User login

Purpura Fulminans in the Setting of Escherichia coli Septicemia

To the Editor:

Purpura fulminans is a severe and rapidly fatal thrombotic disorder that can occur in association with either hereditary or acquired deficiencies of the natural anticoagulants protein C and protein S.1 It most commonly results from the acute inflammatory response and subsequent disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) seen in severe bacterial septicemia. Excessive bleeding, retiform purpura, and skin necrosis may develop as a result of the coagulopathies of typical DIC.1Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus, and Staphylococcus frequently are implicated as pathogens, but Escherichia coli–associated purpura fulminans in adults is rare.2,3 We report a case of purpura fulminans in the setting of E coli septicemia.

A 62-year-old woman with a history of end-stage liver disease secondary to alcoholic liver cirrhosis diagnosed 13 years prior complicated by ascites and esophageal varices presented to a primary care clinic for evaluation of a recent-onset nontender lesion on the left buttock. She was hypotensive with a blood pressure of 62/48 mmHg. The patient was prescribed ciprofloxacin 250 mg twice daily and hydrocodone/acetominophen 5 mg/325 mg twice daily as needed for pain management and was discharged. Six hours later, the patient presented to the emergency department with new onset symptoms of confusion and dark-colored spots on the abdomen and lower legs, which her family members noted had developed shortly after the patient took ciprofloxacin. In the emergency department, the patient was noted to be hypotensive and febrile with a severe metabolic acidosis. She was intubated for respiratory failure and received intravenous fluid resuscitation, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and vasopressors. Blood cultures were obtained, and the dermatology department was consulted.

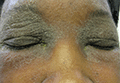

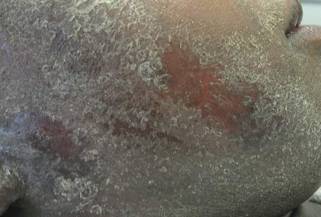

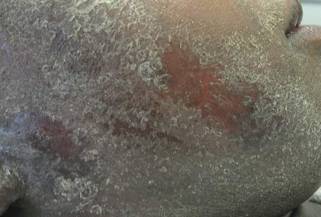

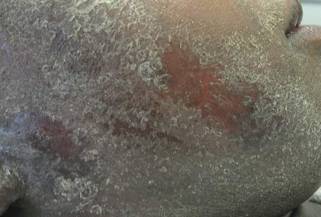

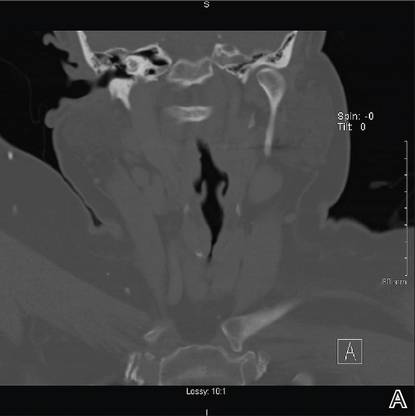

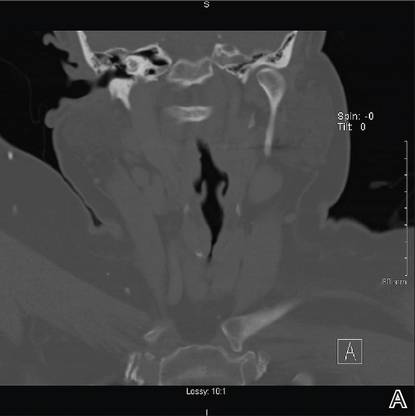

On physical examination, extensive purpuric, reticulated, and stellate plaques with central necrosis and hemorrhagic bullae were noted on the abdomen (Figure, A) and bilateral lower legs (Figure, B) extending onto the thighs. The patient was coagulopathic with persistent sanguineous oozing at intravenous sites and bilateral nares. A small erythematous ulcer with overlying black eschar was noted on the left medial buttock.

Laboratory test results showed new-onset thrombocytopenia, prolonged prothrombin time/international normalized ratio and partial thromboplastin time, and low fibrinogen levels, which confirmed a diagnosis of acute DIC. Blood cultures were positive for gram-negative rods in 4 out of 4 bottles within 12 hours of being drawn. Further testing identified the microorganism as E coli, and antibiotic susceptibility testing revealed it was sensitive to most antibiotics.

The patient was clinically diagnosed with purpura fulminans secondary to severe E coli septicemia and DIC. This life-threatening disorder is considered a medical emergency with a high mortality rate. Laboratory findings supporting DIC include the presence of schistocytes on a peripheral blood smear, thrombocytopenia, positive plasma protamine paracoagulation test, low fibrinogen levels, and positive fibrin degradation products. Reported cases of purpura fulminans in the setting of E coli septicemia are rare, and meningococcemia is the most common presentation.2,3 Bacterial components (eg, lipopolysaccharides found in the cell walls of gram-negative bacteria) may contribute to the progression of septicemia. Increased levels of endotoxin lipopolysaccharide can lead to septic shock and organ dysfunction.4 However, the release of lipooligosaccharides is associated with the development of meningococcal septicemia, and the lipopolysaccharide levels are directly correlated with prognosis in patients without meningitis.5-7

Human activated protein C concentrate (and its precursor, protein C concentrate) replacement therapy has been shown to improve outcomes in patients with meningococcemia-associated–purpura fulminans and severe sepsis, respectively.8 Heparin may be considered in the treatment of patients with purpura fulminans in addition to the replacement of any missing clotting factors or blood products.9 The international guidelines for the management of severe sepsis and septic shock include early quantitative resuscitation of the patient during the first 6 hours after recognition of sepsis, performing blood cultures before antibiotic therapy, and administering broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy within 1 hour of recognition of septic shock.10 The elapsed time from triage to the actual administration of appropriate antimicrobials are primary determinants of patient mortality.11 Therefore, physicians must act quickly to stabilize the patient.

Gram-positive bacteria and gram-negative diplococci are common infectious agents implicated in purpura fulminans. Escherichia coli rarely has been identified as the inciting agent for purpura fulminans in adults. The increasing frequency of E coli strains that produce extended-spectrum β-lactamases—enzymes that mediate resistance to extended-spectrum (third generation) cephalosporins (eg, ceftazidime, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone) and monobactams (eg, aztreonam)—complicates matters further when deciding on appropriate antibiotics. Patients who have infections from extended-spectrum β-lactamase strains will require more potent carbapenems (eg, meropenem, imipenem) for treatment of infections. Despite undergoing treatment for septicemia, our patient went into cardiac arrest within 24 hours of presentation to the emergency department and died a few hours later. Physicians should consider E coli as an inciting agent of purpura fulminans and consider appropriate empiric antibiotics with gram-negative coverage to include E coli.

- Madden RM, Gill JC, Marlar RA. Protein C and protein S levels in two patients with acquired purpura fulminans. Br J Haematol. 1990;75:112-117.

- Nolan J, Sinclair R. Review of management of purpura fulminans and two case reports. Br J Anaesth. 2001;86:581-586.

- Huemer GM, Bonatti H, Dunst KM. Purpura fulminans due to E. coli septicemia. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2004;116:82.

- Pugin J. Recognition of bacteria and bacterial products by host immune cells in sepsis. In: Vincent JL, ed. Yearbook of Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1997:11-12.

- Brandtzaeg P, Oktedalen O, Kierulf P, et al. Elevated VIP and endotoxin plasma levels in human gram-negative septic shock. Regul Pept. 1989;24:37-44.

- Brandtzaeg P, Kierulf P, Gaustad P, et al. Plasma endotoxin as a predictor of multiple organ failure and death in systemic meningococcal disease. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:195-204.

- Brandtzaeg P, Ovstebøo R, Kierulf P. Compartmentalization of lipopolysaccharide production correlates with clinical presentation in meningococcal disease. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:650-652.

- Hodgson A, Ryan T, Moriarty J, et al. Plasma exchange as a source of protein C for acute onset protein C pathway failure. Br J Haematol. 2002;116:905-908.

- Feinstein DI. Diagnosis and management of disseminated intravascular coagulation: the role of heparin therapy. Blood. 1982;60:284-287.

- Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign guidelines committee including the pediatric subgroup. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:580-637.

- Gaieski DF, Mikkelsen ME, Band RA, et al. Impact of time to antibiotics on survival in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock in whom early goal-directed therapy was initiated in the emergency department. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1045-1053.

To the Editor:

Purpura fulminans is a severe and rapidly fatal thrombotic disorder that can occur in association with either hereditary or acquired deficiencies of the natural anticoagulants protein C and protein S.1 It most commonly results from the acute inflammatory response and subsequent disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) seen in severe bacterial septicemia. Excessive bleeding, retiform purpura, and skin necrosis may develop as a result of the coagulopathies of typical DIC.1Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus, and Staphylococcus frequently are implicated as pathogens, but Escherichia coli–associated purpura fulminans in adults is rare.2,3 We report a case of purpura fulminans in the setting of E coli septicemia.

A 62-year-old woman with a history of end-stage liver disease secondary to alcoholic liver cirrhosis diagnosed 13 years prior complicated by ascites and esophageal varices presented to a primary care clinic for evaluation of a recent-onset nontender lesion on the left buttock. She was hypotensive with a blood pressure of 62/48 mmHg. The patient was prescribed ciprofloxacin 250 mg twice daily and hydrocodone/acetominophen 5 mg/325 mg twice daily as needed for pain management and was discharged. Six hours later, the patient presented to the emergency department with new onset symptoms of confusion and dark-colored spots on the abdomen and lower legs, which her family members noted had developed shortly after the patient took ciprofloxacin. In the emergency department, the patient was noted to be hypotensive and febrile with a severe metabolic acidosis. She was intubated for respiratory failure and received intravenous fluid resuscitation, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and vasopressors. Blood cultures were obtained, and the dermatology department was consulted.

