User login

Opioid use curbed with patient education and lower prescription quantities

Patients given lower prescription quantities of opioid tablets with and without opioid education used significantly less of the medication compared with those given more tablets and no education, according to data from 264 adults and adolescents who underwent anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) surgery.

Although lower default prescription programs have been shown to reduce the number of tablets prescribed, “the effect of reduced prescription quantities on actual patient opioid consumption remains undetermined,” wrote Kevin X. Farley, BS, of Emory University, Atlanta, and colleagues.

In a study published in JAMA, the researchers examined whether patients took fewer tablets if given fewer, and whether patient education about opioids further reduced the number of tablets taken.

The study population included adults and adolescents who underwent ACL surgery at a single center. The patients were divided into three groups: 109 patients received 50 opioid tablets after surgery, 78 received 30 tablets plus education prior to surgery about appropriate opioid use and alternative pain management, and 77 received 30 tablets but no education on opioid use.

Patients given 50 tablets consumed an average of 25 tablets for an average of 5.8 days. By contrast, patients given 30 tablets but no opioid education consumed an average of 16 tablets for an average of 4.5 days, and those given 30 tablets and preoperative education consumed an average of 12 tablets for an average of 3.5 days.

In addition, patients given 30 tablets reported lower levels of constipation and fatigue compared with patients given 50 tablets. No differences were seen in medication refills among the groups.

The findings were limited by several factors including the use of data from a single center, the lack of randomization, and the potential for recall bias, the researchers noted. However, the results suggest that prescribing fewer tablets may further reduce use, as each group consumed approximately half of the tablets given, the researchers added.

“Further investigation should evaluate whether similar opioid stewardship and education protocols would be successful in other patient populations,” they said.

Corresponding author John Xerogeanes, MD, disclosed personal fees from Arthrex and stock options from Trice. The other researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Patients given lower prescription quantities of opioid tablets with and without opioid education used significantly less of the medication compared with those given more tablets and no education, according to data from 264 adults and adolescents who underwent anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) surgery.

Although lower default prescription programs have been shown to reduce the number of tablets prescribed, “the effect of reduced prescription quantities on actual patient opioid consumption remains undetermined,” wrote Kevin X. Farley, BS, of Emory University, Atlanta, and colleagues.

In a study published in JAMA, the researchers examined whether patients took fewer tablets if given fewer, and whether patient education about opioids further reduced the number of tablets taken.

The study population included adults and adolescents who underwent ACL surgery at a single center. The patients were divided into three groups: 109 patients received 50 opioid tablets after surgery, 78 received 30 tablets plus education prior to surgery about appropriate opioid use and alternative pain management, and 77 received 30 tablets but no education on opioid use.

Patients given 50 tablets consumed an average of 25 tablets for an average of 5.8 days. By contrast, patients given 30 tablets but no opioid education consumed an average of 16 tablets for an average of 4.5 days, and those given 30 tablets and preoperative education consumed an average of 12 tablets for an average of 3.5 days.

In addition, patients given 30 tablets reported lower levels of constipation and fatigue compared with patients given 50 tablets. No differences were seen in medication refills among the groups.

The findings were limited by several factors including the use of data from a single center, the lack of randomization, and the potential for recall bias, the researchers noted. However, the results suggest that prescribing fewer tablets may further reduce use, as each group consumed approximately half of the tablets given, the researchers added.

“Further investigation should evaluate whether similar opioid stewardship and education protocols would be successful in other patient populations,” they said.

Corresponding author John Xerogeanes, MD, disclosed personal fees from Arthrex and stock options from Trice. The other researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Patients given lower prescription quantities of opioid tablets with and without opioid education used significantly less of the medication compared with those given more tablets and no education, according to data from 264 adults and adolescents who underwent anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) surgery.

Although lower default prescription programs have been shown to reduce the number of tablets prescribed, “the effect of reduced prescription quantities on actual patient opioid consumption remains undetermined,” wrote Kevin X. Farley, BS, of Emory University, Atlanta, and colleagues.

In a study published in JAMA, the researchers examined whether patients took fewer tablets if given fewer, and whether patient education about opioids further reduced the number of tablets taken.

The study population included adults and adolescents who underwent ACL surgery at a single center. The patients were divided into three groups: 109 patients received 50 opioid tablets after surgery, 78 received 30 tablets plus education prior to surgery about appropriate opioid use and alternative pain management, and 77 received 30 tablets but no education on opioid use.

Patients given 50 tablets consumed an average of 25 tablets for an average of 5.8 days. By contrast, patients given 30 tablets but no opioid education consumed an average of 16 tablets for an average of 4.5 days, and those given 30 tablets and preoperative education consumed an average of 12 tablets for an average of 3.5 days.

In addition, patients given 30 tablets reported lower levels of constipation and fatigue compared with patients given 50 tablets. No differences were seen in medication refills among the groups.

The findings were limited by several factors including the use of data from a single center, the lack of randomization, and the potential for recall bias, the researchers noted. However, the results suggest that prescribing fewer tablets may further reduce use, as each group consumed approximately half of the tablets given, the researchers added.

“Further investigation should evaluate whether similar opioid stewardship and education protocols would be successful in other patient populations,” they said.

Corresponding author John Xerogeanes, MD, disclosed personal fees from Arthrex and stock options from Trice. The other researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Patient education and fewer tablets prescribed significantly reduced the amount of opioid tablets taken compared with no education and more tablets prescribed.

Major finding: Patients given 50 tablets and no patient education, 30 tablets and no patient education, and 30 tablets plus education consumed an average of 25, 16, and 12 tablets, respectively.

Study details: The data come from 264 adolescents and adults who underwent ACL surgery at a single center.

Disclosures: Corresponding author John Xerogeanes, MD, disclosed personal fees from Arthrex and stock options from Trice. The other researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Farley KX et al. JAMA. 2019 June 25.321(24):2465-7.

