User login

Postmenopausal dyspareunia— a problem for the 21st century

The author reports that he serves on the speaker’s bureau for Novogyne, TherRx, Warner-Chilcott, and Solvay, and on the advisory board for Upsher-Smith, Novogyne, QuatRx, and Wyeth.

CASE: History of dyspareunia

At her latest visit, a 56-year-old woman who is 7 years postmenopausal relates that she has been experiencing worsening pain with intercourse to the point that she now has very little sex drive at all. This problem began approximately 1 year after she discontinued hormone therapy in the wake of reports that it causes cancer and heart attack. She has been offered both local vaginal and systemic hormone therapy, but is too frightened to use any hormones at all. Sexual lubricants no longer seem to work.

How do you counsel her about these symptoms? And what therapy do you offer?

Physicians and other health-care practitioners are seeing a large and growing number of genitourinary and sexual-related complaints among menopausal women—so much so that it has reached epidemic proportions. Yet dyspareunia is underreported and undertreated, and quality of life suffers for these women.

In this article, I focus on two interrelated causes of this epidemic:

- vaginal dryness and vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) and the impact of these conditions on women’s sexual function and psychosocial well-being

- barriers to optimal treatment.

I also explore how ObGyns’ role in this area of care is evolving—as a way to understand how you can better serve this expanding segment of our patient population.

Dyspareunia can have many causes, including endometriosis, interstitial cystitis, surgical scarring, injury that occurs during childbirth, and psychosocial origin (such as a history of sexual abuse). Our focus here is on dyspareunia due to VVA.

during sex. What should you do?

- Sexual pain as a category of female sexual dysfunction is relevant at any age; for postmenopausal women dealing with vaginal dryness as a result of estrogen deficiency, it may well be the dominant issue. When determining the cause of a sexual problem in a postmenopausal woman, put dyspareunia caused by vaginal dryness (as well as its psychosocial consequences) at the top of the list of possibilities.

- Bring up the topic of vaginal dryness and sexual pain with postmenopausal patients as part of the routine yearly exam, and explain the therapeutic capabilities of all available options.

- Estrogen therapy, either local or systemic, remains the standard when lubricants are inadequate. Make every effort to counsel the patient about the real risk:benefit ratio of estrogen use.

- If the patient is reluctant to use estrogen therapy, discuss with her the option of short-term local estrogen use, with the understanding that more acceptable options may become available in the near future. This may facilitate acceptance of short-term hormonal treatment and allow the patient to maintain her vaginal health and much of her vaginal sexual function.

- Keep abreast of both present and future options for therapy.

Just how sizable is the postmenopausal population?

About 32% of the female population is older than 50 years.1 That means that around 48 million women are currently menopausal, or will become so over the next few years.

Because average life expectancy approaches 80 years in the United States and other countries of the industrialized world,2 many women will live approximately 40 years beyond menopause or their final menstrual period. Their quality of life during the second half of their life is dependent on both physical and psychosocial health.

Postmenopausal dyspareunia isn’t new

Sexual issues arising from physical causes—dyspareunia among them—have long accounted for a large share of medical concerns reported by postmenopausal women. In a 1985 survey, for example, dyspareunia accounted for 42.5% of their complaints.3

But epidemiologic studies to determine the prevalence of female sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women are difficult to carry out. Why? Because researchers would need to 1) address changes over time and 2) distinguish problems of sexual function from those brought on by aging.4

The techniques and methodology for researching female sexual dysfunction continue to evolve, creating new definitions of the stages of menopause and new diagnostic approaches to female sexual dysfunction.

However, based on available studies, Dennerstein and Hayes concluded that:

- postmenopausal women report a high rate of sexual dysfunction (higher than men)

- psychosocial factors can ameliorate a decline in sexual function

- “vaginal dryness and dyspareunia seem to be driven primarily by declining estradiol.”4

The WHI and its domino effect

Millions of postmenopausal women stopped taking estrogen-based therapy in the wake of widespread media coverage after 2002 publication of data from the estrogen–progestin arm of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), which purported to show, among other things, an increased risk of breast cancer.5

For decades, many postmenopausal women achieved medical management of VVA through long-term use of systemic hormone replacement therapy (HRT), which they used primarily to control other chronic symptoms of menopause, such as hot flashes.

After the WHI data were published (and misrepresented), reduced usage of estrogen-based HRT “unmasked” vaginal symptoms, including sexual pain, due to the effects of estrogen deficiency on the vaginal epithelium and vaginal blood flow. Since then, we have been forced to examine anew the natural history of menopause.

Within days or weeks of discontinuing HRT, women may reexperience the acute vasomotor symptoms that accompany estrogen withdrawal—most commonly hot flashes, night sweats, sleeplessness, palpitations, and headaches. Over time—anywhere from 6 months to several years—the body adjusts to the loss or withdrawal of estrogen, and these vasomotor symptoms eventually diminish or resolve. Not so for the longer-term physical effects of chronic low serum levels of estrogen, which worsen over time.

Approximately 6 months after discontinuing estrogen therapy, postmenopausal women may begin to experience vaginal dryness and VVA. As the years pass, other side effects of estrogen deficiency arise: bone loss, joint pain, mood alteration (including depression), change in skin tone, hair loss, and cardiac and central nervous system changes. These side effects do not resolve spontaneously; in fact, they grow worse as a woman ages. They may have deleterious psychosocial as well as physical impacts on her life—especially on the quality of her intimate relationship.

Clarify the report (adjust appropriately for same-sex partner)

- Where does it hurt? Describe the pain.

- When does it hurt? Does the pain occur 1) with penile contact at the opening of the vagina, 2) once the penis is partially in, 3) with full entry, 4) after some thrusting, 5) after deep thrusting, 6) with the partner’s ejaculation, 7) after withdrawal, or 8) with subsequent micturition?

- Does your body tense when your partner is attempting, or you are attempting, to insert his penis? What are your thoughts and feelings at this time?

- How long does the pain last?

- Does touching cause pain? Does it hurt when you ride a bicycle or wear tight clothes? Does penetration by tampons or fingers hurt?

Assess the pelvic floor

- Do you recognize the feeling of pelvic floor muscle tension during sexual contact?

- Do you recognize the feeling of pelvic floor muscle tension in other (nonsexual) situations?

Evaluate arousal

- Do you feel subjectively excited when you attempt intercourse?

- Does your vagina become sufficiently moist? Do you recognize the feeling of drying up?

Determine the consequences of the complaint

- What do you do when you experience pain during sexual contact? Do you continue? Or do you stop whatever is causing the pain?

- Do you continue to include intercourse or attempts at intercourse in your lovemaking, or do you use other methods of achieving sexual fulfillment? If you use other ways to make love, do you and your partner clearly understand that intercourse will not be attempted?

- What other effect does the pain have on your sexual relationship?

Explore biomedical antecedents

- When and how did the pain start?

- What tests have you undergone?

- What treatment have you received?

Source: Adapted from Basson R, et al.12

Is 60 the new 40?

Many women and men in the large cohort known as the Baby Boomer generation continue to be sexually active into their 60s, 70s, and 80s, as demonstrated by a 2007 study of sexuality and health in older adults.6 In the 57- to 64-year-old age group, 61.6% of women and 83.7% of men were sexually active (defined as sexual activity with a partner within the past 12 months). In the 65- to 74-year-old group, 39.5% of women and 67% of men were sexually active; and in the 75- to 85-year-old group, 16.7% of women and 38.5% of men were sexually active (TABLE).

These findings indicate that fewer women than men remain sexually active during their later years. One reason may be the epidemic of sexual-related symptoms among postmenopausal women. In the same survey, 34.3% of women 57 to 64 years old reported avoiding sex because of:

- pain during intercourse (17.8%)

- difficulty with lubrication (35.9%).

Across all groups, the most prevalent sexual problem was low desire (43%).6 Around 40% of postmenopausal women reported no sexual activity in the past 12 months, as well as lack of interest in sex. This number may include women who have ceased to have sex because of vaginal dryness and dyspareunia, thereby reducing the percentage reporting these symptoms (TABLE).

