User login

Differences in COVID-19 Outcomes Among Patients With Type 1 Diabetes: First vs Later Surges

From Hassenfeld Children’s Hospital at NYU Langone Health, New York, NY (Dr Gallagher), T1D Exchange, Boston, MA (Saketh Rompicherla; Drs Ebekozien, Noor, Odugbesan, and Mungmode; Nicole Rioles, Emma Ospelt), University of Mississippi School of Population Health, Jackson, MS (Dr. Ebekozien), Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY (Drs. Wilkes, O’Malley, and Rapaport), Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY (Drs. Antal and Feuer), NYU Long Island School of Medicine, Mineola, NY (Dr. Gabriel), NYU Langone Health, New York, NY (Dr. Golden), Barbara Davis Center, Aurora, CO (Dr. Alonso), Texas Children’s Hospital/Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX (Dr. Lyons), Stanford University, Stanford, CA (Dr. Prahalad), Children Mercy Kansas City, MO (Dr. Clements), Indiana University School of Medicine, IN (Dr. Neyman), Rady Children’s Hospital, University of California, San Diego, CA (Dr. Demeterco-Berggren).

Background: Patient outcomes of COVID-19 have improved throughout the pandemic. However, because it is not known whether outcomes of COVID-19 in the type 1 diabetes (T1D) population improved over time, we investigated differences in COVID-19 outcomes for patients with T1D in the United States.

Methods: We analyzed data collected via a registry of patients with T1D and COVID-19 from 56 sites between April 2020 and January 2021. We grouped cases into first surge (April 9, 2020, to July 31, 2020, n = 188) and late surge (August 1, 2020, to January 31, 2021, n = 410), and then compared outcomes between both groups using descriptive statistics and logistic regression models.

Results: Adverse outcomes were more frequent during the first surge, including diabetic ketoacidosis (32% vs 15%, P < .001), severe hypoglycemia (4% vs 1%, P = .04), and hospitalization (52% vs 22%, P < .001). Patients in the first surge were older (28 [SD,18.8] years vs 18.0 [SD, 11.1] years, P < .001), had higher median hemoglobin A1c levels (9.3 [interquartile range {IQR}, 4.0] vs 8.4 (IQR, 2.8), P < .001), and were more likely to use public insurance (107 [57%] vs 154 [38%], P < .001). The odds of hospitalization for adults in the first surge were 5 times higher compared to the late surge (odds ratio, 5.01; 95% CI, 2.11-12.63).

Conclusion: Patients with T1D who presented with COVID-19 during the first surge had a higher proportion of adverse outcomes than those who presented in a later surge.

Keywords: TD1, diabetic ketoacidosis, hypoglycemia.

After the World Health Organization declared the disease caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, a pandemic on March 11, 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention identified patients with diabetes as high risk for severe illness.1-7 The case-fatality rate for COVID-19 has significantly improved over the past 2 years. Public health measures, less severe COVID-19 variants, increased access to testing, and new treatments for COVID-19 have contributed to improved outcomes.

The T1D Exchange has previously published findings on COVID-19 outcomes for patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D) using data from the T1D COVID-19 Surveillance Registry.8-12 Given improved outcomes in COVID-19 in the general population, we sought to determine if outcomes for cases of COVID-19 reported to this registry changed over time.

Methods

This study was coordinated by the T1D Exchange and approved as nonhuman subject research by the Western Institutional Review Board. All participating centers also obtained local institutional review board approval. No identifiable patient information was collected as part of this noninterventional, cross-sectional study.

The T1D Exchange Multi-center COVID-19 Surveillance Study collected data from endocrinology clinics that completed a retrospective chart review and submitted information to T1D Exchange via an online questionnaire for all patients with T1D at their sites who tested positive for COVID-19.13,14 The questionnaire was administered using the Qualtrics survey platform (www.qualtrics.com version XM) and contained 33 pre-coded and free-text response fields to collect patient and clinical attributes.

Each participating center identified 1 team member for reporting to avoid duplicate case submission. Each submitted case was reviewed for potential errors and incomplete information. The coordinating center verified the number of cases per site for data quality assurance.

Quantitative data were represented as mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range). Categorical data were described as the number (percentage) of patients. Summary statistics, including frequency and percentage for categorical variables, were calculated for all patient-related and clinical characteristics. The date August 1, 2021, was selected as the end of the first surge based on a review of national COVID-19 surges.

We used the Fisher’s exact test to assess associations between hospitalization and demographics, HbA1c, diabetes duration, symptoms, and adverse outcomes. In addition, multivariate logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratios (OR). Logistic regression models were used to determine the association between time of surge and hospitalization separately for both the pediatric and adult populations. Each model was adjusted for potential sociodemographic confounders, specifically age, sex, race, insurance, and HbA1c.

All tests were 2-sided, with type 1 error set at 5%. Fisher’s exact test and logistic regression were performed using statistical software R, version 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

