User login

Journal of Hospital Medicine launches new clinical guidelines series

The Journal of Hospital Medicine, the official peer-reviewed journal of the Society of Hospital Medicine, has launched its second new series this year, entitled Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist. Alongside the new Leadership and Professional Development series, this addition plays a large role in the vision for the future of the journal, spearheaded by new editor in chief, Samir Shah, MD, MSCE, MHM.

“As a new deputy editor for reviews and perspectives, I’m thrilled to help execute Dr. Shah’s vision for a series of articles that aims to facilitate the rapid translation of the latest evidence-based guidelines into hospitalist practice,” said Erin Shaughnessy, MD. “My coeditor, Dr. Read Pierce, and I envision these reviews as tools to enable busy clinicians to quickly understand the latest research and apply it to practice.”

The March issue of JHM features an introduction to the series as well as the first two articles, “The Use of Intravenous Fluids in the Hospitalized Adult” and “Maintenance Intravenous Fluids in Infants and Children.” The introduction provides details on the formatting of the series and discusses a second format that will be introduced in 2019 called Progress Notes, which will be shorter than JHM’s traditional review format. Progress Notes will accept two types or articles, clinical and methodological, and will focus on diagnostics, therapeutics, or risk assessment and prevention of a clinical problem relevant to hospitalists.

“National guidelines and society position statements are important in informing care standards but can be time consuming to read, and only a small portion may be pertinent to the practice of hospital medicine,” Dr. Shah said. “Our Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist series, under the leadership of Dr. Shaughnessy and Dr. Pierce, will distill the key elements of national guidelines with a focus on recommendations that are most relevant to the practicing hospitalist. Authors include a brief critique to ensure hospitalists understand the strength of evidence behind the guideline when making decisions.”

Along with this series comes another new feature for the journal, Hospital Medicine: The Year in Review. This annual feature “concisely compiles and critiques the top articles in both adult and pediatric hospital medicine in the past year” and “will serve as a written corollary to the popular ‘Updates in Hospital Medicine’ presentation at the SHM Annual Conference.”

With so many updates, “JHM’s overarching commitment remains unchanged: support clinicians, leaders, and scholars in our field in their pursuit of delivering evidence-based, high-value clinical care.” The journal will continue to accept traditional, long-form review on topics relevant to hospitalists.

Visit www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com for the Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist series and additional research.

The Journal of Hospital Medicine, the official peer-reviewed journal of the Society of Hospital Medicine, has launched its second new series this year, entitled Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist. Alongside the new Leadership and Professional Development series, this addition plays a large role in the vision for the future of the journal, spearheaded by new editor in chief, Samir Shah, MD, MSCE, MHM.

“As a new deputy editor for reviews and perspectives, I’m thrilled to help execute Dr. Shah’s vision for a series of articles that aims to facilitate the rapid translation of the latest evidence-based guidelines into hospitalist practice,” said Erin Shaughnessy, MD. “My coeditor, Dr. Read Pierce, and I envision these reviews as tools to enable busy clinicians to quickly understand the latest research and apply it to practice.”

The March issue of JHM features an introduction to the series as well as the first two articles, “The Use of Intravenous Fluids in the Hospitalized Adult” and “Maintenance Intravenous Fluids in Infants and Children.” The introduction provides details on the formatting of the series and discusses a second format that will be introduced in 2019 called Progress Notes, which will be shorter than JHM’s traditional review format. Progress Notes will accept two types or articles, clinical and methodological, and will focus on diagnostics, therapeutics, or risk assessment and prevention of a clinical problem relevant to hospitalists.

“National guidelines and society position statements are important in informing care standards but can be time consuming to read, and only a small portion may be pertinent to the practice of hospital medicine,” Dr. Shah said. “Our Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist series, under the leadership of Dr. Shaughnessy and Dr. Pierce, will distill the key elements of national guidelines with a focus on recommendations that are most relevant to the practicing hospitalist. Authors include a brief critique to ensure hospitalists understand the strength of evidence behind the guideline when making decisions.”

Along with this series comes another new feature for the journal, Hospital Medicine: The Year in Review. This annual feature “concisely compiles and critiques the top articles in both adult and pediatric hospital medicine in the past year” and “will serve as a written corollary to the popular ‘Updates in Hospital Medicine’ presentation at the SHM Annual Conference.”

With so many updates, “JHM’s overarching commitment remains unchanged: support clinicians, leaders, and scholars in our field in their pursuit of delivering evidence-based, high-value clinical care.” The journal will continue to accept traditional, long-form review on topics relevant to hospitalists.

Visit www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com for the Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist series and additional research.

The Journal of Hospital Medicine, the official peer-reviewed journal of the Society of Hospital Medicine, has launched its second new series this year, entitled Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist. Alongside the new Leadership and Professional Development series, this addition plays a large role in the vision for the future of the journal, spearheaded by new editor in chief, Samir Shah, MD, MSCE, MHM.

“As a new deputy editor for reviews and perspectives, I’m thrilled to help execute Dr. Shah’s vision for a series of articles that aims to facilitate the rapid translation of the latest evidence-based guidelines into hospitalist practice,” said Erin Shaughnessy, MD. “My coeditor, Dr. Read Pierce, and I envision these reviews as tools to enable busy clinicians to quickly understand the latest research and apply it to practice.”

The March issue of JHM features an introduction to the series as well as the first two articles, “The Use of Intravenous Fluids in the Hospitalized Adult” and “Maintenance Intravenous Fluids in Infants and Children.” The introduction provides details on the formatting of the series and discusses a second format that will be introduced in 2019 called Progress Notes, which will be shorter than JHM’s traditional review format. Progress Notes will accept two types or articles, clinical and methodological, and will focus on diagnostics, therapeutics, or risk assessment and prevention of a clinical problem relevant to hospitalists.

“National guidelines and society position statements are important in informing care standards but can be time consuming to read, and only a small portion may be pertinent to the practice of hospital medicine,” Dr. Shah said. “Our Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist series, under the leadership of Dr. Shaughnessy and Dr. Pierce, will distill the key elements of national guidelines with a focus on recommendations that are most relevant to the practicing hospitalist. Authors include a brief critique to ensure hospitalists understand the strength of evidence behind the guideline when making decisions.”

Along with this series comes another new feature for the journal, Hospital Medicine: The Year in Review. This annual feature “concisely compiles and critiques the top articles in both adult and pediatric hospital medicine in the past year” and “will serve as a written corollary to the popular ‘Updates in Hospital Medicine’ presentation at the SHM Annual Conference.”

With so many updates, “JHM’s overarching commitment remains unchanged: support clinicians, leaders, and scholars in our field in their pursuit of delivering evidence-based, high-value clinical care.” The journal will continue to accept traditional, long-form review on topics relevant to hospitalists.

Visit www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com for the Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist series and additional research.

Advance care planning codes not being used

Starting in 2016, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services began paying physicians for advance care planning discussions with the approval of two new codes: 99497 and 99498. The codes pay about $86 for the first 30 minutes of a face-to-face conversation with a patient, family member, and/or surrogate and about $75 for additional sessions. Services can be furnished in both inpatient and ambulatory settings, and payment is not limited to particular physician specialties.

In 2016, health care professionals in New England (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont) billed Medicare 26,522 times for the advance care planning (ACP) codes for a total of 24,536 patients, which represented less than 1% of Medicare beneficiaries in New England at the time, according to Kimberly Pelland, MPH, of Healthcentric Advisors, Providence, R.I., and her colleagues. Most claims were billed in the office, followed by in nursing homes, and in hospitals; 40% of conversations occurred during an annual wellness visit (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 March 11. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8107).

Internists billed Medicare the most for ACP claims (65%), followed by family physicians (22%) gerontologists (5%), and oncologist/hematologists (0.3%), according to the analysis based on 2016 Medicare claims data and Census Bureau data. A greater proportion of patients with ACP claims were female, aged 85 years or older, enrolled in hospice, and died in the study year. Patients had higher odds of having an ACP claim if they were older and had lower income, and if they had cancer, heart failure, stroke, chronic kidney disease, or dementia. Male patients who were Asian, black, and Hispanic had lower chances of having an ACP claim.

