User login

Happiness in my solo practice

I don’t want to rule the world.

Some doctors do, albeit in a non–Attila-the-Hun sort of way. They want to have offices on every street corner, in every suburb of a given city, sometimes more than one city. Like the Starbucks of medicine.

That’s not me. I’m happy in my little one-office world.

Maybe I just don’t have the ambition, or the business mindset, or whatever it takes to want to do that. I understand it’s all part of wanting to be successful, and obviously those doctors are more driven in that direction than I am. The more offices, the more patients can be seen, and the more money you make.

It’s not quite that simple, though. No one can be in more than one place at the same time, so to see more patients at more places you need more doctors. To pay more doctors requires more money, which in turn requires more patients.

There’s nothing wrong with taking over the world (or at least a suburb) if you like that sort of thing. But to me, more money brings more headaches. More offices to rent, more staff to hire, more people to handle billing, IT, HR, payroll, accounting, contracts, and so on.

You can have it. I’ve taken over all the world I want, in my case a 1,200-square-foot suite on the second floor of a small-to-medium-size medical building. To some that may sound unambitious, but to me, it’s perfect.

I know where my Keurig, Sodastream, and office supplies are. Except for my secretary and her cheerfully rambunctious young daughter, I don’t have to worry about sharing stuff here, or if anyone wants a different carpet color, or what’s going on at a satellite office halfway across town.

If other doctors want to try and take over the world, more power to them, but I’m happy with this. Enough is as good as a feast.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I don’t want to rule the world.

Some doctors do, albeit in a non–Attila-the-Hun sort of way. They want to have offices on every street corner, in every suburb of a given city, sometimes more than one city. Like the Starbucks of medicine.

That’s not me. I’m happy in my little one-office world.

Maybe I just don’t have the ambition, or the business mindset, or whatever it takes to want to do that. I understand it’s all part of wanting to be successful, and obviously those doctors are more driven in that direction than I am. The more offices, the more patients can be seen, and the more money you make.

It’s not quite that simple, though. No one can be in more than one place at the same time, so to see more patients at more places you need more doctors. To pay more doctors requires more money, which in turn requires more patients.

There’s nothing wrong with taking over the world (or at least a suburb) if you like that sort of thing. But to me, more money brings more headaches. More offices to rent, more staff to hire, more people to handle billing, IT, HR, payroll, accounting, contracts, and so on.

You can have it. I’ve taken over all the world I want, in my case a 1,200-square-foot suite on the second floor of a small-to-medium-size medical building. To some that may sound unambitious, but to me, it’s perfect.

I know where my Keurig, Sodastream, and office supplies are. Except for my secretary and her cheerfully rambunctious young daughter, I don’t have to worry about sharing stuff here, or if anyone wants a different carpet color, or what’s going on at a satellite office halfway across town.

If other doctors want to try and take over the world, more power to them, but I’m happy with this. Enough is as good as a feast.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I don’t want to rule the world.

Some doctors do, albeit in a non–Attila-the-Hun sort of way. They want to have offices on every street corner, in every suburb of a given city, sometimes more than one city. Like the Starbucks of medicine.

That’s not me. I’m happy in my little one-office world.

Maybe I just don’t have the ambition, or the business mindset, or whatever it takes to want to do that. I understand it’s all part of wanting to be successful, and obviously those doctors are more driven in that direction than I am. The more offices, the more patients can be seen, and the more money you make.

It’s not quite that simple, though. No one can be in more than one place at the same time, so to see more patients at more places you need more doctors. To pay more doctors requires more money, which in turn requires more patients.

There’s nothing wrong with taking over the world (or at least a suburb) if you like that sort of thing. But to me, more money brings more headaches. More offices to rent, more staff to hire, more people to handle billing, IT, HR, payroll, accounting, contracts, and so on.

You can have it. I’ve taken over all the world I want, in my case a 1,200-square-foot suite on the second floor of a small-to-medium-size medical building. To some that may sound unambitious, but to me, it’s perfect.

I know where my Keurig, Sodastream, and office supplies are. Except for my secretary and her cheerfully rambunctious young daughter, I don’t have to worry about sharing stuff here, or if anyone wants a different carpet color, or what’s going on at a satellite office halfway across town.

If other doctors want to try and take over the world, more power to them, but I’m happy with this. Enough is as good as a feast.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Does this patient have bacterial conjunctivitis?

A 54-year-old pharmacist with a history of gout, hypertension, and conjunctivitis presents for evaluation of pink eye in the summer. The morning before coming into the office, he noticed that his right eye was red and inflamed. He self-treated with saline washes and eye drops, but upon awakening the next day, he found his right eye to be crusted shut with surrounding yellow discharge. He has not had any changes to his vision but endorses a somewhat uncomfortable, “gritty” sensation. He reports no recent cough, nasal congestion, or allergies, and he has not been around any sick contacts. His blood pressure is 102/58 mm Hg, pulse is 76 bpm, and body mass index is 27.3 kg/m2. His eye exam reveals unilateral conjunctival injections but no hyperemia of the conjunctiva adjacent to the cornea. Mucopurulent discharge was neither found on the undersurface of the eyelid nor emerging from the eye. Which of the following is the best treatment for this patient’s condition?

A) Erythromycin 5 mg/gram ophthalmic ointment.

B) Ofloxacin 0.3% ophthalmic drops.

C) Antihistamine drops.

D) Eye lubricant drops.

E) No treatment necessary.

This patient is an adult presenting with presumed conjunctivitis. Because he is presenting in the summer without observed purulent discharge, his condition is unlikely to be bacterial. This patient does not need treatment, although eye lubricant drops could reduce his discomfort.

After ruling out serious eye disease, clinicians need to determine which cases of suspected conjunctivitis are most likely to be bacterial to allow for judicious use of antibiotic eye drops. This is an important undertaking as most patients assume that antibiotics are needed.

How do we know which history and clinical exam findings to lean on when attempting to categorize conjunctivitis as bacterial or not? If a patient reports purulent discharge, doesn’t that mean it is bacterial? Surprisingly, a systematic review published in 2016 by Narayana and McGee found that a patient’s self-report of “purulent drainage” is diagnostically unhelpful, but if a clinician finds it on exam, the likelihood of a bacterial etiology increases.3

Narayana and McGee analyzed three studies that enrolled a total of 281 patients with presumed conjunctivitis who underwent bacterial cultures. They then determined which findings increased the probability of positive bacterial culture. From strongest to weakest, the best indicators of a bacterial cause were found to be: complete redness of the conjunctival membrane obscuring tarsal vessels (the vessels visible on the inside of everted upper or lower eyelids) (likelihood ratio, 4.6), observed purulent discharge (LR, 3.9), matting of both eyes in the morning (LR, 3.6), and presence during winter/spring months (LR, 1.9). On the other hand, failure to observe a red eye at 20 feet (LR, 0.2), absence of morning gluing of either eye (LR, 0.3), and presentation during summer months (LR, 0.4) all decreased the probability of a bacterial cause. This review and different study by Stenson et al. unfortunately have conflicting evidence regarding whether the following findings are diagnostically helpful: qualities of eye discomfort (such as burning or itching), preauricular adenopathy, conjunctival follicles, and conjunctival papillae.3,4 Rietveld and colleagues found that a history of conjunctivitis decreased the likelihood of bacterial conjunctivitis.5

Ultimately, if the former indicators are kept in mind, primary care clinicians should be able to decrease the prescribing of topical antimicrobials to patients with non-bacterial conjunctivitis.

Pearl: The best indicators of a bacterial cause in patients with presumed conjunctivitis are complete redness of the conjunctival membrane obscuring tarsal vessels, observed purulent discharge, and matting of both eyes in the morning. Presentation during the summer months and having a history of conjunctivitis decreases the likelihood of bacterial conjunctivitis.

