User login

Isolated Nodule and Generalized Lymphadenopathy

The Diagnosis: Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm

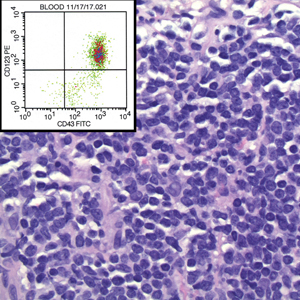

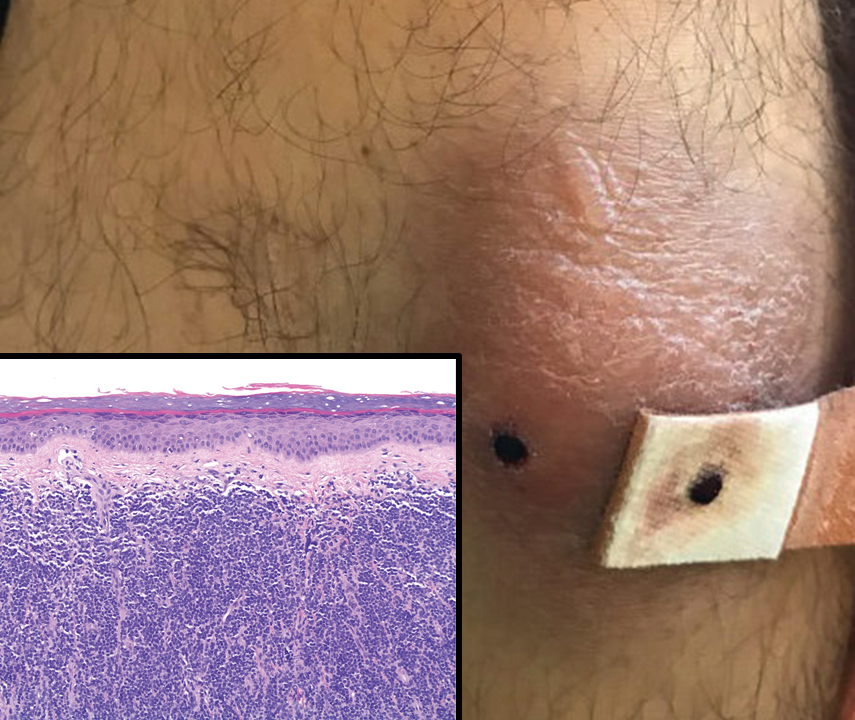

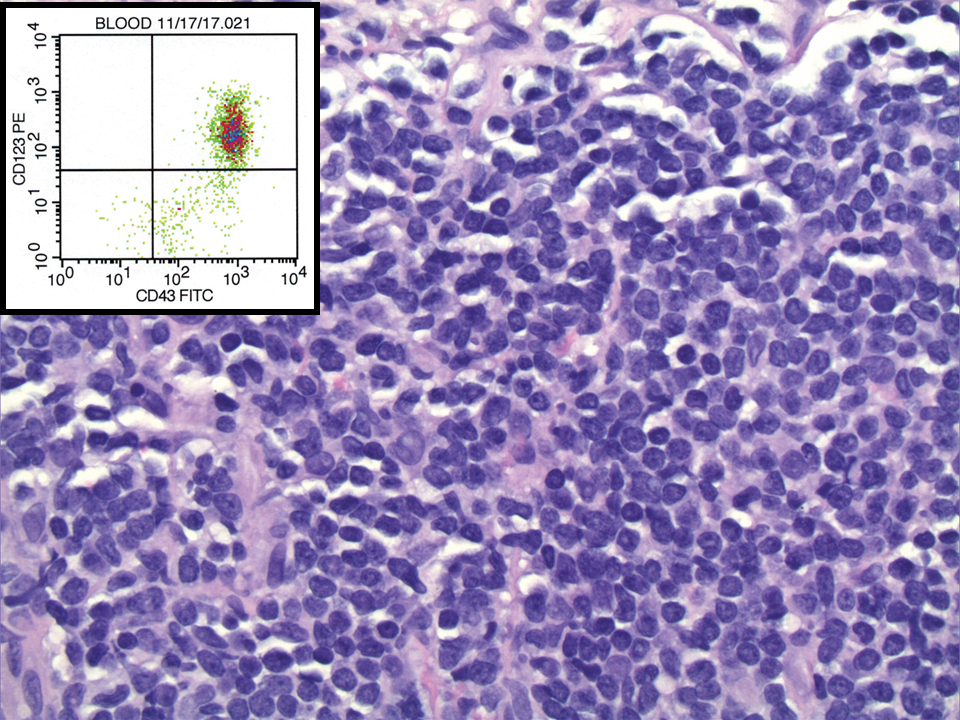

A diagnosis of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN) was rendered. Subsequent needle core biopsy of a left axillary lymph node as well as bone marrow aspiration and biopsy revealed a similar diffuse blastoid infiltrate with an identical immunophenotype to that in the skin biopsy from the pretibial mass and peripheral blood.

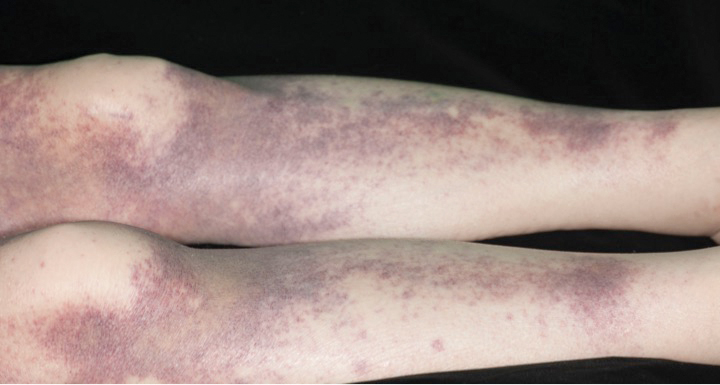

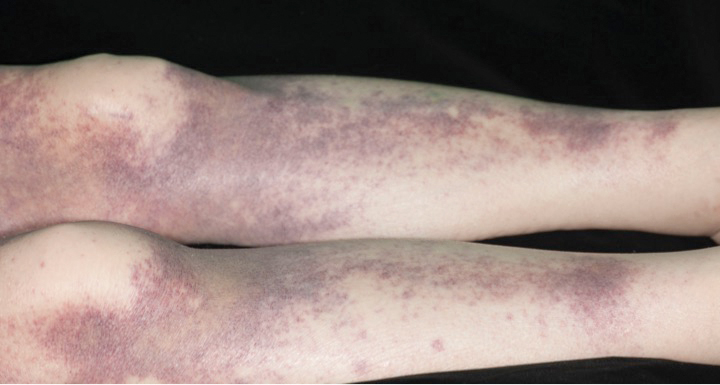

Previously known as blastic natural killer cell leukemia/lymphoma or agranular CD4+/CD56+ hematodermic neoplasm/tumor, BPDCN is a rare, clinically aggressive hematologic malignancy derived from the precursors of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. It often is diagnostically challenging, particularly when presenting at noncutaneous sites and in unusual (young) patient populations.1 It was included with other myeloid neoplasms in the 2008 World Health Organization classification; however, in the 2017 classification it was categorized as a separate entity. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm typically presents in the skin of elderly patients (age range at diagnosis, 61–67 years) with or without bone marrow involvement and systemic dissemination.1,2 The skin is the most common clinical site of disease in typical cases of BPDCN and often precedes bone marrow involvement. Thus, skin biopsy often is the key to making the diagnosis. Diagnosis of BPDCN may be delayed because of diagnostic pitfalls. Patients usually present with asymptomatic solitary or multiple lesions.3-5 Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm can present as an isolated purplish nodule or bruiselike papule or more commonly as disseminated purplish nodules, papules, and macules. Isolated nodules are found on the head and lower limbs and can be more than 10 cm in diameter. Peripheral blood and bone marrow may be minimally involved at presentation but invariably become involved with the progression of disease. Cytopenia can occur at diagnosis and in a minority of severe cases indicates bone marrow failure.2-6

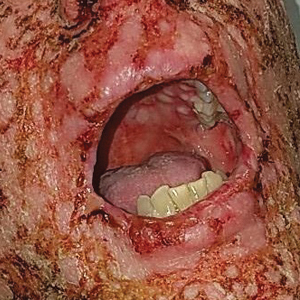

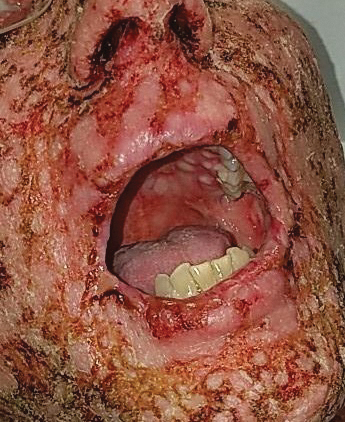

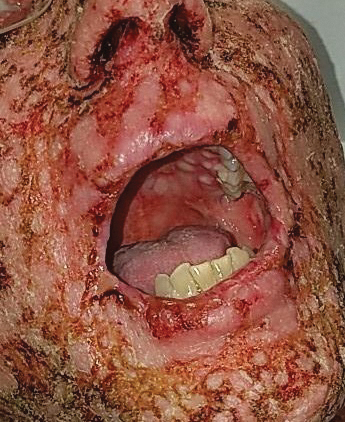

Skin involvement of BPDCN is thought to be secondary to the expression of skin migration molecules, such as cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen, one of the E-selectin ligands, which binds to E-selectin on high endothelial venules. In addition, the local dermal microenvironment of chemokines binding CXCR3, CXCR4, CCR6, or CCR7 present on neoplastic cells possibly leads to skin involvement. The full mechanism underlying the cutaneous tropism is still to be elucidated.4-7 Infiltration of the oral mucosa is seen in some patients, but it may be underreported. Mucosal disease typically appears similarly to cutaneous disease.

The cutaneous differential diagnosis for BPDCN depends on the clinical presentation, extent of disease spread, and thickness of infiltration. It includes common nonneoplastic diseases such as traumatic ecchymoses; purpuric disorders; extramedullary hematopoiesis; and soft-tissue neoplasms such as angiosarcoma, Kaposi sarcoma, neuroblastoma, and vascular metastases, as well as skin involvement by other hematologic neoplasms. An adequate incisional biopsy rather than a punch or shave biopsy is recommended for diagnosis. Dermatologists should alert the pathologist that BPDCN is in the clinical differential diagnosis when possible so that judicious use of appropriate immunophenotypic markers such as CD123, CD4, CD56, and T-cell leukemia/lymphoma protein 1 will avoid misdiagnosis of this aggressive condition, in addition to excluding acute myeloid leukemia, which also may express 3 of the above markers. However, most cases of acute myeloid leukemia lack terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) and express monocytic and other myeloid markers. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase is positive in approximately one-third of cases of BPDCN, with expression in 10% to 80% of cells.1

