User login

Hysterectomy: Which route for which patient?

- Moderator Mickey Karram, MD, Director of Urogynecology, Good Samaritan Hospital, Cincinnati, and Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Cincinnati, Ohio.

- Tommaso Falcone, MD, Professor and Chairman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio.

- Thomas Herzog, MD, Director, Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Physicians and Surgeons Alumni Professor, Columbia University Medical Center, New York City.

- Barbara S. Levy, MD, Medical Director, Women’s Health Center, Franciscan Health System, Federal Way, Wash. Dr. Levy serves on the OBG MANAGEMENT Board of Editors.

Why the continued reliance on the abdominal approach despite convincing evidence that vaginal and laparoscopicassisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH) offer faster recovery, better cosmesis, and, in many cases, a shorter operation with fewer complications?

OBG Management convened a panel of experts in different aspects of gynecologic surgery to explore this issue. They discuss the reasons most physicians prefer the abdominal approach, how residency programs affect the choice of hysterectomy route, indications for LAVH and supracervical hysterectomy, the issue of ovarian conservation, and management of uterine fibroids.

Why the abdominal route remains the old standby

Physicians use the procedure they are most comfortable with, and residents lack sufficient hands-on experience with laparoscopic and vaginal surgery. Medicolegal risk and reimbursement also have an impact.

KARRAM: Hysterectomy is one of the most widely performed surgeries in the United States, but approximately 60% to 80% of these surgeries still involve the abdominal route.2 Why do you think that is?

FALCONE: Most physicians practice in the manner they were trained, and most residency programs train residents to perform abdominal hysterectomy.

LEVY: I agree. Residents in obstetrics and gynecology have a limited time frame in which to learn and become facile with surgical gynecology. The requirements for primary care training and continuity clinics leave little time for the resident to become comfortable with endoscopic and vaginal surgery. However, they do get substantial exposure to abdominal surgery, both in obstetrics (with cesarean sections constituting 27.5% of all deliveries in the United States3) and gynecologic oncology rotations.

Furthermore, the volume of benign gynecologic surgery is low and the technical skills required for laparoscopic and vaginal surgery are more challenging than “slash and gash” abdominal surgery, so residents don’t get enough exposure to develop a comfort level with these procedures.

HERZOG: This trend is likely to change in the future because recent and current trainees have much more exposure to the laparoscopic approach than in the past, and the equipment has continued to improve. However, I have serious doubts about whether adequate amounts of vaginal surgery are performed in training programs to educate the next generation of vaginal surgeons.

LEVY: Another factor is the type of practice physicians enter after training. Most join practices in which the bulk of their income for many years derives from obstetrics. Without a mentor in the practice who is skilled at minimally invasive surgery, most of these young physicians appropriately resort to the hysterectomy approach for which they have the most comfort and skill: the abdominal route.

HERZOG: Secondary barriers to nonabdominal procedures are lower reimbursement and heightened medicolegal risk, since time and complications are greater for laparoscopic surgery and, to a lesser degree, vaginal procedures. Surgeons are not adequately compensated for either the increased time or risk.

Patients also tend to have higher expectations when the planned approach is minimally invasive. When conversion to laparotomy is necessary, the patient and her family may have trouble understanding why.

KARRAM: I agree that there is a serious lack of training in simple and complicated vaginal hysterectomy. Many inaccurate perceptions have been handed down over the years about its absolute and relative contraindications, such as the belief that any history of pelvic infection, endometriosis, or cesarean section is a contraindication for the vaginal approach.

When is laparoscopic assistance appropriate?

At a fundamental level, its value lies in converting abdominal hysterectomy intovaginal hysterectomy.

KARRAM: In my experience, LAVH is appropriate in the presence of benign adnexal pathology: The adnexa can be evaluated and detached laparoscopically followed by vaginal hysterectomy and vaginal removal of the adnexa. It also is appropriate in any situation that involves excessive pelvic adhesions. The uterus can be mobilized laparoscopically, followed by removal through the vagina.

FALCONE: Any patient who is not a candidate for vaginal hysterectomy should be considered for laparoscopic assistance. The general rationale for the surgery is to convert an abdominal hysterectomy into a vaginal one, so the surgeon should start laparoscopically and then switch to the vaginal approach as soon as possible. Of course, it is impossible to proceed vaginally in some cases. When it is, the entire case can be performed laparoscopically.

LEVY: In my hands, patients with an unidentified adnexal mass who also need or request hysterectomy are appropriate candidates for laparoscopic abdominal exploration followed by vaginal hysterectomy if appropriate. Women with a very contracted pelvis, which precludes transvaginal access to the uterine vasculature, may also be candidates for the laparoscopic approach. However, as surgeons become more skilled at vaginal surgery and learn to use newer instrumentation, the need for laparoscopy to access a tight pelvis will diminish.

Using a laparoscopic approach for patients with fibroids wedged into the pelvis carries serious risk to the pelvic sidewall. It is very difficult to access the sidewall safely laparoscopically in the presence of a large lower segment or cervical myomas.

HERZOG: When LAVH was introduced, many clinicians challenged the utility of combined laparoscopic and vaginal surgery, with some referring to this surgical exercise as a procedure looking for an indication. However, as operative laparoscopy has gained acceptance, some benefits of LAVH have become apparent. The greatest advantage is the potential to convert a procedure that would have been performed abdominally into a vaginal hysterectomy.

The most commonly cited indications for LAVH are to lyse adhesions secondary to prior abdominopelvic surgery, substantial endometriosis, or a pelvic mass.

Is oophorectomy an indication for LAVH?

The need to remove the ovaries does not mean laparoscopic assistance is imperative.

HERZOG: Simple removal of the ovaries can often be performed using the vaginal route, and is not in itself an indication for LAVH.

LEVY: I agree. The ovaries can usually be accessed transvaginally, especially with good fiberoptic lighting and vessel-sealing technology.

FALCONE: Several studies, most notably the one by Ballard and Walters,4 demonstrate that oophorectomy can be carried out vaginally in most cases. In their study, they did not use special instruments.

HERZOG: But LAVH is indicated to facilitate complete removal of the ovaries in riskreduction surgery for documented or suspected BrCa 1 or 2 mutations. The entire ovary and as much of the tube as possible must be removed in these women. Thus, if the patient has other indications for hysterectomy, LAVH may be the preferred route to assure that the blood supply is taken proximally enough to remove absolutely all ovarian tissue. Simply clamping directly along the side of the ovary is not an adequate removal technique for these patients, since an ovarian remnant may become a fatal oversight.

LEVY: Yes, laparoscopy is indicated for riskreducing salpingo-oophorectomy in order to adequately assess the entire peritoneal cavity. Up to 2% of these patients will have occult invasive ovarian or peritoneal carcinoma at the time of their prophylactic surgery, so full surgical abdominal exploration is mandatory and can be nicely accomplished via laparoscopy.5

How endometriosis history affects choice of route

In some women, laparoscopic surgery is preferred over the vaginal route.

FALCONE: Hysterectomy with or without salpingo-oophorectomy can be considered in women whose endometriosis fails to respond to conservative management and who do not desire fertility. Most studies have shown substantial pain relief with definitive surgery.6,7 Although ovarian conservation may be advisable in younger women, in some women it increases the probability of recurrent pain and the need for reoperation. The main concern is whether the endometriosis is completely removed during hysterectomy.

A history of cul-de-sac obliteration or extensive pelvic adhesions from endometriosis is an indication for laparoscopic hysterectomy rather than vaginal hysterectomy. Women with less severe disease will benefit from a diagnostic laparoscopy prior to a vaginal hysterectomy to evaluate the pelvis and excise any endometriosis.

Is there any benefit to leaving the cervix?

There is no evidence of any benefit except in selected cases of heavy bleeding, postpartum hemorrhage, advanced endometriosis, or ovarian cancer surgery.

KARRAM: What about supracervical hysterectomy? The only time I have performed one was at the time of a cesareanhysterectomy because blood loss was significant and dissection of the cervix could have led to more morbidity. What are the indications for this procedure?

