User login

Aerosolization of COVID-19 and Contamination Risks During Respiratory Treatments

Beyond asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), inhalation therapy is a mainstay in the management of bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis, and pulmonary artery hypertension. Several US Food and Drug Administration off-label indications for inhalational medications include hypoxia secondary to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and intraoperative and postoperative pulmonary hypertension during and following cardiac surgery, respectively.1-11 Therapeutic delivery of aerosols to the lung may be provided via nebulization, pressurized metered-dose inhalers (pMDI), and other devices (eg, dry powder inhalers, soft-mist inhalers, and smart inhalers).12 The most common aerosolized medications given in the clinical setting are bronchodilators.12

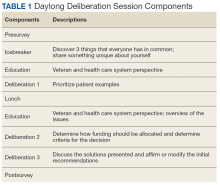

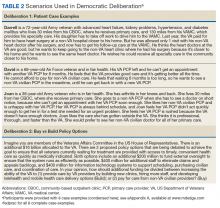

Product selection is often guided by practice guidelines (Table 1), consideration of the formulation’s advantages and disadvantages (Table 2), and/or formulary considerations. For example, current guidelines for COPD state that there is no evidence for superiority of nebulized bronchodilator therapy over handheld devices in patients who can use them properly.2 Due to equivalence, nebulized formulations are commonly used in hospitals, emergency departments (EDs) and ambulatory clinics based on the drug’s unit cost. In contrast, a pMDI is often more cost-effective for use in ambulatory patients who are administering multiple doses from the same canister.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend droplet and contact precautions for all patients suspected or diagnosed with novel coronavirus-19 (COVID-19).13,14 Airborne precautions must be applied when performing aerosol-generating medical procedures (AGMPs), including but not limited to, open suctioning of the respiratory tract, intubation, bronchoscopy, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). Data from the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV) epidemic suggest that nebulization of medication is also an AGMP.15-17

Institutions must ensure that their health care workers (HCWs) are wearing appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) including gloves, long-sleeved gowns, eye protection, and fit-tested particulate respirators (N95 mask) for airborne procedures and are carefully discarding PPE after use.13,14 Due to severe shortages in available respirators in the US supply chain, the CDC has temporarily modified WHO recommendations. Face masks are now an acceptable alternative to protect HCWs from splashes and sprays from procedures not likely to generate aerosols and for cleaning of rooms, although there is no evidence to support this decision.

Internationally, HCWs are falling ill with COVID-19. Data from Italy and Spain show that about 9% to 13% of these countries’ cases are HCWs.18,19 Within the US, the Ohio health department reports approximately 16% of cases are HCWs.20 It is possible that 20% of frontline HCWs will become infected.21 Evolving laboratory research shows that COVID-19 remains viable in aerosols for up to 3 hours postaerosolization, thus making aerosol transmission plausible.22 Nebulizers convert liquids into aerosols and during dispersal may potentially cause secondary inhalation of fugitive emissions.23 Since interim CDC infection control guidance is to allow only essential personnel to enter the room of patients with COVID-19, many facilities will rely on their frontline nursing staff to clean and disinfect high-touch surfaces following routine care activities.24

Achieving adequate fomite disinfection following viral aerosolization may pose a significant problem for any patient receiving scheduled doses of nebulized medications. Additionally, for personnel who clean rooms following intermittent drug nebulization while wearing PPE that includes a face mask, protection from aerosolized virus may be inadequate. Subsequently, fugitive emissions from nebulized medications may potentially contribute to both nosocomial COVID-19 transmission and viral infections in the medical staff until proven otherwise by studies conducted outside of the laboratory. Prevention of infection in the medical staff is imperative since federal health care systems cannot sustain a significant loss of its workforce.

Recommendations

We recommend that health care systems stop business as usual and adopt public health recommendations issued by Canadian and Hong Kong health care authorities for the management of suspected or confirmed COVID-19 disease.25-28 We have further clarified and expanded on these interventions. During viral pandemics, prescribers and health care systems should:

- Deprescribe nebulized therapies on medical wards and intensive care units as an infection control measure. Also avoid use in any outpatient health care setting (eg, community-based clinics, EDs, triage).

- Avoid initiation of nebulized unproven therapies (eg, n-acetylcysteine, hypertonic saline).1

- Use alternative bronchodilator formulations as appropriate (eg, oral β-2 agonist, recognizing its slower onset) before prescribing nebulized agents to patients who are uncooperative or unable to follow directions needed to use a pMDI with a spacer or have experienced a prior poor response to a pMDI with spacer (eg, OptiChamber Diamond, Philips).25,27

- Limit nebulized drug utilization (eg, bronchodilators, epoprostenol) to patients who are on mechanical ventilation and will receive nebulized therapies via a closed system or to patients housed in negative pressure hospital rooms.22 Use a viral filter (eg, Salter Labs system) to decrease the spread of infection for those receiving epoprostenol via face mask.25

- Adjust procurement practices (eg, pharmacy, logistics) to address the transition from nebulized drugs to alternatives.

- Add a safety net to the drug-ordering process by restricting new orders for nebulized therapies to the prior authorization process.27 Apply the exclusion criterion of suspected or definite COVID-19.

- Add a safety net to environmental service practices. Nursing staff should track patients who received ≥ 1 nebulizations via open (before diagnosis) or closed systems so that staff wear suitable PPE to include a N-95 mask while cleaning the room.

Conclusions

To implement the aggressive infection control guidance promulgated here, we recommend collaboration with infection control, pharmacy service (eg, prior authorization team, clinical pharmacy team, and procurement team), respiratory therapy, pulmonary and other critical care physicians, EDs, CPR committee, and other stakeholders. When making significant transitions in clinical care during a viral pandemic, guidelines must be timely, use imperative wording, and consist of easily identifiable education and/or instructions for the affected frontline staff in order to change attitudes.29 Additionally, when transitioning from nebulized bronchodilators to pMDI, educational in-services should be provided to frontline staff to avoid misconceptions regarding pMDI treatment efficacy and patients’ ability to use their pMDI with spacer.30

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System in Nashville.

1. Strickland SL, Rubin BK, Haas CF, Volsko TA, Drescher GS, O’Malley CA. AARC Clinical Practice Guideline: effectiveness of pharmacologic airway clearance therapies in hospitalized patients. Respir Care. 2015;60(7):1071-1077.

2. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2020 GOLD Report. https://goldcopd.org/gold-reports/. Accessed March 26, 2020.

3. Van Geffen WH, Douma WR, Slebos DJ, Kerstjens HAM. Bronchodilators delivered by nebulizer versus pMDI with spacer or DPI for exacerbations of COPD (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;8:CD011826.

4. Global Initiative for Asthma. https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/GINA-2019-main-report-June-2019-wms.pdf. Accessed March 26, 2020.

5. Global Initiative for Asthma. Difficult-to-treat and severe asthma in adolescent and adult patients: diagnosis and management. https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/GINA-Severe-asthma-Pocket-Guide-v2.0-wms-1.pdf. Accessed March 26, 2020.

6. Cates CJ, Welsh EJ, Rowe BH. Holding chambers (spacers) versus nebulizers for beta-agonist treatment of acute asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;9:CD000052.

7. Welsh EJ, Evans DJ, Fowler SJ, Spencer S. Interventions for bronchiectasis: an overview of Cochrane systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;7:CD010337.

8. Taichman DB, Ornelas J, Chung L, et al. Pharmacologic therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension in adults: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. CHEST. 2014;146(2):449-475.

9. Griffiths MJD, McAuley DF, Perkins GD, et al. Guidelines on the management of acute respiratory distress syndrome. BMJ Open Resp Res. 2019;6(1):e000420.

10. McGinn K, Reichert M. A comparison of inhaled nitric oxide versus inhaled epoprostenol for acute pulmonary hypertension following cardiac surgery. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50(1):22-26.

