User login

Azathioprine Hypersensitivity Presenting as Neutrophilic Dermatosis and Erythema Nodosum

To the Editor:

Azathioprine (AZA) hypersensitivity is an immunologically mediated reaction that presents within 1 to 4 weeks of drug initiation.1 Its cutaneous manifestations include Sweet syndrome, erythema nodosum (EN), and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, with 88% of cases presenting as neutrophilic dermatoses.2 Confirmation with cutaneous biopsy and cessation of medication is essential to prevent life-threatening anaphylactoid reactions.

A 58-year-old man with a history of Crohn disease was admitted with high fevers (>38.9°C); abdominal pain; diarrhea; and a nonpruritic “pimplelike” rash on the face, chest, and back with a tender nodule on the right leg of 5 days’ duration. Eight days prior to admission, he had started AZA for treatment of Crohn disease. In the hospital he received intravenous metronidazole for a presumed bowel infection; however, the lesions and symptoms did not resolve. Other medical history included psoriatic arthritis for which he was taking oral prednisone 50 mg daily; prednisone was continued during hospitalization.

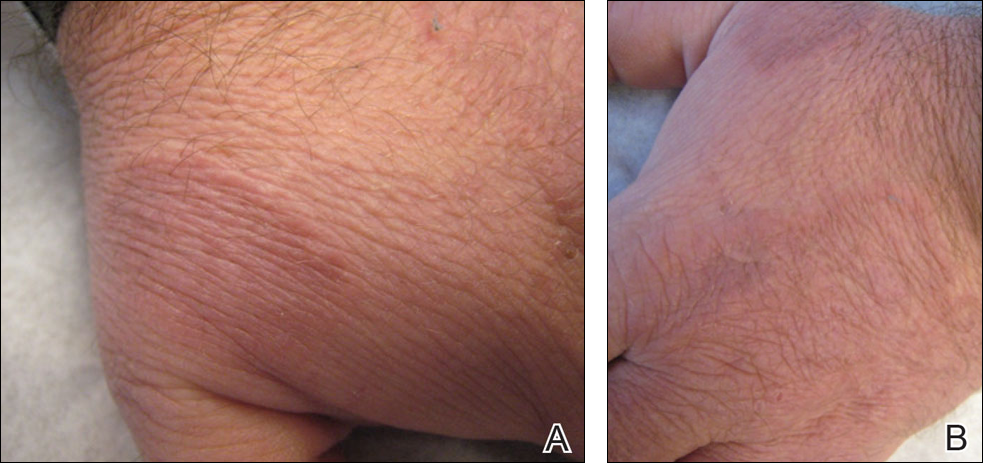

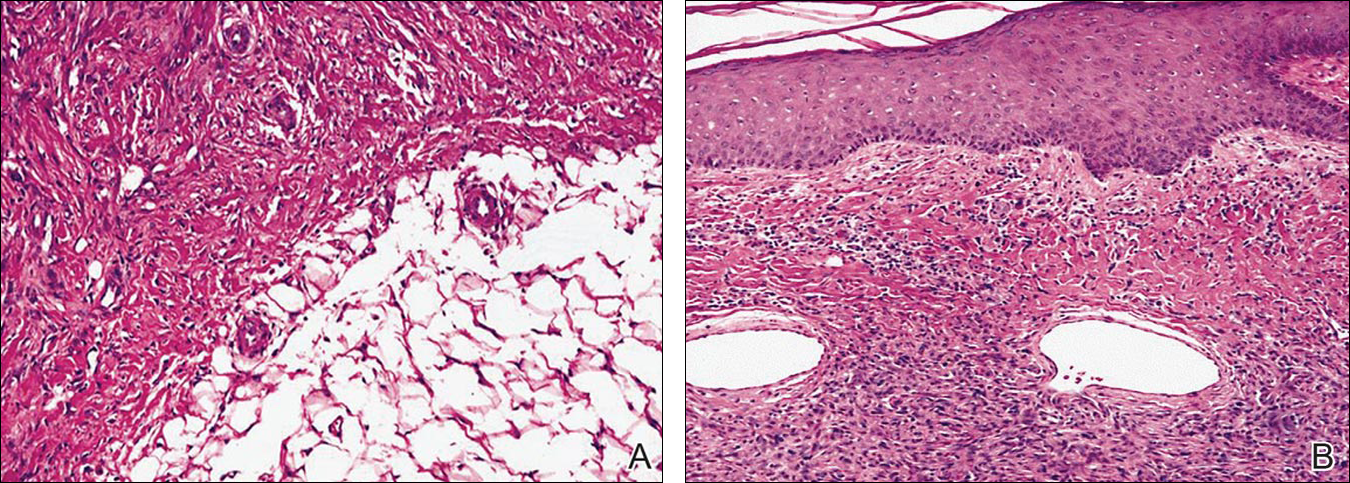

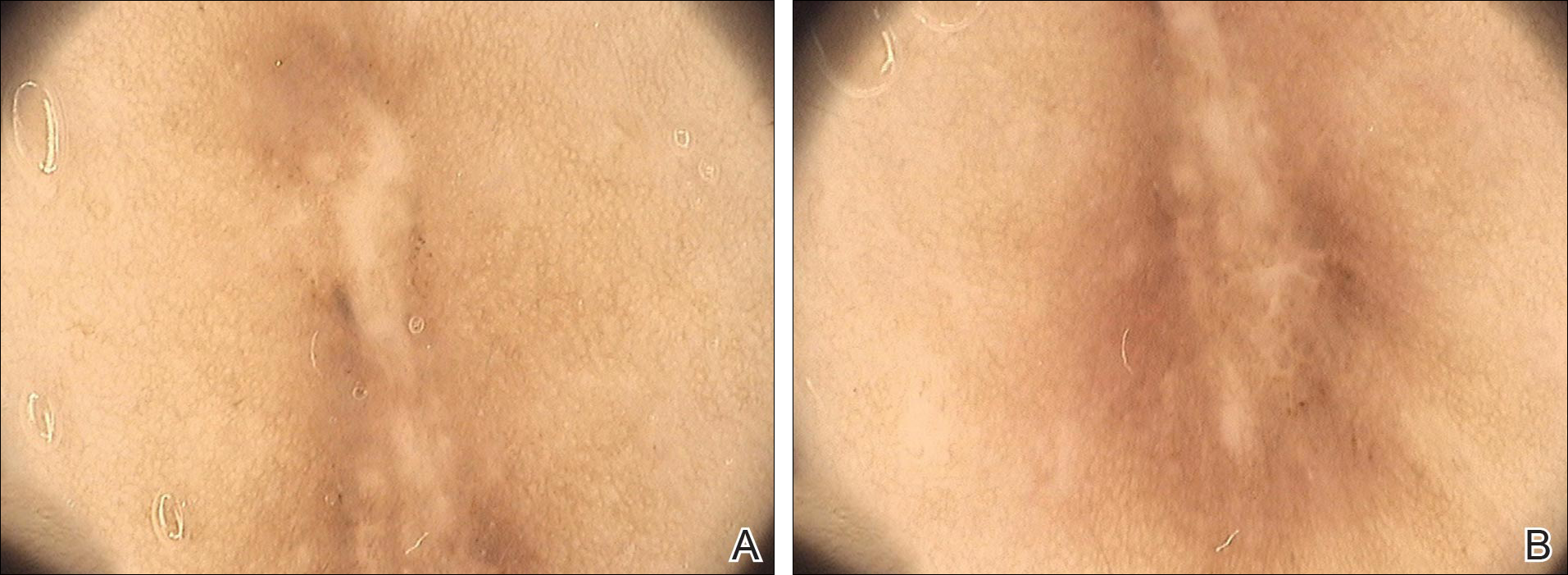

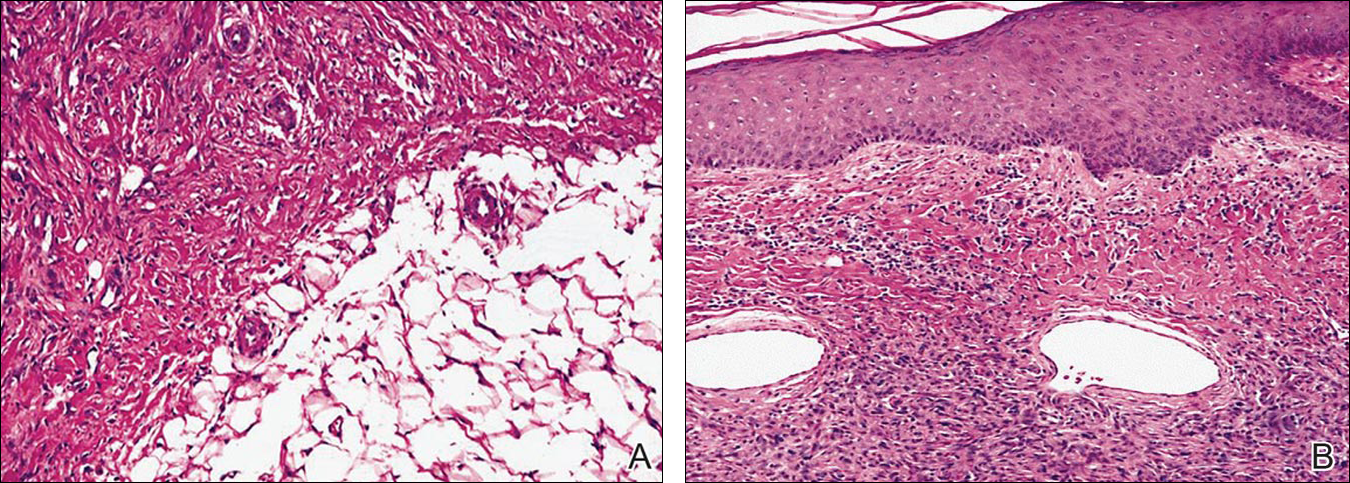

Physical examination showed that the patient was alert and well appearing. On the face, upper chest and back (Figure 1), shoulders, and knees were fewer than 20 sparsely distributed, nontender, 3- to 4-mm pustules. The patient’s scalp, lower back, abdomen, arms, and feet were spared. There also was a solitary 3.5-cm, tender, erythematous nodule on the right lower leg (Figure 2). Blood tests revealed leukocytosis (15,000/mm3 [reference range, 4300–10,300/mm3]) with neutrophilia (90%) and an elevated C-reactive protein level of 173 mg/L (reference range, <10 mg/L). Liver function tests were normal. Thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) was on the low end of the reference range. Tissue culture of a shoulder pustule grew only Staphylococcus non-aureus. Blood cultures were negative. A 4-mm punch biopsy specimen from the right leg nodule revealed septal panniculitis with neutrophilic and granulomatous infiltrate consistent with EN.

A clinical diagnosis of AZA hypersensitivity was made. Antibiotics and AZA were discontinued and the patient’s lesions resolved within 6 days. Medication rechallenge was not attempted and the patient is now managed with infliximab.

Azathioprine is a well-known and commonly used drug for inflammatory bowel diseases, rheumatoid arthritis, and prevention of transplant rejection. Hypersensitivity is a lesser-known complication of AZA therapy, with most reactions occurring within 4 weeks of treatment initiation. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms azathioprine and hypersensitivity found only 67 documented cases of AZA hypersensitivity between 1986 and 2009.2 Common findings include fever, malaise, arthralgia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, and neutrophilic dermatoses.

Previously reported cases of AZA hypersensitivity with cutaneous manifestations include Sweet syndrome (17.9%), small vessel vasculitis (10.4%), EN (4.4%), acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (4.4%), and nonspecific cutaneous findings (11.9%).2 One other case reported AZA hypersensitivity presenting as EN with a neutrophilic pustular dermatosis.3 Although Sweet syndrome–like lesions, EN, and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis have been reported in the context of inflammatory bowel disease, in this case the appearance of these symptoms within 1 week of AZA initiation and resolution after AZA discontinuation is highly suggestive of AZA hypersensitivity. Also, several reports have documented rapid (within a few hours) recurrence of symptoms on rechallenge with AZA.4-6 Moreover, cases of cutaneous AZA hypersensitivity reactions in patients with no history of inflammatory bowel diseases have been reported.6-8

As in this case, cutaneous AZA hypersensitivity can occur even in the setting of normal TPMT levels, suggesting that this phenomenon is a dose-independent reaction.2 Abnormal metabolism of AZA does not appear to be related to previously reported neutrophilic pustular dermatosis3,4 or EN.4 Although the mechanism of hypersensitivity is unclear, there is a report of a patient who developed AZA hypersensitivity but was able to tolerate 6-mercaptopurine, a metabolite of AZA. The authors suggested that the imidazole component of AZA might be responsible for hypersensitivity reactions.9

The differential diagnosis of a patient with these findings includes infectious, rheumatologic, neurologic, or autoimmune diseases, as well as septic shock. Hence, negative cultures and a failure to respond to antibiotics make infection less likely. An appropriate time course of AZA initiation, the development of rash, and a cutaneous biopsy can lead to prompt diagnosis and cessation of AZA.

