User login

Cystocele and rectocele repair: More success with mesh?

CASE Symptoms point to yet another prolapse recurrence

A 52-year-old woman presents with a bulge and pressure in her vagina. She has undergone 2 prior reconstructive surgeries. The first was a vaginal hysterectomy, anterior and posterior repair, and sling; the second was an abdominal procedure that included a sacrocolpopexy and paravaginal repair.

A physical examination reveals a recurrent 4th-degree cystocele that protrudes 2 cm beyond the hymenal ring. The vault and posterior compartment are well supported, and the patient reports no incontinence, a fact confirmed by urodynamics testing. She asks that you do everything in your power to prevent further recurrence.

How do you proceed?

This patient ultimately underwent anterior colporrhaphy and vaginal paravaginal repair using a decellularized dermal cadaveric implant. She was still doing well 1 year later, with no recurrence.

Despite success stories like this one, the use of graft materials to repair cystoceles and rectoceles is controversial. One reason is the difficulty of interpreting published data, since studies lack uniformity in technique, patient characteristics, graft shape, type of material, attachment sites, and duration of follow-up. Level I evidence that augmented repairs have a clear benefit over traditional repairs is sparse.

Advocates of graft materials argue that native tissue is already compromised—hence, the prolapse—making surgical failure likely.1 They claim graft materials help strengthen repairs, especially in the case of cystoceles. They also point out that adjuvant materials have been used in burns, plastic surgery, and orthopedics for more than 10 years and are generally well tolerated. Their success in hernia repairs prompted their consideration for the pelvic floor.

A pervasive problem, but only 10% to 20% seek help

Roughly 1 of 2 parous women lose pelvic support as they age, but only 10% to 20% seek medical care, with a lifetime risk of surgery for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) of 11% by age 80.2

With women living longer than ever and remaining active later in life, this percentage is likely to rise. Unfortunately, few alternatives to surgical treatment exist, and the reoperation rate for recurrence is 29%, according to a 1995 review.2 If surgical management is the only hope of cure, how can we lower the 29% recurrence rate?

Graft materials may provide part or all of the solution.

Elements of prolapse

Anterior compartment

Central and/or lateral defects can occur in the anterior compartment.

Lateral (paravaginal) defects indicate that the endopelvic connective tissue has separated from the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis. Lateral defects can be repaired vaginally or abdominally.

One study3 found that 67% of women with anterior wall prolapse had paravaginal defects, but no randomized trials have evaluated the clinical benefit of repairing these defects, compared with traditional colporrhaphies.

Central defects involve site-specific defects and/or general attenuation of the endopelvic connective tissue. These are usually repaired vaginally.

Recurrence rates for lateral and central defects range from 3% to 70%.4-8

Two large series of vaginal paravaginal repairs noted the following recurrence rates:

- Shull et al6 found a recurrence rate of 7% to the hymenal ring or beyond.

- Young et al7 observed a recurrence rate for lateral defects of 2%, with recurrence rates as high as 22% for central defects.

In a comparison of 3 techniques for vaginal repair of central defects, using strict criteria to assess anatomic outcomes, Weber et al4 found recurrence rates of 54% to 70%. Other studies show symptomatic recurrence rates of 3% to 22% for cystoceles.5,8

With grafts, both paravaginal and central defects can be repaired. Vaginal paravaginal repairs are not popular due to the technical difficulty involved. With the use of grafts, however, both paravaginal and central defects can be addressed simultaneously with relative ease.

Posterior compartment

Defects in the posterior compartment are less likely to recur. Reported success rates range from 80% to 90%.9,10

Posterior compartment defects include general attenuation of Denonvillier’s fascia or a tear anywhere along the fascia or any of its attachments.

Recurrence rates. Site-specific repairs are thought to minimize complications such as dyspareunia. However, few studies have compared the efficacy of site-specific repairs with that of traditional colporrhaphies. At our institution, women who underwent traditional colporrhaphy had fewer recurrences than controls (33% vs 14%), with no differences in postoperative symptoms such as dyspareunia, constipation, and fecal incontinence.11

Graft materials of questionable benefit. In the posterior compartment, these materials have not been shown to be beneficial, compared with traditional or site-specific repairs. Sand et al12 found no benefit for repairs in which absorbable Vicryl mesh was imbricated, but this randomized trial may have lacked sufficient power to show statistical significance. Large cohorts would be needed to show significant benefit of meshes in the posterior compartment.

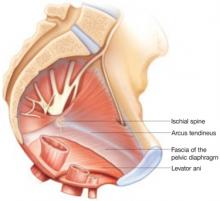

A complex web of support

In the normal pelvis, support of reproductive organs depends on a complex web of muscles, fascia, and connective tissue. To ensure success, prolapse repairs should correct any separation or attenuation of tissue and preserve or enhance tissue resilience.

Risk factors for recurrent prolapse

- Poor tissue (assess tissue quality before and during surgery)

- Impaired healing

- Chronic increases in intraabdominal pressure due to obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, or constipation

- High-grade cystocele

- Age 60 or above13

Patients with these conditions may benefit from the use of adjuvant materials in the anterior compartment.

Note that women who have had recurrences after earlier repairs may experience repeat recurrence.

Advantages of grafts

Using graft materials, the surgeon can repair all vaginal defects faster and with less effort. In the anterior compartment, a graft can be placed and anchored bilaterally from arcus to arcus tendineus, and posteriorly to the level of the spine, recreating level I support. Graft materials also offer the potential to treat stress urinary incontinence concomitantly using different shaped materials. Two authors have already described their success performing this type of repair.14

Nevertheless, great care and consideration should be devoted to actual and theoretical short- and long-term risks, many of which have not been fully elucidated.

Once a successful material is identified or developed, it may decrease operating time and morbidity in vaginal surgeries. It may also reduce the higher hospital costs normally associated with abdominal procedures.

Types of graft materials

There are 2 types of materials: synthetic or biologic. Synthetic materials can be further classified into permanent or absorbable.

The most widely used biologic materials include allografts such as human freeze-dried or solvent-dehydrated fascia lata (Tutoplast), decellularized human cadaveric dermis (Alloderm, Repliform), porcine dermal xenografts such as Pelvicol or Intexene, and bovine pericardial implants (Veritas).

