User login

CDC gives final approval to Omicron COVID-19 vaccine boosters

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on Sept. 1 approved the use of vaccines designed to target both Omicron and the older variants of the coronavirus, a step that may aid a goal of a widespread immunization campaign before winter arrives in the United States.

The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted 13-1 on two separate questions. One sought the panel’s backing for the use of a single dose of a new version of the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccines for people aged 12 and older. The second question dealt with a single dose of the reworked Moderna vaccine for people aged 18 and older.

The federal government wants to speed use of revamped COVID-19 shots, which the Food and Drug Administration on Sept. 1 cleared for use in the United States. Hours later, CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, agreed with the panel’s recommendation.

“The updated COVID-19 boosters are formulated to better protect against the most recently circulating COVID-19 variant,” Dr. Walensky said in a statement. “They can help restore protection that has waned since previous vaccination and were designed to provide broader protection against newer variants. This recommendation followed a comprehensive scientific evaluation and robust scientific discussion. If you are eligible, there is no bad time to get your COVID-19 booster and I strongly encourage you to receive it.”

The FDA vote on Aug. 31 expanded the emergency use authorization EUA for both Moderna and Pfizer’s original COVID-19 vaccines. The new products are also called “updated boosters.” Both contain two mRNA components of SARS-CoV-2 virus, one of the original strain and another that is found in the BA.4 and BA.5 strains of the Omicron variant, the FDA said.

Basically, the FDA cleared the way for these new boosters after it relied heavily on results of certain blood tests that suggested an immune response boost from the new formulas, plus 18 months of mostly safe use of the original versions of the shots.

What neither the FDA nor the CDC has, however, is evidence from studies in humans on how well these new vaccines work or whether they are as safe as the originals. But the FDA did consider clinical evidence for the older shots and results from studies on the new boosters that were done in mice.

ACIP Committee member Pablo Sanchez, MD, of Ohio State University was the sole “no” vote on each question.

“It’s a new vaccine, it’s a new platform. There’s a lot of hesitancy already. We need the human data,” Dr. Sanchez said.

Dr. Sanchez did not doubt that the newer versions of the vaccine would prove safe.

“I personally am in the age group where I’m at high risk and I’m almost sure that I will receive it,” Dr. Sanchez said. “I just feel that this was a bit premature, and I wish that we had seen that data. Having said that, I am comfortable that the vaccine will likely be safe like the others.”

Dr. Sanchez was not alone in raising concerns about backing new COVID-19 shots for which there is not direct clinical evidence from human studies.

Committee member Sarah Long, MD, of Drexel University in Philadelphia, said during the discussion she would “reluctantly” vote in favor of the updated vaccines. She said she believes they will have the potential to reduce hospitalizations and even deaths, even with questions remaining about the data.

Dr. Long joined other committee members in pointing to the approach to updating flu vaccines as a model. In an attempt to keep ahead of influenza, companies seek to defeat new strains through tweaks to their FDA-approved vaccines. There is not much clinical information available about these revised products, Dr. Long said. She compared it to remodeling an existing home.

“It is the same scaffolding, part of the same roof, we’re just putting in some dormers and windows,” with the revisions to the flu vaccine, she said.

Earlier in the day, committee member Jamie Loehr, MD, of Cayuga Family Medicine in Ithaca, N.Y., also used changes to the annual flu shots as the model for advancing COVID-19 shots.

“So after thinking about it, I am comfortable even though we don’t have human data,” he said.

There were several questions during the meeting about why the FDA had not convened a meeting of its Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (regarding these specific bivalent vaccines). Typically, the FDA committee of advisers considers new vaccines before the agency authorizes their use. In this case, however, the agency acted on its own.

The FDA said the committee considered the new, bivalent COVID-19 boosters in earlier meetings and that was enough outside feedback.

But holding a meeting of advisers on these specific products could have helped build public confidence in these medicines, Dorit Reiss, PhD, of the University of California Hastings College of Law, said during the public comment session of the CDC advisers’ meeting.

“We could wish the vaccines were more effective against infection, but they’re safe and they prevent hospitalization and death,” she said.

The Department of Health and Human Services anticipated the backing of ACIP. The Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response on Aug. 31 began distributing “millions of doses of the updated booster to tens of thousands of sites nationwide,” Jason Roos, PhD, chief operating officer for HHS Coordination Operations and Response Element, wrote in a blog.

“These boosters will be available at tens of thousands of vaccination sites ... including local pharmacies, their physicians’ offices, and vaccine centers operated by state and local health officials,”Dr. Roos wrote.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on Sept. 1 approved the use of vaccines designed to target both Omicron and the older variants of the coronavirus, a step that may aid a goal of a widespread immunization campaign before winter arrives in the United States.

The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted 13-1 on two separate questions. One sought the panel’s backing for the use of a single dose of a new version of the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccines for people aged 12 and older. The second question dealt with a single dose of the reworked Moderna vaccine for people aged 18 and older.

The federal government wants to speed use of revamped COVID-19 shots, which the Food and Drug Administration on Sept. 1 cleared for use in the United States. Hours later, CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, agreed with the panel’s recommendation.

“The updated COVID-19 boosters are formulated to better protect against the most recently circulating COVID-19 variant,” Dr. Walensky said in a statement. “They can help restore protection that has waned since previous vaccination and were designed to provide broader protection against newer variants. This recommendation followed a comprehensive scientific evaluation and robust scientific discussion. If you are eligible, there is no bad time to get your COVID-19 booster and I strongly encourage you to receive it.”

The FDA vote on Aug. 31 expanded the emergency use authorization EUA for both Moderna and Pfizer’s original COVID-19 vaccines. The new products are also called “updated boosters.” Both contain two mRNA components of SARS-CoV-2 virus, one of the original strain and another that is found in the BA.4 and BA.5 strains of the Omicron variant, the FDA said.

Basically, the FDA cleared the way for these new boosters after it relied heavily on results of certain blood tests that suggested an immune response boost from the new formulas, plus 18 months of mostly safe use of the original versions of the shots.

What neither the FDA nor the CDC has, however, is evidence from studies in humans on how well these new vaccines work or whether they are as safe as the originals. But the FDA did consider clinical evidence for the older shots and results from studies on the new boosters that were done in mice.

ACIP Committee member Pablo Sanchez, MD, of Ohio State University was the sole “no” vote on each question.

“It’s a new vaccine, it’s a new platform. There’s a lot of hesitancy already. We need the human data,” Dr. Sanchez said.

Dr. Sanchez did not doubt that the newer versions of the vaccine would prove safe.

“I personally am in the age group where I’m at high risk and I’m almost sure that I will receive it,” Dr. Sanchez said. “I just feel that this was a bit premature, and I wish that we had seen that data. Having said that, I am comfortable that the vaccine will likely be safe like the others.”

Dr. Sanchez was not alone in raising concerns about backing new COVID-19 shots for which there is not direct clinical evidence from human studies.

Committee member Sarah Long, MD, of Drexel University in Philadelphia, said during the discussion she would “reluctantly” vote in favor of the updated vaccines. She said she believes they will have the potential to reduce hospitalizations and even deaths, even with questions remaining about the data.

Dr. Long joined other committee members in pointing to the approach to updating flu vaccines as a model. In an attempt to keep ahead of influenza, companies seek to defeat new strains through tweaks to their FDA-approved vaccines. There is not much clinical information available about these revised products, Dr. Long said. She compared it to remodeling an existing home.

“It is the same scaffolding, part of the same roof, we’re just putting in some dormers and windows,” with the revisions to the flu vaccine, she said.

Earlier in the day, committee member Jamie Loehr, MD, of Cayuga Family Medicine in Ithaca, N.Y., also used changes to the annual flu shots as the model for advancing COVID-19 shots.

“So after thinking about it, I am comfortable even though we don’t have human data,” he said.

There were several questions during the meeting about why the FDA had not convened a meeting of its Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (regarding these specific bivalent vaccines). Typically, the FDA committee of advisers considers new vaccines before the agency authorizes their use. In this case, however, the agency acted on its own.

The FDA said the committee considered the new, bivalent COVID-19 boosters in earlier meetings and that was enough outside feedback.

But holding a meeting of advisers on these specific products could have helped build public confidence in these medicines, Dorit Reiss, PhD, of the University of California Hastings College of Law, said during the public comment session of the CDC advisers’ meeting.

“We could wish the vaccines were more effective against infection, but they’re safe and they prevent hospitalization and death,” she said.

The Department of Health and Human Services anticipated the backing of ACIP. The Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response on Aug. 31 began distributing “millions of doses of the updated booster to tens of thousands of sites nationwide,” Jason Roos, PhD, chief operating officer for HHS Coordination Operations and Response Element, wrote in a blog.

“These boosters will be available at tens of thousands of vaccination sites ... including local pharmacies, their physicians’ offices, and vaccine centers operated by state and local health officials,”Dr. Roos wrote.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on Sept. 1 approved the use of vaccines designed to target both Omicron and the older variants of the coronavirus, a step that may aid a goal of a widespread immunization campaign before winter arrives in the United States.