Once AZA hypersensitivity is suspected, the drug should be discontinued and the reaction should resolve within 2 to 3 days2 and the skin lesions within 5 to 6 days.2,10 Medication rechallenge is contraindicated because AZA rarely has been associated with shock syndrome and hypotension.11-19

Azathioprine hypersensitivity is a serious yet still underrecognized condition in the dermatologic community. In our case, symptoms appeared rapidly and resolved quickly after AZA was discontinued. Azathioprine-induced neutrophilic dermatosis presenting with EN should be recognized as a potential dermatologic manifestation of AZA hypersensitivity, which is a dose-dependent reaction even with normal TPMT levels. Rechallenge with AZA is not recommended due to the risk of a life-threatening anaphylactoid reaction.

- Meggitt SJ, Anstey AV, Mohd Mustapa MF, et al. British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the safe and effective prescribing of azathioprine 2011. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:711-734.

- Bidinger JJ, Sky K, Battafarano DF, et al. The cutaneous and systemic manifestations of azathioprine hypersensitivity syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:184-191.

- Hurtado-Garcia R, Escribano-Stablé JC, Pascual JC, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis caused by azathioprine hypersensitivity. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1522-1525.

- De Fonclare AL, Khosrotehrani K, Aractingi S, et al. Erythema nodosum-like eruption as a manifestation of azathioprine hypersensitivity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:744-748.

- Jeurissen ME, Boerbooms AM, van de Putte LB, et al. Azathioprine induced fever, chills, rash, and hepatotoxicity in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1990;49:25-27.

- Goldenberg DL, Stor RA. Azathioprine hypersensitivity mimicking an acute exacerbation of dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol. 1975;2:346-349.

- Watts GF, Corston R. Hypersensitivity to azathioprine in myasthenia gravis. Postgrad Med J. 1984;60:362-363.

- El-Azhary RA, Brunner KL, Gibson LE. Sweet syndrome as a manifestation of azathioprine hypersensitivity. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:1026-1030.

- Stetter M, Schmidl M, Krapf R. Azathioprine hypersensitivity mimicking Goodpasture’s syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis. 1994;23:874-877.

- Cyrus N, Stavert R, Mason AR, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis after azathioprine exposure. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:592-597.

- Cunningham T, Barraclough D, Muirdin K. Azathioprine induced shock. Br Med J. 1981;283:823-824.

- Elston GE, Johnston GA, Mortimer NJ, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis associated with azathioprine hypersensitivity. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:52-53.

- Fields CL, Robinson JW, Roy TM, et al. Hypersensitivity reaction to azathioprine. South Med J. 1998;91:471-474.

- Keystone E, Schabas R. Hypotension with oliguria: a side effect of azathioprine. Arthritis Rheum. 1981;24:1453-1454.

- Rosenthal E. Azathioprine shock. Postgrad Med J. 1986;62:677-678.

- Sofat N, Houghton J, McHale J, et al. Azathioprine hypersensitivity. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:719-720.

- Knowles SR, Gupta AK, Shear NH, et al. Azathioprine hypersensitivity-like reactions—a case report and a review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:353-356.

- Demirtaş-Ertan G, Rowshani AT, ten Berge IJ. Azathioprine-induced shock in a patient suffering from undifferentiated erosive oligoarthritis. Neth J Med. 2006;64:124-126.

- Zaltzman M, Kallenbach J, Shapiro T, et al. Life-threatening hypotension associated with azathioprine therapy. a case report. S Afr Med J. 1984;65:306.

To the Editor:

Azathioprine (AZA) hypersensitivity is an immunologically mediated reaction that presents within 1 to 4 weeks of drug initiation.1 Its cutaneous manifestations include Sweet syndrome, erythema nodosum (EN), and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, with 88% of cases presenting as neutrophilic dermatoses.2 Confirmation with cutaneous biopsy and cessation of medication is essential to prevent life-threatening anaphylactoid reactions.

A 58-year-old man with a history of Crohn disease was admitted with high fevers (>38.9°C); abdominal pain; diarrhea; and a nonpruritic “pimplelike” rash on the face, chest, and back with a tender nodule on the right leg of 5 days’ duration. Eight days prior to admission, he had started AZA for treatment of Crohn disease. In the hospital he received intravenous metronidazole for a presumed bowel infection; however, the lesions and symptoms did not resolve. Other medical history included psoriatic arthritis for which he was taking oral prednisone 50 mg daily; prednisone was continued during hospitalization.

Physical examination showed that the patient was alert and well appearing. On the face, upper chest and back (Figure 1), shoulders, and knees were fewer than 20 sparsely distributed, nontender, 3- to 4-mm pustules. The patient’s scalp, lower back, abdomen, arms, and feet were spared. There also was a solitary 3.5-cm, tender, erythematous nodule on the right lower leg (Figure 2). Blood tests revealed leukocytosis (15,000/mm3 [reference range, 4300–10,300/mm3]) with neutrophilia (90%) and an elevated C-reactive protein level of 173 mg/L (reference range, <10 mg/L). Liver function tests were normal. Thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) was on the low end of the reference range. Tissue culture of a shoulder pustule grew only Staphylococcus non-aureus. Blood cultures were negative. A 4-mm punch biopsy specimen from the right leg nodule revealed septal panniculitis with neutrophilic and granulomatous infiltrate consistent with EN.

A clinical diagnosis of AZA hypersensitivity was made. Antibiotics and AZA were discontinued and the patient’s lesions resolved within 6 days. Medication rechallenge was not attempted and the patient is now managed with infliximab.

Azathioprine is a well-known and commonly used drug for inflammatory bowel diseases, rheumatoid arthritis, and prevention of transplant rejection. Hypersensitivity is a lesser-known complication of AZA therapy, with most reactions occurring within 4 weeks of treatment initiation. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms azathioprine and hypersensitivity found only 67 documented cases of AZA hypersensitivity between 1986 and 2009.2 Common findings include fever, malaise, arthralgia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, and neutrophilic dermatoses.

Previously reported cases of AZA hypersensitivity with cutaneous manifestations include Sweet syndrome (17.9%), small vessel vasculitis (10.4%), EN (4.4%), acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (4.4%), and nonspecific cutaneous findings (11.9%).2 One other case reported AZA hypersensitivity presenting as EN with a neutrophilic pustular dermatosis.3 Although Sweet syndrome–like lesions, EN, and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis have been reported in the context of inflammatory bowel disease, in this case the appearance of these symptoms within 1 week of AZA initiation and resolution after AZA discontinuation is highly suggestive of AZA hypersensitivity. Also, several reports have documented rapid (within a few hours) recurrence of symptoms on rechallenge with AZA.4-6 Moreover, cases of cutaneous AZA hypersensitivity reactions in patients with no history of inflammatory bowel diseases have been reported.6-8

As in this case, cutaneous AZA hypersensitivity can occur even in the setting of normal TPMT levels, suggesting that this phenomenon is a dose-independent reaction.2 Abnormal metabolism of AZA does not appear to be related to previously reported neutrophilic pustular dermatosis3,4 or EN.4 Although the mechanism of hypersensitivity is unclear, there is a report of a patient who developed AZA hypersensitivity but was able to tolerate 6-mercaptopurine, a metabolite of AZA. The authors suggested that the imidazole component of AZA might be responsible for hypersensitivity reactions.9

The differential diagnosis of a patient with these findings includes infectious, rheumatologic, neurologic, or autoimmune diseases, as well as septic shock. Hence, negative cultures and a failure to respond to antibiotics make infection less likely. An appropriate time course of AZA initiation, the development of rash, and a cutaneous biopsy can lead to prompt diagnosis and cessation of AZA.

Once AZA hypersensitivity is suspected, the drug should be discontinued and the reaction should resolve within 2 to 3 days2 and the skin lesions within 5 to 6 days.2,10 Medication rechallenge is contraindicated because AZA rarely has been associated with shock syndrome and hypotension.11-19

Azathioprine hypersensitivity is a serious yet still underrecognized condition in the dermatologic community. In our case, symptoms appeared rapidly and resolved quickly after AZA was discontinued. Azathioprine-induced neutrophilic dermatosis presenting with EN should be recognized as a potential dermatologic manifestation of AZA hypersensitivity, which is a dose-dependent reaction even with normal TPMT levels. Rechallenge with AZA is not recommended due to the risk of a life-threatening anaphylactoid reaction.

To the Editor:

Azathioprine (AZA) hypersensitivity is an immunologically mediated reaction that presents within 1 to 4 weeks of drug initiation.1 Its cutaneous manifestations include Sweet syndrome, erythema nodosum (EN), and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, with 88% of cases presenting as neutrophilic dermatoses.2 Confirmation with cutaneous biopsy and cessation of medication is essential to prevent life-threatening anaphylactoid reactions.

A 58-year-old man with a history of Crohn disease was admitted with high fevers (>38.9°C); abdominal pain; diarrhea; and a nonpruritic “pimplelike” rash on the face, chest, and back with a tender nodule on the right leg of 5 days’ duration. Eight days prior to admission, he had started AZA for treatment of Crohn disease. In the hospital he received intravenous metronidazole for a presumed bowel infection; however, the lesions and symptoms did not resolve. Other medical history included psoriatic arthritis for which he was taking oral prednisone 50 mg daily; prednisone was continued during hospitalization.

Physical examination showed that the patient was alert and well appearing. On the face, upper chest and back (Figure 1), shoulders, and knees were fewer than 20 sparsely distributed, nontender, 3- to 4-mm pustules. The patient’s scalp, lower back, abdomen, arms, and feet were spared. There also was a solitary 3.5-cm, tender, erythematous nodule on the right lower leg (Figure 2). Blood tests revealed leukocytosis (15,000/mm3 [reference range, 4300–10,300/mm3]) with neutrophilia (90%) and an elevated C-reactive protein level of 173 mg/L (reference range, <10 mg/L). Liver function tests were normal. Thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) was on the low end of the reference range. Tissue culture of a shoulder pustule grew only Staphylococcus non-aureus. Blood cultures were negative. A 4-mm punch biopsy specimen from the right leg nodule revealed septal panniculitis with neutrophilic and granulomatous infiltrate consistent with EN.

A clinical diagnosis of AZA hypersensitivity was made. Antibiotics and AZA were discontinued and the patient’s lesions resolved within 6 days. Medication rechallenge was not attempted and the patient is now managed with infliximab.

Azathioprine is a well-known and commonly used drug for inflammatory bowel diseases, rheumatoid arthritis, and prevention of transplant rejection. Hypersensitivity is a lesser-known complication of AZA therapy, with most reactions occurring within 4 weeks of treatment initiation. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms azathioprine and hypersensitivity found only 67 documented cases of AZA hypersensitivity between 1986 and 2009.2 Common findings include fever, malaise, arthralgia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, and neutrophilic dermatoses.

Previously reported cases of AZA hypersensitivity with cutaneous manifestations include Sweet syndrome (17.9%), small vessel vasculitis (10.4%), EN (4.4%), acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (4.4%), and nonspecific cutaneous findings (11.9%).2 One other case reported AZA hypersensitivity presenting as EN with a neutrophilic pustular dermatosis.3 Although Sweet syndrome–like lesions, EN, and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis have been reported in the context of inflammatory bowel disease, in this case the appearance of these symptoms within 1 week of AZA initiation and resolution after AZA discontinuation is highly suggestive of AZA hypersensitivity. Also, several reports have documented rapid (within a few hours) recurrence of symptoms on rechallenge with AZA.4-6 Moreover, cases of cutaneous AZA hypersensitivity reactions in patients with no history of inflammatory bowel diseases have been reported.6-8

As in this case, cutaneous AZA hypersensitivity can occur even in the setting of normal TPMT levels, suggesting that this phenomenon is a dose-independent reaction.2 Abnormal metabolism of AZA does not appear to be related to previously reported neutrophilic pustular dermatosis3,4 or EN.4 Although the mechanism of hypersensitivity is unclear, there is a report of a patient who developed AZA hypersensitivity but was able to tolerate 6-mercaptopurine, a metabolite of AZA. The authors suggested that the imidazole component of AZA might be responsible for hypersensitivity reactions.9

The differential diagnosis of a patient with these findings includes infectious, rheumatologic, neurologic, or autoimmune diseases, as well as septic shock. Hence, negative cultures and a failure to respond to antibiotics make infection less likely. An appropriate time course of AZA initiation, the development of rash, and a cutaneous biopsy can lead to prompt diagnosis and cessation of AZA.