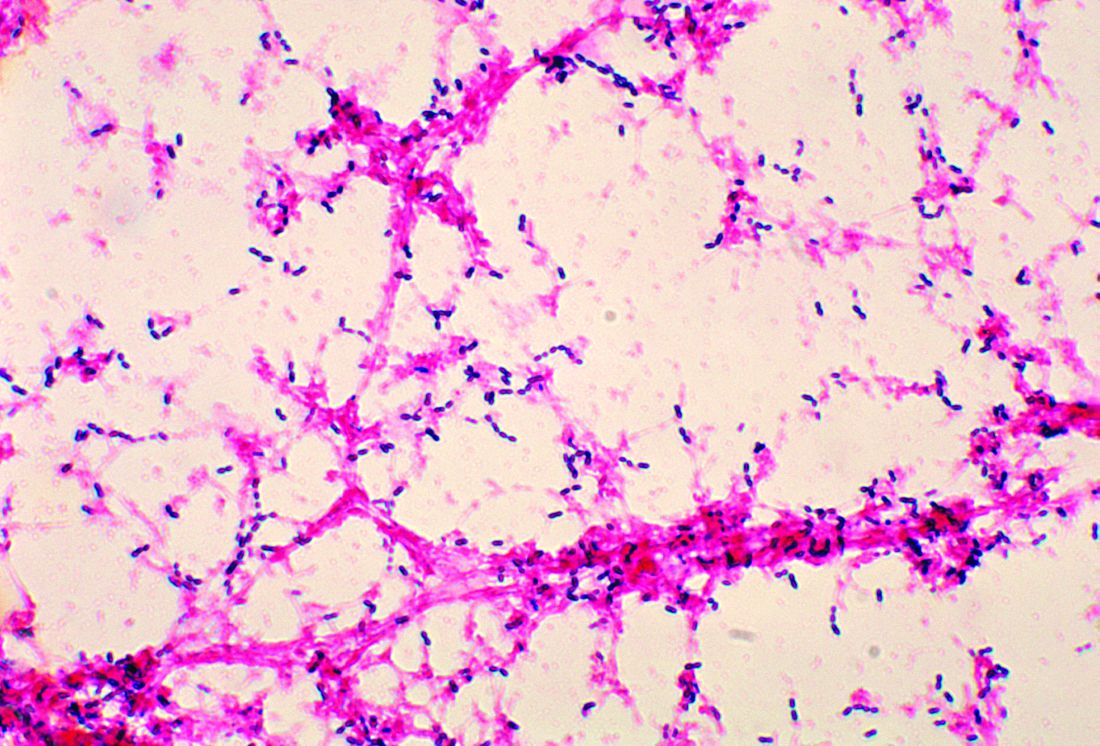

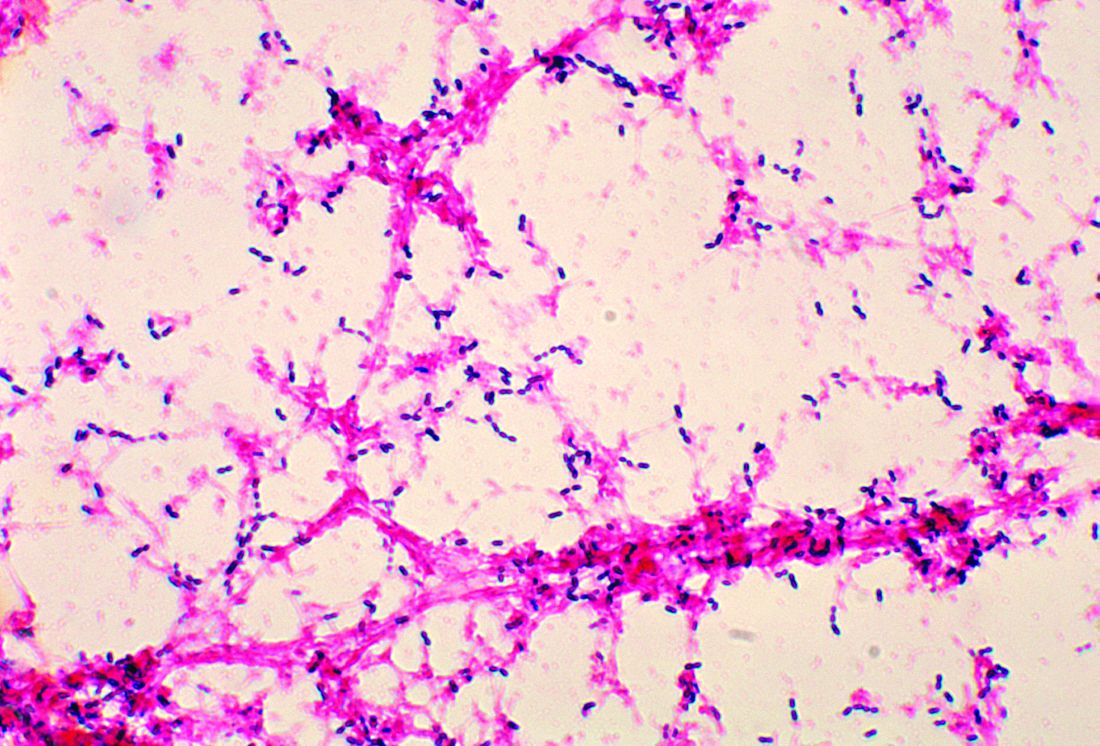

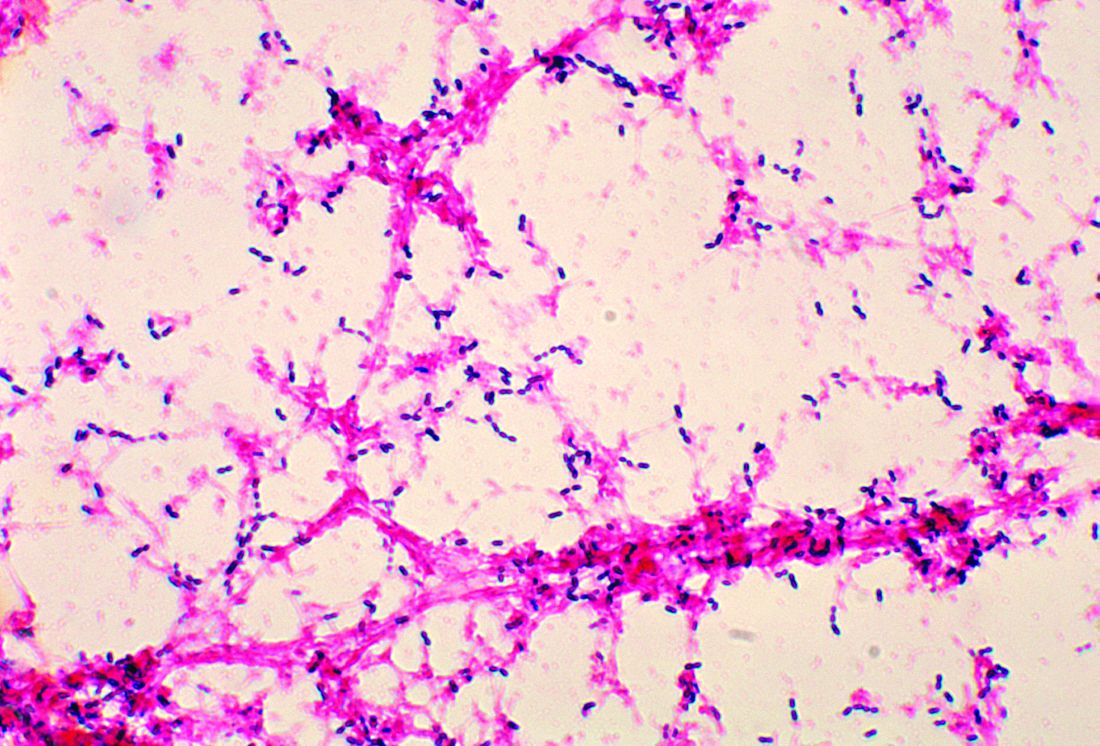

Penicillin-susceptible Streptococcus pneumoniae most common cause of bacteremic CAP

A study found that only 2% of children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) actually had any causative pathogen in their blood culture results, despite national guidelines that recommend blood cultures for all children hospitalized with moderate to severe CAP.

The guidelines are the 2011 guidelines for managing CAP published by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (PIDS) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) (Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Oct;53[7]:617-30).

Cristin O. Fritz, MD, of the Children’s Hospital of Colorado, Aurora, and associates conducted a data analysis of the EPIC (Etiology of Pneumonia in the Community) study to estimate prevalence, risk factors, and clinical outcomes in children hospitalized with bacteremic CAP and to evaluate the relationship between positive blood culture results, empirical antibiotics, and changes in antibiotic treatment regimens.

Data were collected at two Tennessee hospitals and one Utah hospital during Jan. 1, 2010–June 30, 2012. Of the 2,358 children with CAP enrolled in the study, 2,143 (91%) with blood cultures were included in Dr. Fritz’s analysis. Of the 53 patients presenting with positive blood culture results, 46 (2%; 95% confidence interval: 1.6%-2.9%) were identified as having bacteremia. Half of all cases observed were caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, with Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes noted less frequently, according to the study published in Pediatrics.

A previous meta-analysis of smaller studies also found that children with CAP rarely had positive blood culture results, a pooled prevalence of 5% (Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32[7]:736-40). Although it is believed that positive blood culture results are key to narrowing the choice of antibiotic and predicting treatment outcomes, the literature – to date – reveals a paucity of data supporting this assumption.

Overall, children in the study presenting with bacteremia experienced more severe clinical outcomes, including longer length of stay, greater likelihood of ICU admission, and invasive mechanical ventilation and/or shock. The authors also observed that bacteremia was less likely to be detected in children given antibiotics after admission but before cultures were obtained (0.8% vs 3%; P = .021). Pleural effusion detected with chest radiograph also consistently indicated bacteremic pneumonia, an observation made within this and other similar studies.

Also of note in detection is the biomarker procalcitonin, which is typically present with bacterial disease. Dr. Fritz and colleagues stressed that because the procalcitonin rate was higher in patients presenting with bacteremia, “this information could influence decisions around culturing if results are rapidly available.” Risk-stratification tools also might serve a valuable purpose in ferreting out those patients presenting with moderate to severe pneumonia most at increased risk for bacterial CAP.

Compared with other studies reporting prevalence ranges of 1%-7%, the prevalence of bacteremia in this study is lower at 2%. The authors attributed the difference to a possible potential limitation with the other studies, for which culture data was only available for a median 47% of enrollees. Dr. Fritz and her colleagues caution that “because cultures were obtained at the discretion of the treating clinician in a majority of studies, blood cultures were likely obtained more often in those with more severe illness or who had not already received antibiotics.” In this scenario, the likelihood that prevalence of bacteremia was overestimated is noteworthy.

The authors observed that penicillin-susceptible S. pneumonia was the most common cause of bacteremic CAP. They further acknowledged that their study and findings by Neuman et al. in 2017 give credence to the joint 2011 PIDS/IDSA guideline recommending narrow-spectrum aminopenicillins specifically to treat children hospitalized due to suspected bacterial CAP.

Despite its small sample size, the results of this study clearly demonstrate that children with bacteremia because of S. pyogenes or S. aureus experience increased morbidity, compared with children with S. pneumoniae, they said

While this is acknowledged to be one of the largest studies of its kind to date, a key limitation was the small number of observable patients with bacteremia, which prevented the researchers from conducting a more in-depth analysis of risk factors and pathogen-specific differences. That one-fourth of patients received in-patient antibiotics before cultures could be collected also likely led to an underestimation of risk factors and misclassification bias. Lastly, the use of blood culture instead of whole-blood polymerase chain reaction, which is known to be more sensitive, also may have led to underestimation of overall bacteremia prevalence.

“In an era with widespread pneumococcal vaccination and low prevalence of bacteremia in the United States, noted Dr. Fritz and associates.