The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted 13-1 on two separate questions. One sought the panel’s backing for the use of a single dose of a new version of the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccines for people aged 12 and older. The second question dealt with a single dose of the reworked Moderna vaccine for people aged 18 and older.

The federal government wants to speed use of revamped COVID-19 shots, which the Food and Drug Administration on Sept. 1 cleared for use in the United States. Hours later, CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, agreed with the panel’s recommendation.

“The updated COVID-19 boosters are formulated to better protect against the most recently circulating COVID-19 variant,” Dr. Walensky said in a statement. “They can help restore protection that has waned since previous vaccination and were designed to provide broader protection against newer variants. This recommendation followed a comprehensive scientific evaluation and robust scientific discussion. If you are eligible, there is no bad time to get your COVID-19 booster and I strongly encourage you to receive it.”

The FDA vote on Aug. 31 expanded the emergency use authorization EUA for both Moderna and Pfizer’s original COVID-19 vaccines. The new products are also called “updated boosters.” Both contain two mRNA components of SARS-CoV-2 virus, one of the original strain and another that is found in the BA.4 and BA.5 strains of the Omicron variant, the FDA said.

Basically, the FDA cleared the way for these new boosters after it relied heavily on results of certain blood tests that suggested an immune response boost from the new formulas, plus 18 months of mostly safe use of the original versions of the shots.

What neither the FDA nor the CDC has, however, is evidence from studies in humans on how well these new vaccines work or whether they are as safe as the originals. But the FDA did consider clinical evidence for the older shots and results from studies on the new boosters that were done in mice.

ACIP Committee member Pablo Sanchez, MD, of Ohio State University was the sole “no” vote on each question.

“It’s a new vaccine, it’s a new platform. There’s a lot of hesitancy already. We need the human data,” Dr. Sanchez said.

Dr. Sanchez did not doubt that the newer versions of the vaccine would prove safe.

“I personally am in the age group where I’m at high risk and I’m almost sure that I will receive it,” Dr. Sanchez said. “I just feel that this was a bit premature, and I wish that we had seen that data. Having said that, I am comfortable that the vaccine will likely be safe like the others.”

Dr. Sanchez was not alone in raising concerns about backing new COVID-19 shots for which there is not direct clinical evidence from human studies.

Committee member Sarah Long, MD, of Drexel University in Philadelphia, said during the discussion she would “reluctantly” vote in favor of the updated vaccines. She said she believes they will have the potential to reduce hospitalizations and even deaths, even with questions remaining about the data.

Dr. Long joined other committee members in pointing to the approach to updating flu vaccines as a model. In an attempt to keep ahead of influenza, companies seek to defeat new strains through tweaks to their FDA-approved vaccines. There is not much clinical information available about these revised products, Dr. Long said. She compared it to remodeling an existing home.

“It is the same scaffolding, part of the same roof, we’re just putting in some dormers and windows,” with the revisions to the flu vaccine, she said.

Earlier in the day, committee member Jamie Loehr, MD, of Cayuga Family Medicine in Ithaca, N.Y., also used changes to the annual flu shots as the model for advancing COVID-19 shots.

“So after thinking about it, I am comfortable even though we don’t have human data,” he said.

There were several questions during the meeting about why the FDA had not convened a meeting of its Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (regarding these specific bivalent vaccines). Typically, the FDA committee of advisers considers new vaccines before the agency authorizes their use. In this case, however, the agency acted on its own.

The FDA said the committee considered the new, bivalent COVID-19 boosters in earlier meetings and that was enough outside feedback.

But holding a meeting of advisers on these specific products could have helped build public confidence in these medicines, Dorit Reiss, PhD, of the University of California Hastings College of Law, said during the public comment session of the CDC advisers’ meeting.

“We could wish the vaccines were more effective against infection, but they’re safe and they prevent hospitalization and death,” she said.

The Department of Health and Human Services anticipated the backing of ACIP. The Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response on Aug. 31 began distributing “millions of doses of the updated booster to tens of thousands of sites nationwide,” Jason Roos, PhD, chief operating officer for HHS Coordination Operations and Response Element, wrote in a blog.

“These boosters will be available at tens of thousands of vaccination sites ... including local pharmacies, their physicians’ offices, and vaccine centers operated by state and local health officials,”Dr. Roos wrote.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Complete Remission of Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma after COVID-19 Vaccination

Clinical Presentation

A 58-year-old male was diagnosed 6 years ago with stage IV clear cell renal carcinoma (multiple lung nodules and mediastinal adenopathy). He was offered sunitinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, and achieved a partial response with stable disease. Five years later his scans showed worsening disease. Cabozantinib was offered but was poorly tolerated. He tried ipilimumab plus nivolumab but ipilimumab was dropped after 4 cycles due to diarrhea. His scans improved with 4 more cycles of nivolumab but he had to stop immunotherapy due to hypophysitis, diarrhea, and severe jaw pain. He received a COVID-19 booster vaccine and noticed profound fatigue and anorexia soon after. Over 8 weeks he lost 56 lbs (267 to 211 lb). Relapse was suspected but PET CT showed complete resolution of his lung nodules and multiple areas of adenopathy. Asymptomatic and in remission 6 months after vaccination.

Relevant Literature

Clear cell renal carcinoma is resistant to standard chemotherapy/radiation, which usually offers partial responses. Complete remissions are few. Low glycemic diets in animal models have anticancer activity. HIV causes B cell apoptosis. Coxsackievirus A21 oncolytic properties lyse myeloma and CD138+ plasma cells via intercellular adhesion molecule interaction. SARS-CoV-2 (COVID 19) proteins have oncolytic properties.

Intervention

The patient eliminated sugary food from his diet 6 years ago. Stopped bread 2 years ago. Sunitinib 37.5 mg daily × 5 years. Cabozantinib—poorly tolerated. Ipilimumab + nivolumab × 4 cycles followed by nivolumab × 4 cycles. Stopped treatment; immune side effects. COVID-19 booster.

Outcome

15 lb weight loss due to a low glycemic diet, which began since diagnosis. After 4 years he stopped eating bread. After COVID-19 vaccine had a rapid 56 lb. weight loss, fatigue, and nausea over 8 weeks. No evidence of disease. Asymptomatic, off therapy, weight is ideal (219 lb) 6 months after the vaccine.

Implications for Practice

Effects of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) on cancers remain unknown. A few case reports of cancer remissions after infections are emerging. This is the first case of complete remission after COVID-19 vaccination in a patient on immunotherapy/low glycemic diet. Research is needed to study the contribution of a COVID-19 inflammatory response.

Clinical Presentation

A 58-year-old male was diagnosed 6 years ago with stage IV clear cell renal carcinoma (multiple lung nodules and mediastinal adenopathy). He was offered sunitinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, and achieved a partial response with stable disease. Five years later his scans showed worsening disease. Cabozantinib was offered but was poorly tolerated. He tried ipilimumab plus nivolumab but ipilimumab was dropped after 4 cycles due to diarrhea. His scans improved with 4 more cycles of nivolumab but he had to stop immunotherapy due to hypophysitis, diarrhea, and severe jaw pain. He received a COVID-19 booster vaccine and noticed profound fatigue and anorexia soon after. Over 8 weeks he lost 56 lbs (267 to 211 lb). Relapse was suspected but PET CT showed complete resolution of his lung nodules and multiple areas of adenopathy. Asymptomatic and in remission 6 months after vaccination.

Relevant Literature

Clear cell renal carcinoma is resistant to standard chemotherapy/radiation, which usually offers partial responses. Complete remissions are few. Low glycemic diets in animal models have anticancer activity. HIV causes B cell apoptosis. Coxsackievirus A21 oncolytic properties lyse myeloma and CD138+ plasma cells via intercellular adhesion molecule interaction. SARS-CoV-2 (COVID 19) proteins have oncolytic properties.

Intervention

The patient eliminated sugary food from his diet 6 years ago. Stopped bread 2 years ago. Sunitinib 37.5 mg daily × 5 years. Cabozantinib—poorly tolerated. Ipilimumab + nivolumab × 4 cycles followed by nivolumab × 4 cycles. Stopped treatment; immune side effects. COVID-19 booster.

Outcome

15 lb weight loss due to a low glycemic diet, which began since diagnosis. After 4 years he stopped eating bread. After COVID-19 vaccine had a rapid 56 lb. weight loss, fatigue, and nausea over 8 weeks. No evidence of disease. Asymptomatic, off therapy, weight is ideal (219 lb) 6 months after the vaccine.

Implications for Practice

Effects of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) on cancers remain unknown. A few case reports of cancer remissions after infections are emerging. This is the first case of complete remission after COVID-19 vaccination in a patient on immunotherapy/low glycemic diet. Research is needed to study the contribution of a COVID-19 inflammatory response.