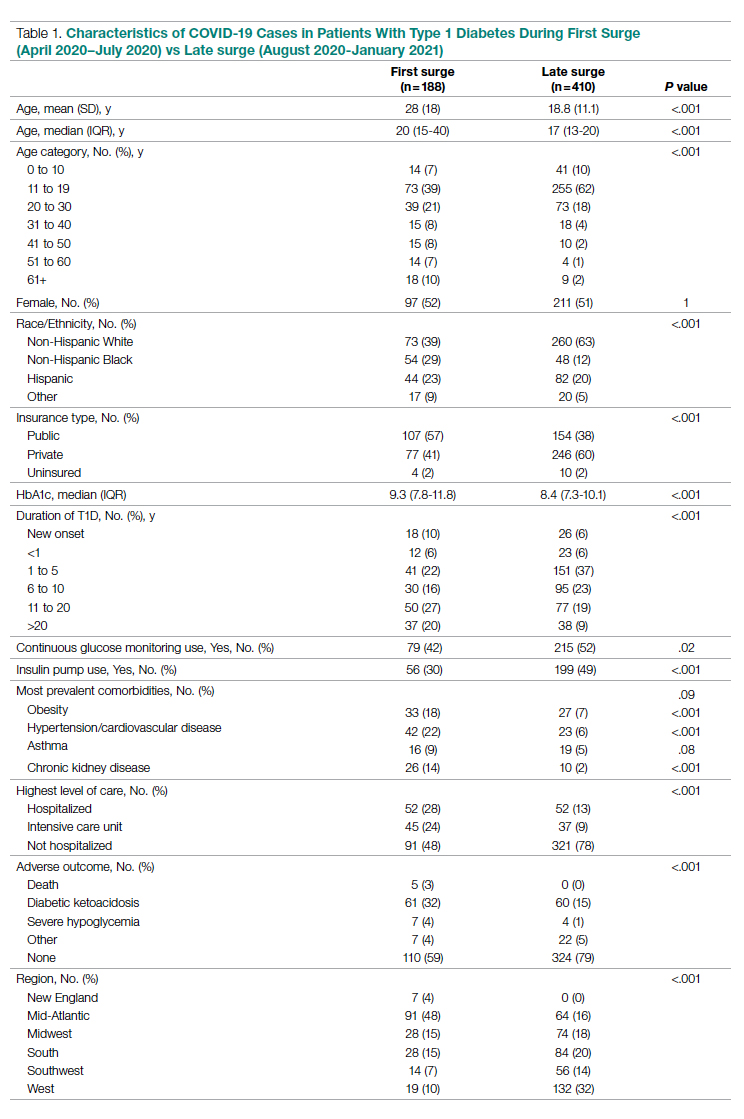

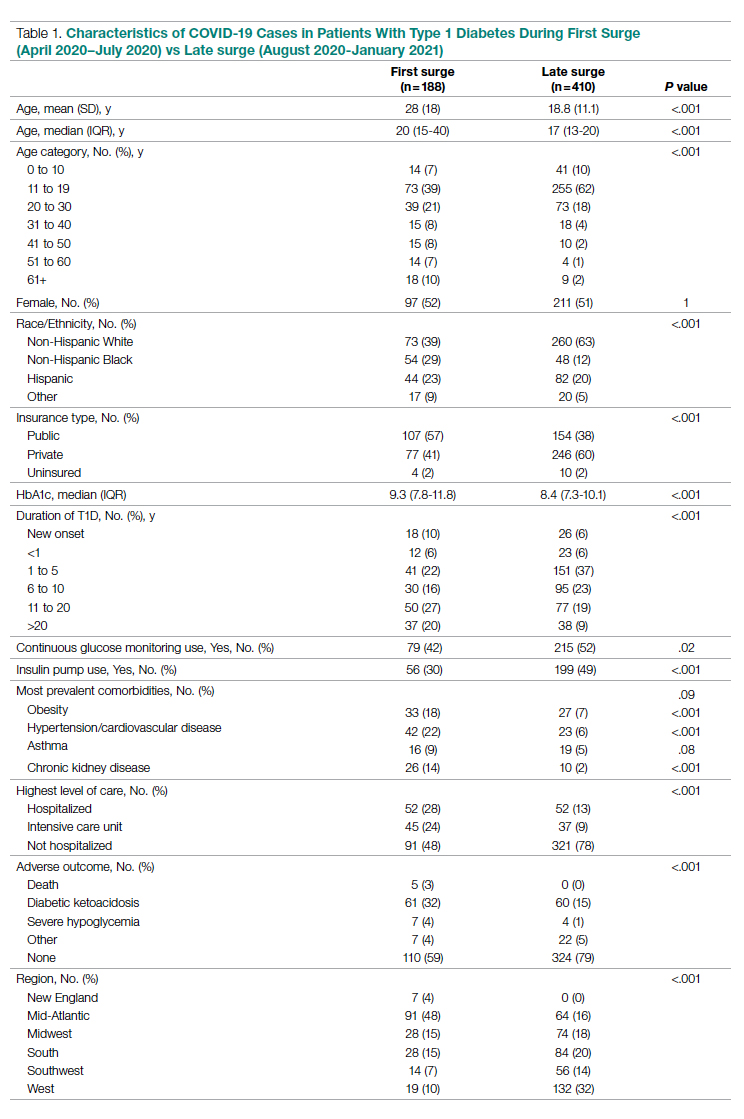

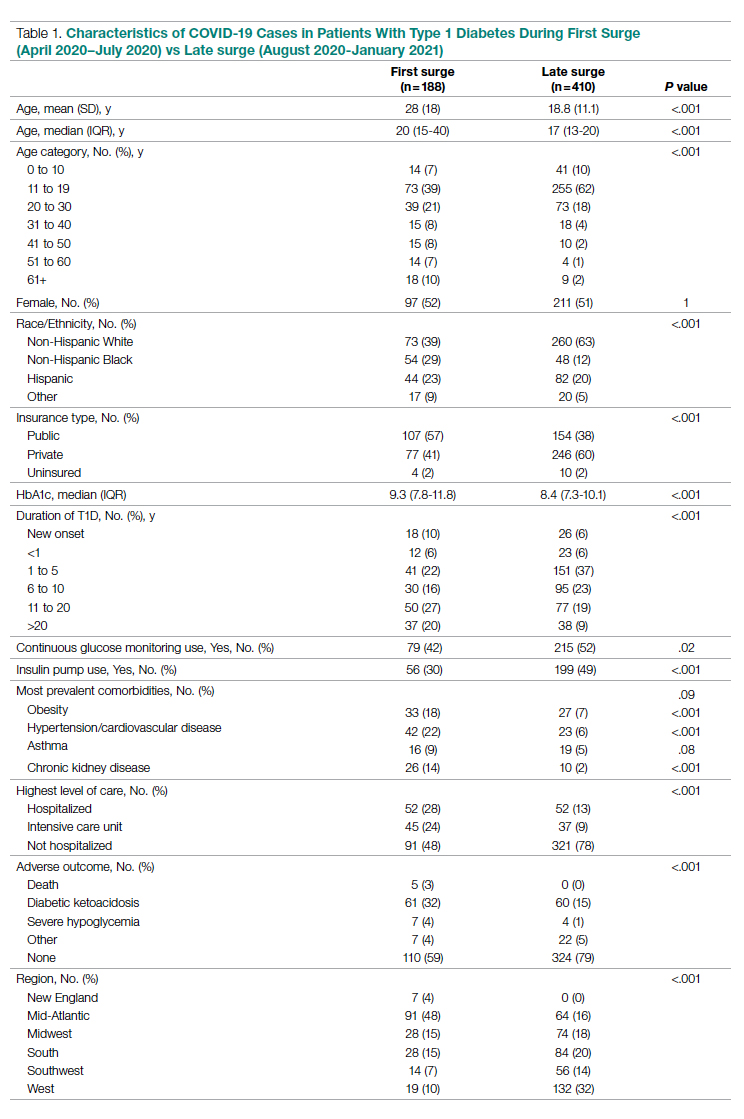

The characteristics of COVID-19 cases in patients with T1D that were reported early in the pandemic, before August 1, 2020 (first surge), compared with those of cases reported on and after August 1, 2020 (later surges) are shown in Table 1.

Patients with T1D who presented with COVID-19 during the first surge as compared to the later surges were older (mean age 28 [SD, 18.0] years vs 18.8 [SD, 11.1] years; P < .001) and had a longer duration of diabetes (P < .001). The first-surge group also had more patients with >20 years’ diabetes duration (20% vs 9%, P < .001). Obesity, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease were also more commonly reported in first-surge cases (all P < .001).

There was a significant difference in race and ethnicity reported in the first surge vs the later surge cases, with fewer patients identifying as non-Hispanic White (39% vs, 63%, P < .001) and more patients identifying as non-Hispanic Black (29% vs 12%, P < .001). The groups also differed significantly in terms of insurance type, with more people on public insurance in the first-surge group (57% vs 38%, P < .001). In addition, median HbA1c was higher (9.3% vs 8.4%, P < .001) and continuous glucose monitor and insulin pump use were less common (P = .02 and <.001, respectively) in the early surge.

All symptoms and adverse outcomes were reported more often in the first surge, including diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA; 32% vs 15%; P < .001) and severe hypoglycemia (4% vs 1%, P = .04). Hospitalization (52% vs 13%, P < .001) and ICU admission (24% vs 9%, P < .001) were reported more often in the first-surge group.

Regression Analyses

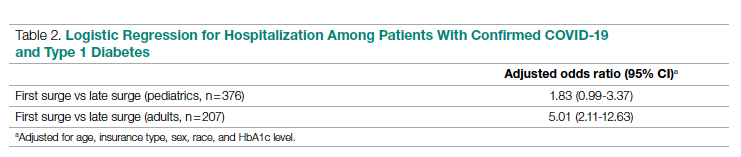

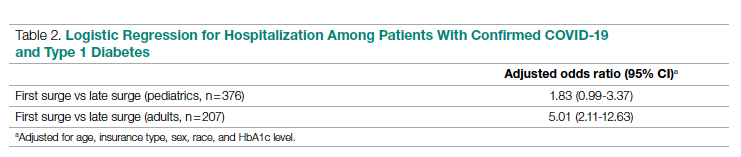

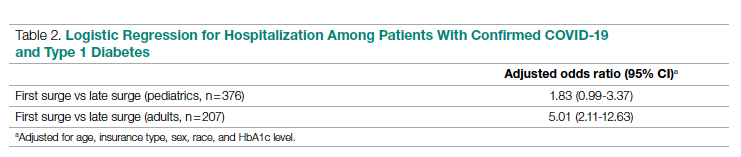

Table 2 shows the results of logistic regression analyses for hospitalization in the pediatric (≤19 years of age) and adult (>19 years of age) groups, along with the odds of hospitalization during the first vs late surge among COVID-positive people with T1D. Adult patients who tested positive in the first surge were about 5 times more likely to be hospitalized than adults who tested positive for infection in the late surge after adjusting for age, insurance type, sex, race, and HbA1c levels. Pediatric patients also had an increased odds for hospitalization during the first surge, but this increase was not statistically significant.

Discussion

Our analysis of COVID-19 cases in patients with T1D reported by diabetes providers across the United States found that adverse outcomes were more prevalent early in the pandemic. There may be a number of reasons for this difference in outcomes between patients who presented in the first surge vs a later surge. First, because testing for COVID-19 was extremely limited and reserved for hospitalized patients early in the pandemic, the first-surge patients with confirmed COVID-19 likely represent a skewed population of higher-acuity patients. This may also explain the relative paucity of cases in younger patients reported early in the pandemic. Second, worse outcomes in the early surge may also have been associated with overwhelmed hospitals in New York City at the start of the outbreak. According to Cummings et al, the abrupt surge of critically ill patients hospitalized with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome initially outpaced their capacity to provide prone-positioning ventilation, which has been expanded since then.15 While there was very little hypertension, cardiovascular disease, or kidney disease reported in the pediatric groups, there was a higher prevalence of obesity in the pediatric group from the mid-Atlantic region. Obesity has been associated with a worse prognosis for COVID-19 illness in children.16 Finally, there were 5 deaths reported in this study, all of which were reported during the first surge. Older age and increased rates of cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease in the first surge cases likely contributed to worse outcomes for adults in mid-Atlantic region relative to the other regions. Minority race and the use of public insurance, risk factors for more severe outcomes in all regions, were also more common in cases reported from the mid-Atlantic region.

This study has several limitations. First, it is a cross-sectional study that relies upon voluntary provider reports. Second, availability of COVID-19 testing was limited in all regions in spring 2020. Third, different regions of the country experienced subsequent surges at different times within the reported timeframes in this analysis. Fourth, this report time period does not include the impact of the newer COVID-19 variants. Finally, trends in COVID-19 outcomes were affected by the evolution of care that developed throughout 2020.

Conclusion

Adult patients with T1D and COVID-19 who reported during the first surge had about 5 times higher hospitalization odds than those who presented in a later surge.

Corresponding author: Osagie Ebekozien, MD, MPH, 11 Avenue de Lafayette, Boston, MA 02111; [email protected]

Disclosures: Dr Ebekozien reports receiving research grants from Medtronic Diabetes, Eli Lilly, and Dexcom, and receiving honoraria from Medtronic Diabetes.

1. Barron E, Bakhai C, Kar P, et al. Associations of type 1 and type 2 diabetes with COVID-19-related mortality in England: a whole-population study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(10):813-822. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30272-2

2. Fisher L, Polonsky W, Asuni A, Jolly Y, Hessler D. The early impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes: A national cohort study. J Diabetes Complications. 2020;34(12):107748. doi:10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2020.107748

3. Holman N, Knighton P, Kar P, et al. Risk factors for COVID-19-related mortality in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes in England: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(10):823-833. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30271-0

4. Wargny M, Gourdy P, Ludwig L, et al. Type 1 diabetes in people hospitalized for COVID-19: new insights from the CORONADO study. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(11):e174-e177. doi:10.2337/dc20-1217

5. Gregory JM, Slaughter JC, Duffus SH, et al. COVID-19 severity is tripled in the diabetes community: a prospective analysis of the pandemic’s impact in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(2):526-532. doi:10.2337/dc20-2260

6. Cardona-Hernandez R, Cherubini V, Iafusco D, Schiaffini R, Luo X, Maahs DM. Children and youth with diabetes are not at increased risk for hospitalization due to COVID-19. Pediatr Diabetes. 2021;22(2):202-206. doi:10.1111/pedi.13158

7. Maahs DM, Alonso GT, Gallagher MP, Ebekozien O. Comment on Gregory et al. COVID-19 severity is tripled in the diabetes community: a prospective analysis of the pandemic’s impact in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:526-532. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(5):e102. doi:10.2337/dc20-3119

8. Ebekozien OA, Noor N, Gallagher MP, Alonso GT. Type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: preliminary findings from a multicenter surveillance study in the US. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(8):e83-e85. doi:10.2337/dc20-1088

9. Beliard K, Ebekozien O, Demeterco-Berggren C, et al. Increased DKA at presentation among newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes patients with or without COVID-19: Data from a multi-site surveillance registry. J Diabetes. 2021;13(3):270-272. doi:10.1111/1753-0407

10. O’Malley G, Ebekozien O, Desimone M, et al. COVID-19 hospitalization in adults with type 1 diabetes: results from the T1D Exchange Multicenter Surveillance study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(2):e936-e942. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgaa825

11. Ebekozien O, Agarwal S, Noor N, et al. Inequities in diabetic ketoacidosis among patients with type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: data from 52 US clinical centers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(4):e1755-e1762. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgaa920

12. Alonso GT, Ebekozien O, Gallagher MP, et al. Diabetic ketoacidosis drives COVID-19 related hospitalizations in children with type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes. 2021;13(8):681-687. doi:10.1111/1753-0407.13184

13. Noor N, Ebekozien O, Levin L, et al. Diabetes technology use for management of type 1 diabetes is associated with fewer adverse COVID-19 outcomes: findings from the T1D Exchange COVID-19 Surveillance Registry. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(8):e160-e162. doi:10.2337/dc21-0074

14. Demeterco-Berggren C, Ebekozien O, Rompicherla S, et al. Age and hospitalization risk in people with type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: Data from the T1D Exchange Surveillance Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;dgab668. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgab668

15. Cummings MJ, Baldwin MR, Abrams D, et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10239):1763-1770. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31189-2

16. Tsankov BK, Allaire JM, Irvine MA, et al. Severe COVID-19 infection and pediatric comorbidities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;103:246-256. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.11.163

From Hassenfeld Children’s Hospital at NYU Langone Health, New York, NY (Dr Gallagher), T1D Exchange, Boston, MA (Saketh Rompicherla; Drs Ebekozien, Noor, Odugbesan, and Mungmode; Nicole Rioles, Emma Ospelt), University of Mississippi School of Population Health, Jackson, MS (Dr. Ebekozien), Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY (Drs. Wilkes, O’Malley, and Rapaport), Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY (Drs. Antal and Feuer), NYU Long Island School of Medicine, Mineola, NY (Dr. Gabriel), NYU Langone Health, New York, NY (Dr. Golden), Barbara Davis Center, Aurora, CO (Dr. Alonso), Texas Children’s Hospital/Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX (Dr. Lyons), Stanford University, Stanford, CA (Dr. Prahalad), Children Mercy Kansas City, MO (Dr. Clements), Indiana University School of Medicine, IN (Dr. Neyman), Rady Children’s Hospital, University of California, San Diego, CA (Dr. Demeterco-Berggren).

