User login

Pandemic-stressed youths call runaway hotline

The calls kept coming into the National Runaway Safeline during the pandemic: the desperate kids who wanted to bike away from home in the middle of the night, the isolated youths who felt suicidal, the teens whose parents had forced them out of the house.

To the surprise of experts who help runaway youths, the pandemic didn’t appear to produce a big rise or fall in the numbers of children and teens who had left home. Still, the crisis hit hard. As schools closed and households sheltered in place, youths reached out to the National Runaway Safeline to report heightened family conflicts and worsening mental health.

The Safeline, based in Chicago, is the country’s 24/7, federally designated communications system for runaway and homeless youths. Each year, it makes about 125,000 connections with young people and their family members through its hotline and other services.

In a typical year, teens aged 15-17 years are the main group that gets in touch by phone, live chat, email, or an online crisis forum, according to Jeff Stern, chief engagement officer at the Safeline.

But in the past 2 years, “contacts have skewed younger,” including many more children under age 12.

“I think this is showing what a hit this is taking on young children,” he said.

Without school, sports, and other activities, younger children might be reaching out because they’ve lost trusted sources of support. Callers have been as young as 9.

“Those ones stand out,” said a crisis center supervisor who asked to go by Michael, which is not his real name, to protect the privacy of his clients.

In November 2020, a child posted in the crisis forum: “I’m 11 and my parents treat me poorly. They have told me many times to ‘kill myself’ and I didn’t let that settle well with me. ... I have tried to run away one time from my house, but they found out, so they took my phone away and put screws on my windows so I couldn’t leave.”

Increasing numbers of children told Safeline counselors that their parents were emotionally or verbally abusive, while others reported physical abuse. Some said they experienced neglect, while others had been thrown out.

“We absolutely have had youths who have either been physically kicked out of the house or just verbally told to leave,” Michael said, “and then the kid does.”

Heightened family conflicts

The Safeline partners with the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, which, despite widespread public perception, doesn’t work mainly with child abduction cases. Each year, the center assists with 29,000-31,000 cases, and 92% involve “endangered runaways,” said John Bischoff, vice president of the Missing Children Division. These children could be running away from home or foster care.

During the pandemic, the center didn’t spot major changes in its missing child numbers, “which honestly was shocking,” Mr. Bischoff said. “We figured we were either going to see an extreme rise or a decrease.

“But the reasons for the run were changing,” he said.

Many youths were fleeing out of frustration with quarantine restrictions, Mr. Bischoff said, as well as frustration with the unknown and their own lack of control over many situations.

At the runaway hotline, calls have been longer and more intense, with family problems topping the list of concerns. In 2019, about 57% of all contacts mentioned family dynamics. In 2020, that number jumped to 88%, according to Mr. Stern.

Some kids sought support for family problems that involved school. In October 2020, one 13-year-old wrote in the Safeline forum: “My mom constantly yells at me for no reason. I want to leave, but I don’t know how. I have also been really stressed about school because they haven’t been giving me the grades I would normally receive during actual school. She thinks I’m lying and that I don’t care. I just need somebody to help me.”

Many adults are under tremendous strain, too, Michael said.

“Parents might have gotten COVID last month and haven’t been able to work for 2 weeks, and they’re missing a paycheck now. Money is tight, there might not be food, everyone’s angry at everything.”

During the pandemic, the National Runaway Safeline found a 16% increase in contacts citing financial challenges.

Some children have felt confined in unsafe homes or have endured violence, as one 15-year-old reported in the forum: “I am the scapegoat out of four kids. Unfortunately, my mom has always been a toxic person. ... I’m the only kid she still hits really hard. She’s left bruises and scratches recently. ... I just have no solution to this.”

Worsening mental health

Besides family dynamics, mental health emerged as a top concern that youths reported in 2020. “This is something notable. It increased by 30% just in 1 year,” Mr. Stern said.

In November 2020, a 16-year-old wrote: “I can’t ever go outside. I’ve been stuck in the house for a very long time now since quarantine started. I’m scared. ... My mother has been taking her anger out on me emotionally. ... I have severe depression and I need help. Please, if there’s any way I can get out of here, let me know.”

The Safeline also has seen a rise in suicide-related contacts. Among children and teens who had cited a mental health concern, 18% said they were suicidal, Stern said. Most were between ages 12 and 16, but some were younger than 12.

When children couldn’t hang out with peers, they felt even more isolated if parents confiscated their phones, a common punishment, Michael said.

During the winter of 2020-21, “It felt like almost every digital contact was a youth reaching out on their Chromebook because they had gotten their phone taken away and they were either suicidal or considering running away,” he said. “That’s kind of their entire social sphere getting taken away.”

Reality check

Roughly 7 in 10 youths report still being at home when they reach out to the Safeline. Among those who do leave, Michael said, “They’re going sometimes to friends’ houses, oftentimes to a significant other’s house, sometimes to extended family members’ houses. Often, they don’t have a place that they’re planning to go. They just left, and that’s why they’re calling us.”

While some youths have been afraid of catching COVID-19 in general, the coronavirus threat hasn’t deterred those who have decided to run away, Michael said. “Usually, they’re more worried about being returned home.”

Many can’t comprehend the risks of setting off on their own.

In October 2021, a 15-year-old boy posted on the forum that his verbally abusive parents had called him a mistake and said they couldn’t wait for him to move out.

“So I’m going to make their dreams come true,” he wrote. “I’m going to go live in California with my friend who is a young YouTuber. I need help getting money to either fly or get a bus ticket, even though I’m all right with trying to ride a bike or fixing my dirt bike and getting the wagon to pull my stuff. But I’m looking for apartments in Los Angeles so I’m not living on the streets and I’m looking for a job. Please help me. My friend can’t send me money because I don’t have a bank account.”

“Often,” Michael said, “we’re reality-checking kids who want to hitchhike 5 hours away to either a friend’s or the closest shelter that we could find them. Or walk for 5 hours at 3 a.m. or bike, so we try to safety-check that.”

Another concern: online enticement by predators. During the pandemic, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children saw cases in which children ran away from home “to go meet with someone who may not be who they thought they were talking to online,” Mr. Bischoff said. “It’s certainly something we’re keeping a close eye on.”

Fewer resources in the pandemic

The National Runaway Safeline provides information and referrals to other hotlines and services, including suicide prevention and mental health organizations. When youths have already run away and have no place to go, Michael said, the Safeline tries to find shelter options or seek out a relative who can provide a safe place to stay.

But finding shelters became tougher during the pandemic, when many had no room or shelter supply was limited. Some had to shut down for COVID-19–related deep cleanings, Michael said. Helping youths find transportation, especially with public transportation shutdowns, also was tough.

The Huckleberry House, a six-bed youth shelter in San Francisco, has stayed open throughout the pandemic with limited staffing, said Douglas Styles, PsyD. He’s the executive director of the Huckleberry Youth Programs, which runs the house.

The shelter, which serves Bay Area runaway and homeless youths ages 12-17, hasn’t seen an overall spike in demand, Dr. Styles said. But “what’s expanded is undocumented [youths] and young people who don’t have any family connections in the area, so they’re unaccompanied as well. We’ve seen that here and there throughout the years, but during the pandemic, that population has actually increased quite a bit.”

The Huckleberry House has sheltered children and teens who have run away from all kinds of homes, including affluent ones, Dr. Styles said.

Once children leave home, the lack of adult supervision leaves them vulnerable. They face multiple dangers, including child sex trafficking and exploitation, substance abuse, gang involvement, and violence. “As an organization, that scares us,” Mr. Bischoff said. “What’s happening at home, we’ll sort that out. The biggest thing we as an organization are trying to do is locate them and ensure their safety.”

To help runaways and their families get in touch, the National Runaway Safeline provides a message service and conference calling. “We can play the middleman, really acting on behalf of the young person – not because they’re right or wrong, but to ensure that their voice is really heard,” Mr. Stern said.

Through its national Home Free program, the Safeline partners with Greyhound to bring children back home or into an alternative, safe living environment by providing a free bus ticket.

These days, technology can expose children to harm online, but it can also speed their return home.

“When I was growing up, if you weren’t home by 5 o’clock, Mom would start to worry, but she really didn’t have any way of reaching you,” Mr. Bischoff said. “More children today have cellphones. More children are easily reachable. That’s a benefit.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The calls kept coming into the National Runaway Safeline during the pandemic: the desperate kids who wanted to bike away from home in the middle of the night, the isolated youths who felt suicidal, the teens whose parents had forced them out of the house.

