User login

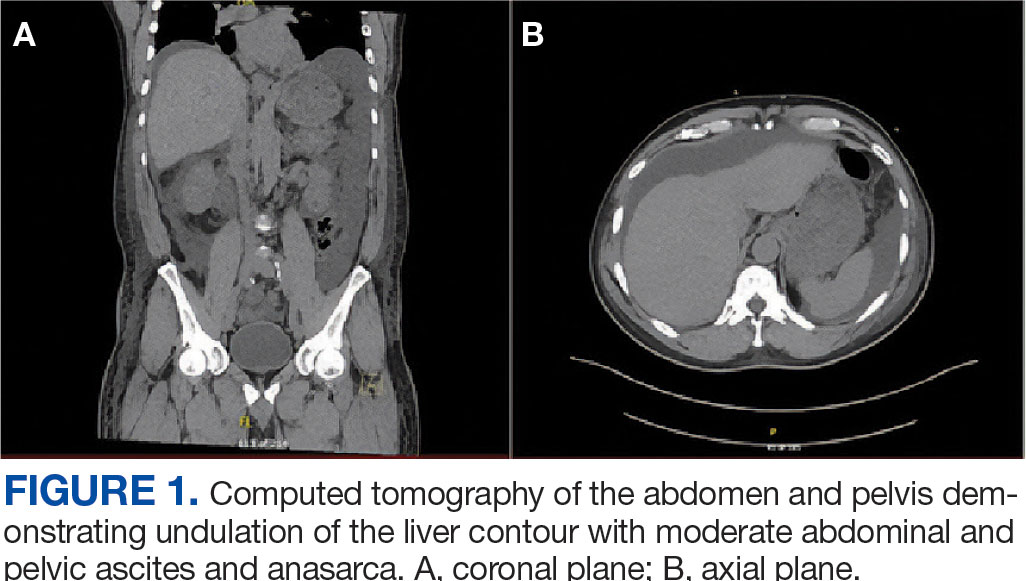

Unique Presentation of Postpartum Hypereosinophilic Syndrome With Atypical Features and Therapeutic Challenges

Unique Presentation of Postpartum Hypereosinophilic Syndrome With Atypical Features and Therapeutic Challenges

Hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) is defined by marked, persistent absolute eosinophil count (AEC) > 1500 cells/μL on ≥ 2 peripheral smears separated by ≥ 1 month with evidence of accompanied end-organ damage, in the absence of other causes of eosinophilia such as malignancy, atopy, or parasitic infections.1-5 Hypereosinophilic infiltration can impact almost every organ system; however, the most profound complications in patients with HES are related to leukemias and cardiac manifestations of the disease.3,4 Although rare, the associated morbidity and mortality of HES are considerable, making prompt recognition and treatment essential. Management involves targeted therapy based on pathologic classification of HES and on decreasing associated inflammation, fibrosis, and end-organ damage.3,5-7

The patient in this case report met the diagnostic criteria for HES. However, this patient had several clinical and laboratory features that made it difficult to characterize a specific HES variant. Moreover, she had additional immunomodulating factors in the setting of pregnancy. This is the first documented case of HES of undetermined etiology diagnosed postpartum and managed in the setting of a new pregnancy.2,8

CASE PRESENTATION

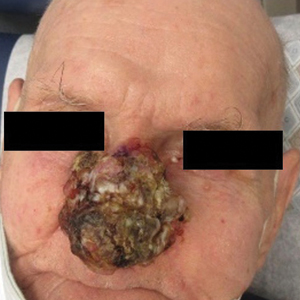

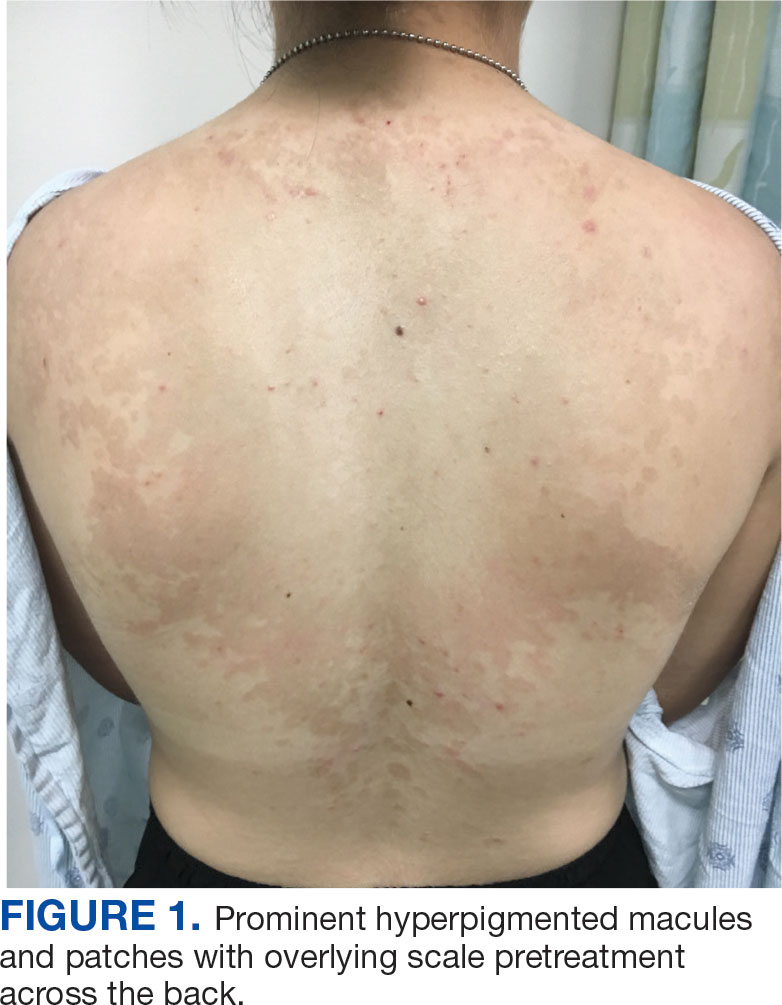

A 32-year-old female active-duty military service member with allergic rhinitis and a history of childhood eczema was referred to allergy/immunology for evaluation of a new, progressive pruritic rash. Symptoms started 3 months after the birth of her first child, with a new diffuse erythematous skin rash sparing her palms, soles, and mucosal surfaces. Given her history of atopy, the rash was initially treated as severe atopic dermatitis with appropriate topical medications. The rash gradually worsened, with the development of intermittent facial swelling, night sweats, dyspnea, recurrent epigastric abdominal pain, and nausea with vomiting, resulting in decreased oral intake and weight loss.