Ms. Momany is a fourth-year medical student at University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at that university. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Azari AA and Barney NP. JAMA. 2013 Oct 23; 310(16):1721-9.

2. Smith AF and Waycaster C. BMC Ophthalmol. 2009 Nov 25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-9-13.

3) Narayana S and McGee S. Am J Med. 2015;128(11):1220-4.e1.

4) Stenson S et al. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100(8):1275-7.

5) Rietveld RP et al. BMJ. 2004 Jul 24;329(7459):206-10.

A 54-year-old pharmacist with a history of gout, hypertension, and conjunctivitis presents for evaluation of pink eye in the summer. The morning before coming into the office, he noticed that his right eye was red and inflamed. He self-treated with saline washes and eye drops, but upon awakening the next day, he found his right eye to be crusted shut with surrounding yellow discharge. He has not had any changes to his vision but endorses a somewhat uncomfortable, “gritty” sensation. He reports no recent cough, nasal congestion, or allergies, and he has not been around any sick contacts. His blood pressure is 102/58 mm Hg, pulse is 76 bpm, and body mass index is 27.3 kg/m2. His eye exam reveals unilateral conjunctival injections but no hyperemia of the conjunctiva adjacent to the cornea. Mucopurulent discharge was neither found on the undersurface of the eyelid nor emerging from the eye. Which of the following is the best treatment for this patient’s condition?

A) Erythromycin 5 mg/gram ophthalmic ointment.

B) Ofloxacin 0.3% ophthalmic drops.

C) Antihistamine drops.

D) Eye lubricant drops.

E) No treatment necessary.

This patient is an adult presenting with presumed conjunctivitis. Because he is presenting in the summer without observed purulent discharge, his condition is unlikely to be bacterial. This patient does not need treatment, although eye lubricant drops could reduce his discomfort.

After ruling out serious eye disease, clinicians need to determine which cases of suspected conjunctivitis are most likely to be bacterial to allow for judicious use of antibiotic eye drops. This is an important undertaking as most patients assume that antibiotics are needed.

How do we know which history and clinical exam findings to lean on when attempting to categorize conjunctivitis as bacterial or not? If a patient reports purulent discharge, doesn’t that mean it is bacterial? Surprisingly, a systematic review published in 2016 by Narayana and McGee found that a patient’s self-report of “purulent drainage” is diagnostically unhelpful, but if a clinician finds it on exam, the likelihood of a bacterial etiology increases.3

Narayana and McGee analyzed three studies that enrolled a total of 281 patients with presumed conjunctivitis who underwent bacterial cultures. They then determined which findings increased the probability of positive bacterial culture. From strongest to weakest, the best indicators of a bacterial cause were found to be: complete redness of the conjunctival membrane obscuring tarsal vessels (the vessels visible on the inside of everted upper or lower eyelids) (likelihood ratio, 4.6), observed purulent discharge (LR, 3.9), matting of both eyes in the morning (LR, 3.6), and presence during winter/spring months (LR, 1.9). On the other hand, failure to observe a red eye at 20 feet (LR, 0.2), absence of morning gluing of either eye (LR, 0.3), and presentation during summer months (LR, 0.4) all decreased the probability of a bacterial cause. This review and different study by Stenson et al. unfortunately have conflicting evidence regarding whether the following findings are diagnostically helpful: qualities of eye discomfort (such as burning or itching), preauricular adenopathy, conjunctival follicles, and conjunctival papillae.3,4 Rietveld and colleagues found that a history of conjunctivitis decreased the likelihood of bacterial conjunctivitis.5

Ultimately, if the former indicators are kept in mind, primary care clinicians should be able to decrease the prescribing of topical antimicrobials to patients with non-bacterial conjunctivitis.

Pearl: The best indicators of a bacterial cause in patients with presumed conjunctivitis are complete redness of the conjunctival membrane obscuring tarsal vessels, observed purulent discharge, and matting of both eyes in the morning. Presentation during the summer months and having a history of conjunctivitis decreases the likelihood of bacterial conjunctivitis.

Ms. Momany is a fourth-year medical student at University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at that university. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Azari AA and Barney NP. JAMA. 2013 Oct 23; 310(16):1721-9.

2. Smith AF and Waycaster C. BMC Ophthalmol. 2009 Nov 25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-9-13.

3) Narayana S and McGee S. Am J Med. 2015;128(11):1220-4.e1.

4) Stenson S et al. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100(8):1275-7.

5) Rietveld RP et al. BMJ. 2004 Jul 24;329(7459):206-10.

A 54-year-old pharmacist with a history of gout, hypertension, and conjunctivitis presents for evaluation of pink eye in the summer. The morning before coming into the office, he noticed that his right eye was red and inflamed. He self-treated with saline washes and eye drops, but upon awakening the next day, he found his right eye to be crusted shut with surrounding yellow discharge. He has not had any changes to his vision but endorses a somewhat uncomfortable, “gritty” sensation. He reports no recent cough, nasal congestion, or allergies, and he has not been around any sick contacts. His blood pressure is 102/58 mm Hg, pulse is 76 bpm, and body mass index is 27.3 kg/m2. His eye exam reveals unilateral conjunctival injections but no hyperemia of the conjunctiva adjacent to the cornea. Mucopurulent discharge was neither found on the undersurface of the eyelid nor emerging from the eye. Which of the following is the best treatment for this patient’s condition?

A) Erythromycin 5 mg/gram ophthalmic ointment.

B) Ofloxacin 0.3% ophthalmic drops.

C) Antihistamine drops.

D) Eye lubricant drops.

E) No treatment necessary.

This patient is an adult presenting with presumed conjunctivitis. Because he is presenting in the summer without observed purulent discharge, his condition is unlikely to be bacterial. This patient does not need treatment, although eye lubricant drops could reduce his discomfort.

After ruling out serious eye disease, clinicians need to determine which cases of suspected conjunctivitis are most likely to be bacterial to allow for judicious use of antibiotic eye drops. This is an important undertaking as most patients assume that antibiotics are needed.

How do we know which history and clinical exam findings to lean on when attempting to categorize conjunctivitis as bacterial or not? If a patient reports purulent discharge, doesn’t that mean it is bacterial? Surprisingly, a systematic review published in 2016 by Narayana and McGee found that a patient’s self-report of “purulent drainage” is diagnostically unhelpful, but if a clinician finds it on exam, the likelihood of a bacterial etiology increases.3

Narayana and McGee analyzed three studies that enrolled a total of 281 patients with presumed conjunctivitis who underwent bacterial cultures. They then determined which findings increased the probability of positive bacterial culture. From strongest to weakest, the best indicators of a bacterial cause were found to be: complete redness of the conjunctival membrane obscuring tarsal vessels (the vessels visible on the inside of everted upper or lower eyelids) (likelihood ratio, 4.6), observed purulent discharge (LR, 3.9), matting of both eyes in the morning (LR, 3.6), and presence during winter/spring months (LR, 1.9). On the other hand, failure to observe a red eye at 20 feet (LR, 0.2), absence of morning gluing of either eye (LR, 0.3), and presentation during summer months (LR, 0.4) all decreased the probability of a bacterial cause. This review and different study by Stenson et al. unfortunately have conflicting evidence regarding whether the following findings are diagnostically helpful: qualities of eye discomfort (such as burning or itching), preauricular adenopathy, conjunctival follicles, and conjunctival papillae.3,4 Rietveld and colleagues found that a history of conjunctivitis decreased the likelihood of bacterial conjunctivitis.5

Ultimately, if the former indicators are kept in mind, primary care clinicians should be able to decrease the prescribing of topical antimicrobials to patients with non-bacterial conjunctivitis.

Pearl: The best indicators of a bacterial cause in patients with presumed conjunctivitis are complete redness of the conjunctival membrane obscuring tarsal vessels, observed purulent discharge, and matting of both eyes in the morning. Presentation during the summer months and having a history of conjunctivitis decreases the likelihood of bacterial conjunctivitis.