Soft polypropylene meshes such as Gynemesh and Atrium are commonly used permanent materials, and polyglactin 910 is an absorbable material (TABLE).

TABLE

How successful are adjuvant materials in cystocele and rectocele repairs?

| MATERIAL (SIZE IN CM) | AUTHOR | NO. IN STUDY | RECURRENCE RATE (%) | SITE OF ATTACHMENT | FOLLOW-UP (MONTHS) | COMPLICATIONS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIOLOGIC MATERIALS | ||||||

| Alloderm 3×7 patch with concomitant sling | Chung29 | 19 | 16 | Pubocervical fascia | 28 | None |

| Intexene 6×8 with sling | Gomelsky et al 200420 | 70 | 9 stage II 4 stage III | Arcus tendineus fascia pelvis | 24 | 1 wound separation |

| Solvent-dehydrated cadaveric fascia lata patch with sling | Gandhi et al 200521 | 76 patch vs 72 no patch | 21 vs 29, respectively (P=.23) | Overlay | 13 | None |

| Alloderm 3×7 trapezoid | Clemons et al 200322 | 33 | 41 stage II 3 symptomatic | Arcus tendineus fascia pelvis | 18 | None |

| SYNTHETIC MATERIALS WITH CONCOMITANT SLINGS* | ||||||

| Marlex 10×3×5 | Nicita 199823 | 44 | 0 | Arcus tendineus fascia pelvis | 13 | 1 vaginal erosion |

| Polyglactin 910 absorbable mesh | Sand et al12 | 80 mesh vs 80 no mesh | 25 vs 43 stage II cystoceles, respectively(P=.02) | Insert in the anterior and posterior colporrhaphy suture line | 12 | None |

| Polyglactin 910 absorbable mesh | Weber et al4 | 26 with mesh + standard repair; 24 with ultra-lateral repair; 33 with standard repair | 58 vs 54 vs 70 stage II, respectively (P=.58) | Overlay | 23 | None |

| SYNTHETIC PERMANENT GRAFTS WITHOUT CONCOMITANT SLINGS | ||||||

| Marlex trapezoid | Julian 199619 | 12 with 12 without | 0 vs 33, respectively | Arcus tendineus fascia pelvis | 24 | 3 vaginal erosions |

| Mixed-fiber mesh (polyglactin 910 and polyester 5×5) | Migliari and Usai 199924 | 12 | 25 | Pubourethral and cardinal ligaments | 20 | None |

| Prolene (Atrium) | Dwyer and O’Reilly25 | 64 anterior 50 posterior | 6 grade II | Tension-free | 29 | 8% vaginal erosion 1 rectovaginal fistula |

| Gynemesh 6×15 | de Tayrac et al 200526 | 87 | 7 stage II 2 stage III | Tension-free | 24 | 8% vaginal erosion |

| Prolene mesh patch | Milani et al 200527 | 32 anterior 31 posterior | 6 stage II | Fixed to endopelvic connective tissue | 17 | 20% anterior, 63% posterior dyspareunia; 13% vaginal erosion (anterior); 1 pelvic abscess (posterior) |

| Prolene mesh (double-wing shape) | Natale et al 2000 28 | 138 | 3 | Tension-free | 18 | 9% vaginal erosion 7% dyspareunia 1 hematoma |

| *Absorbable and permanent. | ||||||

Classification of synthetic materials

- Type 1 grafts are totally macroporous (>75 μm), which allows fibroblast, macrophage, and collagen penetration with angiogenesis. Examples include Prolene and Marlex meshes.

- Type 2 mesh is microporous (<10 μm in 1 dimension). This prevents penetration of fibroblasts, macrophages, or collagen. Gore-Tex is an example of a Type 2 mesh.

- Type 3 mesh is macroporous (>75 μm) with multifilamentous or microporous components. Examples include Mersilene (braided Dacron mesh), Teflon (polytetrafluoroethylene [PTFE]), Surgipro (braided polypropylene mesh), and MycroMesh (perforated PTFE patch).

- Type 4 mesh has a submicron pore size that prevents penetration. Examples include Silastic, Cellgard (polypropylene sheeting), and Preclude pericardial membrane/Preclude dura-substitute.1

2 other important properties are composition of fibers (multifilamentous materials commonly have interstices less than 10 microns) and flexibility (which has a bearing on erosion of the material).1

Bacteria can penetrate pores smaller than 1 μm, whereas polymorphonuclear white blood cells and macrophages need a pore size larger than 10 μm, and capillary ingrowth requires a size larger than 75 microns. Thus, Type 1 offers the advantages of larger pore size and monofilamentous interstices to allow for capillary ingrowth.

Which material is best?

Although the literature is difficult to interpret because of the diversity of studies and other factors, some findings are worth noting:

- Tutoplast and Alloderm appear to have the best tensile strength, maximum load to capacity, and microscopic architecture similar to the original tissue.15-17 However, these qualities were documented prior to implantation in vivo.

- Slings appear to help prevent cystocele recurrences, according to a study by Goldberg et al.18

- A fascial patch had no benefit when placed as an overlay in the anterior compartment in a randomized, controlled trial (involving 162 women) by Sand et al.12

- Marlex. One group of women with recurrent prolapse underwent synthetic graft (Marlex) augmentation with bilateral ATFP attachment, while the other group had anterior colporrhaphy only.19 None of the women who received grafts had further recurrence, while 33% of the control group did. However, 25% of the women with the graft had vaginal erosions.

- Polyglactin 910 had a protective effect when embedded in the plication, according to Sand et al.12 However, it had no benefit when used as an overlay to a traditional repair in a study by Weber et al.4 The discrepancy may be related to small sample size; the study by Weber et al was powered to detect only a 30% difference. However, these studies suggest that it is not only the type of graft that is important, but how it is used or attached.

In general, synthetic grafts may have slightly higher success rates, whereas biologic materials appear to be better tolerated.

Prospective, comparative trials of these materials are desperately needed.

1. Cervigni M, Natale F. The use of synthetics in the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Curr Opin Urol. 2001;11:429-435.

2. Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:501-506.

3. Richardson AC, Lyon JB, Williams NL. A new look at pelvic relaxation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;126:568-573.

4. Weber AM, Walters MD, Piedmonte MR, Ballard LA. Anterior colporrhaphy: a randomized trial of three surgical techniques. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1299-1304.

