User login

Subcutaneous Nodule on the Postauricular Neck

The Diagnosis: Pleomorphic Lipoma

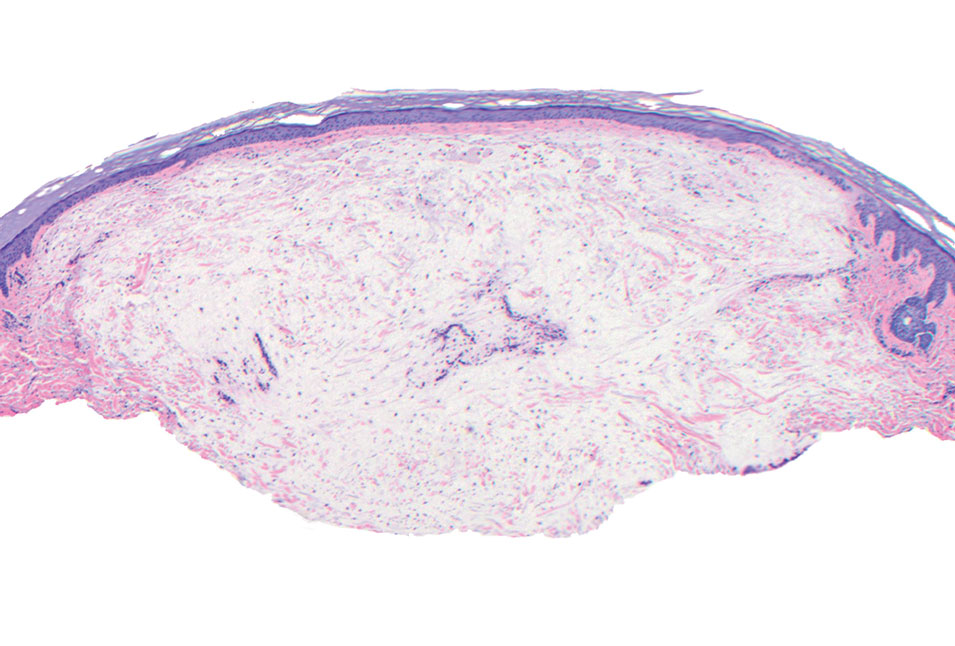

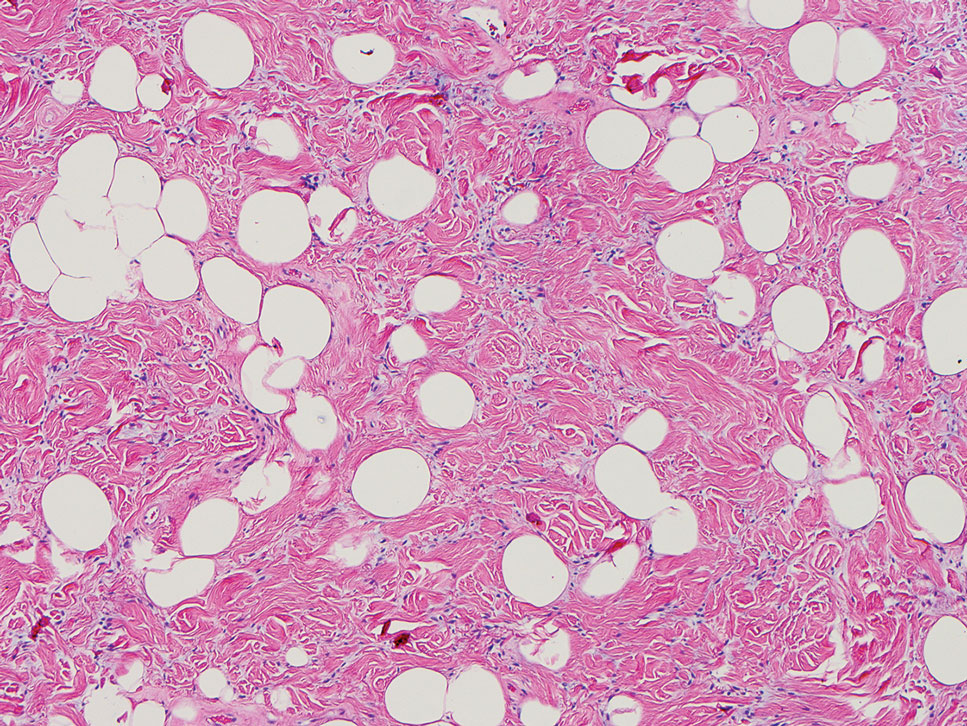

Pleomorphic lipoma is a rare, benign, adipocytic neoplasm that presents in the subcutaneous tissues of the upper shoulder, back, or neck. It predominantly affects men aged 50 to 70 years. Most lesions are situated in the subcutaneous tissues; few cases of intramuscular and retroperitoneal tumors have been reported.1 Clinically, pleomorphic lipomas present as painless, well-circumscribed lesions of the subcutaneous tissue that often resemble a lipoma or occasionally may be mistaken for liposarcoma. Histopathologic examination of ordinary lipomas reveals uniform mature adipocytes. However, pleomorphic lipomas consist of a mixture of multinucleated floretlike giant cells, variable-sized adipocytes, and fibrous tissue (ropy collagen bundles) with some myxoid and spindled areas.1,2 The most characteristic histologic feature of pleomorphic lipoma is multinucleated floretlike giant cells. The nuclei of these giant cells appear hyperchromatic, enlarged, and disposed to the periphery of the cell in a circular pattern. Additionally, tumors frequently contain excess mature dense collagen bundles that are strongly refractile in polarized light. Numerous mast cells are present. Atypical lipoblasts and capillary networks commonly are not visible in pleomorphic lipoma.3 The spindle cells express CD34 on immunohistochemistry. Loss of Rb-1 expression is typical.4

