User login

Focal Palmoplantar Keratoderma and Gingival Keratosis Caused by a KRT16 Mutation

To the Editor:

Focal palmoplantar keratoderma and gingival keratosis (FPGK)(Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM] 148730) is a rare autosomal-dominant syndrome featuring focal, pressure-related, painful palmoplantar keratoderma and gingival hyperkeratosis presenting as leukokeratosis. Focal palmoplantar keratoderma and gingival keratosis was first defined by Gorlin1 in 1976. Since then, only a few cases have been reported, but no causative mutations have been identified.2

Focal pressure-related palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK) and oral hyperkeratosis also are seen in pachyonychia congenita (PC)(OMIM 167200, 615726, 615728, 167210), a rare autosomal-dominant disorder of keratinization characterized by PPK and nail dystrophy. Patients with PC often present with plantar pain; more variable features include oral leukokeratosis, follicular hyperkeratosis, pilosebaceous and epidermal inclusion cysts, hoarseness, hyperhidrosis, and natal teeth. Pachyonychia congenita is caused by mutation in keratin genes KRT6A, KRT6B, KRT16, or KRT17.

Focal palmoplantar keratoderma and gingival keratosis as well as PC are distinct from other forms of PPK with gingival involvement such as

Despite the common features of FPGK and PC, they are considered distinct disorders due to absence of nail changes in FPGK and no prior evidence of a common genetic cause. We present a patient with familial FPGK found by whole exome sequencing to be caused by a mutation in KRT16.