Once AZA hypersensitivity is suspected, the drug should be discontinued and the reaction should resolve within 2 to 3 days2 and the skin lesions within 5 to 6 days.2,10 Medication rechallenge is contraindicated because AZA rarely has been associated with shock syndrome and hypotension.11-19

Azathioprine hypersensitivity is a serious yet still underrecognized condition in the dermatologic community. In our case, symptoms appeared rapidly and resolved quickly after AZA was discontinued. Azathioprine-induced neutrophilic dermatosis presenting with EN should be recognized as a potential dermatologic manifestation of AZA hypersensitivity, which is a dose-dependent reaction even with normal TPMT levels. Rechallenge with AZA is not recommended due to the risk of a life-threatening anaphylactoid reaction.

- Meggitt SJ, Anstey AV, Mohd Mustapa MF, et al. British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the safe and effective prescribing of azathioprine 2011. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:711-734.

- Bidinger JJ, Sky K, Battafarano DF, et al. The cutaneous and systemic manifestations of azathioprine hypersensitivity syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:184-191.

- Hurtado-Garcia R, Escribano-Stablé JC, Pascual JC, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis caused by azathioprine hypersensitivity. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1522-1525.

- De Fonclare AL, Khosrotehrani K, Aractingi S, et al. Erythema nodosum-like eruption as a manifestation of azathioprine hypersensitivity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:744-748.

- Jeurissen ME, Boerbooms AM, van de Putte LB, et al. Azathioprine induced fever, chills, rash, and hepatotoxicity in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1990;49:25-27.

- Goldenberg DL, Stor RA. Azathioprine hypersensitivity mimicking an acute exacerbation of dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol. 1975;2:346-349.

- Watts GF, Corston R. Hypersensitivity to azathioprine in myasthenia gravis. Postgrad Med J. 1984;60:362-363.

- El-Azhary RA, Brunner KL, Gibson LE. Sweet syndrome as a manifestation of azathioprine hypersensitivity. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:1026-1030.

- Stetter M, Schmidl M, Krapf R. Azathioprine hypersensitivity mimicking Goodpasture’s syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis. 1994;23:874-877.

- Cyrus N, Stavert R, Mason AR, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis after azathioprine exposure. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:592-597.

- Cunningham T, Barraclough D, Muirdin K. Azathioprine induced shock. Br Med J. 1981;283:823-824.

- Elston GE, Johnston GA, Mortimer NJ, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis associated with azathioprine hypersensitivity. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:52-53.

- Fields CL, Robinson JW, Roy TM, et al. Hypersensitivity reaction to azathioprine. South Med J. 1998;91:471-474.

- Keystone E, Schabas R. Hypotension with oliguria: a side effect of azathioprine. Arthritis Rheum. 1981;24:1453-1454.

- Rosenthal E. Azathioprine shock. Postgrad Med J. 1986;62:677-678.

- Sofat N, Houghton J, McHale J, et al. Azathioprine hypersensitivity. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:719-720.

- Knowles SR, Gupta AK, Shear NH, et al. Azathioprine hypersensitivity-like reactions—a case report and a review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:353-356.

- Demirtaş-Ertan G, Rowshani AT, ten Berge IJ. Azathioprine-induced shock in a patient suffering from undifferentiated erosive oligoarthritis. Neth J Med. 2006;64:124-126.

- Zaltzman M, Kallenbach J, Shapiro T, et al. Life-threatening hypotension associated with azathioprine therapy. a case report. S Afr Med J. 1984;65:306.

- Meggitt SJ, Anstey AV, Mohd Mustapa MF, et al. British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the safe and effective prescribing of azathioprine 2011. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:711-734.

- Bidinger JJ, Sky K, Battafarano DF, et al. The cutaneous and systemic manifestations of azathioprine hypersensitivity syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:184-191.

- Hurtado-Garcia R, Escribano-Stablé JC, Pascual JC, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis caused by azathioprine hypersensitivity. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1522-1525.

- De Fonclare AL, Khosrotehrani K, Aractingi S, et al. Erythema nodosum-like eruption as a manifestation of azathioprine hypersensitivity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:744-748.

- Jeurissen ME, Boerbooms AM, van de Putte LB, et al. Azathioprine induced fever, chills, rash, and hepatotoxicity in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1990;49:25-27.

- Goldenberg DL, Stor RA. Azathioprine hypersensitivity mimicking an acute exacerbation of dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol. 1975;2:346-349.

- Watts GF, Corston R. Hypersensitivity to azathioprine in myasthenia gravis. Postgrad Med J. 1984;60:362-363.

- El-Azhary RA, Brunner KL, Gibson LE. Sweet syndrome as a manifestation of azathioprine hypersensitivity. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:1026-1030.

- Stetter M, Schmidl M, Krapf R. Azathioprine hypersensitivity mimicking Goodpasture’s syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis. 1994;23:874-877.

- Cyrus N, Stavert R, Mason AR, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis after azathioprine exposure. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:592-597.

- Cunningham T, Barraclough D, Muirdin K. Azathioprine induced shock. Br Med J. 1981;283:823-824.

- Elston GE, Johnston GA, Mortimer NJ, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis associated with azathioprine hypersensitivity. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:52-53.

- Fields CL, Robinson JW, Roy TM, et al. Hypersensitivity reaction to azathioprine. South Med J. 1998;91:471-474.

- Keystone E, Schabas R. Hypotension with oliguria: a side effect of azathioprine. Arthritis Rheum. 1981;24:1453-1454.

- Rosenthal E. Azathioprine shock. Postgrad Med J. 1986;62:677-678.

- Sofat N, Houghton J, McHale J, et al. Azathioprine hypersensitivity. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:719-720.

- Knowles SR, Gupta AK, Shear NH, et al. Azathioprine hypersensitivity-like reactions—a case report and a review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:353-356.

- Demirtaş-Ertan G, Rowshani AT, ten Berge IJ. Azathioprine-induced shock in a patient suffering from undifferentiated erosive oligoarthritis. Neth J Med. 2006;64:124-126.

- Zaltzman M, Kallenbach J, Shapiro T, et al. Life-threatening hypotension associated with azathioprine therapy. a case report. S Afr Med J. 1984;65:306.

Practice Points

- Azathioprine is a well-known immunosuppressant for renal transplant recipients and inflammatory bowel disease with several off-label uses in dermatology including immunobullous dermatoses, neutrophilic dermatoses, and autoimmune connective tissue diseases.

- Azathioprine hypersensitivity is rare and can present with systemic symptoms of fever and a neutrophilic dermatosis, which is usually self-limited but can progress to an anaphylactoid reaction with multiorgan failure.

- If a more mild hypersensitivity reaction is appreciated, then a rechallenge is not recommended and should be avoided.

Resolution of Disseminated Granuloma Annulare With Removal of Surgical Hardware

To the Editor:

Disseminated granuloma annulare is a noninfectious granulomatous disease of unknown etiology. Reported precipitating factors include trauma, sun exposure, viral infection, vaccination, and malignancy.1 In contrast to a localized variant, disseminated granuloma annulare is associated with a later age of onset, longer duration, and recalcitrance to therapy.2 Although a variety of therapeutic approaches exist, there are limited efficacy data, which is complicated by the spontaneous, self-limited nature of the disease.3,4