Dr. Fritz had no conflicts of interest to report. Some coauthors cited multiple sources of potential conflict of interest related to consulting fees, grant support, and research support from various pharmaceutical companies and agencies. The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and in part by a grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

SOURCE: Fritz C et al. Pediatrics. 2019;144(1):e20183090.

A study found that only 2% of children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) actually had any causative pathogen in their blood culture results, despite national guidelines that recommend blood cultures for all children hospitalized with moderate to severe CAP.

The guidelines are the 2011 guidelines for managing CAP published by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (PIDS) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) (Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Oct;53[7]:617-30).

Cristin O. Fritz, MD, of the Children’s Hospital of Colorado, Aurora, and associates conducted a data analysis of the EPIC (Etiology of Pneumonia in the Community) study to estimate prevalence, risk factors, and clinical outcomes in children hospitalized with bacteremic CAP and to evaluate the relationship between positive blood culture results, empirical antibiotics, and changes in antibiotic treatment regimens.

Data were collected at two Tennessee hospitals and one Utah hospital during Jan. 1, 2010–June 30, 2012. Of the 2,358 children with CAP enrolled in the study, 2,143 (91%) with blood cultures were included in Dr. Fritz’s analysis. Of the 53 patients presenting with positive blood culture results, 46 (2%; 95% confidence interval: 1.6%-2.9%) were identified as having bacteremia. Half of all cases observed were caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, with Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes noted less frequently, according to the study published in Pediatrics.

A previous meta-analysis of smaller studies also found that children with CAP rarely had positive blood culture results, a pooled prevalence of 5% (Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32[7]:736-40). Although it is believed that positive blood culture results are key to narrowing the choice of antibiotic and predicting treatment outcomes, the literature – to date – reveals a paucity of data supporting this assumption.

Overall, children in the study presenting with bacteremia experienced more severe clinical outcomes, including longer length of stay, greater likelihood of ICU admission, and invasive mechanical ventilation and/or shock. The authors also observed that bacteremia was less likely to be detected in children given antibiotics after admission but before cultures were obtained (0.8% vs 3%; P = .021). Pleural effusion detected with chest radiograph also consistently indicated bacteremic pneumonia, an observation made within this and other similar studies.

Also of note in detection is the biomarker procalcitonin, which is typically present with bacterial disease. Dr. Fritz and colleagues stressed that because the procalcitonin rate was higher in patients presenting with bacteremia, “this information could influence decisions around culturing if results are rapidly available.” Risk-stratification tools also might serve a valuable purpose in ferreting out those patients presenting with moderate to severe pneumonia most at increased risk for bacterial CAP.

Compared with other studies reporting prevalence ranges of 1%-7%, the prevalence of bacteremia in this study is lower at 2%. The authors attributed the difference to a possible potential limitation with the other studies, for which culture data was only available for a median 47% of enrollees. Dr. Fritz and her colleagues caution that “because cultures were obtained at the discretion of the treating clinician in a majority of studies, blood cultures were likely obtained more often in those with more severe illness or who had not already received antibiotics.” In this scenario, the likelihood that prevalence of bacteremia was overestimated is noteworthy.

The authors observed that penicillin-susceptible S. pneumonia was the most common cause of bacteremic CAP. They further acknowledged that their study and findings by Neuman et al. in 2017 give credence to the joint 2011 PIDS/IDSA guideline recommending narrow-spectrum aminopenicillins specifically to treat children hospitalized due to suspected bacterial CAP.

Despite its small sample size, the results of this study clearly demonstrate that children with bacteremia because of S. pyogenes or S. aureus experience increased morbidity, compared with children with S. pneumoniae, they said

While this is acknowledged to be one of the largest studies of its kind to date, a key limitation was the small number of observable patients with bacteremia, which prevented the researchers from conducting a more in-depth analysis of risk factors and pathogen-specific differences. That one-fourth of patients received in-patient antibiotics before cultures could be collected also likely led to an underestimation of risk factors and misclassification bias. Lastly, the use of blood culture instead of whole-blood polymerase chain reaction, which is known to be more sensitive, also may have led to underestimation of overall bacteremia prevalence.

“In an era with widespread pneumococcal vaccination and low prevalence of bacteremia in the United States, noted Dr. Fritz and associates.

Dr. Fritz had no conflicts of interest to report. Some coauthors cited multiple sources of potential conflict of interest related to consulting fees, grant support, and research support from various pharmaceutical companies and agencies. The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and in part by a grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

SOURCE: Fritz C et al. Pediatrics. 2019;144(1):e20183090.

A study found that only 2% of children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) actually had any causative pathogen in their blood culture results, despite national guidelines that recommend blood cultures for all children hospitalized with moderate to severe CAP.

The guidelines are the 2011 guidelines for managing CAP published by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (PIDS) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) (Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Oct;53[7]:617-30).

Cristin O. Fritz, MD, of the Children’s Hospital of Colorado, Aurora, and associates conducted a data analysis of the EPIC (Etiology of Pneumonia in the Community) study to estimate prevalence, risk factors, and clinical outcomes in children hospitalized with bacteremic CAP and to evaluate the relationship between positive blood culture results, empirical antibiotics, and changes in antibiotic treatment regimens.

Data were collected at two Tennessee hospitals and one Utah hospital during Jan. 1, 2010–June 30, 2012. Of the 2,358 children with CAP enrolled in the study, 2,143 (91%) with blood cultures were included in Dr. Fritz’s analysis. Of the 53 patients presenting with positive blood culture results, 46 (2%; 95% confidence interval: 1.6%-2.9%) were identified as having bacteremia. Half of all cases observed were caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, with Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes noted less frequently, according to the study published in Pediatrics.

A previous meta-analysis of smaller studies also found that children with CAP rarely had positive blood culture results, a pooled prevalence of 5% (Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32[7]:736-40). Although it is believed that positive blood culture results are key to narrowing the choice of antibiotic and predicting treatment outcomes, the literature – to date – reveals a paucity of data supporting this assumption.

Overall, children in the study presenting with bacteremia experienced more severe clinical outcomes, including longer length of stay, greater likelihood of ICU admission, and invasive mechanical ventilation and/or shock. The authors also observed that bacteremia was less likely to be detected in children given antibiotics after admission but before cultures were obtained (0.8% vs 3%; P = .021). Pleural effusion detected with chest radiograph also consistently indicated bacteremic pneumonia, an observation made within this and other similar studies.

Also of note in detection is the biomarker procalcitonin, which is typically present with bacterial disease. Dr. Fritz and colleagues stressed that because the procalcitonin rate was higher in patients presenting with bacteremia, “this information could influence decisions around culturing if results are rapidly available.” Risk-stratification tools also might serve a valuable purpose in ferreting out those patients presenting with moderate to severe pneumonia most at increased risk for bacterial CAP.

Compared with other studies reporting prevalence ranges of 1%-7%, the prevalence of bacteremia in this study is lower at 2%. The authors attributed the difference to a possible potential limitation with the other studies, for which culture data was only available for a median 47% of enrollees. Dr. Fritz and her colleagues caution that “because cultures were obtained at the discretion of the treating clinician in a majority of studies, blood cultures were likely obtained more often in those with more severe illness or who had not already received antibiotics.” In this scenario, the likelihood that prevalence of bacteremia was overestimated is noteworthy.

The authors observed that penicillin-susceptible S. pneumonia was the most common cause of bacteremic CAP. They further acknowledged that their study and findings by Neuman et al. in 2017 give credence to the joint 2011 PIDS/IDSA guideline recommending narrow-spectrum aminopenicillins specifically to treat children hospitalized due to suspected bacterial CAP.

Despite its small sample size, the results of this study clearly demonstrate that children with bacteremia because of S. pyogenes or S. aureus experience increased morbidity, compared with children with S. pneumoniae, they said

While this is acknowledged to be one of the largest studies of its kind to date, a key limitation was the small number of observable patients with bacteremia, which prevented the researchers from conducting a more in-depth analysis of risk factors and pathogen-specific differences. That one-fourth of patients received in-patient antibiotics before cultures could be collected also likely led to an underestimation of risk factors and misclassification bias. Lastly, the use of blood culture instead of whole-blood polymerase chain reaction, which is known to be more sensitive, also may have led to underestimation of overall bacteremia prevalence.

“In an era with widespread pneumococcal vaccination and low prevalence of bacteremia in the United States, noted Dr. Fritz and associates.

Dr. Fritz had no conflicts of interest to report. Some coauthors cited multiple sources of potential conflict of interest related to consulting fees, grant support, and research support from various pharmaceutical companies and agencies. The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and in part by a grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

SOURCE: Fritz C et al. Pediatrics. 2019;144(1):e20183090.

FROM PEDIATRICS

New single-dose influenza therapy effective among outpatients

Clinical question: Is baloxavir marboxil, a selective inhibitor of influenza cap-dependent endonuclease, a safe and effective treatment for acute uncomplicated influenza?

