User login

Cutaneous Collagenous Vasculopathy With Ocular Involvement

To the Editor:

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is an uncommon microangiopathy that presents with progressive telangiectases on the lower extremities that can eventually spread to involve the upper extremities and trunk. Systemic involvement is uncommon. The diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy, which demonstrates dilated capillaries and postcapillary venules with eosinophilic hyalinized walls. Treatment generally has focused on the use of vascular lasers.1 We report a patient with advanced CCV and ocular involvement that responded to a combination of pulsed dye laser (PDL) therapy and sclerotherapy for cutaneous lesions.

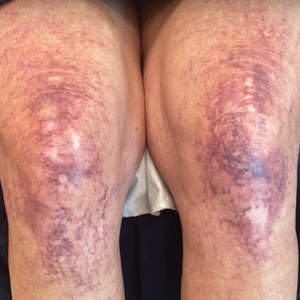

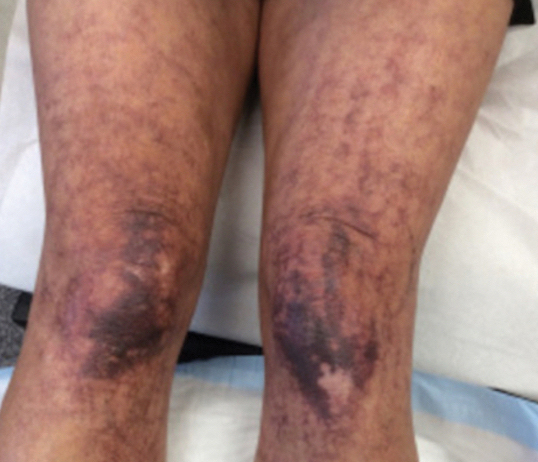

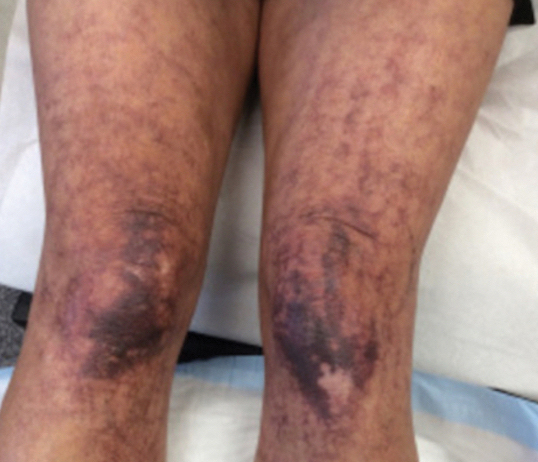

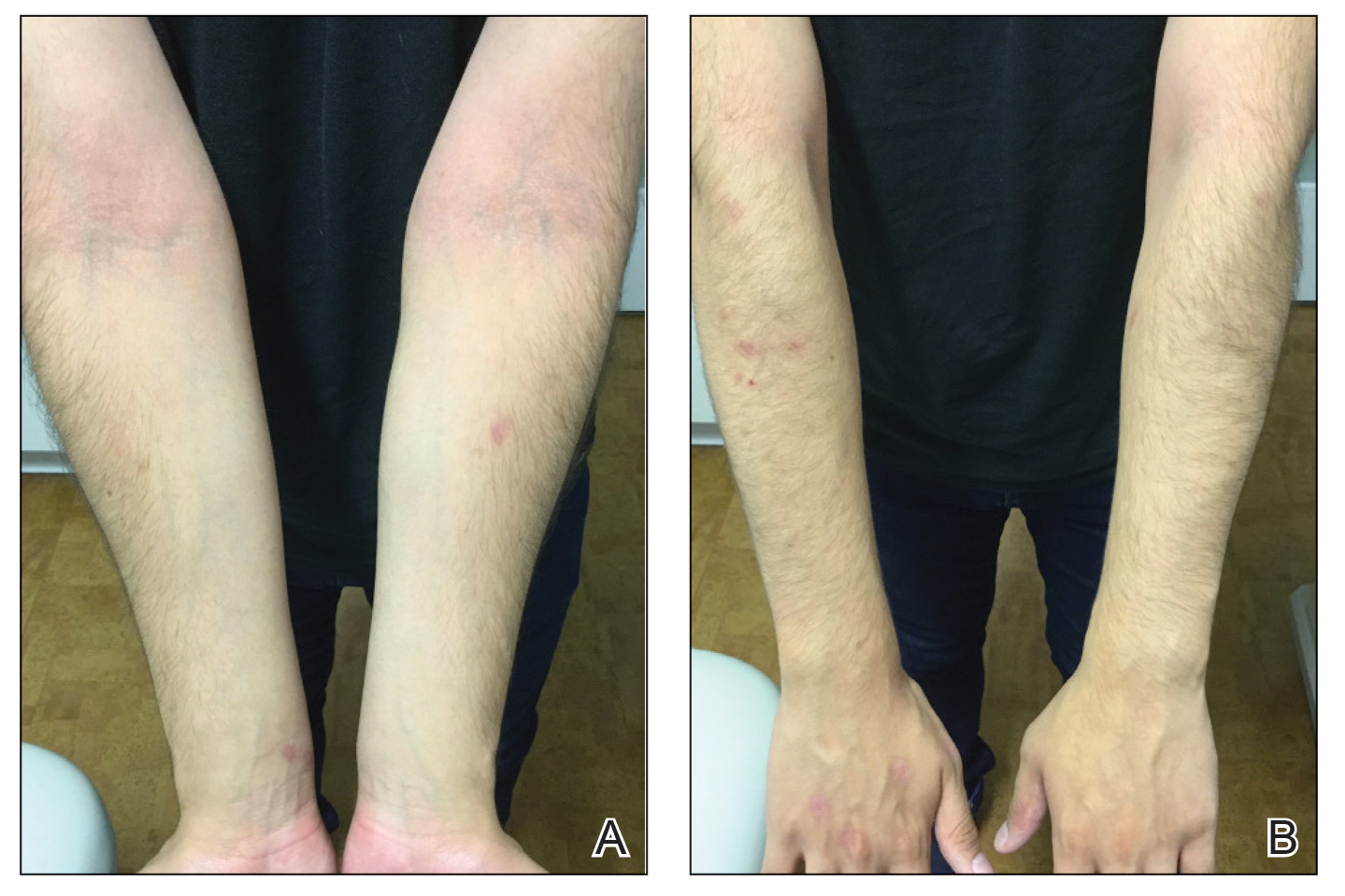

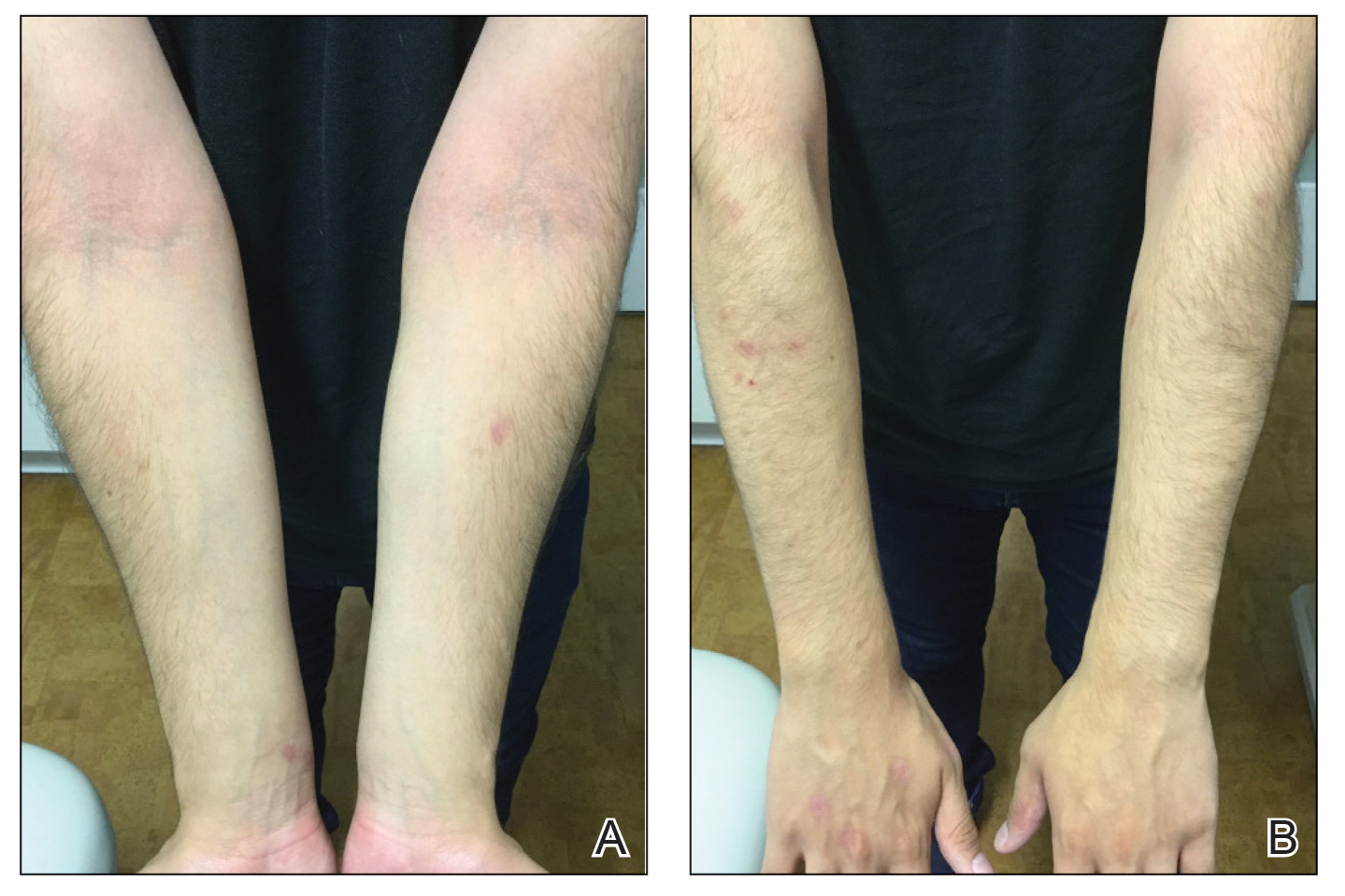

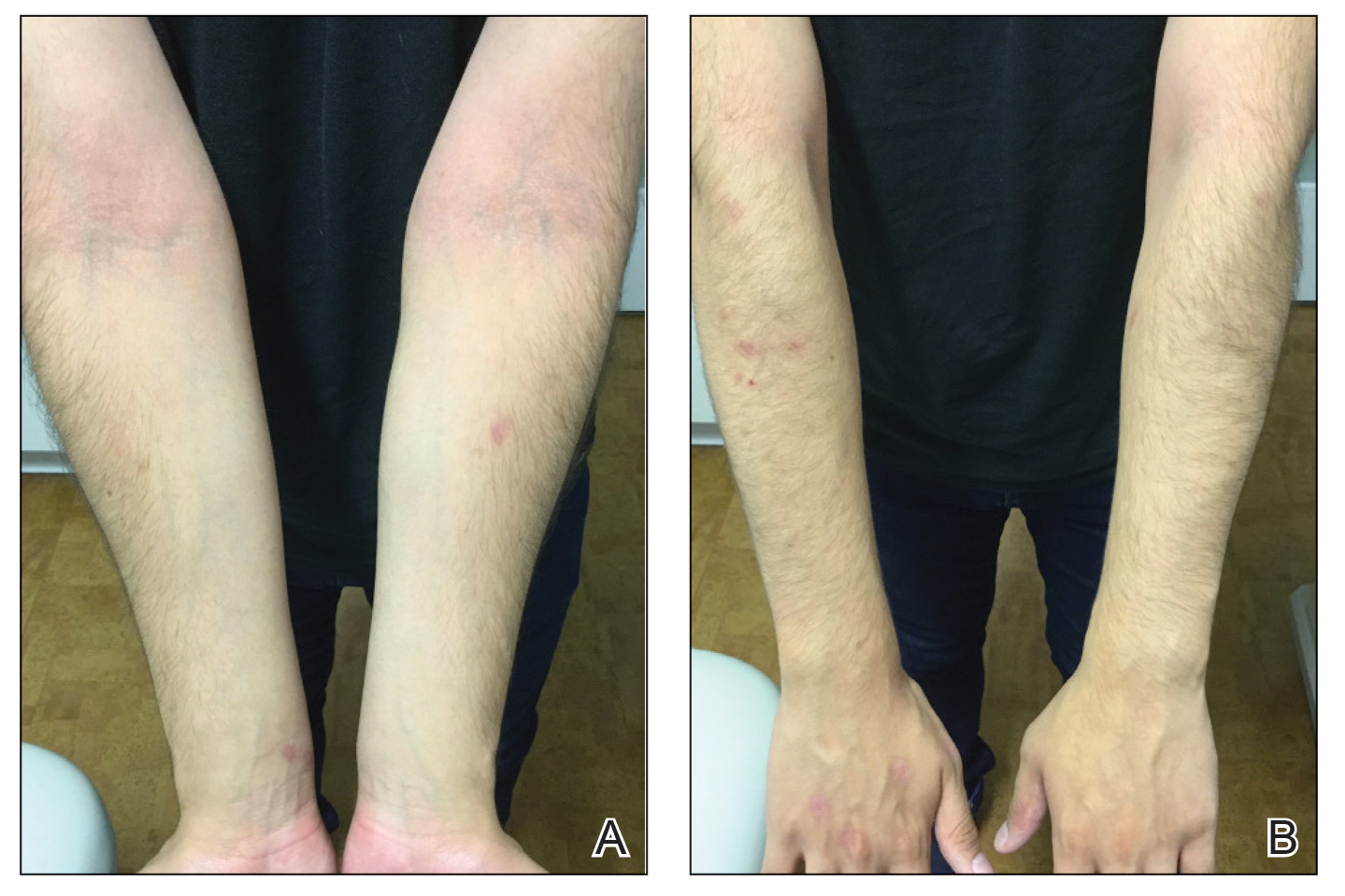

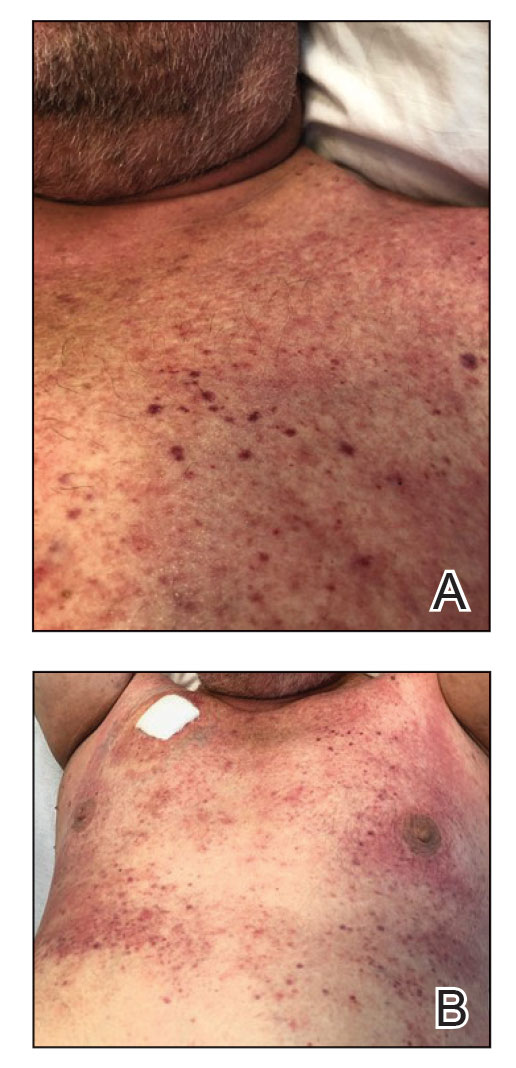

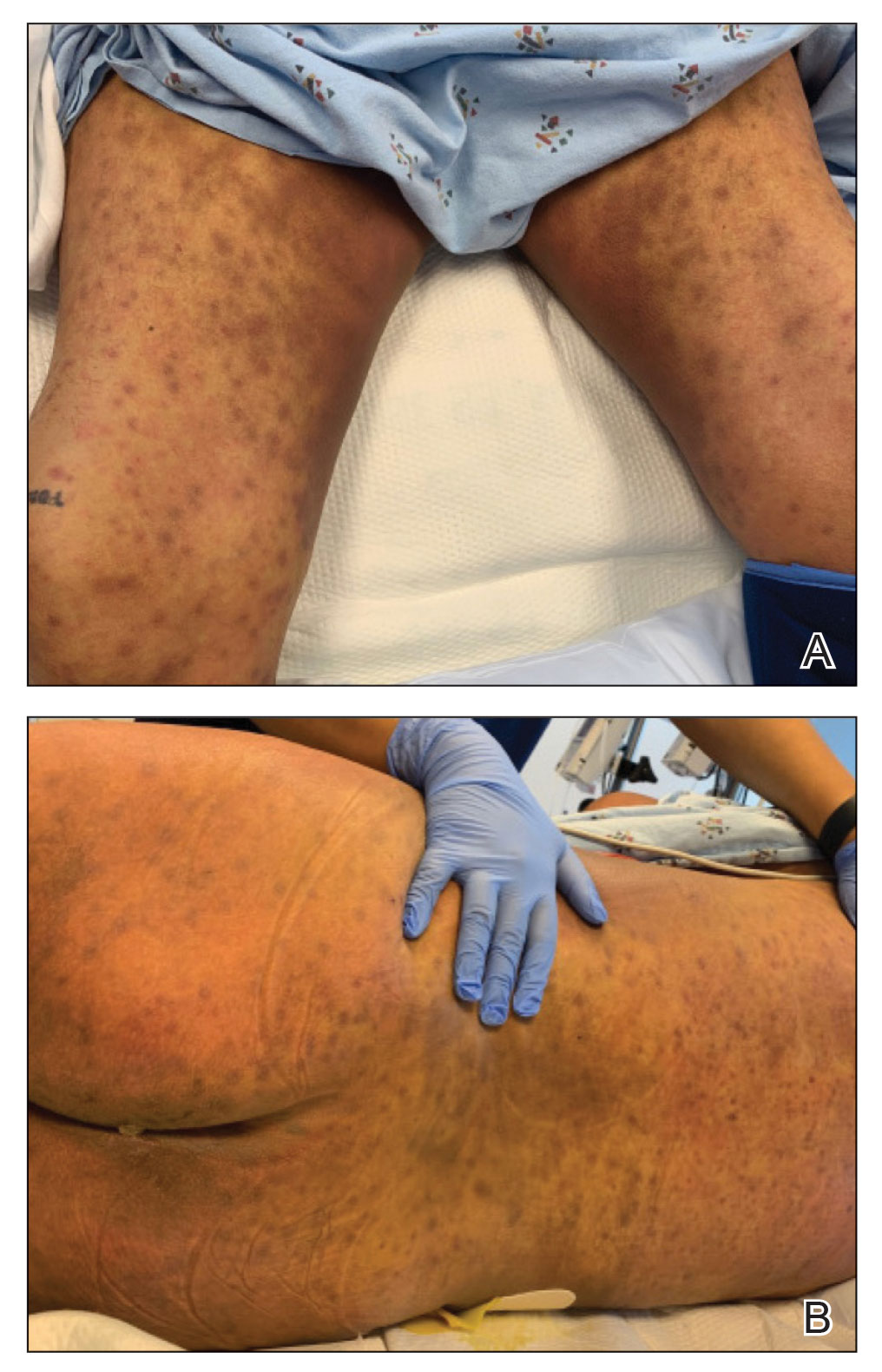

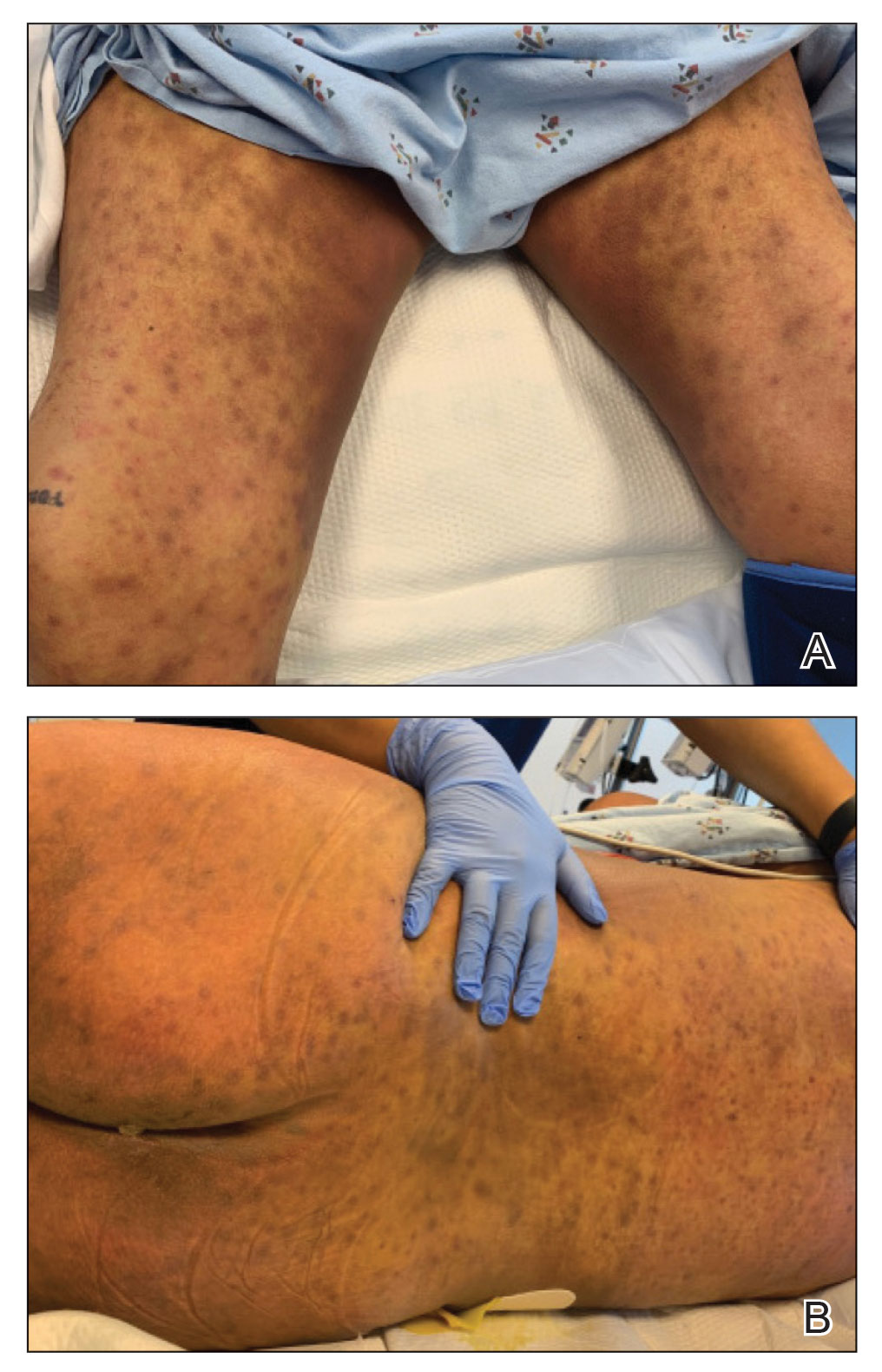

A 63-year-old woman presented with partially blanchable, purple-black patches on the lower extremities (Figure 1). The upper extremities had minimal involvement at the time of presentation. A medical history revealed the lesions presented on the legs 10 years prior but were beginning to form on the arms. She had a history of hypertension and bleeding in the retina.