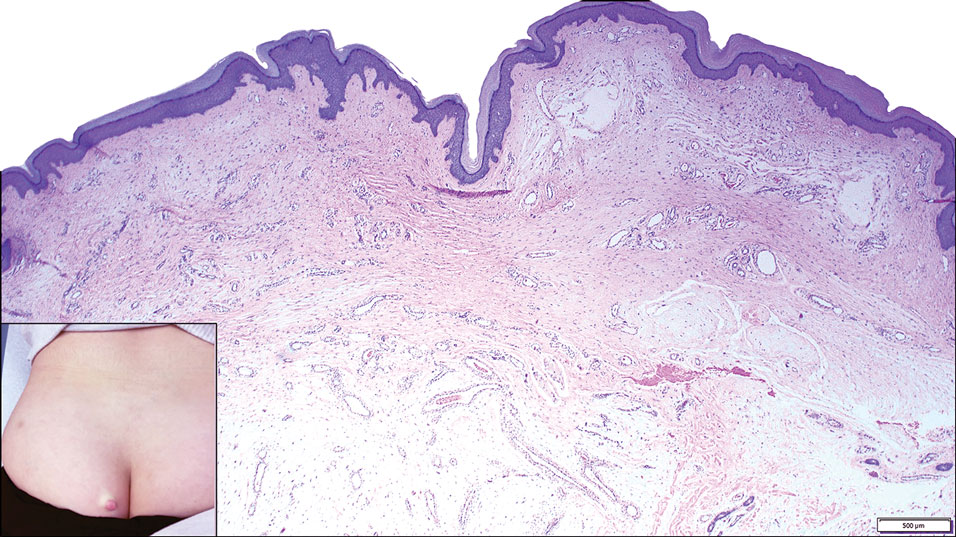

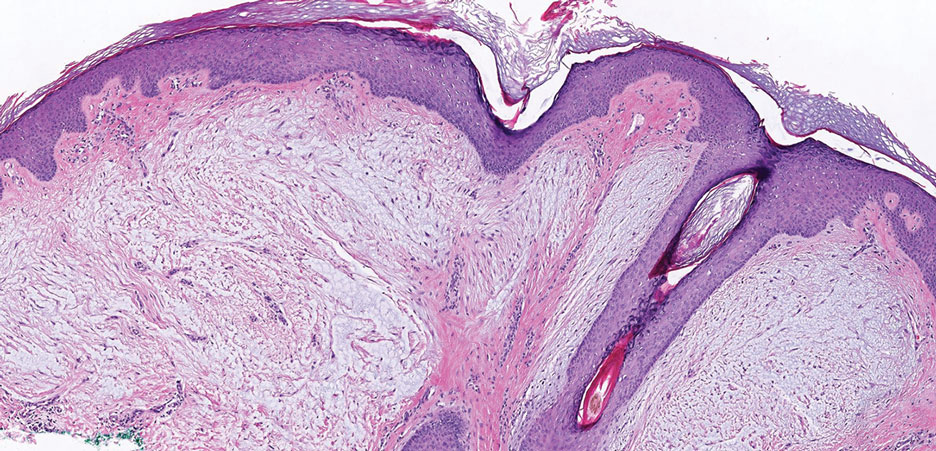

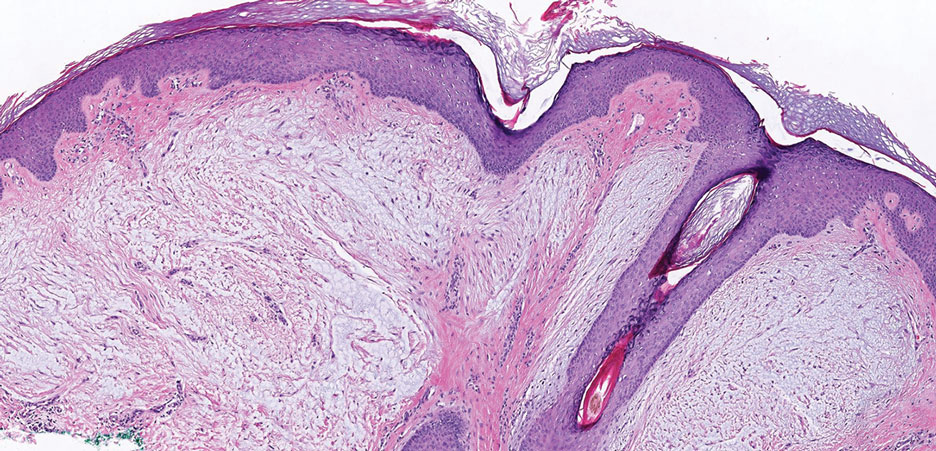

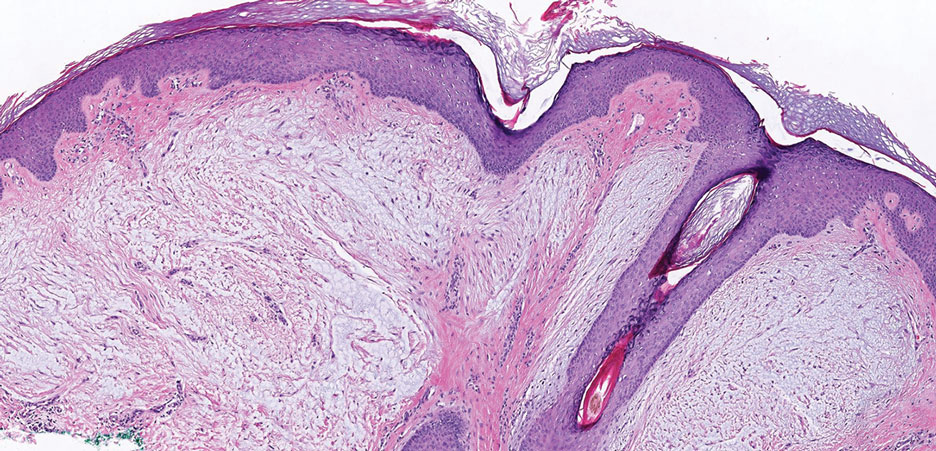

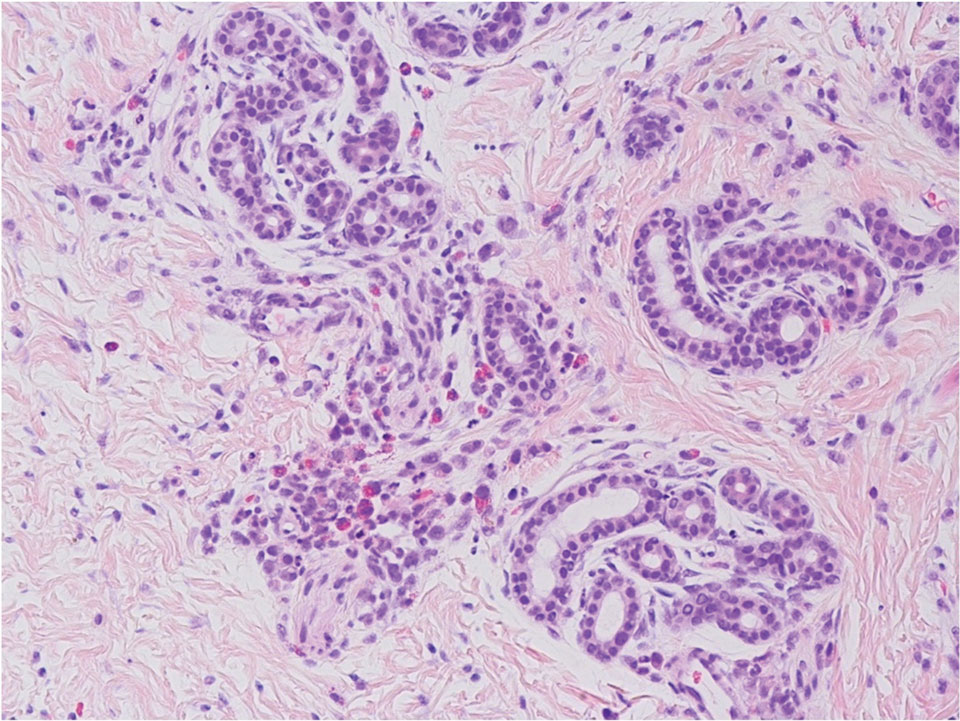

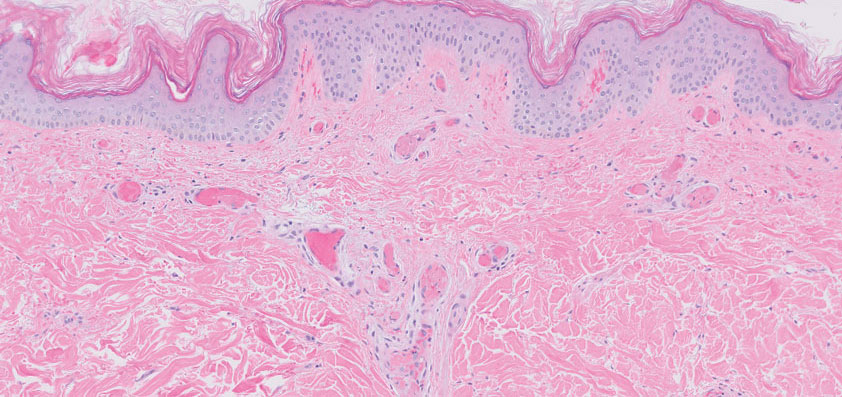

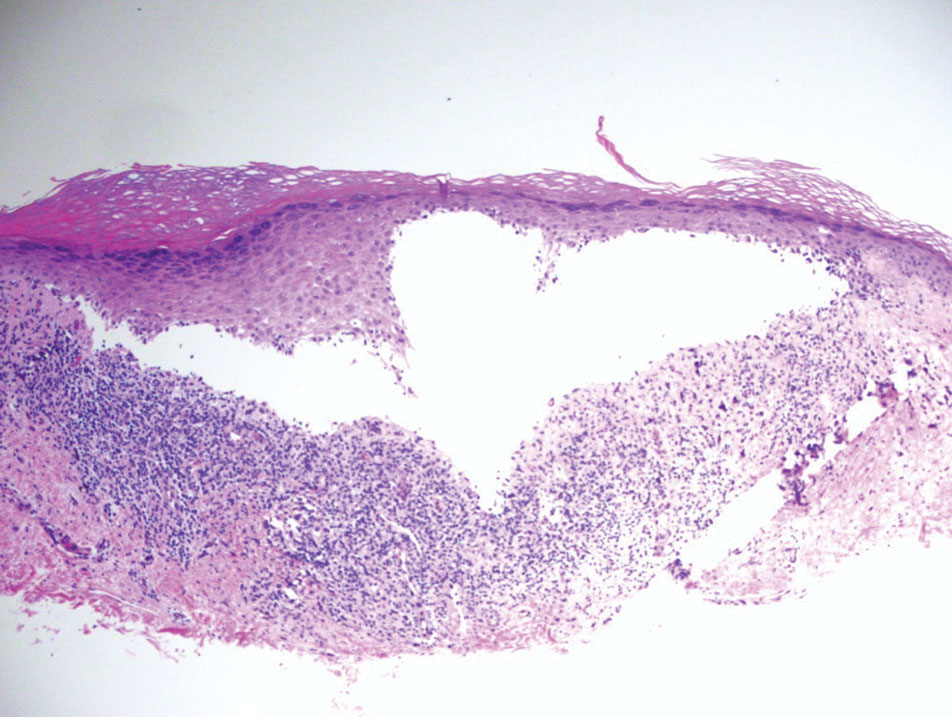

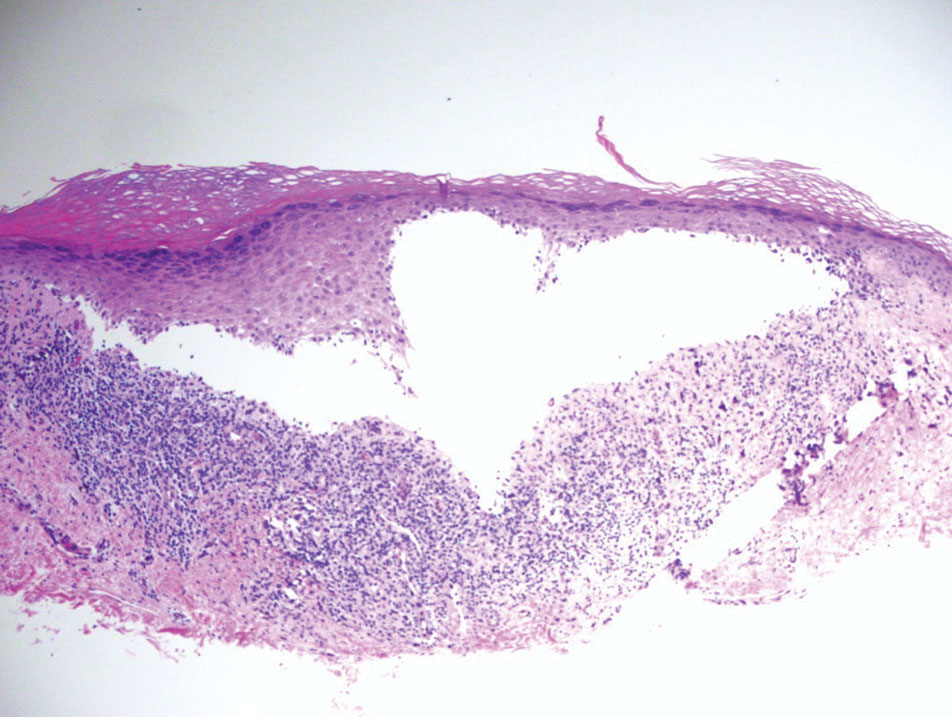

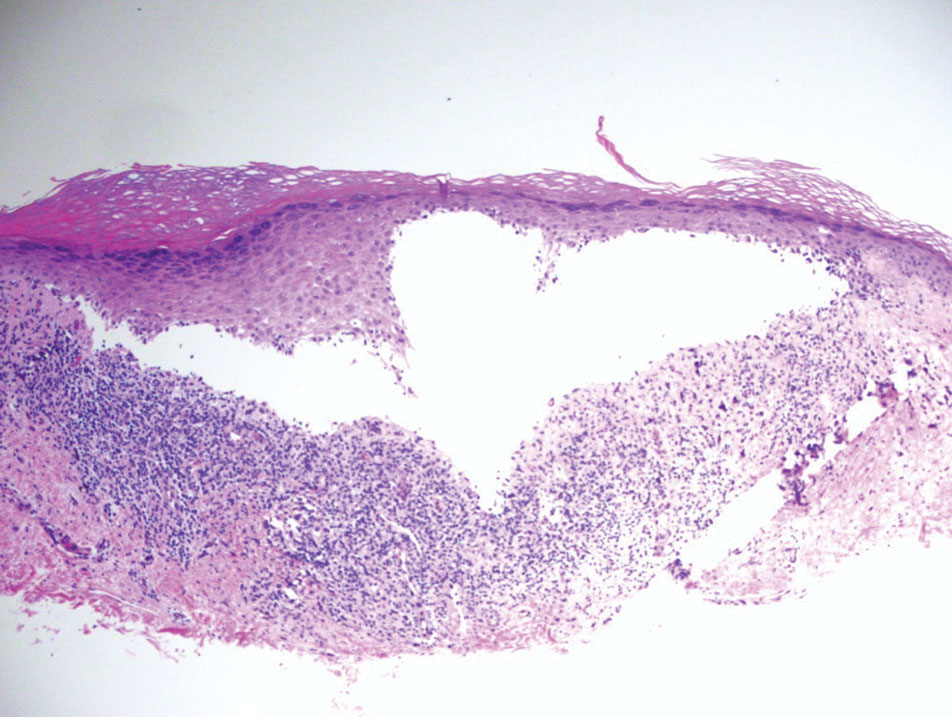

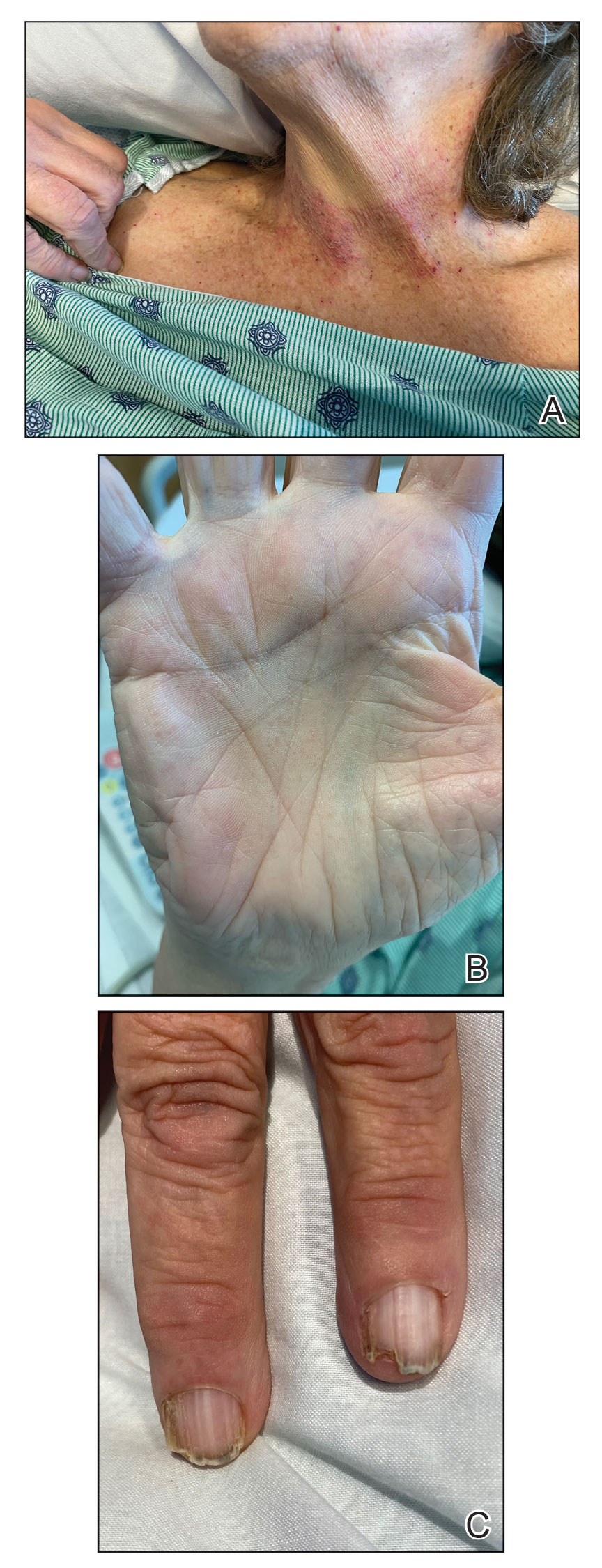

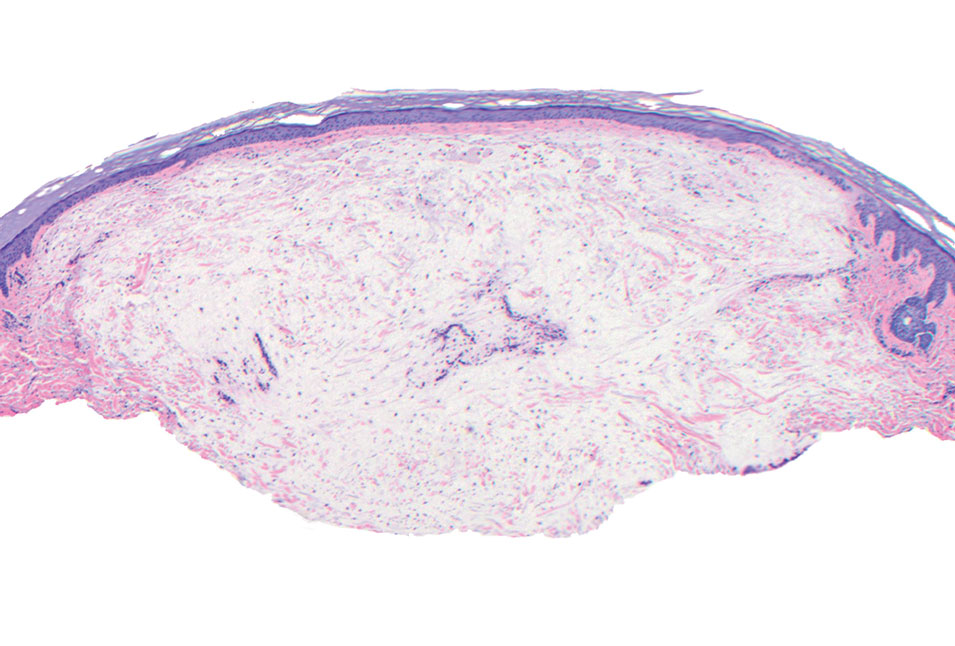

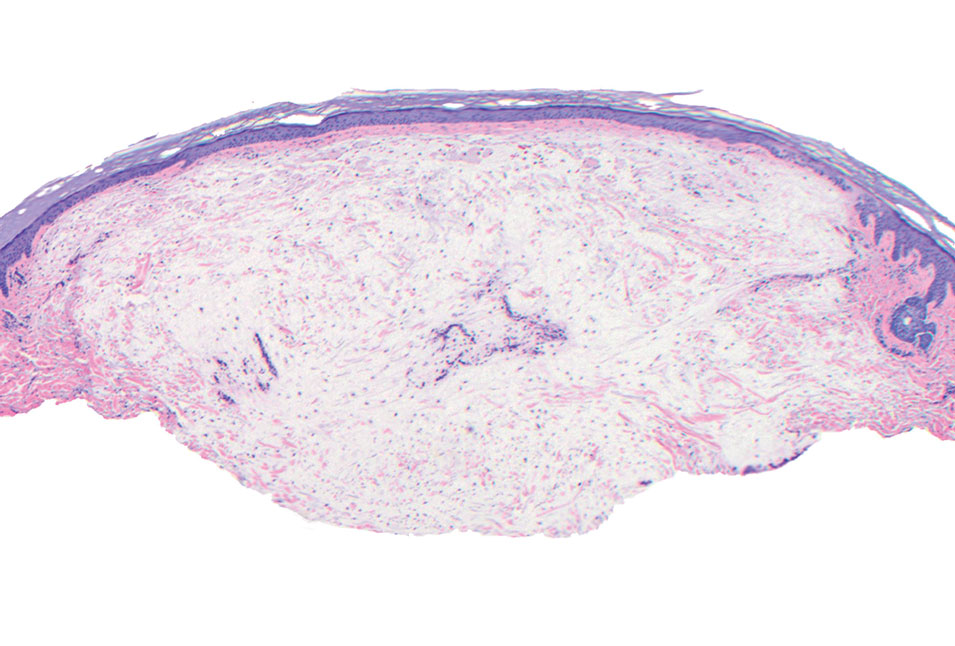

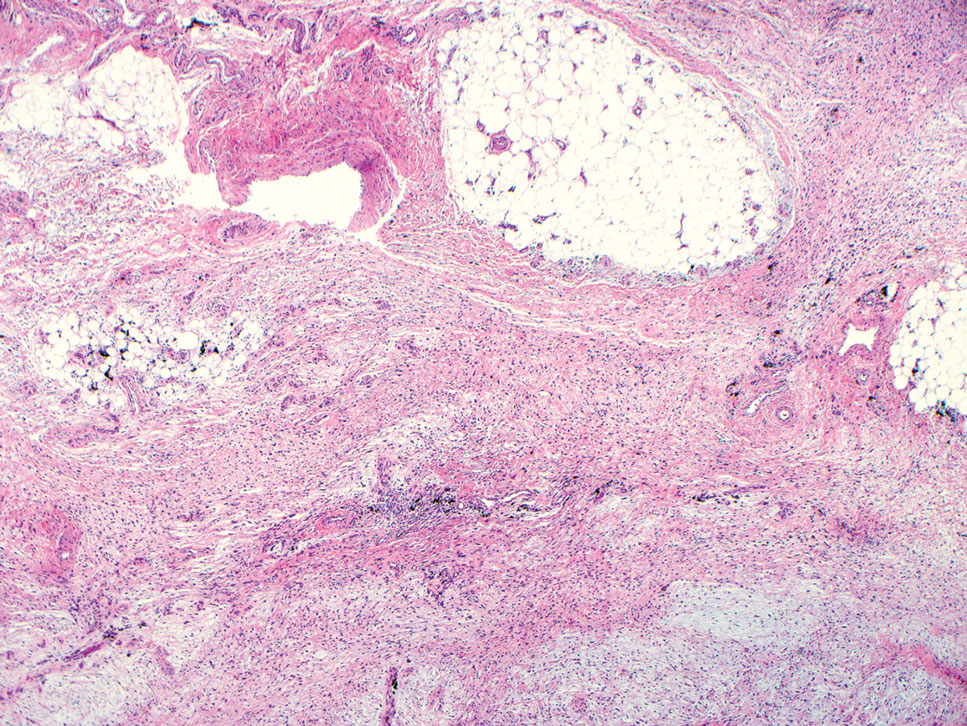

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a slow-growing soft tissue sarcoma that commonly begins as a pink or violet plaque on the trunk or upper limbs. Involvement of the head or neck accounts for only 10% to 15% of cases.5 This tumor has low metastatic potential but is highly infiltrative of surrounding tissues. It is associated with a translocation between chromosomes 22 and 17, leading to the fusion of the platelet-derived growth factor subunit β, PDGFB, and collagen type 1α1, COL1A1, genes.5 Clinically, patients often report that the lesion was present for several years prior to presentation with general stability in size and shape. Eventually, untreated lesions progress to become nodules or tumors and may even bleed or ulcerate. Histology reveals a storiform spindle cell proliferation throughout the dermis with infiltration into subcutaneous fat, commonly appearing in a honeycomblike pattern (Figure 1). Numerous histologic variants exist, including myxoid, sclerosing, pigmented (Bednar tumor), myoid, atrophic, or fibrosarcomatous dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, as well as a giant cell fibroblastoma variant.6 These tumor subtypes can exist independently or in association with one another, creating hybrid lesions that can closely mimic other entities such as pleomorphic lipoma. The spindle cells stain positively for CD34. Treatment of these tumors involves complete surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery; however, recurrence is common for tumors involving the head or neck.5