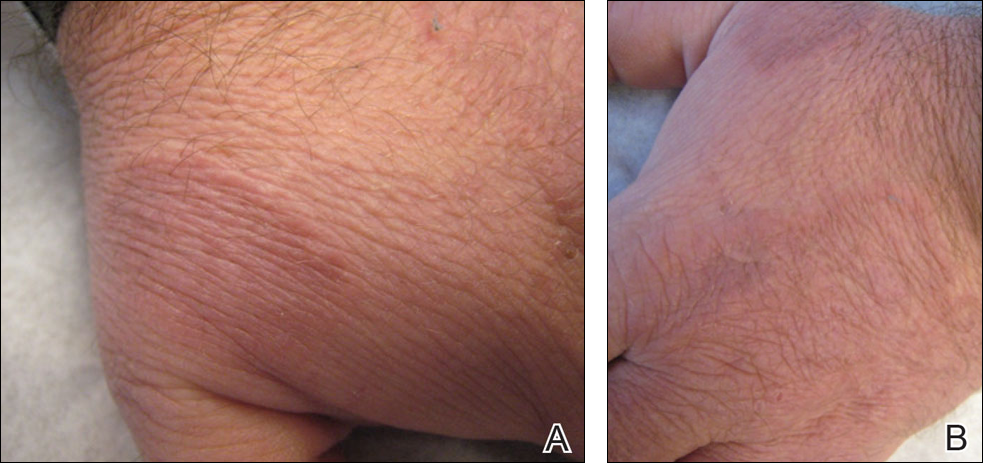

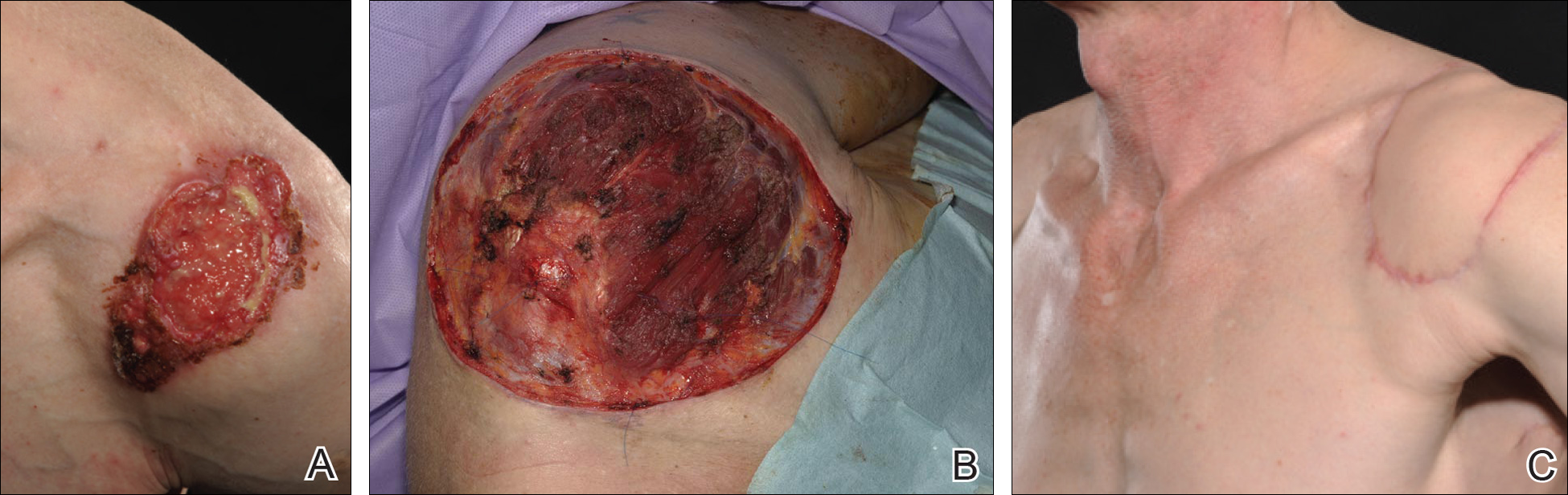

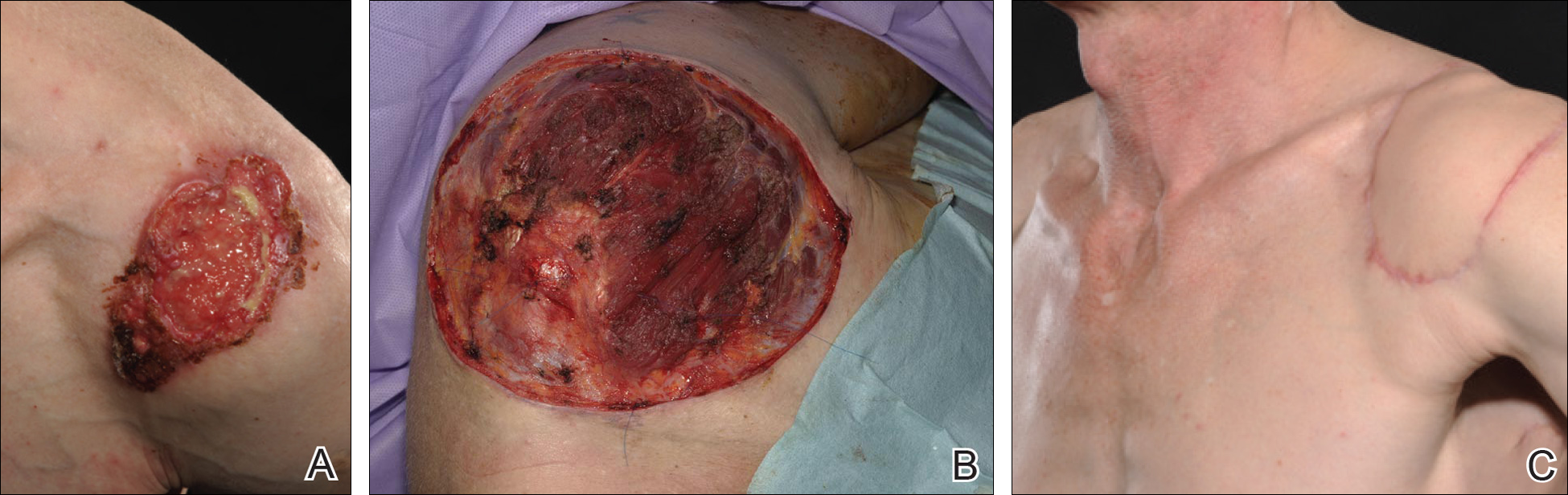

A 47-year-old man presented with an eruption of a thick red plaque on the dorsal aspect of the left hand (Figure). The eruption began 6 weeks following fixation of a Galeazzi fracture of the right radius with a stainless steel volar plate. Subsequent to the initial eruption, similar indurated plaques developed on the left thenar area, bilateral axillae, and bilateral legs. A punch biopsy was conducted to rule out necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum and sarcoidosis as well as to histopathologically confirm the clinical diagnosis of disseminated granuloma annulare. Following diagnosis, the patient received topical clobetasol for application to the advancing borders of the plaques. At 4-month follow-up, additional plaques continued to develop. The patient was not interested in pursuing alternative courses of therapy and felt that the implantation of surgical hardware was the cause. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no reports of precipitation of disseminated granuloma annulare in response to surgical hardware. Given the time course of onset of the eruption it was plausible that the hardware was the inciting event. The orthopedist thought that the fracture had healed sufficiently to remove the volar plate. The patient elected to have the hardware removed to potentially resolve or arrest the progression of the plaques. Resolution of the plaques was observed by the patient 2 weeks following surgical removal of the volar plate. At 4 months following hardware removal, the patient only had 2 slightly pink, hyperpigmented lesions on the left hand in the areas most severely affected, with complete resolution of all other plaques. The patient was given topical clobetasol for the residual lesions.

Precipitation and spontaneous resolution of disseminated granuloma annulare following the implantation and removal of surgical hardware is rare. Resolution following hardware removal is consistent with the theory that pathogenesis is due to a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to an inciting factor.5 Our case suggests that disseminated granuloma annulare may occur as a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to implanted surgical hardware, which should be considered in the etiology and potential therapeutic options for this disorder.

- Mills A, Chetty R. Auricular granuloma annulare. a consequence of trauma? Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:431-433.

- Dicken CH, Carrington SG, Winkelmann RK. Generalized granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:556-563.

- Yun JH, Lee JY, Kim MK, et al. Clinical and pathological features of generalized granuloma annulare with their correlation: a retrospective multicenter study in Korea [published online May 31, 2009]. Ann Dermatol. 2009:21:113-119

- Cyr PR. Diagnosis and management of granuloma annulare. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:1729-1734.

- Buechner SA, Winkelmann RK, Banks PM. Identification of T-cell subpopulations in granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:125-128.

To the Editor:

Disseminated granuloma annulare is a noninfectious granulomatous disease of unknown etiology. Reported precipitating factors include trauma, sun exposure, viral infection, vaccination, and malignancy.1 In contrast to a localized variant, disseminated granuloma annulare is associated with a later age of onset, longer duration, and recalcitrance to therapy.2 Although a variety of therapeutic approaches exist, there are limited efficacy data, which is complicated by the spontaneous, self-limited nature of the disease.3,4

A 47-year-old man presented with an eruption of a thick red plaque on the dorsal aspect of the left hand (Figure). The eruption began 6 weeks following fixation of a Galeazzi fracture of the right radius with a stainless steel volar plate. Subsequent to the initial eruption, similar indurated plaques developed on the left thenar area, bilateral axillae, and bilateral legs. A punch biopsy was conducted to rule out necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum and sarcoidosis as well as to histopathologically confirm the clinical diagnosis of disseminated granuloma annulare. Following diagnosis, the patient received topical clobetasol for application to the advancing borders of the plaques. At 4-month follow-up, additional plaques continued to develop. The patient was not interested in pursuing alternative courses of therapy and felt that the implantation of surgical hardware was the cause. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no reports of precipitation of disseminated granuloma annulare in response to surgical hardware. Given the time course of onset of the eruption it was plausible that the hardware was the inciting event. The orthopedist thought that the fracture had healed sufficiently to remove the volar plate. The patient elected to have the hardware removed to potentially resolve or arrest the progression of the plaques. Resolution of the plaques was observed by the patient 2 weeks following surgical removal of the volar plate. At 4 months following hardware removal, the patient only had 2 slightly pink, hyperpigmented lesions on the left hand in the areas most severely affected, with complete resolution of all other plaques. The patient was given topical clobetasol for the residual lesions.

Precipitation and spontaneous resolution of disseminated granuloma annulare following the implantation and removal of surgical hardware is rare. Resolution following hardware removal is consistent with the theory that pathogenesis is due to a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to an inciting factor.5 Our case suggests that disseminated granuloma annulare may occur as a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to implanted surgical hardware, which should be considered in the etiology and potential therapeutic options for this disorder.

To the Editor:

Disseminated granuloma annulare is a noninfectious granulomatous disease of unknown etiology. Reported precipitating factors include trauma, sun exposure, viral infection, vaccination, and malignancy.1 In contrast to a localized variant, disseminated granuloma annulare is associated with a later age of onset, longer duration, and recalcitrance to therapy.2 Although a variety of therapeutic approaches exist, there are limited efficacy data, which is complicated by the spontaneous, self-limited nature of the disease.3,4

A 47-year-old man presented with an eruption of a thick red plaque on the dorsal aspect of the left hand (Figure). The eruption began 6 weeks following fixation of a Galeazzi fracture of the right radius with a stainless steel volar plate. Subsequent to the initial eruption, similar indurated plaques developed on the left thenar area, bilateral axillae, and bilateral legs. A punch biopsy was conducted to rule out necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum and sarcoidosis as well as to histopathologically confirm the clinical diagnosis of disseminated granuloma annulare. Following diagnosis, the patient received topical clobetasol for application to the advancing borders of the plaques. At 4-month follow-up, additional plaques continued to develop. The patient was not interested in pursuing alternative courses of therapy and felt that the implantation of surgical hardware was the cause. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no reports of precipitation of disseminated granuloma annulare in response to surgical hardware. Given the time course of onset of the eruption it was plausible that the hardware was the inciting event. The orthopedist thought that the fracture had healed sufficiently to remove the volar plate. The patient elected to have the hardware removed to potentially resolve or arrest the progression of the plaques. Resolution of the plaques was observed by the patient 2 weeks following surgical removal of the volar plate. At 4 months following hardware removal, the patient only had 2 slightly pink, hyperpigmented lesions on the left hand in the areas most severely affected, with complete resolution of all other plaques. The patient was given topical clobetasol for the residual lesions.

Precipitation and spontaneous resolution of disseminated granuloma annulare following the implantation and removal of surgical hardware is rare. Resolution following hardware removal is consistent with the theory that pathogenesis is due to a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to an inciting factor.5 Our case suggests that disseminated granuloma annulare may occur as a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to implanted surgical hardware, which should be considered in the etiology and potential therapeutic options for this disorder.

- Mills A, Chetty R. Auricular granuloma annulare. a consequence of trauma? Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:431-433.

- Dicken CH, Carrington SG, Winkelmann RK. Generalized granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:556-563.

- Yun JH, Lee JY, Kim MK, et al. Clinical and pathological features of generalized granuloma annulare with their correlation: a retrospective multicenter study in Korea [published online May 31, 2009]. Ann Dermatol. 2009:21:113-119

- Cyr PR. Diagnosis and management of granuloma annulare. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:1729-1734.

- Buechner SA, Winkelmann RK, Banks PM. Identification of T-cell subpopulations in granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:125-128.

- Mills A, Chetty R. Auricular granuloma annulare. a consequence of trauma? Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:431-433.

- Dicken CH, Carrington SG, Winkelmann RK. Generalized granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:556-563.

- Yun JH, Lee JY, Kim MK, et al. Clinical and pathological features of generalized granuloma annulare with their correlation: a retrospective multicenter study in Korea [published online May 31, 2009]. Ann Dermatol. 2009:21:113-119

- Cyr PR. Diagnosis and management of granuloma annulare. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:1729-1734.

- Buechner SA, Winkelmann RK, Banks PM. Identification of T-cell subpopulations in granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:125-128.

Practice Points

- Disseminated granuloma annulare may occur as a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to implanted surgical hardware.

- Resolution may occur following removal of surgical hardware.

Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma in a Patient With Celiac Disease

To the Editor:

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common form of a heterogeneous group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas known as cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. Celiac disease (CD) is associated with increased risk for development of enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma and other intraintestinal and extraintestinal non-Hodgkin lymphomas, but a firm association between CD and MF has not been established.1 The first and second cases of concomitant MF and CD were reported in 1985 and 2009 by Coulson and Sanderson2 and Moreira et al,3 respectively. Two other reports of celiac-associated dermatitis herpetiformis and MF exist.4,5 We report a patient with a unique constellation of MF, CD, and Sjögren syndrome (SS).