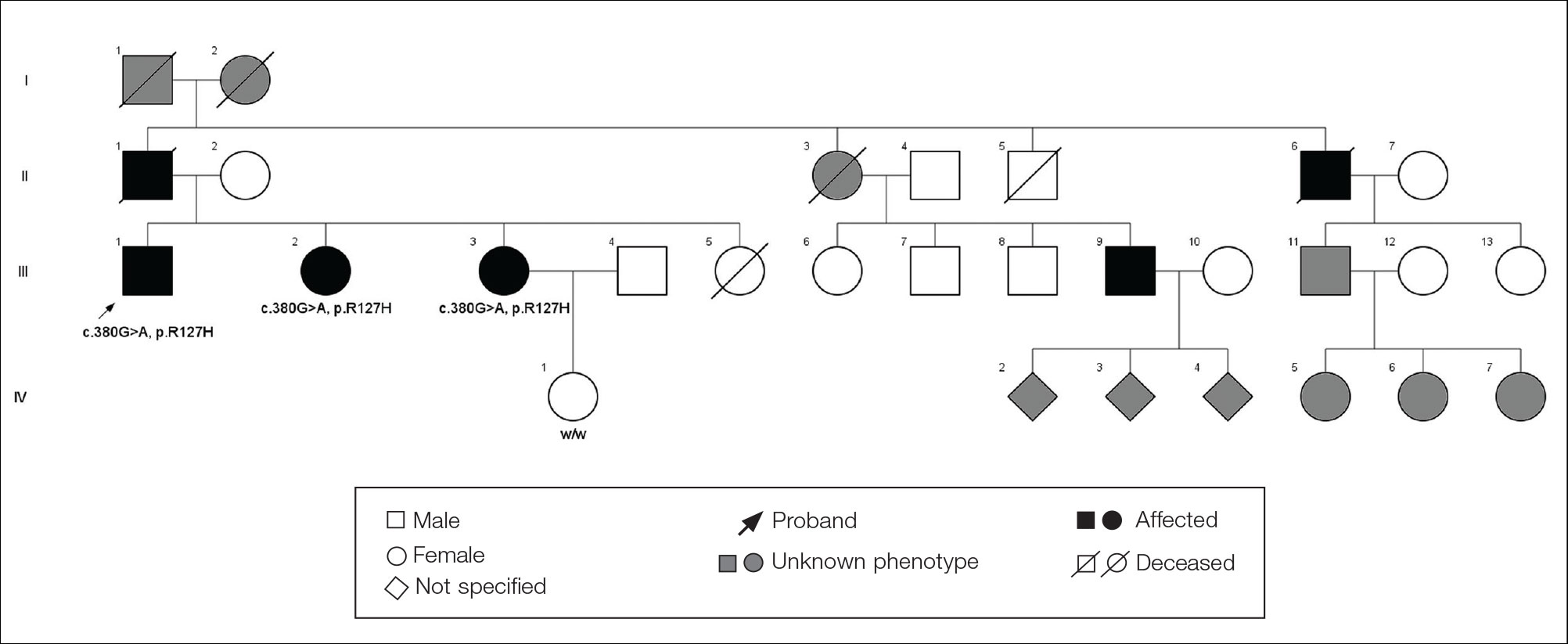

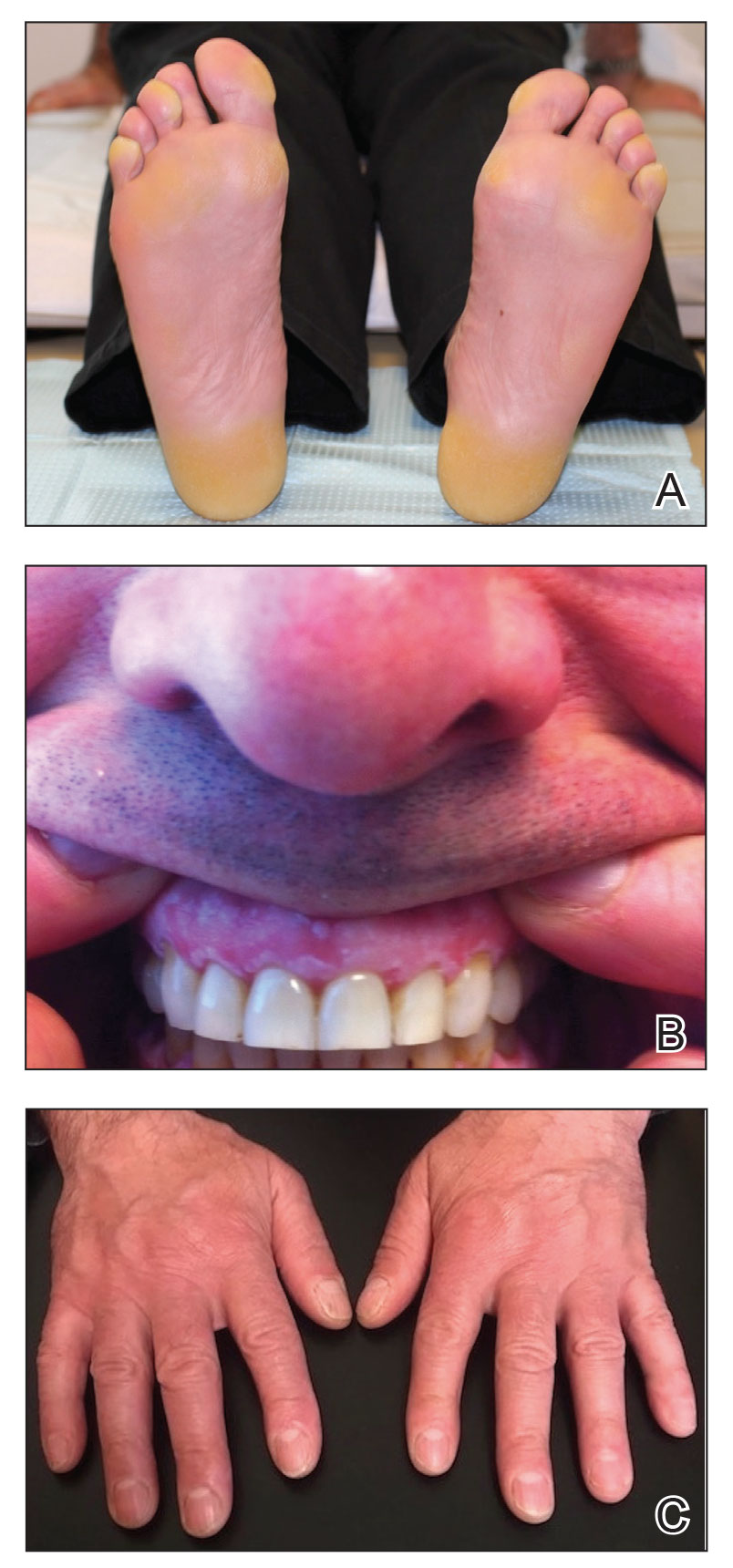

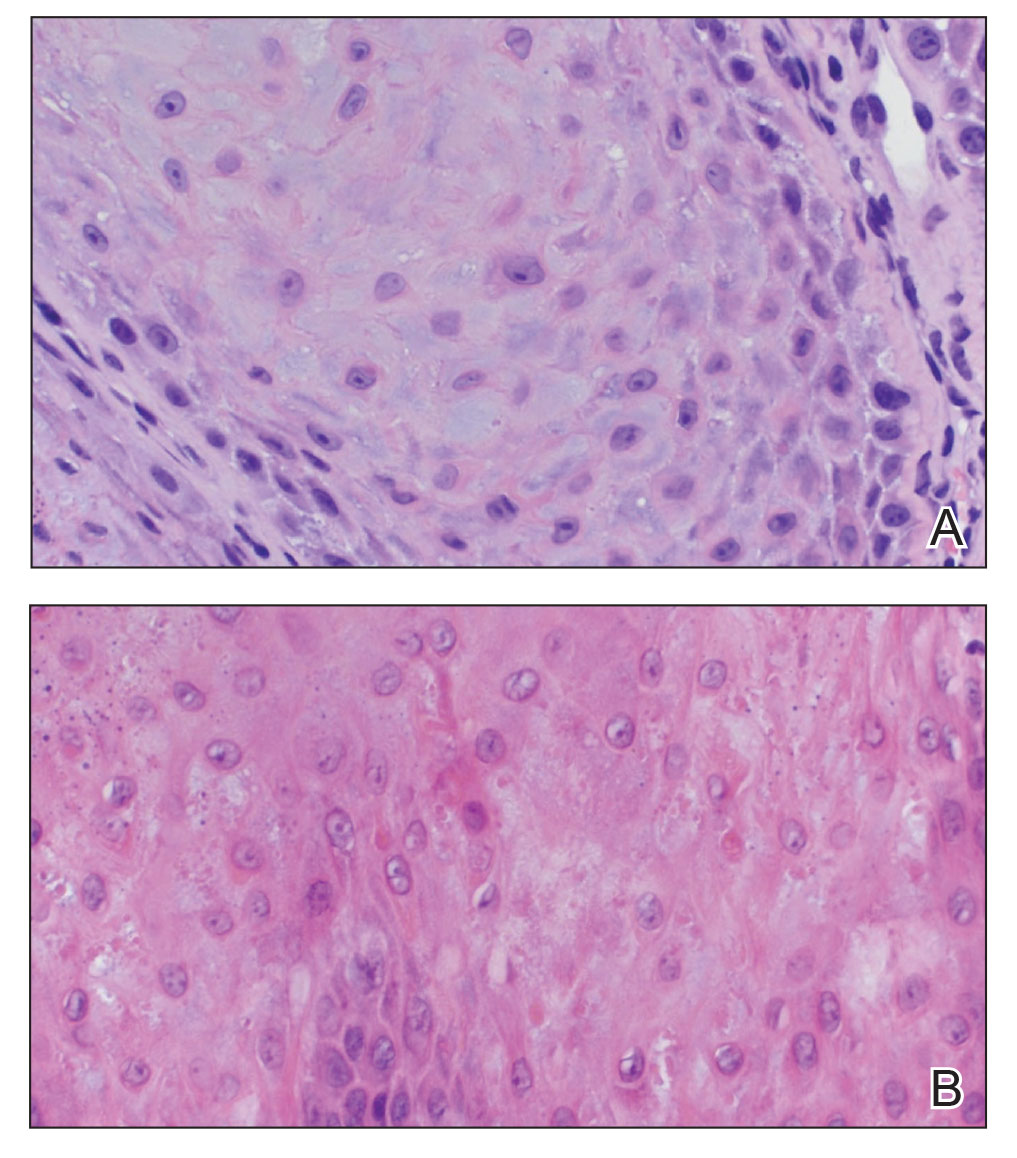

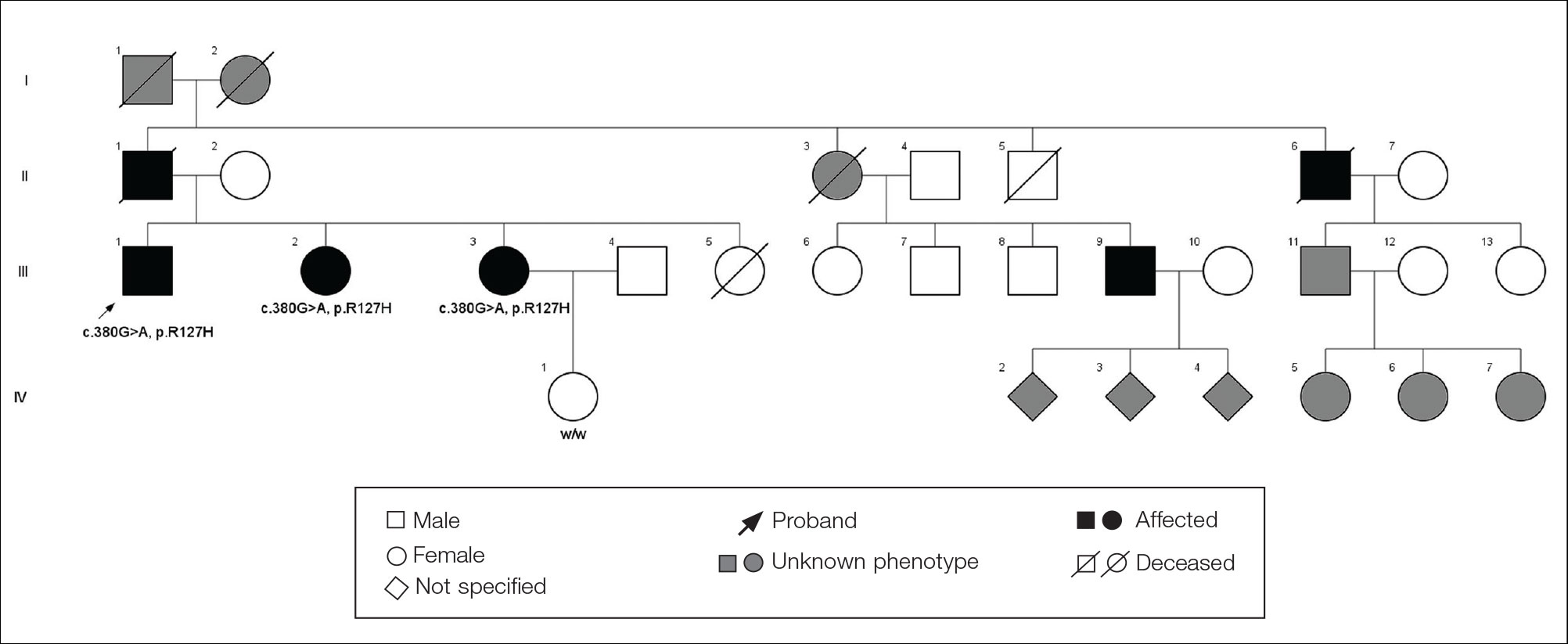

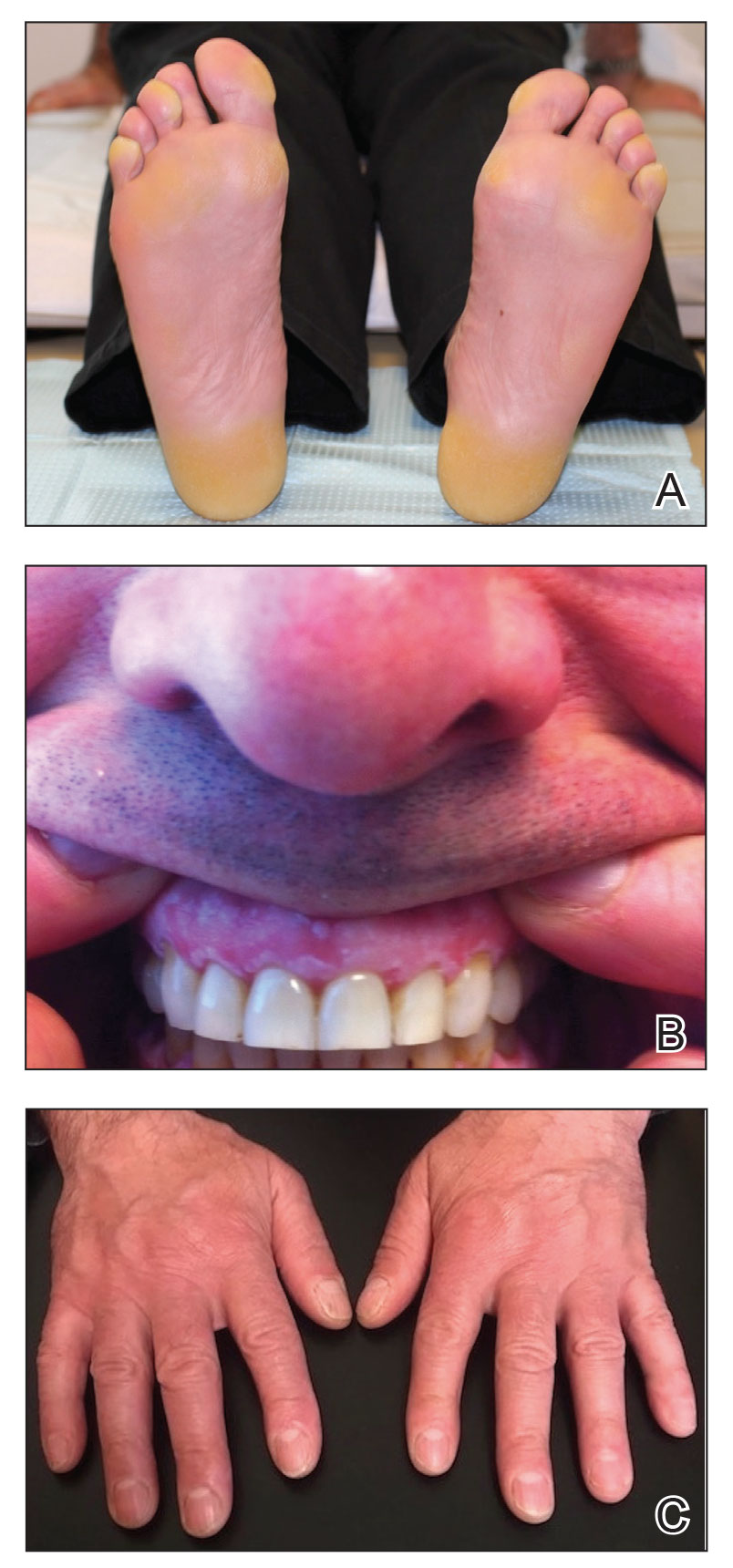

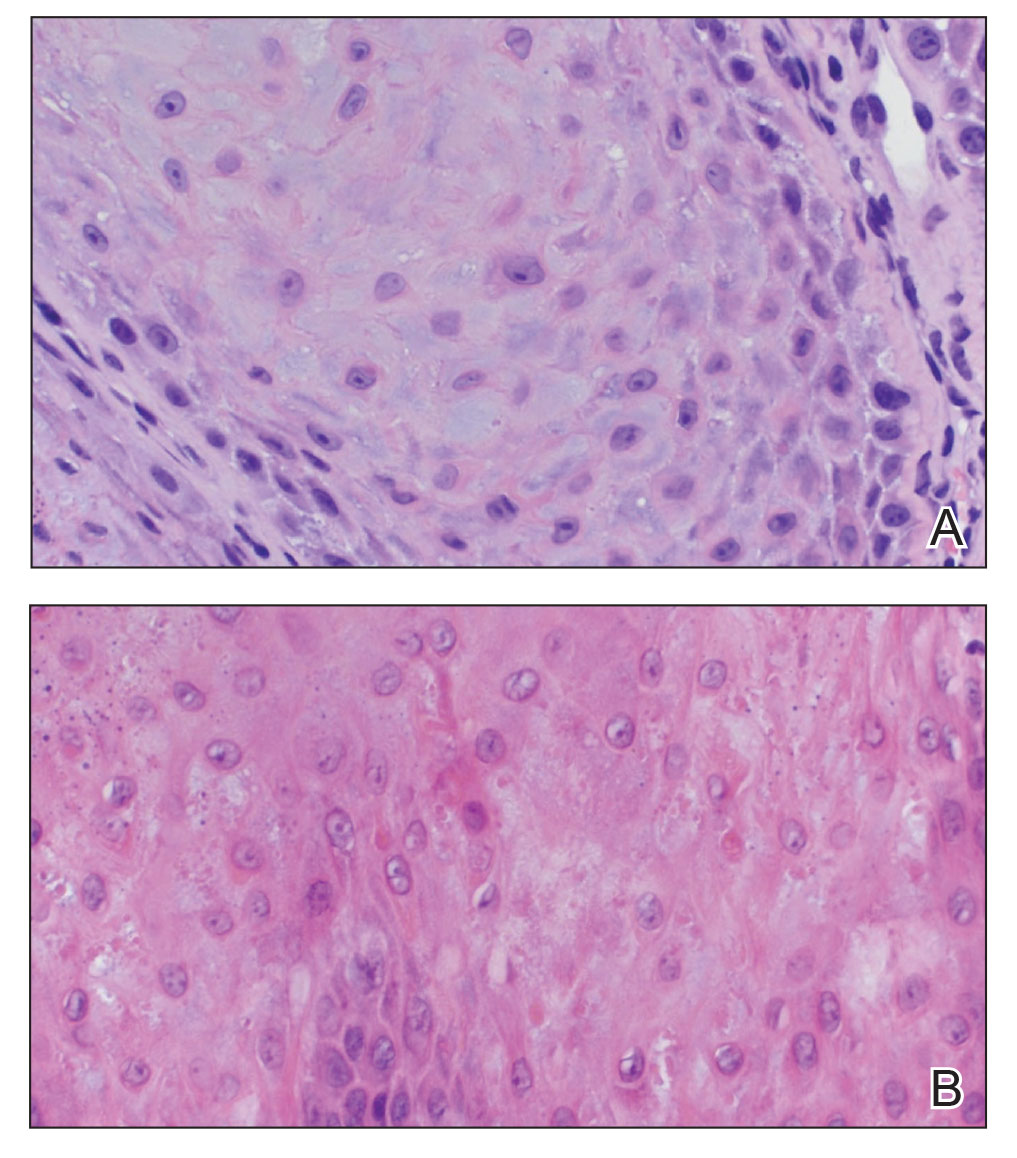

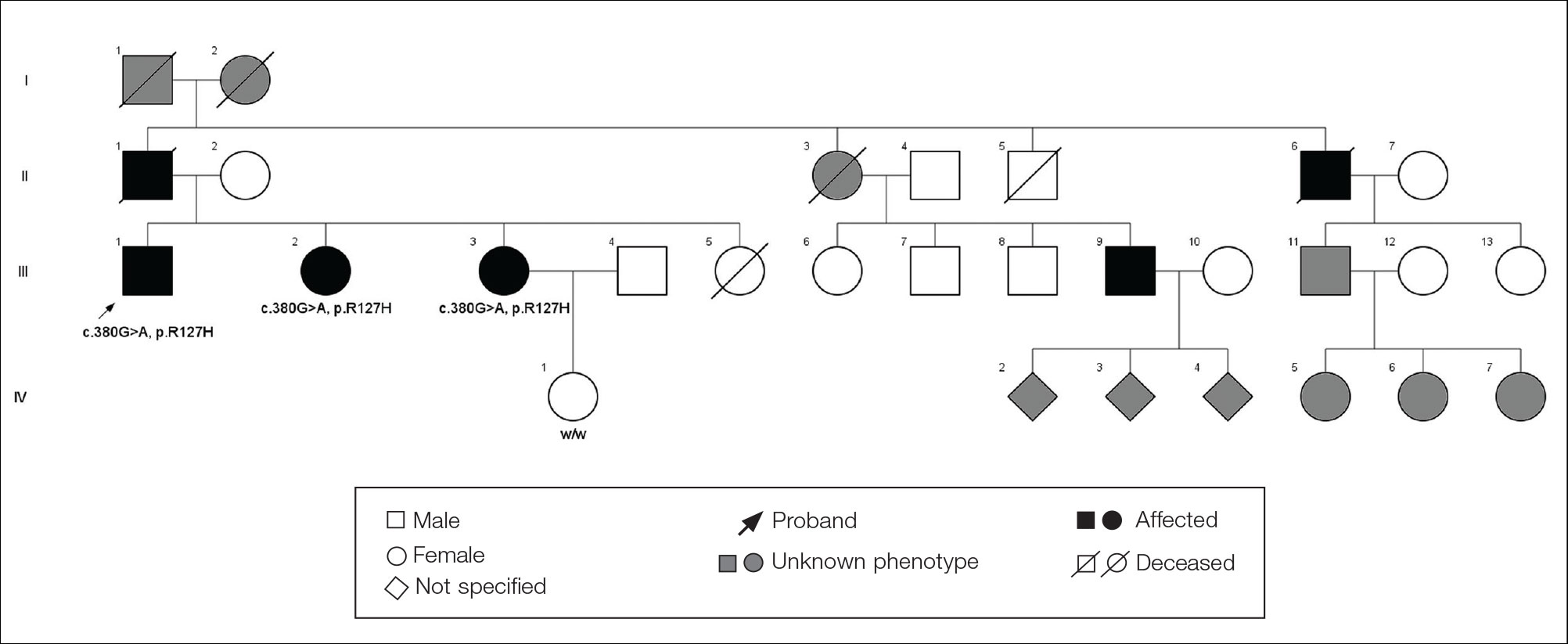

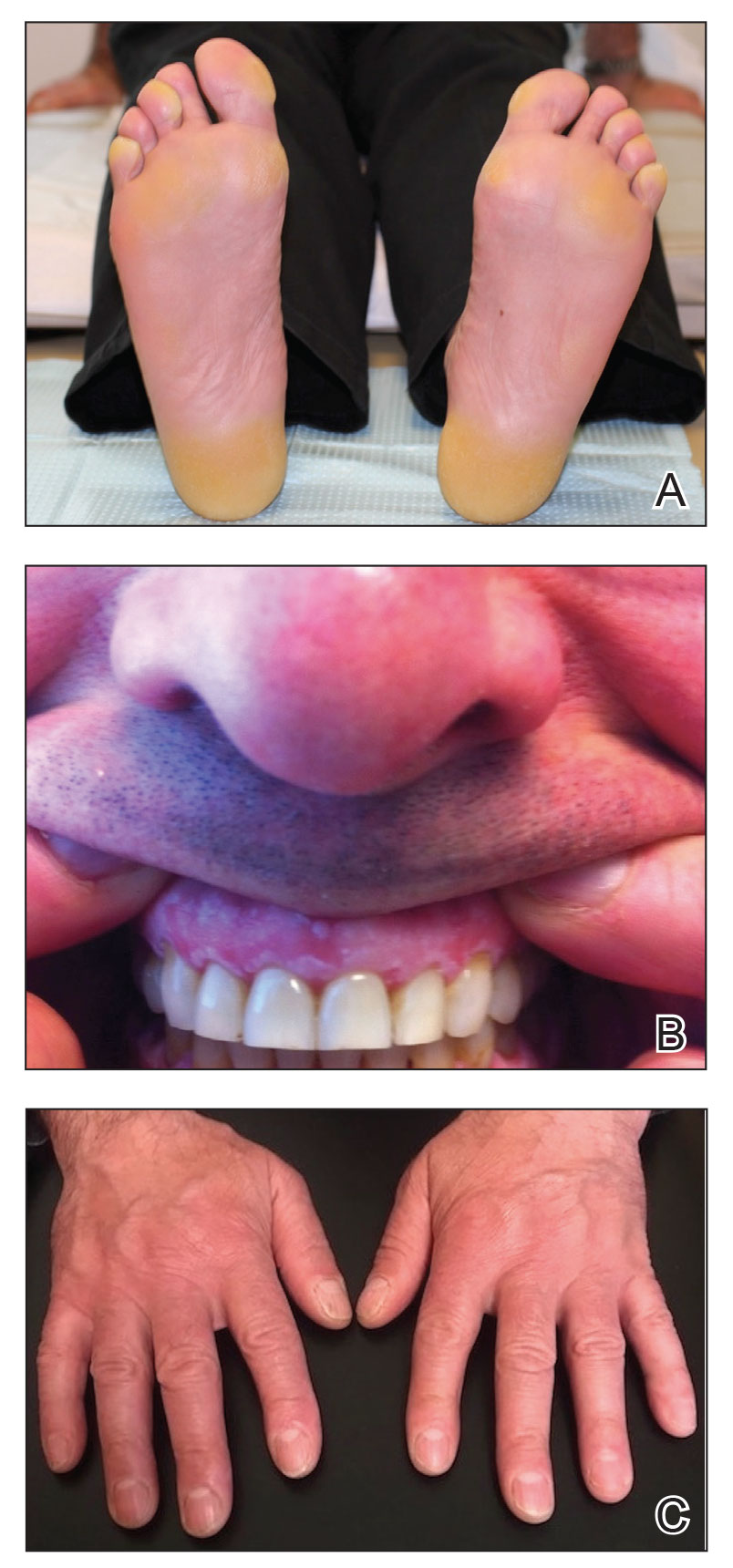

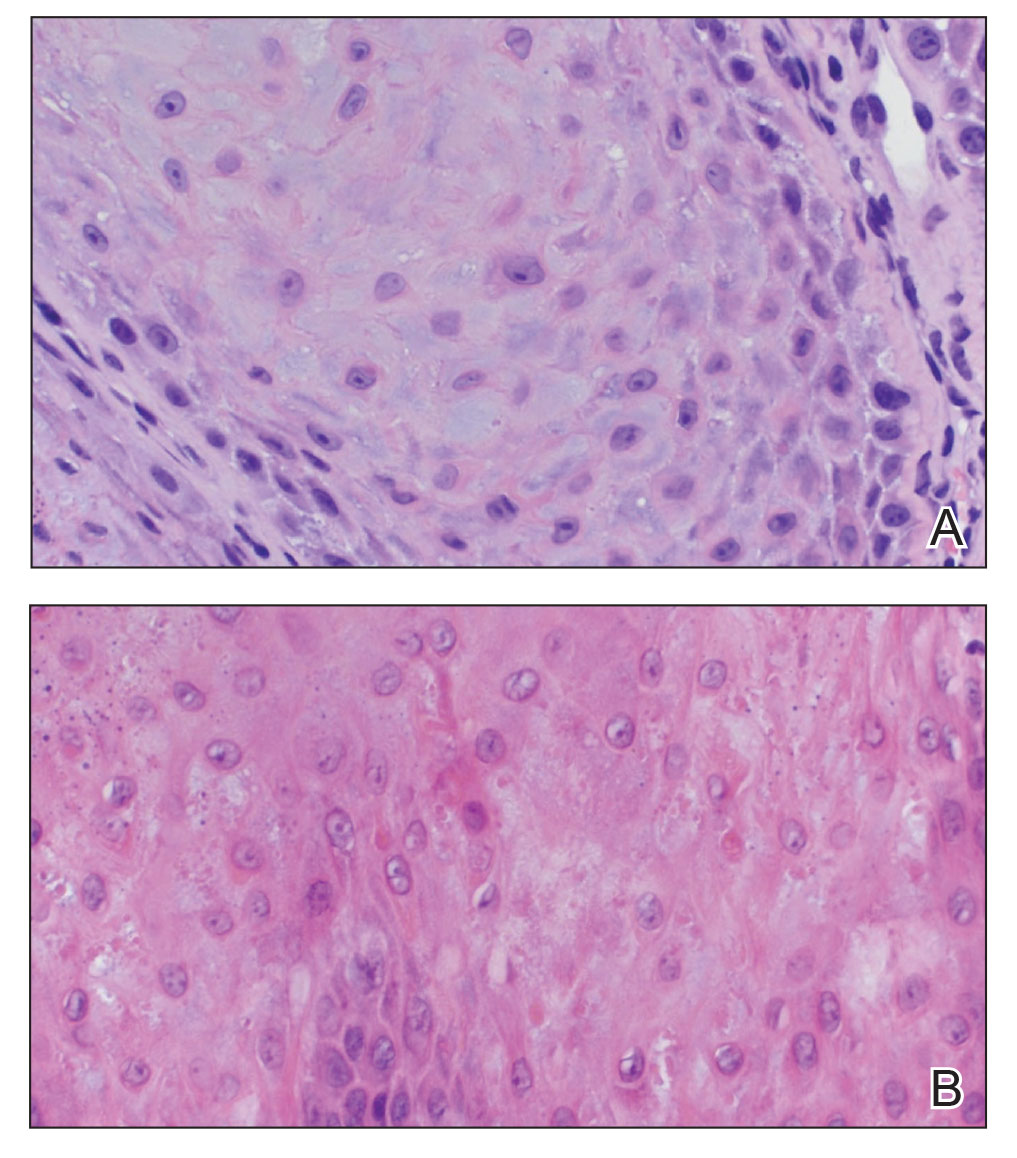

The proband was a 57-year-old man born to unrelated parents (Figure 1). He had no skin problems at birth, and his development was normal. He had painful focal keratoderma since childhood that were most prominent at pressure points on the soles and toes (Figure 2A), in addition to gingival hyperkeratosis and oral leukokeratosis (Figure 2B). He had no associated abnormalities of the skin, hair, or teeth and no nail findings (Figure 2C). He reported that his father and 2 of his 3 sisters were affected with similar symptoms. A punch biopsy of the right fifth toe was consistent with verrucous epidermal hyperplasia with perinuclear keratinization in the spinous layer (Figure 3A). A gingival biopsy showed perinuclear eosinophilic globules and basophilic stranding in the cytoplasm (Figure 3B). His older sister had more severe and painful focal keratoderma of the soles, punctate keratoderma of the palms, gingival hyperkeratosis, and leukokeratosis of the tongue.

Whole exome sequencing of the proband revealed a heterozygous missense mutation in KRT16 (c.380G>A, p.R127H, rs57424749). Sanger sequencing confirmed this mutation and showed that it was heterozygous in both of his affected sisters and absent in his unaffected niece (Figure 1). The patient was treated with topical and systemic retinoids, keratolytics, and mechanical removal to moderate effect, with noted improvement in the appearance and associated pain of the plantar keratoderma.

Phenotypic heterogeneity is common in PC, though PC due to KRT6A mutations demonstrates more severe nail disease with oral lesions, cysts, and follicular hyperkeratosis, while PC caused by KRT16 mutations generally presents with more extensive and painful PPK.4KRT16 mutations affecting p.R127 are frequent causes of PC, and genotype-phenotype correlations have been observed. Individuals with p.R127P mutations exhibit more severe disease with earlier age of onset, more extensive nail involvement and oral leukokeratosis, and greater impact on daily quality of life than in individuals with p.R127C mutations.5 Cases of PC with KRT16 p.R127S and p.R127G mutations also have been observed. The KRT16 c.380G>A, p.R127H mutation we documented has been reported in one kindred with PC who presented with PPK, oral leukokeratosis, toenail thickening, and pilosebaceous and follicular hyperkeratosis.6

Although patients with FPGK lack the thickening of fingernails and/or toenails considered a defining feature of PC, the disorders otherwise are phenotypically similar, suggesting the possibility of common pathogenesis. One linkage study of familial FPGK excluded genetic intervals containing type I and type II keratins but was limited to a single small kindred.2 This study and our data together suggest that, similar to PC, there are multiple genes in which mutations cause FPGK.

Murine Krt16 knockouts show distinct phenotypes depending on the mouse strain in which they are propagated, ranging from perinatal lethality to differences in the severity of oral and PPK lesions.7 These observations provide evidence that additional genetic variants contribute to Krt16 phenotypes in mice and suggest the same could be true for humans.

We propose that some cases of FPGK are due to mutations in KRT16 and thus share a genetic pathogenesis with PC, underscoring the utility of whole exome sequencing in providing genetic diagnoses for disorders that are genetically and clinically heterogeneous. Further biologic investigation of phenotypes caused by KRT16 mutation may reveal respective contributions of additional genetic variation and environmental effects to the variable clinical presentations.

- Gorlin RJ. Focal palmoplantar and marginal gingival hyperkeratosis—a syndrome. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1976;12:239-242.

- Kolde G, Hennies HC, Bethke G, et al. Focal palmoplantar and gingival keratosis: a distinct palmoplantar ectodermal dysplasia with epidermolytic alterations but lack of mutations in known keratins. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(3 pt 1):403-409.

- Duchatelet S, Hovnanian A. Olmsted syndrome: clinical, molecular and therapeutic aspects. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:33.

- Spaunhurst KM, Hogendorf AM, Smith FJ, et al. Pachyonychia congenita patients with mutations in KRT6A have more extensive disease compared with patients who have mutations in KRT16. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:875-878.

- Fu T, Leachman SA, Wilson NJ, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations among pachyonychia congenita patients with K16 mutations. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:1025-1028.

- Wilson NJ, O’Toole EA, Milstone LM, et al. The molecular genetic analysis of the expanding pachyonychia congenita case collection. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:343-355.

- Zieman A, Coulombe PA. The keratin 16 null phenotype is modestly impacted by genetic strain background in mice. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:672-674.

To the Editor:

Focal palmoplantar keratoderma and gingival keratosis (FPGK)(Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM] 148730) is a rare autosomal-dominant syndrome featuring focal, pressure-related, painful palmoplantar keratoderma and gingival hyperkeratosis presenting as leukokeratosis. Focal palmoplantar keratoderma and gingival keratosis was first defined by Gorlin1 in 1976. Since then, only a few cases have been reported, but no causative mutations have been identified.2

Focal pressure-related palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK) and oral hyperkeratosis also are seen in pachyonychia congenita (PC)(OMIM 167200, 615726, 615728, 167210), a rare autosomal-dominant disorder of keratinization characterized by PPK and nail dystrophy. Patients with PC often present with plantar pain; more variable features include oral leukokeratosis, follicular hyperkeratosis, pilosebaceous and epidermal inclusion cysts, hoarseness, hyperhidrosis, and natal teeth. Pachyonychia congenita is caused by mutation in keratin genes KRT6A, KRT6B, KRT16, or KRT17.

Focal palmoplantar keratoderma and gingival keratosis as well as PC are distinct from other forms of PPK with gingival involvement such as

Despite the common features of FPGK and PC, they are considered distinct disorders due to absence of nail changes in FPGK and no prior evidence of a common genetic cause. We present a patient with familial FPGK found by whole exome sequencing to be caused by a mutation in KRT16.

The proband was a 57-year-old man born to unrelated parents (Figure 1). He had no skin problems at birth, and his development was normal. He had painful focal keratoderma since childhood that were most prominent at pressure points on the soles and toes (Figure 2A), in addition to gingival hyperkeratosis and oral leukokeratosis (Figure 2B). He had no associated abnormalities of the skin, hair, or teeth and no nail findings (Figure 2C). He reported that his father and 2 of his 3 sisters were affected with similar symptoms. A punch biopsy of the right fifth toe was consistent with verrucous epidermal hyperplasia with perinuclear keratinization in the spinous layer (Figure 3A). A gingival biopsy showed perinuclear eosinophilic globules and basophilic stranding in the cytoplasm (Figure 3B). His older sister had more severe and painful focal keratoderma of the soles, punctate keratoderma of the palms, gingival hyperkeratosis, and leukokeratosis of the tongue.

Whole exome sequencing of the proband revealed a heterozygous missense mutation in KRT16 (c.380G>A, p.R127H, rs57424749). Sanger sequencing confirmed this mutation and showed that it was heterozygous in both of his affected sisters and absent in his unaffected niece (Figure 1). The patient was treated with topical and systemic retinoids, keratolytics, and mechanical removal to moderate effect, with noted improvement in the appearance and associated pain of the plantar keratoderma.

Phenotypic heterogeneity is common in PC, though PC due to KRT6A mutations demonstrates more severe nail disease with oral lesions, cysts, and follicular hyperkeratosis, while PC caused by KRT16 mutations generally presents with more extensive and painful PPK.4KRT16 mutations affecting p.R127 are frequent causes of PC, and genotype-phenotype correlations have been observed. Individuals with p.R127P mutations exhibit more severe disease with earlier age of onset, more extensive nail involvement and oral leukokeratosis, and greater impact on daily quality of life than in individuals with p.R127C mutations.5 Cases of PC with KRT16 p.R127S and p.R127G mutations also have been observed. The KRT16 c.380G>A, p.R127H mutation we documented has been reported in one kindred with PC who presented with PPK, oral leukokeratosis, toenail thickening, and pilosebaceous and follicular hyperkeratosis.6

Although patients with FPGK lack the thickening of fingernails and/or toenails considered a defining feature of PC, the disorders otherwise are phenotypically similar, suggesting the possibility of common pathogenesis. One linkage study of familial FPGK excluded genetic intervals containing type I and type II keratins but was limited to a single small kindred.2 This study and our data together suggest that, similar to PC, there are multiple genes in which mutations cause FPGK.

Murine Krt16 knockouts show distinct phenotypes depending on the mouse strain in which they are propagated, ranging from perinatal lethality to differences in the severity of oral and PPK lesions.7 These observations provide evidence that additional genetic variants contribute to Krt16 phenotypes in mice and suggest the same could be true for humans.

We propose that some cases of FPGK are due to mutations in KRT16 and thus share a genetic pathogenesis with PC, underscoring the utility of whole exome sequencing in providing genetic diagnoses for disorders that are genetically and clinically heterogeneous. Further biologic investigation of phenotypes caused by KRT16 mutation may reveal respective contributions of additional genetic variation and environmental effects to the variable clinical presentations.

To the Editor:

Focal palmoplantar keratoderma and gingival keratosis (FPGK)(Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM] 148730) is a rare autosomal-dominant syndrome featuring focal, pressure-related, painful palmoplantar keratoderma and gingival hyperkeratosis presenting as leukokeratosis. Focal palmoplantar keratoderma and gingival keratosis was first defined by Gorlin1 in 1976. Since then, only a few cases have been reported, but no causative mutations have been identified.2

Focal pressure-related palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK) and oral hyperkeratosis also are seen in pachyonychia congenita (PC)(OMIM 167200, 615726, 615728, 167210), a rare autosomal-dominant disorder of keratinization characterized by PPK and nail dystrophy. Patients with PC often present with plantar pain; more variable features include oral leukokeratosis, follicular hyperkeratosis, pilosebaceous and epidermal inclusion cysts, hoarseness, hyperhidrosis, and natal teeth. Pachyonychia congenita is caused by mutation in keratin genes KRT6A, KRT6B, KRT16, or KRT17.

Focal palmoplantar keratoderma and gingival keratosis as well as PC are distinct from other forms of PPK with gingival involvement such as

Despite the common features of FPGK and PC, they are considered distinct disorders due to absence of nail changes in FPGK and no prior evidence of a common genetic cause. We present a patient with familial FPGK found by whole exome sequencing to be caused by a mutation in KRT16.

The proband was a 57-year-old man born to unrelated parents (Figure 1). He had no skin problems at birth, and his development was normal. He had painful focal keratoderma since childhood that were most prominent at pressure points on the soles and toes (Figure 2A), in addition to gingival hyperkeratosis and oral leukokeratosis (Figure 2B). He had no associated abnormalities of the skin, hair, or teeth and no nail findings (Figure 2C). He reported that his father and 2 of his 3 sisters were affected with similar symptoms. A punch biopsy of the right fifth toe was consistent with verrucous epidermal hyperplasia with perinuclear keratinization in the spinous layer (Figure 3A). A gingival biopsy showed perinuclear eosinophilic globules and basophilic stranding in the cytoplasm (Figure 3B). His older sister had more severe and painful focal keratoderma of the soles, punctate keratoderma of the palms, gingival hyperkeratosis, and leukokeratosis of the tongue.

Whole exome sequencing of the proband revealed a heterozygous missense mutation in KRT16 (c.380G>A, p.R127H, rs57424749). Sanger sequencing confirmed this mutation and showed that it was heterozygous in both of his affected sisters and absent in his unaffected niece (Figure 1). The patient was treated with topical and systemic retinoids, keratolytics, and mechanical removal to moderate effect, with noted improvement in the appearance and associated pain of the plantar keratoderma.

Phenotypic heterogeneity is common in PC, though PC due to KRT6A mutations demonstrates more severe nail disease with oral lesions, cysts, and follicular hyperkeratosis, while PC caused by KRT16 mutations generally presents with more extensive and painful PPK.4KRT16 mutations affecting p.R127 are frequent causes of PC, and genotype-phenotype correlations have been observed. Individuals with p.R127P mutations exhibit more severe disease with earlier age of onset, more extensive nail involvement and oral leukokeratosis, and greater impact on daily quality of life than in individuals with p.R127C mutations.5 Cases of PC with KRT16 p.R127S and p.R127G mutations also have been observed. The KRT16 c.380G>A, p.R127H mutation we documented has been reported in one kindred with PC who presented with PPK, oral leukokeratosis, toenail thickening, and pilosebaceous and follicular hyperkeratosis.6

Although patients with FPGK lack the thickening of fingernails and/or toenails considered a defining feature of PC, the disorders otherwise are phenotypically similar, suggesting the possibility of common pathogenesis. One linkage study of familial FPGK excluded genetic intervals containing type I and type II keratins but was limited to a single small kindred.2 This study and our data together suggest that, similar to PC, there are multiple genes in which mutations cause FPGK.

Murine Krt16 knockouts show distinct phenotypes depending on the mouse strain in which they are propagated, ranging from perinatal lethality to differences in the severity of oral and PPK lesions.7 These observations provide evidence that additional genetic variants contribute to Krt16 phenotypes in mice and suggest the same could be true for humans.

We propose that some cases of FPGK are due to mutations in KRT16 and thus share a genetic pathogenesis with PC, underscoring the utility of whole exome sequencing in providing genetic diagnoses for disorders that are genetically and clinically heterogeneous. Further biologic investigation of phenotypes caused by KRT16 mutation may reveal respective contributions of additional genetic variation and environmental effects to the variable clinical presentations.

- Gorlin RJ. Focal palmoplantar and marginal gingival hyperkeratosis—a syndrome. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1976;12:239-242.

- Kolde G, Hennies HC, Bethke G, et al. Focal palmoplantar and gingival keratosis: a distinct palmoplantar ectodermal dysplasia with epidermolytic alterations but lack of mutations in known keratins. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(3 pt 1):403-409.

- Duchatelet S, Hovnanian A. Olmsted syndrome: clinical, molecular and therapeutic aspects. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:33.

- Spaunhurst KM, Hogendorf AM, Smith FJ, et al. Pachyonychia congenita patients with mutations in KRT6A have more extensive disease compared with patients who have mutations in KRT16. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:875-878.

- Fu T, Leachman SA, Wilson NJ, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations among pachyonychia congenita patients with K16 mutations. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:1025-1028.

- Wilson NJ, O’Toole EA, Milstone LM, et al. The molecular genetic analysis of the expanding pachyonychia congenita case collection. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:343-355.

- Zieman A, Coulombe PA. The keratin 16 null phenotype is modestly impacted by genetic strain background in mice. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:672-674.

- Gorlin RJ. Focal palmoplantar and marginal gingival hyperkeratosis—a syndrome. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1976;12:239-242.

- Kolde G, Hennies HC, Bethke G, et al. Focal palmoplantar and gingival keratosis: a distinct palmoplantar ectodermal dysplasia with epidermolytic alterations but lack of mutations in known keratins. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(3 pt 1):403-409.

- Duchatelet S, Hovnanian A. Olmsted syndrome: clinical, molecular and therapeutic aspects. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:33.

- Spaunhurst KM, Hogendorf AM, Smith FJ, et al. Pachyonychia congenita patients with mutations in KRT6A have more extensive disease compared with patients who have mutations in KRT16. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:875-878.

- Fu T, Leachman SA, Wilson NJ, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations among pachyonychia congenita patients with K16 mutations. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:1025-1028.

- Wilson NJ, O’Toole EA, Milstone LM, et al. The molecular genetic analysis of the expanding pachyonychia congenita case collection. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:343-355.

- Zieman A, Coulombe PA. The keratin 16 null phenotype is modestly impacted by genetic strain background in mice. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:672-674.

Practice Points

- Focal palmoplantar keratoderma and gingival keratosis (FPGK) is a rare autosomal-dominant syndrome featuring focal, pressure-related, painful palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK) and gingival hyperkeratosis presenting as leukokeratosis.

- Focal pressure-related PPK and oral hyperkeratosis also are seen in pachyonychia congenita (PC), which is caused by mutations in keratin genes and is distinguished from FPGK by characteristic nail changes.

- A shared causative gene suggests that FPGK should be considered part of the PC spectrum.

