User login

Intralymphatic Histiocytosis Associated With an Orthopedic Metal Implant

To the Editor:

|

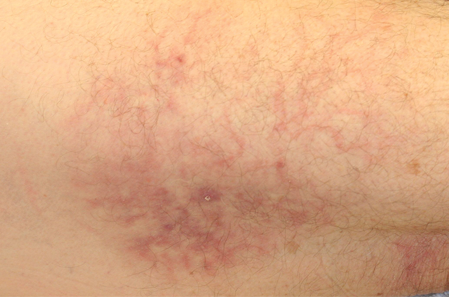

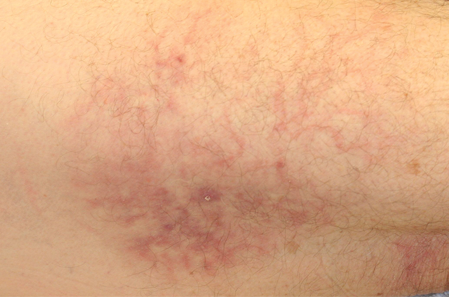

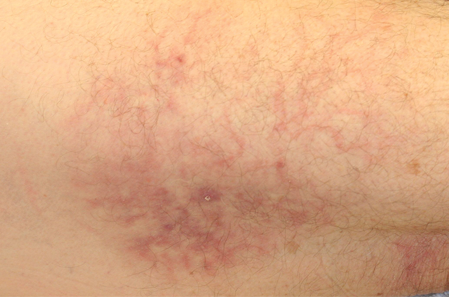

| Figure 1. A 30-cm pink and violaceous, asymmetric, reticulated patch on the lateral aspect of the right thigh. |

|

|

|

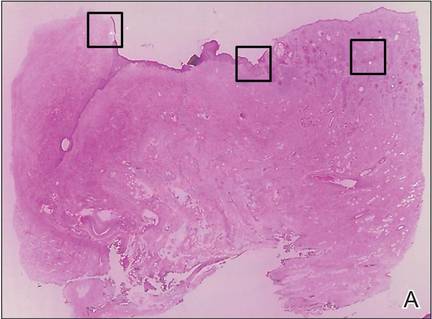

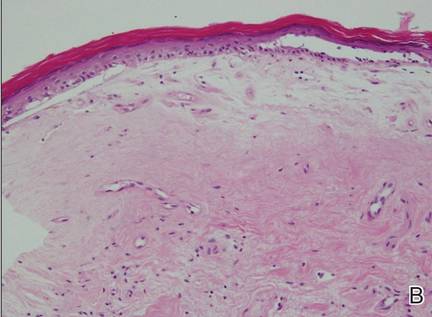

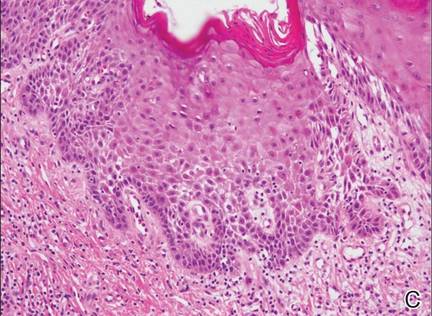

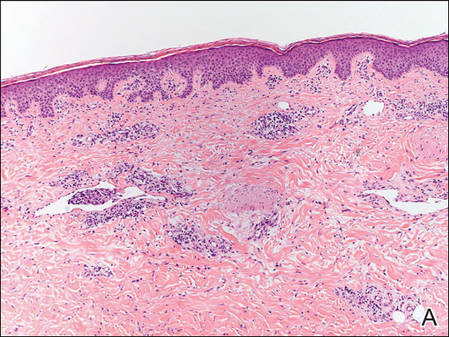

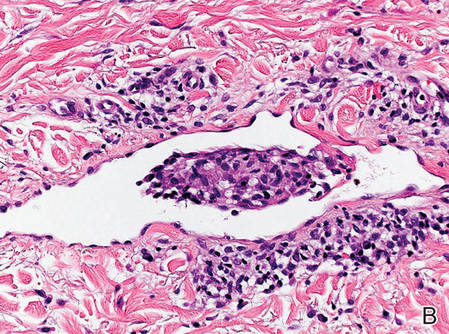

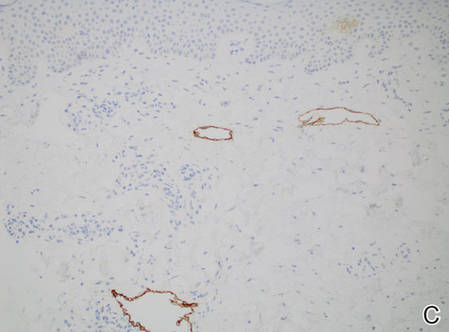

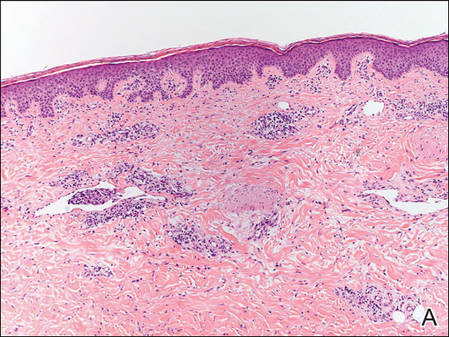

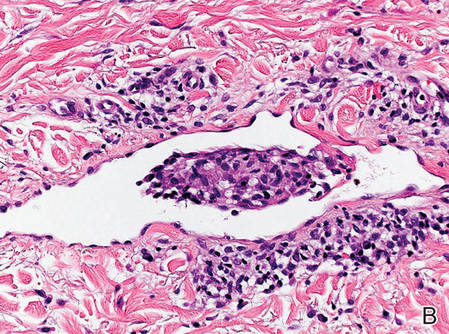

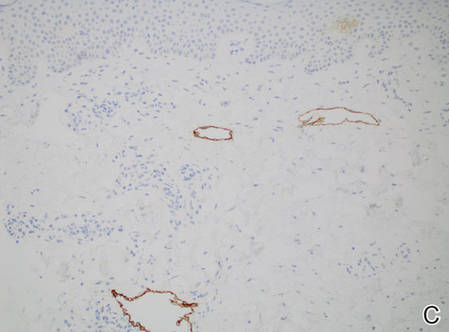

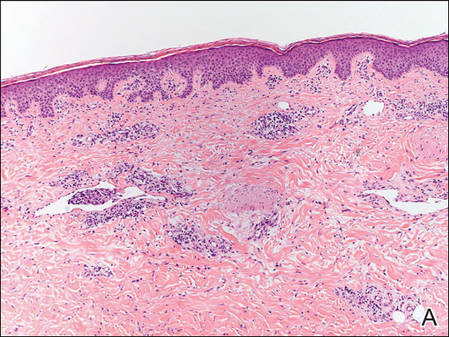

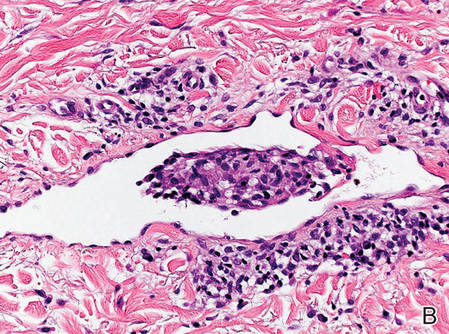

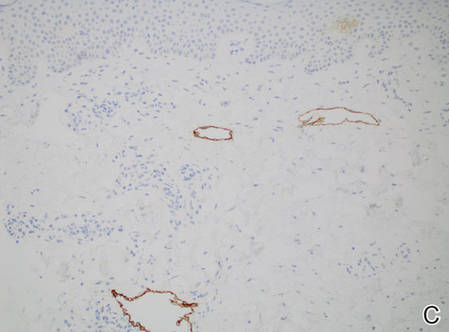

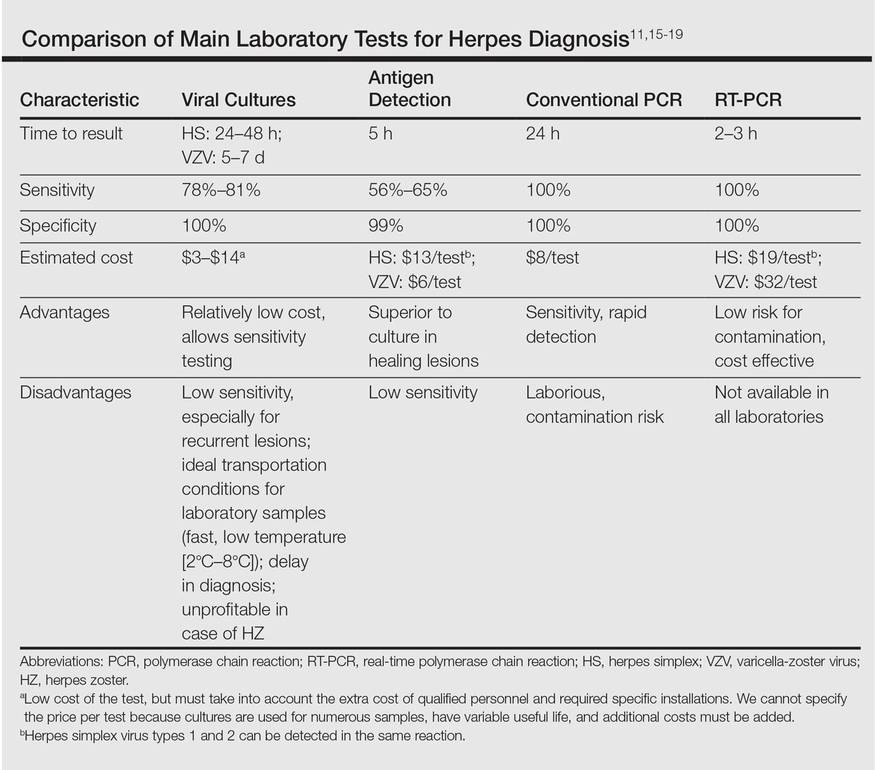

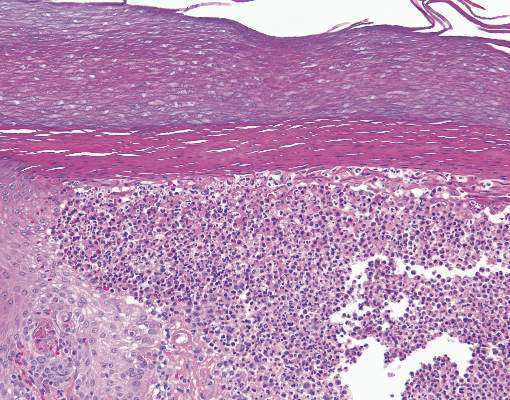

Figure 2. Histopathology revealed widely dilated vascular channels containing collections of histiocytes in the superficial dermis with adjacent features of chronic lymphedema (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10) as well as a collection of histiocytes in a dilated lymphatic channel (B)(H&E, original magnification ×40). D2-40 staining demonstrated ectatic lymphatic vessels in the upper dermins (C)(original magnification ×20).

|

A 70-year-old white man presented with an asymptomatic patch on the lateral aspect of the right thigh of 15 months’ duration. The patient believed the patch correlated with a hip replacement 3 years prior; however, it was 6 inches inferior to the incision site. Physical examination revealed a 30-cm pink and violaceous, asymmetric, reticulated patch (Figure 1). The patch was unresponsive to topical corticosteroids as well as a short course of oral prednisone. The patient’s medical history was notable for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Histopathologic examination revealed widely dilated vascular channels containing collections of histiocytes in the superficial dermis. In addition, adjacent features of chronic lymphedema were present, namely interstitial fibroplasia with dilated lymphatic vessels and a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Figure 2). These findings were consistent with intralymphatic histiocytosis, a rare disease most commonly associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Our patient did not have a history or clinical symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis.

