User login

Better communication with pharmacists can improve postop pain control

LAS VEGAS – . Watch out for overlapping medication orders. Beware of gabapentin mishaps, and embrace Tylenol – but not always.

April Smith, PharmD, associate professor of pharmacy practice at Creighton University, Omaha, offered these tips about postoperative care to surgeons at the 2019 Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“We’re probably one of the most underutilized professions you have on your team,” she said, adding that “we have to know what you’re doing to help you.”

As she explained, “if you’re going to have a new order set, let us know that, so we can be your allies in helping nurses and other people understand why we’re doing what we’re doing. I’m on the same floor, and the nurses are coming up to me and asking me questions. If I can explain to them why we’re doing these things, they’ll get on board a lot faster and save you a lot of phone calls. I know you’re surgeons and you hate that [phone calls].”

Better communication with pharmacists can also boost the stocking of enhanced-recovery medications in automatic dispensing machines, she said, so they’re ready when patients need them.

Dr. Smith offered these tips about specific postsurgery medications:

- Scopolamine is a “great drug for post-op vomiting and nausea,” Dr. Smith said. But do not use it in patients over 65, and it’s contraindicated in glaucoma. Beware of these notable side effects: Blurry vision, constipation, and urinary retention. Dexamethasone and ondansetron can be used as an alternative, she said.

- Use of the blood thinner enoxaparin after discharge may become more common as surgical stays become shorter, Dr. Smith said. She urged surgeons to keep its cost in mind: a 10-day course can be as little as $2 with Medicaid or as much as $140 (a cash price for patients without coverage).

- Make sure to adjust medications based on preoperative or intraoperative doses, she said, to avoid endangering patients by inadvertently doubling up on doses. And watch out for previous use of gabapentin, which is part of enhanced-recovery protocols. Patients who take the drug at home should be put back on their typical dose.

- Also, she warned, “don’t give gabapentin to someone who’s never had it before plus an opioid.” This, she said, can cause delirium.

- Consider starting liquids the night of surgery so patients can begin taking their home medications such as sleep, chronic pain, and psychiatric drugs. Patients will be more stable and satisfied, Dr. Smith said.

- Don’t prescribe hard-to-find medications like oxycodone oral solution or oral ketorolac. These drugs will send patients from pharmacy to pharmacy in search of them, Dr. Smith said.

- Embrace a “Meds to Beds” program if possible. These programs enlist on-site pharmacies to deliver medications to bedside for patients to take home.

- Consider Tylenol as a postoperative painkiller with scheduled doses and be aware that you can prescribe the over-the-counter adult liquid form. However, Dr. Smith cautioned that Tylenol is “not great” on an as-needed basis. Gabapentin and celecoxib (unless contraindicated) are also helpful for postop pain relief, and they’re inexpensive, she said. Three to five days should be enough in most minimally invasive surgeries.

- Don’t overprescribe opioids. “The more we prescribe, the more they will consume,” Dr. Smith said. Check the American College of Surgeons guidelines regarding the ideal number of postsurgery, 5-mg doses of oxycodone to prescribe to opioid-naive patients at discharge. No more than 10 or 15 pills are recommended for several types of general surgery (J Amer Coll Surg. 2018;227:411-8).

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Smith reports no relevant disclosures.

LAS VEGAS – . Watch out for overlapping medication orders. Beware of gabapentin mishaps, and embrace Tylenol – but not always.

April Smith, PharmD, associate professor of pharmacy practice at Creighton University, Omaha, offered these tips about postoperative care to surgeons at the 2019 Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“We’re probably one of the most underutilized professions you have on your team,” she said, adding that “we have to know what you’re doing to help you.”

As she explained, “if you’re going to have a new order set, let us know that, so we can be your allies in helping nurses and other people understand why we’re doing what we’re doing. I’m on the same floor, and the nurses are coming up to me and asking me questions. If I can explain to them why we’re doing these things, they’ll get on board a lot faster and save you a lot of phone calls. I know you’re surgeons and you hate that [phone calls].”

Better communication with pharmacists can also boost the stocking of enhanced-recovery medications in automatic dispensing machines, she said, so they’re ready when patients need them.

Dr. Smith offered these tips about specific postsurgery medications:

- Scopolamine is a “great drug for post-op vomiting and nausea,” Dr. Smith said. But do not use it in patients over 65, and it’s contraindicated in glaucoma. Beware of these notable side effects: Blurry vision, constipation, and urinary retention. Dexamethasone and ondansetron can be used as an alternative, she said.

- Use of the blood thinner enoxaparin after discharge may become more common as surgical stays become shorter, Dr. Smith said. She urged surgeons to keep its cost in mind: a 10-day course can be as little as $2 with Medicaid or as much as $140 (a cash price for patients without coverage).

- Make sure to adjust medications based on preoperative or intraoperative doses, she said, to avoid endangering patients by inadvertently doubling up on doses. And watch out for previous use of gabapentin, which is part of enhanced-recovery protocols. Patients who take the drug at home should be put back on their typical dose.

- Also, she warned, “don’t give gabapentin to someone who’s never had it before plus an opioid.” This, she said, can cause delirium.

- Consider starting liquids the night of surgery so patients can begin taking their home medications such as sleep, chronic pain, and psychiatric drugs. Patients will be more stable and satisfied, Dr. Smith said.

- Don’t prescribe hard-to-find medications like oxycodone oral solution or oral ketorolac. These drugs will send patients from pharmacy to pharmacy in search of them, Dr. Smith said.

- Embrace a “Meds to Beds” program if possible. These programs enlist on-site pharmacies to deliver medications to bedside for patients to take home.

- Consider Tylenol as a postoperative painkiller with scheduled doses and be aware that you can prescribe the over-the-counter adult liquid form. However, Dr. Smith cautioned that Tylenol is “not great” on an as-needed basis. Gabapentin and celecoxib (unless contraindicated) are also helpful for postop pain relief, and they’re inexpensive, she said. Three to five days should be enough in most minimally invasive surgeries.

- Don’t overprescribe opioids. “The more we prescribe, the more they will consume,” Dr. Smith said. Check the American College of Surgeons guidelines regarding the ideal number of postsurgery, 5-mg doses of oxycodone to prescribe to opioid-naive patients at discharge. No more than 10 or 15 pills are recommended for several types of general surgery (J Amer Coll Surg. 2018;227:411-8).

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Smith reports no relevant disclosures.

LAS VEGAS – . Watch out for overlapping medication orders. Beware of gabapentin mishaps, and embrace Tylenol – but not always.

April Smith, PharmD, associate professor of pharmacy practice at Creighton University, Omaha, offered these tips about postoperative care to surgeons at the 2019 Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“We’re probably one of the most underutilized professions you have on your team,” she said, adding that “we have to know what you’re doing to help you.”

As she explained, “if you’re going to have a new order set, let us know that, so we can be your allies in helping nurses and other people understand why we’re doing what we’re doing. I’m on the same floor, and the nurses are coming up to me and asking me questions. If I can explain to them why we’re doing these things, they’ll get on board a lot faster and save you a lot of phone calls. I know you’re surgeons and you hate that [phone calls].”

Better communication with pharmacists can also boost the stocking of enhanced-recovery medications in automatic dispensing machines, she said, so they’re ready when patients need them.

Dr. Smith offered these tips about specific postsurgery medications:

- Scopolamine is a “great drug for post-op vomiting and nausea,” Dr. Smith said. But do not use it in patients over 65, and it’s contraindicated in glaucoma. Beware of these notable side effects: Blurry vision, constipation, and urinary retention. Dexamethasone and ondansetron can be used as an alternative, she said.

- Use of the blood thinner enoxaparin after discharge may become more common as surgical stays become shorter, Dr. Smith said. She urged surgeons to keep its cost in mind: a 10-day course can be as little as $2 with Medicaid or as much as $140 (a cash price for patients without coverage).

- Make sure to adjust medications based on preoperative or intraoperative doses, she said, to avoid endangering patients by inadvertently doubling up on doses. And watch out for previous use of gabapentin, which is part of enhanced-recovery protocols. Patients who take the drug at home should be put back on their typical dose.

- Also, she warned, “don’t give gabapentin to someone who’s never had it before plus an opioid.” This, she said, can cause delirium.

- Consider starting liquids the night of surgery so patients can begin taking their home medications such as sleep, chronic pain, and psychiatric drugs. Patients will be more stable and satisfied, Dr. Smith said.

- Don’t prescribe hard-to-find medications like oxycodone oral solution or oral ketorolac. These drugs will send patients from pharmacy to pharmacy in search of them, Dr. Smith said.

- Embrace a “Meds to Beds” program if possible. These programs enlist on-site pharmacies to deliver medications to bedside for patients to take home.

- Consider Tylenol as a postoperative painkiller with scheduled doses and be aware that you can prescribe the over-the-counter adult liquid form. However, Dr. Smith cautioned that Tylenol is “not great” on an as-needed basis. Gabapentin and celecoxib (unless contraindicated) are also helpful for postop pain relief, and they’re inexpensive, she said. Three to five days should be enough in most minimally invasive surgeries.