TABLE

Older adults are having sex—and experiencing sexual problems

| Activity or problem by gender | Number of respondents | Report, by age group (95% confidence interval*) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 57–64 yr (%) | 65–74 yr (%) | 75–85 yr (%) | ||

| Sexually active in previous 12 months† | ||||

| Men | 1,385 | 83.7 (77.6–89.8) | 67.0 (62.1–72.0) | 38.5 (33.6–43.5) |

| Women | 1,501 | 61.6 (56.7–66.4) | 39.5 (34.6–44.4) | 16.7 (12.5–21.0) |

| Difficulty with lubrication | ||||

| Women | 495 | 35.9 (29.6–42.2) | 43.2 (34.8–51.5) | 43.6 (27.0–60.2) |

| Pain during intercourse | ||||

| Men | 878 | 3.0 (1.1–4.8) | 3.2 (1.2–5.3) | 1.0 (0–2.5) |

| Women | 506 | 17.8 (13.3–22.2) | 18.6 (10.8–26.3) | 11.8 (4.3–19.4) |

| Avoidance of sex due to sexual problems** | ||||

| Men | 533 | 22.1 (17.3–26.9) | 30.1 (23.2–37.0) | 25.7 (14.9–36.4) |

| Women | 357 | 34.3 (25.0–43.7) | 30.5 (21.5–39.4) | 22.7 (9.4–35.9) |

| Source: Adapted from Lindau ST, et al.6 | ||||

| Adjusted odds ratios are based on a logistic regression including the age group and self-rated health status as covariates, estimated separately for men and women. The confidence interval is based on the inversion of the Wald tests constructed with the use of design-based standard errors. | ||||

| † These data exclude 107 respondents who reported at least one sexual problem. | ||||

| ** This question was asked only of respondents who reported at least one sexual problem. | ||||

Assessing menopause-related sexual function is a challenge

Although the transition phases of menopause have been well studied and reported for decades, few of these studies have included questions about the impact of menopause on sexual function.7 When longitudinal studies that included the classification of female sexual dysfunction began to appear, they provided evidence of the important role that VVA and psychosocial factors play in female sexual dysfunction.8

In the fourth year of the Melbourne Women’s Midlife Health Project longitudinal study, six variables related to sexual function were identified. Three were determinate of sexual function:

- feelings for the partner

- problems related to the partner

- vaginal dryness/dyspareunia.

The other three variables—sexual responsiveness, frequency of sexual activity, and libido—were dependent or outcome variables.

By the sixth year of this study, two variables had increased in significance: vaginal dryness/dyspareunia and partner problems.7

Sexual pain and relationship problems can create a vicious cycle

The interrelationship of vaginal dryness, sexual pain, flagging desire, and psychosocial parameters can produce a vicious cycle. A woman experiencing or anticipating pain may have diminished sexual desire or avoid sex altogether. During intercourse, the brain’s awareness of vaginal pain may trigger a physiologic response that can cause the muscles of the vagina to tighten and lubrication to decrease. The result? Greater vaginal pain.

This vicious cycle can contribute to relationship issues with the sexual partner and harm a woman’s psychosocial well-being. Resentment, anger, and misunderstanding may arise when a couple is dealing with problems of sexual function, and these stressors can damage many aspects of the relationship, further exacerbating sexual difficulties.

An additional and very important dimension of these issues is their potential impact on the family unit.

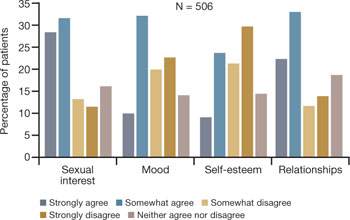

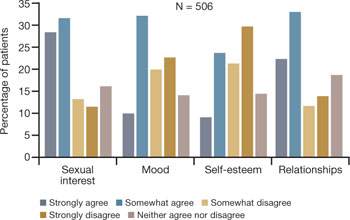

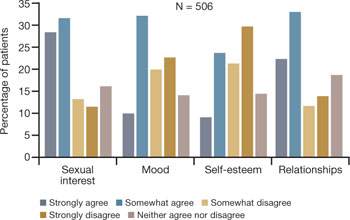

VVA can diminish overall well-being

In a 2007 survey reported at the North American Menopause Society (NAMS), one third to one half of 506 respondents said that VVA had a bad effect on their sexual interest, mood, self-esteem, and the intimate relationship (FIGURE 1).9 Reports from in-depth interviews were consistent with survey results and offered further insight into a woman’s emotional response to the condition of vaginal dryness and its impact on her life. Women found the condition “embarrassing,” something they had to endure but didn’t talk about, and felt that it had a major impact on their self-esteem and intimate relationship.

FIGURE 1 Dyspareunia affects more than interest in sex—relationships, mood, and self-esteem suffer

Simon JA, Komi J. Vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) negatively impacts sexual function, psychosocial well-being, and partner relationships. Poster presented at North American Menopause Association Annual Meeting; October 3-6, 2007; Dallas, Texas.

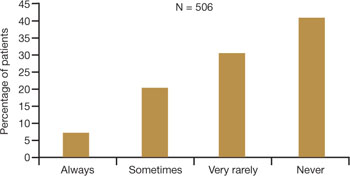

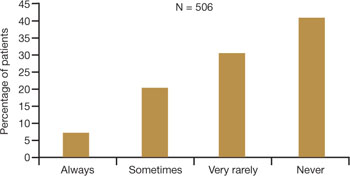

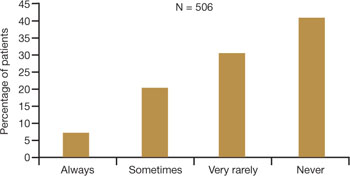

Clinicians often don’t ask about VVA, and patients are reluctant to talk

Among women of all ages, dyspareunia is underreported and undertreated. In the survey reported at NAMS, 40% of respondents said that their physician had never asked them about the problem of VVA (FIGURE 2).9

Women themselves may be reluctant to discuss the problem with physicians, nurse practitioners, or other health-care providers out of embarrassment or the assumption that there is nothing to be done about the problem. Nevertheless, more than 40% of respondents said they would be highly likely to seek treatment for VVA if they had a concern about urogenital complications of the condition (FIGURE 3).9

Another barrier may be the sense that asking the health-care provider about sex may embarrass him or her. As a result, sufferers do not anticipate help from their physician and other members of the health-care profession and fail to seek treatment or counseling for this chronic medical condition.10,11

In a 1999 telephone survey of 500 adults 25 years of age or older, 71% said they thought that their doctor would dismiss concerns about sexual problems, but 85% said they would talk to their physician anyway if they had a problem, even though they might not get treatment.11 In that survey, 91% of married men and 84% of married women rated a satisfying sex life as important to quality of life.11

Another important and often overlooked limitation on this type of discussion is the time constraints that busy clinicians face, especially with the low reimbursement offered by managed care. Sexual problems can hardly be adequately discussed in 7 to 10 minutes.

FIGURE 2 Do physicians ask about dyspareunia? Most women surveyed said “rarely” or “never”

Simon JA, Komi J. Vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) negatively impacts sexual function, psychosocial well-being, and partner relationships. Poster presented at North American Menopause Association Annual Meeting; October 3-6, 2007; Dallas, Texas.

FIGURE 3 Are these women likely to seek treatment?

Simon JA, Komi J. Vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) negatively impacts sexual function, psychosocial well-being, and partner relationships. Poster presented at North American Menopause Association Annual Meeting; October 3-6, 2007; Dallas, Texas.

Women have performance anxiety, too

It is well known that men with even a mild degree of erectile dysfunction can suffer from performance anxiety, but the fact that women can also suffer from this phenomenon is not given as much attention. Such anxiety can be a factor in relationship difficulties. With both partners perhaps feeling anxious about sexual performance, a couple may avoid even simple acts of affection, such as holding hands, to avoid raising the other’s expectations.

Exacerbating the situation is the fact that many men use widely prescribed phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors, whereas women are contending with barriers to continued sexual activity as they age. It does not take a psychologist to understand that this imbalance often adds to emotional strain and tension between partners.

Popular media address the issue

Look beyond what our postmenopausal patients tell us directly—to the popular media and online forums—to appreciate the scope of sexual pain as a major issue among postmenopausal women. Evidence of psychosocial effects is found on numerous Web sites—some from organizations, others designed by women seeking help from each other.

Red Hot Mamas

This organization aims to empower women through menopause education. Highlighted in the Winter 2007/2008 Red Hot Mamas Report is a survey done in conjunction with Harris Interactive exploring the impact of menopausal symptoms on a woman’s sex life, which found that 47% of women who have VVA have avoided or stopped sex completely because it was uncomfortable, compared with 23% of normal women.

Power Surge

This Web site offers a list of strategies for dealing with sexual pain, including an overview of hormone-based prescription and nonprescription products, along with a variety of over-the-counter, natural, holistic, and herbal therapies for treating dyspareunia.

What is the physician’s role?

Given the epidemic of sexual pain, it is crucial that physicians and others who care for postmenopausal women increase their awareness of this issue and pay special attention to its psychosocial parameters.

