithelioid sarcoma, perforating granuloma annulare, necrobiotic xanthogranuloma, and necrobiosis lipoidica.

Epithelioid sarcoma is a malignant soft tissue tumor typically found on the upper extremities of adolescent or young adult males. They usually present as hard tender nodules that commonly ulcerate. Epithelioid sarcoma makes up less than 1% of soft tissue sarcomas.9 Although rare, they present a diagnostic pitfall, as the histology may mimic an inflammatory palisaded granulomatous dermatitis similar to RN and granuloma annulare, thus a high index of suspicion is required to not overlook this aggressive malignancy. Histology is typified by nodular aggregates of epithelioid cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and often with central zones of necrosis (Figure 1). Epithelioid sarcoma displays immunoreactivity to cytokeratin, CD34, and epithelial membrane antigen, but loss of integrase interactor 1 expression. Cytologic abnormalities such as pleomorphism and hyperchromatism can be helpful in distinguishing between epithelioid sarcoma and RN.

Perforating granuloma annulare is a rare subtype of granuloma annulare that presents with flesh- to red-colored papules that develop central crust or scale. Perforating granuloma annulare composes approximately 5% of granuloma annulare cases. Perforating granuloma annulare can develop on any region of the body but has an affinity for the extensor surfaces of the extremities. It most frequently occurs in young women and rarely presents as a single lesion.10 Granuloma annulare typically is not associated with joint pain, and thus it differs from most cases of RNs. Histologically, it presents with an inflammatory palisading granuloma. There may be overlying epidermal thinning or parakeratosis, which can progress to perforation and extrusion of necrobiotic material. In comparison with RN, perforating granuloma annulare displays mucin deposition in the necrobiotic zones in lieu of fibrin (Figure 2).10,11

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is a rare chronic form of non-Langerhans histiocytosis that characteristically presents with yellow or violaceous indurated plaques and nodules in a periorbital distribution. It often is associated with monoclonal gammopathy of IgG-κ. Lesions will ulcerate in 40% to 50% of patients.12 The mean age at presentation is in the sixth decade of life, and it is moderately predominant in females.13 Histopathology demonstrates palisading granulomatous formations with a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and zones of necrobiosis in the mid dermis extending into the panniculus. Characteristic histologic features that are variably present in necrobiotic xanthogranuloma but typically absent in RN include neutrophilic debris, cholesterol clefts, and Touton or foreign body giant cells (Figure 3).13

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a rare chronic granulomatous disease characterized by well-demarcated, atrophic, yellow-brown plaques on the pretibial surfaces. It typically presents in the third decade of life in women, and most cases are associated with diabetes mellitus types 1 or 2 or autoimmune conditions.14 Necrobiosis lipoidica begins as asymptomatic papules that enlarge progressively over months to years. They can become pruritic or painful and often develop ulceration. Histopathology shows horizontal zones of palisading histiocytes with intervening necrobiosis. An inflammatory infiltrate containing plasma cells also may be present (Figure 4).

The Diagnosis: Perforating Rheumatoid Nodule

Perforating rheumatoid nodule (RN) is a variant of RN that demonstrates necrobiotic material extruding through the epidermis via the process of transepidermal elimination.1 The necrobiotic material contains fibrin and often harbors karyorrhectic debris. The pathogenesis of RN remains unclear; possible mechanisms include a small vessel vasculitis or mechanical trauma inciting a localized aggregation of inflammatory products and rheumatoid factor complexes. This induces macrophage activation, fibrin deposition, and necrosis.2 The majority of patients with RNs have detectable rheumatoid factor and anticyclic citrullinated protein in the blood.3 Rheumatoid nodules are the most common cutaneous manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and will develop in 30% to 40% of RA patients.4,5 They typically are associated with advanced RA but may precede the onset of clinically severe RA in 5% to 10% of patients.5 Rheumatoid nodules generally range in size from 2 mm to 5 cm and are slightly more prevalent in men than in women. They present as firm painless masses typically on the extensor surfaces of the hands and olecranon process but can occur over any tendinous or ligamentlike structure.6,7 Perforating RNs are most common on areas subjected to pressure or repeated trauma, such as the sacrum.

The diagnosis usually is clinical; however, in cases of diagnostic uncertainty, RN can be distinguished by its histologic appearance. Rheumatoid nodules demonstrate granulomatous palisading necrobiosis with a central zone of highly eosinophilic fibrinoid necrobiosis surrounded by palisading mononuclear cells and an outer zone of granulation tissue. There may be a mixed chronic inflammatory infiltrate predominantly composed of lymphocytes and histiocytes in the background.