On physical examination, extensive purpuric, reticulated, and stellate plaques with central necrosis and hemorrhagic bullae were noted on the abdomen (Figure, A) and bilateral lower legs (Figure, B) extending onto the thighs. The patient was coagulopathic with persistent sanguineous oozing at intravenous sites and bilateral nares. A small erythematous ulcer with overlying black eschar was noted on the left medial buttock.

Laboratory test results showed new-onset thrombocytopenia, prolonged prothrombin time/international normalized ratio and partial thromboplastin time, and low fibrinogen levels, which confirmed a diagnosis of acute DIC. Blood cultures were positive for gram-negative rods in 4 out of 4 bottles within 12 hours of being drawn. Further testing identified the microorganism as E coli, and antibiotic susceptibility testing revealed it was sensitive to most antibiotics.

The patient was clinically diagnosed with purpura fulminans secondary to severe E coli septicemia and DIC. This life-threatening disorder is considered a medical emergency with a high mortality rate. Laboratory findings supporting DIC include the presence of schistocytes on a peripheral blood smear, thrombocytopenia, positive plasma protamine paracoagulation test, low fibrinogen levels, and positive fibrin degradation products. Reported cases of purpura fulminans in the setting of E coli septicemia are rare, and meningococcemia is the most common presentation.2,3 Bacterial components (eg, lipopolysaccharides found in the cell walls of gram-negative bacteria) may contribute to the progression of septicemia. Increased levels of endotoxin lipopolysaccharide can lead to septic shock and organ dysfunction.4 However, the release of lipooligosaccharides is associated with the development of meningococcal septicemia, and the lipopolysaccharide levels are directly correlated with prognosis in patients without meningitis.5-7

Human activated protein C concentrate (and its precursor, protein C concentrate) replacement therapy has been shown to improve outcomes in patients with meningococcemia-associated–purpura fulminans and severe sepsis, respectively.8 Heparin may be considered in the treatment of patients with purpura fulminans in addition to the replacement of any missing clotting factors or blood products.9 The international guidelines for the management of severe sepsis and septic shock include early quantitative resuscitation of the patient during the first 6 hours after recognition of sepsis, performing blood cultures before antibiotic therapy, and administering broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy within 1 hour of recognition of septic shock.10 The elapsed time from triage to the actual administration of appropriate antimicrobials are primary determinants of patient mortality.11 Therefore, physicians must act quickly to stabilize the patient.

Gram-positive bacteria and gram-negative diplococci are common infectious agents implicated in purpura fulminans. Escherichia coli rarely has been identified as the inciting agent for purpura fulminans in adults. The increasing frequency of E coli strains that produce extended-spectrum β-lactamases—enzymes that mediate resistance to extended-spectrum (third generation) cephalosporins (eg, ceftazidime, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone) and monobactams (eg, aztreonam)—complicates matters further when deciding on appropriate antibiotics. Patients who have infections from extended-spectrum β-lactamase strains will require more potent carbapenems (eg, meropenem, imipenem) for treatment of infections. Despite undergoing treatment for septicemia, our patient went into cardiac arrest within 24 hours of presentation to the emergency department and died a few hours later. Physicians should consider E coli as an inciting agent of purpura fulminans and consider appropriate empiric antibiotics with gram-negative coverage to include E coli.

To the Editor:

Purpura fulminans is a severe and rapidly fatal thrombotic disorder that can occur in association with either hereditary or acquired deficiencies of the natural anticoagulants protein C and protein S.1 It most commonly results from the acute inflammatory response and subsequent disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) seen in severe bacterial septicemia. Excessive bleeding, retiform purpura, and skin necrosis may develop as a result of the coagulopathies of typical DIC.1Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus, and Staphylococcus frequently are implicated as pathogens, but Escherichia coli–associated purpura fulminans in adults is rare.2,3 We report a case of purpura fulminans in the setting of E coli septicemia.

A 62-year-old woman with a history of end-stage liver disease secondary to alcoholic liver cirrhosis diagnosed 13 years prior complicated by ascites and esophageal varices presented to a primary care clinic for evaluation of a recent-onset nontender lesion on the left buttock. She was hypotensive with a blood pressure of 62/48 mmHg. The patient was prescribed ciprofloxacin 250 mg twice daily and hydrocodone/acetominophen 5 mg/325 mg twice daily as needed for pain management and was discharged. Six hours later, the patient presented to the emergency department with new onset symptoms of confusion and dark-colored spots on the abdomen and lower legs, which her family members noted had developed shortly after the patient took ciprofloxacin. In the emergency department, the patient was noted to be hypotensive and febrile with a severe metabolic acidosis. She was intubated for respiratory failure and received intravenous fluid resuscitation, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and vasopressors. Blood cultures were obtained, and the dermatology department was consulted.

On physical examination, extensive purpuric, reticulated, and stellate plaques with central necrosis and hemorrhagic bullae were noted on the abdomen (Figure, A) and bilateral lower legs (Figure, B) extending onto the thighs. The patient was coagulopathic with persistent sanguineous oozing at intravenous sites and bilateral nares. A small erythematous ulcer with overlying black eschar was noted on the left medial buttock.

Laboratory test results showed new-onset thrombocytopenia, prolonged prothrombin time/international normalized ratio and partial thromboplastin time, and low fibrinogen levels, which confirmed a diagnosis of acute DIC. Blood cultures were positive for gram-negative rods in 4 out of 4 bottles within 12 hours of being drawn. Further testing identified the microorganism as E coli, and antibiotic susceptibility testing revealed it was sensitive to most antibiotics.

The patient was clinically diagnosed with purpura fulminans secondary to severe E coli septicemia and DIC. This life-threatening disorder is considered a medical emergency with a high mortality rate. Laboratory findings supporting DIC include the presence of schistocytes on a peripheral blood smear, thrombocytopenia, positive plasma protamine paracoagulation test, low fibrinogen levels, and positive fibrin degradation products. Reported cases of purpura fulminans in the setting of E coli septicemia are rare, and meningococcemia is the most common presentation.2,3 Bacterial components (eg, lipopolysaccharides found in the cell walls of gram-negative bacteria) may contribute to the progression of septicemia. Increased levels of endotoxin lipopolysaccharide can lead to septic shock and organ dysfunction.4 However, the release of lipooligosaccharides is associated with the development of meningococcal septicemia, and the lipopolysaccharide levels are directly correlated with prognosis in patients without meningitis.5-7

Human activated protein C concentrate (and its precursor, protein C concentrate) replacement therapy has been shown to improve outcomes in patients with meningococcemia-associated–purpura fulminans and severe sepsis, respectively.8 Heparin may be considered in the treatment of patients with purpura fulminans in addition to the replacement of any missing clotting factors or blood products.9 The international guidelines for the management of severe sepsis and septic shock include early quantitative resuscitation of the patient during the first 6 hours after recognition of sepsis, performing blood cultures before antibiotic therapy, and administering broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy within 1 hour of recognition of septic shock.10 The elapsed time from triage to the actual administration of appropriate antimicrobials are primary determinants of patient mortality.11 Therefore, physicians must act quickly to stabilize the patient.

Gram-positive bacteria and gram-negative diplococci are common infectious agents implicated in purpura fulminans. Escherichia coli rarely has been identified as the inciting agent for purpura fulminans in adults. The increasing frequency of E coli strains that produce extended-spectrum β-lactamases—enzymes that mediate resistance to extended-spectrum (third generation) cephalosporins (eg, ceftazidime, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone) and monobactams (eg, aztreonam)—complicates matters further when deciding on appropriate antibiotics. Patients who have infections from extended-spectrum β-lactamase strains will require more potent carbapenems (eg, meropenem, imipenem) for treatment of infections. Despite undergoing treatment for septicemia, our patient went into cardiac arrest within 24 hours of presentation to the emergency department and died a few hours later. Physicians should consider E coli as an inciting agent of purpura fulminans and consider appropriate empiric antibiotics with gram-negative coverage to include E coli.

- Madden RM, Gill JC, Marlar RA. Protein C and protein S levels in two patients with acquired purpura fulminans. Br J Haematol. 1990;75:112-117.

- Nolan J, Sinclair R. Review of management of purpura fulminans and two case reports. Br J Anaesth. 2001;86:581-586.

- Huemer GM, Bonatti H, Dunst KM. Purpura fulminans due to E. coli septicemia. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2004;116:82.

- Pugin J. Recognition of bacteria and bacterial products by host immune cells in sepsis. In: Vincent JL, ed. Yearbook of Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1997:11-12.

- Brandtzaeg P, Oktedalen O, Kierulf P, et al. Elevated VIP and endotoxin plasma levels in human gram-negative septic shock. Regul Pept. 1989;24:37-44.

- Brandtzaeg P, Kierulf P, Gaustad P, et al. Plasma endotoxin as a predictor of multiple organ failure and death in systemic meningococcal disease. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:195-204.

- Brandtzaeg P, Ovstebøo R, Kierulf P. Compartmentalization of lipopolysaccharide production correlates with clinical presentation in meningococcal disease. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:650-652.

- Hodgson A, Ryan T, Moriarty J, et al. Plasma exchange as a source of protein C for acute onset protein C pathway failure. Br J Haematol. 2002;116:905-908.

- Feinstein DI. Diagnosis and management of disseminated intravascular coagulation: the role of heparin therapy. Blood. 1982;60:284-287.

- Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign guidelines committee including the pediatric subgroup. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:580-637.

- Gaieski DF, Mikkelsen ME, Band RA, et al. Impact of time to antibiotics on survival in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock in whom early goal-directed therapy was initiated in the emergency department. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1045-1053.

- Madden RM, Gill JC, Marlar RA. Protein C and protein S levels in two patients with acquired purpura fulminans. Br J Haematol. 1990;75:112-117.

- Nolan J, Sinclair R. Review of management of purpura fulminans and two case reports. Br J Anaesth. 2001;86:581-586.

- Huemer GM, Bonatti H, Dunst KM. Purpura fulminans due to E. coli septicemia. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2004;116:82.

- Pugin J. Recognition of bacteria and bacterial products by host immune cells in sepsis. In: Vincent JL, ed. Yearbook of Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1997:11-12.

- Brandtzaeg P, Oktedalen O, Kierulf P, et al. Elevated VIP and endotoxin plasma levels in human gram-negative septic shock. Regul Pept. 1989;24:37-44.

- Brandtzaeg P, Kierulf P, Gaustad P, et al. Plasma endotoxin as a predictor of multiple organ failure and death in systemic meningococcal disease. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:195-204.

- Brandtzaeg P, Ovstebøo R, Kierulf P. Compartmentalization of lipopolysaccharide production correlates with clinical presentation in meningococcal disease. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:650-652.

- Hodgson A, Ryan T, Moriarty J, et al. Plasma exchange as a source of protein C for acute onset protein C pathway failure. Br J Haematol. 2002;116:905-908.

- Feinstein DI. Diagnosis and management of disseminated intravascular coagulation: the role of heparin therapy. Blood. 1982;60:284-287.

- Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign guidelines committee including the pediatric subgroup. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:580-637.

- Gaieski DF, Mikkelsen ME, Band RA, et al. Impact of time to antibiotics on survival in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock in whom early goal-directed therapy was initiated in the emergency department. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1045-1053.

Factors Associated with Missed Dermatology Appointments

To the Editor:

Missed appointments are a major issue in every discipline of medicine1 and can be detrimental for dermatologists,2,3 whose clinics often have long wait times for referred patients and can lose up to $200 for each missed appointment.4 The purpose of this study was to quantify the rate of missed appointments at an academic dermatology clinic and identify factors associated with patient nonattendance.

After approval by an institutional review board, appointment data was collected from the electronic medical record at the dermatology clinic at Wake Forest Baptist Health, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, for the period from May 1, 2013, to April 30, 2014. Variables that were evaluated included age, race, sex, primary language, employment status, zip code, appointment time, insurance coverage, scheduled provider, patient status (new vs returning), and the nature of the visit (cosmetic vs noncosmetic visits and procedural vs nonprocedural visits). Zip codes served as a representation of distance traveled and were stratified into 4 concentric zones: zone 1 represented the region corresponding to the clinic’s zip code; zone 2 represented regions with zip codes adjacent to zone 1; and the remaining zones were determined by regions with zip codes adjacent to the prior zone. Primary language spoken was categorized as English or non-English. Insurance coverage was categorized as private, Medicaid, Medicare, self-pay, and other. Using stepwise selection, both a univariate model and a multivariable logistic regression model were created (variable inclusion, P≤.10; variable exclusion, P>.05). Of the 28,772 appointments scheduled during the study period, 5584 (19.4%) were missed. Univariate and multivariable analyses of the factors associated with missed appointments are shown in Table 1.

A telephone survey also was conducted to evaluate patient-reported factors associated with missed dermatology appointments. A list of patients who missed appointments during the period from January 1, 2014, to April 30, 2014, was extracted and every fourth patient was called within 6 weeks of the appointment to minimize recall bias. Patients were excluded from the study if they could not be reached after 3 attempts. Of the 799 patients contacted, 300 (38%) responded to the survey; 98 (12%) had phone numbers on record that were incorrect or were no longer in service; and 401 (50%) could not be reached after 3 attempts. The results of the telephone survey are provided in Table 2.

The demographic data suggested that characteristics associated with higher rates of missed appointments tended to reflect physical or financial barriers, such as dependency on others for transportation (eg, pediatric patients), longer distance traveled to the clinic, and lack of insurance coverage; however, only 4% and 8% of the survey respondents reported that they missed their appointment due to financial reasons or that they were unable to obtain transportation, respectively. Of the patients surveyed, 35% cited that the reason they missed their appointment was that they forgot about the appointment; additionally, 24% of respondents reported that they had not been reminded of the appointment.

Although physicians cannot directly address physical or financial barriers to attendance, we can introduce more effective methods of communication for patient reminders. Of the 799 patients who were called for the telephone survey, 12.3% had phone numbers on record that were either incorrect or no longer in service. As these patients’ phone numbers were listed in the electronic medical record for contact purposes, they likely did not receive telephone calls reminding them about their appointments. Although it was not formally evaluated in this study, many respondents expressed that they had other preferred methods of receiving appointment reminders (eg, e-mail, text message) than those that are currently considered commonplace (ie, telephone calls, voicemails).

This study was limited in that the appointment data came from a single academic dermatology clinic. There also were limitations in the data set for subgroup analysis; for example, to appropriately assess socioeconomic barriers to attendance of dermatology appointments, it would be valuable to stratify income within established factors of socioeconomic barriers (eg, race, employment status) to avoid research bias. Although many variables assessed were statistically significant (P<.05), the odds ratios often were close to 1, suggesting that they may not be clinically or practically relevant.

By identifying factors associated with missed dermatology appointments, interventions can be instituted to target high-risk groups and alter patient reminder protocols. If possible, identifying patients’ preferred contact methods (eg, telephone call, text message, etc) and verifying contact information may be cost-effective ways to reduce missed appointments in dermatology offices.

1. George A, Rubin G. Non-attendance in general practice: a systematic review and its implications for access to primary health care. Fam Pract. 2003;20:178-184.

2. Canizares MJ, Penneys NS. The incidence of nonattendance at an urgent care dermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:457-459.

3. Cronin PR, DeCoste L, Kimball AB. A multivariate analysis of dermatology missed appointment predictors. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1435-1437.

4. Perez FD, Xie J, Sin A, et al. Characteristics and direct costs of academic pediatric subspecialty outpatient no-show events. J Healthc Qual. 2014;36:32-42.

To the Editor:

Missed appointments are a major issue in every discipline of medicine1 and can be detrimental for dermatologists,2,3 whose clinics often have long wait times for referred patients and can lose up to $200 for each missed appointment.4 The purpose of this study was to quantify the rate of missed appointments at an academic dermatology clinic and identify factors associated with patient nonattendance.

After approval by an institutional review board, appointment data was collected from the electronic medical record at the dermatology clinic at Wake Forest Baptist Health, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, for the period from May 1, 2013, to April 30, 2014. Variables that were evaluated included age, race, sex, primary language, employment status, zip code, appointment time, insurance coverage, scheduled provider, patient status (new vs returning), and the nature of the visit (cosmetic vs noncosmetic visits and procedural vs nonprocedural visits). Zip codes served as a representation of distance traveled and were stratified into 4 concentric zones: zone 1 represented the region corresponding to the clinic’s zip code; zone 2 represented regions with zip codes adjacent to zone 1; and the remaining zones were determined by regions with zip codes adjacent to the prior zone. Primary language spoken was categorized as English or non-English. Insurance coverage was categorized as private, Medicaid, Medicare, self-pay, and other. Using stepwise selection, both a univariate model and a multivariable logistic regression model were created (variable inclusion, P≤.10; variable exclusion, P>.05). Of the 28,772 appointments scheduled during the study period, 5584 (19.4%) were missed. Univariate and multivariable analyses of the factors associated with missed appointments are shown in Table 1.

A telephone survey also was conducted to evaluate patient-reported factors associated with missed dermatology appointments. A list of patients who missed appointments during the period from January 1, 2014, to April 30, 2014, was extracted and every fourth patient was called within 6 weeks of the appointment to minimize recall bias. Patients were excluded from the study if they could not be reached after 3 attempts. Of the 799 patients contacted, 300 (38%) responded to the survey; 98 (12%) had phone numbers on record that were incorrect or were no longer in service; and 401 (50%) could not be reached after 3 attempts. The results of the telephone survey are provided in Table 2.

The demographic data suggested that characteristics associated with higher rates of missed appointments tended to reflect physical or financial barriers, such as dependency on others for transportation (eg, pediatric patients), longer distance traveled to the clinic, and lack of insurance coverage; however, only 4% and 8% of the survey respondents reported that they missed their appointment due to financial reasons or that they were unable to obtain transportation, respectively. Of the patients surveyed, 35% cited that the reason they missed their appointment was that they forgot about the appointment; additionally, 24% of respondents reported that they had not been reminded of the appointment.

Although physicians cannot directly address physical or financial barriers to attendance, we can introduce more effective methods of communication for patient reminders. Of the 799 patients who were called for the telephone survey, 12.3% had phone numbers on record that were either incorrect or no longer in service. As these patients’ phone numbers were listed in the electronic medical record for contact purposes, they likely did not receive telephone calls reminding them about their appointments. Although it was not formally evaluated in this study, many respondents expressed that they had other preferred methods of receiving appointment reminders (eg, e-mail, text message) than those that are currently considered commonplace (ie, telephone calls, voicemails).

This study was limited in that the appointment data came from a single academic dermatology clinic. There also were limitations in the data set for subgroup analysis; for example, to appropriately assess socioeconomic barriers to attendance of dermatology appointments, it would be valuable to stratify income within established factors of socioeconomic barriers (eg, race, employment status) to avoid research bias. Although many variables assessed were statistically significant (P<.05), the odds ratios often were close to 1, suggesting that they may not be clinically or practically relevant.