To the surprise of experts who help runaway youths, the pandemic didn’t appear to produce a big rise or fall in the numbers of children and teens who had left home. Still, the crisis hit hard. As schools closed and households sheltered in place, youths reached out to the National Runaway Safeline to report heightened family conflicts and worsening mental health.

The Safeline, based in Chicago, is the country’s 24/7, federally designated communications system for runaway and homeless youths. Each year, it makes about 125,000 connections with young people and their family members through its hotline and other services.

In a typical year, teens aged 15-17 years are the main group that gets in touch by phone, live chat, email, or an online crisis forum, according to Jeff Stern, chief engagement officer at the Safeline.

But in the past 2 years, “contacts have skewed younger,” including many more children under age 12.

“I think this is showing what a hit this is taking on young children,” he said.

Without school, sports, and other activities, younger children might be reaching out because they’ve lost trusted sources of support. Callers have been as young as 9.

“Those ones stand out,” said a crisis center supervisor who asked to go by Michael, which is not his real name, to protect the privacy of his clients.

In November 2020, a child posted in the crisis forum: “I’m 11 and my parents treat me poorly. They have told me many times to ‘kill myself’ and I didn’t let that settle well with me. ... I have tried to run away one time from my house, but they found out, so they took my phone away and put screws on my windows so I couldn’t leave.”

Increasing numbers of children told Safeline counselors that their parents were emotionally or verbally abusive, while others reported physical abuse. Some said they experienced neglect, while others had been thrown out.

“We absolutely have had youths who have either been physically kicked out of the house or just verbally told to leave,” Michael said, “and then the kid does.”

Heightened family conflicts

The Safeline partners with the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, which, despite widespread public perception, doesn’t work mainly with child abduction cases. Each year, the center assists with 29,000-31,000 cases, and 92% involve “endangered runaways,” said John Bischoff, vice president of the Missing Children Division. These children could be running away from home or foster care.

During the pandemic, the center didn’t spot major changes in its missing child numbers, “which honestly was shocking,” Mr. Bischoff said. “We figured we were either going to see an extreme rise or a decrease.

“But the reasons for the run were changing,” he said.

Many youths were fleeing out of frustration with quarantine restrictions, Mr. Bischoff said, as well as frustration with the unknown and their own lack of control over many situations.

At the runaway hotline, calls have been longer and more intense, with family problems topping the list of concerns. In 2019, about 57% of all contacts mentioned family dynamics. In 2020, that number jumped to 88%, according to Mr. Stern.

Some kids sought support for family problems that involved school. In October 2020, one 13-year-old wrote in the Safeline forum: “My mom constantly yells at me for no reason. I want to leave, but I don’t know how. I have also been really stressed about school because they haven’t been giving me the grades I would normally receive during actual school. She thinks I’m lying and that I don’t care. I just need somebody to help me.”

Many adults are under tremendous strain, too, Michael said.

“Parents might have gotten COVID last month and haven’t been able to work for 2 weeks, and they’re missing a paycheck now. Money is tight, there might not be food, everyone’s angry at everything.”

During the pandemic, the National Runaway Safeline found a 16% increase in contacts citing financial challenges.

Some children have felt confined in unsafe homes or have endured violence, as one 15-year-old reported in the forum: “I am the scapegoat out of four kids. Unfortunately, my mom has always been a toxic person. ... I’m the only kid she still hits really hard. She’s left bruises and scratches recently. ... I just have no solution to this.”

Worsening mental health

Besides family dynamics, mental health emerged as a top concern that youths reported in 2020. “This is something notable. It increased by 30% just in 1 year,” Mr. Stern said.

In November 2020, a 16-year-old wrote: “I can’t ever go outside. I’ve been stuck in the house for a very long time now since quarantine started. I’m scared. ... My mother has been taking her anger out on me emotionally. ... I have severe depression and I need help. Please, if there’s any way I can get out of here, let me know.”

The Safeline also has seen a rise in suicide-related contacts. Among children and teens who had cited a mental health concern, 18% said they were suicidal, Stern said. Most were between ages 12 and 16, but some were younger than 12.

When children couldn’t hang out with peers, they felt even more isolated if parents confiscated their phones, a common punishment, Michael said.

During the winter of 2020-21, “It felt like almost every digital contact was a youth reaching out on their Chromebook because they had gotten their phone taken away and they were either suicidal or considering running away,” he said. “That’s kind of their entire social sphere getting taken away.”

Reality check

Roughly 7 in 10 youths report still being at home when they reach out to the Safeline. Among those who do leave, Michael said, “They’re going sometimes to friends’ houses, oftentimes to a significant other’s house, sometimes to extended family members’ houses. Often, they don’t have a place that they’re planning to go. They just left, and that’s why they’re calling us.”

While some youths have been afraid of catching COVID-19 in general, the coronavirus threat hasn’t deterred those who have decided to run away, Michael said. “Usually, they’re more worried about being returned home.”

Many can’t comprehend the risks of setting off on their own.

In October 2021, a 15-year-old boy posted on the forum that his verbally abusive parents had called him a mistake and said they couldn’t wait for him to move out.

“So I’m going to make their dreams come true,” he wrote. “I’m going to go live in California with my friend who is a young YouTuber. I need help getting money to either fly or get a bus ticket, even though I’m all right with trying to ride a bike or fixing my dirt bike and getting the wagon to pull my stuff. But I’m looking for apartments in Los Angeles so I’m not living on the streets and I’m looking for a job. Please help me. My friend can’t send me money because I don’t have a bank account.”

“Often,” Michael said, “we’re reality-checking kids who want to hitchhike 5 hours away to either a friend’s or the closest shelter that we could find them. Or walk for 5 hours at 3 a.m. or bike, so we try to safety-check that.”

Another concern: online enticement by predators. During the pandemic, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children saw cases in which children ran away from home “to go meet with someone who may not be who they thought they were talking to online,” Mr. Bischoff said. “It’s certainly something we’re keeping a close eye on.”

Fewer resources in the pandemic

The National Runaway Safeline provides information and referrals to other hotlines and services, including suicide prevention and mental health organizations. When youths have already run away and have no place to go, Michael said, the Safeline tries to find shelter options or seek out a relative who can provide a safe place to stay.

But finding shelters became tougher during the pandemic, when many had no room or shelter supply was limited. Some had to shut down for COVID-19–related deep cleanings, Michael said. Helping youths find transportation, especially with public transportation shutdowns, also was tough.

The Huckleberry House, a six-bed youth shelter in San Francisco, has stayed open throughout the pandemic with limited staffing, said Douglas Styles, PsyD. He’s the executive director of the Huckleberry Youth Programs, which runs the house.

The shelter, which serves Bay Area runaway and homeless youths ages 12-17, hasn’t seen an overall spike in demand, Dr. Styles said. But “what’s expanded is undocumented [youths] and young people who don’t have any family connections in the area, so they’re unaccompanied as well. We’ve seen that here and there throughout the years, but during the pandemic, that population has actually increased quite a bit.”

The Huckleberry House has sheltered children and teens who have run away from all kinds of homes, including affluent ones, Dr. Styles said.

Once children leave home, the lack of adult supervision leaves them vulnerable. They face multiple dangers, including child sex trafficking and exploitation, substance abuse, gang involvement, and violence. “As an organization, that scares us,” Mr. Bischoff said. “What’s happening at home, we’ll sort that out. The biggest thing we as an organization are trying to do is locate them and ensure their safety.”

To help runaways and their families get in touch, the National Runaway Safeline provides a message service and conference calling. “We can play the middleman, really acting on behalf of the young person – not because they’re right or wrong, but to ensure that their voice is really heard,” Mr. Stern said.

Through its national Home Free program, the Safeline partners with Greyhound to bring children back home or into an alternative, safe living environment by providing a free bus ticket.

These days, technology can expose children to harm online, but it can also speed their return home.

“When I was growing up, if you weren’t home by 5 o’clock, Mom would start to worry, but she really didn’t have any way of reaching you,” Mr. Bischoff said. “More children today have cellphones. More children are easily reachable. That’s a benefit.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The calls kept coming into the National Runaway Safeline during the pandemic: the desperate kids who wanted to bike away from home in the middle of the night, the isolated youths who felt suicidal, the teens whose parents had forced them out of the house.

