User login

MDedge latest news is breaking news from medical conferences, journals, guidelines, the FDA and CDC.

Cholecystectomy Delay Linked to Substantially Increased Complication Risk

, regardless of the receipt of sphincterotomy or stenting, new research showed.

“These findings suggest an opportunity for systemic interventions, including prioritization algorithms and better perioperative coordination, to address preventable delays,” reported the authors in the study, presented at American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting.

Choledocholithiasis can occur in up to 20% of symptomatic gallstone cases, and while guidelines recommend having a cholecystectomy concurrently with ERCP, data on the best timing is inconsistent and delays in gall bladder removal are consequently common.

One large study, for instance, the PONCHO trial conducted at 23 hospitals in Netherlands, showed complications to be significantly lower with same-admission vs interval cholecystectomy (4.7% vs 16.9%; P = .02).

Meanwhile, other research has suggested that delayed cholecystectomy is a preferred approach, allowing for removal when there is less inflammation.

Real world data meanwhile shows, despite the guidelines, the procedures are performed at the same time as ERCP only in about 41% of cases, first author Jessica El Halabi, MD, of the Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, said.

To further investigate outcomes associated with those delays, El Halabi and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study involving 507 patients admitted with choledocholithiasis at the hospital and community hospitals between 2005 and 2023 who had 12 months or more follow-up.

The patients had a mean age of 59 years and 59.4% were women.

Of the patients, 265 (52.3%) underwent early cholecystectomy, defined as surgery during the index admission, while 242 (47.7%) underwent delayed cholecystectomy, defined as postdischarge cholecystectomy or if cholecystectomy was not performed.

Overall, biliary complications occurred in as many as 23% of those who had delayed cholecystectomy compared with just 0.8% among those having the early cholecystectomy (P < .001).

Of patients who had delayed cholecystectomy and developed complications, 15.5% did so within 3 months, 6.5% by 6 months, and 1% by 12 months.

Among those who had ERCP with sphincterotomy, there were no significant differences in rates of biliary complications vs those who did not have sphincterotomy (26% vs 21%; P = .74), while stenting also did not reduce the risk (25% vs 27%; P = .81).

The leading reasons for delayed cholecystectomy included patients having a high surgical risk (27.3%), concurrent biliary pathology (19.2%), and physician preference (14%).

The findings underscore that “concurrent cholecystectomy is associated with the lowest risk of biliary complications,” El Halabi said.

“Delayed cholecystectomy is associated with an approximately 23% incidence of biliary complications with 1 year of initial admission, with the highest incidence occurring within 3 months,” she added. “Neither sphincterotomy nor stenting during ERCP mitigates this risk.”

“Early cholecystectomy during the index admission remains the most reliable strategy to reduce recurrent events.”

Findings Underscore Importance of Timing

Commenting on the study, Luis F. Lara, MD, division chief of digestive diseases at the University of Cincinnati, who co-moderated the session, agreed that evidence soundly supports early cholecystectomy.

“We also did a large study looking at this and there’s no doubt that doing it during the index admission has a tremendous effect on long-term outcomes,” Lara told GI & Hepatology News.

Lara noted that “part of it is people don’t show up again until they get sick again, so we don’t want to lose that opportunity the first time, during the index admission,” he said.

Lara’s previous studies have specifically documented how early cholecystectomy for acute biliary pancreatitis improves outcomes of hospitalization for cirrhosis and factors associated with early unplanned readmissions following same-admission cholecystectomy for acute biliary pancreatitis.

Akwi W. Asombang, MD, an interventional gastroenterologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, agreed that the findings are important.

“We know that if a cholecystectomy is not performed in the same admission as ERCP, the stones in the gallbladder remain and may migrate out into the bile duct, resulting in further complications as described in the study,” Asombang, also a session co-moderator, told GI & Hepatology News.

She noted that the practice can vary between institutions based on factors including the availability of physicians to perform the cholecystectomy.

Potential complications in delaying the procedure can range from inflammation and pancreatitis to obstruction of the bile duct, “which then can result in cholangitis and eventually sepsis or even death,” Asombang cautioned.

“So the timing of the procedure with ERCP is definitely significant,” she said.

El Halabi and Asombang had no disclosures to report. Lara reported a relationship with AbbVie.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, regardless of the receipt of sphincterotomy or stenting, new research showed.

“These findings suggest an opportunity for systemic interventions, including prioritization algorithms and better perioperative coordination, to address preventable delays,” reported the authors in the study, presented at American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting.

Choledocholithiasis can occur in up to 20% of symptomatic gallstone cases, and while guidelines recommend having a cholecystectomy concurrently with ERCP, data on the best timing is inconsistent and delays in gall bladder removal are consequently common.

One large study, for instance, the PONCHO trial conducted at 23 hospitals in Netherlands, showed complications to be significantly lower with same-admission vs interval cholecystectomy (4.7% vs 16.9%; P = .02).

Meanwhile, other research has suggested that delayed cholecystectomy is a preferred approach, allowing for removal when there is less inflammation.

Real world data meanwhile shows, despite the guidelines, the procedures are performed at the same time as ERCP only in about 41% of cases, first author Jessica El Halabi, MD, of the Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, said.

To further investigate outcomes associated with those delays, El Halabi and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study involving 507 patients admitted with choledocholithiasis at the hospital and community hospitals between 2005 and 2023 who had 12 months or more follow-up.

The patients had a mean age of 59 years and 59.4% were women.

Of the patients, 265 (52.3%) underwent early cholecystectomy, defined as surgery during the index admission, while 242 (47.7%) underwent delayed cholecystectomy, defined as postdischarge cholecystectomy or if cholecystectomy was not performed.

Overall, biliary complications occurred in as many as 23% of those who had delayed cholecystectomy compared with just 0.8% among those having the early cholecystectomy (P < .001).

Of patients who had delayed cholecystectomy and developed complications, 15.5% did so within 3 months, 6.5% by 6 months, and 1% by 12 months.

Among those who had ERCP with sphincterotomy, there were no significant differences in rates of biliary complications vs those who did not have sphincterotomy (26% vs 21%; P = .74), while stenting also did not reduce the risk (25% vs 27%; P = .81).

The leading reasons for delayed cholecystectomy included patients having a high surgical risk (27.3%), concurrent biliary pathology (19.2%), and physician preference (14%).

The findings underscore that “concurrent cholecystectomy is associated with the lowest risk of biliary complications,” El Halabi said.

“Delayed cholecystectomy is associated with an approximately 23% incidence of biliary complications with 1 year of initial admission, with the highest incidence occurring within 3 months,” she added. “Neither sphincterotomy nor stenting during ERCP mitigates this risk.”

“Early cholecystectomy during the index admission remains the most reliable strategy to reduce recurrent events.”

Findings Underscore Importance of Timing

Commenting on the study, Luis F. Lara, MD, division chief of digestive diseases at the University of Cincinnati, who co-moderated the session, agreed that evidence soundly supports early cholecystectomy.

“We also did a large study looking at this and there’s no doubt that doing it during the index admission has a tremendous effect on long-term outcomes,” Lara told GI & Hepatology News.

Lara noted that “part of it is people don’t show up again until they get sick again, so we don’t want to lose that opportunity the first time, during the index admission,” he said.

Lara’s previous studies have specifically documented how early cholecystectomy for acute biliary pancreatitis improves outcomes of hospitalization for cirrhosis and factors associated with early unplanned readmissions following same-admission cholecystectomy for acute biliary pancreatitis.

Akwi W. Asombang, MD, an interventional gastroenterologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, agreed that the findings are important.

“We know that if a cholecystectomy is not performed in the same admission as ERCP, the stones in the gallbladder remain and may migrate out into the bile duct, resulting in further complications as described in the study,” Asombang, also a session co-moderator, told GI & Hepatology News.

She noted that the practice can vary between institutions based on factors including the availability of physicians to perform the cholecystectomy.