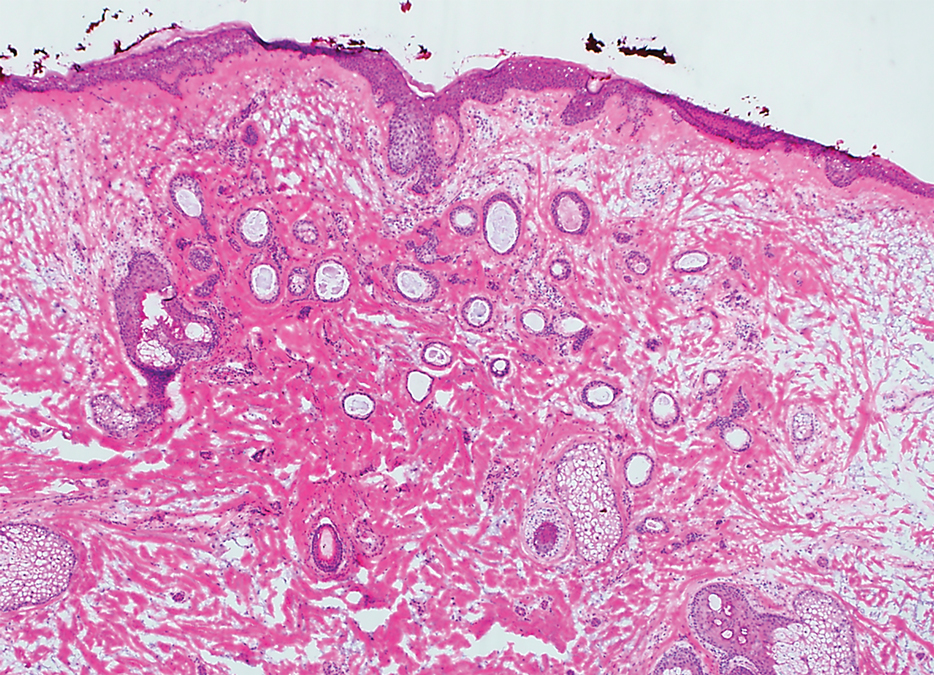

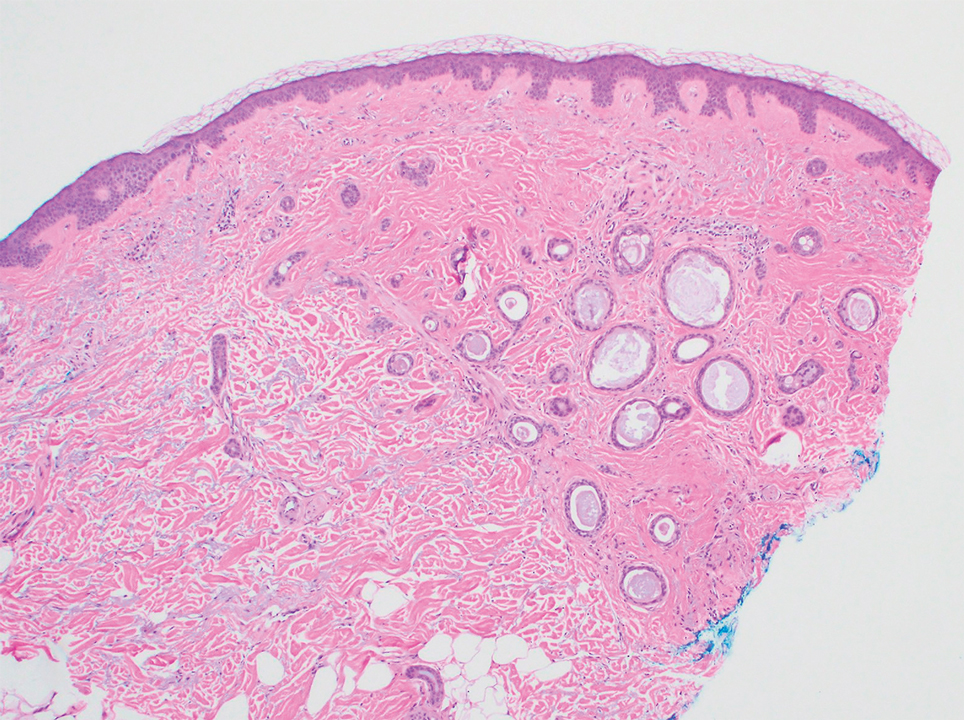

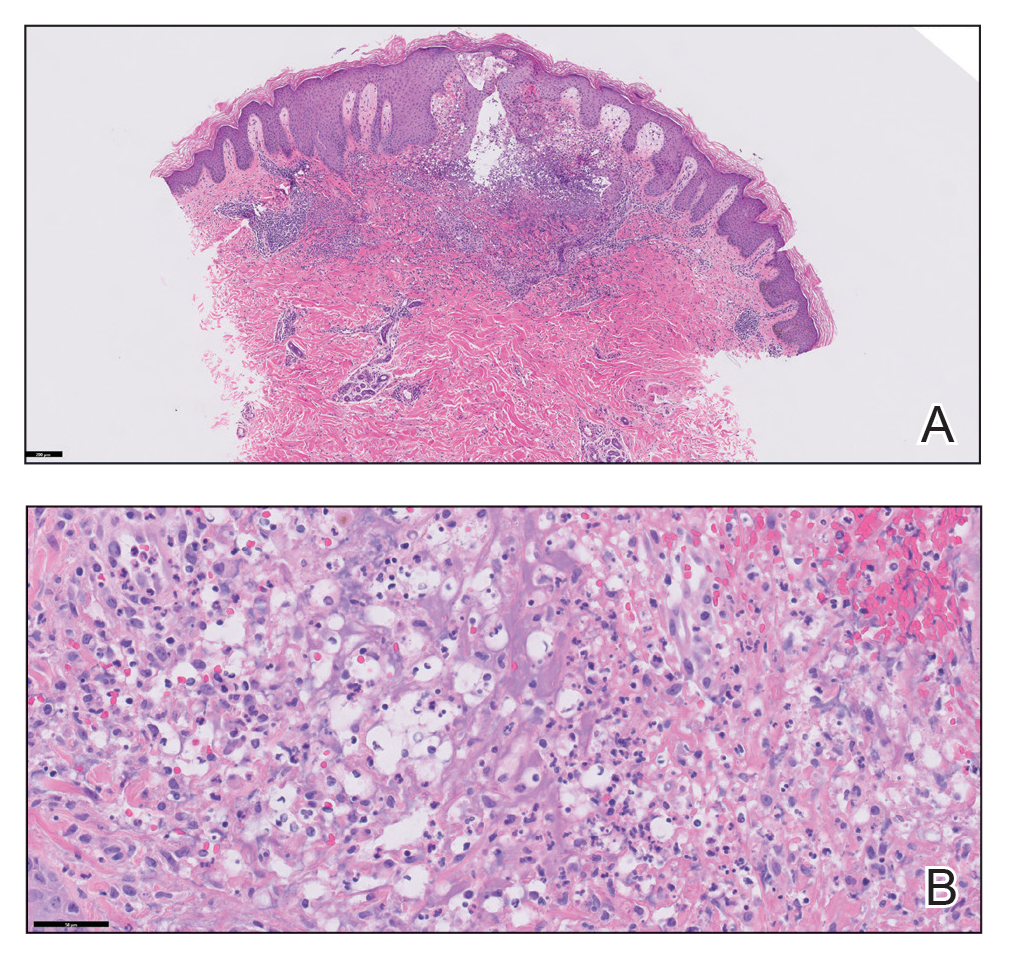

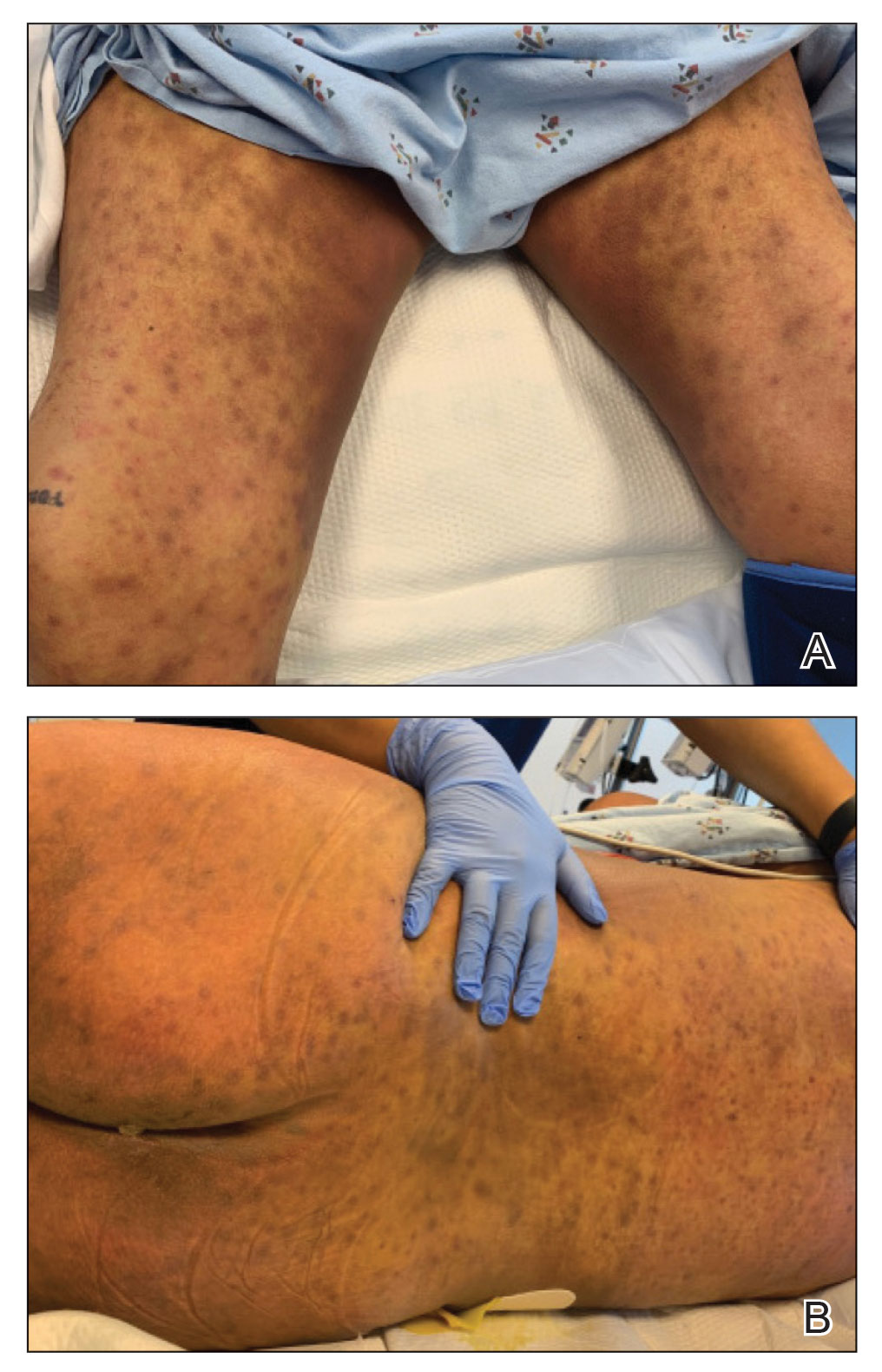

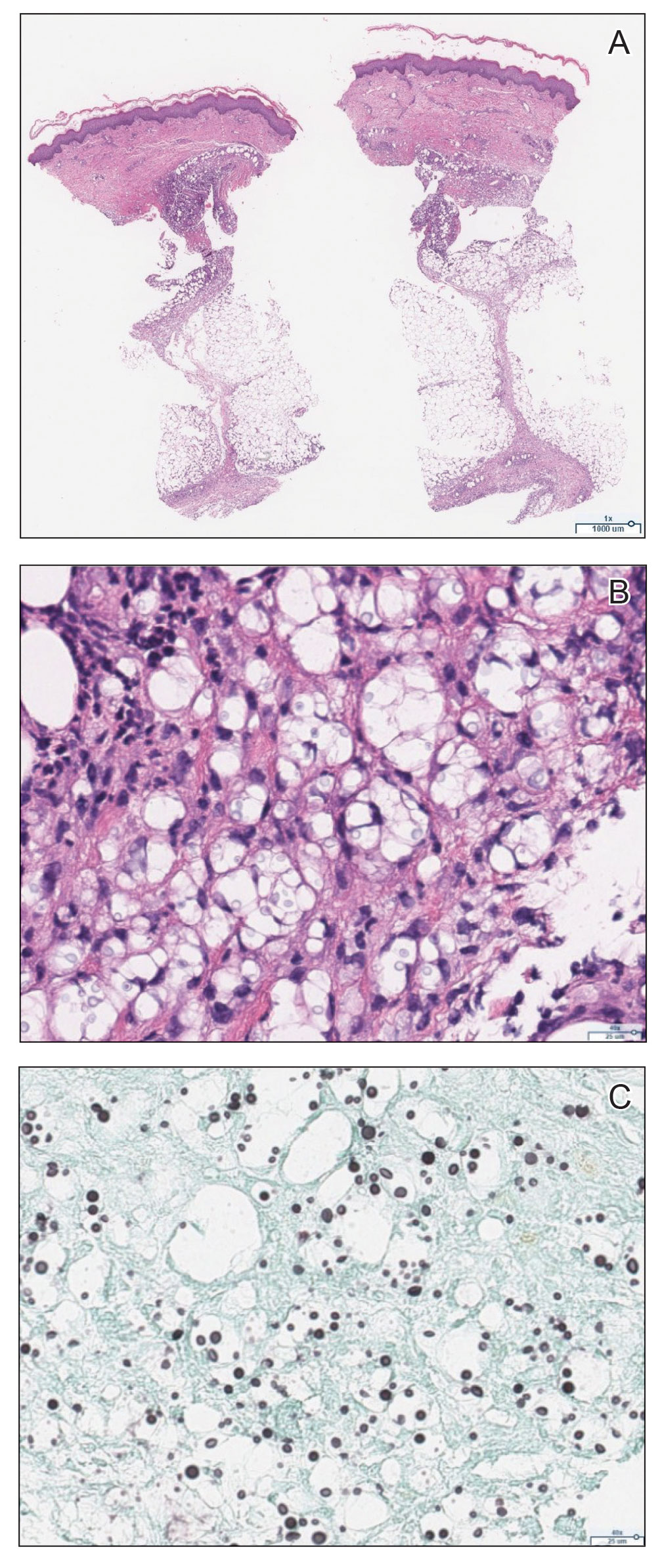

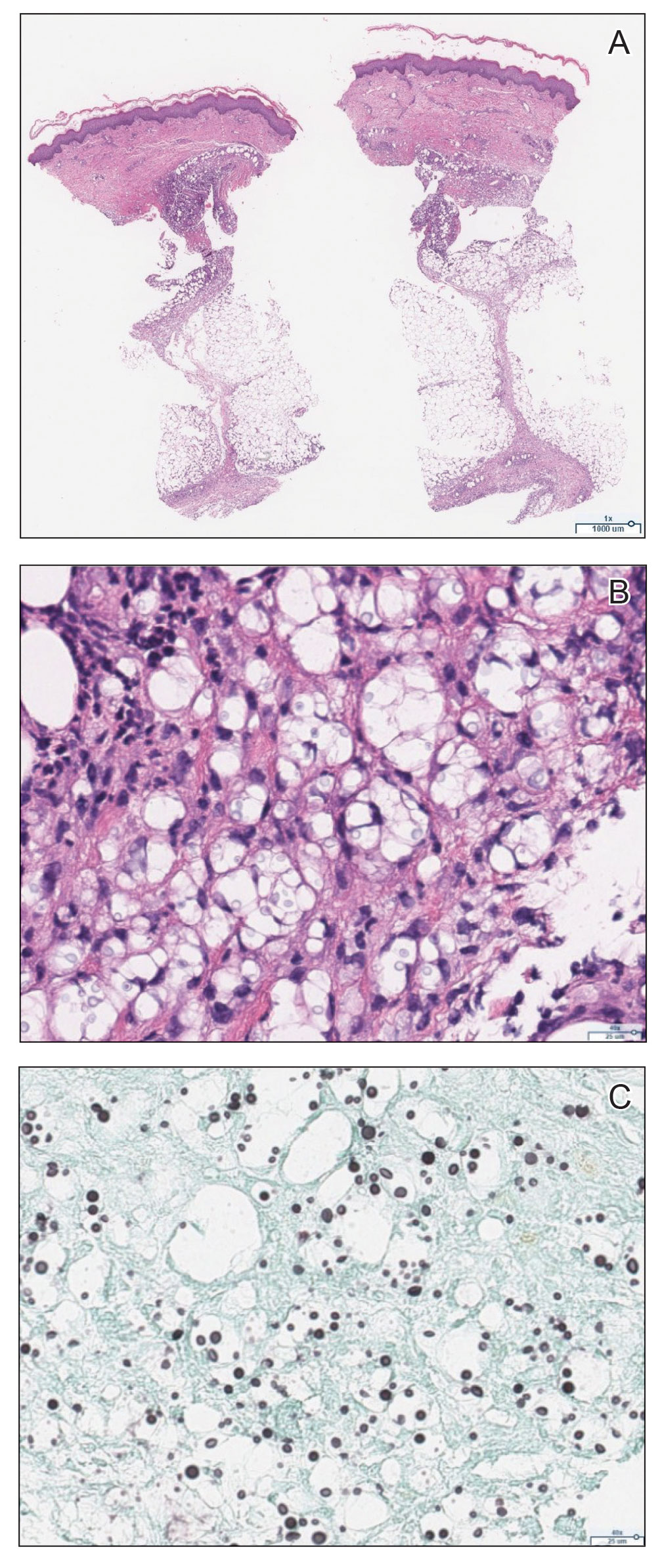

Histopathology revealed prominent dilation of postcapillary venules with eosinophilic collagenous materials in the vessel walls that was positive on periodic acid–Schiff stain, confirming the diagnosis of CCV. The perivascular collagenous material failed to stain with Congo red. Laboratory testing for serum protein electrophoresis, antinuclear antibodies, and baseline hematologic and metabolic panels revealed no abnormalities.