HERZOG: It is unclear whether there are any definitive indications for supracervical hysterectomy. A number of benefits have been proposed, such as better support and improved sexual function. Some of the perceived benefits have been supported by nonrandomized trials, but critical analysis of the randomized data has failed to support most of these contentions.8,9 However, the procedure can be a valuable intervention to decrease critical blood loss intraoperatively, as you point out, or to simplify complicated pelvic surgery in selected cases, such as postpartum hemorrhage, advanced endometriosis, ovarian cancer debulking (when the cervix is not involved), or significant bleeding in patients who object to transfusion on ethical or religious grounds.

FALCONE: There are clear contraindications to supracervical hysterectomy, namely the presence of a malignant or premalignant condition of the uterine corpus or cervix, but no indications, except perhaps for an unstable patient undergoing hysterectomy in whom you want to finish quickly. None of the randomized clinical trials have shown supracervical hysterectomy to be superior to total hysterectomy. The randomized trials involved the abdominal route; the time to complete a laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy is less than for a laparoscopic total hysterectomy.

Nevertheless, many patients ask for the procedure. After I present the risks and benefits, I leave the choice up to them. Of course, it is important to explain that total hysterectomy implies removal of the cervix and not the ovaries.

LEVY: In rare cases of immunocompromised patients or women with widely disseminated intraperitoneal carcinoma, one could make an argument for avoiding entry into the vagina to reduce infectious risk, speed healing, or avoid tumor seeding. Otherwise, there is absolutely no evidence to support an indication for supracervical hysterectomy.

Does leaving the cervix affect long-term function?

The residual cervix can become the site of later neoplasia or disease.

HERZOG: Supracervical hysterectomy can be associated with several problems with longterm implications. One is the potential for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Another concern relates to bleeding from a portion of active endometrium at the top of the endocervical canal. Rarer problems include the development of endometriosis or invasive cancer in the residual cervix. These potential drawbacks need to be strongly considered and included in patient counseling.

KARRAM: One study followed 67 patients for 66 months after supracervical hysterectomy; trachelectomy was ultimately required in 22.8% of patients.10

The $64,0000 question: Remove the ovaries?

Overall, the decision should be made case by case.

KARRAM: Should routine oophorectomy be performed at the time of hysterectomy in postmenopausal women to decrease the potential for ovarian cancer later in life?

HERZOG: This is a very important question. Conventional thinking used to be that, for women over the age of 45, and certainly for women older than 50, ovarian removal should be strongly considered to reduce the risk of cancer of the ovary or fallopian tubes at a later date. Studies focusing on the number of ovarian cancer cases possibly prevented with routine oophorectomy at the time of hysterectomy reinforced this concept. One single-institution study showed that more than 60 cases of ovarian cancer would have been prevented over a 14-year period if ovaries were routinely removed in women older than 40 undergoing hysterectomy. By extrapolation, that would result in more than 1,000 cases prevented annually in the United States.11

Recent data refute the rationale for routine oophorectomy. One study that used statistical modeling with Markov decision analysis to determine life expectancy concluded that, at least until the age of 65, women are best served with ovarian conservation if their risk of developing ovarian cancer is average or less.12 Researchers found that women who underwent oophorectomy before age 55 experienced 8.6% excess mortality by age 80. The validity of certain assumptions used to construct this model has been challenged; nevertheless, this cogent study certainly challenges previous concepts regarding agebased routine prophylactic oophorectomy. Until further study results are reported, it is important to counsel women who are considering having their ovaries removed about the potential risks and benefits. Furthermore, these decisions must be made on a case-by-case basis, with special deliberation given to women at any increased risk for breast or ovarian cancer.

What route is preferred when fibroids are present?

Assuming hysterectomy is the optimal treatment, the vaginal route is feasible.

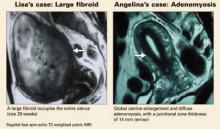

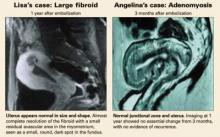

KARRAM: Uterine fibroids are still the No. 1 indication for hysterectomy. Are minimally invasive laparoscopic procedures with morcellation techniques the best way to manage these women?

FALCONE: The management of symptomatic leiomyomas depends on the patient’s desire to preserve her fertility. If she does not have an interest in future fertility and there are no myomas that are largely submucous or pedunculated, then uterine fibroid embolization is the treatment of choice. Many studies have shown an excellent response, few complications, and rapid return to work.

If the woman wants to preserve fertility, myomectomy is the treatment of choice. If there are few myomas of moderate size, laparoscopic myomectomy is as effective as laparotomy in the hands of experienced laparoscopists who have the ability to suture.

HERZOG: I also want to stress that we now have a number of options, including uterine artery embolization, medications, and surgery, available for women with symptomatic fibroids. The surgical approaches are numerous and include hysteroscopic and/or laparoscopic myomectomy with or without morcellation, as well as hysterectomy. The approach should be determined by the symptoms, size, and distribution of the fibroids, as well as by individual patient characteristics such as prior surgeries, body mass index, and so on. Just because a procedure is technically feasible does not mean it is the preferred method, and this tenet certainly applies to morcellation. In some instances, women with very large fibroids may be better served by laparotomy to decrease blood loss and the duration of surgery while optimizing uterine wall reconstruction, especially when future fertility is an important consideration. Once again, proper patient selection is paramount in achieving favorable outcomes, especially for those who may be undergoing morcellation.

LEVY: For women who have completed childbearing and who desire hysterectomy, I always attempt a vaginal approach first. Most uteri, regardless of size, can be safely and efficiently removed vaginally as long as there is access to the uterine vasculature. Morcellation is easily performed vaginally once hemostasis is assured. For the rare patient with a large fundal myoma that cannot be brought into the pelvis for morcellation, minilaparotomy or laparoscopic approaches are appropriate.

KARRAM: I think randomized trials are needed in this area. It is important to remember that most cases performed laparoscopically result in supracervical hysterectomies and that significant costs are accrued from the equipment required for morcellation. These factors need to be weighed against potential advantages over abdominal hysterectomy, which include shorter hospital stay, potentially decreased morbidity, and faster recovery. The only way to make any objective conclusions about the options would be a randomized trial with appropriate power involving surgeons equally skilled in laparoscopic and open techniques.

Are residents adequately trained?

It depends on the program but, on the whole, more concentrated experience in minimally invasive surgery is needed.

KARRAM: Let’s focus on residency training for a moment. We seem to agree there is a lack of it in vaginal hysterectomy. It seems to me that the lack of training increases as time goes on. Because the current generation of gynecologists-in-training is ultimately the next generation of teachers, it bodes ill for the future when they are reluctant to attempt vaginal hysterectomy, except in the simplest and most straightforward cases. The medicolegal climate also plays a role, as Dr. Herzog mentioned.

Any other thoughts?

FALCONE: The training across residency programs is not homogenous. Some institutions promote vaginal hysterectomy as the primary access, and others do not.

HERZOG: I agree that some institutions do provide an adequate volume of cases, but many others offer a paucity of vaginal surgeries. Many reasons have combined to cause this shortage of training cases over the past 15 years, including a decrease in the number of hysterectomies performed overall, thanks to a number of nonsurgical or less radical surgical treatments for the most common indications for hysterectomy. These approaches generally are mandated by third-party payers prior to invasive surgery. These mandates were not as rigidly enforced in the past.

In a survey of gynecologic oncologists—the vast majority of whom were at academic training centers—the consensus was that residents had fewer surgical experiences and were less skillful than their predecessors over a 5-year period. More than 80% of respondents thought residents needed more surgical experience to achieve competence.13

Compounding the problem, resident work hours have been restricted and additional educational objectives and nonsurgical rotations have been added to the curriculum without any lengthening of the residency tenure. The adverse effects of these factors on residency case volume has prompted some educators to propose major changes in the residency curriculum, either by lengthening training or developing distinct tracks that facilitate early concentration on an area of interest, thereby allowing residents who choose a surgical track to gain increased training and volume.

Until substantive changes occur, educators must rely on surgical simulators and other in vitro models, especially for laparoscopic training. These have benefit but are not a perfect substitute for actual operative experience. A recent study explored the value of a surgical bench skills training program and concluded that, while residents showed definite improvement in bench laboratory tasks, this improvement did not translate into statistically significant improvement in global skills intraoperatively.14 Clearly, educators must continue to explore options to enhance surgical training, especially for vaginal surgery, or this route will become nearly obsolete in the gynecologic generalist’s armamentarium.

