User login

Hypopigmentation

Hypopigmentation or depigmentation of the skin is very challenging to treat. The loss of melanin in the skin is often a frustrating problem, resulting from acne, burn scars, vitiligo, topically applied chemicals, or cryotherapy. To date, there is no universally accepted treatment that restores skin pigmentation. In our clinic, the induction of trauma to the skin via a series of microneedling or subcision treatments has shown promise in increasing the pigmentation of skin with localized hypo- or depigmented patches.

to improve the appearance of fine lines, acne scars, photoaging, stretch marks, enlarged pores, and other cosmetic issues characterized by loss of collagen or altered collagen remodeling. The skin-needling technique involves fine sterile needles 0.1 mm–2.5 mm in length that repeatedly pierce the stratum corneum producing microscopic “holes” in the dermis. These microscopic wounds lead to the release of growth factors stimulating the formation of new collagen, elastin, and neovascularization in the dermis. Similar to microneedling, subcision uses repeat trauma to the dermis and subcutis through the insertion and repeat movement of a needle.

In our practice, patients presenting with hypopigmentation of the skin from a variety of causes have been treated with a series of five subcision or microneedling procedures, resulting in rapid repigmentation of the skin with minimal to no side effects. Trauma to the skin causes regenerative mechanisms and wound healing. The release of cytokines that induce neoangiogenesis, neocollagenesis, and the deposition of hemosiderin from dermal bleeding induce the activation of melanocytes and stimulate skin pigmentation.

Subcision and microneedling are safe, effective, in-office procedures with vast indications that now can be applied to depigmented and hypopigmented skin. Patients have little to no downtime and results are permanent.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

Dermatol Surg. 1995 Jun;21(6):543-9.

Aesthet Plast Surg. 1997 Jan-Feb;21(1):48-51.

Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2005 Feb;17(1):51-63.

Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008 Apr;121(4):1421-9.

Clin Dermatol. 2008 Mar-Apr;26(2):192-9.Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008 Nov;122(5):1553-63.

J Dermatolog Treat. 2012 Apr;23(2):144-52.

J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2009 Jan;2(1):26-30.

J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2009 Jul;2(2):110-1.

J Cosmet Dermatol. 2014 Sep;13(3):180-7.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Nov;75(5):e195-e197.

Hypopigmentation or depigmentation of the skin is very challenging to treat. The loss of melanin in the skin is often a frustrating problem, resulting from acne, burn scars, vitiligo, topically applied chemicals, or cryotherapy. To date, there is no universally accepted treatment that restores skin pigmentation. In our clinic, the induction of trauma to the skin via a series of microneedling or subcision treatments has shown promise in increasing the pigmentation of skin with localized hypo- or depigmented patches.

to improve the appearance of fine lines, acne scars, photoaging, stretch marks, enlarged pores, and other cosmetic issues characterized by loss of collagen or altered collagen remodeling. The skin-needling technique involves fine sterile needles 0.1 mm–2.5 mm in length that repeatedly pierce the stratum corneum producing microscopic “holes” in the dermis. These microscopic wounds lead to the release of growth factors stimulating the formation of new collagen, elastin, and neovascularization in the dermis. Similar to microneedling, subcision uses repeat trauma to the dermis and subcutis through the insertion and repeat movement of a needle.

In our practice, patients presenting with hypopigmentation of the skin from a variety of causes have been treated with a series of five subcision or microneedling procedures, resulting in rapid repigmentation of the skin with minimal to no side effects. Trauma to the skin causes regenerative mechanisms and wound healing. The release of cytokines that induce neoangiogenesis, neocollagenesis, and the deposition of hemosiderin from dermal bleeding induce the activation of melanocytes and stimulate skin pigmentation.

Subcision and microneedling are safe, effective, in-office procedures with vast indications that now can be applied to depigmented and hypopigmented skin. Patients have little to no downtime and results are permanent.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

Dermatol Surg. 1995 Jun;21(6):543-9.

Aesthet Plast Surg. 1997 Jan-Feb;21(1):48-51.

Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2005 Feb;17(1):51-63.

Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008 Apr;121(4):1421-9.

Clin Dermatol. 2008 Mar-Apr;26(2):192-9.Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008 Nov;122(5):1553-63.

J Dermatolog Treat. 2012 Apr;23(2):144-52.

J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2009 Jan;2(1):26-30.

J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2009 Jul;2(2):110-1.

J Cosmet Dermatol. 2014 Sep;13(3):180-7.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Nov;75(5):e195-e197.

Hypopigmentation or depigmentation of the skin is very challenging to treat. The loss of melanin in the skin is often a frustrating problem, resulting from acne, burn scars, vitiligo, topically applied chemicals, or cryotherapy. To date, there is no universally accepted treatment that restores skin pigmentation. In our clinic, the induction of trauma to the skin via a series of microneedling or subcision treatments has shown promise in increasing the pigmentation of skin with localized hypo- or depigmented patches.

to improve the appearance of fine lines, acne scars, photoaging, stretch marks, enlarged pores, and other cosmetic issues characterized by loss of collagen or altered collagen remodeling. The skin-needling technique involves fine sterile needles 0.1 mm–2.5 mm in length that repeatedly pierce the stratum corneum producing microscopic “holes” in the dermis. These microscopic wounds lead to the release of growth factors stimulating the formation of new collagen, elastin, and neovascularization in the dermis. Similar to microneedling, subcision uses repeat trauma to the dermis and subcutis through the insertion and repeat movement of a needle.

In our practice, patients presenting with hypopigmentation of the skin from a variety of causes have been treated with a series of five subcision or microneedling procedures, resulting in rapid repigmentation of the skin with minimal to no side effects. Trauma to the skin causes regenerative mechanisms and wound healing. The release of cytokines that induce neoangiogenesis, neocollagenesis, and the deposition of hemosiderin from dermal bleeding induce the activation of melanocytes and stimulate skin pigmentation.

Subcision and microneedling are safe, effective, in-office procedures with vast indications that now can be applied to depigmented and hypopigmented skin. Patients have little to no downtime and results are permanent.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

Dermatol Surg. 1995 Jun;21(6):543-9.

Aesthet Plast Surg. 1997 Jan-Feb;21(1):48-51.

Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2005 Feb;17(1):51-63.

Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008 Apr;121(4):1421-9.

Clin Dermatol. 2008 Mar-Apr;26(2):192-9.Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008 Nov;122(5):1553-63.

J Dermatolog Treat. 2012 Apr;23(2):144-52.

J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2009 Jan;2(1):26-30.

J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2009 Jul;2(2):110-1.

J Cosmet Dermatol. 2014 Sep;13(3):180-7.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Nov;75(5):e195-e197.

Pediatric Skin Care: Survey of the Cutis Editorial Board

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists from the Cutis Editorial Board answered 5 questions on pediatric skin care. Here’s what we found.