To the surprise of experts who help runaway youths, the pandemic didn’t appear to produce a big rise or fall in the numbers of children and teens who had left home. Still, the crisis hit hard. As schools closed and households sheltered in place, youths reached out to the National Runaway Safeline to report heightened family conflicts and worsening mental health.

The Safeline, based in Chicago, is the country’s 24/7, federally designated communications system for runaway and homeless youths. Each year, it makes about 125,000 connections with young people and their family members through its hotline and other services.

In a typical year, teens aged 15-17 years are the main group that gets in touch by phone, live chat, email, or an online crisis forum, according to Jeff Stern, chief engagement officer at the Safeline.

But in the past 2 years, “contacts have skewed younger,” including many more children under age 12.

“I think this is showing what a hit this is taking on young children,” he said.

Without school, sports, and other activities, younger children might be reaching out because they’ve lost trusted sources of support. Callers have been as young as 9.

“Those ones stand out,” said a crisis center supervisor who asked to go by Michael, which is not his real name, to protect the privacy of his clients.

In November 2020, a child posted in the crisis forum: “I’m 11 and my parents treat me poorly. They have told me many times to ‘kill myself’ and I didn’t let that settle well with me. ... I have tried to run away one time from my house, but they found out, so they took my phone away and put screws on my windows so I couldn’t leave.”

Increasing numbers of children told Safeline counselors that their parents were emotionally or verbally abusive, while others reported physical abuse. Some said they experienced neglect, while others had been thrown out.

“We absolutely have had youths who have either been physically kicked out of the house or just verbally told to leave,” Michael said, “and then the kid does.”

Heightened family conflicts

The Safeline partners with the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, which, despite widespread public perception, doesn’t work mainly with child abduction cases. Each year, the center assists with 29,000-31,000 cases, and 92% involve “endangered runaways,” said John Bischoff, vice president of the Missing Children Division. These children could be running away from home or foster care.

During the pandemic, the center didn’t spot major changes in its missing child numbers, “which honestly was shocking,” Mr. Bischoff said. “We figured we were either going to see an extreme rise or a decrease.

“But the reasons for the run were changing,” he said.

Many youths were fleeing out of frustration with quarantine restrictions, Mr. Bischoff said, as well as frustration with the unknown and their own lack of control over many situations.

At the runaway hotline, calls have been longer and more intense, with family problems topping the list of concerns. In 2019, about 57% of all contacts mentioned family dynamics. In 2020, that number jumped to 88%, according to Mr. Stern.

Some kids sought support for family problems that involved school. In October 2020, one 13-year-old wrote in the Safeline forum: “My mom constantly yells at me for no reason. I want to leave, but I don’t know how. I have also been really stressed about school because they haven’t been giving me the grades I would normally receive during actual school. She thinks I’m lying and that I don’t care. I just need somebody to help me.”

Many adults are under tremendous strain, too, Michael said.

“Parents might have gotten COVID last month and haven’t been able to work for 2 weeks, and they’re missing a paycheck now. Money is tight, there might not be food, everyone’s angry at everything.”

During the pandemic, the National Runaway Safeline found a 16% increase in contacts citing financial challenges.

Some children have felt confined in unsafe homes or have endured violence, as one 15-year-old reported in the forum: “I am the scapegoat out of four kids. Unfortunately, my mom has always been a toxic person. ... I’m the only kid she still hits really hard. She’s left bruises and scratches recently. ... I just have no solution to this.”

Worsening mental health

Besides family dynamics, mental health emerged as a top concern that youths reported in 2020. “This is something notable. It increased by 30% just in 1 year,” Mr. Stern said.

In November 2020, a 16-year-old wrote: “I can’t ever go outside. I’ve been stuck in the house for a very long time now since quarantine started. I’m scared. ... My mother has been taking her anger out on me emotionally. ... I have severe depression and I need help. Please, if there’s any way I can get out of here, let me know.”

The Safeline also has seen a rise in suicide-related contacts. Among children and teens who had cited a mental health concern, 18% said they were suicidal, Stern said. Most were between ages 12 and 16, but some were younger than 12.

When children couldn’t hang out with peers, they felt even more isolated if parents confiscated their phones, a common punishment, Michael said.

During the winter of 2020-21, “It felt like almost every digital contact was a youth reaching out on their Chromebook because they had gotten their phone taken away and they were either suicidal or considering running away,” he said. “That’s kind of their entire social sphere getting taken away.”

Reality check

Roughly 7 in 10 youths report still being at home when they reach out to the Safeline. Among those who do leave, Michael said, “They’re going sometimes to friends’ houses, oftentimes to a significant other’s house, sometimes to extended family members’ houses. Often, they don’t have a place that they’re planning to go. They just left, and that’s why they’re calling us.”

While some youths have been afraid of catching COVID-19 in general, the coronavirus threat hasn’t deterred those who have decided to run away, Michael said. “Usually, they’re more worried about being returned home.”

Many can’t comprehend the risks of setting off on their own.

In October 2021, a 15-year-old boy posted on the forum that his verbally abusive parents had called him a mistake and said they couldn’t wait for him to move out.

“So I’m going to make their dreams come true,” he wrote. “I’m going to go live in California with my friend who is a young YouTuber. I need help getting money to either fly or get a bus ticket, even though I’m all right with trying to ride a bike or fixing my dirt bike and getting the wagon to pull my stuff. But I’m looking for apartments in Los Angeles so I’m not living on the streets and I’m looking for a job. Please help me. My friend can’t send me money because I don’t have a bank account.”

“Often,” Michael said, “we’re reality-checking kids who want to hitchhike 5 hours away to either a friend’s or the closest shelter that we could find them. Or walk for 5 hours at 3 a.m. or bike, so we try to safety-check that.”

Another concern: online enticement by predators. During the pandemic, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children saw cases in which children ran away from home “to go meet with someone who may not be who they thought they were talking to online,” Mr. Bischoff said. “It’s certainly something we’re keeping a close eye on.”

Fewer resources in the pandemic

The National Runaway Safeline provides information and referrals to other hotlines and services, including suicide prevention and mental health organizations. When youths have already run away and have no place to go, Michael said, the Safeline tries to find shelter options or seek out a relative who can provide a safe place to stay.

But finding shelters became tougher during the pandemic, when many had no room or shelter supply was limited. Some had to shut down for COVID-19–related deep cleanings, Michael said. Helping youths find transportation, especially with public transportation shutdowns, also was tough.

The Huckleberry House, a six-bed youth shelter in San Francisco, has stayed open throughout the pandemic with limited staffing, said Douglas Styles, PsyD. He’s the executive director of the Huckleberry Youth Programs, which runs the house.

The shelter, which serves Bay Area runaway and homeless youths ages 12-17, hasn’t seen an overall spike in demand, Dr. Styles said. But “what’s expanded is undocumented [youths] and young people who don’t have any family connections in the area, so they’re unaccompanied as well. We’ve seen that here and there throughout the years, but during the pandemic, that population has actually increased quite a bit.”

The Huckleberry House has sheltered children and teens who have run away from all kinds of homes, including affluent ones, Dr. Styles said.

Once children leave home, the lack of adult supervision leaves them vulnerable. They face multiple dangers, including child sex trafficking and exploitation, substance abuse, gang involvement, and violence. “As an organization, that scares us,” Mr. Bischoff said. “What’s happening at home, we’ll sort that out. The biggest thing we as an organization are trying to do is locate them and ensure their safety.”

To help runaways and their families get in touch, the National Runaway Safeline provides a message service and conference calling. “We can play the middleman, really acting on behalf of the young person – not because they’re right or wrong, but to ensure that their voice is really heard,” Mr. Stern said.

Through its national Home Free program, the Safeline partners with Greyhound to bring children back home or into an alternative, safe living environment by providing a free bus ticket.

These days, technology can expose children to harm online, but it can also speed their return home.

“When I was growing up, if you weren’t home by 5 o’clock, Mom would start to worry, but she really didn’t have any way of reaching you,” Mr. Bischoff said. “More children today have cellphones. More children are easily reachable. That’s a benefit.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Children and COVID: The Omicron surge has become a retreat

The Omicron decline continued for a fourth consecutive week as new cases of COVID-19 in children fell by 42% from the week before, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

That 42% represents a drop from the 299,000 new cases reported for Feb. 4-10 down to 174,000 for the most recent week, Feb. 11-17.

