User login

Endometrial ablation devices: How to make them truly safe

CASE: Leaking fluid causes intraoperative burns

G.S. is a 45-year-old mother of three who is admitted for surgery for persistent menorrhagia. She has experienced at least two menstrual periods every month for several months, each of them associated with heavy bleeding. She has a history of hypothyroidism and hypertension, but no serious disease or surgery, and considers herself to be in good physical and mental health.

G.S. undergoes endometrial hydrothermablation (HTA) under general inhalation anesthesia. After the HTA mechanism is primed, the heating cycle is started, with a good seal and no fluid leaking from the cervix.

Approximately 8 minutes into the procedure, a 5-mL fluid deficit is noted, and a small amount of hot fluid is observed to be leaking from the cervical os. Examination reveals a thermal injury to the cervix and anterior vaginal wall. The wound is irrigated with cool, sterile saline, and silver sulfadiazine cream is applied. The patient is discharged.

Could this injury have been avoided? Is further treatment warranted?

A minimally invasive operation does not necessarily translate to minimal risk of serious complications. Although few studies of nonhysteroscopic endometrial ablation techniques report any complications,1,2 Baggish and Savells3 found a number of injuries when they searched hospital records and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) database (TABLE). They identified serious complications associated with the following devices:

- HydroThermablator (Boston Scientific), which utilizes a modified operating hysteroscope to deliver 10 to 12 mL of preheated saline into the uterus under low pressure.4 Complications: 16 adverse events were reported to the FDA, 13 of which involved the retrograde leakage of hot water, causing burns to the cervix, vagina, and vulva. Six additional injuries not reported to the FDA were identified at a single institution.

- Novasure (Cytyc), which employs bipolar electrodes that cover a porous bag.5,6 Complications: 32 injuries, 26 of them uterine perforations.

- Thermachoice (Gynecare), a fluid-distended balloon ablator.7 Complications: 22 injuries included retrograde leakage of hot water after balloon failure and transmural thermal injury, with spread to, and injury of, proximal structures. One death was reported.

- Microsulis (MEA), which uses microwave energy to ablate the endometrium.8-10 Complications: 19 injuries, including 13 thermal injuries to the intestines.

Baggish and Savells3 initiated this study after discovering six adverse events within their own hospital system utilizing a single device (HTA). Because these injuries were not reported to the FDA, the overall number of complications is likely higher than the figures given here.

This article describes the proper use of nonhysteroscopic endometrial ablation devices, the best ways to avert serious injury, and optimal treatment when complication occurs.

TABLE

Complications associated with 4 endometrial ablation devices

| COMPLICATION | HYDRO THERMABLATOR* | THERMACHOICE | NOVASURE | MICROSULIS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uterine perforation | 2 | 3 | 26 | 19 |

| Intestinal injury | 1† | 1† | – | 13† |

| Retrograde leakage burn | 19 | 6 | – | – |

| Infection/sepsis | – | 1† | 2 | 1 |

| Fistula/sinus | – | 1† | 1 | – |

| Transmural uterine burn | – | 1 | – | – |

| Cervical stenosis | – | 8 | 1 | – |

| Cardiac arrest | 1 | – | 1 | – |

| Death | – | 1 | – | – |

| Other major | – | 3 | 1 | 4† |

| Total | 22 | 22 | 32 | 20 |

| * Includes author’s data; 6 retrograde leaks | ||||

| † Collateral injury | ||||

CASE continued: Patient opts for hysterectomy

In the case just described, G.S. was examined 1 week after surgery and found to have an exophytic burn over the entire right half of the cervix, extending into the vagina. She was readmitted for 3 days of intravenous (IV) antibiotic treatment and wound care. Computed tomography imaging showed gas formation within the damaged cervix.

Six weeks after surgery, the patient was still menstruating heavily, but her cervix and vagina had healed. Six months later, she underwent total abdominal hysterectomy for continued menorrhagia.

When is endometrial ablation an option?

Indications for endometrial ablation using a nonhysteroscopic, minimally invasive technique are no different from those for hysteroscopic ablation.11 Abnormal, or dysfunctional, uterine bleeding is the principal reason for this operation. Dysfunctional bleeding is heavy or prolonged menses over 6 months or longer that fail to respond to conservative measures and occur in the absence of tumor, pregnancy, or inflammation (ie, infection).

A woman who meets these criteria should have a desire to retain her uterus if she is to be a candidate for a nonhysteroscopic, minimally invasive technique. She also should understand that ablation can render pregnancy unlikely and even pathologic. Her understanding of this consequence should be documented in the chart! Last, she should be informed that ablation will not necessarily render her sterile, so contraception or sterilization will be required to avoid pregnancy. This should also be clearly documented in the medical record.

Endometrial ablation may also be an alternative to hysterectomy for a mentally retarded woman who is unable to manage menses. Abnormal uterine bleeding in conjunction with bleeding diathesis, significant obesity, or serious medical disorders can also be treated by endometrial ablation.

Avoid endometrial ablation in certain circumstances

These circumstances include the presence of endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial cancer, endocervical neoplasia, cervical stenosis, an undiagnosed adnexal mass, moderate to severe dysmenorrhea, adenomyosis, or a uterine cavity larger than 10 cm.12-15

Valle and Baggish15 reported eight cases in which women developed endometrial carcinoma following ablation, and identified the following major risk factors for postablation cancer:

- endometrial hyperplasia unresponsive to progesterone or progestin therapy

- complex endometrial hyperplasia

- atypical hyperplasia.

These conditions are contraindications to endometrial ablation.

Avoid a rush to ablation

The growing popularity of office-based, minimally invasive, nonhysteroscopic techniques, coupled with an increasing desire for and acceptance of elective cessation of menses, may stretch the indications listed above and cut short the discovery of contraindications. Clearly, thorough endometrial sampling and precise histopathologic interpretation are required before embarking on any type of endometrial ablation, to minimize the risk of complications.

How to prevent injury

Reduce the risk of perforation

Uterine perforation occurs for a variety of reasons:

- position of the uterus is unknown

- uterus has not been gently and carefully sounded

- cervix is insufficiently dilated to permit passage of the probe

- device is too long (large) to be accommodated in an individual patient’s uterus

- uterine cavity is distorted by pathology, such as adhesions, myomas, etc.

Attention to these details before surgery can prevent perforation.

When uterine injury occurs, the bowel is also at risk

The intestines can be injured following perforation or transmural injury of the uterus. Bowel injury has been reported with hysteroscopic ablation and resection as well as with Nd-YAG laser ablation.16-18

Do not activate hot water or electrosurgical energy unless you are 100% certain that the device is within the uterine cavity.

Ideally, manufacturers’ safety studies should guarantee no risk of transtubal spillage of hot liquid.

Hot fluid adds to risk of burns

Devices that permit retrograde leakage of hot fluid, such as the HTA, should be modified to ensure sealing at the level of the external and internal cervical os. The Enable device (Innerdyne), no longer marketed in the United States, had such a sealing mechanism, which minimized retrograde leakage of hot water.

Balloon failure may be an unavoidable injury, but pretesting of the device and careful attention to pressure readings—particularly in a small uterus—may mitigate the risk.

Be alert for electrical leakage

The microwave device operates at the megahertz range of frequency. At this high frequency, the risk of leakage is much greater than with devices that operate in the kilohertz range. Therefore, it is important to pay close attention to grounding sites, such as cardiovascular-monitoring electrodes.

High-power monopolar devices, prolonged application of energy to tissue, and high generator frequency are all associated with leakage and subsequent burns.

- Keep the success rate above 90%

- Minimize complications by proper technique and instrument selection

- Press the market to develop a range of device sizes that will individualize the procedure

- Keep the price of a procedure under $1,000

- Establish and adhere to careful patient selection criteria

Early recognition and treatment are vital to ensure the patient’s safety and reduce the risk of medicolegal liability. I recommend the following steps:

- Stop the procedure immediately if perforation is suspected. If you suspect that hot water has been dispersed within the abdominal cavity, switch to laparotomy and consult a general surgeon to inspect the entire intestine for injury. If perforation occurs during the use of electrosurgical energy, the same action is warranted. If uterine perforation occurs in isolation (ie, there is no thermal energy compounding the problem), admit the patient for careful observation, appropriate blood chemistries and hematologic studies, and radiologic examination.

- When hot liquids are spilled, switch to retrograde flow immediately and generously flush the vulva, vagina, and cervix with cold water. Cleanse the entire area with a soapless detergent, and apply clindamycin cream to the vagina and silver sulfadiazine cream to the vulva. Admit the patient for application of cold compresses, ice packs, and burn therapy, and obtain baseline cultures and hematologic studies and a plastic surgery consult. If third-degree (full thickness) burns are suspected, treat any suspected wound infection aggressively after obtaining cultures. Severe and inordinate pain should be investigated as a possible sign of necrotizing fasciitis. After discharge, follow the patient’s progress at weekly intervals.