5. Porges RF, Smilen SW. Long-term analysis of the surgical management of pelvic support defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:1518-1526.

6. Shull BL, Benn SJ, Kuehl TJ. Surgical management of prolapse of the anterior vaginal segment: an analysis of support defects, operative morbidity, and anatomic outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:1429-1436.

7. Young SB, Daman JJ, Bony LG. Vaginal paravaginal repair: one-year outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1360-1366.

8. Macer GA. Transabdominal repair of cystocele, a 20-year experience, compared with the traditional vaginal approach. Trans Pac Coast Obstet Gynecol Soc. 1978;45:116-120.

9. Cundiff GW, Weidner AC, Visco AG, Addison WA, Bump RC. An anatomic and functional assessment of the discrete defect rectocele repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:1451-1456.

10. Paraiso MF, Ballard LA, Walters MD, Lee JC, et al. Pelvic support defects and visceral and sexual function in women treated with sacrospinous ligament suspension and pelvic reconstruction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1423-1430.

11. Abramov Y, et al. Site-specific rectocele repair compared with standard posterior colporrhaphy. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:314-318.

12. Sand PK, et al. Prospective randomized trial of polyglactin 910 mesh to prevent recurrence of cystoceles and rectoceles. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:1357-1362.

13. Whitesides JL, Weber AM, Meyn LA, Walters MD. Risk factors for prolapse recurrence after vaginal repair. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2005;60:164-165.

14. Kobashi KC, Mee SL, Leach GE. A new technique for cystocele repair and transvaginal sling: the cadaveric prolapse repair and sling (CAPS). Urology. 2000;56:9-14.

15. Lemer ML, Chaikin DC, Blaivas JG. Tissue strength analysis of autologous and cadaveric allografts for the pubovaginal sling. Neurourol Urodyn. 1999;18:497-503.

16. Choe JM, Kothandapani R, et al. Autologous, cadaveric, and synthetic materials used in sling surgery: comparative biomechanical analysis. Urology. 2001;58:482-486.

17. Scalfani AP. Biophysical and microscopic analysis of homologous dermal and fascial materials for facial aesthetic and reconstructive uses. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2002;4:164-171.

18. Goldberg RP, et al. Protective effect of suburethral slings on postoperative cystocele recurrence after reconstructive pelvic operation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1307-1312.

19. Julian TM. The efficacy of Marlex mesh in the repair of severe, recurrent vaginal prolapse of the anterior midvaginal wall. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1472-1475.

20. Gomelsky A, Rudy DC, Dmochowski RR. Porcine dermis interposition graft for repair of high grade anterior compartment defects with or without concomitant pelvic organ prolapse procedures. J Urol. 2004;171:1581-1584.

21. Gandhi S, et al. A prospective randomized trial of solvent dehydrated fascia lata for the prevention of recurrent anterior vaginal wall prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1649-1654.

22. Clemons JL, Myers DL, Aguilar VC, Arya LA. Vaginal paravaginal repair with an AlloDerm graft. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1612-1618.

23. Nicita G. A new operation for genitourinary prolapse. J Urol. 1998;160:741-745.

24. Migliari R, Usai E. Treatment results using a mixed fiber mesh in patients with grade IV cystocele. J Urol. 1999;161:1255-1258.

25. Dwyer PL, O’Reilly BA. Transvaginal repair of anterior and posterior compartment prolapse with Atrium polypropylene mesh. BJOG. 2004;111:831-836.

26. de Tayrac R, Gervaise A, Chauveaud A, Fernandez H. Tension-free polypropylene mesh for vaginal repair of anterior vaginal wall prolapse. J Reprod Med. 2005;50:75-80.

27. Milani R, et al. Functional and anatomical outcome of anterior and posterior vaginal prolapse repair with prolene mesh. BJOG. 2005;112:107-111.

28. Natale F, Marziali S, Cervigni M. Tension-free cystocele repair (TCR): long-term follow-up. Proceedings of the 25th annual meeting of the International Urogynecological Association. 2000;22-25.

29. Chung SY, et al. Technique of combined pubovaginal sling and cystocele using a single piece of cadaveric dermal graft. Urology. 2002;59:538-541.

Dr. Botros has no financial relationships relevant to this article. Dr. Sand receives grant/research support from Boston Scientific, and is a consultant and speaker for American Medical Systems and Boston Scientific.

CASE Symptoms point to yet another prolapse recurrence

A 52-year-old woman presents with a bulge and pressure in her vagina. She has undergone 2 prior reconstructive surgeries. The first was a vaginal hysterectomy, anterior and posterior repair, and sling; the second was an abdominal procedure that included a sacrocolpopexy and paravaginal repair.

A physical examination reveals a recurrent 4th-degree cystocele that protrudes 2 cm beyond the hymenal ring. The vault and posterior compartment are well supported, and the patient reports no incontinence, a fact confirmed by urodynamics testing. She asks that you do everything in your power to prevent further recurrence.

How do you proceed?

This patient ultimately underwent anterior colporrhaphy and vaginal paravaginal repair using a decellularized dermal cadaveric implant. She was still doing well 1 year later, with no recurrence.

Despite success stories like this one, the use of graft materials to repair cystoceles and rectoceles is controversial. One reason is the difficulty of interpreting published data, since studies lack uniformity in technique, patient characteristics, graft shape, type of material, attachment sites, and duration of follow-up. Level I evidence that augmented repairs have a clear benefit over traditional repairs is sparse.

Advocates of graft materials argue that native tissue is already compromised—hence, the prolapse—making surgical failure likely.1 They claim graft materials help strengthen repairs, especially in the case of cystoceles. They also point out that adjuvant materials have been used in burns, plastic surgery, and orthopedics for more than 10 years and are generally well tolerated. Their success in hernia repairs prompted their consideration for the pelvic floor.

A pervasive problem, but only 10% to 20% seek help

Roughly 1 of 2 parous women lose pelvic support as they age, but only 10% to 20% seek medical care, with a lifetime risk of surgery for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) of 11% by age 80.2

With women living longer than ever and remaining active later in life, this percentage is likely to rise. Unfortunately, few alternatives to surgical treatment exist, and the reoperation rate for recurrence is 29%, according to a 1995 review.2 If surgical management is the only hope of cure, how can we lower the 29% recurrence rate?