Ms. Momany is a fourth-year medical student at University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at that university. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Azari AA and Barney NP. JAMA. 2013 Oct 23; 310(16):1721-9.

2. Smith AF and Waycaster C. BMC Ophthalmol. 2009 Nov 25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-9-13.

3) Narayana S and McGee S. Am J Med. 2015;128(11):1220-4.e1.

4) Stenson S et al. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100(8):1275-7.

5) Rietveld RP et al. BMJ. 2004 Jul 24;329(7459):206-10.

Financial Education for Health Care Providers

Health care provider (HCP) well-being has become a central topic as health care agencies increasingly recognize that stress leads to turnover and reduced efficacy.1 Financial health of HCPs is one aspect of overall well-being that has received little attention. We all work at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) as psychologists and believe that there is a need to attend to financial literacy within the health care professions, a call that also has been made by physicians.2 For instance, a frequently mentioned aspect of financial literacy involves learning to effectively manage student loan debt. Another less often discussed facet is the need to save money for retirement early in one’s career to reap the benefits of compound interest: This is a particular concern for HCPs who were in graduate/medical school when they would have optimally started saving for retirement. Delaying retirement savings can have significant financial consequences, which can have a negative effect on well-being.

A few years ago, we started teaching advanced psychology trainees about financial well-being and were startled at the students’ lack of knowledge. For example, many students did not understand basic financial concepts, including the difference between a pension and a 401k/403b system of retirement savings—a knowledge gap that the authors speculate persists throughout some professionals’ careers. Research suggests that lack of knowledge in an area feels aversive and may result in procrastination or an inability to move toward a goal.3,4 Yet, postponing saving is problematic as it attenuates the effect of compound interest, thus making it difficult to accrue wealth.5 To address the lack of financial training among psychologists, the authors designed a seminar to provide retirement/financial-planning information to early career psychologists. This information fits the concept of “just in time” education: Disseminating knowledge when it is most likely to be useful, put into practice, and thus retained.6

Methods

In consultation with human resources officials at the VA, a 90-minute seminar was created to educate psychologists about saving for retirement. The seminar was recorded so that psychologists who were not able to attend in-person could view it at a later date. The seminar mainly covered systems of retirement (especially the VAspecific Thrift Savings Plan [TSP]), basic concepts of investing, ways of determining how much to save for retirement, and tax advantages of increased saving. It also provided simple retirement planning rules of thumb, as such heuristics have been shown to lead to greater behavior change than more unsystematic approaches.7 Key points included:

- Psychologists should try to approximately replace their current salary during retirement;

- There is no option to borrow money for retirement; the only sources of income for the retiree are social security, a possible pension, and any money saved;

- Psychologists and many other HCPs were in school during their prime saving years and tend to have lower salaries than that of other professional groups with similar amounts of education, so they should save aggressively earlier in their career;

- Early career psychologists should ensure that money saved for retirement is invested in relatively “aggressive” options, such as stock index funds (vs bond funds); and

- The tax benefits of allocating more income toward retirement savings in a tax-deferred savings plan such as the TSP can make it seem cheaper to invest, which can make it more attractive to immediately increase one’s savings.

As with any other savings plan, there are no guarantees or one-size-fits-all solutions, and finance professionals typically advise diversifying retirement savings (eg, stocks, bonds, real estate), to include both TSP and non-TSP plans in the case of VA employees.

To assess the usefulness of this seminar, the authors conducted a process improvement case study. The institutional review board of the Milwaukee VA Medical Center (VAMC) determined the study to be exempt as it was considered process improvement rather than research. Two assessment measures were created: a 5-item, anonymous measure of attendee satisfaction was administered immediately following the seminar, which assessed the extent to which presenters were engaging, material was presented clearly, presenters effectively used examples and illustrations, presenters effectively used slides/visual aids, and objectives were met (5-point Likert scale from “Needs major improvement” to “Excellent”).

Second, an internally developed anonymous pre- and postseminar survey was administered to assess changes in retirement- related knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors (3 months before the seminar [8 questions] and 2 months after [9 questions]). The survey assessed knowledge of retirement benefits (eg, difference between Roth and traditional retirement savings plans), general investment actions (eg, investing in TSP, investing in the TSP G fund, and investing sufficiently to earn the full employer match), and postseminar actions taken (eg, logging on to tsp.gov, increasing TSP contribution). Participants’ responses were anonymous, so the authors compared average behavior before and after the seminar rather than comparing individuals’ pre- and postseminar comments.

Results

About one-third (n = 28) of the Milwaukee VAMC psychologists attended, viewed, or presented/designed the seminar. Of the 12 participants who attended the seminar in person, all rated the presentation as excellent in each domain, with the exception of 1 participant (good). Anecdotally, participants approached presenters immediately after the presentation and up to 2 years later to indicate that the presentation was a useful retirement planning resource. A total of 27 psychologists completed the preseminar survey. Sixteen psychologists completed the postseminar survey and indicated that they attended/viewed the retirement seminar. Participants’ perceived knowledge of retirement benefits was assessed with response options, including nonexistent, vague, good, and sophisticated.

There was a significant change from preto postseminar, such that psychologists at postseminar felt that they had a better understanding of their retirement benefit options (Mann-Whitney U = 65.5, n1 = 27, n2 = 16, P < .01). The modal response preseminar was “vague” (67%) and postseminar was “good” (88%). There also were changes that were meaningful though not statistically significant: The percentage who had moved their money from the default, low-yield fund increased from 70% at preseminar to 88% at postseminar (Fisher exact test, 1-sided, P = .31). Also, fewer people reported on the postseminar survey that they were not sure whether they were invested in a Roth individual retirement account (IRA) or traditional TSP, indicating a trend toward significantly increased knowledge of their investments (Fisher exact test, 1-sided, P = .076).

Most important at follow-up, several behavior changes were reported. Most people (56%) had logged on to the TSP website to check on their account. A substantial number (26%) increased their contribution amount, and 6% moved money from the default fund. Overall, every respondent at follow-up confirmed having taken at least 1 of the actions assessed by the survey.

Conclusion

Based on the authors’ experience and research into financial education among HCPs, it is recommended that psychologists and other disciplines offer opportunities for retirement education at all levels of training. Financial education is likely to be most helpful if it is tailored toward a specific discipline, workplace, and time frame (eg, early career physicians may need more information about loan repayment and may need to invest in more aggressive retirement funds).8 Although many employers provide access to general financial education from outside companies, information provided by informed members of one’s field may be particularly helpful (eg, our seminar was curated for a psychology audience).

We found that the process of creating such a seminar was not burdensome and was educational for presenters as well as attendees. Further, it need not be intimidating to accumulate information to share; especially for those health care providers who have not made financial well-being a priority, learning and deploying a few targeted strategies can lead to increased peace of mind about retirement savings. Overall, we encourage a focus on financial literacy for all health care professions, including physicians who often may graduate with greater debts. Emphasizing early and aggressive financial literacy as an important aspect of provider well-being may help to produce healthier, wealthier, and overall better health care providers.2

Acknowledgments

This manuscript is partially the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Clement J. Zablocki VAMC, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. We thank Milwaukee VA retirement specialist, Vicki Heckman, for her invaluable advice in the preparation of these materials and the Psychology Advancement Workgroup at the Milwaukee VAMC for providing the impetus and support for this project.

1. Zhang Y, Feng X. The relationship between job satisfaction, burnout, and turnover intention among physicians from urban state-owned medical institutions in Hubei, China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11(1):235.

2. Chandrakantan A. Why is there no financial literacy 101 for doctors? https://opmed.doximity.com/an-open -call-to-residency-training-programs-and-trainees-to -facilitate-financial-literacy-bb762e585ed8. Published August 21, 2017. Accessed August 22, 2019.