- Talk to the patient and her family. It is a good idea to explain the complication in very clear terms. I believe it is reasonable to explain how the complication occurred, without speculation or theatrical explanations. Also be sure to document this conversation, including date and time. It may be useful to have a neutral witness present during the conversation. By and large, the patient and her family are likely to appreciate an honest account of how the complication occurred. Hiding data or attempting to cover up the injury may motivate the patient to seek legal representation.

The long-term success of endometrial ablation devices as a whole depends on several conditions. Foremost, the entire class of devices should demonstrate efficacy on par with hysteroscopic ablation. Currently, efficacy ranges from 80% to 95% (short-term follow-up).11 The goal of minimally invasive procedures should be a sustainable 92% rate of amenorrhea, hypomenorrhea, or light, periodic menses. A long-term failure rate of 25% is unacceptable.22-24 If the devices can, by their simplicity, be adapted to more or less universal office application and attain a 5-year success rate of 90% or higher, they will become the standard of care.

One size does not really fit all

Serious complications from endometrial ablation devices occur with regular frequency and must be eliminated or greatly reduced. Perforation is a significant problem and may be related to the “one-size-fits-all” design of the device. Perhaps a range of sizes needs to be produced and fitted to the individual uterine cavity.

If such complications as perforation and burns to the bowel, cervix, vagina, and vulva can be eliminated or relegated to rarity, then a happy future for these procedures lies beyond the horizon.

Price ceiling should be set at $1,000

If an operation can consistently be performed for less than $1,000 total cost—the cost of in-hospital endometrial ablation—it will gain mass appeal. In hospitals and so-called surgicenters, ablations are expensive and, therefore, less attractive to self- or third-party payers. If fees are based on the volume of cases, then a procedure may be price-efficient.

Outcome depends on patient selection

Poorly screened patients who have underlying hyperplasia may develop postablation carcinoma. Women who have dysmenorrhea before the procedure can be predicted to suffer from it afterward. Older women (ie, 40 years or older) will have better long-term success than younger women. And women with a large uterus or myomas will have a higher failure rate than women with smaller cavities (ie, less than 10 cm in length).

What this means for the individual surgeon

Although minimally invasive techniques are relatively easy to perform and simple to learn, each part of the procedure requires careful application and great attention to detail. Perforation of the uterus and leakage of scalding hot liquid must be avoided. If these complications occur, prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment are critical. The removal of these procedures from the operating room to the office as well as competitive pricing of instrumentation will make nonhysteroscopic, minimally invasive endometrial ablation more cost-effective.

The modern era of practical endometrial ablation began in 1981, when Goldrath and colleagues19 reported Nd-YAG laser photovaporization of the endometrium via hysteroscopy for treatment of excessive uterine bleeding. Two years later, DeCherney and Polan20 reported hysteroscopic control of abnormal uterine bleeding using the urologic resectoscope.

Over succeeding years, Baggish and Baltoyannis21 and Baggish and Sze22 reported extensive experience with hysteroscopic endometrial ablation in both high- and average-risk patients, including long-term follow-up of 568 cases over 11 years. Garry and colleagues23 reported a large series of 600 cases from the United Kingdom. Not only did these laser techniques prove to be effective, achieving amenorrhea rates ranging from 30% to 60%, but overall control of abnormal bleeding exceeded 90%. In the large series involving approximately 1,200 cases, no uterine perforations were reported.21-23 The major complication: Fluid overload secondary to vascular uptake of distension medium.

In Europe and the United Kingdom, most hysteroscopic treatment of abnormal bleeding involved endometrial resection using the cutting loop of the resectoscope. In the United States, ablation with the ball electrode of the resectoscope largely replaced the Nd-YAG laser because the resectoscopic trigger mechanism required less skill and hand–eye coordination than the hand–finger-controlled movement of the 600- to 1,000-micron laser fiber.24-26

A search for more benign techniques

A 1997 UK survey analyzed 10,686 cases of hysteroscopic endometrial destruction and identified 474 complications.27 Resection alone had a complication rate of 10.9% and an emergency hysterectomy rate of 13 for every 1,000 patients. Laser ablation had a complication rate of 5.5% and an emergency hysterectomy rate of 2 for every 1,000 patients, and the corresponding figures for rollerball ablation were a 4.5% complication rate and 3 emergency hysterectomies for every 1,000 patients. Two deaths occurred (in 10,000 cases) and were associated with loop excision.

Published data indicated that:

- Successful outcomes after endometrial ablation or resection were directly proportional to the skill of the surgeon

- Complications, particularly serious complications, were related to the experience and skill of the surgeon

- Infusion of uterine distension medium, particularly hypo-osmolar solutions, was associated with serious complications when fluid deficits exceeded approximately 500 to 1,000 mL.

As a result, a number of investigators sought to develop new surgical techniques to control abnormal uterine bleeding that would minimize the skill required by the surgeon (requiring only insertion of a cannula into the uterus and a “cookbook” ablation procedure), eliminate the need for distension medium and general anesthesia, and attain efficacy equivalent to earlier techniques.

A quartet of options

Among the devices that resulted were:

- A microwave technique, described by several investigators.8-10 Its chief drawback: High-frequency electrical leakage with the potential to cause thermal burns.

- An intrauterine balloon device distended with sterile water or saline is heated in situ to 85° to 90° Celsius, thereby cooking the endometrium.

- An electrode-bearing device that features an array of monopolar electrodes over the endometrium-facing aspect of a balloon or bipolar electrodes over a porous bag.

- Devices that circulate a small volume of hot saline freely within the uterine cavity. Hydrothermablation delivers 10 to 12 mL of preheated saline into the uterus under low pressure. A similar technique delivers 10 to 12 mL of cool water or saline into the uterus through a sealed cannula, followed by in situ heating and circulation of the fluid at low pressure via a computer-controlled device.

Safety studies were required by the FDA and were performed on all these devices, and the risk of complications appeared to be negligible.1,2 As this article illustrates, that is not the case.

Four devices, four ways of achieving ablation

Since the advent of nonhysteroscopic, minimally invasive endometrial ablation devices, four distinct techniques have gained widespread use

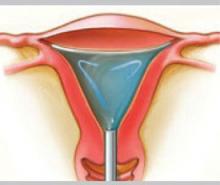

Hydrothermablation

The closed-loop system (HTA) ablates the lining of the endometrium under hysteroscopic visualization by recirculating heated saline within the uterus. The modified hysteroscope allows the operator to view the ablation as it occurs within the uterine cavity.

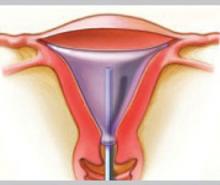

Balloon ablation

Balloon ablation (Thermachoice) features a double-dip balloon construction that conforms to the contours of the uterine cavity. The saline or water in the balloon is heated in situ. This device requires an undistorted uterine cavity, relies on the integrity of the balloon to prevent forward or retrograde spillage of scalding water, and is time-controlled.

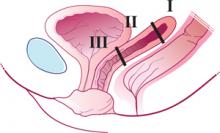

Radiofrequency technology

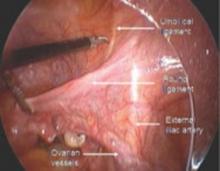

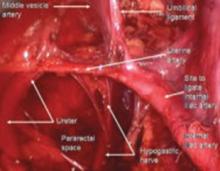

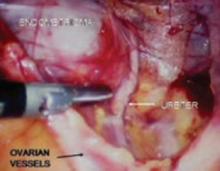

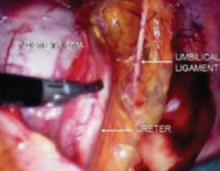

The three-dimensional gold-plated bipolar mesh electrode (NovaSure) is inserted into the uterine cavity and advanced toward the fundus. Once it is properly positioned (above, left), the system is activated to produce 180 W of bipolar power. A moisture-transport vacuum system draws the endometrium into contact with the mesh to enhance tissue vaporization and evacuate debris.

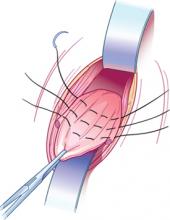

Microwave energy

Microwave energy is emitted from the tip of the device (Microsulis), which is moved back and forth in a sweeping manner, from the fundus to the lower uterine segment. The device directly heats tissue to a depth of 3 mm, with conductive heating of adjacent tissue for an additional 2 to 3 mm. The total 5- to 6-mm depth ensures coagulation and destruction of the basal layer. Microwave energy does not require direct contact with the tissue, as it will “fill the gap” caused by cornual and fibroid distortions.