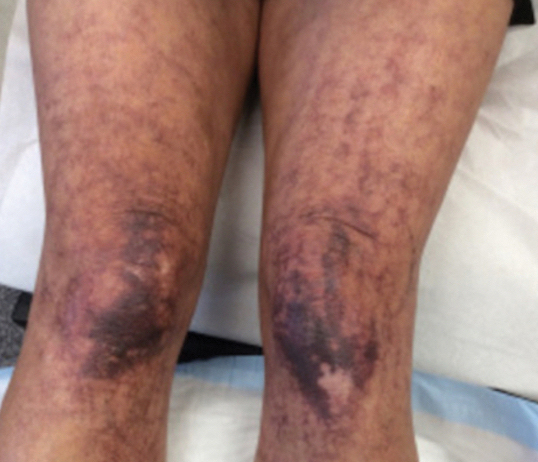

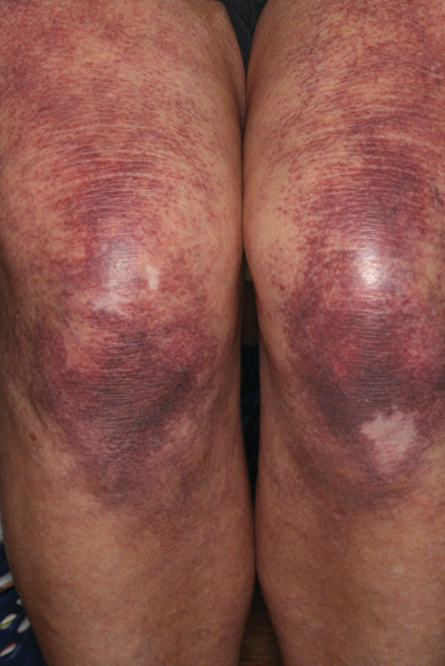

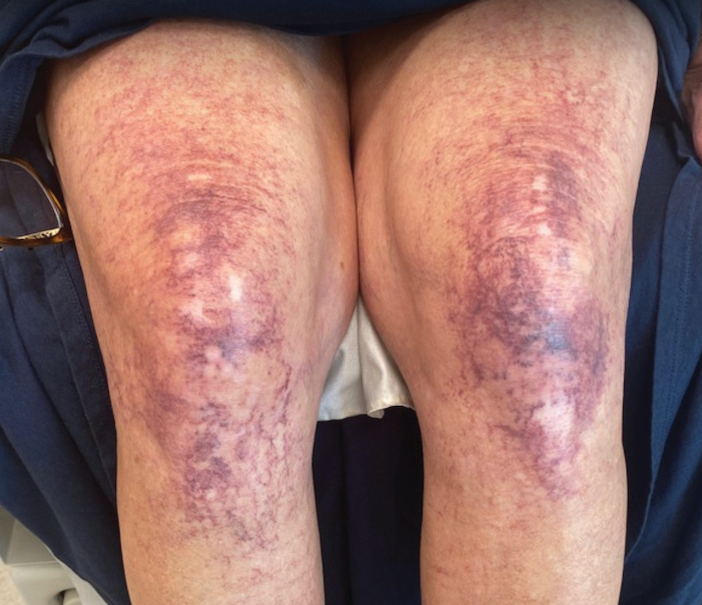

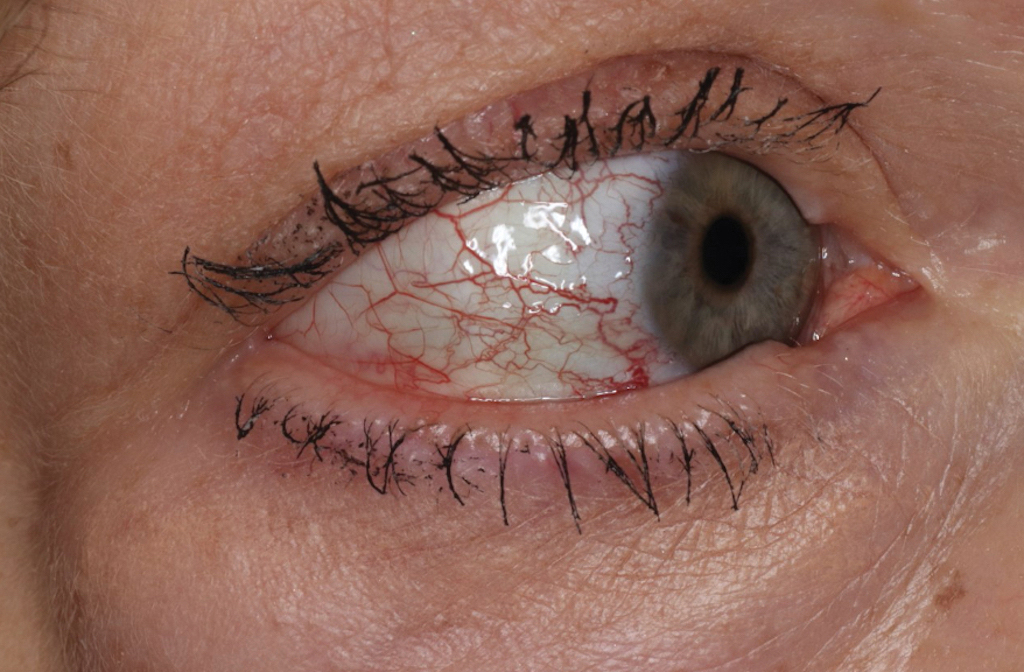

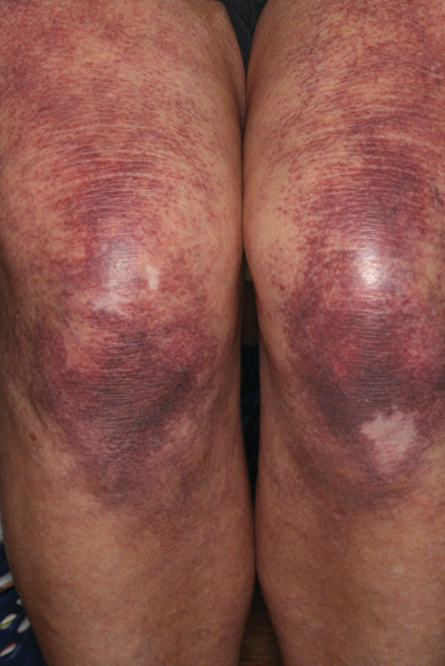

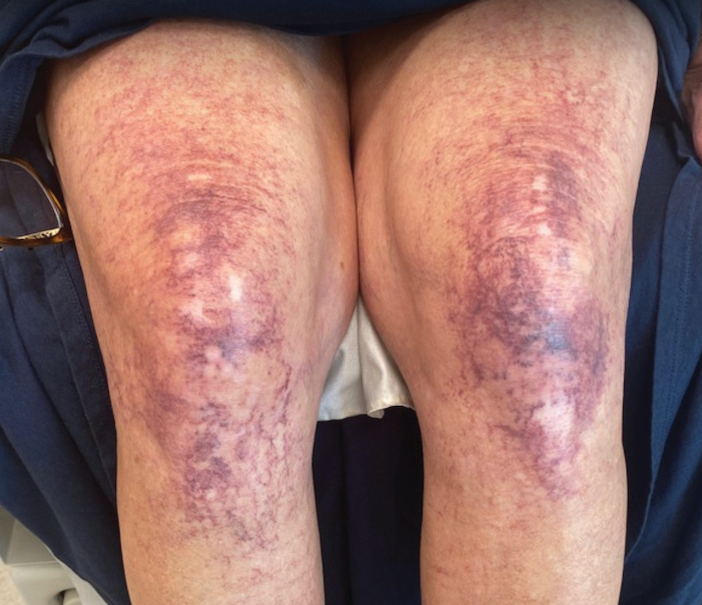

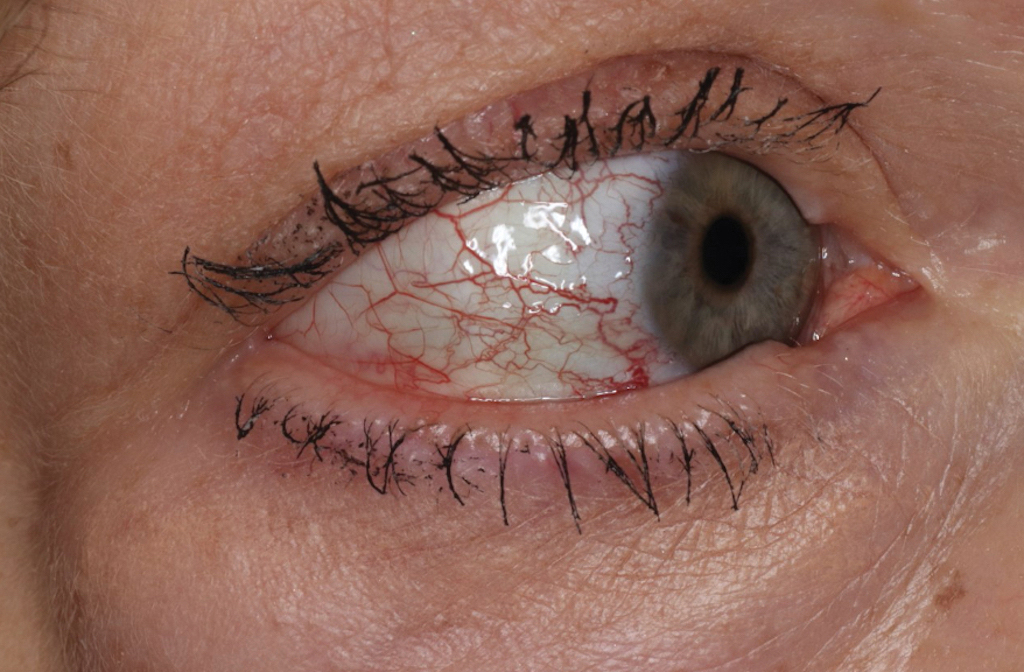

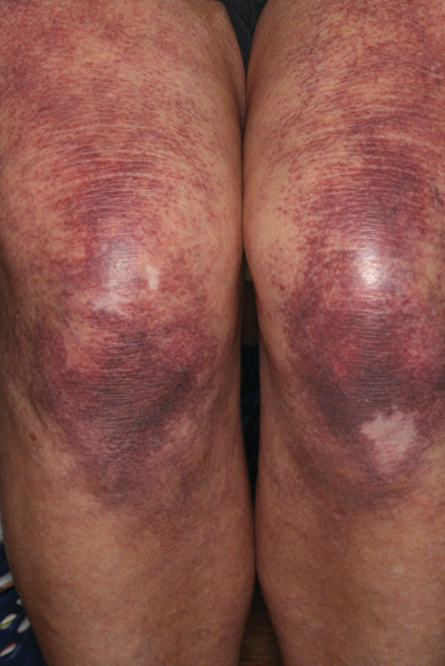

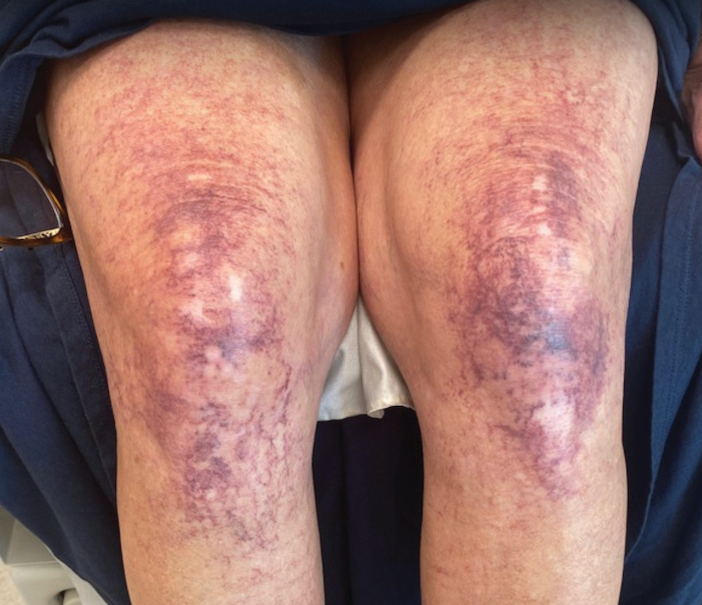

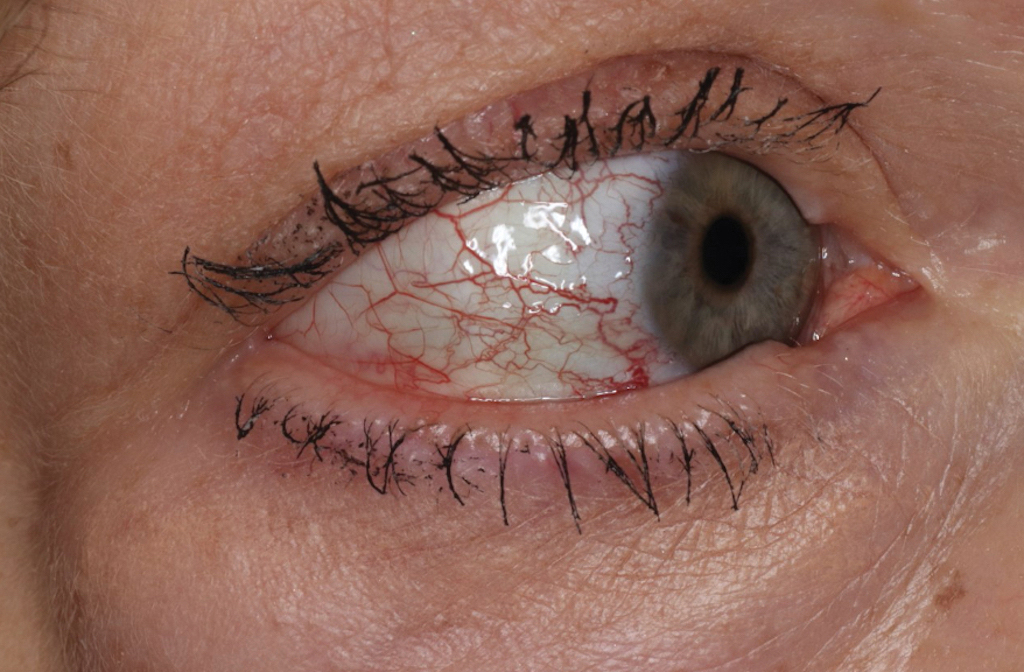

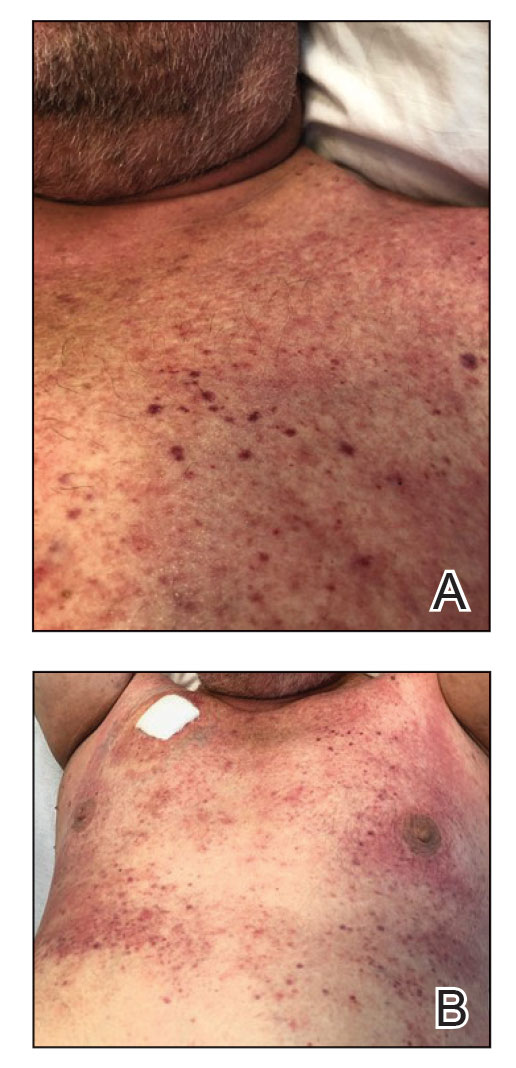

Over 3 years of treatment with PDL, most of the black patches resolved, but prominent telangiectatic vessels remained (Figure 2). Sclerotherapy with polidocanol (10 mg/mL) resulted in clearance of the majority of telangiectatic vessels. After each sclerotherapy treatment, Unna boots were applied for a minimum of 24 hours. The patient had no adverse effects from either PDL or sclerotherapy and was pleased with the results (Figure 3). An ophthalmologist had attributed the retinal bleeding to central serous chorioretinopathy, but tortuosity of superficial scleral and episcleral vessels progressed, suggesting CCV as the more likely cause (Figure 4). Currently, she is being followed for visual changes and further retinal bleeding.

Early CCV typically appears as blanchable pink or red macules, telangiectases, or petechiae on the lower extremities, progressing to involve the trunk and upper extremity.1-3 In rare cases, CCV presents in a papular or annular variant instead of the typical telangiectatic form.4,5 As the lesions progress, they often darken in appearance. Bleeding can occur, and the progressive patches are disfiguring.6,7 Middle-aged to older adults typically present with CCV (range, 16–83 years), with a mean age of 62 years.1,2,6 This disease affects both males and females, predominantly in White individuals.1 Extracutaneous manifestations are rare.1,2,6 One case of mucosal involvement was described in a patient with glossitis and oral erosions.8 We found no prior reports of nail or eye changes.1,2

The etiology of CCV is unknown, but different theories have been proposed. One is that CCV is due to a genetic defect that changes collagen synthesis in the cutaneous microvasculature. Another more widely held belief is that CCV originates from an injury that occurs to the microvasculature endothelial cells. Regardless of the cause of the triggering injury, the result is induced intravascular occlusive microthrombi that cause perivascular fibrosis and endothelial hyperplasia.2,6,7,9

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy may be influenced by systemic diseases. The most common comorbidities are hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia.1,3,6-8 The presentation of CCV with a malignancy is rare; 1 patient was diagnosed with multiple myeloma 18 months after CCV, and another patient’s cutaneous presentation led to discovery of pancreatic cancer with metastasis.8,10 In this setting, the increased growth factors or hypercoagulability of malignancy may play a role in endothelial cell damage and hyperplasia. Autoimmune vascular injury also has been suggested to trigger CCV; 1 case involved antiribonucleoprotein antibodies, while another case involved anti–endothelial cell antibody assays.11 In addition, CCV has been reported in hypercoagulable patients, demonstrating another route for endothelial damage, with 1 patient being heterozygous for prothrombin G20210A, a report of CCV in a patient with cryofibrinogenemia, and another patient being found positive for lupus anticoagulant.11,12 Drugs also have been thought to influence CCV, including corticosteroids, lithium, thiothixene, interferon, isotretinoin, calcium channel blockers, antibiotics, hydroxyurea, and antidepressants.7,11

The diagnosis of CCV is confirmed using light microscopy and collagen-specific immunostaining. Examination shows hyaline eosinophilic deposition of type IV collagen around the affected vessels, with the postcapillary venules showing characteristic duplication of the basal lamina.3,9 The material stains positive with periodic acid-Schiff and Masson trichrome.3

Underreporting may contribute to the low incidence of CCV. The clinical presentation of CCV is similar to generalized essential telangiectasia, with biopsy distinguishing the two. Other diagnoses in the differential include hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, which typically would have mucosal involvement; radiating telangiectatic mats and a strong family history; and hereditary benign telangiectasia, which typically presents in younger patients aged 1 year to adolescence.1

Treatment with vascular lasers has been the main focus, using either the 595-nm PDL or the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.6,13 Pulsed dye laser or intense pulsed light devices can improve patient well-being1,2; intense pulsed light allows for a larger spot size and may be preferred in patients with a larger body surface area involved.13 However, a few other treatments have been proposed. One case report noted poor response to sclerotherapy.1 In another case, a patient treated with a chemotherapy agent, bortezomib, for their concurrent multiple myeloma showed notable CCV cutaneous improvement. The proposed mechanism for bortezomib improving CCV is through its antiproliferative effect on endothelial cells of the superficial dermal vessels.8 Our patient did not achieve an adequate response with PDL, but the addition of sclerotherapy with polidocanol induced a successful response.

Patients should be examined for evidence of ocular involvement and referred to an ophthalmologist for appropriate care. Although there is no definite association with systemic illnesses or mediation, recent associations with an autoimmune disorder or underlying malignancy have been noted.8,10,11 Age-appropriate cancer screening and attention to associated signs and symptoms are recommended.

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52. https://doi.org/10.1097/dad.0000000000000194

- Castiñeiras-Mato I, Rodríguez-Lojo R, Fernández-Díaz ML, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a case report and review of the literature. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:444-447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2015.11.006

- Rambhia KD, Hadawale SD, Khopkar US. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare case report. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:40-42. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-5178.174327

- Conde-Ferreirós A, Roncero-Riesco M, Cañueto J, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: papular form [published online August 15, 2019]. Dermatol Online J. https://doi.org/10.5070/d3258045128

- García-Martínez P, Gomez-Martin I, Lloreta J, et al. Multiple progressive annular telangiectasias: a clinicopathological variant of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy? J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:982-985. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13029

- Sartori DS, de Almeida Jr HL, Dorn TV, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: light and transmission electron microscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:211-213. https://doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20198166

- Basso D, Ribero S, Blazek C, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare form of microangiopathy successfully treated with a combination of multiplex laser and optimized pulsed light with a review of the literature. Dermatology. 2016;232:107-111. https://doi.org/10.1159/000439126

- Dura M, Pock L, Cetkovska P, et al. A case of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with multiple myeloma and with a pathogenic variant of the glucocerebrosidase gene. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:717-721. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14227

- Salama S, Chorneyko K, Belovic B. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with intravascular occlusive fibrin thrombi. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:386-393. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.12285

- Holder E, Schreckenberg C, Lipsker D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy leading to the diagnosis of an advanced pancreatic cancer. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E699-E701. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.18152

- Grossman ME, Cohen M, Ravits M, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a report of three cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:491-495. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14192

- Eldik H, Leisenring NH, Al-Rohil RN, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy in a middle-aged woman with a history of prothrombin G20210A thrombophilia. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:679-682. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13895

- Weiss E, Lazzara DR. Commentary on clinical improvement of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with intense pulsed light therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1412. https://doi.org/10.1097/DSS.0000000000003209

To the Editor:

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is an uncommon microangiopathy that presents with progressive telangiectases on the lower extremities that can eventually spread to involve the upper extremities and trunk. Systemic involvement is uncommon. The diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy, which demonstrates dilated capillaries and postcapillary venules with eosinophilic hyalinized walls. Treatment generally has focused on the use of vascular lasers.1 We report a patient with advanced CCV and ocular involvement that responded to a combination of pulsed dye laser (PDL) therapy and sclerotherapy for cutaneous lesions.

A 63-year-old woman presented with partially blanchable, purple-black patches on the lower extremities (Figure 1). The upper extremities had minimal involvement at the time of presentation. A medical history revealed the lesions presented on the legs 10 years prior but were beginning to form on the arms. She had a history of hypertension and bleeding in the retina.

Histopathology revealed prominent dilation of postcapillary venules with eosinophilic collagenous materials in the vessel walls that was positive on periodic acid–Schiff stain, confirming the diagnosis of CCV. The perivascular collagenous material failed to stain with Congo red. Laboratory testing for serum protein electrophoresis, antinuclear antibodies, and baseline hematologic and metabolic panels revealed no abnormalities.

Over 3 years of treatment with PDL, most of the black patches resolved, but prominent telangiectatic vessels remained (Figure 2). Sclerotherapy with polidocanol (10 mg/mL) resulted in clearance of the majority of telangiectatic vessels. After each sclerotherapy treatment, Unna boots were applied for a minimum of 24 hours. The patient had no adverse effects from either PDL or sclerotherapy and was pleased with the results (Figure 3). An ophthalmologist had attributed the retinal bleeding to central serous chorioretinopathy, but tortuosity of superficial scleral and episcleral vessels progressed, suggesting CCV as the more likely cause (Figure 4). Currently, she is being followed for visual changes and further retinal bleeding.

Early CCV typically appears as blanchable pink or red macules, telangiectases, or petechiae on the lower extremities, progressing to involve the trunk and upper extremity.1-3 In rare cases, CCV presents in a papular or annular variant instead of the typical telangiectatic form.4,5 As the lesions progress, they often darken in appearance. Bleeding can occur, and the progressive patches are disfiguring.6,7 Middle-aged to older adults typically present with CCV (range, 16–83 years), with a mean age of 62 years.1,2,6 This disease affects both males and females, predominantly in White individuals.1 Extracutaneous manifestations are rare.1,2,6 One case of mucosal involvement was described in a patient with glossitis and oral erosions.8 We found no prior reports of nail or eye changes.1,2

The etiology of CCV is unknown, but different theories have been proposed. One is that CCV is due to a genetic defect that changes collagen synthesis in the cutaneous microvasculature. Another more widely held belief is that CCV originates from an injury that occurs to the microvasculature endothelial cells. Regardless of the cause of the triggering injury, the result is induced intravascular occlusive microthrombi that cause perivascular fibrosis and endothelial hyperplasia.2,6,7,9

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy may be influenced by systemic diseases. The most common comorbidities are hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia.1,3,6-8 The presentation of CCV with a malignancy is rare; 1 patient was diagnosed with multiple myeloma 18 months after CCV, and another patient’s cutaneous presentation led to discovery of pancreatic cancer with metastasis.8,10 In this setting, the increased growth factors or hypercoagulability of malignancy may play a role in endothelial cell damage and hyperplasia. Autoimmune vascular injury also has been suggested to trigger CCV; 1 case involved antiribonucleoprotein antibodies, while another case involved anti–endothelial cell antibody assays.11 In addition, CCV has been reported in hypercoagulable patients, demonstrating another route for endothelial damage, with 1 patient being heterozygous for prothrombin G20210A, a report of CCV in a patient with cryofibrinogenemia, and another patient being found positive for lupus anticoagulant.11,12 Drugs also have been thought to influence CCV, including corticosteroids, lithium, thiothixene, interferon, isotretinoin, calcium channel blockers, antibiotics, hydroxyurea, and antidepressants.7,11

The diagnosis of CCV is confirmed using light microscopy and collagen-specific immunostaining. Examination shows hyaline eosinophilic deposition of type IV collagen around the affected vessels, with the postcapillary venules showing characteristic duplication of the basal lamina.3,9 The material stains positive with periodic acid-Schiff and Masson trichrome.3

Underreporting may contribute to the low incidence of CCV. The clinical presentation of CCV is similar to generalized essential telangiectasia, with biopsy distinguishing the two. Other diagnoses in the differential include hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, which typically would have mucosal involvement; radiating telangiectatic mats and a strong family history; and hereditary benign telangiectasia, which typically presents in younger patients aged 1 year to adolescence.1

Treatment with vascular lasers has been the main focus, using either the 595-nm PDL or the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.6,13 Pulsed dye laser or intense pulsed light devices can improve patient well-being1,2; intense pulsed light allows for a larger spot size and may be preferred in patients with a larger body surface area involved.13 However, a few other treatments have been proposed. One case report noted poor response to sclerotherapy.1 In another case, a patient treated with a chemotherapy agent, bortezomib, for their concurrent multiple myeloma showed notable CCV cutaneous improvement. The proposed mechanism for bortezomib improving CCV is through its antiproliferative effect on endothelial cells of the superficial dermal vessels.8 Our patient did not achieve an adequate response with PDL, but the addition of sclerotherapy with polidocanol induced a successful response.

Patients should be examined for evidence of ocular involvement and referred to an ophthalmologist for appropriate care. Although there is no definite association with systemic illnesses or mediation, recent associations with an autoimmune disorder or underlying malignancy have been noted.8,10,11 Age-appropriate cancer screening and attention to associated signs and symptoms are recommended.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is an uncommon microangiopathy that presents with progressive telangiectases on the lower extremities that can eventually spread to involve the upper extremities and trunk. Systemic involvement is uncommon. The diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy, which demonstrates dilated capillaries and postcapillary venules with eosinophilic hyalinized walls. Treatment generally has focused on the use of vascular lasers.1 We report a patient with advanced CCV and ocular involvement that responded to a combination of pulsed dye laser (PDL) therapy and sclerotherapy for cutaneous lesions.

A 63-year-old woman presented with partially blanchable, purple-black patches on the lower extremities (Figure 1). The upper extremities had minimal involvement at the time of presentation. A medical history revealed the lesions presented on the legs 10 years prior but were beginning to form on the arms. She had a history of hypertension and bleeding in the retina.

Histopathology revealed prominent dilation of postcapillary venules with eosinophilic collagenous materials in the vessel walls that was positive on periodic acid–Schiff stain, confirming the diagnosis of CCV. The perivascular collagenous material failed to stain with Congo red. Laboratory testing for serum protein electrophoresis, antinuclear antibodies, and baseline hematologic and metabolic panels revealed no abnormalities.

Over 3 years of treatment with PDL, most of the black patches resolved, but prominent telangiectatic vessels remained (Figure 2). Sclerotherapy with polidocanol (10 mg/mL) resulted in clearance of the majority of telangiectatic vessels. After each sclerotherapy treatment, Unna boots were applied for a minimum of 24 hours. The patient had no adverse effects from either PDL or sclerotherapy and was pleased with the results (Figure 3). An ophthalmologist had attributed the retinal bleeding to central serous chorioretinopathy, but tortuosity of superficial scleral and episcleral vessels progressed, suggesting CCV as the more likely cause (Figure 4). Currently, she is being followed for visual changes and further retinal bleeding.

Early CCV typically appears as blanchable pink or red macules, telangiectases, or petechiae on the lower extremities, progressing to involve the trunk and upper extremity.1-3 In rare cases, CCV presents in a papular or annular variant instead of the typical telangiectatic form.4,5 As the lesions progress, they often darken in appearance. Bleeding can occur, and the progressive patches are disfiguring.6,7 Middle-aged to older adults typically present with CCV (range, 16–83 years), with a mean age of 62 years.1,2,6 This disease affects both males and females, predominantly in White individuals.1 Extracutaneous manifestations are rare.1,2,6 One case of mucosal involvement was described in a patient with glossitis and oral erosions.8 We found no prior reports of nail or eye changes.1,2

The etiology of CCV is unknown, but different theories have been proposed. One is that CCV is due to a genetic defect that changes collagen synthesis in the cutaneous microvasculature. Another more widely held belief is that CCV originates from an injury that occurs to the microvasculature endothelial cells. Regardless of the cause of the triggering injury, the result is induced intravascular occlusive microthrombi that cause perivascular fibrosis and endothelial hyperplasia.2,6,7,9

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy may be influenced by systemic diseases. The most common comorbidities are hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia.1,3,6-8 The presentation of CCV with a malignancy is rare; 1 patient was diagnosed with multiple myeloma 18 months after CCV, and another patient’s cutaneous presentation led to discovery of pancreatic cancer with metastasis.8,10 In this setting, the increased growth factors or hypercoagulability of malignancy may play a role in endothelial cell damage and hyperplasia. Autoimmune vascular injury also has been suggested to trigger CCV; 1 case involved antiribonucleoprotein antibodies, while another case involved anti–endothelial cell antibody assays.11 In addition, CCV has been reported in hypercoagulable patients, demonstrating another route for endothelial damage, with 1 patient being heterozygous for prothrombin G20210A, a report of CCV in a patient with cryofibrinogenemia, and another patient being found positive for lupus anticoagulant.11,12 Drugs also have been thought to influence CCV, including corticosteroids, lithium, thiothixene, interferon, isotretinoin, calcium channel blockers, antibiotics, hydroxyurea, and antidepressants.7,11

The diagnosis of CCV is confirmed using light microscopy and collagen-specific immunostaining. Examination shows hyaline eosinophilic deposition of type IV collagen around the affected vessels, with the postcapillary venules showing characteristic duplication of the basal lamina.3,9 The material stains positive with periodic acid-Schiff and Masson trichrome.3

Underreporting may contribute to the low incidence of CCV. The clinical presentation of CCV is similar to generalized essential telangiectasia, with biopsy distinguishing the two. Other diagnoses in the differential include hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, which typically would have mucosal involvement; radiating telangiectatic mats and a strong family history; and hereditary benign telangiectasia, which typically presents in younger patients aged 1 year to adolescence.1

Treatment with vascular lasers has been the main focus, using either the 595-nm PDL or the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.6,13 Pulsed dye laser or intense pulsed light devices can improve patient well-being1,2; intense pulsed light allows for a larger spot size and may be preferred in patients with a larger body surface area involved.13 However, a few other treatments have been proposed. One case report noted poor response to sclerotherapy.1 In another case, a patient treated with a chemotherapy agent, bortezomib, for their concurrent multiple myeloma showed notable CCV cutaneous improvement. The proposed mechanism for bortezomib improving CCV is through its antiproliferative effect on endothelial cells of the superficial dermal vessels.8 Our patient did not achieve an adequate response with PDL, but the addition of sclerotherapy with polidocanol induced a successful response.

