User login

At what diameter does a scar form after a full-thickness wound?

DENVER – A clinically identifiable scar occurs after full-thickness skin wounds greater than 400-500 mcm in diameter, while wounds of smaller diameter heal with no clinically perceptible scar.

The findings come from a “The broader purpose of this work is to contribute to the development of techniques for harvesting skin tissue with less morbidity than conventional methods,” lead study author Amanda H. Champlain, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “The size threshold at which a full-thickness skin wound can heal without scarring had not been determined prior to this study.”

Dr. Champlain, a fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital and The Wellman Center for Photomedicine, both in Boston, and her colleagues designed a way to evaluate healing responses and safety after collecting skin microbiopsies of different sizes from preabdominoplasty skin. According to the study abstract, the concept “is based on fractional photothermolysis in which a multitude of small, full-thickness thermal burns are produced by a laser on the skin with rapid healing and no scarring.” Measures included the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS), donor site pain scale, subject satisfaction survey, and an assessment of side effects, clinical photographs, and histology.

Preliminary data are available for five subjects. The POSAS-Observer scale ranges from 5 to 50 while the POSAS-Patient scale ranges from 6 to 60. The researchers observed that average final POSAS-Observer scores were 5.6 for scars 200 mcm in diameter, 5.2 for scars 400 mcm in diameter, 7.0 for scars 500 mcm in diameter, 6.8 for scars 600 mcm in diameter, 8.2 for scars 800 mcm in diameter, 9.6 for scars 1 mm in diameter, and 13.2 for those 2 mm in diameter. Meanwhile, the average final POSAS-Subject scores were 6.0 for scars 200 mcm in diameter, 6.0 for scars 400 mcm in diameter, 6.6 for scars 500 mcm in diameter, 6.4 for those 600 mcm in diameter, 7.2 for scars 800 mcm in diameter, 7.4 for scars 1 mm in diameter, and 10.0 for those 2 mm in diameter.

The maximum donor site pain reported was 4 out of 10 in one subject. “The procedure was very well tolerated by the subjects,” Dr. Champlain said. “They healed quickly, and the majority were happy with the cosmetic outcome regardless of the diameter of the microbiopsy used.”

The most common side effects of the study procedures included mild bleeding, scabbing, redness, and hyper/hypopigmentation. “The majority of study participants strongly agree that the study procedure was safe, tolerable, and cosmetically sound,” she said.

Dr. Champlain does not have any disclosures, but she said that the study was funded by the Department of Defense.

DENVER – A clinically identifiable scar occurs after full-thickness skin wounds greater than 400-500 mcm in diameter, while wounds of smaller diameter heal with no clinically perceptible scar.

The findings come from a “The broader purpose of this work is to contribute to the development of techniques for harvesting skin tissue with less morbidity than conventional methods,” lead study author Amanda H. Champlain, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “The size threshold at which a full-thickness skin wound can heal without scarring had not been determined prior to this study.”

Dr. Champlain, a fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital and The Wellman Center for Photomedicine, both in Boston, and her colleagues designed a way to evaluate healing responses and safety after collecting skin microbiopsies of different sizes from preabdominoplasty skin. According to the study abstract, the concept “is based on fractional photothermolysis in which a multitude of small, full-thickness thermal burns are produced by a laser on the skin with rapid healing and no scarring.” Measures included the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS), donor site pain scale, subject satisfaction survey, and an assessment of side effects, clinical photographs, and histology.

Preliminary data are available for five subjects. The POSAS-Observer scale ranges from 5 to 50 while the POSAS-Patient scale ranges from 6 to 60. The researchers observed that average final POSAS-Observer scores were 5.6 for scars 200 mcm in diameter, 5.2 for scars 400 mcm in diameter, 7.0 for scars 500 mcm in diameter, 6.8 for scars 600 mcm in diameter, 8.2 for scars 800 mcm in diameter, 9.6 for scars 1 mm in diameter, and 13.2 for those 2 mm in diameter. Meanwhile, the average final POSAS-Subject scores were 6.0 for scars 200 mcm in diameter, 6.0 for scars 400 mcm in diameter, 6.6 for scars 500 mcm in diameter, 6.4 for those 600 mcm in diameter, 7.2 for scars 800 mcm in diameter, 7.4 for scars 1 mm in diameter, and 10.0 for those 2 mm in diameter.

The maximum donor site pain reported was 4 out of 10 in one subject. “The procedure was very well tolerated by the subjects,” Dr. Champlain said. “They healed quickly, and the majority were happy with the cosmetic outcome regardless of the diameter of the microbiopsy used.”

The most common side effects of the study procedures included mild bleeding, scabbing, redness, and hyper/hypopigmentation. “The majority of study participants strongly agree that the study procedure was safe, tolerable, and cosmetically sound,” she said.

Dr. Champlain does not have any disclosures, but she said that the study was funded by the Department of Defense.

DENVER – A clinically identifiable scar occurs after full-thickness skin wounds greater than 400-500 mcm in diameter, while wounds of smaller diameter heal with no clinically perceptible scar.

The findings come from a “The broader purpose of this work is to contribute to the development of techniques for harvesting skin tissue with less morbidity than conventional methods,” lead study author Amanda H. Champlain, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “The size threshold at which a full-thickness skin wound can heal without scarring had not been determined prior to this study.”

Dr. Champlain, a fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital and The Wellman Center for Photomedicine, both in Boston, and her colleagues designed a way to evaluate healing responses and safety after collecting skin microbiopsies of different sizes from preabdominoplasty skin. According to the study abstract, the concept “is based on fractional photothermolysis in which a multitude of small, full-thickness thermal burns are produced by a laser on the skin with rapid healing and no scarring.” Measures included the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS), donor site pain scale, subject satisfaction survey, and an assessment of side effects, clinical photographs, and histology.

Preliminary data are available for five subjects. The POSAS-Observer scale ranges from 5 to 50 while the POSAS-Patient scale ranges from 6 to 60. The researchers observed that average final POSAS-Observer scores were 5.6 for scars 200 mcm in diameter, 5.2 for scars 400 mcm in diameter, 7.0 for scars 500 mcm in diameter, 6.8 for scars 600 mcm in diameter, 8.2 for scars 800 mcm in diameter, 9.6 for scars 1 mm in diameter, and 13.2 for those 2 mm in diameter. Meanwhile, the average final POSAS-Subject scores were 6.0 for scars 200 mcm in diameter, 6.0 for scars 400 mcm in diameter, 6.6 for scars 500 mcm in diameter, 6.4 for those 600 mcm in diameter, 7.2 for scars 800 mcm in diameter, 7.4 for scars 1 mm in diameter, and 10.0 for those 2 mm in diameter.

The maximum donor site pain reported was 4 out of 10 in one subject. “The procedure was very well tolerated by the subjects,” Dr. Champlain said. “They healed quickly, and the majority were happy with the cosmetic outcome regardless of the diameter of the microbiopsy used.”

The most common side effects of the study procedures included mild bleeding, scabbing, redness, and hyper/hypopigmentation. “The majority of study participants strongly agree that the study procedure was safe, tolerable, and cosmetically sound,” she said.

Dr. Champlain does not have any disclosures, but she said that the study was funded by the Department of Defense.

REPORTING FROM ASLMS 2019

Key clinical point: Collecting skin microbiopsies of different sizes from preabdominoplasty skin is safe and highly tolerable.

Major finding: Full-thickness skin wounds greater than 400-500 mcm in diameter heal with a clinically identifiable scar.

Study details: A pilot trial in five individuals that set out to determine the biopsy size limit at which healing occurs without a scar, as well as demonstrate the safety of performing multiple skin microbiopsies.

Disclosures: Dr. Champlain does not have any disclosures, but she said that the study was funded by the Department of Defense.

More than 1 in 10 dermatology residents report laser-associated adverse events in training

DENVER –

“Incorporating a formal laser safety education curriculum is an opportunity for residency programs and organizations like ASLMS,” study coauthor Daniel J. Bergman, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery.

In what is believed to be the first study of its kind, Dr. Bergman and his coauthor Shari A. Ochoa, MD, created an online survey intended to evaluate the safety education and number of adverse laser-associated events that occurred during dermatology residencies in the United States. After the coauthors sought input for content of the survey from dermatology faculty and their colleagues at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz., they used the Association of Professors of Dermatology email database to distribute the survey to Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)–approved dermatology residency programs. “In general, most studies evaluate the models of education and the number of hours dedicated to learning a skill,” said Dr. Bergman, who is a first-year dermatology resident at the Mayo Clinic. “This study is unique because it identified adverse events experienced by dermatology residents and also evaluated their formal laser safety training.”

To date, 78 dermatology residents have completed responses to the survey. Of these, 10 (13%) identified an adverse event associated with use of a laser. Of those respondents, six respondents knew how to report the event, five felt comfortable operating the laser, three had formal laser safety training, five felt like they understood the risks associated with lasers, and all but one felt properly supervised. One identified plans for postresidency laser training. Of the 68 respondents who have not identified an adverse event, 39 (57%) reported formal laser safety training, and only 24 (35%) indicated that they knew how to report an adverse event.

“I was interested to find that 13% of dermatology residents have already experienced an adverse laser event,” Dr. Bergman said. “I was also surprised to discover that only 54% of all survey respondents identified or recognized formal laser safety training. The ACGME mandates that dermatology residents receive training in the theoretical and practical applications of lasers. This finding may indicate that additional training, focusing on laser safety, should be incorporated more formally into the curriculum at some programs.”

He acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the relatively small number of respondents and the fact that only ACGME-accredited residencies were asked to participate. “Therefore, we are still missing a large amount of data,” Dr. Bergman said. “Most notably, the results are subject to recall bias and participants defined the nature of an adverse laser event.”