Graft materials may provide part or all of the solution.

Elements of prolapse

Anterior compartment

Central and/or lateral defects can occur in the anterior compartment.

Lateral (paravaginal) defects indicate that the endopelvic connective tissue has separated from the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis. Lateral defects can be repaired vaginally or abdominally.

One study3 found that 67% of women with anterior wall prolapse had paravaginal defects, but no randomized trials have evaluated the clinical benefit of repairing these defects, compared with traditional colporrhaphies.

Central defects involve site-specific defects and/or general attenuation of the endopelvic connective tissue. These are usually repaired vaginally.

Recurrence rates for lateral and central defects range from 3% to 70%.4-8

Two large series of vaginal paravaginal repairs noted the following recurrence rates:

- Shull et al6 found a recurrence rate of 7% to the hymenal ring or beyond.

- Young et al7 observed a recurrence rate for lateral defects of 2%, with recurrence rates as high as 22% for central defects.

In a comparison of 3 techniques for vaginal repair of central defects, using strict criteria to assess anatomic outcomes, Weber et al4 found recurrence rates of 54% to 70%. Other studies show symptomatic recurrence rates of 3% to 22% for cystoceles.5,8

With grafts, both paravaginal and central defects can be repaired. Vaginal paravaginal repairs are not popular due to the technical difficulty involved. With the use of grafts, however, both paravaginal and central defects can be addressed simultaneously with relative ease.

Posterior compartment

Defects in the posterior compartment are less likely to recur. Reported success rates range from 80% to 90%.9,10

Posterior compartment defects include general attenuation of Denonvillier’s fascia or a tear anywhere along the fascia or any of its attachments.

Recurrence rates. Site-specific repairs are thought to minimize complications such as dyspareunia. However, few studies have compared the efficacy of site-specific repairs with that of traditional colporrhaphies. At our institution, women who underwent traditional colporrhaphy had fewer recurrences than controls (33% vs 14%), with no differences in postoperative symptoms such as dyspareunia, constipation, and fecal incontinence.11

Graft materials of questionable benefit. In the posterior compartment, these materials have not been shown to be beneficial, compared with traditional or site-specific repairs. Sand et al12 found no benefit for repairs in which absorbable Vicryl mesh was imbricated, but this randomized trial may have lacked sufficient power to show statistical significance. Large cohorts would be needed to show significant benefit of meshes in the posterior compartment.

A complex web of support

In the normal pelvis, support of reproductive organs depends on a complex web of muscles, fascia, and connective tissue. To ensure success, prolapse repairs should correct any separation or attenuation of tissue and preserve or enhance tissue resilience.

Risk factors for recurrent prolapse

- Poor tissue (assess tissue quality before and during surgery)

- Impaired healing

- Chronic increases in intraabdominal pressure due to obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, or constipation

- High-grade cystocele

- Age 60 or above13

Patients with these conditions may benefit from the use of adjuvant materials in the anterior compartment.

Note that women who have had recurrences after earlier repairs may experience repeat recurrence.

Advantages of grafts

Using graft materials, the surgeon can repair all vaginal defects faster and with less effort. In the anterior compartment, a graft can be placed and anchored bilaterally from arcus to arcus tendineus, and posteriorly to the level of the spine, recreating level I support. Graft materials also offer the potential to treat stress urinary incontinence concomitantly using different shaped materials. Two authors have already described their success performing this type of repair.14

Nevertheless, great care and consideration should be devoted to actual and theoretical short- and long-term risks, many of which have not been fully elucidated.

Once a successful material is identified or developed, it may decrease operating time and morbidity in vaginal surgeries. It may also reduce the higher hospital costs normally associated with abdominal procedures.

Types of graft materials

There are 2 types of materials: synthetic or biologic. Synthetic materials can be further classified into permanent or absorbable.

The most widely used biologic materials include allografts such as human freeze-dried or solvent-dehydrated fascia lata (Tutoplast), decellularized human cadaveric dermis (Alloderm, Repliform), porcine dermal xenografts such as Pelvicol or Intexene, and bovine pericardial implants (Veritas).

Soft polypropylene meshes such as Gynemesh and Atrium are commonly used permanent materials, and polyglactin 910 is an absorbable material (TABLE).

TABLE

How successful are adjuvant materials in cystocele and rectocele repairs?

| MATERIAL (SIZE IN CM) | AUTHOR | NO. IN STUDY | RECURRENCE RATE (%) | SITE OF ATTACHMENT | FOLLOW-UP (MONTHS) | COMPLICATIONS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIOLOGIC MATERIALS | ||||||

| Alloderm 3×7 patch with concomitant sling | Chung29 | 19 | 16 | Pubocervical fascia | 28 | None |

| Intexene 6×8 with sling | Gomelsky et al 200420 | 70 | 9 stage II 4 stage III | Arcus tendineus fascia pelvis | 24 | 1 wound separation |

| Solvent-dehydrated cadaveric fascia lata patch with sling | Gandhi et al 200521 | 76 patch vs 72 no patch | 21 vs 29, respectively (P=.23) | Overlay | 13 | None |

| Alloderm 3×7 trapezoid | Clemons et al 200322 | 33 | 41 stage II 3 symptomatic | Arcus tendineus fascia pelvis | 18 | None |

| SYNTHETIC MATERIALS WITH CONCOMITANT SLINGS* | ||||||

| Marlex 10×3×5 | Nicita 199823 | 44 | 0 | Arcus tendineus fascia pelvis | 13 | 1 vaginal erosion |

| Polyglactin 910 absorbable mesh | Sand et al12 | 80 mesh vs 80 no mesh | 25 vs 43 stage II cystoceles, respectively(P=.02) | Insert in the anterior and posterior colporrhaphy suture line | 12 | None |

| Polyglactin 910 absorbable mesh | Weber et al4 | 26 with mesh + standard repair; 24 with ultra-lateral repair; 33 with standard repair | 58 vs 54 vs 70 stage II, respectively (P=.58) | Overlay | 23 | None |

| SYNTHETIC PERMANENT GRAFTS WITHOUT CONCOMITANT SLINGS | ||||||

| Marlex trapezoid | Julian 199619 | 12 with 12 without | 0 vs 33, respectively | Arcus tendineus fascia pelvis | 24 | 3 vaginal erosions |