Patients should be examined for evidence of ocular involvement and referred to an ophthalmologist for appropriate care. Although there is no definite association with systemic illnesses or mediation, recent associations with an autoimmune disorder or underlying malignancy have been noted.8,10,11 Age-appropriate cancer screening and attention to associated signs and symptoms are recommended.

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52. https://doi.org/10.1097/dad.0000000000000194

- Castiñeiras-Mato I, Rodríguez-Lojo R, Fernández-Díaz ML, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a case report and review of the literature. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:444-447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2015.11.006

- Rambhia KD, Hadawale SD, Khopkar US. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare case report. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:40-42. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-5178.174327

- Conde-Ferreirós A, Roncero-Riesco M, Cañueto J, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: papular form [published online August 15, 2019]. Dermatol Online J. https://doi.org/10.5070/d3258045128

- García-Martínez P, Gomez-Martin I, Lloreta J, et al. Multiple progressive annular telangiectasias: a clinicopathological variant of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy? J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:982-985. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13029

- Sartori DS, de Almeida Jr HL, Dorn TV, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: light and transmission electron microscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:211-213. https://doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20198166

- Basso D, Ribero S, Blazek C, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare form of microangiopathy successfully treated with a combination of multiplex laser and optimized pulsed light with a review of the literature. Dermatology. 2016;232:107-111. https://doi.org/10.1159/000439126

- Dura M, Pock L, Cetkovska P, et al. A case of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with multiple myeloma and with a pathogenic variant of the glucocerebrosidase gene. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:717-721. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14227

- Salama S, Chorneyko K, Belovic B. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with intravascular occlusive fibrin thrombi. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:386-393. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.12285

- Holder E, Schreckenberg C, Lipsker D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy leading to the diagnosis of an advanced pancreatic cancer. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E699-E701. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.18152

- Grossman ME, Cohen M, Ravits M, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a report of three cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:491-495. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14192

- Eldik H, Leisenring NH, Al-Rohil RN, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy in a middle-aged woman with a history of prothrombin G20210A thrombophilia. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:679-682. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13895

- Weiss E, Lazzara DR. Commentary on clinical improvement of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with intense pulsed light therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1412. https://doi.org/10.1097/DSS.0000000000003209

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52. https://doi.org/10.1097/dad.0000000000000194

- Castiñeiras-Mato I, Rodríguez-Lojo R, Fernández-Díaz ML, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a case report and review of the literature. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:444-447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2015.11.006

- Rambhia KD, Hadawale SD, Khopkar US. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare case report. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:40-42. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-5178.174327

- Conde-Ferreirós A, Roncero-Riesco M, Cañueto J, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: papular form [published online August 15, 2019]. Dermatol Online J. https://doi.org/10.5070/d3258045128

- García-Martínez P, Gomez-Martin I, Lloreta J, et al. Multiple progressive annular telangiectasias: a clinicopathological variant of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy? J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:982-985. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13029

- Sartori DS, de Almeida Jr HL, Dorn TV, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: light and transmission electron microscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:211-213. https://doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20198166

- Basso D, Ribero S, Blazek C, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare form of microangiopathy successfully treated with a combination of multiplex laser and optimized pulsed light with a review of the literature. Dermatology. 2016;232:107-111. https://doi.org/10.1159/000439126

- Dura M, Pock L, Cetkovska P, et al. A case of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with multiple myeloma and with a pathogenic variant of the glucocerebrosidase gene. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:717-721. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14227

- Salama S, Chorneyko K, Belovic B. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with intravascular occlusive fibrin thrombi. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:386-393. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.12285

- Holder E, Schreckenberg C, Lipsker D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy leading to the diagnosis of an advanced pancreatic cancer. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E699-E701. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.18152

- Grossman ME, Cohen M, Ravits M, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a report of three cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:491-495. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14192

- Eldik H, Leisenring NH, Al-Rohil RN, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy in a middle-aged woman with a history of prothrombin G20210A thrombophilia. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:679-682. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13895

- Weiss E, Lazzara DR. Commentary on clinical improvement of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with intense pulsed light therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1412. https://doi.org/10.1097/DSS.0000000000003209

Practice Points

- Collagenous vasculopathy is an underrecognized entity.

- Although most patients exhibit only cutaneous disease, systemic involvement also should be assessed.

Plaquelike Syringoma Mimicking Microcystic Adnexal Carcinoma: A Potential Histologic Pitfall

To the Editor:

Plaquelike or plaque-type syringoma is a lesser-known variant of syringoma that can appear histologically indistinguishable from the superficial portion of microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC). The plaquelike variant of syringoma holds a benign clinical course, and no treatment is necessary. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma is distinguished from plaquelike syringoma by an aggressive growth pattern with a high risk for local invasion and recurrence if inadequately treated. Thus, treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) has been recommended as the mainstay for MAC. If superficial biopsy specimens reveal suspicion for MAC and patients are referred for MMS, careful consideration should be made to differentiate MAC and plaquelike syringoma early to prevent unnecessary morbidity.

