User login

Harlequin Syndrome: Discovery of an Ancient Schwannoma

To the Editor:

A 52-year-old man who was otherwise healthy and a long-distance runner presented with the sudden onset of diminished sweating on the left side of the body of 6 weeks’ duration. While training for a marathon, he reported that he perspired only on the right side of the body during runs of 12 to 15 miles; he observed a lack of sweating on the left side of the face, left side of the trunk, left arm, and left leg. This absence of sweating was accompanied by intense flushing on the right side of the face and trunk.

The patient did not take any medications. He reported no history of trauma and exhibited no neurologic deficits. A chest radiograph was negative. Thyroid function testing and a comprehensive metabolic panel were normal. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the chest and abdomen revealed a 4.3-cm soft-tissue mass in the left superior mediastinum that was superior to the aortic arch, posterior to the left subclavian artery in proximity to the sympathetic chain, and lateral to the trachea. The patient was diagnosed with Harlequin syndrome (HS).

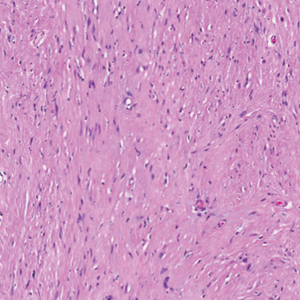

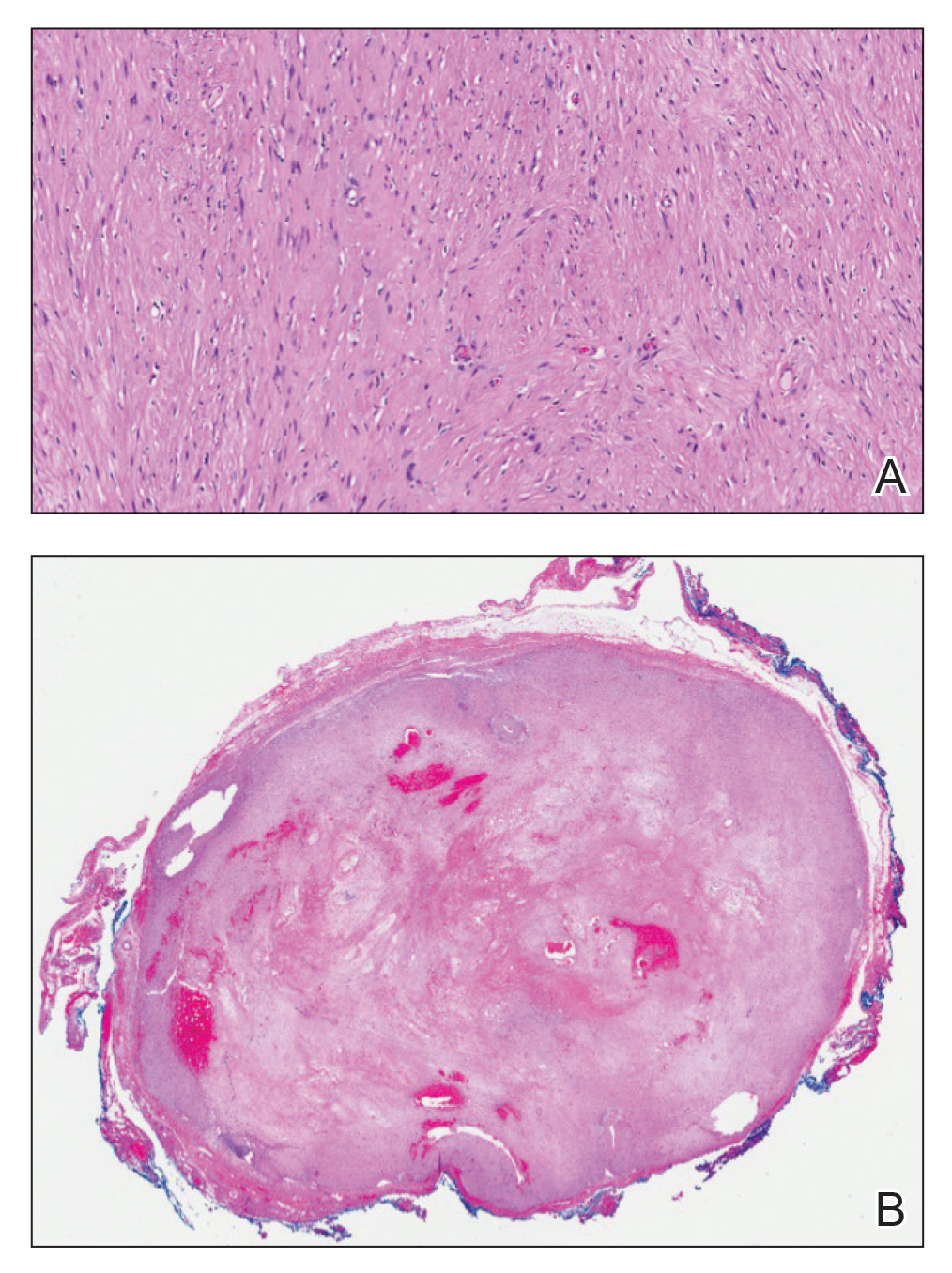

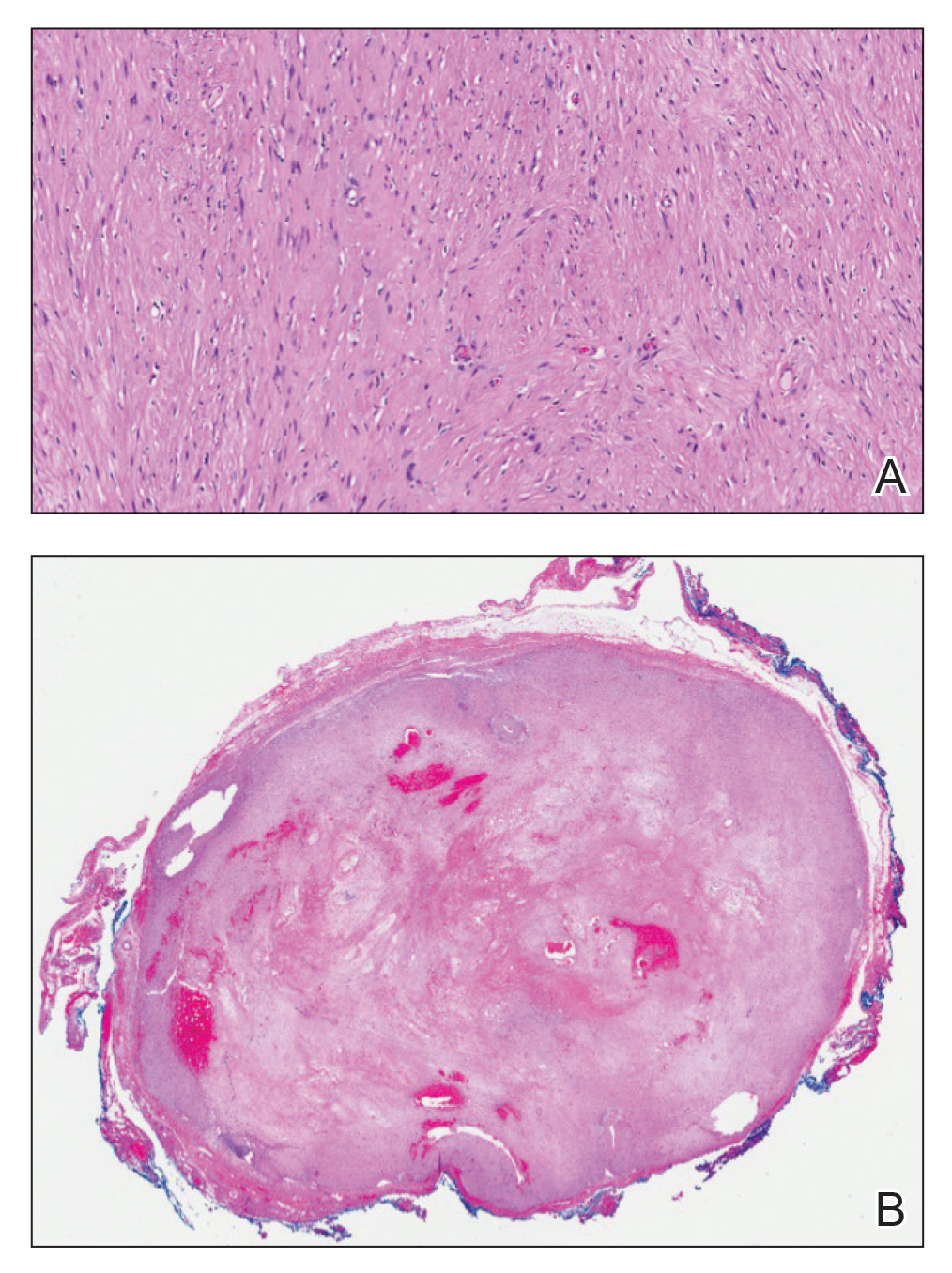

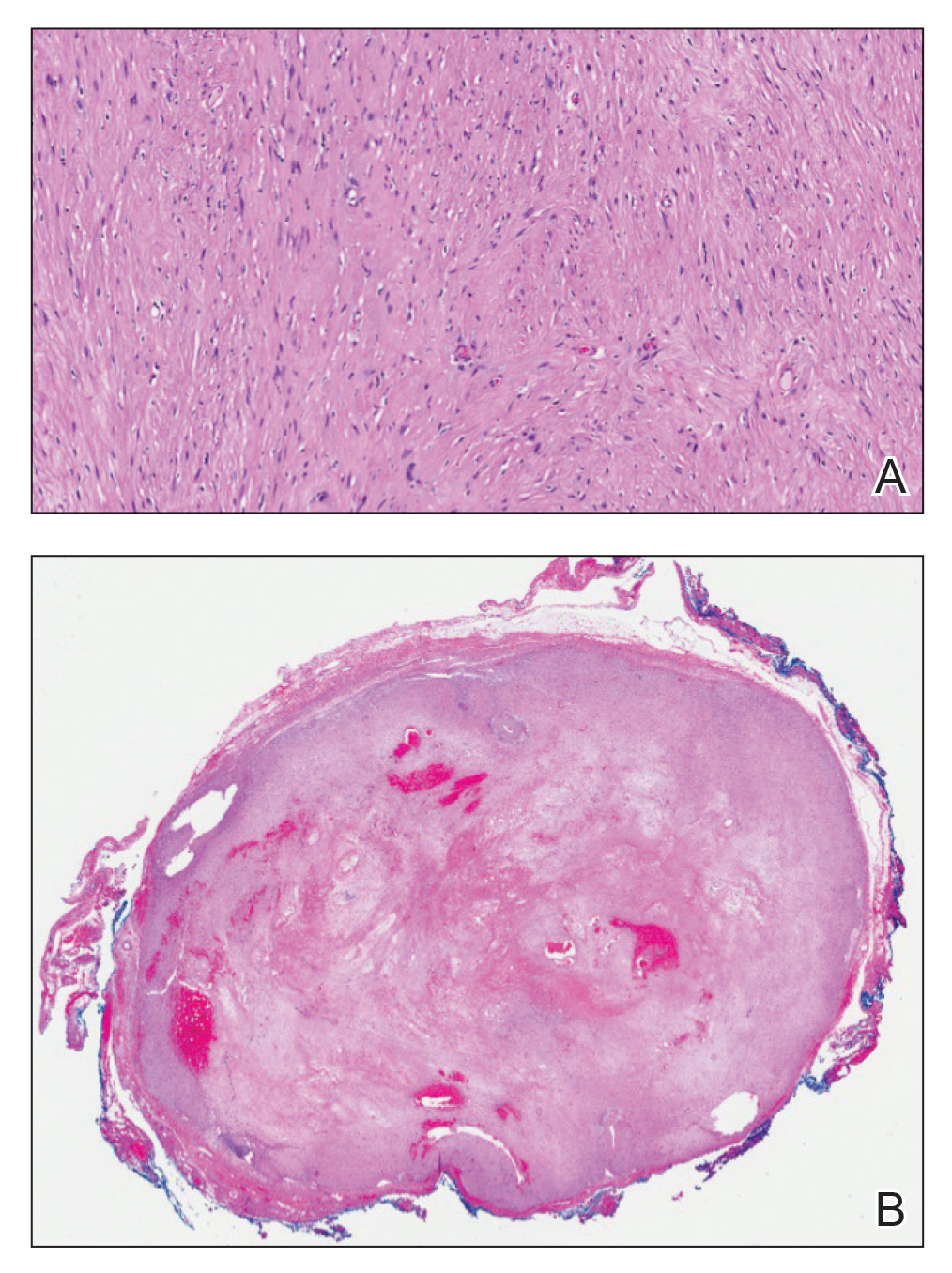

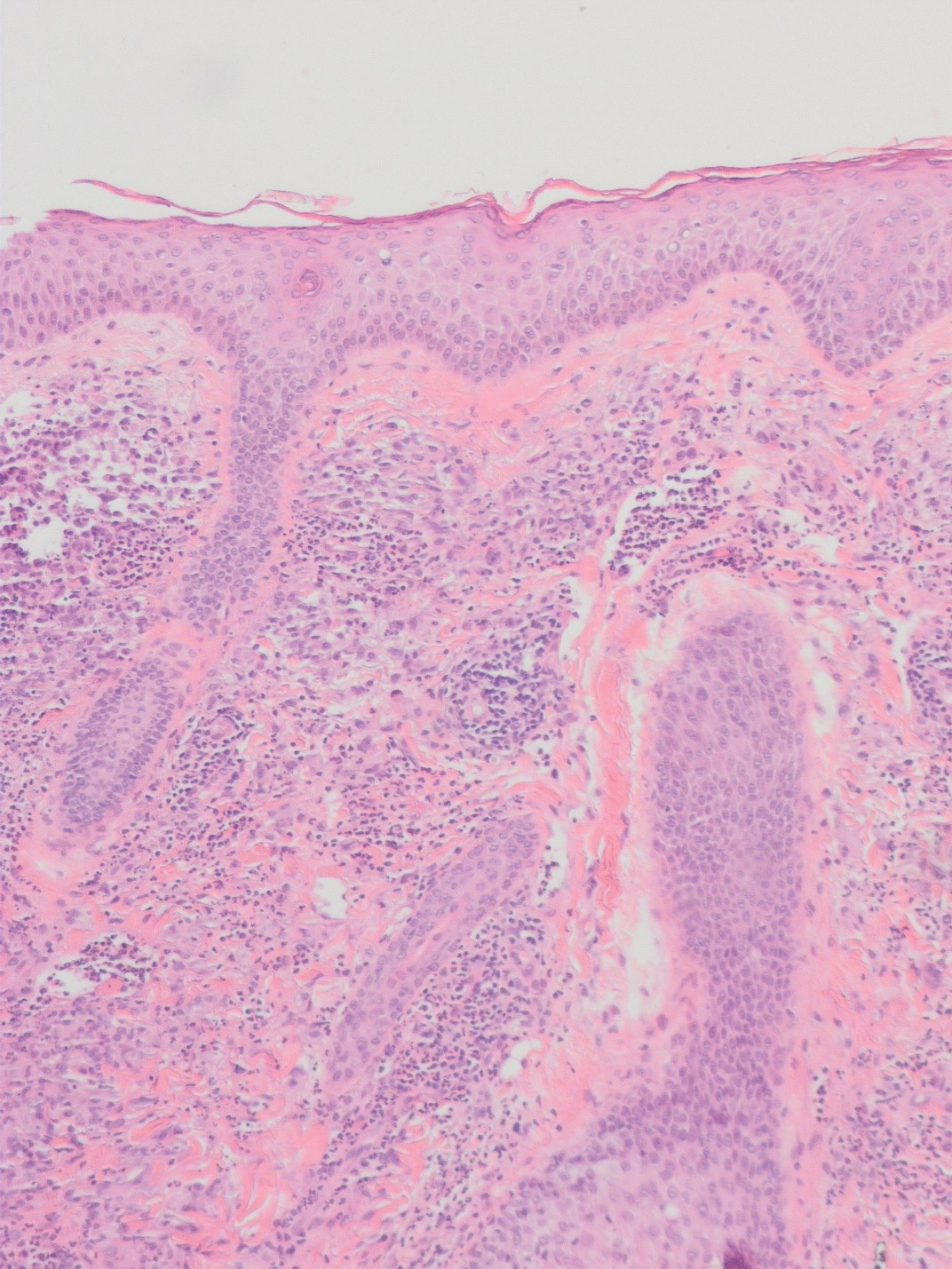

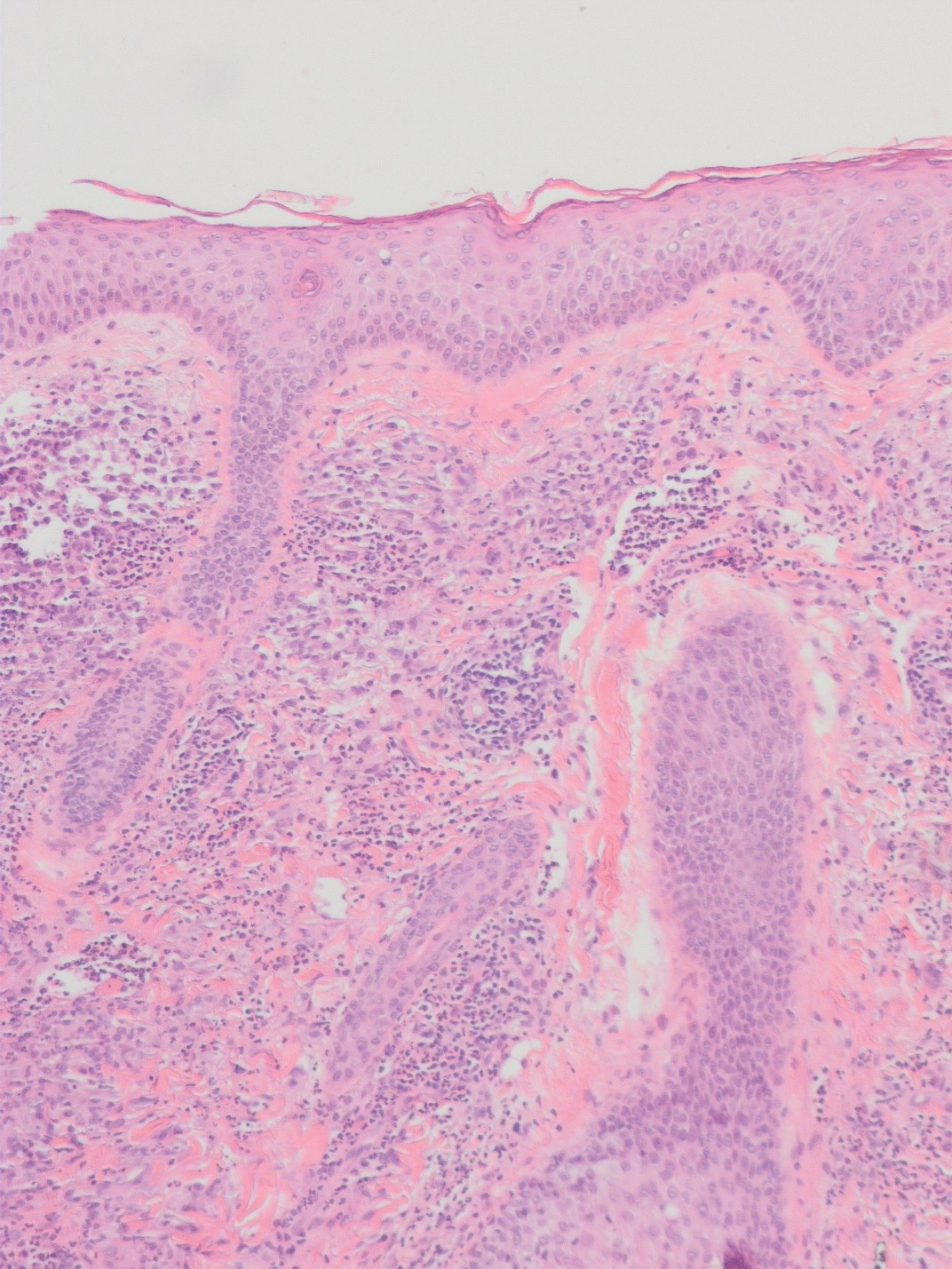

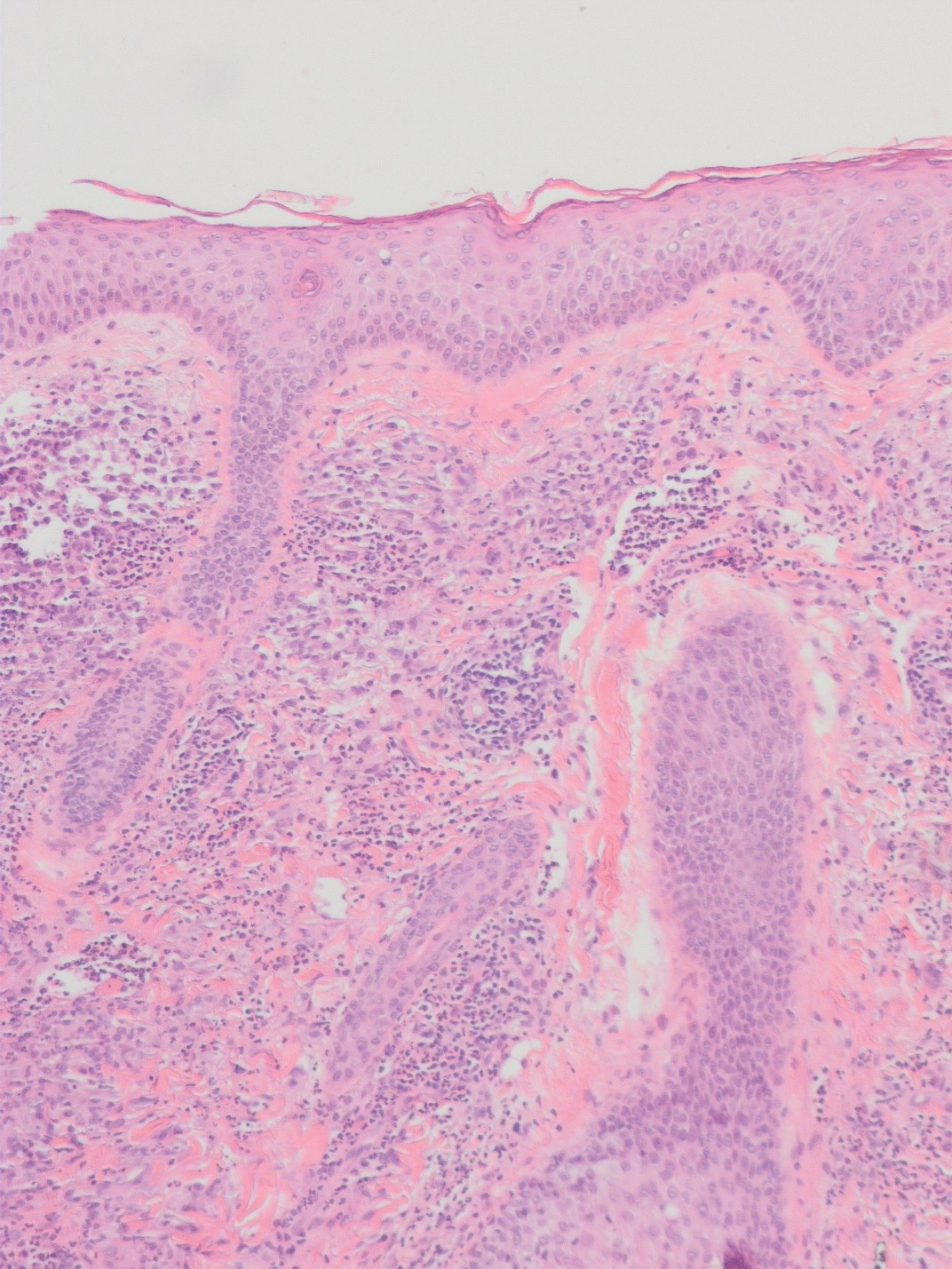

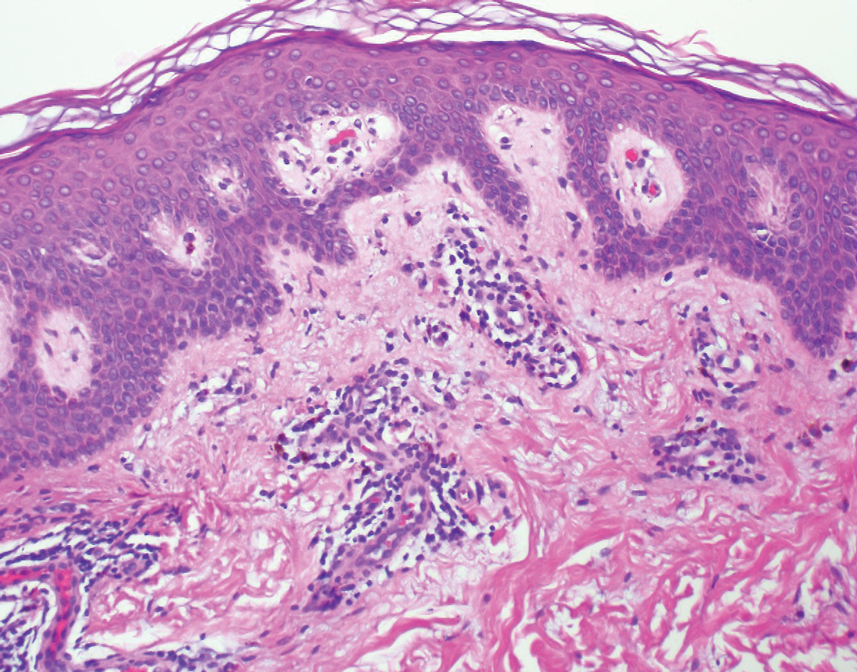

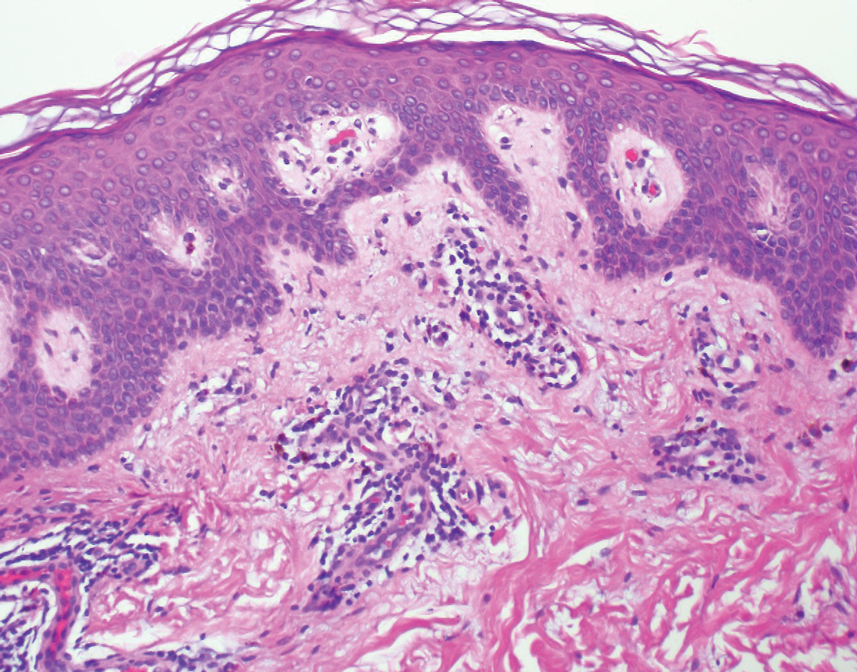

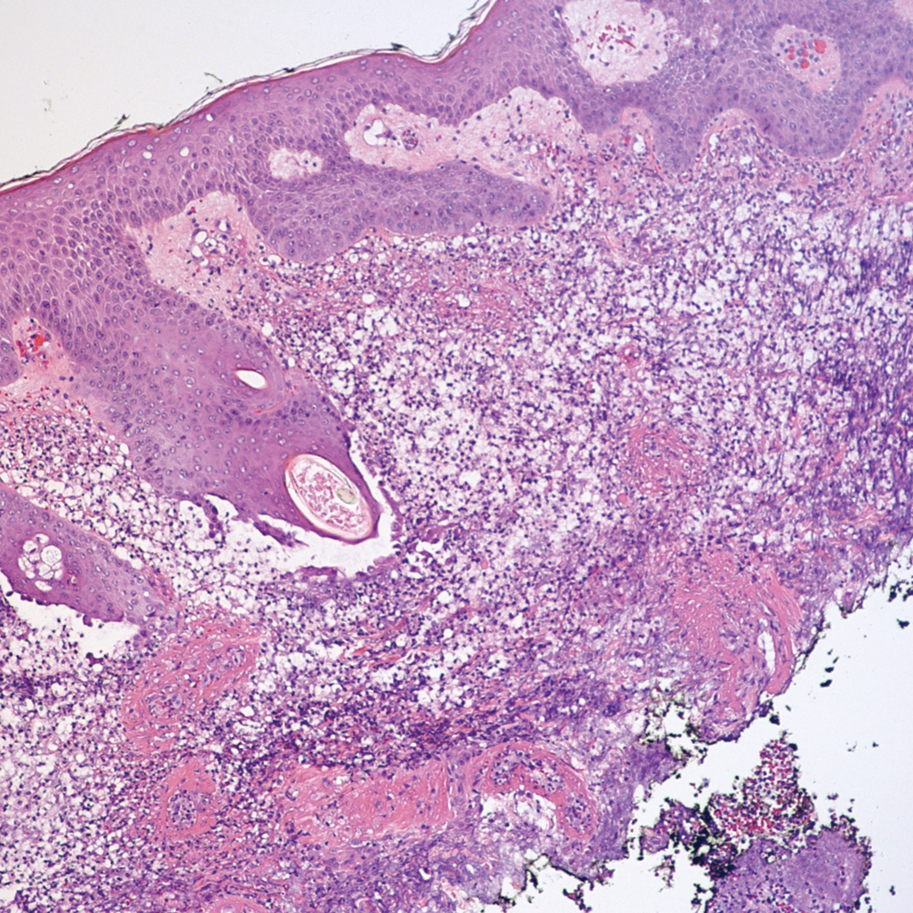

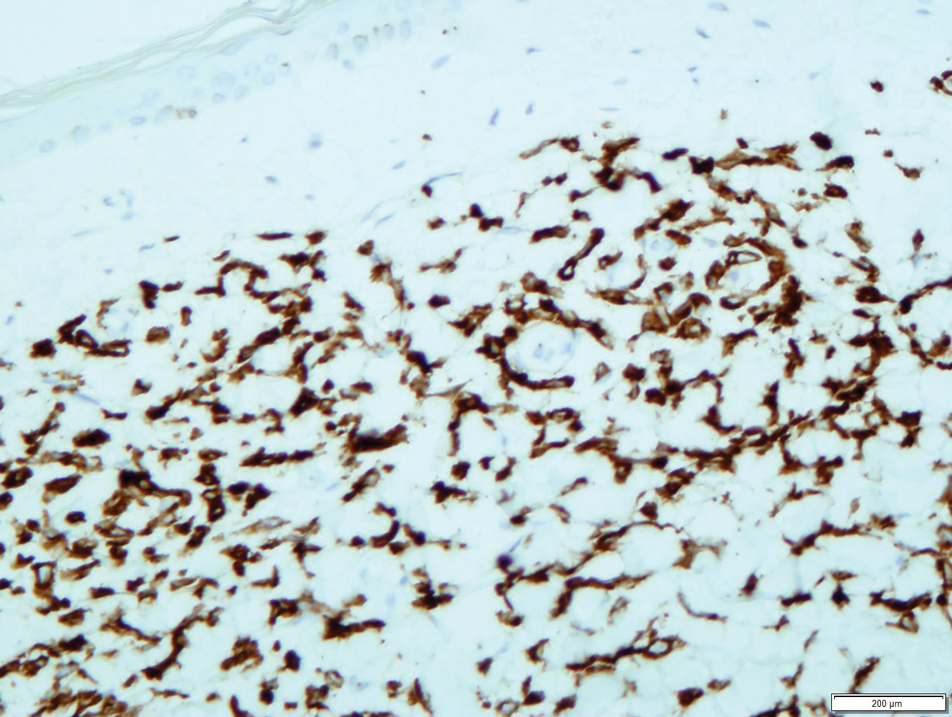

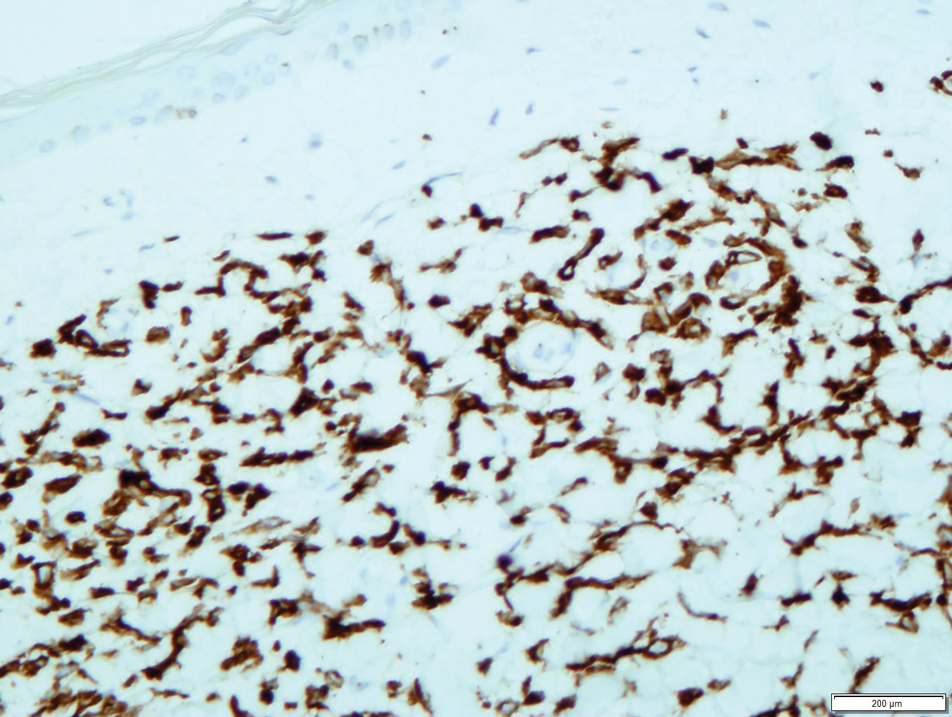

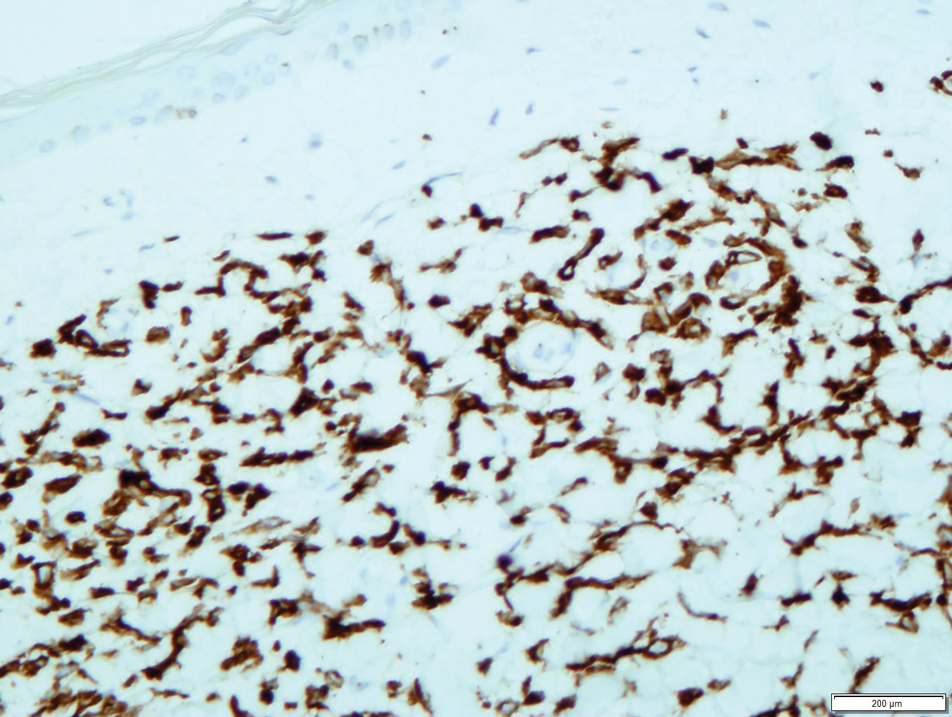

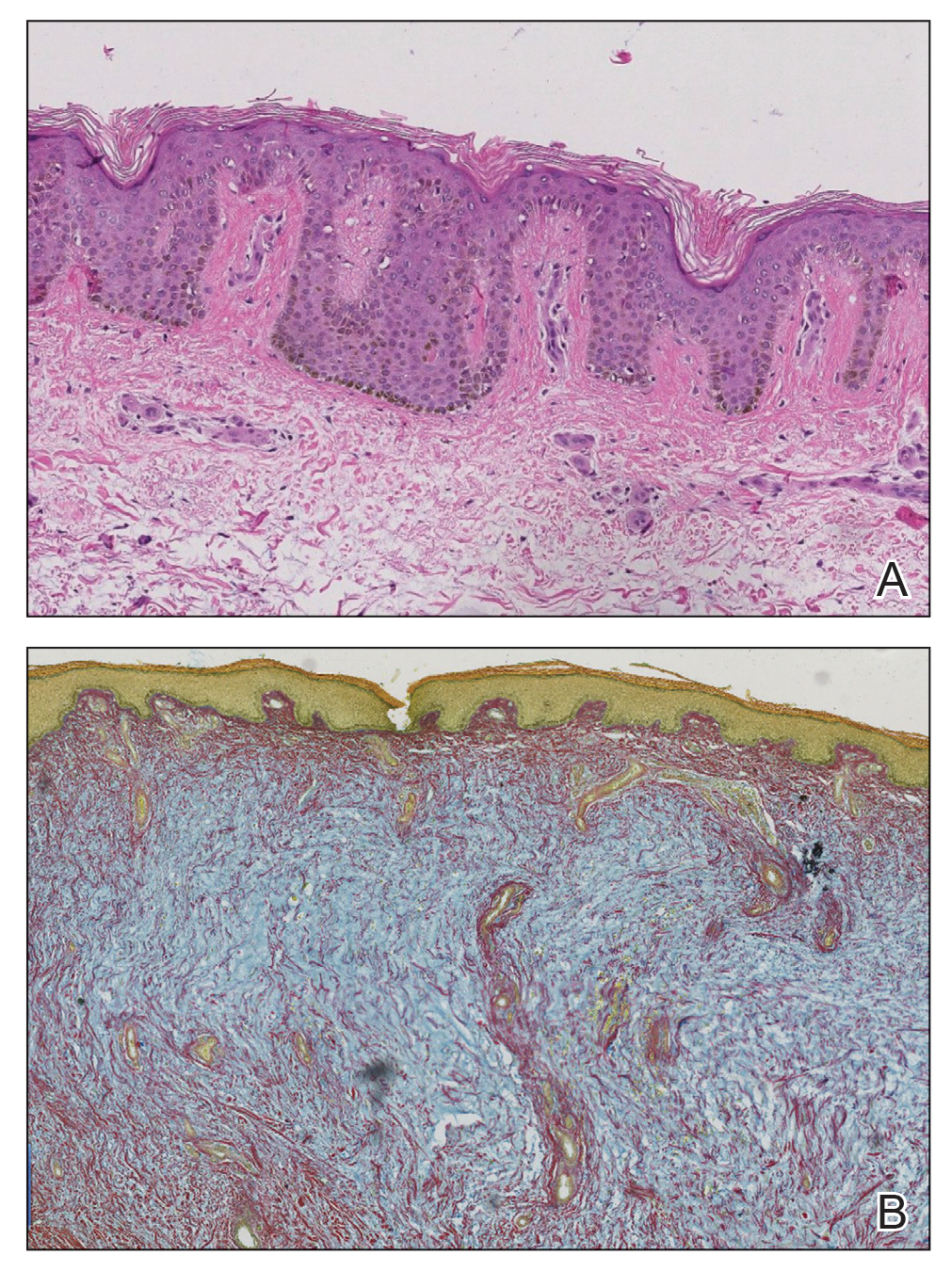

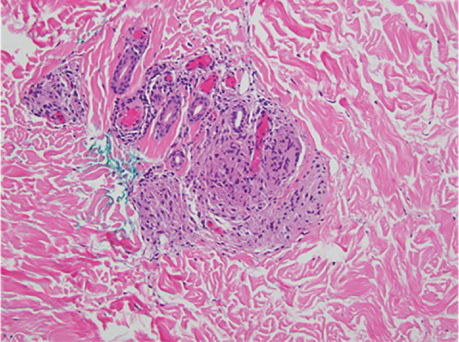

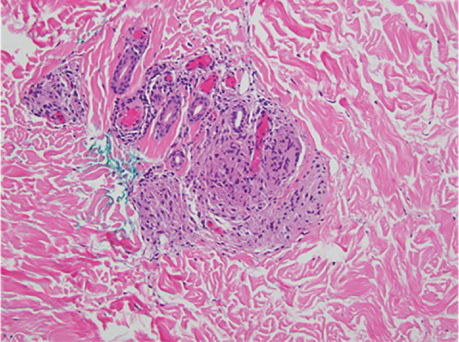

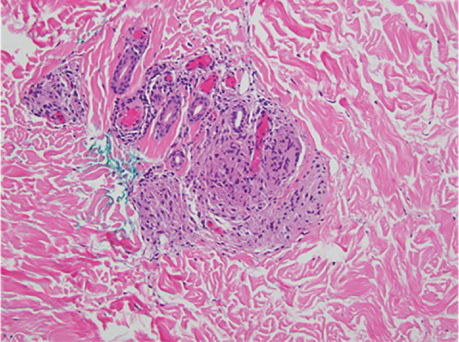

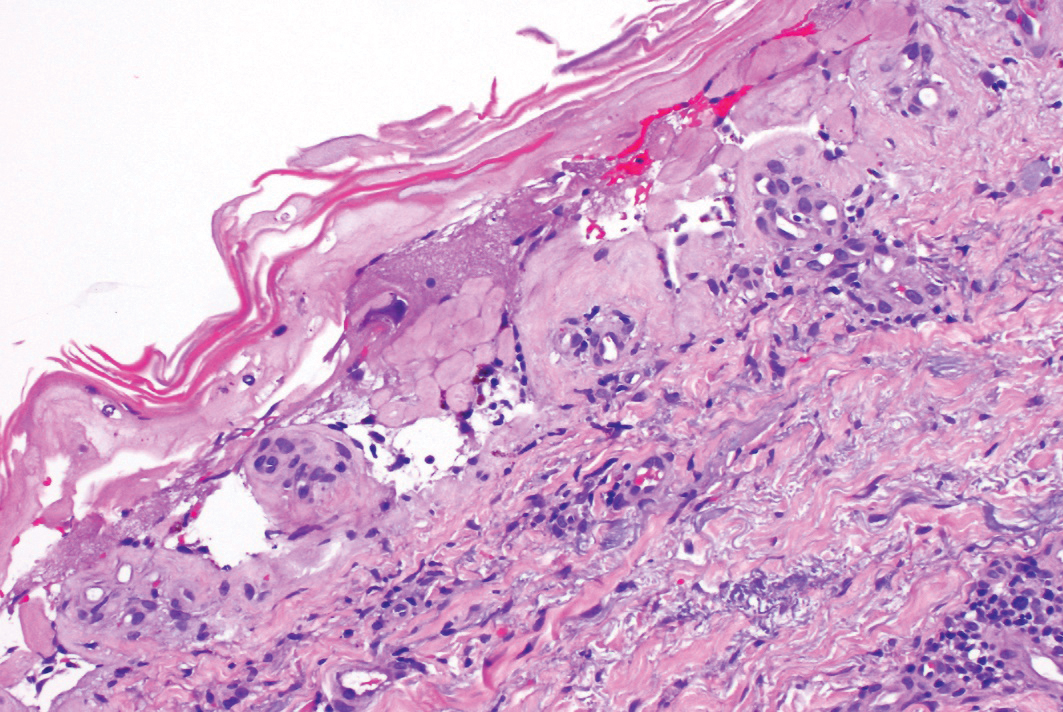

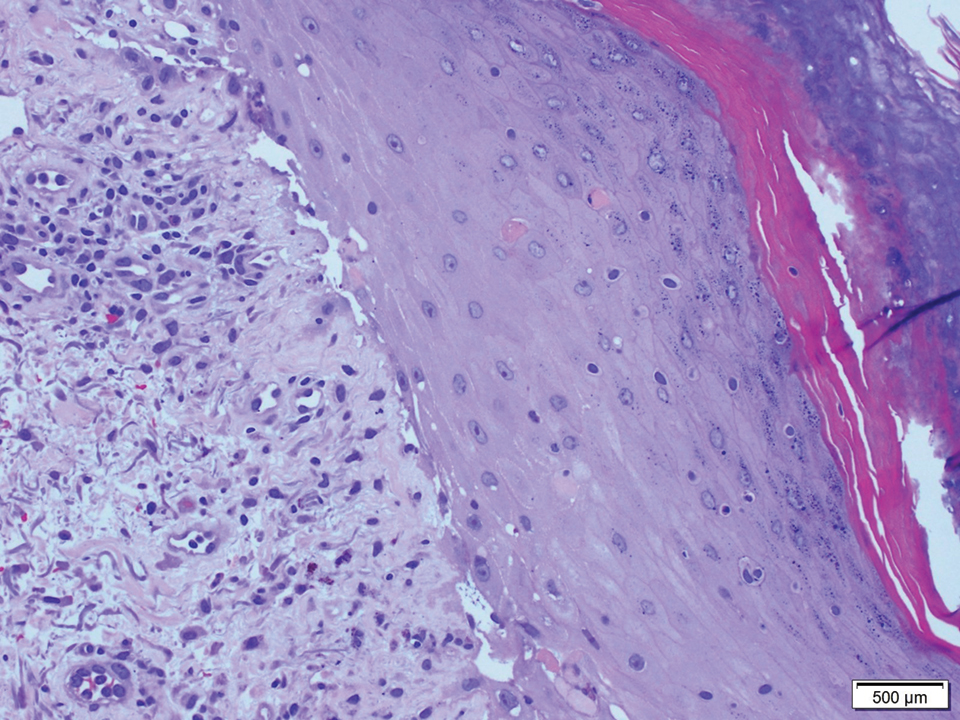

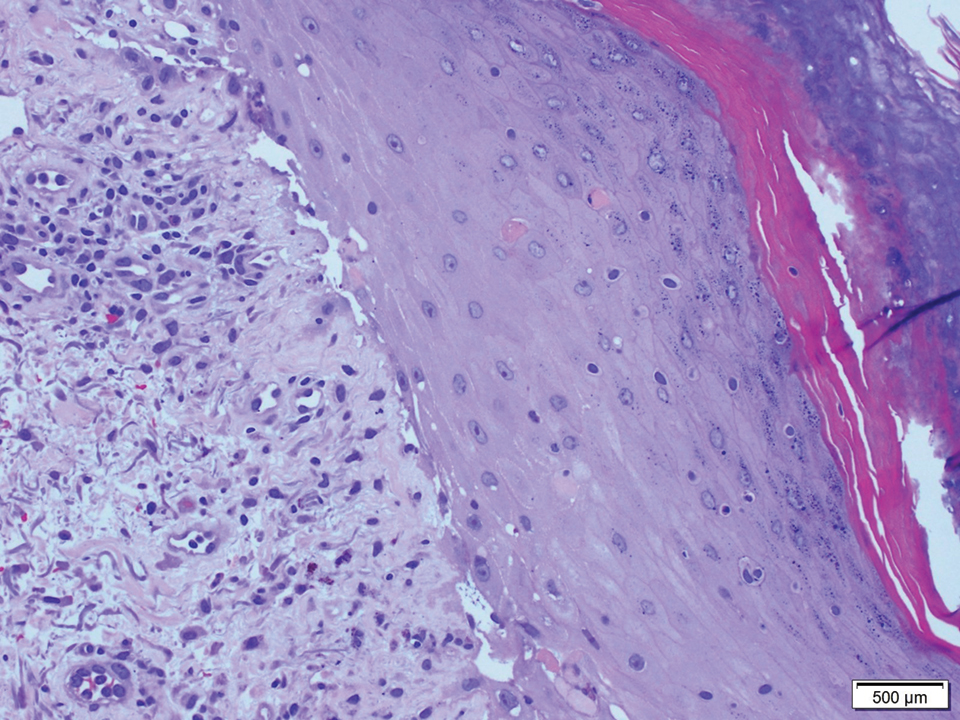

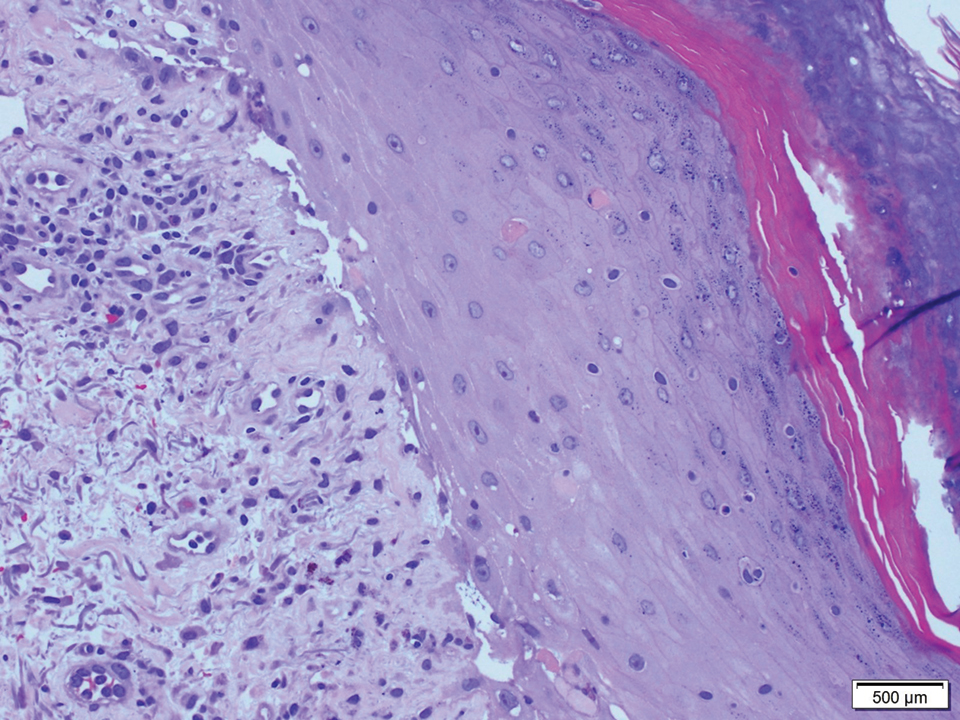

