User login

Colpocleisis: A simple, effective, and underutilized procedure

CASE 1: Problematic prolapse, but no incontinence

An 81-year-old multiparous woman, who has a history of recurrent stage-III pelvic organ prolapse (POP), reports worsening discomfort that makes it difficult for her to care for her ailing husband. She also has “trouble” with bladder emptying and constipation, but denies any loss of urine. She has not had vaginal intercourse in more than a decade because of her husband’s medical condition.

Aside from health issues—she suffers from obesity, coronary artery disease, hypertension, and diabetes—the patient is content with her marriage of 58 years.

Urodynamic testing fails to demonstrate detrusor overactivity, stress urinary incontinence, or intrinsic sphincteric deficiency. A cough stress test is repeated after reduction of her prolapse using a large cotton swab, and confirms the findings of the urodynamic tests.

Is reconstructive surgery appropriate for this patient?

Traditional reconstructive surgical procedures for treating POP fail in as many as 30% of patients, and new approaches—some involving grafts—are proposed every day, often without much data behind them.1

Regardless of the approach, reconstructive surgery is a lengthy procedure that subjects patients who are already medically compromised to significant risk, including bleeding, infection, and fluid shifts. Delayed return to normal activity may be especially costly among elderly women because of the risk of venous thromboembolism.

Because of the high failure rate, slow recovery, and risk of complications, reconstructive surgery may not be as appropriate as colpocleisis for the woman described above. Colpocleisis—suturing the inside walls of the vagina together—has an efficacy rate exceeding 90%.2 This relatively simple operation has been around for almost two centuries and has a good track record, but is often overlooked when counseling a patient about her options.

Any frail, elderly woman who has stage-III or -IV POP who does not desire to preserve coital ability is a candidate for colpocleisis (TABLE). Advantages include:

- a short operating time

- few complications

- amenability of local anesthesia

- short hospitalization

- speedy recovery

- high success rate

- low rate of regret.2-5

Because it precludes coital activity, however, colpocleisis may cause problems with self-image. It also may lead to de novo or worsening urinary incontinence and complicate or delay the diagnosis of cervical and endometrial pathology.

This article explores these issues through a case-based discussion of colpocleisis, including a detailed description of surgical technique.

TABLE

Requirements for colpocleisis

Both of the following must be present

|

Plus at least one of the following

|

Colpocleisis, as noted, entails suturing the inside walls of the vagina together. It is controversial because of its impact on coital activity. With careful patient selection, however, colpocleisis is considered a valid option for frail and elderly women who have POP and do not desire or foresee the possibility of future vaginal intercourse. Such women may represent a surprising percentage of the elderly population. A community-based survey found that 78% of married women 70 to 79 years old are not sexually active,6 and a study from The Netherlands found a prevalence of symptomatic POP of 11.4% among white women 45 to 85 years old.7

The fundamental reason for choosing an obliterative procedure such as colpocleisis over total pelvic reconstruction is to treat the prolapse with the least invasive technique in the shortest time. Hysterectomy, which often adds 30 to 80 minutes to the procedure, should therefore be performed only in patients who have a suspicious finding upon initial evaluation. For the same reason, partial colpocleisis—performed using the LeFort technique with limited dissection—has become the most popular obliterative approach. We try to avoid a total colpocleisis procedure—also known as colpectomy—in which the entire vaginal epithelium is stripped, because it is feasible only when the uterus is already absent or scheduled to be removed concomitantly.

(Note: The term vaginectomy should be reserved for gynecologic oncology procedures performed to remove vaginal cancer. Vaginectomy entails full-thickness excision of the vaginal walls, including the fibromuscular layer, as opposed to excision of the epithelial layer only, as in colpocleisis. In this article, we present the LeFort method, a partial colpocleisis technique, because we believe it is more easily adapted by the general gynecologist.8)

CASE 1 RESOLVED

After detailed counseling, which includes family members, the patient opts to undergo colpocleisis. The procedure takes 45 minutes. She is discharged on postoperative Day 1, and reports substantially improved quality of life.

CASE 2: Recurrent prolapse and problems with a pessary

A 72-year-old multiparous, widowed woman experiences recurrent stage-III isolated apical prolapse. She has already undergone two reconstructive procedures, and was discouraged from undergoing a third because of her chronic obstructive lung disease. She tried to use a Gellhorn-type pessary, which required a doctor’s intervention to insert and remove. Frustrated by the many office visits involved in having the pessary checked, she now demands surgical therapy. Another gynecologist has offered to repair the prolapse using mesh, but the patient has concerns about the safety and efficacy of the procedure because it is a relatively new approach.

In addition to the recurrent prolapse, she loses urine with stress and urge. She often has a postvoid residual volume >100 cc; urodynamic assessment confirms mixed urinary incontinence. The patient does not foresee any change in her social status (unmarried, sexually inactive).

Is colpocleisis a reasonable option?

Although the pessary is a helpful conservative alternative for women who are either unable or unwilling to undergo complex surgical pelvic repair and is considered first-line treatment by a majority of urogynecologists, it sometimes becomes more difficult to maintain than the patient is willing to tolerate.9 When a woman cannot remove and reinsert the device herself, the pessary requires a lifelong commitment to doctor’s visits every 2 or 3 months. This commitment is especially problematic for patients who become unable to drive or who lack social support.

Maintenance of the pessary becomes more frustrating as the patient becomes more dependent. Many gynecologists have seen a patient who developed a serious complication such as vesicovaginal or rectovaginal fistula because of a neglected pessary.10

In Case 2, the patient appears to be a potential candidate for colpocleisis, given her age and single status. Although pelvic floor repair appears to be safe in older women, any perioperative complication in a patient 70 years of age or older doubles the risk of discharge to a care facility.11,12 Women who have already undergone several surgeries or who have advanced medical problems such as coronary artery disease or cancer should be counseled thoroughly about the safety and efficacy of colpocleisis.

As for self-image, colpocleisis eliminates prolapse and reduces the genital hiatus. If the patient understands that colpocleisis is obliterative for the vagina but may improve the external appearance of the genital area, she may be more accepting of the procedure. One recent prospective, multicenter study found that only 2% of women thought their body looked worse 1 year after colpocleisis; 60% thought their body looked better.5

When reviewing treatment options, inform the patient that the pessary is a palliative option, whereas surgical therapy aims to be definitive.

CASE 2 RESOLVED

After comprehensive counseling, the patient elects to undergo colpocleisis, along with placement of a midurethral sling. She is discharged 1 day after surgery, and reports substantially improved urinary function, including bladder emptying, and quality of life. She says she would recommend the procedure to any woman who has a similar condition.

CASE 3: Pessary-related complications, incontinence, and underlying medical conditions

A 92-year-old multiparous widow, whose stage-IV uterovaginal prolapse has been managed by a pessary, develops vaginal ulcers in both anterior and posterior walls. After removal of the pessary and 4 weeks of treatment with vaginal estrogen, a smaller pessary is inserted, but she again develops ulcers and bleeding.

The patient’s medical condition is complicated by hypertension and generalized arthritis. She has urodynamically confirmed mixed urinary incontinence. She lives with her daughter and does not want to be placed in a nursing home.

What treatment options should you offer to her?

Because of this patient’s advanced age, poor health, and pessary-related problems, she is an ideal candidate for colpocleisis, provided she consents to the procedure after thorough counseling about its benefits and limitations.

Preoperative concerns

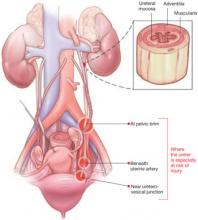

A thorough history, physical examination, and normal Pap test are necessary. If a suspicious pelvic mass or uterine bleeding is present, transvaginal ultrasonography (US) is crucial. In-office endometrial sampling also is necessary in any woman who has unexplained vaginal bleeding. More invasive procedures such as dilatation and curettage and hysteroscopy are needed only when the biopsy is inadequate or endometrial thickness exceeds 4 mm on transvaginal US.13

All elderly women who have high-risk medical problems must be cleared for surgery, with the necessary cardiac and pulmonary workup completed before the procedure.

Because colpocleisis is an extraperitoneal procedure, we have adapted use of over-the-counter enema products on the day before surgery in lieu of mechanical bowel preparation, which may lead to dehydration in very elderly women.

Coordinated consultation between the surgeon and anesthesiologist is necessary to determine the type of anesthesia to be used. Sedation and local anesthesia can be adequate for extremely high-risk women.14,15 Antibiotic prophylaxis is conventional for all patients.