Ask patients about sexual function in general and dyspareunia in particular as part of the routine annual visit. A simple opening “Yes/No” question, such as “Are you sexually active?” can lead to further questions appropriate to the patient. For example, if the answer is “No,” the follow-up question might be, “Does that bother you or your partner?” Further discussion may uncover whether the lack of sexual activity is a cause of distress and identify which variables are involved.

If, instead, the answer is “Yes,” follow-up questions can identify the presence of common postmenopausal physical issues, such as vaginal dryness and difficulty with lubrication. The visit then can turn to strategies to ameliorate those conditions.

When a patient reports dyspareunia, further diagnostic information such as precise location, degree of arousal, and reaction to pain can help determine the appropriate course of treatment. For an approach to this aspect of ascertaining patient history, see the list of sample questions above.12

During the physical, pay particular attention to any physical abnormalities or organic causes of sexual pain. Questions designed to characterize the location and nature of the pain can pinpoint the cause. Sexual pain arising from VVA is likely to 1) be localized at the introitus and 2) occur with penile entry.

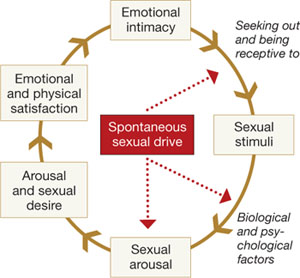

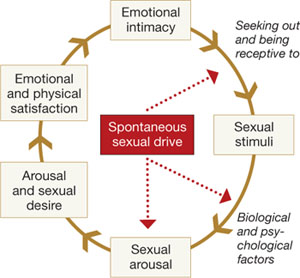

Since the mid-1990s, the availability of validated scales to measure female sexual function has increased rapidly and enabled researchers to better identify, quantify, and evaluate treatments for female sexual dysfunction.7 Over time, we have moved away from the somewhat mechanical sequence inherent in the linear progression of desire leading to genital stimulation followed by arousal and orgasm toward an appreciation of the multiple physical, emotional, and subjective factors that are at play in women’s sexual function.

By 1998, a classification scheme was developed to further the means to study and discuss disorders of desire, arousal, orgasm, and sexual pain.8 Further contextual definitions of sexual dysfunction are under consideration.13

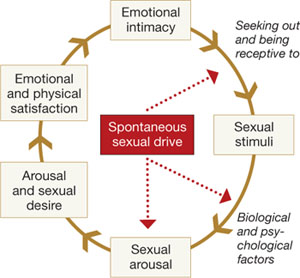

Basson proposed one new model of female sexual function (see the diagram), and observed that

"…women identify many reasons they are sexual over and beyond inherent sexual drive or “hunger.” Women tell of wanting to increase emotional closeness, commitment, sharing, tenderness, and tolerance, and to show the partner that he or she has been missed (emotionally or physically). Such intimacy-based reasons motivate the woman to find a way to become sexually aroused. This arousal is not spontaneous but triggered by deliberately sought sexual stimuli."13

Intimacy-based model of female sexual response cycle

In this flow of physical and emotional variables involved in female sexual function, categories interact. For example, low desire can be and is frequently secondary to the anticipation of pain during sexual intercourse. Arousal can be hampered by lack of vaginal lubrication—perhaps inhibited by the anticipation of pain. Secondary orgasmic disorders can result from low desire, difficulty of arousal, and sexual pain.14 Sexual pain can affect sexual function at any point on this continuum.

Treatments in the pipeline

For decades, hormone-based treatments have been the predominant therapeutic option for vaginal dryness. Often they are a secondary benefit of hormone therapy for vasomotor symptoms and osteoporosis. Estrogen can be delivered in the form of oral tablet, transdermal patch, gel, spray, or vaginal ring for systemic use, or as vaginal cream, ring, or tablet for local use.

However, despite data to the contrary and our reassurances to the patient about overall safety, a large number of women, and many primary care providers, are no longer inclined to use short- or long-term HRT in any presentation.

Other women may have risk factors that contraindicate exogenous hormones.

Nonhormonal options for vaginal dryness and dyspareunia are limited, and there are no approved systemic or oral nonestrogen options. Over-the-counter topical lubricants can ease some of the symptoms of VVA temporarily and allow successful vaginal penetration in many cases. Some may cause vaginal warming and pleasant sensations, but overall they treat the symptom rather than the source of pain. Moreover, many patients consider local lubricants messy and inconvenient and claim they “ruin the mood.”

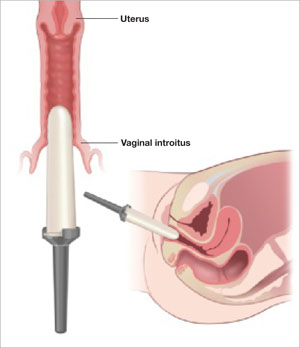

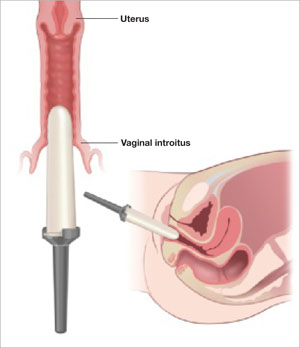

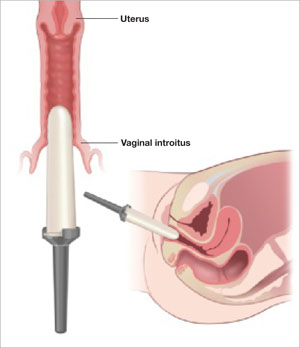

The use of vaginal dilators along with estrogen or lubricant therapy is an often-forgotten adjunct to therapy for dyspareunia caused by VVA (FIGURE 4).

FIGURE 4 Mechanical dilation of the vagina is a useful adjunct

Mechanical dilation is often needed to restore penetration capability in the vagina, even after hormonal treatment. The focus should be on the vaginal introitus, with the top 25% to 35% of the dilator inserted into the opening once a day for 15 minutes, increasing the dilator diameter over time.

New SERMs are in development

Preclinical and clinical research into the diverse class of selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) to treat estrogen-mediated disease produced tamoxifen for breast cancer prevention and raloxifene for both vertebral osteoporosis and breast cancer prevention. Each SERM seems to have unique tissue selectivity. The antiestrogenic activity of tamoxifen and raloxifene extends to the vagina and can exacerbate vaginal dryness.

A new generation of orally active SERMs is under investigation specifically for the treatment of chronic vaginal symptoms. These new agents target the nonvaginal treatment of VVA and associated symptoms. The first oral SERM for long-term treatment of these symptoms, ospemifene (Ophena), may become available in the near future. It is a novel SERM that has both anti-estrogenic and estrogenic actions, depending on the tissue. It was shown to significantly improve both vaginal dryness and dyspareunia in a large placebo-controlled trial.15

1. US Census Bureau. 2006 American community survey. S0101. Age and sex. Available at: http://fact-finder.census.gov/servlet/DatasetMainPageServlet?_program=ACS&_submenuId=&_lang=en&_ts.

2. National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2007, with Chartbook on Trends in the Health of Americans. Hyattsville, Md: NCHS; 2007. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/lifexpec.htm. Accessed February 2, 2009.

3. Sarrel PM, Whitehead MI. Sex and menopause: defining the issues. Maturitas. 1985;7:217-224.

4. Dennerstein L, Hayes RD. Confronting the challenges: epidemiological study of female sexual dysfunction and the menopause. J Sex Med. 2005;2(suppl 3):118-132.

5. Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321-333.

6. Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, Levinson W, O’Muircheartaigh CA, Waite LJ. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:762-774.

7. Dennerstein L, Alexander JL, Kotz K. The menopause and sexual functioning: a review of the population-based studies. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2003;14:64-82.

8. Basson R, Berman J, Burnett A, et al. Report of the international consensus development conference on female sexual dysfunction: definitions and classifications. J Urol. 2000;163:888-993.

9. Simon JA, Komi J. Vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) negatively impacts sexual function, psychosocial well-being, and partner relationships. Poster presented at North American Menopause Association Annual Meeting; October 3-6, 2007; Dallas, Texas.

10. Heim LJ. Evaluation and differential diagnosis of dyspareunia. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:1535-1552.

11. Marwick C. Survey says patients expect little physician help on sex. JAMA. 1999;281:2173-2174.

12. Basson R, Althof S, Davis S, et al. Summary of the recommendations on sexual dysfunctions in women. J Sex Med. 2004;1:24-34.

13. Basson R. Female sexual response: the role of drugs in the management of sexual dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:350-353.