Intralymphatic histiocytosis is a rare cutaneous condition reported by O’Grady et al1 in 1994. This condition has been most frequently associated with rheumatoid arthritis2; however, there has been an emerging association in patients with orthopedic metal implants, with and without a concomitant diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Cases associated with metal implants are rare.2-7

The condition presents as asymptomatic red, brown, or violaceous patches, plaques, papules, or nodules that are ill defined and tend to demonstrate a livedo reticularis–like pattern. The lesions typically are overlying or in close proximity to a joint. Histopathologic findings include dilated vascular structures in the reticular dermis, some with empty lumina and others containing collections of mononuclear histiocytes. There also may be an inflammatory infiltrate in the adjacent dermis composed of a mix of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and/or histiocytes. Endothelial cells lining the dilated lumina express immunoreactivity for CD31, CD34, D2-40, Lyve-1, and Prox-1. Intravascular histiocytes are positive for CD68 and CD31.6

The pathogenesis of intralymphatic histiocytosis remains undefined. Some hypothesize that intralymphatic histiocytosis could be the early stage of reactive angioendotheliomatosis, as these conditions share clinical and histological features.8 Reactive angioendotheliomatosis also is a rare condition that may present as erythematous to violaceous patches or plaques. The lesions are commonly found on the limbs and may be associated with constitutional symptoms. Histologic findings of reactive angioendotheliomatosis include a proliferation of epithelioid, round, or spindle-shaped cells within the lumina of dermal blood vessels, which show positivity for CD31 and CD34.9 Others suggest the lesions of intralymphatic histiocytosis arise from lymphangiectasia; obstruction of lymphatic drainage due to congenital abnormalities; or acquired damage from infection, trauma, surgery, or radiation.2 Due to the common association with rheumatoid arthritis and orthopedic implants, it is likely that lymphatic stasis secondary to chronic inflammation plays a notable role.

Therapies such as topical and systemic corticosteroids, local radiotherapy, cyclophosphamide, pentoxifylline, and arthrocentesis have been attempted without evidence of efficacy.2 Although intralymphatic histiocytosis is chronic and resistant to therapy, patients can be reassured that the condition runs a benign course.

1. O’Grady JT, Shahidullah H, Doherty VR, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis. Histopathology. 1994;24:265-268.

2. Requena L, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, Walsh SN, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis. clinicopathologic study of 16 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:140-151.

3. Saggar S, Lee B, Krivo J, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with orthopedic implants. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:1208-1209.

4. Chiu YE, Maloney JE, Bengana C. Erythematous patch overlying a swollen knee—quiz case. intralymphatic histiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1037-1042.

5. Rossari S, Scatena C, Gori A, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis: cutaneous nodules and metal implants. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:534-535.

6. Grekin S, Mesfin M, Kang S, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis following placement of a metal implant. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:351-353.

7. Watanabe T, Yamada N, Yoshida Y, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis with granuloma formation associated with orthopaedic metal implants. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:402-404.

8. Rieger E, Soyer HP, Leboit PE, et al. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis or intravascular histiocytosis? an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study in two cases of intravascular histiocytic cell proliferation. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:497-504.

9. Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Cutaneous reactive angiomatoses: patterns and classification of reactive vascular proliferation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:887-896.

To the Editor:

|

| Figure 1. A 30-cm pink and violaceous, asymmetric, reticulated patch on the lateral aspect of the right thigh. |

|

|

|

Figure 2. Histopathology revealed widely dilated vascular channels containing collections of histiocytes in the superficial dermis with adjacent features of chronic lymphedema (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10) as well as a collection of histiocytes in a dilated lymphatic channel (B)(H&E, original magnification ×40). D2-40 staining demonstrated ectatic lymphatic vessels in the upper dermins (C)(original magnification ×20).

|

A 70-year-old white man presented with an asymptomatic patch on the lateral aspect of the right thigh of 15 months’ duration. The patient believed the patch correlated with a hip replacement 3 years prior; however, it was 6 inches inferior to the incision site. Physical examination revealed a 30-cm pink and violaceous, asymmetric, reticulated patch (Figure 1). The patch was unresponsive to topical corticosteroids as well as a short course of oral prednisone. The patient’s medical history was notable for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Histopathologic examination revealed widely dilated vascular channels containing collections of histiocytes in the superficial dermis. In addition, adjacent features of chronic lymphedema were present, namely interstitial fibroplasia with dilated lymphatic vessels and a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Figure 2). These findings were consistent with intralymphatic histiocytosis, a rare disease most commonly associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Our patient did not have a history or clinical symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis.

Intralymphatic histiocytosis is a rare cutaneous condition reported by O’Grady et al1 in 1994. This condition has been most frequently associated with rheumatoid arthritis2; however, there has been an emerging association in patients with orthopedic metal implants, with and without a concomitant diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Cases associated with metal implants are rare.2-7

The condition presents as asymptomatic red, brown, or violaceous patches, plaques, papules, or nodules that are ill defined and tend to demonstrate a livedo reticularis–like pattern. The lesions typically are overlying or in close proximity to a joint. Histopathologic findings include dilated vascular structures in the reticular dermis, some with empty lumina and others containing collections of mononuclear histiocytes. There also may be an inflammatory infiltrate in the adjacent dermis composed of a mix of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and/or histiocytes. Endothelial cells lining the dilated lumina express immunoreactivity for CD31, CD34, D2-40, Lyve-1, and Prox-1. Intravascular histiocytes are positive for CD68 and CD31.6

The pathogenesis of intralymphatic histiocytosis remains undefined. Some hypothesize that intralymphatic histiocytosis could be the early stage of reactive angioendotheliomatosis, as these conditions share clinical and histological features.8 Reactive angioendotheliomatosis also is a rare condition that may present as erythematous to violaceous patches or plaques. The lesions are commonly found on the limbs and may be associated with constitutional symptoms. Histologic findings of reactive angioendotheliomatosis include a proliferation of epithelioid, round, or spindle-shaped cells within the lumina of dermal blood vessels, which show positivity for CD31 and CD34.9 Others suggest the lesions of intralymphatic histiocytosis arise from lymphangiectasia; obstruction of lymphatic drainage due to congenital abnormalities; or acquired damage from infection, trauma, surgery, or radiation.2 Due to the common association with rheumatoid arthritis and orthopedic implants, it is likely that lymphatic stasis secondary to chronic inflammation plays a notable role.

Therapies such as topical and systemic corticosteroids, local radiotherapy, cyclophosphamide, pentoxifylline, and arthrocentesis have been attempted without evidence of efficacy.2 Although intralymphatic histiocytosis is chronic and resistant to therapy, patients can be reassured that the condition runs a benign course.

To the Editor:

|

| Figure 1. A 30-cm pink and violaceous, asymmetric, reticulated patch on the lateral aspect of the right thigh. |

|

|

|

Figure 2. Histopathology revealed widely dilated vascular channels containing collections of histiocytes in the superficial dermis with adjacent features of chronic lymphedema (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10) as well as a collection of histiocytes in a dilated lymphatic channel (B)(H&E, original magnification ×40). D2-40 staining demonstrated ectatic lymphatic vessels in the upper dermins (C)(original magnification ×20).

|

A 70-year-old white man presented with an asymptomatic patch on the lateral aspect of the right thigh of 15 months’ duration. The patient believed the patch correlated with a hip replacement 3 years prior; however, it was 6 inches inferior to the incision site. Physical examination revealed a 30-cm pink and violaceous, asymmetric, reticulated patch (Figure 1). The patch was unresponsive to topical corticosteroids as well as a short course of oral prednisone. The patient’s medical history was notable for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Histopathologic examination revealed widely dilated vascular channels containing collections of histiocytes in the superficial dermis. In addition, adjacent features of chronic lymphedema were present, namely interstitial fibroplasia with dilated lymphatic vessels and a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Figure 2). These findings were consistent with intralymphatic histiocytosis, a rare disease most commonly associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Our patient did not have a history or clinical symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis.

Intralymphatic histiocytosis is a rare cutaneous condition reported by O’Grady et al1 in 1994. This condition has been most frequently associated with rheumatoid arthritis2; however, there has been an emerging association in patients with orthopedic metal implants, with and without a concomitant diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Cases associated with metal implants are rare.2-7

The condition presents as asymptomatic red, brown, or violaceous patches, plaques, papules, or nodules that are ill defined and tend to demonstrate a livedo reticularis–like pattern. The lesions typically are overlying or in close proximity to a joint. Histopathologic findings include dilated vascular structures in the reticular dermis, some with empty lumina and others containing collections of mononuclear histiocytes. There also may be an inflammatory infiltrate in the adjacent dermis composed of a mix of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and/or histiocytes. Endothelial cells lining the dilated lumina express immunoreactivity for CD31, CD34, D2-40, Lyve-1, and Prox-1. Intravascular histiocytes are positive for CD68 and CD31.6

The pathogenesis of intralymphatic histiocytosis remains undefined. Some hypothesize that intralymphatic histiocytosis could be the early stage of reactive angioendotheliomatosis, as these conditions share clinical and histological features.8 Reactive angioendotheliomatosis also is a rare condition that may present as erythematous to violaceous patches or plaques. The lesions are commonly found on the limbs and may be associated with constitutional symptoms. Histologic findings of reactive angioendotheliomatosis include a proliferation of epithelioid, round, or spindle-shaped cells within the lumina of dermal blood vessels, which show positivity for CD31 and CD34.9 Others suggest the lesions of intralymphatic histiocytosis arise from lymphangiectasia; obstruction of lymphatic drainage due to congenital abnormalities; or acquired damage from infection, trauma, surgery, or radiation.2 Due to the common association with rheumatoid arthritis and orthopedic implants, it is likely that lymphatic stasis secondary to chronic inflammation plays a notable role.