Clinical Presentation

A 58-year-old male was diagnosed 6 years ago with stage IV clear cell renal carcinoma (multiple lung nodules and mediastinal adenopathy). He was offered sunitinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, and achieved a partial response with stable disease. Five years later his scans showed worsening disease. Cabozantinib was offered but was poorly tolerated. He tried ipilimumab plus nivolumab but ipilimumab was dropped after 4 cycles due to diarrhea. His scans improved with 4 more cycles of nivolumab but he had to stop immunotherapy due to hypophysitis, diarrhea, and severe jaw pain. He received a COVID-19 booster vaccine and noticed profound fatigue and anorexia soon after. Over 8 weeks he lost 56 lbs (267 to 211 lb). Relapse was suspected but PET CT showed complete resolution of his lung nodules and multiple areas of adenopathy. Asymptomatic and in remission 6 months after vaccination.

Relevant Literature

Clear cell renal carcinoma is resistant to standard chemotherapy/radiation, which usually offers partial responses. Complete remissions are few. Low glycemic diets in animal models have anticancer activity. HIV causes B cell apoptosis. Coxsackievirus A21 oncolytic properties lyse myeloma and CD138+ plasma cells via intercellular adhesion molecule interaction. SARS-CoV-2 (COVID 19) proteins have oncolytic properties.

Intervention

The patient eliminated sugary food from his diet 6 years ago. Stopped bread 2 years ago. Sunitinib 37.5 mg daily × 5 years. Cabozantinib—poorly tolerated. Ipilimumab + nivolumab × 4 cycles followed by nivolumab × 4 cycles. Stopped treatment; immune side effects. COVID-19 booster.

Outcome

15 lb weight loss due to a low glycemic diet, which began since diagnosis. After 4 years he stopped eating bread. After COVID-19 vaccine had a rapid 56 lb. weight loss, fatigue, and nausea over 8 weeks. No evidence of disease. Asymptomatic, off therapy, weight is ideal (219 lb) 6 months after the vaccine.

Implications for Practice

Effects of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) on cancers remain unknown. A few case reports of cancer remissions after infections are emerging. This is the first case of complete remission after COVID-19 vaccination in a patient on immunotherapy/low glycemic diet. Research is needed to study the contribution of a COVID-19 inflammatory response.

Many young kids with COVID may show no symptoms

BY WILL PASS

Just 14% of adults who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 were asymptomatic, versus 37% of children aged 0-4 years, in the paper. This raises concern that parents, childcare providers, and preschools may be underestimating infection in seemingly healthy young kids who have been exposed to COVID, wrote lead author Ruth A. Karron, MD, and colleagues in JAMA Network Open.

Methods

The new research involved 690 individuals from 175 households in Maryland who were monitored closely between November 2020 and October 2021. Every week for 8 months, participants completed online symptom checks and underwent PCR testing using nasal swabs, with symptomatic individuals submitting additional swabs for analysis.

“What was different about our study [compared with previous studies] was the intensity of our collection, and the fact that we collected specimens from asymptomatic people,” said Dr. Karron, a pediatrician and professor in the department of international health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, in an interview. “You shed more virus earlier in the infection than later, and the fact that we were sampling every single week meant that we could pick up those early infections.”

The study also stands out for its focus on young children, Dr. Karron said. Enrollment required all households to have at least one child aged 0-4 years, so 256 out of 690 participants (37.1%) were in this youngest age group. The remainder of the population consisted of 100 older children aged 5-17 years (14.5%) and 334 adults aged 18-74 years (48.4%).

Children 4 and under more than twice as likely to be asymptomatic

By the end of the study, 51 participants had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, among whom 14 had no symptoms. A closer look showed that children 0-4 years of age who contracted COVID were more than twice as likely to be asymptomatic as infected adults (36.8% vs. 14.3%).

The relationship between symptoms and viral load also differed between adults and young children.

While adults with high viral loads – suggesting greater contagiousness – typically had more severe COVID symptoms, no correlation was found in young kids, meaning children with mild or no symptoms could still be highly contagious.

Dr. Karron said these findings should help parents and other stakeholders make better-informed decisions based on known risks. She recommended testing young, asymptomatic children for COVID if they have been exposed to infected individuals, then acting accordingly based on the results.

“If a family is infected with the virus, and the 2-year-old is asymptomatic, and people are thinking about a visit to elderly grandparents who may be frail, one shouldn’t assume that the 2-year-old is uninfected,” Dr. Karron said. “That child should be tested along with other family members.”

Testing should also be considered for young children exposed to COVID at childcare facilities, she added.

But not every expert consulted for this piece shared these opinions of Dr. Karron.

“I question whether that effort is worth it,” said Dean Blumberg, MD, professor and chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at UC Davis Health, Sacramento, Calif.

He noted that recent Food and Drug Administration guidance for COVID testing calls for three negative at-home antigen tests to confirm lack of infection.

“That would take 4 days to get those tests done,” he said. “So, it’s a lot of testing. It’s a lot of record keeping, it’s inconvenient, it’s uncomfortable to be tested, and I just question whether it’s worth that effort.”

Applicability of findings to today questioned

Dr. Blumberg also questioned whether the study, which was completed almost a year ago, reflects the current pandemic landscape.

“At the time this study was done, it was predominantly Delta [variant instead of Omicron],” Dr. Blumberg said. “The other issue [with the study] is that … most of the children didn’t have preexisting immunity, so you have to take that into account.”

Preexisting immunity – whether from exposure or vaccination – could lower viral loads, so asymptomatic children today really could be less contagious than they were when the study was done, according to Dr. Blumberg. Kids without symptoms are also less likely to spread the virus, because they aren’t coughing or sneezing, he added.

Sara R. Kim, MD, and Janet A. Englund, MD, of the Seattle Children’s Research Institute, University of Washington, said it’s challenging to know how applicable the findings are, although they sided more with the investigators than Dr. Blumberg.

“Given the higher rate of transmissibility and infectivity of the Omicron variant, it is difficult to make direct associations between findings reported during this study period and those present in the current era during which the Omicron variant is circulating,” they wrote in an accompanying editorial. “However, the higher rates of asymptomatic infection observed among children in this study are likely to be consistent with those observed for current and future viral variants.”

Although the experts offered different interpretations of the findings, they shared similar perspectives on vaccination.

“The most important thing that parents can do is get their kids vaccinated, be vaccinated themselves, and have everybody in the household vaccinated and up to date for all doses that are indicated,” Dr. Blumberg said.

Dr. Karron noted that vaccination will be increasingly important in the coming months.

“Summer is ending; school is starting,” she said. “We’re going to be in large groups indoors again very soon. To keep young children safe, I think it’s really important for them to get vaccinated.”

The study was funded by the CDC. The investigators disclosed no other relationships. Dr. Englund disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and others. Dr. Kim and Dr. Blumberg disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

BY WILL PASS

Just 14% of adults who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 were asymptomatic, versus 37% of children aged 0-4 years, in the paper. This raises concern that parents, childcare providers, and preschools may be underestimating infection in seemingly healthy young kids who have been exposed to COVID, wrote lead author Ruth A. Karron, MD, and colleagues in JAMA Network Open.

Methods

The new research involved 690 individuals from 175 households in Maryland who were monitored closely between November 2020 and October 2021. Every week for 8 months, participants completed online symptom checks and underwent PCR testing using nasal swabs, with symptomatic individuals submitting additional swabs for analysis.

“What was different about our study [compared with previous studies] was the intensity of our collection, and the fact that we collected specimens from asymptomatic people,” said Dr. Karron, a pediatrician and professor in the department of international health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, in an interview. “You shed more virus earlier in the infection than later, and the fact that we were sampling every single week meant that we could pick up those early infections.”

The study also stands out for its focus on young children, Dr. Karron said. Enrollment required all households to have at least one child aged 0-4 years, so 256 out of 690 participants (37.1%) were in this youngest age group. The remainder of the population consisted of 100 older children aged 5-17 years (14.5%) and 334 adults aged 18-74 years (48.4%).

Children 4 and under more than twice as likely to be asymptomatic

By the end of the study, 51 participants had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, among whom 14 had no symptoms. A closer look showed that children 0-4 years of age who contracted COVID were more than twice as likely to be asymptomatic as infected adults (36.8% vs. 14.3%).

The relationship between symptoms and viral load also differed between adults and young children.

While adults with high viral loads – suggesting greater contagiousness – typically had more severe COVID symptoms, no correlation was found in young kids, meaning children with mild or no symptoms could still be highly contagious.

Dr. Karron said these findings should help parents and other stakeholders make better-informed decisions based on known risks. She recommended testing young, asymptomatic children for COVID if they have been exposed to infected individuals, then acting accordingly based on the results.

“If a family is infected with the virus, and the 2-year-old is asymptomatic, and people are thinking about a visit to elderly grandparents who may be frail, one shouldn’t assume that the 2-year-old is uninfected,” Dr. Karron said. “That child should be tested along with other family members.”

Testing should also be considered for young children exposed to COVID at childcare facilities, she added.

But not every expert consulted for this piece shared these opinions of Dr. Karron.

“I question whether that effort is worth it,” said Dean Blumberg, MD, professor and chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at UC Davis Health, Sacramento, Calif.