Surgical technique

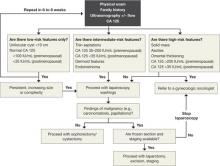

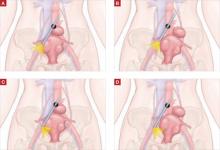

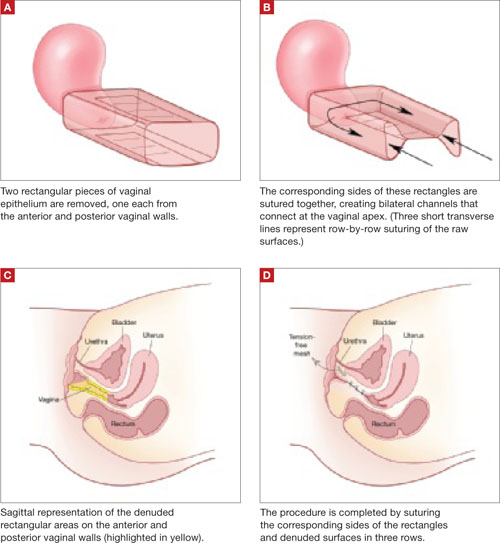

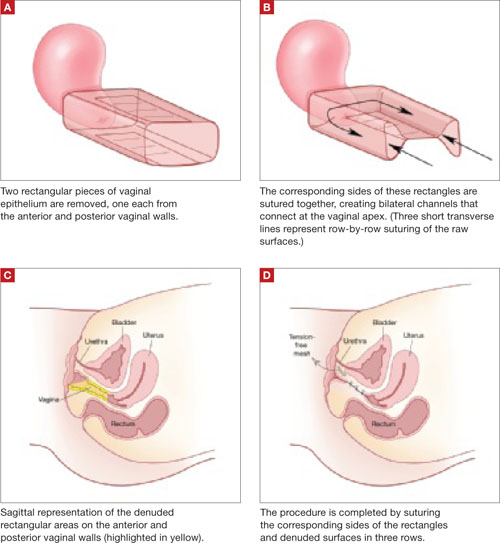

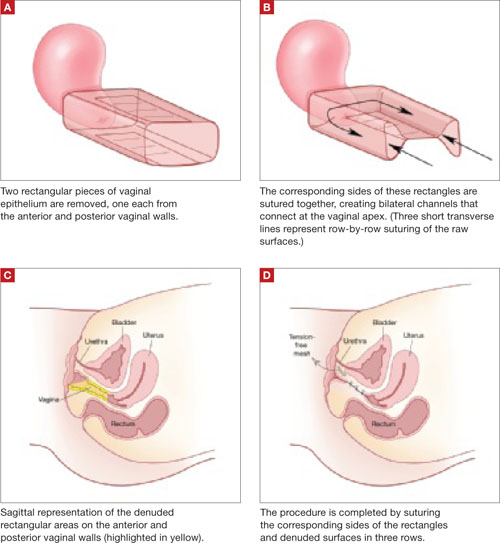

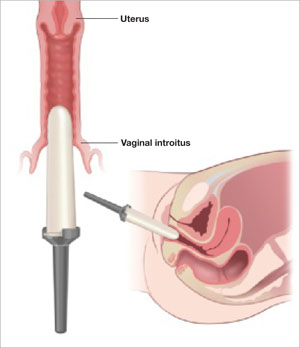

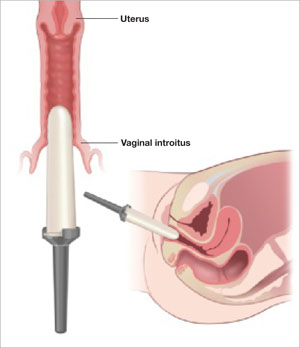

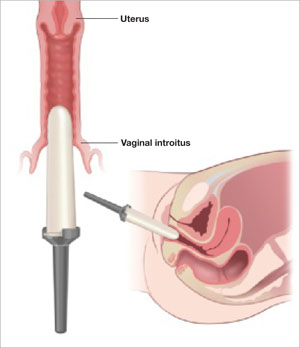

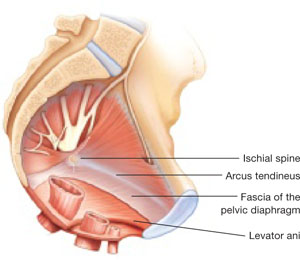

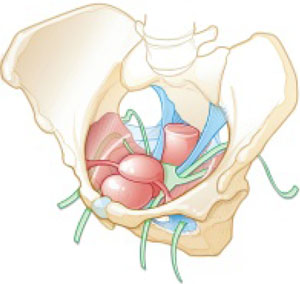

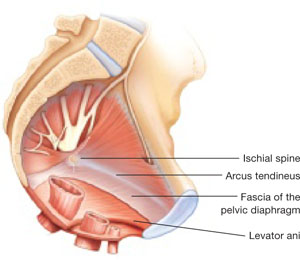

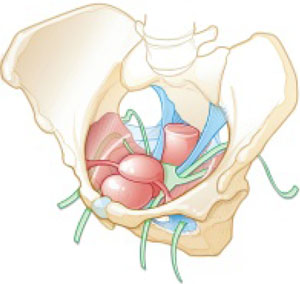

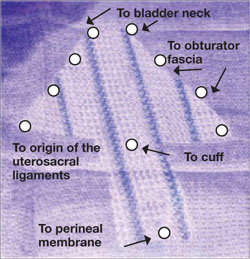

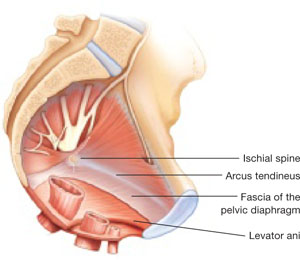

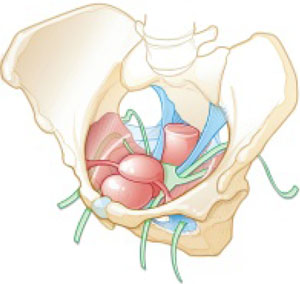

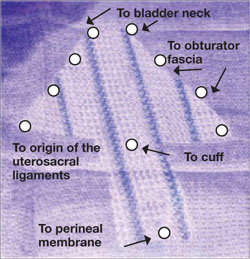

The LeFort method involves denudation and approximation of the midportions of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls.8 This operation creates a longitudinal vaginal septum with bilateral channels on each side, which serve as conduits for any secretion or bleeding from the apical vagina (FIGURE 1A AND B). Aggressive perineorraphy is also needed to shorten the genital hiatus. The following description incorporates perineorraphy into the LeFort technique.

FIGURE 1 Principles of LeFort colpocleisis

The depiction here is not anatomically precise: The vagina is illustrated as a rectangular prism to clarify the relationship between tissues.

Patient positioning

Place the patient in the dorsal lithotomy position, using stirrups to support the entire leg up to the knee. Let the patient’s buttocks overhang the edge of the table by 1 to 2 inches. A slight Trendelenburg position is imperative, especially when operating on the anterior compartment of the vagina. The bladder should be only partially emptied because the leakage of urine from the bladder makes it easier to identify inadvertent cystotomy. Infiltration of local anesthetic solution to develop the surgical planes is acceptable.

Initiating the procedure

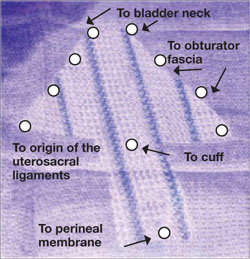

Remove a rectangular piece of vaginal epithelium from the anterior vaginal wall, beginning 2 to 3 cm distal to the vaginal apex (or cervix, if the uterus is present) and ending immediately proximal to the urethrovesical junction to leave space for midurethral sling placement. Remove a similarly sized piece of epithelium from the posterior vaginal wall. This posterior rectangle is an almost geometric projection of the anterior rectangle, but is somewhat longer (2 to 3 cm) (FIGURE 1).

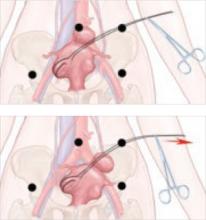

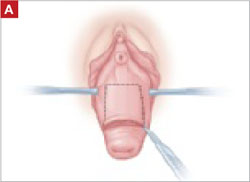

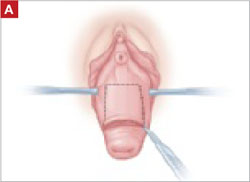

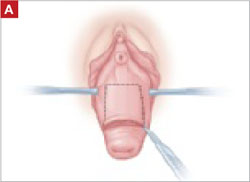

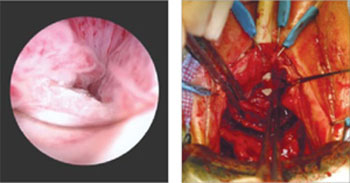

When removing the vaginal epithelium, it may be helpful to use the skills developed for anterior and posterior colporraphy. Our operation begins with a 5- to 6-cm transverse incision at the anterior vaginal apex, which creates the proximal side of the anterior rectangle described above (FIGURE 2A).

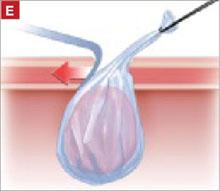

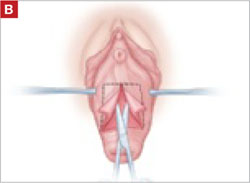

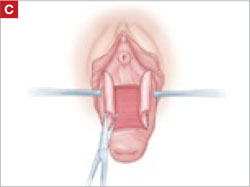

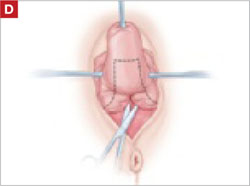

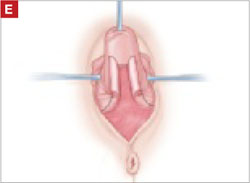

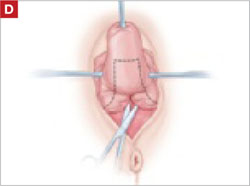

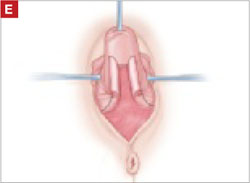

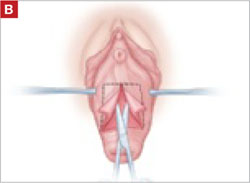

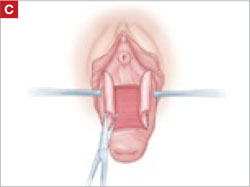

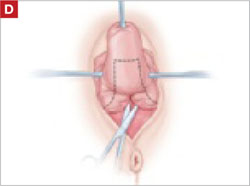

As you develop the plane between the epithelium and fibromuscular layer, make a midline sagittal incision and extend it to the urethrovesical junction (FIGURE 2B). Dissect the epithelium off the fibromuscular layer approximately 3 cm bilaterally, then make a transverse incision at the urethrovesical junction. Finally, remove the anterior rectangle in two pieces by cutting along the lateral sides (FIGURE 2C AND D). Remove the posterior rectangle using the same technique, but also excise a triangular piece of skin from the posterior fourchette for the perineorraphy portion of the procedure (FIGURE 2E).

