User login

Deployed Airbag Causes Bullous Reaction Following a Motor Vehicle Accident

Airbags are lifesaving during motor vehicle accidents (MVAs), but their deployment has been associated with skin issues such as irritant dermatitis1; lacerations2; abrasions3; and thermal, friction, and chemical burns.4-6 Ocular issues such as alkaline chemical keratitis7 and ocular alkali injuries8 also have been described.

Airbag deployment is triggered by rapid deceleration and impact, which ignite a sodium azide cartridge, causing the woven nylon bag to inflate with hydrocarbon gases.8 This leads to release of sodium hydroxide, sodium bicarbonate, and metallic oxides in an aerosolized form. If a tear in the meshwork of the airbag occurs, exposure to an even larger amount of powder containing caustic alkali chemicals can occur.8

We describe a patient who developed a bullous reaction to airbag contents after he was involved in an MVA in which the airbag deployed.

Case Report

A 35-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic hepatitis B presented to the dermatology clinic for an evaluation of new-onset blisters. The rash occurred 1 day after the patient was involved in an MVA in which he was exposed to the airbag’s contents after it burst. He had been evaluated twice in the emergency department for the skin eruption before being referred to dermatology. He noted the lesions were pruritic and painful. Prior treatments included silver sulfadiazine cream 1% and clobetasol cream 0.05%, though he discontinued using the latter because of burning with application. Physical examination revealed tense vesicles and bullae on an erythematous base on the right lower flank, forearms, and legs, with the exception of the lower right leg where a cast had been from a prior injury (Figure 1).