The overall count of COVID-19 cases in children is 12.5 million over the course of the pandemic, and that represents 19% of cases reported among all ages, the AAP and CHA said based on data collected from 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Hospital admissions also continued to fall, with the rate for children aged 0-17 at 0.43 per 100,000 population as of Feb. 20, down by almost 66% from the peak of 1.25 per 100,000 reached on Jan. 16, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

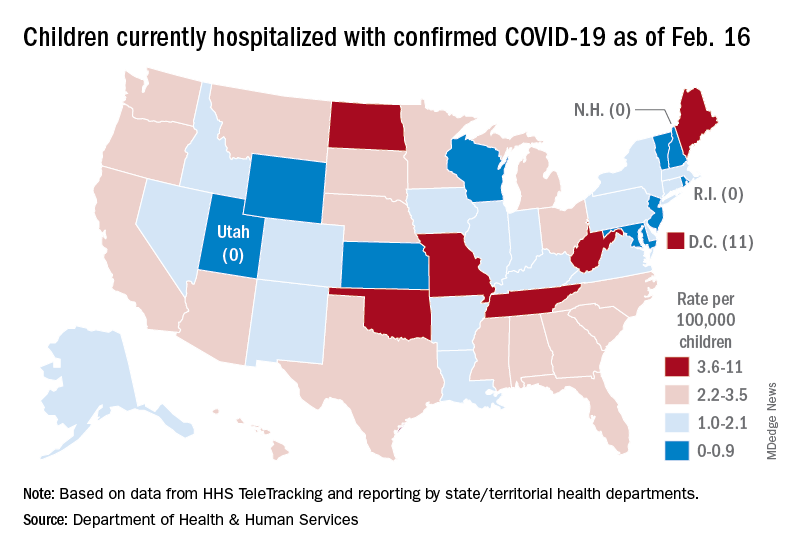

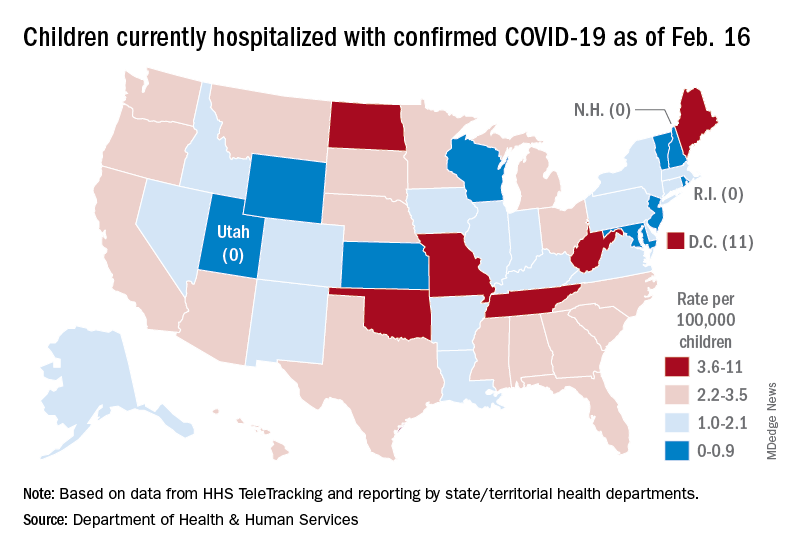

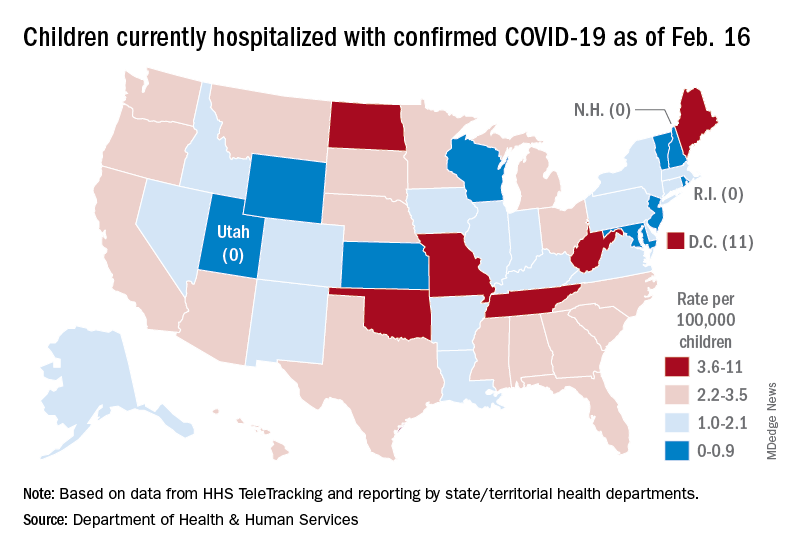

A snapshot of the hospitalization situation shows that 1,687 children were occupying inpatient beds on Feb. 16, compared with 4,070 on Jan. 19, which appears to be the peak of the Omicron surge, according to data from the Department of Health & Human Services.

The state with the highest rate – 5.6 per 100,000 children – on Feb. 16 was North Dakota, although the District of Columbia came in at 11.0 per 100,000. They were followed by Oklahoma (5.3), Missouri (5.2), and West Virginia (4.1). There were three states – New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Utah – with no children in the hospital on that date, the HHS said.

New vaccinations in children aged 5-11 years, which declined in mid- and late January, even as Omicron surged, continued to decline, as did vaccine completions. Vaccinations also fell among children aged 12-17 for the latest reporting week, Feb. 10-16, the AAP said in a separate report.

As more states and school districts drop mask mandates, data from the CDC indicate that 32.5% of 5- to 11-year olds and 67.4% of 12- to 17-year-olds have gotten at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine and that 25.1% and 57.3%, respectively, are fully vaccinated. Meanwhile, 20.5% of those fully vaccinated 12- to 17-year-olds have gotten a booster dose, the CDC said.

The Omicron decline continued for a fourth consecutive week as new cases of COVID-19 in children fell by 42% from the week before, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

That 42% represents a drop from the 299,000 new cases reported for Feb. 4-10 down to 174,000 for the most recent week, Feb. 11-17.

The overall count of COVID-19 cases in children is 12.5 million over the course of the pandemic, and that represents 19% of cases reported among all ages, the AAP and CHA said based on data collected from 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Hospital admissions also continued to fall, with the rate for children aged 0-17 at 0.43 per 100,000 population as of Feb. 20, down by almost 66% from the peak of 1.25 per 100,000 reached on Jan. 16, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

A snapshot of the hospitalization situation shows that 1,687 children were occupying inpatient beds on Feb. 16, compared with 4,070 on Jan. 19, which appears to be the peak of the Omicron surge, according to data from the Department of Health & Human Services.

The state with the highest rate – 5.6 per 100,000 children – on Feb. 16 was North Dakota, although the District of Columbia came in at 11.0 per 100,000. They were followed by Oklahoma (5.3), Missouri (5.2), and West Virginia (4.1). There were three states – New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Utah – with no children in the hospital on that date, the HHS said.

New vaccinations in children aged 5-11 years, which declined in mid- and late January, even as Omicron surged, continued to decline, as did vaccine completions. Vaccinations also fell among children aged 12-17 for the latest reporting week, Feb. 10-16, the AAP said in a separate report.

As more states and school districts drop mask mandates, data from the CDC indicate that 32.5% of 5- to 11-year olds and 67.4% of 12- to 17-year-olds have gotten at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine and that 25.1% and 57.3%, respectively, are fully vaccinated. Meanwhile, 20.5% of those fully vaccinated 12- to 17-year-olds have gotten a booster dose, the CDC said.

The Omicron decline continued for a fourth consecutive week as new cases of COVID-19 in children fell by 42% from the week before, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

That 42% represents a drop from the 299,000 new cases reported for Feb. 4-10 down to 174,000 for the most recent week, Feb. 11-17.

The overall count of COVID-19 cases in children is 12.5 million over the course of the pandemic, and that represents 19% of cases reported among all ages, the AAP and CHA said based on data collected from 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Hospital admissions also continued to fall, with the rate for children aged 0-17 at 0.43 per 100,000 population as of Feb. 20, down by almost 66% from the peak of 1.25 per 100,000 reached on Jan. 16, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

A snapshot of the hospitalization situation shows that 1,687 children were occupying inpatient beds on Feb. 16, compared with 4,070 on Jan. 19, which appears to be the peak of the Omicron surge, according to data from the Department of Health & Human Services.