11. Dzierba AL, Abel EE, Buckley MS, Lat I. A review of inhaled nitric oxide and aerosolized epoprostenol in acute lung injury or acute respiratory distress syndrome. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34(3):279-290.

12. Pleasants RA, Hess DR. Aerosol delivery devices for obstructive lung diseases. Respir Care. 2018;63(6):708-733.

13. World Health Organization. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/clinical-management-of-severe-acute-respiratory-infection-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected Accessed March 26, 2020.

14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim clinical guidance for management of patients with confirmed coronavirus disease (COVID-19). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-guidance-management-patients.html. Revised March 7, 2020. Accessed March 26, 2020.

15. Wong RSM, Hui DS. Index patient and SARS outbreak in Hong Kong. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(2):339-341.

16. Wong T-W, Lee C-K, Tam W, et al; Outbreak Study Group. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(2):269-276.

17. Seto WH, Tsang D, Yung RWH, et al; Advisors of Expert SARS group of Hospital Authority. Effectiveness of precautions against droplets and contact in prevention of nosocomial transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Lancet. 2003;361(9368):1519-1520.

18. Livingston E, Bucher K. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Italy. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2763401?resultClick=1. Published March 17, 2020. Accessed March 26, 2020.

19. Jones S. Spain: doctors struggle to cope as 514 die from coronavirus in a day. The Guardian. March 24, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/24/spain-doctors-lack-protection-coronavirus-covid-19. Accessed March 27, 2020.

20. 16% of Ohio’s diagnosed COVID-19 cases are healthcare workers. https://www.wlwt.com/article/16-of-ohio-s-diagnosed-covid-19-cases-are-healthcare-workers/31930566#. Updated March 25, 2020. Accessed March 27, 2020.

21. Remuzzi A, Remuzzi G. COVID-19 and Italy: what next? Lancet. http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30627-9/fulltext. Accessed March 27, 2020.

22. van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1 [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 17]. N Engl J Med. 2020;10.1056/NEJMc2004973.

23. McGrath JA, O’Sullivan A, Bennett G, et al. Investigation of the quantity of exhaled aerosol released into the environment during nebulization. Pharmaceutics. 2019;11(2):75.

24. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthcare Infection prevention and control FAQs for COVID-19. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/infection-control/infection-prevention-control-faq.html. Revised March 24, 2020. Accessed March 26, 2020.

25. Practice standards of respiratory procedures: post SARS era. Use of aerosolized medications. December 2003. http://www.hkresp.com/hkts.php?page=page/hkts/detail&meid=93742. Accessed March 26, 2020.

26. Wax RS, Christian MD. Practical recommendations for critical care and anesthesiology teams caring for novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) patients. Can J Anesth. 2020. [ePub ahead of print.]

27. Newhouse MT. RE: transmission of coronavirus by nebulizer- as serious, underappreciated risk! https://www.cmaj.ca/content/re-transmission-corona-virus-nebulizer-serious-underappreciated-risk. Accessed March 26, 2020. [ePub ahead of print.]

28. Moira C-Y. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and healthcare workers. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2004;10(4):421-427.

29. Timen A, Hulscher MEJL, Rust L, et al. Barriers to implementing infection prevention and control guidelines during crises: experiences of health care professionals. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38(9):726-733.

30. Khoo SM, Tan LK, Said N, Lim TK. Metered-dose inhaler with spacer instead of nebulizer during the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Singapore. Respir Care. 2009;54(7):855-860.

Beyond asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), inhalation therapy is a mainstay in the management of bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis, and pulmonary artery hypertension. Several US Food and Drug Administration off-label indications for inhalational medications include hypoxia secondary to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and intraoperative and postoperative pulmonary hypertension during and following cardiac surgery, respectively.1-11 Therapeutic delivery of aerosols to the lung may be provided via nebulization, pressurized metered-dose inhalers (pMDI), and other devices (eg, dry powder inhalers, soft-mist inhalers, and smart inhalers).12 The most common aerosolized medications given in the clinical setting are bronchodilators.12

Product selection is often guided by practice guidelines (Table 1), consideration of the formulation’s advantages and disadvantages (Table 2), and/or formulary considerations. For example, current guidelines for COPD state that there is no evidence for superiority of nebulized bronchodilator therapy over handheld devices in patients who can use them properly.2 Due to equivalence, nebulized formulations are commonly used in hospitals, emergency departments (EDs) and ambulatory clinics based on the drug’s unit cost. In contrast, a pMDI is often more cost-effective for use in ambulatory patients who are administering multiple doses from the same canister.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend droplet and contact precautions for all patients suspected or diagnosed with novel coronavirus-19 (COVID-19).13,14 Airborne precautions must be applied when performing aerosol-generating medical procedures (AGMPs), including but not limited to, open suctioning of the respiratory tract, intubation, bronchoscopy, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). Data from the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV) epidemic suggest that nebulization of medication is also an AGMP.15-17

Institutions must ensure that their health care workers (HCWs) are wearing appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) including gloves, long-sleeved gowns, eye protection, and fit-tested particulate respirators (N95 mask) for airborne procedures and are carefully discarding PPE after use.13,14 Due to severe shortages in available respirators in the US supply chain, the CDC has temporarily modified WHO recommendations. Face masks are now an acceptable alternative to protect HCWs from splashes and sprays from procedures not likely to generate aerosols and for cleaning of rooms, although there is no evidence to support this decision.

Internationally, HCWs are falling ill with COVID-19. Data from Italy and Spain show that about 9% to 13% of these countries’ cases are HCWs.18,19 Within the US, the Ohio health department reports approximately 16% of cases are HCWs.20 It is possible that 20% of frontline HCWs will become infected.21 Evolving laboratory research shows that COVID-19 remains viable in aerosols for up to 3 hours postaerosolization, thus making aerosol transmission plausible.22 Nebulizers convert liquids into aerosols and during dispersal may potentially cause secondary inhalation of fugitive emissions.23 Since interim CDC infection control guidance is to allow only essential personnel to enter the room of patients with COVID-19, many facilities will rely on their frontline nursing staff to clean and disinfect high-touch surfaces following routine care activities.24

Achieving adequate fomite disinfection following viral aerosolization may pose a significant problem for any patient receiving scheduled doses of nebulized medications. Additionally, for personnel who clean rooms following intermittent drug nebulization while wearing PPE that includes a face mask, protection from aerosolized virus may be inadequate. Subsequently, fugitive emissions from nebulized medications may potentially contribute to both nosocomial COVID-19 transmission and viral infections in the medical staff until proven otherwise by studies conducted outside of the laboratory. Prevention of infection in the medical staff is imperative since federal health care systems cannot sustain a significant loss of its workforce.

Recommendations

We recommend that health care systems stop business as usual and adopt public health recommendations issued by Canadian and Hong Kong health care authorities for the management of suspected or confirmed COVID-19 disease.25-28 We have further clarified and expanded on these interventions. During viral pandemics, prescribers and health care systems should:

- Deprescribe nebulized therapies on medical wards and intensive care units as an infection control measure. Also avoid use in any outpatient health care setting (eg, community-based clinics, EDs, triage).

- Avoid initiation of nebulized unproven therapies (eg, n-acetylcysteine, hypertonic saline).1

- Use alternative bronchodilator formulations as appropriate (eg, oral β-2 agonist, recognizing its slower onset) before prescribing nebulized agents to patients who are uncooperative or unable to follow directions needed to use a pMDI with a spacer or have experienced a prior poor response to a pMDI with spacer (eg, OptiChamber Diamond, Philips).25,27

- Limit nebulized drug utilization (eg, bronchodilators, epoprostenol) to patients who are on mechanical ventilation and will receive nebulized therapies via a closed system or to patients housed in negative pressure hospital rooms.22 Use a viral filter (eg, Salter Labs system) to decrease the spread of infection for those receiving epoprostenol via face mask.25

- Adjust procurement practices (eg, pharmacy, logistics) to address the transition from nebulized drugs to alternatives.

