User login

Abdominal techniques for surgical management of vaginal vault prolapse

A range of clinical conditions can suggest an abdominal approach for vaginal vault prolapse procedures.

These include, but are not limited to:

- prior unsuccessful vaginal attempts

- obligate need for adnexal access

- markedly foreshortened vagina

- pelvic bony architectural limitations

- high risk for surgical failure (eg, athleticism, obesity, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congenital connective tissue disorder)

- desire for uterine preservation

In Part 1 (November 2005) of this 2-part article, we reviewed the most widely used and the newest vaginal techniques. Part 2 focuses on the abdominal approach, and compares vaginal and abdominal approaches.

High uterosacral ligament suspension

Surgical technique for this procedure for mild to moderate vaginal vault prolapse (stage I or II), using a vaginal approach, was described in Part 1, in the November issue of OBG Management. Abdominal repair involves the same concepts; like the vaginal approach, it is applicable only to the patient with mild to moderate vault prolapse. It will be less successful if it is performed to address complete vault prolapse.

Technique

Identify and tag the remnants of the uterosacral ligaments at the level of the ischial spines. Once the ureters are identified and isolated, address the enterocele by obliterating the cul-de-sac via Halban’s culdoplasty or abdominal McCall’s culdoplasty.

Open the peritoneum over the vaginal apex and trim it back to the level of the endopelvic fascia of the vaginal wall. After excising the redundant peritoneum of the vaginal apex, identify and reapproximate the pubocervical fascia of the anterior vaginal wall and the rectovaginal fascia of the posterior vaginal wall using interrupted or running nonabsorbable suture.

Then use nonabsorbable sutures to suspend each corner of the prolapsed vagina from its respective ipsilateral uterosacral ligament.

Abdominal sacral colpopexy

Abdominal sacral colpopexy was first popularized by Addison and Timmons in the 1980s, and is the abdominal standard of apical prolapse repair due to its long-term durability.

Abdominal sacral colpopexy can be performed with or without uterine extirpation. When a hysterectomy is performed concomitantly, some surgeons prefer a supracervical approach, provided there is no history of cervical dysplasia, because, theoretically, the cervical stump serves as a firm and substantial point of fixation for the synthetic mesh that will be used to perform the repair. This in turn may diminish the likelihood of postoperative mesh erosion.

Technique

Reflect the sigmoid colon as far as possible into the left lateral pelvis to expose the sacral promontory. If it has not already been done, free all adhesions between the colon and pelvic peritoneum to fully mobilize the colon and permit its maximal retraction out of the pelvic field prior to making the peritoneal incision.

Also make it a point to identify all structures at risk during this portion of the procedure—namely, the common iliac vessels, ureters, and middle sacral artery and vein. The left common iliac vein is medial to the left common iliac artery and is particularly susceptible to injury during this phase of the procedure.

Make a longitudinal incision in the peritoneum overlying the sacral promontory and extend it approximately 6 cm from the promontory dorsally into the cul-de-sac, opening the retrorectal space (FIGURE 1, TOP). Using a fine tonsil forceps and cautery, very gently dissect the retroareolar filmy tissue overlying the anterior longitudinal ligament away from S1 in thin layers until the white periosteum of the anterior longitudinal ligament overlying S1 is clearly exposed. It now becomes very easy to visualize the course of the middle sacral artery and vein. With these vessels under direct visualization, place 2 permanent #0 sutures through the periosteum of S1.

Do not attempt to place these sutures deeper in the presacral space than the S1 vertebral body, or life-threatening and uncontrollable bleeding may result.

If there is no uterus, insert a probe such as an end-to-end anastomotic sizer or handheld Harrington retractor into the vagina and extend it, elongating and elevating the vaginal cylinder. It now becomes much easier to identify the interface between the bladder and vagina prior to making the peritoneal incision.

If the interface remains indistinct, instill 150 cc of saline into the bladder to delineate its boundaries. Then elevate and incise the vesicouterine peritoneum overlying the junction between the bladder and vaginal apex; this provides access to the vesicocervical space. Dissect the bladder off the anterior vaginal wall in a caudal direction until the pubocervical fascia can be identified. Do not dissect away the peritoneum over the posterior vaginal wall, but leave it intact.

FIGURE 1Abdominal sacral colpopexy technique

Reconstructive materials

Although many different materials have been described, none have undergone rigorous comparisons. In our institution, we use soft polypropylene (Surgipro; US Surgical, Norwalk, Conn).

Fold a piece of 5-inch mesh over onto itself and suture the layers together to create a double-thickness configuration. Then “fishmouth” the caudal end of this mesh prosthesis, producing both an anterior and posterior leaf. With the obturator still within the vaginal cylinder stretching the vaginal apex, secure the posterior leaf of the mesh to the posterior vaginal wall with 3 to 5 nonabsorbable #0 sutures.

Suture placement. Thread each suture initially through the posterior leaf of the mesh, placed deeply through the fibromuscular thickness of the posterior vaginal wall, then bring it back out through the mesh at the same point. Place the sutures in a transverse line 1 to 2 cm apart and 3 to 4 cm distal to the vaginal apex.

Once all sutures have been placed, tie each of them, thereby securing the posterior leaf of the mesh to the posterior vaginal wall. Now perform a “mirror” procedure to secure the anterior leaf of the mesh prosthesis to the anterior vaginal wall. Then firmly attach the mesh prosthesis to the vaginal apex using several interrupted, permanent sutures.

At this point, the sutures previously placed through the periosteum of the sacral promontory are threaded through the apex of the mesh prosthesis at a point that will allow the vagina to rest comfortably within the pelvis, without undue tension or traction once the sutures are tied into place (FIGURE 1, MIDDLE).

Trim any excess mesh, and close the 6-cm longitudinal peritoneal incision previously created in the cul-de-sac. Close the incision over the top of the mesh, retroperitonealizing the mesh prosthesis (FIGURE 1, BOTTOM).

Paravaginal defect repair

The bladder base is intimately associated with the anterior vaginal wall via a triangular sheet of pubocervical fascia attached to and extending from the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis bilaterally. When the apex of the vagina prolapses through the introitus, as in total vault prolapse, the base of the bladder is torn free from these fascial attachments in the pelvis and herniates through the introitus along with the vaginal apex. By definition, a bilateral paravaginal defect will result. Thus, surgical repair of total vaginal vault prolapse almost invariably requires paravaginal defect repair as well.

The goal of paravaginal defect repair is to reattach, bilaterally, the anterolateral vaginal sulcus and its overlying endopelvic fascia to the pubococcygeus and obturator internus muscles and fascia at the level of the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis.

Technique

Enter and gently develop the retropubic space of Retzius, taking care not to disrupt the myriad venous anastomotic networks of the plexus of Santorini, located on and around the bladder. Bluntly mobilize the bladder bilaterally, exposing the lateral retropubic spaces, the pubococcygeus and obturator internus muscles, and the obturator neurovascular bundles. Within each retropubic space, palpate the ischial spine. Then visualize the arcus, seen as a white ligamentous band, as it courses from the ischial spine caudally toward the ipsilateral posterior pubic symphysis. A lateral paravaginal defect representing avulsion of the vagina off the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis, or of the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis off the obturator internus muscle, can now be visualized.

While gently reflecting the bladder medially with a wide ribbon, insert a few fingers of the nondominant hand into the vagina and elevate the ipsilateral anterolateral vaginal sulcus. Then place a suture through the fibromuscular thickness of the lateral vaginal apex, just above the uplifting fingers in the vagina, and then slightly cephalad into the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis or obturator internus fascia on the pelvic sidewall, at a point 1 to 2 cm distal to the ischial spine. Place 3 to 5 additional sutures in a similar fashion at 1-cm intervals. The most distal suture should be placed as close as possible to the pubic ramus into the pubourethral ligament. If necessary, repeat the procedure on the contralateral side. Then tie all sutures into place, thereby completing the repair.

When a patient has complete vault prolapse, she typically has defects in all 3 levels of pelvic support, and thus may need to undergo several different procedures to correct all anatomic defects and restore function.

In other words, vaginal vault prolapse rarely presents as an isolated defect. It more commonly occurs in conjunction with a cystocele, rectocele, enterocele, or some combination of these.1 Richter reported that 72% of patients with vaginal vault prolapse had a combination of other pelvic floor defects as well.2

If all vaginal support defects are repaired at the time of sacral colpopexy, recurrent vault prolapse is rare. Failures can be minimized by suturing the suspensory mesh to the posterior vagina and anterior vaginal apex over as extended an area as possible. Also test the sutures once they are placed within the periosteum of the sacral promontory to ensure they will not pull free.