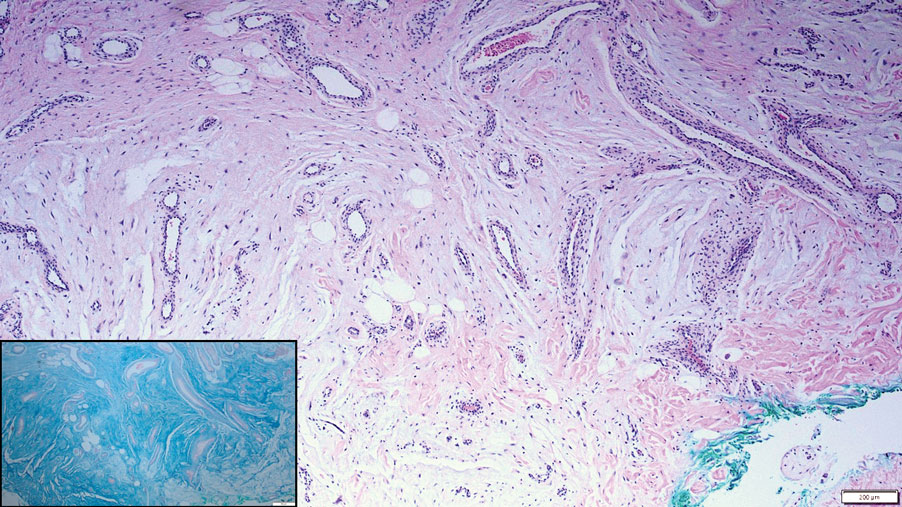

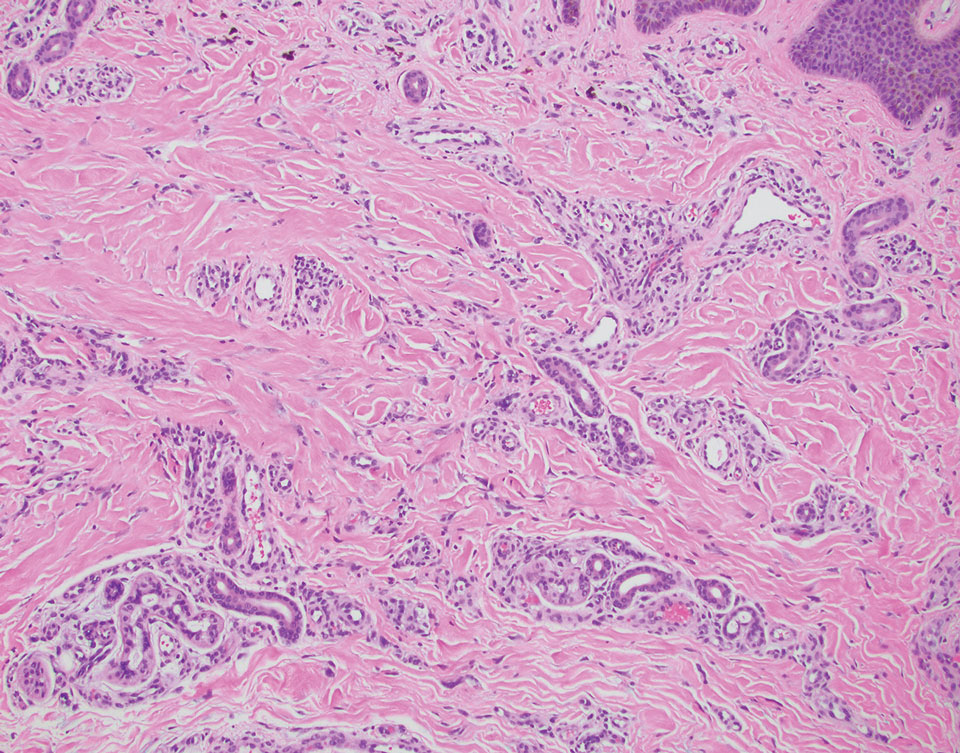

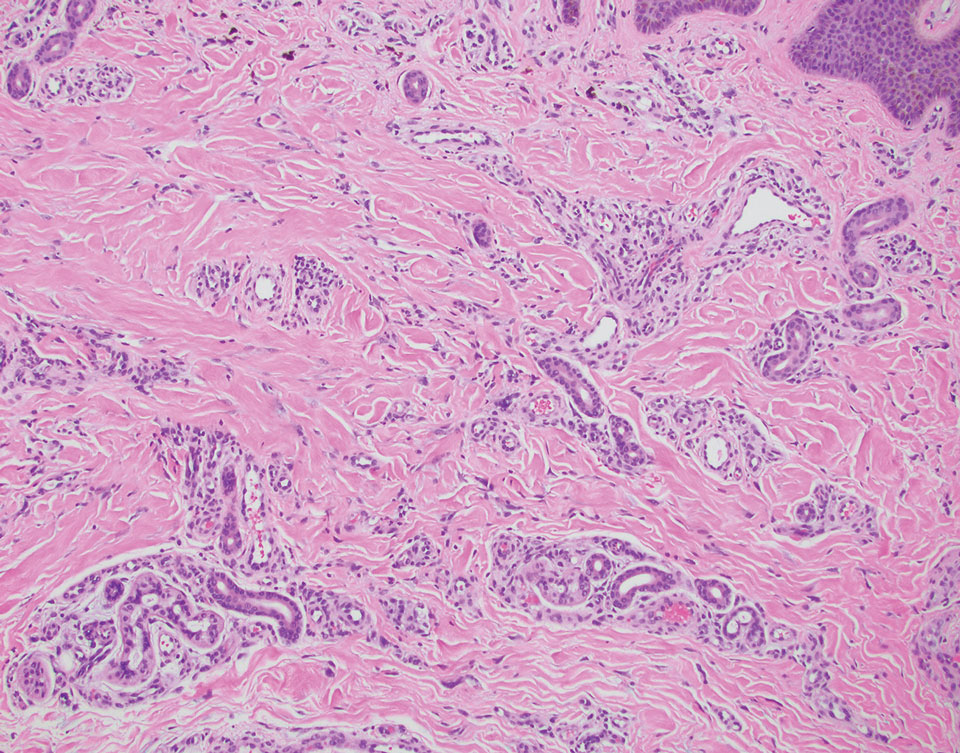

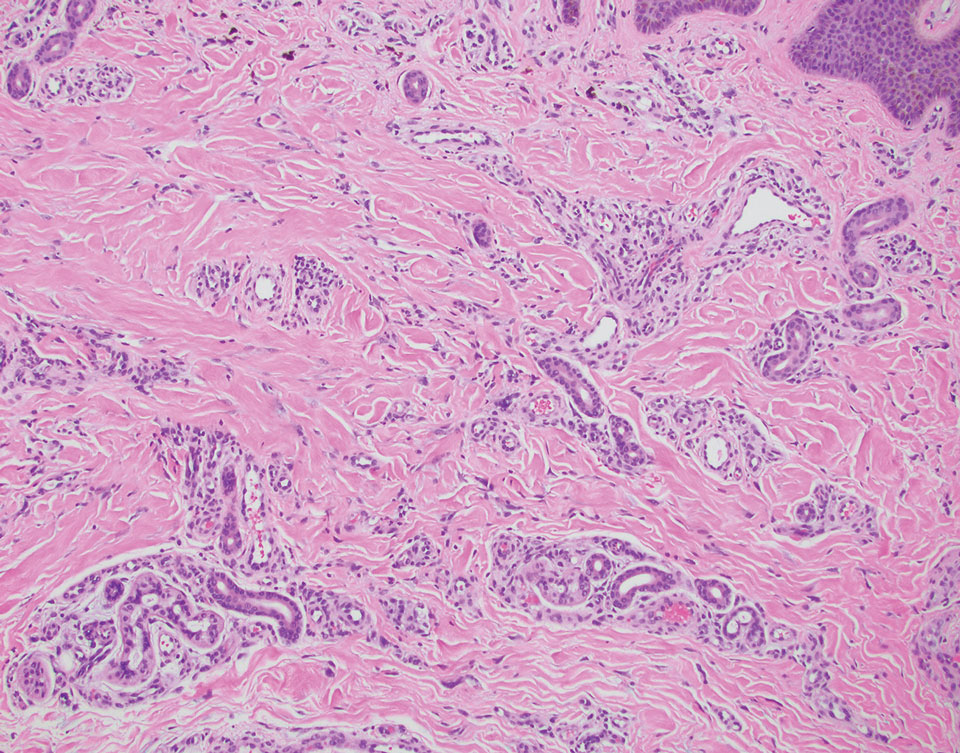

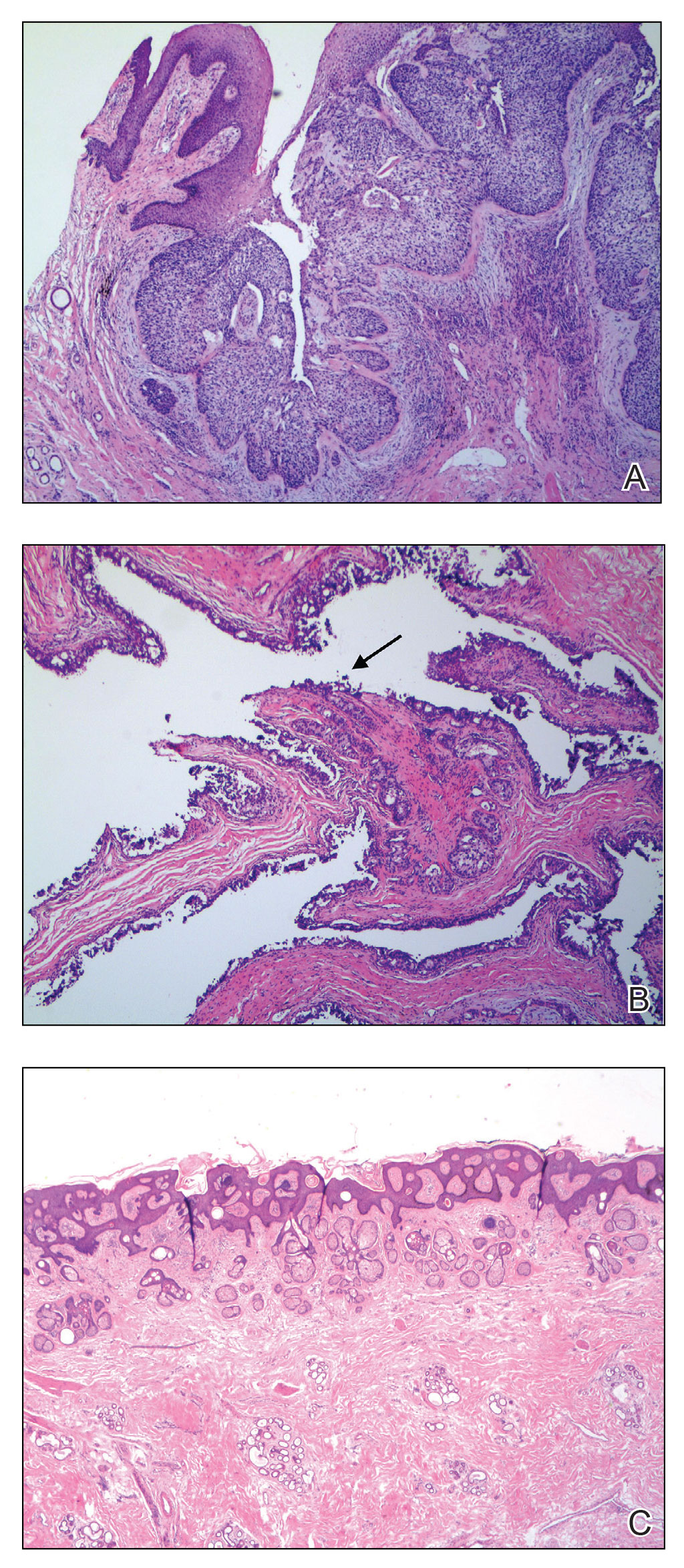

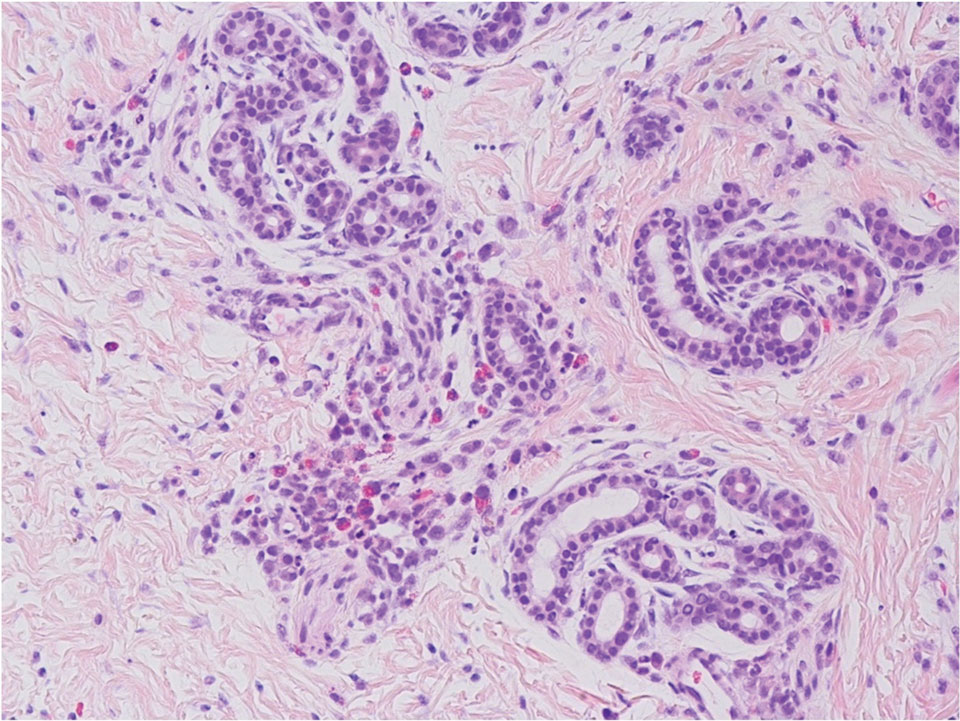

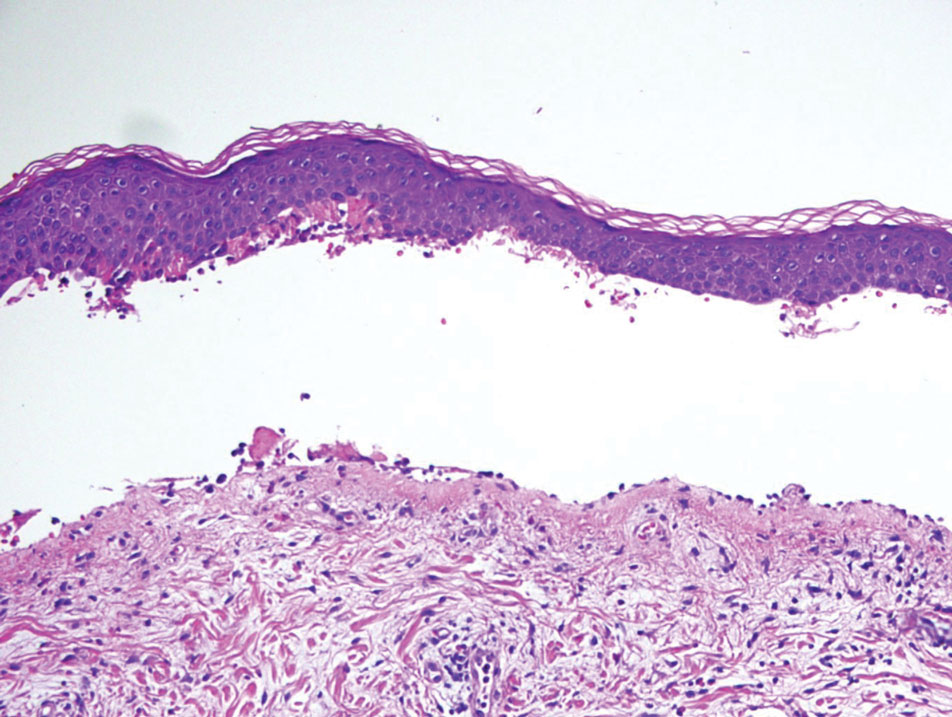

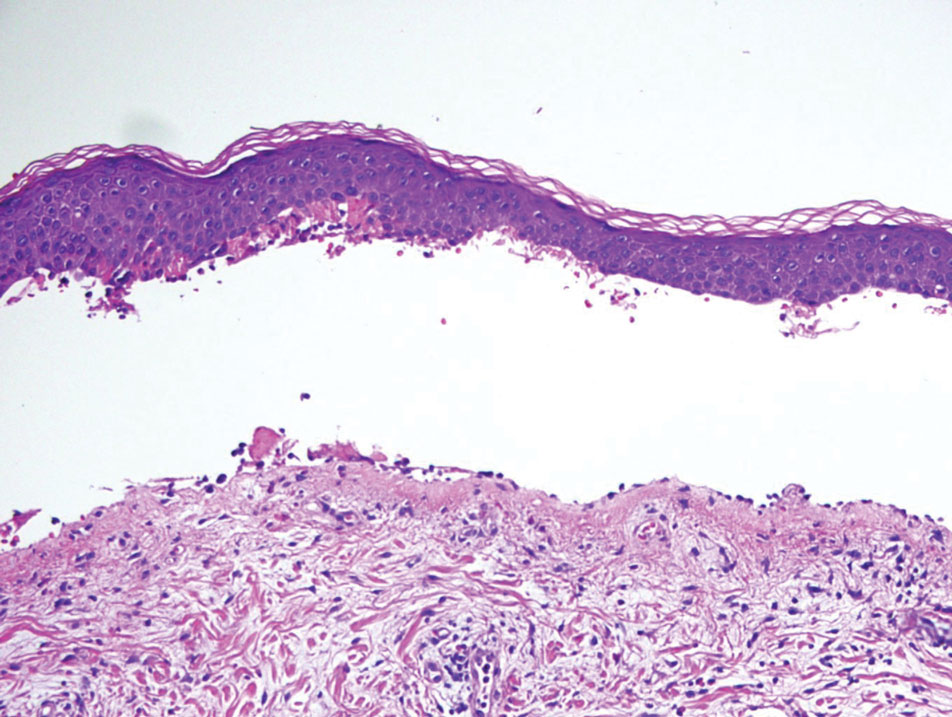

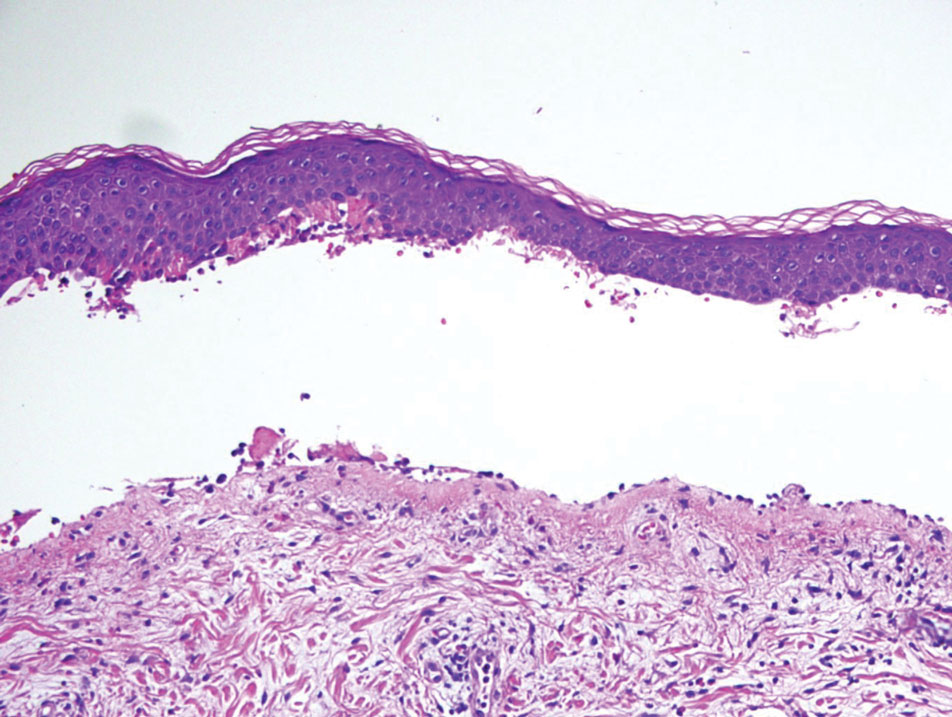

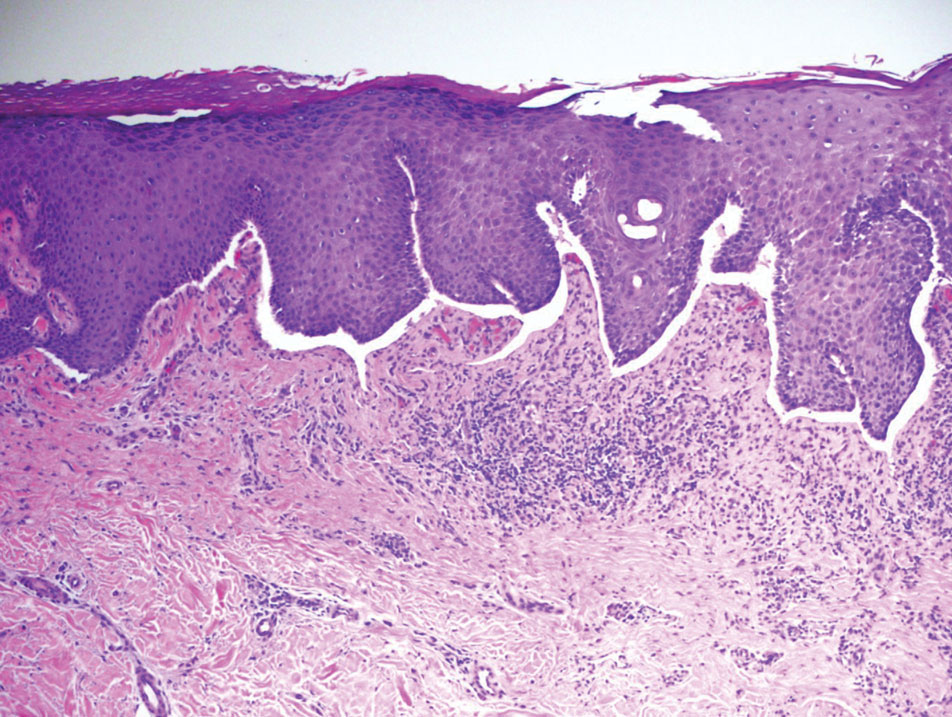

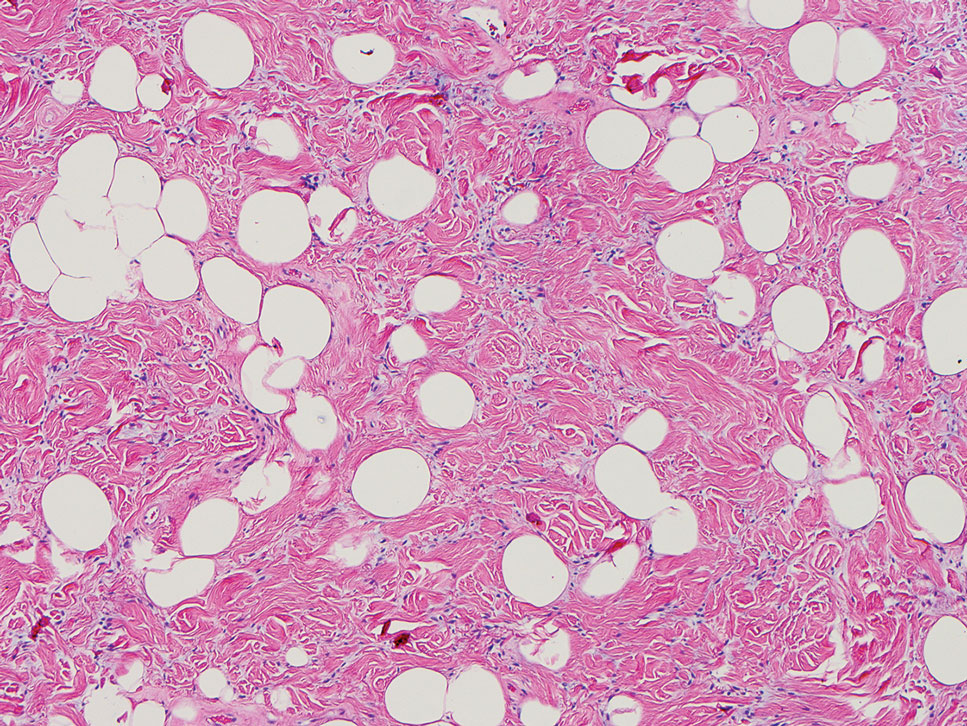

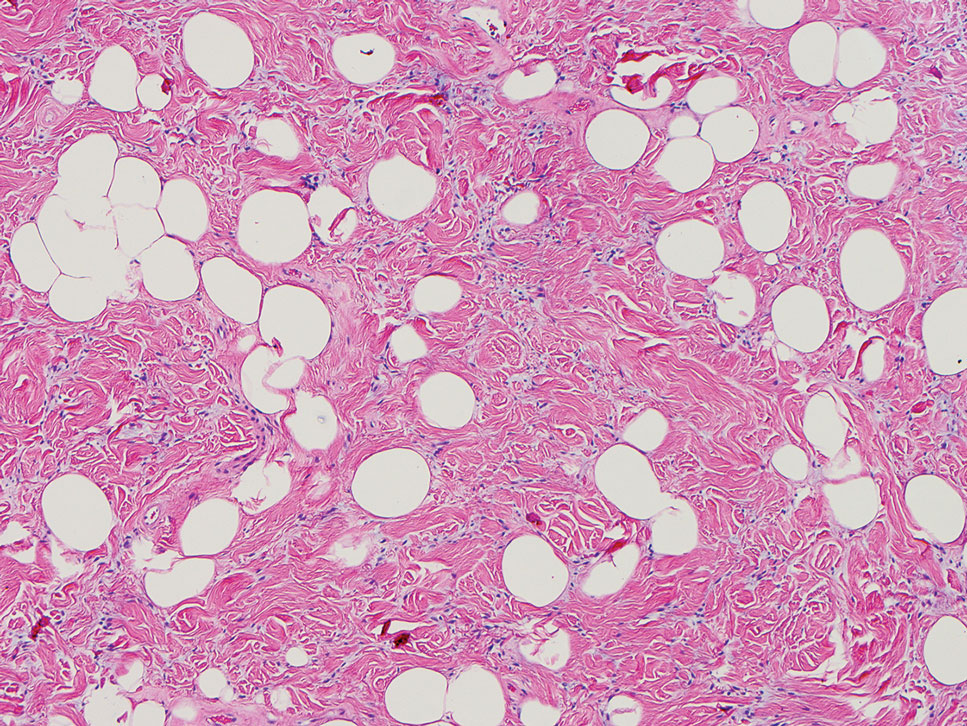

Superficial angiomyxoma is a slow-growing papule that most commonly appears on the trunk, head, or neck in middle-aged adults. Occasionally, patients with Carney complex also can develop lesions on the external ear or breast.7 Histologically, superficial angiomyxoma is a hypocellular tumor characterized by abundant myxoid stroma, thin blood vessels, and small spindled and stellate cells with minimal cytoplasm (Figure 2).8 Superficial angiomyxoma and pleomorphic lipoma present differently on histology; superficial angiomyxoma is not associated with nuclear atypia or pleomorphism, whereas pleomorphic lipoma characteristically contains multinucleated floretlike giant cells and pleomorphism. Frequently, there also is loss of normal PRKAR1A gene expression, which is responsible for protein kinase A regulatory subunit 1-alpha expression.8

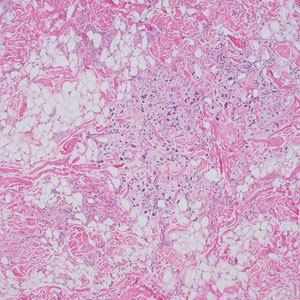

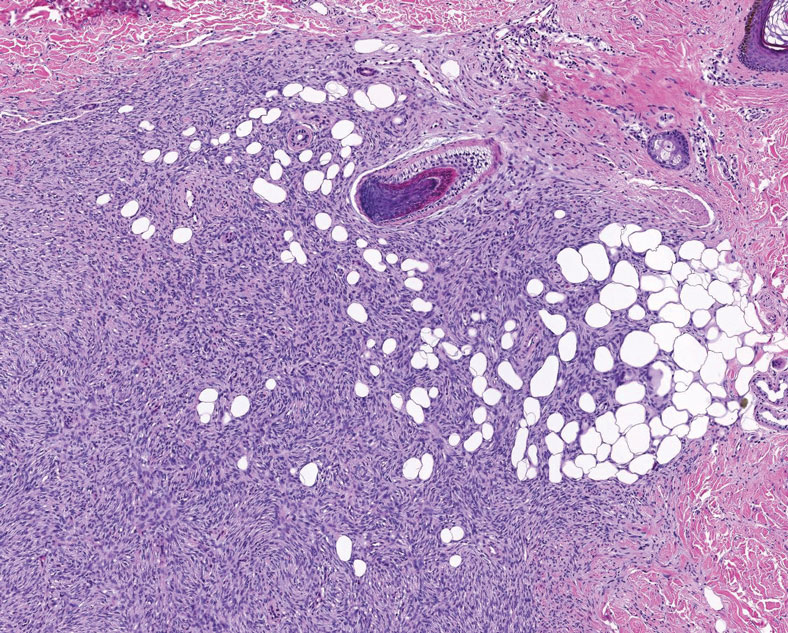

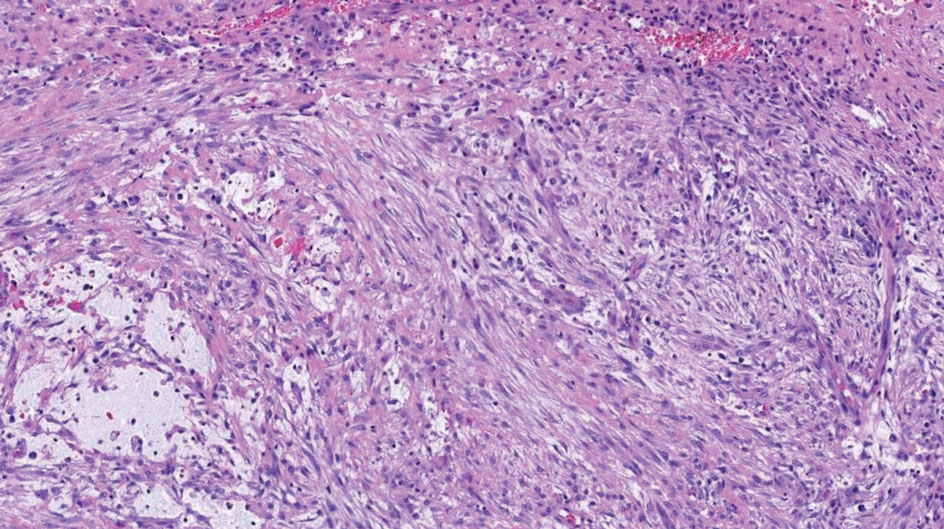

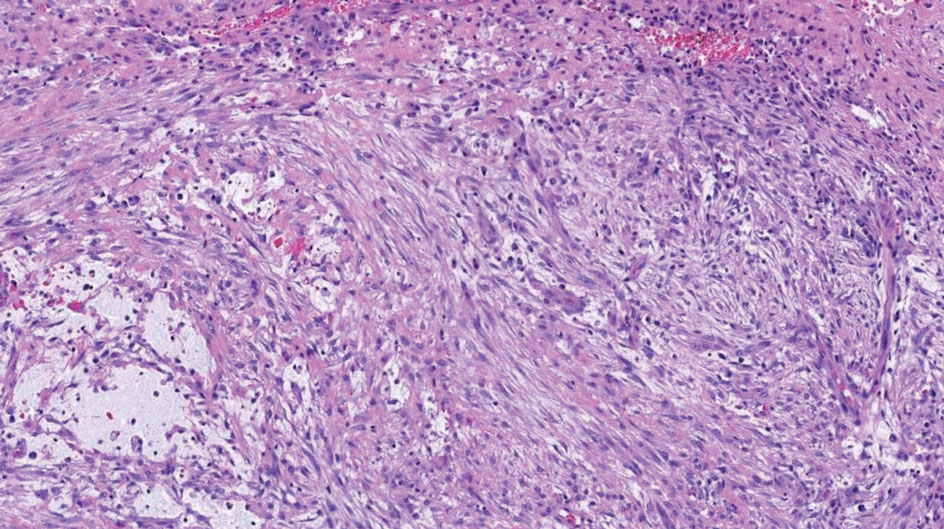

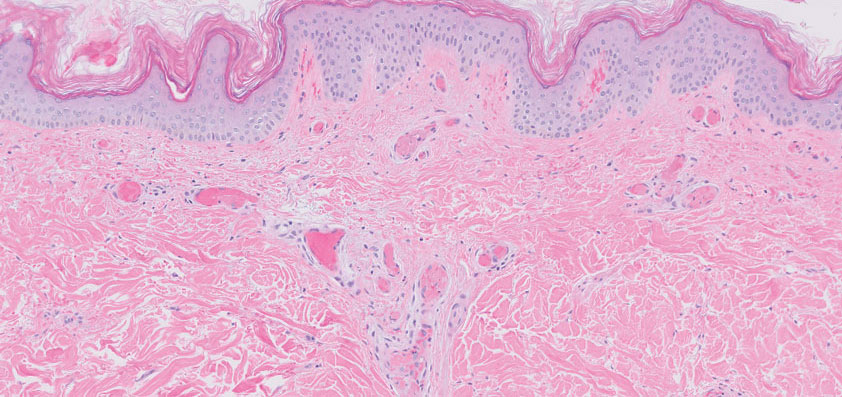

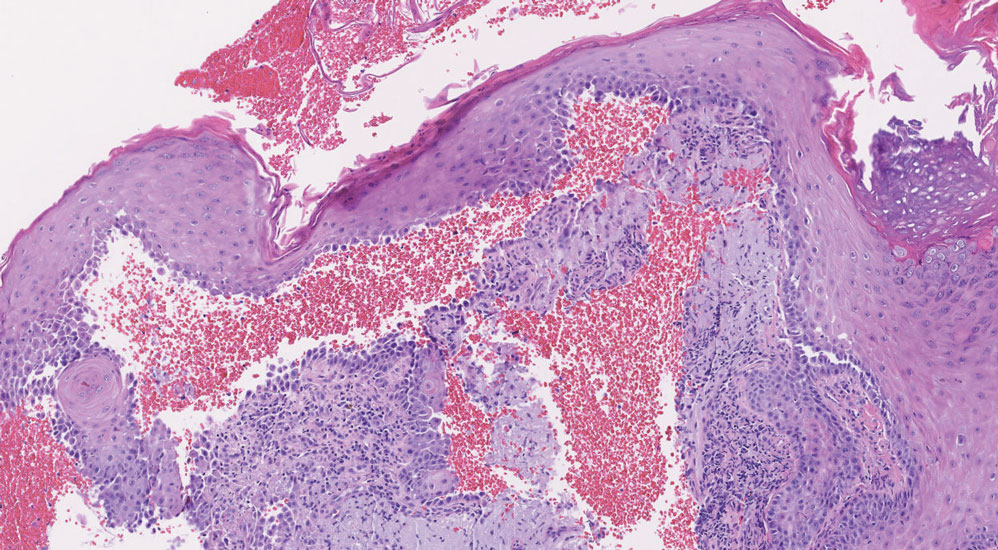

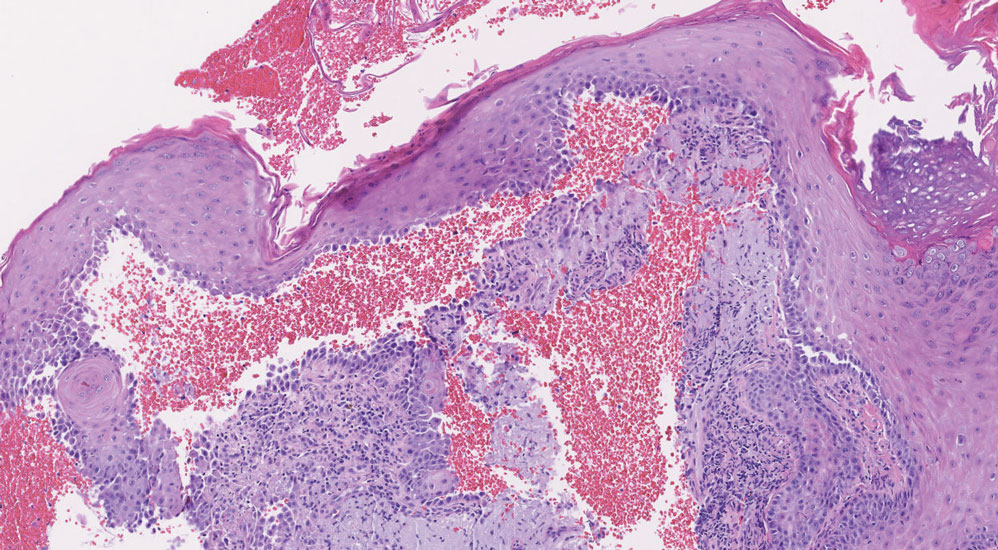

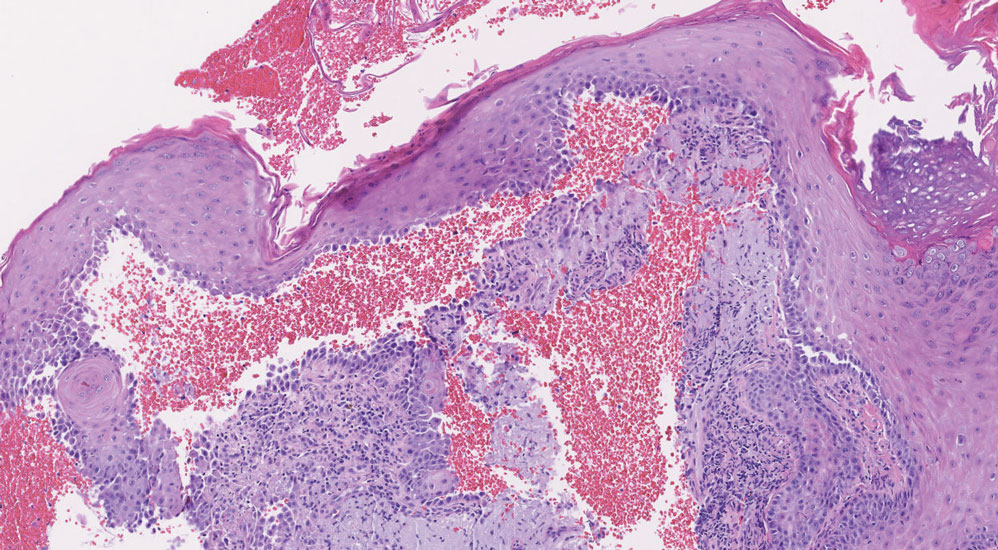

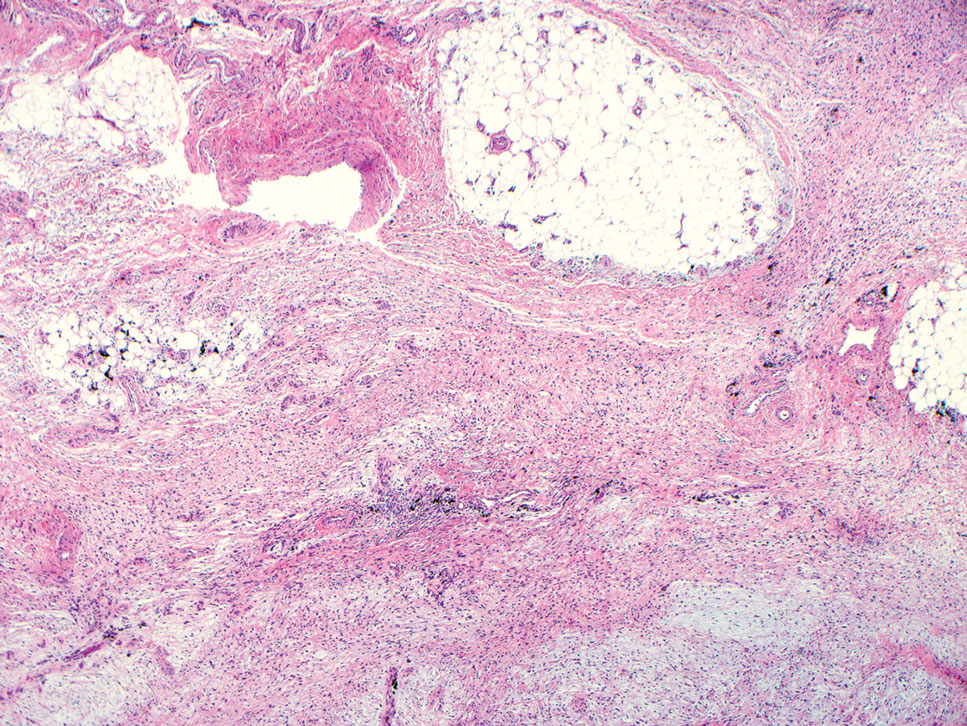

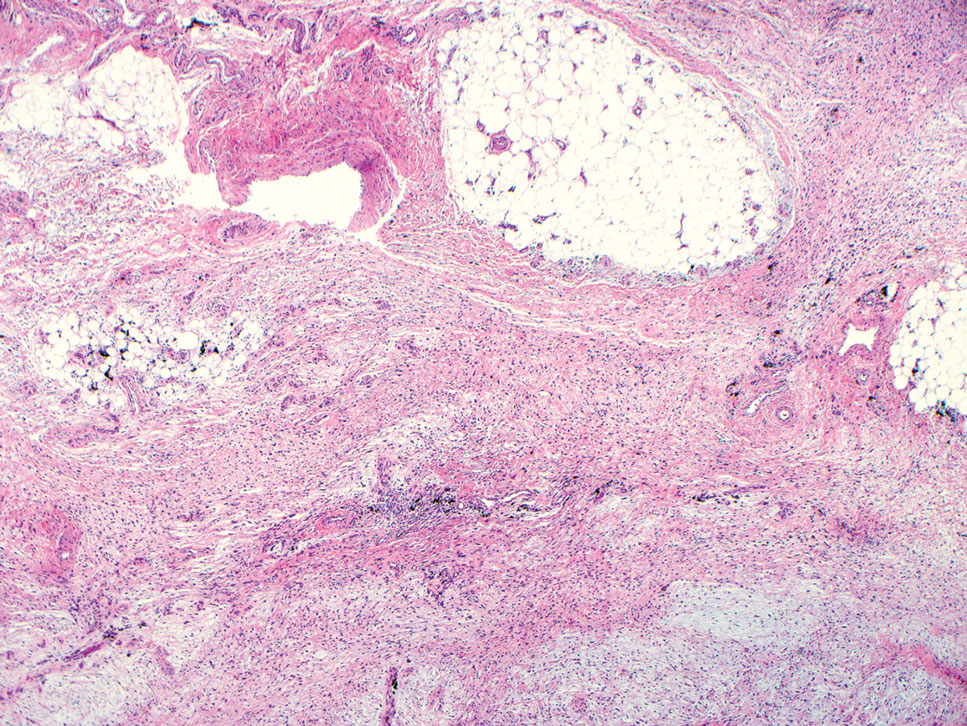

Multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma is a rare benign proliferation that presents with numerous red-violet asymptomatic papules that commonly appear on the upper and lower extremities of women aged 40 to 70 years. Lesions feature both a fibrohistiocytic and vascular component.9 Histologic examination commonly shows multinucleated cells with angular outlining in the superficial dermis accompanied by fibrosis and ectatic small-caliber vessels (Figure 3). Although both pleomorphic lipoma and multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma have similar-appearing multinucleated giant cells, the latter has a proliferation of narrow vessels in thick collagen bundles and lacks an adipocytic component, which distinguishes it from the former.10 Multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma also is characterized by a substantial number of factor XIIIa–positive fibrohistiocytic interstitial cells and vascular hyperplasia.9

