User login

Is long-term outcome with TVT comparable to that of laparoscopic Burch colposuspension?

Just 2 years ago, when Brubaker and colleagues published initial findings from the colpopexy and urinary reduction efforts (CARE) trial in the New England Journal of Medicine,1 Burch colposuspension was a well-established anti-incontinence procedure utilized by many urogynecologists. The procedure remains a reliable intervention, although midurethral sling procedures have surpassed it in popularity and (some would say) efficacy. This issue’s installment of Examining the Evidence highlights two recent investigations of the antiincontinence procedure:

- 2-year follow-up from the CARE trial, which compared sacrocolpopexy, with and without a concomitant Burch procedure, in women who did not have symptoms of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) at the time of surgery

- a comparison of laparoscopic Burch colposuspension and the tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) technique.

Details of the study

Seventy-two women were originally enrolled from 1999 to 2002; 74% of them (25 in the TVT group and 28 in the laparoscopic Burch group) were available for long-term followup 4 to 8 years after surgery. Fifty-seven percent (16/28) of women had subjective urinary incontinence after laparoscopic Burch colposuspension versus 48% (12/25) after TVT. There were no differences between the groups in subjective or objective findings or urinary incontinence. However, the study was severely underpowered to be able to show any difference between the groups.

These cure rates are low, but the authors note that only 11% of the laparoscopic Burch group and 8% of the TVT group had bothersome SUI. Quality of life on the urogenital distress inventory and incontinence impact questionnaire short forms was improved in both groups equally by 2 years and maintained throughout the rest of the trial.

These poor objective results are similar to those found in a 5-year follow-up by Ward and Hilton of their prospective, randomized, controlled trial of Burch versus TVT procedures. There, only 39% of the TVT group and 46% of the Burch group reported no incontinence.

The original trial by Paraiso and colleagues3 showed better outcomes in the TVT group 1 year after surgery, but that difference did not remain 4 to 8 years later. One explanation for that observation may be type-II error resulting from the small number of subjects in the trial.

Laparoscopic Burch colposuspension and the TVT procedure appear to have equal long-term outcomes. Because placing TVT is less invasive, however, it may be the preferable procedure until larger trials or meta-analyses conclusively determine which operation is superior.—PETER K. SAND, MD

1. Ulmsten U, Henriksson L, Johnson P, Varhos G. An ambulatory surgical procedure under local anesthesia for treatment of female urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 1996;7:81-86.

2. Ward KL, Hilton P. On behalf of the UK and Ireland TVT Trial Group. A prospective multicenter randomized trial of tension-free vaginal tape and colposuspension for primary urodynamic stress incontinence: two-year follow-up. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:324-331.

3. Paraiso MF, Walters MD, Karram MM, Barber MD. Laparoscopic Burch colposuspension versus tension-free vaginal tape: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:1249-1258.

Just 2 years ago, when Brubaker and colleagues published initial findings from the colpopexy and urinary reduction efforts (CARE) trial in the New England Journal of Medicine,1 Burch colposuspension was a well-established anti-incontinence procedure utilized by many urogynecologists. The procedure remains a reliable intervention, although midurethral sling procedures have surpassed it in popularity and (some would say) efficacy. This issue’s installment of Examining the Evidence highlights two recent investigations of the antiincontinence procedure:

- 2-year follow-up from the CARE trial, which compared sacrocolpopexy, with and without a concomitant Burch procedure, in women who did not have symptoms of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) at the time of surgery

- a comparison of laparoscopic Burch colposuspension and the tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) technique.

Details of the study

Seventy-two women were originally enrolled from 1999 to 2002; 74% of them (25 in the TVT group and 28 in the laparoscopic Burch group) were available for long-term followup 4 to 8 years after surgery. Fifty-seven percent (16/28) of women had subjective urinary incontinence after laparoscopic Burch colposuspension versus 48% (12/25) after TVT. There were no differences between the groups in subjective or objective findings or urinary incontinence. However, the study was severely underpowered to be able to show any difference between the groups.

These cure rates are low, but the authors note that only 11% of the laparoscopic Burch group and 8% of the TVT group had bothersome SUI. Quality of life on the urogenital distress inventory and incontinence impact questionnaire short forms was improved in both groups equally by 2 years and maintained throughout the rest of the trial.

These poor objective results are similar to those found in a 5-year follow-up by Ward and Hilton of their prospective, randomized, controlled trial of Burch versus TVT procedures. There, only 39% of the TVT group and 46% of the Burch group reported no incontinence.

The original trial by Paraiso and colleagues3 showed better outcomes in the TVT group 1 year after surgery, but that difference did not remain 4 to 8 years later. One explanation for that observation may be type-II error resulting from the small number of subjects in the trial.

Laparoscopic Burch colposuspension and the TVT procedure appear to have equal long-term outcomes. Because placing TVT is less invasive, however, it may be the preferable procedure until larger trials or meta-analyses conclusively determine which operation is superior.—PETER K. SAND, MD

Just 2 years ago, when Brubaker and colleagues published initial findings from the colpopexy and urinary reduction efforts (CARE) trial in the New England Journal of Medicine,1 Burch colposuspension was a well-established anti-incontinence procedure utilized by many urogynecologists. The procedure remains a reliable intervention, although midurethral sling procedures have surpassed it in popularity and (some would say) efficacy. This issue’s installment of Examining the Evidence highlights two recent investigations of the antiincontinence procedure:

- 2-year follow-up from the CARE trial, which compared sacrocolpopexy, with and without a concomitant Burch procedure, in women who did not have symptoms of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) at the time of surgery

- a comparison of laparoscopic Burch colposuspension and the tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) technique.

Details of the study

Seventy-two women were originally enrolled from 1999 to 2002; 74% of them (25 in the TVT group and 28 in the laparoscopic Burch group) were available for long-term followup 4 to 8 years after surgery. Fifty-seven percent (16/28) of women had subjective urinary incontinence after laparoscopic Burch colposuspension versus 48% (12/25) after TVT. There were no differences between the groups in subjective or objective findings or urinary incontinence. However, the study was severely underpowered to be able to show any difference between the groups.

These cure rates are low, but the authors note that only 11% of the laparoscopic Burch group and 8% of the TVT group had bothersome SUI. Quality of life on the urogenital distress inventory and incontinence impact questionnaire short forms was improved in both groups equally by 2 years and maintained throughout the rest of the trial.

These poor objective results are similar to those found in a 5-year follow-up by Ward and Hilton of their prospective, randomized, controlled trial of Burch versus TVT procedures. There, only 39% of the TVT group and 46% of the Burch group reported no incontinence.

The original trial by Paraiso and colleagues3 showed better outcomes in the TVT group 1 year after surgery, but that difference did not remain 4 to 8 years later. One explanation for that observation may be type-II error resulting from the small number of subjects in the trial.

Laparoscopic Burch colposuspension and the TVT procedure appear to have equal long-term outcomes. Because placing TVT is less invasive, however, it may be the preferable procedure until larger trials or meta-analyses conclusively determine which operation is superior.—PETER K. SAND, MD

1. Ulmsten U, Henriksson L, Johnson P, Varhos G. An ambulatory surgical procedure under local anesthesia for treatment of female urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 1996;7:81-86.

2. Ward KL, Hilton P. On behalf of the UK and Ireland TVT Trial Group. A prospective multicenter randomized trial of tension-free vaginal tape and colposuspension for primary urodynamic stress incontinence: two-year follow-up. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:324-331.

3. Paraiso MF, Walters MD, Karram MM, Barber MD. Laparoscopic Burch colposuspension versus tension-free vaginal tape: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:1249-1258.

1. Ulmsten U, Henriksson L, Johnson P, Varhos G. An ambulatory surgical procedure under local anesthesia for treatment of female urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 1996;7:81-86.

2. Ward KL, Hilton P. On behalf of the UK and Ireland TVT Trial Group. A prospective multicenter randomized trial of tension-free vaginal tape and colposuspension for primary urodynamic stress incontinence: two-year follow-up. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:324-331.

3. Paraiso MF, Walters MD, Karram MM, Barber MD. Laparoscopic Burch colposuspension versus tension-free vaginal tape: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:1249-1258.

Cystocele and rectocele repair: More success with mesh?

CASE Symptoms point to yet another prolapse recurrence

A 52-year-old woman presents with a bulge and pressure in her vagina. She has undergone 2 prior reconstructive surgeries. The first was a vaginal hysterectomy, anterior and posterior repair, and sling; the second was an abdominal procedure that included a sacrocolpopexy and paravaginal repair.

A physical examination reveals a recurrent 4th-degree cystocele that protrudes 2 cm beyond the hymenal ring. The vault and posterior compartment are well supported, and the patient reports no incontinence, a fact confirmed by urodynamics testing. She asks that you do everything in your power to prevent further recurrence.