He reported having no financial disclosures.

DENVER –

“Incorporating a formal laser safety education curriculum is an opportunity for residency programs and organizations like ASLMS,” study coauthor Daniel J. Bergman, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery.

In what is believed to be the first study of its kind, Dr. Bergman and his coauthor Shari A. Ochoa, MD, created an online survey intended to evaluate the safety education and number of adverse laser-associated events that occurred during dermatology residencies in the United States. After the coauthors sought input for content of the survey from dermatology faculty and their colleagues at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz., they used the Association of Professors of Dermatology email database to distribute the survey to Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)–approved dermatology residency programs. “In general, most studies evaluate the models of education and the number of hours dedicated to learning a skill,” said Dr. Bergman, who is a first-year dermatology resident at the Mayo Clinic. “This study is unique because it identified adverse events experienced by dermatology residents and also evaluated their formal laser safety training.”

To date, 78 dermatology residents have completed responses to the survey. Of these, 10 (13%) identified an adverse event associated with use of a laser. Of those respondents, six respondents knew how to report the event, five felt comfortable operating the laser, three had formal laser safety training, five felt like they understood the risks associated with lasers, and all but one felt properly supervised. One identified plans for postresidency laser training. Of the 68 respondents who have not identified an adverse event, 39 (57%) reported formal laser safety training, and only 24 (35%) indicated that they knew how to report an adverse event.

“I was interested to find that 13% of dermatology residents have already experienced an adverse laser event,” Dr. Bergman said. “I was also surprised to discover that only 54% of all survey respondents identified or recognized formal laser safety training. The ACGME mandates that dermatology residents receive training in the theoretical and practical applications of lasers. This finding may indicate that additional training, focusing on laser safety, should be incorporated more formally into the curriculum at some programs.”

He acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the relatively small number of respondents and the fact that only ACGME-accredited residencies were asked to participate. “Therefore, we are still missing a large amount of data,” Dr. Bergman said. “Most notably, the results are subject to recall bias and participants defined the nature of an adverse laser event.”

He reported having no financial disclosures.

DENVER –

“Incorporating a formal laser safety education curriculum is an opportunity for residency programs and organizations like ASLMS,” study coauthor Daniel J. Bergman, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery.

In what is believed to be the first study of its kind, Dr. Bergman and his coauthor Shari A. Ochoa, MD, created an online survey intended to evaluate the safety education and number of adverse laser-associated events that occurred during dermatology residencies in the United States. After the coauthors sought input for content of the survey from dermatology faculty and their colleagues at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz., they used the Association of Professors of Dermatology email database to distribute the survey to Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)–approved dermatology residency programs. “In general, most studies evaluate the models of education and the number of hours dedicated to learning a skill,” said Dr. Bergman, who is a first-year dermatology resident at the Mayo Clinic. “This study is unique because it identified adverse events experienced by dermatology residents and also evaluated their formal laser safety training.”

To date, 78 dermatology residents have completed responses to the survey. Of these, 10 (13%) identified an adverse event associated with use of a laser. Of those respondents, six respondents knew how to report the event, five felt comfortable operating the laser, three had formal laser safety training, five felt like they understood the risks associated with lasers, and all but one felt properly supervised. One identified plans for postresidency laser training. Of the 68 respondents who have not identified an adverse event, 39 (57%) reported formal laser safety training, and only 24 (35%) indicated that they knew how to report an adverse event.

“I was interested to find that 13% of dermatology residents have already experienced an adverse laser event,” Dr. Bergman said. “I was also surprised to discover that only 54% of all survey respondents identified or recognized formal laser safety training. The ACGME mandates that dermatology residents receive training in the theoretical and practical applications of lasers. This finding may indicate that additional training, focusing on laser safety, should be incorporated more formally into the curriculum at some programs.”

He acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the relatively small number of respondents and the fact that only ACGME-accredited residencies were asked to participate. “Therefore, we are still missing a large amount of data,” Dr. Bergman said. “Most notably, the results are subject to recall bias and participants defined the nature of an adverse laser event.”

He reported having no financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM ASLMS 2019

Key clinical point: Laser-associated adverse events experienced by dermatology residents are not uncommon.

Major finding: Of 78 dermatology residents, 10 (13%) identified an adverse events associated with use of a laser.

Study details: An online survey of 78 dermatology residents.

Disclosures: Dr. Bergman reported having no financial disclosures.

The 39th ASLMS meeting is now underway

WASHINGTON – At the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, the taking place March 27-31, 2019, in Denver.

“ASLMS is always an amazing meeting, and it’s a unique meeting,” said past president Mathew Avram, MD, director of the Dermatology Laser & Cosmetic Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. “At its core, it’s a scientific meeting ... you can take things back to your practice that change the practice of medicine.”

Current ASLMS president Eric Bernstein, MD, of Main Line Center for Laser Surgery, Ardmore, Pa., pointed out that, in addition to doctors and other health care practitioners, other available and accessible attendees include the engineers who build the lasers. And this year, injectables are being incorporated into the program.

MDedge reporter Doug Brunk will be reporting from the meeting.

WASHINGTON – At the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, the taking place March 27-31, 2019, in Denver.

“ASLMS is always an amazing meeting, and it’s a unique meeting,” said past president Mathew Avram, MD, director of the Dermatology Laser & Cosmetic Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. “At its core, it’s a scientific meeting ... you can take things back to your practice that change the practice of medicine.”

Current ASLMS president Eric Bernstein, MD, of Main Line Center for Laser Surgery, Ardmore, Pa., pointed out that, in addition to doctors and other health care practitioners, other available and accessible attendees include the engineers who build the lasers. And this year, injectables are being incorporated into the program.

MDedge reporter Doug Brunk will be reporting from the meeting.

WASHINGTON – At the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, the taking place March 27-31, 2019, in Denver.

“ASLMS is always an amazing meeting, and it’s a unique meeting,” said past president Mathew Avram, MD, director of the Dermatology Laser & Cosmetic Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. “At its core, it’s a scientific meeting ... you can take things back to your practice that change the practice of medicine.”

Current ASLMS president Eric Bernstein, MD, of Main Line Center for Laser Surgery, Ardmore, Pa., pointed out that, in addition to doctors and other health care practitioners, other available and accessible attendees include the engineers who build the lasers. And this year, injectables are being incorporated into the program.

MDedge reporter Doug Brunk will be reporting from the meeting.

REPORTING FROM AAD 2019

FDA chief calls for release of all data tracking problems with medical devices

Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, announced in a tweet Wednesday that the agency plans to

“We’re now prioritizing making ALL of this data available,” Dr. Gottlieb tweeted.

A recent Kaiser Health News investigation revealed the scope of a hidden reporting pathway for device makers, with the agency accepting more than 1.1 million such reports since the start of 2016.

Device makers for nearly 20 years were able to quietly seek an “exemption” from standard, public harm-reporting rules. Devices with such exemptions have included surgical staplers and balloon pumps used in the vessels of heart-surgery patients.

Dr. Gottlieb’s tweet also referenced the challenge in opening the database, saying it “wasn’t easily accessible electronically owing to the system’s age. But it’s imperative that all safety information be available to the public.”

The agency made changes to the “alternative summary reporting” program in mid-2017 to require a public report summarizing data filed within the FDA. But nearly two decades of data remained cordoned off from doctors, patients, and device-safety researchers who say they could use it to detect problems.

Dr. Gottlieb’s announcement was welcomed by Madris Tomes, who has testified to FDA device-review panels about the importance of making summary data on patient harm open to the public.

“That’s the best news I’ve heard in years,” said Ms. Tomes, president of Device Events, which makes the FDA device-harm data more user-friendly. “I’m really happy that they’re taking notice and realizing that physicians who couldn’t see this data before were using devices that they wouldn’t have used if they had this data in front of them.”

Since September, KHN has filed Freedom of Information Act requests for parts or all of the “alternative summary reporting” database and for other special “exemption” reports, to little effect. A request to expedite delivery of those records was denied, and the FDA cited the lack of “compelling need” for the public to have the information. Officials noted that it might take up to 2 years to get such records through the FOIA process.

As recently as March 22, though, the agency began publishing previously undisclosed reports of harm, suddenly updating the numbers of breast implant malfunctions or injuries submitted over the years. The new data was presented to an FDA advisory panel, which is reviewing the safety of such devices. The panel, which met March 25 and 26, saw a chart showing hundreds of thousands more accounts of harm or malfunctions than had previously been acknowledged.

Michael Carome, MD, director of Public Citizen’s health research group, said his initial reaction to the news is “better late than never.”

“If [Dr. Gottlieb] follows through with his pledge to make all this data public, then that’s certainly a positive development,” he said. “But this is safety information that should have been made available years ago.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, announced in a tweet Wednesday that the agency plans to

“We’re now prioritizing making ALL of this data available,” Dr. Gottlieb tweeted.

A recent Kaiser Health News investigation revealed the scope of a hidden reporting pathway for device makers, with the agency accepting more than 1.1 million such reports since the start of 2016.

Device makers for nearly 20 years were able to quietly seek an “exemption” from standard, public harm-reporting rules. Devices with such exemptions have included surgical staplers and balloon pumps used in the vessels of heart-surgery patients.

Dr. Gottlieb’s tweet also referenced the challenge in opening the database, saying it “wasn’t easily accessible electronically owing to the system’s age. But it’s imperative that all safety information be available to the public.”

The agency made changes to the “alternative summary reporting” program in mid-2017 to require a public report summarizing data filed within the FDA. But nearly two decades of data remained cordoned off from doctors, patients, and device-safety researchers who say they could use it to detect problems.

Dr. Gottlieb’s announcement was welcomed by Madris Tomes, who has testified to FDA device-review panels about the importance of making summary data on patient harm open to the public.