Background: Patient outcomes of COVID-19 have improved throughout the pandemic. However, because it is not known whether outcomes of COVID-19 in the type 1 diabetes (T1D) population improved over time, we investigated differences in COVID-19 outcomes for patients with T1D in the United States.

Methods: We analyzed data collected via a registry of patients with T1D and COVID-19 from 56 sites between April 2020 and January 2021. We grouped cases into first surge (April 9, 2020, to July 31, 2020, n = 188) and late surge (August 1, 2020, to January 31, 2021, n = 410), and then compared outcomes between both groups using descriptive statistics and logistic regression models.

Results: Adverse outcomes were more frequent during the first surge, including diabetic ketoacidosis (32% vs 15%, P < .001), severe hypoglycemia (4% vs 1%, P = .04), and hospitalization (52% vs 22%, P < .001). Patients in the first surge were older (28 [SD,18.8] years vs 18.0 [SD, 11.1] years, P < .001), had higher median hemoglobin A1c levels (9.3 [interquartile range {IQR}, 4.0] vs 8.4 (IQR, 2.8), P < .001), and were more likely to use public insurance (107 [57%] vs 154 [38%], P < .001). The odds of hospitalization for adults in the first surge were 5 times higher compared to the late surge (odds ratio, 5.01; 95% CI, 2.11-12.63).

Conclusion: Patients with T1D who presented with COVID-19 during the first surge had a higher proportion of adverse outcomes than those who presented in a later surge.

Keywords: TD1, diabetic ketoacidosis, hypoglycemia.

After the World Health Organization declared the disease caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, a pandemic on March 11, 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention identified patients with diabetes as high risk for severe illness.1-7 The case-fatality rate for COVID-19 has significantly improved over the past 2 years. Public health measures, less severe COVID-19 variants, increased access to testing, and new treatments for COVID-19 have contributed to improved outcomes.

The T1D Exchange has previously published findings on COVID-19 outcomes for patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D) using data from the T1D COVID-19 Surveillance Registry.8-12 Given improved outcomes in COVID-19 in the general population, we sought to determine if outcomes for cases of COVID-19 reported to this registry changed over time.

Methods

This study was coordinated by the T1D Exchange and approved as nonhuman subject research by the Western Institutional Review Board. All participating centers also obtained local institutional review board approval. No identifiable patient information was collected as part of this noninterventional, cross-sectional study.

The T1D Exchange Multi-center COVID-19 Surveillance Study collected data from endocrinology clinics that completed a retrospective chart review and submitted information to T1D Exchange via an online questionnaire for all patients with T1D at their sites who tested positive for COVID-19.13,14 The questionnaire was administered using the Qualtrics survey platform (www.qualtrics.com version XM) and contained 33 pre-coded and free-text response fields to collect patient and clinical attributes.

Each participating center identified 1 team member for reporting to avoid duplicate case submission. Each submitted case was reviewed for potential errors and incomplete information. The coordinating center verified the number of cases per site for data quality assurance.

Quantitative data were represented as mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range). Categorical data were described as the number (percentage) of patients. Summary statistics, including frequency and percentage for categorical variables, were calculated for all patient-related and clinical characteristics. The date August 1, 2021, was selected as the end of the first surge based on a review of national COVID-19 surges.

We used the Fisher’s exact test to assess associations between hospitalization and demographics, HbA1c, diabetes duration, symptoms, and adverse outcomes. In addition, multivariate logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratios (OR). Logistic regression models were used to determine the association between time of surge and hospitalization separately for both the pediatric and adult populations. Each model was adjusted for potential sociodemographic confounders, specifically age, sex, race, insurance, and HbA1c.

All tests were 2-sided, with type 1 error set at 5%. Fisher’s exact test and logistic regression were performed using statistical software R, version 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

The characteristics of COVID-19 cases in patients with T1D that were reported early in the pandemic, before August 1, 2020 (first surge), compared with those of cases reported on and after August 1, 2020 (later surges) are shown in Table 1.

Patients with T1D who presented with COVID-19 during the first surge as compared to the later surges were older (mean age 28 [SD, 18.0] years vs 18.8 [SD, 11.1] years; P < .001) and had a longer duration of diabetes (P < .001). The first-surge group also had more patients with >20 years’ diabetes duration (20% vs 9%, P < .001). Obesity, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease were also more commonly reported in first-surge cases (all P < .001).

There was a significant difference in race and ethnicity reported in the first surge vs the later surge cases, with fewer patients identifying as non-Hispanic White (39% vs, 63%, P < .001) and more patients identifying as non-Hispanic Black (29% vs 12%, P < .001). The groups also differed significantly in terms of insurance type, with more people on public insurance in the first-surge group (57% vs 38%, P < .001). In addition, median HbA1c was higher (9.3% vs 8.4%, P < .001) and continuous glucose monitor and insulin pump use were less common (P = .02 and <.001, respectively) in the early surge.

All symptoms and adverse outcomes were reported more often in the first surge, including diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA; 32% vs 15%; P < .001) and severe hypoglycemia (4% vs 1%, P = .04). Hospitalization (52% vs 13%, P < .001) and ICU admission (24% vs 9%, P < .001) were reported more often in the first-surge group.

Regression Analyses

Table 2 shows the results of logistic regression analyses for hospitalization in the pediatric (≤19 years of age) and adult (>19 years of age) groups, along with the odds of hospitalization during the first vs late surge among COVID-positive people with T1D. Adult patients who tested positive in the first surge were about 5 times more likely to be hospitalized than adults who tested positive for infection in the late surge after adjusting for age, insurance type, sex, race, and HbA1c levels. Pediatric patients also had an increased odds for hospitalization during the first surge, but this increase was not statistically significant.

Discussion

Our analysis of COVID-19 cases in patients with T1D reported by diabetes providers across the United States found that adverse outcomes were more prevalent early in the pandemic. There may be a number of reasons for this difference in outcomes between patients who presented in the first surge vs a later surge. First, because testing for COVID-19 was extremely limited and reserved for hospitalized patients early in the pandemic, the first-surge patients with confirmed COVID-19 likely represent a skewed population of higher-acuity patients. This may also explain the relative paucity of cases in younger patients reported early in the pandemic. Second, worse outcomes in the early surge may also have been associated with overwhelmed hospitals in New York City at the start of the outbreak. According to Cummings et al, the abrupt surge of critically ill patients hospitalized with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome initially outpaced their capacity to provide prone-positioning ventilation, which has been expanded since then.15 While there was very little hypertension, cardiovascular disease, or kidney disease reported in the pediatric groups, there was a higher prevalence of obesity in the pediatric group from the mid-Atlantic region. Obesity has been associated with a worse prognosis for COVID-19 illness in children.16 Finally, there were 5 deaths reported in this study, all of which were reported during the first surge. Older age and increased rates of cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease in the first surge cases likely contributed to worse outcomes for adults in mid-Atlantic region relative to the other regions. Minority race and the use of public insurance, risk factors for more severe outcomes in all regions, were also more common in cases reported from the mid-Atlantic region.

This study has several limitations. First, it is a cross-sectional study that relies upon voluntary provider reports. Second, availability of COVID-19 testing was limited in all regions in spring 2020. Third, different regions of the country experienced subsequent surges at different times within the reported timeframes in this analysis. Fourth, this report time period does not include the impact of the newer COVID-19 variants. Finally, trends in COVID-19 outcomes were affected by the evolution of care that developed throughout 2020.

Conclusion

Adult patients with T1D and COVID-19 who reported during the first surge had about 5 times higher hospitalization odds than those who presented in a later surge.

Corresponding author: Osagie Ebekozien, MD, MPH, 11 Avenue de Lafayette, Boston, MA 02111; [email protected]

Disclosures: Dr Ebekozien reports receiving research grants from Medtronic Diabetes, Eli Lilly, and Dexcom, and receiving honoraria from Medtronic Diabetes.

From Hassenfeld Children’s Hospital at NYU Langone Health, New York, NY (Dr Gallagher), T1D Exchange, Boston, MA (Saketh Rompicherla; Drs Ebekozien, Noor, Odugbesan, and Mungmode; Nicole Rioles, Emma Ospelt), University of Mississippi School of Population Health, Jackson, MS (Dr. Ebekozien), Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY (Drs. Wilkes, O’Malley, and Rapaport), Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY (Drs. Antal and Feuer), NYU Long Island School of Medicine, Mineola, NY (Dr. Gabriel), NYU Langone Health, New York, NY (Dr. Golden), Barbara Davis Center, Aurora, CO (Dr. Alonso), Texas Children’s Hospital/Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX (Dr. Lyons), Stanford University, Stanford, CA (Dr. Prahalad), Children Mercy Kansas City, MO (Dr. Clements), Indiana University School of Medicine, IN (Dr. Neyman), Rady Children’s Hospital, University of California, San Diego, CA (Dr. Demeterco-Berggren).

Background: Patient outcomes of COVID-19 have improved throughout the pandemic. However, because it is not known whether outcomes of COVID-19 in the type 1 diabetes (T1D) population improved over time, we investigated differences in COVID-19 outcomes for patients with T1D in the United States.

Methods: We analyzed data collected via a registry of patients with T1D and COVID-19 from 56 sites between April 2020 and January 2021. We grouped cases into first surge (April 9, 2020, to July 31, 2020, n = 188) and late surge (August 1, 2020, to January 31, 2021, n = 410), and then compared outcomes between both groups using descriptive statistics and logistic regression models.

Results: Adverse outcomes were more frequent during the first surge, including diabetic ketoacidosis (32% vs 15%, P < .001), severe hypoglycemia (4% vs 1%, P = .04), and hospitalization (52% vs 22%, P < .001). Patients in the first surge were older (28 [SD,18.8] years vs 18.0 [SD, 11.1] years, P < .001), had higher median hemoglobin A1c levels (9.3 [interquartile range {IQR}, 4.0] vs 8.4 (IQR, 2.8), P < .001), and were more likely to use public insurance (107 [57%] vs 154 [38%], P < .001). The odds of hospitalization for adults in the first surge were 5 times higher compared to the late surge (odds ratio, 5.01; 95% CI, 2.11-12.63).

Conclusion: Patients with T1D who presented with COVID-19 during the first surge had a higher proportion of adverse outcomes than those who presented in a later surge.

Keywords: TD1, diabetic ketoacidosis, hypoglycemia.

After the World Health Organization declared the disease caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, a pandemic on March 11, 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention identified patients with diabetes as high risk for severe illness.1-7 The case-fatality rate for COVID-19 has significantly improved over the past 2 years. Public health measures, less severe COVID-19 variants, increased access to testing, and new treatments for COVID-19 have contributed to improved outcomes.

The T1D Exchange has previously published findings on COVID-19 outcomes for patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D) using data from the T1D COVID-19 Surveillance Registry.8-12 Given improved outcomes in COVID-19 in the general population, we sought to determine if outcomes for cases of COVID-19 reported to this registry changed over time.

Methods

This study was coordinated by the T1D Exchange and approved as nonhuman subject research by the Western Institutional Review Board. All participating centers also obtained local institutional review board approval. No identifiable patient information was collected as part of this noninterventional, cross-sectional study.

The T1D Exchange Multi-center COVID-19 Surveillance Study collected data from endocrinology clinics that completed a retrospective chart review and submitted information to T1D Exchange via an online questionnaire for all patients with T1D at their sites who tested positive for COVID-19.13,14 The questionnaire was administered using the Qualtrics survey platform (www.qualtrics.com version XM) and contained 33 pre-coded and free-text response fields to collect patient and clinical attributes.