3. Iyengar SS, Huberman G, Jiang W. How much choice is too much: determinants of individual contributions in 401K retirement plans. In: Mitchell OS, Utkus S, eds. Pension Design and Structure: New Lessons From Behavioral Finance. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004:83-95.

4. Parker AM, de Bruin WB, Yoong J, Willis R. Inappropriate confidence and retirement planning: four studies with a national sample. J Behav Decis Mak. 2012;25(4):382-389.

5. Lusardi A, Mitchell OS. Baby boomer retirement security: the roles of planning, financial literacy, and housing wealth. J Monet Econ. 2007;54(1):205-224.

6. Chub C. It’s time to teach financial literacy to young doctors. https://www.cnbc.com/2016/12/08/teaching -financial-literacy-to-young-doctors.html. Published December 8, 2016. Accessed August 22, 2019.

7. Binswanger J, Carman KG. How real people make longterm decisions: the case of retirement preparation. J Econ Behav Org. 2012;81(1):39-60.

8. Knoll MA. The role of behavioral economics and behavioral decision making in Americans’ retirement savings decisions. Soc Secur Bull. 2010;70(4):1-23.

Health care provider (HCP) well-being has become a central topic as health care agencies increasingly recognize that stress leads to turnover and reduced efficacy.1 Financial health of HCPs is one aspect of overall well-being that has received little attention. We all work at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) as psychologists and believe that there is a need to attend to financial literacy within the health care professions, a call that also has been made by physicians.2 For instance, a frequently mentioned aspect of financial literacy involves learning to effectively manage student loan debt. Another less often discussed facet is the need to save money for retirement early in one’s career to reap the benefits of compound interest: This is a particular concern for HCPs who were in graduate/medical school when they would have optimally started saving for retirement. Delaying retirement savings can have significant financial consequences, which can have a negative effect on well-being.

A few years ago, we started teaching advanced psychology trainees about financial well-being and were startled at the students’ lack of knowledge. For example, many students did not understand basic financial concepts, including the difference between a pension and a 401k/403b system of retirement savings—a knowledge gap that the authors speculate persists throughout some professionals’ careers. Research suggests that lack of knowledge in an area feels aversive and may result in procrastination or an inability to move toward a goal.3,4 Yet, postponing saving is problematic as it attenuates the effect of compound interest, thus making it difficult to accrue wealth.5 To address the lack of financial training among psychologists, the authors designed a seminar to provide retirement/financial-planning information to early career psychologists. This information fits the concept of “just in time” education: Disseminating knowledge when it is most likely to be useful, put into practice, and thus retained.6

Methods

In consultation with human resources officials at the VA, a 90-minute seminar was created to educate psychologists about saving for retirement. The seminar was recorded so that psychologists who were not able to attend in-person could view it at a later date. The seminar mainly covered systems of retirement (especially the VAspecific Thrift Savings Plan [TSP]), basic concepts of investing, ways of determining how much to save for retirement, and tax advantages of increased saving. It also provided simple retirement planning rules of thumb, as such heuristics have been shown to lead to greater behavior change than more unsystematic approaches.7 Key points included:

- Psychologists should try to approximately replace their current salary during retirement;

- There is no option to borrow money for retirement; the only sources of income for the retiree are social security, a possible pension, and any money saved;

- Psychologists and many other HCPs were in school during their prime saving years and tend to have lower salaries than that of other professional groups with similar amounts of education, so they should save aggressively earlier in their career;

- Early career psychologists should ensure that money saved for retirement is invested in relatively “aggressive” options, such as stock index funds (vs bond funds); and

- The tax benefits of allocating more income toward retirement savings in a tax-deferred savings plan such as the TSP can make it seem cheaper to invest, which can make it more attractive to immediately increase one’s savings.

As with any other savings plan, there are no guarantees or one-size-fits-all solutions, and finance professionals typically advise diversifying retirement savings (eg, stocks, bonds, real estate), to include both TSP and non-TSP plans in the case of VA employees.

To assess the usefulness of this seminar, the authors conducted a process improvement case study. The institutional review board of the Milwaukee VA Medical Center (VAMC) determined the study to be exempt as it was considered process improvement rather than research. Two assessment measures were created: a 5-item, anonymous measure of attendee satisfaction was administered immediately following the seminar, which assessed the extent to which presenters were engaging, material was presented clearly, presenters effectively used examples and illustrations, presenters effectively used slides/visual aids, and objectives were met (5-point Likert scale from “Needs major improvement” to “Excellent”).

Second, an internally developed anonymous pre- and postseminar survey was administered to assess changes in retirement- related knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors (3 months before the seminar [8 questions] and 2 months after [9 questions]). The survey assessed knowledge of retirement benefits (eg, difference between Roth and traditional retirement savings plans), general investment actions (eg, investing in TSP, investing in the TSP G fund, and investing sufficiently to earn the full employer match), and postseminar actions taken (eg, logging on to tsp.gov, increasing TSP contribution). Participants’ responses were anonymous, so the authors compared average behavior before and after the seminar rather than comparing individuals’ pre- and postseminar comments.

Results

About one-third (n = 28) of the Milwaukee VAMC psychologists attended, viewed, or presented/designed the seminar. Of the 12 participants who attended the seminar in person, all rated the presentation as excellent in each domain, with the exception of 1 participant (good). Anecdotally, participants approached presenters immediately after the presentation and up to 2 years later to indicate that the presentation was a useful retirement planning resource. A total of 27 psychologists completed the preseminar survey. Sixteen psychologists completed the postseminar survey and indicated that they attended/viewed the retirement seminar. Participants’ perceived knowledge of retirement benefits was assessed with response options, including nonexistent, vague, good, and sophisticated.

There was a significant change from preto postseminar, such that psychologists at postseminar felt that they had a better understanding of their retirement benefit options (Mann-Whitney U = 65.5, n1 = 27, n2 = 16, P < .01). The modal response preseminar was “vague” (67%) and postseminar was “good” (88%). There also were changes that were meaningful though not statistically significant: The percentage who had moved their money from the default, low-yield fund increased from 70% at preseminar to 88% at postseminar (Fisher exact test, 1-sided, P = .31). Also, fewer people reported on the postseminar survey that they were not sure whether they were invested in a Roth individual retirement account (IRA) or traditional TSP, indicating a trend toward significantly increased knowledge of their investments (Fisher exact test, 1-sided, P = .076).

Most important at follow-up, several behavior changes were reported. Most people (56%) had logged on to the TSP website to check on their account. A substantial number (26%) increased their contribution amount, and 6% moved money from the default fund. Overall, every respondent at follow-up confirmed having taken at least 1 of the actions assessed by the survey.

Conclusion

Based on the authors’ experience and research into financial education among HCPs, it is recommended that psychologists and other disciplines offer opportunities for retirement education at all levels of training. Financial education is likely to be most helpful if it is tailored toward a specific discipline, workplace, and time frame (eg, early career physicians may need more information about loan repayment and may need to invest in more aggressive retirement funds).8 Although many employers provide access to general financial education from outside companies, information provided by informed members of one’s field may be particularly helpful (eg, our seminar was curated for a psychology audience).

We found that the process of creating such a seminar was not burdensome and was educational for presenters as well as attendees. Further, it need not be intimidating to accumulate information to share; especially for those health care providers who have not made financial well-being a priority, learning and deploying a few targeted strategies can lead to increased peace of mind about retirement savings. Overall, we encourage a focus on financial literacy for all health care professions, including physicians who often may graduate with greater debts. Emphasizing early and aggressive financial literacy as an important aspect of provider well-being may help to produce healthier, wealthier, and overall better health care providers.2

Acknowledgments

This manuscript is partially the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Clement J. Zablocki VAMC, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. We thank Milwaukee VA retirement specialist, Vicki Heckman, for her invaluable advice in the preparation of these materials and the Psychology Advancement Workgroup at the Milwaukee VAMC for providing the impetus and support for this project.