| Mixed-fiber mesh (polyglactin 910 and polyester 5×5) | Migliari and Usai 199924 | 12 | 25 | Pubourethral and cardinal ligaments | 20 | None |

| Prolene (Atrium) | Dwyer and O’Reilly25 | 64 anterior 50 posterior | 6 grade II | Tension-free | 29 | 8% vaginal erosion 1 rectovaginal fistula |

| Gynemesh 6×15 | de Tayrac et al 200526 | 87 | 7 stage II 2 stage III | Tension-free | 24 | 8% vaginal erosion |

| Prolene mesh patch | Milani et al 200527 | 32 anterior 31 posterior | 6 stage II | Fixed to endopelvic connective tissue | 17 | 20% anterior, 63% posterior dyspareunia; 13% vaginal erosion (anterior); 1 pelvic abscess (posterior) |

| Prolene mesh (double-wing shape) | Natale et al 2000 28 | 138 | 3 | Tension-free | 18 | 9% vaginal erosion 7% dyspareunia 1 hematoma |

| *Absorbable and permanent. | ||||||

Classification of synthetic materials

- Type 1 grafts are totally macroporous (>75 μm), which allows fibroblast, macrophage, and collagen penetration with angiogenesis. Examples include Prolene and Marlex meshes.

- Type 2 mesh is microporous (<10 μm in 1 dimension). This prevents penetration of fibroblasts, macrophages, or collagen. Gore-Tex is an example of a Type 2 mesh.

- Type 3 mesh is macroporous (>75 μm) with multifilamentous or microporous components. Examples include Mersilene (braided Dacron mesh), Teflon (polytetrafluoroethylene [PTFE]), Surgipro (braided polypropylene mesh), and MycroMesh (perforated PTFE patch).

- Type 4 mesh has a submicron pore size that prevents penetration. Examples include Silastic, Cellgard (polypropylene sheeting), and Preclude pericardial membrane/Preclude dura-substitute.1

2 other important properties are composition of fibers (multifilamentous materials commonly have interstices less than 10 microns) and flexibility (which has a bearing on erosion of the material).1

Bacteria can penetrate pores smaller than 1 μm, whereas polymorphonuclear white blood cells and macrophages need a pore size larger than 10 μm, and capillary ingrowth requires a size larger than 75 microns. Thus, Type 1 offers the advantages of larger pore size and monofilamentous interstices to allow for capillary ingrowth.

Which material is best?

Although the literature is difficult to interpret because of the diversity of studies and other factors, some findings are worth noting:

- Tutoplast and Alloderm appear to have the best tensile strength, maximum load to capacity, and microscopic architecture similar to the original tissue.15-17 However, these qualities were documented prior to implantation in vivo.

- Slings appear to help prevent cystocele recurrences, according to a study by Goldberg et al.18

- A fascial patch had no benefit when placed as an overlay in the anterior compartment in a randomized, controlled trial (involving 162 women) by Sand et al.12

- Marlex. One group of women with recurrent prolapse underwent synthetic graft (Marlex) augmentation with bilateral ATFP attachment, while the other group had anterior colporrhaphy only.19 None of the women who received grafts had further recurrence, while 33% of the control group did. However, 25% of the women with the graft had vaginal erosions.

- Polyglactin 910 had a protective effect when embedded in the plication, according to Sand et al.12 However, it had no benefit when used as an overlay to a traditional repair in a study by Weber et al.4 The discrepancy may be related to small sample size; the study by Weber et al was powered to detect only a 30% difference. However, these studies suggest that it is not only the type of graft that is important, but how it is used or attached.

In general, synthetic grafts may have slightly higher success rates, whereas biologic materials appear to be better tolerated.

Prospective, comparative trials of these materials are desperately needed.

CASE Symptoms point to yet another prolapse recurrence

A 52-year-old woman presents with a bulge and pressure in her vagina. She has undergone 2 prior reconstructive surgeries. The first was a vaginal hysterectomy, anterior and posterior repair, and sling; the second was an abdominal procedure that included a sacrocolpopexy and paravaginal repair.

A physical examination reveals a recurrent 4th-degree cystocele that protrudes 2 cm beyond the hymenal ring. The vault and posterior compartment are well supported, and the patient reports no incontinence, a fact confirmed by urodynamics testing. She asks that you do everything in your power to prevent further recurrence.

How do you proceed?

This patient ultimately underwent anterior colporrhaphy and vaginal paravaginal repair using a decellularized dermal cadaveric implant. She was still doing well 1 year later, with no recurrence.

Despite success stories like this one, the use of graft materials to repair cystoceles and rectoceles is controversial. One reason is the difficulty of interpreting published data, since studies lack uniformity in technique, patient characteristics, graft shape, type of material, attachment sites, and duration of follow-up. Level I evidence that augmented repairs have a clear benefit over traditional repairs is sparse.

Advocates of graft materials argue that native tissue is already compromised—hence, the prolapse—making surgical failure likely.1 They claim graft materials help strengthen repairs, especially in the case of cystoceles. They also point out that adjuvant materials have been used in burns, plastic surgery, and orthopedics for more than 10 years and are generally well tolerated. Their success in hernia repairs prompted their consideration for the pelvic floor.

A pervasive problem, but only 10% to 20% seek help

Roughly 1 of 2 parous women lose pelvic support as they age, but only 10% to 20% seek medical care, with a lifetime risk of surgery for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) of 11% by age 80.2

With women living longer than ever and remaining active later in life, this percentage is likely to rise. Unfortunately, few alternatives to surgical treatment exist, and the reoperation rate for recurrence is 29%, according to a 1995 review.2 If surgical management is the only hope of cure, how can we lower the 29% recurrence rate?

Graft materials may provide part or all of the solution.

Elements of prolapse

Anterior compartment

Central and/or lateral defects can occur in the anterior compartment.

Lateral (paravaginal) defects indicate that the endopelvic connective tissue has separated from the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis. Lateral defects can be repaired vaginally or abdominally.

One study3 found that 67% of women with anterior wall prolapse had paravaginal defects, but no randomized trials have evaluated the clinical benefit of repairing these defects, compared with traditional colporrhaphies.

Central defects involve site-specific defects and/or general attenuation of the endopelvic connective tissue. These are usually repaired vaginally.