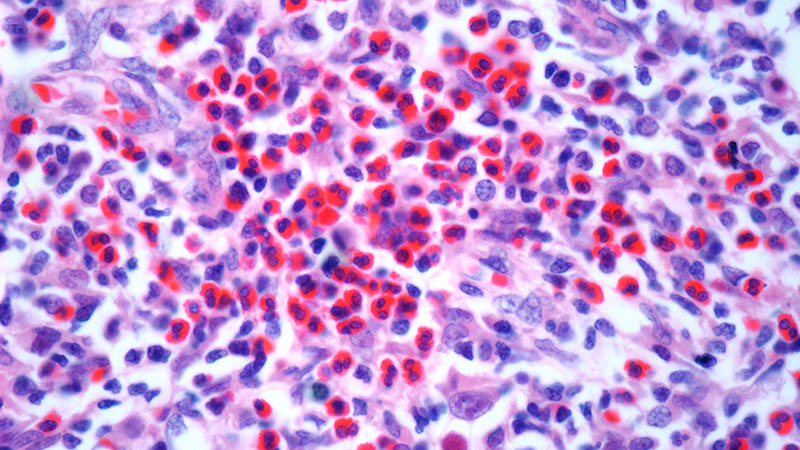

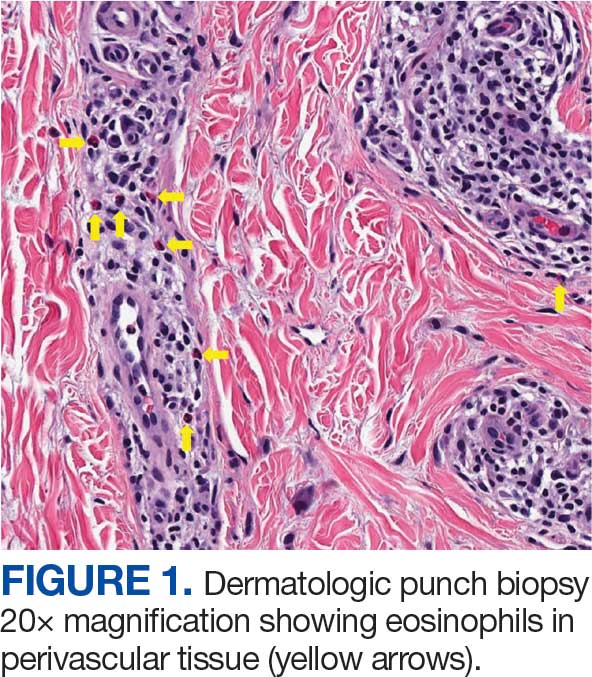

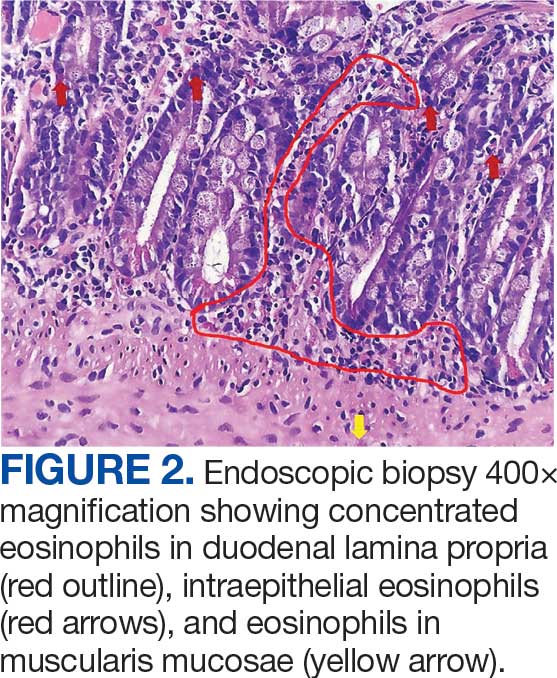

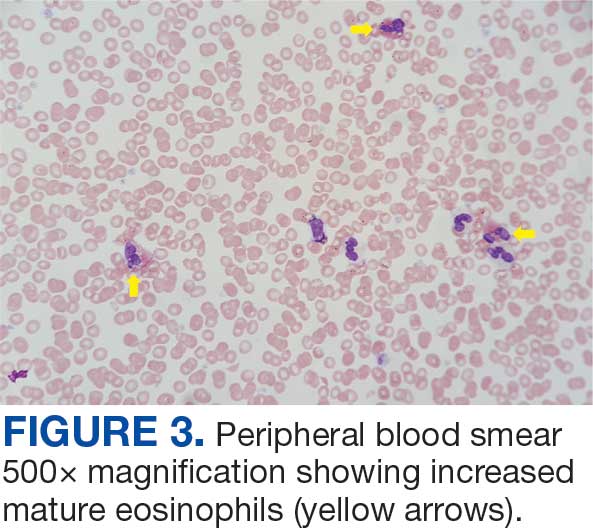

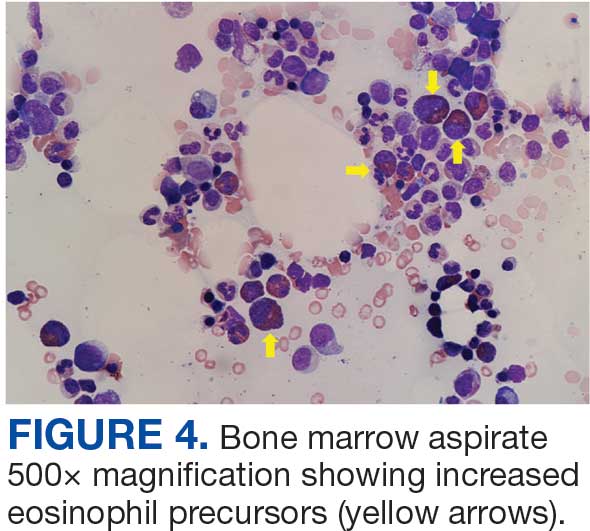

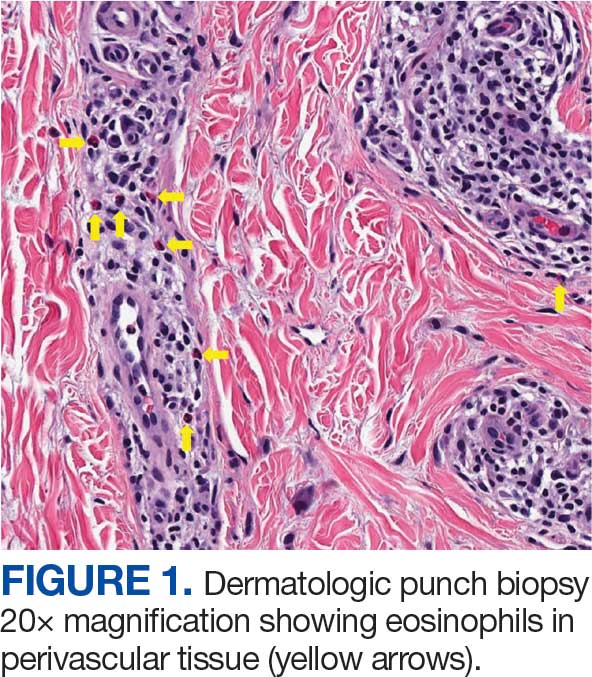

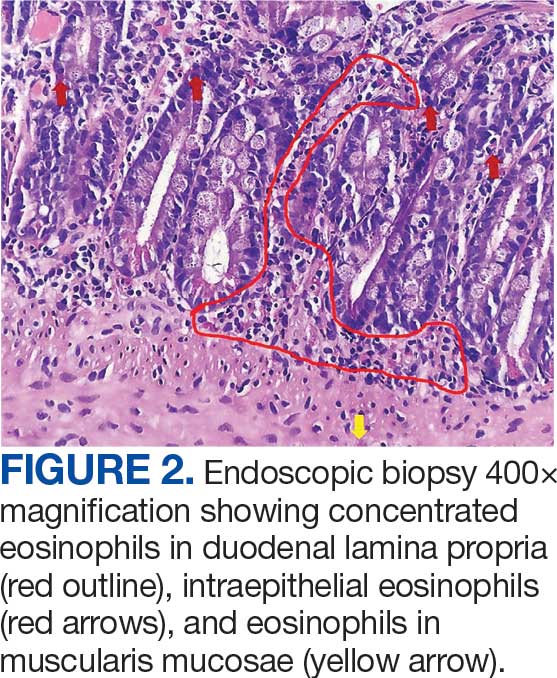

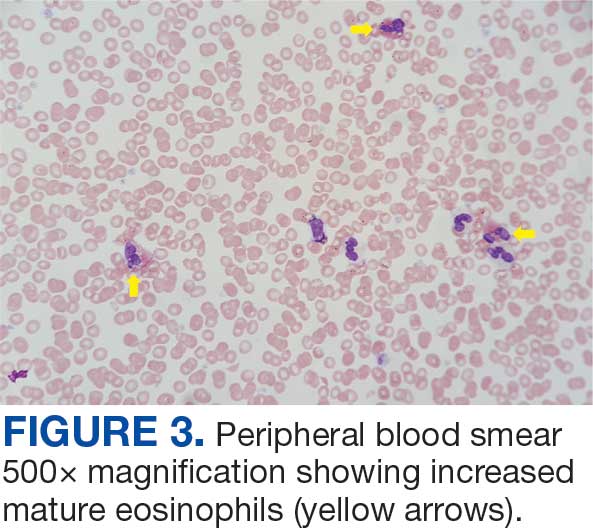

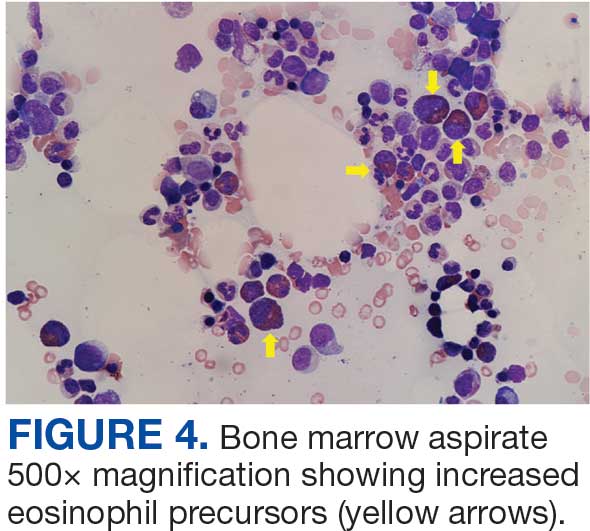

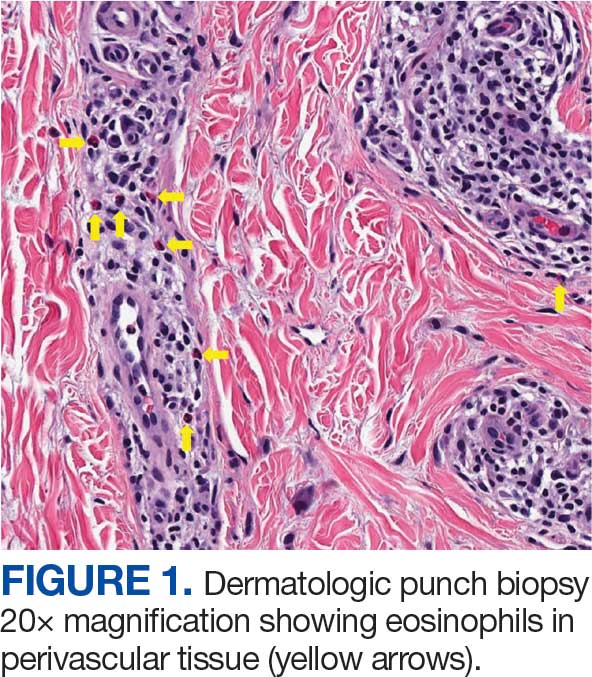

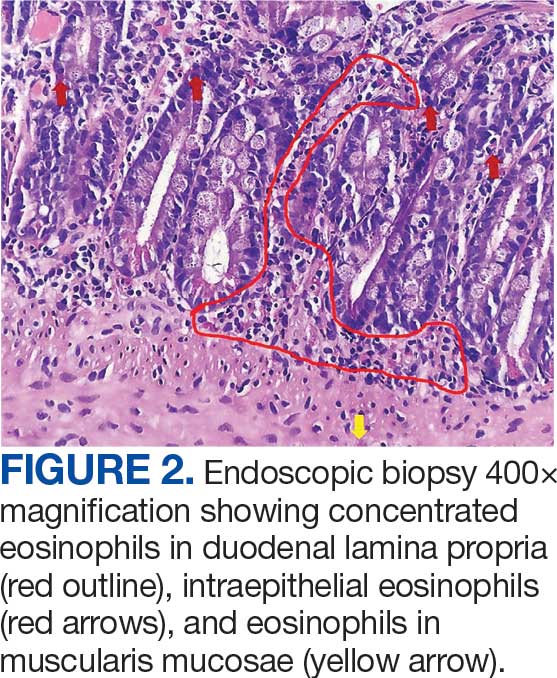

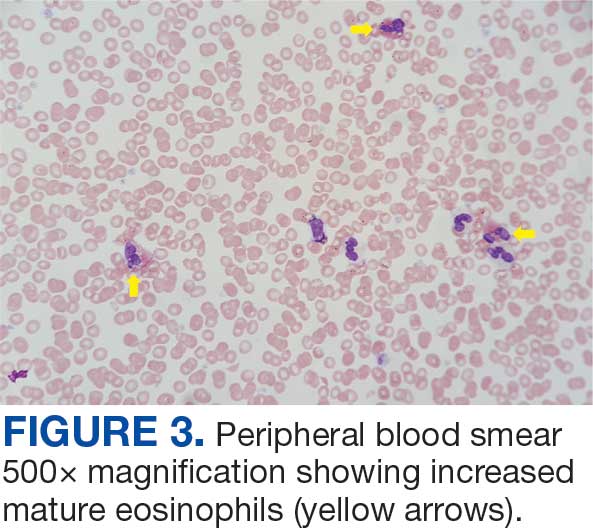

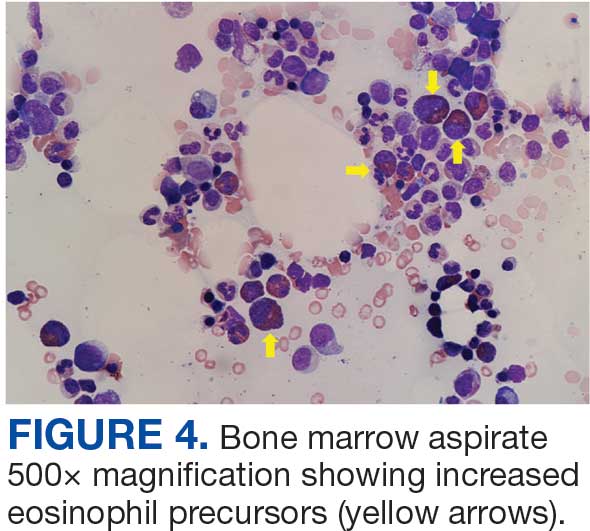

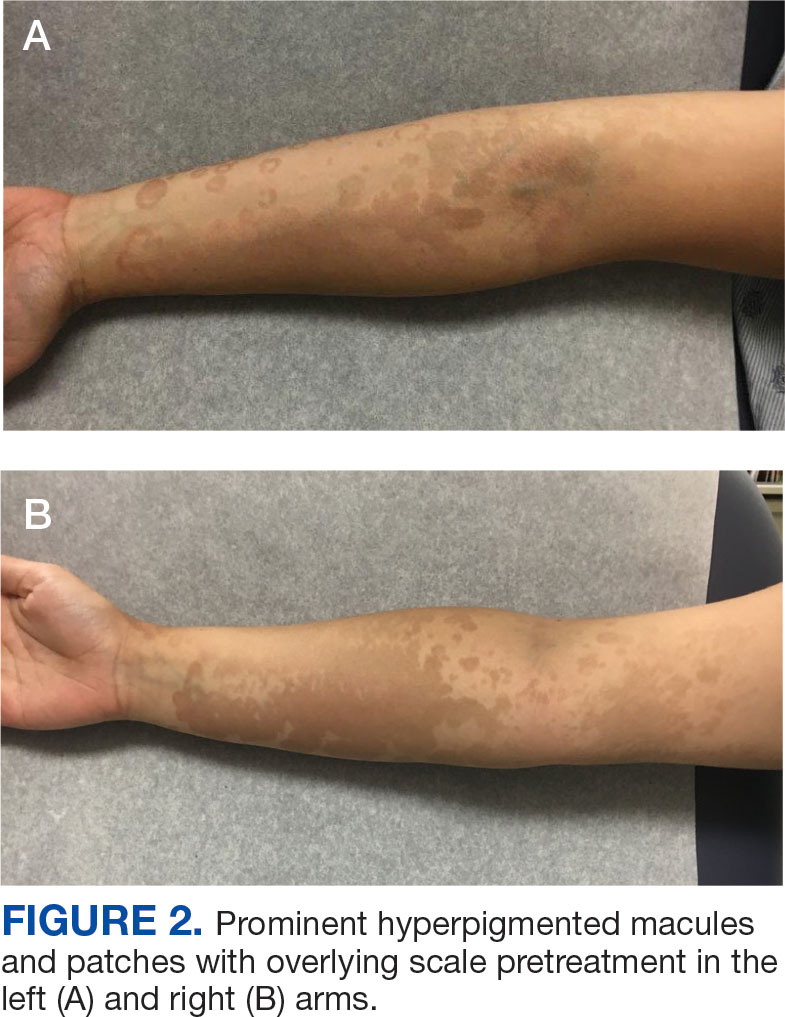

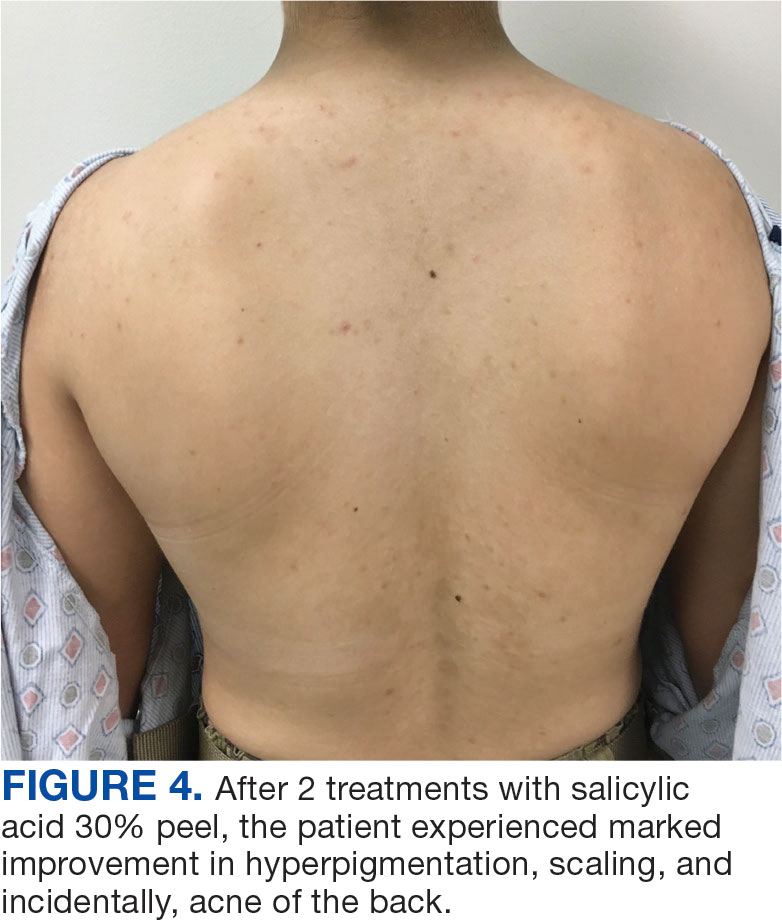

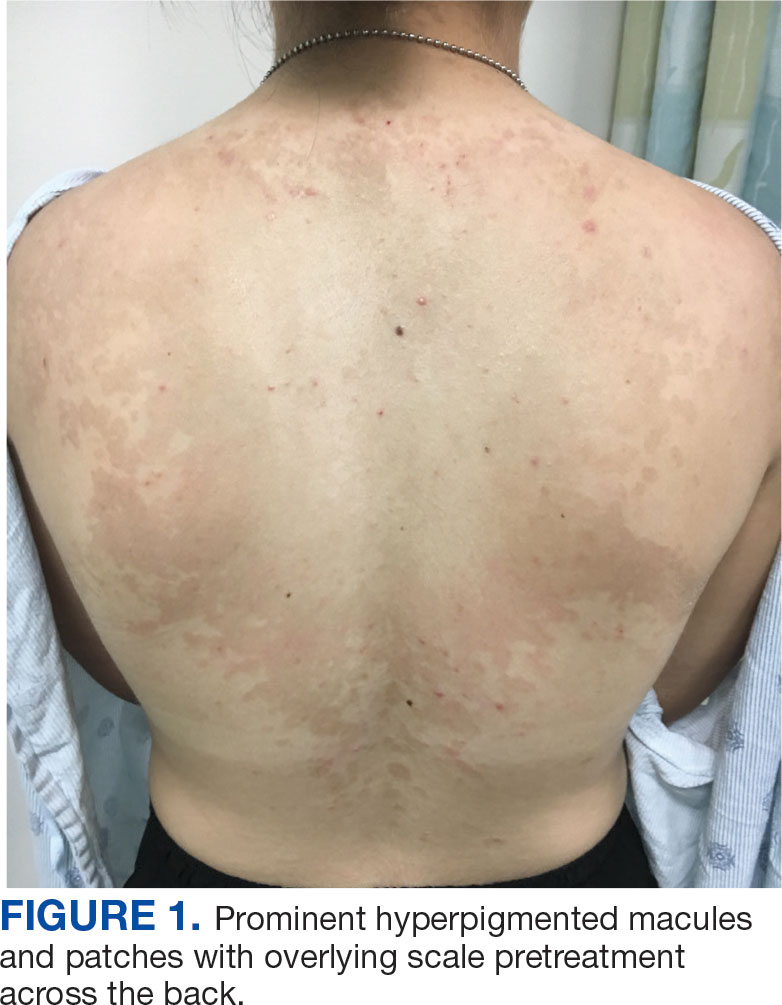

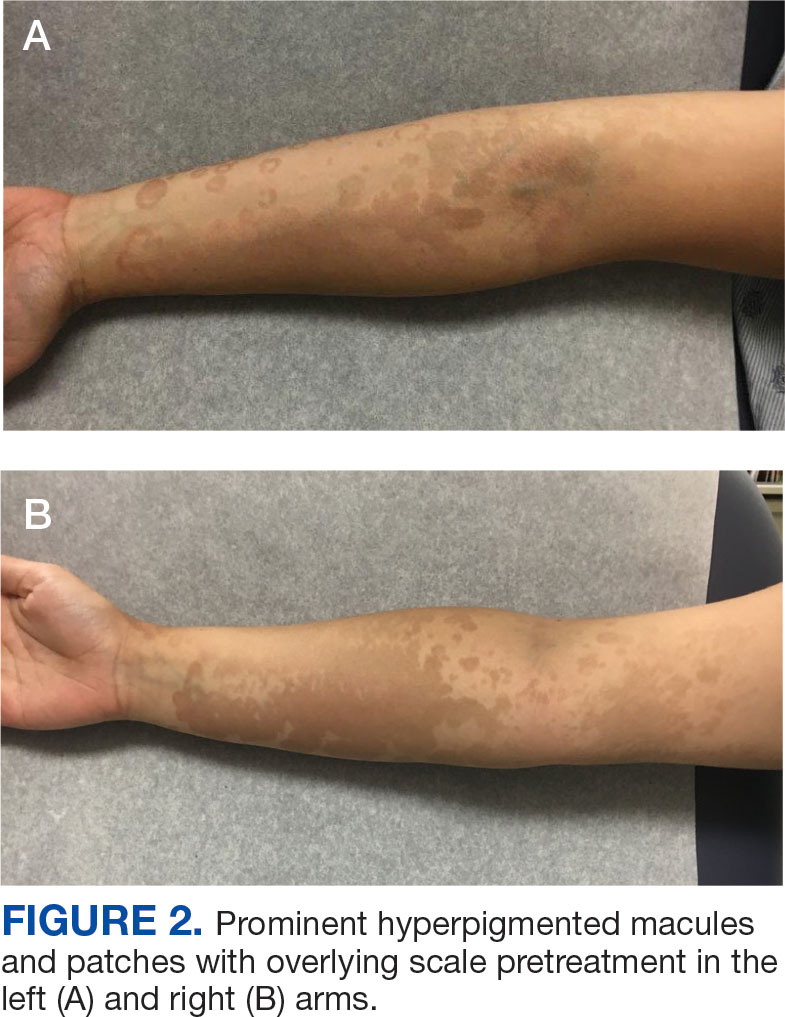

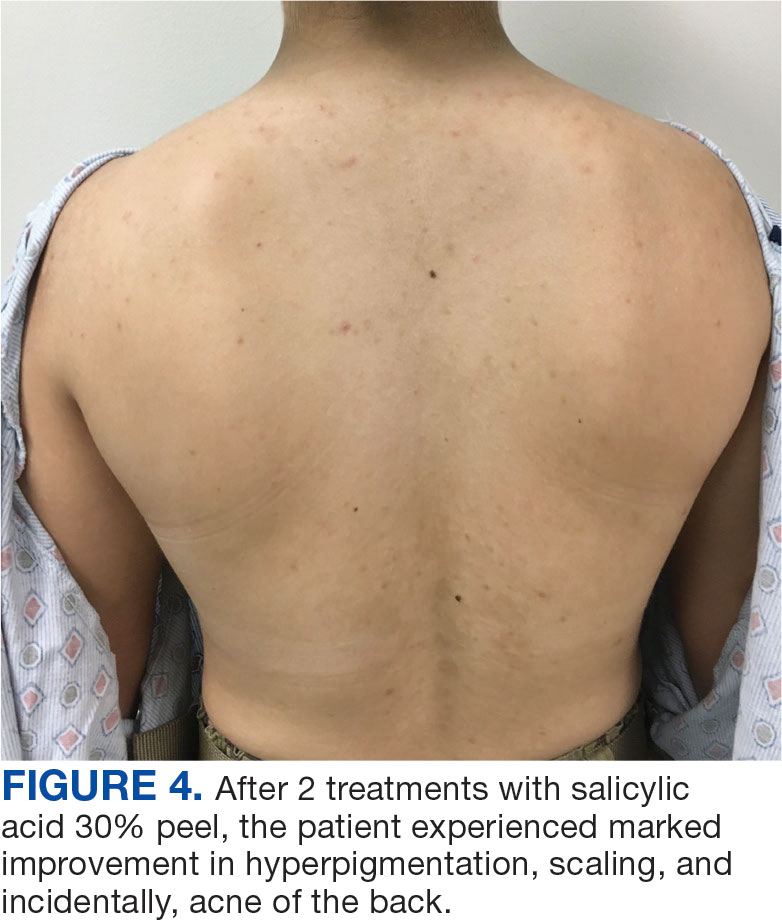

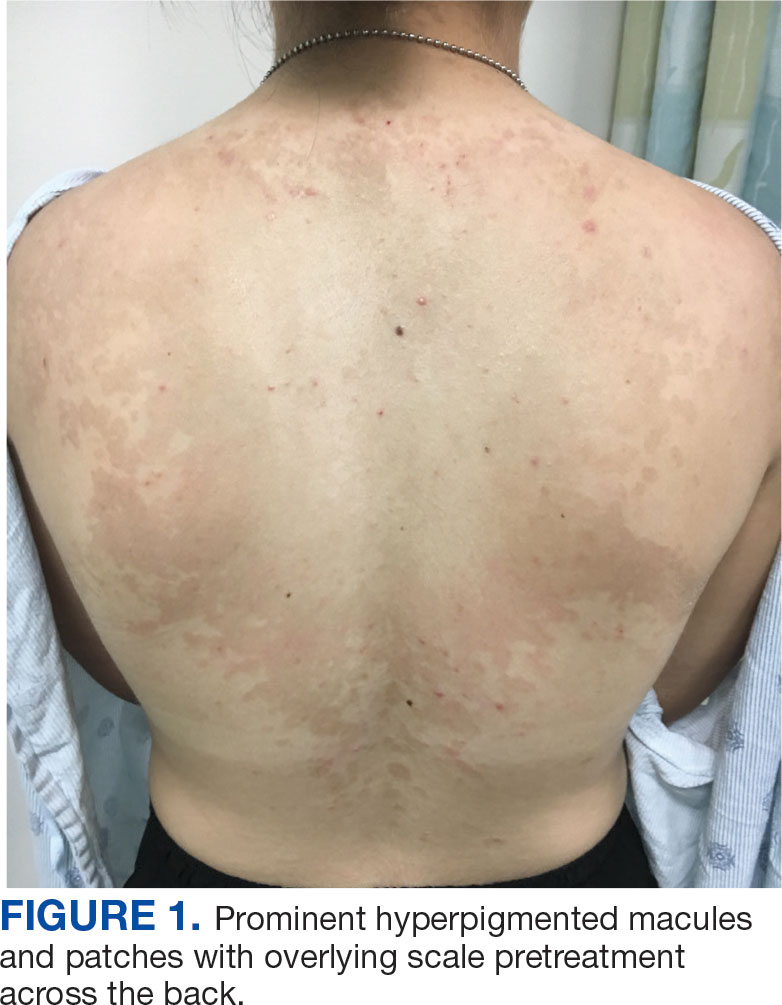

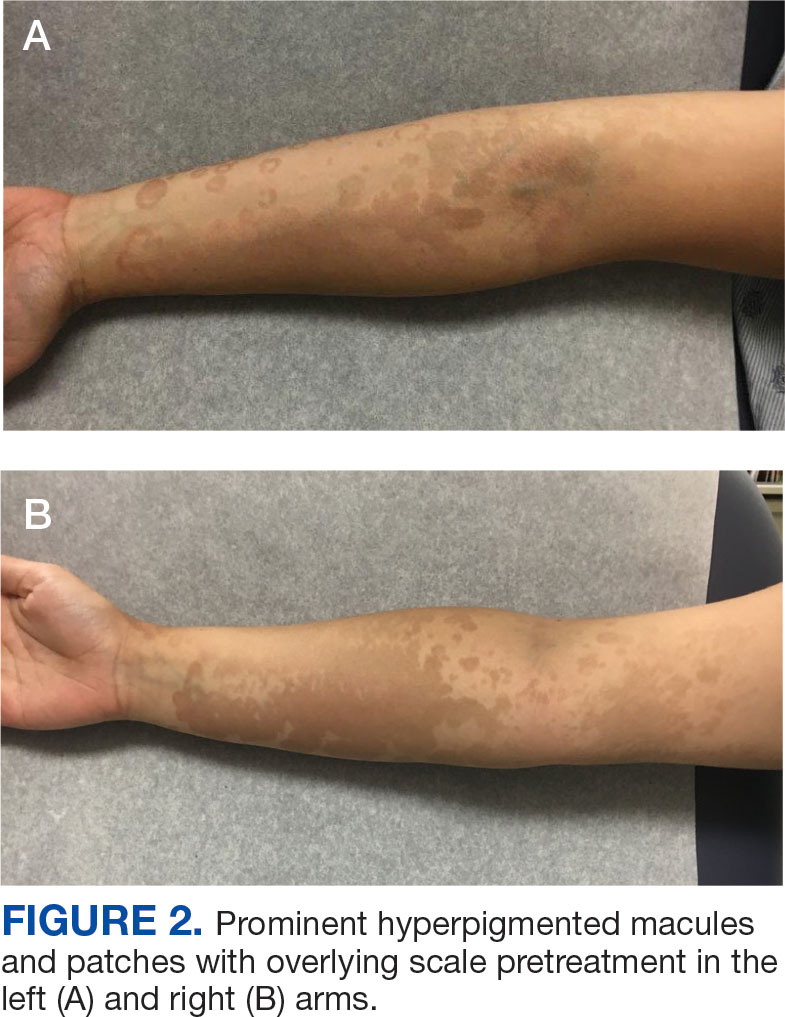

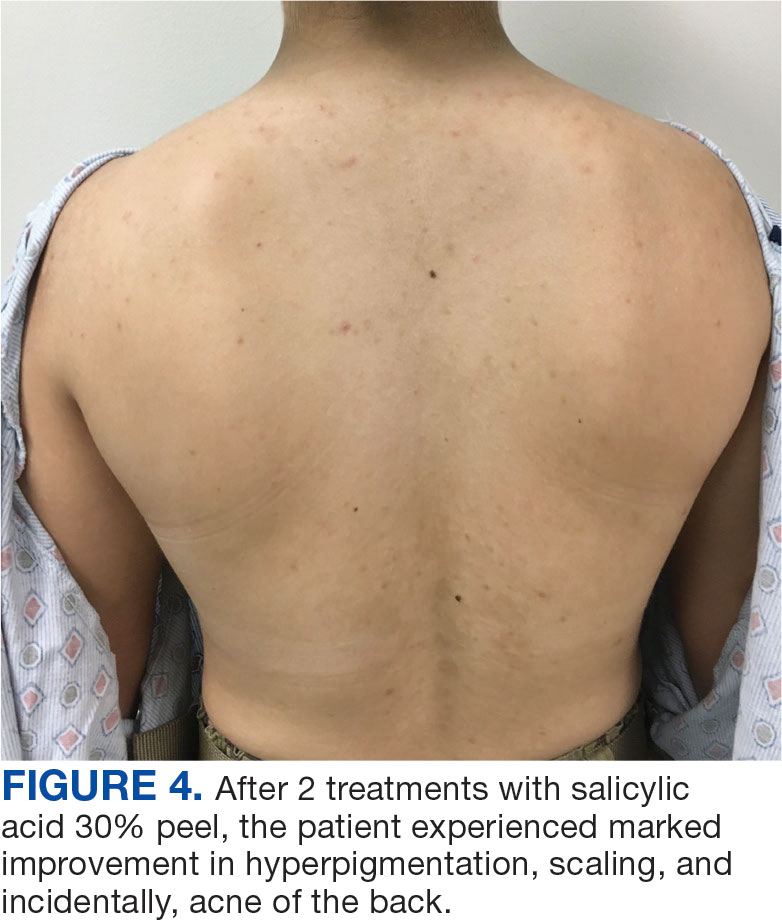

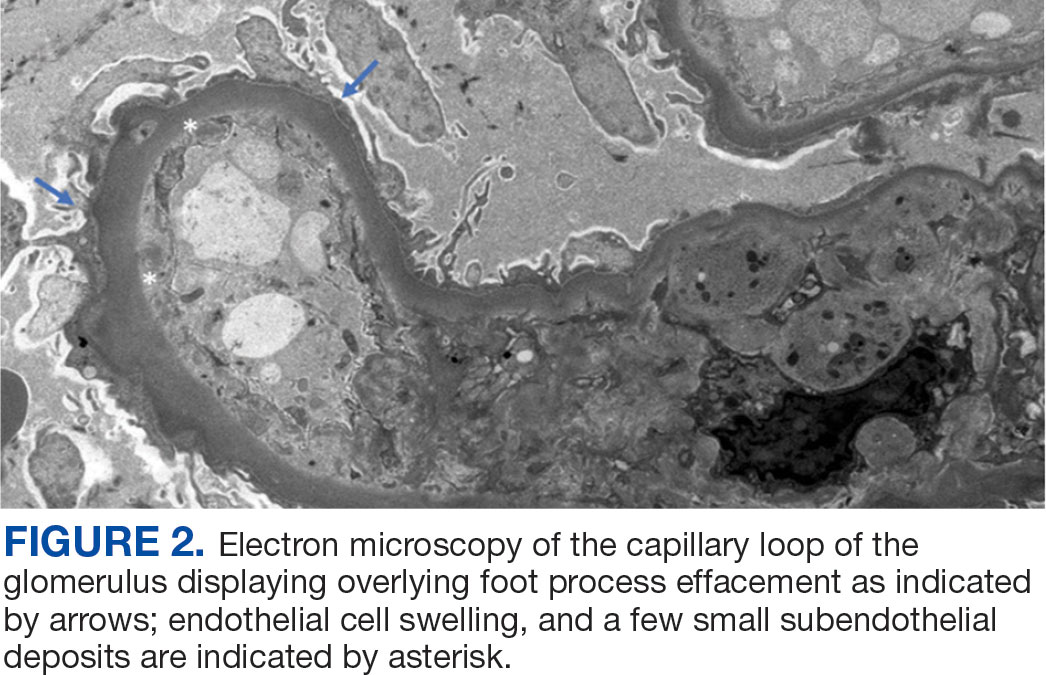

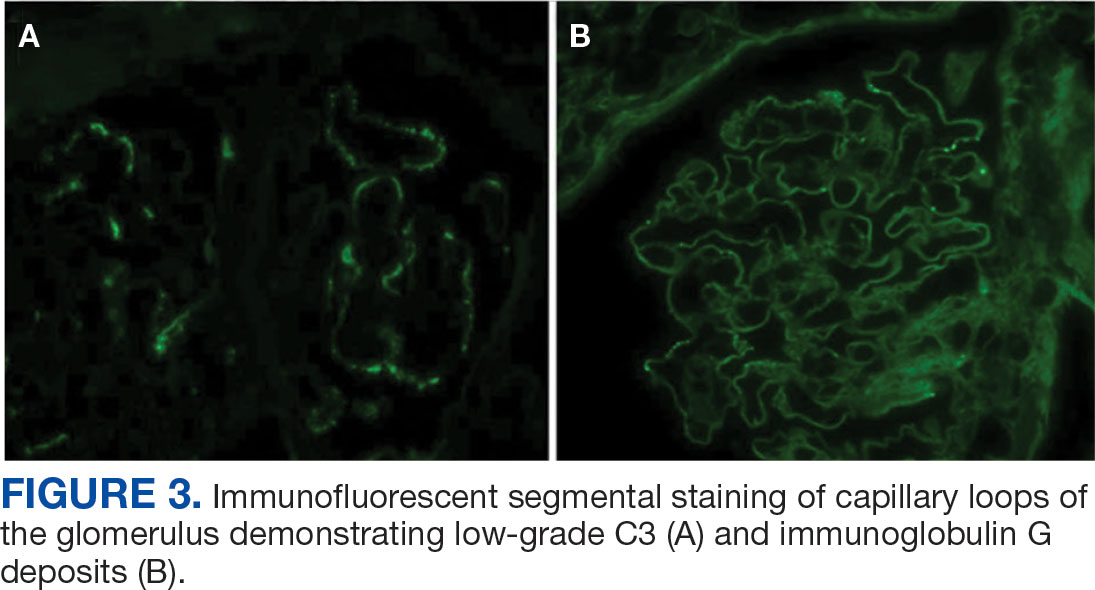

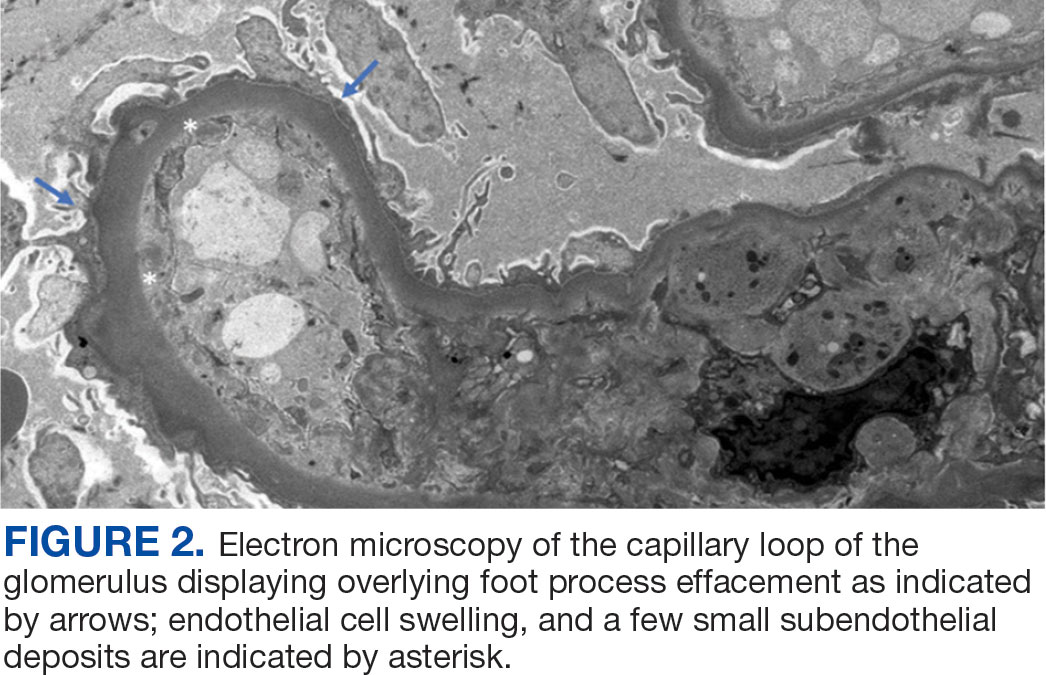

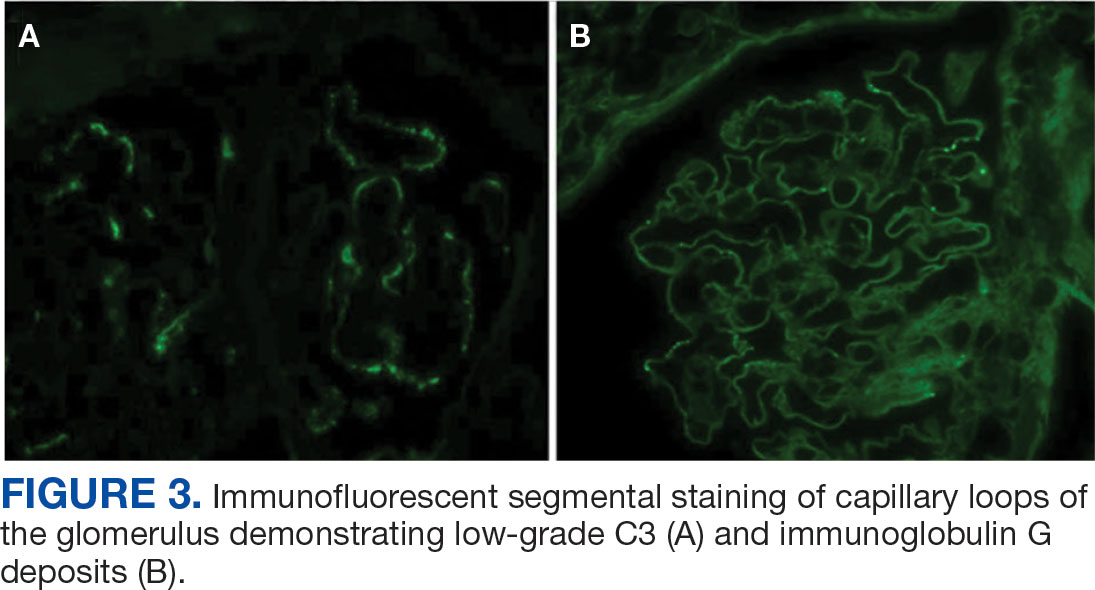

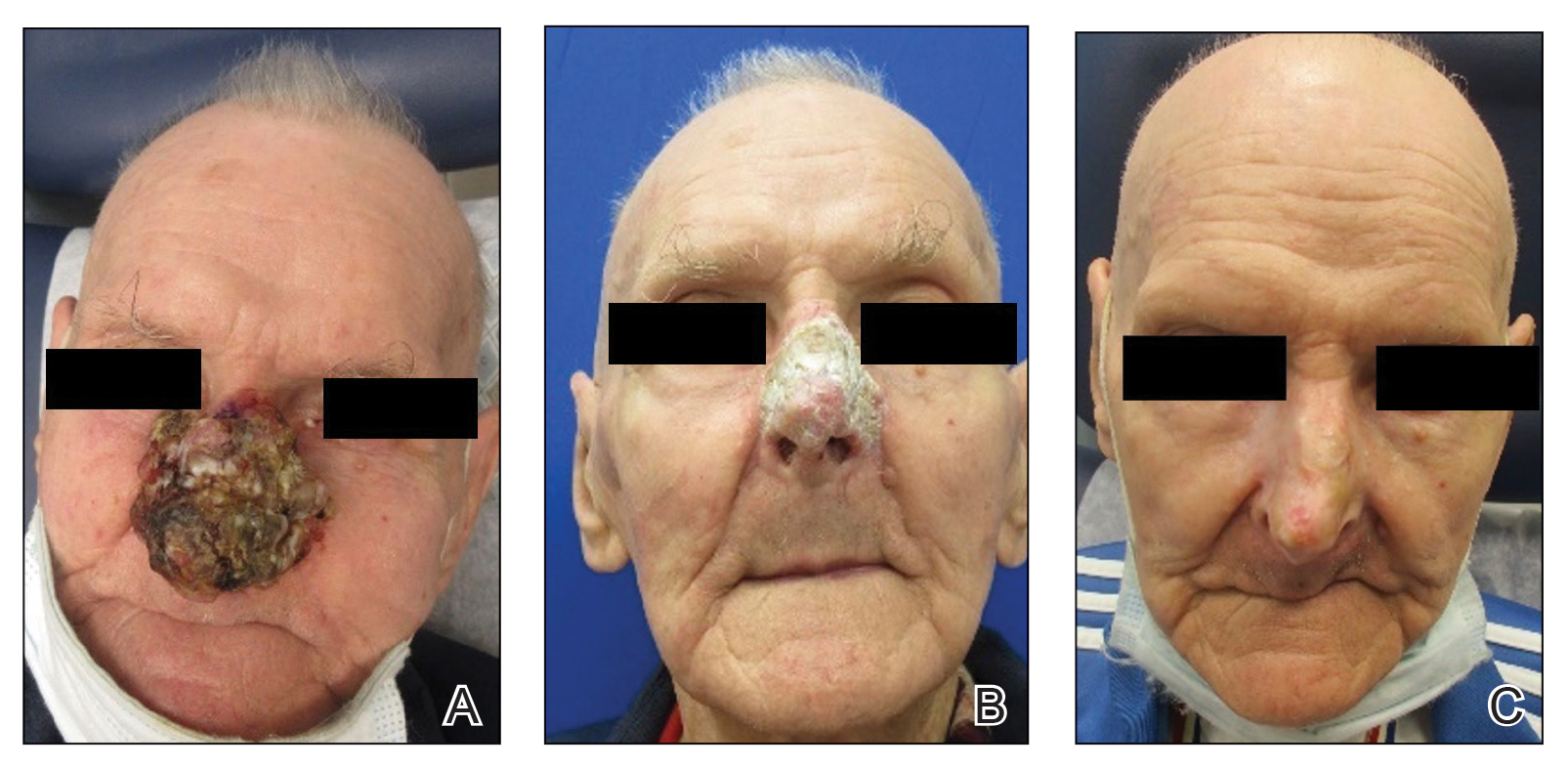

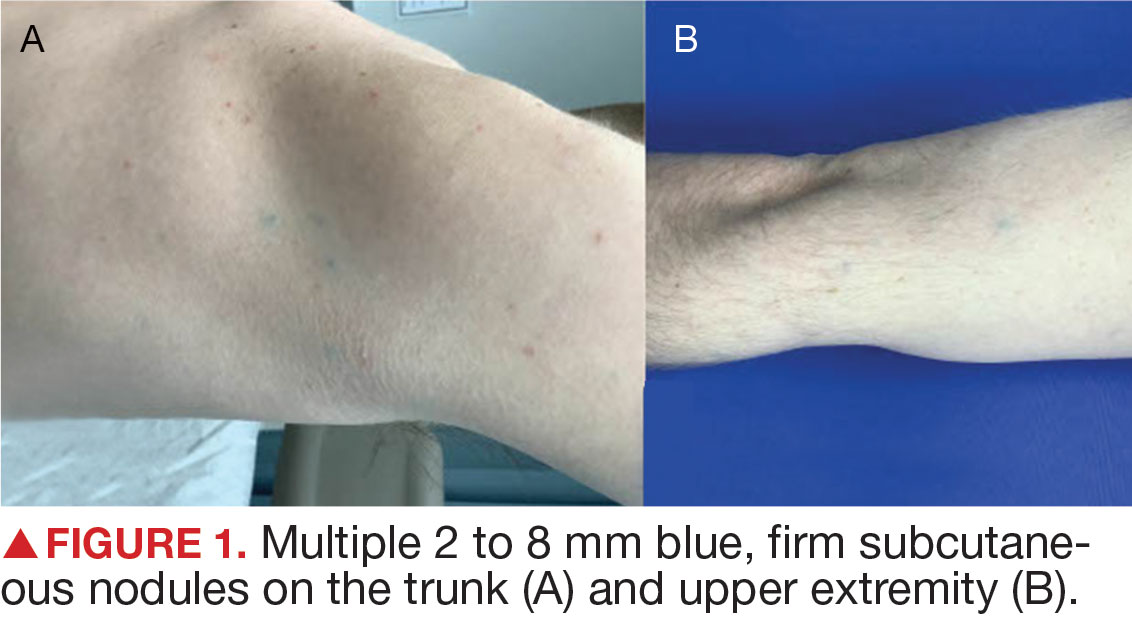

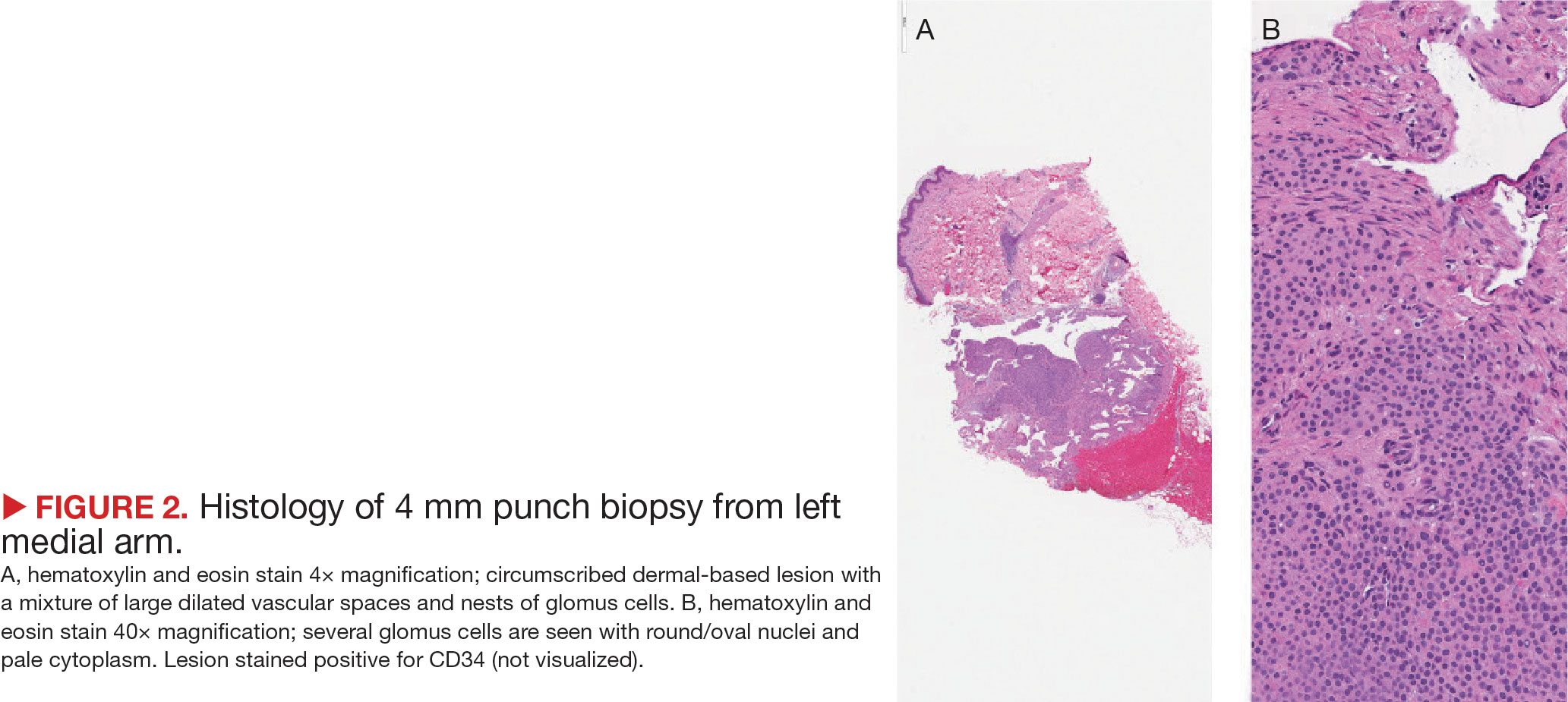

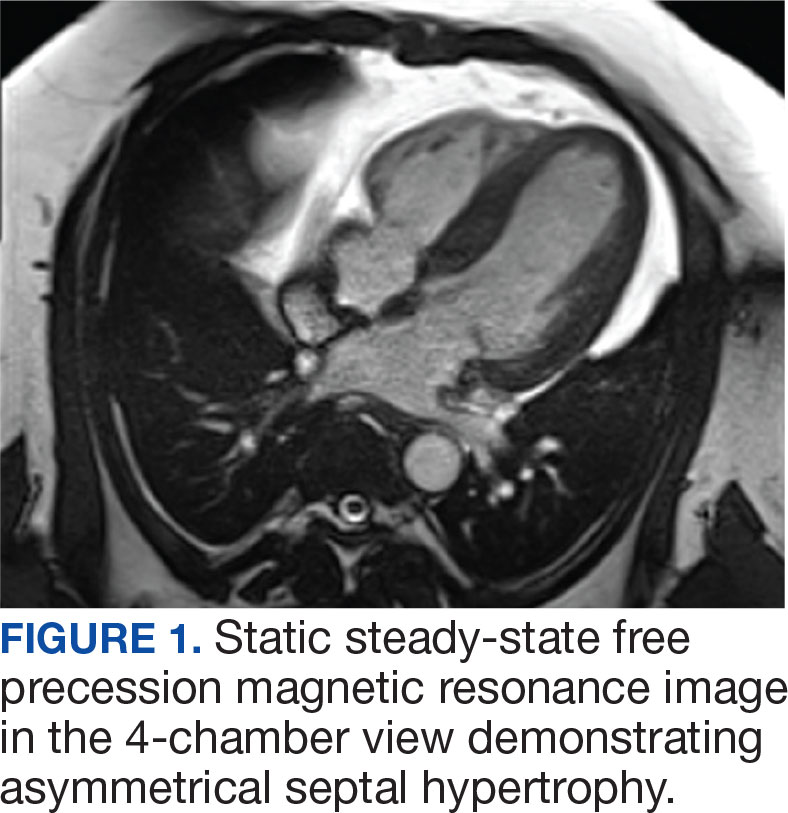

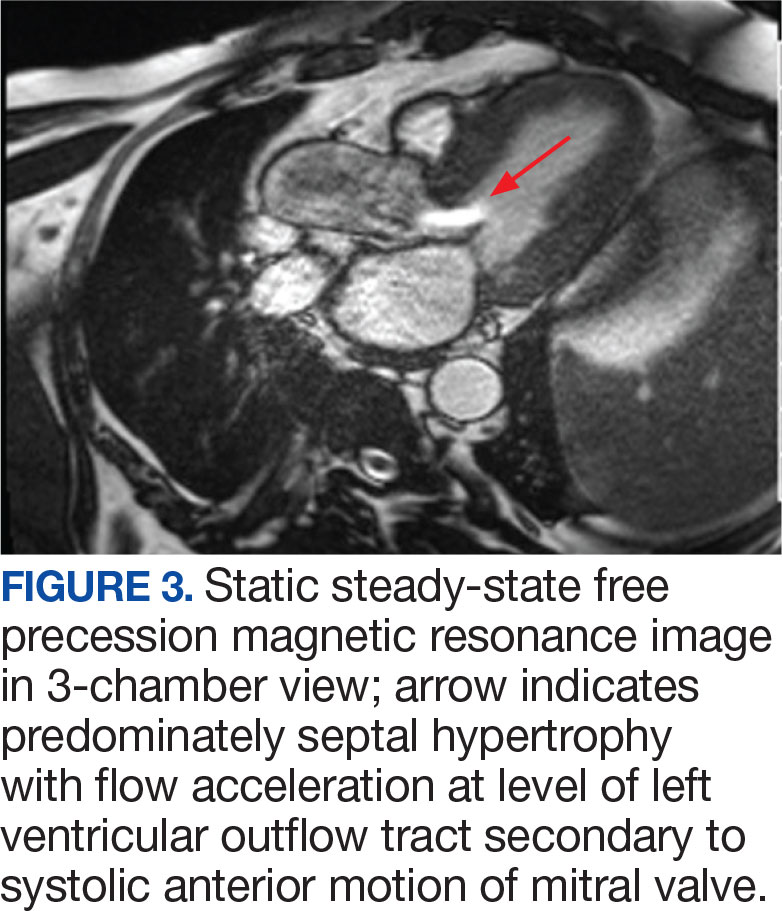

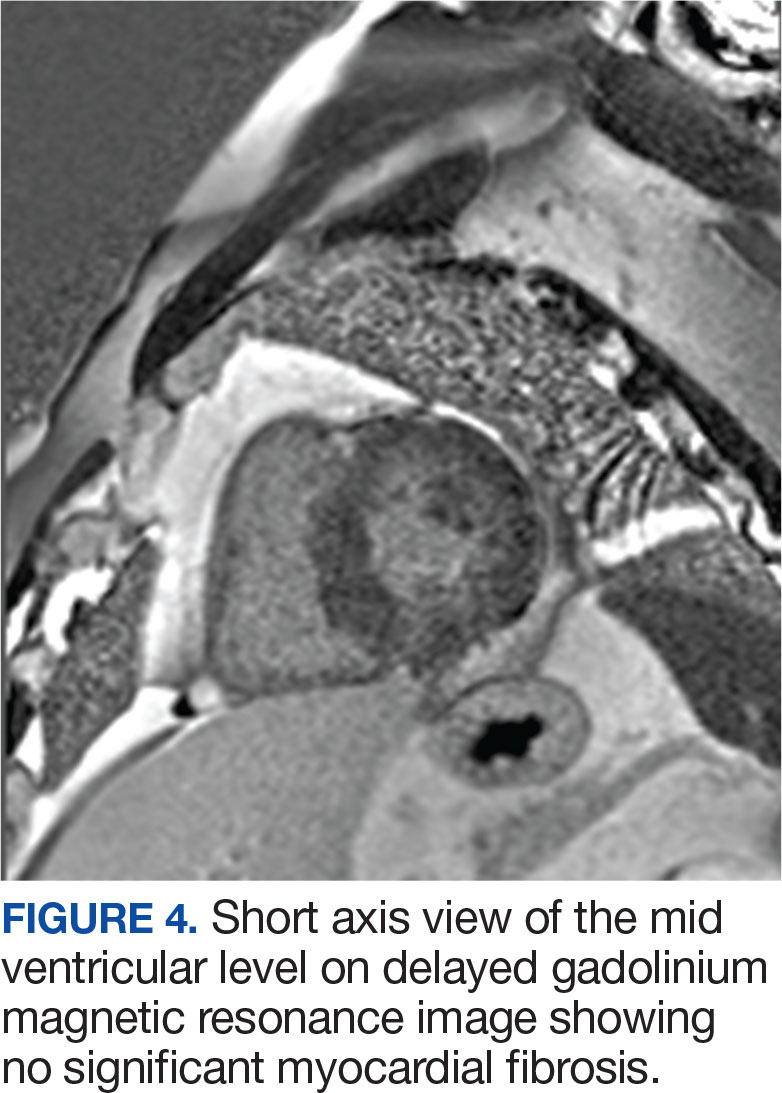

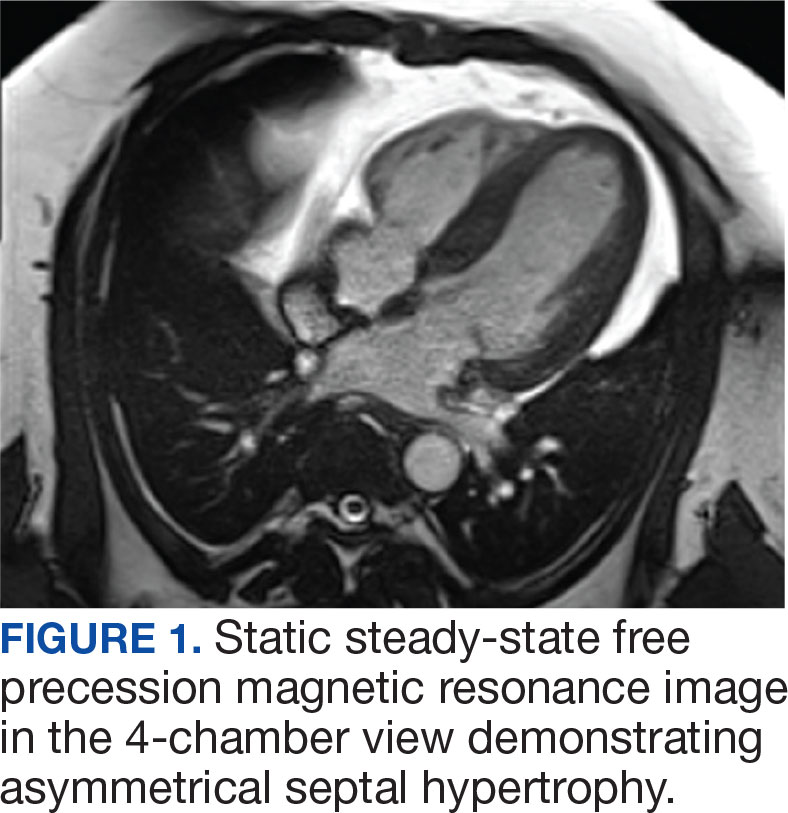

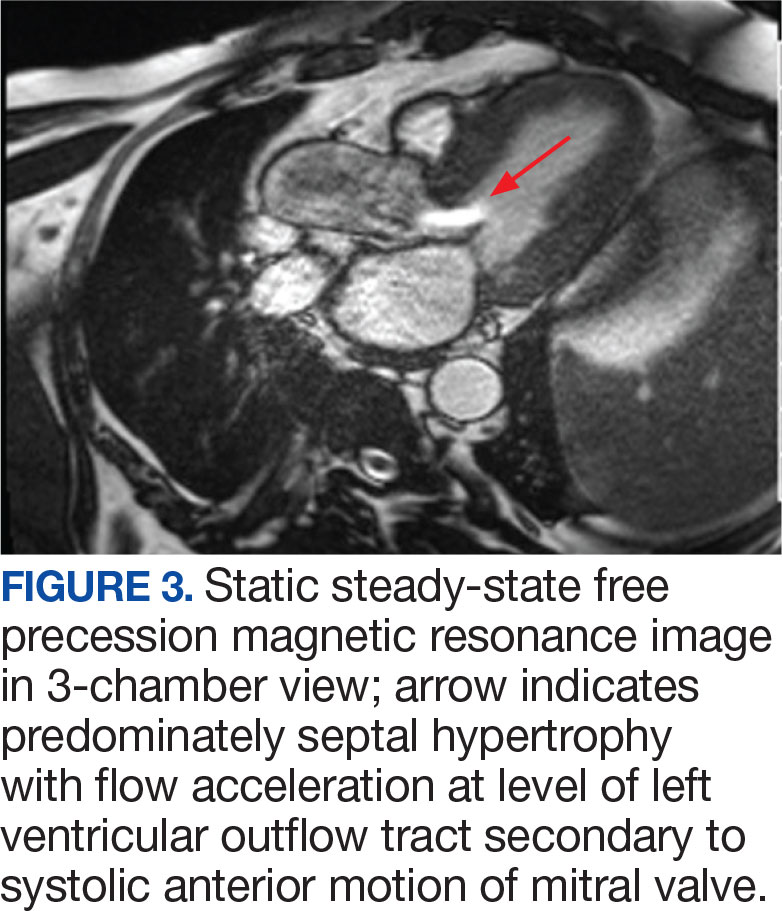

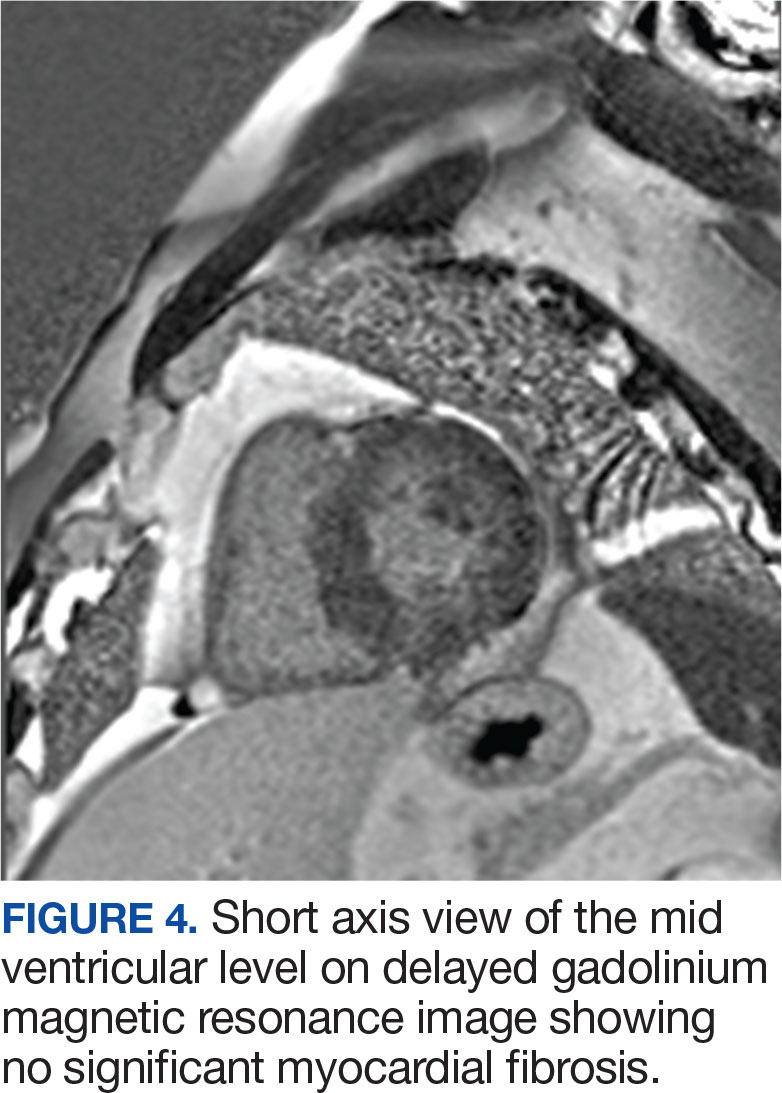

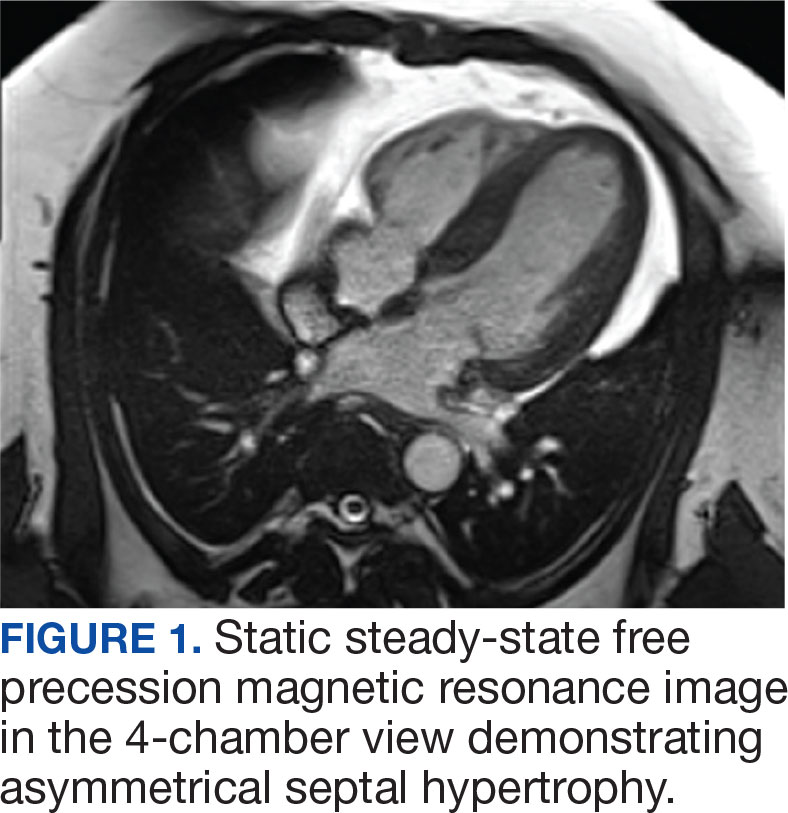

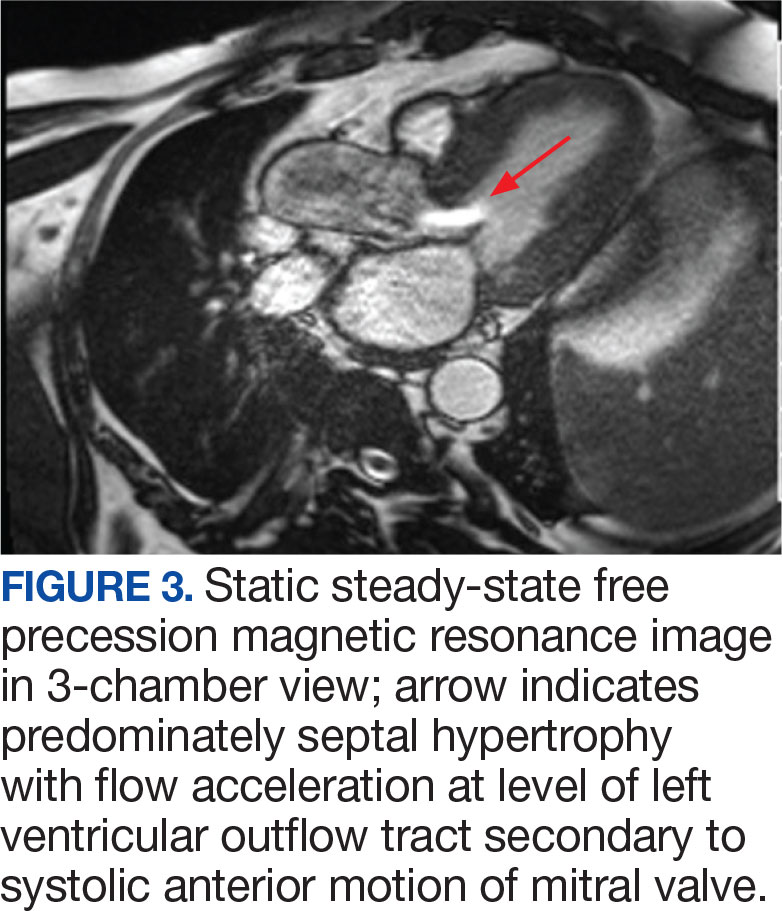

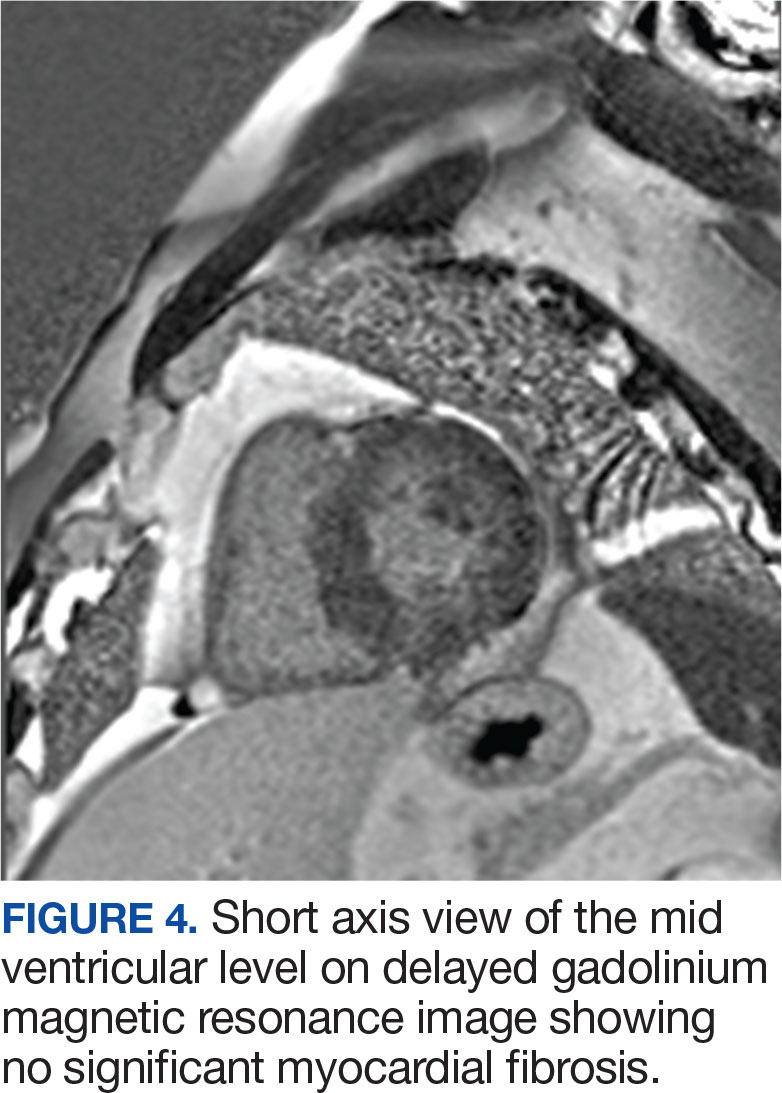

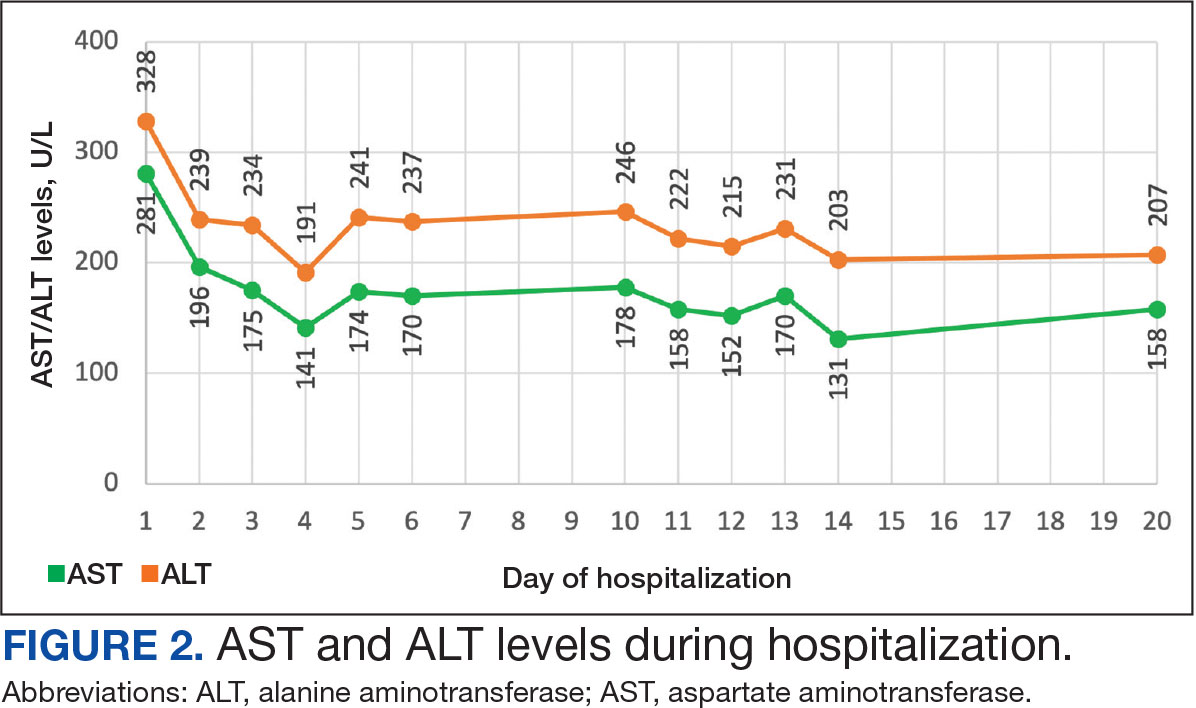

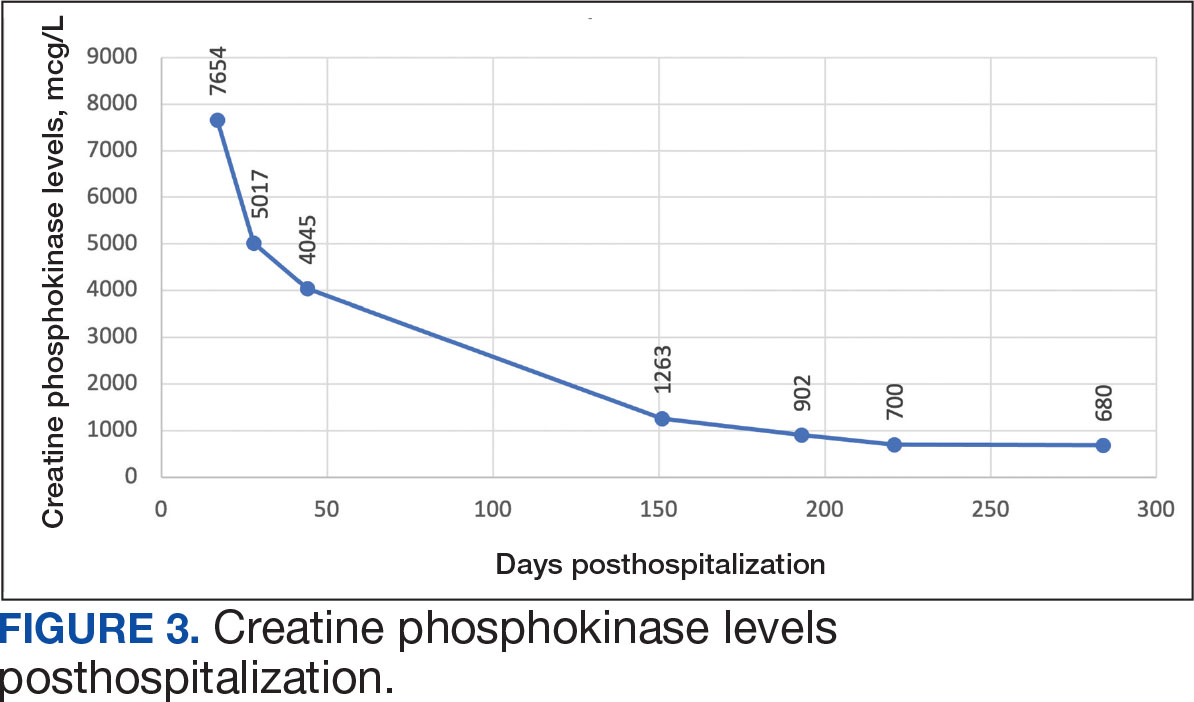

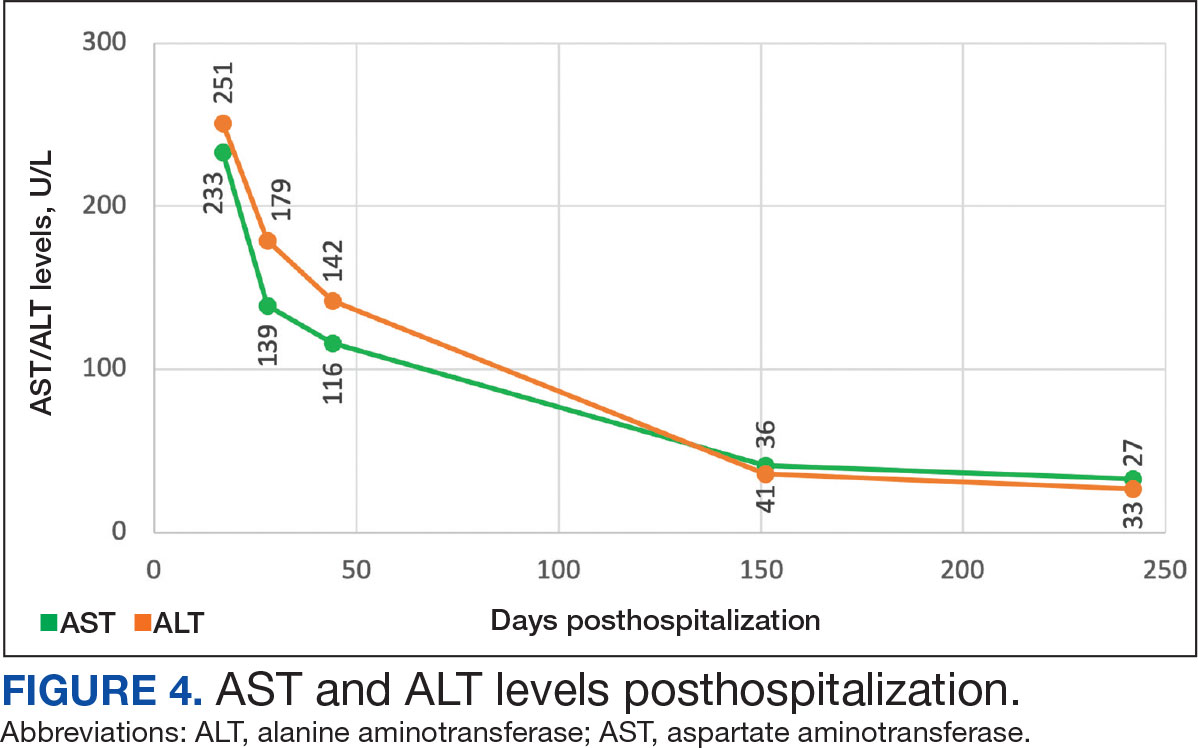

The patient was hospitalized and received an expedited multidisciplinary evaluation by dermatology, hematology/oncology, and gastroenterology. Her AEC of 4787 cells/μL peaked on admission and was markedly elevated from the 1070 cells/μL reported in the third trimester of her pregnancy. She was found to have mature eosinophilia on skin biopsy (Figure 1), endoscopic duodenal biopsy (Figure 2), peripheral blood smear (Figure 3), and bone marrow biopsy (Figure 4).

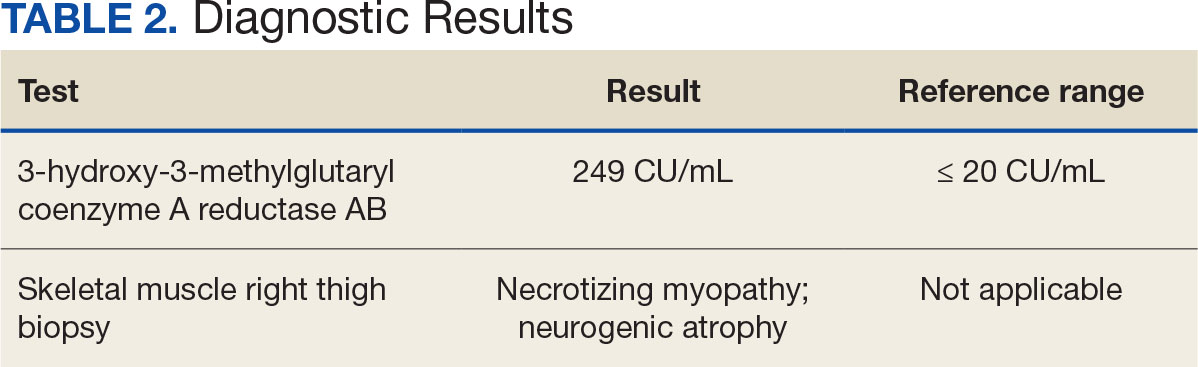

Radiographic imaging of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed hepatomegaly without detectable neoplasm. There was no clinical evidence of cardiac involvement, and evaluation with electrocardiography and echocardiography did not indicate myocarditis. Extensive laboratory testing revealed no genetic mutations indicative of familial, myeloproliferative, or lymphocytic variants of HES.

The patient received topical emollients, omeprazole 40 mg daily, and ondansetron 8 mg 3 times daily as needed for symptom management, and was started on oral prednisone 40 mg daily with improvement in dyspnea, night sweats, and gastrointestinal complaints. During the patient's 6-day hospitalization and treatment, her AECs gradually decreased to 2110 cells/μL, and decreased to 1600 cells/μL over the course of a month, remaining in the hypereosinophilic range. The patient was discovered to be pregnant while symptoms were improving, resulting in stepwise discontinuation of oral steroids, but she reported continued improvement in symptoms.

DISCUSSION

Peripheral eosinophilia has a broad differential diagnoses, including HES, parasitic infections, atopic hypersensitivity diseases, eosinophilic lung diseases, eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases, vasculitides such as eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, genetic syndromes predisposing to eosinophilia, episodic angioedema with eosinophilia, and chronic metabolic disease with adrenal insufficiency.1-5 HES, although rare, is a disease process with potentially devastating associated morbidity and mortality if not promptly recognized and treated. HES is further delineated by hypereosinophilia with associated eosinophil-mediated organ damage or dysfunction.3-5

