User login

Challenges in total laparoscopic hysterectomy: Severe adhesions

Dr. Giesler reports that he serves on the speaker’s bureau for Ethicon Endo-Surgery. Dr. Vyas has no financial relationships relevant to this article.

CASE: Probable adhesions. Is laparoscopy practical?

A 54-year-old woman complains of perimenopausal bleeding that has not been controlled by hormone therapy, as well as increasing pelvic pain that has caused her to miss work. She wants you to perform hysterectomy to end these problems once and for all.

Aside from these complaints, her history is unremarkable except for a laparotomy at 13 years for a ruptured appendix. Her Pap smear, endometrial biopsy, and pelvic sonogram are negative.

Is she a candidate for laparoscopic hysterectomy?

A patient such as this one, who has a history of laparotomy, is likely to have extensive intra-abdominal adhesions. This pathology increases the risk of bowel injury during surgery—whether it is performed via laparotomy or laparoscopy.

The ability to simplify laparoscopic hysterectomy in a woman who has extensive adhesions requires an understanding of the ways in which adhesions form—in order to lyse them skillfully and avoid creating further adhesions. It also requires special techniques to enter the abdomen, identify the site of attachment, separate adhered structures, and conclude the hysterectomy. Attention to the type of energy that is used also is important.

In this article, we describe these techniques and considerations.

In Part 1 of this article, we discussed techniques that facilitate laparoscopic hysterectomy in a woman who has a large uterus.

Don’t overlook preoperative discussion, preparation

The patient needs to understand the risks and benefits of laparoscopic hysterectomy, particularly when extensive adhesions are likely, as well as the fact that it may be necessary to convert the procedure to laparotomy if the laparoscopic approach proves too difficult. She also needs to understand that conversion to laparotomy does not represent a failure of the procedure but an aim for greater safety.

Because bowel injury is a real risk when the patient has extensive adhesions, mechanical bowel preparation is important. Choose the regimen preferred by the colorectal surgeon likely to be consulted if intraoperative injury occurs.

The operating room (OR) and anesthesia staffs also need to be prepared, and the patient should be positioned for optimal access in the OR. These and other preoperative steps are described in Part 1 of this article and remain the same for the patient who has extensive intra-abdominal adhesions.

How adhesions form

When the peritoneum is injured, a fibrinous exudate develops, causing adjacent tissues to stick together. Normal peritoneum immediately initiates a process to break down this exudate, but traumatized peritoneum has limited ability to do so. As a result, a permanent adhesion can form in as few as 5 to 8 days.1,2

Pelvic inflammatory disease and intraperitoneal blood associated with distant endometriosis implants are well known causes of abdominal adhesions; others are listed in the TABLE.

TABLE

7 causes of intra-abdominal adhesions

| Instrument-traumatized tissue |

| Poor hemostasis |

| Devitalized tissue |

| Intraperitoneal infection |

| Ischemic tissue due to sutures |

| Foreign body reaction (carbon particles, suture) |

| Electrical tissue injury |

| Source: Ling FW, et al2 |

The challenge of safe entry

During laparotomy, adhesions can make it difficult to enter the abdomen. The same is true—but more so—for laparoscopic entry. The distortion caused by adhesions can lead to inadvertent injury to blood vessels, bowel, and bladder even in the best surgical hands. An attempt to lyse adhesions laparoscopically often prolongs the surgical procedure and increases the risk of visceral injury, bleeding, and fistula.1

In more than 80% of patients experiencing injury during major abdominal surgery, the injury is associated with omental adhesions to the previous abdominal wall incision, and more than 50% have intestine included in the adhesion complex.1

One study involving 918 patients who underwent laparoscopy found that 54.9% had umbilical adhesions of sufficient size to interfere with umbilical port placement.3 More important, 16% of this study group had only a single midline umbilical incision for laparoscopy before the adhesions were discovered.

The utility of Palmer’s point

Although multiple techniques have been described to minimize entry-related injury, no technique has completely eliminated the risk of inadvertent bowel or major large-vessel injury.3 In 1974, Palmer described an abdominal entry point for the Veress needle and small trocar for women who have a history of abdominal surgery.4 Many surgeons now consider “Palmer’s point,” in the left upper quadrant, as the safest peritoneal entry site.

Technique. After emptying the stomach of its contents using suction, insert the Veress needle into the peritoneal cavity at a point midway between the midclavicular line and the anterior axillary line, 3 cm below the costal margin (FIGURE). Advance it slowly until you hear three pops, signifying entry into the peritoneal cavity. Only minimal insertion is needed; insufflation pressure of less than 10 mm Hg indicates intraperitoneal placement of the needle tip.5

Once pneumoperitoneum pressure of 20 mm Hg is established, insert a 5-mm trocar perpendicular to the abdominal wall, 3 cm below the ribs, midway between the midclavicular line and the anterior axillary line.3 (There is a risk of colon injury at the splenic flexure if the entry point is further lateral.)

Inspect the abdominal cavity with the laparoscope from this access port to determine the best placement of remaining trocars under direct vision; lyse adhesions, if necessary, to perform the procedure.

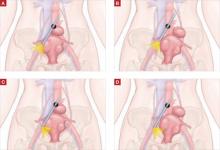

FIGURE Enter the abdomen at Palmer’s point

This entry site (red dot) lies midway between the midclavicular line and the anterior axillary line, 3 cm below the costal margin. The other port sites (black dots) are described in Figure 2 in Part 1 of this article.

Success depends on careful lysis and minimal tissue injury

Adhesions in the abdomen may involve:

- omentum to peritoneum

- omentum to pelvic structures

- intestine to peritoneum

- intestine to pelvic structures.

Adhesions may be filmy and thin or dense and thick, avascular or vascular. They can be minimal, or a veritable curtain that prevents adequate visualization of the primary surgical site. When they are present, they must be managed successfully if the primary procedure is to be accomplished laparoscopically.

Successful management requires techniques to maximize adhesiolysis and minimize new adhesions or tissue injury:

- Use traction and countertraction to define the line of attachment; this is essential to separate two tissues bound by adhesions.

- Use atraumatic graspers to reduce the risk of tissue laceration.

- Avoid sharp dissection with scissors. Although this is the traditional method of lysis, it is often associated with bleeding that stains and obscures the line of dissection.

- Choose tools wisely. Electrosurgery and lasers use obliterative coagulation, working at temperatures of 150°C to 400°C to burn tissue. Blood and tissue are desiccated and oxidized, forming an eschar that covers and seals the bleeding area. Rebleeding during electrosurgery may occur when the instrument sticks to tissue and disrupts the eschar. In addition, monopolar instruments may cause undetected remote thermal injury, causing late complications.6 Both monopolar and bipolar techniques can also leave carbon particles during the oxidation process that become foci for future adhesions.7

- Consider ultrasonic energy. Unlike electrosurgery, ultrasonic energy is mechanical and works at much lower temperatures (50°C to 100°C), controlling bleeding by coaptive coagulation. The ultrasonic blade, vibrating at 55,500 Hz, disrupts and denatures protein to form a coagulum that seals small coapted vessels. When the effect is prolonged, secondary heat seals larger vessels. Ultrasonic energy involves minimal thermal spread, minimal carbon particle formation, and a cavitation effect similar to hydrodissection that helps expose the adhesive line. It creates minimal smoke, improving visibility. Because ultrasonic energy operates at a lower temperature, less char and necrotic tissue—important causes of adhesions—occur than with bipolar or monopolar electrical energy.7

Although different energy sources interact with human tissue using different mechanisms, clinical outcomes appear to be much the same and depend more on the skill of the individual surgeon than on the power source used. Data on this topic are limited.

Many patients have adhesions that involve omentum or intestine that can be managed using simple laparoscopic techniques, but some have organs that are fixed in the pelvis by adhesions. In these cases, traction and countertraction techniques can be tedious and may cause inadvertent injury to critical structures or excessive bleeding that necessitates conversion to laparotomy.

A better way to approach the obliterated, or “frozen,” pelvis is to open the retroperitoneal space and identify critical structures:

- Enter the retroperitoneal space at the pelvic brim in an area free of adhesions. Identify the ureter and follow it to the bladder. This can be accomplished using hydrodissection techniques or cavitation techniques with ultrasonic energy.

- Skeletonize, coagulate, and cut the vessels once you reach the cardinal ligament and identify the ascending uterine blood supply.