- Add a safety net to the drug-ordering process by restricting new orders for nebulized therapies to the prior authorization process.27 Apply the exclusion criterion of suspected or definite COVID-19.

- Add a safety net to environmental service practices. Nursing staff should track patients who received ≥ 1 nebulizations via open (before diagnosis) or closed systems so that staff wear suitable PPE to include a N-95 mask while cleaning the room.

Conclusions

To implement the aggressive infection control guidance promulgated here, we recommend collaboration with infection control, pharmacy service (eg, prior authorization team, clinical pharmacy team, and procurement team), respiratory therapy, pulmonary and other critical care physicians, EDs, CPR committee, and other stakeholders. When making significant transitions in clinical care during a viral pandemic, guidelines must be timely, use imperative wording, and consist of easily identifiable education and/or instructions for the affected frontline staff in order to change attitudes.29 Additionally, when transitioning from nebulized bronchodilators to pMDI, educational in-services should be provided to frontline staff to avoid misconceptions regarding pMDI treatment efficacy and patients’ ability to use their pMDI with spacer.30

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System in Nashville.

Beyond asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), inhalation therapy is a mainstay in the management of bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis, and pulmonary artery hypertension. Several US Food and Drug Administration off-label indications for inhalational medications include hypoxia secondary to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and intraoperative and postoperative pulmonary hypertension during and following cardiac surgery, respectively.1-11 Therapeutic delivery of aerosols to the lung may be provided via nebulization, pressurized metered-dose inhalers (pMDI), and other devices (eg, dry powder inhalers, soft-mist inhalers, and smart inhalers).12 The most common aerosolized medications given in the clinical setting are bronchodilators.12

Product selection is often guided by practice guidelines (Table 1), consideration of the formulation’s advantages and disadvantages (Table 2), and/or formulary considerations. For example, current guidelines for COPD state that there is no evidence for superiority of nebulized bronchodilator therapy over handheld devices in patients who can use them properly.2 Due to equivalence, nebulized formulations are commonly used in hospitals, emergency departments (EDs) and ambulatory clinics based on the drug’s unit cost. In contrast, a pMDI is often more cost-effective for use in ambulatory patients who are administering multiple doses from the same canister.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend droplet and contact precautions for all patients suspected or diagnosed with novel coronavirus-19 (COVID-19).13,14 Airborne precautions must be applied when performing aerosol-generating medical procedures (AGMPs), including but not limited to, open suctioning of the respiratory tract, intubation, bronchoscopy, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). Data from the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV) epidemic suggest that nebulization of medication is also an AGMP.15-17

Institutions must ensure that their health care workers (HCWs) are wearing appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) including gloves, long-sleeved gowns, eye protection, and fit-tested particulate respirators (N95 mask) for airborne procedures and are carefully discarding PPE after use.13,14 Due to severe shortages in available respirators in the US supply chain, the CDC has temporarily modified WHO recommendations. Face masks are now an acceptable alternative to protect HCWs from splashes and sprays from procedures not likely to generate aerosols and for cleaning of rooms, although there is no evidence to support this decision.

Internationally, HCWs are falling ill with COVID-19. Data from Italy and Spain show that about 9% to 13% of these countries’ cases are HCWs.18,19 Within the US, the Ohio health department reports approximately 16% of cases are HCWs.20 It is possible that 20% of frontline HCWs will become infected.21 Evolving laboratory research shows that COVID-19 remains viable in aerosols for up to 3 hours postaerosolization, thus making aerosol transmission plausible.22 Nebulizers convert liquids into aerosols and during dispersal may potentially cause secondary inhalation of fugitive emissions.23 Since interim CDC infection control guidance is to allow only essential personnel to enter the room of patients with COVID-19, many facilities will rely on their frontline nursing staff to clean and disinfect high-touch surfaces following routine care activities.24

Achieving adequate fomite disinfection following viral aerosolization may pose a significant problem for any patient receiving scheduled doses of nebulized medications. Additionally, for personnel who clean rooms following intermittent drug nebulization while wearing PPE that includes a face mask, protection from aerosolized virus may be inadequate. Subsequently, fugitive emissions from nebulized medications may potentially contribute to both nosocomial COVID-19 transmission and viral infections in the medical staff until proven otherwise by studies conducted outside of the laboratory. Prevention of infection in the medical staff is imperative since federal health care systems cannot sustain a significant loss of its workforce.

Recommendations

We recommend that health care systems stop business as usual and adopt public health recommendations issued by Canadian and Hong Kong health care authorities for the management of suspected or confirmed COVID-19 disease.25-28 We have further clarified and expanded on these interventions. During viral pandemics, prescribers and health care systems should:

- Deprescribe nebulized therapies on medical wards and intensive care units as an infection control measure. Also avoid use in any outpatient health care setting (eg, community-based clinics, EDs, triage).

- Avoid initiation of nebulized unproven therapies (eg, n-acetylcysteine, hypertonic saline).1

- Use alternative bronchodilator formulations as appropriate (eg, oral β-2 agonist, recognizing its slower onset) before prescribing nebulized agents to patients who are uncooperative or unable to follow directions needed to use a pMDI with a spacer or have experienced a prior poor response to a pMDI with spacer (eg, OptiChamber Diamond, Philips).25,27

- Limit nebulized drug utilization (eg, bronchodilators, epoprostenol) to patients who are on mechanical ventilation and will receive nebulized therapies via a closed system or to patients housed in negative pressure hospital rooms.22 Use a viral filter (eg, Salter Labs system) to decrease the spread of infection for those receiving epoprostenol via face mask.25

- Adjust procurement practices (eg, pharmacy, logistics) to address the transition from nebulized drugs to alternatives.

- Add a safety net to the drug-ordering process by restricting new orders for nebulized therapies to the prior authorization process.27 Apply the exclusion criterion of suspected or definite COVID-19.

- Add a safety net to environmental service practices. Nursing staff should track patients who received ≥ 1 nebulizations via open (before diagnosis) or closed systems so that staff wear suitable PPE to include a N-95 mask while cleaning the room.

Conclusions

To implement the aggressive infection control guidance promulgated here, we recommend collaboration with infection control, pharmacy service (eg, prior authorization team, clinical pharmacy team, and procurement team), respiratory therapy, pulmonary and other critical care physicians, EDs, CPR committee, and other stakeholders. When making significant transitions in clinical care during a viral pandemic, guidelines must be timely, use imperative wording, and consist of easily identifiable education and/or instructions for the affected frontline staff in order to change attitudes.29 Additionally, when transitioning from nebulized bronchodilators to pMDI, educational in-services should be provided to frontline staff to avoid misconceptions regarding pMDI treatment efficacy and patients’ ability to use their pMDI with spacer.30

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System in Nashville.

1. Strickland SL, Rubin BK, Haas CF, Volsko TA, Drescher GS, O’Malley CA. AARC Clinical Practice Guideline: effectiveness of pharmacologic airway clearance therapies in hospitalized patients. Respir Care. 2015;60(7):1071-1077.

2. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2020 GOLD Report. https://goldcopd.org/gold-reports/. Accessed March 26, 2020.

3. Van Geffen WH, Douma WR, Slebos DJ, Kerstjens HAM. Bronchodilators delivered by nebulizer versus pMDI with spacer or DPI for exacerbations of COPD (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;8:CD011826.

4. Global Initiative for Asthma. https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/GINA-2019-main-report-June-2019-wms.pdf. Accessed March 26, 2020.

5. Global Initiative for Asthma. Difficult-to-treat and severe asthma in adolescent and adult patients: diagnosis and management. https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/GINA-Severe-asthma-Pocket-Guide-v2.0-wms-1.pdf. Accessed March 26, 2020.

6. Cates CJ, Welsh EJ, Rowe BH. Holding chambers (spacers) versus nebulizers for beta-agonist treatment of acute asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;9:CD000052.