The state with the highest rate – 5.6 per 100,000 children – on Feb. 16 was North Dakota, although the District of Columbia came in at 11.0 per 100,000. They were followed by Oklahoma (5.3), Missouri (5.2), and West Virginia (4.1). There were three states – New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Utah – with no children in the hospital on that date, the HHS said.

New vaccinations in children aged 5-11 years, which declined in mid- and late January, even as Omicron surged, continued to decline, as did vaccine completions. Vaccinations also fell among children aged 12-17 for the latest reporting week, Feb. 10-16, the AAP said in a separate report.

As more states and school districts drop mask mandates, data from the CDC indicate that 32.5% of 5- to 11-year olds and 67.4% of 12- to 17-year-olds have gotten at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine and that 25.1% and 57.3%, respectively, are fully vaccinated. Meanwhile, 20.5% of those fully vaccinated 12- to 17-year-olds have gotten a booster dose, the CDC said.

New MIS-C guidance addresses diagnostic challenges, cardiac care

Updated guidance for health care providers on multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) recognizes the evolving nature of the disease and offers strategies for pediatric rheumatologists, who also may be asked to recommend treatment for hyperinflammation in children with acute COVID-19.

Guidance is needed for many reasons, including the variable case definitions for MIS-C, the presence of MIS-C features in other infections and childhood rheumatic diseases, the extrapolation of treatment strategies from other conditions with similar presentations, and the issue of myocardial dysfunction, wrote Lauren A. Henderson, MD, MMSC, of Boston Children’s Hospital, and members of the American College of Rheumatology MIS-C and COVID-19–Related Hyperinflammation Task Force.

However, “modifications to treatment plans, particularly in patients with complex conditions, are highly disease, patient, geography, and time specific, and therefore must be individualized as part of a shared decision-making process,” the authors said. The updated guidance was published in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

Update needed in wake of Omicron

“We continue to see cases of MIS-C across the United States due to the spike in SARS-CoV-2 infections from the Omicron variant,” and therefore updated guidance is important at this time, Dr. Henderson told this news organization.

“MIS-C remains a serious complication of COVID-19 in children and the ACR wanted to continue to provide pediatricians with up-to-date recommendations for the management of MIS-C,” she said.

“Children began to present with MIS-C in April 2020. At that time, little was known about this entity. Most of the recommendations in the first version of the MIS-C guidance were based on expert opinion,” she explained. However, “over the last 2 years, pediatricians have worked very hard to conduct high-quality research studies to better understand MIS-C, so we now have more scientific evidence to guide our recommendations.

“In version three of the MIS-C guidance, there are new recommendations on treatment. Previously, it was unclear what medications should be used for first-line treatment in patients with MIS-C. Some children were given intravenous immunoglobulin while others were given IVIg and steroids together. Several new studies show that children with MIS-C who are treated with a combination of IVIg and steroids have better outcomes. Accordingly, the MIS-C guidance now recommends dual therapy with IVIg and steroids in children with MIS-C.”

Diagnostic evaluation

The guidance calls for maintaining a broad differential diagnosis of MIS-C, given that the condition remains rare, and that most children with COVID-19 present with mild symptoms and have excellent outcomes, the authors noted. The range of clinical features associated with MIS-C include fever, mucocutaneous findings, myocardial dysfunction, cardiac conduction abnormalities, shock, gastrointestinal symptoms, and lymphadenopathy.

Some patients also experience neurologic involvement in the form of severe headache, altered mental status, seizures, cranial nerve palsies, meningismus, cerebral edema, and ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. Given the nonspecific nature of these symptoms, “it is imperative that a diagnostic evaluation for MIS-C include investigation for other possible causes, as deemed appropriate by the treating provider,” the authors emphasized. Other diagnostic considerations include the prevalence and chronology of COVID-19 in the community, which may change over time.

MIS-C and Kawasaki disease phenotypes

Earlier in the pandemic, when MIS-C first emerged, it was compared with Kawasaki disease (KD). “However, a closer examination of the literature shows that only about one-quarter to half of patients with a reported diagnosis of MIS-C meet the full diagnostic criteria for KD,” the authors wrote. Key features that separate MIS-C from KD include the greater incidence of KD among children in Japan and East Asia versus the higher incidence of MIS-C among non-Hispanic Black children. In addition, children with MIS-C have shown a wider age range, more prominent gastrointestinal and neurologic symptoms, and more frequent cardiac dysfunction, compared with those with KD.

Cardiac management

Close follow-up with cardiology is essential for children with MIS-C, according to the authors. The recommendations call for repeat echocardiograms for all children with MIS-C at a minimum of 7-14 days, then again at 4-6 weeks after the initial presentation. The authors also recommended additional echocardiograms for children with left ventricular dysfunction and cardiac aortic aneurysms.

MIS-C treatment

Current treatment recommendations emphasize that patients under investigation for MIS-C with life-threatening manifestations may need immunomodulatory therapy before a full diagnostic evaluation is complete, the authors said. However, patients without life-threatening manifestations should be evaluated before starting immunomodulatory treatment to avoid potentially harmful therapies for pediatric patients who don’t need them.

When MIS-C is refractory to initial immunomodulatory treatment, a second dose of IVIg is not recommended, but intensification therapy is advised with either high-dose (10-30 mg/kg per day) glucocorticoids, anakinra, or infliximab. However, there is little evidence available for selecting a specific agent for intensification therapy.

The task force also advises giving low-dose aspirin (3-5 mg/kg per day, up to 81 mg once daily) to all MIS-C patients without active bleeding or significant bleeding risk until normalization of the platelet count and confirmed normal coronary arteries at least 4 weeks after diagnosis.

COVID-19 and hyperinflammation

The task force also noted a distinction between MIS-C and severe COVID-19 in children. Although many children with MIS-C are previously healthy, most children who develop severe COVID-19 during an initial infection have complex conditions or comorbidities such as developmental delay or genetic anomaly, or chronic conditions such as congenital heart disease, type 1 diabetes, or asthma, the authors said. They recommend that “hospitalized children with COVID-19 requiring supplemental oxygen or respiratory support should be considered for immunomodulatory therapy in addition to supportive care and antiviral medications.”

The authors acknowledged the limitations and evolving nature of the recommendations, which will continue to change and do not replace clinical judgment for the management of individual patients. In the meantime, the ACR will support the task force in reviewing new evidence and providing revised versions of the current document.

Many questions about MIS-C remain, Dr. Henderson said in an interview. “It can be very hard to diagnose children with MIS-C because many of the symptoms are similar to those seen in other febrile illness of childhood. We need to identify better biomarkers to help us make the diagnosis of MIS-C. In addition, we need studies to provide information about what treatments should be used if children fail to respond to IVIg and steroids. Finally, it appears that vaccination [against SARS-CoV-2] protects against severe forms of MIS-C, and studies are needed to see how vaccination protects children from MIS-C.”

The development of the guidance was supported by the American College of Rheumatology. Dr. Henderson disclosed relationships with companies including Sobi, Pfizer, and Adaptive Biotechnologies (less than $10,000) and research support from the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance and research grant support from Bristol-Myers Squibb.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Updated guidance for health care providers on multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) recognizes the evolving nature of the disease and offers strategies for pediatric rheumatologists, who also may be asked to recommend treatment for hyperinflammation in children with acute COVID-19.

Guidance is needed for many reasons, including the variable case definitions for MIS-C, the presence of MIS-C features in other infections and childhood rheumatic diseases, the extrapolation of treatment strategies from other conditions with similar presentations, and the issue of myocardial dysfunction, wrote Lauren A. Henderson, MD, MMSC, of Boston Children’s Hospital, and members of the American College of Rheumatology MIS-C and COVID-19–Related Hyperinflammation Task Force.

However, “modifications to treatment plans, particularly in patients with complex conditions, are highly disease, patient, geography, and time specific, and therefore must be individualized as part of a shared decision-making process,” the authors said. The updated guidance was published in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

Update needed in wake of Omicron

“We continue to see cases of MIS-C across the United States due to the spike in SARS-CoV-2 infections from the Omicron variant,” and therefore updated guidance is important at this time, Dr. Henderson told this news organization.

“MIS-C remains a serious complication of COVID-19 in children and the ACR wanted to continue to provide pediatricians with up-to-date recommendations for the management of MIS-C,” she said.