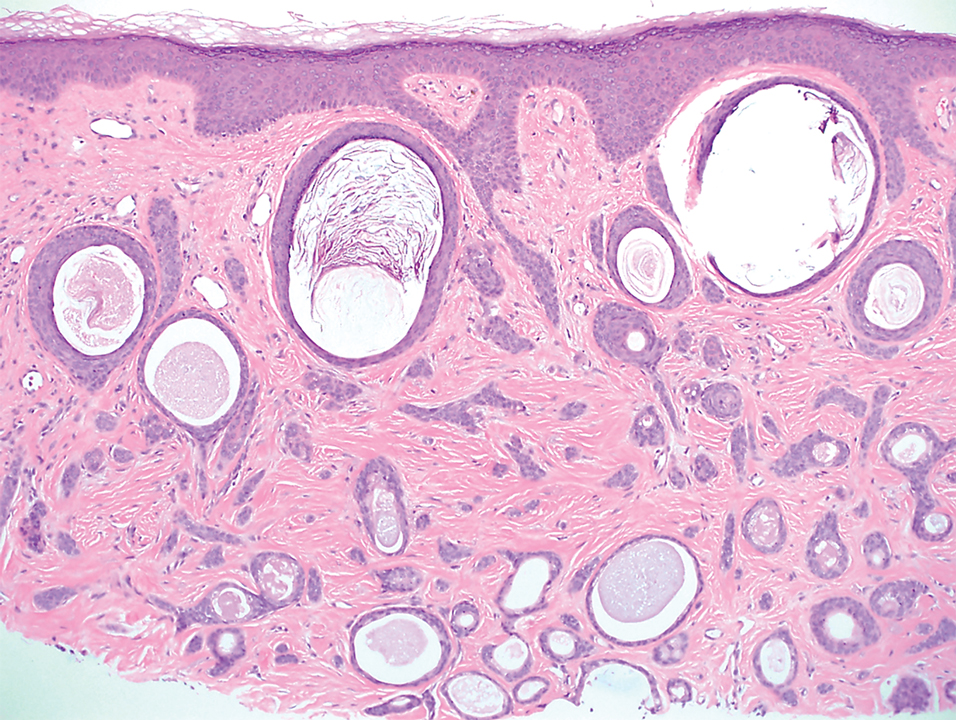

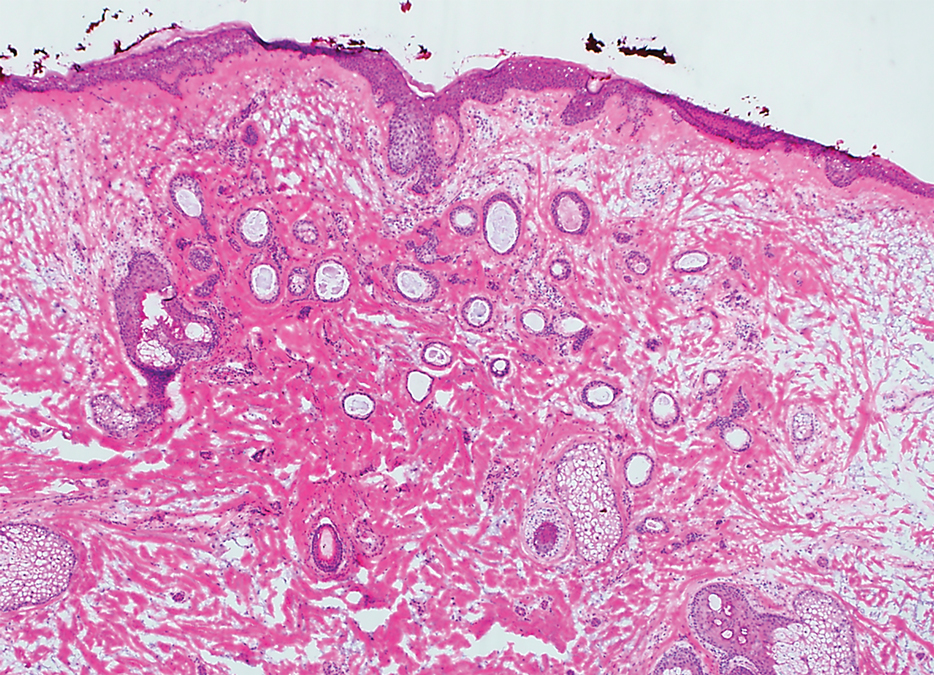

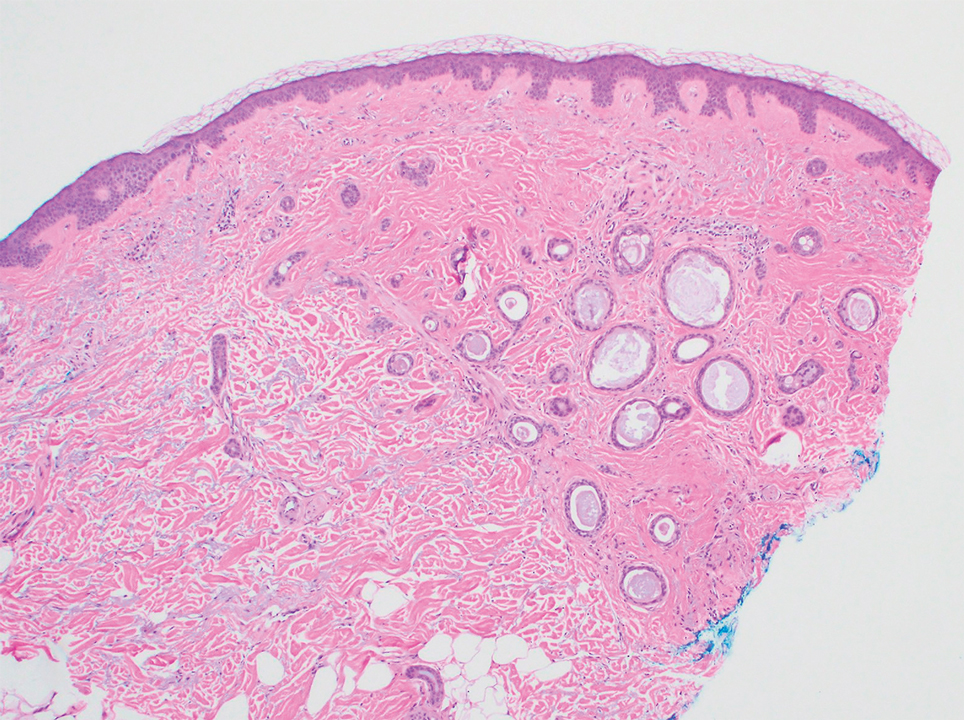

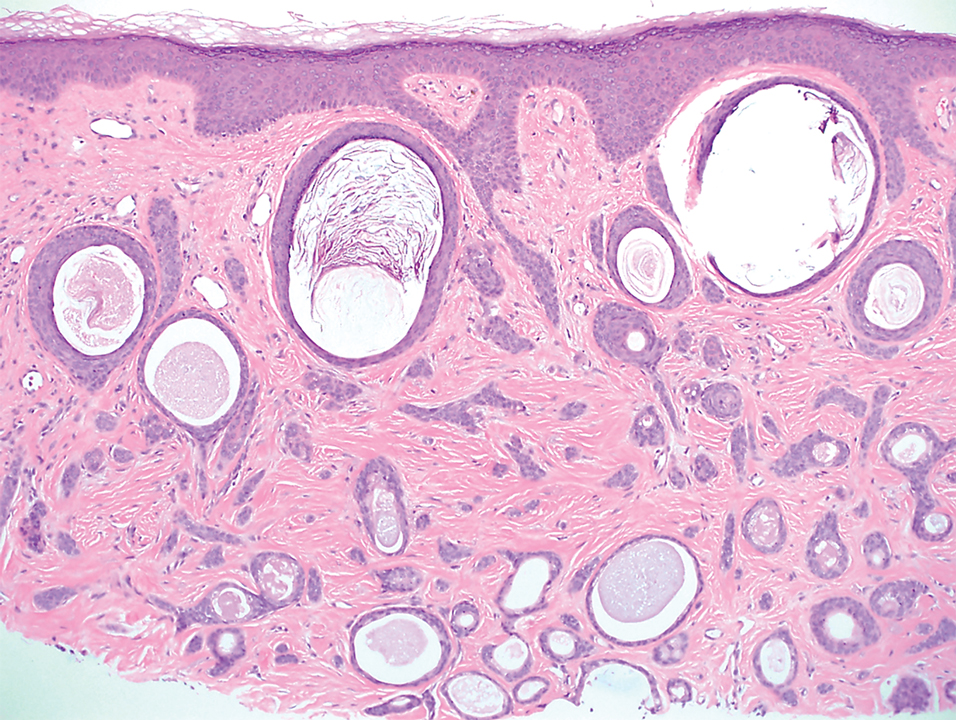

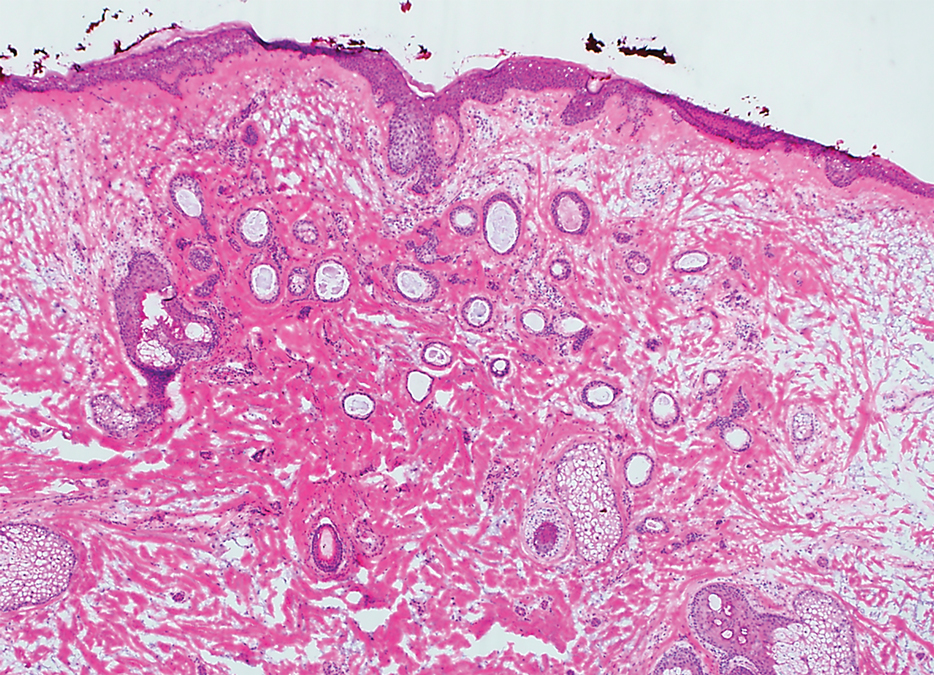

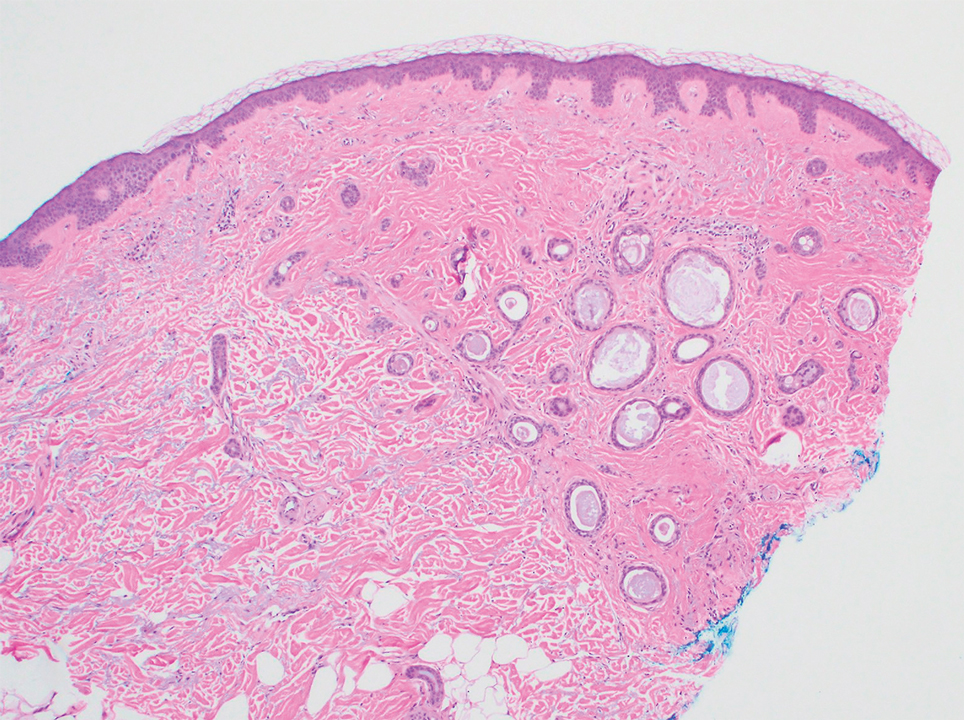

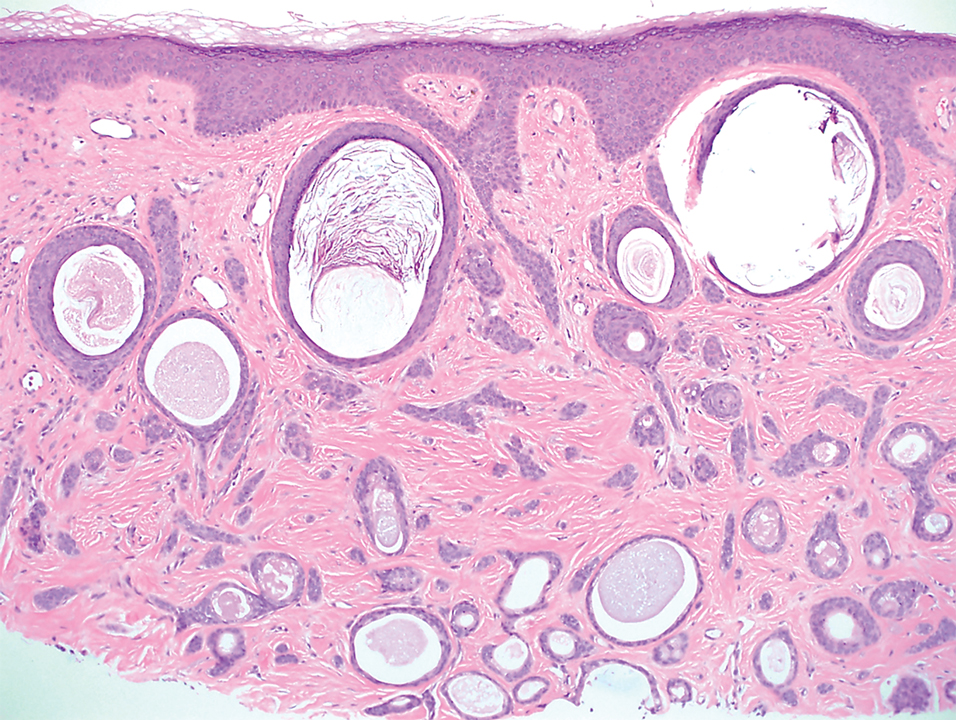

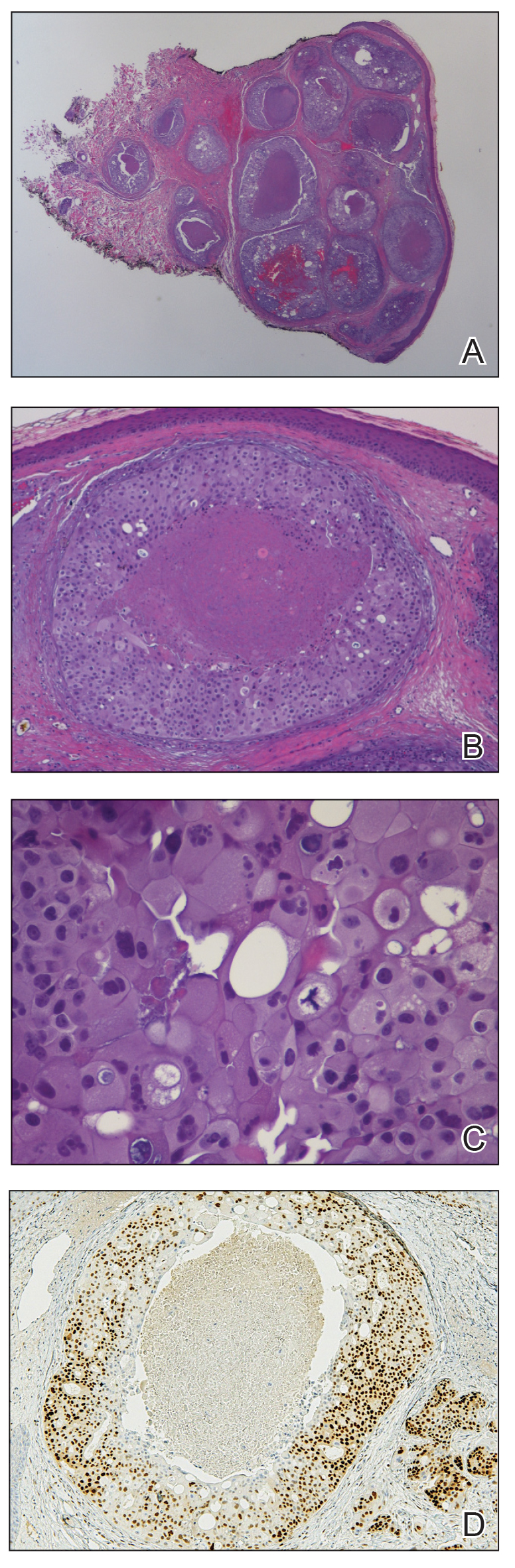

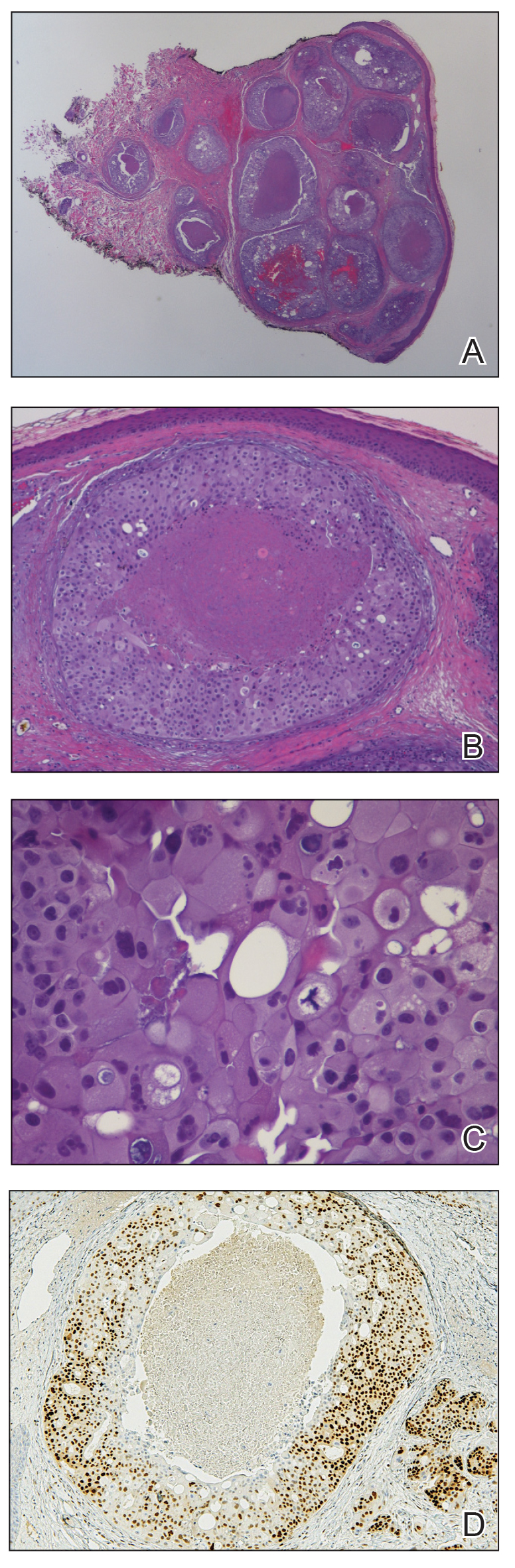

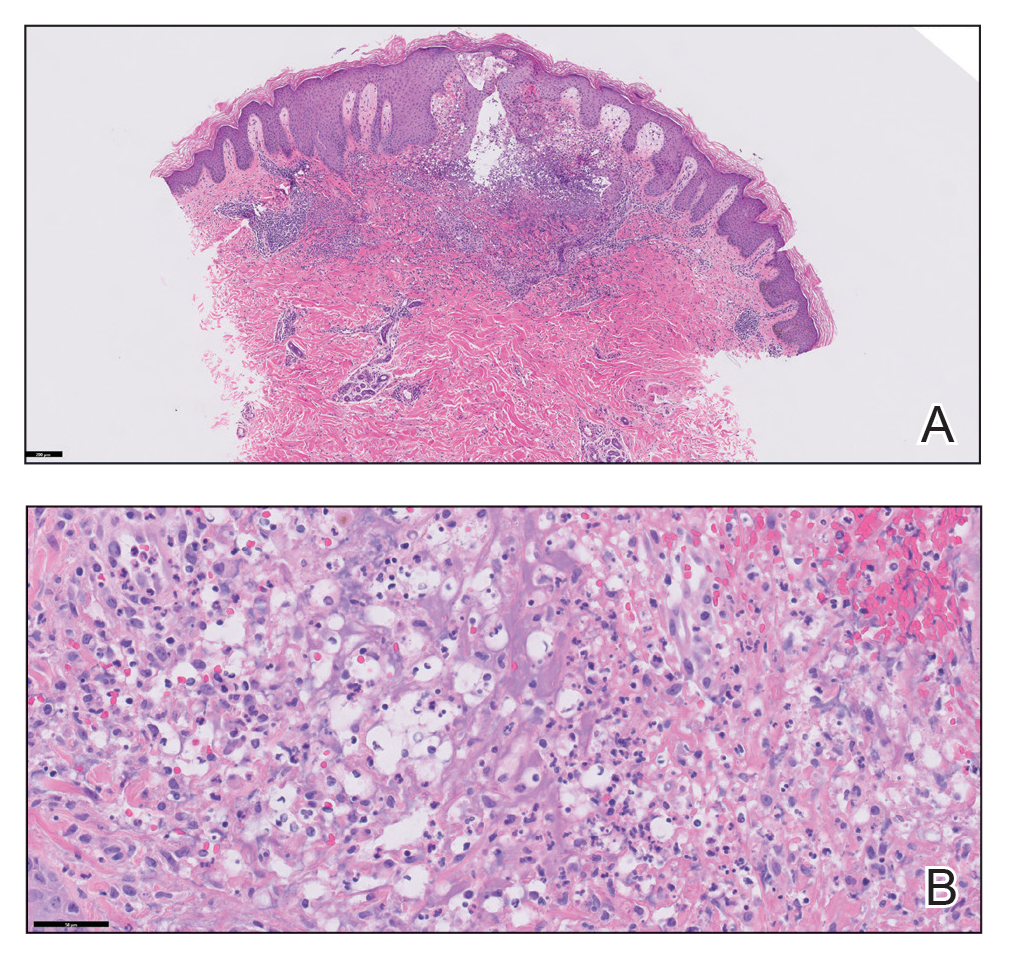

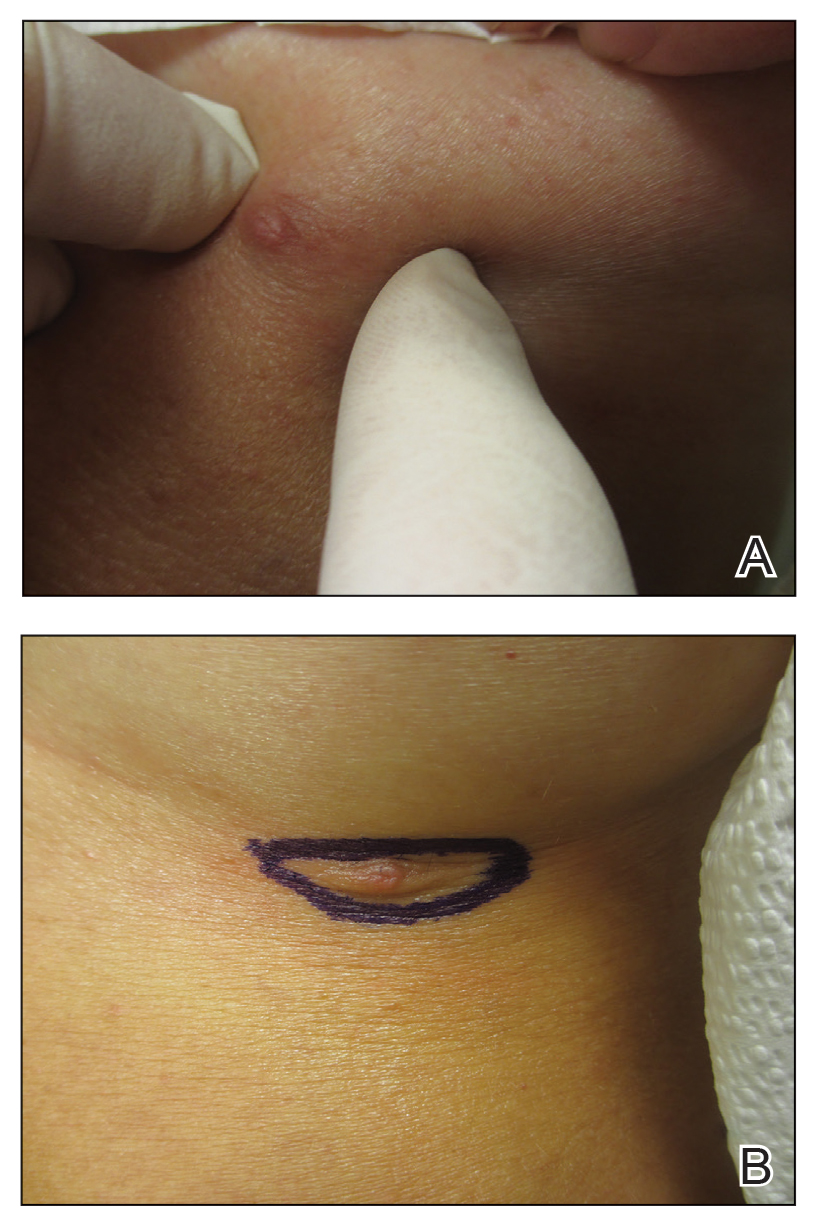

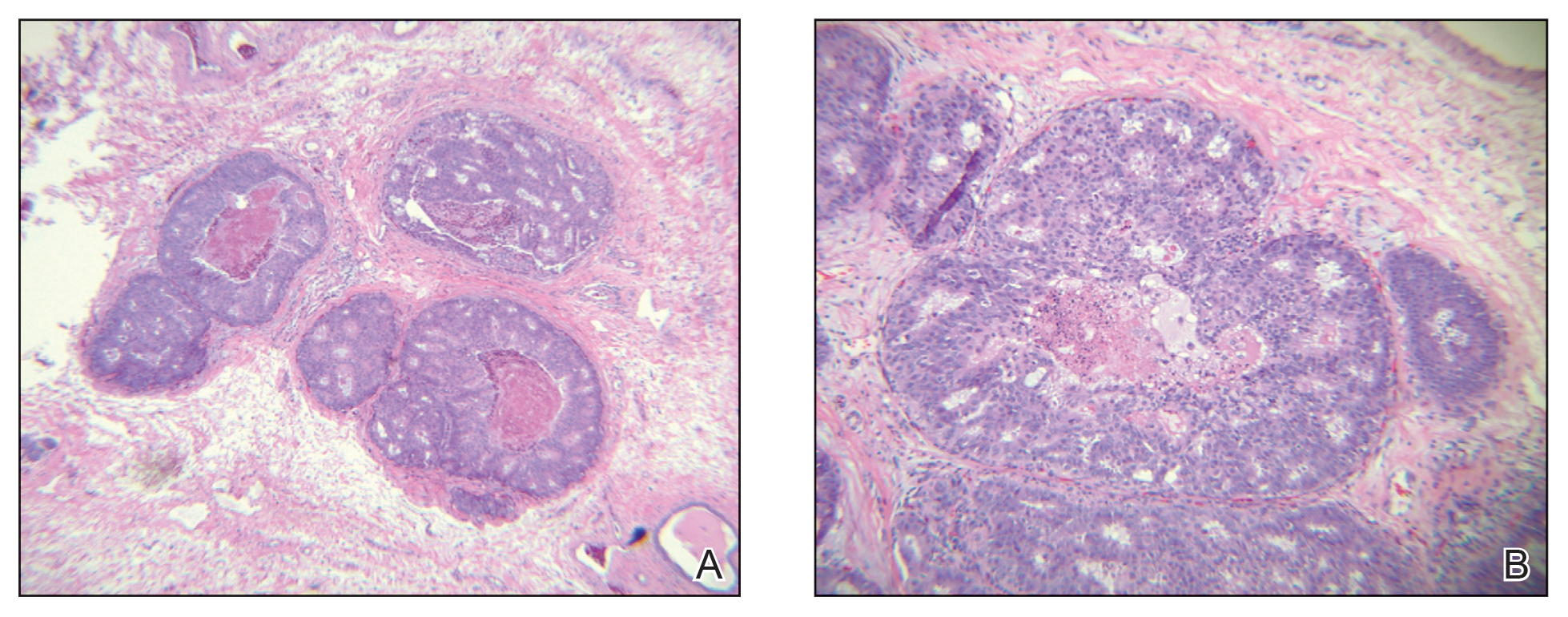

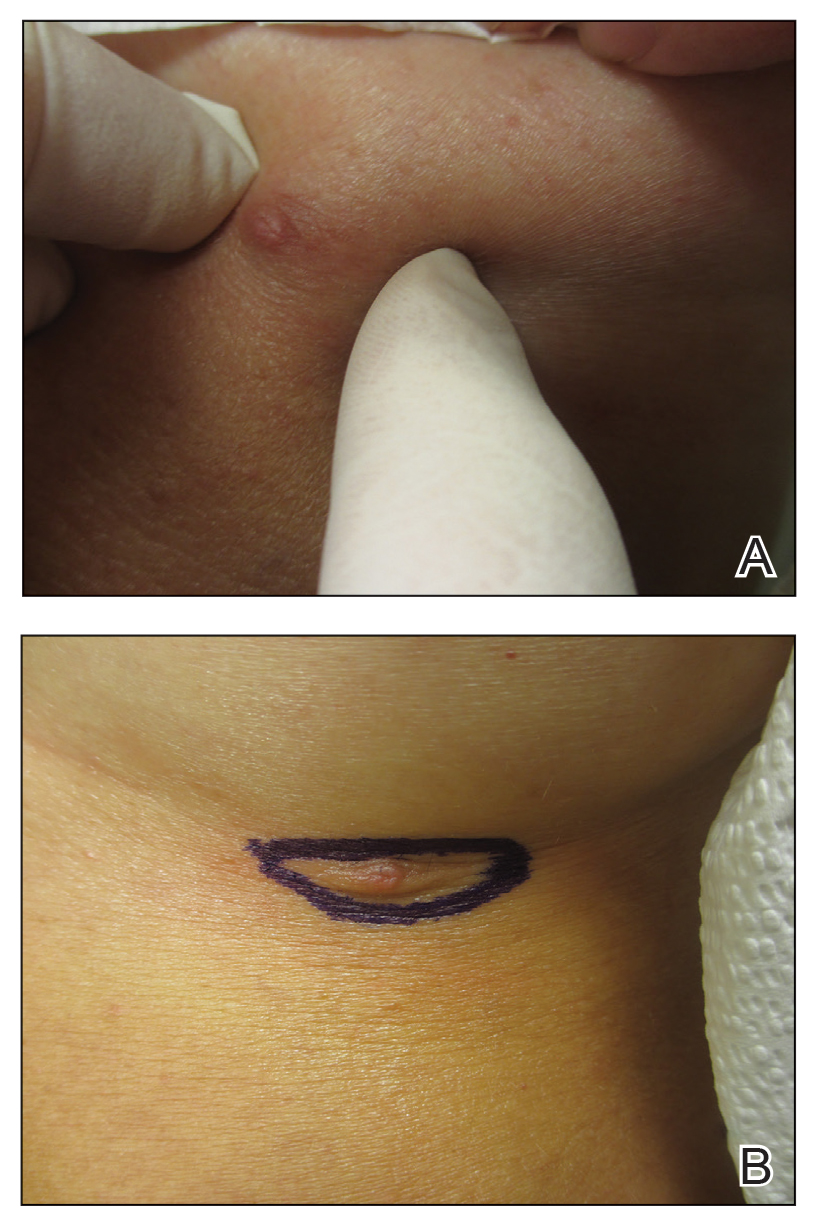

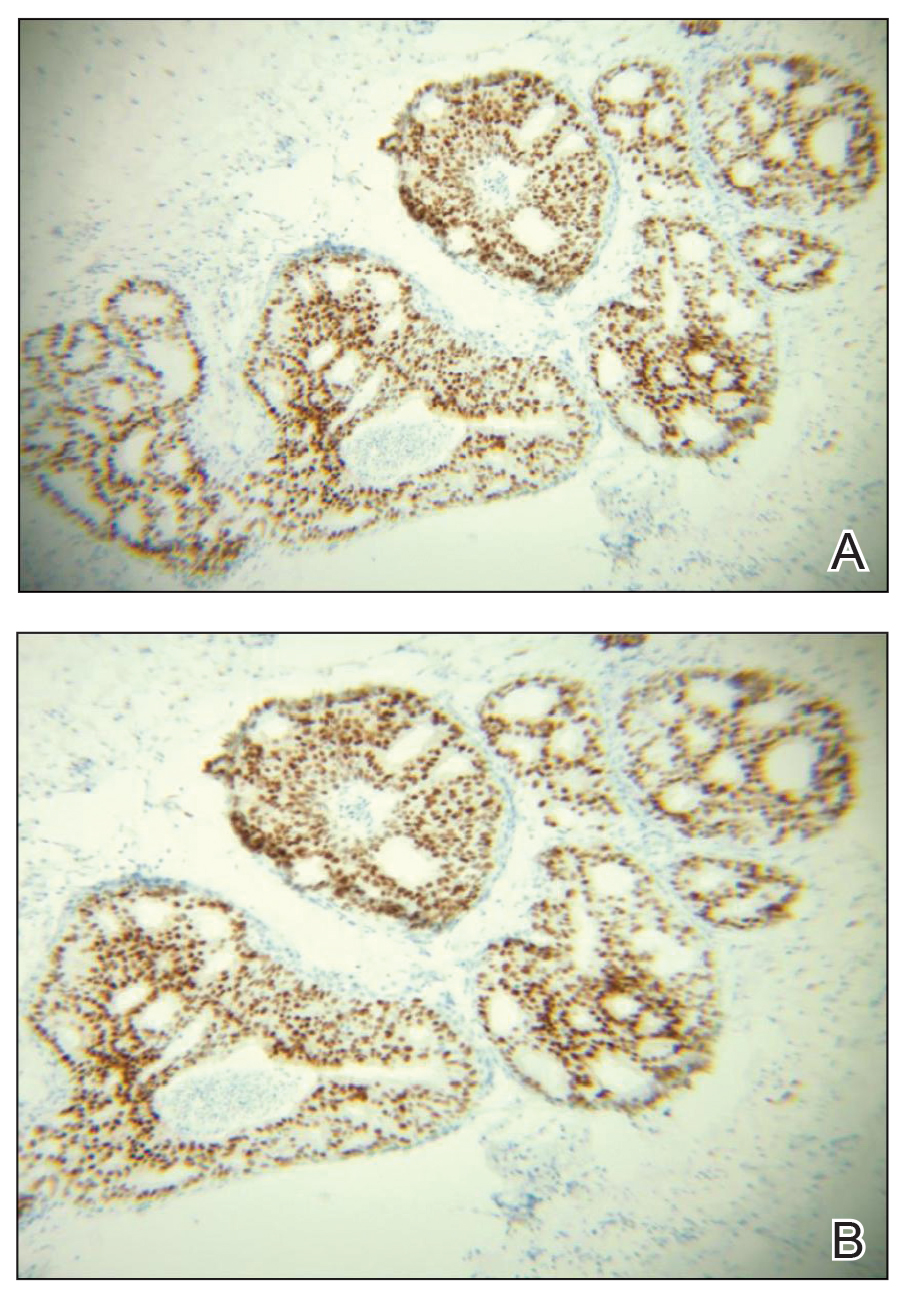

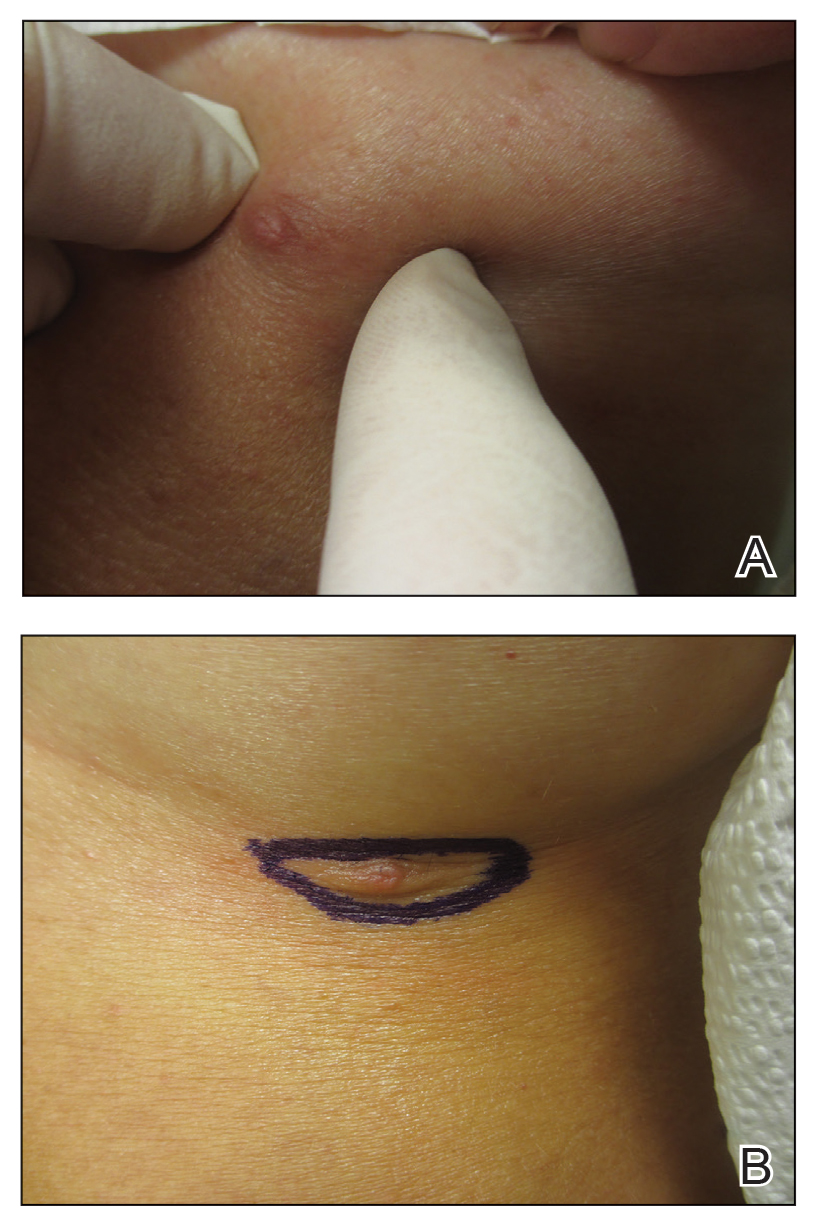

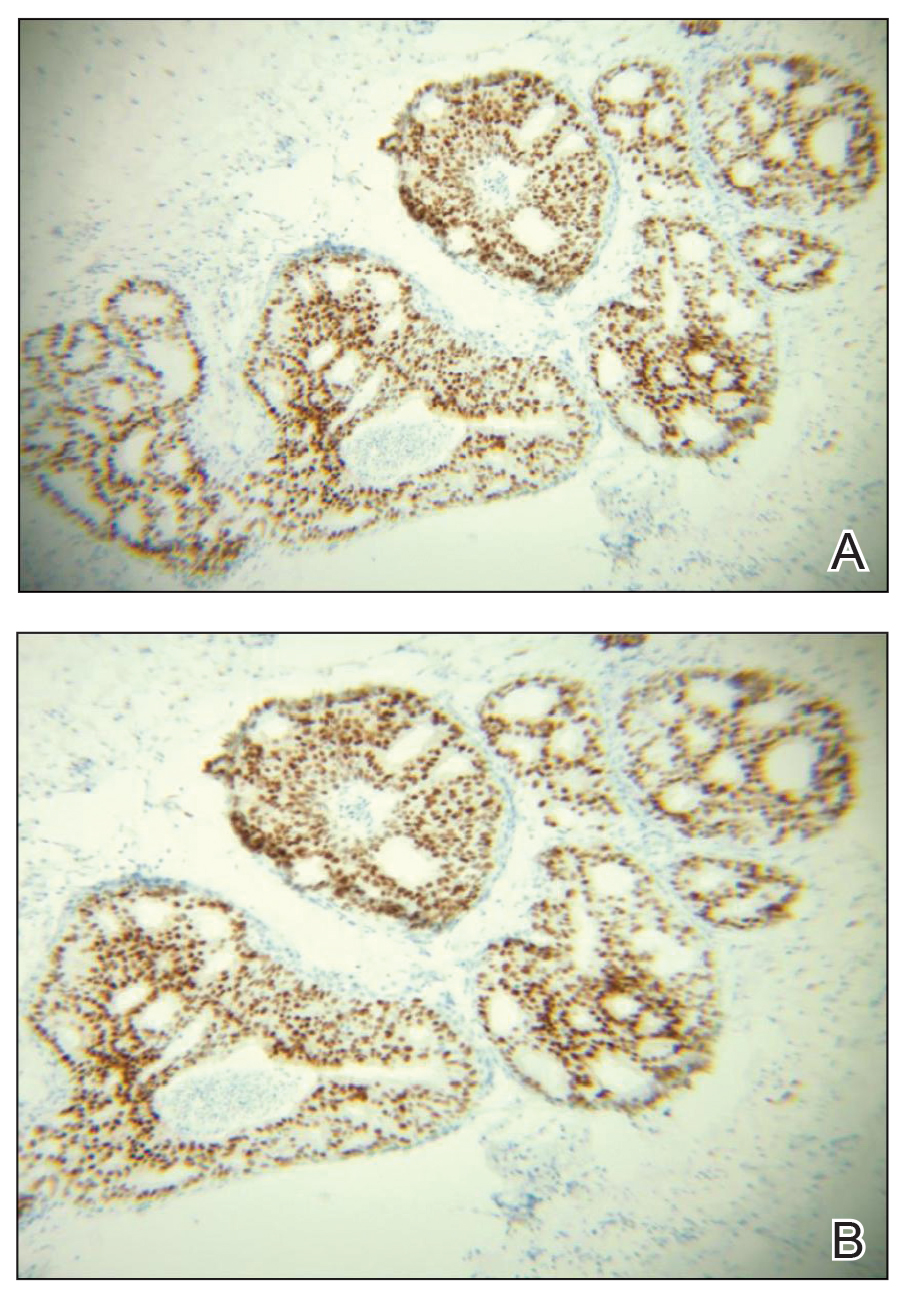

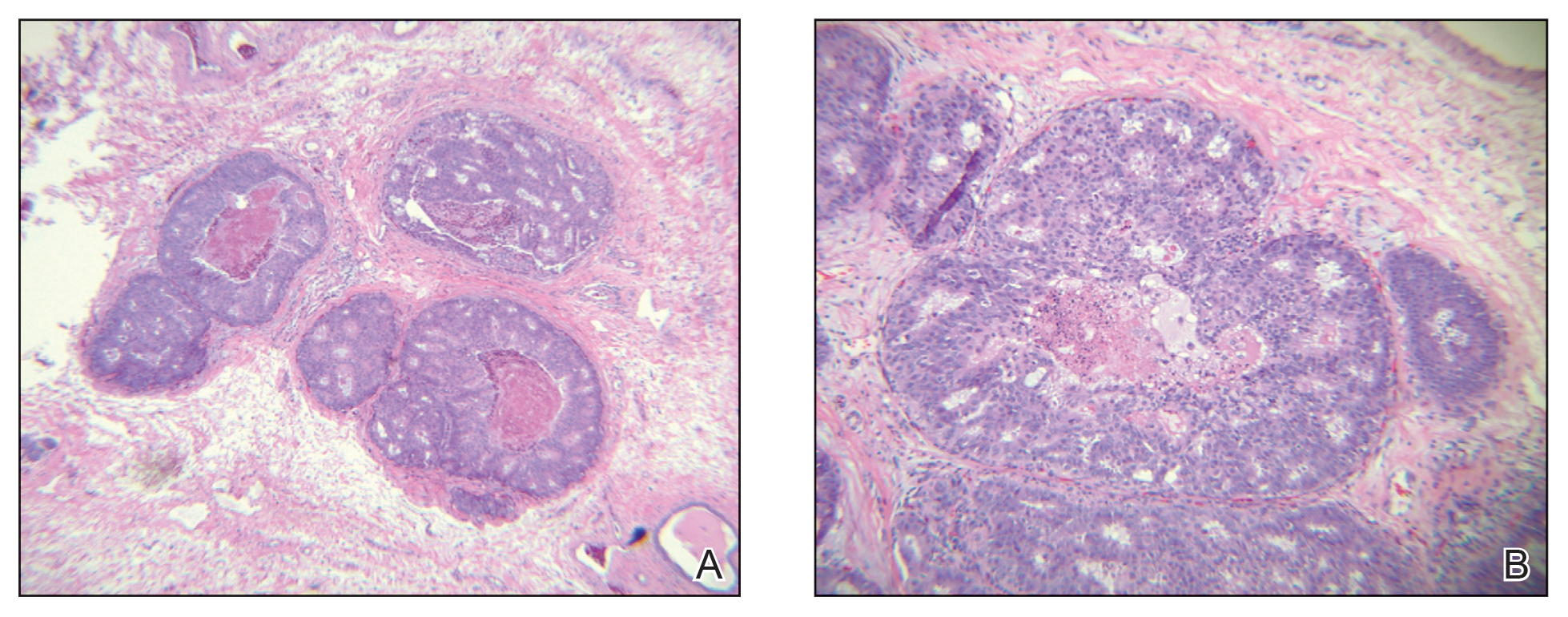

A 78-year-old woman was referred for MMS for a left forehead lesion that was diagnosed via shave biopsy as a desmoplastic and cystic adnexal neoplasm with suspicion for desmoplastic trichoepithelioma or MAC (Figure 1). Upon presentation for MMS, a well-healed, 1.0×0.9-cm scar at the biopsy site on the left forehead was observed (Figure 2A). One stage was obtained by standard MMS technique and sent for intraoperative processing (Figure 2B). Frozen section examination of the first stage demonstrated peripheral margin involvement with syringomatous change confined to the superficial and mid dermis (Figure 3). Before proceeding further, these findings were reviewed with an in-house dermatopathologist, and it was determined that no infiltrative tumor, perineural involvement, or other features to indicate malignancy were noted. A decision was made to refrain from obtaining any additional layers and to send excised Burow triangles for permanent section analysis. A primary linear closure was performed without complication, and the patient was discharged from the ambulatory surgery suite. Histopathologic examination of the Burow triangles later confirmed findings consistent with plaquelike syringoma with no evidence of malignancy (Figure 4).

Syringomas present as small flesh-colored papules in the periorbital areas. These benign neoplasms previously have been classified into 4 major clinical variants: localized, generalized, Down syndrome associated, and familial.1 The lesser-known plaquelike variant of syringoma was first described by Kikuchi et al2 in 1979. Aside from our report, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms plaquelike or plaque-type syringoma yielded 16 cases in the literature.2-14 Of these, 6 were referred to or encountered in the MMS setting.8,9,11,12,14 Plaquelike syringoma can be solitary or multiple in presentation.6 It most commonly involves the head and neck but also can present on the trunk, arms, legs, and groin areas. The clinical size of plaquelike syringoma is variable, with the largest reported cases extending several centimeters in diameter.2,6 Similar to reported associations with conventional syringoma, the plaquelike subtype of syringoma has been reported in association with Down syndrome.13

Histopathologically, plaquelike syringoma shares features with MAC as well as desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and desmoplastic basal cell carcinoma. Plaquelike syringoma demonstrates broad proliferations of small tubules morphologically reminiscent of tadpoles confined within the dermis. Ducts typically are lined with 2 or 3 layers of small cuboidal cells. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma typically features asymmetric ductal structures lined with single cells extending from the dermis into the subcutis and even underlying muscle, cartilage, or bone.8 There are no reliable immunohistochemical stains to differentiate between these 2 entities; thus, the primary distinction lies in the depth of involvement. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma is composed of narrow cords and nests of basaloid cells of follicular origin commonly admixed with small cornifying cysts appearing in the dermis.8 Colonizing Merkel cells positive for cytokeratin 20 often are present in desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and not in syringoma or MAC.15 Desmoplastic basal cell carcinoma demonstrates narrow strands of basaloid cells of follicular origin appearing in the dermis. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and desmoplastic basal cell carcinoma are each fundamentally differentiated from plaquelike syringoma in that proliferations of cords and nests are not of eccrine or apocrine origin.

Several cases of plaquelike syringoma have been challenging to distinguish from MAC in performing MMS.8,9,11 Underlying extension of this syringoma variant can be far-reaching, extending to several centimeters in size and involving multiple cosmetic subunits.6,11,14 Inadvertent overtreatment with multiple MMS stages can be avoided with careful recognition of the differentiating histopathologic features. Syringomatous lesions commonly are encountered in MMS and may even be present at the edge of other tumor types. Plaquelike syringoma has been reported as a coexistent entity with nodular basal cell carcinoma.12 Boos et al16 similarly reported the presence of deceptive ductal proliferations along the immediate peripheral margin of MAC, which prompted multiple re-excisions. Pursuit of permanent section analysis in these cases revealed the appearance of small syringomas, and a diagnosis of benign subclinical syringomatous proliferations was made, averting further intervention.16

Our case sheds light on the threat of commission bias in dermatologic surgery, which is the tendency for action rather than inaction.17 In this context, it is important to avoid the perspective that harm to the patient can only be prevented by active intervention. Cognitive bias has been increasingly recognized as a source of medical error, and methods to mitigate bias in medical practice have been well described.17 Microcystic adnexal carcinoma and plaquelike syringoma can be hard to differentiate especially initially, as demonstrated in our case, which particularly illustrates the importance of slowing down a surgical case at the appropriate time, considering and revisiting alternative diagnoses, implementing checklists, and seeking histopathologic collaboration with colleagues when necessary. Our attempted implementation of these principles, especially early collaboration with colleagues, led to intraoperative recognition of plaquelike syringoma within the first stage of MMS.

We seek to raise the index of suspicion for plaquelike syringoma among dermatologists and dermatologic surgeons, especially when syringomatous structures are limited to the superficial dermis. We encourage familiarity with the plaquelike syringoma entity as well as careful consideration of further investigation via scouting biopsies or permanent section analysis when other characteristic features of MAC are unclear or lacking. Adequate sampling as well as collaboration with a dermatopathologist in cases of suspected syringoma can help to reduce the susceptibility to commission bias and prevent histopathologic pitfalls and unwarranted surgical morbidity.

- Friedman SJ, Butler DF. Syringoma presenting as milia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:310-314.

- Kikuchi I, Idemori M, Okazaki M. Plaque type syringoma. J Dermatol. 1979;6:329-331.

- Dekio S, Jidoi J. Submammary syringoma—report of a case. J Dermatol. 1988;15:351-352.

- Patrizi A, Neri I, Marzaduri S, et al. Syringoma: a review of twenty-nine cases. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:460-462.

- Nguyen DB, Patterson JW, Wilson BB. Syringoma of the moustache area. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:337-339.

- Rongioletti F, Semino MT, Rebora A. Unilateral multiple plaque-like syringomas. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:623-625.

- Chi HI. A case of unusual syringoma: unilateral linear distribution and plaque formation. J Dermatol. 1996;23:505-506.

- Suwatee P, McClelland MC, Huiras EE, et al. Plaque-type syringoma: two cases misdiagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:570-574.

- Wallace JS, Bond JS, Seidel GD, et al. An important mimicker: plaque-type syringoma mistakenly diagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:810-812.

- Mitkov M, Balagula Y, Taube JM, et al. Plaque-like syringoma with involvement of deep reticular dermis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E206-E207.

- Schleich C, Ferringer T, Petrick M. Plaque type syringoma mimicking a microcystic adnexal carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(suppl 1):AB287.

- Yang Y, Srivastava D. Plaque-type syringoma coexisting with basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:1464-1466.

- Motegi SI, Sekiguchi A, Fujiwara C, et al. Milia-like idiopathic calcinosis cutis and plaque-type syringoma in a girl with Down syndrome. J Dermatol. 2019;46:E136-E137.

- Clark M, Duprey C, Sutton A, et al. Plaque-type syringoma masquerading as microcystic adnexal carcinoma: review of the literature and description of a novel technique that emphasizes lesion architecture to help make the diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:E98-E101.

- Abesamis-Cubillan E, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, LeBoit PE. Merkel cells and sclerosing epithelial neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:311-315.

- Boos MD, Elenitsas R, Seykora J, et al. Benign subclinical syringomatous proliferations adjacent to a microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a tumor mimic with significant patient implications. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:174-178.

- O’Sullivan ED, Schofield SJ. Cognitive bias in clinical medicine. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2018;48:225-232.

To the Editor:

Plaquelike or plaque-type syringoma is a lesser-known variant of syringoma that can appear histologically indistinguishable from the superficial portion of microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC). The plaquelike variant of syringoma holds a benign clinical course, and no treatment is necessary. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma is distinguished from plaquelike syringoma by an aggressive growth pattern with a high risk for local invasion and recurrence if inadequately treated. Thus, treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) has been recommended as the mainstay for MAC. If superficial biopsy specimens reveal suspicion for MAC and patients are referred for MMS, careful consideration should be made to differentiate MAC and plaquelike syringoma early to prevent unnecessary morbidity.

A 78-year-old woman was referred for MMS for a left forehead lesion that was diagnosed via shave biopsy as a desmoplastic and cystic adnexal neoplasm with suspicion for desmoplastic trichoepithelioma or MAC (Figure 1). Upon presentation for MMS, a well-healed, 1.0×0.9-cm scar at the biopsy site on the left forehead was observed (Figure 2A). One stage was obtained by standard MMS technique and sent for intraoperative processing (Figure 2B). Frozen section examination of the first stage demonstrated peripheral margin involvement with syringomatous change confined to the superficial and mid dermis (Figure 3). Before proceeding further, these findings were reviewed with an in-house dermatopathologist, and it was determined that no infiltrative tumor, perineural involvement, or other features to indicate malignancy were noted. A decision was made to refrain from obtaining any additional layers and to send excised Burow triangles for permanent section analysis. A primary linear closure was performed without complication, and the patient was discharged from the ambulatory surgery suite. Histopathologic examination of the Burow triangles later confirmed findings consistent with plaquelike syringoma with no evidence of malignancy (Figure 4).

Syringomas present as small flesh-colored papules in the periorbital areas. These benign neoplasms previously have been classified into 4 major clinical variants: localized, generalized, Down syndrome associated, and familial.1 The lesser-known plaquelike variant of syringoma was first described by Kikuchi et al2 in 1979. Aside from our report, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms plaquelike or plaque-type syringoma yielded 16 cases in the literature.2-14 Of these, 6 were referred to or encountered in the MMS setting.8,9,11,12,14 Plaquelike syringoma can be solitary or multiple in presentation.6 It most commonly involves the head and neck but also can present on the trunk, arms, legs, and groin areas. The clinical size of plaquelike syringoma is variable, with the largest reported cases extending several centimeters in diameter.2,6 Similar to reported associations with conventional syringoma, the plaquelike subtype of syringoma has been reported in association with Down syndrome.13