How do you proceed?

This patient ultimately underwent anterior colporrhaphy and vaginal paravaginal repair using a decellularized dermal cadaveric implant. She was still doing well 1 year later, with no recurrence.

Despite success stories like this one, the use of graft materials to repair cystoceles and rectoceles is controversial. One reason is the difficulty of interpreting published data, since studies lack uniformity in technique, patient characteristics, graft shape, type of material, attachment sites, and duration of follow-up. Level I evidence that augmented repairs have a clear benefit over traditional repairs is sparse.

Advocates of graft materials argue that native tissue is already compromised—hence, the prolapse—making surgical failure likely.1 They claim graft materials help strengthen repairs, especially in the case of cystoceles. They also point out that adjuvant materials have been used in burns, plastic surgery, and orthopedics for more than 10 years and are generally well tolerated. Their success in hernia repairs prompted their consideration for the pelvic floor.

A pervasive problem, but only 10% to 20% seek help

Roughly 1 of 2 parous women lose pelvic support as they age, but only 10% to 20% seek medical care, with a lifetime risk of surgery for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) of 11% by age 80.2

With women living longer than ever and remaining active later in life, this percentage is likely to rise. Unfortunately, few alternatives to surgical treatment exist, and the reoperation rate for recurrence is 29%, according to a 1995 review.2 If surgical management is the only hope of cure, how can we lower the 29% recurrence rate?

Graft materials may provide part or all of the solution.

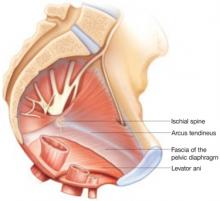

Elements of prolapse

Anterior compartment

Central and/or lateral defects can occur in the anterior compartment.

Lateral (paravaginal) defects indicate that the endopelvic connective tissue has separated from the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis. Lateral defects can be repaired vaginally or abdominally.

One study3 found that 67% of women with anterior wall prolapse had paravaginal defects, but no randomized trials have evaluated the clinical benefit of repairing these defects, compared with traditional colporrhaphies.

Central defects involve site-specific defects and/or general attenuation of the endopelvic connective tissue. These are usually repaired vaginally.

Recurrence rates for lateral and central defects range from 3% to 70%.4-8

Two large series of vaginal paravaginal repairs noted the following recurrence rates:

- Shull et al6 found a recurrence rate of 7% to the hymenal ring or beyond.

- Young et al7 observed a recurrence rate for lateral defects of 2%, with recurrence rates as high as 22% for central defects.

In a comparison of 3 techniques for vaginal repair of central defects, using strict criteria to assess anatomic outcomes, Weber et al4 found recurrence rates of 54% to 70%. Other studies show symptomatic recurrence rates of 3% to 22% for cystoceles.5,8

With grafts, both paravaginal and central defects can be repaired. Vaginal paravaginal repairs are not popular due to the technical difficulty involved. With the use of grafts, however, both paravaginal and central defects can be addressed simultaneously with relative ease.

Posterior compartment

Defects in the posterior compartment are less likely to recur. Reported success rates range from 80% to 90%.9,10

Posterior compartment defects include general attenuation of Denonvillier’s fascia or a tear anywhere along the fascia or any of its attachments.

Recurrence rates. Site-specific repairs are thought to minimize complications such as dyspareunia. However, few studies have compared the efficacy of site-specific repairs with that of traditional colporrhaphies. At our institution, women who underwent traditional colporrhaphy had fewer recurrences than controls (33% vs 14%), with no differences in postoperative symptoms such as dyspareunia, constipation, and fecal incontinence.11

Graft materials of questionable benefit. In the posterior compartment, these materials have not been shown to be beneficial, compared with traditional or site-specific repairs. Sand et al12 found no benefit for repairs in which absorbable Vicryl mesh was imbricated, but this randomized trial may have lacked sufficient power to show statistical significance. Large cohorts would be needed to show significant benefit of meshes in the posterior compartment.

A complex web of support

In the normal pelvis, support of reproductive organs depends on a complex web of muscles, fascia, and connective tissue. To ensure success, prolapse repairs should correct any separation or attenuation of tissue and preserve or enhance tissue resilience.

Risk factors for recurrent prolapse

- Poor tissue (assess tissue quality before and during surgery)

- Impaired healing

- Chronic increases in intraabdominal pressure due to obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, or constipation

- High-grade cystocele

- Age 60 or above13

Patients with these conditions may benefit from the use of adjuvant materials in the anterior compartment.

Note that women who have had recurrences after earlier repairs may experience repeat recurrence.

Advantages of grafts

Using graft materials, the surgeon can repair all vaginal defects faster and with less effort. In the anterior compartment, a graft can be placed and anchored bilaterally from arcus to arcus tendineus, and posteriorly to the level of the spine, recreating level I support. Graft materials also offer the potential to treat stress urinary incontinence concomitantly using different shaped materials. Two authors have already described their success performing this type of repair.14

Nevertheless, great care and consideration should be devoted to actual and theoretical short- and long-term risks, many of which have not been fully elucidated.

Once a successful material is identified or developed, it may decrease operating time and morbidity in vaginal surgeries. It may also reduce the higher hospital costs normally associated with abdominal procedures.

Types of graft materials

There are 2 types of materials: synthetic or biologic. Synthetic materials can be further classified into permanent or absorbable.

The most widely used biologic materials include allografts such as human freeze-dried or solvent-dehydrated fascia lata (Tutoplast), decellularized human cadaveric dermis (Alloderm, Repliform), porcine dermal xenografts such as Pelvicol or Intexene, and bovine pericardial implants (Veritas).

Soft polypropylene meshes such as Gynemesh and Atrium are commonly used permanent materials, and polyglactin 910 is an absorbable material (TABLE).

TABLE

How successful are adjuvant materials in cystocele and rectocele repairs?

| MATERIAL (SIZE IN CM) | AUTHOR | NO. IN STUDY | RECURRENCE RATE (%) | SITE OF ATTACHMENT | FOLLOW-UP (MONTHS) | COMPLICATIONS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIOLOGIC MATERIALS | ||||||

| Alloderm 3×7 patch with concomitant sling | Chung29 | 19 | 16 | Pubocervical fascia | 28 | None |

| Intexene 6×8 with sling | Gomelsky et al 200420 | 70 | 9 stage II 4 stage III | Arcus tendineus fascia pelvis | 24 | 1 wound separation |

| Solvent-dehydrated cadaveric fascia lata patch with sling | Gandhi et al 200521 | 76 patch vs 72 no patch | 21 vs 29, respectively (P=.23) | Overlay | 13 | None |

| Alloderm 3×7 trapezoid | Clemons et al 200322 | 33 | 41 stage II 3 symptomatic | Arcus tendineus fascia pelvis | 18 | None |

| SYNTHETIC MATERIALS WITH CONCOMITANT SLINGS* | ||||||

| Marlex 10×3×5 | Nicita 199823 | 44 | 0 | Arcus tendineus fascia pelvis | 13 | 1 vaginal erosion |

| Polyglactin 910 absorbable mesh | Sand et al12 | 80 mesh vs 80 no mesh | 25 vs 43 stage II cystoceles, respectively(P=.02) | Insert in the anterior and posterior colporrhaphy suture line | 12 | None |

| Polyglactin 910 absorbable mesh | Weber et al4 | 26 with mesh + standard repair; 24 with ultra-lateral repair; 33 with standard repair | 58 vs 54 vs 70 stage II, respectively (P=.58) | Overlay | 23 | None |

| SYNTHETIC PERMANENT GRAFTS WITHOUT CONCOMITANT SLINGS | ||||||

| Marlex trapezoid | Julian 199619 | 12 with 12 without | 0 vs 33, respectively | Arcus tendineus fascia pelvis | 24 | 3 vaginal erosions |

| Mixed-fiber mesh (polyglactin 910 and polyester 5×5) | Migliari and Usai 199924 | 12 | 25 | Pubourethral and cardinal ligaments | 20 | None |

| Prolene (Atrium) | Dwyer and O’Reilly25 | 64 anterior 50 posterior | 6 grade II | Tension-free | 29 | 8% vaginal erosion 1 rectovaginal fistula |

| Gynemesh 6×15 | de Tayrac et al 200526 | 87 | 7 stage II 2 stage III | Tension-free | 24 | 8% vaginal erosion |

| Prolene mesh patch | Milani et al 200527 | 32 anterior 31 posterior | 6 stage II | Fixed to endopelvic connective tissue | 17 | 20% anterior, 63% posterior dyspareunia; 13% vaginal erosion (anterior); 1 pelvic abscess (posterior) |

| Prolene mesh (double-wing shape) | Natale et al 2000 28 | 138 | 3 | Tension-free | 18 | 9% vaginal erosion 7% dyspareunia 1 hematoma |

| *Absorbable and permanent. | ||||||

Classification of synthetic materials

- Type 1 grafts are totally macroporous (>75 μm), which allows fibroblast, macrophage, and collagen penetration with angiogenesis. Examples include Prolene and Marlex meshes.