1. Bustos-Lopez H, Baggish MS, Valle RF, et al. Assessment of the safety of intrauterine instillation of heated saline for endometrial ablation. Fertil Steril. 1998;69:155-160.

2. Baggish MS, Paraiso M, Breznock EM, et al. A computer-controlled, continuously circulating, hot irrigating system for endometrial ablation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:1842-1848.

3. Baggish MS, Savells A. Complications associated with minimally invasive non-hysteroscopic endometrial ablation techniques. J Gynecol Surg. 2007;23:7-12.

4. Goldrath MH. Evaluation of HydroThermablator and rollerball endometrial ablation for menorrhagia: 3 years after treatment. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10:505-511.

5. Abbott J, Hawe J, Hunter D, et al. A double-blind randomized trial comparing the cavaterm and the Novasure endometrial ablation systems for the treatment of dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:203-208.

6. Cooper J, Gimpelson R, Laberge P, et al. A randomized, multi-center trial of safety and efficacy of the Novasure system in the treatment of menorrhagia. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002;9:418-428.

7. Loffer FD, Grainger D. Five-year follow-up of patients participating in a randomized trial of uterine balloon therapy versus rollerball ablation for treatment of menorrhagia. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002;9:429-435.

8. Phipps JH, Lewis BV, Roberts T, et al. Treatment of functional menorrhagia with radiofrequency endometrial ablation. Lancet. 1990;335:374-376.

9. Sharp N, Cronin N, Feldberg I, et al. Microwaves for menorrhagia: a new fast technique for endometrial ablation. Lancet. 1995;346:1003-1004.

10. Thijssen RFA. Radiofrequency-induced endometrial ablation: an update. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:608-613.

11. Baggish MS. Minimally invasive non-hysteroscopic methods for endometrial ablation. In: Baggish MS, Valle RF, Guedj H, eds. Hysteroscopy: Visual Perspectives of Uterine Anatomy, Physiology, and Pathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2007:405-415.

12. Dwyer N, Hutton J, Stirrat GM. Randomized controlled trial comparing endometrial resection with abdominal hysterectomy for the surgical treatment of menorrhagia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;100:237-243.

13. Raiga J, Mage G, Glowaczower E, et al. Factors affecting risk of failure after endometrial resection. J Gynecol Surg. 1995;11:1-5.

14. Shelly-Jones D, Mooney P, Garry R. Factors influencing the outcome of endometrial laser ablation. J Gynecol Surg. 1994;10:211-215.

15. Valle RF, Baggish MS. Endometrial carcinoma after endometrial ablation: high-risk factors predicting its occurrence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;176:569-572.

16. Kanter MH, Kivnick S. Bowel injury from rollerball ablation of the endometrium. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79:833-835.

17. Perry CP, Daniell JF, Gimpelson RJ. Bowel injury from Nd-YAG endometrial ablation. J Gynecol Surg. 1990;6:1999-2003.

18. Scottish Hysteroscopy Audit Group. A Scottish audit of hysteroscopic surgery for menorrhagia: complications and follow-up. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;102:239-254.

19. Goldrath MH, Fuller TA, Segal S. Laser photovaporization of the endometrium for the treatment of menorrhagia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;40:14-19.

20. DeCherney A, Polan ML. Hysteroscopic management of intrauterine lesions and intractable uterine bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 1983;61:392-396.

21. Baggish MS, Baltoyannis P. New techniques for laser ablation of the endometrium in high-risk patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;159:287-292.

22. Baggish MS, Sze EHM. Endometrial ablation: a series of 568 patients treated over an 11-year period. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:908-913.

23. Garry R, Shelly-Jones D, Mooney P, et al. Six hundred endometrial laser ablations. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:24-29.

24. Magos AL, Bauman R, Lockwood GM, et al. Experience with the first 250 endometrial resections for menorrhagia. Lancet. 1991;337:1074-1078.

25. Wortman M, Daggett A. Hysteroscopic endometrial resection: a new technique for the treatment of menorrhagia. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:295-298.

26. Townsend DE, Richart RM, Paskowitz, et al. Rollerball coagulation of the endometrium. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;76:310-313.

27. Overton C, Hargreaves J, Maresh M. A national survey of the complications of endometrial destruction for menstrual disorders: the mistletoe study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:1351-1359.

CASE: Leaking fluid causes intraoperative burns

G.S. is a 45-year-old mother of three who is admitted for surgery for persistent menorrhagia. She has experienced at least two menstrual periods every month for several months, each of them associated with heavy bleeding. She has a history of hypothyroidism and hypertension, but no serious disease or surgery, and considers herself to be in good physical and mental health.

G.S. undergoes endometrial hydrothermablation (HTA) under general inhalation anesthesia. After the HTA mechanism is primed, the heating cycle is started, with a good seal and no fluid leaking from the cervix.

Approximately 8 minutes into the procedure, a 5-mL fluid deficit is noted, and a small amount of hot fluid is observed to be leaking from the cervical os. Examination reveals a thermal injury to the cervix and anterior vaginal wall. The wound is irrigated with cool, sterile saline, and silver sulfadiazine cream is applied. The patient is discharged.

Could this injury have been avoided? Is further treatment warranted?

A minimally invasive operation does not necessarily translate to minimal risk of serious complications. Although few studies of nonhysteroscopic endometrial ablation techniques report any complications,1,2 Baggish and Savells3 found a number of injuries when they searched hospital records and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) database (TABLE). They identified serious complications associated with the following devices:

- HydroThermablator (Boston Scientific), which utilizes a modified operating hysteroscope to deliver 10 to 12 mL of preheated saline into the uterus under low pressure.4 Complications: 16 adverse events were reported to the FDA, 13 of which involved the retrograde leakage of hot water, causing burns to the cervix, vagina, and vulva. Six additional injuries not reported to the FDA were identified at a single institution.

- Novasure (Cytyc), which employs bipolar electrodes that cover a porous bag.5,6 Complications: 32 injuries, 26 of them uterine perforations.

- Thermachoice (Gynecare), a fluid-distended balloon ablator.7 Complications: 22 injuries included retrograde leakage of hot water after balloon failure and transmural thermal injury, with spread to, and injury of, proximal structures. One death was reported.

- Microsulis (MEA), which uses microwave energy to ablate the endometrium.8-10 Complications: 19 injuries, including 13 thermal injuries to the intestines.

Baggish and Savells3 initiated this study after discovering six adverse events within their own hospital system utilizing a single device (HTA). Because these injuries were not reported to the FDA, the overall number of complications is likely higher than the figures given here.

This article describes the proper use of nonhysteroscopic endometrial ablation devices, the best ways to avert serious injury, and optimal treatment when complication occurs.

TABLE

Complications associated with 4 endometrial ablation devices

| COMPLICATION | HYDRO THERMABLATOR* | THERMACHOICE | NOVASURE | MICROSULIS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uterine perforation | 2 | 3 | 26 | 19 |

| Intestinal injury | 1† | 1† | – | 13† |

| Retrograde leakage burn | 19 | 6 | – | – |

| Infection/sepsis | – | 1† | 2 | 1 |

| Fistula/sinus | – | 1† | 1 | – |

| Transmural uterine burn | – | 1 | – | – |

| Cervical stenosis | – | 8 | 1 | – |

| Cardiac arrest | 1 | – | 1 | – |

| Death | – | 1 | – | – |

| Other major | – | 3 | 1 | 4† |

| Total | 22 | 22 | 32 | 20 |

| * Includes author’s data; 6 retrograde leaks | ||||

| † Collateral injury | ||||

CASE continued: Patient opts for hysterectomy

In the case just described, G.S. was examined 1 week after surgery and found to have an exophytic burn over the entire right half of the cervix, extending into the vagina. She was readmitted for 3 days of intravenous (IV) antibiotic treatment and wound care. Computed tomography imaging showed gas formation within the damaged cervix.

Six weeks after surgery, the patient was still menstruating heavily, but her cervix and vagina had healed. Six months later, she underwent total abdominal hysterectomy for continued menorrhagia.

When is endometrial ablation an option?

Indications for endometrial ablation using a nonhysteroscopic, minimally invasive technique are no different from those for hysteroscopic ablation.11 Abnormal, or dysfunctional, uterine bleeding is the principal reason for this operation. Dysfunctional bleeding is heavy or prolonged menses over 6 months or longer that fail to respond to conservative measures and occur in the absence of tumor, pregnancy, or inflammation (ie, infection).