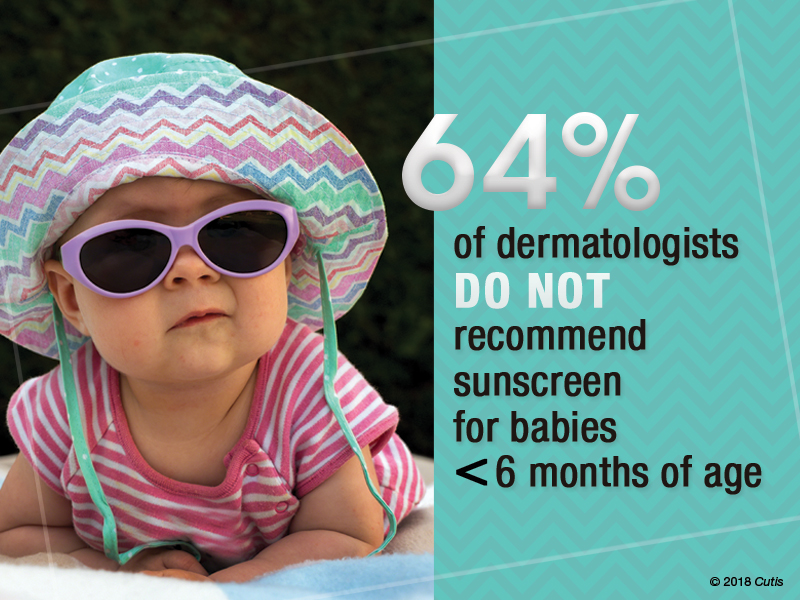

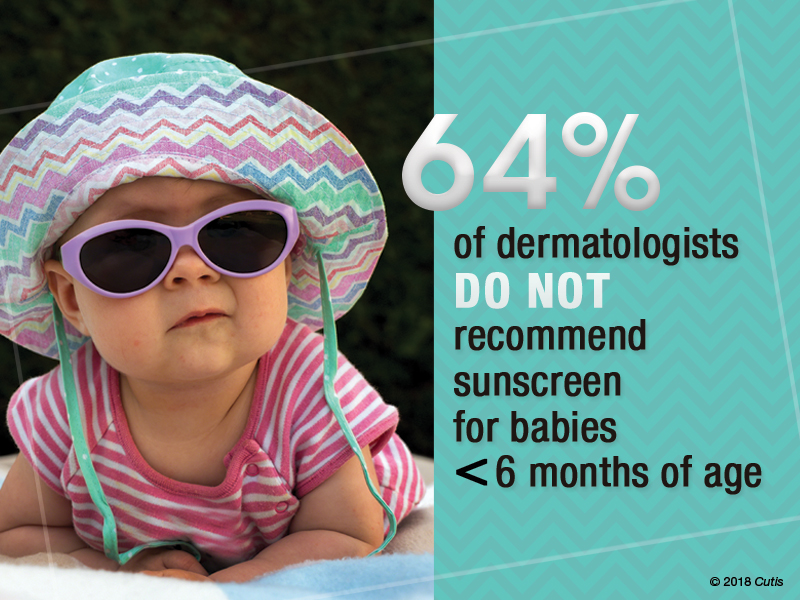

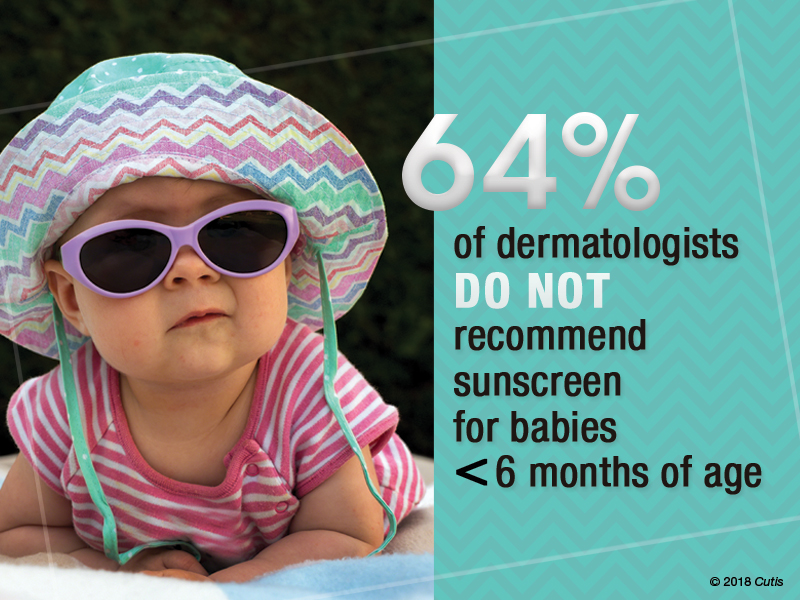

Do you recommend sunscreen in babies younger than 6 months?

More than half (64%) of dermatologists we surveyed do not recommend using sunscreens in babies younger than 6 months; they should stay out of the sun. They recommended sun-protective clothing, hats, and sunglasses in this age group.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Babies younger than 6 months are still developing barrier functionality and have a higher surface area to body weight ratio compared to older children and adults. There is decreased UV light barrier protection and increased risk for systemic drug absorption. Therefore, it is best to avoid sunscreen in babies younger than 6 months. Instead, I recommend avoiding sunlight during peak hours, keeping babies in the shade, and dressing them in sun-protective clothing and hats.

Next page: Bathing and eczema

What advice do you give parents/guardians on bathing for babies with eczema?

Two-thirds of dermatologists (68%) indicated that moisturizers should be applied after bathing babies with eczema. More than half (64%) suggested using fragrance-free cleansers. Results varied on the frequency of bathing; 32% said bathe once daily for short periods with warm water, and 41% suggested to reduce bathing to a few nights a week.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Dry skin is a characteristic feature of atopic dermatitis. We now know that skin barrier dysfunction, such as filaggrin deficiency, contributes to the pathophysiology in some patients. In addition, a paucity of stratum corneum and intercellular lipids increases transepidermal water loss. Therefore, emollients containing humectants to augment stratum corneum hydration and occludents to reduce evaporation are extremely helpful in maintenance treatment of atopic dermatitis.

Next page: Nonsteroidal agents

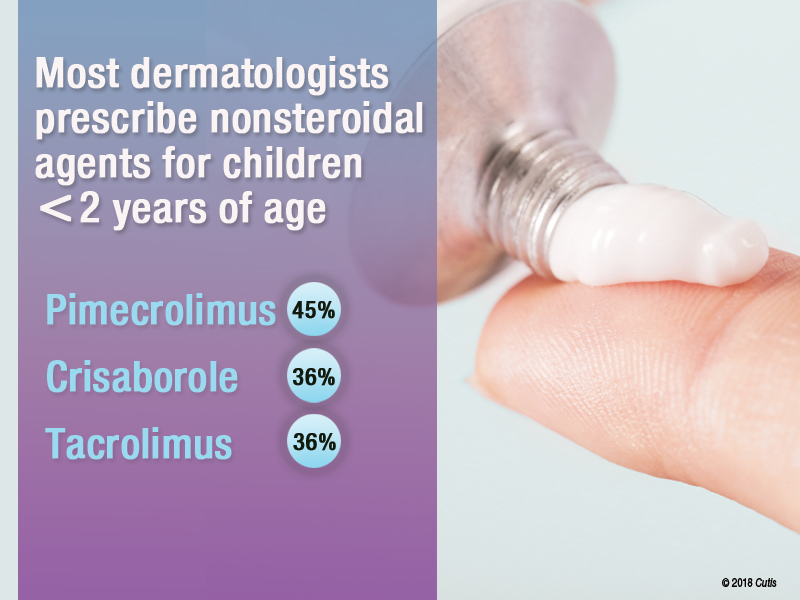

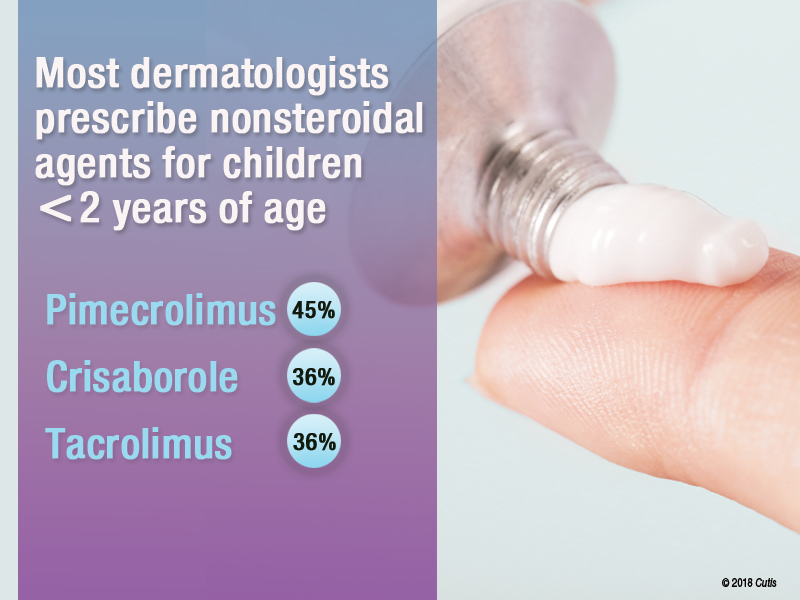

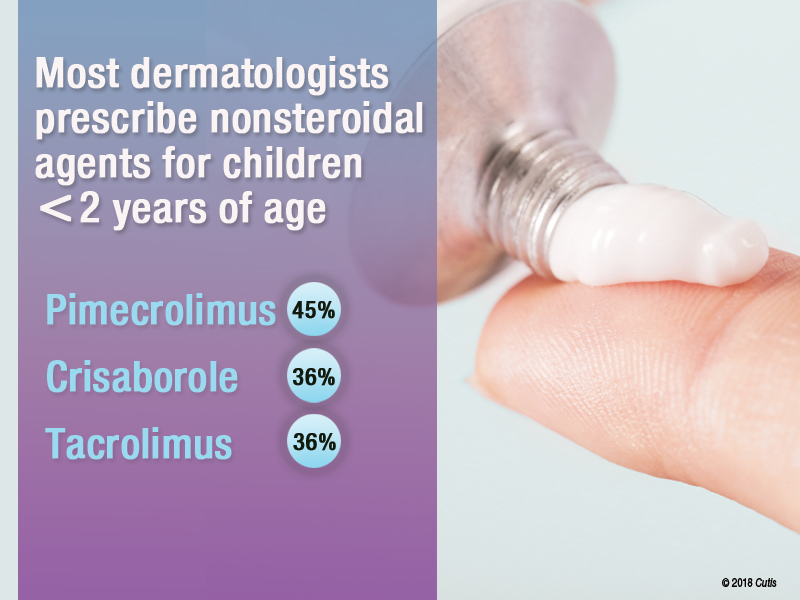

Do you prescribe nonsteroidal agents for children younger than 2 years?

Almost two-thirds (64%) of dermatologists do prescribe nonsteroidal agents for children younger than 2 years.

If yes, which nonsteroidal agents do you prescribe for children?

Of those dermatologists who indicated that they do prescribe nonsteroidal agents for children younger than 2 years, almost half (45%) prescribe pimecrolimus, while 36% prescribe crisaborole or tacrolimus.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

We have limited options for US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved therapies for atopic dermatitis in children younger than 2 years. The risks of adverse effects also are higher in younger children compared to older children and adults, particularly hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal suppression with corticosteroids. Pimecrolimus was the most common nonsteroidal prescribed in this group. It should be noted that pimecrolimus is not FDA approved for use in children younger than 2 years; however, 2 phase 3 studies were conducted with 436 infants aged 3 months to 23 months and they demonstrated safety and efficacy.

Next page: Procedures in adolescents

Which procedures do you perform on adolescents?