Therapies such as topical and systemic corticosteroids, local radiotherapy, cyclophosphamide, pentoxifylline, and arthrocentesis have been attempted without evidence of efficacy.2 Although intralymphatic histiocytosis is chronic and resistant to therapy, patients can be reassured that the condition runs a benign course.

1. O’Grady JT, Shahidullah H, Doherty VR, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis. Histopathology. 1994;24:265-268.

2. Requena L, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, Walsh SN, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis. clinicopathologic study of 16 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:140-151.

3. Saggar S, Lee B, Krivo J, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with orthopedic implants. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:1208-1209.

4. Chiu YE, Maloney JE, Bengana C. Erythematous patch overlying a swollen knee—quiz case. intralymphatic histiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1037-1042.

5. Rossari S, Scatena C, Gori A, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis: cutaneous nodules and metal implants. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:534-535.

6. Grekin S, Mesfin M, Kang S, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis following placement of a metal implant. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:351-353.

7. Watanabe T, Yamada N, Yoshida Y, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis with granuloma formation associated with orthopaedic metal implants. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:402-404.

8. Rieger E, Soyer HP, Leboit PE, et al. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis or intravascular histiocytosis? an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study in two cases of intravascular histiocytic cell proliferation. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:497-504.

9. Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Cutaneous reactive angiomatoses: patterns and classification of reactive vascular proliferation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:887-896.

1. O’Grady JT, Shahidullah H, Doherty VR, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis. Histopathology. 1994;24:265-268.

2. Requena L, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, Walsh SN, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis. clinicopathologic study of 16 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:140-151.

3. Saggar S, Lee B, Krivo J, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with orthopedic implants. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:1208-1209.

4. Chiu YE, Maloney JE, Bengana C. Erythematous patch overlying a swollen knee—quiz case. intralymphatic histiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1037-1042.

5. Rossari S, Scatena C, Gori A, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis: cutaneous nodules and metal implants. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:534-535.

6. Grekin S, Mesfin M, Kang S, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis following placement of a metal implant. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:351-353.

7. Watanabe T, Yamada N, Yoshida Y, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis with granuloma formation associated with orthopaedic metal implants. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:402-404.

8. Rieger E, Soyer HP, Leboit PE, et al. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis or intravascular histiocytosis? an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study in two cases of intravascular histiocytic cell proliferation. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:497-504.

9. Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Cutaneous reactive angiomatoses: patterns and classification of reactive vascular proliferation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:887-896.

Practice Points

- Consider intralymphatic histiocytosis in the differential diagnosis of an asymptomatic skin lesion overlying a joint, particularly in patients with orthopedic metal implants or rheumatoid arthritis.

- Biopsy is essential for the diagnosis of intralymphatic histiocytosis; special stains highlighting dilated lymphatic vessels and intravascular histiocytes may be necessary.

- Intralymphatic histiocytosis is chronic and resistant to therapy; however, patients can be reassured that the condition runs a benign course.

Transition From Lichen Sclerosus to Squamous Cell Carcinoma in a Single Tissue Section

To the Editor:

Lichen sclerosus (LS) is a chronic inflammatory disorder of unknown etiology that most commonly affects the anogenital region. Progressive sclerosis results in scarring with distortion of the normal epithelial architecture.1,2 The lifetime risk for developing squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) as a complication of long-standing LS has been estimated as 4% to 6%.3,4 However, there is no general agreement concerning the exact relationship between anogenital LS and SCC.1 The coexistence of histologic findings of LS, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN), and SCC in the same tissue is rare. We report a case of VIN and SCC developing in a region of preexisting LS.

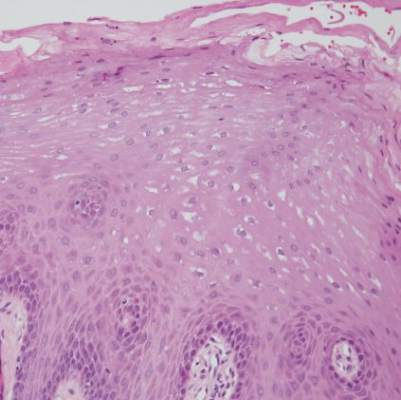

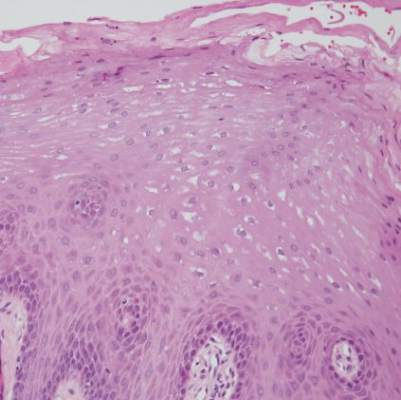

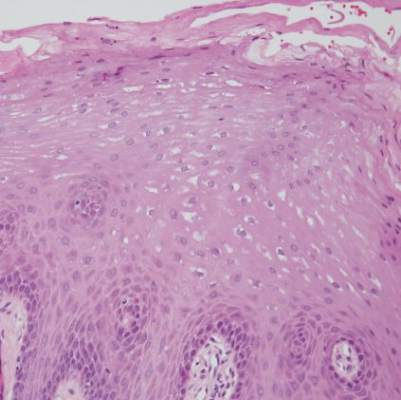

A 76-year-old woman presented with a 7-mm nodule on the clitoris that was surrounded by a pearly white, smooth, glistening area (Figure 1). The patient reported pain and tenderness associated with the nodule. No regional lymphadenopathy was evident. We performed an excisional biopsy of the entire nodule and a small part of the whitish patch (Figure 2A). On histologic examination, the presence of hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, a swollen dermal collagen bundle, and prominent edema was consistent with LS (Figure 2B). The presence of dysplastic changes with mild disturbance of the epithelial architecture as well as acanthosis and dyskeratosis in the same tissue confirmed VIN (Figure 2C). Dermal invasion and transition to SCC were seen in the part of the tissue verified as VIN. The presence of dermal tumor nests and an irregular border between the epidermis and dermis pointed to the existence of fully developed SCC (Figure 2D). To prevent the recurrence of SCC, the patient returned for follow-up periodically. There was no recurrence within 6 months after excision.

|

|

|

|

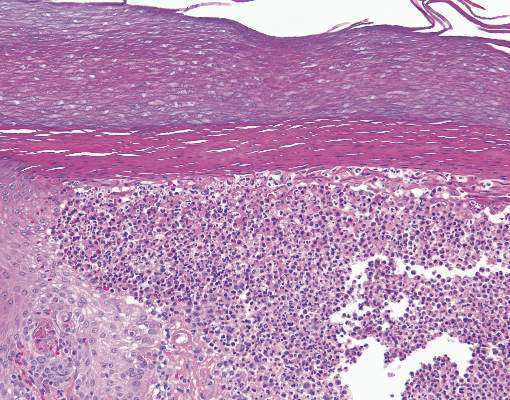

| Figure 2. An excisional biopsy showed epidermal thinning on the left side and invasion of the dermis by a tumor nest on the right side (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10). Left, center, and right boxes indicate areas shown in Figures 2B, 2C and 2D, respectively. Hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, a swollen dermal collagen bundle, and prominent edema was evident (B)(H&E, original magnification ×200). Dysplactic changes with mild disturbance of the epithelial architecture accompanied by acanthosis and nuclear atypia were seen (C)(H&E, original magnification ×200). Irregular masses of atypical squamous cells spread downward into the dermis representing squamous cell carcinoma of a well-differentiated type (D)(H&E, original magnification ×200). | |

Although LS is considered a premalignant condition, only a small portion of patients with LS ultimately develop vulvar SCC.5 There are a number of reasons for linking LS with the development of vulvar SCC. First, in the majority of cases of vulvar SCC, LS, squamous cell hyperplasia, or VIN is present in the adjacent epithelium. Lichen sclerosus is found in adjacent regions in up to 62% of vulvar SCC cases.6 Second, patients with LS may develop vulvar SCC, as frequently reported. Third, in a series of LS patients who underwent long-term follow-up, 4% to 6% were reported to have developed vulvar SCC.3,4,7

Lichen sclerosus is an inflammatory dermatosis characterized by clinicopathologic persistence and hypocellular fibrosis.2 Changes in the local environment of the keratinocyte, including chronic inflammation and sclerosis, may be responsible for the promotion of carcinogenesis.8 However, no molecular markers have been proven to identify the LS lesions that are at risk for developing into vulvar SCC.9,10 It has been suggested that VIN is the direct precursor of vulvar SCC.11,12

Histologic diagnosis of VIN is difficult. Its identification is hindered by a high degree of cellular differentiation combined with the absence of widespread architectural disorder, nuclear pleomorphism, and diffuse nuclear atypia.13 The atypia in VIN lesions is strictly confined to the basal and parabasal layers of the epithelium.11 Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia has seldom been diagnosed as a solitary lesion because it appears to have a short intraepithelial lifetime.

Vulvar SCC can be divided into 2 patterns. The first is found in older women, which is unrelated to human papillomavirus (HPV). This type occurs in a background of LS and/or differentiated VIN. The second is predominantly found in younger women, which is related to high-risk HPV. This type of vulvar SCC frequently is associated with the histologic subtypes of warty and basaloid differentiations and is referred to as undifferentiated VIN. There is no association with LS in these cases.2,14,15

It has been suggested that LS and HPV may not be mutually exclusive but may act as cofactors in SCC pathogenesis.16 Infection with HPV is an early event in the multistep process of vulvar carcinogenesis, and HPV integration into host cell genome seems to be related to the progression of vulvar dysplasia.17 Viral integration generally disrupts the E2 region, resulting in enhanced expression of E6 and E7. E6 and E7 have the ability to bind and inactivate the protein p53 and retinoblastoma protein, which promotes rapid progression through the cell cycle without p53-mediated control of DNA integrity.18 However, the exact influence of HPV in vulvar SCC is uncertain, as divergent prevalence rates have been published.