“Children began to present with MIS-C in April 2020. At that time, little was known about this entity. Most of the recommendations in the first version of the MIS-C guidance were based on expert opinion,” she explained. However, “over the last 2 years, pediatricians have worked very hard to conduct high-quality research studies to better understand MIS-C, so we now have more scientific evidence to guide our recommendations.

“In version three of the MIS-C guidance, there are new recommendations on treatment. Previously, it was unclear what medications should be used for first-line treatment in patients with MIS-C. Some children were given intravenous immunoglobulin while others were given IVIg and steroids together. Several new studies show that children with MIS-C who are treated with a combination of IVIg and steroids have better outcomes. Accordingly, the MIS-C guidance now recommends dual therapy with IVIg and steroids in children with MIS-C.”

Diagnostic evaluation

The guidance calls for maintaining a broad differential diagnosis of MIS-C, given that the condition remains rare, and that most children with COVID-19 present with mild symptoms and have excellent outcomes, the authors noted. The range of clinical features associated with MIS-C include fever, mucocutaneous findings, myocardial dysfunction, cardiac conduction abnormalities, shock, gastrointestinal symptoms, and lymphadenopathy.

Some patients also experience neurologic involvement in the form of severe headache, altered mental status, seizures, cranial nerve palsies, meningismus, cerebral edema, and ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. Given the nonspecific nature of these symptoms, “it is imperative that a diagnostic evaluation for MIS-C include investigation for other possible causes, as deemed appropriate by the treating provider,” the authors emphasized. Other diagnostic considerations include the prevalence and chronology of COVID-19 in the community, which may change over time.

MIS-C and Kawasaki disease phenotypes

Earlier in the pandemic, when MIS-C first emerged, it was compared with Kawasaki disease (KD). “However, a closer examination of the literature shows that only about one-quarter to half of patients with a reported diagnosis of MIS-C meet the full diagnostic criteria for KD,” the authors wrote. Key features that separate MIS-C from KD include the greater incidence of KD among children in Japan and East Asia versus the higher incidence of MIS-C among non-Hispanic Black children. In addition, children with MIS-C have shown a wider age range, more prominent gastrointestinal and neurologic symptoms, and more frequent cardiac dysfunction, compared with those with KD.

Cardiac management

Close follow-up with cardiology is essential for children with MIS-C, according to the authors. The recommendations call for repeat echocardiograms for all children with MIS-C at a minimum of 7-14 days, then again at 4-6 weeks after the initial presentation. The authors also recommended additional echocardiograms for children with left ventricular dysfunction and cardiac aortic aneurysms.

MIS-C treatment

Current treatment recommendations emphasize that patients under investigation for MIS-C with life-threatening manifestations may need immunomodulatory therapy before a full diagnostic evaluation is complete, the authors said. However, patients without life-threatening manifestations should be evaluated before starting immunomodulatory treatment to avoid potentially harmful therapies for pediatric patients who don’t need them.

When MIS-C is refractory to initial immunomodulatory treatment, a second dose of IVIg is not recommended, but intensification therapy is advised with either high-dose (10-30 mg/kg per day) glucocorticoids, anakinra, or infliximab. However, there is little evidence available for selecting a specific agent for intensification therapy.

The task force also advises giving low-dose aspirin (3-5 mg/kg per day, up to 81 mg once daily) to all MIS-C patients without active bleeding or significant bleeding risk until normalization of the platelet count and confirmed normal coronary arteries at least 4 weeks after diagnosis.

COVID-19 and hyperinflammation

The task force also noted a distinction between MIS-C and severe COVID-19 in children. Although many children with MIS-C are previously healthy, most children who develop severe COVID-19 during an initial infection have complex conditions or comorbidities such as developmental delay or genetic anomaly, or chronic conditions such as congenital heart disease, type 1 diabetes, or asthma, the authors said. They recommend that “hospitalized children with COVID-19 requiring supplemental oxygen or respiratory support should be considered for immunomodulatory therapy in addition to supportive care and antiviral medications.”

The authors acknowledged the limitations and evolving nature of the recommendations, which will continue to change and do not replace clinical judgment for the management of individual patients. In the meantime, the ACR will support the task force in reviewing new evidence and providing revised versions of the current document.

Many questions about MIS-C remain, Dr. Henderson said in an interview. “It can be very hard to diagnose children with MIS-C because many of the symptoms are similar to those seen in other febrile illness of childhood. We need to identify better biomarkers to help us make the diagnosis of MIS-C. In addition, we need studies to provide information about what treatments should be used if children fail to respond to IVIg and steroids. Finally, it appears that vaccination [against SARS-CoV-2] protects against severe forms of MIS-C, and studies are needed to see how vaccination protects children from MIS-C.”

The development of the guidance was supported by the American College of Rheumatology. Dr. Henderson disclosed relationships with companies including Sobi, Pfizer, and Adaptive Biotechnologies (less than $10,000) and research support from the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance and research grant support from Bristol-Myers Squibb.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Updated guidance for health care providers on multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) recognizes the evolving nature of the disease and offers strategies for pediatric rheumatologists, who also may be asked to recommend treatment for hyperinflammation in children with acute COVID-19.

Guidance is needed for many reasons, including the variable case definitions for MIS-C, the presence of MIS-C features in other infections and childhood rheumatic diseases, the extrapolation of treatment strategies from other conditions with similar presentations, and the issue of myocardial dysfunction, wrote Lauren A. Henderson, MD, MMSC, of Boston Children’s Hospital, and members of the American College of Rheumatology MIS-C and COVID-19–Related Hyperinflammation Task Force.

However, “modifications to treatment plans, particularly in patients with complex conditions, are highly disease, patient, geography, and time specific, and therefore must be individualized as part of a shared decision-making process,” the authors said. The updated guidance was published in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

Update needed in wake of Omicron

“We continue to see cases of MIS-C across the United States due to the spike in SARS-CoV-2 infections from the Omicron variant,” and therefore updated guidance is important at this time, Dr. Henderson told this news organization.

“MIS-C remains a serious complication of COVID-19 in children and the ACR wanted to continue to provide pediatricians with up-to-date recommendations for the management of MIS-C,” she said.

“Children began to present with MIS-C in April 2020. At that time, little was known about this entity. Most of the recommendations in the first version of the MIS-C guidance were based on expert opinion,” she explained. However, “over the last 2 years, pediatricians have worked very hard to conduct high-quality research studies to better understand MIS-C, so we now have more scientific evidence to guide our recommendations.

“In version three of the MIS-C guidance, there are new recommendations on treatment. Previously, it was unclear what medications should be used for first-line treatment in patients with MIS-C. Some children were given intravenous immunoglobulin while others were given IVIg and steroids together. Several new studies show that children with MIS-C who are treated with a combination of IVIg and steroids have better outcomes. Accordingly, the MIS-C guidance now recommends dual therapy with IVIg and steroids in children with MIS-C.”

Diagnostic evaluation

The guidance calls for maintaining a broad differential diagnosis of MIS-C, given that the condition remains rare, and that most children with COVID-19 present with mild symptoms and have excellent outcomes, the authors noted. The range of clinical features associated with MIS-C include fever, mucocutaneous findings, myocardial dysfunction, cardiac conduction abnormalities, shock, gastrointestinal symptoms, and lymphadenopathy.

Some patients also experience neurologic involvement in the form of severe headache, altered mental status, seizures, cranial nerve palsies, meningismus, cerebral edema, and ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. Given the nonspecific nature of these symptoms, “it is imperative that a diagnostic evaluation for MIS-C include investigation for other possible causes, as deemed appropriate by the treating provider,” the authors emphasized. Other diagnostic considerations include the prevalence and chronology of COVID-19 in the community, which may change over time.

MIS-C and Kawasaki disease phenotypes

Earlier in the pandemic, when MIS-C first emerged, it was compared with Kawasaki disease (KD). “However, a closer examination of the literature shows that only about one-quarter to half of patients with a reported diagnosis of MIS-C meet the full diagnostic criteria for KD,” the authors wrote. Key features that separate MIS-C from KD include the greater incidence of KD among children in Japan and East Asia versus the higher incidence of MIS-C among non-Hispanic Black children. In addition, children with MIS-C have shown a wider age range, more prominent gastrointestinal and neurologic symptoms, and more frequent cardiac dysfunction, compared with those with KD.