“That’s the best news I’ve heard in years,” said Ms. Tomes, president of Device Events, which makes the FDA device-harm data more user-friendly. “I’m really happy that they’re taking notice and realizing that physicians who couldn’t see this data before were using devices that they wouldn’t have used if they had this data in front of them.”

Since September, KHN has filed Freedom of Information Act requests for parts or all of the “alternative summary reporting” database and for other special “exemption” reports, to little effect. A request to expedite delivery of those records was denied, and the FDA cited the lack of “compelling need” for the public to have the information. Officials noted that it might take up to 2 years to get such records through the FOIA process.

As recently as March 22, though, the agency began publishing previously undisclosed reports of harm, suddenly updating the numbers of breast implant malfunctions or injuries submitted over the years. The new data was presented to an FDA advisory panel, which is reviewing the safety of such devices. The panel, which met March 25 and 26, saw a chart showing hundreds of thousands more accounts of harm or malfunctions than had previously been acknowledged.

Michael Carome, MD, director of Public Citizen’s health research group, said his initial reaction to the news is “better late than never.”

“If [Dr. Gottlieb] follows through with his pledge to make all this data public, then that’s certainly a positive development,” he said. “But this is safety information that should have been made available years ago.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, announced in a tweet Wednesday that the agency plans to

“We’re now prioritizing making ALL of this data available,” Dr. Gottlieb tweeted.

A recent Kaiser Health News investigation revealed the scope of a hidden reporting pathway for device makers, with the agency accepting more than 1.1 million such reports since the start of 2016.

Device makers for nearly 20 years were able to quietly seek an “exemption” from standard, public harm-reporting rules. Devices with such exemptions have included surgical staplers and balloon pumps used in the vessels of heart-surgery patients.

Dr. Gottlieb’s tweet also referenced the challenge in opening the database, saying it “wasn’t easily accessible electronically owing to the system’s age. But it’s imperative that all safety information be available to the public.”

The agency made changes to the “alternative summary reporting” program in mid-2017 to require a public report summarizing data filed within the FDA. But nearly two decades of data remained cordoned off from doctors, patients, and device-safety researchers who say they could use it to detect problems.

Dr. Gottlieb’s announcement was welcomed by Madris Tomes, who has testified to FDA device-review panels about the importance of making summary data on patient harm open to the public.

“That’s the best news I’ve heard in years,” said Ms. Tomes, president of Device Events, which makes the FDA device-harm data more user-friendly. “I’m really happy that they’re taking notice and realizing that physicians who couldn’t see this data before were using devices that they wouldn’t have used if they had this data in front of them.”

Since September, KHN has filed Freedom of Information Act requests for parts or all of the “alternative summary reporting” database and for other special “exemption” reports, to little effect. A request to expedite delivery of those records was denied, and the FDA cited the lack of “compelling need” for the public to have the information. Officials noted that it might take up to 2 years to get such records through the FOIA process.

As recently as March 22, though, the agency began publishing previously undisclosed reports of harm, suddenly updating the numbers of breast implant malfunctions or injuries submitted over the years. The new data was presented to an FDA advisory panel, which is reviewing the safety of such devices. The panel, which met March 25 and 26, saw a chart showing hundreds of thousands more accounts of harm or malfunctions than had previously been acknowledged.

Michael Carome, MD, director of Public Citizen’s health research group, said his initial reaction to the news is “better late than never.”

“If [Dr. Gottlieb] follows through with his pledge to make all this data public, then that’s certainly a positive development,” he said. “But this is safety information that should have been made available years ago.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

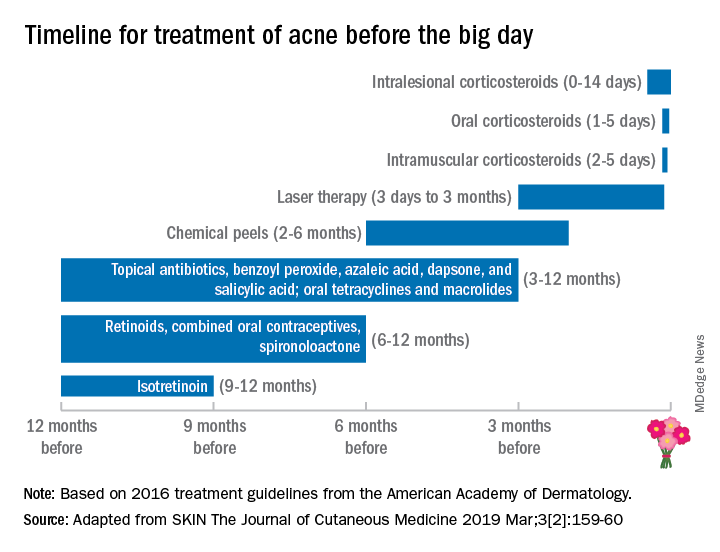

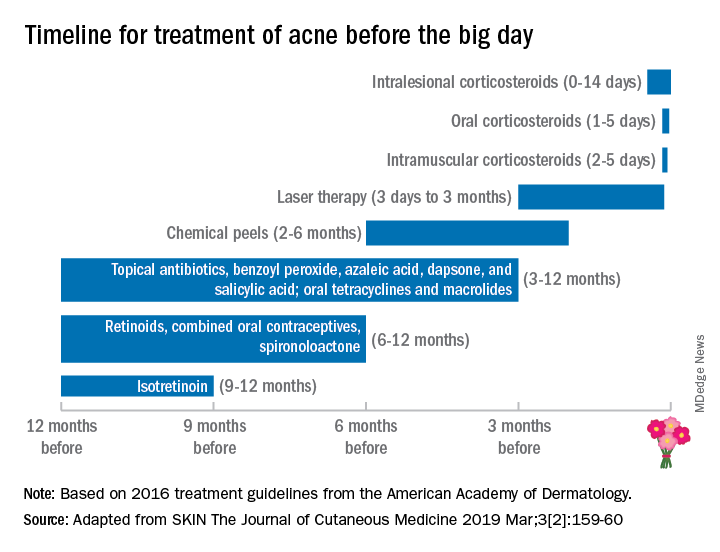

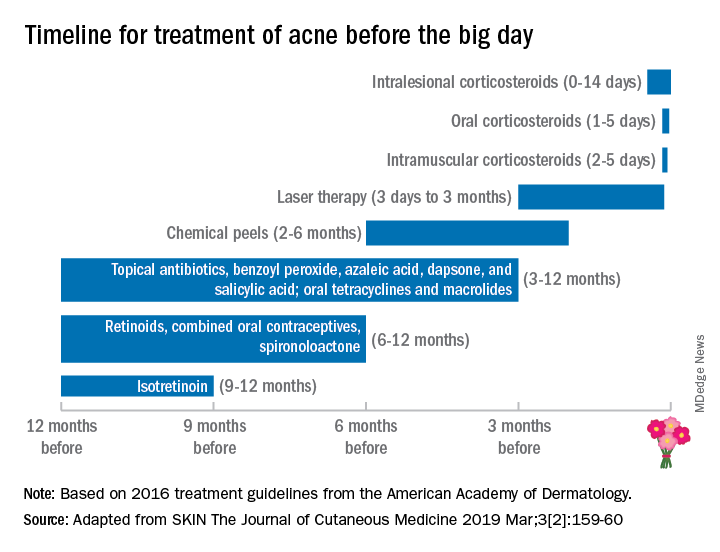

Wedding dermatology

Planning a wedding doesn’t just involve decisions on venues, vows, guests, food, and décor, but also on the betrothed couple’s appearance. Memories and photographs from this day last a lifetime, so it is understandable that people may want to and feel pressured to look their best on this important day – which along with the pressures of planning a wedding, can lead to unnecessary stress, increased cortisol, and unexpected acne and other skin issues.

Because of a complete absence of wedding skin recommendations in the dermatology literature, Winklemann R et al. recently published a paper titled “Wedding Dermatology: A proposed timeline to optimize skin clearance and the avoidance of a true dermatologic emergency” (SKIN The Journal of Cutaneous Medicine 2019 Mar;3[2]:159-60). He focused on acne, using the American Academy of Dermatology acne treatment guidelines and expert opinion, they point out that other than intralesional corticosteroids (which take 0-14 days to have an effect), the majority of acne treatments require at least 3-12 months to achieve clearance or improvement.

This proposed treatment timeline makes sense given that skin cell turnover on the face takes about 6-8 weeks; therefore, it may take that long for acne lesions to resolve or for treatment to have an effect.

Besides acne treatment, cosmetic treatments also have varying healing times and may require multiple sessions with time in between treatments for optimal results. For instance, treatment of photoaging with intense pulsed light or nonablative fractionated resurfacing may require three to six treatments, typically spaced 1 month apart.

Botulinum toxin treatments may take up to 2 weeks to kick in fully, then last 3-4 months. While the lead time for botulinum toxin to kick in is relatively short, I advise people not to get their first botulinum toxin 2 weeks before their wedding. Sometimes, having this treatment 4-6 weeks prior to the wedding date provides enough time for botulinum toxin to kick in – and to start wearing off to the point that the patient has the desired cosmetic effect, but still has some movement for the desired emotional facial expressions on the wedding day. Some patients also may require touch-ups, optimally at the 2-week window, once the botulinum toxin effect has fully kicked in.

With any injectable, there may be bruising and swelling that can take a week or so to heal, even when the bruises are treated with pulse dye laser used to make bruises resolve more quickly. Even a facial may result in blemishes that take a few days to 1-2 weeks to heal, especially with extractions. As such, a facial, especially a hydrafacial, may be beneficial before one’s wedding, but I would recommend having them done at least once or twice to assess an individual’s recovery time (if any) prior to the actual wedding date.