In our case, histologic examination revealed the characteristic findings of LS, VIN, and SCC in succession. This sequence is evidence of progressive transition from LS to VIN and then to SCC. Consequently, this case suggests that vulvar LS may act as both an initiator and a promoter of carcinogenesis and that VIN may be the direct precursor of vulvar SCC. In conclusion, LS has a considerable risk for malignant transformation and requires continuous follow-up in all patients. Early histological detection of invasive lesions is crucial to reduce the risk for vulvar cancer.

1. Bhattacharjee P, Fatteh SM, Lloyd KL. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in long-standing lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:319-320.

2. Funaro D. Lichen sclerosus: a review and practical approach. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:28-37.

3. Ulrich RH. Lichen sclerosus. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith L, Katz S, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2007:546-550.

4. Heymann WR. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:683-684.

5. Cooper SM, Gao XH, Powell JJ, et al. Does treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus influence its prognosis? Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:702-706.

6. Kagie MJ, Kenter GG, Hermans J, et al. The relevance of various vulvar epithelial changes in the early detection of squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 1997;7:50-57.

7. Thomas RH, Ridley CM, McGibbon DH, et al. Anogenital lichen sclerosus in women. J R Soc Med. 1996;89:694-698.

8. Walkden V, Chia Y, Wojnarowska F. The association of squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva and lichen sclerosus: implications for follow-up. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;17:551-553.

9. Tasker GL, Wojnarowska F. Lichen sclerosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:128-133.

10. Wang SH, Chi CC, Wong YW, et al. Genital verrucous carcinoma is associated with lichen sclerosus: a retrospective study and review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:815-819.

11. Hart WR. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: historical aspects and current status. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2001;20:16-30.

12. van de Nieuwenhof HP, Massuger LF, van der Avoort IA, et al. Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma development after diagnosis of VIN increases with age. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:851-856.

13. Taube JM, Badger J, Kong CS, et al. Differentiated (simplex) vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:27-30.

14. Derrick EK, Ridley CM, Kobza-Black A, et al. A clinical study of 23 cases of female anogenital carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1217-1223.

15. Crum C, McLachlin CM, Tate JE, et al. Pathobiology of vulvar squamous neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol Pathol. 1997;9:63-69.

16. Ansink AC, Krul MRL, De Weger RA, et al. Human papillomavirus, lichen sclerosus, and squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva: detection and prognostic significance. Gynecol Oncol. 1994;52:180-184.

17. Hillemanns P, Wang X. Integration of HPV-16 and HPV-18 DNA in vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;100:276-282.

18. Stoler MH. Human papillomaviruses and cervical neoplasia: a model for carcinogenesis. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2000;19:16-28.

To the Editor:

Lichen sclerosus (LS) is a chronic inflammatory disorder of unknown etiology that most commonly affects the anogenital region. Progressive sclerosis results in scarring with distortion of the normal epithelial architecture.1,2 The lifetime risk for developing squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) as a complication of long-standing LS has been estimated as 4% to 6%.3,4 However, there is no general agreement concerning the exact relationship between anogenital LS and SCC.1 The coexistence of histologic findings of LS, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN), and SCC in the same tissue is rare. We report a case of VIN and SCC developing in a region of preexisting LS.

A 76-year-old woman presented with a 7-mm nodule on the clitoris that was surrounded by a pearly white, smooth, glistening area (Figure 1). The patient reported pain and tenderness associated with the nodule. No regional lymphadenopathy was evident. We performed an excisional biopsy of the entire nodule and a small part of the whitish patch (Figure 2A). On histologic examination, the presence of hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, a swollen dermal collagen bundle, and prominent edema was consistent with LS (Figure 2B). The presence of dysplastic changes with mild disturbance of the epithelial architecture as well as acanthosis and dyskeratosis in the same tissue confirmed VIN (Figure 2C). Dermal invasion and transition to SCC were seen in the part of the tissue verified as VIN. The presence of dermal tumor nests and an irregular border between the epidermis and dermis pointed to the existence of fully developed SCC (Figure 2D). To prevent the recurrence of SCC, the patient returned for follow-up periodically. There was no recurrence within 6 months after excision.

|

|

|

|

| Figure 2. An excisional biopsy showed epidermal thinning on the left side and invasion of the dermis by a tumor nest on the right side (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10). Left, center, and right boxes indicate areas shown in Figures 2B, 2C and 2D, respectively. Hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, a swollen dermal collagen bundle, and prominent edema was evident (B)(H&E, original magnification ×200). Dysplactic changes with mild disturbance of the epithelial architecture accompanied by acanthosis and nuclear atypia were seen (C)(H&E, original magnification ×200). Irregular masses of atypical squamous cells spread downward into the dermis representing squamous cell carcinoma of a well-differentiated type (D)(H&E, original magnification ×200). | |

Although LS is considered a premalignant condition, only a small portion of patients with LS ultimately develop vulvar SCC.5 There are a number of reasons for linking LS with the development of vulvar SCC. First, in the majority of cases of vulvar SCC, LS, squamous cell hyperplasia, or VIN is present in the adjacent epithelium. Lichen sclerosus is found in adjacent regions in up to 62% of vulvar SCC cases.6 Second, patients with LS may develop vulvar SCC, as frequently reported. Third, in a series of LS patients who underwent long-term follow-up, 4% to 6% were reported to have developed vulvar SCC.3,4,7

Lichen sclerosus is an inflammatory dermatosis characterized by clinicopathologic persistence and hypocellular fibrosis.2 Changes in the local environment of the keratinocyte, including chronic inflammation and sclerosis, may be responsible for the promotion of carcinogenesis.8 However, no molecular markers have been proven to identify the LS lesions that are at risk for developing into vulvar SCC.9,10 It has been suggested that VIN is the direct precursor of vulvar SCC.11,12

Histologic diagnosis of VIN is difficult. Its identification is hindered by a high degree of cellular differentiation combined with the absence of widespread architectural disorder, nuclear pleomorphism, and diffuse nuclear atypia.13 The atypia in VIN lesions is strictly confined to the basal and parabasal layers of the epithelium.11 Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia has seldom been diagnosed as a solitary lesion because it appears to have a short intraepithelial lifetime.

Vulvar SCC can be divided into 2 patterns. The first is found in older women, which is unrelated to human papillomavirus (HPV). This type occurs in a background of LS and/or differentiated VIN. The second is predominantly found in younger women, which is related to high-risk HPV. This type of vulvar SCC frequently is associated with the histologic subtypes of warty and basaloid differentiations and is referred to as undifferentiated VIN. There is no association with LS in these cases.2,14,15

It has been suggested that LS and HPV may not be mutually exclusive but may act as cofactors in SCC pathogenesis.16 Infection with HPV is an early event in the multistep process of vulvar carcinogenesis, and HPV integration into host cell genome seems to be related to the progression of vulvar dysplasia.17 Viral integration generally disrupts the E2 region, resulting in enhanced expression of E6 and E7. E6 and E7 have the ability to bind and inactivate the protein p53 and retinoblastoma protein, which promotes rapid progression through the cell cycle without p53-mediated control of DNA integrity.18 However, the exact influence of HPV in vulvar SCC is uncertain, as divergent prevalence rates have been published.

In our case, histologic examination revealed the characteristic findings of LS, VIN, and SCC in succession. This sequence is evidence of progressive transition from LS to VIN and then to SCC. Consequently, this case suggests that vulvar LS may act as both an initiator and a promoter of carcinogenesis and that VIN may be the direct precursor of vulvar SCC. In conclusion, LS has a considerable risk for malignant transformation and requires continuous follow-up in all patients. Early histological detection of invasive lesions is crucial to reduce the risk for vulvar cancer.

To the Editor:

Lichen sclerosus (LS) is a chronic inflammatory disorder of unknown etiology that most commonly affects the anogenital region. Progressive sclerosis results in scarring with distortion of the normal epithelial architecture.1,2 The lifetime risk for developing squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) as a complication of long-standing LS has been estimated as 4% to 6%.3,4 However, there is no general agreement concerning the exact relationship between anogenital LS and SCC.1 The coexistence of histologic findings of LS, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN), and SCC in the same tissue is rare. We report a case of VIN and SCC developing in a region of preexisting LS.

A 76-year-old woman presented with a 7-mm nodule on the clitoris that was surrounded by a pearly white, smooth, glistening area (Figure 1). The patient reported pain and tenderness associated with the nodule. No regional lymphadenopathy was evident. We performed an excisional biopsy of the entire nodule and a small part of the whitish patch (Figure 2A). On histologic examination, the presence of hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, a swollen dermal collagen bundle, and prominent edema was consistent with LS (Figure 2B). The presence of dysplastic changes with mild disturbance of the epithelial architecture as well as acanthosis and dyskeratosis in the same tissue confirmed VIN (Figure 2C). Dermal invasion and transition to SCC were seen in the part of the tissue verified as VIN. The presence of dermal tumor nests and an irregular border between the epidermis and dermis pointed to the existence of fully developed SCC (Figure 2D). To prevent the recurrence of SCC, the patient returned for follow-up periodically. There was no recurrence within 6 months after excision.

|

|

|

|

| Figure 2. An excisional biopsy showed epidermal thinning on the left side and invasion of the dermis by a tumor nest on the right side (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10). Left, center, and right boxes indicate areas shown in Figures 2B, 2C and 2D, respectively. Hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, a swollen dermal collagen bundle, and prominent edema was evident (B)(H&E, original magnification ×200). Dysplactic changes with mild disturbance of the epithelial architecture accompanied by acanthosis and nuclear atypia were seen (C)(H&E, original magnification ×200). Irregular masses of atypical squamous cells spread downward into the dermis representing squamous cell carcinoma of a well-differentiated type (D)(H&E, original magnification ×200). | |

Although LS is considered a premalignant condition, only a small portion of patients with LS ultimately develop vulvar SCC.5 There are a number of reasons for linking LS with the development of vulvar SCC. First, in the majority of cases of vulvar SCC, LS, squamous cell hyperplasia, or VIN is present in the adjacent epithelium. Lichen sclerosus is found in adjacent regions in up to 62% of vulvar SCC cases.6 Second, patients with LS may develop vulvar SCC, as frequently reported. Third, in a series of LS patients who underwent long-term follow-up, 4% to 6% were reported to have developed vulvar SCC.3,4,7

Lichen sclerosus is an inflammatory dermatosis characterized by clinicopathologic persistence and hypocellular fibrosis.2 Changes in the local environment of the keratinocyte, including chronic inflammation and sclerosis, may be responsible for the promotion of carcinogenesis.8 However, no molecular markers have been proven to identify the LS lesions that are at risk for developing into vulvar SCC.9,10 It has been suggested that VIN is the direct precursor of vulvar SCC.11,12

Histologic diagnosis of VIN is difficult. Its identification is hindered by a high degree of cellular differentiation combined with the absence of widespread architectural disorder, nuclear pleomorphism, and diffuse nuclear atypia.13 The atypia in VIN lesions is strictly confined to the basal and parabasal layers of the epithelium.11 Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia has seldom been diagnosed as a solitary lesion because it appears to have a short intraepithelial lifetime.