- Dissect the structures of the obliterated cul de sac using standard techniques.

- Use sharp dissection for adhesiolysis. Laparoscopic blunt dissection of adhesions can lead to serosal tears and inadvertent enterotomy. Sharp dissection or mechanical energy devices are preferred to divide the tissue along the line of demarcation—but remember that monopolar and bipolar devices can cause remote thermal damage that goes undetected at the time of use.

When dissection becomes unproductive in one area, switch to another; dissection planes frequently open and demonstrate the relationships between pelvic structures and loops of bowel.8

Occasionally, the visceral peritoneum of the bowel is breached during adhesiolysis. If the mucosa and muscularis remain intact, denuded serosa need not be repaired. Surgical repair is necessary if mucosa is exposed, or perforation may occur.

Because most ObGyn residency programs offer limited training in management of bowel injuries, intraoperative consultation with a general surgeon may be indicated if more than a simple repair is required.8

CASE RESOLVED

You perform total laparoscopic hysterectomy and find multiple adhesions in the right lower quadrant, adjacent to the area of trocar insertion. Small intestine is adherent to the right lateral pelvic wall; sigmoid colon is adherent to the left pelvic wall; and the anterior fundus is adherent to the bladder peritoneal reflection, with the adhesions extending on either side to include the round ligaments.

You begin adhesiolysis in the right lower quadrant to optimize trocar movement. You transect the round ligaments in the mid-position, with dissection extended retroperitoneally on either side to the midline of the lower uterine segment; this opens access to the ascending branch of the uterine vessels. You dissect the intestine free of either pelvic sidewall along the line of demarcation.

Total blood loss is less than 25 mL. The patient is discharged 6 hours after surgery.

1. Liakakos T, Thomakos N, Fine PM, Dervenis C, Young RL. Peritoneal adhesions: etiology, pathophysiology, and clinical significance. Recent advances in prevention and management. Dig Surg. 2001;18:260-273.

2. Ling FW, DeCherney AH, Diamond MP, diZerega GS, Montz FP. The Challenge of Pelvic Adhesions. Crofton, Md: Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics; 2002.

3. Agarwala N, Liu CY. Safe entry techniques during laparoscopy: left upper quadrant entry using the ninth intercostals space—a review of 918 procedures. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12:55-61.

4. Palmer R. Safety in laparoscopy. J Reprod Med. 1974;13(1):1-5.

5. Childers JM, Brzechffa PR, Surwit EA. Laparoscopy using the left upper quadrant as the primary trocar site. Gynecol Oncol. 1993;50:221-225.

6. Shen CC, Wu MP, Lu CH, et al. Small intestine injury in laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10:350-355.

7. Diamantis T, Kontos M, Arvelakis A, et al. Comparison of monopolar electrocoagulation, bipolar electrocoagulation, Ultracision, and Ligasure. Surg Today. 2006;36:908-913.

8. Perkins JD, Dent LL. Avoiding and repairing bowel injury in gynecologic surgery. OBG Management. 2004;16(8):15-28.

Dr. Giesler reports that he serves on the speaker’s bureau for Ethicon Endo-Surgery. Dr. Vyas has no financial relationships relevant to this article.

CASE: Probable adhesions. Is laparoscopy practical?

A 54-year-old woman complains of perimenopausal bleeding that has not been controlled by hormone therapy, as well as increasing pelvic pain that has caused her to miss work. She wants you to perform hysterectomy to end these problems once and for all.

Aside from these complaints, her history is unremarkable except for a laparotomy at 13 years for a ruptured appendix. Her Pap smear, endometrial biopsy, and pelvic sonogram are negative.

Is she a candidate for laparoscopic hysterectomy?

A patient such as this one, who has a history of laparotomy, is likely to have extensive intra-abdominal adhesions. This pathology increases the risk of bowel injury during surgery—whether it is performed via laparotomy or laparoscopy.

The ability to simplify laparoscopic hysterectomy in a woman who has extensive adhesions requires an understanding of the ways in which adhesions form—in order to lyse them skillfully and avoid creating further adhesions. It also requires special techniques to enter the abdomen, identify the site of attachment, separate adhered structures, and conclude the hysterectomy. Attention to the type of energy that is used also is important.

In this article, we describe these techniques and considerations.

In Part 1 of this article, we discussed techniques that facilitate laparoscopic hysterectomy in a woman who has a large uterus.

Don’t overlook preoperative discussion, preparation

The patient needs to understand the risks and benefits of laparoscopic hysterectomy, particularly when extensive adhesions are likely, as well as the fact that it may be necessary to convert the procedure to laparotomy if the laparoscopic approach proves too difficult. She also needs to understand that conversion to laparotomy does not represent a failure of the procedure but an aim for greater safety.

Because bowel injury is a real risk when the patient has extensive adhesions, mechanical bowel preparation is important. Choose the regimen preferred by the colorectal surgeon likely to be consulted if intraoperative injury occurs.

The operating room (OR) and anesthesia staffs also need to be prepared, and the patient should be positioned for optimal access in the OR. These and other preoperative steps are described in Part 1 of this article and remain the same for the patient who has extensive intra-abdominal adhesions.

How adhesions form

When the peritoneum is injured, a fibrinous exudate develops, causing adjacent tissues to stick together. Normal peritoneum immediately initiates a process to break down this exudate, but traumatized peritoneum has limited ability to do so. As a result, a permanent adhesion can form in as few as 5 to 8 days.1,2

Pelvic inflammatory disease and intraperitoneal blood associated with distant endometriosis implants are well known causes of abdominal adhesions; others are listed in the TABLE.

TABLE

7 causes of intra-abdominal adhesions

| Instrument-traumatized tissue |

| Poor hemostasis |

| Devitalized tissue |

| Intraperitoneal infection |

| Ischemic tissue due to sutures |

| Foreign body reaction (carbon particles, suture) |

| Electrical tissue injury |

| Source: Ling FW, et al2 |

The challenge of safe entry

During laparotomy, adhesions can make it difficult to enter the abdomen. The same is true—but more so—for laparoscopic entry. The distortion caused by adhesions can lead to inadvertent injury to blood vessels, bowel, and bladder even in the best surgical hands. An attempt to lyse adhesions laparoscopically often prolongs the surgical procedure and increases the risk of visceral injury, bleeding, and fistula.1

In more than 80% of patients experiencing injury during major abdominal surgery, the injury is associated with omental adhesions to the previous abdominal wall incision, and more than 50% have intestine included in the adhesion complex.1

One study involving 918 patients who underwent laparoscopy found that 54.9% had umbilical adhesions of sufficient size to interfere with umbilical port placement.3 More important, 16% of this study group had only a single midline umbilical incision for laparoscopy before the adhesions were discovered.

The utility of Palmer’s point

Although multiple techniques have been described to minimize entry-related injury, no technique has completely eliminated the risk of inadvertent bowel or major large-vessel injury.3 In 1974, Palmer described an abdominal entry point for the Veress needle and small trocar for women who have a history of abdominal surgery.4 Many surgeons now consider “Palmer’s point,” in the left upper quadrant, as the safest peritoneal entry site.

Technique. After emptying the stomach of its contents using suction, insert the Veress needle into the peritoneal cavity at a point midway between the midclavicular line and the anterior axillary line, 3 cm below the costal margin (FIGURE). Advance it slowly until you hear three pops, signifying entry into the peritoneal cavity. Only minimal insertion is needed; insufflation pressure of less than 10 mm Hg indicates intraperitoneal placement of the needle tip.5

Once pneumoperitoneum pressure of 20 mm Hg is established, insert a 5-mm trocar perpendicular to the abdominal wall, 3 cm below the ribs, midway between the midclavicular line and the anterior axillary line.3 (There is a risk of colon injury at the splenic flexure if the entry point is further lateral.)

Inspect the abdominal cavity with the laparoscope from this access port to determine the best placement of remaining trocars under direct vision; lyse adhesions, if necessary, to perform the procedure.

FIGURE Enter the abdomen at Palmer’s point

This entry site (red dot) lies midway between the midclavicular line and the anterior axillary line, 3 cm below the costal margin. The other port sites (black dots) are described in Figure 2 in Part 1 of this article.

Success depends on careful lysis and minimal tissue injury

Adhesions in the abdomen may involve:

- omentum to peritoneum

- omentum to pelvic structures

- intestine to peritoneum

- intestine to pelvic structures.