Open thoracotomy was performed to remove the lesion. Analysis of the mass showed cystic areas, areas of hemorrhage (Figure 1A), and alternating zones of compact Antoni A spindle cells admixed with areas of less orderly Antoni B spindle cells within a hypocellular stroma (Figure 1B). Individual cells were characterized by eosinophilic cytoplasm and tapered nuclei. The mass appeared to be completely encapsulated. No mitotic figures were seen on multiple slides. The cells stained diffusely positive for S-100 proteins. At 6-month follow-up, the patient reported that he did not notice any return of normal sweating on the left side. However, the right-sided flushing had resolved.

Harlequin syndrome (also called the Harlequin sign) is a rare disorder of the sympathetic nervous system and should not be confused with lethal harlequin-type ichthyosis, an autosomal-recessive congenital disorder in which the affected newborn’s skin is hard and thickened over most of the body.1 Harlequin syndrome usually is characterized by unilateral flushing and sweating that can affect the face, trunk, and extremities.2 Physical stimuli, such as exercising (as in our patient), high body temperature, and the consumption of spicy or pungent food, or an emotional response can unmask or exacerbate symptoms of HS. The syndrome also can present with cluster headache.3 Harlequin syndrome is more common in females (66% of cases).4 Originally, the side of the face marked by increased sweating and flushing was perceived to be the pathologic side; now it is recognized that the anhidrotic side is affected by the causative pathology. The side of the face characterized by flushing might gradually darken as it compensates for lack of thermal regulation on the other side.2,5

Usually, HS is an idiopathic condition associated with localized failure of upper thoracic sympathetic chain ganglia.5 A theory is that HS is part of a spectrum of autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy.6 Typically, the syndrome is asymptomatic at rest, but testing can reveal an underlying sympathetic lesion.7 Structural lesions have been reported as a cause of the syndrome,6 similar to our patient.

Disrupted thermoregulatory vasodilation in HS is caused by an ipsilateral lesion of the sympathetic vasodilator neurons that innervate the face. Hemifacial anhidrosis also occurs because sudomotor neurons travel within the same pathways as vasodilator neurons.4