Clinical manifestations of HES can differ greatly depending on the HES variant and degree of organ involvement at the time of diagnosis and throughout the disease course. Patients with HES, as well as those with asymptomatic eosinophilia or hypereosinophilia, should be closely monitored for disease progression. In addition to trending peripheral AECs, clinicians should screen for symptoms of organ involvement and perform targeted evaluation of the suspected organs to promptly identify early signs of organ involvement and initiate treatment.1-4 Recommendations regarding screening intervals vary widely from monthly to annually, depending on a patient’s specific clinical picture.

HES has been subdivided into clinically relevant variants, including myeloproliferative (M-HES), T lymphocytic (L-HES), organ-restricted (or overlap) HES, familial HES, idiopathic HES, and specific syndromes with associated hypereosinophilia.3-5,9 Patients with M-HES have elevated circulating leukocyte precursors and clinical manifestations, including but not limited to hepatosplenomegaly, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. The most commonly associated genetic mutations include the FIP1L1-PDGFR-α fusion, BCR-ABL1, PDGFRA/B, JAK2, KIT, and FGFR1.3-6 L-HES usually has predominant skin and soft tissue involvement secondary to immunoglobulin E-mediated actions with clonal expansion of T cells (most commonly CD3-4+ or CD3+CD4-CD8-).3,5,6 Familial HES, a rare variant, follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern and is usually present at birth. It involves chromosome 5, which contains genes coding for cytokines that drive eosinophilic proliferation, including interleukin (IL)-3, IL-5, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor.5,9 Hypereosinophilia in the setting of end-organ damage restricted to a single organ is considered organ-restricted HES. There can be significant hepatic and gastrointestinal dysfunction, with or without malabsorption.

HES can also manifest with hematologic malignancy, restrictive obliterative cardiomyopathies, renal injury manifested by hematuria and electrolyte derangements, and neurologic complications including hemiparesis, dysarthria, and even coma.6 Endothelial damage due to eosinophil-driven inflammation can result in thrombus formation and increased risk of thromboembolic events in various organs.3 Idiopathic HES, otherwise known as HES of unknown etiology or significance, is a diagnosis of exclusion and constitutes a cohort of patients who do not fit into the other delineated categories.3-5 These patients often have multisystem involvement, making classification and treatment a challenge.5

The patient described in this case met the diagnostic criteria for HES, but her complicated clinical and laboratory features were challenging to characterize into a specific variant of HES. Organ-restricted HES was ruled out due to skin, marrow, and duodenal infiltration. She also had the potential for lung involvement based on her clinical symptoms, however no biopsy was obtained. Laboratory testing revealed no deletions or mutations indicative of familial, myeloproliferative, or lymphocytic variants. Her multisystem involvement without an underlying associated syndrome suggests idiopathic HES or HES of undetermined significance.1-5

