User login

A pandemic silver lining? Dramatic drop in teen drug use

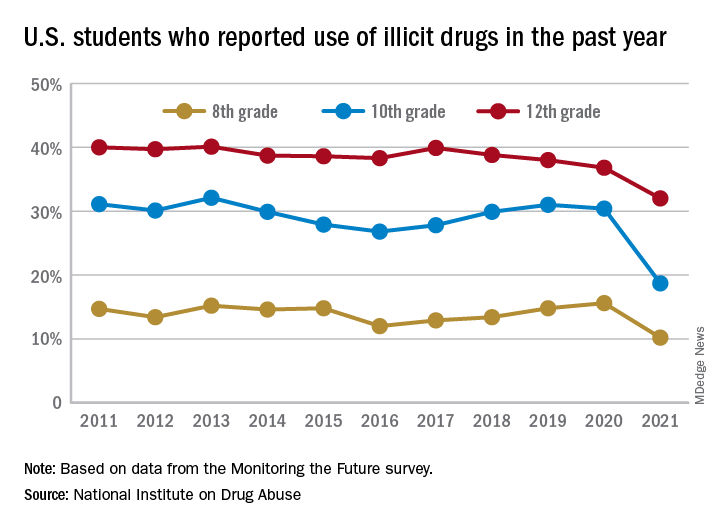

Illicit drug use among U.S. teenagers dropped sharply in 2021, likely because of stay-at-home orders and other restrictions on social activities due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The latest findings, from the Monitoring the Future survey, represent the largest 1-year decrease in overall illicit drug use reported since the survey began in 1975.

“We have never seen such dramatic decreases in drug use among teens in just a 1-year period,” Nora Volkow, MD, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), said in a news release.

“These data are unprecedented and highlight one unexpected potential consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused seismic shifts in the day-to-day lives of adolescents,” said Dr. Volkow.

The annual Monitoring the Future survey is conducted by researchers at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and funded by NIDA, to assess drug and alcohol use and related attitudes among adolescent students across the United States.

This year’s self-reported survey included 32,260 students in grades 8, 10, and 12 across 319 public and private schools.

Compared with 2020, the percentage of students reporting any illicit drug use (other than marijuana) in 2021 decreased significantly for 8th graders (down 5.4%), 10th graders (down 11.7%), and 12th graders (down 4.8%).

For alcohol, about 47% of 12th graders and 29% of 10th graders said they drank alcohol in 2021, down significantly from 55% and 41%, respectively, in 2020. The percentage of 8th graders who said they drank alcohol remained stable (17% in 2021 and 20% in 2020).

For teen vaping, about 27% of 12th graders and 20% of 10th graders said they had vaped nicotine in 2021, down significantly from nearly 35% and 31%, respectively, in 2020. Fewer 8th graders also vaped nicotine in 2021 compared with 2020 (12% vs. 17%).

For marijuana, use dropped significantly for all three grades in 2021 compared with 2020. About 31% of 12th graders and 17% of 10th graders said they used marijuana in 2021, down from 35% and 28% in 2020. Among 8th graders, 7% used marijuana in 2021, down from 11% in 2020.

The latest survey also shows significant declines in use of a range of other drugs for many of the age cohorts, including cocaine, hallucinogens, and nonmedical use of amphetamines, tranquilizers, and prescription opioids.

“We knew that this year’s data would illuminate how the COVID-19 pandemic may have impacted substance use among young people, and in the coming years, we will find out whether those impacts are long-lasting as we continue tracking the drug use patterns of these unique cohorts of adolescents,” Richard A. Miech, PhD, who heads the Monitoring the Future study at the University of Michigan, said in the news release.

“Moving forward, it will be crucial to identify the pivotal elements of this past year that contributed to decreased drug use – whether related to drug availability, family involvement, differences in peer pressure, or other factors – and harness them to inform future prevention efforts,” Dr. Volkow added.

In 2021, students across all age groups reported moderate increases in feelings of boredom, anxiety, depression, loneliness, worry, difficulty sleeping, and other negative mental health indicators since the beginning of the pandemic.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

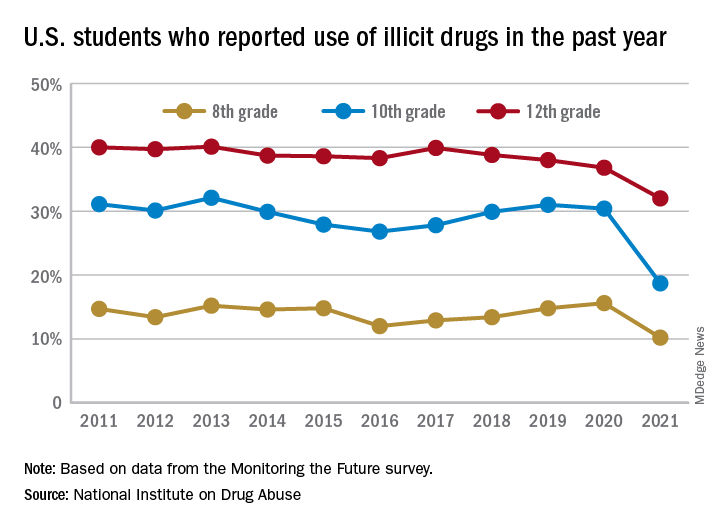

Illicit drug use among U.S. teenagers dropped sharply in 2021, likely because of stay-at-home orders and other restrictions on social activities due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The latest findings, from the Monitoring the Future survey, represent the largest 1-year decrease in overall illicit drug use reported since the survey began in 1975.

“We have never seen such dramatic decreases in drug use among teens in just a 1-year period,” Nora Volkow, MD, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), said in a news release.

“These data are unprecedented and highlight one unexpected potential consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused seismic shifts in the day-to-day lives of adolescents,” said Dr. Volkow.

The annual Monitoring the Future survey is conducted by researchers at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and funded by NIDA, to assess drug and alcohol use and related attitudes among adolescent students across the United States.

This year’s self-reported survey included 32,260 students in grades 8, 10, and 12 across 319 public and private schools.

Compared with 2020, the percentage of students reporting any illicit drug use (other than marijuana) in 2021 decreased significantly for 8th graders (down 5.4%), 10th graders (down 11.7%), and 12th graders (down 4.8%).

For alcohol, about 47% of 12th graders and 29% of 10th graders said they drank alcohol in 2021, down significantly from 55% and 41%, respectively, in 2020. The percentage of 8th graders who said they drank alcohol remained stable (17% in 2021 and 20% in 2020).

For teen vaping, about 27% of 12th graders and 20% of 10th graders said they had vaped nicotine in 2021, down significantly from nearly 35% and 31%, respectively, in 2020. Fewer 8th graders also vaped nicotine in 2021 compared with 2020 (12% vs. 17%).

For marijuana, use dropped significantly for all three grades in 2021 compared with 2020. About 31% of 12th graders and 17% of 10th graders said they used marijuana in 2021, down from 35% and 28% in 2020. Among 8th graders, 7% used marijuana in 2021, down from 11% in 2020.

The latest survey also shows significant declines in use of a range of other drugs for many of the age cohorts, including cocaine, hallucinogens, and nonmedical use of amphetamines, tranquilizers, and prescription opioids.

“We knew that this year’s data would illuminate how the COVID-19 pandemic may have impacted substance use among young people, and in the coming years, we will find out whether those impacts are long-lasting as we continue tracking the drug use patterns of these unique cohorts of adolescents,” Richard A. Miech, PhD, who heads the Monitoring the Future study at the University of Michigan, said in the news release.

“Moving forward, it will be crucial to identify the pivotal elements of this past year that contributed to decreased drug use – whether related to drug availability, family involvement, differences in peer pressure, or other factors – and harness them to inform future prevention efforts,” Dr. Volkow added.