Each participating center identified 1 team member for reporting to avoid duplicate case submission. Each submitted case was reviewed for potential errors and incomplete information. The coordinating center verified the number of cases per site for data quality assurance.

Quantitative data were represented as mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range). Categorical data were described as the number (percentage) of patients. Summary statistics, including frequency and percentage for categorical variables, were calculated for all patient-related and clinical characteristics. The date August 1, 2021, was selected as the end of the first surge based on a review of national COVID-19 surges.

We used the Fisher’s exact test to assess associations between hospitalization and demographics, HbA1c, diabetes duration, symptoms, and adverse outcomes. In addition, multivariate logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratios (OR). Logistic regression models were used to determine the association between time of surge and hospitalization separately for both the pediatric and adult populations. Each model was adjusted for potential sociodemographic confounders, specifically age, sex, race, insurance, and HbA1c.

All tests were 2-sided, with type 1 error set at 5%. Fisher’s exact test and logistic regression were performed using statistical software R, version 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

The characteristics of COVID-19 cases in patients with T1D that were reported early in the pandemic, before August 1, 2020 (first surge), compared with those of cases reported on and after August 1, 2020 (later surges) are shown in Table 1.

Patients with T1D who presented with COVID-19 during the first surge as compared to the later surges were older (mean age 28 [SD, 18.0] years vs 18.8 [SD, 11.1] years; P < .001) and had a longer duration of diabetes (P < .001). The first-surge group also had more patients with >20 years’ diabetes duration (20% vs 9%, P < .001). Obesity, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease were also more commonly reported in first-surge cases (all P < .001).

There was a significant difference in race and ethnicity reported in the first surge vs the later surge cases, with fewer patients identifying as non-Hispanic White (39% vs, 63%, P < .001) and more patients identifying as non-Hispanic Black (29% vs 12%, P < .001). The groups also differed significantly in terms of insurance type, with more people on public insurance in the first-surge group (57% vs 38%, P < .001). In addition, median HbA1c was higher (9.3% vs 8.4%, P < .001) and continuous glucose monitor and insulin pump use were less common (P = .02 and <.001, respectively) in the early surge.

All symptoms and adverse outcomes were reported more often in the first surge, including diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA; 32% vs 15%; P < .001) and severe hypoglycemia (4% vs 1%, P = .04). Hospitalization (52% vs 13%, P < .001) and ICU admission (24% vs 9%, P < .001) were reported more often in the first-surge group.

Regression Analyses

Table 2 shows the results of logistic regression analyses for hospitalization in the pediatric (≤19 years of age) and adult (>19 years of age) groups, along with the odds of hospitalization during the first vs late surge among COVID-positive people with T1D. Adult patients who tested positive in the first surge were about 5 times more likely to be hospitalized than adults who tested positive for infection in the late surge after adjusting for age, insurance type, sex, race, and HbA1c levels. Pediatric patients also had an increased odds for hospitalization during the first surge, but this increase was not statistically significant.

Discussion

Our analysis of COVID-19 cases in patients with T1D reported by diabetes providers across the United States found that adverse outcomes were more prevalent early in the pandemic. There may be a number of reasons for this difference in outcomes between patients who presented in the first surge vs a later surge. First, because testing for COVID-19 was extremely limited and reserved for hospitalized patients early in the pandemic, the first-surge patients with confirmed COVID-19 likely represent a skewed population of higher-acuity patients. This may also explain the relative paucity of cases in younger patients reported early in the pandemic. Second, worse outcomes in the early surge may also have been associated with overwhelmed hospitals in New York City at the start of the outbreak. According to Cummings et al, the abrupt surge of critically ill patients hospitalized with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome initially outpaced their capacity to provide prone-positioning ventilation, which has been expanded since then.15 While there was very little hypertension, cardiovascular disease, or kidney disease reported in the pediatric groups, there was a higher prevalence of obesity in the pediatric group from the mid-Atlantic region. Obesity has been associated with a worse prognosis for COVID-19 illness in children.16 Finally, there were 5 deaths reported in this study, all of which were reported during the first surge. Older age and increased rates of cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease in the first surge cases likely contributed to worse outcomes for adults in mid-Atlantic region relative to the other regions. Minority race and the use of public insurance, risk factors for more severe outcomes in all regions, were also more common in cases reported from the mid-Atlantic region.

This study has several limitations. First, it is a cross-sectional study that relies upon voluntary provider reports. Second, availability of COVID-19 testing was limited in all regions in spring 2020. Third, different regions of the country experienced subsequent surges at different times within the reported timeframes in this analysis. Fourth, this report time period does not include the impact of the newer COVID-19 variants. Finally, trends in COVID-19 outcomes were affected by the evolution of care that developed throughout 2020.

Conclusion

Adult patients with T1D and COVID-19 who reported during the first surge had about 5 times higher hospitalization odds than those who presented in a later surge.

Corresponding author: Osagie Ebekozien, MD, MPH, 11 Avenue de Lafayette, Boston, MA 02111; [email protected]

Disclosures: Dr Ebekozien reports receiving research grants from Medtronic Diabetes, Eli Lilly, and Dexcom, and receiving honoraria from Medtronic Diabetes.

1. Barron E, Bakhai C, Kar P, et al. Associations of type 1 and type 2 diabetes with COVID-19-related mortality in England: a whole-population study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(10):813-822. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30272-2

2. Fisher L, Polonsky W, Asuni A, Jolly Y, Hessler D. The early impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes: A national cohort study. J Diabetes Complications. 2020;34(12):107748. doi:10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2020.107748

3. Holman N, Knighton P, Kar P, et al. Risk factors for COVID-19-related mortality in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes in England: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(10):823-833. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30271-0

4. Wargny M, Gourdy P, Ludwig L, et al. Type 1 diabetes in people hospitalized for COVID-19: new insights from the CORONADO study. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(11):e174-e177. doi:10.2337/dc20-1217

5. Gregory JM, Slaughter JC, Duffus SH, et al. COVID-19 severity is tripled in the diabetes community: a prospective analysis of the pandemic’s impact in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(2):526-532. doi:10.2337/dc20-2260

6. Cardona-Hernandez R, Cherubini V, Iafusco D, Schiaffini R, Luo X, Maahs DM. Children and youth with diabetes are not at increased risk for hospitalization due to COVID-19. Pediatr Diabetes. 2021;22(2):202-206. doi:10.1111/pedi.13158

7. Maahs DM, Alonso GT, Gallagher MP, Ebekozien O. Comment on Gregory et al. COVID-19 severity is tripled in the diabetes community: a prospective analysis of the pandemic’s impact in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:526-532. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(5):e102. doi:10.2337/dc20-3119

8. Ebekozien OA, Noor N, Gallagher MP, Alonso GT. Type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: preliminary findings from a multicenter surveillance study in the US. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(8):e83-e85. doi:10.2337/dc20-1088

9. Beliard K, Ebekozien O, Demeterco-Berggren C, et al. Increased DKA at presentation among newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes patients with or without COVID-19: Data from a multi-site surveillance registry. J Diabetes. 2021;13(3):270-272. doi:10.1111/1753-0407

10. O’Malley G, Ebekozien O, Desimone M, et al. COVID-19 hospitalization in adults with type 1 diabetes: results from the T1D Exchange Multicenter Surveillance study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(2):e936-e942. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgaa825

11. Ebekozien O, Agarwal S, Noor N, et al. Inequities in diabetic ketoacidosis among patients with type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: data from 52 US clinical centers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(4):e1755-e1762. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgaa920

12. Alonso GT, Ebekozien O, Gallagher MP, et al. Diabetic ketoacidosis drives COVID-19 related hospitalizations in children with type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes. 2021;13(8):681-687. doi:10.1111/1753-0407.13184

13. Noor N, Ebekozien O, Levin L, et al. Diabetes technology use for management of type 1 diabetes is associated with fewer adverse COVID-19 outcomes: findings from the T1D Exchange COVID-19 Surveillance Registry. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(8):e160-e162. doi:10.2337/dc21-0074

14. Demeterco-Berggren C, Ebekozien O, Rompicherla S, et al. Age and hospitalization risk in people with type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: Data from the T1D Exchange Surveillance Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;dgab668. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgab668

15. Cummings MJ, Baldwin MR, Abrams D, et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10239):1763-1770. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31189-2

16. Tsankov BK, Allaire JM, Irvine MA, et al. Severe COVID-19 infection and pediatric comorbidities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;103:246-256. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.11.163

1. Barron E, Bakhai C, Kar P, et al. Associations of type 1 and type 2 diabetes with COVID-19-related mortality in England: a whole-population study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(10):813-822. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30272-2

2. Fisher L, Polonsky W, Asuni A, Jolly Y, Hessler D. The early impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes: A national cohort study. J Diabetes Complications. 2020;34(12):107748. doi:10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2020.107748

3. Holman N, Knighton P, Kar P, et al. Risk factors for COVID-19-related mortality in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes in England: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(10):823-833. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30271-0

4. Wargny M, Gourdy P, Ludwig L, et al. Type 1 diabetes in people hospitalized for COVID-19: new insights from the CORONADO study. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(11):e174-e177. doi:10.2337/dc20-1217

5. Gregory JM, Slaughter JC, Duffus SH, et al. COVID-19 severity is tripled in the diabetes community: a prospective analysis of the pandemic’s impact in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(2):526-532. doi:10.2337/dc20-2260

6. Cardona-Hernandez R, Cherubini V, Iafusco D, Schiaffini R, Luo X, Maahs DM. Children and youth with diabetes are not at increased risk for hospitalization due to COVID-19. Pediatr Diabetes. 2021;22(2):202-206. doi:10.1111/pedi.13158

7. Maahs DM, Alonso GT, Gallagher MP, Ebekozien O. Comment on Gregory et al. COVID-19 severity is tripled in the diabetes community: a prospective analysis of the pandemic’s impact in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:526-532. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(5):e102. doi:10.2337/dc20-3119

8. Ebekozien OA, Noor N, Gallagher MP, Alonso GT. Type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: preliminary findings from a multicenter surveillance study in the US. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(8):e83-e85. doi:10.2337/dc20-1088

9. Beliard K, Ebekozien O, Demeterco-Berggren C, et al. Increased DKA at presentation among newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes patients with or without COVID-19: Data from a multi-site surveillance registry. J Diabetes. 2021;13(3):270-272. doi:10.1111/1753-0407

10. O’Malley G, Ebekozien O, Desimone M, et al. COVID-19 hospitalization in adults with type 1 diabetes: results from the T1D Exchange Multicenter Surveillance study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(2):e936-e942. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgaa825

11. Ebekozien O, Agarwal S, Noor N, et al. Inequities in diabetic ketoacidosis among patients with type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: data from 52 US clinical centers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(4):e1755-e1762. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgaa920

12. Alonso GT, Ebekozien O, Gallagher MP, et al. Diabetic ketoacidosis drives COVID-19 related hospitalizations in children with type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes. 2021;13(8):681-687. doi:10.1111/1753-0407.13184

13. Noor N, Ebekozien O, Levin L, et al. Diabetes technology use for management of type 1 diabetes is associated with fewer adverse COVID-19 outcomes: findings from the T1D Exchange COVID-19 Surveillance Registry. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(8):e160-e162. doi:10.2337/dc21-0074

14. Demeterco-Berggren C, Ebekozien O, Rompicherla S, et al. Age and hospitalization risk in people with type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: Data from the T1D Exchange Surveillance Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;dgab668. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgab668

15. Cummings MJ, Baldwin MR, Abrams D, et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10239):1763-1770. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31189-2

16. Tsankov BK, Allaire JM, Irvine MA, et al. Severe COVID-19 infection and pediatric comorbidities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;103:246-256. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.11.163

Role and Experience of a Subintensive Care Unit in Caring for Patients With COVID-19 in Italy: The CO-RESP Study

From the Department of Emergency Medicine, Santa Croce e Carle Hospital, Cuneo, Italy (Drs. Abram, Tosello, Emanuele Bernardi, Allione, Cavalot, Dutto, Corsini, Martini, Sciolla, Sara Bernardi, and Lauria). From the School of Emergency Medicine, University of Turin, Turin, Italy (Drs. Paglietta and Giamello).

