User login

Superficial Vascular Anomaly of the Glabella Mimicking a Cutaneous Cyst

To the Editor:

Cutaneous cysts commonly are treated by dermatologists and typically are diagnosed clinically, followed by intraoperative or histologic confirmation; however, cyst mimickers can be misdiagnosed due to similar appearance and limited diagnostic guidelines.1 Vascular anomalies (VAs) of the face such as a facial aneurysm are rare.2 Preoperative assessment of findings suggestive of vascular etiology vs other common cutaneous tumors such as an epidermal inclusion cyst (EIC) and lipoma can help guide dermatologic management. We present a case of a VA of the glabella manifesting as a flesh-colored nodule that clinically mimicked a cyst and discuss the subsequent surgical management.

A 61-year-old man with a history of benign prostatic hyperplasia was evaluated at our dermatology clinic for an enlarging forehead mass of 1 year’s duration. Physical examination yielded a soft, flesh-colored, 2.5-cm nodule located superficially in the midline glabellar region without pulsation or palpable thrill. The differential diagnosis at the time included lipoma or EIC.

Excision of the lesion was performed utilizing superficial incisions with a descending depth of 1-mm increments to safely reach the target, identify the type of tumor, and prevent rupture of the suspected EIC. After the third incision to the level of the dermis, nonpulsatile bleeding was more than expected for a cyst. Digital pressure was applied, and the area was explored with blunt dissection to identify the source of bleeding. A fusiform, thin-walled aneurysm was identified in the dermal plane with additional tributaries coursing deep into the subcutaneous plane. The visualized tributaries were ligated with 3-0 polyglactin, figure-of-eight sutures resulting in hemostasis. The wound was closed with 5-0 nylon simple interrupted sutures. The patient was closely followed postoperatively for 1 week (Figure) and was referred for head imaging to evaluate for a possible associated intracranial aneurysm. Based on the thin vessel wall and continuous nonpulsatile hemorrhage, this VA was most consistent with venous aneurysm.

A VA can be encountered unexpectedly during dermatologic surgery. An aneurysm is a type of VA and is defined as an abnormal dilatation of a blood vessel that can be arterial, venous, or an arteriovenous malformation. Most reported aneurysms of the head and neck are cirsoid aneurysms or involve the superficial temporal artery.2,3 Reports of superficial venous aneurysms are rare.4 Preoperatively, cutaneous nodules can be evaluated for findings suggestive of a VA in the dermatologist’s office through physical examination. Arterial aneurysms may reveal palpable pulsation and audible bruit, while a venous aneurysm may exhibit a blue color, a size reduction with compression, and variable size with Valsalva maneuver.

The gold standard diagnostic tool for most dermatologic conditions is histopathology; however, dermatologic ultrasonography can provide noninvasive, real-time, important diagnostic characteristics of cutaneous pathologies as well as VA.5-7 Crisan et al6 outlined specific sonographic findings of lipomas, EICs, trichilemmal cysts, and other dermatologic conditions as well as the associated surgical pertinence. Ultrasonography of a venous aneurysm may show a heterogeneous, contiguous, echoic lesion with an adjacent superficial vein, which may be easily compressed by the probe.8 Advanced imaging such as computed tomography with contrast or magnetic resonance imaging may be performed, but these are more costly than ultrasonography. Additionally, point-of-care ultrasonography is becoming more popular and accessible for physicians to carry at bedside with portable tablet options available. Dermatologists may want to consider incorporating it into the outpatient setting to improve procedural planning.9

In conclusion, VAs should be included in the differential diagnosis of soft cutaneous nodules, as management differs from a cyst or lipoma. Dermatologists should use their clinical judgment preoperatively—including a comprehensive history, physical examination, and consideration of color Doppler ultrasonography to assess for findings of VA. We do not recommend intentional surgical exploration of cutaneous aneurysms in the ambulatory setting due to risk for hemorrhage. Furthermore, when clinical suspicion of EIC or lipoma is high, it still is preferable to descend the incision slowly at 1 to 2 mm per cut until the tumor is visualized.

- Ring CM, Kornreich DA, Lee JB. Clinical simulators of cysts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1255-1257.

- Evans CC, Larson MJ, Eichhorn PJ, et al. Traumatic pseudoaneurysm of the superficial temporal artery: two cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(5 suppl):S286-S288.

- Sofela A, Osunronbi T, Hettige S. Scalp cirsoid aneurysms: case illustration and systematic review of literature. Neurosurgery. 2020;86:E98-E107.

- McKesey J, Cohen PR. Spontaneous venous aneurysm: report of a non-traumatic superficial venous aneurysm on the distal arm. Cureus. 2018;10:E2641.

- Wortsman X, Alfageme F, Roustan G, et al. Guidelines for performing dermatologic ultrasound examinations by the DERMUS Group. J Ultrasound Med. 2016;35:577-580.

- Crisan D, Wortsman X, Alfageme F, et al. Ultrasonography in dermatologic surgery: revealing the unseen for improved surgical planning [published online May 26, 2022]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. doi:10.1111/ddg.14781

- Corvino A, Catalano O, Corvino F, et al. Superficial temporal artery pseudoaneurysm: what is the role of ultrasound. J Ultrasound. 2016;19:197-201.

- Lee HY, Lee W, Cho YK, et al. Superficial venous aneurysm: reports of 3 cases and literature review. J Ultrasound Med. 2006;25:771-776.

- Hadian Y, Link D, Dahle SE, et al. Ultrasound as a diagnostic and interventional aid at point-of-care in dermatology clinic: a case report. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:74-76.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous cysts commonly are treated by dermatologists and typically are diagnosed clinically, followed by intraoperative or histologic confirmation; however, cyst mimickers can be misdiagnosed due to similar appearance and limited diagnostic guidelines.1 Vascular anomalies (VAs) of the face such as a facial aneurysm are rare.2 Preoperative assessment of findings suggestive of vascular etiology vs other common cutaneous tumors such as an epidermal inclusion cyst (EIC) and lipoma can help guide dermatologic management. We present a case of a VA of the glabella manifesting as a flesh-colored nodule that clinically mimicked a cyst and discuss the subsequent surgical management.

A 61-year-old man with a history of benign prostatic hyperplasia was evaluated at our dermatology clinic for an enlarging forehead mass of 1 year’s duration. Physical examination yielded a soft, flesh-colored, 2.5-cm nodule located superficially in the midline glabellar region without pulsation or palpable thrill. The differential diagnosis at the time included lipoma or EIC.

Excision of the lesion was performed utilizing superficial incisions with a descending depth of 1-mm increments to safely reach the target, identify the type of tumor, and prevent rupture of the suspected EIC. After the third incision to the level of the dermis, nonpulsatile bleeding was more than expected for a cyst. Digital pressure was applied, and the area was explored with blunt dissection to identify the source of bleeding. A fusiform, thin-walled aneurysm was identified in the dermal plane with additional tributaries coursing deep into the subcutaneous plane. The visualized tributaries were ligated with 3-0 polyglactin, figure-of-eight sutures resulting in hemostasis. The wound was closed with 5-0 nylon simple interrupted sutures. The patient was closely followed postoperatively for 1 week (Figure) and was referred for head imaging to evaluate for a possible associated intracranial aneurysm. Based on the thin vessel wall and continuous nonpulsatile hemorrhage, this VA was most consistent with venous aneurysm.

A VA can be encountered unexpectedly during dermatologic surgery. An aneurysm is a type of VA and is defined as an abnormal dilatation of a blood vessel that can be arterial, venous, or an arteriovenous malformation. Most reported aneurysms of the head and neck are cirsoid aneurysms or involve the superficial temporal artery.2,3 Reports of superficial venous aneurysms are rare.4 Preoperatively, cutaneous nodules can be evaluated for findings suggestive of a VA in the dermatologist’s office through physical examination. Arterial aneurysms may reveal palpable pulsation and audible bruit, while a venous aneurysm may exhibit a blue color, a size reduction with compression, and variable size with Valsalva maneuver.

The gold standard diagnostic tool for most dermatologic conditions is histopathology; however, dermatologic ultrasonography can provide noninvasive, real-time, important diagnostic characteristics of cutaneous pathologies as well as VA.5-7 Crisan et al6 outlined specific sonographic findings of lipomas, EICs, trichilemmal cysts, and other dermatologic conditions as well as the associated surgical pertinence. Ultrasonography of a venous aneurysm may show a heterogeneous, contiguous, echoic lesion with an adjacent superficial vein, which may be easily compressed by the probe.8 Advanced imaging such as computed tomography with contrast or magnetic resonance imaging may be performed, but these are more costly than ultrasonography. Additionally, point-of-care ultrasonography is becoming more popular and accessible for physicians to carry at bedside with portable tablet options available. Dermatologists may want to consider incorporating it into the outpatient setting to improve procedural planning.9

In conclusion, VAs should be included in the differential diagnosis of soft cutaneous nodules, as management differs from a cyst or lipoma. Dermatologists should use their clinical judgment preoperatively—including a comprehensive history, physical examination, and consideration of color Doppler ultrasonography to assess for findings of VA. We do not recommend intentional surgical exploration of cutaneous aneurysms in the ambulatory setting due to risk for hemorrhage. Furthermore, when clinical suspicion of EIC or lipoma is high, it still is preferable to descend the incision slowly at 1 to 2 mm per cut until the tumor is visualized.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous cysts commonly are treated by dermatologists and typically are diagnosed clinically, followed by intraoperative or histologic confirmation; however, cyst mimickers can be misdiagnosed due to similar appearance and limited diagnostic guidelines.1 Vascular anomalies (VAs) of the face such as a facial aneurysm are rare.2 Preoperative assessment of findings suggestive of vascular etiology vs other common cutaneous tumors such as an epidermal inclusion cyst (EIC) and lipoma can help guide dermatologic management. We present a case of a VA of the glabella manifesting as a flesh-colored nodule that clinically mimicked a cyst and discuss the subsequent surgical management.

A 61-year-old man with a history of benign prostatic hyperplasia was evaluated at our dermatology clinic for an enlarging forehead mass of 1 year’s duration. Physical examination yielded a soft, flesh-colored, 2.5-cm nodule located superficially in the midline glabellar region without pulsation or palpable thrill. The differential diagnosis at the time included lipoma or EIC.

Excision of the lesion was performed utilizing superficial incisions with a descending depth of 1-mm increments to safely reach the target, identify the type of tumor, and prevent rupture of the suspected EIC. After the third incision to the level of the dermis, nonpulsatile bleeding was more than expected for a cyst. Digital pressure was applied, and the area was explored with blunt dissection to identify the source of bleeding. A fusiform, thin-walled aneurysm was identified in the dermal plane with additional tributaries coursing deep into the subcutaneous plane. The visualized tributaries were ligated with 3-0 polyglactin, figure-of-eight sutures resulting in hemostasis. The wound was closed with 5-0 nylon simple interrupted sutures. The patient was closely followed postoperatively for 1 week (Figure) and was referred for head imaging to evaluate for a possible associated intracranial aneurysm. Based on the thin vessel wall and continuous nonpulsatile hemorrhage, this VA was most consistent with venous aneurysm.

A VA can be encountered unexpectedly during dermatologic surgery. An aneurysm is a type of VA and is defined as an abnormal dilatation of a blood vessel that can be arterial, venous, or an arteriovenous malformation. Most reported aneurysms of the head and neck are cirsoid aneurysms or involve the superficial temporal artery.2,3 Reports of superficial venous aneurysms are rare.4 Preoperatively, cutaneous nodules can be evaluated for findings suggestive of a VA in the dermatologist’s office through physical examination. Arterial aneurysms may reveal palpable pulsation and audible bruit, while a venous aneurysm may exhibit a blue color, a size reduction with compression, and variable size with Valsalva maneuver.

The gold standard diagnostic tool for most dermatologic conditions is histopathology; however, dermatologic ultrasonography can provide noninvasive, real-time, important diagnostic characteristics of cutaneous pathologies as well as VA.5-7 Crisan et al6 outlined specific sonographic findings of lipomas, EICs, trichilemmal cysts, and other dermatologic conditions as well as the associated surgical pertinence. Ultrasonography of a venous aneurysm may show a heterogeneous, contiguous, echoic lesion with an adjacent superficial vein, which may be easily compressed by the probe.8 Advanced imaging such as computed tomography with contrast or magnetic resonance imaging may be performed, but these are more costly than ultrasonography. Additionally, point-of-care ultrasonography is becoming more popular and accessible for physicians to carry at bedside with portable tablet options available. Dermatologists may want to consider incorporating it into the outpatient setting to improve procedural planning.9

In conclusion, VAs should be included in the differential diagnosis of soft cutaneous nodules, as management differs from a cyst or lipoma. Dermatologists should use their clinical judgment preoperatively—including a comprehensive history, physical examination, and consideration of color Doppler ultrasonography to assess for findings of VA. We do not recommend intentional surgical exploration of cutaneous aneurysms in the ambulatory setting due to risk for hemorrhage. Furthermore, when clinical suspicion of EIC or lipoma is high, it still is preferable to descend the incision slowly at 1 to 2 mm per cut until the tumor is visualized.

- Ring CM, Kornreich DA, Lee JB. Clinical simulators of cysts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1255-1257.

- Evans CC, Larson MJ, Eichhorn PJ, et al. Traumatic pseudoaneurysm of the superficial temporal artery: two cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(5 suppl):S286-S288.

- Sofela A, Osunronbi T, Hettige S. Scalp cirsoid aneurysms: case illustration and systematic review of literature. Neurosurgery. 2020;86:E98-E107.

- McKesey J, Cohen PR. Spontaneous venous aneurysm: report of a non-traumatic superficial venous aneurysm on the distal arm. Cureus. 2018;10:E2641.

- Wortsman X, Alfageme F, Roustan G, et al. Guidelines for performing dermatologic ultrasound examinations by the DERMUS Group. J Ultrasound Med. 2016;35:577-580.

- Crisan D, Wortsman X, Alfageme F, et al. Ultrasonography in dermatologic surgery: revealing the unseen for improved surgical planning [published online May 26, 2022]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. doi:10.1111/ddg.14781

- Corvino A, Catalano O, Corvino F, et al. Superficial temporal artery pseudoaneurysm: what is the role of ultrasound. J Ultrasound. 2016;19:197-201.

- Lee HY, Lee W, Cho YK, et al. Superficial venous aneurysm: reports of 3 cases and literature review. J Ultrasound Med. 2006;25:771-776.

- Hadian Y, Link D, Dahle SE, et al. Ultrasound as a diagnostic and interventional aid at point-of-care in dermatology clinic: a case report. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:74-76.

- Ring CM, Kornreich DA, Lee JB. Clinical simulators of cysts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1255-1257.

- Evans CC, Larson MJ, Eichhorn PJ, et al. Traumatic pseudoaneurysm of the superficial temporal artery: two cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(5 suppl):S286-S288.

- Sofela A, Osunronbi T, Hettige S. Scalp cirsoid aneurysms: case illustration and systematic review of literature. Neurosurgery. 2020;86:E98-E107.

- McKesey J, Cohen PR. Spontaneous venous aneurysm: report of a non-traumatic superficial venous aneurysm on the distal arm. Cureus. 2018;10:E2641.

- Wortsman X, Alfageme F, Roustan G, et al. Guidelines for performing dermatologic ultrasound examinations by the DERMUS Group. J Ultrasound Med. 2016;35:577-580.

- Crisan D, Wortsman X, Alfageme F, et al. Ultrasonography in dermatologic surgery: revealing the unseen for improved surgical planning [published online May 26, 2022]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. doi:10.1111/ddg.14781

- Corvino A, Catalano O, Corvino F, et al. Superficial temporal artery pseudoaneurysm: what is the role of ultrasound. J Ultrasound. 2016;19:197-201.

- Lee HY, Lee W, Cho YK, et al. Superficial venous aneurysm: reports of 3 cases and literature review. J Ultrasound Med. 2006;25:771-776.

- Hadian Y, Link D, Dahle SE, et al. Ultrasound as a diagnostic and interventional aid at point-of-care in dermatology clinic: a case report. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:74-76.

Practice Points

- Vascular anomalies should be included in the differential diagnosis of soft cutaneous nodules, as management differs from cysts or lipomas.

- Preoperative evaluation for a cutaneous cyst excision on the head and neck should include ruling out findings of a vascular lesion through history, physical examination, and consideration of color Doppler ultrasonography in unclear cases.

- Surgical technique should involve sequential superficial incisions, descending at 1 to 2 mm per cut, until the suspected capsule is identified to minimize the risk for inadvertent injury to a cyst mimicker such as a vascular anomaly.

Multiple New-Onset Pyogenic Granulomas During Treatment With Paclitaxel and Ramucirumab

To the Editor:

Pyogenic granuloma (PG) is a benign vascular tumor that clinically is characterized as a small eruptive friable papule.1 Lesions typically are solitary and most commonly occur in children but also are associated with pregnancy; trauma to the skin or mucosa; and use of certain medications such as isotretinoin, capecitabine, vemurafenib, or indinavir.1 Numerous antineoplastic medications have been associated with the development of solitary PGs, including the taxane mitotic inhibitor paclitaxel (PTX) and the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) monoclonal antibody ramucirumab.2 We report a case of multiple PGs in a patient undergoing treatment with PTX and ramucirumab.