In 2021, students across all age groups reported moderate increases in feelings of boredom, anxiety, depression, loneliness, worry, difficulty sleeping, and other negative mental health indicators since the beginning of the pandemic.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

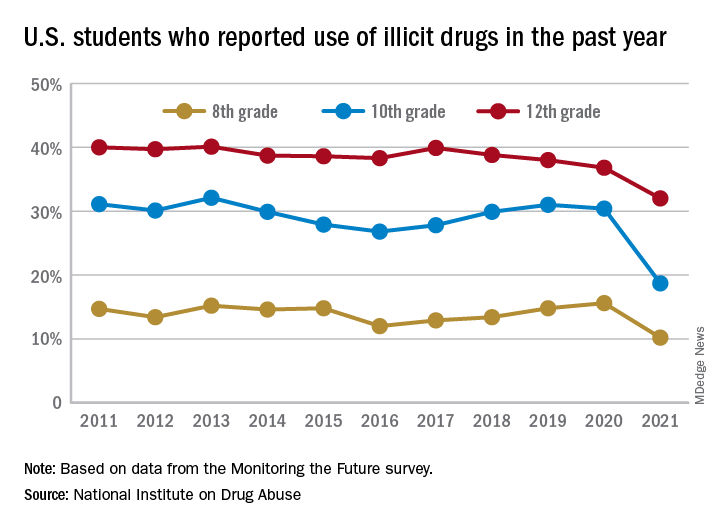

Illicit drug use among U.S. teenagers dropped sharply in 2021, likely because of stay-at-home orders and other restrictions on social activities due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The latest findings, from the Monitoring the Future survey, represent the largest 1-year decrease in overall illicit drug use reported since the survey began in 1975.

“We have never seen such dramatic decreases in drug use among teens in just a 1-year period,” Nora Volkow, MD, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), said in a news release.

“These data are unprecedented and highlight one unexpected potential consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused seismic shifts in the day-to-day lives of adolescents,” said Dr. Volkow.

The annual Monitoring the Future survey is conducted by researchers at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and funded by NIDA, to assess drug and alcohol use and related attitudes among adolescent students across the United States.

This year’s self-reported survey included 32,260 students in grades 8, 10, and 12 across 319 public and private schools.

Compared with 2020, the percentage of students reporting any illicit drug use (other than marijuana) in 2021 decreased significantly for 8th graders (down 5.4%), 10th graders (down 11.7%), and 12th graders (down 4.8%).

For alcohol, about 47% of 12th graders and 29% of 10th graders said they drank alcohol in 2021, down significantly from 55% and 41%, respectively, in 2020. The percentage of 8th graders who said they drank alcohol remained stable (17% in 2021 and 20% in 2020).

For teen vaping, about 27% of 12th graders and 20% of 10th graders said they had vaped nicotine in 2021, down significantly from nearly 35% and 31%, respectively, in 2020. Fewer 8th graders also vaped nicotine in 2021 compared with 2020 (12% vs. 17%).

For marijuana, use dropped significantly for all three grades in 2021 compared with 2020. About 31% of 12th graders and 17% of 10th graders said they used marijuana in 2021, down from 35% and 28% in 2020. Among 8th graders, 7% used marijuana in 2021, down from 11% in 2020.

The latest survey also shows significant declines in use of a range of other drugs for many of the age cohorts, including cocaine, hallucinogens, and nonmedical use of amphetamines, tranquilizers, and prescription opioids.

“We knew that this year’s data would illuminate how the COVID-19 pandemic may have impacted substance use among young people, and in the coming years, we will find out whether those impacts are long-lasting as we continue tracking the drug use patterns of these unique cohorts of adolescents,” Richard A. Miech, PhD, who heads the Monitoring the Future study at the University of Michigan, said in the news release.

“Moving forward, it will be crucial to identify the pivotal elements of this past year that contributed to decreased drug use – whether related to drug availability, family involvement, differences in peer pressure, or other factors – and harness them to inform future prevention efforts,” Dr. Volkow added.

In 2021, students across all age groups reported moderate increases in feelings of boredom, anxiety, depression, loneliness, worry, difficulty sleeping, and other negative mental health indicators since the beginning of the pandemic.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Epilepsy linked to 1.5-fold higher COVID-19 mortality in hospital

according to a new study presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. While the findings are preliminary and not yet adjusted for various confounders, the authors say they are a warning sign that patients with epilepsy may face higher risks.

“These findings suggest that epilepsy may be a pre-existing condition that places patients at increased risk for death if hospitalized with a COVID-19 infection. It may offer neurologists guidance when counseling patients on critical preventative measures such as masking, social distancing, and most importantly, vaccination,” lead author Claire Ufongene, a student at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said in an interview.

According to Ms. Ufongene, there’s sparse data about COVID-19 outcomes in patients with epilepsy, although she highlighted a 2021 meta-analysis of 13 studies that found a higher risk of severity (odds ratio, 1.69; 95% confidence interval, 1.11-2.59, P = .010) and mortality (OR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.14-2.56, P = .010).

For the new study, researchers retrospectively tracked identified 334 patients with epilepsy and COVID-19 and 9,499 other patients with COVID-19 from March 15, 2020, to May 17, 2021. All were treated at hospitals within the New York–based Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

The groups of patients with and without epilepsy were similar in some ways: 45% and 46%, respectively, were female (P = .674), and their ages were similar (average, 62 years and 65 years, respectively; P = .02). Racial makeup was also similar (non-Hispanic groups made up 27.8% of those with epilepsy and 24.5% of those without; the difference was not statistically significant).

“In addition, more of those with epilepsy were English speaking [83.2% vs. 77.9%] and had Medicaid insurance [50.9% vs. 38.9%], while fewer of those with epilepsy had private insurance [16.2% vs. 25.5%] or were Spanish speaking [14.0% vs. 9.3%],” study coauthor Nathalie Jette, MD, MSc, a neurologist at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, said in an interview.

In terms of outcomes, patients with epilepsy were much more likely to need ventilator support (37.7% vs. 14.3%; P < .001), to be admitted to the ICU (39.2% vs. 17.7%; P < .001), and to die in the hospital (29.6% vs. 19.9%; P < .001).

“Most patients we follow in our practices with epilepsy who experienced COVID-19 in general have had symptoms similar to the general population,” Dr. Jette said. “There are rare instances where COVID-19 can result in an exacerbation of seizures in some with pre-existing epilepsy. This is not surprising as infections in particular can decrease the seizure threshold and result in breakthrough seizures in people living with epilepsy.”

Loss of seizure control

How might epilepsy be related to worse outcomes in COVID-19? Andrew Wilner, MD, a neurologist and internist at University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, who’s familiar with the study findings, said COVID-19 itself may not worsen epilepsy. “Evidence to suggest that COVID-19 directly affects the central nervous system is extremely limited. As such, one would not expect that a COVID-19 infection would cause epilepsy or exacerbate epilepsy,” he said. “However, patients with epilepsy who suffer from infections may be predisposed to decreased seizure control. Consequently, it would not be surprising if patients with epilepsy who also had COVID-19 had loss of seizure control and even status epilepticus, which could adversely affect their hospital course. However, there are no data on this potential phenomenon.”

Dr. Wilner suspected that comorbidities explain the higher mortality in patients with epilepsy. “The findings are probably most useful in that they call attention to the fact that epilepsy patients are more vulnerable to a host of comorbidities and resultant poorer outcomes due to any acute illness.”

As for treatment, Dr. Wilner urged colleagues to make sure that hospitalized patients with epilepsy “continue to receive their antiepileptic medications, which they may no longer be able to take orally. They may need to be switched temporarily to an intravenous formulation.”

In an interview, Selim Benbadis, MD, a neurologist from the University of South Florida, Tampa, suggested that antiseizure medications may play a role in the COVID-19 disease course because they can reduce the efficacy of other medications, although he noted that drug treatments for COVID-19 were limited early on. He recommended that neurologists “avoid old enzyme-inducing seizure medications, as is generally recommended.”

No study funding is reported. The study authors and Dr. Benbadis reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Wilner is a medical adviser for the epilepsy disease management program for CVS/Health.

according to a new study presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. While the findings are preliminary and not yet adjusted for various confounders, the authors say they are a warning sign that patients with epilepsy may face higher risks.

“These findings suggest that epilepsy may be a pre-existing condition that places patients at increased risk for death if hospitalized with a COVID-19 infection. It may offer neurologists guidance when counseling patients on critical preventative measures such as masking, social distancing, and most importantly, vaccination,” lead author Claire Ufongene, a student at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said in an interview.

According to Ms. Ufongene, there’s sparse data about COVID-19 outcomes in patients with epilepsy, although she highlighted a 2021 meta-analysis of 13 studies that found a higher risk of severity (odds ratio, 1.69; 95% confidence interval, 1.11-2.59, P = .010) and mortality (OR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.14-2.56, P = .010).

For the new study, researchers retrospectively tracked identified 334 patients with epilepsy and COVID-19 and 9,499 other patients with COVID-19 from March 15, 2020, to May 17, 2021. All were treated at hospitals within the New York–based Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

The groups of patients with and without epilepsy were similar in some ways: 45% and 46%, respectively, were female (P = .674), and their ages were similar (average, 62 years and 65 years, respectively; P = .02). Racial makeup was also similar (non-Hispanic groups made up 27.8% of those with epilepsy and 24.5% of those without; the difference was not statistically significant).