Objective: This retrospective and prospective cohort study was designed to describe the characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection (COVID-19) admitted to subintensive care units (SICU) and to identify the variables associated with outcomes. SICUs have been extremely stressed during the pandemic, but most data regarding critically ill COVID-19 patients come from intensive care units (ICUs). Studies about COVID-19 patients in SICUs are lacking.

Setting and participants: The study included 88 COVID-19 patients admitted to our SICU in Cuneo, Italy, between March and May 2020.

Measurements: Clinical and ventilatory data were collected, and patients were divided by outcome. Multivariable logistic regression analysis examined the variables associated with negative outcomes (transfer to the ICU, palliation, or death in a SICU).

Results: A total of 60 patients (68%) had a positive outcome, and 28 patients (32%) had a negative outcome; 69 patients (78%) underwent continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). Pronation (n = 37 [42%]) had been more frequently adopted in patients who had a positive outcome vs a negative outcome (n = 30 [50%] vs n = 7 [25%]; P = .048), and the median (interquartile range) Pa

Conclusion: SICUs have a fundamental role in the treatment of critically ill patients with COVID-19, who require long-term CPAP and pronation cycles. Diabetes, lymphopenia, and high D-dimer and LDH levels are associated with negative outcomes.

Keywords: emergency medicine, noninvasive ventilation, prone position, continuous positive airway pressure.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to large increases in hospital admissions. Subintensive care units (SICUs) are among the wards most under pressure worldwide,1 dealing with the increased number of critically ill patients who need noninvasive ventilation, as well as serving as the best alternative to overfilled intensive care units (ICUs). In Italy, SICUs are playing a fundamental role in the management of COVID-19 patients, providing early treatment of respiratory failure by continuous noninvasive ventilation in order to reduce the need for intubation.2-5 Nevertheless, the great majority of available data about critically ill COVID-19 patients comes from ICUs. Full studies about outcomes of patients in SICUs are lacking and need to be conducted.

We sought to evaluate the characteristics and outcomes of patients admitted to our SICU for COVID-19 to describe the treatments they needed and their impact on prognosis, and to identify the variables associated with patient outcomes.

Methods

Study Design

This cohort study used data from patients who were admitted in the very first weeks of the pandemic. Data were collected retrospectively as well as prospectively, since the ethical committee approved our project. The quality and quantity of data in the 2 groups were comparable.

Data were collected from electronic and written medical records gathered during the patient’s entire stay in our SICU. Data were entered in a database with limited and controlled access. This study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics committees (ID: MEDURG10).

Study Population

Clinical Data

The past medical history and recent symptoms description were obtained by manually reviewing medical records. Epidemiological exposure was defined as contact with SARS-CoV-2–positive people or staying in an epidemic outbreak area. Initial vital parameters, venous blood tests, arterial blood gas analysis, chest x-ray, as well as the result of the nasopharyngeal swab were gathered from the emergency department (ED) examination. (Additional swabs could be requested when the first one was negative but clinical suspicion for COVID-19 was high.) Upon admission to the SICU, a standardized panel of blood tests was performed, which was repeated the next day and then every 48 hours. Arterial blood gas analysis was performed when clinically indicated, at least twice a day, or following a scheduled time in patients undergoing pronation. Charlson Comorbidity Index7 and MuLBSTA score8 were calculated based on the collected data.

Imaging

Chest ultrasonography was performed in the ED at the time of hospitalization and once a day in the SICU. Pulmonary high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) was performed when clinically indicated or when the results of nasopharyngeal swabs and/or x-ray results were discordant with COVID-19 clinical suspicion. Contrast CT was performed when pulmonary embolism was suspected.

Medical Therapy

Hydroxychloroquine, antiviral agents, tocilizumab, and ruxolitinib were used in the early phase of the pandemic, then were dismissed after evidence of no efficacy.9-11 Steroids and low-molecular-weight heparin were used afterward. Enoxaparin was used at the standard prophylactic dosage, and 70% of the anticoagulant dosage was also adopted in patients with moderate-to-severe COVID-19 and D-dimer values >3 times the normal value.12-14 Antibiotics were given when a bacterial superinfection was suspected.

Oxygen and Ventilatory Therapy

Oxygen support or noninvasive ventilation were started based on patients’ respiratory efficacy, estimated by respiratory rate and the ratio of partial pressure of arterial oxygen and fraction of inspired oxygen (P/F ratio).15,16 Oxygen support was delivered through nasal cannula, Venturi mask, or reservoir mask. Noninvasive ventilation was performed by continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) when the P/F ratio was <250 or the respiratory rate was >25 breaths per minute, using the helmet interface.5,17 Prone positioning during CPAP18-20 was adopted in patients meeting the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) criteria21 and having persistence of respiratory distress and P/F <300 after a 1-hour trial of CPAP.

The prone position was maintained based on patient tolerance. P/F ratio was measured before pronation (T0), after 1 hour of prone position (T1), before resupination (T2), and 6 hours after resupination (T3). With the same timing, the patient was asked to rate their comfort in each position, from 0 (lack of comfort) to 10 (optimal comfort). Delta P/F was defined as the difference between P/F at T3 and basal P/F at T0.

Outcomes

Statistical Analysis

Continuous data are reported as median and interquartile range (IQR); normal distribution of variables was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Categorical variables were reported as absolute number and percentage. The Mann-Whitney test was used to compare continuous variables between groups, and chi-square test with continuity correction was used for categorical variables. The variables that were most significantly associated with a negative outcome on the univariate analysis were included in a stepwise logistic regression analysis, in order to identify independent predictors of patient outcome. Statistical analysis was performed using JASP (JASP Team) software.

Results

Study Population

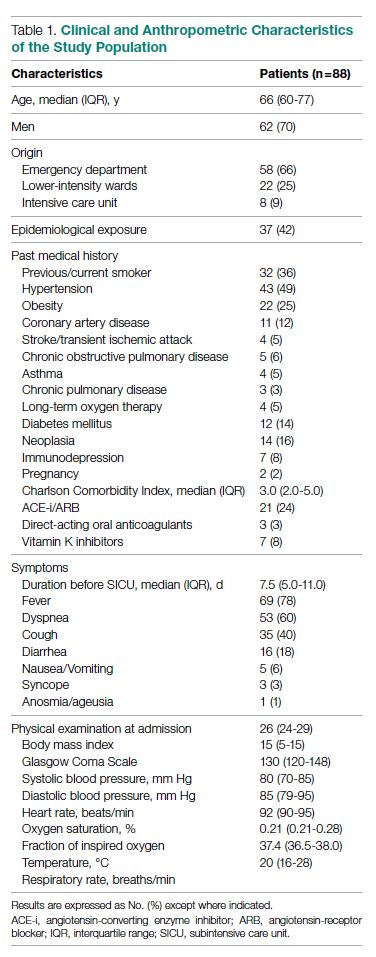

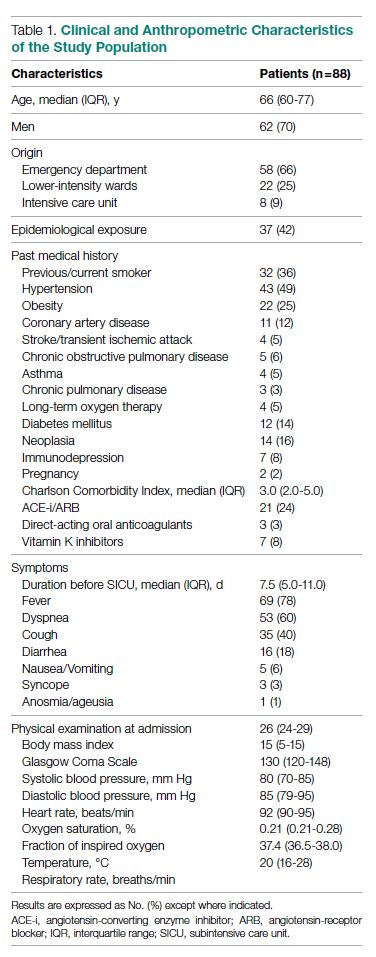

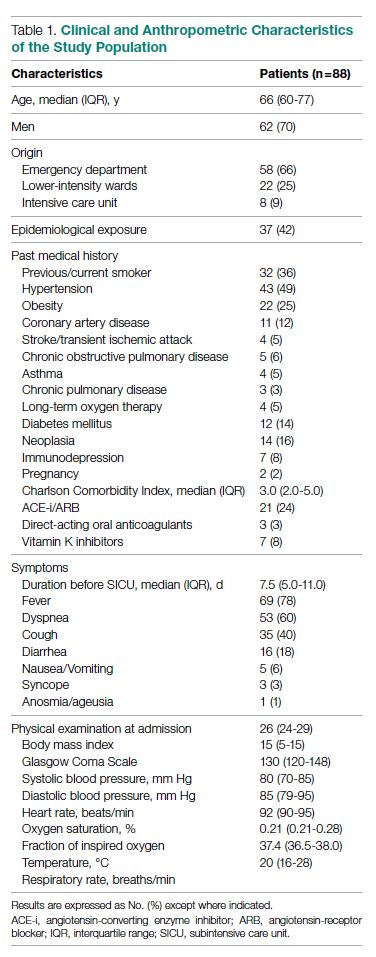

Of the 88 patients included in the study, 70% were male; the median age was 66 years (IQR, 60-77). In most patients, the diagnosis of COVID-19 was derived from a positive SARS-CoV-2 nasopharyngeal swab. Six patients, however, maintained a negative swab at all determinations but had clinical and imaging features strongly suggesting COVID-19. No patients met the exclusion criteria. Most patients came from the ED (n = 58 [66%]) or general wards (n = 22 [25%]), while few were transferred from the ICU (n = 8 [9%]). The median length of stay in the SICU was 4 days (IQR, 2-7). An epidemiological link to affected persons or a known virus exposure was identifiable in 37 patients (42%).

Clinical, Laboratory, and Imaging Data

The clinical and anthropometric characteristics of patients are shown in Table 1. Hypertension and smoking habits were prevalent in our population, and the median Charlson Comorbidity Index was 3. Most patients experienced fever, dyspnea, and cough during the days before hospitalization.