Adhesions may be filmy and thin or dense and thick, avascular or vascular. They can be minimal, or a veritable curtain that prevents adequate visualization of the primary surgical site. When they are present, they must be managed successfully if the primary procedure is to be accomplished laparoscopically.

Successful management requires techniques to maximize adhesiolysis and minimize new adhesions or tissue injury:

- Use traction and countertraction to define the line of attachment; this is essential to separate two tissues bound by adhesions.

- Use atraumatic graspers to reduce the risk of tissue laceration.

- Avoid sharp dissection with scissors. Although this is the traditional method of lysis, it is often associated with bleeding that stains and obscures the line of dissection.

- Choose tools wisely. Electrosurgery and lasers use obliterative coagulation, working at temperatures of 150°C to 400°C to burn tissue. Blood and tissue are desiccated and oxidized, forming an eschar that covers and seals the bleeding area. Rebleeding during electrosurgery may occur when the instrument sticks to tissue and disrupts the eschar. In addition, monopolar instruments may cause undetected remote thermal injury, causing late complications.6 Both monopolar and bipolar techniques can also leave carbon particles during the oxidation process that become foci for future adhesions.7

- Consider ultrasonic energy. Unlike electrosurgery, ultrasonic energy is mechanical and works at much lower temperatures (50°C to 100°C), controlling bleeding by coaptive coagulation. The ultrasonic blade, vibrating at 55,500 Hz, disrupts and denatures protein to form a coagulum that seals small coapted vessels. When the effect is prolonged, secondary heat seals larger vessels. Ultrasonic energy involves minimal thermal spread, minimal carbon particle formation, and a cavitation effect similar to hydrodissection that helps expose the adhesive line. It creates minimal smoke, improving visibility. Because ultrasonic energy operates at a lower temperature, less char and necrotic tissue—important causes of adhesions—occur than with bipolar or monopolar electrical energy.7

Although different energy sources interact with human tissue using different mechanisms, clinical outcomes appear to be much the same and depend more on the skill of the individual surgeon than on the power source used. Data on this topic are limited.

Many patients have adhesions that involve omentum or intestine that can be managed using simple laparoscopic techniques, but some have organs that are fixed in the pelvis by adhesions. In these cases, traction and countertraction techniques can be tedious and may cause inadvertent injury to critical structures or excessive bleeding that necessitates conversion to laparotomy.

A better way to approach the obliterated, or “frozen,” pelvis is to open the retroperitoneal space and identify critical structures:

- Enter the retroperitoneal space at the pelvic brim in an area free of adhesions. Identify the ureter and follow it to the bladder. This can be accomplished using hydrodissection techniques or cavitation techniques with ultrasonic energy.

- Skeletonize, coagulate, and cut the vessels once you reach the cardinal ligament and identify the ascending uterine blood supply.

- Dissect the structures of the obliterated cul de sac using standard techniques.

- Use sharp dissection for adhesiolysis. Laparoscopic blunt dissection of adhesions can lead to serosal tears and inadvertent enterotomy. Sharp dissection or mechanical energy devices are preferred to divide the tissue along the line of demarcation—but remember that monopolar and bipolar devices can cause remote thermal damage that goes undetected at the time of use.

When dissection becomes unproductive in one area, switch to another; dissection planes frequently open and demonstrate the relationships between pelvic structures and loops of bowel.8

Occasionally, the visceral peritoneum of the bowel is breached during adhesiolysis. If the mucosa and muscularis remain intact, denuded serosa need not be repaired. Surgical repair is necessary if mucosa is exposed, or perforation may occur.

Because most ObGyn residency programs offer limited training in management of bowel injuries, intraoperative consultation with a general surgeon may be indicated if more than a simple repair is required.8

CASE RESOLVED

You perform total laparoscopic hysterectomy and find multiple adhesions in the right lower quadrant, adjacent to the area of trocar insertion. Small intestine is adherent to the right lateral pelvic wall; sigmoid colon is adherent to the left pelvic wall; and the anterior fundus is adherent to the bladder peritoneal reflection, with the adhesions extending on either side to include the round ligaments.

You begin adhesiolysis in the right lower quadrant to optimize trocar movement. You transect the round ligaments in the mid-position, with dissection extended retroperitoneally on either side to the midline of the lower uterine segment; this opens access to the ascending branch of the uterine vessels. You dissect the intestine free of either pelvic sidewall along the line of demarcation.

Total blood loss is less than 25 mL. The patient is discharged 6 hours after surgery.

Dr. Giesler reports that he serves on the speaker’s bureau for Ethicon Endo-Surgery. Dr. Vyas has no financial relationships relevant to this article.

CASE: Probable adhesions. Is laparoscopy practical?

A 54-year-old woman complains of perimenopausal bleeding that has not been controlled by hormone therapy, as well as increasing pelvic pain that has caused her to miss work. She wants you to perform hysterectomy to end these problems once and for all.

Aside from these complaints, her history is unremarkable except for a laparotomy at 13 years for a ruptured appendix. Her Pap smear, endometrial biopsy, and pelvic sonogram are negative.

Is she a candidate for laparoscopic hysterectomy?

A patient such as this one, who has a history of laparotomy, is likely to have extensive intra-abdominal adhesions. This pathology increases the risk of bowel injury during surgery—whether it is performed via laparotomy or laparoscopy.

The ability to simplify laparoscopic hysterectomy in a woman who has extensive adhesions requires an understanding of the ways in which adhesions form—in order to lyse them skillfully and avoid creating further adhesions. It also requires special techniques to enter the abdomen, identify the site of attachment, separate adhered structures, and conclude the hysterectomy. Attention to the type of energy that is used also is important.

In this article, we describe these techniques and considerations.

In Part 1 of this article, we discussed techniques that facilitate laparoscopic hysterectomy in a woman who has a large uterus.

Don’t overlook preoperative discussion, preparation

The patient needs to understand the risks and benefits of laparoscopic hysterectomy, particularly when extensive adhesions are likely, as well as the fact that it may be necessary to convert the procedure to laparotomy if the laparoscopic approach proves too difficult. She also needs to understand that conversion to laparotomy does not represent a failure of the procedure but an aim for greater safety.

Because bowel injury is a real risk when the patient has extensive adhesions, mechanical bowel preparation is important. Choose the regimen preferred by the colorectal surgeon likely to be consulted if intraoperative injury occurs.

The operating room (OR) and anesthesia staffs also need to be prepared, and the patient should be positioned for optimal access in the OR. These and other preoperative steps are described in Part 1 of this article and remain the same for the patient who has extensive intra-abdominal adhesions.

How adhesions form

When the peritoneum is injured, a fibrinous exudate develops, causing adjacent tissues to stick together. Normal peritoneum immediately initiates a process to break down this exudate, but traumatized peritoneum has limited ability to do so. As a result, a permanent adhesion can form in as few as 5 to 8 days.1,2

Pelvic inflammatory disease and intraperitoneal blood associated with distant endometriosis implants are well known causes of abdominal adhesions; others are listed in the TABLE.

TABLE

7 causes of intra-abdominal adhesions

| Instrument-traumatized tissue |

| Poor hemostasis |

| Devitalized tissue |

| Intraperitoneal infection |

| Ischemic tissue due to sutures |

| Foreign body reaction (carbon particles, suture) |

| Electrical tissue injury |

| Source: Ling FW, et al2 |

The challenge of safe entry

During laparotomy, adhesions can make it difficult to enter the abdomen. The same is true—but more so—for laparoscopic entry. The distortion caused by adhesions can lead to inadvertent injury to blood vessels, bowel, and bladder even in the best surgical hands. An attempt to lyse adhesions laparoscopically often prolongs the surgical procedure and increases the risk of visceral injury, bleeding, and fistula.1

In more than 80% of patients experiencing injury during major abdominal surgery, the injury is associated with omental adhesions to the previous abdominal wall incision, and more than 50% have intestine included in the adhesion complex.1

One study involving 918 patients who underwent laparoscopy found that 54.9% had umbilical adhesions of sufficient size to interfere with umbilical port placement.3 More important, 16% of this study group had only a single midline umbilical incision for laparoscopy before the adhesions were discovered.