Dr. Karram reports that he receives grant/research support from Gynecare, American Medical Systems, and Pfizer and is a speaker for Gynecare, Ortho-McNeil, and Watson. Dr. Falcone, Dr. Herzog, and Dr. Levy have no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. Kovac SR. Transvaginal hysterectomy: rationale and surgical approach. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:1321-1325.

2. Baggish MS. Total and subtotal abdominal hysterectomy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;19:333-356.

3. National Center for Health Statistics. Births—method of delivery. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/ delivery.htm. Accessed January 18, 2006.

4. Ballard LA, Walters MD. Transvaginal mobilization and removal of ovaries and fallopian tubes after vaginal hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:35-39.

5. Finch A, Shaw P, Rosen B, et al. Clinical and pathologic findings of prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomies in 159 BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;100:58-64.

6. Dmowski WP, Radwanska E, Rana N. Recurrent endometriosis following hysterectomy and oophorectomy: the role of residual ovarian fragments. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1988;26:93-103.

7. Namnoun AB, Hickman NT, Goodman SB, Gehlbach DL, Rock JA. Incidence of symptom recurrence after hysterectomy for endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1995;64:898-902.

8. Kuppermann M, Summitt RL, Jr, Varner RE, et al. Total or Supracervical Hysterectomy Research Group. Sexual functioning after total compared with supracervical hysterectomy: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1309-1318.

9. Learman LA, Summitt RL, Jr, Varner RE, et al. Total or Supracervical Hysterectomy (TOSH) Research Group. A randomized comparison of total or supracervical hysterectomy: surgical complications and clinical outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:453-462.

10. Okaro EO, Jones KD, Sutton C. Long-term outcome following laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy. BJOG. 2001;108:1017-1020.

11. Sightler SE, Boike GM, Estape RE, Averette HE. Ovarian cancer in women with prior hysterectomy: a 14-year experience at the University of Miami. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;78:681-684.

12. Parker WH, Broder MS, Liu Z, Shoupe D, Farquhar C, Berek JS. Ovarian conservation at the time of hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:219-226.

13. Sorosky JI, Anderson B. Surgical experiences and training of residents: perspective of experienced gynecologic oncologists. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;75:222-223.

14. Lentz GM, Mandel LS, Goff BA. A six-year study of surgical teaching and skills evaluation for obstetric/gynecologic residents in porcine and inanimate surgical models. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:2056-2061.

- Moderator Mickey Karram, MD, Director of Urogynecology, Good Samaritan Hospital, Cincinnati, and Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Cincinnati, Ohio.

- Tommaso Falcone, MD, Professor and Chairman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio.

- Thomas Herzog, MD, Director, Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Physicians and Surgeons Alumni Professor, Columbia University Medical Center, New York City.

- Barbara S. Levy, MD, Medical Director, Women’s Health Center, Franciscan Health System, Federal Way, Wash. Dr. Levy serves on the OBG MANAGEMENT Board of Editors.

Why the continued reliance on the abdominal approach despite convincing evidence that vaginal and laparoscopicassisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH) offer faster recovery, better cosmesis, and, in many cases, a shorter operation with fewer complications?

OBG Management convened a panel of experts in different aspects of gynecologic surgery to explore this issue. They discuss the reasons most physicians prefer the abdominal approach, how residency programs affect the choice of hysterectomy route, indications for LAVH and supracervical hysterectomy, the issue of ovarian conservation, and management of uterine fibroids.

Why the abdominal route remains the old standby

Physicians use the procedure they are most comfortable with, and residents lack sufficient hands-on experience with laparoscopic and vaginal surgery. Medicolegal risk and reimbursement also have an impact.

KARRAM: Hysterectomy is one of the most widely performed surgeries in the United States, but approximately 60% to 80% of these surgeries still involve the abdominal route.2 Why do you think that is?

FALCONE: Most physicians practice in the manner they were trained, and most residency programs train residents to perform abdominal hysterectomy.

LEVY: I agree. Residents in obstetrics and gynecology have a limited time frame in which to learn and become facile with surgical gynecology. The requirements for primary care training and continuity clinics leave little time for the resident to become comfortable with endoscopic and vaginal surgery. However, they do get substantial exposure to abdominal surgery, both in obstetrics (with cesarean sections constituting 27.5% of all deliveries in the United States3) and gynecologic oncology rotations.

Furthermore, the volume of benign gynecologic surgery is low and the technical skills required for laparoscopic and vaginal surgery are more challenging than “slash and gash” abdominal surgery, so residents don’t get enough exposure to develop a comfort level with these procedures.

HERZOG: This trend is likely to change in the future because recent and current trainees have much more exposure to the laparoscopic approach than in the past, and the equipment has continued to improve. However, I have serious doubts about whether adequate amounts of vaginal surgery are performed in training programs to educate the next generation of vaginal surgeons.

LEVY: Another factor is the type of practice physicians enter after training. Most join practices in which the bulk of their income for many years derives from obstetrics. Without a mentor in the practice who is skilled at minimally invasive surgery, most of these young physicians appropriately resort to the hysterectomy approach for which they have the most comfort and skill: the abdominal route.

HERZOG: Secondary barriers to nonabdominal procedures are lower reimbursement and heightened medicolegal risk, since time and complications are greater for laparoscopic surgery and, to a lesser degree, vaginal procedures. Surgeons are not adequately compensated for either the increased time or risk.

Patients also tend to have higher expectations when the planned approach is minimally invasive. When conversion to laparotomy is necessary, the patient and her family may have trouble understanding why.

KARRAM: I agree that there is a serious lack of training in simple and complicated vaginal hysterectomy. Many inaccurate perceptions have been handed down over the years about its absolute and relative contraindications, such as the belief that any history of pelvic infection, endometriosis, or cesarean section is a contraindication for the vaginal approach.

When is laparoscopic assistance appropriate?

At a fundamental level, its value lies in converting abdominal hysterectomy intovaginal hysterectomy.

KARRAM: In my experience, LAVH is appropriate in the presence of benign adnexal pathology: The adnexa can be evaluated and detached laparoscopically followed by vaginal hysterectomy and vaginal removal of the adnexa. It also is appropriate in any situation that involves excessive pelvic adhesions. The uterus can be mobilized laparoscopically, followed by removal through the vagina.

FALCONE: Any patient who is not a candidate for vaginal hysterectomy should be considered for laparoscopic assistance. The general rationale for the surgery is to convert an abdominal hysterectomy into a vaginal one, so the surgeon should start laparoscopically and then switch to the vaginal approach as soon as possible. Of course, it is impossible to proceed vaginally in some cases. When it is, the entire case can be performed laparoscopically.

LEVY: In my hands, patients with an unidentified adnexal mass who also need or request hysterectomy are appropriate candidates for laparoscopic abdominal exploration followed by vaginal hysterectomy if appropriate. Women with a very contracted pelvis, which precludes transvaginal access to the uterine vasculature, may also be candidates for the laparoscopic approach. However, as surgeons become more skilled at vaginal surgery and learn to use newer instrumentation, the need for laparoscopy to access a tight pelvis will diminish.

Using a laparoscopic approach for patients with fibroids wedged into the pelvis carries serious risk to the pelvic sidewall. It is very difficult to access the sidewall safely laparoscopically in the presence of a large lower segment or cervical myomas.

HERZOG: When LAVH was introduced, many clinicians challenged the utility of combined laparoscopic and vaginal surgery, with some referring to this surgical exercise as a procedure looking for an indication. However, as operative laparoscopy has gained acceptance, some benefits of LAVH have become apparent. The greatest advantage is the potential to convert a procedure that would have been performed abdominally into a vaginal hysterectomy.

The most commonly cited indications for LAVH are to lyse adhesions secondary to prior abdominopelvic surgery, substantial endometriosis, or a pelvic mass.

Is oophorectomy an indication for LAVH?

The need to remove the ovaries does not mean laparoscopic assistance is imperative.