- Don’t overprescribe opioids. “The more we prescribe, the more they will consume,” Dr. Smith said. Check the American College of Surgeons guidelines regarding the ideal number of postsurgery, 5-mg doses of oxycodone to prescribe to opioid-naive patients at discharge. No more than 10 or 15 pills are recommended for several types of general surgery (J Amer Coll Surg. 2018;227:411-8).

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Smith reports no relevant disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM MISS

Surge of gabapentinoids for pain lacks supporting evidence

Many clinicians are prescribing the gabapentinoid drugs pregabalin (Lyrica) and gabapentin (Neurontin) for off-label treatment of pain, despite a lack of supporting data or approval from the Food and Drug Administration, according to investigators.

Over the past 15 years, use of gabapentinoids has tripled, a level of growth that cannot be explained by prescriptions for approved indications, reported coauthors Christopher W. Goodman, MD, and Allan S. Brett, MD, of the University of South Carolina, Columbia. Instead, clinicians are turning to gabapentinoids, partly as an option to substitute for opioids, which now have greater prescribing restrictions as a result of the current opioid crisis.

Although clinicians may cite guidelines that support off-label use of gabapentinoids for pain, the investigators warned that many of these recommendations stand on shaky ground.

“Clinicians who prescribe gabapentinoids off-label for pain should be aware of the limited evidence and should acknowledge to patients that potential benefits are uncertain for most off-label uses,” the investigators wrote in a clinical review published online March 25 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The investigators narrowed down 677 publications to 84 papers describing the use of gabapentinoids for outpatient noncancer pain syndromes for which they are not FDA approved; 54 for gabapentin and 30 for pregabalin. In the domain of analgesia, both agents are currently FDA-approved for postherpetic neuralgia, while pregabalin is additionally approved for pain associated with fibromyalgia and neuropathic pain from diabetic neuropathy and spinal cord injury. Indications in reviewed studies ranged broadly, from conditions somewhat related to those currently approved, such as unspecified neuropathy, to dissimilar conditions, such as chronic pancreatitis and burn injury.

The investigators summarized findings from randomized clinical trials while using case studies to illustrate potential problems with off-label use. In addition, they reviewed the history of gabapentinoids and sources of recommendations for off-label use, such as guidelines and previous review articles.

Six major findings were reported: (1) evidence supporting gabapentin for diabetic neuropathy pain is “mixed at best”; (2) evidence supporting gabapentin for nondiabetic neuropathies is very limited; (3) evidence does not support gabapentinoids for radiculopathy or low back pain; (4) gabapentin has minimal benefit for fibromyalgia pain, based on minimal evidence; (5) evidence does not support gabapentinoids for acute herpes zoster pain; and (6) in almost all studies for other painful indications, gabapentinoids were ineffective or “associated with small analgesic effects that were statistically significant but of questionable clinical importance.”

Case studies complemented this overview, highlighting related clinical dilemmas that the investigators encounter “repeatedly” during inpatient and outpatient care. Along with off-label use, such as gabapentinoid prescriptions for acute sciatica, the investigators reported cases in which neuropathy was diagnosed in place of nonspecific lower body pain to facilitate gabapentin prescription. They also described apparent disregard for risks of polypharmacy in prescriptions for elderly patients and rote use of gabapentinoids in patients with diabetic neuropathy who did not have sufficient discomfort to warrant prescription.

The investigators also cited a number of problems with the language of reviews and guidelines involving gabapentinoids.

“The wording in many guidelines and review articles reinforces an inflated view of gabapentinoid effectiveness or fails to distinguish carefully between evidence-based and non–evidence-based recommendations,” they wrote, adding that clinicians may have misconceptions about neuropathic pain. “One unintended effect of the broad definition [of neuropathic pain] might be to create a mistaken perception that an effective drug for one type of neuropathic pain is effective for all neuropathic pain, regardless of underlying etiology or mechanism,” the investigators suggested.

Another facet of prescribing behavior could be explained in economic terms. Pregabalin, sold under the brand name Lyrica, is considerably more expensive than gabapentin; however, the investigators warned that the similarity of these agents does not equate with interchangeability, noting differences in bioavailability and rate of absorption.

“Unfortunately, published direct comparisons between the 2 drugs in double-blind studies of patients with chronic noncancer pain are virtually nonexistent,” the investigators wrote.

In addition to questionable effectiveness of gabapentinoids for off-label chronic noncancer pain syndromes, Dr. Goodman and Dr. Brett noted that the drugs produce a “substantial incidence of dizziness, somnolence, and gait disturbance.”

They also described a new trend of gabapentinoid abuse and diversion, which may not be surprising, considering that gabapentinoids are reported to augment opioid-induced euphoria.

“Evidence of misuse of gabapentinoids is accumulating and likely related to the opioid epidemic. A recent review article reported an overall population prevalence of gabapentinoid ‘misuse and abuse’ as high as 1%, with substantially higher prevalence noted among patients with opioid use disorders,” the investigators wrote. “This trend is troubling, particularly because concomitant use of opioids and gabapentinoids is associated with increased odds of opioid-related death. Whether these concerns apply to patients receiving long-term prescribed opioid therapy is unclear.”

In the era of the opioid crisis, the investigators acknowledged that many clinicians have serious concerns about adequately treating chronic noncancer pain.

“Comprehensive management of pain in primary care settings is difficult. It requires time and resources that are frequently unavailable,” the investigators wrote. “Many patients with chronic pain have limited or no access to high-quality pain practices or to nonpharmacologic interventions, such as cognitive behavior therapy.”

The investigators reported no external funding or conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Goodman CW et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Mar 25. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0086

Many clinicians are prescribing the gabapentinoid drugs pregabalin (Lyrica) and gabapentin (Neurontin) for off-label treatment of pain, despite a lack of supporting data or approval from the Food and Drug Administration, according to investigators.

Over the past 15 years, use of gabapentinoids has tripled, a level of growth that cannot be explained by prescriptions for approved indications, reported coauthors Christopher W. Goodman, MD, and Allan S. Brett, MD, of the University of South Carolina, Columbia. Instead, clinicians are turning to gabapentinoids, partly as an option to substitute for opioids, which now have greater prescribing restrictions as a result of the current opioid crisis.

Although clinicians may cite guidelines that support off-label use of gabapentinoids for pain, the investigators warned that many of these recommendations stand on shaky ground.

“Clinicians who prescribe gabapentinoids off-label for pain should be aware of the limited evidence and should acknowledge to patients that potential benefits are uncertain for most off-label uses,” the investigators wrote in a clinical review published online March 25 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The investigators narrowed down 677 publications to 84 papers describing the use of gabapentinoids for outpatient noncancer pain syndromes for which they are not FDA approved; 54 for gabapentin and 30 for pregabalin. In the domain of analgesia, both agents are currently FDA-approved for postherpetic neuralgia, while pregabalin is additionally approved for pain associated with fibromyalgia and neuropathic pain from diabetic neuropathy and spinal cord injury. Indications in reviewed studies ranged broadly, from conditions somewhat related to those currently approved, such as unspecified neuropathy, to dissimilar conditions, such as chronic pancreatitis and burn injury.

The investigators summarized findings from randomized clinical trials while using case studies to illustrate potential problems with off-label use. In addition, they reviewed the history of gabapentinoids and sources of recommendations for off-label use, such as guidelines and previous review articles.

Six major findings were reported: (1) evidence supporting gabapentin for diabetic neuropathy pain is “mixed at best”; (2) evidence supporting gabapentin for nondiabetic neuropathies is very limited; (3) evidence does not support gabapentinoids for radiculopathy or low back pain; (4) gabapentin has minimal benefit for fibromyalgia pain, based on minimal evidence; (5) evidence does not support gabapentinoids for acute herpes zoster pain; and (6) in almost all studies for other painful indications, gabapentinoids were ineffective or “associated with small analgesic effects that were statistically significant but of questionable clinical importance.”

Case studies complemented this overview, highlighting related clinical dilemmas that the investigators encounter “repeatedly” during inpatient and outpatient care. Along with off-label use, such as gabapentinoid prescriptions for acute sciatica, the investigators reported cases in which neuropathy was diagnosed in place of nonspecific lower body pain to facilitate gabapentin prescription. They also described apparent disregard for risks of polypharmacy in prescriptions for elderly patients and rote use of gabapentinoids in patients with diabetic neuropathy who did not have sufficient discomfort to warrant prescription.

The investigators also cited a number of problems with the language of reviews and guidelines involving gabapentinoids.

“The wording in many guidelines and review articles reinforces an inflated view of gabapentinoid effectiveness or fails to distinguish carefully between evidence-based and non–evidence-based recommendations,” they wrote, adding that clinicians may have misconceptions about neuropathic pain. “One unintended effect of the broad definition [of neuropathic pain] might be to create a mistaken perception that an effective drug for one type of neuropathic pain is effective for all neuropathic pain, regardless of underlying etiology or mechanism,” the investigators suggested.