A woman who meets these criteria should have a desire to retain her uterus if she is to be a candidate for a nonhysteroscopic, minimally invasive technique. She also should understand that ablation can render pregnancy unlikely and even pathologic. Her understanding of this consequence should be documented in the chart! Last, she should be informed that ablation will not necessarily render her sterile, so contraception or sterilization will be required to avoid pregnancy. This should also be clearly documented in the medical record.

Endometrial ablation may also be an alternative to hysterectomy for a mentally retarded woman who is unable to manage menses. Abnormal uterine bleeding in conjunction with bleeding diathesis, significant obesity, or serious medical disorders can also be treated by endometrial ablation.

Avoid endometrial ablation in certain circumstances

These circumstances include the presence of endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial cancer, endocervical neoplasia, cervical stenosis, an undiagnosed adnexal mass, moderate to severe dysmenorrhea, adenomyosis, or a uterine cavity larger than 10 cm.12-15

Valle and Baggish15 reported eight cases in which women developed endometrial carcinoma following ablation, and identified the following major risk factors for postablation cancer:

- endometrial hyperplasia unresponsive to progesterone or progestin therapy

- complex endometrial hyperplasia

- atypical hyperplasia.

These conditions are contraindications to endometrial ablation.

Avoid a rush to ablation

The growing popularity of office-based, minimally invasive, nonhysteroscopic techniques, coupled with an increasing desire for and acceptance of elective cessation of menses, may stretch the indications listed above and cut short the discovery of contraindications. Clearly, thorough endometrial sampling and precise histopathologic interpretation are required before embarking on any type of endometrial ablation, to minimize the risk of complications.

How to prevent injury

Reduce the risk of perforation

Uterine perforation occurs for a variety of reasons:

- position of the uterus is unknown

- uterus has not been gently and carefully sounded

- cervix is insufficiently dilated to permit passage of the probe

- device is too long (large) to be accommodated in an individual patient’s uterus

- uterine cavity is distorted by pathology, such as adhesions, myomas, etc.

Attention to these details before surgery can prevent perforation.

When uterine injury occurs, the bowel is also at risk

The intestines can be injured following perforation or transmural injury of the uterus. Bowel injury has been reported with hysteroscopic ablation and resection as well as with Nd-YAG laser ablation.16-18

Do not activate hot water or electrosurgical energy unless you are 100% certain that the device is within the uterine cavity.

Ideally, manufacturers’ safety studies should guarantee no risk of transtubal spillage of hot liquid.

Hot fluid adds to risk of burns

Devices that permit retrograde leakage of hot fluid, such as the HTA, should be modified to ensure sealing at the level of the external and internal cervical os. The Enable device (Innerdyne), no longer marketed in the United States, had such a sealing mechanism, which minimized retrograde leakage of hot water.

Balloon failure may be an unavoidable injury, but pretesting of the device and careful attention to pressure readings—particularly in a small uterus—may mitigate the risk.

Be alert for electrical leakage

The microwave device operates at the megahertz range of frequency. At this high frequency, the risk of leakage is much greater than with devices that operate in the kilohertz range. Therefore, it is important to pay close attention to grounding sites, such as cardiovascular-monitoring electrodes.

High-power monopolar devices, prolonged application of energy to tissue, and high generator frequency are all associated with leakage and subsequent burns.

- Keep the success rate above 90%

- Minimize complications by proper technique and instrument selection

- Press the market to develop a range of device sizes that will individualize the procedure

- Keep the price of a procedure under $1,000

- Establish and adhere to careful patient selection criteria

Early recognition and treatment are vital to ensure the patient’s safety and reduce the risk of medicolegal liability. I recommend the following steps:

- Stop the procedure immediately if perforation is suspected. If you suspect that hot water has been dispersed within the abdominal cavity, switch to laparotomy and consult a general surgeon to inspect the entire intestine for injury. If perforation occurs during the use of electrosurgical energy, the same action is warranted. If uterine perforation occurs in isolation (ie, there is no thermal energy compounding the problem), admit the patient for careful observation, appropriate blood chemistries and hematologic studies, and radiologic examination.

- When hot liquids are spilled, switch to retrograde flow immediately and generously flush the vulva, vagina, and cervix with cold water. Cleanse the entire area with a soapless detergent, and apply clindamycin cream to the vagina and silver sulfadiazine cream to the vulva. Admit the patient for application of cold compresses, ice packs, and burn therapy, and obtain baseline cultures and hematologic studies and a plastic surgery consult. If third-degree (full thickness) burns are suspected, treat any suspected wound infection aggressively after obtaining cultures. Severe and inordinate pain should be investigated as a possible sign of necrotizing fasciitis. After discharge, follow the patient’s progress at weekly intervals.

- Talk to the patient and her family. It is a good idea to explain the complication in very clear terms. I believe it is reasonable to explain how the complication occurred, without speculation or theatrical explanations. Also be sure to document this conversation, including date and time. It may be useful to have a neutral witness present during the conversation. By and large, the patient and her family are likely to appreciate an honest account of how the complication occurred. Hiding data or attempting to cover up the injury may motivate the patient to seek legal representation.

The long-term success of endometrial ablation devices as a whole depends on several conditions. Foremost, the entire class of devices should demonstrate efficacy on par with hysteroscopic ablation. Currently, efficacy ranges from 80% to 95% (short-term follow-up).11 The goal of minimally invasive procedures should be a sustainable 92% rate of amenorrhea, hypomenorrhea, or light, periodic menses. A long-term failure rate of 25% is unacceptable.22-24 If the devices can, by their simplicity, be adapted to more or less universal office application and attain a 5-year success rate of 90% or higher, they will become the standard of care.

One size does not really fit all

Serious complications from endometrial ablation devices occur with regular frequency and must be eliminated or greatly reduced. Perforation is a significant problem and may be related to the “one-size-fits-all” design of the device. Perhaps a range of sizes needs to be produced and fitted to the individual uterine cavity.

If such complications as perforation and burns to the bowel, cervix, vagina, and vulva can be eliminated or relegated to rarity, then a happy future for these procedures lies beyond the horizon.

Price ceiling should be set at $1,000

If an operation can consistently be performed for less than $1,000 total cost—the cost of in-hospital endometrial ablation—it will gain mass appeal. In hospitals and so-called surgicenters, ablations are expensive and, therefore, less attractive to self- or third-party payers. If fees are based on the volume of cases, then a procedure may be price-efficient.

Outcome depends on patient selection

Poorly screened patients who have underlying hyperplasia may develop postablation carcinoma. Women who have dysmenorrhea before the procedure can be predicted to suffer from it afterward. Older women (ie, 40 years or older) will have better long-term success than younger women. And women with a large uterus or myomas will have a higher failure rate than women with smaller cavities (ie, less than 10 cm in length).

What this means for the individual surgeon

Although minimally invasive techniques are relatively easy to perform and simple to learn, each part of the procedure requires careful application and great attention to detail. Perforation of the uterus and leakage of scalding hot liquid must be avoided. If these complications occur, prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment are critical. The removal of these procedures from the operating room to the office as well as competitive pricing of instrumentation will make nonhysteroscopic, minimally invasive endometrial ablation more cost-effective.

The modern era of practical endometrial ablation began in 1981, when Goldrath and colleagues19 reported Nd-YAG laser photovaporization of the endometrium via hysteroscopy for treatment of excessive uterine bleeding. Two years later, DeCherney and Polan20 reported hysteroscopic control of abnormal uterine bleeding using the urologic resectoscope.

Over succeeding years, Baggish and Baltoyannis21 and Baggish and Sze22 reported extensive experience with hysteroscopic endometrial ablation in both high- and average-risk patients, including long-term follow-up of 568 cases over 11 years. Garry and colleagues23 reported a large series of 600 cases from the United Kingdom. Not only did these laser techniques prove to be effective, achieving amenorrhea rates ranging from 30% to 60%, but overall control of abnormal bleeding exceeded 90%. In the large series involving approximately 1,200 cases, no uterine perforations were reported.21-23 The major complication: Fluid overload secondary to vascular uptake of distension medium.

In Europe and the United Kingdom, most hysteroscopic treatment of abnormal bleeding involved endometrial resection using the cutting loop of the resectoscope. In the United States, ablation with the ball electrode of the resectoscope largely replaced the Nd-YAG laser because the resectoscopic trigger mechanism required less skill and hand–eye coordination than the hand–finger-controlled movement of the 600- to 1,000-micron laser fiber.24-26

A search for more benign techniques

A 1997 UK survey analyzed 10,686 cases of hysteroscopic endometrial destruction and identified 474 complications.27 Resection alone had a complication rate of 10.9% and an emergency hysterectomy rate of 13 for every 1,000 patients. Laser ablation had a complication rate of 5.5% and an emergency hysterectomy rate of 2 for every 1,000 patients, and the corresponding figures for rollerball ablation were a 4.5% complication rate and 3 emergency hysterectomies for every 1,000 patients. Two deaths occurred (in 10,000 cases) and were associated with loop excision.