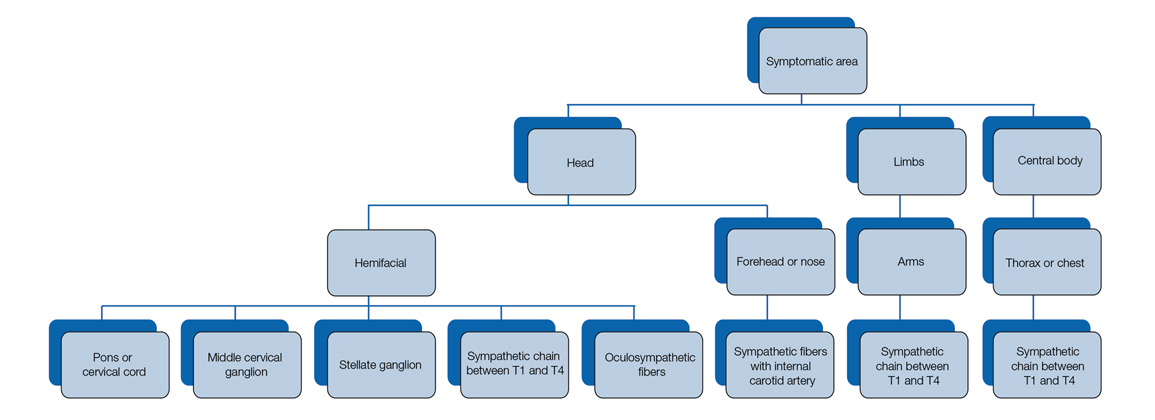

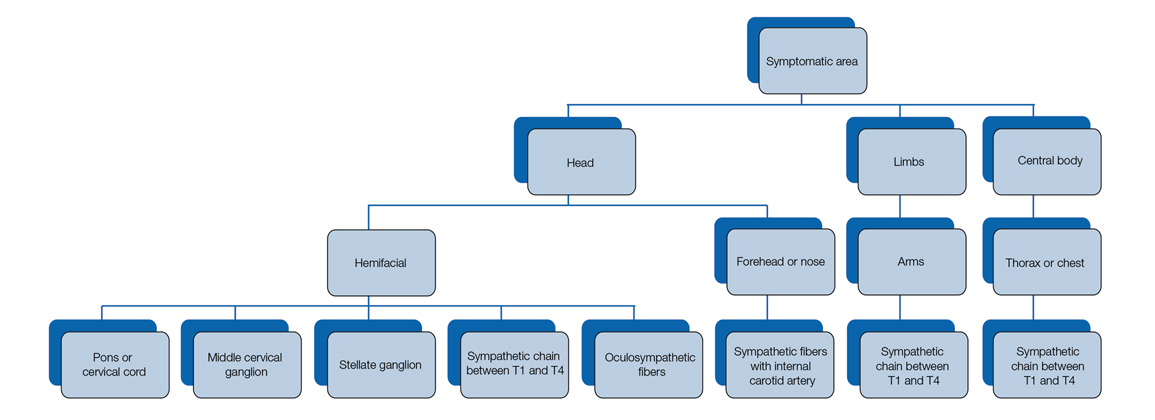

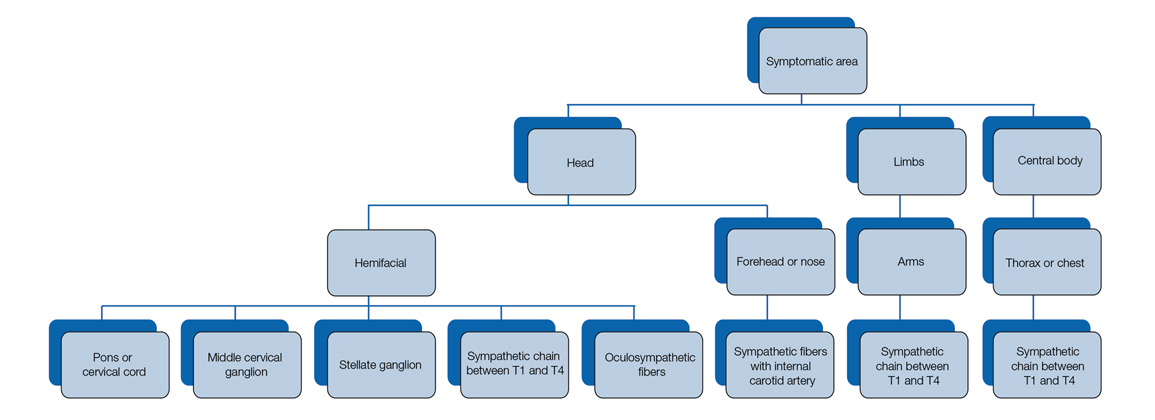

Our patient had a posterior mediastinal ancient schwannoma to the left of the subclavian artery, lateral to the trachea, with ipsilateral anhidrosis of the forehead, cheek, chin, and torso. In the medical literature, the forehead, cheek, and chin are described as being affected in HS when the lesion is located under the bifurcation of the carotid artery.3,5 Most of the sudomotor and vasomotor fibers that innervate the face leave the spinal cord through ventral roots T2-T34 (symptomatic areas are described in Figure 2), which correlates with the hypothesis that HS results from a deficit originating in the third thoracic nerve that is caused by a peripheral lesion affecting sympathetic outflow through the third thoracic root.2 The location of our patient’s lesion supports this claim.

Harlequin syndrome can present simultaneously with ipsilateral Horner, Adie, and Ross syndromes.8 There are varying clinical presentations of Horner syndrome. Some patients with HS show autonomic ocular signs, such as miosis and ptosis, exhibiting Horner syndrome as an additional feature.5 Adie syndrome is characterized by tonic pupils with hyporeflexia and is unilateral in most cases. Ross syndrome is similar to Adie syndrome—including tonic pupils with hyporeflexia—in addition to a finding of segmental anhidrosis; it is bilateral in most cases.4

In some cases, Horner syndrome and HS originate from unilateral pharmaceutical sympathetic denervation (ie, as a consequence of paravertebral spread of local anesthetic to ipsilateral stellate ganglion).9 Facial nonflushing areas in HS typically are identical with anhidrotic areas10; Horner syndrome often is ipsilateral to the affected sympathetic region.11

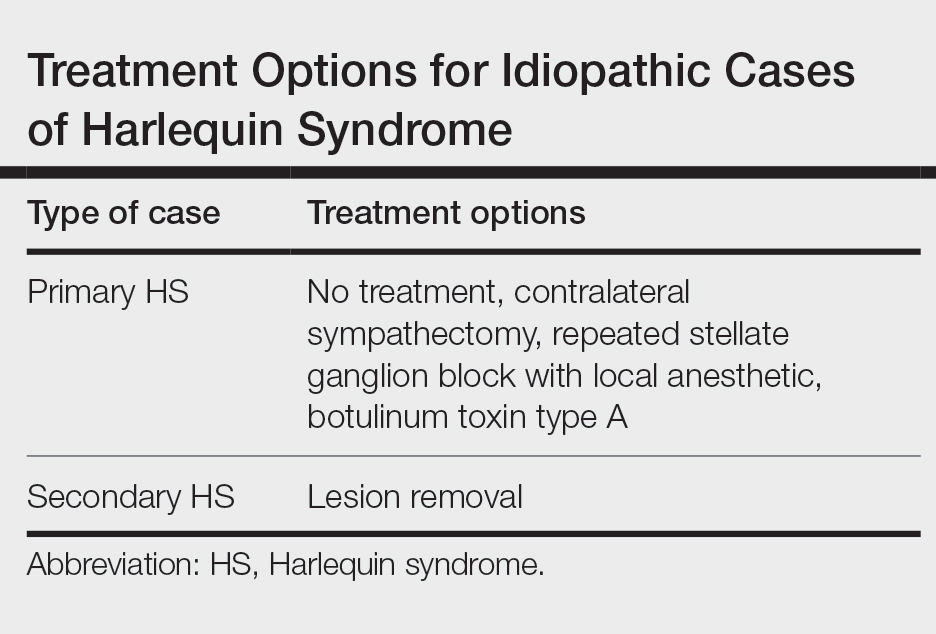

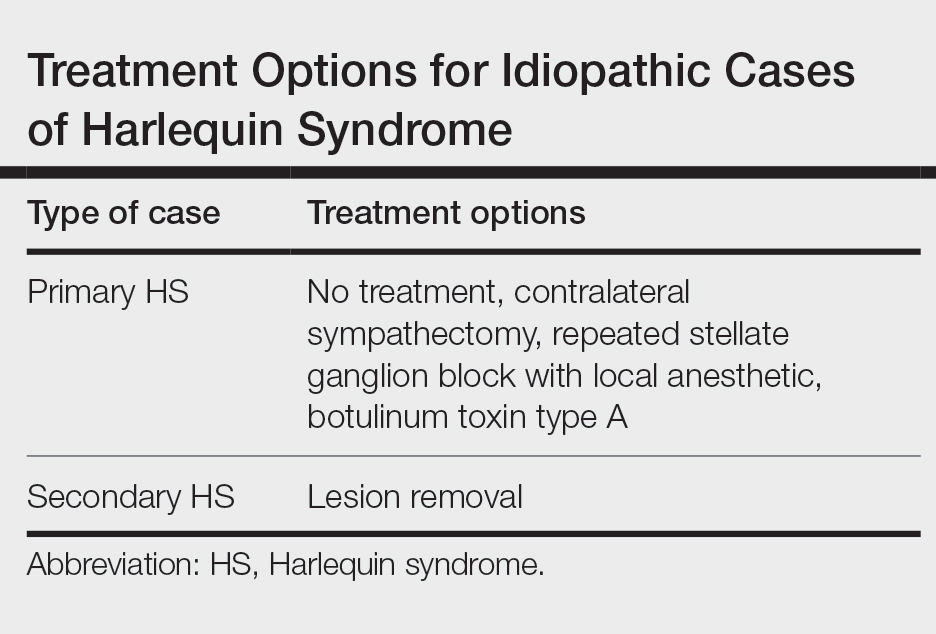

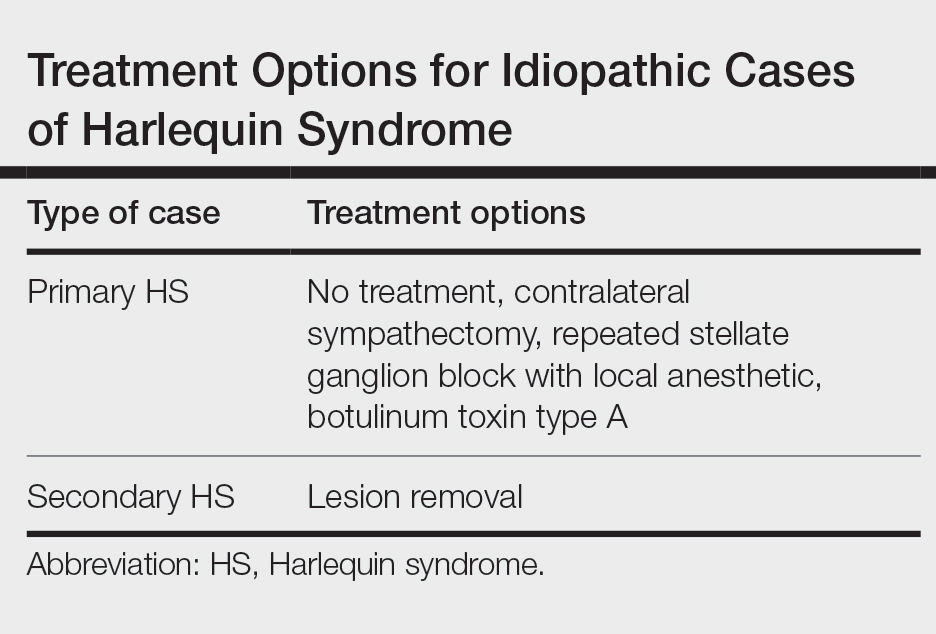

Our patient exhibited secondary HS from a tumor effect; however, an underlying tumor or infarct is absent in many cases. In primary (idiopathic) cases of HS, treatment is not recommended because the syndrome is benign.10,11