“In addition, more of those with epilepsy were English speaking [83.2% vs. 77.9%] and had Medicaid insurance [50.9% vs. 38.9%], while fewer of those with epilepsy had private insurance [16.2% vs. 25.5%] or were Spanish speaking [14.0% vs. 9.3%],” study coauthor Nathalie Jette, MD, MSc, a neurologist at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, said in an interview.

In terms of outcomes, patients with epilepsy were much more likely to need ventilator support (37.7% vs. 14.3%; P < .001), to be admitted to the ICU (39.2% vs. 17.7%; P < .001), and to die in the hospital (29.6% vs. 19.9%; P < .001).

“Most patients we follow in our practices with epilepsy who experienced COVID-19 in general have had symptoms similar to the general population,” Dr. Jette said. “There are rare instances where COVID-19 can result in an exacerbation of seizures in some with pre-existing epilepsy. This is not surprising as infections in particular can decrease the seizure threshold and result in breakthrough seizures in people living with epilepsy.”

Loss of seizure control

How might epilepsy be related to worse outcomes in COVID-19? Andrew Wilner, MD, a neurologist and internist at University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, who’s familiar with the study findings, said COVID-19 itself may not worsen epilepsy. “Evidence to suggest that COVID-19 directly affects the central nervous system is extremely limited. As such, one would not expect that a COVID-19 infection would cause epilepsy or exacerbate epilepsy,” he said. “However, patients with epilepsy who suffer from infections may be predisposed to decreased seizure control. Consequently, it would not be surprising if patients with epilepsy who also had COVID-19 had loss of seizure control and even status epilepticus, which could adversely affect their hospital course. However, there are no data on this potential phenomenon.”

Dr. Wilner suspected that comorbidities explain the higher mortality in patients with epilepsy. “The findings are probably most useful in that they call attention to the fact that epilepsy patients are more vulnerable to a host of comorbidities and resultant poorer outcomes due to any acute illness.”

As for treatment, Dr. Wilner urged colleagues to make sure that hospitalized patients with epilepsy “continue to receive their antiepileptic medications, which they may no longer be able to take orally. They may need to be switched temporarily to an intravenous formulation.”

In an interview, Selim Benbadis, MD, a neurologist from the University of South Florida, Tampa, suggested that antiseizure medications may play a role in the COVID-19 disease course because they can reduce the efficacy of other medications, although he noted that drug treatments for COVID-19 were limited early on. He recommended that neurologists “avoid old enzyme-inducing seizure medications, as is generally recommended.”

No study funding is reported. The study authors and Dr. Benbadis reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Wilner is a medical adviser for the epilepsy disease management program for CVS/Health.

according to a new study presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. While the findings are preliminary and not yet adjusted for various confounders, the authors say they are a warning sign that patients with epilepsy may face higher risks.

“These findings suggest that epilepsy may be a pre-existing condition that places patients at increased risk for death if hospitalized with a COVID-19 infection. It may offer neurologists guidance when counseling patients on critical preventative measures such as masking, social distancing, and most importantly, vaccination,” lead author Claire Ufongene, a student at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said in an interview.

According to Ms. Ufongene, there’s sparse data about COVID-19 outcomes in patients with epilepsy, although she highlighted a 2021 meta-analysis of 13 studies that found a higher risk of severity (odds ratio, 1.69; 95% confidence interval, 1.11-2.59, P = .010) and mortality (OR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.14-2.56, P = .010).

For the new study, researchers retrospectively tracked identified 334 patients with epilepsy and COVID-19 and 9,499 other patients with COVID-19 from March 15, 2020, to May 17, 2021. All were treated at hospitals within the New York–based Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

The groups of patients with and without epilepsy were similar in some ways: 45% and 46%, respectively, were female (P = .674), and their ages were similar (average, 62 years and 65 years, respectively; P = .02). Racial makeup was also similar (non-Hispanic groups made up 27.8% of those with epilepsy and 24.5% of those without; the difference was not statistically significant).

“In addition, more of those with epilepsy were English speaking [83.2% vs. 77.9%] and had Medicaid insurance [50.9% vs. 38.9%], while fewer of those with epilepsy had private insurance [16.2% vs. 25.5%] or were Spanish speaking [14.0% vs. 9.3%],” study coauthor Nathalie Jette, MD, MSc, a neurologist at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, said in an interview.

In terms of outcomes, patients with epilepsy were much more likely to need ventilator support (37.7% vs. 14.3%; P < .001), to be admitted to the ICU (39.2% vs. 17.7%; P < .001), and to die in the hospital (29.6% vs. 19.9%; P < .001).

“Most patients we follow in our practices with epilepsy who experienced COVID-19 in general have had symptoms similar to the general population,” Dr. Jette said. “There are rare instances where COVID-19 can result in an exacerbation of seizures in some with pre-existing epilepsy. This is not surprising as infections in particular can decrease the seizure threshold and result in breakthrough seizures in people living with epilepsy.”

Loss of seizure control

How might epilepsy be related to worse outcomes in COVID-19? Andrew Wilner, MD, a neurologist and internist at University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, who’s familiar with the study findings, said COVID-19 itself may not worsen epilepsy. “Evidence to suggest that COVID-19 directly affects the central nervous system is extremely limited. As such, one would not expect that a COVID-19 infection would cause epilepsy or exacerbate epilepsy,” he said. “However, patients with epilepsy who suffer from infections may be predisposed to decreased seizure control. Consequently, it would not be surprising if patients with epilepsy who also had COVID-19 had loss of seizure control and even status epilepticus, which could adversely affect their hospital course. However, there are no data on this potential phenomenon.”

Dr. Wilner suspected that comorbidities explain the higher mortality in patients with epilepsy. “The findings are probably most useful in that they call attention to the fact that epilepsy patients are more vulnerable to a host of comorbidities and resultant poorer outcomes due to any acute illness.”

As for treatment, Dr. Wilner urged colleagues to make sure that hospitalized patients with epilepsy “continue to receive their antiepileptic medications, which they may no longer be able to take orally. They may need to be switched temporarily to an intravenous formulation.”

In an interview, Selim Benbadis, MD, a neurologist from the University of South Florida, Tampa, suggested that antiseizure medications may play a role in the COVID-19 disease course because they can reduce the efficacy of other medications, although he noted that drug treatments for COVID-19 were limited early on. He recommended that neurologists “avoid old enzyme-inducing seizure medications, as is generally recommended.”

No study funding is reported. The study authors and Dr. Benbadis reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Wilner is a medical adviser for the epilepsy disease management program for CVS/Health.

FROM AES 2021

What the Future May Hold for Covid-19 Survivors

What the Future May Hold for Covid-19 Survivors

More than 3 million Americans1 have been hospitalized with Covid-19, and

And these are just the patients with severe Covid: those who were never hospitalized are also showing deleterious effects from the effects of their illness.

Covid in the ICU

What we know is that prior to Covid, 10% of all patients were admitted to ICU with acute respiratory distress syndrome4 (ARDS), despite receiving such life-saving measures as mechanical ventilation, medication, and supportive nutrition. Those who do survive face a long journey.4 Besides the specific respiratory recovery needed in those with ARDS, patients who have spent time in the ICU can develop multiple non-respiratory complications, including muscle wasting, generalized weakness, and delirium. The physical, cognitive, and psychological impairments that follow an ICU stay are termed postintensive care syndrome (PICS). PICS is an underrecognized phenomenon that describes the immense complications of an ICU stay for any reason. Recognition of this entity, and education of patients, is particularly important now as we face an ongoing pandemic which is creating a burgeoning number of ICU graduates.