Plan on occult incontinence

Total vaginal vault prolapse is commonly associated with some degree of urethral kinking, with subsequent outflow tract obstruction. As a result, most patients with complete vault prolapse do not complain of incontinence at the initial presentation. However, once the anatomic axis of the vagina is restored and the bladder is replaced within the pelvis with subsequent straightening of the urethra, occult incontinence often is uncovered. Although the patient may have a wonderful anatomic repair of severe vault prolapse at the completion of the surgical procedure, she will not be satisfied if she suddenly finds herself floridly incontinent.

Consider formal multichannel cystometrics prior to surgery in all women undergoing repair of total vault prolapse. If genuine stress urinary incontinence is present when the prolapse is reduced, an anti-incontinence procedure can be scheduled at the same time as the surgical repair. A Burch procedure can be performed for type IIA or IIB genuine stress incontinence, or a pubovaginal sling procedure can be performed for type III stress incontinence.

Posterior colporrhaphy/perineorrhaphy

These procedures are now performed to treat the remaining rectocele and perineal defect, when present.

Vaginal vs abdominal route

Somewhat surprisingly, the abdominal route appears to produce better long-term results. In a prospective, randomized controlled trial comparing both routes for the repair of total vault prolapse, Benson et al3 found that, after 5 years of follow-up, women managed vaginally had a 6-fold increased incidence of recurrent vault prolapse, a 3-fold increased incidence of recurrent cystocele, and twice the reoperation rate, compared with women whose initial repair was abdominal.

In the study, 48 women with total vault prolapse underwent vaginal bilateral sacrospinous fixation and paravaginal defect repair, and 40 underwent abdominal sacral colpopexy and paravaginal defect repair. Although the vaginal approach was associated with a shorter operative time and decreased hospital stay in the short term, it necessitated longer postoperative catheter use and was associated with more urinary tract infections and postoperative incontinence and a higher overall failure rate.

Sze and colleagues4 addressed a similar question in retrospective fashion, reviewing the medical records of 117 women surgically treated for total vault prolapse. Sixty-one women underwent vaginal sacrospinous ligament fixation and Raz urethropexy, while 56 underwent abdominal sacral colpopexy and Burch urethropexy. After a mean follow-up of 24 months, 33% of the women managed vaginally developed recurrent pelvic organ prolapse, compared with only 19% of the women managed abdominally. In addition, 26% of the women managed vaginally had recurrent urinary incontinence, compared with only 13% of the women managed abdominally

A separate randomized, prospective study by Maher et al5 compared abdominal sacral colpopexy (n=47) and vaginal sacrospinous ligament fixation (n=48) for stage II to IV vault prolapse. After a mean follow-up of 2 years, subjective and objective success rates did not differ significantly between the 2 routes.

Why is the abdominal route more durable?

Any number of reasons may apply:

- The traditional surgical procedure for vaginal management of total vault prolapse—sacrospinous ligament fixation—distorts the axis of the vagina.

- Native tissues are not as strong as synthetic materials. In postmenopausal women, a repair in which the thin, atrophic vaginal apex is secured to the sacrospinous ligament will not have the same durability as a repair involving mesh.

- In vaginal paravaginal repair, the extensive periurethral dissection required can damage fine branches of the pudendal nerve that innervate and control the urethral sphincter. Such extensive dissection is not required for paravaginal repair from the abdominal approach.

- In the vaginal approach, it can be difficult to gain adequate exposure high in the retroperitoneum to reattach the endopelvic fascia of the vaginal apex to the arcus at its origin just distal to the ischial spine.

The long view

The surgical options described in this article have varying degrees of risk and benefit. Multicenter, prospective surgical trials are needed to clarify these risks and benefits and provide physicians and their patients with reliable information. Ultimately, pursuit of a surgical “cure” will be supplanted by sustainable forms of disease prevention. Until then, decisions about prolapse surgery are best left to the judgment of the surgeon and the desires of his or her patient.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. Herbst A, Mishell D, Stenchever M. Disorders of the abdominal wall and pelvic support. In: Comprehensive Gynecology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby Year Book; 1992:594–612.

2. Richter K. Massive eversion of the vagina: pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapy of the true prolapse of the vaginal stump. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1982;25:897-912.

3. Benson JT, Lucente V, McClellan E. Vaginal versus abdominal reconstructive surgery for the treatment of pelvic support defects: a prospective randomized study with long term outcome evaluation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1418-1422.

4. Sze EH, Kohli N, Miklos JR, Roat T, Karram MM. A retrospective comparison of abdominal sacrocolpopexy with Burch colposuspension versus sacrospinous fixation with transvaginal needle suspension for the management of vaginal vault prolapse and coexisting stress incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 1999;10:390-393.

5. Maher CF, Qatawneh AM, Dwyer PL, Carey MP, Cornish A, Schluter PJ. Abdominal SCP or vaginal sacrospinous colpopexy for vaginal vault prolapse: a prospective randomized study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:20-26.

A range of clinical conditions can suggest an abdominal approach for vaginal vault prolapse procedures.

These include, but are not limited to:

- prior unsuccessful vaginal attempts

- obligate need for adnexal access

- markedly foreshortened vagina

- pelvic bony architectural limitations

- high risk for surgical failure (eg, athleticism, obesity, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congenital connective tissue disorder)

- desire for uterine preservation

In Part 1 (November 2005) of this 2-part article, we reviewed the most widely used and the newest vaginal techniques. Part 2 focuses on the abdominal approach, and compares vaginal and abdominal approaches.

High uterosacral ligament suspension

Surgical technique for this procedure for mild to moderate vaginal vault prolapse (stage I or II), using a vaginal approach, was described in Part 1, in the November issue of OBG Management. Abdominal repair involves the same concepts; like the vaginal approach, it is applicable only to the patient with mild to moderate vault prolapse. It will be less successful if it is performed to address complete vault prolapse.

Technique

Identify and tag the remnants of the uterosacral ligaments at the level of the ischial spines. Once the ureters are identified and isolated, address the enterocele by obliterating the cul-de-sac via Halban’s culdoplasty or abdominal McCall’s culdoplasty.

Open the peritoneum over the vaginal apex and trim it back to the level of the endopelvic fascia of the vaginal wall. After excising the redundant peritoneum of the vaginal apex, identify and reapproximate the pubocervical fascia of the anterior vaginal wall and the rectovaginal fascia of the posterior vaginal wall using interrupted or running nonabsorbable suture.

Then use nonabsorbable sutures to suspend each corner of the prolapsed vagina from its respective ipsilateral uterosacral ligament.

Abdominal sacral colpopexy

Abdominal sacral colpopexy was first popularized by Addison and Timmons in the 1980s, and is the abdominal standard of apical prolapse repair due to its long-term durability.

Abdominal sacral colpopexy can be performed with or without uterine extirpation. When a hysterectomy is performed concomitantly, some surgeons prefer a supracervical approach, provided there is no history of cervical dysplasia, because, theoretically, the cervical stump serves as a firm and substantial point of fixation for the synthetic mesh that will be used to perform the repair. This in turn may diminish the likelihood of postoperative mesh erosion.

Technique

Reflect the sigmoid colon as far as possible into the left lateral pelvis to expose the sacral promontory. If it has not already been done, free all adhesions between the colon and pelvic peritoneum to fully mobilize the colon and permit its maximal retraction out of the pelvic field prior to making the peritoneal incision.

Also make it a point to identify all structures at risk during this portion of the procedure—namely, the common iliac vessels, ureters, and middle sacral artery and vein. The left common iliac vein is medial to the left common iliac artery and is particularly susceptible to injury during this phase of the procedure.

Make a longitudinal incision in the peritoneum overlying the sacral promontory and extend it approximately 6 cm from the promontory dorsally into the cul-de-sac, opening the retrorectal space (FIGURE 1, TOP). Using a fine tonsil forceps and cautery, very gently dissect the retroareolar filmy tissue overlying the anterior longitudinal ligament away from S1 in thin layers until the white periosteum of the anterior longitudinal ligament overlying S1 is clearly exposed. It now becomes very easy to visualize the course of the middle sacral artery and vein. With these vessels under direct visualization, place 2 permanent #0 sutures through the periosteum of S1.

Do not attempt to place these sutures deeper in the presacral space than the S1 vertebral body, or life-threatening and uncontrollable bleeding may result.