Rheumatoid nodules typically do not require treatment; however, perforation is known to increase the risk for infection, and surgical excision generally is indicated for prophylaxis against infection, though nodules may recur in the excision area.1,3,8 Alternatively, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and intralesional corticosteroids may effectively reduce the size of RNs. The differential diagnosis for perforating RNs includes epithelioid sarcoma, perforating granuloma annulare, necrobiotic xanthogranuloma, and necrobiosis lipoidica.

Epithelioid sarcoma is a malignant soft tissue tumor typically found on the upper extremities of adolescent or young adult males. They usually present as hard tender nodules that commonly ulcerate. Epithelioid sarcoma makes up less than 1% of soft tissue sarcomas.9 Although rare, they present a diagnostic pitfall, as the histology may mimic an inflammatory palisaded granulomatous dermatitis similar to RN and granuloma annulare, thus a high index of suspicion is required to not overlook this aggressive malignancy. Histology is typified by nodular aggregates of epithelioid cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and often with central zones of necrosis (Figure 1). Epithelioid sarcoma displays immunoreactivity to cytokeratin, CD34, and epithelial membrane antigen, but loss of integrase interactor 1 expression. Cytologic abnormalities such as pleomorphism and hyperchromatism can be helpful in distinguishing between epithelioid sarcoma and RN.

Perforating granuloma annulare is a rare subtype of granuloma annulare that presents with flesh- to red-colored papules that develop central crust or scale. Perforating granuloma annulare composes approximately 5% of granuloma annulare cases. Perforating granuloma annulare can develop on any region of the body but has an affinity for the extensor surfaces of the extremities. It most frequently occurs in young women and rarely presents as a single lesion.10 Granuloma annulare typically is not associated with joint pain, and thus it differs from most cases of RNs. Histologically, it presents with an inflammatory palisading granuloma. There may be overlying epidermal thinning or parakeratosis, which can progress to perforation and extrusion of necrobiotic material. In comparison with RN, perforating granuloma annulare displays mucin deposition in the necrobiotic zones in lieu of fibrin (Figure 2).10,11

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is a rare chronic form of non-Langerhans histiocytosis that characteristically presents with yellow or violaceous indurated plaques and nodules in a periorbital distribution. It often is associated with monoclonal gammopathy of IgG-κ. Lesions will ulcerate in 40% to 50% of patients.12 The mean age at presentation is in the sixth decade of life, and it is moderately predominant in females.13 Histopathology demonstrates palisading granulomatous formations with a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and zones of necrobiosis in the mid dermis extending into the panniculus. Characteristic histologic features that are variably present in necrobiotic xanthogranuloma but typically absent in RN include neutrophilic debris, cholesterol clefts, and Touton or foreign body giant cells (Figure 3).13

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a rare chronic granulomatous disease characterized by well-demarcated, atrophic, yellow-brown plaques on the pretibial surfaces. It typically presents in the third decade of life in women, and most cases are associated with diabetes mellitus types 1 or 2 or autoimmune conditions.14 Necrobiosis lipoidica begins as asymptomatic papules that enlarge progressively over months to years. They can become pruritic or painful and often develop ulceration. Histopathology shows horizontal zones of palisading histiocytes with intervening necrobiosis. An inflammatory infiltrate containing plasma cells also may be present (Figure 4).

- Horn RT Jr, Goette DK. Perforating rheumatoid nodule. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:696-697.

- Tilstra JS, Lienesch DW. Rheumatoid nodules. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:361-371. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.004

- Kaye BR, Kaye RL, Bobrove A. Rheumatoid nodules. review of the spectrum of associated conditions and proposal of a new classification, with a report of four seronegative cases. Am J Med. 1984;76:279-292. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(84)90787-3

- Nyhäll-Wåhlin BM, Jacobsson LT, Petersson IF, et al; BARFOT study group. Smoking is a strong risk factor for rheumatoid nodules in early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:601-606. doi:10.1136/ard.2005.039172

- Turesson C, O’Fallon WM, Crowson CS, et al. Occurrence of extraarticular disease manifestations is associated with excess mortality in a community-based cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:62-67.

- Bang S, Kim Y, Jang K, et al. Clinicopathologic features of rheumatoid nodules: a retrospective analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38:3041-3048. doi:10.1007/s10067-019-04668-1

- Chaganti S, Joshy S, Hariharan K, et al. Rheumatoid nodule presenting as Morton’s neuroma. J Orthop Traumatol. 2013;14:219-222. doi:10.1007/s10195-012-0215-x

- Sayah A, English JC 3rd. Rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:191-209; quiz 210-212. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.07.023