Potential complications in delaying the procedure can range from inflammation and pancreatitis to obstruction of the bile duct, “which then can result in cholangitis and eventually sepsis or even death,” Asombang cautioned.

“So the timing of the procedure with ERCP is definitely significant,” she said.

El Halabi and Asombang had no disclosures to report. Lara reported a relationship with AbbVie.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, regardless of the receipt of sphincterotomy or stenting, new research showed.

“These findings suggest an opportunity for systemic interventions, including prioritization algorithms and better perioperative coordination, to address preventable delays,” reported the authors in the study, presented at American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting.

Choledocholithiasis can occur in up to 20% of symptomatic gallstone cases, and while guidelines recommend having a cholecystectomy concurrently with ERCP, data on the best timing is inconsistent and delays in gall bladder removal are consequently common.

One large study, for instance, the PONCHO trial conducted at 23 hospitals in Netherlands, showed complications to be significantly lower with same-admission vs interval cholecystectomy (4.7% vs 16.9%; P = .02).

Meanwhile, other research has suggested that delayed cholecystectomy is a preferred approach, allowing for removal when there is less inflammation.

Real world data meanwhile shows, despite the guidelines, the procedures are performed at the same time as ERCP only in about 41% of cases, first author Jessica El Halabi, MD, of the Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, said.

To further investigate outcomes associated with those delays, El Halabi and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study involving 507 patients admitted with choledocholithiasis at the hospital and community hospitals between 2005 and 2023 who had 12 months or more follow-up.

The patients had a mean age of 59 years and 59.4% were women.

Of the patients, 265 (52.3%) underwent early cholecystectomy, defined as surgery during the index admission, while 242 (47.7%) underwent delayed cholecystectomy, defined as postdischarge cholecystectomy or if cholecystectomy was not performed.

Overall, biliary complications occurred in as many as 23% of those who had delayed cholecystectomy compared with just 0.8% among those having the early cholecystectomy (P < .001).

Of patients who had delayed cholecystectomy and developed complications, 15.5% did so within 3 months, 6.5% by 6 months, and 1% by 12 months.

Among those who had ERCP with sphincterotomy, there were no significant differences in rates of biliary complications vs those who did not have sphincterotomy (26% vs 21%; P = .74), while stenting also did not reduce the risk (25% vs 27%; P = .81).

The leading reasons for delayed cholecystectomy included patients having a high surgical risk (27.3%), concurrent biliary pathology (19.2%), and physician preference (14%).

The findings underscore that “concurrent cholecystectomy is associated with the lowest risk of biliary complications,” El Halabi said.

“Delayed cholecystectomy is associated with an approximately 23% incidence of biliary complications with 1 year of initial admission, with the highest incidence occurring within 3 months,” she added. “Neither sphincterotomy nor stenting during ERCP mitigates this risk.”

“Early cholecystectomy during the index admission remains the most reliable strategy to reduce recurrent events.”

Findings Underscore Importance of Timing

Commenting on the study, Luis F. Lara, MD, division chief of digestive diseases at the University of Cincinnati, who co-moderated the session, agreed that evidence soundly supports early cholecystectomy.

“We also did a large study looking at this and there’s no doubt that doing it during the index admission has a tremendous effect on long-term outcomes,” Lara told GI & Hepatology News.

Lara noted that “part of it is people don’t show up again until they get sick again, so we don’t want to lose that opportunity the first time, during the index admission,” he said.

Lara’s previous studies have specifically documented how early cholecystectomy for acute biliary pancreatitis improves outcomes of hospitalization for cirrhosis and factors associated with early unplanned readmissions following same-admission cholecystectomy for acute biliary pancreatitis.

Akwi W. Asombang, MD, an interventional gastroenterologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, agreed that the findings are important.

“We know that if a cholecystectomy is not performed in the same admission as ERCP, the stones in the gallbladder remain and may migrate out into the bile duct, resulting in further complications as described in the study,” Asombang, also a session co-moderator, told GI & Hepatology News.

She noted that the practice can vary between institutions based on factors including the availability of physicians to perform the cholecystectomy.

Potential complications in delaying the procedure can range from inflammation and pancreatitis to obstruction of the bile duct, “which then can result in cholangitis and eventually sepsis or even death,” Asombang cautioned.

“So the timing of the procedure with ERCP is definitely significant,” she said.

El Halabi and Asombang had no disclosures to report. Lara reported a relationship with AbbVie.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ACG 2025

Is AI a Cure for Clinician Burnout?

The practice of medicine is evolving rapidly, with clinicians facing enhanced pressure to maximize productivity while managing increasingly complex patients and related clinical documentation. Indeed, clinicians are spending less time seeing patients, and more time in front of a computer screen.

Despite the many rewards of clinical medicine, rates of clinical practice attrition have increased among physicians in all specialties since 2013 with enhanced administrative burdens identified as a prominent driver. Among its many applications, artificial intelligence (AI) has immense potential to reduce the administrative and cognitive burdens that contribute to clinician burnout and attrition through tools such as AI scribes – these technologies have been rapidly adopted across healthcare systems and are already in use by ~30% of physician practices. The hope is that AI scribes will significantly reduce documentation time, leading to improvements in clinician wellbeing and expanding capacity for patient care. Indeed, some studies have shown up to a 20-30% improvement in documentation efficiency.

So, is AI a cure for physician burnout? The answer depends on what is done with these efficiency gains. If healthcare organizations respond to this enhanced efficiency by increasing patient volume expectations rather than allowing clinicians to recapture some of this time for meaningful work and professional wellbeing, it could create a so-called “workload paradox” where modest time savings are offset by greater productivity demands and the cognitive burden of reviewing AI-generated errors. that prioritizes clinician well-being and patient safety in addition to productivity.

In our final issue of 2025, we highlight a recent RCT from Annals of Internal Medicine finding that fecal microbiota transplantation is at least as effective as vancomycin in treating primary C. difficile infection. In this month’s Member Spotlight, we feature Andrew Ofosu, MD, MPH (University of Cincinnati Health), who stresses the importance of transparency and compassion in communicating effectively with patients, particularly around complex diagnoses. We hope you enjoy this and all the exciting content in our December issue.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor in Chief

The practice of medicine is evolving rapidly, with clinicians facing enhanced pressure to maximize productivity while managing increasingly complex patients and related clinical documentation. Indeed, clinicians are spending less time seeing patients, and more time in front of a computer screen.

Despite the many rewards of clinical medicine, rates of clinical practice attrition have increased among physicians in all specialties since 2013 with enhanced administrative burdens identified as a prominent driver. Among its many applications, artificial intelligence (AI) has immense potential to reduce the administrative and cognitive burdens that contribute to clinician burnout and attrition through tools such as AI scribes – these technologies have been rapidly adopted across healthcare systems and are already in use by ~30% of physician practices. The hope is that AI scribes will significantly reduce documentation time, leading to improvements in clinician wellbeing and expanding capacity for patient care. Indeed, some studies have shown up to a 20-30% improvement in documentation efficiency.

So, is AI a cure for physician burnout? The answer depends on what is done with these efficiency gains. If healthcare organizations respond to this enhanced efficiency by increasing patient volume expectations rather than allowing clinicians to recapture some of this time for meaningful work and professional wellbeing, it could create a so-called “workload paradox” where modest time savings are offset by greater productivity demands and the cognitive burden of reviewing AI-generated errors. that prioritizes clinician well-being and patient safety in addition to productivity.

In our final issue of 2025, we highlight a recent RCT from Annals of Internal Medicine finding that fecal microbiota transplantation is at least as effective as vancomycin in treating primary C. difficile infection. In this month’s Member Spotlight, we feature Andrew Ofosu, MD, MPH (University of Cincinnati Health), who stresses the importance of transparency and compassion in communicating effectively with patients, particularly around complex diagnoses. We hope you enjoy this and all the exciting content in our December issue.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor in Chief

The practice of medicine is evolving rapidly, with clinicians facing enhanced pressure to maximize productivity while managing increasingly complex patients and related clinical documentation. Indeed, clinicians are spending less time seeing patients, and more time in front of a computer screen.