Published data indicated that:

- Successful outcomes after endometrial ablation or resection were directly proportional to the skill of the surgeon

- Complications, particularly serious complications, were related to the experience and skill of the surgeon

- Infusion of uterine distension medium, particularly hypo-osmolar solutions, was associated with serious complications when fluid deficits exceeded approximately 500 to 1,000 mL.

As a result, a number of investigators sought to develop new surgical techniques to control abnormal uterine bleeding that would minimize the skill required by the surgeon (requiring only insertion of a cannula into the uterus and a “cookbook” ablation procedure), eliminate the need for distension medium and general anesthesia, and attain efficacy equivalent to earlier techniques.

A quartet of options

Among the devices that resulted were:

- A microwave technique, described by several investigators.8-10 Its chief drawback: High-frequency electrical leakage with the potential to cause thermal burns.

- An intrauterine balloon device distended with sterile water or saline is heated in situ to 85° to 90° Celsius, thereby cooking the endometrium.

- An electrode-bearing device that features an array of monopolar electrodes over the endometrium-facing aspect of a balloon or bipolar electrodes over a porous bag.

- Devices that circulate a small volume of hot saline freely within the uterine cavity. Hydrothermablation delivers 10 to 12 mL of preheated saline into the uterus under low pressure. A similar technique delivers 10 to 12 mL of cool water or saline into the uterus through a sealed cannula, followed by in situ heating and circulation of the fluid at low pressure via a computer-controlled device.

Safety studies were required by the FDA and were performed on all these devices, and the risk of complications appeared to be negligible.1,2 As this article illustrates, that is not the case.

Four devices, four ways of achieving ablation

Since the advent of nonhysteroscopic, minimally invasive endometrial ablation devices, four distinct techniques have gained widespread use

Hydrothermablation

The closed-loop system (HTA) ablates the lining of the endometrium under hysteroscopic visualization by recirculating heated saline within the uterus. The modified hysteroscope allows the operator to view the ablation as it occurs within the uterine cavity.

Balloon ablation

Balloon ablation (Thermachoice) features a double-dip balloon construction that conforms to the contours of the uterine cavity. The saline or water in the balloon is heated in situ. This device requires an undistorted uterine cavity, relies on the integrity of the balloon to prevent forward or retrograde spillage of scalding water, and is time-controlled.

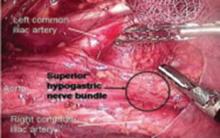

Radiofrequency technology

The three-dimensional gold-plated bipolar mesh electrode (NovaSure) is inserted into the uterine cavity and advanced toward the fundus. Once it is properly positioned (above, left), the system is activated to produce 180 W of bipolar power. A moisture-transport vacuum system draws the endometrium into contact with the mesh to enhance tissue vaporization and evacuate debris.

Microwave energy

Microwave energy is emitted from the tip of the device (Microsulis), which is moved back and forth in a sweeping manner, from the fundus to the lower uterine segment. The device directly heats tissue to a depth of 3 mm, with conductive heating of adjacent tissue for an additional 2 to 3 mm. The total 5- to 6-mm depth ensures coagulation and destruction of the basal layer. Microwave energy does not require direct contact with the tissue, as it will “fill the gap” caused by cornual and fibroid distortions.

CASE: Leaking fluid causes intraoperative burns

G.S. is a 45-year-old mother of three who is admitted for surgery for persistent menorrhagia. She has experienced at least two menstrual periods every month for several months, each of them associated with heavy bleeding. She has a history of hypothyroidism and hypertension, but no serious disease or surgery, and considers herself to be in good physical and mental health.

G.S. undergoes endometrial hydrothermablation (HTA) under general inhalation anesthesia. After the HTA mechanism is primed, the heating cycle is started, with a good seal and no fluid leaking from the cervix.

Approximately 8 minutes into the procedure, a 5-mL fluid deficit is noted, and a small amount of hot fluid is observed to be leaking from the cervical os. Examination reveals a thermal injury to the cervix and anterior vaginal wall. The wound is irrigated with cool, sterile saline, and silver sulfadiazine cream is applied. The patient is discharged.

Could this injury have been avoided? Is further treatment warranted?

A minimally invasive operation does not necessarily translate to minimal risk of serious complications. Although few studies of nonhysteroscopic endometrial ablation techniques report any complications,1,2 Baggish and Savells3 found a number of injuries when they searched hospital records and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) database (TABLE). They identified serious complications associated with the following devices:

- HydroThermablator (Boston Scientific), which utilizes a modified operating hysteroscope to deliver 10 to 12 mL of preheated saline into the uterus under low pressure.4 Complications: 16 adverse events were reported to the FDA, 13 of which involved the retrograde leakage of hot water, causing burns to the cervix, vagina, and vulva. Six additional injuries not reported to the FDA were identified at a single institution.

- Novasure (Cytyc), which employs bipolar electrodes that cover a porous bag.5,6 Complications: 32 injuries, 26 of them uterine perforations.

- Thermachoice (Gynecare), a fluid-distended balloon ablator.7 Complications: 22 injuries included retrograde leakage of hot water after balloon failure and transmural thermal injury, with spread to, and injury of, proximal structures. One death was reported.

- Microsulis (MEA), which uses microwave energy to ablate the endometrium.8-10 Complications: 19 injuries, including 13 thermal injuries to the intestines.

Baggish and Savells3 initiated this study after discovering six adverse events within their own hospital system utilizing a single device (HTA). Because these injuries were not reported to the FDA, the overall number of complications is likely higher than the figures given here.

This article describes the proper use of nonhysteroscopic endometrial ablation devices, the best ways to avert serious injury, and optimal treatment when complication occurs.

TABLE

Complications associated with 4 endometrial ablation devices

| COMPLICATION | HYDRO THERMABLATOR* | THERMACHOICE | NOVASURE | MICROSULIS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uterine perforation | 2 | 3 | 26 | 19 |

| Intestinal injury | 1† | 1† | – | 13† |

| Retrograde leakage burn | 19 | 6 | – | – |

| Infection/sepsis | – | 1† | 2 | 1 |

| Fistula/sinus | – | 1† | 1 | – |

| Transmural uterine burn | – | 1 | – | – |

| Cervical stenosis | – | 8 | 1 | – |

| Cardiac arrest | 1 | – | 1 | – |

| Death | – | 1 | – | – |

| Other major | – | 3 | 1 | 4† |

| Total | 22 | 22 | 32 | 20 |

| * Includes author’s data; 6 retrograde leaks | ||||

| † Collateral injury | ||||

CASE continued: Patient opts for hysterectomy

In the case just described, G.S. was examined 1 week after surgery and found to have an exophytic burn over the entire right half of the cervix, extending into the vagina. She was readmitted for 3 days of intravenous (IV) antibiotic treatment and wound care. Computed tomography imaging showed gas formation within the damaged cervix.

Six weeks after surgery, the patient was still menstruating heavily, but her cervix and vagina had healed. Six months later, she underwent total abdominal hysterectomy for continued menorrhagia.

When is endometrial ablation an option?

Indications for endometrial ablation using a nonhysteroscopic, minimally invasive technique are no different from those for hysteroscopic ablation.11 Abnormal, or dysfunctional, uterine bleeding is the principal reason for this operation. Dysfunctional bleeding is heavy or prolonged menses over 6 months or longer that fail to respond to conservative measures and occur in the absence of tumor, pregnancy, or inflammation (ie, infection).

A woman who meets these criteria should have a desire to retain her uterus if she is to be a candidate for a nonhysteroscopic, minimally invasive technique. She also should understand that ablation can render pregnancy unlikely and even pathologic. Her understanding of this consequence should be documented in the chart! Last, she should be informed that ablation will not necessarily render her sterile, so contraception or sterilization will be required to avoid pregnancy. This should also be clearly documented in the medical record.

Endometrial ablation may also be an alternative to hysterectomy for a mentally retarded woman who is unable to manage menses. Abnormal uterine bleeding in conjunction with bleeding diathesis, significant obesity, or serious medical disorders can also be treated by endometrial ablation.

Avoid endometrial ablation in certain circumstances

These circumstances include the presence of endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial cancer, endocervical neoplasia, cervical stenosis, an undiagnosed adnexal mass, moderate to severe dysmenorrhea, adenomyosis, or a uterine cavity larger than 10 cm.12-15

Valle and Baggish15 reported eight cases in which women developed endometrial carcinoma following ablation, and identified the following major risk factors for postablation cancer:

- endometrial hyperplasia unresponsive to progesterone or progestin therapy

- complex endometrial hyperplasia

- atypical hyperplasia.