Histopathologically, plaquelike syringoma shares features with MAC as well as desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and desmoplastic basal cell carcinoma. Plaquelike syringoma demonstrates broad proliferations of small tubules morphologically reminiscent of tadpoles confined within the dermis. Ducts typically are lined with 2 or 3 layers of small cuboidal cells. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma typically features asymmetric ductal structures lined with single cells extending from the dermis into the subcutis and even underlying muscle, cartilage, or bone.8 There are no reliable immunohistochemical stains to differentiate between these 2 entities; thus, the primary distinction lies in the depth of involvement. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma is composed of narrow cords and nests of basaloid cells of follicular origin commonly admixed with small cornifying cysts appearing in the dermis.8 Colonizing Merkel cells positive for cytokeratin 20 often are present in desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and not in syringoma or MAC.15 Desmoplastic basal cell carcinoma demonstrates narrow strands of basaloid cells of follicular origin appearing in the dermis. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and desmoplastic basal cell carcinoma are each fundamentally differentiated from plaquelike syringoma in that proliferations of cords and nests are not of eccrine or apocrine origin.

Several cases of plaquelike syringoma have been challenging to distinguish from MAC in performing MMS.8,9,11 Underlying extension of this syringoma variant can be far-reaching, extending to several centimeters in size and involving multiple cosmetic subunits.6,11,14 Inadvertent overtreatment with multiple MMS stages can be avoided with careful recognition of the differentiating histopathologic features. Syringomatous lesions commonly are encountered in MMS and may even be present at the edge of other tumor types. Plaquelike syringoma has been reported as a coexistent entity with nodular basal cell carcinoma.12 Boos et al16 similarly reported the presence of deceptive ductal proliferations along the immediate peripheral margin of MAC, which prompted multiple re-excisions. Pursuit of permanent section analysis in these cases revealed the appearance of small syringomas, and a diagnosis of benign subclinical syringomatous proliferations was made, averting further intervention.16

Our case sheds light on the threat of commission bias in dermatologic surgery, which is the tendency for action rather than inaction.17 In this context, it is important to avoid the perspective that harm to the patient can only be prevented by active intervention. Cognitive bias has been increasingly recognized as a source of medical error, and methods to mitigate bias in medical practice have been well described.17 Microcystic adnexal carcinoma and plaquelike syringoma can be hard to differentiate especially initially, as demonstrated in our case, which particularly illustrates the importance of slowing down a surgical case at the appropriate time, considering and revisiting alternative diagnoses, implementing checklists, and seeking histopathologic collaboration with colleagues when necessary. Our attempted implementation of these principles, especially early collaboration with colleagues, led to intraoperative recognition of plaquelike syringoma within the first stage of MMS.

We seek to raise the index of suspicion for plaquelike syringoma among dermatologists and dermatologic surgeons, especially when syringomatous structures are limited to the superficial dermis. We encourage familiarity with the plaquelike syringoma entity as well as careful consideration of further investigation via scouting biopsies or permanent section analysis when other characteristic features of MAC are unclear or lacking. Adequate sampling as well as collaboration with a dermatopathologist in cases of suspected syringoma can help to reduce the susceptibility to commission bias and prevent histopathologic pitfalls and unwarranted surgical morbidity.

To the Editor:

Plaquelike or plaque-type syringoma is a lesser-known variant of syringoma that can appear histologically indistinguishable from the superficial portion of microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC). The plaquelike variant of syringoma holds a benign clinical course, and no treatment is necessary. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma is distinguished from plaquelike syringoma by an aggressive growth pattern with a high risk for local invasion and recurrence if inadequately treated. Thus, treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) has been recommended as the mainstay for MAC. If superficial biopsy specimens reveal suspicion for MAC and patients are referred for MMS, careful consideration should be made to differentiate MAC and plaquelike syringoma early to prevent unnecessary morbidity.

A 78-year-old woman was referred for MMS for a left forehead lesion that was diagnosed via shave biopsy as a desmoplastic and cystic adnexal neoplasm with suspicion for desmoplastic trichoepithelioma or MAC (Figure 1). Upon presentation for MMS, a well-healed, 1.0×0.9-cm scar at the biopsy site on the left forehead was observed (Figure 2A). One stage was obtained by standard MMS technique and sent for intraoperative processing (Figure 2B). Frozen section examination of the first stage demonstrated peripheral margin involvement with syringomatous change confined to the superficial and mid dermis (Figure 3). Before proceeding further, these findings were reviewed with an in-house dermatopathologist, and it was determined that no infiltrative tumor, perineural involvement, or other features to indicate malignancy were noted. A decision was made to refrain from obtaining any additional layers and to send excised Burow triangles for permanent section analysis. A primary linear closure was performed without complication, and the patient was discharged from the ambulatory surgery suite. Histopathologic examination of the Burow triangles later confirmed findings consistent with plaquelike syringoma with no evidence of malignancy (Figure 4).

Syringomas present as small flesh-colored papules in the periorbital areas. These benign neoplasms previously have been classified into 4 major clinical variants: localized, generalized, Down syndrome associated, and familial.1 The lesser-known plaquelike variant of syringoma was first described by Kikuchi et al2 in 1979. Aside from our report, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms plaquelike or plaque-type syringoma yielded 16 cases in the literature.2-14 Of these, 6 were referred to or encountered in the MMS setting.8,9,11,12,14 Plaquelike syringoma can be solitary or multiple in presentation.6 It most commonly involves the head and neck but also can present on the trunk, arms, legs, and groin areas. The clinical size of plaquelike syringoma is variable, with the largest reported cases extending several centimeters in diameter.2,6 Similar to reported associations with conventional syringoma, the plaquelike subtype of syringoma has been reported in association with Down syndrome.13

Histopathologically, plaquelike syringoma shares features with MAC as well as desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and desmoplastic basal cell carcinoma. Plaquelike syringoma demonstrates broad proliferations of small tubules morphologically reminiscent of tadpoles confined within the dermis. Ducts typically are lined with 2 or 3 layers of small cuboidal cells. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma typically features asymmetric ductal structures lined with single cells extending from the dermis into the subcutis and even underlying muscle, cartilage, or bone.8 There are no reliable immunohistochemical stains to differentiate between these 2 entities; thus, the primary distinction lies in the depth of involvement. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma is composed of narrow cords and nests of basaloid cells of follicular origin commonly admixed with small cornifying cysts appearing in the dermis.8 Colonizing Merkel cells positive for cytokeratin 20 often are present in desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and not in syringoma or MAC.15 Desmoplastic basal cell carcinoma demonstrates narrow strands of basaloid cells of follicular origin appearing in the dermis. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and desmoplastic basal cell carcinoma are each fundamentally differentiated from plaquelike syringoma in that proliferations of cords and nests are not of eccrine or apocrine origin.

Several cases of plaquelike syringoma have been challenging to distinguish from MAC in performing MMS.8,9,11 Underlying extension of this syringoma variant can be far-reaching, extending to several centimeters in size and involving multiple cosmetic subunits.6,11,14 Inadvertent overtreatment with multiple MMS stages can be avoided with careful recognition of the differentiating histopathologic features. Syringomatous lesions commonly are encountered in MMS and may even be present at the edge of other tumor types. Plaquelike syringoma has been reported as a coexistent entity with nodular basal cell carcinoma.12 Boos et al16 similarly reported the presence of deceptive ductal proliferations along the immediate peripheral margin of MAC, which prompted multiple re-excisions. Pursuit of permanent section analysis in these cases revealed the appearance of small syringomas, and a diagnosis of benign subclinical syringomatous proliferations was made, averting further intervention.16

Our case sheds light on the threat of commission bias in dermatologic surgery, which is the tendency for action rather than inaction.17 In this context, it is important to avoid the perspective that harm to the patient can only be prevented by active intervention. Cognitive bias has been increasingly recognized as a source of medical error, and methods to mitigate bias in medical practice have been well described.17 Microcystic adnexal carcinoma and plaquelike syringoma can be hard to differentiate especially initially, as demonstrated in our case, which particularly illustrates the importance of slowing down a surgical case at the appropriate time, considering and revisiting alternative diagnoses, implementing checklists, and seeking histopathologic collaboration with colleagues when necessary. Our attempted implementation of these principles, especially early collaboration with colleagues, led to intraoperative recognition of plaquelike syringoma within the first stage of MMS.

We seek to raise the index of suspicion for plaquelike syringoma among dermatologists and dermatologic surgeons, especially when syringomatous structures are limited to the superficial dermis. We encourage familiarity with the plaquelike syringoma entity as well as careful consideration of further investigation via scouting biopsies or permanent section analysis when other characteristic features of MAC are unclear or lacking. Adequate sampling as well as collaboration with a dermatopathologist in cases of suspected syringoma can help to reduce the susceptibility to commission bias and prevent histopathologic pitfalls and unwarranted surgical morbidity.

- Friedman SJ, Butler DF. Syringoma presenting as milia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:310-314.

- Kikuchi I, Idemori M, Okazaki M. Plaque type syringoma. J Dermatol. 1979;6:329-331.

- Dekio S, Jidoi J. Submammary syringoma—report of a case. J Dermatol. 1988;15:351-352.

- Patrizi A, Neri I, Marzaduri S, et al. Syringoma: a review of twenty-nine cases. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:460-462.

- Nguyen DB, Patterson JW, Wilson BB. Syringoma of the moustache area. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:337-339.

- Rongioletti F, Semino MT, Rebora A. Unilateral multiple plaque-like syringomas. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:623-625.

- Chi HI. A case of unusual syringoma: unilateral linear distribution and plaque formation. J Dermatol. 1996;23:505-506.

- Suwatee P, McClelland MC, Huiras EE, et al. Plaque-type syringoma: two cases misdiagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:570-574.

- Wallace JS, Bond JS, Seidel GD, et al. An important mimicker: plaque-type syringoma mistakenly diagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:810-812.

- Mitkov M, Balagula Y, Taube JM, et al. Plaque-like syringoma with involvement of deep reticular dermis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E206-E207.

- Schleich C, Ferringer T, Petrick M. Plaque type syringoma mimicking a microcystic adnexal carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(suppl 1):AB287.

- Yang Y, Srivastava D. Plaque-type syringoma coexisting with basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:1464-1466.

- Motegi SI, Sekiguchi A, Fujiwara C, et al. Milia-like idiopathic calcinosis cutis and plaque-type syringoma in a girl with Down syndrome. J Dermatol. 2019;46:E136-E137.

- Clark M, Duprey C, Sutton A, et al. Plaque-type syringoma masquerading as microcystic adnexal carcinoma: review of the literature and description of a novel technique that emphasizes lesion architecture to help make the diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:E98-E101.

- Abesamis-Cubillan E, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, LeBoit PE. Merkel cells and sclerosing epithelial neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:311-315.

- Boos MD, Elenitsas R, Seykora J, et al. Benign subclinical syringomatous proliferations adjacent to a microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a tumor mimic with significant patient implications. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:174-178.