He noted that recent Food and Drug Administration guidance for COVID testing calls for three negative at-home antigen tests to confirm lack of infection.

“That would take 4 days to get those tests done,” he said. “So, it’s a lot of testing. It’s a lot of record keeping, it’s inconvenient, it’s uncomfortable to be tested, and I just question whether it’s worth that effort.”

Applicability of findings to today questioned

Dr. Blumberg also questioned whether the study, which was completed almost a year ago, reflects the current pandemic landscape.

“At the time this study was done, it was predominantly Delta [variant instead of Omicron],” Dr. Blumberg said. “The other issue [with the study] is that … most of the children didn’t have preexisting immunity, so you have to take that into account.”

Preexisting immunity – whether from exposure or vaccination – could lower viral loads, so asymptomatic children today really could be less contagious than they were when the study was done, according to Dr. Blumberg. Kids without symptoms are also less likely to spread the virus, because they aren’t coughing or sneezing, he added.

Sara R. Kim, MD, and Janet A. Englund, MD, of the Seattle Children’s Research Institute, University of Washington, said it’s challenging to know how applicable the findings are, although they sided more with the investigators than Dr. Blumberg.

“Given the higher rate of transmissibility and infectivity of the Omicron variant, it is difficult to make direct associations between findings reported during this study period and those present in the current era during which the Omicron variant is circulating,” they wrote in an accompanying editorial. “However, the higher rates of asymptomatic infection observed among children in this study are likely to be consistent with those observed for current and future viral variants.”

Although the experts offered different interpretations of the findings, they shared similar perspectives on vaccination.

“The most important thing that parents can do is get their kids vaccinated, be vaccinated themselves, and have everybody in the household vaccinated and up to date for all doses that are indicated,” Dr. Blumberg said.

Dr. Karron noted that vaccination will be increasingly important in the coming months.

“Summer is ending; school is starting,” she said. “We’re going to be in large groups indoors again very soon. To keep young children safe, I think it’s really important for them to get vaccinated.”

The study was funded by the CDC. The investigators disclosed no other relationships. Dr. Englund disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and others. Dr. Kim and Dr. Blumberg disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

BY WILL PASS

Just 14% of adults who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 were asymptomatic, versus 37% of children aged 0-4 years, in the paper. This raises concern that parents, childcare providers, and preschools may be underestimating infection in seemingly healthy young kids who have been exposed to COVID, wrote lead author Ruth A. Karron, MD, and colleagues in JAMA Network Open.

Methods

The new research involved 690 individuals from 175 households in Maryland who were monitored closely between November 2020 and October 2021. Every week for 8 months, participants completed online symptom checks and underwent PCR testing using nasal swabs, with symptomatic individuals submitting additional swabs for analysis.

“What was different about our study [compared with previous studies] was the intensity of our collection, and the fact that we collected specimens from asymptomatic people,” said Dr. Karron, a pediatrician and professor in the department of international health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, in an interview. “You shed more virus earlier in the infection than later, and the fact that we were sampling every single week meant that we could pick up those early infections.”

The study also stands out for its focus on young children, Dr. Karron said. Enrollment required all households to have at least one child aged 0-4 years, so 256 out of 690 participants (37.1%) were in this youngest age group. The remainder of the population consisted of 100 older children aged 5-17 years (14.5%) and 334 adults aged 18-74 years (48.4%).

Children 4 and under more than twice as likely to be asymptomatic

By the end of the study, 51 participants had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, among whom 14 had no symptoms. A closer look showed that children 0-4 years of age who contracted COVID were more than twice as likely to be asymptomatic as infected adults (36.8% vs. 14.3%).

The relationship between symptoms and viral load also differed between adults and young children.

While adults with high viral loads – suggesting greater contagiousness – typically had more severe COVID symptoms, no correlation was found in young kids, meaning children with mild or no symptoms could still be highly contagious.

Dr. Karron said these findings should help parents and other stakeholders make better-informed decisions based on known risks. She recommended testing young, asymptomatic children for COVID if they have been exposed to infected individuals, then acting accordingly based on the results.

“If a family is infected with the virus, and the 2-year-old is asymptomatic, and people are thinking about a visit to elderly grandparents who may be frail, one shouldn’t assume that the 2-year-old is uninfected,” Dr. Karron said. “That child should be tested along with other family members.”

Testing should also be considered for young children exposed to COVID at childcare facilities, she added.

But not every expert consulted for this piece shared these opinions of Dr. Karron.

“I question whether that effort is worth it,” said Dean Blumberg, MD, professor and chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at UC Davis Health, Sacramento, Calif.

He noted that recent Food and Drug Administration guidance for COVID testing calls for three negative at-home antigen tests to confirm lack of infection.

“That would take 4 days to get those tests done,” he said. “So, it’s a lot of testing. It’s a lot of record keeping, it’s inconvenient, it’s uncomfortable to be tested, and I just question whether it’s worth that effort.”

Applicability of findings to today questioned

Dr. Blumberg also questioned whether the study, which was completed almost a year ago, reflects the current pandemic landscape.

“At the time this study was done, it was predominantly Delta [variant instead of Omicron],” Dr. Blumberg said. “The other issue [with the study] is that … most of the children didn’t have preexisting immunity, so you have to take that into account.”

Preexisting immunity – whether from exposure or vaccination – could lower viral loads, so asymptomatic children today really could be less contagious than they were when the study was done, according to Dr. Blumberg. Kids without symptoms are also less likely to spread the virus, because they aren’t coughing or sneezing, he added.

Sara R. Kim, MD, and Janet A. Englund, MD, of the Seattle Children’s Research Institute, University of Washington, said it’s challenging to know how applicable the findings are, although they sided more with the investigators than Dr. Blumberg.

“Given the higher rate of transmissibility and infectivity of the Omicron variant, it is difficult to make direct associations between findings reported during this study period and those present in the current era during which the Omicron variant is circulating,” they wrote in an accompanying editorial. “However, the higher rates of asymptomatic infection observed among children in this study are likely to be consistent with those observed for current and future viral variants.”

Although the experts offered different interpretations of the findings, they shared similar perspectives on vaccination.

“The most important thing that parents can do is get their kids vaccinated, be vaccinated themselves, and have everybody in the household vaccinated and up to date for all doses that are indicated,” Dr. Blumberg said.

Dr. Karron noted that vaccination will be increasingly important in the coming months.

“Summer is ending; school is starting,” she said. “We’re going to be in large groups indoors again very soon. To keep young children safe, I think it’s really important for them to get vaccinated.”

The study was funded by the CDC. The investigators disclosed no other relationships. Dr. Englund disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and others. Dr. Kim and Dr. Blumberg disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

FDA authorizes updated COVID boosters to target newest variants

The agency cited data to support the safety and efficacy of this next generation of mRNA vaccines targeted toward variants of concern.

The Pfizer EUA corresponds to the company’s combination booster shot that includes the original COVID-19 vaccine as well as a vaccine specifically designed to protect against the most recent Omicron variants, BA.4 and BA.5.

The Moderna combination vaccine will contain both the firm’s original COVID-19 vaccine and a vaccine to protect specifically against Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 subvariants.

As of Aug. 27, BA.4 and BA.4.6 account for about 11% of circulating variants and BA.5 accounts for almost all the remaining 89%, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data show.

The next step will be review of the scientific data by the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, which is set to meet Sept. 1 and 2. The final hurdle before distribution of the new vaccines will be sign-off on CDC recommendations for use by agency Director Rochelle Walensky, MD.

This is a developing story. A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The agency cited data to support the safety and efficacy of this next generation of mRNA vaccines targeted toward variants of concern.

The Pfizer EUA corresponds to the company’s combination booster shot that includes the original COVID-19 vaccine as well as a vaccine specifically designed to protect against the most recent Omicron variants, BA.4 and BA.5.

The Moderna combination vaccine will contain both the firm’s original COVID-19 vaccine and a vaccine to protect specifically against Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 subvariants.

As of Aug. 27, BA.4 and BA.4.6 account for about 11% of circulating variants and BA.5 accounts for almost all the remaining 89%, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data show.

The next step will be review of the scientific data by the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, which is set to meet Sept. 1 and 2. The final hurdle before distribution of the new vaccines will be sign-off on CDC recommendations for use by agency Director Rochelle Walensky, MD.

This is a developing story. A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The agency cited data to support the safety and efficacy of this next generation of mRNA vaccines targeted toward variants of concern.

The Pfizer EUA corresponds to the company’s combination booster shot that includes the original COVID-19 vaccine as well as a vaccine specifically designed to protect against the most recent Omicron variants, BA.4 and BA.5.

The Moderna combination vaccine will contain both the firm’s original COVID-19 vaccine and a vaccine to protect specifically against Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 subvariants.

As of Aug. 27, BA.4 and BA.4.6 account for about 11% of circulating variants and BA.5 accounts for almost all the remaining 89%, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data show.

The next step will be review of the scientific data by the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, which is set to meet Sept. 1 and 2. The final hurdle before distribution of the new vaccines will be sign-off on CDC recommendations for use by agency Director Rochelle Walensky, MD.