- Type 2 mesh is microporous (<10 μm in 1 dimension). This prevents penetration of fibroblasts, macrophages, or collagen. Gore-Tex is an example of a Type 2 mesh.

- Type 3 mesh is macroporous (>75 μm) with multifilamentous or microporous components. Examples include Mersilene (braided Dacron mesh), Teflon (polytetrafluoroethylene [PTFE]), Surgipro (braided polypropylene mesh), and MycroMesh (perforated PTFE patch).

- Type 4 mesh has a submicron pore size that prevents penetration. Examples include Silastic, Cellgard (polypropylene sheeting), and Preclude pericardial membrane/Preclude dura-substitute.1

2 other important properties are composition of fibers (multifilamentous materials commonly have interstices less than 10 microns) and flexibility (which has a bearing on erosion of the material).1

Bacteria can penetrate pores smaller than 1 μm, whereas polymorphonuclear white blood cells and macrophages need a pore size larger than 10 μm, and capillary ingrowth requires a size larger than 75 microns. Thus, Type 1 offers the advantages of larger pore size and monofilamentous interstices to allow for capillary ingrowth.

Which material is best?

Although the literature is difficult to interpret because of the diversity of studies and other factors, some findings are worth noting:

- Tutoplast and Alloderm appear to have the best tensile strength, maximum load to capacity, and microscopic architecture similar to the original tissue.15-17 However, these qualities were documented prior to implantation in vivo.

- Slings appear to help prevent cystocele recurrences, according to a study by Goldberg et al.18

- A fascial patch had no benefit when placed as an overlay in the anterior compartment in a randomized, controlled trial (involving 162 women) by Sand et al.12

- Marlex. One group of women with recurrent prolapse underwent synthetic graft (Marlex) augmentation with bilateral ATFP attachment, while the other group had anterior colporrhaphy only.19 None of the women who received grafts had further recurrence, while 33% of the control group did. However, 25% of the women with the graft had vaginal erosions.

- Polyglactin 910 had a protective effect when embedded in the plication, according to Sand et al.12 However, it had no benefit when used as an overlay to a traditional repair in a study by Weber et al.4 The discrepancy may be related to small sample size; the study by Weber et al was powered to detect only a 30% difference. However, these studies suggest that it is not only the type of graft that is important, but how it is used or attached.

In general, synthetic grafts may have slightly higher success rates, whereas biologic materials appear to be better tolerated.

Prospective, comparative trials of these materials are desperately needed.

1. Cervigni M, Natale F. The use of synthetics in the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Curr Opin Urol. 2001;11:429-435.

2. Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:501-506.

3. Richardson AC, Lyon JB, Williams NL. A new look at pelvic relaxation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;126:568-573.

4. Weber AM, Walters MD, Piedmonte MR, Ballard LA. Anterior colporrhaphy: a randomized trial of three surgical techniques. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1299-1304.

5. Porges RF, Smilen SW. Long-term analysis of the surgical management of pelvic support defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:1518-1526.

6. Shull BL, Benn SJ, Kuehl TJ. Surgical management of prolapse of the anterior vaginal segment: an analysis of support defects, operative morbidity, and anatomic outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:1429-1436.

7. Young SB, Daman JJ, Bony LG. Vaginal paravaginal repair: one-year outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1360-1366.

8. Macer GA. Transabdominal repair of cystocele, a 20-year experience, compared with the traditional vaginal approach. Trans Pac Coast Obstet Gynecol Soc. 1978;45:116-120.

9. Cundiff GW, Weidner AC, Visco AG, Addison WA, Bump RC. An anatomic and functional assessment of the discrete defect rectocele repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:1451-1456.

10. Paraiso MF, Ballard LA, Walters MD, Lee JC, et al. Pelvic support defects and visceral and sexual function in women treated with sacrospinous ligament suspension and pelvic reconstruction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1423-1430.

11. Abramov Y, et al. Site-specific rectocele repair compared with standard posterior colporrhaphy. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:314-318.

12. Sand PK, et al. Prospective randomized trial of polyglactin 910 mesh to prevent recurrence of cystoceles and rectoceles. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:1357-1362.

13. Whitesides JL, Weber AM, Meyn LA, Walters MD. Risk factors for prolapse recurrence after vaginal repair. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2005;60:164-165.

14. Kobashi KC, Mee SL, Leach GE. A new technique for cystocele repair and transvaginal sling: the cadaveric prolapse repair and sling (CAPS). Urology. 2000;56:9-14.

15. Lemer ML, Chaikin DC, Blaivas JG. Tissue strength analysis of autologous and cadaveric allografts for the pubovaginal sling. Neurourol Urodyn. 1999;18:497-503.

16. Choe JM, Kothandapani R, et al. Autologous, cadaveric, and synthetic materials used in sling surgery: comparative biomechanical analysis. Urology. 2001;58:482-486.

17. Scalfani AP. Biophysical and microscopic analysis of homologous dermal and fascial materials for facial aesthetic and reconstructive uses. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2002;4:164-171.

18. Goldberg RP, et al. Protective effect of suburethral slings on postoperative cystocele recurrence after reconstructive pelvic operation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1307-1312.

19. Julian TM. The efficacy of Marlex mesh in the repair of severe, recurrent vaginal prolapse of the anterior midvaginal wall. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1472-1475.

20. Gomelsky A, Rudy DC, Dmochowski RR. Porcine dermis interposition graft for repair of high grade anterior compartment defects with or without concomitant pelvic organ prolapse procedures. J Urol. 2004;171:1581-1584.

21. Gandhi S, et al. A prospective randomized trial of solvent dehydrated fascia lata for the prevention of recurrent anterior vaginal wall prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1649-1654.

22. Clemons JL, Myers DL, Aguilar VC, Arya LA. Vaginal paravaginal repair with an AlloDerm graft. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1612-1618.

23. Nicita G. A new operation for genitourinary prolapse. J Urol. 1998;160:741-745.

24. Migliari R, Usai E. Treatment results using a mixed fiber mesh in patients with grade IV cystocele. J Urol. 1999;161:1255-1258.

25. Dwyer PL, O’Reilly BA. Transvaginal repair of anterior and posterior compartment prolapse with Atrium polypropylene mesh. BJOG. 2004;111:831-836.

26. de Tayrac R, Gervaise A, Chauveaud A, Fernandez H. Tension-free polypropylene mesh for vaginal repair of anterior vaginal wall prolapse. J Reprod Med. 2005;50:75-80.

27. Milani R, et al. Functional and anatomical outcome of anterior and posterior vaginal prolapse repair with prolene mesh. BJOG. 2005;112:107-111.

28. Natale F, Marziali S, Cervigni M. Tension-free cystocele repair (TCR): long-term follow-up. Proceedings of the 25th annual meeting of the International Urogynecological Association. 2000;22-25.

29. Chung SY, et al. Technique of combined pubovaginal sling and cystocele using a single piece of cadaveric dermal graft. Urology. 2002;59:538-541.

Dr. Botros has no financial relationships relevant to this article. Dr. Sand receives grant/research support from Boston Scientific, and is a consultant and speaker for American Medical Systems and Boston Scientific.

CASE Symptoms point to yet another prolapse recurrence

A 52-year-old woman presents with a bulge and pressure in her vagina. She has undergone 2 prior reconstructive surgeries. The first was a vaginal hysterectomy, anterior and posterior repair, and sling; the second was an abdominal procedure that included a sacrocolpopexy and paravaginal repair.

A physical examination reveals a recurrent 4th-degree cystocele that protrudes 2 cm beyond the hymenal ring. The vault and posterior compartment are well supported, and the patient reports no incontinence, a fact confirmed by urodynamics testing. She asks that you do everything in your power to prevent further recurrence.

How do you proceed?

This patient ultimately underwent anterior colporrhaphy and vaginal paravaginal repair using a decellularized dermal cadaveric implant. She was still doing well 1 year later, with no recurrence.

Despite success stories like this one, the use of graft materials to repair cystoceles and rectoceles is controversial. One reason is the difficulty of interpreting published data, since studies lack uniformity in technique, patient characteristics, graft shape, type of material, attachment sites, and duration of follow-up. Level I evidence that augmented repairs have a clear benefit over traditional repairs is sparse.