FIGURE 2 LeFort technique, step by step

Begin with a 5–6 cm transverse incision at the anterior vaginal apex.

Dissect the epithelium off the fibromuscular layer, with a midline sagittal incision extending to the urethrovesical junction.

After dissection is completed, make a transverse incision at the urethrovesical junction, and remove the anterior rectangle in two pieces by cutting along the lateral sides.

Denude the posterior rectangle using the same technique. In addition, excise a triangular piece of skin from the perineum.

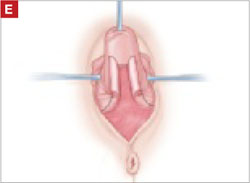

The posterior rectangle is ready for removal.

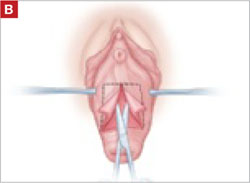

Suturing

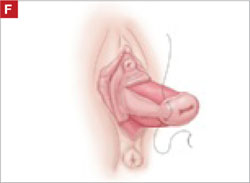

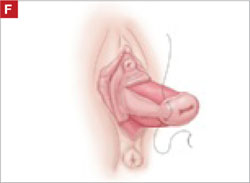

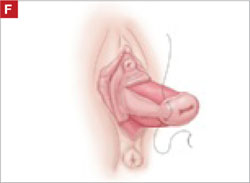

Suture the apical sides of the anterior and posterior rectangles together using a continuous running technique (FIGURE 2F). Then approximate the lateral sides bilaterally using continuous sutures.

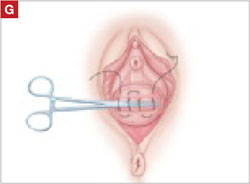

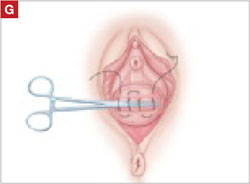

To ensure adherence of the anterior and posterior rectangles, stitch the raw surfaces together in three rows (FIGURE 2G). Do not include the distal 2 cm of the posterior vagina because you will need to leave room for perineorraphy.

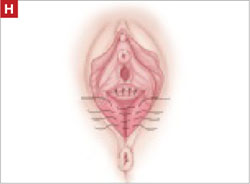

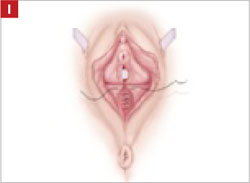

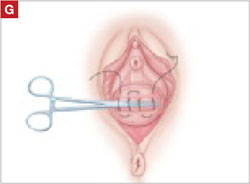

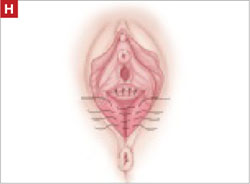

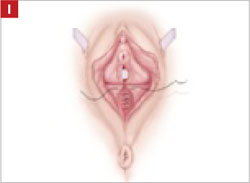

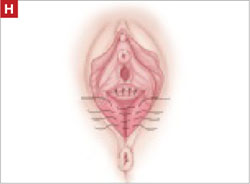

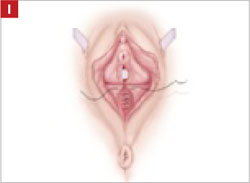

Using several sutures, reapproximate the torn perineal fibromuscular structures in the midline to perform perineorraphy (FIGURE 2H). Close the distal vagina, beginning at the midpoint of the anterior transverse side, which lies at the urethrovesical junction (FIGURE 2I). Continue this suture on the posterior vagina and then the perineal body, sagittally, creating a small invagination in the distal vagina (FIGURE 2J).

FIGURE 2 LeFort technique, step by step

Suture all but the distal sides of the rectangles between the anterior and posterior vaginal walls.

Also stitch together the raw surfaces in three rows in an imbricating fashion.

Perform perineorraphy.

Close the distal vagina, starting at the midpoint of the anterior transverse side. If indicated, place a midurethral sling.

Final appearance.

Sling procedure

We place a midurethral sling as part of most colpocleisis operations. It is best to do this after the colpocleisis but before the perineorraphy.

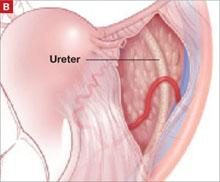

In our cases, cystoscopy with simultaneous intravenous indigo carmine injection is standard before perineorraphy, even when a sling procedure is not planned. This safeguard ensures ureteral patency, which can be compromised (although rarely) in these procedures. Cutting and replacement of one of the sutures that approximate the raw tissues typically resolve the problem.16

Special considerations

Here are additional key points about colpocleisis, based on our experience:

- If an ulcer lies within the area designated to be denuded, some debridement to freshen up the surface will suffice. An ulcer is not an indication to deviate from the standard procedure.

- A modification developed by Goodall and Power may allow coitus by removing only a triangular piece of epithelium from each wall, leaving more room for the channels.17

- We have been unable to find any report of uterine or cervical cancer after colpocleisis, despite a MEDLINE search of the literature in English. Even so, the lateral channels created by the LeFort procedure allow any bleeding to escape the vagina, and may therefore enable recognition of malignancy. When noninvasive imaging techniques such as US or magnetic resonance are inadequate, vaginoscopy and hysteroscopy may be accomplished via these channels.

- When colpocleisis is performed in a hysterectomized woman, no lateral channel is necessary. Therefore, it is appropriate to do total colpocleisis.18,19

- When a patient with POP has a rectovaginal or vesicovaginal fistula caused by a neglected pessary, the addition of LeFort colpocleisis to the fistula repair may provide an effective treatment for both problems.10

Surgical outcomes

Success rate

Evidence concerning colpocleisis comes from case series, some of which are more than 30 years old. Although the definition of success is not clear in some series, the reported success rate has always exceeded 90% over the past three decades.2,18-22 Moreover, some of these reports involve as many as 30 years of follow-up.

Perioperative complication

In a recent review of the literature, the procedure-related mortality rate was 0.025%.2 When the authors focused only on studies published since 1980, major complications due to the patient’s underlying cardiovascular and pulmonary condition were seen in 2% of cases. Major surgical complications such as pyelonephritis and bleeding requiring transfusion occurred in 4% of cases, and less severe complications occurred in 15%.

In a study that included women who underwent concomitant vaginal hysterectomy, hysterectomy prolonged the surgery by 52 minutes, with a 5% rate of laparotomy as a result of intraoperative bleeding.22

In our series of 40 colpocleisis cases, we noted no instance in which a patient regretted the procedure.18 Others have also reported a low rate of regret—the highest being 9%.3-5,19-21

Using validated questionnaires, FitzGerald and colleagues found significant improvement in mental and physical quality of life, as well as urinary, colorectal, and bulge-related pelvic floor symptoms, 1 year after colpocleisis.5

De novo or worsening urinary incontinence is one of the drawbacks of colpocleisis. However, the same risk is present in approximately 40% of women who undergo surgical reconstructive procedures for POP without a continence operation.23 Because preoperative urinary retention is common in women who have POP, the decision to add a potentially harmful continence procedure is complicated in colpocleisis candidates. A small case series reported that the success rate ranged from 90% to 94% in women who underwent a midurethral tension-free sling procedure for the treatment of urinary incontinence at the time of colpocleisis.5

Preoperative urodynamic studies to detect urethral intrinsic deficiency and detrusor dysfunction are prudent, and detailed counseling of the patient about urinary control is vital. We perform a midurethral sling procedure in most of our colpocleisis cases, and have had pleasing results.

CASE 3 RESOLVED

The patient decides to undergo partial colpocleisis using the LeFort procedure, along with placement of a midurethral sling, for a total operative time of 75 minutes. She is discharged 1 day later and reports substantial improvement in urinary function and quality of life.

1. Luber KM, Boero S, Choe JY. The demographics of pelvic floor disorders: current observations and future projections. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:1496-1503.

2. FitzGerald MP, Richter HE, Siddique S, Thompson P, Zyczynski H, Weber A. For the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Colpocleisis: a review. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17:261-271.

3. Wheeler TL, Jr, Richter HE, Burgio KL, et al. Regret, satisfaction, and symptom improvement: analysis of the impact of partial colpocleisis for the management of severe pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:2067-2070.

4. Hullfish KL, Bovbjerg VE, Steers WD. Colpocleisis for pelvic organ prolapse: patient goals, quality of life, and satisfaction. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(2 Pt 1):341-345.

5. FitzGerald MP, Richter HE, Bradley CS, et al. For the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Pelvic support, pelvic symptoms, and patient satisfaction after colpocleisis. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:1603-1609.

6. Patel D, Gillespie B, Foxman B. Sexual behavior of older women: results of a random-digit-dialing survey of 2,000 women in the United States. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:216-220.

7. Slieker-ten Hove MC, Pool-Goudzwaard AL, Eijkemans MJ, Steegers-Theunissen RP, Burger CW, Vierhout ME. Symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse and possible risk factors in a general population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:184.e1-184.e7.

8. Berlin F. Three cases of complete prolapsus uteri operated upon according to the method of Leon LeFort. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1881;14:866-868.