Health care provider (HCP) well-being has become a central topic as health care agencies increasingly recognize that stress leads to turnover and reduced efficacy.1 Financial health of HCPs is one aspect of overall well-being that has received little attention. We all work at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) as psychologists and believe that there is a need to attend to financial literacy within the health care professions, a call that also has been made by physicians.2 For instance, a frequently mentioned aspect of financial literacy involves learning to effectively manage student loan debt. Another less often discussed facet is the need to save money for retirement early in one’s career to reap the benefits of compound interest: This is a particular concern for HCPs who were in graduate/medical school when they would have optimally started saving for retirement. Delaying retirement savings can have significant financial consequences, which can have a negative effect on well-being.

A few years ago, we started teaching advanced psychology trainees about financial well-being and were startled at the students’ lack of knowledge. For example, many students did not understand basic financial concepts, including the difference between a pension and a 401k/403b system of retirement savings—a knowledge gap that the authors speculate persists throughout some professionals’ careers. Research suggests that lack of knowledge in an area feels aversive and may result in procrastination or an inability to move toward a goal.3,4 Yet, postponing saving is problematic as it attenuates the effect of compound interest, thus making it difficult to accrue wealth.5 To address the lack of financial training among psychologists, the authors designed a seminar to provide retirement/financial-planning information to early career psychologists. This information fits the concept of “just in time” education: Disseminating knowledge when it is most likely to be useful, put into practice, and thus retained.6

Methods

In consultation with human resources officials at the VA, a 90-minute seminar was created to educate psychologists about saving for retirement. The seminar was recorded so that psychologists who were not able to attend in-person could view it at a later date. The seminar mainly covered systems of retirement (especially the VAspecific Thrift Savings Plan [TSP]), basic concepts of investing, ways of determining how much to save for retirement, and tax advantages of increased saving. It also provided simple retirement planning rules of thumb, as such heuristics have been shown to lead to greater behavior change than more unsystematic approaches.7 Key points included:

- Psychologists should try to approximately replace their current salary during retirement;

- There is no option to borrow money for retirement; the only sources of income for the retiree are social security, a possible pension, and any money saved;

- Psychologists and many other HCPs were in school during their prime saving years and tend to have lower salaries than that of other professional groups with similar amounts of education, so they should save aggressively earlier in their career;

- Early career psychologists should ensure that money saved for retirement is invested in relatively “aggressive” options, such as stock index funds (vs bond funds); and

- The tax benefits of allocating more income toward retirement savings in a tax-deferred savings plan such as the TSP can make it seem cheaper to invest, which can make it more attractive to immediately increase one’s savings.

As with any other savings plan, there are no guarantees or one-size-fits-all solutions, and finance professionals typically advise diversifying retirement savings (eg, stocks, bonds, real estate), to include both TSP and non-TSP plans in the case of VA employees.

To assess the usefulness of this seminar, the authors conducted a process improvement case study. The institutional review board of the Milwaukee VA Medical Center (VAMC) determined the study to be exempt as it was considered process improvement rather than research. Two assessment measures were created: a 5-item, anonymous measure of attendee satisfaction was administered immediately following the seminar, which assessed the extent to which presenters were engaging, material was presented clearly, presenters effectively used examples and illustrations, presenters effectively used slides/visual aids, and objectives were met (5-point Likert scale from “Needs major improvement” to “Excellent”).

Second, an internally developed anonymous pre- and postseminar survey was administered to assess changes in retirement- related knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors (3 months before the seminar [8 questions] and 2 months after [9 questions]). The survey assessed knowledge of retirement benefits (eg, difference between Roth and traditional retirement savings plans), general investment actions (eg, investing in TSP, investing in the TSP G fund, and investing sufficiently to earn the full employer match), and postseminar actions taken (eg, logging on to tsp.gov, increasing TSP contribution). Participants’ responses were anonymous, so the authors compared average behavior before and after the seminar rather than comparing individuals’ pre- and postseminar comments.

Results

About one-third (n = 28) of the Milwaukee VAMC psychologists attended, viewed, or presented/designed the seminar. Of the 12 participants who attended the seminar in person, all rated the presentation as excellent in each domain, with the exception of 1 participant (good). Anecdotally, participants approached presenters immediately after the presentation and up to 2 years later to indicate that the presentation was a useful retirement planning resource. A total of 27 psychologists completed the preseminar survey. Sixteen psychologists completed the postseminar survey and indicated that they attended/viewed the retirement seminar. Participants’ perceived knowledge of retirement benefits was assessed with response options, including nonexistent, vague, good, and sophisticated.

There was a significant change from preto postseminar, such that psychologists at postseminar felt that they had a better understanding of their retirement benefit options (Mann-Whitney U = 65.5, n1 = 27, n2 = 16, P < .01). The modal response preseminar was “vague” (67%) and postseminar was “good” (88%). There also were changes that were meaningful though not statistically significant: The percentage who had moved their money from the default, low-yield fund increased from 70% at preseminar to 88% at postseminar (Fisher exact test, 1-sided, P = .31). Also, fewer people reported on the postseminar survey that they were not sure whether they were invested in a Roth individual retirement account (IRA) or traditional TSP, indicating a trend toward significantly increased knowledge of their investments (Fisher exact test, 1-sided, P = .076).

Most important at follow-up, several behavior changes were reported. Most people (56%) had logged on to the TSP website to check on their account. A substantial number (26%) increased their contribution amount, and 6% moved money from the default fund. Overall, every respondent at follow-up confirmed having taken at least 1 of the actions assessed by the survey.

Conclusion

Based on the authors’ experience and research into financial education among HCPs, it is recommended that psychologists and other disciplines offer opportunities for retirement education at all levels of training. Financial education is likely to be most helpful if it is tailored toward a specific discipline, workplace, and time frame (eg, early career physicians may need more information about loan repayment and may need to invest in more aggressive retirement funds).8 Although many employers provide access to general financial education from outside companies, information provided by informed members of one’s field may be particularly helpful (eg, our seminar was curated for a psychology audience).

We found that the process of creating such a seminar was not burdensome and was educational for presenters as well as attendees. Further, it need not be intimidating to accumulate information to share; especially for those health care providers who have not made financial well-being a priority, learning and deploying a few targeted strategies can lead to increased peace of mind about retirement savings. Overall, we encourage a focus on financial literacy for all health care professions, including physicians who often may graduate with greater debts. Emphasizing early and aggressive financial literacy as an important aspect of provider well-being may help to produce healthier, wealthier, and overall better health care providers.2

Acknowledgments

This manuscript is partially the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Clement J. Zablocki VAMC, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. We thank Milwaukee VA retirement specialist, Vicki Heckman, for her invaluable advice in the preparation of these materials and the Psychology Advancement Workgroup at the Milwaukee VAMC for providing the impetus and support for this project.

1. Zhang Y, Feng X. The relationship between job satisfaction, burnout, and turnover intention among physicians from urban state-owned medical institutions in Hubei, China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11(1):235.

2. Chandrakantan A. Why is there no financial literacy 101 for doctors? https://opmed.doximity.com/an-open -call-to-residency-training-programs-and-trainees-to -facilitate-financial-literacy-bb762e585ed8. Published August 21, 2017. Accessed August 22, 2019.

3. Iyengar SS, Huberman G, Jiang W. How much choice is too much: determinants of individual contributions in 401K retirement plans. In: Mitchell OS, Utkus S, eds. Pension Design and Structure: New Lessons From Behavioral Finance. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004:83-95.

4. Parker AM, de Bruin WB, Yoong J, Willis R. Inappropriate confidence and retirement planning: four studies with a national sample. J Behav Decis Mak. 2012;25(4):382-389.

5. Lusardi A, Mitchell OS. Baby boomer retirement security: the roles of planning, financial literacy, and housing wealth. J Monet Econ. 2007;54(1):205-224.