Cardiac management

Close follow-up with cardiology is essential for children with MIS-C, according to the authors. The recommendations call for repeat echocardiograms for all children with MIS-C at a minimum of 7-14 days, then again at 4-6 weeks after the initial presentation. The authors also recommended additional echocardiograms for children with left ventricular dysfunction and cardiac aortic aneurysms.

MIS-C treatment

Current treatment recommendations emphasize that patients under investigation for MIS-C with life-threatening manifestations may need immunomodulatory therapy before a full diagnostic evaluation is complete, the authors said. However, patients without life-threatening manifestations should be evaluated before starting immunomodulatory treatment to avoid potentially harmful therapies for pediatric patients who don’t need them.

When MIS-C is refractory to initial immunomodulatory treatment, a second dose of IVIg is not recommended, but intensification therapy is advised with either high-dose (10-30 mg/kg per day) glucocorticoids, anakinra, or infliximab. However, there is little evidence available for selecting a specific agent for intensification therapy.

The task force also advises giving low-dose aspirin (3-5 mg/kg per day, up to 81 mg once daily) to all MIS-C patients without active bleeding or significant bleeding risk until normalization of the platelet count and confirmed normal coronary arteries at least 4 weeks after diagnosis.

COVID-19 and hyperinflammation

The task force also noted a distinction between MIS-C and severe COVID-19 in children. Although many children with MIS-C are previously healthy, most children who develop severe COVID-19 during an initial infection have complex conditions or comorbidities such as developmental delay or genetic anomaly, or chronic conditions such as congenital heart disease, type 1 diabetes, or asthma, the authors said. They recommend that “hospitalized children with COVID-19 requiring supplemental oxygen or respiratory support should be considered for immunomodulatory therapy in addition to supportive care and antiviral medications.”

The authors acknowledged the limitations and evolving nature of the recommendations, which will continue to change and do not replace clinical judgment for the management of individual patients. In the meantime, the ACR will support the task force in reviewing new evidence and providing revised versions of the current document.

Many questions about MIS-C remain, Dr. Henderson said in an interview. “It can be very hard to diagnose children with MIS-C because many of the symptoms are similar to those seen in other febrile illness of childhood. We need to identify better biomarkers to help us make the diagnosis of MIS-C. In addition, we need studies to provide information about what treatments should be used if children fail to respond to IVIg and steroids. Finally, it appears that vaccination [against SARS-CoV-2] protects against severe forms of MIS-C, and studies are needed to see how vaccination protects children from MIS-C.”

The development of the guidance was supported by the American College of Rheumatology. Dr. Henderson disclosed relationships with companies including Sobi, Pfizer, and Adaptive Biotechnologies (less than $10,000) and research support from the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance and research grant support from Bristol-Myers Squibb.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ARTHRITIS AND RHEUMATOLOGY

Subvariant may be more dangerous than original Omicron strain

, a lab study from Japan says.

“Our multiscale investigations suggest that the risk of BA.2 for global health is potentially higher than that of BA.1,” the researchers said in the study published on the preprint server bioRxiv. The study has not been peer-reviewed.

The researchers infected hamsters with BA.1 and BA.2. The hamsters infected with BA.2 got sicker, with more lung damage and loss of body weight. Results were similar when mice were infected with BA.1 and BA.2.

“Infection experiments using hamsters show that BA.2 is more pathogenic than BA.1,” the study said.

BA.1 and BA.2 both appear to evade immunity created by COVID-19 vaccines, the study said. But a booster shot makes illness after infection 74% less likely, CNN said.

What’s more, therapeutic monoclonal antibodies used to treat people infected with COVID didn’t have much effect on BA.2.

BA.2 was “almost completely resistant” to casirivimab and imdevimab and was 35 times more resistant to sotrovimab, compared to the original B.1.1 virus, the researchers wrote.

“In summary, our data suggest the possibility that BA.2 would be the most concerned variant to global health,” the researchers wrote. “Currently, both BA.2 and BA.1 are recognised together as Omicron and these are almost undistinguishable. Based on our findings, we propose that BA.2 should be recognised as a unique variant of concern, and this SARS-CoV-2 variant should be monitored in depth.”

If the World Health Organization recognized BA.2 as a “unique variant of concern,” it would be given its own Greek letter.

But some scientists noted that findings in the lab don’t always reflect what’s happening in the real world of people.

“I think it’s always hard to translate differences in animal and cell culture models to what’s going on with regards to human disease,” Jeremy Kamil, PhD, an associate professor of microbiology and immunology at Louisiana State University Health Shreveport, told Newsweek. “That said, the differences do look real.”

“It might be, from a human’s perspective, a worse virus than BA.1 and might be able to transmit better and cause worse disease,” Daniel Rhoads, MD, section head of microbiology at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, told CNN. He reviewed the Japanese study but was not involved in it.

Another scientist who reviewed the study but was not involved in the research noted that human immune systems are evolving along with the COVID variants.

“One of the caveats that we have to think about, as we get new variants that might seem more dangerous, is the fact that there’s two sides to the story,” Deborah Fuller, PhD, a virologist at the University of Washington School of Medicine, told CNN. “Our immune system is evolving as well. And so that’s pushing back on things.”

Scientists have already established that BA.2 is more transmissible than BA.1. The Omicron subvariant has been detected in 74 countries and 47 U.S. states, according to CNN. About 4% of Americans with COVID were infected with BA.2, the outlet reported, citing the CDC, but it’s now the dominant strain in other nations.

It’s not clear yet if BA.2 causes more severe illness in people. While BA.2 spreads faster than BA.1, there’s no evidence the subvariant makes people any sicker, an official with the World Health Organization said, according to CNBC.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, a lab study from Japan says.

“Our multiscale investigations suggest that the risk of BA.2 for global health is potentially higher than that of BA.1,” the researchers said in the study published on the preprint server bioRxiv. The study has not been peer-reviewed.

The researchers infected hamsters with BA.1 and BA.2. The hamsters infected with BA.2 got sicker, with more lung damage and loss of body weight. Results were similar when mice were infected with BA.1 and BA.2.

“Infection experiments using hamsters show that BA.2 is more pathogenic than BA.1,” the study said.

BA.1 and BA.2 both appear to evade immunity created by COVID-19 vaccines, the study said. But a booster shot makes illness after infection 74% less likely, CNN said.

What’s more, therapeutic monoclonal antibodies used to treat people infected with COVID didn’t have much effect on BA.2.

BA.2 was “almost completely resistant” to casirivimab and imdevimab and was 35 times more resistant to sotrovimab, compared to the original B.1.1 virus, the researchers wrote.

“In summary, our data suggest the possibility that BA.2 would be the most concerned variant to global health,” the researchers wrote. “Currently, both BA.2 and BA.1 are recognised together as Omicron and these are almost undistinguishable. Based on our findings, we propose that BA.2 should be recognised as a unique variant of concern, and this SARS-CoV-2 variant should be monitored in depth.”

If the World Health Organization recognized BA.2 as a “unique variant of concern,” it would be given its own Greek letter.

But some scientists noted that findings in the lab don’t always reflect what’s happening in the real world of people.

“I think it’s always hard to translate differences in animal and cell culture models to what’s going on with regards to human disease,” Jeremy Kamil, PhD, an associate professor of microbiology and immunology at Louisiana State University Health Shreveport, told Newsweek. “That said, the differences do look real.”

“It might be, from a human’s perspective, a worse virus than BA.1 and might be able to transmit better and cause worse disease,” Daniel Rhoads, MD, section head of microbiology at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, told CNN. He reviewed the Japanese study but was not involved in it.

Another scientist who reviewed the study but was not involved in the research noted that human immune systems are evolving along with the COVID variants.

“One of the caveats that we have to think about, as we get new variants that might seem more dangerous, is the fact that there’s two sides to the story,” Deborah Fuller, PhD, a virologist at the University of Washington School of Medicine, told CNN. “Our immune system is evolving as well. And so that’s pushing back on things.”

Scientists have already established that BA.2 is more transmissible than BA.1. The Omicron subvariant has been detected in 74 countries and 47 U.S. states, according to CNN. About 4% of Americans with COVID were infected with BA.2, the outlet reported, citing the CDC, but it’s now the dominant strain in other nations.

It’s not clear yet if BA.2 causes more severe illness in people. While BA.2 spreads faster than BA.1, there’s no evidence the subvariant makes people any sicker, an official with the World Health Organization said, according to CNBC.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, a lab study from Japan says.