Vulvar SCC can be divided into 2 patterns. The first is found in older women, which is unrelated to human papillomavirus (HPV). This type occurs in a background of LS and/or differentiated VIN. The second is predominantly found in younger women, which is related to high-risk HPV. This type of vulvar SCC frequently is associated with the histologic subtypes of warty and basaloid differentiations and is referred to as undifferentiated VIN. There is no association with LS in these cases.2,14,15

It has been suggested that LS and HPV may not be mutually exclusive but may act as cofactors in SCC pathogenesis.16 Infection with HPV is an early event in the multistep process of vulvar carcinogenesis, and HPV integration into host cell genome seems to be related to the progression of vulvar dysplasia.17 Viral integration generally disrupts the E2 region, resulting in enhanced expression of E6 and E7. E6 and E7 have the ability to bind and inactivate the protein p53 and retinoblastoma protein, which promotes rapid progression through the cell cycle without p53-mediated control of DNA integrity.18 However, the exact influence of HPV in vulvar SCC is uncertain, as divergent prevalence rates have been published.

In our case, histologic examination revealed the characteristic findings of LS, VIN, and SCC in succession. This sequence is evidence of progressive transition from LS to VIN and then to SCC. Consequently, this case suggests that vulvar LS may act as both an initiator and a promoter of carcinogenesis and that VIN may be the direct precursor of vulvar SCC. In conclusion, LS has a considerable risk for malignant transformation and requires continuous follow-up in all patients. Early histological detection of invasive lesions is crucial to reduce the risk for vulvar cancer.

1. Bhattacharjee P, Fatteh SM, Lloyd KL. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in long-standing lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:319-320.

2. Funaro D. Lichen sclerosus: a review and practical approach. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:28-37.

3. Ulrich RH. Lichen sclerosus. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith L, Katz S, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2007:546-550.

4. Heymann WR. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:683-684.

5. Cooper SM, Gao XH, Powell JJ, et al. Does treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus influence its prognosis? Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:702-706.

6. Kagie MJ, Kenter GG, Hermans J, et al. The relevance of various vulvar epithelial changes in the early detection of squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 1997;7:50-57.

7. Thomas RH, Ridley CM, McGibbon DH, et al. Anogenital lichen sclerosus in women. J R Soc Med. 1996;89:694-698.

8. Walkden V, Chia Y, Wojnarowska F. The association of squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva and lichen sclerosus: implications for follow-up. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;17:551-553.

9. Tasker GL, Wojnarowska F. Lichen sclerosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:128-133.

10. Wang SH, Chi CC, Wong YW, et al. Genital verrucous carcinoma is associated with lichen sclerosus: a retrospective study and review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:815-819.

11. Hart WR. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: historical aspects and current status. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2001;20:16-30.

12. van de Nieuwenhof HP, Massuger LF, van der Avoort IA, et al. Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma development after diagnosis of VIN increases with age. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:851-856.

13. Taube JM, Badger J, Kong CS, et al. Differentiated (simplex) vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:27-30.

14. Derrick EK, Ridley CM, Kobza-Black A, et al. A clinical study of 23 cases of female anogenital carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1217-1223.

15. Crum C, McLachlin CM, Tate JE, et al. Pathobiology of vulvar squamous neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol Pathol. 1997;9:63-69.

16. Ansink AC, Krul MRL, De Weger RA, et al. Human papillomavirus, lichen sclerosus, and squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva: detection and prognostic significance. Gynecol Oncol. 1994;52:180-184.

17. Hillemanns P, Wang X. Integration of HPV-16 and HPV-18 DNA in vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;100:276-282.

18. Stoler MH. Human papillomaviruses and cervical neoplasia: a model for carcinogenesis. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2000;19:16-28.

1. Bhattacharjee P, Fatteh SM, Lloyd KL. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in long-standing lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:319-320.

2. Funaro D. Lichen sclerosus: a review and practical approach. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:28-37.

3. Ulrich RH. Lichen sclerosus. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith L, Katz S, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2007:546-550.

4. Heymann WR. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:683-684.

5. Cooper SM, Gao XH, Powell JJ, et al. Does treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus influence its prognosis? Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:702-706.

6. Kagie MJ, Kenter GG, Hermans J, et al. The relevance of various vulvar epithelial changes in the early detection of squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 1997;7:50-57.

7. Thomas RH, Ridley CM, McGibbon DH, et al. Anogenital lichen sclerosus in women. J R Soc Med. 1996;89:694-698.

8. Walkden V, Chia Y, Wojnarowska F. The association of squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva and lichen sclerosus: implications for follow-up. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;17:551-553.

9. Tasker GL, Wojnarowska F. Lichen sclerosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:128-133.

10. Wang SH, Chi CC, Wong YW, et al. Genital verrucous carcinoma is associated with lichen sclerosus: a retrospective study and review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:815-819.

11. Hart WR. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: historical aspects and current status. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2001;20:16-30.

12. van de Nieuwenhof HP, Massuger LF, van der Avoort IA, et al. Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma development after diagnosis of VIN increases with age. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:851-856.

13. Taube JM, Badger J, Kong CS, et al. Differentiated (simplex) vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:27-30.

14. Derrick EK, Ridley CM, Kobza-Black A, et al. A clinical study of 23 cases of female anogenital carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1217-1223.

15. Crum C, McLachlin CM, Tate JE, et al. Pathobiology of vulvar squamous neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol Pathol. 1997;9:63-69.

16. Ansink AC, Krul MRL, De Weger RA, et al. Human papillomavirus, lichen sclerosus, and squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva: detection and prognostic significance. Gynecol Oncol. 1994;52:180-184.

17. Hillemanns P, Wang X. Integration of HPV-16 and HPV-18 DNA in vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;100:276-282.

18. Stoler MH. Human papillomaviruses and cervical neoplasia: a model for carcinogenesis. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2000;19:16-28.

Practice Points

- Lichen sclerosus has a considerable risk for malignant transformation and requires continuous follow-up in all patients.

- Early histological detection of invasive lesions is crucial to reduce the risk for vulvar cancer.

Non–Drug-Induced Pemphigus Foliaceus in a Patient With Rheumatoid Arthritis

To the Editor:

The term pemphigus describes a group of autoimmune blistering diseases that are histologically characterized by intraepidermal blisters caused by acantholysis. There are several types of pemphigus foliaceus, such as classic and endemic pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus erythematosus, pemphigus herpetiformis, and drug-induced pemphigus foliaceus.1

|

| Figure 1. Multiple erosions and crusted lesions were present on the back. |

|

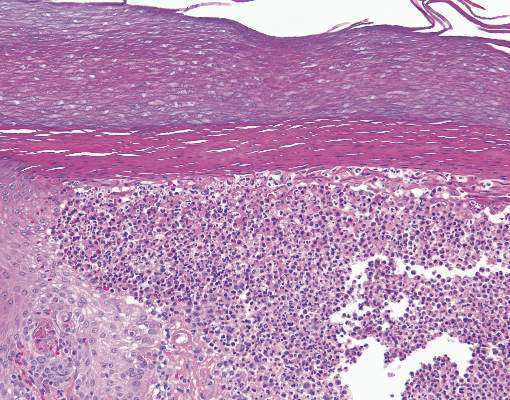

| Figure 2. Subcorneal bulla containing acantholytic keratinocytes and neutrophils (H&E, original magnification ×100). |

Drug-induced pemphigus foliaceus in patients treated with penicillamine for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is well documented in the literature.2 An association between pemphigus foliaceus and RA without penicillamine therapy is rare. We present a case of a patient with a history of RA who developed this bullous disease.

A 67-year-old woman with a 15-year history of seropositive RA presented with widespread skin lesions of 4 weeks’ duration. Confluent scaly crusted erosions on an erythematous base were present on the back (Figure 1), chest, and abdomen. There was no alteration of the mucous membranes. Medical treatment consisted of methotrexate (10 mg weekly), folic acid (5 mg twice weekly), prednisolone (5 mg daily), and ketoprofen (50 mg daily). Routine blood analysis was unremarkable, except for a positive rheumatoid factor. Histologic examination showed a subcorneal bulla containing acantholytic keratinocytes and neutrophils. There was a mild lymphocytic and eosinophilic infiltrate in the papillary dermis (Figure 2).

Determination of anti-desmoglein 1 and 3 antibodies was performed by a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Desmoglein 1 antibodies were positive with titers of 30 U/mL (positive, ≥20 U/mL), whereas desmoglein 3 antibody was negative. Thus, a diagnosis of pemphigus foliaceus was established. The polymerase chain reaction ligation-based typing method and the nucleotide sequence was used to examine the protein drought-repressed 4 gene complex, DR4, which tested positive.

Based on a diagnosis of pemphigus foliaceus, the patient’s corticosteroid treatment was changed from 5 mg daily of prednisolone to 40 mg daily of methylprednisolone, leading to marked improvement of the cutaneous lesions. After tapering the steroid dosage over a period of 3 months, no relapse occurred.

Pemphigus foliaceus is a rare autoimmune blistering disease. It can be induced by drugs, such as penicillamine and captopril.2,3 Captopril, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, is closely related to penicillamine structurally. Both drugs have highly active thiol groups capable of reducing disulfide bonds and inducing acantholysis.4 The drugs taken by our patient typically are not known to induce pemphigus foliaceus.

The association of pemphigus foliaceus with RA in the absence of penicillamine therapy was first described by Wilkinson et al.4 Since then, additional cases have been published.5,6 Pemphigus foliaceus also has been described with other autoimmune conditions such as autoimmune thyroid disease.7

Rheumatoid arthritis has been genetically linked to the HLA-DR4 gene complex, which also was found in our patient. Patients with pemphigus foliaceus and RA have an increased frequency of the class II major histocompatibility complex, serologically defined HLA-DR4, and HLA-DRw6 haplotypes.4 Therefore, we believe that the association of pemphigus foliaceus and RA in our patient might not be fortuitous.

1. Chams-Davatchi C, Valikhani M, Daneshpazhooh M, et al. Pemphigus: analysis of 1209 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:470-476.

2. Sugita K, Hirokawa H, Izu K, et al. D-penicillamine-induced pemphigus successfully treated with combination therapy of mizoribine and prednisolone. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:214-217.