6. Chub C. It’s time to teach financial literacy to young doctors. https://www.cnbc.com/2016/12/08/teaching -financial-literacy-to-young-doctors.html. Published December 8, 2016. Accessed August 22, 2019.

7. Binswanger J, Carman KG. How real people make longterm decisions: the case of retirement preparation. J Econ Behav Org. 2012;81(1):39-60.

8. Knoll MA. The role of behavioral economics and behavioral decision making in Americans’ retirement savings decisions. Soc Secur Bull. 2010;70(4):1-23.

1. Zhang Y, Feng X. The relationship between job satisfaction, burnout, and turnover intention among physicians from urban state-owned medical institutions in Hubei, China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11(1):235.

2. Chandrakantan A. Why is there no financial literacy 101 for doctors? https://opmed.doximity.com/an-open -call-to-residency-training-programs-and-trainees-to -facilitate-financial-literacy-bb762e585ed8. Published August 21, 2017. Accessed August 22, 2019.

3. Iyengar SS, Huberman G, Jiang W. How much choice is too much: determinants of individual contributions in 401K retirement plans. In: Mitchell OS, Utkus S, eds. Pension Design and Structure: New Lessons From Behavioral Finance. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004:83-95.

4. Parker AM, de Bruin WB, Yoong J, Willis R. Inappropriate confidence and retirement planning: four studies with a national sample. J Behav Decis Mak. 2012;25(4):382-389.

5. Lusardi A, Mitchell OS. Baby boomer retirement security: the roles of planning, financial literacy, and housing wealth. J Monet Econ. 2007;54(1):205-224.

6. Chub C. It’s time to teach financial literacy to young doctors. https://www.cnbc.com/2016/12/08/teaching -financial-literacy-to-young-doctors.html. Published December 8, 2016. Accessed August 22, 2019.

7. Binswanger J, Carman KG. How real people make longterm decisions: the case of retirement preparation. J Econ Behav Org. 2012;81(1):39-60.

8. Knoll MA. The role of behavioral economics and behavioral decision making in Americans’ retirement savings decisions. Soc Secur Bull. 2010;70(4):1-23.

Talking to overweight children

You are seeing a 9-year-old for her annual health maintenance visit. A quick look at her growth chart easily confirms your first impression that she is obese. How are you going to address the weight that you know, and she probably suspects, is going to make her vulnerable to a myriad of health problems as she gets older?

If she has been your patient since she was in preschool, this is certainly not the first time that her growth chart has been concerning. When did you first start discussing her weight with her parents? What words did you use? What strategies have you suggested? What referrals have you made? Maybe you have already given up and decided to not even “go there” at this visit because your experience with overweight patients has been so disappointing.

In her op ed in the New York Times, Dr. Perri Klass reconsiders these kinds of questions as she reviews an article in the journal Childhood Obesity (“Let’s Not Just Dismiss the Weight Watchers Kurbo App,” by Michelle I. Cardel, PhD, MS, RD, and Elsie M. Taveras, MD, MPH, August 2019) written by a nutrition scientist and a pediatrician who are concerned about a new weight loss app for children recently released by Weight Watchers. (The Checkup, “Helping Children Learn to Eat Well,” The New York Times, Aug. 26, 2019). Although the authors of the journal article question some of the science behind the app, their primary concerns are that the app is aimed at children without a way to guarantee parental involvement, and in their opinion the app also places too much emphasis on weight loss.

Their concerns go right to the heart of what troubles me about managing obesity in children. How should I talk to a child about her weight? What words can I choose without shaming? Maybe I shouldn’t be talking to her at all. When a child is 18 months old, we don’t talk to her about her growth chart. Not because she couldn’t understand, but because the solution rests not with her but with her parents.

Does that point come when we have given up on the parents’ ability to create and maintain an environment that discourages obesity? Is that the point when we begin asking the child to unlearn a complex set of behaviors that have been enabled or at least tolerated and poorly modeled at home?

When we begin to talk to a child about his weight do we begin by telling him that he may not have been a contributor to the problem when it began but from now on he needs to be a major player in its management? Of course we don’t share that reality with an 8-year-old, but sometime during his struggle to manage his weight he will connect the dots.

If you are beginning to suspect that I have built my pediatric career around a scaffolding of parent blaming and shaming you are wrong. I know that there are children who have inherited a suite of genes that make them vulnerable to obesity. And I know that too many children grow up in environments in which their parents are powerless to control the family diet for economic reasons. But I am sure that like me you mutter to yourself and your colleagues about the number of patients you are seeing each day whose growth charts are a clear reflection of less than optimal parenting.

Does all of this mean we throw in the towel and stop trying to help overweight children after they turn 6 years old? Of course not. But, it does mean we must redouble our efforts to help parents manage their children’s diets and activity levels in those first critical preschool years.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

You are seeing a 9-year-old for her annual health maintenance visit. A quick look at her growth chart easily confirms your first impression that she is obese. How are you going to address the weight that you know, and she probably suspects, is going to make her vulnerable to a myriad of health problems as she gets older?

If she has been your patient since she was in preschool, this is certainly not the first time that her growth chart has been concerning. When did you first start discussing her weight with her parents? What words did you use? What strategies have you suggested? What referrals have you made? Maybe you have already given up and decided to not even “go there” at this visit because your experience with overweight patients has been so disappointing.

In her op ed in the New York Times, Dr. Perri Klass reconsiders these kinds of questions as she reviews an article in the journal Childhood Obesity (“Let’s Not Just Dismiss the Weight Watchers Kurbo App,” by Michelle I. Cardel, PhD, MS, RD, and Elsie M. Taveras, MD, MPH, August 2019) written by a nutrition scientist and a pediatrician who are concerned about a new weight loss app for children recently released by Weight Watchers. (The Checkup, “Helping Children Learn to Eat Well,” The New York Times, Aug. 26, 2019). Although the authors of the journal article question some of the science behind the app, their primary concerns are that the app is aimed at children without a way to guarantee parental involvement, and in their opinion the app also places too much emphasis on weight loss.

Their concerns go right to the heart of what troubles me about managing obesity in children. How should I talk to a child about her weight? What words can I choose without shaming? Maybe I shouldn’t be talking to her at all. When a child is 18 months old, we don’t talk to her about her growth chart. Not because she couldn’t understand, but because the solution rests not with her but with her parents.

Does that point come when we have given up on the parents’ ability to create and maintain an environment that discourages obesity? Is that the point when we begin asking the child to unlearn a complex set of behaviors that have been enabled or at least tolerated and poorly modeled at home?

When we begin to talk to a child about his weight do we begin by telling him that he may not have been a contributor to the problem when it began but from now on he needs to be a major player in its management? Of course we don’t share that reality with an 8-year-old, but sometime during his struggle to manage his weight he will connect the dots.

If you are beginning to suspect that I have built my pediatric career around a scaffolding of parent blaming and shaming you are wrong. I know that there are children who have inherited a suite of genes that make them vulnerable to obesity. And I know that too many children grow up in environments in which their parents are powerless to control the family diet for economic reasons. But I am sure that like me you mutter to yourself and your colleagues about the number of patients you are seeing each day whose growth charts are a clear reflection of less than optimal parenting.

Does all of this mean we throw in the towel and stop trying to help overweight children after they turn 6 years old? Of course not. But, it does mean we must redouble our efforts to help parents manage their children’s diets and activity levels in those first critical preschool years.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

You are seeing a 9-year-old for her annual health maintenance visit. A quick look at her growth chart easily confirms your first impression that she is obese. How are you going to address the weight that you know, and she probably suspects, is going to make her vulnerable to a myriad of health problems as she gets older?

If she has been your patient since she was in preschool, this is certainly not the first time that her growth chart has been concerning. When did you first start discussing her weight with her parents? What words did you use? What strategies have you suggested? What referrals have you made? Maybe you have already given up and decided to not even “go there” at this visit because your experience with overweight patients has been so disappointing.