Another facet of prescribing behavior could be explained in economic terms. Pregabalin, sold under the brand name Lyrica, is considerably more expensive than gabapentin; however, the investigators warned that the similarity of these agents does not equate with interchangeability, noting differences in bioavailability and rate of absorption.

“Unfortunately, published direct comparisons between the 2 drugs in double-blind studies of patients with chronic noncancer pain are virtually nonexistent,” the investigators wrote.

In addition to questionable effectiveness of gabapentinoids for off-label chronic noncancer pain syndromes, Dr. Goodman and Dr. Brett noted that the drugs produce a “substantial incidence of dizziness, somnolence, and gait disturbance.”

They also described a new trend of gabapentinoid abuse and diversion, which may not be surprising, considering that gabapentinoids are reported to augment opioid-induced euphoria.

“Evidence of misuse of gabapentinoids is accumulating and likely related to the opioid epidemic. A recent review article reported an overall population prevalence of gabapentinoid ‘misuse and abuse’ as high as 1%, with substantially higher prevalence noted among patients with opioid use disorders,” the investigators wrote. “This trend is troubling, particularly because concomitant use of opioids and gabapentinoids is associated with increased odds of opioid-related death. Whether these concerns apply to patients receiving long-term prescribed opioid therapy is unclear.”

In the era of the opioid crisis, the investigators acknowledged that many clinicians have serious concerns about adequately treating chronic noncancer pain.

“Comprehensive management of pain in primary care settings is difficult. It requires time and resources that are frequently unavailable,” the investigators wrote. “Many patients with chronic pain have limited or no access to high-quality pain practices or to nonpharmacologic interventions, such as cognitive behavior therapy.”

The investigators reported no external funding or conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Goodman CW et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Mar 25. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0086

Many clinicians are prescribing the gabapentinoid drugs pregabalin (Lyrica) and gabapentin (Neurontin) for off-label treatment of pain, despite a lack of supporting data or approval from the Food and Drug Administration, according to investigators.

Over the past 15 years, use of gabapentinoids has tripled, a level of growth that cannot be explained by prescriptions for approved indications, reported coauthors Christopher W. Goodman, MD, and Allan S. Brett, MD, of the University of South Carolina, Columbia. Instead, clinicians are turning to gabapentinoids, partly as an option to substitute for opioids, which now have greater prescribing restrictions as a result of the current opioid crisis.

Although clinicians may cite guidelines that support off-label use of gabapentinoids for pain, the investigators warned that many of these recommendations stand on shaky ground.

“Clinicians who prescribe gabapentinoids off-label for pain should be aware of the limited evidence and should acknowledge to patients that potential benefits are uncertain for most off-label uses,” the investigators wrote in a clinical review published online March 25 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The investigators narrowed down 677 publications to 84 papers describing the use of gabapentinoids for outpatient noncancer pain syndromes for which they are not FDA approved; 54 for gabapentin and 30 for pregabalin. In the domain of analgesia, both agents are currently FDA-approved for postherpetic neuralgia, while pregabalin is additionally approved for pain associated with fibromyalgia and neuropathic pain from diabetic neuropathy and spinal cord injury. Indications in reviewed studies ranged broadly, from conditions somewhat related to those currently approved, such as unspecified neuropathy, to dissimilar conditions, such as chronic pancreatitis and burn injury.

The investigators summarized findings from randomized clinical trials while using case studies to illustrate potential problems with off-label use. In addition, they reviewed the history of gabapentinoids and sources of recommendations for off-label use, such as guidelines and previous review articles.

Six major findings were reported: (1) evidence supporting gabapentin for diabetic neuropathy pain is “mixed at best”; (2) evidence supporting gabapentin for nondiabetic neuropathies is very limited; (3) evidence does not support gabapentinoids for radiculopathy or low back pain; (4) gabapentin has minimal benefit for fibromyalgia pain, based on minimal evidence; (5) evidence does not support gabapentinoids for acute herpes zoster pain; and (6) in almost all studies for other painful indications, gabapentinoids were ineffective or “associated with small analgesic effects that were statistically significant but of questionable clinical importance.”

Case studies complemented this overview, highlighting related clinical dilemmas that the investigators encounter “repeatedly” during inpatient and outpatient care. Along with off-label use, such as gabapentinoid prescriptions for acute sciatica, the investigators reported cases in which neuropathy was diagnosed in place of nonspecific lower body pain to facilitate gabapentin prescription. They also described apparent disregard for risks of polypharmacy in prescriptions for elderly patients and rote use of gabapentinoids in patients with diabetic neuropathy who did not have sufficient discomfort to warrant prescription.

The investigators also cited a number of problems with the language of reviews and guidelines involving gabapentinoids.

“The wording in many guidelines and review articles reinforces an inflated view of gabapentinoid effectiveness or fails to distinguish carefully between evidence-based and non–evidence-based recommendations,” they wrote, adding that clinicians may have misconceptions about neuropathic pain. “One unintended effect of the broad definition [of neuropathic pain] might be to create a mistaken perception that an effective drug for one type of neuropathic pain is effective for all neuropathic pain, regardless of underlying etiology or mechanism,” the investigators suggested.

Another facet of prescribing behavior could be explained in economic terms. Pregabalin, sold under the brand name Lyrica, is considerably more expensive than gabapentin; however, the investigators warned that the similarity of these agents does not equate with interchangeability, noting differences in bioavailability and rate of absorption.

“Unfortunately, published direct comparisons between the 2 drugs in double-blind studies of patients with chronic noncancer pain are virtually nonexistent,” the investigators wrote.

In addition to questionable effectiveness of gabapentinoids for off-label chronic noncancer pain syndromes, Dr. Goodman and Dr. Brett noted that the drugs produce a “substantial incidence of dizziness, somnolence, and gait disturbance.”

They also described a new trend of gabapentinoid abuse and diversion, which may not be surprising, considering that gabapentinoids are reported to augment opioid-induced euphoria.

“Evidence of misuse of gabapentinoids is accumulating and likely related to the opioid epidemic. A recent review article reported an overall population prevalence of gabapentinoid ‘misuse and abuse’ as high as 1%, with substantially higher prevalence noted among patients with opioid use disorders,” the investigators wrote. “This trend is troubling, particularly because concomitant use of opioids and gabapentinoids is associated with increased odds of opioid-related death. Whether these concerns apply to patients receiving long-term prescribed opioid therapy is unclear.”

In the era of the opioid crisis, the investigators acknowledged that many clinicians have serious concerns about adequately treating chronic noncancer pain.

“Comprehensive management of pain in primary care settings is difficult. It requires time and resources that are frequently unavailable,” the investigators wrote. “Many patients with chronic pain have limited or no access to high-quality pain practices or to nonpharmacologic interventions, such as cognitive behavior therapy.”

The investigators reported no external funding or conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Goodman CW et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Mar 25. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0086