14. Walsh KE, Berman JR. Sexual dysfunction in the older woman: an overview of the current understanding and management. Drugs Aging. 2004;21:655-675.

15. Bachmann GA, Komi J, Hanley R. A new SERM, Ophena (ospemifene), effectively treats vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: results from a pivotal phase 3 study. Presented at the Endocrine Society annual meeting, San Francisco, Calif, June 2008.

The author reports that he serves on the speaker’s bureau for Novogyne, TherRx, Warner-Chilcott, and Solvay, and on the advisory board for Upsher-Smith, Novogyne, QuatRx, and Wyeth.

CASE: History of dyspareunia

At her latest visit, a 56-year-old woman who is 7 years postmenopausal relates that she has been experiencing worsening pain with intercourse to the point that she now has very little sex drive at all. This problem began approximately 1 year after she discontinued hormone therapy in the wake of reports that it causes cancer and heart attack. She has been offered both local vaginal and systemic hormone therapy, but is too frightened to use any hormones at all. Sexual lubricants no longer seem to work.

How do you counsel her about these symptoms? And what therapy do you offer?

Physicians and other health-care practitioners are seeing a large and growing number of genitourinary and sexual-related complaints among menopausal women—so much so that it has reached epidemic proportions. Yet dyspareunia is underreported and undertreated, and quality of life suffers for these women.

In this article, I focus on two interrelated causes of this epidemic:

- vaginal dryness and vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) and the impact of these conditions on women’s sexual function and psychosocial well-being

- barriers to optimal treatment.

I also explore how ObGyns’ role in this area of care is evolving—as a way to understand how you can better serve this expanding segment of our patient population.

Dyspareunia can have many causes, including endometriosis, interstitial cystitis, surgical scarring, injury that occurs during childbirth, and psychosocial origin (such as a history of sexual abuse). Our focus here is on dyspareunia due to VVA.

during sex. What should you do?

- Sexual pain as a category of female sexual dysfunction is relevant at any age; for postmenopausal women dealing with vaginal dryness as a result of estrogen deficiency, it may well be the dominant issue. When determining the cause of a sexual problem in a postmenopausal woman, put dyspareunia caused by vaginal dryness (as well as its psychosocial consequences) at the top of the list of possibilities.

- Bring up the topic of vaginal dryness and sexual pain with postmenopausal patients as part of the routine yearly exam, and explain the therapeutic capabilities of all available options.

- Estrogen therapy, either local or systemic, remains the standard when lubricants are inadequate. Make every effort to counsel the patient about the real risk:benefit ratio of estrogen use.

- If the patient is reluctant to use estrogen therapy, discuss with her the option of short-term local estrogen use, with the understanding that more acceptable options may become available in the near future. This may facilitate acceptance of short-term hormonal treatment and allow the patient to maintain her vaginal health and much of her vaginal sexual function.

- Keep abreast of both present and future options for therapy.

Just how sizable is the postmenopausal population?

About 32% of the female population is older than 50 years.1 That means that around 48 million women are currently menopausal, or will become so over the next few years.

Because average life expectancy approaches 80 years in the United States and other countries of the industrialized world,2 many women will live approximately 40 years beyond menopause or their final menstrual period. Their quality of life during the second half of their life is dependent on both physical and psychosocial health.

Postmenopausal dyspareunia isn’t new

Sexual issues arising from physical causes—dyspareunia among them—have long accounted for a large share of medical concerns reported by postmenopausal women. In a 1985 survey, for example, dyspareunia accounted for 42.5% of their complaints.3

But epidemiologic studies to determine the prevalence of female sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women are difficult to carry out. Why? Because researchers would need to 1) address changes over time and 2) distinguish problems of sexual function from those brought on by aging.4

The techniques and methodology for researching female sexual dysfunction continue to evolve, creating new definitions of the stages of menopause and new diagnostic approaches to female sexual dysfunction.

However, based on available studies, Dennerstein and Hayes concluded that:

- postmenopausal women report a high rate of sexual dysfunction (higher than men)

- psychosocial factors can ameliorate a decline in sexual function

- “vaginal dryness and dyspareunia seem to be driven primarily by declining estradiol.”4

The WHI and its domino effect

Millions of postmenopausal women stopped taking estrogen-based therapy in the wake of widespread media coverage after 2002 publication of data from the estrogen–progestin arm of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), which purported to show, among other things, an increased risk of breast cancer.5

For decades, many postmenopausal women achieved medical management of VVA through long-term use of systemic hormone replacement therapy (HRT), which they used primarily to control other chronic symptoms of menopause, such as hot flashes.

After the WHI data were published (and misrepresented), reduced usage of estrogen-based HRT “unmasked” vaginal symptoms, including sexual pain, due to the effects of estrogen deficiency on the vaginal epithelium and vaginal blood flow. Since then, we have been forced to examine anew the natural history of menopause.

Within days or weeks of discontinuing HRT, women may reexperience the acute vasomotor symptoms that accompany estrogen withdrawal—most commonly hot flashes, night sweats, sleeplessness, palpitations, and headaches. Over time—anywhere from 6 months to several years—the body adjusts to the loss or withdrawal of estrogen, and these vasomotor symptoms eventually diminish or resolve. Not so for the longer-term physical effects of chronic low serum levels of estrogen, which worsen over time.

Approximately 6 months after discontinuing estrogen therapy, postmenopausal women may begin to experience vaginal dryness and VVA. As the years pass, other side effects of estrogen deficiency arise: bone loss, joint pain, mood alteration (including depression), change in skin tone, hair loss, and cardiac and central nervous system changes. These side effects do not resolve spontaneously; in fact, they grow worse as a woman ages. They may have deleterious psychosocial as well as physical impacts on her life—especially on the quality of her intimate relationship.

Clarify the report (adjust appropriately for same-sex partner)

- Where does it hurt? Describe the pain.

- When does it hurt? Does the pain occur 1) with penile contact at the opening of the vagina, 2) once the penis is partially in, 3) with full entry, 4) after some thrusting, 5) after deep thrusting, 6) with the partner’s ejaculation, 7) after withdrawal, or 8) with subsequent micturition?

- Does your body tense when your partner is attempting, or you are attempting, to insert his penis? What are your thoughts and feelings at this time?

- How long does the pain last?

- Does touching cause pain? Does it hurt when you ride a bicycle or wear tight clothes? Does penetration by tampons or fingers hurt?

Assess the pelvic floor

- Do you recognize the feeling of pelvic floor muscle tension during sexual contact?

- Do you recognize the feeling of pelvic floor muscle tension in other (nonsexual) situations?

Evaluate arousal

- Do you feel subjectively excited when you attempt intercourse?

- Does your vagina become sufficiently moist? Do you recognize the feeling of drying up?

Determine the consequences of the complaint

- What do you do when you experience pain during sexual contact? Do you continue? Or do you stop whatever is causing the pain?

- Do you continue to include intercourse or attempts at intercourse in your lovemaking, or do you use other methods of achieving sexual fulfillment? If you use other ways to make love, do you and your partner clearly understand that intercourse will not be attempted?

- What other effect does the pain have on your sexual relationship?

Explore biomedical antecedents

- When and how did the pain start?

- What tests have you undergone?

- What treatment have you received?

Source: Adapted from Basson R, et al.12

Is 60 the new 40?

Many women and men in the large cohort known as the Baby Boomer generation continue to be sexually active into their 60s, 70s, and 80s, as demonstrated by a 2007 study of sexuality and health in older adults.6 In the 57- to 64-year-old age group, 61.6% of women and 83.7% of men were sexually active (defined as sexual activity with a partner within the past 12 months). In the 65- to 74-year-old group, 39.5% of women and 67% of men were sexually active; and in the 75- to 85-year-old group, 16.7% of women and 38.5% of men were sexually active (TABLE).

These findings indicate that fewer women than men remain sexually active during their later years. One reason may be the epidemic of sexual-related symptoms among postmenopausal women. In the same survey, 34.3% of women 57 to 64 years old reported avoiding sex because of:

- pain during intercourse (17.8%)

- difficulty with lubrication (35.9%).

Across all groups, the most prevalent sexual problem was low desire (43%).6 Around 40% of postmenopausal women reported no sexual activity in the past 12 months, as well as lack of interest in sex. This number may include women who have ceased to have sex because of vaginal dryness and dyspareunia, thereby reducing the percentage reporting these symptoms (TABLE).

