User login

Effect of COVID-19 Vaccination on Disease Severity in Patients With Stable Plaque Psoriasis: A Cross-sectional Study

To the Editor:

COVID-19 infection has resulted in 6.9 million deaths worldwide. India has the third highest mortality from COVID-19 infection after the United States and Brazil.1 Vaccination plays a crucial role in containing COVID-19 infection and reducing its severity. At present, 11 vaccines have been approved by the World Health Organization. India started its vaccination program on January 16, 2021, with approval for use of Covaxin (Bharat Biotech) and Covishield (Oxford/AstraZeneca formulation)(Serum Institute of India). More than 2 billion doses have been administered since then.2,3

Patients with psoriasis are prone to develop a severe form of COVID-19 due to comorbidities and the intake of immunosuppressive drugs.4 These patients often are hesitant to receive the vaccine without an expert opinion. COVID-19 vaccines are considered to increase tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells. Tumor necrosis factor α is a key proinflammatory cytokine implicated in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. COVID-19 messenger RNA vaccines induce elevation of IL-6 and helper T cells (TH17), which can induce a flare of psoriasis in a subset of patients.5The International Psoriasis Council recommends that patients with psoriasis receive one of the vaccines approved to prevent COVID-19 infection as soon as possible.6 Reports of new-onset psoriasis and flare of psoriasis after the use of COVID-19 vaccines, such as those manufactured by Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna, and AstraZeneca, have been published from different parts of the world.7 India used locally developed whole virion inactivated BBV152 (Covaxin) and nonreplicating viral vaccine ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (Covishield) in its vaccination program and exported them to other developing countries. There is a dearth of data on the safety of these vaccines in patients with psoriasis, which needs to be assessed. Later, Covaxin, ZyCoV-D (DNA plasmid vaccine; Cadila Healthcare), and CorbeVax (protein subunit vaccine; Biological E) were approved for usage in children.8 We conducted a cross-sectional study using the direct interview method.

Patients with psoriasis who attended the outpatient department of the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (Chandigarh, India) from April 2022 to June 2022 were invited to participate in the study after written informed consent was received. Patients 18 years and older with chronic plaque psoriasis who had received a COVID-19 vaccine dose in the last 90 days were enrolled. Data on demographics, comorbidities, treatment received for psoriasis, vaccination concerns, history of COVID-19 infection, type of vaccine received with doses, adverse effects, and psoriasis flare after receiving the vaccine (considered up to 2 weeks from the date of vaccination) were collected. Ordinal logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with a psoriasis flare following vaccination. P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