If there is no uterus, insert a probe such as an end-to-end anastomotic sizer or handheld Harrington retractor into the vagina and extend it, elongating and elevating the vaginal cylinder. It now becomes much easier to identify the interface between the bladder and vagina prior to making the peritoneal incision.

If the interface remains indistinct, instill 150 cc of saline into the bladder to delineate its boundaries. Then elevate and incise the vesicouterine peritoneum overlying the junction between the bladder and vaginal apex; this provides access to the vesicocervical space. Dissect the bladder off the anterior vaginal wall in a caudal direction until the pubocervical fascia can be identified. Do not dissect away the peritoneum over the posterior vaginal wall, but leave it intact.

FIGURE 1Abdominal sacral colpopexy technique

Reconstructive materials

Although many different materials have been described, none have undergone rigorous comparisons. In our institution, we use soft polypropylene (Surgipro; US Surgical, Norwalk, Conn).

Fold a piece of 5-inch mesh over onto itself and suture the layers together to create a double-thickness configuration. Then “fishmouth” the caudal end of this mesh prosthesis, producing both an anterior and posterior leaf. With the obturator still within the vaginal cylinder stretching the vaginal apex, secure the posterior leaf of the mesh to the posterior vaginal wall with 3 to 5 nonabsorbable #0 sutures.

Suture placement. Thread each suture initially through the posterior leaf of the mesh, placed deeply through the fibromuscular thickness of the posterior vaginal wall, then bring it back out through the mesh at the same point. Place the sutures in a transverse line 1 to 2 cm apart and 3 to 4 cm distal to the vaginal apex.

Once all sutures have been placed, tie each of them, thereby securing the posterior leaf of the mesh to the posterior vaginal wall. Now perform a “mirror” procedure to secure the anterior leaf of the mesh prosthesis to the anterior vaginal wall. Then firmly attach the mesh prosthesis to the vaginal apex using several interrupted, permanent sutures.

At this point, the sutures previously placed through the periosteum of the sacral promontory are threaded through the apex of the mesh prosthesis at a point that will allow the vagina to rest comfortably within the pelvis, without undue tension or traction once the sutures are tied into place (FIGURE 1, MIDDLE).

Trim any excess mesh, and close the 6-cm longitudinal peritoneal incision previously created in the cul-de-sac. Close the incision over the top of the mesh, retroperitonealizing the mesh prosthesis (FIGURE 1, BOTTOM).

Paravaginal defect repair

The bladder base is intimately associated with the anterior vaginal wall via a triangular sheet of pubocervical fascia attached to and extending from the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis bilaterally. When the apex of the vagina prolapses through the introitus, as in total vault prolapse, the base of the bladder is torn free from these fascial attachments in the pelvis and herniates through the introitus along with the vaginal apex. By definition, a bilateral paravaginal defect will result. Thus, surgical repair of total vaginal vault prolapse almost invariably requires paravaginal defect repair as well.

The goal of paravaginal defect repair is to reattach, bilaterally, the anterolateral vaginal sulcus and its overlying endopelvic fascia to the pubococcygeus and obturator internus muscles and fascia at the level of the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis.

Technique

Enter and gently develop the retropubic space of Retzius, taking care not to disrupt the myriad venous anastomotic networks of the plexus of Santorini, located on and around the bladder. Bluntly mobilize the bladder bilaterally, exposing the lateral retropubic spaces, the pubococcygeus and obturator internus muscles, and the obturator neurovascular bundles. Within each retropubic space, palpate the ischial spine. Then visualize the arcus, seen as a white ligamentous band, as it courses from the ischial spine caudally toward the ipsilateral posterior pubic symphysis. A lateral paravaginal defect representing avulsion of the vagina off the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis, or of the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis off the obturator internus muscle, can now be visualized.

While gently reflecting the bladder medially with a wide ribbon, insert a few fingers of the nondominant hand into the vagina and elevate the ipsilateral anterolateral vaginal sulcus. Then place a suture through the fibromuscular thickness of the lateral vaginal apex, just above the uplifting fingers in the vagina, and then slightly cephalad into the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis or obturator internus fascia on the pelvic sidewall, at a point 1 to 2 cm distal to the ischial spine. Place 3 to 5 additional sutures in a similar fashion at 1-cm intervals. The most distal suture should be placed as close as possible to the pubic ramus into the pubourethral ligament. If necessary, repeat the procedure on the contralateral side. Then tie all sutures into place, thereby completing the repair.

When a patient has complete vault prolapse, she typically has defects in all 3 levels of pelvic support, and thus may need to undergo several different procedures to correct all anatomic defects and restore function.

In other words, vaginal vault prolapse rarely presents as an isolated defect. It more commonly occurs in conjunction with a cystocele, rectocele, enterocele, or some combination of these.1 Richter reported that 72% of patients with vaginal vault prolapse had a combination of other pelvic floor defects as well.2

If all vaginal support defects are repaired at the time of sacral colpopexy, recurrent vault prolapse is rare. Failures can be minimized by suturing the suspensory mesh to the posterior vagina and anterior vaginal apex over as extended an area as possible. Also test the sutures once they are placed within the periosteum of the sacral promontory to ensure they will not pull free.

Plan on occult incontinence

Total vaginal vault prolapse is commonly associated with some degree of urethral kinking, with subsequent outflow tract obstruction. As a result, most patients with complete vault prolapse do not complain of incontinence at the initial presentation. However, once the anatomic axis of the vagina is restored and the bladder is replaced within the pelvis with subsequent straightening of the urethra, occult incontinence often is uncovered. Although the patient may have a wonderful anatomic repair of severe vault prolapse at the completion of the surgical procedure, she will not be satisfied if she suddenly finds herself floridly incontinent.

Consider formal multichannel cystometrics prior to surgery in all women undergoing repair of total vault prolapse. If genuine stress urinary incontinence is present when the prolapse is reduced, an anti-incontinence procedure can be scheduled at the same time as the surgical repair. A Burch procedure can be performed for type IIA or IIB genuine stress incontinence, or a pubovaginal sling procedure can be performed for type III stress incontinence.

Posterior colporrhaphy/perineorrhaphy

These procedures are now performed to treat the remaining rectocele and perineal defect, when present.

Vaginal vs abdominal route

Somewhat surprisingly, the abdominal route appears to produce better long-term results. In a prospective, randomized controlled trial comparing both routes for the repair of total vault prolapse, Benson et al3 found that, after 5 years of follow-up, women managed vaginally had a 6-fold increased incidence of recurrent vault prolapse, a 3-fold increased incidence of recurrent cystocele, and twice the reoperation rate, compared with women whose initial repair was abdominal.

In the study, 48 women with total vault prolapse underwent vaginal bilateral sacrospinous fixation and paravaginal defect repair, and 40 underwent abdominal sacral colpopexy and paravaginal defect repair. Although the vaginal approach was associated with a shorter operative time and decreased hospital stay in the short term, it necessitated longer postoperative catheter use and was associated with more urinary tract infections and postoperative incontinence and a higher overall failure rate.

Sze and colleagues4 addressed a similar question in retrospective fashion, reviewing the medical records of 117 women surgically treated for total vault prolapse. Sixty-one women underwent vaginal sacrospinous ligament fixation and Raz urethropexy, while 56 underwent abdominal sacral colpopexy and Burch urethropexy. After a mean follow-up of 24 months, 33% of the women managed vaginally developed recurrent pelvic organ prolapse, compared with only 19% of the women managed abdominally. In addition, 26% of the women managed vaginally had recurrent urinary incontinence, compared with only 13% of the women managed abdominally

A separate randomized, prospective study by Maher et al5 compared abdominal sacral colpopexy (n=47) and vaginal sacrospinous ligament fixation (n=48) for stage II to IV vault prolapse. After a mean follow-up of 2 years, subjective and objective success rates did not differ significantly between the 2 routes.

Why is the abdominal route more durable?

Any number of reasons may apply:

- The traditional surgical procedure for vaginal management of total vault prolapse—sacrospinous ligament fixation—distorts the axis of the vagina.

- Native tissues are not as strong as synthetic materials. In postmenopausal women, a repair in which the thin, atrophic vaginal apex is secured to the sacrospinous ligament will not have the same durability as a repair involving mesh.

- In vaginal paravaginal repair, the extensive periurethral dissection required can damage fine branches of the pudendal nerve that innervate and control the urethral sphincter. Such extensive dissection is not required for paravaginal repair from the abdominal approach.