Advocates of graft materials argue that native tissue is already compromised—hence, the prolapse—making surgical failure likely.1 They claim graft materials help strengthen repairs, especially in the case of cystoceles. They also point out that adjuvant materials have been used in burns, plastic surgery, and orthopedics for more than 10 years and are generally well tolerated. Their success in hernia repairs prompted their consideration for the pelvic floor.

A pervasive problem, but only 10% to 20% seek help

Roughly 1 of 2 parous women lose pelvic support as they age, but only 10% to 20% seek medical care, with a lifetime risk of surgery for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) of 11% by age 80.2

With women living longer than ever and remaining active later in life, this percentage is likely to rise. Unfortunately, few alternatives to surgical treatment exist, and the reoperation rate for recurrence is 29%, according to a 1995 review.2 If surgical management is the only hope of cure, how can we lower the 29% recurrence rate?

Graft materials may provide part or all of the solution.

Elements of prolapse

Anterior compartment

Central and/or lateral defects can occur in the anterior compartment.

Lateral (paravaginal) defects indicate that the endopelvic connective tissue has separated from the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis. Lateral defects can be repaired vaginally or abdominally.

One study3 found that 67% of women with anterior wall prolapse had paravaginal defects, but no randomized trials have evaluated the clinical benefit of repairing these defects, compared with traditional colporrhaphies.

Central defects involve site-specific defects and/or general attenuation of the endopelvic connective tissue. These are usually repaired vaginally.

Recurrence rates for lateral and central defects range from 3% to 70%.4-8

Two large series of vaginal paravaginal repairs noted the following recurrence rates:

- Shull et al6 found a recurrence rate of 7% to the hymenal ring or beyond.

- Young et al7 observed a recurrence rate for lateral defects of 2%, with recurrence rates as high as 22% for central defects.

In a comparison of 3 techniques for vaginal repair of central defects, using strict criteria to assess anatomic outcomes, Weber et al4 found recurrence rates of 54% to 70%. Other studies show symptomatic recurrence rates of 3% to 22% for cystoceles.5,8

With grafts, both paravaginal and central defects can be repaired. Vaginal paravaginal repairs are not popular due to the technical difficulty involved. With the use of grafts, however, both paravaginal and central defects can be addressed simultaneously with relative ease.

Posterior compartment

Defects in the posterior compartment are less likely to recur. Reported success rates range from 80% to 90%.9,10

Posterior compartment defects include general attenuation of Denonvillier’s fascia or a tear anywhere along the fascia or any of its attachments.

Recurrence rates. Site-specific repairs are thought to minimize complications such as dyspareunia. However, few studies have compared the efficacy of site-specific repairs with that of traditional colporrhaphies. At our institution, women who underwent traditional colporrhaphy had fewer recurrences than controls (33% vs 14%), with no differences in postoperative symptoms such as dyspareunia, constipation, and fecal incontinence.11

Graft materials of questionable benefit. In the posterior compartment, these materials have not been shown to be beneficial, compared with traditional or site-specific repairs. Sand et al12 found no benefit for repairs in which absorbable Vicryl mesh was imbricated, but this randomized trial may have lacked sufficient power to show statistical significance. Large cohorts would be needed to show significant benefit of meshes in the posterior compartment.

A complex web of support

In the normal pelvis, support of reproductive organs depends on a complex web of muscles, fascia, and connective tissue. To ensure success, prolapse repairs should correct any separation or attenuation of tissue and preserve or enhance tissue resilience.

Risk factors for recurrent prolapse

- Poor tissue (assess tissue quality before and during surgery)

- Impaired healing

- Chronic increases in intraabdominal pressure due to obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, or constipation

- High-grade cystocele

- Age 60 or above13

Patients with these conditions may benefit from the use of adjuvant materials in the anterior compartment.

Note that women who have had recurrences after earlier repairs may experience repeat recurrence.

Advantages of grafts

Using graft materials, the surgeon can repair all vaginal defects faster and with less effort. In the anterior compartment, a graft can be placed and anchored bilaterally from arcus to arcus tendineus, and posteriorly to the level of the spine, recreating level I support. Graft materials also offer the potential to treat stress urinary incontinence concomitantly using different shaped materials. Two authors have already described their success performing this type of repair.14

Nevertheless, great care and consideration should be devoted to actual and theoretical short- and long-term risks, many of which have not been fully elucidated.

Once a successful material is identified or developed, it may decrease operating time and morbidity in vaginal surgeries. It may also reduce the higher hospital costs normally associated with abdominal procedures.

Types of graft materials

There are 2 types of materials: synthetic or biologic. Synthetic materials can be further classified into permanent or absorbable.

The most widely used biologic materials include allografts such as human freeze-dried or solvent-dehydrated fascia lata (Tutoplast), decellularized human cadaveric dermis (Alloderm, Repliform), porcine dermal xenografts such as Pelvicol or Intexene, and bovine pericardial implants (Veritas).

Soft polypropylene meshes such as Gynemesh and Atrium are commonly used permanent materials, and polyglactin 910 is an absorbable material (TABLE).

TABLE

How successful are adjuvant materials in cystocele and rectocele repairs?

| MATERIAL (SIZE IN CM) | AUTHOR | NO. IN STUDY | RECURRENCE RATE (%) | SITE OF ATTACHMENT | FOLLOW-UP (MONTHS) | COMPLICATIONS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIOLOGIC MATERIALS | ||||||

| Alloderm 3×7 patch with concomitant sling | Chung29 | 19 | 16 | Pubocervical fascia | 28 | None |

| Intexene 6×8 with sling | Gomelsky et al 200420 | 70 | 9 stage II 4 stage III | Arcus tendineus fascia pelvis | 24 | 1 wound separation |

| Solvent-dehydrated cadaveric fascia lata patch with sling | Gandhi et al 200521 | 76 patch vs 72 no patch | 21 vs 29, respectively (P=.23) | Overlay | 13 | None |

| Alloderm 3×7 trapezoid | Clemons et al 200322 | 33 | 41 stage II 3 symptomatic | Arcus tendineus fascia pelvis | 18 | None |

| SYNTHETIC MATERIALS WITH CONCOMITANT SLINGS* | ||||||

| Marlex 10×3×5 | Nicita 199823 | 44 | 0 | Arcus tendineus fascia pelvis | 13 | 1 vaginal erosion |

| Polyglactin 910 absorbable mesh | Sand et al12 | 80 mesh vs 80 no mesh | 25 vs 43 stage II cystoceles, respectively(P=.02) | Insert in the anterior and posterior colporrhaphy suture line | 12 | None |

| Polyglactin 910 absorbable mesh | Weber et al4 | 26 with mesh + standard repair; 24 with ultra-lateral repair; 33 with standard repair | 58 vs 54 vs 70 stage II, respectively (P=.58) | Overlay | 23 | None |

| SYNTHETIC PERMANENT GRAFTS WITHOUT CONCOMITANT SLINGS | ||||||

| Marlex trapezoid | Julian 199619 | 12 with 12 without | 0 vs 33, respectively | Arcus tendineus fascia pelvis | 24 | 3 vaginal erosions |

| Mixed-fiber mesh (polyglactin 910 and polyester 5×5) | Migliari and Usai 199924 | 12 | 25 | Pubourethral and cardinal ligaments | 20 | None |

| Prolene (Atrium) | Dwyer and O’Reilly25 | 64 anterior 50 posterior | 6 grade II | Tension-free | 29 | 8% vaginal erosion 1 rectovaginal fistula |

| Gynemesh 6×15 | de Tayrac et al 200526 | 87 | 7 stage II 2 stage III | Tension-free | 24 | 8% vaginal erosion |

| Prolene mesh patch | Milani et al 200527 | 32 anterior 31 posterior | 6 stage II | Fixed to endopelvic connective tissue | 17 | 20% anterior, 63% posterior dyspareunia; 13% vaginal erosion (anterior); 1 pelvic abscess (posterior) |

| Prolene mesh (double-wing shape) | Natale et al 2000 28 | 138 | 3 | Tension-free | 18 | 9% vaginal erosion 7% dyspareunia 1 hematoma |

| *Absorbable and permanent. | ||||||

Classification of synthetic materials

- Type 1 grafts are totally macroporous (>75 μm), which allows fibroblast, macrophage, and collagen penetration with angiogenesis. Examples include Prolene and Marlex meshes.

- Type 2 mesh is microporous (<10 μm in 1 dimension). This prevents penetration of fibroblasts, macrophages, or collagen. Gore-Tex is an example of a Type 2 mesh.

- Type 3 mesh is macroporous (>75 μm) with multifilamentous or microporous components. Examples include Mersilene (braided Dacron mesh), Teflon (polytetrafluoroethylene [PTFE]), Surgipro (braided polypropylene mesh), and MycroMesh (perforated PTFE patch).