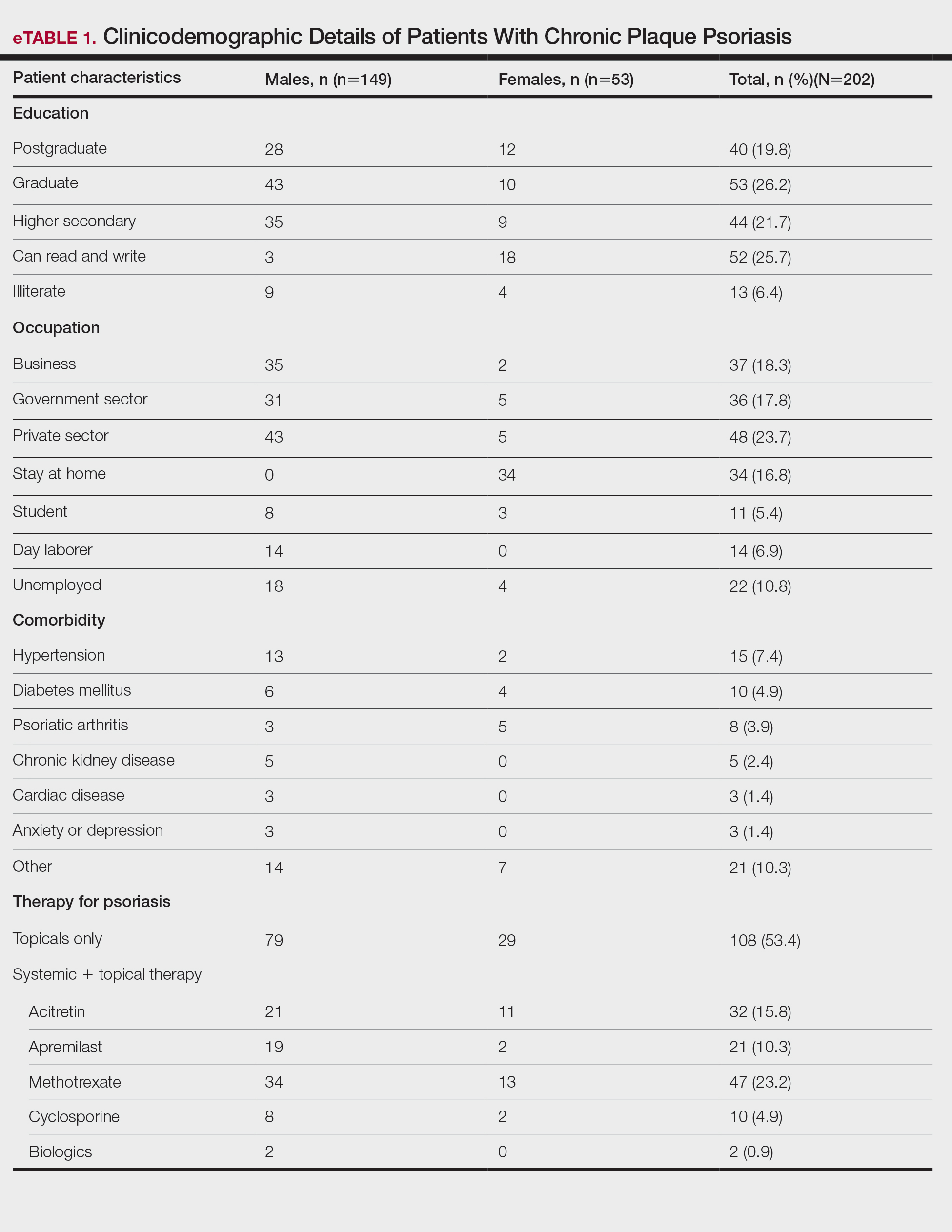

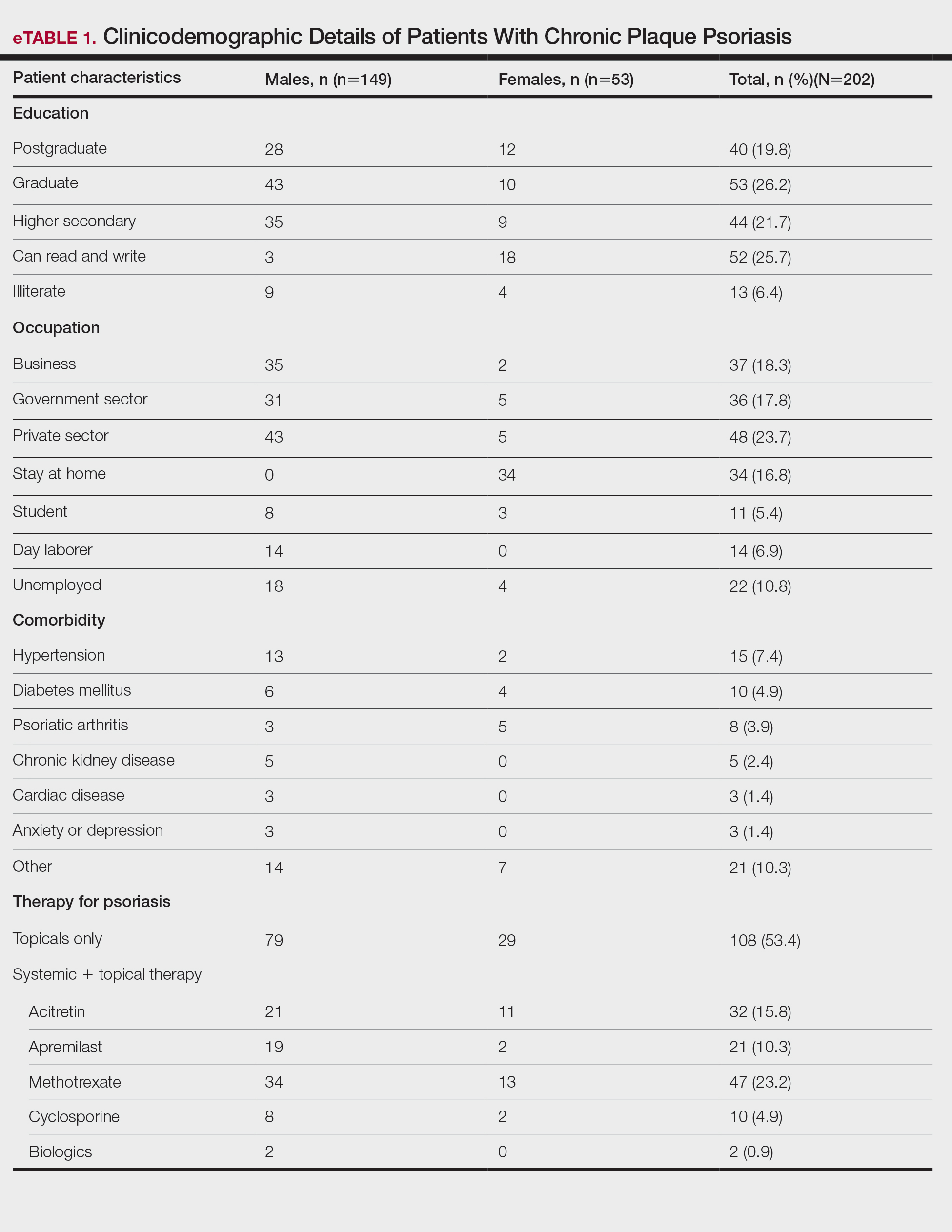

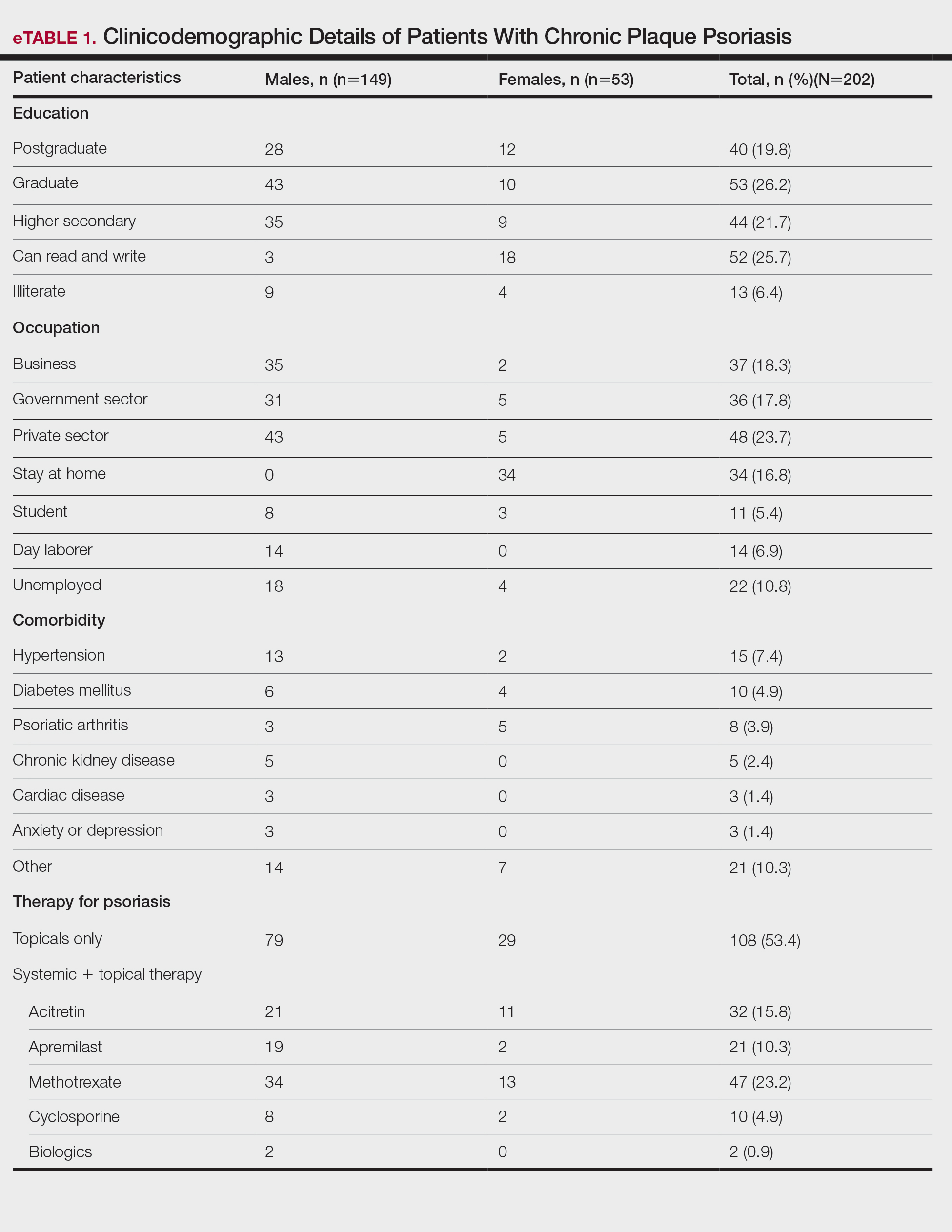

A total of 202 patients with chronic plaque psoriasis who received either Covaxin or Covishield were enrolled during the study period. The mean age (SD) was 40.3 (13.1) years, and 149 (73.8%) patients were male. One hundred thirty-five (66.8%) patients completed 2 doses of the vaccine. eTable 1 provides the clinicodemographic details of the patients. Eighty-three (41.1%) patients had a fear of psoriasis flare after vaccination. Seventy-two (35.6%) patients received the vaccine after clearance from their treating physician/dermatologist. One hundred sixty-four (81.2%) patients received the Covishield vaccine, and 38 (18.8%) patients received Covaxin. Eighty-three (41.1%) patients reported flulike symptoms, such as fever, myalgia, or body pain, within the first week of vaccination. Sixty-one (30.2%) patients reported a psoriasis flare after vaccination in the form of new lesions or worsening of pre-existing lesions. Of these patients, 51 reported a flare after receiving the first dose of vaccine, 8 patients reported a flare after receiving the second dose of vaccine, and 2 patients reported a flare after receiving both doses of vaccine. The mean (SD) flare onset was 8.1 (3.4) days after the vaccination. Eighteen patients considered the flare to be severe. Seventeen (8.4%) patients reported a positive history of COVID-19 infection before vaccination. None of the patients reported breakthrough COVID-19 infection or pustular aggravation of psoriasis following the vaccination.

The self-reported psoriasis flare after receiving the COVID-19 vaccine was significantly higher in patients who experienced immediate adverse effects (P=.005), which included fever, myalgia, joint pain, and injection-site reaction. The reported postvaccination psoriasis flare was not significantly associated with patient sex, history of COVID-19 infection, type of vaccine received, comorbidities, or therapy for psoriasis (eTable 2).

Nearly 30% of our patients reported a postvaccination psoriasis flare, which was more common after the first vaccine dose. Sotiriou et al7 reported 14 cases of psoriasis flare in patients after receiving Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna, and AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccines. These patients experienced an exacerbation of disease soon after the second dose of vaccine (mean [SD], 10.36 [7.71] days), and 21% of the 713 enrolled patients wanted to forego the immunization due to concern of a postvaccination psoriasis flare.7 In another report, 14 (27%) patients developed a psoriasis flare after COVID-19 vaccination; the mean (SD) flare onset was 9.3 (4.3) days after vaccination.9

Data on the safety of the COVID-19 vaccine in patients using immunosuppressive drugs are limited. We did not find a significant association between the psoriasis flare and use of immunosuppressive drugs or type of vaccine received. Huang and Tsai9 observed similar results, with no association between psoriasis flare and use of immunosuppressive drugs or biologics, while Damiani et al10 demonstrated a protective role of biologics in preventing vaccine-induced psoriasis flare.

Similar to another study from India,11 the immediate adverse effects due to immunization with Covaxin and Covishield were mild in our study and resolved within a week. The incidence of psoriasis flare was significantly higher in patients who reported adverse effects (P=.005). Activation of immune response after vaccination leads to the release of proinflammatory and pyrogenic cytokines (ie, IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α), which may explain the higher incidence of psoriasis flare in patients experiencing adverse effects to vaccination.12

Our study showed approximately 30% of patients developed a psoriasis flare after COVID-19 vaccination, with no patients experiencing any vaccine-related serious adverse events, which suggests that Covaxin and Covishield are safe for patients with psoriasis in India. Limitations of our study include potential inaccuracy of the patient’s self-assessment of symptoms and disease flare, recall bias that may lead to errors in estimating patient-reported outcomes, the flare of psoriasis potentially being a part of disease fluctuation, and flare being enhanced by the psychological stress of vaccination.

Considering a high risk for severe COVID-19 infection in patients with psoriasis with comorbidities and those using immunosuppressive drugs, Covaxin and Covishield can be safely recommended in India. However, caution needs to be exercised when vaccinating patients with an unstable disease or severe psoriasis.

- COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic: weekly trends. Worldometer. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

- National COVID-19 vaccination programme meets its goals by overcoming R&D and logistical challenges, says economic survey 2022-23. Government of India Press Information Bureau website. Published January 31, 2023. Accessed August 24, 2023. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1894907

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. CoWIN. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.cowin.gov.in/

- Griffiths CEM, Armstrong AW, Gudjonsson JE, et al. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2021;397:1301-1315.

- Wu D, Yang XO. TH17 responses in cytokine storm of COVID-19: anemerging target of JAK2 inhibitor fedratinib. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020;53:368-370.

- International Psoriasis Council. Revised IPC statement on COVID-19. Published December 19, 2022. Accessed August 24, 2023. https://psoriasiscouncil.org/covid-19/revised-statement-covid-19/

- Sotiriou E, Tsentemeidou A, Bakirtzi K, et al. Psoriasis exacerbation after COVID-19 vaccination: a report of 14 cases from a single centre. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:E857-E859.