Recurrence rates for lateral and central defects range from 3% to 70%.4-8

Two large series of vaginal paravaginal repairs noted the following recurrence rates:

- Shull et al6 found a recurrence rate of 7% to the hymenal ring or beyond.

- Young et al7 observed a recurrence rate for lateral defects of 2%, with recurrence rates as high as 22% for central defects.

In a comparison of 3 techniques for vaginal repair of central defects, using strict criteria to assess anatomic outcomes, Weber et al4 found recurrence rates of 54% to 70%. Other studies show symptomatic recurrence rates of 3% to 22% for cystoceles.5,8

With grafts, both paravaginal and central defects can be repaired. Vaginal paravaginal repairs are not popular due to the technical difficulty involved. With the use of grafts, however, both paravaginal and central defects can be addressed simultaneously with relative ease.

Posterior compartment

Defects in the posterior compartment are less likely to recur. Reported success rates range from 80% to 90%.9,10

Posterior compartment defects include general attenuation of Denonvillier’s fascia or a tear anywhere along the fascia or any of its attachments.

Recurrence rates. Site-specific repairs are thought to minimize complications such as dyspareunia. However, few studies have compared the efficacy of site-specific repairs with that of traditional colporrhaphies. At our institution, women who underwent traditional colporrhaphy had fewer recurrences than controls (33% vs 14%), with no differences in postoperative symptoms such as dyspareunia, constipation, and fecal incontinence.11

Graft materials of questionable benefit. In the posterior compartment, these materials have not been shown to be beneficial, compared with traditional or site-specific repairs. Sand et al12 found no benefit for repairs in which absorbable Vicryl mesh was imbricated, but this randomized trial may have lacked sufficient power to show statistical significance. Large cohorts would be needed to show significant benefit of meshes in the posterior compartment.

A complex web of support

In the normal pelvis, support of reproductive organs depends on a complex web of muscles, fascia, and connective tissue. To ensure success, prolapse repairs should correct any separation or attenuation of tissue and preserve or enhance tissue resilience.

Risk factors for recurrent prolapse

- Poor tissue (assess tissue quality before and during surgery)

- Impaired healing

- Chronic increases in intraabdominal pressure due to obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, or constipation

- High-grade cystocele

- Age 60 or above13

Patients with these conditions may benefit from the use of adjuvant materials in the anterior compartment.

Note that women who have had recurrences after earlier repairs may experience repeat recurrence.

Advantages of grafts

Using graft materials, the surgeon can repair all vaginal defects faster and with less effort. In the anterior compartment, a graft can be placed and anchored bilaterally from arcus to arcus tendineus, and posteriorly to the level of the spine, recreating level I support. Graft materials also offer the potential to treat stress urinary incontinence concomitantly using different shaped materials. Two authors have already described their success performing this type of repair.14

Nevertheless, great care and consideration should be devoted to actual and theoretical short- and long-term risks, many of which have not been fully elucidated.

Once a successful material is identified or developed, it may decrease operating time and morbidity in vaginal surgeries. It may also reduce the higher hospital costs normally associated with abdominal procedures.

Types of graft materials

There are 2 types of materials: synthetic or biologic. Synthetic materials can be further classified into permanent or absorbable.

The most widely used biologic materials include allografts such as human freeze-dried or solvent-dehydrated fascia lata (Tutoplast), decellularized human cadaveric dermis (Alloderm, Repliform), porcine dermal xenografts such as Pelvicol or Intexene, and bovine pericardial implants (Veritas).

Soft polypropylene meshes such as Gynemesh and Atrium are commonly used permanent materials, and polyglactin 910 is an absorbable material (TABLE).

TABLE

How successful are adjuvant materials in cystocele and rectocele repairs?

| MATERIAL (SIZE IN CM) | AUTHOR | NO. IN STUDY | RECURRENCE RATE (%) | SITE OF ATTACHMENT | FOLLOW-UP (MONTHS) | COMPLICATIONS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIOLOGIC MATERIALS | ||||||

| Alloderm 3×7 patch with concomitant sling | Chung29 | 19 | 16 | Pubocervical fascia | 28 | None |

| Intexene 6×8 with sling | Gomelsky et al 200420 | 70 | 9 stage II 4 stage III | Arcus tendineus fascia pelvis | 24 | 1 wound separation |

| Solvent-dehydrated cadaveric fascia lata patch with sling | Gandhi et al 200521 | 76 patch vs 72 no patch | 21 vs 29, respectively (P=.23) | Overlay | 13 | None |

| Alloderm 3×7 trapezoid | Clemons et al 200322 | 33 | 41 stage II 3 symptomatic | Arcus tendineus fascia pelvis | 18 | None |

| SYNTHETIC MATERIALS WITH CONCOMITANT SLINGS* | ||||||

| Marlex 10×3×5 | Nicita 199823 | 44 | 0 | Arcus tendineus fascia pelvis | 13 | 1 vaginal erosion |

| Polyglactin 910 absorbable mesh | Sand et al12 | 80 mesh vs 80 no mesh | 25 vs 43 stage II cystoceles, respectively(P=.02) | Insert in the anterior and posterior colporrhaphy suture line | 12 | None |

| Polyglactin 910 absorbable mesh | Weber et al4 | 26 with mesh + standard repair; 24 with ultra-lateral repair; 33 with standard repair | 58 vs 54 vs 70 stage II, respectively (P=.58) | Overlay | 23 | None |

| SYNTHETIC PERMANENT GRAFTS WITHOUT CONCOMITANT SLINGS | ||||||

| Marlex trapezoid | Julian 199619 | 12 with 12 without | 0 vs 33, respectively | Arcus tendineus fascia pelvis | 24 | 3 vaginal erosions |

| Mixed-fiber mesh (polyglactin 910 and polyester 5×5) | Migliari and Usai 199924 | 12 | 25 | Pubourethral and cardinal ligaments | 20 | None |

| Prolene (Atrium) | Dwyer and O’Reilly25 | 64 anterior 50 posterior | 6 grade II | Tension-free | 29 | 8% vaginal erosion 1 rectovaginal fistula |

| Gynemesh 6×15 | de Tayrac et al 200526 | 87 | 7 stage II 2 stage III | Tension-free | 24 | 8% vaginal erosion |

| Prolene mesh patch | Milani et al 200527 | 32 anterior 31 posterior | 6 stage II | Fixed to endopelvic connective tissue | 17 | 20% anterior, 63% posterior dyspareunia; 13% vaginal erosion (anterior); 1 pelvic abscess (posterior) |

| Prolene mesh (double-wing shape) | Natale et al 2000 28 | 138 | 3 | Tension-free | 18 | 9% vaginal erosion 7% dyspareunia 1 hematoma |

| *Absorbable and permanent. | ||||||

Classification of synthetic materials

- Type 1 grafts are totally macroporous (>75 μm), which allows fibroblast, macrophage, and collagen penetration with angiogenesis. Examples include Prolene and Marlex meshes.