3. Kaplan RP, Potter TS, Fox JN. Drug-induced pemphigus related to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26(2, pt 2):364-366.

4. Wilkinson SM, Smith AG, Davis MJ, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis: an association with pemphigus foliaceus. Acta Derm Venereol. 1992;72:289-291.

5. Sáez-de-Ocariz M, Granados J, Yamamoto-Furusho JK, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis associated with pemphigus foliaceus in a patient not taking penicillamine. Skinmed. 2007;6:252-254.

6. Gürcan HM, Ahmed RA. Analysis of current data on the use of methotrexate in the treatment of pemphigus and pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:723-731.

7. Leshem YA, Katzenelson V, Yosipovitch G, et al. Autoimmune diseases in patients with pemphigus and their first-degree relatives. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:827-831.

To the Editor:

The term pemphigus describes a group of autoimmune blistering diseases that are histologically characterized by intraepidermal blisters caused by acantholysis. There are several types of pemphigus foliaceus, such as classic and endemic pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus erythematosus, pemphigus herpetiformis, and drug-induced pemphigus foliaceus.1

|

| Figure 1. Multiple erosions and crusted lesions were present on the back. |

|

| Figure 2. Subcorneal bulla containing acantholytic keratinocytes and neutrophils (H&E, original magnification ×100). |

Drug-induced pemphigus foliaceus in patients treated with penicillamine for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is well documented in the literature.2 An association between pemphigus foliaceus and RA without penicillamine therapy is rare. We present a case of a patient with a history of RA who developed this bullous disease.

A 67-year-old woman with a 15-year history of seropositive RA presented with widespread skin lesions of 4 weeks’ duration. Confluent scaly crusted erosions on an erythematous base were present on the back (Figure 1), chest, and abdomen. There was no alteration of the mucous membranes. Medical treatment consisted of methotrexate (10 mg weekly), folic acid (5 mg twice weekly), prednisolone (5 mg daily), and ketoprofen (50 mg daily). Routine blood analysis was unremarkable, except for a positive rheumatoid factor. Histologic examination showed a subcorneal bulla containing acantholytic keratinocytes and neutrophils. There was a mild lymphocytic and eosinophilic infiltrate in the papillary dermis (Figure 2).

Determination of anti-desmoglein 1 and 3 antibodies was performed by a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Desmoglein 1 antibodies were positive with titers of 30 U/mL (positive, ≥20 U/mL), whereas desmoglein 3 antibody was negative. Thus, a diagnosis of pemphigus foliaceus was established. The polymerase chain reaction ligation-based typing method and the nucleotide sequence was used to examine the protein drought-repressed 4 gene complex, DR4, which tested positive.

Based on a diagnosis of pemphigus foliaceus, the patient’s corticosteroid treatment was changed from 5 mg daily of prednisolone to 40 mg daily of methylprednisolone, leading to marked improvement of the cutaneous lesions. After tapering the steroid dosage over a period of 3 months, no relapse occurred.

Pemphigus foliaceus is a rare autoimmune blistering disease. It can be induced by drugs, such as penicillamine and captopril.2,3 Captopril, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, is closely related to penicillamine structurally. Both drugs have highly active thiol groups capable of reducing disulfide bonds and inducing acantholysis.4 The drugs taken by our patient typically are not known to induce pemphigus foliaceus.

The association of pemphigus foliaceus with RA in the absence of penicillamine therapy was first described by Wilkinson et al.4 Since then, additional cases have been published.5,6 Pemphigus foliaceus also has been described with other autoimmune conditions such as autoimmune thyroid disease.7

Rheumatoid arthritis has been genetically linked to the HLA-DR4 gene complex, which also was found in our patient. Patients with pemphigus foliaceus and RA have an increased frequency of the class II major histocompatibility complex, serologically defined HLA-DR4, and HLA-DRw6 haplotypes.4 Therefore, we believe that the association of pemphigus foliaceus and RA in our patient might not be fortuitous.

To the Editor:

The term pemphigus describes a group of autoimmune blistering diseases that are histologically characterized by intraepidermal blisters caused by acantholysis. There are several types of pemphigus foliaceus, such as classic and endemic pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus erythematosus, pemphigus herpetiformis, and drug-induced pemphigus foliaceus.1

|

| Figure 1. Multiple erosions and crusted lesions were present on the back. |

|

| Figure 2. Subcorneal bulla containing acantholytic keratinocytes and neutrophils (H&E, original magnification ×100). |

Drug-induced pemphigus foliaceus in patients treated with penicillamine for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is well documented in the literature.2 An association between pemphigus foliaceus and RA without penicillamine therapy is rare. We present a case of a patient with a history of RA who developed this bullous disease.

A 67-year-old woman with a 15-year history of seropositive RA presented with widespread skin lesions of 4 weeks’ duration. Confluent scaly crusted erosions on an erythematous base were present on the back (Figure 1), chest, and abdomen. There was no alteration of the mucous membranes. Medical treatment consisted of methotrexate (10 mg weekly), folic acid (5 mg twice weekly), prednisolone (5 mg daily), and ketoprofen (50 mg daily). Routine blood analysis was unremarkable, except for a positive rheumatoid factor. Histologic examination showed a subcorneal bulla containing acantholytic keratinocytes and neutrophils. There was a mild lymphocytic and eosinophilic infiltrate in the papillary dermis (Figure 2).

Determination of anti-desmoglein 1 and 3 antibodies was performed by a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Desmoglein 1 antibodies were positive with titers of 30 U/mL (positive, ≥20 U/mL), whereas desmoglein 3 antibody was negative. Thus, a diagnosis of pemphigus foliaceus was established. The polymerase chain reaction ligation-based typing method and the nucleotide sequence was used to examine the protein drought-repressed 4 gene complex, DR4, which tested positive.

Based on a diagnosis of pemphigus foliaceus, the patient’s corticosteroid treatment was changed from 5 mg daily of prednisolone to 40 mg daily of methylprednisolone, leading to marked improvement of the cutaneous lesions. After tapering the steroid dosage over a period of 3 months, no relapse occurred.

Pemphigus foliaceus is a rare autoimmune blistering disease. It can be induced by drugs, such as penicillamine and captopril.2,3 Captopril, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, is closely related to penicillamine structurally. Both drugs have highly active thiol groups capable of reducing disulfide bonds and inducing acantholysis.4 The drugs taken by our patient typically are not known to induce pemphigus foliaceus.

The association of pemphigus foliaceus with RA in the absence of penicillamine therapy was first described by Wilkinson et al.4 Since then, additional cases have been published.5,6 Pemphigus foliaceus also has been described with other autoimmune conditions such as autoimmune thyroid disease.7

Rheumatoid arthritis has been genetically linked to the HLA-DR4 gene complex, which also was found in our patient. Patients with pemphigus foliaceus and RA have an increased frequency of the class II major histocompatibility complex, serologically defined HLA-DR4, and HLA-DRw6 haplotypes.4 Therefore, we believe that the association of pemphigus foliaceus and RA in our patient might not be fortuitous.

1. Chams-Davatchi C, Valikhani M, Daneshpazhooh M, et al. Pemphigus: analysis of 1209 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:470-476.

2. Sugita K, Hirokawa H, Izu K, et al. D-penicillamine-induced pemphigus successfully treated with combination therapy of mizoribine and prednisolone. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:214-217.

3. Kaplan RP, Potter TS, Fox JN. Drug-induced pemphigus related to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26(2, pt 2):364-366.

4. Wilkinson SM, Smith AG, Davis MJ, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis: an association with pemphigus foliaceus. Acta Derm Venereol. 1992;72:289-291.

5. Sáez-de-Ocariz M, Granados J, Yamamoto-Furusho JK, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis associated with pemphigus foliaceus in a patient not taking penicillamine. Skinmed. 2007;6:252-254.

6. Gürcan HM, Ahmed RA. Analysis of current data on the use of methotrexate in the treatment of pemphigus and pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:723-731.

7. Leshem YA, Katzenelson V, Yosipovitch G, et al. Autoimmune diseases in patients with pemphigus and their first-degree relatives. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:827-831.

1. Chams-Davatchi C, Valikhani M, Daneshpazhooh M, et al. Pemphigus: analysis of 1209 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:470-476.

2. Sugita K, Hirokawa H, Izu K, et al. D-penicillamine-induced pemphigus successfully treated with combination therapy of mizoribine and prednisolone. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:214-217.

3. Kaplan RP, Potter TS, Fox JN. Drug-induced pemphigus related to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26(2, pt 2):364-366.

4. Wilkinson SM, Smith AG, Davis MJ, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis: an association with pemphigus foliaceus. Acta Derm Venereol. 1992;72:289-291.

5. Sáez-de-Ocariz M, Granados J, Yamamoto-Furusho JK, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis associated with pemphigus foliaceus in a patient not taking penicillamine. Skinmed. 2007;6:252-254.

6. Gürcan HM, Ahmed RA. Analysis of current data on the use of methotrexate in the treatment of pemphigus and pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:723-731.

7. Leshem YA, Katzenelson V, Yosipovitch G, et al. Autoimmune diseases in patients with pemphigus and their first-degree relatives. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:827-831.

Practice Points

- Physicians should consider pemphigus foliaceus in the differential diagnosis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and blistering eruptions.

- Appropriate analyses should be performed, including skin biopsy for histologic and immunohistochemical examination as well as search for circulating antibodies.

Concomitant Herpes Zoster and Herpes Simplex Infection

To the Editor:

Infections caused by herpes simplex (HS) and herpes zoster (HZ) usually can be recognized by clinical findings; however, laboratory confirmation sometimes is required. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) laboratory tests detect HS or HZ in a sensible and specific manner. New PCR systems such as real-time PCR (RT-PCR) give faster and more precise results. We report a case of recurrent concomitant HZ and HS diagnosed by RT-PCR.

A 62-year-old woman presented with recurrent painful cutaneous lesions on the left buttock and thigh of 9 years’ duration. This eruption was preceded by a burning sensation of 1 week’s duration that extended toward the heel. Cutaneous lesions normally were sparse and persisted for a few days. She also had annular erythematous lesions of 3 years’ duration on the upper trunk and shoulders after sun exposure. On physical examination, an atrophic hypopigmented patch was seen with a few vesicles located on the thigh. Whitish atrophic patches also were found in a linear distribution on the left buttock and thigh (Figure).