- Kaul R. India clears 2 vaccines for kids under 12 years. Hindustan Times. Published April 27, 2022. Accessed August 24, 2023. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/india-clears-2-vaccines-for-kids-under-12-years-101650998027336.html

- Huang YW, Tsai TF. Exacerbation of psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination: report from a single center. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:812010.

- Damiani G, Allocco F, Young Dermatologists Italian Network, et al. COVID-19 vaccination and patients with psoriasis under biologics: real-life evidence on safety and effectiveness from Italian vaccinated healthcare workers. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;460:1106-1108.

- Joshi RK, Muralidharan CG, Gulati DS, et al. Higher incidence of reported adverse events following immunisation (AEFI) after first dose of COVID-19 vaccine among previously infected health care workers. Med J Armed Forces India. 2021;77(suppl 2):S505-S507.

- Hervé C, Laupèze B, Del Giudice G, et al. The how’s and what’s of vaccine reactogenicity. NPJ Vaccines. 2019;4:39.

To the Editor:

COVID-19 infection has resulted in 6.9 million deaths worldwide. India has the third highest mortality from COVID-19 infection after the United States and Brazil.1 Vaccination plays a crucial role in containing COVID-19 infection and reducing its severity. At present, 11 vaccines have been approved by the World Health Organization. India started its vaccination program on January 16, 2021, with approval for use of Covaxin (Bharat Biotech) and Covishield (Oxford/AstraZeneca formulation)(Serum Institute of India). More than 2 billion doses have been administered since then.2,3

Patients with psoriasis are prone to develop a severe form of COVID-19 due to comorbidities and the intake of immunosuppressive drugs.4 These patients often are hesitant to receive the vaccine without an expert opinion. COVID-19 vaccines are considered to increase tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells. Tumor necrosis factor α is a key proinflammatory cytokine implicated in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. COVID-19 messenger RNA vaccines induce elevation of IL-6 and helper T cells (TH17), which can induce a flare of psoriasis in a subset of patients.5The International Psoriasis Council recommends that patients with psoriasis receive one of the vaccines approved to prevent COVID-19 infection as soon as possible.6 Reports of new-onset psoriasis and flare of psoriasis after the use of COVID-19 vaccines, such as those manufactured by Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna, and AstraZeneca, have been published from different parts of the world.7 India used locally developed whole virion inactivated BBV152 (Covaxin) and nonreplicating viral vaccine ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (Covishield) in its vaccination program and exported them to other developing countries. There is a dearth of data on the safety of these vaccines in patients with psoriasis, which needs to be assessed. Later, Covaxin, ZyCoV-D (DNA plasmid vaccine; Cadila Healthcare), and CorbeVax (protein subunit vaccine; Biological E) were approved for usage in children.8 We conducted a cross-sectional study using the direct interview method.

Patients with psoriasis who attended the outpatient department of the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (Chandigarh, India) from April 2022 to June 2022 were invited to participate in the study after written informed consent was received. Patients 18 years and older with chronic plaque psoriasis who had received a COVID-19 vaccine dose in the last 90 days were enrolled. Data on demographics, comorbidities, treatment received for psoriasis, vaccination concerns, history of COVID-19 infection, type of vaccine received with doses, adverse effects, and psoriasis flare after receiving the vaccine (considered up to 2 weeks from the date of vaccination) were collected. Ordinal logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with a psoriasis flare following vaccination. P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 202 patients with chronic plaque psoriasis who received either Covaxin or Covishield were enrolled during the study period. The mean age (SD) was 40.3 (13.1) years, and 149 (73.8%) patients were male. One hundred thirty-five (66.8%) patients completed 2 doses of the vaccine. eTable 1 provides the clinicodemographic details of the patients. Eighty-three (41.1%) patients had a fear of psoriasis flare after vaccination. Seventy-two (35.6%) patients received the vaccine after clearance from their treating physician/dermatologist. One hundred sixty-four (81.2%) patients received the Covishield vaccine, and 38 (18.8%) patients received Covaxin. Eighty-three (41.1%) patients reported flulike symptoms, such as fever, myalgia, or body pain, within the first week of vaccination. Sixty-one (30.2%) patients reported a psoriasis flare after vaccination in the form of new lesions or worsening of pre-existing lesions. Of these patients, 51 reported a flare after receiving the first dose of vaccine, 8 patients reported a flare after receiving the second dose of vaccine, and 2 patients reported a flare after receiving both doses of vaccine. The mean (SD) flare onset was 8.1 (3.4) days after the vaccination. Eighteen patients considered the flare to be severe. Seventeen (8.4%) patients reported a positive history of COVID-19 infection before vaccination. None of the patients reported breakthrough COVID-19 infection or pustular aggravation of psoriasis following the vaccination.

The self-reported psoriasis flare after receiving the COVID-19 vaccine was significantly higher in patients who experienced immediate adverse effects (P=.005), which included fever, myalgia, joint pain, and injection-site reaction. The reported postvaccination psoriasis flare was not significantly associated with patient sex, history of COVID-19 infection, type of vaccine received, comorbidities, or therapy for psoriasis (eTable 2).

Nearly 30% of our patients reported a postvaccination psoriasis flare, which was more common after the first vaccine dose. Sotiriou et al7 reported 14 cases of psoriasis flare in patients after receiving Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna, and AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccines. These patients experienced an exacerbation of disease soon after the second dose of vaccine (mean [SD], 10.36 [7.71] days), and 21% of the 713 enrolled patients wanted to forego the immunization due to concern of a postvaccination psoriasis flare.7 In another report, 14 (27%) patients developed a psoriasis flare after COVID-19 vaccination; the mean (SD) flare onset was 9.3 (4.3) days after vaccination.9

Data on the safety of the COVID-19 vaccine in patients using immunosuppressive drugs are limited. We did not find a significant association between the psoriasis flare and use of immunosuppressive drugs or type of vaccine received. Huang and Tsai9 observed similar results, with no association between psoriasis flare and use of immunosuppressive drugs or biologics, while Damiani et al10 demonstrated a protective role of biologics in preventing vaccine-induced psoriasis flare.

Similar to another study from India,11 the immediate adverse effects due to immunization with Covaxin and Covishield were mild in our study and resolved within a week. The incidence of psoriasis flare was significantly higher in patients who reported adverse effects (P=.005). Activation of immune response after vaccination leads to the release of proinflammatory and pyrogenic cytokines (ie, IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α), which may explain the higher incidence of psoriasis flare in patients experiencing adverse effects to vaccination.12

Our study showed approximately 30% of patients developed a psoriasis flare after COVID-19 vaccination, with no patients experiencing any vaccine-related serious adverse events, which suggests that Covaxin and Covishield are safe for patients with psoriasis in India. Limitations of our study include potential inaccuracy of the patient’s self-assessment of symptoms and disease flare, recall bias that may lead to errors in estimating patient-reported outcomes, the flare of psoriasis potentially being a part of disease fluctuation, and flare being enhanced by the psychological stress of vaccination.

Considering a high risk for severe COVID-19 infection in patients with psoriasis with comorbidities and those using immunosuppressive drugs, Covaxin and Covishield can be safely recommended in India. However, caution needs to be exercised when vaccinating patients with an unstable disease or severe psoriasis.

To the Editor:

COVID-19 infection has resulted in 6.9 million deaths worldwide. India has the third highest mortality from COVID-19 infection after the United States and Brazil.1 Vaccination plays a crucial role in containing COVID-19 infection and reducing its severity. At present, 11 vaccines have been approved by the World Health Organization. India started its vaccination program on January 16, 2021, with approval for use of Covaxin (Bharat Biotech) and Covishield (Oxford/AstraZeneca formulation)(Serum Institute of India). More than 2 billion doses have been administered since then.2,3

Patients with psoriasis are prone to develop a severe form of COVID-19 due to comorbidities and the intake of immunosuppressive drugs.4 These patients often are hesitant to receive the vaccine without an expert opinion. COVID-19 vaccines are considered to increase tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells. Tumor necrosis factor α is a key proinflammatory cytokine implicated in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. COVID-19 messenger RNA vaccines induce elevation of IL-6 and helper T cells (TH17), which can induce a flare of psoriasis in a subset of patients.5The International Psoriasis Council recommends that patients with psoriasis receive one of the vaccines approved to prevent COVID-19 infection as soon as possible.6 Reports of new-onset psoriasis and flare of psoriasis after the use of COVID-19 vaccines, such as those manufactured by Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna, and AstraZeneca, have been published from different parts of the world.7 India used locally developed whole virion inactivated BBV152 (Covaxin) and nonreplicating viral vaccine ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (Covishield) in its vaccination program and exported them to other developing countries. There is a dearth of data on the safety of these vaccines in patients with psoriasis, which needs to be assessed. Later, Covaxin, ZyCoV-D (DNA plasmid vaccine; Cadila Healthcare), and CorbeVax (protein subunit vaccine; Biological E) were approved for usage in children.8 We conducted a cross-sectional study using the direct interview method.