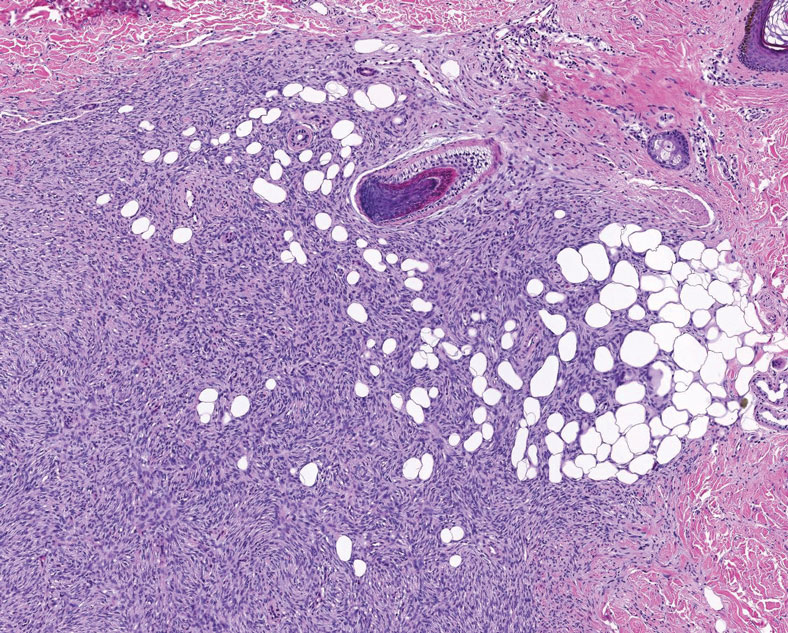

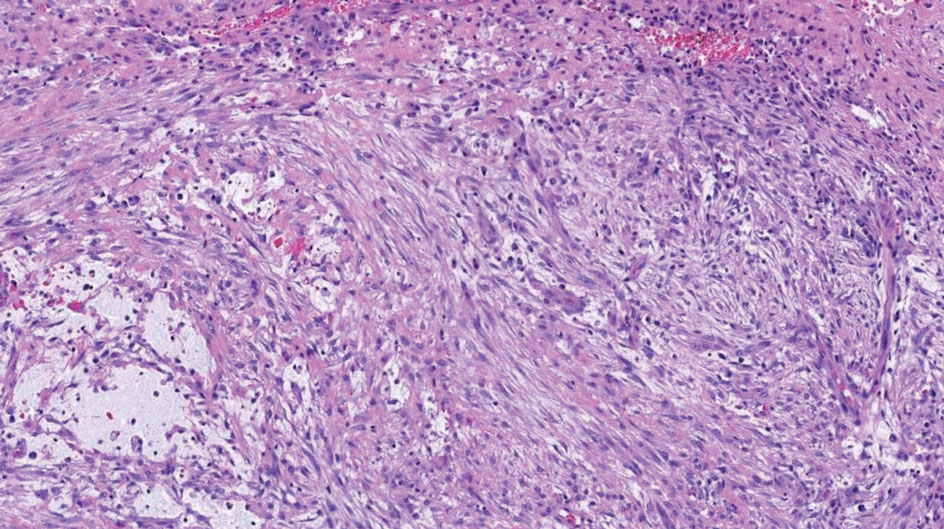

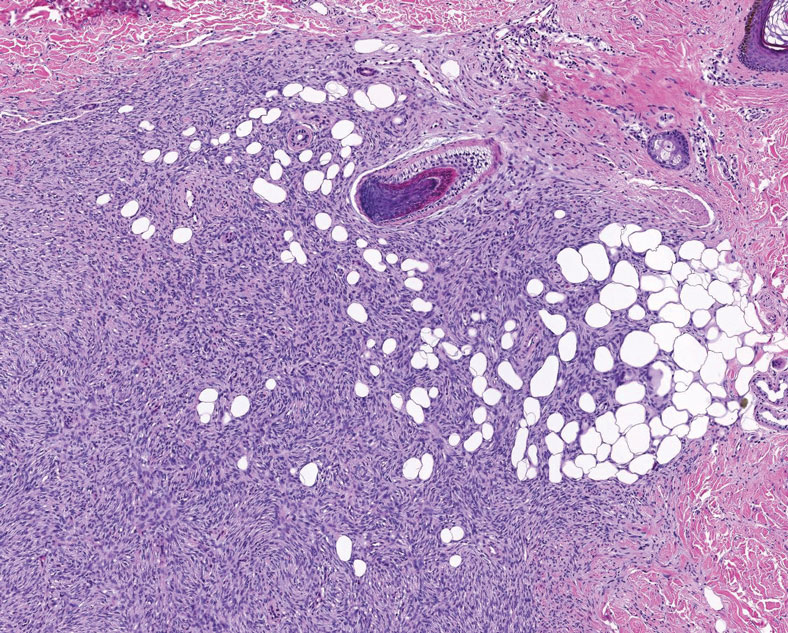

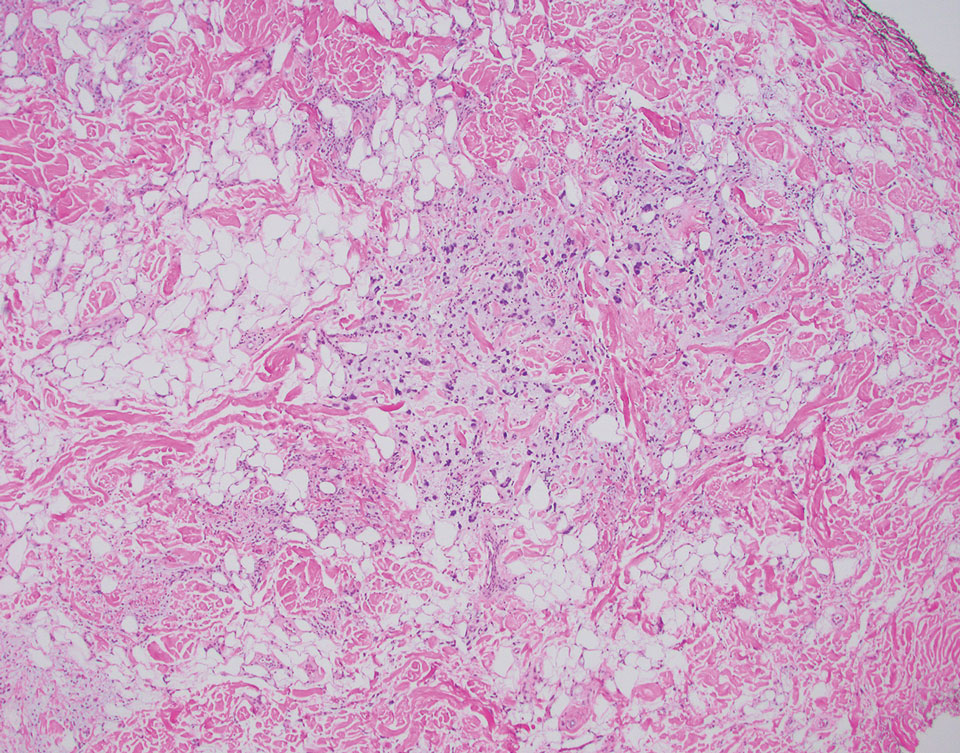

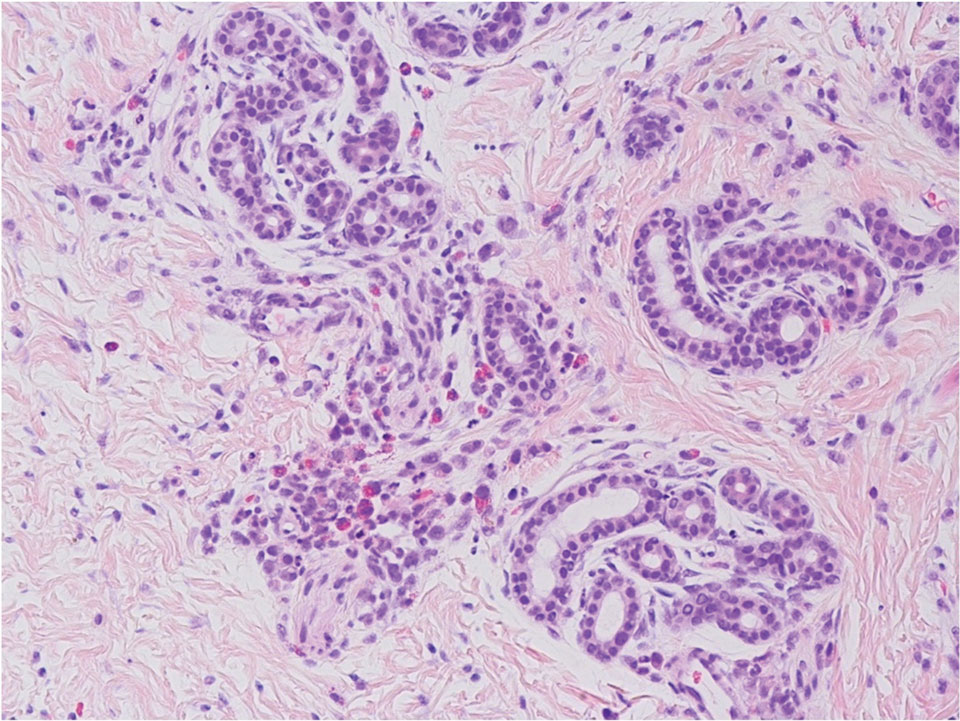

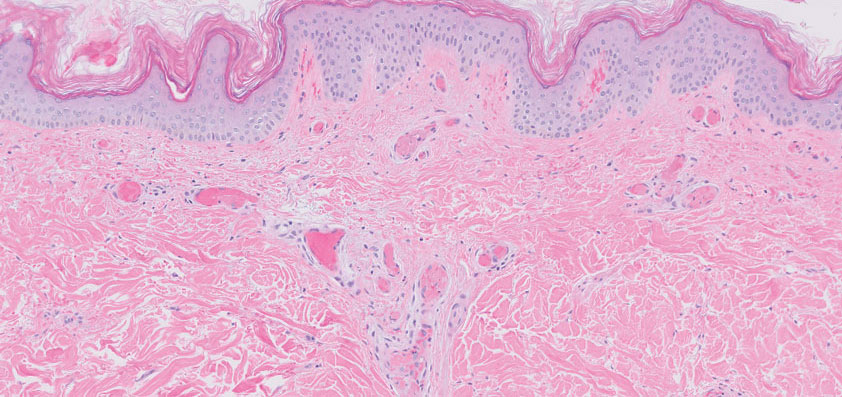

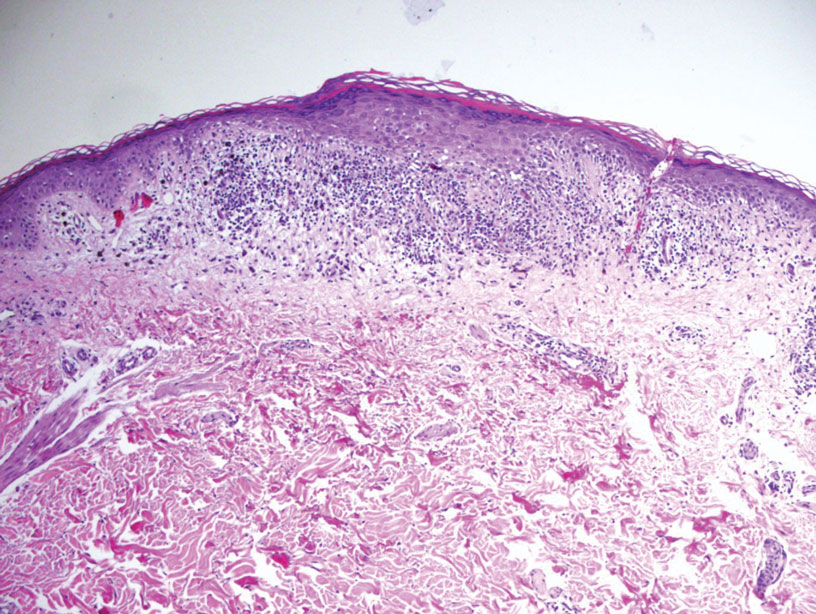

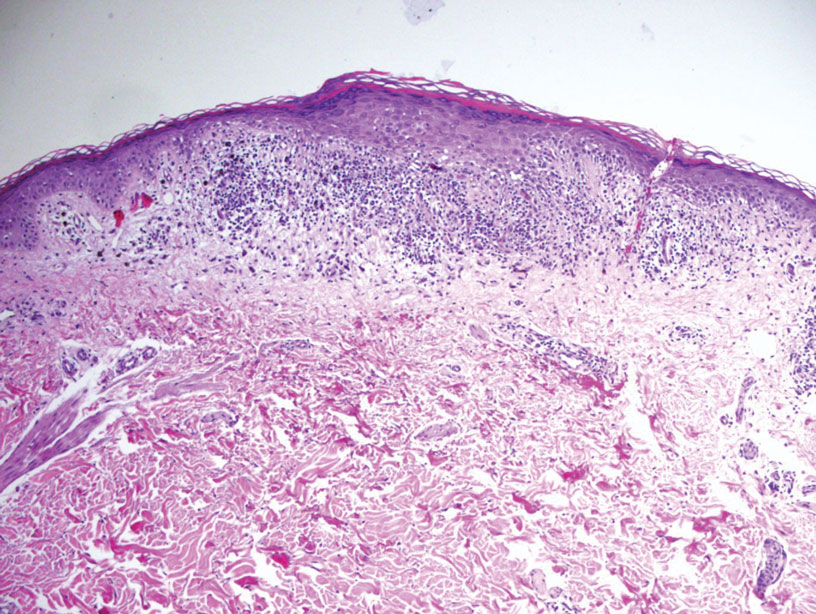

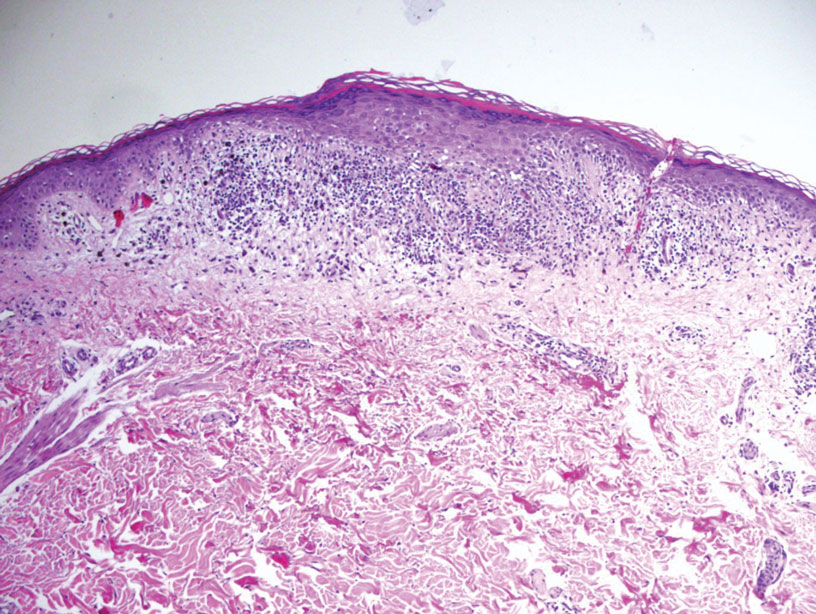

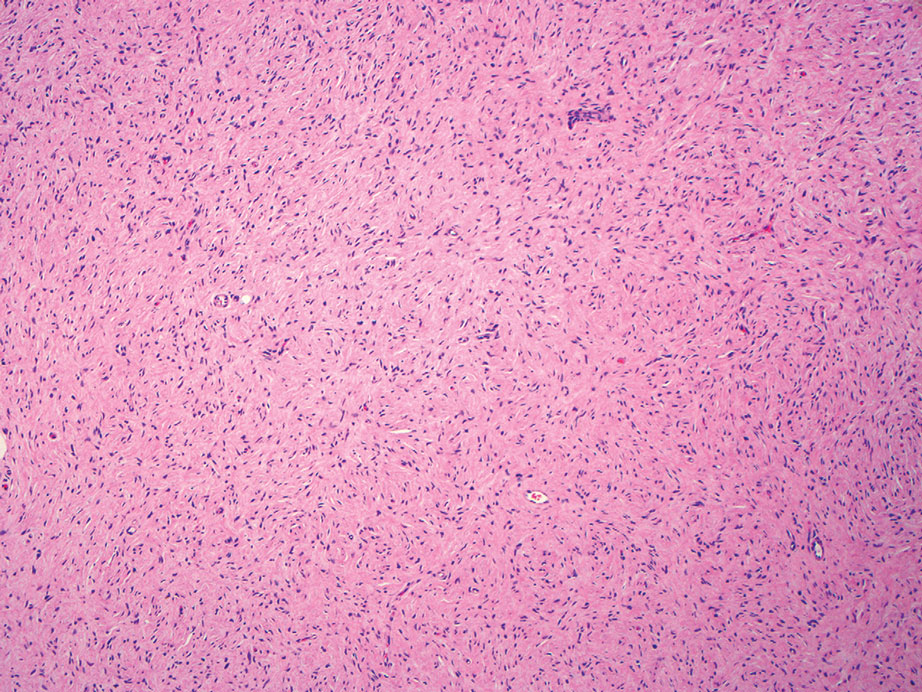

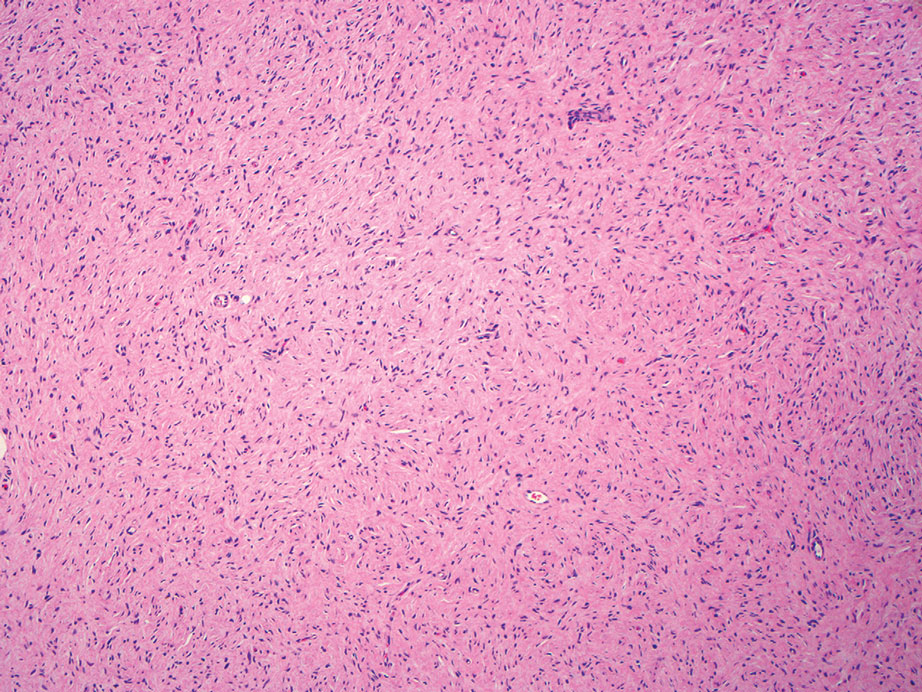

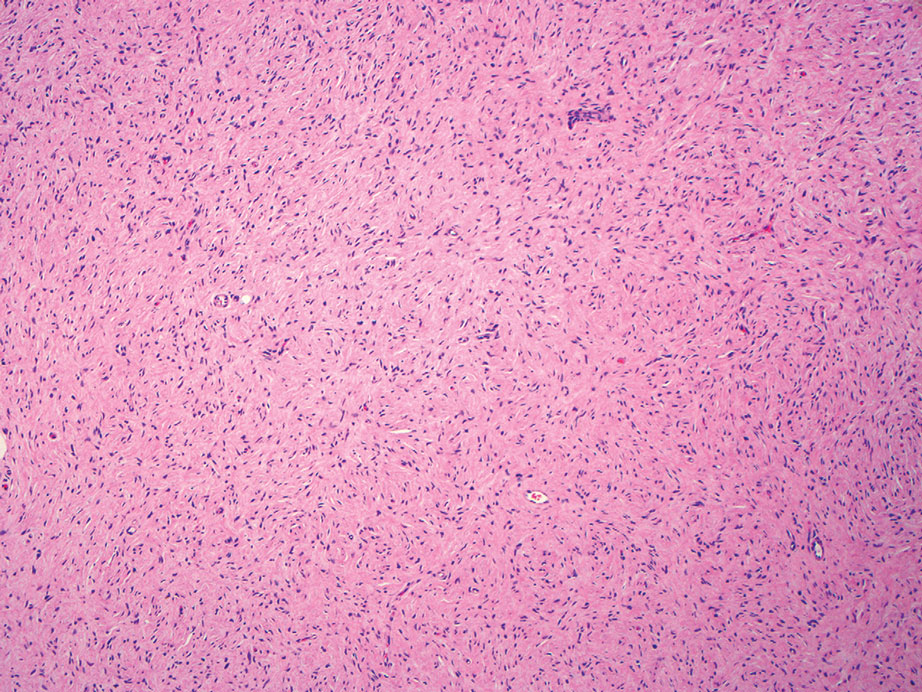

Nodular fasciitis is a benign lesion involving the rapid proliferation of myofibroblasts and fibroblasts in the subcutaneous tissue and most commonly is encountered on the extremities or head and neck regions. Many cases appear at sites of prior trauma, especially in patients aged 20 to 40 years. However, in infants and children the lesions typically are found in the head and neck regions.11 Clinically, lesions present as subcutaneous nodules. Histology reveals an infiltrative and poorly circumscribed proliferation of spindled myofibroblasts associated with myxoid stroma and dense collagen depositions. The spindled cells are loosely associated, rendering a tissue culture–like appearance (Figure 4). It also is common to see erythrocyte extravasation adjacent to myxoid stroma.11 Positive stains include vimentin, smooth muscle actin, and CD68, though immunohistochemistry often is not necessary for diagnosis.12 There often is abundant mitotic activity in nodular fasciitis, especially in early lesions, and the differential diagnosis includes sarcoma. Although nodular fasciitis is mitotically active, it does not show atypical mitotic figures. Nodular fasciitis commonly harbors a gene translocation of the MYH9 gene’s promoter region to the USP6 gene’s coding region.13

- Sakhadeo U, Mundhe R, DeSouza MA, et al. Pleomorphic lipoma: a gentle giant of pathology. J Cytol. 2015;32:201-203. doi:10.4103 /0970-9371.168904

- Shmookler BM, Enzinger FM. Pleomorphic lipoma: a benign tumor simulating liposarcoma. a clinicopathologic analysis of 48 cases. Cancer. 1981;47:126-133.

- Azzopardi JG, Iocco J, Salm R. Pleomorphic lipoma: a tumour simulating liposarcoma. Histopathology. 1983;7:511-523. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.1983.tb02264.x

- Jäger M, Winkelmann R, Eichler K, et al. Pleomorphic lipoma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:208-210. doi:10.1111/ddg.13422

- Allen A, Ahn C, Sangüeza OP. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:483-488. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.05.006

- Socoliuc C, Zurac S, Andrei R, et al. Multiple histological subtypes of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans occurring in the same tumor. Rom J Intern Med. 2015;53:79-88. doi:10.1515/rjim-2015-0011

- Abarzúa-Araya A, Lallas A, Piana S, et al. Superficial angiomyxoma of the skin. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2016;6:47-49. doi:10.5826 /dpc.0603a09

- Hornick J. Practical Soft Tissue Pathology A Diagnostic Approach. 2nd ed. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2017.