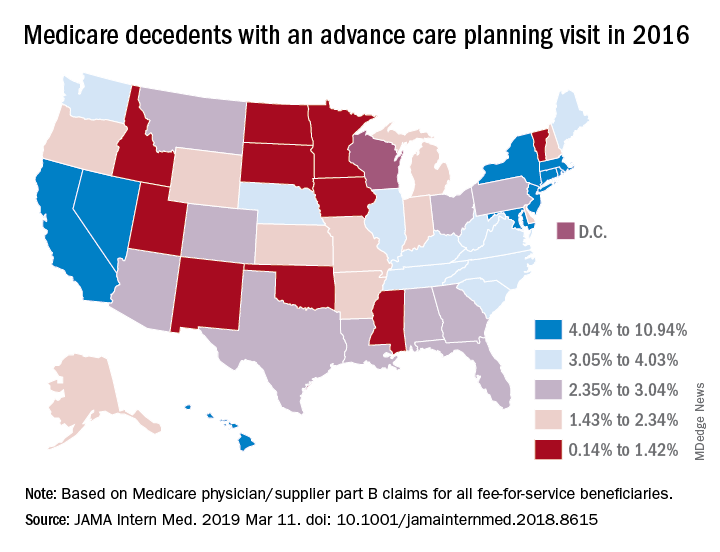

In a related study, Emmanuelle Belanger, PhD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and her colleagues examined national Medicare data from 2016 to the third quarter of 2017. Across the United States, 2% of Medicare patients aged 65 years and older received advance care planning services that were billed under the ACP codes (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 March 11. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8615). Visits billed under the ACP codes increased from 538,275 to 633,214 during the same time period. Claim rates were higher among patients who died within the study period, reaching 3% in 2016 and 6% in 2017. The percentage of decedents with an ACP billed visit varied strongly across states, with states such as North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming having the fewest ACP visits billed and states such as California and Nevada having the most. ACP billed visits increased in all settings in 2017, but primarily in hospitals and nursing homes. Nationally, internists billed the codes most (48%), followed by family physicians (28%).

While the two studies indicate low usage of the ACP codes, many physicians are discussing advance care planning with their patients, said Mary M. Newman, MD, an internist based in Lutherville, Md., and former American College of Physicians adviser to the American Medical Association Relative Scale Value Update Committee (RUC).

“What cannot be captured by tracking under Medicare claims data are those shorter conversations that we have frequently,” Dr. Newman said in an interview. “If we have a short conversation about advance care planning, it gets folded into our evaluation and management visit. It’s not going to be separately billed.”

At the same time, some patients are not ready to discuss end-of-life options and decline the discussions when asked, Dr. Newman said. Particularly for healthier patients, end of life care is not a primary focus, she noted.

“Not everybody’s ready to have an advance care planning [discussion] that lasts 16-45 minutes,” she said. “Many people over age 65 are not ready to deal with advance care planning in their day-to-day lives, and it may not be what they wish to discuss. I offer the option to patients and some say, ‘Yes, I’d love to,’ and others decline or postpone.”

Low usage of the ACP codes may be associated with lack of awareness, uncertainty about appropriate code use, or associated billing that is not part of the standard workflow, Ankita Mehta, MD, of Mount Sinai in New York wrote an editorial accompanying the studies (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 March 11. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8105).

“Regardless, the low rates of utilization of ACP codes is alarming and highlights the need to create strategies to integrate ACP discussions into standard practice and build ACP documentation and billing in clinical workflow,” Dr. Mehta said.

Dr. Newman agreed that more education among physicians is needed.

“The amount of education clinicians have received varies tremendously across the geography of the country,” she said. “I think the codes are going to be slowly adopted. The challenge to us is to make sure we’re all better educated on palliative care as people age and get sick and that we are sensitive to our patients explicit and implicit needs for these discussions.”

Starting in 2016, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services began paying physicians for advance care planning discussions with the approval of two new codes: 99497 and 99498. The codes pay about $86 for the first 30 minutes of a face-to-face conversation with a patient, family member, and/or surrogate and about $75 for additional sessions. Services can be furnished in both inpatient and ambulatory settings, and payment is not limited to particular physician specialties.

In 2016, health care professionals in New England (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont) billed Medicare 26,522 times for the advance care planning (ACP) codes for a total of 24,536 patients, which represented less than 1% of Medicare beneficiaries in New England at the time, according to Kimberly Pelland, MPH, of Healthcentric Advisors, Providence, R.I., and her colleagues. Most claims were billed in the office, followed by in nursing homes, and in hospitals; 40% of conversations occurred during an annual wellness visit (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 March 11. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8107).

Internists billed Medicare the most for ACP claims (65%), followed by family physicians (22%) gerontologists (5%), and oncologist/hematologists (0.3%), according to the analysis based on 2016 Medicare claims data and Census Bureau data. A greater proportion of patients with ACP claims were female, aged 85 years or older, enrolled in hospice, and died in the study year. Patients had higher odds of having an ACP claim if they were older and had lower income, and if they had cancer, heart failure, stroke, chronic kidney disease, or dementia. Male patients who were Asian, black, and Hispanic had lower chances of having an ACP claim.

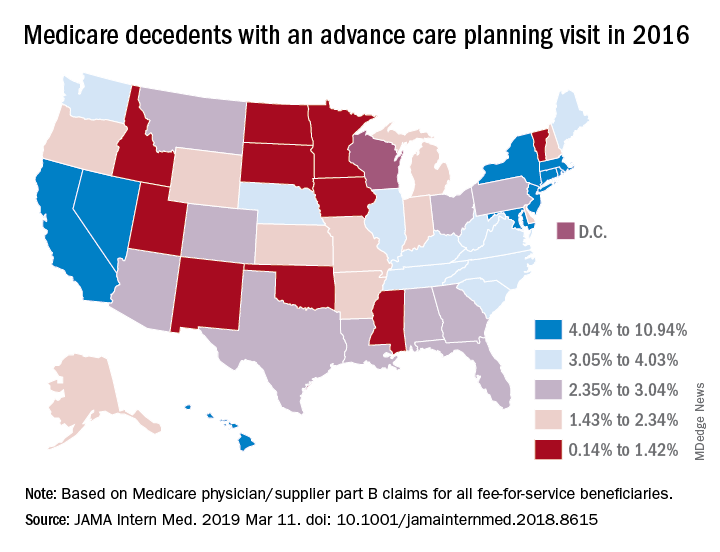

In a related study, Emmanuelle Belanger, PhD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and her colleagues examined national Medicare data from 2016 to the third quarter of 2017. Across the United States, 2% of Medicare patients aged 65 years and older received advance care planning services that were billed under the ACP codes (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 March 11. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8615). Visits billed under the ACP codes increased from 538,275 to 633,214 during the same time period. Claim rates were higher among patients who died within the study period, reaching 3% in 2016 and 6% in 2017. The percentage of decedents with an ACP billed visit varied strongly across states, with states such as North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming having the fewest ACP visits billed and states such as California and Nevada having the most. ACP billed visits increased in all settings in 2017, but primarily in hospitals and nursing homes. Nationally, internists billed the codes most (48%), followed by family physicians (28%).

While the two studies indicate low usage of the ACP codes, many physicians are discussing advance care planning with their patients, said Mary M. Newman, MD, an internist based in Lutherville, Md., and former American College of Physicians adviser to the American Medical Association Relative Scale Value Update Committee (RUC).

“What cannot be captured by tracking under Medicare claims data are those shorter conversations that we have frequently,” Dr. Newman said in an interview. “If we have a short conversation about advance care planning, it gets folded into our evaluation and management visit. It’s not going to be separately billed.”

At the same time, some patients are not ready to discuss end-of-life options and decline the discussions when asked, Dr. Newman said. Particularly for healthier patients, end of life care is not a primary focus, she noted.

“Not everybody’s ready to have an advance care planning [discussion] that lasts 16-45 minutes,” she said. “Many people over age 65 are not ready to deal with advance care planning in their day-to-day lives, and it may not be what they wish to discuss. I offer the option to patients and some say, ‘Yes, I’d love to,’ and others decline or postpone.”

Low usage of the ACP codes may be associated with lack of awareness, uncertainty about appropriate code use, or associated billing that is not part of the standard workflow, Ankita Mehta, MD, of Mount Sinai in New York wrote an editorial accompanying the studies (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 March 11. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8105).