Forty-one percent of dermatologists surveyed indicated that they do not perform procedures on adolescents. Of those that do, 32% use laser hair removal or chemical peels in adolescents, while only 23% each use light therapy for acne or onabotulinumtoxinA for hyperhidrosis. Pulsed dye laser use was reported in only 18% of dermatologists.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

The results of this survey are a reflection of the relatively recent trends in dermatology training. Now that there is board certification in pediatric dermatology, many dermatologists now refer to pediatric dermatologists for children who need or want procedures.

Next page: More tips from derms

More Tips From Dermatologists

The dermatologists we polled had the following advice for their peers:

Keep the regimen as simple as possible and make sure your skin care advice is culturally relevant.—Craig Burkhart, MD (Chapel Hill, North Carolina)

Please, avoid direct sun exposure as much as possible by wearing protective garments and finding shades in the outside.—Jisun Cha, MD (New Brunswick, New Jersey)

Good habits start early. Teach children how to care for their skin and they will carry that practice with them over the course of their lifetime, and hopefully pass it on.—James Q. Del Rosso, DO (Las Vegas, Nevada)

About This Survey

The survey was fielded electronically to Cutis Editorial Board Members within the United States from September 13, 2018, to October 4, 2018. A total of 22 usable responses were received.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists from the Cutis Editorial Board answered 5 questions on pediatric skin care. Here’s what we found.

Do you recommend sunscreen in babies younger than 6 months?

More than half (64%) of dermatologists we surveyed do not recommend using sunscreens in babies younger than 6 months; they should stay out of the sun. They recommended sun-protective clothing, hats, and sunglasses in this age group.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Babies younger than 6 months are still developing barrier functionality and have a higher surface area to body weight ratio compared to older children and adults. There is decreased UV light barrier protection and increased risk for systemic drug absorption. Therefore, it is best to avoid sunscreen in babies younger than 6 months. Instead, I recommend avoiding sunlight during peak hours, keeping babies in the shade, and dressing them in sun-protective clothing and hats.

Next page: Bathing and eczema

What advice do you give parents/guardians on bathing for babies with eczema?

Two-thirds of dermatologists (68%) indicated that moisturizers should be applied after bathing babies with eczema. More than half (64%) suggested using fragrance-free cleansers. Results varied on the frequency of bathing; 32% said bathe once daily for short periods with warm water, and 41% suggested to reduce bathing to a few nights a week.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Dry skin is a characteristic feature of atopic dermatitis. We now know that skin barrier dysfunction, such as filaggrin deficiency, contributes to the pathophysiology in some patients. In addition, a paucity of stratum corneum and intercellular lipids increases transepidermal water loss. Therefore, emollients containing humectants to augment stratum corneum hydration and occludents to reduce evaporation are extremely helpful in maintenance treatment of atopic dermatitis.

Next page: Nonsteroidal agents

Do you prescribe nonsteroidal agents for children younger than 2 years?

Almost two-thirds (64%) of dermatologists do prescribe nonsteroidal agents for children younger than 2 years.

If yes, which nonsteroidal agents do you prescribe for children?

Of those dermatologists who indicated that they do prescribe nonsteroidal agents for children younger than 2 years, almost half (45%) prescribe pimecrolimus, while 36% prescribe crisaborole or tacrolimus.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

We have limited options for US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved therapies for atopic dermatitis in children younger than 2 years. The risks of adverse effects also are higher in younger children compared to older children and adults, particularly hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal suppression with corticosteroids. Pimecrolimus was the most common nonsteroidal prescribed in this group. It should be noted that pimecrolimus is not FDA approved for use in children younger than 2 years; however, 2 phase 3 studies were conducted with 436 infants aged 3 months to 23 months and they demonstrated safety and efficacy.

Next page: Procedures in adolescents

Which procedures do you perform on adolescents?

Forty-one percent of dermatologists surveyed indicated that they do not perform procedures on adolescents. Of those that do, 32% use laser hair removal or chemical peels in adolescents, while only 23% each use light therapy for acne or onabotulinumtoxinA for hyperhidrosis. Pulsed dye laser use was reported in only 18% of dermatologists.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

The results of this survey are a reflection of the relatively recent trends in dermatology training. Now that there is board certification in pediatric dermatology, many dermatologists now refer to pediatric dermatologists for children who need or want procedures.

Next page: More tips from derms

More Tips From Dermatologists

The dermatologists we polled had the following advice for their peers:

Keep the regimen as simple as possible and make sure your skin care advice is culturally relevant.—Craig Burkhart, MD (Chapel Hill, North Carolina)

Please, avoid direct sun exposure as much as possible by wearing protective garments and finding shades in the outside.—Jisun Cha, MD (New Brunswick, New Jersey)

Good habits start early. Teach children how to care for their skin and they will carry that practice with them over the course of their lifetime, and hopefully pass it on.—James Q. Del Rosso, DO (Las Vegas, Nevada)

About This Survey

The survey was fielded electronically to Cutis Editorial Board Members within the United States from September 13, 2018, to October 4, 2018. A total of 22 usable responses were received.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists from the Cutis Editorial Board answered 5 questions on pediatric skin care. Here’s what we found.

Do you recommend sunscreen in babies younger than 6 months?

More than half (64%) of dermatologists we surveyed do not recommend using sunscreens in babies younger than 6 months; they should stay out of the sun. They recommended sun-protective clothing, hats, and sunglasses in this age group.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Babies younger than 6 months are still developing barrier functionality and have a higher surface area to body weight ratio compared to older children and adults. There is decreased UV light barrier protection and increased risk for systemic drug absorption. Therefore, it is best to avoid sunscreen in babies younger than 6 months. Instead, I recommend avoiding sunlight during peak hours, keeping babies in the shade, and dressing them in sun-protective clothing and hats.

Next page: Bathing and eczema

What advice do you give parents/guardians on bathing for babies with eczema?

Two-thirds of dermatologists (68%) indicated that moisturizers should be applied after bathing babies with eczema. More than half (64%) suggested using fragrance-free cleansers. Results varied on the frequency of bathing; 32% said bathe once daily for short periods with warm water, and 41% suggested to reduce bathing to a few nights a week.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Dry skin is a characteristic feature of atopic dermatitis. We now know that skin barrier dysfunction, such as filaggrin deficiency, contributes to the pathophysiology in some patients. In addition, a paucity of stratum corneum and intercellular lipids increases transepidermal water loss. Therefore, emollients containing humectants to augment stratum corneum hydration and occludents to reduce evaporation are extremely helpful in maintenance treatment of atopic dermatitis.

Next page: Nonsteroidal agents

Do you prescribe nonsteroidal agents for children younger than 2 years?

Almost two-thirds (64%) of dermatologists do prescribe nonsteroidal agents for children younger than 2 years.

If yes, which nonsteroidal agents do you prescribe for children?

Of those dermatologists who indicated that they do prescribe nonsteroidal agents for children younger than 2 years, almost half (45%) prescribe pimecrolimus, while 36% prescribe crisaborole or tacrolimus.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

We have limited options for US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved therapies for atopic dermatitis in children younger than 2 years. The risks of adverse effects also are higher in younger children compared to older children and adults, particularly hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal suppression with corticosteroids. Pimecrolimus was the most common nonsteroidal prescribed in this group. It should be noted that pimecrolimus is not FDA approved for use in children younger than 2 years; however, 2 phase 3 studies were conducted with 436 infants aged 3 months to 23 months and they demonstrated safety and efficacy.

Next page: Procedures in adolescents

Which procedures do you perform on adolescents?

Forty-one percent of dermatologists surveyed indicated that they do not perform procedures on adolescents. Of those that do, 32% use laser hair removal or chemical peels in adolescents, while only 23% each use light therapy for acne or onabotulinumtoxinA for hyperhidrosis. Pulsed dye laser use was reported in only 18% of dermatologists.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

The results of this survey are a reflection of the relatively recent trends in dermatology training. Now that there is board certification in pediatric dermatology, many dermatologists now refer to pediatric dermatologists for children who need or want procedures.

Next page: More tips from derms

More Tips From Dermatologists

The dermatologists we polled had the following advice for their peers:

Keep the regimen as simple as possible and make sure your skin care advice is culturally relevant.—Craig Burkhart, MD (Chapel Hill, North Carolina)

Please, avoid direct sun exposure as much as possible by wearing protective garments and finding shades in the outside.—Jisun Cha, MD (New Brunswick, New Jersey)

Good habits start early. Teach children how to care for their skin and they will carry that practice with them over the course of their lifetime, and hopefully pass it on.—James Q. Del Rosso, DO (Las Vegas, Nevada)

About This Survey

The survey was fielded electronically to Cutis Editorial Board Members within the United States from September 13, 2018, to October 4, 2018. A total of 22 usable responses were received.

FDA expands CoolSculpting indication to submandibular area

FDA clearance of the expanded indication was based on results of a 22-week study in which patients achieved a mean 33% reduction in fat layer thickness after two treatments. In addition, 85% of patients reported satisfaction with their treatment in that and two other studies. The data were provided in Allergan’s press release announcing the clearance for the cryolipolysis device.

Adverse events associated with the CoolSculpting treatment include temporary redness, swelling, blanching, bruising, firmness, tingling, stinging, tenderness, cramping, aching, itching, and skin sensitivity. People with cryoglobulinemia, cold agglutinin disease, or paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria should not receive CoolSculpting treatments, according to the company.