If symptoms of HS cause notable social embarrassment, contralateral sympathectomy can be considered.5,12 Repeated stellate ganglion block with a local anesthetic could be a less invasive treatment option.13 When considered on a case-by-case-basis, botulinum toxin type A has been effective as a treatment of compensatory hyperhidrosis on the unaffected side.14

In cases of secondary HS, surgical removal of the lesion may alleviate symptoms, though thoracotomy in our patient to remove the schwannoma did not alleviate anhidrosis. The Table lists treatment options for primary and secondary HS.4,5,11

- Harlequin ichthyosis. MedlinePlus. National Library of Medicine [Internet]. Updated January 7, 2022. Accessed April 5, 2022. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/harlequin-ichthyosis

- Lance JW, Drummond PD, Gandevia SC, et al. Harlequin syndrome: the sudden onset of unilateral flushing and sweating. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 1988;51:635-642. doi:10.1136/jnnp.51.5.635

- Lehman K, Kumar N, Vu Q, et al. Harlequin syndrome in cluster headache. Headache. 2016;56:1053-1054. doi:10.1111/head.12852

- Willaert WIM, Scheltinga MRM, Steenhuisen SF, et al. Harlequin syndrome: two new cases and a management proposal. Acta Neurol Belg. 2009;109:214-220.

- Duddy ME, Baker MR. Images in clinical medicine. Harlequin’s darker side. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:E22. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm067851

- Karam C. Harlequin syndrome in a patient with putative autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy. Auton Neurosci. 2016;194:58-59. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2015.12.004

- Wasner G, Maag R, Ludwig J, et al. Harlequin syndrome—one face of many etiologies. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2005;1:54-59. doi:10.1038/ncpneuro0040

- Guilloton L, Demarquay G, Quesnel L, et al. Dysautonomic syndrome of the face with Harlequin sign and syndrome: three new cases and a review of the literature. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2013;169:884-891. doi:10.1016/j.neurol.2013.01.628

- Burlacu CL, Buggy DJ. Coexisting Harlequin and Horner syndromes after high thoracic paravertebral anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95:822-824. doi:10.1093/bja/aei258

- Morrison DA, Bibby K, Woodruff G. The “Harlequin” sign and congenital Horner’s syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 1997;62:626-628. doi:10.1136/jnnp.62.6.626

- Bremner F, Smith S. Pupillographic findings in 39 consecutive cases of Harlequin syndrome. J Neuroophthalmol. 2008;28:171-177. doi:10.1097/WNO.0b013e318183c885

- Kaur S, Aggarwal P, Jindal N, et al. Harlequin syndrome: a mask of rare dysautonomic syndromes. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21:13030/qt3q39d7mz.

- Reddy H, Fatah S, Gulve A, et al. Novel management of Harlequin syndrome with stellate ganglion block. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:954-956. doi:10.1111/bjd.12561

- ManhRKJV, Spitz M, Vasconcellos LF. Botulinum toxin for treatment of Harlequin syndrome. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;23:112-113. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.11.030

To the Editor:

A 52-year-old man who was otherwise healthy and a long-distance runner presented with the sudden onset of diminished sweating on the left side of the body of 6 weeks’ duration. While training for a marathon, he reported that he perspired only on the right side of the body during runs of 12 to 15 miles; he observed a lack of sweating on the left side of the face, left side of the trunk, left arm, and left leg. This absence of sweating was accompanied by intense flushing on the right side of the face and trunk.

The patient did not take any medications. He reported no history of trauma and exhibited no neurologic deficits. A chest radiograph was negative. Thyroid function testing and a comprehensive metabolic panel were normal. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the chest and abdomen revealed a 4.3-cm soft-tissue mass in the left superior mediastinum that was superior to the aortic arch, posterior to the left subclavian artery in proximity to the sympathetic chain, and lateral to the trachea. The patient was diagnosed with Harlequin syndrome (HS).

Open thoracotomy was performed to remove the lesion. Analysis of the mass showed cystic areas, areas of hemorrhage (Figure 1A), and alternating zones of compact Antoni A spindle cells admixed with areas of less orderly Antoni B spindle cells within a hypocellular stroma (Figure 1B). Individual cells were characterized by eosinophilic cytoplasm and tapered nuclei. The mass appeared to be completely encapsulated. No mitotic figures were seen on multiple slides. The cells stained diffusely positive for S-100 proteins. At 6-month follow-up, the patient reported that he did not notice any return of normal sweating on the left side. However, the right-sided flushing had resolved.

Harlequin syndrome (also called the Harlequin sign) is a rare disorder of the sympathetic nervous system and should not be confused with lethal harlequin-type ichthyosis, an autosomal-recessive congenital disorder in which the affected newborn’s skin is hard and thickened over most of the body.1 Harlequin syndrome usually is characterized by unilateral flushing and sweating that can affect the face, trunk, and extremities.2 Physical stimuli, such as exercising (as in our patient), high body temperature, and the consumption of spicy or pungent food, or an emotional response can unmask or exacerbate symptoms of HS. The syndrome also can present with cluster headache.3 Harlequin syndrome is more common in females (66% of cases).4 Originally, the side of the face marked by increased sweating and flushing was perceived to be the pathologic side; now it is recognized that the anhidrotic side is affected by the causative pathology. The side of the face characterized by flushing might gradually darken as it compensates for lack of thermal regulation on the other side.2,5

Usually, HS is an idiopathic condition associated with localized failure of upper thoracic sympathetic chain ganglia.5 A theory is that HS is part of a spectrum of autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy.6 Typically, the syndrome is asymptomatic at rest, but testing can reveal an underlying sympathetic lesion.7 Structural lesions have been reported as a cause of the syndrome,6 similar to our patient.

Disrupted thermoregulatory vasodilation in HS is caused by an ipsilateral lesion of the sympathetic vasodilator neurons that innervate the face. Hemifacial anhidrosis also occurs because sudomotor neurons travel within the same pathways as vasodilator neurons.4

Our patient had a posterior mediastinal ancient schwannoma to the left of the subclavian artery, lateral to the trachea, with ipsilateral anhidrosis of the forehead, cheek, chin, and torso. In the medical literature, the forehead, cheek, and chin are described as being affected in HS when the lesion is located under the bifurcation of the carotid artery.3,5 Most of the sudomotor and vasomotor fibers that innervate the face leave the spinal cord through ventral roots T2-T34 (symptomatic areas are described in Figure 2), which correlates with the hypothesis that HS results from a deficit originating in the third thoracic nerve that is caused by a peripheral lesion affecting sympathetic outflow through the third thoracic root.2 The location of our patient’s lesion supports this claim.

Harlequin syndrome can present simultaneously with ipsilateral Horner, Adie, and Ross syndromes.8 There are varying clinical presentations of Horner syndrome. Some patients with HS show autonomic ocular signs, such as miosis and ptosis, exhibiting Horner syndrome as an additional feature.5 Adie syndrome is characterized by tonic pupils with hyporeflexia and is unilateral in most cases. Ross syndrome is similar to Adie syndrome—including tonic pupils with hyporeflexia—in addition to a finding of segmental anhidrosis; it is bilateral in most cases.4

In some cases, Horner syndrome and HS originate from unilateral pharmaceutical sympathetic denervation (ie, as a consequence of paravertebral spread of local anesthetic to ipsilateral stellate ganglion).9 Facial nonflushing areas in HS typically are identical with anhidrotic areas10; Horner syndrome often is ipsilateral to the affected sympathetic region.11

Our patient exhibited secondary HS from a tumor effect; however, an underlying tumor or infarct is absent in many cases. In primary (idiopathic) cases of HS, treatment is not recommended because the syndrome is benign.10,11

If symptoms of HS cause notable social embarrassment, contralateral sympathectomy can be considered.5,12 Repeated stellate ganglion block with a local anesthetic could be a less invasive treatment option.13 When considered on a case-by-case-basis, botulinum toxin type A has been effective as a treatment of compensatory hyperhidrosis on the unaffected side.14

In cases of secondary HS, surgical removal of the lesion may alleviate symptoms, though thoracotomy in our patient to remove the schwannoma did not alleviate anhidrosis. The Table lists treatment options for primary and secondary HS.4,5,11

To the Editor:

A 52-year-old man who was otherwise healthy and a long-distance runner presented with the sudden onset of diminished sweating on the left side of the body of 6 weeks’ duration. While training for a marathon, he reported that he perspired only on the right side of the body during runs of 12 to 15 miles; he observed a lack of sweating on the left side of the face, left side of the trunk, left arm, and left leg. This absence of sweating was accompanied by intense flushing on the right side of the face and trunk.

The patient did not take any medications. He reported no history of trauma and exhibited no neurologic deficits. A chest radiograph was negative. Thyroid function testing and a comprehensive metabolic panel were normal. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the chest and abdomen revealed a 4.3-cm soft-tissue mass in the left superior mediastinum that was superior to the aortic arch, posterior to the left subclavian artery in proximity to the sympathetic chain, and lateral to the trachea. The patient was diagnosed with Harlequin syndrome (HS).

Open thoracotomy was performed to remove the lesion. Analysis of the mass showed cystic areas, areas of hemorrhage (Figure 1A), and alternating zones of compact Antoni A spindle cells admixed with areas of less orderly Antoni B spindle cells within a hypocellular stroma (Figure 1B). Individual cells were characterized by eosinophilic cytoplasm and tapered nuclei. The mass appeared to be completely encapsulated. No mitotic figures were seen on multiple slides. The cells stained diffusely positive for S-100 proteins. At 6-month follow-up, the patient reported that he did not notice any return of normal sweating on the left side. However, the right-sided flushing had resolved.

Harlequin syndrome (also called the Harlequin sign) is a rare disorder of the sympathetic nervous system and should not be confused with lethal harlequin-type ichthyosis, an autosomal-recessive congenital disorder in which the affected newborn’s skin is hard and thickened over most of the body.1 Harlequin syndrome usually is characterized by unilateral flushing and sweating that can affect the face, trunk, and extremities.2 Physical stimuli, such as exercising (as in our patient), high body temperature, and the consumption of spicy or pungent food, or an emotional response can unmask or exacerbate symptoms of HS. The syndrome also can present with cluster headache.3 Harlequin syndrome is more common in females (66% of cases).4 Originally, the side of the face marked by increased sweating and flushing was perceived to be the pathologic side; now it is recognized that the anhidrotic side is affected by the causative pathology. The side of the face characterized by flushing might gradually darken as it compensates for lack of thermal regulation on the other side.2,5

Usually, HS is an idiopathic condition associated with localized failure of upper thoracic sympathetic chain ganglia.5 A theory is that HS is part of a spectrum of autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy.6 Typically, the syndrome is asymptomatic at rest, but testing can reveal an underlying sympathetic lesion.7 Structural lesions have been reported as a cause of the syndrome,6 similar to our patient.

Disrupted thermoregulatory vasodilation in HS is caused by an ipsilateral lesion of the sympathetic vasodilator neurons that innervate the face. Hemifacial anhidrosis also occurs because sudomotor neurons travel within the same pathways as vasodilator neurons.4

Our patient had a posterior mediastinal ancient schwannoma to the left of the subclavian artery, lateral to the trachea, with ipsilateral anhidrosis of the forehead, cheek, chin, and torso. In the medical literature, the forehead, cheek, and chin are described as being affected in HS when the lesion is located under the bifurcation of the carotid artery.3,5 Most of the sudomotor and vasomotor fibers that innervate the face leave the spinal cord through ventral roots T2-T34 (symptomatic areas are described in Figure 2), which correlates with the hypothesis that HS results from a deficit originating in the third thoracic nerve that is caused by a peripheral lesion affecting sympathetic outflow through the third thoracic root.2 The location of our patient’s lesion supports this claim.

Harlequin syndrome can present simultaneously with ipsilateral Horner, Adie, and Ross syndromes.8 There are varying clinical presentations of Horner syndrome. Some patients with HS show autonomic ocular signs, such as miosis and ptosis, exhibiting Horner syndrome as an additional feature.5 Adie syndrome is characterized by tonic pupils with hyporeflexia and is unilateral in most cases. Ross syndrome is similar to Adie syndrome—including tonic pupils with hyporeflexia—in addition to a finding of segmental anhidrosis; it is bilateral in most cases.4

In some cases, Horner syndrome and HS originate from unilateral pharmaceutical sympathetic denervation (ie, as a consequence of paravertebral spread of local anesthetic to ipsilateral stellate ganglion).9 Facial nonflushing areas in HS typically are identical with anhidrotic areas10; Horner syndrome often is ipsilateral to the affected sympathetic region.11

Our patient exhibited secondary HS from a tumor effect; however, an underlying tumor or infarct is absent in many cases. In primary (idiopathic) cases of HS, treatment is not recommended because the syndrome is benign.10,11

If symptoms of HS cause notable social embarrassment, contralateral sympathectomy can be considered.5,12 Repeated stellate ganglion block with a local anesthetic could be a less invasive treatment option.13 When considered on a case-by-case-basis, botulinum toxin type A has been effective as a treatment of compensatory hyperhidrosis on the unaffected side.14

In cases of secondary HS, surgical removal of the lesion may alleviate symptoms, though thoracotomy in our patient to remove the schwannoma did not alleviate anhidrosis. The Table lists treatment options for primary and secondary HS.4,5,11

- Harlequin ichthyosis. MedlinePlus. National Library of Medicine [Internet]. Updated January 7, 2022. Accessed April 5, 2022. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/harlequin-ichthyosis

- Lance JW, Drummond PD, Gandevia SC, et al. Harlequin syndrome: the sudden onset of unilateral flushing and sweating. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 1988;51:635-642. doi:10.1136/jnnp.51.5.635

- Lehman K, Kumar N, Vu Q, et al. Harlequin syndrome in cluster headache. Headache. 2016;56:1053-1054. doi:10.1111/head.12852

- Willaert WIM, Scheltinga MRM, Steenhuisen SF, et al. Harlequin syndrome: two new cases and a management proposal. Acta Neurol Belg. 2009;109:214-220.

- Duddy ME, Baker MR. Images in clinical medicine. Harlequin’s darker side. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:E22. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm067851

- Karam C. Harlequin syndrome in a patient with putative autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy. Auton Neurosci. 2016;194:58-59. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2015.12.004

- Wasner G, Maag R, Ludwig J, et al. Harlequin syndrome—one face of many etiologies. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2005;1:54-59. doi:10.1038/ncpneuro0040

- Guilloton L, Demarquay G, Quesnel L, et al. Dysautonomic syndrome of the face with Harlequin sign and syndrome: three new cases and a review of the literature. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2013;169:884-891. doi:10.1016/j.neurol.2013.01.628

- Burlacu CL, Buggy DJ. Coexisting Harlequin and Horner syndromes after high thoracic paravertebral anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95:822-824. doi:10.1093/bja/aei258

- Morrison DA, Bibby K, Woodruff G. The “Harlequin” sign and congenital Horner’s syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 1997;62:626-628. doi:10.1136/jnnp.62.6.626

- Bremner F, Smith S. Pupillographic findings in 39 consecutive cases of Harlequin syndrome. J Neuroophthalmol. 2008;28:171-177. doi:10.1097/WNO.0b013e318183c885

- Kaur S, Aggarwal P, Jindal N, et al. Harlequin syndrome: a mask of rare dysautonomic syndromes. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21:13030/qt3q39d7mz.

- Reddy H, Fatah S, Gulve A, et al. Novel management of Harlequin syndrome with stellate ganglion block. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:954-956. doi:10.1111/bjd.12561

- ManhRKJV, Spitz M, Vasconcellos LF. Botulinum toxin for treatment of Harlequin syndrome. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;23:112-113. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.11.030

- Harlequin ichthyosis. MedlinePlus. National Library of Medicine [Internet]. Updated January 7, 2022. Accessed April 5, 2022. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/harlequin-ichthyosis

- Lance JW, Drummond PD, Gandevia SC, et al. Harlequin syndrome: the sudden onset of unilateral flushing and sweating. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 1988;51:635-642. doi:10.1136/jnnp.51.5.635

- Lehman K, Kumar N, Vu Q, et al. Harlequin syndrome in cluster headache. Headache. 2016;56:1053-1054. doi:10.1111/head.12852

- Willaert WIM, Scheltinga MRM, Steenhuisen SF, et al. Harlequin syndrome: two new cases and a management proposal. Acta Neurol Belg. 2009;109:214-220.

- Duddy ME, Baker MR. Images in clinical medicine. Harlequin’s darker side. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:E22. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm067851

- Karam C. Harlequin syndrome in a patient with putative autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy. Auton Neurosci. 2016;194:58-59. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2015.12.004

- Wasner G, Maag R, Ludwig J, et al. Harlequin syndrome—one face of many etiologies. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2005;1:54-59. doi:10.1038/ncpneuro0040

- Guilloton L, Demarquay G, Quesnel L, et al. Dysautonomic syndrome of the face with Harlequin sign and syndrome: three new cases and a review of the literature. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2013;169:884-891. doi:10.1016/j.neurol.2013.01.628

- Burlacu CL, Buggy DJ. Coexisting Harlequin and Horner syndromes after high thoracic paravertebral anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95:822-824. doi:10.1093/bja/aei258

- Morrison DA, Bibby K, Woodruff G. The “Harlequin” sign and congenital Horner’s syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 1997;62:626-628. doi:10.1136/jnnp.62.6.626

- Bremner F, Smith S. Pupillographic findings in 39 consecutive cases of Harlequin syndrome. J Neuroophthalmol. 2008;28:171-177. doi:10.1097/WNO.0b013e318183c885

- Kaur S, Aggarwal P, Jindal N, et al. Harlequin syndrome: a mask of rare dysautonomic syndromes. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21:13030/qt3q39d7mz.

- Reddy H, Fatah S, Gulve A, et al. Novel management of Harlequin syndrome with stellate ganglion block. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:954-956. doi:10.1111/bjd.12561

- ManhRKJV, Spitz M, Vasconcellos LF. Botulinum toxin for treatment of Harlequin syndrome. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;23:112-113. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.11.030

Practice Points

- Harlequin syndrome is a rare disorder of the sympathetic nervous system that is characterized by unilateral flushing and sweating that can affect the face, trunk, and extremities.

- Secondary causes can be from schwannomas in the cervical chain ganglion.

Granuloma Faciale in Woman With Levamisole-Induced Vasculitis

To the Editor:

A 53-year-old Hispanic woman presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of an expanding plaque on the right cheek of 2 months’ duration. The patient stated the plaque began as a pimple, which she picked with subsequent spread laterally across the cheek. The area was intermittently tender, but she denied tingling, burning, or pruritus of the site. She had been treated with doxycycline and amoxicillin–clavulanic acid prior to presentation without improvement. She had a history of levamisole-induced vasculitis approximately 6 months prior. A review of systems was notable for diffuse joint pain. The patient denied tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use in the preceding 3 months and denied any changes in her medications or in health within the last year.