- O’Sullivan ED, Schofield SJ. Cognitive bias in clinical medicine. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2018;48:225-232.

- Friedman SJ, Butler DF. Syringoma presenting as milia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:310-314.

- Kikuchi I, Idemori M, Okazaki M. Plaque type syringoma. J Dermatol. 1979;6:329-331.

- Dekio S, Jidoi J. Submammary syringoma—report of a case. J Dermatol. 1988;15:351-352.

- Patrizi A, Neri I, Marzaduri S, et al. Syringoma: a review of twenty-nine cases. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:460-462.

- Nguyen DB, Patterson JW, Wilson BB. Syringoma of the moustache area. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:337-339.

- Rongioletti F, Semino MT, Rebora A. Unilateral multiple plaque-like syringomas. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:623-625.

- Chi HI. A case of unusual syringoma: unilateral linear distribution and plaque formation. J Dermatol. 1996;23:505-506.

- Suwatee P, McClelland MC, Huiras EE, et al. Plaque-type syringoma: two cases misdiagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:570-574.

- Wallace JS, Bond JS, Seidel GD, et al. An important mimicker: plaque-type syringoma mistakenly diagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:810-812.

- Mitkov M, Balagula Y, Taube JM, et al. Plaque-like syringoma with involvement of deep reticular dermis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E206-E207.

- Schleich C, Ferringer T, Petrick M. Plaque type syringoma mimicking a microcystic adnexal carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(suppl 1):AB287.

- Yang Y, Srivastava D. Plaque-type syringoma coexisting with basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:1464-1466.

- Motegi SI, Sekiguchi A, Fujiwara C, et al. Milia-like idiopathic calcinosis cutis and plaque-type syringoma in a girl with Down syndrome. J Dermatol. 2019;46:E136-E137.

- Clark M, Duprey C, Sutton A, et al. Plaque-type syringoma masquerading as microcystic adnexal carcinoma: review of the literature and description of a novel technique that emphasizes lesion architecture to help make the diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:E98-E101.

- Abesamis-Cubillan E, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, LeBoit PE. Merkel cells and sclerosing epithelial neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:311-315.

- Boos MD, Elenitsas R, Seykora J, et al. Benign subclinical syringomatous proliferations adjacent to a microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a tumor mimic with significant patient implications. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:174-178.

- O’Sullivan ED, Schofield SJ. Cognitive bias in clinical medicine. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2018;48:225-232.

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should familiarize themselves with the plaquelike subtype of syringoma, which can histologically mimic the superficial portion of microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC).

- Careful recognition of plaquelike syringoma in the Mohs micrographic surgery setting may prevent unnecessary surgical morbidity.

- Further diagnostic investigation is warranted for superficial biopsies suggestive of MAC or when other characteristic features are lacking.

Atopic Dermatitis Triggered by Omalizumab and Treated With Dupilumab

To the Editor:

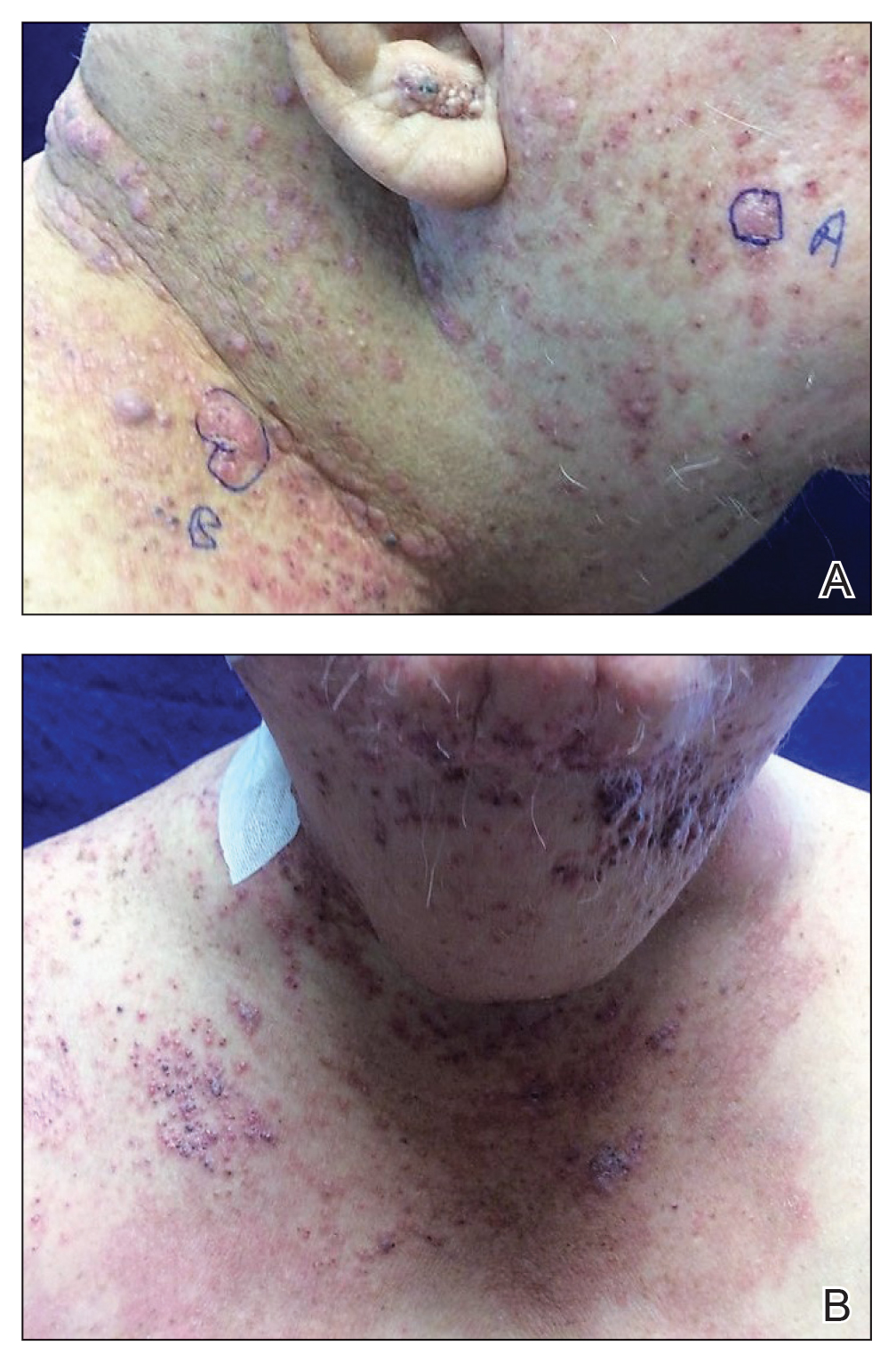

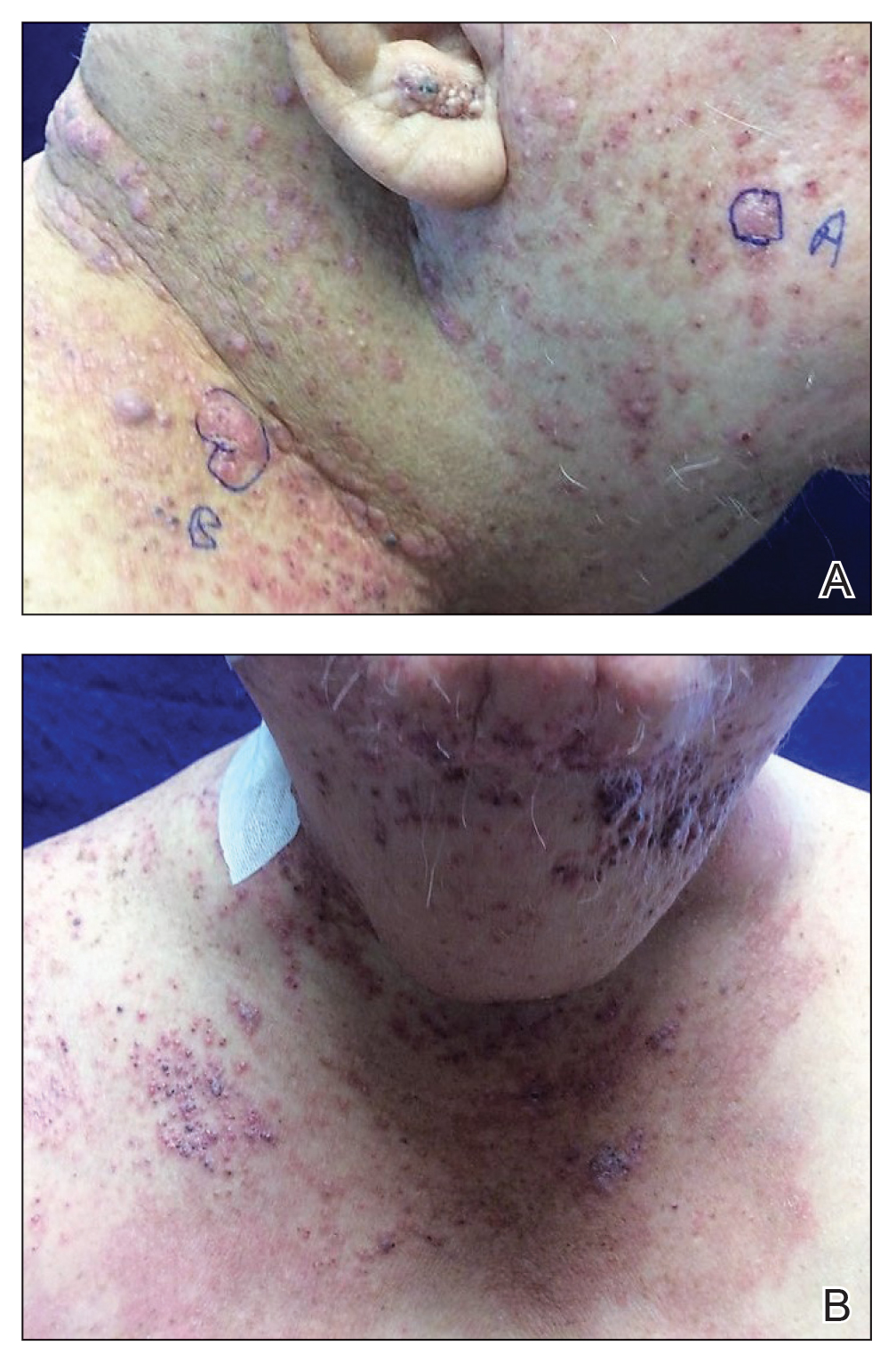

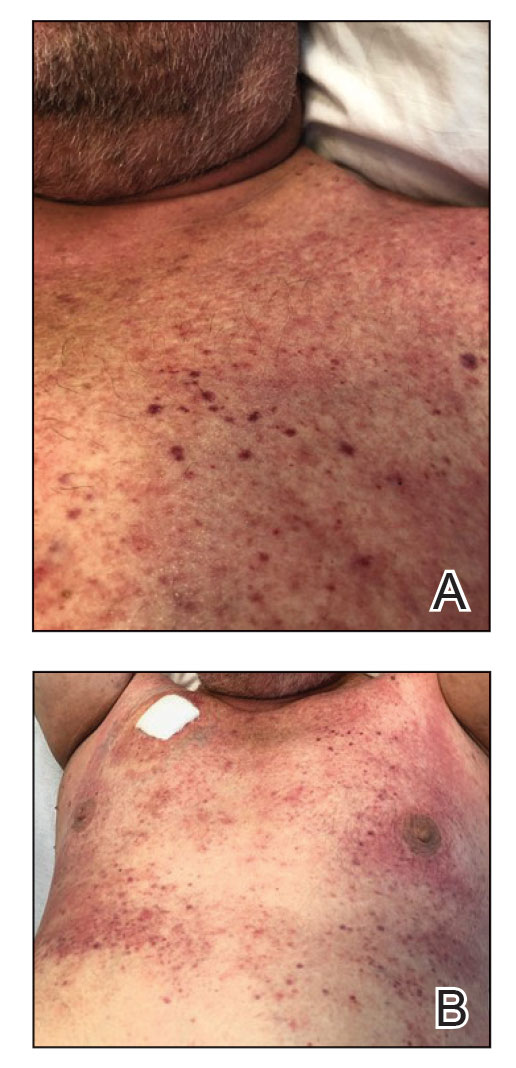

A 16-year-old adolescent boy presented to our pediatric dermatology clinic for evaluation of long-standing mild atopic dermatitis (AD) that had become severe over the last year after omalizumab was initiated for severe asthma. The patient had a history of multiple hospitalizations for severe asthma. Despite excellent control of asthma with omalizumab given every 2 weeks, he developed widespread eczematous plaques on the neck, trunk, and extremities over the course of a year. The AD often was complicated by superimposed folliculitis due to scratching from severe pruritus. Treatment with topical corticosteroids including triamcinolone ointment 0.1% to AD on the body, plus clobetasol ointment 0.05% for prurigolike lesions on the legs resulted in modest improvement; however, the AD consistently recurred within a few days after the biweekly omalizumab injection (Figure 1). When the omalizumab injections were delayed, the flares temporarily improved, and when injections were decreased to once monthly, the exacerbations subsided partially but not fully.

Because omalizumab resulted in dramatic improvement in the patient’s asthma, there was hesitation to discontinue it initially; however, the patient and his parents in conjunction with the dermatology and pulmonary teams decided to transition to dupilumab. The patient reported vast improvement of AD 1 month after initiation of dupilumab (Figure 2), which remained well controlled more than 1 year later. Mid-potency topical corticosteroids for the treatment of occasional mild eczematous flares on the extremities were used. The patient’s asthma has remained well controlled on dupilumab without any exacerbations.

Omalizumab is a recombinant DNA-derived humanized monoclonal antibody that binds both circulating and membrane-bound IgE. It has been proposed as a possible treatment for severe and/or recalcitrant AD, with mixed treatment results.1 A case series and review of 174 patients demonstrated a moderate to complete AD response to treatment with omalizumab in 74.1% of patients.2 The Atopic Dermatitis Anti-IgE Pediatric Trial (ADAPT) showed a statistically significant reduction in the Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index (P=.01), along with improved quality of life in children treated with omalizumab vs those treated with placebo.3 However, a prior randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study did not show a significant difference in clinical disease parameters in patients treated with omalizumab.4

The humanized monoclonal antibody dupilumab, an anti–IL-4/IL-13 agent, has demonstrated more consistent efficacy for the treatment of AD in children and adults.1 Dupilumab is effective for both intrinsic and extrinsic AD1 because its clinical efficacy is unrelated to circulating levels of IgE in the bloodstream. Although IgE may have a role in childhood AD, our case demonstrated a different pathophysiologic mechanism independent of IgE. Our patient’s AD flares occurred within a few days of omalizumab injection, which may have resulted in a paradoxical increase in basophil sensitivity to other cytokines such as IL-335 and led to an increase in IL-4/IL-13 production within the skin. In our patient, this increase was successfully blocked by dupilumab. Furthermore, omalizumab has been shown to modulate helper T cell (TH2) cytokine response such as thymic stromal lymphopoietin.6 A cytokine imbalance could have exacerbated AD in our case.

Although additional work to clarify the pathogenesis of AD is needed, it is important to recognize the potential for the occurrence of paradoxical AD flares in patients treated with omalizumab, which is analogous to the well-documented entity of tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced psoriasis. It is equally important to recognize the potential benefit for patients treated with dupilumab.

- Nygaard U, Vestergaard C, Deleuran M. Emerging treatment options in atopic dermatitis: systemic therapies. Dermatology. 2017;233:344-357.

- Holm JG, Agner T, Sand C, et al. Omalizumab for atopic dermatitis: case series and a systematic review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:18-26.

- Chan S, Cornelius V, Cro S, et al. Treatment effect of omalizumab on severe pediatric atopic dermatitis: the ADAPT randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:29-37.

- Heil PM, Maurer D, Klein B, et al. Omalizumab therapy in atopic dermatitis: depletion of IgE does not improve the clinical course – a randomized placebo-controlled and double blind pilot study. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:990-998.

- Imai Y. Interleukin-33 in atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol Sci. 2019;96:2-7.

- Iyengar SR, Hoyte EG, Loza A, et al. Immunologic effects of omalizumab in children with severe refractory atopic dermatitis: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2013;162:89-93.

To the Editor:

A 16-year-old adolescent boy presented to our pediatric dermatology clinic for evaluation of long-standing mild atopic dermatitis (AD) that had become severe over the last year after omalizumab was initiated for severe asthma. The patient had a history of multiple hospitalizations for severe asthma. Despite excellent control of asthma with omalizumab given every 2 weeks, he developed widespread eczematous plaques on the neck, trunk, and extremities over the course of a year. The AD often was complicated by superimposed folliculitis due to scratching from severe pruritus. Treatment with topical corticosteroids including triamcinolone ointment 0.1% to AD on the body, plus clobetasol ointment 0.05% for prurigolike lesions on the legs resulted in modest improvement; however, the AD consistently recurred within a few days after the biweekly omalizumab injection (Figure 1). When the omalizumab injections were delayed, the flares temporarily improved, and when injections were decreased to once monthly, the exacerbations subsided partially but not fully.

Because omalizumab resulted in dramatic improvement in the patient’s asthma, there was hesitation to discontinue it initially; however, the patient and his parents in conjunction with the dermatology and pulmonary teams decided to transition to dupilumab. The patient reported vast improvement of AD 1 month after initiation of dupilumab (Figure 2), which remained well controlled more than 1 year later. Mid-potency topical corticosteroids for the treatment of occasional mild eczematous flares on the extremities were used. The patient’s asthma has remained well controlled on dupilumab without any exacerbations.

Omalizumab is a recombinant DNA-derived humanized monoclonal antibody that binds both circulating and membrane-bound IgE. It has been proposed as a possible treatment for severe and/or recalcitrant AD, with mixed treatment results.1 A case series and review of 174 patients demonstrated a moderate to complete AD response to treatment with omalizumab in 74.1% of patients.2 The Atopic Dermatitis Anti-IgE Pediatric Trial (ADAPT) showed a statistically significant reduction in the Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index (P=.01), along with improved quality of life in children treated with omalizumab vs those treated with placebo.3 However, a prior randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study did not show a significant difference in clinical disease parameters in patients treated with omalizumab.4

The humanized monoclonal antibody dupilumab, an anti–IL-4/IL-13 agent, has demonstrated more consistent efficacy for the treatment of AD in children and adults.1 Dupilumab is effective for both intrinsic and extrinsic AD1 because its clinical efficacy is unrelated to circulating levels of IgE in the bloodstream. Although IgE may have a role in childhood AD, our case demonstrated a different pathophysiologic mechanism independent of IgE. Our patient’s AD flares occurred within a few days of omalizumab injection, which may have resulted in a paradoxical increase in basophil sensitivity to other cytokines such as IL-335 and led to an increase in IL-4/IL-13 production within the skin. In our patient, this increase was successfully blocked by dupilumab. Furthermore, omalizumab has been shown to modulate helper T cell (TH2) cytokine response such as thymic stromal lymphopoietin.6 A cytokine imbalance could have exacerbated AD in our case.

Although additional work to clarify the pathogenesis of AD is needed, it is important to recognize the potential for the occurrence of paradoxical AD flares in patients treated with omalizumab, which is analogous to the well-documented entity of tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced psoriasis. It is equally important to recognize the potential benefit for patients treated with dupilumab.

To the Editor:

A 16-year-old adolescent boy presented to our pediatric dermatology clinic for evaluation of long-standing mild atopic dermatitis (AD) that had become severe over the last year after omalizumab was initiated for severe asthma. The patient had a history of multiple hospitalizations for severe asthma. Despite excellent control of asthma with omalizumab given every 2 weeks, he developed widespread eczematous plaques on the neck, trunk, and extremities over the course of a year. The AD often was complicated by superimposed folliculitis due to scratching from severe pruritus. Treatment with topical corticosteroids including triamcinolone ointment 0.1% to AD on the body, plus clobetasol ointment 0.05% for prurigolike lesions on the legs resulted in modest improvement; however, the AD consistently recurred within a few days after the biweekly omalizumab injection (Figure 1). When the omalizumab injections were delayed, the flares temporarily improved, and when injections were decreased to once monthly, the exacerbations subsided partially but not fully.

Because omalizumab resulted in dramatic improvement in the patient’s asthma, there was hesitation to discontinue it initially; however, the patient and his parents in conjunction with the dermatology and pulmonary teams decided to transition to dupilumab. The patient reported vast improvement of AD 1 month after initiation of dupilumab (Figure 2), which remained well controlled more than 1 year later. Mid-potency topical corticosteroids for the treatment of occasional mild eczematous flares on the extremities were used. The patient’s asthma has remained well controlled on dupilumab without any exacerbations.

Omalizumab is a recombinant DNA-derived humanized monoclonal antibody that binds both circulating and membrane-bound IgE. It has been proposed as a possible treatment for severe and/or recalcitrant AD, with mixed treatment results.1 A case series and review of 174 patients demonstrated a moderate to complete AD response to treatment with omalizumab in 74.1% of patients.2 The Atopic Dermatitis Anti-IgE Pediatric Trial (ADAPT) showed a statistically significant reduction in the Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index (P=.01), along with improved quality of life in children treated with omalizumab vs those treated with placebo.3 However, a prior randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study did not show a significant difference in clinical disease parameters in patients treated with omalizumab.4

The humanized monoclonal antibody dupilumab, an anti–IL-4/IL-13 agent, has demonstrated more consistent efficacy for the treatment of AD in children and adults.1 Dupilumab is effective for both intrinsic and extrinsic AD1 because its clinical efficacy is unrelated to circulating levels of IgE in the bloodstream. Although IgE may have a role in childhood AD, our case demonstrated a different pathophysiologic mechanism independent of IgE. Our patient’s AD flares occurred within a few days of omalizumab injection, which may have resulted in a paradoxical increase in basophil sensitivity to other cytokines such as IL-335 and led to an increase in IL-4/IL-13 production within the skin. In our patient, this increase was successfully blocked by dupilumab. Furthermore, omalizumab has been shown to modulate helper T cell (TH2) cytokine response such as thymic stromal lymphopoietin.6 A cytokine imbalance could have exacerbated AD in our case.

Although additional work to clarify the pathogenesis of AD is needed, it is important to recognize the potential for the occurrence of paradoxical AD flares in patients treated with omalizumab, which is analogous to the well-documented entity of tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced psoriasis. It is equally important to recognize the potential benefit for patients treated with dupilumab.

- Nygaard U, Vestergaard C, Deleuran M. Emerging treatment options in atopic dermatitis: systemic therapies. Dermatology. 2017;233:344-357.

- Holm JG, Agner T, Sand C, et al. Omalizumab for atopic dermatitis: case series and a systematic review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:18-26.

- Chan S, Cornelius V, Cro S, et al. Treatment effect of omalizumab on severe pediatric atopic dermatitis: the ADAPT randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:29-37.

- Heil PM, Maurer D, Klein B, et al. Omalizumab therapy in atopic dermatitis: depletion of IgE does not improve the clinical course – a randomized placebo-controlled and double blind pilot study. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:990-998.

- Imai Y. Interleukin-33 in atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol Sci. 2019;96:2-7.

- Iyengar SR, Hoyte EG, Loza A, et al. Immunologic effects of omalizumab in children with severe refractory atopic dermatitis: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2013;162:89-93.

- Nygaard U, Vestergaard C, Deleuran M. Emerging treatment options in atopic dermatitis: systemic therapies. Dermatology. 2017;233:344-357.

- Holm JG, Agner T, Sand C, et al. Omalizumab for atopic dermatitis: case series and a systematic review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:18-26.

- Chan S, Cornelius V, Cro S, et al. Treatment effect of omalizumab on severe pediatric atopic dermatitis: the ADAPT randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:29-37.

- Heil PM, Maurer D, Klein B, et al. Omalizumab therapy in atopic dermatitis: depletion of IgE does not improve the clinical course – a randomized placebo-controlled and double blind pilot study. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:990-998.

- Imai Y. Interleukin-33 in atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol Sci. 2019;96:2-7.

- Iyengar SR, Hoyte EG, Loza A, et al. Immunologic effects of omalizumab in children with severe refractory atopic dermatitis: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2013;162:89-93.

Practice Points

- Monoclonal antibodies are promising therapies for atopic conditions, although its efficacy for atopic dermatitis (AD) is debated and the side-effect profile is not entirely known.

- Omalizumab may cause a paradoxical exacerbation of AD in select patients analogous to tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced psoriasis.