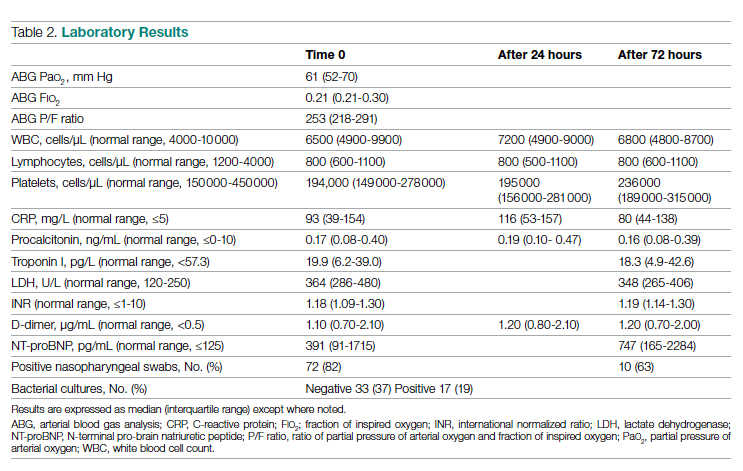

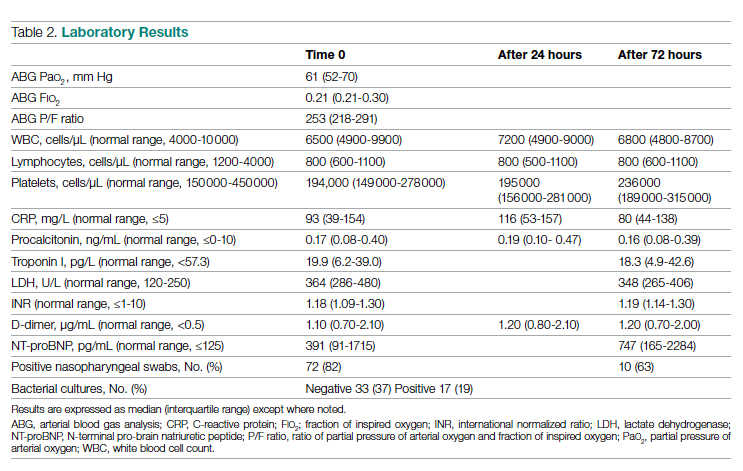

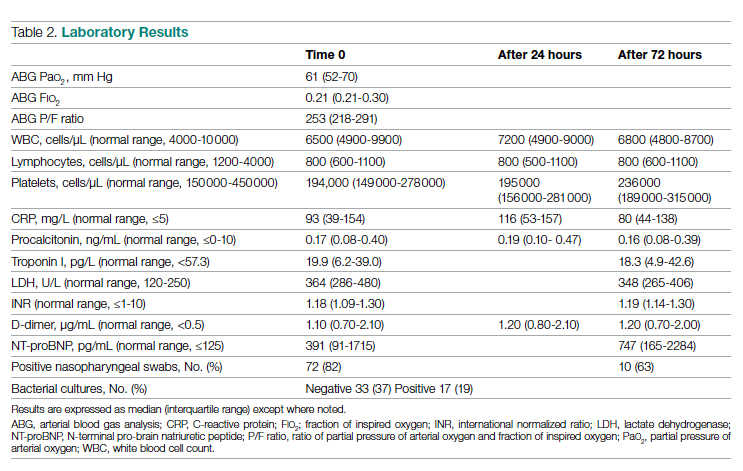

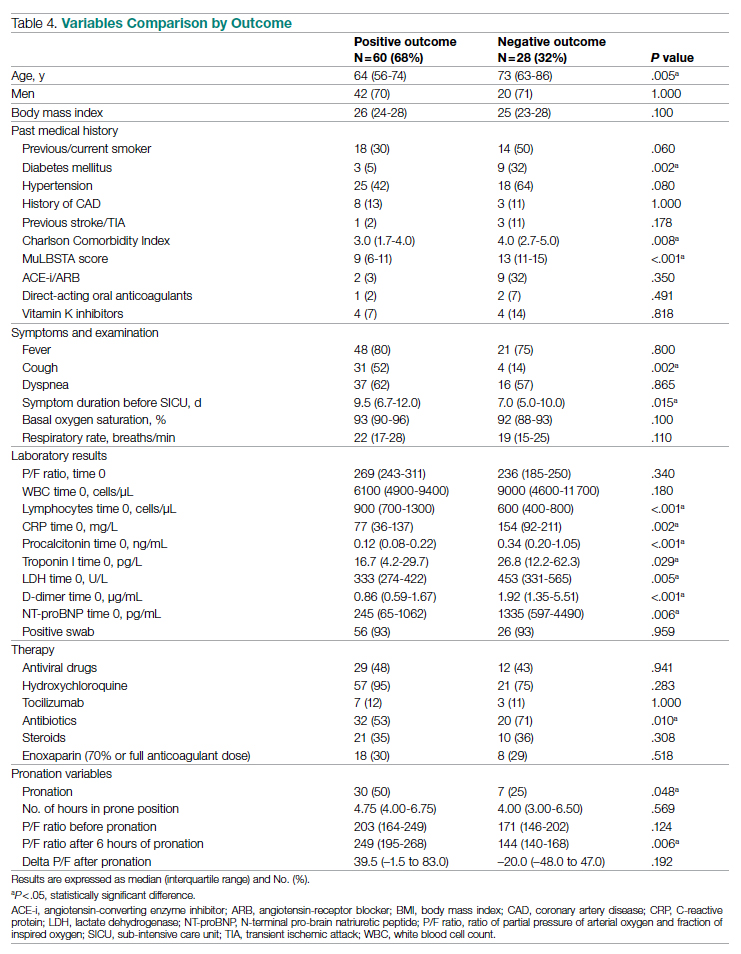

Laboratory data showed a marked inflammatory milieu in all studied patients, both at baseline and after 24 and 72 hours. Lymphopenia was observed, along with a significant increase of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), C-reactive protein (CPR), and D-dimer, and a mild increase of procalcitonin. N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) values were also increased, with normal troponin I values (Table 2).

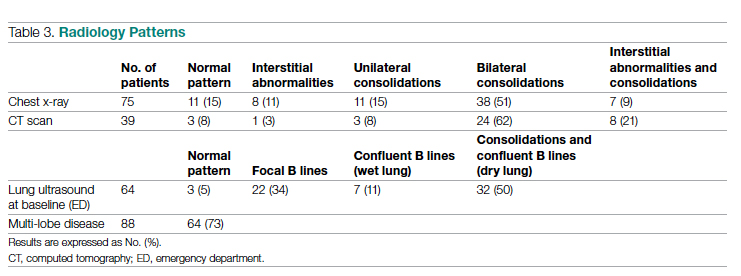

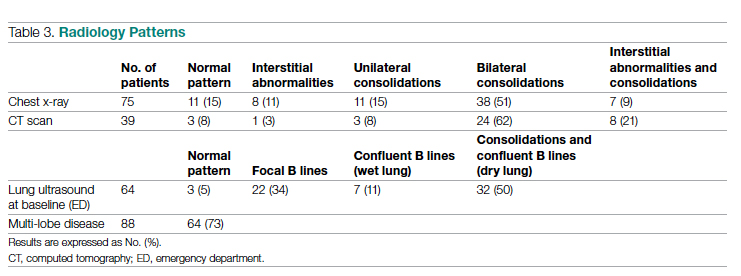

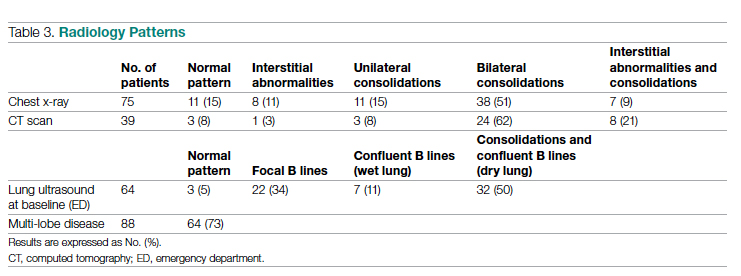

Chest x-rays were obtained in almost all patients, while HRCT was performed in nearly half of patients. Complete bedside pulmonary ultrasonography data were available for 64 patients. Heterogeneous pulmonary alterations were found, regardless of the radiological technique, and multilobe infiltrates were the prevalent radiological pattern (73%) (Table 3). Seven patients (8%) were diagnosed with associated pulmonary embolism.

Medical Therapy

Most patients (89%) received hydroxychloroquine, whereas steroids were used in one-third of the population (36%). Immunomodulators (tocilizumab and ruxolitinib) were restricted to 12 patients (14%). Empirical antiviral therapy was introduced in the first 41 patients (47%). Enoxaparin was the default agent for thromboembolism prophylaxis, and 6 patients (7%) received 70% of the anticoagulating dose.