- Rato M, Monteiro AF, Parente J, et al. Case for diagnosis. multinucleated cell angiohistiocytoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:291-293. doi:10.1590 /abd1806-4841.20186821

- Grgurich E, Quinn K, Oram C, et al. Multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma: case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:59-61. doi:10.1111/cup.13361

- Zuber TJ, Finley JL. Nodular fasciitis. South Med J. 1994;87:842-844. doi:10.1097/00007611-199408000-00020

- Yver CM, Husson MA, Friedman O. Pathology clinic: nodular fasciitis involving the external ear [published online March 18, 2021]. Ear Nose Throat J. doi:10.1177/01455613211001958

- Erickson-Johnson M, Chou M, Evers B, et al. Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1427-1433. https://doi.org/10.1038 /labinvest.2011.118

The Diagnosis: Pleomorphic Lipoma

Pleomorphic lipoma is a rare, benign, adipocytic neoplasm that presents in the subcutaneous tissues of the upper shoulder, back, or neck. It predominantly affects men aged 50 to 70 years. Most lesions are situated in the subcutaneous tissues; few cases of intramuscular and retroperitoneal tumors have been reported.1 Clinically, pleomorphic lipomas present as painless, well-circumscribed lesions of the subcutaneous tissue that often resemble a lipoma or occasionally may be mistaken for liposarcoma. Histopathologic examination of ordinary lipomas reveals uniform mature adipocytes. However, pleomorphic lipomas consist of a mixture of multinucleated floretlike giant cells, variable-sized adipocytes, and fibrous tissue (ropy collagen bundles) with some myxoid and spindled areas.1,2 The most characteristic histologic feature of pleomorphic lipoma is multinucleated floretlike giant cells. The nuclei of these giant cells appear hyperchromatic, enlarged, and disposed to the periphery of the cell in a circular pattern. Additionally, tumors frequently contain excess mature dense collagen bundles that are strongly refractile in polarized light. Numerous mast cells are present. Atypical lipoblasts and capillary networks commonly are not visible in pleomorphic lipoma.3 The spindle cells express CD34 on immunohistochemistry. Loss of Rb-1 expression is typical.4

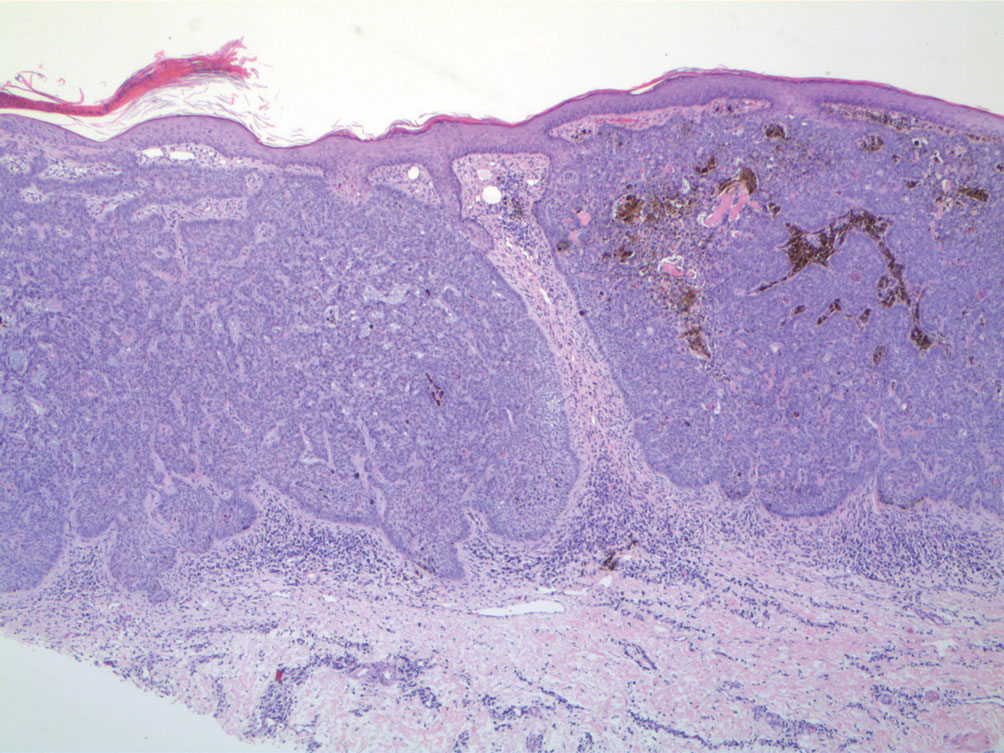

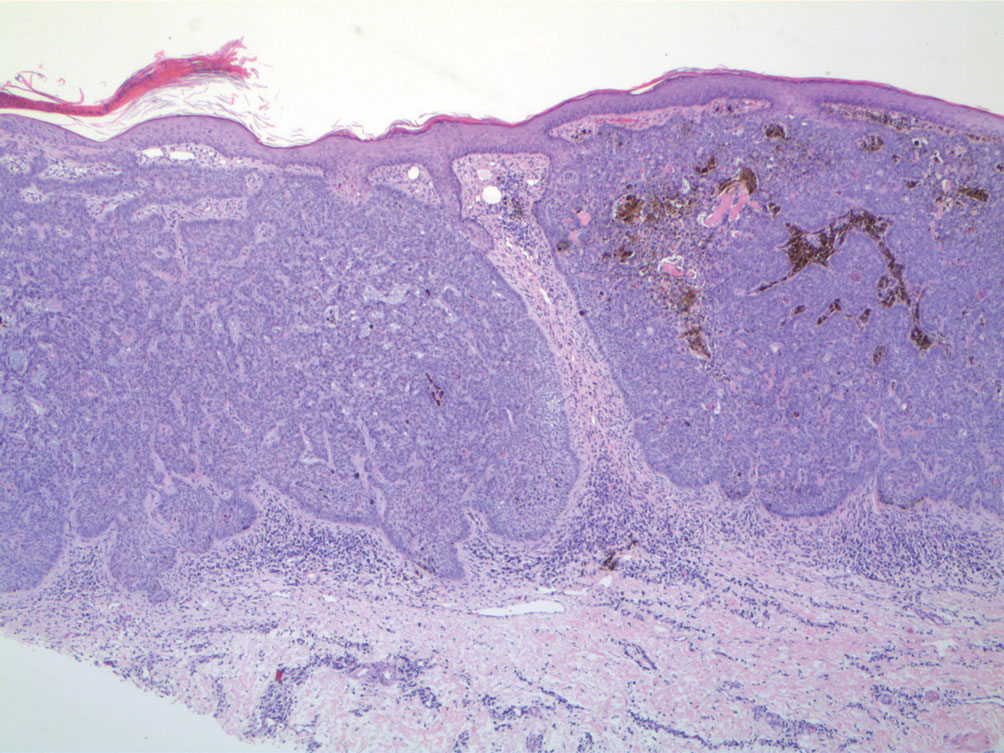

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a slow-growing soft tissue sarcoma that commonly begins as a pink or violet plaque on the trunk or upper limbs. Involvement of the head or neck accounts for only 10% to 15% of cases.5 This tumor has low metastatic potential but is highly infiltrative of surrounding tissues. It is associated with a translocation between chromosomes 22 and 17, leading to the fusion of the platelet-derived growth factor subunit β, PDGFB, and collagen type 1α1, COL1A1, genes.5 Clinically, patients often report that the lesion was present for several years prior to presentation with general stability in size and shape. Eventually, untreated lesions progress to become nodules or tumors and may even bleed or ulcerate. Histology reveals a storiform spindle cell proliferation throughout the dermis with infiltration into subcutaneous fat, commonly appearing in a honeycomblike pattern (Figure 1). Numerous histologic variants exist, including myxoid, sclerosing, pigmented (Bednar tumor), myoid, atrophic, or fibrosarcomatous dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, as well as a giant cell fibroblastoma variant.6 These tumor subtypes can exist independently or in association with one another, creating hybrid lesions that can closely mimic other entities such as pleomorphic lipoma. The spindle cells stain positively for CD34. Treatment of these tumors involves complete surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery; however, recurrence is common for tumors involving the head or neck.5

Superficial angiomyxoma is a slow-growing papule that most commonly appears on the trunk, head, or neck in middle-aged adults. Occasionally, patients with Carney complex also can develop lesions on the external ear or breast.7 Histologically, superficial angiomyxoma is a hypocellular tumor characterized by abundant myxoid stroma, thin blood vessels, and small spindled and stellate cells with minimal cytoplasm (Figure 2).8 Superficial angiomyxoma and pleomorphic lipoma present differently on histology; superficial angiomyxoma is not associated with nuclear atypia or pleomorphism, whereas pleomorphic lipoma characteristically contains multinucleated floretlike giant cells and pleomorphism. Frequently, there also is loss of normal PRKAR1A gene expression, which is responsible for protein kinase A regulatory subunit 1-alpha expression.8

Multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma is a rare benign proliferation that presents with numerous red-violet asymptomatic papules that commonly appear on the upper and lower extremities of women aged 40 to 70 years. Lesions feature both a fibrohistiocytic and vascular component.9 Histologic examination commonly shows multinucleated cells with angular outlining in the superficial dermis accompanied by fibrosis and ectatic small-caliber vessels (Figure 3). Although both pleomorphic lipoma and multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma have similar-appearing multinucleated giant cells, the latter has a proliferation of narrow vessels in thick collagen bundles and lacks an adipocytic component, which distinguishes it from the former.10 Multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma also is characterized by a substantial number of factor XIIIa–positive fibrohistiocytic interstitial cells and vascular hyperplasia.9

Nodular fasciitis is a benign lesion involving the rapid proliferation of myofibroblasts and fibroblasts in the subcutaneous tissue and most commonly is encountered on the extremities or head and neck regions. Many cases appear at sites of prior trauma, especially in patients aged 20 to 40 years. However, in infants and children the lesions typically are found in the head and neck regions.11 Clinically, lesions present as subcutaneous nodules. Histology reveals an infiltrative and poorly circumscribed proliferation of spindled myofibroblasts associated with myxoid stroma and dense collagen depositions. The spindled cells are loosely associated, rendering a tissue culture–like appearance (Figure 4). It also is common to see erythrocyte extravasation adjacent to myxoid stroma.11 Positive stains include vimentin, smooth muscle actin, and CD68, though immunohistochemistry often is not necessary for diagnosis.12 There often is abundant mitotic activity in nodular fasciitis, especially in early lesions, and the differential diagnosis includes sarcoma. Although nodular fasciitis is mitotically active, it does not show atypical mitotic figures. Nodular fasciitis commonly harbors a gene translocation of the MYH9 gene’s promoter region to the USP6 gene’s coding region.13

The Diagnosis: Pleomorphic Lipoma

Pleomorphic lipoma is a rare, benign, adipocytic neoplasm that presents in the subcutaneous tissues of the upper shoulder, back, or neck. It predominantly affects men aged 50 to 70 years. Most lesions are situated in the subcutaneous tissues; few cases of intramuscular and retroperitoneal tumors have been reported.1 Clinically, pleomorphic lipomas present as painless, well-circumscribed lesions of the subcutaneous tissue that often resemble a lipoma or occasionally may be mistaken for liposarcoma. Histopathologic examination of ordinary lipomas reveals uniform mature adipocytes. However, pleomorphic lipomas consist of a mixture of multinucleated floretlike giant cells, variable-sized adipocytes, and fibrous tissue (ropy collagen bundles) with some myxoid and spindled areas.1,2 The most characteristic histologic feature of pleomorphic lipoma is multinucleated floretlike giant cells. The nuclei of these giant cells appear hyperchromatic, enlarged, and disposed to the periphery of the cell in a circular pattern. Additionally, tumors frequently contain excess mature dense collagen bundles that are strongly refractile in polarized light. Numerous mast cells are present. Atypical lipoblasts and capillary networks commonly are not visible in pleomorphic lipoma.3 The spindle cells express CD34 on immunohistochemistry. Loss of Rb-1 expression is typical.4

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a slow-growing soft tissue sarcoma that commonly begins as a pink or violet plaque on the trunk or upper limbs. Involvement of the head or neck accounts for only 10% to 15% of cases.5 This tumor has low metastatic potential but is highly infiltrative of surrounding tissues. It is associated with a translocation between chromosomes 22 and 17, leading to the fusion of the platelet-derived growth factor subunit β, PDGFB, and collagen type 1α1, COL1A1, genes.5 Clinically, patients often report that the lesion was present for several years prior to presentation with general stability in size and shape. Eventually, untreated lesions progress to become nodules or tumors and may even bleed or ulcerate. Histology reveals a storiform spindle cell proliferation throughout the dermis with infiltration into subcutaneous fat, commonly appearing in a honeycomblike pattern (Figure 1). Numerous histologic variants exist, including myxoid, sclerosing, pigmented (Bednar tumor), myoid, atrophic, or fibrosarcomatous dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, as well as a giant cell fibroblastoma variant.6 These tumor subtypes can exist independently or in association with one another, creating hybrid lesions that can closely mimic other entities such as pleomorphic lipoma. The spindle cells stain positively for CD34. Treatment of these tumors involves complete surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery; however, recurrence is common for tumors involving the head or neck.5

Superficial angiomyxoma is a slow-growing papule that most commonly appears on the trunk, head, or neck in middle-aged adults. Occasionally, patients with Carney complex also can develop lesions on the external ear or breast.7 Histologically, superficial angiomyxoma is a hypocellular tumor characterized by abundant myxoid stroma, thin blood vessels, and small spindled and stellate cells with minimal cytoplasm (Figure 2).8 Superficial angiomyxoma and pleomorphic lipoma present differently on histology; superficial angiomyxoma is not associated with nuclear atypia or pleomorphism, whereas pleomorphic lipoma characteristically contains multinucleated floretlike giant cells and pleomorphism. Frequently, there also is loss of normal PRKAR1A gene expression, which is responsible for protein kinase A regulatory subunit 1-alpha expression.8

Multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma is a rare benign proliferation that presents with numerous red-violet asymptomatic papules that commonly appear on the upper and lower extremities of women aged 40 to 70 years. Lesions feature both a fibrohistiocytic and vascular component.9 Histologic examination commonly shows multinucleated cells with angular outlining in the superficial dermis accompanied by fibrosis and ectatic small-caliber vessels (Figure 3). Although both pleomorphic lipoma and multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma have similar-appearing multinucleated giant cells, the latter has a proliferation of narrow vessels in thick collagen bundles and lacks an adipocytic component, which distinguishes it from the former.10 Multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma also is characterized by a substantial number of factor XIIIa–positive fibrohistiocytic interstitial cells and vascular hyperplasia.9

Nodular fasciitis is a benign lesion involving the rapid proliferation of myofibroblasts and fibroblasts in the subcutaneous tissue and most commonly is encountered on the extremities or head and neck regions. Many cases appear at sites of prior trauma, especially in patients aged 20 to 40 years. However, in infants and children the lesions typically are found in the head and neck regions.11 Clinically, lesions present as subcutaneous nodules. Histology reveals an infiltrative and poorly circumscribed proliferation of spindled myofibroblasts associated with myxoid stroma and dense collagen depositions. The spindled cells are loosely associated, rendering a tissue culture–like appearance (Figure 4). It also is common to see erythrocyte extravasation adjacent to myxoid stroma.11 Positive stains include vimentin, smooth muscle actin, and CD68, though immunohistochemistry often is not necessary for diagnosis.12 There often is abundant mitotic activity in nodular fasciitis, especially in early lesions, and the differential diagnosis includes sarcoma. Although nodular fasciitis is mitotically active, it does not show atypical mitotic figures. Nodular fasciitis commonly harbors a gene translocation of the MYH9 gene’s promoter region to the USP6 gene’s coding region.13

- Sakhadeo U, Mundhe R, DeSouza MA, et al. Pleomorphic lipoma: a gentle giant of pathology. J Cytol. 2015;32:201-203. doi:10.4103 /0970-9371.168904

- Shmookler BM, Enzinger FM. Pleomorphic lipoma: a benign tumor simulating liposarcoma. a clinicopathologic analysis of 48 cases. Cancer. 1981;47:126-133.

- Azzopardi JG, Iocco J, Salm R. Pleomorphic lipoma: a tumour simulating liposarcoma. Histopathology. 1983;7:511-523. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.1983.tb02264.x

- Jäger M, Winkelmann R, Eichler K, et al. Pleomorphic lipoma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:208-210. doi:10.1111/ddg.13422

- Allen A, Ahn C, Sangüeza OP. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:483-488. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.05.006

- Socoliuc C, Zurac S, Andrei R, et al. Multiple histological subtypes of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans occurring in the same tumor. Rom J Intern Med. 2015;53:79-88. doi:10.1515/rjim-2015-0011

- Abarzúa-Araya A, Lallas A, Piana S, et al. Superficial angiomyxoma of the skin. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2016;6:47-49. doi:10.5826 /dpc.0603a09

- Hornick J. Practical Soft Tissue Pathology A Diagnostic Approach. 2nd ed. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2017.

- Rato M, Monteiro AF, Parente J, et al. Case for diagnosis. multinucleated cell angiohistiocytoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:291-293. doi:10.1590 /abd1806-4841.20186821

- Grgurich E, Quinn K, Oram C, et al. Multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma: case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:59-61. doi:10.1111/cup.13361

- Zuber TJ, Finley JL. Nodular fasciitis. South Med J. 1994;87:842-844. doi:10.1097/00007611-199408000-00020

- Yver CM, Husson MA, Friedman O. Pathology clinic: nodular fasciitis involving the external ear [published online March 18, 2021]. Ear Nose Throat J. doi:10.1177/01455613211001958

- Erickson-Johnson M, Chou M, Evers B, et al. Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1427-1433. https://doi.org/10.1038 /labinvest.2011.118

- Sakhadeo U, Mundhe R, DeSouza MA, et al. Pleomorphic lipoma: a gentle giant of pathology. J Cytol. 2015;32:201-203. doi:10.4103 /0970-9371.168904

- Shmookler BM, Enzinger FM. Pleomorphic lipoma: a benign tumor simulating liposarcoma. a clinicopathologic analysis of 48 cases. Cancer. 1981;47:126-133.

- Azzopardi JG, Iocco J, Salm R. Pleomorphic lipoma: a tumour simulating liposarcoma. Histopathology. 1983;7:511-523. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.1983.tb02264.x

- Jäger M, Winkelmann R, Eichler K, et al. Pleomorphic lipoma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:208-210. doi:10.1111/ddg.13422

- Allen A, Ahn C, Sangüeza OP. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:483-488. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.05.006

- Socoliuc C, Zurac S, Andrei R, et al. Multiple histological subtypes of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans occurring in the same tumor. Rom J Intern Med. 2015;53:79-88. doi:10.1515/rjim-2015-0011

- Abarzúa-Araya A, Lallas A, Piana S, et al. Superficial angiomyxoma of the skin. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2016;6:47-49. doi:10.5826 /dpc.0603a09

- Hornick J. Practical Soft Tissue Pathology A Diagnostic Approach. 2nd ed. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2017.

- Rato M, Monteiro AF, Parente J, et al. Case for diagnosis. multinucleated cell angiohistiocytoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:291-293. doi:10.1590 /abd1806-4841.20186821

- Grgurich E, Quinn K, Oram C, et al. Multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma: case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:59-61. doi:10.1111/cup.13361

- Zuber TJ, Finley JL. Nodular fasciitis. South Med J. 1994;87:842-844. doi:10.1097/00007611-199408000-00020

- Yver CM, Husson MA, Friedman O. Pathology clinic: nodular fasciitis involving the external ear [published online March 18, 2021]. Ear Nose Throat J. doi:10.1177/01455613211001958

- Erickson-Johnson M, Chou M, Evers B, et al. Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1427-1433. https://doi.org/10.1038 /labinvest.2011.118

An otherwise healthy 56-year-old man with a family history of lymphoma presented with a raised lesion on the postauricular neck. He first noticed the nodule 3 months prior and was unsure if it was still getting larger. It was predominantly asymptomatic. Physical examination revealed a 1.5×1.5-cm, mobile, subcutaneous nodule. An incisional biopsy was performed and submitted for histologic evaluation.

Collision Course of a Basal Cell Carcinoma and Apocrine Hidrocystoma on the Scalp

To the Editor:

A collision tumor is the coexistence of 2 discrete tumors in the same neoplasm, possibly comprising a malignant tumor and a benign tumor, and thereby complicating appropriate diagnosis and treatment. We present a case of a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) of the scalp that was later found to be in collision with an apocrine hidrocystoma that might have arisen from a nevus sebaceus. Although rare, BCC can coexist with apocrine hidrocystoma. Jayaprakasam and Rene1 reported a case of a collision tumor containing BCC and hidrocystoma on the eyelid.1 We present a case of a BCC on the scalp that was later found to be in collision with an apocrine hidrocystoma that possibly arose from a nevus sebaceus.