7. Welsh EJ, Evans DJ, Fowler SJ, Spencer S. Interventions for bronchiectasis: an overview of Cochrane systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;7:CD010337.

8. Taichman DB, Ornelas J, Chung L, et al. Pharmacologic therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension in adults: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. CHEST. 2014;146(2):449-475.

9. Griffiths MJD, McAuley DF, Perkins GD, et al. Guidelines on the management of acute respiratory distress syndrome. BMJ Open Resp Res. 2019;6(1):e000420.

10. McGinn K, Reichert M. A comparison of inhaled nitric oxide versus inhaled epoprostenol for acute pulmonary hypertension following cardiac surgery. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50(1):22-26.

11. Dzierba AL, Abel EE, Buckley MS, Lat I. A review of inhaled nitric oxide and aerosolized epoprostenol in acute lung injury or acute respiratory distress syndrome. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34(3):279-290.

12. Pleasants RA, Hess DR. Aerosol delivery devices for obstructive lung diseases. Respir Care. 2018;63(6):708-733.

13. World Health Organization. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/clinical-management-of-severe-acute-respiratory-infection-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected Accessed March 26, 2020.

14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim clinical guidance for management of patients with confirmed coronavirus disease (COVID-19). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-guidance-management-patients.html. Revised March 7, 2020. Accessed March 26, 2020.

15. Wong RSM, Hui DS. Index patient and SARS outbreak in Hong Kong. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(2):339-341.

16. Wong T-W, Lee C-K, Tam W, et al; Outbreak Study Group. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(2):269-276.

17. Seto WH, Tsang D, Yung RWH, et al; Advisors of Expert SARS group of Hospital Authority. Effectiveness of precautions against droplets and contact in prevention of nosocomial transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Lancet. 2003;361(9368):1519-1520.

18. Livingston E, Bucher K. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Italy. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2763401?resultClick=1. Published March 17, 2020. Accessed March 26, 2020.

19. Jones S. Spain: doctors struggle to cope as 514 die from coronavirus in a day. The Guardian. March 24, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/24/spain-doctors-lack-protection-coronavirus-covid-19. Accessed March 27, 2020.

20. 16% of Ohio’s diagnosed COVID-19 cases are healthcare workers. https://www.wlwt.com/article/16-of-ohio-s-diagnosed-covid-19-cases-are-healthcare-workers/31930566#. Updated March 25, 2020. Accessed March 27, 2020.

21. Remuzzi A, Remuzzi G. COVID-19 and Italy: what next? Lancet. http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30627-9/fulltext. Accessed March 27, 2020.

22. van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1 [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 17]. N Engl J Med. 2020;10.1056/NEJMc2004973.

23. McGrath JA, O’Sullivan A, Bennett G, et al. Investigation of the quantity of exhaled aerosol released into the environment during nebulization. Pharmaceutics. 2019;11(2):75.

24. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthcare Infection prevention and control FAQs for COVID-19. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/infection-control/infection-prevention-control-faq.html. Revised March 24, 2020. Accessed March 26, 2020.

25. Practice standards of respiratory procedures: post SARS era. Use of aerosolized medications. December 2003. http://www.hkresp.com/hkts.php?page=page/hkts/detail&meid=93742. Accessed March 26, 2020.

26. Wax RS, Christian MD. Practical recommendations for critical care and anesthesiology teams caring for novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) patients. Can J Anesth. 2020. [ePub ahead of print.]

27. Newhouse MT. RE: transmission of coronavirus by nebulizer- as serious, underappreciated risk! https://www.cmaj.ca/content/re-transmission-corona-virus-nebulizer-serious-underappreciated-risk. Accessed March 26, 2020. [ePub ahead of print.]

28. Moira C-Y. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and healthcare workers. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2004;10(4):421-427.

29. Timen A, Hulscher MEJL, Rust L, et al. Barriers to implementing infection prevention and control guidelines during crises: experiences of health care professionals. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38(9):726-733.

30. Khoo SM, Tan LK, Said N, Lim TK. Metered-dose inhaler with spacer instead of nebulizer during the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Singapore. Respir Care. 2009;54(7):855-860.

1. Strickland SL, Rubin BK, Haas CF, Volsko TA, Drescher GS, O’Malley CA. AARC Clinical Practice Guideline: effectiveness of pharmacologic airway clearance therapies in hospitalized patients. Respir Care. 2015;60(7):1071-1077.

2. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2020 GOLD Report. https://goldcopd.org/gold-reports/. Accessed March 26, 2020.

3. Van Geffen WH, Douma WR, Slebos DJ, Kerstjens HAM. Bronchodilators delivered by nebulizer versus pMDI with spacer or DPI for exacerbations of COPD (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;8:CD011826.

4. Global Initiative for Asthma. https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/GINA-2019-main-report-June-2019-wms.pdf. Accessed March 26, 2020.

5. Global Initiative for Asthma. Difficult-to-treat and severe asthma in adolescent and adult patients: diagnosis and management. https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/GINA-Severe-asthma-Pocket-Guide-v2.0-wms-1.pdf. Accessed March 26, 2020.

6. Cates CJ, Welsh EJ, Rowe BH. Holding chambers (spacers) versus nebulizers for beta-agonist treatment of acute asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;9:CD000052.

7. Welsh EJ, Evans DJ, Fowler SJ, Spencer S. Interventions for bronchiectasis: an overview of Cochrane systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;7:CD010337.

8. Taichman DB, Ornelas J, Chung L, et al. Pharmacologic therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension in adults: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. CHEST. 2014;146(2):449-475.

9. Griffiths MJD, McAuley DF, Perkins GD, et al. Guidelines on the management of acute respiratory distress syndrome. BMJ Open Resp Res. 2019;6(1):e000420.

10. McGinn K, Reichert M. A comparison of inhaled nitric oxide versus inhaled epoprostenol for acute pulmonary hypertension following cardiac surgery. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50(1):22-26.

11. Dzierba AL, Abel EE, Buckley MS, Lat I. A review of inhaled nitric oxide and aerosolized epoprostenol in acute lung injury or acute respiratory distress syndrome. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34(3):279-290.

12. Pleasants RA, Hess DR. Aerosol delivery devices for obstructive lung diseases. Respir Care. 2018;63(6):708-733.

13. World Health Organization. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/clinical-management-of-severe-acute-respiratory-infection-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected Accessed March 26, 2020.

14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim clinical guidance for management of patients with confirmed coronavirus disease (COVID-19). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-guidance-management-patients.html. Revised March 7, 2020. Accessed March 26, 2020.

15. Wong RSM, Hui DS. Index patient and SARS outbreak in Hong Kong. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(2):339-341.

16. Wong T-W, Lee C-K, Tam W, et al; Outbreak Study Group. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(2):269-276.

17. Seto WH, Tsang D, Yung RWH, et al; Advisors of Expert SARS group of Hospital Authority. Effectiveness of precautions against droplets and contact in prevention of nosocomial transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Lancet. 2003;361(9368):1519-1520.

18. Livingston E, Bucher K. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Italy. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2763401?resultClick=1. Published March 17, 2020. Accessed March 26, 2020.

19. Jones S. Spain: doctors struggle to cope as 514 die from coronavirus in a day. The Guardian. March 24, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/24/spain-doctors-lack-protection-coronavirus-covid-19. Accessed March 27, 2020.

20. 16% of Ohio’s diagnosed COVID-19 cases are healthcare workers. https://www.wlwt.com/article/16-of-ohio-s-diagnosed-covid-19-cases-are-healthcare-workers/31930566#. Updated March 25, 2020. Accessed March 27, 2020.

21. Remuzzi A, Remuzzi G. COVID-19 and Italy: what next? Lancet. http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30627-9/fulltext. Accessed March 27, 2020.

22. van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1 [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 17]. N Engl J Med. 2020;10.1056/NEJMc2004973.