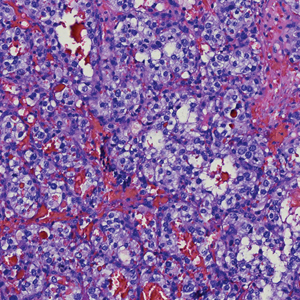

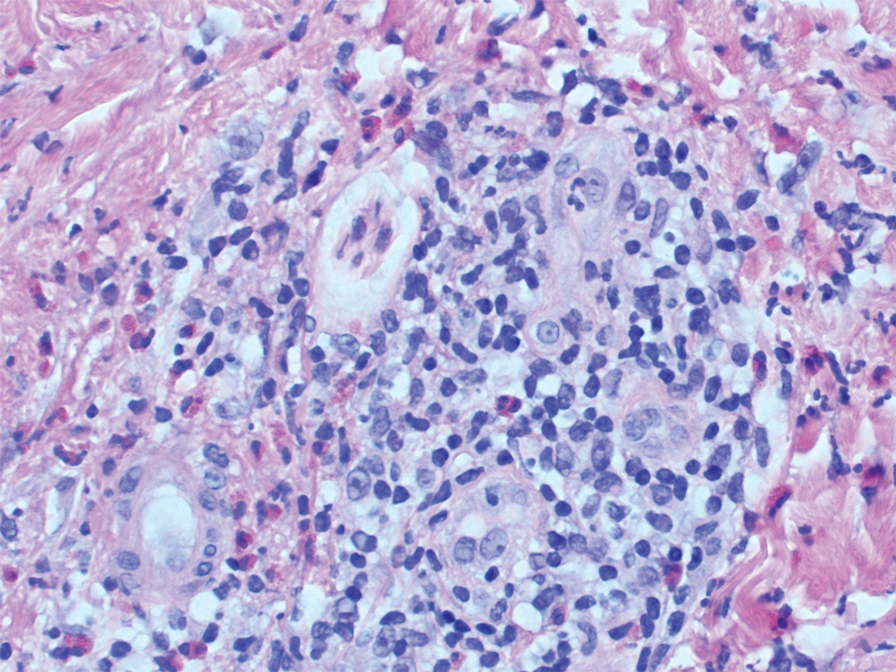

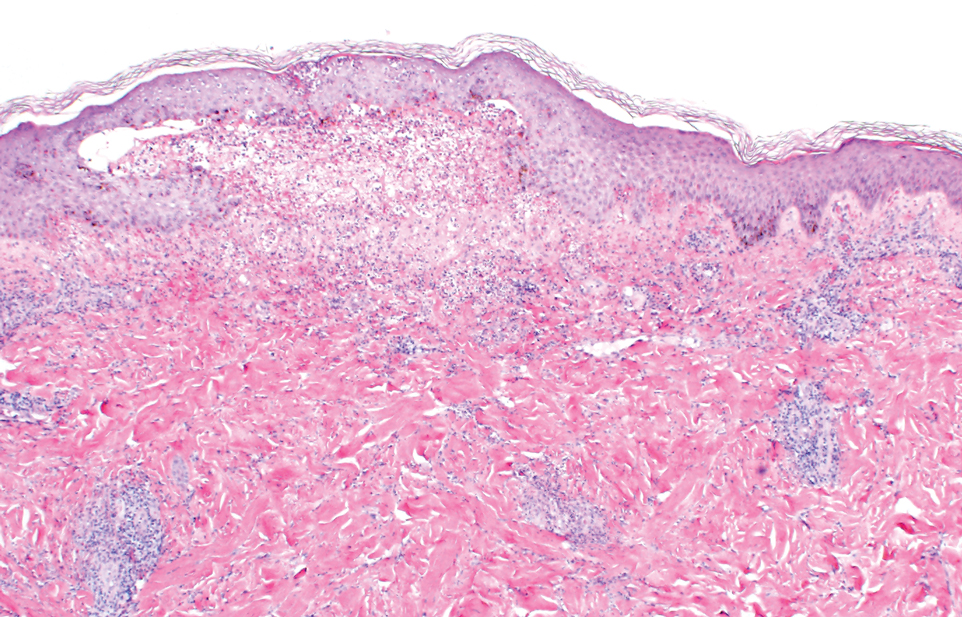

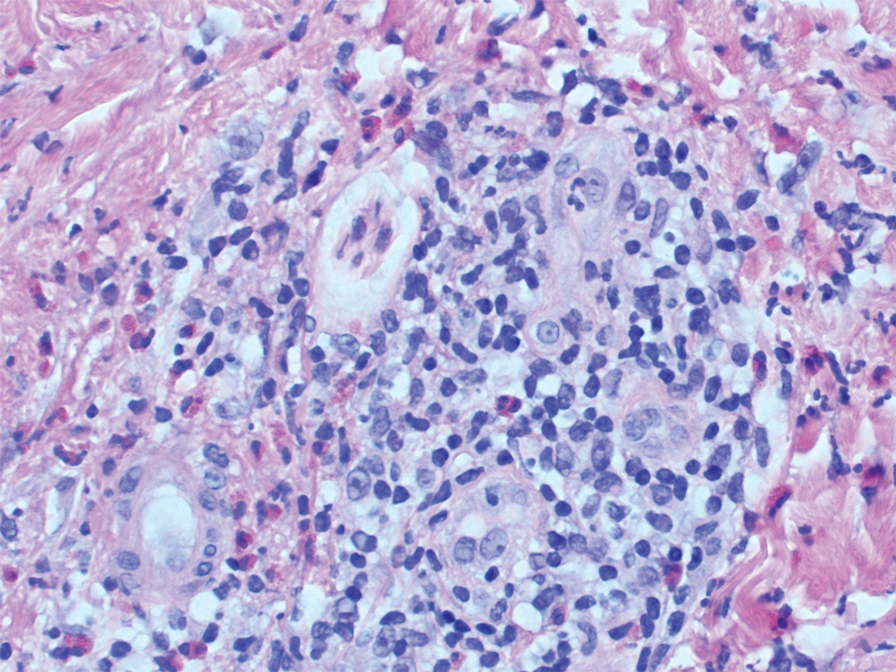

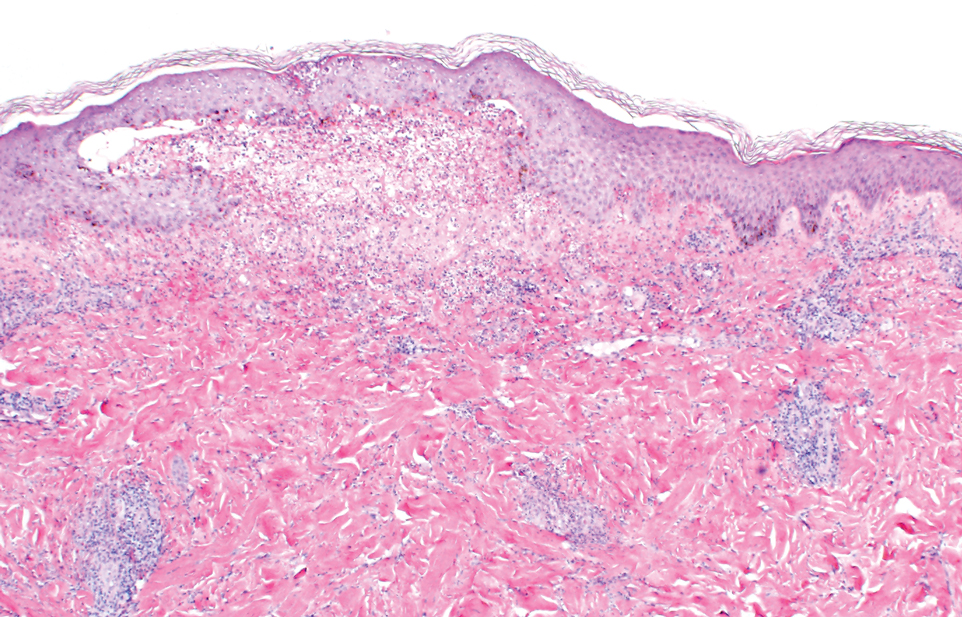

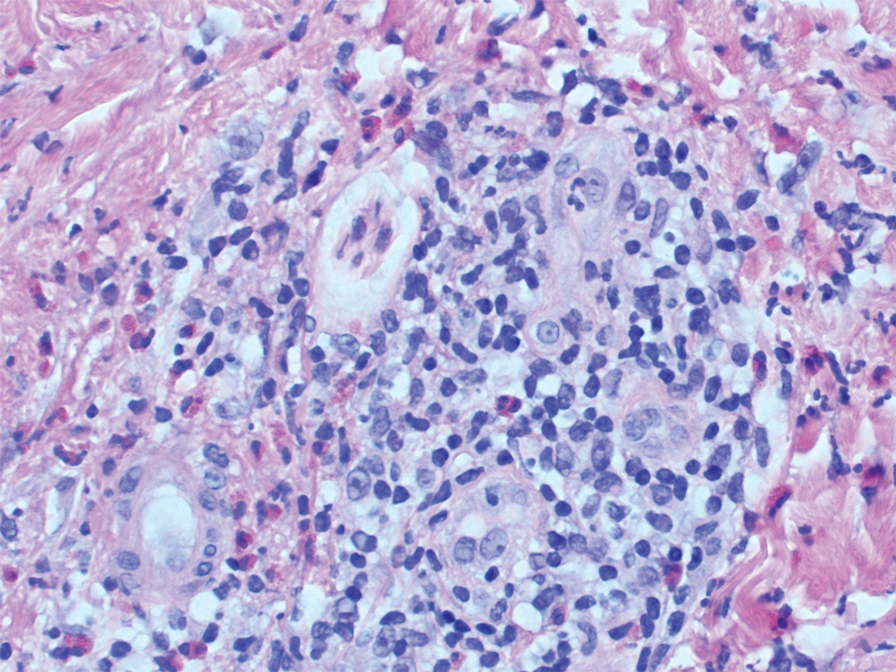

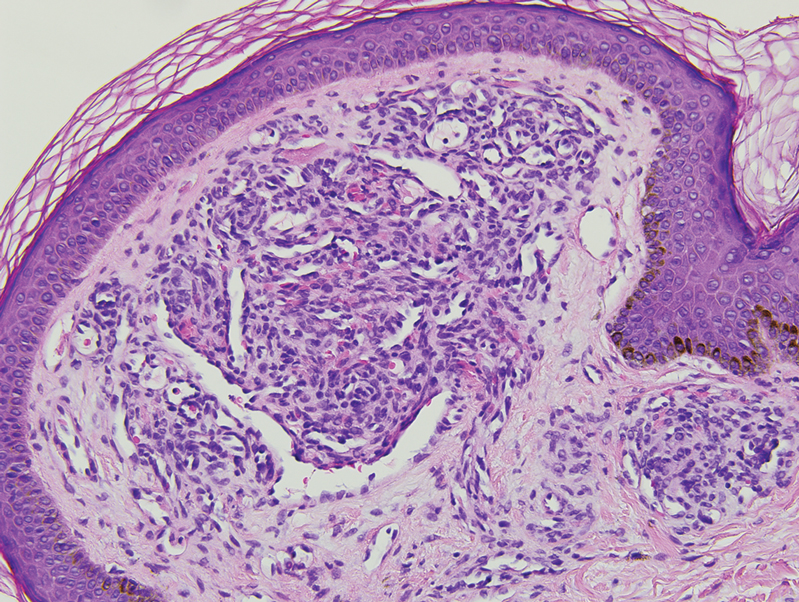

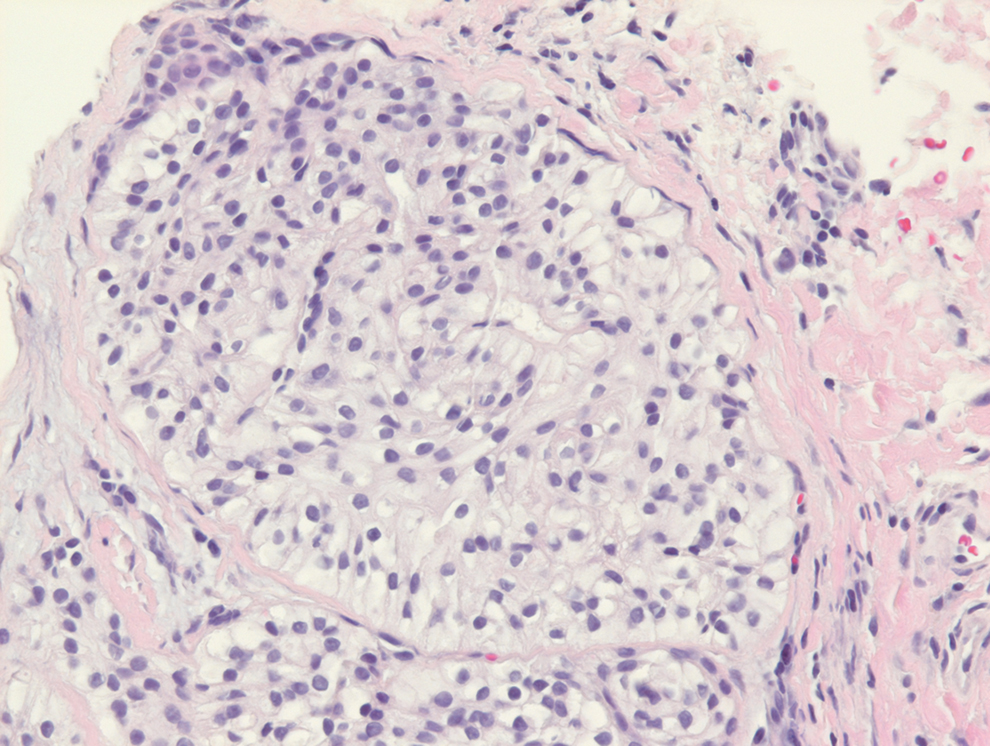

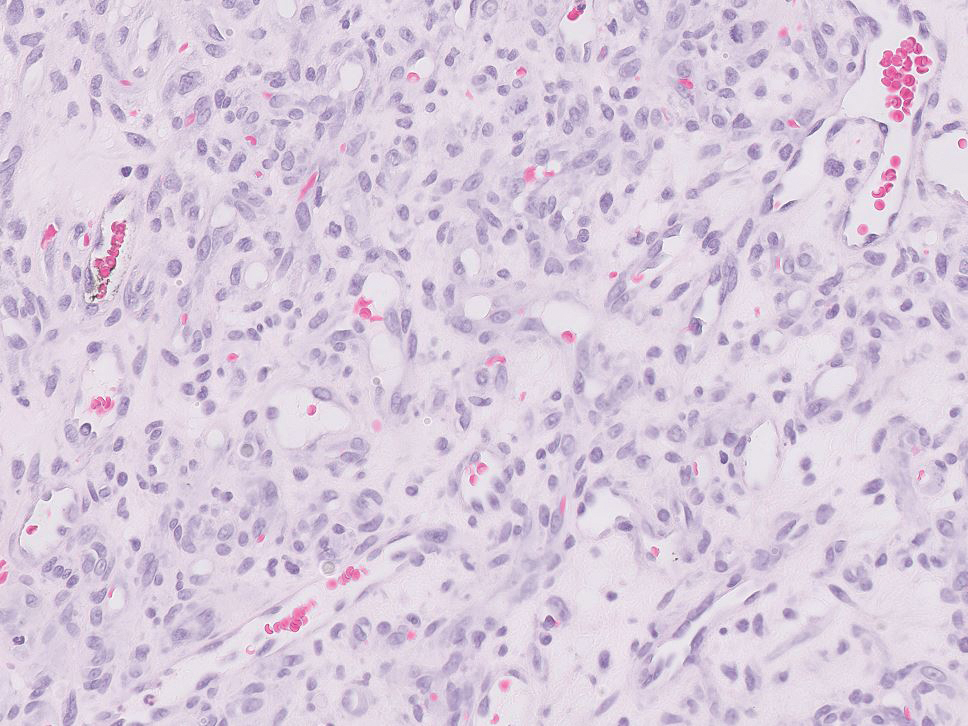

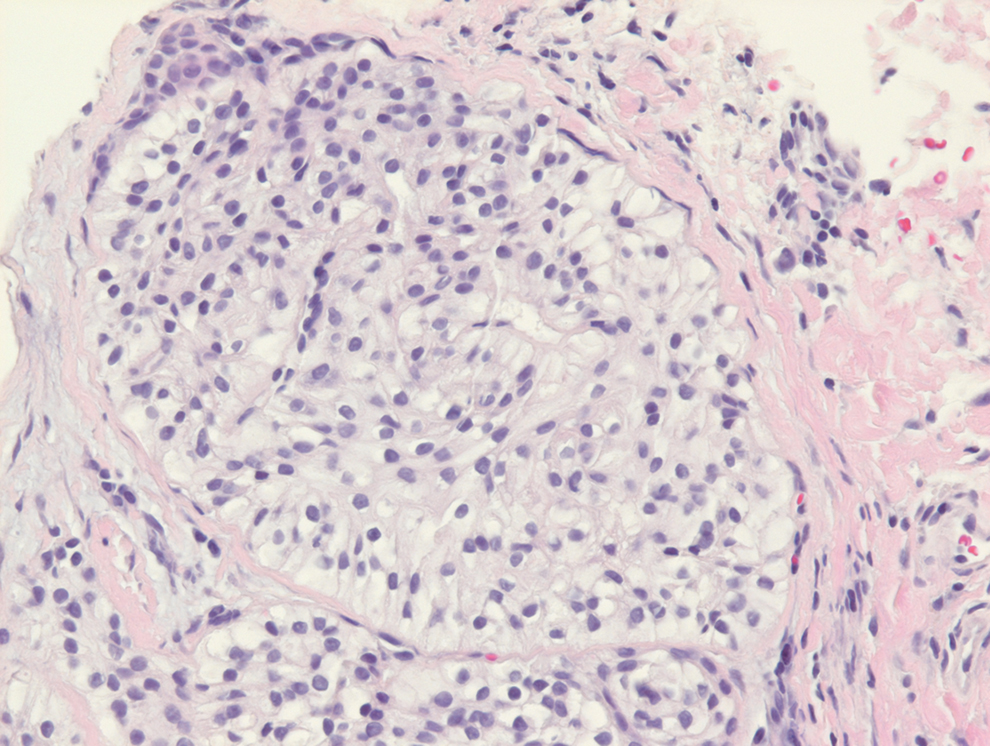

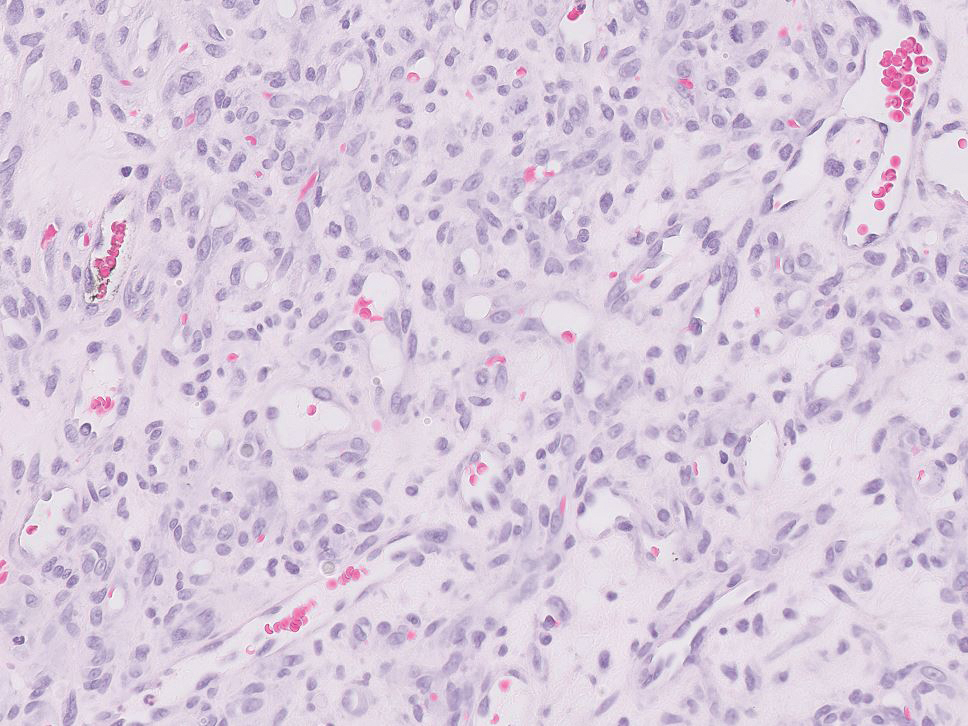

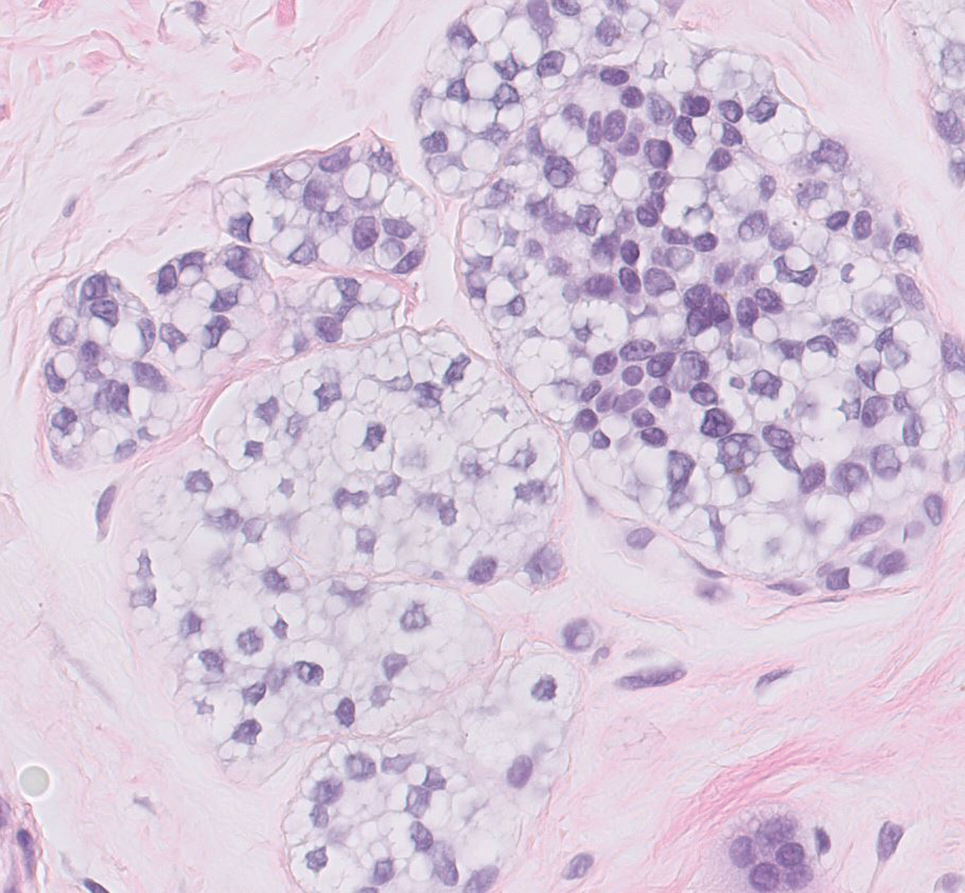

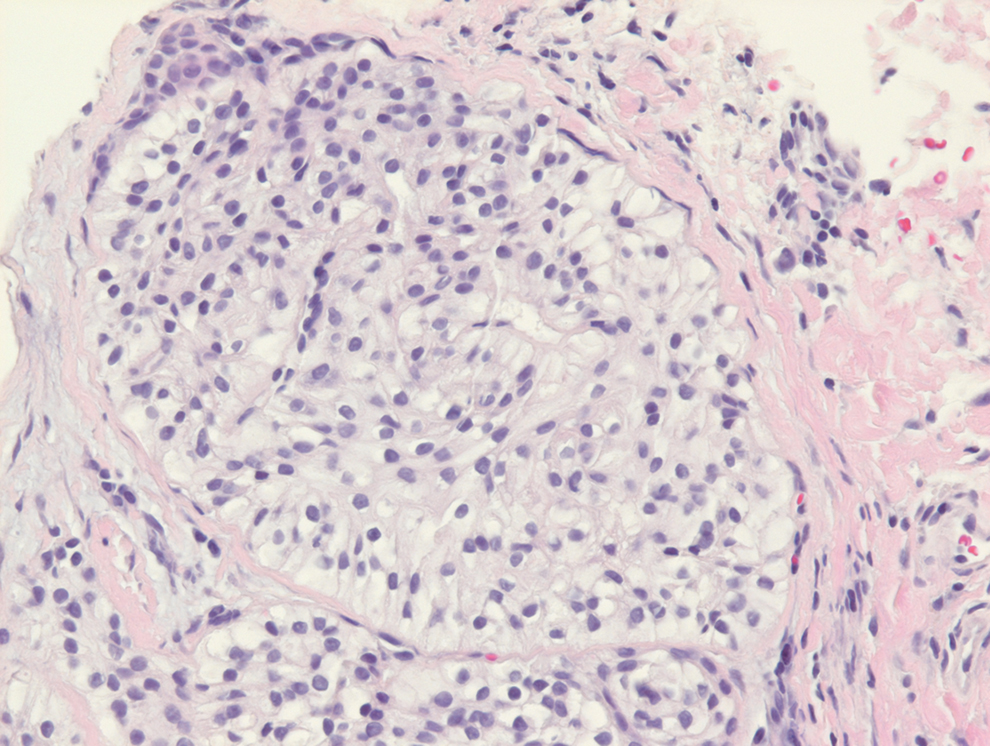

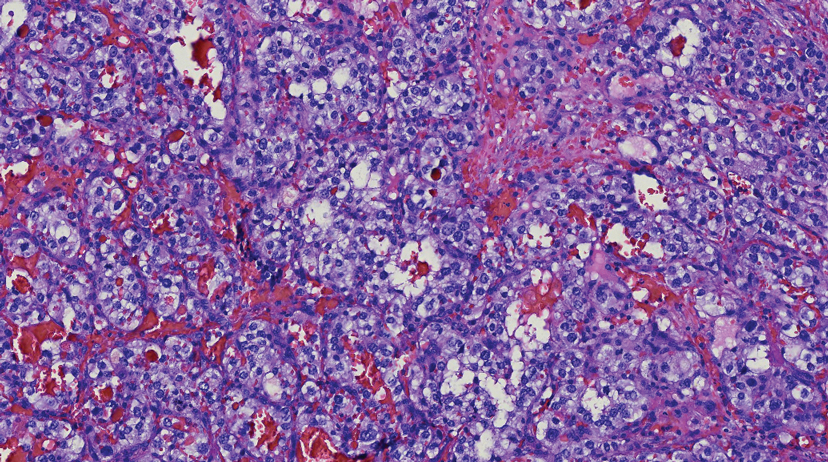

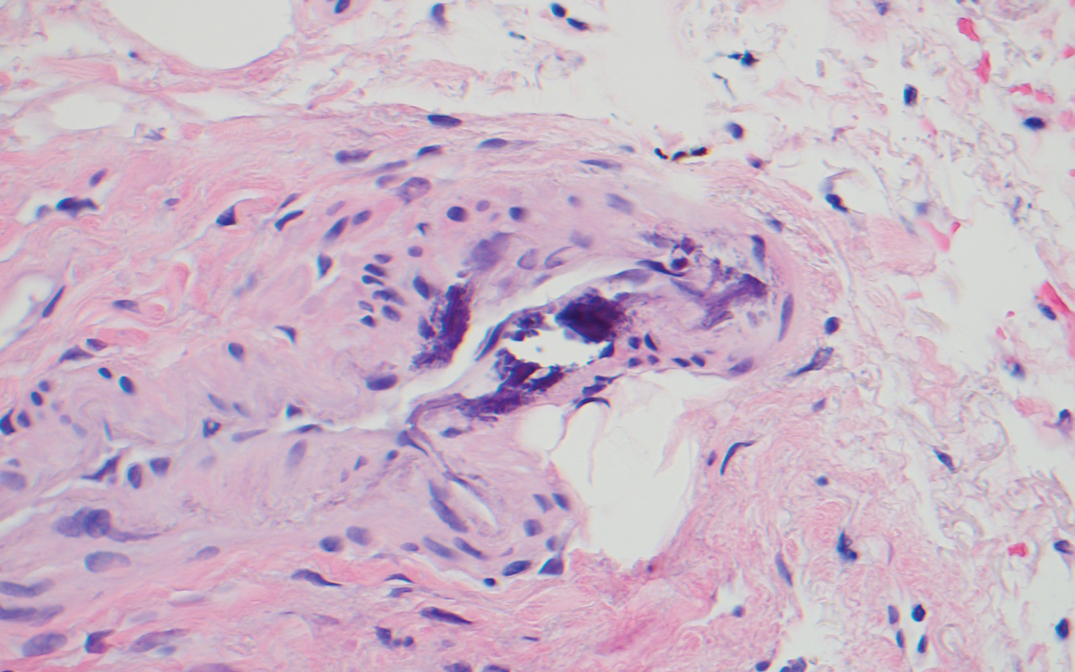

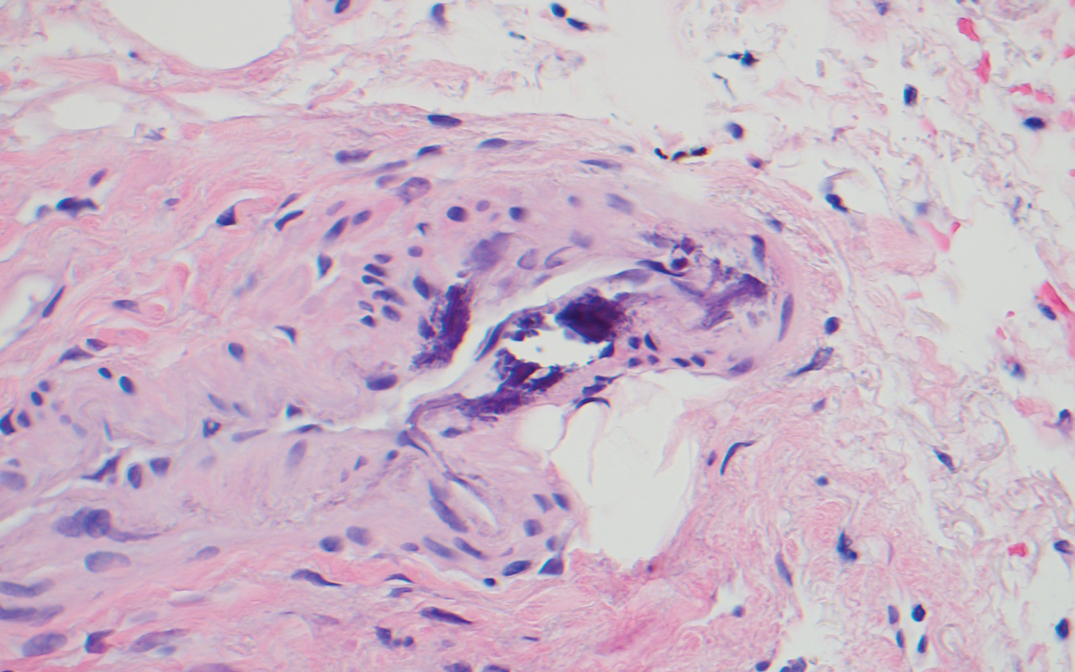

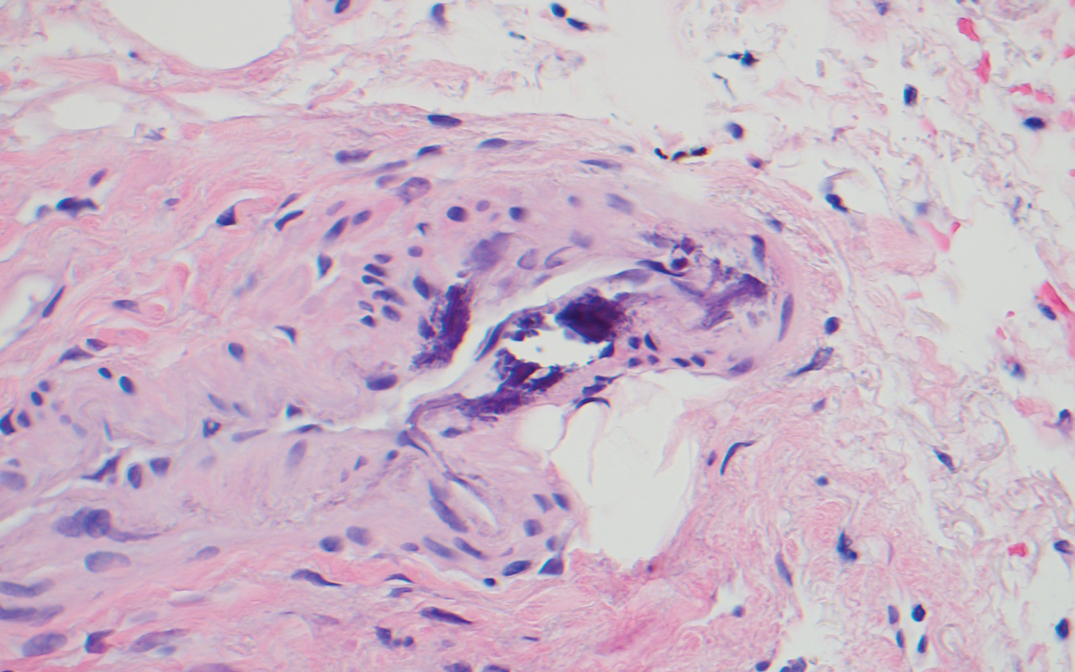

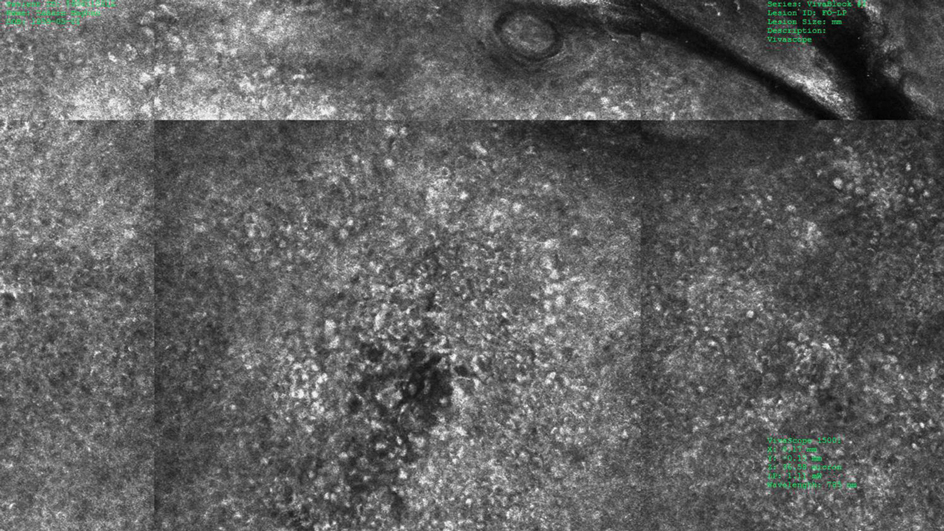

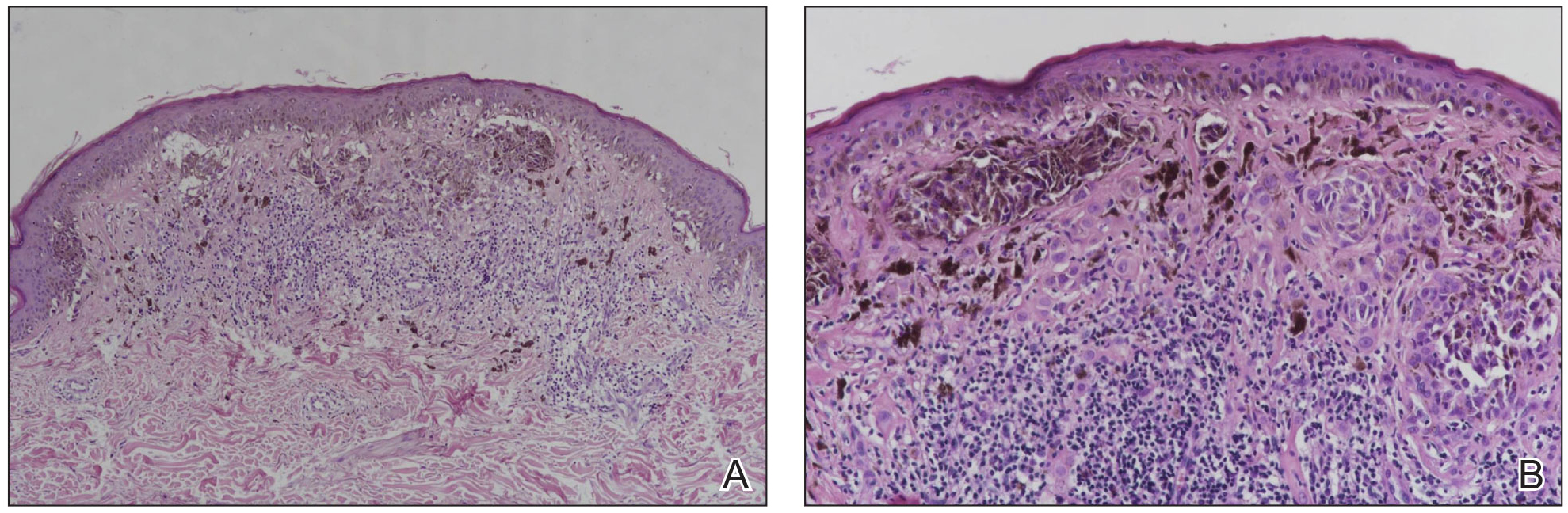

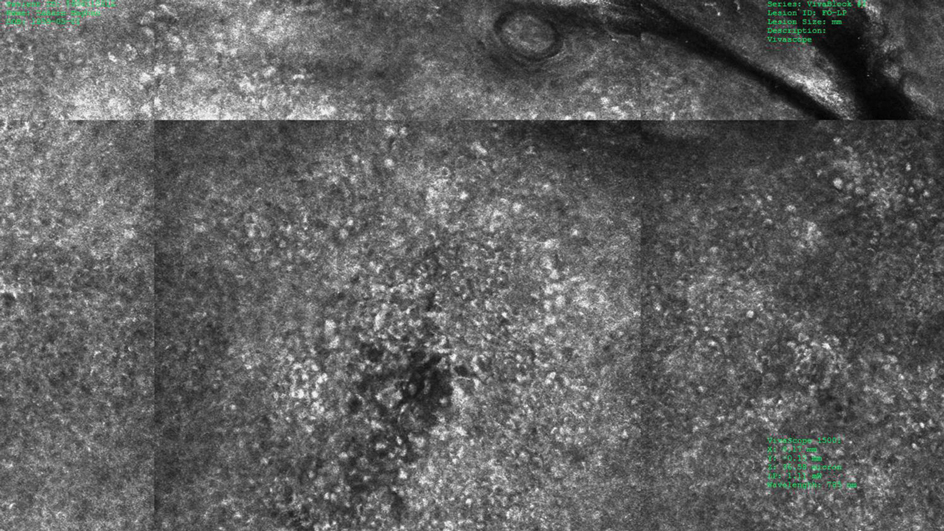

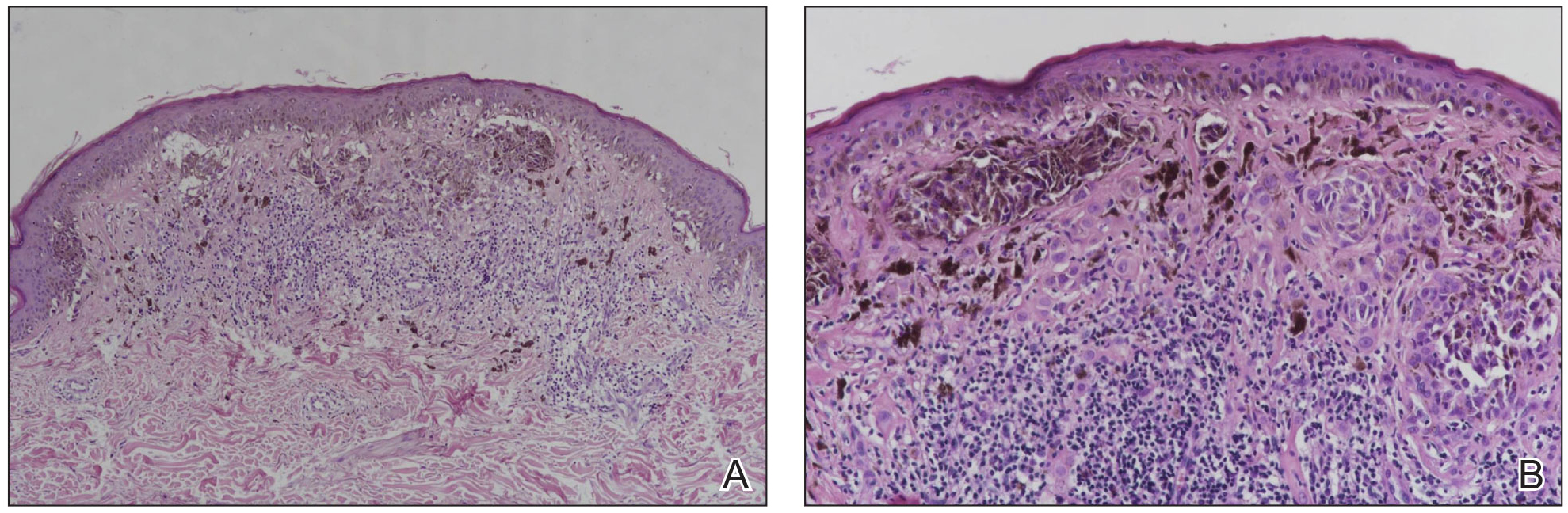

Two punch biopsies of the left arm were performed and sent for hematoxylin and eosin staining and direct immunofluorescence to rule out bullous diseases, such as bullous pemphigoid, linear IgA, and bullous lupus. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed extensive spongiosis with blister formation and a dense perivascular infiltrate in the superficial and mid dermis composed of lymphocytes with numerous scattered eosinophils (Figures 2 and 3). Direct immunofluorescence studies were negative. Treatment with oral prednisone and oral antihistamines was initiated.

At 10-day follow-up, the patient had a few residual bullae; most lesions were demonstrating various stages of healing (Figure 4). The patient’s cast had been removed, and there were no lesions in this previously covered area. At 6-week follow-up he had continued healing of the bullae and erosions as well as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (Figure 5).

Comment

With the advent of airbags for safety purposes, these potentially lifesaving devices also have been known to cause injury.9 In 1998, the most commonly reported airbag injuries were ocular injuries.10 Cutaneous manifestations of airbag injury are less well known.11

Two cases of airbag deployment with skin blistering have been reported in the literature based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms airbag blistering or airbag bullae12,13; however, the blistering was described in the context of a burn. One case of the effects of airbag deployment residue highlights a patient arriving to the emergency department with erythema and blisters on the hands within 48 hours of airbag deployment in an MVA, and the treatment was standard burn therapy.12 Another case report described a patient with a second-degree burn with a 12-cm blister occurring on the radial side of the hand and distal forearm following an MVA and airbag deployment, which was treated conservatively.13 Cases of thermal burns, chemical burns, and irritant contact dermatitis after airbag deployment have been described in the literature.4-6,11,12,14,15 Our patient’s distal right lower leg was covered with a cast for osteomyelitis, and no blisters had developed in this area. It is likely that the transfer of airbag contents occurred during the process of unbuckling his seatbelt, which could explain the bullae that developed on the right flank. Per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, individuals should quickly remove clothing and wash their body with large amounts of soap and water following exposure to sodium azide.16

In 1989, the Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard No. 208 (occupant crash protection) became effective, stating all cars must have vehicle crash protection.12 Prior to 1993, it was reported that there had been no associated chemical injuries with airbag deployment. Subsequently, a 6-month retrospective study in 1993 showed that dermal injuries were found in connection with the presence of sodium hydroxide in automobile airbags.12 By 2004, it was known that airbags could cause chemical and thermal burns in addition to traumatic injuries from deployment.1 Since 2007, all motor vehicles have been required to have advanced airbags, which are engineered to sense the presence of passengers and determine if the airbag will deploy, and if so, how much to deploy to minimize airbag-related injury.3

The brand of car that our patient drove during the MVA is one with known airbag recalls due to safety defects; however, the year and actual model of the vehicle are not known, so specific information about the airbag in question is not available. It has been noted that some defective airbag inflators that were exposed to excess moisture during the manufacturing process could explode during deployment, causing shrapnel and airbag rupture, which has been linked to nearly 300 injuries worldwide.17

Conclusion

It is evident that the use of airbag devices reduces morbidity and mortality due to MVAs.9 It also had been reported that up to 96% of airbag-related injuries are relatively minor, which many would argue justifies their use.18 Furthermore, it has been reported that 99.8% of skin injuries following airbag deployment are minor.19 In the United States, it is mandated that every vehicle have functional airbags installed.8

This case highlights the potential for substantial airbag-induced skin reactions, specifically a bullous reaction, following airbag deployment. The persistent pruritus and lasting postinflammatory hyperpigmentation seen in this case were certainly worrisome for our patient. We also present this case to remind dermatology providers of possible treatment approaches to these skin reactions. Immediate cleansing of the affected areas of skin may help avoid such reactions.

- Corazza M, Trincone S, Zampino MR, et al. Air bags and the skin. Skinmed. 2004;3:256-258.

- Corazza M, Trincone S, Virgili A. Effects of airbag deployment: lesions, epidemiology, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:295-300.

- Kuska TC. Air bag safety: an update. J Emerg Nurs. 2016;42:438-441.

- Ulrich D, Noah EM, Fuchs P, et al. Burn injuries caused by air bag deployment. Burns. 2001;27:196-199.

- Erpenbeck SP, Roy E, Ziembicki JA, et al. A systematic review on airbag-induced burns. J Burn Care Res. 2021;42:481-487.

- Skibba KEH, Cleveland CN, Bell DE. Airbag burns: an unfortunate consequence of motor vehicle safety. J Burn Care Res. 2021;42:71-73.

- Smally AJ, Binzer A, Dolin S, et al. Alkaline chemical keratitis: eye injury from airbags. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21:1400-1402.

- Barnes SS, Wong W Jr, Affeldt JC. A case of severe airbag related ocular alkali injury. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2012;71:229-231.

- Wallis LA, Greaves I. Injuries associated with airbag deployment. Emerg Med J. 2002;19:490-493.

- Mohamed AA, Banerjee A. Patterns of injury associated with automobile airbag use. Postgrad Med J. 1998;74:455-458.

- Foley E, Helm TN. Air bag injury and the dermatologist. Cutis. 2000;66:251-252.

- Swanson-Biearman B, Mrvos R, Dean BS, et al. Air bags: lifesaving with toxic potential? Am J Emerg Med. 1993;11:38-39.

- Roth T, Meredith P. Traumatic lesions caused by the “air-bag” system [in French]. Z Unfallchir Versicherungsmed. 1993;86:189-193.

- Wu JJ, Sanchez-Palacios C, Brieva J, et al. A case of air bag dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1383-1384.