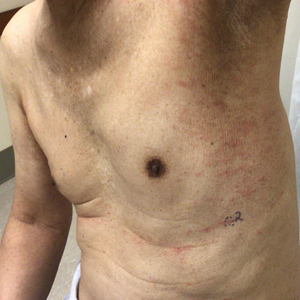

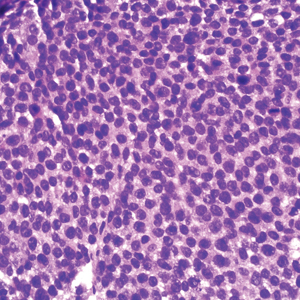

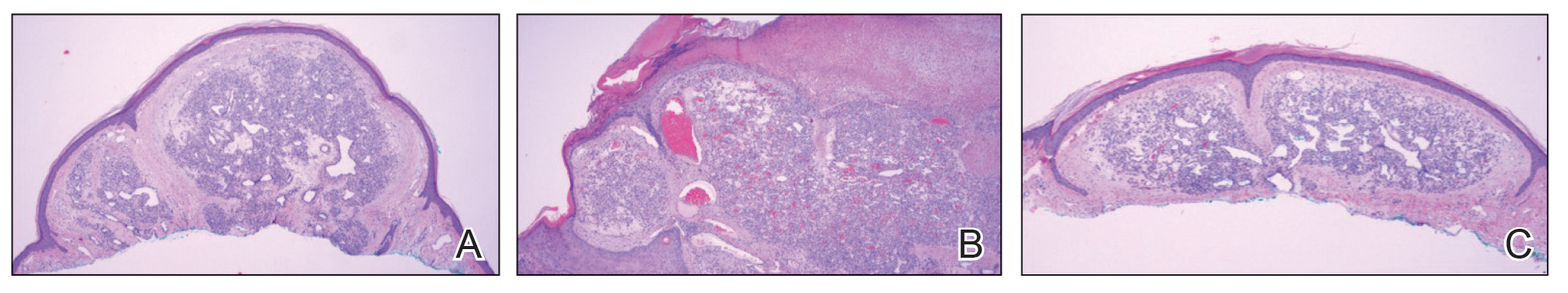

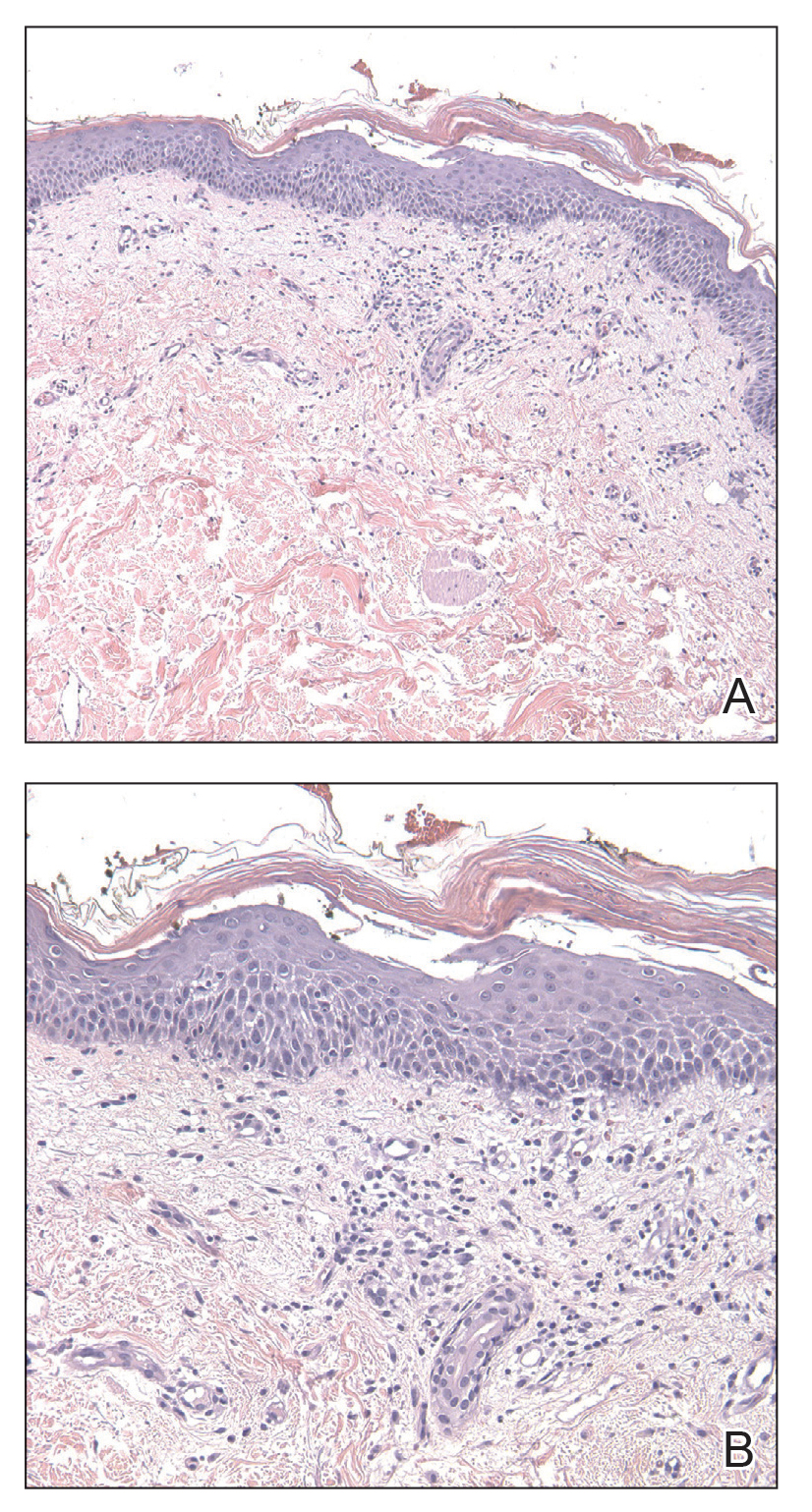

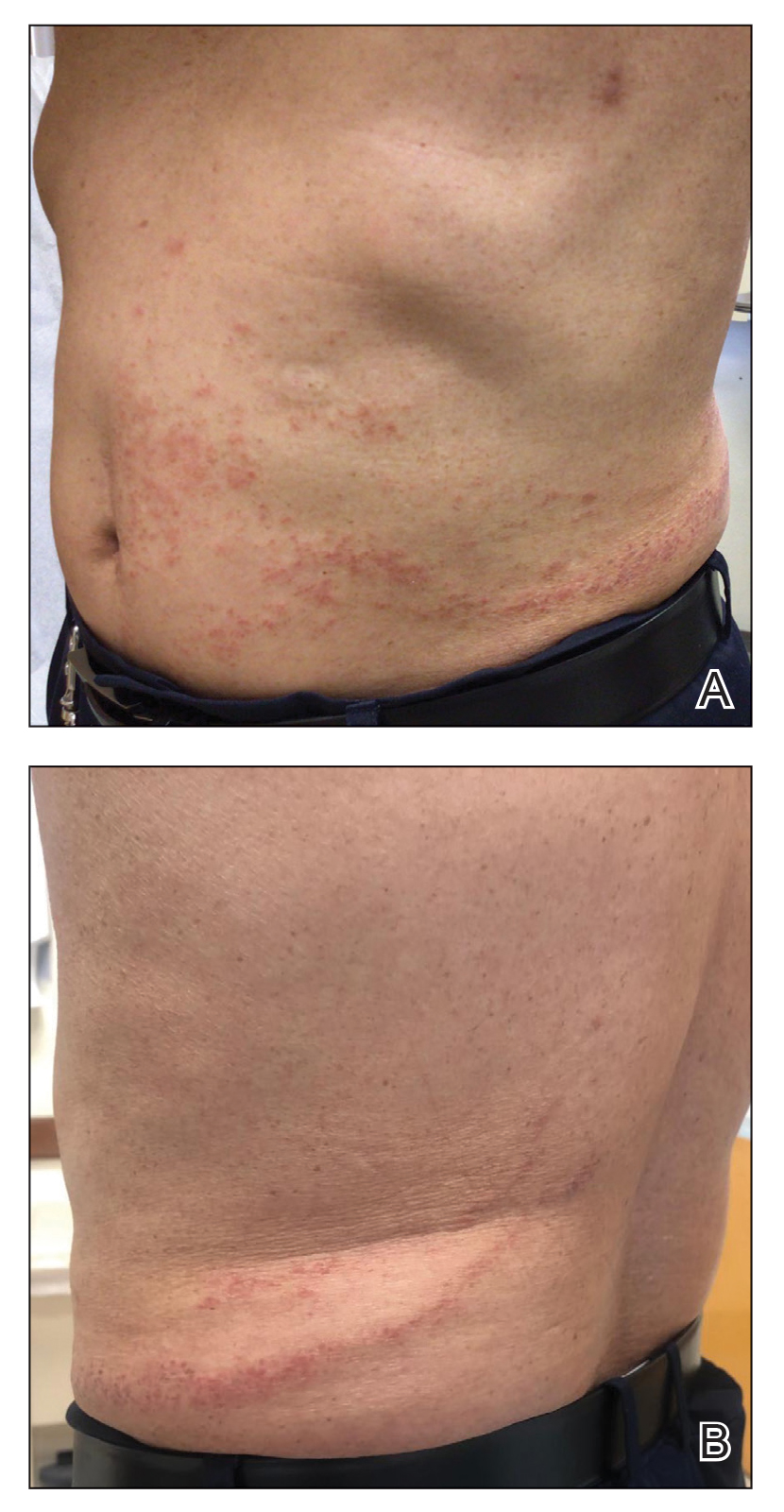

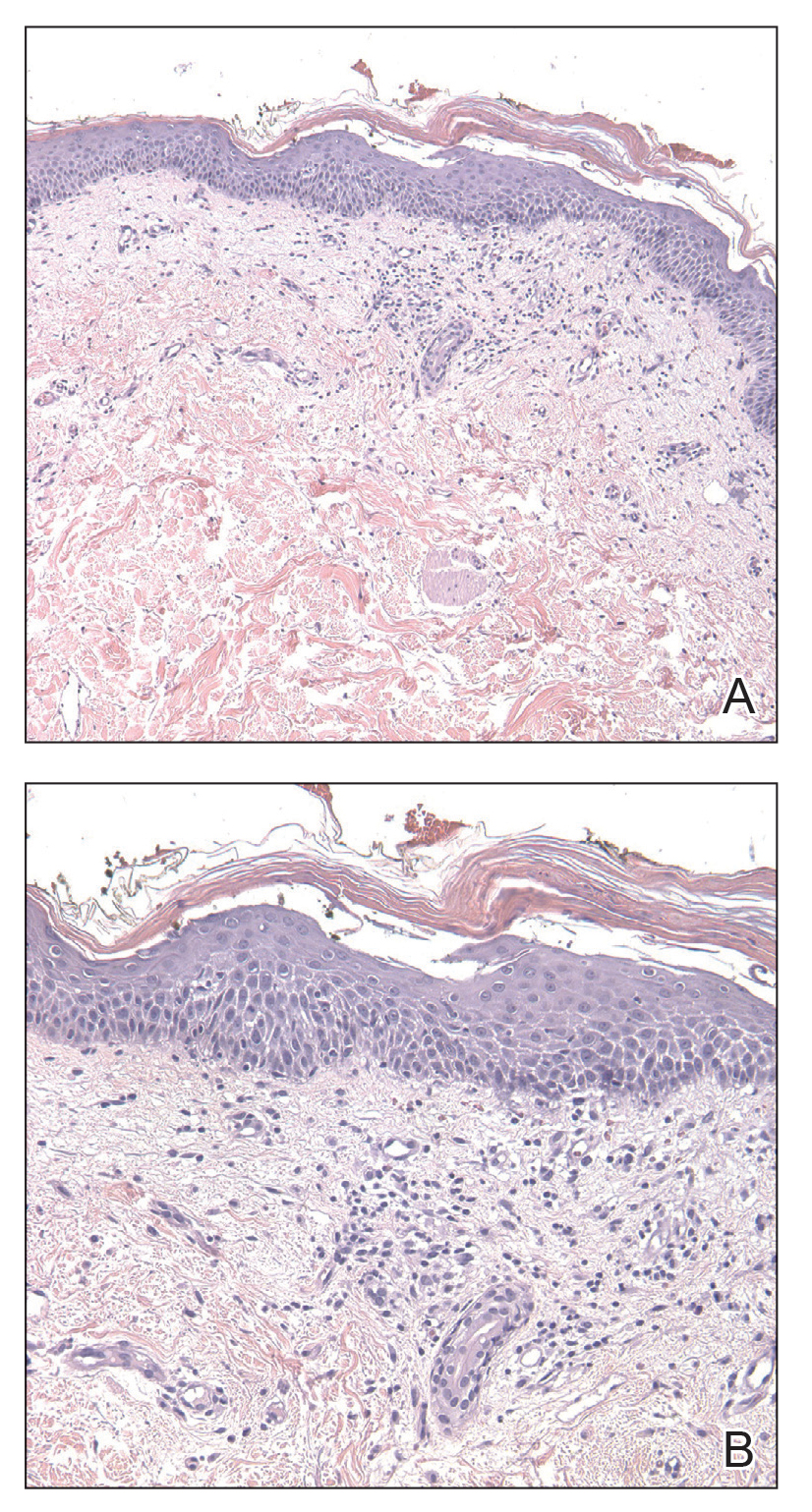

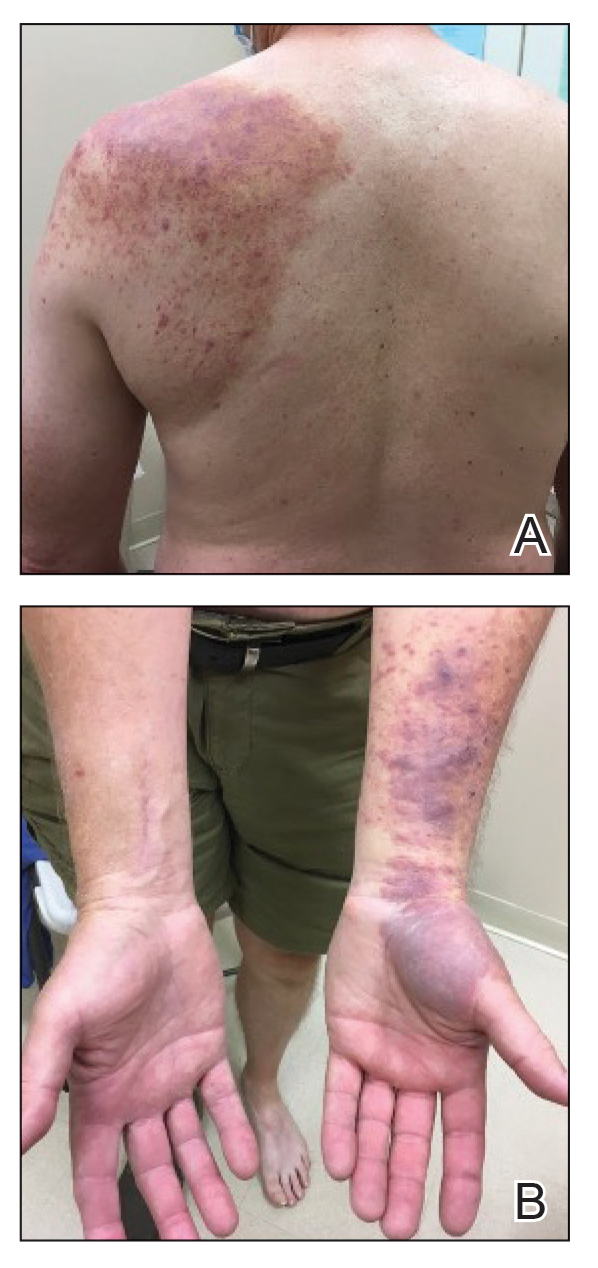

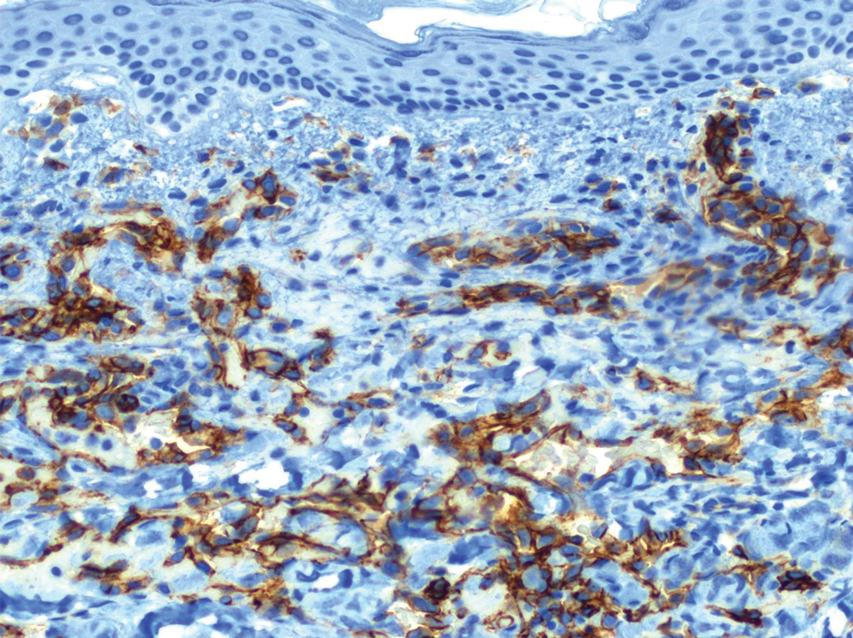

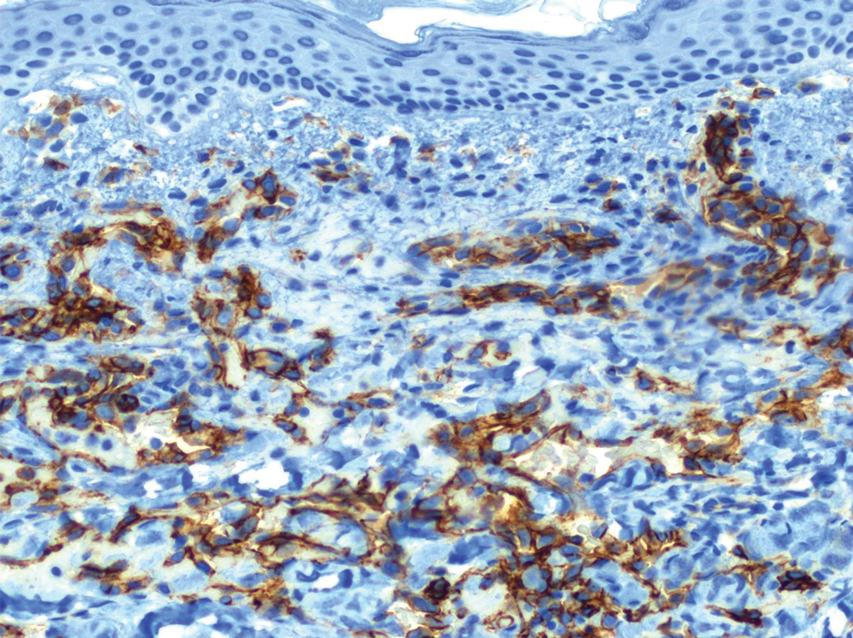

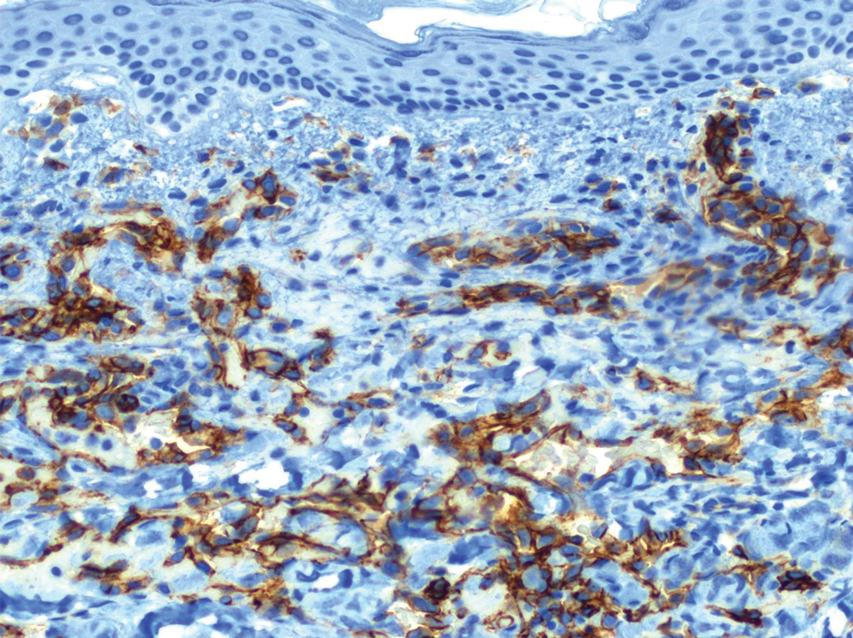

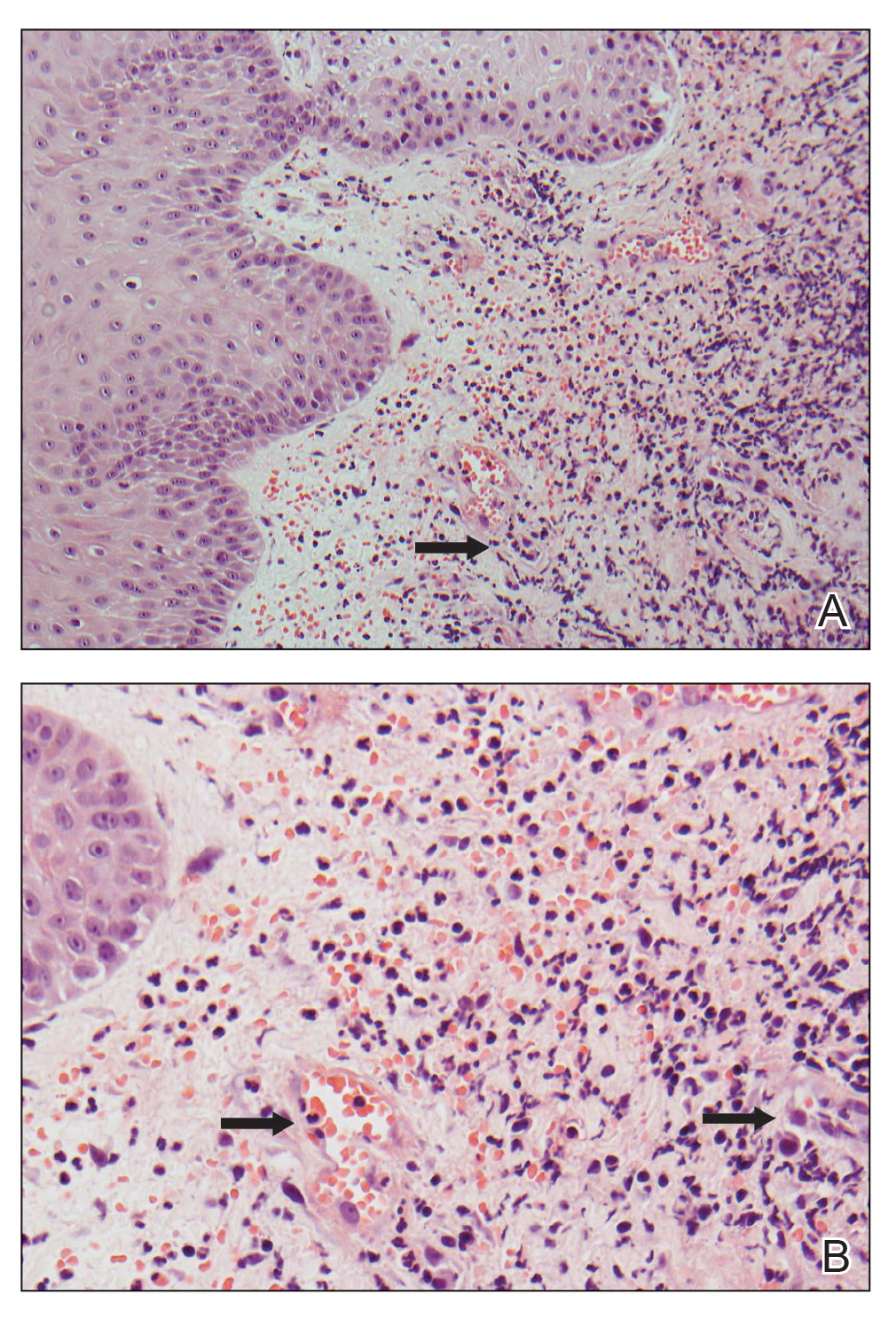

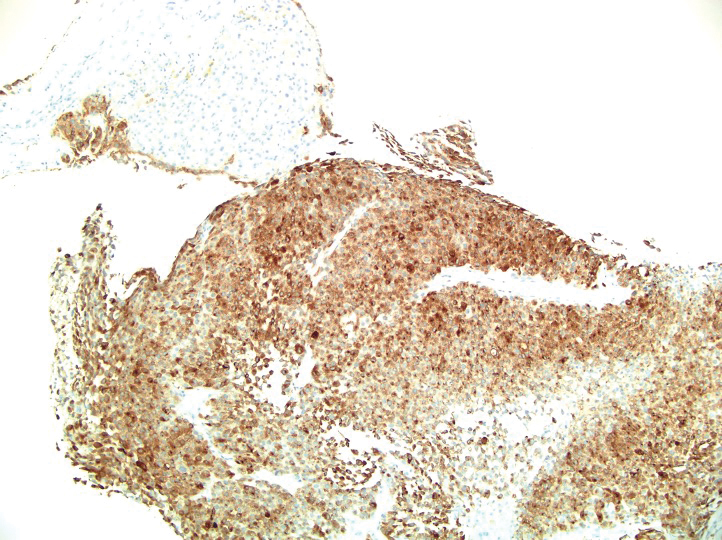

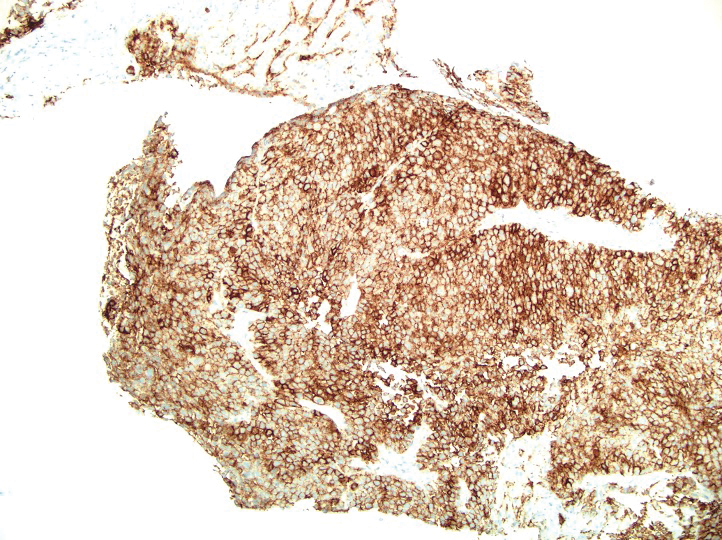

A 59-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with red, itchy, bleeding skin lesions on the breast, superior chest, left cheek, and forearm of 1 month’s duration. She denied any preceding trauma to the areas. Her medical history was notable for gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma diagnosed more than 2 years prior to presentation. Her original treatment regimen included nivolumab, which was discontinued for unknown reasons 5 months prior to presentation, and she was started on combination therapy with PTX and ramucirumab at that time. She noted the formation of small red papules 2 months after the initiation of PTX-ramucirumab combination therapy, which grew larger over the course of the next month. Physical examination revealed 5 friable hemorrhagic papules and nodules ranging in size from 3 to 10 mm on the chest, cheek, and forearm consistent with PGs (Figure 1). Several scattered cherry angiomas were noted on the scalp and torso, but the patient reported these were not new. Biopsies of the PGs demonstrated lobular aggregates of small-caliber vessels set in an edematous inflamed stroma and partially enclosed by small collarettes of adnexal epithelium, confirming the clinical diagnosis of multiple PGs (Figure 2).

The first case of PTX-associated PG was reported in 2012.3 Based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms pyogenic granuloma, lobular capillary hemangioma, paclitaxel, taxane, and ramucirumab, there have been 9 cases of solitary PG development in the setting of PTX alone or in combination with ramucirumab since 2019 (Table).3-8 Pyogenic granulomas reported in patients who were treated exclusively with PTX were subungual, while the cases resulting from combined therapy were present on the scalp, face, oral mucosa, and surfaces of the hands sparing the nails. Ibe et al6 reported PG in a patient who received ramucirumab therapy without PTX but in combination with another taxane, docetaxel, which itself has been reported to cause subungual PG when used alone.9 Our case of the simultaneous development of multiple PGs in the setting of combined PTX and ramucirumab therapy added to the cutaneous distributions for which therapy-induced PGs have been observed (Table).

The development of PG, a vascular tumor, during treatment with the VEGFR2 inhibitor ramucirumab—whose mechanism of action is to inhibit angioneogenesis—is inherently paradoxical. In 2015, a rapidly expanding angioma with a mutation in the kinase domain receptor gene, KDR, that encodes VEGFR2 was identified in a patient undergoing ramucirumab therapy. The authors suggested that KDR mutation resulted in paradoxical activation of VEGFR2 in the setting of ramucirumab therapy.10 Since then, ramucirumab and PTX were suggested to have a synergistic effect in vascular proliferation,5 though an exact mechanism has not been proposed. Other authors have identified increased expression of VEGFR2 in biopsy specimens of PG during combined ramucirumab and taxane therapy.6 Although genetic studies have not been used to evaluate for the presence of KDR mutations specifically in our patient population, it is possible that patients who develop PG and other vascular tumors during combined taxane and ramucirumab therapy have a mutation that makes them more susceptible to VEGFR2 upregulation. UV exposure may have a role in the formation of PG in patients on combined ramucirumab and taxane therapy7; however, our patient’s lesions were distributed on both sun-exposed and unexposed areas. Although potential clinical implications have not yet been thoroughly investigated, following long-term outcomes for these patients may provide important information on the efficacy of the antineoplastic regimen in the subset of patients who develop cutaneous vascular tumors during antiangiogenic treatment.

Combination therapy with PTX and ramucirumab has been associated with the paradoxical development of cutaneous vascular tumors. We report a case of multiple new-onset PGs in a patient undergoing this treatment regimen.

- Elston D, Neuhaus I, James WD, et al. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2020.

- Pierson JC. Pyogenic granuloma (lobular capillary hemangioma) clinical presentation. Medscape. Updated February 21, 2020. Accessed December 26, 2023. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1084701-clinical#showall

- Paul LJ, Cohen PR. Paclitaxel-associated subungual pyogenic granuloma: report in a patient with breast cancer receiving paclitaxel and review of drug-induced pyogenic granulomas adjacent to and beneath the nail. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:262-268.

- Alessandrini A, Starace M, Cerè G, et al. Management and outcome of taxane-induced nail side effects: experience of 79 patients from a single centre. Skin Appendage Disord. 2019;5:276-282.

- Watanabe R, Nakano E, Kawazoe A, et al. Four cases of paradoxical cephalocervical pyogenic granuloma during treatment with paclitaxel and ramucirumab. J Dermatol. 2019;46:E178-E180.

- Ibe T, Hamamoto Y, Takabatake M, et al. Development of pyogenic granuloma with strong vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 expression during ramucirumab treatment. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12:E231464.

- Choi YH, Byun HJ, Lee JH, et al. Multiple cherry angiomas and pyogenic granuloma in a patient treated with ramucirumab and paclitaxel. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:199-202.

- Aragaki T, Tomomatsu N, Michi Y, et al. Ramucirumab-related oral pyogenic granuloma: a report of two cases [published online March 8, 2021]. Intern Med. 2021;60:2601-2605. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.6650-20

- Devillers C, Vanhooteghem O, Henrijean A, et al. Subungual pyogenic granuloma secondary to docetaxel therapy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:251-252.

- Lim YH, Odell ID, Ko CJ, et al. Somatic p.T771R KDR (VEGFR2) mutation arising in a sporadic angioma during ramucirumab therapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1240-1243.

To the Editor:

Pyogenic granuloma (PG) is a benign vascular tumor that clinically is characterized as a small eruptive friable papule.1 Lesions typically are solitary and most commonly occur in children but also are associated with pregnancy; trauma to the skin or mucosa; and use of certain medications such as isotretinoin, capecitabine, vemurafenib, or indinavir.1 Numerous antineoplastic medications have been associated with the development of solitary PGs, including the taxane mitotic inhibitor paclitaxel (PTX) and the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) monoclonal antibody ramucirumab.2 We report a case of multiple PGs in a patient undergoing treatment with PTX and ramucirumab.

A 59-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with red, itchy, bleeding skin lesions on the breast, superior chest, left cheek, and forearm of 1 month’s duration. She denied any preceding trauma to the areas. Her medical history was notable for gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma diagnosed more than 2 years prior to presentation. Her original treatment regimen included nivolumab, which was discontinued for unknown reasons 5 months prior to presentation, and she was started on combination therapy with PTX and ramucirumab at that time. She noted the formation of small red papules 2 months after the initiation of PTX-ramucirumab combination therapy, which grew larger over the course of the next month. Physical examination revealed 5 friable hemorrhagic papules and nodules ranging in size from 3 to 10 mm on the chest, cheek, and forearm consistent with PGs (Figure 1). Several scattered cherry angiomas were noted on the scalp and torso, but the patient reported these were not new. Biopsies of the PGs demonstrated lobular aggregates of small-caliber vessels set in an edematous inflamed stroma and partially enclosed by small collarettes of adnexal epithelium, confirming the clinical diagnosis of multiple PGs (Figure 2).