Laboratory results included the following: antinuclear antibody, 1:400 on a nuclear dotted pattern; extractable nuclear antigens (anti-Ro60 and anti-Ro52) were positive (reference range, >15); and rheumatoid factor was 24.1 U/mL (reference range, 0–15 U/mL). The patient did not meet any other American College of Rheumatology criteria1,2 of systemic lupus erythematosus apart from photosensitivity. The rest of the analysis—complete blood cell count, liver enzymes, and biochemistry—was normal or negative. Human immunodeficiency virus, herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 (HHV-1 and HHV-2), and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) IgM serologies were negative, whereas IgG VZV serology was positive.

The microbiological study via swab obtained from the roof and fluid from the vesicles showed an indeterminate result from the rapid direct antigen detection with immunofluorescent antibodies. Viral cultures were HHV-2 positive and VZV negative. Conventional PCR showed positive results, both for HHV-2 and VZV. A second analysis, performed with RT-PCR from a new sample taken 2 months later, showed the same results, which led to the diagnosis of recurrent concomitant HS and HZ with a recurrent HZ clinical pattern. The patient was started on valacyclovir 1 g daily, and the number and intensity of flares diminished in the months following treatment.

Concomitant HS and HZ on the same dermatome has been described in the literature.3,4 In a retrospective series of 20 immunocompetent patients, HZ was the main presumed diagnosis before laboratory confirmation of diagnosis, and only 1 case corresponded to recurrent HZ.3 Other cases of simultaneous HS and HZ have been described, but they did not occur on the same dermatome. Half of these reported cases were in immunosuppressed patients.5,6

The recurrent nature of HS is well known; however, recurrent cases of HZ are rare. Nevertheless, in a population-based cohort study of patients with a confirmed prior episode of HZ (N=1669), recurrences were found in 6% of patients.7 Recurrence was more common if the patient was immunosuppressed, was female and 50 years or older, and had pain for more than 30 days.7

The recurrence rate was high in our case, but no immunosuppressive factor could be found apart from probable subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Systemic lupus erythematosus has been associated with a high risk for developing HZ secondary to cell-mediated immunosuppression. The annual incidence of HZ can reach 32 of 1000 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, while in the general population the incidence is only 1.5 to 3 of 1000 patients.8-10

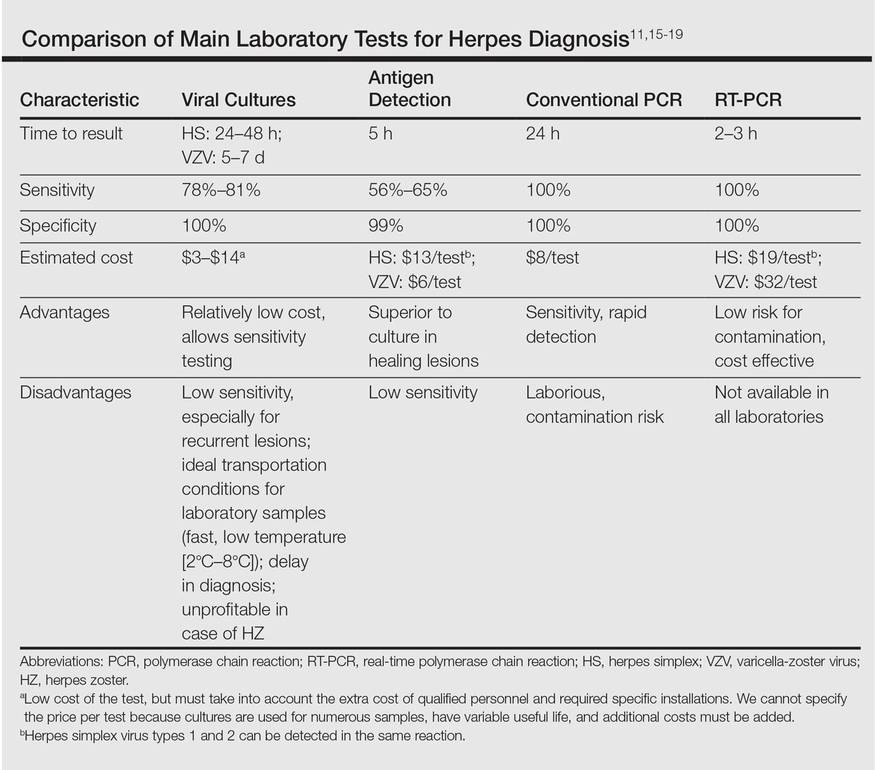

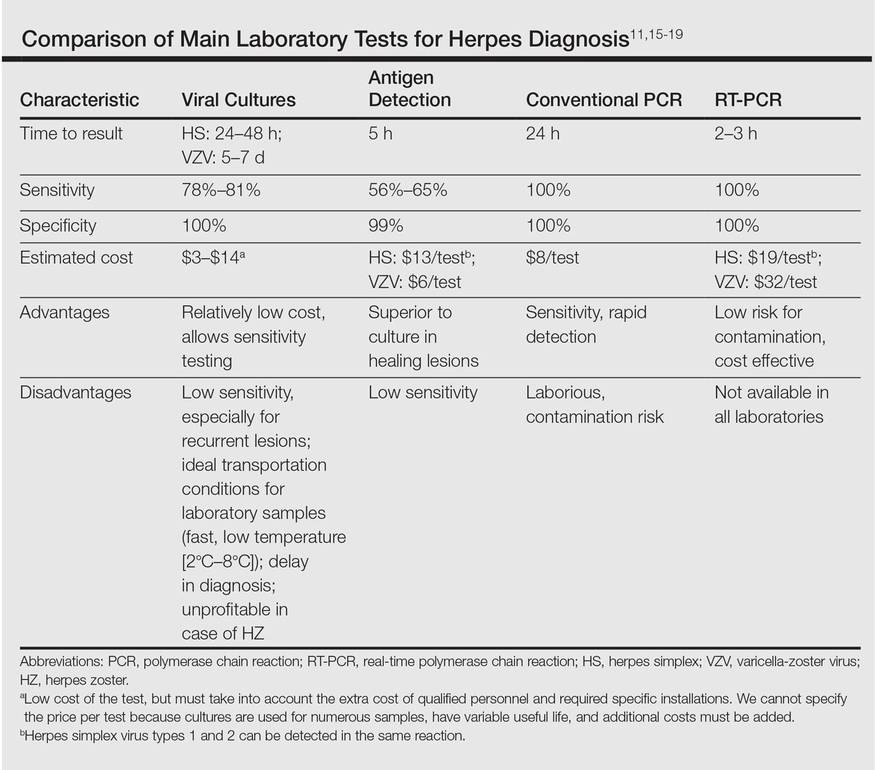

Direct detection of antigens of HS and HZ is a fast and inexpensive technique but lacks the sensitivity of viral cultures. Viral cultures used to be considered the gold standard; however, they are less sensitive than PCR.11 Furthermore, VZV detection is more difficult than HS, leading to a notable percentage of false-negative results.12 Polymerase chain reaction is a fast, reliable, and sensitive laboratory technique. Real-time PCR permits faster results than conventional PCR, specifically for HHV-1, HHV-2, and HZ detection. It also has minimal risk for contamination.13,14 In our opinion, PCR should be the gold standard instead of viral cultures. It has proven its superiority as a rapid method for detection, it is the most sensitive test, it is easier to perform, and it is cost effective (Table).11,15-19 However, viral cultures can allow sensitivity testing and are still an option for determination of susceptibility to antivirals.

In our case, a false-positive was excluded because no sign of possible contamination was found, repeated internal analysis from the same sample confirmed the results, and a new analysis from a new flare showed the same results 2 months later. However, we cannot rule out that the positivity for HZ of the second sample was due to the high sensitivity of the test and a virus latency in nerves.

We propose the use of PCR as a method of choice. Presumably more cases of recurrent HZ and concomitant HS and HZ will be seen with PCR use. In the case of a concomitant infection of HS and HZ, it is reasonable to use an antiviral dosage as in HZ treatment. No literature regarding outcomes from therapy could be found.

- Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, et al. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25:1271-1277.

- Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725.

- Giehl KA, Müller-Sander E, Rottenkolber M, et al. Identification and characterization of 20 immunocompetent patients with simultaneous varicella zoster and herpes simplex virus infection. JEADV. 2008;22:722-728.

- De Vivo C, Bansal MG, Olarte M, et al. Concurrent herpes simplex type 1 and varicella-zoster in the V2 dermatome in an immunocompetent patient. Cutis. 2001;68:120-122.

- Hyun-Ho P, Mu-Hyoung L. Concurrent reactivation of varicella zoster virus and herpes simplex virus in an immunocompetent child. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19:598-600.

- Godet C, Beby-Defaux A, Landron C, et al. Concomitant disseminated herpes simplex virus type 2 infection and varicella zoster virus primoinfection in a pregnant woman. Scand J Infect Dis. 2005;37:774-776.

- Yawn BP, Wollan PC, Kurland MJ, et al. Herpes zoster recurrences more frequent than previously reported. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86:88-93.

- Borba EF, Ribeiro AC, Martin P, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcome or herpes systemic lupus erythematosus. JCR. 2010;16:119-122.

- Nagasawa K, Yamauchi Y, Tada Y, et al. High incidence of herpes zoster in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: an immunological analysis. Ann Rheumatic Dis. 1990;49:630-633.

- Kang TY, Lee HS, Kim TH, et al. Clinical and genetic risk factors of herpes zoster in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol Int. 2005;25:97-102.

- Slomka MJ, Emery L, Munday PE, et al. A comparison of PCR with virus isolation and direct antigen detection for diagnosis and typing of genital herpes. J Med Virol. 1998;55:177-183.

- Nahass GT, Goldstein BA, Zhu WY, et al. Comparison of Tzanck smear, viral culture, and DNA diagnostic methods in detection of herpes simplex and varicella-zoster infection. JAMA. 1992;268:2541-2544.

- Burrows J, Nitsche A, Bayly B, et al. Detection and subtyping of herpes simplex virus in clinical samples by LightCycler PCR, enzyme immunoassay and cell culture. BMC Microbiology. 2002;2:12.

- Bezold GD, Lange ME, Gall H, et al. Detection of cutaneous varicella zoster virus infections by immunofluorescence versus PCR. Eur J Dermatol. 2001;11:108-111.

- Ramaswamy M, McDonald C, Smith M, et al. Diagnosis of genital herpes by real time PCR in routine clinical practice. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80:406-410.

- Wald A, Huang ML, Carrell D, et al. Polymerase chain reaction for detection of herpes simplex virus DNA on mucosal surfaces: comparison with HSV isolation in cell culture. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:1345-1351.

- Marshall DS, Linfert DR, Draghi A, et al. Identification of herpes simplex virus genital infection: comparison of a multiplex PCR assay and traditional viral isolation techniques. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:152-156.