Fungated Eroded Plaque on the Arm

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Blastomycosis

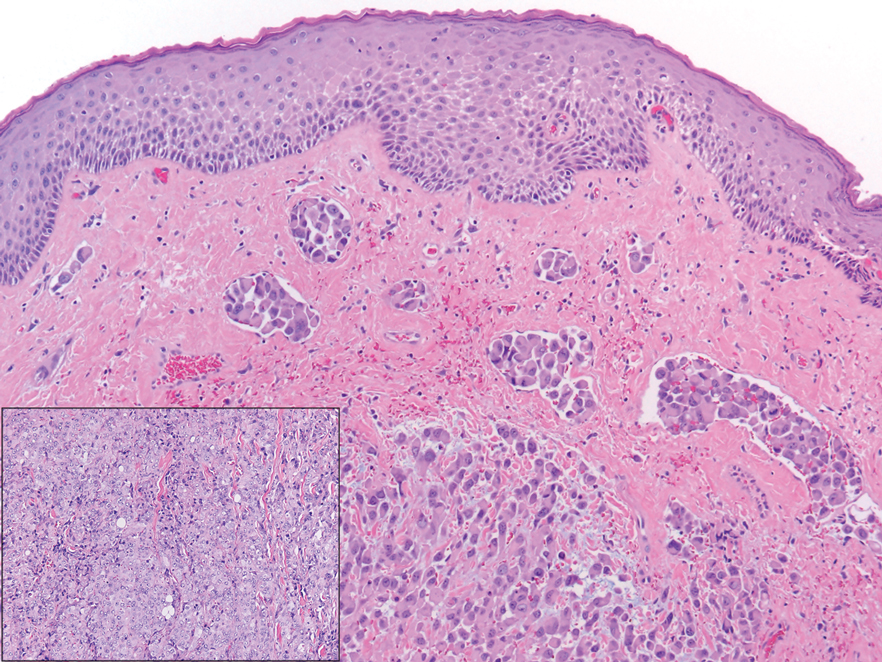

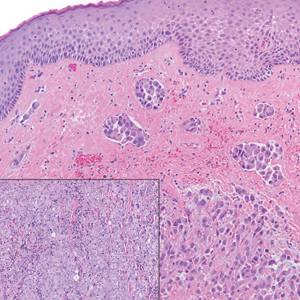

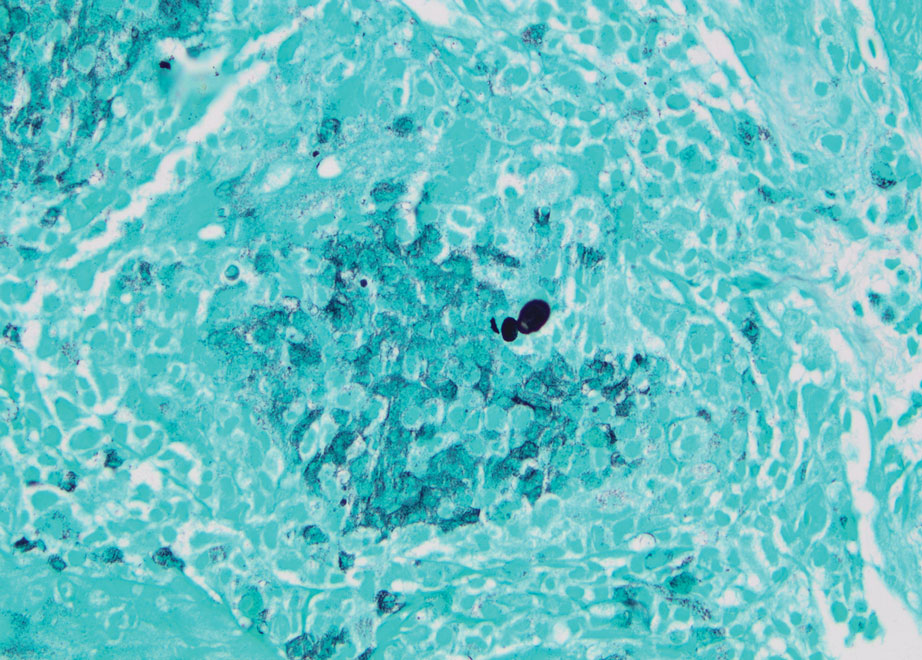

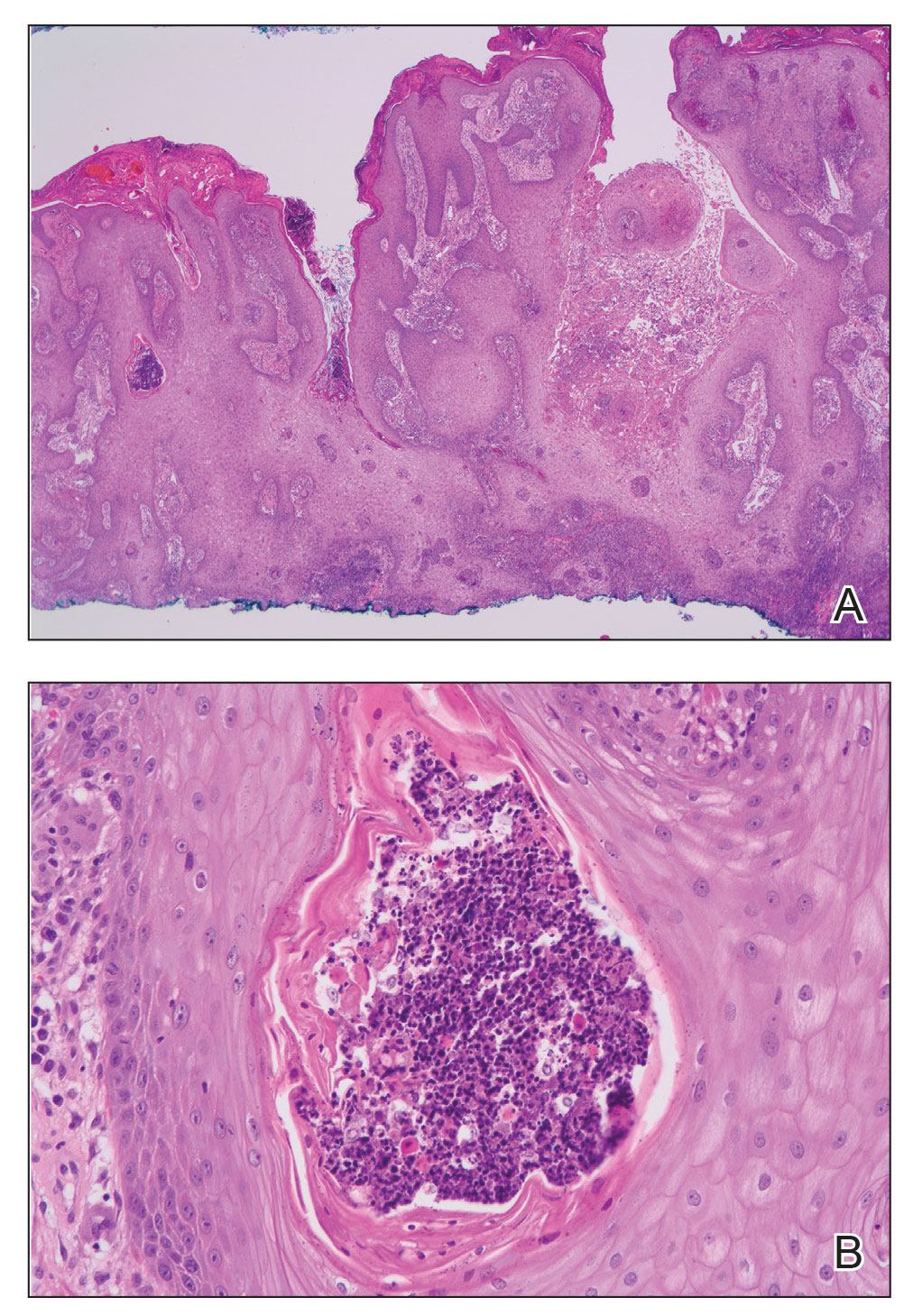

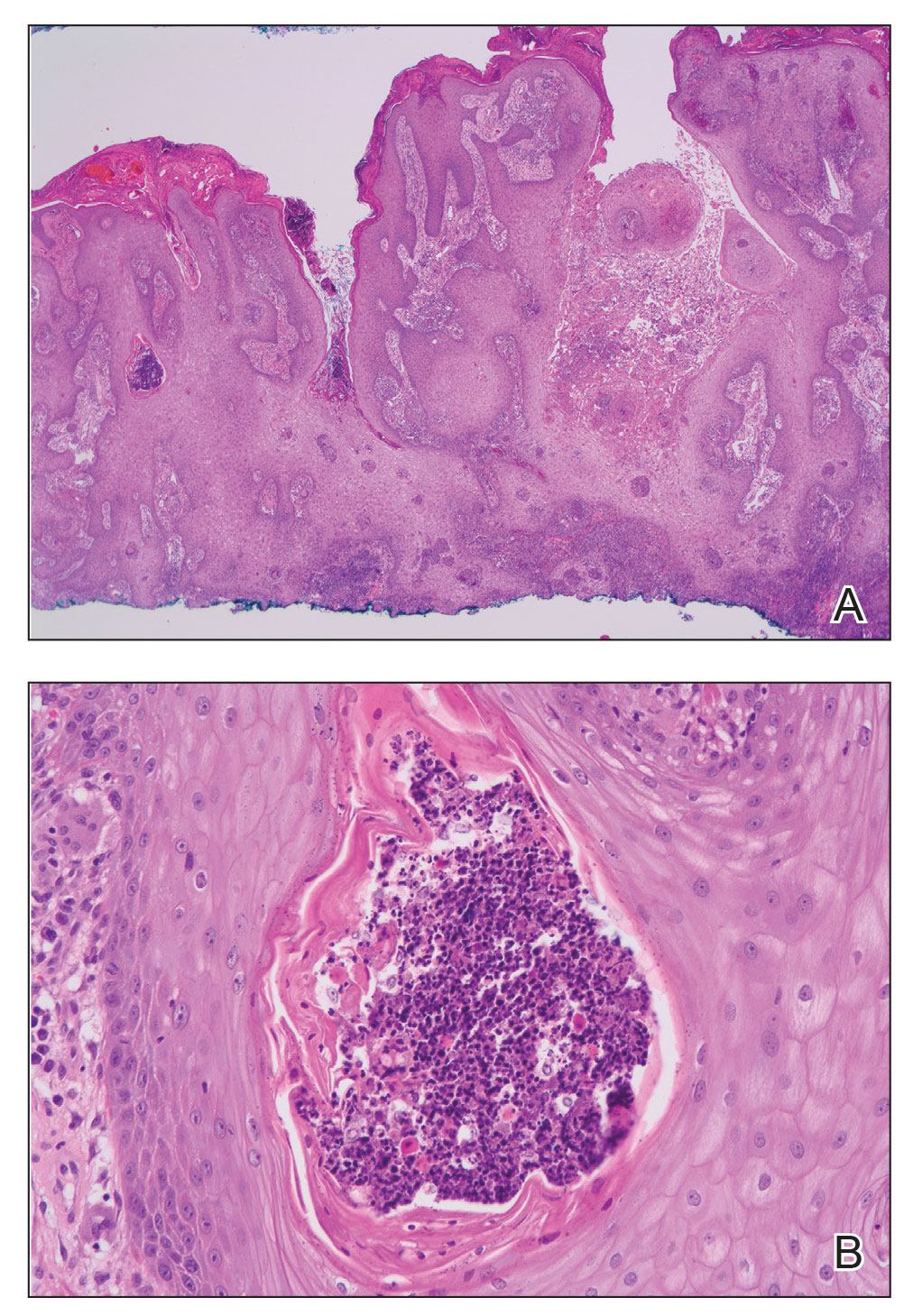

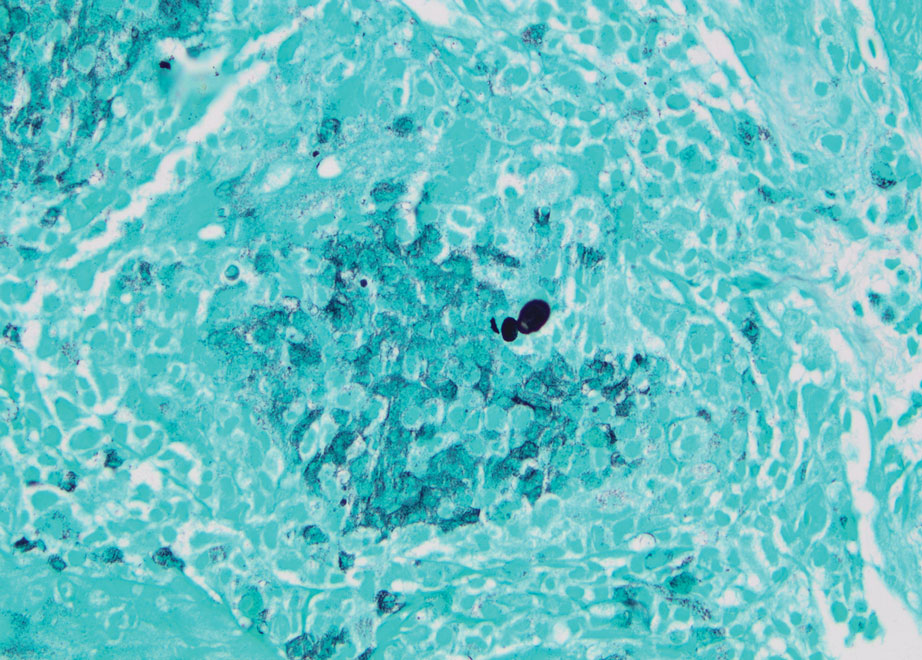

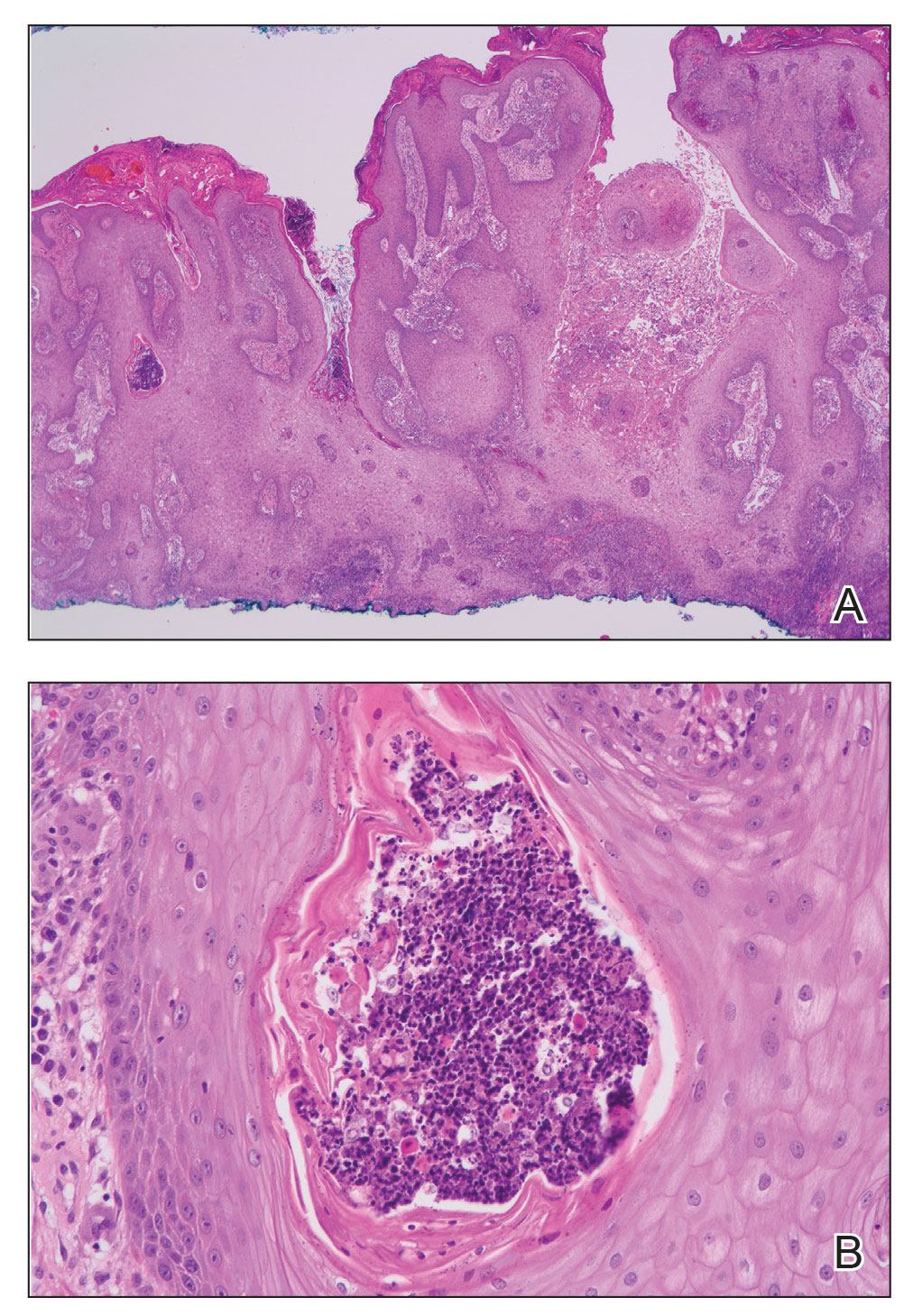

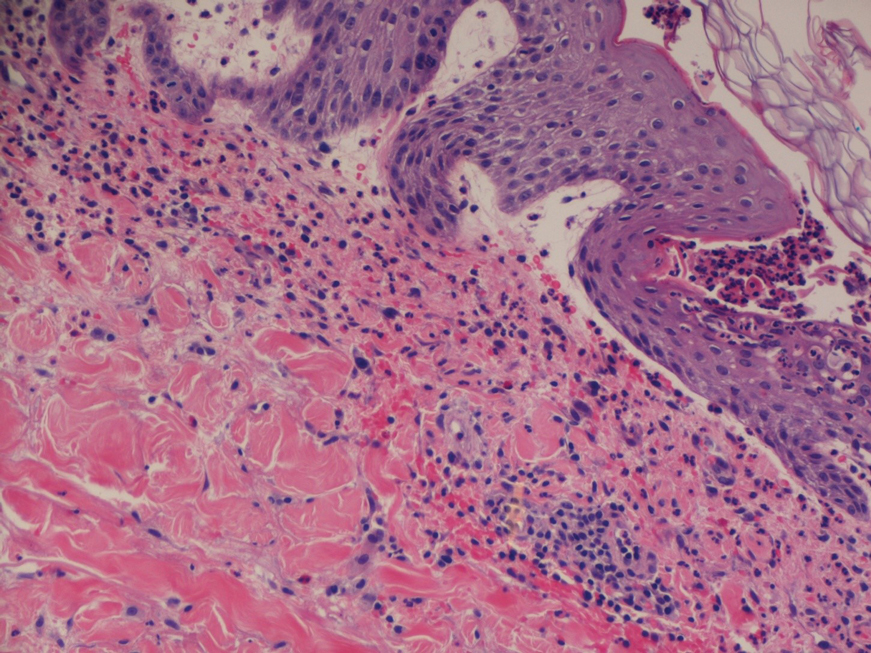

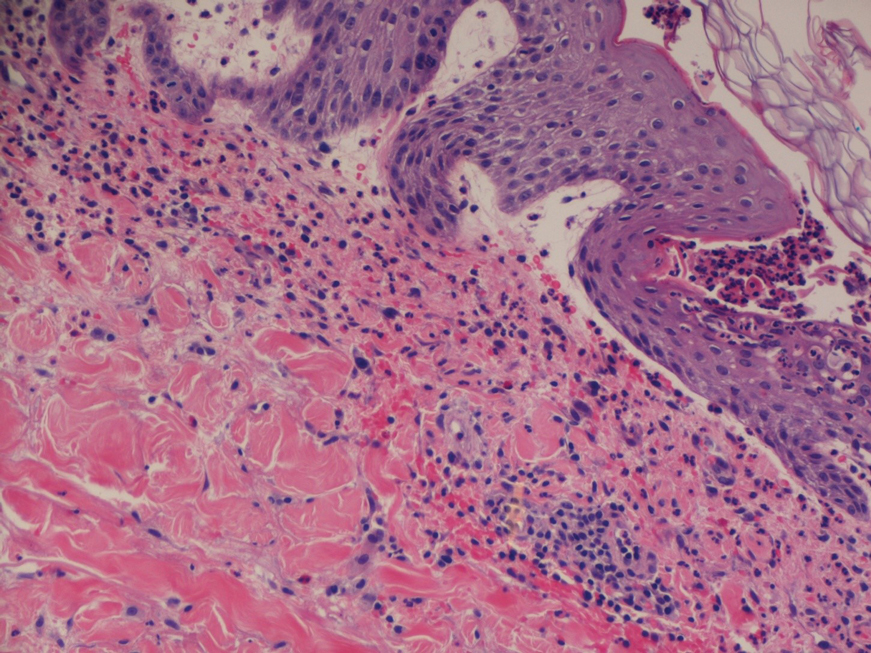

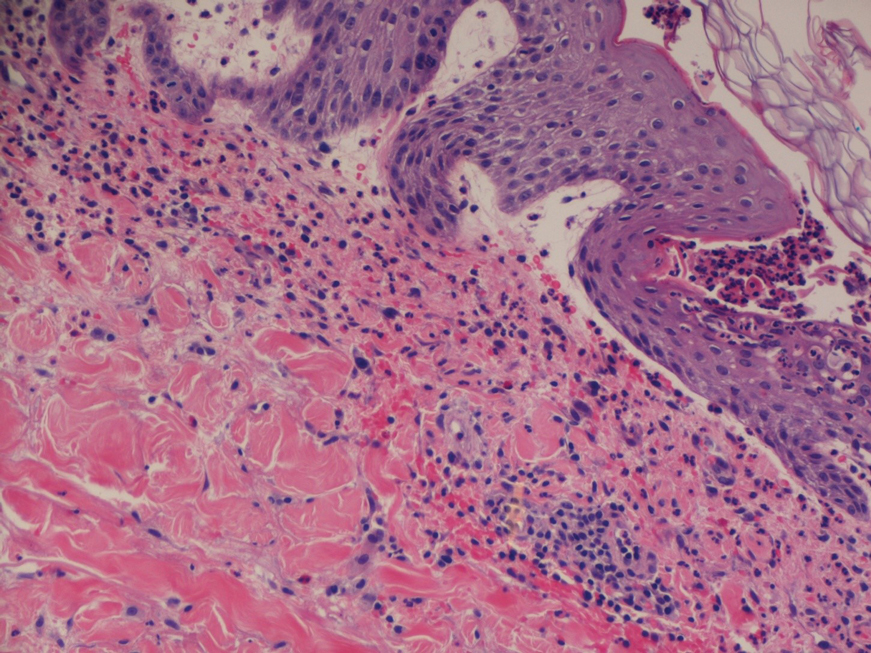

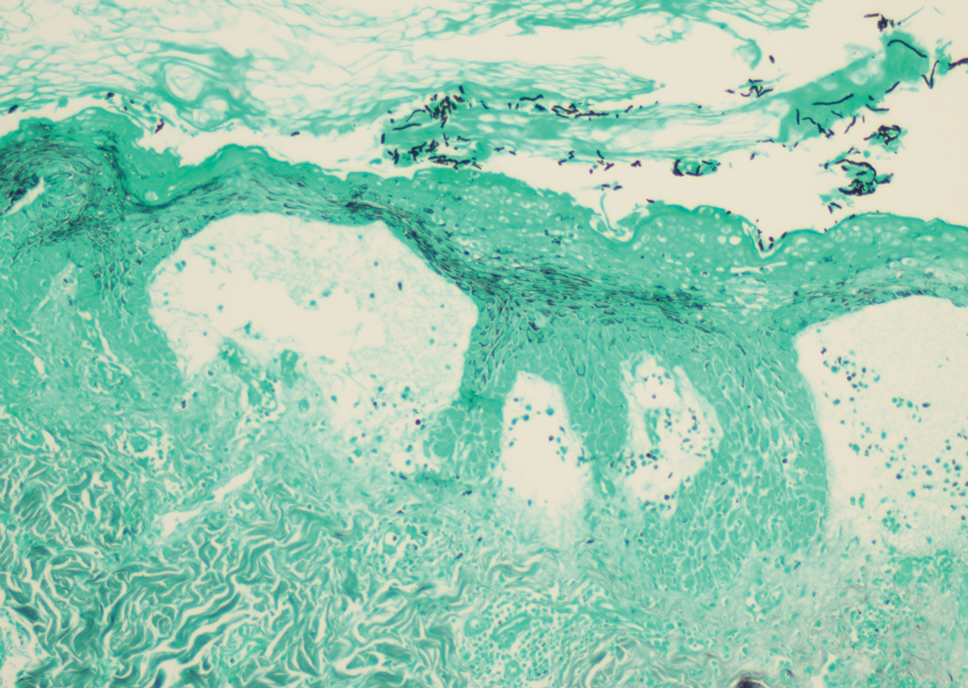

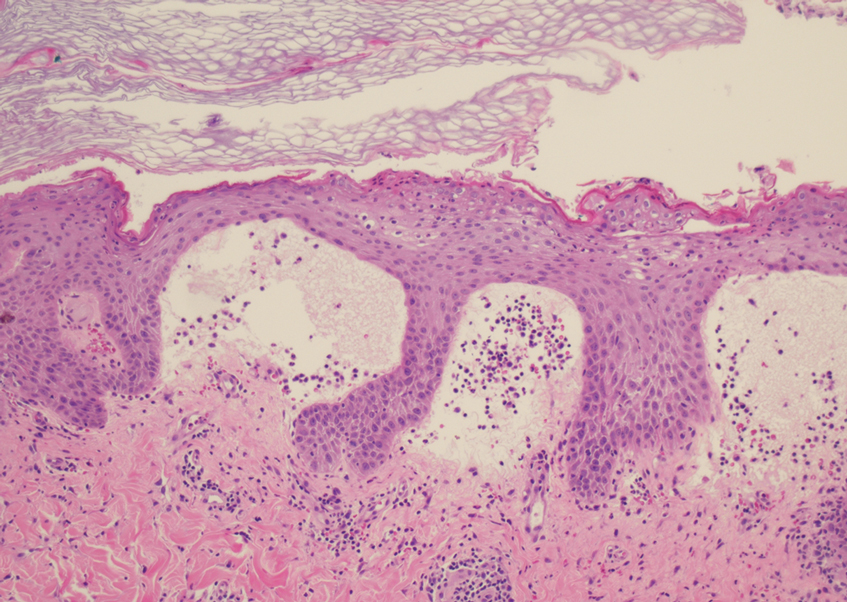

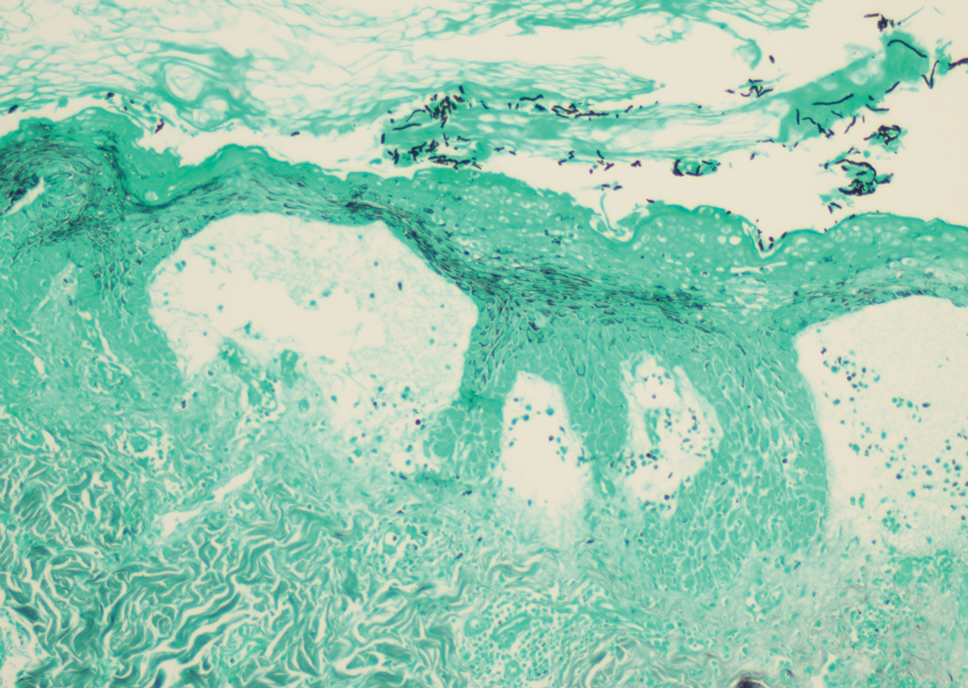

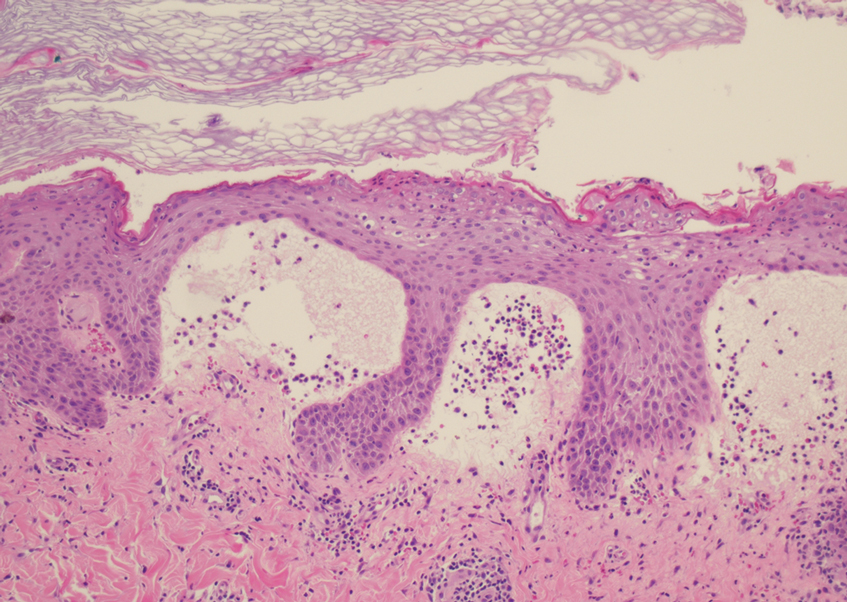

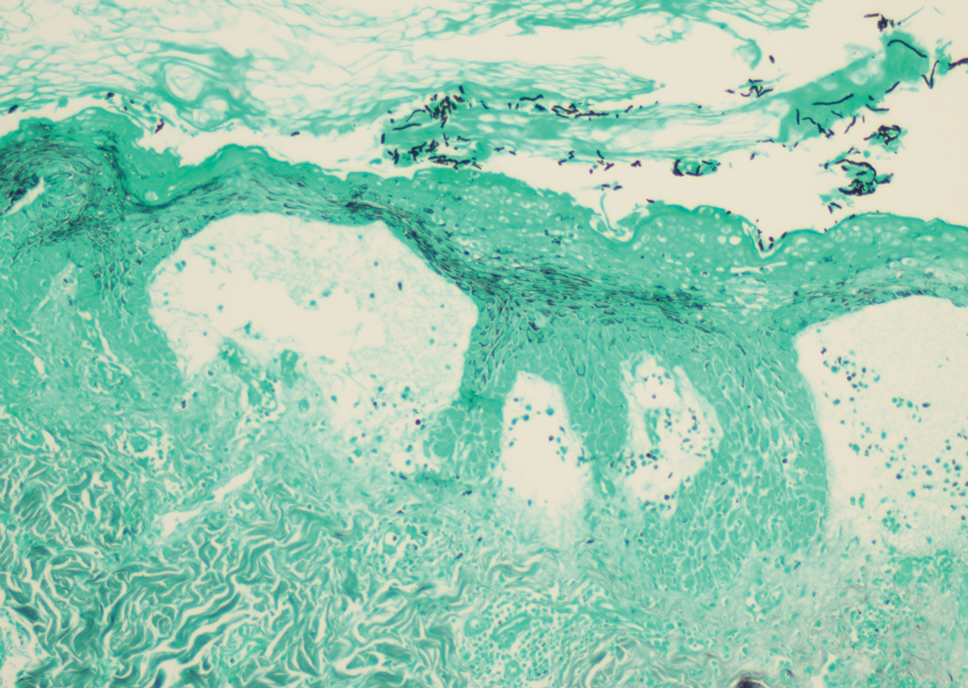

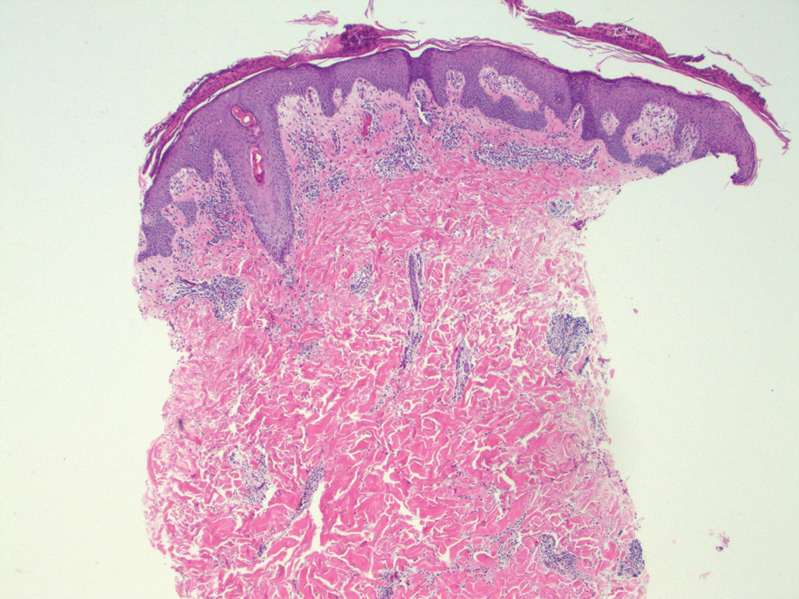

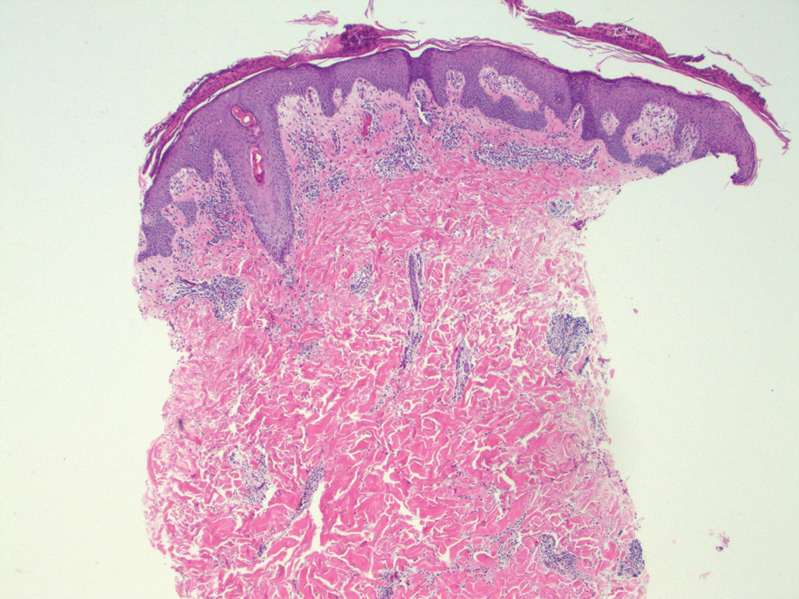

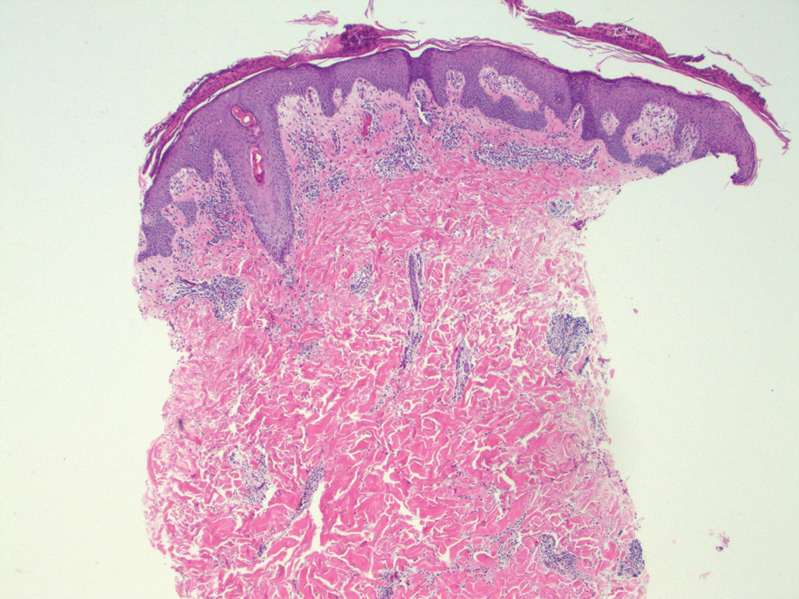

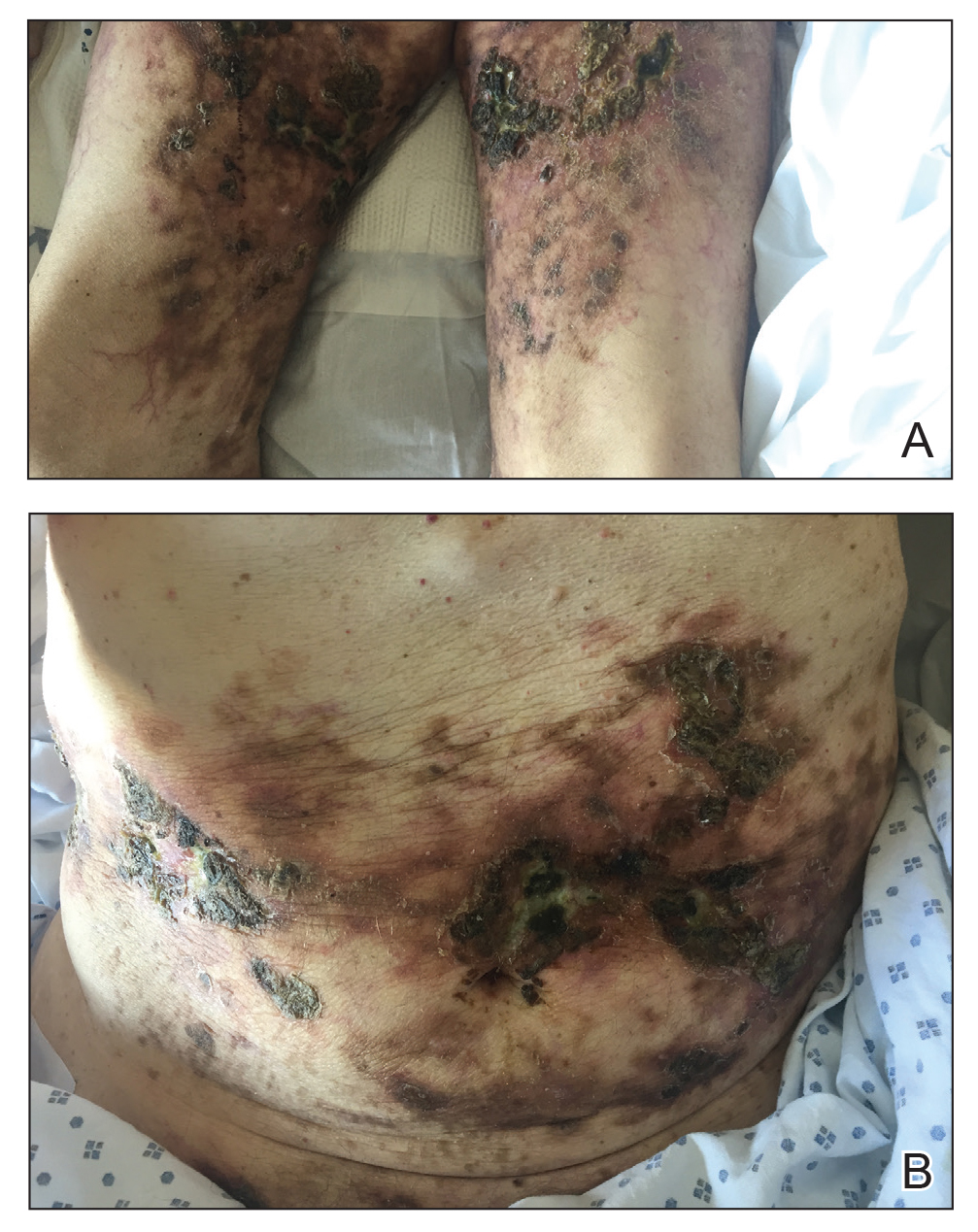

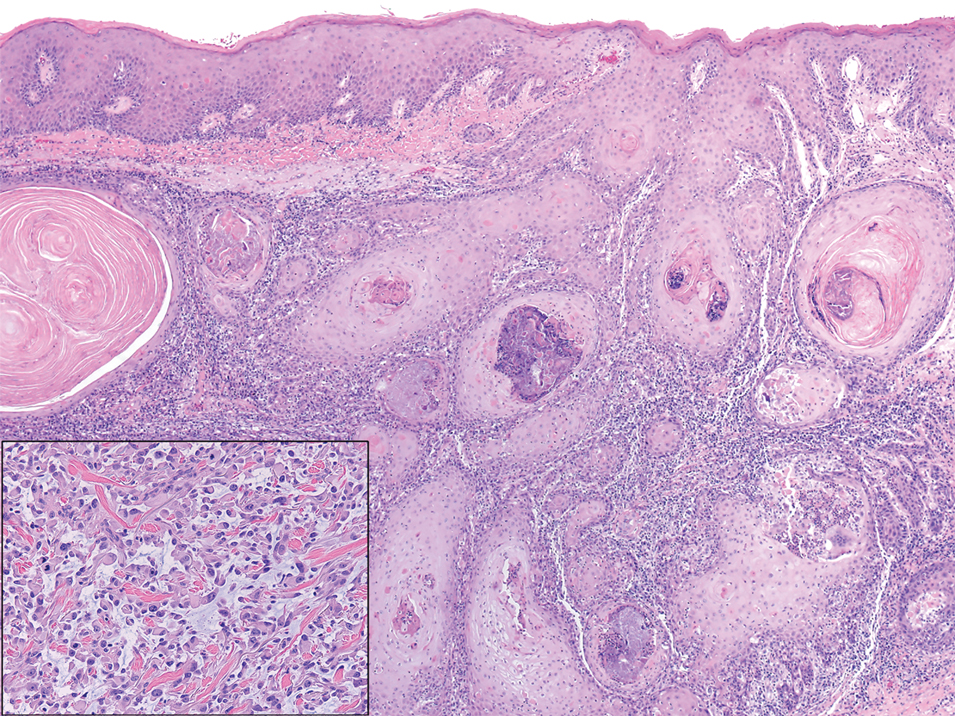

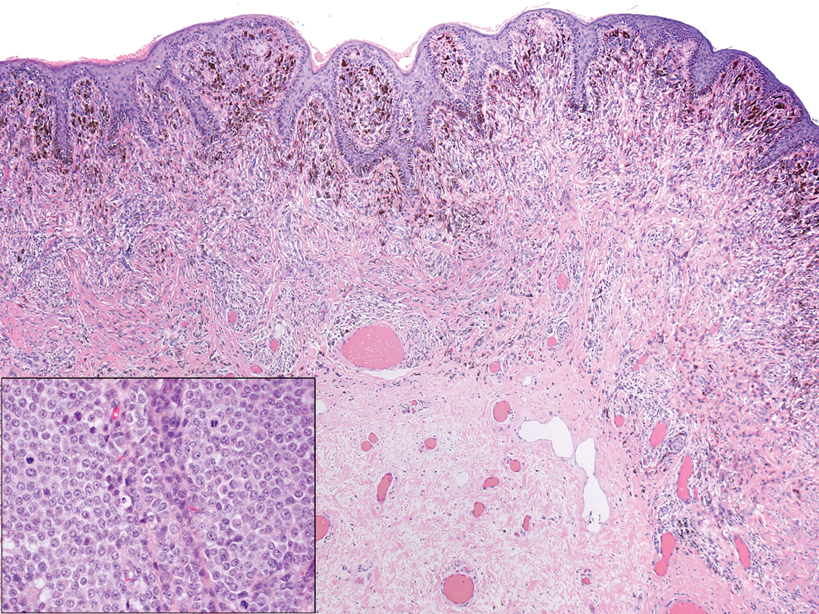

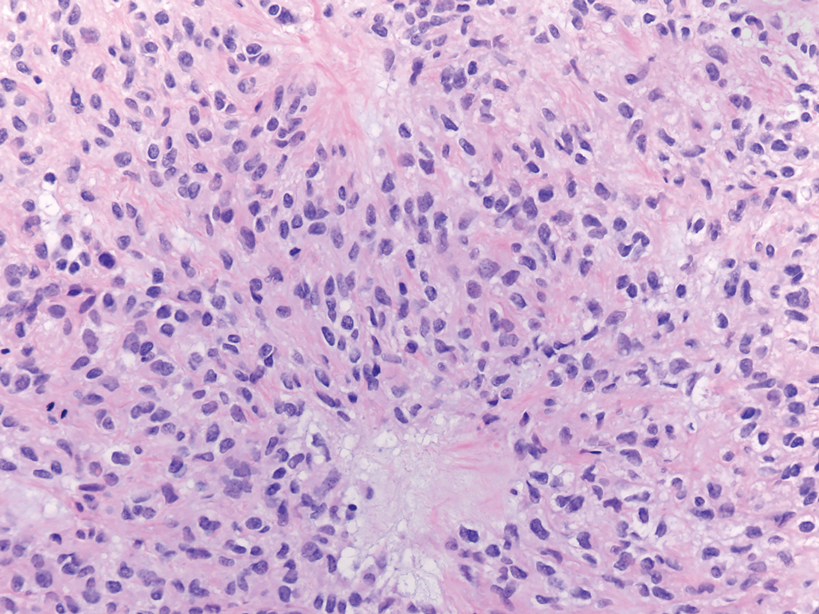