- Type 2 mesh is microporous (<10 μm in 1 dimension). This prevents penetration of fibroblasts, macrophages, or collagen. Gore-Tex is an example of a Type 2 mesh.

- Type 3 mesh is macroporous (>75 μm) with multifilamentous or microporous components. Examples include Mersilene (braided Dacron mesh), Teflon (polytetrafluoroethylene [PTFE]), Surgipro (braided polypropylene mesh), and MycroMesh (perforated PTFE patch).

- Type 4 mesh has a submicron pore size that prevents penetration. Examples include Silastic, Cellgard (polypropylene sheeting), and Preclude pericardial membrane/Preclude dura-substitute.1

2 other important properties are composition of fibers (multifilamentous materials commonly have interstices less than 10 microns) and flexibility (which has a bearing on erosion of the material).1

Bacteria can penetrate pores smaller than 1 μm, whereas polymorphonuclear white blood cells and macrophages need a pore size larger than 10 μm, and capillary ingrowth requires a size larger than 75 microns. Thus, Type 1 offers the advantages of larger pore size and monofilamentous interstices to allow for capillary ingrowth.

Which material is best?

Although the literature is difficult to interpret because of the diversity of studies and other factors, some findings are worth noting:

- Tutoplast and Alloderm appear to have the best tensile strength, maximum load to capacity, and microscopic architecture similar to the original tissue.15-17 However, these qualities were documented prior to implantation in vivo.

- Slings appear to help prevent cystocele recurrences, according to a study by Goldberg et al.18

- A fascial patch had no benefit when placed as an overlay in the anterior compartment in a randomized, controlled trial (involving 162 women) by Sand et al.12

- Marlex. One group of women with recurrent prolapse underwent synthetic graft (Marlex) augmentation with bilateral ATFP attachment, while the other group had anterior colporrhaphy only.19 None of the women who received grafts had further recurrence, while 33% of the control group did. However, 25% of the women with the graft had vaginal erosions.

- Polyglactin 910 had a protective effect when embedded in the plication, according to Sand et al.12 However, it had no benefit when used as an overlay to a traditional repair in a study by Weber et al.4 The discrepancy may be related to small sample size; the study by Weber et al was powered to detect only a 30% difference. However, these studies suggest that it is not only the type of graft that is important, but how it is used or attached.

In general, synthetic grafts may have slightly higher success rates, whereas biologic materials appear to be better tolerated.

Prospective, comparative trials of these materials are desperately needed.

1. Cervigni M, Natale F. The use of synthetics in the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Curr Opin Urol. 2001;11:429-435.

2. Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:501-506.

3. Richardson AC, Lyon JB, Williams NL. A new look at pelvic relaxation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;126:568-573.

4. Weber AM, Walters MD, Piedmonte MR, Ballard LA. Anterior colporrhaphy: a randomized trial of three surgical techniques. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1299-1304.

5. Porges RF, Smilen SW. Long-term analysis of the surgical management of pelvic support defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:1518-1526.

6. Shull BL, Benn SJ, Kuehl TJ. Surgical management of prolapse of the anterior vaginal segment: an analysis of support defects, operative morbidity, and anatomic outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:1429-1436.

7. Young SB, Daman JJ, Bony LG. Vaginal paravaginal repair: one-year outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1360-1366.

8. Macer GA. Transabdominal repair of cystocele, a 20-year experience, compared with the traditional vaginal approach. Trans Pac Coast Obstet Gynecol Soc. 1978;45:116-120.

9. Cundiff GW, Weidner AC, Visco AG, Addison WA, Bump RC. An anatomic and functional assessment of the discrete defect rectocele repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:1451-1456.

10. Paraiso MF, Ballard LA, Walters MD, Lee JC, et al. Pelvic support defects and visceral and sexual function in women treated with sacrospinous ligament suspension and pelvic reconstruction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1423-1430.

11. Abramov Y, et al. Site-specific rectocele repair compared with standard posterior colporrhaphy. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:314-318.

12. Sand PK, et al. Prospective randomized trial of polyglactin 910 mesh to prevent recurrence of cystoceles and rectoceles. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:1357-1362.

13. Whitesides JL, Weber AM, Meyn LA, Walters MD. Risk factors for prolapse recurrence after vaginal repair. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2005;60:164-165.

14. Kobashi KC, Mee SL, Leach GE. A new technique for cystocele repair and transvaginal sling: the cadaveric prolapse repair and sling (CAPS). Urology. 2000;56:9-14.

15. Lemer ML, Chaikin DC, Blaivas JG. Tissue strength analysis of autologous and cadaveric allografts for the pubovaginal sling. Neurourol Urodyn. 1999;18:497-503.

16. Choe JM, Kothandapani R, et al. Autologous, cadaveric, and synthetic materials used in sling surgery: comparative biomechanical analysis. Urology. 2001;58:482-486.

17. Scalfani AP. Biophysical and microscopic analysis of homologous dermal and fascial materials for facial aesthetic and reconstructive uses. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2002;4:164-171.

18. Goldberg RP, et al. Protective effect of suburethral slings on postoperative cystocele recurrence after reconstructive pelvic operation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1307-1312.

19. Julian TM. The efficacy of Marlex mesh in the repair of severe, recurrent vaginal prolapse of the anterior midvaginal wall. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1472-1475.

20. Gomelsky A, Rudy DC, Dmochowski RR. Porcine dermis interposition graft for repair of high grade anterior compartment defects with or without concomitant pelvic organ prolapse procedures. J Urol. 2004;171:1581-1584.

21. Gandhi S, et al. A prospective randomized trial of solvent dehydrated fascia lata for the prevention of recurrent anterior vaginal wall prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1649-1654.