9. Cundiff GW, Weidner AC, Visco AG, Bump RC, Addison WA. A survey of pessary use by members of the American Urogynecologic Society. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(6 Pt 1):931-935.

10. Esin S, Harmanli OH. Large vesicovaginal fistula in women with pelvic organ prolapse: the role of colpocleisis revisited. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:1711-1713.

11. Gerten KA, Markland AD, Lloyd LK, Richter HE. Prolapse and incontinence surgery in older women. J Urol. 2008;179:2111-2118.

12. Manku K, Bacchetti P, Leung JM. Prognostic significance of postoperative in-hospital complications in elderly patients. I. Long-term survival. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:583-589.

13. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 426: The role of transvaginal ultrasonography in the evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(2 Pt 1):462-464.

14. Moore RD, Miklos JR. Colpocleisis and tension-free vaginal tape sling for severe uterine and vaginal prolapse and stress urinary incontinence under local anesthesia. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10:276-280.

15. Buchsbaum GM, Albushies DT, Schoenecker E, Duecy EE, Glantz JC. Local anesthesia with sedation for vaginal reconstructive surgery. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17:211-214.

16. Gustilo-Ashby AM, Jelovsek JE, Barber MD, Yoo EH, Paraiso MF, Walters MD. The incidence of ureteral obstruction and the value of intraoperative cystoscopy during vaginal surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1478-1485.

17. Goodall JR, Power RMH. A modification of the Le Fort operation for increasing its scope. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1937;34:968-976.

18. Harmanli OH, Dandolu V, Chatwani AJ, Grody MT. Total colpocleisis for severe pelvic organ prolapse. J Reprod Med. 2003;48:703-706.

19. DeLancey JOL, Morley GW. Total colpocleisis for vaginal eversion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:1228-1232.

20. Goldman J, Ovadia J, Feldberg D. The Neugebauer-Le Fort operation: a review of 118 partial colpocleises. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1981;12:31-35.

21. Ubachs JM, van Sante TJ, Schellekens LA. Partial colpocleisis by a modification of Le Fort’s operation. Obstet Gynecol. 1973;42:415-420.

22. Von Pechmann WS, Mutone MD, Fyffe J, Hale DS. Total colpocleisis with high levator plication for the treatment of advanced pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:121-126.

23. Albo ME, Richter HE, Brubaker L, et al. For Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network. Burch colposuspension versus fascial sling to reduce urinary stress incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2143-2155.

CASE 1: Problematic prolapse, but no incontinence

An 81-year-old multiparous woman, who has a history of recurrent stage-III pelvic organ prolapse (POP), reports worsening discomfort that makes it difficult for her to care for her ailing husband. She also has “trouble” with bladder emptying and constipation, but denies any loss of urine. She has not had vaginal intercourse in more than a decade because of her husband’s medical condition.

Aside from health issues—she suffers from obesity, coronary artery disease, hypertension, and diabetes—the patient is content with her marriage of 58 years.

Urodynamic testing fails to demonstrate detrusor overactivity, stress urinary incontinence, or intrinsic sphincteric deficiency. A cough stress test is repeated after reduction of her prolapse using a large cotton swab, and confirms the findings of the urodynamic tests.

Is reconstructive surgery appropriate for this patient?

Traditional reconstructive surgical procedures for treating POP fail in as many as 30% of patients, and new approaches—some involving grafts—are proposed every day, often without much data behind them.1

Regardless of the approach, reconstructive surgery is a lengthy procedure that subjects patients who are already medically compromised to significant risk, including bleeding, infection, and fluid shifts. Delayed return to normal activity may be especially costly among elderly women because of the risk of venous thromboembolism.

Because of the high failure rate, slow recovery, and risk of complications, reconstructive surgery may not be as appropriate as colpocleisis for the woman described above. Colpocleisis—suturing the inside walls of the vagina together—has an efficacy rate exceeding 90%.2 This relatively simple operation has been around for almost two centuries and has a good track record, but is often overlooked when counseling a patient about her options.

Any frail, elderly woman who has stage-III or -IV POP who does not desire to preserve coital ability is a candidate for colpocleisis (TABLE). Advantages include:

- a short operating time

- few complications

- amenability of local anesthesia

- short hospitalization

- speedy recovery

- high success rate

- low rate of regret.2-5

Because it precludes coital activity, however, colpocleisis may cause problems with self-image. It also may lead to de novo or worsening urinary incontinence and complicate or delay the diagnosis of cervical and endometrial pathology.

This article explores these issues through a case-based discussion of colpocleisis, including a detailed description of surgical technique.

TABLE

Requirements for colpocleisis

Both of the following must be present

|

Plus at least one of the following

|

Colpocleisis, as noted, entails suturing the inside walls of the vagina together. It is controversial because of its impact on coital activity. With careful patient selection, however, colpocleisis is considered a valid option for frail and elderly women who have POP and do not desire or foresee the possibility of future vaginal intercourse. Such women may represent a surprising percentage of the elderly population. A community-based survey found that 78% of married women 70 to 79 years old are not sexually active,6 and a study from The Netherlands found a prevalence of symptomatic POP of 11.4% among white women 45 to 85 years old.7

The fundamental reason for choosing an obliterative procedure such as colpocleisis over total pelvic reconstruction is to treat the prolapse with the least invasive technique in the shortest time. Hysterectomy, which often adds 30 to 80 minutes to the procedure, should therefore be performed only in patients who have a suspicious finding upon initial evaluation. For the same reason, partial colpocleisis—performed using the LeFort technique with limited dissection—has become the most popular obliterative approach. We try to avoid a total colpocleisis procedure—also known as colpectomy—in which the entire vaginal epithelium is stripped, because it is feasible only when the uterus is already absent or scheduled to be removed concomitantly.

(Note: The term vaginectomy should be reserved for gynecologic oncology procedures performed to remove vaginal cancer. Vaginectomy entails full-thickness excision of the vaginal walls, including the fibromuscular layer, as opposed to excision of the epithelial layer only, as in colpocleisis. In this article, we present the LeFort method, a partial colpocleisis technique, because we believe it is more easily adapted by the general gynecologist.8)

CASE 1 RESOLVED

After detailed counseling, which includes family members, the patient opts to undergo colpocleisis. The procedure takes 45 minutes. She is discharged on postoperative Day 1, and reports substantially improved quality of life.

CASE 2: Recurrent prolapse and problems with a pessary

A 72-year-old multiparous, widowed woman experiences recurrent stage-III isolated apical prolapse. She has already undergone two reconstructive procedures, and was discouraged from undergoing a third because of her chronic obstructive lung disease. She tried to use a Gellhorn-type pessary, which required a doctor’s intervention to insert and remove. Frustrated by the many office visits involved in having the pessary checked, she now demands surgical therapy. Another gynecologist has offered to repair the prolapse using mesh, but the patient has concerns about the safety and efficacy of the procedure because it is a relatively new approach.

In addition to the recurrent prolapse, she loses urine with stress and urge. She often has a postvoid residual volume >100 cc; urodynamic assessment confirms mixed urinary incontinence. The patient does not foresee any change in her social status (unmarried, sexually inactive).

Is colpocleisis a reasonable option?

Although the pessary is a helpful conservative alternative for women who are either unable or unwilling to undergo complex surgical pelvic repair and is considered first-line treatment by a majority of urogynecologists, it sometimes becomes more difficult to maintain than the patient is willing to tolerate.9 When a woman cannot remove and reinsert the device herself, the pessary requires a lifelong commitment to doctor’s visits every 2 or 3 months. This commitment is especially problematic for patients who become unable to drive or who lack social support.

Maintenance of the pessary becomes more frustrating as the patient becomes more dependent. Many gynecologists have seen a patient who developed a serious complication such as vesicovaginal or rectovaginal fistula because of a neglected pessary.10

In Case 2, the patient appears to be a potential candidate for colpocleisis, given her age and single status. Although pelvic floor repair appears to be safe in older women, any perioperative complication in a patient 70 years of age or older doubles the risk of discharge to a care facility.11,12 Women who have already undergone several surgeries or who have advanced medical problems such as coronary artery disease or cancer should be counseled thoroughly about the safety and efficacy of colpocleisis.

As for self-image, colpocleisis eliminates prolapse and reduces the genital hiatus. If the patient understands that colpocleisis is obliterative for the vagina but may improve the external appearance of the genital area, she may be more accepting of the procedure. One recent prospective, multicenter study found that only 2% of women thought their body looked worse 1 year after colpocleisis; 60% thought their body looked better.5

When reviewing treatment options, inform the patient that the pessary is a palliative option, whereas surgical therapy aims to be definitive.

CASE 2 RESOLVED

After comprehensive counseling, the patient elects to undergo colpocleisis, along with placement of a midurethral sling. She is discharged 1 day after surgery, and reports substantially improved urinary function, including bladder emptying, and quality of life. She says she would recommend the procedure to any woman who has a similar condition.

CASE 3: Pessary-related complications, incontinence, and underlying medical conditions

A 92-year-old multiparous widow, whose stage-IV uterovaginal prolapse has been managed by a pessary, develops vaginal ulcers in both anterior and posterior walls. After removal of the pessary and 4 weeks of treatment with vaginal estrogen, a smaller pessary is inserted, but she again develops ulcers and bleeding.

The patient’s medical condition is complicated by hypertension and generalized arthritis. She has urodynamically confirmed mixed urinary incontinence. She lives with her daughter and does not want to be placed in a nursing home.

What treatment options should you offer to her?

Because of this patient’s advanced age, poor health, and pessary-related problems, she is an ideal candidate for colpocleisis, provided she consents to the procedure after thorough counseling about its benefits and limitations.