HERZOG: Simple removal of the ovaries can often be performed using the vaginal route, and is not in itself an indication for LAVH.

LEVY: I agree. The ovaries can usually be accessed transvaginally, especially with good fiberoptic lighting and vessel-sealing technology.

FALCONE: Several studies, most notably the one by Ballard and Walters,4 demonstrate that oophorectomy can be carried out vaginally in most cases. In their study, they did not use special instruments.

HERZOG: But LAVH is indicated to facilitate complete removal of the ovaries in riskreduction surgery for documented or suspected BrCa 1 or 2 mutations. The entire ovary and as much of the tube as possible must be removed in these women. Thus, if the patient has other indications for hysterectomy, LAVH may be the preferred route to assure that the blood supply is taken proximally enough to remove absolutely all ovarian tissue. Simply clamping directly along the side of the ovary is not an adequate removal technique for these patients, since an ovarian remnant may become a fatal oversight.

LEVY: Yes, laparoscopy is indicated for riskreducing salpingo-oophorectomy in order to adequately assess the entire peritoneal cavity. Up to 2% of these patients will have occult invasive ovarian or peritoneal carcinoma at the time of their prophylactic surgery, so full surgical abdominal exploration is mandatory and can be nicely accomplished via laparoscopy.5

How endometriosis history affects choice of route

In some women, laparoscopic surgery is preferred over the vaginal route.

FALCONE: Hysterectomy with or without salpingo-oophorectomy can be considered in women whose endometriosis fails to respond to conservative management and who do not desire fertility. Most studies have shown substantial pain relief with definitive surgery.6,7 Although ovarian conservation may be advisable in younger women, in some women it increases the probability of recurrent pain and the need for reoperation. The main concern is whether the endometriosis is completely removed during hysterectomy.

A history of cul-de-sac obliteration or extensive pelvic adhesions from endometriosis is an indication for laparoscopic hysterectomy rather than vaginal hysterectomy. Women with less severe disease will benefit from a diagnostic laparoscopy prior to a vaginal hysterectomy to evaluate the pelvis and excise any endometriosis.

Is there any benefit to leaving the cervix?

There is no evidence of any benefit except in selected cases of heavy bleeding, postpartum hemorrhage, advanced endometriosis, or ovarian cancer surgery.

KARRAM: What about supracervical hysterectomy? The only time I have performed one was at the time of a cesareanhysterectomy because blood loss was significant and dissection of the cervix could have led to more morbidity. What are the indications for this procedure?

HERZOG: It is unclear whether there are any definitive indications for supracervical hysterectomy. A number of benefits have been proposed, such as better support and improved sexual function. Some of the perceived benefits have been supported by nonrandomized trials, but critical analysis of the randomized data has failed to support most of these contentions.8,9 However, the procedure can be a valuable intervention to decrease critical blood loss intraoperatively, as you point out, or to simplify complicated pelvic surgery in selected cases, such as postpartum hemorrhage, advanced endometriosis, ovarian cancer debulking (when the cervix is not involved), or significant bleeding in patients who object to transfusion on ethical or religious grounds.

FALCONE: There are clear contraindications to supracervical hysterectomy, namely the presence of a malignant or premalignant condition of the uterine corpus or cervix, but no indications, except perhaps for an unstable patient undergoing hysterectomy in whom you want to finish quickly. None of the randomized clinical trials have shown supracervical hysterectomy to be superior to total hysterectomy. The randomized trials involved the abdominal route; the time to complete a laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy is less than for a laparoscopic total hysterectomy.

Nevertheless, many patients ask for the procedure. After I present the risks and benefits, I leave the choice up to them. Of course, it is important to explain that total hysterectomy implies removal of the cervix and not the ovaries.

LEVY: In rare cases of immunocompromised patients or women with widely disseminated intraperitoneal carcinoma, one could make an argument for avoiding entry into the vagina to reduce infectious risk, speed healing, or avoid tumor seeding. Otherwise, there is absolutely no evidence to support an indication for supracervical hysterectomy.

Does leaving the cervix affect long-term function?

The residual cervix can become the site of later neoplasia or disease.

HERZOG: Supracervical hysterectomy can be associated with several problems with longterm implications. One is the potential for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Another concern relates to bleeding from a portion of active endometrium at the top of the endocervical canal. Rarer problems include the development of endometriosis or invasive cancer in the residual cervix. These potential drawbacks need to be strongly considered and included in patient counseling.

KARRAM: One study followed 67 patients for 66 months after supracervical hysterectomy; trachelectomy was ultimately required in 22.8% of patients.10

The $64,0000 question: Remove the ovaries?

Overall, the decision should be made case by case.

KARRAM: Should routine oophorectomy be performed at the time of hysterectomy in postmenopausal women to decrease the potential for ovarian cancer later in life?

HERZOG: This is a very important question. Conventional thinking used to be that, for women over the age of 45, and certainly for women older than 50, ovarian removal should be strongly considered to reduce the risk of cancer of the ovary or fallopian tubes at a later date. Studies focusing on the number of ovarian cancer cases possibly prevented with routine oophorectomy at the time of hysterectomy reinforced this concept. One single-institution study showed that more than 60 cases of ovarian cancer would have been prevented over a 14-year period if ovaries were routinely removed in women older than 40 undergoing hysterectomy. By extrapolation, that would result in more than 1,000 cases prevented annually in the United States.11

Recent data refute the rationale for routine oophorectomy. One study that used statistical modeling with Markov decision analysis to determine life expectancy concluded that, at least until the age of 65, women are best served with ovarian conservation if their risk of developing ovarian cancer is average or less.12 Researchers found that women who underwent oophorectomy before age 55 experienced 8.6% excess mortality by age 80. The validity of certain assumptions used to construct this model has been challenged; nevertheless, this cogent study certainly challenges previous concepts regarding agebased routine prophylactic oophorectomy. Until further study results are reported, it is important to counsel women who are considering having their ovaries removed about the potential risks and benefits. Furthermore, these decisions must be made on a case-by-case basis, with special deliberation given to women at any increased risk for breast or ovarian cancer.

What route is preferred when fibroids are present?

Assuming hysterectomy is the optimal treatment, the vaginal route is feasible.

KARRAM: Uterine fibroids are still the No. 1 indication for hysterectomy. Are minimally invasive laparoscopic procedures with morcellation techniques the best way to manage these women?

FALCONE: The management of symptomatic leiomyomas depends on the patient’s desire to preserve her fertility. If she does not have an interest in future fertility and there are no myomas that are largely submucous or pedunculated, then uterine fibroid embolization is the treatment of choice. Many studies have shown an excellent response, few complications, and rapid return to work.

If the woman wants to preserve fertility, myomectomy is the treatment of choice. If there are few myomas of moderate size, laparoscopic myomectomy is as effective as laparotomy in the hands of experienced laparoscopists who have the ability to suture.

HERZOG: I also want to stress that we now have a number of options, including uterine artery embolization, medications, and surgery, available for women with symptomatic fibroids. The surgical approaches are numerous and include hysteroscopic and/or laparoscopic myomectomy with or without morcellation, as well as hysterectomy. The approach should be determined by the symptoms, size, and distribution of the fibroids, as well as by individual patient characteristics such as prior surgeries, body mass index, and so on. Just because a procedure is technically feasible does not mean it is the preferred method, and this tenet certainly applies to morcellation. In some instances, women with very large fibroids may be better served by laparotomy to decrease blood loss and the duration of surgery while optimizing uterine wall reconstruction, especially when future fertility is an important consideration. Once again, proper patient selection is paramount in achieving favorable outcomes, especially for those who may be undergoing morcellation.

LEVY: For women who have completed childbearing and who desire hysterectomy, I always attempt a vaginal approach first. Most uteri, regardless of size, can be safely and efficiently removed vaginally as long as there is access to the uterine vasculature. Morcellation is easily performed vaginally once hemostasis is assured. For the rare patient with a large fundal myoma that cannot be brought into the pelvis for morcellation, minilaparotomy or laparoscopic approaches are appropriate.