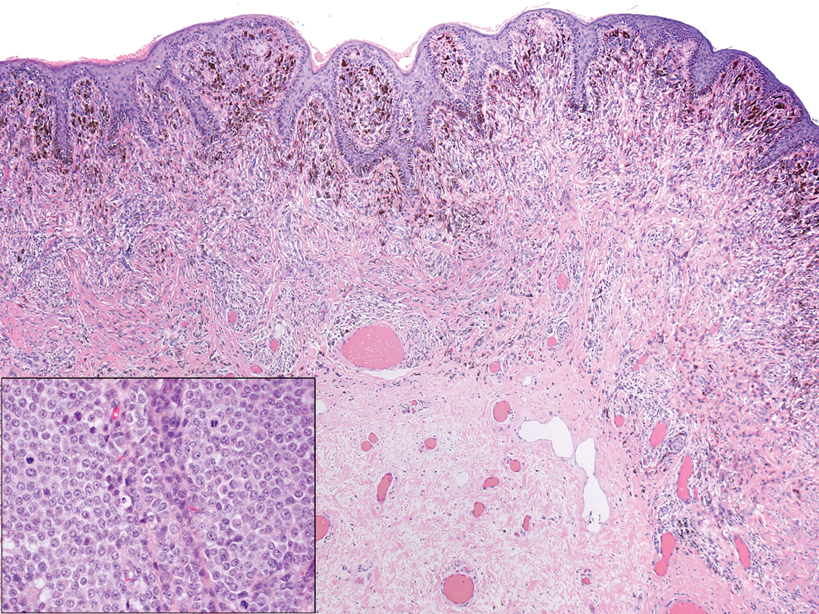

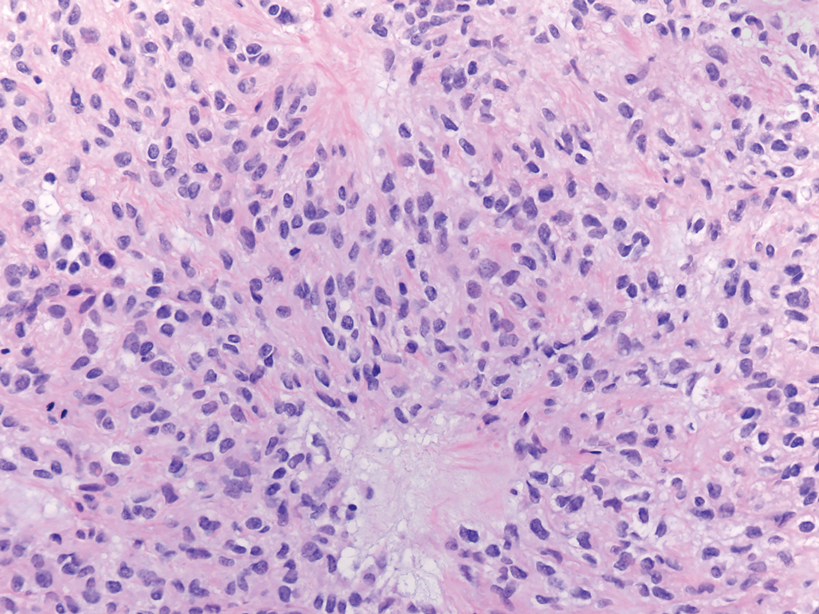

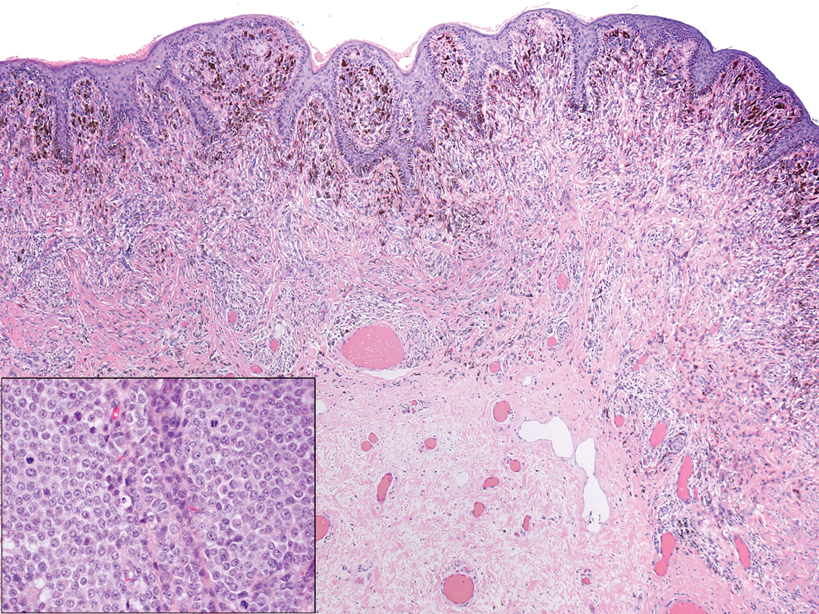

A skin biopsy and fungal cultures confirmed the diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis. Grocott- Gomori methenamine-silver staining highlighted fungal organisms with refractile walls and broad-based budding consistent with cutaneous blastomycosis (Figure 1). The histopathologic specimen also demonstrated marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (Figure 2A) with neutrophilic microabscesses (Figure 2B). Acid-fast bacillus and Fite staining were negative for bacterial organisms. A fungal culture was positive for Blastomyces dermatitidis. Urine and serum blastomycosis antigen were positive. Although Histoplasma serum antigen also was positive, this likely was from cross-reactivity. Chest radiography was negative for lung involvement, and the patient displayed no neurologic symptoms. He was started on oral itraconazole therapy for the treatment of cutaneous blastomycosis.