The FDA also expanded the CoolSculpting indication to people with a body mass index up to 46.2 kg/m2 when treating the submental and submandibular areas.

FDA clearance of the expanded indication was based on results of a 22-week study in which patients achieved a mean 33% reduction in fat layer thickness after two treatments. In addition, 85% of patients reported satisfaction with their treatment in that and two other studies. The data were provided in Allergan’s press release announcing the clearance for the cryolipolysis device.

Adverse events associated with the CoolSculpting treatment include temporary redness, swelling, blanching, bruising, firmness, tingling, stinging, tenderness, cramping, aching, itching, and skin sensitivity. People with cryoglobulinemia, cold agglutinin disease, or paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria should not receive CoolSculpting treatments, according to the company.

The FDA also expanded the CoolSculpting indication to people with a body mass index up to 46.2 kg/m2 when treating the submental and submandibular areas.

FDA clearance of the expanded indication was based on results of a 22-week study in which patients achieved a mean 33% reduction in fat layer thickness after two treatments. In addition, 85% of patients reported satisfaction with their treatment in that and two other studies. The data were provided in Allergan’s press release announcing the clearance for the cryolipolysis device.

Adverse events associated with the CoolSculpting treatment include temporary redness, swelling, blanching, bruising, firmness, tingling, stinging, tenderness, cramping, aching, itching, and skin sensitivity. People with cryoglobulinemia, cold agglutinin disease, or paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria should not receive CoolSculpting treatments, according to the company.

The FDA also expanded the CoolSculpting indication to people with a body mass index up to 46.2 kg/m2 when treating the submental and submandibular areas.

Platelet-rich plasma injections yield substantial improvement in androgenetic alopecia

Autologous treatment with injected (AGA) after three monthly treatments, in a study that compared two treatment regimens.

PRP is gaining popularity because of its efficacy in stimulating fibroblast proliferation, triggering the production of collagen and elastin, and boosting the quantity and quality of the extracellular matrix, noted the investigators, Amelia K. Hausauer, MD, in private practice in Campbell, Calif., and Derek H. Jones, MD, in private practice in Los Angeles. Both are also with the department of dermatology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

They undertook this study to determine the optimal number and timing of treatments in patients with AGA, comparing two different injection protocols over a 6-month period. The study evaluated 40 healthy men (30) and women (10), whose mean age was 44 years, with AGA stages Norwood-Hamilton II-V (in men) and Ludwig I2-II1 (in women), recruited from a private practice in Los Angeles between November 2016 and January 2017. They were randomly assigned to one of two treatment groups: three monthly sessions followed by a fourth injection 3 months later (group 1), or two treatments, one at baseline and the second 3 months later (group 2). One of the men dropped out for reasons unrelated to the treatment.

Those with clinically stable effects of Food and Drug Administration–approved AGA treatments for 12 months were permitted to participate while continuing those treatments (topical minoxidil and/or oral finasteride), since PRP is often coadministered with other therapies. But additional products, devices, or medications used for hair regrowth were not allowed. The washout period for antiandrogen therapies was 90 days.

At 3 months, the mean increase in hair counts was significant in the first group only, but at 6 months, both groups experienced significant increases in hair count (P less than .001). However, those in the first group had superior results at 6 months, with a mean 30% increase in hair counts from baseline, compared with a 7% increase in the second group (P less than .001).

Both groups had significant increases in the mean hair shaft caliber at 3 and 6 months.

Overall, 82% of participants who completed treatment reported being satisfied or highly satisfied, and 72% expressed interest in continuing treatment after the study period; almost two-thirds considered the procedure “tolerable.”

While the authors stipulated that they did not undertake the study primarily to predict treatment response to PRP, they uncovered some significant trends that they said warranted further evaluation, including the finding that those who had experienced hair loss for less than 5-6 years were more likely to have rapid and pronounced treatment response.

Their overall findings correlated with those of previous studies supporting the increase in density of hair or hair numbers, but the existing literature draws from studies that have been open label or unblinded, which makes it difficult to evaluate them head to head. The novel, subdermal injection technique used in the study “allows for fewer, more widely spaced injection points than the traditional nappage procedure ... because PRP can diffuse further once in the deeper, subgaleal space,” they wrote. The investigators noted similar response between men and women, which is important given sparse data on the efficacy of PRP in women.

Weaknesses of the study included its small sample size and short follow-up period, the authors noted. Longer-duration studies have reported relapse between 3 and 12 months.

This study is the first of its kind to directly compare efficacy rates of two injection protocols, the authors wrote, cautioning that future studies are necessary to “fine-tune preparation methods, determine optimal maintenance schedule(s), and parse out clinical predictors of efficacy.”

Eclipse Aesthetics (the manufacturer of the PRP preparation kits) provided funding for this study, but the authors acknowledged no significant interest with commercial supporters.

SOURCE: Hausauer A et al. Dermatol Surg. 2018 Sep;44(9):1191-200.

Autologous treatment with injected (AGA) after three monthly treatments, in a study that compared two treatment regimens.

PRP is gaining popularity because of its efficacy in stimulating fibroblast proliferation, triggering the production of collagen and elastin, and boosting the quantity and quality of the extracellular matrix, noted the investigators, Amelia K. Hausauer, MD, in private practice in Campbell, Calif., and Derek H. Jones, MD, in private practice in Los Angeles. Both are also with the department of dermatology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

They undertook this study to determine the optimal number and timing of treatments in patients with AGA, comparing two different injection protocols over a 6-month period. The study evaluated 40 healthy men (30) and women (10), whose mean age was 44 years, with AGA stages Norwood-Hamilton II-V (in men) and Ludwig I2-II1 (in women), recruited from a private practice in Los Angeles between November 2016 and January 2017. They were randomly assigned to one of two treatment groups: three monthly sessions followed by a fourth injection 3 months later (group 1), or two treatments, one at baseline and the second 3 months later (group 2). One of the men dropped out for reasons unrelated to the treatment.

Those with clinically stable effects of Food and Drug Administration–approved AGA treatments for 12 months were permitted to participate while continuing those treatments (topical minoxidil and/or oral finasteride), since PRP is often coadministered with other therapies. But additional products, devices, or medications used for hair regrowth were not allowed. The washout period for antiandrogen therapies was 90 days.

At 3 months, the mean increase in hair counts was significant in the first group only, but at 6 months, both groups experienced significant increases in hair count (P less than .001). However, those in the first group had superior results at 6 months, with a mean 30% increase in hair counts from baseline, compared with a 7% increase in the second group (P less than .001).

Both groups had significant increases in the mean hair shaft caliber at 3 and 6 months.

Overall, 82% of participants who completed treatment reported being satisfied or highly satisfied, and 72% expressed interest in continuing treatment after the study period; almost two-thirds considered the procedure “tolerable.”

While the authors stipulated that they did not undertake the study primarily to predict treatment response to PRP, they uncovered some significant trends that they said warranted further evaluation, including the finding that those who had experienced hair loss for less than 5-6 years were more likely to have rapid and pronounced treatment response.

Their overall findings correlated with those of previous studies supporting the increase in density of hair or hair numbers, but the existing literature draws from studies that have been open label or unblinded, which makes it difficult to evaluate them head to head. The novel, subdermal injection technique used in the study “allows for fewer, more widely spaced injection points than the traditional nappage procedure ... because PRP can diffuse further once in the deeper, subgaleal space,” they wrote. The investigators noted similar response between men and women, which is important given sparse data on the efficacy of PRP in women.

Weaknesses of the study included its small sample size and short follow-up period, the authors noted. Longer-duration studies have reported relapse between 3 and 12 months.

This study is the first of its kind to directly compare efficacy rates of two injection protocols, the authors wrote, cautioning that future studies are necessary to “fine-tune preparation methods, determine optimal maintenance schedule(s), and parse out clinical predictors of efficacy.”

Eclipse Aesthetics (the manufacturer of the PRP preparation kits) provided funding for this study, but the authors acknowledged no significant interest with commercial supporters.

SOURCE: Hausauer A et al. Dermatol Surg. 2018 Sep;44(9):1191-200.

Autologous treatment with injected (AGA) after three monthly treatments, in a study that compared two treatment regimens.

PRP is gaining popularity because of its efficacy in stimulating fibroblast proliferation, triggering the production of collagen and elastin, and boosting the quantity and quality of the extracellular matrix, noted the investigators, Amelia K. Hausauer, MD, in private practice in Campbell, Calif., and Derek H. Jones, MD, in private practice in Los Angeles. Both are also with the department of dermatology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

They undertook this study to determine the optimal number and timing of treatments in patients with AGA, comparing two different injection protocols over a 6-month period. The study evaluated 40 healthy men (30) and women (10), whose mean age was 44 years, with AGA stages Norwood-Hamilton II-V (in men) and Ludwig I2-II1 (in women), recruited from a private practice in Los Angeles between November 2016 and January 2017. They were randomly assigned to one of two treatment groups: three monthly sessions followed by a fourth injection 3 months later (group 1), or two treatments, one at baseline and the second 3 months later (group 2). One of the men dropped out for reasons unrelated to the treatment.

Those with clinically stable effects of Food and Drug Administration–approved AGA treatments for 12 months were permitted to participate while continuing those treatments (topical minoxidil and/or oral finasteride), since PRP is often coadministered with other therapies. But additional products, devices, or medications used for hair regrowth were not allowed. The washout period for antiandrogen therapies was 90 days.