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

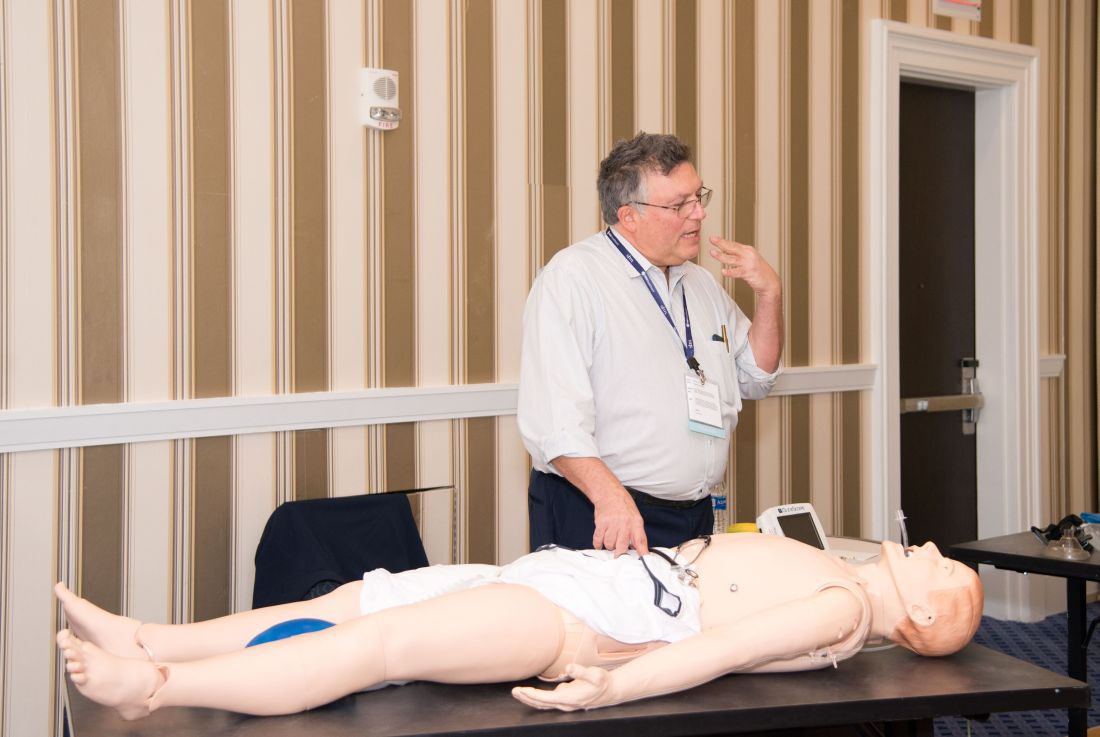

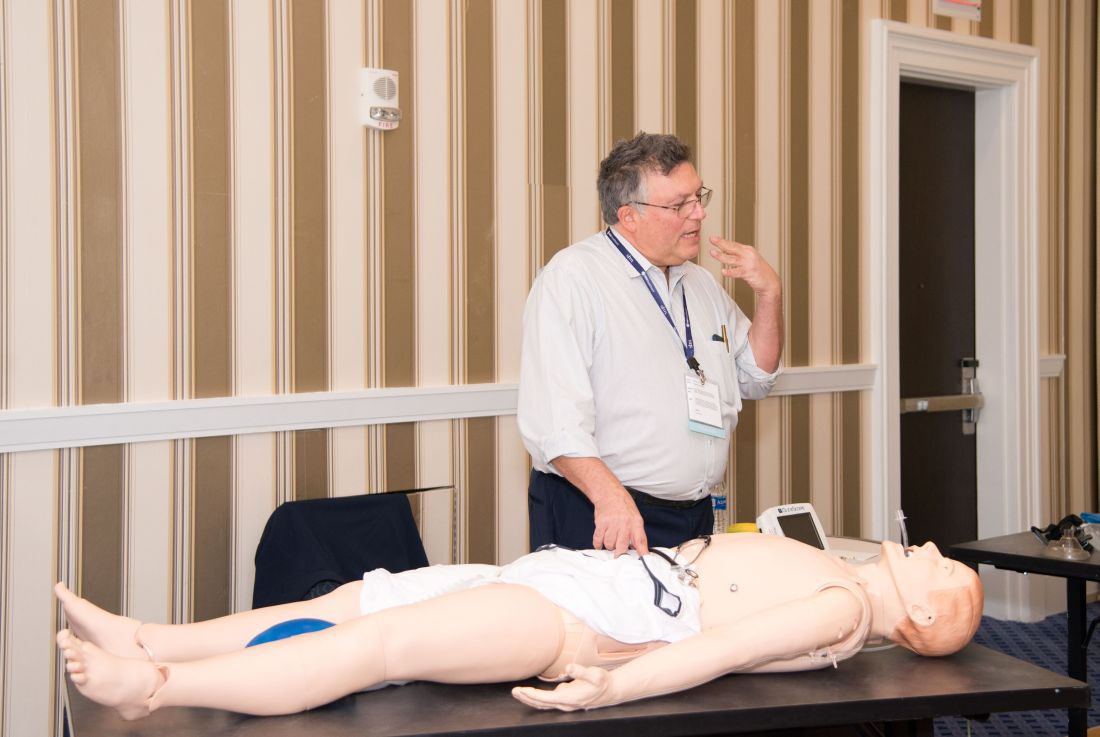

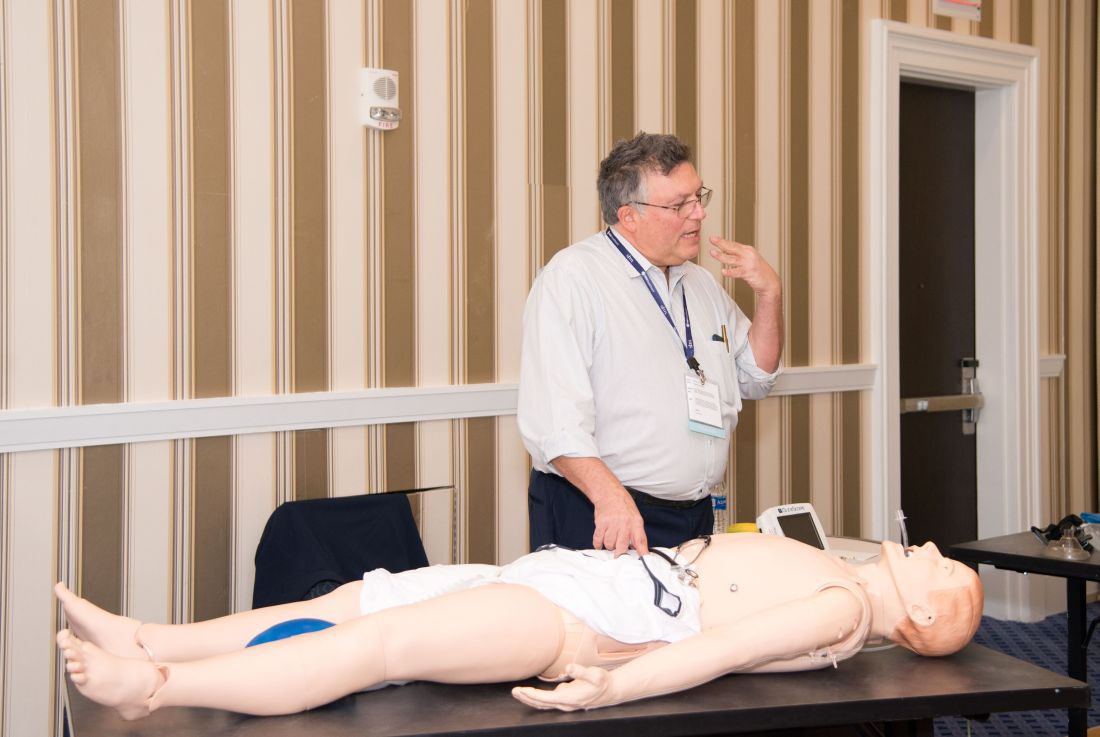

Hands-on critical care lessons provided at HM19

As the hospitalist tried to position the portable video laryngoscope properly in the airway of the critically ill “patient,” HM19 faculty moderator Brian Kaufman, MD, professor of medicine, anesthesiology, and neurology at New York University (NYU) School of Medicine, issued a word of caution: Rotating it into position should be done gently or there’s a risk of tearing tissue.

One step at a time, hospitalists attending the session grew more confident and knowledgeable in handling urgent matters involving patients who are critically ill, including cases of shock, mechanical ventilation, overdoses, and ultrasound.

Kevin Felner, MD, associate professor of medicine at NYU School of Medicine, said there’s a growing need for more exposure to caring for the critically ill, including intubation.

“There are a lot of hospitalists who are intubating, and they’re not formally trained in it because medicine residencies don’t typically train people to manage airways,” he said. “We’ve met hospitalists who’ve said, ‘I was hired and was told I had to manage an airway.’”

“It might massage some of the things you’re doing, make you afraid of things you should be afraid of, make you think about something that’s easy to do that you’re not doing, and make things safer,” Dr. Felner said.

In a simulation room, James Horowitz, MD, clinical assistant professor and cardiologist at NYU School of Medicine, demonstrated how to use a laryngeal mask airway (LMA), a simpler alternative to intubating the trachea for keeping an airway open. Dr. Kaufman, standing next to him, clarified how important a skill this is, especially when someone needs air in the next minute or is at risk of death.

“Knowing how to put an LMA in can be life-saving,” Dr. Kaufman said.

In a lecture on shock in the critically ill, Dr. Felner said it’s important to be nimble in handling this common problem –quickly identifying the cause, whether it’s a cardiogenic issue, a low-volume circulation problem, a question of vasodilation, or an obstructive problem. He said guidelines – such as aiming for a mean arterial pressure of 65 mm Hg –are helpful generally, but individuals routinely call for making exceptions to guidelines.

Anthony Andriotis, MD, a pulmonologist at NYU who specializes in critical care, offered an array of key points when managing patients with a ventilator. For instance, when you need to prolong a patient’s expiratory time so they can exhale air more effectively to get rid of entrapped air in their lungs, lowering their respiratory rate is far more effective than decreasing the time it takes them to breathe in or increasing the flow rate of the air they’re breathing.

Some basic points – such as remembering that it’s important to be aware of the pressure when volume control has been imposed and to be aware of volume control when the pressure has been set – are crucial, he said.

The idea behind the pre-course, Dr. Felner said, was to give hospitalists a chance to enter tricky situations with everything to gain, but nothing to lose. He described it as giving students “learning scars” – those times you made a serious error that left you with a lesson you’ll never forget.

“We’re trying to create learning scars, but in a safe scenario.”

As the hospitalist tried to position the portable video laryngoscope properly in the airway of the critically ill “patient,” HM19 faculty moderator Brian Kaufman, MD, professor of medicine, anesthesiology, and neurology at New York University (NYU) School of Medicine, issued a word of caution: Rotating it into position should be done gently or there’s a risk of tearing tissue.

One step at a time, hospitalists attending the session grew more confident and knowledgeable in handling urgent matters involving patients who are critically ill, including cases of shock, mechanical ventilation, overdoses, and ultrasound.