PICS

Cognitive dysfunction is one hallmark of PICS. Delirium is a common complication of any hospitalization, with critically ill patients particularly susceptible given the severity of their illness and their exposure to medications such as sedatives. However, persistent global cognitive impairment is unique to PICS. Up to

The second aspect of PICS is its psychological component. In the Hopkins study,5

The final component of PICS is physical impairment. Those who are critically ill commonly suffer intensive care unit

Covid in the ICU

Estimates of the incidence of PICS due to Covid are evolving. A report on 1700 Covid hospitalized patients in Wuhan, China demonstrated a large prevalence of residual symptoms at 6 months. The most common symptoms were fatigue and weakness (63%), insomnia (26%), and anxiety or depression (

As more centers track the progress of their ICU graduates over time, we can better understand the profound impact of critical illness on our Covid patients and better educate our patients and families on what to expect. One might be able to gain some clues from what is known regarding the prior coronavirus epidemics, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). In these diseases, a meta-analysis showed significant rates of

Additional issues

What is particularly unique to Covid is the prevalence of long-term symptoms in those who were never hospitalized for Covid. Recent estimates of non-hospitalized patients who had Covid are showing at least 25% of them have had long-lasting effects, including stomach pain and respiratory

Financially

Conclusion

The long-term effects of hospitalization from Covid argues further for continued work on increasing the vaccination rate of our population. Even with Delta variant, vaccines decrease the risk of hospitalization and death by more than a factor of

- CDC. Covid Data Tracker. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#new-hospital-admissions

- CDC. Covid Data Tracker. Trends total death. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#trends_totaldeaths_currenthospitaladmissions|tot_deaths|sum_inpatient_beds_used_covid_7DayAvg

- Johns Hopkins. Weekly hospital trends. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/hospitalization-7-day-trend

- Bellani G, Laffey JG, Pham T, et al.; LUNG SAFE Investigators; ESICM Trials Group. Epidemiology, Patterns of Care, and Mortality for Patients with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Intensive Care Units in 50 Countries. JAMA. 2016 Feb 23;315(8):788-800

- Ramona O. Hopkins, Lindell K. Weaver, Dave Collingridge, et al. Two-Year Cognitive, Emotional, and Quality-of-Life Outcomes in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Amer J Resp Crit Care Med. 2005; (171):4.

- Stevens, Robert D, Marshall, Scott A, Cornblath, David R, et al. A framework for diagnosing and classifying intensive care unit-acquired weakness, Critic Care Medic. 2009; (37)10: S299-S308.

- Chaolin Huang, Lixue Huang, Yeming Wang, et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from om hospital: a cohort study. The Lancet 2021; 397(10270): 220-232.

- Gamberini L, Mazzoli CA, Sintonen H, et al.; ICU-RER COVID-19 Collaboration. Quality of life of COVID-19 critically ill survivors after ICU discharge: 90 days follow-up. Qual Life Res. 2021 Oct;30(10):2805-2817.

- Chopra V, Flanders SA, O'Malley M, et al. Sixty-Day Outcomes Among Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2021 Apr;174(4):576-578.

- The Writing Committee for the COMEBAC Study Group. Four-Month Clinical Status of a Cohort of Patients After Hospitalization for COVID-19. JAMA. 2021;325(15):1525–1534.

- Ahmed H, Patel K, Greenwood DC, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus outbreaks after hospitalisation or ICU admission: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Rehabil Med. 2020 May 31;52(5): jrm00063.

- Logue JK, Franko NM, McCulloch DJ, et al. Sequelae in Adults at 6 Months After COVID-19 Infection. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2): e210830.

- Brenda Goodman. Major study will investigate long-haul Covid-19. WebMD News Brief. Sept. 15, 2021. https://www.webmd.com/lung/news/20210915/major-study-will-investigate-long-haul-covid

- Vineet Chopra, Scott A. Flanders, Megan O’Malley, et al. Sixty-Day Outcomes Among Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. Letters. 2021; Apr.

- Yuping Tsai, Tara M. Vogt, Fangjun Zhou. Patient Characteristics and Costs Associated With COVID-19–Related Medical Care Among Medicare Fee-for-Service Beneficiaries. Ann Intern Med. 2021; Aug.

- Lavery AM, Preston LE, Ko JY, et al. Characteristics of Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients Discharged and Experiencing Same-Hospital Readmission — United States, March–August 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69:1695–1699.

- Scobie HM, Johnson AG, Suthar AB, et al. Monitoring Incidence of COVID-19 Cases, Hospitalizations, and Deaths, by Vaccination Status — 13 U.S. Jurisdictions, April 4–July 17, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021; 70:1284–1290.

What the Future May Hold for Covid-19 Survivors

More than 3 million Americans1 have been hospitalized with Covid-19, and

And these are just the patients with severe Covid: those who were never hospitalized are also showing deleterious effects from the effects of their illness.

Covid in the ICU

What we know is that prior to Covid, 10% of all patients were admitted to ICU with acute respiratory distress syndrome4 (ARDS), despite receiving such life-saving measures as mechanical ventilation, medication, and supportive nutrition. Those who do survive face a long journey.4 Besides the specific respiratory recovery needed in those with ARDS, patients who have spent time in the ICU can develop multiple non-respiratory complications, including muscle wasting, generalized weakness, and delirium. The physical, cognitive, and psychological impairments that follow an ICU stay are termed postintensive care syndrome (PICS). PICS is an underrecognized phenomenon that describes the immense complications of an ICU stay for any reason. Recognition of this entity, and education of patients, is particularly important now as we face an ongoing pandemic which is creating a burgeoning number of ICU graduates.

PICS

Cognitive dysfunction is one hallmark of PICS. Delirium is a common complication of any hospitalization, with critically ill patients particularly susceptible given the severity of their illness and their exposure to medications such as sedatives. However, persistent global cognitive impairment is unique to PICS. Up to

The second aspect of PICS is its psychological component. In the Hopkins study,5

The final component of PICS is physical impairment. Those who are critically ill commonly suffer intensive care unit

Covid in the ICU

Estimates of the incidence of PICS due to Covid are evolving. A report on 1700 Covid hospitalized patients in Wuhan, China demonstrated a large prevalence of residual symptoms at 6 months. The most common symptoms were fatigue and weakness (63%), insomnia (26%), and anxiety or depression (

As more centers track the progress of their ICU graduates over time, we can better understand the profound impact of critical illness on our Covid patients and better educate our patients and families on what to expect. One might be able to gain some clues from what is known regarding the prior coronavirus epidemics, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). In these diseases, a meta-analysis showed significant rates of

Additional issues

What is particularly unique to Covid is the prevalence of long-term symptoms in those who were never hospitalized for Covid. Recent estimates of non-hospitalized patients who had Covid are showing at least 25% of them have had long-lasting effects, including stomach pain and respiratory

Financially

Conclusion

The long-term effects of hospitalization from Covid argues further for continued work on increasing the vaccination rate of our population. Even with Delta variant, vaccines decrease the risk of hospitalization and death by more than a factor of

What the Future May Hold for Covid-19 Survivors

More than 3 million Americans1 have been hospitalized with Covid-19, and

And these are just the patients with severe Covid: those who were never hospitalized are also showing deleterious effects from the effects of their illness.

Covid in the ICU

What we know is that prior to Covid, 10% of all patients were admitted to ICU with acute respiratory distress syndrome4 (ARDS), despite receiving such life-saving measures as mechanical ventilation, medication, and supportive nutrition. Those who do survive face a long journey.4 Besides the specific respiratory recovery needed in those with ARDS, patients who have spent time in the ICU can develop multiple non-respiratory complications, including muscle wasting, generalized weakness, and delirium. The physical, cognitive, and psychological impairments that follow an ICU stay are termed postintensive care syndrome (PICS). PICS is an underrecognized phenomenon that describes the immense complications of an ICU stay for any reason. Recognition of this entity, and education of patients, is particularly important now as we face an ongoing pandemic which is creating a burgeoning number of ICU graduates.

PICS

Cognitive dysfunction is one hallmark of PICS. Delirium is a common complication of any hospitalization, with critically ill patients particularly susceptible given the severity of their illness and their exposure to medications such as sedatives. However, persistent global cognitive impairment is unique to PICS. Up to

The second aspect of PICS is its psychological component. In the Hopkins study,5

The final component of PICS is physical impairment. Those who are critically ill commonly suffer intensive care unit

Covid in the ICU

Estimates of the incidence of PICS due to Covid are evolving. A report on 1700 Covid hospitalized patients in Wuhan, China demonstrated a large prevalence of residual symptoms at 6 months. The most common symptoms were fatigue and weakness (63%), insomnia (26%), and anxiety or depression (

As more centers track the progress of their ICU graduates over time, we can better understand the profound impact of critical illness on our Covid patients and better educate our patients and families on what to expect. One might be able to gain some clues from what is known regarding the prior coronavirus epidemics, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). In these diseases, a meta-analysis showed significant rates of

Additional issues

What is particularly unique to Covid is the prevalence of long-term symptoms in those who were never hospitalized for Covid. Recent estimates of non-hospitalized patients who had Covid are showing at least 25% of them have had long-lasting effects, including stomach pain and respiratory

Financially

Conclusion

The long-term effects of hospitalization from Covid argues further for continued work on increasing the vaccination rate of our population. Even with Delta variant, vaccines decrease the risk of hospitalization and death by more than a factor of

- CDC. Covid Data Tracker. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#new-hospital-admissions

- CDC. Covid Data Tracker. Trends total death. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#trends_totaldeaths_currenthospitaladmissions|tot_deaths|sum_inpatient_beds_used_covid_7DayAvg

- Johns Hopkins. Weekly hospital trends. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/hospitalization-7-day-trend

- Bellani G, Laffey JG, Pham T, et al.; LUNG SAFE Investigators; ESICM Trials Group. Epidemiology, Patterns of Care, and Mortality for Patients with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Intensive Care Units in 50 Countries. JAMA. 2016 Feb 23;315(8):788-800

- Ramona O. Hopkins, Lindell K. Weaver, Dave Collingridge, et al. Two-Year Cognitive, Emotional, and Quality-of-Life Outcomes in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Amer J Resp Crit Care Med. 2005; (171):4.