At 3 months, the mean increase in hair counts was significant in the first group only, but at 6 months, both groups experienced significant increases in hair count (P less than .001). However, those in the first group had superior results at 6 months, with a mean 30% increase in hair counts from baseline, compared with a 7% increase in the second group (P less than .001).

Both groups had significant increases in the mean hair shaft caliber at 3 and 6 months.

Overall, 82% of participants who completed treatment reported being satisfied or highly satisfied, and 72% expressed interest in continuing treatment after the study period; almost two-thirds considered the procedure “tolerable.”

While the authors stipulated that they did not undertake the study primarily to predict treatment response to PRP, they uncovered some significant trends that they said warranted further evaluation, including the finding that those who had experienced hair loss for less than 5-6 years were more likely to have rapid and pronounced treatment response.

Their overall findings correlated with those of previous studies supporting the increase in density of hair or hair numbers, but the existing literature draws from studies that have been open label or unblinded, which makes it difficult to evaluate them head to head. The novel, subdermal injection technique used in the study “allows for fewer, more widely spaced injection points than the traditional nappage procedure ... because PRP can diffuse further once in the deeper, subgaleal space,” they wrote. The investigators noted similar response between men and women, which is important given sparse data on the efficacy of PRP in women.

Weaknesses of the study included its small sample size and short follow-up period, the authors noted. Longer-duration studies have reported relapse between 3 and 12 months.

This study is the first of its kind to directly compare efficacy rates of two injection protocols, the authors wrote, cautioning that future studies are necessary to “fine-tune preparation methods, determine optimal maintenance schedule(s), and parse out clinical predictors of efficacy.”

Eclipse Aesthetics (the manufacturer of the PRP preparation kits) provided funding for this study, but the authors acknowledged no significant interest with commercial supporters.

SOURCE: Hausauer A et al. Dermatol Surg. 2018 Sep;44(9):1191-200.

FROM DERMATOLOGIC SURGERY

Key clinical point: Starting off with monthly PRP injections may yield more hair growth than a protocol that uses less frequently administered injections.

Major finding: Of the patients who completed treatment, 82% were satisfied with the results.

Study details: A prospective, randomized trial comparing two early-phase treatment protocols in 40 patients.

Disclosures: Eclipse Aesthetics provided funding for this study; the authors said they had no significant interest with commercial supporters.

Source: Hausauer A et al. Dermatol Surg. 2018 Sep;44(9):1191-200.

Noninvasive Vaginal Rejuvenation

Vaginal rejuvenation encompasses a group of procedures that alter the vaginal anatomy to improve cosmesis or achieve more pleasurable sexual intercourse. External vaginal procedures are defined as those performed on the female genitalia outside of the vaginal introitus, with major structures including the labia majora, mons pubis, labia minora, clitoral hood, clitoral glans, and vaginal vestibule. Internal vaginal procedures are defined as those performed within the vagina, extending from the vaginal introitus to the cervix.

The prevalence of elective vaginal rejuvenation procedures has increased in recent years, a trend that may be attributed to greater exposure through the media, including reality television and pornography. In a survey of 482 women undergoing labiaplasty, nearly all had heard about rejuvenation procedures within the last 2.2 years, and 78% had received their information through the media.1 Additionally, genital self-image can have a considerable effect on a woman’s sexual behavior and relationships. Genital dissatisfaction has been associated with decreased sexual activity, whereas positive genital self-image correlates with increased sexual desire and less sexual distress or depression.2,3

Currently, the 2 primary applications of noninvasive vaginal rejuvenation are vaginal laxity and genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). Vaginal laxity occurs in premenopausal or postmenopausal women and is caused by aging, childbearing, or hormonal imbalances. These factors can lead to decreased friction within the vagina during intercourse, which in turn can decrease sexual pleasure. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause, previously known as vulvovaginal atrophy, encompasses genital (eg, dryness, burning, irritation), sexual (eg, lack of lubrication, discomfort or pain, impaired function), and urinary (eg, urgency, dysuria, recurrent urinary tract infections) symptoms of menopause.4

Noninvasive procedures are designed to apply ablative or nonablative energy to the vaginal mucosa to tighten a lax upper vagina, also known as a wide vagina.5 A wide vagina has been defined as a widened vaginal diameter that interferes with sexual function and sensation.6 Decreased sexual sensation also may result from fibrosis or scarring of the vaginal mucosa after prior vaginal surgery, episiotomy, or tears during childbirth.7 The objective of rejuvenation procedures to treat the vaginal mucosa is to create increased frictional forces that may lead to increased sexual sensation.8 Although there are numerous reports of heightened sexual satisfaction after reduction of the vaginal diameter, a formal link between sexual pleasure and vaginal laxity has yet to be established.8,9 At present, there are no US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved energy-based devices to treat urinary incontinence or sexual function, and the FDA recently issued an alert cautioning patients on the current lack of safety and efficacy regulations.10

In this article we review the safety and efficacy data behind lasers and radiofrequency (RF) devices used in noninvasive vaginal rejuvenation procedures.

Lasers

CO2 Laser

The infrared CO2 laser utilizes 10,600-nm energy to target and vaporize water molecules within the target tissue. This thermal heating extends to the dermal collagen, which stimulates inflammatory pathways and neocollagenesis.11 The depth of penetration ranges from 20 to 125 μm.12 Zerbinati et al13 demonstrated the histologic and ultrastructural effects of a fractional CO2 laser on atrophic vaginal mucosa. Comparing pretreatment and posttreatment mucosal biopsies in 5 postmenopausal women, the investigators found that fractional CO2 laser treatment caused increased epithelial thickness, vascularity, and fibroblast activity, which led to augmented synthesis of collagen and ground substance proteins.13

New devices seek to translate these histologic improvements to the aesthetic appearance and function of female genitalia. The MonaLisa Touch (Cynosure), a new fractional CO2 laser specifically designed for treatment of the vaginal mucosa, uses dermal optical thermolysis (DOT) therapy to apply energy in a noncontinuous mode at 200-μm dots. Salvatore et al14 examined the use of this device in a noncontrolled study of 50 patients with GSM, with each patient undergoing 3 treatment sessions at monthly intervals. Intravaginal treatments were performed at the following settings: DOT (microablative zone) power of 30 W, dwell time of 1000 μs, DOT spacing of 1000 μm, and SmartStack parameter of 1 to 3. The investigators used the Vaginal Health Index (VHI) to objectively assess vaginal elasticity, secretions, pH, mucosa integrity, and moisture. Total VHI scores significantly improved between baseline and 1 month following the final treatment (mean score [SD], 13.1 [2.5] vs 23.1 [1.9]; P<.0001). There were no significant adverse events, and 84% of patients reported being satisfied with their outcome; however, the study lacked a comparison or control group, raising the possibility of placebo effect.14

Other noncontrolled series have corroborated the benefits of CO2 laser in GSM patients.15,16 In one of the largest studies to date, Filippini et al17 reviewed the outcomes of 386 menopausal women treated for GSM. Patients underwent 3 intravaginal laser sessions with the MonaLisa Touch. Intravaginal treatments were performed at a DOT power of 40 W, dwell time of 1000 μs, DOT spacing of 1000 μm, and SmartStack of 2. For the vulva, the DOT power was reduced to 30 W, dwell time of 1000 μs, DOT spacing of 1000 μm, and SmartStack of 1. Two months after the final treatment session, patients completed a nonvalidated questionnaire about their symptoms, with improved dryness reported in 60% of patients, improved burning in 56%, improved dyspareunia in 49%, improved itch in 56%, improved soreness in 73%, and improved vaginal introitus pain in 49%. Although most patients did not experience discomfort with the procedure, a minority noted a burning sensation (11%), bother with handpiece movement (6%), or vulvar pain (5%).17

Recently, Cruz et al18 performed one of the first randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials comparing fractional CO2 laser therapy, topical estrogen therapy, and the combination of both treatments in patients with GSM. Forty-five women were included in the study, and validated assessments were performed at baseline and weeks 8 and 20. Intravaginal treatments were performed at a DOT power of 30 W, dwell time of 1000 μs, DOT spacing of 1000 μm, and SmartStack of 2. Importantly, the study incorporated placebo laser treatments (with the power adjusted to 0.0 W) in the topical estrogen group, thereby decreasing result bias. There was a significant increase in VHI scores from baseline to week 8 (P<.05) and week 20 (P<.01) in all study arms. At week 20, the laser group and laser plus estrogen group showed significant improvements in reported dyspareunia, burning, and dryness, whereas the estrogen arm only reported improvements in dryness (all values P<.05).18

Erbium-Doped YAG Laser

The erbium-doped YAG (Er:YAG) laser is an ablative laser emitting light at 2940 nm. This wavelength provides an absorption coefficient for water 16 times greater than the CO2 laser, leading to decreased penetration depth of 1 to 3 μm and reduced damage to the surrounding tissues.19,20 As such, the Er:YAG laser results in milder postoperative discomfort and faster overall healing times.21