Treatment needs will vary considerably depending on the patient’s baseline skin health. As dermatologists, our patients depend greatly on us to help them look and feel their best, especially during a time when they are about to embark on a new journey like marriage. Patients need to be given realistic treatment options and time frames to achieve their goals. Whether the goal is treating acne or acne scars, starting or fine-tuning cosmetic treatments, or deciding on a skin-care regimen, the bottom line is making an appointment with the dermatologist early – 6-12 months in advance, if possible – to figure out the right plan.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

Planning a wedding doesn’t just involve decisions on venues, vows, guests, food, and décor, but also on the betrothed couple’s appearance. Memories and photographs from this day last a lifetime, so it is understandable that people may want to and feel pressured to look their best on this important day – which along with the pressures of planning a wedding, can lead to unnecessary stress, increased cortisol, and unexpected acne and other skin issues.

Because of a complete absence of wedding skin recommendations in the dermatology literature, Winklemann R et al. recently published a paper titled “Wedding Dermatology: A proposed timeline to optimize skin clearance and the avoidance of a true dermatologic emergency” (SKIN The Journal of Cutaneous Medicine 2019 Mar;3[2]:159-60). He focused on acne, using the American Academy of Dermatology acne treatment guidelines and expert opinion, they point out that other than intralesional corticosteroids (which take 0-14 days to have an effect), the majority of acne treatments require at least 3-12 months to achieve clearance or improvement.

This proposed treatment timeline makes sense given that skin cell turnover on the face takes about 6-8 weeks; therefore, it may take that long for acne lesions to resolve or for treatment to have an effect.

Besides acne treatment, cosmetic treatments also have varying healing times and may require multiple sessions with time in between treatments for optimal results. For instance, treatment of photoaging with intense pulsed light or nonablative fractionated resurfacing may require three to six treatments, typically spaced 1 month apart.

Botulinum toxin treatments may take up to 2 weeks to kick in fully, then last 3-4 months. While the lead time for botulinum toxin to kick in is relatively short, I advise people not to get their first botulinum toxin 2 weeks before their wedding. Sometimes, having this treatment 4-6 weeks prior to the wedding date provides enough time for botulinum toxin to kick in – and to start wearing off to the point that the patient has the desired cosmetic effect, but still has some movement for the desired emotional facial expressions on the wedding day. Some patients also may require touch-ups, optimally at the 2-week window, once the botulinum toxin effect has fully kicked in.

With any injectable, there may be bruising and swelling that can take a week or so to heal, even when the bruises are treated with pulse dye laser used to make bruises resolve more quickly. Even a facial may result in blemishes that take a few days to 1-2 weeks to heal, especially with extractions. As such, a facial, especially a hydrafacial, may be beneficial before one’s wedding, but I would recommend having them done at least once or twice to assess an individual’s recovery time (if any) prior to the actual wedding date.

Treatment needs will vary considerably depending on the patient’s baseline skin health. As dermatologists, our patients depend greatly on us to help them look and feel their best, especially during a time when they are about to embark on a new journey like marriage. Patients need to be given realistic treatment options and time frames to achieve their goals. Whether the goal is treating acne or acne scars, starting or fine-tuning cosmetic treatments, or deciding on a skin-care regimen, the bottom line is making an appointment with the dermatologist early – 6-12 months in advance, if possible – to figure out the right plan.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

Planning a wedding doesn’t just involve decisions on venues, vows, guests, food, and décor, but also on the betrothed couple’s appearance. Memories and photographs from this day last a lifetime, so it is understandable that people may want to and feel pressured to look their best on this important day – which along with the pressures of planning a wedding, can lead to unnecessary stress, increased cortisol, and unexpected acne and other skin issues.

Because of a complete absence of wedding skin recommendations in the dermatology literature, Winklemann R et al. recently published a paper titled “Wedding Dermatology: A proposed timeline to optimize skin clearance and the avoidance of a true dermatologic emergency” (SKIN The Journal of Cutaneous Medicine 2019 Mar;3[2]:159-60). He focused on acne, using the American Academy of Dermatology acne treatment guidelines and expert opinion, they point out that other than intralesional corticosteroids (which take 0-14 days to have an effect), the majority of acne treatments require at least 3-12 months to achieve clearance or improvement.

This proposed treatment timeline makes sense given that skin cell turnover on the face takes about 6-8 weeks; therefore, it may take that long for acne lesions to resolve or for treatment to have an effect.

Besides acne treatment, cosmetic treatments also have varying healing times and may require multiple sessions with time in between treatments for optimal results. For instance, treatment of photoaging with intense pulsed light or nonablative fractionated resurfacing may require three to six treatments, typically spaced 1 month apart.

Botulinum toxin treatments may take up to 2 weeks to kick in fully, then last 3-4 months. While the lead time for botulinum toxin to kick in is relatively short, I advise people not to get their first botulinum toxin 2 weeks before their wedding. Sometimes, having this treatment 4-6 weeks prior to the wedding date provides enough time for botulinum toxin to kick in – and to start wearing off to the point that the patient has the desired cosmetic effect, but still has some movement for the desired emotional facial expressions on the wedding day. Some patients also may require touch-ups, optimally at the 2-week window, once the botulinum toxin effect has fully kicked in.

With any injectable, there may be bruising and swelling that can take a week or so to heal, even when the bruises are treated with pulse dye laser used to make bruises resolve more quickly. Even a facial may result in blemishes that take a few days to 1-2 weeks to heal, especially with extractions. As such, a facial, especially a hydrafacial, may be beneficial before one’s wedding, but I would recommend having them done at least once or twice to assess an individual’s recovery time (if any) prior to the actual wedding date.

Treatment needs will vary considerably depending on the patient’s baseline skin health. As dermatologists, our patients depend greatly on us to help them look and feel their best, especially during a time when they are about to embark on a new journey like marriage. Patients need to be given realistic treatment options and time frames to achieve their goals. Whether the goal is treating acne or acne scars, starting or fine-tuning cosmetic treatments, or deciding on a skin-care regimen, the bottom line is making an appointment with the dermatologist early – 6-12 months in advance, if possible – to figure out the right plan.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

Case report may link gluteal implants to lymphoma

Patients with textured silicone gluteal implants could be at risk of anaplastic large cell lymphoma, based on a possible case of ALCL in a patient diagnosed 1 year after implant placement.

The 49-year-old woman was initially diagnosed with anaplastic lymphoma kinase–negative ALCL via a lung mass and pleural fluid before bilateral gluteal ulceration occurred 1 month later, reported Orr Shauly of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, and his colleagues.

Soft-tissue disease and fluid accumulation around the gluteal implants suggested that the lung mass had metastasized from primary neoplasia in the gluteal region. If ALCL did originate at the site of the gluteal implants, it would represent a first for silicone implant–associated ALCL, which has historically been associated exclusively with breast implants.

“As many as 200 cases of [breast implant-associated ALCL] have been described worldwide, with a majority in the context of cosmetic primary breast augmentation or cancer-related breast reconstruction with the use of a textured implant (57% of all cases),” the investigators wrote in Aesthetic Surgery Journal. “Recently however, it has been hypothesized that the relationship of ALCL with the placement of textured silicone implants may not [be] limited to the breast due to its multifactorial nature and association with texturization of the implant surface.”

During the initial work-up, a CT showed fluid collection and enhancement around the gluteal implants. Following ALCL diagnosis via lung mass biopsy and histopathology, the patient was transferred to a different facility for chemotherapy. When the patient presented 1 month later to the original facility with gluteal ulceration, the oncology team suspected infection; however, all cultures from fluid around the implants were negative.

Because of the possibility of false-negative tests, the patient was started on a regimen of acyclovir, vancomycin, metronidazole, and isavuconazole. Explantation was planned, but before this could occur, the patient deteriorated rapidly and died of respiratory and renal failure.

ALCL was not confirmed via cytology or histopathology in the gluteal region, and the patient’s family did not consent to autopsy, so a definitive diagnosis of gluteal implant–associated ALCL remained elusive.

“In this instance, it can only be concluded that the patient’s condition may have been associated with placement of textured silicone gluteal implants, but [we] still lack evidence of causation,” the investigators wrote. “It should also be noted that ALCL does not typically present with skin ulceration, and this may be a unique disease process in this patient or as a result of her bedridden state given the late stage of her disease. Furthermore, this presentation was uniquely aggressive and presented extremely quickly after placement of the gluteal implants. In most patients, ALCL develops and presents approximately 10 years after implantation.”

The investigators cautioned that “care should be taken to avoid sensationalizing all implant-associated ALCL.”

The authors reported having no conflicts of interest and the study did not receive funding.

SOURCE: Shauly O et al. Aesthet Surg J. 2019 Feb 15. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjz044.

Patients with textured silicone gluteal implants could be at risk of anaplastic large cell lymphoma, based on a possible case of ALCL in a patient diagnosed 1 year after implant placement.

The 49-year-old woman was initially diagnosed with anaplastic lymphoma kinase–negative ALCL via a lung mass and pleural fluid before bilateral gluteal ulceration occurred 1 month later, reported Orr Shauly of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, and his colleagues.

Soft-tissue disease and fluid accumulation around the gluteal implants suggested that the lung mass had metastasized from primary neoplasia in the gluteal region. If ALCL did originate at the site of the gluteal implants, it would represent a first for silicone implant–associated ALCL, which has historically been associated exclusively with breast implants.

“As many as 200 cases of [breast implant-associated ALCL] have been described worldwide, with a majority in the context of cosmetic primary breast augmentation or cancer-related breast reconstruction with the use of a textured implant (57% of all cases),” the investigators wrote in Aesthetic Surgery Journal. “Recently however, it has been hypothesized that the relationship of ALCL with the placement of textured silicone implants may not [be] limited to the breast due to its multifactorial nature and association with texturization of the implant surface.”

