User login

Communication Modality (CM) Among Veterans Using National TeleOncology (NTO) Services

Background

We examined characteristics of Veterans receiving care through NTO and their CM (e.g., telephone only [T], video only [V], or both [TV]). Relevant background: In-person VA cancer care can be challenging for many Veterans due to rurality, transportation, finances, and distance to subspecialists. Such factors may impact care modality preferences.

Methods

We linked a list of all Veterans who received NTO care with Corporate Data Warehouse data to confirm an ICD-10 diagnostic code for malignancy, and to define the number of NTO interactions, latency of days between diagnosis and first NTO interaction, and demographics. The Office of Rural Health categories for rurality and NIH categories for race were used.

Data analysis

We report descriptive statistics for CM. To compare differences between Veterans by CM, we report chi-squared tests for categorical variables and ANOVAs for continuous variables.

Results

Among 13,902 NTO Veterans with CM data, most were V (9,998, 72%), few were T 2% (n= 295), and some were TV 26% (n= 3,609). There were statistically significant differences between CM in number of interactions, latency between diagnosis and first NTO interaction, age at first NTO interaction, sex, race, rurality, and cancer type. Veterans diagnosed with lung cancer were more likely to exclusively use T. Veterans with breast cancer were more likely to exclusively use V. Specifically, T were oldest (mean age = 74.3), followed by TV (69.0) and V (61.6; p < .001). Women were most represented in V (28.3%) and Rural or highly rural residence was most common among T users (54.6%), compared to V (36.8%) and TV (43.0%; p < .001). Urban users were more prevalent in the TV group (61.9%) than in the T only group (45.4%).

Implications

We identified differences in communication modality based on Veteran characteristics. This could suggest differences in Veteran or provider preference, feasibility, or acceptability, based on CM.

Significance

While V communications appear to be achievable for many Veterans, more work is needed to determine preference, feasibility, and acceptability among Veterans and their care teams regarding V and T only cancer care.

Background

We examined characteristics of Veterans receiving care through NTO and their CM (e.g., telephone only [T], video only [V], or both [TV]). Relevant background: In-person VA cancer care can be challenging for many Veterans due to rurality, transportation, finances, and distance to subspecialists. Such factors may impact care modality preferences.

Methods

We linked a list of all Veterans who received NTO care with Corporate Data Warehouse data to confirm an ICD-10 diagnostic code for malignancy, and to define the number of NTO interactions, latency of days between diagnosis and first NTO interaction, and demographics. The Office of Rural Health categories for rurality and NIH categories for race were used.

Data analysis

We report descriptive statistics for CM. To compare differences between Veterans by CM, we report chi-squared tests for categorical variables and ANOVAs for continuous variables.

Results

Among 13,902 NTO Veterans with CM data, most were V (9,998, 72%), few were T 2% (n= 295), and some were TV 26% (n= 3,609). There were statistically significant differences between CM in number of interactions, latency between diagnosis and first NTO interaction, age at first NTO interaction, sex, race, rurality, and cancer type. Veterans diagnosed with lung cancer were more likely to exclusively use T. Veterans with breast cancer were more likely to exclusively use V. Specifically, T were oldest (mean age = 74.3), followed by TV (69.0) and V (61.6; p < .001). Women were most represented in V (28.3%) and Rural or highly rural residence was most common among T users (54.6%), compared to V (36.8%) and TV (43.0%; p < .001). Urban users were more prevalent in the TV group (61.9%) than in the T only group (45.4%).

Implications

We identified differences in communication modality based on Veteran characteristics. This could suggest differences in Veteran or provider preference, feasibility, or acceptability, based on CM.

Significance

While V communications appear to be achievable for many Veterans, more work is needed to determine preference, feasibility, and acceptability among Veterans and their care teams regarding V and T only cancer care.

Background

We examined characteristics of Veterans receiving care through NTO and their CM (e.g., telephone only [T], video only [V], or both [TV]). Relevant background: In-person VA cancer care can be challenging for many Veterans due to rurality, transportation, finances, and distance to subspecialists. Such factors may impact care modality preferences.

Methods

We linked a list of all Veterans who received NTO care with Corporate Data Warehouse data to confirm an ICD-10 diagnostic code for malignancy, and to define the number of NTO interactions, latency of days between diagnosis and first NTO interaction, and demographics. The Office of Rural Health categories for rurality and NIH categories for race were used.

Data analysis

We report descriptive statistics for CM. To compare differences between Veterans by CM, we report chi-squared tests for categorical variables and ANOVAs for continuous variables.

Results

Among 13,902 NTO Veterans with CM data, most were V (9,998, 72%), few were T 2% (n= 295), and some were TV 26% (n= 3,609). There were statistically significant differences between CM in number of interactions, latency between diagnosis and first NTO interaction, age at first NTO interaction, sex, race, rurality, and cancer type. Veterans diagnosed with lung cancer were more likely to exclusively use T. Veterans with breast cancer were more likely to exclusively use V. Specifically, T were oldest (mean age = 74.3), followed by TV (69.0) and V (61.6; p < .001). Women were most represented in V (28.3%) and Rural or highly rural residence was most common among T users (54.6%), compared to V (36.8%) and TV (43.0%; p < .001). Urban users were more prevalent in the TV group (61.9%) than in the T only group (45.4%).

Implications

We identified differences in communication modality based on Veteran characteristics. This could suggest differences in Veteran or provider preference, feasibility, or acceptability, based on CM.

Significance

While V communications appear to be achievable for many Veterans, more work is needed to determine preference, feasibility, and acceptability among Veterans and their care teams regarding V and T only cancer care.

Organs of Metastasis Predominate with Age in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Subtypes: National Cancer Database Analysis

Background

Patients diagnosed with lung cancer are predominantly non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), a leading cause of cancer-related deaths. Thus, it is imperative to investigate and distinguish the differences present at diagnosis to possibly improve survival outcomes. NSCLC commonly metastasizes within older patients near the mean age of 71 years, but also in early onset patients which represents the patients younger than the earliest lung cancer screening age of 50.

Objective

To reveal differences in ratios of metastasis locations in squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), adenocarcinoma (ACC), and adenosquamous carcinoma (ASC).

Methods

The National Cancer Database (NCDB) was utilized to identify patients diagnosed with SCC, ACC, and ASC using the histology codes 8070, 8140, and 8560 from the ICD-O-3.2 from 2004 to 2022. Age groups were 70 years. Metastases located to the brain, liver, bone, and lung were included. Chi-Square tests were performed. The data was analyzed using R version 4.4.2 and statistical significance was set to α = 0.05.

Results

In this study, 1,445,119 patients were analyzed. Chi-Square tests identified significant differences in the ratios of organ metastasis locations between age groups in each subtype (p < 0.001). SCC in each age group similarly metastasized most to bone (36.3%, 34.7%, 34.5%), but notably more local lung metastasis was observed in the oldest group (33.6%). In ACC and ASC, the oldest group also had greater ratios of spread within the lungs (28.0%, 27.2%). Overall, the younger the age group, distant spread to the brain increased (ex. 29.0%, 24.4%, 17.5%). This suggests a widely heterogenous distribution of metastases at diagnosis of NSCLC subtypes and patient age.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that patients with SCC, ACC, or ASC subtypes of NSCLC share similar predominant locations based in part on patient age, irrespective of cancer origin. NSCLC may more distantly metastasize in younger patients to the brain, while older patients may have locally metastatic cancer. Further analysis of key demographic variables as well as common undertaken treatment options may prove informative and reveal existing differences in survival outcomes.

Background

Patients diagnosed with lung cancer are predominantly non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), a leading cause of cancer-related deaths. Thus, it is imperative to investigate and distinguish the differences present at diagnosis to possibly improve survival outcomes. NSCLC commonly metastasizes within older patients near the mean age of 71 years, but also in early onset patients which represents the patients younger than the earliest lung cancer screening age of 50.

Objective

To reveal differences in ratios of metastasis locations in squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), adenocarcinoma (ACC), and adenosquamous carcinoma (ASC).

Methods

The National Cancer Database (NCDB) was utilized to identify patients diagnosed with SCC, ACC, and ASC using the histology codes 8070, 8140, and 8560 from the ICD-O-3.2 from 2004 to 2022. Age groups were 70 years. Metastases located to the brain, liver, bone, and lung were included. Chi-Square tests were performed. The data was analyzed using R version 4.4.2 and statistical significance was set to α = 0.05.

Results

In this study, 1,445,119 patients were analyzed. Chi-Square tests identified significant differences in the ratios of organ metastasis locations between age groups in each subtype (p < 0.001). SCC in each age group similarly metastasized most to bone (36.3%, 34.7%, 34.5%), but notably more local lung metastasis was observed in the oldest group (33.6%). In ACC and ASC, the oldest group also had greater ratios of spread within the lungs (28.0%, 27.2%). Overall, the younger the age group, distant spread to the brain increased (ex. 29.0%, 24.4%, 17.5%). This suggests a widely heterogenous distribution of metastases at diagnosis of NSCLC subtypes and patient age.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that patients with SCC, ACC, or ASC subtypes of NSCLC share similar predominant locations based in part on patient age, irrespective of cancer origin. NSCLC may more distantly metastasize in younger patients to the brain, while older patients may have locally metastatic cancer. Further analysis of key demographic variables as well as common undertaken treatment options may prove informative and reveal existing differences in survival outcomes.

Background

Patients diagnosed with lung cancer are predominantly non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), a leading cause of cancer-related deaths. Thus, it is imperative to investigate and distinguish the differences present at diagnosis to possibly improve survival outcomes. NSCLC commonly metastasizes within older patients near the mean age of 71 years, but also in early onset patients which represents the patients younger than the earliest lung cancer screening age of 50.

Objective

To reveal differences in ratios of metastasis locations in squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), adenocarcinoma (ACC), and adenosquamous carcinoma (ASC).

Methods

The National Cancer Database (NCDB) was utilized to identify patients diagnosed with SCC, ACC, and ASC using the histology codes 8070, 8140, and 8560 from the ICD-O-3.2 from 2004 to 2022. Age groups were 70 years. Metastases located to the brain, liver, bone, and lung were included. Chi-Square tests were performed. The data was analyzed using R version 4.4.2 and statistical significance was set to α = 0.05.

Results

In this study, 1,445,119 patients were analyzed. Chi-Square tests identified significant differences in the ratios of organ metastasis locations between age groups in each subtype (p < 0.001). SCC in each age group similarly metastasized most to bone (36.3%, 34.7%, 34.5%), but notably more local lung metastasis was observed in the oldest group (33.6%). In ACC and ASC, the oldest group also had greater ratios of spread within the lungs (28.0%, 27.2%). Overall, the younger the age group, distant spread to the brain increased (ex. 29.0%, 24.4%, 17.5%). This suggests a widely heterogenous distribution of metastases at diagnosis of NSCLC subtypes and patient age.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that patients with SCC, ACC, or ASC subtypes of NSCLC share similar predominant locations based in part on patient age, irrespective of cancer origin. NSCLC may more distantly metastasize in younger patients to the brain, while older patients may have locally metastatic cancer. Further analysis of key demographic variables as well as common undertaken treatment options may prove informative and reveal existing differences in survival outcomes.

Shifting Demographics: A Temporal Analysis of the Alarming Rise in Rectal Adenocarcinoma Among Young Adults

Background

Rectal adenocarcinoma has long been associated with older adults, with routine screening typically beginning at age 45 or older. However, recent data reveal a concerning rise in rectal cancer incidence among adults under 40. These early-onset cases often present at later stages and may have distinct biological features. While some research attributes this trend to genetic or environmental factors, the contribution of socioeconomic disparities and healthcare access has not been fully explored. Identifying these influences is essential to shaping targeted prevention and early detection strategies for younger populations.

Objective

To evaluate temporal trends in rectal adenocarcinoma among young adults and assess demographic and socioeconomic predictors of early-onset diagnosis.

Methods

Data were drawn from the National Cancer Database (NCDB) for patients diagnosed with rectal adenocarcinoma from 2004 to 2022. Among 440,316 cases, 17,842 (4.1%) occurred in individuals under 40. Linear regression assessed temporal trends, while logistic regression evaluated associations between early-onset diagnosis and variables including sex, race, insurance status, income level, Charlson-Deyo comorbidity score, and tumor stage. Statistical significance was defined as α = 0.05.

Results

The number of young adults diagnosed rose from 424 in 2004 to 937 in 2022—an increase of over 120%. Each year was associated with a 1.7% rise in odds of early diagnosis (OR = 1.017, p < 0.001). Male patients had 24.7% higher odds (OR = 1.247, p < 0.001), and Black patients had 59.3% higher odds compared to White patients (OR = 1.593, p < 0.001). Non-private insurance was linked to a 41.6% decrease in early diagnosis (OR = 0.584, p < 0.001). Income level was not significant (p = 0.426). Lower Charlson-Deyo scores and higher tumor stages were also associated with early-onset cases.

Conclusions

Rectal adenocarcinoma is increasingly affecting younger adults, with significant associations across demographic and insurance variables. These findings call for improved awareness, early diagnostic strategies, and further research into underlying causes to mitigate this growing public health concern.

Background

Rectal adenocarcinoma has long been associated with older adults, with routine screening typically beginning at age 45 or older. However, recent data reveal a concerning rise in rectal cancer incidence among adults under 40. These early-onset cases often present at later stages and may have distinct biological features. While some research attributes this trend to genetic or environmental factors, the contribution of socioeconomic disparities and healthcare access has not been fully explored. Identifying these influences is essential to shaping targeted prevention and early detection strategies for younger populations.