“Regardless, the low rates of utilization of ACP codes is alarming and highlights the need to create strategies to integrate ACP discussions into standard practice and build ACP documentation and billing in clinical workflow,” Dr. Mehta said.

Dr. Newman agreed that more education among physicians is needed.

“The amount of education clinicians have received varies tremendously across the geography of the country,” she said. “I think the codes are going to be slowly adopted. The challenge to us is to make sure we’re all better educated on palliative care as people age and get sick and that we are sensitive to our patients explicit and implicit needs for these discussions.”

Starting in 2016, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services began paying physicians for advance care planning discussions with the approval of two new codes: 99497 and 99498. The codes pay about $86 for the first 30 minutes of a face-to-face conversation with a patient, family member, and/or surrogate and about $75 for additional sessions. Services can be furnished in both inpatient and ambulatory settings, and payment is not limited to particular physician specialties.

In 2016, health care professionals in New England (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont) billed Medicare 26,522 times for the advance care planning (ACP) codes for a total of 24,536 patients, which represented less than 1% of Medicare beneficiaries in New England at the time, according to Kimberly Pelland, MPH, of Healthcentric Advisors, Providence, R.I., and her colleagues. Most claims were billed in the office, followed by in nursing homes, and in hospitals; 40% of conversations occurred during an annual wellness visit (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 March 11. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8107).

Internists billed Medicare the most for ACP claims (65%), followed by family physicians (22%) gerontologists (5%), and oncologist/hematologists (0.3%), according to the analysis based on 2016 Medicare claims data and Census Bureau data. A greater proportion of patients with ACP claims were female, aged 85 years or older, enrolled in hospice, and died in the study year. Patients had higher odds of having an ACP claim if they were older and had lower income, and if they had cancer, heart failure, stroke, chronic kidney disease, or dementia. Male patients who were Asian, black, and Hispanic had lower chances of having an ACP claim.

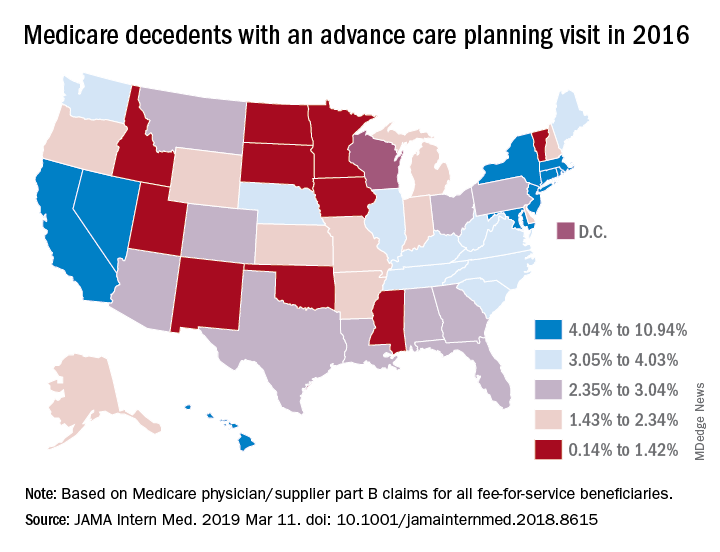

In a related study, Emmanuelle Belanger, PhD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and her colleagues examined national Medicare data from 2016 to the third quarter of 2017. Across the United States, 2% of Medicare patients aged 65 years and older received advance care planning services that were billed under the ACP codes (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 March 11. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8615). Visits billed under the ACP codes increased from 538,275 to 633,214 during the same time period. Claim rates were higher among patients who died within the study period, reaching 3% in 2016 and 6% in 2017. The percentage of decedents with an ACP billed visit varied strongly across states, with states such as North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming having the fewest ACP visits billed and states such as California and Nevada having the most. ACP billed visits increased in all settings in 2017, but primarily in hospitals and nursing homes. Nationally, internists billed the codes most (48%), followed by family physicians (28%).

While the two studies indicate low usage of the ACP codes, many physicians are discussing advance care planning with their patients, said Mary M. Newman, MD, an internist based in Lutherville, Md., and former American College of Physicians adviser to the American Medical Association Relative Scale Value Update Committee (RUC).

“What cannot be captured by tracking under Medicare claims data are those shorter conversations that we have frequently,” Dr. Newman said in an interview. “If we have a short conversation about advance care planning, it gets folded into our evaluation and management visit. It’s not going to be separately billed.”

At the same time, some patients are not ready to discuss end-of-life options and decline the discussions when asked, Dr. Newman said. Particularly for healthier patients, end of life care is not a primary focus, she noted.

“Not everybody’s ready to have an advance care planning [discussion] that lasts 16-45 minutes,” she said. “Many people over age 65 are not ready to deal with advance care planning in their day-to-day lives, and it may not be what they wish to discuss. I offer the option to patients and some say, ‘Yes, I’d love to,’ and others decline or postpone.”

Low usage of the ACP codes may be associated with lack of awareness, uncertainty about appropriate code use, or associated billing that is not part of the standard workflow, Ankita Mehta, MD, of Mount Sinai in New York wrote an editorial accompanying the studies (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 March 11. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8105).

“Regardless, the low rates of utilization of ACP codes is alarming and highlights the need to create strategies to integrate ACP discussions into standard practice and build ACP documentation and billing in clinical workflow,” Dr. Mehta said.

Dr. Newman agreed that more education among physicians is needed.

“The amount of education clinicians have received varies tremendously across the geography of the country,” she said. “I think the codes are going to be slowly adopted. The challenge to us is to make sure we’re all better educated on palliative care as people age and get sick and that we are sensitive to our patients explicit and implicit needs for these discussions.”

Hospital-onset sepsis twice as lethal as community-onset disease

SAN DIEGO – Patients who develop sepsis in the hospital appear to be in greater risk for mortality than those who bring it with them, a new study suggests. Patients with hospital-onset sepsis were twice as likely to die as those infected in the outside world.

“There could be some differences in quality of care that explains the difference in mortality,” said study lead author Chanu Rhee, MD, assistant professor of population medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, in a presentation about the findings at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

In an interview, Dr. Rhee said researchers launched the study to gain a greater understanding of the epidemiology of sepsis in the hospital. They relied on a new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention definition of sepsis that is “enhancing the consistency of surveillance across hospitals and allowing more precise differentiation between hospital-onset versus community-onset sepsis.”

The study authors retrospectively tracked more than 2.2 million patients who were treated at 136 U.S. hospitals from 2009 to 2015. In general, hospital-onset sepsis was defined as patients who had a blood culture, initial antibiotic therapy, and organ dysfunction on their third day in the hospital or later.*

Of the patients, 83,600 had community-onset sepsis and 11,500 had hospital-onset sepsis. Those with sepsis were more likely to be men and have comorbidities such as cancer, congestive heart failure, diabetes, and renal disease.

Patients with hospital-onset sepsis had longer median lengths of stay (19 days) than the community-onset group (8 days) and the no-sepsis group (4 days). The hospital-onset group also had a greater likelihood of ICU admission (61%) than the community-onset (44%) and no-sepsis (9%) groups.

About 34% of those with hospital-onset sepsis died, compared with 17% of the community-onset group and 2% of the patients who didn’t have sepsis. After adjustment, those with hospital-onset sepsis were still more likely to have died (odds ratio, 2.1; 95% confidence interval, 2.0-2.2).

“Other studies have suggested that there may be delays in the recognition and care of patients who develop sepsis in the hospital as opposed to presenting to the hospital with sepsis,” Dr. Rhee said. “It is also possible that hospital-onset sepsis tends to be caused by organisms that are more virulent and resistant to antibiotics.”

Overall, he said, “our findings underscore the importance of targeting hospital-onset sepsis with surveillance, prevention, and quality improvement efforts.”

The study was funded by the CDC and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Rhee C et al. CCC48, Abstract 29.

*Correction, 3/19/19: An earlier version of this article misstated the definition of sepsis.

SAN DIEGO – Patients who develop sepsis in the hospital appear to be in greater risk for mortality than those who bring it with them, a new study suggests. Patients with hospital-onset sepsis were twice as likely to die as those infected in the outside world.