- Vitello W, Kim M, Johnson RM, et al. Full-thickness burn to the hand from an automobile airbag. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1999;20:212-215.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Facts about sodium azide. Updated April 4, 2018. Accessed May 15, 2022. https://emergency.cdc.gov/agent/sodiumazide/basics/facts.asp

- Shepardson D. Honda to recall 1.2 million vehicles in North America to replace Takata airbags. March 12, 2019. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-honda-takata-recall/honda-to-recall-1-2-million-vehicles-in-north-america-to-replace-takata-airbags-idUSKBN1QT1C9

- Gabauer DJ, Gabler HC. The effects of airbags and seatbelts on occupant injury in longitudinal barrier crashes. J Safety Res. 2010;41:9-15.

- Rath AL, Jernigan MV, Stitzel JD, et al. The effects of depowered airbags on skin injuries in frontal automobile crashes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:428-435.

Airbags are lifesaving during motor vehicle accidents (MVAs), but their deployment has been associated with skin issues such as irritant dermatitis1; lacerations2; abrasions3; and thermal, friction, and chemical burns.4-6 Ocular issues such as alkaline chemical keratitis7 and ocular alkali injuries8 also have been described.

Airbag deployment is triggered by rapid deceleration and impact, which ignite a sodium azide cartridge, causing the woven nylon bag to inflate with hydrocarbon gases.8 This leads to release of sodium hydroxide, sodium bicarbonate, and metallic oxides in an aerosolized form. If a tear in the meshwork of the airbag occurs, exposure to an even larger amount of powder containing caustic alkali chemicals can occur.8

We describe a patient who developed a bullous reaction to airbag contents after he was involved in an MVA in which the airbag deployed.

Case Report

A 35-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic hepatitis B presented to the dermatology clinic for an evaluation of new-onset blisters. The rash occurred 1 day after the patient was involved in an MVA in which he was exposed to the airbag’s contents after it burst. He had been evaluated twice in the emergency department for the skin eruption before being referred to dermatology. He noted the lesions were pruritic and painful. Prior treatments included silver sulfadiazine cream 1% and clobetasol cream 0.05%, though he discontinued using the latter because of burning with application. Physical examination revealed tense vesicles and bullae on an erythematous base on the right lower flank, forearms, and legs, with the exception of the lower right leg where a cast had been from a prior injury (Figure 1).

Two punch biopsies of the left arm were performed and sent for hematoxylin and eosin staining and direct immunofluorescence to rule out bullous diseases, such as bullous pemphigoid, linear IgA, and bullous lupus. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed extensive spongiosis with blister formation and a dense perivascular infiltrate in the superficial and mid dermis composed of lymphocytes with numerous scattered eosinophils (Figures 2 and 3). Direct immunofluorescence studies were negative. Treatment with oral prednisone and oral antihistamines was initiated.

At 10-day follow-up, the patient had a few residual bullae; most lesions were demonstrating various stages of healing (Figure 4). The patient’s cast had been removed, and there were no lesions in this previously covered area. At 6-week follow-up he had continued healing of the bullae and erosions as well as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (Figure 5).

Comment

With the advent of airbags for safety purposes, these potentially lifesaving devices also have been known to cause injury.9 In 1998, the most commonly reported airbag injuries were ocular injuries.10 Cutaneous manifestations of airbag injury are less well known.11

Two cases of airbag deployment with skin blistering have been reported in the literature based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms airbag blistering or airbag bullae12,13; however, the blistering was described in the context of a burn. One case of the effects of airbag deployment residue highlights a patient arriving to the emergency department with erythema and blisters on the hands within 48 hours of airbag deployment in an MVA, and the treatment was standard burn therapy.12 Another case report described a patient with a second-degree burn with a 12-cm blister occurring on the radial side of the hand and distal forearm following an MVA and airbag deployment, which was treated conservatively.13 Cases of thermal burns, chemical burns, and irritant contact dermatitis after airbag deployment have been described in the literature.4-6,11,12,14,15 Our patient’s distal right lower leg was covered with a cast for osteomyelitis, and no blisters had developed in this area. It is likely that the transfer of airbag contents occurred during the process of unbuckling his seatbelt, which could explain the bullae that developed on the right flank. Per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, individuals should quickly remove clothing and wash their body with large amounts of soap and water following exposure to sodium azide.16

In 1989, the Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard No. 208 (occupant crash protection) became effective, stating all cars must have vehicle crash protection.12 Prior to 1993, it was reported that there had been no associated chemical injuries with airbag deployment. Subsequently, a 6-month retrospective study in 1993 showed that dermal injuries were found in connection with the presence of sodium hydroxide in automobile airbags.12 By 2004, it was known that airbags could cause chemical and thermal burns in addition to traumatic injuries from deployment.1 Since 2007, all motor vehicles have been required to have advanced airbags, which are engineered to sense the presence of passengers and determine if the airbag will deploy, and if so, how much to deploy to minimize airbag-related injury.3

The brand of car that our patient drove during the MVA is one with known airbag recalls due to safety defects; however, the year and actual model of the vehicle are not known, so specific information about the airbag in question is not available. It has been noted that some defective airbag inflators that were exposed to excess moisture during the manufacturing process could explode during deployment, causing shrapnel and airbag rupture, which has been linked to nearly 300 injuries worldwide.17

Conclusion

It is evident that the use of airbag devices reduces morbidity and mortality due to MVAs.9 It also had been reported that up to 96% of airbag-related injuries are relatively minor, which many would argue justifies their use.18 Furthermore, it has been reported that 99.8% of skin injuries following airbag deployment are minor.19 In the United States, it is mandated that every vehicle have functional airbags installed.8

This case highlights the potential for substantial airbag-induced skin reactions, specifically a bullous reaction, following airbag deployment. The persistent pruritus and lasting postinflammatory hyperpigmentation seen in this case were certainly worrisome for our patient. We also present this case to remind dermatology providers of possible treatment approaches to these skin reactions. Immediate cleansing of the affected areas of skin may help avoid such reactions.

Airbags are lifesaving during motor vehicle accidents (MVAs), but their deployment has been associated with skin issues such as irritant dermatitis1; lacerations2; abrasions3; and thermal, friction, and chemical burns.4-6 Ocular issues such as alkaline chemical keratitis7 and ocular alkali injuries8 also have been described.

Airbag deployment is triggered by rapid deceleration and impact, which ignite a sodium azide cartridge, causing the woven nylon bag to inflate with hydrocarbon gases.8 This leads to release of sodium hydroxide, sodium bicarbonate, and metallic oxides in an aerosolized form. If a tear in the meshwork of the airbag occurs, exposure to an even larger amount of powder containing caustic alkali chemicals can occur.8

We describe a patient who developed a bullous reaction to airbag contents after he was involved in an MVA in which the airbag deployed.

Case Report

A 35-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic hepatitis B presented to the dermatology clinic for an evaluation of new-onset blisters. The rash occurred 1 day after the patient was involved in an MVA in which he was exposed to the airbag’s contents after it burst. He had been evaluated twice in the emergency department for the skin eruption before being referred to dermatology. He noted the lesions were pruritic and painful. Prior treatments included silver sulfadiazine cream 1% and clobetasol cream 0.05%, though he discontinued using the latter because of burning with application. Physical examination revealed tense vesicles and bullae on an erythematous base on the right lower flank, forearms, and legs, with the exception of the lower right leg where a cast had been from a prior injury (Figure 1).

Two punch biopsies of the left arm were performed and sent for hematoxylin and eosin staining and direct immunofluorescence to rule out bullous diseases, such as bullous pemphigoid, linear IgA, and bullous lupus. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed extensive spongiosis with blister formation and a dense perivascular infiltrate in the superficial and mid dermis composed of lymphocytes with numerous scattered eosinophils (Figures 2 and 3). Direct immunofluorescence studies were negative. Treatment with oral prednisone and oral antihistamines was initiated.

At 10-day follow-up, the patient had a few residual bullae; most lesions were demonstrating various stages of healing (Figure 4). The patient’s cast had been removed, and there were no lesions in this previously covered area. At 6-week follow-up he had continued healing of the bullae and erosions as well as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (Figure 5).

Comment

With the advent of airbags for safety purposes, these potentially lifesaving devices also have been known to cause injury.9 In 1998, the most commonly reported airbag injuries were ocular injuries.10 Cutaneous manifestations of airbag injury are less well known.11

Two cases of airbag deployment with skin blistering have been reported in the literature based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms airbag blistering or airbag bullae12,13; however, the blistering was described in the context of a burn. One case of the effects of airbag deployment residue highlights a patient arriving to the emergency department with erythema and blisters on the hands within 48 hours of airbag deployment in an MVA, and the treatment was standard burn therapy.12 Another case report described a patient with a second-degree burn with a 12-cm blister occurring on the radial side of the hand and distal forearm following an MVA and airbag deployment, which was treated conservatively.13 Cases of thermal burns, chemical burns, and irritant contact dermatitis after airbag deployment have been described in the literature.4-6,11,12,14,15 Our patient’s distal right lower leg was covered with a cast for osteomyelitis, and no blisters had developed in this area. It is likely that the transfer of airbag contents occurred during the process of unbuckling his seatbelt, which could explain the bullae that developed on the right flank. Per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, individuals should quickly remove clothing and wash their body with large amounts of soap and water following exposure to sodium azide.16

In 1989, the Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard No. 208 (occupant crash protection) became effective, stating all cars must have vehicle crash protection.12 Prior to 1993, it was reported that there had been no associated chemical injuries with airbag deployment. Subsequently, a 6-month retrospective study in 1993 showed that dermal injuries were found in connection with the presence of sodium hydroxide in automobile airbags.12 By 2004, it was known that airbags could cause chemical and thermal burns in addition to traumatic injuries from deployment.1 Since 2007, all motor vehicles have been required to have advanced airbags, which are engineered to sense the presence of passengers and determine if the airbag will deploy, and if so, how much to deploy to minimize airbag-related injury.3

The brand of car that our patient drove during the MVA is one with known airbag recalls due to safety defects; however, the year and actual model of the vehicle are not known, so specific information about the airbag in question is not available. It has been noted that some defective airbag inflators that were exposed to excess moisture during the manufacturing process could explode during deployment, causing shrapnel and airbag rupture, which has been linked to nearly 300 injuries worldwide.17

Conclusion

It is evident that the use of airbag devices reduces morbidity and mortality due to MVAs.9 It also had been reported that up to 96% of airbag-related injuries are relatively minor, which many would argue justifies their use.18 Furthermore, it has been reported that 99.8% of skin injuries following airbag deployment are minor.19 In the United States, it is mandated that every vehicle have functional airbags installed.8

This case highlights the potential for substantial airbag-induced skin reactions, specifically a bullous reaction, following airbag deployment. The persistent pruritus and lasting postinflammatory hyperpigmentation seen in this case were certainly worrisome for our patient. We also present this case to remind dermatology providers of possible treatment approaches to these skin reactions. Immediate cleansing of the affected areas of skin may help avoid such reactions.

- Corazza M, Trincone S, Zampino MR, et al. Air bags and the skin. Skinmed. 2004;3:256-258.

- Corazza M, Trincone S, Virgili A. Effects of airbag deployment: lesions, epidemiology, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:295-300.

- Kuska TC. Air bag safety: an update. J Emerg Nurs. 2016;42:438-441.

- Ulrich D, Noah EM, Fuchs P, et al. Burn injuries caused by air bag deployment. Burns. 2001;27:196-199.

- Erpenbeck SP, Roy E, Ziembicki JA, et al. A systematic review on airbag-induced burns. J Burn Care Res. 2021;42:481-487.

- Skibba KEH, Cleveland CN, Bell DE. Airbag burns: an unfortunate consequence of motor vehicle safety. J Burn Care Res. 2021;42:71-73.

- Smally AJ, Binzer A, Dolin S, et al. Alkaline chemical keratitis: eye injury from airbags. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21:1400-1402.

- Barnes SS, Wong W Jr, Affeldt JC. A case of severe airbag related ocular alkali injury. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2012;71:229-231.

- Wallis LA, Greaves I. Injuries associated with airbag deployment. Emerg Med J. 2002;19:490-493.

- Mohamed AA, Banerjee A. Patterns of injury associated with automobile airbag use. Postgrad Med J. 1998;74:455-458.

- Foley E, Helm TN. Air bag injury and the dermatologist. Cutis. 2000;66:251-252.

- Swanson-Biearman B, Mrvos R, Dean BS, et al. Air bags: lifesaving with toxic potential? Am J Emerg Med. 1993;11:38-39.

- Roth T, Meredith P. Traumatic lesions caused by the “air-bag” system [in French]. Z Unfallchir Versicherungsmed. 1993;86:189-193.

- Wu JJ, Sanchez-Palacios C, Brieva J, et al. A case of air bag dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1383-1384.

- Vitello W, Kim M, Johnson RM, et al. Full-thickness burn to the hand from an automobile airbag. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1999;20:212-215.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Facts about sodium azide. Updated April 4, 2018. Accessed May 15, 2022. https://emergency.cdc.gov/agent/sodiumazide/basics/facts.asp

- Shepardson D. Honda to recall 1.2 million vehicles in North America to replace Takata airbags. March 12, 2019. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-honda-takata-recall/honda-to-recall-1-2-million-vehicles-in-north-america-to-replace-takata-airbags-idUSKBN1QT1C9

- Gabauer DJ, Gabler HC. The effects of airbags and seatbelts on occupant injury in longitudinal barrier crashes. J Safety Res. 2010;41:9-15.

- Rath AL, Jernigan MV, Stitzel JD, et al. The effects of depowered airbags on skin injuries in frontal automobile crashes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:428-435.

- Corazza M, Trincone S, Zampino MR, et al. Air bags and the skin. Skinmed. 2004;3:256-258.

- Corazza M, Trincone S, Virgili A. Effects of airbag deployment: lesions, epidemiology, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:295-300.

- Kuska TC. Air bag safety: an update. J Emerg Nurs. 2016;42:438-441.

- Ulrich D, Noah EM, Fuchs P, et al. Burn injuries caused by air bag deployment. Burns. 2001;27:196-199.

- Erpenbeck SP, Roy E, Ziembicki JA, et al. A systematic review on airbag-induced burns. J Burn Care Res. 2021;42:481-487.

- Skibba KEH, Cleveland CN, Bell DE. Airbag burns: an unfortunate consequence of motor vehicle safety. J Burn Care Res. 2021;42:71-73.

- Smally AJ, Binzer A, Dolin S, et al. Alkaline chemical keratitis: eye injury from airbags. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21:1400-1402.

- Barnes SS, Wong W Jr, Affeldt JC. A case of severe airbag related ocular alkali injury. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2012;71:229-231.

- Wallis LA, Greaves I. Injuries associated with airbag deployment. Emerg Med J. 2002;19:490-493.

- Mohamed AA, Banerjee A. Patterns of injury associated with automobile airbag use. Postgrad Med J. 1998;74:455-458.

- Foley E, Helm TN. Air bag injury and the dermatologist. Cutis. 2000;66:251-252.

- Swanson-Biearman B, Mrvos R, Dean BS, et al. Air bags: lifesaving with toxic potential? Am J Emerg Med. 1993;11:38-39.

- Roth T, Meredith P. Traumatic lesions caused by the “air-bag” system [in French]. Z Unfallchir Versicherungsmed. 1993;86:189-193.

- Wu JJ, Sanchez-Palacios C, Brieva J, et al. A case of air bag dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1383-1384.

- Vitello W, Kim M, Johnson RM, et al. Full-thickness burn to the hand from an automobile airbag. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1999;20:212-215.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Facts about sodium azide. Updated April 4, 2018. Accessed May 15, 2022. https://emergency.cdc.gov/agent/sodiumazide/basics/facts.asp

- Shepardson D. Honda to recall 1.2 million vehicles in North America to replace Takata airbags. March 12, 2019. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-honda-takata-recall/honda-to-recall-1-2-million-vehicles-in-north-america-to-replace-takata-airbags-idUSKBN1QT1C9

- Gabauer DJ, Gabler HC. The effects of airbags and seatbelts on occupant injury in longitudinal barrier crashes. J Safety Res. 2010;41:9-15.

- Rath AL, Jernigan MV, Stitzel JD, et al. The effects of depowered airbags on skin injuries in frontal automobile crashes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:428-435.

Practice Points

- This case highlights the potential for a bullous reaction following airbag deployment.

- After airbag deployment, it is important to immediately cleanse the affected areas of skin with soap and water.