KARRAM: I think randomized trials are needed in this area. It is important to remember that most cases performed laparoscopically result in supracervical hysterectomies and that significant costs are accrued from the equipment required for morcellation. These factors need to be weighed against potential advantages over abdominal hysterectomy, which include shorter hospital stay, potentially decreased morbidity, and faster recovery. The only way to make any objective conclusions about the options would be a randomized trial with appropriate power involving surgeons equally skilled in laparoscopic and open techniques.

Are residents adequately trained?

It depends on the program but, on the whole, more concentrated experience in minimally invasive surgery is needed.

KARRAM: Let’s focus on residency training for a moment. We seem to agree there is a lack of it in vaginal hysterectomy. It seems to me that the lack of training increases as time goes on. Because the current generation of gynecologists-in-training is ultimately the next generation of teachers, it bodes ill for the future when they are reluctant to attempt vaginal hysterectomy, except in the simplest and most straightforward cases. The medicolegal climate also plays a role, as Dr. Herzog mentioned.

Any other thoughts?

FALCONE: The training across residency programs is not homogenous. Some institutions promote vaginal hysterectomy as the primary access, and others do not.

HERZOG: I agree that some institutions do provide an adequate volume of cases, but many others offer a paucity of vaginal surgeries. Many reasons have combined to cause this shortage of training cases over the past 15 years, including a decrease in the number of hysterectomies performed overall, thanks to a number of nonsurgical or less radical surgical treatments for the most common indications for hysterectomy. These approaches generally are mandated by third-party payers prior to invasive surgery. These mandates were not as rigidly enforced in the past.

In a survey of gynecologic oncologists—the vast majority of whom were at academic training centers—the consensus was that residents had fewer surgical experiences and were less skillful than their predecessors over a 5-year period. More than 80% of respondents thought residents needed more surgical experience to achieve competence.13

Compounding the problem, resident work hours have been restricted and additional educational objectives and nonsurgical rotations have been added to the curriculum without any lengthening of the residency tenure. The adverse effects of these factors on residency case volume has prompted some educators to propose major changes in the residency curriculum, either by lengthening training or developing distinct tracks that facilitate early concentration on an area of interest, thereby allowing residents who choose a surgical track to gain increased training and volume.

Until substantive changes occur, educators must rely on surgical simulators and other in vitro models, especially for laparoscopic training. These have benefit but are not a perfect substitute for actual operative experience. A recent study explored the value of a surgical bench skills training program and concluded that, while residents showed definite improvement in bench laboratory tasks, this improvement did not translate into statistically significant improvement in global skills intraoperatively.14 Clearly, educators must continue to explore options to enhance surgical training, especially for vaginal surgery, or this route will become nearly obsolete in the gynecologic generalist’s armamentarium.

Dr. Karram reports that he receives grant/research support from Gynecare, American Medical Systems, and Pfizer and is a speaker for Gynecare, Ortho-McNeil, and Watson. Dr. Falcone, Dr. Herzog, and Dr. Levy have no financial relationships relevant to this article.

- Moderator Mickey Karram, MD, Director of Urogynecology, Good Samaritan Hospital, Cincinnati, and Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Cincinnati, Ohio.

- Tommaso Falcone, MD, Professor and Chairman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio.

- Thomas Herzog, MD, Director, Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Physicians and Surgeons Alumni Professor, Columbia University Medical Center, New York City.

- Barbara S. Levy, MD, Medical Director, Women’s Health Center, Franciscan Health System, Federal Way, Wash. Dr. Levy serves on the OBG MANAGEMENT Board of Editors.

Why the continued reliance on the abdominal approach despite convincing evidence that vaginal and laparoscopicassisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH) offer faster recovery, better cosmesis, and, in many cases, a shorter operation with fewer complications?

OBG Management convened a panel of experts in different aspects of gynecologic surgery to explore this issue. They discuss the reasons most physicians prefer the abdominal approach, how residency programs affect the choice of hysterectomy route, indications for LAVH and supracervical hysterectomy, the issue of ovarian conservation, and management of uterine fibroids.

Why the abdominal route remains the old standby

Physicians use the procedure they are most comfortable with, and residents lack sufficient hands-on experience with laparoscopic and vaginal surgery. Medicolegal risk and reimbursement also have an impact.

KARRAM: Hysterectomy is one of the most widely performed surgeries in the United States, but approximately 60% to 80% of these surgeries still involve the abdominal route.2 Why do you think that is?

FALCONE: Most physicians practice in the manner they were trained, and most residency programs train residents to perform abdominal hysterectomy.

LEVY: I agree. Residents in obstetrics and gynecology have a limited time frame in which to learn and become facile with surgical gynecology. The requirements for primary care training and continuity clinics leave little time for the resident to become comfortable with endoscopic and vaginal surgery. However, they do get substantial exposure to abdominal surgery, both in obstetrics (with cesarean sections constituting 27.5% of all deliveries in the United States3) and gynecologic oncology rotations.

Furthermore, the volume of benign gynecologic surgery is low and the technical skills required for laparoscopic and vaginal surgery are more challenging than “slash and gash” abdominal surgery, so residents don’t get enough exposure to develop a comfort level with these procedures.

HERZOG: This trend is likely to change in the future because recent and current trainees have much more exposure to the laparoscopic approach than in the past, and the equipment has continued to improve. However, I have serious doubts about whether adequate amounts of vaginal surgery are performed in training programs to educate the next generation of vaginal surgeons.

LEVY: Another factor is the type of practice physicians enter after training. Most join practices in which the bulk of their income for many years derives from obstetrics. Without a mentor in the practice who is skilled at minimally invasive surgery, most of these young physicians appropriately resort to the hysterectomy approach for which they have the most comfort and skill: the abdominal route.

HERZOG: Secondary barriers to nonabdominal procedures are lower reimbursement and heightened medicolegal risk, since time and complications are greater for laparoscopic surgery and, to a lesser degree, vaginal procedures. Surgeons are not adequately compensated for either the increased time or risk.

Patients also tend to have higher expectations when the planned approach is minimally invasive. When conversion to laparotomy is necessary, the patient and her family may have trouble understanding why.

KARRAM: I agree that there is a serious lack of training in simple and complicated vaginal hysterectomy. Many inaccurate perceptions have been handed down over the years about its absolute and relative contraindications, such as the belief that any history of pelvic infection, endometriosis, or cesarean section is a contraindication for the vaginal approach.

When is laparoscopic assistance appropriate?

At a fundamental level, its value lies in converting abdominal hysterectomy intovaginal hysterectomy.

KARRAM: In my experience, LAVH is appropriate in the presence of benign adnexal pathology: The adnexa can be evaluated and detached laparoscopically followed by vaginal hysterectomy and vaginal removal of the adnexa. It also is appropriate in any situation that involves excessive pelvic adhesions. The uterus can be mobilized laparoscopically, followed by removal through the vagina.

FALCONE: Any patient who is not a candidate for vaginal hysterectomy should be considered for laparoscopic assistance. The general rationale for the surgery is to convert an abdominal hysterectomy into a vaginal one, so the surgeon should start laparoscopically and then switch to the vaginal approach as soon as possible. Of course, it is impossible to proceed vaginally in some cases. When it is, the entire case can be performed laparoscopically.

LEVY: In my hands, patients with an unidentified adnexal mass who also need or request hysterectomy are appropriate candidates for laparoscopic abdominal exploration followed by vaginal hysterectomy if appropriate. Women with a very contracted pelvis, which precludes transvaginal access to the uterine vasculature, may also be candidates for the laparoscopic approach. However, as surgeons become more skilled at vaginal surgery and learn to use newer instrumentation, the need for laparoscopy to access a tight pelvis will diminish.

Using a laparoscopic approach for patients with fibroids wedged into the pelvis carries serious risk to the pelvic sidewall. It is very difficult to access the sidewall safely laparoscopically in the presence of a large lower segment or cervical myomas.

HERZOG: When LAVH was introduced, many clinicians challenged the utility of combined laparoscopic and vaginal surgery, with some referring to this surgical exercise as a procedure looking for an indication. However, as operative laparoscopy has gained acceptance, some benefits of LAVH have become apparent. The greatest advantage is the potential to convert a procedure that would have been performed abdominally into a vaginal hysterectomy.