Most patients with HES are diagnosed between the ages of 20 and 50 years.10 While HES has its peak incidence in the fourth decade of life, acute onset of new symptoms 3 months postpartum makes this an unusual presentation. In this unique case, it is important to highlight the role of the physiologic changes of pregnancy in inflammatory mediation. The physiologic changes that occur in pregnancy to ensure fetal tolerance can have profound implications for leukocyte count, AEC, and subsequent inflammatory responses. The phenomenon of inflammatory amelioration during pregnancy is well-documented, but there has only been 1 known published case report discussing decreasing HES symptoms during pregnancy with prepregnancy and postpartum hypereosinophilia.8 It is suggested that this amelioration is secondary to cortisol and progesterone shifts that occur in pregnancy. Physiologic increases in adrenocorticotropic hormone in pregnancy leads to subsequent secretion of endogenous steroids by the adrenal cortex. In turn, pregnancy can lead to leukocytosis and eosinopenia.8 Overall, pregnancy can have beneficial immunomodulating properties in the spectrum of hypereosinophilic syndromes. Even so, this patient with HES diagnosed postpartum remains at risk for the sequelae of hypereosinophilia, regardless of potential for AEC reduction during pregnancy. Therefore, treatment considerations need to be made with the safety of the maternal-fetal dyad as a priority.

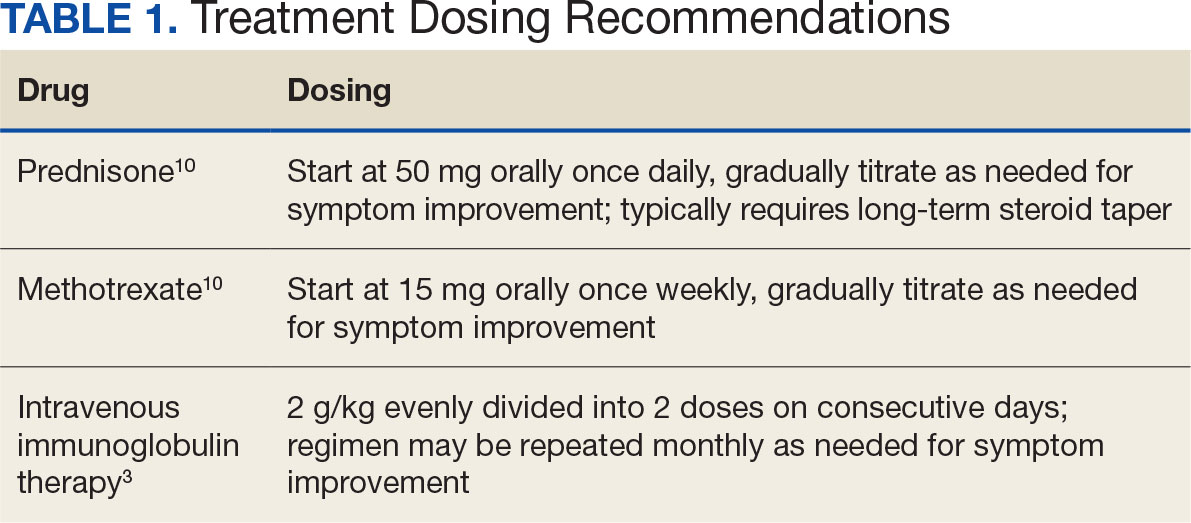

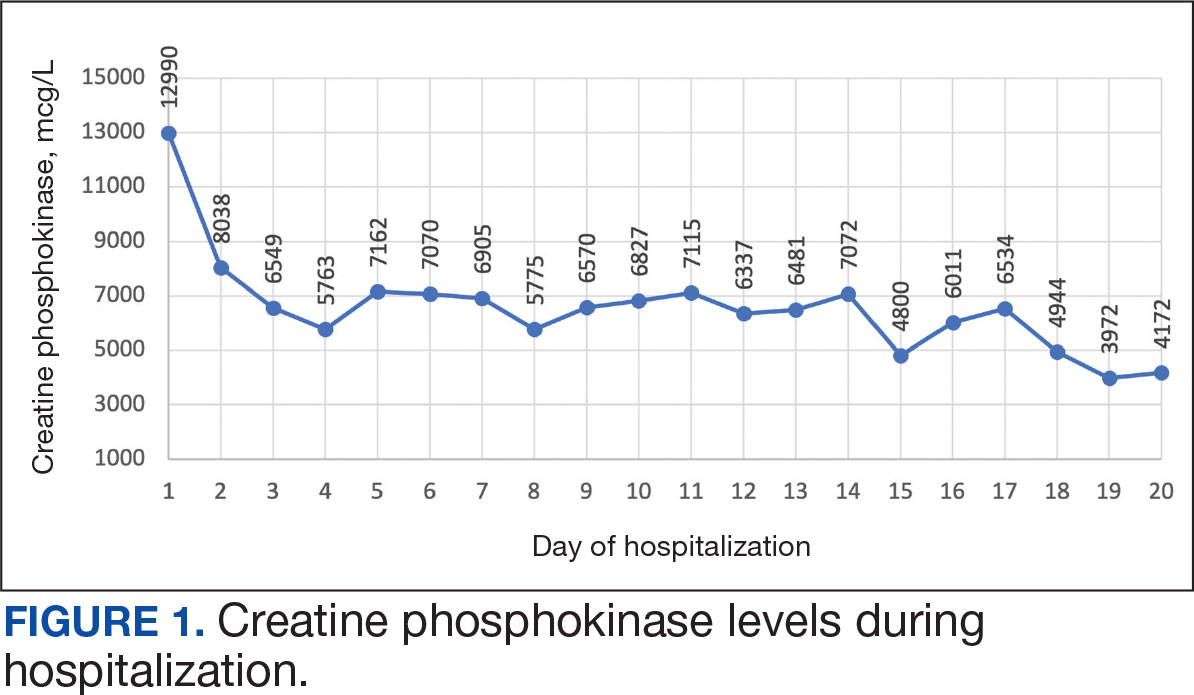

Treatment

The treatment of symptomatic HES without acute life-threatening features or associated malignancy is generally determined by clinical variant.2-4 There is insufficient data to support initiation of treatment solely based on persistently elevated AEC. Patients with peripheral eosinophilia and hypereosinophilia should be monitored periodically with appropriate subspecialist evaluation for occult end-organ involvement, and targeted therapies should be deferred until an HES diagnosis.1-4 First-line therapy in most HES variants is systemic glucocorticoids.2,3,7 Since the disease course for this patient did not precisely match an HES variant, it was challenging to ascertain the optimal personalized treatment regimen. The approach to therapy was further complicated by newly identified pregnancy necessitating cessation of systemic glucocorticoids. In addition to glucocorticoids, hydroxyurea and interferon-α are among treatments historically used for HES, with tyrosine kinase inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies targeting IL-5 becoming more common.1-4 Although this patient may ultimately benefit from an IL-5 targeting biologic medication such as mepolizumab, safety in pregnancy is not well-studied and may require close clinical monitoring with treatment deferred until after delivery if possible.3,7,8,11

Military service members with frequent geographic relocation have additional barriers to timely diagnosis with often-limited access to subspecialty care depending on the duty station. While the patient was able to receive care at a large military medical center with many subspecialists, prompt recognition and timely referral to specialists would be even more critical at a smaller treatment facility. Depending on the severity and variant of HES, patients may warrant evaluation and treatment by hematology/oncology, cardiology, pulmonology, and immunology. Although HES can present in young children and older adults, this condition is most often diagnosed during the third and fourth decades of life, putting clinicians on the front line of hypereosinophilia identification and evaluation.10 Military physicians have the additional duty to not only think ahead in their diverse clinical settings to ensure proper care for patients, but also maintain a broad differential inclusive of more rare disease processes such as HES.

CONCLUSIONS

This case emphasizes how uncontrolled or untreated HES can lead to significant end-organ damage involving multiple systems and high morbidity. Prompt recognition of hypereosinophilia with potential HES can help expedite coordination of multidisciplinary care across multiple specialties to minimize delays in diagnosis and treatment. Doing so may minimize associated morbidity and mortality, especially in individuals located at more remote duty stations or deployed to austere environments.