“There could be some differences in quality of care that explains the difference in mortality,” said study lead author Chanu Rhee, MD, assistant professor of population medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, in a presentation about the findings at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

In an interview, Dr. Rhee said researchers launched the study to gain a greater understanding of the epidemiology of sepsis in the hospital. They relied on a new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention definition of sepsis that is “enhancing the consistency of surveillance across hospitals and allowing more precise differentiation between hospital-onset versus community-onset sepsis.”

The study authors retrospectively tracked more than 2.2 million patients who were treated at 136 U.S. hospitals from 2009 to 2015. In general, hospital-onset sepsis was defined as patients who had a blood culture, initial antibiotic therapy, and organ dysfunction on their third day in the hospital or later.*

Of the patients, 83,600 had community-onset sepsis and 11,500 had hospital-onset sepsis. Those with sepsis were more likely to be men and have comorbidities such as cancer, congestive heart failure, diabetes, and renal disease.

Patients with hospital-onset sepsis had longer median lengths of stay (19 days) than the community-onset group (8 days) and the no-sepsis group (4 days). The hospital-onset group also had a greater likelihood of ICU admission (61%) than the community-onset (44%) and no-sepsis (9%) groups.

About 34% of those with hospital-onset sepsis died, compared with 17% of the community-onset group and 2% of the patients who didn’t have sepsis. After adjustment, those with hospital-onset sepsis were still more likely to have died (odds ratio, 2.1; 95% confidence interval, 2.0-2.2).

“Other studies have suggested that there may be delays in the recognition and care of patients who develop sepsis in the hospital as opposed to presenting to the hospital with sepsis,” Dr. Rhee said. “It is also possible that hospital-onset sepsis tends to be caused by organisms that are more virulent and resistant to antibiotics.”

Overall, he said, “our findings underscore the importance of targeting hospital-onset sepsis with surveillance, prevention, and quality improvement efforts.”

The study was funded by the CDC and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Rhee C et al. CCC48, Abstract 29.

*Correction, 3/19/19: An earlier version of this article misstated the definition of sepsis.

SAN DIEGO – Patients who develop sepsis in the hospital appear to be in greater risk for mortality than those who bring it with them, a new study suggests. Patients with hospital-onset sepsis were twice as likely to die as those infected in the outside world.

“There could be some differences in quality of care that explains the difference in mortality,” said study lead author Chanu Rhee, MD, assistant professor of population medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, in a presentation about the findings at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

In an interview, Dr. Rhee said researchers launched the study to gain a greater understanding of the epidemiology of sepsis in the hospital. They relied on a new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention definition of sepsis that is “enhancing the consistency of surveillance across hospitals and allowing more precise differentiation between hospital-onset versus community-onset sepsis.”

The study authors retrospectively tracked more than 2.2 million patients who were treated at 136 U.S. hospitals from 2009 to 2015. In general, hospital-onset sepsis was defined as patients who had a blood culture, initial antibiotic therapy, and organ dysfunction on their third day in the hospital or later.*

Of the patients, 83,600 had community-onset sepsis and 11,500 had hospital-onset sepsis. Those with sepsis were more likely to be men and have comorbidities such as cancer, congestive heart failure, diabetes, and renal disease.

Patients with hospital-onset sepsis had longer median lengths of stay (19 days) than the community-onset group (8 days) and the no-sepsis group (4 days). The hospital-onset group also had a greater likelihood of ICU admission (61%) than the community-onset (44%) and no-sepsis (9%) groups.

About 34% of those with hospital-onset sepsis died, compared with 17% of the community-onset group and 2% of the patients who didn’t have sepsis. After adjustment, those with hospital-onset sepsis were still more likely to have died (odds ratio, 2.1; 95% confidence interval, 2.0-2.2).

“Other studies have suggested that there may be delays in the recognition and care of patients who develop sepsis in the hospital as opposed to presenting to the hospital with sepsis,” Dr. Rhee said. “It is also possible that hospital-onset sepsis tends to be caused by organisms that are more virulent and resistant to antibiotics.”

Overall, he said, “our findings underscore the importance of targeting hospital-onset sepsis with surveillance, prevention, and quality improvement efforts.”

The study was funded by the CDC and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Rhee C et al. CCC48, Abstract 29.

*Correction, 3/19/19: An earlier version of this article misstated the definition of sepsis.

REPORTING FROM CCC48

Developing clinical mastery at HM19

Boosting your bedside diagnostic skills

A new three-session minitrack devoted to the clinical mastery of diagnostic and treatment skills at the hospitalized patient’s bedside should be a highlight of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s 2019 annual conference.

The “Clinical Mastery” track is designed to help hospitalists enhance their skills in making expert diagnoses at the bedside, said Dustin T. Smith, MD, SFHM, course director for HM19, and associate professor of medicine at Emory University, Atlanta. “We feel that all of the didactic sessions offered at HM19 are highly useful for hospitalists, but there is growing interest in having sessions devoted to learning clinical pearls that can aid in practicing medicine and acquiring the skill set of a master clinician.”

The three clinical mastery sessions at HM19 will address neurologic symptoms, ECG interpretation, and the role of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS), currently a hot topic in hospital medicine. Recent advances in ultrasound technology have resulted in probes that can cost as little as $2,000, fit inside a lab coat pocket, and be read from a smartphone – making ultrasound far easier to bring to the bedside of hospitalized patients, said Ria Dancel, MD, FHM, associate professor of internal medicine and pediatrics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Dr. Dancel will copresent the POCUS clinical mastery track at HM19. “Our focus will be on how POCUS and the physical exam relate to each other. These are not competing technologies but complementary, reflecting the evolution in bedside medicine. Because these new devices will soon be in the pockets of your colleagues, residents, physician assistants, and others, you should at least have the knowledge and vocabulary to communicate with them,” she said.

POCUS is a new technology that is not yet in wide use at the hospital bedside, but clearly a wave is building, said Dr. Dancel’s copresenter, Michael Janjigian, MD, associate professor in the department of medicine at NYU Langone Health in New York City.

“We’re at the inflection point where the cost of the machine and the availability of training means that hospitals need to decide if it’s time to embrace it,” he said. Hospitalists may also consider petitioning their hospital’s leadership to offer the machines and training.

“Hospitalists’ competencies and strengths lie primarily in making diagnoses,” Dr. Janjigian said. “We like to think of ourselves as master diagnosticians. Our session at HM19 will explore the strengths and weaknesses of both the physical exam and POCUS, presenting clinical scenarios common to hospital medicine. This course is designed for those who have never picked up an ultrasound probe and want to better understand why they should, and for those who want a better sense of how they might integrate it into their practice.”

While radiology and cardiology have been using ultrasound for decades, internists are finding uses at the bedside to speed diagnosis or focus their next diagnostic steps, Dr. Dancel noted. For certain diagnoses, the physical exam is still the tool of choice. But when looking for fluid around the heart or ascites buildup in the abdomen or when looking at the heart itself, she said, there is no better tool at the bedside than ultrasound.

In January 2019, the SHM issued a position statement on POCUS1, which is intended to inform hospitalists about the technology and its uses, encourage them to be more integrally involved in decision making processes surrounding POCUS program management for their hospitals, and promote development of standards for hospitalists in POCUS training and assessment. The SHM has also developed a pathway to teach the use of ultrasound, the Point-of-Care Ultrasound Certificate of Completion.

In order to qualify, clinicians complete online training modules, attend two live learning courses, compile a portfolio of ultrasound video clips on the job that are reviewed by a panel of experts, and then pass a final exam. The exam will be offered at HM19 for clinicians who have completed preliminary work for this new certificate – as well as precourses devoted to ultrasound and other procedures – and another workshop on POCUS.

Earning the POCUS certificate of completion requires a lot of effort, Dr. Dancel acknowledged. “It is a big commitment, and we don’t want hospitalists thinking that just because they have completed the certificate that they have fully mastered ultrasound. We encourage hospitalists to find a proctor in their own hospitals and to work with them to continue to refine their skills.”

Dr. Dancel and Dr. Janjigian reported no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Soni NJ et al. Point-of-care ultrasound for hospitalists: A position statement of the Society of Hospital Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019 Jan 2. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3079.

Boosting your bedside diagnostic skills

Boosting your bedside diagnostic skills

A new three-session minitrack devoted to the clinical mastery of diagnostic and treatment skills at the hospitalized patient’s bedside should be a highlight of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s 2019 annual conference.