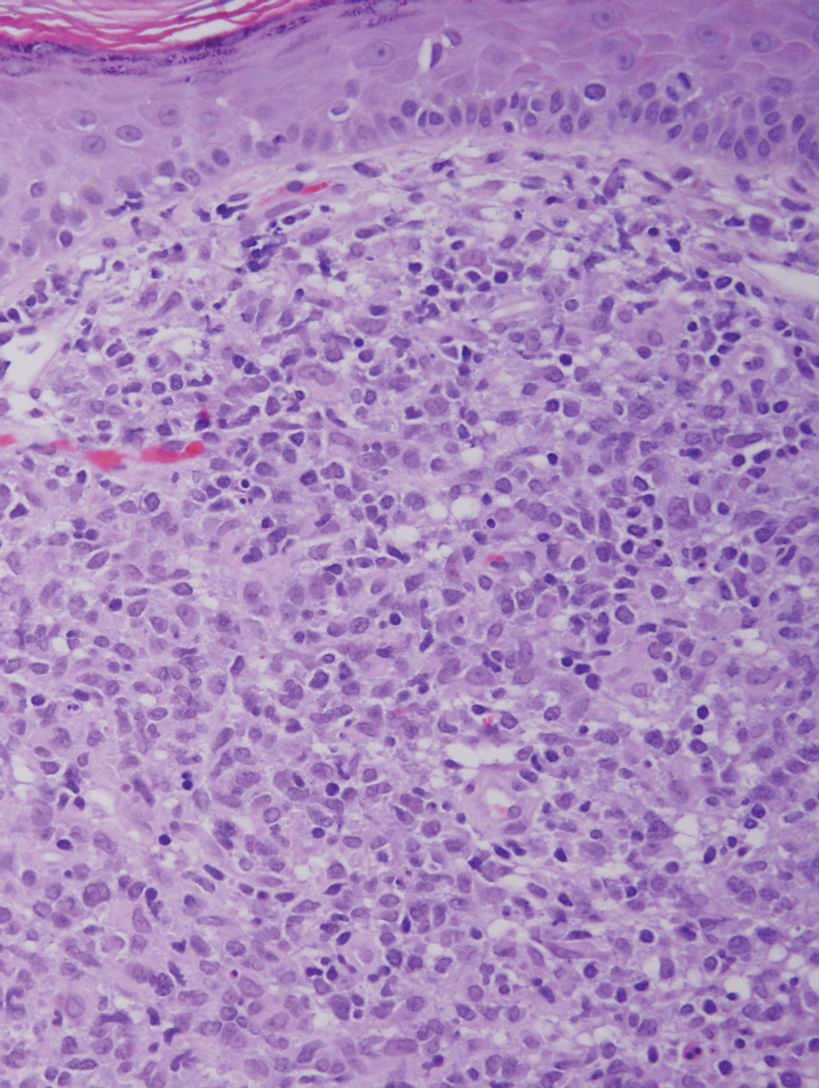

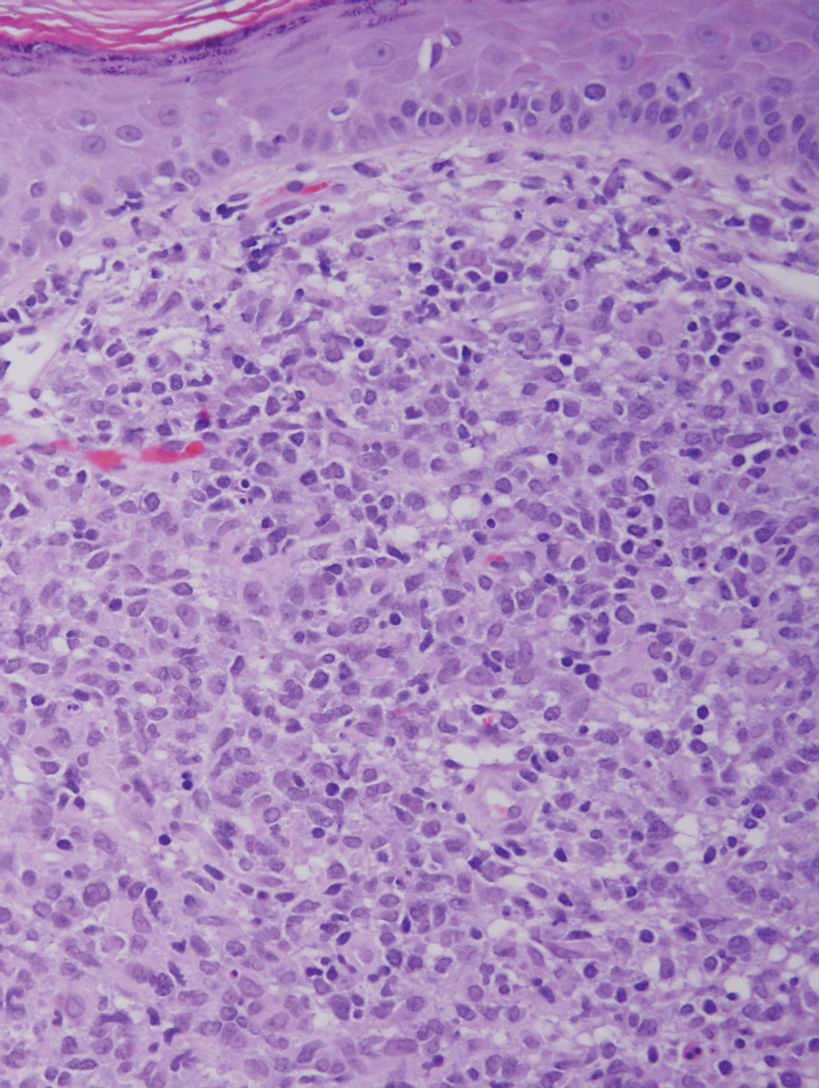

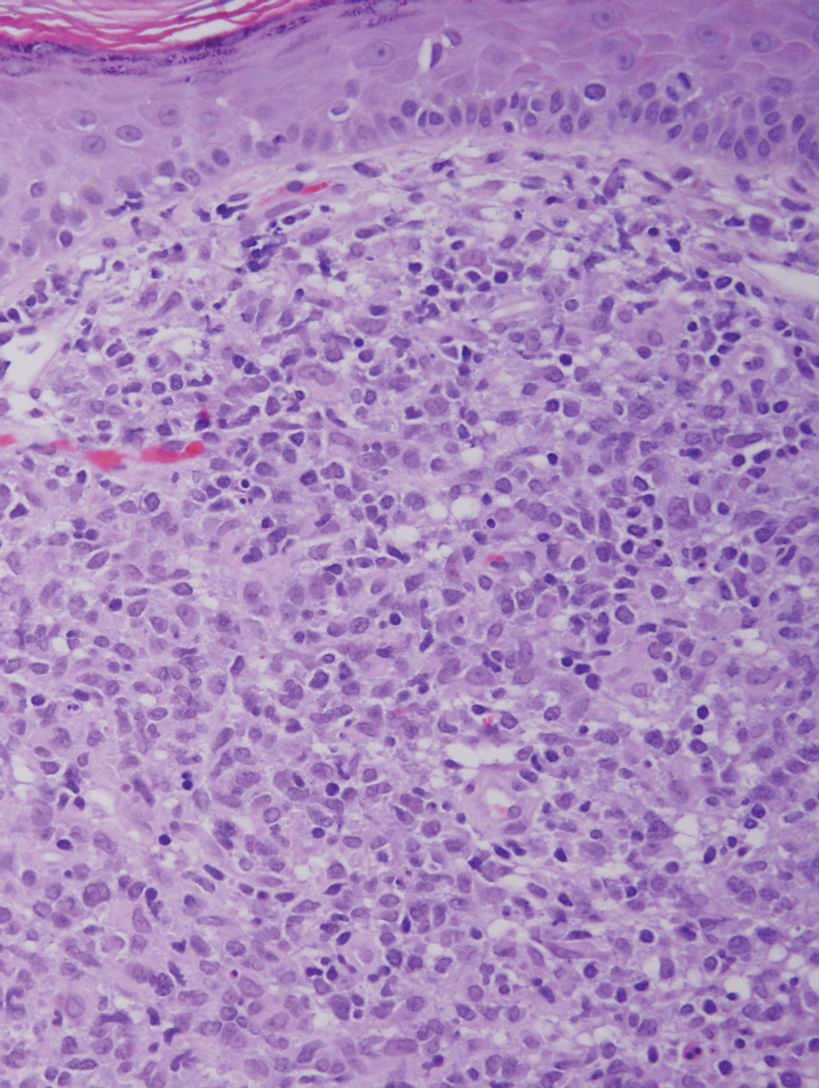

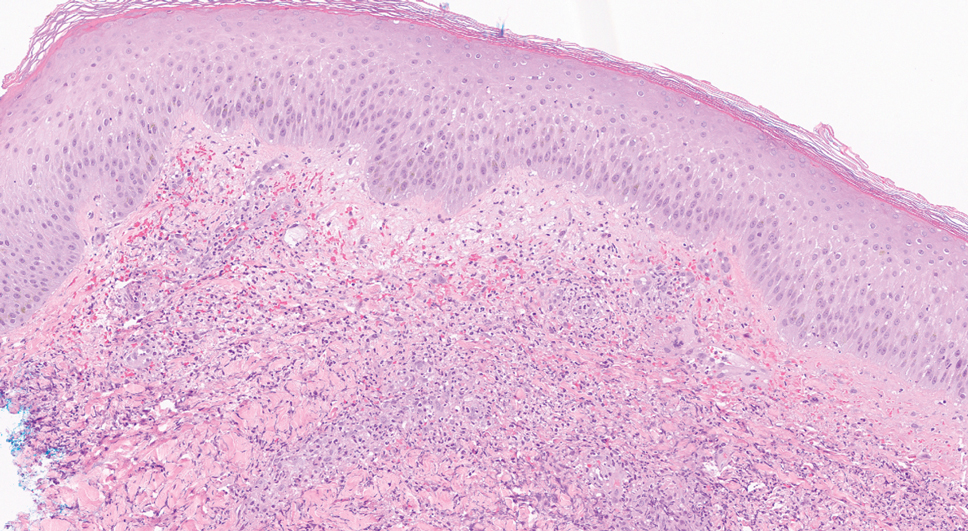

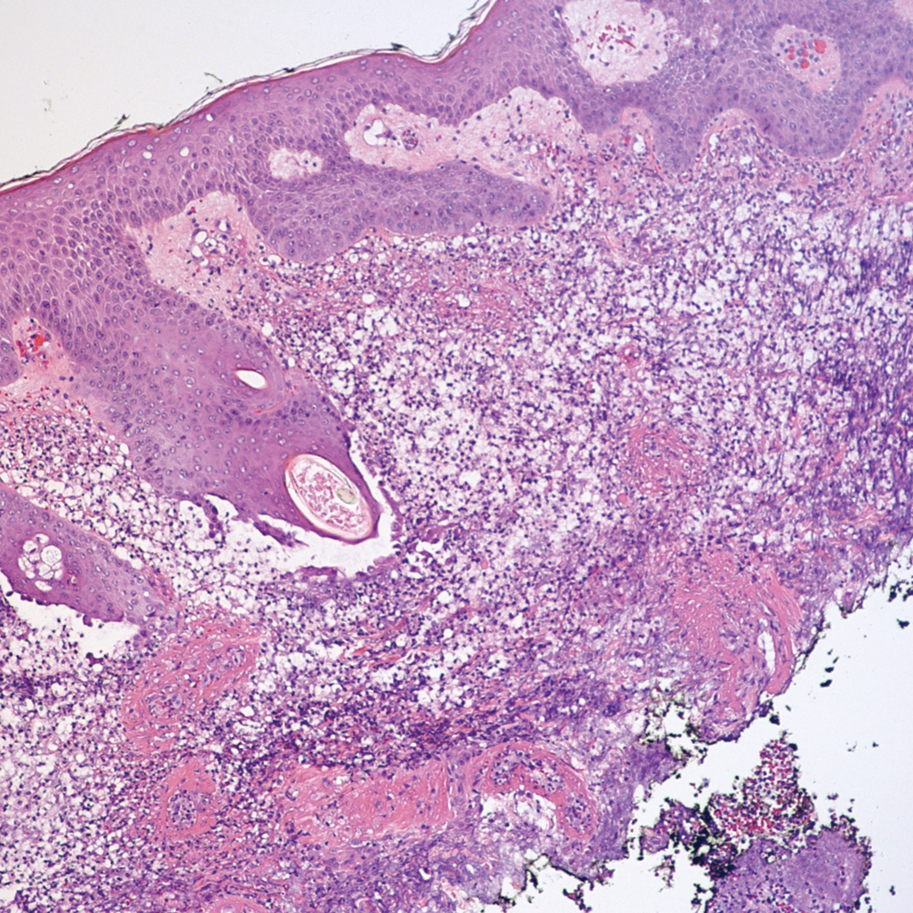

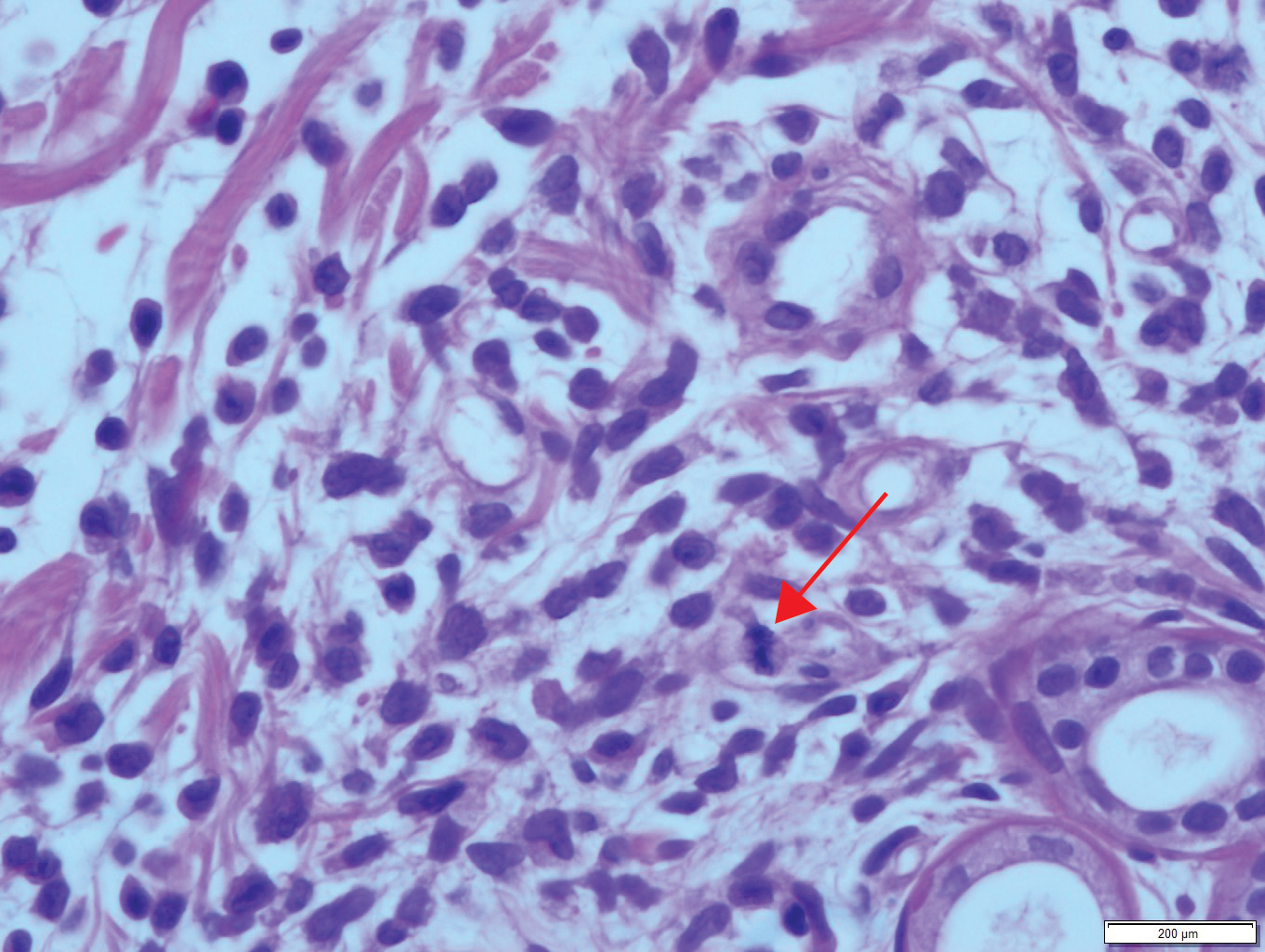

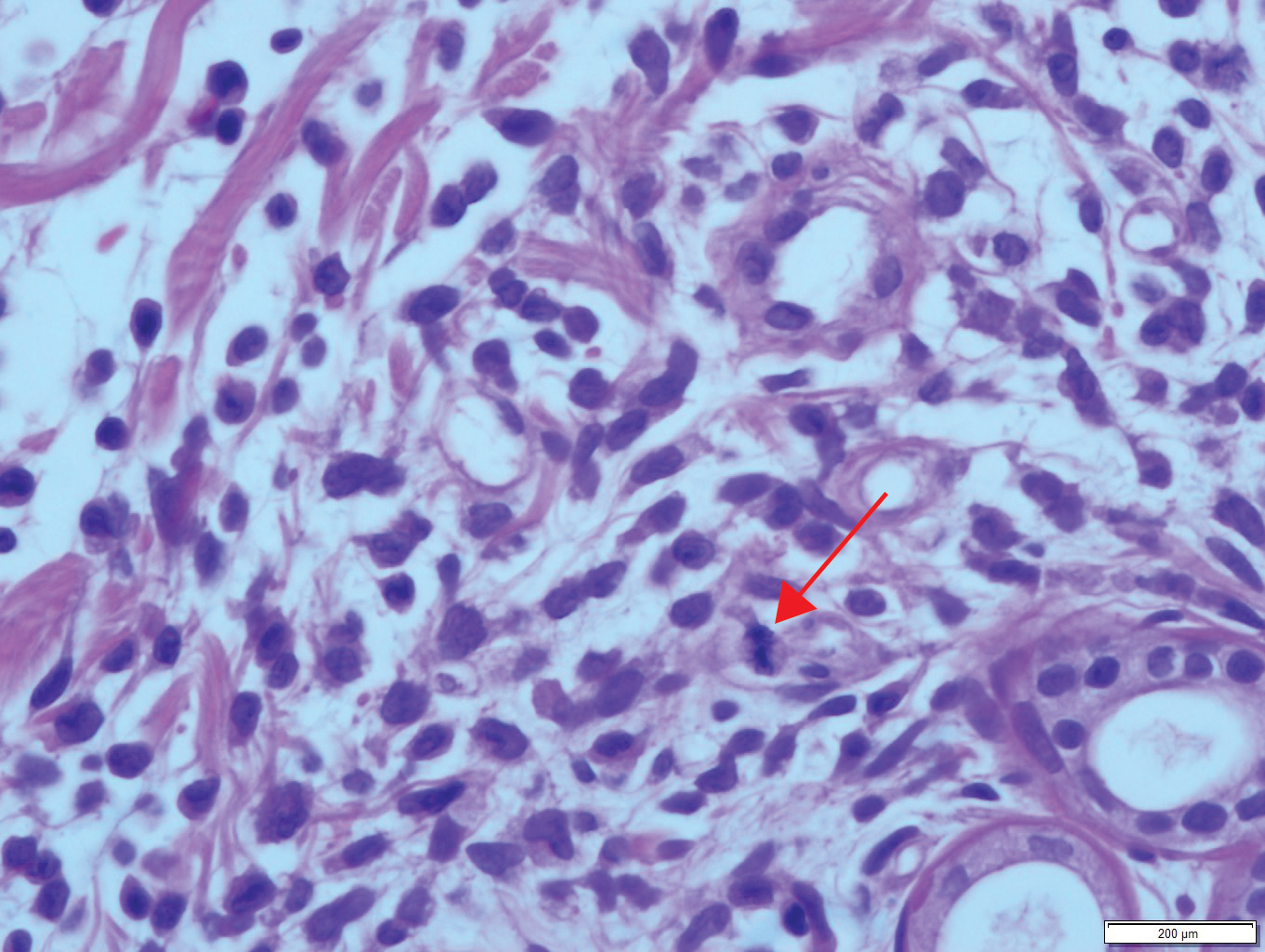

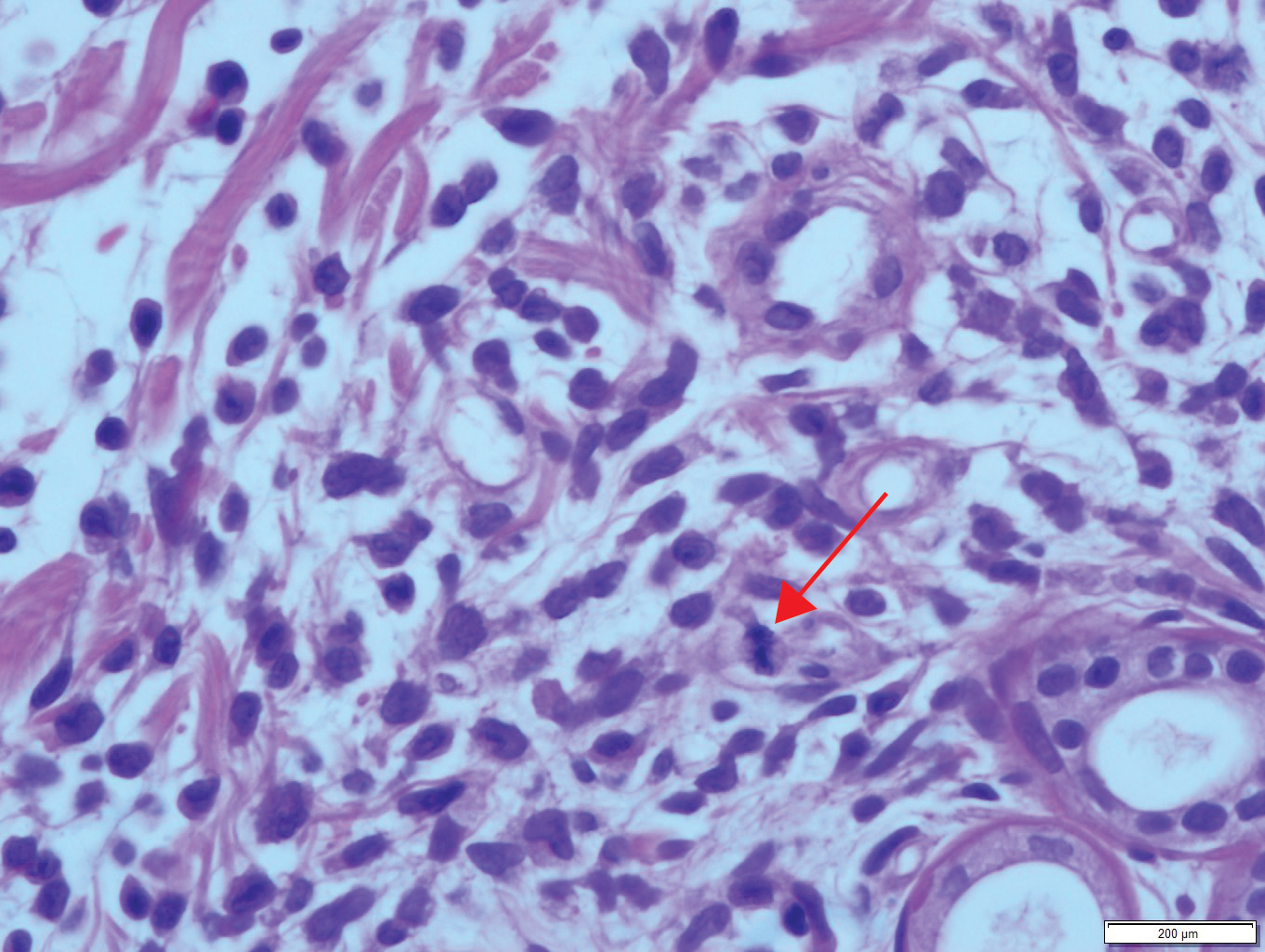

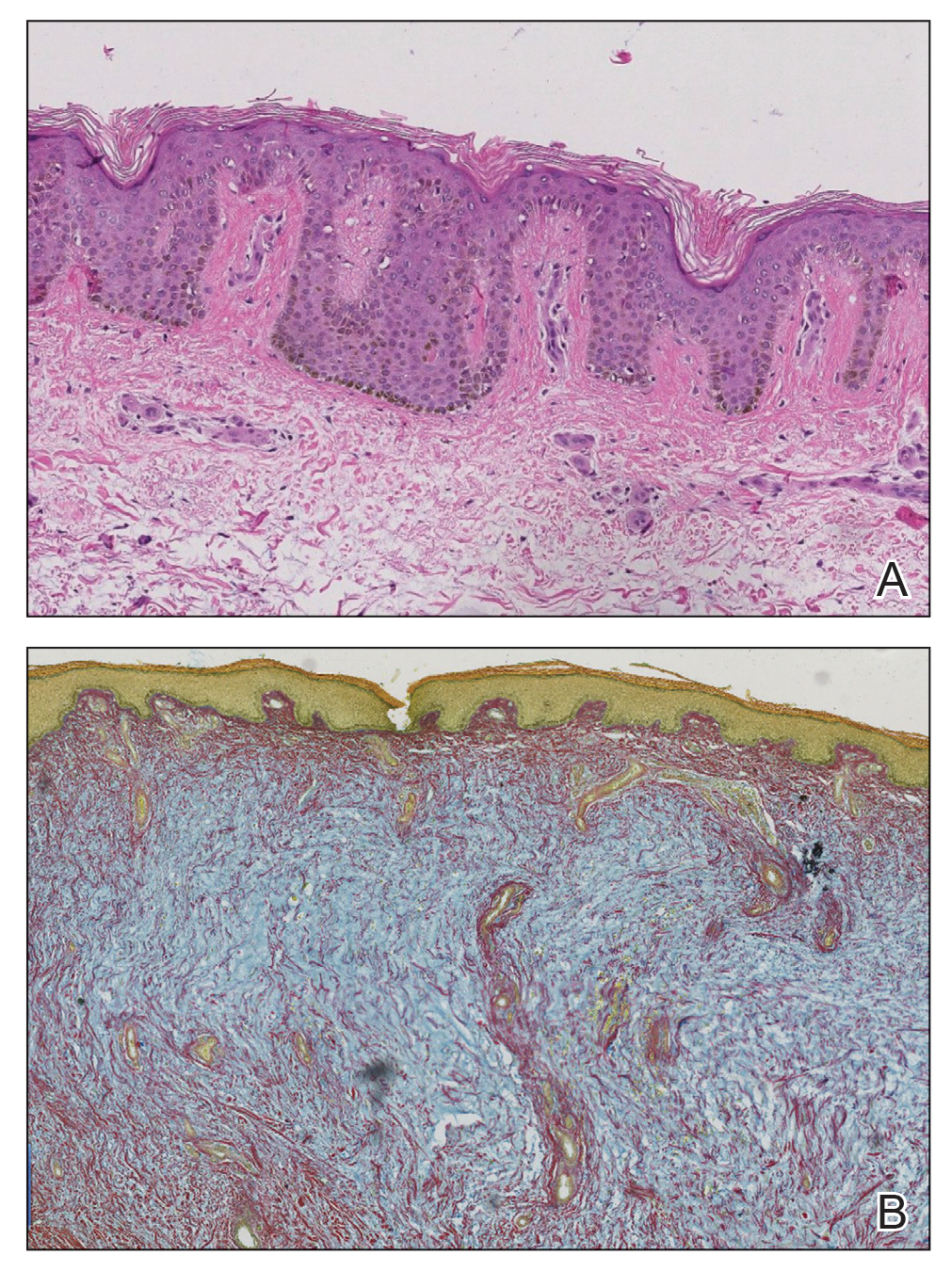

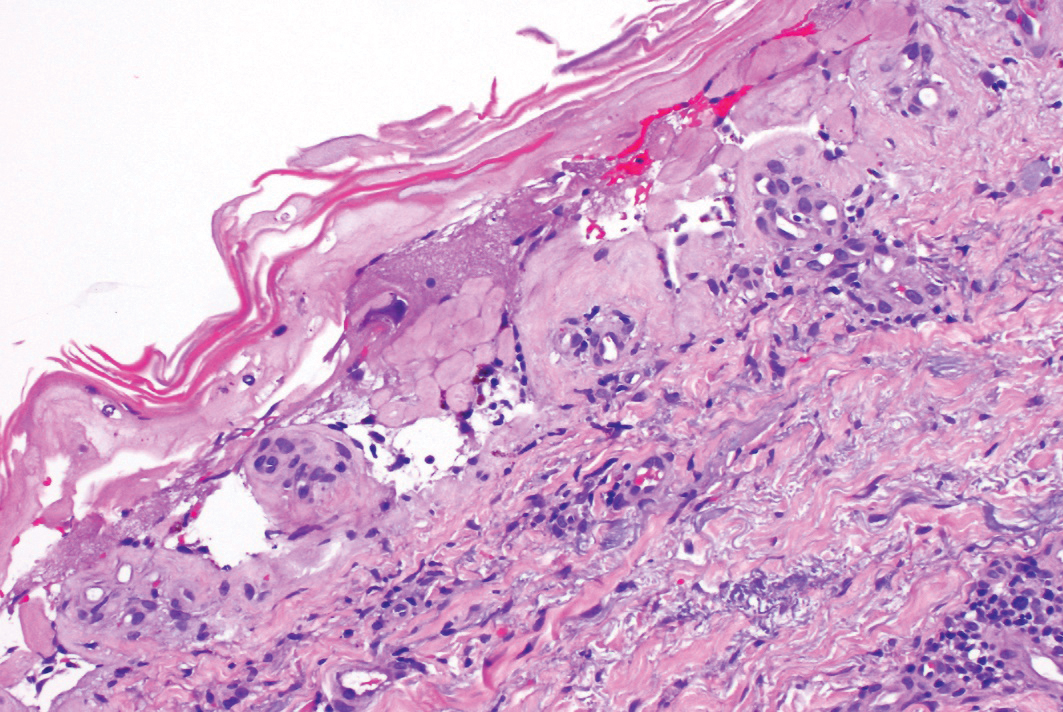

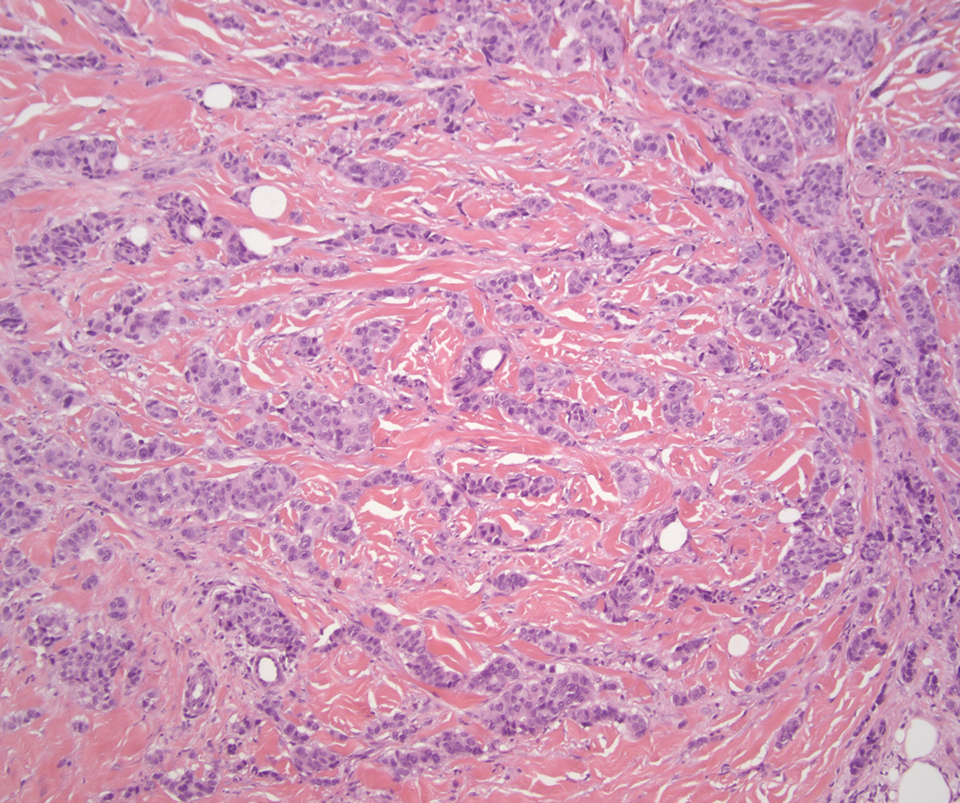

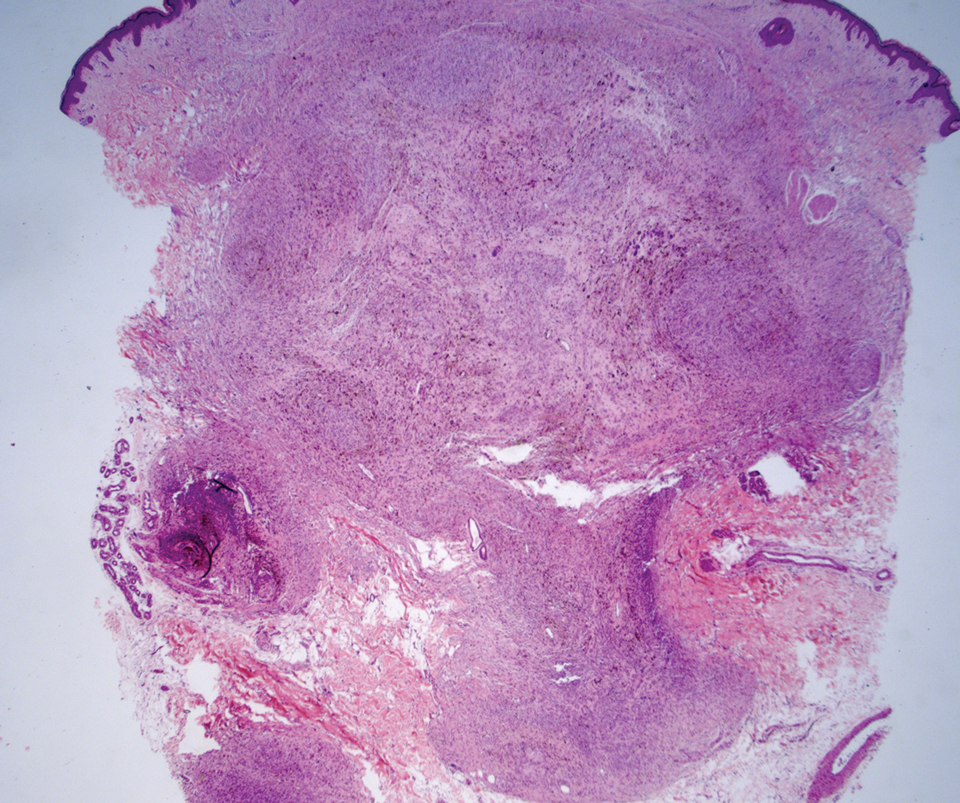

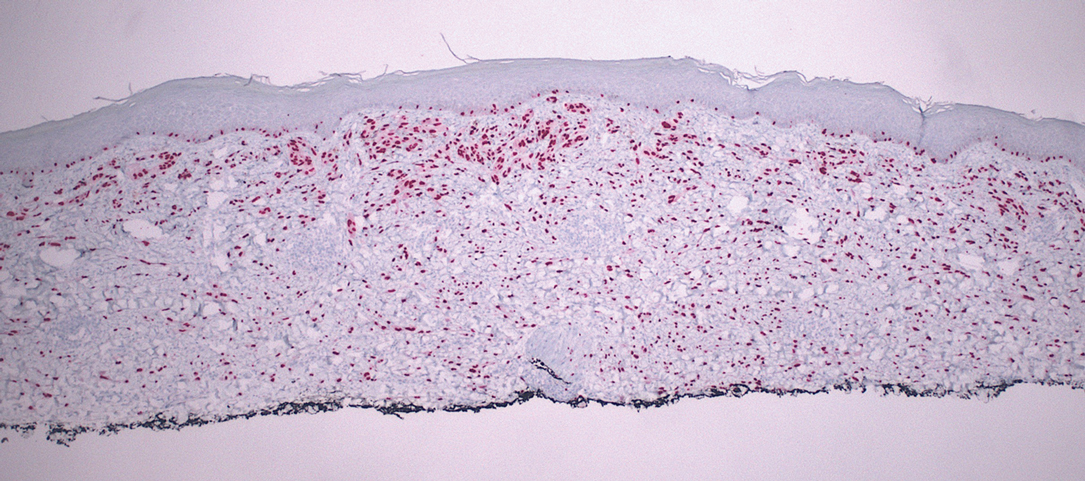

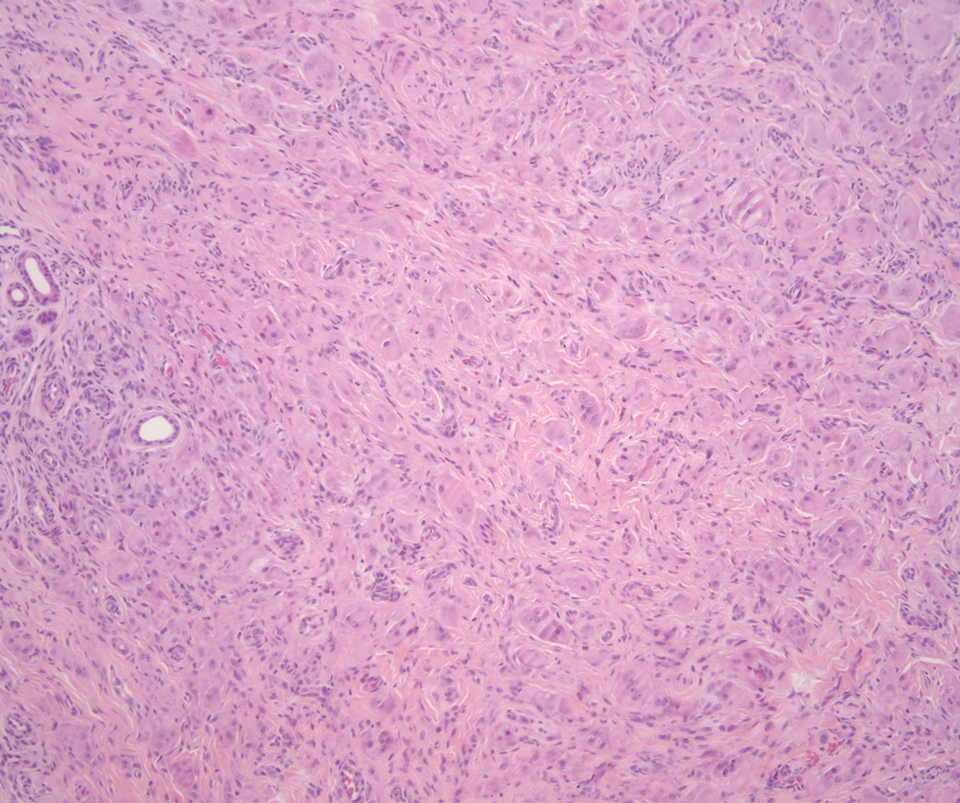

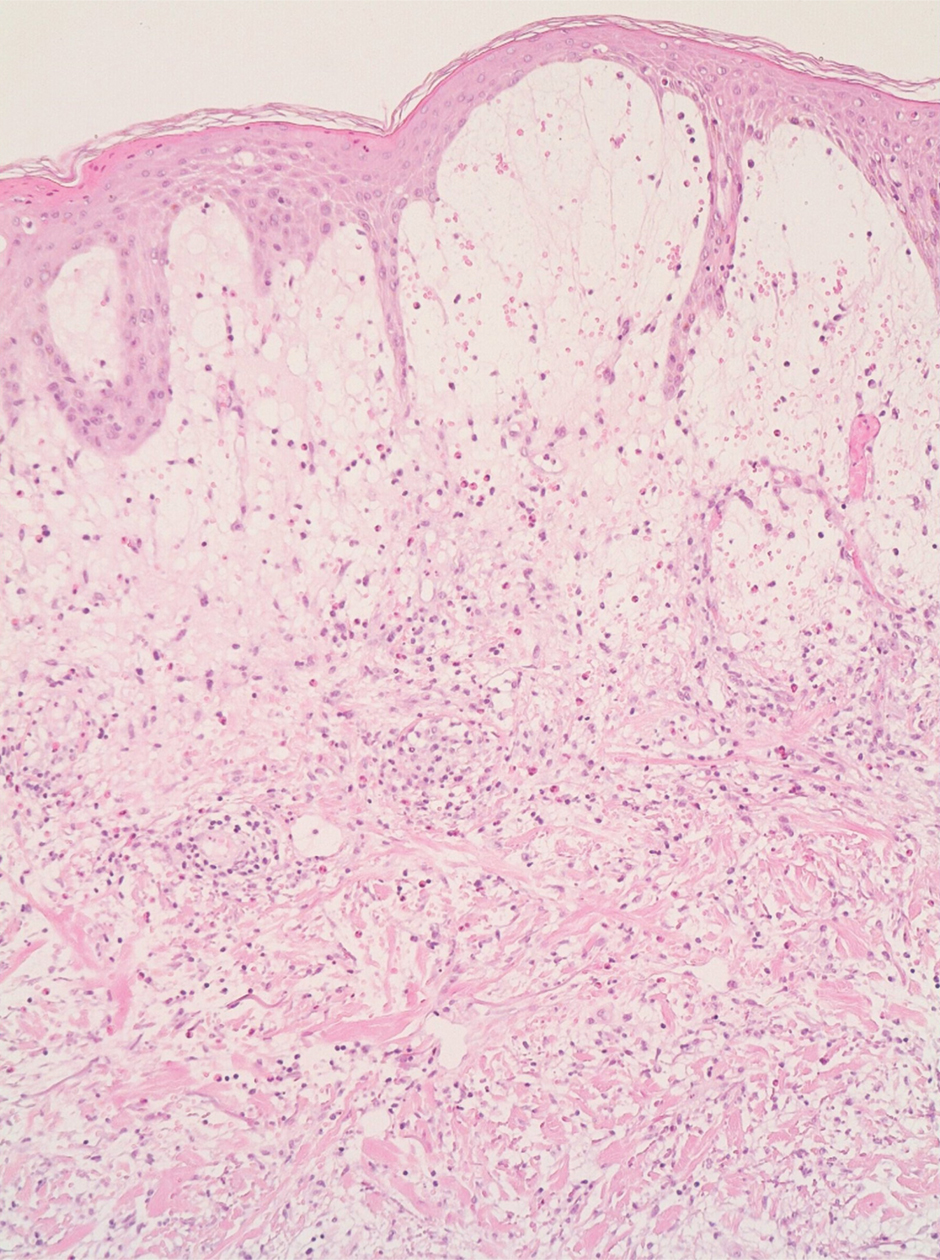

It is important to include BPDCN in the differential diagnosis of immunophenotypically aberrant hematologic tumors. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, accounts for 4% of all primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas.1 Compared with BPDCN, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma usually occurs in an older age group and is of B-cell lineage. Morphologically, these neoplasms are composed of a monotonous, diffuse, nonepidermotropic infiltrate of confluent sheets of centroblasts and immunoblasts (Figure 1). They may share immunohistochemical markers of CD79a, multiple myeloma 1, Bcl-2, and Bcl-6; however, they lack plasmacytoid dendritic cell (PDC)– associated antigens such as CD4, CD56, CD123, and T-cell leukemia/lymphoma protein 1.1