- Cogan E, Roufosse F. Clinical management of the hypereosinophilic syndromes. Expert Rev Hematol. 2012;5:275-290. doi: 10.1586/ehm.12.14

- Klion A. Hypereosinophilic syndrome: approach to treatment in the era of precision medicine. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2018;2018:326-331. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2018.1.326

- Shomali W, Gotlib J. World health organization-defined eosinophilic disorders: 2022 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2022;97:129-148. doi:10.1002/ajh.26352

- Helbig G, Klion AD. Hypereosinophilic syndromes - an enigmatic group of disorders with an intriguing clinical spectrum and challenging treatment. Blood Rev. 2021;49:100809. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2021.100809

- Valent P, Klion AD, Horny HP, et al. Contemporary consensus proposal on criteria and classification of eosinophilic disorders and related syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:607-612.e9. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.019

- Roufosse FE, Goldman M, Cogan E. Hypereosinophilic syndromes. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:37. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-2-37

- Pitlick MM, Li JT, Pongdee T. Current and emerging biologic therapies targeting eosinophilic disorders. World Allergy Organ J. 2022;15:100676. doi:10.1016/j.waojou.2022.10067

- Ault P, Cortes J, Lynn A, Keating M, Verstovsek S. Pregnancy in a patient with hypereosinophilic syndrome. Leuk Res. 2009;33:186-187. doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2008.05.013

- Rioux JD, Stone VA, Daly MJ, et al. Familial eosinophilia maps to the cytokine gene cluster on human chromosomal region 5q31-q33. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:1086-1094. doi:10.1086/302053

- Williams KW, Ware J, Abiodun A, et al. Hypereosinophilia in children and adults: a retrospective comparison. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4:941-947.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2016.03.020

- Pane F, Lefevre G, Kwon N, et al. Characterization of disease flares and impact of mepolizumab in patients with hypereosinophilic syndrome. Front Immunol. 2022;13:935996. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.935996

Hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) is defined by marked, persistent absolute eosinophil count (AEC) > 1500 cells/μL on ≥ 2 peripheral smears separated by ≥ 1 month with evidence of accompanied end-organ damage, in the absence of other causes of eosinophilia such as malignancy, atopy, or parasitic infections.1-5 Hypereosinophilic infiltration can impact almost every organ system; however, the most profound complications in patients with HES are related to leukemias and cardiac manifestations of the disease.3,4 Although rare, the associated morbidity and mortality of HES are considerable, making prompt recognition and treatment essential. Management involves targeted therapy based on pathologic classification of HES and on decreasing associated inflammation, fibrosis, and end-organ damage.3,5-7

The patient in this case report met the diagnostic criteria for HES. However, this patient had several clinical and laboratory features that made it difficult to characterize a specific HES variant. Moreover, she had additional immunomodulating factors in the setting of pregnancy. This is the first documented case of HES of undetermined etiology diagnosed postpartum and managed in the setting of a new pregnancy.2,8

CASE PRESENTATION

A 32-year-old female active-duty military service member with allergic rhinitis and a history of childhood eczema was referred to allergy/immunology for evaluation of a new, progressive pruritic rash. Symptoms started 3 months after the birth of her first child, with a new diffuse erythematous skin rash sparing her palms, soles, and mucosal surfaces. Given her history of atopy, the rash was initially treated as severe atopic dermatitis with appropriate topical medications. The rash gradually worsened, with the development of intermittent facial swelling, night sweats, dyspnea, recurrent epigastric abdominal pain, and nausea with vomiting, resulting in decreased oral intake and weight loss.

The patient was hospitalized and received an expedited multidisciplinary evaluation by dermatology, hematology/oncology, and gastroenterology. Her AEC of 4787 cells/μL peaked on admission and was markedly elevated from the 1070 cells/μL reported in the third trimester of her pregnancy. She was found to have mature eosinophilia on skin biopsy (Figure 1), endoscopic duodenal biopsy (Figure 2), peripheral blood smear (Figure 3), and bone marrow biopsy (Figure 4).

Radiographic imaging of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed hepatomegaly without detectable neoplasm. There was no clinical evidence of cardiac involvement, and evaluation with electrocardiography and echocardiography did not indicate myocarditis. Extensive laboratory testing revealed no genetic mutations indicative of familial, myeloproliferative, or lymphocytic variants of HES.

The patient received topical emollients, omeprazole 40 mg daily, and ondansetron 8 mg 3 times daily as needed for symptom management, and was started on oral prednisone 40 mg daily with improvement in dyspnea, night sweats, and gastrointestinal complaints. During the patient's 6-day hospitalization and treatment, her AECs gradually decreased to 2110 cells/μL, and decreased to 1600 cells/μL over the course of a month, remaining in the hypereosinophilic range. The patient was discovered to be pregnant while symptoms were improving, resulting in stepwise discontinuation of oral steroids, but she reported continued improvement in symptoms.

DISCUSSION

Peripheral eosinophilia has a broad differential diagnoses, including HES, parasitic infections, atopic hypersensitivity diseases, eosinophilic lung diseases, eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases, vasculitides such as eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, genetic syndromes predisposing to eosinophilia, episodic angioedema with eosinophilia, and chronic metabolic disease with adrenal insufficiency.1-5 HES, although rare, is a disease process with potentially devastating associated morbidity and mortality if not promptly recognized and treated. HES is further delineated by hypereosinophilia with associated eosinophil-mediated organ damage or dysfunction.3-5

Clinical manifestations of HES can differ greatly depending on the HES variant and degree of organ involvement at the time of diagnosis and throughout the disease course. Patients with HES, as well as those with asymptomatic eosinophilia or hypereosinophilia, should be closely monitored for disease progression. In addition to trending peripheral AECs, clinicians should screen for symptoms of organ involvement and perform targeted evaluation of the suspected organs to promptly identify early signs of organ involvement and initiate treatment.1-4 Recommendations regarding screening intervals vary widely from monthly to annually, depending on a patient’s specific clinical picture.

HES has been subdivided into clinically relevant variants, including myeloproliferative (M-HES), T lymphocytic (L-HES), organ-restricted (or overlap) HES, familial HES, idiopathic HES, and specific syndromes with associated hypereosinophilia.3-5,9 Patients with M-HES have elevated circulating leukocyte precursors and clinical manifestations, including but not limited to hepatosplenomegaly, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. The most commonly associated genetic mutations include the FIP1L1-PDGFR-α fusion, BCR-ABL1, PDGFRA/B, JAK2, KIT, and FGFR1.3-6 L-HES usually has predominant skin and soft tissue involvement secondary to immunoglobulin E-mediated actions with clonal expansion of T cells (most commonly CD3-4+ or CD3+CD4-CD8-).3,5,6 Familial HES, a rare variant, follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern and is usually present at birth. It involves chromosome 5, which contains genes coding for cytokines that drive eosinophilic proliferation, including interleukin (IL)-3, IL-5, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor.5,9 Hypereosinophilia in the setting of end-organ damage restricted to a single organ is considered organ-restricted HES. There can be significant hepatic and gastrointestinal dysfunction, with or without malabsorption.

HES can also manifest with hematologic malignancy, restrictive obliterative cardiomyopathies, renal injury manifested by hematuria and electrolyte derangements, and neurologic complications including hemiparesis, dysarthria, and even coma.6 Endothelial damage due to eosinophil-driven inflammation can result in thrombus formation and increased risk of thromboembolic events in various organs.3 Idiopathic HES, otherwise known as HES of unknown etiology or significance, is a diagnosis of exclusion and constitutes a cohort of patients who do not fit into the other delineated categories.3-5 These patients often have multisystem involvement, making classification and treatment a challenge.5

The patient described in this case met the diagnostic criteria for HES, but her complicated clinical and laboratory features were challenging to characterize into a specific variant of HES. Organ-restricted HES was ruled out due to skin, marrow, and duodenal infiltration. She also had the potential for lung involvement based on her clinical symptoms, however no biopsy was obtained. Laboratory testing revealed no deletions or mutations indicative of familial, myeloproliferative, or lymphocytic variants. Her multisystem involvement without an underlying associated syndrome suggests idiopathic HES or HES of undetermined significance.1-5

Most patients with HES are diagnosed between the ages of 20 and 50 years.10 While HES has its peak incidence in the fourth decade of life, acute onset of new symptoms 3 months postpartum makes this an unusual presentation. In this unique case, it is important to highlight the role of the physiologic changes of pregnancy in inflammatory mediation. The physiologic changes that occur in pregnancy to ensure fetal tolerance can have profound implications for leukocyte count, AEC, and subsequent inflammatory responses. The phenomenon of inflammatory amelioration during pregnancy is well-documented, but there has only been 1 known published case report discussing decreasing HES symptoms during pregnancy with prepregnancy and postpartum hypereosinophilia.8 It is suggested that this amelioration is secondary to cortisol and progesterone shifts that occur in pregnancy. Physiologic increases in adrenocorticotropic hormone in pregnancy leads to subsequent secretion of endogenous steroids by the adrenal cortex. In turn, pregnancy can lead to leukocytosis and eosinopenia.8 Overall, pregnancy can have beneficial immunomodulating properties in the spectrum of hypereosinophilic syndromes. Even so, this patient with HES diagnosed postpartum remains at risk for the sequelae of hypereosinophilia, regardless of potential for AEC reduction during pregnancy. Therefore, treatment considerations need to be made with the safety of the maternal-fetal dyad as a priority.

Treatment

The treatment of symptomatic HES without acute life-threatening features or associated malignancy is generally determined by clinical variant.2-4 There is insufficient data to support initiation of treatment solely based on persistently elevated AEC. Patients with peripheral eosinophilia and hypereosinophilia should be monitored periodically with appropriate subspecialist evaluation for occult end-organ involvement, and targeted therapies should be deferred until an HES diagnosis.1-4 First-line therapy in most HES variants is systemic glucocorticoids.2,3,7 Since the disease course for this patient did not precisely match an HES variant, it was challenging to ascertain the optimal personalized treatment regimen. The approach to therapy was further complicated by newly identified pregnancy necessitating cessation of systemic glucocorticoids. In addition to glucocorticoids, hydroxyurea and interferon-α are among treatments historically used for HES, with tyrosine kinase inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies targeting IL-5 becoming more common.1-4 Although this patient may ultimately benefit from an IL-5 targeting biologic medication such as mepolizumab, safety in pregnancy is not well-studied and may require close clinical monitoring with treatment deferred until after delivery if possible.3,7,8,11

Military service members with frequent geographic relocation have additional barriers to timely diagnosis with often-limited access to subspecialty care depending on the duty station. While the patient was able to receive care at a large military medical center with many subspecialists, prompt recognition and timely referral to specialists would be even more critical at a smaller treatment facility. Depending on the severity and variant of HES, patients may warrant evaluation and treatment by hematology/oncology, cardiology, pulmonology, and immunology. Although HES can present in young children and older adults, this condition is most often diagnosed during the third and fourth decades of life, putting clinicians on the front line of hypereosinophilia identification and evaluation.10 Military physicians have the additional duty to not only think ahead in their diverse clinical settings to ensure proper care for patients, but also maintain a broad differential inclusive of more rare disease processes such as HES.

CONCLUSIONS

This case emphasizes how uncontrolled or untreated HES can lead to significant end-organ damage involving multiple systems and high morbidity. Prompt recognition of hypereosinophilia with potential HES can help expedite coordination of multidisciplinary care across multiple specialties to minimize delays in diagnosis and treatment. Doing so may minimize associated morbidity and mortality, especially in individuals located at more remote duty stations or deployed to austere environments.

Hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) is defined by marked, persistent absolute eosinophil count (AEC) > 1500 cells/μL on ≥ 2 peripheral smears separated by ≥ 1 month with evidence of accompanied end-organ damage, in the absence of other causes of eosinophilia such as malignancy, atopy, or parasitic infections.1-5 Hypereosinophilic infiltration can impact almost every organ system; however, the most profound complications in patients with HES are related to leukemias and cardiac manifestations of the disease.3,4 Although rare, the associated morbidity and mortality of HES are considerable, making prompt recognition and treatment essential. Management involves targeted therapy based on pathologic classification of HES and on decreasing associated inflammation, fibrosis, and end-organ damage.3,5-7

The patient in this case report met the diagnostic criteria for HES. However, this patient had several clinical and laboratory features that made it difficult to characterize a specific HES variant. Moreover, she had additional immunomodulating factors in the setting of pregnancy. This is the first documented case of HES of undetermined etiology diagnosed postpartum and managed in the setting of a new pregnancy.2,8

CASE PRESENTATION

A 32-year-old female active-duty military service member with allergic rhinitis and a history of childhood eczema was referred to allergy/immunology for evaluation of a new, progressive pruritic rash. Symptoms started 3 months after the birth of her first child, with a new diffuse erythematous skin rash sparing her palms, soles, and mucosal surfaces. Given her history of atopy, the rash was initially treated as severe atopic dermatitis with appropriate topical medications. The rash gradually worsened, with the development of intermittent facial swelling, night sweats, dyspnea, recurrent epigastric abdominal pain, and nausea with vomiting, resulting in decreased oral intake and weight loss.

The patient was hospitalized and received an expedited multidisciplinary evaluation by dermatology, hematology/oncology, and gastroenterology. Her AEC of 4787 cells/μL peaked on admission and was markedly elevated from the 1070 cells/μL reported in the third trimester of her pregnancy. She was found to have mature eosinophilia on skin biopsy (Figure 1), endoscopic duodenal biopsy (Figure 2), peripheral blood smear (Figure 3), and bone marrow biopsy (Figure 4).

Radiographic imaging of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed hepatomegaly without detectable neoplasm. There was no clinical evidence of cardiac involvement, and evaluation with electrocardiography and echocardiography did not indicate myocarditis. Extensive laboratory testing revealed no genetic mutations indicative of familial, myeloproliferative, or lymphocytic variants of HES.

The patient received topical emollients, omeprazole 40 mg daily, and ondansetron 8 mg 3 times daily as needed for symptom management, and was started on oral prednisone 40 mg daily with improvement in dyspnea, night sweats, and gastrointestinal complaints. During the patient's 6-day hospitalization and treatment, her AECs gradually decreased to 2110 cells/μL, and decreased to 1600 cells/μL over the course of a month, remaining in the hypereosinophilic range. The patient was discovered to be pregnant while symptoms were improving, resulting in stepwise discontinuation of oral steroids, but she reported continued improvement in symptoms.

DISCUSSION

Peripheral eosinophilia has a broad differential diagnoses, including HES, parasitic infections, atopic hypersensitivity diseases, eosinophilic lung diseases, eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases, vasculitides such as eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, genetic syndromes predisposing to eosinophilia, episodic angioedema with eosinophilia, and chronic metabolic disease with adrenal insufficiency.1-5 HES, although rare, is a disease process with potentially devastating associated morbidity and mortality if not promptly recognized and treated. HES is further delineated by hypereosinophilia with associated eosinophil-mediated organ damage or dysfunction.3-5

Clinical manifestations of HES can differ greatly depending on the HES variant and degree of organ involvement at the time of diagnosis and throughout the disease course. Patients with HES, as well as those with asymptomatic eosinophilia or hypereosinophilia, should be closely monitored for disease progression. In addition to trending peripheral AECs, clinicians should screen for symptoms of organ involvement and perform targeted evaluation of the suspected organs to promptly identify early signs of organ involvement and initiate treatment.1-4 Recommendations regarding screening intervals vary widely from monthly to annually, depending on a patient’s specific clinical picture.

HES has been subdivided into clinically relevant variants, including myeloproliferative (M-HES), T lymphocytic (L-HES), organ-restricted (or overlap) HES, familial HES, idiopathic HES, and specific syndromes with associated hypereosinophilia.3-5,9 Patients with M-HES have elevated circulating leukocyte precursors and clinical manifestations, including but not limited to hepatosplenomegaly, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. The most commonly associated genetic mutations include the FIP1L1-PDGFR-α fusion, BCR-ABL1, PDGFRA/B, JAK2, KIT, and FGFR1.3-6 L-HES usually has predominant skin and soft tissue involvement secondary to immunoglobulin E-mediated actions with clonal expansion of T cells (most commonly CD3-4+ or CD3+CD4-CD8-).3,5,6 Familial HES, a rare variant, follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern and is usually present at birth. It involves chromosome 5, which contains genes coding for cytokines that drive eosinophilic proliferation, including interleukin (IL)-3, IL-5, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor.5,9 Hypereosinophilia in the setting of end-organ damage restricted to a single organ is considered organ-restricted HES. There can be significant hepatic and gastrointestinal dysfunction, with or without malabsorption.

HES can also manifest with hematologic malignancy, restrictive obliterative cardiomyopathies, renal injury manifested by hematuria and electrolyte derangements, and neurologic complications including hemiparesis, dysarthria, and even coma.6 Endothelial damage due to eosinophil-driven inflammation can result in thrombus formation and increased risk of thromboembolic events in various organs.3 Idiopathic HES, otherwise known as HES of unknown etiology or significance, is a diagnosis of exclusion and constitutes a cohort of patients who do not fit into the other delineated categories.3-5 These patients often have multisystem involvement, making classification and treatment a challenge.5

The patient described in this case met the diagnostic criteria for HES, but her complicated clinical and laboratory features were challenging to characterize into a specific variant of HES. Organ-restricted HES was ruled out due to skin, marrow, and duodenal infiltration. She also had the potential for lung involvement based on her clinical symptoms, however no biopsy was obtained. Laboratory testing revealed no deletions or mutations indicative of familial, myeloproliferative, or lymphocytic variants. Her multisystem involvement without an underlying associated syndrome suggests idiopathic HES or HES of undetermined significance.1-5

Most patients with HES are diagnosed between the ages of 20 and 50 years.10 While HES has its peak incidence in the fourth decade of life, acute onset of new symptoms 3 months postpartum makes this an unusual presentation. In this unique case, it is important to highlight the role of the physiologic changes of pregnancy in inflammatory mediation. The physiologic changes that occur in pregnancy to ensure fetal tolerance can have profound implications for leukocyte count, AEC, and subsequent inflammatory responses. The phenomenon of inflammatory amelioration during pregnancy is well-documented, but there has only been 1 known published case report discussing decreasing HES symptoms during pregnancy with prepregnancy and postpartum hypereosinophilia.8 It is suggested that this amelioration is secondary to cortisol and progesterone shifts that occur in pregnancy. Physiologic increases in adrenocorticotropic hormone in pregnancy leads to subsequent secretion of endogenous steroids by the adrenal cortex. In turn, pregnancy can lead to leukocytosis and eosinopenia.8 Overall, pregnancy can have beneficial immunomodulating properties in the spectrum of hypereosinophilic syndromes. Even so, this patient with HES diagnosed postpartum remains at risk for the sequelae of hypereosinophilia, regardless of potential for AEC reduction during pregnancy. Therefore, treatment considerations need to be made with the safety of the maternal-fetal dyad as a priority.

Treatment

The treatment of symptomatic HES without acute life-threatening features or associated malignancy is generally determined by clinical variant.2-4 There is insufficient data to support initiation of treatment solely based on persistently elevated AEC. Patients with peripheral eosinophilia and hypereosinophilia should be monitored periodically with appropriate subspecialist evaluation for occult end-organ involvement, and targeted therapies should be deferred until an HES diagnosis.1-4 First-line therapy in most HES variants is systemic glucocorticoids.2,3,7 Since the disease course for this patient did not precisely match an HES variant, it was challenging to ascertain the optimal personalized treatment regimen. The approach to therapy was further complicated by newly identified pregnancy necessitating cessation of systemic glucocorticoids. In addition to glucocorticoids, hydroxyurea and interferon-α are among treatments historically used for HES, with tyrosine kinase inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies targeting IL-5 becoming more common.1-4 Although this patient may ultimately benefit from an IL-5 targeting biologic medication such as mepolizumab, safety in pregnancy is not well-studied and may require close clinical monitoring with treatment deferred until after delivery if possible.3,7,8,11

Military service members with frequent geographic relocation have additional barriers to timely diagnosis with often-limited access to subspecialty care depending on the duty station. While the patient was able to receive care at a large military medical center with many subspecialists, prompt recognition and timely referral to specialists would be even more critical at a smaller treatment facility. Depending on the severity and variant of HES, patients may warrant evaluation and treatment by hematology/oncology, cardiology, pulmonology, and immunology. Although HES can present in young children and older adults, this condition is most often diagnosed during the third and fourth decades of life, putting clinicians on the front line of hypereosinophilia identification and evaluation.10 Military physicians have the additional duty to not only think ahead in their diverse clinical settings to ensure proper care for patients, but also maintain a broad differential inclusive of more rare disease processes such as HES.

CONCLUSIONS

This case emphasizes how uncontrolled or untreated HES can lead to significant end-organ damage involving multiple systems and high morbidity. Prompt recognition of hypereosinophilia with potential HES can help expedite coordination of multidisciplinary care across multiple specialties to minimize delays in diagnosis and treatment. Doing so may minimize associated morbidity and mortality, especially in individuals located at more remote duty stations or deployed to austere environments.

- Cogan E, Roufosse F. Clinical management of the hypereosinophilic syndromes. Expert Rev Hematol. 2012;5:275-290. doi: 10.1586/ehm.12.14

- Klion A. Hypereosinophilic syndrome: approach to treatment in the era of precision medicine. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2018;2018:326-331. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2018.1.326

- Shomali W, Gotlib J. World health organization-defined eosinophilic disorders: 2022 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2022;97:129-148. doi:10.1002/ajh.26352

- Helbig G, Klion AD. Hypereosinophilic syndromes - an enigmatic group of disorders with an intriguing clinical spectrum and challenging treatment. Blood Rev. 2021;49:100809. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2021.100809

- Valent P, Klion AD, Horny HP, et al. Contemporary consensus proposal on criteria and classification of eosinophilic disorders and related syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:607-612.e9. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.019

- Roufosse FE, Goldman M, Cogan E. Hypereosinophilic syndromes. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:37. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-2-37

- Pitlick MM, Li JT, Pongdee T. Current and emerging biologic therapies targeting eosinophilic disorders. World Allergy Organ J. 2022;15:100676. doi:10.1016/j.waojou.2022.10067

- Ault P, Cortes J, Lynn A, Keating M, Verstovsek S. Pregnancy in a patient with hypereosinophilic syndrome. Leuk Res. 2009;33:186-187. doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2008.05.013

- Rioux JD, Stone VA, Daly MJ, et al. Familial eosinophilia maps to the cytokine gene cluster on human chromosomal region 5q31-q33. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:1086-1094. doi:10.1086/302053

- Williams KW, Ware J, Abiodun A, et al. Hypereosinophilia in children and adults: a retrospective comparison. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4:941-947.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2016.03.020

- Pane F, Lefevre G, Kwon N, et al. Characterization of disease flares and impact of mepolizumab in patients with hypereosinophilic syndrome. Front Immunol. 2022;13:935996. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.935996

- Cogan E, Roufosse F. Clinical management of the hypereosinophilic syndromes. Expert Rev Hematol. 2012;5:275-290. doi: 10.1586/ehm.12.14

- Klion A. Hypereosinophilic syndrome: approach to treatment in the era of precision medicine. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2018;2018:326-331. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2018.1.326

- Shomali W, Gotlib J. World health organization-defined eosinophilic disorders: 2022 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2022;97:129-148. doi:10.1002/ajh.26352

- Helbig G, Klion AD. Hypereosinophilic syndromes - an enigmatic group of disorders with an intriguing clinical spectrum and challenging treatment. Blood Rev. 2021;49:100809. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2021.100809

- Valent P, Klion AD, Horny HP, et al. Contemporary consensus proposal on criteria and classification of eosinophilic disorders and related syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:607-612.e9. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.019

- Roufosse FE, Goldman M, Cogan E. Hypereosinophilic syndromes. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:37. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-2-37

- Pitlick MM, Li JT, Pongdee T. Current and emerging biologic therapies targeting eosinophilic disorders. World Allergy Organ J. 2022;15:100676. doi:10.1016/j.waojou.2022.10067

- Ault P, Cortes J, Lynn A, Keating M, Verstovsek S. Pregnancy in a patient with hypereosinophilic syndrome. Leuk Res. 2009;33:186-187. doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2008.05.013

- Rioux JD, Stone VA, Daly MJ, et al. Familial eosinophilia maps to the cytokine gene cluster on human chromosomal region 5q31-q33. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:1086-1094. doi:10.1086/302053

- Williams KW, Ware J, Abiodun A, et al. Hypereosinophilia in children and adults: a retrospective comparison. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4:941-947.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2016.03.020

- Pane F, Lefevre G, Kwon N, et al. Characterization of disease flares and impact of mepolizumab in patients with hypereosinophilic syndrome. Front Immunol. 2022;13:935996. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.935996

Unique Presentation of Postpartum Hypereosinophilic Syndrome With Atypical Features and Therapeutic Challenges

Unique Presentation of Postpartum Hypereosinophilic Syndrome With Atypical Features and Therapeutic Challenges

Case Presentation: First Ever VA "Bloodless" Autologous Stem Cell Transplant Was a Success

Background

Autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) is an important part of the treatment paradigm for patients with multiple myeloma (MM) and remains the standard of care for newly diagnosed patients. Blood product transfusion support in the form of platelets and packed red blood cells (pRBCs) is part of the standard of practice as supportive measures during the severely pancytopenic period. Some MM patients, such as those of Jehovah’s Witness (JW) faith, may have religious beliefs or preferences that preclude acceptance of such blood products. Some transplant centers have developed protocols to allow safe “bloodless” ASCT that allows these patients to receive this important treatment while adhering to their beliefs or preferences.

Case Presentation

A 61-year-old veteran of JW faith with newly diagnosed IgG Kappa Multiple Myeloma was referred to the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System (TVHS) Stem Cell Transplant program for consideration of “bloodless” ASCT. With the assistance and expertise of the academic affiliate, Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s established bloodless ASCT protocol, this same protocol was established at TVHS to optimize the patient’s care pretransplant (use of erythropoiesis stimulating agents, intravenous iron, B12 supplementation) as well as post-transplant (use of antifibrinolytics, close inpatient monitoring). Both Ethics and Legal consultation was obtained, and guidance was provided to create a life sustaining treatment (LST) note in the veteran’s electronic health record that captured the veteran’s blood product preference. Once all protocols and guidance were in place, the TVHS SCT/CT program proceeded to treat the veteran with a myeloablative melphalan ASCT. The patient tolerated the procedure exceptionally well with minimal complications. He achieved full engraftment on day +14 after ASCT as expected and was discharged from the inpatient setting. He was monitored in the outpatient setting until day +30 without further complications.

Conclusions

The TVHS SCT/CT performed the first ever bloodless autologous stem cell transplant within the VA. This pioneering effort to establish such protocols to provide care to all veterans whatever their personal or religious preferences is a testament to commitment of VA to provide care for all veterans and the willingness to innovate to do so.

Background

Autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) is an important part of the treatment paradigm for patients with multiple myeloma (MM) and remains the standard of care for newly diagnosed patients. Blood product transfusion support in the form of platelets and packed red blood cells (pRBCs) is part of the standard of practice as supportive measures during the severely pancytopenic period. Some MM patients, such as those of Jehovah’s Witness (JW) faith, may have religious beliefs or preferences that preclude acceptance of such blood products. Some transplant centers have developed protocols to allow safe “bloodless” ASCT that allows these patients to receive this important treatment while adhering to their beliefs or preferences.