The “Clinical Mastery” track is designed to help hospitalists enhance their skills in making expert diagnoses at the bedside, said Dustin T. Smith, MD, SFHM, course director for HM19, and associate professor of medicine at Emory University, Atlanta. “We feel that all of the didactic sessions offered at HM19 are highly useful for hospitalists, but there is growing interest in having sessions devoted to learning clinical pearls that can aid in practicing medicine and acquiring the skill set of a master clinician.”

The three clinical mastery sessions at HM19 will address neurologic symptoms, ECG interpretation, and the role of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS), currently a hot topic in hospital medicine. Recent advances in ultrasound technology have resulted in probes that can cost as little as $2,000, fit inside a lab coat pocket, and be read from a smartphone – making ultrasound far easier to bring to the bedside of hospitalized patients, said Ria Dancel, MD, FHM, associate professor of internal medicine and pediatrics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Dr. Dancel will copresent the POCUS clinical mastery track at HM19. “Our focus will be on how POCUS and the physical exam relate to each other. These are not competing technologies but complementary, reflecting the evolution in bedside medicine. Because these new devices will soon be in the pockets of your colleagues, residents, physician assistants, and others, you should at least have the knowledge and vocabulary to communicate with them,” she said.

POCUS is a new technology that is not yet in wide use at the hospital bedside, but clearly a wave is building, said Dr. Dancel’s copresenter, Michael Janjigian, MD, associate professor in the department of medicine at NYU Langone Health in New York City.

“We’re at the inflection point where the cost of the machine and the availability of training means that hospitals need to decide if it’s time to embrace it,” he said. Hospitalists may also consider petitioning their hospital’s leadership to offer the machines and training.

“Hospitalists’ competencies and strengths lie primarily in making diagnoses,” Dr. Janjigian said. “We like to think of ourselves as master diagnosticians. Our session at HM19 will explore the strengths and weaknesses of both the physical exam and POCUS, presenting clinical scenarios common to hospital medicine. This course is designed for those who have never picked up an ultrasound probe and want to better understand why they should, and for those who want a better sense of how they might integrate it into their practice.”

While radiology and cardiology have been using ultrasound for decades, internists are finding uses at the bedside to speed diagnosis or focus their next diagnostic steps, Dr. Dancel noted. For certain diagnoses, the physical exam is still the tool of choice. But when looking for fluid around the heart or ascites buildup in the abdomen or when looking at the heart itself, she said, there is no better tool at the bedside than ultrasound.

In January 2019, the SHM issued a position statement on POCUS1, which is intended to inform hospitalists about the technology and its uses, encourage them to be more integrally involved in decision making processes surrounding POCUS program management for their hospitals, and promote development of standards for hospitalists in POCUS training and assessment. The SHM has also developed a pathway to teach the use of ultrasound, the Point-of-Care Ultrasound Certificate of Completion.

In order to qualify, clinicians complete online training modules, attend two live learning courses, compile a portfolio of ultrasound video clips on the job that are reviewed by a panel of experts, and then pass a final exam. The exam will be offered at HM19 for clinicians who have completed preliminary work for this new certificate – as well as precourses devoted to ultrasound and other procedures – and another workshop on POCUS.

Earning the POCUS certificate of completion requires a lot of effort, Dr. Dancel acknowledged. “It is a big commitment, and we don’t want hospitalists thinking that just because they have completed the certificate that they have fully mastered ultrasound. We encourage hospitalists to find a proctor in their own hospitals and to work with them to continue to refine their skills.”

Dr. Dancel and Dr. Janjigian reported no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Soni NJ et al. Point-of-care ultrasound for hospitalists: A position statement of the Society of Hospital Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019 Jan 2. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3079.

A new three-session minitrack devoted to the clinical mastery of diagnostic and treatment skills at the hospitalized patient’s bedside should be a highlight of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s 2019 annual conference.

The “Clinical Mastery” track is designed to help hospitalists enhance their skills in making expert diagnoses at the bedside, said Dustin T. Smith, MD, SFHM, course director for HM19, and associate professor of medicine at Emory University, Atlanta. “We feel that all of the didactic sessions offered at HM19 are highly useful for hospitalists, but there is growing interest in having sessions devoted to learning clinical pearls that can aid in practicing medicine and acquiring the skill set of a master clinician.”

The three clinical mastery sessions at HM19 will address neurologic symptoms, ECG interpretation, and the role of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS), currently a hot topic in hospital medicine. Recent advances in ultrasound technology have resulted in probes that can cost as little as $2,000, fit inside a lab coat pocket, and be read from a smartphone – making ultrasound far easier to bring to the bedside of hospitalized patients, said Ria Dancel, MD, FHM, associate professor of internal medicine and pediatrics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Dr. Dancel will copresent the POCUS clinical mastery track at HM19. “Our focus will be on how POCUS and the physical exam relate to each other. These are not competing technologies but complementary, reflecting the evolution in bedside medicine. Because these new devices will soon be in the pockets of your colleagues, residents, physician assistants, and others, you should at least have the knowledge and vocabulary to communicate with them,” she said.

POCUS is a new technology that is not yet in wide use at the hospital bedside, but clearly a wave is building, said Dr. Dancel’s copresenter, Michael Janjigian, MD, associate professor in the department of medicine at NYU Langone Health in New York City.

“We’re at the inflection point where the cost of the machine and the availability of training means that hospitals need to decide if it’s time to embrace it,” he said. Hospitalists may also consider petitioning their hospital’s leadership to offer the machines and training.

“Hospitalists’ competencies and strengths lie primarily in making diagnoses,” Dr. Janjigian said. “We like to think of ourselves as master diagnosticians. Our session at HM19 will explore the strengths and weaknesses of both the physical exam and POCUS, presenting clinical scenarios common to hospital medicine. This course is designed for those who have never picked up an ultrasound probe and want to better understand why they should, and for those who want a better sense of how they might integrate it into their practice.”

While radiology and cardiology have been using ultrasound for decades, internists are finding uses at the bedside to speed diagnosis or focus their next diagnostic steps, Dr. Dancel noted. For certain diagnoses, the physical exam is still the tool of choice. But when looking for fluid around the heart or ascites buildup in the abdomen or when looking at the heart itself, she said, there is no better tool at the bedside than ultrasound.

In January 2019, the SHM issued a position statement on POCUS1, which is intended to inform hospitalists about the technology and its uses, encourage them to be more integrally involved in decision making processes surrounding POCUS program management for their hospitals, and promote development of standards for hospitalists in POCUS training and assessment. The SHM has also developed a pathway to teach the use of ultrasound, the Point-of-Care Ultrasound Certificate of Completion.

In order to qualify, clinicians complete online training modules, attend two live learning courses, compile a portfolio of ultrasound video clips on the job that are reviewed by a panel of experts, and then pass a final exam. The exam will be offered at HM19 for clinicians who have completed preliminary work for this new certificate – as well as precourses devoted to ultrasound and other procedures – and another workshop on POCUS.

Earning the POCUS certificate of completion requires a lot of effort, Dr. Dancel acknowledged. “It is a big commitment, and we don’t want hospitalists thinking that just because they have completed the certificate that they have fully mastered ultrasound. We encourage hospitalists to find a proctor in their own hospitals and to work with them to continue to refine their skills.”

Dr. Dancel and Dr. Janjigian reported no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Soni NJ et al. Point-of-care ultrasound for hospitalists: A position statement of the Society of Hospital Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019 Jan 2. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3079.

Higher blood pressure after thrombectomy links with bad stroke outcomes

HONOLULU – Acute ischemic stroke patients who underwent endovascular thrombectomy and then had a peak systolic blood pressure of greater than 158 mm Hg during the next 24 hours had worse 90-day outcomes than did patients whose peak systolic pressure remained at or below 158 mm Hg in a prospective, multicenter, observational study with 485 patients.

The results hint that maintaining a lower systolic blood pressure after thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke patients may improve outcomes, but because the current study was observational, the hypothesis that patients benefit when treatment keeps their systolic pressure at or below 158 mm Hg must undergo testing in a prospective, randomized trial, Eva A. Mistry, MBBS, said at the International Stroke Conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

The finding from this study that 158 mm Hg provided the best dichotomous division between systolic blood pressures linked with good or bad outcomes is a first step toward trying to devise a more systematic and evidence-based approach to blood pressure management in acute ischemic stroke patients following endovascular thrombectomy, said Dr. Mistry, a neurologist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn.