Background: The emergence of oseltamivir-resistant influenza A(H1NI) infection in 2007 highlights the risk of future neuraminidase-resistant global pandemics. Baloxavir represents a new class of antiviral agent that may help treat such outbreaks.

Study design: Phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: Outpatients in the United States and Japan.

Synopsis: The trial recruited 1,436 otherwise healthy patients aged 12-64 years of age (median age, 33 years) with a clinical diagnosis of acute uncomplicated influenza pneumonia. The patients were randomly assigned to receive either a single dose of oral baloxavir, oseltamivir 75 mg twice daily for 5 days, or matching placebo within 48 hours of symptom onset. The primary outcome was patient self-assessment of symptomatology.

Among the 1,064 adult patients (age 20-64) with influenza diagnosis confirmed by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), the median time to alleviation of symptoms was lower in the baloxavir group than it was in the placebo group (53.7 hours vs. 80.2 hours; P less than .001). There was no significant difference in time to alleviation of symptoms in the baloxavir group when compared with the oseltamivir group. Adverse events were reported in 21% of baloxavir patients, 25% of placebo patients, and 25% of oseltamivir patients.

The enrolled patients were predominantly young, healthy, and treated as an outpatient. Patients hospitalized with influenza pneumonia are often older, have significant comorbidities, and are at higher risk of poor outcomes. This trial does not directly support the safety or efficacy of baloxavir in this population.

Bottom line: A single dose of baloxavir provides similar clinical benefit as 5 days of oseltamivir therapy in the early treatment of healthy patients with acute influenza.

Citation: Hayden FG et al. Baloxavir marboxil for uncomplicated influenza in adults and adolescents. N Eng J Med. 2018:379(10):914-23.

Dr. Holzer is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Clinical question: Is baloxavir marboxil, a selective inhibitor of influenza cap-dependent endonuclease, a safe and effective treatment for acute uncomplicated influenza?

Background: The emergence of oseltamivir-resistant influenza A(H1NI) infection in 2007 highlights the risk of future neuraminidase-resistant global pandemics. Baloxavir represents a new class of antiviral agent that may help treat such outbreaks.

Study design: Phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: Outpatients in the United States and Japan.

Synopsis: The trial recruited 1,436 otherwise healthy patients aged 12-64 years of age (median age, 33 years) with a clinical diagnosis of acute uncomplicated influenza pneumonia. The patients were randomly assigned to receive either a single dose of oral baloxavir, oseltamivir 75 mg twice daily for 5 days, or matching placebo within 48 hours of symptom onset. The primary outcome was patient self-assessment of symptomatology.

Among the 1,064 adult patients (age 20-64) with influenza diagnosis confirmed by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), the median time to alleviation of symptoms was lower in the baloxavir group than it was in the placebo group (53.7 hours vs. 80.2 hours; P less than .001). There was no significant difference in time to alleviation of symptoms in the baloxavir group when compared with the oseltamivir group. Adverse events were reported in 21% of baloxavir patients, 25% of placebo patients, and 25% of oseltamivir patients.

The enrolled patients were predominantly young, healthy, and treated as an outpatient. Patients hospitalized with influenza pneumonia are often older, have significant comorbidities, and are at higher risk of poor outcomes. This trial does not directly support the safety or efficacy of baloxavir in this population.

Bottom line: A single dose of baloxavir provides similar clinical benefit as 5 days of oseltamivir therapy in the early treatment of healthy patients with acute influenza.

Citation: Hayden FG et al. Baloxavir marboxil for uncomplicated influenza in adults and adolescents. N Eng J Med. 2018:379(10):914-23.

Dr. Holzer is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Clinical question: Is baloxavir marboxil, a selective inhibitor of influenza cap-dependent endonuclease, a safe and effective treatment for acute uncomplicated influenza?

Background: The emergence of oseltamivir-resistant influenza A(H1NI) infection in 2007 highlights the risk of future neuraminidase-resistant global pandemics. Baloxavir represents a new class of antiviral agent that may help treat such outbreaks.

Study design: Phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: Outpatients in the United States and Japan.

Synopsis: The trial recruited 1,436 otherwise healthy patients aged 12-64 years of age (median age, 33 years) with a clinical diagnosis of acute uncomplicated influenza pneumonia. The patients were randomly assigned to receive either a single dose of oral baloxavir, oseltamivir 75 mg twice daily for 5 days, or matching placebo within 48 hours of symptom onset. The primary outcome was patient self-assessment of symptomatology.

Among the 1,064 adult patients (age 20-64) with influenza diagnosis confirmed by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), the median time to alleviation of symptoms was lower in the baloxavir group than it was in the placebo group (53.7 hours vs. 80.2 hours; P less than .001). There was no significant difference in time to alleviation of symptoms in the baloxavir group when compared with the oseltamivir group. Adverse events were reported in 21% of baloxavir patients, 25% of placebo patients, and 25% of oseltamivir patients.

The enrolled patients were predominantly young, healthy, and treated as an outpatient. Patients hospitalized with influenza pneumonia are often older, have significant comorbidities, and are at higher risk of poor outcomes. This trial does not directly support the safety or efficacy of baloxavir in this population.

Bottom line: A single dose of baloxavir provides similar clinical benefit as 5 days of oseltamivir therapy in the early treatment of healthy patients with acute influenza.

Citation: Hayden FG et al. Baloxavir marboxil for uncomplicated influenza in adults and adolescents. N Eng J Med. 2018:379(10):914-23.

Dr. Holzer is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

No Pip/Tazo for patients with ESBL blood stream infections

Background: ESBL-producing gram-negative bacilli are becoming increasingly common. Carbapenems are considered the treatment of choice for these infections, but they may in turn select for carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacilli.

Study design: Open-label, noninferiority, randomized clinical trial.

Setting: Adult inpatients from nine countries (not including the United States).

Synopsis: Patients with at least one positive blood culture for ESBL E. coli or K. pneumoniae were screened. Of the initial 1,646 patients assessed, only 391 were enrolled (866 met exclusion criteria, 218 patients declined, and 123 treating physicians declined). Patients were randomized within 72 hours of the positive blood culture collection to either piperacillin/tazobactam 4.5 g every 6 hours or meropenem 1 g every 8 hours. Patients were treated from 4 to 14 days, with the total duration of antibiotics left up to the treating physician.

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality at 30 days after randomization. The study was stopped early because of a significant mortality difference between the two groups (12.3% in the piperacillin/tazobactam group versus 3.7% in the meropenem group).

The overall mortality rate was lower than expected. The sickest patients may have been excluded because the treating physician needed to approve enrollment. Because of the necessity for empiric antibiotic therapy, there was substantial crossover in antibiotics between the groups, although this would have biased the study toward noninferiority.

Bottom line: For patients with ESBL E. coli or K. pneumoniae blood stream infections, treatment with piperacillin/tazobactam was inferior to meropenem for 30-day mortality.

Citation: Harris PNA et al. Effect of piperacillin-tazobactam vs meropenem on 30-day mortality for patients with E coli or Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infection and ceftriaxone resistance: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(10):984-94.

Dr. Gabriel is assistant professor of medicine and director of Preoperative Medicine and Medicine Consult Service in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Background: ESBL-producing gram-negative bacilli are becoming increasingly common. Carbapenems are considered the treatment of choice for these infections, but they may in turn select for carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacilli.

Study design: Open-label, noninferiority, randomized clinical trial.

Setting: Adult inpatients from nine countries (not including the United States).

Synopsis: Patients with at least one positive blood culture for ESBL E. coli or K. pneumoniae were screened. Of the initial 1,646 patients assessed, only 391 were enrolled (866 met exclusion criteria, 218 patients declined, and 123 treating physicians declined). Patients were randomized within 72 hours of the positive blood culture collection to either piperacillin/tazobactam 4.5 g every 6 hours or meropenem 1 g every 8 hours. Patients were treated from 4 to 14 days, with the total duration of antibiotics left up to the treating physician.

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality at 30 days after randomization. The study was stopped early because of a significant mortality difference between the two groups (12.3% in the piperacillin/tazobactam group versus 3.7% in the meropenem group).

The overall mortality rate was lower than expected. The sickest patients may have been excluded because the treating physician needed to approve enrollment. Because of the necessity for empiric antibiotic therapy, there was substantial crossover in antibiotics between the groups, although this would have biased the study toward noninferiority.

Bottom line: For patients with ESBL E. coli or K. pneumoniae blood stream infections, treatment with piperacillin/tazobactam was inferior to meropenem for 30-day mortality.

Citation: Harris PNA et al. Effect of piperacillin-tazobactam vs meropenem on 30-day mortality for patients with E coli or Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infection and ceftriaxone resistance: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(10):984-94.

Dr. Gabriel is assistant professor of medicine and director of Preoperative Medicine and Medicine Consult Service in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Background: ESBL-producing gram-negative bacilli are becoming increasingly common. Carbapenems are considered the treatment of choice for these infections, but they may in turn select for carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacilli.