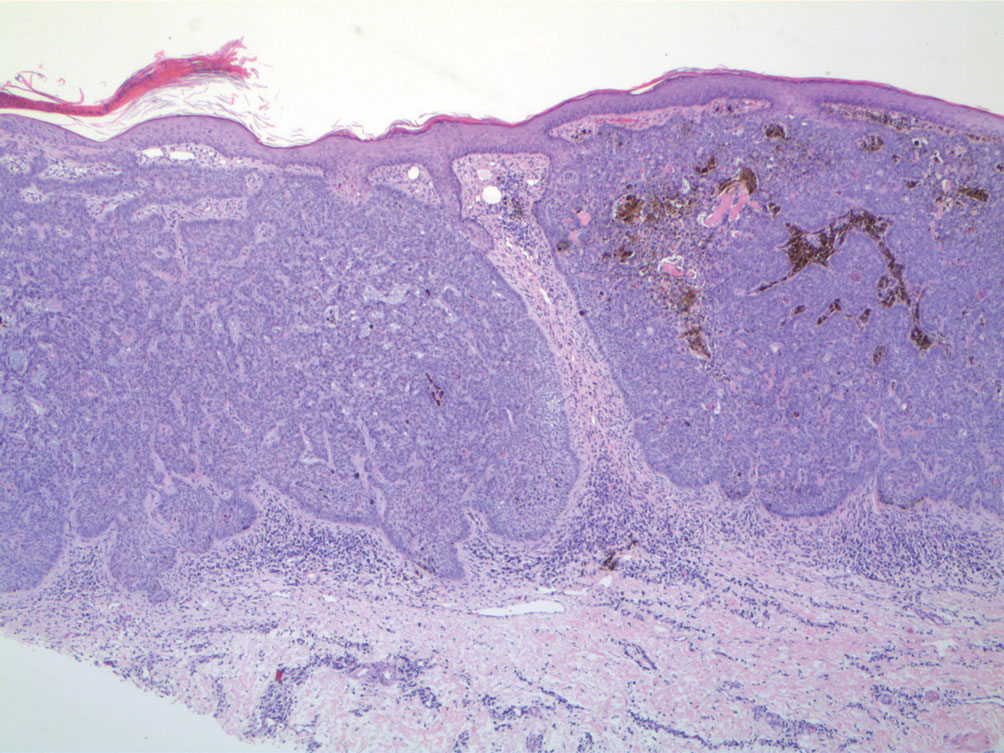

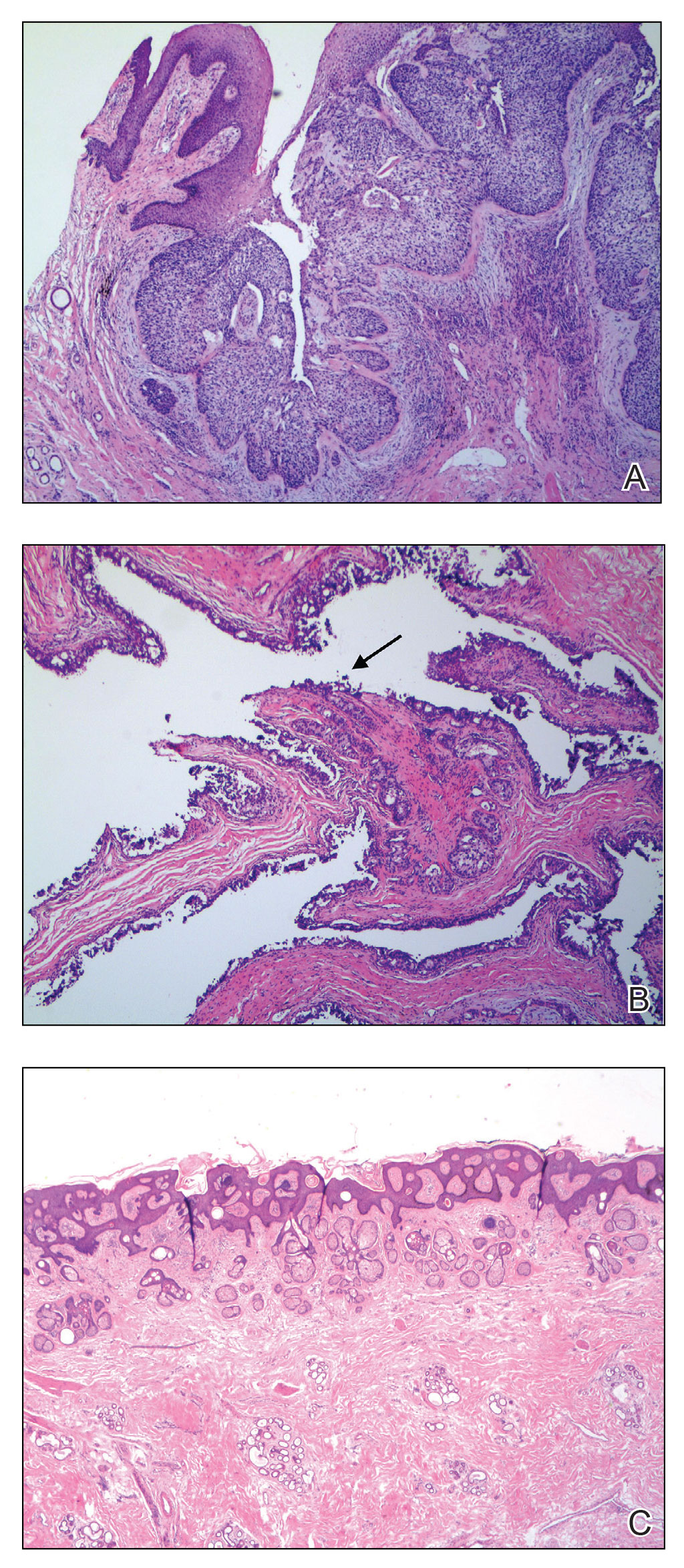

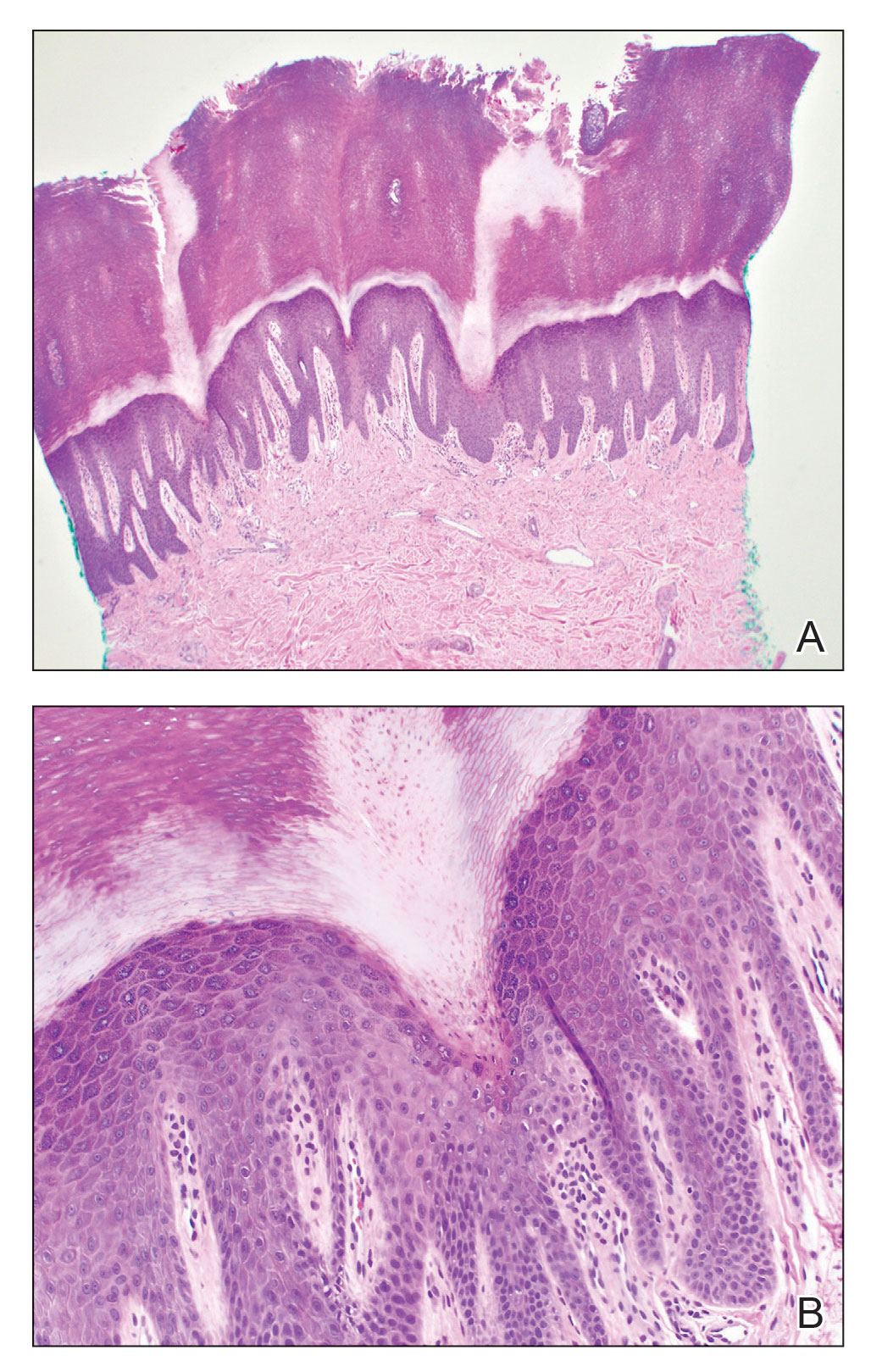

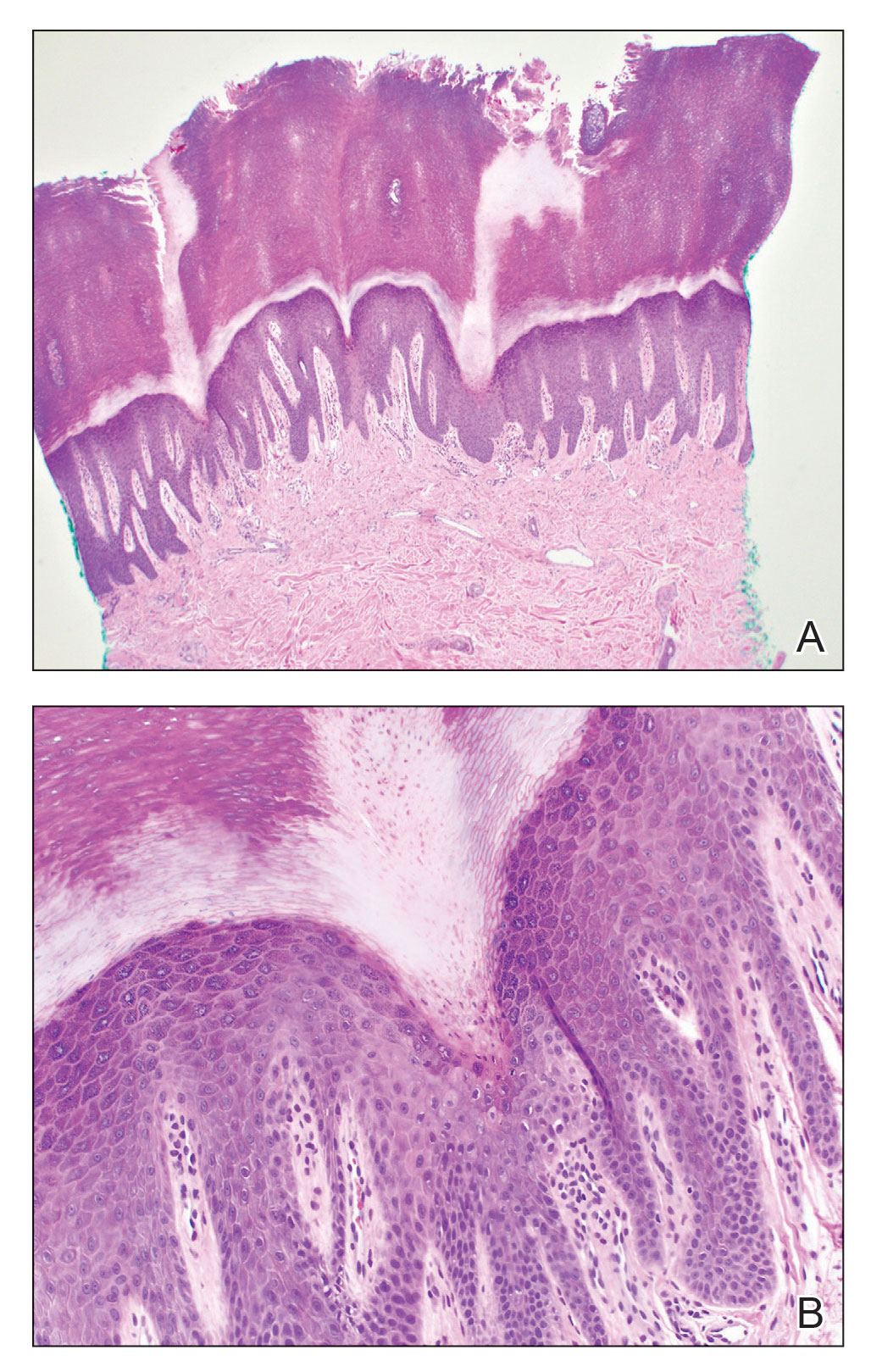

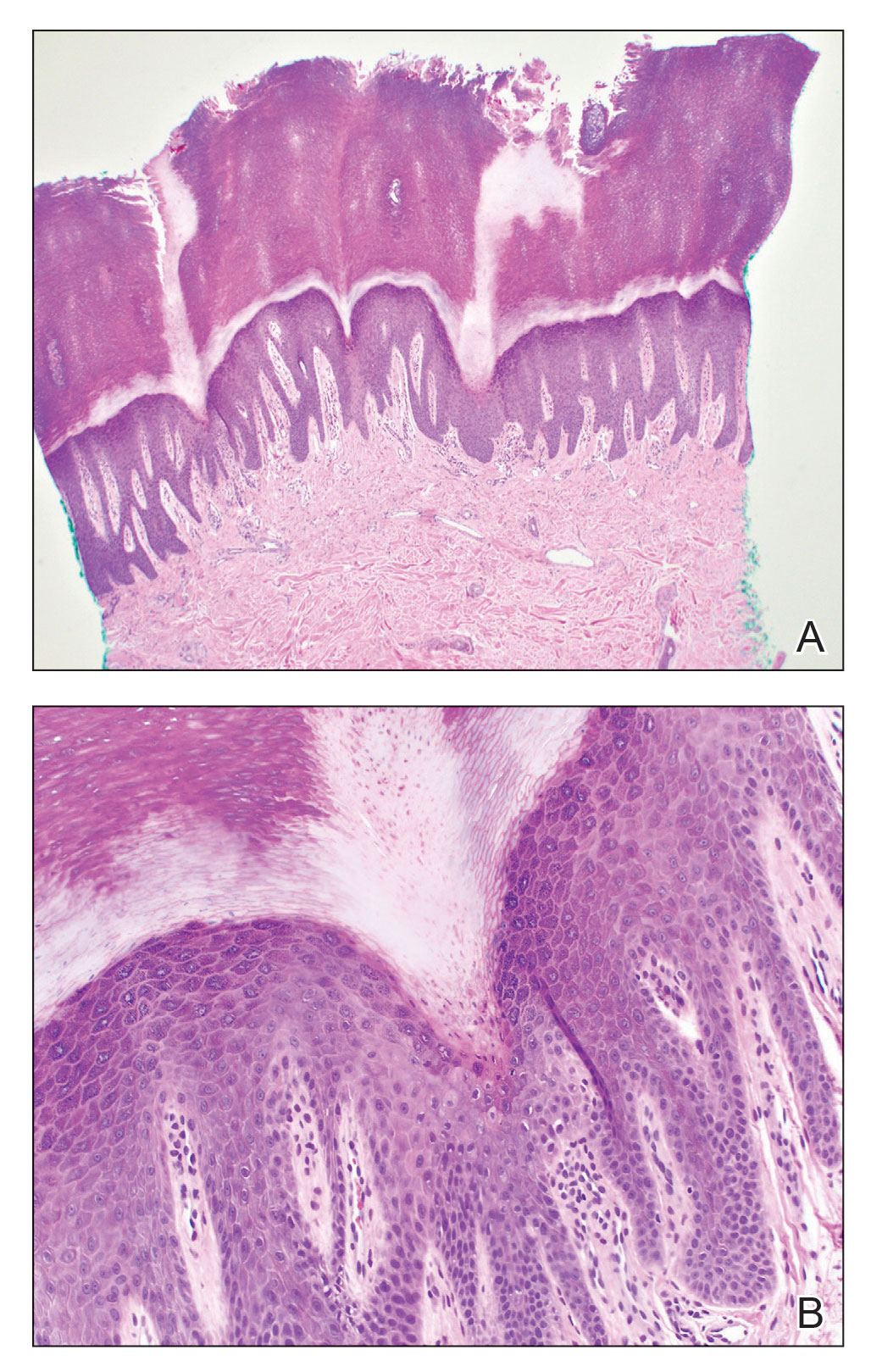

A 92-year-old Black woman with a biopsy-confirmed primary BCC of the left parietal scalp presented for Mohs micrographic surgery. The pathology report from an outside facility was reviewed. The initial diagnosis had been made with 2 punch biopsies from separate areas of the large nodule—one consistent with nodular and pigmented BCC (Figure 1), and the other revealed nodular ulcerated BCC. Physical examination prior to Mohs surgery revealed a mobile, flesh-colored, 6.2×6.0-cm nodule with minimal overlying hair on the left parietal scalp (Figure 2). During stage-I processing by the histopathology laboratory, large cystic structures were encountered; en face frozen sections showed a cystic tumor. Excised tissue was submitted for permanent processing to aid in diagnosis; the initial diagnostic biopsy slides were requested from the outside facility for review.

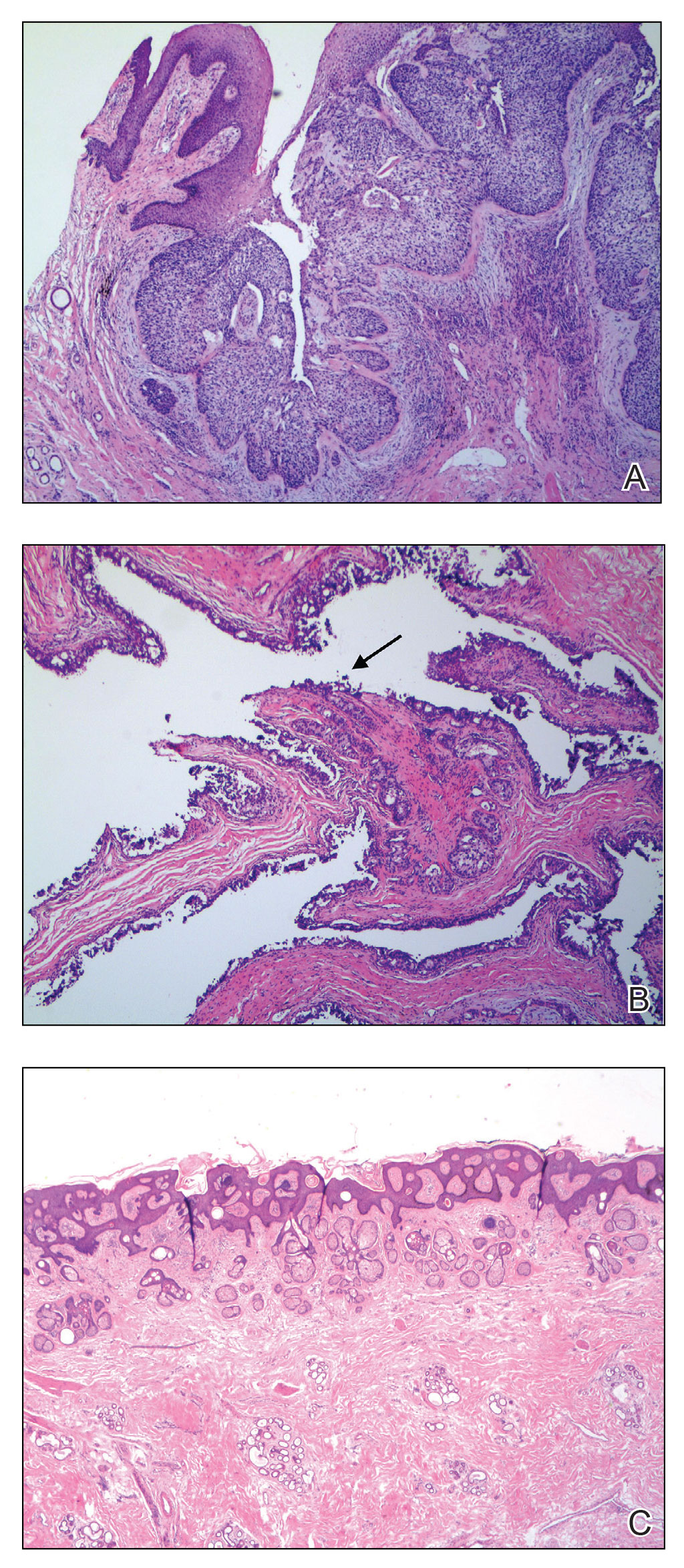

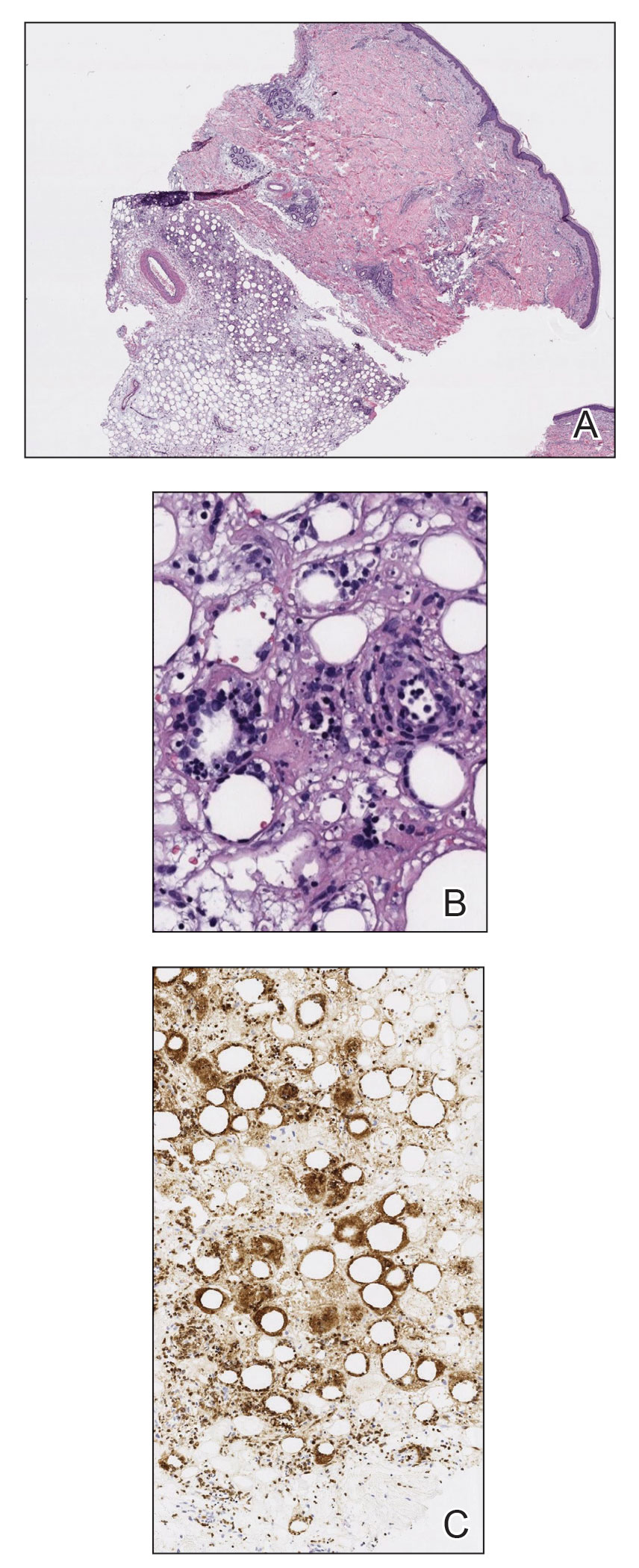

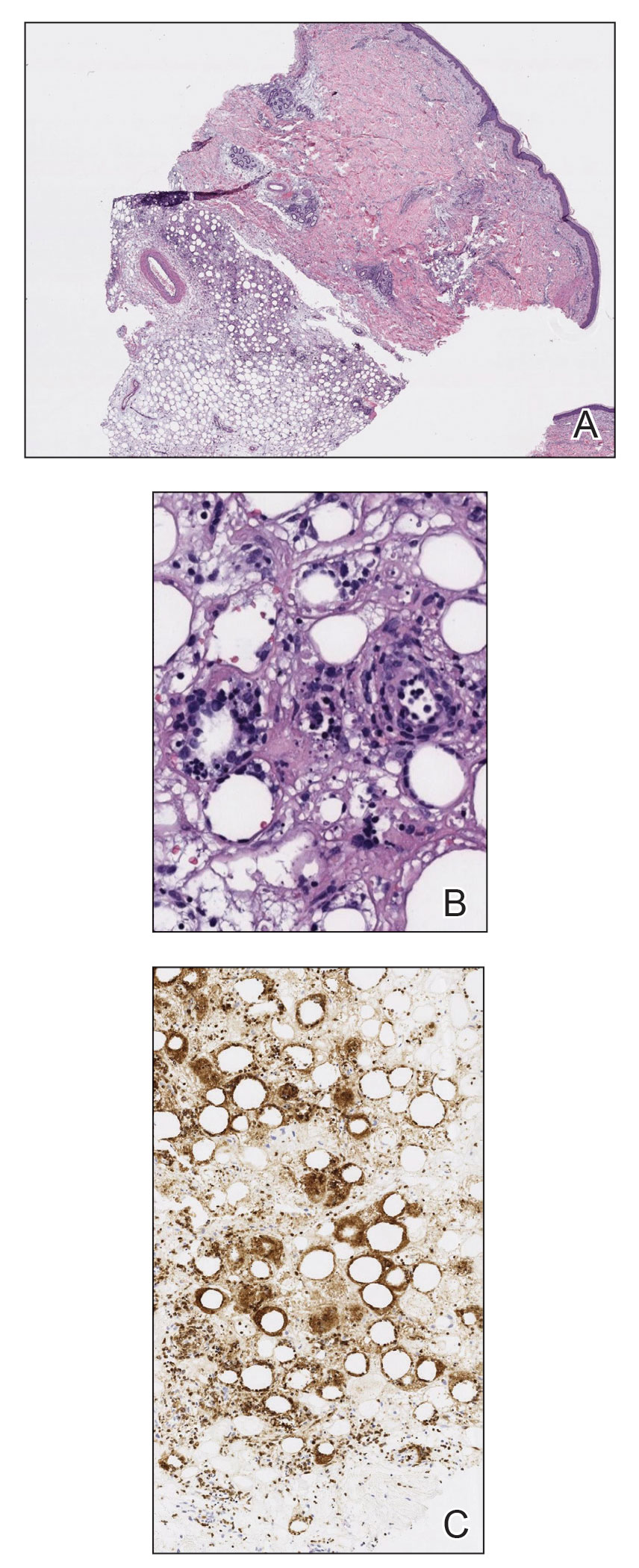

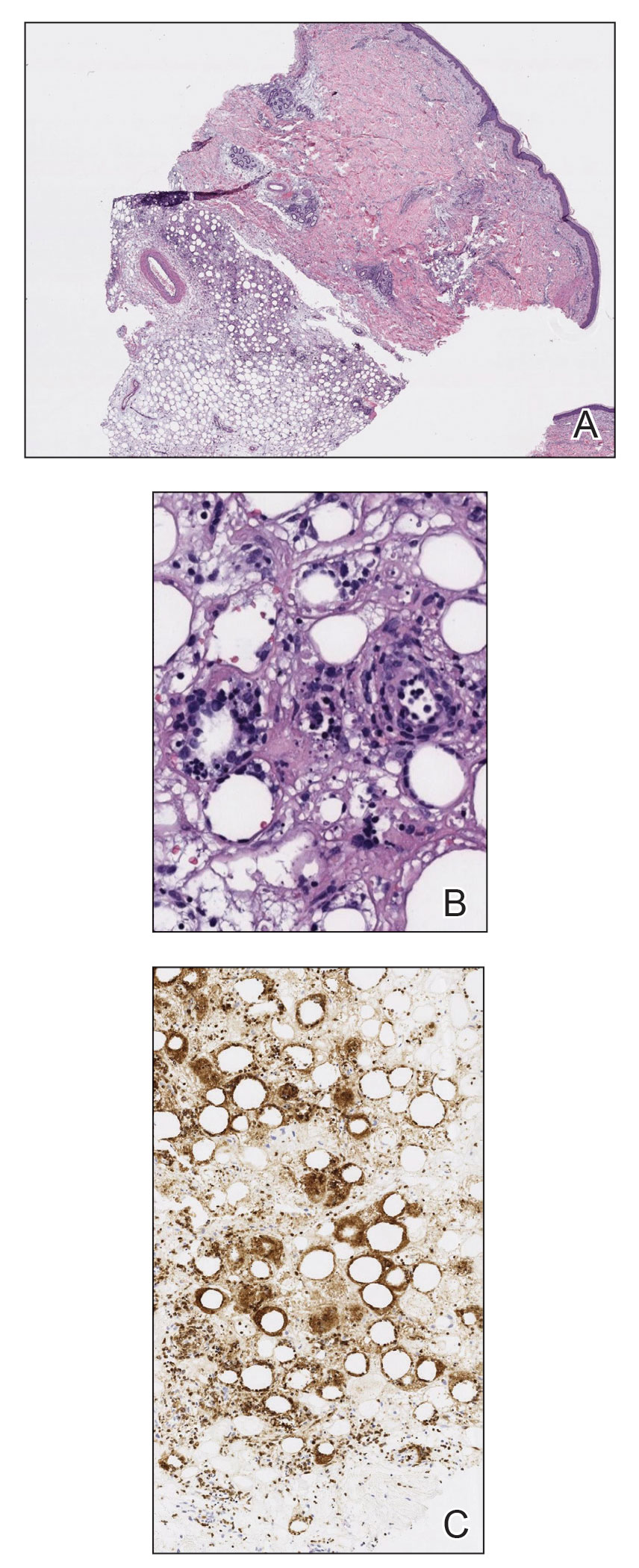

The initial diagnostic biopsy slides were reviewed and found to be consistent with nodular and pigmented BCC, as previously reported. Findings from hematoxylin and eosin staining of tissue obtained from Mohs sections were consistent with a combined neoplasm comprising BCC (Figure 3A) and apocrine hidrocystoma (Figure 3B). In addition, one section was characterized by acanthosis, papillomatosis, and sebaceous glands—similar to findings that are seen in a nevus sebaceus (Figure 3C).

The BCC was cleared after stage I; the final wound size was 7×6.6 cm. Although benign apocrine hidrocystoma was still evident at the margin, further excision was not performed at the request of the patient and her family. Partial primary wound closure was performed with pulley sutures. A xenograft was placed over the unclosed central portion. The wound was permitted to heal by second intention.