- Stevens, Robert D, Marshall, Scott A, Cornblath, David R, et al. A framework for diagnosing and classifying intensive care unit-acquired weakness, Critic Care Medic. 2009; (37)10: S299-S308.

- Chaolin Huang, Lixue Huang, Yeming Wang, et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from om hospital: a cohort study. The Lancet 2021; 397(10270): 220-232.

- Gamberini L, Mazzoli CA, Sintonen H, et al.; ICU-RER COVID-19 Collaboration. Quality of life of COVID-19 critically ill survivors after ICU discharge: 90 days follow-up. Qual Life Res. 2021 Oct;30(10):2805-2817.

- Chopra V, Flanders SA, O'Malley M, et al. Sixty-Day Outcomes Among Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2021 Apr;174(4):576-578.

- The Writing Committee for the COMEBAC Study Group. Four-Month Clinical Status of a Cohort of Patients After Hospitalization for COVID-19. JAMA. 2021;325(15):1525–1534.

- Ahmed H, Patel K, Greenwood DC, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus outbreaks after hospitalisation or ICU admission: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Rehabil Med. 2020 May 31;52(5): jrm00063.

- Logue JK, Franko NM, McCulloch DJ, et al. Sequelae in Adults at 6 Months After COVID-19 Infection. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2): e210830.

- Brenda Goodman. Major study will investigate long-haul Covid-19. WebMD News Brief. Sept. 15, 2021. https://www.webmd.com/lung/news/20210915/major-study-will-investigate-long-haul-covid

- Vineet Chopra, Scott A. Flanders, Megan O’Malley, et al. Sixty-Day Outcomes Among Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. Letters. 2021; Apr.

- Yuping Tsai, Tara M. Vogt, Fangjun Zhou. Patient Characteristics and Costs Associated With COVID-19–Related Medical Care Among Medicare Fee-for-Service Beneficiaries. Ann Intern Med. 2021; Aug.

- Lavery AM, Preston LE, Ko JY, et al. Characteristics of Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients Discharged and Experiencing Same-Hospital Readmission — United States, March–August 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69:1695–1699.

- Scobie HM, Johnson AG, Suthar AB, et al. Monitoring Incidence of COVID-19 Cases, Hospitalizations, and Deaths, by Vaccination Status — 13 U.S. Jurisdictions, April 4–July 17, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021; 70:1284–1290.

- CDC. Covid Data Tracker. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#new-hospital-admissions

- CDC. Covid Data Tracker. Trends total death. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#trends_totaldeaths_currenthospitaladmissions|tot_deaths|sum_inpatient_beds_used_covid_7DayAvg

- Johns Hopkins. Weekly hospital trends. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/hospitalization-7-day-trend

- Bellani G, Laffey JG, Pham T, et al.; LUNG SAFE Investigators; ESICM Trials Group. Epidemiology, Patterns of Care, and Mortality for Patients with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Intensive Care Units in 50 Countries. JAMA. 2016 Feb 23;315(8):788-800

- Ramona O. Hopkins, Lindell K. Weaver, Dave Collingridge, et al. Two-Year Cognitive, Emotional, and Quality-of-Life Outcomes in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Amer J Resp Crit Care Med. 2005; (171):4.

- Stevens, Robert D, Marshall, Scott A, Cornblath, David R, et al. A framework for diagnosing and classifying intensive care unit-acquired weakness, Critic Care Medic. 2009; (37)10: S299-S308.

- Chaolin Huang, Lixue Huang, Yeming Wang, et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from om hospital: a cohort study. The Lancet 2021; 397(10270): 220-232.

- Gamberini L, Mazzoli CA, Sintonen H, et al.; ICU-RER COVID-19 Collaboration. Quality of life of COVID-19 critically ill survivors after ICU discharge: 90 days follow-up. Qual Life Res. 2021 Oct;30(10):2805-2817.

- Chopra V, Flanders SA, O'Malley M, et al. Sixty-Day Outcomes Among Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2021 Apr;174(4):576-578.

- The Writing Committee for the COMEBAC Study Group. Four-Month Clinical Status of a Cohort of Patients After Hospitalization for COVID-19. JAMA. 2021;325(15):1525–1534.

- Ahmed H, Patel K, Greenwood DC, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus outbreaks after hospitalisation or ICU admission: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Rehabil Med. 2020 May 31;52(5): jrm00063.

- Logue JK, Franko NM, McCulloch DJ, et al. Sequelae in Adults at 6 Months After COVID-19 Infection. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2): e210830.

- Brenda Goodman. Major study will investigate long-haul Covid-19. WebMD News Brief. Sept. 15, 2021. https://www.webmd.com/lung/news/20210915/major-study-will-investigate-long-haul-covid

- Vineet Chopra, Scott A. Flanders, Megan O’Malley, et al. Sixty-Day Outcomes Among Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. Letters. 2021; Apr.

- Yuping Tsai, Tara M. Vogt, Fangjun Zhou. Patient Characteristics and Costs Associated With COVID-19–Related Medical Care Among Medicare Fee-for-Service Beneficiaries. Ann Intern Med. 2021; Aug.

- Lavery AM, Preston LE, Ko JY, et al. Characteristics of Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients Discharged and Experiencing Same-Hospital Readmission — United States, March–August 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69:1695–1699.

- Scobie HM, Johnson AG, Suthar AB, et al. Monitoring Incidence of COVID-19 Cases, Hospitalizations, and Deaths, by Vaccination Status — 13 U.S. Jurisdictions, April 4–July 17, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021; 70:1284–1290.

Risk for severe COVID-19 and death plummets with Pfizer booster

Both studies were completed before the advent of the Omicron variant.

In one study that included data on more than 4 million patients, led by Yinon M. Bar-On, MSc, of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, the rate of confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection was lower in the booster group than in the nonbooster group by a factor of about 10.

This was true across all five age groups studied (range among the groups [starting with age 16], 9.0-17.2).

The risk for severe COVID-19 in the primary analysis decreased in the booster group by a factor of 17.9 (95% confidence interval, 15.1-21.2), among those aged 60 years or older. Risk for severe illness in those ages 40-59 was lower by a factor of 21.7 (95% CI, 10.6-44.2).

Among the 60 and older age group, risk for death was also reduced by a factor of 14.7 (95% CI, 10.0-21.4).

Researchers analyzed data for the period from July 30 to Oct. 10, 2021, from the Israel Ministry of Health database on 4.69 million people at least 16 years old who had received two Pfizer doses at least 5 months earlier.

In the main analysis, the researchers compared the rates of confirmed COVID-19, severe disease, and death among those who had gotten a booster at least 12 days earlier with the rates in a nonbooster group.

The authors wrote: “Booster vaccination programs may provide a way to control transmission without costly social-distancing measures and quarantines. Our findings provide evidence for the short-term effectiveness of the booster dose against the currently dominant Delta variant in persons 16 years of age or older.”

Death risk down by 90%

A second study, led by Ronen Arbel, PhD, with the community medical services division, Clalit Health Services (CHS), Tel Aviv, which included more than 800,000 participants, also found mortality risk was greatly reduced among those who received the booster compared with those who didn’t get the booster.

Participants aged 50 years or older who received a booster at least 5 months after a second Pfizer dose had 90% lower mortality risk because of COVID-19 than participants who did not get the booster.

The adjusted hazard ratio for death as a result of COVID-19 in the booster group, as compared with the nonbooster group, was 0.10 (95% CI, 0.07-0.14; P < .001). Of the 843,208 eligible participants, 758,118 (90%) received the booster during the 54-day study period.

The study included all CHS members who were aged 50 years or older on the study start date and had received two Pfizer doses at least 5 months earlier. CHS covers about 52% of the Israeli population and is the largest of four health care organizations in Israel that provide mandatory health care.

The authors noted that, although the study period was only 54 days (Aug. 6–Sept. 29), during that time “the incidence of COVID-19 in Israel was one of the highest in the world.”

The authors of both original articles pointed out that the studies are limited by short time periods and that longer-term studies are needed to see how the booster shots stand up to known and future variants, such as Omicron.

None of the authors involved in both studies reported relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Both studies were completed before the advent of the Omicron variant.

In one study that included data on more than 4 million patients, led by Yinon M. Bar-On, MSc, of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, the rate of confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection was lower in the booster group than in the nonbooster group by a factor of about 10.

This was true across all five age groups studied (range among the groups [starting with age 16], 9.0-17.2).

The risk for severe COVID-19 in the primary analysis decreased in the booster group by a factor of 17.9 (95% confidence interval, 15.1-21.2), among those aged 60 years or older. Risk for severe illness in those ages 40-59 was lower by a factor of 21.7 (95% CI, 10.6-44.2).

Among the 60 and older age group, risk for death was also reduced by a factor of 14.7 (95% CI, 10.0-21.4).

Researchers analyzed data for the period from July 30 to Oct. 10, 2021, from the Israel Ministry of Health database on 4.69 million people at least 16 years old who had received two Pfizer doses at least 5 months earlier.

In the main analysis, the researchers compared the rates of confirmed COVID-19, severe disease, and death among those who had gotten a booster at least 12 days earlier with the rates in a nonbooster group.

The authors wrote: “Booster vaccination programs may provide a way to control transmission without costly social-distancing measures and quarantines. Our findings provide evidence for the short-term effectiveness of the booster dose against the currently dominant Delta variant in persons 16 years of age or older.”

Death risk down by 90%

A second study, led by Ronen Arbel, PhD, with the community medical services division, Clalit Health Services (CHS), Tel Aviv, which included more than 800,000 participants, also found mortality risk was greatly reduced among those who received the booster compared with those who didn’t get the booster.

Participants aged 50 years or older who received a booster at least 5 months after a second Pfizer dose had 90% lower mortality risk because of COVID-19 than participants who did not get the booster.

The adjusted hazard ratio for death as a result of COVID-19 in the booster group, as compared with the nonbooster group, was 0.10 (95% CI, 0.07-0.14; P < .001). Of the 843,208 eligible participants, 758,118 (90%) received the booster during the 54-day study period.

The study included all CHS members who were aged 50 years or older on the study start date and had received two Pfizer doses at least 5 months earlier. CHS covers about 52% of the Israeli population and is the largest of four health care organizations in Israel that provide mandatory health care.

The authors noted that, although the study period was only 54 days (Aug. 6–Sept. 29), during that time “the incidence of COVID-19 in Israel was one of the highest in the world.”

The authors of both original articles pointed out that the studies are limited by short time periods and that longer-term studies are needed to see how the booster shots stand up to known and future variants, such as Omicron.

None of the authors involved in both studies reported relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Both studies were completed before the advent of the Omicron variant.

In one study that included data on more than 4 million patients, led by Yinon M. Bar-On, MSc, of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, the rate of confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection was lower in the booster group than in the nonbooster group by a factor of about 10.

This was true across all five age groups studied (range among the groups [starting with age 16], 9.0-17.2).

The risk for severe COVID-19 in the primary analysis decreased in the booster group by a factor of 17.9 (95% confidence interval, 15.1-21.2), among those aged 60 years or older. Risk for severe illness in those ages 40-59 was lower by a factor of 21.7 (95% CI, 10.6-44.2).

Among the 60 and older age group, risk for death was also reduced by a factor of 14.7 (95% CI, 10.0-21.4).

Researchers analyzed data for the period from July 30 to Oct. 10, 2021, from the Israel Ministry of Health database on 4.69 million people at least 16 years old who had received two Pfizer doses at least 5 months earlier.

In the main analysis, the researchers compared the rates of confirmed COVID-19, severe disease, and death among those who had gotten a booster at least 12 days earlier with the rates in a nonbooster group.

The authors wrote: “Booster vaccination programs may provide a way to control transmission without costly social-distancing measures and quarantines. Our findings provide evidence for the short-term effectiveness of the booster dose against the currently dominant Delta variant in persons 16 years of age or older.”

Death risk down by 90%

A second study, led by Ronen Arbel, PhD, with the community medical services division, Clalit Health Services (CHS), Tel Aviv, which included more than 800,000 participants, also found mortality risk was greatly reduced among those who received the booster compared with those who didn’t get the booster.

Participants aged 50 years or older who received a booster at least 5 months after a second Pfizer dose had 90% lower mortality risk because of COVID-19 than participants who did not get the booster.

The adjusted hazard ratio for death as a result of COVID-19 in the booster group, as compared with the nonbooster group, was 0.10 (95% CI, 0.07-0.14; P < .001). Of the 843,208 eligible participants, 758,118 (90%) received the booster during the 54-day study period.

The study included all CHS members who were aged 50 years or older on the study start date and had received two Pfizer doses at least 5 months earlier. CHS covers about 52% of the Israeli population and is the largest of four health care organizations in Israel that provide mandatory health care.

The authors noted that, although the study period was only 54 days (Aug. 6–Sept. 29), during that time “the incidence of COVID-19 in Israel was one of the highest in the world.”

The authors of both original articles pointed out that the studies are limited by short time periods and that longer-term studies are needed to see how the booster shots stand up to known and future variants, such as Omicron.

None of the authors involved in both studies reported relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

CLL and COVID-19: Outcome trends and lessons learned

Retrospective but the data also highlight areas for further investigation, according to the researchers.

Specifically, “the data highlight opportunities for further investigation into optimal management of COVID-19, immune response after infection, and effective vaccination strategy for patients with CLL,” Lindsey E. Roeker, MD, a hematologic oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and colleagues wrote in a Nov. 4, 2021, letter to the editor of Blood.

The researchers noted that recently reported COVID-19 case fatality rates from two large series of patients with CLL ranged from 31% to 33%, but trends over time were unclear.

“To understand change in outcomes over time, we present this follow-up study, which builds upon a previously reported cohort with extended follow up and addition of more recently diagnosed cases,” they wrote, explaining that “early data from a small series suggest that patients with CLL may not consistently generate anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies after infection.”

“This finding, along with previous reports of inadequate response to vaccines in patients with CLL, highlight significant questions regarding COVID-19 vaccine efficacy in this population,” they added.

Trends in outcomes

The review of outcomes in 374 CLL patients from 45 centers who were diagnosed with COVID-19 between Feb. 17, 2020, and Feb. 1, 2021, showed an overall case fatality rate (CFR) of 28%. Among the 278 patients (75%) admitted to the hospital, the CFR was 36%; among those not admitted, the CFR was 4.3%.

Independent predictors of poor survival were ages over 75 years (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.6) and Cumulative Illness Rating Scale–Geriatric (CIRS) scores greater than 6 (aHR, 1.6).

Updated data for 254 patients diagnosed from Feb. 17 to April 30, 2020, and 120 diagnosed from May 1, 2020, to Feb. 1, 2021, showed that more patients in the early versus later cohort were admitted to the hospital (85% vs. 55%) and more required ICU admission (32% vs. 11%).

The overall case fatality rates in the early and later cohorts were 35% and 11%, respectively (P < .001), and among those requiring hospitalization, the rates were 40% and 20% (P = .003).

“The proportion of hospitalized patients requiring ICU-level care was lower in the later cohort (37% vs. 29%), whereas the CFR remained high for the subset of patients who required ICU-level care (52% vs. 50%; P = .89),” the investigators wrote, noting that “[a] difference in management of BTKi[Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor]-treated patients was observed in the early versus the later cohort.”

“In the early cohort, 76% of patients receiving BTKi had their drug therapy suspended or discontinued. In the later cohort, only 20% of BTKi-treated patients had their therapy suspended or discontinued,” they added.

Univariate analyses showed significant associations between use of remdesivir and OS (HR, 0.48) and use of convalescent plasma and OS (HR, 0.50) in patients who were admitted, whereas admitted patients who received corticosteroids or hydroxychloroquine had an increased risk of death (HRs, 1.73 and 1.53, respectively).

“Corticosteroids were associated with increased risk of death when the data were adjusted for admission status (HR, 1.8) and the need for mechanical ventilation (HR, 2.0), although they were not significantly associated with survival when the data were adjusted for use of supplemental oxygen (HR, 1.4),” they wrote, also noting that admitted patients treated with corticosteroids in the later cohort did not experience an OS benefit (HR, 2.6).

The findings mirror population-based studies with decreasing CFR (35% in those diagnosed before May 1, 2020, versus 11% in those diagnosed after that date), they said, adding that “these trends suggest that patients in the later cohort experienced a less severe clinical course and that the observed difference in CFR over time may not just be due to more frequent testing and identification of less symptomatic patients.”