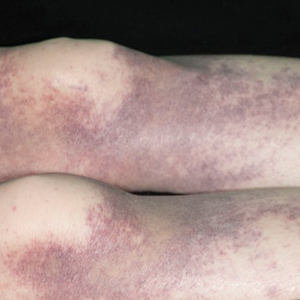

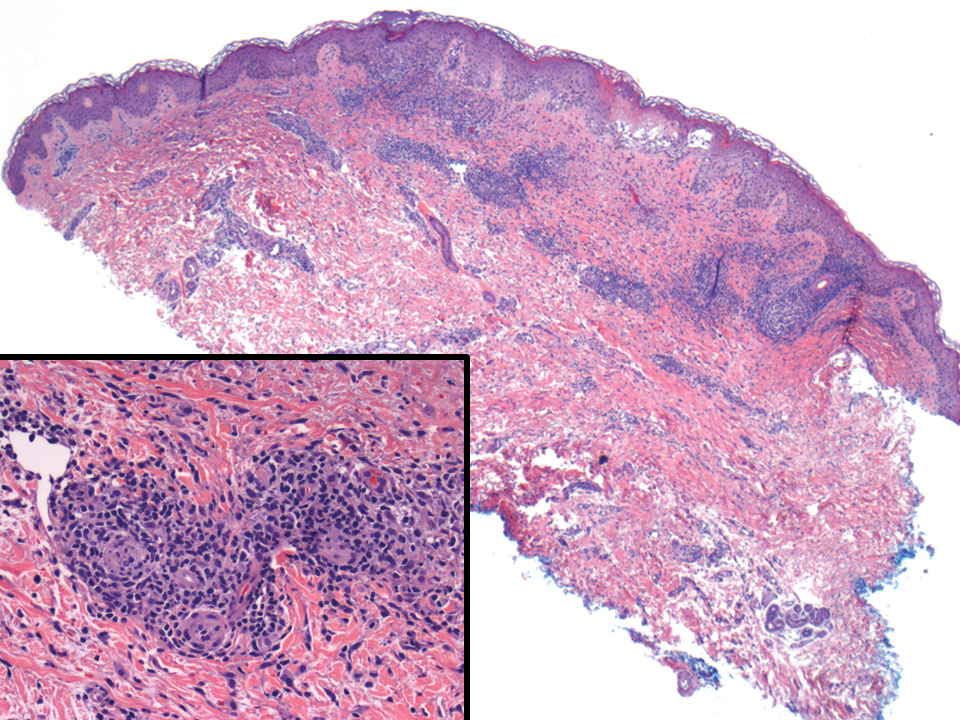

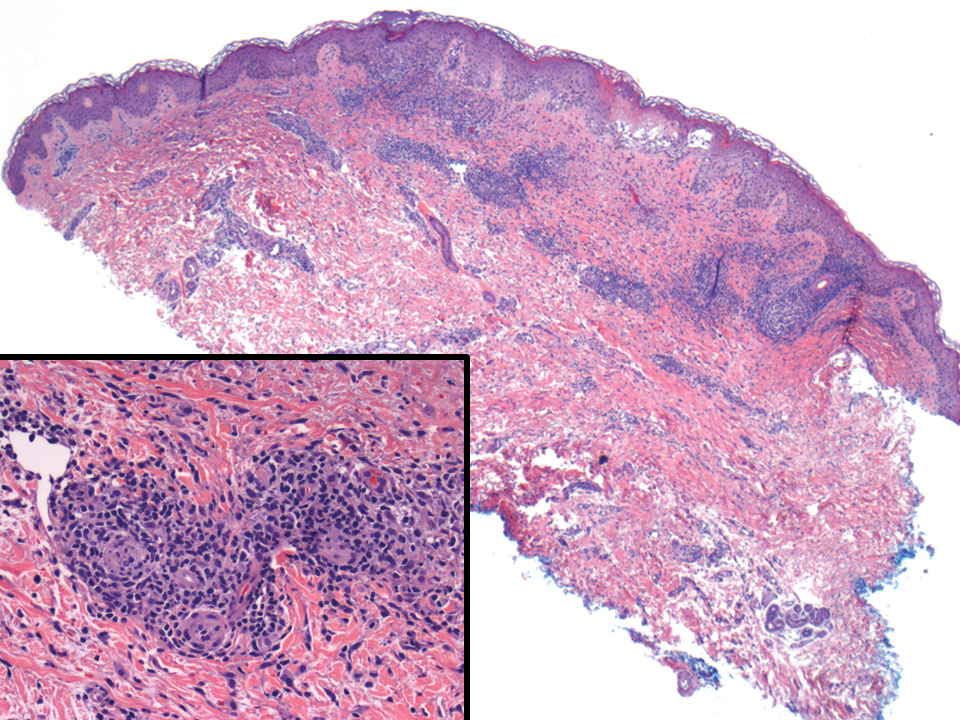

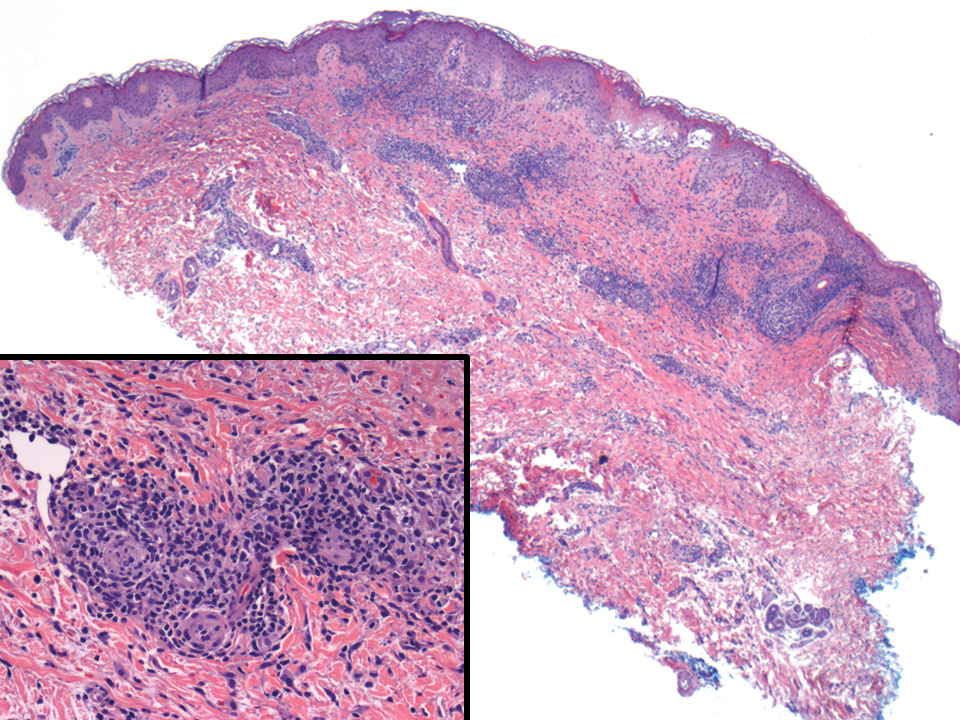

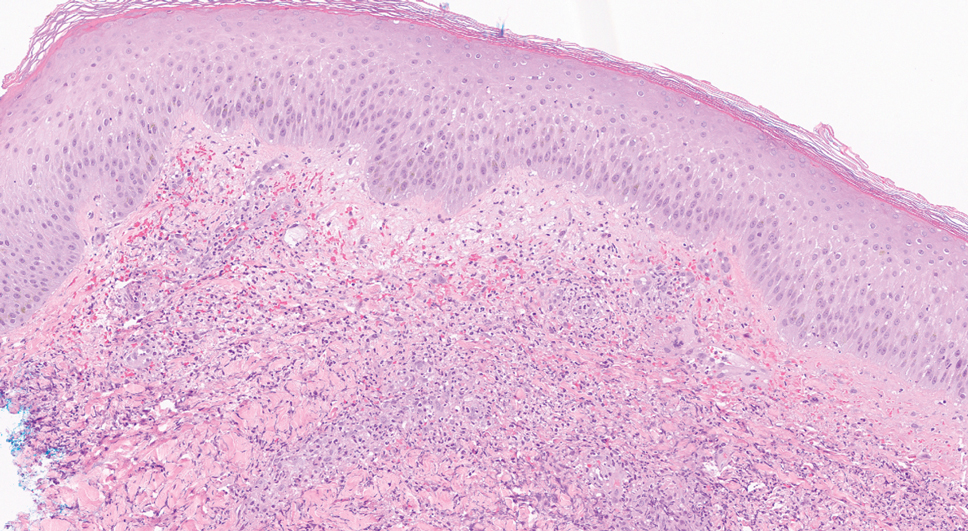

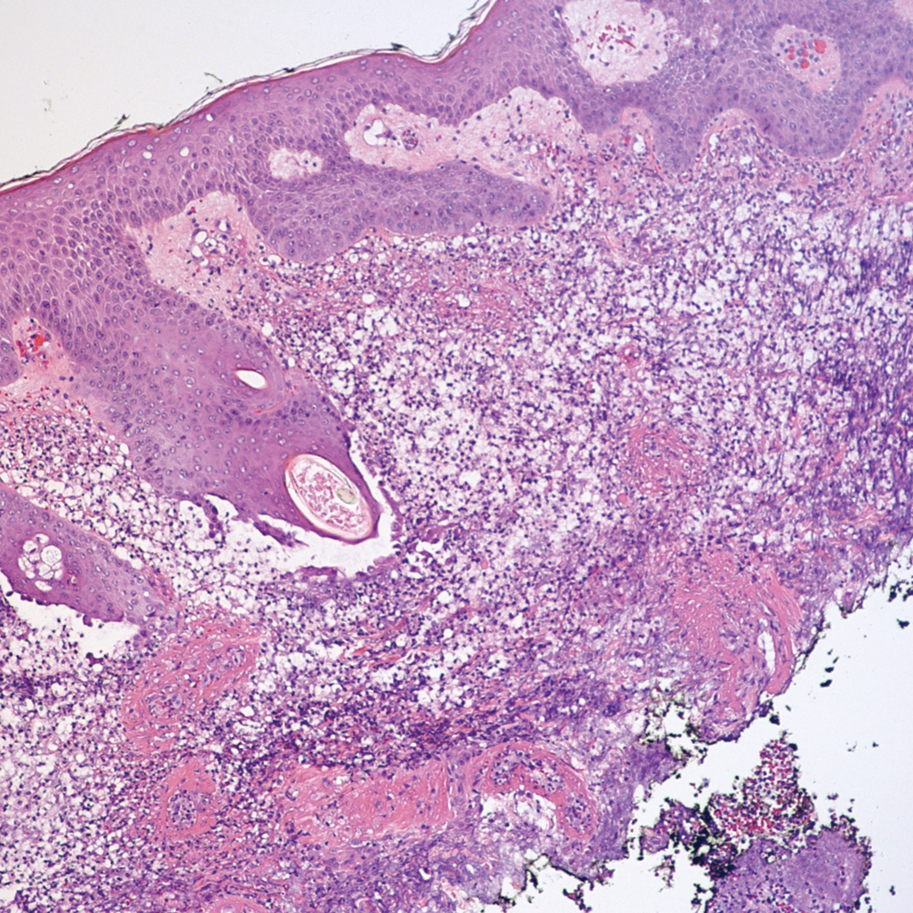

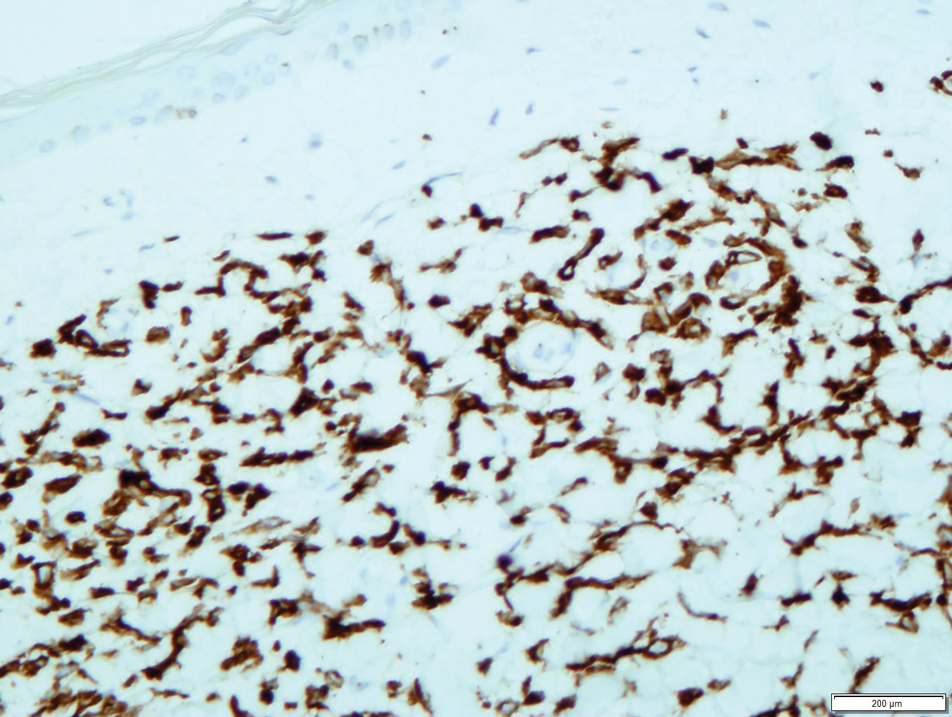

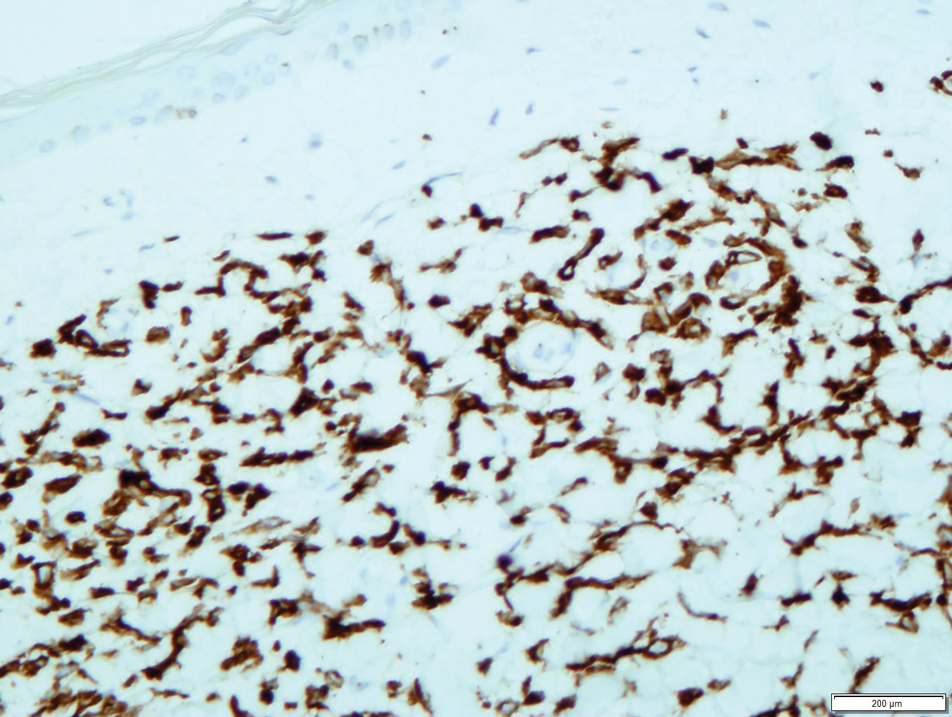

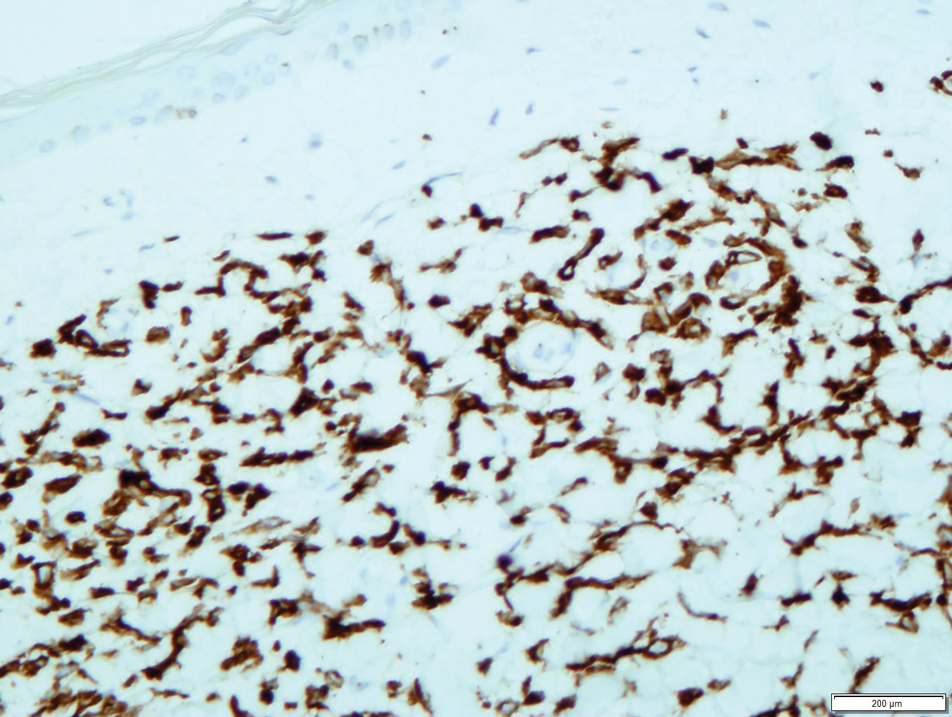

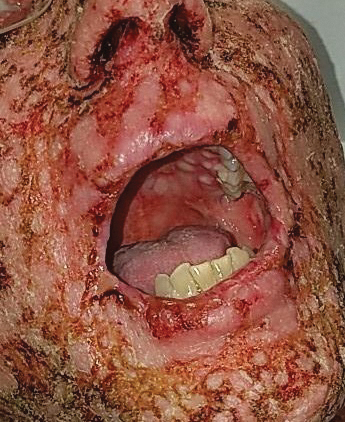

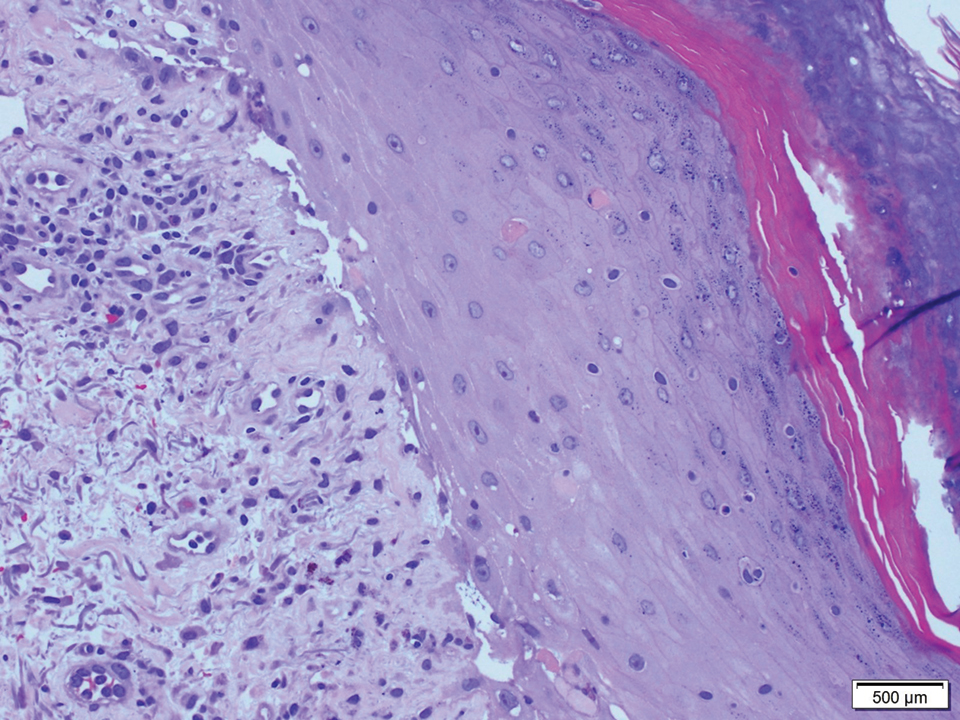

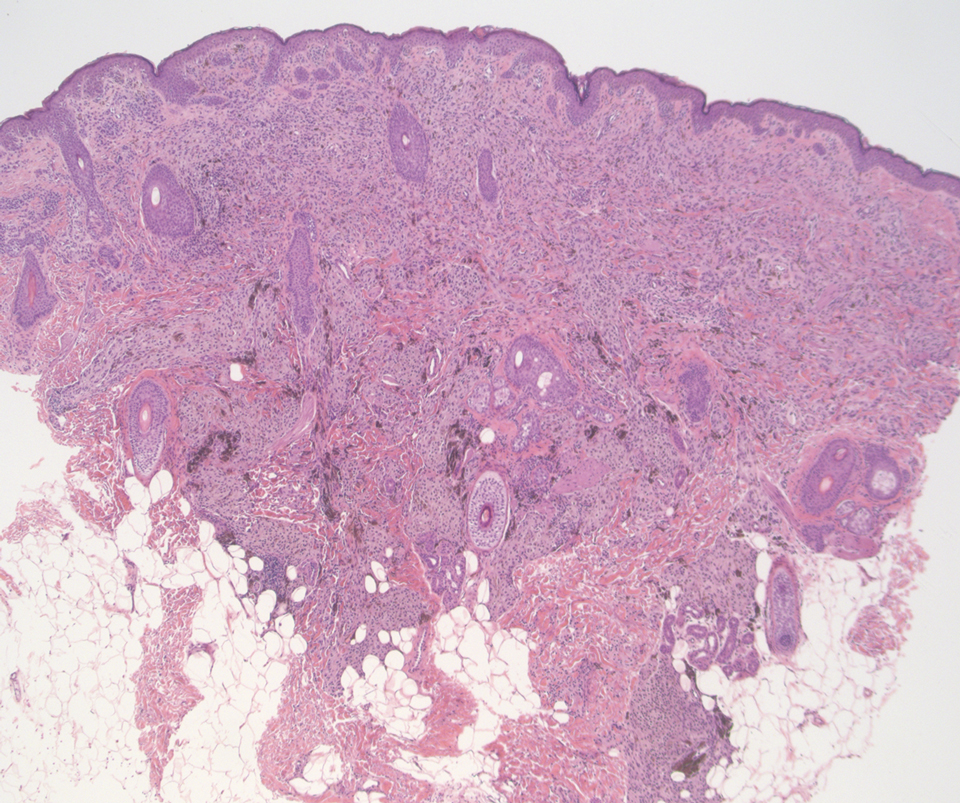

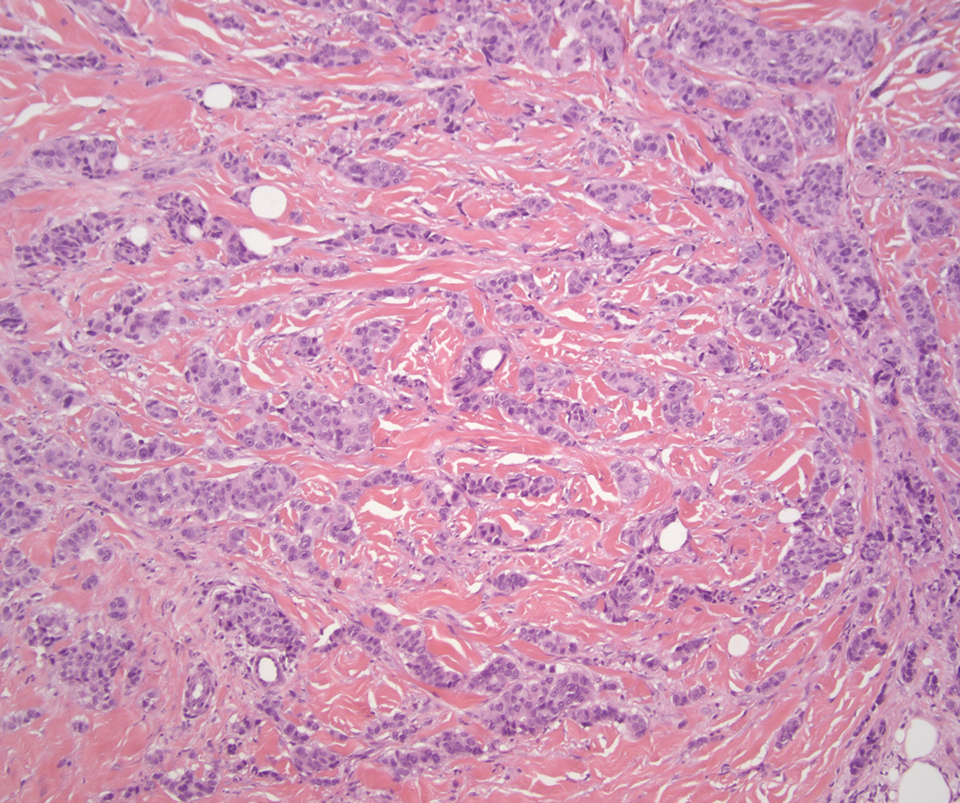

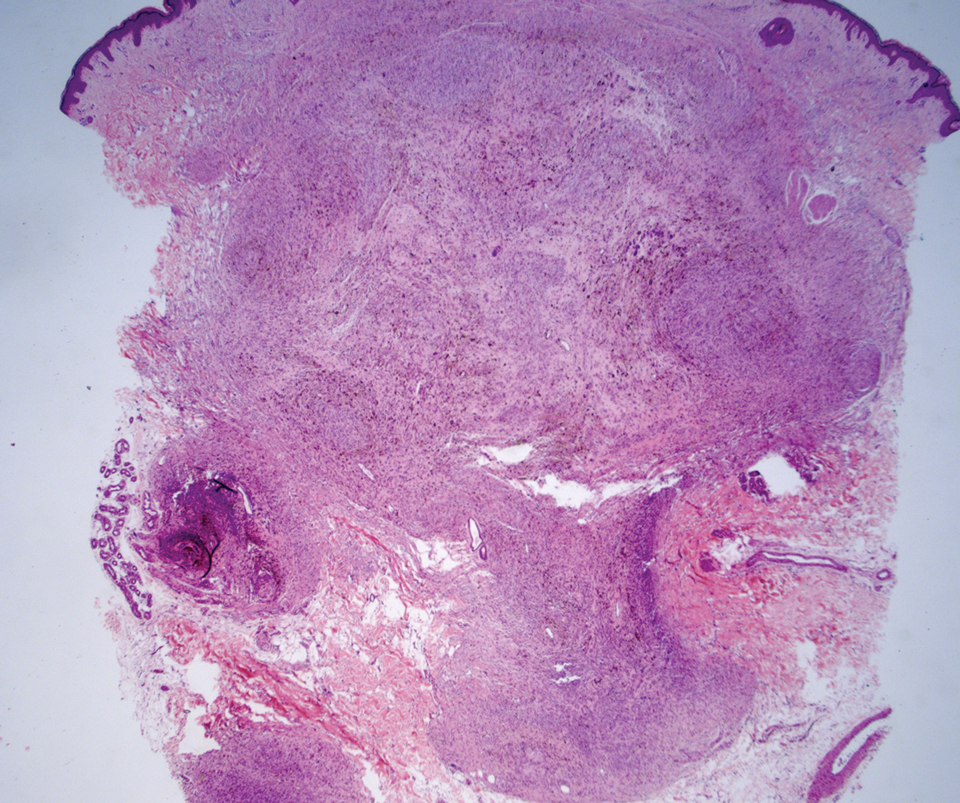

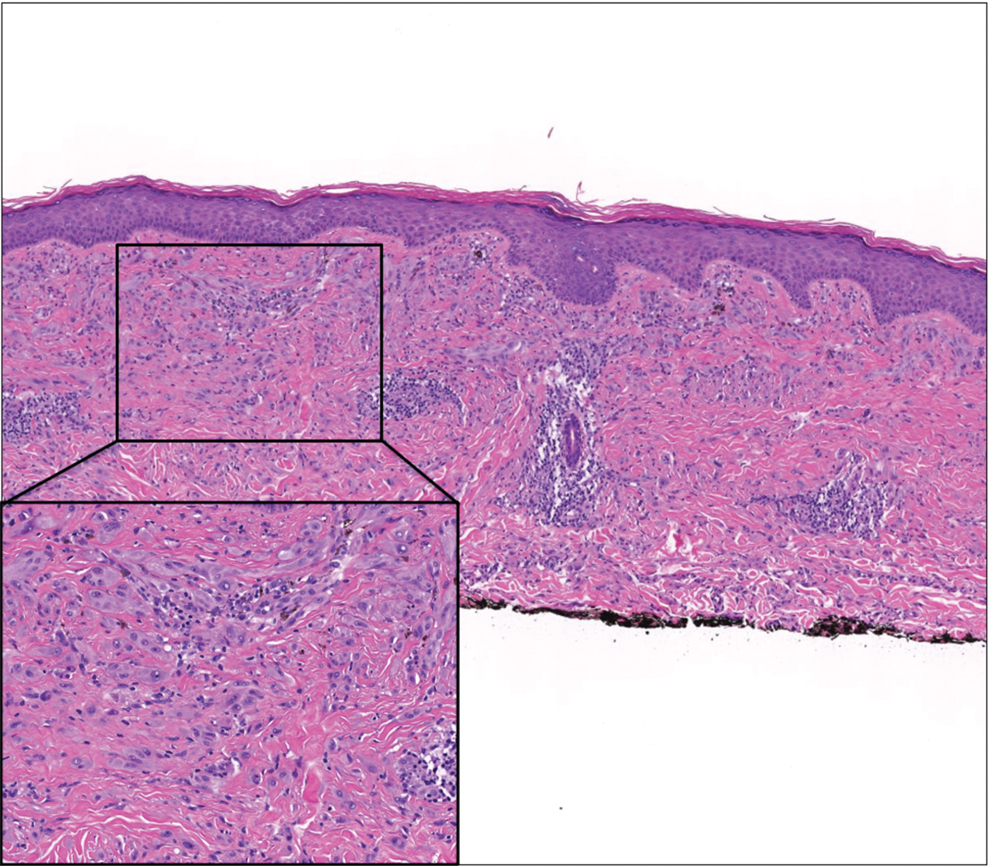

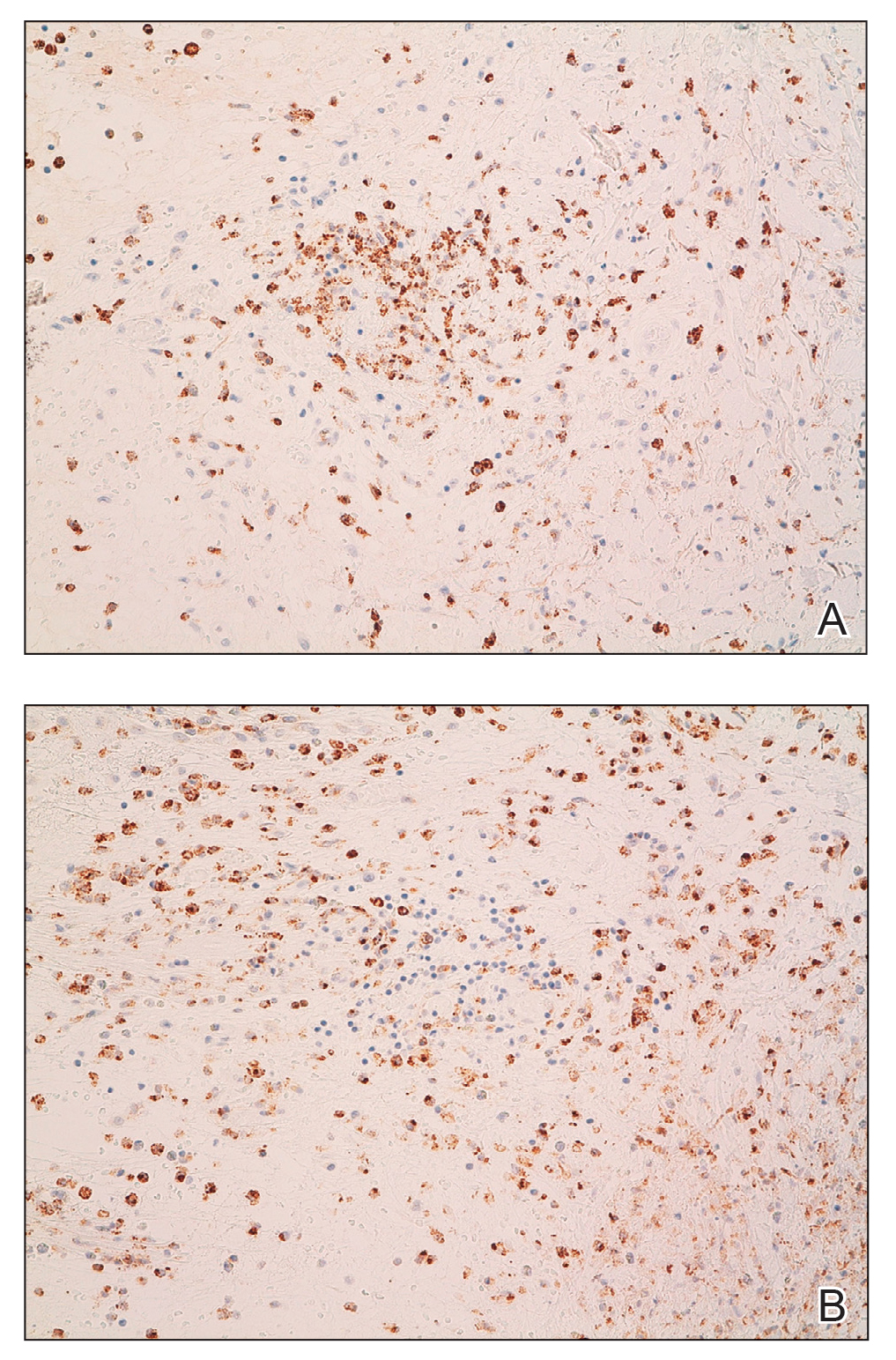

Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma is a neoplasm histologically composed of highly pleomorphic medium- to large-sized T cells with an irregular multilobated nuclear contour, so-called flower cells, in the peripheral blood. The nuclear chromatin is coarse and clumped with prominent nucleoli. Blastlike cells with dispersed chromatin are present in variable proportions. Most patients present with widespread lymph node and peripheral blood involvement. Skin is involved in more than half of patients with an epidermal as well as dermal pattern of infiltration (mainly perivascular)(Figure 2). Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma is endemic in several regions of the world, and the distribution is closely linked to the prevalence of human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 in the population. This neoplasm is of T-cell lineage and may share CD4 but not PDC-associated antigens with BPDCN.1