This is a developing story. A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Children and COVID: New cases increase; hospital admissions could follow

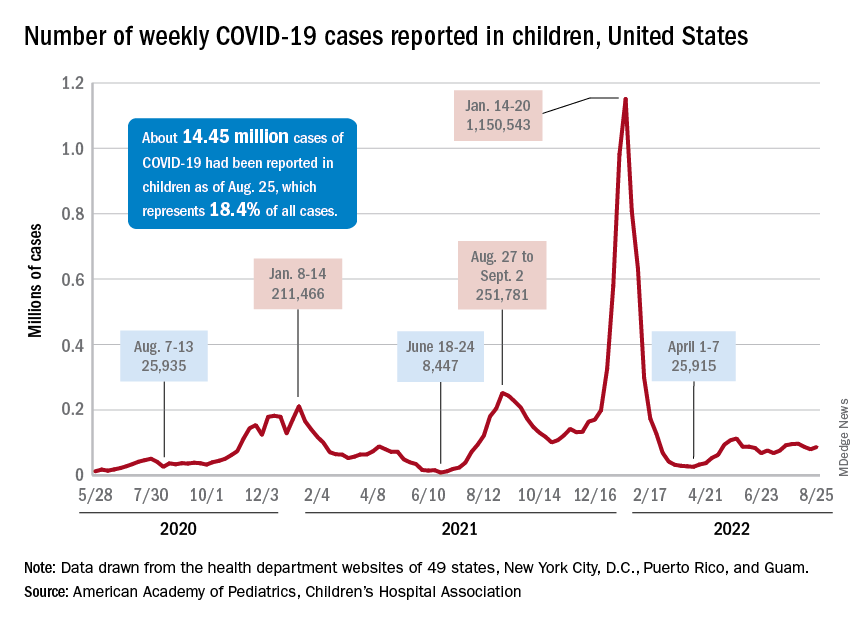

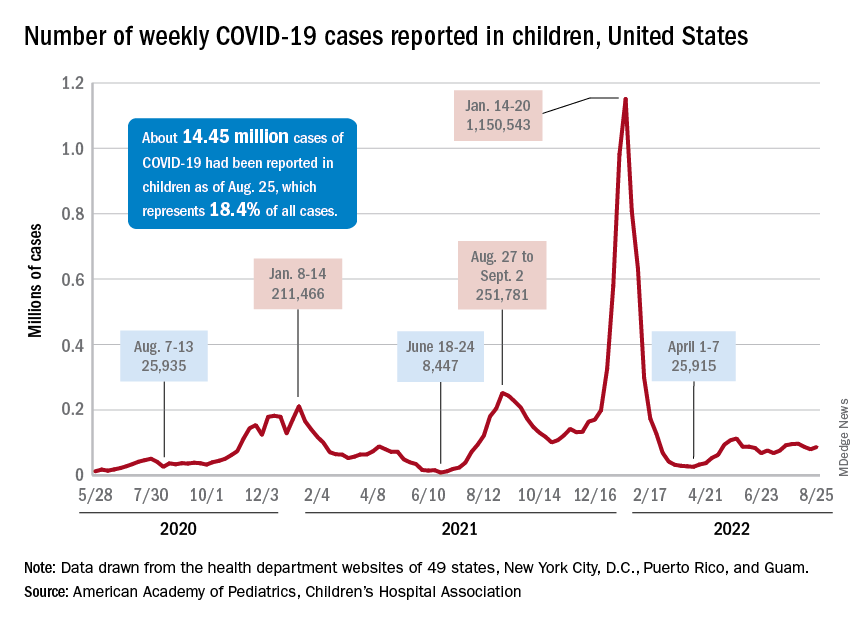

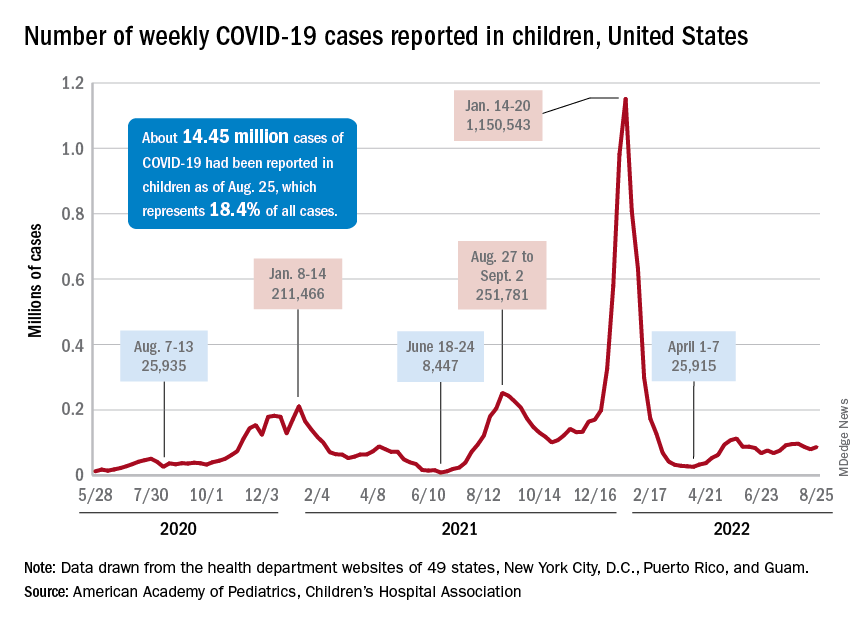

New cases of COVID-19 in children were up again after 2 weeks of declines, and preliminary data suggest that hospitalizations may be on the rise as well.

, based on data collected by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association from state and territorial health departments.

A similar increase seems to be reflected by hospital-level data. The latest 7-day (Aug. 21-27) average is 305 new admissions with diagnosed COVID per day among children aged 0-17 years, compared with 290 per day for the week of Aug. 14-20, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported, while also noting the potential for reporting delays in the most recent 7-day period.

Daily hospital admissions for COVID had been headed downward through the first half of August, falling from 0.46 per 100,000 population at the end of July to 0.40 on Aug. 19, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker. Since then, however, admissions have gone the other way, with the preliminary nature of the latest data suggesting that the numbers will be even higher as more hospitals report over the next few days.