The first case of PTX-associated PG was reported in 2012.3 Based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms pyogenic granuloma, lobular capillary hemangioma, paclitaxel, taxane, and ramucirumab, there have been 9 cases of solitary PG development in the setting of PTX alone or in combination with ramucirumab since 2019 (Table).3-8 Pyogenic granulomas reported in patients who were treated exclusively with PTX were subungual, while the cases resulting from combined therapy were present on the scalp, face, oral mucosa, and surfaces of the hands sparing the nails. Ibe et al6 reported PG in a patient who received ramucirumab therapy without PTX but in combination with another taxane, docetaxel, which itself has been reported to cause subungual PG when used alone.9 Our case of the simultaneous development of multiple PGs in the setting of combined PTX and ramucirumab therapy added to the cutaneous distributions for which therapy-induced PGs have been observed (Table).

The development of PG, a vascular tumor, during treatment with the VEGFR2 inhibitor ramucirumab—whose mechanism of action is to inhibit angioneogenesis—is inherently paradoxical. In 2015, a rapidly expanding angioma with a mutation in the kinase domain receptor gene, KDR, that encodes VEGFR2 was identified in a patient undergoing ramucirumab therapy. The authors suggested that KDR mutation resulted in paradoxical activation of VEGFR2 in the setting of ramucirumab therapy.10 Since then, ramucirumab and PTX were suggested to have a synergistic effect in vascular proliferation,5 though an exact mechanism has not been proposed. Other authors have identified increased expression of VEGFR2 in biopsy specimens of PG during combined ramucirumab and taxane therapy.6 Although genetic studies have not been used to evaluate for the presence of KDR mutations specifically in our patient population, it is possible that patients who develop PG and other vascular tumors during combined taxane and ramucirumab therapy have a mutation that makes them more susceptible to VEGFR2 upregulation. UV exposure may have a role in the formation of PG in patients on combined ramucirumab and taxane therapy7; however, our patient’s lesions were distributed on both sun-exposed and unexposed areas. Although potential clinical implications have not yet been thoroughly investigated, following long-term outcomes for these patients may provide important information on the efficacy of the antineoplastic regimen in the subset of patients who develop cutaneous vascular tumors during antiangiogenic treatment.

Combination therapy with PTX and ramucirumab has been associated with the paradoxical development of cutaneous vascular tumors. We report a case of multiple new-onset PGs in a patient undergoing this treatment regimen.

To the Editor:

Pyogenic granuloma (PG) is a benign vascular tumor that clinically is characterized as a small eruptive friable papule.1 Lesions typically are solitary and most commonly occur in children but also are associated with pregnancy; trauma to the skin or mucosa; and use of certain medications such as isotretinoin, capecitabine, vemurafenib, or indinavir.1 Numerous antineoplastic medications have been associated with the development of solitary PGs, including the taxane mitotic inhibitor paclitaxel (PTX) and the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) monoclonal antibody ramucirumab.2 We report a case of multiple PGs in a patient undergoing treatment with PTX and ramucirumab.

A 59-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with red, itchy, bleeding skin lesions on the breast, superior chest, left cheek, and forearm of 1 month’s duration. She denied any preceding trauma to the areas. Her medical history was notable for gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma diagnosed more than 2 years prior to presentation. Her original treatment regimen included nivolumab, which was discontinued for unknown reasons 5 months prior to presentation, and she was started on combination therapy with PTX and ramucirumab at that time. She noted the formation of small red papules 2 months after the initiation of PTX-ramucirumab combination therapy, which grew larger over the course of the next month. Physical examination revealed 5 friable hemorrhagic papules and nodules ranging in size from 3 to 10 mm on the chest, cheek, and forearm consistent with PGs (Figure 1). Several scattered cherry angiomas were noted on the scalp and torso, but the patient reported these were not new. Biopsies of the PGs demonstrated lobular aggregates of small-caliber vessels set in an edematous inflamed stroma and partially enclosed by small collarettes of adnexal epithelium, confirming the clinical diagnosis of multiple PGs (Figure 2).

The first case of PTX-associated PG was reported in 2012.3 Based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms pyogenic granuloma, lobular capillary hemangioma, paclitaxel, taxane, and ramucirumab, there have been 9 cases of solitary PG development in the setting of PTX alone or in combination with ramucirumab since 2019 (Table).3-8 Pyogenic granulomas reported in patients who were treated exclusively with PTX were subungual, while the cases resulting from combined therapy were present on the scalp, face, oral mucosa, and surfaces of the hands sparing the nails. Ibe et al6 reported PG in a patient who received ramucirumab therapy without PTX but in combination with another taxane, docetaxel, which itself has been reported to cause subungual PG when used alone.9 Our case of the simultaneous development of multiple PGs in the setting of combined PTX and ramucirumab therapy added to the cutaneous distributions for which therapy-induced PGs have been observed (Table).

The development of PG, a vascular tumor, during treatment with the VEGFR2 inhibitor ramucirumab—whose mechanism of action is to inhibit angioneogenesis—is inherently paradoxical. In 2015, a rapidly expanding angioma with a mutation in the kinase domain receptor gene, KDR, that encodes VEGFR2 was identified in a patient undergoing ramucirumab therapy. The authors suggested that KDR mutation resulted in paradoxical activation of VEGFR2 in the setting of ramucirumab therapy.10 Since then, ramucirumab and PTX were suggested to have a synergistic effect in vascular proliferation,5 though an exact mechanism has not been proposed. Other authors have identified increased expression of VEGFR2 in biopsy specimens of PG during combined ramucirumab and taxane therapy.6 Although genetic studies have not been used to evaluate for the presence of KDR mutations specifically in our patient population, it is possible that patients who develop PG and other vascular tumors during combined taxane and ramucirumab therapy have a mutation that makes them more susceptible to VEGFR2 upregulation. UV exposure may have a role in the formation of PG in patients on combined ramucirumab and taxane therapy7; however, our patient’s lesions were distributed on both sun-exposed and unexposed areas. Although potential clinical implications have not yet been thoroughly investigated, following long-term outcomes for these patients may provide important information on the efficacy of the antineoplastic regimen in the subset of patients who develop cutaneous vascular tumors during antiangiogenic treatment.

Combination therapy with PTX and ramucirumab has been associated with the paradoxical development of cutaneous vascular tumors. We report a case of multiple new-onset PGs in a patient undergoing this treatment regimen.

- Elston D, Neuhaus I, James WD, et al. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2020.

- Pierson JC. Pyogenic granuloma (lobular capillary hemangioma) clinical presentation. Medscape. Updated February 21, 2020. Accessed December 26, 2023. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1084701-clinical#showall

- Paul LJ, Cohen PR. Paclitaxel-associated subungual pyogenic granuloma: report in a patient with breast cancer receiving paclitaxel and review of drug-induced pyogenic granulomas adjacent to and beneath the nail. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:262-268.

- Alessandrini A, Starace M, Cerè G, et al. Management and outcome of taxane-induced nail side effects: experience of 79 patients from a single centre. Skin Appendage Disord. 2019;5:276-282.

- Watanabe R, Nakano E, Kawazoe A, et al. Four cases of paradoxical cephalocervical pyogenic granuloma during treatment with paclitaxel and ramucirumab. J Dermatol. 2019;46:E178-E180.

- Ibe T, Hamamoto Y, Takabatake M, et al. Development of pyogenic granuloma with strong vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 expression during ramucirumab treatment. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12:E231464.

- Choi YH, Byun HJ, Lee JH, et al. Multiple cherry angiomas and pyogenic granuloma in a patient treated with ramucirumab and paclitaxel. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:199-202.

- Aragaki T, Tomomatsu N, Michi Y, et al. Ramucirumab-related oral pyogenic granuloma: a report of two cases [published online March 8, 2021]. Intern Med. 2021;60:2601-2605. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.6650-20

- Devillers C, Vanhooteghem O, Henrijean A, et al. Subungual pyogenic granuloma secondary to docetaxel therapy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:251-252.