- Type 4 mesh has a submicron pore size that prevents penetration. Examples include Silastic, Cellgard (polypropylene sheeting), and Preclude pericardial membrane/Preclude dura-substitute.1

2 other important properties are composition of fibers (multifilamentous materials commonly have interstices less than 10 microns) and flexibility (which has a bearing on erosion of the material).1

Bacteria can penetrate pores smaller than 1 μm, whereas polymorphonuclear white blood cells and macrophages need a pore size larger than 10 μm, and capillary ingrowth requires a size larger than 75 microns. Thus, Type 1 offers the advantages of larger pore size and monofilamentous interstices to allow for capillary ingrowth.

Which material is best?

Although the literature is difficult to interpret because of the diversity of studies and other factors, some findings are worth noting:

- Tutoplast and Alloderm appear to have the best tensile strength, maximum load to capacity, and microscopic architecture similar to the original tissue.15-17 However, these qualities were documented prior to implantation in vivo.

- Slings appear to help prevent cystocele recurrences, according to a study by Goldberg et al.18

- A fascial patch had no benefit when placed as an overlay in the anterior compartment in a randomized, controlled trial (involving 162 women) by Sand et al.12

- Marlex. One group of women with recurrent prolapse underwent synthetic graft (Marlex) augmentation with bilateral ATFP attachment, while the other group had anterior colporrhaphy only.19 None of the women who received grafts had further recurrence, while 33% of the control group did. However, 25% of the women with the graft had vaginal erosions.

- Polyglactin 910 had a protective effect when embedded in the plication, according to Sand et al.12 However, it had no benefit when used as an overlay to a traditional repair in a study by Weber et al.4 The discrepancy may be related to small sample size; the study by Weber et al was powered to detect only a 30% difference. However, these studies suggest that it is not only the type of graft that is important, but how it is used or attached.

In general, synthetic grafts may have slightly higher success rates, whereas biologic materials appear to be better tolerated.

Prospective, comparative trials of these materials are desperately needed.

CASE Symptoms point to yet another prolapse recurrence

A 52-year-old woman presents with a bulge and pressure in her vagina. She has undergone 2 prior reconstructive surgeries. The first was a vaginal hysterectomy, anterior and posterior repair, and sling; the second was an abdominal procedure that included a sacrocolpopexy and paravaginal repair.

A physical examination reveals a recurrent 4th-degree cystocele that protrudes 2 cm beyond the hymenal ring. The vault and posterior compartment are well supported, and the patient reports no incontinence, a fact confirmed by urodynamics testing. She asks that you do everything in your power to prevent further recurrence.

How do you proceed?

This patient ultimately underwent anterior colporrhaphy and vaginal paravaginal repair using a decellularized dermal cadaveric implant. She was still doing well 1 year later, with no recurrence.

Despite success stories like this one, the use of graft materials to repair cystoceles and rectoceles is controversial. One reason is the difficulty of interpreting published data, since studies lack uniformity in technique, patient characteristics, graft shape, type of material, attachment sites, and duration of follow-up. Level I evidence that augmented repairs have a clear benefit over traditional repairs is sparse.

Advocates of graft materials argue that native tissue is already compromised—hence, the prolapse—making surgical failure likely.1 They claim graft materials help strengthen repairs, especially in the case of cystoceles. They also point out that adjuvant materials have been used in burns, plastic surgery, and orthopedics for more than 10 years and are generally well tolerated. Their success in hernia repairs prompted their consideration for the pelvic floor.

A pervasive problem, but only 10% to 20% seek help

Roughly 1 of 2 parous women lose pelvic support as they age, but only 10% to 20% seek medical care, with a lifetime risk of surgery for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) of 11% by age 80.2

With women living longer than ever and remaining active later in life, this percentage is likely to rise. Unfortunately, few alternatives to surgical treatment exist, and the reoperation rate for recurrence is 29%, according to a 1995 review.2 If surgical management is the only hope of cure, how can we lower the 29% recurrence rate?

Graft materials may provide part or all of the solution.

Elements of prolapse

Anterior compartment

Central and/or lateral defects can occur in the anterior compartment.

Lateral (paravaginal) defects indicate that the endopelvic connective tissue has separated from the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis. Lateral defects can be repaired vaginally or abdominally.

One study3 found that 67% of women with anterior wall prolapse had paravaginal defects, but no randomized trials have evaluated the clinical benefit of repairing these defects, compared with traditional colporrhaphies.

Central defects involve site-specific defects and/or general attenuation of the endopelvic connective tissue. These are usually repaired vaginally.

Recurrence rates for lateral and central defects range from 3% to 70%.4-8

Two large series of vaginal paravaginal repairs noted the following recurrence rates:

- Shull et al6 found a recurrence rate of 7% to the hymenal ring or beyond.

- Young et al7 observed a recurrence rate for lateral defects of 2%, with recurrence rates as high as 22% for central defects.

In a comparison of 3 techniques for vaginal repair of central defects, using strict criteria to assess anatomic outcomes, Weber et al4 found recurrence rates of 54% to 70%. Other studies show symptomatic recurrence rates of 3% to 22% for cystoceles.5,8

With grafts, both paravaginal and central defects can be repaired. Vaginal paravaginal repairs are not popular due to the technical difficulty involved. With the use of grafts, however, both paravaginal and central defects can be addressed simultaneously with relative ease.

Posterior compartment

Defects in the posterior compartment are less likely to recur. Reported success rates range from 80% to 90%.9,10

Posterior compartment defects include general attenuation of Denonvillier’s fascia or a tear anywhere along the fascia or any of its attachments.

Recurrence rates. Site-specific repairs are thought to minimize complications such as dyspareunia. However, few studies have compared the efficacy of site-specific repairs with that of traditional colporrhaphies. At our institution, women who underwent traditional colporrhaphy had fewer recurrences than controls (33% vs 14%), with no differences in postoperative symptoms such as dyspareunia, constipation, and fecal incontinence.11

Graft materials of questionable benefit. In the posterior compartment, these materials have not been shown to be beneficial, compared with traditional or site-specific repairs. Sand et al12 found no benefit for repairs in which absorbable Vicryl mesh was imbricated, but this randomized trial may have lacked sufficient power to show statistical significance. Large cohorts would be needed to show significant benefit of meshes in the posterior compartment.

A complex web of support

In the normal pelvis, support of reproductive organs depends on a complex web of muscles, fascia, and connective tissue. To ensure success, prolapse repairs should correct any separation or attenuation of tissue and preserve or enhance tissue resilience.

Risk factors for recurrent prolapse

- Poor tissue (assess tissue quality before and during surgery)

- Impaired healing

- Chronic increases in intraabdominal pressure due to obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, or constipation

- High-grade cystocele

- Age 60 or above13

Patients with these conditions may benefit from the use of adjuvant materials in the anterior compartment.

Note that women who have had recurrences after earlier repairs may experience repeat recurrence.

Advantages of grafts

Using graft materials, the surgeon can repair all vaginal defects faster and with less effort. In the anterior compartment, a graft can be placed and anchored bilaterally from arcus to arcus tendineus, and posteriorly to the level of the spine, recreating level I support. Graft materials also offer the potential to treat stress urinary incontinence concomitantly using different shaped materials. Two authors have already described their success performing this type of repair.14

Nevertheless, great care and consideration should be devoted to actual and theoretical short- and long-term risks, many of which have not been fully elucidated.

Once a successful material is identified or developed, it may decrease operating time and morbidity in vaginal surgeries. It may also reduce the higher hospital costs normally associated with abdominal procedures.

Types of graft materials

There are 2 types of materials: synthetic or biologic. Synthetic materials can be further classified into permanent or absorbable.

The most widely used biologic materials include allografts such as human freeze-dried or solvent-dehydrated fascia lata (Tutoplast), decellularized human cadaveric dermis (Alloderm, Repliform), porcine dermal xenografts such as Pelvicol or Intexene, and bovine pericardial implants (Veritas).

Soft polypropylene meshes such as Gynemesh and Atrium are commonly used permanent materials, and polyglactin 910 is an absorbable material (TABLE).