- In the vaginal approach, it can be difficult to gain adequate exposure high in the retroperitoneum to reattach the endopelvic fascia of the vaginal apex to the arcus at its origin just distal to the ischial spine.

The long view

The surgical options described in this article have varying degrees of risk and benefit. Multicenter, prospective surgical trials are needed to clarify these risks and benefits and provide physicians and their patients with reliable information. Ultimately, pursuit of a surgical “cure” will be supplanted by sustainable forms of disease prevention. Until then, decisions about prolapse surgery are best left to the judgment of the surgeon and the desires of his or her patient.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

A range of clinical conditions can suggest an abdominal approach for vaginal vault prolapse procedures.

These include, but are not limited to:

- prior unsuccessful vaginal attempts

- obligate need for adnexal access

- markedly foreshortened vagina

- pelvic bony architectural limitations

- high risk for surgical failure (eg, athleticism, obesity, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congenital connective tissue disorder)

- desire for uterine preservation

In Part 1 (November 2005) of this 2-part article, we reviewed the most widely used and the newest vaginal techniques. Part 2 focuses on the abdominal approach, and compares vaginal and abdominal approaches.

High uterosacral ligament suspension

Surgical technique for this procedure for mild to moderate vaginal vault prolapse (stage I or II), using a vaginal approach, was described in Part 1, in the November issue of OBG Management. Abdominal repair involves the same concepts; like the vaginal approach, it is applicable only to the patient with mild to moderate vault prolapse. It will be less successful if it is performed to address complete vault prolapse.

Technique

Identify and tag the remnants of the uterosacral ligaments at the level of the ischial spines. Once the ureters are identified and isolated, address the enterocele by obliterating the cul-de-sac via Halban’s culdoplasty or abdominal McCall’s culdoplasty.

Open the peritoneum over the vaginal apex and trim it back to the level of the endopelvic fascia of the vaginal wall. After excising the redundant peritoneum of the vaginal apex, identify and reapproximate the pubocervical fascia of the anterior vaginal wall and the rectovaginal fascia of the posterior vaginal wall using interrupted or running nonabsorbable suture.

Then use nonabsorbable sutures to suspend each corner of the prolapsed vagina from its respective ipsilateral uterosacral ligament.

Abdominal sacral colpopexy

Abdominal sacral colpopexy was first popularized by Addison and Timmons in the 1980s, and is the abdominal standard of apical prolapse repair due to its long-term durability.

Abdominal sacral colpopexy can be performed with or without uterine extirpation. When a hysterectomy is performed concomitantly, some surgeons prefer a supracervical approach, provided there is no history of cervical dysplasia, because, theoretically, the cervical stump serves as a firm and substantial point of fixation for the synthetic mesh that will be used to perform the repair. This in turn may diminish the likelihood of postoperative mesh erosion.

Technique

Reflect the sigmoid colon as far as possible into the left lateral pelvis to expose the sacral promontory. If it has not already been done, free all adhesions between the colon and pelvic peritoneum to fully mobilize the colon and permit its maximal retraction out of the pelvic field prior to making the peritoneal incision.

Also make it a point to identify all structures at risk during this portion of the procedure—namely, the common iliac vessels, ureters, and middle sacral artery and vein. The left common iliac vein is medial to the left common iliac artery and is particularly susceptible to injury during this phase of the procedure.

Make a longitudinal incision in the peritoneum overlying the sacral promontory and extend it approximately 6 cm from the promontory dorsally into the cul-de-sac, opening the retrorectal space (FIGURE 1, TOP). Using a fine tonsil forceps and cautery, very gently dissect the retroareolar filmy tissue overlying the anterior longitudinal ligament away from S1 in thin layers until the white periosteum of the anterior longitudinal ligament overlying S1 is clearly exposed. It now becomes very easy to visualize the course of the middle sacral artery and vein. With these vessels under direct visualization, place 2 permanent #0 sutures through the periosteum of S1.

Do not attempt to place these sutures deeper in the presacral space than the S1 vertebral body, or life-threatening and uncontrollable bleeding may result.

If there is no uterus, insert a probe such as an end-to-end anastomotic sizer or handheld Harrington retractor into the vagina and extend it, elongating and elevating the vaginal cylinder. It now becomes much easier to identify the interface between the bladder and vagina prior to making the peritoneal incision.

If the interface remains indistinct, instill 150 cc of saline into the bladder to delineate its boundaries. Then elevate and incise the vesicouterine peritoneum overlying the junction between the bladder and vaginal apex; this provides access to the vesicocervical space. Dissect the bladder off the anterior vaginal wall in a caudal direction until the pubocervical fascia can be identified. Do not dissect away the peritoneum over the posterior vaginal wall, but leave it intact.

FIGURE 1Abdominal sacral colpopexy technique

Reconstructive materials

Although many different materials have been described, none have undergone rigorous comparisons. In our institution, we use soft polypropylene (Surgipro; US Surgical, Norwalk, Conn).

Fold a piece of 5-inch mesh over onto itself and suture the layers together to create a double-thickness configuration. Then “fishmouth” the caudal end of this mesh prosthesis, producing both an anterior and posterior leaf. With the obturator still within the vaginal cylinder stretching the vaginal apex, secure the posterior leaf of the mesh to the posterior vaginal wall with 3 to 5 nonabsorbable #0 sutures.

Suture placement. Thread each suture initially through the posterior leaf of the mesh, placed deeply through the fibromuscular thickness of the posterior vaginal wall, then bring it back out through the mesh at the same point. Place the sutures in a transverse line 1 to 2 cm apart and 3 to 4 cm distal to the vaginal apex.

Once all sutures have been placed, tie each of them, thereby securing the posterior leaf of the mesh to the posterior vaginal wall. Now perform a “mirror” procedure to secure the anterior leaf of the mesh prosthesis to the anterior vaginal wall. Then firmly attach the mesh prosthesis to the vaginal apex using several interrupted, permanent sutures.

At this point, the sutures previously placed through the periosteum of the sacral promontory are threaded through the apex of the mesh prosthesis at a point that will allow the vagina to rest comfortably within the pelvis, without undue tension or traction once the sutures are tied into place (FIGURE 1, MIDDLE).

Trim any excess mesh, and close the 6-cm longitudinal peritoneal incision previously created in the cul-de-sac. Close the incision over the top of the mesh, retroperitonealizing the mesh prosthesis (FIGURE 1, BOTTOM).

Paravaginal defect repair

The bladder base is intimately associated with the anterior vaginal wall via a triangular sheet of pubocervical fascia attached to and extending from the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis bilaterally. When the apex of the vagina prolapses through the introitus, as in total vault prolapse, the base of the bladder is torn free from these fascial attachments in the pelvis and herniates through the introitus along with the vaginal apex. By definition, a bilateral paravaginal defect will result. Thus, surgical repair of total vaginal vault prolapse almost invariably requires paravaginal defect repair as well.

The goal of paravaginal defect repair is to reattach, bilaterally, the anterolateral vaginal sulcus and its overlying endopelvic fascia to the pubococcygeus and obturator internus muscles and fascia at the level of the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis.

Technique

Enter and gently develop the retropubic space of Retzius, taking care not to disrupt the myriad venous anastomotic networks of the plexus of Santorini, located on and around the bladder. Bluntly mobilize the bladder bilaterally, exposing the lateral retropubic spaces, the pubococcygeus and obturator internus muscles, and the obturator neurovascular bundles. Within each retropubic space, palpate the ischial spine. Then visualize the arcus, seen as a white ligamentous band, as it courses from the ischial spine caudally toward the ipsilateral posterior pubic symphysis. A lateral paravaginal defect representing avulsion of the vagina off the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis, or of the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis off the obturator internus muscle, can now be visualized.

While gently reflecting the bladder medially with a wide ribbon, insert a few fingers of the nondominant hand into the vagina and elevate the ipsilateral anterolateral vaginal sulcus. Then place a suture through the fibromuscular thickness of the lateral vaginal apex, just above the uplifting fingers in the vagina, and then slightly cephalad into the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis or obturator internus fascia on the pelvic sidewall, at a point 1 to 2 cm distal to the ischial spine. Place 3 to 5 additional sutures in a similar fashion at 1-cm intervals. The most distal suture should be placed as close as possible to the pubic ramus into the pubourethral ligament. If necessary, repeat the procedure on the contralateral side. Then tie all sutures into place, thereby completing the repair.