Patients with psoriasis who attended the outpatient department of the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (Chandigarh, India) from April 2022 to June 2022 were invited to participate in the study after written informed consent was received. Patients 18 years and older with chronic plaque psoriasis who had received a COVID-19 vaccine dose in the last 90 days were enrolled. Data on demographics, comorbidities, treatment received for psoriasis, vaccination concerns, history of COVID-19 infection, type of vaccine received with doses, adverse effects, and psoriasis flare after receiving the vaccine (considered up to 2 weeks from the date of vaccination) were collected. Ordinal logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with a psoriasis flare following vaccination. P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 202 patients with chronic plaque psoriasis who received either Covaxin or Covishield were enrolled during the study period. The mean age (SD) was 40.3 (13.1) years, and 149 (73.8%) patients were male. One hundred thirty-five (66.8%) patients completed 2 doses of the vaccine. eTable 1 provides the clinicodemographic details of the patients. Eighty-three (41.1%) patients had a fear of psoriasis flare after vaccination. Seventy-two (35.6%) patients received the vaccine after clearance from their treating physician/dermatologist. One hundred sixty-four (81.2%) patients received the Covishield vaccine, and 38 (18.8%) patients received Covaxin. Eighty-three (41.1%) patients reported flulike symptoms, such as fever, myalgia, or body pain, within the first week of vaccination. Sixty-one (30.2%) patients reported a psoriasis flare after vaccination in the form of new lesions or worsening of pre-existing lesions. Of these patients, 51 reported a flare after receiving the first dose of vaccine, 8 patients reported a flare after receiving the second dose of vaccine, and 2 patients reported a flare after receiving both doses of vaccine. The mean (SD) flare onset was 8.1 (3.4) days after the vaccination. Eighteen patients considered the flare to be severe. Seventeen (8.4%) patients reported a positive history of COVID-19 infection before vaccination. None of the patients reported breakthrough COVID-19 infection or pustular aggravation of psoriasis following the vaccination.

The self-reported psoriasis flare after receiving the COVID-19 vaccine was significantly higher in patients who experienced immediate adverse effects (P=.005), which included fever, myalgia, joint pain, and injection-site reaction. The reported postvaccination psoriasis flare was not significantly associated with patient sex, history of COVID-19 infection, type of vaccine received, comorbidities, or therapy for psoriasis (eTable 2).

Nearly 30% of our patients reported a postvaccination psoriasis flare, which was more common after the first vaccine dose. Sotiriou et al7 reported 14 cases of psoriasis flare in patients after receiving Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna, and AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccines. These patients experienced an exacerbation of disease soon after the second dose of vaccine (mean [SD], 10.36 [7.71] days), and 21% of the 713 enrolled patients wanted to forego the immunization due to concern of a postvaccination psoriasis flare.7 In another report, 14 (27%) patients developed a psoriasis flare after COVID-19 vaccination; the mean (SD) flare onset was 9.3 (4.3) days after vaccination.9

Data on the safety of the COVID-19 vaccine in patients using immunosuppressive drugs are limited. We did not find a significant association between the psoriasis flare and use of immunosuppressive drugs or type of vaccine received. Huang and Tsai9 observed similar results, with no association between psoriasis flare and use of immunosuppressive drugs or biologics, while Damiani et al10 demonstrated a protective role of biologics in preventing vaccine-induced psoriasis flare.

Similar to another study from India,11 the immediate adverse effects due to immunization with Covaxin and Covishield were mild in our study and resolved within a week. The incidence of psoriasis flare was significantly higher in patients who reported adverse effects (P=.005). Activation of immune response after vaccination leads to the release of proinflammatory and pyrogenic cytokines (ie, IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α), which may explain the higher incidence of psoriasis flare in patients experiencing adverse effects to vaccination.12

Our study showed approximately 30% of patients developed a psoriasis flare after COVID-19 vaccination, with no patients experiencing any vaccine-related serious adverse events, which suggests that Covaxin and Covishield are safe for patients with psoriasis in India. Limitations of our study include potential inaccuracy of the patient’s self-assessment of symptoms and disease flare, recall bias that may lead to errors in estimating patient-reported outcomes, the flare of psoriasis potentially being a part of disease fluctuation, and flare being enhanced by the psychological stress of vaccination.

Considering a high risk for severe COVID-19 infection in patients with psoriasis with comorbidities and those using immunosuppressive drugs, Covaxin and Covishield can be safely recommended in India. However, caution needs to be exercised when vaccinating patients with an unstable disease or severe psoriasis.

- COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic: weekly trends. Worldometer. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

- National COVID-19 vaccination programme meets its goals by overcoming R&D and logistical challenges, says economic survey 2022-23. Government of India Press Information Bureau website. Published January 31, 2023. Accessed August 24, 2023. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1894907

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. CoWIN. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.cowin.gov.in/

- Griffiths CEM, Armstrong AW, Gudjonsson JE, et al. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2021;397:1301-1315.

- Wu D, Yang XO. TH17 responses in cytokine storm of COVID-19: anemerging target of JAK2 inhibitor fedratinib. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020;53:368-370.

- International Psoriasis Council. Revised IPC statement on COVID-19. Published December 19, 2022. Accessed August 24, 2023. https://psoriasiscouncil.org/covid-19/revised-statement-covid-19/

- Sotiriou E, Tsentemeidou A, Bakirtzi K, et al. Psoriasis exacerbation after COVID-19 vaccination: a report of 14 cases from a single centre. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:E857-E859.

- Kaul R. India clears 2 vaccines for kids under 12 years. Hindustan Times. Published April 27, 2022. Accessed August 24, 2023. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/india-clears-2-vaccines-for-kids-under-12-years-101650998027336.html

- Huang YW, Tsai TF. Exacerbation of psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination: report from a single center. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:812010.

- Damiani G, Allocco F, Young Dermatologists Italian Network, et al. COVID-19 vaccination and patients with psoriasis under biologics: real-life evidence on safety and effectiveness from Italian vaccinated healthcare workers. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;460:1106-1108.

- Joshi RK, Muralidharan CG, Gulati DS, et al. Higher incidence of reported adverse events following immunisation (AEFI) after first dose of COVID-19 vaccine among previously infected health care workers. Med J Armed Forces India. 2021;77(suppl 2):S505-S507.

- Hervé C, Laupèze B, Del Giudice G, et al. The how’s and what’s of vaccine reactogenicity. NPJ Vaccines. 2019;4:39.

- COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic: weekly trends. Worldometer. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

- National COVID-19 vaccination programme meets its goals by overcoming R&D and logistical challenges, says economic survey 2022-23. Government of India Press Information Bureau website. Published January 31, 2023. Accessed August 24, 2023. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1894907

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. CoWIN. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.cowin.gov.in/

- Griffiths CEM, Armstrong AW, Gudjonsson JE, et al. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2021;397:1301-1315.

- Wu D, Yang XO. TH17 responses in cytokine storm of COVID-19: anemerging target of JAK2 inhibitor fedratinib. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020;53:368-370.

- International Psoriasis Council. Revised IPC statement on COVID-19. Published December 19, 2022. Accessed August 24, 2023. https://psoriasiscouncil.org/covid-19/revised-statement-covid-19/

- Sotiriou E, Tsentemeidou A, Bakirtzi K, et al. Psoriasis exacerbation after COVID-19 vaccination: a report of 14 cases from a single centre. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:E857-E859.

- Kaul R. India clears 2 vaccines for kids under 12 years. Hindustan Times. Published April 27, 2022. Accessed August 24, 2023. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/india-clears-2-vaccines-for-kids-under-12-years-101650998027336.html

- Huang YW, Tsai TF. Exacerbation of psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination: report from a single center. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:812010.

- Damiani G, Allocco F, Young Dermatologists Italian Network, et al. COVID-19 vaccination and patients with psoriasis under biologics: real-life evidence on safety and effectiveness from Italian vaccinated healthcare workers. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;460:1106-1108.

- Joshi RK, Muralidharan CG, Gulati DS, et al. Higher incidence of reported adverse events following immunisation (AEFI) after first dose of COVID-19 vaccine among previously infected health care workers. Med J Armed Forces India. 2021;77(suppl 2):S505-S507.

- Hervé C, Laupèze B, Del Giudice G, et al. The how’s and what’s of vaccine reactogenicity. NPJ Vaccines. 2019;4:39.

Practice Points

- Vaccines are known to induce a psoriasis flare.

- Given the high risk for severe COVID infection in individuals with psoriasis who have comorbidities, vaccination with Covaxin and Covishield can be safely recommended in India for this population.

Q&A: What to know about the new BA 2.86 COVID variant

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization have dubbed the BA 2.86 variant of COVID-19 as a variant to watch.

So far, only 26 cases of “Pirola,” as the new variant is being called, have been identified: 10 in Denmark, four each in Sweden and the United States, three in South Africa, two in Portugal, and one each the United Kingdom, Israel, and Canada. BA 2.86 is a subvariant of Omicron, but according to reports from the CDC, the strain has many more mutations than the ones that came before it.

With so many facts still unknown about this new variant, this news organization asked experts what people need to be aware of as it continues to spread.

What is unique about the BA 2.86 variant?

“It is unique in that it has more than three mutations on the spike protein,” said Purvi S. Parikh, MD, an infectious disease expert at New York University’s Langone Health. The virus uses the spike proteins to enter our cells.

This “may mean it will be more transmissible, cause more severe disease, and/or our vaccines and treatments may not work as well, as compared to other variants,” she said.

What do we need to watch with BA 2.86 going forward?