The clinical differential diagnosis of a scalp nodule includes a pilar cyst, BCC, squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma, cutaneous metastasis, adnexal tumor, atypical fibroxanthoma, and collision tumor. A collision tumor—the association of 2 or more benign or malignant neoplasms—represents a well-known pitfall in making a correct clinical and pathologic diagnosis.2 Many theories have been proposed to explain the pathophysiology of collision tumors. Some authors have speculated that they arise from involvement of related cell types.1 Other theories include induction by cytokines and growth factors secreted from one tumor that provides an ideal environment for proliferation of other cell types, a field cancerization effect of sun-damaged skin, or a coincidence.2

In our case, it is possible that the 2 tumors arose from a nevus sebaceus. One retrospective study of 706 cases of nevus sebaceus (707 specimens) found that 22.5% of cases developed secondary proliferation; of those cases, 18.9% were benign.3 Additionally, in 4.2% of cases of nevus sebaceus, proliferation of 2 or more tumors developed. The most common malignant neoplasm to develop from nevus sebaceus was BCC, followed by squamous cell carcinoma and sebaceous carcinoma. The most common benign neoplasm to develop from nevus sebaceus was trichoblastoma, followed by syringocystadenoma papilliferum.3

Our case highlights the possibility of a sampling error when performing a biopsy of any large neoplasm. Additionally, Mohs surgeons should maintain high clinical suspicion for collision tumors when encountering a large tumor with pathology inconsistent with the original biopsy. Apocrine hidrocystoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a large cystic mass of the scalp. Also, it is important to recognize that malignant lesions, such as BCC, can coexist with another benign tumor. Basal cell carcinoma is rare in Black patients, supporting our belief that our patient’s tumors arose from a nevus sebaceus.

It also is important for Mohs surgeons to consider any potential discrepancy between the initial pathology report and Mohs intraoperative pathology that can impact diagnosis, the aggressiveness of the tumors identified, and how such aggressiveness may affect management options.4,5 Some dermatology practices request biopsy slides from patients who are referred for Mohs micrographic surgery for internal review by a dermatopathologist before surgery is performed; however, this protocol requires additional time and adds costs for the overall health care system.4 One study found that internal review of outside biopsy slides resulted in a change in diagnosis in 2.2% of patients (N=3345)—affecting management in 61% of cases in which the diagnosis was changed.4 Another study (N=163) found that the reported aggressiveness of 50.5% of nonmelanoma cases in an initial biopsy report was changed during Mohs micrographic surgery.5 Mohs surgeons should be aware that discrepancies can occur, and if a discrepancy is discovered, the procedure may be paused until the initial biopsy slide is reviewed and further information is collected.

- Jayaprakasam A, Rene C. A benign or malignant eyelid lump—can you tell? an unusual collision tumour highlighting the difficulty differentiating a hidrocystoma from a basal cell carcinoma. BMJ Case Reports. 2012;2012:bcr1220115307. doi:10.1136/bcr.12.2011.5307

- Miteva M, Herschthal D, Ricotti C, et al. A rare case of a cutaneous squamomelanocytic tumor: revisiting the histogenesis of combined neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:599-603. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181a88116

- Idriss MH, Elston DM. Secondary neoplasms associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 707 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:332-337. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.004

- Butler ST, Youker SR, Mandrell J, et al. The importance of reviewing pathology specimens before Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:407-412. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.01056.x

- Stiegel E, Lam C, Schowalter M, et al. Correlation between original biopsy pathology and Mohs intraoperative pathology. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:193-197. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001276

To the Editor:

A collision tumor is the coexistence of 2 discrete tumors in the same neoplasm, possibly comprising a malignant tumor and a benign tumor, and thereby complicating appropriate diagnosis and treatment. We present a case of a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) of the scalp that was later found to be in collision with an apocrine hidrocystoma that might have arisen from a nevus sebaceus. Although rare, BCC can coexist with apocrine hidrocystoma. Jayaprakasam and Rene1 reported a case of a collision tumor containing BCC and hidrocystoma on the eyelid.1 We present a case of a BCC on the scalp that was later found to be in collision with an apocrine hidrocystoma that possibly arose from a nevus sebaceus.

A 92-year-old Black woman with a biopsy-confirmed primary BCC of the left parietal scalp presented for Mohs micrographic surgery. The pathology report from an outside facility was reviewed. The initial diagnosis had been made with 2 punch biopsies from separate areas of the large nodule—one consistent with nodular and pigmented BCC (Figure 1), and the other revealed nodular ulcerated BCC. Physical examination prior to Mohs surgery revealed a mobile, flesh-colored, 6.2×6.0-cm nodule with minimal overlying hair on the left parietal scalp (Figure 2). During stage-I processing by the histopathology laboratory, large cystic structures were encountered; en face frozen sections showed a cystic tumor. Excised tissue was submitted for permanent processing to aid in diagnosis; the initial diagnostic biopsy slides were requested from the outside facility for review.

The initial diagnostic biopsy slides were reviewed and found to be consistent with nodular and pigmented BCC, as previously reported. Findings from hematoxylin and eosin staining of tissue obtained from Mohs sections were consistent with a combined neoplasm comprising BCC (Figure 3A) and apocrine hidrocystoma (Figure 3B). In addition, one section was characterized by acanthosis, papillomatosis, and sebaceous glands—similar to findings that are seen in a nevus sebaceus (Figure 3C).

The BCC was cleared after stage I; the final wound size was 7×6.6 cm. Although benign apocrine hidrocystoma was still evident at the margin, further excision was not performed at the request of the patient and her family. Partial primary wound closure was performed with pulley sutures. A xenograft was placed over the unclosed central portion. The wound was permitted to heal by second intention.

The clinical differential diagnosis of a scalp nodule includes a pilar cyst, BCC, squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma, cutaneous metastasis, adnexal tumor, atypical fibroxanthoma, and collision tumor. A collision tumor—the association of 2 or more benign or malignant neoplasms—represents a well-known pitfall in making a correct clinical and pathologic diagnosis.2 Many theories have been proposed to explain the pathophysiology of collision tumors. Some authors have speculated that they arise from involvement of related cell types.1 Other theories include induction by cytokines and growth factors secreted from one tumor that provides an ideal environment for proliferation of other cell types, a field cancerization effect of sun-damaged skin, or a coincidence.2

In our case, it is possible that the 2 tumors arose from a nevus sebaceus. One retrospective study of 706 cases of nevus sebaceus (707 specimens) found that 22.5% of cases developed secondary proliferation; of those cases, 18.9% were benign.3 Additionally, in 4.2% of cases of nevus sebaceus, proliferation of 2 or more tumors developed. The most common malignant neoplasm to develop from nevus sebaceus was BCC, followed by squamous cell carcinoma and sebaceous carcinoma. The most common benign neoplasm to develop from nevus sebaceus was trichoblastoma, followed by syringocystadenoma papilliferum.3

Our case highlights the possibility of a sampling error when performing a biopsy of any large neoplasm. Additionally, Mohs surgeons should maintain high clinical suspicion for collision tumors when encountering a large tumor with pathology inconsistent with the original biopsy. Apocrine hidrocystoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a large cystic mass of the scalp. Also, it is important to recognize that malignant lesions, such as BCC, can coexist with another benign tumor. Basal cell carcinoma is rare in Black patients, supporting our belief that our patient’s tumors arose from a nevus sebaceus.

It also is important for Mohs surgeons to consider any potential discrepancy between the initial pathology report and Mohs intraoperative pathology that can impact diagnosis, the aggressiveness of the tumors identified, and how such aggressiveness may affect management options.4,5 Some dermatology practices request biopsy slides from patients who are referred for Mohs micrographic surgery for internal review by a dermatopathologist before surgery is performed; however, this protocol requires additional time and adds costs for the overall health care system.4 One study found that internal review of outside biopsy slides resulted in a change in diagnosis in 2.2% of patients (N=3345)—affecting management in 61% of cases in which the diagnosis was changed.4 Another study (N=163) found that the reported aggressiveness of 50.5% of nonmelanoma cases in an initial biopsy report was changed during Mohs micrographic surgery.5 Mohs surgeons should be aware that discrepancies can occur, and if a discrepancy is discovered, the procedure may be paused until the initial biopsy slide is reviewed and further information is collected.

To the Editor:

A collision tumor is the coexistence of 2 discrete tumors in the same neoplasm, possibly comprising a malignant tumor and a benign tumor, and thereby complicating appropriate diagnosis and treatment. We present a case of a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) of the scalp that was later found to be in collision with an apocrine hidrocystoma that might have arisen from a nevus sebaceus. Although rare, BCC can coexist with apocrine hidrocystoma. Jayaprakasam and Rene1 reported a case of a collision tumor containing BCC and hidrocystoma on the eyelid.1 We present a case of a BCC on the scalp that was later found to be in collision with an apocrine hidrocystoma that possibly arose from a nevus sebaceus.

A 92-year-old Black woman with a biopsy-confirmed primary BCC of the left parietal scalp presented for Mohs micrographic surgery. The pathology report from an outside facility was reviewed. The initial diagnosis had been made with 2 punch biopsies from separate areas of the large nodule—one consistent with nodular and pigmented BCC (Figure 1), and the other revealed nodular ulcerated BCC. Physical examination prior to Mohs surgery revealed a mobile, flesh-colored, 6.2×6.0-cm nodule with minimal overlying hair on the left parietal scalp (Figure 2). During stage-I processing by the histopathology laboratory, large cystic structures were encountered; en face frozen sections showed a cystic tumor. Excised tissue was submitted for permanent processing to aid in diagnosis; the initial diagnostic biopsy slides were requested from the outside facility for review.

The initial diagnostic biopsy slides were reviewed and found to be consistent with nodular and pigmented BCC, as previously reported. Findings from hematoxylin and eosin staining of tissue obtained from Mohs sections were consistent with a combined neoplasm comprising BCC (Figure 3A) and apocrine hidrocystoma (Figure 3B). In addition, one section was characterized by acanthosis, papillomatosis, and sebaceous glands—similar to findings that are seen in a nevus sebaceus (Figure 3C).

The BCC was cleared after stage I; the final wound size was 7×6.6 cm. Although benign apocrine hidrocystoma was still evident at the margin, further excision was not performed at the request of the patient and her family. Partial primary wound closure was performed with pulley sutures. A xenograft was placed over the unclosed central portion. The wound was permitted to heal by second intention.

The clinical differential diagnosis of a scalp nodule includes a pilar cyst, BCC, squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma, cutaneous metastasis, adnexal tumor, atypical fibroxanthoma, and collision tumor. A collision tumor—the association of 2 or more benign or malignant neoplasms—represents a well-known pitfall in making a correct clinical and pathologic diagnosis.2 Many theories have been proposed to explain the pathophysiology of collision tumors. Some authors have speculated that they arise from involvement of related cell types.1 Other theories include induction by cytokines and growth factors secreted from one tumor that provides an ideal environment for proliferation of other cell types, a field cancerization effect of sun-damaged skin, or a coincidence.2

In our case, it is possible that the 2 tumors arose from a nevus sebaceus. One retrospective study of 706 cases of nevus sebaceus (707 specimens) found that 22.5% of cases developed secondary proliferation; of those cases, 18.9% were benign.3 Additionally, in 4.2% of cases of nevus sebaceus, proliferation of 2 or more tumors developed. The most common malignant neoplasm to develop from nevus sebaceus was BCC, followed by squamous cell carcinoma and sebaceous carcinoma. The most common benign neoplasm to develop from nevus sebaceus was trichoblastoma, followed by syringocystadenoma papilliferum.3

Our case highlights the possibility of a sampling error when performing a biopsy of any large neoplasm. Additionally, Mohs surgeons should maintain high clinical suspicion for collision tumors when encountering a large tumor with pathology inconsistent with the original biopsy. Apocrine hidrocystoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a large cystic mass of the scalp. Also, it is important to recognize that malignant lesions, such as BCC, can coexist with another benign tumor. Basal cell carcinoma is rare in Black patients, supporting our belief that our patient’s tumors arose from a nevus sebaceus.

It also is important for Mohs surgeons to consider any potential discrepancy between the initial pathology report and Mohs intraoperative pathology that can impact diagnosis, the aggressiveness of the tumors identified, and how such aggressiveness may affect management options.4,5 Some dermatology practices request biopsy slides from patients who are referred for Mohs micrographic surgery for internal review by a dermatopathologist before surgery is performed; however, this protocol requires additional time and adds costs for the overall health care system.4 One study found that internal review of outside biopsy slides resulted in a change in diagnosis in 2.2% of patients (N=3345)—affecting management in 61% of cases in which the diagnosis was changed.4 Another study (N=163) found that the reported aggressiveness of 50.5% of nonmelanoma cases in an initial biopsy report was changed during Mohs micrographic surgery.5 Mohs surgeons should be aware that discrepancies can occur, and if a discrepancy is discovered, the procedure may be paused until the initial biopsy slide is reviewed and further information is collected.

- Jayaprakasam A, Rene C. A benign or malignant eyelid lump—can you tell? an unusual collision tumour highlighting the difficulty differentiating a hidrocystoma from a basal cell carcinoma. BMJ Case Reports. 2012;2012:bcr1220115307. doi:10.1136/bcr.12.2011.5307

- Miteva M, Herschthal D, Ricotti C, et al. A rare case of a cutaneous squamomelanocytic tumor: revisiting the histogenesis of combined neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:599-603. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181a88116

- Idriss MH, Elston DM. Secondary neoplasms associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 707 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:332-337. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.004

- Butler ST, Youker SR, Mandrell J, et al. The importance of reviewing pathology specimens before Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:407-412. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.01056.x

- Stiegel E, Lam C, Schowalter M, et al. Correlation between original biopsy pathology and Mohs intraoperative pathology. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:193-197. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001276

- Jayaprakasam A, Rene C. A benign or malignant eyelid lump—can you tell? an unusual collision tumour highlighting the difficulty differentiating a hidrocystoma from a basal cell carcinoma. BMJ Case Reports. 2012;2012:bcr1220115307. doi:10.1136/bcr.12.2011.5307

- Miteva M, Herschthal D, Ricotti C, et al. A rare case of a cutaneous squamomelanocytic tumor: revisiting the histogenesis of combined neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:599-603. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181a88116

- Idriss MH, Elston DM. Secondary neoplasms associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 707 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:332-337. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.004

- Butler ST, Youker SR, Mandrell J, et al. The importance of reviewing pathology specimens before Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:407-412. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.01056.x

- Stiegel E, Lam C, Schowalter M, et al. Correlation between original biopsy pathology and Mohs intraoperative pathology. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:193-197. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001276

PRACTICE POINTS

- When collision tumors are encountered during Mohs micrographic surgery, review of the initial diagnostic material is recommended.

- Permanent processing of Mohs excisions may be helpful in determining the diagnosis of the occult second tumor diagnosis.

Scattered Red-Brown, Centrally Violaceous, Blanching Papules on an Infant

The Diagnosis: Neonatal-Onset Multisystem Inflammatory Disorder (NOMID)

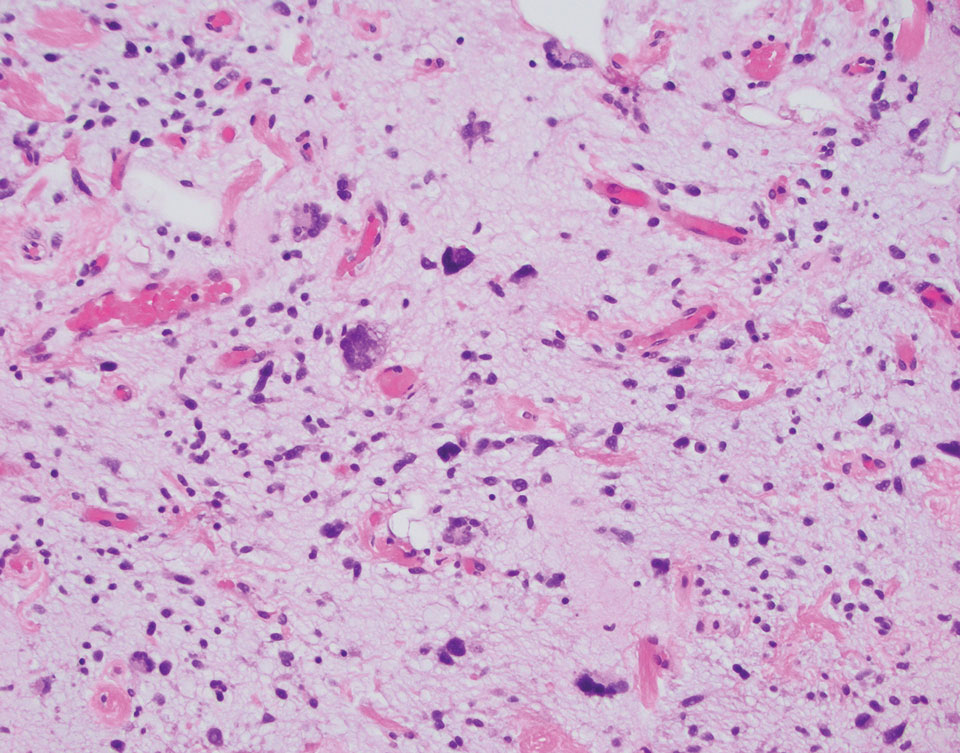

The punch biopsy demonstrated a predominantly deep but somewhat superficial, periadnexal, neutrophilic and eosinophilic infiltrate (Figure). The eruption resolved 3 days later with supportive treatment, including appropriate wound care. Genetic analysis revealed an autosomal-dominant NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 gene, NLRP3, de novo variant associated with neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disorder (NOMID). Additional workup to characterize our patient’s inflammatory profile revealed elevated IL-18, CD3, CD4, S100A12, and S100A8/A9 levels. On day 48 of life, she was started on anakinra, an IL-1 inhibitor, at a dose of 1 mg/kg subcutaneously, which eventually was titrated to 10 mg/kg at hospital discharge. Hearing screenings were within normal limits.

Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS) consist of 3 rare, IL-1–associated, autoinflammatory disorders, including familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome (FCAS), Muckle-Wells syndrome (MWS), and NOMID (also known as chronic infantile neurologic cutaneous and articular syndrome). These conditions result from a sporadic or autosomal-dominant gain-of-function mutations in a single gene, NLRP3, on chromosome 1q44. NLRP3 encodes for cryopyrin, an important component of an IL-1 and IL-18 activating inflammasome.1 The most severe manifestation of CAPS is NOMID, which typically presents at birth as a migratory urticarial eruption, growth failure, myalgia, fever, and abnormal facial features, including frontal bossing, saddle-shaped nose, and protruding eyes.2 The illness also can manifest with hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, uveitis, sensorineural hearing loss, cerebral atrophy, and other neurologic manifestations.3 A diagnosis of chronic atypical neutrophilic dermatosis with lipodystrophy and elevated temperature (CANDLE) syndrome was less likely given that our patient remained afebrile and did not show signs of lipodystrophy and persistent violaceous eyelid swelling. Both FCAS and MWS are less severe forms of CAPS when compared to NOMID. Familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome was less likely given the absence of the typical periodic fever pattern associated with the condition and severity of our patient’s symptoms. Muckle-Wells syndrome typically presents in adolescence with symptoms of FCAS, painful urticarial plaques, and progressive sensorinueral hearing loss. Tumor necrosis factor receptor–associated periodic fever (TRAPS) usually is associated with episodic fevers, abdominal pain, periorbital edema, migratory erythema, and arthralgia.1,3,4

Diagnostic criteria for CAPS include elevated inflammatory markers and serum amyloid, plus at least 2 of the typical CAPS symptoms: urticarial rash, cold-triggered episodes, sensorineural hearing loss, musculoskeletal symptoms, chronic aseptic meningitis, and skeletal abnormalities.4 The sensitivity and specificity of these diagnostic criteria are 84% and 91%, respectively. Additional findings that can be seen but are not part of the diagnostic criteria include intermittent fever, transient joint swelling, bony overgrowths, uveitis, optic disc edema, impaired growth, and hepatosplenomegaly.5 Laboratory findings may reveal leukocytosis, eosinophilia, anemia, and/or thrombocytopenia.3,5

Genetic testing, skin biopsies, ophthalmic examinations, neuroimaging, joint radiography, cerebrospinal fluid tests, and hearing examinations can be performed for confirmation of diagnosis and evaluation of systemic complications.4 A skin biopsy may reveal a neutrophilic infiltrate. Ophthalmic examination can demonstrate uveitis and optic disk edema. Neuroimaging may reveal cerebral atrophy or ventricular dilation. Lastly, joint radiography can be used to evaluate for the presence of premature long bone ossification or osseous overgrowth.4

In summary, NOMID is a multisystemic disorder with cutaneous manifestations. Early recognition of this entity is important given the severe sequelae and available efficacious therapy. Dermatologists should be aware of these manifestations, as dermatologic consultation and a skin biopsy may aid in diagnosis.

- Lachmann HJ. Periodic fever syndromes. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2017;31:596-609. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2017.12.001

- Hull KM, Shoham N, Jin Chae J, et al. The expanding spectrum of systemic autoinflammatory disorders and their rheumatic manifestations. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2003;15:61-69. doi:10.1097/00002281-200301000-00011

- Ahmadi N, Brewer CC, Zalewski C, et al. Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes: otolaryngologic and audiologic manifestations. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145:295-302. doi:10.1177/0194599811402296

- Kuemmerle-Deschner JB, Ozen S, Tyrrell PN, et al. Diagnostic criteria for cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS). Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:942-947. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209686

- Aksentijevich I, Nowak M, Mallah M, et al. De novo CIAS1 mutations, cytokine activation, and evidence for genetic heterogeneity in patients with neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID): a new member of the expanding family of pyrinassociated autoinflammatory diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2002; 46:3340-3348. doi:10.1002/art.10688

The Diagnosis: Neonatal-Onset Multisystem Inflammatory Disorder (NOMID)

The punch biopsy demonstrated a predominantly deep but somewhat superficial, periadnexal, neutrophilic and eosinophilic infiltrate (Figure). The eruption resolved 3 days later with supportive treatment, including appropriate wound care. Genetic analysis revealed an autosomal-dominant NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 gene, NLRP3, de novo variant associated with neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disorder (NOMID). Additional workup to characterize our patient’s inflammatory profile revealed elevated IL-18, CD3, CD4, S100A12, and S100A8/A9 levels. On day 48 of life, she was started on anakinra, an IL-1 inhibitor, at a dose of 1 mg/kg subcutaneously, which eventually was titrated to 10 mg/kg at hospital discharge. Hearing screenings were within normal limits.

Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS) consist of 3 rare, IL-1–associated, autoinflammatory disorders, including familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome (FCAS), Muckle-Wells syndrome (MWS), and NOMID (also known as chronic infantile neurologic cutaneous and articular syndrome). These conditions result from a sporadic or autosomal-dominant gain-of-function mutations in a single gene, NLRP3, on chromosome 1q44. NLRP3 encodes for cryopyrin, an important component of an IL-1 and IL-18 activating inflammasome.1 The most severe manifestation of CAPS is NOMID, which typically presents at birth as a migratory urticarial eruption, growth failure, myalgia, fever, and abnormal facial features, including frontal bossing, saddle-shaped nose, and protruding eyes.2 The illness also can manifest with hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, uveitis, sensorineural hearing loss, cerebral atrophy, and other neurologic manifestations.3 A diagnosis of chronic atypical neutrophilic dermatosis with lipodystrophy and elevated temperature (CANDLE) syndrome was less likely given that our patient remained afebrile and did not show signs of lipodystrophy and persistent violaceous eyelid swelling. Both FCAS and MWS are less severe forms of CAPS when compared to NOMID. Familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome was less likely given the absence of the typical periodic fever pattern associated with the condition and severity of our patient’s symptoms. Muckle-Wells syndrome typically presents in adolescence with symptoms of FCAS, painful urticarial plaques, and progressive sensorinueral hearing loss. Tumor necrosis factor receptor–associated periodic fever (TRAPS) usually is associated with episodic fevers, abdominal pain, periorbital edema, migratory erythema, and arthralgia.1,3,4

Diagnostic criteria for CAPS include elevated inflammatory markers and serum amyloid, plus at least 2 of the typical CAPS symptoms: urticarial rash, cold-triggered episodes, sensorineural hearing loss, musculoskeletal symptoms, chronic aseptic meningitis, and skeletal abnormalities.4 The sensitivity and specificity of these diagnostic criteria are 84% and 91%, respectively. Additional findings that can be seen but are not part of the diagnostic criteria include intermittent fever, transient joint swelling, bony overgrowths, uveitis, optic disc edema, impaired growth, and hepatosplenomegaly.5 Laboratory findings may reveal leukocytosis, eosinophilia, anemia, and/or thrombocytopenia.3,5

Genetic testing, skin biopsies, ophthalmic examinations, neuroimaging, joint radiography, cerebrospinal fluid tests, and hearing examinations can be performed for confirmation of diagnosis and evaluation of systemic complications.4 A skin biopsy may reveal a neutrophilic infiltrate. Ophthalmic examination can demonstrate uveitis and optic disk edema. Neuroimaging may reveal cerebral atrophy or ventricular dilation. Lastly, joint radiography can be used to evaluate for the presence of premature long bone ossification or osseous overgrowth.4

In summary, NOMID is a multisystemic disorder with cutaneous manifestations. Early recognition of this entity is important given the severe sequelae and available efficacious therapy. Dermatologists should be aware of these manifestations, as dermatologic consultation and a skin biopsy may aid in diagnosis.