During the initial work-up, a CT showed fluid collection and enhancement around the gluteal implants. Following ALCL diagnosis via lung mass biopsy and histopathology, the patient was transferred to a different facility for chemotherapy. When the patient presented 1 month later to the original facility with gluteal ulceration, the oncology team suspected infection; however, all cultures from fluid around the implants were negative.

Because of the possibility of false-negative tests, the patient was started on a regimen of acyclovir, vancomycin, metronidazole, and isavuconazole. Explantation was planned, but before this could occur, the patient deteriorated rapidly and died of respiratory and renal failure.

ALCL was not confirmed via cytology or histopathology in the gluteal region, and the patient’s family did not consent to autopsy, so a definitive diagnosis of gluteal implant–associated ALCL remained elusive.

“In this instance, it can only be concluded that the patient’s condition may have been associated with placement of textured silicone gluteal implants, but [we] still lack evidence of causation,” the investigators wrote. “It should also be noted that ALCL does not typically present with skin ulceration, and this may be a unique disease process in this patient or as a result of her bedridden state given the late stage of her disease. Furthermore, this presentation was uniquely aggressive and presented extremely quickly after placement of the gluteal implants. In most patients, ALCL develops and presents approximately 10 years after implantation.”

The investigators cautioned that “care should be taken to avoid sensationalizing all implant-associated ALCL.”

The authors reported having no conflicts of interest and the study did not receive funding.

SOURCE: Shauly O et al. Aesthet Surg J. 2019 Feb 15. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjz044.

Patients with textured silicone gluteal implants could be at risk of anaplastic large cell lymphoma, based on a possible case of ALCL in a patient diagnosed 1 year after implant placement.

The 49-year-old woman was initially diagnosed with anaplastic lymphoma kinase–negative ALCL via a lung mass and pleural fluid before bilateral gluteal ulceration occurred 1 month later, reported Orr Shauly of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, and his colleagues.

Soft-tissue disease and fluid accumulation around the gluteal implants suggested that the lung mass had metastasized from primary neoplasia in the gluteal region. If ALCL did originate at the site of the gluteal implants, it would represent a first for silicone implant–associated ALCL, which has historically been associated exclusively with breast implants.

“As many as 200 cases of [breast implant-associated ALCL] have been described worldwide, with a majority in the context of cosmetic primary breast augmentation or cancer-related breast reconstruction with the use of a textured implant (57% of all cases),” the investigators wrote in Aesthetic Surgery Journal. “Recently however, it has been hypothesized that the relationship of ALCL with the placement of textured silicone implants may not [be] limited to the breast due to its multifactorial nature and association with texturization of the implant surface.”

During the initial work-up, a CT showed fluid collection and enhancement around the gluteal implants. Following ALCL diagnosis via lung mass biopsy and histopathology, the patient was transferred to a different facility for chemotherapy. When the patient presented 1 month later to the original facility with gluteal ulceration, the oncology team suspected infection; however, all cultures from fluid around the implants were negative.

Because of the possibility of false-negative tests, the patient was started on a regimen of acyclovir, vancomycin, metronidazole, and isavuconazole. Explantation was planned, but before this could occur, the patient deteriorated rapidly and died of respiratory and renal failure.

ALCL was not confirmed via cytology or histopathology in the gluteal region, and the patient’s family did not consent to autopsy, so a definitive diagnosis of gluteal implant–associated ALCL remained elusive.

“In this instance, it can only be concluded that the patient’s condition may have been associated with placement of textured silicone gluteal implants, but [we] still lack evidence of causation,” the investigators wrote. “It should also be noted that ALCL does not typically present with skin ulceration, and this may be a unique disease process in this patient or as a result of her bedridden state given the late stage of her disease. Furthermore, this presentation was uniquely aggressive and presented extremely quickly after placement of the gluteal implants. In most patients, ALCL develops and presents approximately 10 years after implantation.”

The investigators cautioned that “care should be taken to avoid sensationalizing all implant-associated ALCL.”

The authors reported having no conflicts of interest and the study did not receive funding.

SOURCE: Shauly O et al. Aesthet Surg J. 2019 Feb 15. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjz044.