“We don’t know if this variant will be associated with a change in the disease severity. We currently see increased numbers of cases in general, even though we don’t yet see the BA.2.86 in our system,” said Heba Mostafa, PhD, director of the molecular virology laboratory at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore.

“It is important to monitor BA.2.86 (and other variants) and understand how its evolution impacts the number of cases and disease outcomes,” she said. “We should all be aware of the current increase in cases, though, and try to get tested and be treated as soon as possible, as antivirals should be effective against the circulating variants.”

What should doctors know?

Dr. Parikh said doctors should generally expect more COVID cases in their clinics and make sure to screen patients even if their symptoms are mild.

“We have tools that can be used – antivirals like Paxlovid are still efficacious with current dominant strains such as EG.5,” she said. “And encourage your patients to get their boosters, mask, wash hands, and social distance.”

How well can our vaccines fight BA 2.86?

“Vaccine coverage for the BA.2.86 is an area of uncertainty right now,” said Dr. Mostafa.

In its report, the CDC said scientists are still figuring out how well the updated COVID vaccine works. It’s expected to be available in the fall, and for now, they believe the new shot will still make infections less severe, new variants and all.

Prior vaccinations and infections have created antibodies in many people, and that will likely provide some protection, Dr. Mostafa said. “When we experienced the Omicron wave in December 2021, even though the variant was distant from what circulated before its emergence and was associated with a very large increase in the number of cases, vaccinations were still protective against severe disease.”

What is the most important thing to keep track of when it comes to this variant?

According to Dr. Parikh, “it’s most important to monitor how transmissible [BA 2.86] is, how severe it is, and if our current treatments and vaccines work.”

Dr. Mostafa said how well the new variants escape existing antibody protection should also be studied and watched closely.

What does this stage of the virus mutation tell us about where we are in the pandemic?

The history of the coronavirus over the past few years shows that variants with many changes evolve and can spread very quickly, Dr. Mostafa said. “Now that the virus is endemic, it is essential to monitor, update vaccinations if necessary, diagnose, treat, and implement infection control measures when necessary.”

With the limited data we have so far, experts seem to agree that while the variant’s makeup raises some red flags, it is too soon to jump to any conclusions about how easy it is to catch it and the ways it may change how the virus impacts those who contract it.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization have dubbed the BA 2.86 variant of COVID-19 as a variant to watch.

So far, only 26 cases of “Pirola,” as the new variant is being called, have been identified: 10 in Denmark, four each in Sweden and the United States, three in South Africa, two in Portugal, and one each the United Kingdom, Israel, and Canada. BA 2.86 is a subvariant of Omicron, but according to reports from the CDC, the strain has many more mutations than the ones that came before it.

With so many facts still unknown about this new variant, this news organization asked experts what people need to be aware of as it continues to spread.

What is unique about the BA 2.86 variant?

“It is unique in that it has more than three mutations on the spike protein,” said Purvi S. Parikh, MD, an infectious disease expert at New York University’s Langone Health. The virus uses the spike proteins to enter our cells.

This “may mean it will be more transmissible, cause more severe disease, and/or our vaccines and treatments may not work as well, as compared to other variants,” she said.

What do we need to watch with BA 2.86 going forward?

“We don’t know if this variant will be associated with a change in the disease severity. We currently see increased numbers of cases in general, even though we don’t yet see the BA.2.86 in our system,” said Heba Mostafa, PhD, director of the molecular virology laboratory at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore.

“It is important to monitor BA.2.86 (and other variants) and understand how its evolution impacts the number of cases and disease outcomes,” she said. “We should all be aware of the current increase in cases, though, and try to get tested and be treated as soon as possible, as antivirals should be effective against the circulating variants.”

What should doctors know?

Dr. Parikh said doctors should generally expect more COVID cases in their clinics and make sure to screen patients even if their symptoms are mild.

“We have tools that can be used – antivirals like Paxlovid are still efficacious with current dominant strains such as EG.5,” she said. “And encourage your patients to get their boosters, mask, wash hands, and social distance.”

How well can our vaccines fight BA 2.86?

“Vaccine coverage for the BA.2.86 is an area of uncertainty right now,” said Dr. Mostafa.

In its report, the CDC said scientists are still figuring out how well the updated COVID vaccine works. It’s expected to be available in the fall, and for now, they believe the new shot will still make infections less severe, new variants and all.

Prior vaccinations and infections have created antibodies in many people, and that will likely provide some protection, Dr. Mostafa said. “When we experienced the Omicron wave in December 2021, even though the variant was distant from what circulated before its emergence and was associated with a very large increase in the number of cases, vaccinations were still protective against severe disease.”

What is the most important thing to keep track of when it comes to this variant?

According to Dr. Parikh, “it’s most important to monitor how transmissible [BA 2.86] is, how severe it is, and if our current treatments and vaccines work.”

Dr. Mostafa said how well the new variants escape existing antibody protection should also be studied and watched closely.

What does this stage of the virus mutation tell us about where we are in the pandemic?

The history of the coronavirus over the past few years shows that variants with many changes evolve and can spread very quickly, Dr. Mostafa said. “Now that the virus is endemic, it is essential to monitor, update vaccinations if necessary, diagnose, treat, and implement infection control measures when necessary.”

With the limited data we have so far, experts seem to agree that while the variant’s makeup raises some red flags, it is too soon to jump to any conclusions about how easy it is to catch it and the ways it may change how the virus impacts those who contract it.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization have dubbed the BA 2.86 variant of COVID-19 as a variant to watch.

So far, only 26 cases of “Pirola,” as the new variant is being called, have been identified: 10 in Denmark, four each in Sweden and the United States, three in South Africa, two in Portugal, and one each the United Kingdom, Israel, and Canada. BA 2.86 is a subvariant of Omicron, but according to reports from the CDC, the strain has many more mutations than the ones that came before it.

With so many facts still unknown about this new variant, this news organization asked experts what people need to be aware of as it continues to spread.

What is unique about the BA 2.86 variant?

“It is unique in that it has more than three mutations on the spike protein,” said Purvi S. Parikh, MD, an infectious disease expert at New York University’s Langone Health. The virus uses the spike proteins to enter our cells.

This “may mean it will be more transmissible, cause more severe disease, and/or our vaccines and treatments may not work as well, as compared to other variants,” she said.

What do we need to watch with BA 2.86 going forward?

“We don’t know if this variant will be associated with a change in the disease severity. We currently see increased numbers of cases in general, even though we don’t yet see the BA.2.86 in our system,” said Heba Mostafa, PhD, director of the molecular virology laboratory at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore.

“It is important to monitor BA.2.86 (and other variants) and understand how its evolution impacts the number of cases and disease outcomes,” she said. “We should all be aware of the current increase in cases, though, and try to get tested and be treated as soon as possible, as antivirals should be effective against the circulating variants.”

What should doctors know?

Dr. Parikh said doctors should generally expect more COVID cases in their clinics and make sure to screen patients even if their symptoms are mild.

“We have tools that can be used – antivirals like Paxlovid are still efficacious with current dominant strains such as EG.5,” she said. “And encourage your patients to get their boosters, mask, wash hands, and social distance.”

How well can our vaccines fight BA 2.86?

“Vaccine coverage for the BA.2.86 is an area of uncertainty right now,” said Dr. Mostafa.

In its report, the CDC said scientists are still figuring out how well the updated COVID vaccine works. It’s expected to be available in the fall, and for now, they believe the new shot will still make infections less severe, new variants and all.

Prior vaccinations and infections have created antibodies in many people, and that will likely provide some protection, Dr. Mostafa said. “When we experienced the Omicron wave in December 2021, even though the variant was distant from what circulated before its emergence and was associated with a very large increase in the number of cases, vaccinations were still protective against severe disease.”

What is the most important thing to keep track of when it comes to this variant?

According to Dr. Parikh, “it’s most important to monitor how transmissible [BA 2.86] is, how severe it is, and if our current treatments and vaccines work.”

Dr. Mostafa said how well the new variants escape existing antibody protection should also be studied and watched closely.

What does this stage of the virus mutation tell us about where we are in the pandemic?

The history of the coronavirus over the past few years shows that variants with many changes evolve and can spread very quickly, Dr. Mostafa said. “Now that the virus is endemic, it is essential to monitor, update vaccinations if necessary, diagnose, treat, and implement infection control measures when necessary.”

With the limited data we have so far, experts seem to agree that while the variant’s makeup raises some red flags, it is too soon to jump to any conclusions about how easy it is to catch it and the ways it may change how the virus impacts those who contract it.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Five questions for COVID experts: How concerned should we be?

COVID-19 hospitalizations have been on the rise for weeks as summer nears its end, but how concerned should you be? SARS-CoV-2, the virus behind COVID, continues to evolve and surprise us. So COVID transmission, hospitalization, and death rates can be difficult to predict.

, especially now that testing and vaccinations are no longer free of charge.

Question 1: Are you expecting an end-of-summer COVID wave to be substantial?

Eric Topol, MD: “This wave won’t likely be substantial and could be more of a ‘wavelet.’ I’m not thinking that physicians are too concerned,” said Dr. Topol, founder and director of Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla, Calif.