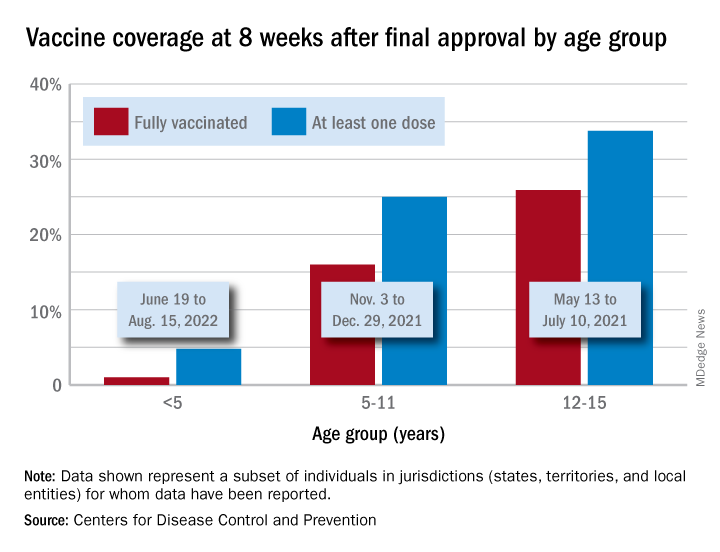

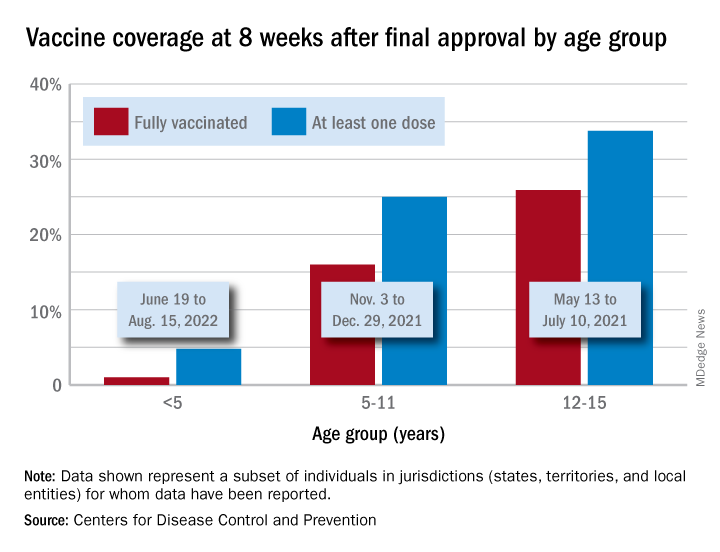

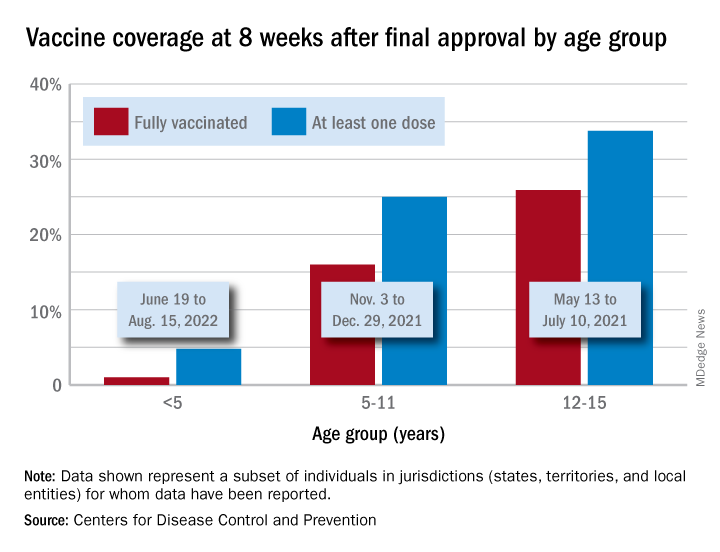

Vaccine initiations continue to fall

Initiations among school-age children have fallen for 3 consecutive weeks since Aug. 3, when numbers receiving their first vaccinations reached late-summer highs for those aged 5-11 and 12-17 years. Children under age 5, included in the CDC data for the first time on Aug. 11 as separate groups – under 2 years and 2-4 years – have had vaccine initiations drop by 8.0% and 19.8% over the 2 following weeks, the CDC said.

Through their first 8 weeks of vaccine eligibility (June 19 to Aug. 15), 4.8% of children under 5 years of age had received a first vaccination and 1.0% were fully vaccinated. For the two other age groups (5-11 and 12-15) who became eligible after the very first emergency authorization back in 2020, the respective proportions were 25.0% and 16.0% (5-11) and 33.8% and 26.1% (12-15) through the first 8 weeks, according to CDC data.

New cases of COVID-19 in children were up again after 2 weeks of declines, and preliminary data suggest that hospitalizations may be on the rise as well.

, based on data collected by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association from state and territorial health departments.

A similar increase seems to be reflected by hospital-level data. The latest 7-day (Aug. 21-27) average is 305 new admissions with diagnosed COVID per day among children aged 0-17 years, compared with 290 per day for the week of Aug. 14-20, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported, while also noting the potential for reporting delays in the most recent 7-day period.

Daily hospital admissions for COVID had been headed downward through the first half of August, falling from 0.46 per 100,000 population at the end of July to 0.40 on Aug. 19, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker. Since then, however, admissions have gone the other way, with the preliminary nature of the latest data suggesting that the numbers will be even higher as more hospitals report over the next few days.

Vaccine initiations continue to fall

Initiations among school-age children have fallen for 3 consecutive weeks since Aug. 3, when numbers receiving their first vaccinations reached late-summer highs for those aged 5-11 and 12-17 years. Children under age 5, included in the CDC data for the first time on Aug. 11 as separate groups – under 2 years and 2-4 years – have had vaccine initiations drop by 8.0% and 19.8% over the 2 following weeks, the CDC said.

Through their first 8 weeks of vaccine eligibility (June 19 to Aug. 15), 4.8% of children under 5 years of age had received a first vaccination and 1.0% were fully vaccinated. For the two other age groups (5-11 and 12-15) who became eligible after the very first emergency authorization back in 2020, the respective proportions were 25.0% and 16.0% (5-11) and 33.8% and 26.1% (12-15) through the first 8 weeks, according to CDC data.

New cases of COVID-19 in children were up again after 2 weeks of declines, and preliminary data suggest that hospitalizations may be on the rise as well.

, based on data collected by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association from state and territorial health departments.

A similar increase seems to be reflected by hospital-level data. The latest 7-day (Aug. 21-27) average is 305 new admissions with diagnosed COVID per day among children aged 0-17 years, compared with 290 per day for the week of Aug. 14-20, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported, while also noting the potential for reporting delays in the most recent 7-day period.

Daily hospital admissions for COVID had been headed downward through the first half of August, falling from 0.46 per 100,000 population at the end of July to 0.40 on Aug. 19, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker. Since then, however, admissions have gone the other way, with the preliminary nature of the latest data suggesting that the numbers will be even higher as more hospitals report over the next few days.

Vaccine initiations continue to fall

Initiations among school-age children have fallen for 3 consecutive weeks since Aug. 3, when numbers receiving their first vaccinations reached late-summer highs for those aged 5-11 and 12-17 years. Children under age 5, included in the CDC data for the first time on Aug. 11 as separate groups – under 2 years and 2-4 years – have had vaccine initiations drop by 8.0% and 19.8% over the 2 following weeks, the CDC said.

Through their first 8 weeks of vaccine eligibility (June 19 to Aug. 15), 4.8% of children under 5 years of age had received a first vaccination and 1.0% were fully vaccinated. For the two other age groups (5-11 and 12-15) who became eligible after the very first emergency authorization back in 2020, the respective proportions were 25.0% and 16.0% (5-11) and 33.8% and 26.1% (12-15) through the first 8 weeks, according to CDC data.

How do you live with COVID? One doctor’s personal experience

Early in 2020, Anne Peters, MD, caught COVID-19. The author of Medscape’s “Peters on Diabetes” column was sick in March 2020 before state-mandated lockdowns, and well before there were any vaccines.

She remembers sitting in a small exam room with two patients who had flown to her Los Angeles office from New York. The elderly couple had hearing difficulties, so Dr. Peters sat close to them, putting on a continuous glucose monitor. “At that time, we didn’t think of COVID-19 as being in L.A.,” Dr. Peters recalled, “so I think we were not terribly consistent at mask-wearing due to the need to educate.”

“Several days later, I got COVID, but I didn’t know I had COVID per se. I felt crappy, had a terrible sore throat, lost my sense of taste and smell [which was not yet described as a COVID symptom], was completely exhausted, but had no fever or cough, which were the only criteria for getting COVID tested at the time. I didn’t know I had been exposed until 2 weeks later, when the patient’s assistant returned the sensor warning us to ‘be careful’ with it because the patient and his wife were recovering from COVID.”

That early battle with COVID-19 was just the beginning of what would become a 2-year struggle, including familial loss amid her own health problems and concerns about the under-resourced patients she cares for. Here, she shares her journey through the pandemic with this news organization.

Question: Thanks for talking to us. Let’s discuss your journey over these past 2.5 years.

Answer: Everybody has their own COVID story because we all went through this together. Some of us have worse COVID stories, and some of us have better ones, but all have been impacted.

I’m not a sick person. I’m a very healthy person but COVID made me so unwell for 2 years. The brain fog and fatigue were nothing compared to the autonomic neuropathy that affected my heart. It was really limiting for me. And I still don’t know the long-term implications, looking 20-30 years from now.

Q: When you initially had COVID, what were your symptoms? What was the impact?

A: I had all the symptoms of COVID, except for a cough and fever. I lost my sense of taste and smell. I had a horrible headache, a sore throat, and I was exhausted. I couldn’t get tested because I didn’t have the right symptoms.

Despite being sick, I never stopped working but just switched to telemedicine. I also took my regular monthly trip to our cabin in Montana. I unknowingly flew on a plane with COVID. I wore a well-fitted N95 mask, so I don’t think I gave anybody COVID. I didn’t give COVID to my partner, Eric, which is hard to believe as – at 77 – he’s older than me. He has diabetes, heart disease, and every other high-risk characteristic. If he’d gotten COVID back then, it would have been terrible, as there were no treatments, but luckily he didn’t get it.

Q: When were you officially diagnosed?

A: Two or 3 months after I thought I might have had COVID, I checked my antibodies, which tested strongly positive for a prior COVID infection. That was when I knew all the symptoms I’d had were due to the disease.

Q: Not only were you dealing with your own illness, but also that of those close to you. Can you talk about that?

A: In April 2020, my mother who was in her 90s and otherwise healthy except for dementia, got COVID. She could have gotten it from me. I visited often but wore a mask. She had all the horrible pulmonary symptoms. In her advance directive, she didn’t want to be hospitalized so I kept her in her home. She died from COVID in her own bed. It was fairly brutal, but at least I kept her where she felt comforted.

My 91-year-old dad was living in a different residential facility. Throughout COVID he had become very depressed because his social patterns had changed. Prior to COVID, they all ate together, but during the pandemic they were unable to. He missed his social connections, disliked being isolated in his room, hated everyone in masks.

He was a bit demented, but not so much that he couldn’t communicate with me or remember where his grandson was going to law school. I wasn’t allowed inside the facility, which was hard on him. I hadn’t told him his wife died because the hospice social workers advised me that I shouldn’t give him news that he couldn’t process readily until I could spend time with him. Unfortunately, that time never came. In December 2020, he got COVID. One of the people in that facility had gone to the hospital, came back, and tested negative, but actually had COVID and gave it to my dad. The guy who gave it to my dad didn’t die but my dad was terribly ill. He died 2 weeks short of getting his vaccine. He was coherent enough to have a conversation. I asked him: ‘Do you want to go to the hospital?’ And he said: ‘No, because it would be too scary,’ since he couldn’t be with me. I put him on hospice and held his hand as he died from pulmonary COVID, which was awful. I couldn’t give him enough morphine or valium to ease his breathing. But his last words to me were “I love you,” and at the very end he seemed peaceful, which was a blessing.