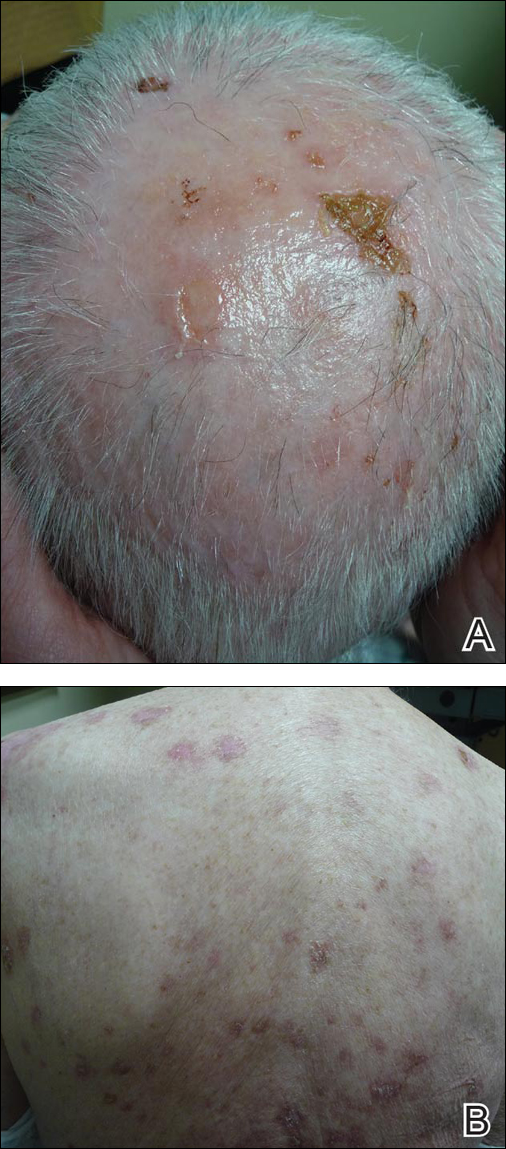

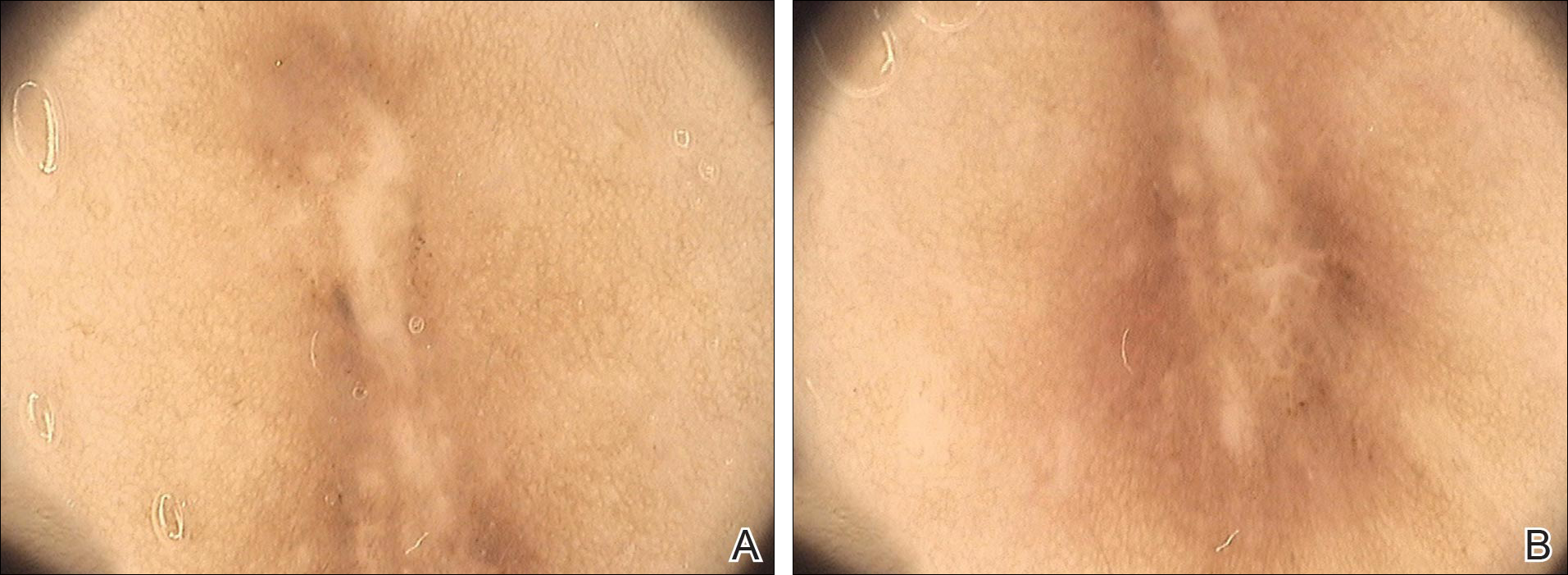

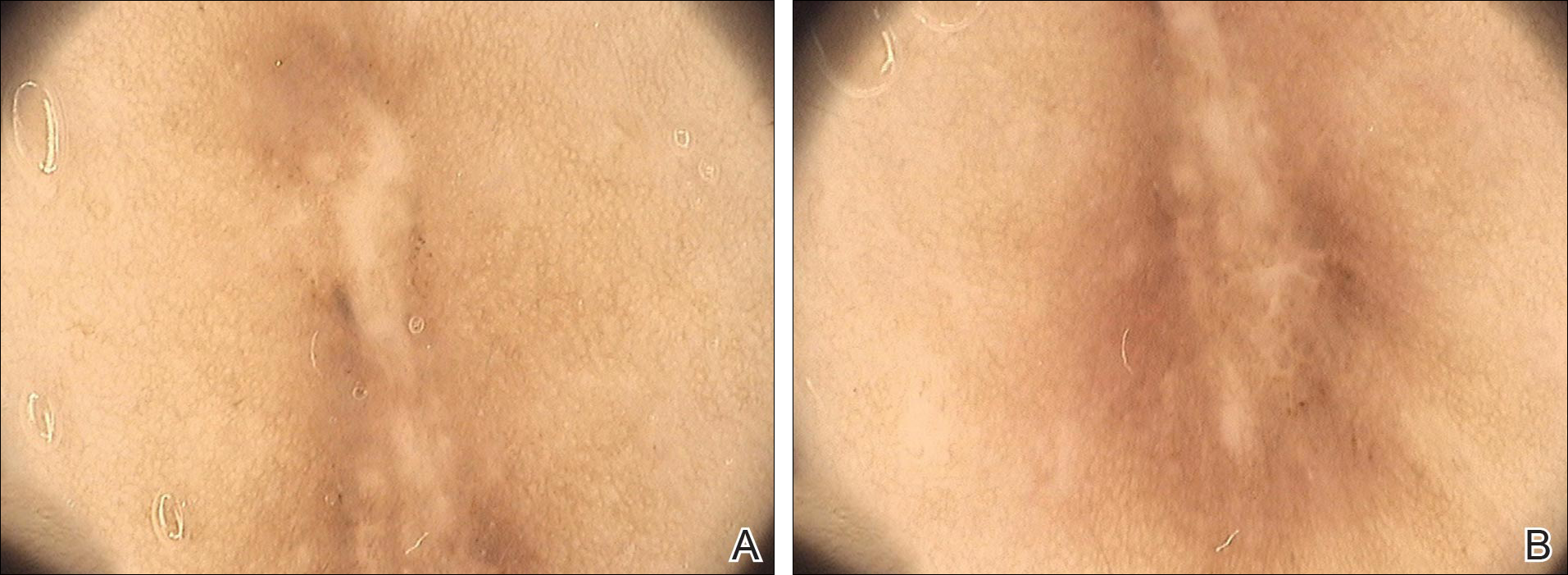

A 54-year-old woman presented with a worsening nonpruritic, slightly tender, eczematous patch on the back of 19 years’ duration. She had a history of SS diagnosed by salivary gland biopsy. She also had a diagnosis of CD confirmed with positive antigliadin IgA antibodies, with a dramatic improvement in symptoms on a gluten-free diet (GFD) after having abdominal pain and diarrhea for many years. She had no evidence of dermatitis herpetiformis. Recently, more red-brown areas of confluent light pink erythema without clear-cut borders had appeared on the axillae, trunk, and thigh (Figure). The patient also noted new lesions and more erythema of the patches when not adhering to a GFD. A biopsy specimen from the left side of the lateral trunk revealed a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate with irregular nuclear contours displaying epidermotropism with a few Pautrier microabscesses. Immunohistochemistry showed strong CD3 and CD4 positivity with loss of CD7 and scattered CD8 staining. Peripheral blood flow cytometry showed no aberrant cell populations. The patient was diagnosed with MF stage IB and treated with topical corticosteroids and natural light with improvement.

It has been hypothesized that early MF is an autoimmune process caused by dysregulation of a lymphocytic reaction against chronic exogenous or endogenous antigens.4,5 The association of MF with CD supports the possibility of lymphocytic stimulation by a persistent antigen (ie, gluten) in the gastrointestinal tract. Porter et al4 suggested that in susceptible individuals, the resulting clonal T cells may migrate into the epidermis, causing MF. This theory also is supported by the finding that adherence to a GFD leads to decreased risk for malignancy and morbidity.6 In our patient, the chronic autoimmune stimulation in SS could be a factor in the pathogenesis of MF. Additionally, SS, CD, and MF are all strongly associated with increased incidence of specific but different HLA class II antigens. Mycosis fungoides is associated with HLA-DR5 and DQB1*03 alleles, CD with HLA-DQ2 and DQ8, and SS with HLA-DR15 and DR3. We do not know the HLA type of our patient, but she likely possessed multiple alleles, leading to the unique aggregation of diseases.

Furthermore, studies have shown that lymphocytes in CD patients display impaired regulatory T-cell function, causing increased incidence of autoimmune diseases and malignancy.7,8 By this theory, the occurrence of MF in patients is facilitated by the inability of CD lymphocytes to control the abnormal T-cell proliferation in the skin. Interestingly, the finding of SS in our patient supports the possibility of impaired regulatory T-cell function.

Although the occurrence of both MF and CD in our patient could be coincidental, the possibility of correlation must be considered as more cases are documented.

- Catassi C, Fabiani E, Corrao G, et al; Italian Working Group on Coeliac Disease and Non-Hodgkin’s-Lymphoma. Risk of non-Hodgkin Lymphoma in celiac disease. JAMA. 2002;287:1413-1419.

- Coulson IH, Sanderson KV. T-cell lymphoma presenting as tumour d’emblée mycosis fungoides associated with coeliac disease. J R Soc Med. 1985;78(suppl 11):23-24.

- Moreira AI, Menezes N, Varela P, et al. Primary cutaneous peripheral T cell lymphoma and celiac disease [in Portuguese]. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2009;55:253-256.

- Porter WM, Dawe SA, Bunker CB. Dermatitis herpetiformis and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:304-305.

- Sun G, Berthelot C, Duvic M. A second case of dermatitis herpetiformis and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:506-507.

- Holmes GK, Prior P, Lane MR, et al. Malignancy in coeliac disease—effect of a gluten free diet. Gut. 1989;30:333-338.

- Granzotto M, dal Bo S, Quaglia S, et al. Regulatory T-cell function is impaired in celiac disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1513-1519.

- Roychoudhuri R, Hirahara K, Mousavi K, et al. BACH2 represses effector programs to stabilize T(reg)-mediated immune homeostasis [published online June 2, 2013]. Nature. 2013;498:506-510.

To the Editor:

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common form of a heterogeneous group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas known as cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. Celiac disease (CD) is associated with increased risk for development of enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma and other intraintestinal and extraintestinal non-Hodgkin lymphomas, but a firm association between CD and MF has not been established.1 The first and second cases of concomitant MF and CD were reported in 1985 and 2009 by Coulson and Sanderson2 and Moreira et al,3 respectively. Two other reports of celiac-associated dermatitis herpetiformis and MF exist.4,5 We report a patient with a unique constellation of MF, CD, and Sjögren syndrome (SS).

A 54-year-old woman presented with a worsening nonpruritic, slightly tender, eczematous patch on the back of 19 years’ duration. She had a history of SS diagnosed by salivary gland biopsy. She also had a diagnosis of CD confirmed with positive antigliadin IgA antibodies, with a dramatic improvement in symptoms on a gluten-free diet (GFD) after having abdominal pain and diarrhea for many years. She had no evidence of dermatitis herpetiformis. Recently, more red-brown areas of confluent light pink erythema without clear-cut borders had appeared on the axillae, trunk, and thigh (Figure). The patient also noted new lesions and more erythema of the patches when not adhering to a GFD. A biopsy specimen from the left side of the lateral trunk revealed a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate with irregular nuclear contours displaying epidermotropism with a few Pautrier microabscesses. Immunohistochemistry showed strong CD3 and CD4 positivity with loss of CD7 and scattered CD8 staining. Peripheral blood flow cytometry showed no aberrant cell populations. The patient was diagnosed with MF stage IB and treated with topical corticosteroids and natural light with improvement.

It has been hypothesized that early MF is an autoimmune process caused by dysregulation of a lymphocytic reaction against chronic exogenous or endogenous antigens.4,5 The association of MF with CD supports the possibility of lymphocytic stimulation by a persistent antigen (ie, gluten) in the gastrointestinal tract. Porter et al4 suggested that in susceptible individuals, the resulting clonal T cells may migrate into the epidermis, causing MF. This theory also is supported by the finding that adherence to a GFD leads to decreased risk for malignancy and morbidity.6 In our patient, the chronic autoimmune stimulation in SS could be a factor in the pathogenesis of MF. Additionally, SS, CD, and MF are all strongly associated with increased incidence of specific but different HLA class II antigens. Mycosis fungoides is associated with HLA-DR5 and DQB1*03 alleles, CD with HLA-DQ2 and DQ8, and SS with HLA-DR15 and DR3. We do not know the HLA type of our patient, but she likely possessed multiple alleles, leading to the unique aggregation of diseases.

Furthermore, studies have shown that lymphocytes in CD patients display impaired regulatory T-cell function, causing increased incidence of autoimmune diseases and malignancy.7,8 By this theory, the occurrence of MF in patients is facilitated by the inability of CD lymphocytes to control the abnormal T-cell proliferation in the skin. Interestingly, the finding of SS in our patient supports the possibility of impaired regulatory T-cell function.

Although the occurrence of both MF and CD in our patient could be coincidental, the possibility of correlation must be considered as more cases are documented.

To the Editor:

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common form of a heterogeneous group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas known as cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. Celiac disease (CD) is associated with increased risk for development of enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma and other intraintestinal and extraintestinal non-Hodgkin lymphomas, but a firm association between CD and MF has not been established.1 The first and second cases of concomitant MF and CD were reported in 1985 and 2009 by Coulson and Sanderson2 and Moreira et al,3 respectively. Two other reports of celiac-associated dermatitis herpetiformis and MF exist.4,5 We report a patient with a unique constellation of MF, CD, and Sjögren syndrome (SS).

A 54-year-old woman presented with a worsening nonpruritic, slightly tender, eczematous patch on the back of 19 years’ duration. She had a history of SS diagnosed by salivary gland biopsy. She also had a diagnosis of CD confirmed with positive antigliadin IgA antibodies, with a dramatic improvement in symptoms on a gluten-free diet (GFD) after having abdominal pain and diarrhea for many years. She had no evidence of dermatitis herpetiformis. Recently, more red-brown areas of confluent light pink erythema without clear-cut borders had appeared on the axillae, trunk, and thigh (Figure). The patient also noted new lesions and more erythema of the patches when not adhering to a GFD. A biopsy specimen from the left side of the lateral trunk revealed a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate with irregular nuclear contours displaying epidermotropism with a few Pautrier microabscesses. Immunohistochemistry showed strong CD3 and CD4 positivity with loss of CD7 and scattered CD8 staining. Peripheral blood flow cytometry showed no aberrant cell populations. The patient was diagnosed with MF stage IB and treated with topical corticosteroids and natural light with improvement.