Despite the many rewards of clinical medicine, rates of clinical practice attrition have increased among physicians in all specialties since 2013 with enhanced administrative burdens identified as a prominent driver. Among its many applications, artificial intelligence (AI) has immense potential to reduce the administrative and cognitive burdens that contribute to clinician burnout and attrition through tools such as AI scribes – these technologies have been rapidly adopted across healthcare systems and are already in use by ~30% of physician practices. The hope is that AI scribes will significantly reduce documentation time, leading to improvements in clinician wellbeing and expanding capacity for patient care. Indeed, some studies have shown up to a 20-30% improvement in documentation efficiency.

So, is AI a cure for physician burnout? The answer depends on what is done with these efficiency gains. If healthcare organizations respond to this enhanced efficiency by increasing patient volume expectations rather than allowing clinicians to recapture some of this time for meaningful work and professional wellbeing, it could create a so-called “workload paradox” where modest time savings are offset by greater productivity demands and the cognitive burden of reviewing AI-generated errors. that prioritizes clinician well-being and patient safety in addition to productivity.

In our final issue of 2025, we highlight a recent RCT from Annals of Internal Medicine finding that fecal microbiota transplantation is at least as effective as vancomycin in treating primary C. difficile infection. In this month’s Member Spotlight, we feature Andrew Ofosu, MD, MPH (University of Cincinnati Health), who stresses the importance of transparency and compassion in communicating effectively with patients, particularly around complex diagnoses. We hope you enjoy this and all the exciting content in our December issue.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor in Chief

New Drug Eases Side Effects of Weight-Loss Meds

A new drug currently known as NG101 reduced nausea and vomiting in patients with obesity using GLP-1s by 40% and 67%, respectively, based on data from a phase 2 trial presented at the Obesity Society’s Obesity Week 2025 in Atlanta.

Previous research published in JAMA Network Open showed a nearly 65% discontinuation rate for three GLP-1s (liraglutide, semaglutide, or tirzepatide) among adults with overweight or obesity and without type 2 diabetes. Gastrointestinal (GI) side effects topped the list of reasons for dropping the medications.

Given the impact of nausea and vomiting on discontinuation, there is an unmet need for therapies to manage GI symptoms, said Kimberley Cummings, PhD, of Neurogastrx, Inc., in her presentation.

In the new study, Cummings and colleagues randomly assigned 90 adults aged 18-55 years with overweight or obesity (defined as a BMI ranging from 22.0 to 35.0) to receive a single subcutaneous dose of semaglutide (0.5 mg) plus 5 days of NG101 at 20 mg twice daily, or a placebo.

NG101 is a peripherally acting D2 antagonist designed to reduce nausea and vomiting associated with GLP-1 use, Cummings said. NG101 targets the nausea center of the brain but is peripherally restricted to prevent central nervous system side effects, she explained.

Compared with placebo, NG101 significantly reduced the incidence of nausea and vomiting by 40% and 67%, respectively. Use of NG101 also was associated with a significant reduction in the duration of nausea and vomiting; GI events lasting longer than 1 day were reported in 22% and 51% of the NG101 patients and placebo patients, respectively.

In addition, participants who received NG101 reported a 70% decrease in nausea severity from baseline.

Overall, patients in the NG101 group also reported significantly fewer adverse events than those in the placebo group (74 vs 135), suggesting an improved safety profile when semaglutide is administered in conjunction with NG101, the researchers noted. No serious adverse events related to the study drug were reported in either group.

The findings were limited by several factors including the relatively small sample size. Additional research is needed with other GLP-1 agonists in larger populations with longer follow-up periods, Cummings said. However, the results suggest that NG101 was safe and effectively improved side effects associated with GLP-1 agonists.

“We know there are receptors for GLP-1 in the area postrema (nausea center of the brain), and that NG101 works on this area to reduce nausea and vomiting, so the study findings were not unexpected,” said Jim O’Mara, president and CEO of Neurogastrx, in an interview.

The study was a single-dose study designed to show proof of concept, and future studies would involve treating patients going through the recommended titration schedule for their GLP-1s, O’Mara said. However, NG101 offers an opportunity to keep more patients on GLP-1 therapy and help them reach their long-term therapeutic goals, he said.

Decrease Side Effects for Weight-Loss Success

“GI side effects are often the rate-limiting step in implementing an effective medication that patients want to take but may not be able to tolerate,” said Sean Wharton, MD, PharmD, medical director of the Wharton Medical Clinic for Weight and Diabetes Management, Burlington, Ontario, Canada, in an interview. “If we can decrease side effects, these medications could improve patients’ lives,” said Wharton, who was not involved in the study.

The improvement after a single dose of NG101 in patients receiving a single dose of semaglutide was impressive and in keeping with the mechanism of the drug action, said Wharton. “I was not surprised by the result but pleased that this single dose was shown to reduce the overall incidence of nausea and vomiting, the duration of nausea, the severity of nausea as rated by the study participants compared to placebo,” he said.

Ultimately, the clinical implications for NG101 are improved patient tolerance for GLP-1s and the ability to titrate and stay on them long term, incurring greater cardiometabolic benefit, Wharton told this news organization.

The current trial was limited to GLP1-1s on the market; newer medications may have fewer side effects, Wharton noted. “In clinical practice, patients often decrease the medication or titrate slower, and this could be the comparator,” he added.

The study was funded by Neurogastrx.

Wharton disclosed serving as a consultant for Neurogastrx but not as an investigator on the current study. He also reported having disclosed research on various GLP-1 medications.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new drug currently known as NG101 reduced nausea and vomiting in patients with obesity using GLP-1s by 40% and 67%, respectively, based on data from a phase 2 trial presented at the Obesity Society’s Obesity Week 2025 in Atlanta.

Previous research published in JAMA Network Open showed a nearly 65% discontinuation rate for three GLP-1s (liraglutide, semaglutide, or tirzepatide) among adults with overweight or obesity and without type 2 diabetes. Gastrointestinal (GI) side effects topped the list of reasons for dropping the medications.

Given the impact of nausea and vomiting on discontinuation, there is an unmet need for therapies to manage GI symptoms, said Kimberley Cummings, PhD, of Neurogastrx, Inc., in her presentation.

In the new study, Cummings and colleagues randomly assigned 90 adults aged 18-55 years with overweight or obesity (defined as a BMI ranging from 22.0 to 35.0) to receive a single subcutaneous dose of semaglutide (0.5 mg) plus 5 days of NG101 at 20 mg twice daily, or a placebo.

NG101 is a peripherally acting D2 antagonist designed to reduce nausea and vomiting associated with GLP-1 use, Cummings said. NG101 targets the nausea center of the brain but is peripherally restricted to prevent central nervous system side effects, she explained.

Compared with placebo, NG101 significantly reduced the incidence of nausea and vomiting by 40% and 67%, respectively. Use of NG101 also was associated with a significant reduction in the duration of nausea and vomiting; GI events lasting longer than 1 day were reported in 22% and 51% of the NG101 patients and placebo patients, respectively.

In addition, participants who received NG101 reported a 70% decrease in nausea severity from baseline.

Overall, patients in the NG101 group also reported significantly fewer adverse events than those in the placebo group (74 vs 135), suggesting an improved safety profile when semaglutide is administered in conjunction with NG101, the researchers noted. No serious adverse events related to the study drug were reported in either group.

The findings were limited by several factors including the relatively small sample size. Additional research is needed with other GLP-1 agonists in larger populations with longer follow-up periods, Cummings said. However, the results suggest that NG101 was safe and effectively improved side effects associated with GLP-1 agonists.

“We know there are receptors for GLP-1 in the area postrema (nausea center of the brain), and that NG101 works on this area to reduce nausea and vomiting, so the study findings were not unexpected,” said Jim O’Mara, president and CEO of Neurogastrx, in an interview.