23. McGrath JA, O’Sullivan A, Bennett G, et al. Investigation of the quantity of exhaled aerosol released into the environment during nebulization. Pharmaceutics. 2019;11(2):75.

24. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthcare Infection prevention and control FAQs for COVID-19. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/infection-control/infection-prevention-control-faq.html. Revised March 24, 2020. Accessed March 26, 2020.

25. Practice standards of respiratory procedures: post SARS era. Use of aerosolized medications. December 2003. http://www.hkresp.com/hkts.php?page=page/hkts/detail&meid=93742. Accessed March 26, 2020.

26. Wax RS, Christian MD. Practical recommendations for critical care and anesthesiology teams caring for novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) patients. Can J Anesth. 2020. [ePub ahead of print.]

27. Newhouse MT. RE: transmission of coronavirus by nebulizer- as serious, underappreciated risk! https://www.cmaj.ca/content/re-transmission-corona-virus-nebulizer-serious-underappreciated-risk. Accessed March 26, 2020. [ePub ahead of print.]

28. Moira C-Y. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and healthcare workers. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2004;10(4):421-427.

29. Timen A, Hulscher MEJL, Rust L, et al. Barriers to implementing infection prevention and control guidelines during crises: experiences of health care professionals. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38(9):726-733.

30. Khoo SM, Tan LK, Said N, Lim TK. Metered-dose inhaler with spacer instead of nebulizer during the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Singapore. Respir Care. 2009;54(7):855-860.

FDA provides flexibility to improve COVID-19 test availability

First, the FDA is giving states more flexibility to approve and implement testing for COVID-19.

“States can set up a system in which they take responsibility for authorizing such tests and the laboratories will not engage with the FDA,” agency Commissioner Stephen Hahn, MD, said in a March 16 statement announcing the policy updates. “Laboratories developing tests in these states can engage directly with the appropriate state authorities, instead of with the FDA.”

A copy of the updated guidance document can be found here.

Dr. Hahn added that laboratories working within this authority granted to states will not have to pursue an emergency use authorization (EUA). New York state was previously granted a waiver to allow for more state oversight over the introduction of diagnostic testing.

Second, the FDA is expanding guidance issued on Feb. 29 on who can develop diagnostic tests. Originally, the Feb. 29 guidance was aimed at labs certified to perform high-complexity testing consistent with requirements outlined in the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments.

“Under the update published today, the agency does not intend to object to commercial manufacturers distributing and labs using new commercially developed tests prior to the FDA granting an EUA, under certain circumstances,” Commissioner Hahn said, adding that a number of commercial manufacturers are developing tests for the coronavirus with the intent of submitting an EUA request.

“During this public health emergency, the FDA does not intend to object to the distribution and use of these tests for specimen testing for a reasonable period of time after the manufacturer’s validation of the test while the manufacturer is preparing its EUA request,” he added.

The updated guidance also provides recommendations for test developers working on serologic tests for COVID-19.

During a March 16 conference call with reporters, Commissioner Hahn said the flexibility would add a “significant number of tests and we believe this will be a surge to meet the demand that we expect to see, although it is somewhat difficult” to quantify the number of tests this new flexibility will bring to the market.

First, the FDA is giving states more flexibility to approve and implement testing for COVID-19.

“States can set up a system in which they take responsibility for authorizing such tests and the laboratories will not engage with the FDA,” agency Commissioner Stephen Hahn, MD, said in a March 16 statement announcing the policy updates. “Laboratories developing tests in these states can engage directly with the appropriate state authorities, instead of with the FDA.”

A copy of the updated guidance document can be found here.

Dr. Hahn added that laboratories working within this authority granted to states will not have to pursue an emergency use authorization (EUA). New York state was previously granted a waiver to allow for more state oversight over the introduction of diagnostic testing.

Second, the FDA is expanding guidance issued on Feb. 29 on who can develop diagnostic tests. Originally, the Feb. 29 guidance was aimed at labs certified to perform high-complexity testing consistent with requirements outlined in the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments.

“Under the update published today, the agency does not intend to object to commercial manufacturers distributing and labs using new commercially developed tests prior to the FDA granting an EUA, under certain circumstances,” Commissioner Hahn said, adding that a number of commercial manufacturers are developing tests for the coronavirus with the intent of submitting an EUA request.

“During this public health emergency, the FDA does not intend to object to the distribution and use of these tests for specimen testing for a reasonable period of time after the manufacturer’s validation of the test while the manufacturer is preparing its EUA request,” he added.

The updated guidance also provides recommendations for test developers working on serologic tests for COVID-19.

During a March 16 conference call with reporters, Commissioner Hahn said the flexibility would add a “significant number of tests and we believe this will be a surge to meet the demand that we expect to see, although it is somewhat difficult” to quantify the number of tests this new flexibility will bring to the market.

First, the FDA is giving states more flexibility to approve and implement testing for COVID-19.

“States can set up a system in which they take responsibility for authorizing such tests and the laboratories will not engage with the FDA,” agency Commissioner Stephen Hahn, MD, said in a March 16 statement announcing the policy updates. “Laboratories developing tests in these states can engage directly with the appropriate state authorities, instead of with the FDA.”

A copy of the updated guidance document can be found here.

Dr. Hahn added that laboratories working within this authority granted to states will not have to pursue an emergency use authorization (EUA). New York state was previously granted a waiver to allow for more state oversight over the introduction of diagnostic testing.

Second, the FDA is expanding guidance issued on Feb. 29 on who can develop diagnostic tests. Originally, the Feb. 29 guidance was aimed at labs certified to perform high-complexity testing consistent with requirements outlined in the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments.

“Under the update published today, the agency does not intend to object to commercial manufacturers distributing and labs using new commercially developed tests prior to the FDA granting an EUA, under certain circumstances,” Commissioner Hahn said, adding that a number of commercial manufacturers are developing tests for the coronavirus with the intent of submitting an EUA request.

“During this public health emergency, the FDA does not intend to object to the distribution and use of these tests for specimen testing for a reasonable period of time after the manufacturer’s validation of the test while the manufacturer is preparing its EUA request,” he added.

The updated guidance also provides recommendations for test developers working on serologic tests for COVID-19.

During a March 16 conference call with reporters, Commissioner Hahn said the flexibility would add a “significant number of tests and we believe this will be a surge to meet the demand that we expect to see, although it is somewhat difficult” to quantify the number of tests this new flexibility will bring to the market.

To Prevent Pernicious Political Activities: The Hatch Act and Government Ethics

The impeachment trial has concluded. By the time you read this editorial, Super Tuesday will be over. Then there will be the political party conventions, and finally the general election. Politics is everywhere and will be for the rest of 2020. As a preventive ethics measure, the legal arms of almost every federal agency will be sending cautionary e-mails to employees to remind us that any political activity undertaken must comply with the Hatch Act. Many of you who have worked in federal health care for some years may have heard a fellow employee say, “be careful you don’t violate the Hatch Act.”

Most readers probably had not heard of the statute before entering federal service. And you may have had an experience similar to mine in my early federal career when through osmosis I absorbed my peers fear and trembling when the Hatch Act was mentioned. This was the situation even though you were not at all sure you understood what the lawyers were warning you not to do. In my decades in federal service, I have heard that the Hatch Act dictates everything from you cannot vote to you can run for political office.

All this makes the timing right to review a piece of legislation that governs the political actions of every federal health and administrative professional. The Hatch Act sets apart federal employees from many, if not most, of our civilian counterparts, who, depending on your perspective, have more freedom to express their political views or are not held to such a high standard of ethical conduct.