TABLE

How successful are adjuvant materials in cystocele and rectocele repairs?

| MATERIAL (SIZE IN CM) | AUTHOR | NO. IN STUDY | RECURRENCE RATE (%) | SITE OF ATTACHMENT | FOLLOW-UP (MONTHS) | COMPLICATIONS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIOLOGIC MATERIALS | ||||||

| Alloderm 3×7 patch with concomitant sling | Chung29 | 19 | 16 | Pubocervical fascia | 28 | None |

| Intexene 6×8 with sling | Gomelsky et al 200420 | 70 | 9 stage II 4 stage III | Arcus tendineus fascia pelvis | 24 | 1 wound separation |

| Solvent-dehydrated cadaveric fascia lata patch with sling | Gandhi et al 200521 | 76 patch vs 72 no patch | 21 vs 29, respectively (P=.23) | Overlay | 13 | None |

| Alloderm 3×7 trapezoid | Clemons et al 200322 | 33 | 41 stage II 3 symptomatic | Arcus tendineus fascia pelvis | 18 | None |

| SYNTHETIC MATERIALS WITH CONCOMITANT SLINGS* | ||||||

| Marlex 10×3×5 | Nicita 199823 | 44 | 0 | Arcus tendineus fascia pelvis | 13 | 1 vaginal erosion |

| Polyglactin 910 absorbable mesh | Sand et al12 | 80 mesh vs 80 no mesh | 25 vs 43 stage II cystoceles, respectively(P=.02) | Insert in the anterior and posterior colporrhaphy suture line | 12 | None |

| Polyglactin 910 absorbable mesh | Weber et al4 | 26 with mesh + standard repair; 24 with ultra-lateral repair; 33 with standard repair | 58 vs 54 vs 70 stage II, respectively (P=.58) | Overlay | 23 | None |

| SYNTHETIC PERMANENT GRAFTS WITHOUT CONCOMITANT SLINGS | ||||||

| Marlex trapezoid | Julian 199619 | 12 with 12 without | 0 vs 33, respectively | Arcus tendineus fascia pelvis | 24 | 3 vaginal erosions |

| Mixed-fiber mesh (polyglactin 910 and polyester 5×5) | Migliari and Usai 199924 | 12 | 25 | Pubourethral and cardinal ligaments | 20 | None |

| Prolene (Atrium) | Dwyer and O’Reilly25 | 64 anterior 50 posterior | 6 grade II | Tension-free | 29 | 8% vaginal erosion 1 rectovaginal fistula |

| Gynemesh 6×15 | de Tayrac et al 200526 | 87 | 7 stage II 2 stage III | Tension-free | 24 | 8% vaginal erosion |

| Prolene mesh patch | Milani et al 200527 | 32 anterior 31 posterior | 6 stage II | Fixed to endopelvic connective tissue | 17 | 20% anterior, 63% posterior dyspareunia; 13% vaginal erosion (anterior); 1 pelvic abscess (posterior) |

| Prolene mesh (double-wing shape) | Natale et al 2000 28 | 138 | 3 | Tension-free | 18 | 9% vaginal erosion 7% dyspareunia 1 hematoma |

| *Absorbable and permanent. | ||||||

Classification of synthetic materials

- Type 1 grafts are totally macroporous (>75 μm), which allows fibroblast, macrophage, and collagen penetration with angiogenesis. Examples include Prolene and Marlex meshes.

- Type 2 mesh is microporous (<10 μm in 1 dimension). This prevents penetration of fibroblasts, macrophages, or collagen. Gore-Tex is an example of a Type 2 mesh.

- Type 3 mesh is macroporous (>75 μm) with multifilamentous or microporous components. Examples include Mersilene (braided Dacron mesh), Teflon (polytetrafluoroethylene [PTFE]), Surgipro (braided polypropylene mesh), and MycroMesh (perforated PTFE patch).

- Type 4 mesh has a submicron pore size that prevents penetration. Examples include Silastic, Cellgard (polypropylene sheeting), and Preclude pericardial membrane/Preclude dura-substitute.1

2 other important properties are composition of fibers (multifilamentous materials commonly have interstices less than 10 microns) and flexibility (which has a bearing on erosion of the material).1

Bacteria can penetrate pores smaller than 1 μm, whereas polymorphonuclear white blood cells and macrophages need a pore size larger than 10 μm, and capillary ingrowth requires a size larger than 75 microns. Thus, Type 1 offers the advantages of larger pore size and monofilamentous interstices to allow for capillary ingrowth.

Which material is best?

Although the literature is difficult to interpret because of the diversity of studies and other factors, some findings are worth noting:

- Tutoplast and Alloderm appear to have the best tensile strength, maximum load to capacity, and microscopic architecture similar to the original tissue.15-17 However, these qualities were documented prior to implantation in vivo.

- Slings appear to help prevent cystocele recurrences, according to a study by Goldberg et al.18

- A fascial patch had no benefit when placed as an overlay in the anterior compartment in a randomized, controlled trial (involving 162 women) by Sand et al.12

- Marlex. One group of women with recurrent prolapse underwent synthetic graft (Marlex) augmentation with bilateral ATFP attachment, while the other group had anterior colporrhaphy only.19 None of the women who received grafts had further recurrence, while 33% of the control group did. However, 25% of the women with the graft had vaginal erosions.

- Polyglactin 910 had a protective effect when embedded in the plication, according to Sand et al.12 However, it had no benefit when used as an overlay to a traditional repair in a study by Weber et al.4 The discrepancy may be related to small sample size; the study by Weber et al was powered to detect only a 30% difference. However, these studies suggest that it is not only the type of graft that is important, but how it is used or attached.

In general, synthetic grafts may have slightly higher success rates, whereas biologic materials appear to be better tolerated.

Prospective, comparative trials of these materials are desperately needed.

1. Cervigni M, Natale F. The use of synthetics in the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Curr Opin Urol. 2001;11:429-435.

2. Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:501-506.

3. Richardson AC, Lyon JB, Williams NL. A new look at pelvic relaxation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;126:568-573.

4. Weber AM, Walters MD, Piedmonte MR, Ballard LA. Anterior colporrhaphy: a randomized trial of three surgical techniques. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1299-1304.

5. Porges RF, Smilen SW. Long-term analysis of the surgical management of pelvic support defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:1518-1526.

6. Shull BL, Benn SJ, Kuehl TJ. Surgical management of prolapse of the anterior vaginal segment: an analysis of support defects, operative morbidity, and anatomic outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:1429-1436.

7. Young SB, Daman JJ, Bony LG. Vaginal paravaginal repair: one-year outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1360-1366.

8. Macer GA. Transabdominal repair of cystocele, a 20-year experience, compared with the traditional vaginal approach. Trans Pac Coast Obstet Gynecol Soc. 1978;45:116-120.

9. Cundiff GW, Weidner AC, Visco AG, Addison WA, Bump RC. An anatomic and functional assessment of the discrete defect rectocele repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:1451-1456.

10. Paraiso MF, Ballard LA, Walters MD, Lee JC, et al. Pelvic support defects and visceral and sexual function in women treated with sacrospinous ligament suspension and pelvic reconstruction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1423-1430.

11. Abramov Y, et al. Site-specific rectocele repair compared with standard posterior colporrhaphy. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:314-318.

12. Sand PK, et al. Prospective randomized trial of polyglactin 910 mesh to prevent recurrence of cystoceles and rectoceles. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:1357-1362.

13. Whitesides JL, Weber AM, Meyn LA, Walters MD. Risk factors for prolapse recurrence after vaginal repair. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2005;60:164-165.

14. Kobashi KC, Mee SL, Leach GE. A new technique for cystocele repair and transvaginal sling: the cadaveric prolapse repair and sling (CAPS). Urology. 2000;56:9-14.

15. Lemer ML, Chaikin DC, Blaivas JG. Tissue strength analysis of autologous and cadaveric allografts for the pubovaginal sling. Neurourol Urodyn. 1999;18:497-503.

16. Choe JM, Kothandapani R, et al. Autologous, cadaveric, and synthetic materials used in sling surgery: comparative biomechanical analysis. Urology. 2001;58:482-486.

17. Scalfani AP. Biophysical and microscopic analysis of homologous dermal and fascial materials for facial aesthetic and reconstructive uses. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2002;4:164-171.

18. Goldberg RP, et al. Protective effect of suburethral slings on postoperative cystocele recurrence after reconstructive pelvic operation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1307-1312.

19. Julian TM. The efficacy of Marlex mesh in the repair of severe, recurrent vaginal prolapse of the anterior midvaginal wall. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1472-1475.

20. Gomelsky A, Rudy DC, Dmochowski RR. Porcine dermis interposition graft for repair of high grade anterior compartment defects with or without concomitant pelvic organ prolapse procedures. J Urol. 2004;171:1581-1584.

21. Gandhi S, et al. A prospective randomized trial of solvent dehydrated fascia lata for the prevention of recurrent anterior vaginal wall prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1649-1654.

22. Clemons JL, Myers DL, Aguilar VC, Arya LA. Vaginal paravaginal repair with an AlloDerm graft. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1612-1618.

23. Nicita G. A new operation for genitourinary prolapse. J Urol. 1998;160:741-745.

24. Migliari R, Usai E. Treatment results using a mixed fiber mesh in patients with grade IV cystocele. J Urol. 1999;161:1255-1258.