Neither Vanderbilt nor any of the other 11 major U.S. stroke centers that participated in the current study currently have an established protocol for blood pressure management after thrombectomy, Dr. Mistry said in an interview.

“We usually treat to reduce blood pressure, but we don’t have a [broadly agreed on] threshold” to trigger treatment. “It depends on a collective decision” by the various medical specialists who care for an individual acute stroke patient. In addition, no consensus yet exists for the best treatment strategy for blood pressure lowering in acute ischemic stroke patients. Intravenous nicardipine is often the top choice because it is fast-acting and easy to administer and control as an intravenous agent. Those same properties make the beta blocker labetalol a frequently used second drug, she said.

The BEST (Blood Pressure After Endovascular Stroke Therapy) study ran at 12 U.S. centers and enrolled 485 patients who underwent endovascular thrombectomy to treat an acute ischemic stroke. The patients averaged 69 years old, and 48% also underwent thrombolytic treatment. The study’s primary outcome was the percentage of patients with a modified Rankin Scale score of 0-2 at 90 days after their stroke, an outcome reached by 39% of all patients in the study.

Statistical analysis of the collected data showed that a peak systolic blood pressure of 158 mm Hg reached during the 24 hours following thrombectomy best divided patients with good 90-day outcomes from those with worse outcomes. Patients with a postthrombectomy peak systolic pressure above 158 mm Hg had a 2.2-fold increased rate of having a modified Rankin Scale score of 3 or higher after 90 days, a statistically significant relationship, Dr. Mistry reported. However, in an analysis that also adjusted for age, baseline stroke severity, glucose level, time to reperfusion, ASPECTS score, history of hypertension, and recanalization status, the elevated risk for a bad outcome linked with higher systolic pressure dropped to 39% greater than that for patients with systolic pressures that did not rise above 158 mm Hg, a difference that was not statistically significant. This suggests that these adjustments were unable to account for all confounders and further highlighted the need for a prospective, randomized trial to test the value of controlling blood pressure following thrombectomy, Dr. Mistry said. The unadjusted results confirmed a prior report from Dr. Mistry and her associates that found a link between higher blood pressure after stroke thrombectomy and worse outcomes (J Am Heart Assoc. 2017 May 18. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006167).

The analysis also showed that patients who were successfully recanalized by thrombectomy, achieving a thrombolysis in cerebral infarction (TICI) score of 2b or 3, had lower peak systolic blood pressures than did patients who failed to get this level of restored cerebral blood flow from thrombectomy.

BEST received no commercial funding. Dr. Mistry had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Mistry EA et al. Stroke. 2019 Feb;50(Suppl_1): Abstract 94.

HONOLULU – Acute ischemic stroke patients who underwent endovascular thrombectomy and then had a peak systolic blood pressure of greater than 158 mm Hg during the next 24 hours had worse 90-day outcomes than did patients whose peak systolic pressure remained at or below 158 mm Hg in a prospective, multicenter, observational study with 485 patients.

The results hint that maintaining a lower systolic blood pressure after thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke patients may improve outcomes, but because the current study was observational, the hypothesis that patients benefit when treatment keeps their systolic pressure at or below 158 mm Hg must undergo testing in a prospective, randomized trial, Eva A. Mistry, MBBS, said at the International Stroke Conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

The finding from this study that 158 mm Hg provided the best dichotomous division between systolic blood pressures linked with good or bad outcomes is a first step toward trying to devise a more systematic and evidence-based approach to blood pressure management in acute ischemic stroke patients following endovascular thrombectomy, said Dr. Mistry, a neurologist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn.

Neither Vanderbilt nor any of the other 11 major U.S. stroke centers that participated in the current study currently have an established protocol for blood pressure management after thrombectomy, Dr. Mistry said in an interview.

“We usually treat to reduce blood pressure, but we don’t have a [broadly agreed on] threshold” to trigger treatment. “It depends on a collective decision” by the various medical specialists who care for an individual acute stroke patient. In addition, no consensus yet exists for the best treatment strategy for blood pressure lowering in acute ischemic stroke patients. Intravenous nicardipine is often the top choice because it is fast-acting and easy to administer and control as an intravenous agent. Those same properties make the beta blocker labetalol a frequently used second drug, she said.

The BEST (Blood Pressure After Endovascular Stroke Therapy) study ran at 12 U.S. centers and enrolled 485 patients who underwent endovascular thrombectomy to treat an acute ischemic stroke. The patients averaged 69 years old, and 48% also underwent thrombolytic treatment. The study’s primary outcome was the percentage of patients with a modified Rankin Scale score of 0-2 at 90 days after their stroke, an outcome reached by 39% of all patients in the study.

Statistical analysis of the collected data showed that a peak systolic blood pressure of 158 mm Hg reached during the 24 hours following thrombectomy best divided patients with good 90-day outcomes from those with worse outcomes. Patients with a postthrombectomy peak systolic pressure above 158 mm Hg had a 2.2-fold increased rate of having a modified Rankin Scale score of 3 or higher after 90 days, a statistically significant relationship, Dr. Mistry reported. However, in an analysis that also adjusted for age, baseline stroke severity, glucose level, time to reperfusion, ASPECTS score, history of hypertension, and recanalization status, the elevated risk for a bad outcome linked with higher systolic pressure dropped to 39% greater than that for patients with systolic pressures that did not rise above 158 mm Hg, a difference that was not statistically significant. This suggests that these adjustments were unable to account for all confounders and further highlighted the need for a prospective, randomized trial to test the value of controlling blood pressure following thrombectomy, Dr. Mistry said. The unadjusted results confirmed a prior report from Dr. Mistry and her associates that found a link between higher blood pressure after stroke thrombectomy and worse outcomes (J Am Heart Assoc. 2017 May 18. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006167).

The analysis also showed that patients who were successfully recanalized by thrombectomy, achieving a thrombolysis in cerebral infarction (TICI) score of 2b or 3, had lower peak systolic blood pressures than did patients who failed to get this level of restored cerebral blood flow from thrombectomy.

BEST received no commercial funding. Dr. Mistry had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Mistry EA et al. Stroke. 2019 Feb;50(Suppl_1): Abstract 94.

HONOLULU – Acute ischemic stroke patients who underwent endovascular thrombectomy and then had a peak systolic blood pressure of greater than 158 mm Hg during the next 24 hours had worse 90-day outcomes than did patients whose peak systolic pressure remained at or below 158 mm Hg in a prospective, multicenter, observational study with 485 patients.

The results hint that maintaining a lower systolic blood pressure after thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke patients may improve outcomes, but because the current study was observational, the hypothesis that patients benefit when treatment keeps their systolic pressure at or below 158 mm Hg must undergo testing in a prospective, randomized trial, Eva A. Mistry, MBBS, said at the International Stroke Conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

The finding from this study that 158 mm Hg provided the best dichotomous division between systolic blood pressures linked with good or bad outcomes is a first step toward trying to devise a more systematic and evidence-based approach to blood pressure management in acute ischemic stroke patients following endovascular thrombectomy, said Dr. Mistry, a neurologist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn.

Neither Vanderbilt nor any of the other 11 major U.S. stroke centers that participated in the current study currently have an established protocol for blood pressure management after thrombectomy, Dr. Mistry said in an interview.

“We usually treat to reduce blood pressure, but we don’t have a [broadly agreed on] threshold” to trigger treatment. “It depends on a collective decision” by the various medical specialists who care for an individual acute stroke patient. In addition, no consensus yet exists for the best treatment strategy for blood pressure lowering in acute ischemic stroke patients. Intravenous nicardipine is often the top choice because it is fast-acting and easy to administer and control as an intravenous agent. Those same properties make the beta blocker labetalol a frequently used second drug, she said.

The BEST (Blood Pressure After Endovascular Stroke Therapy) study ran at 12 U.S. centers and enrolled 485 patients who underwent endovascular thrombectomy to treat an acute ischemic stroke. The patients averaged 69 years old, and 48% also underwent thrombolytic treatment. The study’s primary outcome was the percentage of patients with a modified Rankin Scale score of 0-2 at 90 days after their stroke, an outcome reached by 39% of all patients in the study.