Oxygen and Ventilatory Therapy

Outcomes

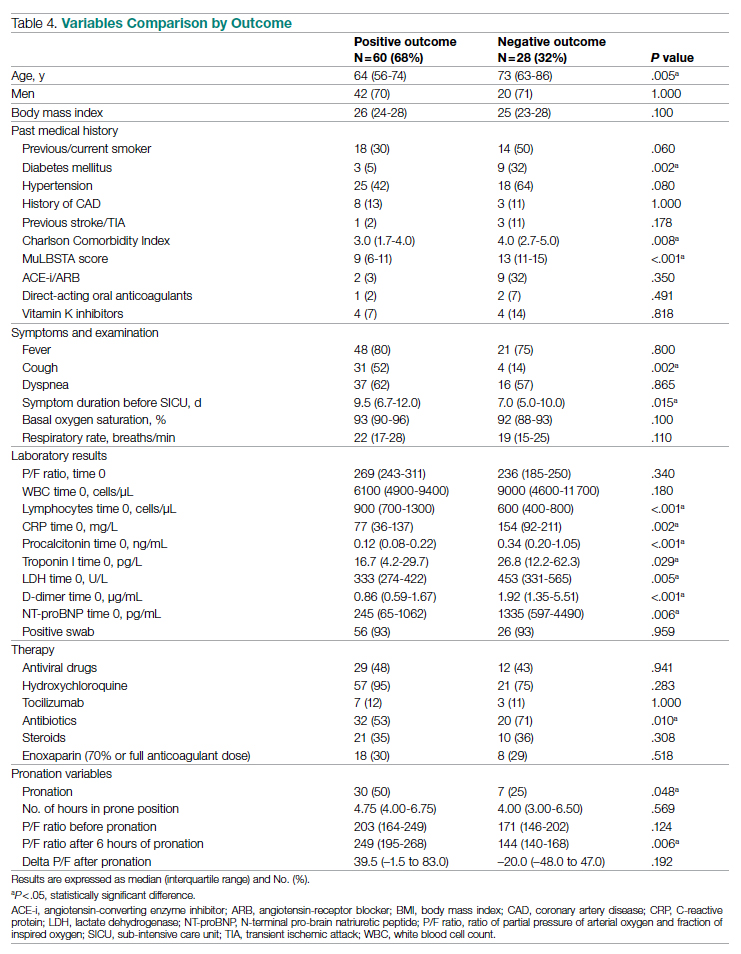

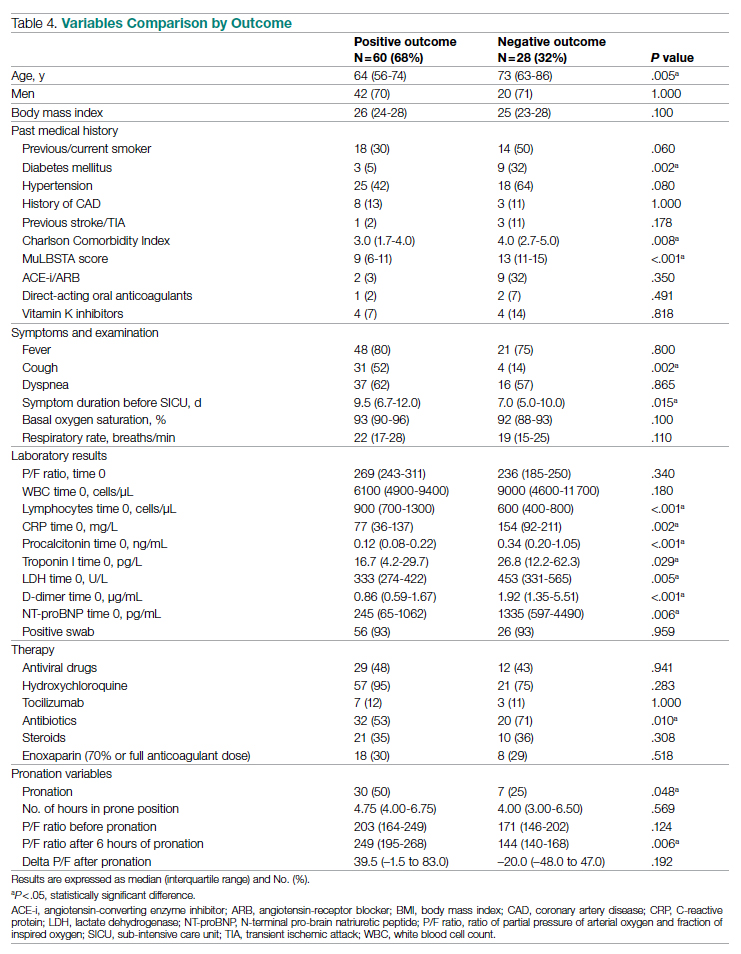

A total of 28 patients (32%) had a negative outcome in the SICU: 8 patients (9%) died, having no clinical indication for higher-intensity care; 6 patients (7%) were transferred to general wards for palliation; and 14 patients (16%) needed an upgrade of cure intensity and were transferred to the ICU. Of these 14 patients, 9 died in the ICU. The total in-hospital mortality of COVID-19 patients, including patients transferred from the SICU to general wards in fair condition, was 27% (n = 24). Clinical, laboratory, and therapeutic characteristics between the 2 groups are shown in Table 4.

Patients who had a negative outcome were significantly older and had more comorbidities, as suggested by a significantly higher prevalence of diabetes and higher Charlson Comorbidity scores (reflecting the mortality risk based on age and comorbidities). The median MuLBSTA score, which estimates the 90-day mortality risk from viral pneumonia, was also higher in patients who had a negative outcome (9.33%). Symptom occurrence was not different in patients with a negative outcome (apart from cough, which was less frequent), but these patients underwent hospitalization earlier—since the appearance of their first COVID-19 symptoms—compared to patients who had a positive outcome. No difference was found in antihypertensive therapy with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers among outcome groups.

More pronounced laboratory abnormalities were found in patients who had a negative outcome, compared to patients who had a positive outcome: lower lymphocytes and higher C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin, D-dimer, LDH, and NT-proBNP. We found no differences in the radiological distribution of pulmonary involvement in patients who had negative or positive outcomes, nor in the adopted medical treatment.

Data showed no difference in CPAP implementation in the 2 groups. However, prone positioning had been more frequently adopted in the group of patients who had a positive outcome, compared with patients who had a negative outcome. No differences of basal P/F were found in patients who had a negative or positive outcome, but the median P/F after 6 hours of prone position was significantly lower in patients who had a negative outcome. The delta P/F ratio did not differ in the 2 groups of patients.

Discussion

Role of Subintensive Units and Mortality

The novelty of our report is its attempt to investigate the specific group of COVID-19 patients admitted to a SICU. In Italy, SICUs receive acutely ill, spontaneously breathing patients who need (invasive) hemodynamic monitoring, vasoactive medication, renal replacement therapy, chest- tube placement, thrombolysis, and respiratory noninvasive support. The nurse-to-patient ratio is higher than for general wards (usually 1 nurse to every 4 or 5 patients), though lower than for ICUs. In northern Italy, a great number of COVID-19 patients have required this kind of high-intensity care during the pandemic: Noninvasive ventilation support had to be maintained for several days, pronation maneuvers required a high number of people 2 or 3 times a day, and strict monitoring had to be assured. The SICU setting allows patients to buy time as a bridge to progressive reduction of pulmonary involvement, sometimes preventing the need for intubation.

The high prevalence of negative outcomes in the SICU underlines the complexity of COVID-19 patients in this setting. In fact, published data about mortality for patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia are similar to ours.22,23

Clinical, Laboratory, and Imaging Data

Our analysis confirmed a high rate of comorbidities in COVID-19 patients24 and their prognostic role with age.25,26 A marked inflammatory milieu was a negative prognostic indicator, and associated concomitant bacterial superinfection could have led to a worse prognosis (procalcitonin was associated with negative outcomes).27 The cardiovascular system was nevertheless stressed, as suggested by higher values of NT-proBNP in patients with negative outcomes, which could reflect sepsis-related systemic involvement.28

It is known that the pulmonary damage caused by SARS-CoV-2 has a dynamic radiological and clinical course, with early areas of subsegmental consolidation, and bilateral ground-glass opacities predominating later in the course of the disease.29 This could explain why in our population we found no specific radiological pattern leading to a worse outcome.

Medical Therapy

No specific pharmacological therapy was found to be associated with a positive outcome in our study, just like antiviral and immunomodulator therapies failed to demonstrate effectiveness in subsequent pandemic surges. The low statistical power of our study did not allow us to give insight into the effectiveness of steroids and heparin at any dosage.

PEEP Support and Prone Positioning

Continuous positive airway pressure was initiated in the majority of patients and maintained for several days. This was an absolute novelty, because we rarely had to keep patients in helmets for long. This was feasible thanks to the SICU’s high nurse-to-patient ratio and the possibility of providing monitored sedation. Patients who could no longer tolerate CPAP helmets or did not improve with CPAP support were evaluated with anesthetists for programming further management. No initial data on respiratory rate, level of hypoxemia, or oxygen support need (level of PEEP and F

Prone positioning during CPAP was implemented in 42% of our study population: P/F ratio amelioration after prone positioning was highly variable, ranging from very good P/F ratio improvements to few responses or no response. No significantly greater delta P/F ratio was seen after the first prone positioning cycle in patients who had a positive outcome, probably due to the small size of our population, but we observed a clear positive trend. Interestingly, patients showing a negative outcome had a lower percentage of long-term responses to prone positioning: 6 hours after resupination, they lost the benefit of prone positioning in terms of P/F ratio amelioration. Similarly, a greater number of patients tolerating prone positioning had a positive outcome. These data give insight on the possible benefits of prone positioning in a noninvasively supported cohort of patients, which has been mentioned in previous studies.30,31

Outcomes and Variables Associated With Negative Outcomes

After correction for age and sex, we found in multiple regression analysis that higher D-dimer and LDH values, lymphopenia, and history of diabetes were independently associated with a worse outcome. Although our results had low statistical significance, we consider the trend of the obtained odds ratios important from a clinical point of view. These results could lead to greater attention being placed on COVID-19 patients who present with these characteristics upon their arrival to the ED because they have increased risk of death or intensive care need. Clinicians should consider SICU admission for these patients in order to guarantee closer monitoring and possibly more aggressive ventilatory treatments, earlier pronation, or earlier transfer to the ICU.

Limitations

The major limitation to our study is undoubtedly its statistical power, due to its relatively low patient population. Particularly, the small number of patients who underwent pronation did not allow speculation about the efficacy of this technique, although preliminary data seem promising. However, ours is among the first studies regarding patients with COVID-19 admitted to a SICU, and these preliminary data truthfully describe the Italian, and perhaps international, experience with the first surge of the pandemic.

Conclusions

Our data highlight the primary role of the SICU in COVID-19 in adequately treating critically ill patients who have high care needs different from intubation, and who require noninvasive ventilation for prolonged times as well as frequent pronation cycles. This setting of care may represent a valid, reliable, and effective option for critically ill respiratory patients. History of diabetes, lymphopenia, and high D-dimer and LDH values are independently associated with negative outcomes, and patients presenting with these characteristics should be strictly monitored.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank the Informatica System S.R.L., as well as Allessando Mendolia for the pro bono creation of the ISCovidCollect data collecting app.

Corresponding author: Sara Abram, MD, via Coppino, 12100 Cuneo, Italy; [email protected].

Disclosures: None.

1. Plate JDJ, Leenen LPH, Houwert M, Hietbrink F. Utilisation of intermediate care units: a systematic review. Crit Care Res Pract. 2017;2017:8038460. doi:10.1155/2017/8038460

2. Antonelli M, Conti G, Esquinas A, et al. A multiple-center survey on the use in clinical practice of noninvasive ventilation as a first-line intervention for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(1):18-25. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000251821.44259.F3

3. Patel BK, Wolfe KS, Pohlman AS, Hall JB, Kress JP. Effect of noninvasive ventilation delivered by helmet vs face mask on the rate of endotracheal intubation in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(22):2435-2441. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.6338

4. Mas A, Masip J. Noninvasive ventilation in acute respiratory failure. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:837-852. doi:10.2147/COPD.S42664

5. Bellani G, Patroniti N, Greco M, Foti G, Pesenti A. The use of helmets to deliver non-invasive continuous positive airway pressure in hypoxemic acute respiratory failure. Minerva Anestesiol. 2008;74(11):651-656.

6. Lomoro P, Verde F, Zerboni F, et al. COVID-19 pneumonia manifestations at the admission on chest ultrasound, radiographs, and CT: single-center study and comprehensive radiologic literature review. Eur J Radiol Open. 2020;7:100231. doi:10.1016/j.ejro.2020.100231

7. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373-383. doi:10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

8. Guo L, Wei D, Zhang X, et al. Clinical features predicting mortality risk in patients with viral pneumonia: the MuLBSTA score. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:2752. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2019.02752

9. Lombardy Section Italian Society Infectious and Tropical Disease. Vademecum for the treatment of people with COVID-19. Edition 2.0, 13 March 2020. Infez Med. 2020;28(2):143-152.