25. Dwyer PL, O’Reilly BA. Transvaginal repair of anterior and posterior compartment prolapse with Atrium polypropylene mesh. BJOG. 2004;111:831-836.

26. de Tayrac R, Gervaise A, Chauveaud A, Fernandez H. Tension-free polypropylene mesh for vaginal repair of anterior vaginal wall prolapse. J Reprod Med. 2005;50:75-80.

27. Milani R, et al. Functional and anatomical outcome of anterior and posterior vaginal prolapse repair with prolene mesh. BJOG. 2005;112:107-111.

28. Natale F, Marziali S, Cervigni M. Tension-free cystocele repair (TCR): long-term follow-up. Proceedings of the 25th annual meeting of the International Urogynecological Association. 2000;22-25.

29. Chung SY, et al. Technique of combined pubovaginal sling and cystocele using a single piece of cadaveric dermal graft. Urology. 2002;59:538-541.

Dr. Botros has no financial relationships relevant to this article. Dr. Sand receives grant/research support from Boston Scientific, and is a consultant and speaker for American Medical Systems and Boston Scientific.

1. Cervigni M, Natale F. The use of synthetics in the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Curr Opin Urol. 2001;11:429-435.

2. Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:501-506.

3. Richardson AC, Lyon JB, Williams NL. A new look at pelvic relaxation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;126:568-573.

4. Weber AM, Walters MD, Piedmonte MR, Ballard LA. Anterior colporrhaphy: a randomized trial of three surgical techniques. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1299-1304.

5. Porges RF, Smilen SW. Long-term analysis of the surgical management of pelvic support defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:1518-1526.

6. Shull BL, Benn SJ, Kuehl TJ. Surgical management of prolapse of the anterior vaginal segment: an analysis of support defects, operative morbidity, and anatomic outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:1429-1436.

7. Young SB, Daman JJ, Bony LG. Vaginal paravaginal repair: one-year outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1360-1366.

8. Macer GA. Transabdominal repair of cystocele, a 20-year experience, compared with the traditional vaginal approach. Trans Pac Coast Obstet Gynecol Soc. 1978;45:116-120.

9. Cundiff GW, Weidner AC, Visco AG, Addison WA, Bump RC. An anatomic and functional assessment of the discrete defect rectocele repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:1451-1456.

10. Paraiso MF, Ballard LA, Walters MD, Lee JC, et al. Pelvic support defects and visceral and sexual function in women treated with sacrospinous ligament suspension and pelvic reconstruction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1423-1430.

11. Abramov Y, et al. Site-specific rectocele repair compared with standard posterior colporrhaphy. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:314-318.

12. Sand PK, et al. Prospective randomized trial of polyglactin 910 mesh to prevent recurrence of cystoceles and rectoceles. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:1357-1362.

13. Whitesides JL, Weber AM, Meyn LA, Walters MD. Risk factors for prolapse recurrence after vaginal repair. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2005;60:164-165.

14. Kobashi KC, Mee SL, Leach GE. A new technique for cystocele repair and transvaginal sling: the cadaveric prolapse repair and sling (CAPS). Urology. 2000;56:9-14.

15. Lemer ML, Chaikin DC, Blaivas JG. Tissue strength analysis of autologous and cadaveric allografts for the pubovaginal sling. Neurourol Urodyn. 1999;18:497-503.

16. Choe JM, Kothandapani R, et al. Autologous, cadaveric, and synthetic materials used in sling surgery: comparative biomechanical analysis. Urology. 2001;58:482-486.

17. Scalfani AP. Biophysical and microscopic analysis of homologous dermal and fascial materials for facial aesthetic and reconstructive uses. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2002;4:164-171.

18. Goldberg RP, et al. Protective effect of suburethral slings on postoperative cystocele recurrence after reconstructive pelvic operation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1307-1312.

19. Julian TM. The efficacy of Marlex mesh in the repair of severe, recurrent vaginal prolapse of the anterior midvaginal wall. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1472-1475.

20. Gomelsky A, Rudy DC, Dmochowski RR. Porcine dermis interposition graft for repair of high grade anterior compartment defects with or without concomitant pelvic organ prolapse procedures. J Urol. 2004;171:1581-1584.

21. Gandhi S, et al. A prospective randomized trial of solvent dehydrated fascia lata for the prevention of recurrent anterior vaginal wall prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1649-1654.

22. Clemons JL, Myers DL, Aguilar VC, Arya LA. Vaginal paravaginal repair with an AlloDerm graft. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1612-1618.

23. Nicita G. A new operation for genitourinary prolapse. J Urol. 1998;160:741-745.

24. Migliari R, Usai E. Treatment results using a mixed fiber mesh in patients with grade IV cystocele. J Urol. 1999;161:1255-1258.

25. Dwyer PL, O’Reilly BA. Transvaginal repair of anterior and posterior compartment prolapse with Atrium polypropylene mesh. BJOG. 2004;111:831-836.

26. de Tayrac R, Gervaise A, Chauveaud A, Fernandez H. Tension-free polypropylene mesh for vaginal repair of anterior vaginal wall prolapse. J Reprod Med. 2005;50:75-80.

27. Milani R, et al. Functional and anatomical outcome of anterior and posterior vaginal prolapse repair with prolene mesh. BJOG. 2005;112:107-111.

28. Natale F, Marziali S, Cervigni M. Tension-free cystocele repair (TCR): long-term follow-up. Proceedings of the 25th annual meeting of the International Urogynecological Association. 2000;22-25.

29. Chung SY, et al. Technique of combined pubovaginal sling and cystocele using a single piece of cadaveric dermal graft. Urology. 2002;59:538-541.

Dr. Botros has no financial relationships relevant to this article. Dr. Sand receives grant/research support from Boston Scientific, and is a consultant and speaker for American Medical Systems and Boston Scientific.

IN THIS ARTICLE

Stress urinary incontinence: A closer look at nonsurgical therapies

- Peter K. Sand, MD, moderator of this discussion, is professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Evanston, Ill.

- G. Willy Davila, MD, is chairman, department of gynecology, Cleveland Clinic Florida, Weston, Fla.

- Karl Luber, MD, is assistant clinical professor, division of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery, University of California School of Medicine, San Diego, and director of the female continence program at Kaiser Permanente, San Diego.

- Deborah L. Myers, MD, is associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology, Brown University School of Medicine, Providence, RI.

We know what it is: The involuntary loss of urine during activities that increase intra-abdominal pressure. And we know what it isn’t: Rare. We even know how to treat stress incontinence, since it affects women of all ages and generally can be attributed to urethral hypermobility and/or intrinsic sphincter deficiency. But are we upto-date on all the management options, both tried and true and brand new? To address this question, OBG Management convened a panel of expert urogynecologists. Their focus was conservative therapies.

A wide range of options to preserve fertility

SAND: We are fortunate to have a number of very effective nonsurgical treatments for stress urinary incontinence (SUI). Why don’t we begin by laying out the full complement of options? Dr. Davila, when a premenopausal woman presents to your center with SUI, what therapies do you offer if she is waiting to complete childbearing? And how do you counsel her?

DAVILA: We first try to determine what effect the incontinence is having so we can develop a suitable treatment plan. For example, if the patient leaks urine with minimal exercise, it may be more difficult to treat her than a woman who leaks only with significant exertion. It also may be more difficult to treat SUI in a woman for whom exercise is very important, compared with someone who exercises sporadically.

Fortunately, with the current options, it isn’t necessary to do a full urodynamic evaluation and spend a lot of time and energy assessing the patient. We take a history in which we focus on behavioral patterns, looking especially at fluid intake. A high caffeine intake is particularly telling. Then we look at voiding patterns to make sure the patient is urinating regularly. A bladder diary is typically very helpful for that—and it doesn’t need to be a full 7-day diary; a 3-day diary should suffice. If the patient is going to be treated nonsurgically, completion of a diary has significant educational value regarding fluid intake and voiding patterns.

Once we have assessed behavioral patterns, we do a physical exam to evaluate the neuromuscular integrity of the pelvis. If the patient has good pelvic tone—with minimal prolapse and the ability to perform an effective Kegel contraction of the pelvic floor muscles—she should do very well with physiotherapeutic or conservative means of enhancing pelvic floor strength. So behaviormodification strategies work very well for patients with mild stress incontinence. We typically begin with a trial of biofeedbackguided or self-directed pelvic floor exercises.

Patients with significant prolapse who leak very easily don’t do as well with simple conservative therapies. Examples include a woman whose empty-bladder stress test suggests severe degrees of sphincteric incontinence with urinary leakage and patients who cannot contract their pelvic floor muscles—some women are simply unable to identify these muscles. Those are the patients we tend to test more extensively.

SAND: Dr. Myers, how do you treat these patients?