Statistical analysis of the collected data showed that a peak systolic blood pressure of 158 mm Hg reached during the 24 hours following thrombectomy best divided patients with good 90-day outcomes from those with worse outcomes. Patients with a postthrombectomy peak systolic pressure above 158 mm Hg had a 2.2-fold increased rate of having a modified Rankin Scale score of 3 or higher after 90 days, a statistically significant relationship, Dr. Mistry reported. However, in an analysis that also adjusted for age, baseline stroke severity, glucose level, time to reperfusion, ASPECTS score, history of hypertension, and recanalization status, the elevated risk for a bad outcome linked with higher systolic pressure dropped to 39% greater than that for patients with systolic pressures that did not rise above 158 mm Hg, a difference that was not statistically significant. This suggests that these adjustments were unable to account for all confounders and further highlighted the need for a prospective, randomized trial to test the value of controlling blood pressure following thrombectomy, Dr. Mistry said. The unadjusted results confirmed a prior report from Dr. Mistry and her associates that found a link between higher blood pressure after stroke thrombectomy and worse outcomes (J Am Heart Assoc. 2017 May 18. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006167).

The analysis also showed that patients who were successfully recanalized by thrombectomy, achieving a thrombolysis in cerebral infarction (TICI) score of 2b or 3, had lower peak systolic blood pressures than did patients who failed to get this level of restored cerebral blood flow from thrombectomy.

BEST received no commercial funding. Dr. Mistry had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Mistry EA et al. Stroke. 2019 Feb;50(Suppl_1): Abstract 94.

REPORTING FROM ISC 2019

Newer antihyperglycemic drugs have distinctive CV, kidney benefits

The two newer classes of antihyperglycemic drugs that lower cardiovascular risk have different effects on specific cardiovascular and kidney disease outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes, results of a meta-analysis suggest. Sodium-glucose contransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors significantly reduced hospitalization from heart failure, whereas glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) did not, according to the reported results.

The GLP-1–RA class reduced risk of kidney disease progression, largely driven by a reduction in macroalbuminuria, according to the authors, whereas only the SGLT2 inhibitors reduced adverse kidney disease outcomes in a composite excluding that biomarker.

“The prevention of heart failure and progression of kidney disease by SGLT2 [inhibitors] should be considered in the decision-making process when treating patients with type 2 diabetes,” study senior author Marc S. Sabatine, MD, MPH, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and his coauthors wrote in a report on the study appearing in Circulation.

Both GLP-1 RAs and SGLT2 inhibitors significantly reduced major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and, as shown in other recent findings, their benefits were confined to patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, Dr. Sabatine and his colleagues wrote.

The systematic review and meta-analysis of eight cardiovascular outcomes trials included 77,242 patients, of whom about 56% participated in GLP-1–RA studies and 44% in SGLT2-inhibitor trials. Just under three-quarters of the patients had established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, while the remainder had multiple risk factors for it.

Relative risk of hospitalization for heart failure was reduced by 31% with SGLT2 inhibitors, but it was not significantly reduced by GLP-1 RAs, the authors noted.

Risk of kidney disease progression was reduced by 38% with SGLT2 inhibitors and by 18% with GLP-1 RAs when the researchers used a broad composite endpoint including macroalbuminuria, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), end-stage kidney disease, and death due to renal causes.

By contrast, SGLT2 inhibitors reduced by 45% the relative risk of a narrower kidney outcome that excluded macroalbuminuria, whereas GLP-1 RAs had only a nonsignificant effect on the risk of doubling serum creatinine. That suggests the relative risk reduction of the kidney composite with GLP-1 RAs was driven mainly by a reduction in macroalbuminuria, the authors wrote.

Although albuminuria is an established biomarker for kidney and cardiovascular disease, it is a surrogate marker and can even be absent in patients with reduced eGFR, they said.

“Reduction in eGFR has emerged as a more meaningful endpoint of greater importance and is used in ongoing diabetes trials for kidney outcomes,” the authors said in a discussion of their results.

Relative risk of the composite MACE endpoint, including myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular death, was reduced by 12% for GLP-1 RAs and by 11% for SGLT2 [inhibitors], according to results of the analysis. However, the benefit was confined to patients with established cardiovascular disease, who had a 14% reduction of risk, compared with no treatment effect in patients who had multiple risk factors only.

Looking at individual MACE components, investigators found that both drug classes significantly reduced relative risk of myocardial infarction and of cardiovascular death, whereas only GLP-1 RAs significantly reduced relative risk of stroke.

Study authors provided disclosures related to AstraZeneca, Amgen, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Intarcia, Janssen Research and Development, and Medimmune, among others.

SOURCE: Zelniker TA et al. Circulation. 2019 Feb 21. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038868.

The two newer classes of antihyperglycemic drugs that lower cardiovascular risk have different effects on specific cardiovascular and kidney disease outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes, results of a meta-analysis suggest. Sodium-glucose contransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors significantly reduced hospitalization from heart failure, whereas glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) did not, according to the reported results.

The GLP-1–RA class reduced risk of kidney disease progression, largely driven by a reduction in macroalbuminuria, according to the authors, whereas only the SGLT2 inhibitors reduced adverse kidney disease outcomes in a composite excluding that biomarker.

“The prevention of heart failure and progression of kidney disease by SGLT2 [inhibitors] should be considered in the decision-making process when treating patients with type 2 diabetes,” study senior author Marc S. Sabatine, MD, MPH, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and his coauthors wrote in a report on the study appearing in Circulation.

Both GLP-1 RAs and SGLT2 inhibitors significantly reduced major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and, as shown in other recent findings, their benefits were confined to patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, Dr. Sabatine and his colleagues wrote.

The systematic review and meta-analysis of eight cardiovascular outcomes trials included 77,242 patients, of whom about 56% participated in GLP-1–RA studies and 44% in SGLT2-inhibitor trials. Just under three-quarters of the patients had established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, while the remainder had multiple risk factors for it.

Relative risk of hospitalization for heart failure was reduced by 31% with SGLT2 inhibitors, but it was not significantly reduced by GLP-1 RAs, the authors noted.

Risk of kidney disease progression was reduced by 38% with SGLT2 inhibitors and by 18% with GLP-1 RAs when the researchers used a broad composite endpoint including macroalbuminuria, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), end-stage kidney disease, and death due to renal causes.

By contrast, SGLT2 inhibitors reduced by 45% the relative risk of a narrower kidney outcome that excluded macroalbuminuria, whereas GLP-1 RAs had only a nonsignificant effect on the risk of doubling serum creatinine. That suggests the relative risk reduction of the kidney composite with GLP-1 RAs was driven mainly by a reduction in macroalbuminuria, the authors wrote.

Although albuminuria is an established biomarker for kidney and cardiovascular disease, it is a surrogate marker and can even be absent in patients with reduced eGFR, they said.

“Reduction in eGFR has emerged as a more meaningful endpoint of greater importance and is used in ongoing diabetes trials for kidney outcomes,” the authors said in a discussion of their results.

Relative risk of the composite MACE endpoint, including myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular death, was reduced by 12% for GLP-1 RAs and by 11% for SGLT2 [inhibitors], according to results of the analysis. However, the benefit was confined to patients with established cardiovascular disease, who had a 14% reduction of risk, compared with no treatment effect in patients who had multiple risk factors only.

Looking at individual MACE components, investigators found that both drug classes significantly reduced relative risk of myocardial infarction and of cardiovascular death, whereas only GLP-1 RAs significantly reduced relative risk of stroke.

Study authors provided disclosures related to AstraZeneca, Amgen, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Intarcia, Janssen Research and Development, and Medimmune, among others.

SOURCE: Zelniker TA et al. Circulation. 2019 Feb 21. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038868.

The two newer classes of antihyperglycemic drugs that lower cardiovascular risk have different effects on specific cardiovascular and kidney disease outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes, results of a meta-analysis suggest. Sodium-glucose contransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors significantly reduced hospitalization from heart failure, whereas glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) did not, according to the reported results.