Vascular Plaque in a Pregnant Patient With a History of Breast Cancer

The Diagnosis: Tufted Angioma

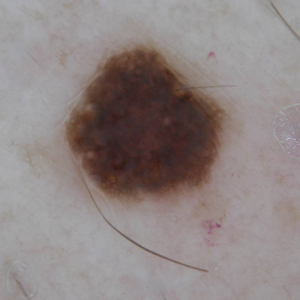

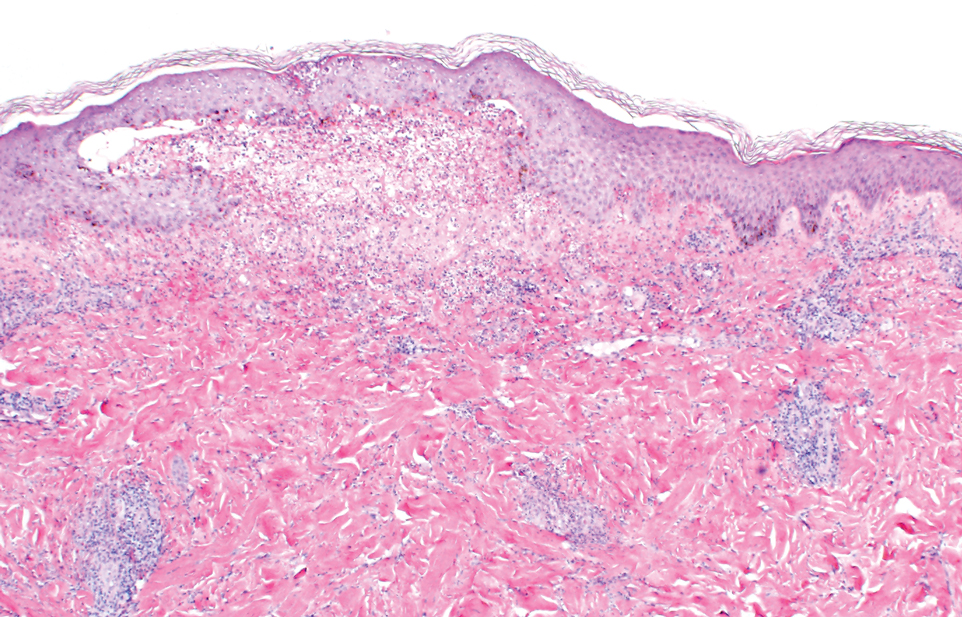

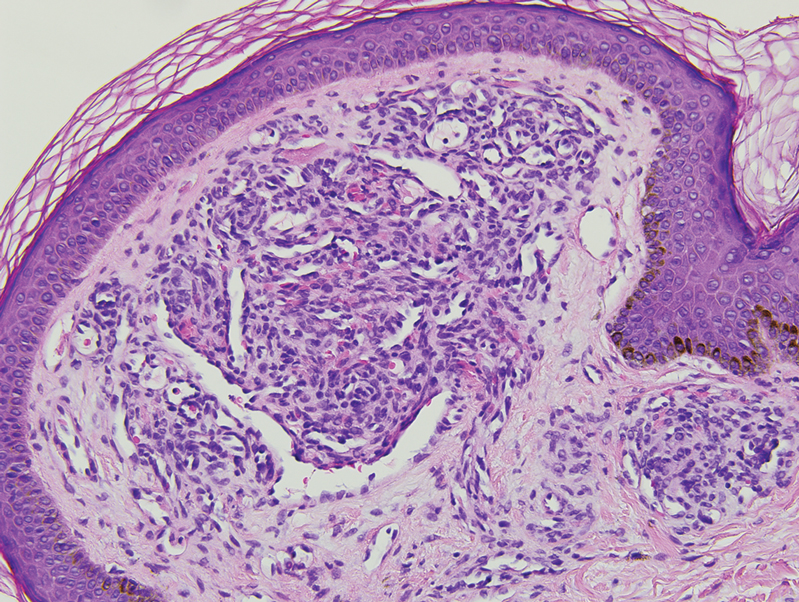

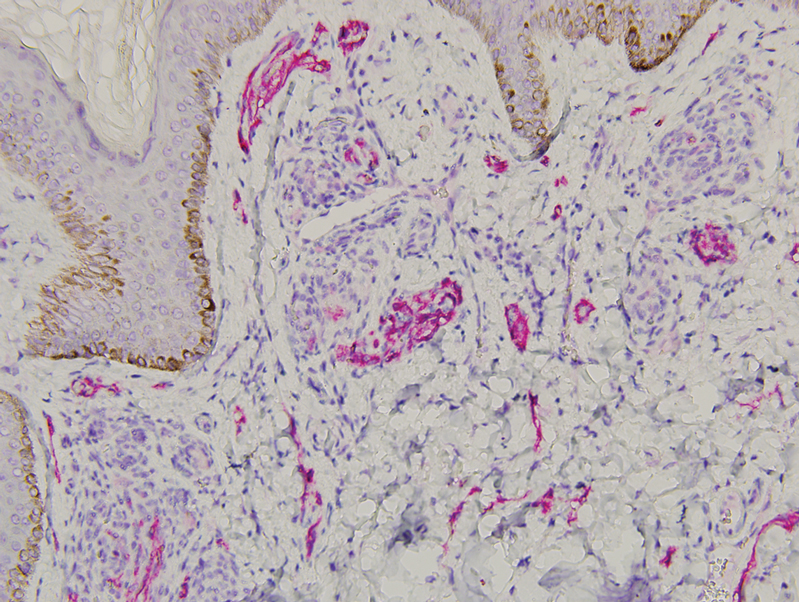

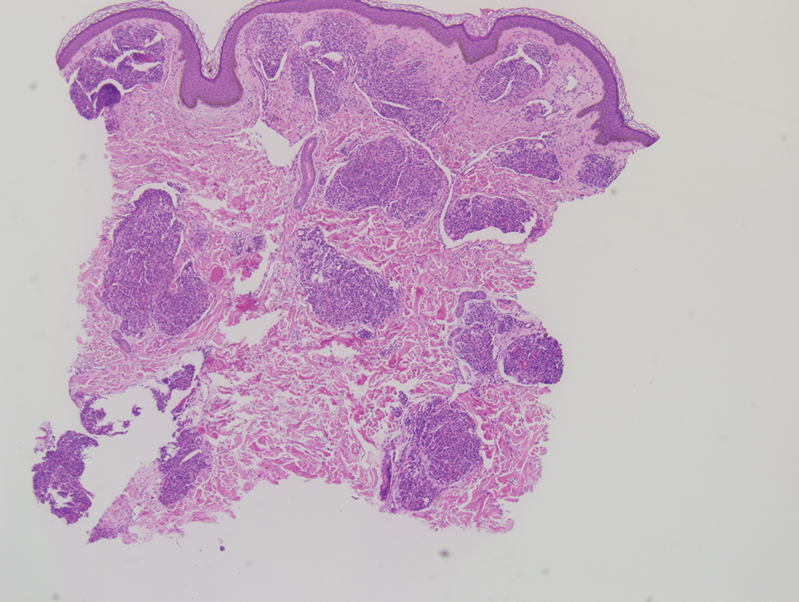

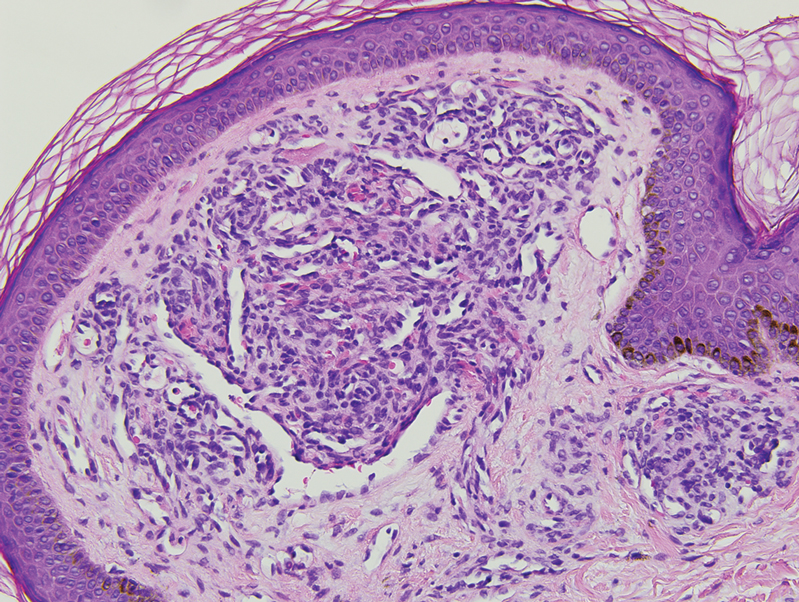

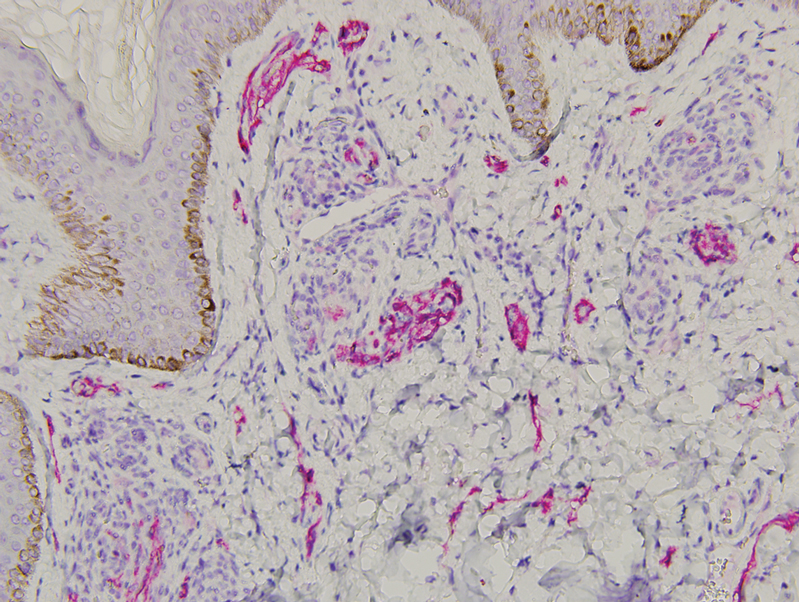

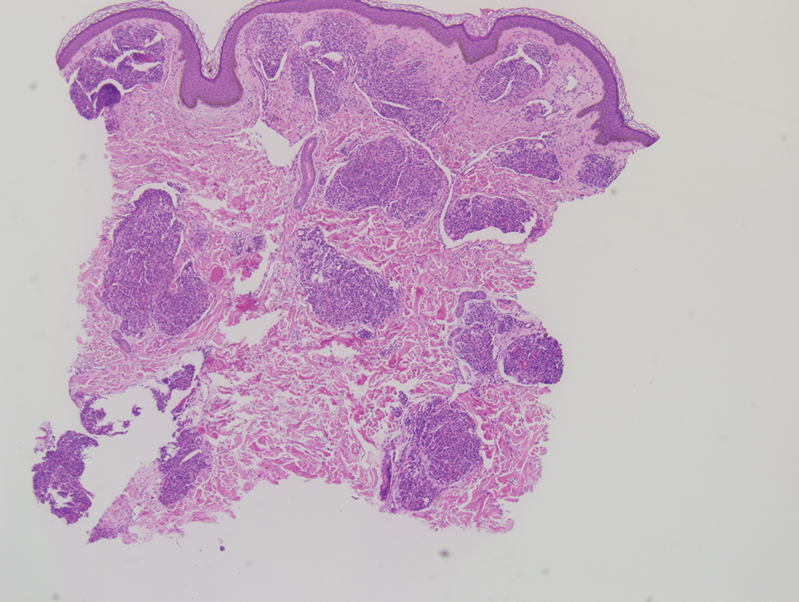

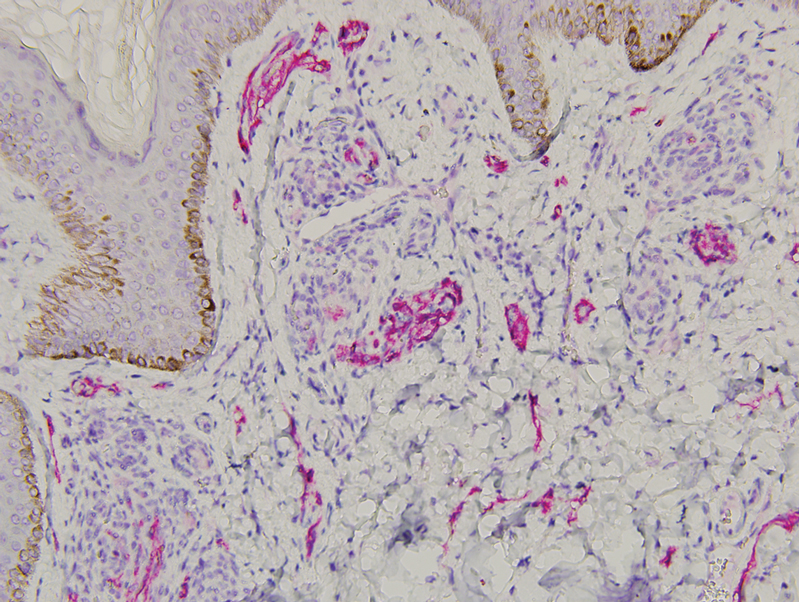

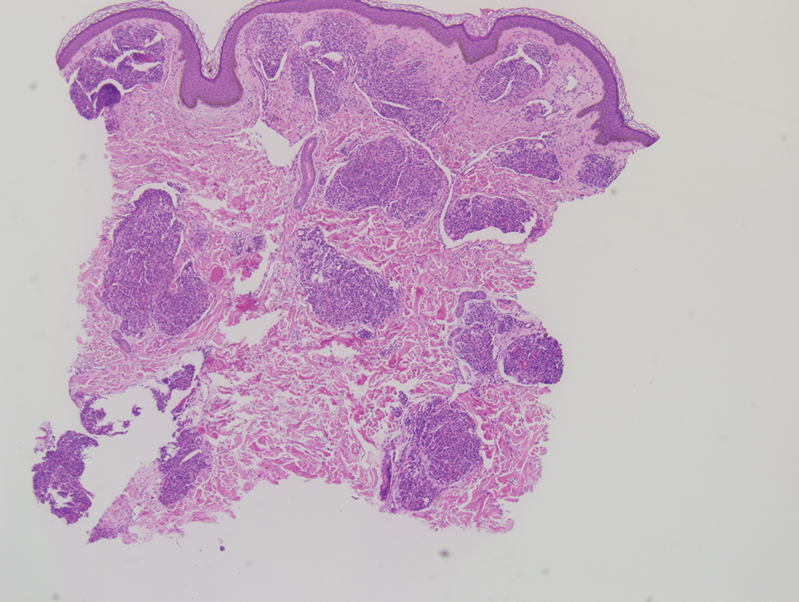

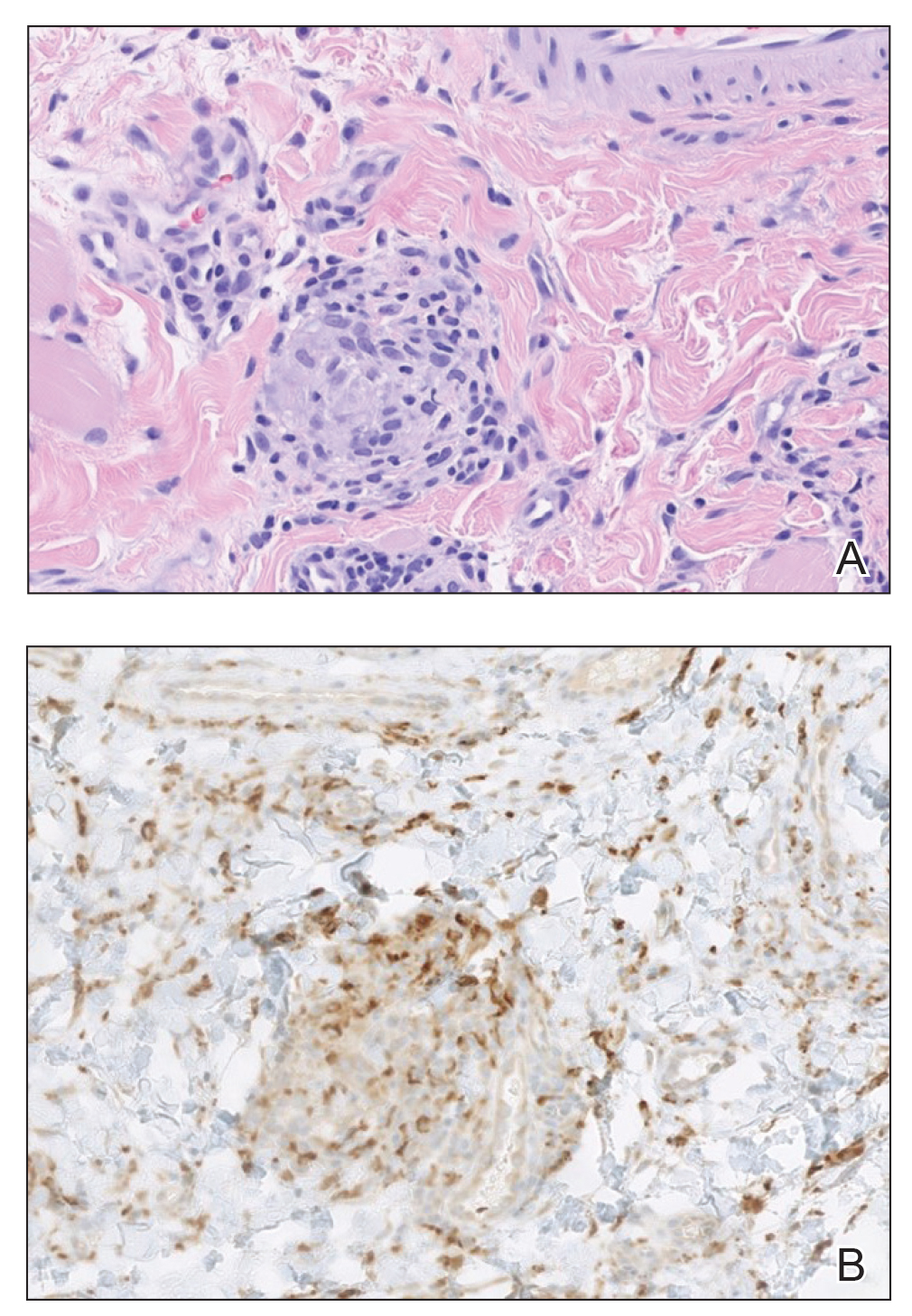

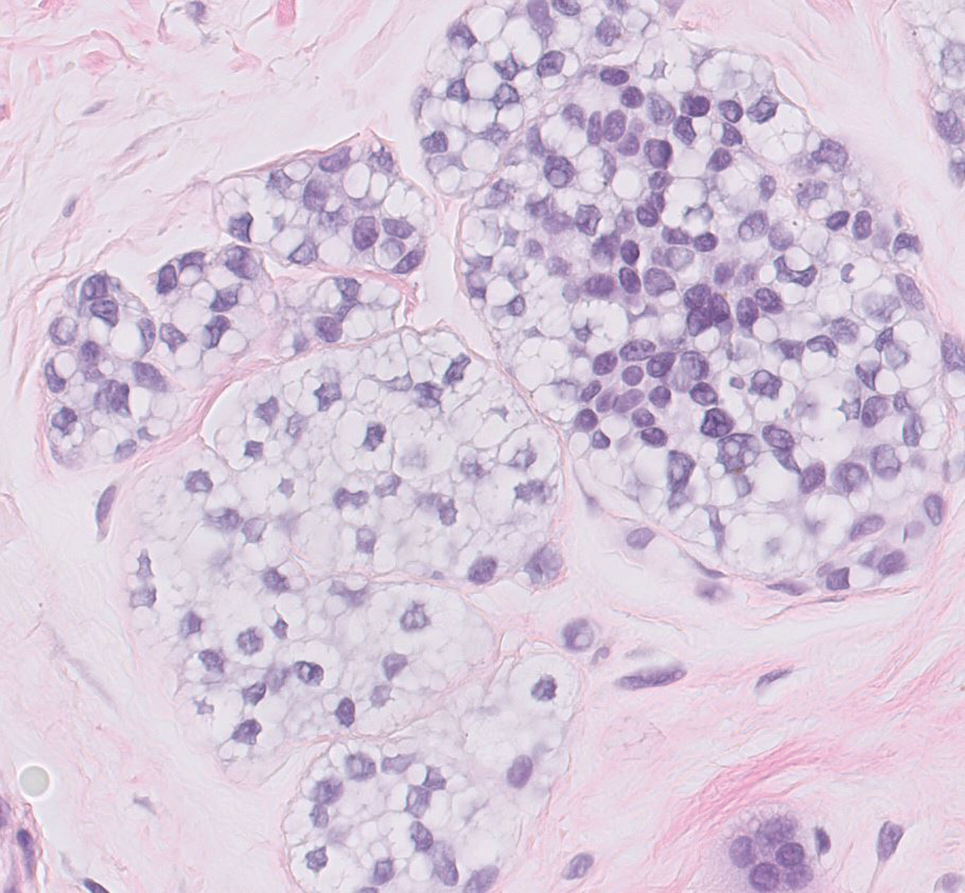

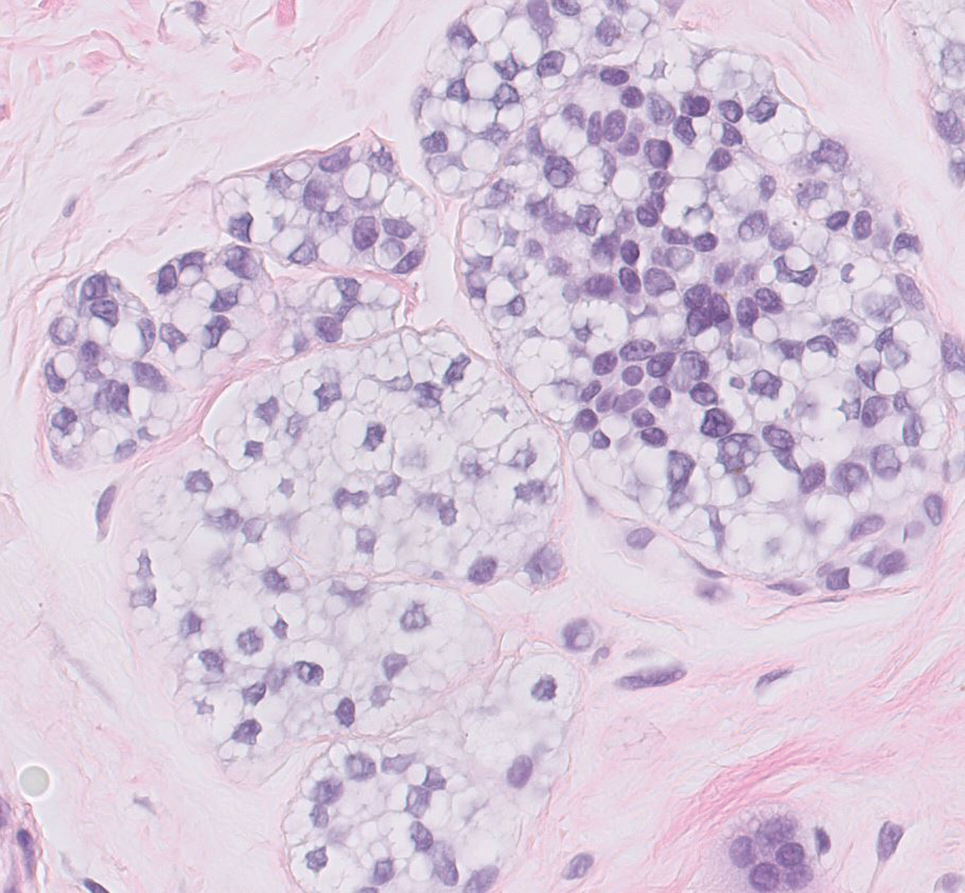

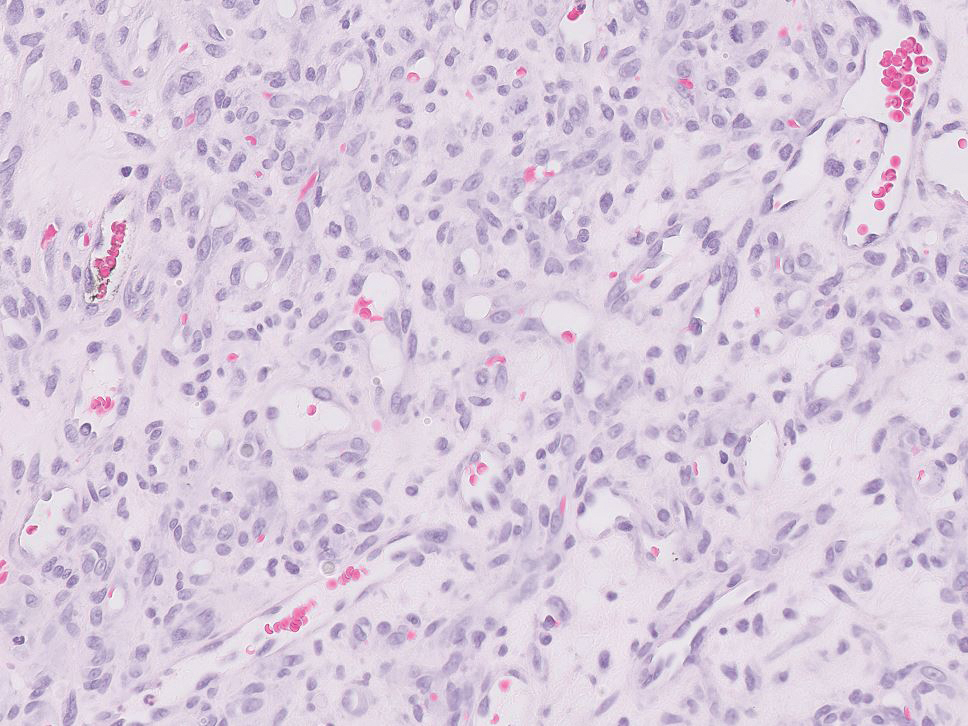

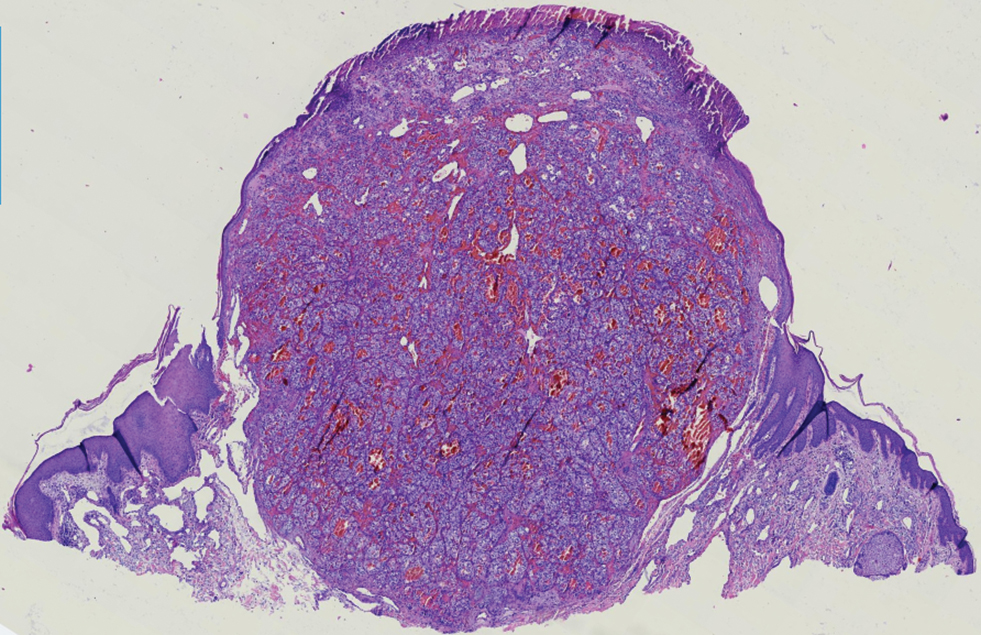

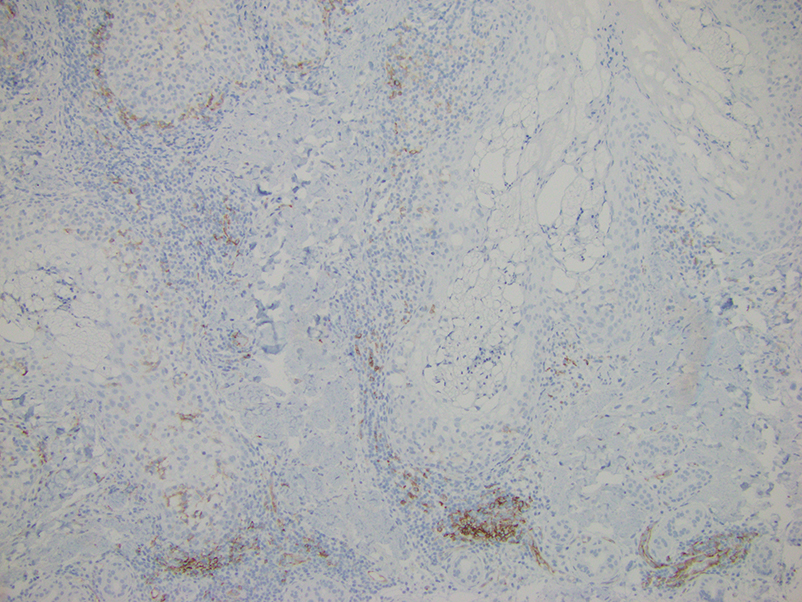

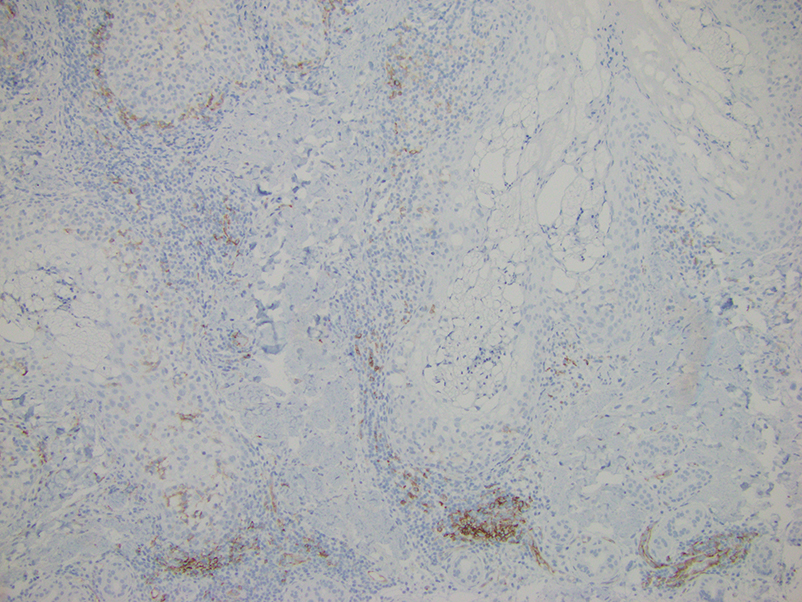