FROM AESTHETIC SURGERY JOURNAL

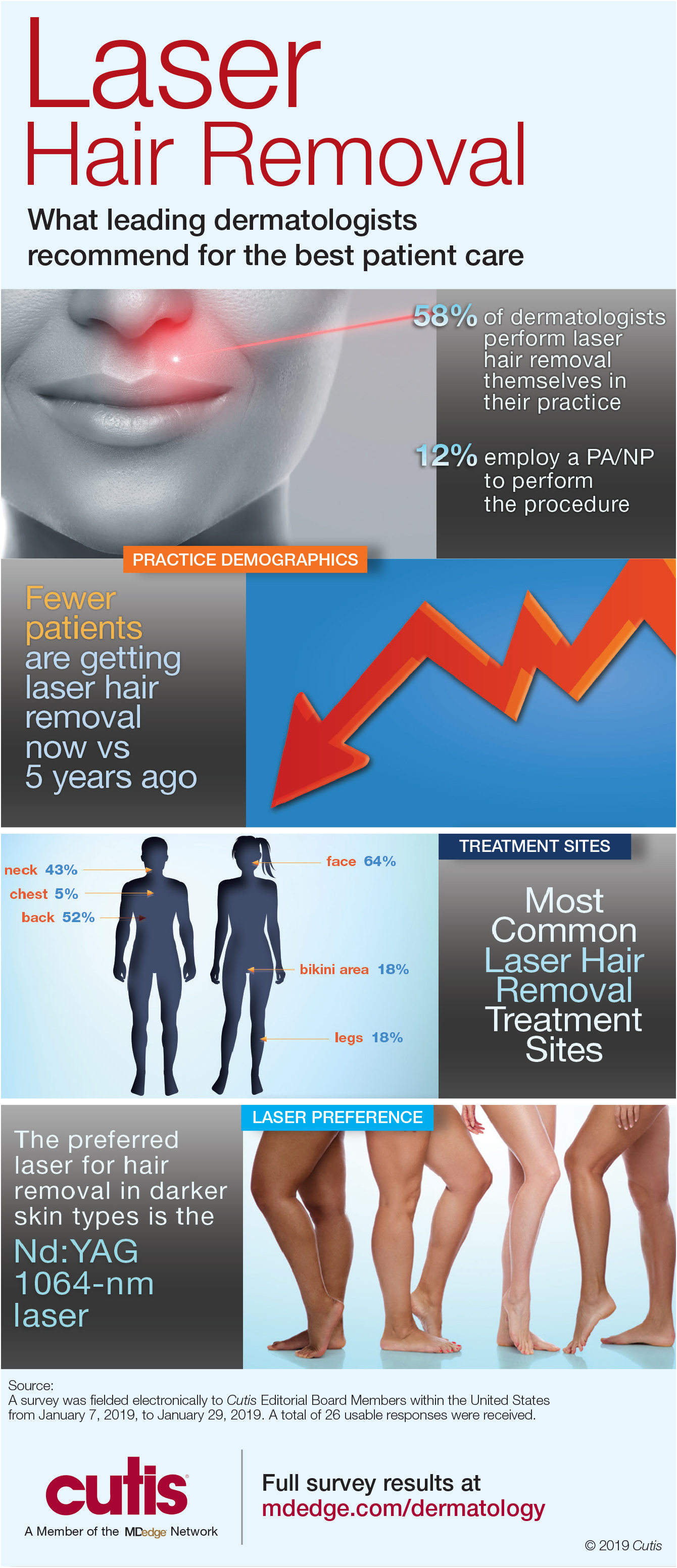

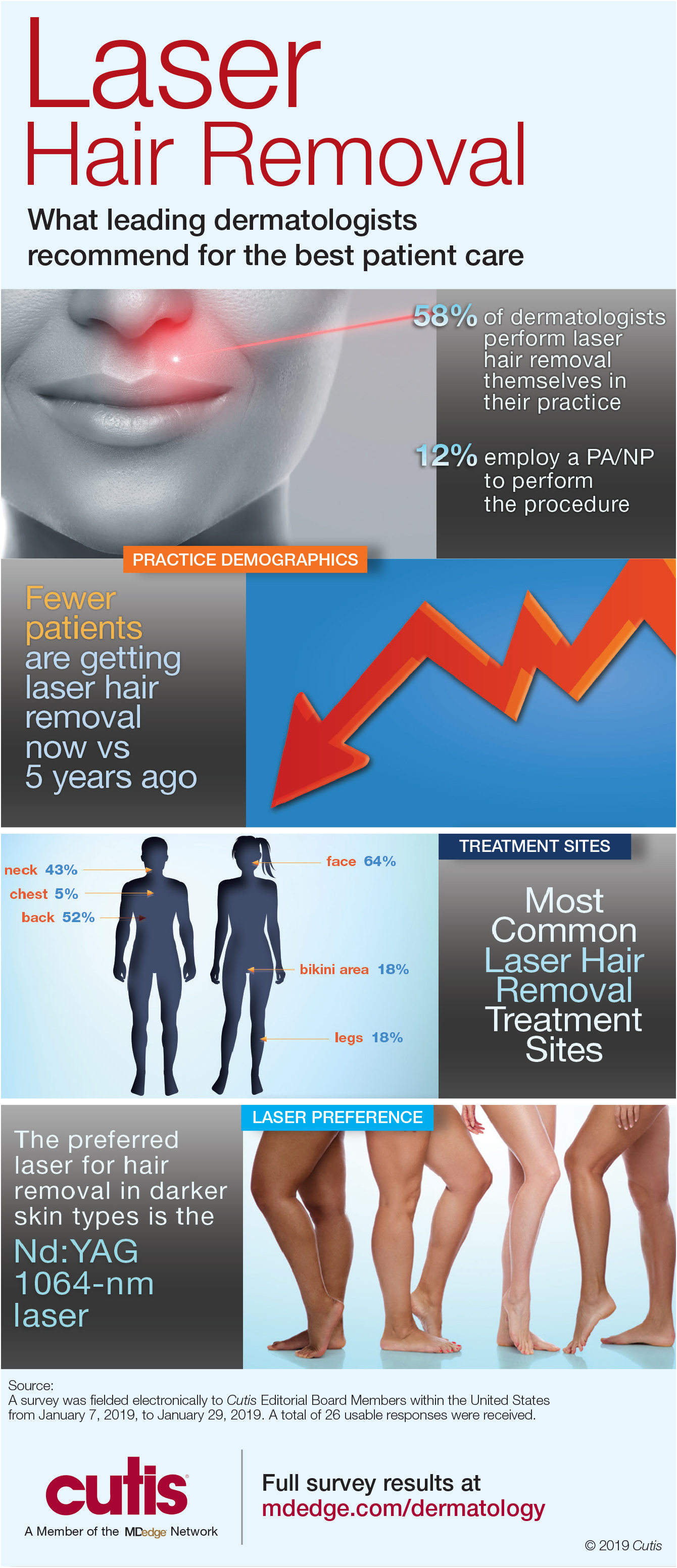

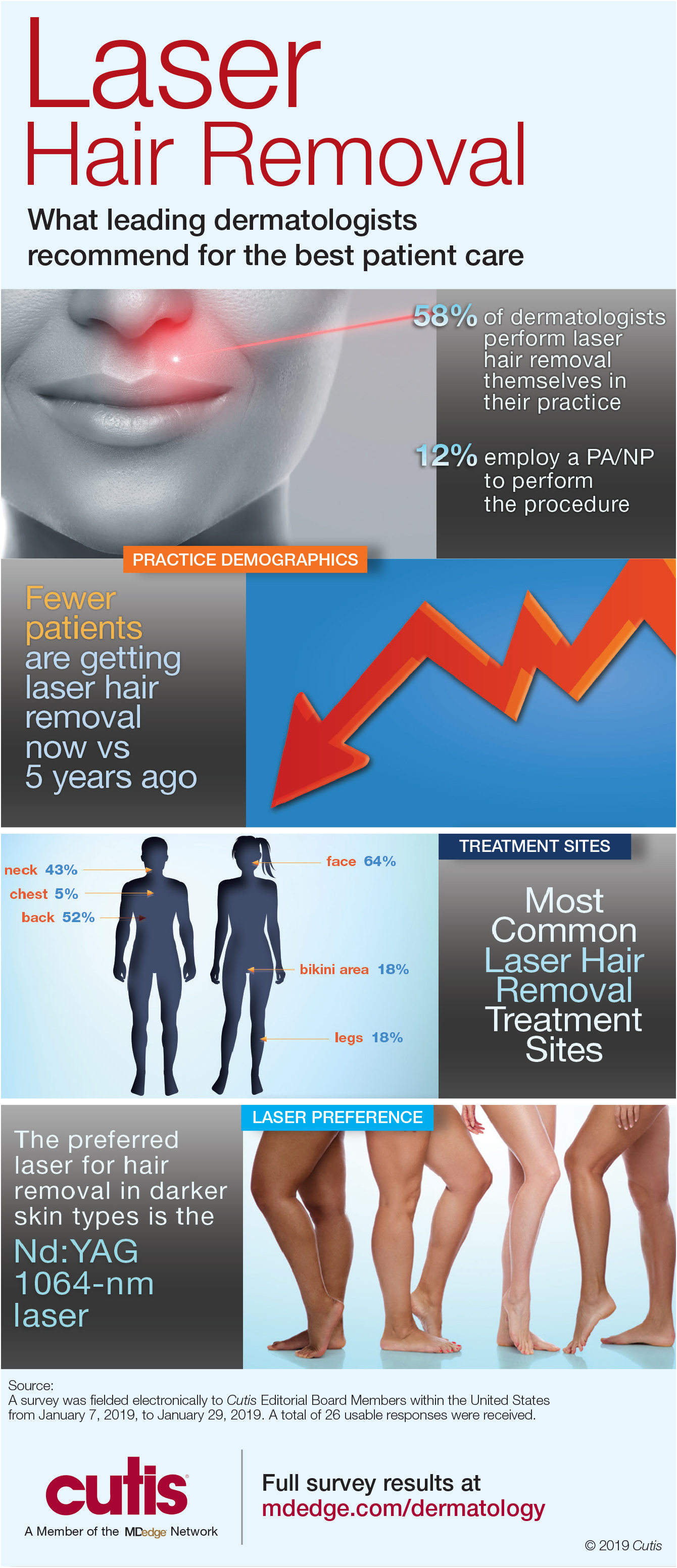

Infographic: Laser Hair Removal

Dermatologists are best equipped to treat patients who are interested in removing unwanted hair safely and effectively. Unfortunately, many patients often undergo laser hair removal treatments at spas by practitioners with limited training. Dermatologists must encourage patients to seek treatment from a board-certified dermatologist.

Full survey results and commentary from Dr. Shari Lipner are available at bit.ly/2tzNbSg.

Dermatologists are best equipped to treat patients who are interested in removing unwanted hair safely and effectively. Unfortunately, many patients often undergo laser hair removal treatments at spas by practitioners with limited training. Dermatologists must encourage patients to seek treatment from a board-certified dermatologist.

Full survey results and commentary from Dr. Shari Lipner are available at bit.ly/2tzNbSg.

Dermatologists are best equipped to treat patients who are interested in removing unwanted hair safely and effectively. Unfortunately, many patients often undergo laser hair removal treatments at spas by practitioners with limited training. Dermatologists must encourage patients to seek treatment from a board-certified dermatologist.

Full survey results and commentary from Dr. Shari Lipner are available at bit.ly/2tzNbSg.

Vaginal and Scrotal Rejuvenation: The Potential Role of Dermatologists in Genital Rejuvenation

To the Editor:

I read with interest the informative Cutis article by Hashim et al,1 which not only summarized the key features of vaginal rejuvenation but also concisely reviewed noninvasive treatments, including lasers and radiofrequency devices, that can be used to address this important issue. The authors emphasized that these treatments may represent a valuable addition to the cosmetic landscape. In addition, they also asserted that noninvasive vaginal rejuvenation is an expanding focus of cosmetic dermatology.1

Genital rejuvenation includes rejuvenation of the vagina in women and the scrotum in men. Since the term initially appeared in the literature in 2007,2 a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE yields an increasing number of articles on vaginal rejuvenation. More recently, the concept of scrotal rejuvenation was introduced in 2018.3

Similar to vaginal rejuvenation, scrotal rejuvenation includes procedures to remedy medical or cosmetic conditions of the scrotum. Hashim et al1 focused on morphology-associated vaginal changes for which rejuvenation techniques have been successful, such as excess clitoral hood; excess labia majora or minora; vaginal laxity; and vulvovaginal atrophy, which is considered to be a component of genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Morphology-associated changes of the scrotum include wrinkling (cutis scrotum gyratum or scrotum rugosum) and laxity (low-hanging or sagging scrotum or scrotomegaly

Intrinsic (aging) and extrinsic (trauma) alterations also can result in other changes that may be amenable to vaginal or scrotal rejuvenation; for example, in addition to changes in morphology, there are hair (eg, alopecia, hypertrichosis) and vascular (eg, angiokeratomas) conditions of the vagina and scrotum that may be suitable for rejuvenation.3-5 Dermatologists have the opportunity to provide treatment for the genital rejuvenation of their patients.

- Hashim PW, Nia JK, Zade J, et al. Noninvasive vaginal rejuvenation. Cutis. 2018;102:243-246.

- Committee on Gynecologic Practice, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 378: vaginal “rejuvenation” and cosmetic vaginal procedures. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:737-738.

- Cohen PR. Scrotal rejuvenation. Cureus. 2018;10:e2316.

- Cohen PR. Genital rejuvenation: the next frontier in medical and cosmetic dermatology. Dermatol Online J. 2018:24. http://escholarship.org/uc/item/27v774t5. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- Cohen PR. A case report of scrotal rejuvenation: laser treatment of angiokeratomas of the scrotum [published online November 26, 2018]. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). doi:10.1007/s13555-018-0272-z.

To the Editor:

I read with interest the informative Cutis article by Hashim et al,1 which not only summarized the key features of vaginal rejuvenation but also concisely reviewed noninvasive treatments, including lasers and radiofrequency devices, that can be used to address this important issue. The authors emphasized that these treatments may represent a valuable addition to the cosmetic landscape. In addition, they also asserted that noninvasive vaginal rejuvenation is an expanding focus of cosmetic dermatology.1

Genital rejuvenation includes rejuvenation of the vagina in women and the scrotum in men. Since the term initially appeared in the literature in 2007,2 a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE yields an increasing number of articles on vaginal rejuvenation. More recently, the concept of scrotal rejuvenation was introduced in 2018.3

Similar to vaginal rejuvenation, scrotal rejuvenation includes procedures to remedy medical or cosmetic conditions of the scrotum. Hashim et al1 focused on morphology-associated vaginal changes for which rejuvenation techniques have been successful, such as excess clitoral hood; excess labia majora or minora; vaginal laxity; and vulvovaginal atrophy, which is considered to be a component of genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Morphology-associated changes of the scrotum include wrinkling (cutis scrotum gyratum or scrotum rugosum) and laxity (low-hanging or sagging scrotum or scrotomegaly

Intrinsic (aging) and extrinsic (trauma) alterations also can result in other changes that may be amenable to vaginal or scrotal rejuvenation; for example, in addition to changes in morphology, there are hair (eg, alopecia, hypertrichosis) and vascular (eg, angiokeratomas) conditions of the vagina and scrotum that may be suitable for rejuvenation.3-5 Dermatologists have the opportunity to provide treatment for the genital rejuvenation of their patients.