The study was a single-dose study designed to show proof of concept, and future studies would involve treating patients going through the recommended titration schedule for their GLP-1s, O’Mara said. However, NG101 offers an opportunity to keep more patients on GLP-1 therapy and help them reach their long-term therapeutic goals, he said.

Decrease Side Effects for Weight-Loss Success

“GI side effects are often the rate-limiting step in implementing an effective medication that patients want to take but may not be able to tolerate,” said Sean Wharton, MD, PharmD, medical director of the Wharton Medical Clinic for Weight and Diabetes Management, Burlington, Ontario, Canada, in an interview. “If we can decrease side effects, these medications could improve patients’ lives,” said Wharton, who was not involved in the study.

The improvement after a single dose of NG101 in patients receiving a single dose of semaglutide was impressive and in keeping with the mechanism of the drug action, said Wharton. “I was not surprised by the result but pleased that this single dose was shown to reduce the overall incidence of nausea and vomiting, the duration of nausea, the severity of nausea as rated by the study participants compared to placebo,” he said.

Ultimately, the clinical implications for NG101 are improved patient tolerance for GLP-1s and the ability to titrate and stay on them long term, incurring greater cardiometabolic benefit, Wharton told this news organization.

The current trial was limited to GLP1-1s on the market; newer medications may have fewer side effects, Wharton noted. “In clinical practice, patients often decrease the medication or titrate slower, and this could be the comparator,” he added.

The study was funded by Neurogastrx.

Wharton disclosed serving as a consultant for Neurogastrx but not as an investigator on the current study. He also reported having disclosed research on various GLP-1 medications.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new drug currently known as NG101 reduced nausea and vomiting in patients with obesity using GLP-1s by 40% and 67%, respectively, based on data from a phase 2 trial presented at the Obesity Society’s Obesity Week 2025 in Atlanta.

Previous research published in JAMA Network Open showed a nearly 65% discontinuation rate for three GLP-1s (liraglutide, semaglutide, or tirzepatide) among adults with overweight or obesity and without type 2 diabetes. Gastrointestinal (GI) side effects topped the list of reasons for dropping the medications.

Given the impact of nausea and vomiting on discontinuation, there is an unmet need for therapies to manage GI symptoms, said Kimberley Cummings, PhD, of Neurogastrx, Inc., in her presentation.

In the new study, Cummings and colleagues randomly assigned 90 adults aged 18-55 years with overweight or obesity (defined as a BMI ranging from 22.0 to 35.0) to receive a single subcutaneous dose of semaglutide (0.5 mg) plus 5 days of NG101 at 20 mg twice daily, or a placebo.

NG101 is a peripherally acting D2 antagonist designed to reduce nausea and vomiting associated with GLP-1 use, Cummings said. NG101 targets the nausea center of the brain but is peripherally restricted to prevent central nervous system side effects, she explained.

Compared with placebo, NG101 significantly reduced the incidence of nausea and vomiting by 40% and 67%, respectively. Use of NG101 also was associated with a significant reduction in the duration of nausea and vomiting; GI events lasting longer than 1 day were reported in 22% and 51% of the NG101 patients and placebo patients, respectively.

In addition, participants who received NG101 reported a 70% decrease in nausea severity from baseline.

Overall, patients in the NG101 group also reported significantly fewer adverse events than those in the placebo group (74 vs 135), suggesting an improved safety profile when semaglutide is administered in conjunction with NG101, the researchers noted. No serious adverse events related to the study drug were reported in either group.

The findings were limited by several factors including the relatively small sample size. Additional research is needed with other GLP-1 agonists in larger populations with longer follow-up periods, Cummings said. However, the results suggest that NG101 was safe and effectively improved side effects associated with GLP-1 agonists.

“We know there are receptors for GLP-1 in the area postrema (nausea center of the brain), and that NG101 works on this area to reduce nausea and vomiting, so the study findings were not unexpected,” said Jim O’Mara, president and CEO of Neurogastrx, in an interview.

The study was a single-dose study designed to show proof of concept, and future studies would involve treating patients going through the recommended titration schedule for their GLP-1s, O’Mara said. However, NG101 offers an opportunity to keep more patients on GLP-1 therapy and help them reach their long-term therapeutic goals, he said.

Decrease Side Effects for Weight-Loss Success

“GI side effects are often the rate-limiting step in implementing an effective medication that patients want to take but may not be able to tolerate,” said Sean Wharton, MD, PharmD, medical director of the Wharton Medical Clinic for Weight and Diabetes Management, Burlington, Ontario, Canada, in an interview. “If we can decrease side effects, these medications could improve patients’ lives,” said Wharton, who was not involved in the study.

The improvement after a single dose of NG101 in patients receiving a single dose of semaglutide was impressive and in keeping with the mechanism of the drug action, said Wharton. “I was not surprised by the result but pleased that this single dose was shown to reduce the overall incidence of nausea and vomiting, the duration of nausea, the severity of nausea as rated by the study participants compared to placebo,” he said.

Ultimately, the clinical implications for NG101 are improved patient tolerance for GLP-1s and the ability to titrate and stay on them long term, incurring greater cardiometabolic benefit, Wharton told this news organization.

The current trial was limited to GLP1-1s on the market; newer medications may have fewer side effects, Wharton noted. “In clinical practice, patients often decrease the medication or titrate slower, and this could be the comparator,” he added.

The study was funded by Neurogastrx.

Wharton disclosed serving as a consultant for Neurogastrx but not as an investigator on the current study. He also reported having disclosed research on various GLP-1 medications.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM OBESITY WEEK 2025

Is There Really a Cancer Epidemic in Younger Adults?

A global analysis challenged the notion that a rise in cancer is disproportionately affecting younger adults, finding instead that several cancer types previously seen rising in younger adults are also increasing in older adults.

More specifically, the analysis found that incidence rates for thyroid cancer, breast cancer, kidney cancer, endometrial cancer, and leukemia increased similarly in both younger and older adults in most countries over a 15-year period. Colorectal cancer (CRC) was the exception, where incidence rates increased in younger adults in most countries but only increased slightly in older adults in about half and decreased in about one quarter.

“Our findings suggest that whatever is triggering the rise in these cancers is more likely to be common across all age groups, rather than specific to cancers in the under 50s, since there were similar increases in younger and older adults,” Amy Berrington de González, DPhil, The Institute of Cancer Research, London, England, who led the study, said in a statement.

The authors of an editorial agreed, adding that the growing “concern about increasing cancer rates should recognize that this increase is not restricted to young adults but affects all generations.”

The study and editorial were published recently in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Data Defy Early-Onset Cancer Epidemic Narrative

A growing body of evidence suggests that cancer incidence rates are increasing among younger adults in many countries. However, studies tracking international trends have largely evaluated cancer incidence in younger adults without comparing these trends in older adults or analyses have focused the age comparison in individual countries, Berrington de González and colleagues explained.

To better understand cancer incidence trends across countries and age groups, the researchers evaluated cancer trends in 42 countries between 2003 and 2017, focusing on 13 cancer types previously reported to be climbing in adults younger than age 50 years.

The researchers found that incidence rates for six of the 13 cancer types increased among younger adults (aged 20-49 years) in more than three quarters of the countries studied.

The largest increase was in thyroid cancer (median average annual percentage change [AAPC], 3.57%), followed by kidney cancer (median AAPC, 2.21%), endometrial cancer (median AAPC, 1.66%), CRC (median AAPC, 1.45%), breast cancer (median AAPC, 0.89%), and leukemia (median AAPC, 0.78%).

But with the exception of CRC, incidence rates for these cancers increased to a similar degree in adults aged 50 years or older — with median AAPCs of 3% (vs 3.57%) for thyroid cancer, 1.65% (vs 2.21%) for kidney cancer, 1.20% (vs 1.66%) for endometrial cancer, 0.86% (vs 0.89%) for breast cancer, and 0.61% (vs 0.78%) for leukemia.