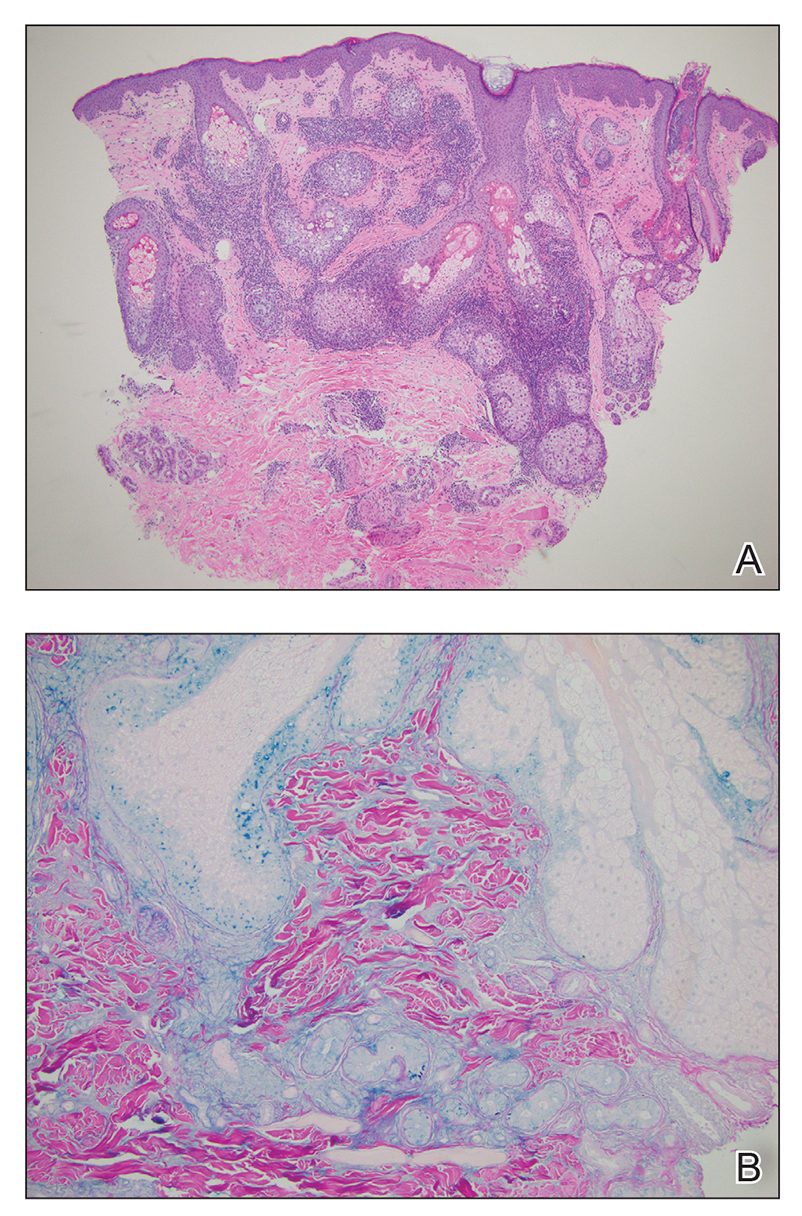

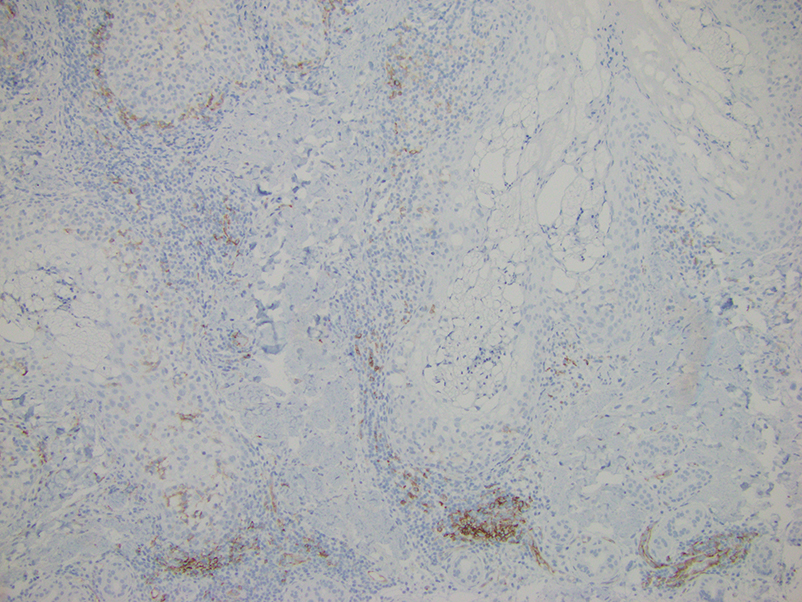

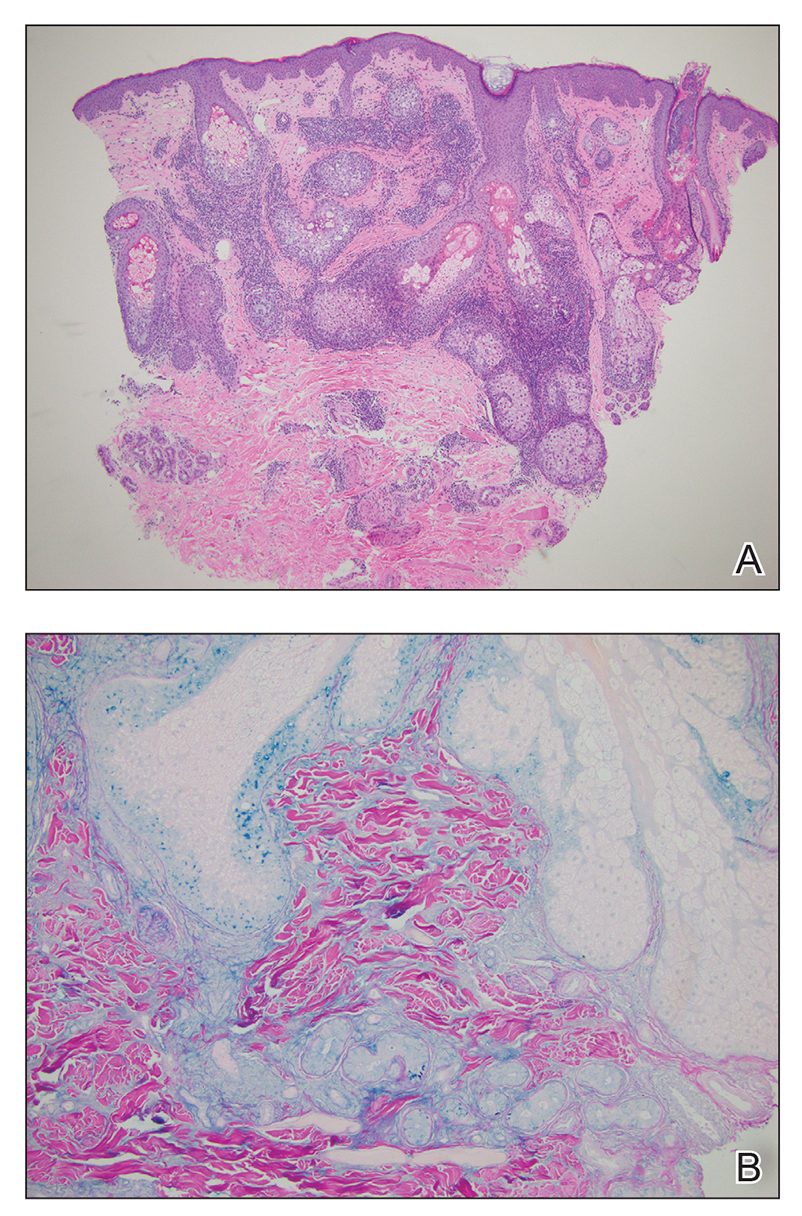

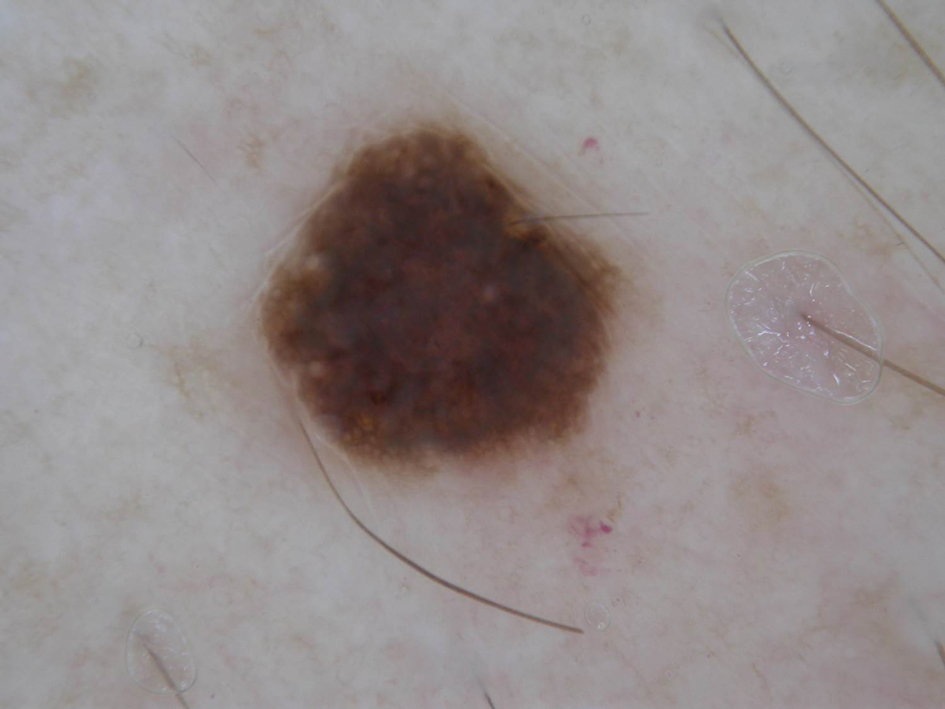

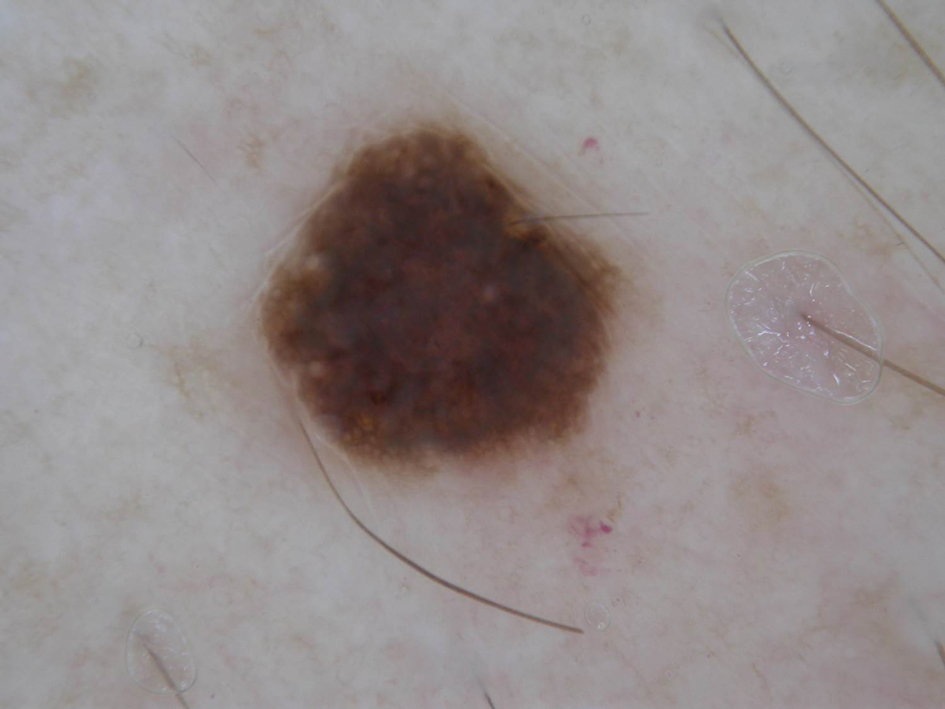

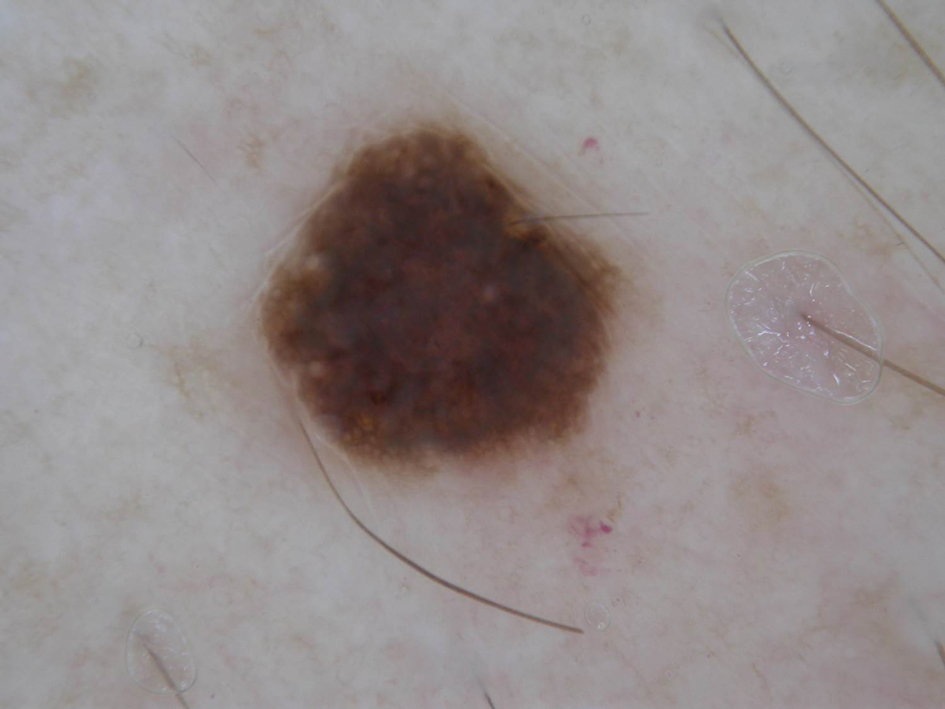

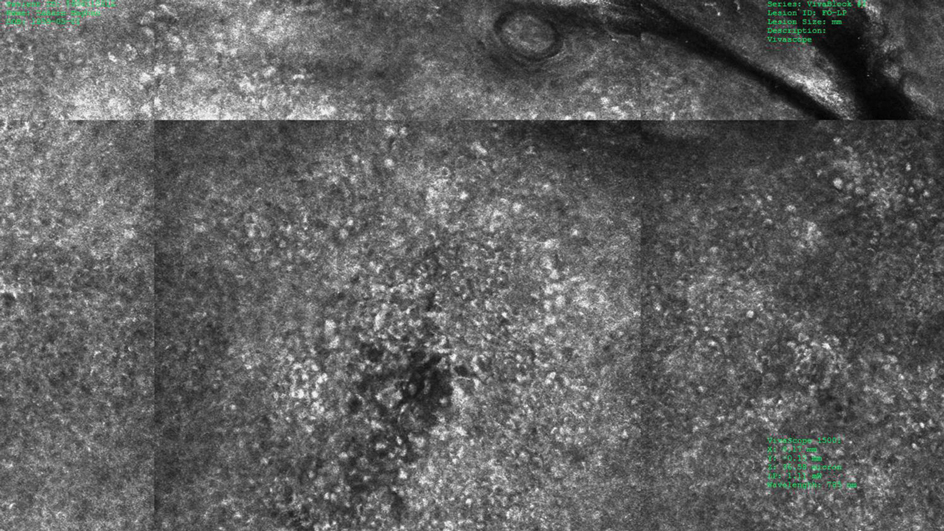

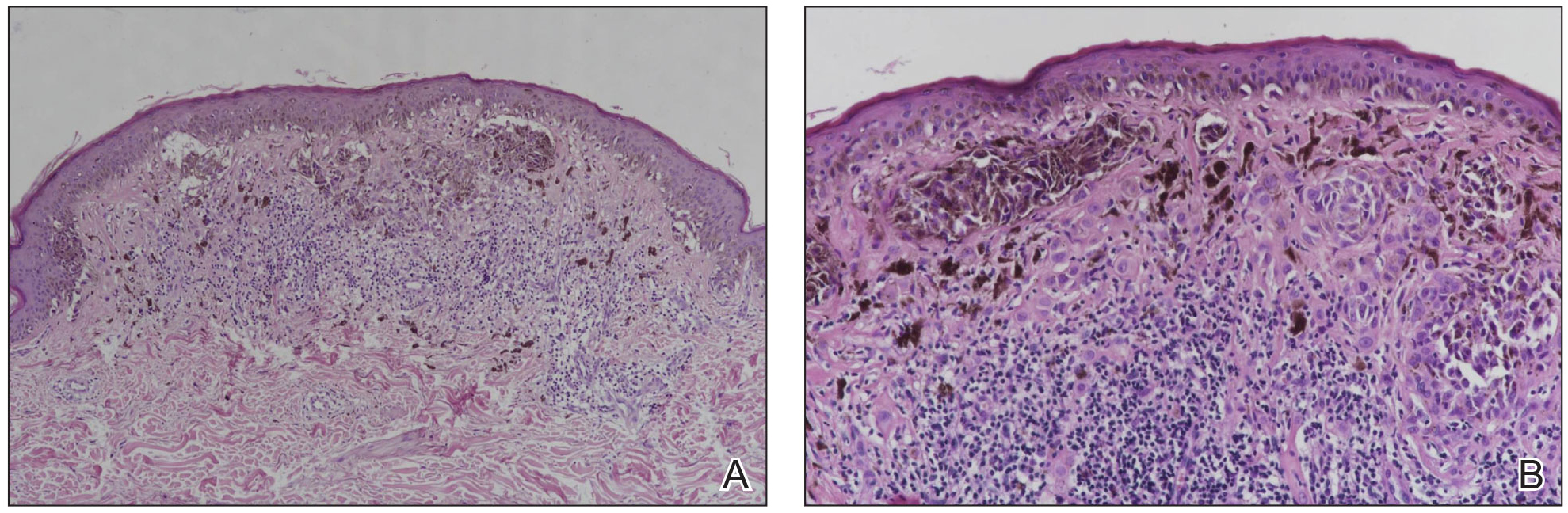

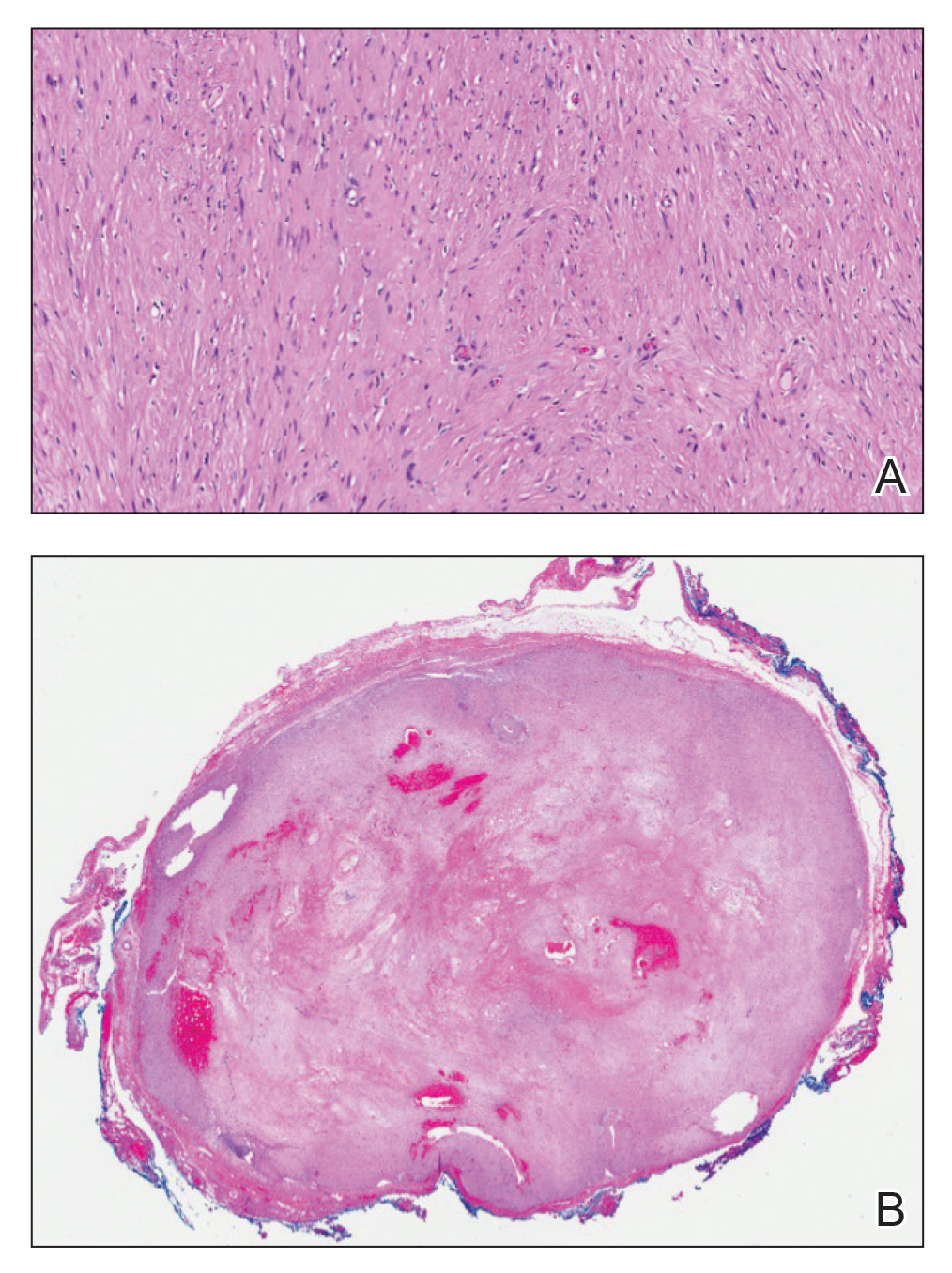

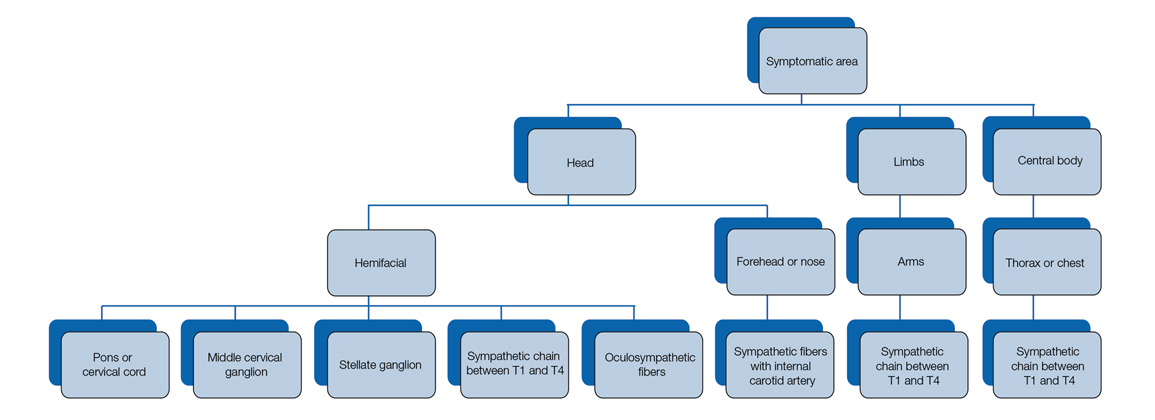

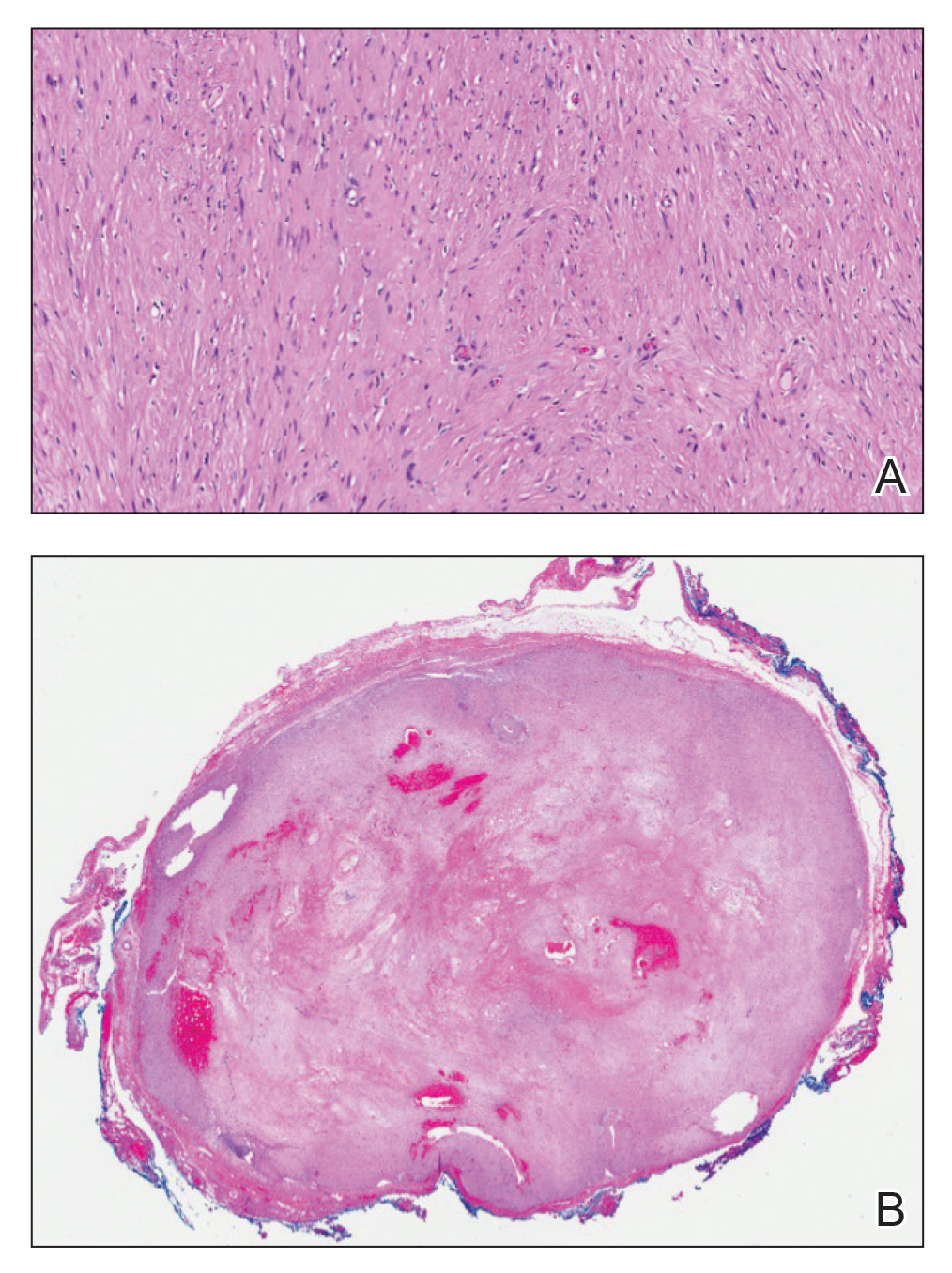

Histopathology revealed discrete lobules of closely packed capillaries with bland endothelial cells throughout the upper and lower dermis (Figure 1). The surrounding crescentlike vessels and lymphatics stained with D2-40 (Figure 2). These histologic findings were consistent with tufted angioma, and the patient elected for observation.