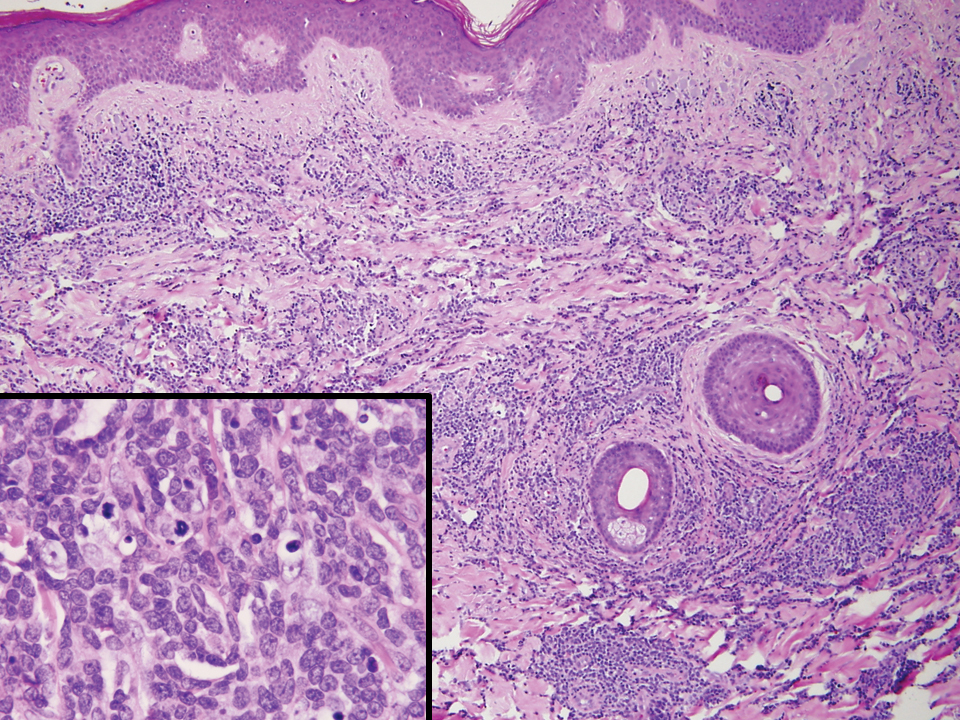

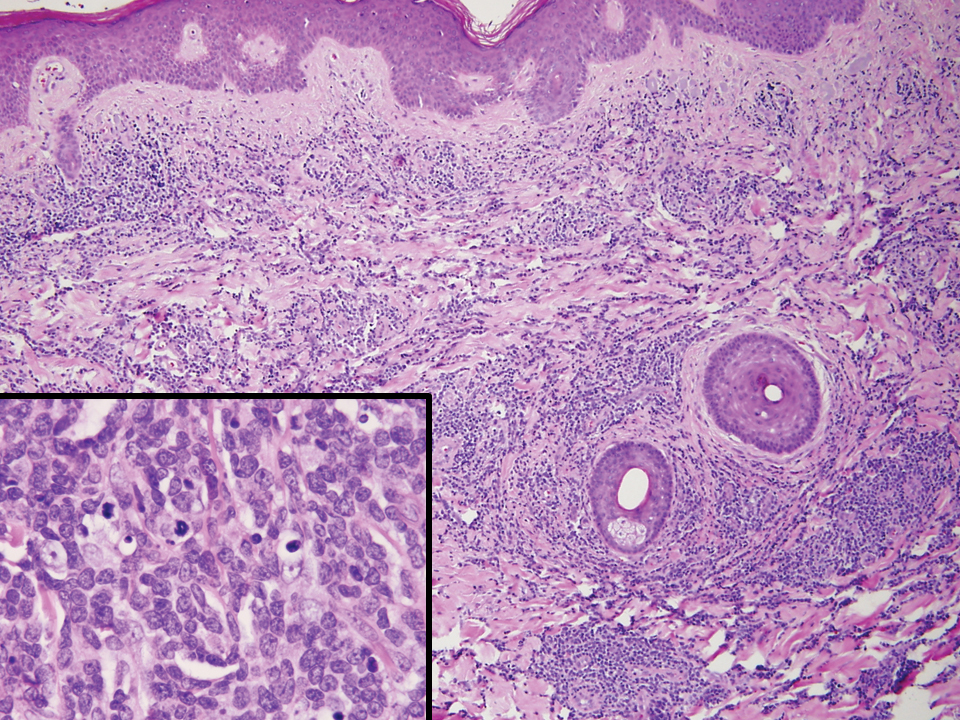

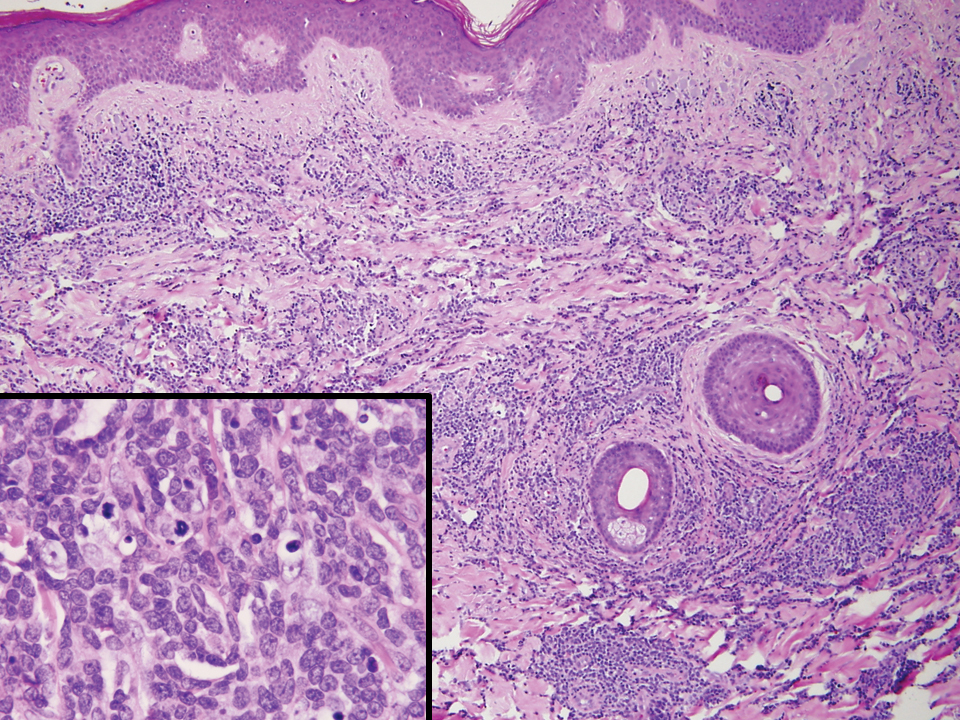

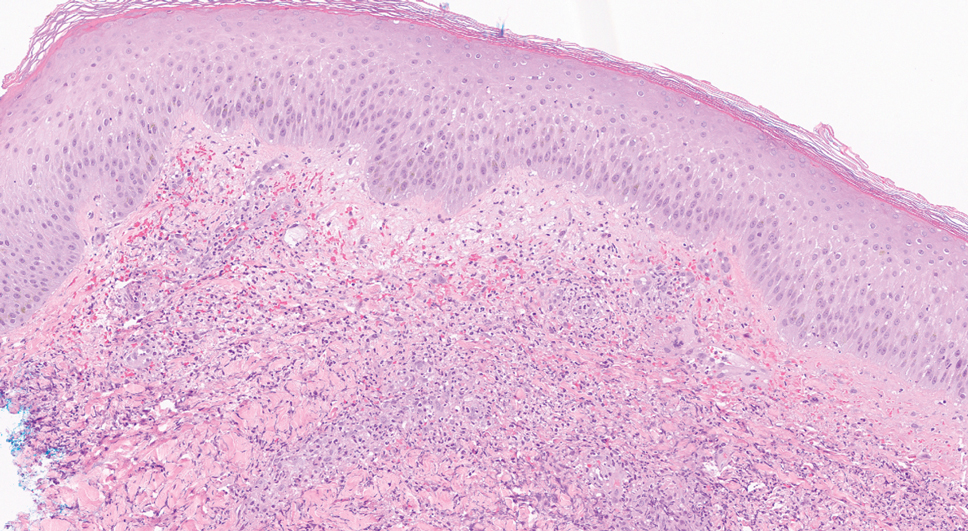

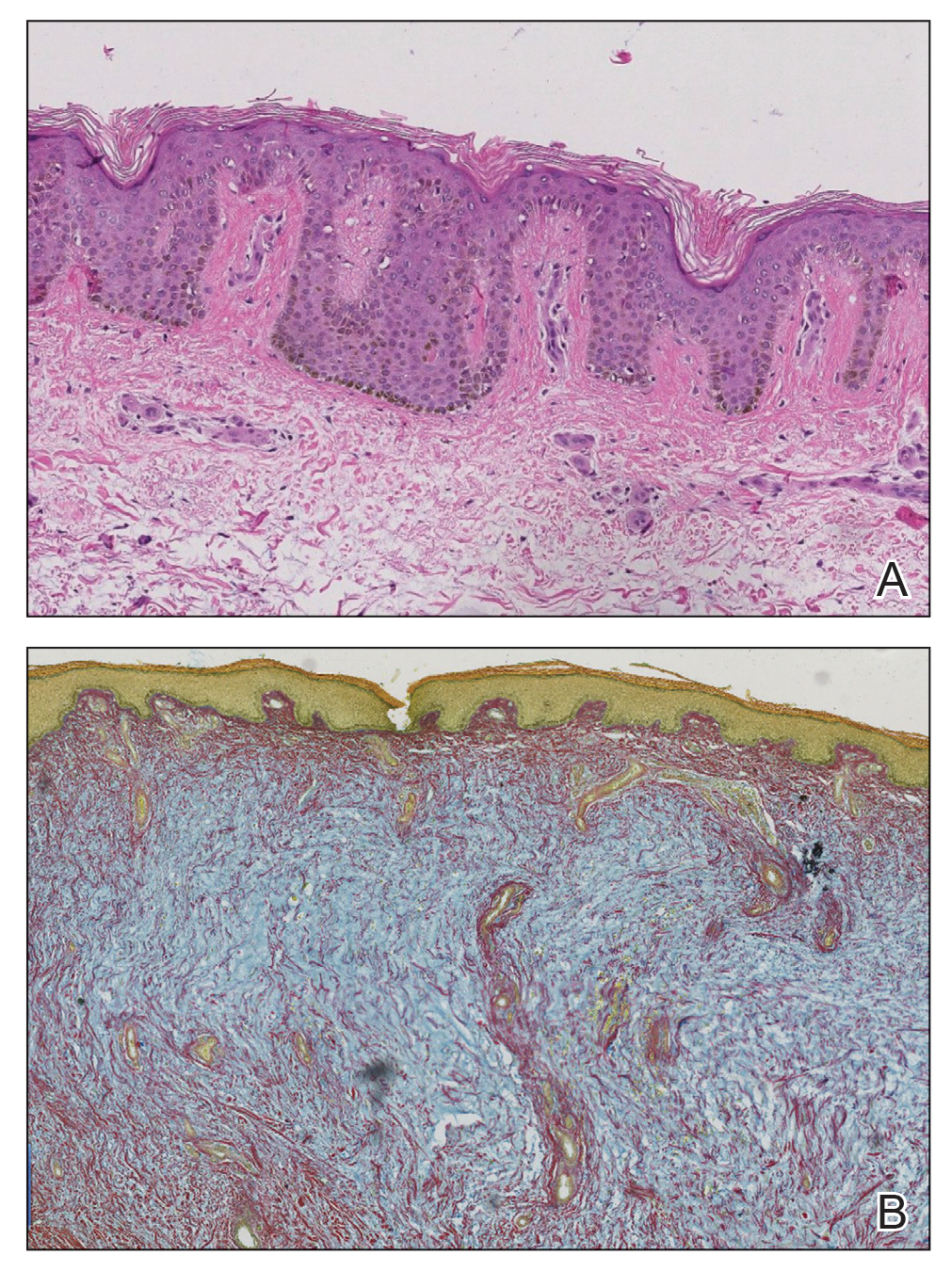

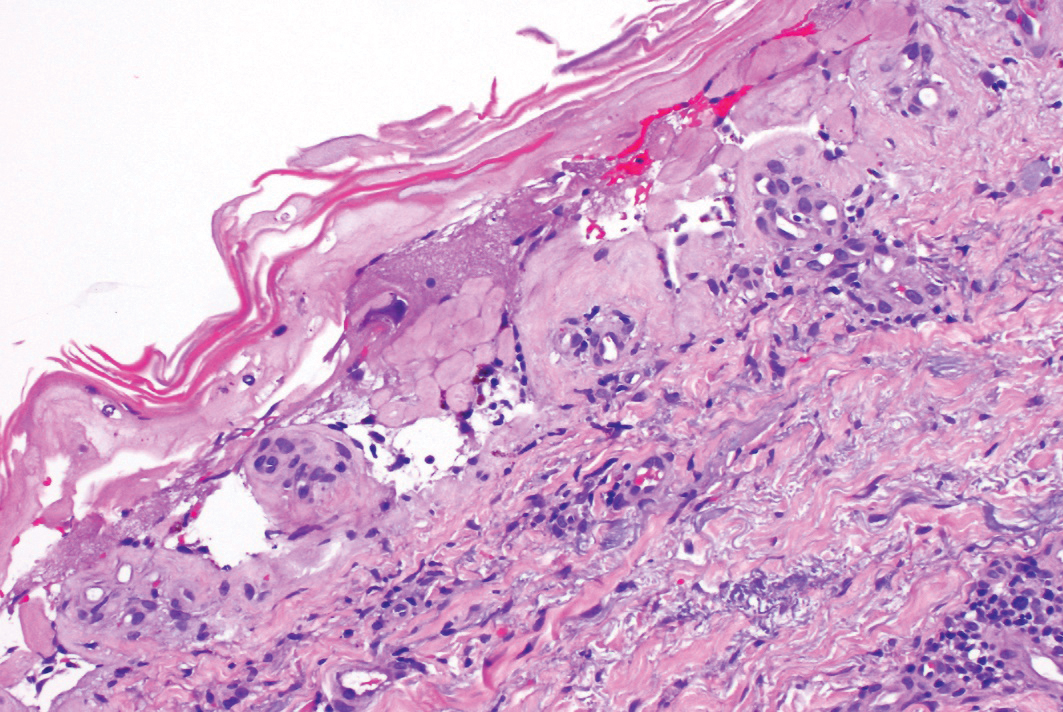

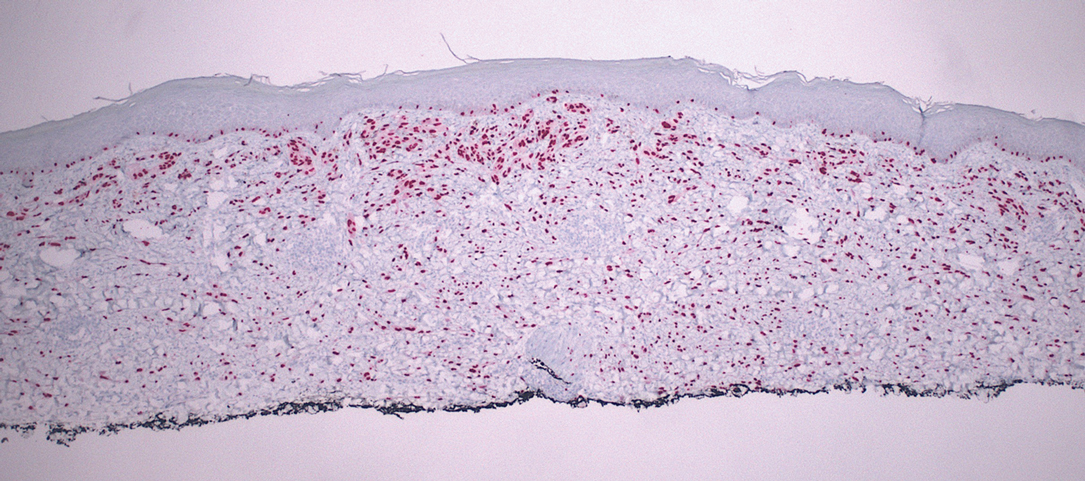

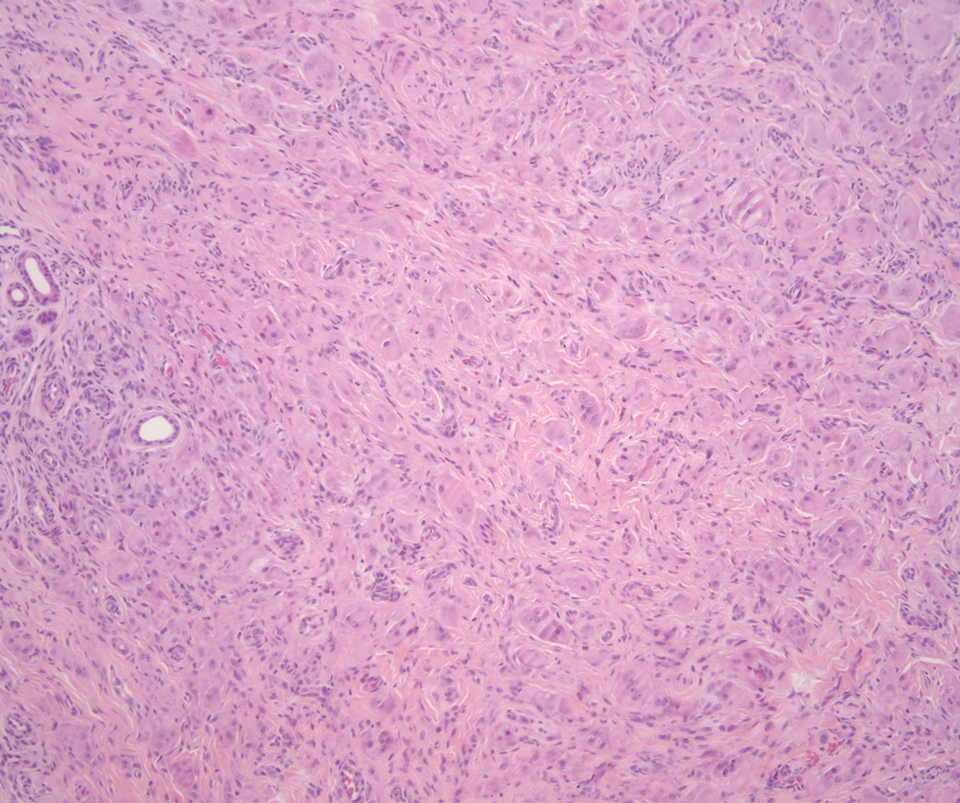

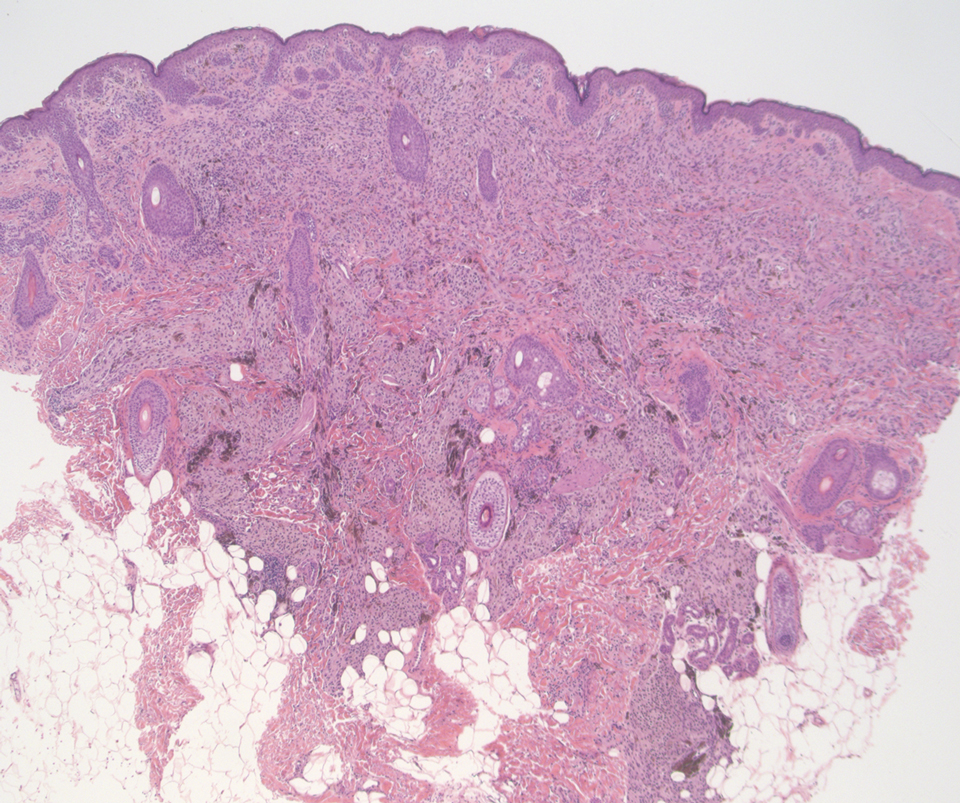

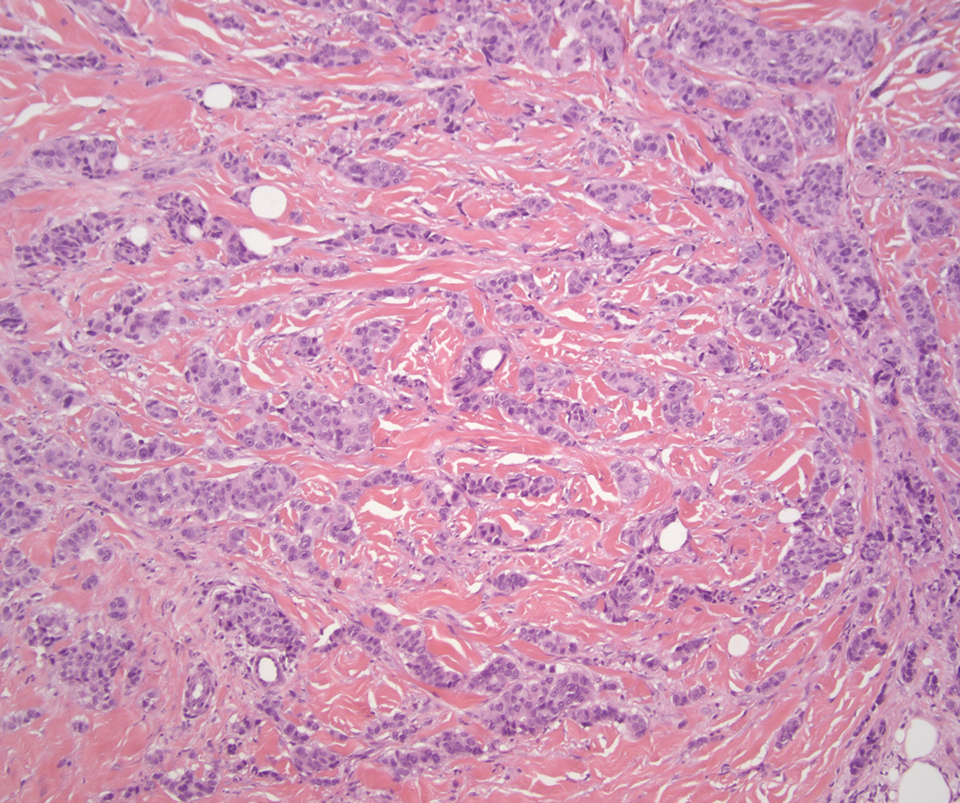

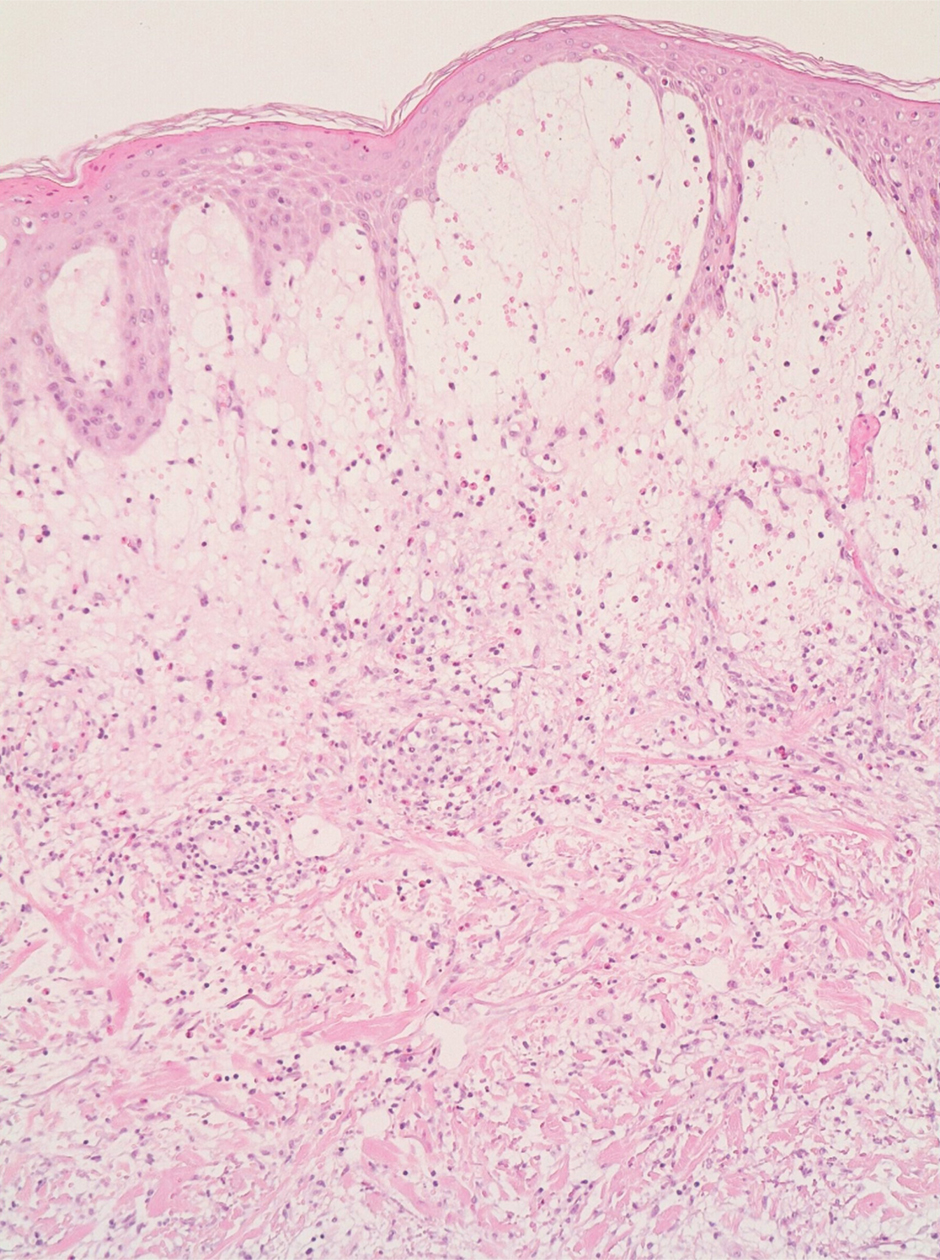

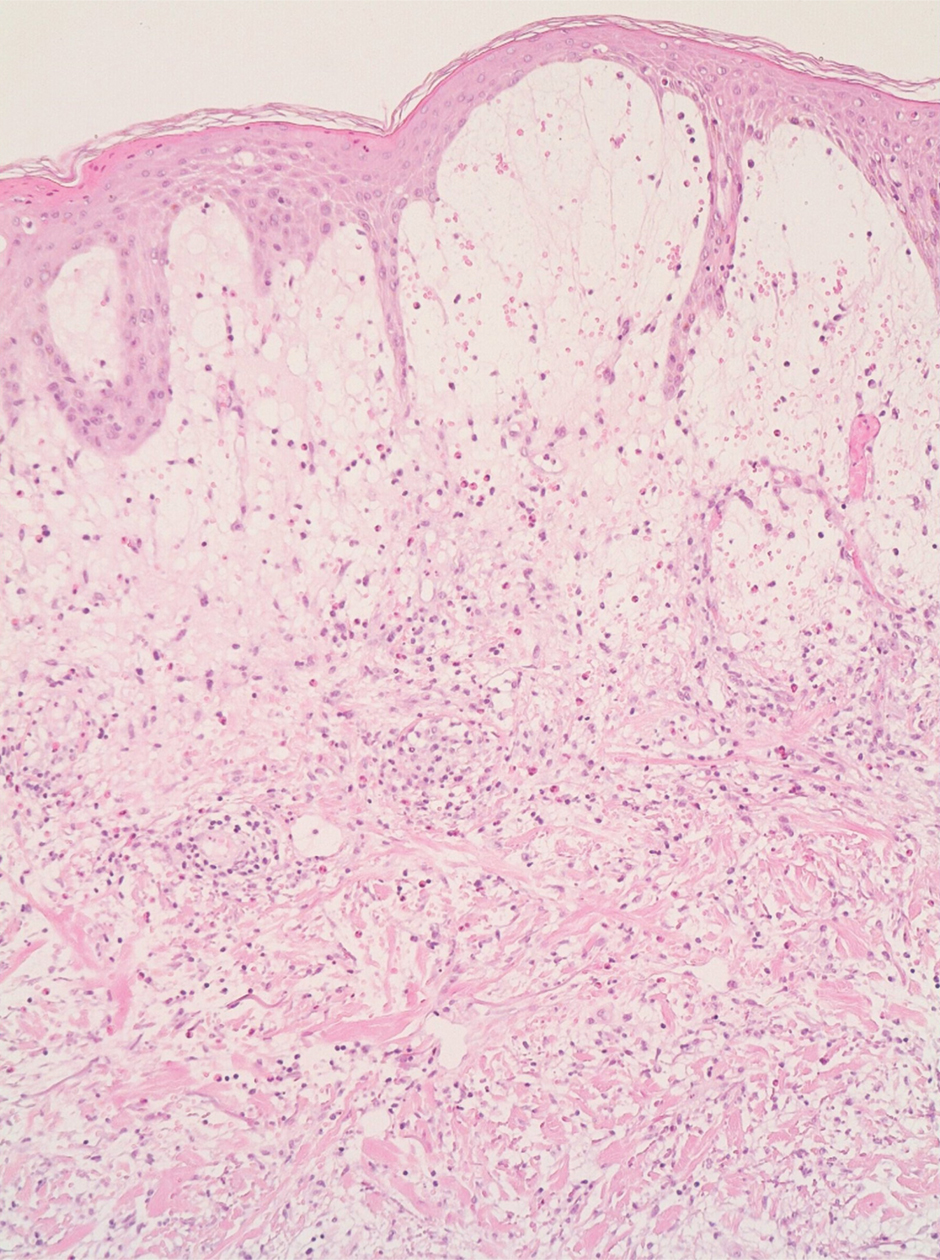

Cutaneous involvement by T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (T-LBL) is a rare occurrence with a frequency of approximately 4.3%.8 T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma usually presents as multiple skin lesions throughout the body. Almost all cutaneous T-LBL cases are seen in association with bone marrow and/or mediastinal, lymph node, or extranodal involvement. Cutaneous T-LBLs present as a diffuse monomorphous infiltrate located in the entire dermis and subcutis without epidermotropism, composed of medium to large blasts with finely dispersed chromatin and relatively prominent nucleoli (Figure 3). Immunophenotyping studies show an immature T-cell immunophenotype, with expression of TdT (usually uniform), CD7, and cytoplasmic CD3 and an absence of PDC-associated antigens.8