TABLE

Older adults are having sex—and experiencing sexual problems

| Activity or problem by gender | Number of respondents | Report, by age group (95% confidence interval*) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 57–64 yr (%) | 65–74 yr (%) | 75–85 yr (%) | ||

| Sexually active in previous 12 months† | ||||

| Men | 1,385 | 83.7 (77.6–89.8) | 67.0 (62.1–72.0) | 38.5 (33.6–43.5) |

| Women | 1,501 | 61.6 (56.7–66.4) | 39.5 (34.6–44.4) | 16.7 (12.5–21.0) |

| Difficulty with lubrication | ||||

| Women | 495 | 35.9 (29.6–42.2) | 43.2 (34.8–51.5) | 43.6 (27.0–60.2) |

| Pain during intercourse | ||||

| Men | 878 | 3.0 (1.1–4.8) | 3.2 (1.2–5.3) | 1.0 (0–2.5) |

| Women | 506 | 17.8 (13.3–22.2) | 18.6 (10.8–26.3) | 11.8 (4.3–19.4) |

| Avoidance of sex due to sexual problems** | ||||

| Men | 533 | 22.1 (17.3–26.9) | 30.1 (23.2–37.0) | 25.7 (14.9–36.4) |

| Women | 357 | 34.3 (25.0–43.7) | 30.5 (21.5–39.4) | 22.7 (9.4–35.9) |

| Source: Adapted from Lindau ST, et al.6 | ||||

| Adjusted odds ratios are based on a logistic regression including the age group and self-rated health status as covariates, estimated separately for men and women. The confidence interval is based on the inversion of the Wald tests constructed with the use of design-based standard errors. | ||||

| † These data exclude 107 respondents who reported at least one sexual problem. | ||||

| ** This question was asked only of respondents who reported at least one sexual problem. | ||||

Assessing menopause-related sexual function is a challenge

Although the transition phases of menopause have been well studied and reported for decades, few of these studies have included questions about the impact of menopause on sexual function.7 When longitudinal studies that included the classification of female sexual dysfunction began to appear, they provided evidence of the important role that VVA and psychosocial factors play in female sexual dysfunction.8

In the fourth year of the Melbourne Women’s Midlife Health Project longitudinal study, six variables related to sexual function were identified. Three were determinate of sexual function:

- feelings for the partner

- problems related to the partner

- vaginal dryness/dyspareunia.

The other three variables—sexual responsiveness, frequency of sexual activity, and libido—were dependent or outcome variables.

By the sixth year of this study, two variables had increased in significance: vaginal dryness/dyspareunia and partner problems.7

Sexual pain and relationship problems can create a vicious cycle

The interrelationship of vaginal dryness, sexual pain, flagging desire, and psychosocial parameters can produce a vicious cycle. A woman experiencing or anticipating pain may have diminished sexual desire or avoid sex altogether. During intercourse, the brain’s awareness of vaginal pain may trigger a physiologic response that can cause the muscles of the vagina to tighten and lubrication to decrease. The result? Greater vaginal pain.

This vicious cycle can contribute to relationship issues with the sexual partner and harm a woman’s psychosocial well-being. Resentment, anger, and misunderstanding may arise when a couple is dealing with problems of sexual function, and these stressors can damage many aspects of the relationship, further exacerbating sexual difficulties.

An additional and very important dimension of these issues is their potential impact on the family unit.

VVA can diminish overall well-being

In a 2007 survey reported at the North American Menopause Society (NAMS), one third to one half of 506 respondents said that VVA had a bad effect on their sexual interest, mood, self-esteem, and the intimate relationship (FIGURE 1).9 Reports from in-depth interviews were consistent with survey results and offered further insight into a woman’s emotional response to the condition of vaginal dryness and its impact on her life. Women found the condition “embarrassing,” something they had to endure but didn’t talk about, and felt that it had a major impact on their self-esteem and intimate relationship.

FIGURE 1 Dyspareunia affects more than interest in sex—relationships, mood, and self-esteem suffer

Simon JA, Komi J. Vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) negatively impacts sexual function, psychosocial well-being, and partner relationships. Poster presented at North American Menopause Association Annual Meeting; October 3-6, 2007; Dallas, Texas.

Clinicians often don’t ask about VVA, and patients are reluctant to talk

Among women of all ages, dyspareunia is underreported and undertreated. In the survey reported at NAMS, 40% of respondents said that their physician had never asked them about the problem of VVA (FIGURE 2).9

Women themselves may be reluctant to discuss the problem with physicians, nurse practitioners, or other health-care providers out of embarrassment or the assumption that there is nothing to be done about the problem. Nevertheless, more than 40% of respondents said they would be highly likely to seek treatment for VVA if they had a concern about urogenital complications of the condition (FIGURE 3).9

Another barrier may be the sense that asking the health-care provider about sex may embarrass him or her. As a result, sufferers do not anticipate help from their physician and other members of the health-care profession and fail to seek treatment or counseling for this chronic medical condition.10,11

In a 1999 telephone survey of 500 adults 25 years of age or older, 71% said they thought that their doctor would dismiss concerns about sexual problems, but 85% said they would talk to their physician anyway if they had a problem, even though they might not get treatment.11 In that survey, 91% of married men and 84% of married women rated a satisfying sex life as important to quality of life.11

Another important and often overlooked limitation on this type of discussion is the time constraints that busy clinicians face, especially with the low reimbursement offered by managed care. Sexual problems can hardly be adequately discussed in 7 to 10 minutes.

FIGURE 2 Do physicians ask about dyspareunia? Most women surveyed said “rarely” or “never”

Simon JA, Komi J. Vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) negatively impacts sexual function, psychosocial well-being, and partner relationships. Poster presented at North American Menopause Association Annual Meeting; October 3-6, 2007; Dallas, Texas.

FIGURE 3 Are these women likely to seek treatment?

Simon JA, Komi J. Vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) negatively impacts sexual function, psychosocial well-being, and partner relationships. Poster presented at North American Menopause Association Annual Meeting; October 3-6, 2007; Dallas, Texas.

Women have performance anxiety, too

It is well known that men with even a mild degree of erectile dysfunction can suffer from performance anxiety, but the fact that women can also suffer from this phenomenon is not given as much attention. Such anxiety can be a factor in relationship difficulties. With both partners perhaps feeling anxious about sexual performance, a couple may avoid even simple acts of affection, such as holding hands, to avoid raising the other’s expectations.

Exacerbating the situation is the fact that many men use widely prescribed phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors, whereas women are contending with barriers to continued sexual activity as they age. It does not take a psychologist to understand that this imbalance often adds to emotional strain and tension between partners.

Popular media address the issue

Look beyond what our postmenopausal patients tell us directly—to the popular media and online forums—to appreciate the scope of sexual pain as a major issue among postmenopausal women. Evidence of psychosocial effects is found on numerous Web sites—some from organizations, others designed by women seeking help from each other.

Red Hot Mamas

This organization aims to empower women through menopause education. Highlighted in the Winter 2007/2008 Red Hot Mamas Report is a survey done in conjunction with Harris Interactive exploring the impact of menopausal symptoms on a woman’s sex life, which found that 47% of women who have VVA have avoided or stopped sex completely because it was uncomfortable, compared with 23% of normal women.

Power Surge

This Web site offers a list of strategies for dealing with sexual pain, including an overview of hormone-based prescription and nonprescription products, along with a variety of over-the-counter, natural, holistic, and herbal therapies for treating dyspareunia.

What is the physician’s role?

Given the epidemic of sexual pain, it is crucial that physicians and others who care for postmenopausal women increase their awareness of this issue and pay special attention to its psychosocial parameters.

Ask patients about sexual function in general and dyspareunia in particular as part of the routine annual visit. A simple opening “Yes/No” question, such as “Are you sexually active?” can lead to further questions appropriate to the patient. For example, if the answer is “No,” the follow-up question might be, “Does that bother you or your partner?” Further discussion may uncover whether the lack of sexual activity is a cause of distress and identify which variables are involved.

If, instead, the answer is “Yes,” follow-up questions can identify the presence of common postmenopausal physical issues, such as vaginal dryness and difficulty with lubrication. The visit then can turn to strategies to ameliorate those conditions.

When a patient reports dyspareunia, further diagnostic information such as precise location, degree of arousal, and reaction to pain can help determine the appropriate course of treatment. For an approach to this aspect of ascertaining patient history, see the list of sample questions above.12

During the physical, pay particular attention to any physical abnormalities or organic causes of sexual pain. Questions designed to characterize the location and nature of the pain can pinpoint the cause. Sexual pain arising from VVA is likely to 1) be localized at the introitus and 2) occur with penile entry.