The utility of Palmer’s point

Although multiple techniques have been described to minimize entry-related injury, no technique has completely eliminated the risk of inadvertent bowel or major large-vessel injury.3 In 1974, Palmer described an abdominal entry point for the Veress needle and small trocar for women who have a history of abdominal surgery.4 Many surgeons now consider “Palmer’s point,” in the left upper quadrant, as the safest peritoneal entry site.

Technique. After emptying the stomach of its contents using suction, insert the Veress needle into the peritoneal cavity at a point midway between the midclavicular line and the anterior axillary line, 3 cm below the costal margin (FIGURE). Advance it slowly until you hear three pops, signifying entry into the peritoneal cavity. Only minimal insertion is needed; insufflation pressure of less than 10 mm Hg indicates intraperitoneal placement of the needle tip.5

Once pneumoperitoneum pressure of 20 mm Hg is established, insert a 5-mm trocar perpendicular to the abdominal wall, 3 cm below the ribs, midway between the midclavicular line and the anterior axillary line.3 (There is a risk of colon injury at the splenic flexure if the entry point is further lateral.)

Inspect the abdominal cavity with the laparoscope from this access port to determine the best placement of remaining trocars under direct vision; lyse adhesions, if necessary, to perform the procedure.

FIGURE Enter the abdomen at Palmer’s point

This entry site (red dot) lies midway between the midclavicular line and the anterior axillary line, 3 cm below the costal margin. The other port sites (black dots) are described in Figure 2 in Part 1 of this article.

Success depends on careful lysis and minimal tissue injury

Adhesions in the abdomen may involve:

- omentum to peritoneum

- omentum to pelvic structures

- intestine to peritoneum

- intestine to pelvic structures.

Adhesions may be filmy and thin or dense and thick, avascular or vascular. They can be minimal, or a veritable curtain that prevents adequate visualization of the primary surgical site. When they are present, they must be managed successfully if the primary procedure is to be accomplished laparoscopically.

Successful management requires techniques to maximize adhesiolysis and minimize new adhesions or tissue injury:

- Use traction and countertraction to define the line of attachment; this is essential to separate two tissues bound by adhesions.

- Use atraumatic graspers to reduce the risk of tissue laceration.

- Avoid sharp dissection with scissors. Although this is the traditional method of lysis, it is often associated with bleeding that stains and obscures the line of dissection.

- Choose tools wisely. Electrosurgery and lasers use obliterative coagulation, working at temperatures of 150°C to 400°C to burn tissue. Blood and tissue are desiccated and oxidized, forming an eschar that covers and seals the bleeding area. Rebleeding during electrosurgery may occur when the instrument sticks to tissue and disrupts the eschar. In addition, monopolar instruments may cause undetected remote thermal injury, causing late complications.6 Both monopolar and bipolar techniques can also leave carbon particles during the oxidation process that become foci for future adhesions.7

- Consider ultrasonic energy. Unlike electrosurgery, ultrasonic energy is mechanical and works at much lower temperatures (50°C to 100°C), controlling bleeding by coaptive coagulation. The ultrasonic blade, vibrating at 55,500 Hz, disrupts and denatures protein to form a coagulum that seals small coapted vessels. When the effect is prolonged, secondary heat seals larger vessels. Ultrasonic energy involves minimal thermal spread, minimal carbon particle formation, and a cavitation effect similar to hydrodissection that helps expose the adhesive line. It creates minimal smoke, improving visibility. Because ultrasonic energy operates at a lower temperature, less char and necrotic tissue—important causes of adhesions—occur than with bipolar or monopolar electrical energy.7

Although different energy sources interact with human tissue using different mechanisms, clinical outcomes appear to be much the same and depend more on the skill of the individual surgeon than on the power source used. Data on this topic are limited.

Many patients have adhesions that involve omentum or intestine that can be managed using simple laparoscopic techniques, but some have organs that are fixed in the pelvis by adhesions. In these cases, traction and countertraction techniques can be tedious and may cause inadvertent injury to critical structures or excessive bleeding that necessitates conversion to laparotomy.

A better way to approach the obliterated, or “frozen,” pelvis is to open the retroperitoneal space and identify critical structures:

- Enter the retroperitoneal space at the pelvic brim in an area free of adhesions. Identify the ureter and follow it to the bladder. This can be accomplished using hydrodissection techniques or cavitation techniques with ultrasonic energy.

- Skeletonize, coagulate, and cut the vessels once you reach the cardinal ligament and identify the ascending uterine blood supply.

- Dissect the structures of the obliterated cul de sac using standard techniques.

- Use sharp dissection for adhesiolysis. Laparoscopic blunt dissection of adhesions can lead to serosal tears and inadvertent enterotomy. Sharp dissection or mechanical energy devices are preferred to divide the tissue along the line of demarcation—but remember that monopolar and bipolar devices can cause remote thermal damage that goes undetected at the time of use.

When dissection becomes unproductive in one area, switch to another; dissection planes frequently open and demonstrate the relationships between pelvic structures and loops of bowel.8

Occasionally, the visceral peritoneum of the bowel is breached during adhesiolysis. If the mucosa and muscularis remain intact, denuded serosa need not be repaired. Surgical repair is necessary if mucosa is exposed, or perforation may occur.

Because most ObGyn residency programs offer limited training in management of bowel injuries, intraoperative consultation with a general surgeon may be indicated if more than a simple repair is required.8

CASE RESOLVED

You perform total laparoscopic hysterectomy and find multiple adhesions in the right lower quadrant, adjacent to the area of trocar insertion. Small intestine is adherent to the right lateral pelvic wall; sigmoid colon is adherent to the left pelvic wall; and the anterior fundus is adherent to the bladder peritoneal reflection, with the adhesions extending on either side to include the round ligaments.

You begin adhesiolysis in the right lower quadrant to optimize trocar movement. You transect the round ligaments in the mid-position, with dissection extended retroperitoneally on either side to the midline of the lower uterine segment; this opens access to the ascending branch of the uterine vessels. You dissect the intestine free of either pelvic sidewall along the line of demarcation.

Total blood loss is less than 25 mL. The patient is discharged 6 hours after surgery.

1. Liakakos T, Thomakos N, Fine PM, Dervenis C, Young RL. Peritoneal adhesions: etiology, pathophysiology, and clinical significance. Recent advances in prevention and management. Dig Surg. 2001;18:260-273.

2. Ling FW, DeCherney AH, Diamond MP, diZerega GS, Montz FP. The Challenge of Pelvic Adhesions. Crofton, Md: Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics; 2002.

3. Agarwala N, Liu CY. Safe entry techniques during laparoscopy: left upper quadrant entry using the ninth intercostals space—a review of 918 procedures. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12:55-61.

4. Palmer R. Safety in laparoscopy. J Reprod Med. 1974;13(1):1-5.

5. Childers JM, Brzechffa PR, Surwit EA. Laparoscopy using the left upper quadrant as the primary trocar site. Gynecol Oncol. 1993;50:221-225.

6. Shen CC, Wu MP, Lu CH, et al. Small intestine injury in laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10:350-355.

7. Diamantis T, Kontos M, Arvelakis A, et al. Comparison of monopolar electrocoagulation, bipolar electrocoagulation, Ultracision, and Ligasure. Surg Today. 2006;36:908-913.

8. Perkins JD, Dent LL. Avoiding and repairing bowel injury in gynecologic surgery. OBG Management. 2004;16(8):15-28.

1. Liakakos T, Thomakos N, Fine PM, Dervenis C, Young RL. Peritoneal adhesions: etiology, pathophysiology, and clinical significance. Recent advances in prevention and management. Dig Surg. 2001;18:260-273.

2. Ling FW, DeCherney AH, Diamond MP, diZerega GS, Montz FP. The Challenge of Pelvic Adhesions. Crofton, Md: Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics; 2002.

3. Agarwala N, Liu CY. Safe entry techniques during laparoscopy: left upper quadrant entry using the ninth intercostals space—a review of 918 procedures. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12:55-61.

4. Palmer R. Safety in laparoscopy. J Reprod Med. 1974;13(1):1-5.

5. Childers JM, Brzechffa PR, Surwit EA. Laparoscopy using the left upper quadrant as the primary trocar site. Gynecol Oncol. 1993;50:221-225.

6. Shen CC, Wu MP, Lu CH, et al. Small intestine injury in laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10:350-355.