In older adults, CRC incidence rates only increased in about half the countries (median AAPC, 0.37%), and the annual percentage change was much greater in younger than older adults in nearly 70% of countries. CRC incidence rates in older individuals also decreased in nearly 25% of countries.

Why is CRC an apparent outlier?

“Bowel cancer screening not only helps detect cancer at earlier stages but also helps prevent cancer through the removal of premalignant lesions,” Berrington de González said. “This could be why bowel cancer cases seem to be rising faster in younger adults — we’re getting better at preventing them developing in older adults.”

The incidence of certain cancers also declined in younger adults. Specifically, rates of liver, oral, esophageal, and stomach cancers decreased in younger adults in more than half of countries assessed, with median AAPCs of -0.14% for liver, -0.42% for oral, -0.92% for esophageal, and -1.62% for stomach cancers.

Over half of countries also saw declining rates of stomach (median AAPC, -2.05%) and esophageal (median AAPC, -0.25%) cancers among older adults, while rates of liver and oral cancers increased in older individuals (median AAPC, 2.17% and 0.49%, respectively).

For gallbladder, pancreatic, and prostate cancers — three other cancers previously found to be increasing in younger adults — the researchers reported that incidence rates increased in younger adults in just over half of countries (median AAPCs, 3.2% for prostate cancer, 0.49% for gallbladder cancer, and 1% for pancreatic cancer). Incidence rates also often increased in older adults but to a lesser extent (median AAPCs, 0.75% for prostate cancer, -0.10% for gallbladder, and 0.96% for pancreatic cancer).

True Rise or Increased Scrutiny?

Why are cancer rates increasing?

“Understanding factors that contribute to the increase in incidence across the age spectrum was beyond the scope of the study,” editorialists Christopher Cann, MD, Fox Chase Cancer Center, and Efrat Dotan, MD, University of Pennsylvania Health System, both in Philadelphia, wrote.

Several studies have suggested that rising rates of obesity could help explain increasing cancer incidence, particularly in younger adults. In fact, “the cancers that we identified as increasing are all obesity-related cancers, including endometrial and kidney cancer,” Berrington de González said. However, so far, the evidence on this link remains unclear, she acknowledged.

Weighing in on the study, Gilbert Welch, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, told this news organization that it’s “critically important” to distinguish between two explanations for rising cancer incidence.

There may be an increase in the true occurrence of clinically meaningful cancer, which “warrants investigation into biologic explanations, better treatment, and perhaps more testing,” Welch said.

But it may instead reflect changes in diagnostic scrutiny. “Simply put, whenever we doctors look harder for cancer, we find more,” Welch said. “And there are lots of ways to look harder: testing more people, testing people more frequently, using tests with increasing ability to detect small irregularities, and using lower diagnostic thresholds for labeling these as cancer.”

If increased incidence is the result of greater diagnostic scrutiny, searching for biologic causes is bound to be unproductive and more testing will only aggravate the problem, he explained.

Welch pointed out that the fastest rising cancer in both younger and older adults was thyroid cancer (AAPC, ≥ 3%), which is “exquisitely sensitive” to diagnostic scrutiny.

Take what happened in South Korea. Around 2000, the government of South Korea started a national screening program for breast, colon, and stomach cancers. Doctors and hospitals often added on ultrasound scans for thyroid cancer for a small additional fee.

“A decade later the rate of thyroid cancer diagnosis had increased 15-fold, turning what was once a rare cancer into the most common cancer in Korea,” Welch said. “But the death rate from thyroid cancer did not change. This was not an epidemic of disease; this was an epidemic of diagnosis.”

Welch also noted that the study authors and editorialists put the finding in perspective by explaining that, despite the rising rates of certain cancers in younger adults, cancer remains rare in these adults.

Welch highlighted that, for younger adults in the US, cancer death rates in young adults have cut in half over the last 30 years. “Cancer accounts for only 10% of deaths in young people in the US — and that number is falling,” Welch said.

The study was funded by the Institute of Cancer Research and the National Institutes of Health Intramural Research Program. Disclosures for authors and editorial writers are available with the original articles. Welch reported receiving royalties from three books including “Should I be tested for cancer?”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A global analysis challenged the notion that a rise in cancer is disproportionately affecting younger adults, finding instead that several cancer types previously seen rising in younger adults are also increasing in older adults.

More specifically, the analysis found that incidence rates for thyroid cancer, breast cancer, kidney cancer, endometrial cancer, and leukemia increased similarly in both younger and older adults in most countries over a 15-year period. Colorectal cancer (CRC) was the exception, where incidence rates increased in younger adults in most countries but only increased slightly in older adults in about half and decreased in about one quarter.

“Our findings suggest that whatever is triggering the rise in these cancers is more likely to be common across all age groups, rather than specific to cancers in the under 50s, since there were similar increases in younger and older adults,” Amy Berrington de González, DPhil, The Institute of Cancer Research, London, England, who led the study, said in a statement.

The authors of an editorial agreed, adding that the growing “concern about increasing cancer rates should recognize that this increase is not restricted to young adults but affects all generations.”

The study and editorial were published recently in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Data Defy Early-Onset Cancer Epidemic Narrative

A growing body of evidence suggests that cancer incidence rates are increasing among younger adults in many countries. However, studies tracking international trends have largely evaluated cancer incidence in younger adults without comparing these trends in older adults or analyses have focused the age comparison in individual countries, Berrington de González and colleagues explained.

To better understand cancer incidence trends across countries and age groups, the researchers evaluated cancer trends in 42 countries between 2003 and 2017, focusing on 13 cancer types previously reported to be climbing in adults younger than age 50 years.

The researchers found that incidence rates for six of the 13 cancer types increased among younger adults (aged 20-49 years) in more than three quarters of the countries studied.

The largest increase was in thyroid cancer (median average annual percentage change [AAPC], 3.57%), followed by kidney cancer (median AAPC, 2.21%), endometrial cancer (median AAPC, 1.66%), CRC (median AAPC, 1.45%), breast cancer (median AAPC, 0.89%), and leukemia (median AAPC, 0.78%).

But with the exception of CRC, incidence rates for these cancers increased to a similar degree in adults aged 50 years or older — with median AAPCs of 3% (vs 3.57%) for thyroid cancer, 1.65% (vs 2.21%) for kidney cancer, 1.20% (vs 1.66%) for endometrial cancer, 0.86% (vs 0.89%) for breast cancer, and 0.61% (vs 0.78%) for leukemia.

In older adults, CRC incidence rates only increased in about half the countries (median AAPC, 0.37%), and the annual percentage change was much greater in younger than older adults in nearly 70% of countries. CRC incidence rates in older individuals also decreased in nearly 25% of countries.

Why is CRC an apparent outlier?

“Bowel cancer screening not only helps detect cancer at earlier stages but also helps prevent cancer through the removal of premalignant lesions,” Berrington de González said. “This could be why bowel cancer cases seem to be rising faster in younger adults — we’re getting better at preventing them developing in older adults.”

The incidence of certain cancers also declined in younger adults. Specifically, rates of liver, oral, esophageal, and stomach cancers decreased in younger adults in more than half of countries assessed, with median AAPCs of -0.14% for liver, -0.42% for oral, -0.92% for esophageal, and -1.62% for stomach cancers.

Over half of countries also saw declining rates of stomach (median AAPC, -2.05%) and esophageal (median AAPC, -0.25%) cancers among older adults, while rates of liver and oral cancers increased in older individuals (median AAPC, 2.17% and 0.49%, respectively).

For gallbladder, pancreatic, and prostate cancers — three other cancers previously found to be increasing in younger adults — the researchers reported that incidence rates increased in younger adults in just over half of countries (median AAPCs, 3.2% for prostate cancer, 0.49% for gallbladder cancer, and 1% for pancreatic cancer). Incidence rates also often increased in older adults but to a lesser extent (median AAPCs, 0.75% for prostate cancer, -0.10% for gallbladder, and 0.96% for pancreatic cancer).