Thomas Gut, DO: “It’s always impossible to predict the severity of COVID waves. Although the virus has generally mutated in ways that favor easier transmission and milder illness, there have been a handful of surprising mutations that were more dangerous and deadly than the preceding strain,” said Dr. Gut, associate chair of medicine at Staten Island University Hospital/Northwell Health in New York.

Robert Atmar, MD: “I’ll start with the caveat that prognosticating for SARS-CoV-2 is a bit hazardous as we remain in unknown territory for some aspects of its epidemiology and evolution,” said Dr. Atmar, a professor of infectious diseases at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. “It depends on your definition of substantial. We, at least in Houston, are already in the midst of a substantial surge in the burden of infection, at least as monitored through wastewater surveillance. The amount of virus in the wastewater already exceeds the peak level we saw last winter. That said, the increased infection burden has not translated into large increases in hospitalizations for COVID-19. Most persons hospitalized in our hospital are admitted with infection, not for the consequences of infection.”

Stuart Campbell Ray, MD: “It looks like there is a rise in infections, but the proportional rise in hospitalizations from severe cases is lower than in the past, suggesting that folks are protected by the immunity we’ve gained over the past few years through vaccination and prior infections. Of course, we should be thinking about how that applies to each of us – how recently we had a vaccine or COVID-19, and whether we might see more severe infections as immunity wanes,” said Dr. Ray, who is a professor of medicine in the division of infectious diseases at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

Question 2: Is a return to masks or mask mandates coming this fall or winter?

Dr. Topol: “Mandating masks doesn’t work very well, but we may see wide use again if a descendant of [variant] BA.2.86 takes off.”

Dr. Gut: “It’s difficult to predict if there are any mask mandates returning at any point. Ever since the Omicron strains emerged, COVID has been relatively mild, compared to previous strains, so there probably won’t be any plan to start masking in public unless a more deadly strain appears.”

Dr. Atmar: “I do not think we will see a return to mask mandates this fall or winter for a variety of reasons. The primary one is that I don’t think the public will accept mask mandates. However, I think masking can continue to be an adjunctive measure to enhance protection from infection, along with booster vaccination.”

Dr. Ray: “Some people will choose to wear masks during a surge, particularly in situations like commuting where they don’t interfere with what they’re doing. They will wear masks particularly if they want to avoid infection due to concerns about others they care about, disruption of work or travel plans, or concerns about long-term consequences of repeated COVID-19.”

Question 3: Now that COVID testing and vaccinations are no longer free of charge, how might that affect their use?

Dr. Topol: “It was already low, and this will undoubtedly further compromise their uptake.”

Dr. Gut: “I do expect that testing will become less common now that tests are no longer free. I’m sure there will be a lower amount of detection in patients with milder or asymptomatic disease compared to what we had previously.”

Dr. Atmar: “If there are out-of-pocket costs for the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, or if the administrative paperwork attached to getting a vaccine is increased, the uptake of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines will likely decrease. It will be important to communicate to the populations targeted for vaccination the potential benefits of such vaccination.”

Dr. Ray: “A challenge with COVID-19, all along, has been disparities in access to care, and this will be worse without public support for prevention and testing. This applies to everyone but is especially burdensome for those who are often marginalized in our health care system and society in general. I hope that we’ll find ways to ensure that people who need tests and vaccinations are able to access them, as good health is in everyone’s interest.”

Question 4: Will the new vaccines against COVID work for the currently circulating variants?

Dr. Topol: “The XBB.1.5 boosters will be out Sept. 14. They should help versus EG.5.1 and FL.1.5.1. The FL.1.5.1 variant is gaining now.”

Dr. Gut: “In the next several weeks, we expect the newer monovalent XBB-based vaccines to be offered that offer good protection against current circulating COVID variants along with the new Eris variant.”

Dr. Atmar: “The vaccines are expected to induce immune responses to the currently circulating variants, most of which are strains that evolved from the vaccine strain. The vaccine is expected to be most effective in preventing severe illness and will likely be less effective in preventing infection and mild illness.”

Dr. Ray: “Yes, the updated vaccine design has a spike antigen (XBB.1.5) nearly identical to the current dominant variant (EG.5). Even as variants change, the boosters stimulate B cells and T cells to help protect in a way that is safer than getting COVID-19 infection.”

Question 5: Is there anything we should watch out for regarding the BA.2.86 variant in particular?

Dr. Topol: “The scenario could change if there are new functional mutations added to it.”

Dr. Gut: “BA.2.86 is still fairly uncommon and does not have much data to directly make any informed guesses. However, in general, people that have been exposed to more recent mutations of the COVID virus have been shown to have more protection from newer upcoming mutations. It’s fair to guess that people that have not had recent infection from COVID, or have not had a recent booster, are at higher risk for being infected by any XBB- or BA.2-based strains.”

Dr. Atmar: BA.2.86 has been designated as a variant under monitoring. We will want to see whether it becomes more common and if there are any unexpected characteristics associated with infection by this variant.”

Dr. Ray: “It’s still rare, but it’s been seen in geographically dispersed places, so it’s got legs. The question is how effectively it will bypass some of the immunity we’ve gained. T cells are likely to remain protective, because they target so many parts of the virus that change more slowly, but antibodies from B cells to spike protein may have more trouble recognizing BA.2.86, whether those antibodies were made to a vaccine or a prior variant.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

COVID-19 hospitalizations have been on the rise for weeks as summer nears its end, but how concerned should you be? SARS-CoV-2, the virus behind COVID, continues to evolve and surprise us. So COVID transmission, hospitalization, and death rates can be difficult to predict.

, especially now that testing and vaccinations are no longer free of charge.

Question 1: Are you expecting an end-of-summer COVID wave to be substantial?

Eric Topol, MD: “This wave won’t likely be substantial and could be more of a ‘wavelet.’ I’m not thinking that physicians are too concerned,” said Dr. Topol, founder and director of Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla, Calif.

Thomas Gut, DO: “It’s always impossible to predict the severity of COVID waves. Although the virus has generally mutated in ways that favor easier transmission and milder illness, there have been a handful of surprising mutations that were more dangerous and deadly than the preceding strain,” said Dr. Gut, associate chair of medicine at Staten Island University Hospital/Northwell Health in New York.

Robert Atmar, MD: “I’ll start with the caveat that prognosticating for SARS-CoV-2 is a bit hazardous as we remain in unknown territory for some aspects of its epidemiology and evolution,” said Dr. Atmar, a professor of infectious diseases at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. “It depends on your definition of substantial. We, at least in Houston, are already in the midst of a substantial surge in the burden of infection, at least as monitored through wastewater surveillance. The amount of virus in the wastewater already exceeds the peak level we saw last winter. That said, the increased infection burden has not translated into large increases in hospitalizations for COVID-19. Most persons hospitalized in our hospital are admitted with infection, not for the consequences of infection.”

Stuart Campbell Ray, MD: “It looks like there is a rise in infections, but the proportional rise in hospitalizations from severe cases is lower than in the past, suggesting that folks are protected by the immunity we’ve gained over the past few years through vaccination and prior infections. Of course, we should be thinking about how that applies to each of us – how recently we had a vaccine or COVID-19, and whether we might see more severe infections as immunity wanes,” said Dr. Ray, who is a professor of medicine in the division of infectious diseases at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

Question 2: Is a return to masks or mask mandates coming this fall or winter?

Dr. Topol: “Mandating masks doesn’t work very well, but we may see wide use again if a descendant of [variant] BA.2.86 takes off.”

Dr. Gut: “It’s difficult to predict if there are any mask mandates returning at any point. Ever since the Omicron strains emerged, COVID has been relatively mild, compared to previous strains, so there probably won’t be any plan to start masking in public unless a more deadly strain appears.”

Dr. Atmar: “I do not think we will see a return to mask mandates this fall or winter for a variety of reasons. The primary one is that I don’t think the public will accept mask mandates. However, I think masking can continue to be an adjunctive measure to enhance protection from infection, along with booster vaccination.”

Dr. Ray: “Some people will choose to wear masks during a surge, particularly in situations like commuting where they don’t interfere with what they’re doing. They will wear masks particularly if they want to avoid infection due to concerns about others they care about, disruption of work or travel plans, or concerns about long-term consequences of repeated COVID-19.”

Question 3: Now that COVID testing and vaccinations are no longer free of charge, how might that affect their use?

Dr. Topol: “It was already low, and this will undoubtedly further compromise their uptake.”

Dr. Gut: “I do expect that testing will become less common now that tests are no longer free. I’m sure there will be a lower amount of detection in patients with milder or asymptomatic disease compared to what we had previously.”

Dr. Atmar: “If there are out-of-pocket costs for the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, or if the administrative paperwork attached to getting a vaccine is increased, the uptake of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines will likely decrease. It will be important to communicate to the populations targeted for vaccination the potential benefits of such vaccination.”

Dr. Ray: “A challenge with COVID-19, all along, has been disparities in access to care, and this will be worse without public support for prevention and testing. This applies to everyone but is especially burdensome for those who are often marginalized in our health care system and society in general. I hope that we’ll find ways to ensure that people who need tests and vaccinations are able to access them, as good health is in everyone’s interest.”

Question 4: Will the new vaccines against COVID work for the currently circulating variants?

Dr. Topol: “The XBB.1.5 boosters will be out Sept. 14. They should help versus EG.5.1 and FL.1.5.1. The FL.1.5.1 variant is gaining now.”