Study design: Open-label, noninferiority, randomized clinical trial.

Setting: Adult inpatients from nine countries (not including the United States).

Synopsis: Patients with at least one positive blood culture for ESBL E. coli or K. pneumoniae were screened. Of the initial 1,646 patients assessed, only 391 were enrolled (866 met exclusion criteria, 218 patients declined, and 123 treating physicians declined). Patients were randomized within 72 hours of the positive blood culture collection to either piperacillin/tazobactam 4.5 g every 6 hours or meropenem 1 g every 8 hours. Patients were treated from 4 to 14 days, with the total duration of antibiotics left up to the treating physician.

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality at 30 days after randomization. The study was stopped early because of a significant mortality difference between the two groups (12.3% in the piperacillin/tazobactam group versus 3.7% in the meropenem group).

The overall mortality rate was lower than expected. The sickest patients may have been excluded because the treating physician needed to approve enrollment. Because of the necessity for empiric antibiotic therapy, there was substantial crossover in antibiotics between the groups, although this would have biased the study toward noninferiority.

Bottom line: For patients with ESBL E. coli or K. pneumoniae blood stream infections, treatment with piperacillin/tazobactam was inferior to meropenem for 30-day mortality.

Citation: Harris PNA et al. Effect of piperacillin-tazobactam vs meropenem on 30-day mortality for patients with E coli or Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infection and ceftriaxone resistance: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(10):984-94.

Dr. Gabriel is assistant professor of medicine and director of Preoperative Medicine and Medicine Consult Service in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

HM19: Sepsis care update

Presenter

Patricia Kritek MD, EdM

Session Title

Sepsis update: From screening to refractory shock

Background

Each year 1.7 million adults in America develop sepsis, and 270,000 Americans die from sepsis annually. Sepsis costs U.S. health care over $27 billion dollars each year. Because of the wide range of etiologies and variation in presentation and intensity, it is a challenge to establish homogeneous evidence based guidelines.1

The definition of sepsis based on the “SIRS” criterion was developed initially in 1992, later revised as Sepsis-2 in 2001. The latest Sepsis-3 definition – “life-threatening organ dysfunction due to a dysregulated host response to infection” – was developed in 2016 by the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock. This newest definition has renounced the SIRS criterion and adopted the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score. Treatment guidelines in sepsis were developed by the Surviving Sepsis Campaign starting with the Barcelona Declaration in 2002 and revised multiple times, with the development of 3-hour and 6-hour care bundles in 2012. The latest revision, in 2018, consolidated to a 1-hour bundle.2

Sepsis is a continuum of every severe infection, and with the combined efforts of the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine, evidence-based guidelines have been developed over the past 2 decades, with the latest iteration in 2018. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services still uses Sepsis-2 for diagnosis, and the 3-hr/6-hr bundle compliance (2016) for expected care.3

Session summary

Dr. Kritek, of the division of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, presented to a room of over 1,000 enthusiastic hospitalists. She was able to capture everyone’s attention with a great presentation. As sepsis is one of the most common and serious conditions we encounter, most hospitalists are fairly well versed in evidence-based practices, and Dr. Kritek was able to keep us engaged, describing in detail the evolving definition, pathophysiology, and screening procedures for sepsis. She also spoke about important studies and the latest evidence that will positively impact each hospitalist’s practice in treating sepsis.

Dr. Kritek explained clearly how the Surviving Sepsis Campaign developed a vital and nontraditional guideline that “recommends health systems have a performance improvement program for sepsis including screening for high-risk patients.” In a 1-hour session, Dr. Kritek did a commendable job untangling this bewildering health care challenge, and aligned each component to explain how to best use available resources and address sepsis in individual hospitals.

She talked about the statistics and historical aspects involved in the definition of sepsis, and the Surviving Sepsis Campaign. With three good case scenarios, Dr. Kritek explained how it was difficult to accurately diagnose sepsis using the Sepsis-2/SIRS criterion, and how the SIRS criterion led to several false positives. This created a need for the new Sepsis-3 definition, which used delta SOFA score of 2 indicating “organ failure.”

Key takeaways: Screening

- Sepsis-3 with delta SOFA score of at least 2 and Quick SOFA (qSOFA) of at least 2 was best at predicting in-hospital death, ICU admission, and long ICU stay in ED.

- qSOFA was not helpful in the admitted ICU population. An increase of at least 2 points in SOFA score within 24 hours of admission to the ICU was the best predictor of in-hospital mortality and long ICU stays.

- SIRS has high sensitivity and low specificity. The Early Warning Score has accuracy similar to qSOFA.

- Understanding that there is no perfect answer regarding screening, but having a process is vital for each organization. This approach led to the Surviving Sepsis Campaign guideline: “Recommend health systems have a performance improvement program for sepsis including screening for high-risk patients.”

Key takeaways: Treatment

- Meta-analysis showed that specifically targeted, early goal–directed treatment (specifically, central venous pressure 8-12 mm Hg, central venous oxygen saturation greater than 70%, packed red blood cell inotropes used) did not show any improvement in 90-day mortality, and actually generated worse outcomes, including cirrhosis, as well as higher costs of care.

- Antibiotics: Though part of the 3-hour bundle, antibiotics are recommended to be administered within 1 hour.

- Intravenous fluids: Patients with sepsis-induced hypoperfusion need 30 mL/kg crystalloids. Normal saline and lactated ringer are preferred. Lactated ringer has the advantage over normal saline, with a reduced incidence of major adverse kidney events.

- Importance of bundle compliance: N.Y. study showed use of protocols cut mortality from 30.2% to 25.4%.

Refractory septic shock

- Adding hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone improved mortality at 28 days, helped patients get off vasopressors sooner, and ultimately resulted in less organ failure. But no difference in 90-day mortality.

- A study of vitamin C use in septic patients needs further studies to validate, as it only included 47 patients.

- Early renal replacement therapy showed no difference in mortality or length of stay.

Dr. Kritek’s presentation made a positive impact by helping to explain the reasoning behind the established and evolving best practices and guidelines for care of patients with sepsis and septic shock. Her approach will help hospitalists provide cost-effective care, by understanding which expensive interventions and practices do not make a difference in patient care.

Dr. Odeti is hospitalist medical director at Johnston Memorial Hospital in Abingdon, Va. JMH is part of Ballad Health, a health system operating 21 hospitals in northeast Tennessee and southwest Virginia.

References

1. https://www.sepsis.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Sepsis-Fact-Sheet-2018.pdf.

2. http://www.survivingsepsis.org/News/Pages/SCCM-and-ACEP-Release-Joint-Statement-About-the-Surviving-Sepsis-Campaign-Hour-1-Bundle.aspx

3. Specifications Manual for National Hospital Inpatient Quality Measures Discharges 01-01-17 (1Q17) through 12-31-17 (4Q17).

Presenter

Patricia Kritek MD, EdM

Session Title

Sepsis update: From screening to refractory shock

Background

Each year 1.7 million adults in America develop sepsis, and 270,000 Americans die from sepsis annually. Sepsis costs U.S. health care over $27 billion dollars each year. Because of the wide range of etiologies and variation in presentation and intensity, it is a challenge to establish homogeneous evidence based guidelines.1

The definition of sepsis based on the “SIRS” criterion was developed initially in 1992, later revised as Sepsis-2 in 2001. The latest Sepsis-3 definition – “life-threatening organ dysfunction due to a dysregulated host response to infection” – was developed in 2016 by the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock. This newest definition has renounced the SIRS criterion and adopted the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score. Treatment guidelines in sepsis were developed by the Surviving Sepsis Campaign starting with the Barcelona Declaration in 2002 and revised multiple times, with the development of 3-hour and 6-hour care bundles in 2012. The latest revision, in 2018, consolidated to a 1-hour bundle.2

Sepsis is a continuum of every severe infection, and with the combined efforts of the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine, evidence-based guidelines have been developed over the past 2 decades, with the latest iteration in 2018. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services still uses Sepsis-2 for diagnosis, and the 3-hr/6-hr bundle compliance (2016) for expected care.3

Session summary

Dr. Kritek, of the division of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, presented to a room of over 1,000 enthusiastic hospitalists. She was able to capture everyone’s attention with a great presentation. As sepsis is one of the most common and serious conditions we encounter, most hospitalists are fairly well versed in evidence-based practices, and Dr. Kritek was able to keep us engaged, describing in detail the evolving definition, pathophysiology, and screening procedures for sepsis. She also spoke about important studies and the latest evidence that will positively impact each hospitalist’s practice in treating sepsis.

Dr. Kritek explained clearly how the Surviving Sepsis Campaign developed a vital and nontraditional guideline that “recommends health systems have a performance improvement program for sepsis including screening for high-risk patients.” In a 1-hour session, Dr. Kritek did a commendable job untangling this bewildering health care challenge, and aligned each component to explain how to best use available resources and address sepsis in individual hospitals.