True Rise or Increased Scrutiny?

Why are cancer rates increasing?

“Understanding factors that contribute to the increase in incidence across the age spectrum was beyond the scope of the study,” editorialists Christopher Cann, MD, Fox Chase Cancer Center, and Efrat Dotan, MD, University of Pennsylvania Health System, both in Philadelphia, wrote.

Several studies have suggested that rising rates of obesity could help explain increasing cancer incidence, particularly in younger adults. In fact, “the cancers that we identified as increasing are all obesity-related cancers, including endometrial and kidney cancer,” Berrington de González said. However, so far, the evidence on this link remains unclear, she acknowledged.

Weighing in on the study, Gilbert Welch, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, told this news organization that it’s “critically important” to distinguish between two explanations for rising cancer incidence.

There may be an increase in the true occurrence of clinically meaningful cancer, which “warrants investigation into biologic explanations, better treatment, and perhaps more testing,” Welch said.

But it may instead reflect changes in diagnostic scrutiny. “Simply put, whenever we doctors look harder for cancer, we find more,” Welch said. “And there are lots of ways to look harder: testing more people, testing people more frequently, using tests with increasing ability to detect small irregularities, and using lower diagnostic thresholds for labeling these as cancer.”

If increased incidence is the result of greater diagnostic scrutiny, searching for biologic causes is bound to be unproductive and more testing will only aggravate the problem, he explained.

Welch pointed out that the fastest rising cancer in both younger and older adults was thyroid cancer (AAPC, ≥ 3%), which is “exquisitely sensitive” to diagnostic scrutiny.

Take what happened in South Korea. Around 2000, the government of South Korea started a national screening program for breast, colon, and stomach cancers. Doctors and hospitals often added on ultrasound scans for thyroid cancer for a small additional fee.

“A decade later the rate of thyroid cancer diagnosis had increased 15-fold, turning what was once a rare cancer into the most common cancer in Korea,” Welch said. “But the death rate from thyroid cancer did not change. This was not an epidemic of disease; this was an epidemic of diagnosis.”

Welch also noted that the study authors and editorialists put the finding in perspective by explaining that, despite the rising rates of certain cancers in younger adults, cancer remains rare in these adults.

Welch highlighted that, for younger adults in the US, cancer death rates in young adults have cut in half over the last 30 years. “Cancer accounts for only 10% of deaths in young people in the US — and that number is falling,” Welch said.

The study was funded by the Institute of Cancer Research and the National Institutes of Health Intramural Research Program. Disclosures for authors and editorial writers are available with the original articles. Welch reported receiving royalties from three books including “Should I be tested for cancer?”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A global analysis challenged the notion that a rise in cancer is disproportionately affecting younger adults, finding instead that several cancer types previously seen rising in younger adults are also increasing in older adults.

More specifically, the analysis found that incidence rates for thyroid cancer, breast cancer, kidney cancer, endometrial cancer, and leukemia increased similarly in both younger and older adults in most countries over a 15-year period. Colorectal cancer (CRC) was the exception, where incidence rates increased in younger adults in most countries but only increased slightly in older adults in about half and decreased in about one quarter.

“Our findings suggest that whatever is triggering the rise in these cancers is more likely to be common across all age groups, rather than specific to cancers in the under 50s, since there were similar increases in younger and older adults,” Amy Berrington de González, DPhil, The Institute of Cancer Research, London, England, who led the study, said in a statement.

The authors of an editorial agreed, adding that the growing “concern about increasing cancer rates should recognize that this increase is not restricted to young adults but affects all generations.”

The study and editorial were published recently in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Data Defy Early-Onset Cancer Epidemic Narrative

A growing body of evidence suggests that cancer incidence rates are increasing among younger adults in many countries. However, studies tracking international trends have largely evaluated cancer incidence in younger adults without comparing these trends in older adults or analyses have focused the age comparison in individual countries, Berrington de González and colleagues explained.

To better understand cancer incidence trends across countries and age groups, the researchers evaluated cancer trends in 42 countries between 2003 and 2017, focusing on 13 cancer types previously reported to be climbing in adults younger than age 50 years.

The researchers found that incidence rates for six of the 13 cancer types increased among younger adults (aged 20-49 years) in more than three quarters of the countries studied.

The largest increase was in thyroid cancer (median average annual percentage change [AAPC], 3.57%), followed by kidney cancer (median AAPC, 2.21%), endometrial cancer (median AAPC, 1.66%), CRC (median AAPC, 1.45%), breast cancer (median AAPC, 0.89%), and leukemia (median AAPC, 0.78%).

But with the exception of CRC, incidence rates for these cancers increased to a similar degree in adults aged 50 years or older — with median AAPCs of 3% (vs 3.57%) for thyroid cancer, 1.65% (vs 2.21%) for kidney cancer, 1.20% (vs 1.66%) for endometrial cancer, 0.86% (vs 0.89%) for breast cancer, and 0.61% (vs 0.78%) for leukemia.

In older adults, CRC incidence rates only increased in about half the countries (median AAPC, 0.37%), and the annual percentage change was much greater in younger than older adults in nearly 70% of countries. CRC incidence rates in older individuals also decreased in nearly 25% of countries.

Why is CRC an apparent outlier?

“Bowel cancer screening not only helps detect cancer at earlier stages but also helps prevent cancer through the removal of premalignant lesions,” Berrington de González said. “This could be why bowel cancer cases seem to be rising faster in younger adults — we’re getting better at preventing them developing in older adults.”

The incidence of certain cancers also declined in younger adults. Specifically, rates of liver, oral, esophageal, and stomach cancers decreased in younger adults in more than half of countries assessed, with median AAPCs of -0.14% for liver, -0.42% for oral, -0.92% for esophageal, and -1.62% for stomach cancers.

Over half of countries also saw declining rates of stomach (median AAPC, -2.05%) and esophageal (median AAPC, -0.25%) cancers among older adults, while rates of liver and oral cancers increased in older individuals (median AAPC, 2.17% and 0.49%, respectively).

For gallbladder, pancreatic, and prostate cancers — three other cancers previously found to be increasing in younger adults — the researchers reported that incidence rates increased in younger adults in just over half of countries (median AAPCs, 3.2% for prostate cancer, 0.49% for gallbladder cancer, and 1% for pancreatic cancer). Incidence rates also often increased in older adults but to a lesser extent (median AAPCs, 0.75% for prostate cancer, -0.10% for gallbladder, and 0.96% for pancreatic cancer).

True Rise or Increased Scrutiny?

Why are cancer rates increasing?

“Understanding factors that contribute to the increase in incidence across the age spectrum was beyond the scope of the study,” editorialists Christopher Cann, MD, Fox Chase Cancer Center, and Efrat Dotan, MD, University of Pennsylvania Health System, both in Philadelphia, wrote.

Several studies have suggested that rising rates of obesity could help explain increasing cancer incidence, particularly in younger adults. In fact, “the cancers that we identified as increasing are all obesity-related cancers, including endometrial and kidney cancer,” Berrington de González said. However, so far, the evidence on this link remains unclear, she acknowledged.

Weighing in on the study, Gilbert Welch, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, told this news organization that it’s “critically important” to distinguish between two explanations for rising cancer incidence.

There may be an increase in the true occurrence of clinically meaningful cancer, which “warrants investigation into biologic explanations, better treatment, and perhaps more testing,” Welch said.

But it may instead reflect changes in diagnostic scrutiny. “Simply put, whenever we doctors look harder for cancer, we find more,” Welch said. “And there are lots of ways to look harder: testing more people, testing people more frequently, using tests with increasing ability to detect small irregularities, and using lower diagnostic thresholds for labeling these as cancer.”

If increased incidence is the result of greater diagnostic scrutiny, searching for biologic causes is bound to be unproductive and more testing will only aggravate the problem, he explained.