Kevin Felner, MD, associate professor of medicine at NYU School of Medicine, said there’s a growing need for more exposure to caring for the critically ill, including intubation.

“There are a lot of hospitalists who are intubating, and they’re not formally trained in it because medicine residencies don’t typically train people to manage airways,” he said. “We’ve met hospitalists who’ve said, ‘I was hired and was told I had to manage an airway.’”

“It might massage some of the things you’re doing, make you afraid of things you should be afraid of, make you think about something that’s easy to do that you’re not doing, and make things safer,” Dr. Felner said.

In a simulation room, James Horowitz, MD, clinical assistant professor and cardiologist at NYU School of Medicine, demonstrated how to use a laryngeal mask airway (LMA), a simpler alternative to intubating the trachea for keeping an airway open. Dr. Kaufman, standing next to him, clarified how important a skill this is, especially when someone needs air in the next minute or is at risk of death.

“Knowing how to put an LMA in can be life-saving,” Dr. Kaufman said.

In a lecture on shock in the critically ill, Dr. Felner said it’s important to be nimble in handling this common problem –quickly identifying the cause, whether it’s a cardiogenic issue, a low-volume circulation problem, a question of vasodilation, or an obstructive problem. He said guidelines – such as aiming for a mean arterial pressure of 65 mm Hg –are helpful generally, but individuals routinely call for making exceptions to guidelines.

Anthony Andriotis, MD, a pulmonologist at NYU who specializes in critical care, offered an array of key points when managing patients with a ventilator. For instance, when you need to prolong a patient’s expiratory time so they can exhale air more effectively to get rid of entrapped air in their lungs, lowering their respiratory rate is far more effective than decreasing the time it takes them to breathe in or increasing the flow rate of the air they’re breathing.

Some basic points – such as remembering that it’s important to be aware of the pressure when volume control has been imposed and to be aware of volume control when the pressure has been set – are crucial, he said.

The idea behind the pre-course, Dr. Felner said, was to give hospitalists a chance to enter tricky situations with everything to gain, but nothing to lose. He described it as giving students “learning scars” – those times you made a serious error that left you with a lesson you’ll never forget.

“We’re trying to create learning scars, but in a safe scenario.”

As the hospitalist tried to position the portable video laryngoscope properly in the airway of the critically ill “patient,” HM19 faculty moderator Brian Kaufman, MD, professor of medicine, anesthesiology, and neurology at New York University (NYU) School of Medicine, issued a word of caution: Rotating it into position should be done gently or there’s a risk of tearing tissue.

One step at a time, hospitalists attending the session grew more confident and knowledgeable in handling urgent matters involving patients who are critically ill, including cases of shock, mechanical ventilation, overdoses, and ultrasound.

Kevin Felner, MD, associate professor of medicine at NYU School of Medicine, said there’s a growing need for more exposure to caring for the critically ill, including intubation.

“There are a lot of hospitalists who are intubating, and they’re not formally trained in it because medicine residencies don’t typically train people to manage airways,” he said. “We’ve met hospitalists who’ve said, ‘I was hired and was told I had to manage an airway.’”

“It might massage some of the things you’re doing, make you afraid of things you should be afraid of, make you think about something that’s easy to do that you’re not doing, and make things safer,” Dr. Felner said.

In a simulation room, James Horowitz, MD, clinical assistant professor and cardiologist at NYU School of Medicine, demonstrated how to use a laryngeal mask airway (LMA), a simpler alternative to intubating the trachea for keeping an airway open. Dr. Kaufman, standing next to him, clarified how important a skill this is, especially when someone needs air in the next minute or is at risk of death.

“Knowing how to put an LMA in can be life-saving,” Dr. Kaufman said.

In a lecture on shock in the critically ill, Dr. Felner said it’s important to be nimble in handling this common problem –quickly identifying the cause, whether it’s a cardiogenic issue, a low-volume circulation problem, a question of vasodilation, or an obstructive problem. He said guidelines – such as aiming for a mean arterial pressure of 65 mm Hg –are helpful generally, but individuals routinely call for making exceptions to guidelines.

Anthony Andriotis, MD, a pulmonologist at NYU who specializes in critical care, offered an array of key points when managing patients with a ventilator. For instance, when you need to prolong a patient’s expiratory time so they can exhale air more effectively to get rid of entrapped air in their lungs, lowering their respiratory rate is far more effective than decreasing the time it takes them to breathe in or increasing the flow rate of the air they’re breathing.

Some basic points – such as remembering that it’s important to be aware of the pressure when volume control has been imposed and to be aware of volume control when the pressure has been set – are crucial, he said.

The idea behind the pre-course, Dr. Felner said, was to give hospitalists a chance to enter tricky situations with everything to gain, but nothing to lose. He described it as giving students “learning scars” – those times you made a serious error that left you with a lesson you’ll never forget.

“We’re trying to create learning scars, but in a safe scenario.”

Occurrence of pulmonary embolisms in hospitalized patients nearly doubled during 2004-2015

NEW ORLEANS –

During 2004-2015 the incidence of all diagnosed pulmonary embolism (PE), based on discharge diagnoses, rose from 5.4 cases/1,000 hospitalized patients in 2004 to 9.7 cases/1,000 hospitalized patients in 2015, an 80% increase, Joshua B. Goldberg, MD said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology. The incidence of major PE – defined as a patient who needed vasopressor treatment, mechanical ventilation, or had nonseptic shock – rose from 7.9% of all hospitalized PE diagnoses in 2004 to 9.7% in 2015, a 23% relative increase.

The data also documented a shifting pattern of treatment for all hospitalized patients with PE, and especially among patients with major PE. During the study period, treatment with systemic thrombolysis for all PE rose nearly threefold, and catheter-directed therapy began to show a steady rise in use from 0.2% of all patients in 2011 (and before) to 1% of all patients by 2015. Surgical intervention remained lightly used throughout, with about 0.2% of all PE patients undergoing surgery annually.

Most of these intervention options focused on patients with major PE. Among patients in this subgroup with more severe disease, use of one of these three types of interventions rose from 6% in 2004 to 12% in 2015, mostly driven by a rise in systemic thrombolysis, which jumped from 3% of major PE in 2004 to 9% in 2015. However, the efficacy of systemic thrombolysis in patients with major PE remains suspect. In 2004, 39% of patients with major PE treated with systemic thrombolysis died in hospital; in 2015 the number was 47%. “The data don’t support using systemic thrombolysis to treat major PE; the mortality is high,” noted Dr. Goldberg, a cardiothoracic surgeon at Westchester Medical Center in Valhalla, N.Y.

Although catheter-directed therapy began to be much more widely used in U.S. practice starting in about 2015, during the period studied its use for major PE held fairly steady at roughly 2%-3%, but this approach also showed substantial shortcomings for the major PE population. These sicker patients treated with catheter-directed therapy had 37% mortality in 2004 and a 31% mortality in 2015, a difference that was not statistically significant. In general, PE patients enrolled in the catheter-directed therapy trials were not as sick as the major PE patients who get treated with surgery in routine practice, Dr. Goldberg said in an interview.

The data showed much better performance using surgery, although only 1,237 patients of the entire group of 713,083 PE patients studied in the database underwent surgical embolectomy. Overall, in-hospital mortality in these patients was 22%, but in a time trend analysis, mortality among all PE patients treated with surgery fell from 32% in 2004 to 14% in 2015; among patients with major PE treated with surgery, mortality fell from 52% in 2004 to 21% in 2015.

Dr. Goldberg attributed the success of surgery in severe PE patients to the definitive nature of embolectomy and the concurrent use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation that helps stabilize acutely ill PE patients. He also cited refinements that surgery underwent during the 2004-2015 period based on the experience managing chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, including routine use of cardiopulmonary bypass during surgery. “Very high risk [PE] patients should go straight to surgery, unless the patient is at high risk for surgery because of conditions like prior sternotomy or very advanced age, in which case catheter-directed therapy may be a safer option, he said. He cited a recent 5% death rate after surgery at his center among patients with major PE who did not require cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

The database Dr. Goldberg and his collaborator reviewed included 12,735 patients treated by systemic thrombolysis, and 2,595 treated by catheter-directed therapy. Patients averaged 63 years old. The most common indicator of major PE was mechanical ventilation, used on 8% of all PE patients in the study. Non-septic shock occurred in 2%, and just under 1% needed vasopressor treatment.

Published guidelines on PE management from several medical groups are “vague and have numerous caveats,” Dr. Goldberg said. He is participating in an update to the 2011 PE management statement from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (Circulation. 2011 April 26;123[16]:1788-1830).

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Goldberg had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Haider A et al. J Amer Coll Cardiol. 2019 March;73:9[suppl 1]: doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(19)32507-0

At my center, Allegheny General Hospital, we often rely on catheter-directed therapy to treat major pulmonary embolism. We now perform more catheter-directed interventions than surgical embolectomies. Generally, when treating patients with major pulmonary embolism it comes down to a choice between those two options. We rarely use systemic thrombolysis for major pulmonary embolism any more.