In legalese, the Hatch Act is Political Activity Authorized; Prohibitions, 5 USC §7323 (1939). The title of this editorial, “To Prevent Pernicious Political Activities” is the formal title of the Hatch Act enacted at a time when government legislation was written in more ornamental rhetoric than the staid language of the current bureaucratic style. The alliterative title phrase of the act is an apt, if dated, encapsulation of the legislative intention of the act, which in modern parlance:

The law’s purpose is to ensure that federal programs are administered in a nonpartisan fashion, to protect federal employees from political coercion in the workplace, and to ensure that federal employees are advanced based on merit and not based on political affiliation. 2

For all its poetic turn of phrase, the title is historically accurate. The Hatch Act was passed in response to rampant partisan activity in public office. It was a key part of an effort to professionalize civil service, and as an essential aspect of that process, to protect federal employees from widespread political influence. The ethical principle behind the legislation is the one that still stands as the ideal for federal practitioners: to serve the people and act for the good of the public and republic.

The Hatch Act was intended to prevent unscrupulous politicians from intimidating federal employees and usurping the machinery of major government agencies to achieve their political ambitions. Imagine if your supervisor was running for office or supporting a particular candidate and ordered you to put a campaign sign in your yard, attend a political rally, and wear a campaign button on your lapel or you would be fired. All that and far worse happened in the good old USA before the Hatch Act.3

The Office of Special Counsel (OSC) is the authoritative guardian of the Hatch Act providing opinions on whether an activity is permitted under the act; investigating compliance with the provisions of the act; taking disciplinary action against the employee for serious violations; and prosecuting those violations before the Merit Systems Protection Board. Now I understand why the incantation “Hatch Act” casts a chill on our civil service souls. While there have been recent allegations against a high-profile political appointee, federal practitioners are not immune to prosecution.4 In 2017, Federal Times reported that the OSC sought disciplinary action against a VA physician for 15 violations of the Hatch Act after he ran for a state Senate seat in 2014.5

Fortunately, the OSC has produced a handy list of “Though Shalt Nots” and “You Cans” as a guide to the Hatch Act.6 Only the highpoints are mentioned here:

- Thou shalt not be a candidate for nomination or election to a partisan public office;

- Thou shalt not use a position of official public authority to influence or interfere with the result of an election;

- Thou shalt not solicit or host, accept, or receive a donation or contribution to a partisan political party, candidate, or group; and

- Thou shalt not engage in political activity on behalf of a partisan political party, candidate, or group while on duty, in a federal space, wearing a federal uniform, or driving a federal vehicle.

Covered under these daunting prohibitions is ordinary American politicking like hosting fundraisers or inviting your coworkers to a political rally, distributing campaign materials, and wearing a T-shirt with your favorite candidates smiling face at work. The new hotbed of concern for the Hatch Act is, you guessed it, social media—you cannot use your blog, Facebook, Instagram, or e-mail account to comment pro or con for a partisan candidate, party, office, or group.6

You may be asking at this point whether you can even watch the political debates? Yes, that is allowed under the Hatch Act along with running for nonpartisan election and participating in nonpartisan campaigns; voting, and registering others to vote; you can contribute money to political campaigns, parties, or partisan groups; attend political rallies, meetings and fundraisers; and even join a political party. Of course these activities must be on your own time and dime, not that of your federal employer. All of these “You Cans” enable a federal employee to engage in the bare minimum of democracy: voting in elections, but opponents argue they bar the civil servant from fully participating in the complex richness of the American political process.7

Nonetheless, since its inception the Hatch Act has been a matter of fierce debate among federal employees and other advocates of civil liberties. Those who feel it should be relaxed contend that the modern merit-based system of government service has rendered the provisions of the Hatch Act unnecessary, even obsolete. In addition, unlike in 1939, critics of the act claim there are now formidable whistleblower protections for employees who experience political coercion. Over the years there have been several efforts to weaken the conflict of interest safeguards that the act contains, leading many commentators to think that some of the amendments and reforms have blurred the tight boundaries between the professional and the political. Others such as the government unions and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) believe that the tight line drawn between public and private binds the liberty of civil servants.8 Those who defend the Hatch Act believe that the wall it erects between professional and personal in the realm of political activities for federal employees must remain high and strong to protect the integrity of the administrative branch and the public trust.9

So, as political advertisements dominate television programming and the texts never stop asking for campaign donations, you can cast your own vote for or against the Hatch Act. As for me and my house, we will follow President Jefferson in preferring to be the property of the people rather than be indebted to the powerful. You need never encounter a true conflict of interest if you have no false conflict of obligation: history teaches us that serving 2 masters usually turns out badly for the slave. Many of you will completely disagree with my stance, holding that your constitutional rights as a citizen are being curtailed, if not outright denied, simply because you choose to serve your country. Our ability to freely hold and express our differences of opinions about the Hatch Act and so much else is what keeps democracy alive.

1. Rayner BL. Life of Thomas Jefferson With Selections From the Most Valuable Portions of his Voluminous and Unrivalled Private Correspondence. Boston, MA: Lilly, Wait, Colman, and Holden; 1834:356.

2. US Office of Special Counsel. Hatch Act overview. https://osc.gov/Services/Pages/HatchAct.aspx. Accessed February 24, 2020.

3. Brown AJ. Public employee participation: Hatch Acts in the federal and state governments. Public Integrity. 2000;2(2):105-120.

4. Phillips A. What is the Hatch Act, and why did Kellyanne Conway get accused of violating it so egregiously? Washington Post. June 13, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/06/13/what-is-hatch-act-why-did-kellyanne-conway-get-accused-violating-it-so-egregiously. Accessed February 24, 2020.

5. Bur J. Special counsel: VA doctor violated Hatch Act while campaigning. https://www.federaltimes.com/federal-oversight/watchdogs/2017/11/22/special-counsel-va-doctor-violated-hatch-act-while-campaigning. Published November 22, 2017. Accessed February 24, 2020.

6. US Office of Special Counsel. A guide to the Hatch Act for the federal employee. https://osc.gov/Documents/Outreach%20and%20Training/Handouts/A%20Guide%20to%20the%20Hatch%20Act%20for%20Federal%20Employees.pdf. Published September 2014. Accessed February 24, 2020.

7. Brown C, Maskell J. Hatch Act restrictions on federal employee’s political activities in the digital age. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R44469.pdf. Published April 13, 2016. Accessed February 24, 2020.

8. Thurber KT Jr. Revising the Hatch Act: a practitioner’s perspective. Public Manag. 1993;22(1):43.

9. Pearson WM, Castle DS. Expanding the opportunity for partisan activity among government employees: potential effects of federal executive’s political involvement. Int J Public Adm. 2007;16(4):511-525.

The impeachment trial has concluded. By the time you read this editorial, Super Tuesday will be over. Then there will be the political party conventions, and finally the general election. Politics is everywhere and will be for the rest of 2020. As a preventive ethics measure, the legal arms of almost every federal agency will be sending cautionary e-mails to employees to remind us that any political activity undertaken must comply with the Hatch Act. Many of you who have worked in federal health care for some years may have heard a fellow employee say, “be careful you don’t violate the Hatch Act.”

Most readers probably had not heard of the statute before entering federal service. And you may have had an experience similar to mine in my early federal career when through osmosis I absorbed my peers fear and trembling when the Hatch Act was mentioned. This was the situation even though you were not at all sure you understood what the lawyers were warning you not to do. In my decades in federal service, I have heard that the Hatch Act dictates everything from you cannot vote to you can run for political office.

All this makes the timing right to review a piece of legislation that governs the political actions of every federal health and administrative professional. The Hatch Act sets apart federal employees from many, if not most, of our civilian counterparts, who, depending on your perspective, have more freedom to express their political views or are not held to such a high standard of ethical conduct.