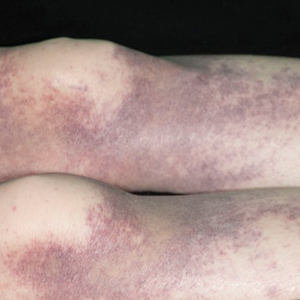

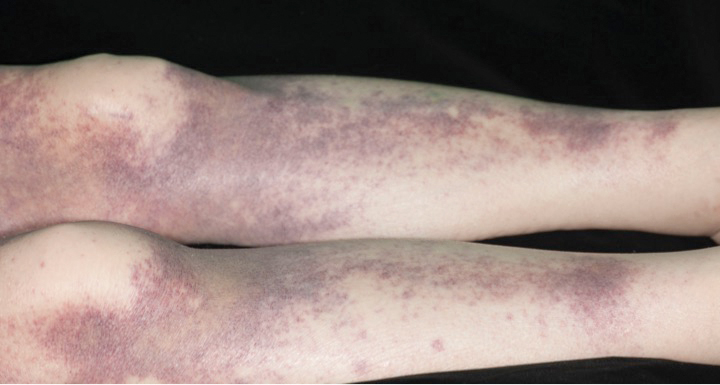

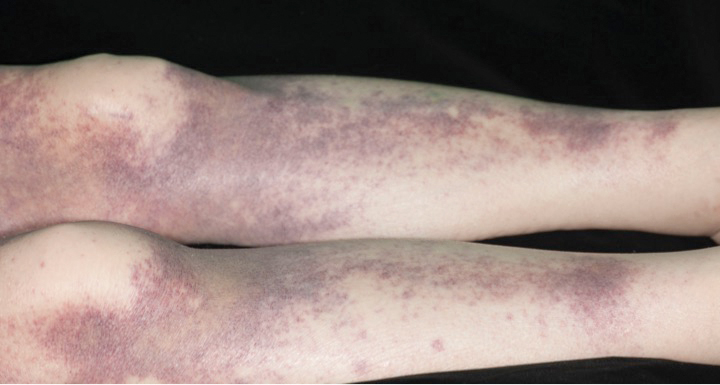

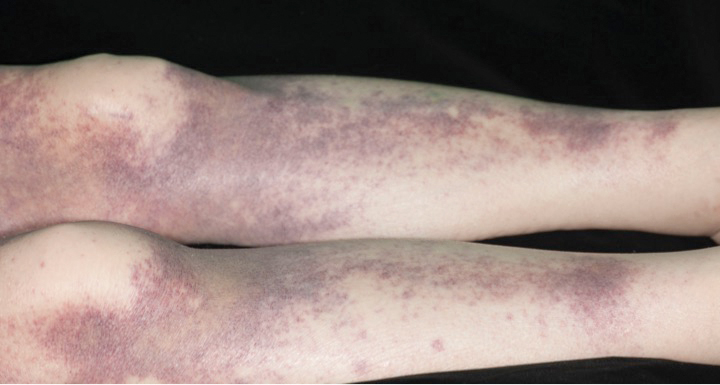

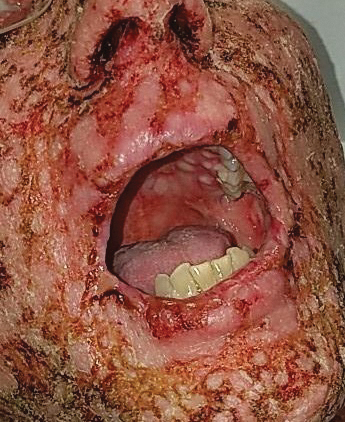

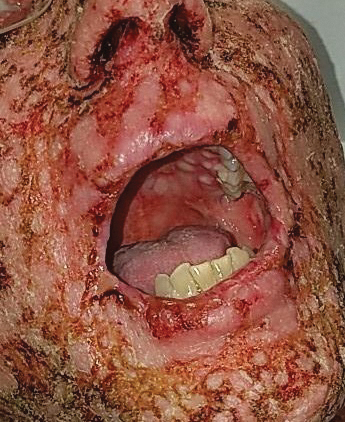

Physical examination revealed a well-appearing, alert, and afebrile patient with a pink, well-demarcated plaque on the right cheek (Figure 1). The borders of the plaque were indurated, and the lateral aspect of the plaque was eroded secondary to digital manipulation by the patient. She had no cervical lymphadenopathy. There were no other abnormal cutaneous findings.