By identifying factors associated with missed dermatology appointments, interventions can be instituted to target high-risk groups and alter patient reminder protocols. If possible, identifying patients’ preferred contact methods (eg, telephone call, text message, etc) and verifying contact information may be cost-effective ways to reduce missed appointments in dermatology offices.

To the Editor:

Missed appointments are a major issue in every discipline of medicine1 and can be detrimental for dermatologists,2,3 whose clinics often have long wait times for referred patients and can lose up to $200 for each missed appointment.4 The purpose of this study was to quantify the rate of missed appointments at an academic dermatology clinic and identify factors associated with patient nonattendance.

After approval by an institutional review board, appointment data was collected from the electronic medical record at the dermatology clinic at Wake Forest Baptist Health, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, for the period from May 1, 2013, to April 30, 2014. Variables that were evaluated included age, race, sex, primary language, employment status, zip code, appointment time, insurance coverage, scheduled provider, patient status (new vs returning), and the nature of the visit (cosmetic vs noncosmetic visits and procedural vs nonprocedural visits). Zip codes served as a representation of distance traveled and were stratified into 4 concentric zones: zone 1 represented the region corresponding to the clinic’s zip code; zone 2 represented regions with zip codes adjacent to zone 1; and the remaining zones were determined by regions with zip codes adjacent to the prior zone. Primary language spoken was categorized as English or non-English. Insurance coverage was categorized as private, Medicaid, Medicare, self-pay, and other. Using stepwise selection, both a univariate model and a multivariable logistic regression model were created (variable inclusion, P≤.10; variable exclusion, P>.05). Of the 28,772 appointments scheduled during the study period, 5584 (19.4%) were missed. Univariate and multivariable analyses of the factors associated with missed appointments are shown in Table 1.

A telephone survey also was conducted to evaluate patient-reported factors associated with missed dermatology appointments. A list of patients who missed appointments during the period from January 1, 2014, to April 30, 2014, was extracted and every fourth patient was called within 6 weeks of the appointment to minimize recall bias. Patients were excluded from the study if they could not be reached after 3 attempts. Of the 799 patients contacted, 300 (38%) responded to the survey; 98 (12%) had phone numbers on record that were incorrect or were no longer in service; and 401 (50%) could not be reached after 3 attempts. The results of the telephone survey are provided in Table 2.

The demographic data suggested that characteristics associated with higher rates of missed appointments tended to reflect physical or financial barriers, such as dependency on others for transportation (eg, pediatric patients), longer distance traveled to the clinic, and lack of insurance coverage; however, only 4% and 8% of the survey respondents reported that they missed their appointment due to financial reasons or that they were unable to obtain transportation, respectively. Of the patients surveyed, 35% cited that the reason they missed their appointment was that they forgot about the appointment; additionally, 24% of respondents reported that they had not been reminded of the appointment.

Although physicians cannot directly address physical or financial barriers to attendance, we can introduce more effective methods of communication for patient reminders. Of the 799 patients who were called for the telephone survey, 12.3% had phone numbers on record that were either incorrect or no longer in service. As these patients’ phone numbers were listed in the electronic medical record for contact purposes, they likely did not receive telephone calls reminding them about their appointments. Although it was not formally evaluated in this study, many respondents expressed that they had other preferred methods of receiving appointment reminders (eg, e-mail, text message) than those that are currently considered commonplace (ie, telephone calls, voicemails).

This study was limited in that the appointment data came from a single academic dermatology clinic. There also were limitations in the data set for subgroup analysis; for example, to appropriately assess socioeconomic barriers to attendance of dermatology appointments, it would be valuable to stratify income within established factors of socioeconomic barriers (eg, race, employment status) to avoid research bias. Although many variables assessed were statistically significant (P<.05), the odds ratios often were close to 1, suggesting that they may not be clinically or practically relevant.

By identifying factors associated with missed dermatology appointments, interventions can be instituted to target high-risk groups and alter patient reminder protocols. If possible, identifying patients’ preferred contact methods (eg, telephone call, text message, etc) and verifying contact information may be cost-effective ways to reduce missed appointments in dermatology offices.

1. George A, Rubin G. Non-attendance in general practice: a systematic review and its implications for access to primary health care. Fam Pract. 2003;20:178-184.

2. Canizares MJ, Penneys NS. The incidence of nonattendance at an urgent care dermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:457-459.

3. Cronin PR, DeCoste L, Kimball AB. A multivariate analysis of dermatology missed appointment predictors. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1435-1437.

4. Perez FD, Xie J, Sin A, et al. Characteristics and direct costs of academic pediatric subspecialty outpatient no-show events. J Healthc Qual. 2014;36:32-42.

1. George A, Rubin G. Non-attendance in general practice: a systematic review and its implications for access to primary health care. Fam Pract. 2003;20:178-184.

2. Canizares MJ, Penneys NS. The incidence of nonattendance at an urgent care dermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:457-459.

3. Cronin PR, DeCoste L, Kimball AB. A multivariate analysis of dermatology missed appointment predictors. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1435-1437.

4. Perez FD, Xie J, Sin A, et al. Characteristics and direct costs of academic pediatric subspecialty outpatient no-show events. J Healthc Qual. 2014;36:32-42.

Transient Reactive Papulotranslucent Acrokeratoderma: A Report of 3 Cases Showing Excellent Response to Topical Calcipotriene

To the Editor:

Transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma (TRPA) is a rare disorder that also has been described using the terms aquagenic syringeal acrokeratoderma, aquagenic palmoplantar keratoderma, aquagenic acrokeratoderma, aquagenic papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma, and aquagenic wrinkling of the palms.1 It was initially described in 1996 by English and McCollough,2 and since then fewer than 100 cases have been reported.1-12

A 38-year-old man presented with prominent palmar hyperhidrosis with whitish papules on the palms of 10 days’ duration. The lesions were exacerbated following exposure to water but were asymptomatic aside from their unsightly cosmetic appearance. Dermatologic examination revealed translucent, whitish, pebbly papules confined to the central palmar creases (Figure 1) that were intensified following a 5-minute water immersion test.