These conditions are contraindications to endometrial ablation.

Avoid a rush to ablation

The growing popularity of office-based, minimally invasive, nonhysteroscopic techniques, coupled with an increasing desire for and acceptance of elective cessation of menses, may stretch the indications listed above and cut short the discovery of contraindications. Clearly, thorough endometrial sampling and precise histopathologic interpretation are required before embarking on any type of endometrial ablation, to minimize the risk of complications.

How to prevent injury

Reduce the risk of perforation

Uterine perforation occurs for a variety of reasons:

- position of the uterus is unknown

- uterus has not been gently and carefully sounded

- cervix is insufficiently dilated to permit passage of the probe

- device is too long (large) to be accommodated in an individual patient’s uterus

- uterine cavity is distorted by pathology, such as adhesions, myomas, etc.

Attention to these details before surgery can prevent perforation.

When uterine injury occurs, the bowel is also at risk

The intestines can be injured following perforation or transmural injury of the uterus. Bowel injury has been reported with hysteroscopic ablation and resection as well as with Nd-YAG laser ablation.16-18

Do not activate hot water or electrosurgical energy unless you are 100% certain that the device is within the uterine cavity.

Ideally, manufacturers’ safety studies should guarantee no risk of transtubal spillage of hot liquid.

Hot fluid adds to risk of burns

Devices that permit retrograde leakage of hot fluid, such as the HTA, should be modified to ensure sealing at the level of the external and internal cervical os. The Enable device (Innerdyne), no longer marketed in the United States, had such a sealing mechanism, which minimized retrograde leakage of hot water.

Balloon failure may be an unavoidable injury, but pretesting of the device and careful attention to pressure readings—particularly in a small uterus—may mitigate the risk.

Be alert for electrical leakage

The microwave device operates at the megahertz range of frequency. At this high frequency, the risk of leakage is much greater than with devices that operate in the kilohertz range. Therefore, it is important to pay close attention to grounding sites, such as cardiovascular-monitoring electrodes.

High-power monopolar devices, prolonged application of energy to tissue, and high generator frequency are all associated with leakage and subsequent burns.

- Keep the success rate above 90%

- Minimize complications by proper technique and instrument selection

- Press the market to develop a range of device sizes that will individualize the procedure

- Keep the price of a procedure under $1,000

- Establish and adhere to careful patient selection criteria

Early recognition and treatment are vital to ensure the patient’s safety and reduce the risk of medicolegal liability. I recommend the following steps:

- Stop the procedure immediately if perforation is suspected. If you suspect that hot water has been dispersed within the abdominal cavity, switch to laparotomy and consult a general surgeon to inspect the entire intestine for injury. If perforation occurs during the use of electrosurgical energy, the same action is warranted. If uterine perforation occurs in isolation (ie, there is no thermal energy compounding the problem), admit the patient for careful observation, appropriate blood chemistries and hematologic studies, and radiologic examination.

- When hot liquids are spilled, switch to retrograde flow immediately and generously flush the vulva, vagina, and cervix with cold water. Cleanse the entire area with a soapless detergent, and apply clindamycin cream to the vagina and silver sulfadiazine cream to the vulva. Admit the patient for application of cold compresses, ice packs, and burn therapy, and obtain baseline cultures and hematologic studies and a plastic surgery consult. If third-degree (full thickness) burns are suspected, treat any suspected wound infection aggressively after obtaining cultures. Severe and inordinate pain should be investigated as a possible sign of necrotizing fasciitis. After discharge, follow the patient’s progress at weekly intervals.

- Talk to the patient and her family. It is a good idea to explain the complication in very clear terms. I believe it is reasonable to explain how the complication occurred, without speculation or theatrical explanations. Also be sure to document this conversation, including date and time. It may be useful to have a neutral witness present during the conversation. By and large, the patient and her family are likely to appreciate an honest account of how the complication occurred. Hiding data or attempting to cover up the injury may motivate the patient to seek legal representation.

The long-term success of endometrial ablation devices as a whole depends on several conditions. Foremost, the entire class of devices should demonstrate efficacy on par with hysteroscopic ablation. Currently, efficacy ranges from 80% to 95% (short-term follow-up).11 The goal of minimally invasive procedures should be a sustainable 92% rate of amenorrhea, hypomenorrhea, or light, periodic menses. A long-term failure rate of 25% is unacceptable.22-24 If the devices can, by their simplicity, be adapted to more or less universal office application and attain a 5-year success rate of 90% or higher, they will become the standard of care.

One size does not really fit all

Serious complications from endometrial ablation devices occur with regular frequency and must be eliminated or greatly reduced. Perforation is a significant problem and may be related to the “one-size-fits-all” design of the device. Perhaps a range of sizes needs to be produced and fitted to the individual uterine cavity.

If such complications as perforation and burns to the bowel, cervix, vagina, and vulva can be eliminated or relegated to rarity, then a happy future for these procedures lies beyond the horizon.

Price ceiling should be set at $1,000

If an operation can consistently be performed for less than $1,000 total cost—the cost of in-hospital endometrial ablation—it will gain mass appeal. In hospitals and so-called surgicenters, ablations are expensive and, therefore, less attractive to self- or third-party payers. If fees are based on the volume of cases, then a procedure may be price-efficient.

Outcome depends on patient selection

Poorly screened patients who have underlying hyperplasia may develop postablation carcinoma. Women who have dysmenorrhea before the procedure can be predicted to suffer from it afterward. Older women (ie, 40 years or older) will have better long-term success than younger women. And women with a large uterus or myomas will have a higher failure rate than women with smaller cavities (ie, less than 10 cm in length).

What this means for the individual surgeon

Although minimally invasive techniques are relatively easy to perform and simple to learn, each part of the procedure requires careful application and great attention to detail. Perforation of the uterus and leakage of scalding hot liquid must be avoided. If these complications occur, prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment are critical. The removal of these procedures from the operating room to the office as well as competitive pricing of instrumentation will make nonhysteroscopic, minimally invasive endometrial ablation more cost-effective.

The modern era of practical endometrial ablation began in 1981, when Goldrath and colleagues19 reported Nd-YAG laser photovaporization of the endometrium via hysteroscopy for treatment of excessive uterine bleeding. Two years later, DeCherney and Polan20 reported hysteroscopic control of abnormal uterine bleeding using the urologic resectoscope.

Over succeeding years, Baggish and Baltoyannis21 and Baggish and Sze22 reported extensive experience with hysteroscopic endometrial ablation in both high- and average-risk patients, including long-term follow-up of 568 cases over 11 years. Garry and colleagues23 reported a large series of 600 cases from the United Kingdom. Not only did these laser techniques prove to be effective, achieving amenorrhea rates ranging from 30% to 60%, but overall control of abnormal bleeding exceeded 90%. In the large series involving approximately 1,200 cases, no uterine perforations were reported.21-23 The major complication: Fluid overload secondary to vascular uptake of distension medium.

In Europe and the United Kingdom, most hysteroscopic treatment of abnormal bleeding involved endometrial resection using the cutting loop of the resectoscope. In the United States, ablation with the ball electrode of the resectoscope largely replaced the Nd-YAG laser because the resectoscopic trigger mechanism required less skill and hand–eye coordination than the hand–finger-controlled movement of the 600- to 1,000-micron laser fiber.24-26

A search for more benign techniques

A 1997 UK survey analyzed 10,686 cases of hysteroscopic endometrial destruction and identified 474 complications.27 Resection alone had a complication rate of 10.9% and an emergency hysterectomy rate of 13 for every 1,000 patients. Laser ablation had a complication rate of 5.5% and an emergency hysterectomy rate of 2 for every 1,000 patients, and the corresponding figures for rollerball ablation were a 4.5% complication rate and 3 emergency hysterectomies for every 1,000 patients. Two deaths occurred (in 10,000 cases) and were associated with loop excision.

Published data indicated that:

- Successful outcomes after endometrial ablation or resection were directly proportional to the skill of the surgeon

- Complications, particularly serious complications, were related to the experience and skill of the surgeon

- Infusion of uterine distension medium, particularly hypo-osmolar solutions, was associated with serious complications when fluid deficits exceeded approximately 500 to 1,000 mL.

As a result, a number of investigators sought to develop new surgical techniques to control abnormal uterine bleeding that would minimize the skill required by the surgeon (requiring only insertion of a cannula into the uterus and a “cookbook” ablation procedure), eliminate the need for distension medium and general anesthesia, and attain efficacy equivalent to earlier techniques.

A quartet of options

Among the devices that resulted were:

- A microwave technique, described by several investigators.8-10 Its chief drawback: High-frequency electrical leakage with the potential to cause thermal burns.