- Koening M, Reynolds KS, Aldous W, et al. Comparison of Light-Cycler PCR, enzyme immunoassay, and tissue culture for detection of herpes simplex virus. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2001;40:107-110.

- Coyle PV, Desai A, Wyatt D, et al. A comparison of virus isolation, indirect immunofluorescence and nested multiplex polymerase chain reaction for the diagnosis of primary and recurrent herpes simplex type 1 and type 2 infections. J Virol Methods. 1999;83:75-82.

To the Editor:

Infections caused by herpes simplex (HS) and herpes zoster (HZ) usually can be recognized by clinical findings; however, laboratory confirmation sometimes is required. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) laboratory tests detect HS or HZ in a sensible and specific manner. New PCR systems such as real-time PCR (RT-PCR) give faster and more precise results. We report a case of recurrent concomitant HZ and HS diagnosed by RT-PCR.

A 62-year-old woman presented with recurrent painful cutaneous lesions on the left buttock and thigh of 9 years’ duration. This eruption was preceded by a burning sensation of 1 week’s duration that extended toward the heel. Cutaneous lesions normally were sparse and persisted for a few days. She also had annular erythematous lesions of 3 years’ duration on the upper trunk and shoulders after sun exposure. On physical examination, an atrophic hypopigmented patch was seen with a few vesicles located on the thigh. Whitish atrophic patches also were found in a linear distribution on the left buttock and thigh (Figure).

Laboratory results included the following: antinuclear antibody, 1:400 on a nuclear dotted pattern; extractable nuclear antigens (anti-Ro60 and anti-Ro52) were positive (reference range, >15); and rheumatoid factor was 24.1 U/mL (reference range, 0–15 U/mL). The patient did not meet any other American College of Rheumatology criteria1,2 of systemic lupus erythematosus apart from photosensitivity. The rest of the analysis—complete blood cell count, liver enzymes, and biochemistry—was normal or negative. Human immunodeficiency virus, herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 (HHV-1 and HHV-2), and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) IgM serologies were negative, whereas IgG VZV serology was positive.

The microbiological study via swab obtained from the roof and fluid from the vesicles showed an indeterminate result from the rapid direct antigen detection with immunofluorescent antibodies. Viral cultures were HHV-2 positive and VZV negative. Conventional PCR showed positive results, both for HHV-2 and VZV. A second analysis, performed with RT-PCR from a new sample taken 2 months later, showed the same results, which led to the diagnosis of recurrent concomitant HS and HZ with a recurrent HZ clinical pattern. The patient was started on valacyclovir 1 g daily, and the number and intensity of flares diminished in the months following treatment.

Concomitant HS and HZ on the same dermatome has been described in the literature.3,4 In a retrospective series of 20 immunocompetent patients, HZ was the main presumed diagnosis before laboratory confirmation of diagnosis, and only 1 case corresponded to recurrent HZ.3 Other cases of simultaneous HS and HZ have been described, but they did not occur on the same dermatome. Half of these reported cases were in immunosuppressed patients.5,6

The recurrent nature of HS is well known; however, recurrent cases of HZ are rare. Nevertheless, in a population-based cohort study of patients with a confirmed prior episode of HZ (N=1669), recurrences were found in 6% of patients.7 Recurrence was more common if the patient was immunosuppressed, was female and 50 years or older, and had pain for more than 30 days.7

The recurrence rate was high in our case, but no immunosuppressive factor could be found apart from probable subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Systemic lupus erythematosus has been associated with a high risk for developing HZ secondary to cell-mediated immunosuppression. The annual incidence of HZ can reach 32 of 1000 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, while in the general population the incidence is only 1.5 to 3 of 1000 patients.8-10

Direct detection of antigens of HS and HZ is a fast and inexpensive technique but lacks the sensitivity of viral cultures. Viral cultures used to be considered the gold standard; however, they are less sensitive than PCR.11 Furthermore, VZV detection is more difficult than HS, leading to a notable percentage of false-negative results.12 Polymerase chain reaction is a fast, reliable, and sensitive laboratory technique. Real-time PCR permits faster results than conventional PCR, specifically for HHV-1, HHV-2, and HZ detection. It also has minimal risk for contamination.13,14 In our opinion, PCR should be the gold standard instead of viral cultures. It has proven its superiority as a rapid method for detection, it is the most sensitive test, it is easier to perform, and it is cost effective (Table).11,15-19 However, viral cultures can allow sensitivity testing and are still an option for determination of susceptibility to antivirals.

In our case, a false-positive was excluded because no sign of possible contamination was found, repeated internal analysis from the same sample confirmed the results, and a new analysis from a new flare showed the same results 2 months later. However, we cannot rule out that the positivity for HZ of the second sample was due to the high sensitivity of the test and a virus latency in nerves.

We propose the use of PCR as a method of choice. Presumably more cases of recurrent HZ and concomitant HS and HZ will be seen with PCR use. In the case of a concomitant infection of HS and HZ, it is reasonable to use an antiviral dosage as in HZ treatment. No literature regarding outcomes from therapy could be found.

To the Editor:

Infections caused by herpes simplex (HS) and herpes zoster (HZ) usually can be recognized by clinical findings; however, laboratory confirmation sometimes is required. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) laboratory tests detect HS or HZ in a sensible and specific manner. New PCR systems such as real-time PCR (RT-PCR) give faster and more precise results. We report a case of recurrent concomitant HZ and HS diagnosed by RT-PCR.

A 62-year-old woman presented with recurrent painful cutaneous lesions on the left buttock and thigh of 9 years’ duration. This eruption was preceded by a burning sensation of 1 week’s duration that extended toward the heel. Cutaneous lesions normally were sparse and persisted for a few days. She also had annular erythematous lesions of 3 years’ duration on the upper trunk and shoulders after sun exposure. On physical examination, an atrophic hypopigmented patch was seen with a few vesicles located on the thigh. Whitish atrophic patches also were found in a linear distribution on the left buttock and thigh (Figure).

Laboratory results included the following: antinuclear antibody, 1:400 on a nuclear dotted pattern; extractable nuclear antigens (anti-Ro60 and anti-Ro52) were positive (reference range, >15); and rheumatoid factor was 24.1 U/mL (reference range, 0–15 U/mL). The patient did not meet any other American College of Rheumatology criteria1,2 of systemic lupus erythematosus apart from photosensitivity. The rest of the analysis—complete blood cell count, liver enzymes, and biochemistry—was normal or negative. Human immunodeficiency virus, herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 (HHV-1 and HHV-2), and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) IgM serologies were negative, whereas IgG VZV serology was positive.

The microbiological study via swab obtained from the roof and fluid from the vesicles showed an indeterminate result from the rapid direct antigen detection with immunofluorescent antibodies. Viral cultures were HHV-2 positive and VZV negative. Conventional PCR showed positive results, both for HHV-2 and VZV. A second analysis, performed with RT-PCR from a new sample taken 2 months later, showed the same results, which led to the diagnosis of recurrent concomitant HS and HZ with a recurrent HZ clinical pattern. The patient was started on valacyclovir 1 g daily, and the number and intensity of flares diminished in the months following treatment.

Concomitant HS and HZ on the same dermatome has been described in the literature.3,4 In a retrospective series of 20 immunocompetent patients, HZ was the main presumed diagnosis before laboratory confirmation of diagnosis, and only 1 case corresponded to recurrent HZ.3 Other cases of simultaneous HS and HZ have been described, but they did not occur on the same dermatome. Half of these reported cases were in immunosuppressed patients.5,6

The recurrent nature of HS is well known; however, recurrent cases of HZ are rare. Nevertheless, in a population-based cohort study of patients with a confirmed prior episode of HZ (N=1669), recurrences were found in 6% of patients.7 Recurrence was more common if the patient was immunosuppressed, was female and 50 years or older, and had pain for more than 30 days.7

The recurrence rate was high in our case, but no immunosuppressive factor could be found apart from probable subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Systemic lupus erythematosus has been associated with a high risk for developing HZ secondary to cell-mediated immunosuppression. The annual incidence of HZ can reach 32 of 1000 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, while in the general population the incidence is only 1.5 to 3 of 1000 patients.8-10

Direct detection of antigens of HS and HZ is a fast and inexpensive technique but lacks the sensitivity of viral cultures. Viral cultures used to be considered the gold standard; however, they are less sensitive than PCR.11 Furthermore, VZV detection is more difficult than HS, leading to a notable percentage of false-negative results.12 Polymerase chain reaction is a fast, reliable, and sensitive laboratory technique. Real-time PCR permits faster results than conventional PCR, specifically for HHV-1, HHV-2, and HZ detection. It also has minimal risk for contamination.13,14 In our opinion, PCR should be the gold standard instead of viral cultures. It has proven its superiority as a rapid method for detection, it is the most sensitive test, it is easier to perform, and it is cost effective (Table).11,15-19 However, viral cultures can allow sensitivity testing and are still an option for determination of susceptibility to antivirals.

In our case, a false-positive was excluded because no sign of possible contamination was found, repeated internal analysis from the same sample confirmed the results, and a new analysis from a new flare showed the same results 2 months later. However, we cannot rule out that the positivity for HZ of the second sample was due to the high sensitivity of the test and a virus latency in nerves.

We propose the use of PCR as a method of choice. Presumably more cases of recurrent HZ and concomitant HS and HZ will be seen with PCR use. In the case of a concomitant infection of HS and HZ, it is reasonable to use an antiviral dosage as in HZ treatment. No literature regarding outcomes from therapy could be found.

- Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, et al. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25:1271-1277.

- Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725.

- Giehl KA, Müller-Sander E, Rottenkolber M, et al. Identification and characterization of 20 immunocompetent patients with simultaneous varicella zoster and herpes simplex virus infection. JEADV. 2008;22:722-728.

- De Vivo C, Bansal MG, Olarte M, et al. Concurrent herpes simplex type 1 and varicella-zoster in the V2 dermatome in an immunocompetent patient. Cutis. 2001;68:120-122.

- Hyun-Ho P, Mu-Hyoung L. Concurrent reactivation of varicella zoster virus and herpes simplex virus in an immunocompetent child. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19:598-600.

- Godet C, Beby-Defaux A, Landron C, et al. Concomitant disseminated herpes simplex virus type 2 infection and varicella zoster virus primoinfection in a pregnant woman. Scand J Infect Dis. 2005;37:774-776.

- Yawn BP, Wollan PC, Kurland MJ, et al. Herpes zoster recurrences more frequent than previously reported. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86:88-93.

- Borba EF, Ribeiro AC, Martin P, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcome or herpes systemic lupus erythematosus. JCR. 2010;16:119-122.