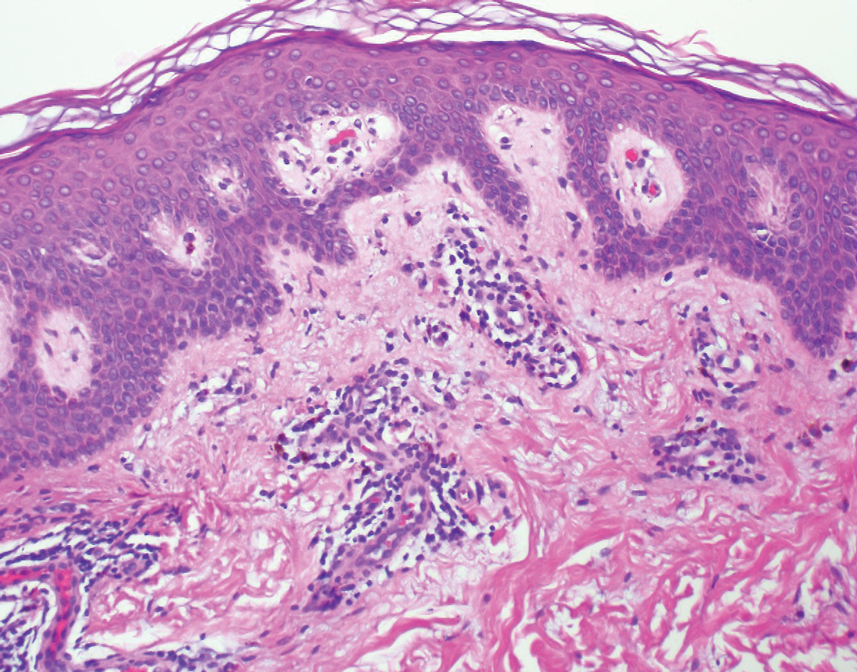

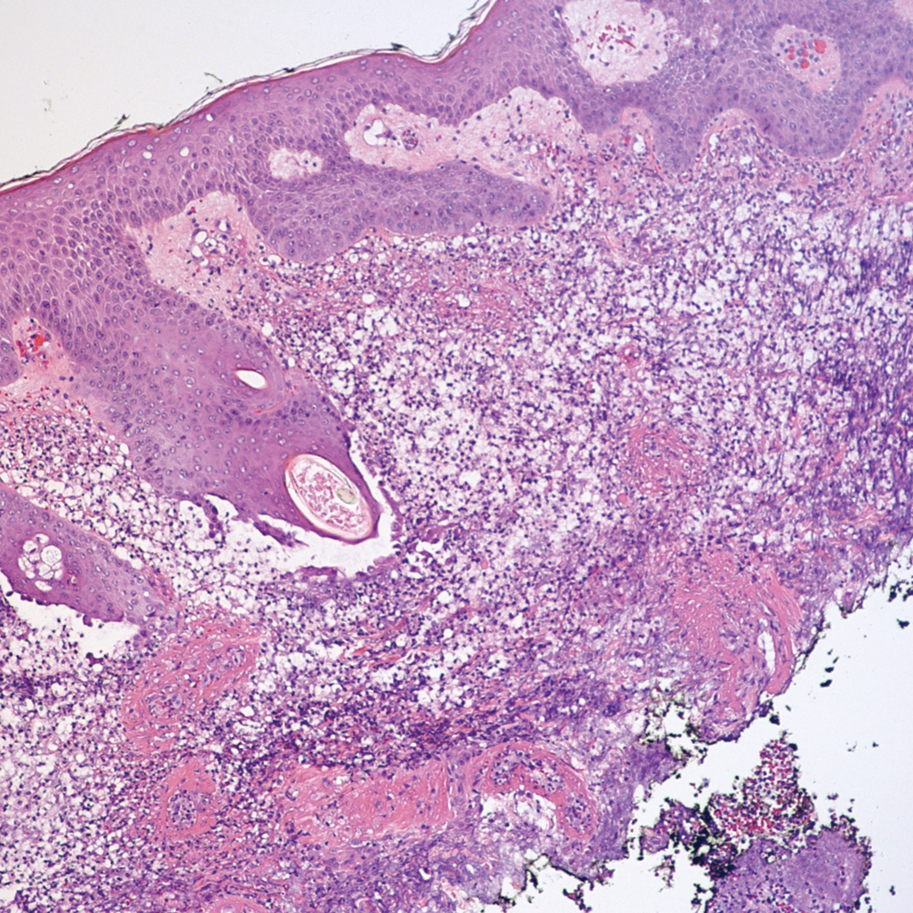

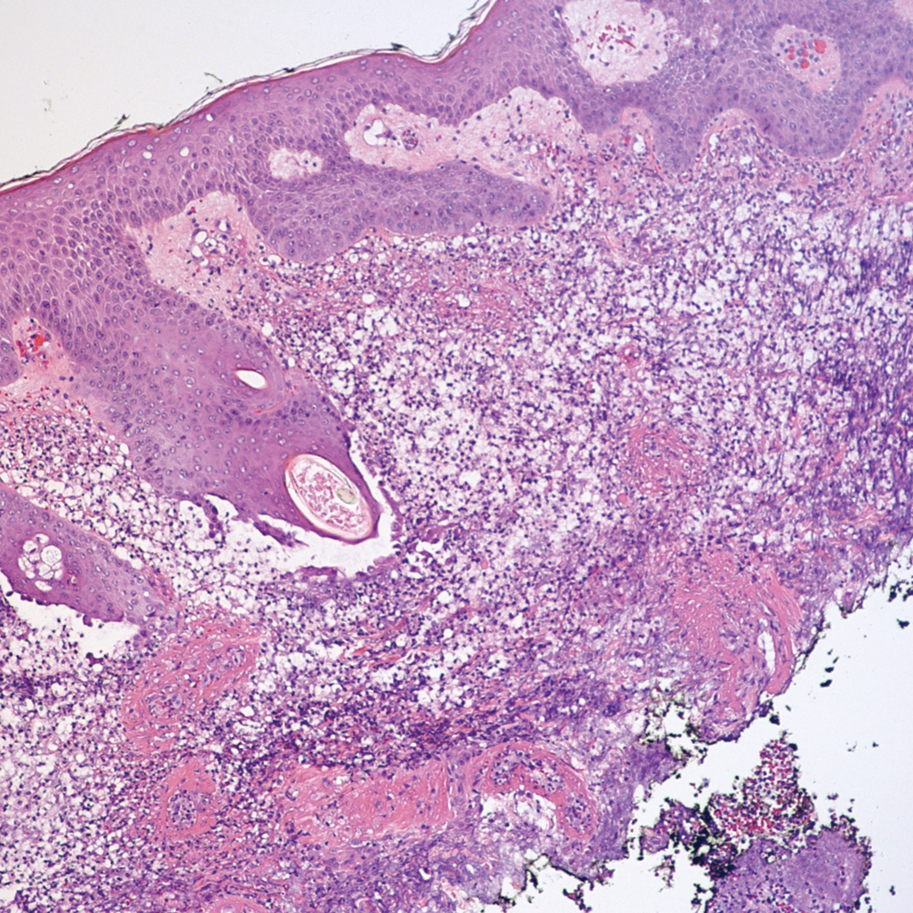

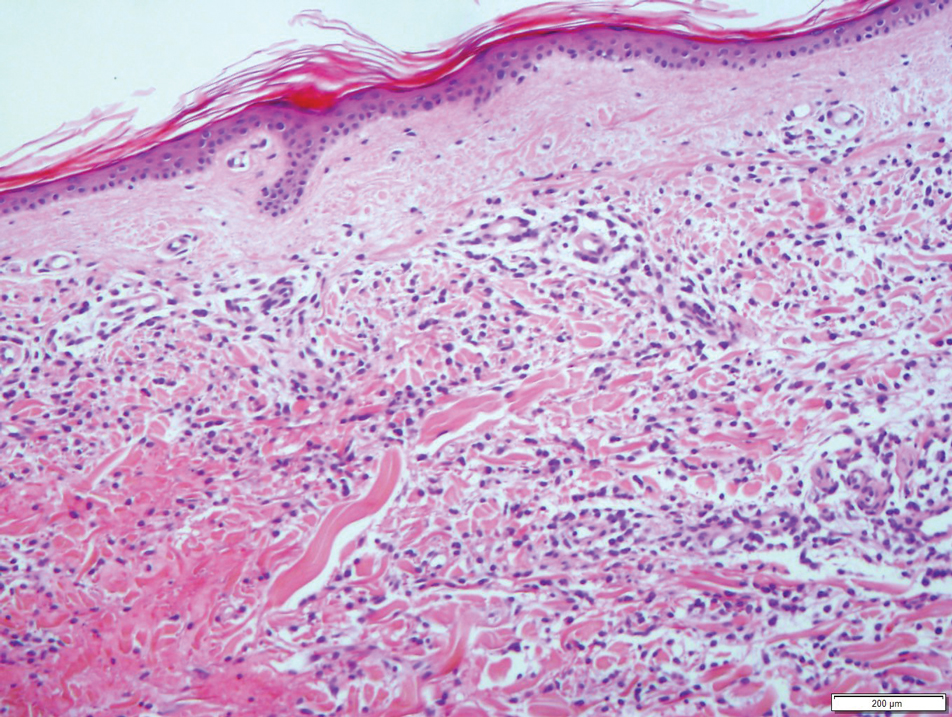

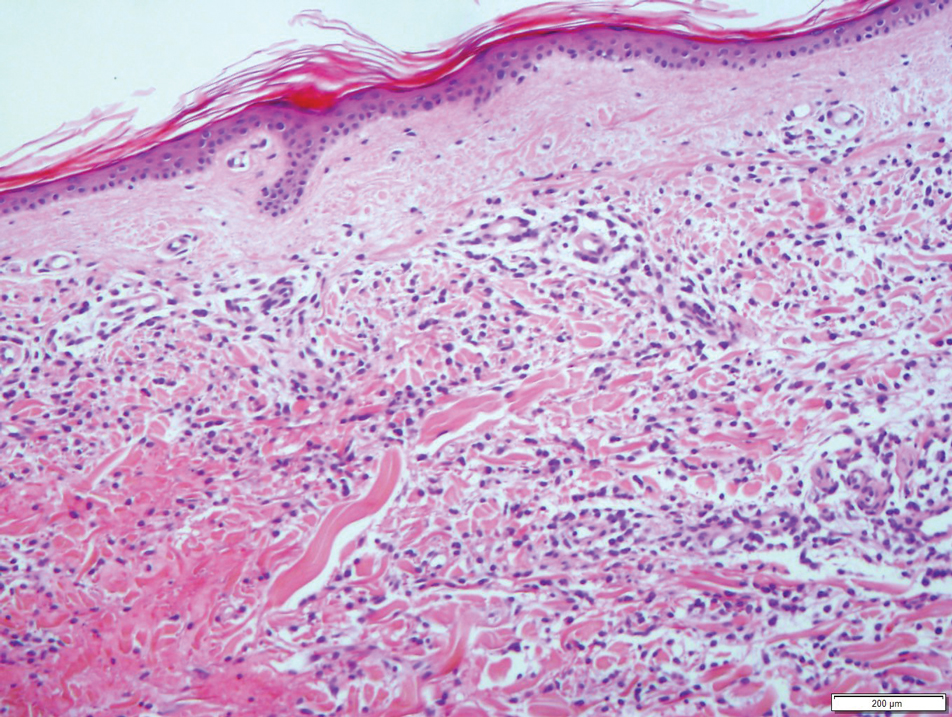

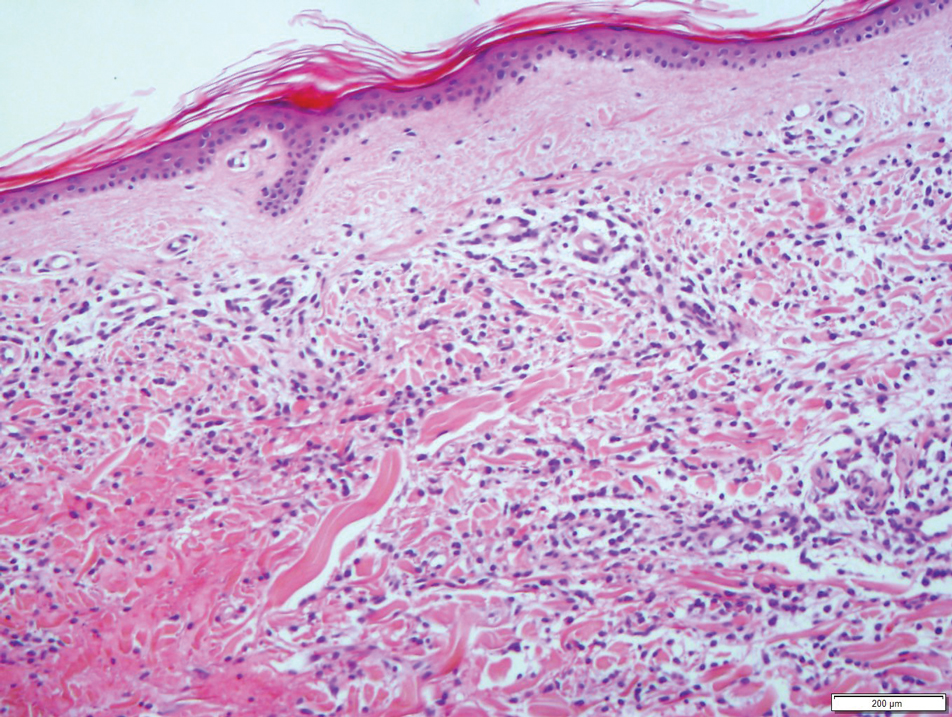

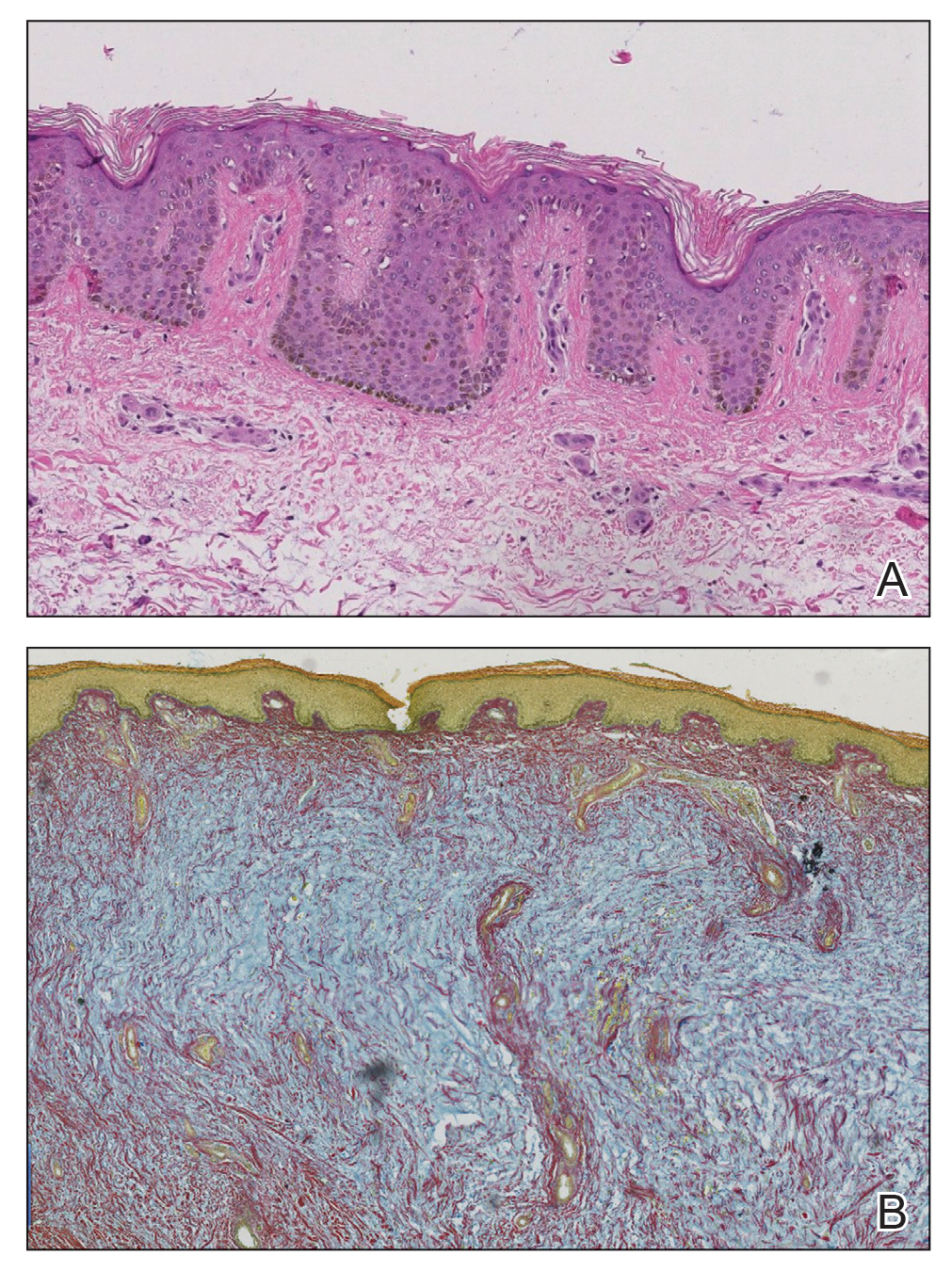

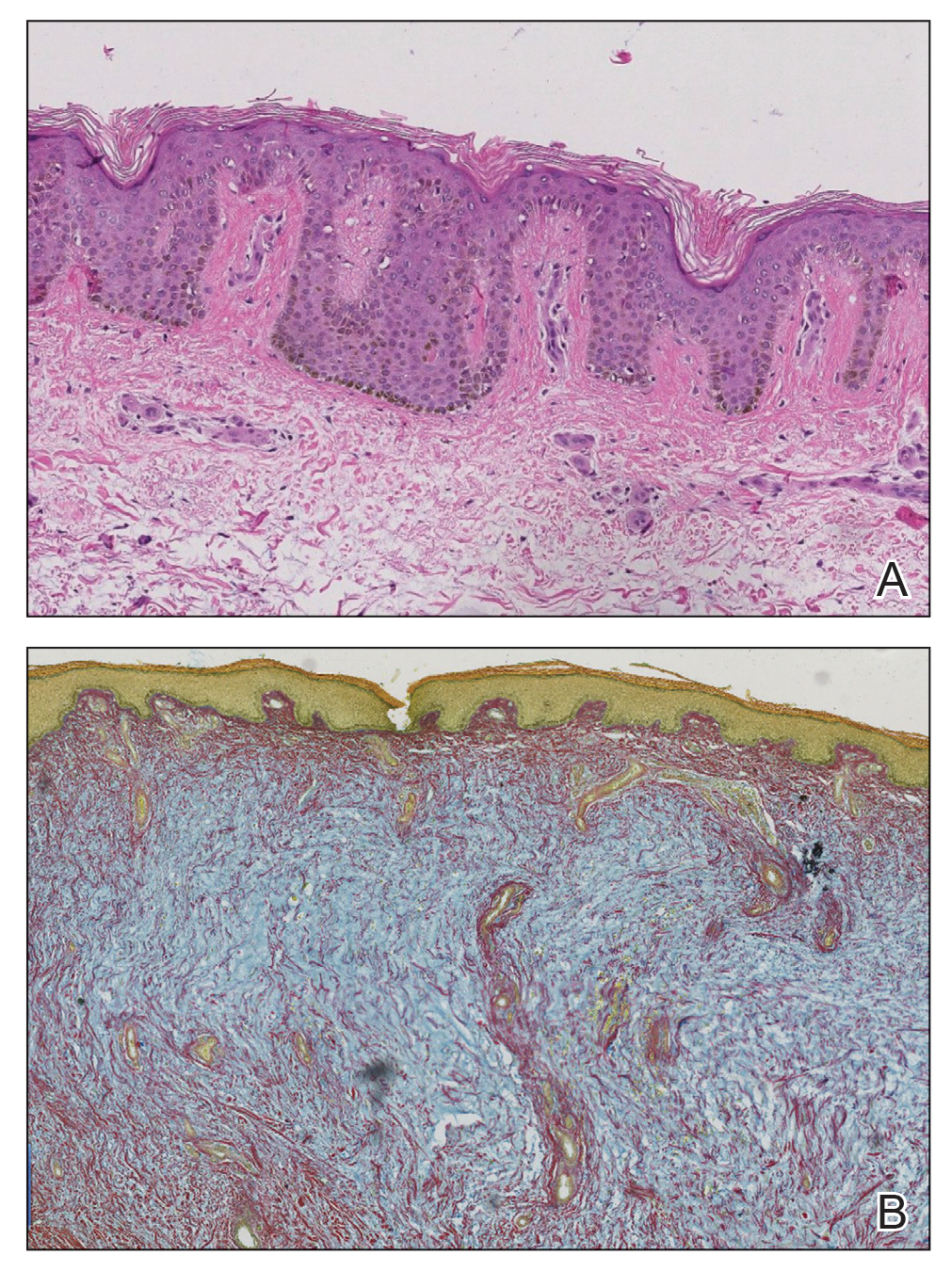

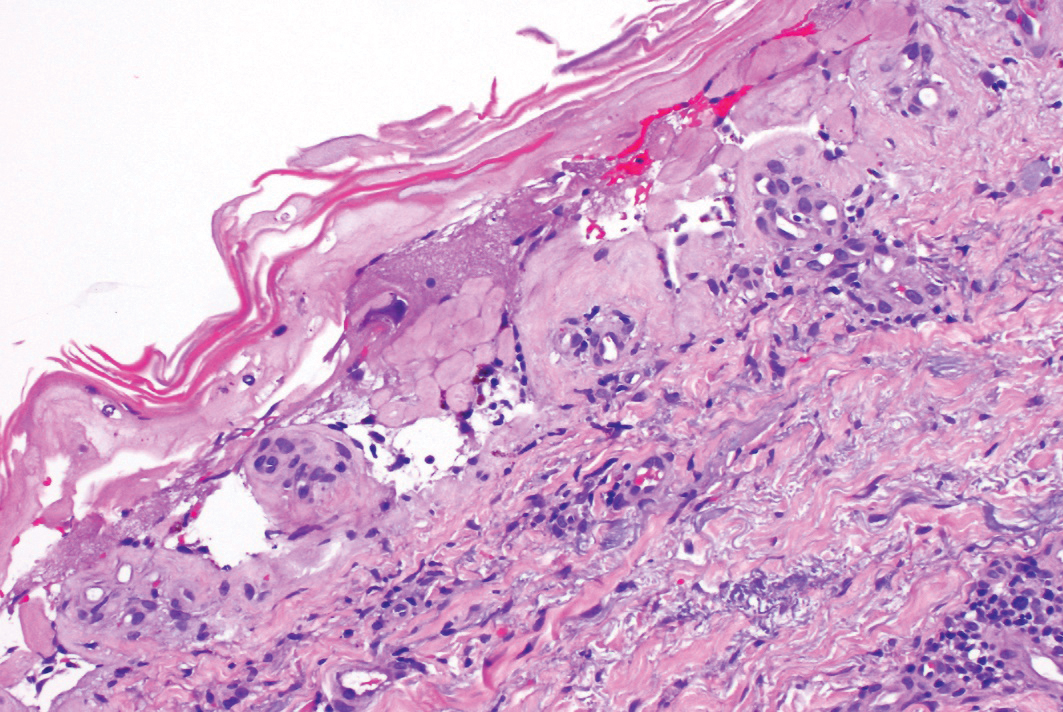

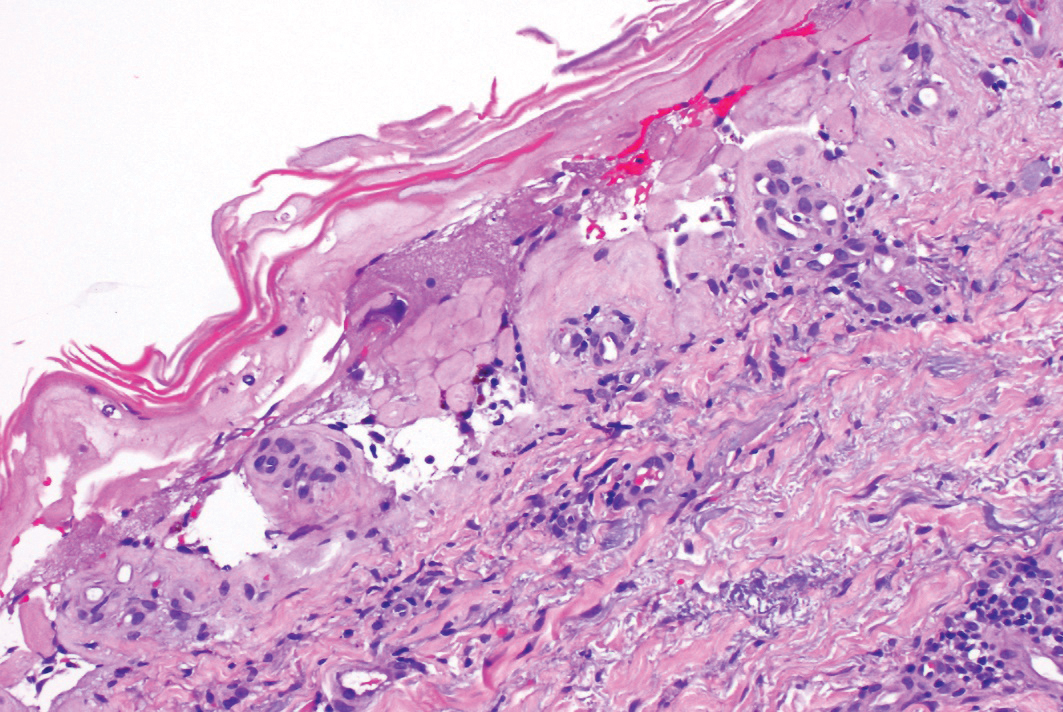

There is a broad differential diagnosis for a pink expanding plaque on the face, which requires histopathologic correlation for correct diagnosis. Three broad categories in the differential are infectious (eg, bacterial, fungal), medication related (eg, fixed drug eruption), and granulomatous (eg, granuloma faciale [GF], sarcoidosis, tumid lupus, leprosy, granulomatous rosacea). A biopsy of the lesion revealed a mixed inflammatory cell dermal infiltrate with perivascular accentuation and intense vasculitis that was consistent with GF (Figure 2). Gomori methenamine-silver, periodic acid–Schiff, Fite-Faraco, acid-fast bacilli, and Gram staining were negative for organisms. Tissue cultures were negative for bacterial, mycobacterial, and fungal etiology. The patient was started on high-potency topical steroids with a 50% improvement in the appearance of the skin lesion at 1-month follow-up.

Granuloma faciale is a rare chronic inflammatory dermatosis with a predilection for the face that is difficult to diagnose and treat. The diagnosis is based on clinical and histologic findings, and it typically presents as single or multiple, well-demarcated, red-brown nodules, papules, or plaques that range from several millimeters to centimeters in diameter.1,2 Extrafacial lesions may be seen.3 Granuloma faciale usually is asymptomatic but occasionally has associated pruritus and rarely ulceration. The prevalence and pathophysiology of GF is not well defined; however, GF more commonly is reported in middle-aged White males.1

Histologic examination of GF reveals a mixed inflammatory cellular infiltrate in the upper dermis. A grenz zone, which is a narrow area of the papillary dermis uninvolved by the underlying pathology, may be seen.1 Contrary to the name, granulomas are not found histologically. Rather, vascular changes or damage frequently are present and may indicate a small vessel vasculitis pathologic mechanism. Granuloma faciale also has been associated with follicular ostia accentuation and telangiectases.4

Many cases of GF have been misdiagnosed as sarcoidosis, lymphoma, lupus, and basal cell carcinoma.1 In addition, GF shares many clinical and histologic features with erythema elevatum diutinum (EED). However, the defining features that suggest EED over GF is that EED has a predilection for the skin overlying the joints. Histopathologically, EED displays granulomas and fibrosis with few eosinophils.5,6

The variable response of GF to treatments and lack of efficacy data have contributed to the complexity and uncertainty of managing GF. The current first-line therapies are topical tacrolimus,7 cryotherapy,8 or corticosteroid therapy.9

- Ortonne N, Wechsler J, Bagot M, et al. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathologic study of 66 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1002-1009.

- Marcoval J, Moreno A, Peyr J. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:269-273.

- Nasiri S, Rahimi H, Farnaghi A, et al. Granuloma faciale with disseminated extra facial lesions. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:5.

- Roustan G, Sánchez Yus E, Salas C, et al. Granuloma faciale with extrafacial lesions. Dermatology. 1999;198:79-82.

- LeBoit PE. Granuloma faciale: a diagnosis deserving of dignity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:440-443.

- Ziemer M, Koehler MJ, Weyers W. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a chronic leukocytoclastic vasculitis microscopically indistinguishable from granuloma faciale? J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:876-883.

- Cecchi R, Pavesi M, Bartoli L, et al. Topical tacrolimus in the treatment of granuloma faciale. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1463-1465.

- Panagiotopoulos A, Anyfantakis V, Rallis E, et al. Assessment of the efficacy of cryosurgery in the treatment of granuloma faciale. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:357-360.

- Radin DA, Mehregan DR. Granuloma faciale: distribution of the lesions and review of the literature. Cutis. 2003;72:213-219.

To the Editor:

A 53-year-old Hispanic woman presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of an expanding plaque on the right cheek of 2 months’ duration. The patient stated the plaque began as a pimple, which she picked with subsequent spread laterally across the cheek. The area was intermittently tender, but she denied tingling, burning, or pruritus of the site. She had been treated with doxycycline and amoxicillin–clavulanic acid prior to presentation without improvement. She had a history of levamisole-induced vasculitis approximately 6 months prior. A review of systems was notable for diffuse joint pain. The patient denied tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use in the preceding 3 months and denied any changes in her medications or in health within the last year.

Physical examination revealed a well-appearing, alert, and afebrile patient with a pink, well-demarcated plaque on the right cheek (Figure 1). The borders of the plaque were indurated, and the lateral aspect of the plaque was eroded secondary to digital manipulation by the patient. She had no cervical lymphadenopathy. There were no other abnormal cutaneous findings.

There is a broad differential diagnosis for a pink expanding plaque on the face, which requires histopathologic correlation for correct diagnosis. Three broad categories in the differential are infectious (eg, bacterial, fungal), medication related (eg, fixed drug eruption), and granulomatous (eg, granuloma faciale [GF], sarcoidosis, tumid lupus, leprosy, granulomatous rosacea). A biopsy of the lesion revealed a mixed inflammatory cell dermal infiltrate with perivascular accentuation and intense vasculitis that was consistent with GF (Figure 2). Gomori methenamine-silver, periodic acid–Schiff, Fite-Faraco, acid-fast bacilli, and Gram staining were negative for organisms. Tissue cultures were negative for bacterial, mycobacterial, and fungal etiology. The patient was started on high-potency topical steroids with a 50% improvement in the appearance of the skin lesion at 1-month follow-up.

Granuloma faciale is a rare chronic inflammatory dermatosis with a predilection for the face that is difficult to diagnose and treat. The diagnosis is based on clinical and histologic findings, and it typically presents as single or multiple, well-demarcated, red-brown nodules, papules, or plaques that range from several millimeters to centimeters in diameter.1,2 Extrafacial lesions may be seen.3 Granuloma faciale usually is asymptomatic but occasionally has associated pruritus and rarely ulceration. The prevalence and pathophysiology of GF is not well defined; however, GF more commonly is reported in middle-aged White males.1

Histologic examination of GF reveals a mixed inflammatory cellular infiltrate in the upper dermis. A grenz zone, which is a narrow area of the papillary dermis uninvolved by the underlying pathology, may be seen.1 Contrary to the name, granulomas are not found histologically. Rather, vascular changes or damage frequently are present and may indicate a small vessel vasculitis pathologic mechanism. Granuloma faciale also has been associated with follicular ostia accentuation and telangiectases.4

Many cases of GF have been misdiagnosed as sarcoidosis, lymphoma, lupus, and basal cell carcinoma.1 In addition, GF shares many clinical and histologic features with erythema elevatum diutinum (EED). However, the defining features that suggest EED over GF is that EED has a predilection for the skin overlying the joints. Histopathologically, EED displays granulomas and fibrosis with few eosinophils.5,6

The variable response of GF to treatments and lack of efficacy data have contributed to the complexity and uncertainty of managing GF. The current first-line therapies are topical tacrolimus,7 cryotherapy,8 or corticosteroid therapy.9

To the Editor:

A 53-year-old Hispanic woman presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of an expanding plaque on the right cheek of 2 months’ duration. The patient stated the plaque began as a pimple, which she picked with subsequent spread laterally across the cheek. The area was intermittently tender, but she denied tingling, burning, or pruritus of the site. She had been treated with doxycycline and amoxicillin–clavulanic acid prior to presentation without improvement. She had a history of levamisole-induced vasculitis approximately 6 months prior. A review of systems was notable for diffuse joint pain. The patient denied tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use in the preceding 3 months and denied any changes in her medications or in health within the last year.

Physical examination revealed a well-appearing, alert, and afebrile patient with a pink, well-demarcated plaque on the right cheek (Figure 1). The borders of the plaque were indurated, and the lateral aspect of the plaque was eroded secondary to digital manipulation by the patient. She had no cervical lymphadenopathy. There were no other abnormal cutaneous findings.

There is a broad differential diagnosis for a pink expanding plaque on the face, which requires histopathologic correlation for correct diagnosis. Three broad categories in the differential are infectious (eg, bacterial, fungal), medication related (eg, fixed drug eruption), and granulomatous (eg, granuloma faciale [GF], sarcoidosis, tumid lupus, leprosy, granulomatous rosacea). A biopsy of the lesion revealed a mixed inflammatory cell dermal infiltrate with perivascular accentuation and intense vasculitis that was consistent with GF (Figure 2). Gomori methenamine-silver, periodic acid–Schiff, Fite-Faraco, acid-fast bacilli, and Gram staining were negative for organisms. Tissue cultures were negative for bacterial, mycobacterial, and fungal etiology. The patient was started on high-potency topical steroids with a 50% improvement in the appearance of the skin lesion at 1-month follow-up.

Granuloma faciale is a rare chronic inflammatory dermatosis with a predilection for the face that is difficult to diagnose and treat. The diagnosis is based on clinical and histologic findings, and it typically presents as single or multiple, well-demarcated, red-brown nodules, papules, or plaques that range from several millimeters to centimeters in diameter.1,2 Extrafacial lesions may be seen.3 Granuloma faciale usually is asymptomatic but occasionally has associated pruritus and rarely ulceration. The prevalence and pathophysiology of GF is not well defined; however, GF more commonly is reported in middle-aged White males.1

Histologic examination of GF reveals a mixed inflammatory cellular infiltrate in the upper dermis. A grenz zone, which is a narrow area of the papillary dermis uninvolved by the underlying pathology, may be seen.1 Contrary to the name, granulomas are not found histologically. Rather, vascular changes or damage frequently are present and may indicate a small vessel vasculitis pathologic mechanism. Granuloma faciale also has been associated with follicular ostia accentuation and telangiectases.4

Many cases of GF have been misdiagnosed as sarcoidosis, lymphoma, lupus, and basal cell carcinoma.1 In addition, GF shares many clinical and histologic features with erythema elevatum diutinum (EED). However, the defining features that suggest EED over GF is that EED has a predilection for the skin overlying the joints. Histopathologically, EED displays granulomas and fibrosis with few eosinophils.5,6

The variable response of GF to treatments and lack of efficacy data have contributed to the complexity and uncertainty of managing GF. The current first-line therapies are topical tacrolimus,7 cryotherapy,8 or corticosteroid therapy.9

- Ortonne N, Wechsler J, Bagot M, et al. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathologic study of 66 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1002-1009.

- Marcoval J, Moreno A, Peyr J. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:269-273.

- Nasiri S, Rahimi H, Farnaghi A, et al. Granuloma faciale with disseminated extra facial lesions. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:5.

- Roustan G, Sánchez Yus E, Salas C, et al. Granuloma faciale with extrafacial lesions. Dermatology. 1999;198:79-82.

- LeBoit PE. Granuloma faciale: a diagnosis deserving of dignity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:440-443.

- Ziemer M, Koehler MJ, Weyers W. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a chronic leukocytoclastic vasculitis microscopically indistinguishable from granuloma faciale? J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:876-883.

- Cecchi R, Pavesi M, Bartoli L, et al. Topical tacrolimus in the treatment of granuloma faciale. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1463-1465.

- Panagiotopoulos A, Anyfantakis V, Rallis E, et al. Assessment of the efficacy of cryosurgery in the treatment of granuloma faciale. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:357-360.

- Radin DA, Mehregan DR. Granuloma faciale: distribution of the lesions and review of the literature. Cutis. 2003;72:213-219.

- Ortonne N, Wechsler J, Bagot M, et al. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathologic study of 66 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1002-1009.

- Marcoval J, Moreno A, Peyr J. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:269-273.

- Nasiri S, Rahimi H, Farnaghi A, et al. Granuloma faciale with disseminated extra facial lesions. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:5.

- Roustan G, Sánchez Yus E, Salas C, et al. Granuloma faciale with extrafacial lesions. Dermatology. 1999;198:79-82.

- LeBoit PE. Granuloma faciale: a diagnosis deserving of dignity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:440-443.

- Ziemer M, Koehler MJ, Weyers W. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a chronic leukocytoclastic vasculitis microscopically indistinguishable from granuloma faciale? J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:876-883.

- Cecchi R, Pavesi M, Bartoli L, et al. Topical tacrolimus in the treatment of granuloma faciale. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1463-1465.

- Panagiotopoulos A, Anyfantakis V, Rallis E, et al. Assessment of the efficacy of cryosurgery in the treatment of granuloma faciale. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:357-360.

- Radin DA, Mehregan DR. Granuloma faciale: distribution of the lesions and review of the literature. Cutis. 2003;72:213-219.

Practice Points

- Granuloma faciale is a benign dermal process presenting with a red-brown plaque on the face of adults that typically is not ulcerated unless physically manipulated.