Since the mid-1990s, the availability of validated scales to measure female sexual function has increased rapidly and enabled researchers to better identify, quantify, and evaluate treatments for female sexual dysfunction.7 Over time, we have moved away from the somewhat mechanical sequence inherent in the linear progression of desire leading to genital stimulation followed by arousal and orgasm toward an appreciation of the multiple physical, emotional, and subjective factors that are at play in women’s sexual function.

By 1998, a classification scheme was developed to further the means to study and discuss disorders of desire, arousal, orgasm, and sexual pain.8 Further contextual definitions of sexual dysfunction are under consideration.13

Basson proposed one new model of female sexual function (see the diagram), and observed that

"…women identify many reasons they are sexual over and beyond inherent sexual drive or “hunger.” Women tell of wanting to increase emotional closeness, commitment, sharing, tenderness, and tolerance, and to show the partner that he or she has been missed (emotionally or physically). Such intimacy-based reasons motivate the woman to find a way to become sexually aroused. This arousal is not spontaneous but triggered by deliberately sought sexual stimuli."13

Intimacy-based model of female sexual response cycle

In this flow of physical and emotional variables involved in female sexual function, categories interact. For example, low desire can be and is frequently secondary to the anticipation of pain during sexual intercourse. Arousal can be hampered by lack of vaginal lubrication—perhaps inhibited by the anticipation of pain. Secondary orgasmic disorders can result from low desire, difficulty of arousal, and sexual pain.14 Sexual pain can affect sexual function at any point on this continuum.

Treatments in the pipeline

For decades, hormone-based treatments have been the predominant therapeutic option for vaginal dryness. Often they are a secondary benefit of hormone therapy for vasomotor symptoms and osteoporosis. Estrogen can be delivered in the form of oral tablet, transdermal patch, gel, spray, or vaginal ring for systemic use, or as vaginal cream, ring, or tablet for local use.

However, despite data to the contrary and our reassurances to the patient about overall safety, a large number of women, and many primary care providers, are no longer inclined to use short- or long-term HRT in any presentation.

Other women may have risk factors that contraindicate exogenous hormones.

Nonhormonal options for vaginal dryness and dyspareunia are limited, and there are no approved systemic or oral nonestrogen options. Over-the-counter topical lubricants can ease some of the symptoms of VVA temporarily and allow successful vaginal penetration in many cases. Some may cause vaginal warming and pleasant sensations, but overall they treat the symptom rather than the source of pain. Moreover, many patients consider local lubricants messy and inconvenient and claim they “ruin the mood.”

The use of vaginal dilators along with estrogen or lubricant therapy is an often-forgotten adjunct to therapy for dyspareunia caused by VVA (FIGURE 4).

FIGURE 4 Mechanical dilation of the vagina is a useful adjunct

Mechanical dilation is often needed to restore penetration capability in the vagina, even after hormonal treatment. The focus should be on the vaginal introitus, with the top 25% to 35% of the dilator inserted into the opening once a day for 15 minutes, increasing the dilator diameter over time.

New SERMs are in development

Preclinical and clinical research into the diverse class of selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) to treat estrogen-mediated disease produced tamoxifen for breast cancer prevention and raloxifene for both vertebral osteoporosis and breast cancer prevention. Each SERM seems to have unique tissue selectivity. The antiestrogenic activity of tamoxifen and raloxifene extends to the vagina and can exacerbate vaginal dryness.

A new generation of orally active SERMs is under investigation specifically for the treatment of chronic vaginal symptoms. These new agents target the nonvaginal treatment of VVA and associated symptoms. The first oral SERM for long-term treatment of these symptoms, ospemifene (Ophena), may become available in the near future. It is a novel SERM that has both anti-estrogenic and estrogenic actions, depending on the tissue. It was shown to significantly improve both vaginal dryness and dyspareunia in a large placebo-controlled trial.15

The author reports that he serves on the speaker’s bureau for Novogyne, TherRx, Warner-Chilcott, and Solvay, and on the advisory board for Upsher-Smith, Novogyne, QuatRx, and Wyeth.

CASE: History of dyspareunia

At her latest visit, a 56-year-old woman who is 7 years postmenopausal relates that she has been experiencing worsening pain with intercourse to the point that she now has very little sex drive at all. This problem began approximately 1 year after she discontinued hormone therapy in the wake of reports that it causes cancer and heart attack. She has been offered both local vaginal and systemic hormone therapy, but is too frightened to use any hormones at all. Sexual lubricants no longer seem to work.

How do you counsel her about these symptoms? And what therapy do you offer?

Physicians and other health-care practitioners are seeing a large and growing number of genitourinary and sexual-related complaints among menopausal women—so much so that it has reached epidemic proportions. Yet dyspareunia is underreported and undertreated, and quality of life suffers for these women.

In this article, I focus on two interrelated causes of this epidemic:

- vaginal dryness and vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) and the impact of these conditions on women’s sexual function and psychosocial well-being

- barriers to optimal treatment.

I also explore how ObGyns’ role in this area of care is evolving—as a way to understand how you can better serve this expanding segment of our patient population.

Dyspareunia can have many causes, including endometriosis, interstitial cystitis, surgical scarring, injury that occurs during childbirth, and psychosocial origin (such as a history of sexual abuse). Our focus here is on dyspareunia due to VVA.

during sex. What should you do?

- Sexual pain as a category of female sexual dysfunction is relevant at any age; for postmenopausal women dealing with vaginal dryness as a result of estrogen deficiency, it may well be the dominant issue. When determining the cause of a sexual problem in a postmenopausal woman, put dyspareunia caused by vaginal dryness (as well as its psychosocial consequences) at the top of the list of possibilities.

- Bring up the topic of vaginal dryness and sexual pain with postmenopausal patients as part of the routine yearly exam, and explain the therapeutic capabilities of all available options.

- Estrogen therapy, either local or systemic, remains the standard when lubricants are inadequate. Make every effort to counsel the patient about the real risk:benefit ratio of estrogen use.

- If the patient is reluctant to use estrogen therapy, discuss with her the option of short-term local estrogen use, with the understanding that more acceptable options may become available in the near future. This may facilitate acceptance of short-term hormonal treatment and allow the patient to maintain her vaginal health and much of her vaginal sexual function.

- Keep abreast of both present and future options for therapy.

Just how sizable is the postmenopausal population?

About 32% of the female population is older than 50 years.1 That means that around 48 million women are currently menopausal, or will become so over the next few years.

Because average life expectancy approaches 80 years in the United States and other countries of the industrialized world,2 many women will live approximately 40 years beyond menopause or their final menstrual period. Their quality of life during the second half of their life is dependent on both physical and psychosocial health.

Postmenopausal dyspareunia isn’t new

Sexual issues arising from physical causes—dyspareunia among them—have long accounted for a large share of medical concerns reported by postmenopausal women. In a 1985 survey, for example, dyspareunia accounted for 42.5% of their complaints.3

But epidemiologic studies to determine the prevalence of female sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women are difficult to carry out. Why? Because researchers would need to 1) address changes over time and 2) distinguish problems of sexual function from those brought on by aging.4

The techniques and methodology for researching female sexual dysfunction continue to evolve, creating new definitions of the stages of menopause and new diagnostic approaches to female sexual dysfunction.

However, based on available studies, Dennerstein and Hayes concluded that:

- postmenopausal women report a high rate of sexual dysfunction (higher than men)

- psychosocial factors can ameliorate a decline in sexual function

- “vaginal dryness and dyspareunia seem to be driven primarily by declining estradiol.”4

The WHI and its domino effect

Millions of postmenopausal women stopped taking estrogen-based therapy in the wake of widespread media coverage after 2002 publication of data from the estrogen–progestin arm of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), which purported to show, among other things, an increased risk of breast cancer.5

For decades, many postmenopausal women achieved medical management of VVA through long-term use of systemic hormone replacement therapy (HRT), which they used primarily to control other chronic symptoms of menopause, such as hot flashes.

After the WHI data were published (and misrepresented), reduced usage of estrogen-based HRT “unmasked” vaginal symptoms, including sexual pain, due to the effects of estrogen deficiency on the vaginal epithelium and vaginal blood flow. Since then, we have been forced to examine anew the natural history of menopause.

Within days or weeks of discontinuing HRT, women may reexperience the acute vasomotor symptoms that accompany estrogen withdrawal—most commonly hot flashes, night sweats, sleeplessness, palpitations, and headaches. Over time—anywhere from 6 months to several years—the body adjusts to the loss or withdrawal of estrogen, and these vasomotor symptoms eventually diminish or resolve. Not so for the longer-term physical effects of chronic low serum levels of estrogen, which worsen over time.