In a noncontrolled study of vaginal relaxation syndrome, Lee22 used an Er:YAG laser fitted with Petit Lady (Lutronic) 90° and 360° vaginal scanning scopes. Thirty patients were divided into 2 groups and were treated with 4 sessions at weekly intervals. In group A, the first 2 sessions were performed with the 360° scope, and the last 2 sessions with the 90° scope in multiple micropulse mode (3 multishots; pulse width of 250 μs; 1.7 J delivered per shot). Group B was treated with the 90° scope in all 4 sessions in multiple micropulse mode (same parameters as group A), and during the last 2 sessions patients were additionally treated with 2 passes per session with the 360° scope (long-pulsed mode; pulse width of 1000 μs; 3.7 J delivered per shot). Perineometer measurements taken 2 months after the final treatment showed that the combined patient population experienced significant increases in both maximal vaginal pressure (P<.01) and average vaginal pressure (P<.05). Roughly 76% of patients’ partners noted improved vaginal tightening, and 70% of patients reported being satisfied with their treatment outcome. Histologic specimens taken at baseline and 2 months postprocedure showed evidence of thicker and more cellular epithelia along with more compact lamina propria with denser connective tissue. The sessions were well tolerated, with patients reporting a nonpainful heating sensation in the vagina during treatment. Three patients from the combined patient population experienced a mild burning sensation and vaginal ecchymoses, which lasted 24 to 48 hours following treatment and resolved spontaneously. There was no control group and no reports of major or long-term adverse events.22

Investigations also have shown the benefit of Er:YAG in the treatment of GSM.23,24 In a study by Gambacciani et al,24 patients treated with the Er:YAG laser FotonaSmooth (Fotona) every 30 days for 3 months reported significant improvements in vaginal dryness and dyspareunia (P<.01), which lasted up to 6 months posttreatment, though there was no placebo group comparator. Similar results were seen by Gaspar et al23 using 3 treatments at 3-week intervals, with results sustained up to 18 months after the final session.

Radiofrequency Devices

Radiofrequency devices emit focused electromagnetic waves that heat underlying tissues without targeting melanin. The release of thermal energy induces collagen contraction, neocollagenesis, and neovascularization, all of which aid in restoring the elasticity and moisture of the vaginal mucosa.25 Devices also may be equipped with cooling probes and reverse-heating gradients to protect the surface mucosa while deeper tissues are heated.

Millheiser et al26 performed a noncontrolled pilot study in 24 women with vaginal laxity using the Viveve System (Viveve), a cryogen-cooled monopolar RF device. Participants underwent a single 30-minute session (energy ranging from 75–90 J/cm2) during which the mucosal surface of the vaginal introitus (excluding the urethra) was treated with pulses at 0.5-cm overlapping intervals. Follow-up assessments were completed at 1, 3, and 6 months posttreatment. Self-reported vaginal tightness improved in 67% of participants at 1-month posttreatment and in 87% of participants at 6 months posttreatment (P<.001). There were no adverse events reported.26 Sekiguchi et al27 reported similar benefits lasting up to 12 months after a single 26-minute session at 90 J/cm2.

A prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial using the Viveve system was recently completed by Krychman et al.28 Participants (N=186) were randomized to receive a single session of active treatment (90 J/cm2) or placebo treatment (1 J/cm2). In both groups, the vaginal introitus was treated with pulses at 0.5 cm in overlapping intervals, with the entire area (excluding the urethra) treated 5 times up to a total of 110 pulses. The primary end point was the proportion of randomized participants reporting no vaginal laxity at 6 months postin-tervention, which was assessed using the Vaginal Laxity Questionnaire. A grade of no vaginal laxity was achieved by 43.5% of participants in the active treatment group and 19.6% of participants in the sham group (P=.002). Overall numbers of treatment-emergent adverse events were comparable between the 2 groups, with the most commonly reported being vaginal discharge (2.6% in the active treatment group vs 3.5% in the sham group). There were no serious adverse events reported in the active treatment group.28

ThermiVa (ThermiGen, LLC), a unipolar RF device, was evaluated by Alinsod29 in the treatment of orgasmic dysfunction. The noncontrolled study included 25 women with self-reported difficulty achieving orgasm during intercourse, each of whom underwent 3 treatment sessions at 1-month intervals. Of the 25 enrolled women, 19 (76%) reported an average reduction in time to orgasm of at least 50%. All anorgasmic patients (n=10) at baseline reported renewed ability to achieve orgasms. Two (8%) patients failed to achieve a significant benefit from the treatments. Of note, the study did not include a control group, and specific data on the durability of beneficial effects was lacking.29

The Ultra Femme 360 (BLT Industries Inc), a monopolar RF device, was evaluated by Lalji and Lozanova30 in a noncontrolled study of 27 women with mild to moderate vaginal laxity and urinary incontinence. Participants underwent 3 treatment sessions at weekly intervals. Vaginal laxity was assessed by a subjective vulvovaginal laxity questionnaire, and data were collected before the first treatment and at 1-month follow-up. All 27 participants reported improvements in vaginal laxity, with the average grade (SD) increasing from very loose (2.19 [1.08]) to moderately tight (5.74 [0.76]; P<.05) on the questionnaire’s 7-point scale. The trial did not include a control group.30

Conclusion

With growing patient interest in vaginal rejuvenation, clinicians are increasingly incorporating a variety of procedures into their practice. Although long-term data on the safety and efficacy of these treatments has yet to be established, current evidence indicates that fractional ablative lasers and RF devices can improve vaginal laxity, sexual sensation, and symptoms of GSM.

To date, major complications have not been reported, but the FDA has advocated caution until regulatory approval is achieved.10 Concerns exist over the limited number of robust clinical trials as well as the prevalence of advertising campaigns that promise wide-ranging improvements without sufficient evidence. Definitive statements on medical or cosmetic indications will undoubtedly require more thorough investigation. At this time, the safety profile of these devices appears to be favorable, and high rates of patient satisfaction have been reported. As such, noninvasive vaginal rejuvenation procedures may represent a valuable addition to the cosmetic landscape.

- Koning M, Zeijlmans IA, Bouman TK, et al. Female attitudes regarding labia minora appearance and reduction with consideration of media influence. Aesthet Surg J. 2009;29:65-71.

- Rowen TS, Gaither TW, Shindel AW, et al. Characteristics of genital dissatisfaction among a nationally representative sample of U.S. women. J Sex Med. 2018;15:698-704.

- Berman L, Berman J, Miles M, et al. Genital self-image as a component of sexual health: relationship between genital self-image, female sexual function, and quality of life measures. J Sex Marital Ther. 2003;29(suppl 1):11-21.

- Portman DJ, Gass ML; Vulvovaginal Atrophy Terminology Consensus Conference Panel. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2014;21:1063-1068.

- Goodman MP, Placik OJ, Benson RH 3rd, et al. A large multicenter outcome study of female genital plastic surgery. J Sex Med. 2010;7(4 pt 1):1565-1577.

- Ostrzenski A. Vaginal rugation rejuvenation (restoration): a new surgical technique for an acquired sensation of wide/smooth vagina. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2012;73:48-52.

- Singh A, Swift S, Khullar V, et al. Laser vaginal rejuvenation: not ready for prime time. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26:163-164.

- Iglesia CB, Yurteri-Kaplan L, Alinsod R. Female genital cosmetic surgery: a review of techniques and outcomes. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:1997-2009.

- Dobbeleir JM, Landuyt KV, Monstrey SJ. Aesthetic surgery of the female genitalia. Semin Plast Surg. 2011;25:130-141.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA warns against use of energy-based devices to perform vaginal ‘rejuvenation’ or vaginal cosmetic procedures: FDA safety communication. July 30, 2018. https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm615013.htm. Accessed September 10, 2018.

- Patil UA, Dhami LD. Overview of lasers. Indian J Plast Surg. 2008;41(suppl):S101-S113.

- Qureshi AA, Tenenbaum MM, Myckatyn TM. Nonsurgical vulvovaginal rejuvenation with radiofrequency and laser devices: a literature review and comprehensive update for aesthetic surgeons. Aesthet Surg J. 2018;38:302-311.

- Zerbinati N, Serati M, Origoni M, et al. Microscopic and ultrastructural modifications of postmenopausal atrophic vaginal mucosa after fractional carbon dioxide laser treatment. Lasers Med Sci. 2015;30:429-436.

- Salvatore S, Nappi RE, Zerbinati N, et al. A 12-week treatment with fractional CO2 laser for vulvovaginal atrophy: a pilot study. Climacteric. 2014;17:363-369.

- Eder SE. Early effect of fractional CO2 laser treatment in post-menopausal women with vaginal atrophy. Laser Ther. 2018;27:41-47.

- Perino A, Calligaro A, Forlani F, et al. Vulvo-vaginal atrophy: a new treatment modality using thermo-ablative fractional CO2 laser. Maturitas. 2015;80:296-301.

- Filippini M, Del Duca E, Negosanti F, et al. Fractional CO2 laser: from skin rejuvenation to vulvo-vaginal reshaping. Photomed Laser Surg. 2017;35:171-175.

- Cruz VL, Steiner ML, Pompei LM, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial for evaluating the efficacy of fractional CO2 laser compared with topical estriol in the treatment of vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2018;25:21-28.

- Preissig J, Hamilton K, Markus R. Current laser resurfacing technologies: a review that delves beneath the surface. Semin Plast Surg. 2012;26:109-116.

- Kaushik SB, Alexis AF. Nonablative fractional laser resurfacing in skin of color: evidence-based review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10:51-67.

- Alexiades-Armenakas MR, Dover JS, Arndt KA. Fractional laser skin resurfacing. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:1274-1287.