- Skin biopsy often is required for correct diagnosis.

- Granuloma faciale does not resolve spontaneously and tends to be chronic.

A Fixed Drug Eruption to Medroxyprogesterone Acetate Injectable Suspension

To the Editor:

A fixed drug eruption (FDE) is a well-documented form of cutaneous hypersensitivity that typically manifests as a sharply demarcated, dusky, round to oval, edematous, red-violaceous macule or patch on the skin and mucous membranes. The lesion often resolves with residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, most commonly as a reaction to ingested drugs or drug components.1 Lesions generally occur at the same anatomic site with repeated exposure to the offending drug. Typically, a single site is affected, but additional sites with more generalized involvement have been reported to occur with subsequent exposure to the offending medication. The diagnosis usually is clinical, but histopathologic findings can help confirm the diagnosis in unusual presentations. We present a novel case of a patient with an FDE from medroxyprogesterone acetate, a contraceptive injection that contains the hormone progestin.

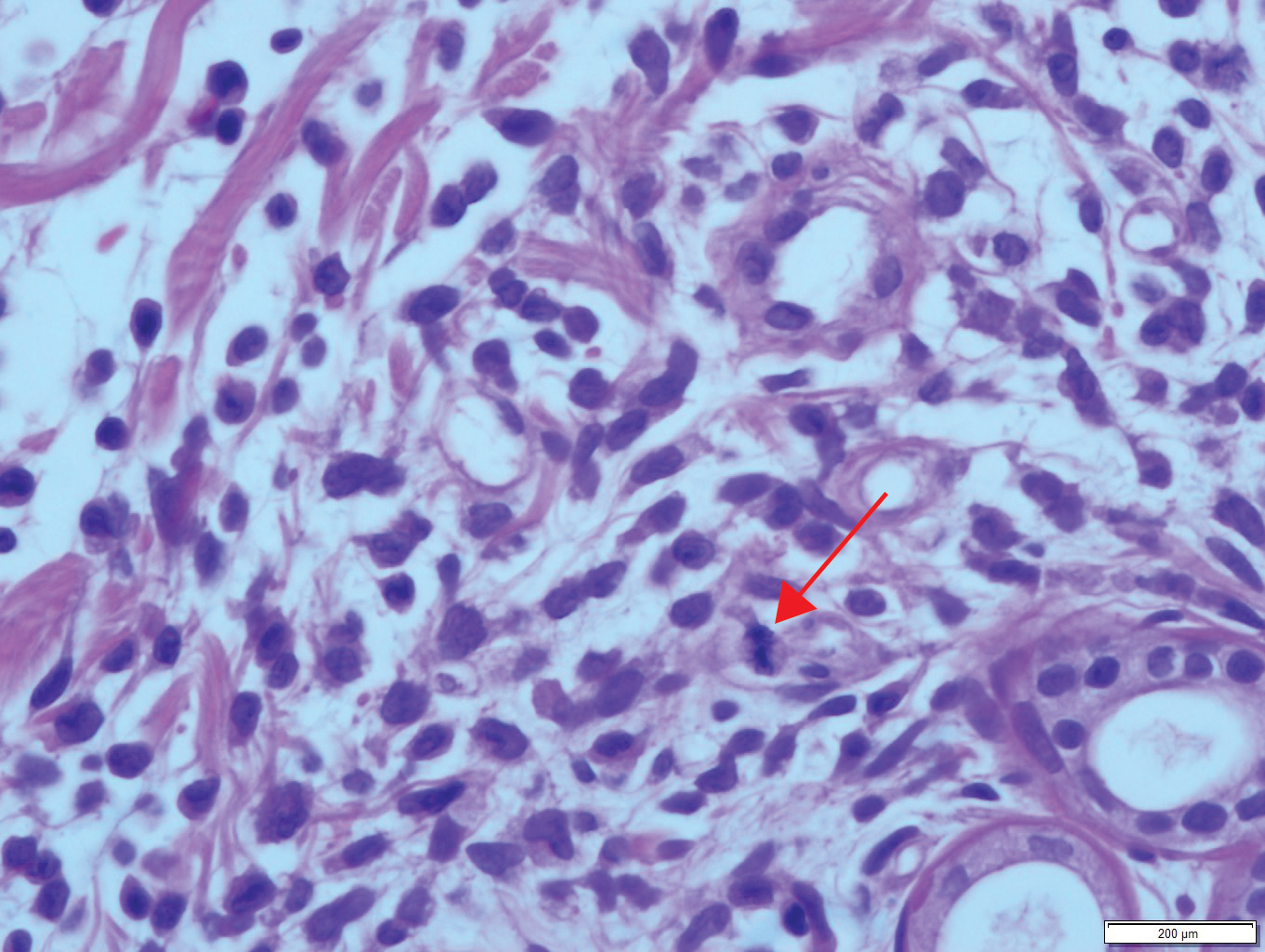

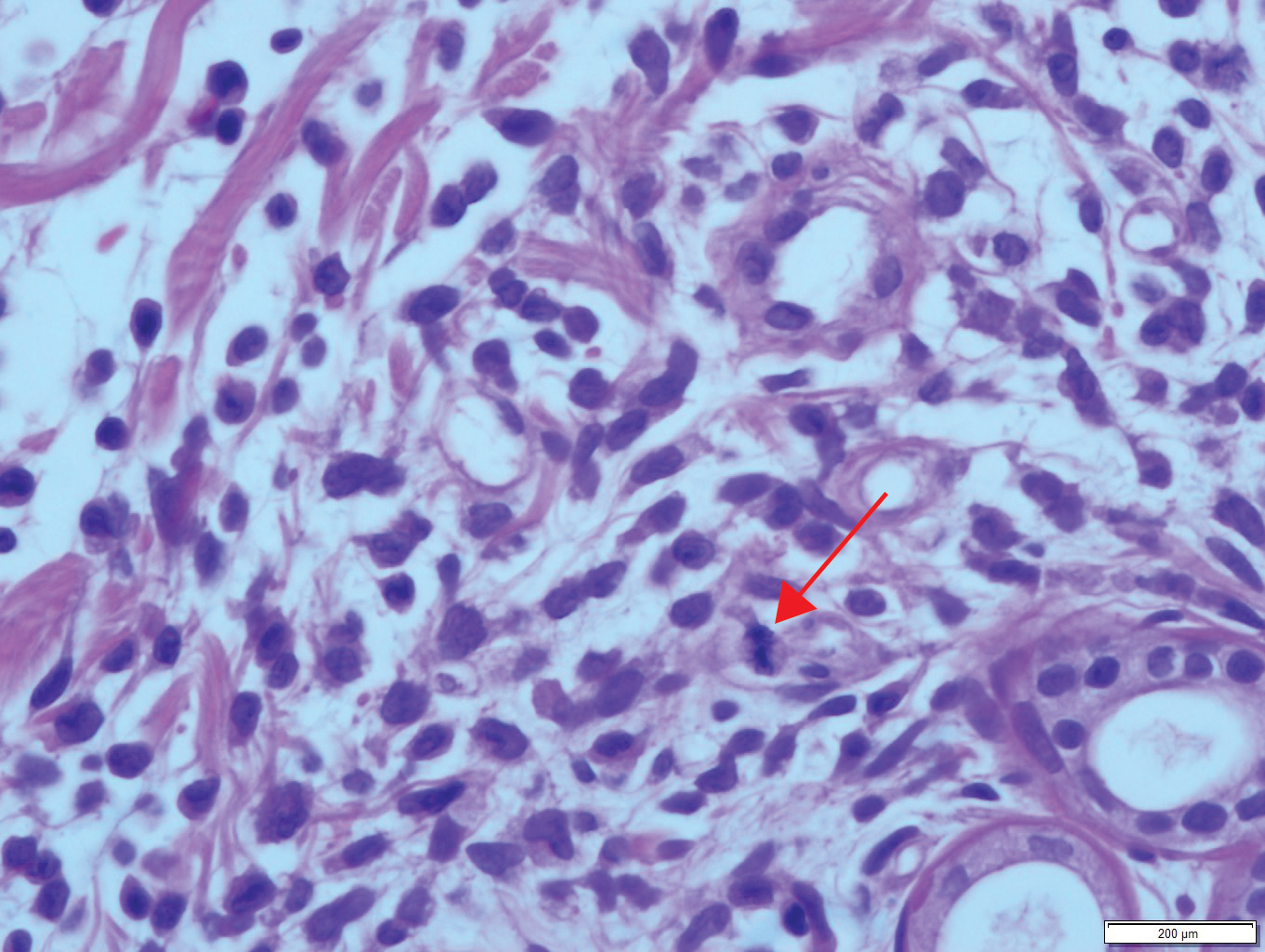

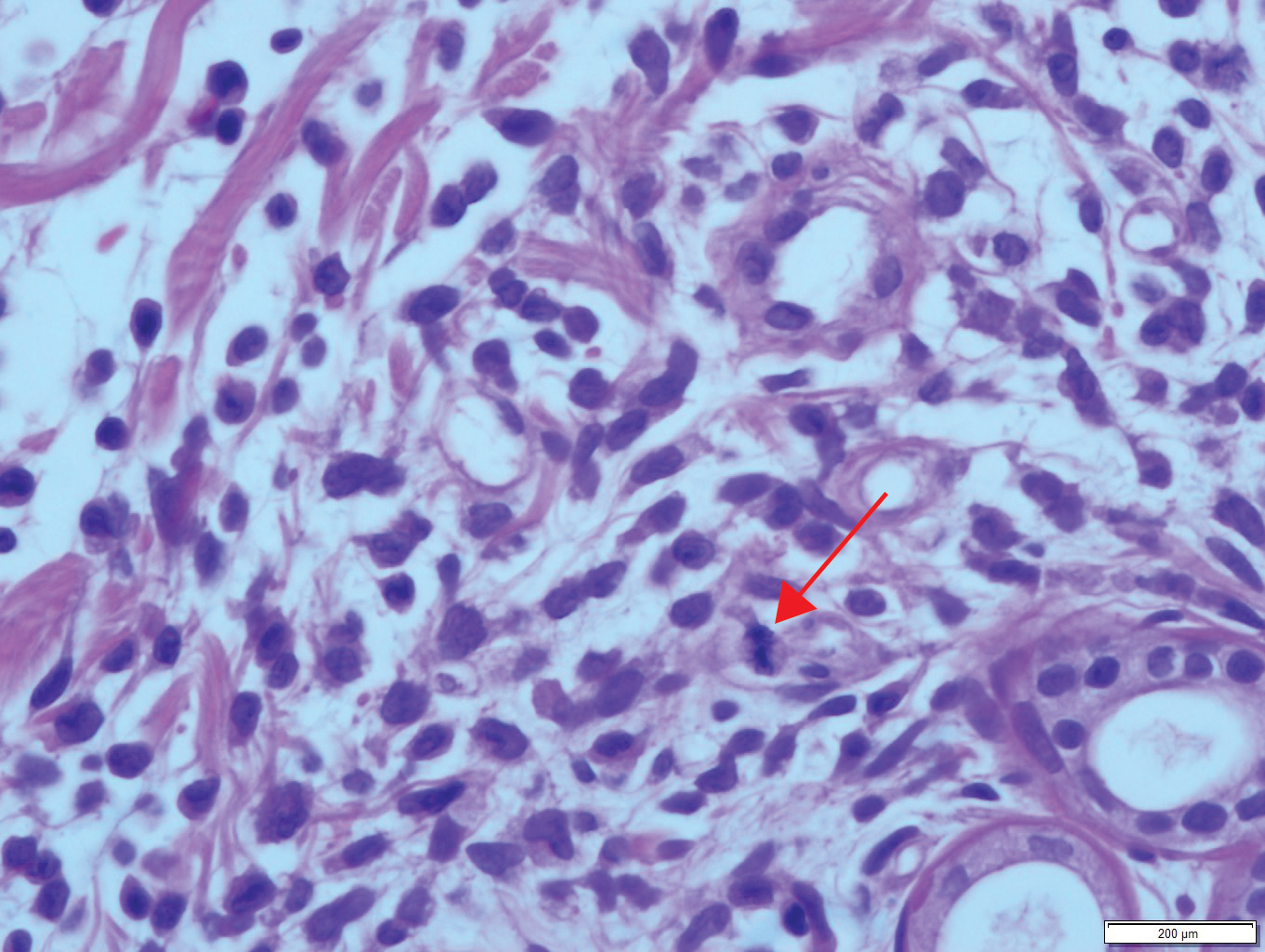

A 35-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a lesion on the left lower buttock of 1 year’s duration. She reported periodic swelling and associated pruritus of the lesion. She denied any growth in size, and no other similar lesions were present. The patient reported a medication history of medroxyprogesterone acetate for birth control, but she denied any other prescription or over-the-counter medication, oral supplements, or recreational drug use. Upon further inquiry, she reported that the recurrence of symptoms appeared to coincide with each administration of medroxyprogesterone acetate, which occurred approximately every 3 months. The eruption cleared between injections and recurred in the same location following subsequent injections. The lesion appeared approximately 2 weeks after the first injection (approximately 1 year prior to presentation to dermatology) and within 2 to 3 days after each subsequent injection. Physical examination revealed a 2×2-cm, circular, slightly violaceous patch on the left buttock (Figure 1). A biopsy was recommended to aid in diagnosis, and the patient was offered a topical steroid for symptomatic relief. A punch biopsy revealed subtle interface dermatitis with superficial perivascular lymphoid infiltrate and marked pigmentary incontinence consistent with an FDE (Figure 2).

An FDE was first reported in 1889 by Bourns,2 and over time more implicated agents and varying clinical presentations have been linked to the disease. The FDE can be accompanied by symptoms of pruritus or paresthesia. Most cases are devoid of systemic symptoms. An FDE can be located anywhere on the body, but it most frequently manifests on the lips, face, hands, feet, and genitalia. Although the eruption often heals with residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, a nonpigmenting FDE due to pseudoephedrine has been reported.3

Common culprits include antibiotics (eg, sulfonamides, trimethoprim, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (eg, naproxen sodium, ibuprofen, celecoxib), barbiturates, antimalarials, and anticonvulsants. Rare cases of FDE induced by foods and food additives also have been reported.4 Oral fluconazole, levocetirizine dihydrochloride, loperamide, and multivitamin-mineral preparations are other rare inducers of FDE.5-8 In 2004, Ritter and Meffert9 described an FDE to the green dye used in inactive oral contraceptive pills. A similar case was reported by Rea et al10 that described an FDE from the inactive sugar pills in ethinyl estradiol and levonorgestrel, which is another combined oral contraceptive.

The time between ingestion of the offending agent and the manifestation of the disease usually is 1 to 2 weeks; however, upon subsequent exposure, the disease has been reported to manifest within hours.1 CD8+ memory T cells have been shown to be major players in the development of FDE and can be found along the dermoepidermal junction as part of a delayed type IV hypersensitivity reaction.11 Histopathology reveals superficial and deep interstitial and perivascular infiltrates consisting of lymphocytes with admixed eosinophils and possibly neutrophils in the dermis. In the epidermis, necrotic keratinocytes can be present. In rare cases, FDE may have atypical features, such as in generalized bullous FDE and nonpigmenting FDE, the latter of which more commonly is associated with pseudoephedrine.1

The differential diagnosis for FDE includes erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, autoimmune progesterone dermatitis, and large plaque parapsoriasis. The number and morphology of lesions in erythema multiforme help differentiate it from FDE, as erythema multiforme presents with multiple targetoid lesions. The lesions of generalized bullous FDE can be similar to those of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, and the pigmented patches of FDE can resemble large plaque parapsoriasis.

It is important to consider any medication ingested in the 1- to 2-week period before FDE onset, including over-the-counter medications, health food supplements, and prescription medications. Discontinuation of the implicated medication or any medication potentially cross-reacting with another medication is the most important step in management. Wound care may be needed for any bullous or eroded lesions. Lesions typically resolve within a few days to weeks of stopping the offending agent. Importantly, patients should be counseled on the secondary pigment alterations that may be persistent for several months. Other treatment for FDEs is aimed at symptomatic relief and may include topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines.1

Medroxyprogesterone acetate is a highly effective contraceptive drug with low rates of failure.12 It is a weak androgenic progestin that is administered as a single 150-mg intramuscular injection every 3 months and inhibits gonadotropins. Common side effects include local injection-site reactions, unscheduled bleeding, amenorrhea, weight gain, headache, and mood changes. However, FDE has not been reported as an adverse effect to medroxyprogesterone acetate, both in official US Food and Drug Administration information and in the current literature.12

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (also known as progestin hypersensitivity) is a well-characterized cyclic hypersensitivity reaction to the hormone progesterone that occurs during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. It is known to have a variable clinical presentation including urticaria, erythema multiforme, eczema, and angioedema.13 Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis also has been reported to present as an FDE.14-16 The onset of the cutaneous manifestation often starts a few days before the onset of menses, with spontaneous resolution occurring after the onset of menstruation. The mechanism by which endogenous progesterone or other secretory products become antigenic is unknown. It has been suggested that there is an alteration in the properties of the hormone that would predispose it to be antigenic as it would not be considered self. In 2001, Warin17 proposed the following diagnostic criteria for autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: (1) skin lesions associated with menstrual cycle (premenstrual flare); (2) a positive response to the progesterone intradermal or intramuscular test; and (3) symptomatic improvement after inhibiting progesterone secretion by suppressing ovulation.17 The treatment includes antiallergy medications, progesterone desensitization, omalizumab injection, and leuprolide acetate injection.

Our case represents FDE from medroxyprogesterone acetate. Although we did not formally investigate the antigenicity of the exogenous progesterone, we postulate that the pathophysiology likely is similar to an FDE associated with endogenous progesterone. This reasoning is supported by the time course of the patient’s lesion as well as the worsening of symptoms in the days following the administration of the medication. Additionally, the patient had no history of skin lesions prior to the initiation of medroxyprogesterone acetate or similar lesions associated with her menstrual cycles.

A careful and detailed review of medication history is necessary to evaluate FDEs. Our case emphasizes that not only endogenous but also exogenous forms of progesterone may cause hypersensitivity, leading to an FDE. With more than 2 million prescriptions of medroxyprogesterone acetate written every year, dermatologists should be aware of the rare but potential risk for an FDE in patients using this medication.18

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Mosby; 2008.

- Bourns DCG. Unusual effects of antipyrine. Br Med J. 1889;2:818-820.

- Shelley WB, Shelley ED. Nonpigmenting fixed drug eruption as a distinctive reaction pattern: examples caused by sensitivity to pseudoephedrine hydrochloride and tetrahydrozoline. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:403-407.

- Sohn KH, Kim BK, Kim JY, et al. Fixed food eruption caused by Actinidia arguta (hardy kiwi): a case report and literature review. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2017;9:182-184.

- Nakai N, Katoh N. Fixed drug eruption caused by fluconazole: a case report and mini-review of the literature. Allergol Int. 2013;6:139-141.

- An I, Demir V, Ibiloglu I, et al. Fixed drug eruption induced by levocetirizine. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:276-278.

- Matarredona J, Borrás Blasco J, Navarro-Ruiz A, et al. Fixed drug eruption associated to loperamide [in Spanish]. Med Clin (Barc). 2005;124:198-199.

- Gohel D. Fixed drug eruption due to multi-vitamin multi-mineral preparation. J Assoc Physicians India. 2000;48:268.

- Ritter SE, Meffert J. A refractory fixed drug reaction to a dye used in an oral contraceptive. Cutis. 2004;74:243-244.

- Rea S, McMeniman E, Darch K, et al. A fixed drug eruption to the sugar pills of a combined oral contraceptive. Poster presented at: The Australasian College of Dermatologists 51st Annual Scientific Meeting; May 22, 2018; Queensland, Australia.

- Shiohara T, Mizukawa Y. Fixed drug eruption: a disease mediated by self-inflicted responses of intraepidermal T cells. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:201-208.

- Depo-Provera CI. Prescribing information. Pfizer; 2020. Accessed March 10, 2022. https://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?format=PDF&id=522

- George R, Badawy SZ. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: a case report. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2012;2012:757854.

- Mokhtari R, Sepaskhah M, Aslani FS, et al. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting as fixed drug eruption: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt685685p4.

- Asai J, Katoh N, Nakano M, et al. Case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting as fixed drug eruption. J Dermatol. 2009;36:643-645.

- Bhardwaj N, Jindal R, Chauhan P. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting as fixed drug eruption. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12:E231873.

- Warin AP. Case 2. diagnosis: erythema multiforme as a presentation of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:107-108.

- Medroxyprogesterone Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013-2019. ClinCalc website. Updated September 15, 2021. Accessed March 17, 2022. https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Drugs/Medroxyprogesterone

To the Editor:

A fixed drug eruption (FDE) is a well-documented form of cutaneous hypersensitivity that typically manifests as a sharply demarcated, dusky, round to oval, edematous, red-violaceous macule or patch on the skin and mucous membranes. The lesion often resolves with residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, most commonly as a reaction to ingested drugs or drug components.1 Lesions generally occur at the same anatomic site with repeated exposure to the offending drug. Typically, a single site is affected, but additional sites with more generalized involvement have been reported to occur with subsequent exposure to the offending medication. The diagnosis usually is clinical, but histopathologic findings can help confirm the diagnosis in unusual presentations. We present a novel case of a patient with an FDE from medroxyprogesterone acetate, a contraceptive injection that contains the hormone progestin.