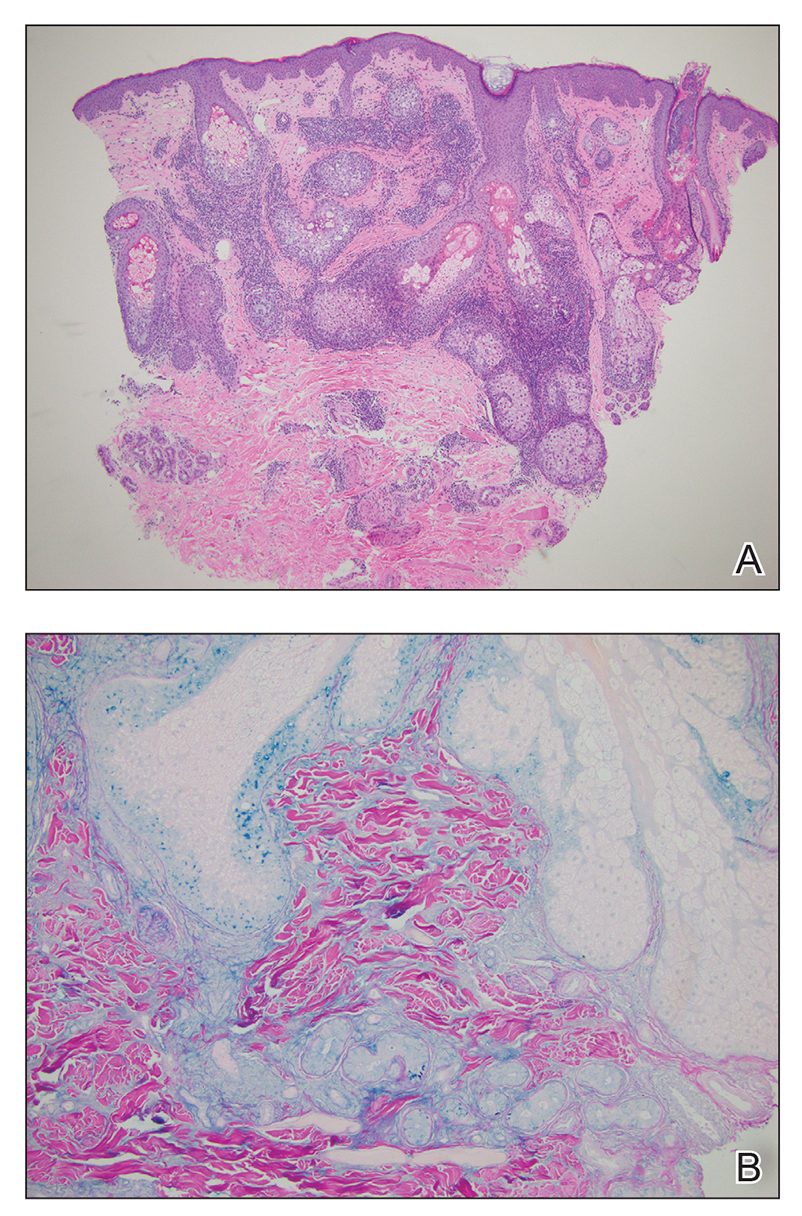

Tufted angiomas are benign vascular lesions named for the tufted appearance of capillaries on histology.1 They commonly present in children, with a lower incidence in adults and rare cases in pregnancy.2 Tufted angiomas typically present as solitary, slowly expanding, erythematous macules, plaques, or nodules on the neck or trunk ranging in size from less than 1 to 10 cm.2-4 They can be histologically distinguished from other vascular tumors, including aggressive malignant neoplasms.1

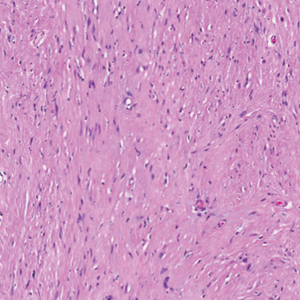

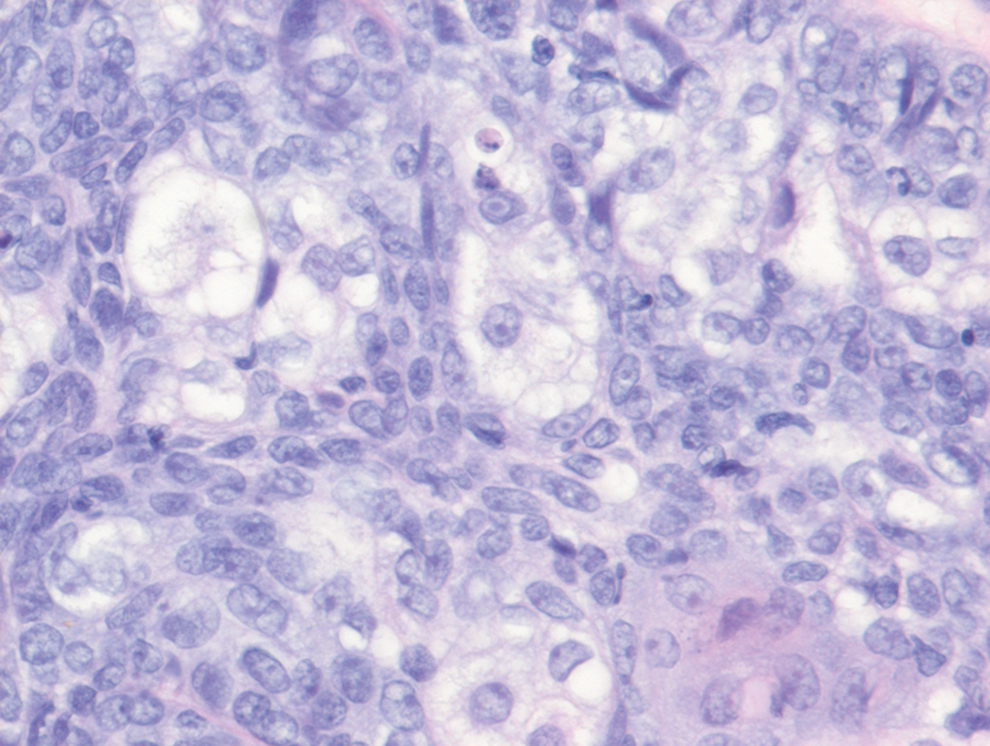

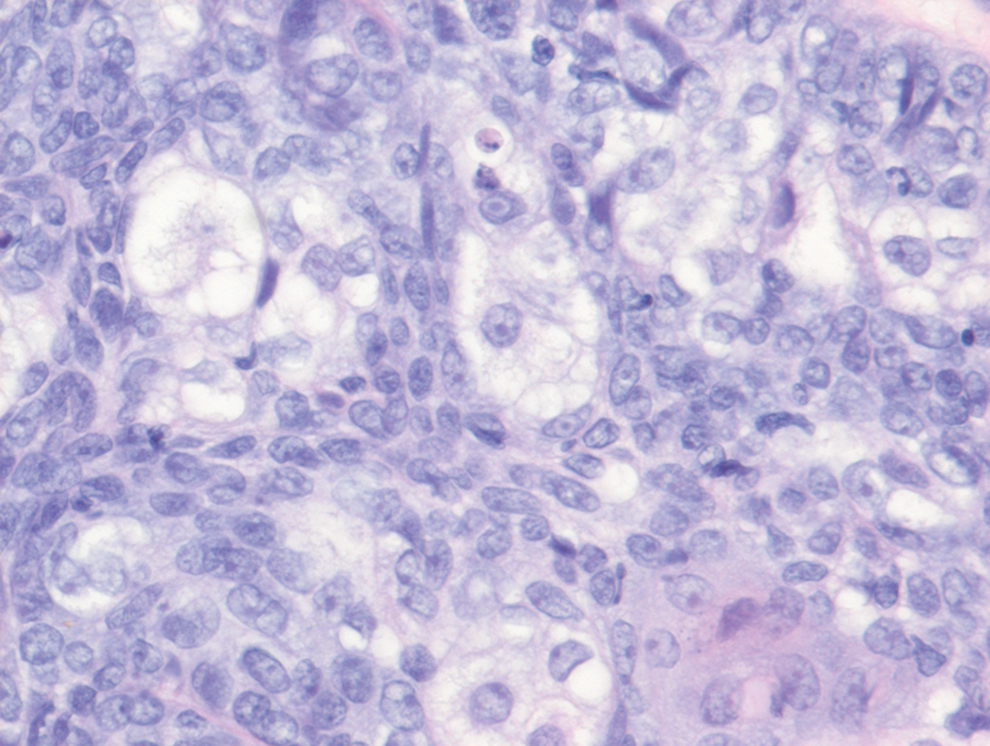

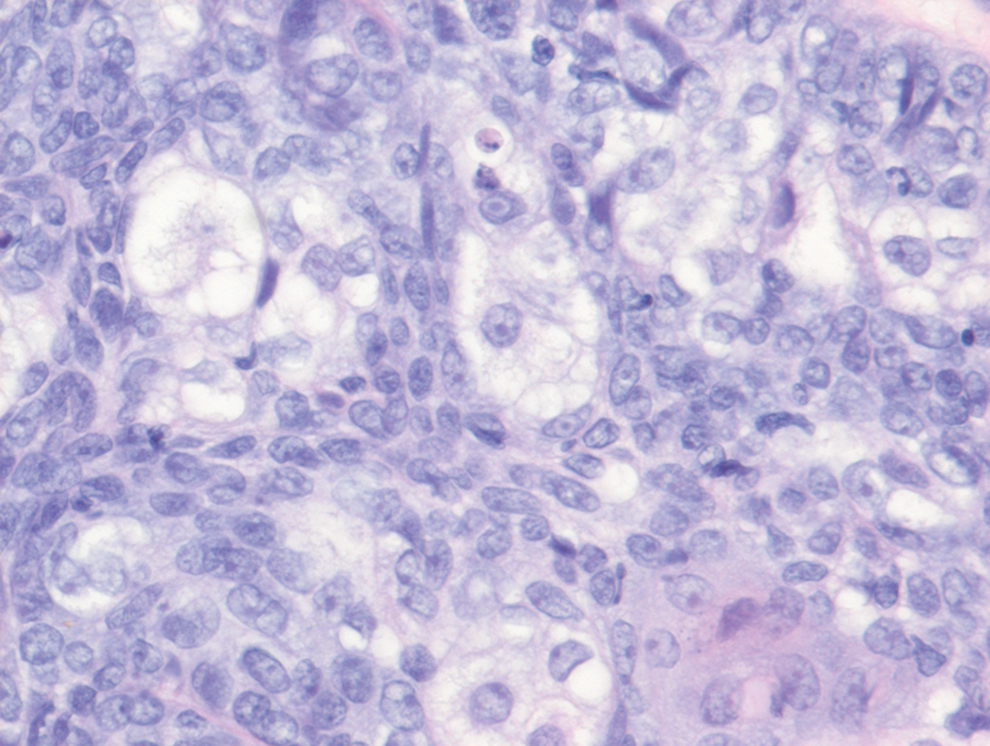

Tufted angiomas are identified by characteristic “cannon ball tufts” of capillaries in the dermis and subcutis at low power.3,5 Distinct cellular lobules may be found bulging into thin-walled vascular channels at the margins of the lobules in the dermis and subcutis (Figure 3).4 The lobules are formed by cells with spindle-shaped nuclei.6 Some mitotic figures may be present, but no cellular atypia is seen.2 The capillaries at the periphery appear as dilated semilunar vessels.4 Dilated lymphatics, which stain with D2-40, can be found at the periphery of the tufted capillaries and throughout the remaining dermis.3,4

Tufted angiomas may arise independently in adults but also have been associated with conditions such as pregnancy. Omori et al7 identified an acquired tufted angioma in pregnancy that was positive for estrogen and progesterone receptors. Reports of tufted angiomas in pregnancy vary; some are multiple lesions, some regress postpartum, and some undergo successful surgical treatment.3,5

Vascular lesions such as tufted angiomas specifically may appear in pregnancy due to a high-volume state with vasodilation and increased vascular proliferation. Although tumor angiogenesis has been linked to specific growth factors and cytokines, it has been hypothesized that the systemic hormones of pregnancy such as human chorionic gonadotropin, estradiol, and progesterone also shift the body to a more angiogenic state.8 In a study of cutaneous changes in pregnant women (N=905), 41% developed a vascular skin change, including spider veins, varicosities, hemangiomas, and granulomas.9 The most common vascular tumor in pregnancy is pyogenic granuloma. Pyogenic granulomas are small, solitary, friable papules that commonly are found on the hands, forearms, face, or in the mouth; histologically they demonstrate dilated capillaries in lobular structures accompanied by larger thick-walled vessels.3,10,11

Tufted angiomas may mimic a variety of other conditions. Epithelioid hemangioma, considered by some to be on the same morphologic spectrum as angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia, classically occurs in young adults on the head and in the neck region. It histologically demonstrates a lobular appearance at low power; however, these lobules are made up of vessels with histiocytoid to epithelioid endothelial cells surrounded by a prominent inflammatory infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes and eosinophils.12

Kaposi sarcoma may appear on the neck but most often presents as macules and patches on the extremities that may form nodules with a rubbery consistency. In tufted angiomas, the cellular nodules with dilated channels at the margins bear a resemblance to Kaposi sarcoma or kaposiform hemangioendothelioma; however, in tufted angiomas the lobules are composed of bland spindle cells and slitlike vessels at the periphery.3,13,14 Tufted angiomas are negative for human herpesvirus 8 and typically do not have an associated inflammatory infiltrate with plasma cells.11,15

Moreover, it is important to differentiate tufted angioma from a cutaneous manifestation of an underlying malignancy, which has been described previously in cases of breast cancer.16,17 Our case illustrates a rare vascular tumor arising in the novel context of a pregnant patient with breast cancer. Distinguishing tufted angioma from other benign or malignant vascular tumors is necessary to avoid inappropriate therapeutic interventions.

- Jones EW, Orkin M. Tufted angioma (angioblastoma). a benign progressive angioma, not to be confused with Kaposi’s sarcoma or low-grade angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(2 pt 1):214-225.

- Lee B, Chiu M, Soriano T, et al. Adult-onset tufted angioma: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2006;78:341-345.

- Kim YK, Kim HJ, Lee KG. Acquired tufted angioma associated with pregnancy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:458-459.

- Feito-Rodriguez M, Sanchez-Orta A, De Lucas R, et al. Congenital tufted angioma: a multicenter retrospective study of 30 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:808-816.

- Pietroletti R, Leardi S, Simi M. Perianal acquired tufted angioma associated with pregnancy: case report. Tech Coloproctol. 2002;6:117-119.

- Osio A, Fraitag S, Hadj-Rabia S, et al. Clinical spectrum of tufted angiomas in childhood: a report of 13 cases and a review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:758-763.

- Omori M, Bito T, Nishigori C. Acquired tufted angioma in pregnancy showing expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23:898-899.

- Boeldt DS, Bird IM. Vascular adaptation in pregnancy and endothelial dysfunction in preeclampsia. J Endocrinol. 2017;232:R27-R44.

- Fernandes LB, Amaral W. Clinical study of skin changes in low and high risk pregnant women. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:822-826.

- Walker JL, Wang AR, Kroumpouzos G, et al. Cutaneous tumors in pregnancy. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:359-367.

- Sarwal P, Lapumnuaypol K. Pyogenic granuloma. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Ortins-Pina A, Llamas-Velasco M, Turpin S, et al. FOSB immunoreactivity in endothelia of epithelioid hemangioma (angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia). J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:395-402.

- Arai E, Kuramochi A, Tsuchida T, et al. Usefulness of D2-40 immunohistochemistry for differentiation between kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and tufted angioma. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:492-497.

- Grassi S, Carugno A, Vignini M, et al. Adult-onset tufted angiomas associated with an arteriovenous malformation in a renal transplant recipient: case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:162-165.

- Lyons LL, North PE, Mac-Moune Lai F, et al. Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma: a study of 33 cases emphasizing its pathologic, immunophenotypic, and biologic uniqueness from juvenile hemangioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:559-568.

- Putra HP, Djawad K, Nurdin AR. Cutaneous lesions as the first manifestation of breast cancer: a rare case. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;37:383.

- Thiers BH, Sahn RE, Callen JP. Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:73-98.

The Diagnosis: Tufted Angioma

Histopathology revealed discrete lobules of closely packed capillaries with bland endothelial cells throughout the upper and lower dermis (Figure 1). The surrounding crescentlike vessels and lymphatics stained with D2-40 (Figure 2). These histologic findings were consistent with tufted angioma, and the patient elected for observation.

Tufted angiomas are benign vascular lesions named for the tufted appearance of capillaries on histology.1 They commonly present in children, with a lower incidence in adults and rare cases in pregnancy.2 Tufted angiomas typically present as solitary, slowly expanding, erythematous macules, plaques, or nodules on the neck or trunk ranging in size from less than 1 to 10 cm.2-4 They can be histologically distinguished from other vascular tumors, including aggressive malignant neoplasms.1

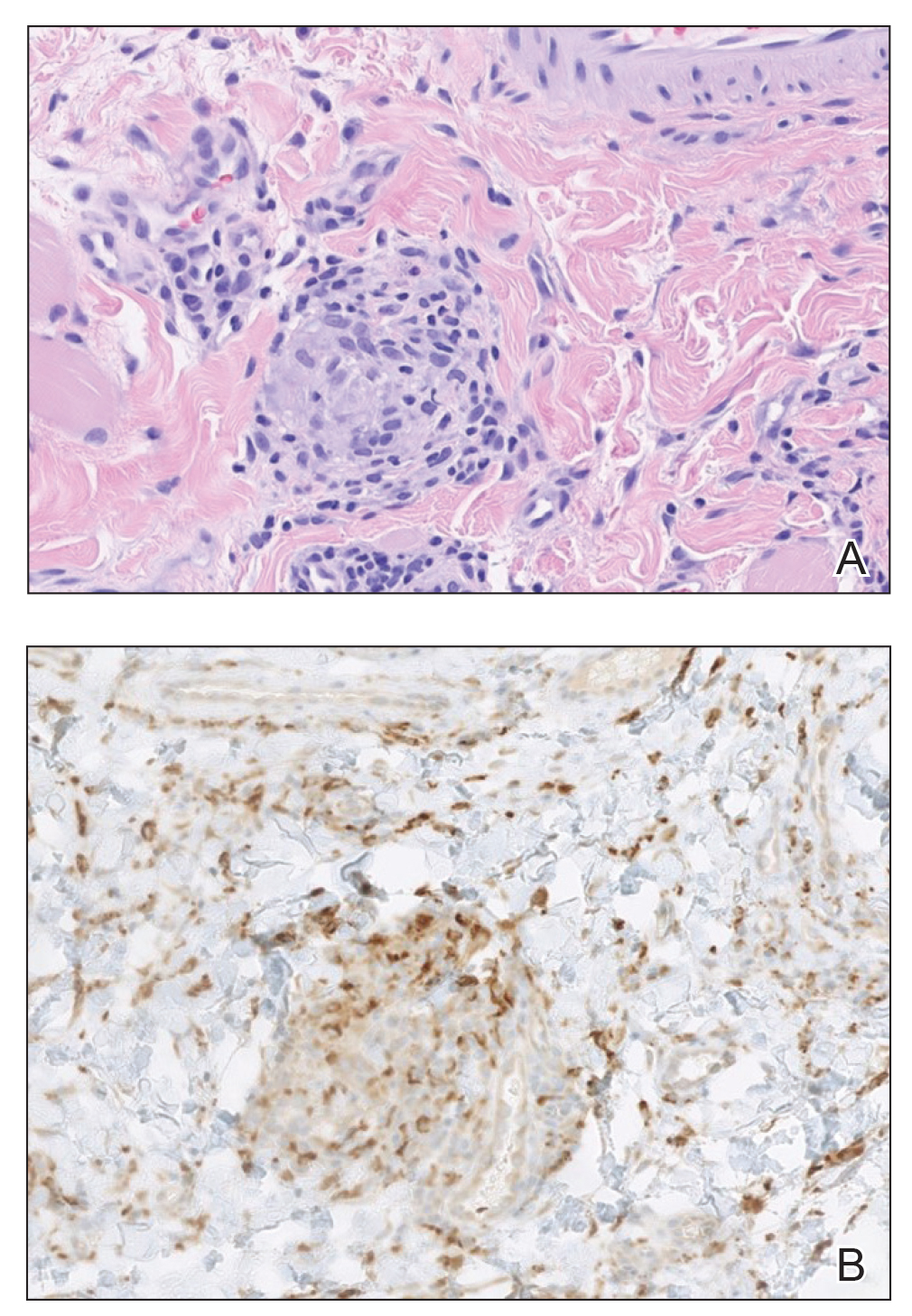

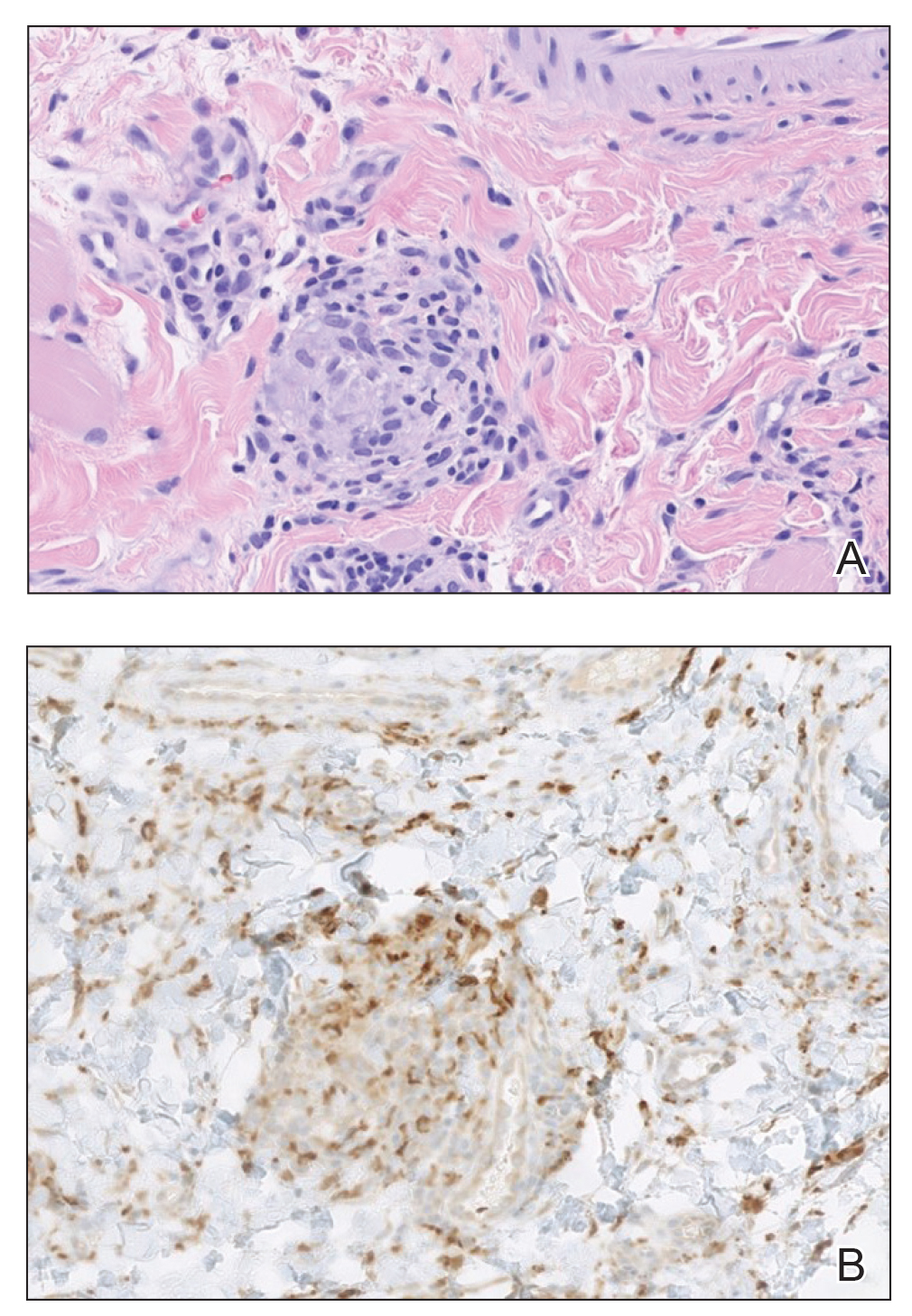

Tufted angiomas are identified by characteristic “cannon ball tufts” of capillaries in the dermis and subcutis at low power.3,5 Distinct cellular lobules may be found bulging into thin-walled vascular channels at the margins of the lobules in the dermis and subcutis (Figure 3).4 The lobules are formed by cells with spindle-shaped nuclei.6 Some mitotic figures may be present, but no cellular atypia is seen.2 The capillaries at the periphery appear as dilated semilunar vessels.4 Dilated lymphatics, which stain with D2-40, can be found at the periphery of the tufted capillaries and throughout the remaining dermis.3,4