Welch pointed out that the fastest rising cancer in both younger and older adults was thyroid cancer (AAPC, ≥ 3%), which is “exquisitely sensitive” to diagnostic scrutiny.

Take what happened in South Korea. Around 2000, the government of South Korea started a national screening program for breast, colon, and stomach cancers. Doctors and hospitals often added on ultrasound scans for thyroid cancer for a small additional fee.

“A decade later the rate of thyroid cancer diagnosis had increased 15-fold, turning what was once a rare cancer into the most common cancer in Korea,” Welch said. “But the death rate from thyroid cancer did not change. This was not an epidemic of disease; this was an epidemic of diagnosis.”

Welch also noted that the study authors and editorialists put the finding in perspective by explaining that, despite the rising rates of certain cancers in younger adults, cancer remains rare in these adults.

Welch highlighted that, for younger adults in the US, cancer death rates in young adults have cut in half over the last 30 years. “Cancer accounts for only 10% of deaths in young people in the US — and that number is falling,” Welch said.

The study was funded by the Institute of Cancer Research and the National Institutes of Health Intramural Research Program. Disclosures for authors and editorial writers are available with the original articles. Welch reported receiving royalties from three books including “Should I be tested for cancer?”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Military Deployment Raises Respiratory Disease Risk

Individuals who served in Iraq or Afghanistan had significantly higher rates of new-onset respiratory diseases after deployment compared to non-deployed control peers, based on data from more than 48,000 veterans. The findings were presented at the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (ACAAI) 2025 Annual Meeting.

“Veterans deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan were often exposed to airborne hazards such as burn pits and dust storms,” said Patrick Gleeson, MD, an allergist at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, in a press release.

“We found that these exposures may have long-term health impacts, particularly for respiratory diseases that can affect quality of life for years after service,” said Gleeson, who presented the results at the meeting.

Gleeson and colleagues used data from the Veterans Affairs Corporate Data Warehouse and Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership to identify veterans with a single deployment as part of Operation Iraqi Freedom or Operation Enduring Freedom. Participants had at least one outpatient visit prior to deployment with no baseline history of asthma, chronic rhinitis, chronic rhinosinusitis, or nasal polyposis. The mean age of the participants at deployment was 26.7 years, 84% were male, 75% were White, and 11% were Hispanic or Latino. Each was matched with a similar non-deployed veteran control.

The primary outcome was outpatient diagnoses or problem list entries for asthma, chronic rhinitis, chronic rhinosinusitis, or nasal polyposis.

Compared to non-deployed peers, deployed veterans had a 55% increased risk of asthma, a 48% increased risk of nasal polyposis, a 41% increased risk of chronic rhinitis, and a 27% increased risk of chronic rhinosinusitis, based on Cox proportional hazards models (P < .0005 for all).

The findings were limited by the retrospective design. However, “Recognizing the link between deployment and respiratory disease can help guide medical support, policy, and preventive strategies for those affected,” Gleeson said in the press release.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers disclosed no financial conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Individuals who served in Iraq or Afghanistan had significantly higher rates of new-onset respiratory diseases after deployment compared to non-deployed control peers, based on data from more than 48,000 veterans. The findings were presented at the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (ACAAI) 2025 Annual Meeting.

“Veterans deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan were often exposed to airborne hazards such as burn pits and dust storms,” said Patrick Gleeson, MD, an allergist at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, in a press release.

“We found that these exposures may have long-term health impacts, particularly for respiratory diseases that can affect quality of life for years after service,” said Gleeson, who presented the results at the meeting.

Gleeson and colleagues used data from the Veterans Affairs Corporate Data Warehouse and Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership to identify veterans with a single deployment as part of Operation Iraqi Freedom or Operation Enduring Freedom. Participants had at least one outpatient visit prior to deployment with no baseline history of asthma, chronic rhinitis, chronic rhinosinusitis, or nasal polyposis. The mean age of the participants at deployment was 26.7 years, 84% were male, 75% were White, and 11% were Hispanic or Latino. Each was matched with a similar non-deployed veteran control.

The primary outcome was outpatient diagnoses or problem list entries for asthma, chronic rhinitis, chronic rhinosinusitis, or nasal polyposis.

Compared to non-deployed peers, deployed veterans had a 55% increased risk of asthma, a 48% increased risk of nasal polyposis, a 41% increased risk of chronic rhinitis, and a 27% increased risk of chronic rhinosinusitis, based on Cox proportional hazards models (P < .0005 for all).

The findings were limited by the retrospective design. However, “Recognizing the link between deployment and respiratory disease can help guide medical support, policy, and preventive strategies for those affected,” Gleeson said in the press release.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers disclosed no financial conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Individuals who served in Iraq or Afghanistan had significantly higher rates of new-onset respiratory diseases after deployment compared to non-deployed control peers, based on data from more than 48,000 veterans. The findings were presented at the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (ACAAI) 2025 Annual Meeting.

“Veterans deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan were often exposed to airborne hazards such as burn pits and dust storms,” said Patrick Gleeson, MD, an allergist at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, in a press release.

“We found that these exposures may have long-term health impacts, particularly for respiratory diseases that can affect quality of life for years after service,” said Gleeson, who presented the results at the meeting.

Gleeson and colleagues used data from the Veterans Affairs Corporate Data Warehouse and Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership to identify veterans with a single deployment as part of Operation Iraqi Freedom or Operation Enduring Freedom. Participants had at least one outpatient visit prior to deployment with no baseline history of asthma, chronic rhinitis, chronic rhinosinusitis, or nasal polyposis. The mean age of the participants at deployment was 26.7 years, 84% were male, 75% were White, and 11% were Hispanic or Latino. Each was matched with a similar non-deployed veteran control.

The primary outcome was outpatient diagnoses or problem list entries for asthma, chronic rhinitis, chronic rhinosinusitis, or nasal polyposis.

Compared to non-deployed peers, deployed veterans had a 55% increased risk of asthma, a 48% increased risk of nasal polyposis, a 41% increased risk of chronic rhinitis, and a 27% increased risk of chronic rhinosinusitis, based on Cox proportional hazards models (P < .0005 for all).

The findings were limited by the retrospective design. However, “Recognizing the link between deployment and respiratory disease can help guide medical support, policy, and preventive strategies for those affected,” Gleeson said in the press release.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers disclosed no financial conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ACAAI 2025

Approach to Weight Management in GI Practice

Introduction

The majority of patients in the United States are now overweight or obese, and as gastroenterologists we treat a number of conditions that are caused or worsened by obesity.1 Cirrhosis related to metabolic associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is now a leading indication for liver transplantation in the US2 and obesity is a clear risk factor for all major malignancies of the GI tract, including esophageal, gastric cardia, pancreatic, liver, gallbladder, colon, and rectum.3 Obesity is associated with dysbiosis and impacts barrier function: increasing permeability, abnormal gut bacterial translocation, and inflammation.4 It is more common than malnutrition in our patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), where it impacts response to biologic drugs, increases the technical difficulty of surgeries, such as IPAA, and is associated with worse surgical outcomes.5 Furthermore, patients with obesity may be less likely to undergo preventative cancer screenings and are at increased risk related to sedation for endoscopic procedures.6 With over 40% of Americans suffering from obesity, and increasingly effective treatments available,

Understanding the Mechanisms of Obesity

There are complex orexigenic and anorexigenic brain pathways in the hypothalamus which control global energy balance.7 Obesity results when energy intake exceeds energy expenditure. While overeating and a sedentary lifestyle are commonly blamed, there are a number of elements that contribute, including genetics, medical conditions, medications, psychosocial factors, and environmental components. For example, sleep loss contributes to weight gain by several mechanisms including increasing ghrelin and decreasing leptin levels, thereby increasing hunger and appetite, as well as by decreasing insulin sensitivity and increasing cortisol. Subjects exposed to sleep deprivation in research settings take in 550 kcal more the following day.8 Medications used commonly in GI practice including corticosteroids, antihistamines, propranolol, and amitriptyline, are obesogenic9 and cannabis can impact hypothalamic pathways to stimulate hunger.10

When patients diet or exercise to lose weight, as we have traditionally advised, there are strong hormonal changes and metabolic adaptations that occur to preserve the defended fat mass or “set point.” Loss of adipose tissue results in decreased production of leptin, a hormone that stimulates satiety pathways and inhibits orexigenic pathways, greatly increasing hunger and cravings. Increases in ghrelin production by the stomach decreases perceptions of fullness. With weight loss, energy requirements decrease, and muscles become more efficient, meaning fewer kcal are needed to maintain bodily processes.11 Eventually a plateau is reached, while motivation to diet and restraint around food wane, and hedonistic (reward) pathways are activated. These powerful factors result in the regain of lost weight within one year in the majority of patients.