7. Diamantis T, Kontos M, Arvelakis A, et al. Comparison of monopolar electrocoagulation, bipolar electrocoagulation, Ultracision, and Ligasure. Surg Today. 2006;36:908-913.

8. Perkins JD, Dent LL. Avoiding and repairing bowel injury in gynecologic surgery. OBG Management. 2004;16(8):15-28.

Laparoscopic challenges: The large uterus

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

CASE: Large fibroid uterus. Is laparoscopy feasible?

A 41-year-old woman known to have uterine fibroids consults you after two other gynecologists have recommended abdominal hysterectomy. She weighs 320 lb, stands 5 ft 2 in, and is nulliparous and sexually inactive. Pelvic ultrasonography reveals multiple fibroids approximating 18 weeks’ gestational size. Although she has hypertension and reactive airway disease, these conditions are well controlled by medication. Her Pap smear and endometrial biopsy are negative.

Because her professional commitments limit her time for recovery, she hopes to bypass abdominal hysterectomy in favor of the laparoscopic approach.

Is this desire realistic?

Twenty years have passed since Reich performed the first total laparoscopic hysterectomy,1 but only a small percentage of hysterectomies performed in the United States utilize that approach. In 2003, 12% of 602,457 hysterectomies were done laparoscopically; the rest were performed using the abdominal or vaginal approach (66% and 22%, respectively).2

Yet laparoscopic hysterectomy has much to recommend it. Compared with abdominal hysterectomy, it involves a shorter hospital stay, less blood loss, a speedier return to normal activities, and fewer wound infections.3 Unlike vaginal hysterectomy, it also facilitates intra-abdominal inspection.

Although the opening case represents potentially difficult surgery because of the size of the uterus, the laparoscopic approach is feasible. When the uterus weighs more than 450 g, contains fibroids larger than 6 cm, or exceeds 12 to 14 cm in size,4-7 there is an increased risk of visceral injury, bleeding necessitating transfusion, prolonged operative time, and conversion to laparotomy. This article describes techniques that simplify laparoscopic management when the uterus exceeds 14 weeks’ size. By incorporating these techniques, we have performed laparoscopic hysterectomy in uteri as large as 22 to 24 weeks’ size without increased complications.

In Part 2 of this article, we address techniques that simplify laparoscopy when extensive intra-abdominal adhesions are present.

Why do some surgeons avoid laparoscopy?

Major complications occur in approximately 5% to 6% of women who undergo total laparoscopic hysterectomy.8,9 That is one of the reasons many surgeons who perform laparoscopic procedures revert to the more traditional vaginal or abdominal approach when faced with a potentially difficult hysterectomy. These surgeons cite uteri larger than 14 weeks’ size, extensive intra-abdominal adhesions, and morbid obesity as common indications for a more conservative approach. Others cite the limitations of working with inexperienced surgeons or residents, inadequate laparoscopic instruments, and distorted pelvic anatomy. Still others avoid laparoscopy when the patient has medical problems that preclude use of pneumoperitoneum or a steep Trendelenburg position.

In some cases, laparoscopic hysterectomy is simply not practical. In others, however, such as the presence of a large uterus, it can be achieved with attention to detail, a few key techniques, and proper counseling of the patient.

Success begins preop

All surgical decisions begin with the patient. A comprehensive preoperative discussion of pertinent management options allows both patient and surgeon to proceed with confidence. Easing the patient’s preoperative anxiety is important. It can be achieved by explaining what to expect—not only the normal recovery for laparoscopic hysterectomy, but also the expected recovery if it becomes necessary to convert to laparotomy. If the patient has clear expectations, unexpected outcomes such as conversion are better tolerated. When it comes down to a choice between the surgeon’s ego or patient safety, the patient always wins. Conversion is not failure.

Another important topic to discuss with the patient is the risk of bowel injury. Mechanical bowel preparation is not essential for every patient who undergoes laparoscopic hysterectomy, but the risk of injury to the bowel necessitating colorectal surgical assistance may be heightened in women who have a large uterus or extensive intra-abdominal adhesions. Because of this risk, mechanical bowel preparation with oral polyethylene glycol solution or sodium phosphate should be considered. Most patients prefer the latter.10

What data show about bowel preps

The literature provides conflicting messages about the effectiveness of mechanical bowel preparation in averting additional complications when bowel injury occurs. Nichols and colleagues surveyed 808 active board-certified colorectal surgeons in the United States and Canada in 1995.11 All of the 471 (58%) surgeons who responded reported using some form of mechanical bowel preparation for their elective and emergency colorectal procedures.

Zmora and associates described the difficulty of designing a multicenter study to evaluate the role of mechanical bowel preparation in patient outcome.10 Of the many variables that warrant consideration, surgical technique was the single most important factor influencing surgical outcome.

In a review of evidence supporting the need for prophylactic mechanical bowel preparation prior to elective colorectal surgery, Guenaga and colleagues concluded that this practice is unsupported by the data.12

Bottom line. Given these data, the gynecologist wanting to practice evidence-based medicine should base his or her recommendations about bowel preparation on the preferences of the general or colorectal surgeon who will be called if a bowel injury occurs.

Don’t forget the team

After preparing the patient, prepare your support team—the operating room (OR) and anesthesia staffs. The OR staff should ensure that extra sutures, instruments, and retractors are unopened, in the room, and available in case conversion is necessary. Inform the anesthesia staff of your anticipated surgical time and potential pitfalls. Let them know you will need maximum Trendelenburg position for pelvic exposure, but remain flexible if the patient has trouble with oxygenation and ventilation. Making your anesthesiologist aware of your willingness to work together will benefit both you and your patient immensely.

Preparation continues in the OR

Appropriate patient positioning is key to successful completion of difficult laparoscopic cases. Position the patient’s buttocks several inches beyond the table break to facilitate maximal uterine manipulation, which may be needed for completion of the colpotomy.

Place the patient in the dorsal lithotomy position using Allen stirrups, with the knees flexed at a 90° angle. Keep the knees level with the hips and the hips extended neutrally.

Arm position is important to maximize room for the surgeon alongside the OR table. Space is limited when the patient’s arms are positioned on arm boards. Tucking the arms at the patient’s sides, with the antecubital fossa anterior and the palm cupping the hip, improves the surgical field and secures the patient to the OR table (FIGURE 1). Protect the elbows and hands with cushions.

Place sequential compression devices (on the calf or foot) for the duration of the procedure to minimize the risk of blood stasis and clots that sometimes develop in the legs with prolonged surgical times. Many complex laparoscopic cases last longer than 2 hours.

FIGURE 1 Positioning the patient

Tuck the arms at the patient’s sides, with the antecubital fossa anterior and the palm cupping the hip, to improve the surgical field.

Maximum Trendelenburg position is a must

This positioning is essential for successful anatomic exposure in complex laparoscopic surgical cases. If the patient is positioned securely, maximum Trendelenburg position does not increase the risk of the patient sliding off the OR table, nor does it affect oxygenation in most morbidly obese patients. Rather, it allows the intestines to drop out of the pelvis into the upper abdomen, facilitating visualization and decreasing the risk of bowel injury.

Anesthesia staffers often limit the degree of Trendelenburg position unless the surgeon insists otherwise. Alternating patient position between maximum Trendelenburg for optimal surgical exposure and a less steep angle when patient oxygenation requires it allows the gynecologic surgeon and anesthesiologist to work together in the patient’s best interest.

Video monitor placement is key

It helps determine how efficiently you operate. Use of a single central monitor requires both the surgeon and assistant to turn their heads acutely during prolonged procedures, accelerating their fatigue and potentially increasing the risk of injury. Using two monitors—each placed to allow the surgeon and assistant to maintain neutral head position—minimizes fatigue and its attendant risks.

Entering the abdomen

Abdominal entry poses theoretical obstacles when the patient has a large uterus, but all types of entry remain safe as long as laparoscopic surgical principles are followed scrupulously. We have successfully used traditional Veress needle entry, open laparoscopic entry, and left upper quadrant entry.

Is entry above the umbilicus helpful?

Anecdotal reports suggest a midline port above the umbilicus when the uterus extends above the umbilicus, but we do not alter standard port placement in these cases. By tenting the abdominal wall at the umbilicus, we create adequate distance to achieve pneumoperitoneum and space for directed trocar entry to avoid injury to the uterus. The conventional umbilical primary port allows use of standard-length instruments. The cephalad uterine blood supply (infundibulopelvic ligament vessels or utero-ovarian ligament vessels) remains at or below the level of the umbilicus in almost all of these patients.