She talked about the statistics and historical aspects involved in the definition of sepsis, and the Surviving Sepsis Campaign. With three good case scenarios, Dr. Kritek explained how it was difficult to accurately diagnose sepsis using the Sepsis-2/SIRS criterion, and how the SIRS criterion led to several false positives. This created a need for the new Sepsis-3 definition, which used delta SOFA score of 2 indicating “organ failure.”

Key takeaways: Screening

- Sepsis-3 with delta SOFA score of at least 2 and Quick SOFA (qSOFA) of at least 2 was best at predicting in-hospital death, ICU admission, and long ICU stay in ED.

- qSOFA was not helpful in the admitted ICU population. An increase of at least 2 points in SOFA score within 24 hours of admission to the ICU was the best predictor of in-hospital mortality and long ICU stays.

- SIRS has high sensitivity and low specificity. The Early Warning Score has accuracy similar to qSOFA.

- Understanding that there is no perfect answer regarding screening, but having a process is vital for each organization. This approach led to the Surviving Sepsis Campaign guideline: “Recommend health systems have a performance improvement program for sepsis including screening for high-risk patients.”

Key takeaways: Treatment

- Meta-analysis showed that specifically targeted, early goal–directed treatment (specifically, central venous pressure 8-12 mm Hg, central venous oxygen saturation greater than 70%, packed red blood cell inotropes used) did not show any improvement in 90-day mortality, and actually generated worse outcomes, including cirrhosis, as well as higher costs of care.

- Antibiotics: Though part of the 3-hour bundle, antibiotics are recommended to be administered within 1 hour.

- Intravenous fluids: Patients with sepsis-induced hypoperfusion need 30 mL/kg crystalloids. Normal saline and lactated ringer are preferred. Lactated ringer has the advantage over normal saline, with a reduced incidence of major adverse kidney events.

- Importance of bundle compliance: N.Y. study showed use of protocols cut mortality from 30.2% to 25.4%.

Refractory septic shock

- Adding hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone improved mortality at 28 days, helped patients get off vasopressors sooner, and ultimately resulted in less organ failure. But no difference in 90-day mortality.

- A study of vitamin C use in septic patients needs further studies to validate, as it only included 47 patients.

- Early renal replacement therapy showed no difference in mortality or length of stay.

Dr. Kritek’s presentation made a positive impact by helping to explain the reasoning behind the established and evolving best practices and guidelines for care of patients with sepsis and septic shock. Her approach will help hospitalists provide cost-effective care, by understanding which expensive interventions and practices do not make a difference in patient care.

Dr. Odeti is hospitalist medical director at Johnston Memorial Hospital in Abingdon, Va. JMH is part of Ballad Health, a health system operating 21 hospitals in northeast Tennessee and southwest Virginia.

References

1. https://www.sepsis.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Sepsis-Fact-Sheet-2018.pdf.

2. http://www.survivingsepsis.org/News/Pages/SCCM-and-ACEP-Release-Joint-Statement-About-the-Surviving-Sepsis-Campaign-Hour-1-Bundle.aspx

3. Specifications Manual for National Hospital Inpatient Quality Measures Discharges 01-01-17 (1Q17) through 12-31-17 (4Q17).

Presenter

Patricia Kritek MD, EdM

Session Title

Sepsis update: From screening to refractory shock

Background

Each year 1.7 million adults in America develop sepsis, and 270,000 Americans die from sepsis annually. Sepsis costs U.S. health care over $27 billion dollars each year. Because of the wide range of etiologies and variation in presentation and intensity, it is a challenge to establish homogeneous evidence based guidelines.1

The definition of sepsis based on the “SIRS” criterion was developed initially in 1992, later revised as Sepsis-2 in 2001. The latest Sepsis-3 definition – “life-threatening organ dysfunction due to a dysregulated host response to infection” – was developed in 2016 by the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock. This newest definition has renounced the SIRS criterion and adopted the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score. Treatment guidelines in sepsis were developed by the Surviving Sepsis Campaign starting with the Barcelona Declaration in 2002 and revised multiple times, with the development of 3-hour and 6-hour care bundles in 2012. The latest revision, in 2018, consolidated to a 1-hour bundle.2

Sepsis is a continuum of every severe infection, and with the combined efforts of the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine, evidence-based guidelines have been developed over the past 2 decades, with the latest iteration in 2018. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services still uses Sepsis-2 for diagnosis, and the 3-hr/6-hr bundle compliance (2016) for expected care.3

Session summary

Dr. Kritek, of the division of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, presented to a room of over 1,000 enthusiastic hospitalists. She was able to capture everyone’s attention with a great presentation. As sepsis is one of the most common and serious conditions we encounter, most hospitalists are fairly well versed in evidence-based practices, and Dr. Kritek was able to keep us engaged, describing in detail the evolving definition, pathophysiology, and screening procedures for sepsis. She also spoke about important studies and the latest evidence that will positively impact each hospitalist’s practice in treating sepsis.

Dr. Kritek explained clearly how the Surviving Sepsis Campaign developed a vital and nontraditional guideline that “recommends health systems have a performance improvement program for sepsis including screening for high-risk patients.” In a 1-hour session, Dr. Kritek did a commendable job untangling this bewildering health care challenge, and aligned each component to explain how to best use available resources and address sepsis in individual hospitals.

She talked about the statistics and historical aspects involved in the definition of sepsis, and the Surviving Sepsis Campaign. With three good case scenarios, Dr. Kritek explained how it was difficult to accurately diagnose sepsis using the Sepsis-2/SIRS criterion, and how the SIRS criterion led to several false positives. This created a need for the new Sepsis-3 definition, which used delta SOFA score of 2 indicating “organ failure.”

Key takeaways: Screening

- Sepsis-3 with delta SOFA score of at least 2 and Quick SOFA (qSOFA) of at least 2 was best at predicting in-hospital death, ICU admission, and long ICU stay in ED.

- qSOFA was not helpful in the admitted ICU population. An increase of at least 2 points in SOFA score within 24 hours of admission to the ICU was the best predictor of in-hospital mortality and long ICU stays.

- SIRS has high sensitivity and low specificity. The Early Warning Score has accuracy similar to qSOFA.

- Understanding that there is no perfect answer regarding screening, but having a process is vital for each organization. This approach led to the Surviving Sepsis Campaign guideline: “Recommend health systems have a performance improvement program for sepsis including screening for high-risk patients.”

Key takeaways: Treatment

- Meta-analysis showed that specifically targeted, early goal–directed treatment (specifically, central venous pressure 8-12 mm Hg, central venous oxygen saturation greater than 70%, packed red blood cell inotropes used) did not show any improvement in 90-day mortality, and actually generated worse outcomes, including cirrhosis, as well as higher costs of care.

- Antibiotics: Though part of the 3-hour bundle, antibiotics are recommended to be administered within 1 hour.

- Intravenous fluids: Patients with sepsis-induced hypoperfusion need 30 mL/kg crystalloids. Normal saline and lactated ringer are preferred. Lactated ringer has the advantage over normal saline, with a reduced incidence of major adverse kidney events.

- Importance of bundle compliance: N.Y. study showed use of protocols cut mortality from 30.2% to 25.4%.

Refractory septic shock

- Adding hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone improved mortality at 28 days, helped patients get off vasopressors sooner, and ultimately resulted in less organ failure. But no difference in 90-day mortality.

- A study of vitamin C use in septic patients needs further studies to validate, as it only included 47 patients.

- Early renal replacement therapy showed no difference in mortality or length of stay.

Dr. Kritek’s presentation made a positive impact by helping to explain the reasoning behind the established and evolving best practices and guidelines for care of patients with sepsis and septic shock. Her approach will help hospitalists provide cost-effective care, by understanding which expensive interventions and practices do not make a difference in patient care.

Dr. Odeti is hospitalist medical director at Johnston Memorial Hospital in Abingdon, Va. JMH is part of Ballad Health, a health system operating 21 hospitals in northeast Tennessee and southwest Virginia.

References

1. https://www.sepsis.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Sepsis-Fact-Sheet-2018.pdf.

2. http://www.survivingsepsis.org/News/Pages/SCCM-and-ACEP-Release-Joint-Statement-About-the-Surviving-Sepsis-Campaign-Hour-1-Bundle.aspx

3. Specifications Manual for National Hospital Inpatient Quality Measures Discharges 01-01-17 (1Q17) through 12-31-17 (4Q17).

Abuse rate of gabapentin, pregabalin far below that of opioids

SAN ANTONIO – Prescription opioid abuse has continued declining since 2011, but opioids remain far more commonly abused than other prescription drugs, including gabapentin and pregabalin, new research shows.

“Both gabapentin and pregabalin are abused but at rates that are 6-56 times less frequent than for opioid analgesics,” wrote Kofi Asomaning, DSci, of Pfizer, and associates at Pfizer and Denver Health’s Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center.