In her op ed in the New York Times, Dr. Perri Klass reconsiders these kinds of questions as she reviews an article in the journal Childhood Obesity (“Let’s Not Just Dismiss the Weight Watchers Kurbo App,” by Michelle I. Cardel, PhD, MS, RD, and Elsie M. Taveras, MD, MPH, August 2019) written by a nutrition scientist and a pediatrician who are concerned about a new weight loss app for children recently released by Weight Watchers. (The Checkup, “Helping Children Learn to Eat Well,” The New York Times, Aug. 26, 2019). Although the authors of the journal article question some of the science behind the app, their primary concerns are that the app is aimed at children without a way to guarantee parental involvement, and in their opinion the app also places too much emphasis on weight loss.

Their concerns go right to the heart of what troubles me about managing obesity in children. How should I talk to a child about her weight? What words can I choose without shaming? Maybe I shouldn’t be talking to her at all. When a child is 18 months old, we don’t talk to her about her growth chart. Not because she couldn’t understand, but because the solution rests not with her but with her parents.

Does that point come when we have given up on the parents’ ability to create and maintain an environment that discourages obesity? Is that the point when we begin asking the child to unlearn a complex set of behaviors that have been enabled or at least tolerated and poorly modeled at home?

When we begin to talk to a child about his weight do we begin by telling him that he may not have been a contributor to the problem when it began but from now on he needs to be a major player in its management? Of course we don’t share that reality with an 8-year-old, but sometime during his struggle to manage his weight he will connect the dots.

If you are beginning to suspect that I have built my pediatric career around a scaffolding of parent blaming and shaming you are wrong. I know that there are children who have inherited a suite of genes that make them vulnerable to obesity. And I know that too many children grow up in environments in which their parents are powerless to control the family diet for economic reasons. But I am sure that like me you mutter to yourself and your colleagues about the number of patients you are seeing each day whose growth charts are a clear reflection of less than optimal parenting.

Does all of this mean we throw in the towel and stop trying to help overweight children after they turn 6 years old? Of course not. But, it does mean we must redouble our efforts to help parents manage their children’s diets and activity levels in those first critical preschool years.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

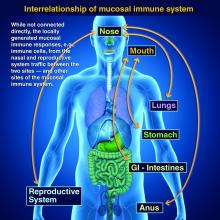

Taking vaccines to the next level via mucosal immunity

Vaccines are marvelous, and there are many well documented success stories, including rotavirus (RV) vaccines, where a live vaccine is administered to the gastrointestinal mucosa via oral drops. Antigens presented at the mucosal/epithelial surface not only induce systemic serum IgG – as do injectable vaccines – but also induce secretory IgA (sIgA), which is most helpful in diseases that directly affect the mucosa.

Mucosal vs. systemic immunity

Antibody being present on mucosal surfaces (point of initial pathogen contact) has a chance to neutralize the pathogen before it gains a foothold. Pathogen-specific mucosal lymphoid elements (e.g. in Peyer’s patches in the gut) also appear critical for optimal protection.1 The presence of both mucosal immune elements means that infection is severely limited or at times entirely prevented. So virus entering the GI tract causes minimal to no gut lining injury. Hence, there is no or mostly reduced vomiting/diarrhea. A downside of mucosally-administered live vaccines is that preexisting antibody to the vaccine antigens can reduce or block vaccine virus replication in the vaccinee, blunting or preventing protection. Note: Preexisting antibody also affects injectable live vaccines, such as the measles vaccine, similarly.

Classic injectable live or nonlive vaccines provide their most potent protection via systemic cellular responses antibody and/or antibodies in serum and extracellular fluid (ECF) where IgG and IgM are in highest concentrations. So even successful injectable vaccines still allow mucosal infection to start but then intercept further spread and prevent most of the downstream damage (think pertussis) or neutralize an infection-generated toxin (pertussis or tetanus). It usually is only after infection-induced damage occurs that systemic IgG and IgM gain better access to respiratory epithelial surfaces, but still only at a fraction of circulating concentrations. Indeed, pertussis vaccine–induced systemic immunity allows the pathogen to attack and replicate in/on host surface cells, causing toxin release and variable amounts of local mucosal injury/inflammation before vaccine-induced systemic immunity gains adequate access to the pathogen and/or to its toxin which may enter systemic circulation.

Live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) induces mucosal immunity

Another “standard” vaccine that induces mucosal immunity – LAIV – was developed to improve on protection afforded by injectable influenza vaccines (IIVs), but LAIV has had hiccups in the United States. One example is several years of negligible protection against H1N1 disease. As long as LAIV’s vaccine strain had reasonably matched the circulating strains, LAIV worked at least as well as injectable influenza vaccine, and even offered some cross-protection against mildly mismatched strains. But after a number of years of LAIV use, vaccine effectiveness in the United States vs. H1N1 strains appeared to fade due to previously undetected but significant changes in the circulating H1N1 strain. The lesson is that mucosal immunity’s advantages are lost if too much change occurs in the pathogen target for sIgA and mucosally-associated lymphoid tissue cells (MALT)).

Other vaccines likely need to induce mucosal immunity

Protection at the mucosal level will likely be needed for success against norovirus, parainfluenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), Neisseria gonorrhea, and chlamydia. Another helpful aspect of mucosal immunity is that immune cells and sIgA not only reside on the mucosa where the antigen was originally presented, but there is also a reasonable chance that these components will traffic to other mucosal surfaces.2

So intranasal vaccine could be expected to protect distant mucosal surfaces (urogenital, GI, and respiratory), leading to vaccine-induced systemic antibody plus mucosal immunity (sIGA and MALT responses) at each site.

Let’s look at a novel “two-site” chlamydia vaccine

Recently a phase 1 chlamydia vaccine that used a novel two-pronged administration site/schedule was successful at inducing both mucosal and systemic immunity in a proof-of-concept study – achieving the best of both worlds.3 This may be a template for vaccines in years to come. British investigators studied 50 healthy women aged 19-45 years in a double-blind, parallel, randomized, placebo-controlled trial that used a recombinant chlamydia protein subunit antigen (CTH522). The vaccine schedule involved three injectable priming doses followed soon thereafter by two intranasal boosting doses. There were three groups:

1. CTH522 adjuvanted with CAF01 liposomes (CTH522:CAF01).

2. CTH522 adjuvanted with aluminum hydroxide (CTH522:AH).

3. Placebo (saline).

The intramuscular (IM) priming schedule was 0, 1, and 4 months. The intranasal vaccine booster doses or placebo were given at 4.5 and 5 months. No related serious adverse reactions occurred. For injectable dosing, the most frequent adverse event was mild local injection-site reactions in all subjects in both vaccine groups vs. in 60% of placebo recipients (P = .053). The adjuvants were the likely cause for local reactions. Intranasal doses had local reactions in 47% of both vaccine groups and 60% of placebo recipients; P = 1.000).

Both vaccines produced systemic IgG seroconversion (including neutralizing antibody) plus small amounts of IgG in the nasal cavity and genital tract in all vaccine recipients; no placebo recipient seroconverted. Interestingly, liposomally-adjuvanted vaccine produced a more rapid systemic IgG response and higher serum titers than the alum-adjuvanted vaccine. Likewise, the IM liposomal vaccine also induced higher but still small mucosal IgG antibody responses (P = .0091). Intranasal IM-induced IgG titers were not boosted by later intranasal vaccine dosing.

Subjects getting liposomal vaccine (but not alum vaccine or placebo) boosters had detectable sIgA titers in both nasal and genital tract secretions. Liposomal vaccine recipients also had fivefold to sixfold higher median titers than alum vaccine recipients after the priming dose, and these higher titers persisted to the end of the study. All liposomal vaccine recipients developed antichlamydial cell-mediated responses vs. 57% alum-adjuvanted vaccine recipients. (P = .01). So both use of two-site dosing and the liposomal adjuvant appeared critical to better responses.