When a patient has complete vault prolapse, she typically has defects in all 3 levels of pelvic support, and thus may need to undergo several different procedures to correct all anatomic defects and restore function.

In other words, vaginal vault prolapse rarely presents as an isolated defect. It more commonly occurs in conjunction with a cystocele, rectocele, enterocele, or some combination of these.1 Richter reported that 72% of patients with vaginal vault prolapse had a combination of other pelvic floor defects as well.2

If all vaginal support defects are repaired at the time of sacral colpopexy, recurrent vault prolapse is rare. Failures can be minimized by suturing the suspensory mesh to the posterior vagina and anterior vaginal apex over as extended an area as possible. Also test the sutures once they are placed within the periosteum of the sacral promontory to ensure they will not pull free.

Plan on occult incontinence

Total vaginal vault prolapse is commonly associated with some degree of urethral kinking, with subsequent outflow tract obstruction. As a result, most patients with complete vault prolapse do not complain of incontinence at the initial presentation. However, once the anatomic axis of the vagina is restored and the bladder is replaced within the pelvis with subsequent straightening of the urethra, occult incontinence often is uncovered. Although the patient may have a wonderful anatomic repair of severe vault prolapse at the completion of the surgical procedure, she will not be satisfied if she suddenly finds herself floridly incontinent.

Consider formal multichannel cystometrics prior to surgery in all women undergoing repair of total vault prolapse. If genuine stress urinary incontinence is present when the prolapse is reduced, an anti-incontinence procedure can be scheduled at the same time as the surgical repair. A Burch procedure can be performed for type IIA or IIB genuine stress incontinence, or a pubovaginal sling procedure can be performed for type III stress incontinence.

Posterior colporrhaphy/perineorrhaphy

These procedures are now performed to treat the remaining rectocele and perineal defect, when present.

Vaginal vs abdominal route

Somewhat surprisingly, the abdominal route appears to produce better long-term results. In a prospective, randomized controlled trial comparing both routes for the repair of total vault prolapse, Benson et al3 found that, after 5 years of follow-up, women managed vaginally had a 6-fold increased incidence of recurrent vault prolapse, a 3-fold increased incidence of recurrent cystocele, and twice the reoperation rate, compared with women whose initial repair was abdominal.

In the study, 48 women with total vault prolapse underwent vaginal bilateral sacrospinous fixation and paravaginal defect repair, and 40 underwent abdominal sacral colpopexy and paravaginal defect repair. Although the vaginal approach was associated with a shorter operative time and decreased hospital stay in the short term, it necessitated longer postoperative catheter use and was associated with more urinary tract infections and postoperative incontinence and a higher overall failure rate.

Sze and colleagues4 addressed a similar question in retrospective fashion, reviewing the medical records of 117 women surgically treated for total vault prolapse. Sixty-one women underwent vaginal sacrospinous ligament fixation and Raz urethropexy, while 56 underwent abdominal sacral colpopexy and Burch urethropexy. After a mean follow-up of 24 months, 33% of the women managed vaginally developed recurrent pelvic organ prolapse, compared with only 19% of the women managed abdominally. In addition, 26% of the women managed vaginally had recurrent urinary incontinence, compared with only 13% of the women managed abdominally

A separate randomized, prospective study by Maher et al5 compared abdominal sacral colpopexy (n=47) and vaginal sacrospinous ligament fixation (n=48) for stage II to IV vault prolapse. After a mean follow-up of 2 years, subjective and objective success rates did not differ significantly between the 2 routes.

Why is the abdominal route more durable?

Any number of reasons may apply:

- The traditional surgical procedure for vaginal management of total vault prolapse—sacrospinous ligament fixation—distorts the axis of the vagina.

- Native tissues are not as strong as synthetic materials. In postmenopausal women, a repair in which the thin, atrophic vaginal apex is secured to the sacrospinous ligament will not have the same durability as a repair involving mesh.

- In vaginal paravaginal repair, the extensive periurethral dissection required can damage fine branches of the pudendal nerve that innervate and control the urethral sphincter. Such extensive dissection is not required for paravaginal repair from the abdominal approach.

- In the vaginal approach, it can be difficult to gain adequate exposure high in the retroperitoneum to reattach the endopelvic fascia of the vaginal apex to the arcus at its origin just distal to the ischial spine.

The long view

The surgical options described in this article have varying degrees of risk and benefit. Multicenter, prospective surgical trials are needed to clarify these risks and benefits and provide physicians and their patients with reliable information. Ultimately, pursuit of a surgical “cure” will be supplanted by sustainable forms of disease prevention. Until then, decisions about prolapse surgery are best left to the judgment of the surgeon and the desires of his or her patient.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. Herbst A, Mishell D, Stenchever M. Disorders of the abdominal wall and pelvic support. In: Comprehensive Gynecology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby Year Book; 1992:594–612.

2. Richter K. Massive eversion of the vagina: pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapy of the true prolapse of the vaginal stump. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1982;25:897-912.

3. Benson JT, Lucente V, McClellan E. Vaginal versus abdominal reconstructive surgery for the treatment of pelvic support defects: a prospective randomized study with long term outcome evaluation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1418-1422.

4. Sze EH, Kohli N, Miklos JR, Roat T, Karram MM. A retrospective comparison of abdominal sacrocolpopexy with Burch colposuspension versus sacrospinous fixation with transvaginal needle suspension for the management of vaginal vault prolapse and coexisting stress incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 1999;10:390-393.

5. Maher CF, Qatawneh AM, Dwyer PL, Carey MP, Cornish A, Schluter PJ. Abdominal SCP or vaginal sacrospinous colpopexy for vaginal vault prolapse: a prospective randomized study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:20-26.

1. Herbst A, Mishell D, Stenchever M. Disorders of the abdominal wall and pelvic support. In: Comprehensive Gynecology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby Year Book; 1992:594–612.

2. Richter K. Massive eversion of the vagina: pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapy of the true prolapse of the vaginal stump. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1982;25:897-912.

3. Benson JT, Lucente V, McClellan E. Vaginal versus abdominal reconstructive surgery for the treatment of pelvic support defects: a prospective randomized study with long term outcome evaluation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1418-1422.

4. Sze EH, Kohli N, Miklos JR, Roat T, Karram MM. A retrospective comparison of abdominal sacrocolpopexy with Burch colposuspension versus sacrospinous fixation with transvaginal needle suspension for the management of vaginal vault prolapse and coexisting stress incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 1999;10:390-393.

5. Maher CF, Qatawneh AM, Dwyer PL, Carey MP, Cornish A, Schluter PJ. Abdominal SCP or vaginal sacrospinous colpopexy for vaginal vault prolapse: a prospective randomized study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:20-26.

Surgical management of vaginal vault prolapse

First, the good news: We have numerous techniques to choose from to repair prolapse of the vaginal vault, which affects as many as 50% of parous women.1 The bad news: Most of the data on these techniques are anecdotal or retrospective, not the result of randomized, controlled trials. Few investigators have compared the vaginal and abdominal approaches.

So how should we decide on a procedure? It is a judgment call, ultimately. After taking into account the patient’s age, functional status, comorbidities, desire for coitus, and surgical history, the surgeon must weigh the risks and benefits of the procedures that seem most appropriate. Part 1 of this 2-part article reviews what is known about the most widely used and newest vaginal techniques:

- sacrospinous ligament fixation,

- iliococcygeal fixation,

- modified McCall culdoplasty,

- high uterosacral ligament suspension with fascial reconstruction, and

- posterior intravaginal slingplasty (infracoccygeal sacropexy).

In Part 2, next month, we focus on the abdominal approach, and survey the data comparing vaginal and abdominal repairs.

Unfortunately, success and failure rates are still poorly defined because of a lack of standardization, and because techniques and materials continually change. This underscores the need for better understanding of the pathophysiology of genital prolapse, improved preoperative assessment, and more effective and durable repair techniques.

Why prolapse occurs

Pelvic support involves a complex interplay of anatomic, histologic, genetic, and electrophysiologic factors that, although incompletely understood, are frequently disrupted. For example, MacLennan et al2 reported that 46.2% of women aged 15 to 97 years experience pelvic floor dysfunction; a large retrospective study by Olsen and colleagues3 found that 11.1% of women undergo surgery for prolapse by the age of 80, and 29.2% of these women require repeat surgery.