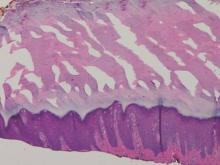

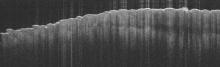

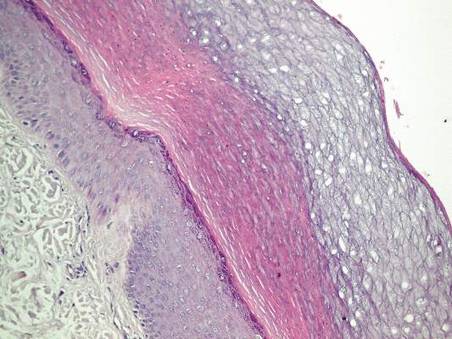

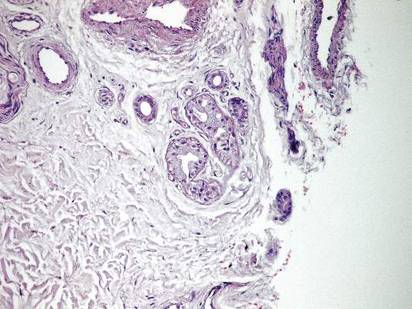

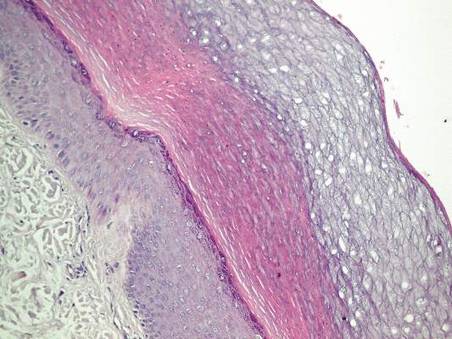

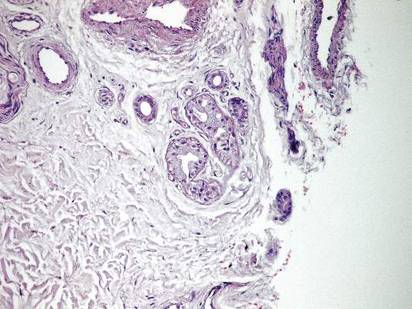

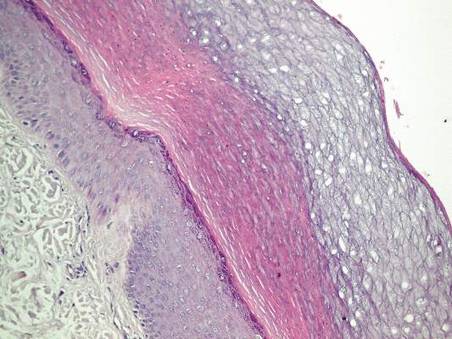

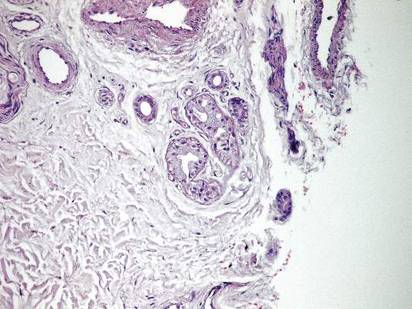

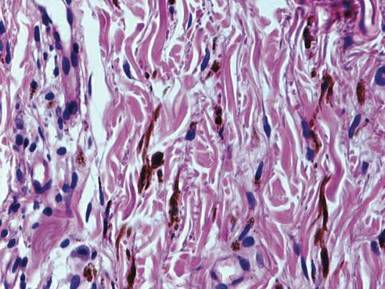

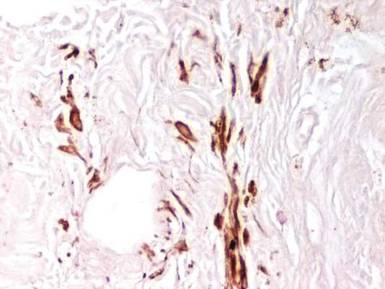

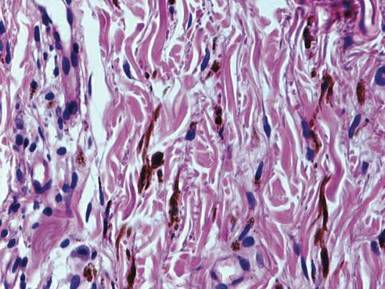

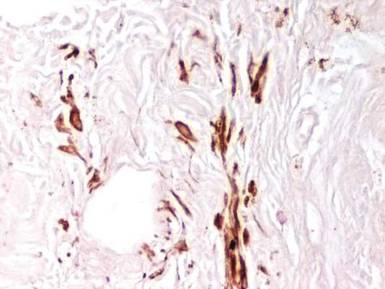

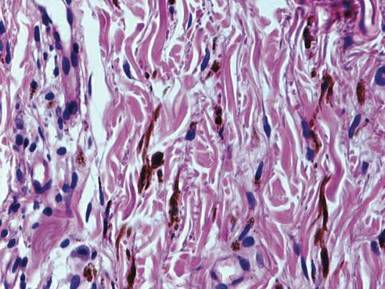

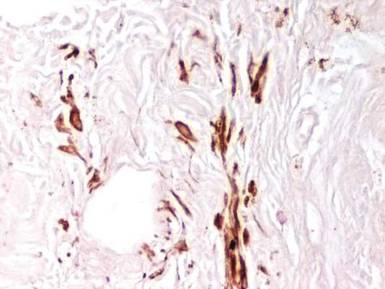

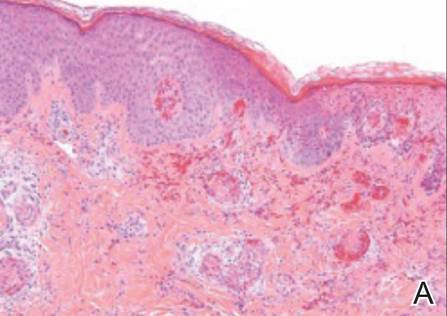

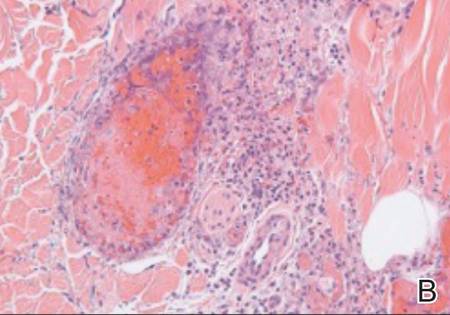

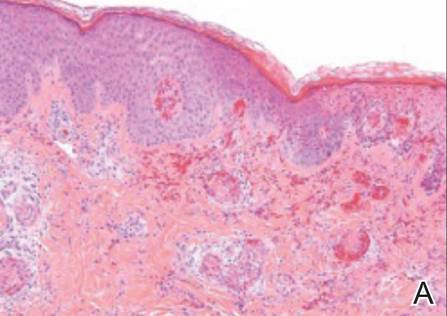

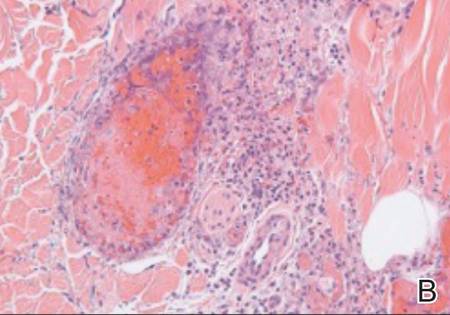

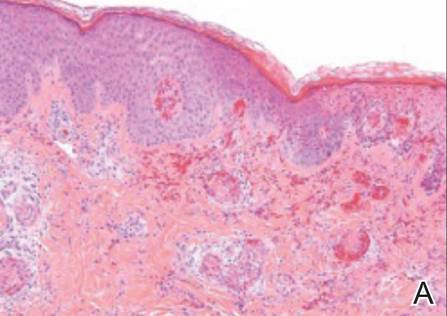

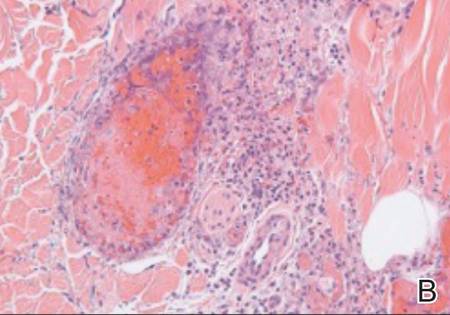

Histopathologic examination of a punch biopsy specimen from the right palm revealed orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis and slight hypergranulosis in the epidermis (Figure 2). Subtle eccrine glandular hyperplasia was evident in the dermis (Figure 3). Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative. Based on the clinical findings and results of the water immersion test, a diagnosis of TRPA was made. A therapeutic trial of calcipotriene ointment 0.005% twice daily was initiated and resulted in dramatic clearance of the lesions within 2 weeks (Figure 4). At 1-month follow-up, the patient was virtually free of all symptoms and no disease recurrence was noted at 5-year follow-up.

|

| ||

Figure 1. Whitish, pebbly papules confined to the central palmar creases in a 38-year-old man. | Figure 2. Orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis and mild hypergranulosis was noted in the epidermis (H&E, original magnification ×100). | ||

|

| ||

| Figure 3. Luminal dilatation in the eccrine glands with a prominence of glandular epithelial cells, which displayed abundant cytoplasm with a granular appearance (H&E, original magnification ×100). | Figure 4. Remarkable response to calcipotriene ointment 0.005%. The white punctuate scar indicates the previous punch biopsy site. |

A 25-year-old woman presented with whitish plaques on the palms of 7 days’ duration. She reported frequent use of household cleansers in the month prior to presentation. The lesions were associated with prominent hyperhidrosis, pruritus, and a tingling sensation in the palms. Dermatologic examination revealed confluent, macerated, white, pavement stone–like papules with prominent puncta around the palmar flexures on both palms. Lesions were exacerbated after a 5-minute water immersion test (Figure 5).

The patient refused skin biopsy, and conservative treatment with a barrier cream and limited water exposure were of no benefit. Based on the clinical findings and results of the water immersion test, a diagnosis of TRPA was made. Due to the excellent outcome experienced in treating the previous patient, a trial of calcipotriene ointment 0.005% twice daily was initiated, and the patient reported complete resolution of signs and symptoms within the initial 2 weeks of treatment. Treatment was terminated at 1-month follow-up.

A 6-year-old boy presented with swollen, itchy palms of 2 months’ duration that the patient described as “wet” and “white.” Due to a recent epidemic of bird flu, the patient’s mother had advised him to use liquid cleansers and antiseptic gels on the hands for the past 2 months, which is when the symptoms on the palms started to develop. On dermatologic examination, whitish, cobblestonelike papules were noted near the palmar creases in association with profuse hyperhidrosis (Figure 6). Based on the clinical findings, a diagnosis of TRPA was made. Biopsy was not attempted and the patient was treated with calcipotriene ointment 0.005% twice daily. At 1-month follow-up, complete clearance of the lesions was noted.

Transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma is an acquired and sporadic disorder that can occur in both sexes.2,4,6,8-11 Onset generally occurs during adolescence or young adulthood.1,3,8,9 Clinically, TRPA is characterized by edema and wrinkling of the palms following 5 to 10 minutes of contact with water that typically resolves within 1 hour after cessation of exposure.2,3,6-8,10 The “hand-in-the-bucket” sign refers to accentuation of physical findings upon immersion of the hand in water.6,10,11 Patients frequently report itching, burning, or tingling sensations in the affected areas.2,4,6,7,9,11 Transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma usually affects the palms in a diffuse, bilateral, and symmetrical pattern,2,4,6-10 but cases showing involvement of the soles,6,7 marginal distribution of lesions,3 unilateral involvement,1 and prominence on the dorsal fingers5 also have been reported. The natural disease course involves reactive episodes and quiescent intervals.2,7,9 Spontaneous resolution of TRPA has been reported.4,6,8

The histological characteristics described in previous reports involve compact orthohyperkeratosis with dilated acrosyringia,2-6,9,11 hyperkeratosis and hypergranulosis in the epidermis,4,8,12 and eccrine glandular hyperplasia.5,12 Alternatively, the skin may appear completely normal on histology.1,7

Originally, it was proposed that TRPA is a variant of punctate keratoderma or hereditary papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma.2,3 However, its position within the keratoderma spectrum is unclear and the etiopathogenesis has not been fully elucidated. Some investigators believe that transient structural and functional alterations in the epidermal milieu prompt epidermal swelling and compensatory dilation of eccrine ducts.3,4,7,8,10 Other reports implicate the inherent structural weakness of eccrine duct walls3,4,11 or aberrations in eccrine glands.5,12 Whether the fundamental pathology lies within the epidermis, eccrine ducts, or the eccrine glands remains to be determined. Nevertheless, reports of TRPA in the setting of cystic fibrosis and its carrier state3,11 as well as the presence of hyperhidrosis in most affected patients and the accumulation of lesions along the palmar creases may implicate oversaturation of the epidermis (due to salt retention or abnormal water absorption by the stratum corneum) as the pivotal event in TRPA pathogenesis.1,10 Once the disease is expressed in susceptible individuals, episodes might be provoked by external factors such as friction, occlusion, sweating, liquid cleansers, antiseptic gels, gloves, topical preparations, and oral medications (eg, salicylic acid, cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors).1,4

Treatment alternatives such as hydrophilic petrolatum and glycerin, ammonium lactate, salicylic acid (with or without urea), aluminum chloride hexahydrate, and topical corticosteroids are limited by unsuccessful or temporary outcomes.1,4,6,8-10 Botulinum toxin injections were effective in a patient with TRPA associated with hyperhidrosis.7 In the cases reported here, topical calcipotriene accomplished dramatic clearance of the lesions within the initial weeks of therapy. Spontaneous resolution was unlikely in these cases, as conservative therapies had not alleviated the signs and symptoms in any of the patients. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that improvement of the skin barrier function associated with other ingredients in the calcipotriene ointment (eg, petrolatum, mineral oil, α-tocopherol) may have led to the resolution of the lesions.