A 35-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a lesion on the left lower buttock of 1 year’s duration. She reported periodic swelling and associated pruritus of the lesion. She denied any growth in size, and no other similar lesions were present. The patient reported a medication history of medroxyprogesterone acetate for birth control, but she denied any other prescription or over-the-counter medication, oral supplements, or recreational drug use. Upon further inquiry, she reported that the recurrence of symptoms appeared to coincide with each administration of medroxyprogesterone acetate, which occurred approximately every 3 months. The eruption cleared between injections and recurred in the same location following subsequent injections. The lesion appeared approximately 2 weeks after the first injection (approximately 1 year prior to presentation to dermatology) and within 2 to 3 days after each subsequent injection. Physical examination revealed a 2×2-cm, circular, slightly violaceous patch on the left buttock (Figure 1). A biopsy was recommended to aid in diagnosis, and the patient was offered a topical steroid for symptomatic relief. A punch biopsy revealed subtle interface dermatitis with superficial perivascular lymphoid infiltrate and marked pigmentary incontinence consistent with an FDE (Figure 2).

An FDE was first reported in 1889 by Bourns,2 and over time more implicated agents and varying clinical presentations have been linked to the disease. The FDE can be accompanied by symptoms of pruritus or paresthesia. Most cases are devoid of systemic symptoms. An FDE can be located anywhere on the body, but it most frequently manifests on the lips, face, hands, feet, and genitalia. Although the eruption often heals with residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, a nonpigmenting FDE due to pseudoephedrine has been reported.3

Common culprits include antibiotics (eg, sulfonamides, trimethoprim, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (eg, naproxen sodium, ibuprofen, celecoxib), barbiturates, antimalarials, and anticonvulsants. Rare cases of FDE induced by foods and food additives also have been reported.4 Oral fluconazole, levocetirizine dihydrochloride, loperamide, and multivitamin-mineral preparations are other rare inducers of FDE.5-8 In 2004, Ritter and Meffert9 described an FDE to the green dye used in inactive oral contraceptive pills. A similar case was reported by Rea et al10 that described an FDE from the inactive sugar pills in ethinyl estradiol and levonorgestrel, which is another combined oral contraceptive.

The time between ingestion of the offending agent and the manifestation of the disease usually is 1 to 2 weeks; however, upon subsequent exposure, the disease has been reported to manifest within hours.1 CD8+ memory T cells have been shown to be major players in the development of FDE and can be found along the dermoepidermal junction as part of a delayed type IV hypersensitivity reaction.11 Histopathology reveals superficial and deep interstitial and perivascular infiltrates consisting of lymphocytes with admixed eosinophils and possibly neutrophils in the dermis. In the epidermis, necrotic keratinocytes can be present. In rare cases, FDE may have atypical features, such as in generalized bullous FDE and nonpigmenting FDE, the latter of which more commonly is associated with pseudoephedrine.1

The differential diagnosis for FDE includes erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, autoimmune progesterone dermatitis, and large plaque parapsoriasis. The number and morphology of lesions in erythema multiforme help differentiate it from FDE, as erythema multiforme presents with multiple targetoid lesions. The lesions of generalized bullous FDE can be similar to those of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, and the pigmented patches of FDE can resemble large plaque parapsoriasis.

It is important to consider any medication ingested in the 1- to 2-week period before FDE onset, including over-the-counter medications, health food supplements, and prescription medications. Discontinuation of the implicated medication or any medication potentially cross-reacting with another medication is the most important step in management. Wound care may be needed for any bullous or eroded lesions. Lesions typically resolve within a few days to weeks of stopping the offending agent. Importantly, patients should be counseled on the secondary pigment alterations that may be persistent for several months. Other treatment for FDEs is aimed at symptomatic relief and may include topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines.1

Medroxyprogesterone acetate is a highly effective contraceptive drug with low rates of failure.12 It is a weak androgenic progestin that is administered as a single 150-mg intramuscular injection every 3 months and inhibits gonadotropins. Common side effects include local injection-site reactions, unscheduled bleeding, amenorrhea, weight gain, headache, and mood changes. However, FDE has not been reported as an adverse effect to medroxyprogesterone acetate, both in official US Food and Drug Administration information and in the current literature.12

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (also known as progestin hypersensitivity) is a well-characterized cyclic hypersensitivity reaction to the hormone progesterone that occurs during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. It is known to have a variable clinical presentation including urticaria, erythema multiforme, eczema, and angioedema.13 Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis also has been reported to present as an FDE.14-16 The onset of the cutaneous manifestation often starts a few days before the onset of menses, with spontaneous resolution occurring after the onset of menstruation. The mechanism by which endogenous progesterone or other secretory products become antigenic is unknown. It has been suggested that there is an alteration in the properties of the hormone that would predispose it to be antigenic as it would not be considered self. In 2001, Warin17 proposed the following diagnostic criteria for autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: (1) skin lesions associated with menstrual cycle (premenstrual flare); (2) a positive response to the progesterone intradermal or intramuscular test; and (3) symptomatic improvement after inhibiting progesterone secretion by suppressing ovulation.17 The treatment includes antiallergy medications, progesterone desensitization, omalizumab injection, and leuprolide acetate injection.

Our case represents FDE from medroxyprogesterone acetate. Although we did not formally investigate the antigenicity of the exogenous progesterone, we postulate that the pathophysiology likely is similar to an FDE associated with endogenous progesterone. This reasoning is supported by the time course of the patient’s lesion as well as the worsening of symptoms in the days following the administration of the medication. Additionally, the patient had no history of skin lesions prior to the initiation of medroxyprogesterone acetate or similar lesions associated with her menstrual cycles.

A careful and detailed review of medication history is necessary to evaluate FDEs. Our case emphasizes that not only endogenous but also exogenous forms of progesterone may cause hypersensitivity, leading to an FDE. With more than 2 million prescriptions of medroxyprogesterone acetate written every year, dermatologists should be aware of the rare but potential risk for an FDE in patients using this medication.18

To the Editor:

A fixed drug eruption (FDE) is a well-documented form of cutaneous hypersensitivity that typically manifests as a sharply demarcated, dusky, round to oval, edematous, red-violaceous macule or patch on the skin and mucous membranes. The lesion often resolves with residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, most commonly as a reaction to ingested drugs or drug components.1 Lesions generally occur at the same anatomic site with repeated exposure to the offending drug. Typically, a single site is affected, but additional sites with more generalized involvement have been reported to occur with subsequent exposure to the offending medication. The diagnosis usually is clinical, but histopathologic findings can help confirm the diagnosis in unusual presentations. We present a novel case of a patient with an FDE from medroxyprogesterone acetate, a contraceptive injection that contains the hormone progestin.

A 35-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a lesion on the left lower buttock of 1 year’s duration. She reported periodic swelling and associated pruritus of the lesion. She denied any growth in size, and no other similar lesions were present. The patient reported a medication history of medroxyprogesterone acetate for birth control, but she denied any other prescription or over-the-counter medication, oral supplements, or recreational drug use. Upon further inquiry, she reported that the recurrence of symptoms appeared to coincide with each administration of medroxyprogesterone acetate, which occurred approximately every 3 months. The eruption cleared between injections and recurred in the same location following subsequent injections. The lesion appeared approximately 2 weeks after the first injection (approximately 1 year prior to presentation to dermatology) and within 2 to 3 days after each subsequent injection. Physical examination revealed a 2×2-cm, circular, slightly violaceous patch on the left buttock (Figure 1). A biopsy was recommended to aid in diagnosis, and the patient was offered a topical steroid for symptomatic relief. A punch biopsy revealed subtle interface dermatitis with superficial perivascular lymphoid infiltrate and marked pigmentary incontinence consistent with an FDE (Figure 2).

An FDE was first reported in 1889 by Bourns,2 and over time more implicated agents and varying clinical presentations have been linked to the disease. The FDE can be accompanied by symptoms of pruritus or paresthesia. Most cases are devoid of systemic symptoms. An FDE can be located anywhere on the body, but it most frequently manifests on the lips, face, hands, feet, and genitalia. Although the eruption often heals with residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, a nonpigmenting FDE due to pseudoephedrine has been reported.3

Common culprits include antibiotics (eg, sulfonamides, trimethoprim, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (eg, naproxen sodium, ibuprofen, celecoxib), barbiturates, antimalarials, and anticonvulsants. Rare cases of FDE induced by foods and food additives also have been reported.4 Oral fluconazole, levocetirizine dihydrochloride, loperamide, and multivitamin-mineral preparations are other rare inducers of FDE.5-8 In 2004, Ritter and Meffert9 described an FDE to the green dye used in inactive oral contraceptive pills. A similar case was reported by Rea et al10 that described an FDE from the inactive sugar pills in ethinyl estradiol and levonorgestrel, which is another combined oral contraceptive.

The time between ingestion of the offending agent and the manifestation of the disease usually is 1 to 2 weeks; however, upon subsequent exposure, the disease has been reported to manifest within hours.1 CD8+ memory T cells have been shown to be major players in the development of FDE and can be found along the dermoepidermal junction as part of a delayed type IV hypersensitivity reaction.11 Histopathology reveals superficial and deep interstitial and perivascular infiltrates consisting of lymphocytes with admixed eosinophils and possibly neutrophils in the dermis. In the epidermis, necrotic keratinocytes can be present. In rare cases, FDE may have atypical features, such as in generalized bullous FDE and nonpigmenting FDE, the latter of which more commonly is associated with pseudoephedrine.1

The differential diagnosis for FDE includes erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, autoimmune progesterone dermatitis, and large plaque parapsoriasis. The number and morphology of lesions in erythema multiforme help differentiate it from FDE, as erythema multiforme presents with multiple targetoid lesions. The lesions of generalized bullous FDE can be similar to those of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, and the pigmented patches of FDE can resemble large plaque parapsoriasis.

It is important to consider any medication ingested in the 1- to 2-week period before FDE onset, including over-the-counter medications, health food supplements, and prescription medications. Discontinuation of the implicated medication or any medication potentially cross-reacting with another medication is the most important step in management. Wound care may be needed for any bullous or eroded lesions. Lesions typically resolve within a few days to weeks of stopping the offending agent. Importantly, patients should be counseled on the secondary pigment alterations that may be persistent for several months. Other treatment for FDEs is aimed at symptomatic relief and may include topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines.1

Medroxyprogesterone acetate is a highly effective contraceptive drug with low rates of failure.12 It is a weak androgenic progestin that is administered as a single 150-mg intramuscular injection every 3 months and inhibits gonadotropins. Common side effects include local injection-site reactions, unscheduled bleeding, amenorrhea, weight gain, headache, and mood changes. However, FDE has not been reported as an adverse effect to medroxyprogesterone acetate, both in official US Food and Drug Administration information and in the current literature.12

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (also known as progestin hypersensitivity) is a well-characterized cyclic hypersensitivity reaction to the hormone progesterone that occurs during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. It is known to have a variable clinical presentation including urticaria, erythema multiforme, eczema, and angioedema.13 Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis also has been reported to present as an FDE.14-16 The onset of the cutaneous manifestation often starts a few days before the onset of menses, with spontaneous resolution occurring after the onset of menstruation. The mechanism by which endogenous progesterone or other secretory products become antigenic is unknown. It has been suggested that there is an alteration in the properties of the hormone that would predispose it to be antigenic as it would not be considered self. In 2001, Warin17 proposed the following diagnostic criteria for autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: (1) skin lesions associated with menstrual cycle (premenstrual flare); (2) a positive response to the progesterone intradermal or intramuscular test; and (3) symptomatic improvement after inhibiting progesterone secretion by suppressing ovulation.17 The treatment includes antiallergy medications, progesterone desensitization, omalizumab injection, and leuprolide acetate injection.

Our case represents FDE from medroxyprogesterone acetate. Although we did not formally investigate the antigenicity of the exogenous progesterone, we postulate that the pathophysiology likely is similar to an FDE associated with endogenous progesterone. This reasoning is supported by the time course of the patient’s lesion as well as the worsening of symptoms in the days following the administration of the medication. Additionally, the patient had no history of skin lesions prior to the initiation of medroxyprogesterone acetate or similar lesions associated with her menstrual cycles.

A careful and detailed review of medication history is necessary to evaluate FDEs. Our case emphasizes that not only endogenous but also exogenous forms of progesterone may cause hypersensitivity, leading to an FDE. With more than 2 million prescriptions of medroxyprogesterone acetate written every year, dermatologists should be aware of the rare but potential risk for an FDE in patients using this medication.18

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Mosby; 2008.

- Bourns DCG. Unusual effects of antipyrine. Br Med J. 1889;2:818-820.

- Shelley WB, Shelley ED. Nonpigmenting fixed drug eruption as a distinctive reaction pattern: examples caused by sensitivity to pseudoephedrine hydrochloride and tetrahydrozoline. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:403-407.

- Sohn KH, Kim BK, Kim JY, et al. Fixed food eruption caused by Actinidia arguta (hardy kiwi): a case report and literature review. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2017;9:182-184.

- Nakai N, Katoh N. Fixed drug eruption caused by fluconazole: a case report and mini-review of the literature. Allergol Int. 2013;6:139-141.

- An I, Demir V, Ibiloglu I, et al. Fixed drug eruption induced by levocetirizine. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:276-278.

- Matarredona J, Borrás Blasco J, Navarro-Ruiz A, et al. Fixed drug eruption associated to loperamide [in Spanish]. Med Clin (Barc). 2005;124:198-199.

- Gohel D. Fixed drug eruption due to multi-vitamin multi-mineral preparation. J Assoc Physicians India. 2000;48:268.

- Ritter SE, Meffert J. A refractory fixed drug reaction to a dye used in an oral contraceptive. Cutis. 2004;74:243-244.

- Rea S, McMeniman E, Darch K, et al. A fixed drug eruption to the sugar pills of a combined oral contraceptive. Poster presented at: The Australasian College of Dermatologists 51st Annual Scientific Meeting; May 22, 2018; Queensland, Australia.

- Shiohara T, Mizukawa Y. Fixed drug eruption: a disease mediated by self-inflicted responses of intraepidermal T cells. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:201-208.

- Depo-Provera CI. Prescribing information. Pfizer; 2020. Accessed March 10, 2022. https://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?format=PDF&id=522

- George R, Badawy SZ. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: a case report. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2012;2012:757854.

- Mokhtari R, Sepaskhah M, Aslani FS, et al. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting as fixed drug eruption: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt685685p4.

- Asai J, Katoh N, Nakano M, et al. Case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting as fixed drug eruption. J Dermatol. 2009;36:643-645.

- Bhardwaj N, Jindal R, Chauhan P. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting as fixed drug eruption. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12:E231873.

- Warin AP. Case 2. diagnosis: erythema multiforme as a presentation of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:107-108.

- Medroxyprogesterone Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013-2019. ClinCalc website. Updated September 15, 2021. Accessed March 17, 2022. https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Drugs/Medroxyprogesterone

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Mosby; 2008.

- Bourns DCG. Unusual effects of antipyrine. Br Med J. 1889;2:818-820.

- Shelley WB, Shelley ED. Nonpigmenting fixed drug eruption as a distinctive reaction pattern: examples caused by sensitivity to pseudoephedrine hydrochloride and tetrahydrozoline. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:403-407.

- Sohn KH, Kim BK, Kim JY, et al. Fixed food eruption caused by Actinidia arguta (hardy kiwi): a case report and literature review. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2017;9:182-184.

- Nakai N, Katoh N. Fixed drug eruption caused by fluconazole: a case report and mini-review of the literature. Allergol Int. 2013;6:139-141.

- An I, Demir V, Ibiloglu I, et al. Fixed drug eruption induced by levocetirizine. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:276-278.

- Matarredona J, Borrás Blasco J, Navarro-Ruiz A, et al. Fixed drug eruption associated to loperamide [in Spanish]. Med Clin (Barc). 2005;124:198-199.

- Gohel D. Fixed drug eruption due to multi-vitamin multi-mineral preparation. J Assoc Physicians India. 2000;48:268.

- Ritter SE, Meffert J. A refractory fixed drug reaction to a dye used in an oral contraceptive. Cutis. 2004;74:243-244.

- Rea S, McMeniman E, Darch K, et al. A fixed drug eruption to the sugar pills of a combined oral contraceptive. Poster presented at: The Australasian College of Dermatologists 51st Annual Scientific Meeting; May 22, 2018; Queensland, Australia.

- Shiohara T, Mizukawa Y. Fixed drug eruption: a disease mediated by self-inflicted responses of intraepidermal T cells. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:201-208.

- Depo-Provera CI. Prescribing information. Pfizer; 2020. Accessed March 10, 2022. https://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?format=PDF&id=522

- George R, Badawy SZ. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: a case report. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2012;2012:757854.

- Mokhtari R, Sepaskhah M, Aslani FS, et al. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting as fixed drug eruption: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt685685p4.

- Asai J, Katoh N, Nakano M, et al. Case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting as fixed drug eruption. J Dermatol. 2009;36:643-645.

- Bhardwaj N, Jindal R, Chauhan P. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting as fixed drug eruption. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12:E231873.

- Warin AP. Case 2. diagnosis: erythema multiforme as a presentation of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:107-108.

- Medroxyprogesterone Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013-2019. ClinCalc website. Updated September 15, 2021. Accessed March 17, 2022. https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Drugs/Medroxyprogesterone

Practice Points

- Exogenous progesterone from the administration of the contraceptive injectable medroxyprogesterone acetate has the potential to cause a cutaneous hypersensitivity reaction in the form of a fixed drug eruption (FDE).

- Dermatologists should perform a careful and detailed review of medication history to evaluate drug eruptions.

Iododerma Following Exposure to Iodine: A Case of Explosive Acneform Eruption Overnight

To the Editor:

Iododerma is a rare dermatologic condition caused by exposure to iodinated contrast media, oral iodine suspensions, or topical povidone-iodine that can manifest as eruptive acneform lesions.1-3

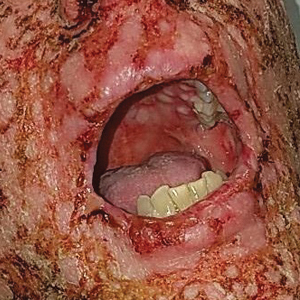

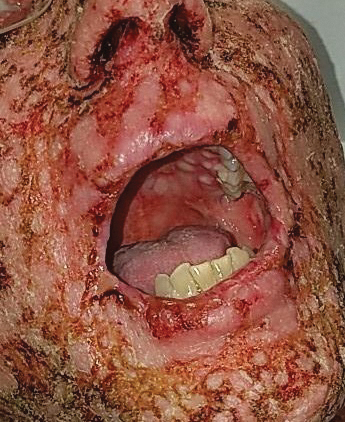

A 27-year-old woman in septic shock presented for worsening facial lesions that showed no improvement on broad-spectrum antibiotics, antifungals, and antivirals. She initially presented to an outside hospital with abdominal pain and underwent computed tomography (CT) with intravenous (IV) iodinated contrast; 24 hours after this imaging study, the family reported the appearance of “explosive acne overnight.” The lesions first appeared as vegetative and acneform ulcerations on the face. A second abdominal CT scan with IV contrast was performed 4 days after the initial scan, given the concern for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Hours after the second study, the lesions progressed to involve the buccal mucosae, tongue, mucosal airway, and distal arms and legs. She became progressively disoriented and developed an altered mentation over the course of the following week. Due to progressive facial edema, she required intubation 5 days after the second CT scan.

The patient had a medical history of end-stage renal disease secondary to crescenteric glomerulonephritis on peritoneal dialysis. Physical examination revealed numerous beefy-red, heaped-up, weepy, crusted nodules clustered on the face (Figure 1) and a few newer bullous-appearing lesions on the hands and feet. She had similar lesions involving the buccal mucosae and tongue with substantial facial edema. Infectious workup was notable for a positive skin culture growing methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus. All blood and tissue cultures as well as serologies for fungal and viral etiologies were negative. A tissue biopsy revealed necrosis with a neutrophilic infiltrate with mixed cell inflammation (Figure 2), and direct immunofluorescence was negative.

The patient initially was thought to be septic due to viral or bacterial infection. She was transferred from an outside hospital 7 days after the initial appearance of the acneform lesions, having already received IV contrast on 2 occasions within the first 48 hours of illness. Infectious disease was consulted and initiated broad-spectrum antiviral, antimicrobial, and antifungal therapy with acyclovir, linezolid, meropenem, and later micafungin without improvement. The diagnosis of iododerma ultimately was established based on the patient’s elevated urinary iodine levels with preceding iodine exposure in the context of renal failure. The preferential involvement of sebaceous areas and pathology findings were supportive of this diagnosis. Aggressive supportive measures including respiratory support, IV fluids, and dialysis were initiated. Topical iodine solutions, iodine-containing medications, and additional contrast subsequently were avoided. Despite these supportive measures, the patient died within 48 hours of admission from acute respiratory failure. Her autopsy attributed “septic complications of multifocal ulcerative cutaneous disease” as the anatomic cause of death.