“Gabapentin is generally more frequently abused than pregabalin,” they reported in a research poster at the annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence.

The researchers analyzed data from the RADARS System Survey of Non-Medical Use of Prescription Drugs Program (NMURx), the RADARS System Treatment Center Programs Combined, and the American Association of Poison Control Centers National Poison Data System (NPDS).

All those use self-reported data. The first is a confidential, anonymous web-based survey used to estimate population-level prevalence, and the second surveys patients with opioid use disorder entering treatment. The NPDS tracks all cases reported to poison control centers nationally.

Analysis of the NMURx data revealed similar lifetime abuse prevalence rates for gabapentin and pregabalin at 0.4%, several magnitudes lower than the 5.3% rate identified with opioids.

Gabapentin, however, had higher rates of abuse in the past month in the Treatment Center Programs Combined. For the third to fourth quarter of 2017, 0.12 per 100,000 population reportedly abused gabapentin, compared with 0.01 per 100,000 for pregabalin. The rate for past-month abuse of opioids was 0.79 per 100,000.

A similar pattern for the same quarter emerged from the NPDS data: Rate of gabapentin abuse was 0.06 per 100,000, rate for pregabalin was 0.01 per 100,000, and rate for opioids was 0.40 per 100,000.

Both pregabalin and opioids were predominantly ingested, though a very small amount of each was inhaled and a similarly small amount of opioids was injected. Data on exposure route for gabapentin were not provided, though it was used more frequently than pregabalin.

The research was funded by Pfizer. The RADARS system is owned by Denver Health and Hospital Authority under the Colorado state government. RADARS receives some funding from pharmaceutical industry subscriptions. Dr. Asomaning and Diane L. Martire, MD, MPH, are Pfizer employees who have financial interests with Pfizer.

SAN ANTONIO – Prescription opioid abuse has continued declining since 2011, but opioids remain far more commonly abused than other prescription drugs, including gabapentin and pregabalin, new research shows.

“Both gabapentin and pregabalin are abused but at rates that are 6-56 times less frequent than for opioid analgesics,” wrote Kofi Asomaning, DSci, of Pfizer, and associates at Pfizer and Denver Health’s Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center.

“Gabapentin is generally more frequently abused than pregabalin,” they reported in a research poster at the annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence.

The researchers analyzed data from the RADARS System Survey of Non-Medical Use of Prescription Drugs Program (NMURx), the RADARS System Treatment Center Programs Combined, and the American Association of Poison Control Centers National Poison Data System (NPDS).

All those use self-reported data. The first is a confidential, anonymous web-based survey used to estimate population-level prevalence, and the second surveys patients with opioid use disorder entering treatment. The NPDS tracks all cases reported to poison control centers nationally.

Analysis of the NMURx data revealed similar lifetime abuse prevalence rates for gabapentin and pregabalin at 0.4%, several magnitudes lower than the 5.3% rate identified with opioids.

Gabapentin, however, had higher rates of abuse in the past month in the Treatment Center Programs Combined. For the third to fourth quarter of 2017, 0.12 per 100,000 population reportedly abused gabapentin, compared with 0.01 per 100,000 for pregabalin. The rate for past-month abuse of opioids was 0.79 per 100,000.

A similar pattern for the same quarter emerged from the NPDS data: Rate of gabapentin abuse was 0.06 per 100,000, rate for pregabalin was 0.01 per 100,000, and rate for opioids was 0.40 per 100,000.

Both pregabalin and opioids were predominantly ingested, though a very small amount of each was inhaled and a similarly small amount of opioids was injected. Data on exposure route for gabapentin were not provided, though it was used more frequently than pregabalin.

The research was funded by Pfizer. The RADARS system is owned by Denver Health and Hospital Authority under the Colorado state government. RADARS receives some funding from pharmaceutical industry subscriptions. Dr. Asomaning and Diane L. Martire, MD, MPH, are Pfizer employees who have financial interests with Pfizer.

SAN ANTONIO – Prescription opioid abuse has continued declining since 2011, but opioids remain far more commonly abused than other prescription drugs, including gabapentin and pregabalin, new research shows.

“Both gabapentin and pregabalin are abused but at rates that are 6-56 times less frequent than for opioid analgesics,” wrote Kofi Asomaning, DSci, of Pfizer, and associates at Pfizer and Denver Health’s Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center.

“Gabapentin is generally more frequently abused than pregabalin,” they reported in a research poster at the annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence.

The researchers analyzed data from the RADARS System Survey of Non-Medical Use of Prescription Drugs Program (NMURx), the RADARS System Treatment Center Programs Combined, and the American Association of Poison Control Centers National Poison Data System (NPDS).

All those use self-reported data. The first is a confidential, anonymous web-based survey used to estimate population-level prevalence, and the second surveys patients with opioid use disorder entering treatment. The NPDS tracks all cases reported to poison control centers nationally.

Analysis of the NMURx data revealed similar lifetime abuse prevalence rates for gabapentin and pregabalin at 0.4%, several magnitudes lower than the 5.3% rate identified with opioids.

Gabapentin, however, had higher rates of abuse in the past month in the Treatment Center Programs Combined. For the third to fourth quarter of 2017, 0.12 per 100,000 population reportedly abused gabapentin, compared with 0.01 per 100,000 for pregabalin. The rate for past-month abuse of opioids was 0.79 per 100,000.

A similar pattern for the same quarter emerged from the NPDS data: Rate of gabapentin abuse was 0.06 per 100,000, rate for pregabalin was 0.01 per 100,000, and rate for opioids was 0.40 per 100,000.

Both pregabalin and opioids were predominantly ingested, though a very small amount of each was inhaled and a similarly small amount of opioids was injected. Data on exposure route for gabapentin were not provided, though it was used more frequently than pregabalin.

The research was funded by Pfizer. The RADARS system is owned by Denver Health and Hospital Authority under the Colorado state government. RADARS receives some funding from pharmaceutical industry subscriptions. Dr. Asomaning and Diane L. Martire, MD, MPH, are Pfizer employees who have financial interests with Pfizer.

REPORTING FROM CPDD 2019

Adjuvant corticosteroids in hospitalized patients with CAP

When is it appropriate to treat?

Case

A 55-year-old male with a history of tobacco use disorder presents with 2 days of productive cough, fever, chills, and mild shortness of breath. T 38.4, HR 89, RR 32, BP 100/65, 02 sat 86% on room air. Exam reveals diminished breath sounds and positive egophony over the right lung base. WBC is 16,000 and BUN 22. Chest x-ray reveals right lower lobe consolidation. He is given ceftriaxone and azithromycin.

Brief overview of the issue

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is the leading cause of infectious disease–related death in the United States. Mortality associated with CAP is estimated at 57,000 deaths annually and occurs largely in patients requiring hospitalization.1 The 30-day mortality rate in patients who are hospitalized for CAP is approximately 10%-12%.2 After discharge from the hospital, about 18% of patients are readmitted within 30 days.3 An excessive inflammatory cytokine response may be a major contributor to the high mortality rate in CAP and systemic corticosteroids may reduce the inflammatory response from the infection by down-regulating this proinflammatory cytokine production.

Almost all of the major decisions regarding management of CAP, including diagnostic and treatment issues, revolve around the initial assessment of severity of illness. Between 40% and 60% of patients who present to the emergency department with CAP are admitted4 and approximately 10% of hospitalized patients with CAP require ICU admission.5 Validated instruments such as CURB-65, the pneumonia severity index (PSI), and guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA)/American Thoracic Society (ATS) may predict severity of illness but should always be supplemented with physician determination of subjective factors when determining treatment.5 Although there is no census definition of severe pneumonia, studies generally define the condition in the following order of preference: PSI score of IV or V followed by CURB-65 score of two or greater. If these scoring modalities were not available, the IDSA/ATS criteria was used (1 major or 3 minor). Others define severe CAP as pneumonia requiring supportive therapy within a critical care environment.

Overview of the data

The use of corticosteroids in addition to antibiotics in the treatment of CAP was proposed as early as the 1950s and yet only in the last decade has the body of evidence grown significantly.5 There is evidence that corticosteroids suppress inflammation without acutely impairing the immune response as evidenced by a rapid and sustained decrease in circulating inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein and interleukin 6 and no effect on the anti-inflammatory interleukin 10.6 Within the last year, three meta-analyses, one by the Cochrane Library, one by the IDSA, and a third in the American Journal of Emergency Medicine, addressed the role of routine low dose (20-60 mg of prednisone or equivalent), short-course (3-7 days) systemic corticosteroids in hospitalized patients with CAP of varying severities.