Blastomyces dermatitidis, the causative organism of blastomycosis, is endemic to the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys, Great Lakes region, and southeastern United States. It is a thermally dimorphic fungus found in soils that grows as a mold at 25 °C and yeast at 37 °C. Primary infection of the lungs—blastomycosis pneumonia—often is the only clinical manifestation1; however, subsequent hematogenous dissemination to extrapulmonary sites such as the skin, bones, and genitourinary system can occur. Cutaneous blastomycosis, the most common extrapulmonary manifestation, typically follows pulmonary infection. In rare cases, it can occur from direct inoculation.2,3 Skin lesions can occur anywhere but frequently are found on exposed surfaces of the head, neck, and extremities. Lesions classically present as verrucous crusting plaques with draining microabscesses. Violaceous nodules, ulcers, and pustules also may occur.1

Diagnosis involves obtaining a thorough history of possible environmental exposures such as the patient’s geographic area of residence, occupation, and outdoor activities involving soil or decaying wood. Because blastomycosis can remain latent, remote exposures are relevant. Definitive diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis involves skin biopsy of the lesion with fungal culture, but the yeast’s distinctive thick wall and broad-based budding seen with periodic acid–Schiff or Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining provides a rapid presumptive diagnosis.3 Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and microabscesses also are characteristic features.2 Urine antigen testing for a component of the polysaccharide cell wall has a sensitivity of 93% but a lower specificity of 79% due to cross-reactivity with histoplasmosis.4 Treatment consists of itraconazole for mild to moderate blastomycosis or amphotericin B for those with severe disease or central nervous system involvement or those who are immunosuppressed.1

The differential diagnosis for our patient’s lesion included infectious vs neoplastic etiologies. Histoplasma capsulatum, the dimorphic fungus that causes histoplasmosis, also is endemic to the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys. It is found in soil and droppings of some bats and birds such as chickens and pigeons. Similar to blastomycosis, the primary infection site most commonly is the lungs. It subsequently may disseminate to the skin or less commonly via direct inoculation of injured skin. It can present as papules, plaques, ulcers, purpura, or abscesses. Unlike blastomycosis, tissue biopsy of a cutaneous lesion reveals granuloma formation and distinctive oval, narrow-based budding yeast.5 Atypical mycobacteria are another source of infection to consider. For example, cutaneous Mycobacterium kansasii may present as papules and pustules forming verrucous or granulomatous plaques and ulceration. Histopathologic findings distinguishing mycobacterial infection from blastomycosis include granulomas and acid-fast bacilli in histiocytes.6

Noninfectious etiologies in the differential may include cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma or pemphigus vegetans. Squamous cell carcinoma may present with a broad range of clinical features—papules, plaques, or nodules with smooth, scaly, verrucous, or ulcerative secondary features all are possible presentations.7 Fairskinned individuals, such as our patient, would be at a higher risk in sun-damaged skin. Histologically, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is defined as an invasion of the dermis by neoplastic squamous epithelial cells in the form of cords, sheets, individual cells, nodules, or cystic structures.7 Pemphigus vegetans is the rarest variant of a group of autoimmune vesiculobullous diseases known as pemphigus. It can be differentiated from the most common variant—pemphigus vulgaris—by the presence of vegetative plaques in intertriginous areas. However, these verrucous vegetations can be misleading and make clinical diagnosis difficult. Histopathologic findings of hyperkeratosis, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, papillomatosis, and acantholysis with a suprabasal cleft would confirm the diagnosis.8

In summary, cutaneous blastomycosis classically presents as verrucous crusting plaques, as seen in our patient. It is important to conduct a thorough history for environmental exposures, but definitive diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis involves skin biopsy with fungal culture. Treatment depends on the severity of disease and organ involvement. Itraconazole would be appropriate for mild to moderate blastomycosis.

- Miceli A, Krishnamurthy K. Blastomycosis. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441987/

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Schwartz IS, Kauffman CA. Blastomycosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;41:31-41. doi:10.1055/s-0039-3400281

- Castillo CG, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:247-264. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.002

- Raggio B. Primary cutaneous histoplasmosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2018;97:346-348.

- Bhambri S, Bhambri A, Del Rosso JQ. Atypical mycobacterial cutaneous infections. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:63-73. doi:10.1016/j.det.2008.07.009

- Parekh V, Seykora JT. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:503-525. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2017.06.003

- Messersmith L, Krauland K. Pemphigus vegetans. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545229/

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Blastomycosis

A skin biopsy and fungal cultures confirmed the diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis. Grocott- Gomori methenamine-silver staining highlighted fungal organisms with refractile walls and broad-based budding consistent with cutaneous blastomycosis (Figure 1). The histopathologic specimen also demonstrated marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (Figure 2A) with neutrophilic microabscesses (Figure 2B). Acid-fast bacillus and Fite staining were negative for bacterial organisms. A fungal culture was positive for Blastomyces dermatitidis. Urine and serum blastomycosis antigen were positive. Although Histoplasma serum antigen also was positive, this likely was from cross-reactivity. Chest radiography was negative for lung involvement, and the patient displayed no neurologic symptoms. He was started on oral itraconazole therapy for the treatment of cutaneous blastomycosis.

Blastomyces dermatitidis, the causative organism of blastomycosis, is endemic to the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys, Great Lakes region, and southeastern United States. It is a thermally dimorphic fungus found in soils that grows as a mold at 25 °C and yeast at 37 °C. Primary infection of the lungs—blastomycosis pneumonia—often is the only clinical manifestation1; however, subsequent hematogenous dissemination to extrapulmonary sites such as the skin, bones, and genitourinary system can occur. Cutaneous blastomycosis, the most common extrapulmonary manifestation, typically follows pulmonary infection. In rare cases, it can occur from direct inoculation.2,3 Skin lesions can occur anywhere but frequently are found on exposed surfaces of the head, neck, and extremities. Lesions classically present as verrucous crusting plaques with draining microabscesses. Violaceous nodules, ulcers, and pustules also may occur.1

Diagnosis involves obtaining a thorough history of possible environmental exposures such as the patient’s geographic area of residence, occupation, and outdoor activities involving soil or decaying wood. Because blastomycosis can remain latent, remote exposures are relevant. Definitive diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis involves skin biopsy of the lesion with fungal culture, but the yeast’s distinctive thick wall and broad-based budding seen with periodic acid–Schiff or Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining provides a rapid presumptive diagnosis.3 Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and microabscesses also are characteristic features.2 Urine antigen testing for a component of the polysaccharide cell wall has a sensitivity of 93% but a lower specificity of 79% due to cross-reactivity with histoplasmosis.4 Treatment consists of itraconazole for mild to moderate blastomycosis or amphotericin B for those with severe disease or central nervous system involvement or those who are immunosuppressed.1

The differential diagnosis for our patient’s lesion included infectious vs neoplastic etiologies. Histoplasma capsulatum, the dimorphic fungus that causes histoplasmosis, also is endemic to the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys. It is found in soil and droppings of some bats and birds such as chickens and pigeons. Similar to blastomycosis, the primary infection site most commonly is the lungs. It subsequently may disseminate to the skin or less commonly via direct inoculation of injured skin. It can present as papules, plaques, ulcers, purpura, or abscesses. Unlike blastomycosis, tissue biopsy of a cutaneous lesion reveals granuloma formation and distinctive oval, narrow-based budding yeast.5 Atypical mycobacteria are another source of infection to consider. For example, cutaneous Mycobacterium kansasii may present as papules and pustules forming verrucous or granulomatous plaques and ulceration. Histopathologic findings distinguishing mycobacterial infection from blastomycosis include granulomas and acid-fast bacilli in histiocytes.6

Noninfectious etiologies in the differential may include cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma or pemphigus vegetans. Squamous cell carcinoma may present with a broad range of clinical features—papules, plaques, or nodules with smooth, scaly, verrucous, or ulcerative secondary features all are possible presentations.7 Fairskinned individuals, such as our patient, would be at a higher risk in sun-damaged skin. Histologically, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is defined as an invasion of the dermis by neoplastic squamous epithelial cells in the form of cords, sheets, individual cells, nodules, or cystic structures.7 Pemphigus vegetans is the rarest variant of a group of autoimmune vesiculobullous diseases known as pemphigus. It can be differentiated from the most common variant—pemphigus vulgaris—by the presence of vegetative plaques in intertriginous areas. However, these verrucous vegetations can be misleading and make clinical diagnosis difficult. Histopathologic findings of hyperkeratosis, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, papillomatosis, and acantholysis with a suprabasal cleft would confirm the diagnosis.8

In summary, cutaneous blastomycosis classically presents as verrucous crusting plaques, as seen in our patient. It is important to conduct a thorough history for environmental exposures, but definitive diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis involves skin biopsy with fungal culture. Treatment depends on the severity of disease and organ involvement. Itraconazole would be appropriate for mild to moderate blastomycosis.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Blastomycosis

A skin biopsy and fungal cultures confirmed the diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis. Grocott- Gomori methenamine-silver staining highlighted fungal organisms with refractile walls and broad-based budding consistent with cutaneous blastomycosis (Figure 1). The histopathologic specimen also demonstrated marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (Figure 2A) with neutrophilic microabscesses (Figure 2B). Acid-fast bacillus and Fite staining were negative for bacterial organisms. A fungal culture was positive for Blastomyces dermatitidis. Urine and serum blastomycosis antigen were positive. Although Histoplasma serum antigen also was positive, this likely was from cross-reactivity. Chest radiography was negative for lung involvement, and the patient displayed no neurologic symptoms. He was started on oral itraconazole therapy for the treatment of cutaneous blastomycosis.

Blastomyces dermatitidis, the causative organism of blastomycosis, is endemic to the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys, Great Lakes region, and southeastern United States. It is a thermally dimorphic fungus found in soils that grows as a mold at 25 °C and yeast at 37 °C. Primary infection of the lungs—blastomycosis pneumonia—often is the only clinical manifestation1; however, subsequent hematogenous dissemination to extrapulmonary sites such as the skin, bones, and genitourinary system can occur. Cutaneous blastomycosis, the most common extrapulmonary manifestation, typically follows pulmonary infection. In rare cases, it can occur from direct inoculation.2,3 Skin lesions can occur anywhere but frequently are found on exposed surfaces of the head, neck, and extremities. Lesions classically present as verrucous crusting plaques with draining microabscesses. Violaceous nodules, ulcers, and pustules also may occur.1

Diagnosis involves obtaining a thorough history of possible environmental exposures such as the patient’s geographic area of residence, occupation, and outdoor activities involving soil or decaying wood. Because blastomycosis can remain latent, remote exposures are relevant. Definitive diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis involves skin biopsy of the lesion with fungal culture, but the yeast’s distinctive thick wall and broad-based budding seen with periodic acid–Schiff or Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining provides a rapid presumptive diagnosis.3 Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and microabscesses also are characteristic features.2 Urine antigen testing for a component of the polysaccharide cell wall has a sensitivity of 93% but a lower specificity of 79% due to cross-reactivity with histoplasmosis.4 Treatment consists of itraconazole for mild to moderate blastomycosis or amphotericin B for those with severe disease or central nervous system involvement or those who are immunosuppressed.1

The differential diagnosis for our patient’s lesion included infectious vs neoplastic etiologies. Histoplasma capsulatum, the dimorphic fungus that causes histoplasmosis, also is endemic to the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys. It is found in soil and droppings of some bats and birds such as chickens and pigeons. Similar to blastomycosis, the primary infection site most commonly is the lungs. It subsequently may disseminate to the skin or less commonly via direct inoculation of injured skin. It can present as papules, plaques, ulcers, purpura, or abscesses. Unlike blastomycosis, tissue biopsy of a cutaneous lesion reveals granuloma formation and distinctive oval, narrow-based budding yeast.5 Atypical mycobacteria are another source of infection to consider. For example, cutaneous Mycobacterium kansasii may present as papules and pustules forming verrucous or granulomatous plaques and ulceration. Histopathologic findings distinguishing mycobacterial infection from blastomycosis include granulomas and acid-fast bacilli in histiocytes.6

Noninfectious etiologies in the differential may include cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma or pemphigus vegetans. Squamous cell carcinoma may present with a broad range of clinical features—papules, plaques, or nodules with smooth, scaly, verrucous, or ulcerative secondary features all are possible presentations.7 Fairskinned individuals, such as our patient, would be at a higher risk in sun-damaged skin. Histologically, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is defined as an invasion of the dermis by neoplastic squamous epithelial cells in the form of cords, sheets, individual cells, nodules, or cystic structures.7 Pemphigus vegetans is the rarest variant of a group of autoimmune vesiculobullous diseases known as pemphigus. It can be differentiated from the most common variant—pemphigus vulgaris—by the presence of vegetative plaques in intertriginous areas. However, these verrucous vegetations can be misleading and make clinical diagnosis difficult. Histopathologic findings of hyperkeratosis, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, papillomatosis, and acantholysis with a suprabasal cleft would confirm the diagnosis.8

In summary, cutaneous blastomycosis classically presents as verrucous crusting plaques, as seen in our patient. It is important to conduct a thorough history for environmental exposures, but definitive diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis involves skin biopsy with fungal culture. Treatment depends on the severity of disease and organ involvement. Itraconazole would be appropriate for mild to moderate blastomycosis.

- Miceli A, Krishnamurthy K. Blastomycosis. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441987/

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Schwartz IS, Kauffman CA. Blastomycosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;41:31-41. doi:10.1055/s-0039-3400281

- Castillo CG, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:247-264. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.002

- Raggio B. Primary cutaneous histoplasmosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2018;97:346-348.

- Bhambri S, Bhambri A, Del Rosso JQ. Atypical mycobacterial cutaneous infections. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:63-73. doi:10.1016/j.det.2008.07.009

- Parekh V, Seykora JT. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:503-525. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2017.06.003

- Messersmith L, Krauland K. Pemphigus vegetans. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545229/

- Miceli A, Krishnamurthy K. Blastomycosis. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441987/

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Schwartz IS, Kauffman CA. Blastomycosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;41:31-41. doi:10.1055/s-0039-3400281

- Castillo CG, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:247-264. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.002

- Raggio B. Primary cutaneous histoplasmosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2018;97:346-348.

- Bhambri S, Bhambri A, Del Rosso JQ. Atypical mycobacterial cutaneous infections. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:63-73. doi:10.1016/j.det.2008.07.009

- Parekh V, Seykora JT. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:503-525. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2017.06.003

- Messersmith L, Krauland K. Pemphigus vegetans. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545229/

A 39-year-old man from Ohio presented with a tender, 10×6-cm, fungated, eroded plaque on the right medial upper arm that developed over the last 4 years. He initially noticed a firm lump under the right arm 4 years prior that was diagnosed as possible cellulitis at an outside clinic and treated with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. The lesion then began to erode and became a chronic nonhealing wound. Approximately 1 year prior to the current presentation, the patient recalled unloading a truckload of soil around the same time the wound began to enlarge in diameter and depth. He denied any prior or current respiratory or systemic symptoms including fevers, chills, or weight loss.

Erythematous Papules on the Ears

The Diagnosis: Borrelial Lymphocytoma (Lymphocytoma Cutis)