- Lim YH, Odell ID, Ko CJ, et al. Somatic p.T771R KDR (VEGFR2) mutation arising in a sporadic angioma during ramucirumab therapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1240-1243.

- Elston D, Neuhaus I, James WD, et al. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2020.

- Pierson JC. Pyogenic granuloma (lobular capillary hemangioma) clinical presentation. Medscape. Updated February 21, 2020. Accessed December 26, 2023. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1084701-clinical#showall

- Paul LJ, Cohen PR. Paclitaxel-associated subungual pyogenic granuloma: report in a patient with breast cancer receiving paclitaxel and review of drug-induced pyogenic granulomas adjacent to and beneath the nail. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:262-268.

- Alessandrini A, Starace M, Cerè G, et al. Management and outcome of taxane-induced nail side effects: experience of 79 patients from a single centre. Skin Appendage Disord. 2019;5:276-282.

- Watanabe R, Nakano E, Kawazoe A, et al. Four cases of paradoxical cephalocervical pyogenic granuloma during treatment with paclitaxel and ramucirumab. J Dermatol. 2019;46:E178-E180.

- Ibe T, Hamamoto Y, Takabatake M, et al. Development of pyogenic granuloma with strong vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 expression during ramucirumab treatment. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12:E231464.

- Choi YH, Byun HJ, Lee JH, et al. Multiple cherry angiomas and pyogenic granuloma in a patient treated with ramucirumab and paclitaxel. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:199-202.

- Aragaki T, Tomomatsu N, Michi Y, et al. Ramucirumab-related oral pyogenic granuloma: a report of two cases [published online March 8, 2021]. Intern Med. 2021;60:2601-2605. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.6650-20

- Devillers C, Vanhooteghem O, Henrijean A, et al. Subungual pyogenic granuloma secondary to docetaxel therapy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:251-252.

- Lim YH, Odell ID, Ko CJ, et al. Somatic p.T771R KDR (VEGFR2) mutation arising in a sporadic angioma during ramucirumab therapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1240-1243.

Practice Points

- Pyogenic granulomas (PGs) are benign vascular tumors that clinically are characterized as small, eruptive, friable papules.

- Ramucirumab is a monoclonal antibody against vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2.

- Some patients experience paradoxical formation of vascular tumors such as PGs when treated with combination therapy with ramucirumab and a taxane such as paclitaxel.

Cemiplimab-Associated Eruption of Generalized Eruptive Keratoacanthoma of Grzybowski

To the Editor:

Treatment of cancer, including cutaneous malignancy, has been transformed by the use of immunotherapeutic agents such as immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) that target cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4, programmed cell-death protein 1 (PD-1), or programmed cell-death ligand 1 (PD-L1). However, these drugs are associated with a distinct set of immune-related adverse events (IRAEs). We present a case of generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma of Grzybowski associated with the ICI cemiplimab.

A 94-year-old White woman presented to the dermatology clinic with acute onset of extensive, locally advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) of the upper right posterolateral calf as well as multiple noninvasive cSCCs of the arms and legs. Her medical history was remarkable for widespread actinic keratoses and numerous cSCCs. The patient had no personal or family history of melanoma. Various cSCCs had required treatment with electrodesiccation and curettage, topical or intralesional 5-fluorouracil, and Mohs micrographic surgery. Approximately 1 year prior to presentation, oral acitretin was initiated to help control the cSCC. Given the extent of locally advanced disease, which was considered unresectable, she was referred to oncology but continued to follow up with dermatology. Positron emission tomography was remarkable for hypermetabolic cutaneous thickening in the upper right posterolateral calf with no evidence of visceral disease.