Of note, the outcomes observed for steroid-treated patients in the current cohort contrast with those from the RECOVERY trial as published in July 2020, which “may be an artifact of their use in patients with more severe disease,” they suggested.

They added that these data “are hypothesis generating and suggest that COVID-19 directed interventions, particularly immunomodulatory agents, require prospective study, specifically in immunocompromised populations.”

The investigators also noted that, consistent with a prior single-center study, 60% of patients with CLL developed positive anti–SARS-CoV-2 serology results after polymerase chain reaction diagnosis of COVID-19, adding further evidence of nonuniform antibody production after COVID-19 in patients with CLL.

Study is ongoing to gain understanding of the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with CLL, they said.

Changing the odds

In a related commentary also published in Blood, Yair Herishanu, MD, and Chava Perry, MD, PhD, of Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center called the reduction in mortality over time as reported by Dr. Roeker and colleagues “encouraging and intriguing.”

“One explanation is that the later cohort included a larger proportion of patients with mild symptoms who were diagnosed because of increased awareness of COVID-19 and more extensive screening to detect SARS-CoV-2 over time. That is supported by the lower hospitalization rates and lower rates of hospitalized patients requiring ICU care in the later cohort,” they wrote. “Another possibility is better patient management owing to increasing experience, expanding therapeutic options, and improved capacity of health systems to manage an influx of patients.”

The lower mortality in hospitalized patients over time may reflect better management of patients over time, but it also highlights the significance of “early introduction of various anti–COVID-19 therapies to prevent clinical deterioration to ICU-level care,” they added.

Also intriguing, according to Dr. Herishanu and Dr. Perry, was the finding of increased secondary infections and death rates among corticosteroid-treatment patients.

In the RECOVERY trial, the use of dexamethasone improved survival in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 who received respiratory support. Perhaps the impaired immune reactions in patients with CLL moderate the hyperinflammatory reactions to COVID-19, thus turning corticosteroids beneficial effects to somewhat redundant in this frail population,” they wrote.

Further, the finding that only 60% of patients with CLL seroconvert after the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection suggests CLL patients may be at risk for reinfection, which “justifies vaccinating all patients with CLL who have recovered from COVID-19.”

“Likewise, patients with CLL may develop persistent COVID-19 infection,” they added, explaining that “prolonged shedding of infectious SARS-CoV-2 virus and within-host genomic evolution may eventually lead to emergence of new virus variants.”

Given the high risk of severe COVID-19 disease and impaired antibody-mediated immune response to the virus and its vaccine, a booster dose may be warranted in patients with CLL who fail to achieve seropositivity after 2 vaccine doses, they said.

The available data to date “call for early application of antiviral drugs, [monoclonal antibodies], and convalescent plasma as well as improved vaccination strategy, to improve the odds for patients with CLL confronting COVID-19,” they concluded, adding that large-scale prospective studies on the clinical disease course, outcomes, efficacy of treatments, and vaccination timing and schedule in patients with CLL and COVID-19 are still warranted.

The research was supported by a National Cancer Institute Cancer Center support grant. Dr. Roeker, Dr. Herishanu, and Dr. Perry reported having no financial disclosures.

Retrospective but the data also highlight areas for further investigation, according to the researchers.

Specifically, “the data highlight opportunities for further investigation into optimal management of COVID-19, immune response after infection, and effective vaccination strategy for patients with CLL,” Lindsey E. Roeker, MD, a hematologic oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and colleagues wrote in a Nov. 4, 2021, letter to the editor of Blood.

The researchers noted that recently reported COVID-19 case fatality rates from two large series of patients with CLL ranged from 31% to 33%, but trends over time were unclear.

“To understand change in outcomes over time, we present this follow-up study, which builds upon a previously reported cohort with extended follow up and addition of more recently diagnosed cases,” they wrote, explaining that “early data from a small series suggest that patients with CLL may not consistently generate anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies after infection.”

“This finding, along with previous reports of inadequate response to vaccines in patients with CLL, highlight significant questions regarding COVID-19 vaccine efficacy in this population,” they added.

Trends in outcomes

The review of outcomes in 374 CLL patients from 45 centers who were diagnosed with COVID-19 between Feb. 17, 2020, and Feb. 1, 2021, showed an overall case fatality rate (CFR) of 28%. Among the 278 patients (75%) admitted to the hospital, the CFR was 36%; among those not admitted, the CFR was 4.3%.

Independent predictors of poor survival were ages over 75 years (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.6) and Cumulative Illness Rating Scale–Geriatric (CIRS) scores greater than 6 (aHR, 1.6).

Updated data for 254 patients diagnosed from Feb. 17 to April 30, 2020, and 120 diagnosed from May 1, 2020, to Feb. 1, 2021, showed that more patients in the early versus later cohort were admitted to the hospital (85% vs. 55%) and more required ICU admission (32% vs. 11%).

The overall case fatality rates in the early and later cohorts were 35% and 11%, respectively (P < .001), and among those requiring hospitalization, the rates were 40% and 20% (P = .003).

“The proportion of hospitalized patients requiring ICU-level care was lower in the later cohort (37% vs. 29%), whereas the CFR remained high for the subset of patients who required ICU-level care (52% vs. 50%; P = .89),” the investigators wrote, noting that “[a] difference in management of BTKi[Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor]-treated patients was observed in the early versus the later cohort.”

“In the early cohort, 76% of patients receiving BTKi had their drug therapy suspended or discontinued. In the later cohort, only 20% of BTKi-treated patients had their therapy suspended or discontinued,” they added.

Univariate analyses showed significant associations between use of remdesivir and OS (HR, 0.48) and use of convalescent plasma and OS (HR, 0.50) in patients who were admitted, whereas admitted patients who received corticosteroids or hydroxychloroquine had an increased risk of death (HRs, 1.73 and 1.53, respectively).

“Corticosteroids were associated with increased risk of death when the data were adjusted for admission status (HR, 1.8) and the need for mechanical ventilation (HR, 2.0), although they were not significantly associated with survival when the data were adjusted for use of supplemental oxygen (HR, 1.4),” they wrote, also noting that admitted patients treated with corticosteroids in the later cohort did not experience an OS benefit (HR, 2.6).

The findings mirror population-based studies with decreasing CFR (35% in those diagnosed before May 1, 2020, versus 11% in those diagnosed after that date), they said, adding that “these trends suggest that patients in the later cohort experienced a less severe clinical course and that the observed difference in CFR over time may not just be due to more frequent testing and identification of less symptomatic patients.”

Of note, the outcomes observed for steroid-treated patients in the current cohort contrast with those from the RECOVERY trial as published in July 2020, which “may be an artifact of their use in patients with more severe disease,” they suggested.

They added that these data “are hypothesis generating and suggest that COVID-19 directed interventions, particularly immunomodulatory agents, require prospective study, specifically in immunocompromised populations.”

The investigators also noted that, consistent with a prior single-center study, 60% of patients with CLL developed positive anti–SARS-CoV-2 serology results after polymerase chain reaction diagnosis of COVID-19, adding further evidence of nonuniform antibody production after COVID-19 in patients with CLL.

Study is ongoing to gain understanding of the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with CLL, they said.

Changing the odds

In a related commentary also published in Blood, Yair Herishanu, MD, and Chava Perry, MD, PhD, of Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center called the reduction in mortality over time as reported by Dr. Roeker and colleagues “encouraging and intriguing.”

“One explanation is that the later cohort included a larger proportion of patients with mild symptoms who were diagnosed because of increased awareness of COVID-19 and more extensive screening to detect SARS-CoV-2 over time. That is supported by the lower hospitalization rates and lower rates of hospitalized patients requiring ICU care in the later cohort,” they wrote. “Another possibility is better patient management owing to increasing experience, expanding therapeutic options, and improved capacity of health systems to manage an influx of patients.”

The lower mortality in hospitalized patients over time may reflect better management of patients over time, but it also highlights the significance of “early introduction of various anti–COVID-19 therapies to prevent clinical deterioration to ICU-level care,” they added.

Also intriguing, according to Dr. Herishanu and Dr. Perry, was the finding of increased secondary infections and death rates among corticosteroid-treatment patients.

In the RECOVERY trial, the use of dexamethasone improved survival in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 who received respiratory support. Perhaps the impaired immune reactions in patients with CLL moderate the hyperinflammatory reactions to COVID-19, thus turning corticosteroids beneficial effects to somewhat redundant in this frail population,” they wrote.