Port placement in the patient who has a large uterus is the same as it is for other laparoscopic hysterectomies in our practice. We use an 11-mm trocar at the umbilicus for a 10-mm endoscope. We use the 10-mm endoscope because the light it provides to the surgical field is superior to that of a 5-mm endoscope, and the 10-mm scope is more durable.

We place a 5-mm trocar just above the anterior iliac crest on each side, lateral to the ascending inferior epigastric vessels (FIGURE 2). We place an 11-mm trocar 10 cm medial and cephalad to the lower iliac crest port on the side of the primary surgeon. This trocar serves a dual purpose: It is the primary port for the surgeon, and removal of the trocar sleeve later in the procedure allows for easy insertion of the morcellator.

Some patients will require a fifth port on the side opposite the primary surgeon to allow better access to the uterine blood supply or to facilitate uterine manipulation.

FIGURE 2 Port placement when the uterus is large

A midline umbilical port (A) is possible even when the uterus is large. Other ports include a 5-mm trocar just above the anterior iliac crest on each side (B), and an 11-mm trocar 10 cm medial and cephalad to the lower iliac crest port nearest the primary surgeon (C).

Why an angled scope is superior

Many gynecologists fear laparoscopic surgery in patients who have a large uterus. The reason? Poor visualization of the surgical field. However, the type of endoscope that is used has a bearing on visualization.

Most gynecologists are trained to use a 0° endoscope for laparoscopic surgery. However, when the uterus is large, the 0° scope yields an inadequate field of view, whether the endoscope is placed at the umbilicus or through a lateral port. Critical structures like the vascular bundles, ureters, and even the bladder may be inadequately visualized using the 0° endoscope (FIGURE 3).

Gynecologists routinely use angled scopes in hysteroscopy and cystoscopy, but tend to avoid them in laparoscopy because of difficulty orienting the surgical field. As gynecologists, we readily accept that use of an angled scope in hysteroscopy and cystoscopy requires rotation of the scope while the camera maintains its horizontal position. The same concept applies to laparoscopy.

Use of the angled scope in the abdomen is a two-step process. First, it must be rotated to achieve the desired field of view. Then, as the endoscope is held firmly to maintain this view, the camera head must be rotated on the scope to return the field to a horizontal position.

Many surgeons find this action difficult because they or the assistant are holding the camera in one hand and an instrument in the other. We solve this problem by using a mechanical scope holder to secure the camera and endoscope in the position we desire.

In some cases, the camera head does not attach securely to the eyepiece, and the scope rotates on the camera as soon as it is released. This difficulty arises when the eyepiece of the endoscope is slightly smaller than the camera attachment. The problem is easily solved by placing a small piece of surgical skin closure tape on one edge of the eyepiece, slightly increasing its diameter. The camera attachment then holds the scope securely.

Human scope holders may tire during long cases, causing field drift at critical moments. In contrast, a mechanical scope holder is easily and intermittently adjusted for field of view, producing a steady field of view and minimizing the impact of manual manipulation of the scope on surgical outcome. It also allows the surgeon and first assistant to use two hands while operating.

General surgeons and urologists often use 30° endoscopes. Gynecologists working in the pelvis see better using a 45° scope (FIGURE 3). Most ORs offer a 30° endoscope but do not always have a 45° endoscope available in the instrument room. This is regrettable. Compared with the 30° scope, the 45° instrument provides better visual access to the low lateral uterine blood supply and bladder flap, particularly when the patient has a globular uterus or large, low anterior fibroid. We include both 5-mm and 10-mm 45° endoscopes in our laparoscopic tool chest, and believe they are essential options.

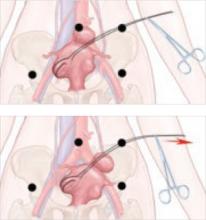

FIGURE 3 The 45° laparoscope provides better visual access

(A) 0° scope, uterus midline: Right broad ligament view obstructed. (B) 0° scope, uterus to left: Right broad ligament view still obstructed. (C) 45° scope, uterus midline: Right broad ligament view improved. (D) 45° scope, uterus to left: Right broad ligament view optimal.

Control the blood supply

Our laparoscopic approach is very similar to our technique for abdominal hysterectomy, beginning with the blood supply. The main blood supply to the uterus enters at only four points. If this blood supply is adequately controlled, morcellation of the large uterus can proceed without excessive blood loss.

Visualization of the blood supply is normally restricted because of tense, taut round ligaments that limit mobility of the large uterus. A simple step to improve mobility is to transect each round ligament in its middle position before addressing the uterine blood supply.

If the ovaries are being conserved, transect the utero-ovarian ligament and tube as close to the ovary as possible with your instrument and technique of choice (electrical or mechanical energy, etc); they all work. Stay close to the ovary to avert bleeding that might otherwise occur when the ascending uterine vascular coils are cut tangentially.

If the ovaries are being removed, transect the infundibulopelvic ligament close to the ovary, being careful not to include ovarian tissue in the pedicle. Use your method of choice, but relieve tension on the pedicle as it is being transected to minimize the risk of pedicle bleeding.

Now, 20% to 40% of the uterine blood supply is controlled, with minimal blood loss.

The key to controlling the remaining blood supply is transecting the ascending vascular bundle as low as possible on either side. The 45° endoscope provides optimal visualization for this part of the procedure. Many times the field of view attained using the 45° endoscope is all that is necessary to facilitate occlusion and transection of these vessels at the level of the internal cervical os.

We commonly use ultrasonic energy to coagulate and cut the ascending vascular bundle. Ultrasonic energy provides excellent hemostasis for this part of the procedure. Again, use the technique of your choice.

Use a laparoscopic “leash”

At times, large broad-ligament fibroids obscure the field of view and access to the ascending vascular bundle. Standard laparoscopic graspers cannot maintain a firm hold on the tissue to improve visibility or access. The solution? A laparoscopic “leash,” first described in 1999 by Tsin and colleagues.13

Giesler extended that concept with a “puppet string” variation to maximize exposure in difficult cases. To apply the “puppet string” technique, using No. 1 Prolene suture, place a large figure-of-eight suture through the tissue to be retracted (FIGURE 4). Bring the suture out of the abdomen adjacent to the trocar sleeve in a location that provides optimal traction. (First, bring the suture through the trocar sleeve. Then remove the trocar sleeve and reinsert it adjacent to the retraction suture.) This secure attachment allows better visualization and greater access to the blood supply at a lower level. It also is possible to manipulate this suture inside the abdomen using traditional graspers to provide reliable repositioning of the uterus. This degree of tissue control improves field of vision and allows the procedure to advance smoothly.

FIGURE 4 A “puppet string” improves access

This secure attachment allows better visualization and greater access to the blood supply at a lower level. Manipulation of this suture inside the abdomen using traditional graspers also helps reposition the uterus.

Morcellation techniques

Once the ascending blood supply has been managed on both sides, morcellation can be performed with minimal blood loss using one of two techniques:

- Amputate the body of the uterus above the level where the blood supply has been interrupted

- Morcellate the uterine body to a point just above the level where the blood supply has been interrupted.

Use basic principles, regardless of the technique chosen

- Hold the morcellator in one hand and a toothed grasper in the other hand to pull tissue into the morcellator. Do not push the morcellator into tissue or you may injure nonvisualized structures on the other side.

- Morcellate tissue in half-moon portions, skimming along the top of the fundus, instead of coring the uterus like an apple; it creates longer strips of tissue and is faster. This technique also allows continuous observation of the active blade, which helps avoid inadvertent injury to tissues behind the blade.

- Attempt morcellation in the anterior abdominal space to avoid injury to blood vessels, ureters, and bowel in the posterior abdominal space. The assistant feeds uterine tissue to the surgeon in the anterior space.

It is essential to control the blood supply to the tissue to be morcellated before morcellation to avoid massive hemorrhage.

Amputating the upper uterine body

Amputation of the large body of the uterus from the lower uterine segment assures complete control of the blood supply and avoids further blood loss during morcellation, but it also poses difficulties. The free uterine mass is held in position by the assistant using only one grasper. If this grasper slips, the mass can be inadvertently released while the morcellator blade is active. If the assistant is also holding the camera, there are no options for stabilizing the free uterine mass. If a mechanical scope holder or second assistant is available to hold the camera, a second trocar port can be placed on the side of the assistant to provide access for a second grasper to stabilize the uterine body during morcellation. The need for a stable uterine mass is important to minimize the risk of injury.