In legalese, the Hatch Act is Political Activity Authorized; Prohibitions, 5 USC §7323 (1939). The title of this editorial, “To Prevent Pernicious Political Activities” is the formal title of the Hatch Act enacted at a time when government legislation was written in more ornamental rhetoric than the staid language of the current bureaucratic style. The alliterative title phrase of the act is an apt, if dated, encapsulation of the legislative intention of the act, which in modern parlance:

The law’s purpose is to ensure that federal programs are administered in a nonpartisan fashion, to protect federal employees from political coercion in the workplace, and to ensure that federal employees are advanced based on merit and not based on political affiliation. 2

For all its poetic turn of phrase, the title is historically accurate. The Hatch Act was passed in response to rampant partisan activity in public office. It was a key part of an effort to professionalize civil service, and as an essential aspect of that process, to protect federal employees from widespread political influence. The ethical principle behind the legislation is the one that still stands as the ideal for federal practitioners: to serve the people and act for the good of the public and republic.

The Hatch Act was intended to prevent unscrupulous politicians from intimidating federal employees and usurping the machinery of major government agencies to achieve their political ambitions. Imagine if your supervisor was running for office or supporting a particular candidate and ordered you to put a campaign sign in your yard, attend a political rally, and wear a campaign button on your lapel or you would be fired. All that and far worse happened in the good old USA before the Hatch Act.3

The Office of Special Counsel (OSC) is the authoritative guardian of the Hatch Act providing opinions on whether an activity is permitted under the act; investigating compliance with the provisions of the act; taking disciplinary action against the employee for serious violations; and prosecuting those violations before the Merit Systems Protection Board. Now I understand why the incantation “Hatch Act” casts a chill on our civil service souls. While there have been recent allegations against a high-profile political appointee, federal practitioners are not immune to prosecution.4 In 2017, Federal Times reported that the OSC sought disciplinary action against a VA physician for 15 violations of the Hatch Act after he ran for a state Senate seat in 2014.5

Fortunately, the OSC has produced a handy list of “Though Shalt Nots” and “You Cans” as a guide to the Hatch Act.6 Only the highpoints are mentioned here:

- Thou shalt not be a candidate for nomination or election to a partisan public office;

- Thou shalt not use a position of official public authority to influence or interfere with the result of an election;

- Thou shalt not solicit or host, accept, or receive a donation or contribution to a partisan political party, candidate, or group; and

- Thou shalt not engage in political activity on behalf of a partisan political party, candidate, or group while on duty, in a federal space, wearing a federal uniform, or driving a federal vehicle.

Covered under these daunting prohibitions is ordinary American politicking like hosting fundraisers or inviting your coworkers to a political rally, distributing campaign materials, and wearing a T-shirt with your favorite candidates smiling face at work. The new hotbed of concern for the Hatch Act is, you guessed it, social media—you cannot use your blog, Facebook, Instagram, or e-mail account to comment pro or con for a partisan candidate, party, office, or group.6

You may be asking at this point whether you can even watch the political debates? Yes, that is allowed under the Hatch Act along with running for nonpartisan election and participating in nonpartisan campaigns; voting, and registering others to vote; you can contribute money to political campaigns, parties, or partisan groups; attend political rallies, meetings and fundraisers; and even join a political party. Of course these activities must be on your own time and dime, not that of your federal employer. All of these “You Cans” enable a federal employee to engage in the bare minimum of democracy: voting in elections, but opponents argue they bar the civil servant from fully participating in the complex richness of the American political process.7

Nonetheless, since its inception the Hatch Act has been a matter of fierce debate among federal employees and other advocates of civil liberties. Those who feel it should be relaxed contend that the modern merit-based system of government service has rendered the provisions of the Hatch Act unnecessary, even obsolete. In addition, unlike in 1939, critics of the act claim there are now formidable whistleblower protections for employees who experience political coercion. Over the years there have been several efforts to weaken the conflict of interest safeguards that the act contains, leading many commentators to think that some of the amendments and reforms have blurred the tight boundaries between the professional and the political. Others such as the government unions and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) believe that the tight line drawn between public and private binds the liberty of civil servants.8 Those who defend the Hatch Act believe that the wall it erects between professional and personal in the realm of political activities for federal employees must remain high and strong to protect the integrity of the administrative branch and the public trust.9

So, as political advertisements dominate television programming and the texts never stop asking for campaign donations, you can cast your own vote for or against the Hatch Act. As for me and my house, we will follow President Jefferson in preferring to be the property of the people rather than be indebted to the powerful. You need never encounter a true conflict of interest if you have no false conflict of obligation: history teaches us that serving 2 masters usually turns out badly for the slave. Many of you will completely disagree with my stance, holding that your constitutional rights as a citizen are being curtailed, if not outright denied, simply because you choose to serve your country. Our ability to freely hold and express our differences of opinions about the Hatch Act and so much else is what keeps democracy alive.

The impeachment trial has concluded. By the time you read this editorial, Super Tuesday will be over. Then there will be the political party conventions, and finally the general election. Politics is everywhere and will be for the rest of 2020. As a preventive ethics measure, the legal arms of almost every federal agency will be sending cautionary e-mails to employees to remind us that any political activity undertaken must comply with the Hatch Act. Many of you who have worked in federal health care for some years may have heard a fellow employee say, “be careful you don’t violate the Hatch Act.”

Most readers probably had not heard of the statute before entering federal service. And you may have had an experience similar to mine in my early federal career when through osmosis I absorbed my peers fear and trembling when the Hatch Act was mentioned. This was the situation even though you were not at all sure you understood what the lawyers were warning you not to do. In my decades in federal service, I have heard that the Hatch Act dictates everything from you cannot vote to you can run for political office.

All this makes the timing right to review a piece of legislation that governs the political actions of every federal health and administrative professional. The Hatch Act sets apart federal employees from many, if not most, of our civilian counterparts, who, depending on your perspective, have more freedom to express their political views or are not held to such a high standard of ethical conduct.

In legalese, the Hatch Act is Political Activity Authorized; Prohibitions, 5 USC §7323 (1939). The title of this editorial, “To Prevent Pernicious Political Activities” is the formal title of the Hatch Act enacted at a time when government legislation was written in more ornamental rhetoric than the staid language of the current bureaucratic style. The alliterative title phrase of the act is an apt, if dated, encapsulation of the legislative intention of the act, which in modern parlance:

The law’s purpose is to ensure that federal programs are administered in a nonpartisan fashion, to protect federal employees from political coercion in the workplace, and to ensure that federal employees are advanced based on merit and not based on political affiliation. 2

For all its poetic turn of phrase, the title is historically accurate. The Hatch Act was passed in response to rampant partisan activity in public office. It was a key part of an effort to professionalize civil service, and as an essential aspect of that process, to protect federal employees from widespread political influence. The ethical principle behind the legislation is the one that still stands as the ideal for federal practitioners: to serve the people and act for the good of the public and republic.

The Hatch Act was intended to prevent unscrupulous politicians from intimidating federal employees and usurping the machinery of major government agencies to achieve their political ambitions. Imagine if your supervisor was running for office or supporting a particular candidate and ordered you to put a campaign sign in your yard, attend a political rally, and wear a campaign button on your lapel or you would be fired. All that and far worse happened in the good old USA before the Hatch Act.3

The Office of Special Counsel (OSC) is the authoritative guardian of the Hatch Act providing opinions on whether an activity is permitted under the act; investigating compliance with the provisions of the act; taking disciplinary action against the employee for serious violations; and prosecuting those violations before the Merit Systems Protection Board. Now I understand why the incantation “Hatch Act” casts a chill on our civil service souls. While there have been recent allegations against a high-profile political appointee, federal practitioners are not immune to prosecution.4 In 2017, Federal Times reported that the OSC sought disciplinary action against a VA physician for 15 violations of the Hatch Act after he ran for a state Senate seat in 2014.5

Fortunately, the OSC has produced a handy list of “Though Shalt Nots” and “You Cans” as a guide to the Hatch Act.6 Only the highpoints are mentioned here:

- Thou shalt not be a candidate for nomination or election to a partisan public office;

- Thou shalt not use a position of official public authority to influence or interfere with the result of an election;

- Thou shalt not solicit or host, accept, or receive a donation or contribution to a partisan political party, candidate, or group; and

- Thou shalt not engage in political activity on behalf of a partisan political party, candidate, or group while on duty, in a federal space, wearing a federal uniform, or driving a federal vehicle.