Raymond L. Benza, MD , is professor of medicine at Temple University College of Medicine and program director for advanced heart failure at the Allegheny Health Network in Pittsburgh. He has been a consultant to Actelion, Gilead, and United Therapeutics, and he has received research funding from Bayer. He made these comments in an interview.

At my center, Allegheny General Hospital, we often rely on catheter-directed therapy to treat major pulmonary embolism. We now perform more catheter-directed interventions than surgical embolectomies. Generally, when treating patients with major pulmonary embolism it comes down to a choice between those two options. We rarely use systemic thrombolysis for major pulmonary embolism any more.

Raymond L. Benza, MD , is professor of medicine at Temple University College of Medicine and program director for advanced heart failure at the Allegheny Health Network in Pittsburgh. He has been a consultant to Actelion, Gilead, and United Therapeutics, and he has received research funding from Bayer. He made these comments in an interview.

At my center, Allegheny General Hospital, we often rely on catheter-directed therapy to treat major pulmonary embolism. We now perform more catheter-directed interventions than surgical embolectomies. Generally, when treating patients with major pulmonary embolism it comes down to a choice between those two options. We rarely use systemic thrombolysis for major pulmonary embolism any more.

Raymond L. Benza, MD , is professor of medicine at Temple University College of Medicine and program director for advanced heart failure at the Allegheny Health Network in Pittsburgh. He has been a consultant to Actelion, Gilead, and United Therapeutics, and he has received research funding from Bayer. He made these comments in an interview.

NEW ORLEANS –

During 2004-2015 the incidence of all diagnosed pulmonary embolism (PE), based on discharge diagnoses, rose from 5.4 cases/1,000 hospitalized patients in 2004 to 9.7 cases/1,000 hospitalized patients in 2015, an 80% increase, Joshua B. Goldberg, MD said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology. The incidence of major PE – defined as a patient who needed vasopressor treatment, mechanical ventilation, or had nonseptic shock – rose from 7.9% of all hospitalized PE diagnoses in 2004 to 9.7% in 2015, a 23% relative increase.

The data also documented a shifting pattern of treatment for all hospitalized patients with PE, and especially among patients with major PE. During the study period, treatment with systemic thrombolysis for all PE rose nearly threefold, and catheter-directed therapy began to show a steady rise in use from 0.2% of all patients in 2011 (and before) to 1% of all patients by 2015. Surgical intervention remained lightly used throughout, with about 0.2% of all PE patients undergoing surgery annually.

Most of these intervention options focused on patients with major PE. Among patients in this subgroup with more severe disease, use of one of these three types of interventions rose from 6% in 2004 to 12% in 2015, mostly driven by a rise in systemic thrombolysis, which jumped from 3% of major PE in 2004 to 9% in 2015. However, the efficacy of systemic thrombolysis in patients with major PE remains suspect. In 2004, 39% of patients with major PE treated with systemic thrombolysis died in hospital; in 2015 the number was 47%. “The data don’t support using systemic thrombolysis to treat major PE; the mortality is high,” noted Dr. Goldberg, a cardiothoracic surgeon at Westchester Medical Center in Valhalla, N.Y.

Although catheter-directed therapy began to be much more widely used in U.S. practice starting in about 2015, during the period studied its use for major PE held fairly steady at roughly 2%-3%, but this approach also showed substantial shortcomings for the major PE population. These sicker patients treated with catheter-directed therapy had 37% mortality in 2004 and a 31% mortality in 2015, a difference that was not statistically significant. In general, PE patients enrolled in the catheter-directed therapy trials were not as sick as the major PE patients who get treated with surgery in routine practice, Dr. Goldberg said in an interview.

The data showed much better performance using surgery, although only 1,237 patients of the entire group of 713,083 PE patients studied in the database underwent surgical embolectomy. Overall, in-hospital mortality in these patients was 22%, but in a time trend analysis, mortality among all PE patients treated with surgery fell from 32% in 2004 to 14% in 2015; among patients with major PE treated with surgery, mortality fell from 52% in 2004 to 21% in 2015.

Dr. Goldberg attributed the success of surgery in severe PE patients to the definitive nature of embolectomy and the concurrent use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation that helps stabilize acutely ill PE patients. He also cited refinements that surgery underwent during the 2004-2015 period based on the experience managing chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, including routine use of cardiopulmonary bypass during surgery. “Very high risk [PE] patients should go straight to surgery, unless the patient is at high risk for surgery because of conditions like prior sternotomy or very advanced age, in which case catheter-directed therapy may be a safer option, he said. He cited a recent 5% death rate after surgery at his center among patients with major PE who did not require cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

The database Dr. Goldberg and his collaborator reviewed included 12,735 patients treated by systemic thrombolysis, and 2,595 treated by catheter-directed therapy. Patients averaged 63 years old. The most common indicator of major PE was mechanical ventilation, used on 8% of all PE patients in the study. Non-septic shock occurred in 2%, and just under 1% needed vasopressor treatment.

Published guidelines on PE management from several medical groups are “vague and have numerous caveats,” Dr. Goldberg said. He is participating in an update to the 2011 PE management statement from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (Circulation. 2011 April 26;123[16]:1788-1830).

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Goldberg had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Haider A et al. J Amer Coll Cardiol. 2019 March;73:9[suppl 1]: doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(19)32507-0

NEW ORLEANS –

During 2004-2015 the incidence of all diagnosed pulmonary embolism (PE), based on discharge diagnoses, rose from 5.4 cases/1,000 hospitalized patients in 2004 to 9.7 cases/1,000 hospitalized patients in 2015, an 80% increase, Joshua B. Goldberg, MD said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology. The incidence of major PE – defined as a patient who needed vasopressor treatment, mechanical ventilation, or had nonseptic shock – rose from 7.9% of all hospitalized PE diagnoses in 2004 to 9.7% in 2015, a 23% relative increase.

The data also documented a shifting pattern of treatment for all hospitalized patients with PE, and especially among patients with major PE. During the study period, treatment with systemic thrombolysis for all PE rose nearly threefold, and catheter-directed therapy began to show a steady rise in use from 0.2% of all patients in 2011 (and before) to 1% of all patients by 2015. Surgical intervention remained lightly used throughout, with about 0.2% of all PE patients undergoing surgery annually.

Most of these intervention options focused on patients with major PE. Among patients in this subgroup with more severe disease, use of one of these three types of interventions rose from 6% in 2004 to 12% in 2015, mostly driven by a rise in systemic thrombolysis, which jumped from 3% of major PE in 2004 to 9% in 2015. However, the efficacy of systemic thrombolysis in patients with major PE remains suspect. In 2004, 39% of patients with major PE treated with systemic thrombolysis died in hospital; in 2015 the number was 47%. “The data don’t support using systemic thrombolysis to treat major PE; the mortality is high,” noted Dr. Goldberg, a cardiothoracic surgeon at Westchester Medical Center in Valhalla, N.Y.

Although catheter-directed therapy began to be much more widely used in U.S. practice starting in about 2015, during the period studied its use for major PE held fairly steady at roughly 2%-3%, but this approach also showed substantial shortcomings for the major PE population. These sicker patients treated with catheter-directed therapy had 37% mortality in 2004 and a 31% mortality in 2015, a difference that was not statistically significant. In general, PE patients enrolled in the catheter-directed therapy trials were not as sick as the major PE patients who get treated with surgery in routine practice, Dr. Goldberg said in an interview.

The data showed much better performance using surgery, although only 1,237 patients of the entire group of 713,083 PE patients studied in the database underwent surgical embolectomy. Overall, in-hospital mortality in these patients was 22%, but in a time trend analysis, mortality among all PE patients treated with surgery fell from 32% in 2004 to 14% in 2015; among patients with major PE treated with surgery, mortality fell from 52% in 2004 to 21% in 2015.

Dr. Goldberg attributed the success of surgery in severe PE patients to the definitive nature of embolectomy and the concurrent use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation that helps stabilize acutely ill PE patients. He also cited refinements that surgery underwent during the 2004-2015 period based on the experience managing chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, including routine use of cardiopulmonary bypass during surgery. “Very high risk [PE] patients should go straight to surgery, unless the patient is at high risk for surgery because of conditions like prior sternotomy or very advanced age, in which case catheter-directed therapy may be a safer option, he said. He cited a recent 5% death rate after surgery at his center among patients with major PE who did not require cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

The database Dr. Goldberg and his collaborator reviewed included 12,735 patients treated by systemic thrombolysis, and 2,595 treated by catheter-directed therapy. Patients averaged 63 years old. The most common indicator of major PE was mechanical ventilation, used on 8% of all PE patients in the study. Non-septic shock occurred in 2%, and just under 1% needed vasopressor treatment.

Published guidelines on PE management from several medical groups are “vague and have numerous caveats,” Dr. Goldberg said. He is participating in an update to the 2011 PE management statement from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (Circulation. 2011 April 26;123[16]:1788-1830).