10. Wang M, Cao R, Zhang L, et al. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30(3):269-271. doi:10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0

11. Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D, et al. A trial of lopinavir-ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(19):1787-1799. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001282

12. Stone JH, Frigault MJ, Serling-Boyd NJ, et al; BACC Bay Tocilizumab Trial Investigators. Efficacy of tocilizumab in patients hospitalized with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(24):2333-2344. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2028836

13. Shastri MD, Stewart N, Horne J, et al. In-vitro suppression of IL-6 and IL-8 release from human pulmonary epithelial cells by non-anticoagulant fraction of enoxaparin. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0126763. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0126763

14. Milewska A, Zarebski M, Nowak P, Stozek K, Potempa J, Pyrc K. Human coronavirus NL63 utilizes heparin sulfate proteoglycans for attachment to target cells. J Virol. 2014;88(22):13221-13230. doi:10.1128/JVI.02078-14

15. Marietta M, Vandelli P, Mighali P, Vicini R, Coluccio V, D’Amico R; COVID-19 HD Study Group. Randomised controlled trial comparing efficacy and safety of high versus low low-molecular weight heparin dosages in hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia and coagulopathy not requiring invasive mechanical ventilation (COVID-19 HD): a structured summary of a study protocol. Trials. 2020;21(1):574. doi:10.1186/s13063-020-04475-z

16. Marshall JC, Cook DJ, Christou NV, Bernard GR, Sprung CL, Sibbald WJ. Multiple organ dysfunction score: a reliable descriptor of a complex clinical outcome. Crit Care Med. 1995;23(10):1638-1652. doi:10.1097/00003246-199510000-00007

17. Sinha P, Calfee CS. Phenotypes in acute respiratory distress syndrome: moving towards precision medicine. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2019;25(1):12-20. doi:10.1097/MCC.0000000000000571

18. Lucchini A, Giani M, Isgrò S, Rona R, Foti G. The “helmet bundle” in COVID-19 patients undergoing non-invasive ventilation. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2020;58:102859. doi:10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102859

19. Ding L, Wang L, Ma W, He H. Efficacy and safety of early prone positioning combined with HFNC or NIV in moderate to severe ARDS: a multi-center prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):28. doi:10.1186/s13054-020-2738-5

20. Scaravilli V, Grasselli G, Castagna L, et al. Prone positioning improves oxygenation in spontaneously breathing nonintubated patients with hypoxemic acute respiratory failure: a retrospective study. J Crit Care. 2015;30(6):1390-1394. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.07.008

21. Caputo ND, Strayer RJ, Levitan R. Early self-proning in awake, non-intubated patients in the emergency department: a single ED’s experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27(5):375-378. doi:10.1111/acem.13994

22. ARDS Definition Task Force; Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2526-2533. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.5669

23. Petrilli CM, Jones SA, Yang J, et al. Factors associated with hospital admission and critical illness among 5279 people with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York City: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1966. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1966

24. Docherty AB, Harrison EM, Green CA, et al; ISARIC4C investigators. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with Covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1985. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1985

25. Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2052-2059. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6775

26. Muniyappa R, Gubbi S. COVID-19 pandemic, coronaviruses, and diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2020;318(5):E736-E741. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00124.2020

27. Guo W, Li M, Dong Y, et al. Diabetes is a risk factor for the progression and prognosis of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020:e3319. doi:10.1002/dmrr.3319

28. Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507-513. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7

29. Kooraki S, Hosseiny M, Myers L, Gholamrezanezhad A. Coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: what the Department of Radiology should know. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17(4):447-451. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2020.02.008

30. Coppo A, Bellani G, Winterton D, et al. Feasibility and physiological effects of prone positioning in non-intubated patients with acute respiratory failure due to COVID-19 (PRON-COVID): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(8):765-774. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30268-X

31. Weatherald J, Solverson K, Zuege DJ, Loroff N, Fiest KM, Parhar KKS. Awake prone positioning for COVID-19 hypoxemic respiratory failure: a rapid review. J Crit Care. 2021;61:63-70. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.08.018

From the Department of Emergency Medicine, Santa Croce e Carle Hospital, Cuneo, Italy (Drs. Abram, Tosello, Emanuele Bernardi, Allione, Cavalot, Dutto, Corsini, Martini, Sciolla, Sara Bernardi, and Lauria). From the School of Emergency Medicine, University of Turin, Turin, Italy (Drs. Paglietta and Giamello).

Objective: This retrospective and prospective cohort study was designed to describe the characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection (COVID-19) admitted to subintensive care units (SICU) and to identify the variables associated with outcomes. SICUs have been extremely stressed during the pandemic, but most data regarding critically ill COVID-19 patients come from intensive care units (ICUs). Studies about COVID-19 patients in SICUs are lacking.

Setting and participants: The study included 88 COVID-19 patients admitted to our SICU in Cuneo, Italy, between March and May 2020.

Measurements: Clinical and ventilatory data were collected, and patients were divided by outcome. Multivariable logistic regression analysis examined the variables associated with negative outcomes (transfer to the ICU, palliation, or death in a SICU).

Results: A total of 60 patients (68%) had a positive outcome, and 28 patients (32%) had a negative outcome; 69 patients (78%) underwent continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). Pronation (n = 37 [42%]) had been more frequently adopted in patients who had a positive outcome vs a negative outcome (n = 30 [50%] vs n = 7 [25%]; P = .048), and the median (interquartile range) Pa

Conclusion: SICUs have a fundamental role in the treatment of critically ill patients with COVID-19, who require long-term CPAP and pronation cycles. Diabetes, lymphopenia, and high D-dimer and LDH levels are associated with negative outcomes.

Keywords: emergency medicine, noninvasive ventilation, prone position, continuous positive airway pressure.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to large increases in hospital admissions. Subintensive care units (SICUs) are among the wards most under pressure worldwide,1 dealing with the increased number of critically ill patients who need noninvasive ventilation, as well as serving as the best alternative to overfilled intensive care units (ICUs). In Italy, SICUs are playing a fundamental role in the management of COVID-19 patients, providing early treatment of respiratory failure by continuous noninvasive ventilation in order to reduce the need for intubation.2-5 Nevertheless, the great majority of available data about critically ill COVID-19 patients comes from ICUs. Full studies about outcomes of patients in SICUs are lacking and need to be conducted.

We sought to evaluate the characteristics and outcomes of patients admitted to our SICU for COVID-19 to describe the treatments they needed and their impact on prognosis, and to identify the variables associated with patient outcomes.

Methods

Study Design

This cohort study used data from patients who were admitted in the very first weeks of the pandemic. Data were collected retrospectively as well as prospectively, since the ethical committee approved our project. The quality and quantity of data in the 2 groups were comparable.

Data were collected from electronic and written medical records gathered during the patient’s entire stay in our SICU. Data were entered in a database with limited and controlled access. This study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics committees (ID: MEDURG10).

Study Population

Clinical Data

The past medical history and recent symptoms description were obtained by manually reviewing medical records. Epidemiological exposure was defined as contact with SARS-CoV-2–positive people or staying in an epidemic outbreak area. Initial vital parameters, venous blood tests, arterial blood gas analysis, chest x-ray, as well as the result of the nasopharyngeal swab were gathered from the emergency department (ED) examination. (Additional swabs could be requested when the first one was negative but clinical suspicion for COVID-19 was high.) Upon admission to the SICU, a standardized panel of blood tests was performed, which was repeated the next day and then every 48 hours. Arterial blood gas analysis was performed when clinically indicated, at least twice a day, or following a scheduled time in patients undergoing pronation. Charlson Comorbidity Index7 and MuLBSTA score8 were calculated based on the collected data.

Imaging

Chest ultrasonography was performed in the ED at the time of hospitalization and once a day in the SICU. Pulmonary high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) was performed when clinically indicated or when the results of nasopharyngeal swabs and/or x-ray results were discordant with COVID-19 clinical suspicion. Contrast CT was performed when pulmonary embolism was suspected.

Medical Therapy

Hydroxychloroquine, antiviral agents, tocilizumab, and ruxolitinib were used in the early phase of the pandemic, then were dismissed after evidence of no efficacy.9-11 Steroids and low-molecular-weight heparin were used afterward. Enoxaparin was used at the standard prophylactic dosage, and 70% of the anticoagulant dosage was also adopted in patients with moderate-to-severe COVID-19 and D-dimer values >3 times the normal value.12-14 Antibiotics were given when a bacterial superinfection was suspected.

Oxygen and Ventilatory Therapy

Oxygen support or noninvasive ventilation were started based on patients’ respiratory efficacy, estimated by respiratory rate and the ratio of partial pressure of arterial oxygen and fraction of inspired oxygen (P/F ratio).15,16 Oxygen support was delivered through nasal cannula, Venturi mask, or reservoir mask. Noninvasive ventilation was performed by continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) when the P/F ratio was <250 or the respiratory rate was >25 breaths per minute, using the helmet interface.5,17 Prone positioning during CPAP18-20 was adopted in patients meeting the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) criteria21 and having persistence of respiratory distress and P/F <300 after a 1-hour trial of CPAP.

The prone position was maintained based on patient tolerance. P/F ratio was measured before pronation (T0), after 1 hour of prone position (T1), before resupination (T2), and 6 hours after resupination (T3). With the same timing, the patient was asked to rate their comfort in each position, from 0 (lack of comfort) to 10 (optimal comfort). Delta P/F was defined as the difference between P/F at T3 and basal P/F at T0.

Outcomes

Statistical Analysis

Continuous data are reported as median and interquartile range (IQR); normal distribution of variables was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Categorical variables were reported as absolute number and percentage. The Mann-Whitney test was used to compare continuous variables between groups, and chi-square test with continuity correction was used for categorical variables. The variables that were most significantly associated with a negative outcome on the univariate analysis were included in a stepwise logistic regression analysis, in order to identify independent predictors of patient outcome. Statistical analysis was performed using JASP (JASP Team) software.

Results

Study Population

Of the 88 patients included in the study, 70% were male; the median age was 66 years (IQR, 60-77). In most patients, the diagnosis of COVID-19 was derived from a positive SARS-CoV-2 nasopharyngeal swab. Six patients, however, maintained a negative swab at all determinations but had clinical and imaging features strongly suggesting COVID-19. No patients met the exclusion criteria. Most patients came from the ED (n = 58 [66%]) or general wards (n = 22 [25%]), while few were transferred from the ICU (n = 8 [9%]). The median length of stay in the SICU was 4 days (IQR, 2-7). An epidemiological link to affected persons or a known virus exposure was identifiable in 37 patients (42%).

Clinical, Laboratory, and Imaging Data

The clinical and anthropometric characteristics of patients are shown in Table 1. Hypertension and smoking habits were prevalent in our population, and the median Charlson Comorbidity Index was 3. Most patients experienced fever, dyspnea, and cough during the days before hospitalization.

Laboratory data showed a marked inflammatory milieu in all studied patients, both at baseline and after 24 and 72 hours. Lymphopenia was observed, along with a significant increase of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), C-reactive protein (CPR), and D-dimer, and a mild increase of procalcitonin. N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) values were also increased, with normal troponin I values (Table 2).

Chest x-rays were obtained in almost all patients, while HRCT was performed in nearly half of patients. Complete bedside pulmonary ultrasonography data were available for 64 patients. Heterogeneous pulmonary alterations were found, regardless of the radiological technique, and multilobe infiltrates were the prevalent radiological pattern (73%) (Table 3). Seven patients (8%) were diagnosed with associated pulmonary embolism.

Medical Therapy

Most patients (89%) received hydroxychloroquine, whereas steroids were used in one-third of the population (36%). Immunomodulators (tocilizumab and ruxolitinib) were restricted to 12 patients (14%). Empirical antiviral therapy was introduced in the first 41 patients (47%). Enoxaparin was the default agent for thromboembolism prophylaxis, and 6 patients (7%) received 70% of the anticoagulating dose.

Oxygen and Ventilatory Therapy

Outcomes