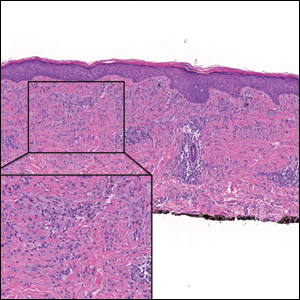

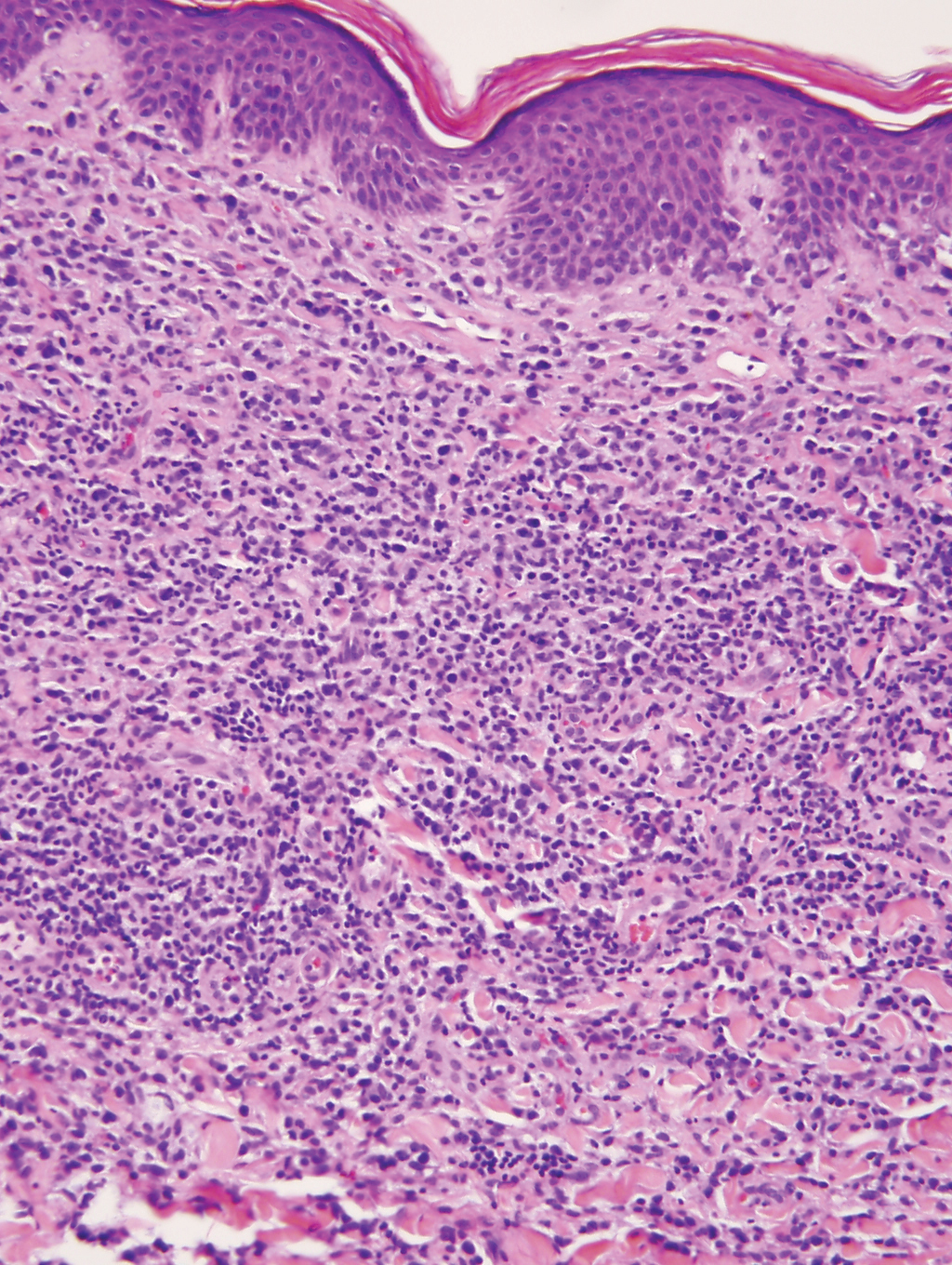

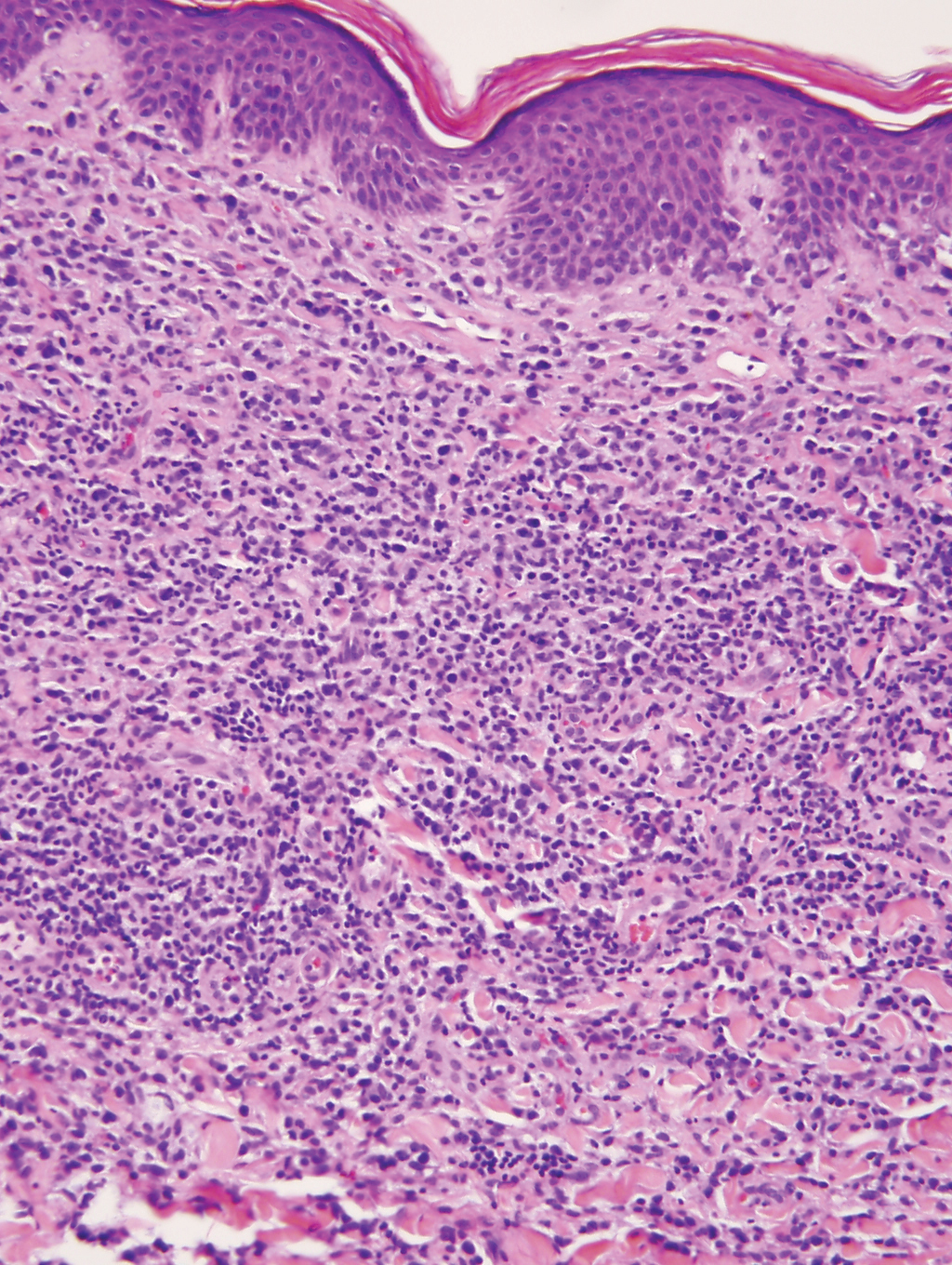

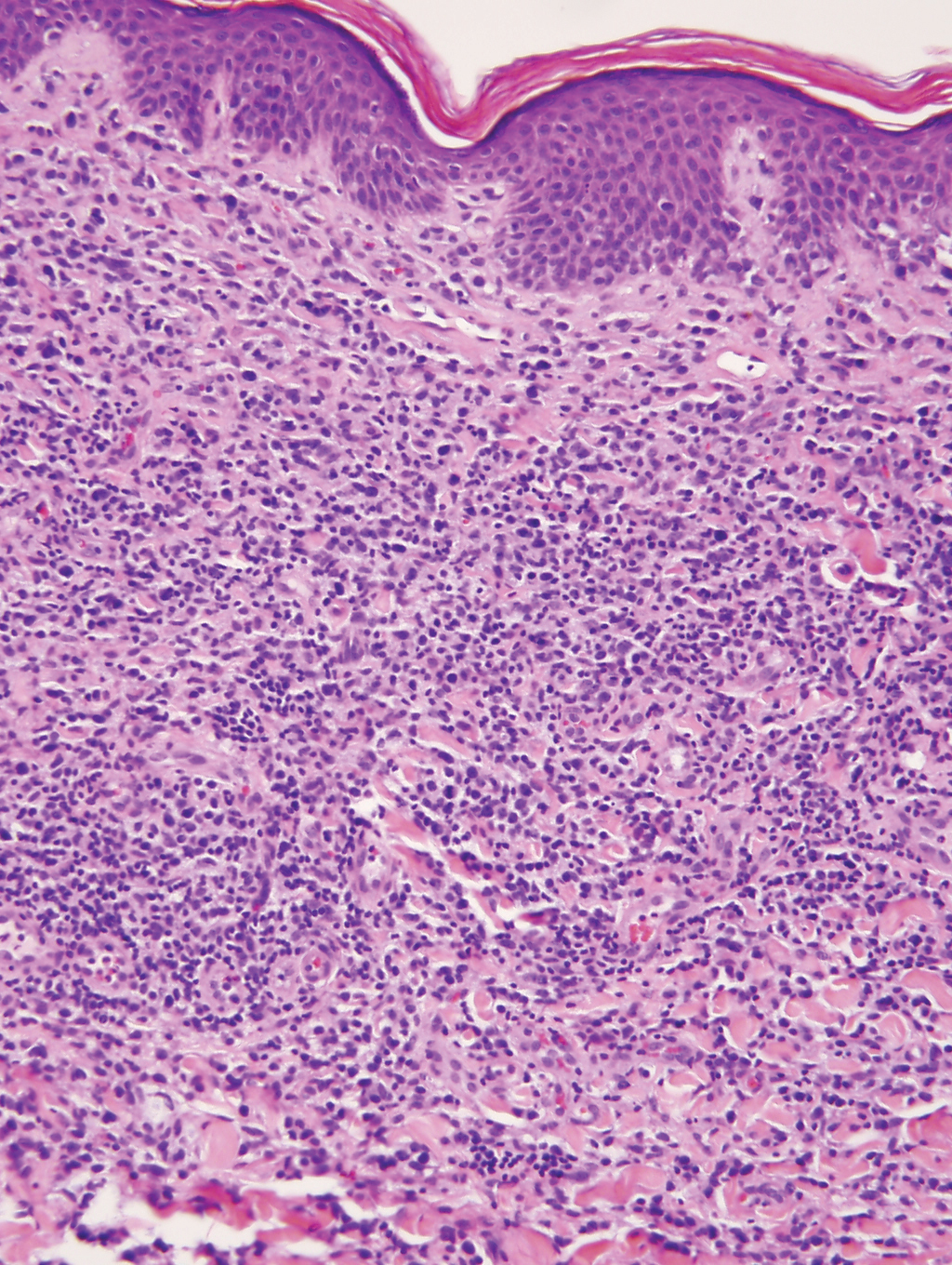

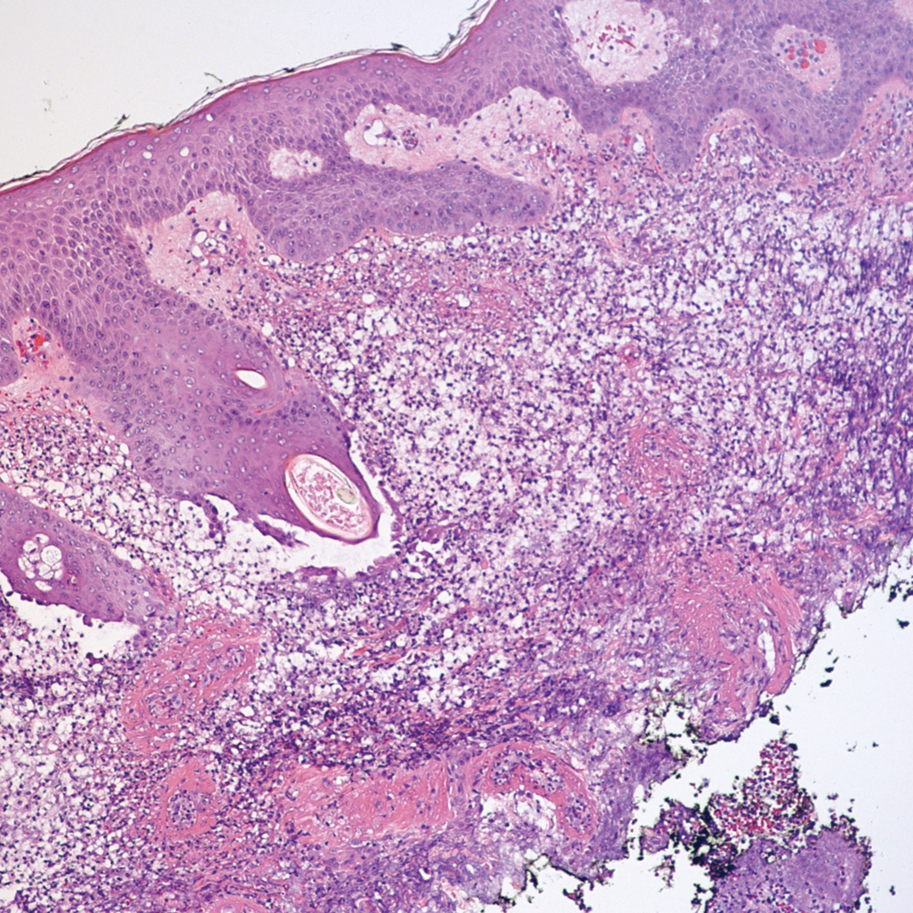

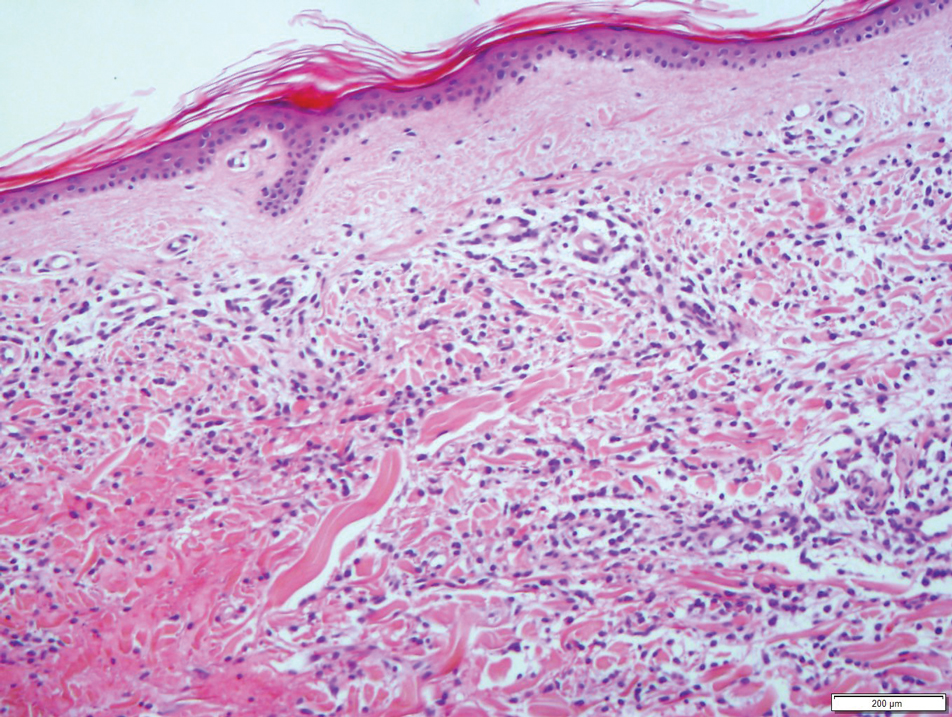

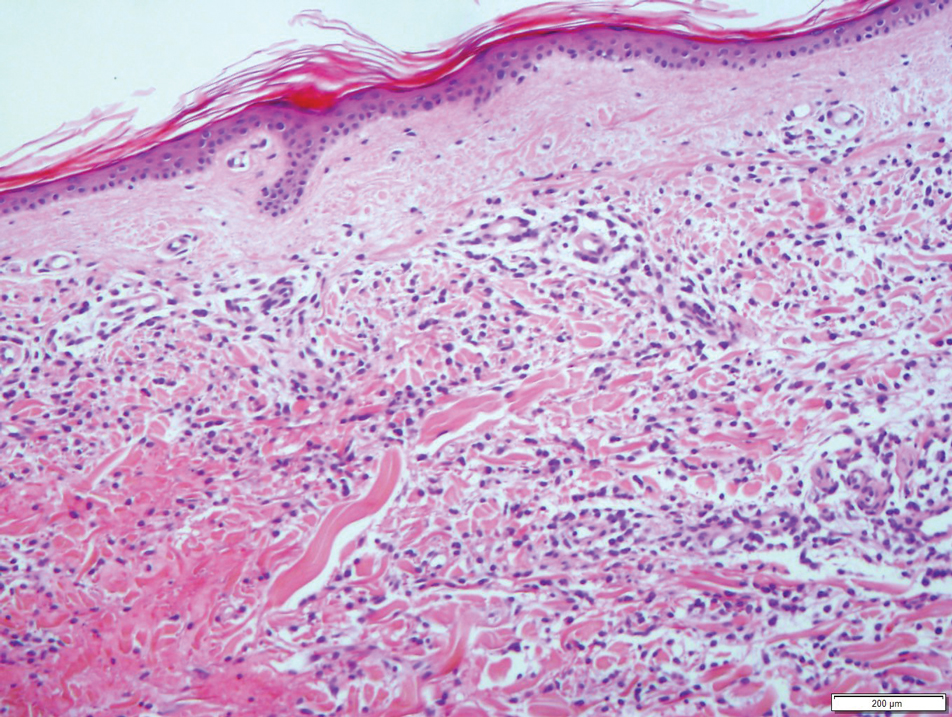

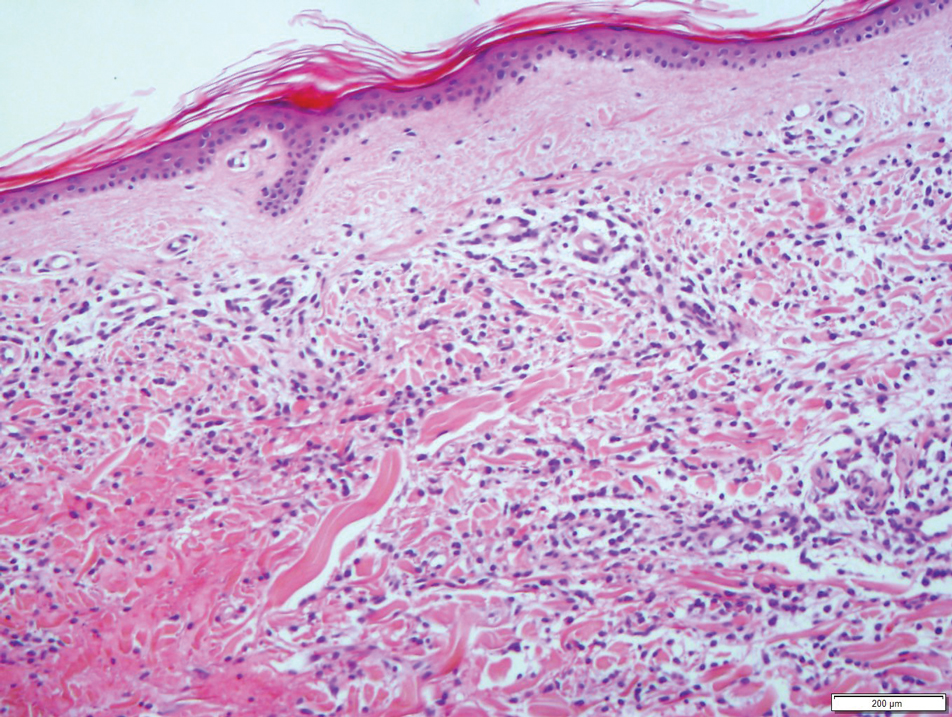

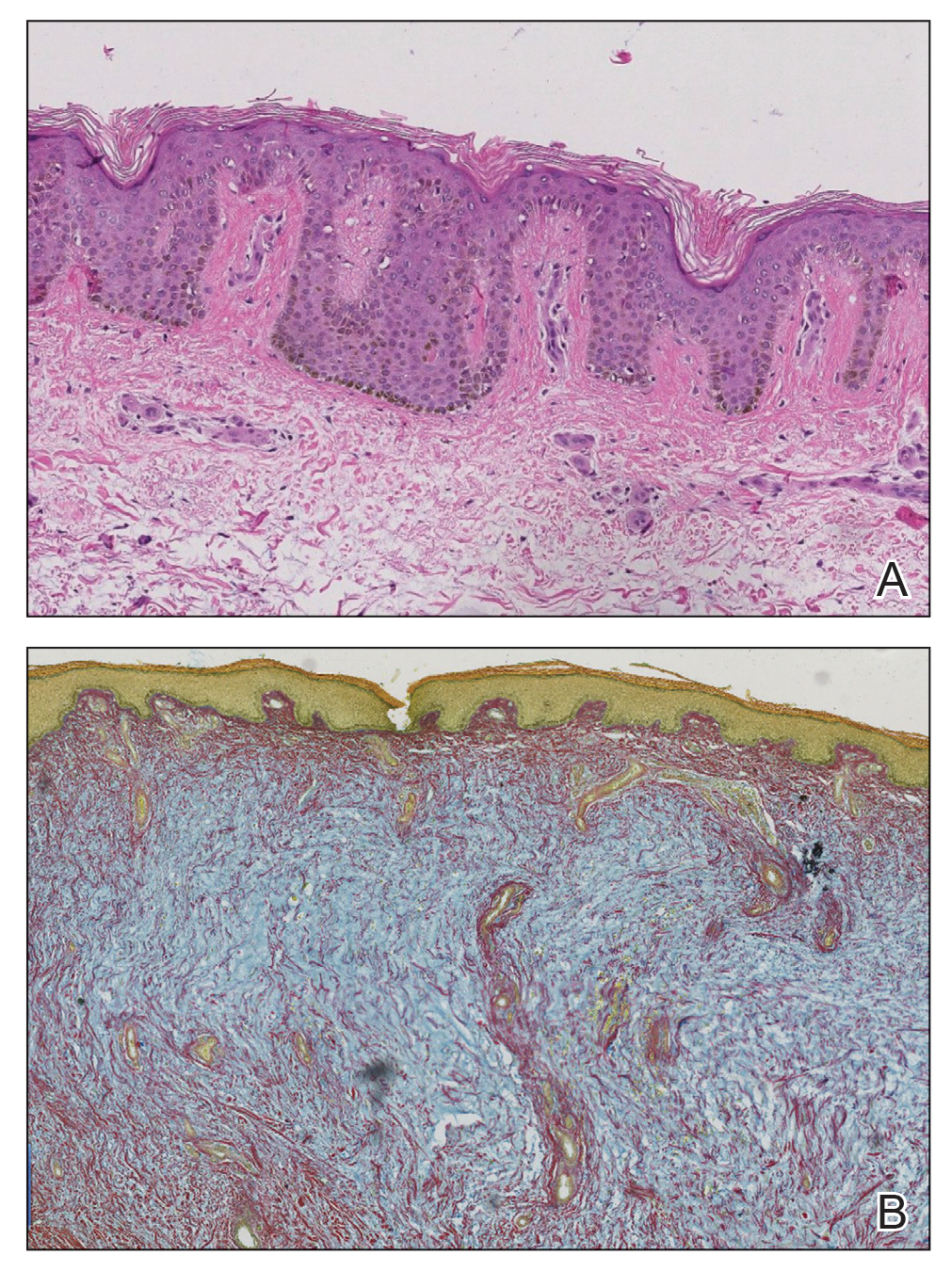

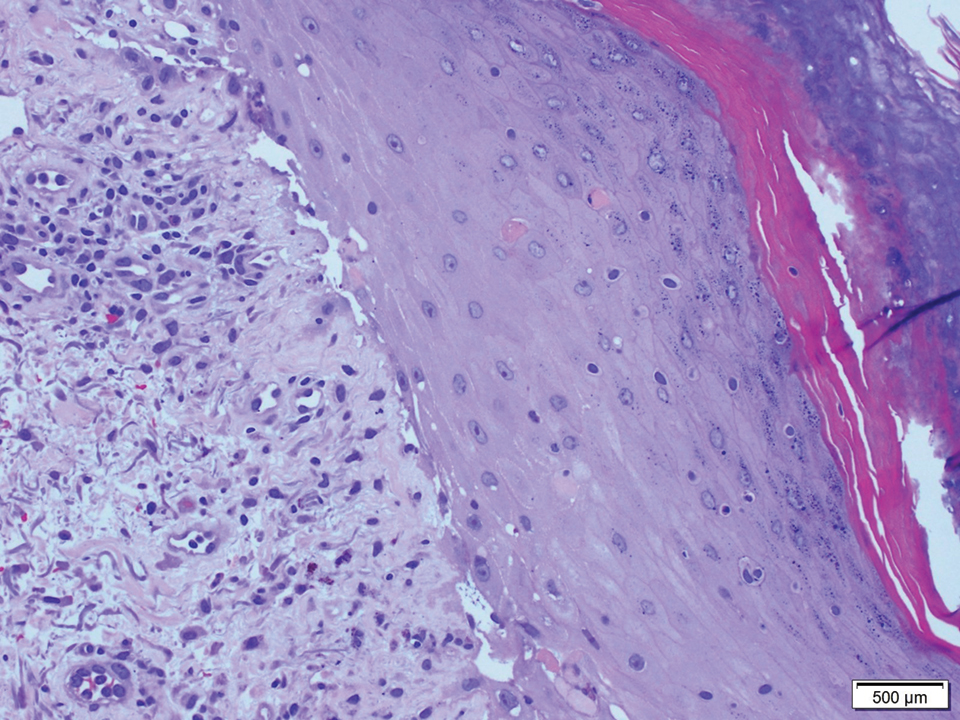

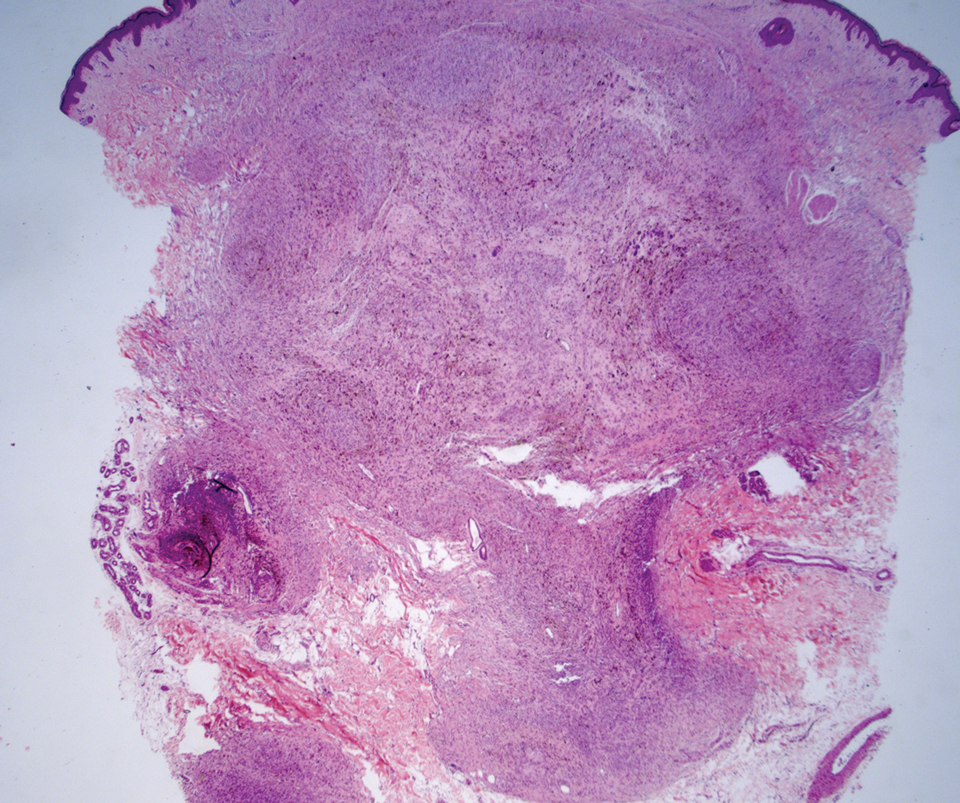

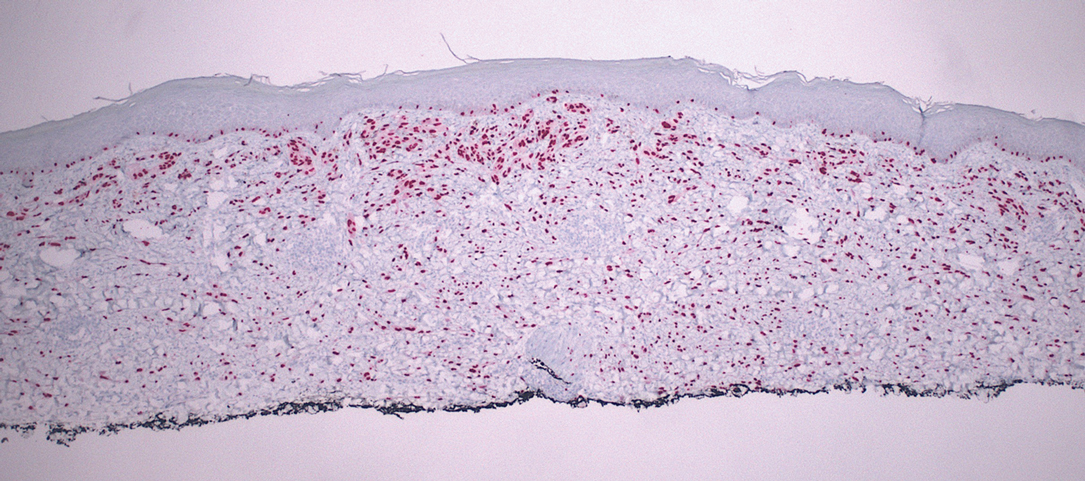

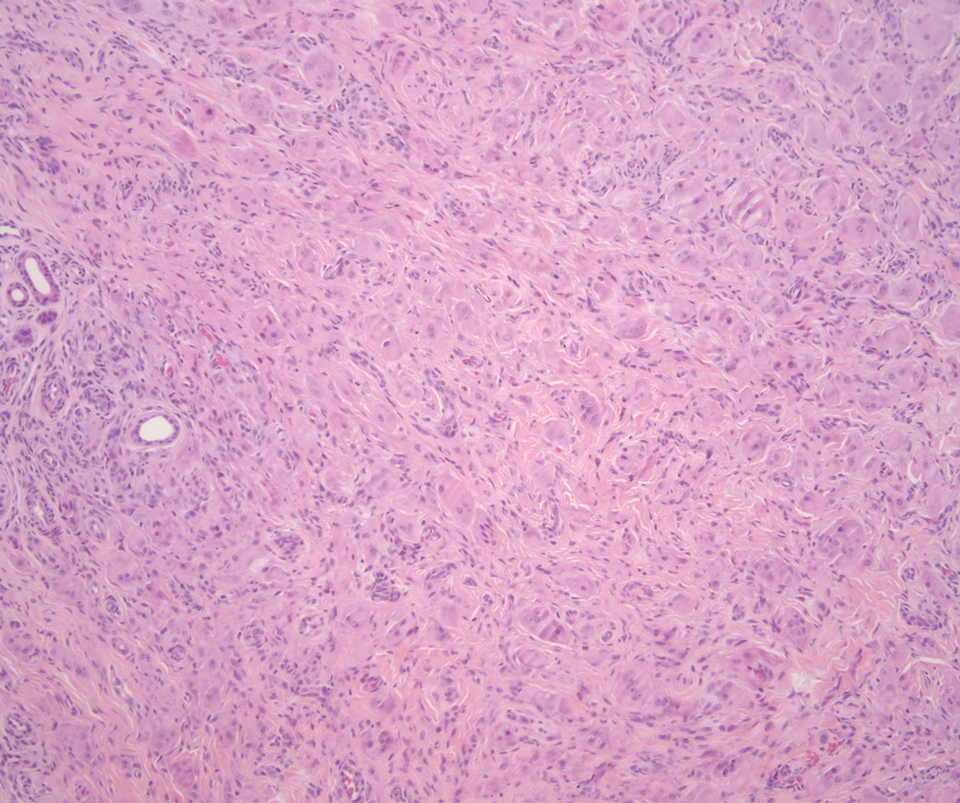

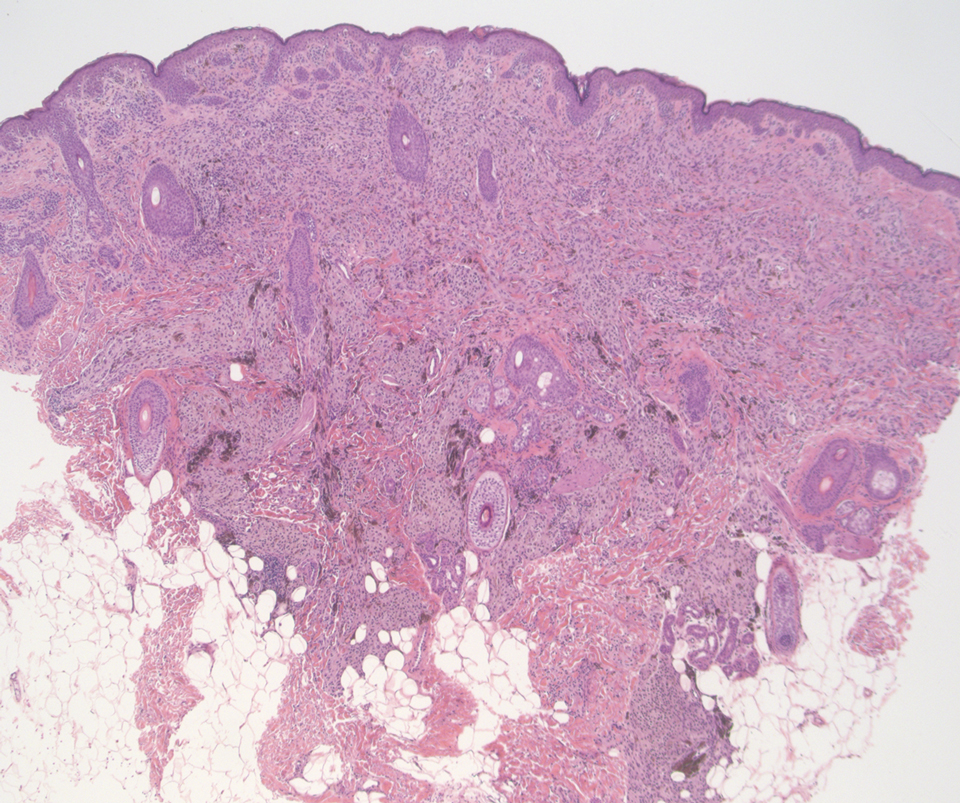

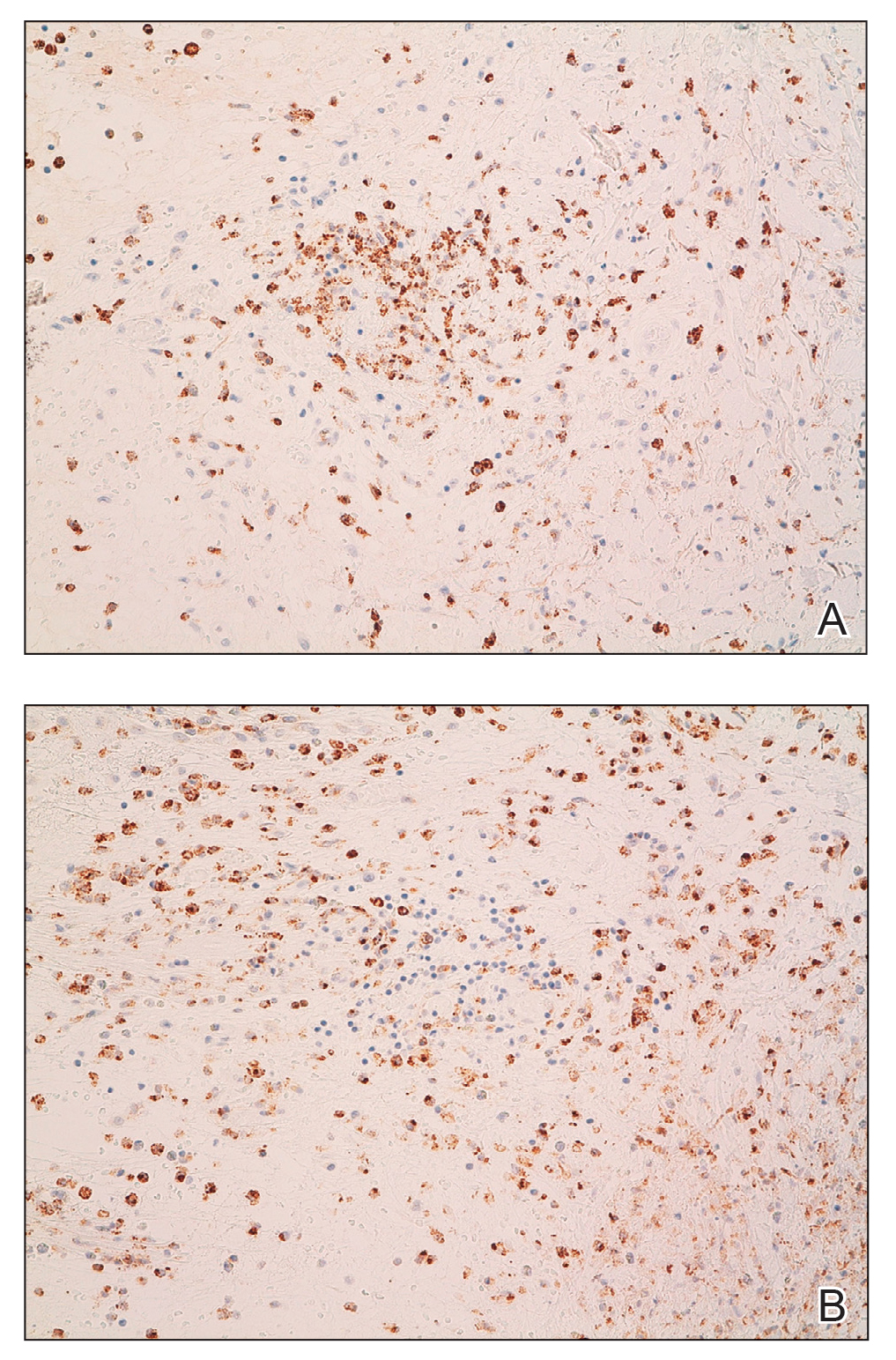

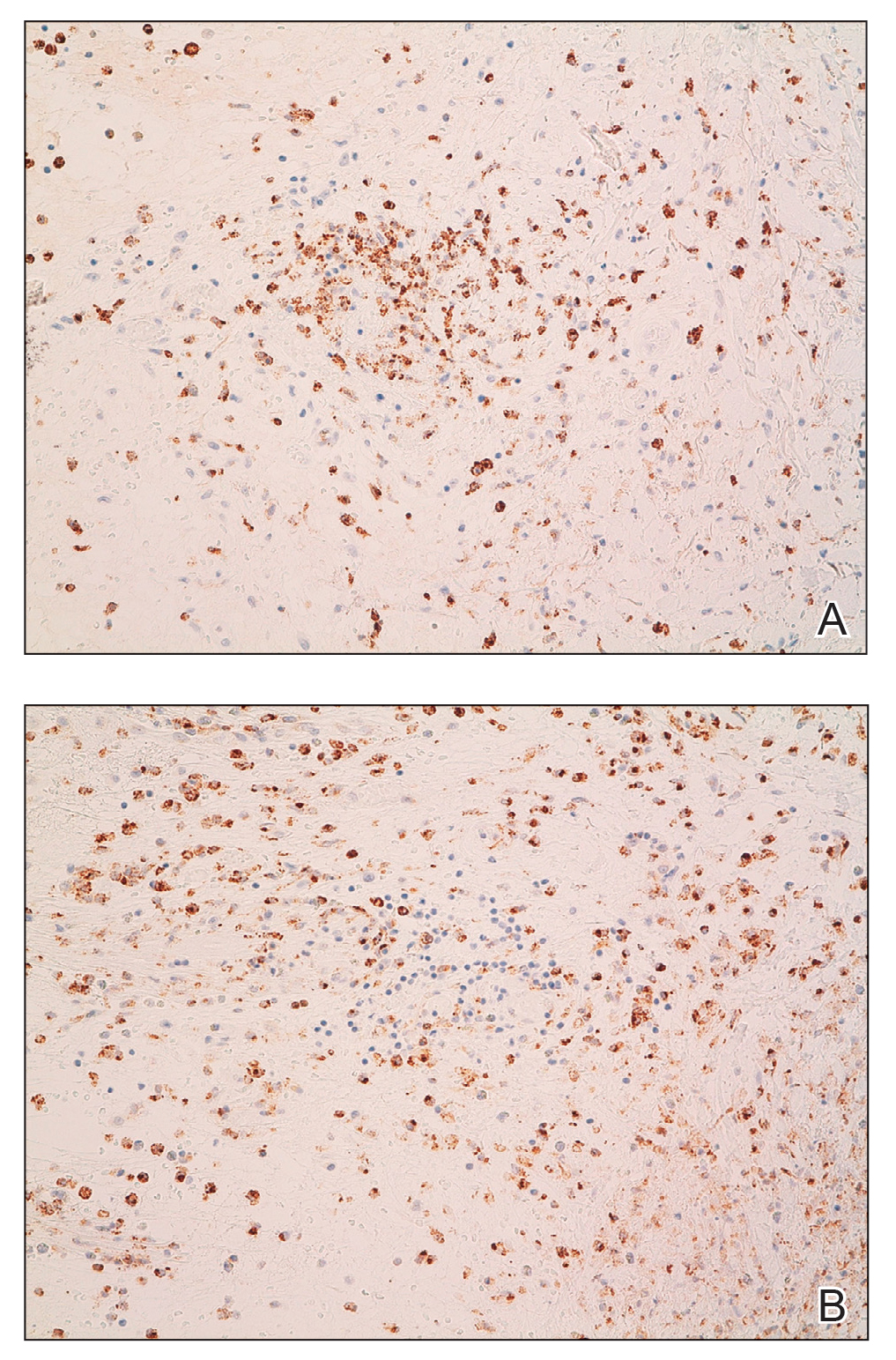

Primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma (PCGDTL) is a neoplasm primarily involving the skin. Often rapidly fatal, PCGDTL has a broad clinical spectrum that may include indolent variants—subcutaneous, epidermotropic, and dermal. Patients typically present with nodular lesions that progress to ulceration and necrosis. Early lesions can be confused with erythema nodosum, mycosis fungoides, or infection. Histologically, they show variable epidermotropism as well as dermal and subcutaneous involvement by medium to large cells with coarse clumped chromatin (Figure 4). Large blastic cells with vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli are infrequent. In contrast to BPCDN, the neoplastic lymphocytes in dermal and subcutaneous PCGDTL typically are positive for T-cell intracellular antigen-1 and granzyme B with loss of CD4.9

At the time of presentation, 27% to 87% of BPDCN patients will have bone marrow involvement, 22% to 28% will have blood involvement, and 6% to 41% will have lymph node involvement.1-4,6,7,10,11 The clinical course is aggressive, with a median survival of 10.0 to 19.8 months, irrespective of the initial pattern of disease.1 Most cases have shown initial response to multiagent chemotherapy, but relapses with subsequent resistance to drugs regularly have been observed. Age has an adverse impact of prognosis. Low TdT expression has been associated with shorter survival.1 Approximately 10% to 20% of cases of BPDCN are associated with or develop into chronic myelogenous leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, or acute myeloid leukemia.1,4 Pediatric patients have a greater 5-year overall survival rate than older patients, and overall survival worsens with increasing age. The extent of cutaneous involvement and presence of systemic involvement at initial presentation do not seem to be strong predictors of survival.1,2,5-7,10-12 In a retrospective analysis of 90 patients, Julia et al12 found that the type of skin disease did not predict survival. Specifically, the presence of nodular lesions and disseminated skin involvement were not adverse prognostic factors compared with macular lesions limited to 1 or 2 body areas.12

- Facchetti F, Petrella T, Pileri SA. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cells neoplasm. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. 4th ed. World Health Organization; 2017:174-177.

- Jegalian AG, Facchetti F, Jaffe ES. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells: physiologic roles and pathologic states. Adv Anat Pathol. 2009;16:392-404.

- Shi Y, Wang E. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: a clinicopathologic review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138:564-569.

- Khoury JD, Medeiros LJ, Manning JT, et al. CD56(+) TdT(+) blastic natural killer cell tumor of the skin: a primitive systemic malignancy related to myelomonocytic leukemia. Cancer. 2002;94:2401-2408.

- Kolerova A, Sergeeva I, Krinitsyna J, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: case report and literature overview. Indian J Dermatol. 2020;65:217-221.

- Hirner JP, O’Malley JT, LeBoeuf NR. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: the dermatologist’s perspective. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2020;34:501-509.

- Guiducii C, Tripodo C, Gong M, et al. Autoimmune skin inflammation is dependent on plasmacytoid dendritic cell activation by nucleic acids via TLR7 and TLR9. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2931-2942.

- Khurana S, Beltran M, Jiang L, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma: case report and literature review. Case Rep Hematol. 2019;2019:3540487. doi:10.1155/2019/3540487

- Gladys TE, Helm MF, Anderson BE, et al. Rapid onset of widespread nodules and lymphadenopathy. Cutis. 2020;106:132, 153-155.

- Gregorio J, Meller S, Conrad C, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells sense skin injury and promote wound healing through type I interferons. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2921-2930.

- Guru Murthy GS, Pemmaraju N, Attallah E. Epidemiology and survival of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm. Leuk Res. 2018;73:21-23.

- Julia F, Petrella T, Beylot-Barry M, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: clinical features in 90 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2012;169:579-586.

The Diagnosis: Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm

A diagnosis of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN) was rendered. Subsequent needle core biopsy of a left axillary lymph node as well as bone marrow aspiration and biopsy revealed a similar diffuse blastoid infiltrate with an identical immunophenotype to that in the skin biopsy from the pretibial mass and peripheral blood.

Previously known as blastic natural killer cell leukemia/lymphoma or agranular CD4+/CD56+ hematodermic neoplasm/tumor, BPDCN is a rare, clinically aggressive hematologic malignancy derived from the precursors of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. It often is diagnostically challenging, particularly when presenting at noncutaneous sites and in unusual (young) patient populations.1 It was included with other myeloid neoplasms in the 2008 World Health Organization classification; however, in the 2017 classification it was categorized as a separate entity. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm typically presents in the skin of elderly patients (age range at diagnosis, 61–67 years) with or without bone marrow involvement and systemic dissemination.1,2 The skin is the most common clinical site of disease in typical cases of BPDCN and often precedes bone marrow involvement. Thus, skin biopsy often is the key to making the diagnosis. Diagnosis of BPDCN may be delayed because of diagnostic pitfalls. Patients usually present with asymptomatic solitary or multiple lesions.3-5 Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm can present as an isolated purplish nodule or bruiselike papule or more commonly as disseminated purplish nodules, papules, and macules. Isolated nodules are found on the head and lower limbs and can be more than 10 cm in diameter. Peripheral blood and bone marrow may be minimally involved at presentation but invariably become involved with the progression of disease. Cytopenia can occur at diagnosis and in a minority of severe cases indicates bone marrow failure.2-6

Skin involvement of BPDCN is thought to be secondary to the expression of skin migration molecules, such as cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen, one of the E-selectin ligands, which binds to E-selectin on high endothelial venules. In addition, the local dermal microenvironment of chemokines binding CXCR3, CXCR4, CCR6, or CCR7 present on neoplastic cells possibly leads to skin involvement. The full mechanism underlying the cutaneous tropism is still to be elucidated.4-7 Infiltration of the oral mucosa is seen in some patients, but it may be underreported. Mucosal disease typically appears similarly to cutaneous disease.

The cutaneous differential diagnosis for BPDCN depends on the clinical presentation, extent of disease spread, and thickness of infiltration. It includes common nonneoplastic diseases such as traumatic ecchymoses; purpuric disorders; extramedullary hematopoiesis; and soft-tissue neoplasms such as angiosarcoma, Kaposi sarcoma, neuroblastoma, and vascular metastases, as well as skin involvement by other hematologic neoplasms. An adequate incisional biopsy rather than a punch or shave biopsy is recommended for diagnosis. Dermatologists should alert the pathologist that BPDCN is in the clinical differential diagnosis when possible so that judicious use of appropriate immunophenotypic markers such as CD123, CD4, CD56, and T-cell leukemia/lymphoma protein 1 will avoid misdiagnosis of this aggressive condition, in addition to excluding acute myeloid leukemia, which also may express 3 of the above markers. However, most cases of acute myeloid leukemia lack terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) and express monocytic and other myeloid markers. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase is positive in approximately one-third of cases of BPDCN, with expression in 10% to 80% of cells.1

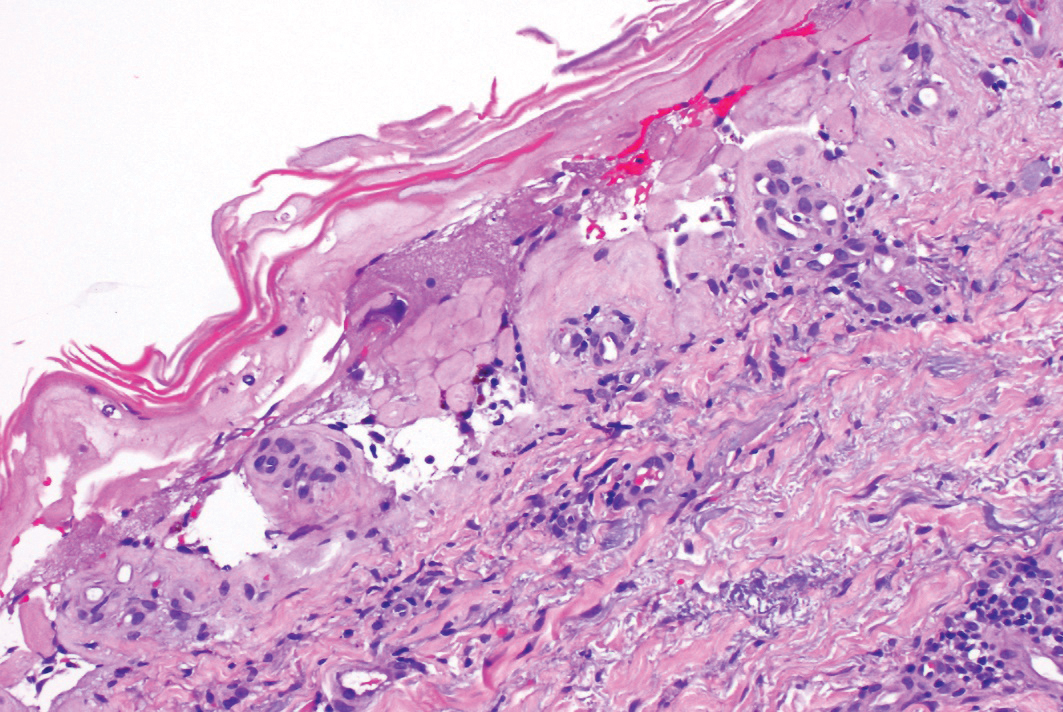

It is important to include BPDCN in the differential diagnosis of immunophenotypically aberrant hematologic tumors. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, accounts for 4% of all primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas.1 Compared with BPDCN, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma usually occurs in an older age group and is of B-cell lineage. Morphologically, these neoplasms are composed of a monotonous, diffuse, nonepidermotropic infiltrate of confluent sheets of centroblasts and immunoblasts (Figure 1). They may share immunohistochemical markers of CD79a, multiple myeloma 1, Bcl-2, and Bcl-6; however, they lack plasmacytoid dendritic cell (PDC)– associated antigens such as CD4, CD56, CD123, and T-cell leukemia/lymphoma protein 1.1

Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma is a neoplasm histologically composed of highly pleomorphic medium- to large-sized T cells with an irregular multilobated nuclear contour, so-called flower cells, in the peripheral blood. The nuclear chromatin is coarse and clumped with prominent nucleoli. Blastlike cells with dispersed chromatin are present in variable proportions. Most patients present with widespread lymph node and peripheral blood involvement. Skin is involved in more than half of patients with an epidermal as well as dermal pattern of infiltration (mainly perivascular)(Figure 2). Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma is endemic in several regions of the world, and the distribution is closely linked to the prevalence of human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 in the population. This neoplasm is of T-cell lineage and may share CD4 but not PDC-associated antigens with BPDCN.1

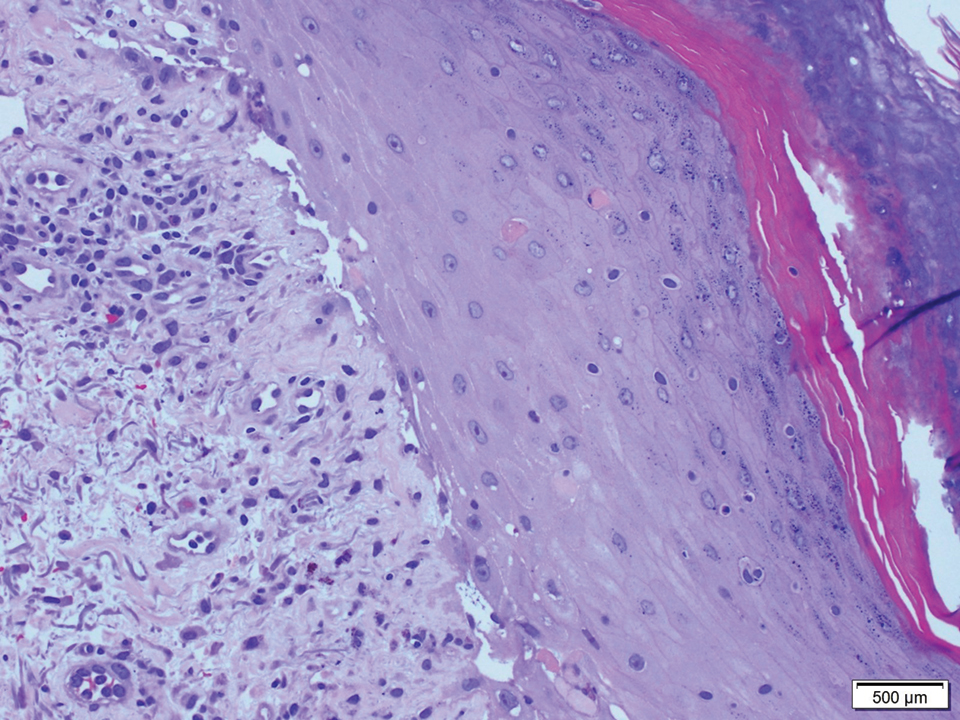

Cutaneous involvement by T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (T-LBL) is a rare occurrence with a frequency of approximately 4.3%.8 T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma usually presents as multiple skin lesions throughout the body. Almost all cutaneous T-LBL cases are seen in association with bone marrow and/or mediastinal, lymph node, or extranodal involvement. Cutaneous T-LBLs present as a diffuse monomorphous infiltrate located in the entire dermis and subcutis without epidermotropism, composed of medium to large blasts with finely dispersed chromatin and relatively prominent nucleoli (Figure 3). Immunophenotyping studies show an immature T-cell immunophenotype, with expression of TdT (usually uniform), CD7, and cytoplasmic CD3 and an absence of PDC-associated antigens.8

Primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma (PCGDTL) is a neoplasm primarily involving the skin. Often rapidly fatal, PCGDTL has a broad clinical spectrum that may include indolent variants—subcutaneous, epidermotropic, and dermal. Patients typically present with nodular lesions that progress to ulceration and necrosis. Early lesions can be confused with erythema nodosum, mycosis fungoides, or infection. Histologically, they show variable epidermotropism as well as dermal and subcutaneous involvement by medium to large cells with coarse clumped chromatin (Figure 4). Large blastic cells with vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli are infrequent. In contrast to BPCDN, the neoplastic lymphocytes in dermal and subcutaneous PCGDTL typically are positive for T-cell intracellular antigen-1 and granzyme B with loss of CD4.9