- Lee MS. Treatment of vaginal relaxation syndrome with an erbium:YAG laser using 90 degrees and 360 degrees scanning scopes: a pilot study & short-term results. Laser Ther. 2014;23:129-138.

- Gaspar A, Brandi H, Gomez V, et al. Efficacy of erbium:YAG laser treatment compared to topical estriol treatment for symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:160-168.

- Gambacciani M, Levancini M, Cervigni M. Vaginal erbium laser: the second-generation thermotherapy for the genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Climacteric. 2015;18:757-763.

- Tadir Y, Gaspar A, Lev-Sagie A, et al. Light and energy based therapeutics for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: consensus and controversies. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:137-159.

- Millheiser LS, Pauls RN, Herbst SJ, et al. Radiofrequency treatment of vaginal laxity after vaginal delivery: nonsurgical vaginal tightening. J Sex Med. 2010;7:3088-3095.

- Sekiguchi Y, Utsugisawa Y, Azekosi Y, et al. Laxity of the vaginal introitus after childbirth: nonsurgical outpatient procedure for vaginal tissue restoration and improved sexual satisfaction using low-energy radiofrequency thermal therapy. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2013;22:775-781.

- Krychman M, Rowan CG, Allan BB, et al. Effect of single-treatment, surface-cooled radiofrequency therapy on vaginal laxity and female sexual function: the VIVEVE I randomized controlled trial. J Sex Med. 2017;14:215-225.

- Alinsod RM. Transcutaneous temperature controlled radiofrequency for orgasmic dysfunction. Lasers Surg Med. 2016;48:641-645.

- Lalji S, Lozanova P. Evaluation of the safety and efficacy of a monopolar nonablative radiofrequency device for the improvement of vulvo-vaginal laxity and urinary incontinence. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017;16:230-234.

Vaginal rejuvenation encompasses a group of procedures that alter the vaginal anatomy to improve cosmesis or achieve more pleasurable sexual intercourse. External vaginal procedures are defined as those performed on the female genitalia outside of the vaginal introitus, with major structures including the labia majora, mons pubis, labia minora, clitoral hood, clitoral glans, and vaginal vestibule. Internal vaginal procedures are defined as those performed within the vagina, extending from the vaginal introitus to the cervix.

The prevalence of elective vaginal rejuvenation procedures has increased in recent years, a trend that may be attributed to greater exposure through the media, including reality television and pornography. In a survey of 482 women undergoing labiaplasty, nearly all had heard about rejuvenation procedures within the last 2.2 years, and 78% had received their information through the media.1 Additionally, genital self-image can have a considerable effect on a woman’s sexual behavior and relationships. Genital dissatisfaction has been associated with decreased sexual activity, whereas positive genital self-image correlates with increased sexual desire and less sexual distress or depression.2,3

Currently, the 2 primary applications of noninvasive vaginal rejuvenation are vaginal laxity and genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). Vaginal laxity occurs in premenopausal or postmenopausal women and is caused by aging, childbearing, or hormonal imbalances. These factors can lead to decreased friction within the vagina during intercourse, which in turn can decrease sexual pleasure. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause, previously known as vulvovaginal atrophy, encompasses genital (eg, dryness, burning, irritation), sexual (eg, lack of lubrication, discomfort or pain, impaired function), and urinary (eg, urgency, dysuria, recurrent urinary tract infections) symptoms of menopause.4

Noninvasive procedures are designed to apply ablative or nonablative energy to the vaginal mucosa to tighten a lax upper vagina, also known as a wide vagina.5 A wide vagina has been defined as a widened vaginal diameter that interferes with sexual function and sensation.6 Decreased sexual sensation also may result from fibrosis or scarring of the vaginal mucosa after prior vaginal surgery, episiotomy, or tears during childbirth.7 The objective of rejuvenation procedures to treat the vaginal mucosa is to create increased frictional forces that may lead to increased sexual sensation.8 Although there are numerous reports of heightened sexual satisfaction after reduction of the vaginal diameter, a formal link between sexual pleasure and vaginal laxity has yet to be established.8,9 At present, there are no US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved energy-based devices to treat urinary incontinence or sexual function, and the FDA recently issued an alert cautioning patients on the current lack of safety and efficacy regulations.10

In this article we review the safety and efficacy data behind lasers and radiofrequency (RF) devices used in noninvasive vaginal rejuvenation procedures.

Lasers

CO2 Laser

The infrared CO2 laser utilizes 10,600-nm energy to target and vaporize water molecules within the target tissue. This thermal heating extends to the dermal collagen, which stimulates inflammatory pathways and neocollagenesis.11 The depth of penetration ranges from 20 to 125 μm.12 Zerbinati et al13 demonstrated the histologic and ultrastructural effects of a fractional CO2 laser on atrophic vaginal mucosa. Comparing pretreatment and posttreatment mucosal biopsies in 5 postmenopausal women, the investigators found that fractional CO2 laser treatment caused increased epithelial thickness, vascularity, and fibroblast activity, which led to augmented synthesis of collagen and ground substance proteins.13

New devices seek to translate these histologic improvements to the aesthetic appearance and function of female genitalia. The MonaLisa Touch (Cynosure), a new fractional CO2 laser specifically designed for treatment of the vaginal mucosa, uses dermal optical thermolysis (DOT) therapy to apply energy in a noncontinuous mode at 200-μm dots. Salvatore et al14 examined the use of this device in a noncontrolled study of 50 patients with GSM, with each patient undergoing 3 treatment sessions at monthly intervals. Intravaginal treatments were performed at the following settings: DOT (microablative zone) power of 30 W, dwell time of 1000 μs, DOT spacing of 1000 μm, and SmartStack parameter of 1 to 3. The investigators used the Vaginal Health Index (VHI) to objectively assess vaginal elasticity, secretions, pH, mucosa integrity, and moisture. Total VHI scores significantly improved between baseline and 1 month following the final treatment (mean score [SD], 13.1 [2.5] vs 23.1 [1.9]; P<.0001). There were no significant adverse events, and 84% of patients reported being satisfied with their outcome; however, the study lacked a comparison or control group, raising the possibility of placebo effect.14

Other noncontrolled series have corroborated the benefits of CO2 laser in GSM patients.15,16 In one of the largest studies to date, Filippini et al17 reviewed the outcomes of 386 menopausal women treated for GSM. Patients underwent 3 intravaginal laser sessions with the MonaLisa Touch. Intravaginal treatments were performed at a DOT power of 40 W, dwell time of 1000 μs, DOT spacing of 1000 μm, and SmartStack of 2. For the vulva, the DOT power was reduced to 30 W, dwell time of 1000 μs, DOT spacing of 1000 μm, and SmartStack of 1. Two months after the final treatment session, patients completed a nonvalidated questionnaire about their symptoms, with improved dryness reported in 60% of patients, improved burning in 56%, improved dyspareunia in 49%, improved itch in 56%, improved soreness in 73%, and improved vaginal introitus pain in 49%. Although most patients did not experience discomfort with the procedure, a minority noted a burning sensation (11%), bother with handpiece movement (6%), or vulvar pain (5%).17

Recently, Cruz et al18 performed one of the first randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials comparing fractional CO2 laser therapy, topical estrogen therapy, and the combination of both treatments in patients with GSM. Forty-five women were included in the study, and validated assessments were performed at baseline and weeks 8 and 20. Intravaginal treatments were performed at a DOT power of 30 W, dwell time of 1000 μs, DOT spacing of 1000 μm, and SmartStack of 2. Importantly, the study incorporated placebo laser treatments (with the power adjusted to 0.0 W) in the topical estrogen group, thereby decreasing result bias. There was a significant increase in VHI scores from baseline to week 8 (P<.05) and week 20 (P<.01) in all study arms. At week 20, the laser group and laser plus estrogen group showed significant improvements in reported dyspareunia, burning, and dryness, whereas the estrogen arm only reported improvements in dryness (all values P<.05).18

Erbium-Doped YAG Laser

The erbium-doped YAG (Er:YAG) laser is an ablative laser emitting light at 2940 nm. This wavelength provides an absorption coefficient for water 16 times greater than the CO2 laser, leading to decreased penetration depth of 1 to 3 μm and reduced damage to the surrounding tissues.19,20 As such, the Er:YAG laser results in milder postoperative discomfort and faster overall healing times.21

In a noncontrolled study of vaginal relaxation syndrome, Lee22 used an Er:YAG laser fitted with Petit Lady (Lutronic) 90° and 360° vaginal scanning scopes. Thirty patients were divided into 2 groups and were treated with 4 sessions at weekly intervals. In group A, the first 2 sessions were performed with the 360° scope, and the last 2 sessions with the 90° scope in multiple micropulse mode (3 multishots; pulse width of 250 μs; 1.7 J delivered per shot). Group B was treated with the 90° scope in all 4 sessions in multiple micropulse mode (same parameters as group A), and during the last 2 sessions patients were additionally treated with 2 passes per session with the 360° scope (long-pulsed mode; pulse width of 1000 μs; 3.7 J delivered per shot). Perineometer measurements taken 2 months after the final treatment showed that the combined patient population experienced significant increases in both maximal vaginal pressure (P<.01) and average vaginal pressure (P<.05). Roughly 76% of patients’ partners noted improved vaginal tightening, and 70% of patients reported being satisfied with their treatment outcome. Histologic specimens taken at baseline and 2 months postprocedure showed evidence of thicker and more cellular epithelia along with more compact lamina propria with denser connective tissue. The sessions were well tolerated, with patients reporting a nonpainful heating sensation in the vagina during treatment. Three patients from the combined patient population experienced a mild burning sensation and vaginal ecchymoses, which lasted 24 to 48 hours following treatment and resolved spontaneously. There was no control group and no reports of major or long-term adverse events.22

Investigations also have shown the benefit of Er:YAG in the treatment of GSM.23,24 In a study by Gambacciani et al,24 patients treated with the Er:YAG laser FotonaSmooth (Fotona) every 30 days for 3 months reported significant improvements in vaginal dryness and dyspareunia (P<.01), which lasted up to 6 months posttreatment, though there was no placebo group comparator. Similar results were seen by Gaspar et al23 using 3 treatments at 3-week intervals, with results sustained up to 18 months after the final session.