“Our multiscale investigations suggest that the risk of BA.2 for global health is potentially higher than that of BA.1,” the researchers said in the study published on the preprint server bioRxiv. The study has not been peer-reviewed.

The researchers infected hamsters with BA.1 and BA.2. The hamsters infected with BA.2 got sicker, with more lung damage and loss of body weight. Results were similar when mice were infected with BA.1 and BA.2.

“Infection experiments using hamsters show that BA.2 is more pathogenic than BA.1,” the study said.

BA.1 and BA.2 both appear to evade immunity created by COVID-19 vaccines, the study said. But a booster shot makes illness after infection 74% less likely, CNN said.

What’s more, therapeutic monoclonal antibodies used to treat people infected with COVID didn’t have much effect on BA.2.

BA.2 was “almost completely resistant” to casirivimab and imdevimab and was 35 times more resistant to sotrovimab, compared to the original B.1.1 virus, the researchers wrote.

“In summary, our data suggest the possibility that BA.2 would be the most concerned variant to global health,” the researchers wrote. “Currently, both BA.2 and BA.1 are recognised together as Omicron and these are almost undistinguishable. Based on our findings, we propose that BA.2 should be recognised as a unique variant of concern, and this SARS-CoV-2 variant should be monitored in depth.”

If the World Health Organization recognized BA.2 as a “unique variant of concern,” it would be given its own Greek letter.

But some scientists noted that findings in the lab don’t always reflect what’s happening in the real world of people.

“I think it’s always hard to translate differences in animal and cell culture models to what’s going on with regards to human disease,” Jeremy Kamil, PhD, an associate professor of microbiology and immunology at Louisiana State University Health Shreveport, told Newsweek. “That said, the differences do look real.”

“It might be, from a human’s perspective, a worse virus than BA.1 and might be able to transmit better and cause worse disease,” Daniel Rhoads, MD, section head of microbiology at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, told CNN. He reviewed the Japanese study but was not involved in it.

Another scientist who reviewed the study but was not involved in the research noted that human immune systems are evolving along with the COVID variants.

“One of the caveats that we have to think about, as we get new variants that might seem more dangerous, is the fact that there’s two sides to the story,” Deborah Fuller, PhD, a virologist at the University of Washington School of Medicine, told CNN. “Our immune system is evolving as well. And so that’s pushing back on things.”

Scientists have already established that BA.2 is more transmissible than BA.1. The Omicron subvariant has been detected in 74 countries and 47 U.S. states, according to CNN. About 4% of Americans with COVID were infected with BA.2, the outlet reported, citing the CDC, but it’s now the dominant strain in other nations.

It’s not clear yet if BA.2 causes more severe illness in people. While BA.2 spreads faster than BA.1, there’s no evidence the subvariant makes people any sicker, an official with the World Health Organization said, according to CNBC.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Two factors linked to higher risk of long COVID in IBD

Two features are significantly associated with a higher risk for developing long COVID symptoms among people with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), according to a large Danish population study.

People with Crohn’s disease (CD) who experienced adverse acute COVID-19, defined as requiring hospitalization, were nearly three times more likely to report persistent symptoms 12 weeks after acute infection.

“Long-term, persisting symptoms following COVID-19 is a frequently occurring problem, which is probably underappreciated. IBD specialists should therefore be aware of any of these symptoms and actively ask patients whether they have these problems,” lead author Mohamed Attauabi, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Dr. Attauabi and colleagues also found that people with ulcerative colitis (UC) who discontinued immunosuppressive agents because of COVID-19 were 1.5 times more likely to experience long COVID symptoms, a result that surprised the researchers.

“This has not been shown before and remains to be confirmed,” said Dr. Attauabi, a fellow in the department of gastroenterology at Herlev Hospital at the University of Copenhagen.

Attauabi presented the results as a digital oral presentation at the 17th congress of the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation.

A closer look at IBD and COVID-19

Large, hospital-based studies of symptoms consistent with long COVID reveal a high prevalence of fatigue, sleep difficulties, and anxiety at 12 weeks or more post acute infection. However, these were not specific to people with CD or UC, Dr. Attauabi said.

“In patients with IBD, the risk of long-term sequelae of COVID-19 remains to be investigated,” he said.

Dr. Attauabi and colleagues studied 197 people with CD and 319 with UC, all of whom had polymerase chain reaction–confirmed COVID-19. Participants were prospectively enrolled in the population-based Danish IBD-COVID registry from January 28, 2020 to April 1, 2021. At a median of 5.1 months, a subset of 85 people with CD and 137 with UC agreed to report any post-COVID symptoms.

Older age, smoking, IBD disease activity, and presence of comorbidities were not associated with a significantly elevated risk of long COVID.

In a multivariate analysis, hospitalization for COVID-19 among people with CD was significantly associated with long COVID (odds ratio, 2.76; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-3.90; P = .04).

Furthermore, people with UC who stopped taking immunosuppressive agents also had a significantly higher risk (OR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.07-10.22; P = .01).

“However, IBD medications such as systemic steroids were not associated with this outcome,” Dr. Attauabi said.

Fatigue most common long COVID symptom

Fatigue was the most common long COVID symptom, reported by 37% of patients with CD and 36% with UC.

Anosmia and ageusia were also common, reported by 29% and 28% of patients with CD, and 27% and 19% of those with UC, respectively.

“In our cohort of patients with UC or CD who developed COVID-19, the long-term health effects of COVID-19 did not appear to differ among patients with UC or CD nor according to IBD medications,” Dr. Attauabi said.

That is a “great study,” said session cochair Torsten Kucharzik, MD, PhD, head of internal medicine and gastroenterology at Lueneburg (Germany) Hospital.

When Dr. Kucharzik asked about smoking, Dr. Attauabi responded that they collected information on current and previous smoking, but they chose not to include the data because it was not statistically significant.

Dr. Attauabi has reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Kucharzik has reported receiving grants from Takeda and personal fees from companies including MSD/Essex, AbbVie, Falk Foundation, Biogen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Arena, Celgene, Celltrion, Ferring, Janssen, Galapagos, Olympus, Mundipharma, Takeda, Amgen, Pfizer, Roche, and Vifor Pharma.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two features are significantly associated with a higher risk for developing long COVID symptoms among people with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), according to a large Danish population study.

People with Crohn’s disease (CD) who experienced adverse acute COVID-19, defined as requiring hospitalization, were nearly three times more likely to report persistent symptoms 12 weeks after acute infection.

“Long-term, persisting symptoms following COVID-19 is a frequently occurring problem, which is probably underappreciated. IBD specialists should therefore be aware of any of these symptoms and actively ask patients whether they have these problems,” lead author Mohamed Attauabi, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Dr. Attauabi and colleagues also found that people with ulcerative colitis (UC) who discontinued immunosuppressive agents because of COVID-19 were 1.5 times more likely to experience long COVID symptoms, a result that surprised the researchers.

“This has not been shown before and remains to be confirmed,” said Dr. Attauabi, a fellow in the department of gastroenterology at Herlev Hospital at the University of Copenhagen.

Attauabi presented the results as a digital oral presentation at the 17th congress of the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation.

A closer look at IBD and COVID-19

Large, hospital-based studies of symptoms consistent with long COVID reveal a high prevalence of fatigue, sleep difficulties, and anxiety at 12 weeks or more post acute infection. However, these were not specific to people with CD or UC, Dr. Attauabi said.

“In patients with IBD, the risk of long-term sequelae of COVID-19 remains to be investigated,” he said.

Dr. Attauabi and colleagues studied 197 people with CD and 319 with UC, all of whom had polymerase chain reaction–confirmed COVID-19. Participants were prospectively enrolled in the population-based Danish IBD-COVID registry from January 28, 2020 to April 1, 2021. At a median of 5.1 months, a subset of 85 people with CD and 137 with UC agreed to report any post-COVID symptoms.

Older age, smoking, IBD disease activity, and presence of comorbidities were not associated with a significantly elevated risk of long COVID.

In a multivariate analysis, hospitalization for COVID-19 among people with CD was significantly associated with long COVID (odds ratio, 2.76; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-3.90; P = .04).

Furthermore, people with UC who stopped taking immunosuppressive agents also had a significantly higher risk (OR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.07-10.22; P = .01).

“However, IBD medications such as systemic steroids were not associated with this outcome,” Dr. Attauabi said.

Fatigue most common long COVID symptom

Fatigue was the most common long COVID symptom, reported by 37% of patients with CD and 36% with UC.