It has been hypothesized that early MF is an autoimmune process caused by dysregulation of a lymphocytic reaction against chronic exogenous or endogenous antigens.4,5 The association of MF with CD supports the possibility of lymphocytic stimulation by a persistent antigen (ie, gluten) in the gastrointestinal tract. Porter et al4 suggested that in susceptible individuals, the resulting clonal T cells may migrate into the epidermis, causing MF. This theory also is supported by the finding that adherence to a GFD leads to decreased risk for malignancy and morbidity.6 In our patient, the chronic autoimmune stimulation in SS could be a factor in the pathogenesis of MF. Additionally, SS, CD, and MF are all strongly associated with increased incidence of specific but different HLA class II antigens. Mycosis fungoides is associated with HLA-DR5 and DQB1*03 alleles, CD with HLA-DQ2 and DQ8, and SS with HLA-DR15 and DR3. We do not know the HLA type of our patient, but she likely possessed multiple alleles, leading to the unique aggregation of diseases.

Furthermore, studies have shown that lymphocytes in CD patients display impaired regulatory T-cell function, causing increased incidence of autoimmune diseases and malignancy.7,8 By this theory, the occurrence of MF in patients is facilitated by the inability of CD lymphocytes to control the abnormal T-cell proliferation in the skin. Interestingly, the finding of SS in our patient supports the possibility of impaired regulatory T-cell function.

Although the occurrence of both MF and CD in our patient could be coincidental, the possibility of correlation must be considered as more cases are documented.

- Catassi C, Fabiani E, Corrao G, et al; Italian Working Group on Coeliac Disease and Non-Hodgkin’s-Lymphoma. Risk of non-Hodgkin Lymphoma in celiac disease. JAMA. 2002;287:1413-1419.

- Coulson IH, Sanderson KV. T-cell lymphoma presenting as tumour d’emblée mycosis fungoides associated with coeliac disease. J R Soc Med. 1985;78(suppl 11):23-24.

- Moreira AI, Menezes N, Varela P, et al. Primary cutaneous peripheral T cell lymphoma and celiac disease [in Portuguese]. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2009;55:253-256.

- Porter WM, Dawe SA, Bunker CB. Dermatitis herpetiformis and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:304-305.

- Sun G, Berthelot C, Duvic M. A second case of dermatitis herpetiformis and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:506-507.

- Holmes GK, Prior P, Lane MR, et al. Malignancy in coeliac disease—effect of a gluten free diet. Gut. 1989;30:333-338.

- Granzotto M, dal Bo S, Quaglia S, et al. Regulatory T-cell function is impaired in celiac disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1513-1519.

- Roychoudhuri R, Hirahara K, Mousavi K, et al. BACH2 represses effector programs to stabilize T(reg)-mediated immune homeostasis [published online June 2, 2013]. Nature. 2013;498:506-510.

- Catassi C, Fabiani E, Corrao G, et al; Italian Working Group on Coeliac Disease and Non-Hodgkin’s-Lymphoma. Risk of non-Hodgkin Lymphoma in celiac disease. JAMA. 2002;287:1413-1419.

- Coulson IH, Sanderson KV. T-cell lymphoma presenting as tumour d’emblée mycosis fungoides associated with coeliac disease. J R Soc Med. 1985;78(suppl 11):23-24.

- Moreira AI, Menezes N, Varela P, et al. Primary cutaneous peripheral T cell lymphoma and celiac disease [in Portuguese]. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2009;55:253-256.

- Porter WM, Dawe SA, Bunker CB. Dermatitis herpetiformis and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:304-305.

- Sun G, Berthelot C, Duvic M. A second case of dermatitis herpetiformis and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:506-507.

- Holmes GK, Prior P, Lane MR, et al. Malignancy in coeliac disease—effect of a gluten free diet. Gut. 1989;30:333-338.

- Granzotto M, dal Bo S, Quaglia S, et al. Regulatory T-cell function is impaired in celiac disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1513-1519.

- Roychoudhuri R, Hirahara K, Mousavi K, et al. BACH2 represses effector programs to stabilize T(reg)-mediated immune homeostasis [published online June 2, 2013]. Nature. 2013;498:506-510.

Practice Points

- Mycosis fungoides, the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, is an entity for which the pathogenesis is largely unknown.

- Our case and other cases of celiac disease and mycosis fungoides seem to support the immunologic hypothesis of lymphocytic stimulation by a persistent antigen.

Pemphigus Vulgaris Successfully Treated With Doxycycline Monotherapy

To the Editor:

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is an acquired autoimmune bullous disease with notable morbidity and mortality if not treated appropriately due to loss of epidermal barrier function and subsequent infection and loss of body fluids. Although the use of systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents has improved the prognosis, these drugs also may have severe adverse effects, especially in elderly patients. Hence, alternative and safer therapies with anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory agents such as tetracyclines and nicotinamide have been used with variable results. We report a case of PV that was successfully treated with doxycycline.

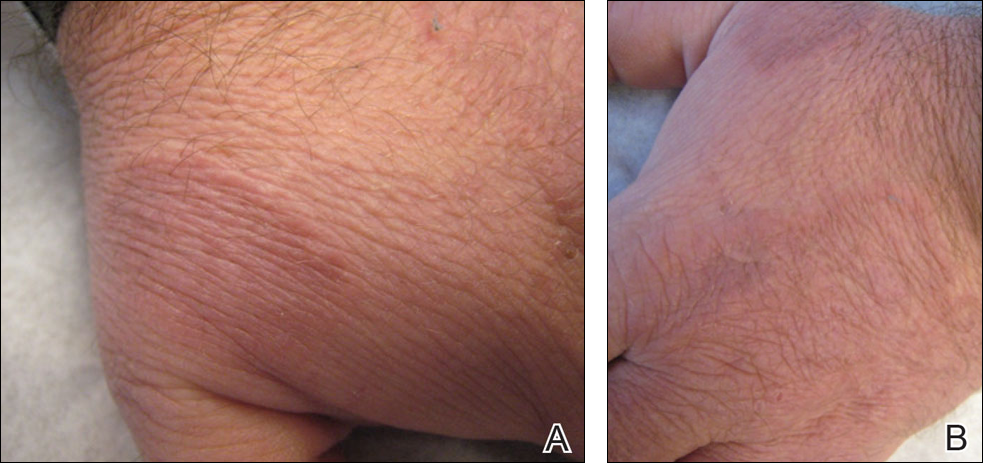

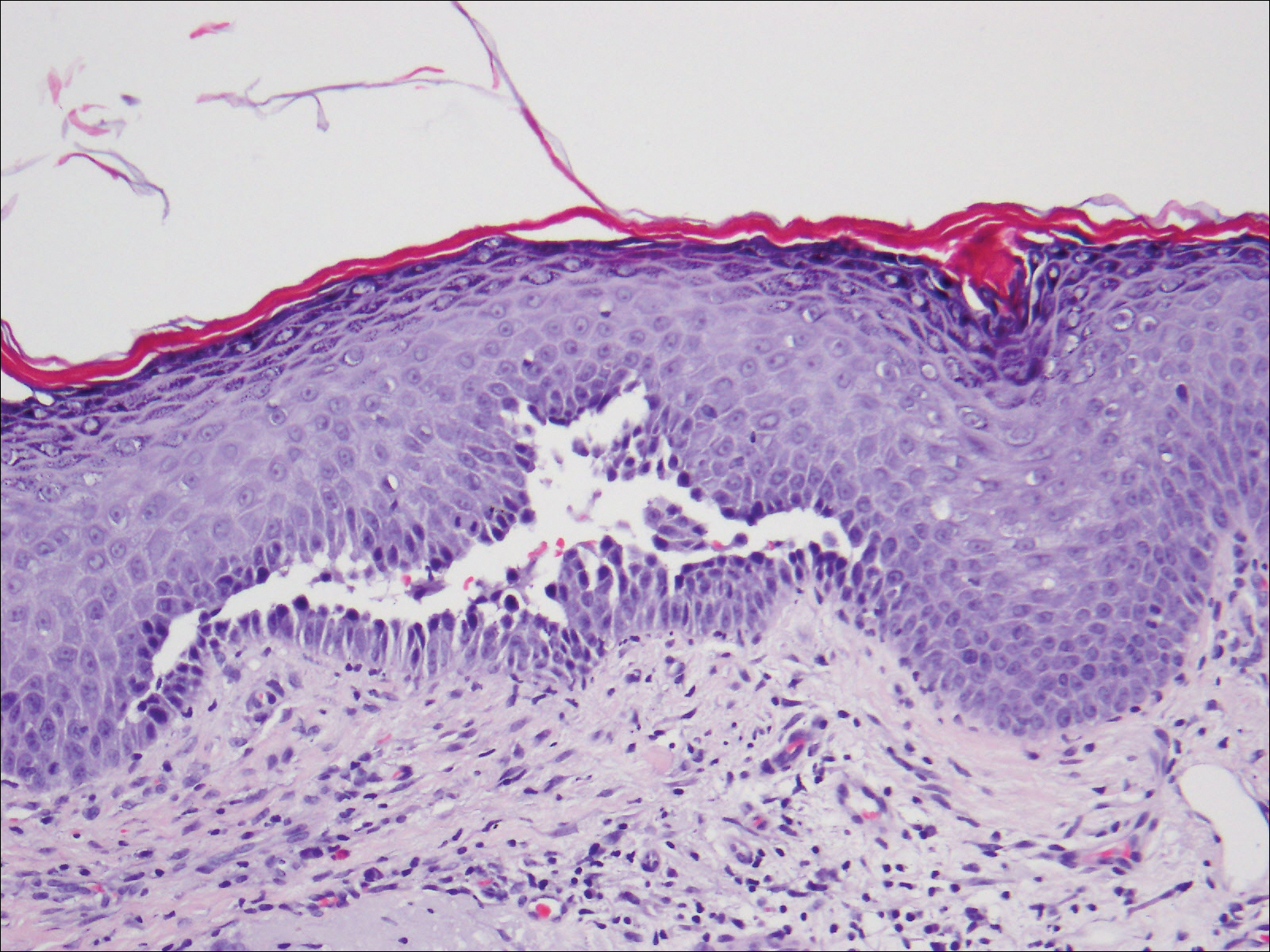

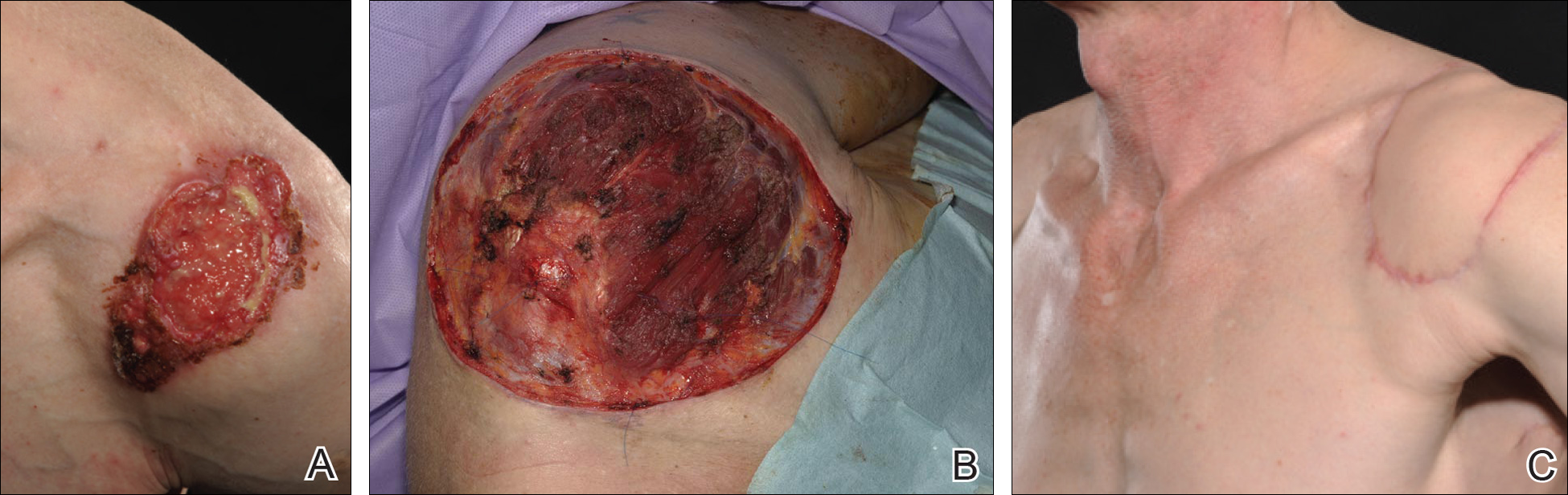

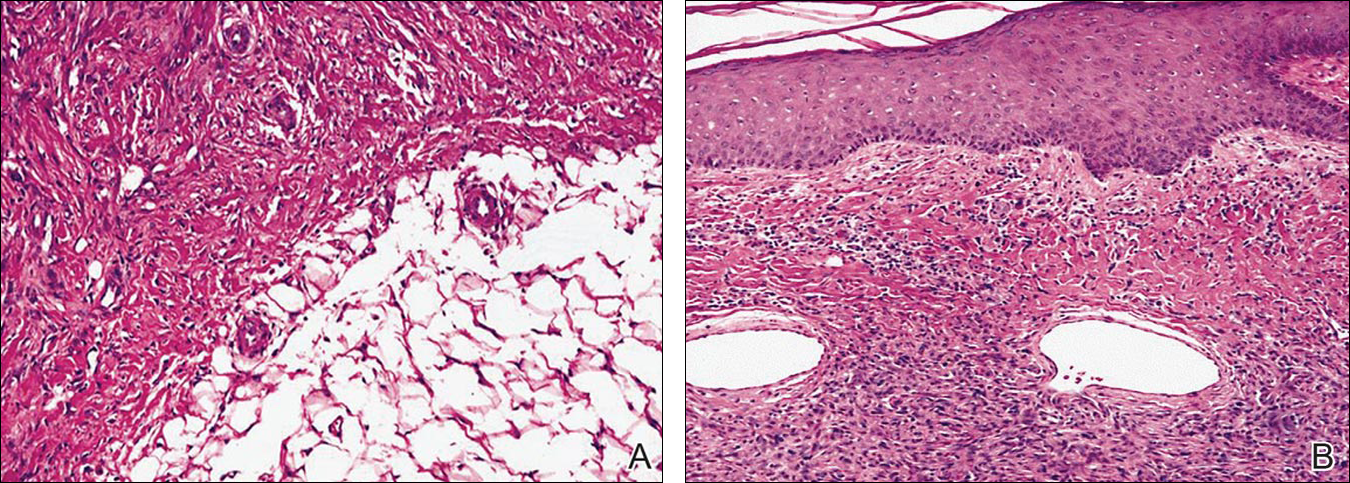

An 81-year-old man presented with well-demarcated erosions with overlying yellow crust as well as vesicles and pustules on the scalp (Figure 1A), forehead, bilateral cheeks, and upper back (Figure 1B) of 6 months’ duration. He used topical fluorouracil in the month prior to presentation for suspected actinic keratosis but had stopped its use after 2 weeks. At the first visit, a diagnosis of a reaction to topical fluorouracil with secondary bacterial infection was made and he was prescribed doxycycline hyclate 100 mg twice daily. The patient returned 4 weeks later for follow-up and reported initial notable improvement with subsequent worsening of lesions after he ran out of doxycycline. On physical examination the lesions had considerably improved from the last visit, but he still had a few erosions on the scalp and a few in the oral mucosa. A 1-cm shallow erosion with minimal surrounding erythema on the forehead was present, along with fewer scattered, edematous, erythematous plaques on the back and chest. Pemphigus vulgaris was suspected and 2 shave biopsies from the lesions on the back and cheek were obtained for confirmation. Histopathologic examination revealed epidermal hyperplasia and suprabasal acantholysis as well as moderate perivascular and perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate with several eosinophils and plasma cells, characteristic of PV (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence showed moderate intercellular deposition of IgG within the basal layer and to a lesser extent within suprabasal layers as well as moderate intercellular deposition of C3 within the basal layer, characteristic of PV. IgA and IgM were not present. Indirect immunofluorescence using monkey esophagus revealed no antibodies against the intercellular space of the basement membrane zone. Due to the dramatic response, he continued on doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and remained in complete remission. Ten months after initiating treatment he discontinued doxycycline for 2 days and developed a 1-cm lesion on the left cheek. He resumed treatment with clearing of lesions and was slowly tapered to 50 mg of doxycycline once daily, remaining in complete remission (Figure 3). Doxycycline was discontinued 16 months after initiation; he has remained clear at 13 weeks.

The treatment of PV is challenging given the multiple side effects of steroids, especially in elderly patients. Tetracyclines have an advantageous side-effect profile and they have been shown to be efficacious in treating PV when combined with nicotinamide or when used as adjuvant therapy to steroids.1-3 Our case shows a patient who was treated exclusively with doxycycline and achieved complete remission.

Tetracyclines have multiple biological activities in addition to their antimicrobial function that may provide a therapeutic benefit in PV. They possess immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting leukocyte chemotaxis and activation4-8 and inhibiting cytokine release. They inhibit matrix metalloproteinases, which are the major enzymes responsible for breakdown of the extracellular matrix,9 and they indirectly inhibit neutrophil elastase by protecting α1-protease inhibitor from matrix metalloproteinase degradation.10 Additionally, tetracyclines increase the cohesion of the dermoepidermal junction11; whether they increase the adhesion between epidermal cells is unknown. It has been determined that CD4+ T cells play an essential role in the pathogenesis of PV by promoting anti-desmoglein 3 antibody production.12 Szeto et al13 reported that minocycline, a member of the tetracycline family, has suppressive effects on CD4+ T-cell activation by hindering the activation of nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT), a key regulatory factor in T-cell activation. We hypothesize that doxycycline exerted what appears to be immunomodulatory properties in our patient by suppressing CD4+ T-cell activity.

In conclusion, tetracyclines can be an effective and promising therapy for PV given their relatively few side effects and immunomodulating properties. However, further randomized controlled trials will be important to support our conclusion.

- Chaffins ML, Collison D, Fivenson DP. Treatment of pemphigus and linear IgA dermatosis with nicotinamide and tetracycline: a review of 13 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:998-1000.

- Caelbotta A, Saenz AM, Gonzalez F, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris: benefits of tetracycline as adjuvant therapy in series of thirteen patients. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:217-221.

- McCarty M, Fivenson D. Two decades of using the combination of tetracycline derivatives and niacinamide as steroid-sparing agents in the management of pemphigus defining a niche for these low toxicity agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:475-479.

- Majeski JA, McClellan MA, Alexander JW. Effect of antibiotics on the in vitro neutrophil chemotactic response. Am Surg. 1976;42:785-788.

- Esterly NB, Furley NL, Flanagan LE. The effect of antimicrobial agents on leukocyte chemotaxis. J Invest Dermatol. 1978;70:51-55.

- Gabler WL, Creamer HR. Suppression of human neutrophil functions by tetracyclines. J Periodontal Res. 1991;26:52-58.

- Esterly NB, Koransky JS, Furey NL, et al. Neutrophil chemotaxis in patients with acne receiving oral tetracycline therapy. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1308-1313.

- Sapadin AN, Fleischmajer R. Tetracyclines: nonantibiotic properties and their clinical implications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:258-265.

- Monk E, Shalita A, Siegel DM. Clinical applications of non-antimicrobial tetracyclines in dermatology. Pharmacol Res. 2011;63:130-145.

- Golub LM, Evans RT, McNamara TF, et al. A nonantimicrobial tetracycline inhibits gingival matrix metalloproteinases and bone loss in Porphyromonas gingivalis–induced periodontitis in rats. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;732:96-111.

- Humbert P, Treffel P, Chapius JF, et al. The tetracyclines in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:691-697.

- Nishifuji K, Amagai M, Kuwana M, et al. Detection of antigen-specific B cells in patients with pemphigus vulgaris by enzyme-linked immunospot assay: requirement of T cell collaboration for autoantibody production. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;114:88-94.

- Szeto GL, Pomerantz JL, Graham DRM, et al. Minocycline suppresses activation of nuclear factor of activated T cells 1 (NFAT1) in human CD4 T Cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:11275-11282.

To the Editor:

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is an acquired autoimmune bullous disease with notable morbidity and mortality if not treated appropriately due to loss of epidermal barrier function and subsequent infection and loss of body fluids. Although the use of systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents has improved the prognosis, these drugs also may have severe adverse effects, especially in elderly patients. Hence, alternative and safer therapies with anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory agents such as tetracyclines and nicotinamide have been used with variable results. We report a case of PV that was successfully treated with doxycycline.

An 81-year-old man presented with well-demarcated erosions with overlying yellow crust as well as vesicles and pustules on the scalp (Figure 1A), forehead, bilateral cheeks, and upper back (Figure 1B) of 6 months’ duration. He used topical fluorouracil in the month prior to presentation for suspected actinic keratosis but had stopped its use after 2 weeks. At the first visit, a diagnosis of a reaction to topical fluorouracil with secondary bacterial infection was made and he was prescribed doxycycline hyclate 100 mg twice daily. The patient returned 4 weeks later for follow-up and reported initial notable improvement with subsequent worsening of lesions after he ran out of doxycycline. On physical examination the lesions had considerably improved from the last visit, but he still had a few erosions on the scalp and a few in the oral mucosa. A 1-cm shallow erosion with minimal surrounding erythema on the forehead was present, along with fewer scattered, edematous, erythematous plaques on the back and chest. Pemphigus vulgaris was suspected and 2 shave biopsies from the lesions on the back and cheek were obtained for confirmation. Histopathologic examination revealed epidermal hyperplasia and suprabasal acantholysis as well as moderate perivascular and perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate with several eosinophils and plasma cells, characteristic of PV (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence showed moderate intercellular deposition of IgG within the basal layer and to a lesser extent within suprabasal layers as well as moderate intercellular deposition of C3 within the basal layer, characteristic of PV. IgA and IgM were not present. Indirect immunofluorescence using monkey esophagus revealed no antibodies against the intercellular space of the basement membrane zone. Due to the dramatic response, he continued on doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and remained in complete remission. Ten months after initiating treatment he discontinued doxycycline for 2 days and developed a 1-cm lesion on the left cheek. He resumed treatment with clearing of lesions and was slowly tapered to 50 mg of doxycycline once daily, remaining in complete remission (Figure 3). Doxycycline was discontinued 16 months after initiation; he has remained clear at 13 weeks.

The treatment of PV is challenging given the multiple side effects of steroids, especially in elderly patients. Tetracyclines have an advantageous side-effect profile and they have been shown to be efficacious in treating PV when combined with nicotinamide or when used as adjuvant therapy to steroids.1-3 Our case shows a patient who was treated exclusively with doxycycline and achieved complete remission.

Tetracyclines have multiple biological activities in addition to their antimicrobial function that may provide a therapeutic benefit in PV. They possess immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting leukocyte chemotaxis and activation4-8 and inhibiting cytokine release. They inhibit matrix metalloproteinases, which are the major enzymes responsible for breakdown of the extracellular matrix,9 and they indirectly inhibit neutrophil elastase by protecting α1-protease inhibitor from matrix metalloproteinase degradation.10 Additionally, tetracyclines increase the cohesion of the dermoepidermal junction11; whether they increase the adhesion between epidermal cells is unknown. It has been determined that CD4+ T cells play an essential role in the pathogenesis of PV by promoting anti-desmoglein 3 antibody production.12 Szeto et al13 reported that minocycline, a member of the tetracycline family, has suppressive effects on CD4+ T-cell activation by hindering the activation of nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT), a key regulatory factor in T-cell activation. We hypothesize that doxycycline exerted what appears to be immunomodulatory properties in our patient by suppressing CD4+ T-cell activity.

In conclusion, tetracyclines can be an effective and promising therapy for PV given their relatively few side effects and immunomodulating properties. However, further randomized controlled trials will be important to support our conclusion.

To the Editor:

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is an acquired autoimmune bullous disease with notable morbidity and mortality if not treated appropriately due to loss of epidermal barrier function and subsequent infection and loss of body fluids. Although the use of systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents has improved the prognosis, these drugs also may have severe adverse effects, especially in elderly patients. Hence, alternative and safer therapies with anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory agents such as tetracyclines and nicotinamide have been used with variable results. We report a case of PV that was successfully treated with doxycycline.

An 81-year-old man presented with well-demarcated erosions with overlying yellow crust as well as vesicles and pustules on the scalp (Figure 1A), forehead, bilateral cheeks, and upper back (Figure 1B) of 6 months’ duration. He used topical fluorouracil in the month prior to presentation for suspected actinic keratosis but had stopped its use after 2 weeks. At the first visit, a diagnosis of a reaction to topical fluorouracil with secondary bacterial infection was made and he was prescribed doxycycline hyclate 100 mg twice daily. The patient returned 4 weeks later for follow-up and reported initial notable improvement with subsequent worsening of lesions after he ran out of doxycycline. On physical examination the lesions had considerably improved from the last visit, but he still had a few erosions on the scalp and a few in the oral mucosa. A 1-cm shallow erosion with minimal surrounding erythema on the forehead was present, along with fewer scattered, edematous, erythematous plaques on the back and chest. Pemphigus vulgaris was suspected and 2 shave biopsies from the lesions on the back and cheek were obtained for confirmation. Histopathologic examination revealed epidermal hyperplasia and suprabasal acantholysis as well as moderate perivascular and perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate with several eosinophils and plasma cells, characteristic of PV (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence showed moderate intercellular deposition of IgG within the basal layer and to a lesser extent within suprabasal layers as well as moderate intercellular deposition of C3 within the basal layer, characteristic of PV. IgA and IgM were not present. Indirect immunofluorescence using monkey esophagus revealed no antibodies against the intercellular space of the basement membrane zone. Due to the dramatic response, he continued on doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and remained in complete remission. Ten months after initiating treatment he discontinued doxycycline for 2 days and developed a 1-cm lesion on the left cheek. He resumed treatment with clearing of lesions and was slowly tapered to 50 mg of doxycycline once daily, remaining in complete remission (Figure 3). Doxycycline was discontinued 16 months after initiation; he has remained clear at 13 weeks.

The treatment of PV is challenging given the multiple side effects of steroids, especially in elderly patients. Tetracyclines have an advantageous side-effect profile and they have been shown to be efficacious in treating PV when combined with nicotinamide or when used as adjuvant therapy to steroids.1-3 Our case shows a patient who was treated exclusively with doxycycline and achieved complete remission.

Tetracyclines have multiple biological activities in addition to their antimicrobial function that may provide a therapeutic benefit in PV. They possess immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting leukocyte chemotaxis and activation4-8 and inhibiting cytokine release. They inhibit matrix metalloproteinases, which are the major enzymes responsible for breakdown of the extracellular matrix,9 and they indirectly inhibit neutrophil elastase by protecting α1-protease inhibitor from matrix metalloproteinase degradation.10 Additionally, tetracyclines increase the cohesion of the dermoepidermal junction11; whether they increase the adhesion between epidermal cells is unknown. It has been determined that CD4+ T cells play an essential role in the pathogenesis of PV by promoting anti-desmoglein 3 antibody production.12 Szeto et al13 reported that minocycline, a member of the tetracycline family, has suppressive effects on CD4+ T-cell activation by hindering the activation of nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT), a key regulatory factor in T-cell activation. We hypothesize that doxycycline exerted what appears to be immunomodulatory properties in our patient by suppressing CD4+ T-cell activity.

In conclusion, tetracyclines can be an effective and promising therapy for PV given their relatively few side effects and immunomodulating properties. However, further randomized controlled trials will be important to support our conclusion.

- Chaffins ML, Collison D, Fivenson DP. Treatment of pemphigus and linear IgA dermatosis with nicotinamide and tetracycline: a review of 13 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:998-1000.

- Caelbotta A, Saenz AM, Gonzalez F, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris: benefits of tetracycline as adjuvant therapy in series of thirteen patients. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:217-221.

- McCarty M, Fivenson D. Two decades of using the combination of tetracycline derivatives and niacinamide as steroid-sparing agents in the management of pemphigus defining a niche for these low toxicity agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:475-479.

- Majeski JA, McClellan MA, Alexander JW. Effect of antibiotics on the in vitro neutrophil chemotactic response. Am Surg. 1976;42:785-788.

- Esterly NB, Furley NL, Flanagan LE. The effect of antimicrobial agents on leukocyte chemotaxis. J Invest Dermatol. 1978;70:51-55.

- Gabler WL, Creamer HR. Suppression of human neutrophil functions by tetracyclines. J Periodontal Res. 1991;26:52-58.

- Esterly NB, Koransky JS, Furey NL, et al. Neutrophil chemotaxis in patients with acne receiving oral tetracycline therapy. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1308-1313.

- Sapadin AN, Fleischmajer R. Tetracyclines: nonantibiotic properties and their clinical implications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:258-265.

- Monk E, Shalita A, Siegel DM. Clinical applications of non-antimicrobial tetracyclines in dermatology. Pharmacol Res. 2011;63:130-145.

- Golub LM, Evans RT, McNamara TF, et al. A nonantimicrobial tetracycline inhibits gingival matrix metalloproteinases and bone loss in Porphyromonas gingivalis–induced periodontitis in rats. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;732:96-111.

- Humbert P, Treffel P, Chapius JF, et al. The tetracyclines in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:691-697.

- Nishifuji K, Amagai M, Kuwana M, et al. Detection of antigen-specific B cells in patients with pemphigus vulgaris by enzyme-linked immunospot assay: requirement of T cell collaboration for autoantibody production. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;114:88-94.

- Szeto GL, Pomerantz JL, Graham DRM, et al. Minocycline suppresses activation of nuclear factor of activated T cells 1 (NFAT1) in human CD4 T Cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:11275-11282.

- Chaffins ML, Collison D, Fivenson DP. Treatment of pemphigus and linear IgA dermatosis with nicotinamide and tetracycline: a review of 13 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:998-1000.

- Caelbotta A, Saenz AM, Gonzalez F, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris: benefits of tetracycline as adjuvant therapy in series of thirteen patients. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:217-221.

- McCarty M, Fivenson D. Two decades of using the combination of tetracycline derivatives and niacinamide as steroid-sparing agents in the management of pemphigus defining a niche for these low toxicity agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:475-479.

- Majeski JA, McClellan MA, Alexander JW. Effect of antibiotics on the in vitro neutrophil chemotactic response. Am Surg. 1976;42:785-788.

- Esterly NB, Furley NL, Flanagan LE. The effect of antimicrobial agents on leukocyte chemotaxis. J Invest Dermatol. 1978;70:51-55.

- Gabler WL, Creamer HR. Suppression of human neutrophil functions by tetracyclines. J Periodontal Res. 1991;26:52-58.

- Esterly NB, Koransky JS, Furey NL, et al. Neutrophil chemotaxis in patients with acne receiving oral tetracycline therapy. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1308-1313.

- Sapadin AN, Fleischmajer R. Tetracyclines: nonantibiotic properties and their clinical implications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:258-265.

- Monk E, Shalita A, Siegel DM. Clinical applications of non-antimicrobial tetracyclines in dermatology. Pharmacol Res. 2011;63:130-145.

- Golub LM, Evans RT, McNamara TF, et al. A nonantimicrobial tetracycline inhibits gingival matrix metalloproteinases and bone loss in Porphyromonas gingivalis–induced periodontitis in rats. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;732:96-111.

- Humbert P, Treffel P, Chapius JF, et al. The tetracyclines in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:691-697.

- Nishifuji K, Amagai M, Kuwana M, et al. Detection of antigen-specific B cells in patients with pemphigus vulgaris by enzyme-linked immunospot assay: requirement of T cell collaboration for autoantibody production. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;114:88-94.

- Szeto GL, Pomerantz JL, Graham DRM, et al. Minocycline suppresses activation of nuclear factor of activated T cells 1 (NFAT1) in human CD4 T Cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:11275-11282.

Practice Points

- The treatment of pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is challenging given the side-effect profile of commonly used systemic medications, including steroids, especially in elderly patients.

- Tetracyclines have an advantageous side-effect profile and may be efficacious in treating PV.

Primary Herpes Simplex Virus Infection of the Nipple in a Breastfeeding Woman

To the Editor:

A 33-year-old woman presented with tenderness of the left breast and nipple of 2 weeks’ duration and fever of 2 days’ duration. The pain was so severe it precluded nursing. She rented a hospital-grade electric breast pump to continue lactation but only could produce 1 ounce of milk daily. The mother had been breastfeeding her 13-month-old twins since birth and did not report any prior difficulties with breastfeeding. Both twins had a history of mucosal sores 2 months prior and a recent outbreak of perioral vesicles following an upper respiratory tract illness that was consistent with gingivostomatitis, followed by a cutaneous outbreak secondary to herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1 infection. The patient had no known history of HSV infection. Prior to presentation the patient was treated with oral dicloxacillin and then cephalexin for suspected bacterial mastitis. She also had used combination clotrimazole-betamethasone cream for possible superficial candidiasis. The patient had no relief with these treatments.

Physical examination revealed approximately 20 microvesicles (<1 mm) on an erythematous base clustered around the left areola (Figure). Erythematous streaks were noted from the medial aspect of the areolar margin extending to the central sternum. The left breast was firm and engorged but without apparent plugged lactiferous ducts. There was no lymphadenopathy. No lesions were present on the palms, soles, and oral mucosa.

The patient was empirically treated with valacyclovir, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs while awaiting laboratory results. Bacterial cultures were negative. Viral titers revealed positive combination HSV-1 and HSV-2 IgM (4.64 [<0.91=negative, 0.91–1.09=equivocal, >1.09=positive]) and negative HSV-1 and HSV-2 IgG (<0.91[<0.91=negative, 0.91–1.09=equivocal, >1.09=positive]), which confirmed the diagnosis of primary HSV infection. Two months later viral titers were positive for HSV-1 IgG (1.3) and negative for HSV-2 IgG (<0.91).

At 1-week follow-up the patient reported that the fever had subsided 1 day after initial presentation. After commencement of antiviral therapy, she continued to have some mild residual tenderness, but the vesicles had crusted over and markedly improved. Upon further questioning, the patient’s husband had a history of oral HSV-1 and was likely the primary source for the infection in the infants.

Herpes simplex virus infection primarily is transmitted through direct mucocutaneous contact with either oral or genital lesions of an infected individual. Transmission of HSV from infant to mother rarely is described. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms herpes mastitis, herpes of the breast, infant to maternal transmission, gingivostomatitis, primary herpes, and breastfeeding yielded 4 reported cases of HSV of the nipple in breastfeeding women from children with herpetic gingivostomatitis.1-4

Herpes simplex virus infection is common in neonatal and pediatric populations. In the United States, more than 30% of children (aged <14 years) have evidence of HSV-1 infection on serology. Herpes simplex virus infections in children can range from uncomplicated mucocutaneous diseases to severe life-threatening infections involving the central nervous system. In children, antivirals should be initiated within 72 hours of symptom onset to prevent more serious complications. Diagnostic testing was not performed on the infants in this case because the 72-hour treatment window had passed. In particular, neonates (aged <3 months) will require intravenous antivirals to prevent the development of central nervous system disease, which occurs in 33% of neonatal HSV infections.5 It is critically important to confirm the diagnosis of HSV in a breastfeeding woman, when clinically indicated, with a viral culture, serology, direct immunofluorescence assay, polymerase chain reaction, or Tzanck smear because other conditions such as plugged lactiferous ducts, candidal mastitis, or bacterial mastitis may mimic HSV. Rapid and accurate diagnosis of the breastfeeding woman with HSV of the nipple can help identify children with herpetic gingivostomatitis that is not readily apparent.

- Quinn PT, Lofberg JV. Maternal herpetic breast infection: another hazard of neonatal herpes simplex. Med J Aust. 1978;2:411-412.

- Dekio S, Kawasaki Y, Jidoi J. Herpes simplex on nipples inoculated from herpetic gingivostomatitis of a baby. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1986;11:664-666.

- Sealander JY, Kerr CP. Herpes simplex of the nipple: infant-to-mother transmission. Am Fam Physician. 1989;39:111-113.

- Gupta S, Malhotra AK, Dash SS. Child to mother transmission of herpes simplex virus-1 infection at an unusual site. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:878-879.

- James SH, Whitley RJ. Treatment of herpes simplex virus infections in pediatric patients: current status and future needs. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;88:720-724.

To the Editor:

A 33-year-old woman presented with tenderness of the left breast and nipple of 2 weeks’ duration and fever of 2 days’ duration. The pain was so severe it precluded nursing. She rented a hospital-grade electric breast pump to continue lactation but only could produce 1 ounce of milk daily. The mother had been breastfeeding her 13-month-old twins since birth and did not report any prior difficulties with breastfeeding. Both twins had a history of mucosal sores 2 months prior and a recent outbreak of perioral vesicles following an upper respiratory tract illness that was consistent with gingivostomatitis, followed by a cutaneous outbreak secondary to herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1 infection. The patient had no known history of HSV infection. Prior to presentation the patient was treated with oral dicloxacillin and then cephalexin for suspected bacterial mastitis. She also had used combination clotrimazole-betamethasone cream for possible superficial candidiasis. The patient had no relief with these treatments.