Approximately 6 months after discontinuing estrogen therapy, postmenopausal women may begin to experience vaginal dryness and VVA. As the years pass, other side effects of estrogen deficiency arise: bone loss, joint pain, mood alteration (including depression), change in skin tone, hair loss, and cardiac and central nervous system changes. These side effects do not resolve spontaneously; in fact, they grow worse as a woman ages. They may have deleterious psychosocial as well as physical impacts on her life—especially on the quality of her intimate relationship.

Clarify the report (adjust appropriately for same-sex partner)

- Where does it hurt? Describe the pain.

- When does it hurt? Does the pain occur 1) with penile contact at the opening of the vagina, 2) once the penis is partially in, 3) with full entry, 4) after some thrusting, 5) after deep thrusting, 6) with the partner’s ejaculation, 7) after withdrawal, or 8) with subsequent micturition?

- Does your body tense when your partner is attempting, or you are attempting, to insert his penis? What are your thoughts and feelings at this time?

- How long does the pain last?

- Does touching cause pain? Does it hurt when you ride a bicycle or wear tight clothes? Does penetration by tampons or fingers hurt?

Assess the pelvic floor

- Do you recognize the feeling of pelvic floor muscle tension during sexual contact?

- Do you recognize the feeling of pelvic floor muscle tension in other (nonsexual) situations?

Evaluate arousal

- Do you feel subjectively excited when you attempt intercourse?

- Does your vagina become sufficiently moist? Do you recognize the feeling of drying up?

Determine the consequences of the complaint

- What do you do when you experience pain during sexual contact? Do you continue? Or do you stop whatever is causing the pain?

- Do you continue to include intercourse or attempts at intercourse in your lovemaking, or do you use other methods of achieving sexual fulfillment? If you use other ways to make love, do you and your partner clearly understand that intercourse will not be attempted?

- What other effect does the pain have on your sexual relationship?

Explore biomedical antecedents

- When and how did the pain start?

- What tests have you undergone?

- What treatment have you received?

Source: Adapted from Basson R, et al.12

Is 60 the new 40?

Many women and men in the large cohort known as the Baby Boomer generation continue to be sexually active into their 60s, 70s, and 80s, as demonstrated by a 2007 study of sexuality and health in older adults.6 In the 57- to 64-year-old age group, 61.6% of women and 83.7% of men were sexually active (defined as sexual activity with a partner within the past 12 months). In the 65- to 74-year-old group, 39.5% of women and 67% of men were sexually active; and in the 75- to 85-year-old group, 16.7% of women and 38.5% of men were sexually active (TABLE).

These findings indicate that fewer women than men remain sexually active during their later years. One reason may be the epidemic of sexual-related symptoms among postmenopausal women. In the same survey, 34.3% of women 57 to 64 years old reported avoiding sex because of:

- pain during intercourse (17.8%)

- difficulty with lubrication (35.9%).

Across all groups, the most prevalent sexual problem was low desire (43%).6 Around 40% of postmenopausal women reported no sexual activity in the past 12 months, as well as lack of interest in sex. This number may include women who have ceased to have sex because of vaginal dryness and dyspareunia, thereby reducing the percentage reporting these symptoms (TABLE).

TABLE

Older adults are having sex—and experiencing sexual problems

| Activity or problem by gender | Number of respondents | Report, by age group (95% confidence interval*) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 57–64 yr (%) | 65–74 yr (%) | 75–85 yr (%) | ||

| Sexually active in previous 12 months† | ||||

| Men | 1,385 | 83.7 (77.6–89.8) | 67.0 (62.1–72.0) | 38.5 (33.6–43.5) |

| Women | 1,501 | 61.6 (56.7–66.4) | 39.5 (34.6–44.4) | 16.7 (12.5–21.0) |

| Difficulty with lubrication | ||||

| Women | 495 | 35.9 (29.6–42.2) | 43.2 (34.8–51.5) | 43.6 (27.0–60.2) |

| Pain during intercourse | ||||

| Men | 878 | 3.0 (1.1–4.8) | 3.2 (1.2–5.3) | 1.0 (0–2.5) |

| Women | 506 | 17.8 (13.3–22.2) | 18.6 (10.8–26.3) | 11.8 (4.3–19.4) |

| Avoidance of sex due to sexual problems** | ||||

| Men | 533 | 22.1 (17.3–26.9) | 30.1 (23.2–37.0) | 25.7 (14.9–36.4) |

| Women | 357 | 34.3 (25.0–43.7) | 30.5 (21.5–39.4) | 22.7 (9.4–35.9) |

| Source: Adapted from Lindau ST, et al.6 | ||||

| Adjusted odds ratios are based on a logistic regression including the age group and self-rated health status as covariates, estimated separately for men and women. The confidence interval is based on the inversion of the Wald tests constructed with the use of design-based standard errors. | ||||

| † These data exclude 107 respondents who reported at least one sexual problem. | ||||

| ** This question was asked only of respondents who reported at least one sexual problem. | ||||

Assessing menopause-related sexual function is a challenge

Although the transition phases of menopause have been well studied and reported for decades, few of these studies have included questions about the impact of menopause on sexual function.7 When longitudinal studies that included the classification of female sexual dysfunction began to appear, they provided evidence of the important role that VVA and psychosocial factors play in female sexual dysfunction.8

In the fourth year of the Melbourne Women’s Midlife Health Project longitudinal study, six variables related to sexual function were identified. Three were determinate of sexual function:

- feelings for the partner

- problems related to the partner

- vaginal dryness/dyspareunia.

The other three variables—sexual responsiveness, frequency of sexual activity, and libido—were dependent or outcome variables.

By the sixth year of this study, two variables had increased in significance: vaginal dryness/dyspareunia and partner problems.7

Sexual pain and relationship problems can create a vicious cycle

The interrelationship of vaginal dryness, sexual pain, flagging desire, and psychosocial parameters can produce a vicious cycle. A woman experiencing or anticipating pain may have diminished sexual desire or avoid sex altogether. During intercourse, the brain’s awareness of vaginal pain may trigger a physiologic response that can cause the muscles of the vagina to tighten and lubrication to decrease. The result? Greater vaginal pain.

This vicious cycle can contribute to relationship issues with the sexual partner and harm a woman’s psychosocial well-being. Resentment, anger, and misunderstanding may arise when a couple is dealing with problems of sexual function, and these stressors can damage many aspects of the relationship, further exacerbating sexual difficulties.

An additional and very important dimension of these issues is their potential impact on the family unit.

VVA can diminish overall well-being

In a 2007 survey reported at the North American Menopause Society (NAMS), one third to one half of 506 respondents said that VVA had a bad effect on their sexual interest, mood, self-esteem, and the intimate relationship (FIGURE 1).9 Reports from in-depth interviews were consistent with survey results and offered further insight into a woman’s emotional response to the condition of vaginal dryness and its impact on her life. Women found the condition “embarrassing,” something they had to endure but didn’t talk about, and felt that it had a major impact on their self-esteem and intimate relationship.

FIGURE 1 Dyspareunia affects more than interest in sex—relationships, mood, and self-esteem suffer

Simon JA, Komi J. Vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) negatively impacts sexual function, psychosocial well-being, and partner relationships. Poster presented at North American Menopause Association Annual Meeting; October 3-6, 2007; Dallas, Texas.

Clinicians often don’t ask about VVA, and patients are reluctant to talk

Among women of all ages, dyspareunia is underreported and undertreated. In the survey reported at NAMS, 40% of respondents said that their physician had never asked them about the problem of VVA (FIGURE 2).9

Women themselves may be reluctant to discuss the problem with physicians, nurse practitioners, or other health-care providers out of embarrassment or the assumption that there is nothing to be done about the problem. Nevertheless, more than 40% of respondents said they would be highly likely to seek treatment for VVA if they had a concern about urogenital complications of the condition (FIGURE 3).9

Another barrier may be the sense that asking the health-care provider about sex may embarrass him or her. As a result, sufferers do not anticipate help from their physician and other members of the health-care profession and fail to seek treatment or counseling for this chronic medical condition.10,11

In a 1999 telephone survey of 500 adults 25 years of age or older, 71% said they thought that their doctor would dismiss concerns about sexual problems, but 85% said they would talk to their physician anyway if they had a problem, even though they might not get treatment.11 In that survey, 91% of married men and 84% of married women rated a satisfying sex life as important to quality of life.11

Another important and often overlooked limitation on this type of discussion is the time constraints that busy clinicians face, especially with the low reimbursement offered by managed care. Sexual problems can hardly be adequately discussed in 7 to 10 minutes.