Dr. Gut: “In the next several weeks, we expect the newer monovalent XBB-based vaccines to be offered that offer good protection against current circulating COVID variants along with the new Eris variant.”

Dr. Atmar: “The vaccines are expected to induce immune responses to the currently circulating variants, most of which are strains that evolved from the vaccine strain. The vaccine is expected to be most effective in preventing severe illness and will likely be less effective in preventing infection and mild illness.”

Dr. Ray: “Yes, the updated vaccine design has a spike antigen (XBB.1.5) nearly identical to the current dominant variant (EG.5). Even as variants change, the boosters stimulate B cells and T cells to help protect in a way that is safer than getting COVID-19 infection.”

Question 5: Is there anything we should watch out for regarding the BA.2.86 variant in particular?

Dr. Topol: “The scenario could change if there are new functional mutations added to it.”

Dr. Gut: “BA.2.86 is still fairly uncommon and does not have much data to directly make any informed guesses. However, in general, people that have been exposed to more recent mutations of the COVID virus have been shown to have more protection from newer upcoming mutations. It’s fair to guess that people that have not had recent infection from COVID, or have not had a recent booster, are at higher risk for being infected by any XBB- or BA.2-based strains.”

Dr. Atmar: BA.2.86 has been designated as a variant under monitoring. We will want to see whether it becomes more common and if there are any unexpected characteristics associated with infection by this variant.”

Dr. Ray: “It’s still rare, but it’s been seen in geographically dispersed places, so it’s got legs. The question is how effectively it will bypass some of the immunity we’ve gained. T cells are likely to remain protective, because they target so many parts of the virus that change more slowly, but antibodies from B cells to spike protein may have more trouble recognizing BA.2.86, whether those antibodies were made to a vaccine or a prior variant.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

COVID-19 hospitalizations have been on the rise for weeks as summer nears its end, but how concerned should you be? SARS-CoV-2, the virus behind COVID, continues to evolve and surprise us. So COVID transmission, hospitalization, and death rates can be difficult to predict.

, especially now that testing and vaccinations are no longer free of charge.

Question 1: Are you expecting an end-of-summer COVID wave to be substantial?

Eric Topol, MD: “This wave won’t likely be substantial and could be more of a ‘wavelet.’ I’m not thinking that physicians are too concerned,” said Dr. Topol, founder and director of Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla, Calif.

Thomas Gut, DO: “It’s always impossible to predict the severity of COVID waves. Although the virus has generally mutated in ways that favor easier transmission and milder illness, there have been a handful of surprising mutations that were more dangerous and deadly than the preceding strain,” said Dr. Gut, associate chair of medicine at Staten Island University Hospital/Northwell Health in New York.

Robert Atmar, MD: “I’ll start with the caveat that prognosticating for SARS-CoV-2 is a bit hazardous as we remain in unknown territory for some aspects of its epidemiology and evolution,” said Dr. Atmar, a professor of infectious diseases at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. “It depends on your definition of substantial. We, at least in Houston, are already in the midst of a substantial surge in the burden of infection, at least as monitored through wastewater surveillance. The amount of virus in the wastewater already exceeds the peak level we saw last winter. That said, the increased infection burden has not translated into large increases in hospitalizations for COVID-19. Most persons hospitalized in our hospital are admitted with infection, not for the consequences of infection.”

Stuart Campbell Ray, MD: “It looks like there is a rise in infections, but the proportional rise in hospitalizations from severe cases is lower than in the past, suggesting that folks are protected by the immunity we’ve gained over the past few years through vaccination and prior infections. Of course, we should be thinking about how that applies to each of us – how recently we had a vaccine or COVID-19, and whether we might see more severe infections as immunity wanes,” said Dr. Ray, who is a professor of medicine in the division of infectious diseases at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

Question 2: Is a return to masks or mask mandates coming this fall or winter?

Dr. Topol: “Mandating masks doesn’t work very well, but we may see wide use again if a descendant of [variant] BA.2.86 takes off.”

Dr. Gut: “It’s difficult to predict if there are any mask mandates returning at any point. Ever since the Omicron strains emerged, COVID has been relatively mild, compared to previous strains, so there probably won’t be any plan to start masking in public unless a more deadly strain appears.”

Dr. Atmar: “I do not think we will see a return to mask mandates this fall or winter for a variety of reasons. The primary one is that I don’t think the public will accept mask mandates. However, I think masking can continue to be an adjunctive measure to enhance protection from infection, along with booster vaccination.”

Dr. Ray: “Some people will choose to wear masks during a surge, particularly in situations like commuting where they don’t interfere with what they’re doing. They will wear masks particularly if they want to avoid infection due to concerns about others they care about, disruption of work or travel plans, or concerns about long-term consequences of repeated COVID-19.”

Question 3: Now that COVID testing and vaccinations are no longer free of charge, how might that affect their use?

Dr. Topol: “It was already low, and this will undoubtedly further compromise their uptake.”

Dr. Gut: “I do expect that testing will become less common now that tests are no longer free. I’m sure there will be a lower amount of detection in patients with milder or asymptomatic disease compared to what we had previously.”

Dr. Atmar: “If there are out-of-pocket costs for the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, or if the administrative paperwork attached to getting a vaccine is increased, the uptake of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines will likely decrease. It will be important to communicate to the populations targeted for vaccination the potential benefits of such vaccination.”

Dr. Ray: “A challenge with COVID-19, all along, has been disparities in access to care, and this will be worse without public support for prevention and testing. This applies to everyone but is especially burdensome for those who are often marginalized in our health care system and society in general. I hope that we’ll find ways to ensure that people who need tests and vaccinations are able to access them, as good health is in everyone’s interest.”

Question 4: Will the new vaccines against COVID work for the currently circulating variants?

Dr. Topol: “The XBB.1.5 boosters will be out Sept. 14. They should help versus EG.5.1 and FL.1.5.1. The FL.1.5.1 variant is gaining now.”

Dr. Gut: “In the next several weeks, we expect the newer monovalent XBB-based vaccines to be offered that offer good protection against current circulating COVID variants along with the new Eris variant.”

Dr. Atmar: “The vaccines are expected to induce immune responses to the currently circulating variants, most of which are strains that evolved from the vaccine strain. The vaccine is expected to be most effective in preventing severe illness and will likely be less effective in preventing infection and mild illness.”

Dr. Ray: “Yes, the updated vaccine design has a spike antigen (XBB.1.5) nearly identical to the current dominant variant (EG.5). Even as variants change, the boosters stimulate B cells and T cells to help protect in a way that is safer than getting COVID-19 infection.”

Question 5: Is there anything we should watch out for regarding the BA.2.86 variant in particular?

Dr. Topol: “The scenario could change if there are new functional mutations added to it.”

Dr. Gut: “BA.2.86 is still fairly uncommon and does not have much data to directly make any informed guesses. However, in general, people that have been exposed to more recent mutations of the COVID virus have been shown to have more protection from newer upcoming mutations. It’s fair to guess that people that have not had recent infection from COVID, or have not had a recent booster, are at higher risk for being infected by any XBB- or BA.2-based strains.”

Dr. Atmar: BA.2.86 has been designated as a variant under monitoring. We will want to see whether it becomes more common and if there are any unexpected characteristics associated with infection by this variant.”

Dr. Ray: “It’s still rare, but it’s been seen in geographically dispersed places, so it’s got legs. The question is how effectively it will bypass some of the immunity we’ve gained. T cells are likely to remain protective, because they target so many parts of the virus that change more slowly, but antibodies from B cells to spike protein may have more trouble recognizing BA.2.86, whether those antibodies were made to a vaccine or a prior variant.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Severe COVID may cause long-term cellular changes: Study

The small study, published in Cell and funded by the National Institutes of Health, details how immune cells were analyzed through blood samples collected from 38 patients recovering from severe COVID and other critical illnesses, and from 19 healthy people. Researchers from Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, and The Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine, Farmington, Conn., found through isolating hematopoietic stem cells that people recovering from severe bouts of COVID had changes to their DNA that were passed down to offspring cells.

The research team, led by Steven Josefowicz, PhD, of Weill Cornell’s pathology department, and Duygu Ucar, PhD, associate professor at The Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine, discovered that this chain reaction of stem cell changes caused a boost in the production of monocytes. The authors found that, due to the innate cellular changes from a severe case of COVID, patients in recovery ended up producing a larger amount of inflammatory cytokines, rather than monocytes – distinct from samples collected from healthy patients and those recovering from other critical illnesses.

These changes to patients’ epigenetic landscapes were observed even a year after the initial COVID-19 infection. While the small participant pool meant that the research team could not establish a direct line between these innate changes and any ensuing health outcomes, the research provides us with clues as to why patients continue to struggle with inflammation and long COVID symptoms well after they recover.

While the authors reiterate the study’s limitations and hesitate to make any clear-cut associations between the results and long-term health outcomes, Wolfgang Leitner, PhD, from the NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, predicts that long COVID can, at least in part, be explained by the changes in innate immune responses.

“Ideally, the authors would have had cells from each patient before they got infected, as a comparator, to see what the epigenetic landscape was before COVID changed it,” said Dr. Leitner. “Clear links between the severity of COVID and genetics were discovered already early in the pandemic and this paper should prompt follow-up studies that link mutations in immune genes with the epigenetic changes described here.”