Preoperative concerns

A thorough history, physical examination, and normal Pap test are necessary. If a suspicious pelvic mass or uterine bleeding is present, transvaginal ultrasonography (US) is crucial. In-office endometrial sampling also is necessary in any woman who has unexplained vaginal bleeding. More invasive procedures such as dilatation and curettage and hysteroscopy are needed only when the biopsy is inadequate or endometrial thickness exceeds 4 mm on transvaginal US.13

All elderly women who have high-risk medical problems must be cleared for surgery, with the necessary cardiac and pulmonary workup completed before the procedure.

Because colpocleisis is an extraperitoneal procedure, we have adapted use of over-the-counter enema products on the day before surgery in lieu of mechanical bowel preparation, which may lead to dehydration in very elderly women.

Coordinated consultation between the surgeon and anesthesiologist is necessary to determine the type of anesthesia to be used. Sedation and local anesthesia can be adequate for extremely high-risk women.14,15 Antibiotic prophylaxis is conventional for all patients.

Surgical technique

The LeFort method involves denudation and approximation of the midportions of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls.8 This operation creates a longitudinal vaginal septum with bilateral channels on each side, which serve as conduits for any secretion or bleeding from the apical vagina (FIGURE 1A AND B). Aggressive perineorraphy is also needed to shorten the genital hiatus. The following description incorporates perineorraphy into the LeFort technique.

FIGURE 1 Principles of LeFort colpocleisis

The depiction here is not anatomically precise: The vagina is illustrated as a rectangular prism to clarify the relationship between tissues.

Patient positioning

Place the patient in the dorsal lithotomy position, using stirrups to support the entire leg up to the knee. Let the patient’s buttocks overhang the edge of the table by 1 to 2 inches. A slight Trendelenburg position is imperative, especially when operating on the anterior compartment of the vagina. The bladder should be only partially emptied because the leakage of urine from the bladder makes it easier to identify inadvertent cystotomy. Infiltration of local anesthetic solution to develop the surgical planes is acceptable.

Initiating the procedure

Remove a rectangular piece of vaginal epithelium from the anterior vaginal wall, beginning 2 to 3 cm distal to the vaginal apex (or cervix, if the uterus is present) and ending immediately proximal to the urethrovesical junction to leave space for midurethral sling placement. Remove a similarly sized piece of epithelium from the posterior vaginal wall. This posterior rectangle is an almost geometric projection of the anterior rectangle, but is somewhat longer (2 to 3 cm) (FIGURE 1).

When removing the vaginal epithelium, it may be helpful to use the skills developed for anterior and posterior colporraphy. Our operation begins with a 5- to 6-cm transverse incision at the anterior vaginal apex, which creates the proximal side of the anterior rectangle described above (FIGURE 2A).

As you develop the plane between the epithelium and fibromuscular layer, make a midline sagittal incision and extend it to the urethrovesical junction (FIGURE 2B). Dissect the epithelium off the fibromuscular layer approximately 3 cm bilaterally, then make a transverse incision at the urethrovesical junction. Finally, remove the anterior rectangle in two pieces by cutting along the lateral sides (FIGURE 2C AND D). Remove the posterior rectangle using the same technique, but also excise a triangular piece of skin from the posterior fourchette for the perineorraphy portion of the procedure (FIGURE 2E).

FIGURE 2 LeFort technique, step by step

Begin with a 5–6 cm transverse incision at the anterior vaginal apex.

Dissect the epithelium off the fibromuscular layer, with a midline sagittal incision extending to the urethrovesical junction.

After dissection is completed, make a transverse incision at the urethrovesical junction, and remove the anterior rectangle in two pieces by cutting along the lateral sides.

Denude the posterior rectangle using the same technique. In addition, excise a triangular piece of skin from the perineum.

The posterior rectangle is ready for removal.

Suturing

Suture the apical sides of the anterior and posterior rectangles together using a continuous running technique (FIGURE 2F). Then approximate the lateral sides bilaterally using continuous sutures.

To ensure adherence of the anterior and posterior rectangles, stitch the raw surfaces together in three rows (FIGURE 2G). Do not include the distal 2 cm of the posterior vagina because you will need to leave room for perineorraphy.

Using several sutures, reapproximate the torn perineal fibromuscular structures in the midline to perform perineorraphy (FIGURE 2H). Close the distal vagina, beginning at the midpoint of the anterior transverse side, which lies at the urethrovesical junction (FIGURE 2I). Continue this suture on the posterior vagina and then the perineal body, sagittally, creating a small invagination in the distal vagina (FIGURE 2J).

FIGURE 2 LeFort technique, step by step

Suture all but the distal sides of the rectangles between the anterior and posterior vaginal walls.

Also stitch together the raw surfaces in three rows in an imbricating fashion.

Perform perineorraphy.

Close the distal vagina, starting at the midpoint of the anterior transverse side. If indicated, place a midurethral sling.

Final appearance.

Sling procedure

We place a midurethral sling as part of most colpocleisis operations. It is best to do this after the colpocleisis but before the perineorraphy.

In our cases, cystoscopy with simultaneous intravenous indigo carmine injection is standard before perineorraphy, even when a sling procedure is not planned. This safeguard ensures ureteral patency, which can be compromised (although rarely) in these procedures. Cutting and replacement of one of the sutures that approximate the raw tissues typically resolve the problem.16

Special considerations

Here are additional key points about colpocleisis, based on our experience:

- If an ulcer lies within the area designated to be denuded, some debridement to freshen up the surface will suffice. An ulcer is not an indication to deviate from the standard procedure.

- A modification developed by Goodall and Power may allow coitus by removing only a triangular piece of epithelium from each wall, leaving more room for the channels.17

- We have been unable to find any report of uterine or cervical cancer after colpocleisis, despite a MEDLINE search of the literature in English. Even so, the lateral channels created by the LeFort procedure allow any bleeding to escape the vagina, and may therefore enable recognition of malignancy. When noninvasive imaging techniques such as US or magnetic resonance are inadequate, vaginoscopy and hysteroscopy may be accomplished via these channels.

- When colpocleisis is performed in a hysterectomized woman, no lateral channel is necessary. Therefore, it is appropriate to do total colpocleisis.18,19

- When a patient with POP has a rectovaginal or vesicovaginal fistula caused by a neglected pessary, the addition of LeFort colpocleisis to the fistula repair may provide an effective treatment for both problems.10

Surgical outcomes

Success rate

Evidence concerning colpocleisis comes from case series, some of which are more than 30 years old. Although the definition of success is not clear in some series, the reported success rate has always exceeded 90% over the past three decades.2,18-22 Moreover, some of these reports involve as many as 30 years of follow-up.

Perioperative complication

In a recent review of the literature, the procedure-related mortality rate was 0.025%.2 When the authors focused only on studies published since 1980, major complications due to the patient’s underlying cardiovascular and pulmonary condition were seen in 2% of cases. Major surgical complications such as pyelonephritis and bleeding requiring transfusion occurred in 4% of cases, and less severe complications occurred in 15%.

In a study that included women who underwent concomitant vaginal hysterectomy, hysterectomy prolonged the surgery by 52 minutes, with a 5% rate of laparotomy as a result of intraoperative bleeding.22

In our series of 40 colpocleisis cases, we noted no instance in which a patient regretted the procedure.18 Others have also reported a low rate of regret—the highest being 9%.3-5,19-21

Using validated questionnaires, FitzGerald and colleagues found significant improvement in mental and physical quality of life, as well as urinary, colorectal, and bulge-related pelvic floor symptoms, 1 year after colpocleisis.5

De novo or worsening urinary incontinence is one of the drawbacks of colpocleisis. However, the same risk is present in approximately 40% of women who undergo surgical reconstructive procedures for POP without a continence operation.23 Because preoperative urinary retention is common in women who have POP, the decision to add a potentially harmful continence procedure is complicated in colpocleisis candidates. A small case series reported that the success rate ranged from 90% to 94% in women who underwent a midurethral tension-free sling procedure for the treatment of urinary incontinence at the time of colpocleisis.5

Preoperative urodynamic studies to detect urethral intrinsic deficiency and detrusor dysfunction are prudent, and detailed counseling of the patient about urinary control is vital. We perform a midurethral sling procedure in most of our colpocleisis cases, and have had pleasing results.

CASE 3 RESOLVED

The patient decides to undergo partial colpocleisis using the LeFort procedure, along with placement of a midurethral sling, for a total operative time of 75 minutes. She is discharged 1 day later and reports substantial improvement in urinary function and quality of life.

CASE 1: Problematic prolapse, but no incontinence

An 81-year-old multiparous woman, who has a history of recurrent stage-III pelvic organ prolapse (POP), reports worsening discomfort that makes it difficult for her to care for her ailing husband. She also has “trouble” with bladder emptying and constipation, but denies any loss of urine. She has not had vaginal intercourse in more than a decade because of her husband’s medical condition.

Aside from health issues—she suffers from obesity, coronary artery disease, hypertension, and diabetes—the patient is content with her marriage of 58 years.

Urodynamic testing fails to demonstrate detrusor overactivity, stress urinary incontinence, or intrinsic sphincteric deficiency. A cough stress test is repeated after reduction of her prolapse using a large cotton swab, and confirms the findings of the urodynamic tests.

Is reconstructive surgery appropriate for this patient?

Traditional reconstructive surgical procedures for treating POP fail in as many as 30% of patients, and new approaches—some involving grafts—are proposed every day, often without much data behind them.1

Regardless of the approach, reconstructive surgery is a lengthy procedure that subjects patients who are already medically compromised to significant risk, including bleeding, infection, and fluid shifts. Delayed return to normal activity may be especially costly among elderly women because of the risk of venous thromboembolism.