22. Clemons JL, Myers DL, Aguilar VC, Arya LA. Vaginal paravaginal repair with an AlloDerm graft. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1612-1618.

23. Nicita G. A new operation for genitourinary prolapse. J Urol. 1998;160:741-745.

24. Migliari R, Usai E. Treatment results using a mixed fiber mesh in patients with grade IV cystocele. J Urol. 1999;161:1255-1258.

25. Dwyer PL, O’Reilly BA. Transvaginal repair of anterior and posterior compartment prolapse with Atrium polypropylene mesh. BJOG. 2004;111:831-836.

26. de Tayrac R, Gervaise A, Chauveaud A, Fernandez H. Tension-free polypropylene mesh for vaginal repair of anterior vaginal wall prolapse. J Reprod Med. 2005;50:75-80.

27. Milani R, et al. Functional and anatomical outcome of anterior and posterior vaginal prolapse repair with prolene mesh. BJOG. 2005;112:107-111.

28. Natale F, Marziali S, Cervigni M. Tension-free cystocele repair (TCR): long-term follow-up. Proceedings of the 25th annual meeting of the International Urogynecological Association. 2000;22-25.

29. Chung SY, et al. Technique of combined pubovaginal sling and cystocele using a single piece of cadaveric dermal graft. Urology. 2002;59:538-541.

Dr. Botros has no financial relationships relevant to this article. Dr. Sand receives grant/research support from Boston Scientific, and is a consultant and speaker for American Medical Systems and Boston Scientific.

1. Cervigni M, Natale F. The use of synthetics in the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Curr Opin Urol. 2001;11:429-435.

2. Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:501-506.

3. Richardson AC, Lyon JB, Williams NL. A new look at pelvic relaxation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;126:568-573.

4. Weber AM, Walters MD, Piedmonte MR, Ballard LA. Anterior colporrhaphy: a randomized trial of three surgical techniques. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1299-1304.

5. Porges RF, Smilen SW. Long-term analysis of the surgical management of pelvic support defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:1518-1526.

6. Shull BL, Benn SJ, Kuehl TJ. Surgical management of prolapse of the anterior vaginal segment: an analysis of support defects, operative morbidity, and anatomic outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:1429-1436.

7. Young SB, Daman JJ, Bony LG. Vaginal paravaginal repair: one-year outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1360-1366.

8. Macer GA. Transabdominal repair of cystocele, a 20-year experience, compared with the traditional vaginal approach. Trans Pac Coast Obstet Gynecol Soc. 1978;45:116-120.

9. Cundiff GW, Weidner AC, Visco AG, Addison WA, Bump RC. An anatomic and functional assessment of the discrete defect rectocele repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:1451-1456.

10. Paraiso MF, Ballard LA, Walters MD, Lee JC, et al. Pelvic support defects and visceral and sexual function in women treated with sacrospinous ligament suspension and pelvic reconstruction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1423-1430.

11. Abramov Y, et al. Site-specific rectocele repair compared with standard posterior colporrhaphy. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:314-318.

12. Sand PK, et al. Prospective randomized trial of polyglactin 910 mesh to prevent recurrence of cystoceles and rectoceles. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:1357-1362.

13. Whitesides JL, Weber AM, Meyn LA, Walters MD. Risk factors for prolapse recurrence after vaginal repair. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2005;60:164-165.

14. Kobashi KC, Mee SL, Leach GE. A new technique for cystocele repair and transvaginal sling: the cadaveric prolapse repair and sling (CAPS). Urology. 2000;56:9-14.

15. Lemer ML, Chaikin DC, Blaivas JG. Tissue strength analysis of autologous and cadaveric allografts for the pubovaginal sling. Neurourol Urodyn. 1999;18:497-503.

16. Choe JM, Kothandapani R, et al. Autologous, cadaveric, and synthetic materials used in sling surgery: comparative biomechanical analysis. Urology. 2001;58:482-486.

17. Scalfani AP. Biophysical and microscopic analysis of homologous dermal and fascial materials for facial aesthetic and reconstructive uses. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2002;4:164-171.

18. Goldberg RP, et al. Protective effect of suburethral slings on postoperative cystocele recurrence after reconstructive pelvic operation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1307-1312.

19. Julian TM. The efficacy of Marlex mesh in the repair of severe, recurrent vaginal prolapse of the anterior midvaginal wall. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1472-1475.

20. Gomelsky A, Rudy DC, Dmochowski RR. Porcine dermis interposition graft for repair of high grade anterior compartment defects with or without concomitant pelvic organ prolapse procedures. J Urol. 2004;171:1581-1584.

21. Gandhi S, et al. A prospective randomized trial of solvent dehydrated fascia lata for the prevention of recurrent anterior vaginal wall prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1649-1654.

22. Clemons JL, Myers DL, Aguilar VC, Arya LA. Vaginal paravaginal repair with an AlloDerm graft. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1612-1618.

23. Nicita G. A new operation for genitourinary prolapse. J Urol. 1998;160:741-745.

24. Migliari R, Usai E. Treatment results using a mixed fiber mesh in patients with grade IV cystocele. J Urol. 1999;161:1255-1258.

25. Dwyer PL, O’Reilly BA. Transvaginal repair of anterior and posterior compartment prolapse with Atrium polypropylene mesh. BJOG. 2004;111:831-836.

26. de Tayrac R, Gervaise A, Chauveaud A, Fernandez H. Tension-free polypropylene mesh for vaginal repair of anterior vaginal wall prolapse. J Reprod Med. 2005;50:75-80.

27. Milani R, et al. Functional and anatomical outcome of anterior and posterior vaginal prolapse repair with prolene mesh. BJOG. 2005;112:107-111.

28. Natale F, Marziali S, Cervigni M. Tension-free cystocele repair (TCR): long-term follow-up. Proceedings of the 25th annual meeting of the International Urogynecological Association. 2000;22-25.

29. Chung SY, et al. Technique of combined pubovaginal sling and cystocele using a single piece of cadaveric dermal graft. Urology. 2002;59:538-541.

Dr. Botros has no financial relationships relevant to this article. Dr. Sand receives grant/research support from Boston Scientific, and is a consultant and speaker for American Medical Systems and Boston Scientific.

IN THIS ARTICLE