- An intrauterine balloon device distended with sterile water or saline is heated in situ to 85° to 90° Celsius, thereby cooking the endometrium.

- An electrode-bearing device that features an array of monopolar electrodes over the endometrium-facing aspect of a balloon or bipolar electrodes over a porous bag.

- Devices that circulate a small volume of hot saline freely within the uterine cavity. Hydrothermablation delivers 10 to 12 mL of preheated saline into the uterus under low pressure. A similar technique delivers 10 to 12 mL of cool water or saline into the uterus through a sealed cannula, followed by in situ heating and circulation of the fluid at low pressure via a computer-controlled device.

Safety studies were required by the FDA and were performed on all these devices, and the risk of complications appeared to be negligible.1,2 As this article illustrates, that is not the case.

Four devices, four ways of achieving ablation

Since the advent of nonhysteroscopic, minimally invasive endometrial ablation devices, four distinct techniques have gained widespread use

Hydrothermablation

The closed-loop system (HTA) ablates the lining of the endometrium under hysteroscopic visualization by recirculating heated saline within the uterus. The modified hysteroscope allows the operator to view the ablation as it occurs within the uterine cavity.

Balloon ablation

Balloon ablation (Thermachoice) features a double-dip balloon construction that conforms to the contours of the uterine cavity. The saline or water in the balloon is heated in situ. This device requires an undistorted uterine cavity, relies on the integrity of the balloon to prevent forward or retrograde spillage of scalding water, and is time-controlled.

Radiofrequency technology

The three-dimensional gold-plated bipolar mesh electrode (NovaSure) is inserted into the uterine cavity and advanced toward the fundus. Once it is properly positioned (above, left), the system is activated to produce 180 W of bipolar power. A moisture-transport vacuum system draws the endometrium into contact with the mesh to enhance tissue vaporization and evacuate debris.

Microwave energy

Microwave energy is emitted from the tip of the device (Microsulis), which is moved back and forth in a sweeping manner, from the fundus to the lower uterine segment. The device directly heats tissue to a depth of 3 mm, with conductive heating of adjacent tissue for an additional 2 to 3 mm. The total 5- to 6-mm depth ensures coagulation and destruction of the basal layer. Microwave energy does not require direct contact with the tissue, as it will “fill the gap” caused by cornual and fibroid distortions.

1. Bustos-Lopez H, Baggish MS, Valle RF, et al. Assessment of the safety of intrauterine instillation of heated saline for endometrial ablation. Fertil Steril. 1998;69:155-160.

2. Baggish MS, Paraiso M, Breznock EM, et al. A computer-controlled, continuously circulating, hot irrigating system for endometrial ablation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:1842-1848.

3. Baggish MS, Savells A. Complications associated with minimally invasive non-hysteroscopic endometrial ablation techniques. J Gynecol Surg. 2007;23:7-12.

4. Goldrath MH. Evaluation of HydroThermablator and rollerball endometrial ablation for menorrhagia: 3 years after treatment. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10:505-511.

5. Abbott J, Hawe J, Hunter D, et al. A double-blind randomized trial comparing the cavaterm and the Novasure endometrial ablation systems for the treatment of dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:203-208.

6. Cooper J, Gimpelson R, Laberge P, et al. A randomized, multi-center trial of safety and efficacy of the Novasure system in the treatment of menorrhagia. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002;9:418-428.

7. Loffer FD, Grainger D. Five-year follow-up of patients participating in a randomized trial of uterine balloon therapy versus rollerball ablation for treatment of menorrhagia. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002;9:429-435.

8. Phipps JH, Lewis BV, Roberts T, et al. Treatment of functional menorrhagia with radiofrequency endometrial ablation. Lancet. 1990;335:374-376.

9. Sharp N, Cronin N, Feldberg I, et al. Microwaves for menorrhagia: a new fast technique for endometrial ablation. Lancet. 1995;346:1003-1004.

10. Thijssen RFA. Radiofrequency-induced endometrial ablation: an update. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:608-613.

11. Baggish MS. Minimally invasive non-hysteroscopic methods for endometrial ablation. In: Baggish MS, Valle RF, Guedj H, eds. Hysteroscopy: Visual Perspectives of Uterine Anatomy, Physiology, and Pathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2007:405-415.

12. Dwyer N, Hutton J, Stirrat GM. Randomized controlled trial comparing endometrial resection with abdominal hysterectomy for the surgical treatment of menorrhagia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;100:237-243.

13. Raiga J, Mage G, Glowaczower E, et al. Factors affecting risk of failure after endometrial resection. J Gynecol Surg. 1995;11:1-5.

14. Shelly-Jones D, Mooney P, Garry R. Factors influencing the outcome of endometrial laser ablation. J Gynecol Surg. 1994;10:211-215.

15. Valle RF, Baggish MS. Endometrial carcinoma after endometrial ablation: high-risk factors predicting its occurrence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;176:569-572.

16. Kanter MH, Kivnick S. Bowel injury from rollerball ablation of the endometrium. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79:833-835.

17. Perry CP, Daniell JF, Gimpelson RJ. Bowel injury from Nd-YAG endometrial ablation. J Gynecol Surg. 1990;6:1999-2003.

18. Scottish Hysteroscopy Audit Group. A Scottish audit of hysteroscopic surgery for menorrhagia: complications and follow-up. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;102:239-254.

19. Goldrath MH, Fuller TA, Segal S. Laser photovaporization of the endometrium for the treatment of menorrhagia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;40:14-19.

20. DeCherney A, Polan ML. Hysteroscopic management of intrauterine lesions and intractable uterine bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 1983;61:392-396.

21. Baggish MS, Baltoyannis P. New techniques for laser ablation of the endometrium in high-risk patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;159:287-292.

22. Baggish MS, Sze EHM. Endometrial ablation: a series of 568 patients treated over an 11-year period. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:908-913.

23. Garry R, Shelly-Jones D, Mooney P, et al. Six hundred endometrial laser ablations. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:24-29.

24. Magos AL, Bauman R, Lockwood GM, et al. Experience with the first 250 endometrial resections for menorrhagia. Lancet. 1991;337:1074-1078.

25. Wortman M, Daggett A. Hysteroscopic endometrial resection: a new technique for the treatment of menorrhagia. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:295-298.

26. Townsend DE, Richart RM, Paskowitz, et al. Rollerball coagulation of the endometrium. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;76:310-313.

27. Overton C, Hargreaves J, Maresh M. A national survey of the complications of endometrial destruction for menstrual disorders: the mistletoe study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:1351-1359.

1. Bustos-Lopez H, Baggish MS, Valle RF, et al. Assessment of the safety of intrauterine instillation of heated saline for endometrial ablation. Fertil Steril. 1998;69:155-160.

2. Baggish MS, Paraiso M, Breznock EM, et al. A computer-controlled, continuously circulating, hot irrigating system for endometrial ablation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:1842-1848.

3. Baggish MS, Savells A. Complications associated with minimally invasive non-hysteroscopic endometrial ablation techniques. J Gynecol Surg. 2007;23:7-12.

4. Goldrath MH. Evaluation of HydroThermablator and rollerball endometrial ablation for menorrhagia: 3 years after treatment. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10:505-511.

5. Abbott J, Hawe J, Hunter D, et al. A double-blind randomized trial comparing the cavaterm and the Novasure endometrial ablation systems for the treatment of dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:203-208.

6. Cooper J, Gimpelson R, Laberge P, et al. A randomized, multi-center trial of safety and efficacy of the Novasure system in the treatment of menorrhagia. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002;9:418-428.

7. Loffer FD, Grainger D. Five-year follow-up of patients participating in a randomized trial of uterine balloon therapy versus rollerball ablation for treatment of menorrhagia. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002;9:429-435.

8. Phipps JH, Lewis BV, Roberts T, et al. Treatment of functional menorrhagia with radiofrequency endometrial ablation. Lancet. 1990;335:374-376.

9. Sharp N, Cronin N, Feldberg I, et al. Microwaves for menorrhagia: a new fast technique for endometrial ablation. Lancet. 1995;346:1003-1004.

10. Thijssen RFA. Radiofrequency-induced endometrial ablation: an update. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:608-613.

11. Baggish MS. Minimally invasive non-hysteroscopic methods for endometrial ablation. In: Baggish MS, Valle RF, Guedj H, eds. Hysteroscopy: Visual Perspectives of Uterine Anatomy, Physiology, and Pathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2007:405-415.

12. Dwyer N, Hutton J, Stirrat GM. Randomized controlled trial comparing endometrial resection with abdominal hysterectomy for the surgical treatment of menorrhagia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;100:237-243.

13. Raiga J, Mage G, Glowaczower E, et al. Factors affecting risk of failure after endometrial resection. J Gynecol Surg. 1995;11:1-5.