Here’s what we know about the anatomy of pelvic support:

Ligaments serve as secondary supports

The uterus and upper third of the vagina are held in place over the levator plate by the fibers of the parametrium (cardinal and uterosacral ligaments) and paracolpium. These fibers arise from a broad area on the pelvic sidewall overlying the fascia of the piriformis muscle, the sacroiliac joint, and lateral sacrum. The fibers represent condensations of the endopelvic fascia of the pelvis, acting as suspensory ligaments that run in a predominantly vertical direction to insert into the lateral upper third of the vagina and lateral and posterolateral aspect of the cervical portion of the uterus.

In the normal, healthy pelvis, these suspensory ligaments represent secondary support mechanisms and are not routinely under tension.

Pelvic-floor muscles play leading role

Gosling4 argued that pelvic floor muscle tone is more crucial to normal positioning of the pelvic viscera than are the fascial and ligamentous supports of the pelvic organs. Specifically, the pubococcygeus, iliococcygeus, and puborectalis muscles collectively define the levator ani of the pelvic floor. Fusion of the right and left bellies of the levator ani, behind the rectum and anterior to the coccyx, creates a muscular platform known as the levator plate. This plate provides indirect support for the upper genital tract by acting as a platform against which the upper vagina and other pelvic viscera are compressed during increases in intra-abdominal pressure.

Contraction of the levator ani pulls the levator plate toward the posterior symphysis pubis, minimizing the size of the urogenital hiatus through which the rectum, vagina, and urethra exit the pelvis on their way to the perineum. Weakness in the muscular pelvic floor—whether caused by disuse, pudendal nerve damage, or muscular trauma—increases the size of the urogenital hiatus, and the pelvic organs begin to prolapse through it.

Ultimately, constant tension on the ligamentous supports of the pelvic organs exceeds their tensile strength, and pelvic organ prolapse results.

Goals of surgery

Successful surgery achieves effective and sustained vault support, obliterates any enterocele sac, and repairs the cystocele and rectocele that occur in approximately two thirds of women with vault prolapse.

The broader goals: anatomic and functional restoration of the lower female genital tract and improvement in quality of life.

Surgery can be reconstructive or obliterative. Reconstructive surgery can be performed vaginally, abdominally, or a combination of both.

Vaginal techniques

Proponents of the vaginal approach argue that, by avoiding the need for laparotomy, it results in fewer complications, less blood loss and postoperative discomfort, a shorter hospital stay, and less expense.5

Sacrospinous ligament fixation

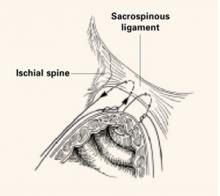

The sacrospinous ligaments extend from the ischial spines on either side to the lower portion of the sacrum and coccyx. Fixation of the vaginal apex to 1 or both of the sacrospinous ligaments is an option for posthysterectomy vault prolapse.

Technique. Nichols6 described the need to penetrate the right rectal pillar into the pararectal space near the ischial spine. The next step is grasping the ligament and muscle with a long Babcock clamp. Place two #2 polyglycolic sutures through the sacrospinous ligament, 1.5 to 2 fingerbreadths medial to the ischial spine. Attach 1 end of the suture to the undersurface of the posterior vaginal wall at the apical area. When the posterior colporrhaphy reaches the midportion of the vagina, tie the sacrospinous suspension sutures, firmly attaching the vaginal apex to the surface of the coccygeal-sacrospinous ligament complex with no intervening suture bridge (FIGURE 1).

Modifications. The most notable modification is the Miyazaki technique, which substitutes the Miya hook for the DesChamps ligature carrier. The Miya hook is reportedly safer for the pudendal complex, which may lie up to 5.5 cm medial to the ischial spine.7 The path of the Miya hook avoids Alcock’s canal and its neurovascular pudendal bundle.

The Caprio ligature carrier (Boston Scientific, Boston, Mass) is also useful for the placement of sacrospinous sutures; unlike the Miya hook, however, the Caprio ligature carrier is a disposable instrument and thus is not reusable.

Potential complications of sacrospinous ligament fixation include hemorrhage, pudendal nerve injury, rectal or bladder injury, and recurrent anterior vaginal wall prolapse.

Outcomes. Follow-up studies in women undergoing this procedure report a roughly 20% incidence of recurrent or persistent anterior vaginal wall relaxation, or symptomatic cystocele, within 1 year after the surgery. Alteration of the vaginal axis in an exaggerated posterolateral direction after this procedure is thought to place undue tension on the anterior segment of the vaginal wall and predispose women to prolapse at a site opposite the repair.8,9

FIGURE 1 2 “pulley stitches” secure the apex

Place 2 nonabsorbable monofilament “pulley stitches” to secure the vaginal apex to the ligament.

Iliococcygeal fixation

Inmon10 was the first to describe a technique in which the everted vaginal apex is secured to the iliococcygeal fascia bilaterally, just below the ischial spine. He performed this technique successfully in 3 women with atrophied uterosacral ligaments.

Technique. Open the posterior vaginal wall in the midline, as if preparing to perform a posterior colporrhaphy. Develop the rectovaginal spaces bluntly and bilaterally—laterally toward the levator muscles and posteriorally toward the ischial spines. Use the nondominant hand to depress the rectum downward and medially, and place a single #0 polyglycolic suture deep into the iliococcygeus muscle and fascia at a point 1 to 2 cm caudad and posterior to the ischial spine. Then pass both ends of the suture through the ipsilateral posterior vaginal apex and hold them with a hemostat. Repeat the procedure contralaterally.

Usually no vaginal epithelium needs excision because the upper vagina is attached bilaterally, resulting in good vaginal length and circumference. When posterior colporrhaphy is completed and the posterior vaginal wall is closed, tie both iliococcygeal-fixation sutures in place.

Complications. Shull and colleagues11 studied 42 women who underwent suspension of the vaginal cuff to iliococcygeus fascia and repair of coexisting pelvic support defects. Of these women, 2 (5%) had recurrence of their cuff prolapse during follow-up, one of whom required further surgery (she also had recurrence of an inguinal hernia that had been repaired at the original surgery). The other patient, who had undergone 5 previous pelvic procedures, developed asymptomatic prolapse of the cuff halfway to the hymen. Six additional patients had loss of support at other sites in the follow-up period, one of whom required repeat surgery. Ninety-five percent of women experienced no persistence or recurrence of cuff prolapse 6 weeks to 5 years after the procedure.

Meeks and colleagues12 also applied the Inmon technique in 110 women with posthysterectomy vault prolapse or total uterine procidentia. In both studies, the most commonly reported complications included hemorrhage (1.2%), bladder/rectal perforation (1.2%), and recurrent vault prolapse (8%).

Benefits. In comparison with sacrospinous ligament fixation, iliococcygeus fixation is technically easier and places less tension on the anterior vaginal wall.

Modified McCall culdoplasty

Symmonds and colleagues13 described this approach to symptomatic vaginal vault prolapse.

Technique. Excise an elliptical wedge of mucosa from the anterior and posterior walls of the prolapsed vagina to narrow the vault and allow access to the lateral fascial supports of the vagina and rectum. The width and length of the excised wedges are determined by the desired dimensions of the reconstructed vagina.

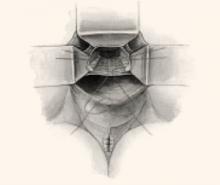

After isolating and excising the enterocele sac, place up to 3 modified McCall stitches, each one slightly higher than its predecessor. Each suture should incorporate the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall, the cul-de-sac peritoneum, the remains of the uterosacral-cardinal complex bilaterally, and the fascial tissue lateral and posterior to the upper vagina and rectum (FIGURE 2).

Once they are in place, tie the sutures in the opposite order in which they were placed. These stitches fix the prolapsed vaginal vault to the uppermost portion of the endopelvic fascia at the same time as they accomplish a high closure of the culdesac peritoneum.

The evidence. Sze and Karram5 found an 11.5% incidence of recurrent vault prolapse and an associated 22% incidence of new-onset dyspareunia.

FIGURE 2 Classic vs modified McCall culdoplasty

In the classic McCall culdoplasty shown here, only the distal-most suture incorporates the posterior vaginal wall. With the “modified” technique, however, all sutures incorporate the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall, as well as the cul-de-sac peritoneum, the remnants of the uterosacral-cardinal complex bilaterally, and the fascial tissue lateral and posterior to the upper vagina and rectum.

High uterosacral ligament suspension with fascial reconstruction

This approach is based on the observations of Richardson,14 who suggested that the endopelvic fascial supports (uterosacral/cardinal complex) do not stretch and attenuate over time, as some have hypothesized, but break at definable points. By identifying these points, the surgeon can reattach the prolapsed vagina to the intact uterosacral complex cephalad to the break.