MYERS: A lot depends on physical exam findings. For example, for a cystocele, a vaginal continence ring may be useful.

If there is excellent support but the Kegel contractions are weak, I would probably look to pelvic floor therapy, which includes biofeedback, electrical stimulation, and other means of strengthening the pelvic floor muscles.

In addition, a number of medications can improve urethral resistance, and simple interventions such as limiting fluid intake and altering behavioral patterns are also useful.

I often will use multiple modalities. Basically, I do everything I can if the patient wants to avoid surgery because of future childbearing.

SAND: Dr. Luber, are your practice patterns different?

LUBER: The emphasis on medical interventions is entirely appropriate. Few things are as satisfying as helping a patient improve without surgery, especially when she expresses concerns about the need for an operation.

I believe in offering the patient a menu of nonsurgical choices. Women are often badly informed about their options, and I like to take some time to educate them once the basic evaluation is complete. Sometimes that can be difficult, but it is extremely helpful to take 5 or 10 minutes to thoroughly explain the cause of the incontinence, using diagrams if necessary. This gives them a better understanding of the nonsurgical approach.

I also try to reinforce use of vaginal support devices such as continence rings and pessaries, which are very helpful in both younger and older women. In addition, I emphasize the importance of pelvic muscle rehabilitation, giving verbal instructions, coaching the patient, and recommending a physical therapist when necessary.

SAND: At our center, we also offer people a full menu of treatment options and try to let them make an independent decision once they have the basic information. One could argue that it’s difficult for patients to make educated decisions about different treatments, even with a small amount of data. Still, we talk with them about behavioral techniques and interventional devices.

We also discuss use of alpha-adrenergic agents (pseudoephedrine) and the tricyclic antidepressant imipramine, as well as electrical stimulation as an alternative to Kegel contractions with biofeedback. When the incontinence is exercise-induced, something as simple as a tampon in the vagina can sometimes be very effective, as Nygaard et al demonstrated.1

Treating the postmenopausal woman

SAND: What about women of advanced age, beyond the reproductive years? How would you treat a patient over 65 if she elected not to have surgery?

LUBER: The pelvic floor is not an area that people exercise on a daily basis in normal activities, as we do our arms and legs. In addition, over the course of time—perhaps in combination with the denervation associated with vaginal birth—the pelvic floor of mature women tends to become very atrophic and nonresponsive. I usually steer my elderly patients with poor pelvic floor recruitment and tone to biofeedback because they are unlikely to get a response to pelvic floor exercises done independently.

MYERS: I make it a point to offer conservative options initially to all patients. As you know, many older patients have other medical problems that render surgical therapy inadvisable. So I proceed with the menu we discussed earlier. I favor electrical stimulation for patients who are unable to do any type of Kegel squeeze. I think it’s important for the patient to get an idea what a levator contraction feels like and, hopefully, learn to perform the exercise on her own.

—Dr. Davila

Rehabilitating the pelvic floor: Electrical stimulation, physiotherapy, and moderation

SAND: I’m not a big fan of independent pelvic floor exercises without biofeedback, as studies at Duke some years ago showed very poor compliance, with only 10% of people staying on self-directed Kegel exercise therapy.2 Roughly one third of those were actually doing a Valsalva maneuver instead of contracting their muscles—and that is destructive over time. So I discuss electrical stimulation as an option, as well as innervation using an electromagnetic chair.

MYERS: In our practice, if someone has an absent Kegel squeeze or only a 1 or 2 on a scale of 5, we will start her on electrical stimulation. Once those muscles have been educated and strengthened, we move to biofeedback. If a woman already has a strong Kegel squeeze, we tend to recommend biofeedback first. I have not had any experience with the electromagnetic chair.

LUBER: I manage patients similarly. In our center, electrostimulation is reserved primarily for those patients who need to be “jump started”—who lack the ability to isolate and contract their pelvic floor muscles. Electrostimulation seems to help. Then they go on to more intensive biofeedback-assisted pelvic muscle rehabilitation.

DAVILA: Some years ago, our center compared voluntary Kegel contractions with electrically stimulated Kegel contractions at various frequencies and found that voluntary Kegel contractions are much stronger than stimulated ones.3

LUBER: We conducted a similar trial, with comparable findings.4

SAND: In the orthopedic area, people can have electrically stimulated contractions that are maximized until they are equal in intensity to voluntary contractions. Unfortunately, we can’t do that for the pelvic floor due to limitations in the delivery system and the electrodynamics of the currents being used.

LUBER:To use an analogy from psychoanalysis, electrical stimulation is like a couch and the physiotherapist is like the psychiatrist. The couch doesn’t do much good without the psychiatrist there. So we use electrical stimulation to help patients recruit those muscles—and we use it in conjunction with a physical therapist. Without the coaching and monitoring of the physical therapist, I don’t think these patients are going to benefit as much from electrostimulation.

DAVILA: A number of years ago, my colleagues and I published a paper describing a multimodality approach to pelvic floor muscle rehabilitation using biofeedback and electrical stimulation. We showed that it is possible to reduce incontinence episodes by 90%.5 In a motivated patient, that reduction can be maintained.

I can’t agree enough about the importance of a physiotherapist, whether that happens to be a physical therapist or your nurse or someone else who takes the time to instruct the patient on how to isolate and contract the pelvic floor muscles. It really takes a team of people to address pelvic floor dysfunction, so that’s where we direct our focus.

SAND: Any other tips to give patients about pelvic floor rehabilitation?

LUBER: Yes. It’s a good idea to stress the importance of moderation. If a sedentary person suddenly decided to rehabilitate the muscles of her arms and set about doing 100 curls with 40-lb weights, the next day she would barely be able to brush her teeth; her arm function would be worse than it was on day 1. And if one of our patients decided to focus on the muscles of her pelvic floor and began with a similarly overzealous program, she might actually report that her stress incontinence had worsened. So we do need to warn patients that the pelvic floor muscles can become extremely debilitated and advise them to start rehabilitation slowly.

MYERS: I agree. Otherwise muscle fatigue develops.

SAND: Let’s talk a few moments about pelvic floor rehabilitation following surgery. Do you recommend it to your patients—or is it only useful as an alternative or prelude to surgery?

DAVILA: I think it is very important. Once an incontinence operation is finished, there is a tendency to think the job is done. That is an incorrect attitude. We see the patient at 3 months, 6 months, and yearly to make sure she is doing her Kegels. While the importance of postoperative Kegel exercises and biofeedback has not been studied in depth, I think they are key to maintaining the success of our surgical interventions.

MYERS: I agree. I think it’s a major weakness of our field that we don’t promote pelvic floor exercises postoperatively. After orthopedic procedures, physical therapy frequently is used, since there is an understanding that the muscles as well as the ligaments need to be rehabilitated. This concept needs to be addressed in pelvic floor reconstructive surgeries as well.

SAND: But we have absolutely no data.

MYERS: We should start to obtain it.

SAND: One of the things that concerns me greatly about postoperative Kegels is the fact that patients don’t do them properly. If a woman is doing the Valsalva maneuver or increasing her intra-abdominal pressure instead of contracting the levators, she may actually undermine the surgery rather than promote its effect. That’s the other side of using Kegel exercise therapy postoperatively.

—Dr. Sand

DAVILA: But at the 6- or 8-week visit, you simply do an exam to see if she can perform a Kegel properly. I tell my patients, “We’re going to do the best surgery we can do. Then you have to take care of your repair.”That means avoiding straining and limiting lifting to 5 lb or so during the healing phase, doing pelvic floor exercises after 6 weeks, and remaining careful about lifting on a long-term basis.

If a patient cannot contract her pelvic floor muscles at the postoperative visit, we send her to our physiotherapist. Frequently, 1 or 2 visits are enough for the patient to learn to perform Kegels.

I do agree that if the patient is performing the Valsalva maneuver instead of contracting her muscles, she can do more damage than good. But proper patient selection and instruction should take care of that.

MYERS: If a patient is doing the Valsalva maneuver every time I ask her to do a Kegel, I tell her not to do them at all. I say: “You are going to need additional help with this for the next 6 to 8 weeks. If you want to maximize your muscle strength, this is something that will be for your benefit.”

As I said before, I think pelvic floor rehabilitation is a very important component of incontinence treatment. Some investigators have emphasized ligament supports and fascial supports to control incontinence, and other investigators emphasize muscular support. It is probably a combination of both.

SAND: I have a different view. Although I would like to believe that stabilizing the pelvic floor will help protect the connectivetissue supports or the “imitation”supports we have instituted surgically, I don’t see the justification for getting all these patients to do pelvic floor therapy without good data demonstrating that fact.

LUBER: But I think we all would agree that simply resupporting a patient’s urethra is unlikely to re-create the continence mechanism that is compromised.