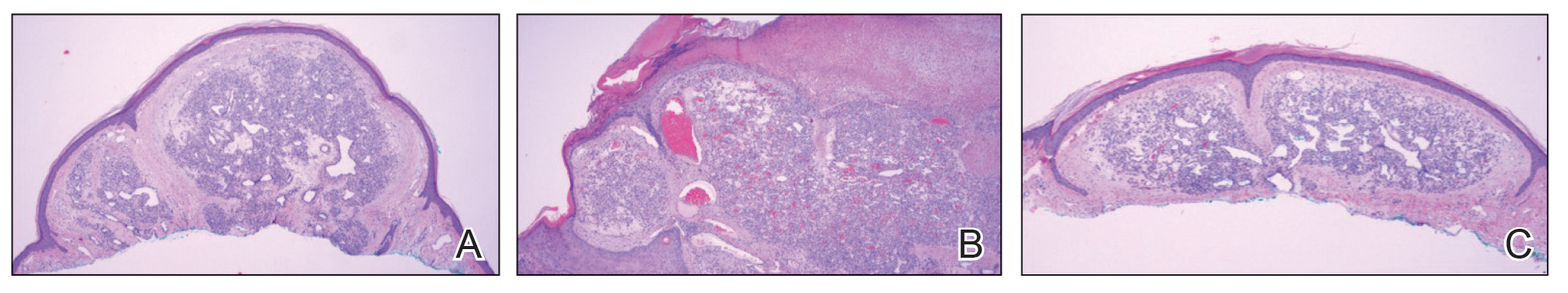

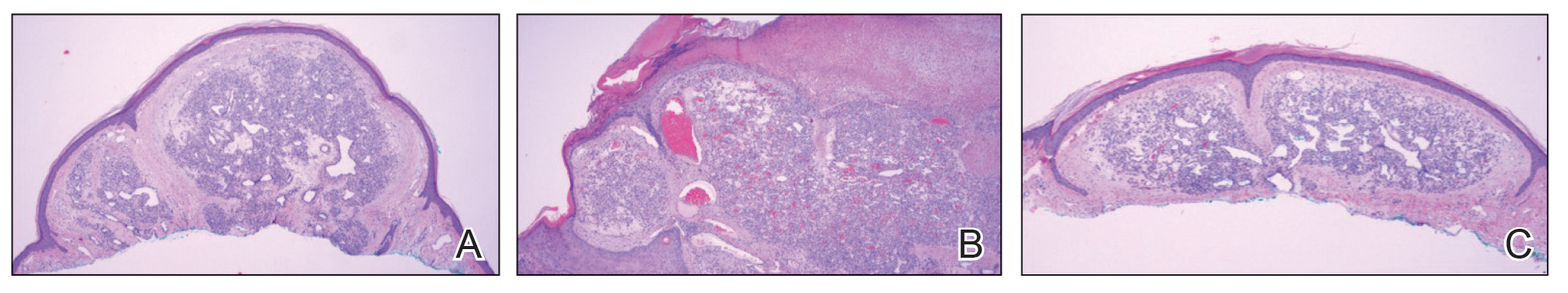

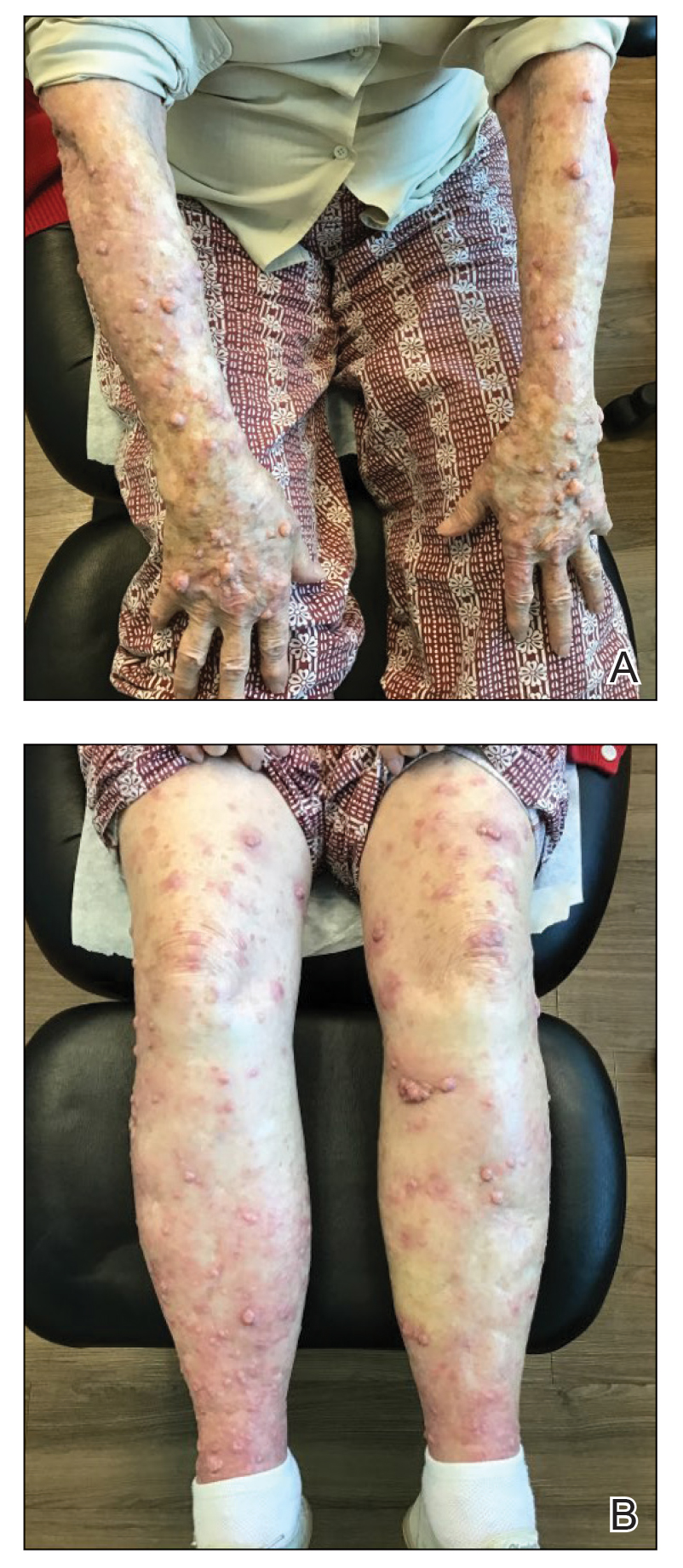

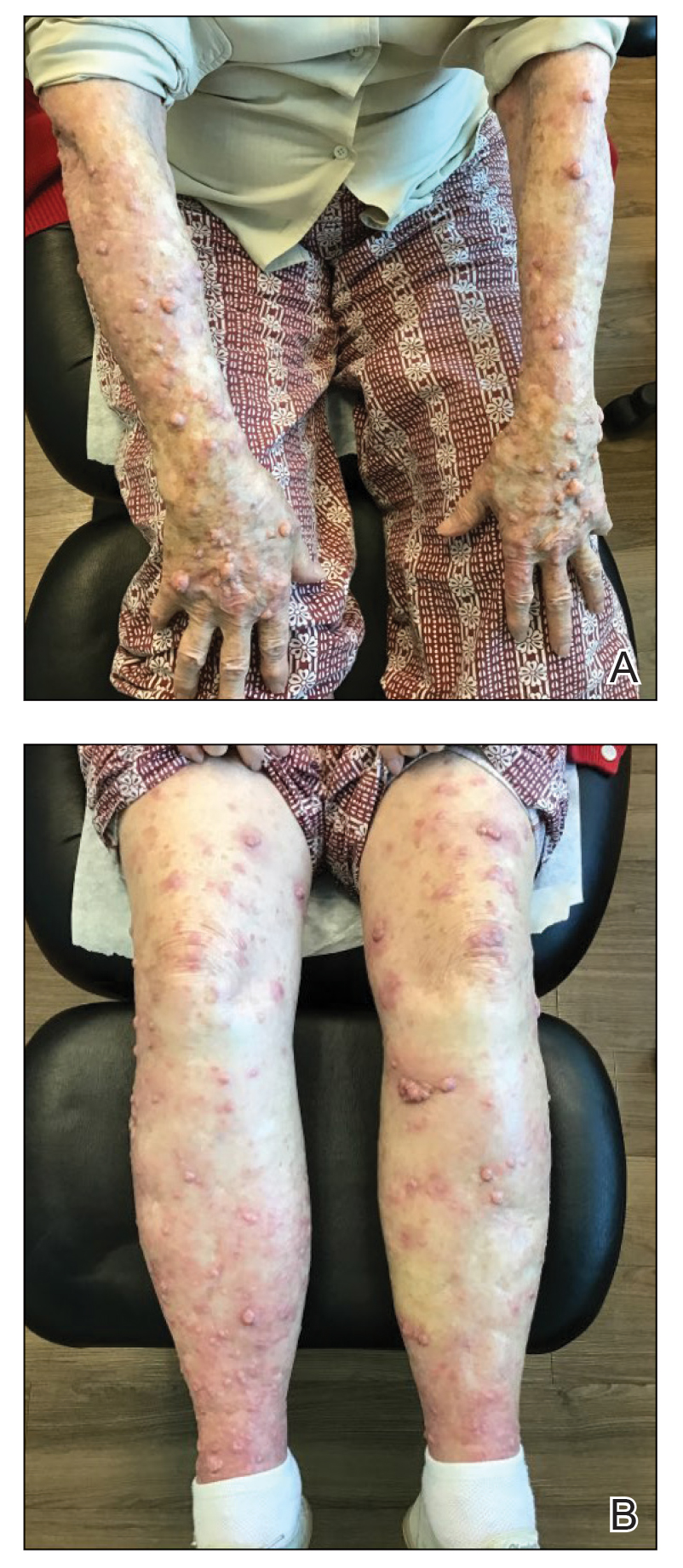

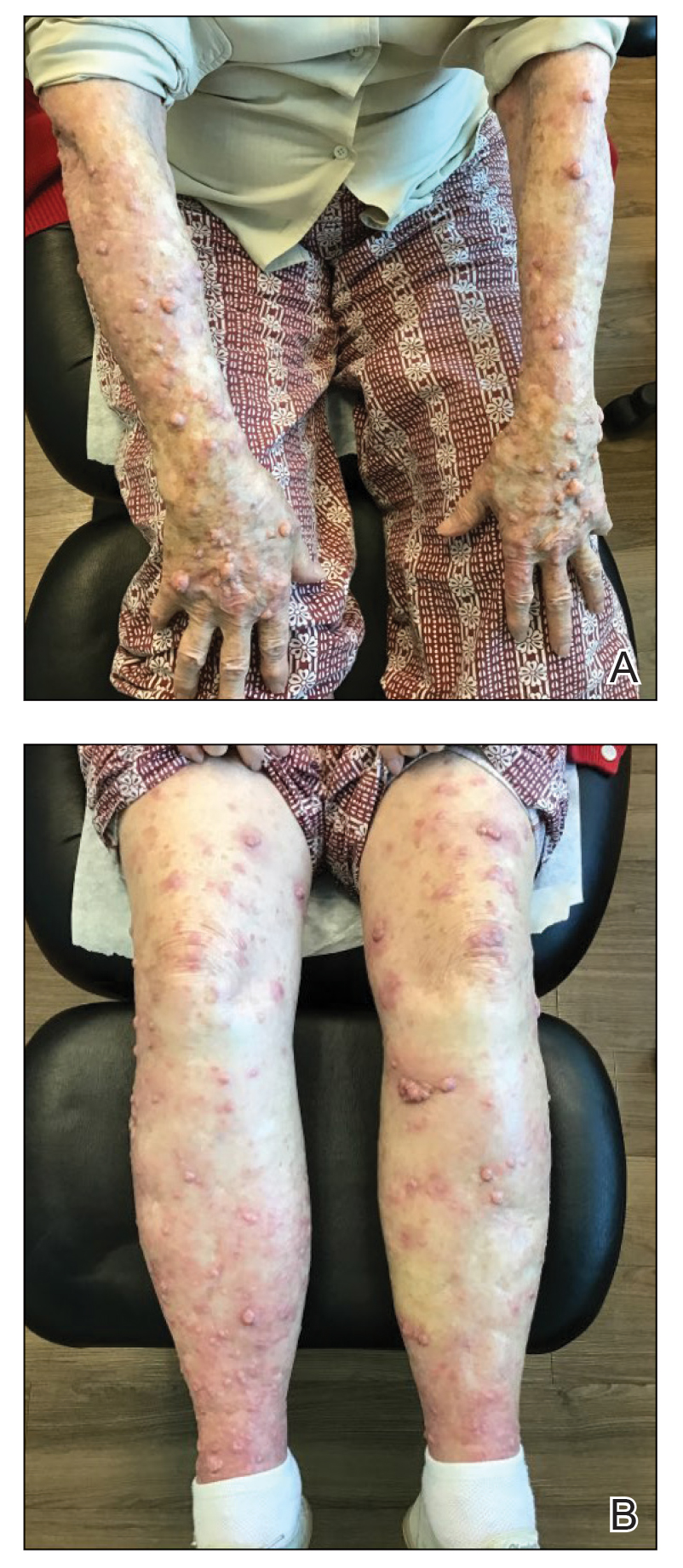

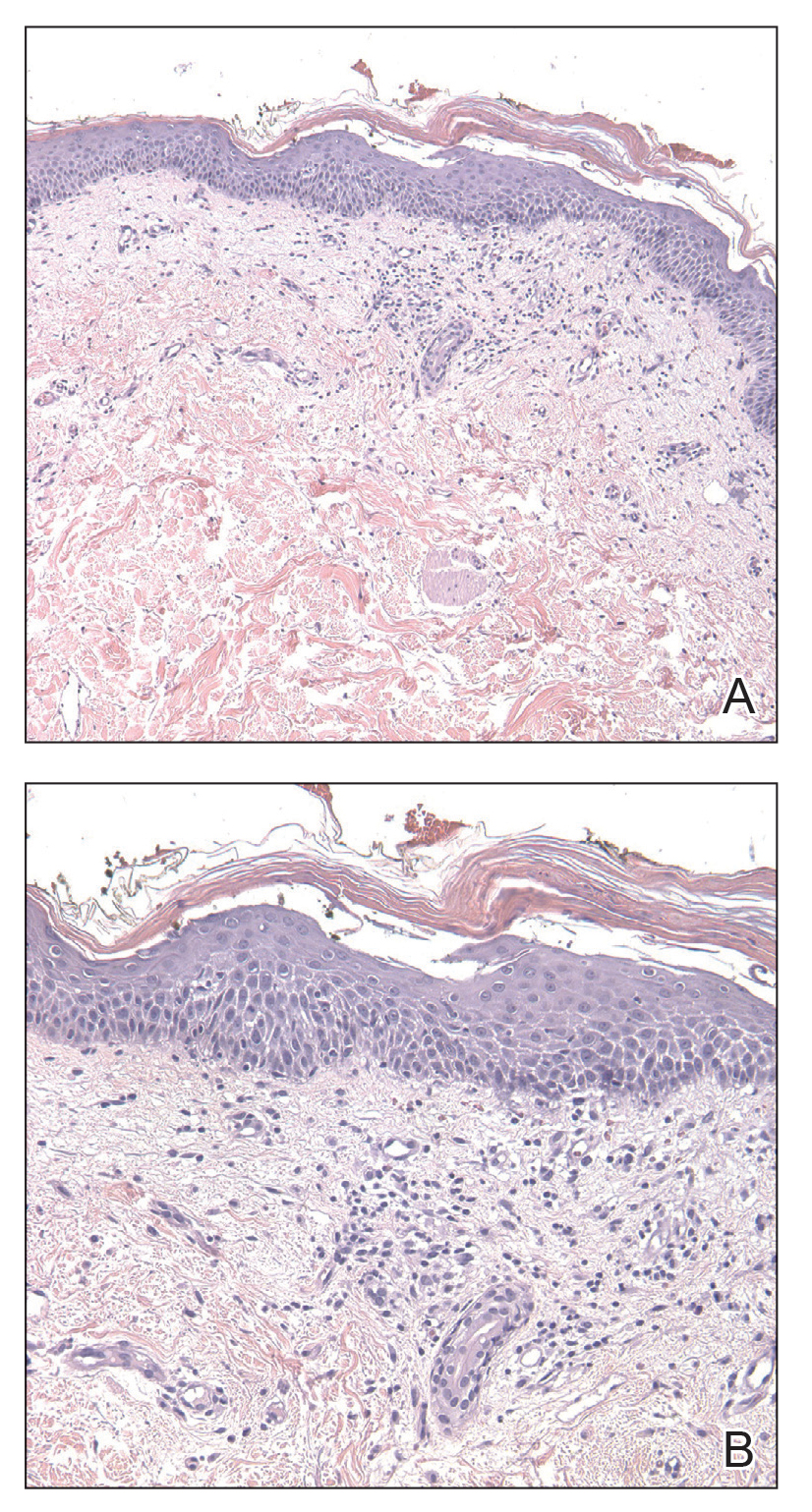

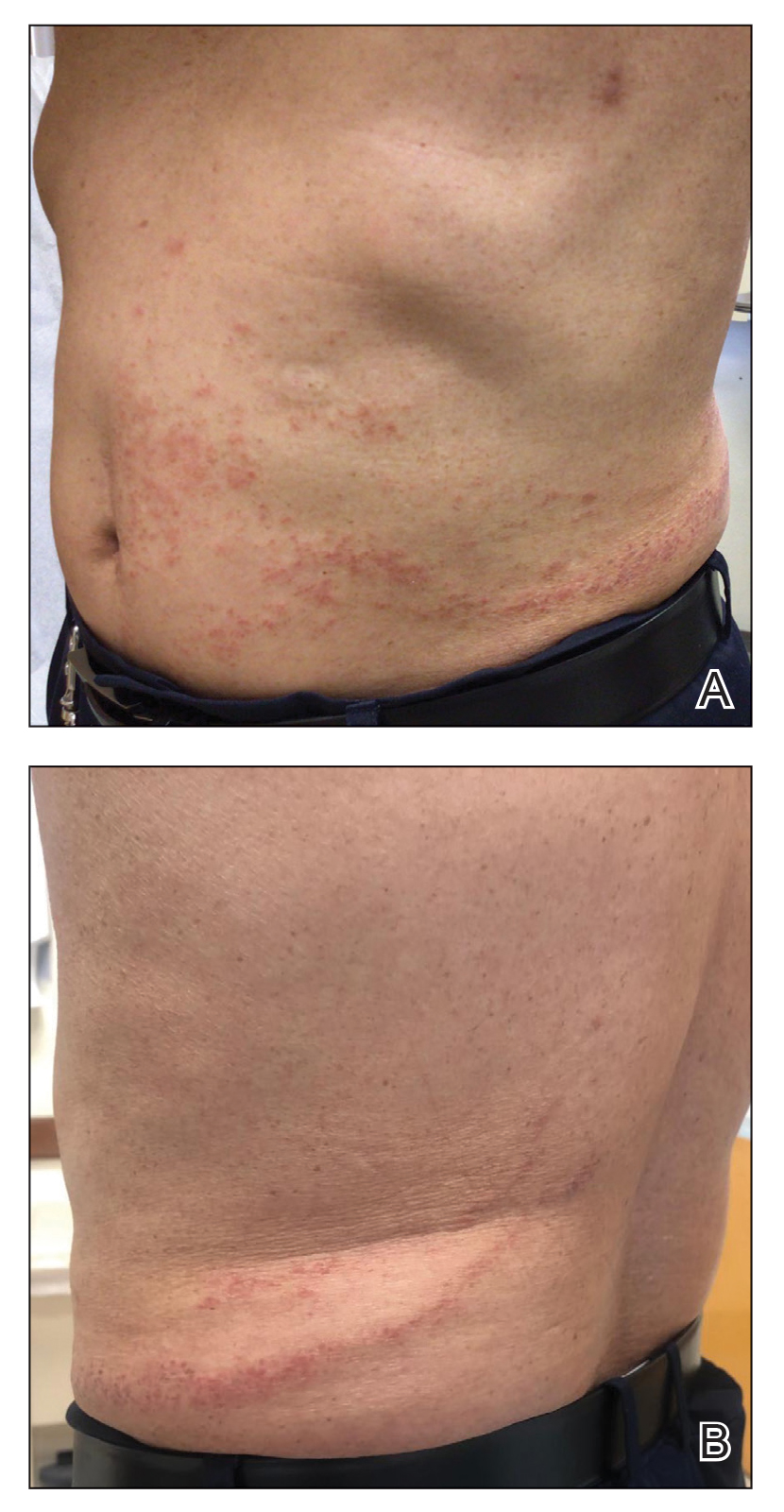

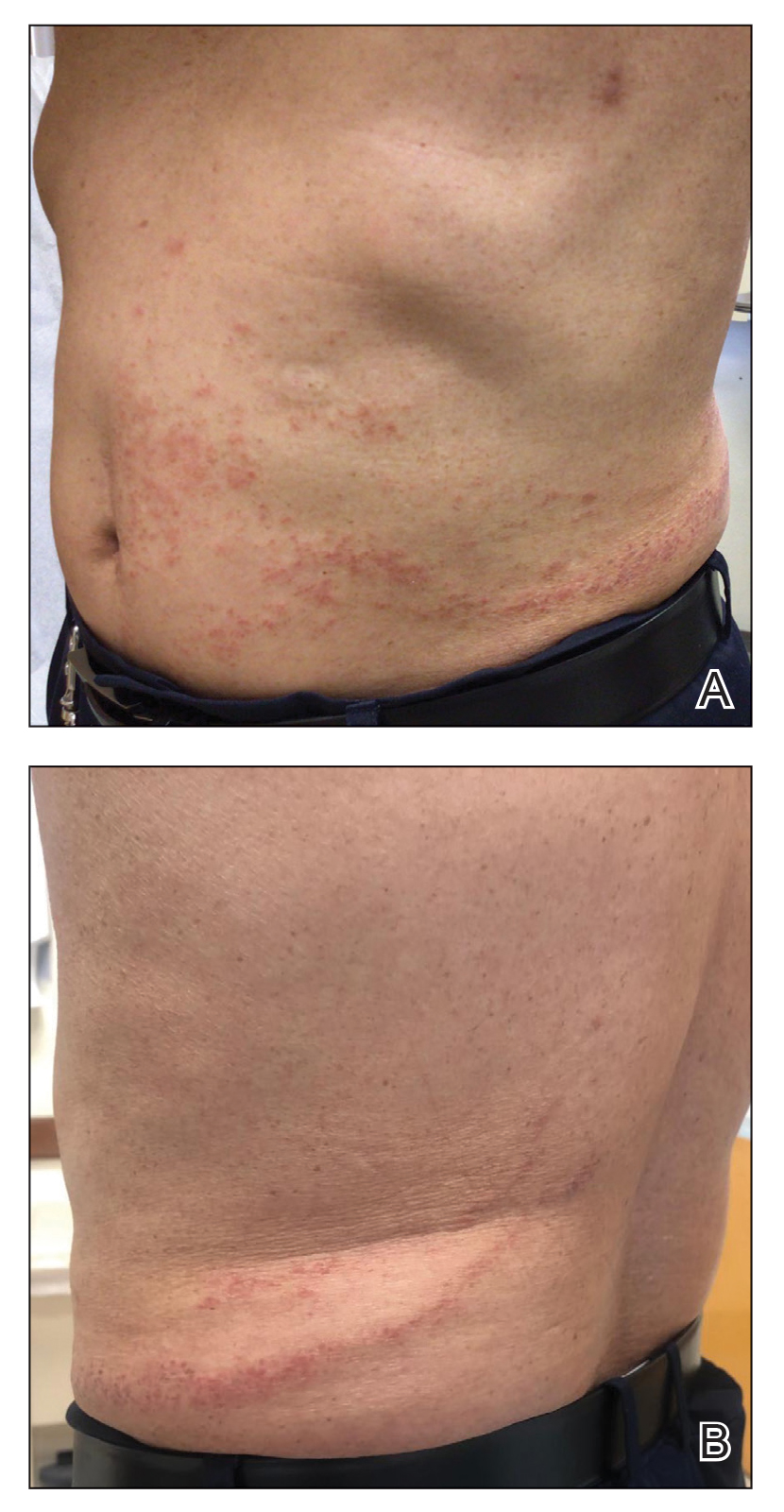

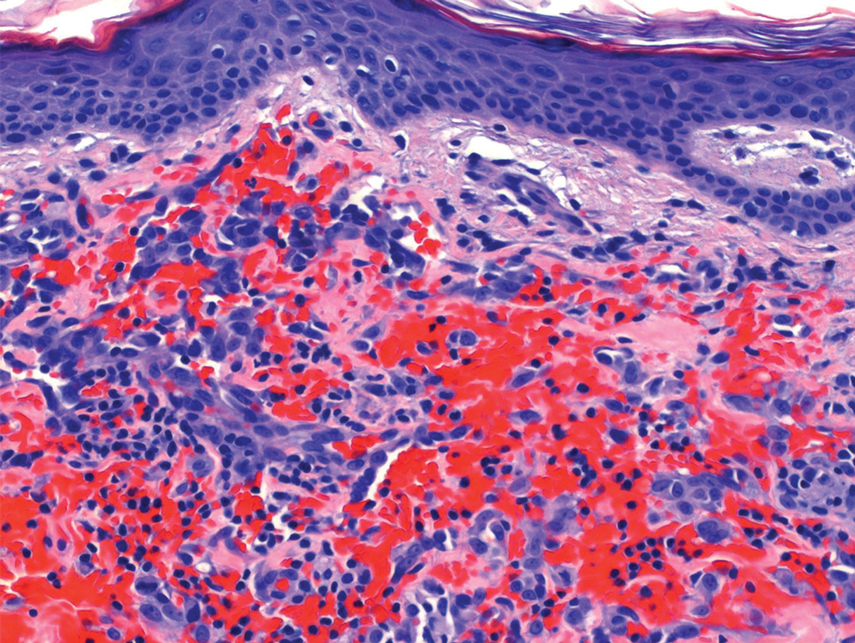

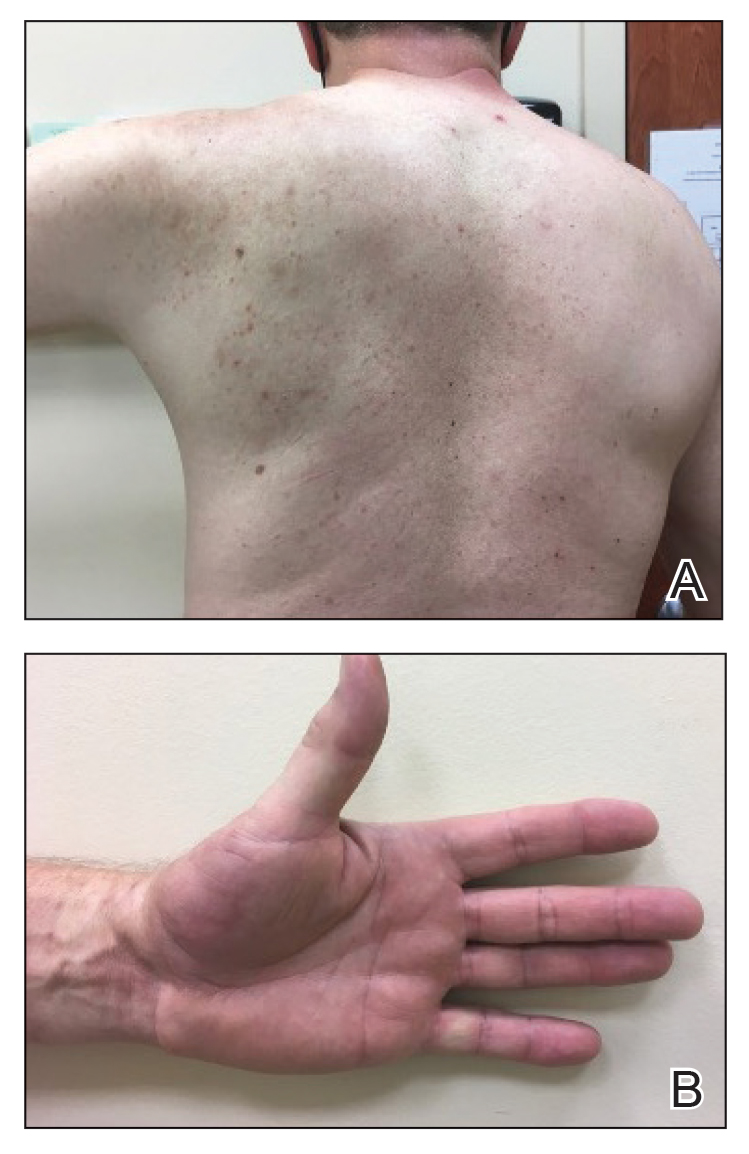

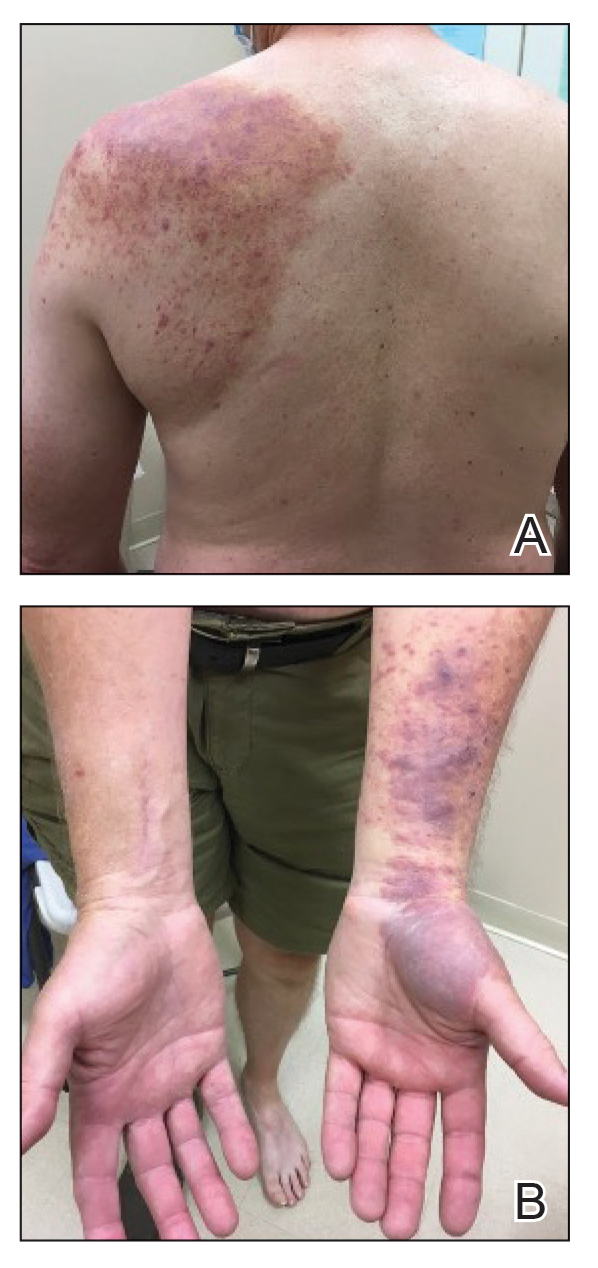

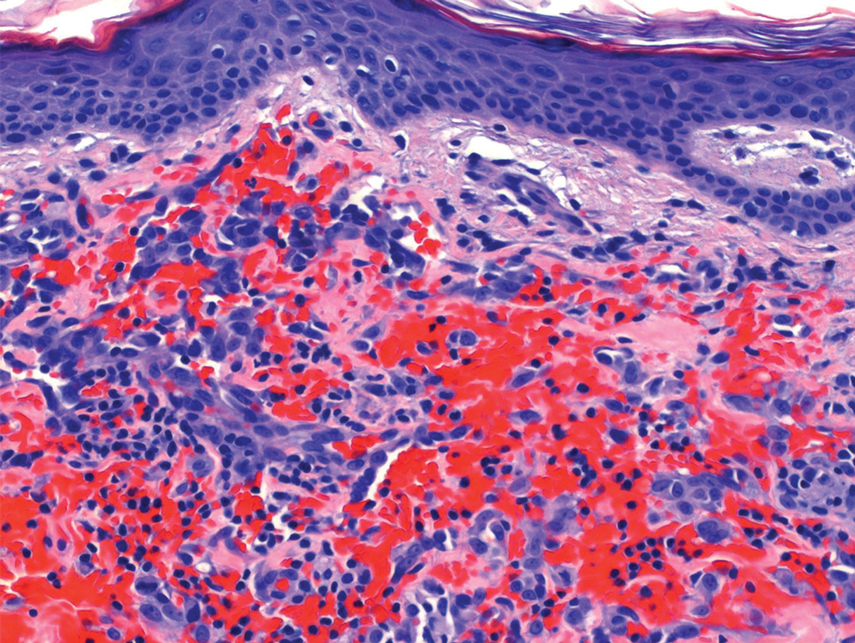

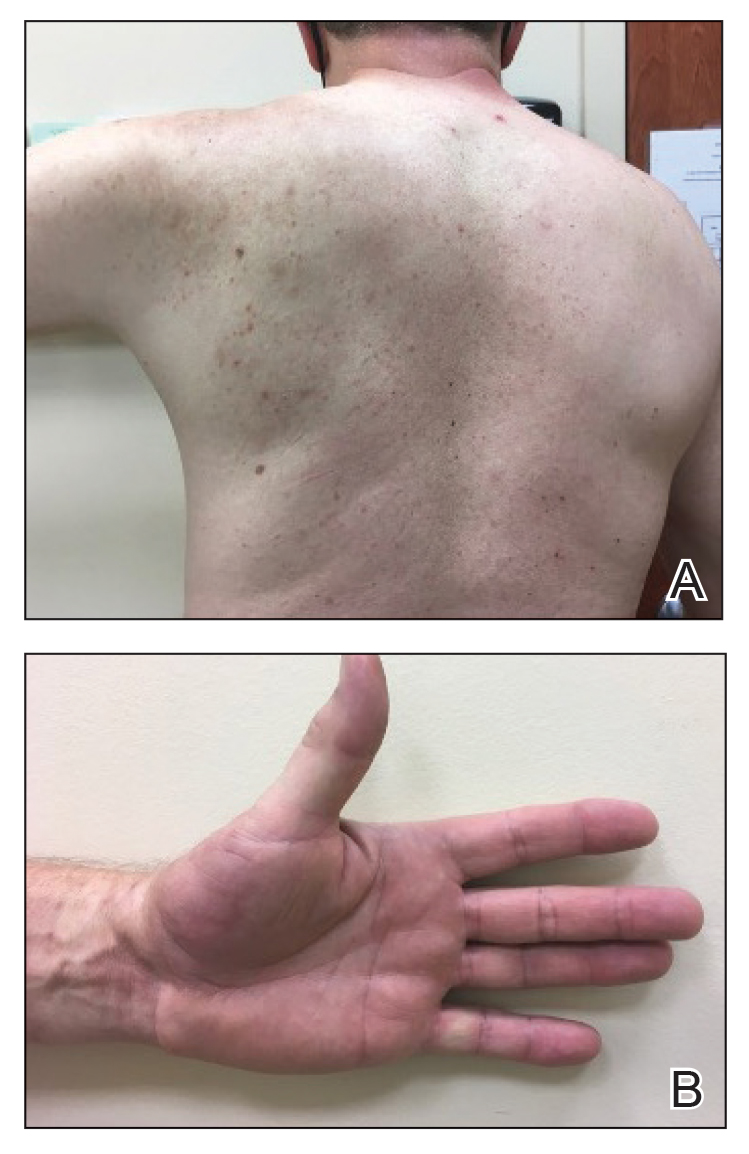

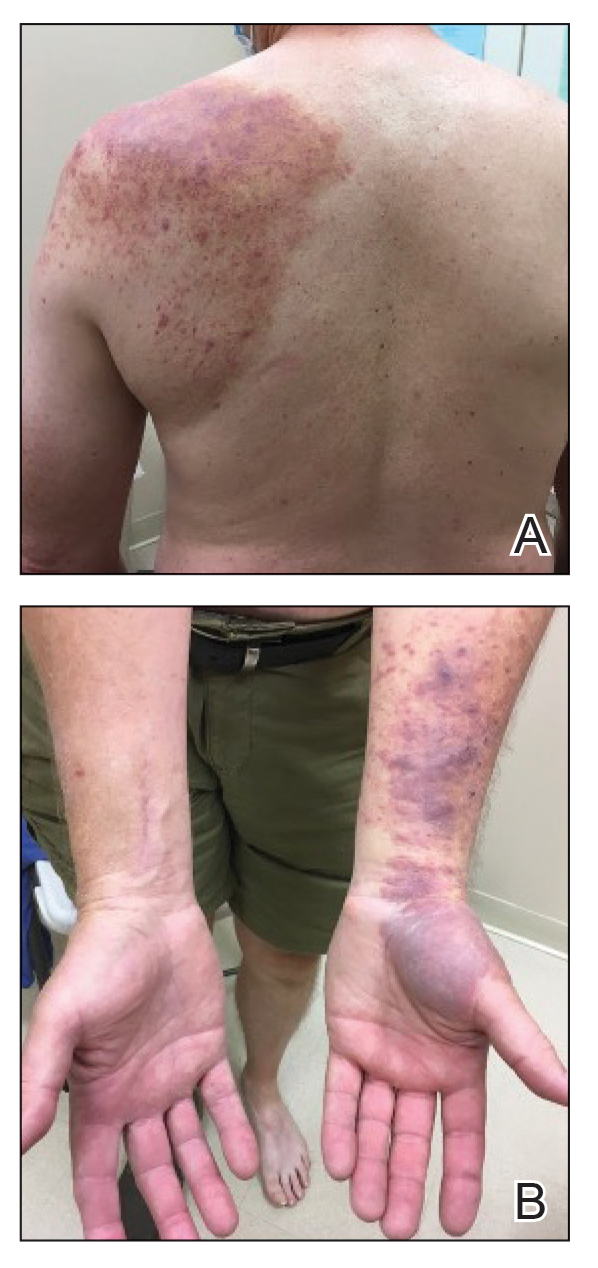

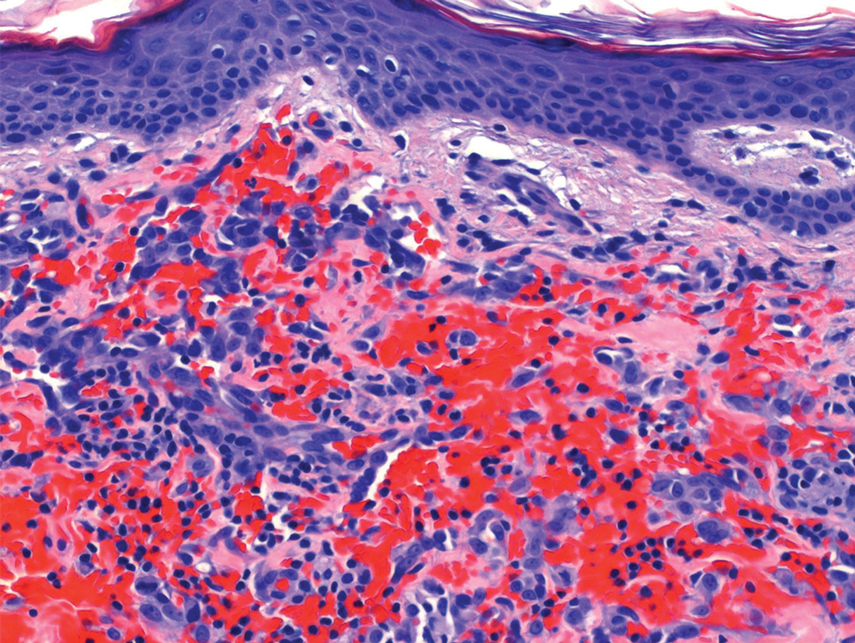

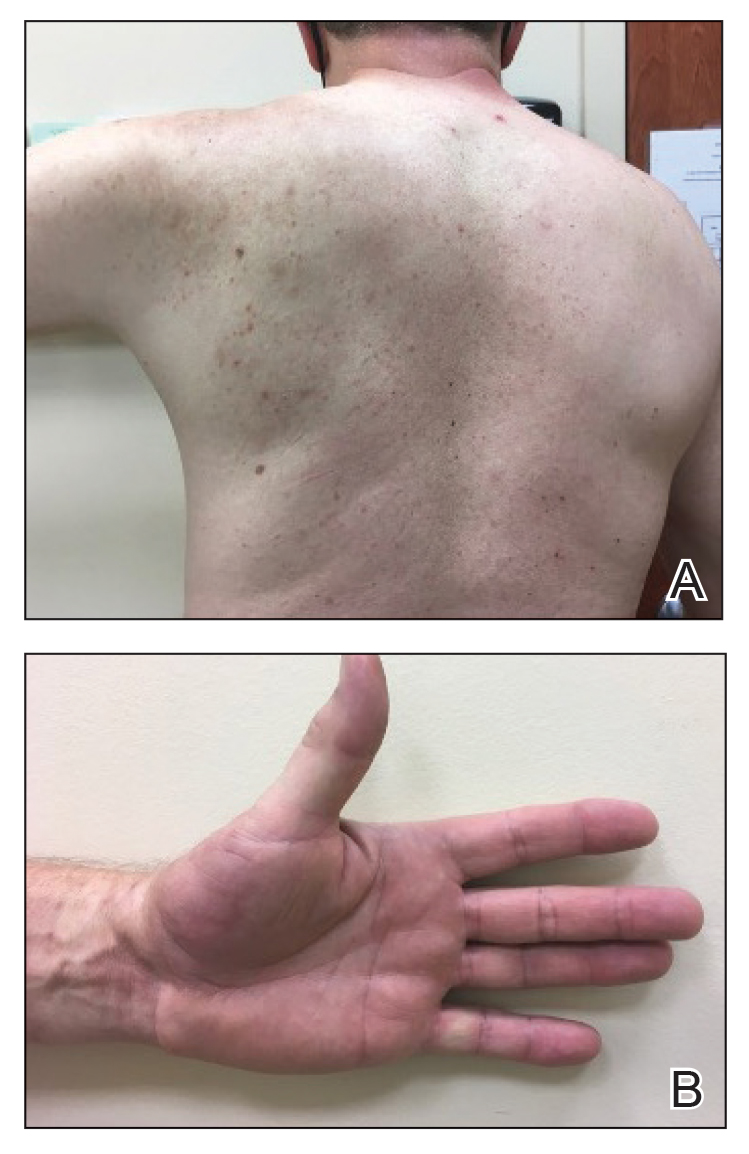

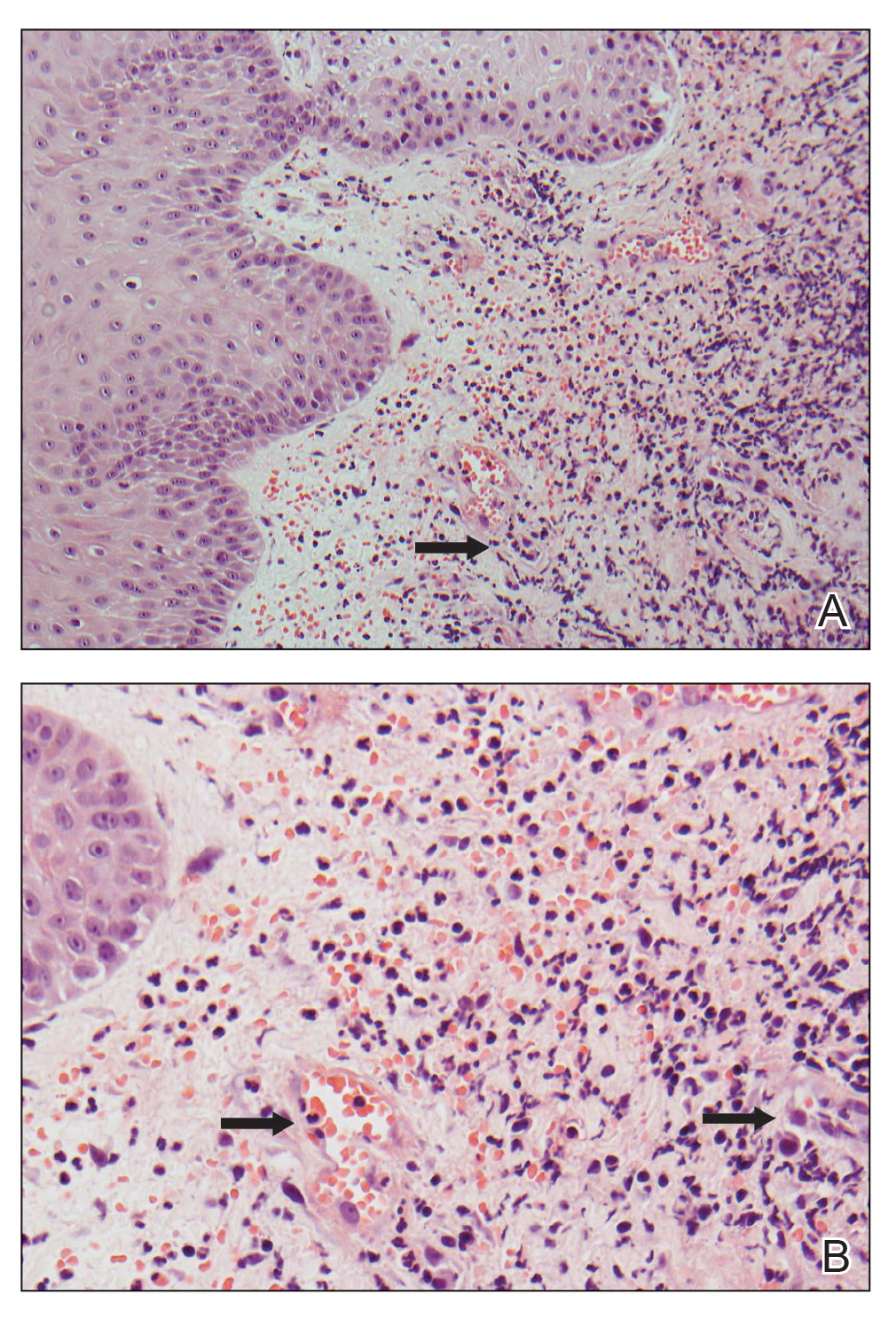

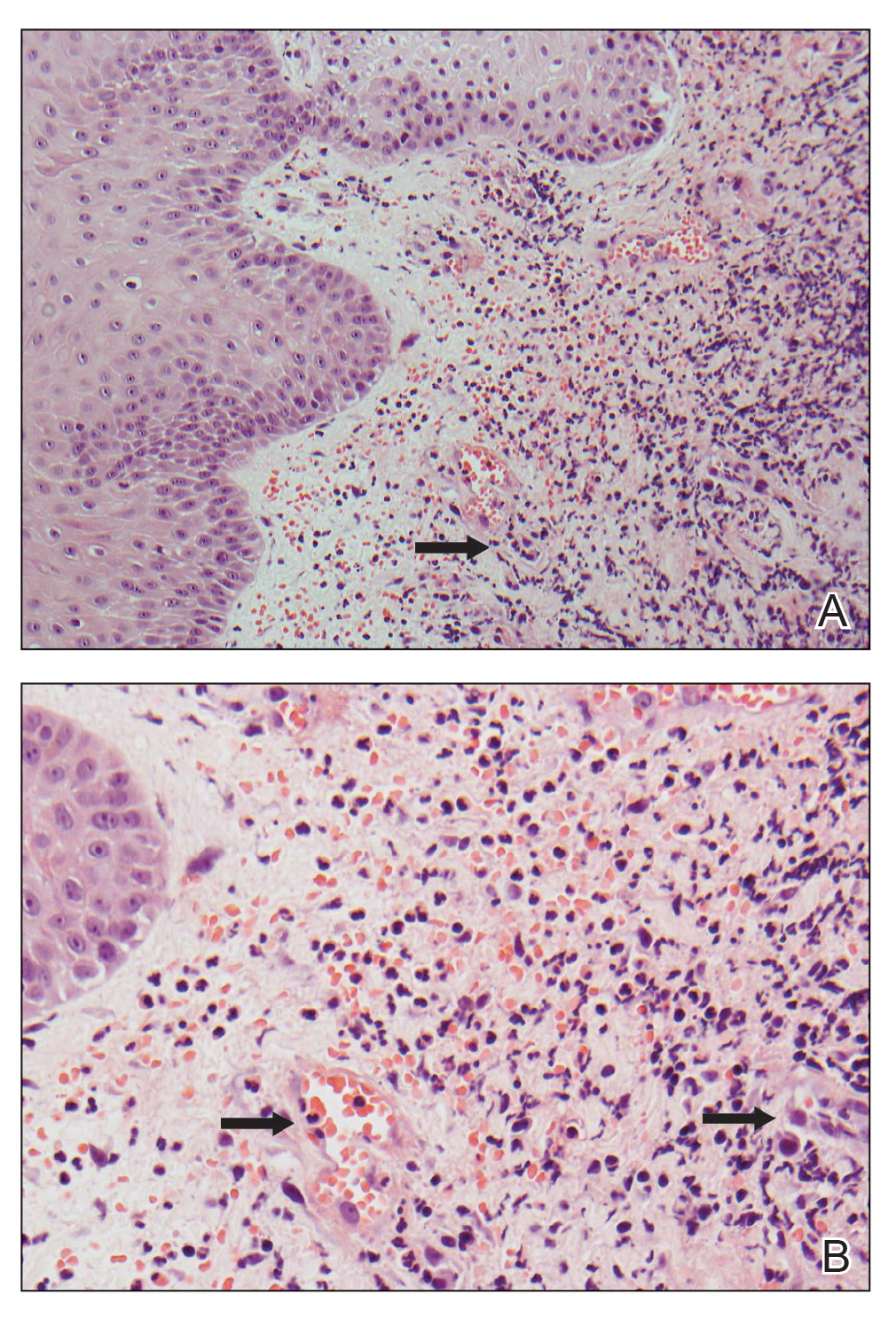

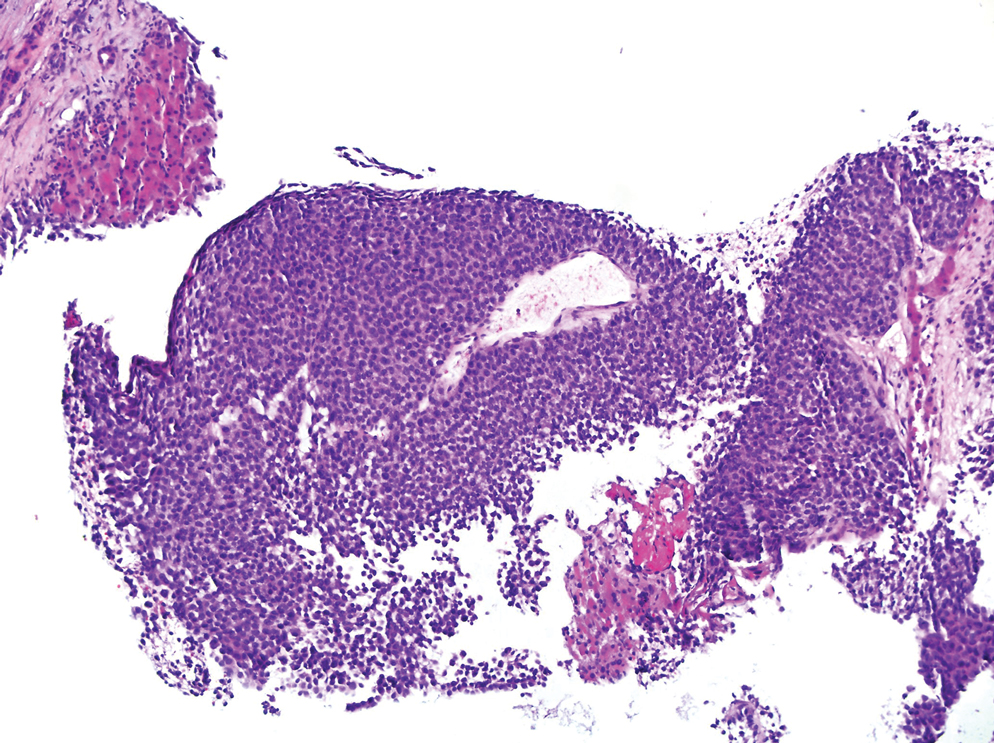

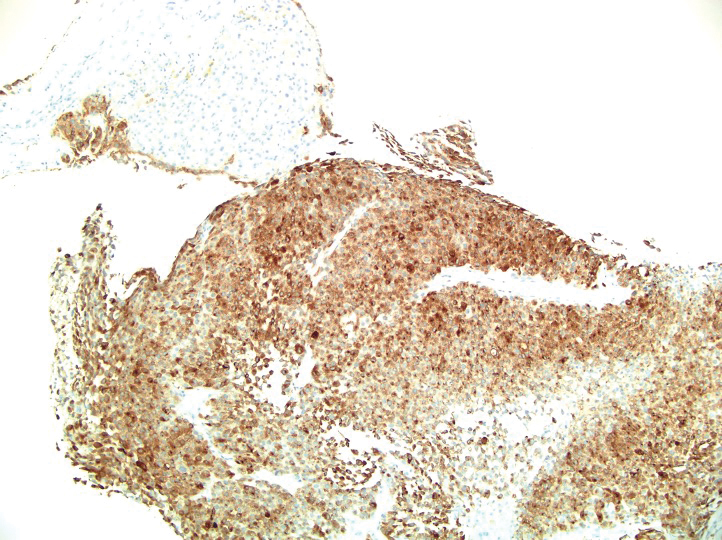

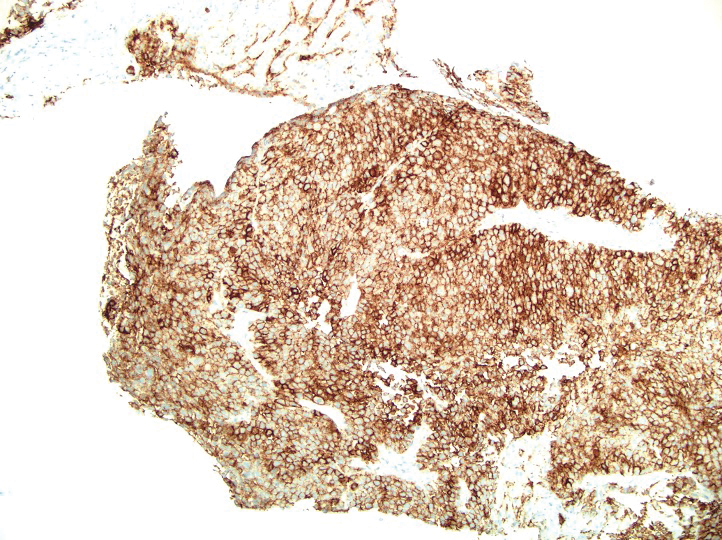

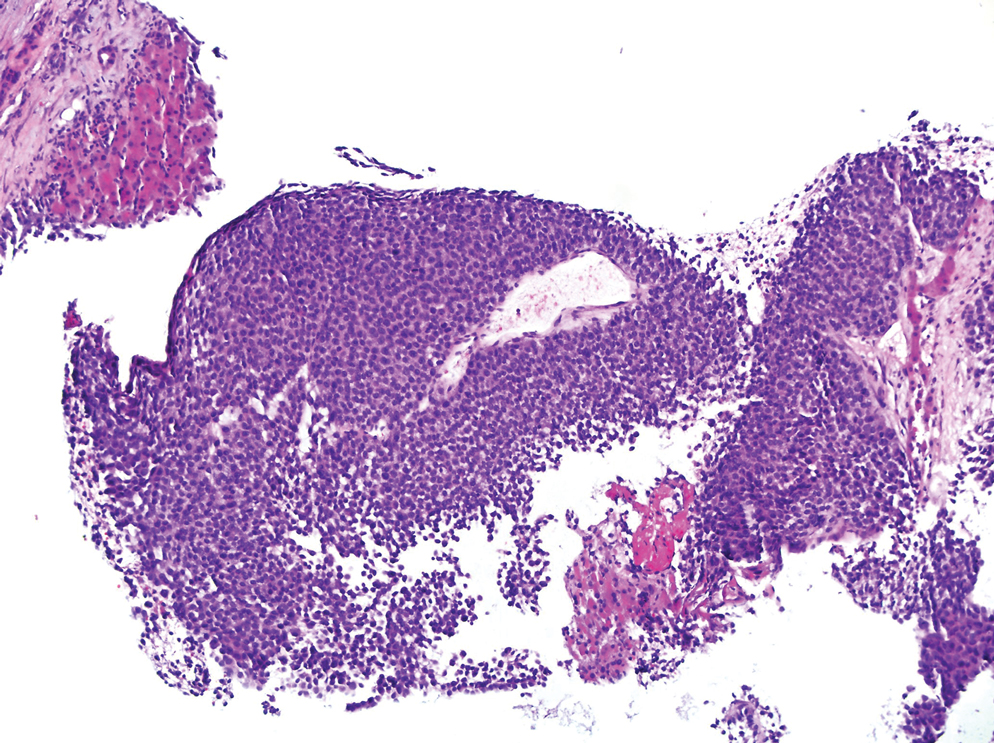

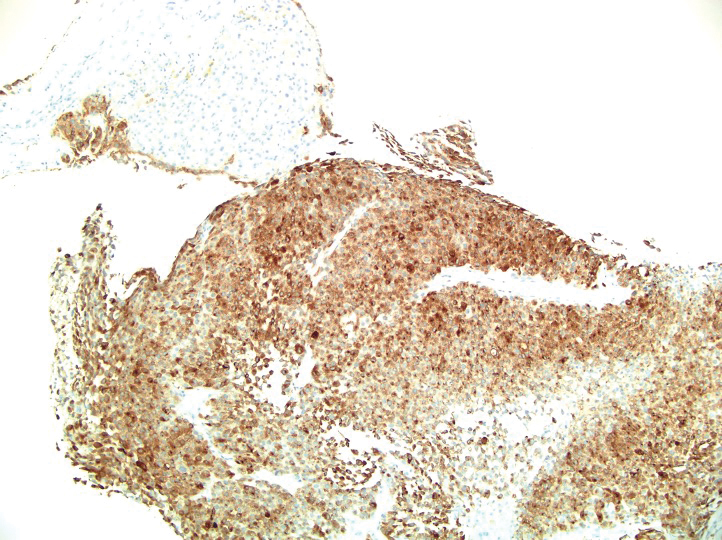

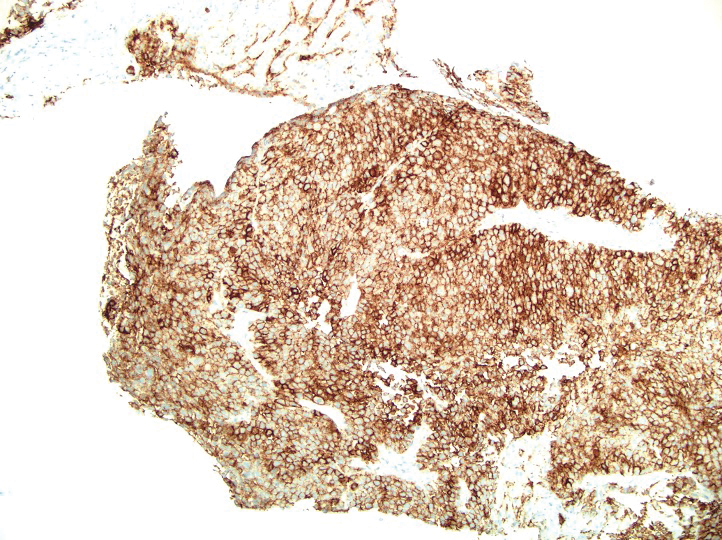

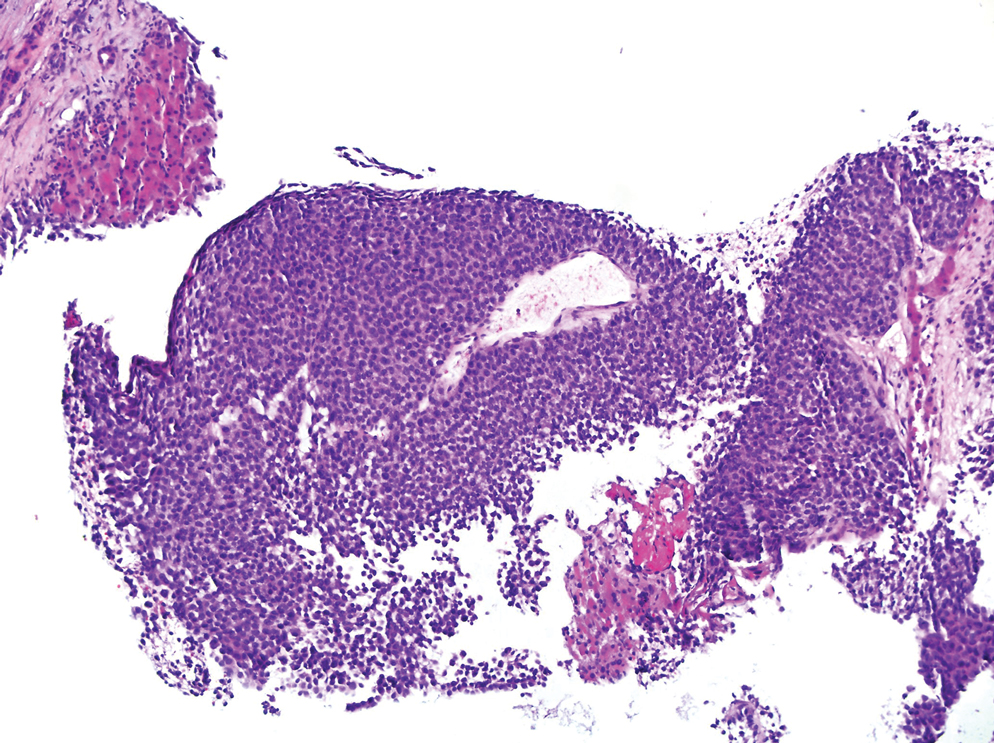

The patient was started on cemiplimab, an anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody ICI indicated for the treatment of both metastatic and advanced cSCC. After 4 cycles of intravenous cemiplimab, the patient developed widespread nodules covering the arms and legs (Figure 1) as well as associated tenderness and pruritus. Biopsies of nodules revealed superficially invasive, well-differentiated cSCC consistent with keratoacanthoma. Although a lymphocytic infiltrate was present, no other specific reaction pattern, such as a lichenoid infiltrate, was present (Figure 2).

Positron emission tomography was repeated, demonstrating resolution of the right calf lesion; however, new diffuse cutaneous lesions and inguinal lymph node involvement were present, again without evidence of visceral disease. Given the clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma of Grzybowski was made. Cemiplimab was discontinued after the fifth cycle. The patient declined further systemic treatment, instead choosing a regimen of topical steroids and an emollient.

Immunotherapeutics have transformed cancer therapy, which includes ICIs that target cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4, PD-1, or PD-L1. Increased activity of these checkpoints allows tumor cells to downregulate T-cell activation, thereby evading immune destruction. When PD-1 on T cells binds PD-L1 on tumor cells, T lymphocytes are inhibited from cytotoxic-mediated killing. Therefore, anti-PD-1 ICIs such as cemiplimab permit T-lymphocyte activation and destruction of malignant cells. However, this unique mechanism of immunotherapy is associated with an array of IRAEs, which often manifest in a delayed and prolonged fashion.1 Immune-related adverse events most commonly affect the gastrointestinal tract as well as the endocrine and dermatologic systems.2 Notably, patients with certain tumors who experience these adverse effects might be more likely to have superior overall survival; therefore, IRAEs are sometimes used as an indicator of favorable treatment response.2,3

Dermatologic IRAEs associated with the use of a PD-1 inhibitor include lichenoid reactions, pruritus, morbilliform eruptions, vitiligo, and bullous pemphigoid.4,5 Eruptions of keratoacanthoma rarely have been reported following treatment with the PD-1 inhibitors nivolumab and pembrolizumab.3,6,7 In our patient, we believe the profound and generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma—a well-differentiated cSCC variant—was related to treatment of locally advanced cSCC with cemiplimab. The mechanism underlying the formation of anti-PD-1 eruptive keratoacanthoma is not well understood. In susceptible patients, it is plausible that the inflammatory environment permitted by ICIs paradoxically induces regression of tumors such as locally invasive cSCC and simultaneously promotes formation of keratoacanthoma.

The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis and progression of cSCC is complex and possibly involves contrasting roles of leukocyte subpopulations.8 The increased incidence of cSCC in the immunocompromised population,8 PD-L1 overexpression in cSCC,9,10 and successful treatment of cSCC with PD-1 inhibition10 all suggest that inhibition of specific inflammatory pathways is pivotal in tumor pathogenesis. However, increased inflammation, particularly inflammation driven by T lymphocytes and Langerhans cells, also is believed to play a key role in the formation of cSCCs, including the degeneration of actinic keratosis into cSCC. Moreover, because keratoacanthomas are believed to be a cSCC variant and also are associated with PD-L1 overexpression,9 it is perplexing that PD-1 blockade may result in eruptive keratoacanthoma in some patients while also treating locally advanced cSCC, as seen in our patient. Successful treatment of keratoacanthoma with anti-inflammatory intralesional or topical corticosteroids adds to this complicated picture.3

We hypothesize that the pathogenesis of invasive cSCC and keratoacanthoma shares certain immune-mediated mechanisms but also differs in distinct manners. To understand the relationship between systemic treatment of cSCC and eruptive keratoacanthoma, further research is required.