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Goldberg had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Haider A et al. J Amer Coll Cardiol. 2019 March;73:9[suppl 1]: doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(19)32507-0

REPORTING FROM ACC 2019

Hospitalists and PTs: Building strong relationships

Optimizing discharge disposition and longitudinal recovery

Sanctimonious, self-righteous, discharge saboteurs. These are just a few descriptors I’ve heard hospitalists use to describe my physical therapy (PT) colleagues.

These charged comments come mostly after a hospitalist reads therapy notes and encounters a contradiction to their chosen discharge location for a patient.

I recently met with hospitalists from four different hospitals. They echoed the frustrations of their physician colleagues across the country. The PTs they work with write “the patient requires 24-hour supervision and 3 hours of therapy a day,” or “the patient is unsafe to go home and needs continued therapy at an inpatient rehabilitation center.” The hospitalists in turn want to know “If I discharge the patient home am I liable if the patient falls or has some other negative outcome?” The frustration hospitalists experience is palpable and understandable as their attempts to support a home recovery are often contradicted.

Outside the four walls

The transition from fee-for-service to value-based care now calls upon hospitalists to be innovators in managing patients in alternative payment models, such as accountable care organizations, bundled payment programs, and Medicare Advantage plans. Each model looks to support a home recovery whenever possible and prevent readmissions.

Case managers for Medicare Advantage programs routinely review PT notes to inform hospital discharge disposition and post-acute authorization for skilled nursing facility (SNF) admissions and days in SNF. Hospitalists, working with care managers, can follow suit to succeed in alternative payment models. They have the advantage of in-person access to PT colleagues for elaboration and push-back as necessary. For hospitalists, working collaboratively with PTs is crucial to improving the value of care provided as patients transition beyond the four walls of the hospital.

The evolution of PT in acute care

Prior to diagnosis-related groups (DRGs), PTs were profit centers for hospitals – rehabilitation departments were well staffed and easily accommodated consults and requests for mobility.

With the advent of DRGs, physical therapy became a cost center, and rehabilitation staffs were reduced. PTs became overextended, were less available for consultations for mobilization, and patients suffered the deleterious effects of immobility. With reduced staffing and a rush to get patients out of the hospital, acute PT practice morphed into evaluating functional status and determining discharge destination.

Now, as members of an aligned health care team, PTs need to facilitate a safe home discharge whenever possible and determine what skilled services a patient needs post-acute stay, not where they should receive them.

Discharge disposition and longitudinal recovery

PTs, as experts in function, have a series of “special tests” at their disposal beyond pain, range of motion, and strength assessments. These include: Activity Measure for Post-Acute Care (AM-PAC) or “6-Clicks” Mobility Score, Timed Up and Go, Six-Minute Walk Test, Tinetti, Berg Balance Scale, Modified Barthel Index, Five Times Chair Rise, and Thirty-Second Chair Rise. These are all objective measures of function that can be used to inform discharge disposition and guide longitudinal recovery.

To elaborate on one tool, the 6-Clicks Mobility Score is a validated test that allows PTs to assess basic mobility.1,2 It rates six functional tasks (hence 6 clicks) that include: turning over in bed, moving from lying to sitting, moving to/from bed to chair, transitioning from sitting to standing from a chair, walking in a hospital room, and climbing three to five steps. These functional tasks are scored based on the amount of assistance needed. The scores, in turn, have been shown to support discharge destination planning.1 In addition to informing discharge destination decisions, hospitalists and the rest of the health care team can use 6-Clicks to estimate prolonged hospital stays, readmissions, and emergency department (ED) visits.3

Of course, discharge disposition is influenced by many factors in addition to functional status. Hospitalists are the obvious choice to lead the health care team in interpreting relevant data and test results, and to communicate these results to patients and caregivers so together they can decide the most appropriate discharge destination.

I envision a conversation between a fully informed hospitalist and a patient as follows: “Based on your past history, your living situation, all of your test results including labs, x-rays and the functional tests performed by your PT, your potential for a full recovery is good. You have a moderate decline in function with a high likelihood of returning home in the next 7-10 days. I recommend you go to a SNF for high-intensity rehabilitation for 7 days and that the SNF order PT and OT twice a day and walks with nursing every evening.”

This fully informed conversation can only take place if hospitalists are provided clear, concise documentation, including results of objective functional testing, by their physical therapy colleagues.

In conclusion, PTs working in the acute setting need to use validated tests to objectively assess function and educate their hospitalist colleagues on the meaning of these tests. Hospitalists in turn can incorporate these assessments into a discussion of discharge disposition and longitudinal recovery with patients. In this way, hospitalists and physical therapists can work together to achieve patient-centered, high-value care during and following a hospitalization.

Ms. Tammany is SVP of clinical strategy & innovation for Remedy Partners, Norwalk, Conn.

References

1. Jette DU et al. AM-PAC “6-Clicks” functional assessment scores predict acute care hospital discharge destination. Phys Ther. 2014 Sep;94(9):1252-61.

2. Jette DU et al. Validity of the AM-PAC “6-Clicks” inpatient daily activity and basic mobility short forms. Phys Ther. 2014 Mar;94(3):379-91.

3. Menendez ME et al. Does “6-Clicks” Day 1 Postoperative Mobility Score Predict Discharge Disposition After Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasties?” J Arthroplasty. 2016 Sep;31(9):1916-20.

Optimizing discharge disposition and longitudinal recovery

Optimizing discharge disposition and longitudinal recovery

Sanctimonious, self-righteous, discharge saboteurs. These are just a few descriptors I’ve heard hospitalists use to describe my physical therapy (PT) colleagues.

These charged comments come mostly after a hospitalist reads therapy notes and encounters a contradiction to their chosen discharge location for a patient.

I recently met with hospitalists from four different hospitals. They echoed the frustrations of their physician colleagues across the country. The PTs they work with write “the patient requires 24-hour supervision and 3 hours of therapy a day,” or “the patient is unsafe to go home and needs continued therapy at an inpatient rehabilitation center.” The hospitalists in turn want to know “If I discharge the patient home am I liable if the patient falls or has some other negative outcome?” The frustration hospitalists experience is palpable and understandable as their attempts to support a home recovery are often contradicted.

Outside the four walls

The transition from fee-for-service to value-based care now calls upon hospitalists to be innovators in managing patients in alternative payment models, such as accountable care organizations, bundled payment programs, and Medicare Advantage plans. Each model looks to support a home recovery whenever possible and prevent readmissions.

Case managers for Medicare Advantage programs routinely review PT notes to inform hospital discharge disposition and post-acute authorization for skilled nursing facility (SNF) admissions and days in SNF. Hospitalists, working with care managers, can follow suit to succeed in alternative payment models. They have the advantage of in-person access to PT colleagues for elaboration and push-back as necessary. For hospitalists, working collaboratively with PTs is crucial to improving the value of care provided as patients transition beyond the four walls of the hospital.

The evolution of PT in acute care

Prior to diagnosis-related groups (DRGs), PTs were profit centers for hospitals – rehabilitation departments were well staffed and easily accommodated consults and requests for mobility.

With the advent of DRGs, physical therapy became a cost center, and rehabilitation staffs were reduced. PTs became overextended, were less available for consultations for mobilization, and patients suffered the deleterious effects of immobility. With reduced staffing and a rush to get patients out of the hospital, acute PT practice morphed into evaluating functional status and determining discharge destination.

Now, as members of an aligned health care team, PTs need to facilitate a safe home discharge whenever possible and determine what skilled services a patient needs post-acute stay, not where they should receive them.

Discharge disposition and longitudinal recovery

PTs, as experts in function, have a series of “special tests” at their disposal beyond pain, range of motion, and strength assessments. These include: Activity Measure for Post-Acute Care (AM-PAC) or “6-Clicks” Mobility Score, Timed Up and Go, Six-Minute Walk Test, Tinetti, Berg Balance Scale, Modified Barthel Index, Five Times Chair Rise, and Thirty-Second Chair Rise. These are all objective measures of function that can be used to inform discharge disposition and guide longitudinal recovery.

To elaborate on one tool, the 6-Clicks Mobility Score is a validated test that allows PTs to assess basic mobility.1,2 It rates six functional tasks (hence 6 clicks) that include: turning over in bed, moving from lying to sitting, moving to/from bed to chair, transitioning from sitting to standing from a chair, walking in a hospital room, and climbing three to five steps. These functional tasks are scored based on the amount of assistance needed. The scores, in turn, have been shown to support discharge destination planning.1 In addition to informing discharge destination decisions, hospitalists and the rest of the health care team can use 6-Clicks to estimate prolonged hospital stays, readmissions, and emergency department (ED) visits.3

Of course, discharge disposition is influenced by many factors in addition to functional status. Hospitalists are the obvious choice to lead the health care team in interpreting relevant data and test results, and to communicate these results to patients and caregivers so together they can decide the most appropriate discharge destination.

I envision a conversation between a fully informed hospitalist and a patient as follows: “Based on your past history, your living situation, all of your test results including labs, x-rays and the functional tests performed by your PT, your potential for a full recovery is good. You have a moderate decline in function with a high likelihood of returning home in the next 7-10 days. I recommend you go to a SNF for high-intensity rehabilitation for 7 days and that the SNF order PT and OT twice a day and walks with nursing every evening.”