Case Presentation

A 61-year-old veteran of JW faith with newly diagnosed IgG Kappa Multiple Myeloma was referred to the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System (TVHS) Stem Cell Transplant program for consideration of “bloodless” ASCT. With the assistance and expertise of the academic affiliate, Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s established bloodless ASCT protocol, this same protocol was established at TVHS to optimize the patient’s care pretransplant (use of erythropoiesis stimulating agents, intravenous iron, B12 supplementation) as well as post-transplant (use of antifibrinolytics, close inpatient monitoring). Both Ethics and Legal consultation was obtained, and guidance was provided to create a life sustaining treatment (LST) note in the veteran’s electronic health record that captured the veteran’s blood product preference. Once all protocols and guidance were in place, the TVHS SCT/CT program proceeded to treat the veteran with a myeloablative melphalan ASCT. The patient tolerated the procedure exceptionally well with minimal complications. He achieved full engraftment on day +14 after ASCT as expected and was discharged from the inpatient setting. He was monitored in the outpatient setting until day +30 without further complications.

Conclusions

The TVHS SCT/CT performed the first ever bloodless autologous stem cell transplant within the VA. This pioneering effort to establish such protocols to provide care to all veterans whatever their personal or religious preferences is a testament to commitment of VA to provide care for all veterans and the willingness to innovate to do so.

Background

Autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) is an important part of the treatment paradigm for patients with multiple myeloma (MM) and remains the standard of care for newly diagnosed patients. Blood product transfusion support in the form of platelets and packed red blood cells (pRBCs) is part of the standard of practice as supportive measures during the severely pancytopenic period. Some MM patients, such as those of Jehovah’s Witness (JW) faith, may have religious beliefs or preferences that preclude acceptance of such blood products. Some transplant centers have developed protocols to allow safe “bloodless” ASCT that allows these patients to receive this important treatment while adhering to their beliefs or preferences.

Case Presentation

A 61-year-old veteran of JW faith with newly diagnosed IgG Kappa Multiple Myeloma was referred to the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System (TVHS) Stem Cell Transplant program for consideration of “bloodless” ASCT. With the assistance and expertise of the academic affiliate, Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s established bloodless ASCT protocol, this same protocol was established at TVHS to optimize the patient’s care pretransplant (use of erythropoiesis stimulating agents, intravenous iron, B12 supplementation) as well as post-transplant (use of antifibrinolytics, close inpatient monitoring). Both Ethics and Legal consultation was obtained, and guidance was provided to create a life sustaining treatment (LST) note in the veteran’s electronic health record that captured the veteran’s blood product preference. Once all protocols and guidance were in place, the TVHS SCT/CT program proceeded to treat the veteran with a myeloablative melphalan ASCT. The patient tolerated the procedure exceptionally well with minimal complications. He achieved full engraftment on day +14 after ASCT as expected and was discharged from the inpatient setting. He was monitored in the outpatient setting until day +30 without further complications.

Conclusions

The TVHS SCT/CT performed the first ever bloodless autologous stem cell transplant within the VA. This pioneering effort to establish such protocols to provide care to all veterans whatever their personal or religious preferences is a testament to commitment of VA to provide care for all veterans and the willingness to innovate to do so.

Profound Hypoxemia in a Patient With Hypertriglyceridemia-Induced Pancreatitis

Profound Hypoxemia in a Patient With Hypertriglyceridemia-Induced Pancreatitis

Acute pancreatitis can be associated with multiorgan system failure, including respiratory failure, which has a high mortality rate. Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a known complication of severe, acute pancreatitis, and is fatal in up to 40% of cases. Mortality rates exceed 80% in patients with PaO2/FiO2 < 100 mm Hg.2 Although ARDS is typically associated with bilateral pulmonary infiltrates, severe hypoxemia in pancreatitis may not be visible in radiography in up to 50% of cases.1

Hypertriglyceridemia is the third-most common cause of acute pancreatitis, with an incidence of 2% to 10% among patients diagnosed with acute pancreatitis.3.4 Elevated serum triglycerides have been proposed to trigger acute pancreatitis by increasing plasma viscosity, which leads to ischemia and inflammation of the pancreas.4 In severe cases of hypertriglyceridemia-induced acute pancreatitis, plasmapheresis is used to rapidly reduce serum chylomicron and triglyceride levels.3

This case report discusses a patient with acute pancreatitis whose hypoxemia coincided with the severity of hypertriglyceridemia, but without radiographic evidence of pulmonary infiltrates or other known pulmonary causes.

Case Presentation

A 60-year-old male presented to the emergency department with several hours of diffuse abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. The patient reported that his symptoms began after eating fried chicken. He reported no dyspnea, fever, chills, or other symptoms. His medical history included type 2 diabetes (hemoglobin A1c, 11.1%), Hashimoto hypothyroidism, severe obstructive sleep apnea not on continuous positive airway pressure (apnea-hypoxia index, 59/h), and obesity (body mass index, 52). Initial vital signs were afebrile, heart rate of 90 beats/min, and oxygen saturation (SpO2) of 85% on 6L oxygen via nasal cannula. He was admitted to the intensive care unit and quickly maximized on high flow nasal cannula, ultimately requiring endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation.

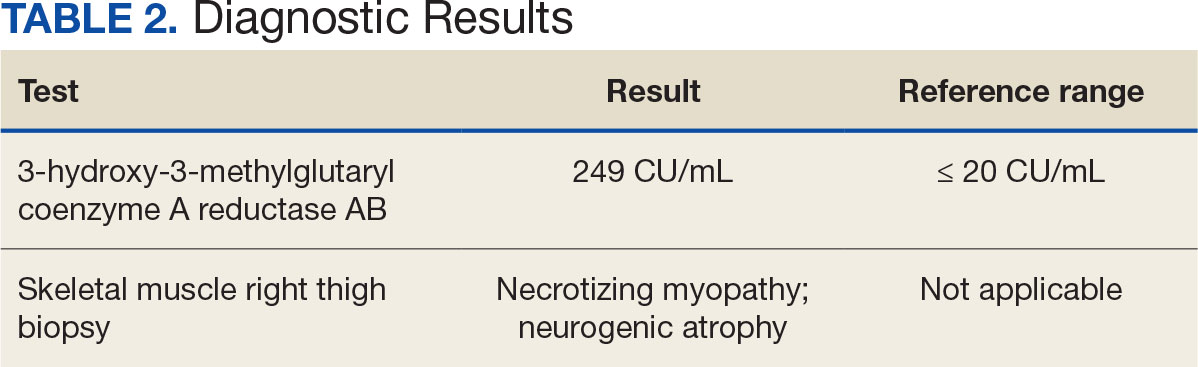

Initial laboratory studies were remarkable for serum sodium of 120 mmol/L (reference range, 136-146 mmol/L), creatinine of 1.65 mg/dL (reference range, 0.52-1.28 mg/dL), anion gap of 18 mEq/L (reference range, 3-11 mEq/L), lipase level of 1115 U/L (reference range, 11-82 U/L), glucose level of 334 mg/dL (reference range, 70-110 mg/dL), white blood count of 13.1 K/uL (reference range, 4.5-11.0 K/uL), lactate level of 3.8 mmol/L (reference range, 0.5-2.2 mmol/L), triglyceride level of 1605 mg/dL (reference range, 40-160 mg/dL), cholesterol level of 565 mg/dL (reference range, < 200 mg/dL), aminotransferase of 21 U/L (reference range, 13-36 U/L), alanine aminotransferase of < 3 U/L (reference range, 7-45 U/L), and total bilirubin level of 1.6 mg/dL (reference range, 0.2-1 mg/dL).

The patient had an initial arterial blood gas pH of 7.26, partial pressure of CO2 and O2 of 64.1 mm Hg and 74.1 mm Hg, respectively, on volume control with a tidal volume of 500 mL, positive end-expiratory pressure of 10 cm H2O, respiratory rate of 26 breaths/min, and FiO2 was 100%, which yielded a PaO2/FiO2 of 74 mm Hg. The patient was maintained in steep reverse-Trendelenburg position with moderate improvement in his SpO2.

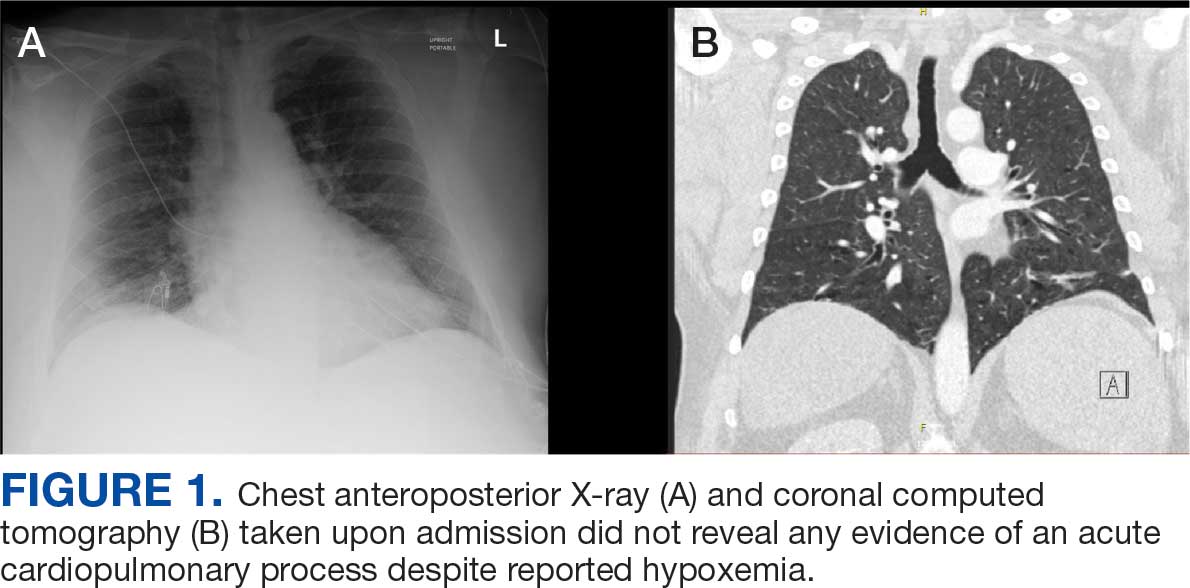

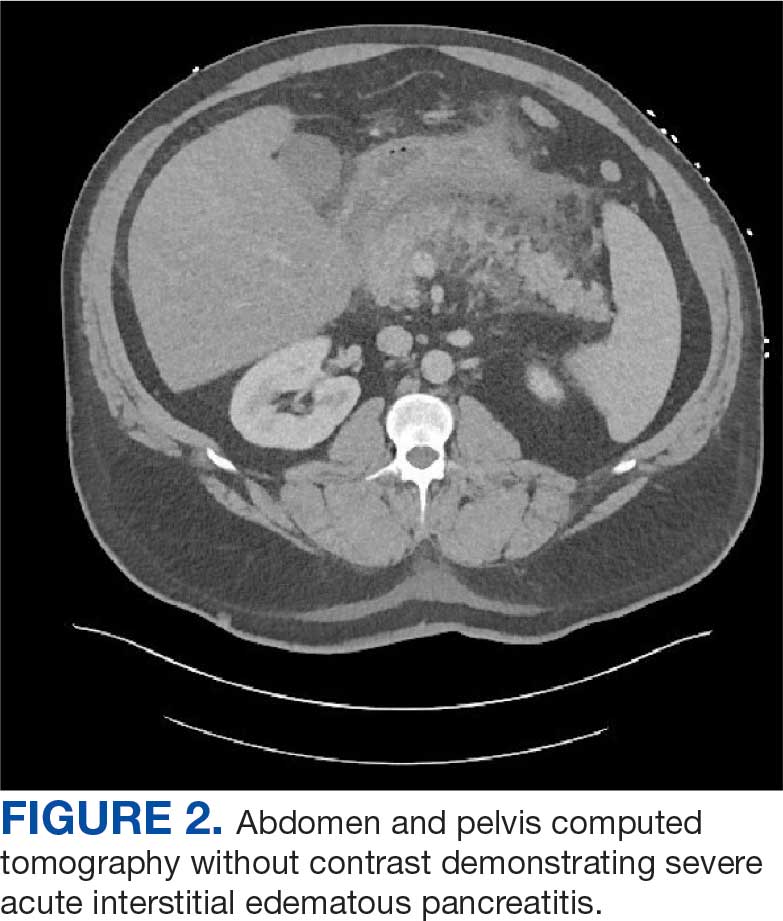

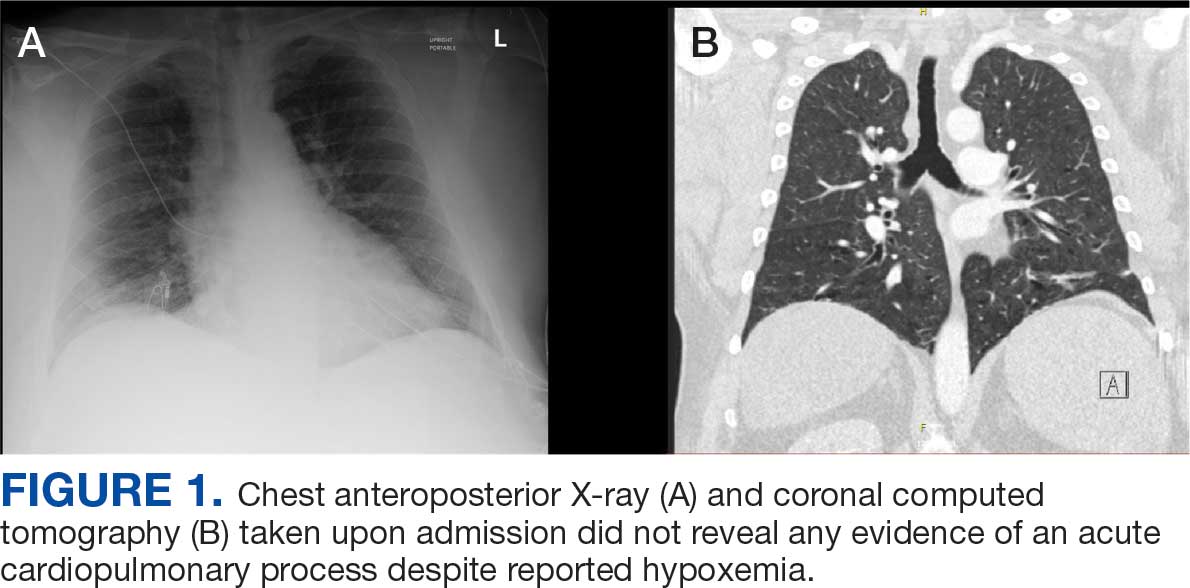

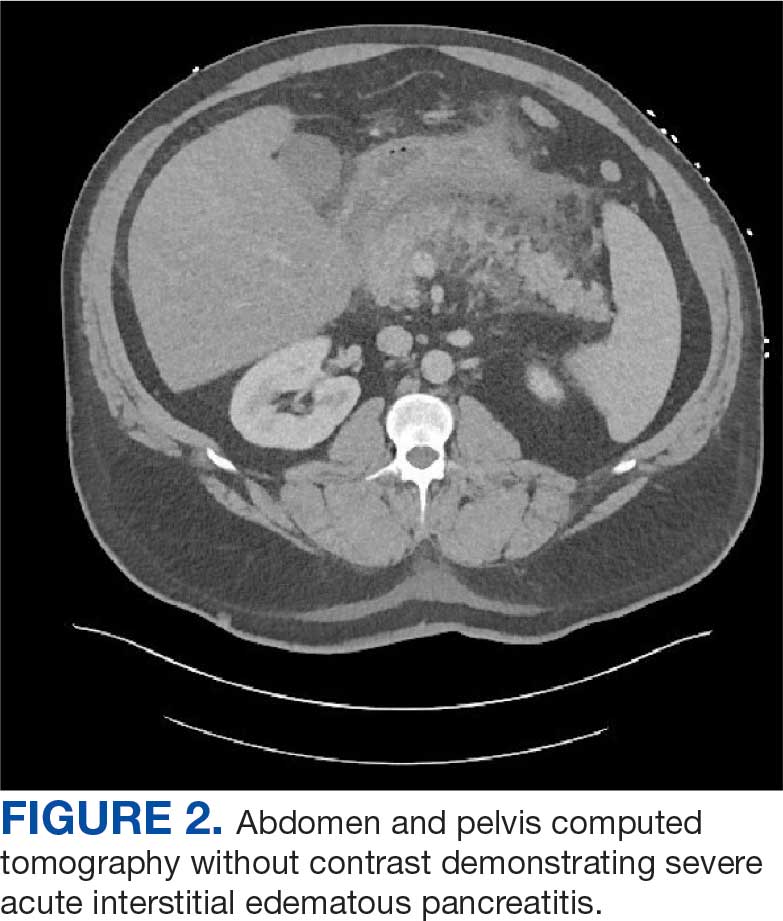

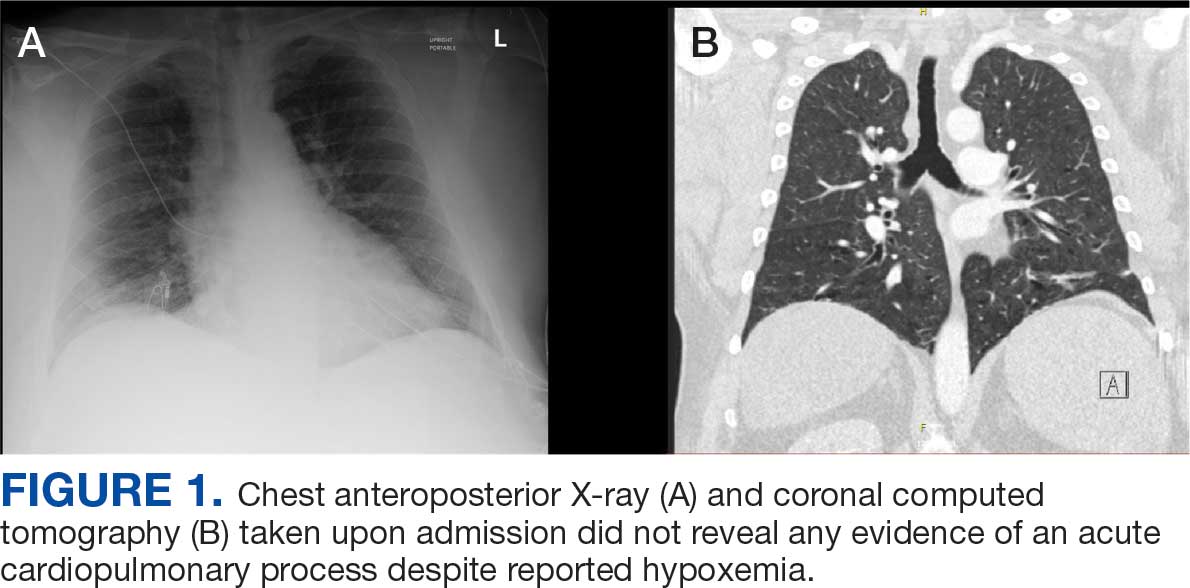

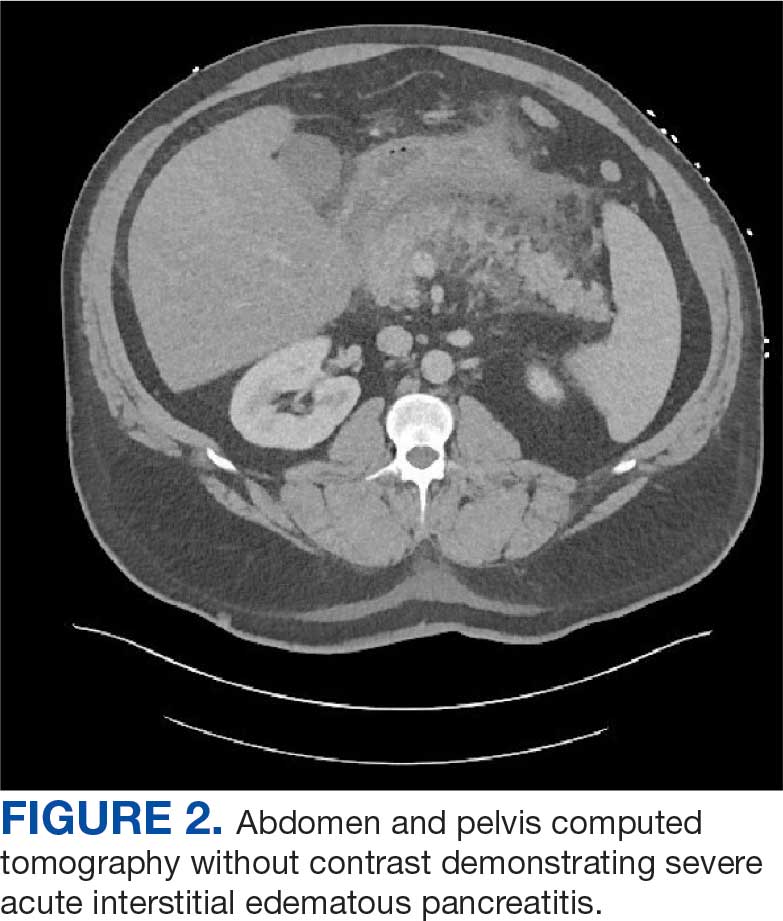

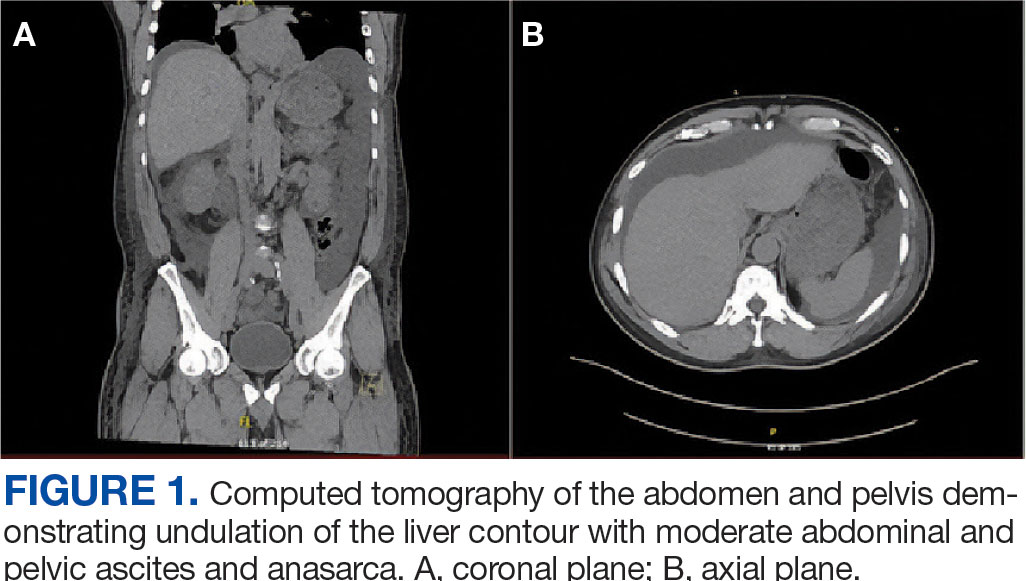

Chest X-ray and computed tomography angiogram did not reveal pleural effusions, pulmonary infiltrates, or pulmonary embolism (Figure 1). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated severe acute interstitial edematous pancreatitis with no evidence of pancreatic necrosis or evidence of gallstones (Figure 2). A transthoracic echocardiogram with bubble was negative for intracardiac right to left shunting.

The leading diagnosis was ARDS secondary to acute pancreatitis with hypoxemia exacerbated by morbid obesity and untreated obstructive sleep apnea leading to hypoventilation.