In addition, the RAS/BRAF/MEK oncogenic pathway may be involved in the development of cSCCs associated with anti-PD-1. It is hypothesized that BRAF and MEK inhibition increases T-cell infiltration and increases PD-L1 expression on tumor cells,11 thus increasing the susceptibility of those cells to PD-1 blockade. Further supporting a relationship between the RAS/BRAF/MEK and PD-1 pathways, BRAF inhibitors are associated with development of SCCs and verrucal keratosis by upregulation of the RAS pathway.12,13 Perhaps a common mechanism underlying these pathways results in their shared association for an increased risk for cSCC upon blockade. More research is needed to fully elucidate the underlying biochemical mechanism of immunotherapy and formation of SCCs, such as keratoacanthoma.

Treatment of solitary keratoacanthoma often involves surgical excision; however, the sheer number of lesions in eruptive keratoacanthoma presents a larger dilemma. Because oral systemic retinoids have been shown to be most effective for treating eruptive keratoacanthoma, they are considered first-line therapy as monotherapy or in combination with surgical excision.3 Other treatment options include intralesional or topical corticosteroids, cyclosporine, 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod, and cryotherapy.3,6

The development of ICIs has revolutionized the treatment of cutaneous malignancy, yet we have a great deal more to comprehend on the systemic effects of these medications. Although IRAEs may signal a better response to therapy, some of these effects regrettably can be dose limiting. In our patient, cemiplimab was successful in treating locally advanced cSCC, but treatment also resulted in devastating widespread eruptive keratoacanthoma. The mechanism of this kind of eruption has yet to be understood; we hypothesize that it likely involves T lymphocyte–driven inflammation and the interplay of molecular and immune-mediated pathways.

- Ramos-Casals M, Brahmer JR, Callahan MK, et al. Immune-related adverse events of checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6:38. doi:10.1038/s41572-020-0160-6

- Das S, Johnson DB. Immune-related adverse events and anti-tumor efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:306. doi:10.1186/s40425-019-0805-8

- Freites-Martinez A, Kwong BY, Rieger KE, et al. Eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with pembrolizumab therapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:694-697. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0989

- Shen J, Chang J, Mendenhall M, et al. Diverse cutaneous adverse eruptions caused by anti-programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) and anti-programmed cell death ligand-1 (PD-L1) immunotherapies: clinicalfeatures and management. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2018;10:1758834017751634. doi:10.1177/1758834017751634

- Bandino JP, Perry DM, Clarke CE, et al. Two cases of anti-programmed cell death 1-associated bullous pemphigoid-like disease and eruptive keratoacanthomas featuring combined histopathology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:E378-E380. doi:10.1111/jdv.14179

- Marsh RL, Kolodney JA, Iyengar S, et al. Formation of eruptive cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas after programmed cell death protein-1 blockade. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:390-393. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.02.024

- Antonov NK, Nair KG, Halasz CL. Transient eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with nivolumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:342-345. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.01.025

- Bottomley MJ, Thomson J, Harwood C, et al. The role of the immune system in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:2009. doi:10.3390/ijms20082009

- Gambichler T, Gnielka M, Rüddel I, et al. Expression of PD-L1 in keratoacanthoma and different stages of progression in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017;66:1199-1204. doi:10.1007/s00262-017-2015-x

- Patel R, Chang ALS. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for treating advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20:477-482. doi:10.1007/s40257-019-00426-w

- Rozeman EA, Blank CU. Combining checkpoint inhibition and targeted therapy in melanoma. Nat Med. 2019;25:879-882. doi:10.1038/s41591-019-0482-7

- Dubauskas Z, Kunishige J, Prieto VG, Jonasch E, Hwu P, Tannir NM. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and inflammation of actinic keratoses associated with sorafenib. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2009;7:20-23. doi:10.3816/CGC.2009.n.003

- Chen P, Chen F, Zhou B. Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence of dermatological toxicities associated with vemurafenib treatment in patients with melanoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:243-251. doi:10.1111/ced.13751

To the Editor:

Treatment of cancer, including cutaneous malignancy, has been transformed by the use of immunotherapeutic agents such as immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) that target cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4, programmed cell-death protein 1 (PD-1), or programmed cell-death ligand 1 (PD-L1). However, these drugs are associated with a distinct set of immune-related adverse events (IRAEs). We present a case of generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma of Grzybowski associated with the ICI cemiplimab.