FIGURE 2 Do physicians ask about dyspareunia? Most women surveyed said “rarely” or “never”

Simon JA, Komi J. Vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) negatively impacts sexual function, psychosocial well-being, and partner relationships. Poster presented at North American Menopause Association Annual Meeting; October 3-6, 2007; Dallas, Texas.

FIGURE 3 Are these women likely to seek treatment?

Simon JA, Komi J. Vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) negatively impacts sexual function, psychosocial well-being, and partner relationships. Poster presented at North American Menopause Association Annual Meeting; October 3-6, 2007; Dallas, Texas.

Women have performance anxiety, too

It is well known that men with even a mild degree of erectile dysfunction can suffer from performance anxiety, but the fact that women can also suffer from this phenomenon is not given as much attention. Such anxiety can be a factor in relationship difficulties. With both partners perhaps feeling anxious about sexual performance, a couple may avoid even simple acts of affection, such as holding hands, to avoid raising the other’s expectations.

Exacerbating the situation is the fact that many men use widely prescribed phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors, whereas women are contending with barriers to continued sexual activity as they age. It does not take a psychologist to understand that this imbalance often adds to emotional strain and tension between partners.

Popular media address the issue

Look beyond what our postmenopausal patients tell us directly—to the popular media and online forums—to appreciate the scope of sexual pain as a major issue among postmenopausal women. Evidence of psychosocial effects is found on numerous Web sites—some from organizations, others designed by women seeking help from each other.

Red Hot Mamas

This organization aims to empower women through menopause education. Highlighted in the Winter 2007/2008 Red Hot Mamas Report is a survey done in conjunction with Harris Interactive exploring the impact of menopausal symptoms on a woman’s sex life, which found that 47% of women who have VVA have avoided or stopped sex completely because it was uncomfortable, compared with 23% of normal women.

Power Surge

This Web site offers a list of strategies for dealing with sexual pain, including an overview of hormone-based prescription and nonprescription products, along with a variety of over-the-counter, natural, holistic, and herbal therapies for treating dyspareunia.

What is the physician’s role?

Given the epidemic of sexual pain, it is crucial that physicians and others who care for postmenopausal women increase their awareness of this issue and pay special attention to its psychosocial parameters.

Ask patients about sexual function in general and dyspareunia in particular as part of the routine annual visit. A simple opening “Yes/No” question, such as “Are you sexually active?” can lead to further questions appropriate to the patient. For example, if the answer is “No,” the follow-up question might be, “Does that bother you or your partner?” Further discussion may uncover whether the lack of sexual activity is a cause of distress and identify which variables are involved.

If, instead, the answer is “Yes,” follow-up questions can identify the presence of common postmenopausal physical issues, such as vaginal dryness and difficulty with lubrication. The visit then can turn to strategies to ameliorate those conditions.

When a patient reports dyspareunia, further diagnostic information such as precise location, degree of arousal, and reaction to pain can help determine the appropriate course of treatment. For an approach to this aspect of ascertaining patient history, see the list of sample questions above.12

During the physical, pay particular attention to any physical abnormalities or organic causes of sexual pain. Questions designed to characterize the location and nature of the pain can pinpoint the cause. Sexual pain arising from VVA is likely to 1) be localized at the introitus and 2) occur with penile entry.

Since the mid-1990s, the availability of validated scales to measure female sexual function has increased rapidly and enabled researchers to better identify, quantify, and evaluate treatments for female sexual dysfunction.7 Over time, we have moved away from the somewhat mechanical sequence inherent in the linear progression of desire leading to genital stimulation followed by arousal and orgasm toward an appreciation of the multiple physical, emotional, and subjective factors that are at play in women’s sexual function.

By 1998, a classification scheme was developed to further the means to study and discuss disorders of desire, arousal, orgasm, and sexual pain.8 Further contextual definitions of sexual dysfunction are under consideration.13

Basson proposed one new model of female sexual function (see the diagram), and observed that

"…women identify many reasons they are sexual over and beyond inherent sexual drive or “hunger.” Women tell of wanting to increase emotional closeness, commitment, sharing, tenderness, and tolerance, and to show the partner that he or she has been missed (emotionally or physically). Such intimacy-based reasons motivate the woman to find a way to become sexually aroused. This arousal is not spontaneous but triggered by deliberately sought sexual stimuli."13

Intimacy-based model of female sexual response cycle

In this flow of physical and emotional variables involved in female sexual function, categories interact. For example, low desire can be and is frequently secondary to the anticipation of pain during sexual intercourse. Arousal can be hampered by lack of vaginal lubrication—perhaps inhibited by the anticipation of pain. Secondary orgasmic disorders can result from low desire, difficulty of arousal, and sexual pain.14 Sexual pain can affect sexual function at any point on this continuum.

Treatments in the pipeline

For decades, hormone-based treatments have been the predominant therapeutic option for vaginal dryness. Often they are a secondary benefit of hormone therapy for vasomotor symptoms and osteoporosis. Estrogen can be delivered in the form of oral tablet, transdermal patch, gel, spray, or vaginal ring for systemic use, or as vaginal cream, ring, or tablet for local use.

However, despite data to the contrary and our reassurances to the patient about overall safety, a large number of women, and many primary care providers, are no longer inclined to use short- or long-term HRT in any presentation.

Other women may have risk factors that contraindicate exogenous hormones.

Nonhormonal options for vaginal dryness and dyspareunia are limited, and there are no approved systemic or oral nonestrogen options. Over-the-counter topical lubricants can ease some of the symptoms of VVA temporarily and allow successful vaginal penetration in many cases. Some may cause vaginal warming and pleasant sensations, but overall they treat the symptom rather than the source of pain. Moreover, many patients consider local lubricants messy and inconvenient and claim they “ruin the mood.”

The use of vaginal dilators along with estrogen or lubricant therapy is an often-forgotten adjunct to therapy for dyspareunia caused by VVA (FIGURE 4).

FIGURE 4 Mechanical dilation of the vagina is a useful adjunct

Mechanical dilation is often needed to restore penetration capability in the vagina, even after hormonal treatment. The focus should be on the vaginal introitus, with the top 25% to 35% of the dilator inserted into the opening once a day for 15 minutes, increasing the dilator diameter over time.

New SERMs are in development

Preclinical and clinical research into the diverse class of selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) to treat estrogen-mediated disease produced tamoxifen for breast cancer prevention and raloxifene for both vertebral osteoporosis and breast cancer prevention. Each SERM seems to have unique tissue selectivity. The antiestrogenic activity of tamoxifen and raloxifene extends to the vagina and can exacerbate vaginal dryness.

A new generation of orally active SERMs is under investigation specifically for the treatment of chronic vaginal symptoms. These new agents target the nonvaginal treatment of VVA and associated symptoms. The first oral SERM for long-term treatment of these symptoms, ospemifene (Ophena), may become available in the near future. It is a novel SERM that has both anti-estrogenic and estrogenic actions, depending on the tissue. It was shown to significantly improve both vaginal dryness and dyspareunia in a large placebo-controlled trial.15

1. US Census Bureau. 2006 American community survey. S0101. Age and sex. Available at: http://fact-finder.census.gov/servlet/DatasetMainPageServlet?_program=ACS&_submenuId=&_lang=en&_ts.

2. National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2007, with Chartbook on Trends in the Health of Americans. Hyattsville, Md: NCHS; 2007. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/lifexpec.htm. Accessed February 2, 2009.

3. Sarrel PM, Whitehead MI. Sex and menopause: defining the issues. Maturitas. 1985;7:217-224.

4. Dennerstein L, Hayes RD. Confronting the challenges: epidemiological study of female sexual dysfunction and the menopause. J Sex Med. 2005;2(suppl 3):118-132.

5. Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321-333.

6. Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, Levinson W, O’Muircheartaigh CA, Waite LJ. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:762-774.

7. Dennerstein L, Alexander JL, Kotz K. The menopause and sexual functioning: a review of the population-based studies. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2003;14:64-82.

8. Basson R, Berman J, Burnett A, et al. Report of the international consensus development conference on female sexual dysfunction: definitions and classifications. J Urol. 2000;163:888-993.

9. Simon JA, Komi J. Vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) negatively impacts sexual function, psychosocial well-being, and partner relationships. Poster presented at North American Menopause Association Annual Meeting; October 3-6, 2007; Dallas, Texas.

10. Heim LJ. Evaluation and differential diagnosis of dyspareunia. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:1535-1552.

11. Marwick C. Survey says patients expect little physician help on sex. JAMA. 1999;281:2173-2174.