To the Editor:

I read with interest the informative Cutis article by Hashim et al,1 which not only summarized the key features of vaginal rejuvenation but also concisely reviewed noninvasive treatments, including lasers and radiofrequency devices, that can be used to address this important issue. The authors emphasized that these treatments may represent a valuable addition to the cosmetic landscape. In addition, they also asserted that noninvasive vaginal rejuvenation is an expanding focus of cosmetic dermatology.1

Genital rejuvenation includes rejuvenation of the vagina in women and the scrotum in men. Since the term initially appeared in the literature in 2007,2 a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE yields an increasing number of articles on vaginal rejuvenation. More recently, the concept of scrotal rejuvenation was introduced in 2018.3

Similar to vaginal rejuvenation, scrotal rejuvenation includes procedures to remedy medical or cosmetic conditions of the scrotum. Hashim et al1 focused on morphology-associated vaginal changes for which rejuvenation techniques have been successful, such as excess clitoral hood; excess labia majora or minora; vaginal laxity; and vulvovaginal atrophy, which is considered to be a component of genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Morphology-associated changes of the scrotum include wrinkling (cutis scrotum gyratum or scrotum rugosum) and laxity (low-hanging or sagging scrotum or scrotomegaly

Intrinsic (aging) and extrinsic (trauma) alterations also can result in other changes that may be amenable to vaginal or scrotal rejuvenation; for example, in addition to changes in morphology, there are hair (eg, alopecia, hypertrichosis) and vascular (eg, angiokeratomas) conditions of the vagina and scrotum that may be suitable for rejuvenation.3-5 Dermatologists have the opportunity to provide treatment for the genital rejuvenation of their patients.

- Hashim PW, Nia JK, Zade J, et al. Noninvasive vaginal rejuvenation. Cutis. 2018;102:243-246.

- Committee on Gynecologic Practice, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 378: vaginal “rejuvenation” and cosmetic vaginal procedures. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:737-738.

- Cohen PR. Scrotal rejuvenation. Cureus. 2018;10:e2316.

- Cohen PR. Genital rejuvenation: the next frontier in medical and cosmetic dermatology. Dermatol Online J. 2018:24. http://escholarship.org/uc/item/27v774t5. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- Cohen PR. A case report of scrotal rejuvenation: laser treatment of angiokeratomas of the scrotum [published online November 26, 2018]. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). doi:10.1007/s13555-018-0272-z.

- Hashim PW, Nia JK, Zade J, et al. Noninvasive vaginal rejuvenation. Cutis. 2018;102:243-246.

- Committee on Gynecologic Practice, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 378: vaginal “rejuvenation” and cosmetic vaginal procedures. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:737-738.

- Cohen PR. Scrotal rejuvenation. Cureus. 2018;10:e2316.

- Cohen PR. Genital rejuvenation: the next frontier in medical and cosmetic dermatology. Dermatol Online J. 2018:24. http://escholarship.org/uc/item/27v774t5. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- Cohen PR. A case report of scrotal rejuvenation: laser treatment of angiokeratomas of the scrotum [published online November 26, 2018]. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). doi:10.1007/s13555-018-0272-z.

The Role of Diet in Preventing Photoaging and Treating Common Skin Conditions

The connection between diet and physical beauty has been an area of increasing interest in popular culture as well as in the scientific community. Numerous supplements, plant derivatives, and antioxidants have been proposed to help improve skin conditions and prevent signs of aging.1 Clinical and basic research has played an important role in confirming or debunking these claims, leading to new insight into oral supplements that may play a role in improving signs of photoaging, as well as symptoms of common skin diseases such as acne vulgaris (AV), atopic dermatitis (AD), and psoriasis. This article reviews some of the vitamins, supplements, and antioxidants that have been studied in the improvement of these conditions.

Photoaging

Recently, there has been increased interest among researchers in the role of antioxidants in combatting photoaging. The main determinants of photoaging are chronic sunlight exposure and melanin density. Photoaging presentation includes deep rhytides, pigmentary changes, dryness, loss of skin tone, leathery appearance, and actinic purpura.2-4

Beta-carotene is a fat-soluble derivative of vitamin A, which has retinol activity and has an inhibitory effect on free radicals. It has been used to decrease the effect of UV light on the skin as well as to treat erythropoietic porphyria.5-7 One study evaluated the efficacy of low-dose and high-dose beta-carotene in improving facial rhytides and elasticity in a cohort of 30 women older than 50 years.8 Participants were given 30 or 90 mg of beta-carotene once daily for 90 days, and the final results were compared to baseline. Those who received the 30-mg dose showed improvements in facial rhytides and elasticity, increased type I procollagen messenger RNA levels, decreased UV-induced thymine dimer staining, and decreased 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine staining. The lower dose of beta-carotene was found to prevent photoaging and was superior to the higher dose, which actually significantly decreased the minimal erythema dose (indicating a deleterious effect)(P=.025).8

Another study compared the role of a 25-mg carotenoid supplement vs a combination of carotenoid and vitamin E (335 mg [500 IU] RRR-α-tocopherol) supplements in preventing erythema development on the back.9 Using a blue light solar stimulator for illumination, erythema on the dorsal back skin was significantly reduced after week 8 (P<.01). The erythema was lower in the combination group than the carotenoid group alone, but the difference was not statistically significant. Furthermore, after 12 weeks, yellowing of the skin was observed in both groups, especially the skin of the palms and face.9

Collagen peptides also have been used in the prevention and repair of photoaging. Proksch et al10 conducted a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to investigate the role of collagen peptides on skin elasticity in 69 women aged 35 to 55 years. At 4 weeks, oral supplementation of collagen hydrolysate (2.5 g once daily or 5 g once daily for 8 weeks) showed significant (P<.05) improvement of skin elasticity in both the low-dose and high-dose groups in women older than 50 years; however, collagen peptides did not lead to statistically significant improvement in skin hydration or transepidermal water loss. No known side effects were reported; thus, collagen peptides may be both efficacious and safe in improving signs of photoaging in elderly patients.10 Thus, these studies have shown potentially positive effects of beta-carotene, vitamin E, and collagen peptides in improving the signs of photoaging.

Acne Vulgaris

Acne vulgaris is a common dermatologic condition seen in the western hemisphere, with 40 to 50 million affected individuals in the United States annually.11,12 A landmark study that examined 1200 Kitavans from Papua New Guinea and 115 Aché individuals from a hunter-gatherer community in Paraguay found no cases of AV in either group.12 These findings have led to the speculation that AV may be associated with environmental factors, particularly the Western diet.

An investigator-blinded randomized clinical trial (RCT) explored the role of a low-glycemic diet compared to a carbohydrate-dense diet on improvement of AV lesions after 12 weeks.13 The results yielded a significant decrease in lesions in the low-glycemic group (mean [SEM], −23.5 [−3.9]) vs the control group (−12.0 [−3.0])(P=.03). Furthermore, the results indicated a significant decrease in weight (P<.001) and body mass index (P=.001) with an improvement in insulin sensitivity in the low-glycemic group vs the control group.13 Kwon et al14 conducted a similar investigator-blinded parallel study with 32 participants receiving either a low-glycemic diet or continuing their normal diet for 10 weeks. Participants in the low-glycemic group demonstrated a significant reduction in mean noninflammatory lesions (−27.6% [P=.04]) and mean inflammatory lesions (−70.9% [P<.05]). Histologic image analysis showed a significant decrease in the mean (SEM) area of sebaceous glands in the low-glycemic group (0.32 [0.03] mm2) compared to baseline (0.24 [0.03] mm2)(P=.03). At 10 weeks, immunohistochemical specimens showed reduction in IL-8 (P=.03) and sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (P=.03), which regulates the synthesis of lipids.14 Thus, both studies concluded that a reduction in glycemic load may improve acne overall.13,14

Another study attempted to investigate the role of additional dietary supplements in improving acne. A double-blinded RCT explored the efficacy of omega-3 fatty acids or γ-linoleic acid compared to a control group in improving mild to moderate AV lesions through clinical and histological evaluations.15 The 10-week prospective study included 45 patients who were allocated to 3 matched groups and randomized to 3 treatment arms. They were given omega-3 fatty acids (1000 mg each of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid) or γ-linoleic acid (borage oil with 400 mg of γ-linoleic acid) or no intervention. After treatment completion, patients in both treatment groups showed significant reduction in mean inflammatory acne lesions, mean noninflammatory acne lesions, and mean acne severity (all P<.05), while the control group showed no significant reduction in acne lesions or acne severity. Furthermore, hematoxylin and eosin and IL-8 immunohistochemical staining of biopsies from the affected areas showed significant reduction of inflammation in both treatment groups (P<.05) but not in the control group. Therefore, the authors concluded that both omega-3 fatty acids and γ-linoleic acid could be used as adjuvant therapies in AV treatment.15

Atopic Dermatitis

The prevalence of atopic dermatitis (AD) in children ranges from approximately 9% to 18% across the United States.16 Pyridoxine, or vitamin B6, is an important water-soluble vitamin and a cofactor for numerous biochemical processes including carbohydrate and amino acid metabolism pathways and glucocorticoid receptor regulation.17,18 However, a double-blinded, placebo-controlled RCT failed to show efficacy of once-daily pyridoxine hydrochloride 50 mg in improving erythema, itching, or nocturnal sleep disturbance associated with AD in a cohort of 48 children. The investigators concluded that pyridoxine supplementation cannot be recommended to improve the symptoms of AD in children.19