Tufted angiomas may arise independently in adults but also have been associated with conditions such as pregnancy. Omori et al7 identified an acquired tufted angioma in pregnancy that was positive for estrogen and progesterone receptors. Reports of tufted angiomas in pregnancy vary; some are multiple lesions, some regress postpartum, and some undergo successful surgical treatment.3,5

Vascular lesions such as tufted angiomas specifically may appear in pregnancy due to a high-volume state with vasodilation and increased vascular proliferation. Although tumor angiogenesis has been linked to specific growth factors and cytokines, it has been hypothesized that the systemic hormones of pregnancy such as human chorionic gonadotropin, estradiol, and progesterone also shift the body to a more angiogenic state.8 In a study of cutaneous changes in pregnant women (N=905), 41% developed a vascular skin change, including spider veins, varicosities, hemangiomas, and granulomas.9 The most common vascular tumor in pregnancy is pyogenic granuloma. Pyogenic granulomas are small, solitary, friable papules that commonly are found on the hands, forearms, face, or in the mouth; histologically they demonstrate dilated capillaries in lobular structures accompanied by larger thick-walled vessels.3,10,11

Tufted angiomas may mimic a variety of other conditions. Epithelioid hemangioma, considered by some to be on the same morphologic spectrum as angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia, classically occurs in young adults on the head and in the neck region. It histologically demonstrates a lobular appearance at low power; however, these lobules are made up of vessels with histiocytoid to epithelioid endothelial cells surrounded by a prominent inflammatory infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes and eosinophils.12

Kaposi sarcoma may appear on the neck but most often presents as macules and patches on the extremities that may form nodules with a rubbery consistency. In tufted angiomas, the cellular nodules with dilated channels at the margins bear a resemblance to Kaposi sarcoma or kaposiform hemangioendothelioma; however, in tufted angiomas the lobules are composed of bland spindle cells and slitlike vessels at the periphery.3,13,14 Tufted angiomas are negative for human herpesvirus 8 and typically do not have an associated inflammatory infiltrate with plasma cells.11,15

Moreover, it is important to differentiate tufted angioma from a cutaneous manifestation of an underlying malignancy, which has been described previously in cases of breast cancer.16,17 Our case illustrates a rare vascular tumor arising in the novel context of a pregnant patient with breast cancer. Distinguishing tufted angioma from other benign or malignant vascular tumors is necessary to avoid inappropriate therapeutic interventions.

The Diagnosis: Tufted Angioma

Histopathology revealed discrete lobules of closely packed capillaries with bland endothelial cells throughout the upper and lower dermis (Figure 1). The surrounding crescentlike vessels and lymphatics stained with D2-40 (Figure 2). These histologic findings were consistent with tufted angioma, and the patient elected for observation.

Tufted angiomas are benign vascular lesions named for the tufted appearance of capillaries on histology.1 They commonly present in children, with a lower incidence in adults and rare cases in pregnancy.2 Tufted angiomas typically present as solitary, slowly expanding, erythematous macules, plaques, or nodules on the neck or trunk ranging in size from less than 1 to 10 cm.2-4 They can be histologically distinguished from other vascular tumors, including aggressive malignant neoplasms.1

Tufted angiomas are identified by characteristic “cannon ball tufts” of capillaries in the dermis and subcutis at low power.3,5 Distinct cellular lobules may be found bulging into thin-walled vascular channels at the margins of the lobules in the dermis and subcutis (Figure 3).4 The lobules are formed by cells with spindle-shaped nuclei.6 Some mitotic figures may be present, but no cellular atypia is seen.2 The capillaries at the periphery appear as dilated semilunar vessels.4 Dilated lymphatics, which stain with D2-40, can be found at the periphery of the tufted capillaries and throughout the remaining dermis.3,4

Tufted angiomas may arise independently in adults but also have been associated with conditions such as pregnancy. Omori et al7 identified an acquired tufted angioma in pregnancy that was positive for estrogen and progesterone receptors. Reports of tufted angiomas in pregnancy vary; some are multiple lesions, some regress postpartum, and some undergo successful surgical treatment.3,5

Vascular lesions such as tufted angiomas specifically may appear in pregnancy due to a high-volume state with vasodilation and increased vascular proliferation. Although tumor angiogenesis has been linked to specific growth factors and cytokines, it has been hypothesized that the systemic hormones of pregnancy such as human chorionic gonadotropin, estradiol, and progesterone also shift the body to a more angiogenic state.8 In a study of cutaneous changes in pregnant women (N=905), 41% developed a vascular skin change, including spider veins, varicosities, hemangiomas, and granulomas.9 The most common vascular tumor in pregnancy is pyogenic granuloma. Pyogenic granulomas are small, solitary, friable papules that commonly are found on the hands, forearms, face, or in the mouth; histologically they demonstrate dilated capillaries in lobular structures accompanied by larger thick-walled vessels.3,10,11

Tufted angiomas may mimic a variety of other conditions. Epithelioid hemangioma, considered by some to be on the same morphologic spectrum as angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia, classically occurs in young adults on the head and in the neck region. It histologically demonstrates a lobular appearance at low power; however, these lobules are made up of vessels with histiocytoid to epithelioid endothelial cells surrounded by a prominent inflammatory infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes and eosinophils.12

Kaposi sarcoma may appear on the neck but most often presents as macules and patches on the extremities that may form nodules with a rubbery consistency. In tufted angiomas, the cellular nodules with dilated channels at the margins bear a resemblance to Kaposi sarcoma or kaposiform hemangioendothelioma; however, in tufted angiomas the lobules are composed of bland spindle cells and slitlike vessels at the periphery.3,13,14 Tufted angiomas are negative for human herpesvirus 8 and typically do not have an associated inflammatory infiltrate with plasma cells.11,15

Moreover, it is important to differentiate tufted angioma from a cutaneous manifestation of an underlying malignancy, which has been described previously in cases of breast cancer.16,17 Our case illustrates a rare vascular tumor arising in the novel context of a pregnant patient with breast cancer. Distinguishing tufted angioma from other benign or malignant vascular tumors is necessary to avoid inappropriate therapeutic interventions.

- Jones EW, Orkin M. Tufted angioma (angioblastoma). a benign progressive angioma, not to be confused with Kaposi’s sarcoma or low-grade angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(2 pt 1):214-225.

- Lee B, Chiu M, Soriano T, et al. Adult-onset tufted angioma: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2006;78:341-345.

- Kim YK, Kim HJ, Lee KG. Acquired tufted angioma associated with pregnancy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:458-459.

- Feito-Rodriguez M, Sanchez-Orta A, De Lucas R, et al. Congenital tufted angioma: a multicenter retrospective study of 30 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:808-816.

- Pietroletti R, Leardi S, Simi M. Perianal acquired tufted angioma associated with pregnancy: case report. Tech Coloproctol. 2002;6:117-119.

- Osio A, Fraitag S, Hadj-Rabia S, et al. Clinical spectrum of tufted angiomas in childhood: a report of 13 cases and a review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:758-763.

- Omori M, Bito T, Nishigori C. Acquired tufted angioma in pregnancy showing expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23:898-899.

- Boeldt DS, Bird IM. Vascular adaptation in pregnancy and endothelial dysfunction in preeclampsia. J Endocrinol. 2017;232:R27-R44.

- Fernandes LB, Amaral W. Clinical study of skin changes in low and high risk pregnant women. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:822-826.

- Walker JL, Wang AR, Kroumpouzos G, et al. Cutaneous tumors in pregnancy. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:359-367.

- Sarwal P, Lapumnuaypol K. Pyogenic granuloma. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Ortins-Pina A, Llamas-Velasco M, Turpin S, et al. FOSB immunoreactivity in endothelia of epithelioid hemangioma (angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia). J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:395-402.

- Arai E, Kuramochi A, Tsuchida T, et al. Usefulness of D2-40 immunohistochemistry for differentiation between kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and tufted angioma. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:492-497.

- Grassi S, Carugno A, Vignini M, et al. Adult-onset tufted angiomas associated with an arteriovenous malformation in a renal transplant recipient: case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:162-165.

- Lyons LL, North PE, Mac-Moune Lai F, et al. Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma: a study of 33 cases emphasizing its pathologic, immunophenotypic, and biologic uniqueness from juvenile hemangioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:559-568.

- Putra HP, Djawad K, Nurdin AR. Cutaneous lesions as the first manifestation of breast cancer: a rare case. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;37:383.

- Thiers BH, Sahn RE, Callen JP. Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:73-98.

- Jones EW, Orkin M. Tufted angioma (angioblastoma). a benign progressive angioma, not to be confused with Kaposi’s sarcoma or low-grade angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(2 pt 1):214-225.

- Lee B, Chiu M, Soriano T, et al. Adult-onset tufted angioma: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2006;78:341-345.

- Kim YK, Kim HJ, Lee KG. Acquired tufted angioma associated with pregnancy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:458-459.

- Feito-Rodriguez M, Sanchez-Orta A, De Lucas R, et al. Congenital tufted angioma: a multicenter retrospective study of 30 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:808-816.

- Pietroletti R, Leardi S, Simi M. Perianal acquired tufted angioma associated with pregnancy: case report. Tech Coloproctol. 2002;6:117-119.

- Osio A, Fraitag S, Hadj-Rabia S, et al. Clinical spectrum of tufted angiomas in childhood: a report of 13 cases and a review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:758-763.

- Omori M, Bito T, Nishigori C. Acquired tufted angioma in pregnancy showing expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23:898-899.

- Boeldt DS, Bird IM. Vascular adaptation in pregnancy and endothelial dysfunction in preeclampsia. J Endocrinol. 2017;232:R27-R44.

- Fernandes LB, Amaral W. Clinical study of skin changes in low and high risk pregnant women. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:822-826.

- Walker JL, Wang AR, Kroumpouzos G, et al. Cutaneous tumors in pregnancy. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:359-367.

- Sarwal P, Lapumnuaypol K. Pyogenic granuloma. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Ortins-Pina A, Llamas-Velasco M, Turpin S, et al. FOSB immunoreactivity in endothelia of epithelioid hemangioma (angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia). J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:395-402.

- Arai E, Kuramochi A, Tsuchida T, et al. Usefulness of D2-40 immunohistochemistry for differentiation between kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and tufted angioma. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:492-497.

- Grassi S, Carugno A, Vignini M, et al. Adult-onset tufted angiomas associated with an arteriovenous malformation in a renal transplant recipient: case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:162-165.

- Lyons LL, North PE, Mac-Moune Lai F, et al. Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma: a study of 33 cases emphasizing its pathologic, immunophenotypic, and biologic uniqueness from juvenile hemangioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:559-568.

- Putra HP, Djawad K, Nurdin AR. Cutaneous lesions as the first manifestation of breast cancer: a rare case. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;37:383.

- Thiers BH, Sahn RE, Callen JP. Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:73-98.

A 31-year-old woman at 34 weeks’ gestation presented with skin discoloration of the anterior neck of 7 months’ duration. Her pregnancy had been complicated by a diagnosis of invasive papillary carcinoma of the breast with unilateral complete mastectomy and negative sentinel lymph node biopsy in the first trimester. The lesion was tender, darkening, and rapidly enlarging. Physical examination demonstrated a linear, violaceous, vascular, and indurated plaque with microvesiculation that was 3.5 cm in width. She had no history of blistering sunburns, frequent UV exposure, or skin cancer.

Persistent Lip Swelling

The Diagnosis: Granulomatous Cheilitis

A punch biopsy of the lip revealed a noncaseating microgranuloma in the submucosa with modest submucosal vascular ectasia and perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates (Figure). Comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood cell count, angiotensinconverting enzyme (ACE) levels, and inflammatory markers (ie, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein) all were within reference range. A serum environmental allergen test was negative except for ragweed. Levels of complements—C1 esterase inhibitor (C1-INH) antigen and function, C1q, C3, and C4—and antinuclear antibodies all were normal. Chest radiography was unremarkable. In lieu of a colonoscopy, a fecal calprotectin obtained by gastroenterology was normal. Given the clinical presentation and histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of granulomatous cheilitis (GC) was made.

Granulomatous cheilitis (also known as Miescher cheilitis) is an idiopathic condition characterized by recurrent or persistent swelling of one or both lips. Granulomatous cheilitis usually is an isolated finding but can occur in the setting of Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome, which refers to a triad of orofacial swelling, facial paralysis, and fissured tongue. Orofacial granulomatosis is a unifying term for any orofacial swelling associated with histologic findings of noncaseating granulomas without evidence of a systemic disease.

Granulomatous cheilitis is a rare disease that most commonly occurs in young adults without any sex predilection.1 The etiology still is unknown, but genetic predisposition, idiopathic influx of inflammatory cells, sensitivity to food or dental materials, and infections have been implicated.2 Granulomatous cheilitis initially presents as soft, nonerythematous, nontender swelling affecting one or both lips. The first episode usually resolves in hours or days, but the frequency and duration of the attacks may increase until the swelling becomes persistent and indurated.3 Granulomatous cheilitis often is a diagnosis of exclusion. A tissue biopsy may show noncaseating epithelioid and multinucleated giant cells with associated lymphedema and fibrosis4; however, histologic findings may be nonspecific, especially early in the disease course, and may be indistinguishable from those of other granulomatous diseases such as sarcoidosis and Crohn disease (CD).5

Lip swelling may be an oral manifestation of CD. Compared with GC, however, CD more commonly is associated with ulcerations, buccal sulcus involvement, abnormalities in complete blood cell count such as anemia and thrombocytosis, and elevated C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Although infrequent, GC may coincide with or precede the onset of CD.6 Thus, a detailed gastrointestinal history and appropriate laboratory tests are needed to rule out undiagnosed CD. Nevertheless, performing a routine colonoscopy in the absence of gastrointestinal symptoms is debated.7,8

Sarcoidosis is a systemic granulomatous disease that can have oral involvement in the form of edema, nodules, or ulcers. Oral sarcoidosis usually occurs in patients with chronic multisystemic sarcoidosis and likely is accompanied by pulmonary manifestations such as hilar adenopathy and infiltrates on chest radiography, which are found in more than 90% of patients with sarcoidosis.9,10 A diagnosis of sarcoidosis is additionally supported by other organ involvement such as the joints, skin, or eyes, as well as elevated ACE and calcium levels.

Foreign bodies are another source of granulomatous inflammation and may present with nonspecific findings of swelling, masses, erythema, pain, or ulceration in oral tissues.11 Foreign body reactions to dental materials, retained sutures, and cosmetic fillers have been reported.12-14 In many cases, the foreign material is evident on biopsy.

Angioedema may mimic GC and should be excluded before more extensive testing is done, as it can result in life-threatening respiratory compromise. Numerous etiologies of angioedema have been identified including allergens, acquired or hereditary C1-INH deficiency, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, ACE inhibitors, autoimmune disorders, and chronic infections.15 Patients with angioedema may have abnormalities in C4 and C1-INH levels or report certain medication use, allergen exposure, or family history of unexplained recurrent swellings or gastrointestinal symptoms.

There currently is no established treatment of GC due to the unclear etiology and unpredictable clinical course that can lead to spontaneous remissions or frequent recurrences. Corticosteroids administered systemically, intralesionally, or topically have been the mainstay treatment of GC.2 In particular, intralesional injections have been reported as effective in reducing swelling and preventing recurrences in several studies.16,17 Numerous other treatments have been reported in the literature with inconsistent outcomes, including antibiotics such as minocycline, metronidazole, and roxithromycin; clofazimine; thalidomide; immunomodulators such as tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and methotrexate; fumaric acid esters; and cheiloplasty in severe cases.16 Our patient showed near-complete resolution of the lip swelling after a single intralesional injection of 0.5 cc of triamcinolone acetonide 5 mg/mL. The patient has since received 5 additional maintenance injections of 0.1 to 0.2 cc of triamcinolone acetonide 2.5 to 5 mg/mL spaced 2 to 4 months apart with excellent control of the lip swelling, which the patient feels has resolved. We anticipate that repeated injections and monitoring of recurrences may be required for long-term remission.

- McCartan BE, Healy CM, McCreary CE, et al. Characteristics of patients with orofacial granulomatosis. Oral Dis. 2011;17:696-704.

- Grave B, McCullough M, Wiesenfeld D. Orofacial granulomatosis—a 20-year review. Oral Dis. 2009;15:46-51.

- Critchlow WA, Chang D. Cheilitis granulomatosa: a review. Head Neck Pathol. 2014;8:209-213.

- Wiesenfeld D, Ferguson MM, Mitchell DN, et al. Oro-facial granulomatosis—a clinical and pathological analysis. Q J Med. 1985;54:101-113.

- Rogers RS 3rd. Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and orofacial granulomatosis. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:371-379.

- Campbell H, Escudier M, Patel P, et al. Distinguishing orofacial granulomatosis from Crohn’s disease: two separate disease entities? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:2109-2115.

- Plauth M, Jenss H, Meyle J. Oral manifestations of Crohn’s disease. an analysis of 79 cases. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1991;13:29-37.

- Van der Waal RI, Schulten EA, van der Meij EH, et al. Cheilitis granulomatosa: overview of 13 patients with long-term follow-up— results of management. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:225-229.

- Bouaziz A, Le Scanff J, Chapelon-Abric C, et al. Oral involvement in sarcoidosis: report of 12 cases. QJM. 2012;105:755-767.

- Statement on sarcoidosis. Joint Statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS Board of Directors and by the ERS Executive Committee, February 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:736-755.

- Alawi F. An update on granulomatous diseases of the oral tissues. Dent Clin North Am. 2013;57:657-671.

- Stewart CM, Watson RE. Experimental oral foreign body reactions. commonly employed dental materials. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;69:713-719.

- Selvig KA, Biagiotti GR, Leknes KN, et al. Oral tissue reactions to suture materials. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1998;18:474-487.

- Jham BC, Nikitakis NG, Scheper MA, et al. Granulomatous foreignbody reaction involving oral and perioral tissues after injection of biomaterials: a series of 7 cases and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:280-285.

- Zingale LC, Beltrami L, Zanichelli A, et al. Angioedema without urticaria: a large clinical survey. CMAJ. 2006;175:1065-1070.

- Banks T, Gada S. A comprehensive review of current treatments for granulomatous cheilitis. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:934-937.

- Fedele S, Fung PP, Bamashmous N, et al. Long-term effectiveness of intralesional triamcinolone acetonide therapy in orofacial granulomatosis: an observational cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:794-801.

The Diagnosis: Granulomatous Cheilitis

A punch biopsy of the lip revealed a noncaseating microgranuloma in the submucosa with modest submucosal vascular ectasia and perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates (Figure). Comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood cell count, angiotensinconverting enzyme (ACE) levels, and inflammatory markers (ie, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein) all were within reference range. A serum environmental allergen test was negative except for ragweed. Levels of complements—C1 esterase inhibitor (C1-INH) antigen and function, C1q, C3, and C4—and antinuclear antibodies all were normal. Chest radiography was unremarkable. In lieu of a colonoscopy, a fecal calprotectin obtained by gastroenterology was normal. Given the clinical presentation and histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of granulomatous cheilitis (GC) was made.

Granulomatous cheilitis (also known as Miescher cheilitis) is an idiopathic condition characterized by recurrent or persistent swelling of one or both lips. Granulomatous cheilitis usually is an isolated finding but can occur in the setting of Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome, which refers to a triad of orofacial swelling, facial paralysis, and fissured tongue. Orofacial granulomatosis is a unifying term for any orofacial swelling associated with histologic findings of noncaseating granulomas without evidence of a systemic disease.

Granulomatous cheilitis is a rare disease that most commonly occurs in young adults without any sex predilection.1 The etiology still is unknown, but genetic predisposition, idiopathic influx of inflammatory cells, sensitivity to food or dental materials, and infections have been implicated.2 Granulomatous cheilitis initially presents as soft, nonerythematous, nontender swelling affecting one or both lips. The first episode usually resolves in hours or days, but the frequency and duration of the attacks may increase until the swelling becomes persistent and indurated.3 Granulomatous cheilitis often is a diagnosis of exclusion. A tissue biopsy may show noncaseating epithelioid and multinucleated giant cells with associated lymphedema and fibrosis4; however, histologic findings may be nonspecific, especially early in the disease course, and may be indistinguishable from those of other granulomatous diseases such as sarcoidosis and Crohn disease (CD).5

Lip swelling may be an oral manifestation of CD. Compared with GC, however, CD more commonly is associated with ulcerations, buccal sulcus involvement, abnormalities in complete blood cell count such as anemia and thrombocytosis, and elevated C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Although infrequent, GC may coincide with or precede the onset of CD.6 Thus, a detailed gastrointestinal history and appropriate laboratory tests are needed to rule out undiagnosed CD. Nevertheless, performing a routine colonoscopy in the absence of gastrointestinal symptoms is debated.7,8

Sarcoidosis is a systemic granulomatous disease that can have oral involvement in the form of edema, nodules, or ulcers. Oral sarcoidosis usually occurs in patients with chronic multisystemic sarcoidosis and likely is accompanied by pulmonary manifestations such as hilar adenopathy and infiltrates on chest radiography, which are found in more than 90% of patients with sarcoidosis.9,10 A diagnosis of sarcoidosis is additionally supported by other organ involvement such as the joints, skin, or eyes, as well as elevated ACE and calcium levels.

Foreign bodies are another source of granulomatous inflammation and may present with nonspecific findings of swelling, masses, erythema, pain, or ulceration in oral tissues.11 Foreign body reactions to dental materials, retained sutures, and cosmetic fillers have been reported.12-14 In many cases, the foreign material is evident on biopsy.

Angioedema may mimic GC and should be excluded before more extensive testing is done, as it can result in life-threatening respiratory compromise. Numerous etiologies of angioedema have been identified including allergens, acquired or hereditary C1-INH deficiency, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, ACE inhibitors, autoimmune disorders, and chronic infections.15 Patients with angioedema may have abnormalities in C4 and C1-INH levels or report certain medication use, allergen exposure, or family history of unexplained recurrent swellings or gastrointestinal symptoms.