A 94-year-old White woman presented to the dermatology clinic with acute onset of extensive, locally advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) of the upper right posterolateral calf as well as multiple noninvasive cSCCs of the arms and legs. Her medical history was remarkable for widespread actinic keratoses and numerous cSCCs. The patient had no personal or family history of melanoma. Various cSCCs had required treatment with electrodesiccation and curettage, topical or intralesional 5-fluorouracil, and Mohs micrographic surgery. Approximately 1 year prior to presentation, oral acitretin was initiated to help control the cSCC. Given the extent of locally advanced disease, which was considered unresectable, she was referred to oncology but continued to follow up with dermatology. Positron emission tomography was remarkable for hypermetabolic cutaneous thickening in the upper right posterolateral calf with no evidence of visceral disease.

The patient was started on cemiplimab, an anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody ICI indicated for the treatment of both metastatic and advanced cSCC. After 4 cycles of intravenous cemiplimab, the patient developed widespread nodules covering the arms and legs (Figure 1) as well as associated tenderness and pruritus. Biopsies of nodules revealed superficially invasive, well-differentiated cSCC consistent with keratoacanthoma. Although a lymphocytic infiltrate was present, no other specific reaction pattern, such as a lichenoid infiltrate, was present (Figure 2).

Positron emission tomography was repeated, demonstrating resolution of the right calf lesion; however, new diffuse cutaneous lesions and inguinal lymph node involvement were present, again without evidence of visceral disease. Given the clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma of Grzybowski was made. Cemiplimab was discontinued after the fifth cycle. The patient declined further systemic treatment, instead choosing a regimen of topical steroids and an emollient.

Immunotherapeutics have transformed cancer therapy, which includes ICIs that target cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4, PD-1, or PD-L1. Increased activity of these checkpoints allows tumor cells to downregulate T-cell activation, thereby evading immune destruction. When PD-1 on T cells binds PD-L1 on tumor cells, T lymphocytes are inhibited from cytotoxic-mediated killing. Therefore, anti-PD-1 ICIs such as cemiplimab permit T-lymphocyte activation and destruction of malignant cells. However, this unique mechanism of immunotherapy is associated with an array of IRAEs, which often manifest in a delayed and prolonged fashion.1 Immune-related adverse events most commonly affect the gastrointestinal tract as well as the endocrine and dermatologic systems.2 Notably, patients with certain tumors who experience these adverse effects might be more likely to have superior overall survival; therefore, IRAEs are sometimes used as an indicator of favorable treatment response.2,3

Dermatologic IRAEs associated with the use of a PD-1 inhibitor include lichenoid reactions, pruritus, morbilliform eruptions, vitiligo, and bullous pemphigoid.4,5 Eruptions of keratoacanthoma rarely have been reported following treatment with the PD-1 inhibitors nivolumab and pembrolizumab.3,6,7 In our patient, we believe the profound and generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma—a well-differentiated cSCC variant—was related to treatment of locally advanced cSCC with cemiplimab. The mechanism underlying the formation of anti-PD-1 eruptive keratoacanthoma is not well understood. In susceptible patients, it is plausible that the inflammatory environment permitted by ICIs paradoxically induces regression of tumors such as locally invasive cSCC and simultaneously promotes formation of keratoacanthoma.

The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis and progression of cSCC is complex and possibly involves contrasting roles of leukocyte subpopulations.8 The increased incidence of cSCC in the immunocompromised population,8 PD-L1 overexpression in cSCC,9,10 and successful treatment of cSCC with PD-1 inhibition10 all suggest that inhibition of specific inflammatory pathways is pivotal in tumor pathogenesis. However, increased inflammation, particularly inflammation driven by T lymphocytes and Langerhans cells, also is believed to play a key role in the formation of cSCCs, including the degeneration of actinic keratosis into cSCC. Moreover, because keratoacanthomas are believed to be a cSCC variant and also are associated with PD-L1 overexpression,9 it is perplexing that PD-1 blockade may result in eruptive keratoacanthoma in some patients while also treating locally advanced cSCC, as seen in our patient. Successful treatment of keratoacanthoma with anti-inflammatory intralesional or topical corticosteroids adds to this complicated picture.3

We hypothesize that the pathogenesis of invasive cSCC and keratoacanthoma shares certain immune-mediated mechanisms but also differs in distinct manners. To understand the relationship between systemic treatment of cSCC and eruptive keratoacanthoma, further research is required.

In addition, the RAS/BRAF/MEK oncogenic pathway may be involved in the development of cSCCs associated with anti-PD-1. It is hypothesized that BRAF and MEK inhibition increases T-cell infiltration and increases PD-L1 expression on tumor cells,11 thus increasing the susceptibility of those cells to PD-1 blockade. Further supporting a relationship between the RAS/BRAF/MEK and PD-1 pathways, BRAF inhibitors are associated with development of SCCs and verrucal keratosis by upregulation of the RAS pathway.12,13 Perhaps a common mechanism underlying these pathways results in their shared association for an increased risk for cSCC upon blockade. More research is needed to fully elucidate the underlying biochemical mechanism of immunotherapy and formation of SCCs, such as keratoacanthoma.