Technique. Grasp the vaginal apex with 2 Allis clamps and incise it with a scalpel. If an enterocele sac is present, dissect it off the vaginal epithelium to the neck of the hernia, open it, and then excise it. Place a delayed absorbable or permanent pursestring suture about the neck of the hernia to close the peritoneal defect. If an anterior colporrhaphy or sling is required, perform them at this time.

Place a moist laparotomy pad in the cul-de-sac, and insert and elevate a Deaver retractor to remove the intestines from the cul-de-sac and improve exposure. Next, palpate the ischial spines transperitoneally.

Once the spines are identified, the remnants of the uterosacral ligaments can be identified posterior and medial to the spines and can be palpated transperitoneally or transrectally. Remember that the ureters are also quite close to the ischial spines at this location, running along the lateral pelvic sidewall 2 to 5 cm ventral and lateral to the ischial spines.

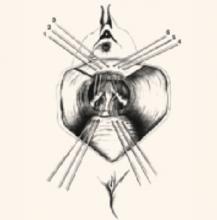

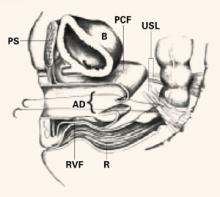

After identifying the uterosacral ligaments, grasp their remnants with Allis clamps and place 2 to 3 delayed absorbable or permanent sutures through the rectovaginal fascia of the inner posterior vaginal wall epithelium at one lateral vaginal apex, through the ipsilateral plicated uterosacral ligament complex, and then through the pubocervical fascia of the anterior vaginal wall of the ipsilateral vaginal apex. Hold these sutures while performing the same procedure contralaterally (FIGURE 3). Close the apex and tie these sutures in place, suspending the corners of the vaginal apex from the uterosacral complex bilaterally, and restoring the continuity of the paracervical ring (FIGURES 4, 5).

Benefits of this technique include:

- creation of an anatomically appropriate and correctly positioned midline vaginal axis,

- preservation of adequate vaginal length,

- reduced risk of nerve injury, and

- restored continuity of the paracervical ring when the pelvic pararectal, uterosacral, and pubocervical fascia are reapproximated circumferentially.

Risks include the potential for ureteral kinking or obstruction. Thus, it is prudent to perform cystoscopy after this procedure to rule out occult injury.

FIGURE 3 Suspend apical corners bilaterally

The corners of the vaginal apex are suspended from the cardinal-uterosacral complex bilaterally, with all sutures placed posterior and medial to the ischial spines. Copyright 1998 by C.G. Bachofen.

FIGURE 4 Suture placement penetrates multiple layers

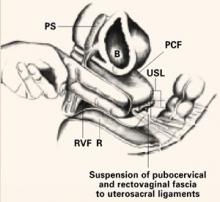

Sagittal view of correct suture placement. PS=pubic symphysis, B=bladder, PCF=pubocervical fascia, USL=uterosacral ligaments, AD=apical defect, RVF=rectovaginal fascia, R=rectum. Copyright 1998 by C.G. Bachofen.

FIGURE 5 Suspend the fascia from uterosacral ligaments

Sagittal view after tying of sutures. Note restoration of the normal anatomic axis. PS=pubic symphysis, B=bladder, PCF=pubocervical fascia, USL=uterosacral ligaments, RVF=rectovaginal fascia, R=rectum. Copyright 1998 by C.G. Bachofen.

Posterior intravaginal slingplasty

This investigative technique, also known as infracoccygeal sacropexy, is a minimally invasive, transperineal approach to vaginal vault prolapse. The anatomic and physiologic concepts are similar to those of the tension-free vaginal tape (Gynecare, Somerville, NJ) in the treatment of stress incontinence. However, because it is a new procedure, further evaluation is needed before it can be adopted into clinical practice.

This is an outpatient surgery.

Technique. Use a narrow tunneling device to pass a synthetic nonabsorbable tape through each pararectal space via a small perineal incision, and make a small vaginal incision to secure the tape to the vault.

The evidence. In the initial case series of 93 patients,15 1 rectal perforation and 1 rectal tape erosion were noted. The cure rate was 91% in short-term follow-up in a small number of patients.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. Beck RP. Pelvic relaxational prolapse. In: Principles and Practice of Clinical Gynecology. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1983;667-685.

2. MacLennan AH, Taylor AW, Wilson DH, Wilson D. The prevalence of pelvic floor disorders and their relationship to gender, age, parity, and mode of delivery. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;107:1460-1470.

3. Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:501-506.

4. Gosling JA. The structure of the bladder neck, urethra and pelvic floor in relation to female urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J. 1996;7:177-178.

5. Sze EHM, Karram MM. Transvaginal repair of vault prolapse: a review. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:466-475.

6. Nichols D. Sacrospinous fixation for massive eversion of the vagina. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;142:901-904.

7. Miyazaki FS. Miya hook ligature carrier for sacrospinous ligament suspension. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;70:286-288.

8. Morley G, DeLancey JO. Sacrospinous ligament fixation for eversion of the vagina. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158:872-878.

9. Shull BL, Capen CV, Riggs MW. Preoperative analysis of site specific pelvic support defects in 81 women treated with sacrospinous ligament suspension and pelvic reconstruction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166:1764-1771.

10. Inmon WB. Pelvic relaxation and repair including prolapse of vagina following hysterectomy. South Med J. 1963;56:577-582.

11. Shull BT, Capen CV, Riggs MW. Bilateral attachment of the vaginal cuff to iliococcygeus fascia: an effective method of cuff suspension. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 193;168:1669-1673.

12. Meeks GR, Washburne JF, McGehrer RP. Repair of vaginal vault prolapse by suspension of the vagina to iliococcygeus (prespinous) fascia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:1444-1449.

13. Symmonds RE, Williams TJ, Lee RA, Webbs MJ. Posthysterectomy enterocoele and vaginal vault prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;140:852-859.

14. Richardson AL. The anatomic defects in rectocoele and enterocoele. J Pelvic Surg. 1995;1:214-218.

15. Farnsworth BN. Posterior intravaginal slingplasty (infracoccygeal sacropexy) for severe posthysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse: a preliminary report on efficacy and safety. Int Urogynecol J. 2002;13:4-8.

First, the good news: We have numerous techniques to choose from to repair prolapse of the vaginal vault, which affects as many as 50% of parous women.1 The bad news: Most of the data on these techniques are anecdotal or retrospective, not the result of randomized, controlled trials. Few investigators have compared the vaginal and abdominal approaches.

So how should we decide on a procedure? It is a judgment call, ultimately. After taking into account the patient’s age, functional status, comorbidities, desire for coitus, and surgical history, the surgeon must weigh the risks and benefits of the procedures that seem most appropriate. Part 1 of this 2-part article reviews what is known about the most widely used and newest vaginal techniques:

- sacrospinous ligament fixation,

- iliococcygeal fixation,

- modified McCall culdoplasty,

- high uterosacral ligament suspension with fascial reconstruction, and

- posterior intravaginal slingplasty (infracoccygeal sacropexy).

In Part 2, next month, we focus on the abdominal approach, and survey the data comparing vaginal and abdominal repairs.

Unfortunately, success and failure rates are still poorly defined because of a lack of standardization, and because techniques and materials continually change. This underscores the need for better understanding of the pathophysiology of genital prolapse, improved preoperative assessment, and more effective and durable repair techniques.

Why prolapse occurs

Pelvic support involves a complex interplay of anatomic, histologic, genetic, and electrophysiologic factors that, although incompletely understood, are frequently disrupted. For example, MacLennan et al2 reported that 46.2% of women aged 15 to 97 years experience pelvic floor dysfunction; a large retrospective study by Olsen and colleagues3 found that 11.1% of women undergo surgery for prolapse by the age of 80, and 29.2% of these women require repeat surgery.

Here’s what we know about the anatomy of pelvic support:

Ligaments serve as secondary supports

The uterus and upper third of the vagina are held in place over the levator plate by the fibers of the parametrium (cardinal and uterosacral ligaments) and paracolpium. These fibers arise from a broad area on the pelvic sidewall overlying the fascia of the piriformis muscle, the sacroiliac joint, and lateral sacrum. The fibers represent condensations of the endopelvic fascia of the pelvis, acting as suspensory ligaments that run in a predominantly vertical direction to insert into the lateral upper third of the vagina and lateral and posterolateral aspect of the cervical portion of the uterus.