Zinc is an essential nutrient that functions as an important cofactor in cell metabolism and growth pathways.20 One study showed that intracellular erythrocyte zinc levels were significantly lower in AD patients compared to healthy controls (P<.001); however, there was no observed difference in serum zinc levels (P=.148). Furthermore, greater disease severity as determined by the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index was negatively correlated with erythrocyte zinc levels (r=−0.791; P<.001).21 Kim et al22 investigated hair zinc levels and the efficacy of oral zinc supplementation in children with mild to moderate AD. Mean (SD) hair zinc levels were lower in the AD group compared to the control group (113.10 [33.6] μg vs 130.90 [36.63] μg [P=.012]). Of 41 AD patients with low zinc levels, 22 were allocated to group A, which received oral zinc oxide 12 mg for 8 weeks, and 19 were allocated to group B, which did not receive any supplementation over the same period. Groups A and B also received oral antihistamines and topical moisturizers. Mean (SD) zinc levels increased significantly in group A from 96.36 (21.05) μg to 131.81 (27.45) μg (P<.001). Furthermore, relative to group B, group A showed significantly greater improvements in eczema area and severity index (P=.044), transepidermal water loss (P=.015), and visual analog scale for pruritus (P<.001) at the end of 8 weeks. The authors concluded that oral zinc supplementation might be an effective adjunctive therapy for AD patients with low hair zinc levels.22

Researchers also have explored the efficacy of fat-soluble vitamins D and E in treating AD. Vitamin D is thought to downregulate IgE-mediated skin reactions and decrease adverse effects of UV light on the skin.23,24 A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial randomized 45 patients with AD to 4 groups: vitamins D and E placebos (n=11), 1600 IU vitamin D3 plus vitamin E placebo (n=12), 600 IU vitamin E (synthetic all-rac-α-tocopherol) plus vitamin D placebo (n=11), and 1600 IU vitamin D3 plus 600 IU vitamin E (synthetic all-rac-α-tocopherol)(n=11).25 After 60 days, the SCORAD index was reduced by 28.9% in the placebo group, 34.8% in the vitamin D3 group, 35.7% in the vitamin E group, and 64.3% in the combined vitamins D and E group (P=.004). Furthermore, prior to intervention, a negative correlation was demonstrated between plasma α-tocopherol concentration and the SCORAD index (r=−.33; P=.025).25 Thus, supplementing vitamins D and E may play a beneficial role in the treatment of AD.

Other emerging studies are investigating the role of the gut microbiome in various pathologies. Prebiotics may alter the gut microbiome and are thought to play a role in reducing intestinal inflammation.26 One randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel study examined the effect of prebiotic oligosaccharide supplementation on the development of AD in at-risk children, defined as having a biological parent with a history of asthma, allergic rhinitis, or AD.27 At 6-month follow-up, 10 infants (9.8%)(95% CI, 5.4%-17.1%) in the intervention group (n=102) and 24 infants (23.1%)(95% CI, 16.0%-32.1%) in the placebo group (n=104) had developed AD. The authors postulated that the prebiotic oligosaccharides might play a role in immune modulation by altering bowel flora and preventing the development of AD in infancy.27

Notably, a 2012 Cochrane review evaluated 11 studies of dietary supplements as possible treatment options for AD. The authors concluded that the evidence was minimal to support the regular use of dietary supplements, especially due to their high cost as well as the possibility that high levels of certain vitamins (eg, vitamin D) may cause long-term complications.26

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is an autoimmune skin condition that has an annual prevalence ranging from approximately 1% to 9% in adults residing in Western countries.28,29 Some have argued that due to decreased bacterial diversity and increased bacterial growth in the small bowel, psoriatic patients are exposed to higher levels of bacterial peptidoglycans and endotoxins.30 To combat the absorption of these substances in psoriasis patients

The effects of very long chain fatty acids also have been examined. A 4-month, double-blind, multicenter RCT compared the effects of daily supplementation with 6 g of either omega-3 fatty acids or omega-6 fatty acids in patients with mild to moderate plaque psoriasis.31 Psoriasis area and severity index scores and patient subjective scores did not change significantly in either group; however, scaling was reduced in both groups (P<.01). The group receiving omega-3 fatty acids had decreased cellular infiltration (P<.01), and the group receiving omega-6 fatty acids had decreased desquamation and redness (P<.05). In the omega-6 group, there was a significant correlation between clinical improvement (decrease in clinical score) and increase in serum eicosapentaenoic acid (r=−0.34; P<.05) and total omega-3 fatty acids (r=−0.36; P<.05). Overall, the authors concluded that supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids (fish oil) was no better than omega-6 fatty acids (corn oil) for treatment of psoriasis.31

Some dermatologists have advocated for the use of oral vitamin D supplementation as an adjunctive treatment of psoriasis, given that it is inexpensive and also may play a role in reducing the risk for cancer and cardiovascular events.32 One study evaluated the level of 25-hydroxy vitamin D in 43 psoriasis patients compared to 43 healthy controls. Mean (SD) vitamin D levels were significantly lower in psoriasis patients (13.3 [6.9]) compared to controls (22.4 [18.4])(P=.004).33 A cross-sectional study similarly found significantly higher rates of vitamin D deficiency (25-hydroxy vitamin D <20 ng/mL) in psoriatic patients (57.8%) compared to patients with rheumatoid arthritis (37.5%) and healthy controls (29.7%)(P<.001). Interestingly, during winter the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency increased to 80.9%, 41.3%, and 30.3% in the 3 groups, respectively; however, no significant correlation was seen between psoriasis severity, as measured by psoriasis area and severity index, and serum vitamin D levels.34 Although vitamin D deficiency may be more prevalent among patients with psoriasis, data regarding the efficacy of treating psoriasis with oral vitamin D supplementation is still lacking.

Conclusion

Our understanding of the link between diet and dermatologic conditions continues to evolve. Recent data for several dietary supplements and therapies showed promising results in repairing signs of photoaging, as well as treating AV, AD, and psoriasis. As patients seek these adjunctive therapies, it is important for physicians to be well informed on the benefits and risks to appropriately counsel patients.

Globally, physicians advocate for a low-glycemic diet rich in fruits and vegetables. Furthermore, the cosmetic diet can be enhanced by the consumption of dietary supplements such as beta-carotene, collagen peptides, zinc, and fat-soluble vitamins such as vitamins D and E. However, prospective RCTs are needed to further investigate the role of these dietary elements in treating and improving dermatologic conditions.

- Khanna R, Shifrin N, Nektalova T, et al. Diet and dermatology: Google search results for acne, psoriasis, and eczema. Cutis. 2018;102:44, 46-48.

- Yaar M, Eller MS, Gilchrest BA. Fifty years of skin aging. J Invest Dermatol Symp Proc. 2002;7:51-58.

- Helfrich YR, Sachs DL, Voorhees JJ. Overview of skin aging and photoaging. Dermatol Nurs. 2008;20:177-183.

- Pandel R, Poljšak B, Godic A, et al. Skin photoaging and the role of antioxidants in its prevention. ISRN Dermatol. 2013;2013:930164.

- Mathews-Roth MM, Pathak MA, Fitzpatrick T, et al. Beta carotene therapy for erythropoietic protoporphyria and other photosensitivity diseases. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:1229-1232.

- Myriam M, Sabatier M, Steiling H, et al. Skin bioavailability of dietary vitamin E, carotenoids, polyphenols, vitamin C, zinc and selenium. Br J Nutr. 2006;96:227-238.

- Cho S. The role of functional foods in cutaneous anti-aging. J Lifestyle Med. 2014;4:8-16.

- Cho S, Lee DH, Won CH, et al. Differential effects of low-dose and high-dose beta-carotene supplementation on the signs of photoaging and type I procollagen gene expression in human skin in vivo. Dermatology. 2010;221:160-171.

- Stahl W, Heinrich U, Jungmann H, et al. Carotenoids and carotenoids plus vitamin E protect against ultraviolet light–induced erythema in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:795-798.

- Proksch E, Segger D, Degwert J, et al. Oral supplementation of specific collagen peptides has beneficial effects on human skin physiology: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2014;27:47-55.

- White GM. Recent findings in the epidemiologic evidence, classification, and subtypes of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2, pt 3):S34-S37.

- Cordain L, Lindeberg S, Hurtado M, et al. Acne vulgaris: a disease of Western civilization. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1584-1590.

- Smith RN, Mann NJ, Braue A, et al. A low-glycemic-load diet improves symptoms in acne vulgaris patients: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:107-115.

- Kwon HH, Yoon JY, Hong JS, et al. Clinical and histological effect of a low glycaemic load diet in treatment of acne vulgaris in Korean patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:241-246.

- Jung JY, Kwon HH, Hong JS, et al. Effect of dietary supplementation with omega-3 fatty acid and gamma-linolenic acid on acne vulgaris: a randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:521-526.

- Shaw TE, Currie GP, Koudelka CW, et al. Eczema prevalence in the United States: data from the 2003 National Survey of Children’s Health. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:67-73.

- Merrill AH Jr, Henderson JM. Diseases associated with defects in vitamin B6 metabolism or utilization. Annu Rev Nutr. 1987;7:137-156.

- Allgood VE, Powell-Oliver FE, Cidlowski JA. The influence of vitamin B6 on the structure and function of the glucocorticoid receptor. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1990;585:452-465.

- Mabin D, Hollis S, Lockwood J, et al. Pyridoxine in atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:764-767.

- Maywald M, Rink L. Zinc homeostasis and immunosenescence. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2015;29:24-30.