Dr. Leitner said he had some initial predictions about the long-term impact of COVID-19, but he had not anticipated some of what the study’s findings now show.

“Unlike in the case of, for example, influenza, where the lungs go into ‘repair mode’ after the infection has been resolved – which leaves people susceptible to secondary infections for up to several months – this study shows that after severe COVID, the immune system remains in ‘emergency mode’ and in a heightened state of inflammation,” said Dr. Leitner.

“That further aggravates the problem the initial strong inflammation causes: even higher risk of autoimmune disease, but also, cancer.”

Commenting on the findings, Eric Topol, MD, editor-in-chief of Medscape Medical News, said the study presents “evidence that a key line of immune cells are essentially irrevocably, epigenetically altered and activated.

“You do not want to have this [COVID],” he added.

The study also highlights the researchers’ novel approach to isolating hematopoietic stem cells, found largely in bone marrow. This type of research has been limited in the past because of how costly and invasive it can be to analyze cells in bone marrow. But, by isolating and enriching hematopoietic stem cells, the team can decipher the full cellular diversity of the cells’ bone marrow counterparts.

“This revelation opened the doors to study, at single-cell resolution, how stem cells are affected upon infection and vaccination with a simple blood draw,” representatives from the Jackson lab said in a press release.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The small study, published in Cell and funded by the National Institutes of Health, details how immune cells were analyzed through blood samples collected from 38 patients recovering from severe COVID and other critical illnesses, and from 19 healthy people. Researchers from Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, and The Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine, Farmington, Conn., found through isolating hematopoietic stem cells that people recovering from severe bouts of COVID had changes to their DNA that were passed down to offspring cells.

The research team, led by Steven Josefowicz, PhD, of Weill Cornell’s pathology department, and Duygu Ucar, PhD, associate professor at The Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine, discovered that this chain reaction of stem cell changes caused a boost in the production of monocytes. The authors found that, due to the innate cellular changes from a severe case of COVID, patients in recovery ended up producing a larger amount of inflammatory cytokines, rather than monocytes – distinct from samples collected from healthy patients and those recovering from other critical illnesses.

These changes to patients’ epigenetic landscapes were observed even a year after the initial COVID-19 infection. While the small participant pool meant that the research team could not establish a direct line between these innate changes and any ensuing health outcomes, the research provides us with clues as to why patients continue to struggle with inflammation and long COVID symptoms well after they recover.

While the authors reiterate the study’s limitations and hesitate to make any clear-cut associations between the results and long-term health outcomes, Wolfgang Leitner, PhD, from the NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, predicts that long COVID can, at least in part, be explained by the changes in innate immune responses.

“Ideally, the authors would have had cells from each patient before they got infected, as a comparator, to see what the epigenetic landscape was before COVID changed it,” said Dr. Leitner. “Clear links between the severity of COVID and genetics were discovered already early in the pandemic and this paper should prompt follow-up studies that link mutations in immune genes with the epigenetic changes described here.”

Dr. Leitner said he had some initial predictions about the long-term impact of COVID-19, but he had not anticipated some of what the study’s findings now show.

“Unlike in the case of, for example, influenza, where the lungs go into ‘repair mode’ after the infection has been resolved – which leaves people susceptible to secondary infections for up to several months – this study shows that after severe COVID, the immune system remains in ‘emergency mode’ and in a heightened state of inflammation,” said Dr. Leitner.

“That further aggravates the problem the initial strong inflammation causes: even higher risk of autoimmune disease, but also, cancer.”

Commenting on the findings, Eric Topol, MD, editor-in-chief of Medscape Medical News, said the study presents “evidence that a key line of immune cells are essentially irrevocably, epigenetically altered and activated.

“You do not want to have this [COVID],” he added.

The study also highlights the researchers’ novel approach to isolating hematopoietic stem cells, found largely in bone marrow. This type of research has been limited in the past because of how costly and invasive it can be to analyze cells in bone marrow. But, by isolating and enriching hematopoietic stem cells, the team can decipher the full cellular diversity of the cells’ bone marrow counterparts.

“This revelation opened the doors to study, at single-cell resolution, how stem cells are affected upon infection and vaccination with a simple blood draw,” representatives from the Jackson lab said in a press release.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The small study, published in Cell and funded by the National Institutes of Health, details how immune cells were analyzed through blood samples collected from 38 patients recovering from severe COVID and other critical illnesses, and from 19 healthy people. Researchers from Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, and The Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine, Farmington, Conn., found through isolating hematopoietic stem cells that people recovering from severe bouts of COVID had changes to their DNA that were passed down to offspring cells.

The research team, led by Steven Josefowicz, PhD, of Weill Cornell’s pathology department, and Duygu Ucar, PhD, associate professor at The Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine, discovered that this chain reaction of stem cell changes caused a boost in the production of monocytes. The authors found that, due to the innate cellular changes from a severe case of COVID, patients in recovery ended up producing a larger amount of inflammatory cytokines, rather than monocytes – distinct from samples collected from healthy patients and those recovering from other critical illnesses.

These changes to patients’ epigenetic landscapes were observed even a year after the initial COVID-19 infection. While the small participant pool meant that the research team could not establish a direct line between these innate changes and any ensuing health outcomes, the research provides us with clues as to why patients continue to struggle with inflammation and long COVID symptoms well after they recover.

While the authors reiterate the study’s limitations and hesitate to make any clear-cut associations between the results and long-term health outcomes, Wolfgang Leitner, PhD, from the NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, predicts that long COVID can, at least in part, be explained by the changes in innate immune responses.

“Ideally, the authors would have had cells from each patient before they got infected, as a comparator, to see what the epigenetic landscape was before COVID changed it,” said Dr. Leitner. “Clear links between the severity of COVID and genetics were discovered already early in the pandemic and this paper should prompt follow-up studies that link mutations in immune genes with the epigenetic changes described here.”

Dr. Leitner said he had some initial predictions about the long-term impact of COVID-19, but he had not anticipated some of what the study’s findings now show.

“Unlike in the case of, for example, influenza, where the lungs go into ‘repair mode’ after the infection has been resolved – which leaves people susceptible to secondary infections for up to several months – this study shows that after severe COVID, the immune system remains in ‘emergency mode’ and in a heightened state of inflammation,” said Dr. Leitner.

“That further aggravates the problem the initial strong inflammation causes: even higher risk of autoimmune disease, but also, cancer.”

Commenting on the findings, Eric Topol, MD, editor-in-chief of Medscape Medical News, said the study presents “evidence that a key line of immune cells are essentially irrevocably, epigenetically altered and activated.

“You do not want to have this [COVID],” he added.

The study also highlights the researchers’ novel approach to isolating hematopoietic stem cells, found largely in bone marrow. This type of research has been limited in the past because of how costly and invasive it can be to analyze cells in bone marrow. But, by isolating and enriching hematopoietic stem cells, the team can decipher the full cellular diversity of the cells’ bone marrow counterparts.

“This revelation opened the doors to study, at single-cell resolution, how stem cells are affected upon infection and vaccination with a simple blood draw,” representatives from the Jackson lab said in a press release.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CELL

Use of mental health services soared during pandemic

By the end of August 2022, overall use of mental health services was almost 40% higher than before the COVID-19 pandemic, while spending increased by 54%, according to a new study by researchers at the RAND Corporation.

During the early phase of the pandemic, from mid-March to mid-December 2020, before the vaccine was available, in-person visits decreased by 40%, while telehealth visits increased by 1,000%, reported Jonathan H. Cantor, PhD, and colleagues at RAND, and at Castlight Health, a benefit coordination provider, in a paper published online in JAMA Health Forum.

Between December 2020 and August 2022, telehealth visits stayed stable, but in-person visits creeped back up, eventually reaching 80% of prepandemic levels. However, “total utilization was higher than before the pandemic,” Dr. Cantor, a policy researcher at RAND, told this news organization.

“It could be that it’s easier for individuals to receive care via telehealth, but it could also just be that there’s a greater demand or need since the pandemic,” said Dr. Cantor. “We’ll just need more research to actually unpack what’s going on,” he said.

Initial per capita spending increased by about a third and was up overall by more than half. But it’s not clear how much of that is due to utilization or to price of services, said Dr. Cantor. Spending for telehealth services remained stable in the post-vaccine period, while spending on in-person visits returned to prepandemic levels.

Dr. Cantor and his colleagues were not able to determine whether utilization was by new or existing patients, but he said that would be good data to have. “It would be really important to know whether or not folks are initiating care because telehealth is making it easier,” he said.

The authors analyzed about 1.5 million claims for anxiety disorders, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and posttraumatic stress disorder, out of claims submitted by 7 million commercially insured adults whose self-insured employers used the Castlight benefit.

Dr. Cantor noted that this is just a small subset of the U.S. population. He said he’d like to have data from Medicare and Medicaid to fully assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and of telehealth visits.

“This is a still-burgeoning field,” he said about telehealth. “We’re still trying to get a handle on how things are operating, given that there’s been so much change so rapidly.”

Meanwhile, 152 major employers responding to a large national survey this summer said that they’ve been grappling with how COVID-19 has affected workers. The employers include 72 Fortune 100 companies and provide health coverage for more than 60 million workers, retirees, and their families.