14. Shelly-Jones D, Mooney P, Garry R. Factors influencing the outcome of endometrial laser ablation. J Gynecol Surg. 1994;10:211-215.

15. Valle RF, Baggish MS. Endometrial carcinoma after endometrial ablation: high-risk factors predicting its occurrence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;176:569-572.

16. Kanter MH, Kivnick S. Bowel injury from rollerball ablation of the endometrium. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79:833-835.

17. Perry CP, Daniell JF, Gimpelson RJ. Bowel injury from Nd-YAG endometrial ablation. J Gynecol Surg. 1990;6:1999-2003.

18. Scottish Hysteroscopy Audit Group. A Scottish audit of hysteroscopic surgery for menorrhagia: complications and follow-up. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;102:239-254.

19. Goldrath MH, Fuller TA, Segal S. Laser photovaporization of the endometrium for the treatment of menorrhagia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;40:14-19.

20. DeCherney A, Polan ML. Hysteroscopic management of intrauterine lesions and intractable uterine bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 1983;61:392-396.

21. Baggish MS, Baltoyannis P. New techniques for laser ablation of the endometrium in high-risk patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;159:287-292.

22. Baggish MS, Sze EHM. Endometrial ablation: a series of 568 patients treated over an 11-year period. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:908-913.

23. Garry R, Shelly-Jones D, Mooney P, et al. Six hundred endometrial laser ablations. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:24-29.

24. Magos AL, Bauman R, Lockwood GM, et al. Experience with the first 250 endometrial resections for menorrhagia. Lancet. 1991;337:1074-1078.

25. Wortman M, Daggett A. Hysteroscopic endometrial resection: a new technique for the treatment of menorrhagia. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:295-298.

26. Townsend DE, Richart RM, Paskowitz, et al. Rollerball coagulation of the endometrium. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;76:310-313.

27. Overton C, Hargreaves J, Maresh M. A national survey of the complications of endometrial destruction for menstrual disorders: the mistletoe study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:1351-1359.

How to manage the cuff at vaginal hysterectomy

CASE 1 What procedures should accompany hysterectomy?

A.E., 44, mother of one, complains of heavy irregular bleeding with no sensation of a vaginal bulge. She has tried oral contraceptives, but they did not improve her bleeding pattern. She also has undergone dilatation and curettage and hysteroscopy (benign findings), also with no improvement.

Examination reveals a 9- to 10-week-size fibroid uterus, which is confirmed by ultrasonography. Pelvic support appears to be excellent.

After a discussion of the options, the patient elects to undergo vaginal hysterectomy. Are other procedures warranted?

Ask a gynecologic surgeon to name the most significant challenges he or she faces, and the answer is likely to include preventing pelvic organ prolapse after surgical intervention. Approximately one third of operations for pelvic organ prolapse involve patients whose prolapse has recurred after previous surgery.1 Although we have advanced our understanding of the anatomy of pelvic support and the pathophysiology of support defects, the various surgical strategies remain largely untested and unproven.

Even women with good pelvic support who are undergoing hysterectomy—like the patient described above—are vulnerable. One particular area of concern: the risk of enterocele or vaginal apical prolapse, or both, after hysterectomy. In this article, I describe a technique to reduce the risk of these defects after vaginal hysterectomy: high uterosacral suspension, or modified McCall culdoplasty.

Enterocele and apical prolapse do not always coexist

Enterocele and apical prolapse are distinct entities. The latter represents a deficiency in the level I supporting structures described by DeLancey2—primarily the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments (FIGURE 1). Enterocele, or peritoneocele, is a herniation of the cul-de-sac peritoneum, with or without intestinal contents. In women who have undergone hysterectomy, enterocele is usually caused by a lack of continuity of level II fibers, namely, the failure to approximate the pubocervical and rectovaginal connective tissues at the time of hysterectomy.3 Careful attention to the vaginal cuff and cul-de-sac at the time of hysterectomy is therefore imperative.

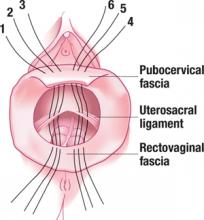

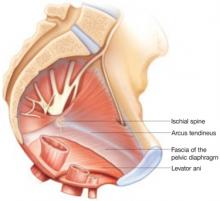

FIGURE 1 Three levels of support

The endopelvic fascia of a posthysterectomy patient divided into DeLancey’s biomechanical levels: level I—proximal suspension, level II—lateral attachment, and level III—distal fusion.

The McCall culdoplasty: 50 years “young”

In 1957, Milton McCall, MD, described a technique to manage the cul-de-sac at the time of vaginal hysterectomy.4 The McCall technique of posterior culdoplasty differs from other approaches by omitting dissection and excision of the hernia sac, or excess cul-de-sac peritoneum. The original McCall culdoplasty begins with the placement of several rows (average of 3) of nonabsorbable suture (“internal” McCall sutures), starting at the left uterosacral ligament about 2 cm above its cut edge, and proceeding across the redundant cul-de-sac to terminate in the right uterosacral ligament. Each subsequent row is placed superior to the first, by applying traction to the previously placed sutures.

Prior to the tying of these sutures, 3 “external” absorbable sutures are placed. These sutures incorporate posterior vaginal epithelium, each uterosacral ligament, and the contralateral vaginal epithelium in a mirror image of the first pass through the vagina. Again, several rows are placed, each more superior to the last, to move the newly created vaginal apex to the highest point on the uterosacral ligaments once all the sutures are tied.

Tying the internal sutures not only creates a firm, shelf-like midline structure, but obliterates the redundant cul-de-sac. The external sutures move the vaginal apex to the uterosacral bridge and are tied at the conclusion of the procedure (FIGURES 2 and 3).

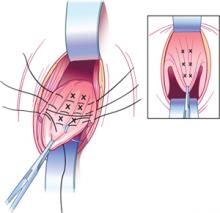

FIGURE 2 Internal McCall sutures

Traction on the most dependent portion of the cul-de-sac and posterior vaginal epithelium allows placement of 3 rows of sutures across the cul-de-sac from one uterosacral ligament to the other.

FIGURE 3 External McCall sutures

Three additional rows of absorbable sutures incorporate vaginal epithelium and uterosacral ligaments to move the vaginal cuff superiorly.

Modifications enhance durability and support

When the surgical indication is significant apical vaginal prolapse, the efficacy of the McCall procedure as both treatment and prevention is uncertain, because we lack adequate studies in this population. However, assuming that identifiable defects or breaks in the uterosacral ligaments lead to apical prolapse,3 use of the portion of the uterosacral ligament nearest the vagina appears unlikely to create a durable repair.

Thus, the concept of a “high” uterosacral attachment came to be proposed to provide a strong midline site of support for the vaginal apex.5,6 Further modifications include attachment of the uterosacral ligaments to pubocervical and rectovaginal connective tissues to create continuity of these level II fibers and prevent subsequent enterocele.7

With a high uterosacral attachment, the uterosacral ligaments need not be brought together in the midline.

Technique for modified approach

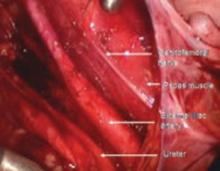

To locate each ligament, place traction on the vaginal apex toward the contralateral side. Palpate the pelvic structures posterior and medial to the ischial spines, at the 4 and 8 o’clock positions, to identify the strong tissue emanating from the sacrum.

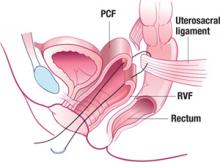

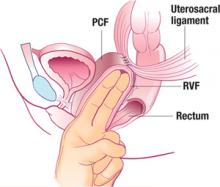

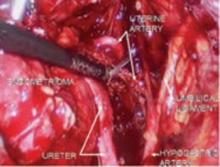

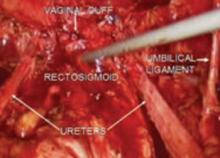

Place several nonabsorbable sutures through the medial aspect of each uterosacral ligament, working from lateral to medial to minimize the risk of ureteral trauma. Then place 1 strand of each suture through the pubocervical and rectovaginal connective tissues. Tie the sutures to move the vaginal apex to the proximal segment of the uterosacral ligament (near the sacrum) and establish continuity of the pubocervical and rectovaginal connective tissues (FIGURES 4-6).

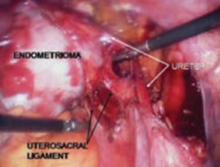

FIGURE 4 Suture placement is bilateral

Three sutures are placed in the uterosacral ligament pedicles on each side, with 1 arm of each suture placed in the transverse portion of the pubocervical and rectovaginal fascia.