I got an autopsy, because he wanted one. Nothing else was wrong with him other than COVID. It destroyed his lungs. The rest of him was fine – no heart disease, cancer, or anything else. He died of COVID-19, the same as my mother.

That same week, my aunt, my only surviving older relative, who was in Des Moines, Iowa, died of COVID-19. All three family members died before the vaccine came out.

It was hard to lose my parents. I’m the only surviving child because my sister died in her 20s. It’s not been an easy pandemic. But what pandemic is easy? I just happened to have lost more people than most. Ironically, my grandfather was one of the legionnaires at the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel in Philadelphia in 1976 and died of Legionnaire’s disease before we knew what was causing the outbreak.

Q: Were you still struggling with COVID?

A: COVID impacted my whole body. I lost a lot of weight. I didn’t want to eat, and my gastrointestinal system was not happy. It took a while for my sense of taste and smell to come back. Nothing tasted good. I’m not a foodie; I don’t really care about food. We could get takeout or whatever, but none of it appealed to me. I’m not so sure it was a taste thing, I just didn’t feel like eating.

I didn’t realize I had “brain fog” per se, because I felt stressed and overwhelmed by the pandemic and my patients’ concerns. But one day, about 3 months after I had developed COVID, I woke up without the fog. Which made me aware that I hadn’t been feeling right up until that point.

The worst symptoms, however, were cardiac. I noticed also immediately that my heart rate went up very quickly with minimal exertion. My pulse has always been in the 55-60 bpm range, and suddenly just walking across a room made it go up to over 140 bpm. If I did any aerobic activity, it went up over 160 and would be associated with dyspnea and chest pain. I believed these were all post-COVID symptoms and felt validated when reports of others having similar issues were published in the literature.

Q: Did you continue seeing patients?

A: Yes, of course. Patients never needed their doctors more. In East L.A., where patients don’t have easy access to telemedicine, I kept going into clinic throughout the pandemic. In the more affluent Westside of Los Angeles, we switched to telemedicine, which was quite effective for most. However, because diabetes was associated with an increased risk of hospitalization and death from COVID, my patients were understandably afraid. I’ve never been busier, but (like all health care providers), I became more of a COVID provider than a diabetologist.

Q: Do you feel your battle with COVID impacted your work?

A: It didn’t affect me at work. If I was sitting still, I was fine. Sitting at home at a desk, I didn’t notice any symptoms. But as a habitual stair-user, I would be gasping for breath in the stairwell because I couldn’t go up the stairs to my office as I once could.

I think you empathize more with people who had COVID (when you’ve had it yourself). There was such a huge patient burden. And I think that’s been the thing that’s affected health care providers the most – no matter what specialty we’re in – that nobody has answers.

Q: What happened after you had your vaccine?

A: The vaccine itself was fine. I didn’t have any reaction to the first two doses. But the first booster made my cardiac issues worse.

By this point, my cardiac problems stopped me from exercising. I even went to the ER with chest pain once because I was having palpitations and chest pressure caused by simply taking my morning shower. Fortunately, I wasn’t having an MI, but I certainly wasn’t “normal.”

My measure of my fitness is the cross-country skiing trail I use in Montana. I know exactly how far I can ski. Usually I can do the loop in 35 minutes. After COVID, I lasted 10 minutes. I would be tachycardic, short of breath with chest pain radiating down my left arm. I would rest and try to keep going. But with each rest period, I only got worse. I would be laying in the snow and strangers would ask if I needed help.

Q: What helped you?

A: I’ve read a lot about long COVID and have tried to learn from the experts. Of course, I never went to a doctor directly, although I did ask colleagues for advice. What I learned was to never push myself. I forced myself to create an exercise schedule where I only exercised three times a week with rest days in between. When exercising, the second my heart rate went above 140 bpm, I stopped until I could get it back down. I would push against this new limit, even though my limit was low.

Additionally, I worked on my breathing patterns and did meditative breathing for 10 minutes twice daily using a commercially available app.

Although progress was slow, I did improve, and by June 2022, I seemed back to normal. I was not as fit as I was prior to COVID and needed to improve, but the tachycardic response to exercise and cardiac symptoms were gone. I felt like my normal self. Normal enough to go on a spot packing trip in the Sierras in August. (Horses carried us and a mule carried the gear over the 12,000-foot pass into the mountains, and then left my friend and me high in the Sierras for a week.) We were camped above 10,000 feet and every day hiked up to another high mountain lake where we fly-fished for trout that we ate for dinner. The hikes were a challenge, but not abnormally so. Not as they would have been while I had long COVID.

Q: What is the current atmosphere in your clinic?

A: COVID is much milder now in my vaccinated patients, but I feel most health care providers are exhausted. Many of my staff left when COVID hit because they didn’t want to keep working. It made practicing medicine exhausting. There’s been a shortage of nurses, a shortage of everything. We’ve been required to do a whole lot more than we ever did before. It’s much harder to be a doctor. This pandemic is the first time I’ve ever thought of quitting. Granted, I lost my whole family, or at least the older generation, but it’s just been almost overwhelming.

On the plus side, almost every one of my patients has been vaccinated, because early on, people would ask: “Do you trust this vaccine?” I would reply: “I saw my parents die from COVID when they weren’t vaccinated, so you’re getting vaccinated. This is real and the vaccines help.” It made me very good at convincing people to get vaccines because I knew what it was like to see someone dying from COVID up close.

Q: What advice do you have for those struggling with the COVID pandemic?

A: People need to decide what their own risk is for getting sick and how many times they want to get COVID. At this point, I want people to go out, but safely. In the beginning, when my patients said, “can I go visit my granddaughter?” I said, “no,” but that was before we had the vaccine. Now I feel it is safe to go out using common sense. I still have my patients wear masks on planes. I still have patients try to eat outside as much as possible. And I tell people to take the precautions that make sense, but I tell them to go out and do things because life is short.

I had a patient in his 70s who has many risk factors like heart disease and diabetes. His granddaughter’s Bat Mitzvah in Florida was coming up. He asked: “Can I go?” I told him “Yes,” but to be safe – to wear an N95 mask on the plane and at the event, and stay in his own hotel room, rather than with the whole family. I said, “You need to do this.” Earlier in the pandemic, I saw people who literally died from loneliness and isolation.

He and his wife flew there. He sent me a picture of himself with his granddaughter. When he returned, he showed me a handwritten note from her that said, “I love you so much. Everyone else canceled, which made me cry. You’re the only one who came. You have no idea how much this meant to me.”

He’s back in L.A., and he didn’t get COVID. He said, “It was the best thing I’ve done in years.” That’s what I need to help people with, navigating this world with COVID and assessing risks and benefits. As with all of medicine, my advice is individualized. My advice changes based on the major circulating variant and the rates of the virus in the population, as well as the risk factors of the individual.

Q: What are you doing now?

A: I’m trying to avoid getting COVID again, or another booster. I could get pre-exposure monoclonal antibodies but am waiting to do anything further until I see what happens over the fall and winter. I still wear a mask inside but now do a mix of in-person and telemedicine visits. I still try to go to outdoor restaurants, which is easy in California. But I’m flying to see my son in New York and plan to go to Europe this fall for a meeting. I also go to my cabin in Montana every month to get my “dose” of the wilderness. Overall, I travel for conferences and speaking engagements much less because I have learned the joy of staying home.

Thinking back on my life as a doctor, my career began as an intern at Stanford rotating through Ward 5B, the AIDS unit at San Francisco General Hospital, and will likely end with COVID. In spite of all our medical advances, my generation of physicians, much as many generations before us, has a front-row seat to the vulnerability of humans to infectious diseases and how far we still need to go to protect our patients from communicable illness.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Anne L. Peters, MD, is a professor of medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and director of the USC clinical diabetes programs. She has published more than 200 articles, reviews, and abstracts; three books on diabetes; and has been an investigator for more than 40 research studies. She has spoken internationally at over 400 programs and serves on many committees of several professional organizations.

Early in 2020, Anne Peters, MD, caught COVID-19. The author of Medscape’s “Peters on Diabetes” column was sick in March 2020 before state-mandated lockdowns, and well before there were any vaccines.

She remembers sitting in a small exam room with two patients who had flown to her Los Angeles office from New York. The elderly couple had hearing difficulties, so Dr. Peters sat close to them, putting on a continuous glucose monitor. “At that time, we didn’t think of COVID-19 as being in L.A.,” Dr. Peters recalled, “so I think we were not terribly consistent at mask-wearing due to the need to educate.”

“Several days later, I got COVID, but I didn’t know I had COVID per se. I felt crappy, had a terrible sore throat, lost my sense of taste and smell [which was not yet described as a COVID symptom], was completely exhausted, but had no fever or cough, which were the only criteria for getting COVID tested at the time. I didn’t know I had been exposed until 2 weeks later, when the patient’s assistant returned the sensor warning us to ‘be careful’ with it because the patient and his wife were recovering from COVID.”

That early battle with COVID-19 was just the beginning of what would become a 2-year struggle, including familial loss amid her own health problems and concerns about the under-resourced patients she cares for. Here, she shares her journey through the pandemic with this news organization.

Question: Thanks for talking to us. Let’s discuss your journey over these past 2.5 years.

Answer: Everybody has their own COVID story because we all went through this together. Some of us have worse COVID stories, and some of us have better ones, but all have been impacted.

I’m not a sick person. I’m a very healthy person but COVID made me so unwell for 2 years. The brain fog and fatigue were nothing compared to the autonomic neuropathy that affected my heart. It was really limiting for me. And I still don’t know the long-term implications, looking 20-30 years from now.

Q: When you initially had COVID, what were your symptoms? What was the impact?

A: I had all the symptoms of COVID, except for a cough and fever. I lost my sense of taste and smell. I had a horrible headache, a sore throat, and I was exhausted. I couldn’t get tested because I didn’t have the right symptoms.

Despite being sick, I never stopped working but just switched to telemedicine. I also took my regular monthly trip to our cabin in Montana. I unknowingly flew on a plane with COVID. I wore a well-fitted N95 mask, so I don’t think I gave anybody COVID. I didn’t give COVID to my partner, Eric, which is hard to believe as – at 77 – he’s older than me. He has diabetes, heart disease, and every other high-risk characteristic. If he’d gotten COVID back then, it would have been terrible, as there were no treatments, but luckily he didn’t get it.

Q: When were you officially diagnosed?

A: Two or 3 months after I thought I might have had COVID, I checked my antibodies, which tested strongly positive for a prior COVID infection. That was when I knew all the symptoms I’d had were due to the disease.

Q: Not only were you dealing with your own illness, but also that of those close to you. Can you talk about that?

A: In April 2020, my mother who was in her 90s and otherwise healthy except for dementia, got COVID. She could have gotten it from me. I visited often but wore a mask. She had all the horrible pulmonary symptoms. In her advance directive, she didn’t want to be hospitalized so I kept her in her home. She died from COVID in her own bed. It was fairly brutal, but at least I kept her where she felt comforted.

My 91-year-old dad was living in a different residential facility. Throughout COVID he had become very depressed because his social patterns had changed. Prior to COVID, they all ate together, but during the pandemic they were unable to. He missed his social connections, disliked being isolated in his room, hated everyone in masks.

He was a bit demented, but not so much that he couldn’t communicate with me or remember where his grandson was going to law school. I wasn’t allowed inside the facility, which was hard on him. I hadn’t told him his wife died because the hospice social workers advised me that I shouldn’t give him news that he couldn’t process readily until I could spend time with him. Unfortunately, that time never came. In December 2020, he got COVID. One of the people in that facility had gone to the hospital, came back, and tested negative, but actually had COVID and gave it to my dad. The guy who gave it to my dad didn’t die but my dad was terribly ill. He died 2 weeks short of getting his vaccine. He was coherent enough to have a conversation. I asked him: ‘Do you want to go to the hospital?’ And he said: ‘No, because it would be too scary,’ since he couldn’t be with me. I put him on hospice and held his hand as he died from pulmonary COVID, which was awful. I couldn’t give him enough morphine or valium to ease his breathing. But his last words to me were “I love you,” and at the very end he seemed peaceful, which was a blessing.

I got an autopsy, because he wanted one. Nothing else was wrong with him other than COVID. It destroyed his lungs. The rest of him was fine – no heart disease, cancer, or anything else. He died of COVID-19, the same as my mother.

That same week, my aunt, my only surviving older relative, who was in Des Moines, Iowa, died of COVID-19. All three family members died before the vaccine came out.

It was hard to lose my parents. I’m the only surviving child because my sister died in her 20s. It’s not been an easy pandemic. But what pandemic is easy? I just happened to have lost more people than most. Ironically, my grandfather was one of the legionnaires at the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel in Philadelphia in 1976 and died of Legionnaire’s disease before we knew what was causing the outbreak.

Q: Were you still struggling with COVID?

A: COVID impacted my whole body. I lost a lot of weight. I didn’t want to eat, and my gastrointestinal system was not happy. It took a while for my sense of taste and smell to come back. Nothing tasted good. I’m not a foodie; I don’t really care about food. We could get takeout or whatever, but none of it appealed to me. I’m not so sure it was a taste thing, I just didn’t feel like eating.

I didn’t realize I had “brain fog” per se, because I felt stressed and overwhelmed by the pandemic and my patients’ concerns. But one day, about 3 months after I had developed COVID, I woke up without the fog. Which made me aware that I hadn’t been feeling right up until that point.

The worst symptoms, however, were cardiac. I noticed also immediately that my heart rate went up very quickly with minimal exertion. My pulse has always been in the 55-60 bpm range, and suddenly just walking across a room made it go up to over 140 bpm. If I did any aerobic activity, it went up over 160 and would be associated with dyspnea and chest pain. I believed these were all post-COVID symptoms and felt validated when reports of others having similar issues were published in the literature.

Q: Did you continue seeing patients?

A: Yes, of course. Patients never needed their doctors more. In East L.A., where patients don’t have easy access to telemedicine, I kept going into clinic throughout the pandemic. In the more affluent Westside of Los Angeles, we switched to telemedicine, which was quite effective for most. However, because diabetes was associated with an increased risk of hospitalization and death from COVID, my patients were understandably afraid. I’ve never been busier, but (like all health care providers), I became more of a COVID provider than a diabetologist.

Q: Do you feel your battle with COVID impacted your work?

A: It didn’t affect me at work. If I was sitting still, I was fine. Sitting at home at a desk, I didn’t notice any symptoms. But as a habitual stair-user, I would be gasping for breath in the stairwell because I couldn’t go up the stairs to my office as I once could.

I think you empathize more with people who had COVID (when you’ve had it yourself). There was such a huge patient burden. And I think that’s been the thing that’s affected health care providers the most – no matter what specialty we’re in – that nobody has answers.

Q: What happened after you had your vaccine?

A: The vaccine itself was fine. I didn’t have any reaction to the first two doses. But the first booster made my cardiac issues worse.

By this point, my cardiac problems stopped me from exercising. I even went to the ER with chest pain once because I was having palpitations and chest pressure caused by simply taking my morning shower. Fortunately, I wasn’t having an MI, but I certainly wasn’t “normal.”

My measure of my fitness is the cross-country skiing trail I use in Montana. I know exactly how far I can ski. Usually I can do the loop in 35 minutes. After COVID, I lasted 10 minutes. I would be tachycardic, short of breath with chest pain radiating down my left arm. I would rest and try to keep going. But with each rest period, I only got worse. I would be laying in the snow and strangers would ask if I needed help.

Q: What helped you?

A: I’ve read a lot about long COVID and have tried to learn from the experts. Of course, I never went to a doctor directly, although I did ask colleagues for advice. What I learned was to never push myself. I forced myself to create an exercise schedule where I only exercised three times a week with rest days in between. When exercising, the second my heart rate went above 140 bpm, I stopped until I could get it back down. I would push against this new limit, even though my limit was low.

Additionally, I worked on my breathing patterns and did meditative breathing for 10 minutes twice daily using a commercially available app.

Although progress was slow, I did improve, and by June 2022, I seemed back to normal. I was not as fit as I was prior to COVID and needed to improve, but the tachycardic response to exercise and cardiac symptoms were gone. I felt like my normal self. Normal enough to go on a spot packing trip in the Sierras in August. (Horses carried us and a mule carried the gear over the 12,000-foot pass into the mountains, and then left my friend and me high in the Sierras for a week.) We were camped above 10,000 feet and every day hiked up to another high mountain lake where we fly-fished for trout that we ate for dinner. The hikes were a challenge, but not abnormally so. Not as they would have been while I had long COVID.

Q: What is the current atmosphere in your clinic?

A: COVID is much milder now in my vaccinated patients, but I feel most health care providers are exhausted. Many of my staff left when COVID hit because they didn’t want to keep working. It made practicing medicine exhausting. There’s been a shortage of nurses, a shortage of everything. We’ve been required to do a whole lot more than we ever did before. It’s much harder to be a doctor. This pandemic is the first time I’ve ever thought of quitting. Granted, I lost my whole family, or at least the older generation, but it’s just been almost overwhelming.

On the plus side, almost every one of my patients has been vaccinated, because early on, people would ask: “Do you trust this vaccine?” I would reply: “I saw my parents die from COVID when they weren’t vaccinated, so you’re getting vaccinated. This is real and the vaccines help.” It made me very good at convincing people to get vaccines because I knew what it was like to see someone dying from COVID up close.

Q: What advice do you have for those struggling with the COVID pandemic?