The most commonly cited indications for LAVH are to lyse adhesions secondary to prior abdominopelvic surgery, substantial endometriosis, or a pelvic mass.

Is oophorectomy an indication for LAVH?

The need to remove the ovaries does not mean laparoscopic assistance is imperative.

HERZOG: Simple removal of the ovaries can often be performed using the vaginal route, and is not in itself an indication for LAVH.

LEVY: I agree. The ovaries can usually be accessed transvaginally, especially with good fiberoptic lighting and vessel-sealing technology.

FALCONE: Several studies, most notably the one by Ballard and Walters,4 demonstrate that oophorectomy can be carried out vaginally in most cases. In their study, they did not use special instruments.

HERZOG: But LAVH is indicated to facilitate complete removal of the ovaries in riskreduction surgery for documented or suspected BrCa 1 or 2 mutations. The entire ovary and as much of the tube as possible must be removed in these women. Thus, if the patient has other indications for hysterectomy, LAVH may be the preferred route to assure that the blood supply is taken proximally enough to remove absolutely all ovarian tissue. Simply clamping directly along the side of the ovary is not an adequate removal technique for these patients, since an ovarian remnant may become a fatal oversight.

LEVY: Yes, laparoscopy is indicated for riskreducing salpingo-oophorectomy in order to adequately assess the entire peritoneal cavity. Up to 2% of these patients will have occult invasive ovarian or peritoneal carcinoma at the time of their prophylactic surgery, so full surgical abdominal exploration is mandatory and can be nicely accomplished via laparoscopy.5

How endometriosis history affects choice of route

In some women, laparoscopic surgery is preferred over the vaginal route.

FALCONE: Hysterectomy with or without salpingo-oophorectomy can be considered in women whose endometriosis fails to respond to conservative management and who do not desire fertility. Most studies have shown substantial pain relief with definitive surgery.6,7 Although ovarian conservation may be advisable in younger women, in some women it increases the probability of recurrent pain and the need for reoperation. The main concern is whether the endometriosis is completely removed during hysterectomy.

A history of cul-de-sac obliteration or extensive pelvic adhesions from endometriosis is an indication for laparoscopic hysterectomy rather than vaginal hysterectomy. Women with less severe disease will benefit from a diagnostic laparoscopy prior to a vaginal hysterectomy to evaluate the pelvis and excise any endometriosis.

Is there any benefit to leaving the cervix?

There is no evidence of any benefit except in selected cases of heavy bleeding, postpartum hemorrhage, advanced endometriosis, or ovarian cancer surgery.

KARRAM: What about supracervical hysterectomy? The only time I have performed one was at the time of a cesareanhysterectomy because blood loss was significant and dissection of the cervix could have led to more morbidity. What are the indications for this procedure?

HERZOG: It is unclear whether there are any definitive indications for supracervical hysterectomy. A number of benefits have been proposed, such as better support and improved sexual function. Some of the perceived benefits have been supported by nonrandomized trials, but critical analysis of the randomized data has failed to support most of these contentions.8,9 However, the procedure can be a valuable intervention to decrease critical blood loss intraoperatively, as you point out, or to simplify complicated pelvic surgery in selected cases, such as postpartum hemorrhage, advanced endometriosis, ovarian cancer debulking (when the cervix is not involved), or significant bleeding in patients who object to transfusion on ethical or religious grounds.

FALCONE: There are clear contraindications to supracervical hysterectomy, namely the presence of a malignant or premalignant condition of the uterine corpus or cervix, but no indications, except perhaps for an unstable patient undergoing hysterectomy in whom you want to finish quickly. None of the randomized clinical trials have shown supracervical hysterectomy to be superior to total hysterectomy. The randomized trials involved the abdominal route; the time to complete a laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy is less than for a laparoscopic total hysterectomy.

Nevertheless, many patients ask for the procedure. After I present the risks and benefits, I leave the choice up to them. Of course, it is important to explain that total hysterectomy implies removal of the cervix and not the ovaries.

LEVY: In rare cases of immunocompromised patients or women with widely disseminated intraperitoneal carcinoma, one could make an argument for avoiding entry into the vagina to reduce infectious risk, speed healing, or avoid tumor seeding. Otherwise, there is absolutely no evidence to support an indication for supracervical hysterectomy.

Does leaving the cervix affect long-term function?

The residual cervix can become the site of later neoplasia or disease.

HERZOG: Supracervical hysterectomy can be associated with several problems with longterm implications. One is the potential for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Another concern relates to bleeding from a portion of active endometrium at the top of the endocervical canal. Rarer problems include the development of endometriosis or invasive cancer in the residual cervix. These potential drawbacks need to be strongly considered and included in patient counseling.

KARRAM: One study followed 67 patients for 66 months after supracervical hysterectomy; trachelectomy was ultimately required in 22.8% of patients.10

The $64,0000 question: Remove the ovaries?

Overall, the decision should be made case by case.

KARRAM: Should routine oophorectomy be performed at the time of hysterectomy in postmenopausal women to decrease the potential for ovarian cancer later in life?

HERZOG: This is a very important question. Conventional thinking used to be that, for women over the age of 45, and certainly for women older than 50, ovarian removal should be strongly considered to reduce the risk of cancer of the ovary or fallopian tubes at a later date. Studies focusing on the number of ovarian cancer cases possibly prevented with routine oophorectomy at the time of hysterectomy reinforced this concept. One single-institution study showed that more than 60 cases of ovarian cancer would have been prevented over a 14-year period if ovaries were routinely removed in women older than 40 undergoing hysterectomy. By extrapolation, that would result in more than 1,000 cases prevented annually in the United States.11

Recent data refute the rationale for routine oophorectomy. One study that used statistical modeling with Markov decision analysis to determine life expectancy concluded that, at least until the age of 65, women are best served with ovarian conservation if their risk of developing ovarian cancer is average or less.12 Researchers found that women who underwent oophorectomy before age 55 experienced 8.6% excess mortality by age 80. The validity of certain assumptions used to construct this model has been challenged; nevertheless, this cogent study certainly challenges previous concepts regarding agebased routine prophylactic oophorectomy. Until further study results are reported, it is important to counsel women who are considering having their ovaries removed about the potential risks and benefits. Furthermore, these decisions must be made on a case-by-case basis, with special deliberation given to women at any increased risk for breast or ovarian cancer.

What route is preferred when fibroids are present?

Assuming hysterectomy is the optimal treatment, the vaginal route is feasible.

KARRAM: Uterine fibroids are still the No. 1 indication for hysterectomy. Are minimally invasive laparoscopic procedures with morcellation techniques the best way to manage these women?

FALCONE: The management of symptomatic leiomyomas depends on the patient’s desire to preserve her fertility. If she does not have an interest in future fertility and there are no myomas that are largely submucous or pedunculated, then uterine fibroid embolization is the treatment of choice. Many studies have shown an excellent response, few complications, and rapid return to work.

If the woman wants to preserve fertility, myomectomy is the treatment of choice. If there are few myomas of moderate size, laparoscopic myomectomy is as effective as laparotomy in the hands of experienced laparoscopists who have the ability to suture.

HERZOG: I also want to stress that we now have a number of options, including uterine artery embolization, medications, and surgery, available for women with symptomatic fibroids. The surgical approaches are numerous and include hysteroscopic and/or laparoscopic myomectomy with or without morcellation, as well as hysterectomy. The approach should be determined by the symptoms, size, and distribution of the fibroids, as well as by individual patient characteristics such as prior surgeries, body mass index, and so on. Just because a procedure is technically feasible does not mean it is the preferred method, and this tenet certainly applies to morcellation. In some instances, women with very large fibroids may be better served by laparotomy to decrease blood loss and the duration of surgery while optimizing uterine wall reconstruction, especially when future fertility is an important consideration. Once again, proper patient selection is paramount in achieving favorable outcomes, especially for those who may be undergoing morcellation.

LEVY: For women who have completed childbearing and who desire hysterectomy, I always attempt a vaginal approach first. Most uteri, regardless of size, can be safely and efficiently removed vaginally as long as there is access to the uterine vasculature. Morcellation is easily performed vaginally once hemostasis is assured. For the rare patient with a large fundal myoma that cannot be brought into the pelvis for morcellation, minilaparotomy or laparoscopic approaches are appropriate.

KARRAM: I think randomized trials are needed in this area. It is important to remember that most cases performed laparoscopically result in supracervical hysterectomies and that significant costs are accrued from the equipment required for morcellation. These factors need to be weighed against potential advantages over abdominal hysterectomy, which include shorter hospital stay, potentially decreased morbidity, and faster recovery. The only way to make any objective conclusions about the options would be a randomized trial with appropriate power involving surgeons equally skilled in laparoscopic and open techniques.

Are residents adequately trained?

It depends on the program but, on the whole, more concentrated experience in minimally invasive surgery is needed.

KARRAM: Let’s focus on residency training for a moment. We seem to agree there is a lack of it in vaginal hysterectomy. It seems to me that the lack of training increases as time goes on. Because the current generation of gynecologists-in-training is ultimately the next generation of teachers, it bodes ill for the future when they are reluctant to attempt vaginal hysterectomy, except in the simplest and most straightforward cases. The medicolegal climate also plays a role, as Dr. Herzog mentioned.

Any other thoughts?

FALCONE: The training across residency programs is not homogenous. Some institutions promote vaginal hysterectomy as the primary access, and others do not.

HERZOG: I agree that some institutions do provide an adequate volume of cases, but many others offer a paucity of vaginal surgeries. Many reasons have combined to cause this shortage of training cases over the past 15 years, including a decrease in the number of hysterectomies performed overall, thanks to a number of nonsurgical or less radical surgical treatments for the most common indications for hysterectomy. These approaches generally are mandated by third-party payers prior to invasive surgery. These mandates were not as rigidly enforced in the past.

In a survey of gynecologic oncologists—the vast majority of whom were at academic training centers—the consensus was that residents had fewer surgical experiences and were less skillful than their predecessors over a 5-year period. More than 80% of respondents thought residents needed more surgical experience to achieve competence.13

Compounding the problem, resident work hours have been restricted and additional educational objectives and nonsurgical rotations have been added to the curriculum without any lengthening of the residency tenure. The adverse effects of these factors on residency case volume has prompted some educators to propose major changes in the residency curriculum, either by lengthening training or developing distinct tracks that facilitate early concentration on an area of interest, thereby allowing residents who choose a surgical track to gain increased training and volume.

Until substantive changes occur, educators must rely on surgical simulators and other in vitro models, especially for laparoscopic training. These have benefit but are not a perfect substitute for actual operative experience. A recent study explored the value of a surgical bench skills training program and concluded that, while residents showed definite improvement in bench laboratory tasks, this improvement did not translate into statistically significant improvement in global skills intraoperatively.14 Clearly, educators must continue to explore options to enhance surgical training, especially for vaginal surgery, or this route will become nearly obsolete in the gynecologic generalist’s armamentarium.

Dr. Karram reports that he receives grant/research support from Gynecare, American Medical Systems, and Pfizer and is a speaker for Gynecare, Ortho-McNeil, and Watson. Dr. Falcone, Dr. Herzog, and Dr. Levy have no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. Kovac SR. Transvaginal hysterectomy: rationale and surgical approach. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:1321-1325.

2. Baggish MS. Total and subtotal abdominal hysterectomy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;19:333-356.

3. National Center for Health Statistics. Births—method of delivery. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/ delivery.htm. Accessed January 18, 2006.

4. Ballard LA, Walters MD. Transvaginal mobilization and removal of ovaries and fallopian tubes after vaginal hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:35-39.

5. Finch A, Shaw P, Rosen B, et al. Clinical and pathologic findings of prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomies in 159 BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;100:58-64.

6. Dmowski WP, Radwanska E, Rana N. Recurrent endometriosis following hysterectomy and oophorectomy: the role of residual ovarian fragments. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1988;26:93-103.

7. Namnoun AB, Hickman NT, Goodman SB, Gehlbach DL, Rock JA. Incidence of symptom recurrence after hysterectomy for endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1995;64:898-902.

8. Kuppermann M, Summitt RL, Jr, Varner RE, et al. Total or Supracervical Hysterectomy Research Group. Sexual functioning after total compared with supracervical hysterectomy: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1309-1318.

9. Learman LA, Summitt RL, Jr, Varner RE, et al. Total or Supracervical Hysterectomy (TOSH) Research Group. A randomized comparison of total or supracervical hysterectomy: surgical complications and clinical outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:453-462.

10. Okaro EO, Jones KD, Sutton C. Long-term outcome following laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy. BJOG. 2001;108:1017-1020.

11. Sightler SE, Boike GM, Estape RE, Averette HE. Ovarian cancer in women with prior hysterectomy: a 14-year experience at the University of Miami. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;78:681-684.

12. Parker WH, Broder MS, Liu Z, Shoupe D, Farquhar C, Berek JS. Ovarian conservation at the time of hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:219-226.

13. Sorosky JI, Anderson B. Surgical experiences and training of residents: perspective of experienced gynecologic oncologists. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;75:222-223.

14. Lentz GM, Mandel LS, Goff BA. A six-year study of surgical teaching and skills evaluation for obstetric/gynecologic residents in porcine and inanimate surgical models. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:2056-2061.

1. Kovac SR. Transvaginal hysterectomy: rationale and surgical approach. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:1321-1325.

2. Baggish MS. Total and subtotal abdominal hysterectomy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;19:333-356.

3. National Center for Health Statistics. Births—method of delivery. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/ delivery.htm. Accessed January 18, 2006.

4. Ballard LA, Walters MD. Transvaginal mobilization and removal of ovaries and fallopian tubes after vaginal hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:35-39.

5. Finch A, Shaw P, Rosen B, et al. Clinical and pathologic findings of prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomies in 159 BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;100:58-64.

6. Dmowski WP, Radwanska E, Rana N. Recurrent endometriosis following hysterectomy and oophorectomy: the role of residual ovarian fragments. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1988;26:93-103.

7. Namnoun AB, Hickman NT, Goodman SB, Gehlbach DL, Rock JA. Incidence of symptom recurrence after hysterectomy for endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1995;64:898-902.

8. Kuppermann M, Summitt RL, Jr, Varner RE, et al. Total or Supracervical Hysterectomy Research Group. Sexual functioning after total compared with supracervical hysterectomy: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1309-1318.

9. Learman LA, Summitt RL, Jr, Varner RE, et al. Total or Supracervical Hysterectomy (TOSH) Research Group. A randomized comparison of total or supracervical hysterectomy: surgical complications and clinical outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:453-462.

10. Okaro EO, Jones KD, Sutton C. Long-term outcome following laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy. BJOG. 2001;108:1017-1020.

11. Sightler SE, Boike GM, Estape RE, Averette HE. Ovarian cancer in women with prior hysterectomy: a 14-year experience at the University of Miami. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;78:681-684.

12. Parker WH, Broder MS, Liu Z, Shoupe D, Farquhar C, Berek JS. Ovarian conservation at the time of hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:219-226.

13. Sorosky JI, Anderson B. Surgical experiences and training of residents: perspective of experienced gynecologic oncologists. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;75:222-223.

14. Lentz GM, Mandel LS, Goff BA. A six-year study of surgical teaching and skills evaluation for obstetric/gynecologic residents in porcine and inanimate surgical models. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:2056-2061.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Editorial We are at the tipping point

Abdominal techniques for surgical management of vaginal vault prolapse

A range of clinical conditions can suggest an abdominal approach for vaginal vault prolapse procedures.

These include, but are not limited to:

- prior unsuccessful vaginal attempts

- obligate need for adnexal access

- markedly foreshortened vagina

- pelvic bony architectural limitations

- high risk for surgical failure (eg, athleticism, obesity, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congenital connective tissue disorder)

- desire for uterine preservation

In Part 1 (November 2005) of this 2-part article, we reviewed the most widely used and the newest vaginal techniques. Part 2 focuses on the abdominal approach, and compares vaginal and abdominal approaches.

High uterosacral ligament suspension

Surgical technique for this procedure for mild to moderate vaginal vault prolapse (stage I or II), using a vaginal approach, was described in Part 1, in the November issue of OBG Management. Abdominal repair involves the same concepts; like the vaginal approach, it is applicable only to the patient with mild to moderate vault prolapse. It will be less successful if it is performed to address complete vault prolapse.

Technique

Identify and tag the remnants of the uterosacral ligaments at the level of the ischial spines. Once the ureters are identified and isolated, address the enterocele by obliterating the cul-de-sac via Halban’s culdoplasty or abdominal McCall’s culdoplasty.

Open the peritoneum over the vaginal apex and trim it back to the level of the endopelvic fascia of the vaginal wall. After excising the redundant peritoneum of the vaginal apex, identify and reapproximate the pubocervical fascia of the anterior vaginal wall and the rectovaginal fascia of the posterior vaginal wall using interrupted or running nonabsorbable suture.

Then use nonabsorbable sutures to suspend each corner of the prolapsed vagina from its respective ipsilateral uterosacral ligament.

Abdominal sacral colpopexy

Abdominal sacral colpopexy was first popularized by Addison and Timmons in the 1980s, and is the abdominal standard of apical prolapse repair due to its long-term durability.

Abdominal sacral colpopexy can be performed with or without uterine extirpation. When a hysterectomy is performed concomitantly, some surgeons prefer a supracervical approach, provided there is no history of cervical dysplasia, because, theoretically, the cervical stump serves as a firm and substantial point of fixation for the synthetic mesh that will be used to perform the repair. This in turn may diminish the likelihood of postoperative mesh erosion.

Technique

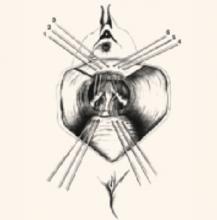

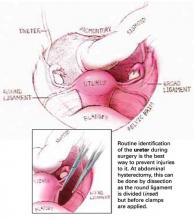

Reflect the sigmoid colon as far as possible into the left lateral pelvis to expose the sacral promontory. If it has not already been done, free all adhesions between the colon and pelvic peritoneum to fully mobilize the colon and permit its maximal retraction out of the pelvic field prior to making the peritoneal incision.

Also make it a point to identify all structures at risk during this portion of the procedure—namely, the common iliac vessels, ureters, and middle sacral artery and vein. The left common iliac vein is medial to the left common iliac artery and is particularly susceptible to injury during this phase of the procedure.

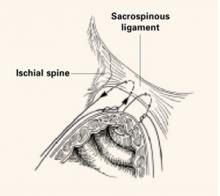

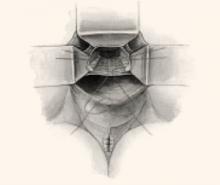

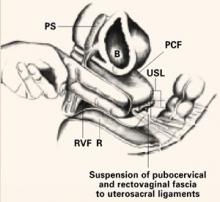

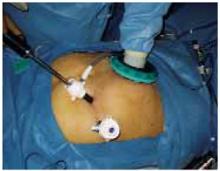

Make a longitudinal incision in the peritoneum overlying the sacral promontory and extend it approximately 6 cm from the promontory dorsally into the cul-de-sac, opening the retrorectal space (FIGURE 1, TOP). Using a fine tonsil forceps and cautery, very gently dissect the retroareolar filmy tissue overlying the anterior longitudinal ligament away from S1 in thin layers until the white periosteum of the anterior longitudinal ligament overlying S1 is clearly exposed. It now becomes very easy to visualize the course of the middle sacral artery and vein. With these vessels under direct visualization, place 2 permanent #0 sutures through the periosteum of S1.

Do not attempt to place these sutures deeper in the presacral space than the S1 vertebral body, or life-threatening and uncontrollable bleeding may result.

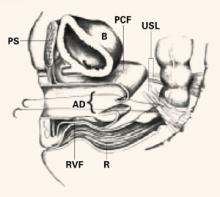

If there is no uterus, insert a probe such as an end-to-end anastomotic sizer or handheld Harrington retractor into the vagina and extend it, elongating and elevating the vaginal cylinder. It now becomes much easier to identify the interface between the bladder and vagina prior to making the peritoneal incision.

If the interface remains indistinct, instill 150 cc of saline into the bladder to delineate its boundaries. Then elevate and incise the vesicouterine peritoneum overlying the junction between the bladder and vaginal apex; this provides access to the vesicocervical space. Dissect the bladder off the anterior vaginal wall in a caudal direction until the pubocervical fascia can be identified. Do not dissect away the peritoneum over the posterior vaginal wall, but leave it intact.

FIGURE 1Abdominal sacral colpopexy technique

Reconstructive materials

Although many different materials have been described, none have undergone rigorous comparisons. In our institution, we use soft polypropylene (Surgipro; US Surgical, Norwalk, Conn).

Fold a piece of 5-inch mesh over onto itself and suture the layers together to create a double-thickness configuration. Then “fishmouth” the caudal end of this mesh prosthesis, producing both an anterior and posterior leaf. With the obturator still within the vaginal cylinder stretching the vaginal apex, secure the posterior leaf of the mesh to the posterior vaginal wall with 3 to 5 nonabsorbable #0 sutures.

Suture placement. Thread each suture initially through the posterior leaf of the mesh, placed deeply through the fibromuscular thickness of the posterior vaginal wall, then bring it back out through the mesh at the same point. Place the sutures in a transverse line 1 to 2 cm apart and 3 to 4 cm distal to the vaginal apex.

Once all sutures have been placed, tie each of them, thereby securing the posterior leaf of the mesh to the posterior vaginal wall. Now perform a “mirror” procedure to secure the anterior leaf of the mesh prosthesis to the anterior vaginal wall. Then firmly attach the mesh prosthesis to the vaginal apex using several interrupted, permanent sutures.

At this point, the sutures previously placed through the periosteum of the sacral promontory are threaded through the apex of the mesh prosthesis at a point that will allow the vagina to rest comfortably within the pelvis, without undue tension or traction once the sutures are tied into place (FIGURE 1, MIDDLE).

Trim any excess mesh, and close the 6-cm longitudinal peritoneal incision previously created in the cul-de-sac. Close the incision over the top of the mesh, retroperitonealizing the mesh prosthesis (FIGURE 1, BOTTOM).

Paravaginal defect repair

The bladder base is intimately associated with the anterior vaginal wall via a triangular sheet of pubocervical fascia attached to and extending from the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis bilaterally. When the apex of the vagina prolapses through the introitus, as in total vault prolapse, the base of the bladder is torn free from these fascial attachments in the pelvis and herniates through the introitus along with the vaginal apex. By definition, a bilateral paravaginal defect will result. Thus, surgical repair of total vaginal vault prolapse almost invariably requires paravaginal defect repair as well.

The goal of paravaginal defect repair is to reattach, bilaterally, the anterolateral vaginal sulcus and its overlying endopelvic fascia to the pubococcygeus and obturator internus muscles and fascia at the level of the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis.

Technique

Enter and gently develop the retropubic space of Retzius, taking care not to disrupt the myriad venous anastomotic networks of the plexus of Santorini, located on and around the bladder. Bluntly mobilize the bladder bilaterally, exposing the lateral retropubic spaces, the pubococcygeus and obturator internus muscles, and the obturator neurovascular bundles. Within each retropubic space, palpate the ischial spine. Then visualize the arcus, seen as a white ligamentous band, as it courses from the ischial spine caudally toward the ipsilateral posterior pubic symphysis. A lateral paravaginal defect representing avulsion of the vagina off the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis, or of the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis off the obturator internus muscle, can now be visualized.

While gently reflecting the bladder medially with a wide ribbon, insert a few fingers of the nondominant hand into the vagina and elevate the ipsilateral anterolateral vaginal sulcus. Then place a suture through the fibromuscular thickness of the lateral vaginal apex, just above the uplifting fingers in the vagina, and then slightly cephalad into the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis or obturator internus fascia on the pelvic sidewall, at a point 1 to 2 cm distal to the ischial spine. Place 3 to 5 additional sutures in a similar fashion at 1-cm intervals. The most distal suture should be placed as close as possible to the pubic ramus into the pubourethral ligament. If necessary, repeat the procedure on the contralateral side. Then tie all sutures into place, thereby completing the repair.