In summary

While this candidate vaccine has hurdles to overcome before coming into routine use, the proof-of-principle that a combination injectable-intranasal vaccine schedule can induce robust systemic and mucosal immunity when given with an appropriate adjuvant is very promising. Adding more vaccines to the schedule then becomes an issue, but that is one of those “good” problems we can deal with later.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospital-Kansas City, Mo. Children’s Mercy Hospital receives grant funding to study two candidate RSV vaccines, receives funding from GlaxoSmithKline for studies on pneumococcal and rotavirus vaccines, and from Pfizer for a study on pneumococcal vaccine on which Dr. Harrison is a sub-investigator. The hospital also receives Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funding under the New Vaccine Surveillance Network for multicenter surveillance of acute respiratory infections, including influenza, RSV, and parainfluenza virus, and also for rotavirus. Email Dr. Harrison at [email protected].

References

1. PLOS Biology. 2012 Sep 1. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001397.

2. Mucosal Immunity in the Human Female Reproductive Tract in “Mucosal Immunology,” 4th ed., Volume 2 (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, 2015, pp. 2097-124).

3. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30279-8.

Vaccines are marvelous, and there are many well documented success stories, including rotavirus (RV) vaccines, where a live vaccine is administered to the gastrointestinal mucosa via oral drops. Antigens presented at the mucosal/epithelial surface not only induce systemic serum IgG – as do injectable vaccines – but also induce secretory IgA (sIgA), which is most helpful in diseases that directly affect the mucosa.

Mucosal vs. systemic immunity

Antibody being present on mucosal surfaces (point of initial pathogen contact) has a chance to neutralize the pathogen before it gains a foothold. Pathogen-specific mucosal lymphoid elements (e.g. in Peyer’s patches in the gut) also appear critical for optimal protection.1 The presence of both mucosal immune elements means that infection is severely limited or at times entirely prevented. So virus entering the GI tract causes minimal to no gut lining injury. Hence, there is no or mostly reduced vomiting/diarrhea. A downside of mucosally-administered live vaccines is that preexisting antibody to the vaccine antigens can reduce or block vaccine virus replication in the vaccinee, blunting or preventing protection. Note: Preexisting antibody also affects injectable live vaccines, such as the measles vaccine, similarly.

Classic injectable live or nonlive vaccines provide their most potent protection via systemic cellular responses antibody and/or antibodies in serum and extracellular fluid (ECF) where IgG and IgM are in highest concentrations. So even successful injectable vaccines still allow mucosal infection to start but then intercept further spread and prevent most of the downstream damage (think pertussis) or neutralize an infection-generated toxin (pertussis or tetanus). It usually is only after infection-induced damage occurs that systemic IgG and IgM gain better access to respiratory epithelial surfaces, but still only at a fraction of circulating concentrations. Indeed, pertussis vaccine–induced systemic immunity allows the pathogen to attack and replicate in/on host surface cells, causing toxin release and variable amounts of local mucosal injury/inflammation before vaccine-induced systemic immunity gains adequate access to the pathogen and/or to its toxin which may enter systemic circulation.

Live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) induces mucosal immunity

Another “standard” vaccine that induces mucosal immunity – LAIV – was developed to improve on protection afforded by injectable influenza vaccines (IIVs), but LAIV has had hiccups in the United States. One example is several years of negligible protection against H1N1 disease. As long as LAIV’s vaccine strain had reasonably matched the circulating strains, LAIV worked at least as well as injectable influenza vaccine, and even offered some cross-protection against mildly mismatched strains. But after a number of years of LAIV use, vaccine effectiveness in the United States vs. H1N1 strains appeared to fade due to previously undetected but significant changes in the circulating H1N1 strain. The lesson is that mucosal immunity’s advantages are lost if too much change occurs in the pathogen target for sIgA and mucosally-associated lymphoid tissue cells (MALT)).

Other vaccines likely need to induce mucosal immunity

Protection at the mucosal level will likely be needed for success against norovirus, parainfluenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), Neisseria gonorrhea, and chlamydia. Another helpful aspect of mucosal immunity is that immune cells and sIgA not only reside on the mucosa where the antigen was originally presented, but there is also a reasonable chance that these components will traffic to other mucosal surfaces.2

So intranasal vaccine could be expected to protect distant mucosal surfaces (urogenital, GI, and respiratory), leading to vaccine-induced systemic antibody plus mucosal immunity (sIGA and MALT responses) at each site.

Let’s look at a novel “two-site” chlamydia vaccine

Recently a phase 1 chlamydia vaccine that used a novel two-pronged administration site/schedule was successful at inducing both mucosal and systemic immunity in a proof-of-concept study – achieving the best of both worlds.3 This may be a template for vaccines in years to come. British investigators studied 50 healthy women aged 19-45 years in a double-blind, parallel, randomized, placebo-controlled trial that used a recombinant chlamydia protein subunit antigen (CTH522). The vaccine schedule involved three injectable priming doses followed soon thereafter by two intranasal boosting doses. There were three groups:

1. CTH522 adjuvanted with CAF01 liposomes (CTH522:CAF01).

2. CTH522 adjuvanted with aluminum hydroxide (CTH522:AH).

3. Placebo (saline).

The intramuscular (IM) priming schedule was 0, 1, and 4 months. The intranasal vaccine booster doses or placebo were given at 4.5 and 5 months. No related serious adverse reactions occurred. For injectable dosing, the most frequent adverse event was mild local injection-site reactions in all subjects in both vaccine groups vs. in 60% of placebo recipients (P = .053). The adjuvants were the likely cause for local reactions. Intranasal doses had local reactions in 47% of both vaccine groups and 60% of placebo recipients; P = 1.000).

Both vaccines produced systemic IgG seroconversion (including neutralizing antibody) plus small amounts of IgG in the nasal cavity and genital tract in all vaccine recipients; no placebo recipient seroconverted. Interestingly, liposomally-adjuvanted vaccine produced a more rapid systemic IgG response and higher serum titers than the alum-adjuvanted vaccine. Likewise, the IM liposomal vaccine also induced higher but still small mucosal IgG antibody responses (P = .0091). Intranasal IM-induced IgG titers were not boosted by later intranasal vaccine dosing.

Subjects getting liposomal vaccine (but not alum vaccine or placebo) boosters had detectable sIgA titers in both nasal and genital tract secretions. Liposomal vaccine recipients also had fivefold to sixfold higher median titers than alum vaccine recipients after the priming dose, and these higher titers persisted to the end of the study. All liposomal vaccine recipients developed antichlamydial cell-mediated responses vs. 57% alum-adjuvanted vaccine recipients. (P = .01). So both use of two-site dosing and the liposomal adjuvant appeared critical to better responses.

In summary

While this candidate vaccine has hurdles to overcome before coming into routine use, the proof-of-principle that a combination injectable-intranasal vaccine schedule can induce robust systemic and mucosal immunity when given with an appropriate adjuvant is very promising. Adding more vaccines to the schedule then becomes an issue, but that is one of those “good” problems we can deal with later.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospital-Kansas City, Mo. Children’s Mercy Hospital receives grant funding to study two candidate RSV vaccines, receives funding from GlaxoSmithKline for studies on pneumococcal and rotavirus vaccines, and from Pfizer for a study on pneumococcal vaccine on which Dr. Harrison is a sub-investigator. The hospital also receives Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funding under the New Vaccine Surveillance Network for multicenter surveillance of acute respiratory infections, including influenza, RSV, and parainfluenza virus, and also for rotavirus. Email Dr. Harrison at [email protected].

References

1. PLOS Biology. 2012 Sep 1. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001397.

2. Mucosal Immunity in the Human Female Reproductive Tract in “Mucosal Immunology,” 4th ed., Volume 2 (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, 2015, pp. 2097-124).