At the time of presentation, 27% to 87% of BPDCN patients will have bone marrow involvement, 22% to 28% will have blood involvement, and 6% to 41% will have lymph node involvement.1-4,6,7,10,11 The clinical course is aggressive, with a median survival of 10.0 to 19.8 months, irrespective of the initial pattern of disease.1 Most cases have shown initial response to multiagent chemotherapy, but relapses with subsequent resistance to drugs regularly have been observed. Age has an adverse impact of prognosis. Low TdT expression has been associated with shorter survival.1 Approximately 10% to 20% of cases of BPDCN are associated with or develop into chronic myelogenous leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, or acute myeloid leukemia.1,4 Pediatric patients have a greater 5-year overall survival rate than older patients, and overall survival worsens with increasing age. The extent of cutaneous involvement and presence of systemic involvement at initial presentation do not seem to be strong predictors of survival.1,2,5-7,10-12 In a retrospective analysis of 90 patients, Julia et al12 found that the type of skin disease did not predict survival. Specifically, the presence of nodular lesions and disseminated skin involvement were not adverse prognostic factors compared with macular lesions limited to 1 or 2 body areas.12

The Diagnosis: Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm

A diagnosis of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN) was rendered. Subsequent needle core biopsy of a left axillary lymph node as well as bone marrow aspiration and biopsy revealed a similar diffuse blastoid infiltrate with an identical immunophenotype to that in the skin biopsy from the pretibial mass and peripheral blood.

Previously known as blastic natural killer cell leukemia/lymphoma or agranular CD4+/CD56+ hematodermic neoplasm/tumor, BPDCN is a rare, clinically aggressive hematologic malignancy derived from the precursors of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. It often is diagnostically challenging, particularly when presenting at noncutaneous sites and in unusual (young) patient populations.1 It was included with other myeloid neoplasms in the 2008 World Health Organization classification; however, in the 2017 classification it was categorized as a separate entity. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm typically presents in the skin of elderly patients (age range at diagnosis, 61–67 years) with or without bone marrow involvement and systemic dissemination.1,2 The skin is the most common clinical site of disease in typical cases of BPDCN and often precedes bone marrow involvement. Thus, skin biopsy often is the key to making the diagnosis. Diagnosis of BPDCN may be delayed because of diagnostic pitfalls. Patients usually present with asymptomatic solitary or multiple lesions.3-5 Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm can present as an isolated purplish nodule or bruiselike papule or more commonly as disseminated purplish nodules, papules, and macules. Isolated nodules are found on the head and lower limbs and can be more than 10 cm in diameter. Peripheral blood and bone marrow may be minimally involved at presentation but invariably become involved with the progression of disease. Cytopenia can occur at diagnosis and in a minority of severe cases indicates bone marrow failure.2-6

Skin involvement of BPDCN is thought to be secondary to the expression of skin migration molecules, such as cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen, one of the E-selectin ligands, which binds to E-selectin on high endothelial venules. In addition, the local dermal microenvironment of chemokines binding CXCR3, CXCR4, CCR6, or CCR7 present on neoplastic cells possibly leads to skin involvement. The full mechanism underlying the cutaneous tropism is still to be elucidated.4-7 Infiltration of the oral mucosa is seen in some patients, but it may be underreported. Mucosal disease typically appears similarly to cutaneous disease.

The cutaneous differential diagnosis for BPDCN depends on the clinical presentation, extent of disease spread, and thickness of infiltration. It includes common nonneoplastic diseases such as traumatic ecchymoses; purpuric disorders; extramedullary hematopoiesis; and soft-tissue neoplasms such as angiosarcoma, Kaposi sarcoma, neuroblastoma, and vascular metastases, as well as skin involvement by other hematologic neoplasms. An adequate incisional biopsy rather than a punch or shave biopsy is recommended for diagnosis. Dermatologists should alert the pathologist that BPDCN is in the clinical differential diagnosis when possible so that judicious use of appropriate immunophenotypic markers such as CD123, CD4, CD56, and T-cell leukemia/lymphoma protein 1 will avoid misdiagnosis of this aggressive condition, in addition to excluding acute myeloid leukemia, which also may express 3 of the above markers. However, most cases of acute myeloid leukemia lack terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) and express monocytic and other myeloid markers. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase is positive in approximately one-third of cases of BPDCN, with expression in 10% to 80% of cells.1

It is important to include BPDCN in the differential diagnosis of immunophenotypically aberrant hematologic tumors. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, accounts for 4% of all primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas.1 Compared with BPDCN, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma usually occurs in an older age group and is of B-cell lineage. Morphologically, these neoplasms are composed of a monotonous, diffuse, nonepidermotropic infiltrate of confluent sheets of centroblasts and immunoblasts (Figure 1). They may share immunohistochemical markers of CD79a, multiple myeloma 1, Bcl-2, and Bcl-6; however, they lack plasmacytoid dendritic cell (PDC)– associated antigens such as CD4, CD56, CD123, and T-cell leukemia/lymphoma protein 1.1

Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma is a neoplasm histologically composed of highly pleomorphic medium- to large-sized T cells with an irregular multilobated nuclear contour, so-called flower cells, in the peripheral blood. The nuclear chromatin is coarse and clumped with prominent nucleoli. Blastlike cells with dispersed chromatin are present in variable proportions. Most patients present with widespread lymph node and peripheral blood involvement. Skin is involved in more than half of patients with an epidermal as well as dermal pattern of infiltration (mainly perivascular)(Figure 2). Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma is endemic in several regions of the world, and the distribution is closely linked to the prevalence of human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 in the population. This neoplasm is of T-cell lineage and may share CD4 but not PDC-associated antigens with BPDCN.1

Cutaneous involvement by T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (T-LBL) is a rare occurrence with a frequency of approximately 4.3%.8 T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma usually presents as multiple skin lesions throughout the body. Almost all cutaneous T-LBL cases are seen in association with bone marrow and/or mediastinal, lymph node, or extranodal involvement. Cutaneous T-LBLs present as a diffuse monomorphous infiltrate located in the entire dermis and subcutis without epidermotropism, composed of medium to large blasts with finely dispersed chromatin and relatively prominent nucleoli (Figure 3). Immunophenotyping studies show an immature T-cell immunophenotype, with expression of TdT (usually uniform), CD7, and cytoplasmic CD3 and an absence of PDC-associated antigens.8

Primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma (PCGDTL) is a neoplasm primarily involving the skin. Often rapidly fatal, PCGDTL has a broad clinical spectrum that may include indolent variants—subcutaneous, epidermotropic, and dermal. Patients typically present with nodular lesions that progress to ulceration and necrosis. Early lesions can be confused with erythema nodosum, mycosis fungoides, or infection. Histologically, they show variable epidermotropism as well as dermal and subcutaneous involvement by medium to large cells with coarse clumped chromatin (Figure 4). Large blastic cells with vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli are infrequent. In contrast to BPCDN, the neoplastic lymphocytes in dermal and subcutaneous PCGDTL typically are positive for T-cell intracellular antigen-1 and granzyme B with loss of CD4.9

At the time of presentation, 27% to 87% of BPDCN patients will have bone marrow involvement, 22% to 28% will have blood involvement, and 6% to 41% will have lymph node involvement.1-4,6,7,10,11 The clinical course is aggressive, with a median survival of 10.0 to 19.8 months, irrespective of the initial pattern of disease.1 Most cases have shown initial response to multiagent chemotherapy, but relapses with subsequent resistance to drugs regularly have been observed. Age has an adverse impact of prognosis. Low TdT expression has been associated with shorter survival.1 Approximately 10% to 20% of cases of BPDCN are associated with or develop into chronic myelogenous leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, or acute myeloid leukemia.1,4 Pediatric patients have a greater 5-year overall survival rate than older patients, and overall survival worsens with increasing age. The extent of cutaneous involvement and presence of systemic involvement at initial presentation do not seem to be strong predictors of survival.1,2,5-7,10-12 In a retrospective analysis of 90 patients, Julia et al12 found that the type of skin disease did not predict survival. Specifically, the presence of nodular lesions and disseminated skin involvement were not adverse prognostic factors compared with macular lesions limited to 1 or 2 body areas.12

- Facchetti F, Petrella T, Pileri SA. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cells neoplasm. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. 4th ed. World Health Organization; 2017:174-177.

- Jegalian AG, Facchetti F, Jaffe ES. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells: physiologic roles and pathologic states. Adv Anat Pathol. 2009;16:392-404.

- Shi Y, Wang E. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: a clinicopathologic review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138:564-569.

- Khoury JD, Medeiros LJ, Manning JT, et al. CD56(+) TdT(+) blastic natural killer cell tumor of the skin: a primitive systemic malignancy related to myelomonocytic leukemia. Cancer. 2002;94:2401-2408.

- Kolerova A, Sergeeva I, Krinitsyna J, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: case report and literature overview. Indian J Dermatol. 2020;65:217-221.

- Hirner JP, O’Malley JT, LeBoeuf NR. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: the dermatologist’s perspective. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2020;34:501-509.

- Guiducii C, Tripodo C, Gong M, et al. Autoimmune skin inflammation is dependent on plasmacytoid dendritic cell activation by nucleic acids via TLR7 and TLR9. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2931-2942.

- Khurana S, Beltran M, Jiang L, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma: case report and literature review. Case Rep Hematol. 2019;2019:3540487. doi:10.1155/2019/3540487

- Gladys TE, Helm MF, Anderson BE, et al. Rapid onset of widespread nodules and lymphadenopathy. Cutis. 2020;106:132, 153-155.

- Gregorio J, Meller S, Conrad C, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells sense skin injury and promote wound healing through type I interferons. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2921-2930.

- Guru Murthy GS, Pemmaraju N, Attallah E. Epidemiology and survival of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm. Leuk Res. 2018;73:21-23.

- Julia F, Petrella T, Beylot-Barry M, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: clinical features in 90 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2012;169:579-586.

- Facchetti F, Petrella T, Pileri SA. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cells neoplasm. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. 4th ed. World Health Organization; 2017:174-177.

- Jegalian AG, Facchetti F, Jaffe ES. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells: physiologic roles and pathologic states. Adv Anat Pathol. 2009;16:392-404.

- Shi Y, Wang E. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: a clinicopathologic review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138:564-569.

- Khoury JD, Medeiros LJ, Manning JT, et al. CD56(+) TdT(+) blastic natural killer cell tumor of the skin: a primitive systemic malignancy related to myelomonocytic leukemia. Cancer. 2002;94:2401-2408.

- Kolerova A, Sergeeva I, Krinitsyna J, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: case report and literature overview. Indian J Dermatol. 2020;65:217-221.

- Hirner JP, O’Malley JT, LeBoeuf NR. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: the dermatologist’s perspective. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2020;34:501-509.

- Guiducii C, Tripodo C, Gong M, et al. Autoimmune skin inflammation is dependent on plasmacytoid dendritic cell activation by nucleic acids via TLR7 and TLR9. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2931-2942.