Calcipotriene has demonstrated efficacy in treating cutaneous disorders characterized by epidermal hyperproliferation and impaired terminal differentiation. Immunohistochemical and molecular biological evidence has indicated that topical calcipotriene exerts more pronounced inhibitory effects on epidermal proliferation than on dermal inflammation. It has been proposed that the bioavailability of calcipotriene in the dermal compartment may be markedly reduced compared to its availability in the epidermal compartment13; therefore it can be deduced that its penetration into the dermis is low in the thick skin of palms and its effect on eccrine sweat glands is negligible. Based on these factors, the clinical benefit of calcipotriene in TRPA could be ascribed directly to its antiproliferative and prodifferentiating effects on epidermal keratinocytes. We believe the primary pathology of TRPA lies in the epidermis and that changes in eccrine ducts and glands are secondary to the epidermal changes.

It is difficult to conduct large-scale studies of TRPA due to its rare presentation. Based on our encouraging preliminary observations in 3 patients, we recommend further therapeutic trials of topical calcipotriene in the treatment of TRPA.

1. Erkek E. Unilateral transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma in a child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:564-566.

2. English JC 3rd, McCollough ML. Transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:686-687.

3. Lowes MA, Khaira GS, Holt D. Transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma associated with cystic fibrosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:172-174.

4. MacCormack MA, Wiss K, Malhotra R. Aquagenic syringeal acrokeratoderma: report of two teenage cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:124-126.

5. Yoon TY, Kim KR, Lee JY, et al. Aquagenic syringeal acrokeratoderma: unusual prominence on the dorsal aspect of fingers [published online ahead of print May 22, 2008]. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:486-488.

6. Yan AC, Aasi SZ, Alms WJ, et al. Aquagenic palmoplantar keratoderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:696-699.

7. Diba VC, Cormack GC, Burrows NP. Botulinum toxin is helpful in aquagenic palmoplantar keratoderma. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:394-395.

8. Saray Y, Seckin D. Familial aquagenic acrokeratoderma: case reports and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:906-909.

9. Yalcin B, Artuz F, Toy GG, et al. Acquired aquagenic papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:654-656.

10. Neri I, Bianchi F, Patrizi A. Transient aquagenic palmar hyperwrinkling: the first instance reported in a young boy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:39-42.

11. Katz KA, Yan AC, Turner ML. Aquagenic wrinkling of the palms in patients with cystic fibrosis homozygous for the delta F508 CFTR mutation. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:621-624.

12. Kabashima K, Shimauchi T, Kobayashi M, et al. Aberrant aquaporin 5 expression in the sweat gland in aquagenic wrinkling of the palms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(suppl 1):S28-S32.

13. Lehmann B, Querings K, Reichrath J. Vitamin D and skin: new aspects for dermatology. Exp Dermatol. 2004;13:11-15.

To the Editor:

Transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma (TRPA) is a rare disorder that also has been described using the terms aquagenic syringeal acrokeratoderma, aquagenic palmoplantar keratoderma, aquagenic acrokeratoderma, aquagenic papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma, and aquagenic wrinkling of the palms.1 It was initially described in 1996 by English and McCollough,2 and since then fewer than 100 cases have been reported.1-12

A 38-year-old man presented with prominent palmar hyperhidrosis with whitish papules on the palms of 10 days’ duration. The lesions were exacerbated following exposure to water but were asymptomatic aside from their unsightly cosmetic appearance. Dermatologic examination revealed translucent, whitish, pebbly papules confined to the central palmar creases (Figure 1) that were intensified following a 5-minute water immersion test.

Histopathologic examination of a punch biopsy specimen from the right palm revealed orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis and slight hypergranulosis in the epidermis (Figure 2). Subtle eccrine glandular hyperplasia was evident in the dermis (Figure 3). Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative. Based on the clinical findings and results of the water immersion test, a diagnosis of TRPA was made. A therapeutic trial of calcipotriene ointment 0.005% twice daily was initiated and resulted in dramatic clearance of the lesions within 2 weeks (Figure 4). At 1-month follow-up, the patient was virtually free of all symptoms and no disease recurrence was noted at 5-year follow-up.

|

| ||

Figure 1. Whitish, pebbly papules confined to the central palmar creases in a 38-year-old man. | Figure 2. Orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis and mild hypergranulosis was noted in the epidermis (H&E, original magnification ×100). | ||

|

| ||

| Figure 3. Luminal dilatation in the eccrine glands with a prominence of glandular epithelial cells, which displayed abundant cytoplasm with a granular appearance (H&E, original magnification ×100). | Figure 4. Remarkable response to calcipotriene ointment 0.005%. The white punctuate scar indicates the previous punch biopsy site. |

A 25-year-old woman presented with whitish plaques on the palms of 7 days’ duration. She reported frequent use of household cleansers in the month prior to presentation. The lesions were associated with prominent hyperhidrosis, pruritus, and a tingling sensation in the palms. Dermatologic examination revealed confluent, macerated, white, pavement stone–like papules with prominent puncta around the palmar flexures on both palms. Lesions were exacerbated after a 5-minute water immersion test (Figure 5).

The patient refused skin biopsy, and conservative treatment with a barrier cream and limited water exposure were of no benefit. Based on the clinical findings and results of the water immersion test, a diagnosis of TRPA was made. Due to the excellent outcome experienced in treating the previous patient, a trial of calcipotriene ointment 0.005% twice daily was initiated, and the patient reported complete resolution of signs and symptoms within the initial 2 weeks of treatment. Treatment was terminated at 1-month follow-up.

A 6-year-old boy presented with swollen, itchy palms of 2 months’ duration that the patient described as “wet” and “white.” Due to a recent epidemic of bird flu, the patient’s mother had advised him to use liquid cleansers and antiseptic gels on the hands for the past 2 months, which is when the symptoms on the palms started to develop. On dermatologic examination, whitish, cobblestonelike papules were noted near the palmar creases in association with profuse hyperhidrosis (Figure 6). Based on the clinical findings, a diagnosis of TRPA was made. Biopsy was not attempted and the patient was treated with calcipotriene ointment 0.005% twice daily. At 1-month follow-up, complete clearance of the lesions was noted.

Transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma is an acquired and sporadic disorder that can occur in both sexes.2,4,6,8-11 Onset generally occurs during adolescence or young adulthood.1,3,8,9 Clinically, TRPA is characterized by edema and wrinkling of the palms following 5 to 10 minutes of contact with water that typically resolves within 1 hour after cessation of exposure.2,3,6-8,10 The “hand-in-the-bucket” sign refers to accentuation of physical findings upon immersion of the hand in water.6,10,11 Patients frequently report itching, burning, or tingling sensations in the affected areas.2,4,6,7,9,11 Transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma usually affects the palms in a diffuse, bilateral, and symmetrical pattern,2,4,6-10 but cases showing involvement of the soles,6,7 marginal distribution of lesions,3 unilateral involvement,1 and prominence on the dorsal fingers5 also have been reported. The natural disease course involves reactive episodes and quiescent intervals.2,7,9 Spontaneous resolution of TRPA has been reported.4,6,8

The histological characteristics described in previous reports involve compact orthohyperkeratosis with dilated acrosyringia,2-6,9,11 hyperkeratosis and hypergranulosis in the epidermis,4,8,12 and eccrine glandular hyperplasia.5,12 Alternatively, the skin may appear completely normal on histology.1,7

Originally, it was proposed that TRPA is a variant of punctate keratoderma or hereditary papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma.2,3 However, its position within the keratoderma spectrum is unclear and the etiopathogenesis has not been fully elucidated. Some investigators believe that transient structural and functional alterations in the epidermal milieu prompt epidermal swelling and compensatory dilation of eccrine ducts.3,4,7,8,10 Other reports implicate the inherent structural weakness of eccrine duct walls3,4,11 or aberrations in eccrine glands.5,12 Whether the fundamental pathology lies within the epidermis, eccrine ducts, or the eccrine glands remains to be determined. Nevertheless, reports of TRPA in the setting of cystic fibrosis and its carrier state3,11 as well as the presence of hyperhidrosis in most affected patients and the accumulation of lesions along the palmar creases may implicate oversaturation of the epidermis (due to salt retention or abnormal water absorption by the stratum corneum) as the pivotal event in TRPA pathogenesis.1,10 Once the disease is expressed in susceptible individuals, episodes might be provoked by external factors such as friction, occlusion, sweating, liquid cleansers, antiseptic gels, gloves, topical preparations, and oral medications (eg, salicylic acid, cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors).1,4

Treatment alternatives such as hydrophilic petrolatum and glycerin, ammonium lactate, salicylic acid (with or without urea), aluminum chloride hexahydrate, and topical corticosteroids are limited by unsuccessful or temporary outcomes.1,4,6,8-10 Botulinum toxin injections were effective in a patient with TRPA associated with hyperhidrosis.7 In the cases reported here, topical calcipotriene accomplished dramatic clearance of the lesions within the initial weeks of therapy. Spontaneous resolution was unlikely in these cases, as conservative therapies had not alleviated the signs and symptoms in any of the patients. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that improvement of the skin barrier function associated with other ingredients in the calcipotriene ointment (eg, petrolatum, mineral oil, α-tocopherol) may have led to the resolution of the lesions.