Treatment of solitary keratoacanthoma often involves surgical excision; however, the sheer number of lesions in eruptive keratoacanthoma presents a larger dilemma. Because oral systemic retinoids have been shown to be most effective for treating eruptive keratoacanthoma, they are considered first-line therapy as monotherapy or in combination with surgical excision.3 Other treatment options include intralesional or topical corticosteroids, cyclosporine, 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod, and cryotherapy.3,6

The development of ICIs has revolutionized the treatment of cutaneous malignancy, yet we have a great deal more to comprehend on the systemic effects of these medications. Although IRAEs may signal a better response to therapy, some of these effects regrettably can be dose limiting. In our patient, cemiplimab was successful in treating locally advanced cSCC, but treatment also resulted in devastating widespread eruptive keratoacanthoma. The mechanism of this kind of eruption has yet to be understood; we hypothesize that it likely involves T lymphocyte–driven inflammation and the interplay of molecular and immune-mediated pathways.

To the Editor:

Treatment of cancer, including cutaneous malignancy, has been transformed by the use of immunotherapeutic agents such as immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) that target cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4, programmed cell-death protein 1 (PD-1), or programmed cell-death ligand 1 (PD-L1). However, these drugs are associated with a distinct set of immune-related adverse events (IRAEs). We present a case of generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma of Grzybowski associated with the ICI cemiplimab.

A 94-year-old White woman presented to the dermatology clinic with acute onset of extensive, locally advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) of the upper right posterolateral calf as well as multiple noninvasive cSCCs of the arms and legs. Her medical history was remarkable for widespread actinic keratoses and numerous cSCCs. The patient had no personal or family history of melanoma. Various cSCCs had required treatment with electrodesiccation and curettage, topical or intralesional 5-fluorouracil, and Mohs micrographic surgery. Approximately 1 year prior to presentation, oral acitretin was initiated to help control the cSCC. Given the extent of locally advanced disease, which was considered unresectable, she was referred to oncology but continued to follow up with dermatology. Positron emission tomography was remarkable for hypermetabolic cutaneous thickening in the upper right posterolateral calf with no evidence of visceral disease.

The patient was started on cemiplimab, an anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody ICI indicated for the treatment of both metastatic and advanced cSCC. After 4 cycles of intravenous cemiplimab, the patient developed widespread nodules covering the arms and legs (Figure 1) as well as associated tenderness and pruritus. Biopsies of nodules revealed superficially invasive, well-differentiated cSCC consistent with keratoacanthoma. Although a lymphocytic infiltrate was present, no other specific reaction pattern, such as a lichenoid infiltrate, was present (Figure 2).

Positron emission tomography was repeated, demonstrating resolution of the right calf lesion; however, new diffuse cutaneous lesions and inguinal lymph node involvement were present, again without evidence of visceral disease. Given the clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma of Grzybowski was made. Cemiplimab was discontinued after the fifth cycle. The patient declined further systemic treatment, instead choosing a regimen of topical steroids and an emollient.

Immunotherapeutics have transformed cancer therapy, which includes ICIs that target cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4, PD-1, or PD-L1. Increased activity of these checkpoints allows tumor cells to downregulate T-cell activation, thereby evading immune destruction. When PD-1 on T cells binds PD-L1 on tumor cells, T lymphocytes are inhibited from cytotoxic-mediated killing. Therefore, anti-PD-1 ICIs such as cemiplimab permit T-lymphocyte activation and destruction of malignant cells. However, this unique mechanism of immunotherapy is associated with an array of IRAEs, which often manifest in a delayed and prolonged fashion.1 Immune-related adverse events most commonly affect the gastrointestinal tract as well as the endocrine and dermatologic systems.2 Notably, patients with certain tumors who experience these adverse effects might be more likely to have superior overall survival; therefore, IRAEs are sometimes used as an indicator of favorable treatment response.2,3

Dermatologic IRAEs associated with the use of a PD-1 inhibitor include lichenoid reactions, pruritus, morbilliform eruptions, vitiligo, and bullous pemphigoid.4,5 Eruptions of keratoacanthoma rarely have been reported following treatment with the PD-1 inhibitors nivolumab and pembrolizumab.3,6,7 In our patient, we believe the profound and generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma—a well-differentiated cSCC variant—was related to treatment of locally advanced cSCC with cemiplimab. The mechanism underlying the formation of anti-PD-1 eruptive keratoacanthoma is not well understood. In susceptible patients, it is plausible that the inflammatory environment permitted by ICIs paradoxically induces regression of tumors such as locally invasive cSCC and simultaneously promotes formation of keratoacanthoma.

The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis and progression of cSCC is complex and possibly involves contrasting roles of leukocyte subpopulations.8 The increased incidence of cSCC in the immunocompromised population,8 PD-L1 overexpression in cSCC,9,10 and successful treatment of cSCC with PD-1 inhibition10 all suggest that inhibition of specific inflammatory pathways is pivotal in tumor pathogenesis. However, increased inflammation, particularly inflammation driven by T lymphocytes and Langerhans cells, also is believed to play a key role in the formation of cSCCs, including the degeneration of actinic keratosis into cSCC. Moreover, because keratoacanthomas are believed to be a cSCC variant and also are associated with PD-L1 overexpression,9 it is perplexing that PD-1 blockade may result in eruptive keratoacanthoma in some patients while also treating locally advanced cSCC, as seen in our patient. Successful treatment of keratoacanthoma with anti-inflammatory intralesional or topical corticosteroids adds to this complicated picture.3

We hypothesize that the pathogenesis of invasive cSCC and keratoacanthoma shares certain immune-mediated mechanisms but also differs in distinct manners. To understand the relationship between systemic treatment of cSCC and eruptive keratoacanthoma, further research is required.

In addition, the RAS/BRAF/MEK oncogenic pathway may be involved in the development of cSCCs associated with anti-PD-1. It is hypothesized that BRAF and MEK inhibition increases T-cell infiltration and increases PD-L1 expression on tumor cells,11 thus increasing the susceptibility of those cells to PD-1 blockade. Further supporting a relationship between the RAS/BRAF/MEK and PD-1 pathways, BRAF inhibitors are associated with development of SCCs and verrucal keratosis by upregulation of the RAS pathway.12,13 Perhaps a common mechanism underlying these pathways results in their shared association for an increased risk for cSCC upon blockade. More research is needed to fully elucidate the underlying biochemical mechanism of immunotherapy and formation of SCCs, such as keratoacanthoma.

Treatment of solitary keratoacanthoma often involves surgical excision; however, the sheer number of lesions in eruptive keratoacanthoma presents a larger dilemma. Because oral systemic retinoids have been shown to be most effective for treating eruptive keratoacanthoma, they are considered first-line therapy as monotherapy or in combination with surgical excision.3 Other treatment options include intralesional or topical corticosteroids, cyclosporine, 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod, and cryotherapy.3,6

The development of ICIs has revolutionized the treatment of cutaneous malignancy, yet we have a great deal more to comprehend on the systemic effects of these medications. Although IRAEs may signal a better response to therapy, some of these effects regrettably can be dose limiting. In our patient, cemiplimab was successful in treating locally advanced cSCC, but treatment also resulted in devastating widespread eruptive keratoacanthoma. The mechanism of this kind of eruption has yet to be understood; we hypothesize that it likely involves T lymphocyte–driven inflammation and the interplay of molecular and immune-mediated pathways.

- Ramos-Casals M, Brahmer JR, Callahan MK, et al. Immune-related adverse events of checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6:38. doi:10.1038/s41572-020-0160-6

- Das S, Johnson DB. Immune-related adverse events and anti-tumor efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:306. doi:10.1186/s40425-019-0805-8

- Freites-Martinez A, Kwong BY, Rieger KE, et al. Eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with pembrolizumab therapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:694-697. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0989

- Shen J, Chang J, Mendenhall M, et al. Diverse cutaneous adverse eruptions caused by anti-programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) and anti-programmed cell death ligand-1 (PD-L1) immunotherapies: clinicalfeatures and management. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2018;10:1758834017751634. doi:10.1177/1758834017751634

- Bandino JP, Perry DM, Clarke CE, et al. Two cases of anti-programmed cell death 1-associated bullous pemphigoid-like disease and eruptive keratoacanthomas featuring combined histopathology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:E378-E380. doi:10.1111/jdv.14179

- Marsh RL, Kolodney JA, Iyengar S, et al. Formation of eruptive cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas after programmed cell death protein-1 blockade. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:390-393. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.02.024

- Antonov NK, Nair KG, Halasz CL. Transient eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with nivolumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:342-345. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.01.025

- Bottomley MJ, Thomson J, Harwood C, et al. The role of the immune system in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:2009. doi:10.3390/ijms20082009

- Gambichler T, Gnielka M, Rüddel I, et al. Expression of PD-L1 in keratoacanthoma and different stages of progression in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017;66:1199-1204. doi:10.1007/s00262-017-2015-x

- Patel R, Chang ALS. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for treating advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20:477-482. doi:10.1007/s40257-019-00426-w

- Rozeman EA, Blank CU. Combining checkpoint inhibition and targeted therapy in melanoma. Nat Med. 2019;25:879-882. doi:10.1038/s41591-019-0482-7

- Dubauskas Z, Kunishige J, Prieto VG, Jonasch E, Hwu P, Tannir NM. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and inflammation of actinic keratoses associated with sorafenib. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2009;7:20-23. doi:10.3816/CGC.2009.n.003

- Chen P, Chen F, Zhou B. Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence of dermatological toxicities associated with vemurafenib treatment in patients with melanoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:243-251. doi:10.1111/ced.13751

- Ramos-Casals M, Brahmer JR, Callahan MK, et al. Immune-related adverse events of checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6:38. doi:10.1038/s41572-020-0160-6

- Das S, Johnson DB. Immune-related adverse events and anti-tumor efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:306. doi:10.1186/s40425-019-0805-8

- Freites-Martinez A, Kwong BY, Rieger KE, et al. Eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with pembrolizumab therapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:694-697. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0989

- Shen J, Chang J, Mendenhall M, et al. Diverse cutaneous adverse eruptions caused by anti-programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) and anti-programmed cell death ligand-1 (PD-L1) immunotherapies: clinicalfeatures and management. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2018;10:1758834017751634. doi:10.1177/1758834017751634

- Bandino JP, Perry DM, Clarke CE, et al. Two cases of anti-programmed cell death 1-associated bullous pemphigoid-like disease and eruptive keratoacanthomas featuring combined histopathology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:E378-E380. doi:10.1111/jdv.14179

- Marsh RL, Kolodney JA, Iyengar S, et al. Formation of eruptive cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas after programmed cell death protein-1 blockade. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:390-393. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.02.024

- Antonov NK, Nair KG, Halasz CL. Transient eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with nivolumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:342-345. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.01.025

- Bottomley MJ, Thomson J, Harwood C, et al. The role of the immune system in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:2009. doi:10.3390/ijms20082009

- Gambichler T, Gnielka M, Rüddel I, et al. Expression of PD-L1 in keratoacanthoma and different stages of progression in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017;66:1199-1204. doi:10.1007/s00262-017-2015-x

- Patel R, Chang ALS. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for treating advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20:477-482. doi:10.1007/s40257-019-00426-w

- Rozeman EA, Blank CU. Combining checkpoint inhibition and targeted therapy in melanoma. Nat Med. 2019;25:879-882. doi:10.1038/s41591-019-0482-7

- Dubauskas Z, Kunishige J, Prieto VG, Jonasch E, Hwu P, Tannir NM. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and inflammation of actinic keratoses associated with sorafenib. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2009;7:20-23. doi:10.3816/CGC.2009.n.003

- Chen P, Chen F, Zhou B. Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence of dermatological toxicities associated with vemurafenib treatment in patients with melanoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:243-251. doi:10.1111/ced.13751

Practice Points

- Immunotherapy, including immune checkpoint inhibitors such as programmed cell-death protein 1 (PD-1) inhibitors, is associated with an array of immune-related adverse events that often manifest in a delayed and prolonged manner. They most commonly affect the gastrointestinal tract as well as the endocrine and dermatologic systems.

- Dermatologic adverse effects associated with PD-1 inhibitors include lichenoid reactions, pruritus, morbilliform eruptions, vitiligo, and bullous pemphigoid.

- Eruptions of keratoacanthoma rarely have been reported following treatment with PD-1 inhibitors such as cemiplimab, nivolumab, and pembrolizumab.

Thalidomide Analogue Drug Eruption Along the Lines of Blaschko

To the Editor:

Lenalidomide is a thalidomide analogue used to treat various hematologic malignancies, including non-Hodgkin lymphoma, myelodysplastic syndrome, and multiple myeloma (MM).1 Lenalidomide is referred to as a degrader therapeutic because it induces targeted protein degradation of disease-relevant proteins (eg, Ikaros family zinc finger protein 1 [IKZF1], Ikaros family zinc finger protein 3 [IKZF3], and casein kinase I isoform-α [CK1α]) as its primary mechanism of action.1,2 Although cutaneous adverse events are relatively common among thalidomide analogues, the morphologic and histopathologic descriptions of these drug eruptions have not been fully elucidated.3,4 We report a novel pityriasiform drug eruption followed by a clinical eruption suggestive of blaschkitis in a patient with MM who was being treated with lenalidomide.

A 76-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a progressive, mildly pruritic eruption on the chest and axillae of 1 year’s duration. He had a medical history of chronic hepatitis B, malignant carcinoid tumor of the colon, prostate cancer, and MM. The eruption emerged 1 to 2 weeks after the patient started oral lenalidomide 10 mg/d and oral dexamethasone40 mg/wk following autologous stem cell transplantation for MM. The patient had not received any other therapy for MM.

Physical examination revealed multiple erythematous, hyperpigmented, scaly papules and plaques on the lateral chest and within the axillae (Figure 1). A skin biopsy from the left axilla demonstrated a mild lichenoid and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with scattered eosinophils, neutrophils, and extravasated erythrocytes. The overlying epidermis showed spongiosis with parakeratosis in addition to lymphocytic exocytosis (Figure 2). No fungal organisms were highlighted on periodic acid–Schiff staining. After this evaluation, we recommended that the patient discontinue lenalidomide and start taking a topical over-the-counter corticosteroid for 2 weeks. Over time, he noted marked improvement in the eruption and associated pruritus.

After a drug holiday of 2 months, the patient resumed a maintenance dosage of oral lenalidomide 10 mg/d. Four or 5 days after restarting lenalidomide, a pruritic eruption appeared that involved the axillae and the left lower abdomen, circling around to the left lower back. The axillary eruption resolved with a topical over-the-counter corticosteroid; the abdominal eruption persisted.

At the 3-month follow-up visit, physical examination revealed erythematous macules and papules that coalesced over a salmon-colored base along the lines of Blaschko extending from the left lower abdominal quadrant, crossing the left flank, and continuing to the left lower back without crossing the midline (Figure 3).

We recommended that the patient continue treatment through this eruption; he was instructed to apply a corticosteroid cream and resume lenalidomide at the maintenance dosage. A month later, he reported that the eruption and associated pruritus resolved with the corticosteroid cream and resumption of the maintenance dose of lenalidomide. The patient noted no further spread of the eruption.

Cutaneous adverse events are common following lenalidomide. In prior trials, the overall incidence of any-grade rash following lenalidomide exposure was 22% to 33%.5 A meta-analysis of 10 trials determined the overall incidence of all-grade and high-grade cutaneous adverse events after exposure to lenalidomide was 27.2% and 3.6%, respectively.6 Our case represents a pityriasiform eruption due to lenalidomide followed by a secondary eruption suggestive of blaschkitis.

The rash due to lenalidomide has been described as morbilliform, urticarial, dermatitic, acneform, and undefined.7 Lenalidomide-induced rash typically develops during the first month of therapy, similar to our patient’s presentation. It has even been observed in the first week of therapy.8 Severe reactions such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis have been reported.5,6 Risk factors associated with rash secondary to lenalidomide include advanced age (≥70 years), presence of Bence-Jones protein-type MM in urine, and no prior chemotherapy.8 Our patient had 2 of these risk factors: advanced age and no prior chemotherapy for MM. The exact pathogenesis by which lenalidomide leads to a pityriasiform eruption, as in our patient, or to a rash in general is unclear. Studies have hypothesized that a lenalidomide-induced rash could be attributable to a delayed hypersensitivity type IV reaction or to a reaction related to the molecular mechanism of action of the drug.9

At the molecular level, the antimyeloma effects of lenalidomide include promoting degradation of transcription factors IKZF1 and IKZF3, which subsequently increases production of IL-2.1,2,9 Recombinant IL-2 has been associated with an increased incidence of rash in other cancers.9 Overexpression of programmed death 1(PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1) has been demonstrated in MM; lenalidomide has been shown to downregulate both PD-1 and PD-L1. Patients receiving PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors commonly have developed rash.9 However, the association between lenalidomide and its downregulation of PD-1 and PD-L1 leading to rash has not been fully elucidated. Given the multiple malignancies in our patient—MM, prostate cancer, malignant carcinoid tumor—an underlying paraneoplastic phenomenon may be possible. Additionally, because our patient initially received dexamethasone along with lenalidomide, the manifestation of the initial pityriasiform rash may have been less severe due to the steroid use. Although our patient underwent a 2-month drug holiday following the initial pityriasiform eruption, most lenalidomide-induced rashes do not necessitate discontinuation of the drug.5,7

Our patient’s secondary drug eruption was clinically suggestive of lenalidomide-induced blaschkitis. A report of a German patient with plasmacytoma described a unilateral papular exanthem that developed 4 months after lenalidomide was initiated.10 The papular exanthem following the lines of Blaschko lines extended from that patient’s posterior left foot to the calf and on to the thigh and flank,10 which was more extensive than our patient’s eruption. Blaschkitis in this patient resolved with a corticosteroid cream and UV light therapy10; lenalidomide was not discontinued, similar to our patient.

The pathogenesis of our patient’s secondary eruption that preferentially involved the lines of Blaschko is unclear. After the initial pityriasiform eruption, the secondary eruption was blaschkitis. Distinguishing dermatomes from the lines of Blaschko, which are thought to represent pathways of epidermal cell migration and proliferation during embryologic development, is important. Genodermatoses such as incontinentia pigmenti and hypomelanosis of Ito involve the lines of Blaschko11; other disorders in the differential diagnosis of linear configurations include linear lichen planus, linear cutaneous lupus erythematosus, linear morphea, and lichen striatus.11 Notably, drug-induced blaschkitis is rare.

Cutaneous adverse reactions from thalidomide analogues are relatively common. Our case of lenalidomide-associated blaschkitis that developed following an initial pityriasiform drug eruption in a patient with MM highlights that dermatologists need to collaborate with the oncologist regarding the severity of drug eruptions to determine if the patient should continue treatment through the cutaneous eruptions or discontinue a vital medication.

- Jan M, Sperling AS, Ebert BL. Cancer therapies based on targeted protein degradation—lessons learned with lenalidomide. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18:401-417. doi:10.1038/s41571-021-00479-z

- Shah UA, Mailankody S. Emerging immunotherapies in multiple myeloma. BMJ. 2020;370:3176. doi:10.1136/BMJ.M3176

- Richardson PG, Blood E, Mitsiades CS, et al. A randomized phase 2 study of lenalidomide therapy for patients with relapsed or relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;108:3458-3464. doi:10.1182/BLOOD-2006-04-015909

- Benboubker L, Dimopoulos MA, Dispenzieri A, et al. Lenalidomide and dexamethasone in transplant-ineligible patients with myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:906-917. doi:10.1056/NEJMOA1402551