Because of the high failure rate, slow recovery, and risk of complications, reconstructive surgery may not be as appropriate as colpocleisis for the woman described above. Colpocleisis—suturing the inside walls of the vagina together—has an efficacy rate exceeding 90%.2 This relatively simple operation has been around for almost two centuries and has a good track record, but is often overlooked when counseling a patient about her options.

Any frail, elderly woman who has stage-III or -IV POP who does not desire to preserve coital ability is a candidate for colpocleisis (TABLE). Advantages include:

- a short operating time

- few complications

- amenability of local anesthesia

- short hospitalization

- speedy recovery

- high success rate

- low rate of regret.2-5

Because it precludes coital activity, however, colpocleisis may cause problems with self-image. It also may lead to de novo or worsening urinary incontinence and complicate or delay the diagnosis of cervical and endometrial pathology.

This article explores these issues through a case-based discussion of colpocleisis, including a detailed description of surgical technique.

TABLE

Requirements for colpocleisis

Both of the following must be present

|

Plus at least one of the following

|

Colpocleisis, as noted, entails suturing the inside walls of the vagina together. It is controversial because of its impact on coital activity. With careful patient selection, however, colpocleisis is considered a valid option for frail and elderly women who have POP and do not desire or foresee the possibility of future vaginal intercourse. Such women may represent a surprising percentage of the elderly population. A community-based survey found that 78% of married women 70 to 79 years old are not sexually active,6 and a study from The Netherlands found a prevalence of symptomatic POP of 11.4% among white women 45 to 85 years old.7

The fundamental reason for choosing an obliterative procedure such as colpocleisis over total pelvic reconstruction is to treat the prolapse with the least invasive technique in the shortest time. Hysterectomy, which often adds 30 to 80 minutes to the procedure, should therefore be performed only in patients who have a suspicious finding upon initial evaluation. For the same reason, partial colpocleisis—performed using the LeFort technique with limited dissection—has become the most popular obliterative approach. We try to avoid a total colpocleisis procedure—also known as colpectomy—in which the entire vaginal epithelium is stripped, because it is feasible only when the uterus is already absent or scheduled to be removed concomitantly.

(Note: The term vaginectomy should be reserved for gynecologic oncology procedures performed to remove vaginal cancer. Vaginectomy entails full-thickness excision of the vaginal walls, including the fibromuscular layer, as opposed to excision of the epithelial layer only, as in colpocleisis. In this article, we present the LeFort method, a partial colpocleisis technique, because we believe it is more easily adapted by the general gynecologist.8)

CASE 1 RESOLVED

After detailed counseling, which includes family members, the patient opts to undergo colpocleisis. The procedure takes 45 minutes. She is discharged on postoperative Day 1, and reports substantially improved quality of life.

CASE 2: Recurrent prolapse and problems with a pessary

A 72-year-old multiparous, widowed woman experiences recurrent stage-III isolated apical prolapse. She has already undergone two reconstructive procedures, and was discouraged from undergoing a third because of her chronic obstructive lung disease. She tried to use a Gellhorn-type pessary, which required a doctor’s intervention to insert and remove. Frustrated by the many office visits involved in having the pessary checked, she now demands surgical therapy. Another gynecologist has offered to repair the prolapse using mesh, but the patient has concerns about the safety and efficacy of the procedure because it is a relatively new approach.

In addition to the recurrent prolapse, she loses urine with stress and urge. She often has a postvoid residual volume >100 cc; urodynamic assessment confirms mixed urinary incontinence. The patient does not foresee any change in her social status (unmarried, sexually inactive).

Is colpocleisis a reasonable option?

Although the pessary is a helpful conservative alternative for women who are either unable or unwilling to undergo complex surgical pelvic repair and is considered first-line treatment by a majority of urogynecologists, it sometimes becomes more difficult to maintain than the patient is willing to tolerate.9 When a woman cannot remove and reinsert the device herself, the pessary requires a lifelong commitment to doctor’s visits every 2 or 3 months. This commitment is especially problematic for patients who become unable to drive or who lack social support.

Maintenance of the pessary becomes more frustrating as the patient becomes more dependent. Many gynecologists have seen a patient who developed a serious complication such as vesicovaginal or rectovaginal fistula because of a neglected pessary.10

In Case 2, the patient appears to be a potential candidate for colpocleisis, given her age and single status. Although pelvic floor repair appears to be safe in older women, any perioperative complication in a patient 70 years of age or older doubles the risk of discharge to a care facility.11,12 Women who have already undergone several surgeries or who have advanced medical problems such as coronary artery disease or cancer should be counseled thoroughly about the safety and efficacy of colpocleisis.

As for self-image, colpocleisis eliminates prolapse and reduces the genital hiatus. If the patient understands that colpocleisis is obliterative for the vagina but may improve the external appearance of the genital area, she may be more accepting of the procedure. One recent prospective, multicenter study found that only 2% of women thought their body looked worse 1 year after colpocleisis; 60% thought their body looked better.5

When reviewing treatment options, inform the patient that the pessary is a palliative option, whereas surgical therapy aims to be definitive.

CASE 2 RESOLVED

After comprehensive counseling, the patient elects to undergo colpocleisis, along with placement of a midurethral sling. She is discharged 1 day after surgery, and reports substantially improved urinary function, including bladder emptying, and quality of life. She says she would recommend the procedure to any woman who has a similar condition.

CASE 3: Pessary-related complications, incontinence, and underlying medical conditions

A 92-year-old multiparous widow, whose stage-IV uterovaginal prolapse has been managed by a pessary, develops vaginal ulcers in both anterior and posterior walls. After removal of the pessary and 4 weeks of treatment with vaginal estrogen, a smaller pessary is inserted, but she again develops ulcers and bleeding.

The patient’s medical condition is complicated by hypertension and generalized arthritis. She has urodynamically confirmed mixed urinary incontinence. She lives with her daughter and does not want to be placed in a nursing home.

What treatment options should you offer to her?

Because of this patient’s advanced age, poor health, and pessary-related problems, she is an ideal candidate for colpocleisis, provided she consents to the procedure after thorough counseling about its benefits and limitations.

Preoperative concerns

A thorough history, physical examination, and normal Pap test are necessary. If a suspicious pelvic mass or uterine bleeding is present, transvaginal ultrasonography (US) is crucial. In-office endometrial sampling also is necessary in any woman who has unexplained vaginal bleeding. More invasive procedures such as dilatation and curettage and hysteroscopy are needed only when the biopsy is inadequate or endometrial thickness exceeds 4 mm on transvaginal US.13

All elderly women who have high-risk medical problems must be cleared for surgery, with the necessary cardiac and pulmonary workup completed before the procedure.

Because colpocleisis is an extraperitoneal procedure, we have adapted use of over-the-counter enema products on the day before surgery in lieu of mechanical bowel preparation, which may lead to dehydration in very elderly women.

Coordinated consultation between the surgeon and anesthesiologist is necessary to determine the type of anesthesia to be used. Sedation and local anesthesia can be adequate for extremely high-risk women.14,15 Antibiotic prophylaxis is conventional for all patients.

Surgical technique

The LeFort method involves denudation and approximation of the midportions of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls.8 This operation creates a longitudinal vaginal septum with bilateral channels on each side, which serve as conduits for any secretion or bleeding from the apical vagina (FIGURE 1A AND B). Aggressive perineorraphy is also needed to shorten the genital hiatus. The following description incorporates perineorraphy into the LeFort technique.

FIGURE 1 Principles of LeFort colpocleisis

The depiction here is not anatomically precise: The vagina is illustrated as a rectangular prism to clarify the relationship between tissues.

Patient positioning

Place the patient in the dorsal lithotomy position, using stirrups to support the entire leg up to the knee. Let the patient’s buttocks overhang the edge of the table by 1 to 2 inches. A slight Trendelenburg position is imperative, especially when operating on the anterior compartment of the vagina. The bladder should be only partially emptied because the leakage of urine from the bladder makes it easier to identify inadvertent cystotomy. Infiltration of local anesthetic solution to develop the surgical planes is acceptable.

Initiating the procedure

Remove a rectangular piece of vaginal epithelium from the anterior vaginal wall, beginning 2 to 3 cm distal to the vaginal apex (or cervix, if the uterus is present) and ending immediately proximal to the urethrovesical junction to leave space for midurethral sling placement. Remove a similarly sized piece of epithelium from the posterior vaginal wall. This posterior rectangle is an almost geometric projection of the anterior rectangle, but is somewhat longer (2 to 3 cm) (FIGURE 1).

When removing the vaginal epithelium, it may be helpful to use the skills developed for anterior and posterior colporraphy. Our operation begins with a 5- to 6-cm transverse incision at the anterior vaginal apex, which creates the proximal side of the anterior rectangle described above (FIGURE 2A).

As you develop the plane between the epithelium and fibromuscular layer, make a midline sagittal incision and extend it to the urethrovesical junction (FIGURE 2B). Dissect the epithelium off the fibromuscular layer approximately 3 cm bilaterally, then make a transverse incision at the urethrovesical junction. Finally, remove the anterior rectangle in two pieces by cutting along the lateral sides (FIGURE 2C AND D). Remove the posterior rectangle using the same technique, but also excise a triangular piece of skin from the posterior fourchette for the perineorraphy portion of the procedure (FIGURE 2E).

FIGURE 2 LeFort technique, step by step

Begin with a 5–6 cm transverse incision at the anterior vaginal apex.