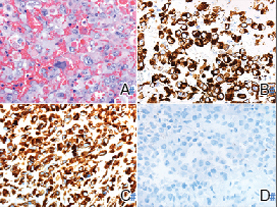

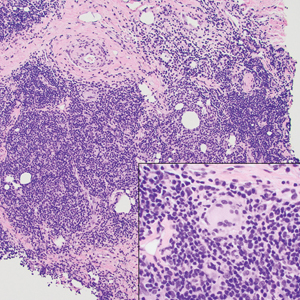

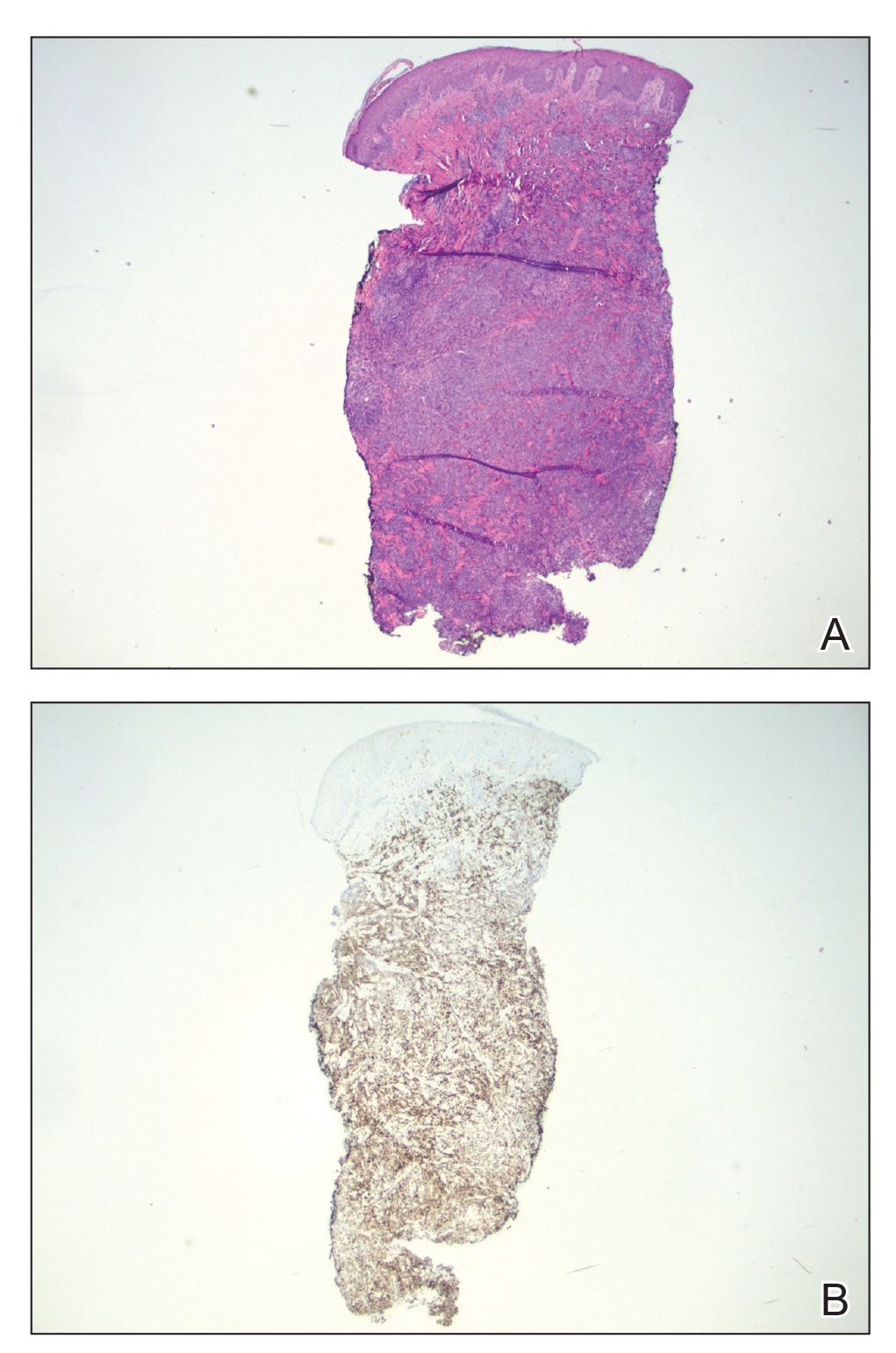

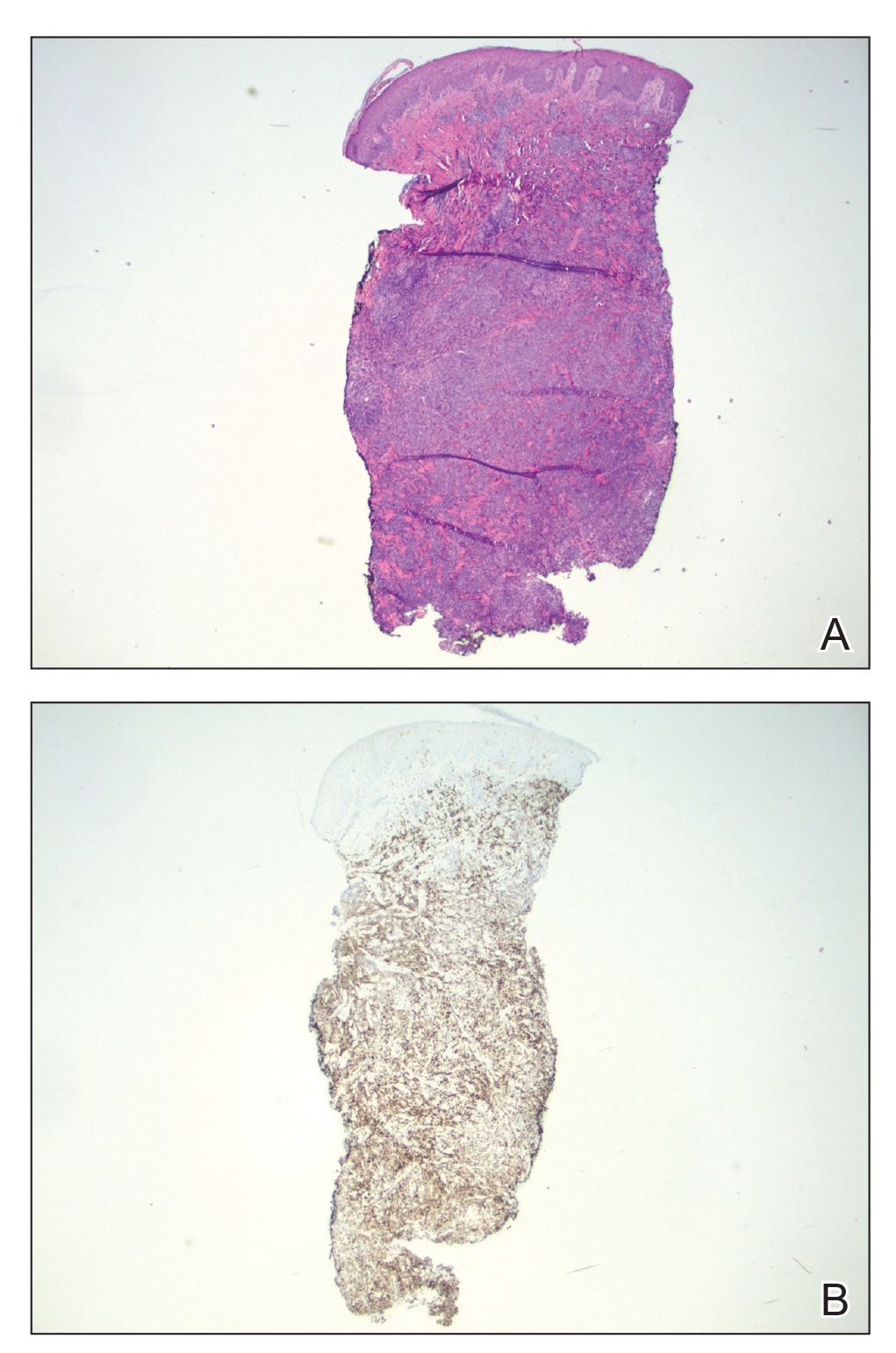

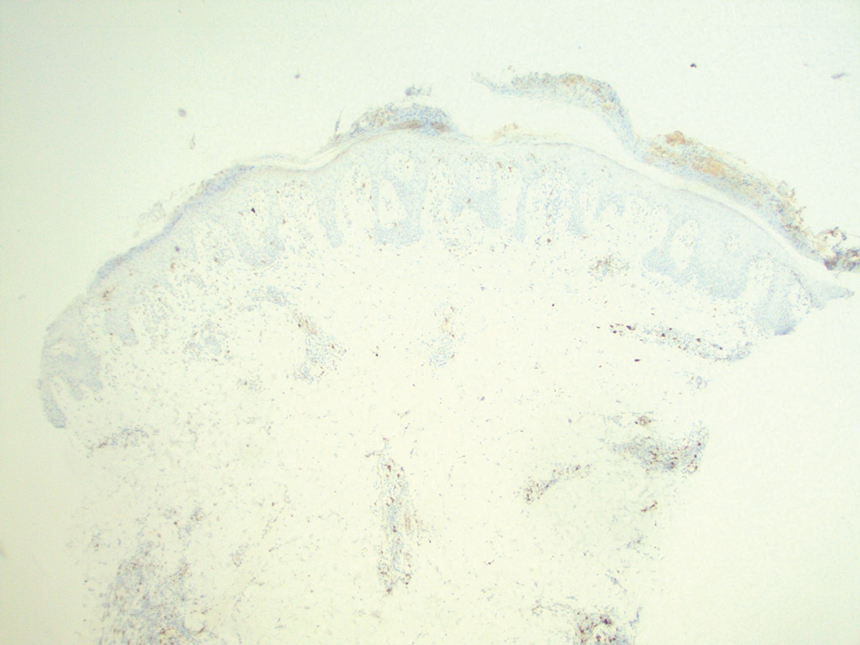

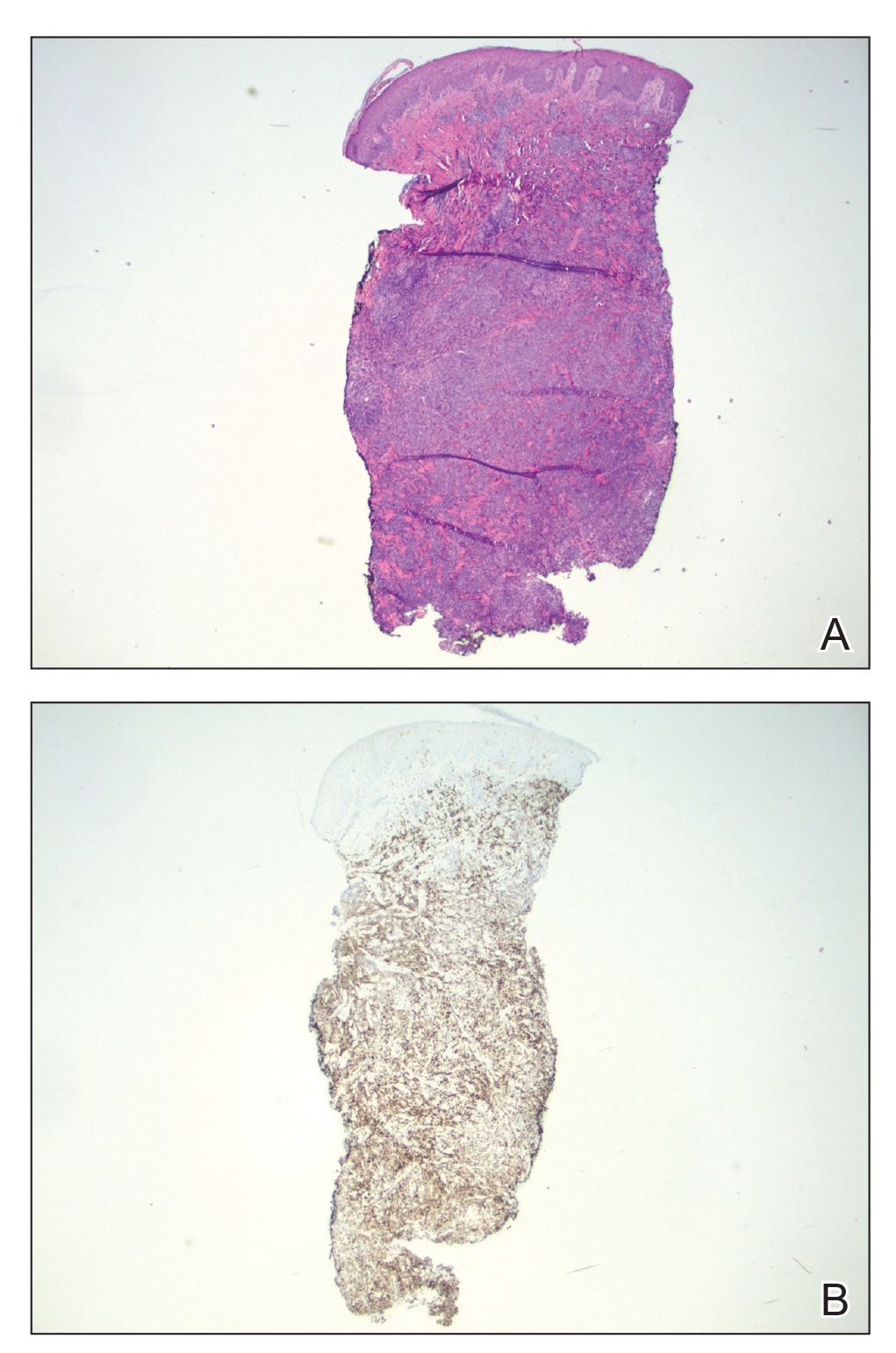

A punch biopsy revealed an atypical lobular lymphoid infiltrate within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue with a mixed composition of CD3+ T cells and CD20+ B cells (quiz image, bottom). Immunohistochemical studies revealed a normal CD4:CD8 ratio with preservation of CD5 and CD7. CD30 was largely negative. CD21 failed to detect follicular dendritic cell networks, and κ/λ light chain staining confirmed a preserved ratio of polytypic plasma cells. There was limited staining with B-cell lymphoma (Bcl-2 and Bcl-6). Polymerase chain reaction studies for both T- and B-cell receptors were negative (polyclonal).

Lyme disease is the most frequently reported vectorborne infectious disease in the United States, and borrelial lymphocytoma (BL) is a rare clinical sequela. Borrelial lymphocytoma is a variant of lymphocytoma cutis (also known as benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia), which is an inflammatory lesion that can mimic malignant lymphoma clinically and histologically. Lymphocytoma cutis is considered the prototypical example of cutaneous B-cell pseudolymphoma.1 Due to suspicion for lymphocytoma cutis based on the histologic findings and characteristic location of the lesions in our patient, Lyme serologies were ordered and were positive for IgM antibodies against p23, p39, and p41 antigens in high titers. Our patient was treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 3 weeks with complete resolution of the lesions at 3-month follow-up.

Clinically, BL appears as erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules commonly on the lobules of the ears (quiz image, top). Most cases of lymphocytoma cutis are idiopathic but may be triggered by identifiable associated etiologies including Borrelia burgdorferi, Leishmania donovani, molluscum contagiosum, herpes zoster virus, vaccinations, tattoos, insect bites, and drugs. The main differential diagnosis of lymphocytoma cutis is cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Pseudolymphoma of the skin can mimic nearly all immunohistochemical staining patterns of true B-cell lymphomas.2

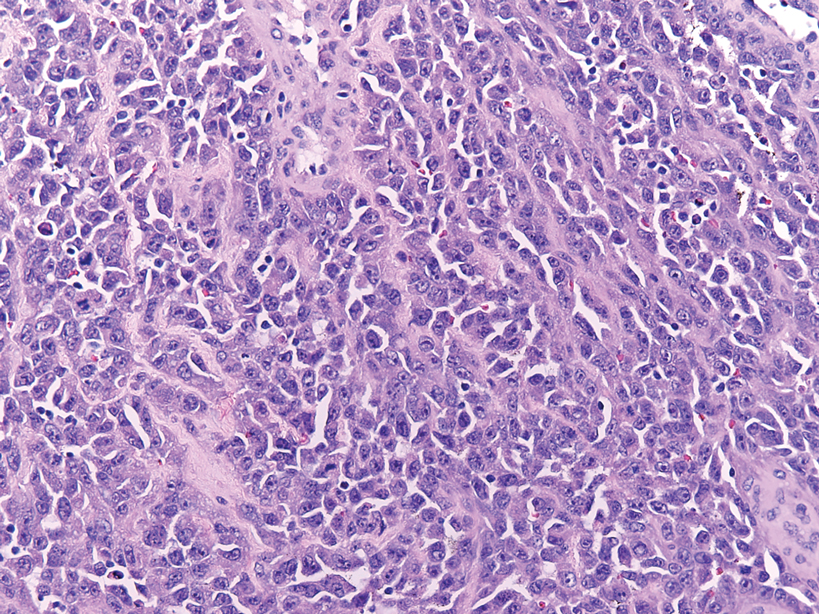

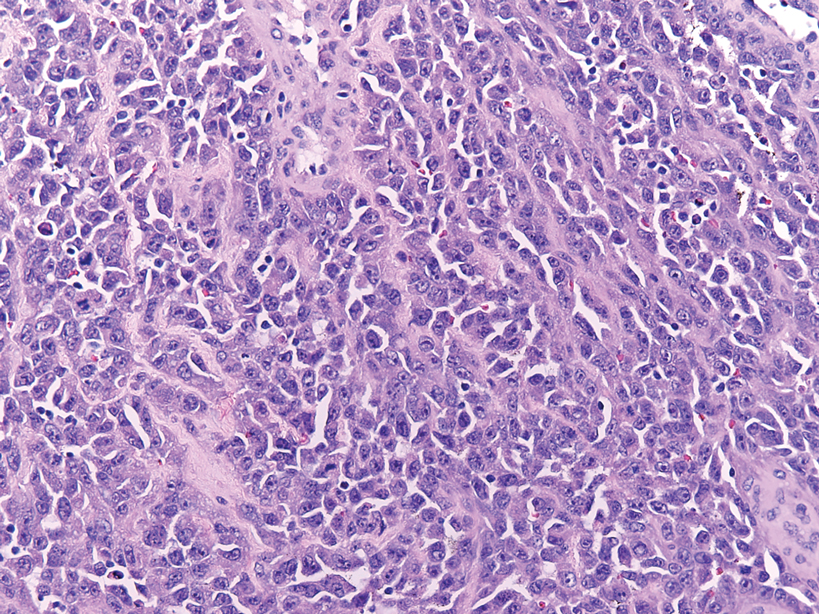

Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma frequently occurs on the head and neck. This true lymphoma of the skin can demonstrate prominent follicle centers with centrocytes and fragmented germinal centers (Figure 1) or show a diffuse pattern.3 Most cases show conspicuous Bcl-6 staining, and IgH gene rearrangements can detect a clonal B-cell population in more than 50% of cases.4

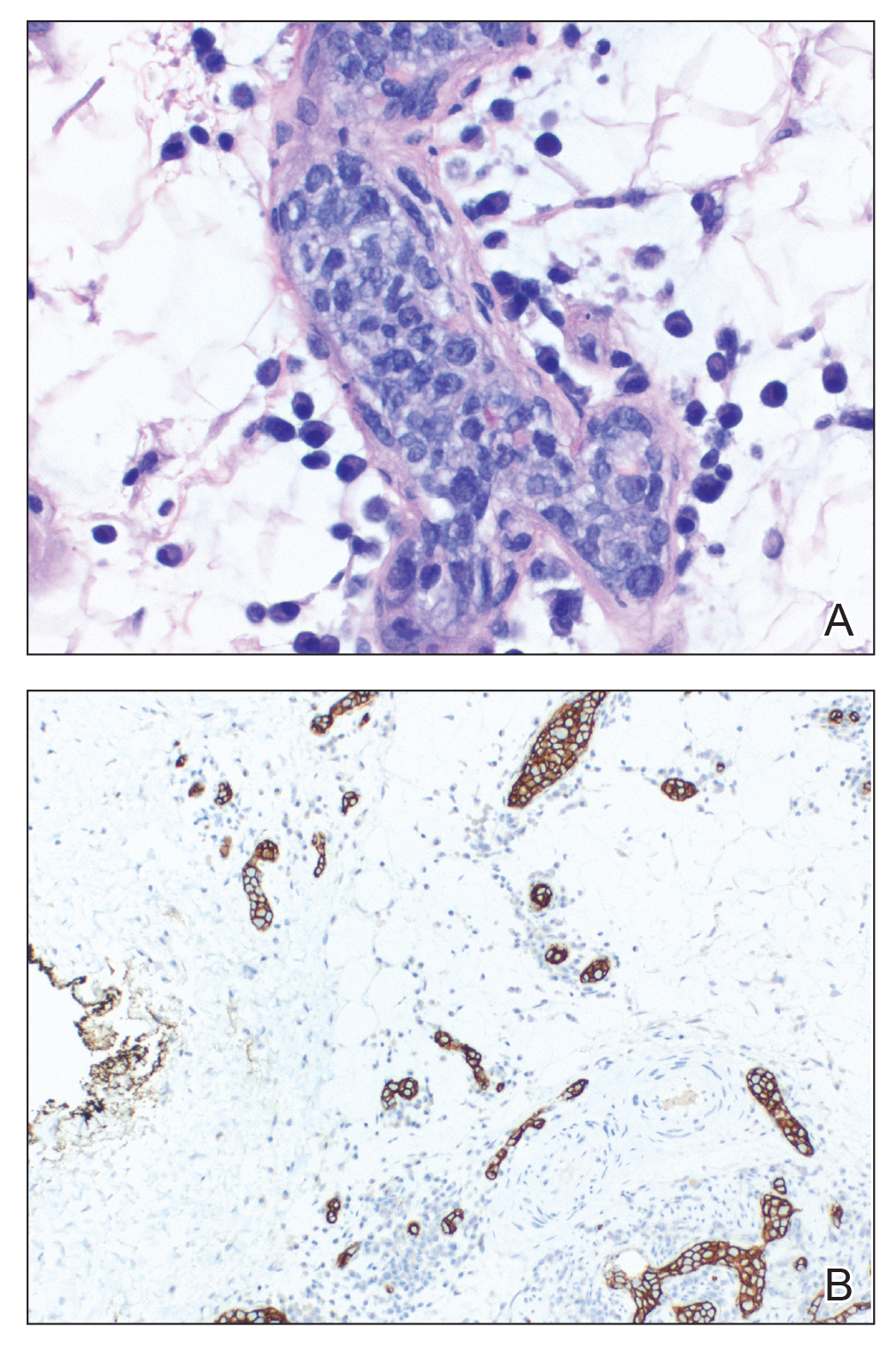

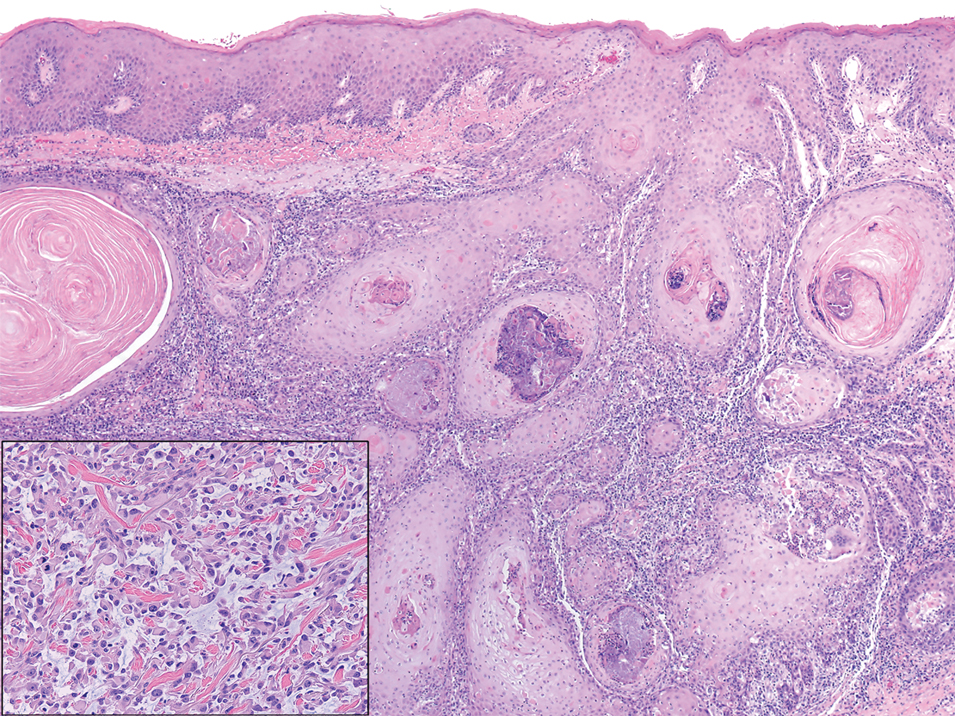

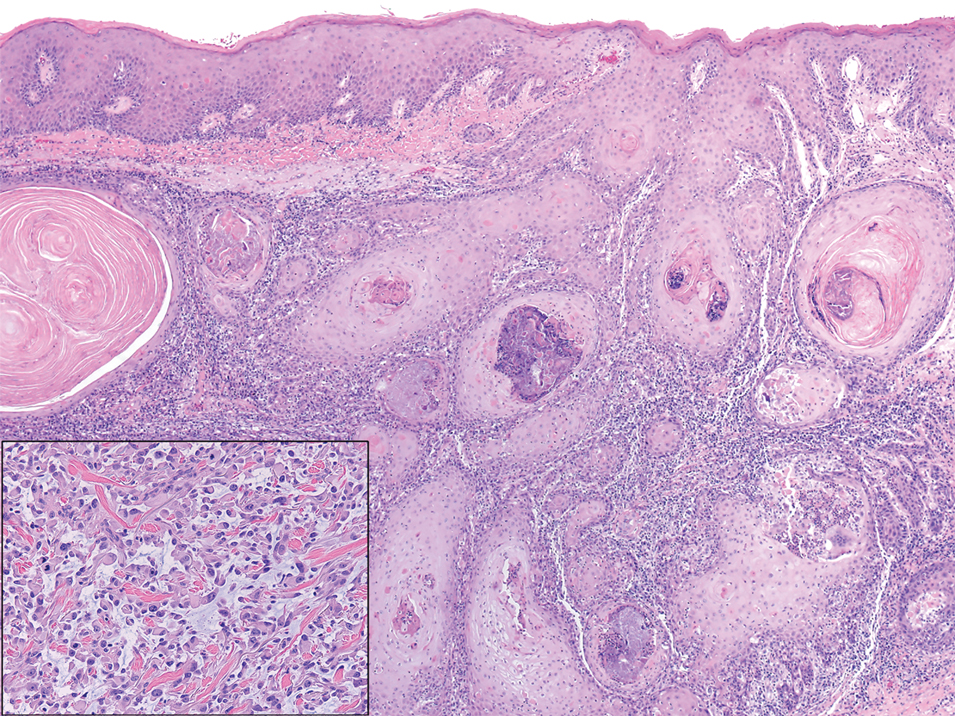

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma can occur as a primary cutaneous malignancy or as a manifestation of systemic disease.4 When arising in the skin, lesions tend to affect the extremities, and the disease is classified as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type. Histologically, sheets of large atypical lymphocytes with numerous mitoses are seen (Figure 2). These cells stain positively with Bcl-2 and frequently demonstrate Bcl-6 and MUM-1, none of which were seen in our case.4 Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) tends to present with relapsing erythematous papules. Patients occasionally develop LyP in association with mycosis fungoides or other lymphomas. Both LyP and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma demonstrate conspicuous CD30+ large cells that can be multinucleated or resemble the Reed-Sternberg cells seen in Hodgkin lymphoma (Figure 3).4 Arthropod bite reactions are common but may be confused with lymphomas and pseudolymphomas. The perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate seen in arthropod bite reactions may be dense and usually is associated with numerous eosinophils (Figure 4). Occasional plasma cells also can be seen, and if the infiltrate closely adheres to vascular structures, a diagnosis of erythema chronicum migrans also can be considered. Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/lymphoma may demonstrate exaggerated or persistent arthropod bite reactions, and atypical lymphocytes can be detected admixed with the otherwise reactive infiltrate.4

Borrelia burgdorferi is primarily endemic to North America and Europe. It is a spirochete bacterium spread by the Ixodes tick that was first recognized as the etiologic agent in 1975 in Old Lyme, Connecticut, where it received its name.5 Most reported cases of Lyme disease occur in the northeastern United States, which correlates with this case given our patient’s place of residence.6 Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis occurs in areas endemic for the Ixodes tick in Europe and North America.7 When describing the genotyping of Borrelia seen in BL, the strain B burgdorferi previously was grouped with Borrelia afzelii and Borrelia garinii.2 In the contemporary literature, however, B burgdorferi is referred to as sensu stricto when specifically talking about the strain B burgdorferi, and the term sensu lato is used when referencing the combination of strains (B burgdorferi, B afzelii, B garinii).

A 2016 study by Maraspin et al8 comprising 144 patients diagnosed with BL showed that the lesions mainly were located on the breast (106 patients [73.6%]) and the earlobe (27 patients [18.8%]), with the remaining cases occurring elsewhere on the body (11 patients [7.6%]). The Borrelia strains isolated from the BL lesions included B afzelii, Borrelia bissettii, and B garinii, with B afzelii being the most commonly identified (84.6% [11/13]).8

Borrelial lymphocytoma usually is categorized as a form of early disseminated Lyme disease and is treated as such. The treatment of choice for early disseminated Lyme disease is doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 to 21 days. Ceftriaxone and azithromycin are reasonable treatment options for patients who have tetracycline allergies or who are pregnant.9

In conclusion, the presentation of red papules or nodules on the ears should prompt clinical suspicion of Lyme disease, particularly in endemic areas. Differentiating pseudolymphomas from true lymphomas and other reactive conditions can be challenging.

- Mitteldorf C, Kempf W. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma. Surg Pathol Clin. 2017;10:455-476. doi:10.1016/j.path.2017.01.002

- Colli C, Leinweber B, Müllegger R, et al. Borrelia burgdorferiassociated lymphocytoma cutis: clinicopathologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular study of 106 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:232-240. doi:10.1111/j.0303-6987.2003.00167.x

- Wehbe AM, Neppalli V, Syrbu S, et al. Diffuse follicle centre lymphoma presents with high frequency of extranodal disease. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15 suppl):19511. doi:10.1200/jco.2008.26.15_suppl.19511

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Cutaneous infiltrates—lymphomatous and leukemic. In: Patterson JW, ed. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2016:1171-1217.

- Cardenas-de la Garza JA, De la Cruz-Valadez E, Ocampo -Candiani J, et al. Clinical spectrum of Lyme disease. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38:201-208. doi:10.1007/s10096-018-3417-1

- Shapiro ED, Gerber MA. Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:533-542. doi:10.1086/313982

- Kandhari R, Kandhari S, Jain S. Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis: a diagnostic dilemma. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:595-597. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.143530

- Maraspin V, Nahtigal Klevišar M, Ružic´-Sabljic´ E, et al. Borrelial lymphocytoma in adult patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:914-921. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw417

- Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006; 43:1089-1134. doi:10.1086/508667

The Diagnosis: Borrelial Lymphocytoma (Lymphocytoma Cutis)

A punch biopsy revealed an atypical lobular lymphoid infiltrate within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue with a mixed composition of CD3+ T cells and CD20+ B cells (quiz image, bottom). Immunohistochemical studies revealed a normal CD4:CD8 ratio with preservation of CD5 and CD7. CD30 was largely negative. CD21 failed to detect follicular dendritic cell networks, and κ/λ light chain staining confirmed a preserved ratio of polytypic plasma cells. There was limited staining with B-cell lymphoma (Bcl-2 and Bcl-6). Polymerase chain reaction studies for both T- and B-cell receptors were negative (polyclonal).

Lyme disease is the most frequently reported vectorborne infectious disease in the United States, and borrelial lymphocytoma (BL) is a rare clinical sequela. Borrelial lymphocytoma is a variant of lymphocytoma cutis (also known as benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia), which is an inflammatory lesion that can mimic malignant lymphoma clinically and histologically. Lymphocytoma cutis is considered the prototypical example of cutaneous B-cell pseudolymphoma.1 Due to suspicion for lymphocytoma cutis based on the histologic findings and characteristic location of the lesions in our patient, Lyme serologies were ordered and were positive for IgM antibodies against p23, p39, and p41 antigens in high titers. Our patient was treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 3 weeks with complete resolution of the lesions at 3-month follow-up.