Once the upper body of the uterus has been removed by morcellation, the lower uterine segment and cervix must be removed—using your procedure of choice—to finish the hysterectomy.

Morcellating the upper uterine body

If the uterus remains attached to the cervix, it already has one fixed point of stability. During morcellation, the assistant has one hand available to direct the camera. Blood loss during morcellation of the uterus while it is still attached to the cervix is minimal because the ascending vascular bundles on either side have been interrupted under direct vision.

For greater control of the large uterus, a second port can be placed on the assistant’s side for a second grasper, as described above. Most of the large uterus that is still connected to the cervix can be morcellated in the anterior abdominal space in horizontal fashion, as for the free uterine mass just described.

Uterine manipulation by the assistant keeps the uterus away from critical structures as it is reduced to 8 to 10 weeks’ size. Once this size is attained, resume normal technique for total laparoscopic hysterectomy to separate the remaining tissue from the vagina.

2 types of morcellators in use today

One has a disposable 15-mm blade that attaches to a drive unit adjacent to the OR table (Gynecare-Ethicon Women’s Health and Urology). The other has a sterile, reusable drive unit with a disposable blade (Storz). Both work well on large uteri.

The reusable drive unit has more power to morcellate calcified fibroids and offers a choice between 12-mm, 15-mm, and 20-mm disposable blades for faster morcellation.

Concluding the procedure

Chips of fibroid and uterine tissue created during morcellation often remain in the pelvis after the uterus has been removed. Place them in a 10-cm specimen-collection bag and extract it through the vagina after removal of the residual uterus and cervix. This is faster and easier than recovering them one at a time with the gall bladder stone scoop through a trocar port. The value of the OR time saved with use of the specimen-collection bag is significantly greater than that of the disposable collection device.

CASE RESOLVED

You perform total laparoscopic hysterectomy and find 6-cm fibroids in both broad ligament areas and over the cervical–vaginal junction on the left. You use a “puppet string” to apply directed traction to the fibroids to simplify their extraction. The 45° endoscope allows clear visualization of the ascending vascular bundle on both sides, and the mechanical scope holder allows a fixed field of view for the meticulous dissection required to remove the broad-ligament fibroids.

You morcellate the entire 663-g uterus and remove it in pieces through the abdominal wall. The extensive morcellation required, coupled with technical issues related to the patient’s morbid obesity, prolong the procedure to more than 4 hours.

Postoperatively, the patient voids without a catheter, walks around the nursing unit, and eats half a sandwich within 4 hours. She is discharged home in less than 24 hours and is able to drive 4 days after her surgery.

1. Reich H, DeCaprio J, McGlynn F. Laparoscopic hysterectomy. J Gynecol Surg. 1989;5:213-216.

2. Wu JM, Wechter ME, Geller EJ, Nguyen TV, Visco AG. Hysterectomy rates in the United States, 2003. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:1091-1095.

3. Johnson N, Barlow D, Lethaby A, Tavender E, Curr E, Garry R. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 Jan 25;(1):CD003677.-

4. Leonard F, Chopin N, Borghese B, et al. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy: preoperative risk factors for conversion to laparotomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12:312-317.

5. Fiaccavento A, Landi S, Barbieri F, et al. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy in cases of very large uteri: a retrospective comparative study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:559-563.

6. Pelosi MA, Kadar N. Laparoscopically assisted hysterectomy for uteri weighing 500 g or more. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1994;1:405-409.

7. Seracchioli R, Venturoli S, Vianello F, et al. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy compared with abdominal hysterectomy in the presence of a large uterus. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002;9:333-338.

8. Hoffman CP, Kennedy J, Borschel L, Burchette R, Kidd A. Laparoscopic hysterectomy: the Kaiser Permanente San Diego experience. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12:16-24.

9. Liu CY, Reich H. Complications of total laparoscopic hysterectomy in 518 cases. Gynaecol Endosc. 1994;3:203-208.

10. Zmora O, Pikarsky AJ, Wexner SD. Bowel preparation for colorectal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1537-1547.

11. Nichols RI, Smith JW, Girch RY, Waterman RS, Holmes JWC. Current practices of preoperative bowel preparation among North American colorectal surgeons. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:609-619.

12. Guenaga KF, Matos D, Castro AA, Atallah AN, Wille-Jørgensen P. Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 Jan 25;(1):CD001544.-

13. Tsin DA, Colombero LT. Laparoscopic leash: a simple technique to prevent specimen loss during operative laparoscopy. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:628-629.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

CASE: Large fibroid uterus. Is laparoscopy feasible?

A 41-year-old woman known to have uterine fibroids consults you after two other gynecologists have recommended abdominal hysterectomy. She weighs 320 lb, stands 5 ft 2 in, and is nulliparous and sexually inactive. Pelvic ultrasonography reveals multiple fibroids approximating 18 weeks’ gestational size. Although she has hypertension and reactive airway disease, these conditions are well controlled by medication. Her Pap smear and endometrial biopsy are negative.

Because her professional commitments limit her time for recovery, she hopes to bypass abdominal hysterectomy in favor of the laparoscopic approach.

Is this desire realistic?

Twenty years have passed since Reich performed the first total laparoscopic hysterectomy,1 but only a small percentage of hysterectomies performed in the United States utilize that approach. In 2003, 12% of 602,457 hysterectomies were done laparoscopically; the rest were performed using the abdominal or vaginal approach (66% and 22%, respectively).2

Yet laparoscopic hysterectomy has much to recommend it. Compared with abdominal hysterectomy, it involves a shorter hospital stay, less blood loss, a speedier return to normal activities, and fewer wound infections.3 Unlike vaginal hysterectomy, it also facilitates intra-abdominal inspection.

Although the opening case represents potentially difficult surgery because of the size of the uterus, the laparoscopic approach is feasible. When the uterus weighs more than 450 g, contains fibroids larger than 6 cm, or exceeds 12 to 14 cm in size,4-7 there is an increased risk of visceral injury, bleeding necessitating transfusion, prolonged operative time, and conversion to laparotomy. This article describes techniques that simplify laparoscopic management when the uterus exceeds 14 weeks’ size. By incorporating these techniques, we have performed laparoscopic hysterectomy in uteri as large as 22 to 24 weeks’ size without increased complications.

In Part 2 of this article, we address techniques that simplify laparoscopy when extensive intra-abdominal adhesions are present.

Why do some surgeons avoid laparoscopy?

Major complications occur in approximately 5% to 6% of women who undergo total laparoscopic hysterectomy.8,9 That is one of the reasons many surgeons who perform laparoscopic procedures revert to the more traditional vaginal or abdominal approach when faced with a potentially difficult hysterectomy. These surgeons cite uteri larger than 14 weeks’ size, extensive intra-abdominal adhesions, and morbid obesity as common indications for a more conservative approach. Others cite the limitations of working with inexperienced surgeons or residents, inadequate laparoscopic instruments, and distorted pelvic anatomy. Still others avoid laparoscopy when the patient has medical problems that preclude use of pneumoperitoneum or a steep Trendelenburg position.

In some cases, laparoscopic hysterectomy is simply not practical. In others, however, such as the presence of a large uterus, it can be achieved with attention to detail, a few key techniques, and proper counseling of the patient.

Success begins preop

All surgical decisions begin with the patient. A comprehensive preoperative discussion of pertinent management options allows both patient and surgeon to proceed with confidence. Easing the patient’s preoperative anxiety is important. It can be achieved by explaining what to expect—not only the normal recovery for laparoscopic hysterectomy, but also the expected recovery if it becomes necessary to convert to laparotomy. If the patient has clear expectations, unexpected outcomes such as conversion are better tolerated. When it comes down to a choice between the surgeon’s ego or patient safety, the patient always wins. Conversion is not failure.