Covered under these daunting prohibitions is ordinary American politicking like hosting fundraisers or inviting your coworkers to a political rally, distributing campaign materials, and wearing a T-shirt with your favorite candidates smiling face at work. The new hotbed of concern for the Hatch Act is, you guessed it, social media—you cannot use your blog, Facebook, Instagram, or e-mail account to comment pro or con for a partisan candidate, party, office, or group.6

You may be asking at this point whether you can even watch the political debates? Yes, that is allowed under the Hatch Act along with running for nonpartisan election and participating in nonpartisan campaigns; voting, and registering others to vote; you can contribute money to political campaigns, parties, or partisan groups; attend political rallies, meetings and fundraisers; and even join a political party. Of course these activities must be on your own time and dime, not that of your federal employer. All of these “You Cans” enable a federal employee to engage in the bare minimum of democracy: voting in elections, but opponents argue they bar the civil servant from fully participating in the complex richness of the American political process.7

Nonetheless, since its inception the Hatch Act has been a matter of fierce debate among federal employees and other advocates of civil liberties. Those who feel it should be relaxed contend that the modern merit-based system of government service has rendered the provisions of the Hatch Act unnecessary, even obsolete. In addition, unlike in 1939, critics of the act claim there are now formidable whistleblower protections for employees who experience political coercion. Over the years there have been several efforts to weaken the conflict of interest safeguards that the act contains, leading many commentators to think that some of the amendments and reforms have blurred the tight boundaries between the professional and the political. Others such as the government unions and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) believe that the tight line drawn between public and private binds the liberty of civil servants.8 Those who defend the Hatch Act believe that the wall it erects between professional and personal in the realm of political activities for federal employees must remain high and strong to protect the integrity of the administrative branch and the public trust.9

So, as political advertisements dominate television programming and the texts never stop asking for campaign donations, you can cast your own vote for or against the Hatch Act. As for me and my house, we will follow President Jefferson in preferring to be the property of the people rather than be indebted to the powerful. You need never encounter a true conflict of interest if you have no false conflict of obligation: history teaches us that serving 2 masters usually turns out badly for the slave. Many of you will completely disagree with my stance, holding that your constitutional rights as a citizen are being curtailed, if not outright denied, simply because you choose to serve your country. Our ability to freely hold and express our differences of opinions about the Hatch Act and so much else is what keeps democracy alive.

1. Rayner BL. Life of Thomas Jefferson With Selections From the Most Valuable Portions of his Voluminous and Unrivalled Private Correspondence. Boston, MA: Lilly, Wait, Colman, and Holden; 1834:356.

2. US Office of Special Counsel. Hatch Act overview. https://osc.gov/Services/Pages/HatchAct.aspx. Accessed February 24, 2020.

3. Brown AJ. Public employee participation: Hatch Acts in the federal and state governments. Public Integrity. 2000;2(2):105-120.

4. Phillips A. What is the Hatch Act, and why did Kellyanne Conway get accused of violating it so egregiously? Washington Post. June 13, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/06/13/what-is-hatch-act-why-did-kellyanne-conway-get-accused-violating-it-so-egregiously. Accessed February 24, 2020.

5. Bur J. Special counsel: VA doctor violated Hatch Act while campaigning. https://www.federaltimes.com/federal-oversight/watchdogs/2017/11/22/special-counsel-va-doctor-violated-hatch-act-while-campaigning. Published November 22, 2017. Accessed February 24, 2020.

6. US Office of Special Counsel. A guide to the Hatch Act for the federal employee. https://osc.gov/Documents/Outreach%20and%20Training/Handouts/A%20Guide%20to%20the%20Hatch%20Act%20for%20Federal%20Employees.pdf. Published September 2014. Accessed February 24, 2020.

7. Brown C, Maskell J. Hatch Act restrictions on federal employee’s political activities in the digital age. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R44469.pdf. Published April 13, 2016. Accessed February 24, 2020.

8. Thurber KT Jr. Revising the Hatch Act: a practitioner’s perspective. Public Manag. 1993;22(1):43.

9. Pearson WM, Castle DS. Expanding the opportunity for partisan activity among government employees: potential effects of federal executive’s political involvement. Int J Public Adm. 2007;16(4):511-525.

1. Rayner BL. Life of Thomas Jefferson With Selections From the Most Valuable Portions of his Voluminous and Unrivalled Private Correspondence. Boston, MA: Lilly, Wait, Colman, and Holden; 1834:356.

2. US Office of Special Counsel. Hatch Act overview. https://osc.gov/Services/Pages/HatchAct.aspx. Accessed February 24, 2020.

3. Brown AJ. Public employee participation: Hatch Acts in the federal and state governments. Public Integrity. 2000;2(2):105-120.

4. Phillips A. What is the Hatch Act, and why did Kellyanne Conway get accused of violating it so egregiously? Washington Post. June 13, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/06/13/what-is-hatch-act-why-did-kellyanne-conway-get-accused-violating-it-so-egregiously. Accessed February 24, 2020.

5. Bur J. Special counsel: VA doctor violated Hatch Act while campaigning. https://www.federaltimes.com/federal-oversight/watchdogs/2017/11/22/special-counsel-va-doctor-violated-hatch-act-while-campaigning. Published November 22, 2017. Accessed February 24, 2020.

6. US Office of Special Counsel. A guide to the Hatch Act for the federal employee. https://osc.gov/Documents/Outreach%20and%20Training/Handouts/A%20Guide%20to%20the%20Hatch%20Act%20for%20Federal%20Employees.pdf. Published September 2014. Accessed February 24, 2020.

7. Brown C, Maskell J. Hatch Act restrictions on federal employee’s political activities in the digital age. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R44469.pdf. Published April 13, 2016. Accessed February 24, 2020.

8. Thurber KT Jr. Revising the Hatch Act: a practitioner’s perspective. Public Manag. 1993;22(1):43.

9. Pearson WM, Castle DS. Expanding the opportunity for partisan activity among government employees: potential effects of federal executive’s political involvement. Int J Public Adm. 2007;16(4):511-525.

Breach of migrant youths’ confidentiality is unethical, unacceptable

We are in the healing profession. We practice a trade. We are doctors, therapists, counselors. We work with children, adults, and couples. We document the physical form of our patient after examination, setting the stage for interventions that heal and alleviate suffering. With those who we do not touch physically, we hold out our psychological arms to embrace them in a therapeutic relationship.

We are privileged to appreciate their deeper selves through voice, unsaid words, and body language. A trust evolves (or might not); deeper exploration where our intuition and technical skill discover what troubles the soul. Healing begins as a delicate dance: As trust is earned, our patients risk vulnerability by revealing their weakest selves.

As healers, we often find ourselves adrift with our own insecurities, our own histories that make us human; our styles may differ but training and the tenets and guidelines set by our professional societies keep us in safe waters. These guidelines are informed by the science of health care research and vetted through centuries of observation and experience of process. “Do no harm” is perhaps one of the major rules of engaging with patients. The scaffolding that our code of ethics provides healing professions trumps external pressures to deviate. If you violate these codes, the consequences are borne by the patient and the potential loss of your license.

Some of you may have read about Kevin Euceda, an adolescent who reportedly was waiting for his immigration interview and ordered to undergo mandatory therapy as part of the immigration protocol. Kevin revealed to his therapist the history of violence he experienced as a child growing up in Honduras. His subsequent initiation into a gang was the only option he had to escape a violent death. Those of us who work with youth from gang cultures know fully that allegiance to a gang is a means to find an identity and brotherhood with the payment by a lifestyle of violence. A therapist faced with this information does not judge but helps the person deal with PTSD, nightmares, and guilt that become part of an identity just as the memories of mines blowing up in the face of combat affect veterans.