Radiofrequency Devices

Radiofrequency devices emit focused electromagnetic waves that heat underlying tissues without targeting melanin. The release of thermal energy induces collagen contraction, neocollagenesis, and neovascularization, all of which aid in restoring the elasticity and moisture of the vaginal mucosa.25 Devices also may be equipped with cooling probes and reverse-heating gradients to protect the surface mucosa while deeper tissues are heated.

Millheiser et al26 performed a noncontrolled pilot study in 24 women with vaginal laxity using the Viveve System (Viveve), a cryogen-cooled monopolar RF device. Participants underwent a single 30-minute session (energy ranging from 75–90 J/cm2) during which the mucosal surface of the vaginal introitus (excluding the urethra) was treated with pulses at 0.5-cm overlapping intervals. Follow-up assessments were completed at 1, 3, and 6 months posttreatment. Self-reported vaginal tightness improved in 67% of participants at 1-month posttreatment and in 87% of participants at 6 months posttreatment (P<.001). There were no adverse events reported.26 Sekiguchi et al27 reported similar benefits lasting up to 12 months after a single 26-minute session at 90 J/cm2.

A prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial using the Viveve system was recently completed by Krychman et al.28 Participants (N=186) were randomized to receive a single session of active treatment (90 J/cm2) or placebo treatment (1 J/cm2). In both groups, the vaginal introitus was treated with pulses at 0.5 cm in overlapping intervals, with the entire area (excluding the urethra) treated 5 times up to a total of 110 pulses. The primary end point was the proportion of randomized participants reporting no vaginal laxity at 6 months postin-tervention, which was assessed using the Vaginal Laxity Questionnaire. A grade of no vaginal laxity was achieved by 43.5% of participants in the active treatment group and 19.6% of participants in the sham group (P=.002). Overall numbers of treatment-emergent adverse events were comparable between the 2 groups, with the most commonly reported being vaginal discharge (2.6% in the active treatment group vs 3.5% in the sham group). There were no serious adverse events reported in the active treatment group.28

ThermiVa (ThermiGen, LLC), a unipolar RF device, was evaluated by Alinsod29 in the treatment of orgasmic dysfunction. The noncontrolled study included 25 women with self-reported difficulty achieving orgasm during intercourse, each of whom underwent 3 treatment sessions at 1-month intervals. Of the 25 enrolled women, 19 (76%) reported an average reduction in time to orgasm of at least 50%. All anorgasmic patients (n=10) at baseline reported renewed ability to achieve orgasms. Two (8%) patients failed to achieve a significant benefit from the treatments. Of note, the study did not include a control group, and specific data on the durability of beneficial effects was lacking.29

The Ultra Femme 360 (BLT Industries Inc), a monopolar RF device, was evaluated by Lalji and Lozanova30 in a noncontrolled study of 27 women with mild to moderate vaginal laxity and urinary incontinence. Participants underwent 3 treatment sessions at weekly intervals. Vaginal laxity was assessed by a subjective vulvovaginal laxity questionnaire, and data were collected before the first treatment and at 1-month follow-up. All 27 participants reported improvements in vaginal laxity, with the average grade (SD) increasing from very loose (2.19 [1.08]) to moderately tight (5.74 [0.76]; P<.05) on the questionnaire’s 7-point scale. The trial did not include a control group.30

Conclusion

With growing patient interest in vaginal rejuvenation, clinicians are increasingly incorporating a variety of procedures into their practice. Although long-term data on the safety and efficacy of these treatments has yet to be established, current evidence indicates that fractional ablative lasers and RF devices can improve vaginal laxity, sexual sensation, and symptoms of GSM.

To date, major complications have not been reported, but the FDA has advocated caution until regulatory approval is achieved.10 Concerns exist over the limited number of robust clinical trials as well as the prevalence of advertising campaigns that promise wide-ranging improvements without sufficient evidence. Definitive statements on medical or cosmetic indications will undoubtedly require more thorough investigation. At this time, the safety profile of these devices appears to be favorable, and high rates of patient satisfaction have been reported. As such, noninvasive vaginal rejuvenation procedures may represent a valuable addition to the cosmetic landscape.

Vaginal rejuvenation encompasses a group of procedures that alter the vaginal anatomy to improve cosmesis or achieve more pleasurable sexual intercourse. External vaginal procedures are defined as those performed on the female genitalia outside of the vaginal introitus, with major structures including the labia majora, mons pubis, labia minora, clitoral hood, clitoral glans, and vaginal vestibule. Internal vaginal procedures are defined as those performed within the vagina, extending from the vaginal introitus to the cervix.

The prevalence of elective vaginal rejuvenation procedures has increased in recent years, a trend that may be attributed to greater exposure through the media, including reality television and pornography. In a survey of 482 women undergoing labiaplasty, nearly all had heard about rejuvenation procedures within the last 2.2 years, and 78% had received their information through the media.1 Additionally, genital self-image can have a considerable effect on a woman’s sexual behavior and relationships. Genital dissatisfaction has been associated with decreased sexual activity, whereas positive genital self-image correlates with increased sexual desire and less sexual distress or depression.2,3

Currently, the 2 primary applications of noninvasive vaginal rejuvenation are vaginal laxity and genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). Vaginal laxity occurs in premenopausal or postmenopausal women and is caused by aging, childbearing, or hormonal imbalances. These factors can lead to decreased friction within the vagina during intercourse, which in turn can decrease sexual pleasure. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause, previously known as vulvovaginal atrophy, encompasses genital (eg, dryness, burning, irritation), sexual (eg, lack of lubrication, discomfort or pain, impaired function), and urinary (eg, urgency, dysuria, recurrent urinary tract infections) symptoms of menopause.4

Noninvasive procedures are designed to apply ablative or nonablative energy to the vaginal mucosa to tighten a lax upper vagina, also known as a wide vagina.5 A wide vagina has been defined as a widened vaginal diameter that interferes with sexual function and sensation.6 Decreased sexual sensation also may result from fibrosis or scarring of the vaginal mucosa after prior vaginal surgery, episiotomy, or tears during childbirth.7 The objective of rejuvenation procedures to treat the vaginal mucosa is to create increased frictional forces that may lead to increased sexual sensation.8 Although there are numerous reports of heightened sexual satisfaction after reduction of the vaginal diameter, a formal link between sexual pleasure and vaginal laxity has yet to be established.8,9 At present, there are no US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved energy-based devices to treat urinary incontinence or sexual function, and the FDA recently issued an alert cautioning patients on the current lack of safety and efficacy regulations.10

In this article we review the safety and efficacy data behind lasers and radiofrequency (RF) devices used in noninvasive vaginal rejuvenation procedures.

Lasers

CO2 Laser

The infrared CO2 laser utilizes 10,600-nm energy to target and vaporize water molecules within the target tissue. This thermal heating extends to the dermal collagen, which stimulates inflammatory pathways and neocollagenesis.11 The depth of penetration ranges from 20 to 125 μm.12 Zerbinati et al13 demonstrated the histologic and ultrastructural effects of a fractional CO2 laser on atrophic vaginal mucosa. Comparing pretreatment and posttreatment mucosal biopsies in 5 postmenopausal women, the investigators found that fractional CO2 laser treatment caused increased epithelial thickness, vascularity, and fibroblast activity, which led to augmented synthesis of collagen and ground substance proteins.13

New devices seek to translate these histologic improvements to the aesthetic appearance and function of female genitalia. The MonaLisa Touch (Cynosure), a new fractional CO2 laser specifically designed for treatment of the vaginal mucosa, uses dermal optical thermolysis (DOT) therapy to apply energy in a noncontinuous mode at 200-μm dots. Salvatore et al14 examined the use of this device in a noncontrolled study of 50 patients with GSM, with each patient undergoing 3 treatment sessions at monthly intervals. Intravaginal treatments were performed at the following settings: DOT (microablative zone) power of 30 W, dwell time of 1000 μs, DOT spacing of 1000 μm, and SmartStack parameter of 1 to 3. The investigators used the Vaginal Health Index (VHI) to objectively assess vaginal elasticity, secretions, pH, mucosa integrity, and moisture. Total VHI scores significantly improved between baseline and 1 month following the final treatment (mean score [SD], 13.1 [2.5] vs 23.1 [1.9]; P<.0001). There were no significant adverse events, and 84% of patients reported being satisfied with their outcome; however, the study lacked a comparison or control group, raising the possibility of placebo effect.14