Dissect the epithelium off the fibromuscular layer, with a midline sagittal incision extending to the urethrovesical junction.

After dissection is completed, make a transverse incision at the urethrovesical junction, and remove the anterior rectangle in two pieces by cutting along the lateral sides.

Denude the posterior rectangle using the same technique. In addition, excise a triangular piece of skin from the perineum.

The posterior rectangle is ready for removal.

Suturing

Suture the apical sides of the anterior and posterior rectangles together using a continuous running technique (FIGURE 2F). Then approximate the lateral sides bilaterally using continuous sutures.

To ensure adherence of the anterior and posterior rectangles, stitch the raw surfaces together in three rows (FIGURE 2G). Do not include the distal 2 cm of the posterior vagina because you will need to leave room for perineorraphy.

Using several sutures, reapproximate the torn perineal fibromuscular structures in the midline to perform perineorraphy (FIGURE 2H). Close the distal vagina, beginning at the midpoint of the anterior transverse side, which lies at the urethrovesical junction (FIGURE 2I). Continue this suture on the posterior vagina and then the perineal body, sagittally, creating a small invagination in the distal vagina (FIGURE 2J).

FIGURE 2 LeFort technique, step by step

Suture all but the distal sides of the rectangles between the anterior and posterior vaginal walls.

Also stitch together the raw surfaces in three rows in an imbricating fashion.

Perform perineorraphy.

Close the distal vagina, starting at the midpoint of the anterior transverse side. If indicated, place a midurethral sling.

Final appearance.

Sling procedure

We place a midurethral sling as part of most colpocleisis operations. It is best to do this after the colpocleisis but before the perineorraphy.

In our cases, cystoscopy with simultaneous intravenous indigo carmine injection is standard before perineorraphy, even when a sling procedure is not planned. This safeguard ensures ureteral patency, which can be compromised (although rarely) in these procedures. Cutting and replacement of one of the sutures that approximate the raw tissues typically resolve the problem.16

Special considerations

Here are additional key points about colpocleisis, based on our experience:

- If an ulcer lies within the area designated to be denuded, some debridement to freshen up the surface will suffice. An ulcer is not an indication to deviate from the standard procedure.

- A modification developed by Goodall and Power may allow coitus by removing only a triangular piece of epithelium from each wall, leaving more room for the channels.17

- We have been unable to find any report of uterine or cervical cancer after colpocleisis, despite a MEDLINE search of the literature in English. Even so, the lateral channels created by the LeFort procedure allow any bleeding to escape the vagina, and may therefore enable recognition of malignancy. When noninvasive imaging techniques such as US or magnetic resonance are inadequate, vaginoscopy and hysteroscopy may be accomplished via these channels.

- When colpocleisis is performed in a hysterectomized woman, no lateral channel is necessary. Therefore, it is appropriate to do total colpocleisis.18,19

- When a patient with POP has a rectovaginal or vesicovaginal fistula caused by a neglected pessary, the addition of LeFort colpocleisis to the fistula repair may provide an effective treatment for both problems.10

Surgical outcomes

Success rate

Evidence concerning colpocleisis comes from case series, some of which are more than 30 years old. Although the definition of success is not clear in some series, the reported success rate has always exceeded 90% over the past three decades.2,18-22 Moreover, some of these reports involve as many as 30 years of follow-up.

Perioperative complication

In a recent review of the literature, the procedure-related mortality rate was 0.025%.2 When the authors focused only on studies published since 1980, major complications due to the patient’s underlying cardiovascular and pulmonary condition were seen in 2% of cases. Major surgical complications such as pyelonephritis and bleeding requiring transfusion occurred in 4% of cases, and less severe complications occurred in 15%.

In a study that included women who underwent concomitant vaginal hysterectomy, hysterectomy prolonged the surgery by 52 minutes, with a 5% rate of laparotomy as a result of intraoperative bleeding.22

In our series of 40 colpocleisis cases, we noted no instance in which a patient regretted the procedure.18 Others have also reported a low rate of regret—the highest being 9%.3-5,19-21

Using validated questionnaires, FitzGerald and colleagues found significant improvement in mental and physical quality of life, as well as urinary, colorectal, and bulge-related pelvic floor symptoms, 1 year after colpocleisis.5

De novo or worsening urinary incontinence is one of the drawbacks of colpocleisis. However, the same risk is present in approximately 40% of women who undergo surgical reconstructive procedures for POP without a continence operation.23 Because preoperative urinary retention is common in women who have POP, the decision to add a potentially harmful continence procedure is complicated in colpocleisis candidates. A small case series reported that the success rate ranged from 90% to 94% in women who underwent a midurethral tension-free sling procedure for the treatment of urinary incontinence at the time of colpocleisis.5

Preoperative urodynamic studies to detect urethral intrinsic deficiency and detrusor dysfunction are prudent, and detailed counseling of the patient about urinary control is vital. We perform a midurethral sling procedure in most of our colpocleisis cases, and have had pleasing results.

CASE 3 RESOLVED

The patient decides to undergo partial colpocleisis using the LeFort procedure, along with placement of a midurethral sling, for a total operative time of 75 minutes. She is discharged 1 day later and reports substantial improvement in urinary function and quality of life.

1. Luber KM, Boero S, Choe JY. The demographics of pelvic floor disorders: current observations and future projections. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:1496-1503.

2. FitzGerald MP, Richter HE, Siddique S, Thompson P, Zyczynski H, Weber A. For the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Colpocleisis: a review. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17:261-271.

3. Wheeler TL, Jr, Richter HE, Burgio KL, et al. Regret, satisfaction, and symptom improvement: analysis of the impact of partial colpocleisis for the management of severe pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:2067-2070.

4. Hullfish KL, Bovbjerg VE, Steers WD. Colpocleisis for pelvic organ prolapse: patient goals, quality of life, and satisfaction. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(2 Pt 1):341-345.

5. FitzGerald MP, Richter HE, Bradley CS, et al. For the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Pelvic support, pelvic symptoms, and patient satisfaction after colpocleisis. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:1603-1609.

6. Patel D, Gillespie B, Foxman B. Sexual behavior of older women: results of a random-digit-dialing survey of 2,000 women in the United States. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:216-220.

7. Slieker-ten Hove MC, Pool-Goudzwaard AL, Eijkemans MJ, Steegers-Theunissen RP, Burger CW, Vierhout ME. Symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse and possible risk factors in a general population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:184.e1-184.e7.

8. Berlin F. Three cases of complete prolapsus uteri operated upon according to the method of Leon LeFort. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1881;14:866-868.

9. Cundiff GW, Weidner AC, Visco AG, Bump RC, Addison WA. A survey of pessary use by members of the American Urogynecologic Society. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(6 Pt 1):931-935.

10. Esin S, Harmanli OH. Large vesicovaginal fistula in women with pelvic organ prolapse: the role of colpocleisis revisited. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:1711-1713.

11. Gerten KA, Markland AD, Lloyd LK, Richter HE. Prolapse and incontinence surgery in older women. J Urol. 2008;179:2111-2118.

12. Manku K, Bacchetti P, Leung JM. Prognostic significance of postoperative in-hospital complications in elderly patients. I. Long-term survival. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:583-589.

13. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 426: The role of transvaginal ultrasonography in the evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(2 Pt 1):462-464.

14. Moore RD, Miklos JR. Colpocleisis and tension-free vaginal tape sling for severe uterine and vaginal prolapse and stress urinary incontinence under local anesthesia. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10:276-280.

15. Buchsbaum GM, Albushies DT, Schoenecker E, Duecy EE, Glantz JC. Local anesthesia with sedation for vaginal reconstructive surgery. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17:211-214.

16. Gustilo-Ashby AM, Jelovsek JE, Barber MD, Yoo EH, Paraiso MF, Walters MD. The incidence of ureteral obstruction and the value of intraoperative cystoscopy during vaginal surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1478-1485.

17. Goodall JR, Power RMH. A modification of the Le Fort operation for increasing its scope. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1937;34:968-976.

18. Harmanli OH, Dandolu V, Chatwani AJ, Grody MT. Total colpocleisis for severe pelvic organ prolapse. J Reprod Med. 2003;48:703-706.

19. DeLancey JOL, Morley GW. Total colpocleisis for vaginal eversion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:1228-1232.

20. Goldman J, Ovadia J, Feldberg D. The Neugebauer-Le Fort operation: a review of 118 partial colpocleises. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1981;12:31-35.

21. Ubachs JM, van Sante TJ, Schellekens LA. Partial colpocleisis by a modification of Le Fort’s operation. Obstet Gynecol. 1973;42:415-420.

22. Von Pechmann WS, Mutone MD, Fyffe J, Hale DS. Total colpocleisis with high levator plication for the treatment of advanced pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:121-126.

23. Albo ME, Richter HE, Brubaker L, et al. For Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network. Burch colposuspension versus fascial sling to reduce urinary stress incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2143-2155.

1. Luber KM, Boero S, Choe JY. The demographics of pelvic floor disorders: current observations and future projections. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:1496-1503.

2. FitzGerald MP, Richter HE, Siddique S, Thompson P, Zyczynski H, Weber A. For the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Colpocleisis: a review. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17:261-271.

3. Wheeler TL, Jr, Richter HE, Burgio KL, et al. Regret, satisfaction, and symptom improvement: analysis of the impact of partial colpocleisis for the management of severe pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:2067-2070.

4. Hullfish KL, Bovbjerg VE, Steers WD. Colpocleisis for pelvic organ prolapse: patient goals, quality of life, and satisfaction. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(2 Pt 1):341-345.