In the normal, healthy pelvis, these suspensory ligaments represent secondary support mechanisms and are not routinely under tension.

Pelvic-floor muscles play leading role

Gosling4 argued that pelvic floor muscle tone is more crucial to normal positioning of the pelvic viscera than are the fascial and ligamentous supports of the pelvic organs. Specifically, the pubococcygeus, iliococcygeus, and puborectalis muscles collectively define the levator ani of the pelvic floor. Fusion of the right and left bellies of the levator ani, behind the rectum and anterior to the coccyx, creates a muscular platform known as the levator plate. This plate provides indirect support for the upper genital tract by acting as a platform against which the upper vagina and other pelvic viscera are compressed during increases in intra-abdominal pressure.

Contraction of the levator ani pulls the levator plate toward the posterior symphysis pubis, minimizing the size of the urogenital hiatus through which the rectum, vagina, and urethra exit the pelvis on their way to the perineum. Weakness in the muscular pelvic floor—whether caused by disuse, pudendal nerve damage, or muscular trauma—increases the size of the urogenital hiatus, and the pelvic organs begin to prolapse through it.

Ultimately, constant tension on the ligamentous supports of the pelvic organs exceeds their tensile strength, and pelvic organ prolapse results.

Goals of surgery

Successful surgery achieves effective and sustained vault support, obliterates any enterocele sac, and repairs the cystocele and rectocele that occur in approximately two thirds of women with vault prolapse.

The broader goals: anatomic and functional restoration of the lower female genital tract and improvement in quality of life.

Surgery can be reconstructive or obliterative. Reconstructive surgery can be performed vaginally, abdominally, or a combination of both.

Vaginal techniques

Proponents of the vaginal approach argue that, by avoiding the need for laparotomy, it results in fewer complications, less blood loss and postoperative discomfort, a shorter hospital stay, and less expense.5

Sacrospinous ligament fixation

The sacrospinous ligaments extend from the ischial spines on either side to the lower portion of the sacrum and coccyx. Fixation of the vaginal apex to 1 or both of the sacrospinous ligaments is an option for posthysterectomy vault prolapse.

Technique. Nichols6 described the need to penetrate the right rectal pillar into the pararectal space near the ischial spine. The next step is grasping the ligament and muscle with a long Babcock clamp. Place two #2 polyglycolic sutures through the sacrospinous ligament, 1.5 to 2 fingerbreadths medial to the ischial spine. Attach 1 end of the suture to the undersurface of the posterior vaginal wall at the apical area. When the posterior colporrhaphy reaches the midportion of the vagina, tie the sacrospinous suspension sutures, firmly attaching the vaginal apex to the surface of the coccygeal-sacrospinous ligament complex with no intervening suture bridge (FIGURE 1).

Modifications. The most notable modification is the Miyazaki technique, which substitutes the Miya hook for the DesChamps ligature carrier. The Miya hook is reportedly safer for the pudendal complex, which may lie up to 5.5 cm medial to the ischial spine.7 The path of the Miya hook avoids Alcock’s canal and its neurovascular pudendal bundle.

The Caprio ligature carrier (Boston Scientific, Boston, Mass) is also useful for the placement of sacrospinous sutures; unlike the Miya hook, however, the Caprio ligature carrier is a disposable instrument and thus is not reusable.

Potential complications of sacrospinous ligament fixation include hemorrhage, pudendal nerve injury, rectal or bladder injury, and recurrent anterior vaginal wall prolapse.

Outcomes. Follow-up studies in women undergoing this procedure report a roughly 20% incidence of recurrent or persistent anterior vaginal wall relaxation, or symptomatic cystocele, within 1 year after the surgery. Alteration of the vaginal axis in an exaggerated posterolateral direction after this procedure is thought to place undue tension on the anterior segment of the vaginal wall and predispose women to prolapse at a site opposite the repair.8,9

FIGURE 1 2 “pulley stitches” secure the apex

Place 2 nonabsorbable monofilament “pulley stitches” to secure the vaginal apex to the ligament.

Iliococcygeal fixation

Inmon10 was the first to describe a technique in which the everted vaginal apex is secured to the iliococcygeal fascia bilaterally, just below the ischial spine. He performed this technique successfully in 3 women with atrophied uterosacral ligaments.

Technique. Open the posterior vaginal wall in the midline, as if preparing to perform a posterior colporrhaphy. Develop the rectovaginal spaces bluntly and bilaterally—laterally toward the levator muscles and posteriorally toward the ischial spines. Use the nondominant hand to depress the rectum downward and medially, and place a single #0 polyglycolic suture deep into the iliococcygeus muscle and fascia at a point 1 to 2 cm caudad and posterior to the ischial spine. Then pass both ends of the suture through the ipsilateral posterior vaginal apex and hold them with a hemostat. Repeat the procedure contralaterally.

Usually no vaginal epithelium needs excision because the upper vagina is attached bilaterally, resulting in good vaginal length and circumference. When posterior colporrhaphy is completed and the posterior vaginal wall is closed, tie both iliococcygeal-fixation sutures in place.

Complications. Shull and colleagues11 studied 42 women who underwent suspension of the vaginal cuff to iliococcygeus fascia and repair of coexisting pelvic support defects. Of these women, 2 (5%) had recurrence of their cuff prolapse during follow-up, one of whom required further surgery (she also had recurrence of an inguinal hernia that had been repaired at the original surgery). The other patient, who had undergone 5 previous pelvic procedures, developed asymptomatic prolapse of the cuff halfway to the hymen. Six additional patients had loss of support at other sites in the follow-up period, one of whom required repeat surgery. Ninety-five percent of women experienced no persistence or recurrence of cuff prolapse 6 weeks to 5 years after the procedure.

Meeks and colleagues12 also applied the Inmon technique in 110 women with posthysterectomy vault prolapse or total uterine procidentia. In both studies, the most commonly reported complications included hemorrhage (1.2%), bladder/rectal perforation (1.2%), and recurrent vault prolapse (8%).

Benefits. In comparison with sacrospinous ligament fixation, iliococcygeus fixation is technically easier and places less tension on the anterior vaginal wall.

Modified McCall culdoplasty

Symmonds and colleagues13 described this approach to symptomatic vaginal vault prolapse.

Technique. Excise an elliptical wedge of mucosa from the anterior and posterior walls of the prolapsed vagina to narrow the vault and allow access to the lateral fascial supports of the vagina and rectum. The width and length of the excised wedges are determined by the desired dimensions of the reconstructed vagina.

After isolating and excising the enterocele sac, place up to 3 modified McCall stitches, each one slightly higher than its predecessor. Each suture should incorporate the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall, the cul-de-sac peritoneum, the remains of the uterosacral-cardinal complex bilaterally, and the fascial tissue lateral and posterior to the upper vagina and rectum (FIGURE 2).

Once they are in place, tie the sutures in the opposite order in which they were placed. These stitches fix the prolapsed vaginal vault to the uppermost portion of the endopelvic fascia at the same time as they accomplish a high closure of the culdesac peritoneum.

The evidence. Sze and Karram5 found an 11.5% incidence of recurrent vault prolapse and an associated 22% incidence of new-onset dyspareunia.

FIGURE 2 Classic vs modified McCall culdoplasty

In the classic McCall culdoplasty shown here, only the distal-most suture incorporates the posterior vaginal wall. With the “modified” technique, however, all sutures incorporate the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall, as well as the cul-de-sac peritoneum, the remnants of the uterosacral-cardinal complex bilaterally, and the fascial tissue lateral and posterior to the upper vagina and rectum.

High uterosacral ligament suspension with fascial reconstruction

This approach is based on the observations of Richardson,14 who suggested that the endopelvic fascial supports (uterosacral/cardinal complex) do not stretch and attenuate over time, as some have hypothesized, but break at definable points. By identifying these points, the surgeon can reattach the prolapsed vagina to the intact uterosacral complex cephalad to the break.

Technique. Grasp the vaginal apex with 2 Allis clamps and incise it with a scalpel. If an enterocele sac is present, dissect it off the vaginal epithelium to the neck of the hernia, open it, and then excise it. Place a delayed absorbable or permanent pursestring suture about the neck of the hernia to close the peritoneal defect. If an anterior colporrhaphy or sling is required, perform them at this time.

Place a moist laparotomy pad in the cul-de-sac, and insert and elevate a Deaver retractor to remove the intestines from the cul-de-sac and improve exposure. Next, palpate the ischial spines transperitoneally.