Clinically, BL appears as erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules commonly on the lobules of the ears (quiz image, top). Most cases of lymphocytoma cutis are idiopathic but may be triggered by identifiable associated etiologies including Borrelia burgdorferi, Leishmania donovani, molluscum contagiosum, herpes zoster virus, vaccinations, tattoos, insect bites, and drugs. The main differential diagnosis of lymphocytoma cutis is cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Pseudolymphoma of the skin can mimic nearly all immunohistochemical staining patterns of true B-cell lymphomas.2

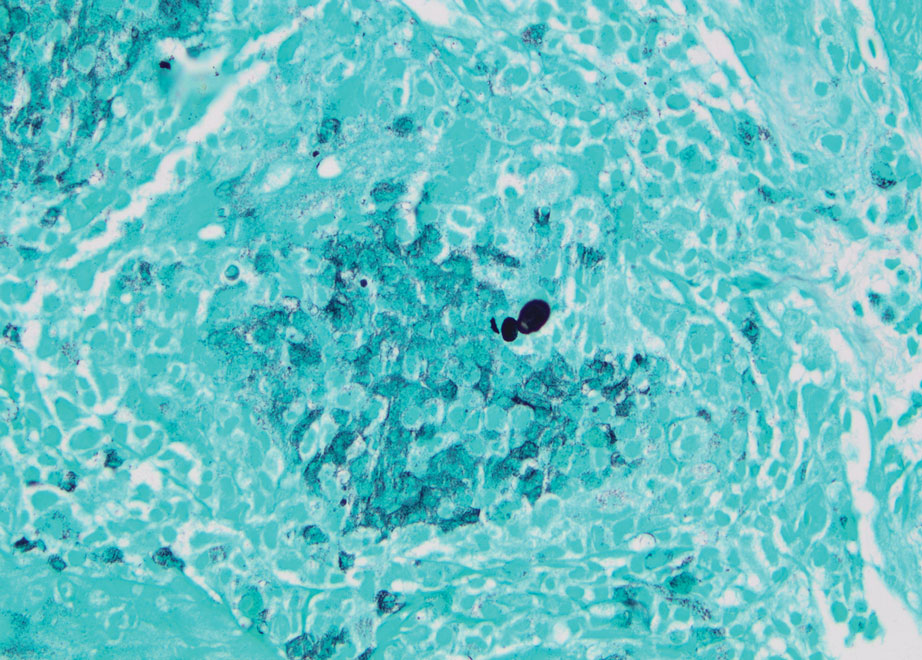

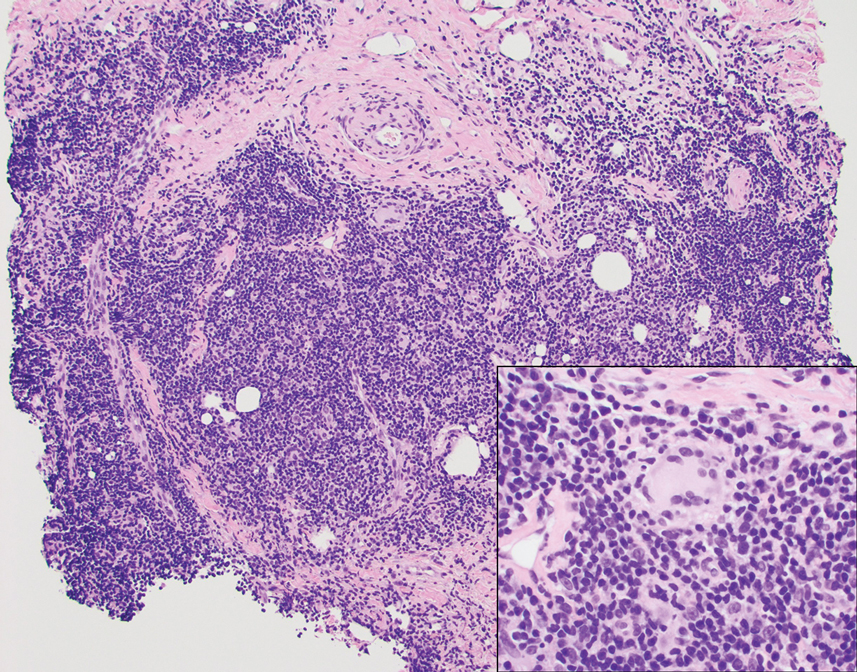

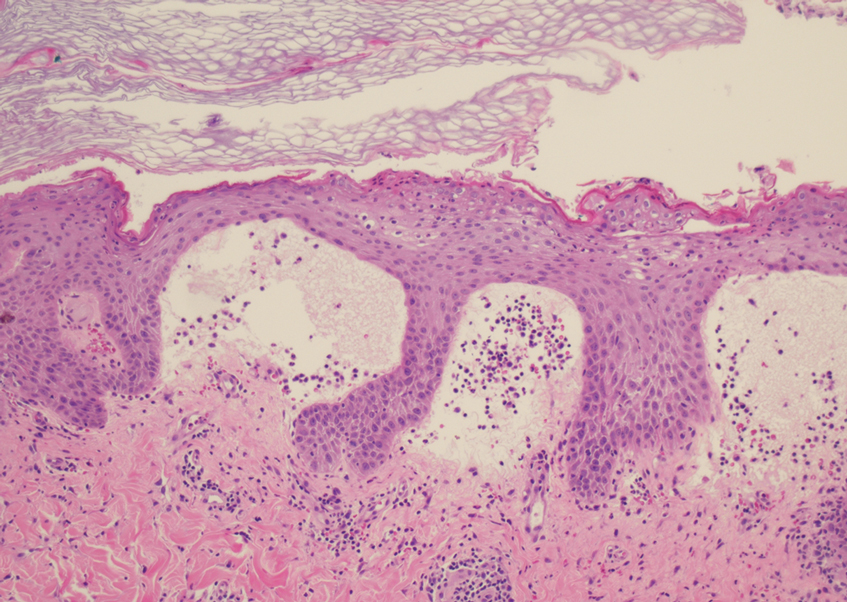

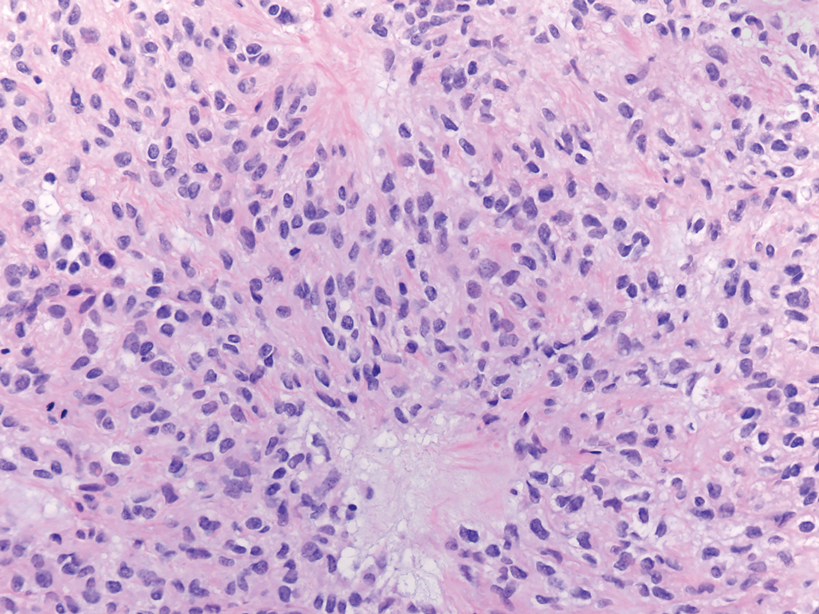

Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma frequently occurs on the head and neck. This true lymphoma of the skin can demonstrate prominent follicle centers with centrocytes and fragmented germinal centers (Figure 1) or show a diffuse pattern.3 Most cases show conspicuous Bcl-6 staining, and IgH gene rearrangements can detect a clonal B-cell population in more than 50% of cases.4

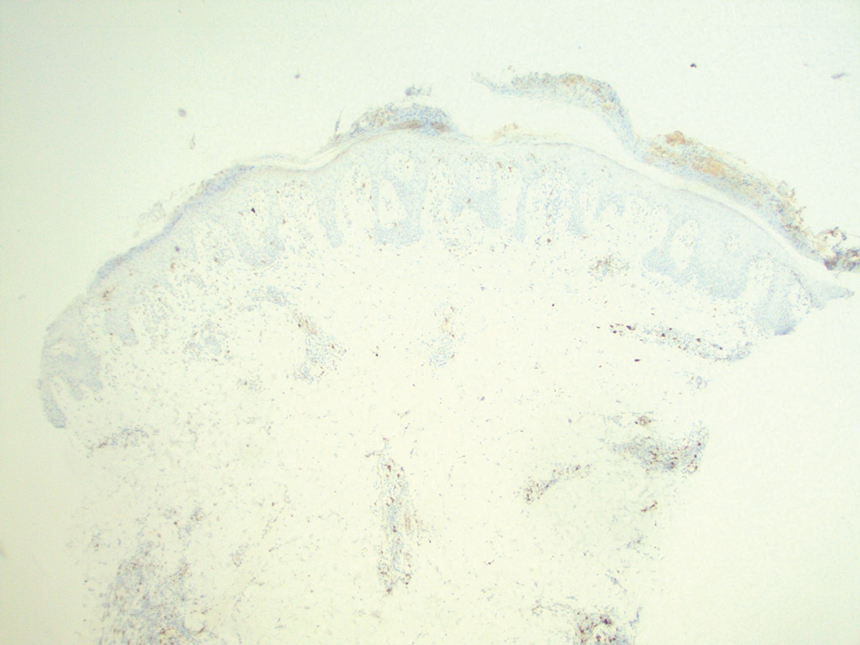

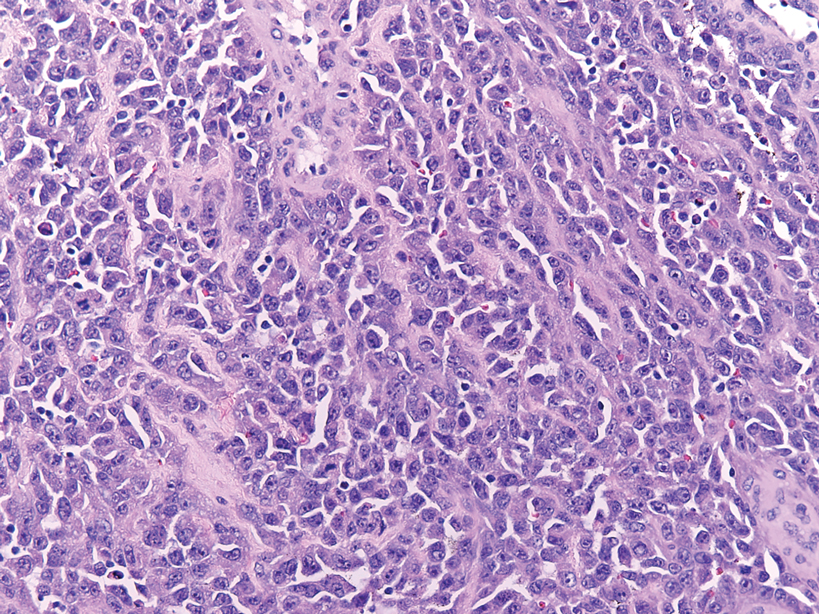

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma can occur as a primary cutaneous malignancy or as a manifestation of systemic disease.4 When arising in the skin, lesions tend to affect the extremities, and the disease is classified as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type. Histologically, sheets of large atypical lymphocytes with numerous mitoses are seen (Figure 2). These cells stain positively with Bcl-2 and frequently demonstrate Bcl-6 and MUM-1, none of which were seen in our case.4 Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) tends to present with relapsing erythematous papules. Patients occasionally develop LyP in association with mycosis fungoides or other lymphomas. Both LyP and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma demonstrate conspicuous CD30+ large cells that can be multinucleated or resemble the Reed-Sternberg cells seen in Hodgkin lymphoma (Figure 3).4 Arthropod bite reactions are common but may be confused with lymphomas and pseudolymphomas. The perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate seen in arthropod bite reactions may be dense and usually is associated with numerous eosinophils (Figure 4). Occasional plasma cells also can be seen, and if the infiltrate closely adheres to vascular structures, a diagnosis of erythema chronicum migrans also can be considered. Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/lymphoma may demonstrate exaggerated or persistent arthropod bite reactions, and atypical lymphocytes can be detected admixed with the otherwise reactive infiltrate.4

Borrelia burgdorferi is primarily endemic to North America and Europe. It is a spirochete bacterium spread by the Ixodes tick that was first recognized as the etiologic agent in 1975 in Old Lyme, Connecticut, where it received its name.5 Most reported cases of Lyme disease occur in the northeastern United States, which correlates with this case given our patient’s place of residence.6 Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis occurs in areas endemic for the Ixodes tick in Europe and North America.7 When describing the genotyping of Borrelia seen in BL, the strain B burgdorferi previously was grouped with Borrelia afzelii and Borrelia garinii.2 In the contemporary literature, however, B burgdorferi is referred to as sensu stricto when specifically talking about the strain B burgdorferi, and the term sensu lato is used when referencing the combination of strains (B burgdorferi, B afzelii, B garinii).

A 2016 study by Maraspin et al8 comprising 144 patients diagnosed with BL showed that the lesions mainly were located on the breast (106 patients [73.6%]) and the earlobe (27 patients [18.8%]), with the remaining cases occurring elsewhere on the body (11 patients [7.6%]). The Borrelia strains isolated from the BL lesions included B afzelii, Borrelia bissettii, and B garinii, with B afzelii being the most commonly identified (84.6% [11/13]).8

Borrelial lymphocytoma usually is categorized as a form of early disseminated Lyme disease and is treated as such. The treatment of choice for early disseminated Lyme disease is doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 to 21 days. Ceftriaxone and azithromycin are reasonable treatment options for patients who have tetracycline allergies or who are pregnant.9

In conclusion, the presentation of red papules or nodules on the ears should prompt clinical suspicion of Lyme disease, particularly in endemic areas. Differentiating pseudolymphomas from true lymphomas and other reactive conditions can be challenging.

The Diagnosis: Borrelial Lymphocytoma (Lymphocytoma Cutis)

A punch biopsy revealed an atypical lobular lymphoid infiltrate within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue with a mixed composition of CD3+ T cells and CD20+ B cells (quiz image, bottom). Immunohistochemical studies revealed a normal CD4:CD8 ratio with preservation of CD5 and CD7. CD30 was largely negative. CD21 failed to detect follicular dendritic cell networks, and κ/λ light chain staining confirmed a preserved ratio of polytypic plasma cells. There was limited staining with B-cell lymphoma (Bcl-2 and Bcl-6). Polymerase chain reaction studies for both T- and B-cell receptors were negative (polyclonal).

Lyme disease is the most frequently reported vectorborne infectious disease in the United States, and borrelial lymphocytoma (BL) is a rare clinical sequela. Borrelial lymphocytoma is a variant of lymphocytoma cutis (also known as benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia), which is an inflammatory lesion that can mimic malignant lymphoma clinically and histologically. Lymphocytoma cutis is considered the prototypical example of cutaneous B-cell pseudolymphoma.1 Due to suspicion for lymphocytoma cutis based on the histologic findings and characteristic location of the lesions in our patient, Lyme serologies were ordered and were positive for IgM antibodies against p23, p39, and p41 antigens in high titers. Our patient was treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 3 weeks with complete resolution of the lesions at 3-month follow-up.

Clinically, BL appears as erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules commonly on the lobules of the ears (quiz image, top). Most cases of lymphocytoma cutis are idiopathic but may be triggered by identifiable associated etiologies including Borrelia burgdorferi, Leishmania donovani, molluscum contagiosum, herpes zoster virus, vaccinations, tattoos, insect bites, and drugs. The main differential diagnosis of lymphocytoma cutis is cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Pseudolymphoma of the skin can mimic nearly all immunohistochemical staining patterns of true B-cell lymphomas.2

Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma frequently occurs on the head and neck. This true lymphoma of the skin can demonstrate prominent follicle centers with centrocytes and fragmented germinal centers (Figure 1) or show a diffuse pattern.3 Most cases show conspicuous Bcl-6 staining, and IgH gene rearrangements can detect a clonal B-cell population in more than 50% of cases.4

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma can occur as a primary cutaneous malignancy or as a manifestation of systemic disease.4 When arising in the skin, lesions tend to affect the extremities, and the disease is classified as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type. Histologically, sheets of large atypical lymphocytes with numerous mitoses are seen (Figure 2). These cells stain positively with Bcl-2 and frequently demonstrate Bcl-6 and MUM-1, none of which were seen in our case.4 Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) tends to present with relapsing erythematous papules. Patients occasionally develop LyP in association with mycosis fungoides or other lymphomas. Both LyP and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma demonstrate conspicuous CD30+ large cells that can be multinucleated or resemble the Reed-Sternberg cells seen in Hodgkin lymphoma (Figure 3).4 Arthropod bite reactions are common but may be confused with lymphomas and pseudolymphomas. The perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate seen in arthropod bite reactions may be dense and usually is associated with numerous eosinophils (Figure 4). Occasional plasma cells also can be seen, and if the infiltrate closely adheres to vascular structures, a diagnosis of erythema chronicum migrans also can be considered. Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/lymphoma may demonstrate exaggerated or persistent arthropod bite reactions, and atypical lymphocytes can be detected admixed with the otherwise reactive infiltrate.4

Borrelia burgdorferi is primarily endemic to North America and Europe. It is a spirochete bacterium spread by the Ixodes tick that was first recognized as the etiologic agent in 1975 in Old Lyme, Connecticut, where it received its name.5 Most reported cases of Lyme disease occur in the northeastern United States, which correlates with this case given our patient’s place of residence.6 Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis occurs in areas endemic for the Ixodes tick in Europe and North America.7 When describing the genotyping of Borrelia seen in BL, the strain B burgdorferi previously was grouped with Borrelia afzelii and Borrelia garinii.2 In the contemporary literature, however, B burgdorferi is referred to as sensu stricto when specifically talking about the strain B burgdorferi, and the term sensu lato is used when referencing the combination of strains (B burgdorferi, B afzelii, B garinii).

A 2016 study by Maraspin et al8 comprising 144 patients diagnosed with BL showed that the lesions mainly were located on the breast (106 patients [73.6%]) and the earlobe (27 patients [18.8%]), with the remaining cases occurring elsewhere on the body (11 patients [7.6%]). The Borrelia strains isolated from the BL lesions included B afzelii, Borrelia bissettii, and B garinii, with B afzelii being the most commonly identified (84.6% [11/13]).8

Borrelial lymphocytoma usually is categorized as a form of early disseminated Lyme disease and is treated as such. The treatment of choice for early disseminated Lyme disease is doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 to 21 days. Ceftriaxone and azithromycin are reasonable treatment options for patients who have tetracycline allergies or who are pregnant.9

In conclusion, the presentation of red papules or nodules on the ears should prompt clinical suspicion of Lyme disease, particularly in endemic areas. Differentiating pseudolymphomas from true lymphomas and other reactive conditions can be challenging.

- Mitteldorf C, Kempf W. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma. Surg Pathol Clin. 2017;10:455-476. doi:10.1016/j.path.2017.01.002

- Colli C, Leinweber B, Müllegger R, et al. Borrelia burgdorferiassociated lymphocytoma cutis: clinicopathologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular study of 106 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:232-240. doi:10.1111/j.0303-6987.2003.00167.x

- Wehbe AM, Neppalli V, Syrbu S, et al. Diffuse follicle centre lymphoma presents with high frequency of extranodal disease. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15 suppl):19511. doi:10.1200/jco.2008.26.15_suppl.19511

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Cutaneous infiltrates—lymphomatous and leukemic. In: Patterson JW, ed. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2016:1171-1217.

- Cardenas-de la Garza JA, De la Cruz-Valadez E, Ocampo -Candiani J, et al. Clinical spectrum of Lyme disease. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38:201-208. doi:10.1007/s10096-018-3417-1

- Shapiro ED, Gerber MA. Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:533-542. doi:10.1086/313982

- Kandhari R, Kandhari S, Jain S. Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis: a diagnostic dilemma. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:595-597. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.143530

- Maraspin V, Nahtigal Klevišar M, Ružic´-Sabljic´ E, et al. Borrelial lymphocytoma in adult patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:914-921. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw417

- Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006; 43:1089-1134. doi:10.1086/508667

- Mitteldorf C, Kempf W. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma. Surg Pathol Clin. 2017;10:455-476. doi:10.1016/j.path.2017.01.002

- Colli C, Leinweber B, Müllegger R, et al. Borrelia burgdorferiassociated lymphocytoma cutis: clinicopathologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular study of 106 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:232-240. doi:10.1111/j.0303-6987.2003.00167.x

- Wehbe AM, Neppalli V, Syrbu S, et al. Diffuse follicle centre lymphoma presents with high frequency of extranodal disease. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15 suppl):19511. doi:10.1200/jco.2008.26.15_suppl.19511

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Cutaneous infiltrates—lymphomatous and leukemic. In: Patterson JW, ed. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2016:1171-1217.

- Cardenas-de la Garza JA, De la Cruz-Valadez E, Ocampo -Candiani J, et al. Clinical spectrum of Lyme disease. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38:201-208. doi:10.1007/s10096-018-3417-1

- Shapiro ED, Gerber MA. Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:533-542. doi:10.1086/313982

- Kandhari R, Kandhari S, Jain S. Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis: a diagnostic dilemma. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:595-597. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.143530

- Maraspin V, Nahtigal Klevišar M, Ružic´-Sabljic´ E, et al. Borrelial lymphocytoma in adult patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:914-921. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw417

- Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006; 43:1089-1134. doi:10.1086/508667

A 53-year-old man with a history of atopic dermatitis presented with pain and redness of the lobules of both ears of 9 months’ duration. He had no known allergies and took no medications. He lived in suburban Virginia and had not recently traveled outside of the region. Physical examination revealed tender erythematous and edematous nodules on the lobules of both ears (top). There was no evidence of arthritis or neurologic deficits. A punch biopsy was performed (bottom).

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Induced by the Second-Generation Antipsychotic Cariprazine

To the Editor:

A 57-year-old woman presented to an outpatient clinic with severe pruritus and burning of the skin as well as subjective fevers and chills. She had been discharged from a psychiatric hospital for attempted suicide 1 day prior. There were no recent changes in the medication regimen, which consisted of linaclotide, fluoxetine, lorazepam, and gabapentin. While admitted, the patient was started on the atypical antipsychotic cariprazine. Within 24 hours of the first dose, she developed severe facial erythema that progressed to diffuse erythema over more than 60% of the body surface area. The attending psychiatrist promptly discontinued cariprazine. During the next 24 hours, there were no reports of fever, leukocytosis, or signs of systemic organ involvement. Given the patient’s mental and medical stability, she was discharged with instructions to follow up with the outpatient dermatology clinic.

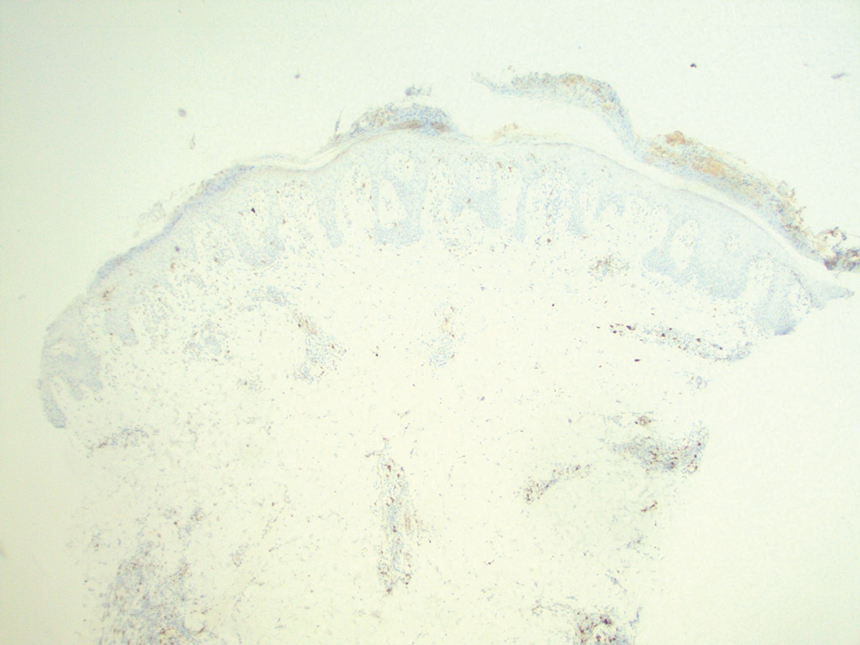

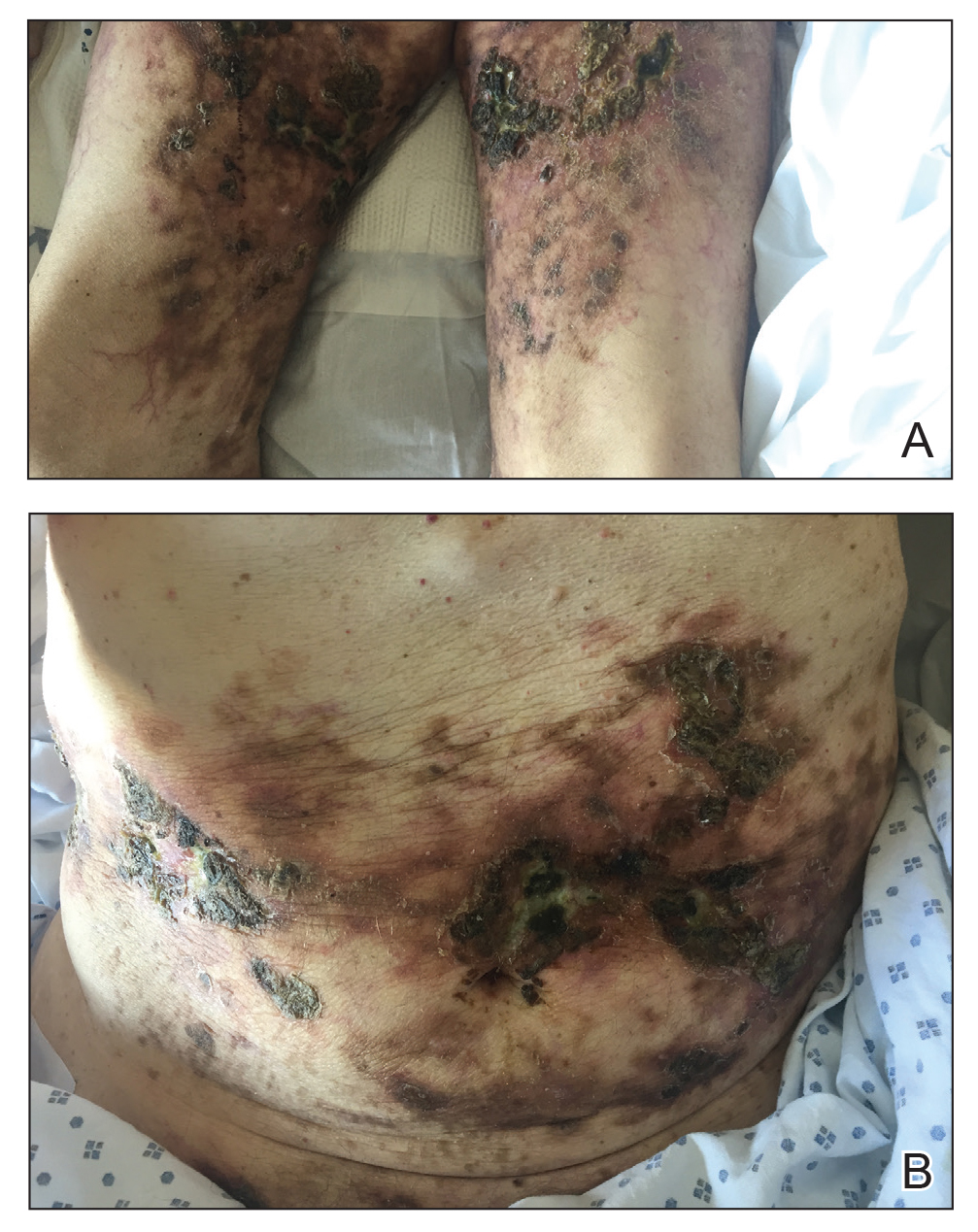

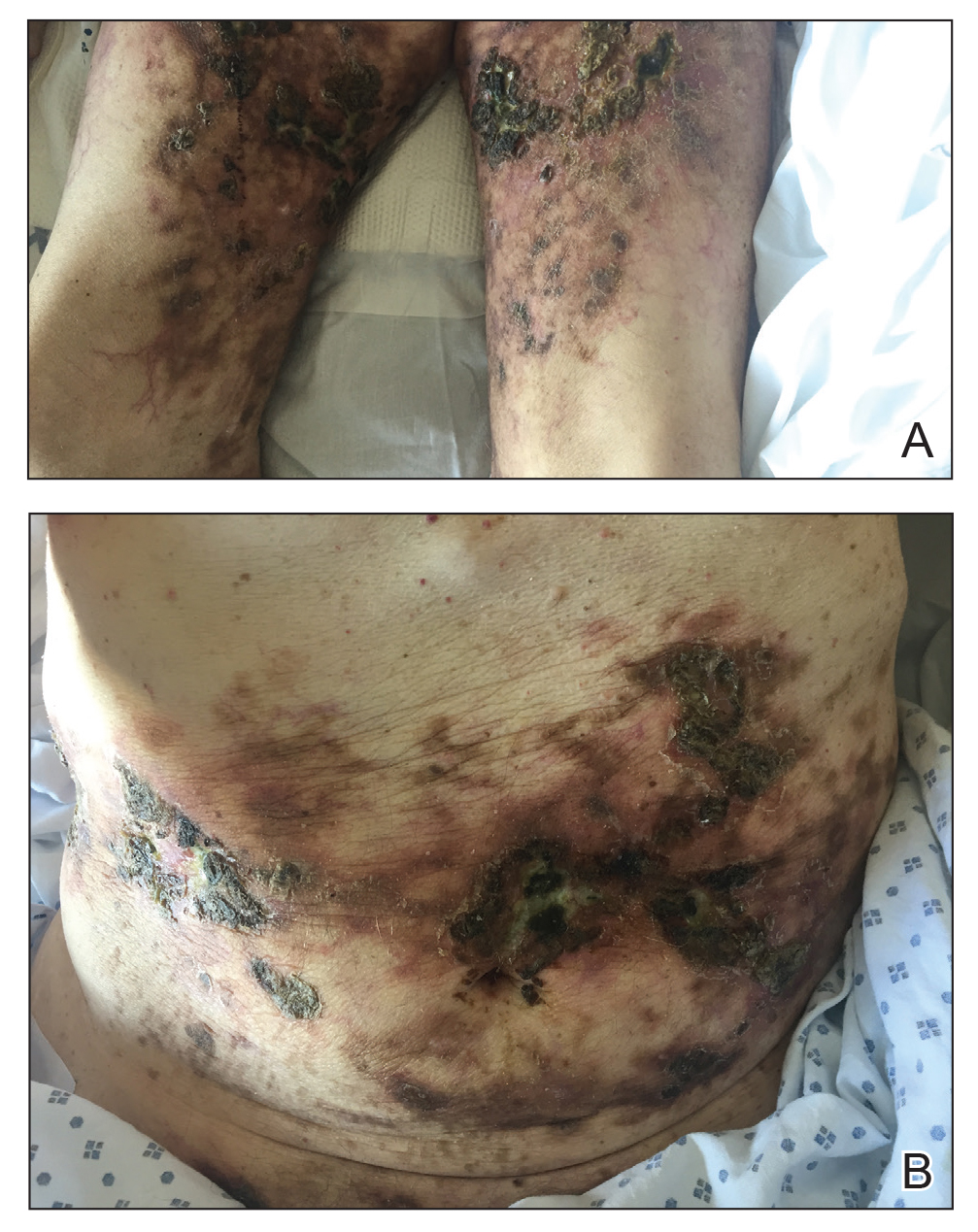

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed innumerable 1- to 4-mm pustules coalescing to lakes of pus on an erythematous base over more than 60% of the body surface area (Figure 1). The mucous membranes were clear of lesions, the Nikolsky sign was negative, and the patient’s temperature was 99.6 °F in the office. Complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panel results were within reference range.

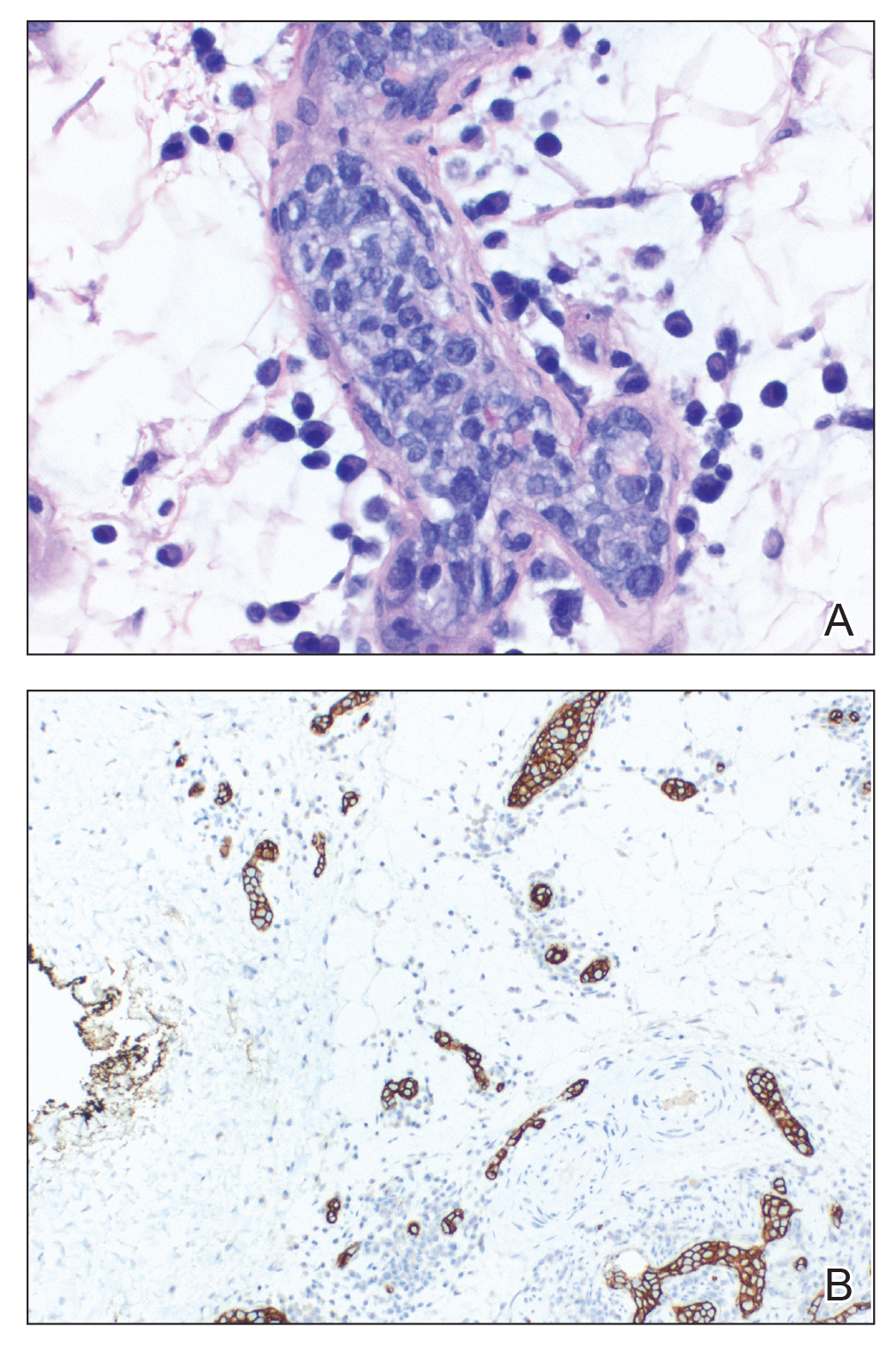

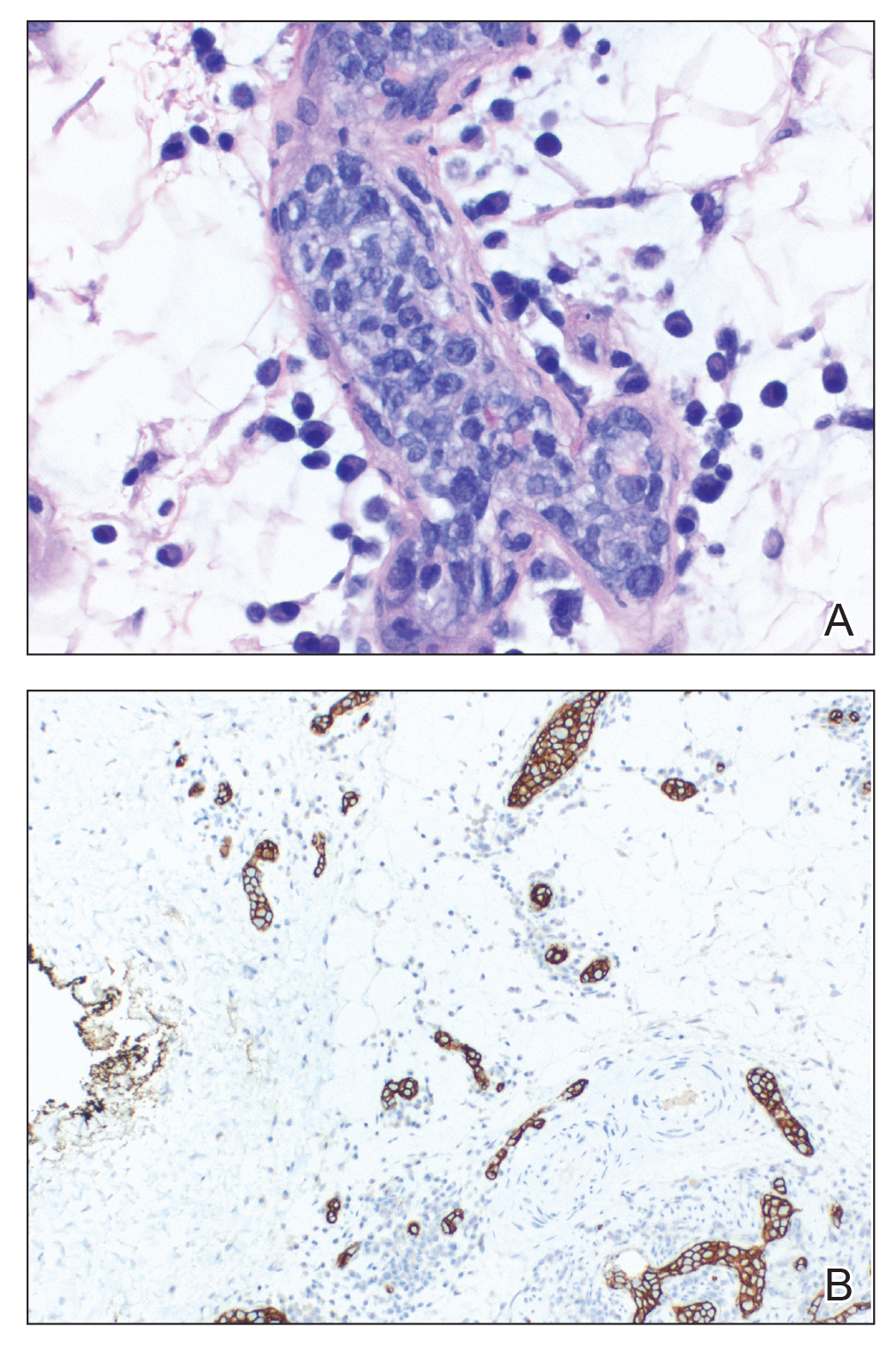

A 4-mm abdominal punch biopsy showed subcorneal neutrophilic pustules, papillary dermal edema, and superficial dermal lymphohistiocytic inflammation with numerous neutrophils, eosinophils, and extravasated red blood cells, consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)(Figure 2). The patient was started on wet wraps with triamcinolone cream 0.1%.

Two days later, physical examination revealed the erythema noted on initial examination had notably decreased, and the patient no longer reported burning or pruritus. One week after initial presentation to the clinic, the patient’s rash had resolved, and only a few small areas of desquamation remained.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is a severe cutaneous adverse reaction characterized by the development of numerous nonfollicular sterile pustules on an edematous and erythematous base. In almost 90% of reported cases, the cause is related to use of antibiotics, antifungals, antimalarials, or diltiazem (a calcium channel blocker). This rare cutaneous reaction occurs in 1 to 5 patients per million per year1; it carries a 1% to 2% mortality rate with proper supportive treatment.

The clinical symptoms of AGEP typically present 24 to 48 hours after drug initiation with the rapid development of dozens to thousands of 1- to 4-mm pustules, typically localized to the flexor surfaces and face. In the setting of AGEP, acute onset of fever and leukocytosis typically occur at the time of the cutaneous eruption. These features were absent in this patient. The eruption usually starts on the face and then migrates to the trunk and extremities, sparing the palms and soles. Systemic involvement most commonly presents as hepatic, renal, or pulmonary insufficiency, which has been seen in 20% of cases.2

The immunologic response associated with the reaction has been studied in vitro. Drug-specific CD8 T cells use perforin/granzyme B and Fas ligand mechanisms to induce apoptosis of the keratinocytes within the epidermis, leading to vesicle formation.3 During the very first stages of formation, vesicles mainly comprise CD8 T cells and keratinocytes. These cells then begin producing CXC-18, a potent neutrophil chemokine, leading to extensive chemotaxis of neutrophils into vesicles, which then rapidly transform to pustules.3 This rapid transformation leads to the lakes of pustules, a description often associated with AGEP.

Treatment of AGEP is mainly supportive and consists of discontinuing use of the causative agent. Topical corticosteroids can be used during the pustular phase for symptom management. There is no evidence that systemic steroids reduce the duration of the disease.2 Other supportive measures such as application of wet wraps can be used to provide comfort.

Cutaneous adverse drug reactions commonly are associated with psychiatric pharmacotherapy, but first-and second-generation antipsychotics rarely are associated with these types of reactions. In this patient, the causative agent of the AGEP was cariprazine, an atypical antipsychotic that had no reported association with AGEP or cutaneous adverse drug reactions prior to this presentation.

- Fernando SL. Acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:87-92.

- Feldmeyer L, Heidemeyer K, Yawalkar N. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: pathogenesis, genetic background, clinical variants and therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1214.

- Szatkowski J, Schwartz RA. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP): a review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:843-848.

To the Editor:

A 57-year-old woman presented to an outpatient clinic with severe pruritus and burning of the skin as well as subjective fevers and chills. She had been discharged from a psychiatric hospital for attempted suicide 1 day prior. There were no recent changes in the medication regimen, which consisted of linaclotide, fluoxetine, lorazepam, and gabapentin. While admitted, the patient was started on the atypical antipsychotic cariprazine. Within 24 hours of the first dose, she developed severe facial erythema that progressed to diffuse erythema over more than 60% of the body surface area. The attending psychiatrist promptly discontinued cariprazine. During the next 24 hours, there were no reports of fever, leukocytosis, or signs of systemic organ involvement. Given the patient’s mental and medical stability, she was discharged with instructions to follow up with the outpatient dermatology clinic.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed innumerable 1- to 4-mm pustules coalescing to lakes of pus on an erythematous base over more than 60% of the body surface area (Figure 1). The mucous membranes were clear of lesions, the Nikolsky sign was negative, and the patient’s temperature was 99.6 °F in the office. Complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panel results were within reference range.

A 4-mm abdominal punch biopsy showed subcorneal neutrophilic pustules, papillary dermal edema, and superficial dermal lymphohistiocytic inflammation with numerous neutrophils, eosinophils, and extravasated red blood cells, consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)(Figure 2). The patient was started on wet wraps with triamcinolone cream 0.1%.

Two days later, physical examination revealed the erythema noted on initial examination had notably decreased, and the patient no longer reported burning or pruritus. One week after initial presentation to the clinic, the patient’s rash had resolved, and only a few small areas of desquamation remained.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is a severe cutaneous adverse reaction characterized by the development of numerous nonfollicular sterile pustules on an edematous and erythematous base. In almost 90% of reported cases, the cause is related to use of antibiotics, antifungals, antimalarials, or diltiazem (a calcium channel blocker). This rare cutaneous reaction occurs in 1 to 5 patients per million per year1; it carries a 1% to 2% mortality rate with proper supportive treatment.

The clinical symptoms of AGEP typically present 24 to 48 hours after drug initiation with the rapid development of dozens to thousands of 1- to 4-mm pustules, typically localized to the flexor surfaces and face. In the setting of AGEP, acute onset of fever and leukocytosis typically occur at the time of the cutaneous eruption. These features were absent in this patient. The eruption usually starts on the face and then migrates to the trunk and extremities, sparing the palms and soles. Systemic involvement most commonly presents as hepatic, renal, or pulmonary insufficiency, which has been seen in 20% of cases.2

The immunologic response associated with the reaction has been studied in vitro. Drug-specific CD8 T cells use perforin/granzyme B and Fas ligand mechanisms to induce apoptosis of the keratinocytes within the epidermis, leading to vesicle formation.3 During the very first stages of formation, vesicles mainly comprise CD8 T cells and keratinocytes. These cells then begin producing CXC-18, a potent neutrophil chemokine, leading to extensive chemotaxis of neutrophils into vesicles, which then rapidly transform to pustules.3 This rapid transformation leads to the lakes of pustules, a description often associated with AGEP.

Treatment of AGEP is mainly supportive and consists of discontinuing use of the causative agent. Topical corticosteroids can be used during the pustular phase for symptom management. There is no evidence that systemic steroids reduce the duration of the disease.2 Other supportive measures such as application of wet wraps can be used to provide comfort.

Cutaneous adverse drug reactions commonly are associated with psychiatric pharmacotherapy, but first-and second-generation antipsychotics rarely are associated with these types of reactions. In this patient, the causative agent of the AGEP was cariprazine, an atypical antipsychotic that had no reported association with AGEP or cutaneous adverse drug reactions prior to this presentation.

To the Editor:

A 57-year-old woman presented to an outpatient clinic with severe pruritus and burning of the skin as well as subjective fevers and chills. She had been discharged from a psychiatric hospital for attempted suicide 1 day prior. There were no recent changes in the medication regimen, which consisted of linaclotide, fluoxetine, lorazepam, and gabapentin. While admitted, the patient was started on the atypical antipsychotic cariprazine. Within 24 hours of the first dose, she developed severe facial erythema that progressed to diffuse erythema over more than 60% of the body surface area. The attending psychiatrist promptly discontinued cariprazine. During the next 24 hours, there were no reports of fever, leukocytosis, or signs of systemic organ involvement. Given the patient’s mental and medical stability, she was discharged with instructions to follow up with the outpatient dermatology clinic.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed innumerable 1- to 4-mm pustules coalescing to lakes of pus on an erythematous base over more than 60% of the body surface area (Figure 1). The mucous membranes were clear of lesions, the Nikolsky sign was negative, and the patient’s temperature was 99.6 °F in the office. Complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panel results were within reference range.

A 4-mm abdominal punch biopsy showed subcorneal neutrophilic pustules, papillary dermal edema, and superficial dermal lymphohistiocytic inflammation with numerous neutrophils, eosinophils, and extravasated red blood cells, consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)(Figure 2). The patient was started on wet wraps with triamcinolone cream 0.1%.

Two days later, physical examination revealed the erythema noted on initial examination had notably decreased, and the patient no longer reported burning or pruritus. One week after initial presentation to the clinic, the patient’s rash had resolved, and only a few small areas of desquamation remained.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is a severe cutaneous adverse reaction characterized by the development of numerous nonfollicular sterile pustules on an edematous and erythematous base. In almost 90% of reported cases, the cause is related to use of antibiotics, antifungals, antimalarials, or diltiazem (a calcium channel blocker). This rare cutaneous reaction occurs in 1 to 5 patients per million per year1; it carries a 1% to 2% mortality rate with proper supportive treatment.

The clinical symptoms of AGEP typically present 24 to 48 hours after drug initiation with the rapid development of dozens to thousands of 1- to 4-mm pustules, typically localized to the flexor surfaces and face. In the setting of AGEP, acute onset of fever and leukocytosis typically occur at the time of the cutaneous eruption. These features were absent in this patient. The eruption usually starts on the face and then migrates to the trunk and extremities, sparing the palms and soles. Systemic involvement most commonly presents as hepatic, renal, or pulmonary insufficiency, which has been seen in 20% of cases.2

The immunologic response associated with the reaction has been studied in vitro. Drug-specific CD8 T cells use perforin/granzyme B and Fas ligand mechanisms to induce apoptosis of the keratinocytes within the epidermis, leading to vesicle formation.3 During the very first stages of formation, vesicles mainly comprise CD8 T cells and keratinocytes. These cells then begin producing CXC-18, a potent neutrophil chemokine, leading to extensive chemotaxis of neutrophils into vesicles, which then rapidly transform to pustules.3 This rapid transformation leads to the lakes of pustules, a description often associated with AGEP.

Treatment of AGEP is mainly supportive and consists of discontinuing use of the causative agent. Topical corticosteroids can be used during the pustular phase for symptom management. There is no evidence that systemic steroids reduce the duration of the disease.2 Other supportive measures such as application of wet wraps can be used to provide comfort.

Cutaneous adverse drug reactions commonly are associated with psychiatric pharmacotherapy, but first-and second-generation antipsychotics rarely are associated with these types of reactions. In this patient, the causative agent of the AGEP was cariprazine, an atypical antipsychotic that had no reported association with AGEP or cutaneous adverse drug reactions prior to this presentation.

- Fernando SL. Acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:87-92.

- Feldmeyer L, Heidemeyer K, Yawalkar N. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: pathogenesis, genetic background, clinical variants and therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1214.

- Szatkowski J, Schwartz RA. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP): a review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:843-848.

- Fernando SL. Acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:87-92.

- Feldmeyer L, Heidemeyer K, Yawalkar N. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: pathogenesis, genetic background, clinical variants and therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1214.

- Szatkowski J, Schwartz RA. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP): a review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:843-848.

Practice Points

- The second-generation antipsychotic cariprazine has been shown to be a potential causative agent in acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP).

- Treatment of AGEP is mainly supportive and consists of discontinuation of the causative agent as well as symptom control using cold compresses and topical corticosteroids.

Itchy Vesicular Rash

The Diagnosis: Tinea Corporis Bullosa