- Khurana S, Beltran M, Jiang L, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma: case report and literature review. Case Rep Hematol. 2019;2019:3540487. doi:10.1155/2019/3540487

- Gladys TE, Helm MF, Anderson BE, et al. Rapid onset of widespread nodules and lymphadenopathy. Cutis. 2020;106:132, 153-155.

- Gregorio J, Meller S, Conrad C, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells sense skin injury and promote wound healing through type I interferons. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2921-2930.

- Guru Murthy GS, Pemmaraju N, Attallah E. Epidemiology and survival of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm. Leuk Res. 2018;73:21-23.

- Julia F, Petrella T, Beylot-Barry M, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: clinical features in 90 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2012;169:579-586.

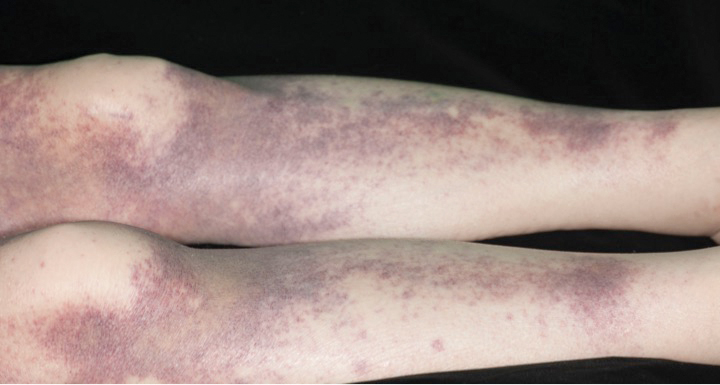

A 23-year-old man presented with skin that bruised easily, pancytopenia, recent fatigue, fever, and loss of appetite, along with a nontender, brown-purple, left anterior pretibial mass of 2 years’ duration (top). Computed tomography showed diffuse lymphadenopathy involving the inguinal, mesenteric, retroperitoneal, mediastinal, and axillary regions. A biopsy of the mass showed a dense monomorphous infiltrate of medium-sized blastoid cells with small or inconspicuous nucleoli (bottom). The lesion diffusely involved the dermis and extended into the subcutaneous tissue but spared the epidermis. Flow cytometry immunophenotyping of peripheral blood neoplastic cells (bottom [inset]) showed high-level expression of CD123 together with expression of CD4, CD56, CD45RA, and CD43 but a lack of expression of any other myelomonocytic or lymphoid lineage–associated markers.

Dermatologic Management of Hidradenitis Suppurativa and Impact on Pregnancy and Breastfeeding

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease associated with hyperandrogenism and is caused by occlusion or rupture of follicular units and inflammation of the apocrine glands.1-3 The disease most commonly affects women (female to male ratio of 3:1) of childbearing age.1,2,4,5 Body areas affected include the axillae and groin, and less commonly the perineum; perianal region; and skin folds, such as gluteal, inframammary, and infraumbilical folds.1,2 Symptoms manifest as painful subcutaneous nodules with possible accompanying purulent drainage, sinus tracts, and/or dermal contractures. Although the pathophysiology is unclear, androgens affect the course of HS during pregnancy by stimulating the affected glands and altering cytokines.1,2,6

During pregnancy, maternal immune function switches from cell-mediated T helper cell (TH1) to humoral TH2 cytokine production. The activity of sebaceous and eccrine glands increases while the activity of apocrine glands decreases, thus changing the inflammatory course of HS during pregnancy.3 Approximately 20% of women with HS experience improvement of symptoms during pregnancy, while the remainder either experience no relief or deterioration of symptoms.1 Improvement in symptoms during pregnancy was found to occur more frequently in those who had worsening symptoms during menses owing to the possible hormonal effect estrogen has on inhibiting TH1 and TH17 proinflammatory cytokines, which promotes an immunosuppressive environment.4

Lactation and breastfeeding abilities may be hindered if a woman has HS affecting the apocrine glands of breast tissue and a symptom flare in the postpartum period. If HS causes notable inflammation in the nipple-areolar complex during pregnancy, the patient may experience difficulties with lactation and milk fistula formation, leading to inability to breastfeed.2 Another reason why mothers with HS may not be able to breastfeed is that the medications required to treat the disease are unsafe if passed to the infant via breast milk. In addition, the teratogenic effects of HS medications may necessitate therapy adjustments in pregnancy.1 Here, we provide a brief overview of the medical management considerations of HS in the setting of pregnancy and the impact on breastfeeding.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT AND DRUG SAFETY

Dermatologists prescribe a myriad of topical and systemic medications to ameliorate symptoms of HS. Therapy regimens often are multimodal and include antibiotics, biologics, and immunosuppressants.1,3

Antibiotics

First-line antibiotics include clindamycin, metronidazole, tetracyclines, erythromycin, rifampin, dapsone, and fluoroquinolones. Topical clindamycin 1%, metronidazole 0.75%, and erythromycin 2% are used for open or active HS lesions and are all safe to use in pregnancy since there is minimal systemic absorption and minimal excretion into breast milk.1 Topical antimicrobial washes such as benzoyl peroxide and chlorhexidine often are used in combination with systemic medications to treat HS. These washes are safe during pregnancy and lactation, as they have minimal systemic absorption.7

Of these first-line antibiotics, only tetracyclines are contraindicated during pregnancy and lactation, as they are deemed to be in category D by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).1 Aside from tetracyclines, these antibiotics do not cause birth defects and are safe for nursing infants.1,8 Systemic clindamycin is safe during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Systemic metronidazole also is safe for use in pregnant patients but needs to be discontinued 12 to 24 hours prior to breastfeeding, which often prohibits appropriate dosing.1

Systemic Erythromycin—There are several forms of systemic erythromycin, including erythromycin base, erythromycin estolate, erythromycin ethylsuccinate (EES), and erythromycin stearate. Erythromycin estolate is contraindicated in pregnancy because it is associated with reversible maternal hepatoxicity and jaundice.9-11 Erythromycin ethylsuccinate is the preferred form for pregnant patients. Providers should exercise caution when prescribing EES to lactating mothers, as small amounts are still secreted through breast milk.11 Some studies have shown an increased risk for development of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis with systemic erythromycin use, especially if a neonate is exposed in the first 14 days of life. Thus, we recommend withholding EES for 2 weeks after delivery if the patient is breastfeeding. A follow-up study did not find any association between erythromycin and infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis; however, the American Academy of Pediatrics still recommends short-term use only of erythromycin if it is to be used in the systemic form.8

Rifampin—Rifampin is excreted into breast milk but without adverse effects to the infant. Rifampin also is safe in pregnancy but should be used on a case-by-case basis in pregnant or nursing women because it is a cytochrome P450 inducer.

Dapsone—Dapsone has no increased risk for congenital anomalies. However, it is associated with hemolytic anemia and neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, especially in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency.12 Newborns exposed to dapsone are at an increased risk for methemoglobinemia owing to increased sensitivity of fetal erythrocytes to oxidizing agents.13 If dapsone use is necessary, stopping dapsone treatment in the last month of gestation is recommended to minimize risk for kernicterus.9 Dapsone can be found in high concentrations in breast milk at 14.3% of the maternal dose. It is still safe to use during breastfeeding, but there is a risk of the infant developing hyperbilirubinemia/G6PD deficiency.1,8 Thus, physicians may consider performing a G6PD screen on infants to determine if breastfeeding is safe.12

Fluoroquinolones—Quinolones are not contraindicated during pregnancy, but they can damage fetal cartilage and thus should be reserved for use in complicated infections when the benefits outweigh the risks.12 Quinolones are believed to increase risk for arthropathy but are safe for use in lactation. When quinolones are digested with milk, exposure decreases below pediatric doses because of the ionized property of calcium in milk.8

Tumor Necrosis Factor α Inhibitors—The safety of anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α biologics in pregnancy is less certain when compared with antibiotics.1 Anti–TNF-α inhibitors such as etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximab are all labeled as FDA category B, meaning there are no well-controlled human studies of the drugs.9 There are limited data that support safe use of TNF-α inhibitors prior to the third trimester before maternal IgG antibodies are transferred to the fetus via the placenta.1,13 Anti–TNF-α inhibitors may be safe when breastfeeding because the drugs have large molecular weights that prevent them from entering breast milk in large amounts. Absorption also is limited due to the infant’s digestive acids and enzymes breaking down the protein structure of the medication.8 Overall, TNF-α inhibitor use is still controversial and only used if the benefits outweigh the risks during pregnancy or if there is no alternative treatment.1,3,9

Ustekinumab and Anakinra—Ustekinumab (an IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor) and anakinra (an IL-1α and IL-1β inhibitor) also are FDA category B drugs and have limited data supporting their use as HS treatment in pregnancy. Anakinra may have evidence of compatibility with breastfeeding, as endogenous IL-1α inhibitor is found in colostrum and mature breast milk.1

Immunosuppressants

Immunosuppressants that are used to treat HS include corticosteroids and cyclosporine.

Corticosteroids—Topical corticosteroids can be used safely in lactation if they are not applied directly to the nipple or any area that makes direct contact with the infant’s mouth. Intralesional corticosteroid injections are safe for use during both pregnancy and breastfeeding to decrease inflammation of acutely flaring lesions and can be considered first-line treatment.1 Oral glucocorticoids also can be safely used for acute flares during pregnancy; however, prolonged use is associated with pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia, eclampsia, premature delivery, and gestational diabetes.12 There also is a small risk of oral cleft deformity in the infant; thus, potent corticosteroids are recommended in short durations during pregnancy, and there are no adverse effects if the maternal dose is less than 10 mg daily.8,12 Systemic steroids are safe to use with breastfeeding, but patients should be advised to wait 4 hours after ingesting medication before breastfeeding.1,8

Cyclosporine—Topical and oral calcineurin inhibitors such as cyclosporine have low risk for transmission into breast milk; however, potential effects of exposure through breast milk are unknown. For that reason, manufacturers state that cyclosporine use is contraindicated during lactation.8 If cyclosporine is to be used by a breastfeeding woman, monitoring cyclosporine concentrations in the infant is suggested to ensure that the exposure is less than 5% to 10% of the therapeutic dose.13 The use of cyclosporine has been extensively studied in pregnant transplant patients and is considered relatively safe for use in pregnancy.14 Cyclosporine is lipid soluble and thus is quickly metabolized and spread throughout the body; it can easily cross the placenta.9,13 Blood concentration in the fetus is 30% to 64% that of the maternal circulation. However, cyclosporine is only toxic to the fetus at maternally toxic doses, which can result in low birth weight and increased prenatal and postnatal mortality.13

Isotretinoin, Oral Contraceptive Pills, and Spironolactone

Isotretinoin and hormonal treatments such as oral contraceptive pills and spironolactone (an androgen receptor blocker) commonly are used to treat HS, but all are contraindicated in pregnancy and lactation. Isotretinoin is a well-established teratogen, but adverse effects on nursing babies have not been described. However, the manufacturer of isotretinoin advises against its use in lactation. Oral contraceptive pill use in early pregnancy is associated with increased risk for Down syndrome. Oral contraceptive pill use also is contraindicated in lactation for 2 reasons: decreased milk production and risk for fetal feminization. Antiandrogenic agents such as spironolactone have been shown to be associated with hypospadias and feminization of the male fetus.7

COMMENT

Women with HS usually require ongoing medical treatment during pregnancy and immediately postpartum; thus, it is important that treatments are proven to be safe for use in this specific population. Current management guidelines are not entirely suitable for pregnant and breastfeeding women given that many HS drugs have teratogenic effects and/or can be excreted into breast milk.1 Several treatments have uncertain safety profiles in pregnancy and breastfeeding, which calls for dermatologists to change or create new regimens for their patients. Close management also is necessary to prevent excess inflammation of breast tissue and milk fistula formation, which would hinder normal breastfeeding.

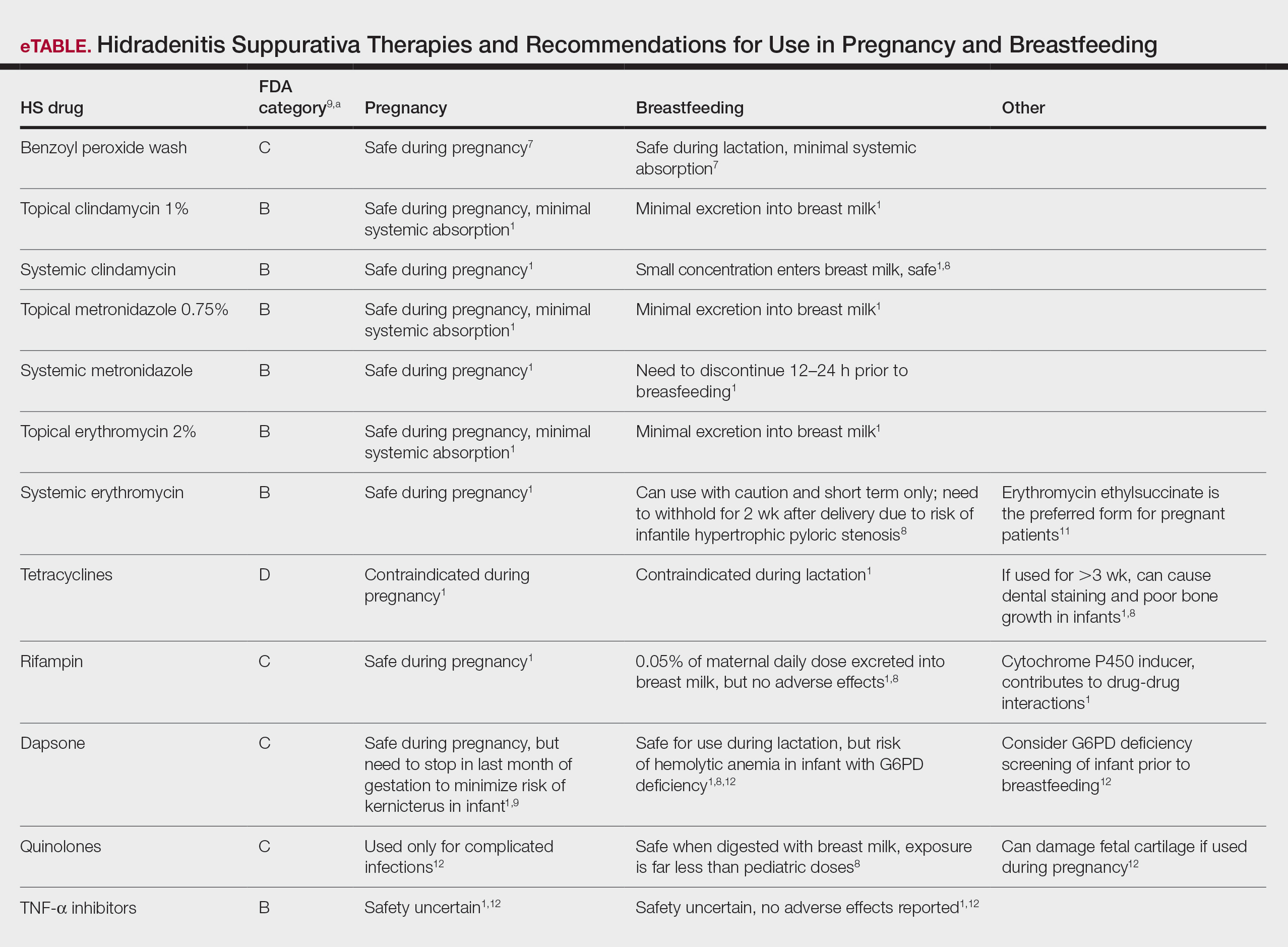

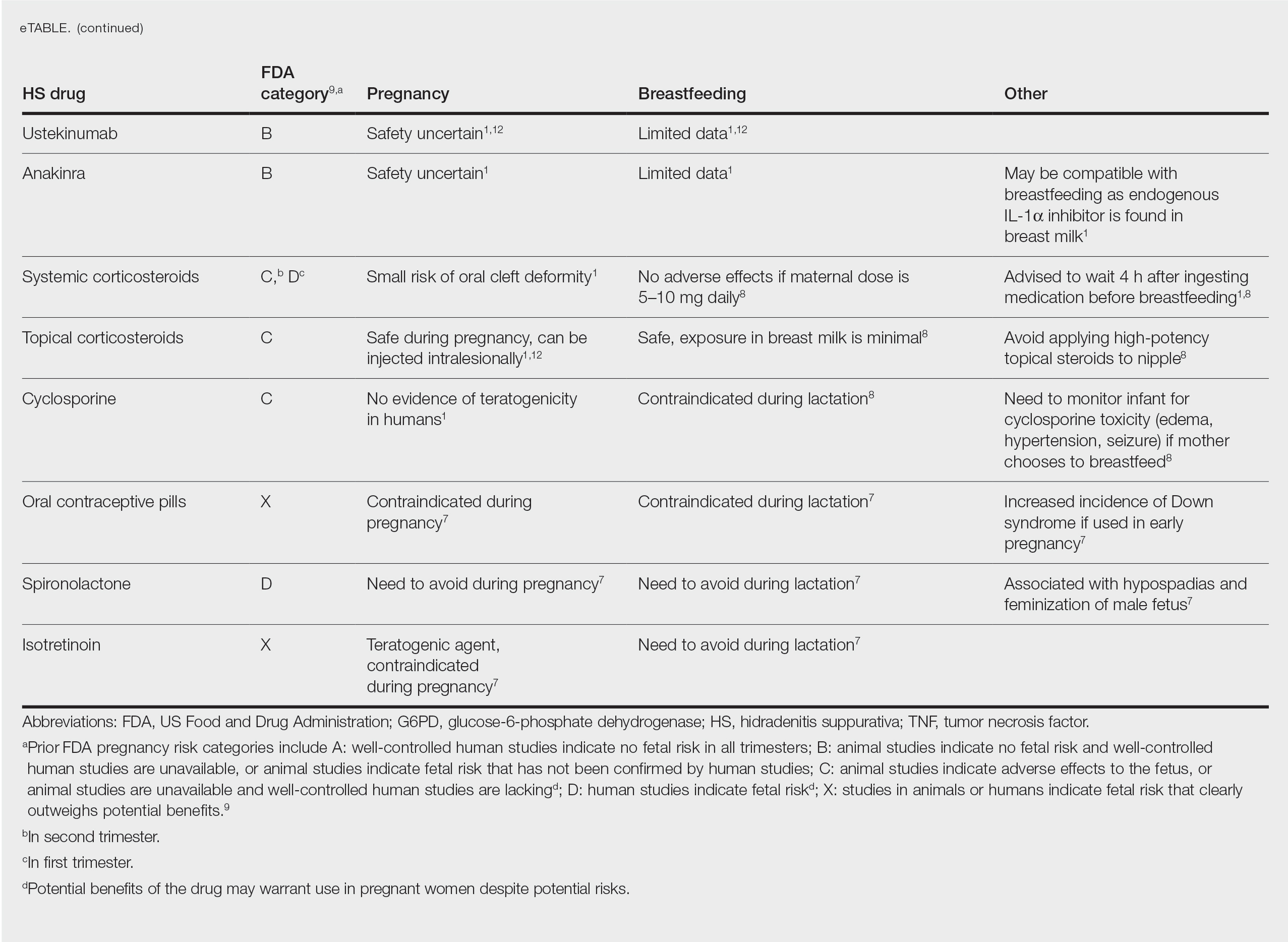

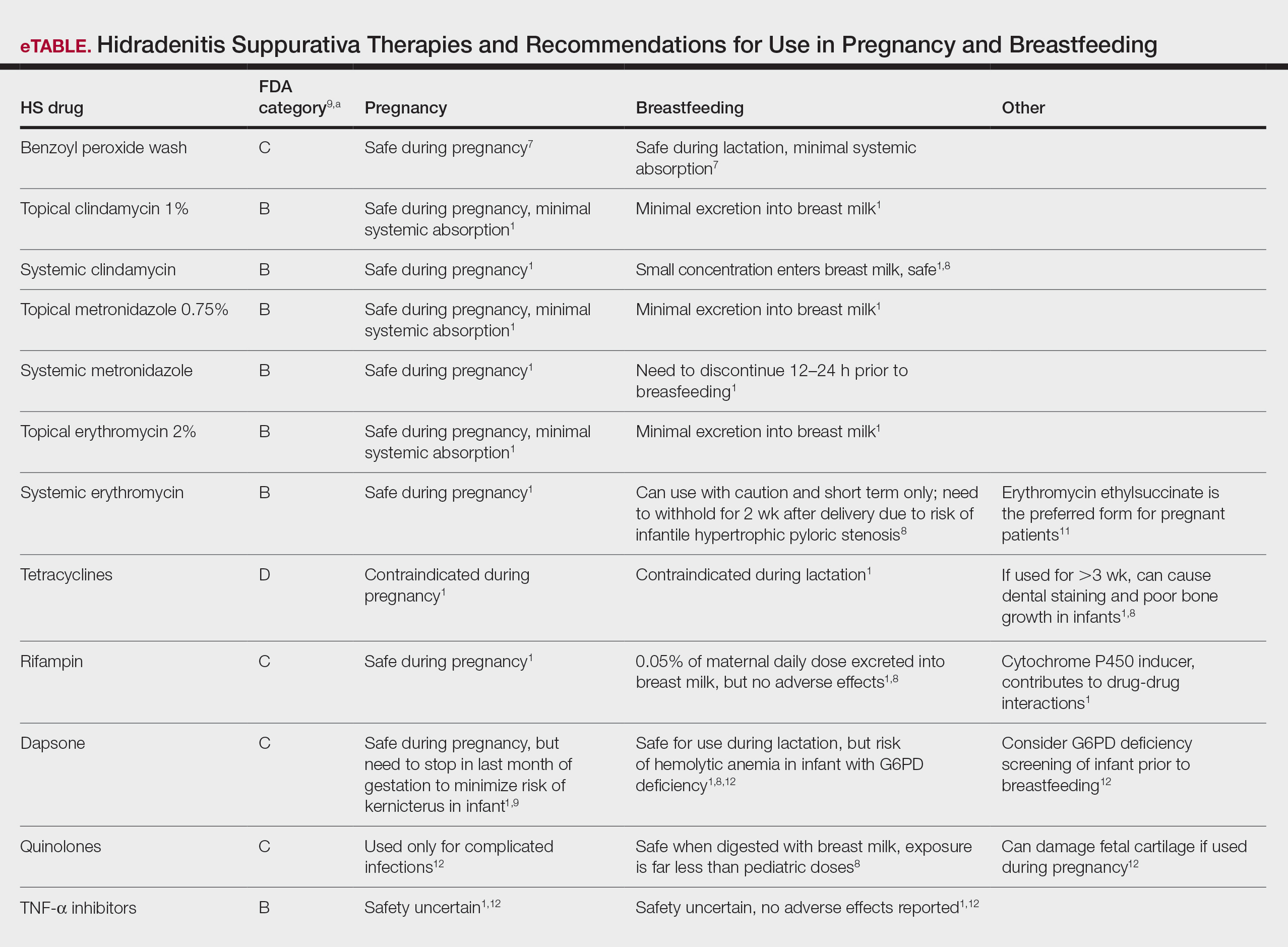

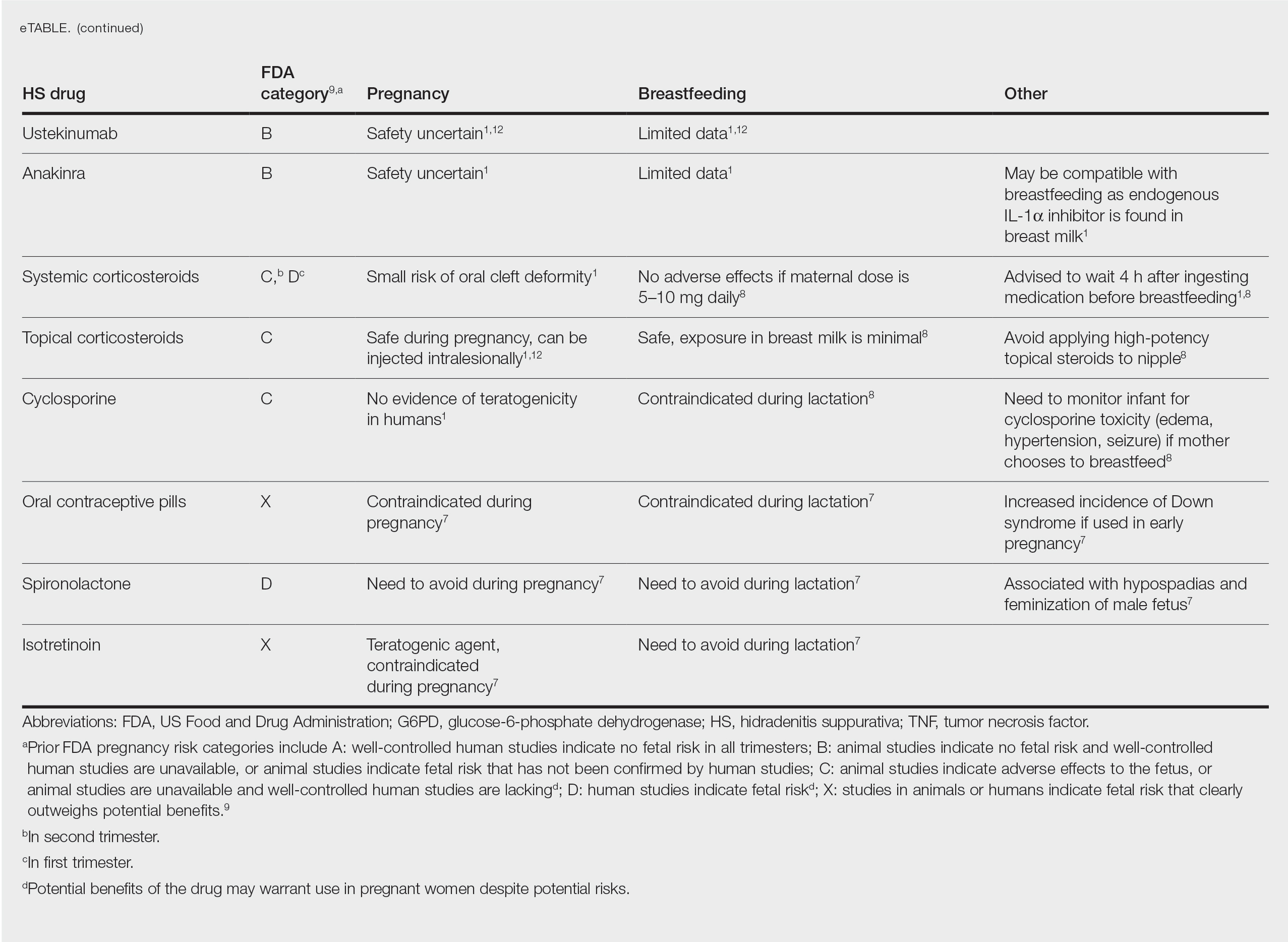

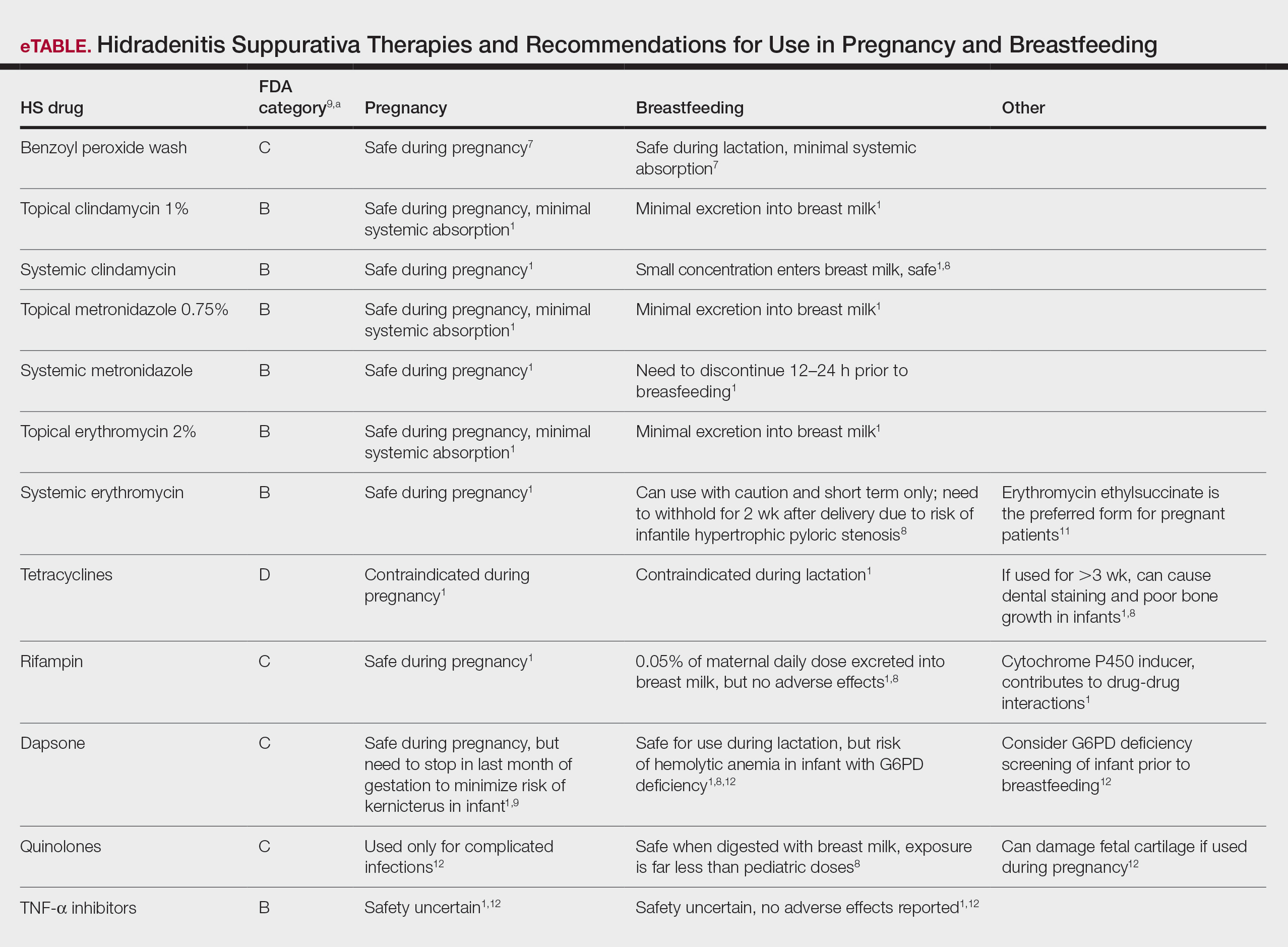

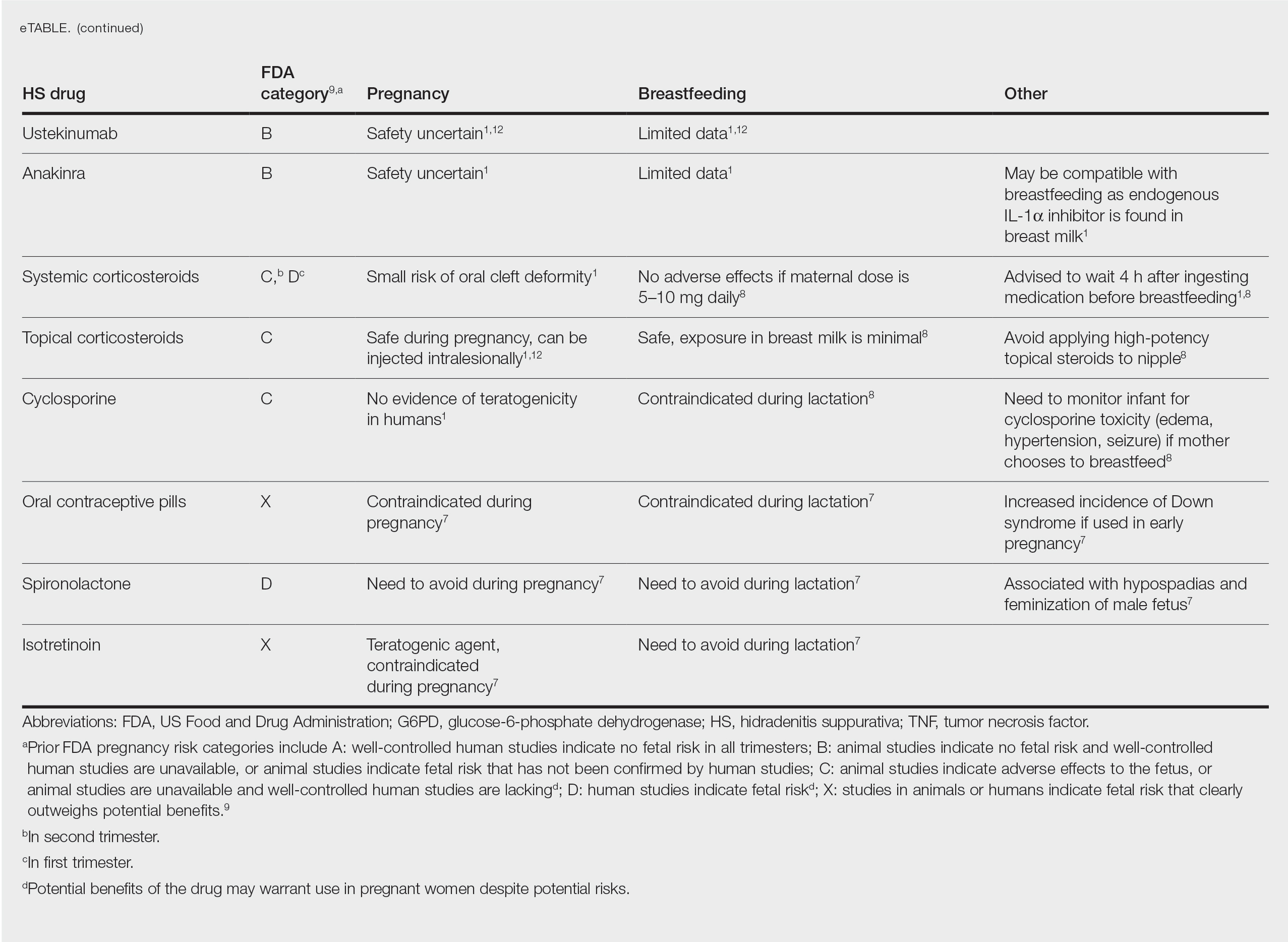

The eTable lists medications used to treat HS. The FDA category is listed next to each drug. However, it should be noted that these FDA letter categories were replaced with the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule in 2015. The letter ratings were deemed overly simplistic and replaced with narrative-based labeling that provides more detailed adverse effects and clinical considerations.9

Risk Factors of HS—Predisposing risk factors for HS flares that are controllable include obesity and smoking.2 Pregnancy weight gain may cause increased skin maceration at intertriginous sites, which can contribute to worsening HS symptoms.1,5 Adipocytes play a role in HS exacerbation by promoting secretion of TNF-α, leading to increased inflammation.5 Dermatologists can help prevent postpartum HS flares by monitoring weight gain during pregnancy, encouraging smoking cessation, and promoting weight and nutrition goals as set by an obstetrician.1 In addition to medications, management of HS should include emotional support and education on wearing loose-fitting clothing to avoid irritation of the affected areas.3 An emphasis on dermatologist counseling for all patients with HS, even for those with milder disease, can reduce exacerbations during pregnancy.5

CONCLUSION

The selection of dermatologic drugs for the treatment of HS in the setting of pregnancy involves complex decision-making. Dermatologists need more guidelines and proven safety data in human trials, especially regarding use of biologics and immunosuppressants to better treat HS in pregnancy. With more data, they can create more evidence-based treatment regimens to help prevent postpartum exacerbations of HS. Thus, patients can breastfeed their infants comfortably and without any risks of impaired child development. In the meantime, dermatologists can continue to work together with obstetricians and psychiatrists to decrease disease flares through counseling patients on nutrition and weight gain and providing emotional support.