This fully informed conversation can only take place if hospitalists are provided clear, concise documentation, including results of objective functional testing, by their physical therapy colleagues.

In conclusion, PTs working in the acute setting need to use validated tests to objectively assess function and educate their hospitalist colleagues on the meaning of these tests. Hospitalists in turn can incorporate these assessments into a discussion of discharge disposition and longitudinal recovery with patients. In this way, hospitalists and physical therapists can work together to achieve patient-centered, high-value care during and following a hospitalization.

Ms. Tammany is SVP of clinical strategy & innovation for Remedy Partners, Norwalk, Conn.

References

1. Jette DU et al. AM-PAC “6-Clicks” functional assessment scores predict acute care hospital discharge destination. Phys Ther. 2014 Sep;94(9):1252-61.

2. Jette DU et al. Validity of the AM-PAC “6-Clicks” inpatient daily activity and basic mobility short forms. Phys Ther. 2014 Mar;94(3):379-91.

3. Menendez ME et al. Does “6-Clicks” Day 1 Postoperative Mobility Score Predict Discharge Disposition After Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasties?” J Arthroplasty. 2016 Sep;31(9):1916-20.

Sanctimonious, self-righteous, discharge saboteurs. These are just a few descriptors I’ve heard hospitalists use to describe my physical therapy (PT) colleagues.

These charged comments come mostly after a hospitalist reads therapy notes and encounters a contradiction to their chosen discharge location for a patient.

I recently met with hospitalists from four different hospitals. They echoed the frustrations of their physician colleagues across the country. The PTs they work with write “the patient requires 24-hour supervision and 3 hours of therapy a day,” or “the patient is unsafe to go home and needs continued therapy at an inpatient rehabilitation center.” The hospitalists in turn want to know “If I discharge the patient home am I liable if the patient falls or has some other negative outcome?” The frustration hospitalists experience is palpable and understandable as their attempts to support a home recovery are often contradicted.

Outside the four walls

The transition from fee-for-service to value-based care now calls upon hospitalists to be innovators in managing patients in alternative payment models, such as accountable care organizations, bundled payment programs, and Medicare Advantage plans. Each model looks to support a home recovery whenever possible and prevent readmissions.

Case managers for Medicare Advantage programs routinely review PT notes to inform hospital discharge disposition and post-acute authorization for skilled nursing facility (SNF) admissions and days in SNF. Hospitalists, working with care managers, can follow suit to succeed in alternative payment models. They have the advantage of in-person access to PT colleagues for elaboration and push-back as necessary. For hospitalists, working collaboratively with PTs is crucial to improving the value of care provided as patients transition beyond the four walls of the hospital.

The evolution of PT in acute care

Prior to diagnosis-related groups (DRGs), PTs were profit centers for hospitals – rehabilitation departments were well staffed and easily accommodated consults and requests for mobility.

With the advent of DRGs, physical therapy became a cost center, and rehabilitation staffs were reduced. PTs became overextended, were less available for consultations for mobilization, and patients suffered the deleterious effects of immobility. With reduced staffing and a rush to get patients out of the hospital, acute PT practice morphed into evaluating functional status and determining discharge destination.

Now, as members of an aligned health care team, PTs need to facilitate a safe home discharge whenever possible and determine what skilled services a patient needs post-acute stay, not where they should receive them.

Discharge disposition and longitudinal recovery

PTs, as experts in function, have a series of “special tests” at their disposal beyond pain, range of motion, and strength assessments. These include: Activity Measure for Post-Acute Care (AM-PAC) or “6-Clicks” Mobility Score, Timed Up and Go, Six-Minute Walk Test, Tinetti, Berg Balance Scale, Modified Barthel Index, Five Times Chair Rise, and Thirty-Second Chair Rise. These are all objective measures of function that can be used to inform discharge disposition and guide longitudinal recovery.

To elaborate on one tool, the 6-Clicks Mobility Score is a validated test that allows PTs to assess basic mobility.1,2 It rates six functional tasks (hence 6 clicks) that include: turning over in bed, moving from lying to sitting, moving to/from bed to chair, transitioning from sitting to standing from a chair, walking in a hospital room, and climbing three to five steps. These functional tasks are scored based on the amount of assistance needed. The scores, in turn, have been shown to support discharge destination planning.1 In addition to informing discharge destination decisions, hospitalists and the rest of the health care team can use 6-Clicks to estimate prolonged hospital stays, readmissions, and emergency department (ED) visits.3

Of course, discharge disposition is influenced by many factors in addition to functional status. Hospitalists are the obvious choice to lead the health care team in interpreting relevant data and test results, and to communicate these results to patients and caregivers so together they can decide the most appropriate discharge destination.

I envision a conversation between a fully informed hospitalist and a patient as follows: “Based on your past history, your living situation, all of your test results including labs, x-rays and the functional tests performed by your PT, your potential for a full recovery is good. You have a moderate decline in function with a high likelihood of returning home in the next 7-10 days. I recommend you go to a SNF for high-intensity rehabilitation for 7 days and that the SNF order PT and OT twice a day and walks with nursing every evening.”

This fully informed conversation can only take place if hospitalists are provided clear, concise documentation, including results of objective functional testing, by their physical therapy colleagues.

In conclusion, PTs working in the acute setting need to use validated tests to objectively assess function and educate their hospitalist colleagues on the meaning of these tests. Hospitalists in turn can incorporate these assessments into a discussion of discharge disposition and longitudinal recovery with patients. In this way, hospitalists and physical therapists can work together to achieve patient-centered, high-value care during and following a hospitalization.

Ms. Tammany is SVP of clinical strategy & innovation for Remedy Partners, Norwalk, Conn.

References

1. Jette DU et al. AM-PAC “6-Clicks” functional assessment scores predict acute care hospital discharge destination. Phys Ther. 2014 Sep;94(9):1252-61.

2. Jette DU et al. Validity of the AM-PAC “6-Clicks” inpatient daily activity and basic mobility short forms. Phys Ther. 2014 Mar;94(3):379-91.

3. Menendez ME et al. Does “6-Clicks” Day 1 Postoperative Mobility Score Predict Discharge Disposition After Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasties?” J Arthroplasty. 2016 Sep;31(9):1916-20.

Quick Byte: Trauma care

Innovating quickly

The U.S. military has completely transformed trauma care over the past 17 years, and that success offers lessons for civilian medicine.

In the civilian world, it takes an average of 17 years for a new discovery to change medical practice, but the military has developed or significantly expanded more than 27 major innovations, such as redesigned tourniquets and new transport procedures, in about a decade. As a result, the death rate from battlefield wounds has decreased by half.

Reference

Kellermann A et al. How the US military reinvented trauma care and what this means for US medicine. Health Aff. 2018 Jul 3. doi: 10.1377/hblog20180628.431867.

Innovating quickly

Innovating quickly

The U.S. military has completely transformed trauma care over the past 17 years, and that success offers lessons for civilian medicine.

In the civilian world, it takes an average of 17 years for a new discovery to change medical practice, but the military has developed or significantly expanded more than 27 major innovations, such as redesigned tourniquets and new transport procedures, in about a decade. As a result, the death rate from battlefield wounds has decreased by half.

Reference

Kellermann A et al. How the US military reinvented trauma care and what this means for US medicine. Health Aff. 2018 Jul 3. doi: 10.1377/hblog20180628.431867.

The U.S. military has completely transformed trauma care over the past 17 years, and that success offers lessons for civilian medicine.

In the civilian world, it takes an average of 17 years for a new discovery to change medical practice, but the military has developed or significantly expanded more than 27 major innovations, such as redesigned tourniquets and new transport procedures, in about a decade. As a result, the death rate from battlefield wounds has decreased by half.

Reference

Kellermann A et al. How the US military reinvented trauma care and what this means for US medicine. Health Aff. 2018 Jul 3. doi: 10.1377/hblog20180628.431867.

Intensive blood pressure lowering may not reduce risk of recurrent stroke

HONOLULU – according to research presented at the International Stroke Conference sponsored by the American Heart Association.

Combined with data from previous trials, these results support a target systolic blood pressure of less than 130 mm Hg and a diastolic blood pressure of less than 80 mm Hg for secondary stroke prevention, said Kazuo Kitagawa, MD, PhD.

Lowering blood pressure reduces the risk of recurrent stroke, but investigators have not identified the best target blood pressure for this indication. The Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes Trial (SPS3) examined the efficacy of intensive blood pressure treatment for secondary stroke prevention. The investigators randomized more than 3,000 patients with recent lacunar stroke to intensive or standard blood pressure treatment. Intensive treatment (a target systolic blood pressure of less than 130 mm Hg) conferred a nonsignificant reduction of the risk of recurrent stroke. A 2018 meta-analysis of SPS3 and two smaller randomized controlled trials also showed that intensive treatment did not significantly reduce the risk of recurrent stroke.

A new multicenter trial