Cutaneous Presentation of Metastatic Salivary Duct Carcinoma

To the Editor:

Metastatic spread of salivary duct carcinoma (SDC) to the skin is rare. Diagnosing SDC can be challenging because the cutaneous manifestations of this disease are variable and include nodules, papules, and erysipelaslike inflammation (also known as shield sign) with purpuric papules and pseudovesicles. We describe a case of cutaneous metastatic SDC that originated from the parotid gland and presented with 2 distinct cutaneous findings: sharply demarcated erythematous plaques and focally hemorrhagic angiomatous papules.

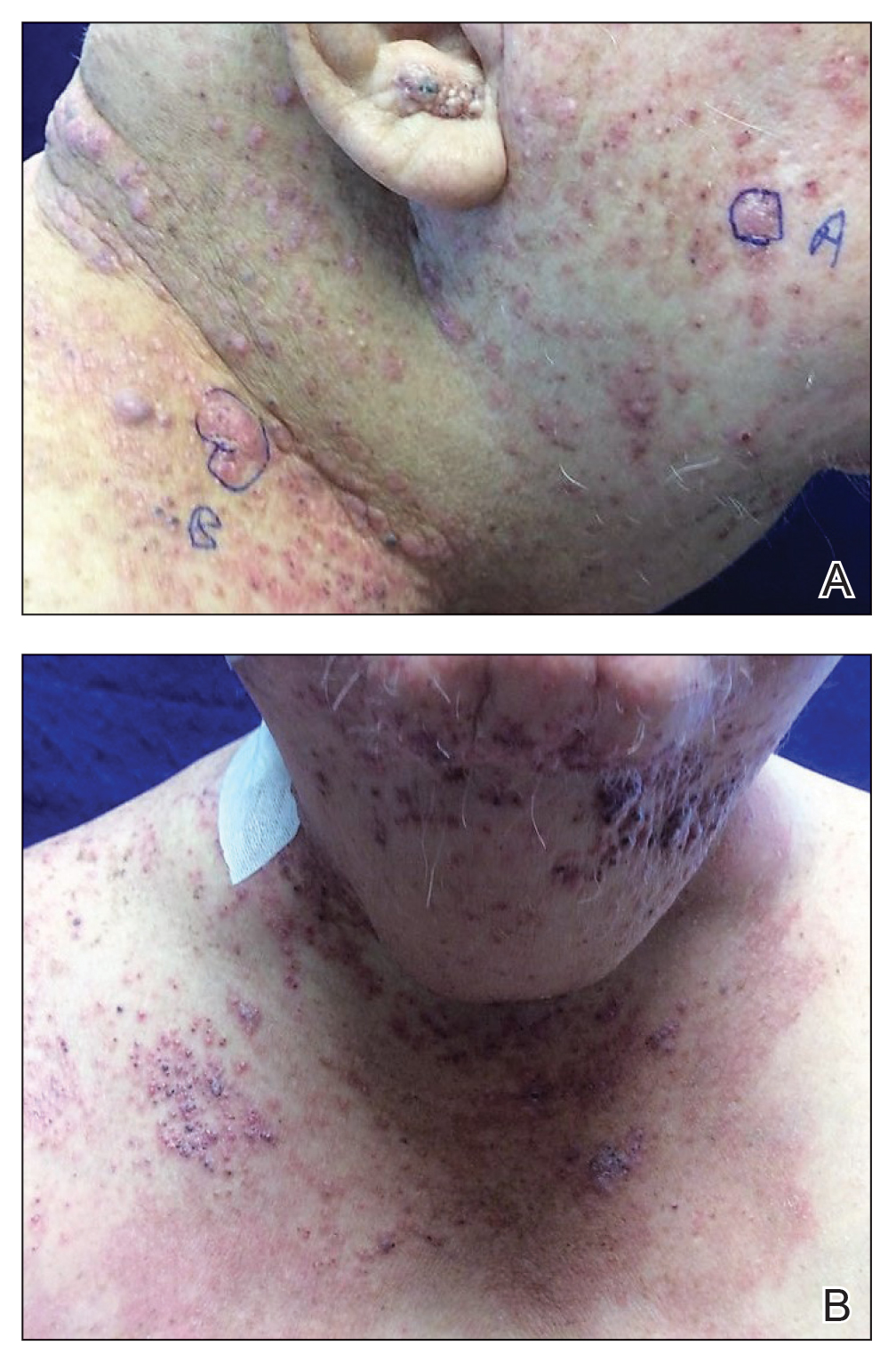

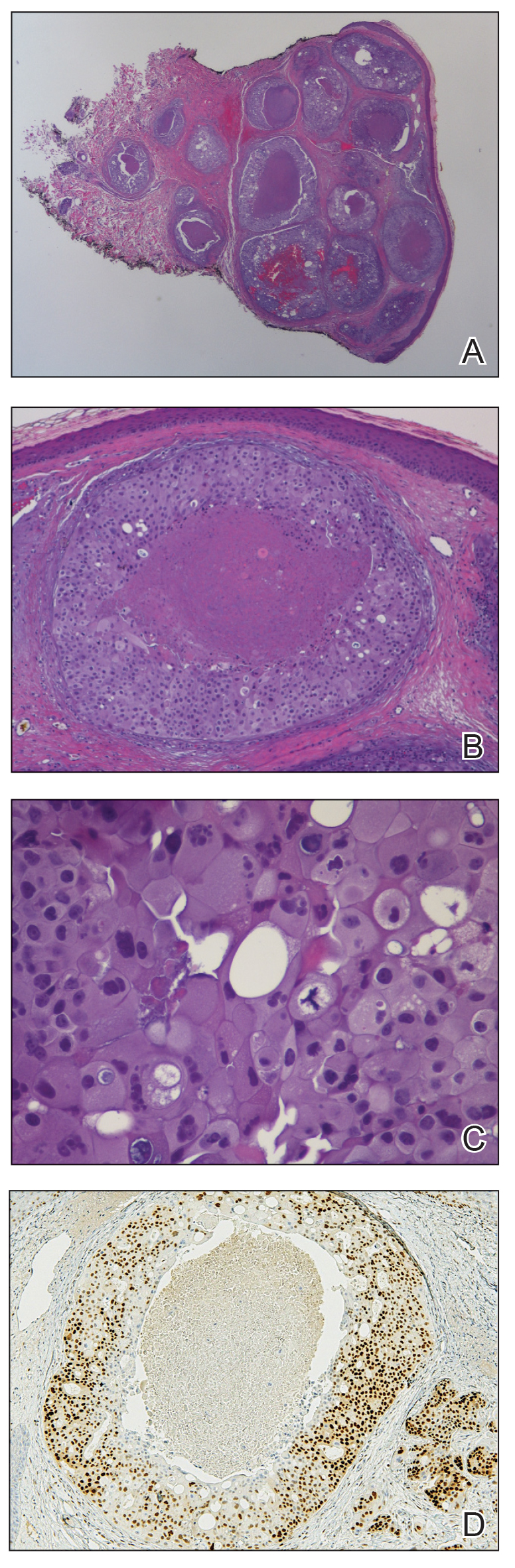

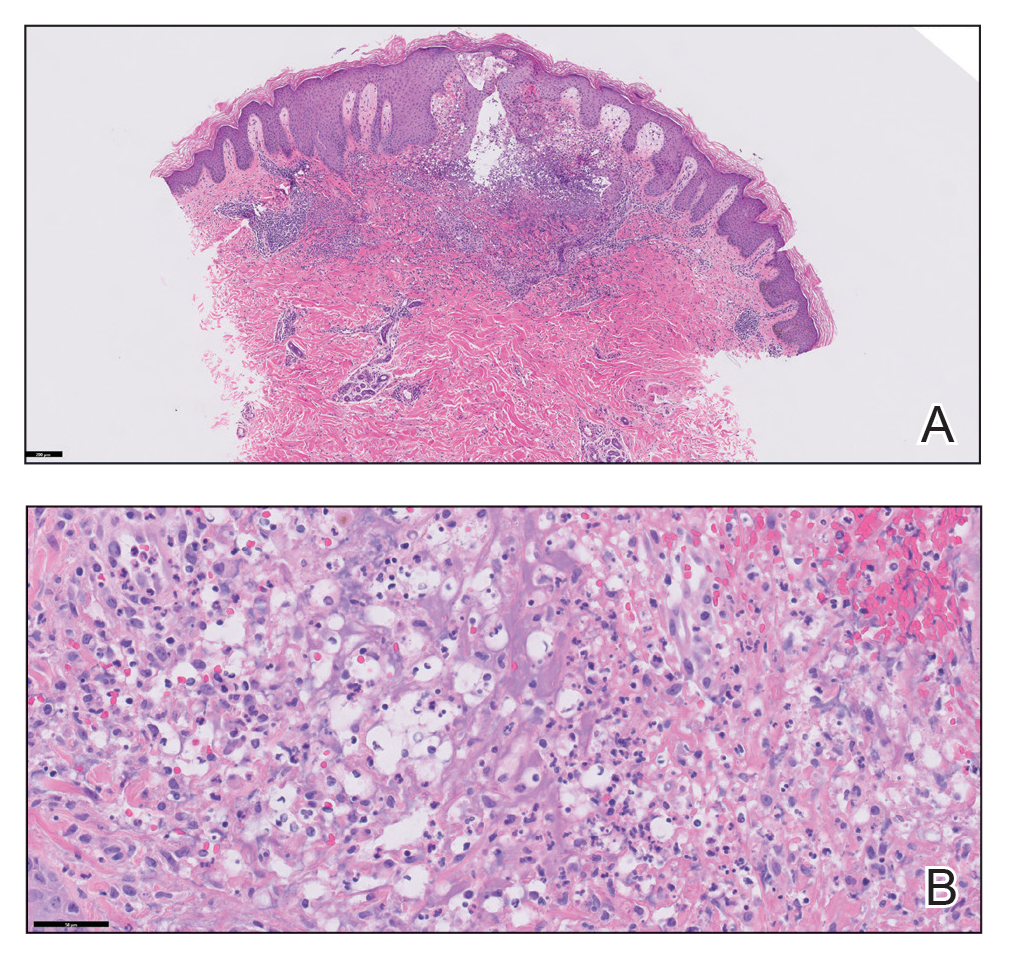

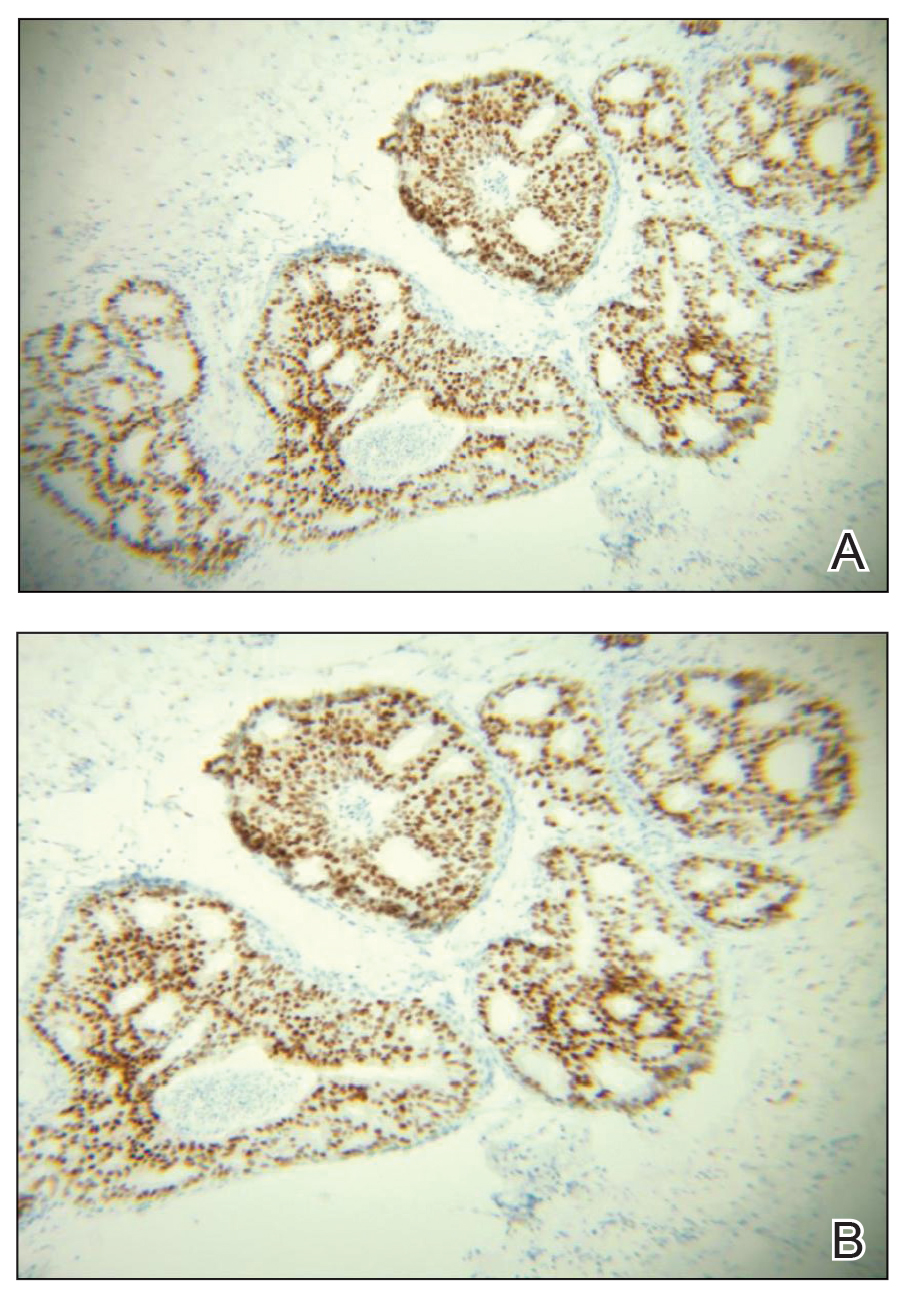

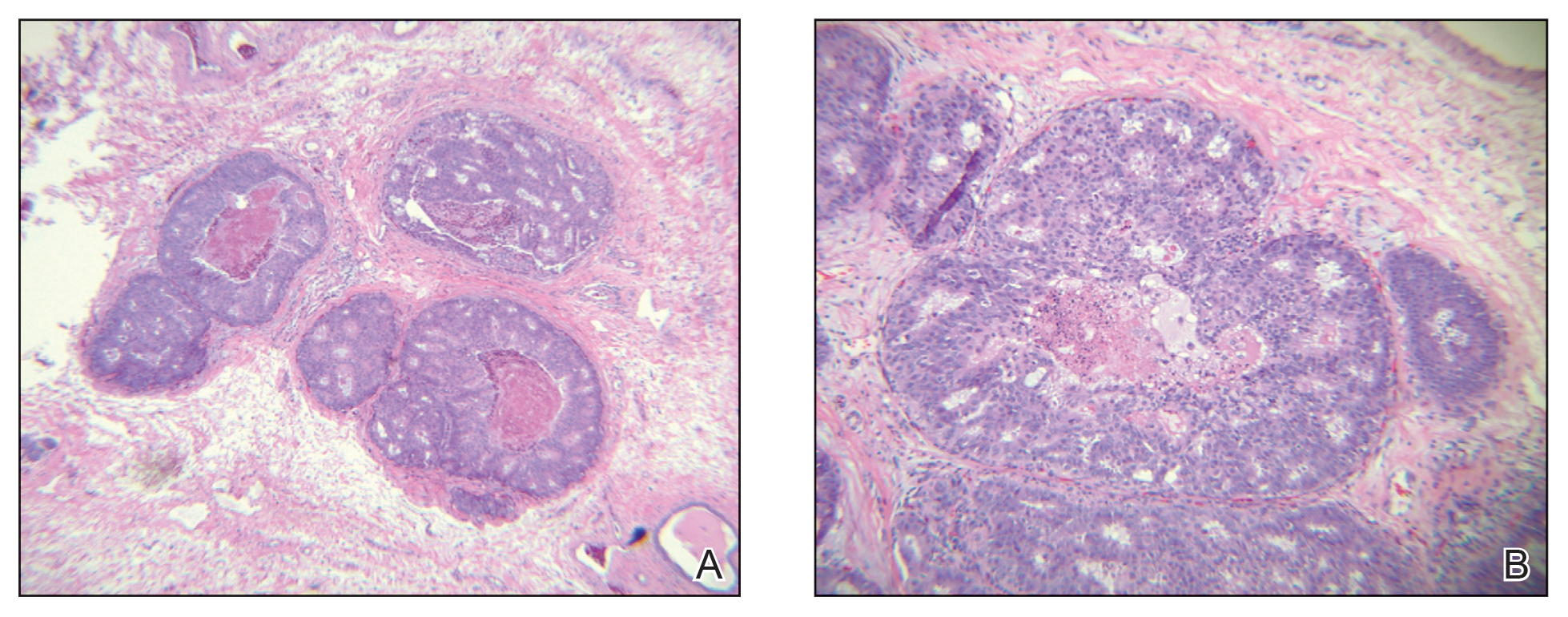

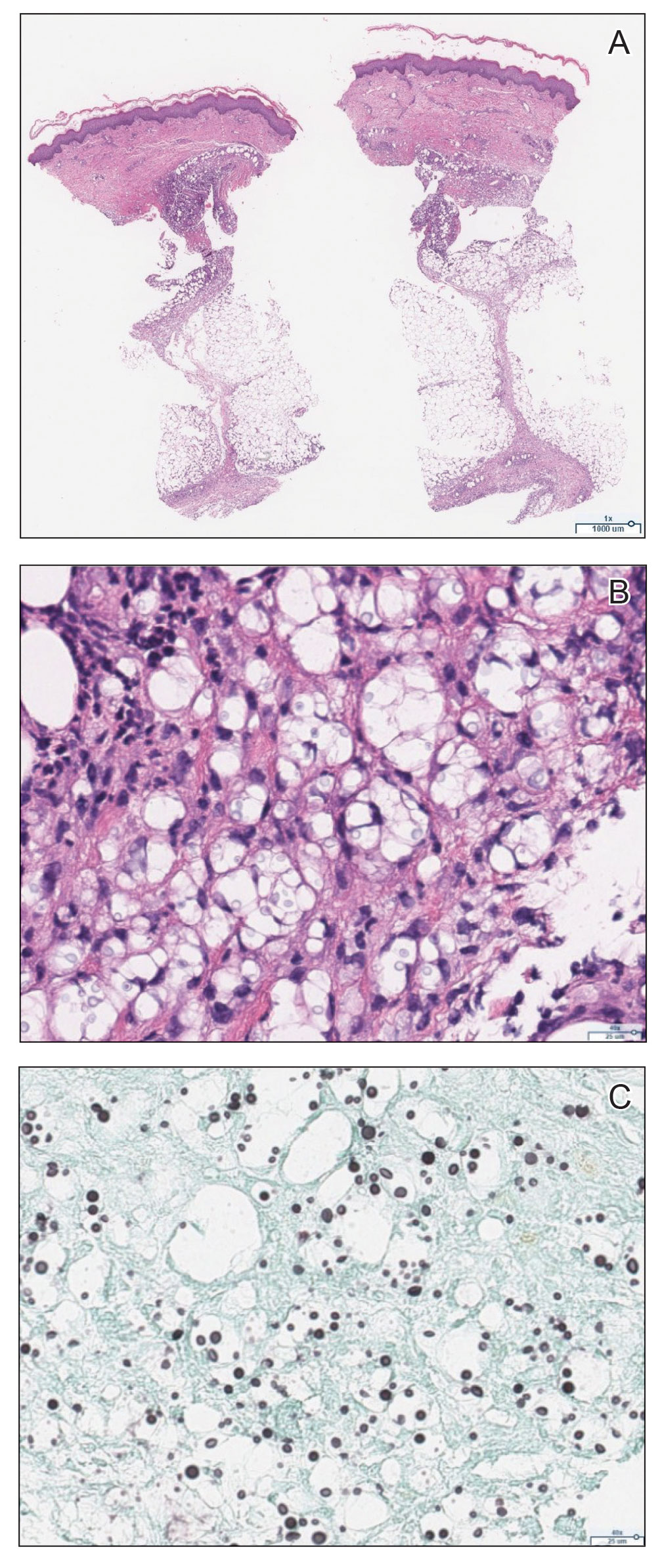

A 60-year-old man presented with a persistent polymorphous pruritic eruption of several months’ duration involving the entire face, ears, neck, and upper chest. He had a history of unspecified adenocarcinoma of the parotid gland diagnosed 2 years prior and underwent multiple treatment cycles with several chemotherapeutic agents over the course of 18 months. Physical examination showed erythematous papules and nodules on the face and neck with slight overlying scale. Sharply demarcated, erythematous plaques studded with focally hemorrhagic, angiomatous papules were noted on the neck and chest (Figure 1). Two 4-mm punch biopsies were sampled from representative nodular areas. Histopathology showed multiple round solid-tumor nodules with central necrosis in the superficial and deep dermis that were not associated with the overlying epidermis (Figures 2A and 2B). The tumor cells appeared polygonal and contained ample eosinophilic cytoplasm. Tumor nuclei showed marked pleomorphism, and numerous atypical mitotic figures were readily identifiable (Figure 2C). There was diffuse cytoplasmic staining with cytokeratin 7 and nuclear staining with androgen receptor (Figure 2D). These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of SDC metastatic to the skin.

The patient underwent 8 cycles of docetaxel chemotherapy. With disease progression, the chemotherapy regimen was changed to gemcitabine and methotrexate. The patient continued to experience disease progression and died 9 months after diagnosis of skin metastases.

Salivary duct carcinoma is rare and is estimated to represent 1% to 3% of all salivary malignancies.1 It is a highly aggressive form of salivary gland carcinoma and is associated with a poor clinical outcome. The 3-year overall survival rate for stage I disease is 42% and only 23% for stage IV disease.2 Salivary duct carcinoma has a high rate of distant metastasis,3 but cases of cutaneous metastases are rare.3-8 Previously reported cases of SDC that metastasized to the skin originated from the parotid gland (n=6) and submandibular gland (n=1).3

The diagnosis of cutaneous metastases is challenging due to the variability of the skin manifestations. Three cases described small firm nodules in patients,3-5 while others presented with purpuric papules and pseudovesicles.6-8 Our patient presented with sharply demarcated, erythematous plaques studded with focally hemorrhagic, angiomatous papules, which further emphasizes the capricious nature of skin findings.

The morphology of SDC is strikingly similar to ductal adenocarcinoma of the breast, which can lead to diagnostic confusion. Both carcinomas may show oncocytic cells, ductal formations, and cribriform structures with central comedo necrosis. Moreover, immunohistochemical features overlap, including positive staining for cytokeratin 7 and gross cystic disease fluid protein 15. Positive immunohistochemistry with androgen receptor is consistent with SDC but also can be expressed in some cases of breast carcinoma.9,10 Therefore, the diagnosis of cutaneous involvement from metastatic SDC requires not just an evaluation of the pathologic features but careful attention to the clinical history and a thorough staging evaluation.

- D’heygere E, Meulemans J, Vander Poorten V. Salivary duct carcinoma. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;26:142-151.

- Gilbert MR, Sharma A, Schmitt NC, et al. A 20-year review of 75 cases of salivary duct carcinoma. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;142:489-495.

- Chakari W, Andersen L, Andersen JL. Cutaneous metastases from salivary duct carcinoma of the submandibular gland. Case Rep Dermatol. 2017;9:254-258.

- Tok J, Kao GF, Berberian BJ, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from a parotid adenocarcinoma. Report of a case with immunohistochemical findings and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:303-306.

- Aygit AC, Top H, Cakir B, et al. Salivary duct carcinoma of the parotid gland metastasizing to the skin: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:48-50.

- Cohen PR, Prieto VG, Piha-Paul SA, et al. The “shield sign” in two men with metastatic salivary duct carcinoma to the skin: cutaneous metastases presenting as carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:27-36.

- Hafiji J, Rytina E, Jani P, et al. A rare cutaneous presentation of metastatic parotid adenocarcinoma. Australas J Dermatol. 2013;54:E40-E42.

- Zanca A, Ferracini U, Bertazzoni MG. Telangiectatic metastasis from ductal carcinoma of the parotid gland. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:113-114.

- Brys´ M, Wójcik M, Romanowicz-Makowska H, et al. Androgen receptor status in female breast cancer: RT-PCR and Western blot studies. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2002;128:85-90.

- Udager AM, Chiosea SI. Salivary duct carcinoma: an update on morphologic mimics and diagnostic use of androgen receptor immunohistochemistry. Head Neck Pathol. 2017;11:288-294.

To the Editor: