User login

Methemoglobinemia Induced by Application of an Anesthetic Cream

To the Editor:

Methemoglobinemia (MetHb) is a condition caused by elevated levels of methemoglobin in the blood, which leads to an overall reduced ability of red blood cells to release oxygen to tissues, causing tissue hypoxia. Methemoglobinemia may be congenital or acquired. Various antibiotics and local anesthetics have been reported to induce acquired MetHb.1 We describe an adult who presented with MetHb resulting from excessive topical application of local anesthetics for painful scrotal ulcers.

A 54-year-old man presented with multiple scrotal and penile shaft ulcers of a few weeks’ duration with no systemic concerns. His medical history included chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) and lumbar disc disease. Physical examination revealed multiple erosions and ulcers on an erythematous base involving the scrotal skin and distal penile shaft (Figure). Histopathology revealed acute leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and a laboratory workup was positive for mixed cryoglobulinemia that was thought to be HCV related. The patient was started on a systemic corticosteroid treatment in addition to sofosbuvir-velpatasvir for the treatment of HCV-related mixed cryoglobulinemic vasculitis. Concomitantly, the patient self-treated for pain with a local anesthetic cream containing lidocaine 2.5% and prilocaine 2.5%, applying it excessively every few hours daily for 2 weeks. He also intermittently used occlusive dressings.

After 2 weeks of application, the patient developed lightheadedness and shortness of breath. He returned and was admitted for further evaluation. He had dyspnea and tachypnea of 22 breaths per minute. He also had mild tachycardia (109 beats per minute). He did not have a fever, and his blood pressure was normal. The oxygen saturation measured in ambient room air by pulse oximetry was 82%. A neurologic examination was normal except for mild drowsiness. The lungs were clear, and heart sounds were normal. A 12-lead electrocardiogram also was normal. A complete blood cell count showed severe macrocytic anemia with a hemoglobin level of 7 g/dL, which was a severe decline from the patient’s baseline level of 14 g/dL (reference range, 13–17 g/dL). A MetHb blood level of 11% was reported on co-oximetry. An arterial blood gas analysis revealed a pH of 7.46; partial pressure of carbon dioxide of 41 mm Hg; and partial pressure of oxygen of 63 mm Hg. The haptoglobin level was low at 2.6 mg/dL (reference range, 30–200 mg/dL). An absolute reticulocyte count was markedly elevated at 0.4×106/mL (reference range, 0.03–0.08×106/mL), lactate dehydrogenase was elevated at 430 U/L (reference range, 125–220 U/L), and indirect billirubin was high at 0.9 mg/dL (reference range, 0–0.5 mg/dL), consistent with hemolytic anemia. Electrolyte serum levels and renal function tests were within reference range. A diagnosis of MetHb induced by the lidocaine-prilocaine cream was rendered, and intravenous methylene blue 72 mg (1 mg/kg) was administered over 10 minutes. Within the next 60 minutes, the patient’s drowsiness and arterial desaturation resolved. A subsequent MetHb measurement taken several hours later was reduced to 4%. The patient remained asymptomatic and was eventually discharged.

Methemoglobinemia is an altered state of hemoglobin where the ferrous (Fe2+) ions of heme are oxidized to the ferric (Fe3+) state. These ferric ions are unable to bind oxygen, resulting in impaired oxygen delivery to tissues.1 Local anesthetics, which are strong oxidizers, have been reported to induce MetHb.2 In our patient, the extensive use of lidocaine 2.5%–prilocaine 2.5% cream resulted in severe life-threatening MetHb. The oxidizing properties of local anesthetics can be attributed to their chemical structure. Benzocaine is metabolized to potent oxidizers such as aniline, phenylhydroxylamine, and nitrobenzene.3 Prilocaine and another potent oxidizer, ortho-toluidine, which is a metabolite of prilocaine, can oxidize the iron in hemoglobin from ferrous (Fe2+) to ferric (Fe3+), leading to MetHb.2,3

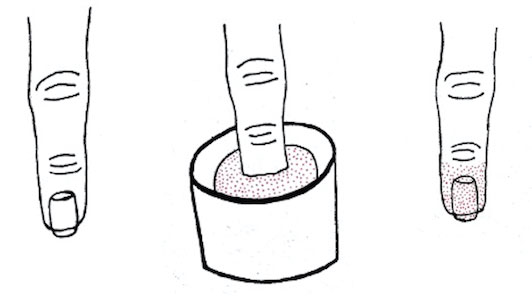

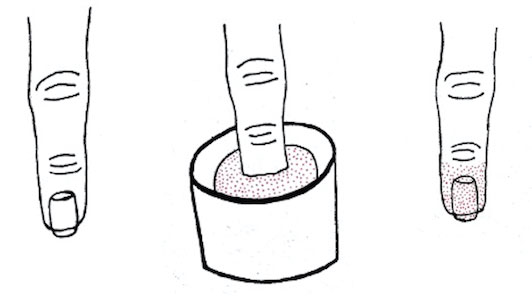

Cases of anesthetic-induced MetHb primarily are associated with overuse of the product by applying it to large surface areas or using it for prolonged periods of time. In one case report, the occlusive dressing of the lidocaine-prilocaine cream applied to skin of the legs that was already abraded by laser epilation therapy resulted in MetHb.4 In our patient, applying the topical anesthetic to the eroded high-absorptive mucosal surface of the scrotal skin and the use of occlusive dressings increased the risk for toxicity. Absorption from scrotal skin is 40-times higher than the forearm.5 The face, axillae, and scalp also exhibit increased absorption compared to the forearm—10-, 4-, and 3-times higher, respectively.

In recent years, the use of topical anesthetics has greatly expanded due to the popularity of aesthetic and cosmetic procedures. These procedures often are performed in an outpatient setting.6 Dermatologists should be well aware of MetHb as a serious adverse effect and guide patients accordingly, as patients do not tend to consider a local anesthetic to be a drug. Drug interactions also may affect free lidocaine concentrations by liver cytochrome P450 metabolism; although this was not the case with our patient, special attention should be given to potential interactions that may exacerbate this serious adverse effect. Consideration should be given to patients applying the anesthetic to areas with high absorption capacity.

- Wright RO, Lewander WJ, Woolf AD. Methemoglobinemia: etiology, pharmacology, and clinical management. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;34:646-656.

- Guay J. Methemoglobinemia related to local anesthetics: a summary of 242 episodes. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:837-845.

- Jakobson B, Nilsson A. Methemoglobinemia associated with a prilocaine-lidocaine cream and trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole. a case report. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1985;29:453-455.

- Hahn I, Hoffman RS, Nelson LS. EMLA®-induced methemoglobinemia and systemic topical anesthetic toxicity. J Emerg Med. 2004;26:85-88.

- Feldmann RJ, Maibach HI. Regional variation in percutaneous penetration of 14C cortisol in man. J Invest Dermatol. 1967;48:181-183.

- Alster T. Review of lidocaine/tetracaine cream as a topical anesthetic for dermatologic laser procedures. Pain Ther. 2013;2:11-19.

To the Editor:

Methemoglobinemia (MetHb) is a condition caused by elevated levels of methemoglobin in the blood, which leads to an overall reduced ability of red blood cells to release oxygen to tissues, causing tissue hypoxia. Methemoglobinemia may be congenital or acquired. Various antibiotics and local anesthetics have been reported to induce acquired MetHb.1 We describe an adult who presented with MetHb resulting from excessive topical application of local anesthetics for painful scrotal ulcers.

A 54-year-old man presented with multiple scrotal and penile shaft ulcers of a few weeks’ duration with no systemic concerns. His medical history included chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) and lumbar disc disease. Physical examination revealed multiple erosions and ulcers on an erythematous base involving the scrotal skin and distal penile shaft (Figure). Histopathology revealed acute leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and a laboratory workup was positive for mixed cryoglobulinemia that was thought to be HCV related. The patient was started on a systemic corticosteroid treatment in addition to sofosbuvir-velpatasvir for the treatment of HCV-related mixed cryoglobulinemic vasculitis. Concomitantly, the patient self-treated for pain with a local anesthetic cream containing lidocaine 2.5% and prilocaine 2.5%, applying it excessively every few hours daily for 2 weeks. He also intermittently used occlusive dressings.

After 2 weeks of application, the patient developed lightheadedness and shortness of breath. He returned and was admitted for further evaluation. He had dyspnea and tachypnea of 22 breaths per minute. He also had mild tachycardia (109 beats per minute). He did not have a fever, and his blood pressure was normal. The oxygen saturation measured in ambient room air by pulse oximetry was 82%. A neurologic examination was normal except for mild drowsiness. The lungs were clear, and heart sounds were normal. A 12-lead electrocardiogram also was normal. A complete blood cell count showed severe macrocytic anemia with a hemoglobin level of 7 g/dL, which was a severe decline from the patient’s baseline level of 14 g/dL (reference range, 13–17 g/dL). A MetHb blood level of 11% was reported on co-oximetry. An arterial blood gas analysis revealed a pH of 7.46; partial pressure of carbon dioxide of 41 mm Hg; and partial pressure of oxygen of 63 mm Hg. The haptoglobin level was low at 2.6 mg/dL (reference range, 30–200 mg/dL). An absolute reticulocyte count was markedly elevated at 0.4×106/mL (reference range, 0.03–0.08×106/mL), lactate dehydrogenase was elevated at 430 U/L (reference range, 125–220 U/L), and indirect billirubin was high at 0.9 mg/dL (reference range, 0–0.5 mg/dL), consistent with hemolytic anemia. Electrolyte serum levels and renal function tests were within reference range. A diagnosis of MetHb induced by the lidocaine-prilocaine cream was rendered, and intravenous methylene blue 72 mg (1 mg/kg) was administered over 10 minutes. Within the next 60 minutes, the patient’s drowsiness and arterial desaturation resolved. A subsequent MetHb measurement taken several hours later was reduced to 4%. The patient remained asymptomatic and was eventually discharged.

Methemoglobinemia is an altered state of hemoglobin where the ferrous (Fe2+) ions of heme are oxidized to the ferric (Fe3+) state. These ferric ions are unable to bind oxygen, resulting in impaired oxygen delivery to tissues.1 Local anesthetics, which are strong oxidizers, have been reported to induce MetHb.2 In our patient, the extensive use of lidocaine 2.5%–prilocaine 2.5% cream resulted in severe life-threatening MetHb. The oxidizing properties of local anesthetics can be attributed to their chemical structure. Benzocaine is metabolized to potent oxidizers such as aniline, phenylhydroxylamine, and nitrobenzene.3 Prilocaine and another potent oxidizer, ortho-toluidine, which is a metabolite of prilocaine, can oxidize the iron in hemoglobin from ferrous (Fe2+) to ferric (Fe3+), leading to MetHb.2,3

Cases of anesthetic-induced MetHb primarily are associated with overuse of the product by applying it to large surface areas or using it for prolonged periods of time. In one case report, the occlusive dressing of the lidocaine-prilocaine cream applied to skin of the legs that was already abraded by laser epilation therapy resulted in MetHb.4 In our patient, applying the topical anesthetic to the eroded high-absorptive mucosal surface of the scrotal skin and the use of occlusive dressings increased the risk for toxicity. Absorption from scrotal skin is 40-times higher than the forearm.5 The face, axillae, and scalp also exhibit increased absorption compared to the forearm—10-, 4-, and 3-times higher, respectively.

In recent years, the use of topical anesthetics has greatly expanded due to the popularity of aesthetic and cosmetic procedures. These procedures often are performed in an outpatient setting.6 Dermatologists should be well aware of MetHb as a serious adverse effect and guide patients accordingly, as patients do not tend to consider a local anesthetic to be a drug. Drug interactions also may affect free lidocaine concentrations by liver cytochrome P450 metabolism; although this was not the case with our patient, special attention should be given to potential interactions that may exacerbate this serious adverse effect. Consideration should be given to patients applying the anesthetic to areas with high absorption capacity.

To the Editor:

Methemoglobinemia (MetHb) is a condition caused by elevated levels of methemoglobin in the blood, which leads to an overall reduced ability of red blood cells to release oxygen to tissues, causing tissue hypoxia. Methemoglobinemia may be congenital or acquired. Various antibiotics and local anesthetics have been reported to induce acquired MetHb.1 We describe an adult who presented with MetHb resulting from excessive topical application of local anesthetics for painful scrotal ulcers.

A 54-year-old man presented with multiple scrotal and penile shaft ulcers of a few weeks’ duration with no systemic concerns. His medical history included chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) and lumbar disc disease. Physical examination revealed multiple erosions and ulcers on an erythematous base involving the scrotal skin and distal penile shaft (Figure). Histopathology revealed acute leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and a laboratory workup was positive for mixed cryoglobulinemia that was thought to be HCV related. The patient was started on a systemic corticosteroid treatment in addition to sofosbuvir-velpatasvir for the treatment of HCV-related mixed cryoglobulinemic vasculitis. Concomitantly, the patient self-treated for pain with a local anesthetic cream containing lidocaine 2.5% and prilocaine 2.5%, applying it excessively every few hours daily for 2 weeks. He also intermittently used occlusive dressings.

After 2 weeks of application, the patient developed lightheadedness and shortness of breath. He returned and was admitted for further evaluation. He had dyspnea and tachypnea of 22 breaths per minute. He also had mild tachycardia (109 beats per minute). He did not have a fever, and his blood pressure was normal. The oxygen saturation measured in ambient room air by pulse oximetry was 82%. A neurologic examination was normal except for mild drowsiness. The lungs were clear, and heart sounds were normal. A 12-lead electrocardiogram also was normal. A complete blood cell count showed severe macrocytic anemia with a hemoglobin level of 7 g/dL, which was a severe decline from the patient’s baseline level of 14 g/dL (reference range, 13–17 g/dL). A MetHb blood level of 11% was reported on co-oximetry. An arterial blood gas analysis revealed a pH of 7.46; partial pressure of carbon dioxide of 41 mm Hg; and partial pressure of oxygen of 63 mm Hg. The haptoglobin level was low at 2.6 mg/dL (reference range, 30–200 mg/dL). An absolute reticulocyte count was markedly elevated at 0.4×106/mL (reference range, 0.03–0.08×106/mL), lactate dehydrogenase was elevated at 430 U/L (reference range, 125–220 U/L), and indirect billirubin was high at 0.9 mg/dL (reference range, 0–0.5 mg/dL), consistent with hemolytic anemia. Electrolyte serum levels and renal function tests were within reference range. A diagnosis of MetHb induced by the lidocaine-prilocaine cream was rendered, and intravenous methylene blue 72 mg (1 mg/kg) was administered over 10 minutes. Within the next 60 minutes, the patient’s drowsiness and arterial desaturation resolved. A subsequent MetHb measurement taken several hours later was reduced to 4%. The patient remained asymptomatic and was eventually discharged.

Methemoglobinemia is an altered state of hemoglobin where the ferrous (Fe2+) ions of heme are oxidized to the ferric (Fe3+) state. These ferric ions are unable to bind oxygen, resulting in impaired oxygen delivery to tissues.1 Local anesthetics, which are strong oxidizers, have been reported to induce MetHb.2 In our patient, the extensive use of lidocaine 2.5%–prilocaine 2.5% cream resulted in severe life-threatening MetHb. The oxidizing properties of local anesthetics can be attributed to their chemical structure. Benzocaine is metabolized to potent oxidizers such as aniline, phenylhydroxylamine, and nitrobenzene.3 Prilocaine and another potent oxidizer, ortho-toluidine, which is a metabolite of prilocaine, can oxidize the iron in hemoglobin from ferrous (Fe2+) to ferric (Fe3+), leading to MetHb.2,3

Cases of anesthetic-induced MetHb primarily are associated with overuse of the product by applying it to large surface areas or using it for prolonged periods of time. In one case report, the occlusive dressing of the lidocaine-prilocaine cream applied to skin of the legs that was already abraded by laser epilation therapy resulted in MetHb.4 In our patient, applying the topical anesthetic to the eroded high-absorptive mucosal surface of the scrotal skin and the use of occlusive dressings increased the risk for toxicity. Absorption from scrotal skin is 40-times higher than the forearm.5 The face, axillae, and scalp also exhibit increased absorption compared to the forearm—10-, 4-, and 3-times higher, respectively.

In recent years, the use of topical anesthetics has greatly expanded due to the popularity of aesthetic and cosmetic procedures. These procedures often are performed in an outpatient setting.6 Dermatologists should be well aware of MetHb as a serious adverse effect and guide patients accordingly, as patients do not tend to consider a local anesthetic to be a drug. Drug interactions also may affect free lidocaine concentrations by liver cytochrome P450 metabolism; although this was not the case with our patient, special attention should be given to potential interactions that may exacerbate this serious adverse effect. Consideration should be given to patients applying the anesthetic to areas with high absorption capacity.

- Wright RO, Lewander WJ, Woolf AD. Methemoglobinemia: etiology, pharmacology, and clinical management. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;34:646-656.

- Guay J. Methemoglobinemia related to local anesthetics: a summary of 242 episodes. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:837-845.

- Jakobson B, Nilsson A. Methemoglobinemia associated with a prilocaine-lidocaine cream and trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole. a case report. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1985;29:453-455.

- Hahn I, Hoffman RS, Nelson LS. EMLA®-induced methemoglobinemia and systemic topical anesthetic toxicity. J Emerg Med. 2004;26:85-88.

- Feldmann RJ, Maibach HI. Regional variation in percutaneous penetration of 14C cortisol in man. J Invest Dermatol. 1967;48:181-183.

- Alster T. Review of lidocaine/tetracaine cream as a topical anesthetic for dermatologic laser procedures. Pain Ther. 2013;2:11-19.

- Wright RO, Lewander WJ, Woolf AD. Methemoglobinemia: etiology, pharmacology, and clinical management. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;34:646-656.

- Guay J. Methemoglobinemia related to local anesthetics: a summary of 242 episodes. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:837-845.

- Jakobson B, Nilsson A. Methemoglobinemia associated with a prilocaine-lidocaine cream and trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole. a case report. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1985;29:453-455.

- Hahn I, Hoffman RS, Nelson LS. EMLA®-induced methemoglobinemia and systemic topical anesthetic toxicity. J Emerg Med. 2004;26:85-88.

- Feldmann RJ, Maibach HI. Regional variation in percutaneous penetration of 14C cortisol in man. J Invest Dermatol. 1967;48:181-183.

- Alster T. Review of lidocaine/tetracaine cream as a topical anesthetic for dermatologic laser procedures. Pain Ther. 2013;2:11-19.

Practice Points

- Consideration should be given to patients applying anesthetic creams to areas with high absorption capacity.

- Dermatologists should be aware of methemoglobinemia as a serious adverse effect of local anesthetics and guide patients accordingly, as patients do not tend to consider these products to be drugs.

Penile Herpes Vegetans in a Patient With Well-controlled HIV

To the Editor:

Herpes vegetans (HV) is an uncommon infection caused by human herpesvirus (HHV) in patients who are immunocompromised, such as those who are HIV positive.1 Unlike typical HHV infection, HV can present with exophytic exudative ulcers and papillomatous vegetations. The presentation of ulcerated genital nodules, especially in an immunocompromised patient, yields an array of disorders in the differential diagnosis, including condyloma latum, condyloma acuminatum, pyogenic granuloma (PG), and verrucous carcinoma.2,3 Histopathology of HV reveals pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, plasma cell infiltration, and positivity for HHV type 1 (HHV-1) and/or HHV type 2 (HHV-2). Herpes vegetans lesions typically require a multimodal treatment approach because many cases are resistant to acyclovir. Treatment options include the nucleoside analogues foscarnet and cidofovir; immunomodulators such as topical imiquimod; and the topical antiviral trifluridine.1,4-6 We describe a case of HV in a patient with a history of well-controlled HIV infection who presented with a painful fungating penile lesion.

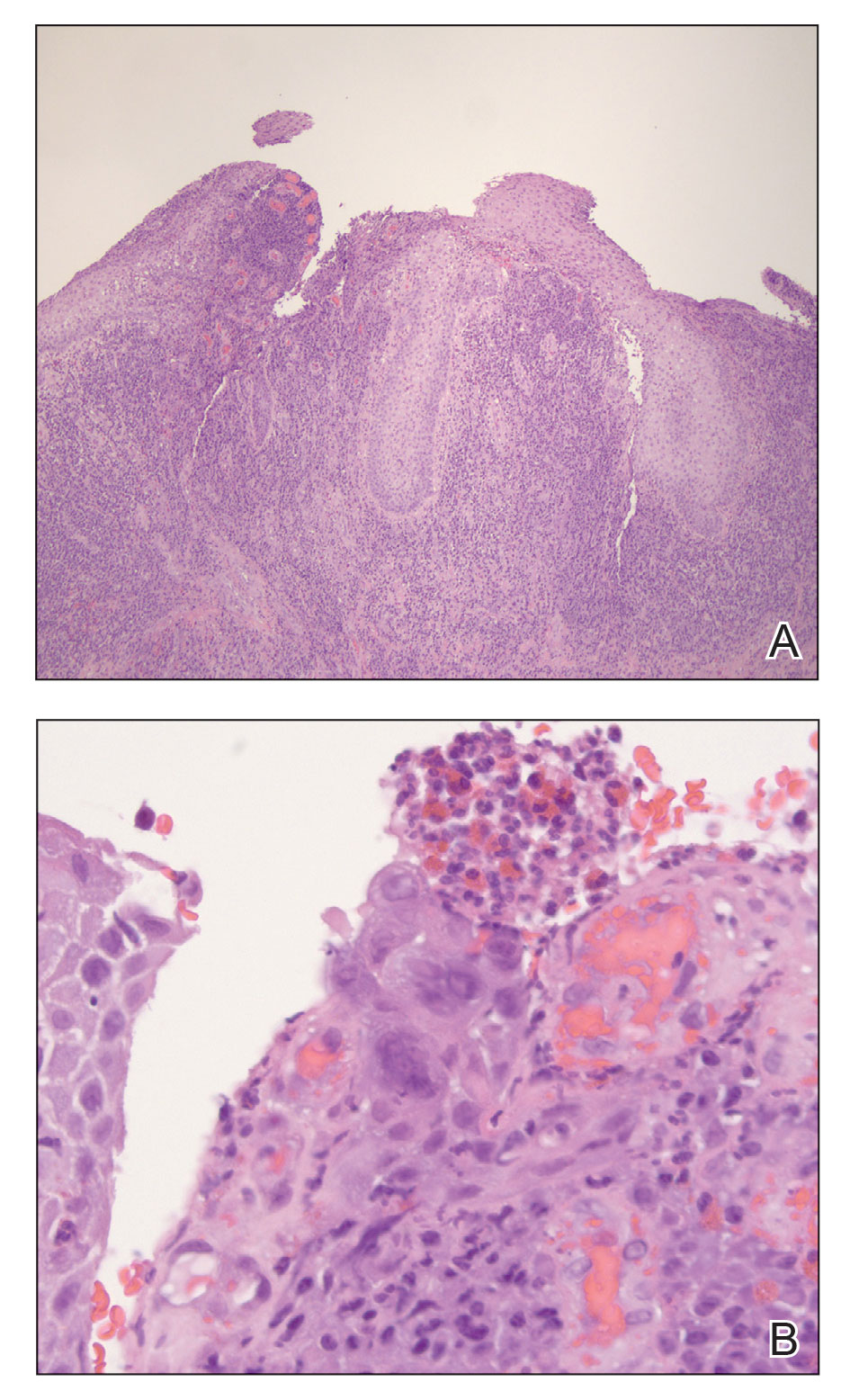

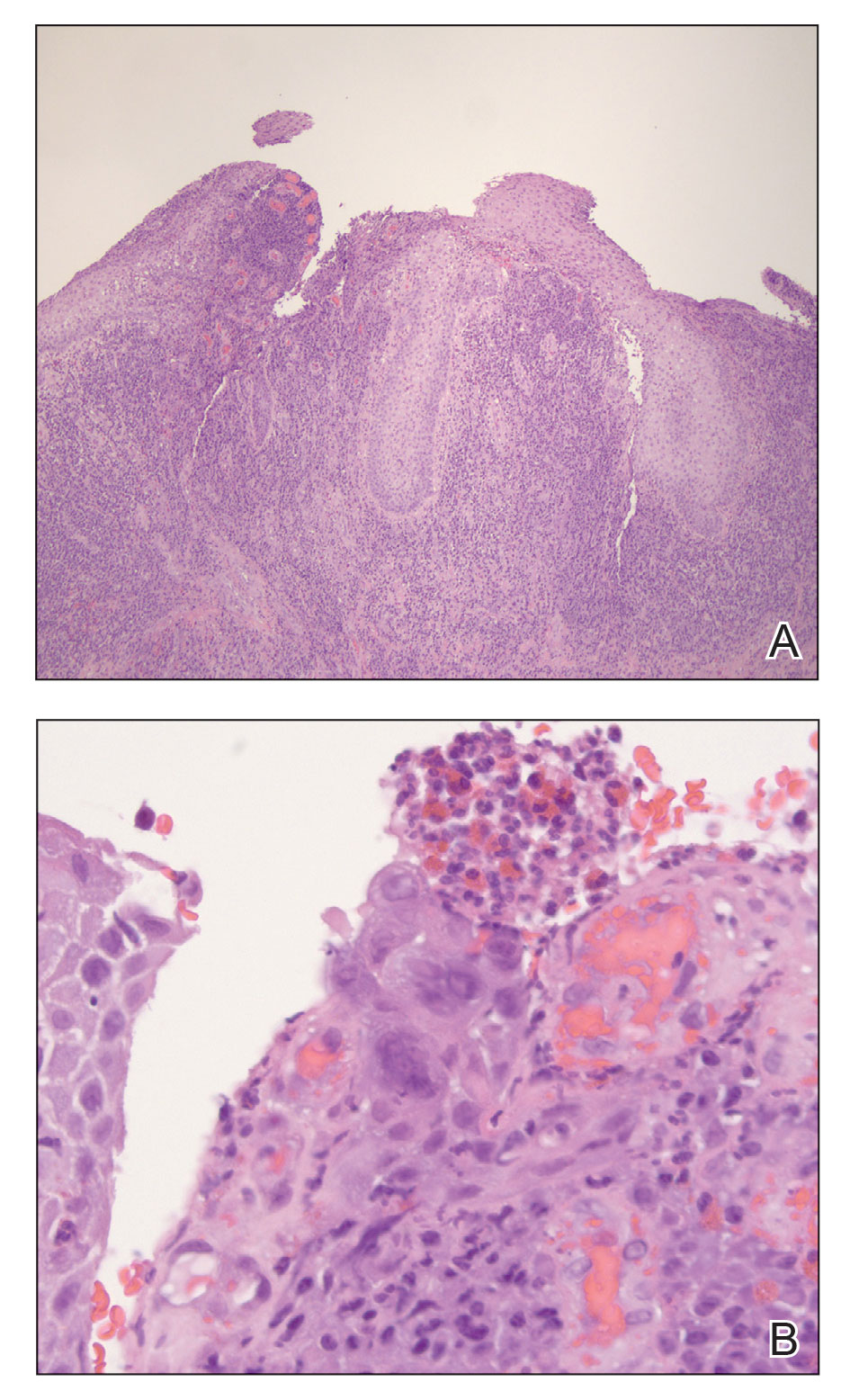

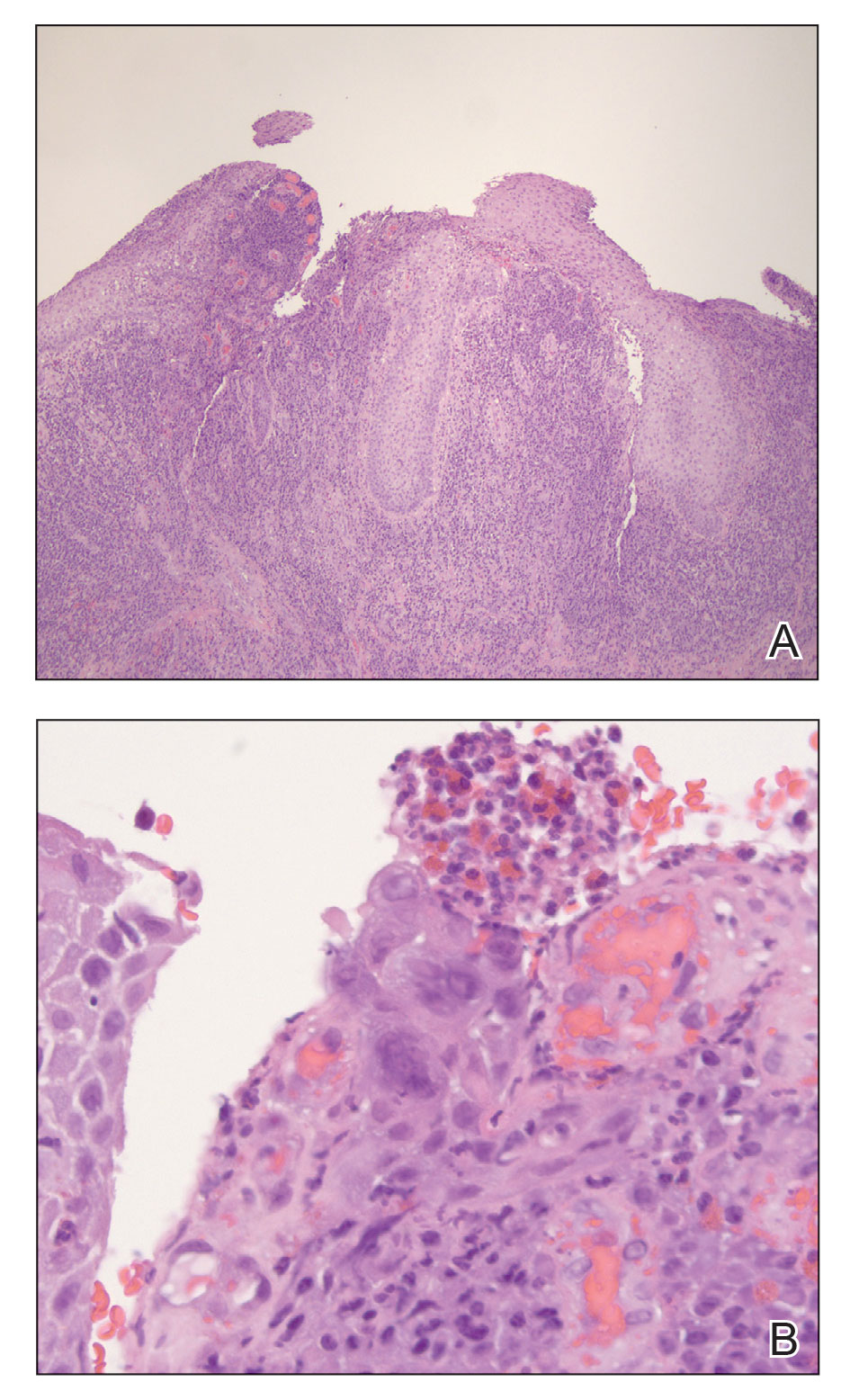

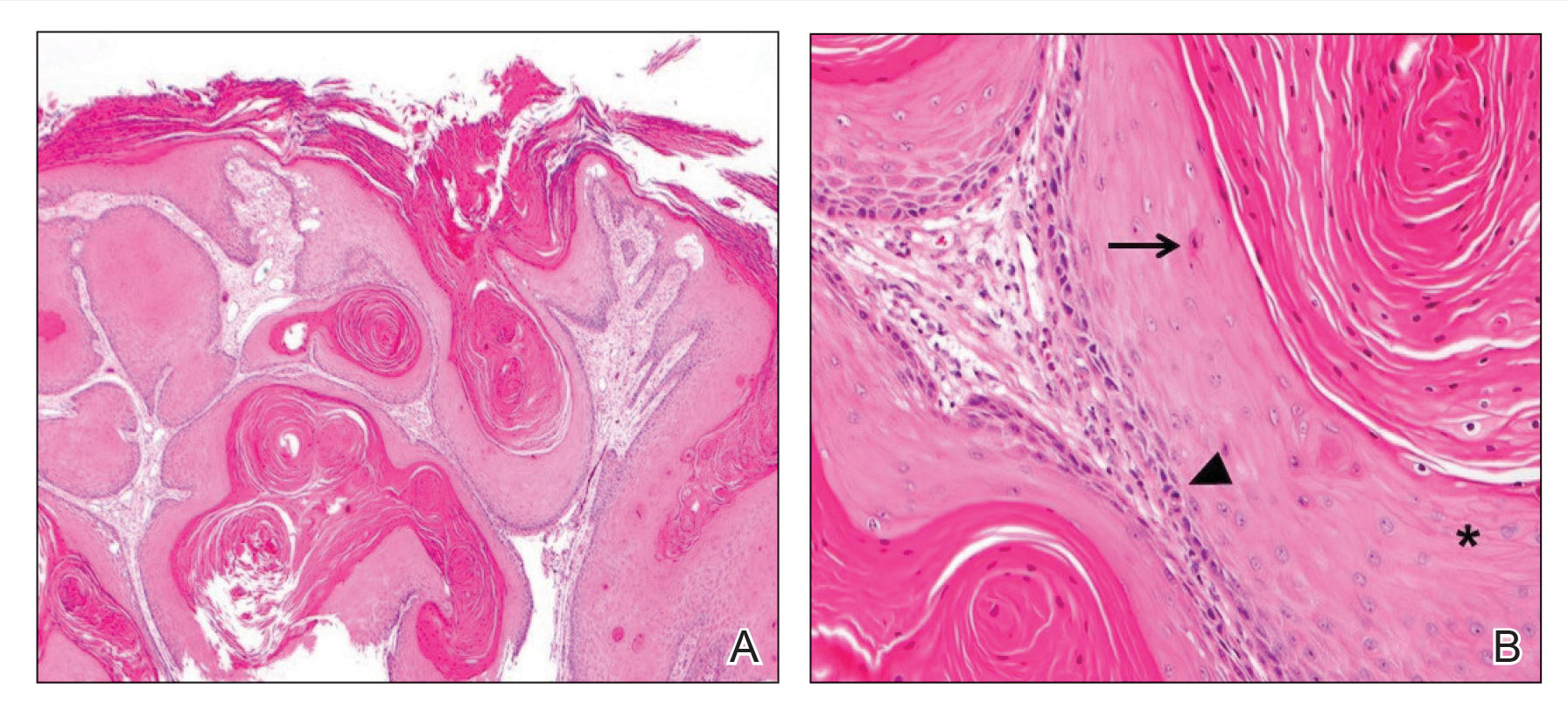

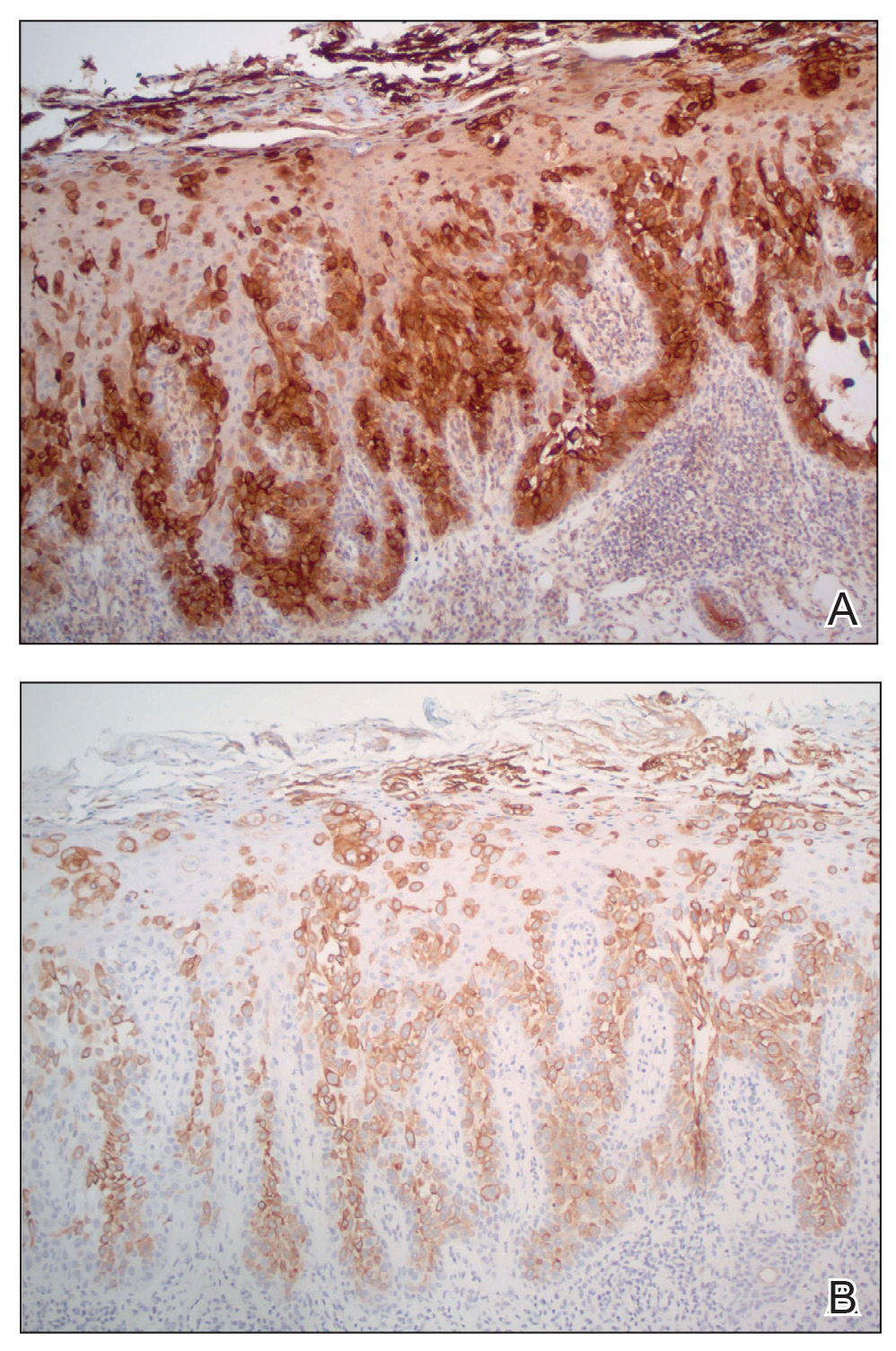

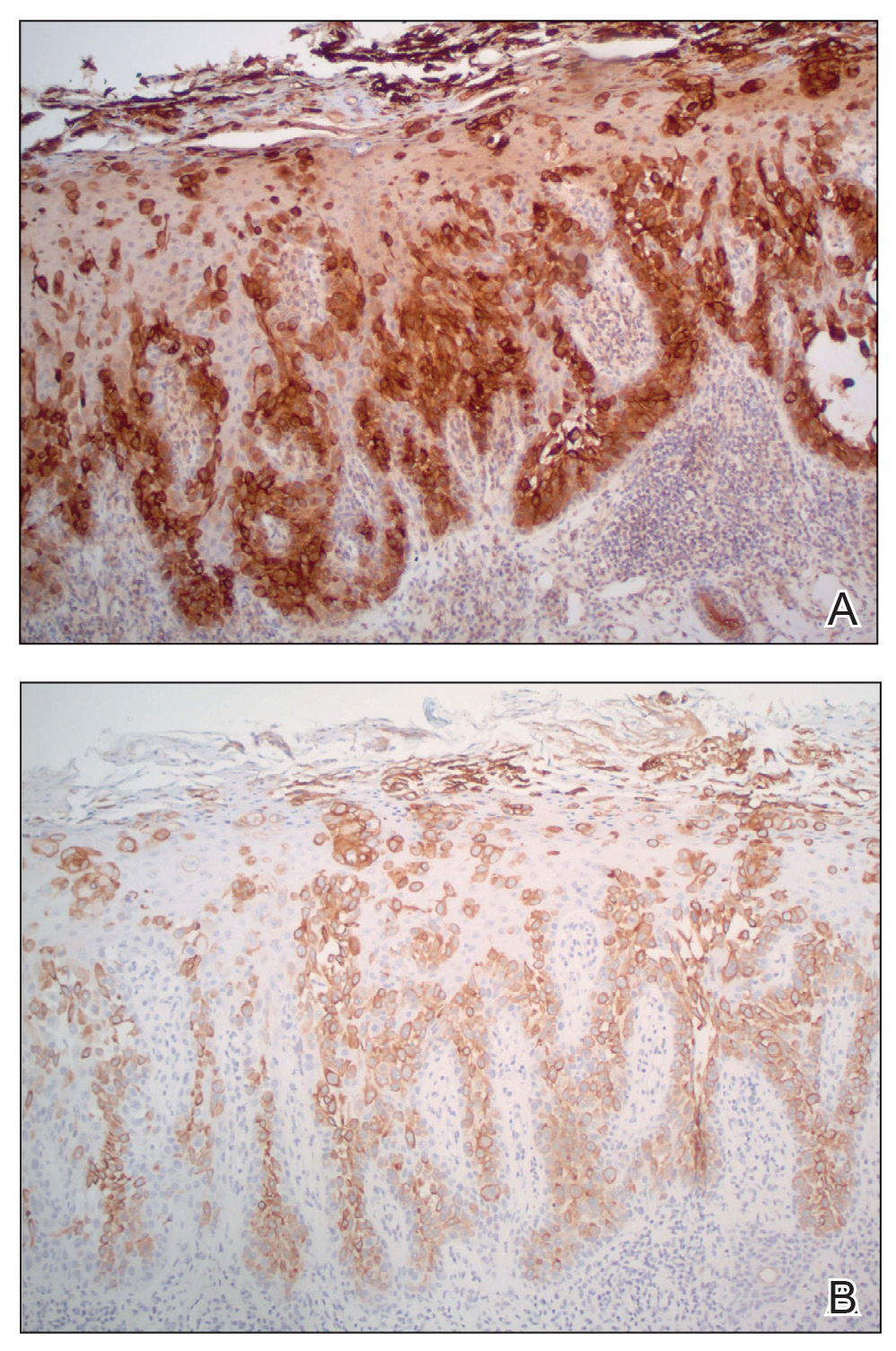

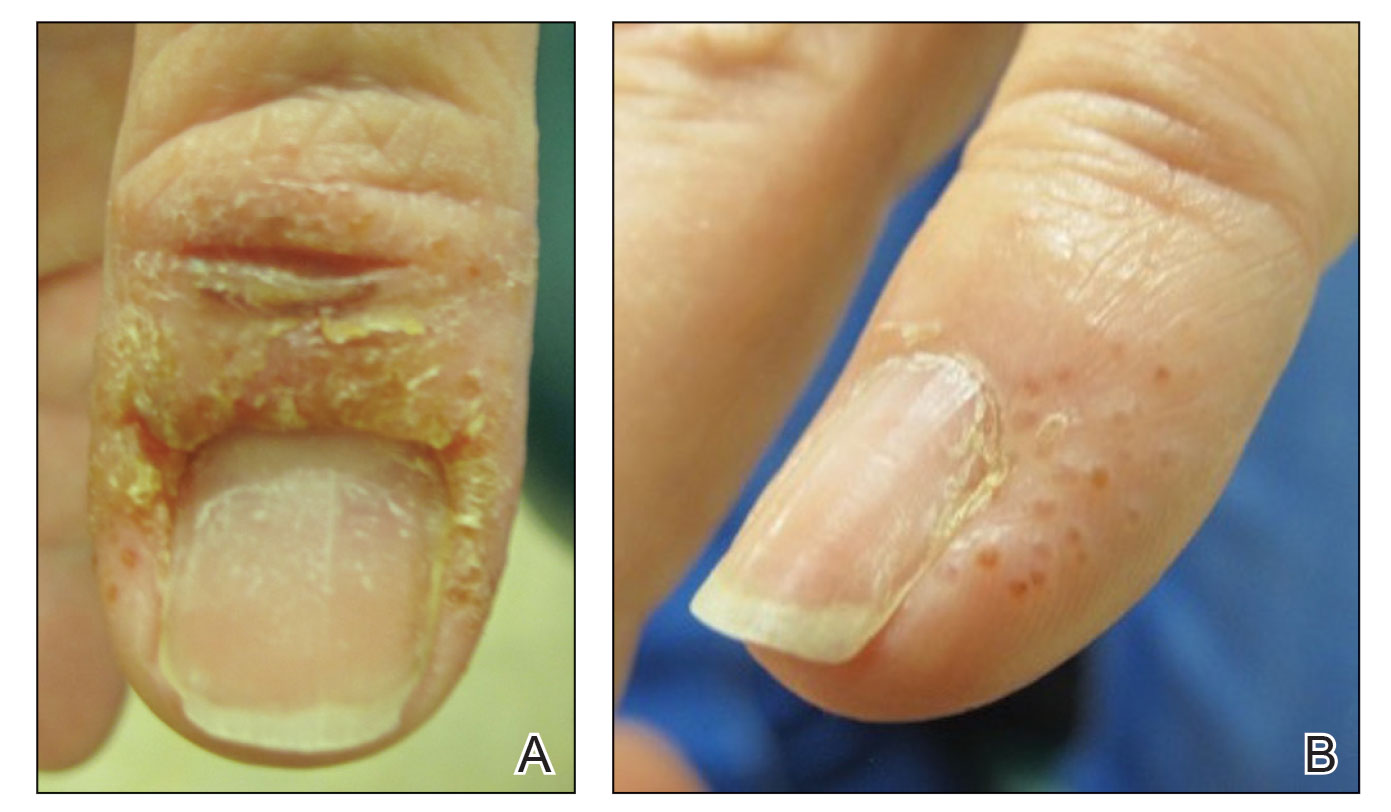

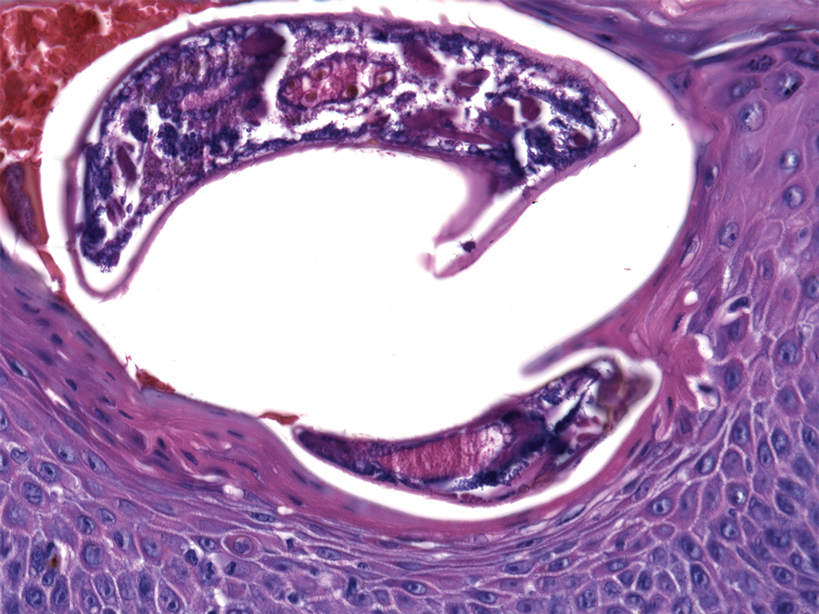

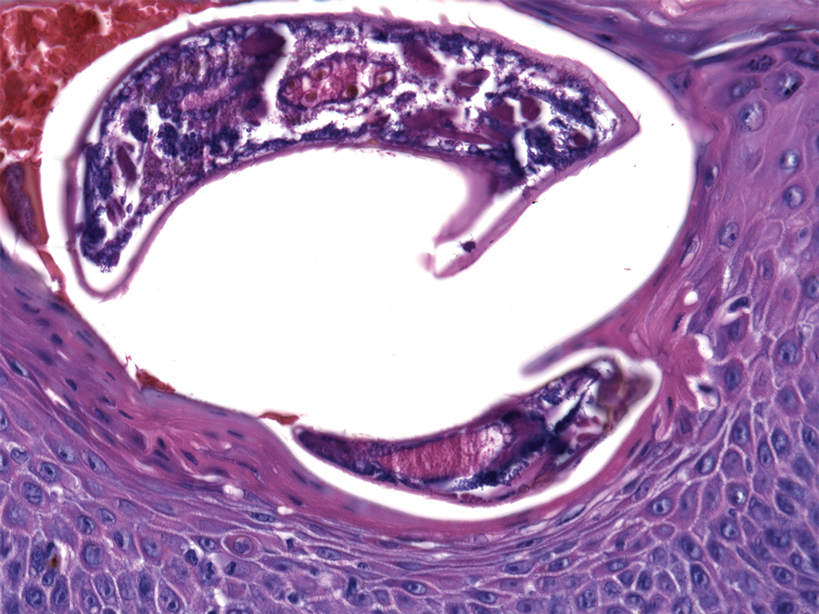

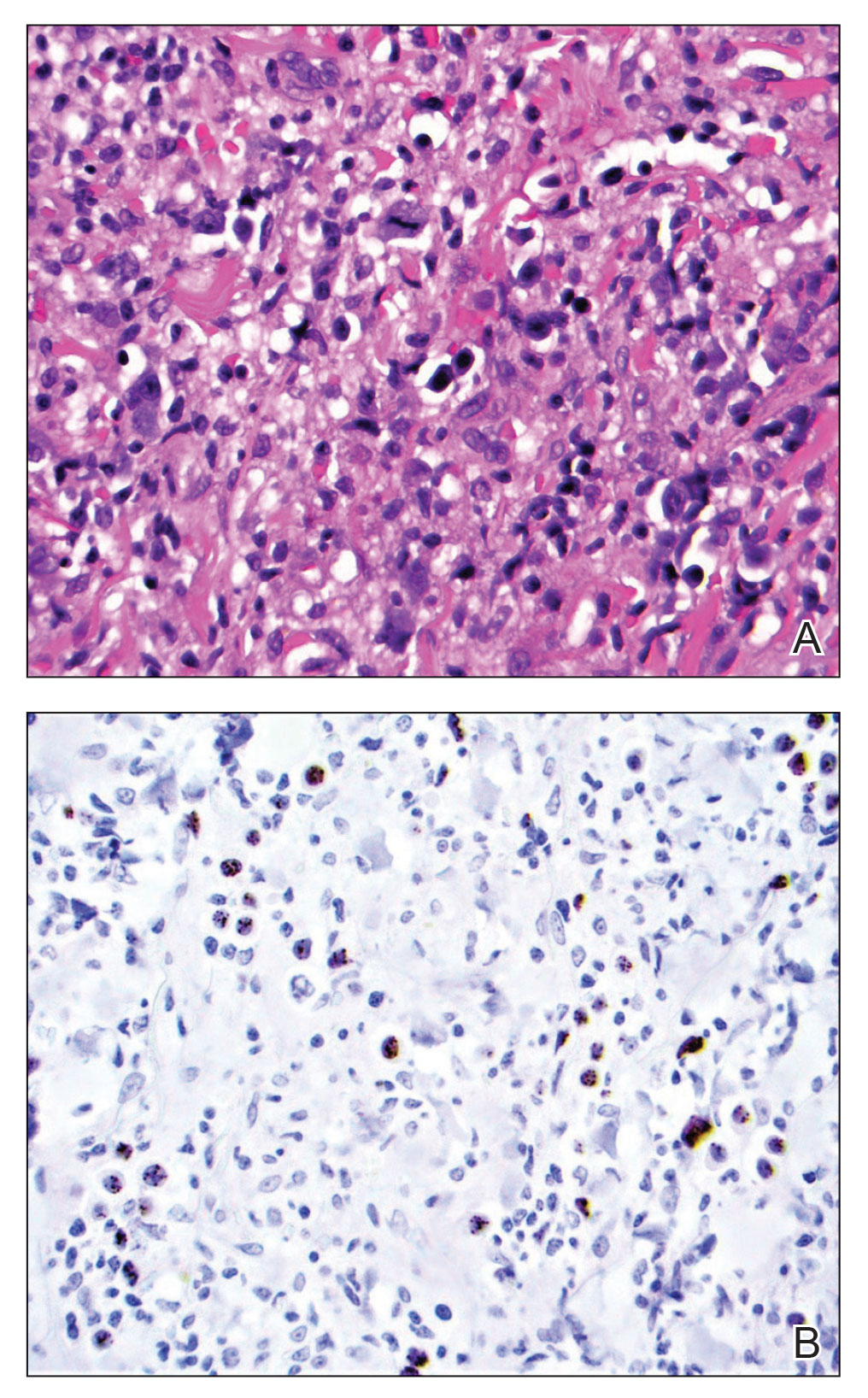

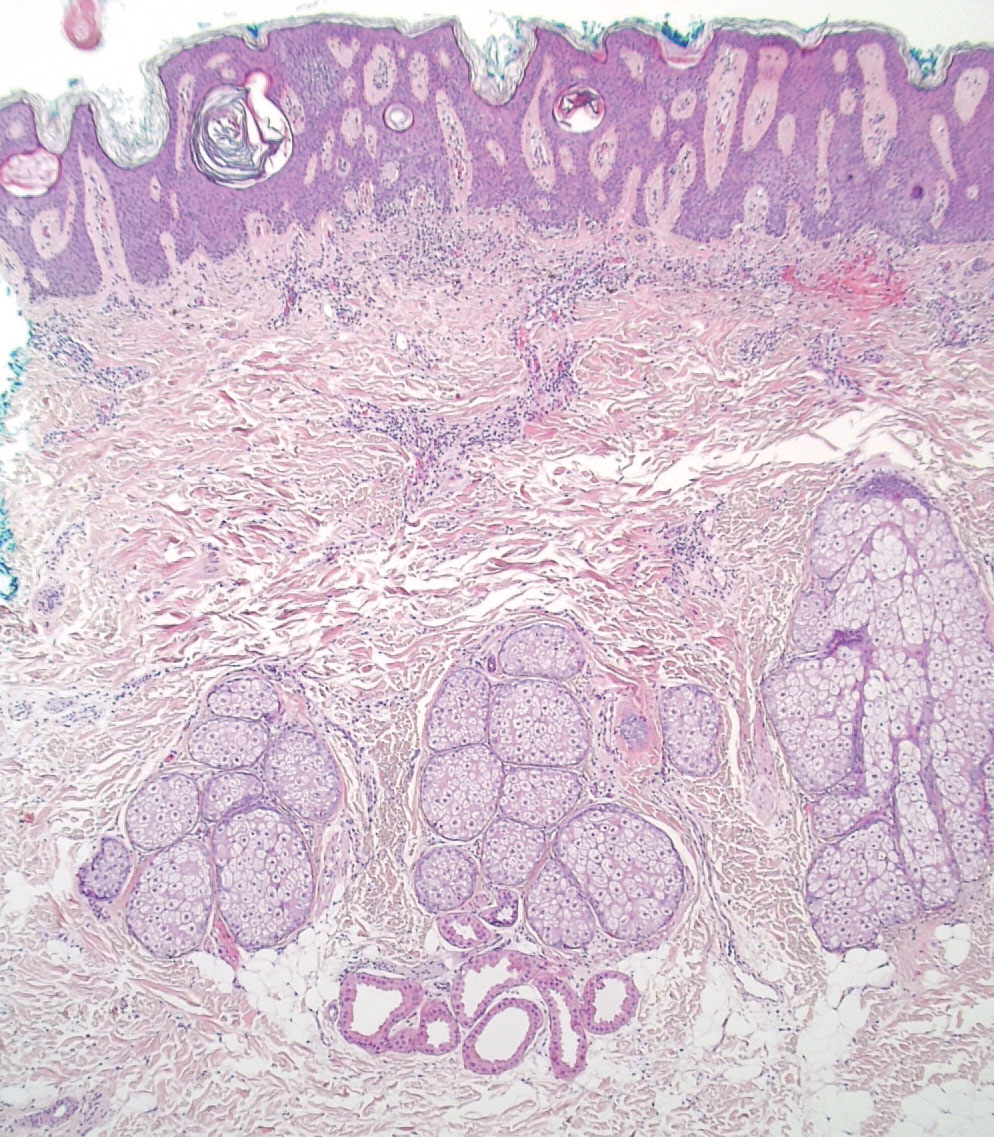

A 55-year-old man presented to the hospital with a painful expanding mass on the distal aspect of the penis of 3 months’ duration. He had a history of HIV infection that was well-controlled by antiretroviral therapy, prior hepatitis B virus infection and acyclovir-resistant genital HHV-2 infection. Physical examination revealed a large, firm, circumferential, exophytic, verrucous plaque with various areas of ulceration and purulent drainage on the distal shaft and glans of the penis (Figure 1). The patient’s most recent absolute CD4 count was 425 cells/mm3 (reference range, 500–1500 cells/mm3). His HIV viral load was undetectable at less than 30 copies/mL. Histopathology with hematoxylin and eosin staining of biopsy material from the penile lesion demonstrated pseudoepitheliomatous epidermal hyperplasia with focal ulceration and a mixed inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 2A). At higher magnification, clear viral cytopathic changes of HHV were noted, including multinucleation, nuclear molding, and homogenous gray nuclei (Figure 2B). Additional staining for fungi, mycobacteria, and spirochetes was negative. In-situ hybridization was negative for human papillomavirus subtypes. A bacterial culture of swabs of the purulent drainage was positive for Staphylococcus aureus and Proteus mirabilis.

Given the patient’s known history of acyclovir-resistant HHV-2 infection, he received a 28-day course of intravenous foscarnet 40 mg/kg every 12 hours. He also was given a 14-day course of intravenous ampicillin-sulbactam 3 g every 6 hours. The patient gradually improved during a 35-day hospital stay. He was discharged with cidofovir cream 1% and oral valacyclovir; the latter was subsequently discontinued by dermatology because of his known history of acyclovir resistance. Four months after discharge, the patient underwent a circumcision performed by urology to decrease the risk for recurrence and achieve the best cosmetic outcome. At the 6-month follow-up visit, dramatic clinical improvement was evident, with complete resolution of the plaque and only isolated areas of scarring (Figure 3). The patient reported that penile function was preserved.

Herpes vegetans represents a rare infection with HHV-1 or HHV-2, typically in patients who are considerably immunosuppressed, such as those with cancer, those undergoing transplantation, and those with uncontrolled HIV infection.1 Few cases of HV have been described in an immunocompetent patient.2 Our case is unique because the patient’s HIV infection was well controlled at the time HV was diagnosed, demonstrated by his modestly low CD4 count and undetectable HIV viral load.

Patients with HV can present diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Typically, a diagnosis of cutaneous HHV infection does not require a biopsy; most cases appear as clustered vesicular lesions, making the disease easy to diagnose clinically. However, biopsies and cultures are necessary to identify the underlying cause of atypical verrucous exophytic lesions. Other conditions with clinical features similar to HV include squamous cell carcinoma, condyloma acuminatum, and deep fungal and mycobacterial infections.2,3 A tissue biopsy, histologic staining, and tissue culture should be performed to identify the causative pathogen and potential targets for treatment. Definitive diagnosis is vital to deliver proper treatment modalities, which often involve a multimodal multidisciplinary approach.

Several pathogenic mechanisms of HV have been proposed. One theory suggests that in an immunocompetent patient, HHV typically triggers a lymphocytic response, which leads to activation of interferon alpha. However, in an immunocompromised patient, such as an individual with AIDS, this interferon response is diminished, which explains why these patients typically have a chronic and resistant HHV infection. HIV has an affinity for infecting dermal dendritic cells, which signals activation of tumor necrosis factor and interleukin.6 Both cytokines contribute to an antiapoptotic environment that promotes continued proliferation of these viral cells in the epidermis. Over time, propagation of disinhibited cells can lead to the verrucous and hyperkeratotic-appearing skin that is common in patients with HV.7

Another theorized mechanism underlying hypertrophic herpetic lesions was described in the context of HHV-1 infection and subsequent PG. El Hayderi et al8 reported that histologic and immunohistochemical examination of a patient’s lesion revealed sparse epithelial cell aggregates within PG as well as HHV-1 antigens in the nuclei and cytoplasm of normal-appearing and cytopathic epithelial cells. Immunohistochemical examination also revealed vascular endothelial growth factor within HHV-1–infected epithelial cells and PG endothelial cells, suggesting that PG formation may be indirectly driven by vascular endothelial growth factor and its proangiogenic properties. The pathogenesis of PG in the setting of HHV-1 infection displays many similarities to hyperkeratotic lesions observed in atypical cutaneous manifestations of HHV-2.8

The management of patients with HV continues to be complex, often requiring a multimodal regimen. Although acyclovir has been shown to be highly effective for treating and preventing most HHV infections, acyclovir resistance frequently has been reported in immunocompromised populations.5 Acyclovir resistance can be correlated with the severity of immunodeficiency as well as the duration of acyclovir exposure. Resistance to acyclovir often results from deficient intracellular phosphorylation, which is required for activation of the drug. If patients show resistance to acyclovir and its derivatives, alternate drug classes that do not depend on thymidine kinase phosphorylation should be considered.

Our patient received a combination of intravenous foscarnet and a course of ampicillin-sulbactam while an inpatient due to his documented history of acyclovir-resistant HHV-2 infection, and he was discharged on cidofovir cream 1%. Cidofovir is US Food and Drug Administration approved for treating cytomegalovirus retinitis in patients with AIDS. Although data are limited, topical and intralesional cidofovir have been used to treat acyclovir-resistant cases of HV with documented success.1,9 In refractory HV or when the disease is slow to resolve, intralesional cidofovir has been documented to be an additional treatment option. Intralesional and topical cidofovir carry a much lower risk for adverse effects such as kidney dysfunction compared to intravenous cidofovir1 and can be considered in patients with minimal clinical improvement and those at increased risk for side effects.

Our case demonstrated how a patient with HV may require a complex and prolonged hospital course for appropriate treatment. Our patient required an array of both medical and surgical modalities to reach the desired outcome. Here, a multitude of specialties including infectious disease, dermatology, and urology worked together to reach a positive clinical and cosmetic outcome for this patient.

- Castelo-Soccio L, Bernardin R, Stern J, et al. Successful treatment of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus with intralesional cidofovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:124-126. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.363

- Bae-Harboe Y-SC, Khachemoune A. Verrucous herpetic infection of the scrotum and the groin in an immuno-competent patient: case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18. https://doi.org/10.5070/D30sv058j6

- Elosiebo RI, Koubek VA, Patel TS, et al. Vegetative sacral plaque in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Cutis. 2015;96:E7-E9.

- Saling C, Slim J, Szabela ME. A case of an atypical resistant granulomatous HHV-1 and HHV-2 ulceration in an AIDS patient treated with intralesional cidofovir. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2019;7:2050313X19847029. doi:10.1177/2050313X19847029

- Martinez V, Molina J-M, Scieux C, et al. Topical imiquimod for recurrent acyclovir-resistant HHV infection. Am J Med. 2006 May;119:E9-E11. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.06.037

- Ronkainen SD, Rothenberger M. Herpes vegetans: an unusual and acyclovir-resistant form of HHV. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:393. doi:10.1007/s11606-017-4256-y

- Quesada AE, Galfione S, Colome M, et al. Verrucous herpes of the scrotum presenting clinically as verrucous squamous cell carcinoma: case report and review of the literature. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2014;44:208-212.

- El Hayderi L, Paurobally D, Fassotte MF, et al. Herpes simplex virus type-I and pyogenic granuloma: a vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated association? Case Rep Dermatol. 2013;5:236-243. doi:10.1159/000354570

- Toro JR, Sanchez S, Turiansky G, et al. Topical cidofovir for the treatment of dermatologic conditions: verruca, condyloma, intraepithelial neoplasia, herpes simplex and its potential use in smallpox. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:301-319. doi:10.1016/s0733-8635(02)00116-x

To the Editor:

Herpes vegetans (HV) is an uncommon infection caused by human herpesvirus (HHV) in patients who are immunocompromised, such as those who are HIV positive.1 Unlike typical HHV infection, HV can present with exophytic exudative ulcers and papillomatous vegetations. The presentation of ulcerated genital nodules, especially in an immunocompromised patient, yields an array of disorders in the differential diagnosis, including condyloma latum, condyloma acuminatum, pyogenic granuloma (PG), and verrucous carcinoma.2,3 Histopathology of HV reveals pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, plasma cell infiltration, and positivity for HHV type 1 (HHV-1) and/or HHV type 2 (HHV-2). Herpes vegetans lesions typically require a multimodal treatment approach because many cases are resistant to acyclovir. Treatment options include the nucleoside analogues foscarnet and cidofovir; immunomodulators such as topical imiquimod; and the topical antiviral trifluridine.1,4-6 We describe a case of HV in a patient with a history of well-controlled HIV infection who presented with a painful fungating penile lesion.

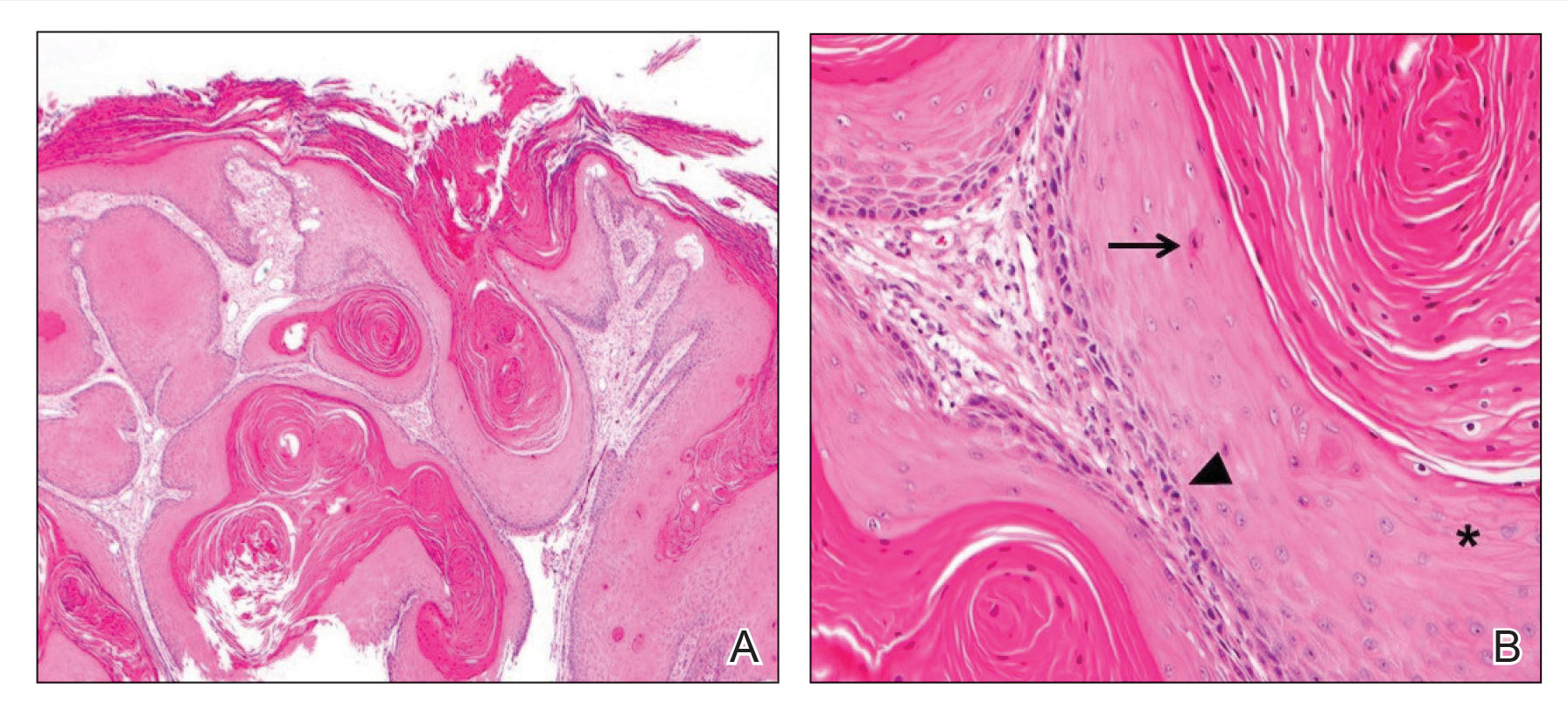

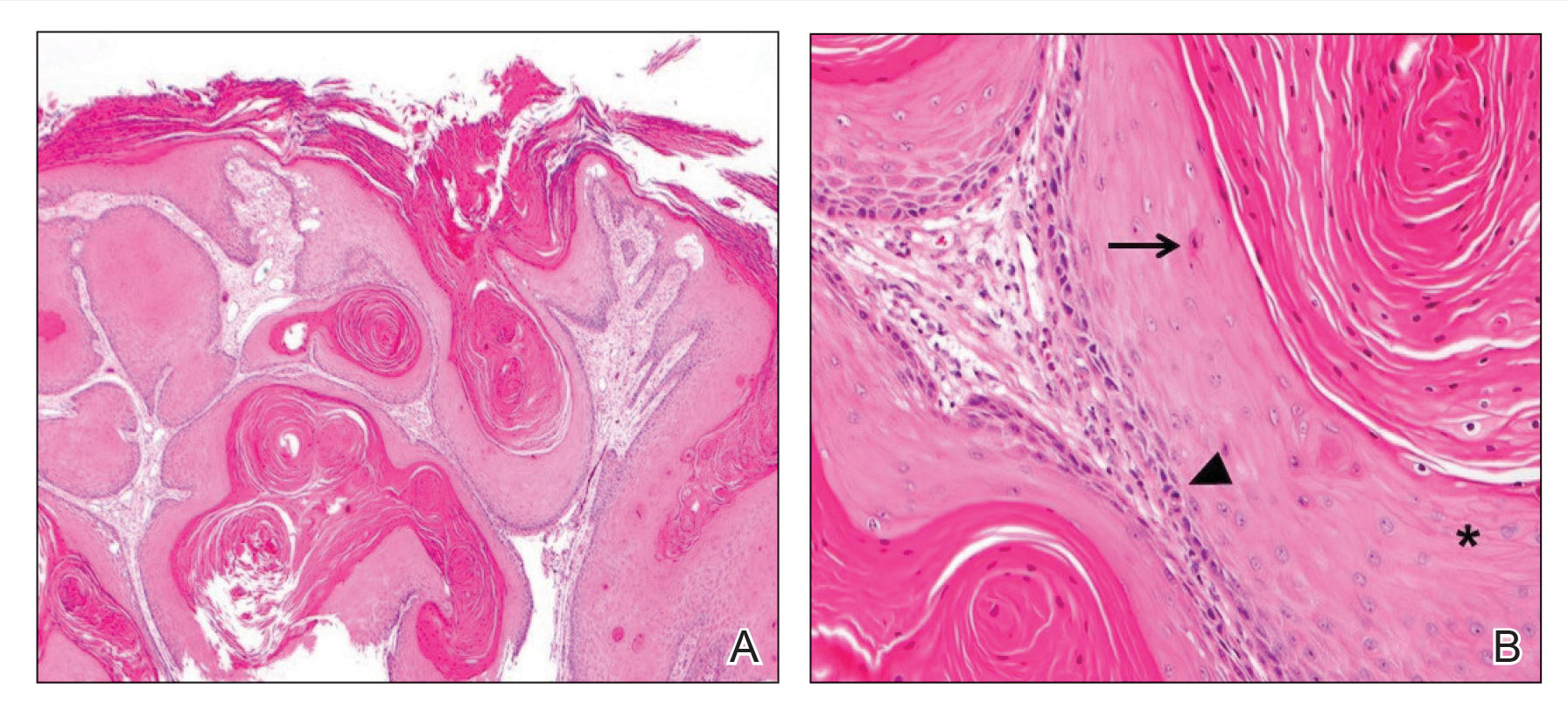

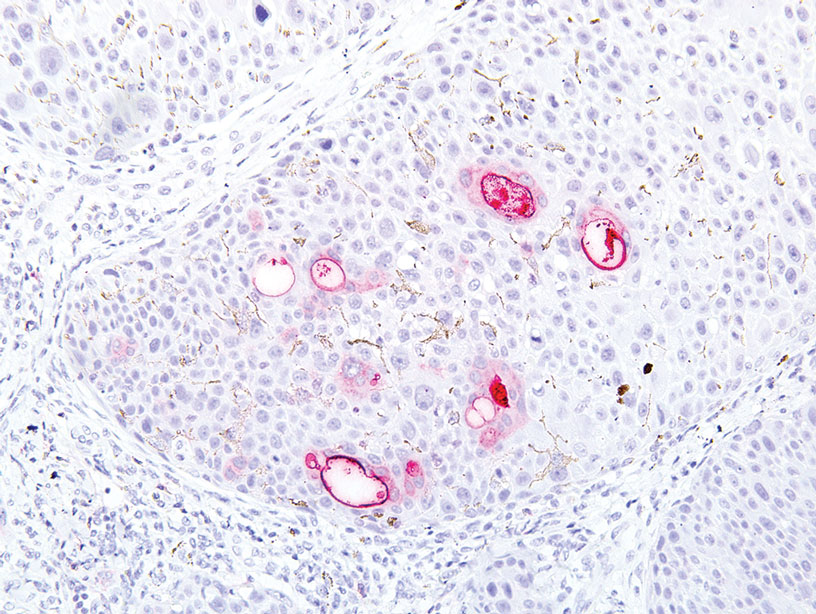

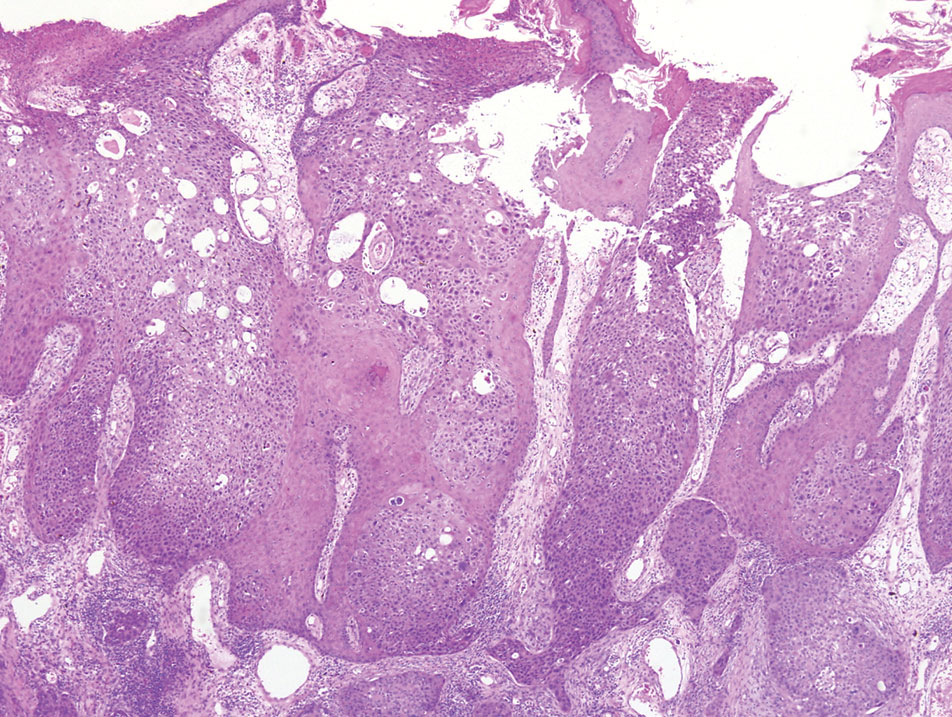

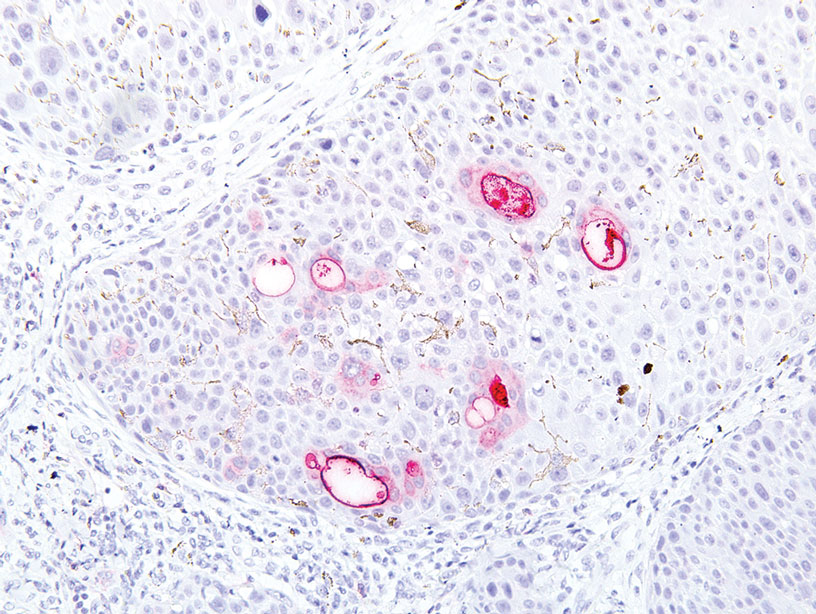

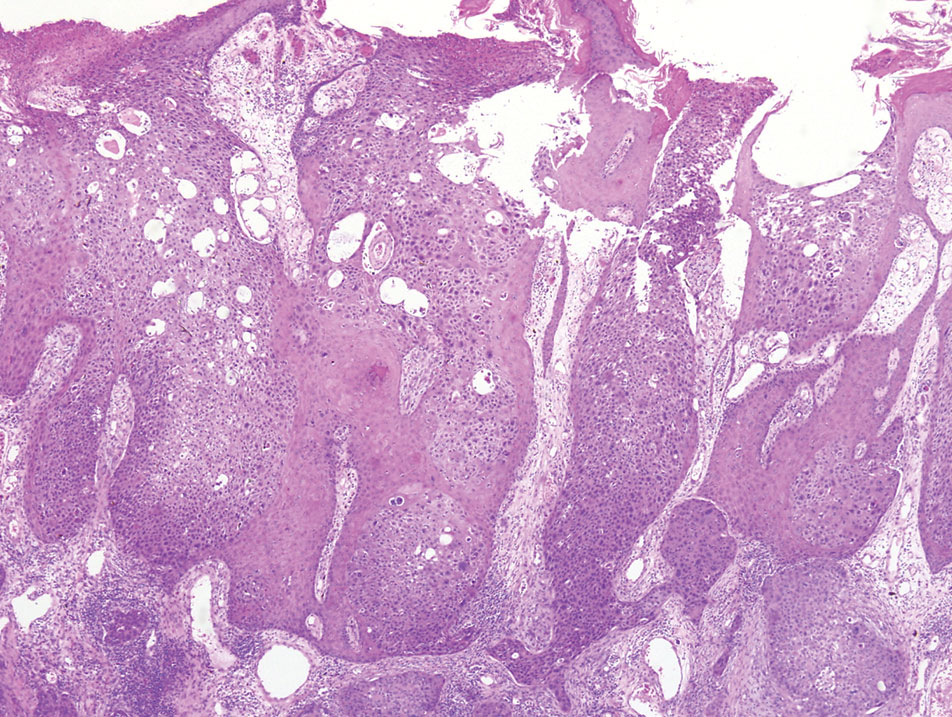

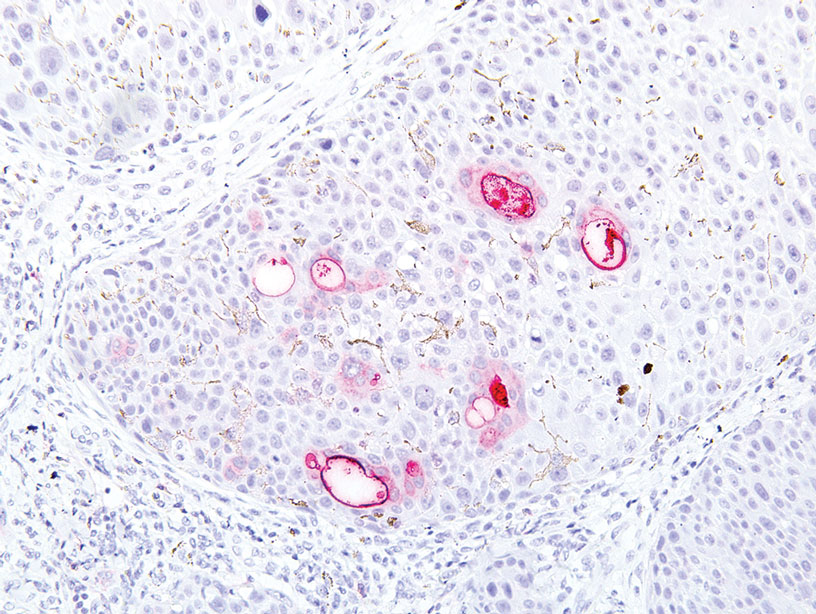

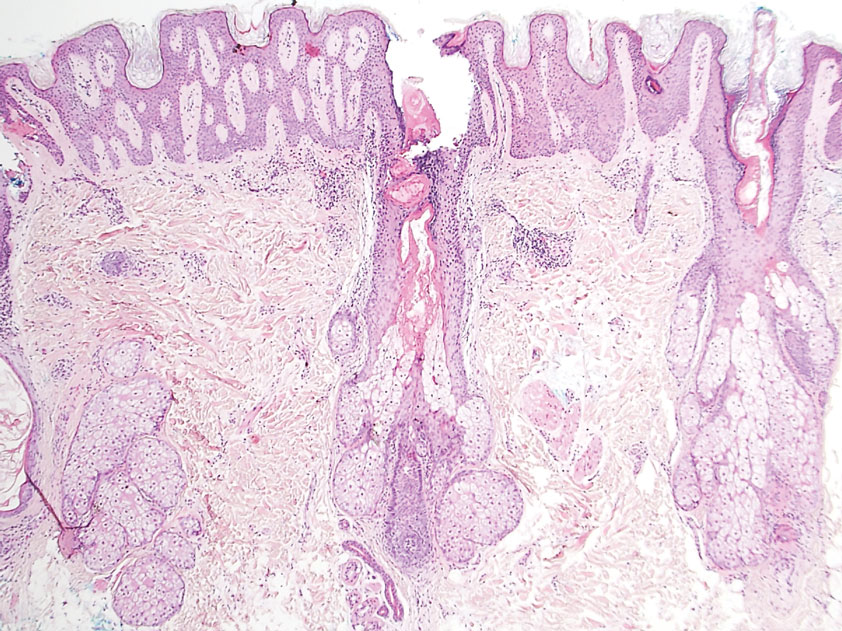

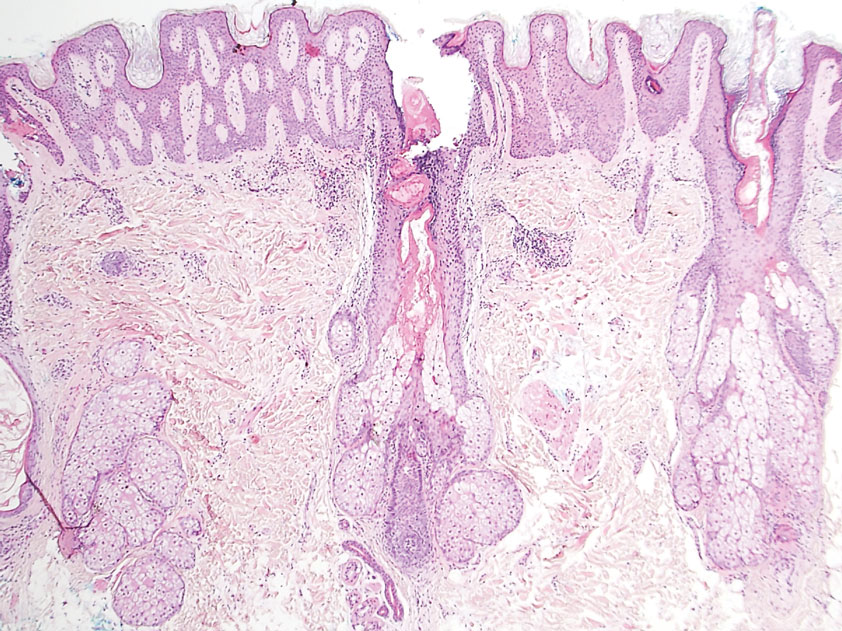

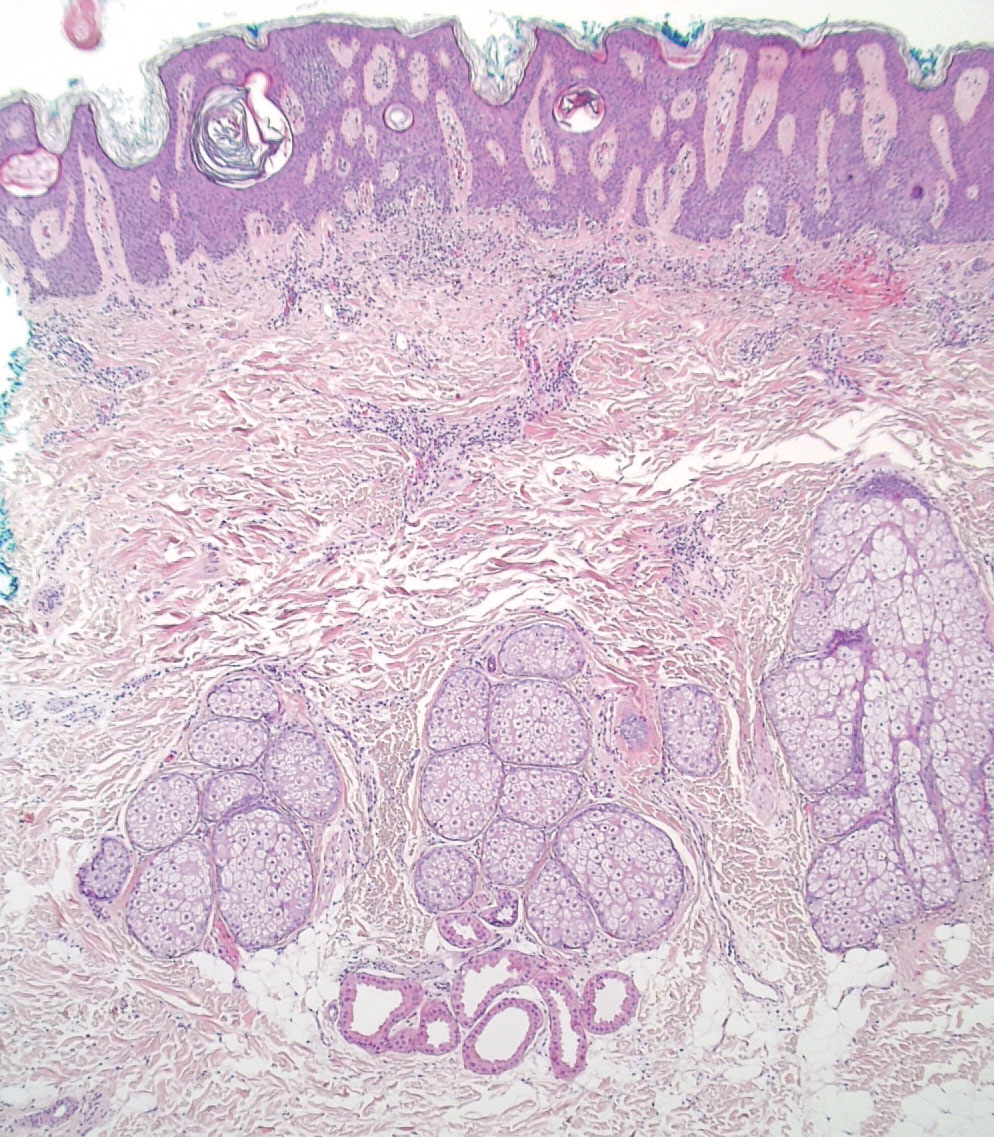

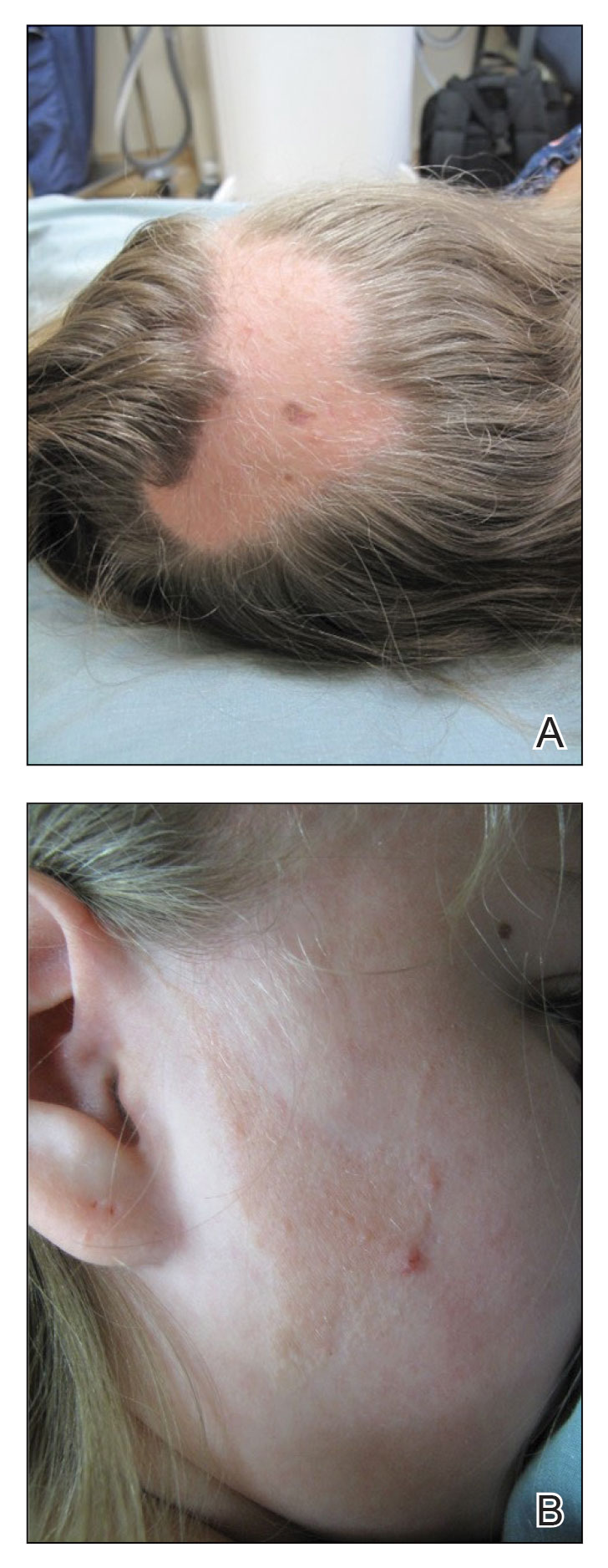

A 55-year-old man presented to the hospital with a painful expanding mass on the distal aspect of the penis of 3 months’ duration. He had a history of HIV infection that was well-controlled by antiretroviral therapy, prior hepatitis B virus infection and acyclovir-resistant genital HHV-2 infection. Physical examination revealed a large, firm, circumferential, exophytic, verrucous plaque with various areas of ulceration and purulent drainage on the distal shaft and glans of the penis (Figure 1). The patient’s most recent absolute CD4 count was 425 cells/mm3 (reference range, 500–1500 cells/mm3). His HIV viral load was undetectable at less than 30 copies/mL. Histopathology with hematoxylin and eosin staining of biopsy material from the penile lesion demonstrated pseudoepitheliomatous epidermal hyperplasia with focal ulceration and a mixed inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 2A). At higher magnification, clear viral cytopathic changes of HHV were noted, including multinucleation, nuclear molding, and homogenous gray nuclei (Figure 2B). Additional staining for fungi, mycobacteria, and spirochetes was negative. In-situ hybridization was negative for human papillomavirus subtypes. A bacterial culture of swabs of the purulent drainage was positive for Staphylococcus aureus and Proteus mirabilis.

Given the patient’s known history of acyclovir-resistant HHV-2 infection, he received a 28-day course of intravenous foscarnet 40 mg/kg every 12 hours. He also was given a 14-day course of intravenous ampicillin-sulbactam 3 g every 6 hours. The patient gradually improved during a 35-day hospital stay. He was discharged with cidofovir cream 1% and oral valacyclovir; the latter was subsequently discontinued by dermatology because of his known history of acyclovir resistance. Four months after discharge, the patient underwent a circumcision performed by urology to decrease the risk for recurrence and achieve the best cosmetic outcome. At the 6-month follow-up visit, dramatic clinical improvement was evident, with complete resolution of the plaque and only isolated areas of scarring (Figure 3). The patient reported that penile function was preserved.

Herpes vegetans represents a rare infection with HHV-1 or HHV-2, typically in patients who are considerably immunosuppressed, such as those with cancer, those undergoing transplantation, and those with uncontrolled HIV infection.1 Few cases of HV have been described in an immunocompetent patient.2 Our case is unique because the patient’s HIV infection was well controlled at the time HV was diagnosed, demonstrated by his modestly low CD4 count and undetectable HIV viral load.

Patients with HV can present diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Typically, a diagnosis of cutaneous HHV infection does not require a biopsy; most cases appear as clustered vesicular lesions, making the disease easy to diagnose clinically. However, biopsies and cultures are necessary to identify the underlying cause of atypical verrucous exophytic lesions. Other conditions with clinical features similar to HV include squamous cell carcinoma, condyloma acuminatum, and deep fungal and mycobacterial infections.2,3 A tissue biopsy, histologic staining, and tissue culture should be performed to identify the causative pathogen and potential targets for treatment. Definitive diagnosis is vital to deliver proper treatment modalities, which often involve a multimodal multidisciplinary approach.

Several pathogenic mechanisms of HV have been proposed. One theory suggests that in an immunocompetent patient, HHV typically triggers a lymphocytic response, which leads to activation of interferon alpha. However, in an immunocompromised patient, such as an individual with AIDS, this interferon response is diminished, which explains why these patients typically have a chronic and resistant HHV infection. HIV has an affinity for infecting dermal dendritic cells, which signals activation of tumor necrosis factor and interleukin.6 Both cytokines contribute to an antiapoptotic environment that promotes continued proliferation of these viral cells in the epidermis. Over time, propagation of disinhibited cells can lead to the verrucous and hyperkeratotic-appearing skin that is common in patients with HV.7

Another theorized mechanism underlying hypertrophic herpetic lesions was described in the context of HHV-1 infection and subsequent PG. El Hayderi et al8 reported that histologic and immunohistochemical examination of a patient’s lesion revealed sparse epithelial cell aggregates within PG as well as HHV-1 antigens in the nuclei and cytoplasm of normal-appearing and cytopathic epithelial cells. Immunohistochemical examination also revealed vascular endothelial growth factor within HHV-1–infected epithelial cells and PG endothelial cells, suggesting that PG formation may be indirectly driven by vascular endothelial growth factor and its proangiogenic properties. The pathogenesis of PG in the setting of HHV-1 infection displays many similarities to hyperkeratotic lesions observed in atypical cutaneous manifestations of HHV-2.8

The management of patients with HV continues to be complex, often requiring a multimodal regimen. Although acyclovir has been shown to be highly effective for treating and preventing most HHV infections, acyclovir resistance frequently has been reported in immunocompromised populations.5 Acyclovir resistance can be correlated with the severity of immunodeficiency as well as the duration of acyclovir exposure. Resistance to acyclovir often results from deficient intracellular phosphorylation, which is required for activation of the drug. If patients show resistance to acyclovir and its derivatives, alternate drug classes that do not depend on thymidine kinase phosphorylation should be considered.

Our patient received a combination of intravenous foscarnet and a course of ampicillin-sulbactam while an inpatient due to his documented history of acyclovir-resistant HHV-2 infection, and he was discharged on cidofovir cream 1%. Cidofovir is US Food and Drug Administration approved for treating cytomegalovirus retinitis in patients with AIDS. Although data are limited, topical and intralesional cidofovir have been used to treat acyclovir-resistant cases of HV with documented success.1,9 In refractory HV or when the disease is slow to resolve, intralesional cidofovir has been documented to be an additional treatment option. Intralesional and topical cidofovir carry a much lower risk for adverse effects such as kidney dysfunction compared to intravenous cidofovir1 and can be considered in patients with minimal clinical improvement and those at increased risk for side effects.

Our case demonstrated how a patient with HV may require a complex and prolonged hospital course for appropriate treatment. Our patient required an array of both medical and surgical modalities to reach the desired outcome. Here, a multitude of specialties including infectious disease, dermatology, and urology worked together to reach a positive clinical and cosmetic outcome for this patient.

To the Editor:

Herpes vegetans (HV) is an uncommon infection caused by human herpesvirus (HHV) in patients who are immunocompromised, such as those who are HIV positive.1 Unlike typical HHV infection, HV can present with exophytic exudative ulcers and papillomatous vegetations. The presentation of ulcerated genital nodules, especially in an immunocompromised patient, yields an array of disorders in the differential diagnosis, including condyloma latum, condyloma acuminatum, pyogenic granuloma (PG), and verrucous carcinoma.2,3 Histopathology of HV reveals pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, plasma cell infiltration, and positivity for HHV type 1 (HHV-1) and/or HHV type 2 (HHV-2). Herpes vegetans lesions typically require a multimodal treatment approach because many cases are resistant to acyclovir. Treatment options include the nucleoside analogues foscarnet and cidofovir; immunomodulators such as topical imiquimod; and the topical antiviral trifluridine.1,4-6 We describe a case of HV in a patient with a history of well-controlled HIV infection who presented with a painful fungating penile lesion.

A 55-year-old man presented to the hospital with a painful expanding mass on the distal aspect of the penis of 3 months’ duration. He had a history of HIV infection that was well-controlled by antiretroviral therapy, prior hepatitis B virus infection and acyclovir-resistant genital HHV-2 infection. Physical examination revealed a large, firm, circumferential, exophytic, verrucous plaque with various areas of ulceration and purulent drainage on the distal shaft and glans of the penis (Figure 1). The patient’s most recent absolute CD4 count was 425 cells/mm3 (reference range, 500–1500 cells/mm3). His HIV viral load was undetectable at less than 30 copies/mL. Histopathology with hematoxylin and eosin staining of biopsy material from the penile lesion demonstrated pseudoepitheliomatous epidermal hyperplasia with focal ulceration and a mixed inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 2A). At higher magnification, clear viral cytopathic changes of HHV were noted, including multinucleation, nuclear molding, and homogenous gray nuclei (Figure 2B). Additional staining for fungi, mycobacteria, and spirochetes was negative. In-situ hybridization was negative for human papillomavirus subtypes. A bacterial culture of swabs of the purulent drainage was positive for Staphylococcus aureus and Proteus mirabilis.

Given the patient’s known history of acyclovir-resistant HHV-2 infection, he received a 28-day course of intravenous foscarnet 40 mg/kg every 12 hours. He also was given a 14-day course of intravenous ampicillin-sulbactam 3 g every 6 hours. The patient gradually improved during a 35-day hospital stay. He was discharged with cidofovir cream 1% and oral valacyclovir; the latter was subsequently discontinued by dermatology because of his known history of acyclovir resistance. Four months after discharge, the patient underwent a circumcision performed by urology to decrease the risk for recurrence and achieve the best cosmetic outcome. At the 6-month follow-up visit, dramatic clinical improvement was evident, with complete resolution of the plaque and only isolated areas of scarring (Figure 3). The patient reported that penile function was preserved.

Herpes vegetans represents a rare infection with HHV-1 or HHV-2, typically in patients who are considerably immunosuppressed, such as those with cancer, those undergoing transplantation, and those with uncontrolled HIV infection.1 Few cases of HV have been described in an immunocompetent patient.2 Our case is unique because the patient’s HIV infection was well controlled at the time HV was diagnosed, demonstrated by his modestly low CD4 count and undetectable HIV viral load.

Patients with HV can present diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Typically, a diagnosis of cutaneous HHV infection does not require a biopsy; most cases appear as clustered vesicular lesions, making the disease easy to diagnose clinically. However, biopsies and cultures are necessary to identify the underlying cause of atypical verrucous exophytic lesions. Other conditions with clinical features similar to HV include squamous cell carcinoma, condyloma acuminatum, and deep fungal and mycobacterial infections.2,3 A tissue biopsy, histologic staining, and tissue culture should be performed to identify the causative pathogen and potential targets for treatment. Definitive diagnosis is vital to deliver proper treatment modalities, which often involve a multimodal multidisciplinary approach.

Several pathogenic mechanisms of HV have been proposed. One theory suggests that in an immunocompetent patient, HHV typically triggers a lymphocytic response, which leads to activation of interferon alpha. However, in an immunocompromised patient, such as an individual with AIDS, this interferon response is diminished, which explains why these patients typically have a chronic and resistant HHV infection. HIV has an affinity for infecting dermal dendritic cells, which signals activation of tumor necrosis factor and interleukin.6 Both cytokines contribute to an antiapoptotic environment that promotes continued proliferation of these viral cells in the epidermis. Over time, propagation of disinhibited cells can lead to the verrucous and hyperkeratotic-appearing skin that is common in patients with HV.7

Another theorized mechanism underlying hypertrophic herpetic lesions was described in the context of HHV-1 infection and subsequent PG. El Hayderi et al8 reported that histologic and immunohistochemical examination of a patient’s lesion revealed sparse epithelial cell aggregates within PG as well as HHV-1 antigens in the nuclei and cytoplasm of normal-appearing and cytopathic epithelial cells. Immunohistochemical examination also revealed vascular endothelial growth factor within HHV-1–infected epithelial cells and PG endothelial cells, suggesting that PG formation may be indirectly driven by vascular endothelial growth factor and its proangiogenic properties. The pathogenesis of PG in the setting of HHV-1 infection displays many similarities to hyperkeratotic lesions observed in atypical cutaneous manifestations of HHV-2.8

The management of patients with HV continues to be complex, often requiring a multimodal regimen. Although acyclovir has been shown to be highly effective for treating and preventing most HHV infections, acyclovir resistance frequently has been reported in immunocompromised populations.5 Acyclovir resistance can be correlated with the severity of immunodeficiency as well as the duration of acyclovir exposure. Resistance to acyclovir often results from deficient intracellular phosphorylation, which is required for activation of the drug. If patients show resistance to acyclovir and its derivatives, alternate drug classes that do not depend on thymidine kinase phosphorylation should be considered.

Our patient received a combination of intravenous foscarnet and a course of ampicillin-sulbactam while an inpatient due to his documented history of acyclovir-resistant HHV-2 infection, and he was discharged on cidofovir cream 1%. Cidofovir is US Food and Drug Administration approved for treating cytomegalovirus retinitis in patients with AIDS. Although data are limited, topical and intralesional cidofovir have been used to treat acyclovir-resistant cases of HV with documented success.1,9 In refractory HV or when the disease is slow to resolve, intralesional cidofovir has been documented to be an additional treatment option. Intralesional and topical cidofovir carry a much lower risk for adverse effects such as kidney dysfunction compared to intravenous cidofovir1 and can be considered in patients with minimal clinical improvement and those at increased risk for side effects.

Our case demonstrated how a patient with HV may require a complex and prolonged hospital course for appropriate treatment. Our patient required an array of both medical and surgical modalities to reach the desired outcome. Here, a multitude of specialties including infectious disease, dermatology, and urology worked together to reach a positive clinical and cosmetic outcome for this patient.

- Castelo-Soccio L, Bernardin R, Stern J, et al. Successful treatment of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus with intralesional cidofovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:124-126. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.363

- Bae-Harboe Y-SC, Khachemoune A. Verrucous herpetic infection of the scrotum and the groin in an immuno-competent patient: case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18. https://doi.org/10.5070/D30sv058j6

- Elosiebo RI, Koubek VA, Patel TS, et al. Vegetative sacral plaque in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Cutis. 2015;96:E7-E9.

- Saling C, Slim J, Szabela ME. A case of an atypical resistant granulomatous HHV-1 and HHV-2 ulceration in an AIDS patient treated with intralesional cidofovir. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2019;7:2050313X19847029. doi:10.1177/2050313X19847029

- Martinez V, Molina J-M, Scieux C, et al. Topical imiquimod for recurrent acyclovir-resistant HHV infection. Am J Med. 2006 May;119:E9-E11. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.06.037

- Ronkainen SD, Rothenberger M. Herpes vegetans: an unusual and acyclovir-resistant form of HHV. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:393. doi:10.1007/s11606-017-4256-y

- Quesada AE, Galfione S, Colome M, et al. Verrucous herpes of the scrotum presenting clinically as verrucous squamous cell carcinoma: case report and review of the literature. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2014;44:208-212.

- El Hayderi L, Paurobally D, Fassotte MF, et al. Herpes simplex virus type-I and pyogenic granuloma: a vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated association? Case Rep Dermatol. 2013;5:236-243. doi:10.1159/000354570

- Toro JR, Sanchez S, Turiansky G, et al. Topical cidofovir for the treatment of dermatologic conditions: verruca, condyloma, intraepithelial neoplasia, herpes simplex and its potential use in smallpox. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:301-319. doi:10.1016/s0733-8635(02)00116-x

- Castelo-Soccio L, Bernardin R, Stern J, et al. Successful treatment of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus with intralesional cidofovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:124-126. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.363

- Bae-Harboe Y-SC, Khachemoune A. Verrucous herpetic infection of the scrotum and the groin in an immuno-competent patient: case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18. https://doi.org/10.5070/D30sv058j6

- Elosiebo RI, Koubek VA, Patel TS, et al. Vegetative sacral plaque in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Cutis. 2015;96:E7-E9.

- Saling C, Slim J, Szabela ME. A case of an atypical resistant granulomatous HHV-1 and HHV-2 ulceration in an AIDS patient treated with intralesional cidofovir. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2019;7:2050313X19847029. doi:10.1177/2050313X19847029

- Martinez V, Molina J-M, Scieux C, et al. Topical imiquimod for recurrent acyclovir-resistant HHV infection. Am J Med. 2006 May;119:E9-E11. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.06.037

- Ronkainen SD, Rothenberger M. Herpes vegetans: an unusual and acyclovir-resistant form of HHV. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:393. doi:10.1007/s11606-017-4256-y

- Quesada AE, Galfione S, Colome M, et al. Verrucous herpes of the scrotum presenting clinically as verrucous squamous cell carcinoma: case report and review of the literature. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2014;44:208-212.

- El Hayderi L, Paurobally D, Fassotte MF, et al. Herpes simplex virus type-I and pyogenic granuloma: a vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated association? Case Rep Dermatol. 2013;5:236-243. doi:10.1159/000354570

- Toro JR, Sanchez S, Turiansky G, et al. Topical cidofovir for the treatment of dermatologic conditions: verruca, condyloma, intraepithelial neoplasia, herpes simplex and its potential use in smallpox. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:301-319. doi:10.1016/s0733-8635(02)00116-x

Practice Points

- Maintain a high clinical suspicion for herpes vegetans (HV) in a patient who has a history of immunosuppression and presents with exophytic genital lesions.

- A history of resistance to acyclovir requires a multimodal approach to treatment of HV lesions, including medical and surgical therapies.

Treatment of an Unresectable Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma With ED&C and 5-FU

To the Editor:

Most cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (cSCCs) are successfully treated with standard modalities such as surgical excision; however, a subset of tumors is not amenable to surgical resection.1,2 Patients who are not able to undergo surgical treatment may instead receive radiation therapy, topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), imiquimod, cryosurgery, photodynamic therapy, or systemic treatment (eg, immunotherapy) in addition to intralesional approaches for localized disease.1-4 However, the adverse effects associated with these treatments and their modest effect in preventing the recurrence of cutaneous lesions limit their efficacy against unresectable cSCC.4-6 We present a case that demonstrates the efficacy of electrodesiccation and curettage (ED&C) followed by topical 5-FU for an invasive cSCC not amenable to surgical therapy.

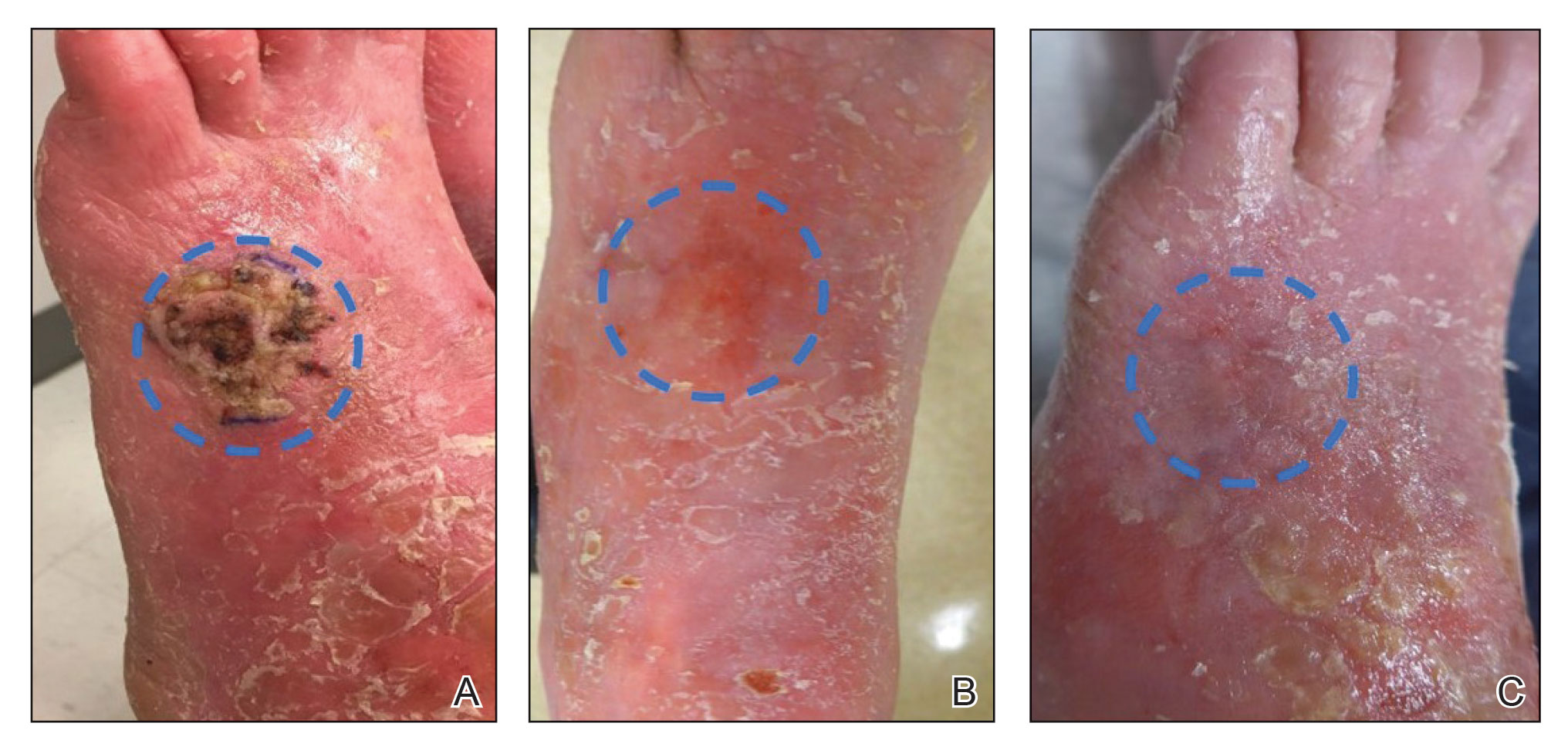

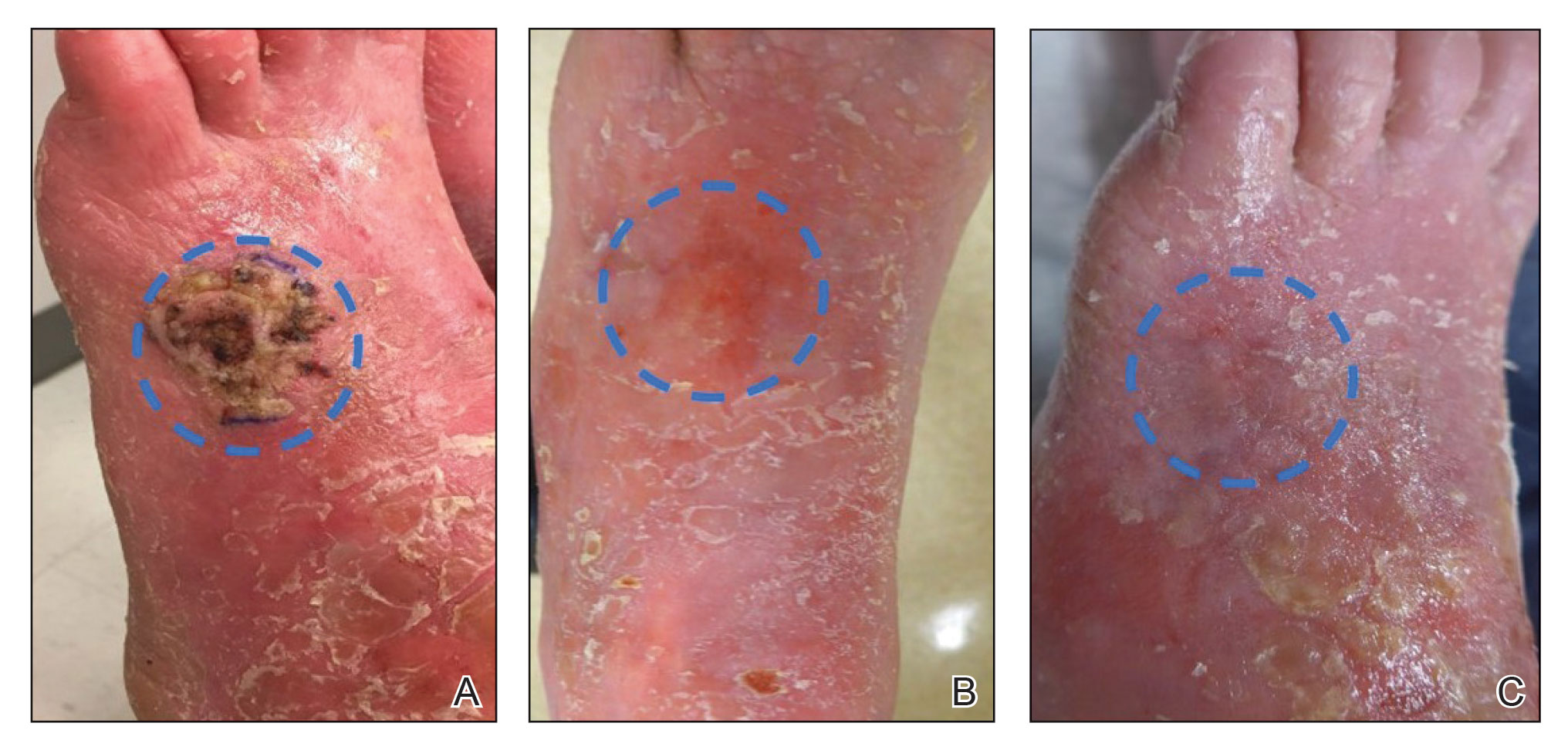

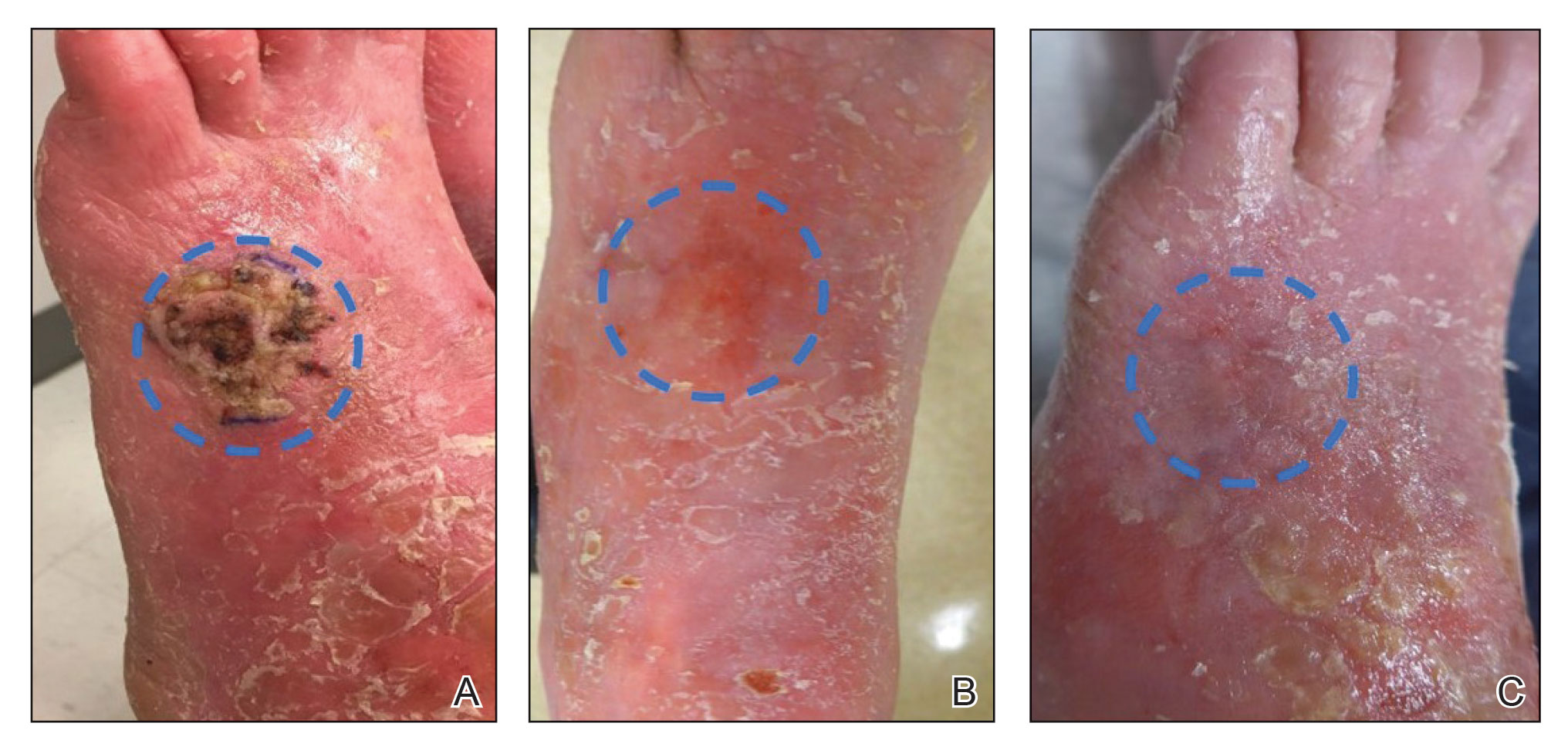

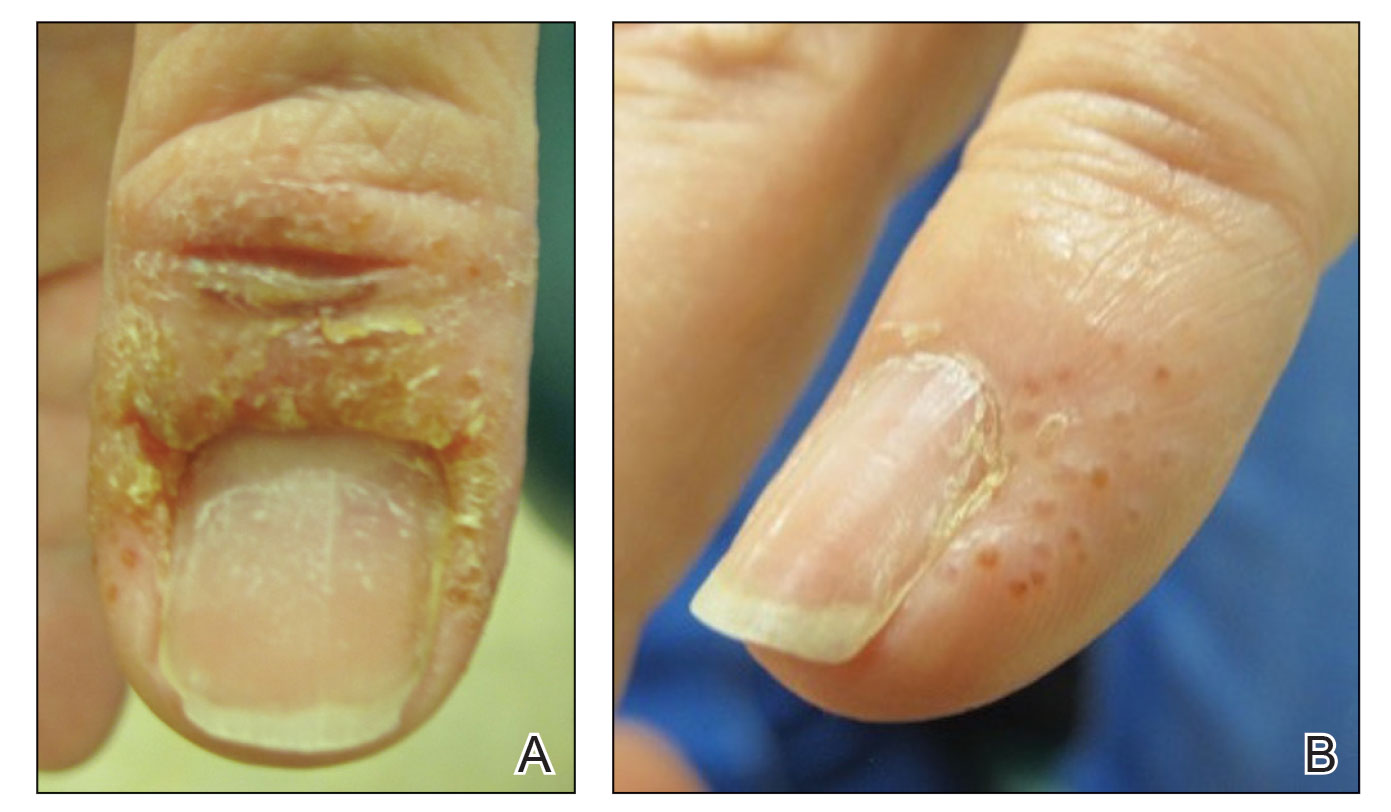

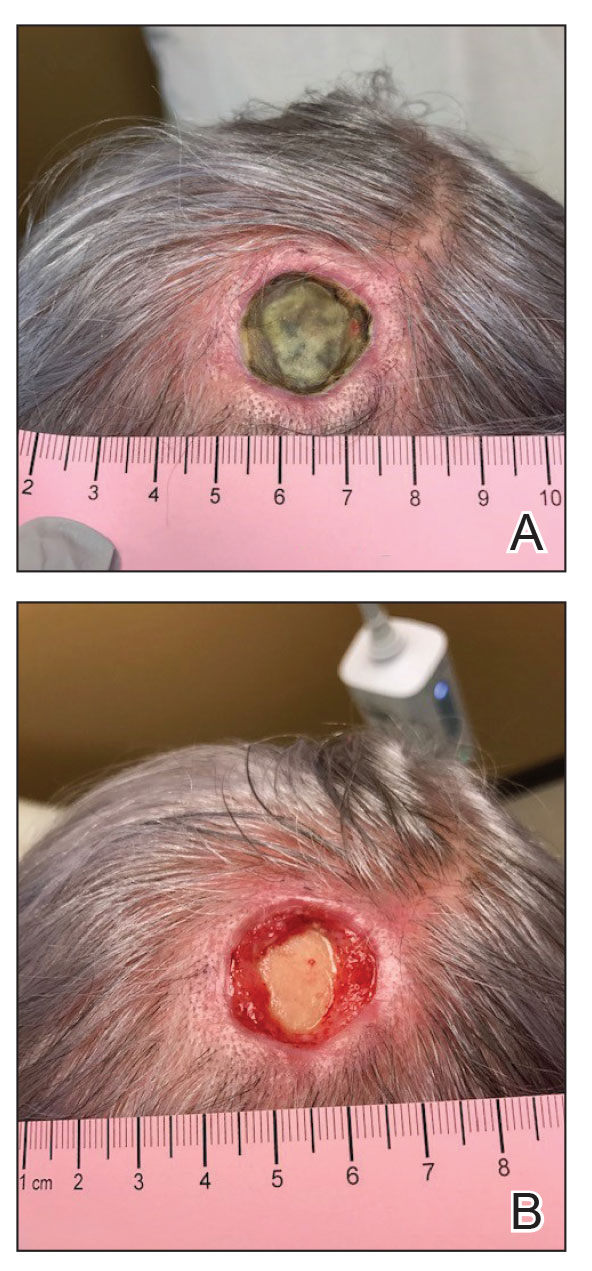

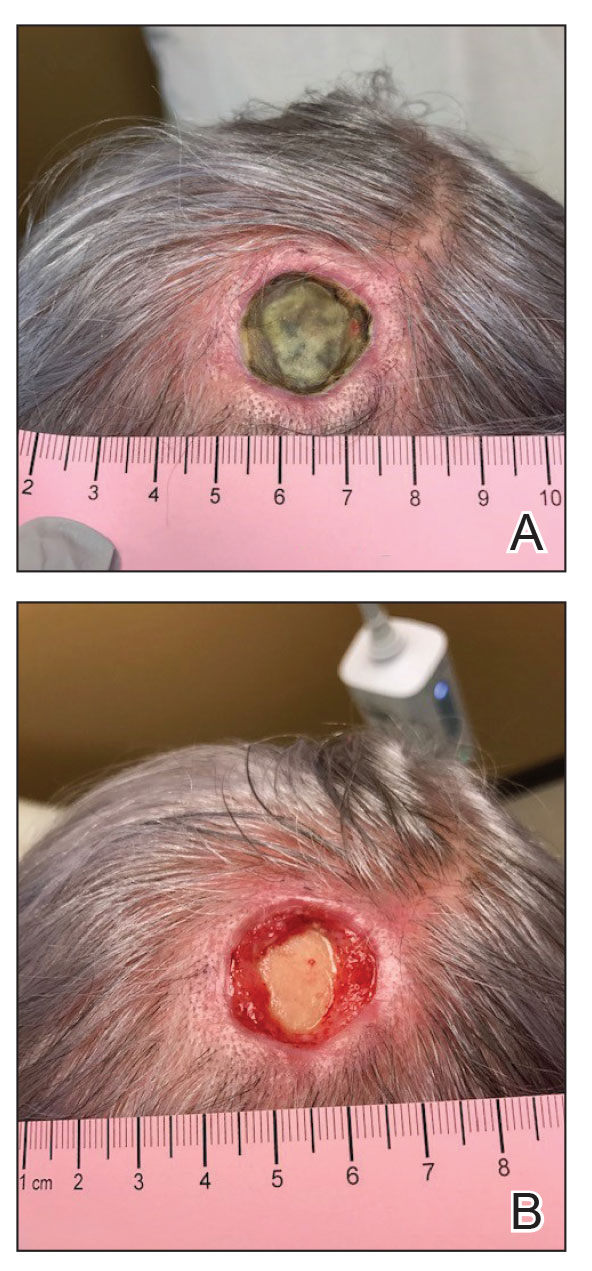

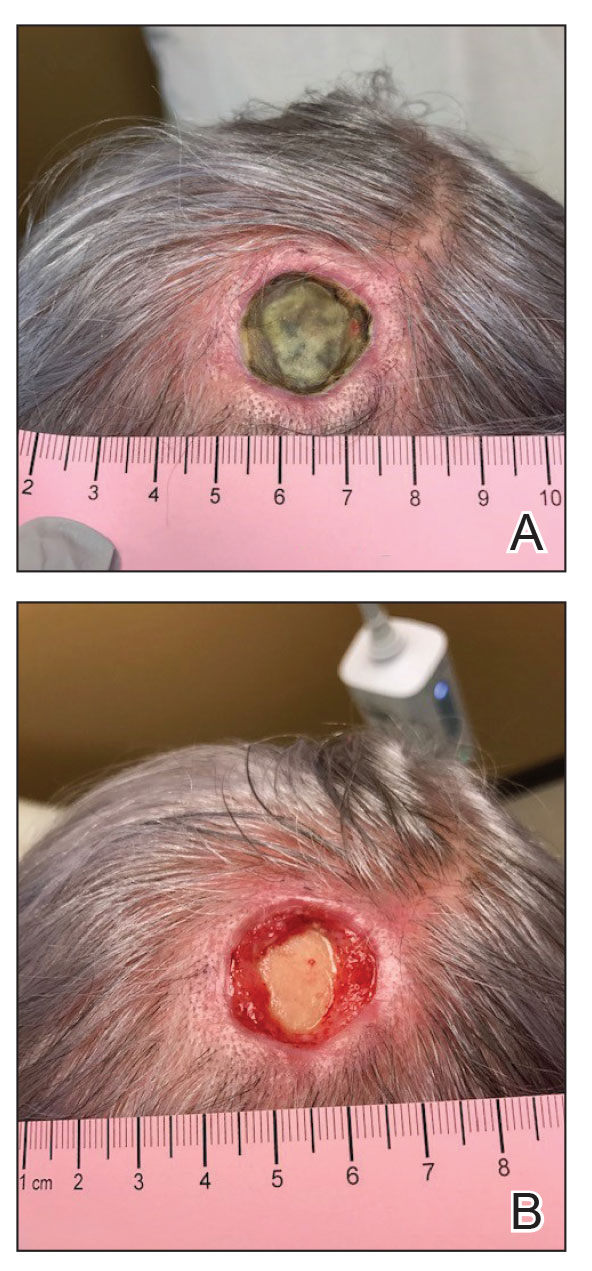

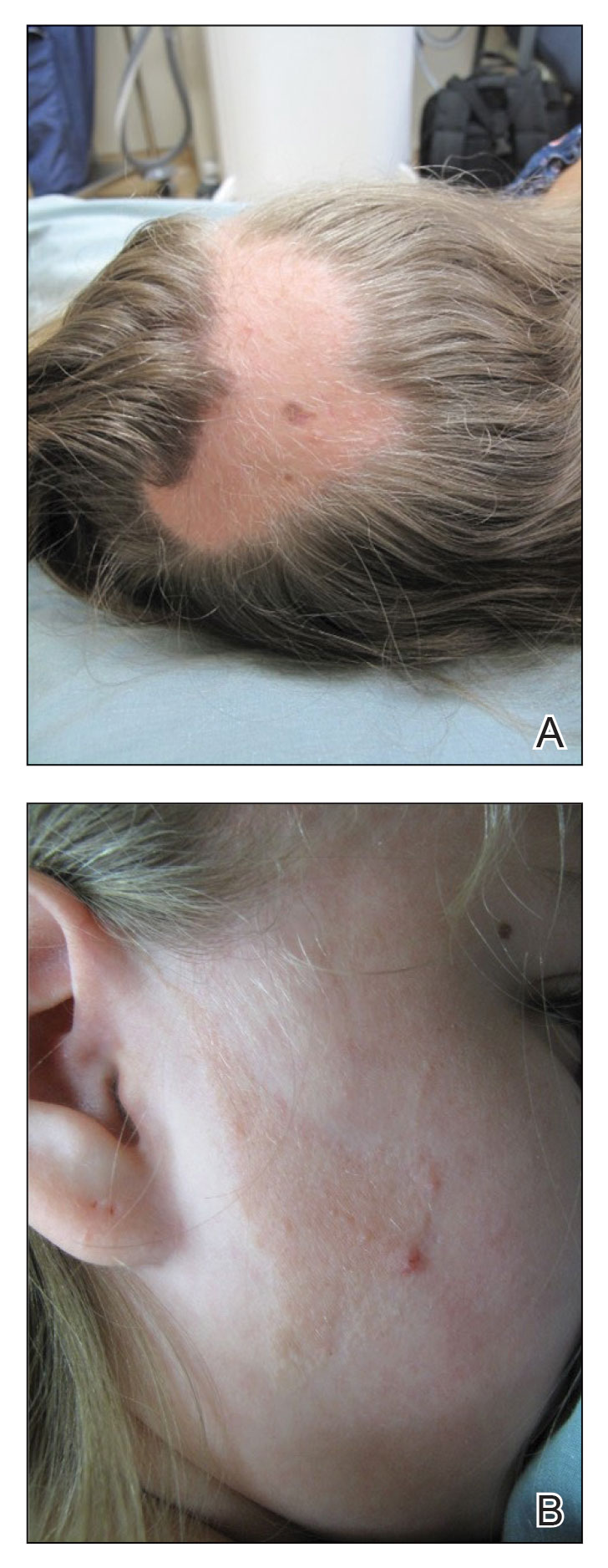

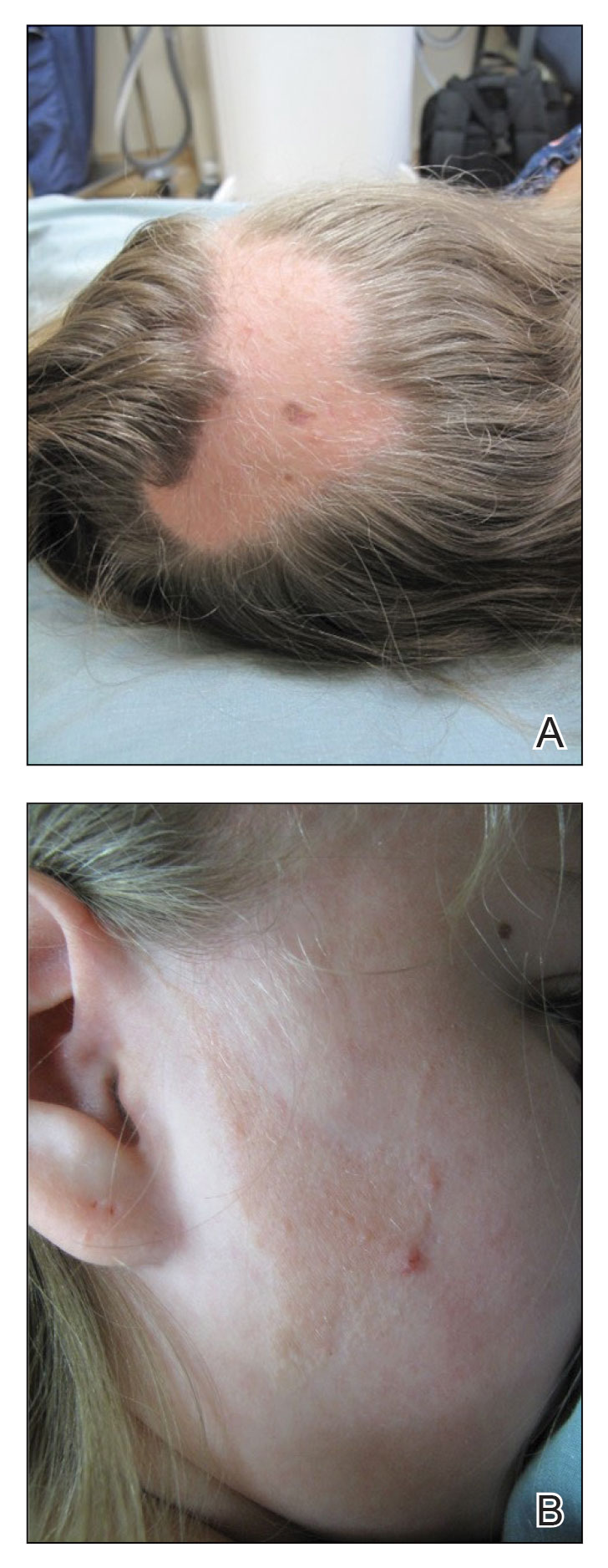

A 58-year-old woman presented for evaluation of a 3.5×3.4-cm, incisional biopsy–proven, invasive stage T2a cSCC (Brigham and Women’s Hospital tumor staging system [Boston, Massachusetts]) on the dorsal aspect of the left foot, which had developed over several months (Figure 1A). She had a history of treatment with psoralen plus UV light therapy for erythroderma of unknown cause and peripheral neuropathy. She was not a surgical candidate because of suspected underlying cutaneous sclerosis and a history of poor wound healing on the lower legs.

Prior to presentation to dermatology, the patient had been treated with intralesional methotrexate, intralesional 5-FU, and the antiangiogenic and antiproliferative combination agent OLCAT-0053—consisting of equal parts [by volume] of diclofenac gel 3%, imiquimod cream 5%, hydrocortisone valerate cream 0.2%, calcipotriene cream 0.005%, and tretinoin cream 0.05—which failed, and the patient reported that OLCAT-005 made the pain from the cSCC worse.

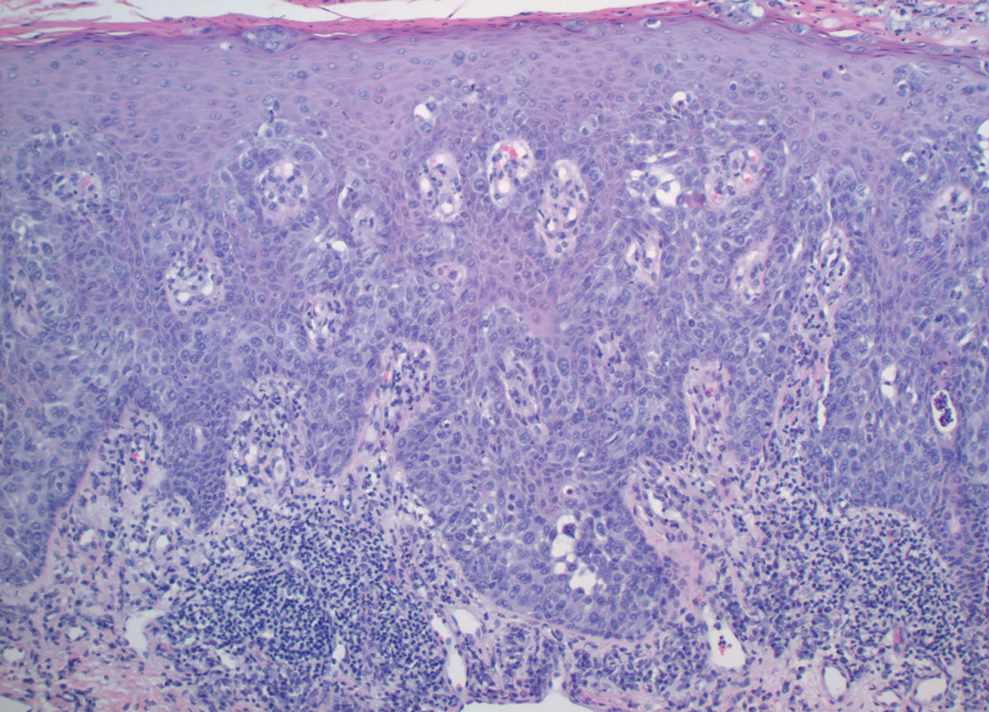

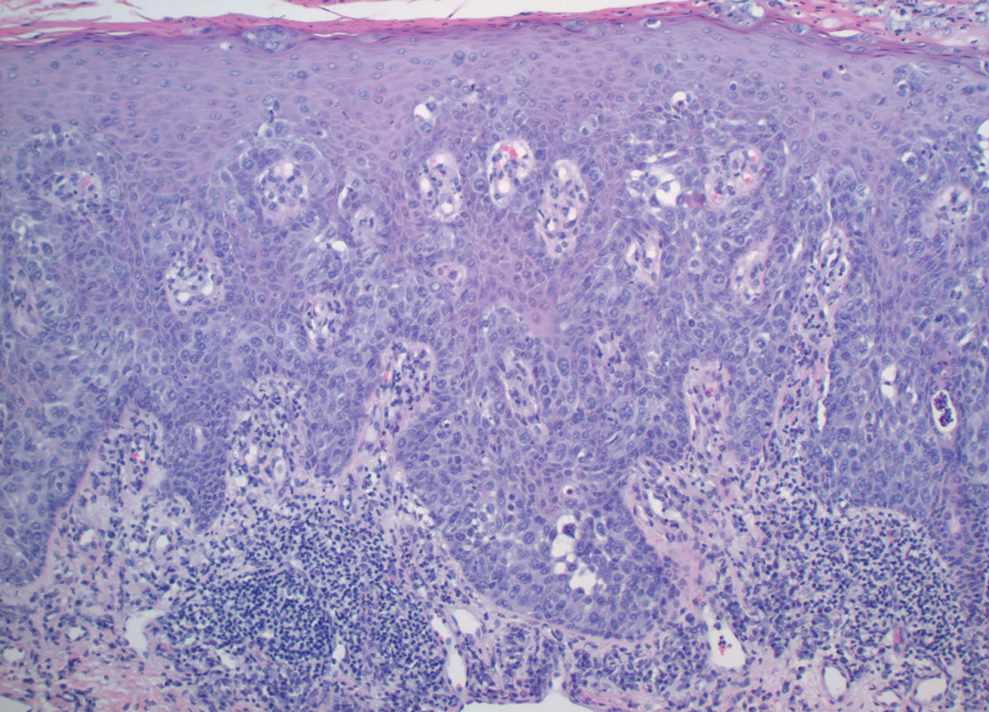

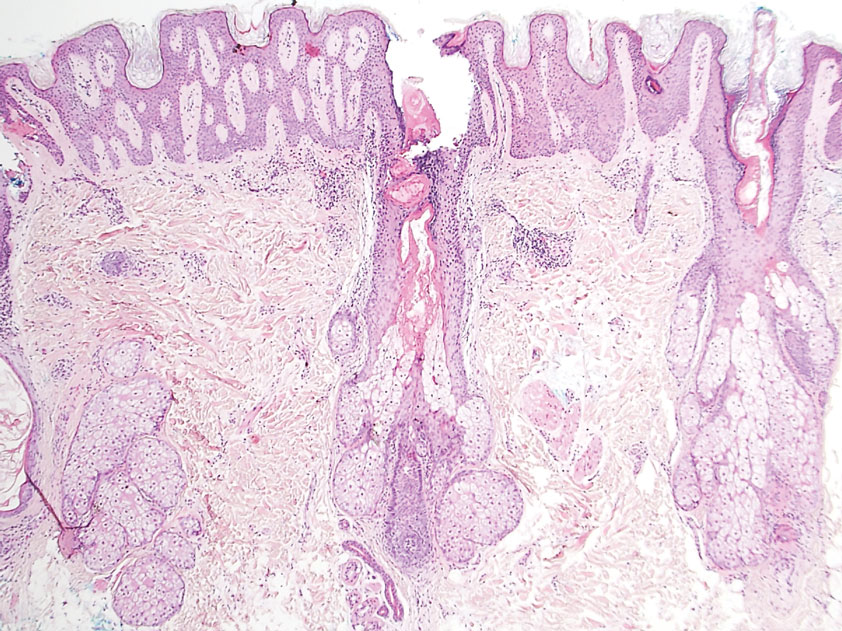

Upon growth of the lesion over several months, the patient was referred to the High-Risk Skin Cancer Clinic at Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, Massachusetts). A repeat biopsy demonstrated an invasive well-differentiated cSCC (Figure 2). The size and invasive features of the lesion on clinical examination prompted a referral to surgical oncology for a wide local excision. However, surgical oncology concluded she was not a surgical candidate.

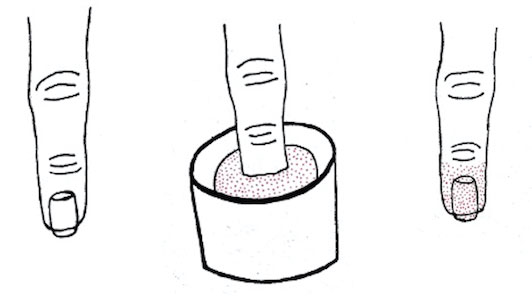

Magnetic resonance imaging showed no deep invasion of the cSCC to the tendons or bones. Electrodesiccation and curettage was performed to debulk the tumor, followed by twice-daily application of topical 5-FU for 4 weeks to improve the odds of tumor clearance (Figure 1B). Fourteen weeks after completion of 5-FU treatment, the cSCC showed complete clinical regression (Figure 1C). No recurrence has been detected clinically more than 3 years following treatment.

Prior to the advent of Mohs micrographic surgery, ED&C commonly was used to treat skin cancer, with a lower cost and a cure rate close to 95%.7,8 We postulate that the mechanism of tumor regression in our patient was ED&C-mediated removal and necrosis of neoplastic tissue combined with 5-FU–induced cancer-cell DNA damage and apoptosis. An antitumor immune response also may have contributed to the complete regression of the cSCC.

Although antiangiogenic and antiproliferative agents are suitable for primary cSCC treatment, it is possible that this patient’s prior therapies alone—in the absence of debulking by ED&C to sufficiently reduce disease burden—did not allow for tumor clearance and were ineffective. Many clinicians are reluctant to apply 5-FU to a wound bed because it can impede wound healing.9 In this case, re-epithelialization likely occurred primarily after completion of 5-FU treatment.

We recommend consideration of ED&C with 5-FU for similar malignant lesions that are not amenable to surgical excision. Nevertheless, Mohs micrographic surgery and wide local excision remain the gold standards for definitive treatment of invasive skin cancer in a patient who is a candidate for surgical treatment.

- Nehal KS, Bichakjian CK. Update on keratinocyte carcinomas. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:363-374. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1708701

- de Jong E, Lammerts MUPA, Genders RE, et al. Update of advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36(suppl 1):6-10. doi:10.1111/jdv.17728

- Li VW, Ball RA, Vasan N, et al. Antiangiogenic therapy for squamous cell carcinoma using combinatorial agents [abstract]. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(16 suppl):3032. doi:10.1200/jco.2005.23.16_suppl.3032

- Lansbury L, Bath-Hextall F, Perkins W, et al. Interventions for non-metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: systematic review and pooled analysis of observational studies. BMJ. 2013;347:f6153. doi:10.1136/bmj.f6153

- Behshad R, Garcia‐Zuazaga J, Bordeaux J. Systemic treatment of locally advanced nonmetastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a review of the literature. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:1169-1177. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10524.x

- Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL Jr. Prognostic factors for local recurrence, metastasis, and survival rates in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, ear, and lip. implications for treatment modality selection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:976-990. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(92)70144-5

- Knox JM, Lyles TW, Shapiro EM, et al. Curettage and electrodesiccation in the treatment of skin cancer. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:197-204.

- Chren M-M, Linos E, Torres JS, et al. Tumor recurrence 5 years after treatment of cutaneous basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:1188-1196. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.403

- Berman B, Maderal A, Raphael B. Keloids and hypertrophic scars: pathophysiology, classification, and treatment. Dermatologic Surgery. 2017;43:S3-S18.

To the Editor:

Most cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (cSCCs) are successfully treated with standard modalities such as surgical excision; however, a subset of tumors is not amenable to surgical resection.1,2 Patients who are not able to undergo surgical treatment may instead receive radiation therapy, topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), imiquimod, cryosurgery, photodynamic therapy, or systemic treatment (eg, immunotherapy) in addition to intralesional approaches for localized disease.1-4 However, the adverse effects associated with these treatments and their modest effect in preventing the recurrence of cutaneous lesions limit their efficacy against unresectable cSCC.4-6 We present a case that demonstrates the efficacy of electrodesiccation and curettage (ED&C) followed by topical 5-FU for an invasive cSCC not amenable to surgical therapy.

A 58-year-old woman presented for evaluation of a 3.5×3.4-cm, incisional biopsy–proven, invasive stage T2a cSCC (Brigham and Women’s Hospital tumor staging system [Boston, Massachusetts]) on the dorsal aspect of the left foot, which had developed over several months (Figure 1A). She had a history of treatment with psoralen plus UV light therapy for erythroderma of unknown cause and peripheral neuropathy. She was not a surgical candidate because of suspected underlying cutaneous sclerosis and a history of poor wound healing on the lower legs.

Prior to presentation to dermatology, the patient had been treated with intralesional methotrexate, intralesional 5-FU, and the antiangiogenic and antiproliferative combination agent OLCAT-0053—consisting of equal parts [by volume] of diclofenac gel 3%, imiquimod cream 5%, hydrocortisone valerate cream 0.2%, calcipotriene cream 0.005%, and tretinoin cream 0.05—which failed, and the patient reported that OLCAT-005 made the pain from the cSCC worse.

Upon growth of the lesion over several months, the patient was referred to the High-Risk Skin Cancer Clinic at Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, Massachusetts). A repeat biopsy demonstrated an invasive well-differentiated cSCC (Figure 2). The size and invasive features of the lesion on clinical examination prompted a referral to surgical oncology for a wide local excision. However, surgical oncology concluded she was not a surgical candidate.

Magnetic resonance imaging showed no deep invasion of the cSCC to the tendons or bones. Electrodesiccation and curettage was performed to debulk the tumor, followed by twice-daily application of topical 5-FU for 4 weeks to improve the odds of tumor clearance (Figure 1B). Fourteen weeks after completion of 5-FU treatment, the cSCC showed complete clinical regression (Figure 1C). No recurrence has been detected clinically more than 3 years following treatment.

Prior to the advent of Mohs micrographic surgery, ED&C commonly was used to treat skin cancer, with a lower cost and a cure rate close to 95%.7,8 We postulate that the mechanism of tumor regression in our patient was ED&C-mediated removal and necrosis of neoplastic tissue combined with 5-FU–induced cancer-cell DNA damage and apoptosis. An antitumor immune response also may have contributed to the complete regression of the cSCC.

Although antiangiogenic and antiproliferative agents are suitable for primary cSCC treatment, it is possible that this patient’s prior therapies alone—in the absence of debulking by ED&C to sufficiently reduce disease burden—did not allow for tumor clearance and were ineffective. Many clinicians are reluctant to apply 5-FU to a wound bed because it can impede wound healing.9 In this case, re-epithelialization likely occurred primarily after completion of 5-FU treatment.

We recommend consideration of ED&C with 5-FU for similar malignant lesions that are not amenable to surgical excision. Nevertheless, Mohs micrographic surgery and wide local excision remain the gold standards for definitive treatment of invasive skin cancer in a patient who is a candidate for surgical treatment.

To the Editor:

Most cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (cSCCs) are successfully treated with standard modalities such as surgical excision; however, a subset of tumors is not amenable to surgical resection.1,2 Patients who are not able to undergo surgical treatment may instead receive radiation therapy, topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), imiquimod, cryosurgery, photodynamic therapy, or systemic treatment (eg, immunotherapy) in addition to intralesional approaches for localized disease.1-4 However, the adverse effects associated with these treatments and their modest effect in preventing the recurrence of cutaneous lesions limit their efficacy against unresectable cSCC.4-6 We present a case that demonstrates the efficacy of electrodesiccation and curettage (ED&C) followed by topical 5-FU for an invasive cSCC not amenable to surgical therapy.

A 58-year-old woman presented for evaluation of a 3.5×3.4-cm, incisional biopsy–proven, invasive stage T2a cSCC (Brigham and Women’s Hospital tumor staging system [Boston, Massachusetts]) on the dorsal aspect of the left foot, which had developed over several months (Figure 1A). She had a history of treatment with psoralen plus UV light therapy for erythroderma of unknown cause and peripheral neuropathy. She was not a surgical candidate because of suspected underlying cutaneous sclerosis and a history of poor wound healing on the lower legs.

Prior to presentation to dermatology, the patient had been treated with intralesional methotrexate, intralesional 5-FU, and the antiangiogenic and antiproliferative combination agent OLCAT-0053—consisting of equal parts [by volume] of diclofenac gel 3%, imiquimod cream 5%, hydrocortisone valerate cream 0.2%, calcipotriene cream 0.005%, and tretinoin cream 0.05—which failed, and the patient reported that OLCAT-005 made the pain from the cSCC worse.

Upon growth of the lesion over several months, the patient was referred to the High-Risk Skin Cancer Clinic at Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, Massachusetts). A repeat biopsy demonstrated an invasive well-differentiated cSCC (Figure 2). The size and invasive features of the lesion on clinical examination prompted a referral to surgical oncology for a wide local excision. However, surgical oncology concluded she was not a surgical candidate.

Magnetic resonance imaging showed no deep invasion of the cSCC to the tendons or bones. Electrodesiccation and curettage was performed to debulk the tumor, followed by twice-daily application of topical 5-FU for 4 weeks to improve the odds of tumor clearance (Figure 1B). Fourteen weeks after completion of 5-FU treatment, the cSCC showed complete clinical regression (Figure 1C). No recurrence has been detected clinically more than 3 years following treatment.

Prior to the advent of Mohs micrographic surgery, ED&C commonly was used to treat skin cancer, with a lower cost and a cure rate close to 95%.7,8 We postulate that the mechanism of tumor regression in our patient was ED&C-mediated removal and necrosis of neoplastic tissue combined with 5-FU–induced cancer-cell DNA damage and apoptosis. An antitumor immune response also may have contributed to the complete regression of the cSCC.

Although antiangiogenic and antiproliferative agents are suitable for primary cSCC treatment, it is possible that this patient’s prior therapies alone—in the absence of debulking by ED&C to sufficiently reduce disease burden—did not allow for tumor clearance and were ineffective. Many clinicians are reluctant to apply 5-FU to a wound bed because it can impede wound healing.9 In this case, re-epithelialization likely occurred primarily after completion of 5-FU treatment.

We recommend consideration of ED&C with 5-FU for similar malignant lesions that are not amenable to surgical excision. Nevertheless, Mohs micrographic surgery and wide local excision remain the gold standards for definitive treatment of invasive skin cancer in a patient who is a candidate for surgical treatment.

- Nehal KS, Bichakjian CK. Update on keratinocyte carcinomas. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:363-374. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1708701

- de Jong E, Lammerts MUPA, Genders RE, et al. Update of advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36(suppl 1):6-10. doi:10.1111/jdv.17728

- Li VW, Ball RA, Vasan N, et al. Antiangiogenic therapy for squamous cell carcinoma using combinatorial agents [abstract]. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(16 suppl):3032. doi:10.1200/jco.2005.23.16_suppl.3032

- Lansbury L, Bath-Hextall F, Perkins W, et al. Interventions for non-metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: systematic review and pooled analysis of observational studies. BMJ. 2013;347:f6153. doi:10.1136/bmj.f6153

- Behshad R, Garcia‐Zuazaga J, Bordeaux J. Systemic treatment of locally advanced nonmetastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a review of the literature. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:1169-1177. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10524.x

- Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL Jr. Prognostic factors for local recurrence, metastasis, and survival rates in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, ear, and lip. implications for treatment modality selection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:976-990. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(92)70144-5

- Knox JM, Lyles TW, Shapiro EM, et al. Curettage and electrodesiccation in the treatment of skin cancer. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:197-204.

- Chren M-M, Linos E, Torres JS, et al. Tumor recurrence 5 years after treatment of cutaneous basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:1188-1196. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.403

- Berman B, Maderal A, Raphael B. Keloids and hypertrophic scars: pathophysiology, classification, and treatment. Dermatologic Surgery. 2017;43:S3-S18.

- Nehal KS, Bichakjian CK. Update on keratinocyte carcinomas. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:363-374. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1708701

- de Jong E, Lammerts MUPA, Genders RE, et al. Update of advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36(suppl 1):6-10. doi:10.1111/jdv.17728

- Li VW, Ball RA, Vasan N, et al. Antiangiogenic therapy for squamous cell carcinoma using combinatorial agents [abstract]. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(16 suppl):3032. doi:10.1200/jco.2005.23.16_suppl.3032

- Lansbury L, Bath-Hextall F, Perkins W, et al. Interventions for non-metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: systematic review and pooled analysis of observational studies. BMJ. 2013;347:f6153. doi:10.1136/bmj.f6153

- Behshad R, Garcia‐Zuazaga J, Bordeaux J. Systemic treatment of locally advanced nonmetastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a review of the literature. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:1169-1177. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10524.x

- Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL Jr. Prognostic factors for local recurrence, metastasis, and survival rates in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, ear, and lip. implications for treatment modality selection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:976-990. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(92)70144-5

- Knox JM, Lyles TW, Shapiro EM, et al. Curettage and electrodesiccation in the treatment of skin cancer. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:197-204.

- Chren M-M, Linos E, Torres JS, et al. Tumor recurrence 5 years after treatment of cutaneous basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:1188-1196. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.403

- Berman B, Maderal A, Raphael B. Keloids and hypertrophic scars: pathophysiology, classification, and treatment. Dermatologic Surgery. 2017;43:S3-S18.

Practice Points

- In a subset of cases of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC), the tumor is not amenable to surgical resection or other standard treatment modalities.

- Electrodesiccation and curettage followed by topical 5-fluorouracil may be an effective option in eliminating unresectable primary cSCCs that do not respond to intralesional treatment.

Porocarcinoma Development in a Prior Trauma Site

To the Editor:

Porocarcinoma, or malignant poroma, is a rare adnexal malignancy of a predominantly glandular origin that comprises less than 0.01% of all cutaneous neoplasms.1,2 Although exposure to UV radiation and immunosuppression have been implicated in the malignant degeneration of benign poromas into porocarcinomas, at least half of all malignant variants will arise de novo.3,4 Patients present with an evolving nodule or plaque and often are in their seventh or eighth decade of life at the time of diagnosis.2 Localized trauma from burns or radiation exposure has been causatively linked to de novo porocarcinoma formation.2,5 These suppressive and traumatic stimuli drive increased genetic heterogeneity along with characteristic gene mutations in known tumor suppressor genes.6

A 62-year-old man presented with a nonhealing wound on the right hand of 5 years’ duration that had previously been attributed to a penetrating injury with a piece of copper from a refrigerant coolant system. The wound initially blistered and then eventually callused and developed areas of ulceration. The patient consulted multiple physicians for treatment of the intensely pruritic and ulcerated lesion. He received prescriptions for cephalexin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, doxycycline, clindamycin, and clobetasol cream, all of which offered minimal improvement. Home therapies including vitamin E and tea tree oil yielded no benefit. The lesion roughly quadrupled in size over the last 5 years.

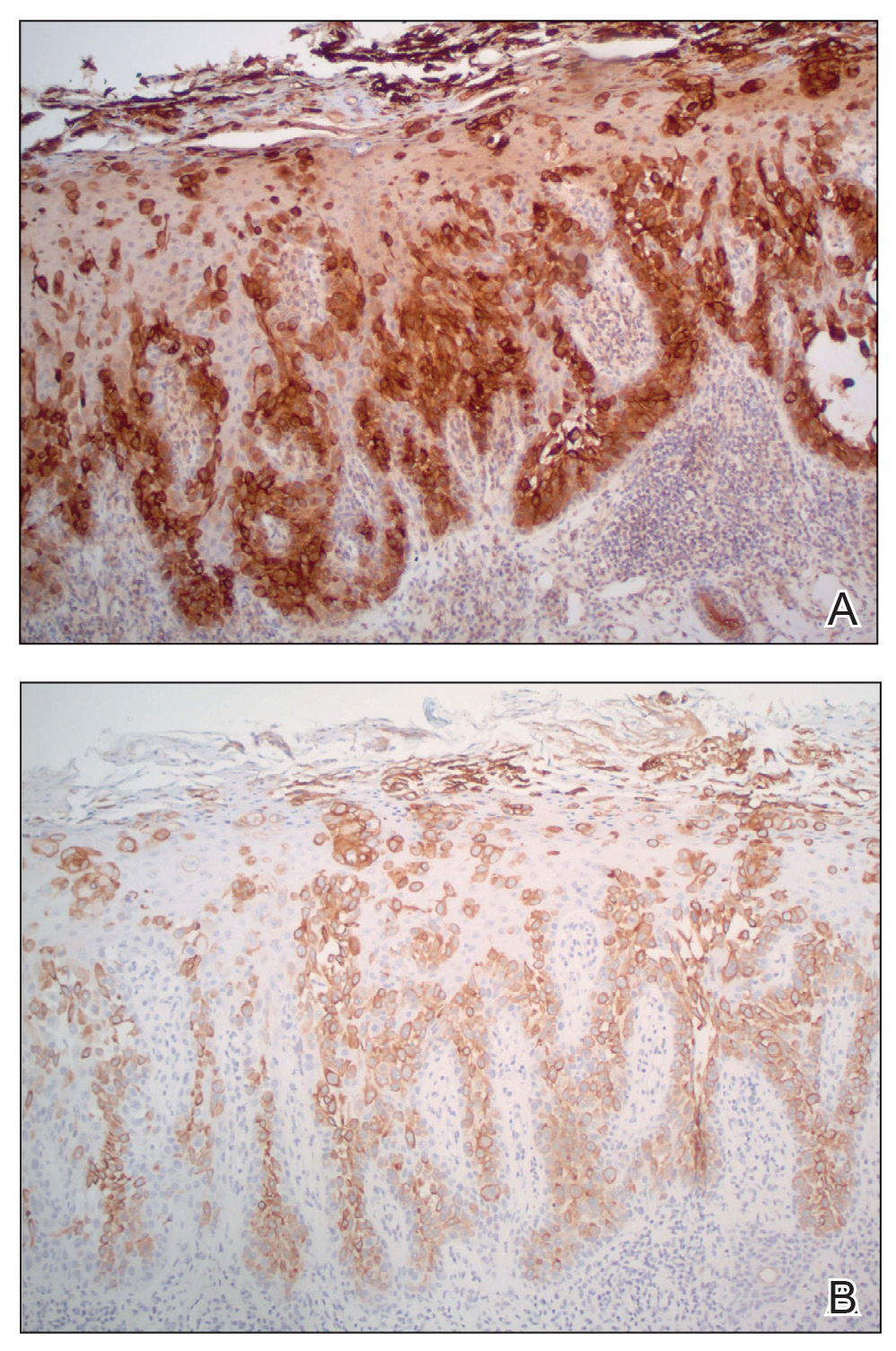

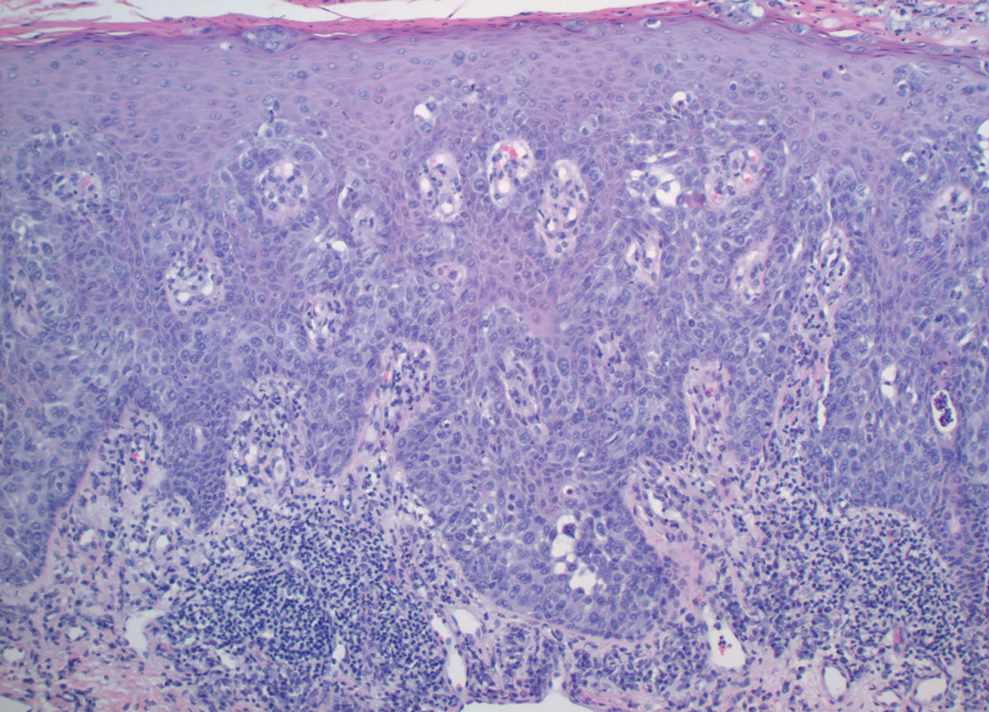

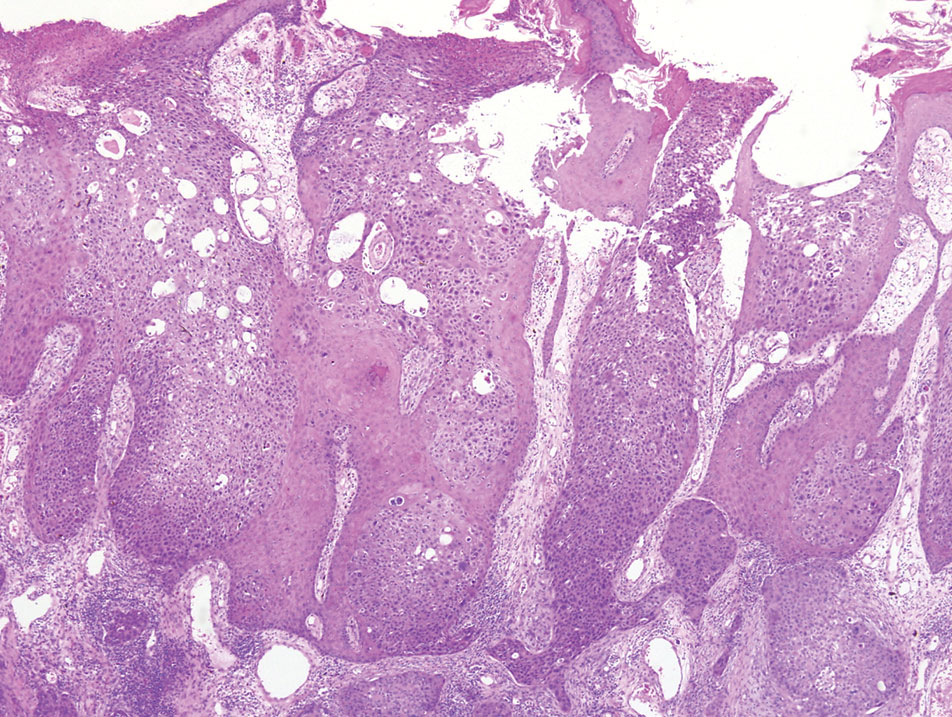

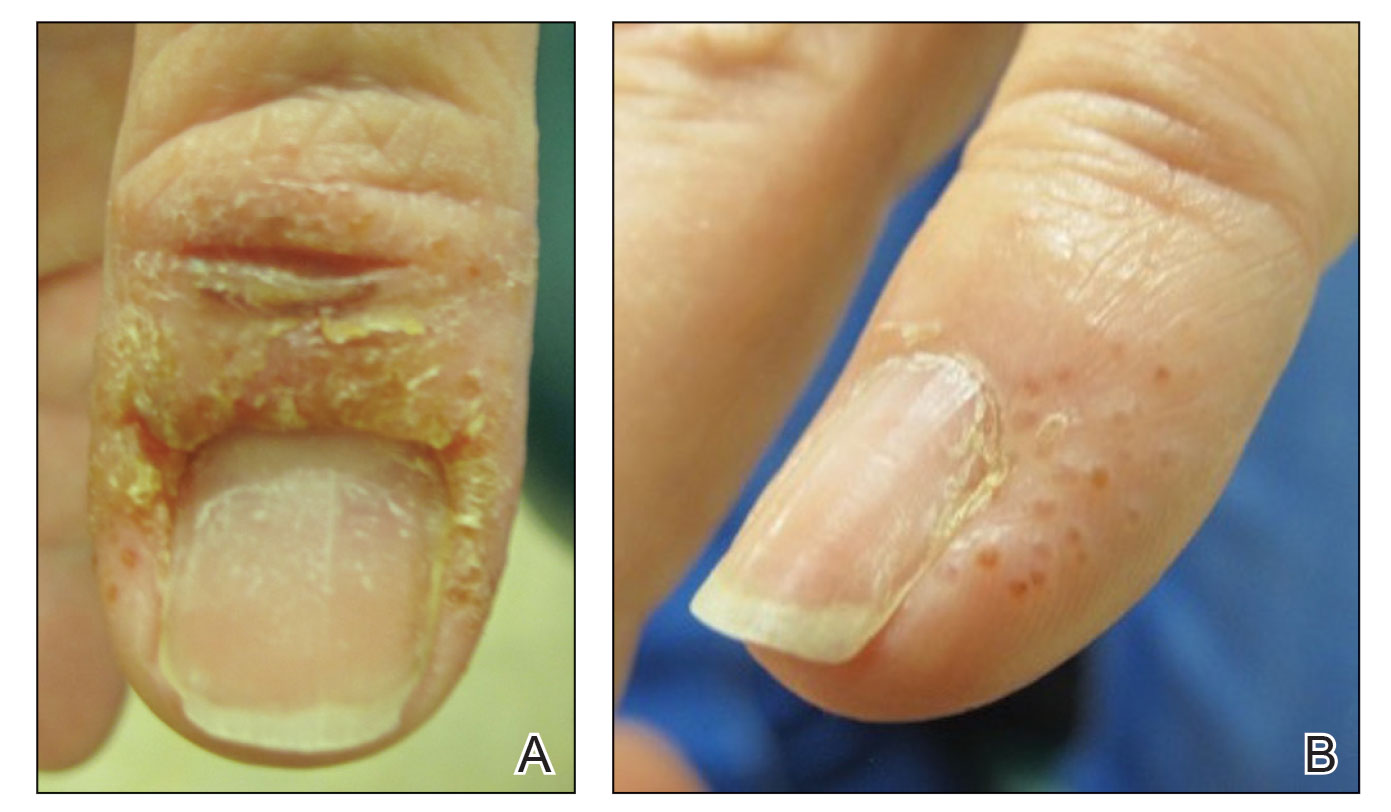

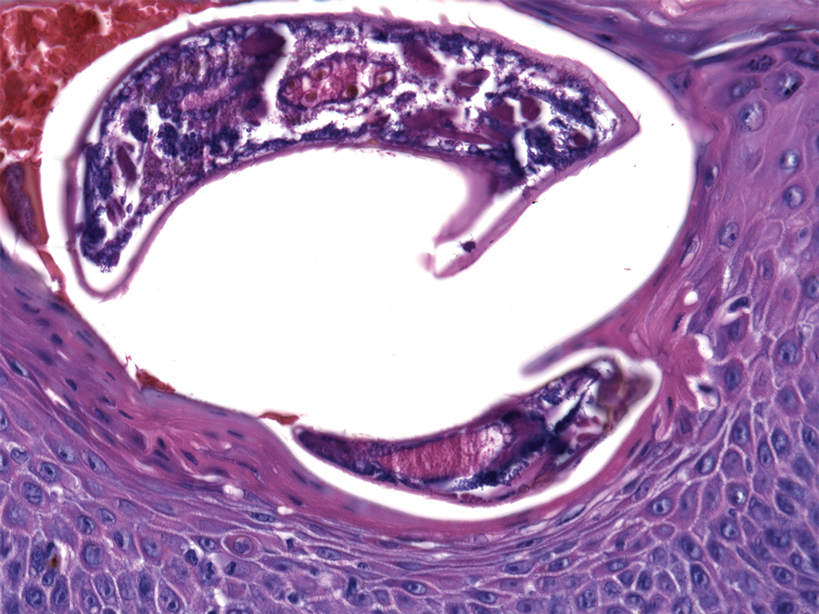

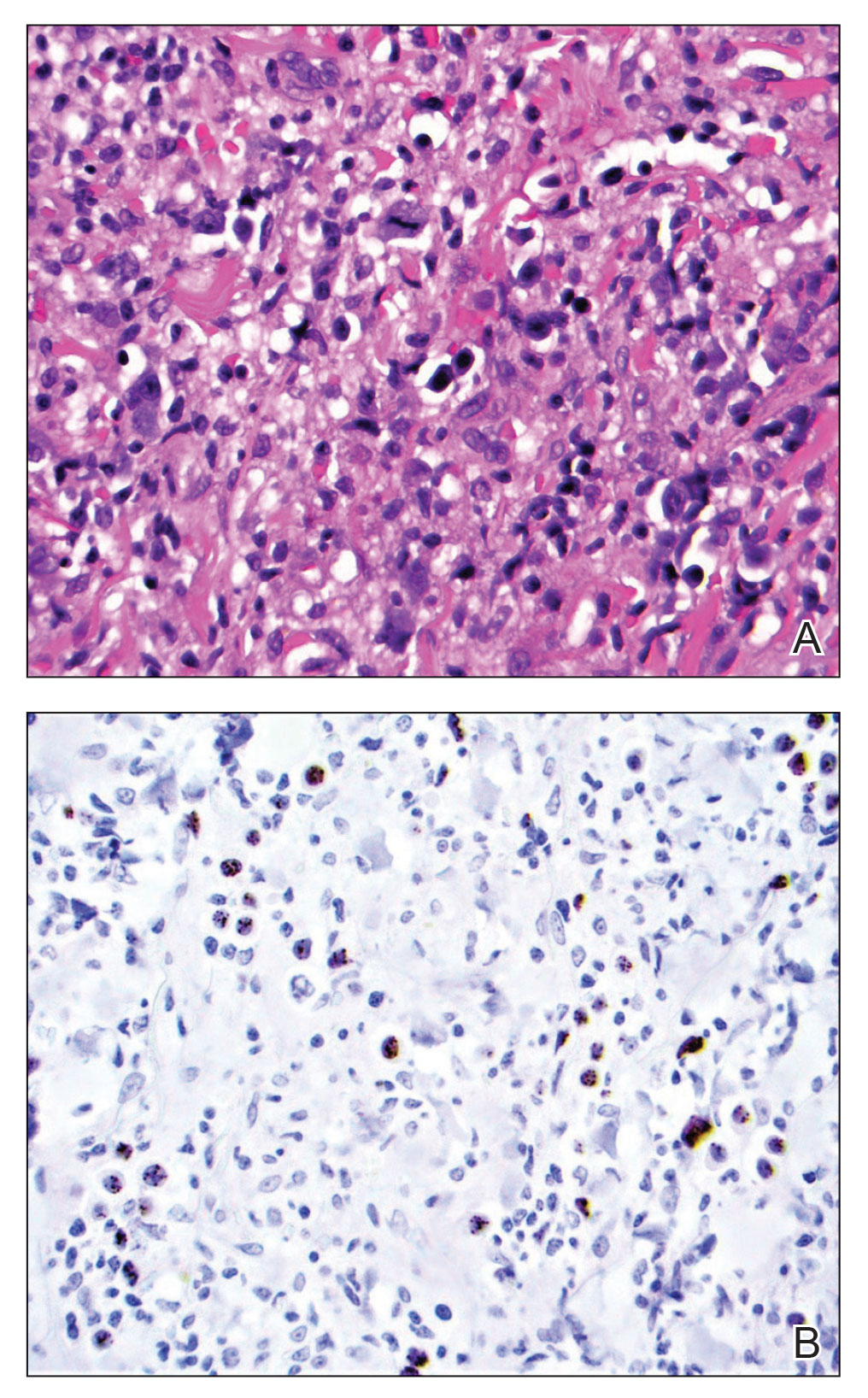

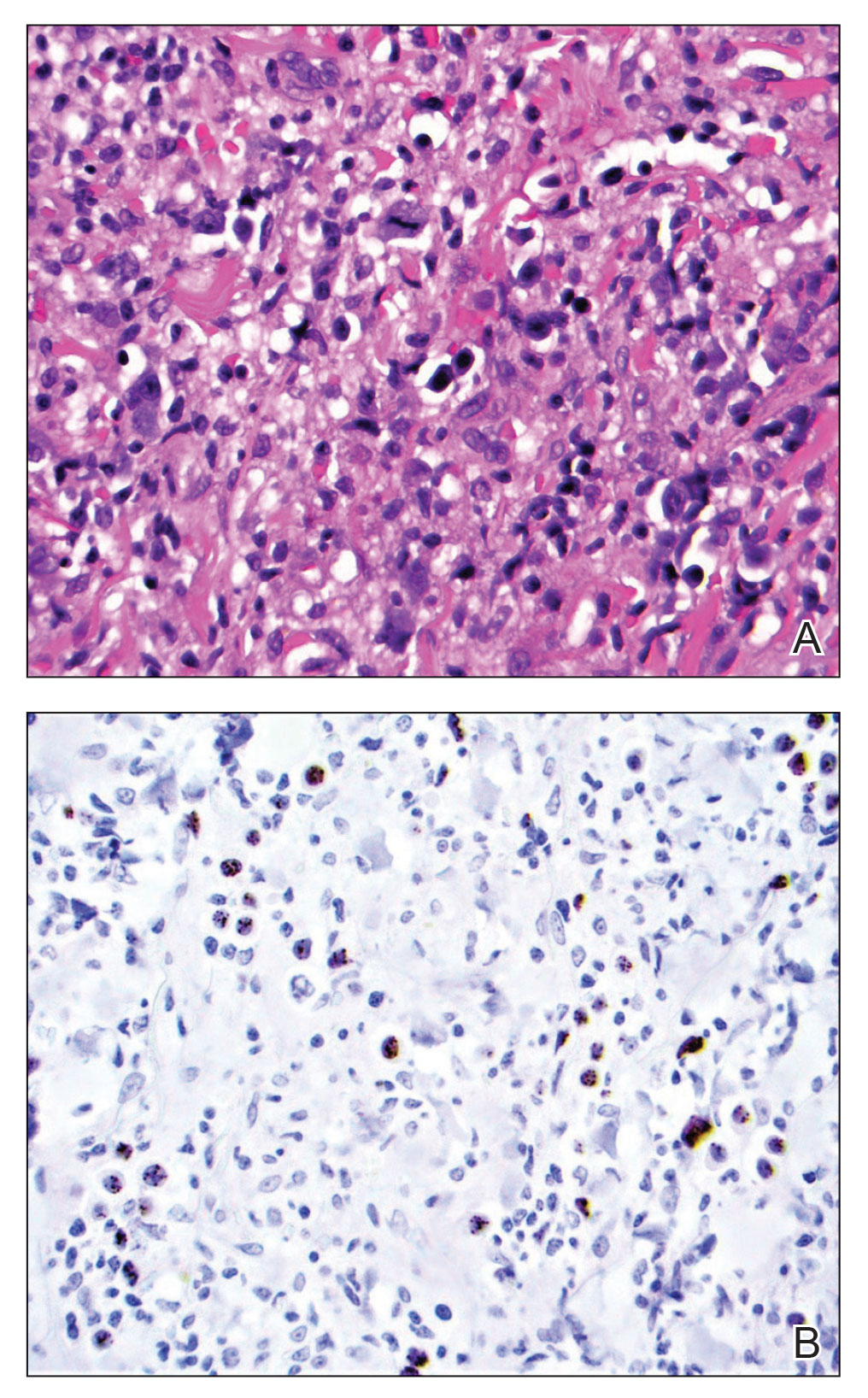

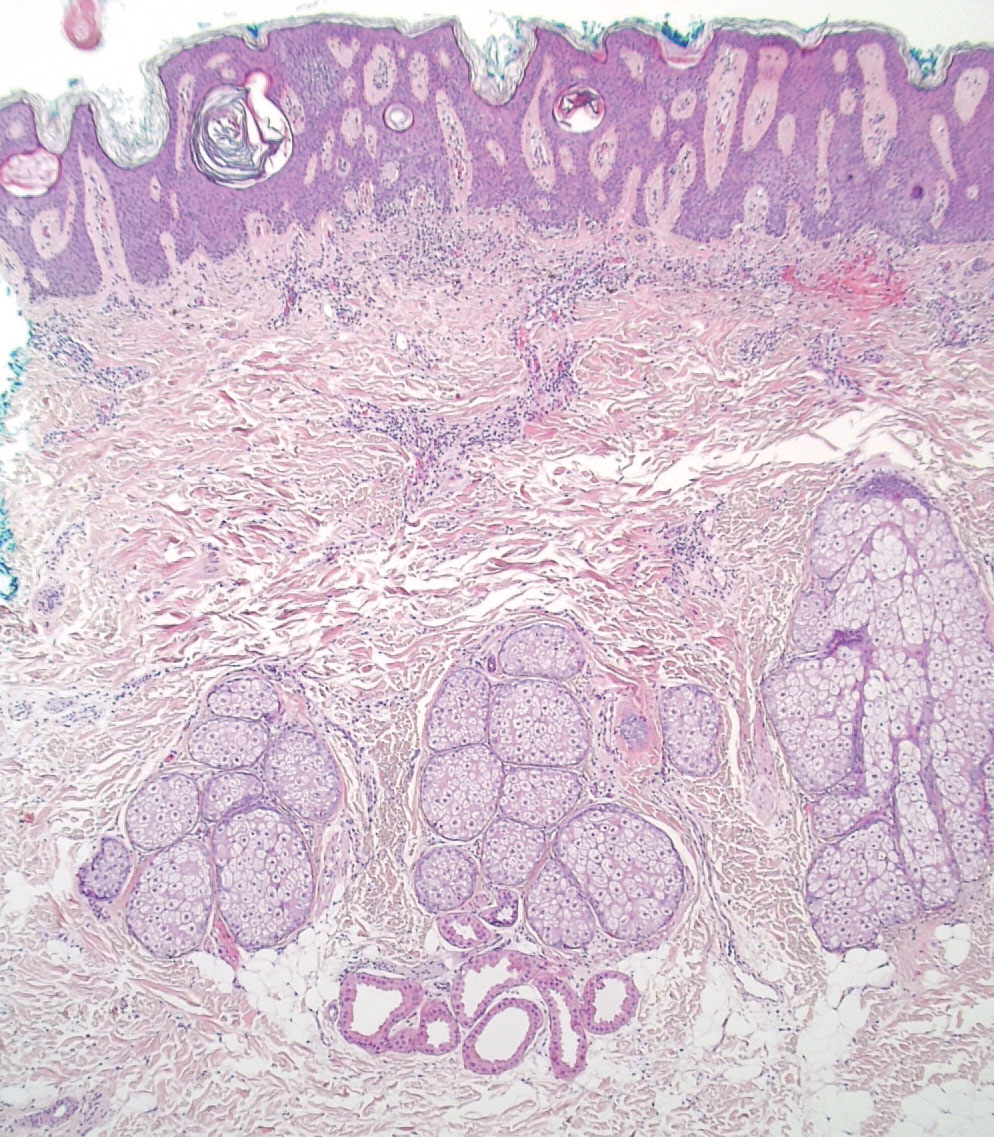

Physical examination revealed a 7.5×4.2-cm ulcerated plaque with ragged borders and abundant central neoepithelialization on the right palmar surface (Figure 1). No gross motor or sensory defects were identified. There was no epitrochlear, axillary, cervical, or supraclavicular lymphadenopathy. A shave biopsy of the plaque’s edge was performed, which demonstrated a hyperplastic epidermis comprising atypical poroid cells with frequent mitoses, scant necrosis, and regular ductal structures confined to the epidermis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical profiling results were positive for anticytokeratin (CAM 5.2) and Ber-EP4 (Figure 3). When evaluated in aggregate, these findings were consistent with porocarcinoma in situ.

The patient was referred to a surgical oncologist for evaluation. At that time, an exophytic mass had developed in the central lesion. Although no lymphadenopathy was identified upon examination, the patient had developed tremoring and a contracture deformity of the right hand. Extensive imaging and urgent surgical resection were recommended, but the patient did not wish to pursue these options, opting instead to continue home remedies. At a 15-month follow-up via telephone, the patient reported that the home therapy had failed and he had moved back to Vietnam. Partial limb amputation had been recommended by a local provider. Unfortunately, the patient was subsequently lost to follow-up, and his current status is unknown.

Porocarcinomas are rare tumors, comprising just 0.005% to 0.01% of all cutaneous epithelial tumors.1,2,5 They affect men and women equally, with an average age at diagnosis of 60 to 70 years.1,2 At least half of all porocarcinomas develop de novo, while 18% to 50% arise from the degeneration of an existing poroma.2,3 Exposure to UV light and immunosuppression, particularly following organ transplantation, represent 2 commonly suspected catalysts for this malignant transformation.4 De novo porocarcinomas are most causatively linked to localized trauma from burns or radiation exposure.5 Gene mutations in classic tumor suppressor genes—tumor protein p53 (TP53), phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), rearranged during transfection (RET), adenomatous polyposis coli (APC)—and increased genetic heterogeneity follow these stimuli.6

The morphologic presentation of porocarcinoma is highly variable and may manifest as papules, nodules, or plaques in various states of erosion, ulceration, or excoriation. Diagnoses of basal and squamous cell carcinoma, primary adnexal tumors, seborrheic keratosis, pyogenic granuloma, and melanoma must all be considered and methodically ruled out.7 Porocarcinomas may arise nearly anywhere on the body, with a particular predilection for the lower extremities (35%), head/neck (24%), and upper extremities (14%).3,4 Primary lesions arising from the extremities, genitalia, or buttocks herald a higher risk for lymphatic invasion and distant metastasis, while head and neck tumors more commonly remain localized.8 Bleeding, ulceration, or rapid expansion of a preexisting poroma is suggestive of malignant transformation and may portend a more aggressive disease pattern.2,9

Unequivocal diagnosis relies on histological and immunohistochemical studies due to the marked clinical variance of this neoplasm.7 An irregular histologic pattern of poromatous basaloid cells with ductal differentiation and cytologic atypia commonly are seen with porocarcinomas.2,8 Nuclear pleomorphism with cellular necrosis, increased mitotic figures, and abortive ductal formation with a distinct lack of retraction around cellular aggregates often are found. Immunohistochemical staining is needed to confirm the primary tumor diagnosis. Histochemical stains commonly employed include carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), cytokeratin AE1/AE3, epithelial membrane antigen, p53, p63, Ki67, and periodic acid-Schiff.10 The use of BerEP4 has been reported as efficacious in highlighting sweat structures, which can be particularly useful in cases when basal cell carcinoma is not in the histologic differential.11 These staining profiles afford confirmation of ductal differentiation with CEA, epithelial membrane antigen, and BerEP4, while p63 and Ki67 are used as surrogates for primary cutaneous neoplasia and cell proliferation, respectively.5,11 Porocarcinoma lesions may be most sensitive to CEA and most specific to CK19 (a component of cytokeratin AE1/AE3), though these findings have not been widely reproduced.7

The treatment and prognosis of porocarcinoma vary widely. Surgically excised lesions recur in roughly 20% of cases, though these rates likely include tumors that were incompletely resected in the primary attempt. Although wide local excision with an average 1-cm margin remains the most employed removal technique, Mohs micrographic surgery may more effectively limit recurrence and metastasis of localized disease.7,8,12 Metastatic disease foretells a mortality rate of at least 65%, which is problematic in that 10% to 20% of patients have metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis and another 20% will show metastasis following primary tumor excision.8,10 Neoplasms with high mitotic rates and depths greater than 7 mm should prompt thorough diagnostic imaging, such as positron emission tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. A sentinel lymph node biopsy should be strongly considered and discussed with the patient.10 Treatment options for nodal and distant metastases include a combination of localized surgery, lymphadenectomy, radiotherapy, and chemotherapeutic agents.2,4,5 The response to systemic treatment and radiotherapy often is quite poor, though the use of combinations of docetaxel, paclitaxel, cetuximab, and immunotherapy have been efficacious in smaller studies.8,10 The highest rates of morbidity and mortality are seen in patients with metastases on presentation or with localized tumors in the groin and buttocks.8

The diagnosis of porocarcinoma may be elusive due to its relatively rare occurrence. Therefore, it is critical to consider this neoplasm in high-risk sites in older patients who present with an evolving nodule or tumor on an extremity. Routine histology and astute histochemical profiling are necessary to exclude diseases that mimic porocarcinoma. Once diagnosis is confirmed, management with prompt excision and diagnostic imaging is recommended, including a lymph node biopsy if appropriate. Due to its high metastatic potential and associated morbidity and mortality, patients with porocarcinoma should be followed closely by a multidisciplinary care team.

- Belin E, Ezzedine K, Stanislas S, et al. Factors in the surgical management of primary eccrine porocarcinoma: prognostic histological factors can guide the surgical procedure. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:985-989.

- Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:710-720.

- Spencer DM, Bigler LR, Hearne DW, et al. Pedal papule. eccrine porocarcinoma (EPC) in association with poroma. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:211, 214.

- Salih AM, Kakamad FH, Essa RA, et al. Porocarcinoma: a systematic review of literature with a single case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017;30:13-16.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Mosby Elsevier; 2018.

- Bosic M, Kirchner M, Brasanac D, et al. Targeted molecular profiling reveals genetic heterogeneity of poromas and porocarcinomas. Pathology. 2018;50:327-332.

- Mahalingam M, Richards JE, Selim MA, et al. An immunohistochemical comparison of cytokeratin 7, cytokeratin 15, cytokeratin 19, CAM 5.2, carcinoembryonic antigen, and nestin in differentiating porocarcinoma from squamous cell carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2012;43:1265-1272.

- Nazemi A, Higgins S, Swift R, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma: new insights and a systematic review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:1247-1261.

- Wen SY. Case report of eccrine porocarcinoma in situ associated with eccrine poroma on the forehead. J Dermatol. 2012;39:649-651.

- Gerber PA, Schulte KW, Ruzicka T, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma of the head: an important differential diagnosis in the elderly patient. Dermatology. 2008;216:229-233.

- Afshar M, Deroide F, Robson A. BerEP4 is widely expressed in tumors of the sweat apparatus: a source of potential diagnostic error. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:259-264.

- Tolkachjov SN, Hocker TL, Camilleri MJ, et al. Treatment of porocarcinoma with Mohs micrographic surgery: the Mayo clinic experience. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:745-750.

To the Editor:

Porocarcinoma, or malignant poroma, is a rare adnexal malignancy of a predominantly glandular origin that comprises less than 0.01% of all cutaneous neoplasms.1,2 Although exposure to UV radiation and immunosuppression have been implicated in the malignant degeneration of benign poromas into porocarcinomas, at least half of all malignant variants will arise de novo.3,4 Patients present with an evolving nodule or plaque and often are in their seventh or eighth decade of life at the time of diagnosis.2 Localized trauma from burns or radiation exposure has been causatively linked to de novo porocarcinoma formation.2,5 These suppressive and traumatic stimuli drive increased genetic heterogeneity along with characteristic gene mutations in known tumor suppressor genes.6