Further, the finding that only 60% of patients with CLL seroconvert after the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection suggests CLL patients may be at risk for reinfection, which “justifies vaccinating all patients with CLL who have recovered from COVID-19.”

“Likewise, patients with CLL may develop persistent COVID-19 infection,” they added, explaining that “prolonged shedding of infectious SARS-CoV-2 virus and within-host genomic evolution may eventually lead to emergence of new virus variants.”

Given the high risk of severe COVID-19 disease and impaired antibody-mediated immune response to the virus and its vaccine, a booster dose may be warranted in patients with CLL who fail to achieve seropositivity after 2 vaccine doses, they said.

The available data to date “call for early application of antiviral drugs, [monoclonal antibodies], and convalescent plasma as well as improved vaccination strategy, to improve the odds for patients with CLL confronting COVID-19,” they concluded, adding that large-scale prospective studies on the clinical disease course, outcomes, efficacy of treatments, and vaccination timing and schedule in patients with CLL and COVID-19 are still warranted.

The research was supported by a National Cancer Institute Cancer Center support grant. Dr. Roeker, Dr. Herishanu, and Dr. Perry reported having no financial disclosures.

Retrospective but the data also highlight areas for further investigation, according to the researchers.

Specifically, “the data highlight opportunities for further investigation into optimal management of COVID-19, immune response after infection, and effective vaccination strategy for patients with CLL,” Lindsey E. Roeker, MD, a hematologic oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and colleagues wrote in a Nov. 4, 2021, letter to the editor of Blood.

The researchers noted that recently reported COVID-19 case fatality rates from two large series of patients with CLL ranged from 31% to 33%, but trends over time were unclear.

“To understand change in outcomes over time, we present this follow-up study, which builds upon a previously reported cohort with extended follow up and addition of more recently diagnosed cases,” they wrote, explaining that “early data from a small series suggest that patients with CLL may not consistently generate anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies after infection.”

“This finding, along with previous reports of inadequate response to vaccines in patients with CLL, highlight significant questions regarding COVID-19 vaccine efficacy in this population,” they added.

Trends in outcomes

The review of outcomes in 374 CLL patients from 45 centers who were diagnosed with COVID-19 between Feb. 17, 2020, and Feb. 1, 2021, showed an overall case fatality rate (CFR) of 28%. Among the 278 patients (75%) admitted to the hospital, the CFR was 36%; among those not admitted, the CFR was 4.3%.

Independent predictors of poor survival were ages over 75 years (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.6) and Cumulative Illness Rating Scale–Geriatric (CIRS) scores greater than 6 (aHR, 1.6).

Updated data for 254 patients diagnosed from Feb. 17 to April 30, 2020, and 120 diagnosed from May 1, 2020, to Feb. 1, 2021, showed that more patients in the early versus later cohort were admitted to the hospital (85% vs. 55%) and more required ICU admission (32% vs. 11%).

The overall case fatality rates in the early and later cohorts were 35% and 11%, respectively (P < .001), and among those requiring hospitalization, the rates were 40% and 20% (P = .003).

“The proportion of hospitalized patients requiring ICU-level care was lower in the later cohort (37% vs. 29%), whereas the CFR remained high for the subset of patients who required ICU-level care (52% vs. 50%; P = .89),” the investigators wrote, noting that “[a] difference in management of BTKi[Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor]-treated patients was observed in the early versus the later cohort.”

“In the early cohort, 76% of patients receiving BTKi had their drug therapy suspended or discontinued. In the later cohort, only 20% of BTKi-treated patients had their therapy suspended or discontinued,” they added.

Univariate analyses showed significant associations between use of remdesivir and OS (HR, 0.48) and use of convalescent plasma and OS (HR, 0.50) in patients who were admitted, whereas admitted patients who received corticosteroids or hydroxychloroquine had an increased risk of death (HRs, 1.73 and 1.53, respectively).

“Corticosteroids were associated with increased risk of death when the data were adjusted for admission status (HR, 1.8) and the need for mechanical ventilation (HR, 2.0), although they were not significantly associated with survival when the data were adjusted for use of supplemental oxygen (HR, 1.4),” they wrote, also noting that admitted patients treated with corticosteroids in the later cohort did not experience an OS benefit (HR, 2.6).

The findings mirror population-based studies with decreasing CFR (35% in those diagnosed before May 1, 2020, versus 11% in those diagnosed after that date), they said, adding that “these trends suggest that patients in the later cohort experienced a less severe clinical course and that the observed difference in CFR over time may not just be due to more frequent testing and identification of less symptomatic patients.”

Of note, the outcomes observed for steroid-treated patients in the current cohort contrast with those from the RECOVERY trial as published in July 2020, which “may be an artifact of their use in patients with more severe disease,” they suggested.

They added that these data “are hypothesis generating and suggest that COVID-19 directed interventions, particularly immunomodulatory agents, require prospective study, specifically in immunocompromised populations.”

The investigators also noted that, consistent with a prior single-center study, 60% of patients with CLL developed positive anti–SARS-CoV-2 serology results after polymerase chain reaction diagnosis of COVID-19, adding further evidence of nonuniform antibody production after COVID-19 in patients with CLL.

Study is ongoing to gain understanding of the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with CLL, they said.

Changing the odds

In a related commentary also published in Blood, Yair Herishanu, MD, and Chava Perry, MD, PhD, of Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center called the reduction in mortality over time as reported by Dr. Roeker and colleagues “encouraging and intriguing.”

“One explanation is that the later cohort included a larger proportion of patients with mild symptoms who were diagnosed because of increased awareness of COVID-19 and more extensive screening to detect SARS-CoV-2 over time. That is supported by the lower hospitalization rates and lower rates of hospitalized patients requiring ICU care in the later cohort,” they wrote. “Another possibility is better patient management owing to increasing experience, expanding therapeutic options, and improved capacity of health systems to manage an influx of patients.”

The lower mortality in hospitalized patients over time may reflect better management of patients over time, but it also highlights the significance of “early introduction of various anti–COVID-19 therapies to prevent clinical deterioration to ICU-level care,” they added.

Also intriguing, according to Dr. Herishanu and Dr. Perry, was the finding of increased secondary infections and death rates among corticosteroid-treatment patients.

In the RECOVERY trial, the use of dexamethasone improved survival in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 who received respiratory support. Perhaps the impaired immune reactions in patients with CLL moderate the hyperinflammatory reactions to COVID-19, thus turning corticosteroids beneficial effects to somewhat redundant in this frail population,” they wrote.

Further, the finding that only 60% of patients with CLL seroconvert after the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection suggests CLL patients may be at risk for reinfection, which “justifies vaccinating all patients with CLL who have recovered from COVID-19.”

“Likewise, patients with CLL may develop persistent COVID-19 infection,” they added, explaining that “prolonged shedding of infectious SARS-CoV-2 virus and within-host genomic evolution may eventually lead to emergence of new virus variants.”

Given the high risk of severe COVID-19 disease and impaired antibody-mediated immune response to the virus and its vaccine, a booster dose may be warranted in patients with CLL who fail to achieve seropositivity after 2 vaccine doses, they said.

The available data to date “call for early application of antiviral drugs, [monoclonal antibodies], and convalescent plasma as well as improved vaccination strategy, to improve the odds for patients with CLL confronting COVID-19,” they concluded, adding that large-scale prospective studies on the clinical disease course, outcomes, efficacy of treatments, and vaccination timing and schedule in patients with CLL and COVID-19 are still warranted.

The research was supported by a National Cancer Institute Cancer Center support grant. Dr. Roeker, Dr. Herishanu, and Dr. Perry reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM BLOOD

Intent to vaccinate kids against COVID higher among vaccinated parents

“Parental vaccine hesitancy is a major issue for schools resuming in-person instruction, potentially requiring regular testing, strict mask wearing, and physical distancing for safe operation,” wrote lead author Madhura S. Rane, PhD, from the City University of New York in New York City, and colleagues in their paper, published online in JAMA Pediatrics.

The survey was conducted in June 2021 of 1,162 parents with children ranging in age from 2 to 17 years. The majority of parents (74.4%) were already vaccinated/vaccine-willing ,while 25.6% were vaccine hesitant. The study cohort, including both 1,652 children and their parents, was part of the nationwide CHASING COVID.

Vaccinated parents overall were more willing to vaccinate or had already vaccinated their eligible children when compared with vaccine-hesitant parents: 64.9% vs. 8.3% for children 2-4 years of age; 77.6% vs. 12.1% for children 5-11 years of age; 81.3% vs. 13.9% for children 12-15 years of age; and 86.4% vs. 12.7% for children 16-17 years of age; P < .001.