Treatment

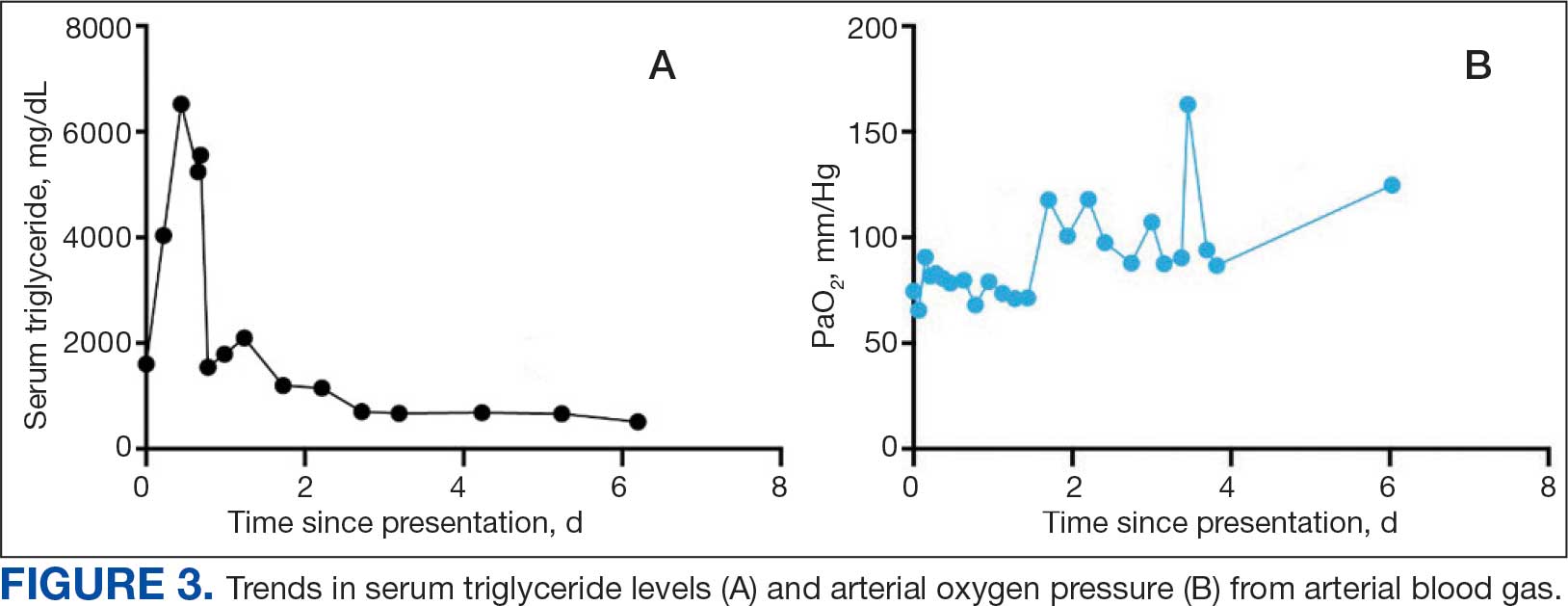

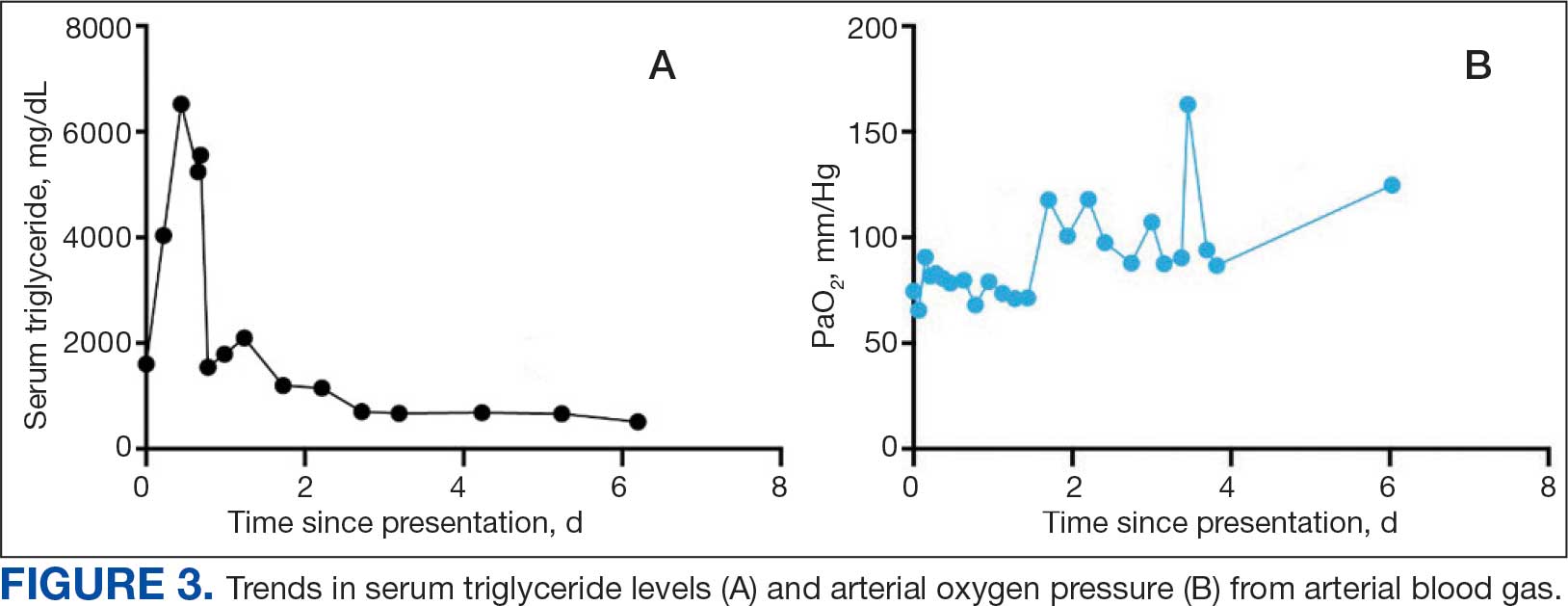

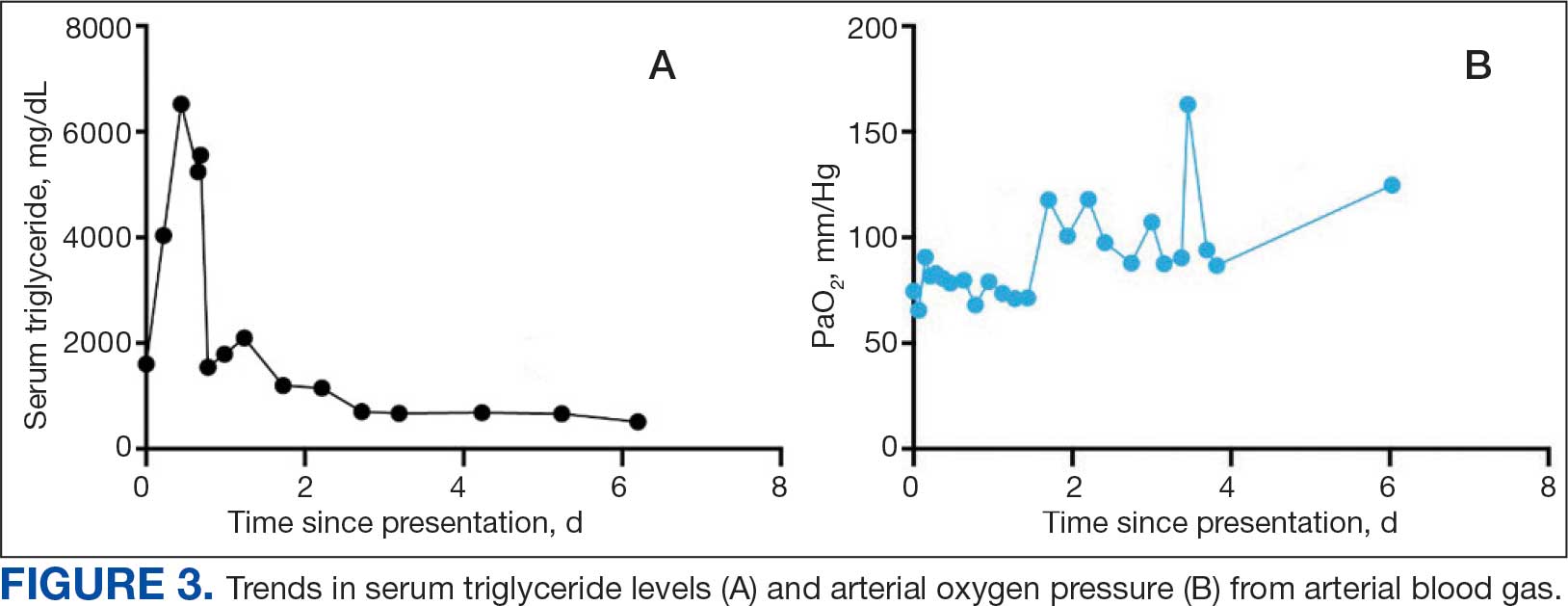

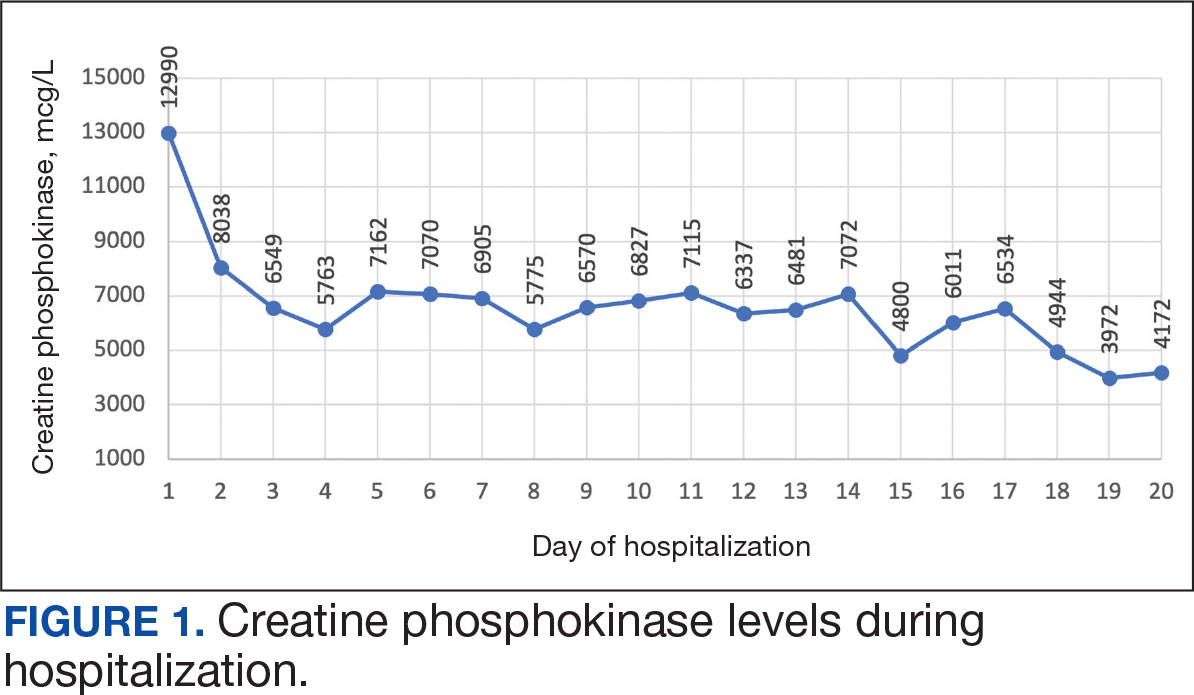

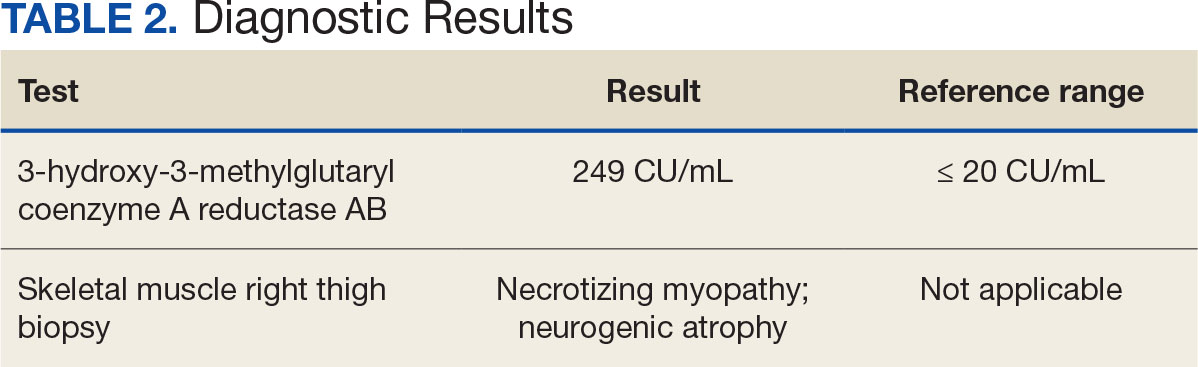

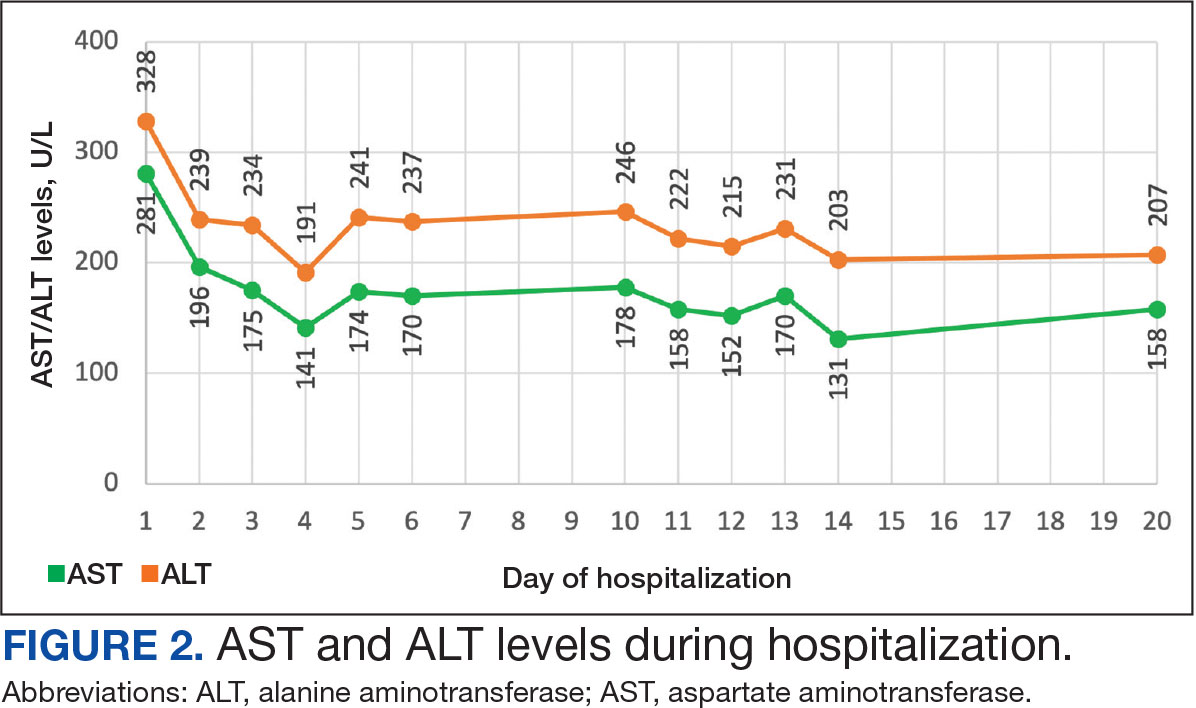

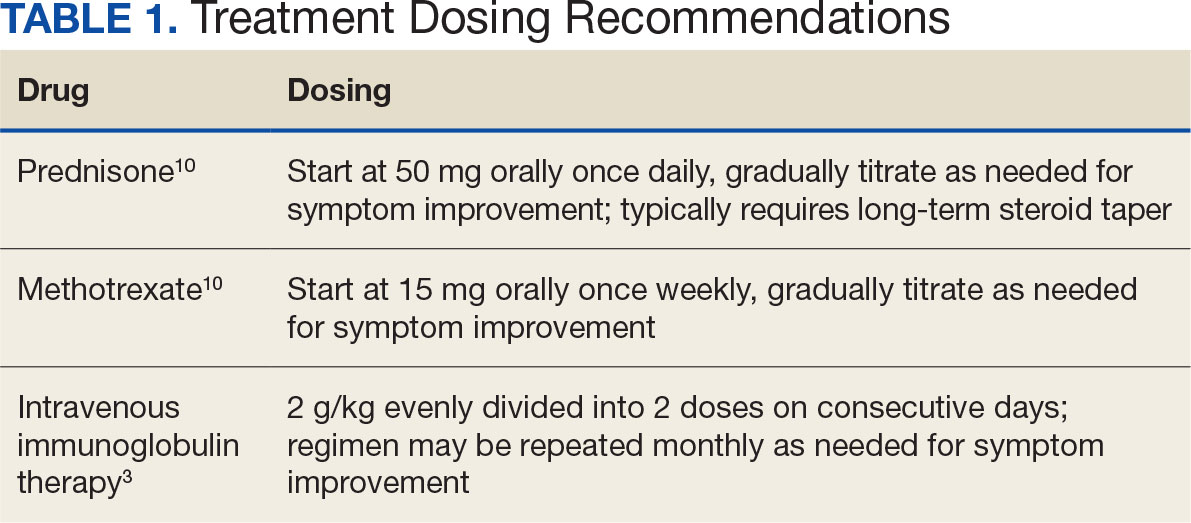

The patient was intubated and restricted to nothing by mouth and provided fluid resuscitation with crystalloids. On hospital day 1, he remained intubated and on mechanical ventilation, started on plasmapheresis and continued insulin infusion for severe hypertriglyceridemia. The patient’s PaO2/FiO2 ratio remained persistently < 100 mm Hg despite maximal ventilatory support. After 3 sessions of plasmapheresis, the serum triglyceride levels and oxygen requirements improved (Figure 3).

Due to prolonged intubation, the patient ultimately required a tracheostomy. By hospital day 48, the patient was successfully weaned off mechanical ventilation. His tracheostomy was decannulated uneventfully on hospital day 55 and the stoma was closed. The patient was discharged to a skilled nursing home for rehabilitation and received intensive physical therapy for deconditioning from prolonged hospitalization.