Calcipotriene has demonstrated efficacy in treating cutaneous disorders characterized by epidermal hyperproliferation and impaired terminal differentiation. Immunohistochemical and molecular biological evidence has indicated that topical calcipotriene exerts more pronounced inhibitory effects on epidermal proliferation than on dermal inflammation. It has been proposed that the bioavailability of calcipotriene in the dermal compartment may be markedly reduced compared to its availability in the epidermal compartment13; therefore it can be deduced that its penetration into the dermis is low in the thick skin of palms and its effect on eccrine sweat glands is negligible. Based on these factors, the clinical benefit of calcipotriene in TRPA could be ascribed directly to its antiproliferative and prodifferentiating effects on epidermal keratinocytes. We believe the primary pathology of TRPA lies in the epidermis and that changes in eccrine ducts and glands are secondary to the epidermal changes.

It is difficult to conduct large-scale studies of TRPA due to its rare presentation. Based on our encouraging preliminary observations in 3 patients, we recommend further therapeutic trials of topical calcipotriene in the treatment of TRPA.

To the Editor:

Transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma (TRPA) is a rare disorder that also has been described using the terms aquagenic syringeal acrokeratoderma, aquagenic palmoplantar keratoderma, aquagenic acrokeratoderma, aquagenic papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma, and aquagenic wrinkling of the palms.1 It was initially described in 1996 by English and McCollough,2 and since then fewer than 100 cases have been reported.1-12

A 38-year-old man presented with prominent palmar hyperhidrosis with whitish papules on the palms of 10 days’ duration. The lesions were exacerbated following exposure to water but were asymptomatic aside from their unsightly cosmetic appearance. Dermatologic examination revealed translucent, whitish, pebbly papules confined to the central palmar creases (Figure 1) that were intensified following a 5-minute water immersion test.

Histopathologic examination of a punch biopsy specimen from the right palm revealed orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis and slight hypergranulosis in the epidermis (Figure 2). Subtle eccrine glandular hyperplasia was evident in the dermis (Figure 3). Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative. Based on the clinical findings and results of the water immersion test, a diagnosis of TRPA was made. A therapeutic trial of calcipotriene ointment 0.005% twice daily was initiated and resulted in dramatic clearance of the lesions within 2 weeks (Figure 4). At 1-month follow-up, the patient was virtually free of all symptoms and no disease recurrence was noted at 5-year follow-up.

|

| ||

Figure 1. Whitish, pebbly papules confined to the central palmar creases in a 38-year-old man. | Figure 2. Orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis and mild hypergranulosis was noted in the epidermis (H&E, original magnification ×100). | ||

|

| ||

| Figure 3. Luminal dilatation in the eccrine glands with a prominence of glandular epithelial cells, which displayed abundant cytoplasm with a granular appearance (H&E, original magnification ×100). | Figure 4. Remarkable response to calcipotriene ointment 0.005%. The white punctuate scar indicates the previous punch biopsy site. |

A 25-year-old woman presented with whitish plaques on the palms of 7 days’ duration. She reported frequent use of household cleansers in the month prior to presentation. The lesions were associated with prominent hyperhidrosis, pruritus, and a tingling sensation in the palms. Dermatologic examination revealed confluent, macerated, white, pavement stone–like papules with prominent puncta around the palmar flexures on both palms. Lesions were exacerbated after a 5-minute water immersion test (Figure 5).

The patient refused skin biopsy, and conservative treatment with a barrier cream and limited water exposure were of no benefit. Based on the clinical findings and results of the water immersion test, a diagnosis of TRPA was made. Due to the excellent outcome experienced in treating the previous patient, a trial of calcipotriene ointment 0.005% twice daily was initiated, and the patient reported complete resolution of signs and symptoms within the initial 2 weeks of treatment. Treatment was terminated at 1-month follow-up.

A 6-year-old boy presented with swollen, itchy palms of 2 months’ duration that the patient described as “wet” and “white.” Due to a recent epidemic of bird flu, the patient’s mother had advised him to use liquid cleansers and antiseptic gels on the hands for the past 2 months, which is when the symptoms on the palms started to develop. On dermatologic examination, whitish, cobblestonelike papules were noted near the palmar creases in association with profuse hyperhidrosis (Figure 6). Based on the clinical findings, a diagnosis of TRPA was made. Biopsy was not attempted and the patient was treated with calcipotriene ointment 0.005% twice daily. At 1-month follow-up, complete clearance of the lesions was noted.

Transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma is an acquired and sporadic disorder that can occur in both sexes.2,4,6,8-11 Onset generally occurs during adolescence or young adulthood.1,3,8,9 Clinically, TRPA is characterized by edema and wrinkling of the palms following 5 to 10 minutes of contact with water that typically resolves within 1 hour after cessation of exposure.2,3,6-8,10 The “hand-in-the-bucket” sign refers to accentuation of physical findings upon immersion of the hand in water.6,10,11 Patients frequently report itching, burning, or tingling sensations in the affected areas.2,4,6,7,9,11 Transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma usually affects the palms in a diffuse, bilateral, and symmetrical pattern,2,4,6-10 but cases showing involvement of the soles,6,7 marginal distribution of lesions,3 unilateral involvement,1 and prominence on the dorsal fingers5 also have been reported. The natural disease course involves reactive episodes and quiescent intervals.2,7,9 Spontaneous resolution of TRPA has been reported.4,6,8

The histological characteristics described in previous reports involve compact orthohyperkeratosis with dilated acrosyringia,2-6,9,11 hyperkeratosis and hypergranulosis in the epidermis,4,8,12 and eccrine glandular hyperplasia.5,12 Alternatively, the skin may appear completely normal on histology.1,7

Originally, it was proposed that TRPA is a variant of punctate keratoderma or hereditary papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma.2,3 However, its position within the keratoderma spectrum is unclear and the etiopathogenesis has not been fully elucidated. Some investigators believe that transient structural and functional alterations in the epidermal milieu prompt epidermal swelling and compensatory dilation of eccrine ducts.3,4,7,8,10 Other reports implicate the inherent structural weakness of eccrine duct walls3,4,11 or aberrations in eccrine glands.5,12 Whether the fundamental pathology lies within the epidermis, eccrine ducts, or the eccrine glands remains to be determined. Nevertheless, reports of TRPA in the setting of cystic fibrosis and its carrier state3,11 as well as the presence of hyperhidrosis in most affected patients and the accumulation of lesions along the palmar creases may implicate oversaturation of the epidermis (due to salt retention or abnormal water absorption by the stratum corneum) as the pivotal event in TRPA pathogenesis.1,10 Once the disease is expressed in susceptible individuals, episodes might be provoked by external factors such as friction, occlusion, sweating, liquid cleansers, antiseptic gels, gloves, topical preparations, and oral medications (eg, salicylic acid, cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors).1,4

Treatment alternatives such as hydrophilic petrolatum and glycerin, ammonium lactate, salicylic acid (with or without urea), aluminum chloride hexahydrate, and topical corticosteroids are limited by unsuccessful or temporary outcomes.1,4,6,8-10 Botulinum toxin injections were effective in a patient with TRPA associated with hyperhidrosis.7 In the cases reported here, topical calcipotriene accomplished dramatic clearance of the lesions within the initial weeks of therapy. Spontaneous resolution was unlikely in these cases, as conservative therapies had not alleviated the signs and symptoms in any of the patients. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that improvement of the skin barrier function associated with other ingredients in the calcipotriene ointment (eg, petrolatum, mineral oil, α-tocopherol) may have led to the resolution of the lesions.

Calcipotriene has demonstrated efficacy in treating cutaneous disorders characterized by epidermal hyperproliferation and impaired terminal differentiation. Immunohistochemical and molecular biological evidence has indicated that topical calcipotriene exerts more pronounced inhibitory effects on epidermal proliferation than on dermal inflammation. It has been proposed that the bioavailability of calcipotriene in the dermal compartment may be markedly reduced compared to its availability in the epidermal compartment13; therefore it can be deduced that its penetration into the dermis is low in the thick skin of palms and its effect on eccrine sweat glands is negligible. Based on these factors, the clinical benefit of calcipotriene in TRPA could be ascribed directly to its antiproliferative and prodifferentiating effects on epidermal keratinocytes. We believe the primary pathology of TRPA lies in the epidermis and that changes in eccrine ducts and glands are secondary to the epidermal changes.

It is difficult to conduct large-scale studies of TRPA due to its rare presentation. Based on our encouraging preliminary observations in 3 patients, we recommend further therapeutic trials of topical calcipotriene in the treatment of TRPA.

1. Erkek E. Unilateral transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma in a child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:564-566.

2. English JC 3rd, McCollough ML. Transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:686-687.

3. Lowes MA, Khaira GS, Holt D. Transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma associated with cystic fibrosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:172-174.

4. MacCormack MA, Wiss K, Malhotra R. Aquagenic syringeal acrokeratoderma: report of two teenage cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:124-126.

5. Yoon TY, Kim KR, Lee JY, et al. Aquagenic syringeal acrokeratoderma: unusual prominence on the dorsal aspect of fingers [published online ahead of print May 22, 2008]. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:486-488.

6. Yan AC, Aasi SZ, Alms WJ, et al. Aquagenic palmoplantar keratoderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:696-699.

7. Diba VC, Cormack GC, Burrows NP. Botulinum toxin is helpful in aquagenic palmoplantar keratoderma. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:394-395.

8. Saray Y, Seckin D. Familial aquagenic acrokeratoderma: case reports and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:906-909.

9. Yalcin B, Artuz F, Toy GG, et al. Acquired aquagenic papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:654-656.

10. Neri I, Bianchi F, Patrizi A. Transient aquagenic palmar hyperwrinkling: the first instance reported in a young boy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:39-42.

11. Katz KA, Yan AC, Turner ML. Aquagenic wrinkling of the palms in patients with cystic fibrosis homozygous for the delta F508 CFTR mutation. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:621-624.

12. Kabashima K, Shimauchi T, Kobayashi M, et al. Aberrant aquaporin 5 expression in the sweat gland in aquagenic wrinkling of the palms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(suppl 1):S28-S32.

13. Lehmann B, Querings K, Reichrath J. Vitamin D and skin: new aspects for dermatology. Exp Dermatol. 2004;13:11-15.

1. Erkek E. Unilateral transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma in a child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:564-566.

2. English JC 3rd, McCollough ML. Transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:686-687.

3. Lowes MA, Khaira GS, Holt D. Transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma associated with cystic fibrosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:172-174.

4. MacCormack MA, Wiss K, Malhotra R. Aquagenic syringeal acrokeratoderma: report of two teenage cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:124-126.

5. Yoon TY, Kim KR, Lee JY, et al. Aquagenic syringeal acrokeratoderma: unusual prominence on the dorsal aspect of fingers [published online ahead of print May 22, 2008]. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:486-488.

6. Yan AC, Aasi SZ, Alms WJ, et al. Aquagenic palmoplantar keratoderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:696-699.

7. Diba VC, Cormack GC, Burrows NP. Botulinum toxin is helpful in aquagenic palmoplantar keratoderma. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:394-395.

8. Saray Y, Seckin D. Familial aquagenic acrokeratoderma: case reports and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:906-909.

9. Yalcin B, Artuz F, Toy GG, et al. Acquired aquagenic papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:654-656.

10. Neri I, Bianchi F, Patrizi A. Transient aquagenic palmar hyperwrinkling: the first instance reported in a young boy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:39-42.

11. Katz KA, Yan AC, Turner ML. Aquagenic wrinkling of the palms in patients with cystic fibrosis homozygous for the delta F508 CFTR mutation. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:621-624.

12. Kabashima K, Shimauchi T, Kobayashi M, et al. Aberrant aquaporin 5 expression in the sweat gland in aquagenic wrinkling of the palms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(suppl 1):S28-S32.

13. Lehmann B, Querings K, Reichrath J. Vitamin D and skin: new aspects for dermatology. Exp Dermatol. 2004;13:11-15.

Recurrent Omphalitis Secondary to a Hair-Containing Umbilical Foreign Body

To the Editor:

We read with great interest the article, “Omphalith-Associated Relapsing Umbilical Cellulitis: Recurrent Omphalitis Secondary to a Hair-Containing Belly Button Bezoar” (Cutis. 2010;86:199-202), which introduced the terms omphalotrich and tricomphalith to describe the pilar composition of a hair-containing umbilical foreign body in an 18-year-old man. We report a similar case.

A 38-year-old man presented with a 10-year history of an unusual odor in the umbilical region with recurrent discharge. He diligently maintained proper hygiene of the umbilicus using cotton swabs and had received recurrent cycles of oral antibiotics prescribed by his general practitioner with temporary improvement of the odor and amount of discharge. Physical examination revealed a normal umbilicus with a deep and tight umbilical cleft that required the use of curved mosquito forceps for further examination (Figure 1). A bezoar comprised of a compact collection of terminal hair shafts was noted deep in the umbilicus (Figure 2). A considerable amount of terminal hairs also were noted on the skin of the abdominal area. Following removal of the bezoar, no umbilical fistula was observed, and the presence of embryologic abnormalities (eg, omphalomesenteric duct remnants) was ruled out on magnetic resonance imaging. A diagnosis of recurrent omphalitis secondary to a hair-containing bezoar was made. Following extraction of the bezoar, the odor and discharge promptly resolved, thereby avoiding the need for oral antibiotics; however, a smaller bezoar comprised of a collection of terminal hair shafts was removed 4 months later.

|

| |

Figure 1. Deep and narrow umbilical cleft with serous exudate in the umbilicus after removal of the foreign body. | Figure 2. A section of the umbilical foreign body composed of a collection of terminal hair shafts. |

An omphalith is an umbilical foreign body that results from the accumulation of keratinous and amorphous sebaceous material.2 Several predisposing factors have been proposed for its pathogenesis, such as the anatomical disposition of the umbilicus and the patient’s hygiene. We hypothesize that a deep umbilicus and a large amount of terminal hairs in the abdominal area were predisposing factors in our patient. Cohen et al1 proposed the terms omphalotrich and trichomphalith to describe the pilar composition of a hair-containing umbilical foreign body that did not have the characteristic stonelike presentation of a traditional omphalith. The authors also referred to the umbilical foreign body in their patient as a trichobezoar, a term used to describe exogenous foreign bodies composed of ingested hair in the gastrointestinal tract, given the embryologic origin of the umbilicus and epithelium of the gastrointestinal tract. We agree that the terms omphalotrich and trichomphalith appropriately describe the current presentation; we also propose the terms omphalitrichia or thricomphalia to describe the findings seen in our patient, which should always be ruled out in patients with recurrent omphalitis that is unresponsive to antibiotics.

1. Cohen PR, Robinson FW, Gray JM. Omphalith-associated relapsing umbilical cellulitis: recurrent omphalitis secondary to a hair-containing belly button bezoar. Cutis. 2010;86:199-202.

2. Swanson SL, Woosley JT, Fleischer AB Jr, et al. Umbilical mass. omphalith. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:1267, 1270.

To the Editor:

We read with great interest the article, “Omphalith-Associated Relapsing Umbilical Cellulitis: Recurrent Omphalitis Secondary to a Hair-Containing Belly Button Bezoar” (Cutis. 2010;86:199-202), which introduced the terms omphalotrich and tricomphalith to describe the pilar composition of a hair-containing umbilical foreign body in an 18-year-old man. We report a similar case.

A 38-year-old man presented with a 10-year history of an unusual odor in the umbilical region with recurrent discharge. He diligently maintained proper hygiene of the umbilicus using cotton swabs and had received recurrent cycles of oral antibiotics prescribed by his general practitioner with temporary improvement of the odor and amount of discharge. Physical examination revealed a normal umbilicus with a deep and tight umbilical cleft that required the use of curved mosquito forceps for further examination (Figure 1). A bezoar comprised of a compact collection of terminal hair shafts was noted deep in the umbilicus (Figure 2). A considerable amount of terminal hairs also were noted on the skin of the abdominal area. Following removal of the bezoar, no umbilical fistula was observed, and the presence of embryologic abnormalities (eg, omphalomesenteric duct remnants) was ruled out on magnetic resonance imaging. A diagnosis of recurrent omphalitis secondary to a hair-containing bezoar was made. Following extraction of the bezoar, the odor and discharge promptly resolved, thereby avoiding the need for oral antibiotics; however, a smaller bezoar comprised of a collection of terminal hair shafts was removed 4 months later.

|

| |

Figure 1. Deep and narrow umbilical cleft with serous exudate in the umbilicus after removal of the foreign body. | Figure 2. A section of the umbilical foreign body composed of a collection of terminal hair shafts. |

An omphalith is an umbilical foreign body that results from the accumulation of keratinous and amorphous sebaceous material.2 Several predisposing factors have been proposed for its pathogenesis, such as the anatomical disposition of the umbilicus and the patient’s hygiene. We hypothesize that a deep umbilicus and a large amount of terminal hairs in the abdominal area were predisposing factors in our patient. Cohen et al1 proposed the terms omphalotrich and trichomphalith to describe the pilar composition of a hair-containing umbilical foreign body that did not have the characteristic stonelike presentation of a traditional omphalith. The authors also referred to the umbilical foreign body in their patient as a trichobezoar, a term used to describe exogenous foreign bodies composed of ingested hair in the gastrointestinal tract, given the embryologic origin of the umbilicus and epithelium of the gastrointestinal tract. We agree that the terms omphalotrich and trichomphalith appropriately describe the current presentation; we also propose the terms omphalitrichia or thricomphalia to describe the findings seen in our patient, which should always be ruled out in patients with recurrent omphalitis that is unresponsive to antibiotics.

To the Editor:

We read with great interest the article, “Omphalith-Associated Relapsing Umbilical Cellulitis: Recurrent Omphalitis Secondary to a Hair-Containing Belly Button Bezoar” (Cutis. 2010;86:199-202), which introduced the terms omphalotrich and tricomphalith to describe the pilar composition of a hair-containing umbilical foreign body in an 18-year-old man. We report a similar case.