Objective

To evaluate temporal trends in rectal adenocarcinoma among young adults and assess demographic and socioeconomic predictors of early-onset diagnosis.

Methods

Data were drawn from the National Cancer Database (NCDB) for patients diagnosed with rectal adenocarcinoma from 2004 to 2022. Among 440,316 cases, 17,842 (4.1%) occurred in individuals under 40. Linear regression assessed temporal trends, while logistic regression evaluated associations between early-onset diagnosis and variables including sex, race, insurance status, income level, Charlson-Deyo comorbidity score, and tumor stage. Statistical significance was defined as α = 0.05.

Results

The number of young adults diagnosed rose from 424 in 2004 to 937 in 2022—an increase of over 120%. Each year was associated with a 1.7% rise in odds of early diagnosis (OR = 1.017, p < 0.001). Male patients had 24.7% higher odds (OR = 1.247, p < 0.001), and Black patients had 59.3% higher odds compared to White patients (OR = 1.593, p < 0.001). Non-private insurance was linked to a 41.6% decrease in early diagnosis (OR = 0.584, p < 0.001). Income level was not significant (p = 0.426). Lower Charlson-Deyo scores and higher tumor stages were also associated with early-onset cases.

Conclusions

Rectal adenocarcinoma is increasingly affecting younger adults, with significant associations across demographic and insurance variables. These findings call for improved awareness, early diagnostic strategies, and further research into underlying causes to mitigate this growing public health concern.

Background

Rectal adenocarcinoma has long been associated with older adults, with routine screening typically beginning at age 45 or older. However, recent data reveal a concerning rise in rectal cancer incidence among adults under 40. These early-onset cases often present at later stages and may have distinct biological features. While some research attributes this trend to genetic or environmental factors, the contribution of socioeconomic disparities and healthcare access has not been fully explored. Identifying these influences is essential to shaping targeted prevention and early detection strategies for younger populations.

Objective

To evaluate temporal trends in rectal adenocarcinoma among young adults and assess demographic and socioeconomic predictors of early-onset diagnosis.

Methods

Data were drawn from the National Cancer Database (NCDB) for patients diagnosed with rectal adenocarcinoma from 2004 to 2022. Among 440,316 cases, 17,842 (4.1%) occurred in individuals under 40. Linear regression assessed temporal trends, while logistic regression evaluated associations between early-onset diagnosis and variables including sex, race, insurance status, income level, Charlson-Deyo comorbidity score, and tumor stage. Statistical significance was defined as α = 0.05.

Results

The number of young adults diagnosed rose from 424 in 2004 to 937 in 2022—an increase of over 120%. Each year was associated with a 1.7% rise in odds of early diagnosis (OR = 1.017, p < 0.001). Male patients had 24.7% higher odds (OR = 1.247, p < 0.001), and Black patients had 59.3% higher odds compared to White patients (OR = 1.593, p < 0.001). Non-private insurance was linked to a 41.6% decrease in early diagnosis (OR = 0.584, p < 0.001). Income level was not significant (p = 0.426). Lower Charlson-Deyo scores and higher tumor stages were also associated with early-onset cases.

Conclusions

Rectal adenocarcinoma is increasingly affecting younger adults, with significant associations across demographic and insurance variables. These findings call for improved awareness, early diagnostic strategies, and further research into underlying causes to mitigate this growing public health concern.

Epidemiology and Survival of Parotid Gland Malignancies With Brain Metastases: A Population- Based Study

Background

Parotid gland malignancies are a rare subset of salivary gland tumors, comprising approximately 1–3% of all head and neck cancers. While distant metastases commonly involve the lungs, brain metastases are exceedingly rare and remain poorly characterized. Management typically includes stereotactic radiosurgery or whole-brain radiation. This study evaluates the incidence, clinicopathologic features, and survival outcomes of patients with parotid gland tumors and brain metastases using data from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database.

Methods

SEER database (2010–2022) was queried for patients diagnosed with primary malignant neoplasms of the parotid gland (ICD-O-3 site code C07.9). Cases of brain metastases were identified using SEER metastatic site variables. Age-adjusted incidence rates (IR) per 100,000 population were calculated using SEER*Stat 8.4.5. Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism, and survival differences were assessed using the log-rank test.

Results

Among 12,951 patients diagnosed with parotid malignancy, 47 (0.36%) had brain metastases. The median age at diagnosis was 67 years, and 77.5% were male. The overall incidence rate (IR) of brain metastases was 0.00235 per 100,000 population, with a significantly higher rate observed in males compared to females (p < 0.0001). The most common histologic subtype associated with brain involvement was squamous cell carcinoma (SCC, n=10), followed by adenocarcinoma. Median overall survival (mOS) for patients with brain metastases was 2 months (hazard ratio [HR] 6.28; 95% CI: 2.71–14.55), compared to 131 months for those without brain involvement (p < 0.001). 1-year cancer-specific survival for patients with brain metastases was 38%. Among patients with parotid SCC and brain metastases, mOS was 3 months, compared to 39 months in those without brain involvement (HR 5.70; 95% CI: 1.09–29.68; p < 0.0001).

Conclusions

Brain metastases from parotid gland cancers, though rare, are associated with markedly poor outcomes. This highlights the importance of early neurologic assessment and brain imaging in high-risk patients, particularly with SCC histology. Prior studies have shown that TP53 mutations are common in parotid SCC, but their role in CNS spread remains unclear. Future research should explore molecular pathways underlying neurotropism in parotid cancers and investigate targeted systemic therapies with CNS penetration to improve outcomes.

Background

Parotid gland malignancies are a rare subset of salivary gland tumors, comprising approximately 1–3% of all head and neck cancers. While distant metastases commonly involve the lungs, brain metastases are exceedingly rare and remain poorly characterized. Management typically includes stereotactic radiosurgery or whole-brain radiation. This study evaluates the incidence, clinicopathologic features, and survival outcomes of patients with parotid gland tumors and brain metastases using data from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database.

Methods

SEER database (2010–2022) was queried for patients diagnosed with primary malignant neoplasms of the parotid gland (ICD-O-3 site code C07.9). Cases of brain metastases were identified using SEER metastatic site variables. Age-adjusted incidence rates (IR) per 100,000 population were calculated using SEER*Stat 8.4.5. Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism, and survival differences were assessed using the log-rank test.

Results

Among 12,951 patients diagnosed with parotid malignancy, 47 (0.36%) had brain metastases. The median age at diagnosis was 67 years, and 77.5% were male. The overall incidence rate (IR) of brain metastases was 0.00235 per 100,000 population, with a significantly higher rate observed in males compared to females (p < 0.0001). The most common histologic subtype associated with brain involvement was squamous cell carcinoma (SCC, n=10), followed by adenocarcinoma. Median overall survival (mOS) for patients with brain metastases was 2 months (hazard ratio [HR] 6.28; 95% CI: 2.71–14.55), compared to 131 months for those without brain involvement (p < 0.001). 1-year cancer-specific survival for patients with brain metastases was 38%. Among patients with parotid SCC and brain metastases, mOS was 3 months, compared to 39 months in those without brain involvement (HR 5.70; 95% CI: 1.09–29.68; p < 0.0001).

Conclusions

Brain metastases from parotid gland cancers, though rare, are associated with markedly poor outcomes. This highlights the importance of early neurologic assessment and brain imaging in high-risk patients, particularly with SCC histology. Prior studies have shown that TP53 mutations are common in parotid SCC, but their role in CNS spread remains unclear. Future research should explore molecular pathways underlying neurotropism in parotid cancers and investigate targeted systemic therapies with CNS penetration to improve outcomes.

Background

Parotid gland malignancies are a rare subset of salivary gland tumors, comprising approximately 1–3% of all head and neck cancers. While distant metastases commonly involve the lungs, brain metastases are exceedingly rare and remain poorly characterized. Management typically includes stereotactic radiosurgery or whole-brain radiation. This study evaluates the incidence, clinicopathologic features, and survival outcomes of patients with parotid gland tumors and brain metastases using data from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database.

Methods

SEER database (2010–2022) was queried for patients diagnosed with primary malignant neoplasms of the parotid gland (ICD-O-3 site code C07.9). Cases of brain metastases were identified using SEER metastatic site variables. Age-adjusted incidence rates (IR) per 100,000 population were calculated using SEER*Stat 8.4.5. Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism, and survival differences were assessed using the log-rank test.

Results

Among 12,951 patients diagnosed with parotid malignancy, 47 (0.36%) had brain metastases. The median age at diagnosis was 67 years, and 77.5% were male. The overall incidence rate (IR) of brain metastases was 0.00235 per 100,000 population, with a significantly higher rate observed in males compared to females (p < 0.0001). The most common histologic subtype associated with brain involvement was squamous cell carcinoma (SCC, n=10), followed by adenocarcinoma. Median overall survival (mOS) for patients with brain metastases was 2 months (hazard ratio [HR] 6.28; 95% CI: 2.71–14.55), compared to 131 months for those without brain involvement (p < 0.001). 1-year cancer-specific survival for patients with brain metastases was 38%. Among patients with parotid SCC and brain metastases, mOS was 3 months, compared to 39 months in those without brain involvement (HR 5.70; 95% CI: 1.09–29.68; p < 0.0001).

Conclusions

Brain metastases from parotid gland cancers, though rare, are associated with markedly poor outcomes. This highlights the importance of early neurologic assessment and brain imaging in high-risk patients, particularly with SCC histology. Prior studies have shown that TP53 mutations are common in parotid SCC, but their role in CNS spread remains unclear. Future research should explore molecular pathways underlying neurotropism in parotid cancers and investigate targeted systemic therapies with CNS penetration to improve outcomes.

Augmenting DNA Damage by Chemotherapy With CDK7 Inhibition to Disrupt PARP Expression in Cholangiocarcinoma

Papillary Cystadenocarcinoma: NCDB Insights on Outcomes and Socioeconomic Disparities

Background

Papillary cystadenocarcinoma is a rare, aggressive malignancy typically arising in the ovaries, often following malignant transformation of benign precursors. Characterized by local invasion and recurrence, it lacks standardized treatment protocols and comprehensive epidemiological data. Existing literature is limited to case reports and small series, leaving gaps in population-level data to guide clinical decision-making. This study uses the National Cancer Database (NCDB) to assess demographic, socioeconomic, and treatment patterns to identify disparities and inform management.

Methods

A retrospective cohort analysis of 345 patients with histologically confirmed papillary cystadenocarcinoma (ICD-O-3 code 8450) was conducted using the 2004–2020 NCDB. Demographic, treatment, and survival data were described; incidence trends were assessed via linear regression; and survival was analyzed using Kaplan-Meier curves.

Results

The cohort was predominantly female (97.1%), mean age 62.1 years (SD = 14.0), and 87.2% White. Most had private insurance (44.9%) or Medicare (40.9%). Over half (51.9%) resided in metropolitan areas >1 million. Primary tumor sites were ovarian (80.0%) and endometrial (5.2%), with 39.7% presenting at Stage III. Surgery was performed in 90.4% of cases, with 51.9% achieving negative margins. Most were treated at comprehensive community (41.0%) or academic/research programs (28.7%). Primary therapies included chemotherapy (62.3%), radiation (6.4%), and hormone therapy (1.7%). Thirty-day mortality was 1.9%, and 90-day mortality was 5.4%. Survival was 97.7% at 2 years, 94.2% at 5 years, and 88.6% at 10 years. Mean survival was 97.5 months (95% CI: 88.2–106.7).

Conclusions

This is the first NCDB-based analysis of papillary cystadenocarcinoma, offering insight into its clinical characteristics. Ovarian and endometrial origins were most common, reinforcing its gynecologic profile. High surgical rates and margin negativity suggest aggressive local treatment is central to management. Disparities emerged: patients were more likely to live in urban areas, hold private insurance, and receive care at community programs. These findings highlight the need for further investigation into socioeconomic inequities and may inform future guidelines to improve equitable care delivery across health systems, including community-based programs such as the VHA.

Background

Papillary cystadenocarcinoma is a rare, aggressive malignancy typically arising in the ovaries, often following malignant transformation of benign precursors. Characterized by local invasion and recurrence, it lacks standardized treatment protocols and comprehensive epidemiological data. Existing literature is limited to case reports and small series, leaving gaps in population-level data to guide clinical decision-making. This study uses the National Cancer Database (NCDB) to assess demographic, socioeconomic, and treatment patterns to identify disparities and inform management.

Methods

A retrospective cohort analysis of 345 patients with histologically confirmed papillary cystadenocarcinoma (ICD-O-3 code 8450) was conducted using the 2004–2020 NCDB. Demographic, treatment, and survival data were described; incidence trends were assessed via linear regression; and survival was analyzed using Kaplan-Meier curves.

Results

The cohort was predominantly female (97.1%), mean age 62.1 years (SD = 14.0), and 87.2% White. Most had private insurance (44.9%) or Medicare (40.9%). Over half (51.9%) resided in metropolitan areas >1 million. Primary tumor sites were ovarian (80.0%) and endometrial (5.2%), with 39.7% presenting at Stage III. Surgery was performed in 90.4% of cases, with 51.9% achieving negative margins. Most were treated at comprehensive community (41.0%) or academic/research programs (28.7%). Primary therapies included chemotherapy (62.3%), radiation (6.4%), and hormone therapy (1.7%). Thirty-day mortality was 1.9%, and 90-day mortality was 5.4%. Survival was 97.7% at 2 years, 94.2% at 5 years, and 88.6% at 10 years. Mean survival was 97.5 months (95% CI: 88.2–106.7).

Conclusions

This is the first NCDB-based analysis of papillary cystadenocarcinoma, offering insight into its clinical characteristics. Ovarian and endometrial origins were most common, reinforcing its gynecologic profile. High surgical rates and margin negativity suggest aggressive local treatment is central to management. Disparities emerged: patients were more likely to live in urban areas, hold private insurance, and receive care at community programs. These findings highlight the need for further investigation into socioeconomic inequities and may inform future guidelines to improve equitable care delivery across health systems, including community-based programs such as the VHA.

Background

Papillary cystadenocarcinoma is a rare, aggressive malignancy typically arising in the ovaries, often following malignant transformation of benign precursors. Characterized by local invasion and recurrence, it lacks standardized treatment protocols and comprehensive epidemiological data. Existing literature is limited to case reports and small series, leaving gaps in population-level data to guide clinical decision-making. This study uses the National Cancer Database (NCDB) to assess demographic, socioeconomic, and treatment patterns to identify disparities and inform management.

Methods

A retrospective cohort analysis of 345 patients with histologically confirmed papillary cystadenocarcinoma (ICD-O-3 code 8450) was conducted using the 2004–2020 NCDB. Demographic, treatment, and survival data were described; incidence trends were assessed via linear regression; and survival was analyzed using Kaplan-Meier curves.

Results

The cohort was predominantly female (97.1%), mean age 62.1 years (SD = 14.0), and 87.2% White. Most had private insurance (44.9%) or Medicare (40.9%). Over half (51.9%) resided in metropolitan areas >1 million. Primary tumor sites were ovarian (80.0%) and endometrial (5.2%), with 39.7% presenting at Stage III. Surgery was performed in 90.4% of cases, with 51.9% achieving negative margins. Most were treated at comprehensive community (41.0%) or academic/research programs (28.7%). Primary therapies included chemotherapy (62.3%), radiation (6.4%), and hormone therapy (1.7%). Thirty-day mortality was 1.9%, and 90-day mortality was 5.4%. Survival was 97.7% at 2 years, 94.2% at 5 years, and 88.6% at 10 years. Mean survival was 97.5 months (95% CI: 88.2–106.7).

Conclusions

This is the first NCDB-based analysis of papillary cystadenocarcinoma, offering insight into its clinical characteristics. Ovarian and endometrial origins were most common, reinforcing its gynecologic profile. High surgical rates and margin negativity suggest aggressive local treatment is central to management. Disparities emerged: patients were more likely to live in urban areas, hold private insurance, and receive care at community programs. These findings highlight the need for further investigation into socioeconomic inequities and may inform future guidelines to improve equitable care delivery across health systems, including community-based programs such as the VHA.

Assessing Geographical Trends in End-of-Life Cancer Care Using CDC WONDER’s Place of Death Data

Background

19.8% of all deaths in the US in 2023 were due to cancer. Despite its prevalence, there is minimal literature analyzing geographical trends in end-of-life care in cancer patients. This study aims to assess the evolution of end-of-life preferences in cancer patients, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, and account for geographical disparities to optimize palliative care delivery.

Methods

The CDC WONDER database was used to collect data on place of death (home, hospice, medical facilities, nursing homes) in patients over 25 years old that died with malignant neoplasms (ICD 10: C00- C97) in the US from 2003-2023. Deaths were stratified by region and urbanization. Proportional mortality was calculated, and statistically significant trends in mortality over time were identified using Joinpoint regression.

Results

There were 13,654,631 total deaths from malignant neoplasms over the study period. Home (40.3%) was the most common place of death followed by medical facilities (30.4%), nursing homes (14.3%), and hospice (8.9%). In 2020, all places experienced a decreased in proportion except for home which rose 7.0% from 41.7% to 48.7%. The South had the highest hospice rates (11.3%); 5.0% greater than the next highest region (Northeast; 8.3%). The West had the highest home rates (47.1%); 6.2% greater than the next closest region (South; 40.9%). The Northeast had the highest medical facility rates (36.0%); 5.5% higher than the next highest region (South, 30.5%). Nonmetro areas (< 50,000 population) had the lowest hospice (4.9%) and highest nursing home rates (15.8%). They also saw a substantial jump (+15.4%) in home deaths from 2019-21. All urbanizations saw a drop in medical facility deaths in 2020 but all have since climbed to surpass their 2019 rates except for nonmetro areas which have dropped 7.3% from 2020-2023.

Conclusion

Hospice and home deaths have increased in frequency with home deaths spiking during the COVID-19 pandemic. Geographical disparities persist in end-of-life care, particularly in nonmetro areas. This highlights the need to increase education and access to palliative care. Further research should aim at why the rural populations have failed to revert to pre-COVID trends like the other urbanization groups.

Background

19.8% of all deaths in the US in 2023 were due to cancer. Despite its prevalence, there is minimal literature analyzing geographical trends in end-of-life care in cancer patients. This study aims to assess the evolution of end-of-life preferences in cancer patients, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, and account for geographical disparities to optimize palliative care delivery.

Methods

The CDC WONDER database was used to collect data on place of death (home, hospice, medical facilities, nursing homes) in patients over 25 years old that died with malignant neoplasms (ICD 10: C00- C97) in the US from 2003-2023. Deaths were stratified by region and urbanization. Proportional mortality was calculated, and statistically significant trends in mortality over time were identified using Joinpoint regression.

Results

There were 13,654,631 total deaths from malignant neoplasms over the study period. Home (40.3%) was the most common place of death followed by medical facilities (30.4%), nursing homes (14.3%), and hospice (8.9%). In 2020, all places experienced a decreased in proportion except for home which rose 7.0% from 41.7% to 48.7%. The South had the highest hospice rates (11.3%); 5.0% greater than the next highest region (Northeast; 8.3%). The West had the highest home rates (47.1%); 6.2% greater than the next closest region (South; 40.9%). The Northeast had the highest medical facility rates (36.0%); 5.5% higher than the next highest region (South, 30.5%). Nonmetro areas (< 50,000 population) had the lowest hospice (4.9%) and highest nursing home rates (15.8%). They also saw a substantial jump (+15.4%) in home deaths from 2019-21. All urbanizations saw a drop in medical facility deaths in 2020 but all have since climbed to surpass their 2019 rates except for nonmetro areas which have dropped 7.3% from 2020-2023.

Conclusion

Hospice and home deaths have increased in frequency with home deaths spiking during the COVID-19 pandemic. Geographical disparities persist in end-of-life care, particularly in nonmetro areas. This highlights the need to increase education and access to palliative care. Further research should aim at why the rural populations have failed to revert to pre-COVID trends like the other urbanization groups.

Background

19.8% of all deaths in the US in 2023 were due to cancer. Despite its prevalence, there is minimal literature analyzing geographical trends in end-of-life care in cancer patients. This study aims to assess the evolution of end-of-life preferences in cancer patients, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, and account for geographical disparities to optimize palliative care delivery.

Methods

The CDC WONDER database was used to collect data on place of death (home, hospice, medical facilities, nursing homes) in patients over 25 years old that died with malignant neoplasms (ICD 10: C00- C97) in the US from 2003-2023. Deaths were stratified by region and urbanization. Proportional mortality was calculated, and statistically significant trends in mortality over time were identified using Joinpoint regression.

Results

There were 13,654,631 total deaths from malignant neoplasms over the study period. Home (40.3%) was the most common place of death followed by medical facilities (30.4%), nursing homes (14.3%), and hospice (8.9%). In 2020, all places experienced a decreased in proportion except for home which rose 7.0% from 41.7% to 48.7%. The South had the highest hospice rates (11.3%); 5.0% greater than the next highest region (Northeast; 8.3%). The West had the highest home rates (47.1%); 6.2% greater than the next closest region (South; 40.9%). The Northeast had the highest medical facility rates (36.0%); 5.5% higher than the next highest region (South, 30.5%). Nonmetro areas (< 50,000 population) had the lowest hospice (4.9%) and highest nursing home rates (15.8%). They also saw a substantial jump (+15.4%) in home deaths from 2019-21. All urbanizations saw a drop in medical facility deaths in 2020 but all have since climbed to surpass their 2019 rates except for nonmetro areas which have dropped 7.3% from 2020-2023.

Conclusion

Hospice and home deaths have increased in frequency with home deaths spiking during the COVID-19 pandemic. Geographical disparities persist in end-of-life care, particularly in nonmetro areas. This highlights the need to increase education and access to palliative care. Further research should aim at why the rural populations have failed to revert to pre-COVID trends like the other urbanization groups.

Demographical Trends in End-of-Life Care in Malignant Neoplasms: A CDC Wonder Analysis Using Place of Death

Background

In 2024, it was estimated that 2,001,140 new cases of cancer were diagnosed in the United States with 611,720 people succumbing to the disease. There is scant literature analyzing how the place of death in cancer patients has evolved over time, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, and how it varies demographically. This study aims to analyze the evolution of end-of-life preferences in cancer patients and assess for racial or sexual disparities to optimize palliative care and ensure it aligns with the patient’s wishes.

Methods

The CDC Wonder database was used to collect data on place of death (home, hospice, medical facilities, nursing homes) in patients over 25 years old who died with malignant neoplasms (ICD-10: C00-C97) in the US from 2003-2023. Deaths were stratified by sex and race. Proportional mortality was calculated, and statistically significant temporal trends in mortality were identified using Joinpoint regression.

Results

From 2003 to 2023, there were 13,654,631 total deaths from malignant cancer. Home deaths were the most common (40.3%) followed by medical facilities (30.4%), nursing homes (14.3%), and hospice (8.9%). In 2020, all places experienced a decrease in proportion except for home which rose 7.1%. From 2003-2023, home (+4.0%) and hospice (+10.0%) rose in frequency while medical facility (-10.9%) and nursing home (-6.8%) declined. Females died in nursing homes at a greater proportion than males (15.8% vs. 13.1%) while males died in medical facilities more frequently (32.4% vs. 28.8%). Black patients were the least likely to die at home (33.1%), 5.9% less than the next lowest (Asian/ Pacific Islander; 39.0%), while Hispanic patients were most likely (46.9%); 5.7% more than the next highest (White, 41.7%). White patients were the least likely to die in medical facilities (28.4%) but were also most likely to die in nursing homes (15.3%).

Conclusions

Hospice and home deaths have increased in frequency with home deaths spiking during the COVID-19 pandemic. Disparities persist in end-of-life care across both sex and racial groups. This highlights the need to increase education and access to palliative care. Further research should elucidate cultural and racial discrepancies surrounding end-of-life treatment and preferences to provide context for these differences.

Background

In 2024, it was estimated that 2,001,140 new cases of cancer were diagnosed in the United States with 611,720 people succumbing to the disease. There is scant literature analyzing how the place of death in cancer patients has evolved over time, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, and how it varies demographically. This study aims to analyze the evolution of end-of-life preferences in cancer patients and assess for racial or sexual disparities to optimize palliative care and ensure it aligns with the patient’s wishes.

Methods

The CDC Wonder database was used to collect data on place of death (home, hospice, medical facilities, nursing homes) in patients over 25 years old who died with malignant neoplasms (ICD-10: C00-C97) in the US from 2003-2023. Deaths were stratified by sex and race. Proportional mortality was calculated, and statistically significant temporal trends in mortality were identified using Joinpoint regression.

Results

From 2003 to 2023, there were 13,654,631 total deaths from malignant cancer. Home deaths were the most common (40.3%) followed by medical facilities (30.4%), nursing homes (14.3%), and hospice (8.9%). In 2020, all places experienced a decrease in proportion except for home which rose 7.1%. From 2003-2023, home (+4.0%) and hospice (+10.0%) rose in frequency while medical facility (-10.9%) and nursing home (-6.8%) declined. Females died in nursing homes at a greater proportion than males (15.8% vs. 13.1%) while males died in medical facilities more frequently (32.4% vs. 28.8%). Black patients were the least likely to die at home (33.1%), 5.9% less than the next lowest (Asian/ Pacific Islander; 39.0%), while Hispanic patients were most likely (46.9%); 5.7% more than the next highest (White, 41.7%). White patients were the least likely to die in medical facilities (28.4%) but were also most likely to die in nursing homes (15.3%).

Conclusions

Hospice and home deaths have increased in frequency with home deaths spiking during the COVID-19 pandemic. Disparities persist in end-of-life care across both sex and racial groups. This highlights the need to increase education and access to palliative care. Further research should elucidate cultural and racial discrepancies surrounding end-of-life treatment and preferences to provide context for these differences.

Background

In 2024, it was estimated that 2,001,140 new cases of cancer were diagnosed in the United States with 611,720 people succumbing to the disease. There is scant literature analyzing how the place of death in cancer patients has evolved over time, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, and how it varies demographically. This study aims to analyze the evolution of end-of-life preferences in cancer patients and assess for racial or sexual disparities to optimize palliative care and ensure it aligns with the patient’s wishes.

Methods

The CDC Wonder database was used to collect data on place of death (home, hospice, medical facilities, nursing homes) in patients over 25 years old who died with malignant neoplasms (ICD-10: C00-C97) in the US from 2003-2023. Deaths were stratified by sex and race. Proportional mortality was calculated, and statistically significant temporal trends in mortality were identified using Joinpoint regression.

Results

From 2003 to 2023, there were 13,654,631 total deaths from malignant cancer. Home deaths were the most common (40.3%) followed by medical facilities (30.4%), nursing homes (14.3%), and hospice (8.9%). In 2020, all places experienced a decrease in proportion except for home which rose 7.1%. From 2003-2023, home (+4.0%) and hospice (+10.0%) rose in frequency while medical facility (-10.9%) and nursing home (-6.8%) declined. Females died in nursing homes at a greater proportion than males (15.8% vs. 13.1%) while males died in medical facilities more frequently (32.4% vs. 28.8%). Black patients were the least likely to die at home (33.1%), 5.9% less than the next lowest (Asian/ Pacific Islander; 39.0%), while Hispanic patients were most likely (46.9%); 5.7% more than the next highest (White, 41.7%). White patients were the least likely to die in medical facilities (28.4%) but were also most likely to die in nursing homes (15.3%).

Conclusions

Hospice and home deaths have increased in frequency with home deaths spiking during the COVID-19 pandemic. Disparities persist in end-of-life care across both sex and racial groups. This highlights the need to increase education and access to palliative care. Further research should elucidate cultural and racial discrepancies surrounding end-of-life treatment and preferences to provide context for these differences.

Findings from (ImPaCT): Improving Patients With Prostate Cancer’s Access to Germline Testing

Background

With the onset of precision oncology, findings from germline mutational analysis have been helpful in treating patients with cancer and aids in cancer prevention, early detection, and improved overall outcomes. Germline genetic testing is now part of the standard of care for certain types of patients with prostate cancer. There is a very limited body of work that investigated demographic, disease- related and social factors that may be influencing Veterans’ participation in germline genetic testing. This study helps to identify whether certain factors may be influencing decisions on participation in prostate germline testing among Veterans with prostate malignancy.

Methods

The study was conducted using retrospective chart review. Data was collected from the periods of August 1, 2022 to December 31, 2023 among Veterans with prostate cancer who met criteria for germline genetic testing. Demographic and clinical information were collected including age, race, extent of disease (high risk, very high-risk or metastatic disease), significant co-morbidities, educational level, family and personal history of cancer, travel time, germline genetic test findings, impact on treatment approaches, referral for genetic counseling, and whether Veterans agreed or declined germline genetic testing. Data was analyzed using descriptive statistics. A total of 180 charts were reviewed, with 171 meeting the criteria for inclusion. The mean age of the participants is 73, with the youngest being 55 and the oldest being 101 years old. Majority of the participants were African American (77%).

Results

Only about two percent of those who met the inclusion criteria declined to undergo testing with the one living the farthest away from the testing hospital residing 18 miles away. Those who declined testing ranged in age from 67 to 88, majority had high risk prostate cancer and no family history of malignancy, and had 0-1 serious co-morbidity. None of their educational informational was available for review.

Conclusions

Participation in germline genetic testing can be enhanced with adequate patient education and availability of accessible resources, even among patient populations that are not always well-represented in clinical research. The presence of multiple serious co-morbidities and distance from a testing facility do not seem to contribute to hesitancy in germline genetic testing participation.

Background

With the onset of precision oncology, findings from germline mutational analysis have been helpful in treating patients with cancer and aids in cancer prevention, early detection, and improved overall outcomes. Germline genetic testing is now part of the standard of care for certain types of patients with prostate cancer. There is a very limited body of work that investigated demographic, disease- related and social factors that may be influencing Veterans’ participation in germline genetic testing. This study helps to identify whether certain factors may be influencing decisions on participation in prostate germline testing among Veterans with prostate malignancy.

Methods

The study was conducted using retrospective chart review. Data was collected from the periods of August 1, 2022 to December 31, 2023 among Veterans with prostate cancer who met criteria for germline genetic testing. Demographic and clinical information were collected including age, race, extent of disease (high risk, very high-risk or metastatic disease), significant co-morbidities, educational level, family and personal history of cancer, travel time, germline genetic test findings, impact on treatment approaches, referral for genetic counseling, and whether Veterans agreed or declined germline genetic testing. Data was analyzed using descriptive statistics. A total of 180 charts were reviewed, with 171 meeting the criteria for inclusion. The mean age of the participants is 73, with the youngest being 55 and the oldest being 101 years old. Majority of the participants were African American (77%).

Results

Only about two percent of those who met the inclusion criteria declined to undergo testing with the one living the farthest away from the testing hospital residing 18 miles away. Those who declined testing ranged in age from 67 to 88, majority had high risk prostate cancer and no family history of malignancy, and had 0-1 serious co-morbidity. None of their educational informational was available for review.

Conclusions

Participation in germline genetic testing can be enhanced with adequate patient education and availability of accessible resources, even among patient populations that are not always well-represented in clinical research. The presence of multiple serious co-morbidities and distance from a testing facility do not seem to contribute to hesitancy in germline genetic testing participation.

Background

With the onset of precision oncology, findings from germline mutational analysis have been helpful in treating patients with cancer and aids in cancer prevention, early detection, and improved overall outcomes. Germline genetic testing is now part of the standard of care for certain types of patients with prostate cancer. There is a very limited body of work that investigated demographic, disease- related and social factors that may be influencing Veterans’ participation in germline genetic testing. This study helps to identify whether certain factors may be influencing decisions on participation in prostate germline testing among Veterans with prostate malignancy.

Methods

The study was conducted using retrospective chart review. Data was collected from the periods of August 1, 2022 to December 31, 2023 among Veterans with prostate cancer who met criteria for germline genetic testing. Demographic and clinical information were collected including age, race, extent of disease (high risk, very high-risk or metastatic disease), significant co-morbidities, educational level, family and personal history of cancer, travel time, germline genetic test findings, impact on treatment approaches, referral for genetic counseling, and whether Veterans agreed or declined germline genetic testing. Data was analyzed using descriptive statistics. A total of 180 charts were reviewed, with 171 meeting the criteria for inclusion. The mean age of the participants is 73, with the youngest being 55 and the oldest being 101 years old. Majority of the participants were African American (77%).

Results

Only about two percent of those who met the inclusion criteria declined to undergo testing with the one living the farthest away from the testing hospital residing 18 miles away. Those who declined testing ranged in age from 67 to 88, majority had high risk prostate cancer and no family history of malignancy, and had 0-1 serious co-morbidity. None of their educational informational was available for review.

Conclusions

Participation in germline genetic testing can be enhanced with adequate patient education and availability of accessible resources, even among patient populations that are not always well-represented in clinical research. The presence of multiple serious co-morbidities and distance from a testing facility do not seem to contribute to hesitancy in germline genetic testing participation.

Advanced Imaging Techniques Use in Giant Cell Arteritis Diagnosis: The Experience at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center

Advanced Imaging Techniques Use in Giant Cell Arteritis Diagnosis: The Experience at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center

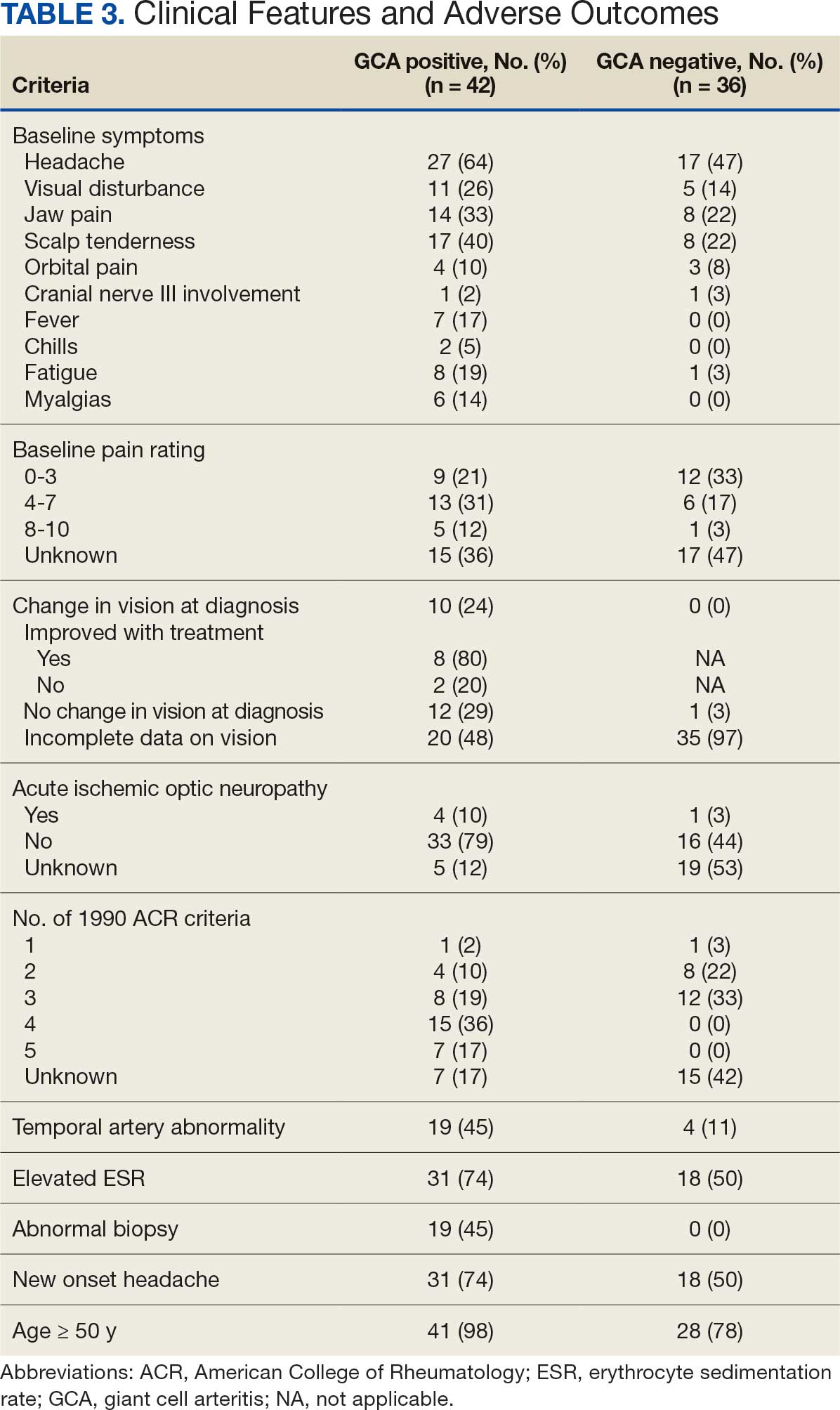

Giant cell arteritis (GCA), the most commonly diagnosed systemic vasculitis, is a large- and medium-vessel vasculitis that can lead to significant morbidity due to aneurysm formation or vascular occlusion if not diagnosed in a timely manner.1,2 Diagnosis is typically based on clinical history and inflammatory markers. Laboratory inflammatory markers may be normal in the early stages of GCA but can be abnormal due to other unrelated reasons leading to a false positive diagnosis.3 Delayed treatment may lead to visual loss, jaw or limb claudication, or ischemic stroke.2 Initial treatment typically includes high-dose steroids that can lead to significant adverse reactions such as hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction, metabolic syndrome, premature atherosclerosis, and increased risk of infection.4-6

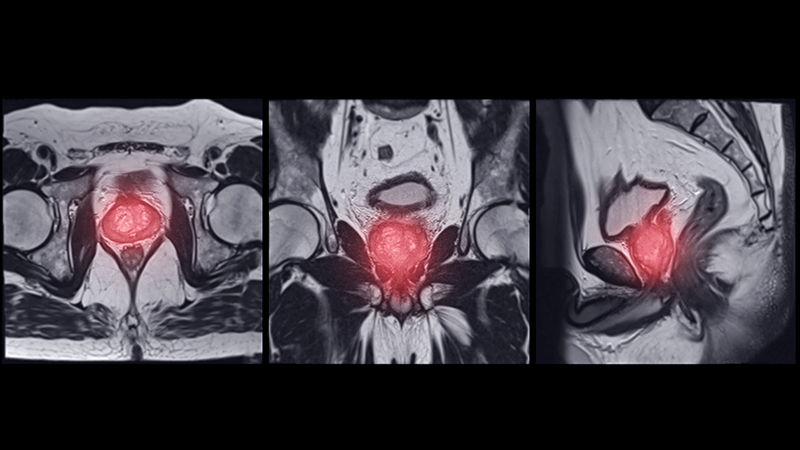

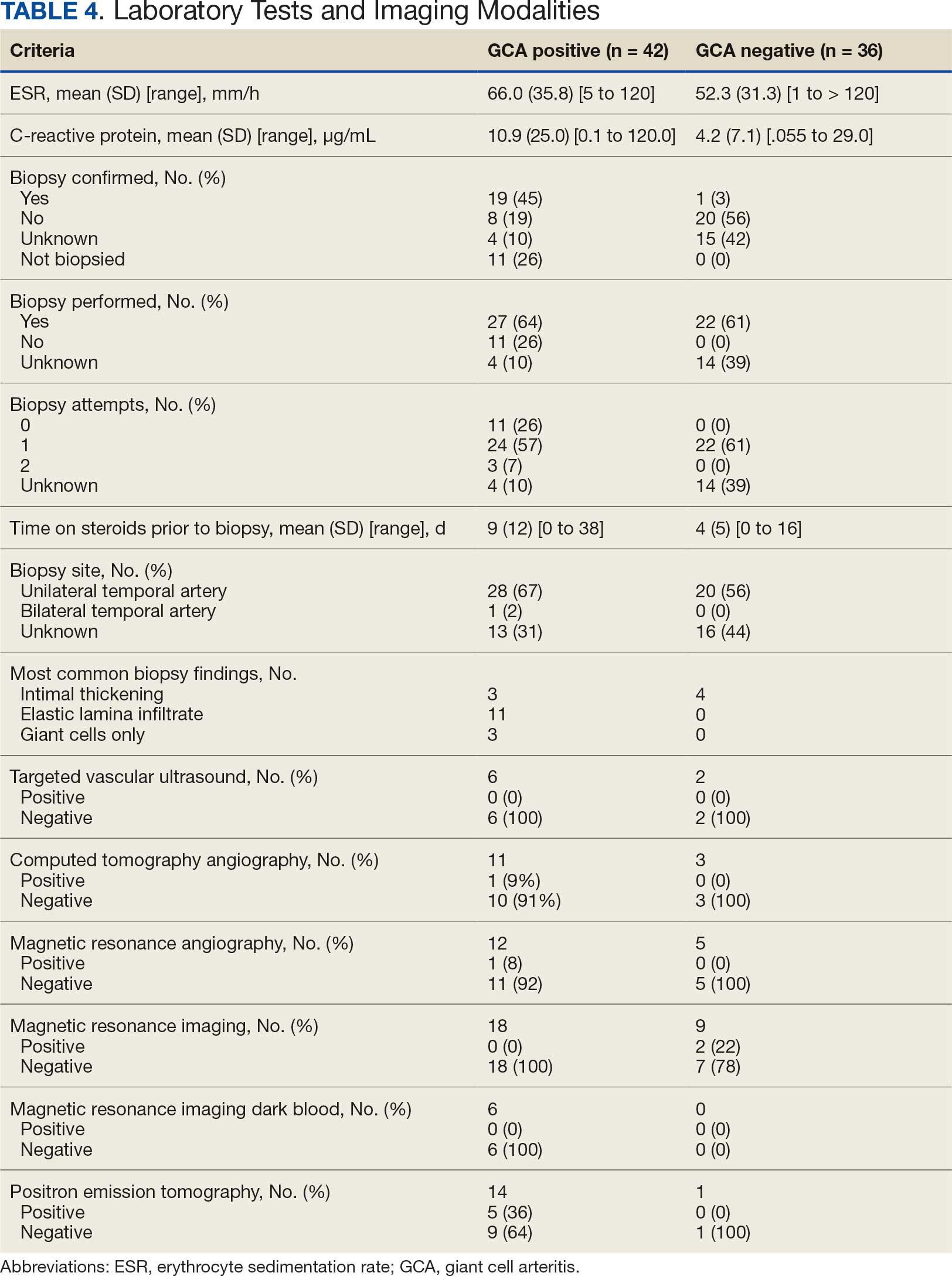

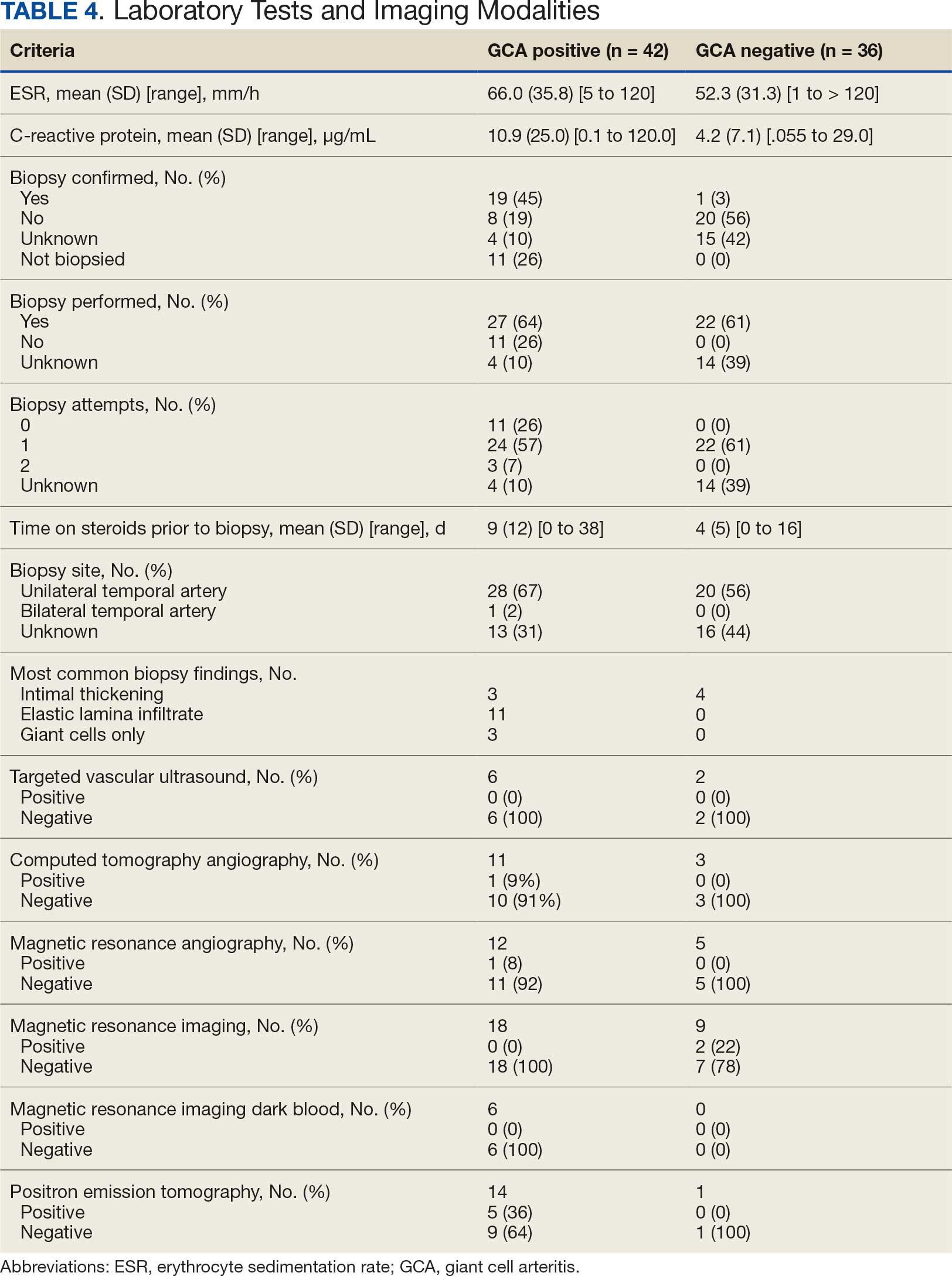

The 1990 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for GCA are widely recognized (Table 1).7 The criteria focuses on clinical manifestations, including new onset headache, temporal artery tenderness, age ≥ 50 years, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) ≥ 50 mm/hr, and temporal artery biopsy with positive anatomical findings.8 When 3 of the 5 1990 ACR criteria are present, the sensitivity and specificity is estimated to be > 90% for GCA vs alternative vasculitides.7

Although the 1990 ACR criteria do not include imaging, modalities such as ultrasound, computed tomography angiography (CTA), 18F-FDG positron emission tomography (PET), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)/magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) may be used in GCA diagnosis.8-10 These imaging modalities have been added to the proposed ACR classification criteria for GCA.11 For this updated point system standard, age ≥ 50 years is a requirement and includes a positive temporal artery biopsy or temporal artery halo sign on ultrasound (+5 points), an ESR ≥ 50 mm/h or C-reactive protein (CRP) ≥ 10 mg/L (+3 points), or sudden visual loss (+3 points). Scalp tenderness, jaw or tongue claudication, new temporal headache, morning stiffness in shoulders or neck, temporal artery abnormality on vascular examination, bilateral axillary vessel involvement on imaging, and 18F-FDG PET activity throughout the aorta are scored +2 points each. With these new criteria, a cumulative score ≥ 6 is classified as GCA. Diagnostic accuracy is further improved with imaging: ultrasonography (sensitivity 55% and specificity 95%) and 18F-FDG PET (sensitivity 69% and specificity 92%), CTA (sensitivity 71% and specificity 86%), and MRI/MRA (sensitivity 73% and specificity 88%).12-15

In recent years, clinicians have reported increased glucose uptake in arteries observed on PET imaging that suggests GCA.9,10,16-20 18F-FDG accumulates in cells with high metabolic activity rates, such as areas of inflammation. In assessing temporal arteries or other involved vasculature (eg, axillary or great vessels) for GCA, this modality indicates increased glucose uptake in the lining of vessel walls. The inflammation of vessel walls can then be visualized with PET. 18F-FDG PET presents a noninvasive imaging technique for evaluating GCA but its use has been limited in the United States due to its high cost.

Methods

Approval for a retrospective chart review of patients evaluated for suspected GCA was obtained from the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC) Institutional Review Board. The review included patients who underwent diagnostic procedures such as ultrasound, MRI, CT angiogram, and PET studies from 2016 through 2022. International Classification of Diseases codes used for case identification included: M31.6, M31.5, I77.6, I77.8, I77.89, I67.7, and I68.2. The Current Procedural Terminology code used for temporal artery biopsy is 37609.

Results

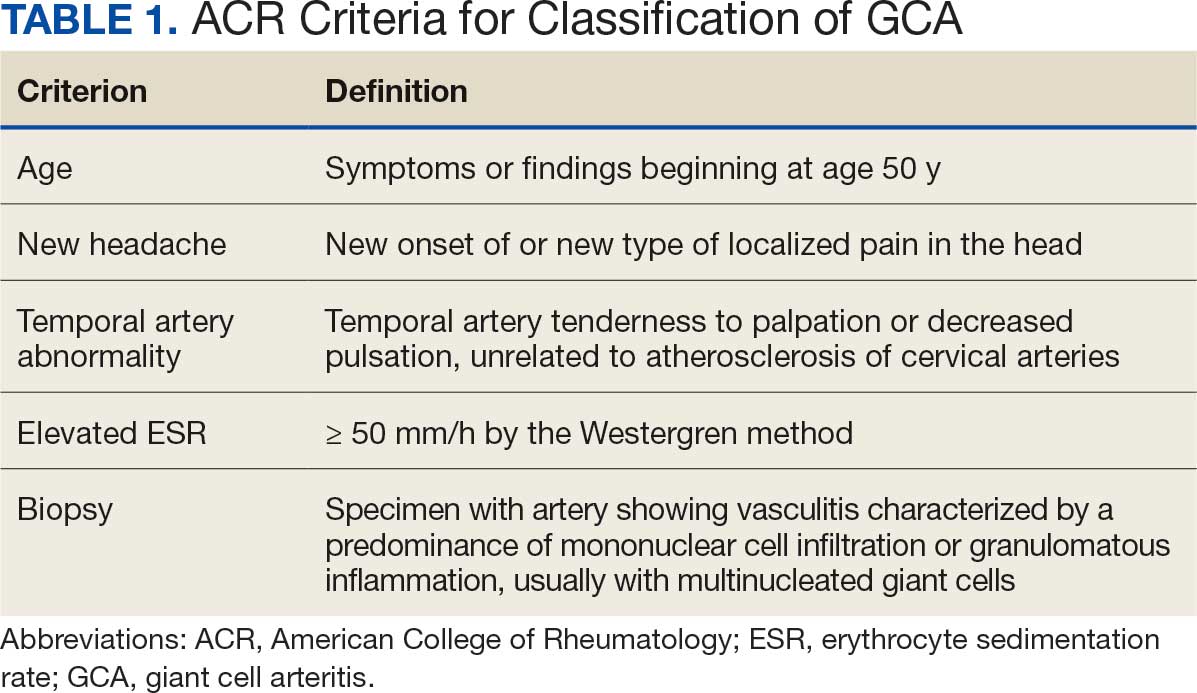

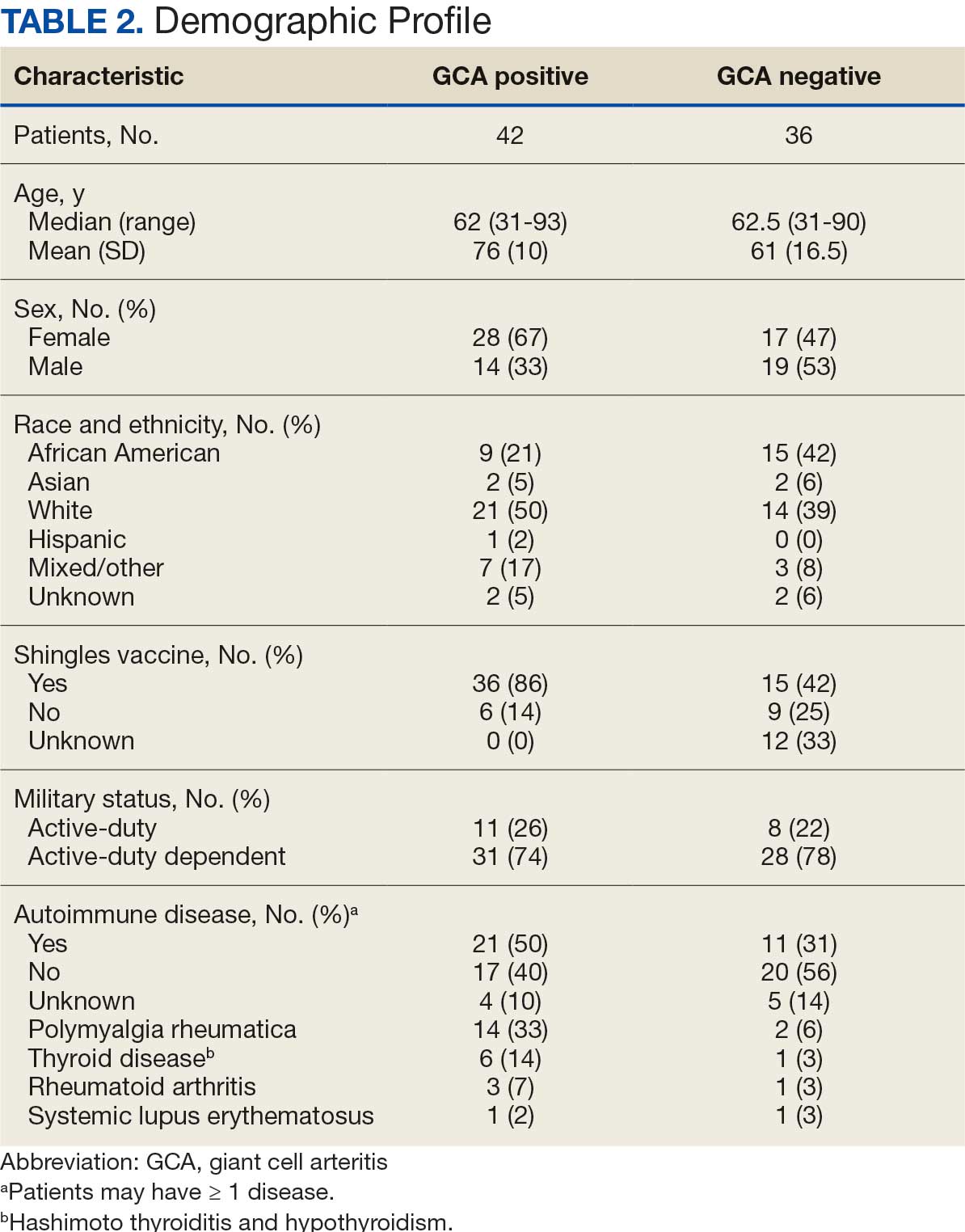

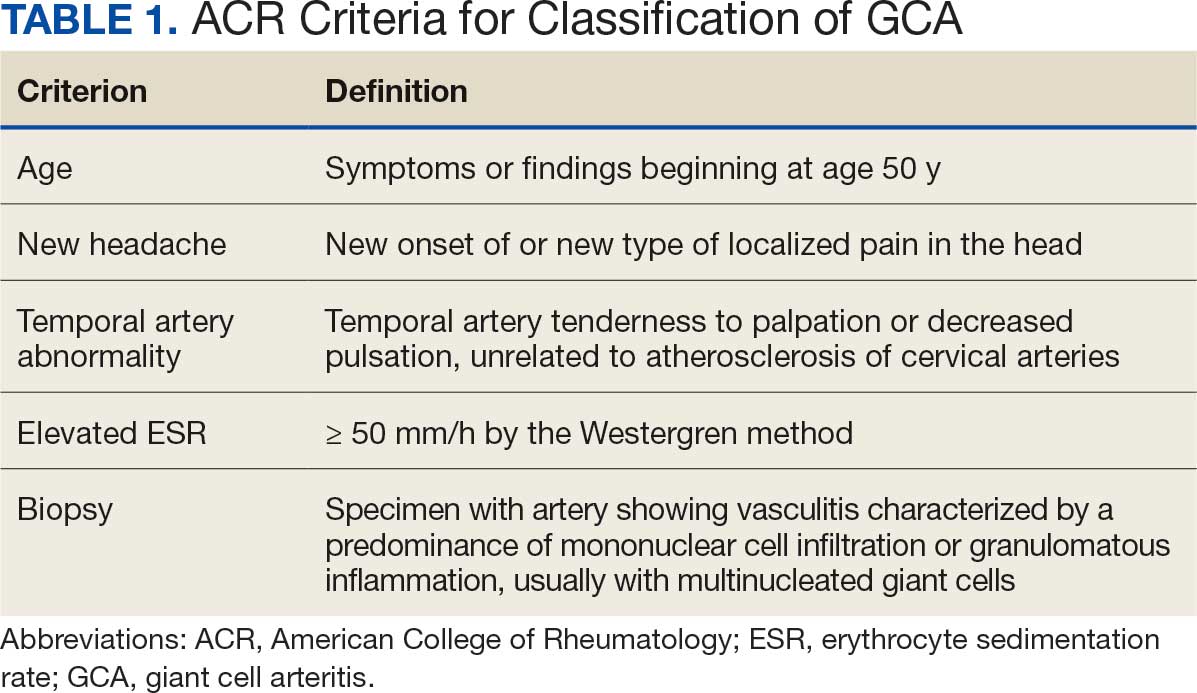

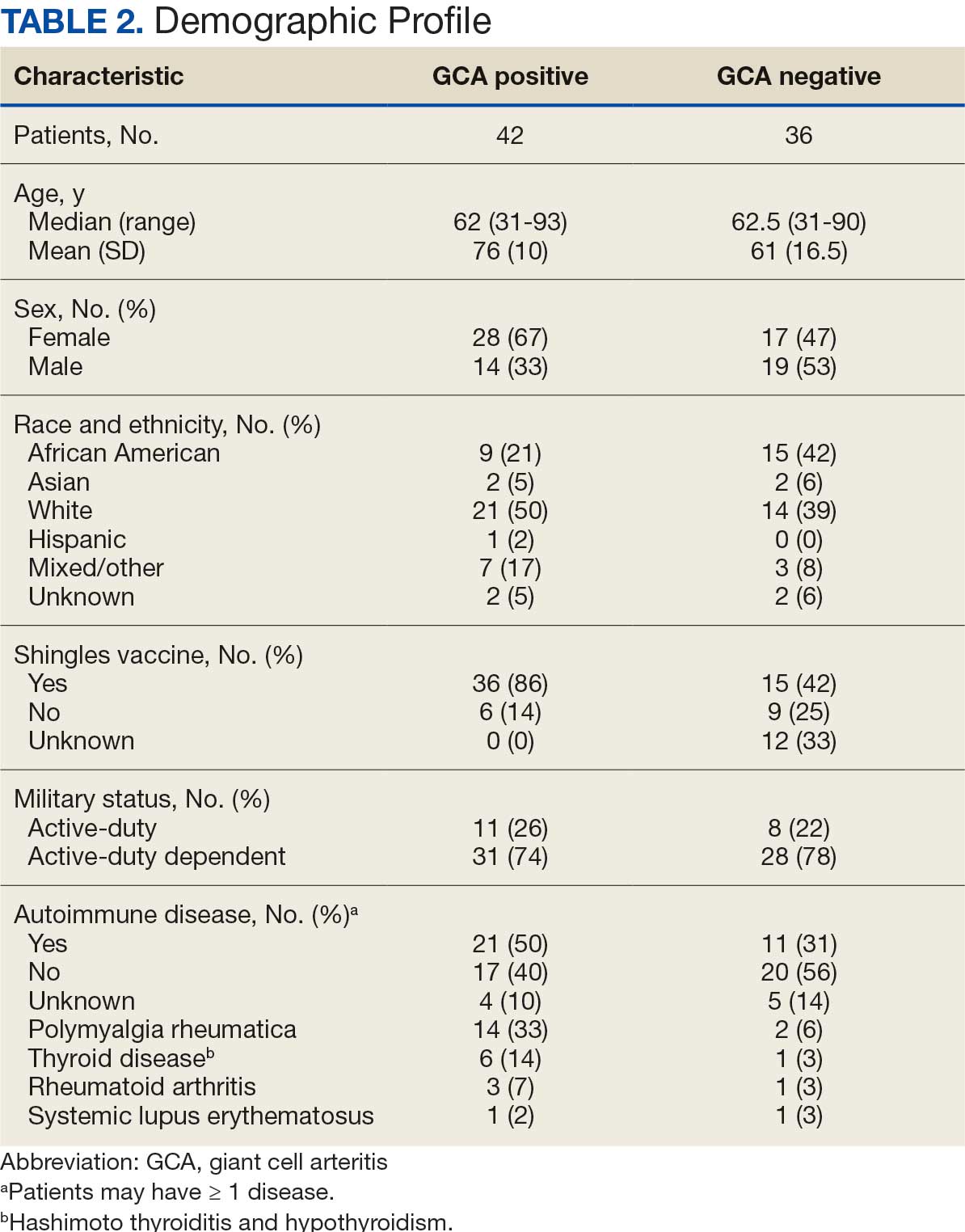

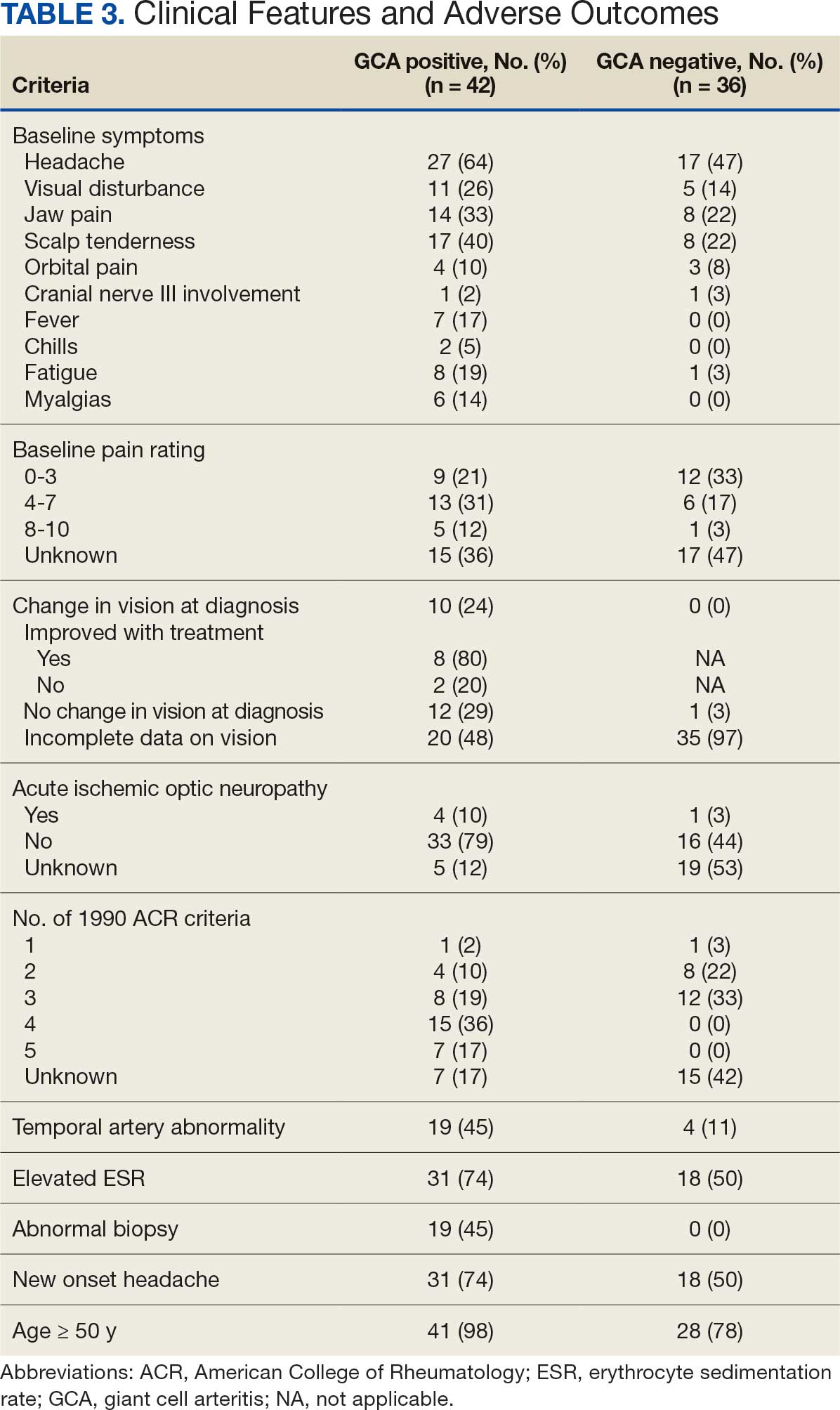

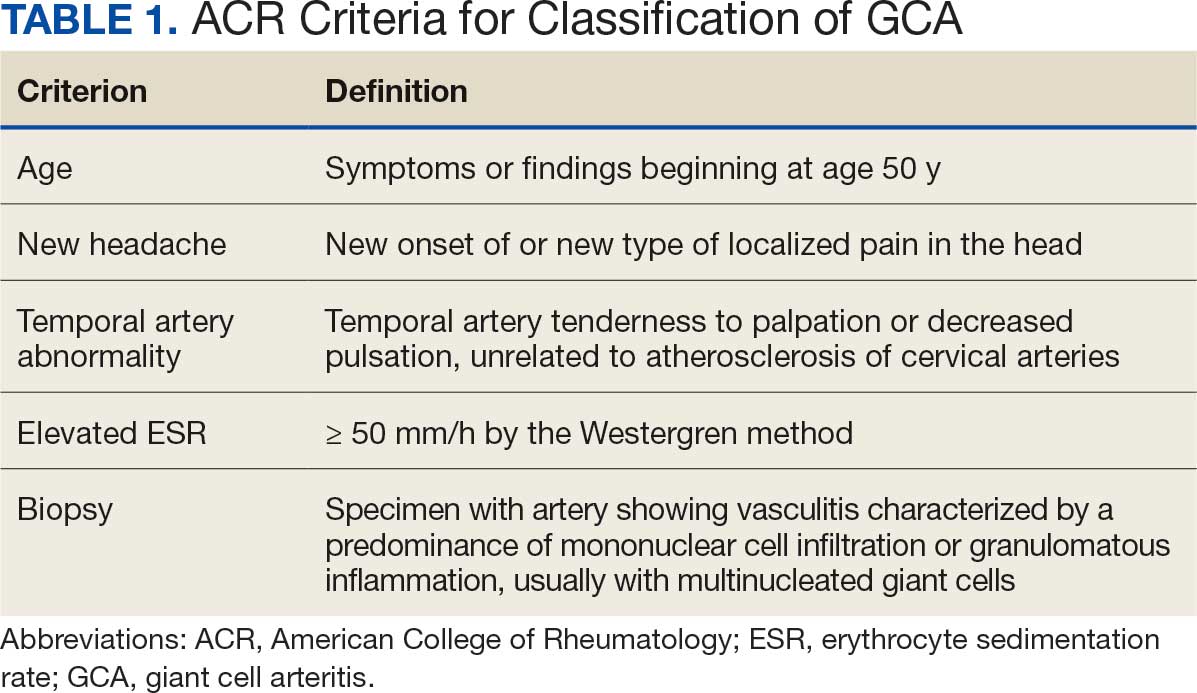

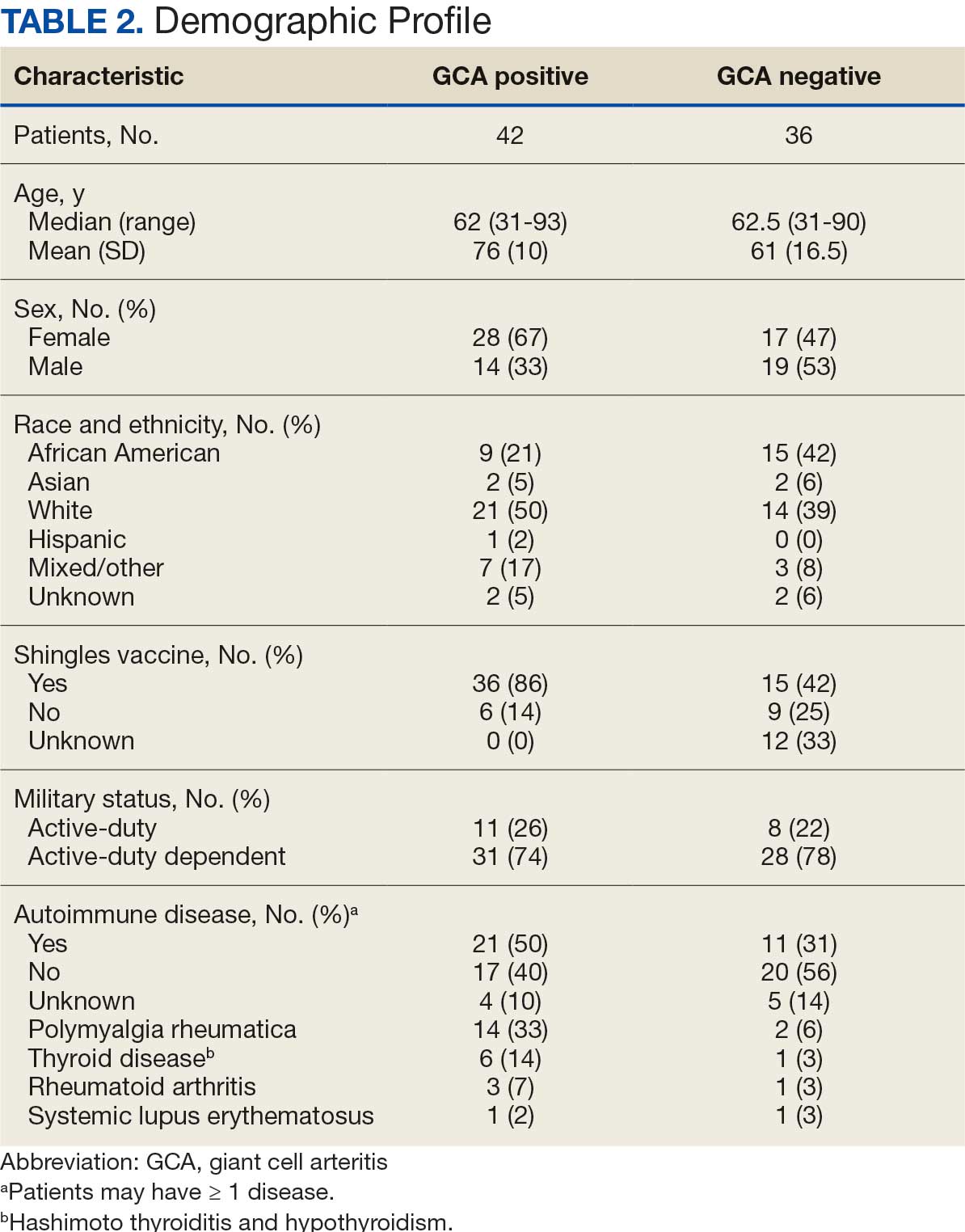

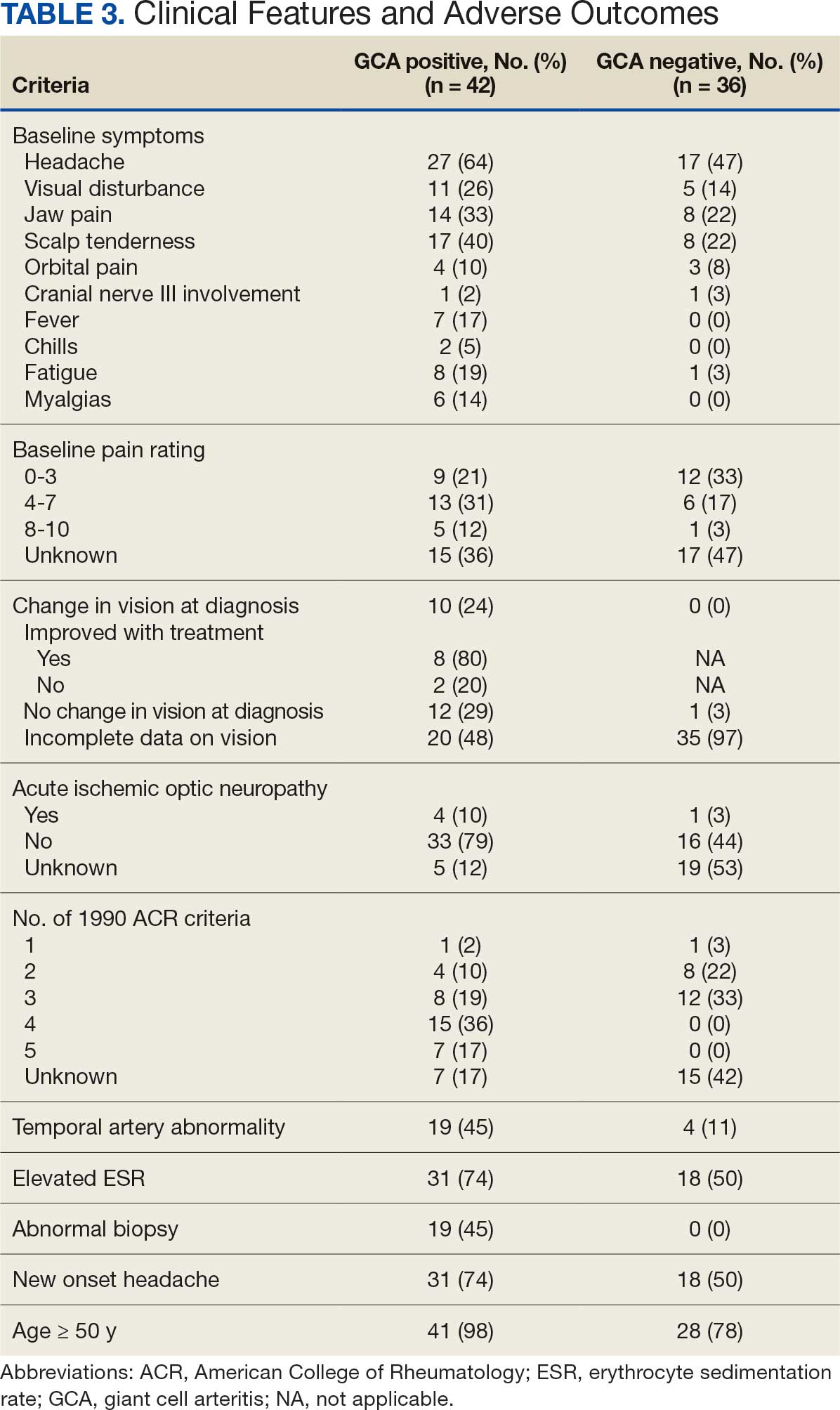

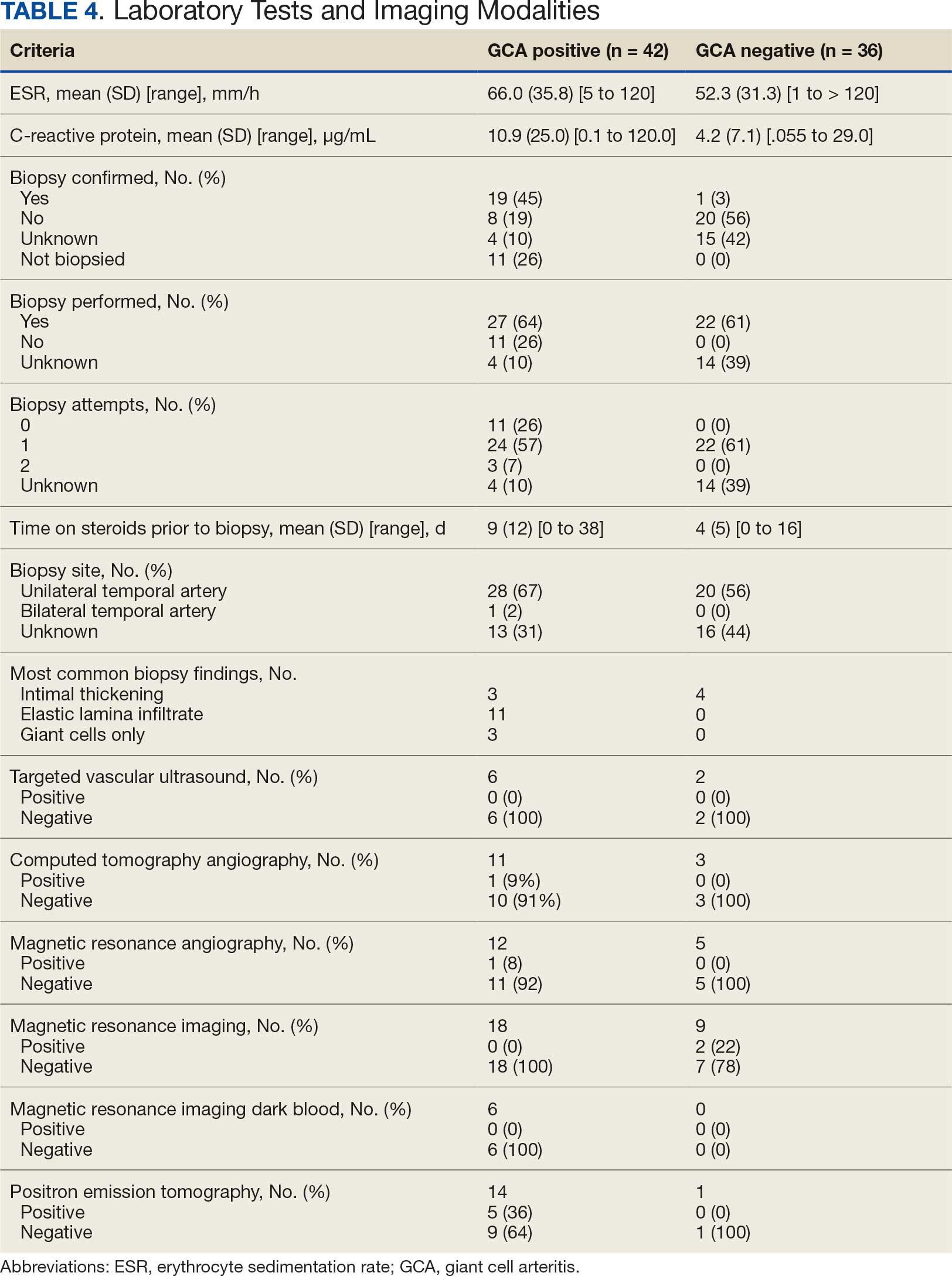

Seventy-eight charts were reviewed and 42 patients (54%) were diagnosed with GCA (Table 2). This study sample had a much higher proportion of African American subjects (31%) when compared with the civilian population, likely reflecting the higher representation of African Americans in the armed forces. Twenty-eight females (67%) were GCA positive. The most common presenting symptoms included 27 patients (64%) with headache, 17 (40%) with scalp tenderness, and 14 (33%) with jaw pain. The mean 1990 ACR score was 3.8 (range, 2-5). With respect to the score criteria: 41 patients (98%) were aged ≥ 50 years, 31 (74%) had new onset headache, and 31 (74%) had elevated ESR (Table 3). Acute ischemic optic neuropathy was documented in 4 patients (10%) with confirmed GCA. The mean ESR and CRP values at diagnosis were 66.2 mm/h (range, 7-122 mm/h) and 8.711 μg/mL (range, 0.054 – 92.690 μg/mL), respectively. Twenty-seven patients (64%) underwent biopsy: 24 (89%) were unilateral and 3 (11%) were bilateral (Table 4). Four patients with GCA (10%) were missing biopsy data. Nineteen patients with GCA (70%) had biopsies with pathologic findings consistent with GCA.

Twenty-five patients with GCA (60%) received ≥ 1 imaging modality. The most common imaging modality was MRI, which was used for 18 (43%) patients. Fourteen patients (33%) had 18F-FDG PET, 12 patients (29%) had MRA, and 11 patients (26%) had CTA. The small number of patients who underwent point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS), brain MRI, or dark blood MRI were negative for disease. Five patients who underwent 18F-FDG PET had findings consistent with GCA. One patient with GCA had CTA of the head and neck with radiographic findings supportive of GCA.

Discussion

The available evidence supports the use of additional screening tests to increase the temporal artery biopsy yield for GCA. Inflammatory laboratory markers demonstrate some sensitivity but are nonspecific for GCA. In this study, only 60% of patients with GCA underwent diagnostic imaging as part of the workup. There are multiple factors that may contribute to the underutilization of advanced imaging in the diagnosis of GCA, including outdated standardized diagnostic criteria, limited resources (direct access to modalities), and lack of clinician awareness of diagnostic testing options. In this retrospective review, 30 patients (71%) were diagnosed with GCA with a 1990 ACR GCA score ≤ 3. Of these 30 patients, 19 underwent confirmatory biopsy followed by prolonged courses of steroid therapy. In addition, only 25 patients underwent advanced imaging to increase diagnostic accuracy of the suspected syndrome.

A large meta-analysis demonstrated a sensitivity of 77.3% (95% CI, 71.8-81.9%) for temporal artery biopsy.21 The overall yield was 40% in the meta-analysis. Advanced noninvasive imaging represents an appropriate method of evaluating GCA.8-20 In our study, 18F-FDG PET demonstrated the highest sensitivity (36%) for the diagnosis of GCA. Ultrasonography is recommended as an initial screening tool to identify the noncompressible halo sign (a hypoechoic circumferential wall thickening due to edema) as a cost-effective and widely available technology.22 Other research has corroborated the beneficial use of ultrasonography in improving diagnostic accuracy by detecting the noncompressible halo sign in temporal arteries.22,23 GCA diagnostic performance has been significantly improved with the use of B-mode probes ≥ 15 MHz as well as proposals to incorporate a compression sign or interrogating the axillary vessels, showing a sensitivity of 54% to 77%.23,24

POCUS may reduce the risk of a false-negative biopsy and improve yield with more frequent utilization. However, ultrasonography may be limited by operator skills and visualization of the great vessels. The accuracy of ultrasonography is dependent on the experience and adeptness of the operator. Additional studies are needed to establish a systematic standard for POCUS training to ensure accurate interpretation and uniform interrogation procedure.24 Artificial intelligence (AI) may aid in interpreting results of POCUS and bridging the operator skill gap among operators.25,26 AI and machine learning techniques can assist in detecting the noncompressible halo sign and compression sign in temporal arteries and other affected vessels.

In comparing the WRNMMC patient population with other US civilian GCA cohorts, there are some differences and similarities. There was a high representation of African American patients in the study, which may reflect a greater severity of autoimmune disease expression in this population.27 We also observed a higher number of females and an association with polymyalgia rheumatica in the data, consistent with previous reports.28,29 The females in this study were primarily civilians and therefore more similar to the general population of individuals with GCA. In contrast, male patients were more likely to be active-duty service members or have prior service experience with increased exposure to novel environmental factors linked to increased risk of autoimmune disease. This includes an increased risk of Guillain-Barré syndrome and Graves disease among Vietnam veterans exposed to Agent Orange.30,31 Other studies have found that veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder are at increased risk for severe autoimmune diseases.32,33 As more women join the active-duty military, the impact of autoimmune disease in the military service population is expected to grow, requiring further research.

Conclusions

Early diagnosis and treatment of GCA are critical to preventing serious outcomes, such as visual loss, jaw or limb claudication, or ischemic stroke. The incidence of autoimmune disease is expected to rise in the armed forces and veteran populations due to exposure to novel environmental factors and the increasing representation of women in the military. The use of additional screening tools can aid in earlier diagnosis of GCA. The 2022 ACR classification criteria for GCA represent significant updates to the 1990 criteria, incorporating ancillary tests such as the temporal artery halo sign on ultrasound, bilateral axillary vessel screening on imaging, and 18F-FDG PET activity throughout the aorta. The updated criteria require further validation and supports the adoption of a multidisciplinary approach that includes ultrasonography, vascular MRI/CT, and 18F-FDG PET. Furthermore, AI may play a future key role in ultrasound interpretation and study interrogation procedure. Ultimately, ultrasonography is a noninvasive and promising technique for the early diagnosis of GCA. A target goal is to increase the yield of positive temporal artery biopsies to ≥ 70%.

- Jennette JC. Overview of the 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2013;17:603-606. doi:10.1007/s10157-013-0869-6

- Kale N, Eggenberger E. Diagnosis and management of giant cell arteritis: a review. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2010;21:417-422. doi:10.1097/ICU.0b013e32833eae8b

- Smetana GW, Shmerling RH. Does this patient have temporal arteritis? JAMA. 2002;287:92-101.

- Schäcke H, Döcke WD, Asadullah K. Mechanisms involved in the side effects of glucocorticoids. Pharmacol Ther. 2002;96:23-43. doi:10.1016/s0163-7258(02)00297-8

- Curtis JR, Patkar N, Xie A, et al. Risk of serious bacterial infections among rheumatoid arthritis patients exposed to tumor necrosis factor alpha antagonists. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1125-1133. doi:10.1002/art.22504

- Hoes JN, van der Goes MC, van Raalte DH, et al. Glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity and ß-cell function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with or without low-to-medium dose glucocorticoids. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1887-1894. doi:10.1136/ard.2011.151464

- Hunder GG, Bloch DA, Michel BA, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:1122-1128. doi:10.1002/art.1780330810

- Dejaco C, Duftner C, Buttgereit F, Matteson EL, Dasgupta B. The spectrum of giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica: revisiting the concept of the disease. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56:506-515. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kew273

- Slart RHJ, Nienhuis PH, Glaudemans AWJM, et al. Role of 18F-FDG PET/CT in large vessel vasculitis and polymyalgia rheumatica. J Nucl Med. 2023;64:515-521. doi:10.2967/jnumed.122.265016

- Shimol JB, Amital H, Lidar M, Domachevsky L, Shoenfeld Y, Davidson T. The utility of PET/CT in large vessel vasculitis. Sci Rep. 2020;10:17709. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-73818-2

- Ponte C, Grayson PC, Robson JC, et al. 2022 American College of Rheumatology/EULAR Classification Criteria for Giant Cell Arteritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022;74:1881-1889. doi:10.1002/art.42325

- He J, Williamson L, Ng B, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of temporal artery ultrasound and temporal artery biopsy in giant cell arteritis: a single center Australian experience over 10 years. Int J Rheum Dis. 2022;25:447-453. doi:10.1111/1756-185X.14288

- Stellingwerff MD, Brouwer E, Lensen KDF, et al. Different scoring methods of FDG PET/CT in giant cell arteritis: need for standardization. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e1542. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000001542

- Conway R, Smyth AE, Kavanagh RG, et al. Diagnostic utility of computed tomographic angiography in giant-cell arteritis. Stroke. 2018;49:2233-2236. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.021995

- Duftner C, Dejaco C, Sepriano A, et al. Imaging in diagnosis, outcome prediction and monitoring of large vessel vasculitis: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis informing the EULAR recommendations. RMD Open. 2018;4:e000612. doi:10.1136/rmdopen-2017-000612

- Rehak Z, Vasina J, Ptacek J, et al. PET/CT in giant cell arteritis: high 18F-FDG uptake in the temporal, occipital and vertebral arteries. Rev Esp Med Nucl Imagen Mol. 2016;35:398-401. doi:10.1016/j.remn.2016.03.007

- Salvarani C, Soriano A, Muratore F, et al. Is PET/CT essential in the diagnosis and follow-up of temporal arteritis? Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16:1125-1130. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2017.09.007

- Brodmann M, Lipp RW, Passath A, et al. The role of 2-18F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography in the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis of the temporal arteries. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43:241-242. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keh025

- Flaus A, Granjon D, Habouzit V, Gaultier JB, Prevot-Bitot N. Unusual and diffuse hypermetabolism in routine 18F-FDG PET/CT of the supra-aortic vessels in biopsy-positive giant cell arteritis. Clin Nucl Med. 2018;43:e336-e337. doi:10.1097/RLU.0000000000002198

- Berger CT, Sommer G, Aschwanden M, et al. The clinical benefit of imaging in the diagnosis and treatment of giant cell arteritis. Swiss Med Wkly. 2018;148:w14661. doi:10.4414/smw.2018.14661

- Rubenstein E, Maldini C, Gonzalez-Chiappe S, et al. Sensitivity of temporal artery biopsy in the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020;59:1011-1020. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kez385

- Tsivgoulis G, Heliopoulos I, Vadikolias K, et al. Teaching neuroimages: ultrasound findings in giant-cell arteritis. Neurology. 2010;75:e67-e68. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f881e9

- Nakajima E, Moon FH, Canvas Jr N, et al. Accuracy of Doppler ultrasound in the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv Rheumatol. 2023;63:5. doi:10.1186/s42358-023-00286-3

- Naumegni SR, Hoffmann C, Cornec D, et al. Temporal artery ultrasound to diagnose giant cell arteritis: a practical guide. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2021;47:201-213. doi:10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2020.10.004

- Kim YH. Artificial intelligence in medical ultrasonography: driving on an unpaved road. Ultrasonography. 2021;40:313-317. doi:10.14366/usg.21031

- Sultan LR, Mohamed MH, Andronikou S. ChatGPT-4: a breakthrough in ultrasound image analysis. Radiol Adv. 2024;1:umae006. doi:10.1093/radadv/umae006

- Cipriani VP, Klein S. Clinical characteristics of multiple sclerosis in African-Americans. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2019;19:87. doi:10.1007/s11910-019-1000-5

- Sturm A, Dechant C, Proft F, et al. Gender differences in giant cell arteritis: a case-control study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2016;34:S70-72.

- Li KJ, Semenov D, Turk M, et al. A meta-analysis of the epidemiology of giant cell arteritis across time and space. Arthritis Res Ther. 2021;23:82. doi:10.1186/s13075-021-02450-w

- Nelson L, Gormley R, Riddle MS, Tribble DR, Porter CK. The epidemiology of Guillain-Barré syndrome in U.S. military personnel: a case-control study. BMC Res Notes. 2009;2:171. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-2-171

- Spaulding SW. The possible roles of environmental factors and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in the prevalence of thyroid diseases in Vietnam era veterans. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2011;18:315-320.

- O’Donovan A, Cohen BE, Seal KH, et al. Elevated risk for autoimmune disorders in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;77:365-374. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.06.015

- Bookwalter DB, Roenfeldt KA, LeardMann CA, Kong SY, Riddle MS, Rull RP. Posttraumatic stress disorder and risk of selected autoimmune diseases among US military personnel. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20:23. doi:10.1186/s12888-020-2432-9

Giant cell arteritis (GCA), the most commonly diagnosed systemic vasculitis, is a large- and medium-vessel vasculitis that can lead to significant morbidity due to aneurysm formation or vascular occlusion if not diagnosed in a timely manner.1,2 Diagnosis is typically based on clinical history and inflammatory markers. Laboratory inflammatory markers may be normal in the early stages of GCA but can be abnormal due to other unrelated reasons leading to a false positive diagnosis.3 Delayed treatment may lead to visual loss, jaw or limb claudication, or ischemic stroke.2 Initial treatment typically includes high-dose steroids that can lead to significant adverse reactions such as hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction, metabolic syndrome, premature atherosclerosis, and increased risk of infection.4-6

The 1990 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for GCA are widely recognized (Table 1).7 The criteria focuses on clinical manifestations, including new onset headache, temporal artery tenderness, age ≥ 50 years, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) ≥ 50 mm/hr, and temporal artery biopsy with positive anatomical findings.8 When 3 of the 5 1990 ACR criteria are present, the sensitivity and specificity is estimated to be > 90% for GCA vs alternative vasculitides.7

Although the 1990 ACR criteria do not include imaging, modalities such as ultrasound, computed tomography angiography (CTA), 18F-FDG positron emission tomography (PET), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)/magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) may be used in GCA diagnosis.8-10 These imaging modalities have been added to the proposed ACR classification criteria for GCA.11 For this updated point system standard, age ≥ 50 years is a requirement and includes a positive temporal artery biopsy or temporal artery halo sign on ultrasound (+5 points), an ESR ≥ 50 mm/h or C-reactive protein (CRP) ≥ 10 mg/L (+3 points), or sudden visual loss (+3 points). Scalp tenderness, jaw or tongue claudication, new temporal headache, morning stiffness in shoulders or neck, temporal artery abnormality on vascular examination, bilateral axillary vessel involvement on imaging, and 18F-FDG PET activity throughout the aorta are scored +2 points each. With these new criteria, a cumulative score ≥ 6 is classified as GCA. Diagnostic accuracy is further improved with imaging: ultrasonography (sensitivity 55% and specificity 95%) and 18F-FDG PET (sensitivity 69% and specificity 92%), CTA (sensitivity 71% and specificity 86%), and MRI/MRA (sensitivity 73% and specificity 88%).12-15

In recent years, clinicians have reported increased glucose uptake in arteries observed on PET imaging that suggests GCA.9,10,16-20 18F-FDG accumulates in cells with high metabolic activity rates, such as areas of inflammation. In assessing temporal arteries or other involved vasculature (eg, axillary or great vessels) for GCA, this modality indicates increased glucose uptake in the lining of vessel walls. The inflammation of vessel walls can then be visualized with PET. 18F-FDG PET presents a noninvasive imaging technique for evaluating GCA but its use has been limited in the United States due to its high cost.

Methods

Approval for a retrospective chart review of patients evaluated for suspected GCA was obtained from the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC) Institutional Review Board. The review included patients who underwent diagnostic procedures such as ultrasound, MRI, CT angiogram, and PET studies from 2016 through 2022. International Classification of Diseases codes used for case identification included: M31.6, M31.5, I77.6, I77.8, I77.89, I67.7, and I68.2. The Current Procedural Terminology code used for temporal artery biopsy is 37609.

Results