Discussion

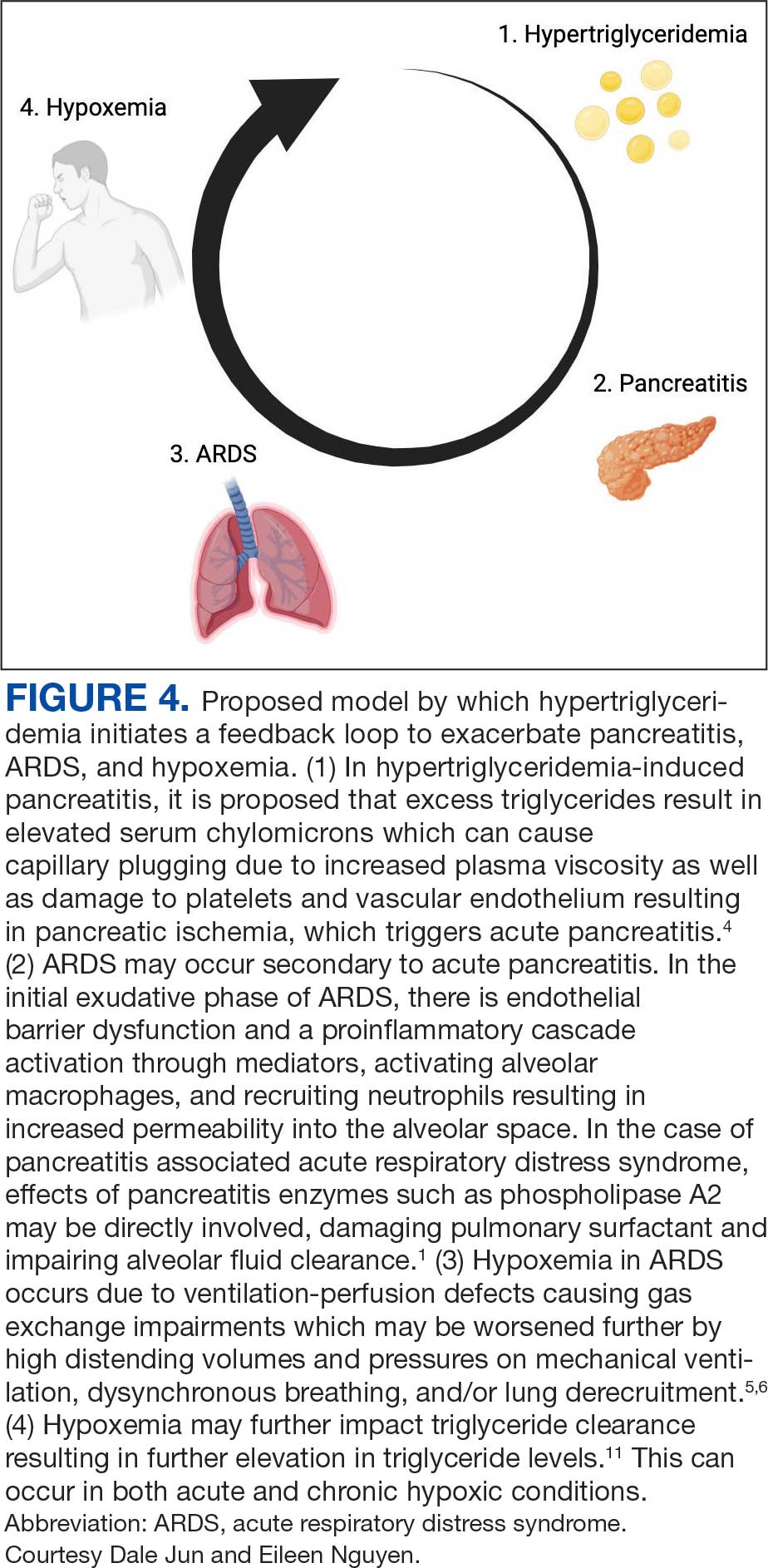

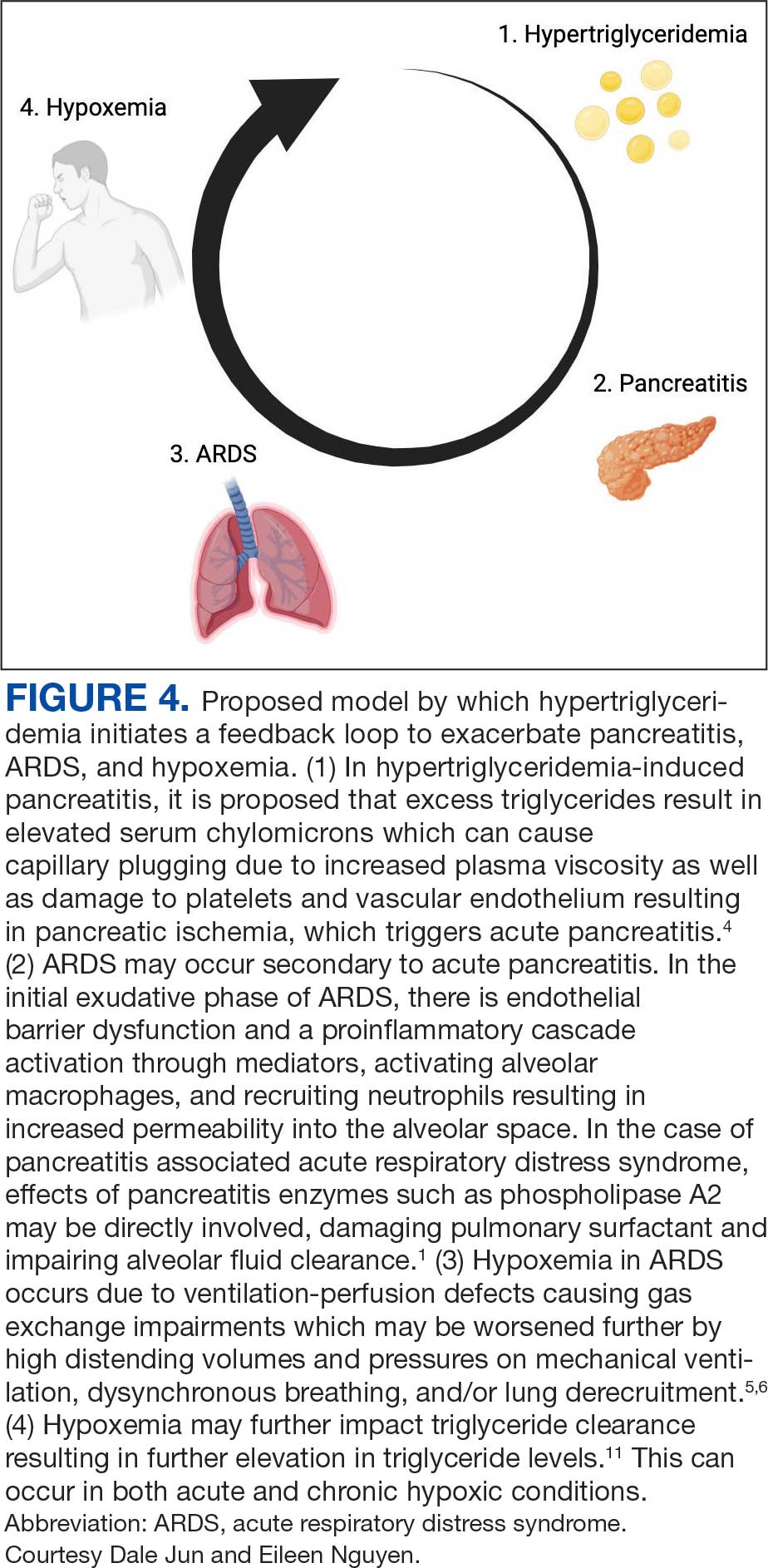

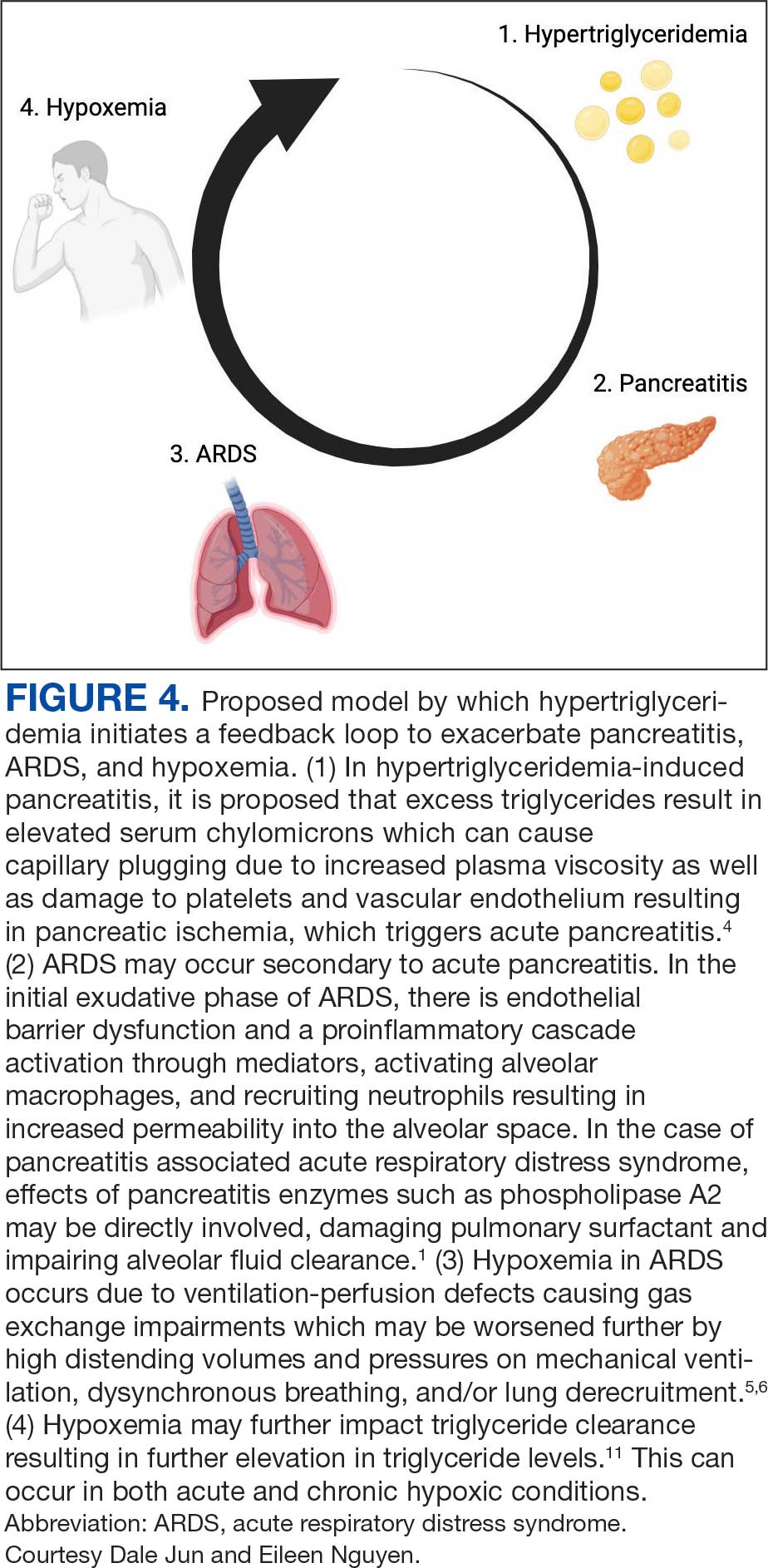

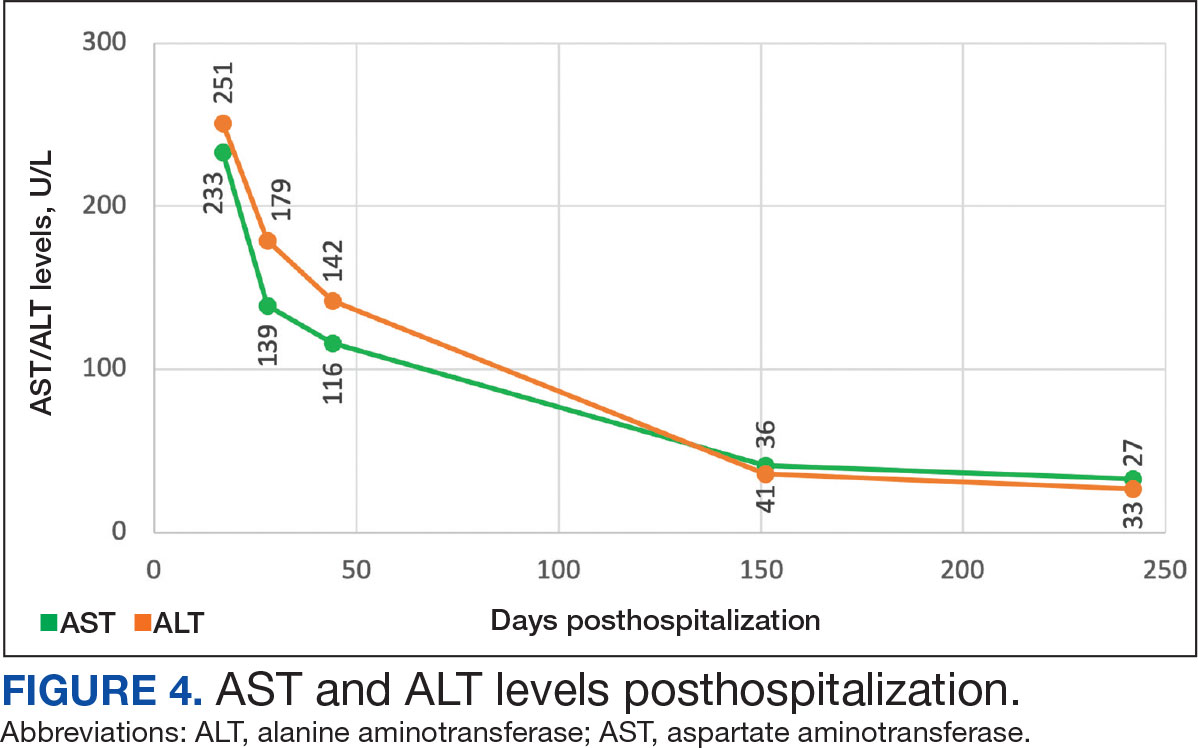

Respiratory insufficiency is a common and potentially lethal complication observed in one-third of patients with acute pancreatitis.1 Radiographic evidence of pleural effusions, atelectasis and pulmonary infiltrates are often present. Acute lung injury (ALI) and ARDS are the most severe pulmonary complications of acute pancreatitis.5 It has been proposed that ALI and ARDS are driven by a hyperinflammatory state, which has multiple downstream effects. Pulmonary parenchymal and vascular damage has been associated with activated proinflammatory cytokines, trypsin, phospholipase A, and free fatty acids (Figure 4).1

Hypoxemia secondary to acute pancreatitis may occur without initial radiographic findings and has been observed in up to half of patients.1 Hypoxemia in ARDS occurs due to ventilation-perfusion defects causing gas exchange impairments which may be worsened further by high distending volumes and pressures on mechanical ventilation, dyssynchronous breathing, and/or lung derecruitment.6 Patients who require intubation for pancreatitis-associated ALI or ARDS eventually exhibit imaging findings consistent with their disease.1 The patient in this case exhibited severe hypoxemia for several days despite persistently negative radiographic studies. His history of obstructive sleep apnea and a body mass index of 52 may have contributed to respiratory failure; however, assessment of other contributors to the acute and profound hypoxemia yielded largely unremarkable results. The patient did not have a history or evidence of heart failure and his hypoxemia did not improve with diuresis. He tested positive for COVID-19 on admission and was briefly treated with remdesivir and dexamethasone, but it was determined that the test was likely a false positive due to negative subsequent tests and elevated cycle thresholds (> 40). A concomitant COVID-19 infection likely did not contribute to his symptoms.

Ventilation-perfusion mismatch is a well-recognized complication of pancreatitis, which results in right-to-left shunting.5 While we considered whether an intracardiac shunt may have contributed to the patient’s hypoxemia, a transthoracic echocardiogram with bubble contrast was negative.

The patient had a peak serum triglyceride of > 6000 mg/dl, which meets the criteria for very severe hypertriglyceridemia.7 As observed in prior reports, the extent of the hypertriglyceridemia in this patient resulted in pronounced lipemic blood, which was appreciable by the eye and necessitated several rounds of centrifugation to analyze the laboratory studies.8 In this case, plasmapheresis was used to rapidly treat the hypertriglyceridemia, thereby reducing inflammation and further damage to the pancreas.9

It is possible the patient’s hypertriglyceridemia may have been associated with his hypoxemia. His hypoxemia was most pronounced approximately 24 hours postadmission, which coincided with the peak of the hypertriglyceridemia. It remains unclear whether the severity of triglyceride elevation could accurately predict the severity of respiratory insufficiency. Hypoxemia is thought to modulate triglyceride metabolism through stimulation of intracellular lipolysis, upregulation of very low-density lipoproteins production in the liver, and inhibition of triglyceride-rich lipoprotein metabolism.10 Evidence from rodent studies supports the idea that acute hypoxemia increases triglycerides, and the degree of hypoxemia correlates with the elevated triglyceride levels.11 However, this has not been consistently observed in humans and may vary by prandial state.12,13 Thus, dysfunction of lipid metabolism may be a relevant clinical indicator of hypoxemia; further work is needed to elucidate this association.

Patient Perspective

The patient continues to undergo extensive rehabilitation following his prolonged illness and hospitalization. He expressed gratitude for the care received. However, he has limited and distorted recollection of the events during his hospitalization and stated that it felt “like an extraterrestrial state.”

Conclusions

This report describes a case of marked hypoxemia in the setting of acute pancreatitis. Pulmonary insufficiency in acute pancreatitis is commonly associated with imaging findings such as atelectasis, pleural effusions, and pulmonary infiltrates; however, up to half of cases initially lack any radiographic findings. Plasmapheresis is an effective treatment for hypertriglyceridemia-induced pancreatitis to both directly reduce circulating triglycerides and inflammation. Plasmapheresis also represents a promising therapy for the prevention of further episodes of pancreatitis in patients with recurrent pancreatitis. We propose a feedback mechanism through which pancreatitis induces severe hypoxemia, which may modulate lipid metabolism and severe hypertriglyceridemia correlates with respiratory failure.

- Zhou M-T, Chen C-S, Chen B-C, Zhang Q-Y, Andersson R. Acute lung injury and ARDS in acute pancreatitis: mechanisms and potential intervention. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(17):2094-2099. doi:10.3748/wjg.v16.i17.2094

- Peek GJ, White S, Scott AD, et al. Severe acute respiratory distress syndrome secondary to acute pancreatitis successfully treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in three patients. Ann Surg. 1998;227(4):572-574. doi:10.1097/00000658-199804000-00020

- Searles GE, Ooi TC. Underrecognition of chylomicronemia as a cause of acute pancreatitis. Can Med Assoc J. 1992;147(12):1806-1808.

- de Pretis N, Amodio A, Frulloni L. Hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis: Epidemiology, pathophysiology and clinical management. United European Gastroenterol J. 2018;6(5):649-655. doi:10.1177/2050640618755002

- Ranson JH, Turner JW, Roses DF, et al. Respiratory compli cations in acute pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 1974;179(5):557-566. doi:10.1097/00000658-197405000-00006 6. Swenson KE, Swenson ER. Pathophysiology of acute respiratory distress syndrome and COVID-19 lung injury. Crit Care Clin. 2021;37(4):749-776. doi:10.1016/j.ccc.2021.05.003

- Swenson KE, Swenson ER. Pathophysiology of acute respiratory distress syndrome and COVID- 19 lung injury. Crit Care Clin. 2021;37(4):749-776. doi:10.1016/j.ccc.2021.05.003

- Berglund L, Brunzell JD, Goldberg AC, et al. Evaluation and treatment of hypertriglyceridemia: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(9):2969-2989. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-3213

- Ahern BJ, Yi HJ, Somma CL. Hypertriglyceridemia-induced pancreatitis and a lipemic blood sample: a case report and brief clinical review. J Emerg Nurs. 2022;48(4):455-459. doi:10.1016/j.jen.2022.02.001

- Garg R, Rustagi T. Management of hypertriglyceridemia induced acute pancreatitis. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:4721357. doi:10.1155/2018/4721357

- Morin R, Goulet N, Mauger J-F, Imbeault P. Physiological responses to hypoxia on triglyceride levels. Front Physiol. 2021;12:730935. doi:10.3389/fphys.2021.730935

- Jun JC, Shin M-K, Yao Q, et al. Acute hypoxia induces hypertriglyceridemia by decreasing plasma triglyceride clearance in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;303(3):E377-88. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00641.2011

- Mahat B, Chassé É, Lindon C, Mauger J-F, Imbeault P. No effect of acute normobaric hypoxia on plasma triglyceride levels in fasting healthy men. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2018;43(7):727-732. doi:10.1139/apnm-2017-0505

- Mauger J-F, Chassé É, Mahat B, Lindon C, Bordenave N, Imbeault P. The effect of acute continuous hypoxia on triglyceride levels in constantly fed healthy men. Front Physiol. 2019;10:752. doi:10.3389/fphys.2019.00752

Acute pancreatitis can be associated with multiorgan system failure, including respiratory failure, which has a high mortality rate. Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a known complication of severe, acute pancreatitis, and is fatal in up to 40% of cases. Mortality rates exceed 80% in patients with PaO2/FiO2 < 100 mm Hg.2 Although ARDS is typically associated with bilateral pulmonary infiltrates, severe hypoxemia in pancreatitis may not be visible in radiography in up to 50% of cases.1

Hypertriglyceridemia is the third-most common cause of acute pancreatitis, with an incidence of 2% to 10% among patients diagnosed with acute pancreatitis.3.4 Elevated serum triglycerides have been proposed to trigger acute pancreatitis by increasing plasma viscosity, which leads to ischemia and inflammation of the pancreas.4 In severe cases of hypertriglyceridemia-induced acute pancreatitis, plasmapheresis is used to rapidly reduce serum chylomicron and triglyceride levels.3

This case report discusses a patient with acute pancreatitis whose hypoxemia coincided with the severity of hypertriglyceridemia, but without radiographic evidence of pulmonary infiltrates or other known pulmonary causes.

Case Presentation

A 60-year-old male presented to the emergency department with several hours of diffuse abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. The patient reported that his symptoms began after eating fried chicken. He reported no dyspnea, fever, chills, or other symptoms. His medical history included type 2 diabetes (hemoglobin A1c, 11.1%), Hashimoto hypothyroidism, severe obstructive sleep apnea not on continuous positive airway pressure (apnea-hypoxia index, 59/h), and obesity (body mass index, 52). Initial vital signs were afebrile, heart rate of 90 beats/min, and oxygen saturation (SpO2) of 85% on 6L oxygen via nasal cannula. He was admitted to the intensive care unit and quickly maximized on high flow nasal cannula, ultimately requiring endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation.

Initial laboratory studies were remarkable for serum sodium of 120 mmol/L (reference range, 136-146 mmol/L), creatinine of 1.65 mg/dL (reference range, 0.52-1.28 mg/dL), anion gap of 18 mEq/L (reference range, 3-11 mEq/L), lipase level of 1115 U/L (reference range, 11-82 U/L), glucose level of 334 mg/dL (reference range, 70-110 mg/dL), white blood count of 13.1 K/uL (reference range, 4.5-11.0 K/uL), lactate level of 3.8 mmol/L (reference range, 0.5-2.2 mmol/L), triglyceride level of 1605 mg/dL (reference range, 40-160 mg/dL), cholesterol level of 565 mg/dL (reference range, < 200 mg/dL), aminotransferase of 21 U/L (reference range, 13-36 U/L), alanine aminotransferase of < 3 U/L (reference range, 7-45 U/L), and total bilirubin level of 1.6 mg/dL (reference range, 0.2-1 mg/dL).

The patient had an initial arterial blood gas pH of 7.26, partial pressure of CO2 and O2 of 64.1 mm Hg and 74.1 mm Hg, respectively, on volume control with a tidal volume of 500 mL, positive end-expiratory pressure of 10 cm H2O, respiratory rate of 26 breaths/min, and FiO2 was 100%, which yielded a PaO2/FiO2 of 74 mm Hg. The patient was maintained in steep reverse-Trendelenburg position with moderate improvement in his SpO2.

Chest X-ray and computed tomography angiogram did not reveal pleural effusions, pulmonary infiltrates, or pulmonary embolism (Figure 1). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated severe acute interstitial edematous pancreatitis with no evidence of pancreatic necrosis or evidence of gallstones (Figure 2). A transthoracic echocardiogram with bubble was negative for intracardiac right to left shunting.

The leading diagnosis was ARDS secondary to acute pancreatitis with hypoxemia exacerbated by morbid obesity and untreated obstructive sleep apnea leading to hypoventilation.

Treatment

The patient was intubated and restricted to nothing by mouth and provided fluid resuscitation with crystalloids. On hospital day 1, he remained intubated and on mechanical ventilation, started on plasmapheresis and continued insulin infusion for severe hypertriglyceridemia. The patient’s PaO2/FiO2 ratio remained persistently < 100 mm Hg despite maximal ventilatory support. After 3 sessions of plasmapheresis, the serum triglyceride levels and oxygen requirements improved (Figure 3).

Due to prolonged intubation, the patient ultimately required a tracheostomy. By hospital day 48, the patient was successfully weaned off mechanical ventilation. His tracheostomy was decannulated uneventfully on hospital day 55 and the stoma was closed. The patient was discharged to a skilled nursing home for rehabilitation and received intensive physical therapy for deconditioning from prolonged hospitalization.

Discussion

Respiratory insufficiency is a common and potentially lethal complication observed in one-third of patients with acute pancreatitis.1 Radiographic evidence of pleural effusions, atelectasis and pulmonary infiltrates are often present. Acute lung injury (ALI) and ARDS are the most severe pulmonary complications of acute pancreatitis.5 It has been proposed that ALI and ARDS are driven by a hyperinflammatory state, which has multiple downstream effects. Pulmonary parenchymal and vascular damage has been associated with activated proinflammatory cytokines, trypsin, phospholipase A, and free fatty acids (Figure 4).1

Hypoxemia secondary to acute pancreatitis may occur without initial radiographic findings and has been observed in up to half of patients.1 Hypoxemia in ARDS occurs due to ventilation-perfusion defects causing gas exchange impairments which may be worsened further by high distending volumes and pressures on mechanical ventilation, dyssynchronous breathing, and/or lung derecruitment.6 Patients who require intubation for pancreatitis-associated ALI or ARDS eventually exhibit imaging findings consistent with their disease.1 The patient in this case exhibited severe hypoxemia for several days despite persistently negative radiographic studies. His history of obstructive sleep apnea and a body mass index of 52 may have contributed to respiratory failure; however, assessment of other contributors to the acute and profound hypoxemia yielded largely unremarkable results. The patient did not have a history or evidence of heart failure and his hypoxemia did not improve with diuresis. He tested positive for COVID-19 on admission and was briefly treated with remdesivir and dexamethasone, but it was determined that the test was likely a false positive due to negative subsequent tests and elevated cycle thresholds (> 40). A concomitant COVID-19 infection likely did not contribute to his symptoms.

Ventilation-perfusion mismatch is a well-recognized complication of pancreatitis, which results in right-to-left shunting.5 While we considered whether an intracardiac shunt may have contributed to the patient’s hypoxemia, a transthoracic echocardiogram with bubble contrast was negative.

The patient had a peak serum triglyceride of > 6000 mg/dl, which meets the criteria for very severe hypertriglyceridemia.7 As observed in prior reports, the extent of the hypertriglyceridemia in this patient resulted in pronounced lipemic blood, which was appreciable by the eye and necessitated several rounds of centrifugation to analyze the laboratory studies.8 In this case, plasmapheresis was used to rapidly treat the hypertriglyceridemia, thereby reducing inflammation and further damage to the pancreas.9

It is possible the patient’s hypertriglyceridemia may have been associated with his hypoxemia. His hypoxemia was most pronounced approximately 24 hours postadmission, which coincided with the peak of the hypertriglyceridemia. It remains unclear whether the severity of triglyceride elevation could accurately predict the severity of respiratory insufficiency. Hypoxemia is thought to modulate triglyceride metabolism through stimulation of intracellular lipolysis, upregulation of very low-density lipoproteins production in the liver, and inhibition of triglyceride-rich lipoprotein metabolism.10 Evidence from rodent studies supports the idea that acute hypoxemia increases triglycerides, and the degree of hypoxemia correlates with the elevated triglyceride levels.11 However, this has not been consistently observed in humans and may vary by prandial state.12,13 Thus, dysfunction of lipid metabolism may be a relevant clinical indicator of hypoxemia; further work is needed to elucidate this association.

Patient Perspective

The patient continues to undergo extensive rehabilitation following his prolonged illness and hospitalization. He expressed gratitude for the care received. However, he has limited and distorted recollection of the events during his hospitalization and stated that it felt “like an extraterrestrial state.”

Conclusions

This report describes a case of marked hypoxemia in the setting of acute pancreatitis. Pulmonary insufficiency in acute pancreatitis is commonly associated with imaging findings such as atelectasis, pleural effusions, and pulmonary infiltrates; however, up to half of cases initially lack any radiographic findings. Plasmapheresis is an effective treatment for hypertriglyceridemia-induced pancreatitis to both directly reduce circulating triglycerides and inflammation. Plasmapheresis also represents a promising therapy for the prevention of further episodes of pancreatitis in patients with recurrent pancreatitis. We propose a feedback mechanism through which pancreatitis induces severe hypoxemia, which may modulate lipid metabolism and severe hypertriglyceridemia correlates with respiratory failure.

Acute pancreatitis can be associated with multiorgan system failure, including respiratory failure, which has a high mortality rate. Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a known complication of severe, acute pancreatitis, and is fatal in up to 40% of cases. Mortality rates exceed 80% in patients with PaO2/FiO2 < 100 mm Hg.2 Although ARDS is typically associated with bilateral pulmonary infiltrates, severe hypoxemia in pancreatitis may not be visible in radiography in up to 50% of cases.1

Hypertriglyceridemia is the third-most common cause of acute pancreatitis, with an incidence of 2% to 10% among patients diagnosed with acute pancreatitis.3.4 Elevated serum triglycerides have been proposed to trigger acute pancreatitis by increasing plasma viscosity, which leads to ischemia and inflammation of the pancreas.4 In severe cases of hypertriglyceridemia-induced acute pancreatitis, plasmapheresis is used to rapidly reduce serum chylomicron and triglyceride levels.3

This case report discusses a patient with acute pancreatitis whose hypoxemia coincided with the severity of hypertriglyceridemia, but without radiographic evidence of pulmonary infiltrates or other known pulmonary causes.

Case Presentation

A 60-year-old male presented to the emergency department with several hours of diffuse abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. The patient reported that his symptoms began after eating fried chicken. He reported no dyspnea, fever, chills, or other symptoms. His medical history included type 2 diabetes (hemoglobin A1c, 11.1%), Hashimoto hypothyroidism, severe obstructive sleep apnea not on continuous positive airway pressure (apnea-hypoxia index, 59/h), and obesity (body mass index, 52). Initial vital signs were afebrile, heart rate of 90 beats/min, and oxygen saturation (SpO2) of 85% on 6L oxygen via nasal cannula. He was admitted to the intensive care unit and quickly maximized on high flow nasal cannula, ultimately requiring endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation.

Initial laboratory studies were remarkable for serum sodium of 120 mmol/L (reference range, 136-146 mmol/L), creatinine of 1.65 mg/dL (reference range, 0.52-1.28 mg/dL), anion gap of 18 mEq/L (reference range, 3-11 mEq/L), lipase level of 1115 U/L (reference range, 11-82 U/L), glucose level of 334 mg/dL (reference range, 70-110 mg/dL), white blood count of 13.1 K/uL (reference range, 4.5-11.0 K/uL), lactate level of 3.8 mmol/L (reference range, 0.5-2.2 mmol/L), triglyceride level of 1605 mg/dL (reference range, 40-160 mg/dL), cholesterol level of 565 mg/dL (reference range, < 200 mg/dL), aminotransferase of 21 U/L (reference range, 13-36 U/L), alanine aminotransferase of < 3 U/L (reference range, 7-45 U/L), and total bilirubin level of 1.6 mg/dL (reference range, 0.2-1 mg/dL).

The patient had an initial arterial blood gas pH of 7.26, partial pressure of CO2 and O2 of 64.1 mm Hg and 74.1 mm Hg, respectively, on volume control with a tidal volume of 500 mL, positive end-expiratory pressure of 10 cm H2O, respiratory rate of 26 breaths/min, and FiO2 was 100%, which yielded a PaO2/FiO2 of 74 mm Hg. The patient was maintained in steep reverse-Trendelenburg position with moderate improvement in his SpO2.

Chest X-ray and computed tomography angiogram did not reveal pleural effusions, pulmonary infiltrates, or pulmonary embolism (Figure 1). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated severe acute interstitial edematous pancreatitis with no evidence of pancreatic necrosis or evidence of gallstones (Figure 2). A transthoracic echocardiogram with bubble was negative for intracardiac right to left shunting.

The leading diagnosis was ARDS secondary to acute pancreatitis with hypoxemia exacerbated by morbid obesity and untreated obstructive sleep apnea leading to hypoventilation.

Treatment

The patient was intubated and restricted to nothing by mouth and provided fluid resuscitation with crystalloids. On hospital day 1, he remained intubated and on mechanical ventilation, started on plasmapheresis and continued insulin infusion for severe hypertriglyceridemia. The patient’s PaO2/FiO2 ratio remained persistently < 100 mm Hg despite maximal ventilatory support. After 3 sessions of plasmapheresis, the serum triglyceride levels and oxygen requirements improved (Figure 3).

Due to prolonged intubation, the patient ultimately required a tracheostomy. By hospital day 48, the patient was successfully weaned off mechanical ventilation. His tracheostomy was decannulated uneventfully on hospital day 55 and the stoma was closed. The patient was discharged to a skilled nursing home for rehabilitation and received intensive physical therapy for deconditioning from prolonged hospitalization.

Discussion

Respiratory insufficiency is a common and potentially lethal complication observed in one-third of patients with acute pancreatitis.1 Radiographic evidence of pleural effusions, atelectasis and pulmonary infiltrates are often present. Acute lung injury (ALI) and ARDS are the most severe pulmonary complications of acute pancreatitis.5 It has been proposed that ALI and ARDS are driven by a hyperinflammatory state, which has multiple downstream effects. Pulmonary parenchymal and vascular damage has been associated with activated proinflammatory cytokines, trypsin, phospholipase A, and free fatty acids (Figure 4).1

Hypoxemia secondary to acute pancreatitis may occur without initial radiographic findings and has been observed in up to half of patients.1 Hypoxemia in ARDS occurs due to ventilation-perfusion defects causing gas exchange impairments which may be worsened further by high distending volumes and pressures on mechanical ventilation, dyssynchronous breathing, and/or lung derecruitment.6 Patients who require intubation for pancreatitis-associated ALI or ARDS eventually exhibit imaging findings consistent with their disease.1 The patient in this case exhibited severe hypoxemia for several days despite persistently negative radiographic studies. His history of obstructive sleep apnea and a body mass index of 52 may have contributed to respiratory failure; however, assessment of other contributors to the acute and profound hypoxemia yielded largely unremarkable results. The patient did not have a history or evidence of heart failure and his hypoxemia did not improve with diuresis. He tested positive for COVID-19 on admission and was briefly treated with remdesivir and dexamethasone, but it was determined that the test was likely a false positive due to negative subsequent tests and elevated cycle thresholds (> 40). A concomitant COVID-19 infection likely did not contribute to his symptoms.

Ventilation-perfusion mismatch is a well-recognized complication of pancreatitis, which results in right-to-left shunting.5 While we considered whether an intracardiac shunt may have contributed to the patient’s hypoxemia, a transthoracic echocardiogram with bubble contrast was negative.

The patient had a peak serum triglyceride of > 6000 mg/dl, which meets the criteria for very severe hypertriglyceridemia.7 As observed in prior reports, the extent of the hypertriglyceridemia in this patient resulted in pronounced lipemic blood, which was appreciable by the eye and necessitated several rounds of centrifugation to analyze the laboratory studies.8 In this case, plasmapheresis was used to rapidly treat the hypertriglyceridemia, thereby reducing inflammation and further damage to the pancreas.9