There currently is no established treatment of GC due to the unclear etiology and unpredictable clinical course that can lead to spontaneous remissions or frequent recurrences. Corticosteroids administered systemically, intralesionally, or topically have been the mainstay treatment of GC.2 In particular, intralesional injections have been reported as effective in reducing swelling and preventing recurrences in several studies.16,17 Numerous other treatments have been reported in the literature with inconsistent outcomes, including antibiotics such as minocycline, metronidazole, and roxithromycin; clofazimine; thalidomide; immunomodulators such as tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and methotrexate; fumaric acid esters; and cheiloplasty in severe cases.16 Our patient showed near-complete resolution of the lip swelling after a single intralesional injection of 0.5 cc of triamcinolone acetonide 5 mg/mL. The patient has since received 5 additional maintenance injections of 0.1 to 0.2 cc of triamcinolone acetonide 2.5 to 5 mg/mL spaced 2 to 4 months apart with excellent control of the lip swelling, which the patient feels has resolved. We anticipate that repeated injections and monitoring of recurrences may be required for long-term remission.

The Diagnosis: Granulomatous Cheilitis

A punch biopsy of the lip revealed a noncaseating microgranuloma in the submucosa with modest submucosal vascular ectasia and perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates (Figure). Comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood cell count, angiotensinconverting enzyme (ACE) levels, and inflammatory markers (ie, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein) all were within reference range. A serum environmental allergen test was negative except for ragweed. Levels of complements—C1 esterase inhibitor (C1-INH) antigen and function, C1q, C3, and C4—and antinuclear antibodies all were normal. Chest radiography was unremarkable. In lieu of a colonoscopy, a fecal calprotectin obtained by gastroenterology was normal. Given the clinical presentation and histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of granulomatous cheilitis (GC) was made.

Granulomatous cheilitis (also known as Miescher cheilitis) is an idiopathic condition characterized by recurrent or persistent swelling of one or both lips. Granulomatous cheilitis usually is an isolated finding but can occur in the setting of Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome, which refers to a triad of orofacial swelling, facial paralysis, and fissured tongue. Orofacial granulomatosis is a unifying term for any orofacial swelling associated with histologic findings of noncaseating granulomas without evidence of a systemic disease.

Granulomatous cheilitis is a rare disease that most commonly occurs in young adults without any sex predilection.1 The etiology still is unknown, but genetic predisposition, idiopathic influx of inflammatory cells, sensitivity to food or dental materials, and infections have been implicated.2 Granulomatous cheilitis initially presents as soft, nonerythematous, nontender swelling affecting one or both lips. The first episode usually resolves in hours or days, but the frequency and duration of the attacks may increase until the swelling becomes persistent and indurated.3 Granulomatous cheilitis often is a diagnosis of exclusion. A tissue biopsy may show noncaseating epithelioid and multinucleated giant cells with associated lymphedema and fibrosis4; however, histologic findings may be nonspecific, especially early in the disease course, and may be indistinguishable from those of other granulomatous diseases such as sarcoidosis and Crohn disease (CD).5

Lip swelling may be an oral manifestation of CD. Compared with GC, however, CD more commonly is associated with ulcerations, buccal sulcus involvement, abnormalities in complete blood cell count such as anemia and thrombocytosis, and elevated C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Although infrequent, GC may coincide with or precede the onset of CD.6 Thus, a detailed gastrointestinal history and appropriate laboratory tests are needed to rule out undiagnosed CD. Nevertheless, performing a routine colonoscopy in the absence of gastrointestinal symptoms is debated.7,8

Sarcoidosis is a systemic granulomatous disease that can have oral involvement in the form of edema, nodules, or ulcers. Oral sarcoidosis usually occurs in patients with chronic multisystemic sarcoidosis and likely is accompanied by pulmonary manifestations such as hilar adenopathy and infiltrates on chest radiography, which are found in more than 90% of patients with sarcoidosis.9,10 A diagnosis of sarcoidosis is additionally supported by other organ involvement such as the joints, skin, or eyes, as well as elevated ACE and calcium levels.

Foreign bodies are another source of granulomatous inflammation and may present with nonspecific findings of swelling, masses, erythema, pain, or ulceration in oral tissues.11 Foreign body reactions to dental materials, retained sutures, and cosmetic fillers have been reported.12-14 In many cases, the foreign material is evident on biopsy.

Angioedema may mimic GC and should be excluded before more extensive testing is done, as it can result in life-threatening respiratory compromise. Numerous etiologies of angioedema have been identified including allergens, acquired or hereditary C1-INH deficiency, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, ACE inhibitors, autoimmune disorders, and chronic infections.15 Patients with angioedema may have abnormalities in C4 and C1-INH levels or report certain medication use, allergen exposure, or family history of unexplained recurrent swellings or gastrointestinal symptoms.

There currently is no established treatment of GC due to the unclear etiology and unpredictable clinical course that can lead to spontaneous remissions or frequent recurrences. Corticosteroids administered systemically, intralesionally, or topically have been the mainstay treatment of GC.2 In particular, intralesional injections have been reported as effective in reducing swelling and preventing recurrences in several studies.16,17 Numerous other treatments have been reported in the literature with inconsistent outcomes, including antibiotics such as minocycline, metronidazole, and roxithromycin; clofazimine; thalidomide; immunomodulators such as tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and methotrexate; fumaric acid esters; and cheiloplasty in severe cases.16 Our patient showed near-complete resolution of the lip swelling after a single intralesional injection of 0.5 cc of triamcinolone acetonide 5 mg/mL. The patient has since received 5 additional maintenance injections of 0.1 to 0.2 cc of triamcinolone acetonide 2.5 to 5 mg/mL spaced 2 to 4 months apart with excellent control of the lip swelling, which the patient feels has resolved. We anticipate that repeated injections and monitoring of recurrences may be required for long-term remission.

- McCartan BE, Healy CM, McCreary CE, et al. Characteristics of patients with orofacial granulomatosis. Oral Dis. 2011;17:696-704.

- Grave B, McCullough M, Wiesenfeld D. Orofacial granulomatosis—a 20-year review. Oral Dis. 2009;15:46-51.

- Critchlow WA, Chang D. Cheilitis granulomatosa: a review. Head Neck Pathol. 2014;8:209-213.

- Wiesenfeld D, Ferguson MM, Mitchell DN, et al. Oro-facial granulomatosis—a clinical and pathological analysis. Q J Med. 1985;54:101-113.

- Rogers RS 3rd. Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and orofacial granulomatosis. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:371-379.

- Campbell H, Escudier M, Patel P, et al. Distinguishing orofacial granulomatosis from Crohn’s disease: two separate disease entities? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:2109-2115.

- Plauth M, Jenss H, Meyle J. Oral manifestations of Crohn’s disease. an analysis of 79 cases. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1991;13:29-37.

- Van der Waal RI, Schulten EA, van der Meij EH, et al. Cheilitis granulomatosa: overview of 13 patients with long-term follow-up— results of management. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:225-229.

- Bouaziz A, Le Scanff J, Chapelon-Abric C, et al. Oral involvement in sarcoidosis: report of 12 cases. QJM. 2012;105:755-767.

- Statement on sarcoidosis. Joint Statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS Board of Directors and by the ERS Executive Committee, February 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:736-755.

- Alawi F. An update on granulomatous diseases of the oral tissues. Dent Clin North Am. 2013;57:657-671.

- Stewart CM, Watson RE. Experimental oral foreign body reactions. commonly employed dental materials. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;69:713-719.

- Selvig KA, Biagiotti GR, Leknes KN, et al. Oral tissue reactions to suture materials. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1998;18:474-487.

- Jham BC, Nikitakis NG, Scheper MA, et al. Granulomatous foreignbody reaction involving oral and perioral tissues after injection of biomaterials: a series of 7 cases and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:280-285.

- Zingale LC, Beltrami L, Zanichelli A, et al. Angioedema without urticaria: a large clinical survey. CMAJ. 2006;175:1065-1070.

- Banks T, Gada S. A comprehensive review of current treatments for granulomatous cheilitis. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:934-937.

- Fedele S, Fung PP, Bamashmous N, et al. Long-term effectiveness of intralesional triamcinolone acetonide therapy in orofacial granulomatosis: an observational cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:794-801.

- McCartan BE, Healy CM, McCreary CE, et al. Characteristics of patients with orofacial granulomatosis. Oral Dis. 2011;17:696-704.

- Grave B, McCullough M, Wiesenfeld D. Orofacial granulomatosis—a 20-year review. Oral Dis. 2009;15:46-51.

- Critchlow WA, Chang D. Cheilitis granulomatosa: a review. Head Neck Pathol. 2014;8:209-213.

- Wiesenfeld D, Ferguson MM, Mitchell DN, et al. Oro-facial granulomatosis—a clinical and pathological analysis. Q J Med. 1985;54:101-113.

- Rogers RS 3rd. Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and orofacial granulomatosis. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:371-379.

- Campbell H, Escudier M, Patel P, et al. Distinguishing orofacial granulomatosis from Crohn’s disease: two separate disease entities? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:2109-2115.

- Plauth M, Jenss H, Meyle J. Oral manifestations of Crohn’s disease. an analysis of 79 cases. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1991;13:29-37.

- Van der Waal RI, Schulten EA, van der Meij EH, et al. Cheilitis granulomatosa: overview of 13 patients with long-term follow-up— results of management. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:225-229.

- Bouaziz A, Le Scanff J, Chapelon-Abric C, et al. Oral involvement in sarcoidosis: report of 12 cases. QJM. 2012;105:755-767.

- Statement on sarcoidosis. Joint Statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS Board of Directors and by the ERS Executive Committee, February 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:736-755.

- Alawi F. An update on granulomatous diseases of the oral tissues. Dent Clin North Am. 2013;57:657-671.

- Stewart CM, Watson RE. Experimental oral foreign body reactions. commonly employed dental materials. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;69:713-719.

- Selvig KA, Biagiotti GR, Leknes KN, et al. Oral tissue reactions to suture materials. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1998;18:474-487.

- Jham BC, Nikitakis NG, Scheper MA, et al. Granulomatous foreignbody reaction involving oral and perioral tissues after injection of biomaterials: a series of 7 cases and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:280-285.

- Zingale LC, Beltrami L, Zanichelli A, et al. Angioedema without urticaria: a large clinical survey. CMAJ. 2006;175:1065-1070.

- Banks T, Gada S. A comprehensive review of current treatments for granulomatous cheilitis. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:934-937.

- Fedele S, Fung PP, Bamashmous N, et al. Long-term effectiveness of intralesional triamcinolone acetonide therapy in orofacial granulomatosis: an observational cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:794-801.

A 36-year-old man with allergic rhinitis presented with lower lip swelling of several months’ duration. The swelling was persistent and predominantly on the left side of the lower lip but occasionally spread to the entire lower lip. The episodes of increased swelling would last for several days and were not associated with any apparent triggers. He denied any pain, pruritus, or dryness. He noted more drooling from the affected side but denied any associated breathing difficulty or throat discomfort. Treatment with an oral antihistamine provided no relief. He denied any recent nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug or angiotensinconverting enzyme inhibitor use. His family history was notable for lupus in his maternal grandmother and maternal aunt. He denied any personal or family history of inflammatory bowel disease or recent gastrointestinal tract symptoms. Physical examination revealed nontender edema in the left side of the lower lip with no surface changes. No warmth or erythema were noted. The tongue and the rest of the oral cavity were unremarkable.

Aquatic Antagonists: Marine Rashes (Seabather’s Eruption and Diver’s Dermatitis)

Background and Clinical Presentation

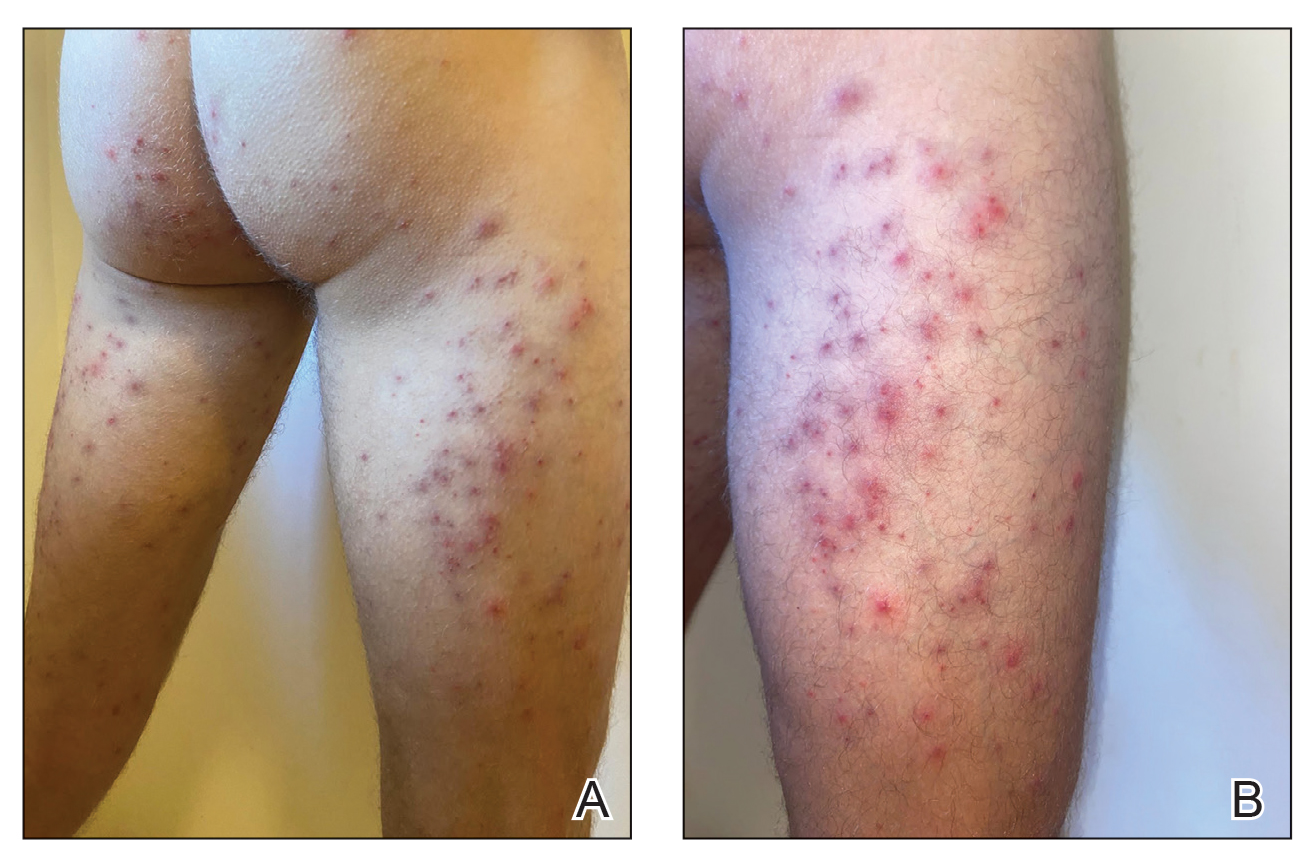

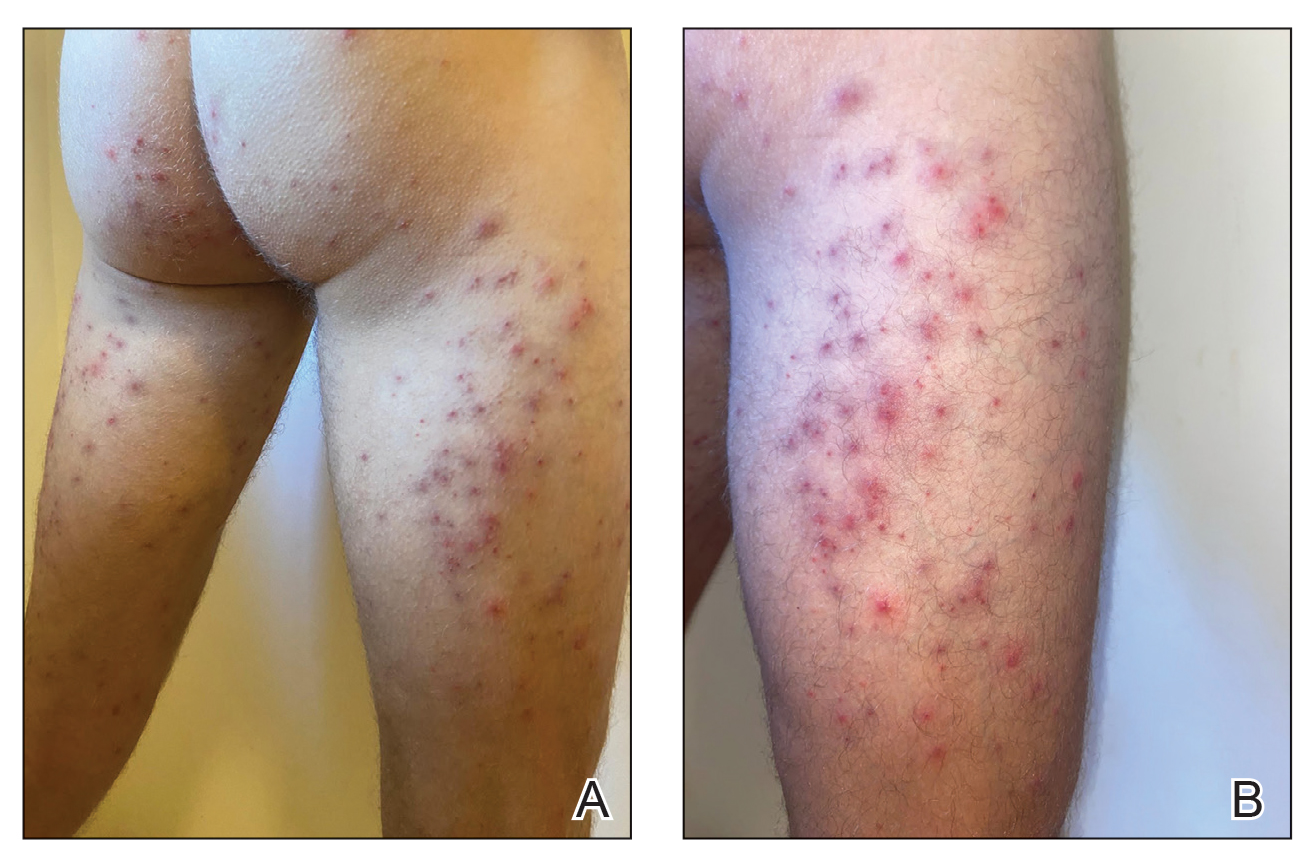

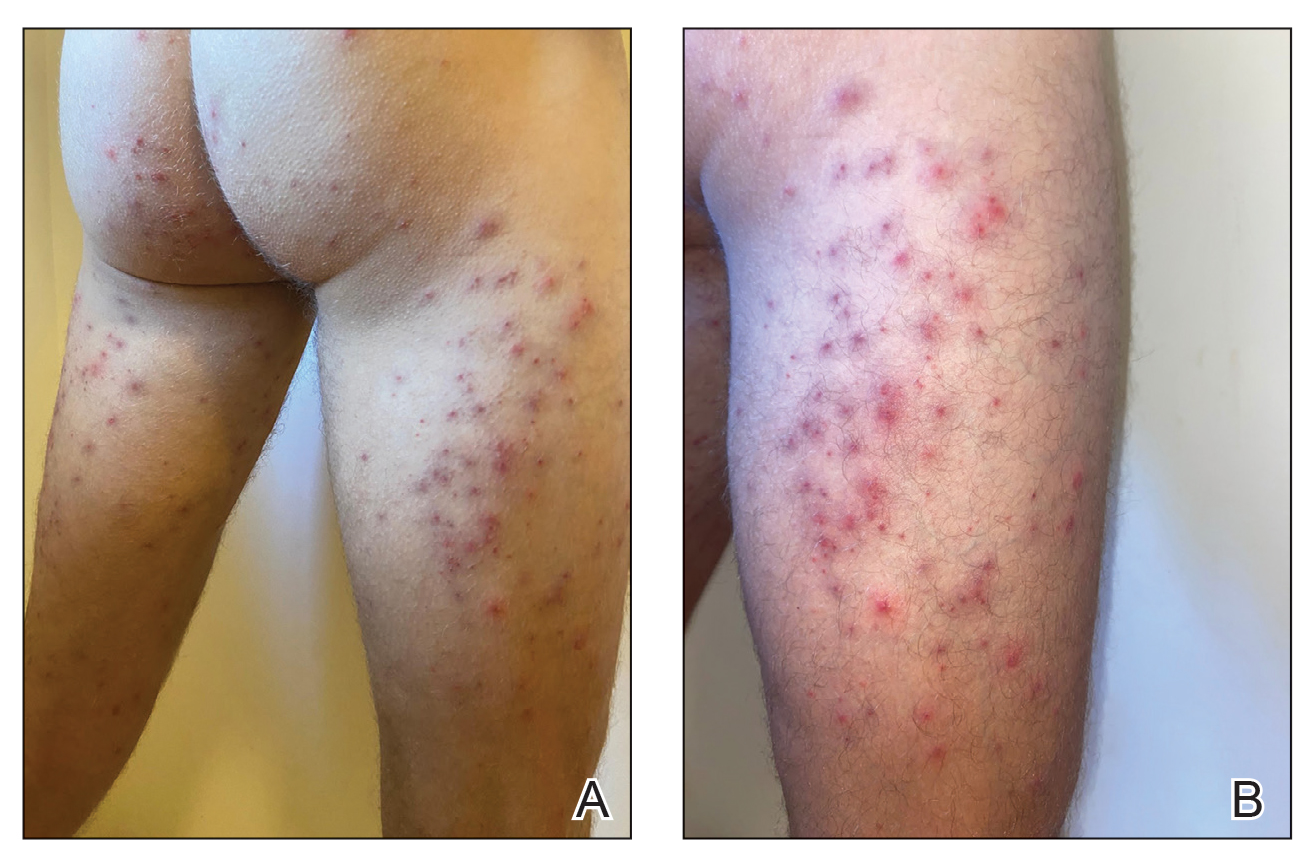

Seabather’s Eruption—Seabather’s eruption is a type I and IV hypersensitivity reaction caused by nematocysts of larval-stage thimble jellyfish (Linuche unguiculata), sea anemones (eg, Edwardsiella lineata), and larval cnidarians.1Linuche unguiculata commonly is found along the southeast coast of the United States and in the Caribbean, the Gulf of Mexico, and the coasts of Florida; less commonly, it has been reported along the coasts of Brazil and Papua New Guinea. Edwardsiella lineata more commonly is seen along the East Coast of the United States.2 Seabather’s eruption presents as numerous scattered, pruritic, red macules and papules (measuring 1 mm to 1.5 cm in size) distributed in areas covered by skin folds, wet clothing, or hair following exposure to marine water (Figure 1). This maculopapular rash generally appears shortly after exiting the water and can last up to several weeks in some cases.3 The cause for this delayed presentation is that the marine organisms become entrapped between the skin of the human contact and another object (eg, swimwear) but do not release their preformed antivenom until they are exposed to air after removal from the water, at which point the organisms die and cell lysis results in injection of the venom.

Diver’s Dermatitis—Diver’s dermatitis (also referred to as “swimmer’s itch”) is a type I and IV hypersensitivity reaction caused by schistosome cercariae released by aquatic snails.4 There are several different cercarial species known to be capable of causing diver dermatitis, but the most commonly implicated genera are Trichobilharzia and Gigantobilharzia. These parasites most commonly are found in freshwater lakes but also occur in oceans, particularly in brackish areas adjacent to freshwater access. Factors associated with increased concentrations of these parasites include shallow, slow-moving water and prolonged onshore wind causing accumulation near the shoreline. It also is thought that the snail host will shed greater concentrations of the parasitic worm in the morning hours and after prolonged exposure to sunlight.4 These flatworm trematodes have a 2-host life cycle. The snails function as intermediate hosts for the parasites before they enter their final host, which are birds. Humans only function as incidental and nonviable hosts for these worms. The parasites gain access to the human body by burrowing into exposed skin. Because the parasite is unable to survive on human hosts, it dies shortly after penetrating the skin, which leads to an intense inflammatory response causing symptoms of pruritus within hours of exposure (Figure 2). The initial eruption progresses over a few days into a diffuse, maculopapular, pruritic rash, similar to that seen in seabather’s eruption. This rash then regresses completely in 1 to 3 weeks. Subsequent exposure to the same parasite is associated with increased severity of future rashes, likely due to antibody-mediated sensitization.4