5. FitzGerald MP, Richter HE, Bradley CS, et al. For the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Pelvic support, pelvic symptoms, and patient satisfaction after colpocleisis. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:1603-1609.

6. Patel D, Gillespie B, Foxman B. Sexual behavior of older women: results of a random-digit-dialing survey of 2,000 women in the United States. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:216-220.

7. Slieker-ten Hove MC, Pool-Goudzwaard AL, Eijkemans MJ, Steegers-Theunissen RP, Burger CW, Vierhout ME. Symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse and possible risk factors in a general population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:184.e1-184.e7.

8. Berlin F. Three cases of complete prolapsus uteri operated upon according to the method of Leon LeFort. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1881;14:866-868.

9. Cundiff GW, Weidner AC, Visco AG, Bump RC, Addison WA. A survey of pessary use by members of the American Urogynecologic Society. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(6 Pt 1):931-935.

10. Esin S, Harmanli OH. Large vesicovaginal fistula in women with pelvic organ prolapse: the role of colpocleisis revisited. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:1711-1713.

11. Gerten KA, Markland AD, Lloyd LK, Richter HE. Prolapse and incontinence surgery in older women. J Urol. 2008;179:2111-2118.

12. Manku K, Bacchetti P, Leung JM. Prognostic significance of postoperative in-hospital complications in elderly patients. I. Long-term survival. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:583-589.

13. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 426: The role of transvaginal ultrasonography in the evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(2 Pt 1):462-464.

14. Moore RD, Miklos JR. Colpocleisis and tension-free vaginal tape sling for severe uterine and vaginal prolapse and stress urinary incontinence under local anesthesia. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10:276-280.

15. Buchsbaum GM, Albushies DT, Schoenecker E, Duecy EE, Glantz JC. Local anesthesia with sedation for vaginal reconstructive surgery. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17:211-214.

16. Gustilo-Ashby AM, Jelovsek JE, Barber MD, Yoo EH, Paraiso MF, Walters MD. The incidence of ureteral obstruction and the value of intraoperative cystoscopy during vaginal surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1478-1485.

17. Goodall JR, Power RMH. A modification of the Le Fort operation for increasing its scope. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1937;34:968-976.

18. Harmanli OH, Dandolu V, Chatwani AJ, Grody MT. Total colpocleisis for severe pelvic organ prolapse. J Reprod Med. 2003;48:703-706.

19. DeLancey JOL, Morley GW. Total colpocleisis for vaginal eversion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:1228-1232.

20. Goldman J, Ovadia J, Feldberg D. The Neugebauer-Le Fort operation: a review of 118 partial colpocleises. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1981;12:31-35.

21. Ubachs JM, van Sante TJ, Schellekens LA. Partial colpocleisis by a modification of Le Fort’s operation. Obstet Gynecol. 1973;42:415-420.

22. Von Pechmann WS, Mutone MD, Fyffe J, Hale DS. Total colpocleisis with high levator plication for the treatment of advanced pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:121-126.

23. Albo ME, Richter HE, Brubaker L, et al. For Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network. Burch colposuspension versus fascial sling to reduce urinary stress incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2143-2155.

Postmenopausal dyspareunia— a problem for the 21st century

The author reports that he serves on the speaker’s bureau for Novogyne, TherRx, Warner-Chilcott, and Solvay, and on the advisory board for Upsher-Smith, Novogyne, QuatRx, and Wyeth.

CASE: History of dyspareunia

At her latest visit, a 56-year-old woman who is 7 years postmenopausal relates that she has been experiencing worsening pain with intercourse to the point that she now has very little sex drive at all. This problem began approximately 1 year after she discontinued hormone therapy in the wake of reports that it causes cancer and heart attack. She has been offered both local vaginal and systemic hormone therapy, but is too frightened to use any hormones at all. Sexual lubricants no longer seem to work.

How do you counsel her about these symptoms? And what therapy do you offer?

Physicians and other health-care practitioners are seeing a large and growing number of genitourinary and sexual-related complaints among menopausal women—so much so that it has reached epidemic proportions. Yet dyspareunia is underreported and undertreated, and quality of life suffers for these women.

In this article, I focus on two interrelated causes of this epidemic:

- vaginal dryness and vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) and the impact of these conditions on women’s sexual function and psychosocial well-being

- barriers to optimal treatment.

I also explore how ObGyns’ role in this area of care is evolving—as a way to understand how you can better serve this expanding segment of our patient population.

Dyspareunia can have many causes, including endometriosis, interstitial cystitis, surgical scarring, injury that occurs during childbirth, and psychosocial origin (such as a history of sexual abuse). Our focus here is on dyspareunia due to VVA.

during sex. What should you do?

- Sexual pain as a category of female sexual dysfunction is relevant at any age; for postmenopausal women dealing with vaginal dryness as a result of estrogen deficiency, it may well be the dominant issue. When determining the cause of a sexual problem in a postmenopausal woman, put dyspareunia caused by vaginal dryness (as well as its psychosocial consequences) at the top of the list of possibilities.

- Bring up the topic of vaginal dryness and sexual pain with postmenopausal patients as part of the routine yearly exam, and explain the therapeutic capabilities of all available options.

- Estrogen therapy, either local or systemic, remains the standard when lubricants are inadequate. Make every effort to counsel the patient about the real risk:benefit ratio of estrogen use.

- If the patient is reluctant to use estrogen therapy, discuss with her the option of short-term local estrogen use, with the understanding that more acceptable options may become available in the near future. This may facilitate acceptance of short-term hormonal treatment and allow the patient to maintain her vaginal health and much of her vaginal sexual function.

- Keep abreast of both present and future options for therapy.

Just how sizable is the postmenopausal population?

About 32% of the female population is older than 50 years.1 That means that around 48 million women are currently menopausal, or will become so over the next few years.

Because average life expectancy approaches 80 years in the United States and other countries of the industrialized world,2 many women will live approximately 40 years beyond menopause or their final menstrual period. Their quality of life during the second half of their life is dependent on both physical and psychosocial health.

Postmenopausal dyspareunia isn’t new

Sexual issues arising from physical causes—dyspareunia among them—have long accounted for a large share of medical concerns reported by postmenopausal women. In a 1985 survey, for example, dyspareunia accounted for 42.5% of their complaints.3

But epidemiologic studies to determine the prevalence of female sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women are difficult to carry out. Why? Because researchers would need to 1) address changes over time and 2) distinguish problems of sexual function from those brought on by aging.4

The techniques and methodology for researching female sexual dysfunction continue to evolve, creating new definitions of the stages of menopause and new diagnostic approaches to female sexual dysfunction.

However, based on available studies, Dennerstein and Hayes concluded that:

- postmenopausal women report a high rate of sexual dysfunction (higher than men)

- psychosocial factors can ameliorate a decline in sexual function

- “vaginal dryness and dyspareunia seem to be driven primarily by declining estradiol.”4

The WHI and its domino effect

Millions of postmenopausal women stopped taking estrogen-based therapy in the wake of widespread media coverage after 2002 publication of data from the estrogen–progestin arm of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), which purported to show, among other things, an increased risk of breast cancer.5

For decades, many postmenopausal women achieved medical management of VVA through long-term use of systemic hormone replacement therapy (HRT), which they used primarily to control other chronic symptoms of menopause, such as hot flashes.

After the WHI data were published (and misrepresented), reduced usage of estrogen-based HRT “unmasked” vaginal symptoms, including sexual pain, due to the effects of estrogen deficiency on the vaginal epithelium and vaginal blood flow. Since then, we have been forced to examine anew the natural history of menopause.

Within days or weeks of discontinuing HRT, women may reexperience the acute vasomotor symptoms that accompany estrogen withdrawal—most commonly hot flashes, night sweats, sleeplessness, palpitations, and headaches. Over time—anywhere from 6 months to several years—the body adjusts to the loss or withdrawal of estrogen, and these vasomotor symptoms eventually diminish or resolve. Not so for the longer-term physical effects of chronic low serum levels of estrogen, which worsen over time.

Approximately 6 months after discontinuing estrogen therapy, postmenopausal women may begin to experience vaginal dryness and VVA. As the years pass, other side effects of estrogen deficiency arise: bone loss, joint pain, mood alteration (including depression), change in skin tone, hair loss, and cardiac and central nervous system changes. These side effects do not resolve spontaneously; in fact, they grow worse as a woman ages. They may have deleterious psychosocial as well as physical impacts on her life—especially on the quality of her intimate relationship.

Clarify the report (adjust appropriately for same-sex partner)

- Where does it hurt? Describe the pain.

- When does it hurt? Does the pain occur 1) with penile contact at the opening of the vagina, 2) once the penis is partially in, 3) with full entry, 4) after some thrusting, 5) after deep thrusting, 6) with the partner’s ejaculation, 7) after withdrawal, or 8) with subsequent micturition?

- Does your body tense when your partner is attempting, or you are attempting, to insert his penis? What are your thoughts and feelings at this time?

- How long does the pain last?

- Does touching cause pain? Does it hurt when you ride a bicycle or wear tight clothes? Does penetration by tampons or fingers hurt?

Assess the pelvic floor

- Do you recognize the feeling of pelvic floor muscle tension during sexual contact?

- Do you recognize the feeling of pelvic floor muscle tension in other (nonsexual) situations?

Evaluate arousal

- Do you feel subjectively excited when you attempt intercourse?

- Does your vagina become sufficiently moist? Do you recognize the feeling of drying up?

Determine the consequences of the complaint

- What do you do when you experience pain during sexual contact? Do you continue? Or do you stop whatever is causing the pain?