The GLP-1–RA class reduced risk of kidney disease progression, largely driven by a reduction in macroalbuminuria, according to the authors, whereas only the SGLT2 inhibitors reduced adverse kidney disease outcomes in a composite excluding that biomarker.

“The prevention of heart failure and progression of kidney disease by SGLT2 [inhibitors] should be considered in the decision-making process when treating patients with type 2 diabetes,” study senior author Marc S. Sabatine, MD, MPH, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and his coauthors wrote in a report on the study appearing in Circulation.

Both GLP-1 RAs and SGLT2 inhibitors significantly reduced major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and, as shown in other recent findings, their benefits were confined to patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, Dr. Sabatine and his colleagues wrote.

The systematic review and meta-analysis of eight cardiovascular outcomes trials included 77,242 patients, of whom about 56% participated in GLP-1–RA studies and 44% in SGLT2-inhibitor trials. Just under three-quarters of the patients had established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, while the remainder had multiple risk factors for it.

Relative risk of hospitalization for heart failure was reduced by 31% with SGLT2 inhibitors, but it was not significantly reduced by GLP-1 RAs, the authors noted.

Risk of kidney disease progression was reduced by 38% with SGLT2 inhibitors and by 18% with GLP-1 RAs when the researchers used a broad composite endpoint including macroalbuminuria, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), end-stage kidney disease, and death due to renal causes.

By contrast, SGLT2 inhibitors reduced by 45% the relative risk of a narrower kidney outcome that excluded macroalbuminuria, whereas GLP-1 RAs had only a nonsignificant effect on the risk of doubling serum creatinine. That suggests the relative risk reduction of the kidney composite with GLP-1 RAs was driven mainly by a reduction in macroalbuminuria, the authors wrote.

Although albuminuria is an established biomarker for kidney and cardiovascular disease, it is a surrogate marker and can even be absent in patients with reduced eGFR, they said.

“Reduction in eGFR has emerged as a more meaningful endpoint of greater importance and is used in ongoing diabetes trials for kidney outcomes,” the authors said in a discussion of their results.

Relative risk of the composite MACE endpoint, including myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular death, was reduced by 12% for GLP-1 RAs and by 11% for SGLT2 [inhibitors], according to results of the analysis. However, the benefit was confined to patients with established cardiovascular disease, who had a 14% reduction of risk, compared with no treatment effect in patients who had multiple risk factors only.

Looking at individual MACE components, investigators found that both drug classes significantly reduced relative risk of myocardial infarction and of cardiovascular death, whereas only GLP-1 RAs significantly reduced relative risk of stroke.

Study authors provided disclosures related to AstraZeneca, Amgen, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Intarcia, Janssen Research and Development, and Medimmune, among others.

SOURCE: Zelniker TA et al. Circulation. 2019 Feb 21. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038868.

FROM CIRCULATION

Five pitfalls in optimizing medical management of HFrEF

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Many of the abundant missed opportunities to optimize pharmacotherapy for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction revolve around not getting fully on board with the guideline-directed medical therapy shown to be highly effective at improving clinical outcomes, Akshay S. Desai, MD, asserted at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass sponsored by the American College of Cardiology.

“If you take nothing else away from this talk, is really quite profound,” declared Dr. Desai, director of the cardiomyopathy and heart failure program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and a cardiologist at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

He highlighted five common traps or pitfalls for physicians with regard to medical therapy of patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF):

Underutilization of guideline-directed medical therapy

The current ACC/American Heart Association/Heart Failure Society of America guidelines on heart failure management (Circulation. 2017 Aug 8;136[6]:e137-61) reflect 20 years of impressive progress in improving heart failure outcomes through the use of increasingly effective guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT). The magnitude of this improvement was nicely captured in a meta-analysis of 57 randomized controlled trials published during 1987-2015. The meta-analysis showed that, although ACE inhibitor therapy alone had no significant impact on all-cause mortality compared to placebo in patients with HFrEF, the sequential addition of guideline-directed drugs conferred stepwise improvements in survival. This approach culminated in a 56% reduction in all-cause mortality with the combination of an ACE inhibitor, beta-blocker, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA), compared with placebo, and a 63% reduction with an angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI), beta-blocker, and MRA (Circ Heart Fail. 2017 Jan;10(1). pii: e003529).

Moreover, the benefits of contemporary GDMT extend beyond reductions in all-cause mortality, death due to heart failure, and heart failure–related hospitalizations into areas where one wouldn’t necessarily have expected to see much benefit. For example, an analysis of data on more than 40,000 HFrEF patients in 12 clinical trials showed a sharp decline in the rate of sudden death over the years as new agents were incorporated into GDMT. The cumulative incidence of sudden death within 90 days after randomization plunged from 2.4% in the earliest trial to 1.0% in the most recent one (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jul 6;377[1]:41-51).

“We’re at the point where we now question whether routine use of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in primary prevention patients with nonischemic heart failure is really worthwhile on the backdrop of effective medical therapy,” Dr. Desai observed.

But there’s a problem: “We don’t do a great job with GDMT, even with this incredible evidence base that we have,” the cardiologist said.

He cited a report from the CHAMP-HF registry that scrutinized the use of GDMT in more than 3,500 ambulatory HFrEF patients in 150 U.S. primary care and cardiology practices. It found that 67% of patients deemed eligible for an MRA weren’t on one. Neither were 33% with no contraindications to beta-blocker therapy and 27% who were eligible for an ACE inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), or ARNI (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Jul 24;72[4]:351-66).

“This highlights a huge opportunity for further guideline-directed optimization of therapy,” he said.

Underdosing of GDMT

The CHAMP-HF registry contained further disappointing news regarding the state of treatment of patients with HFrEF in ambulatory settings: Among those patients who were on GDMT, very few were receiving the recommended target doses of the medications as established in major clinical trials and specified in the guidelines. Only 14% of patients on an ARNI were on the target dose, as were 28% on a beta-blocker, and 17% of those on an ACE inhibitor or ARB. And among patients who were eligible for all classes of GDMT, just 1% were simultaneously on the target doses of an MRA, beta-blocker, and ARNI, ACE inhibitor, or ARB. This despite solid evidence that, although some benefit is derived from initiating these medications, incremental benefit comes from dose titration.

“Even for those of us who feel like we do this quite well, if we examine our practices systematically – and we’ve done this in our own practices at Brigham and Women’s – you see that a lot of eligible patients aren’t on optimal therapy. And you might argue that many of them have contraindications, but even when you do a deep dive into the literature or the electronic medical record and ask the question – Why is this patient with normal renal function and normal potassium with class II HFrEF not on an MRA? – sometimes it’s hard to establish why that’s the case,” said Dr. Desai.

Interrupting GDMT during hospitalizations

This is common practice. But in fact, continuation of GDMT is generally well tolerated in the setting of acute decompensated heart failure in the absence of severe hypotension and cardiogenic shock. Moreover, in-hospital discontinuation or dose reduction is associated with increased risks of readmission and mortality.

And in treatment-naive HFrEF patients, what better place to introduce a medication and assess its tolerability than the hospital? Plus, medications prescribed at discharge are more likely to be continued in the outpatient setting, he noted.

Being seduced by the illusion of stability

The guidelines state that patients with NYHA class II or III HFrEF who tolerate an ACE inhibitor or ARB should be transitioned to an ARNI to further reduce their risk of morbidity and mortality. Yet many physicians wait to make the switch until clinical decompensation occurs. That’s a mistake, as was demonstrated in the landmark PARADIGM-HF trial. Twenty percent of study participants without a prior hospitalization for heart failure experienced cardiovascular death or heart failure hospitalization during the follow-up period. Patients who were clinically stable as defined by no prior heart failure hospitalization or none within 3 months prior to enrollment were as likely to benefit from ARNI therapy with sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto) as were those with a recent decompensation (JACC Heart Fail. 2016 Oct;4[10]:816-22). “A key message is that stability is an illusion in patients with symptomatic heart failure,”said Dr. Desai. “In PARADIGM-HF, the first event for about half of patients was not heralded by a worsening of symptoms or a heart failure hospitalization, it was an abrupt death at home. This may mean that a missed opportunity to optimize treatment may not come back to you down the road, so waiting until patients get worse in order to optimize their therapy may not be the best strategy.”

Inadequate laboratory monitoring