The Cochrane meta-analysis, the largest and most recent dataset, included 13 trials with a combined 1,954 adult patients and found that corticosteroids significantly lowered mortality in hospitalized patients with severe CAP with a number needed to treat of 19.7 In this group with severe CAP, mortality was lowered from 13% to 8% and there were significantly fewer episodes of respiratory failure and shock with the addition of corticosteroids. No effect was seen on mortality in patients with less severe CAP. In those patients who received adjuvant corticosteroids, length of hospital stay decreased by 3 days, regardless of CAP severity.7

The IDSA meta-analysis was similar and included 1,506 patients from six trials.8 In contrast with the Cochrane study, this analysis found corticosteroids did not significantly lower mortality in patients with severe CAP but did reduce time to clinical stability and length of hospital stay by over 1 day. This study also found significantly more CAP-related, 30-day rehospitalizations (5% vs. 3%; defined as recurrent pneumonia, other infection, pleuritic pain, adverse cardiovascular event, or diarrhea) in patient with non-severe CAP treated with corticosteroids.

The study in the American Journal of Emergency Medicine involved ten trials involving more than 700 patients admitted with severe CAP and found in-hospital mortality was cut in half (RR 0.49) and length of hospital stay was reduced when patients were treated with corticosteroids in addition to standard antibiotic therapy.9

In 2015, two randomized clinical trials, one in the Lancet and the other in JAMA, and a meta-analysis in Annals of Internal Medicine assessed the impact of adjuvant corticosteroids in the treatment of hospitalized patients with CAP. The Lancet study of 785 patients hospitalized with CAP of any severity found shortened time to clinical stability (3.0 vs. 4.4 days) as defined by stable vital signs, improved oral intake, and normalized mental status for greater than 24 hours when oral prednisone 50 mg for 7 days was added to standard therapy.10 Patients in the treatment group were also discharged 1 day earlier compared with the placebo control group.

The study in JAMA was small, with only 100 patients at three teaching hospitals in Spain, but found that patients hospitalized with severe CAP and high inflammatory response based on elevated C-reactive protein were less likely to experience a treatment failure, defined as shock, mechanical ventilation, death, or radiographic progression, when intravenous methylprednisolone 0.5 mg/kg was added to standard antibiotic therapy.11

Finally, the meta-analysis in Annals of Internal Medicine assessed 13 randomized controlled placebo trials of 1,974 patients and found that adjuvant corticosteroids in a dose of 20-60 mg of prednisone or equivalent total daily dose significantly lowered mortality in patients with severe CAP and incidence of respiratory distress syndrome, and need for mechanical ventilation in all patients hospitalized with CAP.12

Importantly, nearly all of the described studies showed a significantly higher incidence of hyperglycemia in patients who received corticosteroids.

Application of the data to our patients

The benefit of adjuvant corticosteroids is most clear in hospitalized patients with severe CAP. Recent, strong evidence supports decreased mortality, decreased time to clinical stability, and decreased length of stay in our patient, with severe CAP, if treated with 20-60 mg of prednisone or equivalent total daily dose for 3-7 days. For patients with non-severe CAP, we suggest taking a risk-benefit approach based on other comorbidities, as the risk for CAP-related rehospitalizations may be higher.

For patients with underlying lung disease, specifically COPD or reactive airway disease, we suggest a low threshold for adding corticosteroids. This approach is more anecdotal than data driven, though corticosteroids are a mainstay of treatment for COPD exacerbations and a retrospective analysis of more than 20,000 hospitalized children with CAP and wheezing revealed decreased length of stay with corticosteroid treatment.13 Furthermore, a number of the studies described above included patients with COPD. Our threshold rises significantly in patients with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus.

Bottom line

For patients hospitalized with severe community-acquired pneumonia, recent evidence supports the use of low dose, short-course, systemic corticosteroids in addition to standard therapy.

Dr. Parsons is an assistant professor at the University of Virginia and a hospitalist at the University of Virginia Medical Center in Charlottesville, Va. Dr. Miller is an assistant professor at the University of Virginia and a hospitalist at the University of Virginia Medical Center. Dr. Hoke is Associate Director of Hospital Medicine and Faculty Development at the University of Virginia.

References

1. Ramirez J et al. Adults hospitalized with pneumonia in the United States: Incidence, epidemiology, and mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2017 Dec 1:65(11):1806-12.

2. Musher D et al. Community-acquired pneumonia: Review article. N Engl J Med. 2014 Oct 23;371:1619-28.

3. Wunderink R et al. Community-aquired pneumonia: Clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2014 Feb 6;370:543-51.

4. Mandell L et al. Infectious Diseases Society America/American Thoracic Society Consensus Guidelines on the Management of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:S27-72.

5. Wagner HN et al. The effect of hydrocortisone upon the course of pneumococcal pneumonia treated with penicillin. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1956;98:197-215.

6. Polverino E et al. Systemic corticosteroids for community-acquired pneumonia: Reasons for use and lack of benefit on outcome. Respirology. 2013. Feb;18(2):263-71 (https://doi.org/10.1111/resp.12013).

7. Stern A et al. Corticosteroids for pneumonia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Dec 13; 12:CD007720 (https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007720.pub3).

8. Briel M et al. Corticosteroids in patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia: Systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2018 Feb 1;66:346 (https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix801).

9. Wu W-F et al. Efficacy of corticosteroid treatment for severe community-acquired pneumonia: A meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2017 Jul 15; [e-pub] (http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2017.07.050).

10. Blum CA et al. Adjunct prednisone therapy for patients with community-acquired pneumonia: A multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2015 Jan 18; [e-pub ahead of print] (http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736[14]62447-8).

11. Torres A et al. Effect of corticosteroids on treatment failure among hospitalized patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia and high inflammatory response: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015 Feb 17; 313:677 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.88).

12. Siemieniuk RAC et al. Corticosteroid therapy for patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015 Oct 6;163:519 (http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/M15-0715).

13. Simon LH et al. Management of community-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized children. Current Treat Options Peds (2015) 1:59 (https://doi:.org/10.1007/s40746-014-0011-3).

Key points

• For patients hospitalized with severe CAP, recent evidence supports the use of low-dose, short-course, systemic corticosteroids in addition to standard therapy.

• Among hospitalized patients with non-severe CAP, the benefit is not well defined. Studies suggest these patients may benefit from reduced time to clinical stability and reduced length of hospital stay. However, they may be at risk for significantly more CAP-related, 30-day rehospitalizations and hyperglycemia.

• Further prospective, randomized controlled studies are needed to further delineate the patient population who will most benefit from adjunctive corticosteroids use, including dose and duration of treatment.

QUIZ

Which of the following is FALSE regarding community acquired pneumonia?

A. CAP is the leading cause of infectious disease related death in the United States.

B. An excessive inflammatory cytokine response may contribute to the high mortality rate in CAP.

C. Adjunctive steroid therapy has been shown to decrease mortality in all patients with CAP.

D. Hyperglycemia occurs more frequently in patients receiving steroid therapy.

E. Reasons to avoid adjunctive steroid therapy in CAP include low risk for mortality, poorly controlled diabetes, suspected viral or fungal etiology, and elevated risk for gastrointestinal bleeding.

ANSWER: C. The patient population that may benefit most from the use of adjuvant corticosteroids is poorly defined. However, in patients with severe pneumonia, the use of adjuvant steroids has been shown to decrease mortality, time to clinical stability, and length of stay.

Additional reading

Siemieniuk RAC et al. Corticosteroid therapy for patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015 Oct 6; 163:519. (http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/M15-0715).

Briel M et al. Corticosteroids in patients hospitalized with community-acquired Pneumonia: Systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2018 Feb 1; 66:346 (https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix801).

Blum CA et al. Adjunct prednisone therapy for patients with community-acquired pneumonia: A multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2015 Jan 18; [e-pub ahead of print]. (http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62447-8).

Feldman C et al. Corticosteroids in the adjunctive therapy of community-acquired pneumonia: an appraisal of recent meta-analyses of clinical trials. J Thorac Dis. 2016 Mar; 8(3):E162-E171.

Wan YD et al. Efficacy and safety of corticosteroids for community-acquired pneumonia: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2016 Jan;149(1):209-19.

When is it appropriate to treat?

When is it appropriate to treat?

Case

A 55-year-old male with a history of tobacco use disorder presents with 2 days of productive cough, fever, chills, and mild shortness of breath. T 38.4, HR 89, RR 32, BP 100/65, 02 sat 86% on room air. Exam reveals diminished breath sounds and positive egophony over the right lung base. WBC is 16,000 and BUN 22. Chest x-ray reveals right lower lobe consolidation. He is given ceftriaxone and azithromycin.

Brief overview of the issue

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is the leading cause of infectious disease–related death in the United States. Mortality associated with CAP is estimated at 57,000 deaths annually and occurs largely in patients requiring hospitalization.1 The 30-day mortality rate in patients who are hospitalized for CAP is approximately 10%-12%.2 After discharge from the hospital, about 18% of patients are readmitted within 30 days.3 An excessive inflammatory cytokine response may be a major contributor to the high mortality rate in CAP and systemic corticosteroids may reduce the inflammatory response from the infection by down-regulating this proinflammatory cytokine production.