Another important topic to discuss with the patient is the risk of bowel injury. Mechanical bowel preparation is not essential for every patient who undergoes laparoscopic hysterectomy, but the risk of injury to the bowel necessitating colorectal surgical assistance may be heightened in women who have a large uterus or extensive intra-abdominal adhesions. Because of this risk, mechanical bowel preparation with oral polyethylene glycol solution or sodium phosphate should be considered. Most patients prefer the latter.10

What data show about bowel preps

The literature provides conflicting messages about the effectiveness of mechanical bowel preparation in averting additional complications when bowel injury occurs. Nichols and colleagues surveyed 808 active board-certified colorectal surgeons in the United States and Canada in 1995.11 All of the 471 (58%) surgeons who responded reported using some form of mechanical bowel preparation for their elective and emergency colorectal procedures.

Zmora and associates described the difficulty of designing a multicenter study to evaluate the role of mechanical bowel preparation in patient outcome.10 Of the many variables that warrant consideration, surgical technique was the single most important factor influencing surgical outcome.

In a review of evidence supporting the need for prophylactic mechanical bowel preparation prior to elective colorectal surgery, Guenaga and colleagues concluded that this practice is unsupported by the data.12

Bottom line. Given these data, the gynecologist wanting to practice evidence-based medicine should base his or her recommendations about bowel preparation on the preferences of the general or colorectal surgeon who will be called if a bowel injury occurs.

Don’t forget the team

After preparing the patient, prepare your support team—the operating room (OR) and anesthesia staffs. The OR staff should ensure that extra sutures, instruments, and retractors are unopened, in the room, and available in case conversion is necessary. Inform the anesthesia staff of your anticipated surgical time and potential pitfalls. Let them know you will need maximum Trendelenburg position for pelvic exposure, but remain flexible if the patient has trouble with oxygenation and ventilation. Making your anesthesiologist aware of your willingness to work together will benefit both you and your patient immensely.

Preparation continues in the OR

Appropriate patient positioning is key to successful completion of difficult laparoscopic cases. Position the patient’s buttocks several inches beyond the table break to facilitate maximal uterine manipulation, which may be needed for completion of the colpotomy.

Place the patient in the dorsal lithotomy position using Allen stirrups, with the knees flexed at a 90° angle. Keep the knees level with the hips and the hips extended neutrally.

Arm position is important to maximize room for the surgeon alongside the OR table. Space is limited when the patient’s arms are positioned on arm boards. Tucking the arms at the patient’s sides, with the antecubital fossa anterior and the palm cupping the hip, improves the surgical field and secures the patient to the OR table (FIGURE 1). Protect the elbows and hands with cushions.

Place sequential compression devices (on the calf or foot) for the duration of the procedure to minimize the risk of blood stasis and clots that sometimes develop in the legs with prolonged surgical times. Many complex laparoscopic cases last longer than 2 hours.

FIGURE 1 Positioning the patient

Tuck the arms at the patient’s sides, with the antecubital fossa anterior and the palm cupping the hip, to improve the surgical field.

Maximum Trendelenburg position is a must

This positioning is essential for successful anatomic exposure in complex laparoscopic surgical cases. If the patient is positioned securely, maximum Trendelenburg position does not increase the risk of the patient sliding off the OR table, nor does it affect oxygenation in most morbidly obese patients. Rather, it allows the intestines to drop out of the pelvis into the upper abdomen, facilitating visualization and decreasing the risk of bowel injury.

Anesthesia staffers often limit the degree of Trendelenburg position unless the surgeon insists otherwise. Alternating patient position between maximum Trendelenburg for optimal surgical exposure and a less steep angle when patient oxygenation requires it allows the gynecologic surgeon and anesthesiologist to work together in the patient’s best interest.

Video monitor placement is key

It helps determine how efficiently you operate. Use of a single central monitor requires both the surgeon and assistant to turn their heads acutely during prolonged procedures, accelerating their fatigue and potentially increasing the risk of injury. Using two monitors—each placed to allow the surgeon and assistant to maintain neutral head position—minimizes fatigue and its attendant risks.

Entering the abdomen

Abdominal entry poses theoretical obstacles when the patient has a large uterus, but all types of entry remain safe as long as laparoscopic surgical principles are followed scrupulously. We have successfully used traditional Veress needle entry, open laparoscopic entry, and left upper quadrant entry.

Is entry above the umbilicus helpful?

Anecdotal reports suggest a midline port above the umbilicus when the uterus extends above the umbilicus, but we do not alter standard port placement in these cases. By tenting the abdominal wall at the umbilicus, we create adequate distance to achieve pneumoperitoneum and space for directed trocar entry to avoid injury to the uterus. The conventional umbilical primary port allows use of standard-length instruments. The cephalad uterine blood supply (infundibulopelvic ligament vessels or utero-ovarian ligament vessels) remains at or below the level of the umbilicus in almost all of these patients.

Port placement in the patient who has a large uterus is the same as it is for other laparoscopic hysterectomies in our practice. We use an 11-mm trocar at the umbilicus for a 10-mm endoscope. We use the 10-mm endoscope because the light it provides to the surgical field is superior to that of a 5-mm endoscope, and the 10-mm scope is more durable.

We place a 5-mm trocar just above the anterior iliac crest on each side, lateral to the ascending inferior epigastric vessels (FIGURE 2). We place an 11-mm trocar 10 cm medial and cephalad to the lower iliac crest port on the side of the primary surgeon. This trocar serves a dual purpose: It is the primary port for the surgeon, and removal of the trocar sleeve later in the procedure allows for easy insertion of the morcellator.

Some patients will require a fifth port on the side opposite the primary surgeon to allow better access to the uterine blood supply or to facilitate uterine manipulation.

FIGURE 2 Port placement when the uterus is large

A midline umbilical port (A) is possible even when the uterus is large. Other ports include a 5-mm trocar just above the anterior iliac crest on each side (B), and an 11-mm trocar 10 cm medial and cephalad to the lower iliac crest port nearest the primary surgeon (C).

Why an angled scope is superior

Many gynecologists fear laparoscopic surgery in patients who have a large uterus. The reason? Poor visualization of the surgical field. However, the type of endoscope that is used has a bearing on visualization.

Most gynecologists are trained to use a 0° endoscope for laparoscopic surgery. However, when the uterus is large, the 0° scope yields an inadequate field of view, whether the endoscope is placed at the umbilicus or through a lateral port. Critical structures like the vascular bundles, ureters, and even the bladder may be inadequately visualized using the 0° endoscope (FIGURE 3).

Gynecologists routinely use angled scopes in hysteroscopy and cystoscopy, but tend to avoid them in laparoscopy because of difficulty orienting the surgical field. As gynecologists, we readily accept that use of an angled scope in hysteroscopy and cystoscopy requires rotation of the scope while the camera maintains its horizontal position. The same concept applies to laparoscopy.

Use of the angled scope in the abdomen is a two-step process. First, it must be rotated to achieve the desired field of view. Then, as the endoscope is held firmly to maintain this view, the camera head must be rotated on the scope to return the field to a horizontal position.

Many surgeons find this action difficult because they or the assistant are holding the camera in one hand and an instrument in the other. We solve this problem by using a mechanical scope holder to secure the camera and endoscope in the position we desire.

In some cases, the camera head does not attach securely to the eyepiece, and the scope rotates on the camera as soon as it is released. This difficulty arises when the eyepiece of the endoscope is slightly smaller than the camera attachment. The problem is easily solved by placing a small piece of surgical skin closure tape on one edge of the eyepiece, slightly increasing its diameter. The camera attachment then holds the scope securely.

Human scope holders may tire during long cases, causing field drift at critical moments. In contrast, a mechanical scope holder is easily and intermittently adjusted for field of view, producing a steady field of view and minimizing the impact of manual manipulation of the scope on surgical outcome. It also allows the surgeon and first assistant to use two hands while operating.

General surgeons and urologists often use 30° endoscopes. Gynecologists working in the pelvis see better using a 45° scope (FIGURE 3). Most ORs offer a 30° endoscope but do not always have a 45° endoscope available in the instrument room. This is regrettable. Compared with the 30° scope, the 45° instrument provides better visual access to the low lateral uterine blood supply and bladder flap, particularly when the patient has a globular uterus or large, low anterior fibroid. We include both 5-mm and 10-mm 45° endoscopes in our laparoscopic tool chest, and believe they are essential options.

FIGURE 3 The 45° laparoscope provides better visual access

(A) 0° scope, uterus midline: Right broad ligament view obstructed. (B) 0° scope, uterus to left: Right broad ligament view still obstructed. (C) 45° scope, uterus midline: Right broad ligament view improved. (D) 45° scope, uterus to left: Right broad ligament view optimal.