- Perng P, Zampella JG, Okoye GA. Management of hidradenitis suppurativa in pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:979-989. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.10.032

- Samuel S, Tremelling A, Murray M. Presentation and surgical management of hidradenitis suppurativa of the breast during pregnancy: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;51:21-24. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2018.08.013

- Yang CS, Teeple M, Muglia J, et al. Inflammatory and glandular skin disease in pregnancy. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:335-343. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.02.005

- Vossen AR, van Straalen KR, Prens EP, et al. Menses and pregnancy affect symptoms in hidradenitis suppurativa: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:155-156. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.07.024

- Lyons AB, Peacock A, McKenzie SA, et al. Evaluation of hidradenitis suppurativa disease course during pregnancy and postpartum. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:681-685. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0777

- Riis PT, Ring HC, Themstrup L, et al. The role of androgens and estrogens in hidradenitis suppurativa—a systematic review. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2016;24:239-249.

- Kong YL, Tey HL. Treatment of acne vulgaris during pregnancy and lactation. Drugs. 2013;73:779-787. doi:10.1007/s40265-013-0060-0

- Butler DC, Heller MM, Murase JE. Safety of dermatologic medications in pregnancy and lactation: part II. lactation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:417:E1-E10. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.09.009

- Wilmer E, Chai S, Kroumpouzos G. Drug safety: pregnancy rating classifications and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:401-409. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.02.013

- Inman WH, Rawson NS. Erythromycin estolate and jaundice. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983;286:1954-1955. doi:10.1136/bmj.286.6382.1954

- Workowski KA, Berman SM. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-11):1-94.

- Murase JE, Heller MM, Butler DC. Safety of dermatologic medications in pregnancy and lactation: part I. pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:401.e1-14; quiz 415. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.09.010

- Brown SM, Aljefri K, Waas R, et al. Systemic medications used in treatment of common dermatological conditions: safety profile with respect to pregnancy, breast feeding and content in seminal fluid. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30:2-18. doi:10.1080/09546634.2016.1202402

- Kamarajah SK, Arntdz K, Bundred J, et al. Outcomes of pregnancy in recipients of liver transplants. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:1398-1404.e1. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2018.11.055

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease associated with hyperandrogenism and is caused by occlusion or rupture of follicular units and inflammation of the apocrine glands.1-3 The disease most commonly affects women (female to male ratio of 3:1) of childbearing age.1,2,4,5 Body areas affected include the axillae and groin, and less commonly the perineum; perianal region; and skin folds, such as gluteal, inframammary, and infraumbilical folds.1,2 Symptoms manifest as painful subcutaneous nodules with possible accompanying purulent drainage, sinus tracts, and/or dermal contractures. Although the pathophysiology is unclear, androgens affect the course of HS during pregnancy by stimulating the affected glands and altering cytokines.1,2,6

During pregnancy, maternal immune function switches from cell-mediated T helper cell (TH1) to humoral TH2 cytokine production. The activity of sebaceous and eccrine glands increases while the activity of apocrine glands decreases, thus changing the inflammatory course of HS during pregnancy.3 Approximately 20% of women with HS experience improvement of symptoms during pregnancy, while the remainder either experience no relief or deterioration of symptoms.1 Improvement in symptoms during pregnancy was found to occur more frequently in those who had worsening symptoms during menses owing to the possible hormonal effect estrogen has on inhibiting TH1 and TH17 proinflammatory cytokines, which promotes an immunosuppressive environment.4

Lactation and breastfeeding abilities may be hindered if a woman has HS affecting the apocrine glands of breast tissue and a symptom flare in the postpartum period. If HS causes notable inflammation in the nipple-areolar complex during pregnancy, the patient may experience difficulties with lactation and milk fistula formation, leading to inability to breastfeed.2 Another reason why mothers with HS may not be able to breastfeed is that the medications required to treat the disease are unsafe if passed to the infant via breast milk. In addition, the teratogenic effects of HS medications may necessitate therapy adjustments in pregnancy.1 Here, we provide a brief overview of the medical management considerations of HS in the setting of pregnancy and the impact on breastfeeding.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT AND DRUG SAFETY

Dermatologists prescribe a myriad of topical and systemic medications to ameliorate symptoms of HS. Therapy regimens often are multimodal and include antibiotics, biologics, and immunosuppressants.1,3

Antibiotics

First-line antibiotics include clindamycin, metronidazole, tetracyclines, erythromycin, rifampin, dapsone, and fluoroquinolones. Topical clindamycin 1%, metronidazole 0.75%, and erythromycin 2% are used for open or active HS lesions and are all safe to use in pregnancy since there is minimal systemic absorption and minimal excretion into breast milk.1 Topical antimicrobial washes such as benzoyl peroxide and chlorhexidine often are used in combination with systemic medications to treat HS. These washes are safe during pregnancy and lactation, as they have minimal systemic absorption.7

Of these first-line antibiotics, only tetracyclines are contraindicated during pregnancy and lactation, as they are deemed to be in category D by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).1 Aside from tetracyclines, these antibiotics do not cause birth defects and are safe for nursing infants.1,8 Systemic clindamycin is safe during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Systemic metronidazole also is safe for use in pregnant patients but needs to be discontinued 12 to 24 hours prior to breastfeeding, which often prohibits appropriate dosing.1

Systemic Erythromycin—There are several forms of systemic erythromycin, including erythromycin base, erythromycin estolate, erythromycin ethylsuccinate (EES), and erythromycin stearate. Erythromycin estolate is contraindicated in pregnancy because it is associated with reversible maternal hepatoxicity and jaundice.9-11 Erythromycin ethylsuccinate is the preferred form for pregnant patients. Providers should exercise caution when prescribing EES to lactating mothers, as small amounts are still secreted through breast milk.11 Some studies have shown an increased risk for development of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis with systemic erythromycin use, especially if a neonate is exposed in the first 14 days of life. Thus, we recommend withholding EES for 2 weeks after delivery if the patient is breastfeeding. A follow-up study did not find any association between erythromycin and infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis; however, the American Academy of Pediatrics still recommends short-term use only of erythromycin if it is to be used in the systemic form.8

Rifampin—Rifampin is excreted into breast milk but without adverse effects to the infant. Rifampin also is safe in pregnancy but should be used on a case-by-case basis in pregnant or nursing women because it is a cytochrome P450 inducer.

Dapsone—Dapsone has no increased risk for congenital anomalies. However, it is associated with hemolytic anemia and neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, especially in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency.12 Newborns exposed to dapsone are at an increased risk for methemoglobinemia owing to increased sensitivity of fetal erythrocytes to oxidizing agents.13 If dapsone use is necessary, stopping dapsone treatment in the last month of gestation is recommended to minimize risk for kernicterus.9 Dapsone can be found in high concentrations in breast milk at 14.3% of the maternal dose. It is still safe to use during breastfeeding, but there is a risk of the infant developing hyperbilirubinemia/G6PD deficiency.1,8 Thus, physicians may consider performing a G6PD screen on infants to determine if breastfeeding is safe.12

Fluoroquinolones—Quinolones are not contraindicated during pregnancy, but they can damage fetal cartilage and thus should be reserved for use in complicated infections when the benefits outweigh the risks.12 Quinolones are believed to increase risk for arthropathy but are safe for use in lactation. When quinolones are digested with milk, exposure decreases below pediatric doses because of the ionized property of calcium in milk.8

Tumor Necrosis Factor α Inhibitors—The safety of anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α biologics in pregnancy is less certain when compared with antibiotics.1 Anti–TNF-α inhibitors such as etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximab are all labeled as FDA category B, meaning there are no well-controlled human studies of the drugs.9 There are limited data that support safe use of TNF-α inhibitors prior to the third trimester before maternal IgG antibodies are transferred to the fetus via the placenta.1,13 Anti–TNF-α inhibitors may be safe when breastfeeding because the drugs have large molecular weights that prevent them from entering breast milk in large amounts. Absorption also is limited due to the infant’s digestive acids and enzymes breaking down the protein structure of the medication.8 Overall, TNF-α inhibitor use is still controversial and only used if the benefits outweigh the risks during pregnancy or if there is no alternative treatment.1,3,9

Ustekinumab and Anakinra—Ustekinumab (an IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor) and anakinra (an IL-1α and IL-1β inhibitor) also are FDA category B drugs and have limited data supporting their use as HS treatment in pregnancy. Anakinra may have evidence of compatibility with breastfeeding, as endogenous IL-1α inhibitor is found in colostrum and mature breast milk.1

Immunosuppressants

Immunosuppressants that are used to treat HS include corticosteroids and cyclosporine.

Corticosteroids—Topical corticosteroids can be used safely in lactation if they are not applied directly to the nipple or any area that makes direct contact with the infant’s mouth. Intralesional corticosteroid injections are safe for use during both pregnancy and breastfeeding to decrease inflammation of acutely flaring lesions and can be considered first-line treatment.1 Oral glucocorticoids also can be safely used for acute flares during pregnancy; however, prolonged use is associated with pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia, eclampsia, premature delivery, and gestational diabetes.12 There also is a small risk of oral cleft deformity in the infant; thus, potent corticosteroids are recommended in short durations during pregnancy, and there are no adverse effects if the maternal dose is less than 10 mg daily.8,12 Systemic steroids are safe to use with breastfeeding, but patients should be advised to wait 4 hours after ingesting medication before breastfeeding.1,8

Cyclosporine—Topical and oral calcineurin inhibitors such as cyclosporine have low risk for transmission into breast milk; however, potential effects of exposure through breast milk are unknown. For that reason, manufacturers state that cyclosporine use is contraindicated during lactation.8 If cyclosporine is to be used by a breastfeeding woman, monitoring cyclosporine concentrations in the infant is suggested to ensure that the exposure is less than 5% to 10% of the therapeutic dose.13 The use of cyclosporine has been extensively studied in pregnant transplant patients and is considered relatively safe for use in pregnancy.14 Cyclosporine is lipid soluble and thus is quickly metabolized and spread throughout the body; it can easily cross the placenta.9,13 Blood concentration in the fetus is 30% to 64% that of the maternal circulation. However, cyclosporine is only toxic to the fetus at maternally toxic doses, which can result in low birth weight and increased prenatal and postnatal mortality.13

Isotretinoin, Oral Contraceptive Pills, and Spironolactone

Isotretinoin and hormonal treatments such as oral contraceptive pills and spironolactone (an androgen receptor blocker) commonly are used to treat HS, but all are contraindicated in pregnancy and lactation. Isotretinoin is a well-established teratogen, but adverse effects on nursing babies have not been described. However, the manufacturer of isotretinoin advises against its use in lactation. Oral contraceptive pill use in early pregnancy is associated with increased risk for Down syndrome. Oral contraceptive pill use also is contraindicated in lactation for 2 reasons: decreased milk production and risk for fetal feminization. Antiandrogenic agents such as spironolactone have been shown to be associated with hypospadias and feminization of the male fetus.7

COMMENT

Women with HS usually require ongoing medical treatment during pregnancy and immediately postpartum; thus, it is important that treatments are proven to be safe for use in this specific population. Current management guidelines are not entirely suitable for pregnant and breastfeeding women given that many HS drugs have teratogenic effects and/or can be excreted into breast milk.1 Several treatments have uncertain safety profiles in pregnancy and breastfeeding, which calls for dermatologists to change or create new regimens for their patients. Close management also is necessary to prevent excess inflammation of breast tissue and milk fistula formation, which would hinder normal breastfeeding.

The eTable lists medications used to treat HS. The FDA category is listed next to each drug. However, it should be noted that these FDA letter categories were replaced with the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule in 2015. The letter ratings were deemed overly simplistic and replaced with narrative-based labeling that provides more detailed adverse effects and clinical considerations.9

Risk Factors of HS—Predisposing risk factors for HS flares that are controllable include obesity and smoking.2 Pregnancy weight gain may cause increased skin maceration at intertriginous sites, which can contribute to worsening HS symptoms.1,5 Adipocytes play a role in HS exacerbation by promoting secretion of TNF-α, leading to increased inflammation.5 Dermatologists can help prevent postpartum HS flares by monitoring weight gain during pregnancy, encouraging smoking cessation, and promoting weight and nutrition goals as set by an obstetrician.1 In addition to medications, management of HS should include emotional support and education on wearing loose-fitting clothing to avoid irritation of the affected areas.3 An emphasis on dermatologist counseling for all patients with HS, even for those with milder disease, can reduce exacerbations during pregnancy.5

CONCLUSION

The selection of dermatologic drugs for the treatment of HS in the setting of pregnancy involves complex decision-making. Dermatologists need more guidelines and proven safety data in human trials, especially regarding use of biologics and immunosuppressants to better treat HS in pregnancy. With more data, they can create more evidence-based treatment regimens to help prevent postpartum exacerbations of HS. Thus, patients can breastfeed their infants comfortably and without any risks of impaired child development. In the meantime, dermatologists can continue to work together with obstetricians and psychiatrists to decrease disease flares through counseling patients on nutrition and weight gain and providing emotional support.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease associated with hyperandrogenism and is caused by occlusion or rupture of follicular units and inflammation of the apocrine glands.1-3 The disease most commonly affects women (female to male ratio of 3:1) of childbearing age.1,2,4,5 Body areas affected include the axillae and groin, and less commonly the perineum; perianal region; and skin folds, such as gluteal, inframammary, and infraumbilical folds.1,2 Symptoms manifest as painful subcutaneous nodules with possible accompanying purulent drainage, sinus tracts, and/or dermal contractures. Although the pathophysiology is unclear, androgens affect the course of HS during pregnancy by stimulating the affected glands and altering cytokines.1,2,6

During pregnancy, maternal immune function switches from cell-mediated T helper cell (TH1) to humoral TH2 cytokine production. The activity of sebaceous and eccrine glands increases while the activity of apocrine glands decreases, thus changing the inflammatory course of HS during pregnancy.3 Approximately 20% of women with HS experience improvement of symptoms during pregnancy, while the remainder either experience no relief or deterioration of symptoms.1 Improvement in symptoms during pregnancy was found to occur more frequently in those who had worsening symptoms during menses owing to the possible hormonal effect estrogen has on inhibiting TH1 and TH17 proinflammatory cytokines, which promotes an immunosuppressive environment.4

Lactation and breastfeeding abilities may be hindered if a woman has HS affecting the apocrine glands of breast tissue and a symptom flare in the postpartum period. If HS causes notable inflammation in the nipple-areolar complex during pregnancy, the patient may experience difficulties with lactation and milk fistula formation, leading to inability to breastfeed.2 Another reason why mothers with HS may not be able to breastfeed is that the medications required to treat the disease are unsafe if passed to the infant via breast milk. In addition, the teratogenic effects of HS medications may necessitate therapy adjustments in pregnancy.1 Here, we provide a brief overview of the medical management considerations of HS in the setting of pregnancy and the impact on breastfeeding.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT AND DRUG SAFETY

Dermatologists prescribe a myriad of topical and systemic medications to ameliorate symptoms of HS. Therapy regimens often are multimodal and include antibiotics, biologics, and immunosuppressants.1,3

Antibiotics

First-line antibiotics include clindamycin, metronidazole, tetracyclines, erythromycin, rifampin, dapsone, and fluoroquinolones. Topical clindamycin 1%, metronidazole 0.75%, and erythromycin 2% are used for open or active HS lesions and are all safe to use in pregnancy since there is minimal systemic absorption and minimal excretion into breast milk.1 Topical antimicrobial washes such as benzoyl peroxide and chlorhexidine often are used in combination with systemic medications to treat HS. These washes are safe during pregnancy and lactation, as they have minimal systemic absorption.7

Of these first-line antibiotics, only tetracyclines are contraindicated during pregnancy and lactation, as they are deemed to be in category D by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).1 Aside from tetracyclines, these antibiotics do not cause birth defects and are safe for nursing infants.1,8 Systemic clindamycin is safe during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Systemic metronidazole also is safe for use in pregnant patients but needs to be discontinued 12 to 24 hours prior to breastfeeding, which often prohibits appropriate dosing.1

Systemic Erythromycin—There are several forms of systemic erythromycin, including erythromycin base, erythromycin estolate, erythromycin ethylsuccinate (EES), and erythromycin stearate. Erythromycin estolate is contraindicated in pregnancy because it is associated with reversible maternal hepatoxicity and jaundice.9-11 Erythromycin ethylsuccinate is the preferred form for pregnant patients. Providers should exercise caution when prescribing EES to lactating mothers, as small amounts are still secreted through breast milk.11 Some studies have shown an increased risk for development of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis with systemic erythromycin use, especially if a neonate is exposed in the first 14 days of life. Thus, we recommend withholding EES for 2 weeks after delivery if the patient is breastfeeding. A follow-up study did not find any association between erythromycin and infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis; however, the American Academy of Pediatrics still recommends short-term use only of erythromycin if it is to be used in the systemic form.8

Rifampin—Rifampin is excreted into breast milk but without adverse effects to the infant. Rifampin also is safe in pregnancy but should be used on a case-by-case basis in pregnant or nursing women because it is a cytochrome P450 inducer.

Dapsone—Dapsone has no increased risk for congenital anomalies. However, it is associated with hemolytic anemia and neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, especially in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency.12 Newborns exposed to dapsone are at an increased risk for methemoglobinemia owing to increased sensitivity of fetal erythrocytes to oxidizing agents.13 If dapsone use is necessary, stopping dapsone treatment in the last month of gestation is recommended to minimize risk for kernicterus.9 Dapsone can be found in high concentrations in breast milk at 14.3% of the maternal dose. It is still safe to use during breastfeeding, but there is a risk of the infant developing hyperbilirubinemia/G6PD deficiency.1,8 Thus, physicians may consider performing a G6PD screen on infants to determine if breastfeeding is safe.12

Fluoroquinolones—Quinolones are not contraindicated during pregnancy, but they can damage fetal cartilage and thus should be reserved for use in complicated infections when the benefits outweigh the risks.12 Quinolones are believed to increase risk for arthropathy but are safe for use in lactation. When quinolones are digested with milk, exposure decreases below pediatric doses because of the ionized property of calcium in milk.8

Tumor Necrosis Factor α Inhibitors—The safety of anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α biologics in pregnancy is less certain when compared with antibiotics.1 Anti–TNF-α inhibitors such as etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximab are all labeled as FDA category B, meaning there are no well-controlled human studies of the drugs.9 There are limited data that support safe use of TNF-α inhibitors prior to the third trimester before maternal IgG antibodies are transferred to the fetus via the placenta.1,13 Anti–TNF-α inhibitors may be safe when breastfeeding because the drugs have large molecular weights that prevent them from entering breast milk in large amounts. Absorption also is limited due to the infant’s digestive acids and enzymes breaking down the protein structure of the medication.8 Overall, TNF-α inhibitor use is still controversial and only used if the benefits outweigh the risks during pregnancy or if there is no alternative treatment.1,3,9

Ustekinumab and Anakinra—Ustekinumab (an IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor) and anakinra (an IL-1α and IL-1β inhibitor) also are FDA category B drugs and have limited data supporting their use as HS treatment in pregnancy. Anakinra may have evidence of compatibility with breastfeeding, as endogenous IL-1α inhibitor is found in colostrum and mature breast milk.1

Immunosuppressants

Immunosuppressants that are used to treat HS include corticosteroids and cyclosporine.

Corticosteroids—Topical corticosteroids can be used safely in lactation if they are not applied directly to the nipple or any area that makes direct contact with the infant’s mouth. Intralesional corticosteroid injections are safe for use during both pregnancy and breastfeeding to decrease inflammation of acutely flaring lesions and can be considered first-line treatment.1 Oral glucocorticoids also can be safely used for acute flares during pregnancy; however, prolonged use is associated with pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia, eclampsia, premature delivery, and gestational diabetes.12 There also is a small risk of oral cleft deformity in the infant; thus, potent corticosteroids are recommended in short durations during pregnancy, and there are no adverse effects if the maternal dose is less than 10 mg daily.8,12 Systemic steroids are safe to use with breastfeeding, but patients should be advised to wait 4 hours after ingesting medication before breastfeeding.1,8

Cyclosporine—Topical and oral calcineurin inhibitors such as cyclosporine have low risk for transmission into breast milk; however, potential effects of exposure through breast milk are unknown. For that reason, manufacturers state that cyclosporine use is contraindicated during lactation.8 If cyclosporine is to be used by a breastfeeding woman, monitoring cyclosporine concentrations in the infant is suggested to ensure that the exposure is less than 5% to 10% of the therapeutic dose.13 The use of cyclosporine has been extensively studied in pregnant transplant patients and is considered relatively safe for use in pregnancy.14 Cyclosporine is lipid soluble and thus is quickly metabolized and spread throughout the body; it can easily cross the placenta.9,13 Blood concentration in the fetus is 30% to 64% that of the maternal circulation. However, cyclosporine is only toxic to the fetus at maternally toxic doses, which can result in low birth weight and increased prenatal and postnatal mortality.13

Isotretinoin, Oral Contraceptive Pills, and Spironolactone

Isotretinoin and hormonal treatments such as oral contraceptive pills and spironolactone (an androgen receptor blocker) commonly are used to treat HS, but all are contraindicated in pregnancy and lactation. Isotretinoin is a well-established teratogen, but adverse effects on nursing babies have not been described. However, the manufacturer of isotretinoin advises against its use in lactation. Oral contraceptive pill use in early pregnancy is associated with increased risk for Down syndrome. Oral contraceptive pill use also is contraindicated in lactation for 2 reasons: decreased milk production and risk for fetal feminization. Antiandrogenic agents such as spironolactone have been shown to be associated with hypospadias and feminization of the male fetus.7

COMMENT

Women with HS usually require ongoing medical treatment during pregnancy and immediately postpartum; thus, it is important that treatments are proven to be safe for use in this specific population. Current management guidelines are not entirely suitable for pregnant and breastfeeding women given that many HS drugs have teratogenic effects and/or can be excreted into breast milk.1 Several treatments have uncertain safety profiles in pregnancy and breastfeeding, which calls for dermatologists to change or create new regimens for their patients. Close management also is necessary to prevent excess inflammation of breast tissue and milk fistula formation, which would hinder normal breastfeeding.

The eTable lists medications used to treat HS. The FDA category is listed next to each drug. However, it should be noted that these FDA letter categories were replaced with the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule in 2015. The letter ratings were deemed overly simplistic and replaced with narrative-based labeling that provides more detailed adverse effects and clinical considerations.9

Risk Factors of HS—Predisposing risk factors for HS flares that are controllable include obesity and smoking.2 Pregnancy weight gain may cause increased skin maceration at intertriginous sites, which can contribute to worsening HS symptoms.1,5 Adipocytes play a role in HS exacerbation by promoting secretion of TNF-α, leading to increased inflammation.5 Dermatologists can help prevent postpartum HS flares by monitoring weight gain during pregnancy, encouraging smoking cessation, and promoting weight and nutrition goals as set by an obstetrician.1 In addition to medications, management of HS should include emotional support and education on wearing loose-fitting clothing to avoid irritation of the affected areas.3 An emphasis on dermatologist counseling for all patients with HS, even for those with milder disease, can reduce exacerbations during pregnancy.5

CONCLUSION

The selection of dermatologic drugs for the treatment of HS in the setting of pregnancy involves complex decision-making. Dermatologists need more guidelines and proven safety data in human trials, especially regarding use of biologics and immunosuppressants to better treat HS in pregnancy. With more data, they can create more evidence-based treatment regimens to help prevent postpartum exacerbations of HS. Thus, patients can breastfeed their infants comfortably and without any risks of impaired child development. In the meantime, dermatologists can continue to work together with obstetricians and psychiatrists to decrease disease flares through counseling patients on nutrition and weight gain and providing emotional support.

- Perng P, Zampella JG, Okoye GA. Management of hidradenitis suppurativa in pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:979-989. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.10.032

- Samuel S, Tremelling A, Murray M. Presentation and surgical management of hidradenitis suppurativa of the breast during pregnancy: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;51:21-24. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2018.08.013

- Yang CS, Teeple M, Muglia J, et al. Inflammatory and glandular skin disease in pregnancy. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:335-343. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.02.005

- Vossen AR, van Straalen KR, Prens EP, et al. Menses and pregnancy affect symptoms in hidradenitis suppurativa: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:155-156. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.07.024

- Lyons AB, Peacock A, McKenzie SA, et al. Evaluation of hidradenitis suppurativa disease course during pregnancy and postpartum. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:681-685. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0777

- Riis PT, Ring HC, Themstrup L, et al. The role of androgens and estrogens in hidradenitis suppurativa—a systematic review. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2016;24:239-249.

- Kong YL, Tey HL. Treatment of acne vulgaris during pregnancy and lactation. Drugs. 2013;73:779-787. doi:10.1007/s40265-013-0060-0

- Butler DC, Heller MM, Murase JE. Safety of dermatologic medications in pregnancy and lactation: part II. lactation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:417:E1-E10. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.09.009

- Wilmer E, Chai S, Kroumpouzos G. Drug safety: pregnancy rating classifications and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:401-409. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.02.013

- Inman WH, Rawson NS. Erythromycin estolate and jaundice. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983;286:1954-1955. doi:10.1136/bmj.286.6382.1954

- Workowski KA, Berman SM. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-11):1-94.

- Murase JE, Heller MM, Butler DC. Safety of dermatologic medications in pregnancy and lactation: part I. pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:401.e1-14; quiz 415. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.09.010

- Brown SM, Aljefri K, Waas R, et al. Systemic medications used in treatment of common dermatological conditions: safety profile with respect to pregnancy, breast feeding and content in seminal fluid. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30:2-18. doi:10.1080/09546634.2016.1202402

- Kamarajah SK, Arntdz K, Bundred J, et al. Outcomes of pregnancy in recipients of liver transplants. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:1398-1404.e1. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2018.11.055

- Perng P, Zampella JG, Okoye GA. Management of hidradenitis suppurativa in pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:979-989. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.10.032

- Samuel S, Tremelling A, Murray M. Presentation and surgical management of hidradenitis suppurativa of the breast during pregnancy: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;51:21-24. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2018.08.013

- Yang CS, Teeple M, Muglia J, et al. Inflammatory and glandular skin disease in pregnancy. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:335-343. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.02.005

- Vossen AR, van Straalen KR, Prens EP, et al. Menses and pregnancy affect symptoms in hidradenitis suppurativa: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:155-156. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.07.024

- Lyons AB, Peacock A, McKenzie SA, et al. Evaluation of hidradenitis suppurativa disease course during pregnancy and postpartum. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:681-685. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0777

- Riis PT, Ring HC, Themstrup L, et al. The role of androgens and estrogens in hidradenitis suppurativa—a systematic review. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2016;24:239-249.

- Kong YL, Tey HL. Treatment of acne vulgaris during pregnancy and lactation. Drugs. 2013;73:779-787. doi:10.1007/s40265-013-0060-0

- Butler DC, Heller MM, Murase JE. Safety of dermatologic medications in pregnancy and lactation: part II. lactation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:417:E1-E10. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.09.009

- Wilmer E, Chai S, Kroumpouzos G. Drug safety: pregnancy rating classifications and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:401-409. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.02.013

- Inman WH, Rawson NS. Erythromycin estolate and jaundice. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983;286:1954-1955. doi:10.1136/bmj.286.6382.1954

- Workowski KA, Berman SM. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-11):1-94.