Implementing Weight Management into GI Practice

Given the stigma and bias around obesity, patients often feel shame and vulnerability around the condition. It is important to have empathy in your approach, asking permission to discuss weight and using patient-first language (e.g. “patient with obesity” not “obese patient”). While BMI is predictive of health outcomes, it does not measure body fat percentage and may be misleading, such as in muscular individuals. Other measures of adiposity including waist circumference and body composition testing, such as with DEXA, may provide additional data. A BMI of 30 or above defines obesity, though newer definitions incorporate related symptoms, organ disfunction, and metabolic abnormalities into the term “clinical obesity.”12 Asian patients experience metabolic complications at a lower BMI, and therefore the definition of obese is 27.5kg/m2 in this population.

Begin by taking a weight history. Has this been a lifelong struggle or is there a particular life circumstance, such as working a third shift or recent pregnancy which precipitated weight gain? Patients should be asked about binge eating or eating late into the evening or waking at night to eat, as these disordered eating behaviors are managed with specific medications and behavioral therapies. Inquire about sleep duration and quality and refer for a sleep study if there is suspicion for obstructive sleep apnea. Other weight-related comorbidities including hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and MAFLD should be considered and merit a more aggressive approach, as does more severe obesity (class III, BMI ≥40). Questions about marijuana and alcohol use as well as review of the medication list for obesogenic medications can provide further insight into modifiable contributing factors.

Pillars of Weight Management

The internet is awash with trendy diet recommendations, and widespread misconceptions about obesity management are even ingrained into how physicians approach the disease. It is critical to remember that this is not a consequence of bad choices or lack of self-control. Exercise alone is insufficient to result in significant weight loss.13 Furthermore, whether it is through low fat, low carb, or intermittent fasting, weight loss will occur with calorie deficit.14 Evidence-based diet and lifestyle recommendations to lay the groundwork for success should be discussed at each visit (see Table 1). The Mediterranean diet is recommended for weight loss as well as for several GI disorders (i.e., MAFLD and IBD) and is the optimal eating strategy for cardiovascular health.15 Patients should be advised to engage in 150 minutes of moderate exercise per week, such as brisk walking, and should incorporate resistance training to build muscle and maintain bone density.

Anti-obesity Medications

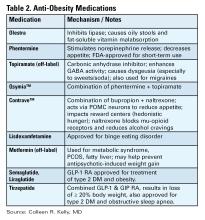

There are a number of medications, either FDA approved or used off label, for treatment of obesity (see Table 2).16 All are indicated for patients with a BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2 or for those with a BMI between 27-29 kg/m2 with weight-related comorbidities and should be used in combination with diet and lifestyle interventions. None are approved or safe in pregnancy. Mechanisms of action vary by type and include decreased appetite, increased energy expenditure, improved insulin sensitivity, and interfere with absorption.

The newest and most effective anti-obesity medications (AOM), the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA) are derived from gut hormones secreted in the distal small bowel and colon in response to a meal, which function to delay gastric emptying, increase insulin release from the pancreas, and reduce hepatic gluconeogenesis. Central nervous system effects are not yet entirely understood, but function to decrease appetite and increase satiety. Initially developed for treatment of T2DM, observed weight reduction in patients treated with GLP-1 RA led to clinical trials for treatment of obesity. Semaglutide treatment resulted in weight reduction of 16.9% of total body weight (TBW), and one third of subjects lost ≥ 20% of TBW.17 Tirzepatide combines GLP-1 RA and a gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) receptor agonist, which also has an incretin effect and functions to slow gastric emptying. In the pivotal SURMOUNT trial, approximately 58% of patients achieved ≥20% loss of TBW18 with 15mg weekly dosing of tirzepatide. This class of drugs is a logical choice in patients with T2DM and obesity. Long-term treatment appears necessary, as patients typically regain two-thirds of lost weight within a year after GLP-1 RA are stopped.

Based on tumors observed in rodents, GLP-1 RA are contraindicated in patients with a personal or family history of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN II) or medullary thyroid cancer. These tumors have not been observed in humans treated with GLP-1 RA. They should be used with caution in patients with history of pancreatitis, gastroparesis, or diabetic retinopathy, though a recent systematic review and meta-analysis suggests showed little to no increased risk for biliary events from GLP-1 RA.19 Side effects are most commonly gastrointestinal in nature (nausea, reflux, constipation or diarrhea) and are typically most severe with initiation of the drug and with dose escalation. Side effects can be mitigated by initiating these drugs at lowest doses and gradually titrating up (every four weeks) based on effectiveness and tolerability. Antisecretory, antiemetic, and laxative medications can also be used to help manage GLP-1 RA related side effects.

There is no reason to escalate to highest doses if patients are experiencing weight loss and reduction in food cravings at lower doses. Both semaglutide and tirzepatide are administered subcutaneously every seven days. Once patients have reached goal weight, they can either continue maintenance therapy at that same dose/interval, or if motivated to do so, may gradually reduce the weekly dose in a stepwise approach to determine the minimally effective dose to maintain weight loss. There are not yet published maintenance studies to guide this process. Currently the price of GLP-1 RA and inconsistent insurance coverage make them inaccessible to many patients. The manufacturers of both semaglutide and tirzepatide offer direct to consumer pricing and home delivery.

Bariatric Surgery

In patients with higher BMI (≥35kg/m2) or those with BMI ≥30kg/m2 and obesity-related metabolic disease and the desire to avoid lifelong medications or who fail or are intolerant of AOM, bariatric options should be considered.20 Sleeve gastrectomy has become the most performed surgery for treatment of obesity. It is a restrictive procedure, removing 80% of the stomach, but a drop in circulating levels of ghrelin afterwards also leads to decreased feelings of hunger. It results in weight loss of 25-30% TBW loss. It is not a good choice for patients who suffer from severe GERD, as this typically worsens afterwards; furthermore, de novo Barrett’s has been observed in nearly 6% of patients who undergo sleeve gastrectomy.21

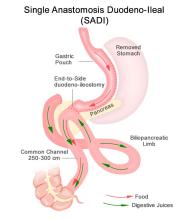

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is a restrictive and malabsorptive procedure, resulting in 30-35% TBW loss. It has beneficial and immediate metabolic effects, including increased release of endogenous GLP-1, which leads to improvements in weight-related T2DM. The newer single anastomosis duodenal-ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy (SADI-S) starts with a sleeve gastrectomy, making a smaller tube-shaped stomach. The duodenum is divided just after the stomach and then a loop of ileum is brought up and connected to the stomach (see Figure 1). This procedure is highly effective, with patients losing 75-95% of excess body weight and is becoming a preferred option for patients with greater BMI (≥50kg/m2). It is also an option for patients who have already had a sleeve gastrectomy and are seeking further weight loss. Because there is only one anastomosis, perioperative complications, such as anastomotic leaks, are reduced. The risk of micronutrient deficiencies is present with all malabsorptive procedures, and these patients must supplement with multivitamins, iron, vitamin D, and calcium.

Endoscopic Therapies