The Diagnosis: Neonatal-Onset Multisystem Inflammatory Disorder (NOMID)

The punch biopsy demonstrated a predominantly deep but somewhat superficial, periadnexal, neutrophilic and eosinophilic infiltrate (Figure). The eruption resolved 3 days later with supportive treatment, including appropriate wound care. Genetic analysis revealed an autosomal-dominant NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 gene, NLRP3, de novo variant associated with neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disorder (NOMID). Additional workup to characterize our patient’s inflammatory profile revealed elevated IL-18, CD3, CD4, S100A12, and S100A8/A9 levels. On day 48 of life, she was started on anakinra, an IL-1 inhibitor, at a dose of 1 mg/kg subcutaneously, which eventually was titrated to 10 mg/kg at hospital discharge. Hearing screenings were within normal limits.

Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS) consist of 3 rare, IL-1–associated, autoinflammatory disorders, including familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome (FCAS), Muckle-Wells syndrome (MWS), and NOMID (also known as chronic infantile neurologic cutaneous and articular syndrome). These conditions result from a sporadic or autosomal-dominant gain-of-function mutations in a single gene, NLRP3, on chromosome 1q44. NLRP3 encodes for cryopyrin, an important component of an IL-1 and IL-18 activating inflammasome.1 The most severe manifestation of CAPS is NOMID, which typically presents at birth as a migratory urticarial eruption, growth failure, myalgia, fever, and abnormal facial features, including frontal bossing, saddle-shaped nose, and protruding eyes.2 The illness also can manifest with hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, uveitis, sensorineural hearing loss, cerebral atrophy, and other neurologic manifestations.3 A diagnosis of chronic atypical neutrophilic dermatosis with lipodystrophy and elevated temperature (CANDLE) syndrome was less likely given that our patient remained afebrile and did not show signs of lipodystrophy and persistent violaceous eyelid swelling. Both FCAS and MWS are less severe forms of CAPS when compared to NOMID. Familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome was less likely given the absence of the typical periodic fever pattern associated with the condition and severity of our patient’s symptoms. Muckle-Wells syndrome typically presents in adolescence with symptoms of FCAS, painful urticarial plaques, and progressive sensorinueral hearing loss. Tumor necrosis factor receptor–associated periodic fever (TRAPS) usually is associated with episodic fevers, abdominal pain, periorbital edema, migratory erythema, and arthralgia.1,3,4

Diagnostic criteria for CAPS include elevated inflammatory markers and serum amyloid, plus at least 2 of the typical CAPS symptoms: urticarial rash, cold-triggered episodes, sensorineural hearing loss, musculoskeletal symptoms, chronic aseptic meningitis, and skeletal abnormalities.4 The sensitivity and specificity of these diagnostic criteria are 84% and 91%, respectively. Additional findings that can be seen but are not part of the diagnostic criteria include intermittent fever, transient joint swelling, bony overgrowths, uveitis, optic disc edema, impaired growth, and hepatosplenomegaly.5 Laboratory findings may reveal leukocytosis, eosinophilia, anemia, and/or thrombocytopenia.3,5

Genetic testing, skin biopsies, ophthalmic examinations, neuroimaging, joint radiography, cerebrospinal fluid tests, and hearing examinations can be performed for confirmation of diagnosis and evaluation of systemic complications.4 A skin biopsy may reveal a neutrophilic infiltrate. Ophthalmic examination can demonstrate uveitis and optic disk edema. Neuroimaging may reveal cerebral atrophy or ventricular dilation. Lastly, joint radiography can be used to evaluate for the presence of premature long bone ossification or osseous overgrowth.4

In summary, NOMID is a multisystemic disorder with cutaneous manifestations. Early recognition of this entity is important given the severe sequelae and available efficacious therapy. Dermatologists should be aware of these manifestations, as dermatologic consultation and a skin biopsy may aid in diagnosis.

- Lachmann HJ. Periodic fever syndromes. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2017;31:596-609. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2017.12.001

- Hull KM, Shoham N, Jin Chae J, et al. The expanding spectrum of systemic autoinflammatory disorders and their rheumatic manifestations. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2003;15:61-69. doi:10.1097/00002281-200301000-00011

- Ahmadi N, Brewer CC, Zalewski C, et al. Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes: otolaryngologic and audiologic manifestations. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145:295-302. doi:10.1177/0194599811402296

- Kuemmerle-Deschner JB, Ozen S, Tyrrell PN, et al. Diagnostic criteria for cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS). Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:942-947. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209686

- Aksentijevich I, Nowak M, Mallah M, et al. De novo CIAS1 mutations, cytokine activation, and evidence for genetic heterogeneity in patients with neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID): a new member of the expanding family of pyrinassociated autoinflammatory diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2002; 46:3340-3348. doi:10.1002/art.10688

- Lachmann HJ. Periodic fever syndromes. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2017;31:596-609. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2017.12.001

- Hull KM, Shoham N, Jin Chae J, et al. The expanding spectrum of systemic autoinflammatory disorders and their rheumatic manifestations. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2003;15:61-69. doi:10.1097/00002281-200301000-00011

- Ahmadi N, Brewer CC, Zalewski C, et al. Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes: otolaryngologic and audiologic manifestations. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145:295-302. doi:10.1177/0194599811402296

- Kuemmerle-Deschner JB, Ozen S, Tyrrell PN, et al. Diagnostic criteria for cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS). Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:942-947. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209686

- Aksentijevich I, Nowak M, Mallah M, et al. De novo CIAS1 mutations, cytokine activation, and evidence for genetic heterogeneity in patients with neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID): a new member of the expanding family of pyrinassociated autoinflammatory diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2002; 46:3340-3348. doi:10.1002/art.10688

A 2-week-old infant girl was transferred to a specialty pediatric hospital where dermatology was consulted for evaluation of a diffuse eruption triggered by cold that was similar to an eruption present at birth. She was born at 31 weeks and 2 days’ gestation at an outside hospital via caesarean delivery. Early delivery was prompted by superimposed pre-eclampsia with severe hypertension after administration of antenatal steroids. At birth, the infant was cyanotic and apneic and had a documented skin eruption, according to the medical record. She had thrombocytopenia, elevated C-reactive protein, and an elevated temperature without fever. Extensive septic workup, including blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid cultures; herpes simplex virus and cytomegalovirus screening; and Toxoplasma polymerase chain reaction were negative. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain revealed no evidence of intracranial congenital infection. Ampicillinsulbactam was initiated for presumed culture-negative sepsis. On day 2 of hospitalization, she developed conjunctival icterus, hepatomegaly, and jaundice. Direct hyperbilirubinemia; anemia; and elevated triglycerides, ferritin, and ammonia all were present. Coagulation studies were normal. Subsequent workup, including abdominal ultrasonography and hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid scan, was concerning for biliary atresia. Despite appropriate treatment, her condition did not improve and she was transferred. Repeat abdominal ultrasonography on day 24 of life confirmed hepatomegaly but did not demonstrate other findings of biliary atresia. At the current presentation, physical examination revealed many scattered, redbrown and centrally violaceous, blanching papules measuring a few millimeters involving the trunk, arms, buttocks, and legs. A punch biopsy was obtained.

A 7-month-old male presents with pustules and inflamed papules on the scalp and extremities

The bacterial, fungal, and atypical mycobacterial cultures from the lesions performed at the emergency department were all negative.

Pediatric dermatology was consulted and a punch biopsy of one of the lesions was done. Histopathologic examination showed a mixed perifollicular infiltrate of predominantly eosinophils with some neutrophils and associated microabscesses. Periodic acid Schiff and Fite stains failed to reveal any organisms. CD1 immunostain was negative. Fresh tissue cultures for bacteria, fungi, and atypical mycobacteria were negative.

Given the clinical presentation of chronic recurrent sterile pustules on an infant with associated eosinophilia and the reported histopathologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with eosinophilic pustular folliculitis of infancy (EPFI).

EPFI is a rare and idiopathic cutaneous disorder present in children. About 70% of the cases reported occur in the first 6 month of life and rarely present past 3 years of age. EPF encompasses a group of conditions including the classic adult form, or Ofuji disease. EPF is seen in immunosuppressed patients, mainly HIV positive, and EPF is also seen in infants and children.

In EPFI, males are most commonly affected. The condition presents, as it did in our patient, with recurrent crops of sterile papules and pustules mainly on the scalp, but they can occur in other parts of the body. The lesions go away within a few weeks to months without leaving any scars but it can take months to years to resolve. Histopathologic analysis of the lesions show an eosinophilic infiltrate which can be follicular, perifollicular, or periadnexal with associated flame figures in about 26% of cases.

Aggressive treatment is usually not needed as lesions are self-limited. Lesions can be treated with topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamine medications like cetirizine if symptomatic.

If the lesions start to present during the neonatal period, one may consider in the differential diagnosis, neonatal rashes like transient neonatal pustular melanosis and erythema toxicum neonatorum. Both of these neonatal conditions tend to resolve in the first month of life, compared with EPFI where lesions can come and go for months to years. EPFI lesions can be described as pustules and inflammatory papules, as well as furuncles and vesicles. All of the lesions may be seen in one patient at one time, which will not be typical for transient neonatal pustular melanosis or erythema toxicum. Eosinophils can be seen in erythema toxicum but folliculitis is not present. The inflammatory infiltrate seen in transient neonatal pustular melanosis is polymorphonuclear, not eosinophilic.

Early in the presentation, infectious conditions like staphylococcal or streptococcal folliculitis, cellulitis and furunculosis, tinea capitis, atypical mycobacterial infections, herpes simplex, and parasitic infections like scabies should be considered. In young infants, empiric antibiotic treatment may be started until cultures are finalized. If there is a family history of pruritic papules and pustules, scabies should be considered. A scabies prep can be done to rule out this entity.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis can also present with pustules and papules in early infancy and also has a predilection for the scalp. When this condition is in question, a skin biopsy should be performed which shows a CD1 positive histiocytic infiltrate.

In conclusion, EPFI is a benign rare condition that can present in infants as recurrent pustules and papules, mainly on the scalp, which are self-limited and if symptomatic can be treated with topical corticosteroids and antihistamines.

References

Alonso-Castro L et al. Dermatol Online J. 2012 Oct 15;18(10):6.

Frølunde AS et al. Clin Case Rep. 2021 May 11;9(5):e04167.

Hernández-Martín Á et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Jan;68(1):150-5.

The bacterial, fungal, and atypical mycobacterial cultures from the lesions performed at the emergency department were all negative.

Pediatric dermatology was consulted and a punch biopsy of one of the lesions was done. Histopathologic examination showed a mixed perifollicular infiltrate of predominantly eosinophils with some neutrophils and associated microabscesses. Periodic acid Schiff and Fite stains failed to reveal any organisms. CD1 immunostain was negative. Fresh tissue cultures for bacteria, fungi, and atypical mycobacteria were negative.

Given the clinical presentation of chronic recurrent sterile pustules on an infant with associated eosinophilia and the reported histopathologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with eosinophilic pustular folliculitis of infancy (EPFI).

EPFI is a rare and idiopathic cutaneous disorder present in children. About 70% of the cases reported occur in the first 6 month of life and rarely present past 3 years of age. EPF encompasses a group of conditions including the classic adult form, or Ofuji disease. EPF is seen in immunosuppressed patients, mainly HIV positive, and EPF is also seen in infants and children.

In EPFI, males are most commonly affected. The condition presents, as it did in our patient, with recurrent crops of sterile papules and pustules mainly on the scalp, but they can occur in other parts of the body. The lesions go away within a few weeks to months without leaving any scars but it can take months to years to resolve. Histopathologic analysis of the lesions show an eosinophilic infiltrate which can be follicular, perifollicular, or periadnexal with associated flame figures in about 26% of cases.

Aggressive treatment is usually not needed as lesions are self-limited. Lesions can be treated with topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamine medications like cetirizine if symptomatic.

If the lesions start to present during the neonatal period, one may consider in the differential diagnosis, neonatal rashes like transient neonatal pustular melanosis and erythema toxicum neonatorum. Both of these neonatal conditions tend to resolve in the first month of life, compared with EPFI where lesions can come and go for months to years. EPFI lesions can be described as pustules and inflammatory papules, as well as furuncles and vesicles. All of the lesions may be seen in one patient at one time, which will not be typical for transient neonatal pustular melanosis or erythema toxicum. Eosinophils can be seen in erythema toxicum but folliculitis is not present. The inflammatory infiltrate seen in transient neonatal pustular melanosis is polymorphonuclear, not eosinophilic.

Early in the presentation, infectious conditions like staphylococcal or streptococcal folliculitis, cellulitis and furunculosis, tinea capitis, atypical mycobacterial infections, herpes simplex, and parasitic infections like scabies should be considered. In young infants, empiric antibiotic treatment may be started until cultures are finalized. If there is a family history of pruritic papules and pustules, scabies should be considered. A scabies prep can be done to rule out this entity.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis can also present with pustules and papules in early infancy and also has a predilection for the scalp. When this condition is in question, a skin biopsy should be performed which shows a CD1 positive histiocytic infiltrate.

In conclusion, EPFI is a benign rare condition that can present in infants as recurrent pustules and papules, mainly on the scalp, which are self-limited and if symptomatic can be treated with topical corticosteroids and antihistamines.

References

Alonso-Castro L et al. Dermatol Online J. 2012 Oct 15;18(10):6.

Frølunde AS et al. Clin Case Rep. 2021 May 11;9(5):e04167.

Hernández-Martín Á et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Jan;68(1):150-5.

The bacterial, fungal, and atypical mycobacterial cultures from the lesions performed at the emergency department were all negative.

Pediatric dermatology was consulted and a punch biopsy of one of the lesions was done. Histopathologic examination showed a mixed perifollicular infiltrate of predominantly eosinophils with some neutrophils and associated microabscesses. Periodic acid Schiff and Fite stains failed to reveal any organisms. CD1 immunostain was negative. Fresh tissue cultures for bacteria, fungi, and atypical mycobacteria were negative.

Given the clinical presentation of chronic recurrent sterile pustules on an infant with associated eosinophilia and the reported histopathologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with eosinophilic pustular folliculitis of infancy (EPFI).

EPFI is a rare and idiopathic cutaneous disorder present in children. About 70% of the cases reported occur in the first 6 month of life and rarely present past 3 years of age. EPF encompasses a group of conditions including the classic adult form, or Ofuji disease. EPF is seen in immunosuppressed patients, mainly HIV positive, and EPF is also seen in infants and children.

In EPFI, males are most commonly affected. The condition presents, as it did in our patient, with recurrent crops of sterile papules and pustules mainly on the scalp, but they can occur in other parts of the body. The lesions go away within a few weeks to months without leaving any scars but it can take months to years to resolve. Histopathologic analysis of the lesions show an eosinophilic infiltrate which can be follicular, perifollicular, or periadnexal with associated flame figures in about 26% of cases.

Aggressive treatment is usually not needed as lesions are self-limited. Lesions can be treated with topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamine medications like cetirizine if symptomatic.

If the lesions start to present during the neonatal period, one may consider in the differential diagnosis, neonatal rashes like transient neonatal pustular melanosis and erythema toxicum neonatorum. Both of these neonatal conditions tend to resolve in the first month of life, compared with EPFI where lesions can come and go for months to years. EPFI lesions can be described as pustules and inflammatory papules, as well as furuncles and vesicles. All of the lesions may be seen in one patient at one time, which will not be typical for transient neonatal pustular melanosis or erythema toxicum. Eosinophils can be seen in erythema toxicum but folliculitis is not present. The inflammatory infiltrate seen in transient neonatal pustular melanosis is polymorphonuclear, not eosinophilic.

Early in the presentation, infectious conditions like staphylococcal or streptococcal folliculitis, cellulitis and furunculosis, tinea capitis, atypical mycobacterial infections, herpes simplex, and parasitic infections like scabies should be considered. In young infants, empiric antibiotic treatment may be started until cultures are finalized. If there is a family history of pruritic papules and pustules, scabies should be considered. A scabies prep can be done to rule out this entity.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis can also present with pustules and papules in early infancy and also has a predilection for the scalp. When this condition is in question, a skin biopsy should be performed which shows a CD1 positive histiocytic infiltrate.

In conclusion, EPFI is a benign rare condition that can present in infants as recurrent pustules and papules, mainly on the scalp, which are self-limited and if symptomatic can be treated with topical corticosteroids and antihistamines.

References

Alonso-Castro L et al. Dermatol Online J. 2012 Oct 15;18(10):6.

Frølunde AS et al. Clin Case Rep. 2021 May 11;9(5):e04167.

Hernández-Martín Á et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Jan;68(1):150-5.

A 7-month-old male is brought to the emergency department for evaluation of pustules and inflamed papules on the scalp and extremities for several weeks of duration. The parents report the lesions started about a month prior and he has already been treated with cephalexin, clindamycin, and sulfamethoxazole without any improvement. Cultures sent prior by the child's pediatrician did not reveal any fungus or bacteria. The parents report a low-grade fever for about 3 days.

He was born via natural vaginal delivery with no instrumentation or external monitoring. Mom had prenatal care. Besides the skin lesions, the baby has been healthy and growing well. He has no history of eczema or severe infections. He has not been hospitalized before.

On physical examination the baby was not febrile. On the scalp and forehead, he had diffusely distributed pustules, erythematous papules, and nodules. He also presented with scattered, fine, small, crusted 1-2-mm pink papules on the trunk and extremities. He had no adenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly.

At the emergency department, samples from one of the pustules were sent for bacterial, fungal, and atypical mycobacteria cultures. Laboratory test showed a normal blood count with associated eosinophilia (2.8 x 109 L), and normal liver and kidney function. A head ultrasound showed three ill-defined hypoechoic foci within the scalp.

The patient was admitted for treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics and dermatology was consulted.

Retiform Purpura on the Lower Legs

The Diagnosis: Type I Cryoglobulinemia

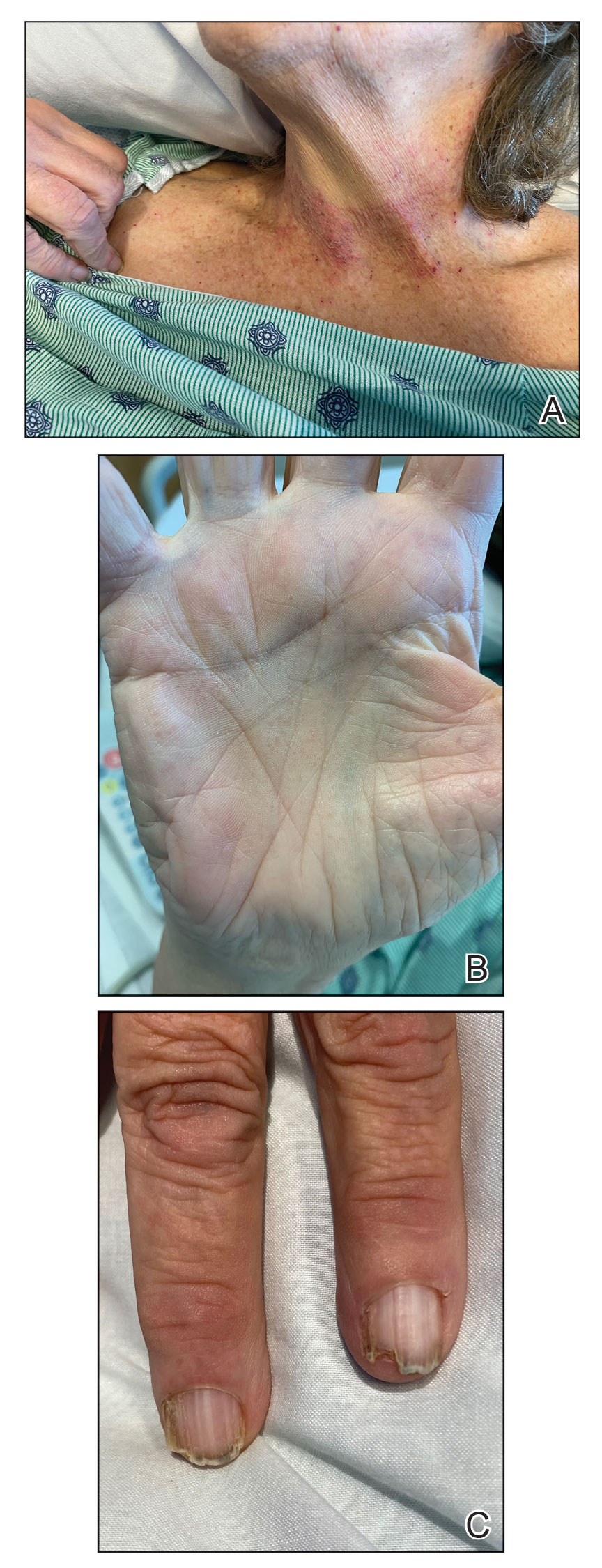

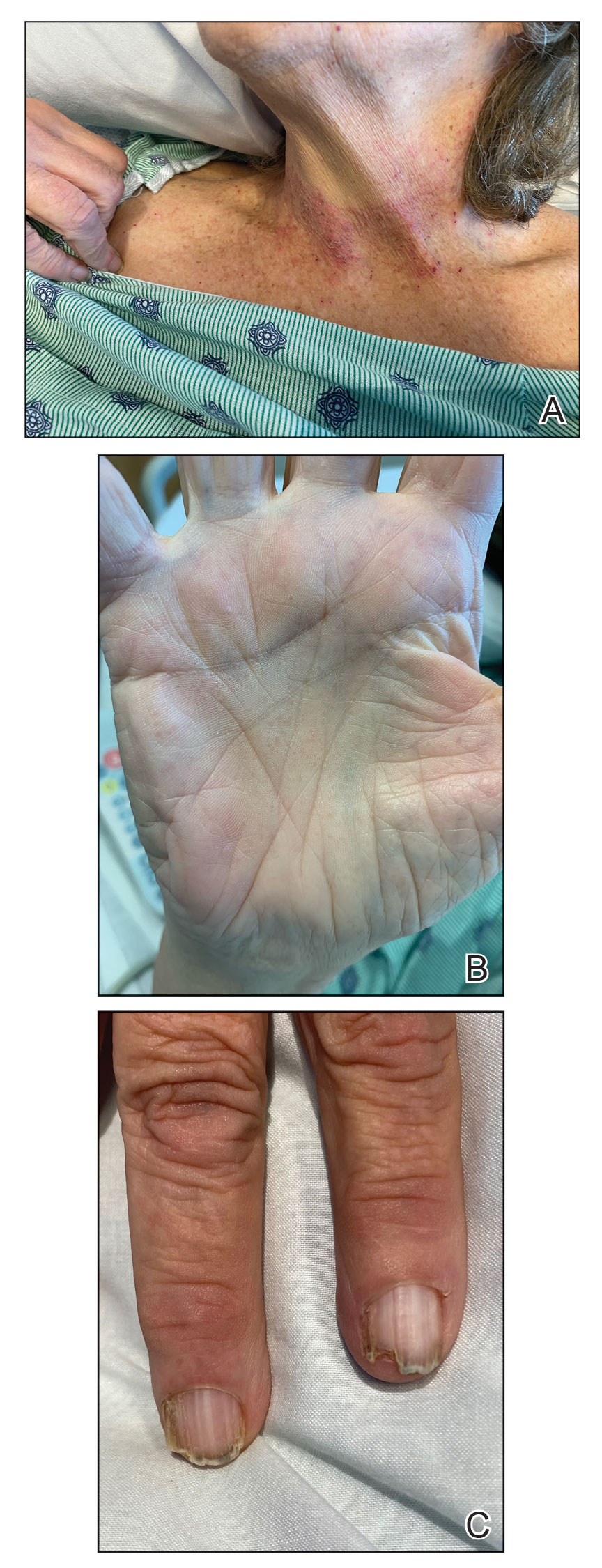

Retiform purpura with overlying necrosis subsequently developed over the course of a week following presentation (Figure 1). A skin biopsy showed fibrin thrombi and congestion of small- and medium-sized blood vessels, consistent with vasculopathy (Figure 2). Urinalysis revealed hematuria and proteinuria. A renal biopsy performed due to a continually elevated serum creatinine level revealed glomerulonephritis with numerous IgG1 lambda–restricted glomerular capillary hyaline thrombi, compatible with a lymphoproliferative disorder–associated type I cryoglobulinemia. A serum cryoglobulin immunofixation test confirmed type I cryoglobulinemia involving monoclonal IgG lambda. The combination of cutaneous, renal, and hematologic findings was consistent with type I cryoglobulinemia. A subsequent bone marrow biopsy demonstrated a CD20+ lambda–restricted plasma cell neoplasm. Initial treatment with high-dose corticosteroids followed by targeted treatment of the underlying hematologic condition with bortezomib, rituximab, and dexamethasone improved the skin disease.

Cryoglobulins are abnormal immunoglobulins that precipitate at temperatures below 37 °C. The persistent presence of cryoglobulins in the serum is termed cryoglobulinemia.1 Type I cryoglobulinemia is distinguished from mixed cryoglobulinemia—types II and III—by the presence of a single monoclonal immunoglobulin, typically IgM or IgG. It is associated with lymphoproliferative disorders, most commonly monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and B-cell malignancies such as Waldenström macroglobulinemia, multiple myeloma, or chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Histopathology shows occlusion of small vessel lumina with homogenous eosinophilic material containing the monoclonal cryoprecipitate.2 Disease manifestations are caused by small vessel occlusion, which leads to ischemia and tissue damage.

Retiform purpura, livedo reticularis/racemosa, and necrosis leading to ulcers are the most common cutaneous clinical findings. Extracutaneous signs include peripheral neuropathy, arthralgia, Raynaud phenomenon, and acrocyanosis. Renal involvement, most commonly glomerulonephritis with associated proteinuria, is noted in 14% to 20% of cases.3,4 An elevated cryocrit can lead to symptoms of hyperviscosity syndrome.2